Rwandan Basketry 9

Rwanda on the globe

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE: THE END

UNDER EVERYONE’S EYES AND NOSES

From late April onwards, the international community began collecting more and more information about the Rwandan situation and the extent of the tragedy that was plunging the country into the darkest hole.

General Roméo Dallaire «used the press to alert the public to the “catastrophic” situation and the continuation of massive killings. He stated that if UNAMIR received the necessary resources, it could halt killings by the militia in Kigali immediately. And he warned: “Unless the international community acts, it may find it is unable to defend itself against accusations of doing nothing to stop genocide”» (Alison Des Forges). He went unheeded.

In the last week of April, Peter Hansen, U.N. Undersecretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs, returned from a brief visit to Kigali, appalled by the extent of the horrors. Moreover, many U.N. officials started to report outflows of hundreds of thousands of refugees, a highly destabilizing situation for the whole Eastern African area.

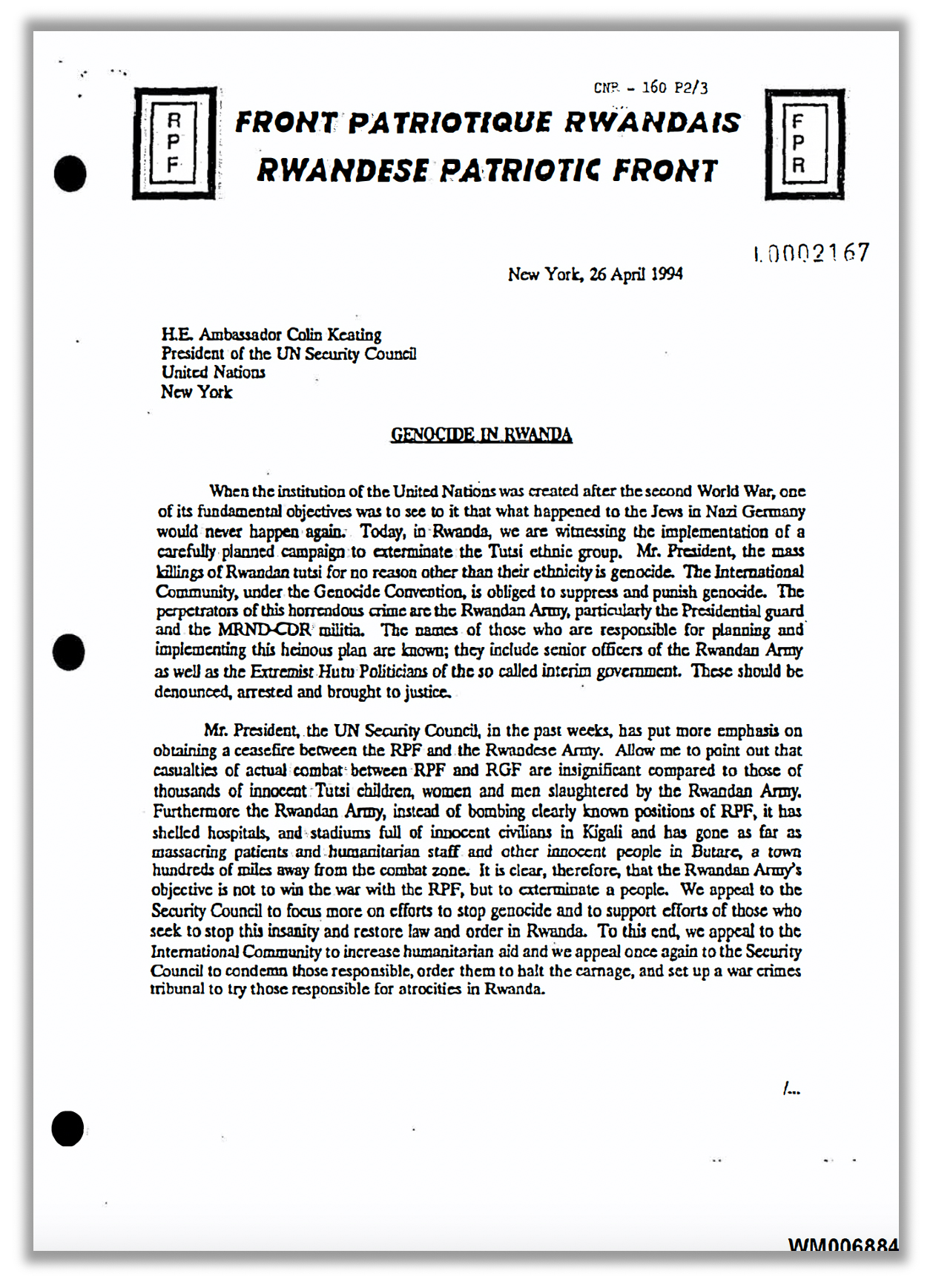

On April 26, Claude Dusaidi – RPF representative in New York «who had been waiting outside the Security Council chamber every day since the genocide began» (L. Melvern, cit.) – wrote a carefully drafted letter to the President of the Security Council, New Zealand ambassador Colin Keating. The letter, that was CC’ed to the Secretary-General Boutros Ghali, was titled GENOCIDE IN RWANDA. Here it is:

GENOCIDE IN RWANDA, the official letter of Claude Dusaidi, RPF representative in New York, to the New Zealand President of the Security Council, ambassador Colin Keating, and Secretary-General Boutros Ghali, dated April 26, 1994. It can be downloaded here.

It reads: « When the institution of the United Nations was created after the second World War, one of its fundamental objectives was to see to it that what happened to the Jews in Nazi Germany would never happen again. Today, in Rwanda, we are witnessing the implementation of a carefully planned campaign to exterminate the Tutsi ethnic group. Mr. President, the mass killings of Rwandan Tutsis for no reason other than their ethnicity is genocide. The International Community, under the Genocide Convention, is obliged to suppress and punish genocide. The perpetrators of this horrendous crime are the Rwandan Army, particularly the Presidential Guard and the MRND-CDR militia. The names of those who are responsible for planning and implementing this heinous plan are known; they include senior officers of the Rwandan Army as well as the Extremist Hutu Politicians of the so-called interim government. These should be denounced, arrested and brought to justice.

Mr. President, the UN Security Council, in the past weeks, has put more emphasis on obtaining a ceasefire between the RPF and the Rwandese Army. Allow me to point out that casualties of actual combat between RPF and RGF are insignificant compared to those of thousands of innocent Tutsi children, women, and men slaughtered by the Rwandan Army. Furthermore, the Rwandan Army, instead of bombing clearly known positions of RPF, it has shelled hospitals, and stadiums full of innocent civilians in Kigali and has gone as far as massacring patients and humanitarian staff and other innocent people in Butare, a town hundreds of miles away from the combat zone. It is clear, therefore, that the Rwandan Army’s objective is not to win the war with the RPF, but to exterminate a people. We appeal to the Security Council to focus more on efforts to stop genocide and to support efforts of those who seek to stop this insanity and restore law and order in Rwanda. To this end, we appeal to the International Community to increase humanitarian aid and we appeal once again to the Security Council to condemn those responsible, order them to halt the carnage, and set up a war crimes tribunal to try those responsible for atrocities in Rwanda.

Mr. President, the media and some in the International Community have endeavored to present the tragic events in Rwanda as a tribal war. How can we talk of a tribal conflict when we have not seen or heard of incidents where Tutsi people have risen up with machetes to slaughter Hutus or incidents where innocent people have died defending themselves against the extremist Hutu Rwandan Army and Militia? To justify the theory of a tribal conflict some have tried to characterize the RPF as a Tutsi organisation. Whereas the Rwandan Army is a purely Hutu Army recruited solely from late President Habyarimana’s home province, the Rwandese Patriotic Front not only has Hutus, Tutsis, and Twas in its ranks but it has Rwandese from all regions in the Country. The RPF is a national organisation with a democratic agenda and it welcomes all Rwandese irrespective of their ethnic or regional origin who share its political ideals.

In conclusion, Mr. President, the simple and innocent Rwandan children, women and men look at the International Community to protect them from a band of Hutu extremists that has gone insane. It will, in itself, be a crime for the civilised International Community to fold its arms and watch the systematic extermination of a people» (The bold is mine).

The word ‘genocide’ was increasingly being used. One of the first was the French newspaper Libération on April 11, followed by Le Soir on April 13, and a French public television channel, TF1, on April 26. On April 27, Pope John Paul II called ‘genocide’ the Rwandan tragedy, and the day after, on April 28, the international NGO Oxfam «issued a press release with the headline, Oxfam fears genocide is happening in Rwanda. It began by pointing out that the death toll was likely to be far higher than expected and that the pattern of the systematic killing of the Tutsi minority group amounted to genocide» (L. Melvern, ibidem). On April 29, «the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), issued the most strongly worded statement in its history. It contained the following description: “Whole families are exterminated, babies, children, old people, women are massacred in the most atrocious conditions, often cut with a machete or a knife, or blown apart by grenades, or burned or buried alive. The cruelty knows no limits”» (Source: Linda Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.).

In those days, the Unites State representatives were still reluctant to classify the killings in Rwanda as ‘genocide’. State Department spokesperson Christine Shelley said in a press conference, on April 28, that the «use of the term ‘genocide’ has a very precise legal meaning, although it’s not strictly a legal determination. There are other factors in there as well». Empty words full of brazen hypocrisy. The truth is that if the Rwandan tragedy is anything but ‘genocide’, there is no obligation to intervene. And the US had neither the desire nor any interest in intervening. However, they had the impudence to bully the weakest non-permanent member of the Security Council, the newly formed Czech Republic.

On April 28, its ambassador, Karel Kovanda, officially complained that the Council had avoided the question of mass killing whose news was coming out of human rights groups. He underlined that, according to some reliable sources, a genocide led by the interim government was underway. «This attempt to lead the council to confront the genocide produced an acrimonious debate that lasted for eight hours» (Alison Des Forges, cit.). The ambassador of Djibouti defined “sensationalist” the news of genocide in Rwanda; «China (…) reportedly opposed the use of the term ‘genocide’ (…) and France continued its campaign to minimize the responsibility of the interim government for the slaughter» (Ibidem). «After this meeting, Kovanda was told by British and American diplomats that on no account was he to use such inflammatory language outside the Council. It was not helpful» (L. Melvern, ibidem). On April 30, the United Nations Security Council condemned the massacres in Rwanda but refused to use the term ‘genocide’, upon the hard insistence of US ambassador Madeleine Albright and the British representative David Hannay, and didn’t recognize the government-directed nature of the mass killings.

The Czech diplomat Karel Kovanda (born in 1944) was the first UN ambassador to use the term “genocide” to describe events in Rwanda.

Video min. 0.45: you can hear and see Karel Kovanda remembering the atmosphere of those days.

Video min. 2.41: June 10, 1994; at a US State Department briefing, spokesperson Christine Shelley, who used the expression ‘acts of genocide’ but refused to use the word ‘genocide’, is provocatively asked: «How many acts of genocide does it take to make genocide?». She answers: «That’s just not a question that I’m in a position to answer». Seriously?

In August 1994, the Security Council adopted the 32-article Statute of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda with the approval of Resolution 955. The photo shows the members voting for the resolution.

Credit: © UN Photo/Milton Grant. Date: 11/8/1994.

The meeting room of the United Nations Security Council in the United Nations Headquarters in New York City, in 2014.

Photo under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

UNAMIR II

In the first week of May, General Roméo Dallaire sent a detailed plan for reinforcements, titled Proposed Future Mandate and Force Structure of UNAMIR, to DPKO in New York.

The non-permanent members of the Security Council, particularly the Czech Republic, New Zealand, Spain, and Argentina, took the initiative and during the first two weeks of May, were among the most persistent members of the council in pushing for action in Rwanda. On May 6, they presented a resolution that called for reinforcements, despite the clear opposition of the US and UK. The US, in particular, «put every obstacle in the way» (the expression is of Linda Melvern).

