Rwandan Basketry 8

Rwanda on the globe

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE: WHO KILLED HABYARIMANA?

THE FRENCH TECHNICAL DOSSIER

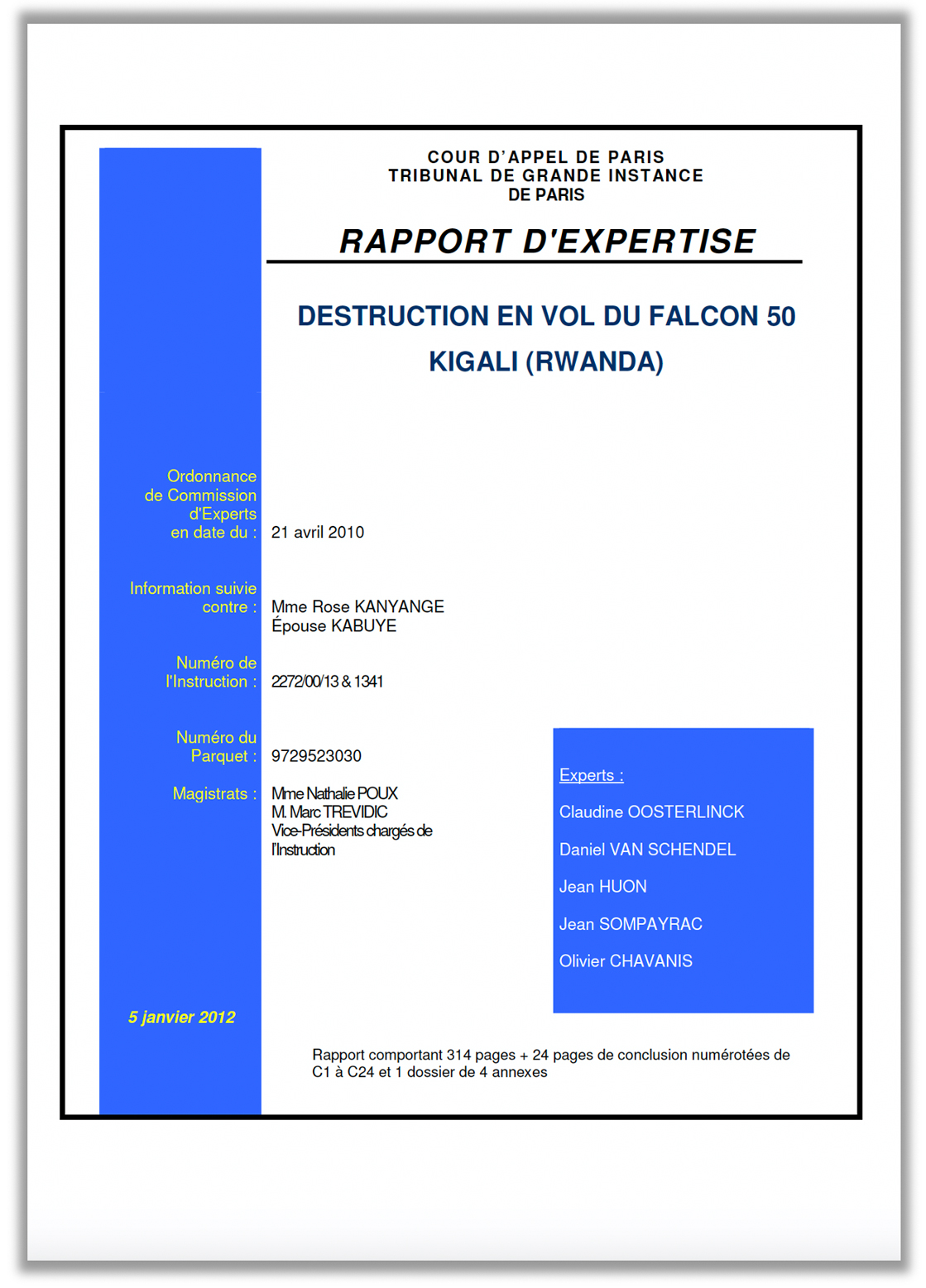

In 2010, two French Magistrates of the Parisian Tribunal de Grande Instance, Marc Trévidic et Nathalie Poux, charged with the investigation of the case opened by Judge Bruguière, suspended the arrest warrants for the nine Rwandan officials and instructed a panel of 6 French independent experts to carry out an in-depth technical investigation on the crash site, the Falcon 50 jet wreckage, and the areas of Kanombe and Masaka Hill in Kigali. The team included experts in missile technology and aviation, an air accident investigator, a geometrician specializing in topographic surveys, an explosives expert, and an acoustics engineer whose task was to analyze the sound waves produced by the missile launchers to better locate the shooting area. Their multidisciplinary report was ready on January 5, 2012. Here it is.

The official technical report entitled Rapport d’Expertise sur la destruction en vol du Falcon 50 Kigali (Rwanda) was drawn up by a panel of independent experts appointed and charged by the investigating magistrates of the Tribunal de Grande Instance de PARIS. It was published in 2012, and signed by the following experts:

-

Claudine OOSTERLINCK, an aviation expert, Falcon 2000 instructor, airline chief pilot, and an expert in Transport Law and Air Safety at the Caen Court of Appeal;

-

Daniel VAN SCHENDEL, an expert in explosives and explosions, and a legal expert at the Toulouse Court of Appeal;

-

Jean HUON, one of the French top experts in weapons, ammunition, and ballistics, author of over 1 500 articles and 70 technical works on this military topic; a legal expert at the Versailles Court of Appeal, approved by the Court of Cassation.

-

Jean-SOMPAYRAC, a surveyor-expert, specializing in planimetric and topographic surveys.

-

Olivier CHAVANIS, an engineer and an expert in aeronautical armaments (anti-aircraft weapons and aviation weapons) and on-board pyrotechnics; member of the National Company of Arms and Ammunition Experts near the Paris Courts of Appeal;

-

Jean-Pascal SERRE, an acoustics engineer.

This report (only in French) can be downloaded here, on the France – Génocide – Tutsi website.

Here there are the most remarkable results of the French investigation.

- Shooting down the plane

Two missiles were fired against the plane with a lag time of 2-3 seconds. The first one missed the target and continued its race on the trajectory for approximately 15 seconds until self-destruction. The second missile hit the plane on the underside of the left wing, near the fuselage. The detonation of 400 g mass of octogen-based explosive contained in the missile head ignited the kerosene in the left-wing fuel tank. The Falcon 50 was hit when approaching the landing strip, flying at 222 km/h, at an altitude of 1,646 m (± 40 m). Immediately after being hit, it became a ball of fire in the night sky. The horizontal distance traveled by aircraft between the missile impact and the crash on the ground is approx. 400 m. The plane fell in 7 seconds and struck the ground still on fire with a speed of 68 m/s and at an angle of about 31.3 degrees. Its debris was scattered inside and outside the boundary wall of the presidential residence, over a length of 145 m and a width of 20 m approximately. The low dispersion and the condition of the debris make the experts exclude the complete disintegration of the aircraft in flight; however, its integrity was greatly altered. The three jet engines were not deformed by the effects of the explosion, and the damages they showed were due to the brutal impact on the ground only. The empennage, the rear fuselage section, and the tail cone were not deformed by the explosion as well.

- The missiles

The experts analyzed 53 anti-aircraft weapons systems from several points of view, including their availability in Rwanda at the time. The presidential plane was shot down by two MANPADS, most likely Soviet-made Igla1 SA-16 shoulder missiles. It is less likely that the Soviet Igla SA-18 or the American Stinger 92A were used, while the employment of other types of missiles or weapons is excluded based on different factual considerations.

[PLEASE, NOTE: MANPADS are man-portable air-defense systems. The 9K310 Igla-1, aka SA-16 Gimlet, are small surface-to-air missiles. They are typically infrared homing weapons, which use the infrared light emission from a target to track and follow it. They are often called “heat-seekers” since infrared is radiated strongly by hot bodies and these anti-aircraft missiles use infra-red seekers to home in on the hot exhaust pipes of jet engines. They are designed to be kept on a soldier’s shoulder and can be fired at a low-flying aircraft from almost any direction, excluding the front. They have a high success rate but need to be used only by specifically trained and skilled operators].

The infrared radiation emitted by the three jet engines could be detected by the ‘heat-seeker’ S-16 missile whether the latter is positioned at 45, 90, 135, or 180 degrees up to a distance of max. 3000 m (considering the weather conditions of that moment). By firing from the front, at 0 degrees, the thermal radiation of the reactors is largely masked, therefore this shooting angle can be excluded and some limits can be safely established as to the possible shooting areas. Given the above-mentioned possible angles, the shooters had only a lapse of time of 1m 30s to 2m 30s to perform all the shooting maneuvers.

- The shooting area

«The study of firing positions is strictly based on:

– the scientific aspects of infrared radiation: emission of the source and detection by the missile

– acoustic studies

– the operational performance of the missile: firing and ballistics

– field surveys

The perceptions of the events by the witnesses will be analyzed afterward to establish whether or not they are likely to support some of our technical results» (Expertise). To prevent any possible controversy, the French experts declared to use the verified testimonies only to confirm or discuss their scientific and technical conclusions. On this basis, they investigated six possible firing positions for attackers.

The first relevant finding is that no zone of Masaka Hill could have been the shooting position for many different irrefutable reasons, including the following two:

1. The missile fired from Masaka Hill would have been guided by its infra-red sensors to an engine and would have impacted most probably the left one, less probably the central. The analysis of the debris, however, leaves no doubt: the three engines were spared by the effects of the missile explosion. Moreover, since the missile fired from Masaka Hill would not have impacted the underside of the left wing and would not have caused any damage to the left-wing fuel tank, the kerosene would not have exploded, forming a fireball. The latter, however, was seen in the sky by many witnesses and left many traces of calcination on the left wing debris.

A Dassault Falcon 50 airplane

2. That night, the Belgian army medical lieutenant colonel Massimo Pasuch, billeted in the Kanombe military camp thanks to the technical military cooperation between Belgium and Rwanda, was at home, located approx. 300 m from the presidential residence, with his wife Brigitte Delneuville, their guests Denise Van Deenen and Ghislain Daubresse. They all gave interesting testimonies. Lieutenant colonel Massimo Pasuch could distinctly hear the characteristic missile “whoosh”, their orange plume, the fireball, and the plane on fire crashing into the nearby ground. If the missile were fired from different positions within the area of Masaka Hill, like ‘La Ferme’, the sounds of the missiles’ firing could not have been distinctly heard, due to the distance of these positions from the reference tell-tale <more than 2 km>. Moreover, the sound of these shots could have been heard by any witness in the Pasuch’s house from 0.45s to 1.50s after the visual perception of the explosion of the aircraft <the variation depends on the specific position on the Masaka Hill> and not before, as per the firing position inside the Kanombe camp (see Expertise, C23).

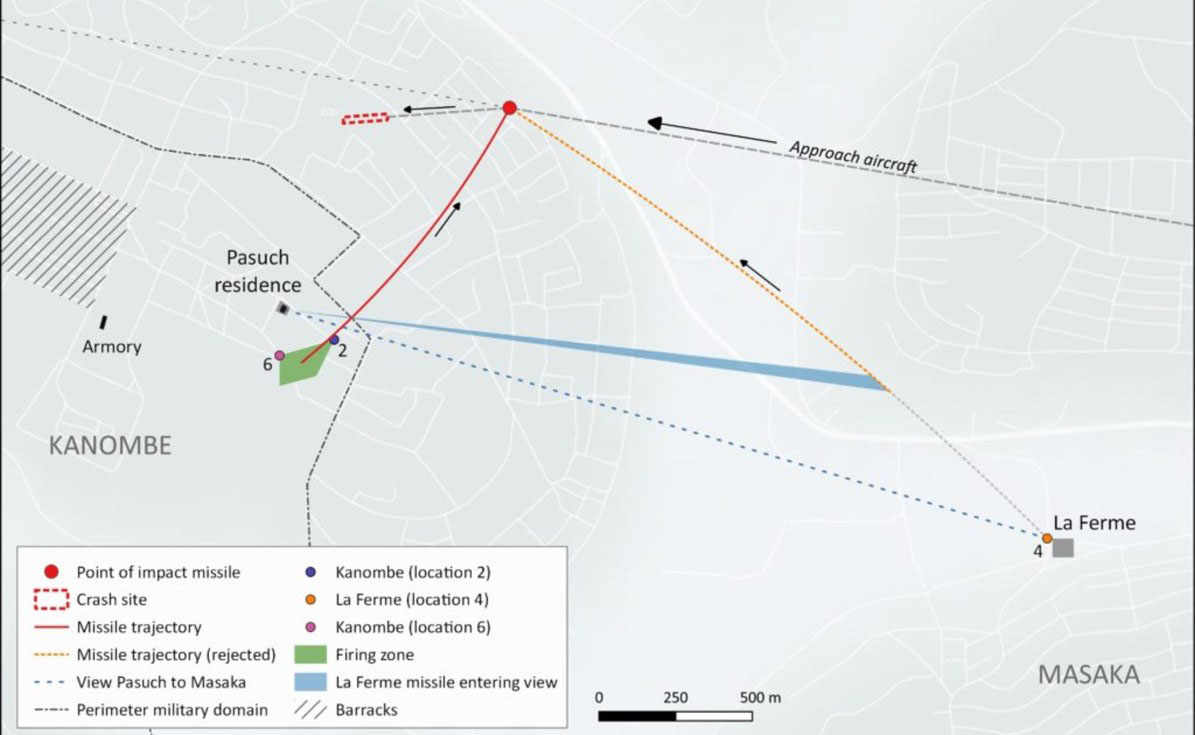

After considering the system of objective and consistent data emerging from cross-multidisciplinary studies, the possible shooting positions can only be located within the perimeter of the Kanombe military camp, near the current cemetery, with an approximation of ± 100 m. Here, the two shooters, placed at a distance ranging from a few meters to about 20 m, aided probably by some assistants, fired the missiles that shot down the presidential plane.

