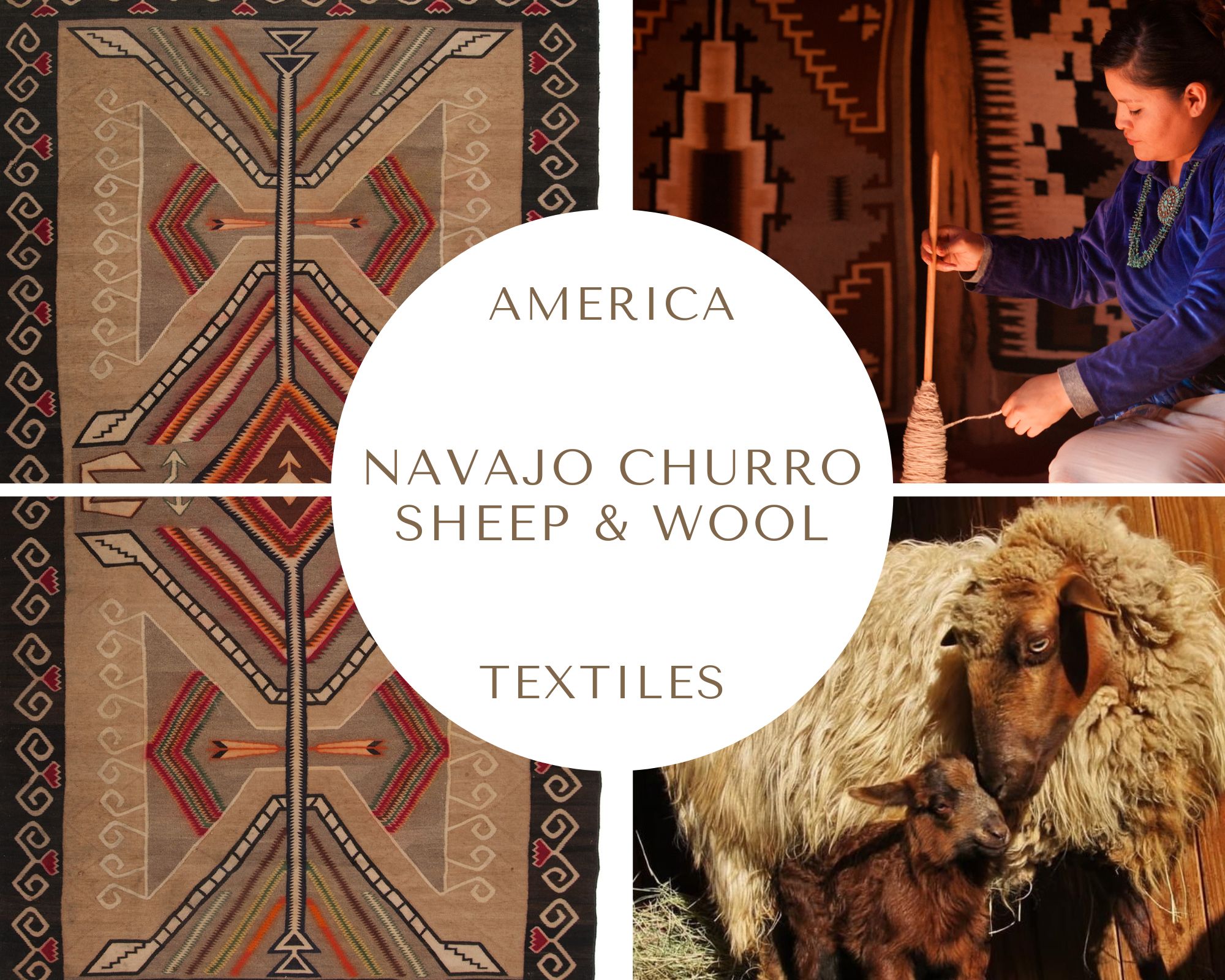

Rwandan Basketry 4

Rwanda on the globe

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

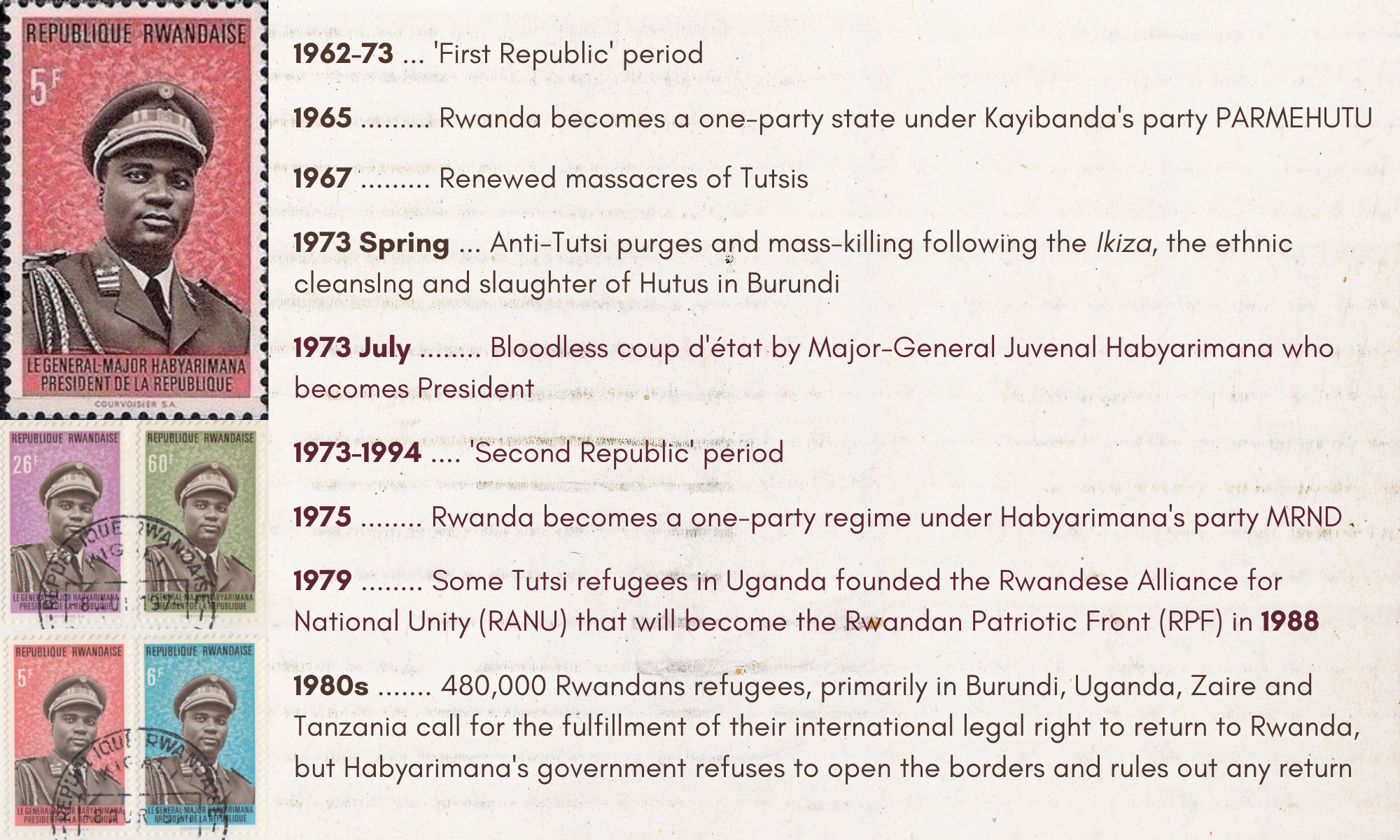

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE – THE IMMEDIATE BACKGROUND

«The ethnic and political violence that marked the revolutionary period of 1959-1962 did not end with Rwanda’s independence in July 1962″ (J.J. Carney, cit.) and with the Bloody Christmas of 1963. On multiple occasions, over the following years, the Hutu government not only permitted but also encouraged vengeance killings against Tutsi civilians to get remarkable political benefits (= the violence against all Tutsis became part of the jingoistic rhetoric of the Kayibanda single-party regime, and the main ingredient of its patriotic recipe). The pogroms of Tutsi civilians involved a material gain (= the grabbing of their properties, especially land and cattle) and therefore got easy support from a part of the Hutu population.

After the Bloody Christmas of 1963 and mass killing in 1967, the major paroxysm of anti-Tutsi violence occurred in 1973.

In Burundi during the spring of 1972, some Hutus rebelled against the Tutsi military regime, killing more than 3,000 Tutsi civilians and soldiers. In retaliation, the Burundian government triggered a horrific wave of ethnic violence that lasted 5 months and cost the lives of approx. 100,000 Hutus and forced another 200,000 to escape to neighboring countries (As to the death toll, different scholars give different estimates: from 100,000 victims according to Israel W. Charny, to 200,000 for René Lemarchand, or even 300,000 according to Robert Krueger and Kathleen Tobin Krueger). This genocide of Hutus, carried out by the Burundian Tutsi-dominated army and government, is known as Ikiza, ‘The Catastrophe’ in Kirundi (the Bantu language spoken in Burundi). It resulted in the slaughter of about 75% of educated Burundian Hutus.

The Rwandan President Grégoire Kaybanda capitalized on the Ikiza to reinforce his troubled ruling power. In 1973, a violent anti-Tutsi campaign orchestrated by the General Staff of the Rwandan Army led to the elimination of several hundred Tutsi in the name of public safety. Soon after, Habyarimana launched a violent purge program to expel Tutsis from positions in government, business, and notably from Catholic seminaries, secondary schools, and the university (there was only one at the time). Approx. 100,000 Rwandan Tutsis fled the country and took refuge in camps beyond borders.

On July 5, 1973, Juvénal Habyarimana, major general and minister of defense, led a group of disgruntled Hutu officers in the overthrow of President Kayibanda. After this bloodless coup d’état, a civilian-military government was established and Habyarimana became president (bloodless cup but only to a point: 55 members of the Kayibanda’s government, army officers, and state functionaries were imprisoned and put to death). His promises to restore order and national unity fell on deaf ears. The Second Republic was a corrupt dictatorship not different from the First one – in July 1975, Habyarimana proclaimed Rwanda a single-party state – with a remarkable difference, however: internationally Habyarimana’s Rwanda wore the mask of a young African democracy, deserving of economic aid. Thanks to Habyarimana’s diplomatic cunning, the country got to count on a remarkable flow of aid. As Daniele Scaglione points out, «Canada sent more aid to Rwanda than to any other sub-Saharan country, Switzerland more than to any other nation in the world» (Daniele Scaglione, Rwanda: Istruzioni per un genocidio, see Bibliography). Moreover, independent Rwanda «for three decades (…) was one of the biggest recipients of Belgian development aid» (Colette Braeckman, Belgium’s role in Rwandan genocide, see Bibliography). The flow of Western money was so substantial that between 1980 and 1990, «the country of a thousand hills became the country of a thousand foreign aid, and the contributions to its development reached 22% of its gross domestic product» (D. Scaglione, cit.).

The international support was oxygen for Habyarimana who would never have been in power for 20 years without the money of some countries and the opportunistic assist of some others.

France, first of all.

«Without France, the dictatorship of Juvénal Habyarimana would bever have lasted as long as it did. Two years after he took power, in 1975, a military cooperation and training agreement was signed with Paris and, over the next 15 years, France slowly replaced Belgium as the most important ally, offering financial and military guarantees <money, training, support, strategic consulting, etc.> that Belgium could not provide» (Linda Melvern, A People Betrayed – The Role of the West in Rwanda’s Genocide, see Bibliography). President Habyarimana developed a close political relationship with French President François Mitterrand (in charge from 1981 to 1995) and a personal friendship with Mitterrand’s son, Jean-Christophe, African affairs advisor to his father from 1986 to 1992, nicknamed ‘Papamadit’ (Daddy-told-me) and worldwide known as an arms smuggler (suspected, arrested, and finally condemned, despite mommy and daddy’s powerful meddling).

Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana with Dutch premier Dries Van Agt, in The Hague, May 13, 1980.

Photo from the Dutch National Archives, licensed under Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0) Public Domain Dedication.