«On 11 May, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights José Ayala Lasso arrived in Rwanda to assess the situation for himself. He met Philippe Gaillard, the chief delegate of the ICRC, who told him that 250,000 people had died. Gaillard, (…) said that it was a genocide in full view» (L. Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.). In his final report, Ayala Lasso described the Rwandan situation in terms of «massive and extremely grave human rights violations committed by all those participating in the conflict». He wrote: «I also appealed to them to use their authority to stop the violence immediately, to work towards a cease-fire and to return to the negotiating table, as called for by the Secretary-General». Two hypotheses: either the Ecuadorian diplomat Ayala Lasso understood absolutely nothing of what he saw in Rwanda, or, more probably, he didn’t want to gamble his brilliant career by disappointing the powerful members of the Security Council. In any case, he was one of an extensive list of opportunists who slowed down or hindered an international intervention while hundreds of thousands of people were dying.

However, the Rwandan hell could not stay hidden much longer, and on May 17, the Security Council, after five hours of debate, voted for Resolution No. 918 which, under Chapter 7 Mandate (and not C6M, as for UNAMIR I), authorized the deployment of 5,500 peacekeepers to Rwanda and extended UNAMIR’s mission «to enable it to contribute to the security and protection of refugees and civilians at risk, through means including the establishment and maintenance of secure humanitarian areas, and the provision of security for relief operations to the degree possible» (UNAMIR II). Resolution 918 imposed also an arms embargo on Rwanda; however, still eschewed the word ‘genocide’.

On May 21, the US Secretary of State, Warren Christopher, authorized his diplomats to use the term ‘acts of genocide’ in reference to Rwanda. Less than a week after, on May 27, the United Nations recognized as genocide the tragedy of Rwanda.

So, all’s well that ends well, isn’t it?

Oh, come on! In this story, nothing and nobody ends well.

UNAMIR II force, planned on May 17, received the final authorization only on June 8, and its deployment was postponed for several more weeks, due to member states’ lack of enthusiasm for contributing human and military resources to the mission. In late July 1994, when the war and the genocide were already over, the RPF had already conquered the entire country, and the latter was already under a secure ceasefire, UNAMIR II could boast in Rwanda the incredible number of 500 men, instead of the 5,500 envisaged.

Two stories are worth telling. Stay with me.

The first. Many years ago, after the Rwandan tragedy, I completed the United Nations Peacekeeping and Peacebuilding Missions Summer School at a prestigious Italian Advanced Studies School. It was a meticulous preparation for Peacekeper Officers, which included also specific military training designed by the Italian elite Paratroopers Brigade “Folgore”. Do you know how many days of discussion and confrontation we devoted to the Rwandan Genocide, UNAMIR I and II, Roméo Dallaire, the DPKO failure? None. Not a single day, nor even an hour or a word. Nothing. None of the former civilian Special Representatives of the Secretary-General (= heads of past missions), and none of the former Force Commanders who taught and lectured at that university course did even say a damn word about the UN failure in Rwanda. Note that the official Independent Enquiry into the actions of the United Nations during the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda, aka “1999 Carlsson Report”, reads: «The failure by the United Nations to prevent, and subsequently, to stop the genocide in Rwanda was a failure by the United Nations system as a whole».

The second story has two parts.

Part One.

The DPKO struggled to find financial resources, weapons and all kinds of equipments, including vehicles, for UNAMIR II. Same old story, a little worse this time.

The United States offered 50 APCs in storage in Turkey, from their unused Cold War stocks. The APCs are armoured personnel carriers, designed to transport personnel and equipment in combat zones. The American APCs were 50 years old, low-valued vehicles but to delay the negotiation, the Clinton administration asked a lease-hold rate of 4 million dollars, plus other 6 millions to cover the transport costs. The negotiation dragged on and on for 7 weeks (yep, 7 damned weeks) as the US administration insisted on requesting an adequate payment for transport and spare parts. «The vehicles arrived in Rwanda when the genocide was over, completely lacking machine guns, radio, tools, spare parts and training manuals. General Dallaire described them as tons of rusting metal» (L. Melvern, cit.).

Part Two.

The UK offered 50 Bedford trucks in return for a sizeable amount of money. All of the Bedford vehicles were manufactured between 1930 and 1961 by British Vauxhall Motors. General Dallaire knew they were fit only to be museum relics and ironically asked if they were in running condition. «The British quietly withdrew the request for money, and some vehicles did arrive , but one at a time, they broke» (Ibidem).

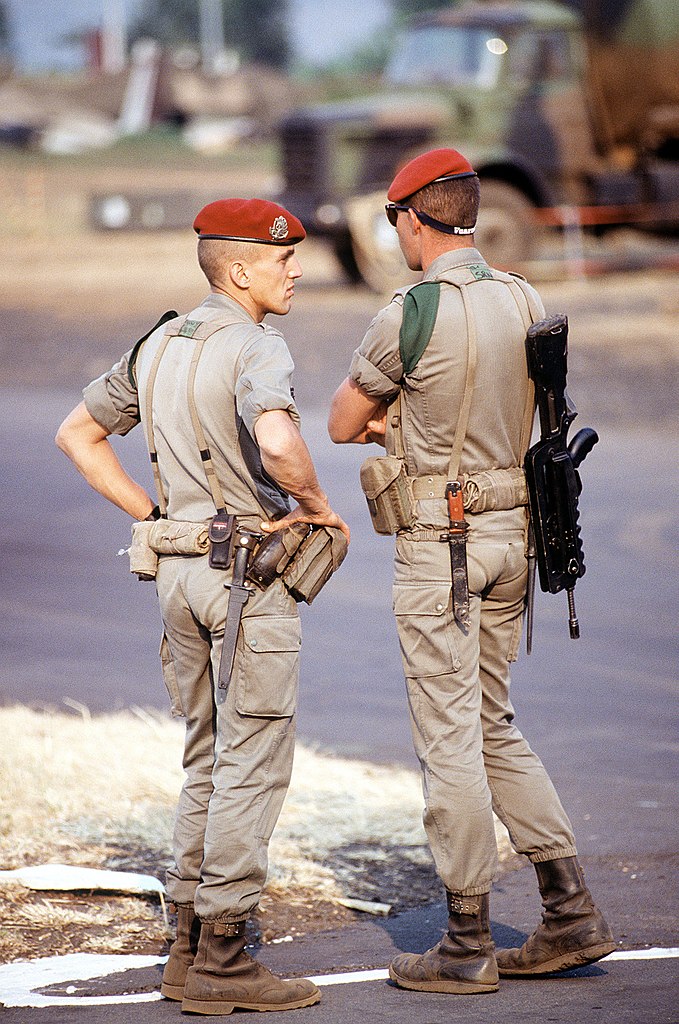

On August 15, 1994, Canadian General Roméo Dallaire (born in 1946, on the left), physically and psychologically exhausted, was replaced by Canadian General Guy Claude Tousignant (born in 1941, on the right), who took command of the UNAMIR II force with only 1,624 soldiers out of 5,500.

L’OPÉRATION TURQUOISE

On June 14, the French Conseil des Ministres (Cabinet), led by President François Mitterrand, decided to launch a French military-humanitarian intervention in Rwanda. The day after, Foreign Minister Alain Juppé, while interviewed by a journalist on Radio France International, made the news public, albeit with some caution.

As the organization and the deployment of UNAMIR II were still stuck in quicksand, on June 22, the UN Security Council voted (without unanimity) for Resolution 929 which authorized the deployment of «a multinational operation to be set up for humanitarian purposes in Rwanda until UNAMIR is brought up to the necessary strength», acting under Chapter VII of the Charter of the United Nations. The mission – the Resolution reads – has to be «a temporary operation under national command and control aimed at contributing, in an impartial way, to the security and protection of displaced persons, refugees, and civilians at risk in Rwanda, on the understanding that the costs of implementing the offer will be borne by the Member States concerned (…)».

The French ‘humanitarian’ mission, called Opération Turquoise, had to be a multinational relief operation for the assistance of civilians. However, it was an almost French mission made up of 2,494 French paratroopers and elite soldiers, plus only 500 soldiers from Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Chad, Mauritania, Egypt, Niger, and Zaïre. In paper, at least. In reality, Senegal was the only African country to send troops: 32 men, 1.4% of the total Turquoise force, with pieces of equipment entirely supplied by France. A multinational operation, sure.

Its military equipment was astonishing: «100 armored vehicles; a battery of heavy 120 mm Marine mortars; 2 light Gazelle helicopters; 8 heavy Super Puma helicopters; 4 Jaguar fighter-bombers; 4 Mirage F1CT ground attack planes; 4 Mirage F1CRS for reconnaissance. To deploy this armada, the Ministry chartered 1 Airbus, 1 Boeing 747, 2 Antonov AN-124s, a squadron of 6 French Air Force Lockheed C-130s, and 9 Transalls. The entire force was placed under the overall command of General Jean-Claude Lafourcade (born in 1943) in Goma <Zaïre> and General Raymond Germanos in Bukavu-Cyangugu <Rwanda>» (G. Prunier, The Rwanda Crisis, cit).

The beginning of the Opération Turquoise: a French C130 Hercules, a four-engine turboprop military transport aircraft, is leaving Libreville in Gabon to get to Goma on the border between Rwanda and Zaïre, on June 24, 1994.

Photo under Creative Commons license.

A French Mirage Mirage F1 CR & CT Armée de l’Air. It was built by the French company Société des Avions Marcel Dassault, the same as Habyarimana’s Falcon 50.

Drawing by Newresid by stephanelhernault@yahoo.fr under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, 2.5 Generic, 2.0 Generic, and 1.0 Generic licenses.

A French Air Force Jaguar A/E Fighter-Bomber aircraft of Escadron de Chasse 1/7 Provence flies a refueling mission over the Adriatic Sea.

Public Domain.

An Eurocopter AS332 Super Puma of the French Armée de l’Air

I know what are you thinking: was it a real ‘humanitarian’ relief mission?

Nobody found it reassuring the presence, among the Turquoise top-ranking officers, of Colonel Didier Thibault, who had previously served as military counselor to the Rwandan Armed Forces in 1992.

Should France have wanted to launch a humanitarian campaign, its government could have accelerated the departure of UNAMIR II by giving it the entire equipment guaranteed to the Turquoise military force, with less expenditure of resources and energies. Therefore, either France had a hidden political-military agenda or it was trying to achieve significant media coverage to clean up its quite dirty image. There was also a third possibility: that France was trying to catch both birds with one stone. And a fourth possibility as well: that the French operation was an awful mess with multiple aims, some of which – not just one – were accurately hidden. Certainly, France wasn’t about to spend millions of francs just to save the lives of those négros slaughtered by a criminal clique it had supported and helped until a few days before.

The French government’s decision, the official UN endorsement of the Opération Turquoise mission on June 22 with 10 members in favor and 5 abstaining (Brazil, China, New Zealand, Nigeria, Pakistan), and the departure of the French military Force on June 23 to create a “safe area” in the Rwandan south-western zone, controlled by the puppet government, kicked a hornet’s nest.

«The RPF had already vociferously condemned the intervention as a French ploy to save the Sindikubwabo regime from eventual defeat. <Théodore Sindikubwabo was the interim President of Rwanda during the genocidal final phase> (…). Faustin Twagiramungu, Prime Minister-designate under the Arusha Agreement, also condemned the intervention (…)» (G. Prunier, The Rwanda Crisis, cit.).

The Tanzanian diplomat Salim Ahmed Salim, Secretary-General of the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), conveyed the condemnation of his entire organization.

«A group of Tutsi Catholic priests who had survived the killings issued a cri de coeur to their superiors: “Those responsible for the genocide are the soldiers and the MRND and the CDR political parties at all levels but especially at the highest levels, backed by the French who trained their militias. That’s why we consider that the French intervention, describing itself as a humanitarian one, is cynical. We note with bitterness that France did not react during the two months when the genocide was being committed, though she was better informed than others. She did not utter a word about the massacres of opposition members. She did not exert the slightest pressure on the self-proclaimed Kigali government, although she had the means to do so. For us, the French have come too late for nothing”» (The Preventable Genocide, 15.62, cit.).