Here’s the best and most accurate map I’ve found. It was sketched by Jos van Oijen, a Dutch independent researcher and author of an interesting article, Michela Wrong’s retelling of the untold story of Rwanda, published In September 2021, on different websites on the Internet.

The French Rapport d’Expertise did not propose any historical reconstruction and avoided any political analysis: its conclusions were technical, correctly proven, and scientifically sound. Its findings give solid support to the technical conclusions of the Mutsinzi Report.

In the video below, you can follow an interview made in 2018 with Guillaume Ancel on the Habyarimana assassination and the technical findings of the 2012 Rapport d’Expertise. Guillaume Ancel was a former French Lieutenant Colonel. In the 1990s was assigned to the 68th African Artillery Regiment (68°RAA) at the La Valbonne camp, in France. He was trained in airstrike guidance as a Forward Air Controller (FAC) and head of the Tactical Air Control Party (TACP). He was deployed in Rwanda in June 1994 with Opération Turquoise as TACP to carry out close guidance of airstrikes. He’s an expert who well knows Rwanda and the technical details linked to the surface-to-air missiles that shot down the Habyarimana’s Falcon 50. Many times he refers to the Rapport d’Expertise and makes relevant comments.

The interview with former Lieutenant Colonel Guillaume Ancel is in French, without English subtitles; therefore, here’s my translation.

«I’m an expert in MANPADS, man-portable air-defense systems, and shoulder surface-to-air missiles. I entered the French Army and that was my specialty. I can say I’ve tested, employed in operations, and destroyed in operations several systems that used these special missiles. Let me, however, make it clear that I have no direct information on the assassination of President Habyarimana. I was not in Rwanda <at that time> and my military unit was never involved in the case. What I’m going to say is based on my expertise and my reading of the Rapport d’Expertise commissioned by the French Justice.

Only in 2012 a complete report, drafted by the best experts on the subject, came out. This report impressed me for its relevance, but what surprised me the most is that it had no operational conclusions whatever: it remained on a purely technical aspect. (…)

In particular, with regard to the missiles used, they were probably SAM <surface-to-air-missiles> SA-16 <Soviet Igla-1 system>. At that time, they were on sale everywhere in the world. After the end of the Warsaw bloc, you could buy a full set of missiles for a hundred thousand dollars. Therefore, just saying they were SAM 16 doesn’t give any indication of their origin and provenance. In France, at the time, we had some of them, which I could test in 1991 to make a comparison with French Mistral missiles <Mistral are French-built infrared homing MANPADS>.

So we know that the missiles were SAM-16. What is most striking was their shooting: they were fired by two perfectly synchronized shooters on a target flying at night. It had to be very difficult to estimate the distance of the aircraft; moreover, there was a short firing window of 2 to 3 minutes, no more. The shooters were perfectly informed and completely protected. Nobody saw them and they left nothing on the site. They had to make some recces, probably several <by day, not by night>. They were professionals. They fired near the Kanombe training camp of the Rwandan para-commando battalion. Do you still doubt about the ‘side’ of the shooters?

When you fire at night, the plume of a missile like the SAM-16 is more than 5 m long, and it’s impossible not to see it within a radius of 2 km. The shooters were not found <by the Kanombe military personnel> simply because the shooters and military personnel were from the same side. Why all the controversy about the shooters? No way! They fired from the Kanombe camp, the side of Hutu extremists. (…)

It seems very clear to me today who was behind the shooting. However, we must make no mistake: it is not because there was this shooting against President Habyarimana that there was a genocide; <the attack> was a simple trigger. Everything was already organized, structured, planned, and tested. And what is even more worrying is that the French observed this preparation and these plans. They permanently had advisers at the highest level of the government, and I am sure that my comrades at the time reported these facts. (…). However, all those who dared to say that we could not continue because our military assistance was extremely dangerous and endangered the image of France were systematically sanctioned and dismissed. (…). Imho and from a purely technical point of view, the shooters were Hutu extremists. It’s a plain fact.

If we had been able to recover the black box immediately <after the crash>, we could have reconstructed the trajectory of both plane and missiles. <We couldn’t> and we had to wait until 2012 for the report, a work made by experts during some years. (…) What about the black box? I think the French made it disappear because they received the order immediately after the attack; a French general I know was there <on the crash site> and probably took the black box. I’m not saying and I don’t want to say that France is behind the attack. These facts only prove that we have done everything to cover our tracks. What is very disturbing is that in the weeks that followed <the assassination>, the direction of French military intelligence published a photo with two SAM-16 missiles whose numbers of identification correspond to stocks coming from an ally of the RPF. What nonsense! What a ridiculous masquerade! Had we been able to carry out a search in the area where the missiles were fired, we could probably have found their launchers. These pieces were made practically one by one and are therefore perfectly identifiable: they could have helped us to identify the two missiles as well. (…) In any case – I wanna say it one more time – SAM SA-16 were available almost everywhere to those who could pay their price. On the other hand, those missiles had to be in perfect working order, and the shooters professional soldiers.

There’s another issue I’ve always found quite surprising, an issue related to the firing of missiles against President Habyarimana’s plane. In those years, in the first half of the 1990s, everyone exercised strict control over man portable missiles, especially the French. Those missiles were and are weapons for attacks. I can’t understand how this attack, in particular, could have been prepared – because it had to be planned and prepared, preceded by specific recces to define the area where the missiles were going to be fired. I can’t understand, I was saying, how this attack could have been prepared while escaping the French secret services. I think they are too professional and top-level to pass these preparations unnoticed: they must have noticed all of them and warned the French government. Two possible hypotheses, then: either this alert drowned in an incessant flood of many alerts (..) and was discarded, or France had an interest in seeing President Habyarimana disappear because his control <over the country> had begun to loosen. The latter is a dramatic hypothesis and only the opening of the archives would allow us to know what happened. I simply point out a fact – and I am not a conspiracy theorist: the day after President Habyarimana’s assassination, President Mitterrand’s Africa adviser, François Durand de Grossouvre, committed suicide at the Elysée. Well, in my world there is no coincidence».

Let me say here that I fully agree with Ancel on a key point: the multidisciplinary technical analyses conducted by two different teams of experts (French and British), in different periods (2007-2009 and 2010-2012), with multiple on-site surveys, offer a series of incontrovertible pieces of evidence. Given these findings and the location of the roadblocks in the Kanombe area of Kigali on April 6, 1994, it’s obvious that only RAF soldiers or mercenaries connected to the RAF could carry out the necessary recces by day and the final attack by night.

What Guillaume Ancel says in the interview can be easily verified, at least in part. In the video below, you can observe the training of some Russian soldiers with SAM SA-16 missiles, similar to those used against Habyarimana’s plane. The noise of the shooting is quite intense and had to be well heard in the Kanombe area of Kigali, during a moment of stillness and silence (there was no air traffic when Habyarimana’s Falcon was hit). The video, moreover, clearly shows the intensity and visibility of the missile plume by the day and at dusk. You can imagine how it could be eye-catching in the complete darkness of a poorly lit city like Kigali at the time.

PLEASE, NOTE:

From 1975 to 2019, over 60 civilian aircraft have been hit by surface-to-air missile platforms known as man-portable air-defense systems (MANPADS), resulting in the deaths of over 1,000 civilians. Terrorist groups like al-Qaeda, the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, and Lebanese Hezbollah are deemed to possess MANPADS, presenting an ongoing concern for civilian air travel in the modern political climate.

Do you think that a group of RPF specialists could have carried out a recce mission in daylight in the most patrolled, controlled, and militarized strategic area of the entire city? Do you think they could have easily entered a tightly controlled military base with an estimated 4,000 troops, a training and billeting area for three elite units, namely Presidential Guard, the Para-Commando battalion, which included the Commandos de Recherche et d’Action en Profondeur (CRAP), and the Anti-Aircraft battalion (LAA)?

Yet, even recently some scholars and journalists (Helen C. Epstein, Judi Rever, Laurie Garret, Michela Wrong, to name only a few) continue to support the responsibility of the RPF whose soldiers allegedly fired from someplace in Masaka Hill. Some of these accusations come from authors extremely critical of RPF’s unaddressed crimes and the repressive regime of Paul Kagame after the Genocide. I think we must neatly separate the evidence related to Habyarimana’s assassination from any criticism of Kagame. There’s no evidence to prove that the Rwandan Patriotic Front killed the President but there are many pieces of evidence to prove the responsibility of the hardliners’ military lobby. Supporting this reasonable position does not entail any uncritical acceptance of the Rwandan official portrait of Kagame as an immaculate savior and patron saint of Rwanda.

There is no mystery on the responsibility of Habyarimana’s assassination but there are still many unanswered questions on the role of Agathe Kanziga, Habyarimana’s wife, and on the role of the Mitterrand government and the French secret services, as Guillaume Ancel said in his interview.

The French secret services alerted the Congolese President and dictator Mobutu Sese Seko of imminent danger and put on the lookout for the French crew of the Falcon 50. Did they witness unusual recces in the Kanombe area? Did they know anything about the attack? Did they alert Habyarimana as they did with Mobutu? And if they did it, why Habyarimana decided to give a lift to the Burundian President and come home that night facing a risk of multiple deaths?

In the Kanombe military camp, there were many Belgian and French officers linked to a project of technical military assistance cooperation that had nothing to do with UNAMIR. As I wrote, the most senior French officer was Commandant (currently Général) Grégoire de Saint-Quentin, who was an adviser to Major Aloys Ntabakuze, head of the para-commando battalion at Kanombe. Saint-Quentin and two sub-officers went to the crash site at 8.45 pm, only 15 minutes after the attack, as declared in Record No. 543/DEF/EMA/ESG by the French Ministry of Defence dated 7 July 1998. He came back to the site a second time, at 8.00 am on April 7. Did he find the black box? Did he see who took the black box that has never been found since then?

[The story of the black box is complicated. In 1995, Dassault Falcon Service, the French manufacturer of the Presidential Falcon 50 and the company responsible for the maintenance of Habyarimana’s Falcon 50, declared no black box was installed on the plane. On June 19, 2001, the company made a complete turnaround on its position, admitting in an information note provided to the French courts that “the presidential jet was indeed equipped with a Cockpit Voice Recorder». According to The Mutsinzi Report, many witnesses saw a French official collecting the black box early in the morning, on April 7. True or not, there was a black box and the French or Rwandan military member/s who were allowed to enter the crash site found it, took it, and hid it forever].

Guillaume Ancel refers to the mysterious death of Mitterrand’s Africa adviser, François Durand de Grossouvre, who, according to the official version, committed suicide at the Elysée on April 7, shortly before 8 pm. Within a few hours, his archives at home and the Elysée disappeared (de Grossouvre had been Mitterrand’s shadow man for many years and knew many unspeakable secrets). The investigation was hasty and the autopsy was full of inconsistencies (de Grossouvre was right-handed but suffered a hemorrhagic dislocation of his left shoulder immediately before dying). His family, some journalists, and some experts, including François Graner, member of the Survie NGO, co-author of the essay L’État français et le génocide des Tutsis, began to suspect he had been killed and suggested a likely African lead. De Grossouvre had been an international councilor of Dassault Aviation in 1985-1986, Africa adviser of the French President, often in opposition to Jean-Christophe ‘papamadit’ Mitterrand, and supervisor of agent Paul Barril. Moreover, he knew Habyarimana. Does his death on April 7 have anything to do with the shooting down of Habyarimana’s plane on April 6, or is it just a coincidence?