The Habyarimana’s regime not only continued the old use of racial identity cards but practiced also a policy of racial discrimination by setting up a system of quotas that in theory was supposed to assure an equitable distribution of opportunities but in reality, was used «to restrict the access of Tutsi to employment and higher education and increasingly discriminate against Hutu from regions other than the north» (= that of Habyarimana family and associates) (Alison Des Forges, Leave None to Tell the Story: Genocide in Rwanda, see Bibliography). Tutsi were restricted to 9% of all public service available jobs; fixed quotas were defined even in any schools.

Habyarimana implemented an apartheid system and many anti-Tutsi campaigns; moreover, he refused to address the problem of hundreds of thousands of Tutsi refugees who repeatedly asked to be allowed to leave the refugee camps set up in the neighboring countries and return home. Their number is uncertain. The UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) gives an estimate of 900,000 Rwandans living in Uganda, Burundi, Zaire, and Tanzania at the beginning of 1990 (not to mention the refugees out of Africa). Other sources (like Alison Des Forges, André Guichaoua, etc.) speak of 600,000 in the late 80s; the US State Department estimated there were 550,000 refugees, predominantly Tutsis, in Central Africa; the Burundian expert M. Ngendakumana gives an estimate of approx. 441,000 refugees in Central Africa in October 1990. In any case, whatever the estimates, this was “the largest refugee problem on the African continent”, according to Linda Melvern. The Rwandan refugees continued to call for the fulfillment of their international legal right to return home, but Habyarimana always denied these people their right, hiding his bad conscience behind some dumb excuses: the overpopulation issue, the absence of economic opportunities, and so on. In 1985, some of Rwanda’s neighbors repeatedly try to negotiate a program of systematic Tutsi repatriation, but Habyarimana consistently stalled, claiming that there was no land, no jobs, no space for the returnees, probably not even oxygen in the Rwandan atmosphere.

The Rwandan refugees did not wait for the help they knew it would never come, and got organized by themselves. In 1979, the Tutsi refugee intelligentsia in Uganda set up the region’s first political refugee organization, the Rwandese Alliance for National Unity (RANU) to discuss a possible return to Rwanda. The RANU soon became militarized and its fighters started both to call themselves the Inkotanyi or the “the indefatigable ones”, and to join the Ugandan rebel leader Yoweri Museveni’s National Resistance Army (NRA) during the Ugandan Bush War. Among them, there was a young Paul Kagame (born in 1957 in a family who fled from the country in the late 1950s) who will become a senior Ugandan army officer. In December 1988, during its 7th Congress in Kampala (Uganda), the RANU renamed itself Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), in French Front Patriotique Rwandais (FPR). It emerged as a political and military movement dominated by some charismatic military leaders like Paul Kagame or Fred Gisa Rwigyema and made up by Tutsi and Hutus (among the 26 members of the executive committee, 11 were Tutsi and 15 were Hutu). The movement’s main goals were the safe repatriation of Rwandans; the implementation of a new system of power-sharing among all Banyarwandans; and the end of the Habyarimana’s apartheid system and dictatorship.

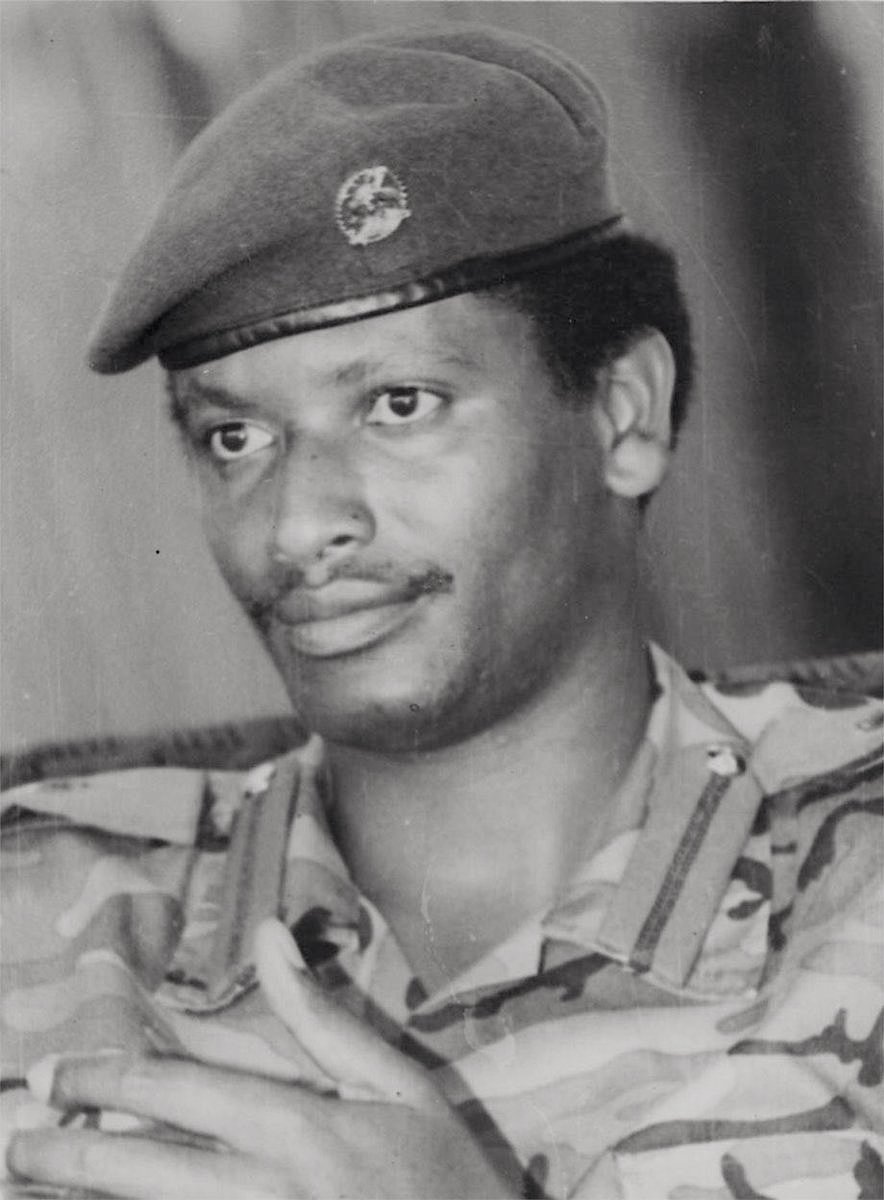

Fred Gisa Rwigyema (or Rwigema), born in 1957, was a charismatic Rwandan politician and military officer among the founders of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF). He was (mysteriously) killed on October 2, 1990, the second day of the Civil War.

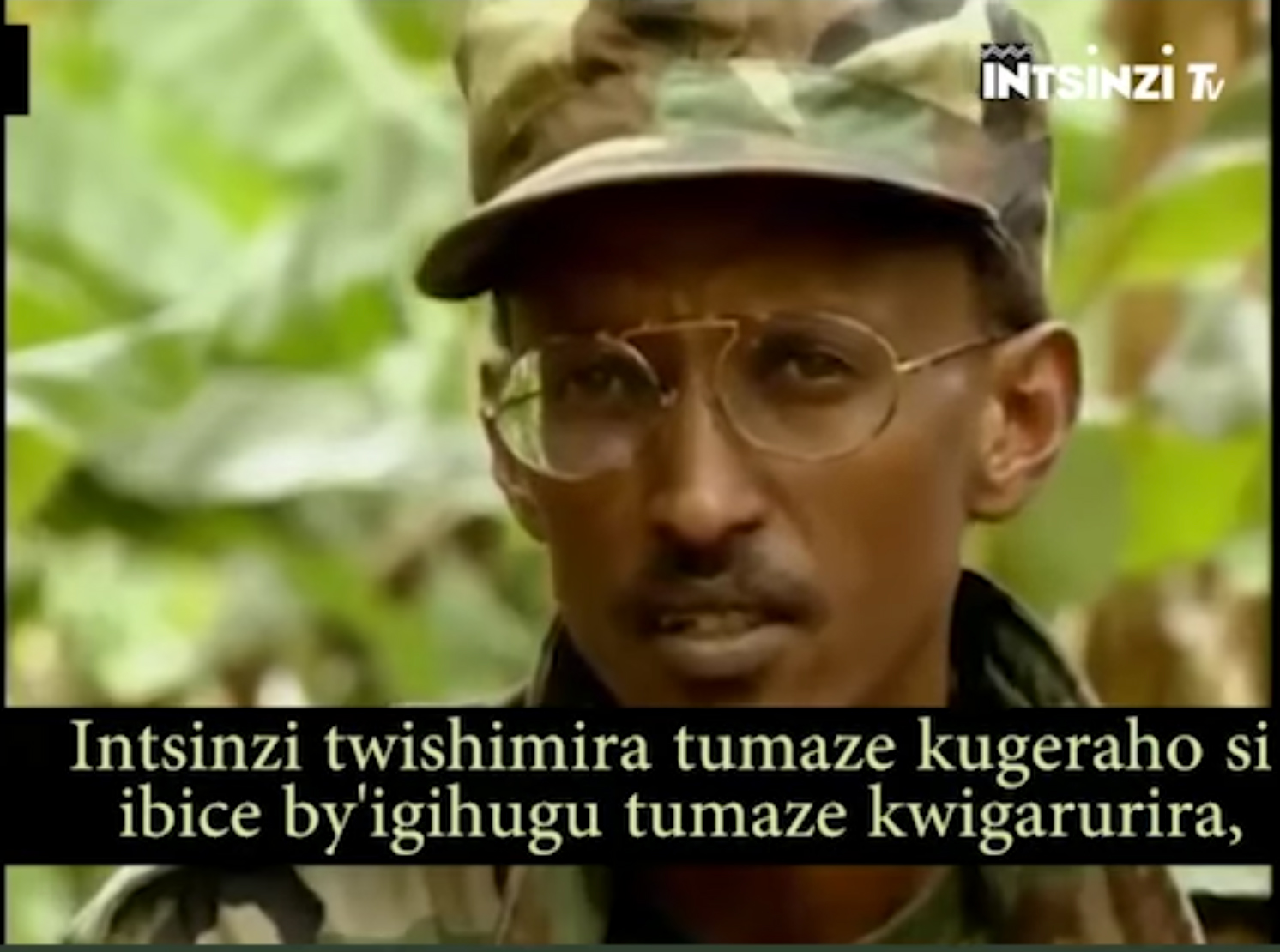

A young Paul Kagame (born in 1957) at the Civil War time. In 1990, he was a senior officer in the Ugandan army. He took command of the RPF after the death of Rwigyema and is the current President of Rwanda.

.

In Rwanda, the state racial segregation, combined with many anti-Tutsi campaigns, pogroms, and purges, had an unacceptable, quantifiable consequence: “Said to represent 17.5 percent of the population in 1952, Tutsi were counted as only 8.4 percent of the total in 1991” (Alison Des Forges, p. 44). Still too many, for the Hutu ruling oligarchy at the beginning of the 1990s.

As to the Catholic Church, in post-colonial Rwanda, it did not speak with one unified voice, as J.J. Carney shows in its essay. The voice of the powerful Archibishop Perraudin, who Pope John Paul II outrageously defined “a model missionary bishop” in 1990, was one of the ‘loudest’, at least till 1989, when he retired (at 75). His policy remained almost the same: he advocated for a close church-state collaboration that granted the former an educational and cultural monopoly (the National University of Rwanda was founded in 1963 thanks to cooperation between the government and the Congregation of the Dominicans from the Province of Quebec, Canada).

As before independence, Perraudin often condemned the use of ethnic cleansing, but he did not denounce the systematic racial persecution as such, but he just decried them as generic outbursts of violence. As J.J. Carney clearly shows, in his speeches and writings, he continued to betray a fundamentally divisive vision of Rwandan society and never advocated for ethnic reconciliation. Even the 1973 bloodless military coup did not change his position: «Far from critiquing the coup d’êtat which ushered in the Second Republic, Perraudin commended Habyarimana in late July as a “Christian and an apostle, a disciple of the Prince of Peace”» (J.J. Carney, cit.). Moreover, he always supported Habyarimana’s regime, even in its choice of racial segregation. This policy was “successful”: «In the years following the 1973 events, the Catholic Church continued to flourish on an institutional level» (J.J. Carney, cit.) and got to control the vast majority of health clinics in the country. In 1993, Perraudin left Rwanda for Switzerland where he died in 2003.