General Roméo Dallaire received the news in Kigali from Bernard Kouchner <former French Minister of Health and former Minister for Humanitarian Affairs> on June 17, and he was totally flabbergasted. He recalls in his memoirs: «I told Kouchner I could not believe the effrontery of the French. As far as I was concerned, they were using a humanitarian cloak to intervene in Rwanda, thus enabling the RGF <Rwandan Governmental Forces> to hold on to a sliver of the country and retain a slice of legitimacy in the face of certain defeat. If France and its allies had actually wanted to stop the genocide, (…) they could have reinforced UNAMIR instead». (R. Dallaire, Shake Hands With The Devil, cit.). Moreover, he got rapidly distressed by the presence in Rwanda of two UN-authorized missions with different mandates and command structures: the French one, with its hidden agenda, could undermine UNAMIR and result in unwanted consequences for the already severely devastated population. «In private, General Dallaire was even more severe. He knew of the French secret arms deliveries to the Rwandan Armed Forces and when he knew of the French initiative, he said: “If they land here to deliver their damn weapons to the government, I’ll have their planes shot down”» (G. Prunier, The Rwanda Crisis, cit.).

In France, the dispute was quite animated. On June 23, Le Monde wrote: «Le projet français d’intervention au Rwanda soulève de plus en plus de critiques, souvent sévères, tant en Afrique qu’en Europe et aux Nations unies, où le Conseil de sécurité continuait d’examiner mercredi 22 juin la proposition de Paris. En France même, des objections se sont exprimées au sein de la majorité gouvernementale». (La Monde, Dans l’attente d’une décision des Nations unies, le projet d’intervention française au Rwanda suscite de plus en plus de critique, 23 Juin 1994). My translation: “The French plan to intervene in Rwanda is raising more and more criticism, often severe, both in Africa, in Europe and at the United Nations, where the Security Council is going to examine the Paris proposal on Wednesday 22 June. In France, objections were expressed within the government majority”.

So, very few naive people believed in the sincere humanitarian commitment of the French who had been politically and militarily supporting Habyarimana’s regime and the following puppet government, always with no moral hesitation.

Truth is that behind the Opération Turquoise, there were many conflicting political positions and politicians (such as the conservative Prime Minister Édouard Balladur and socialist President Mitterrand, for example). Emmanuel Viret wrote: «Most of all, Turquoise was the product of cohabitation (the forced collaboration of different political forces, since different parties had won the presidential and the legislative elections) at the head of the executive branch of the French government. This led to a large number of protagonists participating in decision-making (the President, the Prime Minister, the Foreign Minister, etc.), which more or less forced these parties to reach a consensus. In addition, the Rwandan crisis fueled the rivalry between partisans of Prime Minister Edouard Balladur and of Jacques Chirac (including Foreign Minister Alain Juppé). Edouard Balladur did not support the intervention; conversely, Alain Juppé saw it as an opportunity» (E. Viret, cit.).

Therefore, the Turquoise Operation probably had multiple goals: reversing the trend that saw a constantly diminishing influence of France in Africa; preventing or at least limiting the RPF’s total victory; receiving wide media coverage and giving France the opportunity to play a relevant role in the post-war period; facilitating the flight to France of certain Rwandan politicians and ‘old friends’; securing compromising documents or document containing sensitive information; mitigating the pressure exerted by human rights groups and civil society organizations and getting rid of the consequent poor return of image; etc.

This video shows the first maneuvers of the Turquoise Operation on July 26: a French C130 Hercules is landing at the Bukavu Airport, in South Kivu; troops; a row of jeeps with field guns; some Senegalese soldiers clapping and singing, all in Zaïre. The following scenes – military convoy greeted by people on the roadside, children, soldiers and refugees – are all shot in Rwanda. From the AP Archive.

The Opération Turquoise started on June 23 amidst the controversy and ended on August 21 amidst even worst controversies and fierce accusations whose aftermath persists still today.

Let’s summarize what happened. The Turquoise Operation knew four phases, according to some French scholars:

- FIRST PHASE, from June 22 to 28. It «consisted of conducting reconnaissance missions 15 km inside Rwandan territory, from the towns of Goma and Bukavu, in Zaïre. In the north, the Diego detachment, based in Goma, moved around the Gisenyi region and carried out exfiltration operations. (…). In the south, the Thibault detachment entered Rwanda through Cyangugu and reached the Nyarushishi camp» (E. Viret, cit.). The latter was a refugee camp in Southwestern Rwanda, near the Zairean border, housing between 8,000-10,000 Tutsis, constantly threatened by militiamen. The camp protection was entrusted to a company of the 2e Régiment étranger d’infanterie, one of the two infantry regiments of the Légion étrangère.

On Sunday, June 26, French paratroopers escorted two trucks of relief supplies coming from Goma for the 8,000 Tutsi refugees camped in the Nyarushishi. A 250-member paratrooper force under the command of Colonel Didier Thibaut was based near the camp. From the AP Archive.

- SECOND PHASE, from June 28 to July 4. «The Turquoise detachments entered further into Rwandan territory, near Gikongoro, and reached Butare on July 3. The incursions into northern Rwanda stopped. During this second phase, the French forces had several skirmishes with the RPF troops» (E. Viret, cit.).

The Bisesero massacre

On June 26, the US journalist Sam Kiley «informed the French soldiers of the Omar detachment, under Lieutenant Commander Marin Gillier, of massacres of Tutsis in the Bisesero Valley, in the préfecture of Kibuye, a few kilometers from a French camp» (Ibidem).

On June 27, «alerted by two nuns from Kibuye, Lieutenant-Colonel Duval, the commander of a Turquoise detachment, headed toward the Bisesero Hills in the commune of Gishyita, where Tutsi refugees under threat of extermination had taken refuge». The French soldiers discovered also the visible traces of the past massacres of civilians carried out by Rwandan Armed Forces, Gendarmerie and militiamen. «Duval judged he had insufficient means to secure the area and told the survivors he was returning to Kibuye, promising he would come back as soon as possible» (Ibidem).

On June 29, US journalist Raymond Bonner reproofed the French as no Turquoise reinforcements had not yet reached Bisesero.

On June 30, «Captain Marin Gillier, leading the Omar detachment, went to Bisesero – allegedly by coincidence – and found many massacre sites there, and about 800 to 1,000 survivors. In the three-day interval after their discovery by detachment Diego and before the Omar detachment got them out of harm’s way, around one thousand survivors from Bisesero had been massacred under the leadership of Charles Sikubwabo, the burgomaster of Gishyita. This three-day delay has never been accounted for» (Ibidem). Human rights groups later said that France knowingly failed to prevent the Bisesero massacre. Survie, Ibuka, FIDH, and six survivors of Bisesero accused the French military-humanitarian mission Turquoise and France of “complicity in genocide” for having knowingly abandoned for three days the Tutsi civilians refugees in the hills of Bisesero, allowing the massacre of hundreds of them to be perpetrated by the génocidaires. The investigation into the French military’s conduct in the area was opened in 2005 and closed in July 2018. After more than a decade, none of the French officers being investigated for their conduct have been placed under “formal investigation”, which under French law is a step short of being charged. In May 2021, the prosecutor’s office requested a dismissal of the case, which was granted in September 2022.

The Bisesero Genocide Memorial located on top of Muyira hill, near Karongi-Kibuye, in Western Rwanda.

- THIRD PHASE, from July 4 to July 30. «A safe humanitarian zone or ZHS (Zone Humanitaire Sûre), which all belligerent factions were forbidden to enter, was created in the northwest quarter of the country, along the boundaries of the préfectures of Cyangugu, Kibuye and Gikongoro combined. It was around 4,500 km2 in size. Several hundred thousand civilians and thousands of militiamen and soldiers came to take refuge there. French skirmishes with the RPF proliferated, both along the ZHS periphery and in the north between Gisenyi and Goma. Several members of the interim government took refuge in the ZHS at Cyangugu, then crossed the border and entered Zaire» (E. Viret, cit.). In this period, approximately 10,000 soldiers of the Rwandan Armed Forces mingled with the refugees, passed through the ZHS, and crossed the border with Zaïre. «The members of the interim government took the Rwandan Central Bank currency reserves with them and, along with the RAF Chief of Staff and the national radio staff, took refuge in Zaïre» (E. Viret, cit.).