CHRONICLE OF A DEATH FORETOLD

There are other irrefutable pieces of evidence indicating who killed Habyarimana.

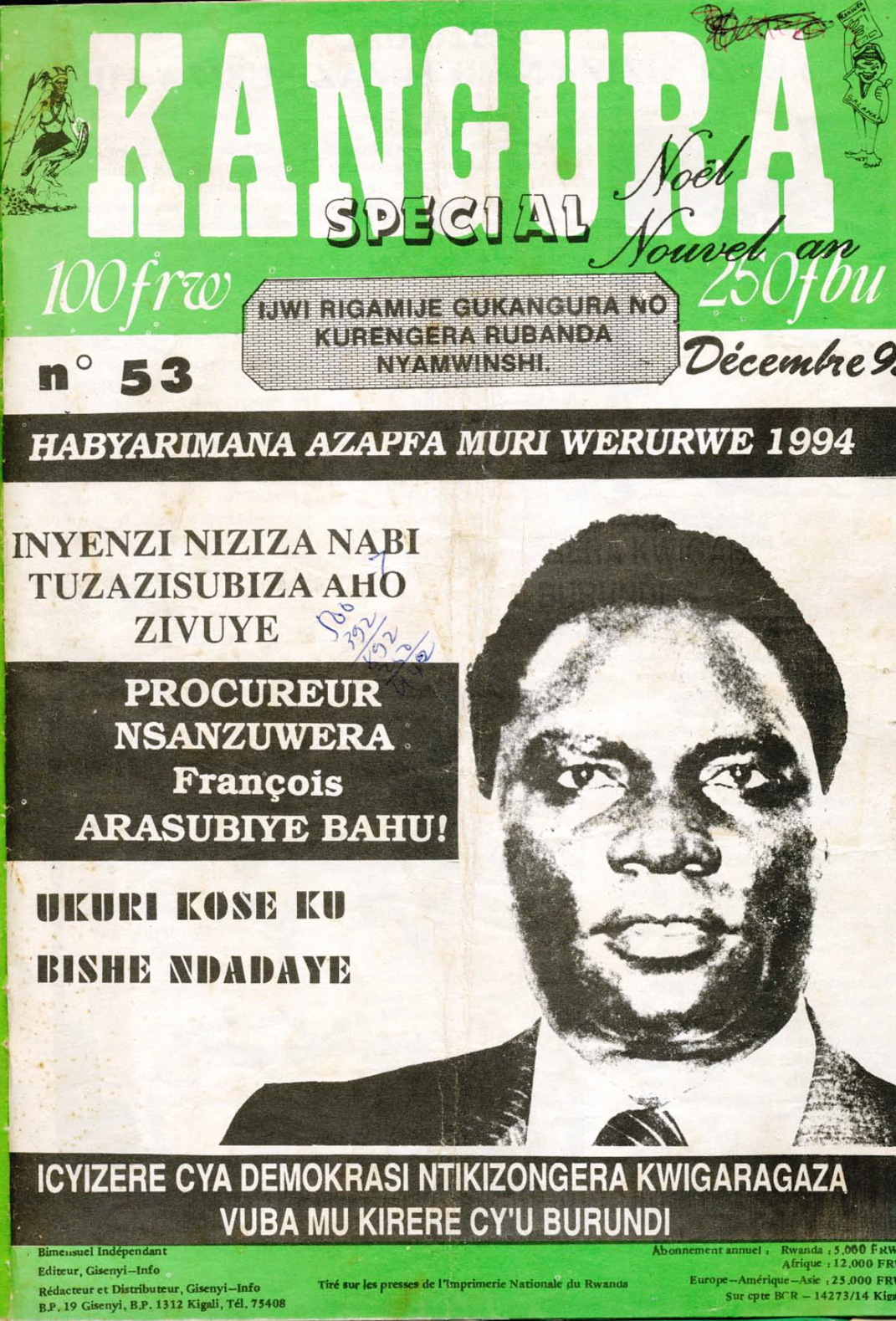

Let’s see a special issue of Kangura, the no. 53, published in December 1993. Here’s the cover.

The photo of President Habyarimana dominates the cover (the first sign of maximum relevance) and his story is screamed on top (the second sign of maximum relevance): HABYARIMANA AZAPFA MURI WERURWE 1994, whose English translation is “Habyarimana will die in March 1994”.

The other screaming headlines on the cover are the following (top to bottom):

INYENZI NZIZA NABI TUZAZISUBIZA AHO ZIVUYE / “We will send the Inyenzi back to where they came from”

PROCURER NSANZUWRA FRANÇOIS ARASUBIYE BAHU! / “Prosecutor François Nsanzuwra is back!”

UKURI KOSE KU BISHE NDADAYE / “The whole truth about the killers of Ndadaye”.

[All translations are mine, as always]

“Habyarimana will die in March 1994”. What does it mean? The answer is in an article signed by Hassan Ngeze, the editor-in-chief of the magazine, on page 3 (the third sign of maximum relevance). The title: “Habyarimana will die in March 1994”.

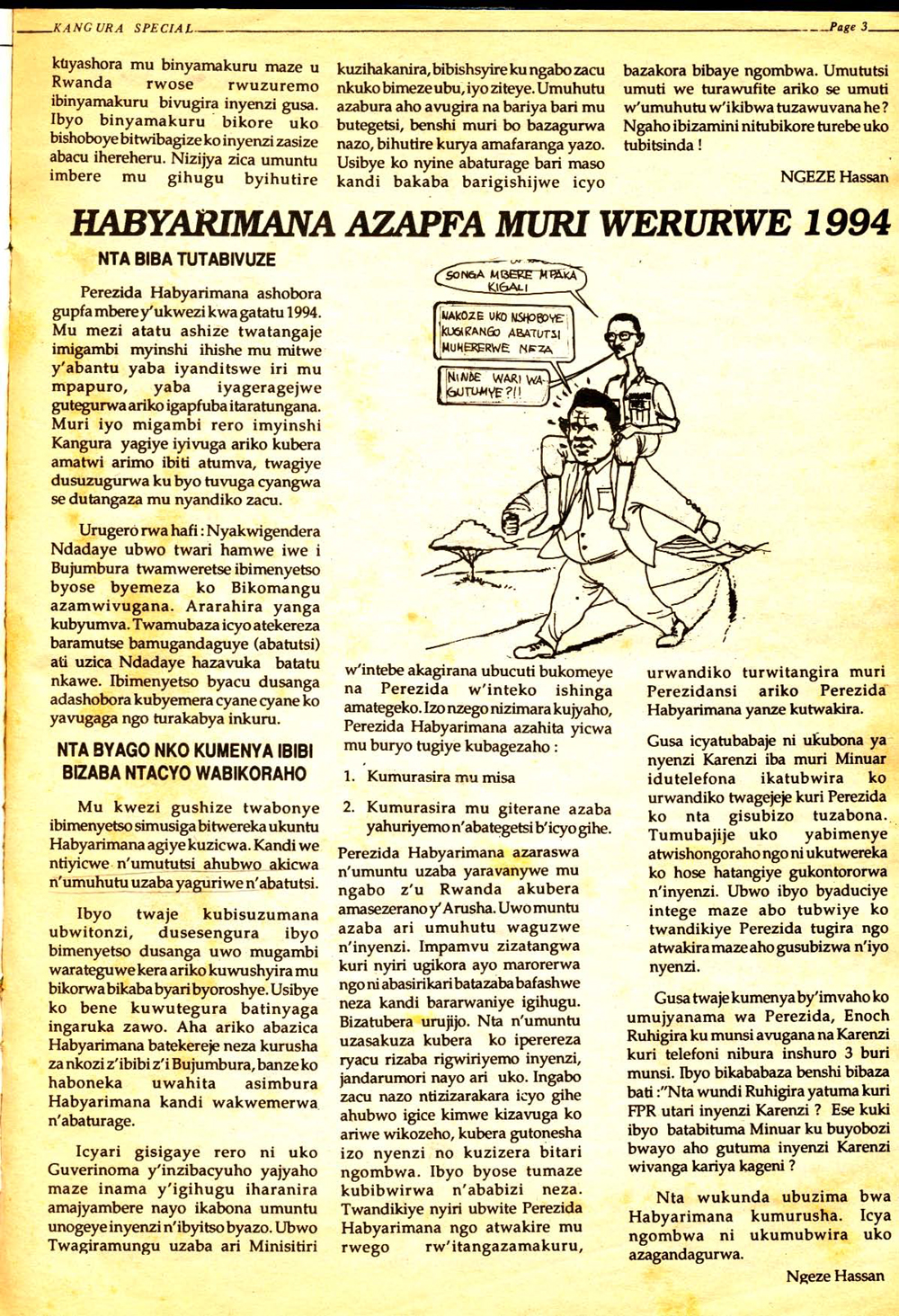

The article reads: “Last month we obtained irrefutable pieces of evidence demonstrating how Habyarimana is about to be assassinated. He will not be murdered by a Tutsi but by a Hutu bribed by some Tutsi!”. Ngeze writes that Habyarimana will be assassinated as soon as both the Transitional Government under the prime minister Faustin Twagiramungu and the Parliament will be set up, two institutions whose implementation is established by the Arusha Accords. “President Habyarimana will be killed in the following way: 1. he will be shot during a Mass; 2. he will be shot during an important meeting with some leaders of the time. He will be killed by one of the RAF demobilized soldiers. This mobilization is expected and planned by the Arusha Accords, and this person will be a Hutu bribed by the Inyenzi. The motive attributed to this abominable act will be linked to the fact that the killer will be one of those ill-rewarded, badly treated soldiers who nevertheless had fought and defended our country <during the war>. (…). No one’s going to complain or protest because our intelligence services and the Gendarmerie will be largely in the hand of the Inyenzi. Our soldiers won’t get too much angry at the news <of Habyarimana’s assasination>. Many of them, indeed, will approve and say that he is the cause of his death because of the undue favors and the trust he has been granting to the Inyenzi”.

Even if it starts with the tone of a lead giving a piece of breaking news to its readers, the article turns out to tell a completely different story. It does not give a piece of news, and there’s no scoop. The article preconizes the murder of Habyarimana in the scenario planned by the Arusha Accords. The meaning of what Ngeze writes is simple: the President will be killed if he starts implementing the Accords, kicking off not only the political institutions provided for by the Second Protocol but also the merging of the two armies and the consequent demobilization of 50% of the RAF, as per Fourth Protocol.

Habyarimana will be killed if… that’s simple. There’s no news here, no revelation from an unknown whistleblower, just a warning to Habyarimana, a veiled death threat in the arrogant style of the Serubuga-Bagosora-Rwagafilita trio.