Habyarimana benefited enormously from the unquestioning and uncritical support by many higher prelates. After the death of bishop Bigirumwami in 1986, Vincent Nsengiyumva, a Hutu native of northern Rwanda, was appointed his successor. Two years later, he became Archbishop of Kigali. «Only 40 at the time of his appointment to the Kigali see, Nsengiyumva cultivated close relations with Habyarimana, especially with Habyarimana’s wife Agathe, and a coterie of Hutu political leaders from Gisenyi known as the akazu» (J.J. Carney, cit.).

The Akazu, or “little house,” was an inner circle of power within the larger network of personal connections that worked to directly support Habyarimana. It was composed mostly of the people of Habyarimana’s home northern region, Gisenyi prefecture, with madame Agathe Kanziga, Habyarimana’s wife, and her relatives playing a major role. «Les personnes suivantes ont été généralement considérées comme les plus influentes : Protais Zigiranyirazo <Monsieur Z>, le colonel Élie Sagatwa <Habyarimana’s personal secretary>, Séraphin Rwabukumba, tous trois « beaux-frères » du président [brother-in-law of the President]; le colonel Laurent Serubuga (ancien chef d’état-major adjoint des FAR) ; le Dr Séraphin Bararengana, frère [brother] du président ; le Dr Charles Nzabagerageza, cousin du président, ex-préfet de Ruhengeri ; Alphonse Ntilivamunda, gendre [son-in-law] du président et Joseph Nzirorera». (André Guichaoua, Rwanda de la guerre au génocide, see Bibliography).

The Akazu was suspected to rely on a death squad to remove any kind of ‘obstacles’, probably thanks to the involvement of a military officer, colonel Pierre-Célestin Rwagafilita. In 1992, Christophe Mfizi, former head of the national information service, denounced the activities of the Akazu members who had taken control of the state and were milking it for private benefit. What is even worse, they used racial hatred to increase their power and sabotage any political change.

They were not the only member of the ‘thieving elite club’: many state employees, local administrators, and military officers among the most faithful to Habyarimana also used access to preferential treatment to build profitable private businesses, while the horizon of the majority population was, ça va sans dire, marked by unavoidable poverty. «By the early 1990s, according to one analysis, 50% of Rwandans were extremely poor (incapable of feeding themselves decently), 40% were poor, 9% were non-poor and 1% – the political and business elite – were positively rich» (Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide, see Bibliography). Even before the 1990 economic crisis and civil war, Rwanda was one of the world’s least-developed countries. Its “African Switzerland” look was the result of good cosmetic makeup. «According to the United Nations Development Programme, Rwanda in 1990 ranked below average of all of the sub-Saharan African countries in life expectancy, child survival, adult literacy, average years of schooling, average calorie intake, and per capita GNP» (Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide, cit., 5.9).

At the end of the 1980s, coffee, which accounted for 75 percent of Rwanda’s foreign exchange, dropped sharply in price on the international market. This entailed a rapid and dramatic economic decline that exposed the real country’s underdevelopment behind the facade. “Suddenly Rwanda found itself among the many debtor nations required to accept strict fiscal measures imposed by the World Bank and the donor nations. The urban elite saw its comfort threatened, but the rural poor suffered even more. A drought beginning in 1989 reduced harvests in the south and left substantial numbers of people short of food. Habyarimana at first refused to acknowledge the gravity of the food shortage, an attitude that exemplified the readiness of the urban elite to ignore suffering out on the hills. (…) Confronted by the dramatic economic decline and the evidence of increasing corruption and favoritism on the part of Habyarimana and his inner circle, political leaders, intellectuals, and journalists began demanding reforms” (Alison Des Forges, cit.). In particular, they solicited a multi-party system and greater transparency to detect the widespread corruption in the country. Habyarimana understood that he had to make some political concessions in order not to risk compromising his good international reputation and, above all, not to lose the abundant river of international aid that swelled not only the state coffers but also his and his inner circle’s purses («Most development aid ended up in the hands of the richest 1% of people in society, those for whom it was least intended». Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide, cit., 5.14).

Among the late 1980s and the early 1990s, Habyarimana’s Rwanda appeared “a country on the verge of collapse, split, drained by corruption” (L. Melvern, cit), suffering from racial and social imbalances. It was during this politically fragile moment that the RPF attacked. It was October the 1st, 1990.

“You are not born Tutsi or Hutu, you become Tutsi or Hutu,” said Yolande Mukagasana, a nurse who survived the 1994 massacre after spending weeks in the forest. “It was at the age of 5 that I discovered that I was Tutsi. Men came to pick up my father, it was in 1964, and they hit my mother. It was the first time I saw someone put their hands on her. It was at school that I learned that we were ‘strangers’. The children were booing me and I came home in tears.”

(…) A genocidal ideology had undermined, divided and administered Rwanda since 1959. For more than thirty years, Tutsis were insulted, called cockroaches, parasites, and traitors.

Mémoire d’un génocide by Yves Simon for Libération, 4 juillet 2000

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE – THE CIVIL WAR

On October the 1st, the Rwandan Patriotic Army (RPA), the fighting force of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), launched a major attack on Rwanda, crossing the border from Uganda, in the north, with a force of 7,000 fighters under the command of Fred Gisa Rwigyema (who died on the second day of the invasion and was eventually succeeded by NRA Major Paul Kagame).

For President Juvénal Habyarimana the attack posed a risk as well as an opportunity.

ON RISKS AND CHANCES

Let’s consider the risk, which was primarily a military risk as the Rwandan Armed Forces (RAF or Forces Armées Rwandaises, FAR) were not made up by elite soldiers. Immediately, President Habyarimana asked for military support from his allies: France, Belgium, and President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire. On October 2, Juvénal Habyarimana called the French President Mitterrand to request a French intervention in Rwanda; the day after, the Rwandan Foreign Minister, Casimir Bizimungu, met Jean-Christophe Mitterrand and Jacques Pelletier, at that time ministre de la Coopération, to reiterate Habyarimana’s request.

During the night between 4 and 5 October, Habyarimana did not hesitate to enact a fake attack by the Kagame’s Army.

The RPF had advanced into Rwanda but was still over 70 km far from Kigali. That night, however, heavy firing shook the capital for several hours. In the morning, the government announced that the city had been attacked by RPF infiltrators, fortunately, driven back by the Rwandan army. It was a complete fabrication, un montage.

The 1998 Official French Mission d’information parlamentaire sur le Rwanda will write: «L’attaque simulée sur Kigali servit non seulement de leurre pour déclencher l’intervention française, mais aussi de levier pour restaurer le régime dans sa plénitude» (Rapport d’information, see Bibliography. My translation: This simulation served not only as a decoy to trigger the French intervention, but also as a lever to restore the regime to its fullness).

That’s true. This Rwandan version of the ‘Reichstag fire’ served (brilliantly) two different purposes. Let’s consider the first: it speeded up the military help from the allies; Habyarimana got immediate military support from Belgium, Zaire, and France.

Belgium sent 535 soldiers, which remained only until the first days of November (they were withdrawn for political reasons). Mobutu’s Zaire sent approx. 1200 men, so lacking in the discipline that Juvénal Habyarimana asked them to return to their country.

Habyarimana’s ‘best friend’, namely François Mitterrand, launched L’Opération Noroît, officially to protect French Embassy and citizens and their evacuation in the event, but in reality to secretly train the Rwandan army, and supply it with weapons and vehicles. France was determined to stay much longer: its soldiers were planned to become a solid support for the Rwandan army and the Habyarimana regime. The first soldiers to arrive were the 2e REP Régiment étranger parachutiste – Légion étrangère and the 3e RPIMa, Régiment de parachutistes d’infanterie de marine, two elite military units.

THE MILITARY AND POLITICAL SUPPORT GIVEN BY MITTERRAND

According to The Human Rights Watch 1994 Report, during the civil war (1990-93), France deployed up to 680 troops in Rwanda, and provided military advisors (Human Rights Watch, Arming Rwanda, see Bibliography). Unfortunately, the commitment of the French Presidency to support Habyarimana’s regime went further. Much further, as we shall see.

In March 1991, France sent confidentially (= in secret) a detachment of military assistance and training of about 30 experts, called DAMI (Détachement d’Assistance Militaire et d’Instruction) in the north of Rwanda. The real purpose of the DAMI mission was to organize, train and supervise the Rwandan military forces. Initially planned to last four months, it was reinforced by an artillery component in 1992 and an engineering component in June 1993 (bringing the total strength to a hundred people) and was extended until December 1993.

The French soldiers, whose number was constantly growing, did not restrict to training or arming the troops of Habyarimana but took part in the fighting against the RPF, in other words, French soldiers secretly played a direct role in the fighting. Colonel Cussac, the military attaché for the French Embassy and the head of the French Military Assistance Mission, said publicly: «French military troops are here in Rwanda to protect French citizens and other foreigners. They have never been given a mission against the RPF». Of course, he lied, aware he was lying.

Lieutenant-Colonel Bernard Cussac in December 1993.

Source: France 3 – France Génocide Tutsi.

Human Rights Watch collected many first-hand witnesses of the direct involvement of French soldiers in many fightings and of their deployment in war zones (like Byumba) where no French citizens had ever lived. In June 1992, troops from the French Eighth Marine Infantry Parachute Regiment joined the 170-strong Noroît unit to counter an RPF offensive against Byumba. In February 1993, a massive RPF attack targeted Byumba and Ruhengeri, and an operation named Chimère was organized to support Habyarimana’s troops. The French Lieutenant-Colonel Chollet, who was in command of the DAMI mission, was appointed counselor to the President of Rwanda and to the RAF Chief of Staff. He allegedly became the operational Commander of the Rwandan Army (See Emmanuel Viret, cit.).

France, moreover, provided Rwanda with both lethal and non-lethal military equipment.

BUSINESS IS BUSINESS: WHO ARMED THE BLOODY RWANDAN REGIME?

«When the war began in October 1990, Rwanda had an army of only 5,000 men. They were equipped with light arms (…). The Army’s most significant weaponry included 8 mortars, 6 anti-tank guns, French Blindicide rocket launchers, 12 French AML-60 armored cars, and 16 French M-3 armored personnel carriers. By the war’s end , the Rwanda armed forces had expanded to at least 30,000 men, armed with a wide range of light arms, heavier guns, grenade launchers, landmines, and mid-to long-range artillery» (Human Rights Watch, Arming Rwanda, cit.). Some sources, like Pierre-Antoine Braud, talks of 40,000 soldiers in 1993; some others, like Linda Melvern, of 28,000. In any case, in three years, the Rwandan Armed Forces almost increased tenfold. In 1992, according to Linda Melvern and other reliable sources, the military spending by Habyarimana’s regime reached 71% of the entire nation’s budget. In late 1993 / early 1994, «anyone in Kigali with the equivalent of US$3 could buy a grenade in the main market» (The Preventable Genocide, cit., 7.30)

Rwanda wasn’t just arming herself. In only three years, under the eyes of the World Bank and the international community, Rwanda – which has more or less the same size as the Italian Sicily island, the French Brittany region, or the US state of Vermont – became the third largest arms importer on the African continent. «This small, impoverished nation, which was already unable to meet its own human needs, devoted its scarce resources to an unprecedented accumulation of a wide variety of arms, including the introduction of heavier, long-range weapon systems» (HRW, Arming Rwanda, cit.). These abnormal data, however, did not alarm anyone. When there’s plenty of pie out there, many gluttons turn a blind eye and often even both.

Who armed the Habyarimana?

France, first of all.

As the HRW Report shows, Mitterrand provided Rwanda with both lethal and non-lethal military equipment, in particular supplied and kept operational (by providing the spare parts and technical assistance) most of the heavy guns, artillery, assault vehicles, and helicopters used by Rwanda in the war. Among them, Panhard Light Armoured Cars AML 60/7 and AML 90, equipped with turret-mounted cannons and 7.62mm machine guns, Panhard M3 Armoured Personnel Carriers, and some fully armed Gazelle helicopters. According to Andrew Wallis (in Silent Accomplice: The Untold Story of France’s Role in the Rwandan Genocide, see Bibliography), in October 1992, a French Gazelle destroyed a column of ten units of the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), to which these helicopters will give a lot of trouble on several other occasions.