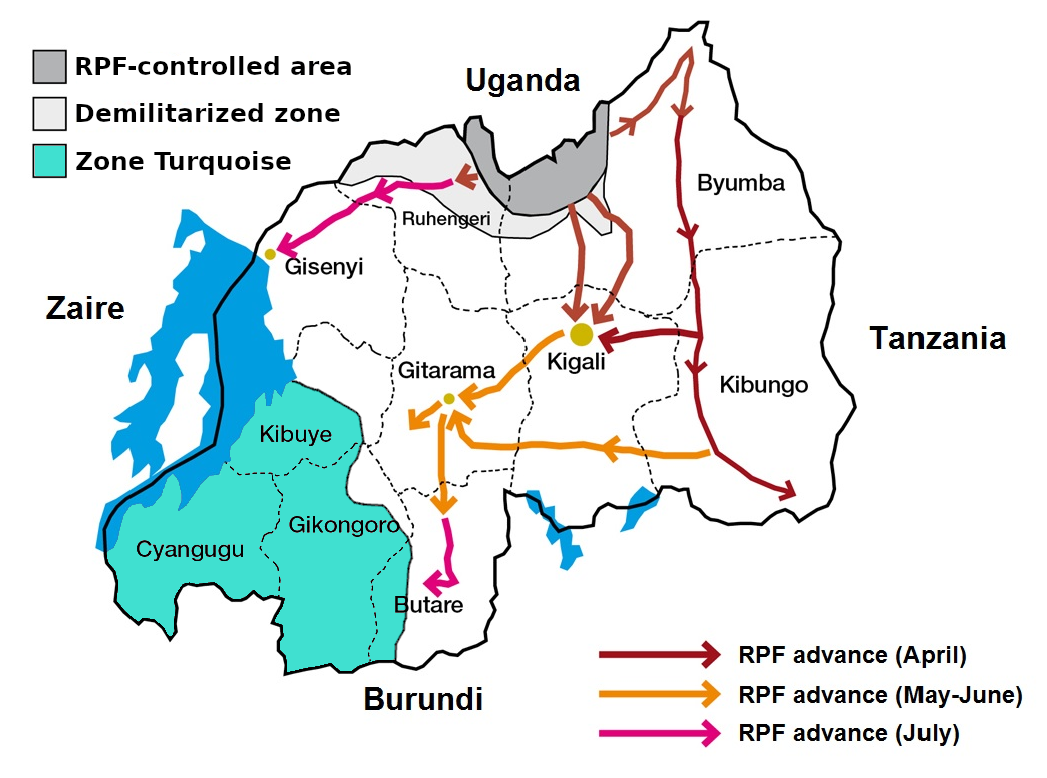

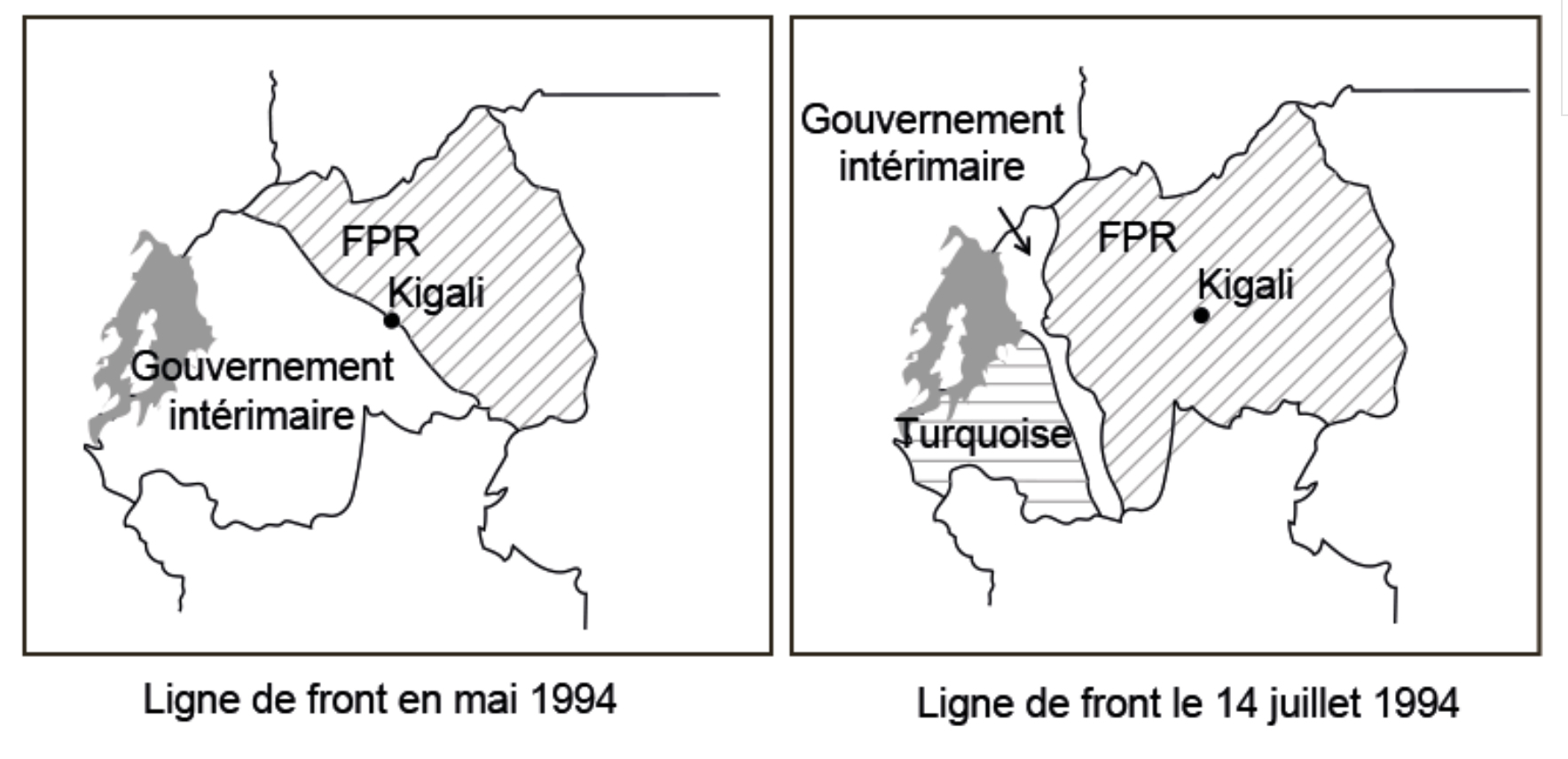

Map showing the Zone Turquoise (ZHS, Zone Humanitaire Sûre) within the Cyangugu-Kibuye-Gikongoro triangle, spread across 1/5 of the country, and the advance of the RPF during the genocidal final phase in spring-summer 1994.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

– FOURTH PHASE, from late July to August 21. «The last phase of Operation Turquoise consisted of preparing for the UNAMIR II force to relieve the French troops. It was characterized by an increase in tension with the Rwandan militias and RAF members inside the ZHS. In certain areas of the zone, since the number of French troops was limited, roadblocks were re-established after their departure, which left the Tutsis under threat of assassination again» (E. Viret, cit.).

French paratrooper soldiers at Kigali airport, on August 14, 1994.

Photo under Creative Commons license.

According to Human Rights Watch, the Turquoise Operation allowed the rescue of 15,000 to 17,000 Rwandans (10,000 to 15,000 according to Lanotte, 2007).

However, the French Forces

- did not systematically disarm the paramilitary militias and the Rwandan Armed Forces soldiers inside the ZHS. According to different sources, some soldiers were left with all their equipment and arms intact, while some others were disarmed before crossing the border with Zaïre;

- let several Rwandan interim government officials and génocidaires enter the ZHS and flee the country crossing the border with Zaïre;

- refused to arrest officials accused of genocide who were taking sanctuary in the ZHS (the French could have done it under the mandate of the Genocide Convention);

- permitted the Rwandan Armed Forces to move back and forth between the safe zone and Zaïre without hindrance;

- permitted the arrival of weapons for the Rwandan Armed Forces inside the French zone via Goma airport in adjacent Zaïre. According to a report by Human Rights Watch (Rearming with Impunity: International Support for the Perpetrators of the Rwandan Genocide), 5 shipments of arms were sent from France to Goma in May and June, while the genocide still raged. «France has constantly denied sending arms to Rwanda once the genocide was unleashed, yet we know France was involved. It is possible that the arms were part of a covert action, not officially endorsed by the government» (The Preventable Genocide, 15.79, cit.).

- «Through July, August, and even September, according to UN officials, the French military flew a raft of génocidaires out of Goma to unidentified destinations» (The Preventable Genocide, 15.80, cit.). Among them, there were Colonel Théoneste Bagasora (who moved to Cameroon), many Interahamwe leaders, and Rwandan Armed Forces high-ranking officers.

«The successful flight to Zaïre of an extensive part of the Hutu Power apparatus, to which France contributed, is beyond question the single most significant post-genocide event in the entire Great Lakes Region, launching a chain of events that eventually engulfed the entire area and beyond in conflict. (…). The consequences of French policy can hardly be overestimated. The escape of génocidaire leaders into Zaïre led, almost inevitably, to a new, more complex stage in the Rwandan tragedy, expanding it into a conflict that soon engulfed the ail of central Africa. That the entire Great Lakes Region would suffer destabilization was both tragic and, to a significant extent, foreseeable. Like the genocide itself, the “convergent catastrophes” that followed suffered from no lack of early warnings. What makes these developments doubly depressing is that each led logically, almost inexorably, to the next. What was lacking, once again, was the international will to take any of the steps needed to interrupt the sequence» (The Preventable Genocide, 15.68 and 15.85, cit.).

In the following years, many former French soldiers and officers declared the ambiguity of the Opération Turquoise. Its commander, General Jean-Claude Lafourcade, «admitted that the safe zone was intended to keep alive the Hutu government in the hope that it would deny the RPF total victory and international recognition as the rulers of Rwanda. It was also an opportunity for France to help leading members of the regime flee. Other killers made their way to France knowing they would find protection from justice» (Chris McGreal, France’s shame?, The Guardian, January 11, 2007).

The most critical French officers were Lieutenant Colonel Guillaume Ancel and Chief Warrant Officer Thierry Prungnaud.

Guillaume Ancel (who we met when we analyzed the Habyarimana’s Falcon 50 shooting down in Rwandan Basketry 7), is the author of Rwanda, la fin du silence témoignage d’un officier français (‘Rwanda, the end of silence: a former officer tells’), published in 2018. The book bluntly denounces the discrepancy between the official French version and what he experienced as a Captain specializing in the guidance of fighter planes in the 68th African Artillery Regiment. He maintains that he was ordered to stop the RPF’s advance when its military victory was becoming inexorable. In particular, he maintains that the initial order he received on June 24 was clear: to prepare a raid on the Rwandan capital, Kigali, then almost entirely under the control of the RPF. The specialty of his unit was airstrike guidance (Tactical Air Control Party – TACP). Once infiltrated near the target to guide fighter jets, the role of Ancel’s unit was to clear a corridor to allow troops to seize their objective before anyone who had time to react. However, his unit never received the final confirmation to act. Then, between June 29 and July 1, he received a new order: his unit had to stop the RPF advance east of the Nyungwe forest, in Southwestern Rwanda. On June 30, in the morning, his soldiers took off in Super-Puma to trigger the air strikes on the columns of the RPF but just as the helicopters were taking off from Bukavu airport, he received a counter-order. The officer in charge of operations told him that an agreement had been reached with the RPF and their new mission was to protect a safe humanitarian zone, the ZHS. On the first days of July, he wrote, the nature of their mission changed into a humanitarian one. In the following interview (in French only), broadcasted by France 24 TV, Ancel confirms what he has already written.

In 2004, the Rwandan Government established a Commission to investigate and ascertain the nature of French involvement in the final phase of the Genocide (1994). The Commission – officially “National Independent Commission Charged With Gathering Evidence to Show the Implication of the French Government in the Genocide Perpetrated in Rwanda in 1994” – was known as “Mucyo Commission” from the name of its chairperson Jean de Dieu Mucyo, former Attorney General of Rwanda. The official Report, signed by a panel of experts and released in August 2008, claimed to detail that France was not only complicit but had engaged in actions on the level of conspiracy to genocide. Of course, it was the subject of fierce debate and criticism. You can read it online.

The integral Mucyo Report on the role of France in the 1994 Genocide final phase can be downloaded or read online here.

THE END OF THE WAR

On April 21, the RPF took the town of Byumba (60 km north of Kigali) and transferred its headquarters there from Mulindi, the small village near the border with Uganda, which has been their longtime base. On May 6, it conquered Ruhengeri, and on May 29, the town of Nyanza. In late May, Kagame took both the airport and the Kanombe military camp in Kigali. «On May 27, the militia leaders and many of their followers fled although Rwandan army troops continued to hold on to part of the capital. On May 29, <the Inkotanyi> took Nyabisindu and on June 2, Kabgayi, only a few miles from Gitarama. The Rwandan army counterattacked, backed by militia and “civilian self-defense” forces, but the RPF routed them and rolled on to take Gitarama on June 13. Leaders of the interim government fled west to Kibuye and then north to Gisenyi. There, they created a new national assembly in a last vain effort to establish legitimacy. As the RPF advanced in each region, authorities managed to galvanize killers to hunt for the last remaining Tutsis. They launched these last attacks in June and early July, on dates that varied according to the moment of the RPF’s arrival nearby. In early June, assailants had surrounded at least one of the three large camps of Tutsi at Kabgayi but were overwhelmed by a rapid RPF advance before they could carry out the planned attack. (…). In June, <Valérie> Bemeriki <on RTLM> pushed killers to complete the elimination of Tutsi, “their total extermination, putting them all to death, their total extinction”. On July 2, Kantano Habimana exultantly invited his listeners to join him in a song of celebration: “Let’s rejoice, friends! The Inkotanyi have been exterminated! Let’s rejoice, friend. God can never be unjust!”. Two days later, the RPF took Kigali and two weeks after that, the authorities responsible for the genocide fled Rwanda» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

On July 6, under colonel Léonidas Rusatira’s leadership, several officers of the Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR) signed the “Kigeme Declaration”, in which they condemned the genocide, pledged to fight it, and called for a ceasefire and negotiations with the RPF. Rusatira was among the first officers to publicly condemn the genocide (he will be arrested in 2002 but the charges against him were dropped off).

For the duration of the entire offensive, Paul Kagame prioritized reaching his military objectives, at the expense of rescuing people under threat: an understandable choice, in some respects a logical one, but open to criticism.

On July 17, the RPF took Gisenyi, and Faustin Twagiramungu was appointed Prime Minister according to the procedure planned in the Arusha Accords. On July 18, the RPF declared a de facto ceasefire. The war was over.

The RPF troops entered Kigali on July 4, 1994.

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE: ANSWERING EXCRUCIATING QUESTIONS

As Mahmood Mamdani wrote, the Rwandan genocide poses a set of deeply troubling questions.

The first.

The Rwandan genocidal violence deeply disturbed most scholars, politicians, journalists, and activists: it was a collective and public violence similar to a fire that spread with frightening speed and unexpected intensity. Samantha Power, former U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, wrote that the Rwandan Genocide «was the fastest, most efficient killing spree of the twentieth century».

Why? What ‘fire-accelerants’ speeded up that arson and made it brutally escalate?

The second question.

Damien de Walque, a senior economist in the World Bank’s Development Research Group, said that «the staggering number of victims over a very short period is one of the most shocking – and defining – features of such a historical event». This extremely high death toll was due to the large-scale civilian involvement in the genocide.

«Why did hundreds of thousands, those who had never killed before, take part in mass slaughter? Why did such a disproportionate number of the educated – not just members of the political elite but, as we shall see, civic leaders such as doctors, nurses, judges, human rights activists, and so on – play a leading role in the genocide? Similarly, why did places of shelter where victims expected sanctuary – churches, hospitals, and schools – turn into slaughterhouses where innocents were murdered in the tens and hundreds, and sometimes even thousands?» (Mahmood Mamdani, cit.).