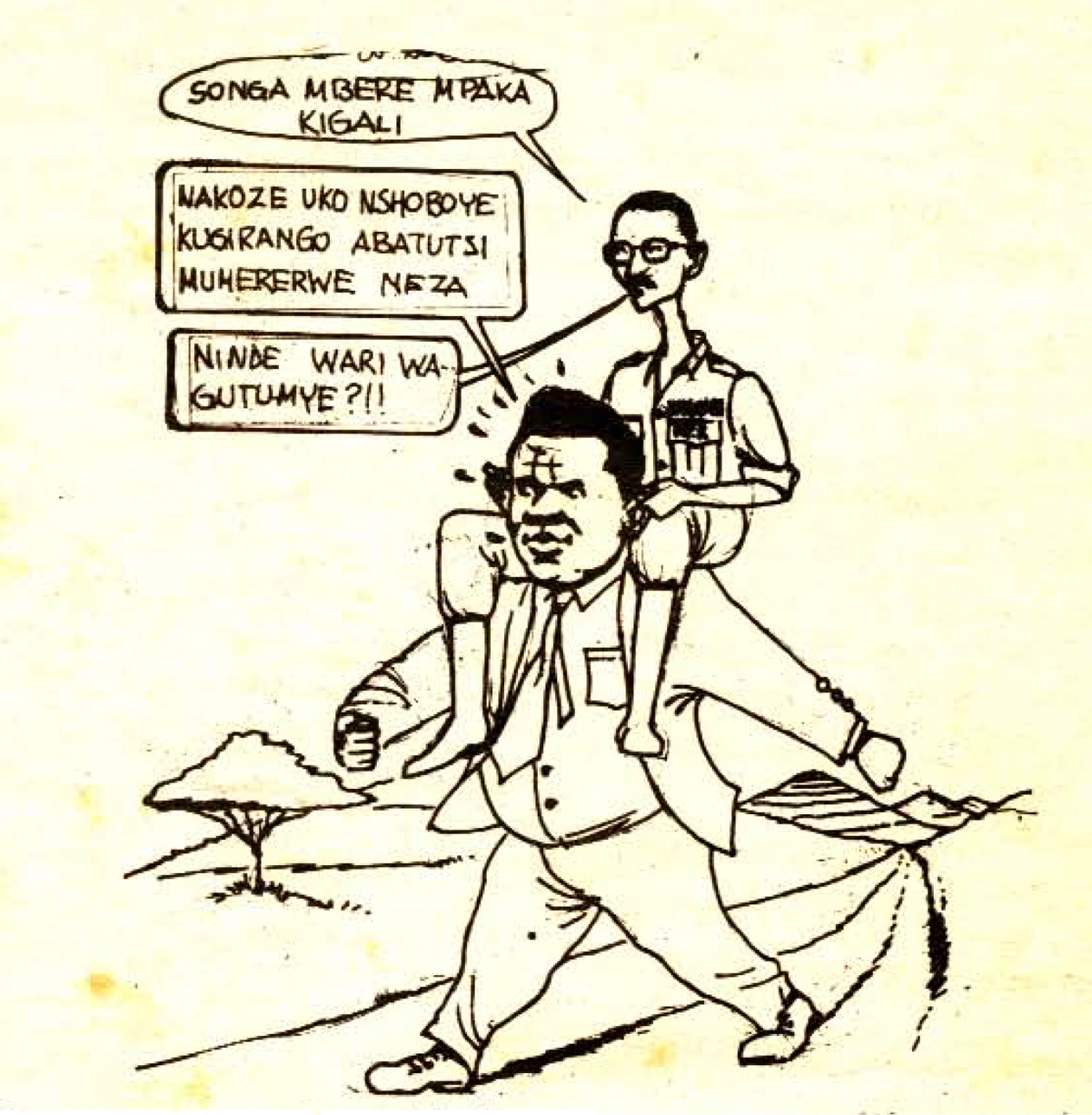

If you’re not convinced about this reading, have a look at the cartoon inside the article: it will sweep away all your doubts.

President Habyarimana is walking on a road holding Paul Kagame on his shoulders; Kagame rides him holding on to his ears. Kagame says in Swahili, the language spoken in Uganda: “Move forward to Kigali!”. Habyarimana says in Kinyarwanda: “I did my best to make you Tutsis feel good”. Then Kagame asks him, this time in Kinyarwanda: “Who gave you this mission?!!”.

What does this cartoon suggest? That Habyarimana sold Rwanda to the Tutsis, that he’s a traitor to his people, his country, and the glorious 1959 Social Revolution. And tell me, what do you think a traitor deserves?

This kind of “news” about the imminent assassination of Habyarimana multiplied during January 1994, relaunched by the different mass media owned by the hardliners, including RTLM, together with the “news” of an imminent attack by the RPF (another typical example of that manipulation tactic named ‘projection’ or ‘accusation in a mirror’ which we talked about in RWANDA BASKETRY 4). Many testimonies collected in the Mutsinzi Report converge consistently on this point. Colonel Habimana Pierre Claver, at the time major of the RAF, said: «Rumours on the probable assassination of President Habyarimana were circulating both in the army and among politicians, but I was not able to find out the origin and substance of this intelligence. What is clear is that it was being talked about» (Source: The Mutsinzi Report). The rumor was taken seriously by the President Security staff, who adopted special protection measures. Between February and March, the hearsay of the probable assassination of Habyarimana was so widespread in Kigali that it ceased to be a simple rumor to become a topic of discussion among the Belgian military, Western diplomats, and agents of many foreign secret services. The civilian head of UNAMIR, Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh knew it and alerted Habyarimana when the two met at the presidential residence on Lake Kivu, in Gisenyi, during the Easter weekend; the President said he was already familiar with those rumors (source: Linda Melvern). The wife of the Falcon 50 captain, Jacky Héraud, revealed that the French crew was aware of intelligence regarding the assassination of the President during the last weeks before the attack. When questioned by French author Sébastien Spitzer, Mrs Héraud revealed that her husband had spoken about “threats hanging over the president” from “certain Hutu extremists who oppose any form of concession (…) of part of the power to men from the RPF” (Sébastien Spitzer, Contre-enquête sur le juge Bruguière. Raisons d’Etat. Justice ou politique?, Paris, Privé, 2007).

Valérie Bemeriki, a cousin of Bagosora and one of the main journalists and presenters on RTLM, said on her radio broadcast on April 3, three days before the attack: «Je vous parlais tout à l’heure des manœuvres du FPR pour diviser nos forces armées en vue de la prise du pouvoir. En effet, les partis favorables au FPR, y compris le MDR de Twagiramungu, auraient convoqué quelques officiers originaires d’une même région du sud du pays chez le Prime Ministre (…) dans la nuit du 1er au 2 avril 1994 pour qu’ils cherchent les voies et moyens de renverse Son Excellence le Président de la République et, en cas d’échec de ce plan, de l’assassiner. Pour de raisons de sécurité, nous ne pouvons pas vous citer les noms de ces officiers, mas nous les connaissons. (…)» (Transcription RTLM 0194 made on June 12, 2000. It can be downloaded here, on the France – Génocide – Tutsi website). My translation: “I’ve been already talking to you about the RPF’s maneuvers to divide our armed forces in order to seize power. Indeed, the pro-RPF parties, including the MDR of Twagiramungu, reportedly summoned some officers from the same southern region at a meeting with the Prime Minister (…) during the night between 1 to 2 April, 1994 to define the ways and the means to overthrow His Excellency the President of the Republic and, in case of planning failure, to kill him. For security reasons, we cannot give you the names of these officers, but we know them”.

Valérie Bemeriki. Photo by Igihe TV.

She was the only female animatrice of RTLM, well-known and appreciated for her conversational register and aggressive style of communication, and a tireless promoter of the Genocide of the Tutsis. She was convicted of and pleaded guilty to planning genocide, inciting violence, and complicity in several murders and sentenced to life imprisonment by a Gacaca court in Rwanda, in 2009. The Gacaca courts (please, pronounce /gatchatcha/) were a system of community justice.

The Mutsinzi Report reads: «To put it clearly, the announcement of the death of President Habyarimana in a context of power seizing and large-scale massacres constituted intelligence spread throughout Rwandan extremist political and military circles, expressed publicly, and known by sources independent of the government, particularly the Belgian and French embassies and military cooperation services».

What we saw was a threatening, intimidating campaign against Habyarimana, launched and spread by a group of hardliners through some of their private mass media (radio and press). It was a cynical and brutal campaign orchestrated by that powerful radicalized lobby within the RAF, the Presidential Guard, and the Gendarmerie we’ve called the ‘Military Fronde’, active against the President since 1993. We can only imagine how he had been feeling in the last months of his life. How could Guichaoua write: «Eminent personalities, usually close to the decision-makers, had not received any information or anticipated the event»? In March and early April, many people in Kigali discussed the likelihood of the rumors that Habyarimana was to be the victim of a coup disguised as a terrorist attack by the RPF in cahoots with Belgian traitors.

The RPF had no reason to plan Habyarimana’s assassination: Kagame had no interest in breaking the cease-fire, resuming the open conflict, and killing Habyarimana. He was the recognized winner of the Arusha Accords whose implementation would have given him good control of the military – the beating heart of Rwanda – and provide him with a good stepping stone to gain – by hook or by crook – the political control of the country. What were his interest and his gain in resuming the war? On this crucial point, I’m not alone. Gérard Prunier, an expert I admire the most for his unconventional life and intelligence, wrote in his essay The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide, published by the Columbia University Press in 1996: «It was not in the political interest of the RPF to kill President Habyarimana. It had obtained a good political settlement from the Arusha Agreements and could not hope for anything better. The President was already a political corpse anyway and the problem for the RPF was not going to be with him, but rather with the ‘Power’ groups in the former opposition parties. Killing him meant renewed civil war, the possibility of direct French military intervention if the plot was uncovered, and a leap into the unknown».

Moreover, Roméo Dallaire writes in his memoirs: «At this time <January 1994> I was beginning to be pressured by Paul Kagame over the snail’s pace of the peace process. He told me he was running out of money to feed and fuel his force. As a result, his soldiers were making dangerous incursions into the demilitarized zone, looking for food and water. If he was already facing serious shortfalls, how were his troops going to survive until the time demobilization began, three months after the BBTG was sworn in?» (R. Dallaire, Shake Hands With The Devil, cit.). What Paul Kagame said to Dallaire sounds plausible. Even if the RPF probably received money and weapons from both declared and hidden sources, it certainly couldn’t boast the economic power and the financial resources of a state. The effort sustained during four years of war had certainly left him slightly short of breath, and the easiest way to catch that breath didn’t pass through Habyarimana’s assassination. However, as a military intelligence expert, he was well aware of the Rwandan situation, the chaos of opposing forces, and the ‘Military Fronde’. At the end of the winter, he began to prepare his troops.

WAS HABYARIMANA’S ASSASSINATION THE CAUSE OF GENOCIDE?

A historical reconstruction of the attack based on objective and verifiable data allows us to distance ourselves from a series of clichés and labels that continue to be stuck to Habyarimana’s assassination as easy captivating payoffs.

The old reading of President Habyarimana’s assassination as the ’cause’ of the Genocide, supported by the hardliners and the French government in 1994, and by Judge Bruguière later on, is quite discredited. Fortunately, I’d say: it’s a biased, far-fetched, ideological interpretation, not only supporting the denial of any genocidal planning but also supporting the denial of the Genocide tout court, regarded as a massive retaliatory killing campaign.

President Habyarimana’s assassination cannot be the ’cause’ of the Genocide for two irrefutable reasons:

- The Genocide of the Tutsis started in the fall of 1990

- President Habyarimana himself was one of the planners of the Genocide

Since defining the attack as the ’cause’ of the Genocide is beyond question, many journalists, historians, and popular sources use a parade of easy labels that seem less compromising and easy to use and understand: the shooting down the Presidential Falcon 50 has been defined the ‘trigger’ (something that initiates a process or course of action or that causes something to start), the ‘catalyst’ (something that precipitates an event, provokes or speeds significant change), the ‘spark’ (a first small event or problem that causes a much worse situation to develop), the ‘pretext’ (a reason given in justification of a course of action that is not the real reason) of the Genocide.

All of them are ready-to-use labels that save the brain a bit of effort, but are misleading and historically unsound as 1. they do not recognize the mass killing of Tutsi systematically carried out from 1990 to 1993 as a Genocide, as they really were (we’ve talked about that in RWANDAN BASKETRY 4); 2. they do miss the main point: Habyarimana’s assassination was essentially a military coup d’état, orchestrated by that powerful radicalized clique within the RAF, the Presidential Guard and the Gendarmerie we’ve called the ‘Military Fonde’, and whose leaders were Serubuga, Bagosora, and Rwagafilita.

Do you remember the military coup carried out on July 5, 1973?

Major General Juvénal Habyarimana led a group of officers, “les Camarades du 5 juillet 1973” (which included Serubuga), in the overthrow of President Kayibanda. The 1973 coup was defined by diplomatic sources in Kigali as a bloodless one, but it wasn’t, to tell the truth: in the coup aftermath, 56 members of the Kayibanda’s government, army officers, and state functionaries, including President Kaybanda and his wife, were imprisoned; some were executed by gunfire and some other starved to death. As army General Juvenal Habyarimana seized power from Rwanda’s first elected president, Grégoire Kayibanda, in 1973, so did a group of former top-ranking officials, which we can call ‘les camarades du 6 Avril 1994’: they seized power from General Habyarimana.

That of 1994 wasn’t an easy coup as there were heterogeneous political stances and many personal and clannish tensions within the military. Habyarimana did not control the armed forces, but neither did the hardliners nor did the criminal trio – Bagosora, Serubuga, and Rwagafilita – who constituted a powerful but small group within the field of those extremists who recognized themselves under the heterogeneous umbrella of the Hutu Pawa.

Bagosora wasn’t a general: he was just an ambitious, retired colonel with an important position at the Ministry of Defense and relevant family ties. He was more of an operational executioner than a charismatic general, more of a coordinator and an organizer than a master tactician, and more of a torturer than an experienced and inspiring military leader. He was an officer whose aspirations and brutality were known, quite feared and decidedly unpopular. We know that Bagosora wanted to chair the military meeting held on the night of April 6. «One of the colonels suggested that it would be more appropriate for Major-General Augustin Ndindiliyimana, chief of staff of the National Gendarmerie, to chair the meeting, but he did not want to. “We could not understand it”, one of the officers recalled. “How could someone with the rank of general refuse and leave the way open to someone like Bagosora?”» (Linda Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.).