«According to declassified French Ministry of Defence documents, between February 1990 and 6 April 1994—the date of the last authorization to export war materials (autorisation d’exportation de matériel de guerre, AEMG) to Rwanda delivered by the Customs General Directorate—France approved the export of a significant volume of major weapons, small arms and ammunition worth a total 136 million French francs. Besides the agreed sales to the Rwandan Government, France also provided direct transfers of arms, weapons platforms, and ammunition. Such transfers are taken directly from existing army stocks and are paid for by either the former French Ministry of Cooperation or the French Ministry of Defence, and not by the recipient. Such exports require fewer administrative steps and are conducted more speedily. There were 36 direct transfers worth 43 million French francs to Rwanda over the 1990–94 period, only five of which were granted the required AEMG licenses, the remaining 31 transfers disregarding standard procedure» (Damien Fruchart, United Nations Arms Embargoes – Their Impact on Arms Flows and Target Behaviour – Case study: Rwanda, 1994–present, SIPRI Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 2007, see Bibliography). I’m gonna do the math: from 1990 to April 1994, 180 million French francs are over the US 31 millions dollars. ‘Papamadit’ had to be quite happy, the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) much less. The latter publicly accused the French government of prolonging the Civil War by supporting the Rwandan military, and for directly firing upon RPF position in Ruhengeri and elsewhere.

A French SA341F2 Gazelle helicopter in the desert during Operation Desert Shield in ca. 1990.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons, Public Domain.

Egypt provided Rwanda with both lethal and non-lethal military equipment. In March 1992, Mubarak’s Egypt sold US$6 million of arms to Habyarimana. The million deal included a wide range of light arms, infantry support weapons, ammunition, landmines, grenades, Egyptian-made Kalashnikov, and many other sweets and candies. This contract with Egypt guaranteed for Rwanda the import of 6 D-30 122-mm towed guns (with 3000 shells), 50 60-mm and 20 82-mm mortars with 10,000 shells, over 6000 shells for 120-mm mortars, 2000 RPG-7 anti-tank rockets, 2000 MAT-79 anti-personnel landmines, 450 Egyptian-made Kalashnikov rifles, 200 kg of plastic explosives, and over 3.2 million rounds of ammunition (source: Damien Fruchart, SIPRI, cit.).

According to the Human Rights Watch 1994 Report and Damien Fruchart-SIPRI, in October 1992, South Africa sold US$5.9 million of arms to Habyarimana including a wide range of light arms, machine guns, and ammunition: 20,000 South African-made Vektor R4 assault rifles (7.62-mm and 5.56-mm caliber), 10,000 M26 fragmentation grenades, 2.5 million rounds of ammunition, 100 M1 mortars, SS-77 7.62-mm machineguns and Browning 12.7-mm heavy machineguns, and 70 hand-held MGL grenade launchers with 10,000 grenades (Source: Damien Fruchart, SIPRI, cit.). Note that this lucrative deal was carried out violating the UN Security Council Resolution 558, adopted on December 13, 1984, which asked nations to refrain from importing arms, ammunition, and military vehicles produced in South Africa.

South African soldier firing his Vektor R4 assault rifle

As to Belgium, this country «has a prohibition on selling lethal military equipment to a country at war. Shortly after hostilities began in Rwanda, Belgium cut off all transfers of lethal military equipment, but still provided Rwanda with 88 million Belgian francs (U.S. $2.75 million) in military assistance in 1992. It included the training of Rwandan officers, commando units, and medical personnel, and the delivery of non-lethal military equipment including boots and uniforms» (HRW, Arming Rwanda, cit.).

China is also reported to have supplied Kigali with arms, providing it with US$1 million in mortars, machineguns, multiple rocket launchers, and grenades (Source: Damien Fruchart, SIPRI, cit.).

The USA sold arms to Rwanda in limited amounts and gave military assistance. «It is worth noting, however, that although the level of U.S. military assistance was small, the U.S. has generally been very supportive of the Rwandan government and Rwandan armed forces. In fact, in its 1992 annual report to Congress justifying military aid programs, the George H.W. Bush Administration stated that “relations with the U.S. are excellent,” and that “there is no evidence of any systematic human rights abuses by the military or any other element of the Government of Rwanda”» (HRW, Arming Rwanda, cit.).

Between 1990 and late 1993, Rwanda was not a poor and small African Cinderella, needing aid and assistance to sustain a shameful military attack from the outside, just when she was trepidatiously starting the glorious journey towards modern democracy.

Nope.

Not at all.

This is what Habyarimana was selling to the international community but no country was so idiot to buy his fib. This is what France, Belgium, the Bush Father administration wanted the world to believe that they honestly believed, in order to carry out economically and politically profitable deals without losing face.

George H.W. Bush Administration lied on the Rwandan situation, perfectly knowing they were lying. As HRW Report says, Belgium’s providing of non-lethal military aid was explicitly linked to respect for human rights, negotiations to end the war, and the process of greater democratization. Similarly, France military aid, assistance, and sales were formally conditional upon democratization in Rwanda: as the important Rapport remis au Président de la République le 26 mars 2021 writes (see Bibliography), France gave «un soutien militaire en échange d’avancées dans la démocratisation du pays et le respect des droits de l’homme» (a military support in exchange for progress in the democratization and in respect for human rights). US, France, and Belgium governments, among others, perfectly knew the real situation of Rwanda (thanks to intelligence reports and diplomatic communications), but nevertheless, this knowledge did not stop their politics and their lies.

Since the 70s, the dictatorial regime of Habyarimana was well known for its violent policy of racial segregation. From 1990 on, it gave the start to bloody political repression and a climate of violence and terror through massive arrests, bombings and terrorist attacks, paramilitary gangs and death squads to get rid of political opponents; it was a country suffering from systematic human rights abuses, a fear and hatred propaganda campaign, mass killings of civilians, all carried out by state agents.

“No systematic human rights abuses by the military and the Government of Rwanda”, isn’t it Bush Father?

The truth is – as the French 2021 Report to Presidency honestly writes – that in October 1990, «la chasse aux Tutsi et aux membres des partis d’opposition», the hunt for Tutsis and political opponents had already begun. The Tutsi Genocide had already begun. Long before 1994. As we shall see, we have to reject the idea that the Genocide of Tutsi started on April 6 or 7, 1994. This idea has no historical basis. It’s a comfortable carpet under which a lot of garbage has been hidden; moreover, it conveys a dangerous misunderstanding about what a genocide really is and what the Rwandan Genocide was.

Human Rights Watch Arms Project, Arming Rwanda – The arms trade and Human Rights Abuses in the Rwandan War, a report published in New York in January 1994, before the final phase of the Tutsi Genocide. You can download this document on the Human Rights Watch website, on this page.

«Human Rights Watch was founded in 1978 as “Helsinki Watch,” when we began investigating rights abuses in countries that signed the Helsinki Accords, most notably those behind the Iron Curtain. Since then, our work has expanded to five continents. We investigated massacres and even genocides, along with government take-overs of media and the baseless arrests of activists and political opposition figures. At the same time, we expanded our work to address abuses against those likely to face discrimination, including women, LGBT people, and people with disabilities» (Source: HRW website).

WHO ARMED THE RWANDAN PATRIOTIC FRONT?

«The most important source of weapons to the RPF has been Uganda and its National Resistance Army (NRA). The RPF has also received substantial funds to buy arms from Banyarwanda exiles, especially in North America and Europe. The RPF also captured weapons and ammunition from the Rwandan army.

The thousands of NRA members who allegedly defected en masse to the RPF brought their uniforms and personal weapons, most of which were Romanian and other ex-Eastern bloc Kalashnikov automatic rifles, as well as ammunition. RPF forces also took other weaponry including landmines, rocket-propelled grenades, 60 mm mortars and recoilless cannons. RPF commanders Jean Birasa and James Rucibira in Kigali on May 26, 1993, and commanders Frank Mugambage, David Byarugaba, and Frank Rusagara in Mulindi on May 30, 1993, told the Arms Project that they left Uganda with at least two Soviet-made Katyusha multiple rocket launcher systems. The Katyusha is a long-range system that can cover an area wider and longer than a soccer field with a concentration of incoming fire. RPF commanders maintain that they “stole” all of these weapons. Both RPF commanders and Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni deny that the NRA has provided any direct support to the RPF» (Human Rights Watch Arms Project, Arming Rwanda, cit.). Just a facade, of course: Uganda gave constant support to the RPF since the very beginning, namely October 1990, throughout the entire conflict; he allowed the RPF soldiers free passage back and forth across the border and was a steady source of light arms, ammunition, uniforms, batteries, food, gasoline, as well as heavier weaponry including artillery. However, both Museveni and the RPF staged a scene for the use and consumption of the international community.

An RPF’s soldier in early 1994 with a fully automatic Romanian PM mod. 65 (Pistol Mitraliera Model 1965), the Romanian version of the Soviet Kalashnikov AK-47 assault rifle.

The Katyusha multiple rocket launcher was built by the Soviet Union during World War II and is used still today. This multiple rocket launcher has pros – it delivers explosives to a target area more intensively than conventional artillery – and cons – it’s not accurate and needs a longer time to be reloaded. It’s easy to operate, low-cost, and can be mounted on any chassis.

BETWEEN THE ANVIL AND THE HAMMER: THE TWO FACADES OF HABYARIMANA’S POLICY

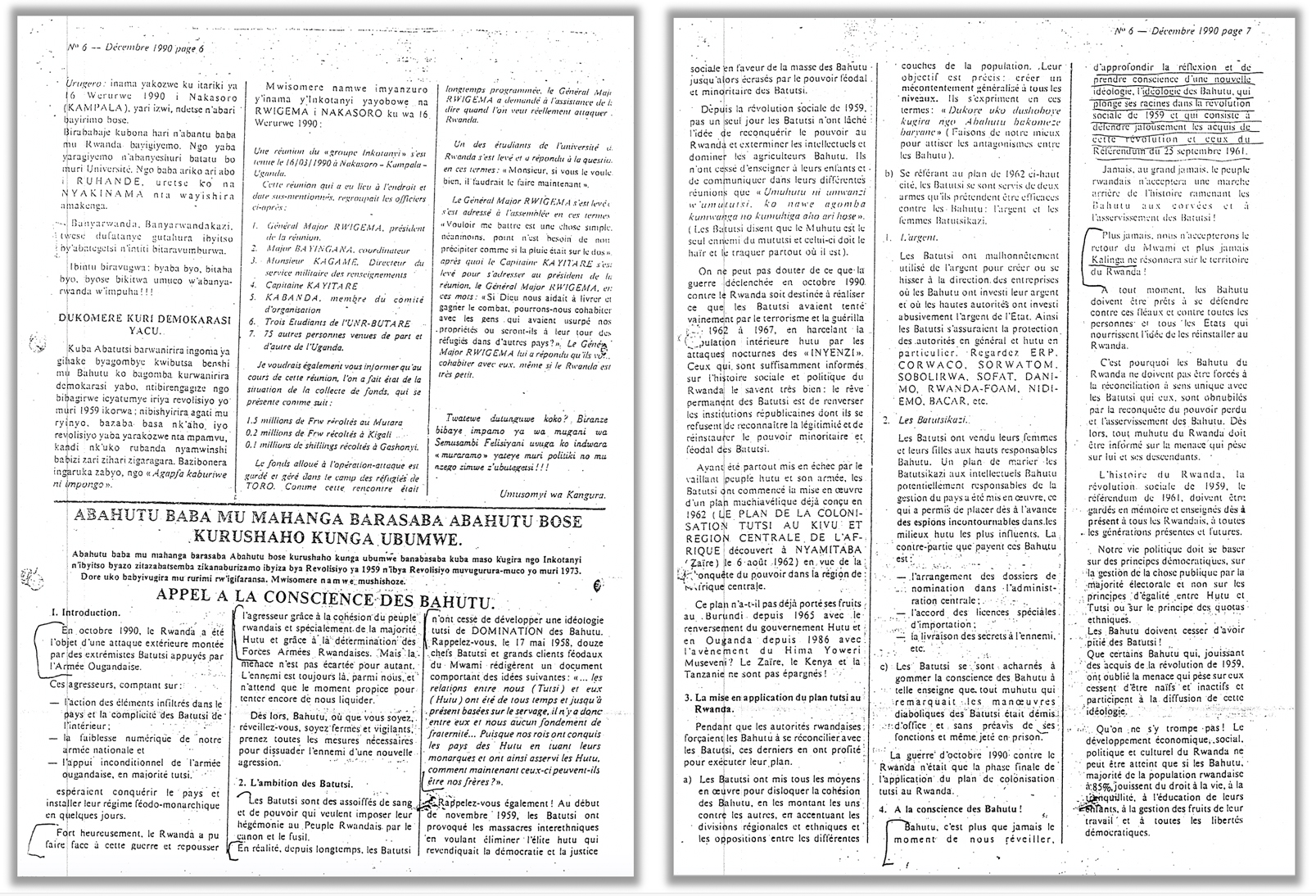

Even before the Civil War, Habyarimana felt the pressure for gradual democratization of the Rwandan political life from both external authorities – foreign aid donors and military supporters – and internal forces – Rwandan political opponents, humanitarian organizations, intellectuals, NGOs, and human rights activists. After the beginning of the Civil War, that pressure increased: the international community urged Habyarimana to open up the political system hoping this would speed up the end of the armed conflict (which, by the way, was dangerously raising the number of Rwandan refugees, thus exacerbating one of the major problems of East Africa). In June 1991, Habyarimana was obliged «to sign a new Constitution which provided for multi-party politics, the creation of prime ministership, a limited Presidential term (a candidate could seek a maximum of two terms of five years each), and separate executive, judicial, and legislative branches of government. Shortly thereafter, five new political parties were legally registered, and by the beginning of 1992, this figure rose to twelve» (E. Viret, cit.).