In the next chapters, I will answer both of these questions.

THE MATHEMATICS OF GENOCIDE

We saw the groundlessness of the common cliché that turns the final phase of the Genocide into “a hundred-day event”. Another common and media darling label is that of “a million-victim genocide”, quite a commonplace in current Rwanda. Is it another nonsense?

Let’s deal with two issues: how many victims? How many perpetrators? These two questions will prove to be less simple and far more challenging than they may appear at first, and for different reasons.

- The victims of the final phase

Well, no one can say with absolute certainty how many Tutsi were killed in Rwanda between April 6 and late July 1994 (mind the date). Truth is that very accurate head counts could not be taken. As we saw in the previous chapter, there’s a wide uncertainty interval for each of the major massacres and a fortiori for the overall death toll.

It’s not an irrelevant question, as someone might think. Different figures and a different balance between the death toll of the Tutsis and that of the Hutus may support different historical interpretations: knowing the number of the Hutus killed during the genocide can give a more specific characterization to the orgy of violence and prove or disprove the double-genocide thesis. Omar Shahabudin McDoom wrote: «The number and identities of the victims have become weapons in the battles waged between those who would deny, minimize, or equate the genocide with other violence, and those who would insist on its moral uniqueness» (O. S. McDoom, Contested Counting: Toward a Rigorous Estimate of the Death Toll in the Rwandan Genocide, see Bibliography). The ‘mathematics of genocide’ has both political and historical relevance. More cynically, genocide has become a numbers game. «In the spectacle of suffering, the bodies of victims literally count» (Jens Meierhenrich, How Many Victims Were There in the Rwandan Genocide? A Statistical Debate, see Bibliography).

In 1995, Gérard Prunier estimated a death toll of 800,000-850,000 Tutsis, with approximately 130,000 Tutsi survivors.

In 2002, Rwanda’s National Commission for the Fight against Genocide and the Ministry of Local Government and Social Affairs (MINALOC), supported by the Rwandan Government, gave a global figure of 1,074,017 victims in the final phase, 93.67% of which were Tutsis.

The casualty figure of a million Tutsi victims seemed not just excessive, but also politically inflated to the large majority of scholars as the August 1991 National Population Census registered 7,099,844 Rwandan nationals, among which 597,459 Tutsis (8.42%). Taking into account the average annual population growth of 2.5%, and according to the Census data, the number of Tutsis before Habyarimana’s assassination could be estimated at approx. 643,000.

Human Rights Watch and « Alison Des Forges, after subtracting from that figure some 150,000 Tutsi survivors, arrive at a total of 507,000 Tutsis killed, or 77% of the total population registered as Tutsis. (…). Using data from the UNDP and HCR, Filip Reyntjens in 1997 reaches the figure of 600,000 Tutsis killed» (René Lemarchand, Rwanda: the State of Research, 2018, see Bibliography).

Is the 1991 Census a reliable source of data or the number of Tutsi was heavily under-reported for political reasons? Was there a deliberate misrepresentation of ethnicity that might complicate how many were Tutsis in 1994? We should note that the 1991 Census was carried out during the civil war, the violent campaign against the ‘cockroaches’, and the first phase of the genocide. It was in Habyarimana’s best interest to reduce the percentage of Tutsis to lower their quota, and it was in wealthy Tutsis’ best interest to become Hutus. We know, furthermore, that since the 1980s, being considered Tutsi had become a cause of discrimination and exclusion; therefore, over the years, several Tutsis had corrupted local authorities in charge of establishing identification papers to have their ethnic identity changed.

Marijke Verpoorten provided evidence for an alleged under-reporting in the 1991 census: she showed that in April 1994, in the Gikongoro prefecture, the number of Tutsis was at least 37% higher than the figure given by the 1991 census. However, she could not show if the extent of under-reporting was similar or not in all prefectures. She found a 1987 official administrative Census of the Rwandan prefectures, and by comparing it with the 1991 Census, she found that in spring 1994, the Tutsi could have reached at least the figure of 811,941. By cross-referencing various data available, in 2020, Verpoorten puts forward a death toll of 562,000-662,000 Tutsis, corresponding to a death rate of 70-80%. «It is much more difficult to establish how many Hutu died. One estimation method led to a guestimate of 542,000 Hutu lives lost , which amounts to 7.5% of the Hutu population in 1996. The uncertainty interval is however large» (Marijke Verpoorten, cit.).

Roland Tissot, in Beyond the ‘Numbers Game’ (2020), estimates that “roughly 600,000 Tutsis (i.e. 80%) perished during the genocide.”

«David Armstrong, Christian Davenport, and Allan Stam, who deliberately avoided a statistical breakdown along ethnic lines, have computed “a total figure of just over 580,000 with a credible interval ranging from just over 500,000 to roughly 687,000.” They also maintain, however, that, methodologically speaking, “the most defensible position is that no clear casualty figure emerges» (J. Meierhenrich, cit.).

Omar Shahabudin McDoom, Associate Professor in Comparative Politics at the London School of Economics, estimates that roughly 800,000 Tutsi were living within Rwanda on the eve of the genocide and that those killed in the country from April 6 to July 19, 1994, were between 491,000 and 522,000. «Nearly two-thirds of Rwanda’s Tutsi population were exterminated between April and July 1994. The finding should leave little doubt as to whether the violence amounted to genocide» (O.S. McDoom, Contested Counting, 2019, cit.). As to the death toll of Hutus (which includes those killed by extremists, the RPF, and various diseases in refugee camps), McDoom suggests a figure of several hundreds of thousands. «This high figure does serve to underscore that forms of violence other than genocide occurred at the same time in Rwanda for which there has been limited recognition The exclusive focus on the genocide, unfortunately, obscures this other violence» (O.S. McDoom, cit.). That’s an interesting remark, worth a deeper reflection.

The death toll provided in 2004 by the Rwandan Government has been contested by the Western scholarly community. J. Meierhenrich writes: «Among other achievements, the existing scholarly literature has repudiated the million-victim-myth. This myth, which the RPF fabricated and continues to peddle, is a quintessential “social fact,” a never fully substantiated and now falsified data point about the Rwandan genocide that many well-meaning observers have taken to be “true” simply because it is “widely believed to be true.” Despite the various methodological disagreements among them, none of the scholars who participated in this forum gives credence to the official figure of 1,074,107 victims. Our diverse group of authors may not agree on how many victims exactly there were in the Rwandan genocide, but – collectively – it casts aspersion on the RPF’s “calculative practices”. Given the rigor of the various quantitative methodologies involved, this forum’s overarching finding that the death toll of 1994 is nowhere near the one-million-mark is – scientifically speaking – incontrovertible» (J. Meierhenrich, cit.).

Tone and words are quite harsh, aren’t they?

We should always criticize everything (yep, everything), but we must emphasize that every criticism is an exercise in legitimate and fruitful cognitive democracy if and only if we had made a previous effort to understand or know what we want to criticize. Professor J. Meierhenrich, why didn’t you read the Rwandan dossier before attacking it in such virulent tones? If you had done so, you would have noticed that the figure counted by the Rwandans, that vexed 1,074,017, is not at all the Tutsi death toll of 1994!

Let’s start by reading this brief document. Here it is:

Government of Rwanda, Dénombrement Des Victimes Du Genocide: Rapport Final, Kigali: Ministère de L’Administration Locale de L’Information et des Affaires Sociales, Kigali, 2002, version révisée 2004.

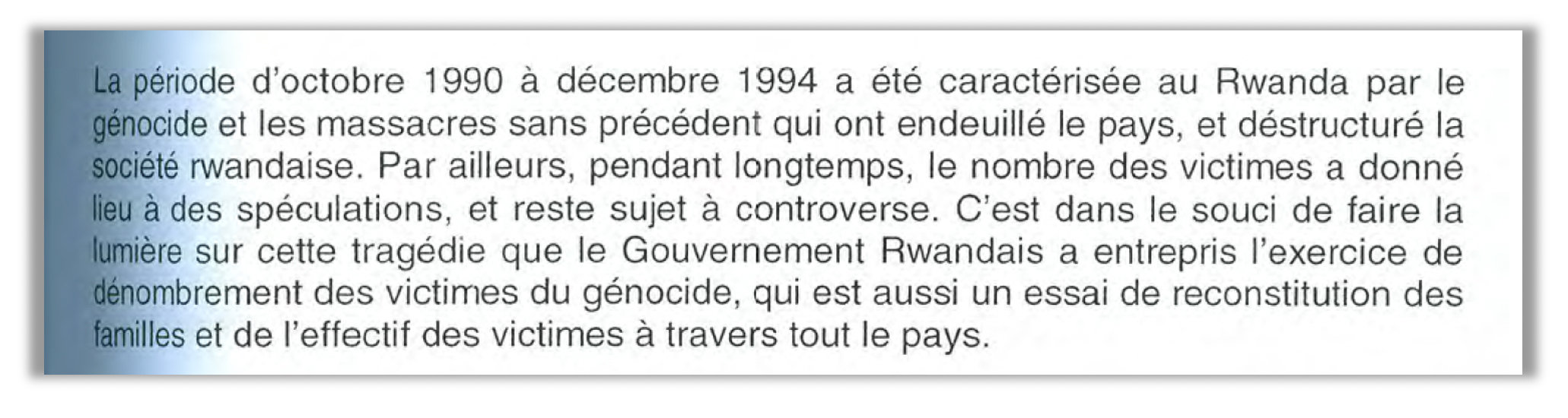

This document adopts the same historiographic perspective I have adopted in these pages: the Jenoside yakorewe abatutsi is not restricted to the final slaughter from April 6 to mid-July, as most Western scholars do, but with a much more mature historiographical approach, is spread over a wider period which began with the Civil War. As we have seen, genocide is not an event that can be objectively enclosed between two dates, namely a t1 or the onset precise time, and a t2 or the precise time of its ending; therefore, the dates given by all scholars are always pure and simple conventions. The convention chosen by the Rwandan government runs from the 1st of October 1990, to December 31, 1994 (see pp. 17 and 37) and is best suited to what happened. The document is straightforward, as you can see:

My translation: “In Rwanda, the period from October 1990 to December 1994 was characterized by genocide and unprecedented massacres that plunged the country into mourning and shattered Rwandan society. For a long time, the number of victims has given rise to speculation and remained controversial. To shed light on this tragedy, the Government of Rwanda has undertaken the genocide victims’ count throughout the country”.

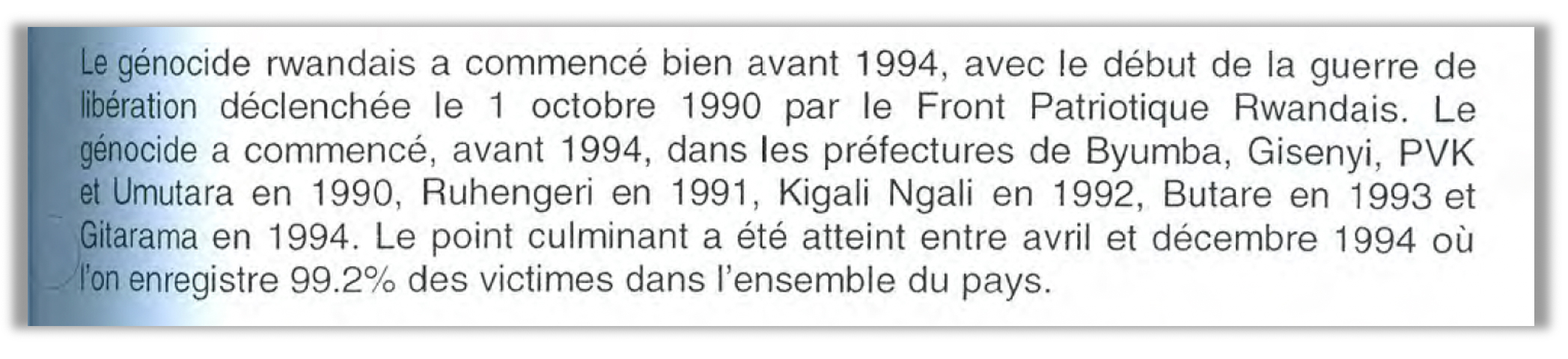

My translation: “The Rwandan genocide began before 1994, with the beginning of the war of liberation unleashed on the 1st of October 1990 by the RPF. Before 1994, the genocide began in the prefectures of Byumba, Gisenyi, Kigali-Ville, and Umutara in 1990, Ruhengeri in 1991, Kigali Ngali in 1992, Butare in 1993, and Gitarama in 1994. The peak was reached between April and December 1994 when 99.2% of victims were recorded throughout the country”.