In the Crisis Committee meeting at 7 p.m on April 7, Bagosora became furious and had a bad outburst of anger when he was refused to chair the meeting and become the Committee president, and was stopped from passing over many fully operational and higher-ranking officers. In the next video, you will see Bagosora changing his tune all of a sudden to threaten a slightly insistent journalist with death.

Albeit very short, this French video can give you an idea of the type of man Théoneste Bagosora was. It’s a part of “La marche du siècle – Rwanda: autopsie d’un génocide”, broadcast on France 2, on September 21, 1994, and directed by Philippe Lallemant. It shows Théoneste Bagosora in Goma (former Zaire), some weeks after the Genocide. The French journalist asks him about the death squads in Rwanda, and Bagosora answers that these squads have never existed in the country and are a mere fabrication made by the RPF which, unlike Rwanda, had them. Then the journalist asks him if he had ever taken part in secret meetings <with genocidal intents>; Bagosora answers that many journalists are biased and prejudiced. Faced with the objection of the journalist, who emphasizes the existence of some witnesses, Bagosora denies everything. Then he is asked if he’s ready to testify and be judged by an International Court in the future; he says: “Yes, sure, but not by the RPF. Even immediately, but an international Court must prove that I have killed”. Put in a tight spot by the journalist, Bagosora then changes his register: «Did you get paid, too? That’s enough. One day you will die. Do you dare to taunt me up to this point?». His final words («Merci») show his willingness to end the interview.

Bagosora was definitely involved in the coup d’état, but probably he was not ‘the brain’ behind it: he was an excellent executor and executioner, advised or directed by Serubuga, Rwagafilita, and probably a few intellectuals or politicians (Mathieu Ngirumpatse?), certainly not by the whole leadership of MRND and CDR, whose members, like many militaries, experienced hours of confusion and uncertainty after Habyarimana’s assassination.

The hypothesis supported by some scholars and quite plausible is that in the shooting down the presidential plane, the criminal trio could count on the support of French soldiers or mercenaries. (It is also known that Serubuga was in close contact with Paul Barril, who in those years worked in Rwanda as a mercenary and a mercenary broker).

The coup is definitely a gamble for the military triad. During the meetings on April 6 and 7, Bagosora was hindered and distressed by senior and more respected officers and was forced to make a series of diplomatic retreats to prevent the coup from turning into an unsuccessful putsch.

Probably, the creation of civilian self-defense groups and control over the training and armament of paramilitary militias were a necessity for the triad (Bagosora has been working on it since February 1993) in view of their objectives: those were ‘weapons’ over which the triad could exercise that direct control it had only over a part of the armed forces.

Which part?

The ‘triad’ had good control of the Presidential Guard and the elite units billeted in the Kanombe and Kigali Camps. According to Alison Des Forges among the senior officers closest to Bagosora there were Major Protais Mpiranya, Commander of the Presidential Guard Battalion, Major Aloys Ntabakuze, Commander of the Para-Commando Battalion, Major François-Xavier Nzuwonemeye, Commander of the Commandos de Recherche et d’Action en Profondeur (CRAP), and his subordinate Innocent Sagahutu, Commander of the CRAP’s A company. The Kanombe military camp was the major military stronghold of the hardliners and Hutu extremisms; many officers, like Major Aloys Ntabakuze, were members of a northern clique, known as Abakigas, the natives of Kiga, members also of the Akazu. Colonel Anatole Nsengiyumva, commander of the Gisenyi operational sector and in charge of the Gisenyi military base, was also a good loyalist to Colonel Bagosora.

The Presidential Guard and all of these units became fully operational a few minutes after the attack in Kigali, and a few hours in Gisenyi, another clear indicator of the long-anticipated plan behind Habyarimana’s assassination, a plan, however, that had to be constantly adapted to circumstances (two examples: the goal of a military junta had to be abandoned soon, and Bagosora had to grin and bear it on the appointment of Gatsinzi as Chief of Staff).

In the days immediately following the coup, there was no indiscriminate massacre of moderate or opposition politicians. On the contrary, in a very short time and with surgical precision, the putschists eliminated the political exponents who could have assumed the leadership of the country under a transitional civilian government, those who would have constituted the pillars of the BBTG, and even the jurists who could have invalidated any military authority. As we saw, the leadership of the Social Democratic Party, the only party that could not have been maneuvered because lacking a Hutu Pawa wing, was literally wiped out. In a span of just 48-72 hours, the ‘triad’ removed all barriers to the seizure of power by using the Presidential Guard, the elite units, and the death squads (Serubuga pulled the strings, among others, of the Réseau Zéro) and the paramilitary militias. The ICTR against Bagosora clearly stated that, in the Chamber’s view, «the killing of the opposition political officials consisted of an organized military operation»; they were not riots nor warm-blooded revenge killings. «Only later would it be established that all that day there had been requests to Bagosora and to Ndindiliyimana from army officers and from the RPF to control the military, and most notably the Presidential Guard, who were murdering civilians. These requests were ignored and Bagosora, according to his ICTR indictment, ordered Ntabakuze, the commander of the para-commando unit, Major François-Xavier Nzuwonemeye, the commander of the reconnaissance battalion, and Lt.-Col. Leonard Nkundiye, former commander of the Presidential Guard, to proceed with massacres» (L. Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit).

As for the slaughter of the Belgian peacekeepers, crippling UNAMIR to the point of allocating it to an almost certain withdrawal was an equally important objective, already defined at the beginning of 1994. It opened, or better to say, it threw wide the doors to the war or, which is the same, to the final extermination of the Tutsi. We already saw that winning the war and carrying out an ‘insecticidal’ operation against all cockroaches were the two sides of a coin. Not by chance, in a handful of days after the shooting down the Presidential plane, the human rights community was literally decimated.

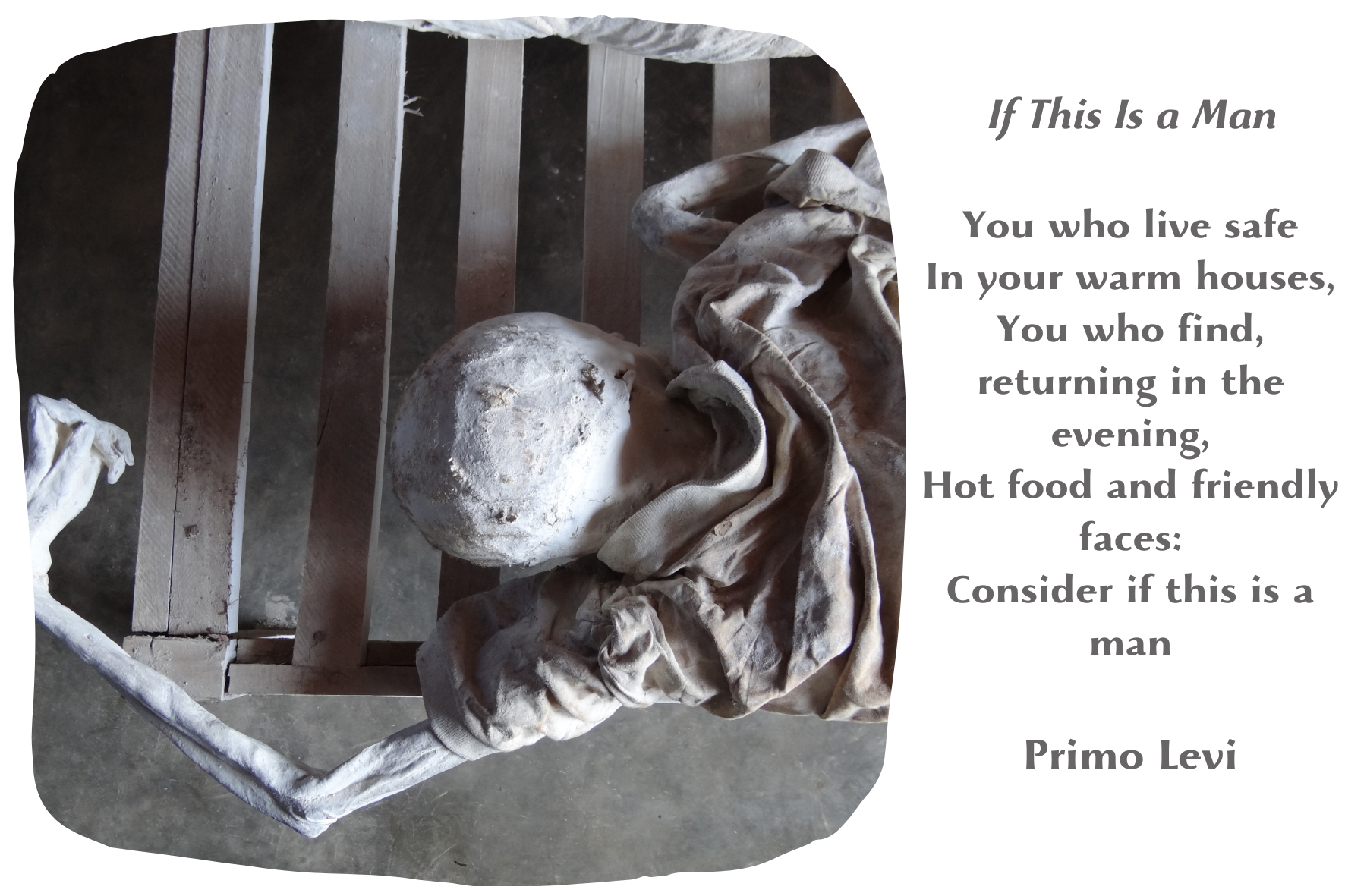

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE: THE ORGY OF VIOLENCE

During the days that followed Habyarimana’s death, «an average of more than five Tutsis were murdered every minute in Rwanda» (data source: Philip Gourevitch, The Genocide Fax, cit.). The final phase of the jenoside yakorewe abatutsi swept away «an estimated 75% of the resident Tutsi population» (data source: Scott Straus, The Order of Genocide, cit.). The victims – women, men, children, even babies – were killed by gunfire or grenades, more often with pangas, “machetes”, spears, hammers, spiked maces, sticks, and farm tools. The level of horror and brutality of the final phase is upsetting, shocking, and unbearable.

Mamdani wrote: «With a machete, killing was hard work, that is why there were often several killers for every single victim. Whereas Nazis made every attempt to separate victims from perpetrators, the Rwandan genocide was very much an intimate affair. It was carried out by hundreds of thousands, perhaps even more, and witnessed by millions. (…). “It was not just a small group that killed and moved,” a political commissar in the police explained to me in Kigali in July 1995. “Because genocide was so extensive, there were killers in every locality – from ministers to peasants – for it to happen in so short a time and on such a large scale.” Opening the “International Conference on Genocide, Impunity and Accountability” in Kigali in late 1995, the country’s president, Pasteur Bizimungu, spoke of “hundreds of thousands of criminals” evenly spread across the land:

Each village of this country has been affected by the tragedy, either because the whole population was mobilized to go and kill elsewhere, or because one section undertook or was pushed to hunt and kill their fellow villagers. The survey conducted in Kigali, Kibungo, Byumba, Gitarama, and Butare Préfectures showed that genocide had been characterized by torture and utmost cruelty. About forty-eight methods of torture were used countrywide. They ranged from burying people alive in graves they had dug up themselves, to cutting and opening wombs of pregnant mothers. People were quartered, impaled, or roasted to death. On many occasions, death was the consequence of the ablation of organs, such as the heart, from alive people. In some cases, victims had to pay fabulous amounts of money to the killers for a quick death. The brutality that characterized the genocide has been unprecedented. (Opening speech by H. E. Pasteur Bizimungu, President of the Republic of Rwanda, “International Conference on Genocide, Impunity, and Accountability”, Kigali, Nov. 1-5, 1995).

A political commissar in the army with whom I talked in July 1995 was one of the few willing to reflect on the moral dilemma involved in this situation. Puzzling over the difference between crimes committed by a minority of state functionaries and political violence by civilians, he recalled: “When we captured Kigali, we thought we would face criminals in the state; instead, we faced a criminal population.” (…).