Unfortunately, Rwanda wasn’t trepidatiously beginning a resplendent journey towards modern democracy and a Western-style bright political future.

In reality, neither Habyarimana nor the ruling oligarchy had the slightest intention of sharing their power and dispersing the conspicuous flow of money that arrived in Rwanda from many ‘generous’ aid donors. (Don’t be naive, please: have you ever heard of instrumental use of aid to support strategic foreign policies?). The powerful circle of the Akazu or better to say, le Clan de Madame, as it had Madame Agathe Habyarimana as its central sun, had no intention at all. «For the President’s wife and her family, the movement toward-power sharing was simply a challenge to their privileges. Once Habyarimana could not resist the pressure to negotiate sharing power (…), the conscious decision was taken to resist this threat using any means available» (Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide, cit., 6.16).

Habyarimana was therefore caught between the need to make up his autocratic face by smearing it with a seductive, democratic-colored foundation and at the same time, the necessity to keep his power base intact, if not strengthened, avoiding internal squabbles.

How did he manage to find a way out?

First of all, he did it by signing concessions and formal openings, knowing from the outset how to boycott and sabotage their implementation on a concrete level. It’s the old method of ‘smoke and mirrors’, seasoned with a pinch of experimented ‘carrots and sticks system’: «At first, Habyarimana used the October 1990 invasion by the Tutsi-dominated RPF as an excuse to terrorize Hutu opponents. But as the RPF advanced, it seemed more prudent to try to woo them with concessions, though it was always evident that the government begrudged every opening it was forced to offer» (Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide, cit., 5.23).

Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide is the title of an impressive essay on the Rwandan Genocide carried out and signed by an international panel of eminent personalities called to investigate the subject by the Organization of African Unity (OAU).

Members of the panel were Sir Quett Ketumile Joni Masire (Chairman; Former President of Botswana), General Ahmadou Toumani Touré (Former Head of State of Mali), Lisbet Palme (Chairperson of the Swedish Committee for UNICEF, Expert on the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child), Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf (Former Liberian Government Minister, Former Executive Director of the Regional Bureau for Africa of the United Nations Development Programme), Justice P .N. Bhagwati (Former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of India), Senator Hocine Djoudi (Former Algerian Ambassador to France and UNESCO, Permanent Representative to the UN), Ambassador Stephen Lewis (Former Ambassador and Permanent Representative of Canada to the UN, former Deputy Executive Director of UNICEF).

Among the historian, experts, and researchers who contributed to this essay there were: Filip Reyntjens (Belgian political scientist, professor at the University of Antwerp, specializing in the Great Lakes region political history), Catherine Newbury (former professor of Political Sciences, Smith College, Massachusetts, US), Thandika Mkandawire (Malawian economist, professor of African Development at the London School of Economics), Jean-Pierre Chretien (French historian, specializing in the Great Lakes region political history), Adama Dieng (Senegalese former UN Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide, former registrar of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda), Kifle Wodajo (Ethiopian diplomat, former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Ethiopia), Colette Braeckman (Belgian journalist specializing in Central African politics), Walter Kamba (Zimbabwean lawyer and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Zimbabwe), and others.

The volume was published in July 2000 and can be downloaded here in pdf.

THE POLITICAL TURMOIL AND THE STRATEGY OF TENSION

The attack of the Rwandan Patriotic Front on October 1, 1990 – as I wrote – gave Habyarimana an interesting series of opportunities.

First of all, he immediately played an easy political card to consolidate his ‘legitimate’ power and unite around him many political opponents and moderate Hutus. It was the so-called card of ‘Unity-against-the-outsiders-or-foreign-invaders’: Rwanda’s legitimate government is under attack! Rwanda is a sovereign country obliged to defend itself from an illegitimate invasion carried out by foreign soldiers! (Do not forget that many Inkotanyi «had probably not even been born in Rwanda, had no known roots in the country, and certainly had no support from the majority of Rwandans»: it was easy to turn them into “non-Rwandans”, Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide, cit., 6.16).

The card of ‘Unity against the alien invaders’ had a backside, called the ‘You-are-either-with-me-or-against-me-dude’ (If you’re against me, you’re against your homeland, the Hutu nation, God, and your family’s security). In other terms, as the French Rapport d’information noted, the invasion by the RPF and the simulated attack on Kigali were used “as levers to restore the regime to its fullness”, namely to justify a harsh iron hand on the whole country.

In October 1990, under the pretext of assuring security, the government began making massive arrests in Kigali and elsewhere in the country. According to Human Rights Watch some 13,000 people, according to History of Rwanda, some 7,000 to 10,000 people were arbitrarily imprisoned without charge, held in degrading conditions, often tortured or raped. Dozens died. Some were released only in March and April 1991 under the pressure of local and international human rights organizations. According to Filip Reyntjens (Belgian political scientist, professor at the University of Antwerp, specializing in the Great Lakes region political history and Habyarimana’s former consultant), only some of them were political opponents who had previously criticized the regime; the majority were Tutsi, especially Tutsis who held important positions. As stated by the 1994 Human Rights Watch Report, «these crimes began immediately after the RPF’s October 1990 invasion, and wholesale violations continued as late as January 1993. Authorities at the highest level, including the President of the Republic, consented to the abuses» (Arming Rwanda, cit.). None has ever paid for these state crimes.

Moreover, «since the war began, Rwanda has been plagued by bombings and other terrorist attacks, which have killed or wounded dozens, and menaced many more. These include the bombing of hotels and nightclubs which cater to wealthier Rwandans and foreigners, the bombing of busy markets which cater to poorer Rwandans, and assassinations of opposition political party leaders. (…) A persuasive number of non-French Western diplomats, Rwandan military officers, and civilians with a long-standing personal relationship with Rwandan President Habyarimana told Arms Project <Human Rights Watch> that they suspected members of the regime, and in particular, the first circle (…) around the President, the Akazu, to be responsible for these terrorist attacks» (HRW, Arming Rwanda, cit.).

«During 1992 and 1993, apparently random attacks by unidentified assailants increased dramatically: grenades thrown into houses, bombs placed in buses, or at markets, and mines laid along roads. The Rwandan army general staff issued a press release identifying RPF infiltrators and their “accomplices” as responsible for this violence, an assessment generally accepted by supporters of Habyarimana. Those opposed to Habyarimana attributed the attacks to his agents, who, they charged, were operating a death squad which they called by Mfizi’s name of the Zero Network (Réseau Zéro in French). The International Commission of Investigation On Human Rights Violations in Rwanda, a group sponsored by four international human rights organizations that examined the situation in Rwanda in early 1993, concluded that the Zero Network was linked to the highest circles of power in Kigali and was responsible for many of the attacks» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

On October 9, 1992, «in a press conference in the Belgian senate in Brussels, professor Filip Reyntjens along with senator Willy Kuypers described how in Rwanda a death squad called Réseau Zéro was killing people and creating havoc and instability with the intention of blocking the political opposition and sabotaging the process of democracy» (L. Melvern, cit).

Through systematic criminal actions and terrorist attacks carried out by state agents, Habyarimana’s inner circle developed a strategy of tension that served two different purposes: firstly, it was useful to hinder and thwart every formal democratic opening. As Linda Melvern wrote, «each time there was a concession towards democracy, there was violence, and violence soon became an integral part of political life». This political turmoil provided the government with the perfect legitimation of many kinds of anti-democratic interferences and abuses and helped Habyarimana to pave the way to democracy with an endless series of obstacles.

Secondly, the climate of pervasive fear and insecurity was functional to blame the violence on a dangerous ‘public enemy’, as we shall see.

“No systematic human rights abuses by the military and the Government of Rwanda”, isn’t it Bush Father?

The US knew.

Belgium knew.

France knew.

They perfectly knew that the government they were supporting with aid and military equipment of all kinds was not an idyllic fairy tale country.

The face-saving ability of Habyarimana, however, worked well and saved the face of many Westerners’ too.

How did he manage that so well?

The answer is clearly stated by Dismas Nsengiyaremye, a member of the Republican Democratic Movement of Rwanda, a party founded in late 1991 in opposition to the Habyarimana’s party. He was prime minister from 2 April 1992 to 18 July 1993; later that very same year, he had to flee to Europe after receiving life threats. He said to HRW during the Civil War: «Shadow groups are behind the <internal> violence, but nobody can provide concrete evidence [against them]. (…). Here <in Rwanda>, the shadow groups are able to build connections and carry out criminal activities with impunity».

SHADOW PARAMILITARY GROUPS AND MILITIAS

The death squad Réseau Zéro, its military members and commanders, and its undisclosed principals inside the Akazu circle were not alone. On the contrary, they were in good company: there were other major paramilitary groups and militias during the years of the Civil War. And it’s precisely to them that Habyarimana entrusted the dirty work.

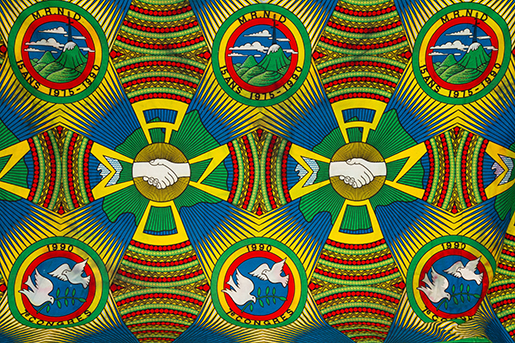

The Interahamwe armed militia was the best organized and the most widespread in Rwanda. This paramilitary group, whose name in Kinyarwanda means “those who work (= fight, attack) together” and is pronounced with a silent ‘t’, was formally created in 1990 as the youth wing of the Habyarimana’s party, the National Republican Movement for Democracy and Development or MRND. It wasn’t a youth political movement, though. Since its origin, it was made up of «uneducated and unemployed young men, including delinquents and petty criminals, experts in thuggery» (L. Melvern, cit.). They were paid (in 1994, during the final phase they received US $3.5 per day, source Rwanda Country Study Guide: Strategic Information and Developments, USA, 2012), militarily instructed and armed to be turned into pro-government paramilitary units, ready to intimidate and kill political opponents, pillage and set fire to homes, slaughter civilians. They were supported by Rwandan Gendarmerie, the Presidential Guard, and the Armed Forces; they received hand grenades, AK47 assault rifles, as well as machetes (panga), knives, and clubs; they were organized to be present in every one of the country’s 146 communes. According to some reliable sources and direct witnesses, they also received some training from French military experts (see History of Rwanda). They acted and looked like out-of-control gangs, but in reality, they were well controlled and managed by the Habyarimana’s inner circle.