Therefore, the figure of 1,074,017 is referred to the entire genocidal period, from October 1, 1990, to December 31, 1994. Moreover, the figure of 1,074,017 is considered the estimated count of reported victims, while 934,218 are the victims counted and supported by more accurate information. The vast majority – approx. 99.2% – was registered from April to the end of December 1994. This 99.7% is not comparable with the approximate figures given by many Western scholars not only for the time lag but also for the definition of ‘victims’ of genocide assumed by the Rwandan document.

My translation: “1.2 Who is a victim of genocide?

This survey uses the definition of “victim of genocide” of Law no. 08/96: “Victim of genocide is any person killed during the period from October 1, 1990, to December 31, 1994, for their being Tutsis or resembling Tutsis or having relationships, ties or special affinities with Tutsis. Victim of genocide is also any person who had political thoughts or was related to people with political thoughts in opposition to the political divisionism and the ideology of pre-1994”.

The Rwandan Government’s categorization of ‘victims of genocide’ is not the same as that used by most western scholars: it includes indeed those whose ID stated they had a Tutsi origin and those who were credited to be Tutsi for a series of reasons and stereotypes (morphological features, thin noses, tall stature, supposed signs of wealth and other fooleries), plus the majority of political opponents, representatives of civil society and intelligentsia, and moderate members killed for their opinions or their work. For most western scholars – except for David Armstrong, Christian Davenport, and Allan Stam, who deliberately avoided a statistical breakdown along ethnic lines – the victims of genocides are Tutsis by definition, and the Hutu death toll is always separate. The Rwandan document carefully avoided this approach. Its concept of ‘victims of genocide’ includes and mixes the so-called Hutus and the so-called Tutsis, but does not include the Rwandans killed by the RPF and by hunger, disease, and despair in the refugee camps. In the post-genocide period, in other words, the government of Rwanda strove to adopt a perspective both able to overcome the old, purely ideological separation between Hutus and Tutsi even in the Genocide death toll and, at the very same time, able to put aside politically embarrassing count as well.

Two conclusions.

Firstly, the data given by the Rwandan Government and the western estimates are not comparable. At a guess, the former is higher than the latter, but not so inflated or so politically biased, as some scholars believed. The number of the victims supported by more accurate information, if roughly separated from the Hutu victims’ count (even assuming that it would be possible) and restricted to mid-July, might be slightly higher than Gérard Prunier’s estimate and slightly lower than Philippe Gaillard’s approximate figure. Gaillard was «the Chief Delegate of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), who had an intimate knowledge of the country, its politics, and population, and was probably the first person to recognize that genocide was likely. (…). He estimates that up to one million people were killed» (L. Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.). In any case, the harsh criticism by J. Meierhenrich is not at all justified.

Secondly, we tend to think of the counting of victims as a measurement procedure wrapped in the reassuring halo of mathematical objectivity, but we are wrong. Even the concept of ‘victim’ turns out to be anything but simple; there are different ways of categorizing it, and each one of them entails a particular political and historiographical perspective. Mathematics is an exact science, but the way we use numbers is far from being objective and universal. All scholars should build a dialogue when facing different perspectives and numbers, but rarely do they do it, and that’s a discouraging attitude.

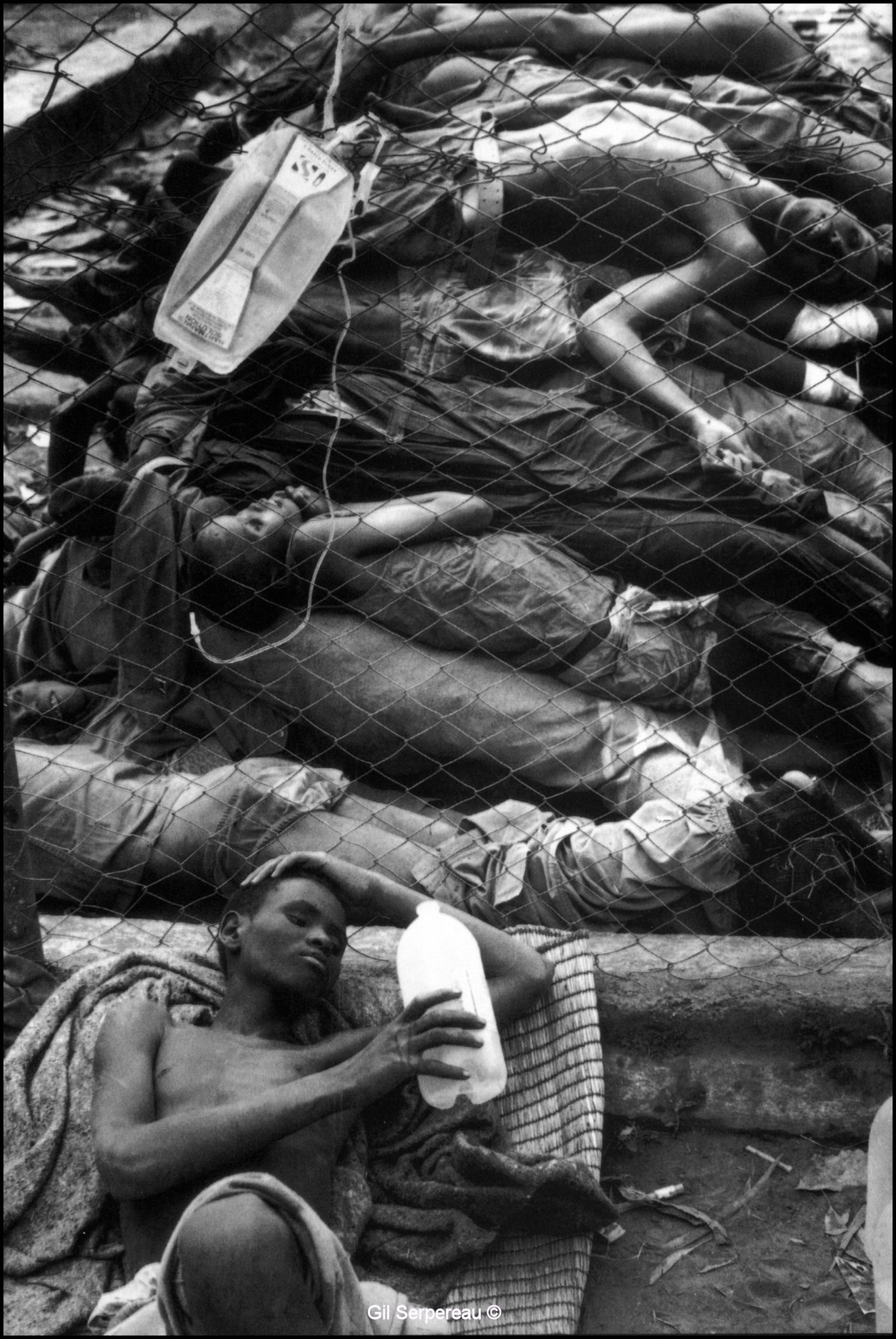

Rwanda genocide, photo by © Gil Serpereau.

Creative Commons License, Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Pictures of victims at the Kigali Genocide Memorial Center, 2012.

Photo by Adm Jones, under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0) license.

- The number of the 1994 refugees

During the final phase of the war, and after the RPF forces took control of Kigali and step-by-step of the entire country, a mass exodus of Hutus began to unfold. Based on data collected before 2000 by Prunier, African Rights, Human Rights Watch, and a United Nations source (Special Unit for Rwanda and Burundi, Information Meeting, Geneva, 16 Nov. 1994), the UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) estimated 2 million Rwandan refugees outside the country at the end of August 1994. This «exodus was far from spontaneous. It was partly motivated by a desire to escape renewed fighting and partly by fear of vengeance on the part of the advancing RPF. It was also the product of a carefully orchestrated panic organized by the collapsing regime, in the hope of emptying the country and taking with it the largest possible share of the population as a human shield. By late August 1994, UNHCR estimated that there were over 2 million refugees in neighboring countries, including some 1.2 million in Zaire, 580,000 in Tanzania, 270,000 in Burundi, and 10,000 in Uganda.

The large camps in Goma, in the Kivu provinces in eastern Zaire, were close to the Rwandan border. They rapidly became the main base for the defeated Rwandan armed forces (…) and members of the Hutu militia group, the Interahamwe. (…). They also became the main base for military activity against the new government in Kigali. From the start, the refugees became political hostages of the former government of Rwanda and its army. The latter’s control of the camps, particularly those around Goma, was undisguised. This created serious security problems for the refugees themselves and it raised difficult dilemmas for UNHCR in its attempt to ensure their effective protection. (…) The refugee camps, especially those in eastern Zaire, were initially in complete disarray. In July 1994, High Commissioner Sadako Ogata described the situation in these terms: “With the rocky volcanic topography and already dense population, the surrounding area is almost totally inadequate for the development of sites to accommodate the refugees. Water resources are severely deficient, and local infrastructure with the capacity of supporting a major humanitarian operation is virtually non-existent”. In July 1994, cholera and other diseases broke out, killing tens of thousands before being brought under control. The Goma camps suffered most» (UNHCR, The State of The World’s Refugees 2000: Fifty Years of Humanitarian Action, Chapter 10: The Rwandan genocide and its aftermath, January 2000; please, see below and the Bibliography).

Goma is the capital of North Kivu province in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zaire, at the time. Human Rights Watch estimated that only in Zaire, in July and August 1994, some 50,000 Hutu refugees died of disease, hunger, and lack of water. Many others were killed by the RPF or during the wars following the genocide.

In addition to the victims of the genocide and the refugees outside Rwanda, some 1.5 million people were internally displaced.

The aftermath of the Rwandan genocide saw tragic sequences of events. It set in the train not just a humanitarian tragedy but political chaos, which included the collapse of the regime of President Mobutu Sese Seko and a civil war in Zaire (renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo in May 1997). The two following Congo wars, the last of which officially ended at the beginning of the 21st century, involved 9 African countries plus 25 armed groups and caused millions of deaths.