The violence of the genocide was the result of both planning and participation. The agenda imposed from above became a gruesome reality to the extent it resonated with perspectives from below. Rather than accent one or the other side of this relationship and thereby arrive at either a state-centered or a society-centered explanation, a complete picture of the genocide needs to take both sides into account. (…). For this was neither just a conspiracy from above that only needed enough time and suitable circumstance to mature, nor was it a popular jacquerie gone berserk. If the violence from below could not have spread without cultivation and direction from above, it is equally true that the conspiracy of the tiny fragment of génocidaires could not have succeeded had it not found resonance from below. The design from above involved a tiny minority and is easier to understand. The response and initiative from below involved multitudes and presents the true moral dilemma of the Rwandan genocide. .

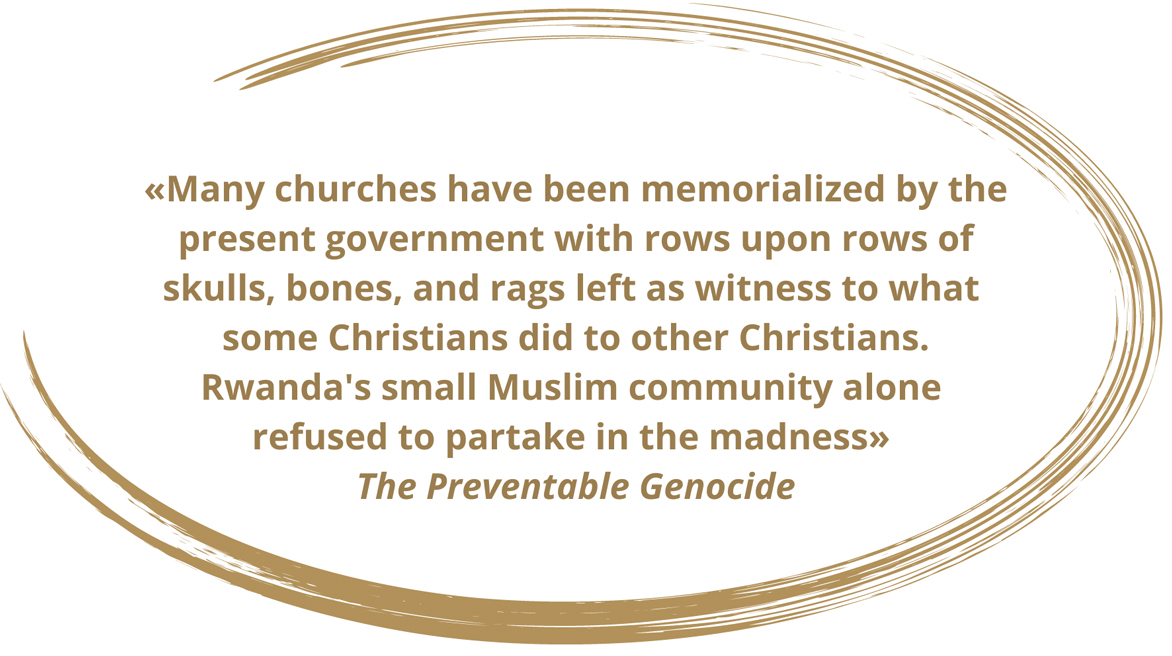

In sum, the Rwandan genocide poses a set of deeply troubling questions. Why did hundreds of thousands of people who had never killed before take part in mass slaughter? Why did such a disproportionate number of the educated – not just members of the political elite but civic leaders such as doctors, nurses, judges, human rights activists, and so on – play a leading role in the genocide? Similarly, why did places of shelter where victims expected sanctuary – churches, hospitals, and schools – turn into slaughterhouses where innocents were murdered in the tens and hundreds, and sometimes even thousands?» (Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers, cit.).

These “troubling questions” raised by Mahmood Mamdani in his essay, When Victims Become Killers (published in 2001), are reinforced by some of the “unanswered and under-explored questions” posed by Scott Straus in his The Order of Genocide (published in 2008): «How and why did so many ordinary Rwandan civilians, with no preexisting history of violence, take part in the killing? The question is especially pertinent in an African context because most African states have a weak capacity for civilian mobilization and shallow roots in the countryside. The question is also relevant because a defining characteristic of the Rwandan genocide is large-scale civilian participation. Thus, how and why did hundreds of thousands of civilians take part in killing?» (Scott Straus, The Order of Genocide – Race, Power, and War in Rwanda, see Bibliography).

I am going to answer many of these troubling and under-explored questions, and I do not mean to evade the true moral dilemma of the Rwandan genocide. I will do it in the final chapter, but first, we need to analyze the most relevant data, the facts, and the empirical details of the genocidal final phase. We can reflect only on what we know well.

THE CASE OF BUTARE

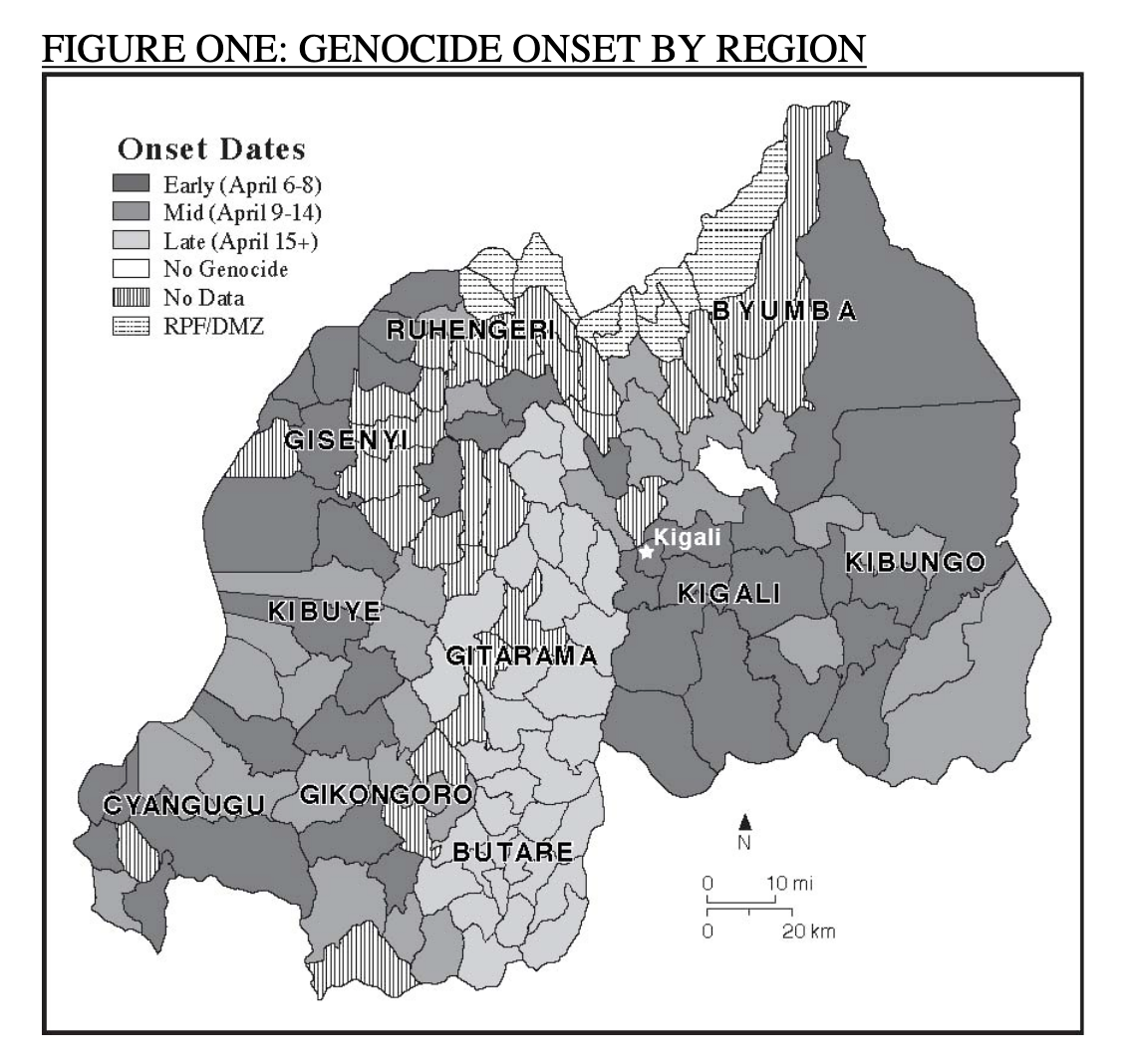

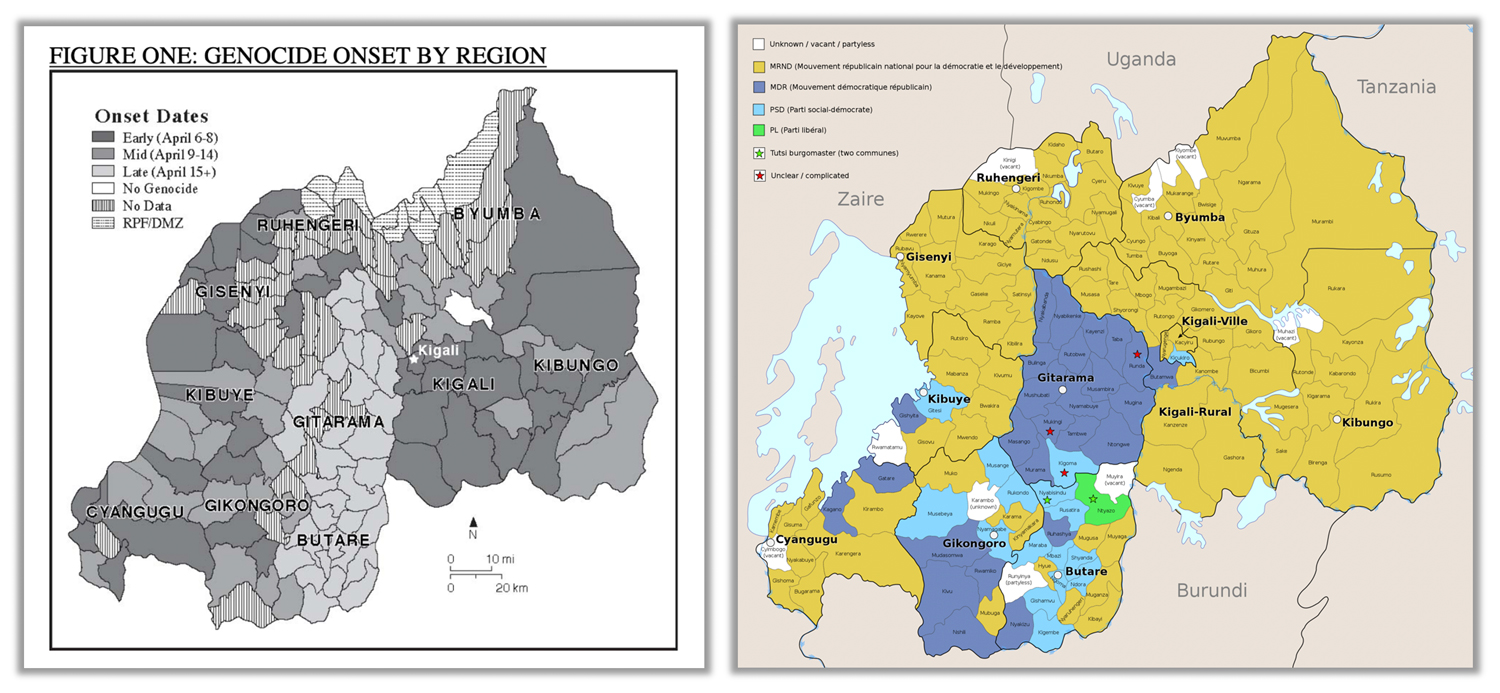

One of the most used and persistent clichés related to the Rwandan Genocide is the one that makes it an event spread over “100 days”, from April 6 until mid-July 1994. It’s a dangerous cliché for two different reasons: firstly, as we saw, the jenoside yakorewe abatutsi was a constant in the Rwandan history of the second half of the 20th century and flared up several times, the last in October 1990, in connection with the RPF attack and the Civil War. Secondly, the final phase of the 1990 Genocide fired up in connection with the military coup d’état by Bagosora & company, but its timing and other variables knew regional differences throughout Rwanda.