The members of Interahamwe paramilitary militias could be easily recognized for their distinctive yellow, blue and green clothes, their rowdy and intimidating behavior, their arms. These gangs were responsible for the main waves of violence and mass killings in 1992, 1993, and 1994. In other words, they played a major role in all of the phases of the Rwandan Genocide.

Detail of the kitenge fabric used to make the uniforms of the Interahamwe paramilitary militia. Worse use of the dove of peace couldn’t have been made.

In March 1992, a new party, among others, was founded: it was named Coalition pour la Défense de la République or CDR (in English, Coalition for the Defense of the Republic) and was a far-right party supporting more extremist and radical views than the Habyarimana’s MRND. It claimed that until that moment, “no party, no institution, no person had been able to defend the interests of the majority [i.e., the Hutu] publicly and consistently” against the Tutsis and their attacks, and filling that void was their main goal. «The CDR openly criticized the MRND and even Habyarimana personally for conceding too much to the opposition parties and to the RPF. Despite this criticism, the CDR collaborated frequently with the MRND, leading some observers to conclude that this bitterly anti-Tutsi party existed only to state positions favored by the MRND but too radical for them to support openly» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

The CDR, in a nutshell, allowed the MRND to maintain a reasonable front open to dialogue while acting a dirty, bloodthirsty backside.

The CDR founded its own youth paramilitary militia, the Impuzamugambi (“Those with the same goal”), trained and equipped by the Rwandan Government Forces and the Presidential Guard. It was smaller and less organized than the Interahamwe militia, but similarly able to terrorize and kill with astonishing rapidity.

Early in 1992, some hard-liner and extremist high-ranking officers of the Rwandan Armed Forces and the National Gendarmerie created a secret society called AMASASU, acronym of Alliance des Militaires Agacés par les Séculaires Actes Sournois des Unaristes, Alliance of Soldiers annoyed with the age-old deceitful actions of the UNAR members (Unar was the name of the old Tutsi party of the late 50s). Amasasu is at the same time a Kinyarwanda term meaning “bullets”. AMASASU handed out weapons to the two paramilitary militias and worked in close collaboration with the death squads of the Zero Network, made up of civilian and military torturers and assassins under the direction of “dragons”, probably top-ranking officers linked to the Akazu (source: The Preventable Genocide, cit.).

The two militias could count on approx. 50,000 men in early 1994 (according to Braud).

They were responsible for the main waves of violence and mass killings in 1992 and 1993, under the supervision of soldiers of the RAF, the Presidential Guard, local and central authorities.

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE – THE FIRST PHASE 1990-93

CONSTRUCTION, CRIMINALIZATION, DEHUMANIZATION OF THE ENEMY, THE TUTSIS

Since the beginning of the Civil War, the Habyarimana’s regime decided to play immediately a second card: «The crime of the Hutu leaders was their cynical and deliberate decision to play the ethnic card» (Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide, cit., 6.13).

They began to play this card at the very beginning of the Civil War, and was quite an easy play: the Habyarimana’s regime – a regime, let us not forget, whose power was stabilized by a policy of racial discrimination – needed only to reawaken the old and dangerous sleeping dog of racial polarization, that beast nicknamed ‘Local Hutus against foreign Tutsi invaders and colonists’. It was a quite sleepy animal in the 80s, but not at all out of the picture. To wake it up, the regime revived and exploited all the old stereotypes of the PARMEHUTU and APROSOMA ideology. «The racist ideology against the Tutsis reappeared in speeches and the national Press. The subject of discussion was that RPF was a reincarnation of the Inyenzi (‘cockroaches’) of the 60s, made up of Tutsi monarchists and ‘feudalists’ who did not accept the 1959 Hutu revolution and the following legitimate Republic» (History of Rwanda, cit.).