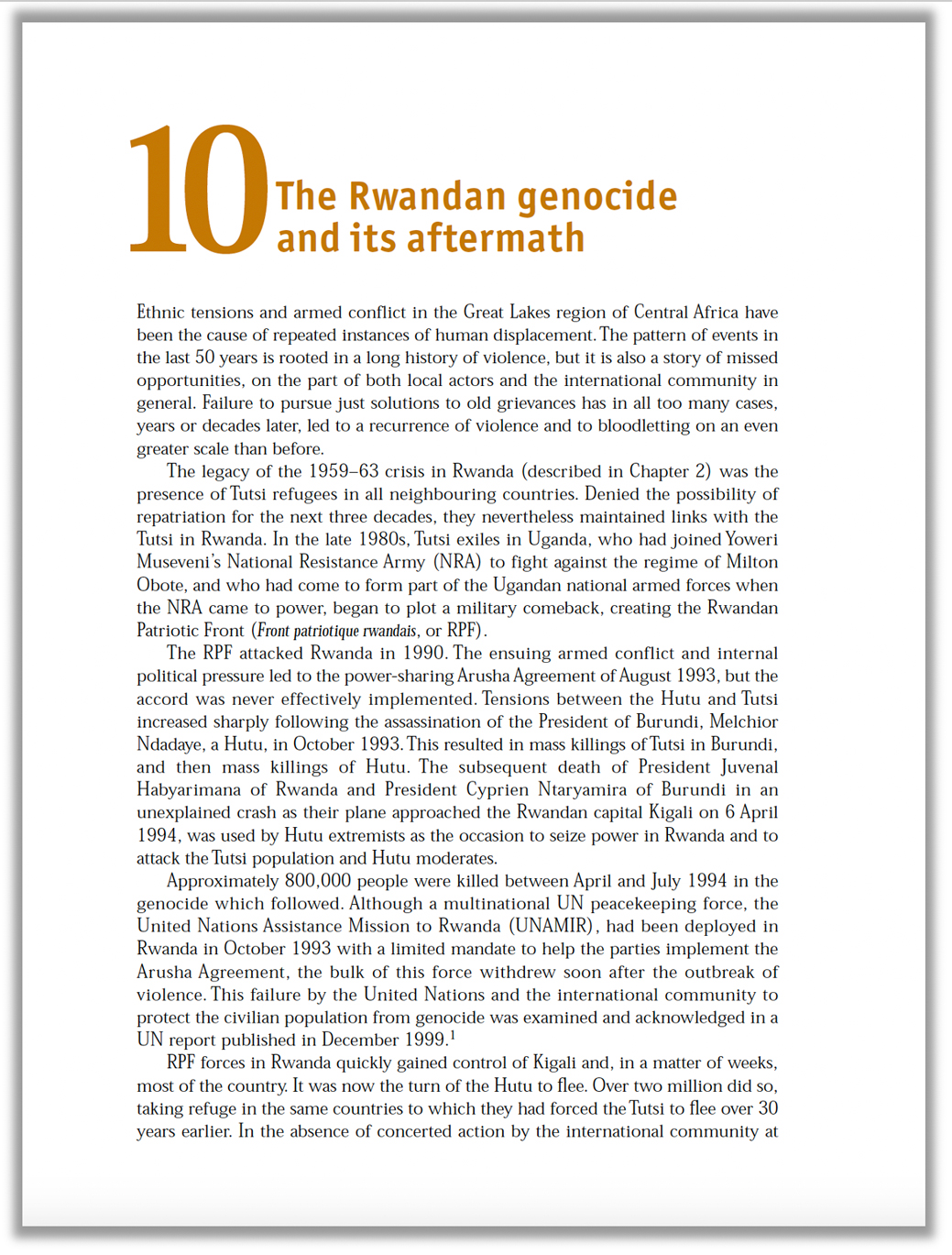

I will not deal with the genocide’s aftermath, which is out of my scope. If you are interested, a good start might be the document below, signed by the UNHCR in 2000.

UNHCR, The State of The World’s Refugees 2000: Fifty Years of Humanitarian Action, Chapter 10: The Rwandan genocide and its aftermath, January the 1st, 2000. It can be downloaded here on the UN Refugee Agency’s website.

Last but not least, let me highlight some usually neglected data about the Rwandan Twa people. They were not the direct target of genocidal violence, nor the génocidaires, and are often marginalized if not, as the Italian scholar Giorgia Donà wrote, «rendered invisible in the dominant account of the genocide’s victims and perpetrators» (“Situated Bystandership” During and After the Rwandan Genocide, see Bibliography).

Many Twas were killed in the 1994 war and genocide. The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization (UNPO) estimates that about 10,000 people, more than a third of the Twa population of Rwanda, were killed and that a similar number fled the country as refugees.

Rwandans fleeing to Tanzania in 1994.

© UNHCR/P. Moumtzis

A view of the Kibumba refugee camp (North Kivu, Zaire).

Photo from the “Series: Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982 – 2007”, US National Archives.

A view of the Kibumba refugee camp (North Kivu, Zaire). An estimated 1.2 million Rwandan refugees fled to Zaire.

Photo from the “Series: Combined Military Service Digital Photographic Files, 1982 – 2007”, US National Archives.

BELOW

Goma camp, Eastern Zaire, 1994.

© Photo by Greg Marinovich

A Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer and filmmaker I really admire, Greg spent 25 years covering conflict around the globe, with his writing and photographs appearing in magazines and newspapers worldwide. He gives lectures and workshops on human rights, justice photography and storytelling. He was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard University in 2013/14 and currently teaches visual journalism at Boston University Journalism school and the Harvard summer school. To know more: Greg Marinovich Photography.

- The victims of sexual violence and genocidal rape

Many journalistic sources say that 250,000 to 500,000 women are estimated to be raped in the final phase of the Rwandan genocide, many of whom were subjected to multiple rapes or gang rape. Is it a reliable figure? An entire chapter, the next one, is dedicated to gender-based violence, genocidal rape and ‘war babies’. So, for the moment, I put this delicate theme in temporary brackets.

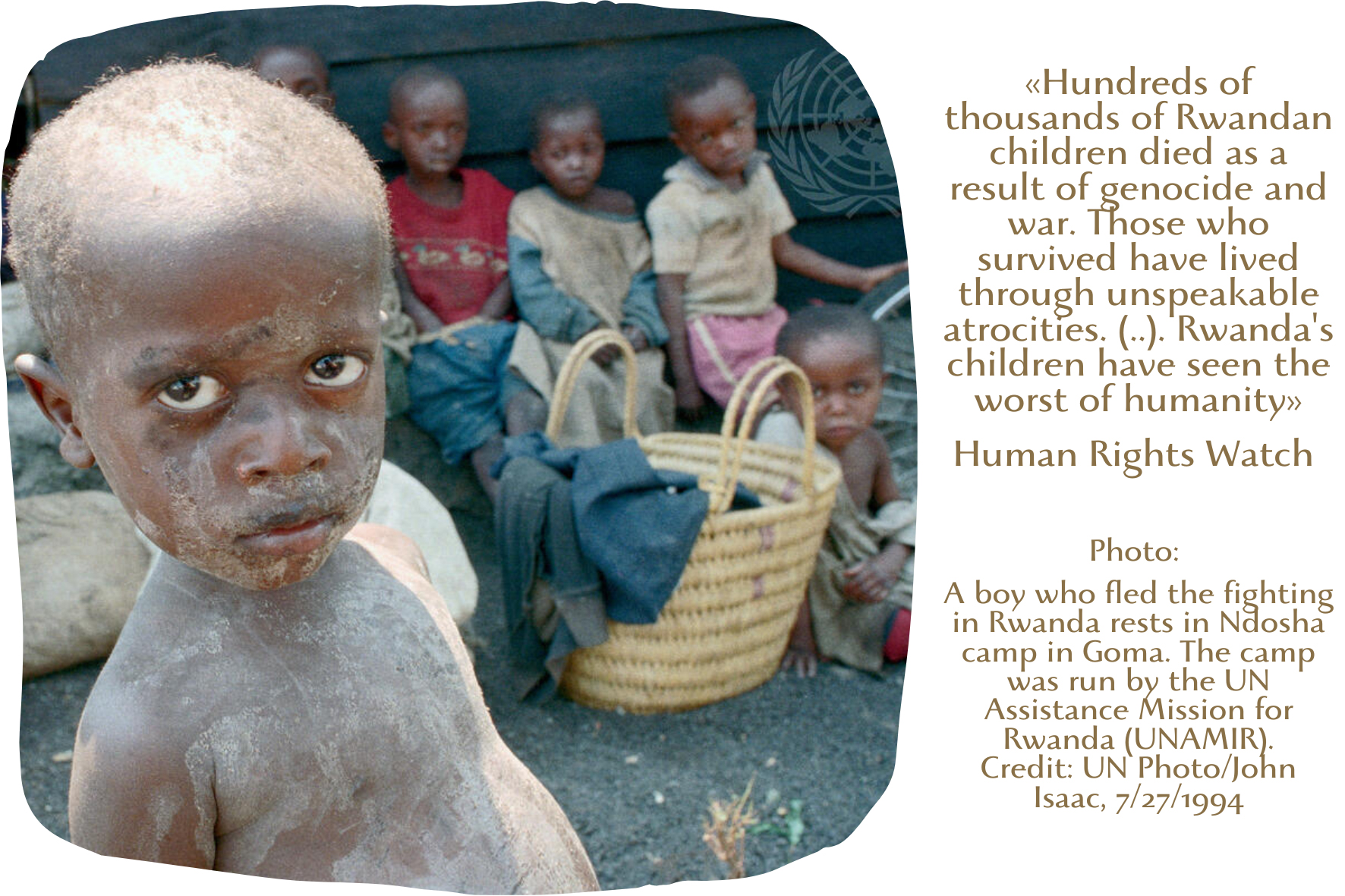

- The tragedies of children

According to the Rwandan document Dénombrement Des Victimes Du Genocide: Rapport Final, 2002-2004, «the proportion of children and youth aged 0 to 24 affected by genocide is 53.77%, higher than that of adults aged 25 to 65, which is 41.32%, except for the prefectures of Kigali Ville and Byumba» (the translation is mine).

The abyss of the Rwandan Genocide and its aftermath come to full light only when we consider what happened to Rwandan children and minors: they have been innocent victims in many ways, each equally atrocious. To understand it, we need to re-categorize the concept of ‘victim’.

Firstly, many thousands of children and minors have been raped (as we will see, the ages of girls raped ranged from as young as 2 years old), tortured, horribly maimed, and eventually slaughtered. Many babies were taken by the feet and slammed against a wall, and not even the fetuses were spared.