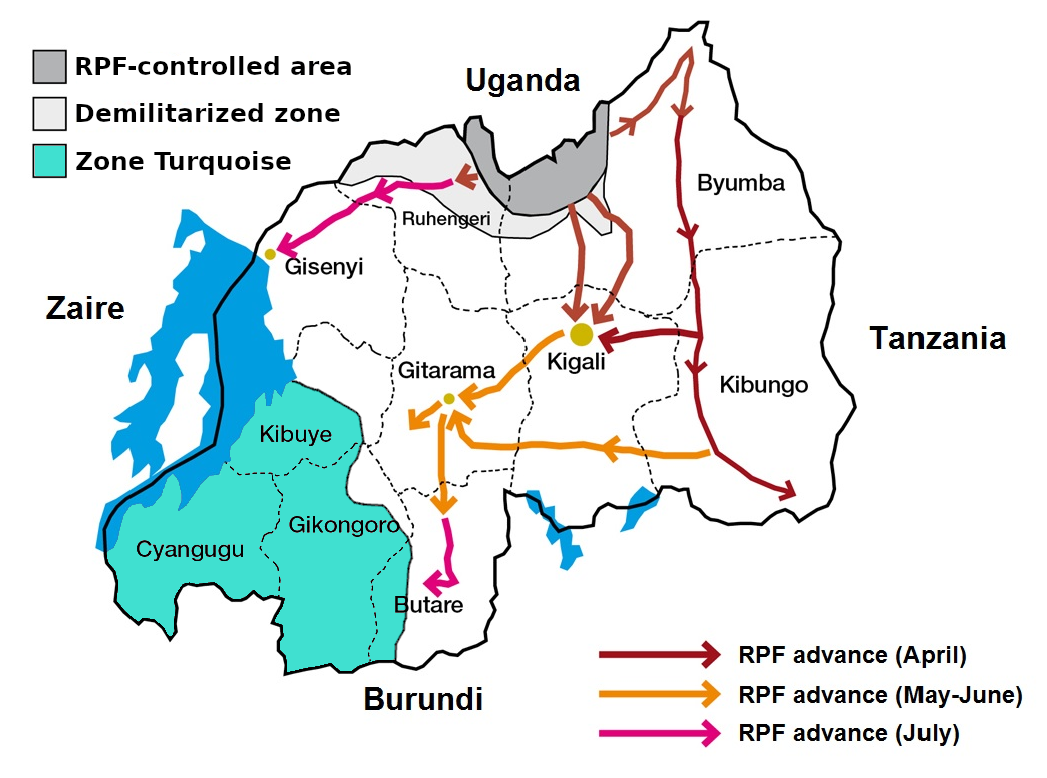

The door-to-door hunting and the systematic killing of Tutsis at the roadblocks began a few hours after the Habyarimana’s plane shooting down in the Kigali district called “Mu Kajagari” (or Kajagali), adjoining the Kanombe military camp. In the following days, the massacres spread throughout Kigali and other areas. As Linda Melvern wrote, in the prefectures of Ruhengeri, Gisenyi in the north, Kibuye in the west, Kibungo in the south-east, Cyangugu in the south-east, and Gikongoro in the south, the massacres began on April 7.

The main holdout areas were Butare and Gitarama Prefectures, where there was considerable resistance.

Butare is a large university town once called Astrida, in the southern part of the country, bordering Burundi. A large area around the town was once the Prefecture of Butare; today is the Huye District. Its history during the final phase of the Jenoside is well told by Alison des Forges (in Leave none to tell the story) and Linda Melvern (in Conspiracy to Murder).

In the 1990s, Butare prefecture had both a high percentage of Tutsi residents (about a quarter of the local population, approx. 140,000 people) and the only Tutsi prefect of Rwanda, Jean-Baptiste Habyalimana. The political city life was dominated by the Social Democratic Party (PSD). As for the military ‘landscape’, in Butare, the Armed Forces were troubled by the same regional and political divisions that existed elsewhere. The local commander of all forces in Butare, general Marcel Gatsinzi, and Lt. Col. Tharcisse Muvunyi, who replaced him when the first was named chief of staff on April 6, did not adhere to the Hutu Pawa movement. The National Police commander Cyriaque Habyarabatuma was moderate, while Capt. Ildephonse Nizeyimana of the junior officers’ school was a relative of Bagosora, and a notorious ‘champion’ of the local extremists, animated by a virulent hatred of Tutsi.

From an administrative point of view, in 1994, Rwanda was divided into 11 Prefectures, 145 Communes (Districts), 1,510 Sectors and 6,300 cellules. Today, the country has a different administrative division: 5 provinces, divided into 30 districts.

Map by Mattias Ugelvik, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

After April 6, the prefect, backed by the local police commander, insisted on protecting Tutsi. «As the killing spread, thousands of people fled to Butare seeking protection from the terror in Kigali, Gikongoro, and Gitarama. Prefect Habyalimana tried to calm people and ordered that meetings be held to try to stop violence from erupting. For two weeks he tried to prevent the spread of the genocide» (L. Melvern, cit.). «In trying to resist this catastrophe, Prefect Jean-Baptiste Habyalimana was at first able to count on the local commander of the National Police and his subordinates, except for the burgomaster of Nyakizu . But otherwise, the prefect was opposed by powerful forces committed to genocide: military officers, the militia, intellectuals, and Burundian refugees. In addition, assailants from both the west and the northeast invaded Butare, attacking Tutsi who had fled from Gikongoro, Kigali, and Gitarama as well as those resident within the prefecture» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

On April 17, in a broadcast on RTLM, Valérie Bemeriki accused Habyalimana of working with the RPF. The following day, the puppet government dismissed him. Prime minister Kambanda arrived in Butare on April 19 for the appointment of the new prefect, Sylvian Nsabimana. Habyalimana was arrested and later on killed. That very same day two military planes landed at Butare airport carrying several hundred Presidential Guard soldiers while Interahamwe militia members arrived mainly by bus. «By April 19, some 12,000 Rwandans had sought safety in Burundi. Many others wanted to leave, but just as the need for escape was becoming more pressing, so flight across the border was becoming more difficult» (A. Des Forges). On the evening of April 21, the systematic massacres of Tutsis and moderate Hutus began at the university, carried out by the soldiers of the Presidential Guard, members of Nizeyimana’s bodyguard, and troops from the Ngoma camp, backed up by militiamen and local killers led by Shalom Ntahobari, head of the MRND Interahamwe. «On April 22, some roadblocks were erected, including one on the main road, by the Presidential Guard. There were soon mass killings throughout the prefecture of Butare. Today, out of 20 communes, 18 have genocide sites containing between 5,000 and 40,000 victims » (L. Melvern).

The genocide in Nyakizu commune

After the removal of prefect Habyalimana, a barrier to horror until April 18, the Butare slid inexorably towards the final stage of genocide. The latter was already in full swing in a small area of the prefecture, the one controlled by the burgomaster of Nyakizu, a well-known hardliner.

We talked above of the burgomaster of Nyakizu, a well-known hardliner. «Nyakizu was much like other communes in Butare, desperately poor and densely populated. It was located in the southwestern corner of the prefecture, on the border with Burundi» (Alison Des Forges). In early 1994, 18% of its population was registered as Tutsi (above the national average level). Extremists and hardliners considered the large number of Tutsi residents as a danger that increased the likelihood of RPF infiltration and even of actual attack across the nearby border.

The Commune of Nyakizu lies in Southern Rwanda at an altitude of 1800-1900 m. It’s located 28 km south of Butare town and 13.7 km north of the Burundian border.

The burgomaster of Nyakizu was a medical assistant, Ladislas Ntaganzwa, head of the local branch of the MDR, a supporter of Hutu Pawa positions, well-known for its authoritarian and violent approach (he removed opponents – personal and political – from the communal payroll). In early 1994, he declared that anyone who was Tutsi or who did not speak the language of Hutu Power was ‘the enemy’, a ‘political truth’ that many Burundian Hutu refugees (who arrived here in late 1993) supported with enthusiasm. The Burundian refugees were engaged in military training and bought arms from Ntaganzwa from November 1993 onwards. At the same time, young men from the commune began their own military training sessions with local military reservists as instructors. The burgomaster received “commando rifles” in an official distribution in January 1994 and other arms through informal channels. On March 30, the burgomaster went to Kigali for a meeting on civilian self-defense at the army headquarters, and he day after, he was in the capital again to take part in another.

«The use of violence against political opponents, the identification of all Tutsi with the RPF, the ideology of Hutu power, growth of insecurity, the pressure from the Burundian refugees, the training of the militia, and the demand for loyalty to the burgomaster all worked together to prepare for genocide in Nyakizu. As elsewhere, the catalyst would be the killing of Habyarimana, but as one informant asserted, “If the president had not died, still something would have happened”» (Alison Des Forges).

In the aftermath of Habyarimana’s assassination, as was so often the case during the genocide, in Nyakizu the public reassurances by the burgomaster masked the secret organization of the killings. «Ntaganzwa used his inner circle of political and personal supporters to carry out the genocide, backing up the cooperative members of the official hierarchy and supplanting those opposed to the slaughter. He sent them first to organize patrols in each sector and particularly to monitor the area to the west and north where people were arriving from Gikongoro. Some were hoping to flee to Burundi, but others expected to find safety at Nyakizu. The burgomaster insisted that the Tutsis go to Cyahinda church rather than seek shelter with families. Ntaganzwa’s supporters, JDR and MDR leaders, communal councilors, cell leaders, and police, both communal and national, all helped direct the new arrivals to the church» (Alison Des Forges).

The first killings in Nyakizu started on April 13, along the banks of the Akanyaru River, in the sector of Nkakwa: Rwandans and Burundians patrolling the border began to pillage and kill the many Tutsis families who were trying to cross the border and find shelter in Burundi. The killings went on for three days. «The bodies of those killed near the river were simply thrown in the water. The others would be buried in a number of mass graves on the hills of Kwishorezo and Mu Gisoro. After finishing at the river’s edge, the killers (local militiamen and young people) set out to hunt down local Tutsi in their homes, both in Nkakwa and in Rutobwe» (Alison Des Forges). They always looted and pillaged goods (dry foods, beer, clothes, mats and cushions, radios, etc.) and animals (cows, pigs, chickens) before slaughtering entire families, babies included.

Many terrified Tutsis sought shelter at the Cyanhinda Catholic Parish in Nyakizu, pushed by the burgomaster, the policemen, and militia members, all reassuring them that the church, with its complex of school buildings and several sizable courtyards, was a safe refuge. On April 15, in the afternoon, the church full of people up to capacity was attacked by the burgomaster, who arrived in the communal pickup truck, accompanied by Damien Biniga, sub-prefect of Munini, Interahamwe militiamen, members both of the National and Communal Police, and civilians armed with guns, machetes, clubs, and spears, «backed by approximately two hundred Burundian refugees, some of whom were also armed, Hutu Pawa activists and one to two thousand others» (Ibidem). One survivor recalled: “We could see that elsewhere people living around there were watching and even assisting in the attack”.

The attack lasted until April 19; during these days, burgomaster «Ntaganzwa and his supporters heightened fear of the Tutsi exactly as the disciple of the propaganda expert Mucchielli had directed. The burgomaster traveled throughout the commune with his head bandaged, warning the population that RPF soldiers were in the church, hiding in the midst of the Tutsi civilians. He insisted that everyone must help defend the commune» (Ibidem).

Popular participation, however, remained below expectations. «The National Police reportedly had to press people to attack persons because they were too focused simply on looting and leaving. (…). To turn pillagers into killers and resisters into participants, Ntaganzwa decided to eliminate several moderate Hutu leaders who were providing a model and a cover for others who would not kill. (…) The national radio reported these murders, but in one of the cynical deceptions common during the genocide, it said the moderates had been slain by Tutsi from Cyahinda church. Thus those committed to the genocide not only rid themselves of dissidents but used their deaths to heighten fear and hatred of the “enemy”». The dissidents quickly understood that «Ntaganzwa’s killings and threats had the backing of those above him both in the administrative hierarchy and in the party system. With no likelihood of support from a higher authority outside the commune and with the local leaders of the opposition dead, those who might have opposed the genocide in Nyakizu gave up. Some fled (…). Those who stayed formed a disapproving but silent block who went into hiding, and refused to participate or participated as little as possible. Many continued to take risks privately to protect Tutsi with whom they had ties, but they did not dare oppose the genocide publicly» (Ibidem).

On April 18, a new massive attack was carried out against the church, this time with more armed civilians than before.

That very same day President Sindikubwabo stopped briefly in Nyakizu during his tour to mobilize the people of southern Rwanda. «His audience was small because most of the people of the commune, including the burgomaster, were busy attacking the church. A witness who was among the 200 or so persons who heard him speak reported that he said: “People of Nyakizu, this is the first time you have had a visit from the president of Rwanda. I have come to encourage you and to thank you for what you have done so far. I am going back now to get some people to help you with this work and to see about a reward for you”. Another witness saw the visit as a turning point. He recalls: “(…) The president just passed through. He gave permission. The participants said to themselves, “We are following the true path. We have been blessed by the president. The others are Inkotanyi» (Ibidem).