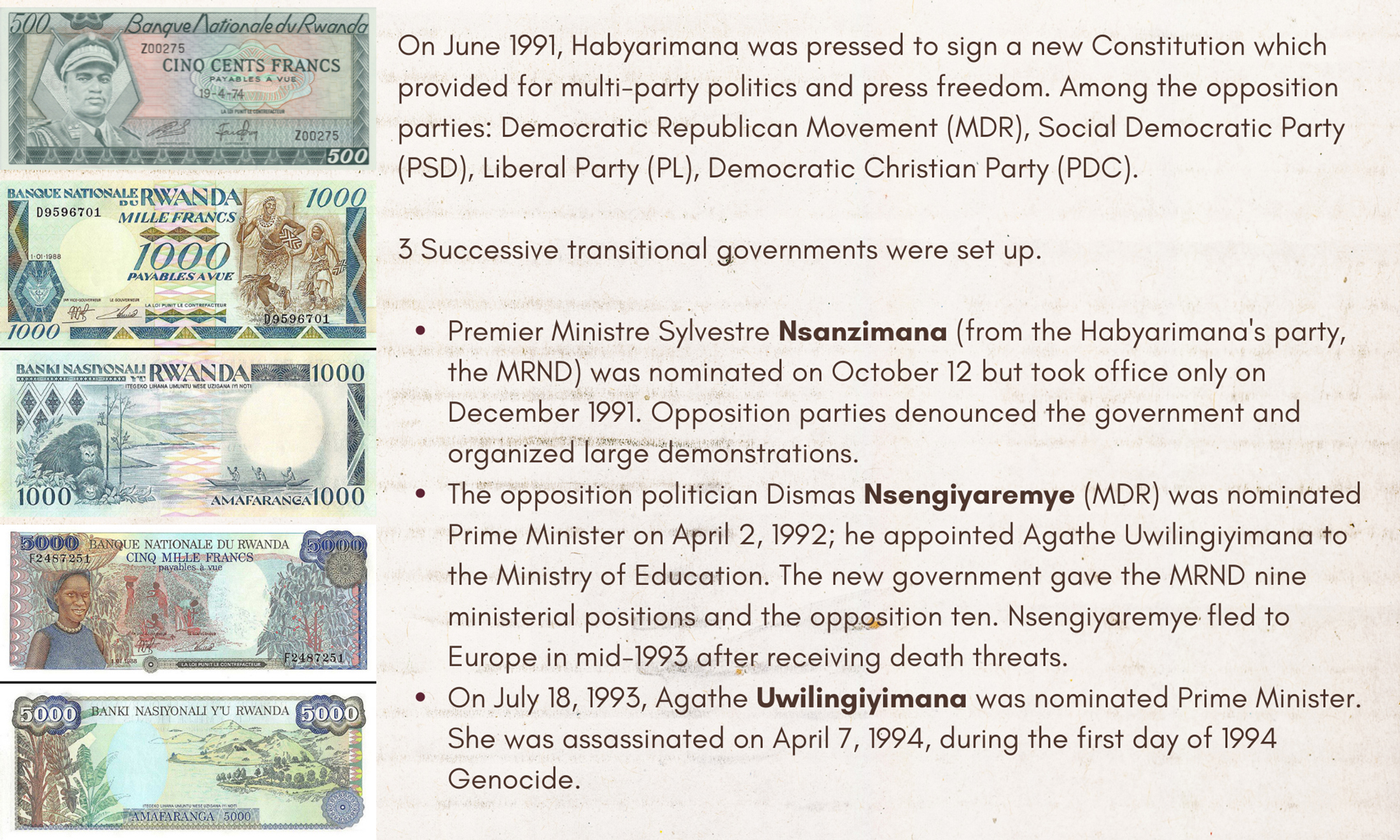

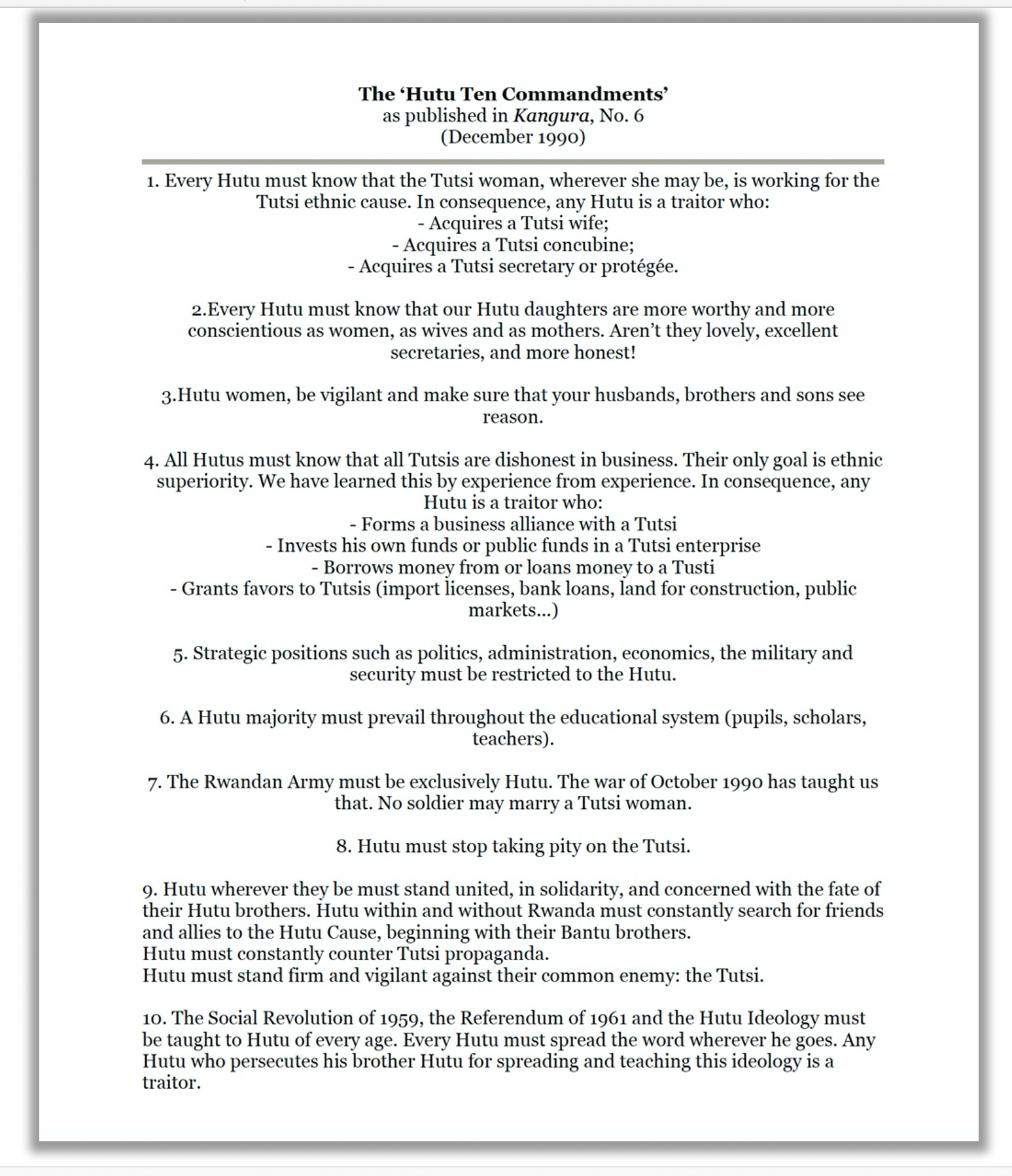

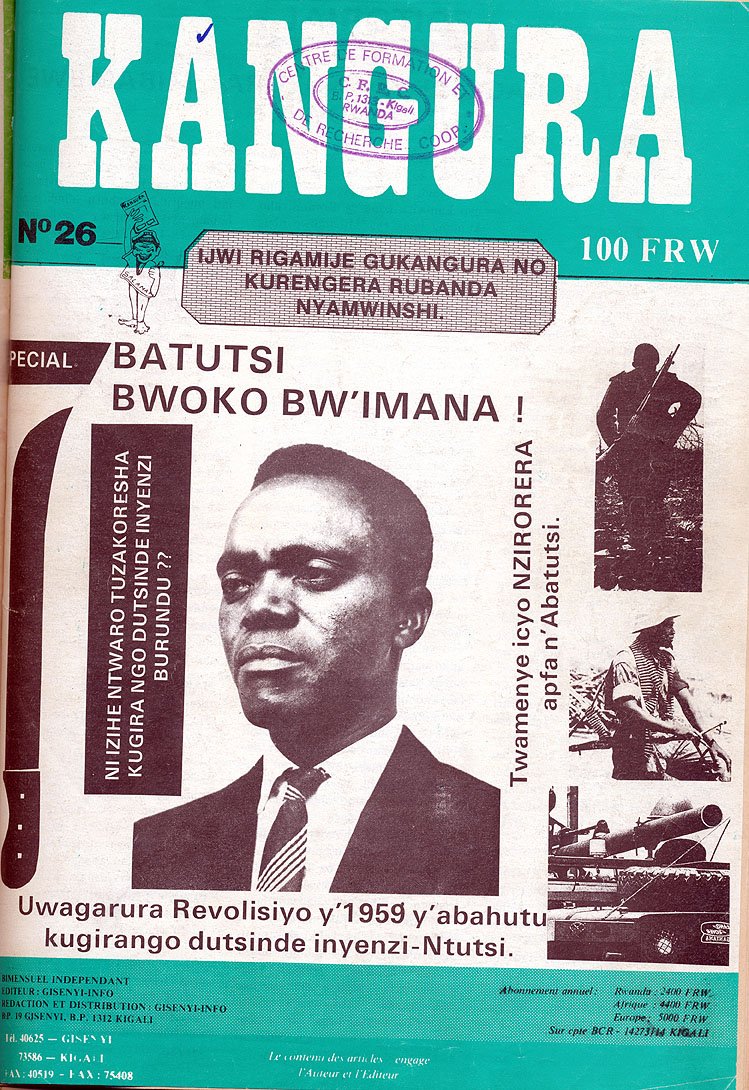

The Ngeze’s Hutu Ten Commandments and the Call, December 1990

Do you remember Joseph Habyarimana Gitera? He was one of the signatories of the Bahutu Manifesto (1957), founder and President of the APROSOMA populist party (1959), promoter of a violent anti-Tutsi campaign and author of a text steeped in hatred and racism against the Tutsis, entitled the Hutu Ten Commandments. Unsurprisingly, the bimonthly magazine Kangura, whose first issue was out in May 1990, published in December 1990 a new Hutu Ten Commandments: a completely different text from Gitera’s, but washed in the same filthy waters. It was written by Hassan Ngeze, the editor-in-chief of the magazine and a founding member of the CDR party. Here’s the integral text: it’s worth reading.

The text exudes violent misogyny: all women are weighed up like cows and the Tutsi ones like bad-quality, treacherous four-legged animals. The labeling of the Tutsi women, their categorization, so full of contempt and disdain, portends the legitimization of their rape.

The polarization takes the extreme form of mutual exclusion: no intermarriage, no business, no social interaction, no contacts; but this systemic discrimination is not an end in itself: it gives way to an antithesis, or better to say, a radical clash between the Hutus on one side, and “their common enemy”, the Tutsis, on the other. Tertium non datur. Therefore, those Hutus who refuse to be ‘brothers’ and ‘allies to the Hutu Cause’ are traitors.

This is the language of war.

However, this is not the language of the Civil War, a conflict between the government of Rwanda and the RPF. This is the language of racial war between all Hutus and all Tutsis.

The international version of Kangura no. 3, published in 1992, will say bluntly that «la guerre oppose les Tutsi aux Hutus», the war opposes the Tutsis to the Hutus. The international version no. 7, 1992, that «la guerre entre les Hutu et les Tutsi a commencé avec l’arrivée du Hamite dans ce pays (…), cette guerre ne cessera pas tant que les deux (…) se regarderont face à face est donc éternelle», the war between the Hutus and the Tutsis began with the arrival of the Hamites in this country (…), it will not end as long as the two (…) keep looking at each other face to face; it’s therefore eternal.

Cover of the issue no. 6, December 1990, of Kangura magazine.

The author of the Hutu Ten Commandments was the editor-in-chief of the magazine: Hassan Ngeze.

The 10th point of the Hutu Ten Commandments text speaks of a “Hutu Ideology”. What does this refer to?

The Ten Commandments claimed not only a policy of more radical segregation of the Tutsis but the exclusive Hutu leadership over Rwanda’s public institutions, especially in the strategic sectors of politics, economy, administration, military affairs, and national security. By what right? Well, by that given to them by the ‘Local Hutus against foreign Tutsi invaders and colonists’ old paradigm, an integral part not just of the PARMEHUTU and APROSOMA ideology, but of the Belgian colonial racial ideology, imbued with racist nonsense like the raving “Hamitic hypothesis” (see Rwandan Basketry 3). The Hutu ideology of the 90s appears, therefore, like a multi-story building whose foundations were developed by Belgians and Western White Fathers in the 20s and 30s, and whose walls are those erected by the Bahutu Manifesto and the racial claims supported by the Hutu emancipation movement from the late 50s to the early 60s. The overall design and the aim of Ngeze’s communication, however, are absolutely new.

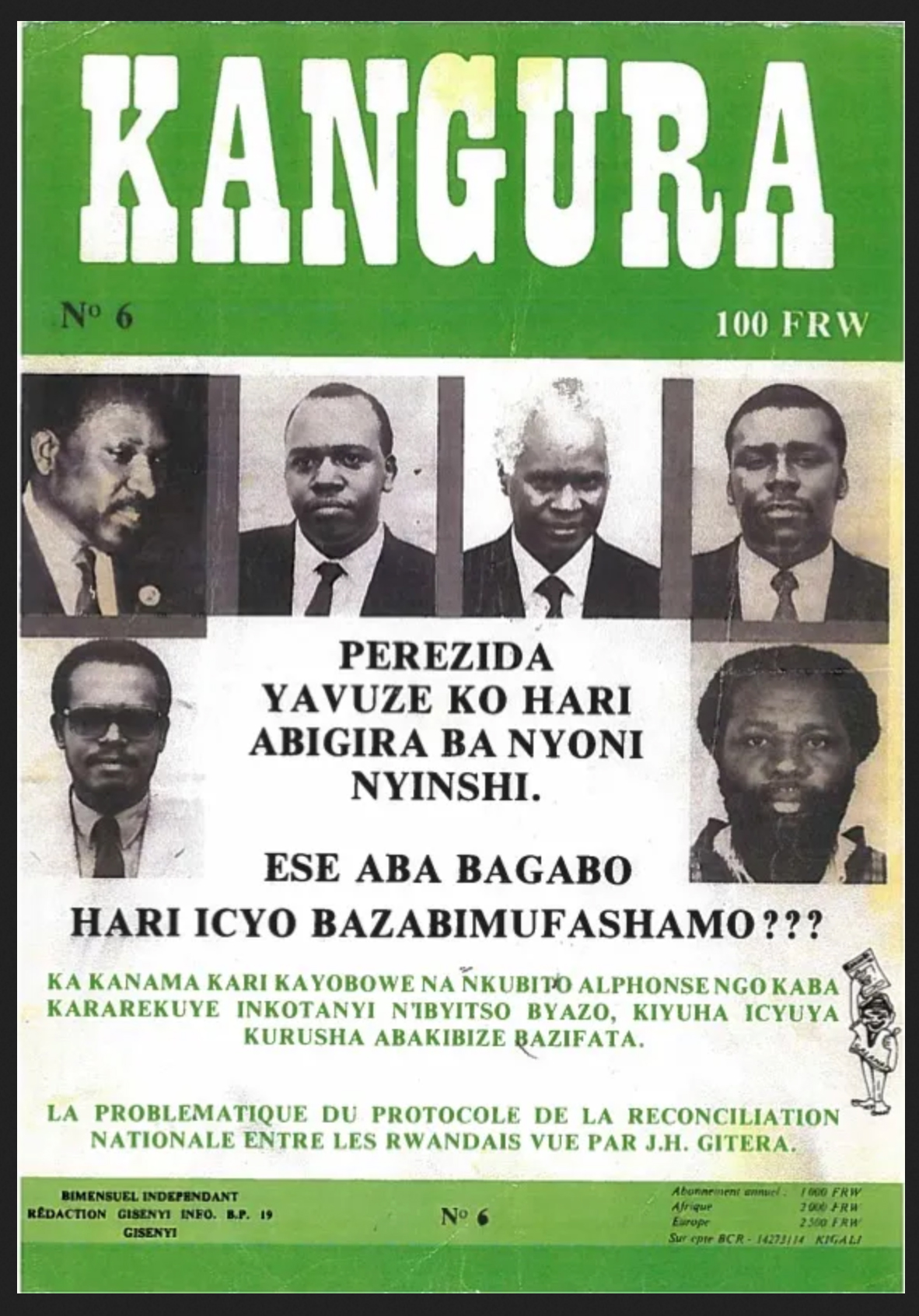

To figure out the meaning of Ngeze’s “Hutu ideology”, we have to read his Introduction to the Hutu Ten Commandments, entitled Appel à la conscience des Bahutu, A call to the consciousness of the Hutus in English. (It’s been often incorrectly translated as Call to the conscience of the Hutus: here, the French term conscience means self-awareness or consciousness).

The French text of the Appel à la conscience des Bahutu by Hassan Ngeze, on the Kangura, issue no. 6, December 1990.

The text can be easily read or downloaded here, on the website of the Library of the University of Texas at Austin. It’s in French, of course.

This is the incipit: «En Octobre 1990, le Rwanda a été l’objet d’une attaque extérieure montée par des extrémistes Batutsi, appuyés par l’Armée Ougandaise. Ces agresseurs (…) esperaient conquérir le pays et installer leur régime féodo-monarchique en quelques jours. Fort hereusement, le Rwanda a pu faire face à cette guerre et repousser l’agresseur (…) mais la menace n’est pas écartée pour autant. L’ennemi est toujours là, parmi nous, et n’attend que le moment propice pour tenter encore de nous liquider» [My translation: In October 1990, Rwanda was the target of an external attack, set up by Tutsi extremists, supported by the Ugandan Army. These aggressors (…) hoped to conquer the country and install their feudal-monarchical regime in a few days. Fortunately, Rwanda was able to face this attack and repel the aggressor (…) but the threat is not at all averted. The enemy is still there and here, among us, only waiting for the right moment to try again and get rid of us].

The text begins by remembering the 1990 attack by the RPF and the war that followed but immediately raises an old specter. All of the contemporary events are immediately subsumed under the ideological horizon of the past. The text recalls what happened in Rwanda in 1958 and 59, the Hutu Social Revolution, the guerrilla incursions carried out by Tutsis rebels from 1962 to 67, and their stubborn counter-revolutionary strategy whose aim is to overthrow the Rwandan legitimate republican institutions and restore the ancient feudal monarchy based on the supremacy over Hutus: «Le rêve permanent des Batutsi est de renverser le institutions républicaines don ils se refusent de reconnaître la légitimité et de réinstaurer le pouvoir minoritaire et féodal des Batutsi» [The Batutsi have always dreamed to overthrow the republican institutions whose legitimacy they refuse to recognize, and re-establish the feudal power of their minority]. Within this ideological horizon, the 1990 attack became the final step of a perverse strategy aimed at subjugating all Hutus: «La guerre d’octobre 1990 contre le Rwanda n’était que la phase finale de l’application du plan de colonisation tutsi au Rwanda». [The October 1990 war against Rwanda is just the final phase of the implementation of the Tutsi colonization plan in Rwanda].

The Tutsi colonization plan entails not just the restoration of the antique Hutu serfdom, or, to use the old language of the Bahutu Manifesto, the shameful racial subjugation of the Hutus, but also a much more dangerous threat: the extermination of many Hutus: «Depuis la révolution sociale del 1959, pas un seul jour les Batutsi n’ont laché l’idée de reconquérir le pouvoir au Rwanda et exterminer les intellectuels et dominer les agriculteurs Bahutu» [Since the 1959 Social Revolution, not a single day have the Batutsi given up on the project of regaining power in Rwanda, exterminating intellectuals and dominating Hutu farmers].