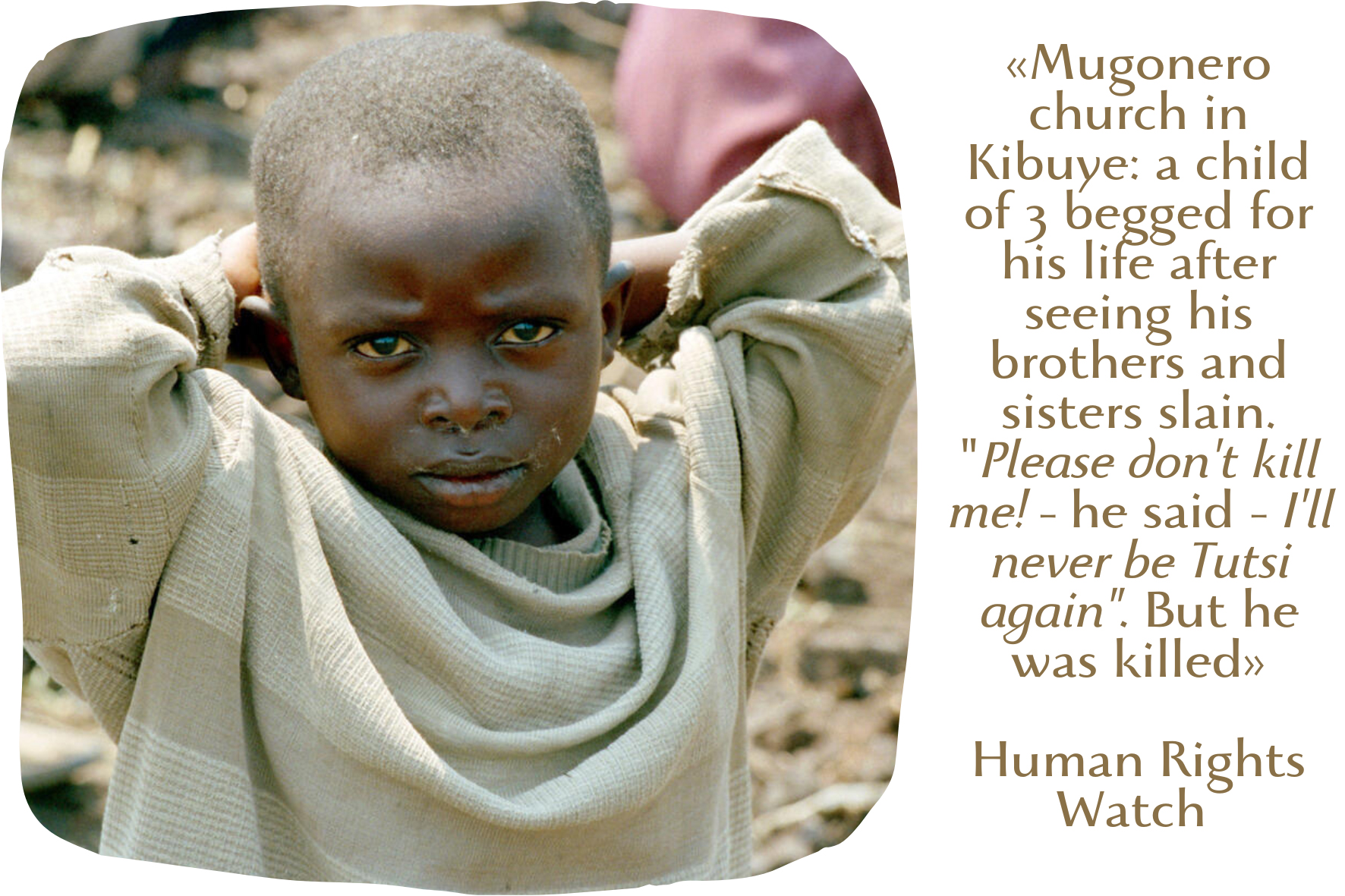

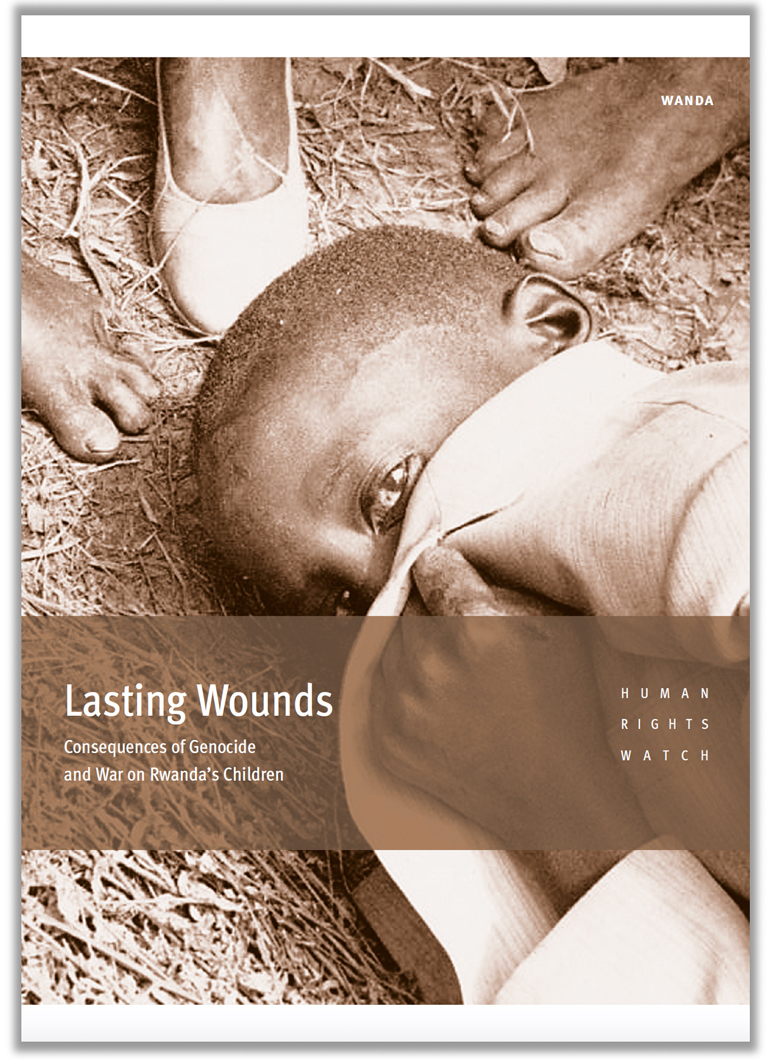

«Those who planned and executed the genocide of 1994 violated children’s rights on a massive scale. Not only did they rape, torture, and slaughter children, along with adults in massacre after massacre around the country. Carrying their genocidal logic to its absurd conclusion, they even targeted children for killing: to exterminate the “big rats” – they said – one must also kill the “little rats”. Countless thousands of children were murdered in the genocide and war» (Human Rights Watch, Lasting Wounds, see above and Bibliography). According to some French official data and Human Rights Watch, among the victims treated by physicians in Western Rwanda, some 30% were children, and most had been injured by a machete. This high percentage is surpassed by another one, even more frightening: some 44% of the bodies exhumed by Human Rights physicians at a mass grave in the Kibuye province were of children under the age of 15, and 31% were under 10. These and similar data show that the killing of the children identified as Tutsis cannot be considered collateral damage: slaying Tutsi minors was a well-defined objective of the extermination campaign (do you remember the Butare case?). The targeting of Tutsi children, even Tutsi babies, and the effectiveness with which this task was carried out give rise to many questions. We’ll talk about that in the following.

Photo: A Rwandan boy in the Ndosha camp in Goma. Credit: UNAMIR – © UN Photo/John Isaac, July 25, 1994

BELOW

Rwanda genocide, photo by © Gil Serpereau.

Creative Commons License, Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Secondly, many Rwandan children were victims of war. «As the RPF fought to take control of the country and defeat the genocidal government, members of its army, too, killed civilians. Most of the victims were Hutu and many of them were children. Some of these killings constituted crimes against humanity» (Human Rights Watch, Lasting Wounds, cit).

Thirdly, the many thousands of children who survived and witnessed the massacres, no matter if Tutsis or Hutus, no matter if still in Rwanda or a refugee camp beyond the border, lost everything they could lose: their family and home, their village, their usual food, horizon, and anchorage, and above all, their childish, innocent eyes. Many of them were physically wounded or sick, and several had been so emotionally and psychologically hurt or shocked by what they saw to show a severe form of post-traumatic stress disorder and be seriously impaired in their growth and development (do you remember Medusa’s head?).

«Many of those who managed to escape death had feared for their own lives, surviving rape or torture, witnessing the killing of family members, hiding under corpses, or seeing children killing other children. Some of these children now say they do not care whether they live or die» (Human Rights Watch, Lasting Wounds, cit). According to a survey of 3,000 children done by UNICEF, 80% of them experienced a death in the family during the final phase of the genocide; 70% witnessed a killing or an injury; 35% saw other children killing or injuring other children; 88% saw dead bodies or body parts; 31% witnessed rape or sexual assault; 80% had to hide for protection; 61% were threatened that they would be killed, and 90% believed that they would die (source: Leila Gupta, UNICEF Trauma Recovery Programme, Exposure to War-Related Violence Among Rwandan Children and Adolescents: A Brief Report on the National Baseline Trauma Survey, February 1996). This math makes me sick.

A huge number of these children were neglected and completely left to themselves. «Perhaps the most devastating legacy of the genocide and war is the sheer number of children left on their own, and the government’s failure to protect them from abuse and exploitation. On Rwanda’s green hills, up to 400,000 children – 10% of Rwandan children – struggle to survive without one or both parents <still in 2003>. Children who were orphaned in the genocide or war, children orphaned by AIDS, and children whose parents are in prison on charges of genocide, alike, are in desperate need of protection. Many Rwandans have exhibited enormous generosity in caring for orphans or other needy children. Yet, because so many Rwandans are living in difficult circumstances themselves, to some, vulnerable children are worth only their labor and their property. Foster families have taken needy children in, but some have also exploited them as domestic servants, denied them education, and unscrupulously taken over their family’s land» (Human Rights Watch, Lasting Wounds, cit).

A forlorn child stands beside a makeshift hut built from the leaves and branches of a eucalyptus tree in the French-protected area, Rwanda, July 27, 1994. UNAMIR – © UN Photo/John Isaac

Fourthly, Rwandan children and teenagers took part in the massacres or the hunting of Tutsis. They are usually counted among the perpetrators, but they are essentially victims. As I wrote, the categorization of victims, perpetrators, and bystanders is not as simple as it appears at first glance. The participation of children in the genocidal massacres was not limited to a few isolated cases: 35% of the children interviewed for a 1995 UNICEF study said they saw children killing or injuring other children (source: Leila Gupta, cit.). «Some 5,000 children were arrested on charges they committed crimes of genocide before they reached the age of 18. Although they garner less sympathy, children who took part in the genocide are also victims. Their rights were violated when adults recruited, manipulated, or incited them to participate in atrocities, and have been violated again by the Rwandan justice system» (Human Rights Watch, Lasting Wounds, cit.). Of these 5,000 minors, approx. 1,000 were under 14 years old in 1994, too young to be held criminally responsible under Rwandan law. Fortunately, they were freed after being transferred from detention facilities to reeducation camps in 2000 and 2001; however, «as many as 4,000 children who were between 14 and 18 years old during the genocide continue to languish in overcrowded prisons» (Human Rights Watch, cit.).

Fifthly, among the children who were ‘victims’ of war, we can count the thousands recruited by force or not, by both armies, especially by the RPF during and after the final phase of the Genocide. These child soldiers turned into mere tools of violence and death are victims as well, and their lives were marked by serious mental disorders, depression, and psychiatric illness.

«The RPF used thousands of kadogo <“little ones” in Swahili>, or child soldiers, in its ranks as it sought to topple first the government of former President Habyarimana and later the genocidal regime. A 1996 Rwandan government study identified 5,000 children who had been part of the RPF forces, 2,600 of whom were under 15 years of age at the time of their military service. Under international pressure to demobilize and rehabilitate the children, the new Rwandan government established a “Kadogo School” at the Non-Commissioned Officers School in Butare in 1995. Some 3,000 children received an education, material assistance, and help with family reunification from 1995 through 1998. Approximately 800 of them later attended secondary school at government expense» (Human Rights Watch, cit.).

Rwanda, child soldiers

The following video is an interview with former UNAMIR commander, General Roméo Dallaire, and Shelly Whitman on child soldiers in Rwanda and Africa. Shelly Whitman is the Executive Director of The Dallaire Institute for Children, Peace and Security since January 2010. The Institute, also known as Roméo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative, is an institute at Dalhousie University that works to end the recruitment and use of child soldiers, founded by Roméo Dallaire and Jacqueline O’Neill in 2007, and based in Halifax, Nova Scotia with offices in Kigali (Rwanda) and Juba (South Sudan).

I quoted many passages from a 2003 complex document by Human Rights Watch that recounts the widespread abuse and exploitation of children that have continued to plague Rwanda since the 1994 genocide, and recommends some steps the Rwandan government should take to protect minors.

Rwanda Lasting Wounds: Consequences of Genocide and War for Rwanda’s Children, by Human Rights Watch, March 2003, Vol. 15, No. 5 (A). The volume can be downloaded here, on the Human Rights Watch website.

Children who fled the fighting in Rwanda rest in the Ndosha camp in Goma. Many of them had witnessed the killings of their parents and were crying for their mothers.

Credit: ©UN Photo/John Isaac. Date: 7/27/1994.

I’d like to conclude this excruciatingly painful chapter with a story of children, resilience, healing, and rebirth: it’s the story of three kids, Jean Bizimana, Mussa Uwitonze, and Gadi Habumugisha, all orphans of Rwanda’s genocide, who passed through the horror, overcame pain and became peace builders and professional art photographers. The story is told by a documentary entitled Camera Kids, directed by Beth Murphy, co-produced with The GroundTruth Project and supported by Chicken & Egg Pictures, Mass Humanities, Artemis Rising, TEDWomen, and Journeys in Film. Here’s the emotional trailer.

Niragira – Murundikazi, feat Joy Slam & Nicole Irakoze; choreography by Axelle Munezero, 2020.

Alex Niragira is a Burundian visual storyteller, artist, music producer, and entrepreneur based in Rwanda. To me, he is one of the most intriguing artists in Kigali. Axelle “Ebony” Munezero is a Burundian choreographer and dancer living in Canada. The music & lyrics are by Gioia Kayaga and Nicole Irakoze. The latter is a Rwandan singer, musician, and teacher at the Music School in Kigali, while Gioia Kayaga, aka Joy Slam, is a Belgian slam poet and performer from Wallonia; her family roots lie in Belgium as well as in Italy and Burundi.

The song is a tribute to the brave and big-hearted women who become mothers of lost children, children of blood, and war orphans.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?