On April 19, a dozen soldiers under the command of a young lieutenant from the Ngoma camp in Butare arrived at the Cyahinda church. «By Tuesday night, April 19, the killing at Cyahinda was complete, and the church and surrounding buildings and grounds were strewn with corpses» (Ibidem).

How many Tutsi were slaughtered inside the Cyahinda Parish?

According to Jean Damascène Rugomboka, author of the Map of Genocide and Massacres Sites in Rwanda, approx. 21,015 people had been exhumed from mass graves and reburied in Nyakizu commune by October 1995. Among the victims, there were 11,213 Tutsis recorded as local residents when the genocide began (Source: Jean Damascène Rugomboka, Map of Genocide and Massacres Sites in Rwanda: Data analysis and mapping, p.11, see Bibliography). The Parish also housed many thousands of Tutsi from other communes (such as Mubuga, Kivu, and Nshili) and even other prefectures (mainly Gikongoro). On April 15, according to Alison Des Forges, prefectural authorities estimated that 20,000 people were at Cyahinda, most of them women, children, and the elderly (adolescent or adult males actively defending the church probably numbered fewer than 4,000 to 5,000). For Rwandan scholars today, the victims slaughtered inside the Cyahinda Parish area could range from a minimum of 20,000 to a maximum of 32,000. As to the attackers and killers, Alison Des Forges estimated they were between 6,000 and 8,000. Among them, there was Pastor François Bazaramba of the Rwandan Union of Baptist Churches.

Ladislas Ntaganzwa, the burgomaster of Nyakizu, was arrested in 2015 in the Democratic Republic of Congo and extradited to Rwanda in 2016 for trial, under an international warrant of arrest issued by the United Nations Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT). He had been indicted in 1996 by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) for genocide, incitement to commit genocide, murder, rape, and crimes against humanity for the massacres of thousands of Tutsis at various locations, including Cyahinda Parish and Gasasa Hill. In Rwanda, the judge convicted Ntaganzwa of genocide, and perpetrating crimes against humanity including rape, but acquitted him of the crime of incitement to commit genocide. On May 28, 2020, he was condemned to a life sentence, the highest that can be prescribed by a Rwandan court (the country abolished the death penalty in 2007).

Let’s come back to the Butare prefecture

In mid-April, the frightened Tutsi families took shelter or were pushed by local authorities to gather in churches, health centers, seminaries, communal offices, public buildings, playing fields, markets, hospitals, and schools, especially outside the town of Butare. There, they were slaughtered with brutality, sometimes in a matter of hours.

The worst killing grounds in Butare prefecture were:

- Matyazo Primary School, Matyazo (April 21)

- Matyazo Dispensary, Matyazo (2,000-3,000 victims, April 21)

- Karama Catholic parish, Runyinya Commune, Huye District (approx. 75,000 Tutsi were killed in 48 hours by Camp Ngoma soldiers, April 21-22)

- Groupe Scolaire, Ngoma (April 27)

- Ngoma parish, Ngoma Commune (476 people in the church, including 302 children, were slaughtered by militiamen and local crowds, April 29-30)

- Beneberika Convent, Sovu, Huye Commune (April 30)

- Economat Générale, Ngoma Commune

- Nyumba parish, Gishamvu, Nyakizu district (between 25,000 and 30,000 Tutsis were killed)

- Nyakibanda seminary, Gishamvu, Nyakizu district (3,000 victims, April 20-23)

- Muslim Quarters, Ngoma commune (Tutsis were slaughtered by soldiers and Interahamwe militiamen)

(Sources: International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, The Prosecutor versus Tharcisse Muvunyi Commander of the Ecole Sous Officiers, ESO, 2003; The Prosecutor v. Case of Prosecutor v. Ildephonse Hategekimana, Commander of the Ngoma Military Camp in Butare Préfecture, lieutenant in the Forces Armées Rwandaises and a member of the Butare Préfectural Security Council, 2010; Alison Des Forges; and others)

Groupe Scolaire, Ngoma (April 27)

«One of the most horrific events in Butare was the murder of orphans and displaced people at the Groupe Scolaire <a secondary school> in Ngoma. Authorities directed several hundred displaced people to the school, where they joined 600-700 orphans. On April 21, Nationale Gendarmerie soldiers and Interahamwe fighters pulled the children and displaced people from their lunch and brought them to a courtyard. After showing their identity cards, the Tutsi children were separated from the Hutu. Soldiers, Interahamwe fighters. and residents then killed the Tutsi children, and the displaced people with machetes and clubs. (…). On May 1st, some soldiers slaughtered 21 more children and 13 Red Cross workers whom they believed to be Tutsi» (Alison Des Forges). According to Human Rights Watch, on April 21, among the killers, there were soldiers, militiamen, and local people. A witness reported that several women killed other women and children.

Karama Catholic parish, Runyinya Commune, Huye District (approx. 75,000 Tutsi were killed in 48 hours by Camp Ngoma soldiers, April 21-22)

The slaughter, defined by the survivor Emile Karuranga as “the massacre to end all massacres”, took place on April 21, at the Catholic Church of Karama, in the commune of Runyinya. Some soldiers from Camp Ngoma and communal police officers shot and threw grenades from 10:00 a.m. until about 3:30 p.m. against a large mass of refugees, sheltered at the parish, the office of the commune, and the post-primary school of CERAI . On April 19, the registered refugees were 75,405, and when the massacre began, 2 days after, they were reasonably more. April 19 was a hard day for all of them. The Tutsi prefect was dismissed, and his protection vanished. The Tutsi families who had tried to reach the border with Burundi have been driven back by roadblocks. The news on the radio was alarming, and the water supply to the parish and the communal office was cut off. A survivor, Séraphine Mukabyusa, said: «We were surrounded, so much so that we could not even go to draw water. Those who tried were beaten and threatened. We became more and more afraid, but the burgomaster kept assuring us not to worry, saying that nothing would happen to us» (the telling of damned lies to the innocent victims before their massacre has always been a genocidal constant).

Mass graves inside the Genocide Memorial in Butare, Rwanda, 2012.

Photo by Meinzahn, © iStock by Getty Images

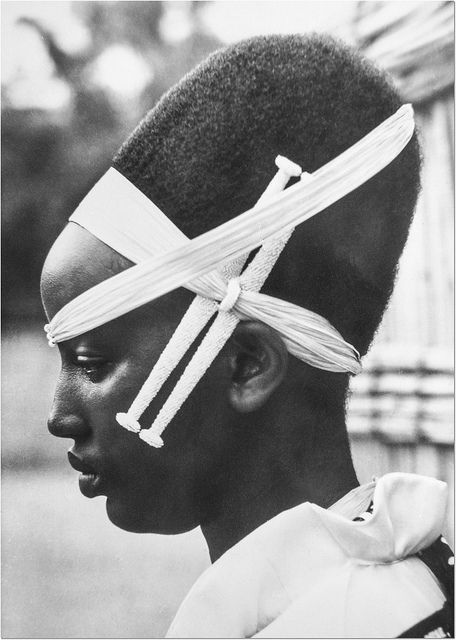

On April 20, Queen Dowager Rosalie Gicanda, widow of the last mwami of Rwanda, king Mutara III Rudahigwa, was kidnapped along with other Tutsis from her residence, brought behind the National Museum, and killed by a detachment of soldiers commanded by Lt. Pierre Bizimana, under the orders of Capt. Ildéphonse Nizeyimana (after the Genocide, the latter was convicted of genocidal crimes and sentenced to 35 years).

An old picture of the young queen Dowager Rosalie Gicanda. She was the wife of the last mwami (king) of Rwanda, Mutara III Rudahigwa, who died in mysterious circumstances in July 1959. In January 1961, with the so-called Gitarama coup d’état, the PARMEHUTU and APROSOMA leaders proclaimed the Republic of Rwanda and the end of the Rwandan Monarchy. The Queen continued to live in Butare, with her mother and several ladies-in-waiting. She was a living symbol for Tutsis, and her murder on April 20 shocked and terrorized most of them.

«By April 21, widespread and systematic violence against Tutsi civilians had become the norm in almost every area of the country that had not yet fallen to the rebels». (Scott Straus, The Order of Genocide, see Bibliography). This holds for the prefecture of Butare, as well. Here, the killings continued in May with a less frenzied rhythm. Many Tutsi survivors, mostly children and women with no protection from local religious, administrative, or political leaders, were finished. «Some Rwandans struggled to protect certain individual Tutsis and clashed with those who aimed to eliminate all the Tutsis of a given area. The head of the rice factory in Mugusa commune, Augustin Nkusi, for example, used the soldiers assigned to protect the factory to assure the safety of his Tutsi relatives and others in the adjacent commune of Rusatira» (Alison Des Forges). However, some clergy, lay people, soldiers, and civilians refused protection to the Tutsis and even yielded the Tutsi survivors to murderers with different justifications. Meanwhile, many local administrators were pushing the population to remain vigilant against the ‘enemies’ and finish the ‘work’ already started.

The sub-prefect of Gisagara District, Dominiko Ntawukuriryayo, declared on May 28: «Anyone who does not help his fellow Rwandans to fight the RPF is also an enemy and must be treated as an Inkotanyi (…) Whoever hides and does not show up to carry out the plans decided on by the administration is also an enemy» (Source: Alison Des Forges). He said it with the same words used by burgomaster Ntaganzwa time before: clearly, it was one of the cheap propaganda slogans coined in Kigali that could be easily turned into a ‘universal truth’ thanks to its constant repetition. Hiding Tutsis was considered an act of treason, and the best way to fight the RPF was to track and kill the local Tutsi survivors by “clearing the bush” or inspecting the caves and the abandoned houses where they might hide.

On June 7, the MRND supporter and senior administrator Callixte Kalimanzira said during a meeting of local authorities that the Inkotanyi «had elaborated a plan to eliminate all the Hutu everywhere in the country», with the support of local spies and even “small children (abana bato)”, thus suggesting that the latter were dangerous accomplices, and therefore enemies to be killed. Here’s another ‘universal truth’ coined in Kigali and endlessly re-chewed throughout the country.

In Butare prefecture, the massacres continued also in June though with a pace even slower – after all, the number of Tutsis still alive was decreasing day by day – often with the help of ordinary citizens acting in accord with the policy of “civilian self-defense”. Not all local authorities had the same criminal zeal as Callixte Kalimanzira: if some of them willingly executed their part in the genocide, «most seemed to have collaborated reluctantly, from fear of losing their posts or their lives» (Alison Des Forges), while others undertook the bureaucratic implementation of the killing campaign like nothing’s wrong. In any post-modern genocide, and the Rwandan is no exception, there are always people who, willingly or not, consciously or not, send trains to Auschwitz right on schedule. «By the regular and supposedly respectable exercise of their public functions, they condemned Tutsis to death for the mere fact of being Tutsis. Silent before the daily horror, they sought to hide behind the bureaucratic routine that divided the genocide into a series of discrete tasks, each ordinary in itself» (Alison Des Forges, p. 407; emphasis is mine).

«“Civilian self-defense” organized a substantial part of the population to hunt down Tutsi, either to kill them immediately or to hand them over to local authorities for execution. It also recruited and trained several thousand young men in the prefecture and provided them with firearms (…).While many citizens appear to have participated with little zeal or under coercion, withdrawing as soon as possible, a small number willingly shouldered the burdens of leadership in the genocidal system. The materials available for this study make clearest the role played by intellectuals in the town, but other community leaders – businessmen, successful farmers, clergy, teachers – apparently played the same role out on the hills. Led into the killing campaign by local and national officials, they were the good “workers who want to work” for their country. (..) Local authorities sometimes confronted situations where part of the community rallied to protect a person whom the rest of the community wanted to kill. The burgomaster of Ndora, known for his continuing reluctance to kill, dealt with several such cases in May» (Alison Des Forges, p. 392).

The more the genocidal violence decreased from mid-May to late-June, the more social disorder and violent crimes increased in the prefecture of Butare. «As the numbers of Tutsi were reduced, the assailants deputed to kill them directed their violence increasingly against other Hutu. The young men who hung around the barriers, often drunk or under the influence of marijuana, plundered, raped, and even killed Hutu passersby. Sometimes they confiscated identity cards from victims so that they could claim that they were Tutsi. They paraded through the sectors with the firearms meant for use at the barriers, extorting what they wanted from unarmed neighbors» (Alison Des Forges). Administrative authorities urged fast and firm action against the ‘degeneration’ of young civilians and militiamen, turned into dangerous troublemakers out of control.