The Hutus have faced hatred – «Les Batutsi disent que le Muhutu est le seul ennemi du Mututsi» [Tutsis say that hutu is enemy to tutsi] – and bloodthirsty threats – «Les Batutsi sont des assoiffés des sang» [The Batutsi are out for blood] – and in present days they’re facing a military attack. Now, it’s time to wake up: «Bahutu, c’est plus que jamais le moment de nous réveiller, d’approfondir la réflexion et de prendre conscience d’une nouvelle idéologie, l’idéologie des Bahutu, qui plonge ses racines dans la révolution sociale du 1959 et qui consiste à défendre jalousement les acquis de cette révolution et ceux du Réferendum du 25 septembre 1961» [Bahutu, now, more than ever, it’s time to wake up, develop a deeper reflexion, become aware of a new ideology, the ideology of the Bahutu, which has its roots in the 1959 Social Revolution and consists in jealously defending the achievements of this revolution and those of the 1961 Referendum]. Now it’s time to develop a true brotherhood among all Hutus because this solidarity and unity is the most poweful tool to repulse «les manœuvres diaboliques», the diabolical machinations of the enemy. Truth is that the defense of Rwanda and its achievements against the enemy is at the very same time the self-defense of the Hutu Nation.

The old racial paradigm of the late 50s is thus exhumed along with some ghosts of the past, such as the alleged will of the Tutsis to restore monarchy and serfdom. Is that nonsense? Yes, it is, but it should better be considered as a resounding falsehood that nevertheless gains credibility within the chosen frame because is perfectly consistent with all of the other elements. The frame chosen by Ngeze is composite and layered, but rich in many elements that could sound ‘familiar’ and therefore ‘plausible’ to many Rwandan of a certain age. And if his communication strategy is rather complex, the final message is quite simple: ‘We do not have to say that RPF did attack the Habyarimana regime. We have to say that the Tutsis attacked Rwanda, and the Hutus, who make up the large majority of its legitimate citizens. The war on Rwanda is a war on all Hutus, their achievements and survival’. Thus, the criminalization of all Tutsis is perfectly paired with the victimization of all Hutus.

Kangura cover, issue no. 26, November 1991

Since the late 50s / early 60s, all Tutsis have been constantly labeled as “the others”, following the racial ideology of Belgian colonialism. During the Civil War, “the Others” became “the Enemy”: all Tutsis including babies were treated as “the public enemy” of Rwanda. For three and a half years since the beginning of the Civil War, the ruling oligarchy, the Habyarimana’s inner circle, and the Akazu, in particular, «worked to redefine the population of Rwanda into “Rwandans,” meaning those who backed the president, and the Ibyitso or “accomplices of the enemy,” meaning the Tutsi minority and Hutu opposed to him» (Alison Des Forges, cit.). During the years of war, the government’s relentless propaganda campaign – Kangura in the lead – labeled many if not all Tutsis living in Rwanda as ‘accomplices’ of the enemy, therefore enemies themselves, and the Hutu members of the opposition parties, politically distant from the ruling oligarchy, as traitors and enemy’s allies.

It was not enough.

Since the beginning of the Civil War, the planned construction of an enemy paired with its planned dehumanization. Degrading and dehumanizing a group of people, already separated, already labeled as ‘different’, whatever this difference might be conceived, are among the conditions of possibility of genocide, as we saw reflecting on the Asian Holocaust, in the 4th part of the article on The Tsuba, the Katana, and the Samurai Soul. There, we saw how and why the failure to recognize other people as fellow human beings is considered today by the vast majority of scholars as a fundamental enabler of violence across cultures and throughout history.

Dehumanization is not racism, but it usually entails racism and often starts with a suprematist and racist ideology. Like that clearly expressed by the Hutu Ten Commandments published by Kangura. This magazine, sponsored by the Habyarimana’s party (the MRND), and edited by founder Hassan Ngeze, went much further. Look at the above image: it’s the cover of an infamous issue of Kangura, the no. 26, released in November 1991.

Cover of the issue no. 26, November 1991, of Kangura magazine. Cover and pages of Kangura can be read and downloaded on different websites. The best English website is by the University of Texas Libraries (the University of Texas at Austin, US): here’s the link to the Kangura page. The best French website is Les médias de la haine : Kangura, on the website France – Génocide – Tutsi, rich in valuable documents.

The photo portrait is that of Grégoire Kaybanda, one of the signatories of the Hutu Manifesto, the founder of PARMEHUTU and the first President of Rwanda (First Republic). On the left, there’s a machete, a panga in Kinyarwanda. The phrase in vertical between Kaybanda and the machete is Ni izihe ntwaro tuzakoresha kugira ngo dutsinde inyenzi burundu ?? which means “Which weapons are we going to use to beat the inyenzi once and for all?”. The answer is suggested by the panga on the side.

Under the Kaybanda photo, we can read its caption: Uwagarura Revolisyo y 1959 y’abahutu kugirango dutsinde inyenzi-Ntutsi. It means: “Should the 1959 Hutu Revolution be brought back, we could finish off the Tutsi cockroaches”. (Translations are mine; they are accurate but of course, I’m in no way a professional translator from Kinyarwanda!).

The Kinyarwanda term of inyenzi means ‘cockroaches’, ‘cafards’ in French, and was tenderly reserved to Tutsis by some Hutus in the late 50s / early 60s.

Had it not been clear, all Tutsis were cockroaches for Kangura, but its core message was more complex and perverse: ‘All Tutsis were already labeled cockroaches at the glorious Kaybanda’s time, and we do nothing but repeat it, as all of them have been doing nothing in all these years but repeating themselves, namely attacking our Hutu Nation’.

In a country that relies uniquely on agriculture, cockroaches are pest insects that can carry disease organisms, viruses, and eggs of worm parasites; their health threat to human populations justifies their control, namely their killing. Tutsi were called inzoka as well and drawn in caricatures like ‘snakes’, another dangerous vermin. What to do with all of them? The answer was often suggested by a cartoon whose meaning could be easily grasped even by a 6 years old child.

Copies of Kangura were read in public meetings and during the rallies of the Interahamwe militia.

Léon Mugesera: Toute la vérité, July 1992, and the Kabaya Speech, November 1992

Ngeze’s texts introduced two topics that, nevertheless, he didn’t fully develop: the equation Rwanda = Hutu Nation, which, as we’ll see, will become increasingly relevant, and the assumption, presented as a fact, that the goal of the ‘Tutsi’ is to shed the blood of the Hutus. To go a step forward will be Léon Mugesera.

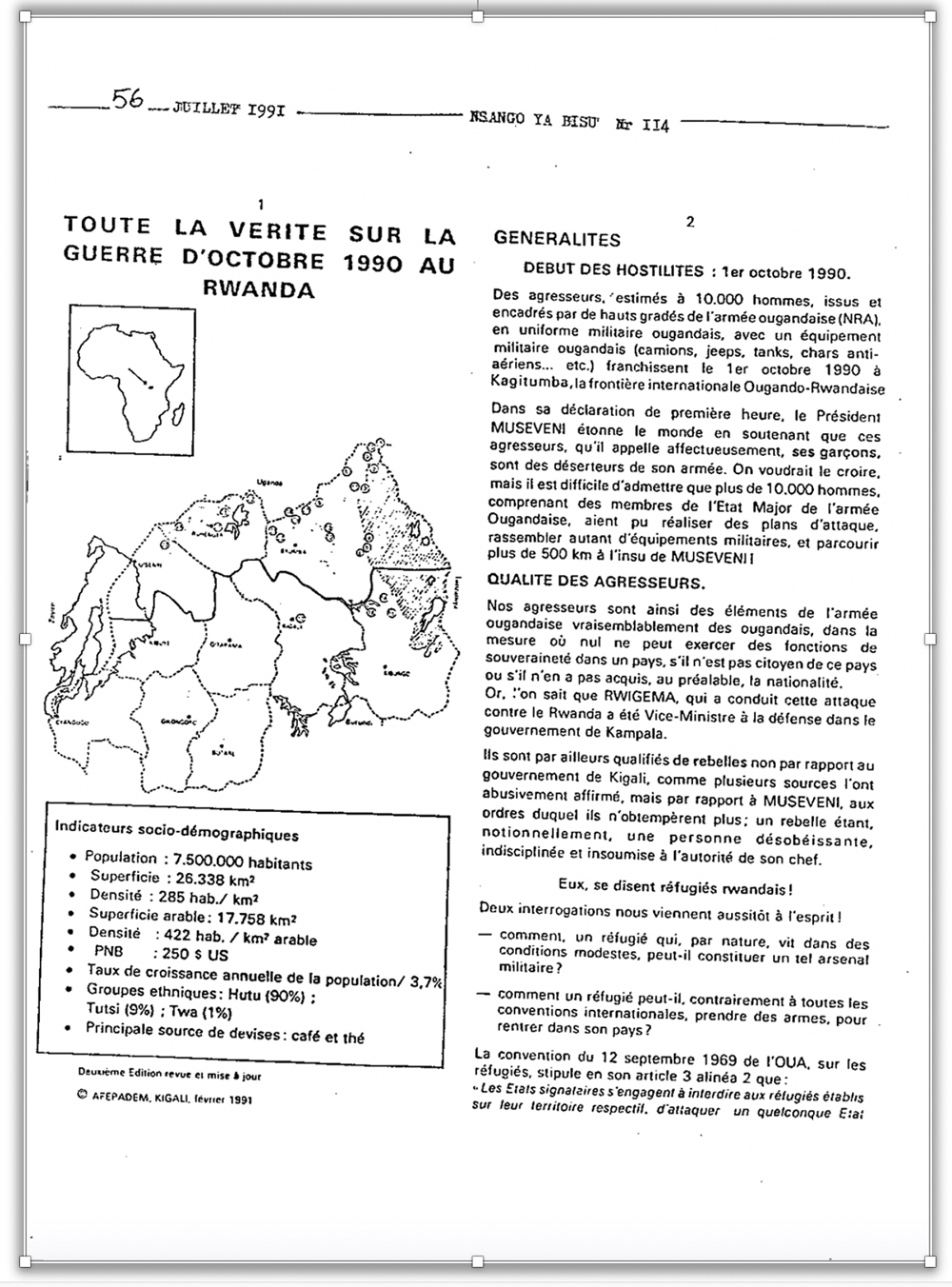

On July 1991, a long article entitled Tout la vérité sur la guerre d’octobre 1990 au Rwanda [The whole truth about the October 1990 war on Rwanda] was published in the issue no. 114 of Nsango Ya Bisu. It was signed by L’Association des Femmes Parlementaires pour la défense des droits de la Mère et de l’Enfant [The Association of the Women Members of Parliament for the Defense of the Rights of Mothers and Children] in collaboration with Léon Mugesera, professor at the National University of Rwanda and a prominent politician (he was MRND Vice-Chairman for the relevant Gisenyi prefecture).

Tout la vérité sur la guerre d’octobre 1990 au Rwanda by Léon Mugesera and L’Association des Femmes Parlementaires pour la défense des droits de la Mère et de l’Enfant, published on the issue no. 114 of Nsango Ya Bisu in July 1991.

This copy can be read and downloaded here in pdf format.

Here too, as in the Call by Ngeze, the invasion by the RPF (never indicated by its name) and the resulting war are brought into a historical framework that has its roots in the monarchical-feudal regime of the past (“Système monarchique basé sur la terreur et le servage exercé par la minorité tutsi sur la majorité hutu” [Monarchical system based on terror and on the serfdom exercised by the Tutsi minority over the Hutu majority]) and has its cornerstones in the Bahutu Manifesto, the political program of PARMEHUTU and APROSOMA, the Social Revolution, and the Referendum of 1961 (all explicitly mentioned).

Here too, as in the Call by Ngeze, Belgian colonialism comes out of history without leaving any trace as as if Belgians strolled through the country just a couple of times, by accident. The bad guys are the Tutsi minority and the good guys are the Hutu majority. The history of Rwanda from independence onwards, summed up in the triumphalist expression “30 ans de démocratie” and “justice sociale”, is remembered in broad terms to address the vexed question of refugees. Mugesera and the congresswomen that signed this political pamphlet claim that these refugees, less in number than commonly said, are frozen in the stubborn refusal to come back, «face aux appels répétés du gouvernement rwandais» [despite the repeated calls made by the Rwandan government]. The reason for this refusal is clearly revealed by the 1990 attempted invasion: they want to finish up an abominable project which has its last step in the recent war on Rwanda.

The salient points of this triumphalist reconstruction, which is to the historical reality as a family breakfast commercial to a low-income real family at 7 in the morning, are intended to build a frame that shares with Ngeze’s texts some elements but includes others which are far more radicalized.

Let’s see them.

Below, you can read two excerpts from the original French text, followed by my translation.

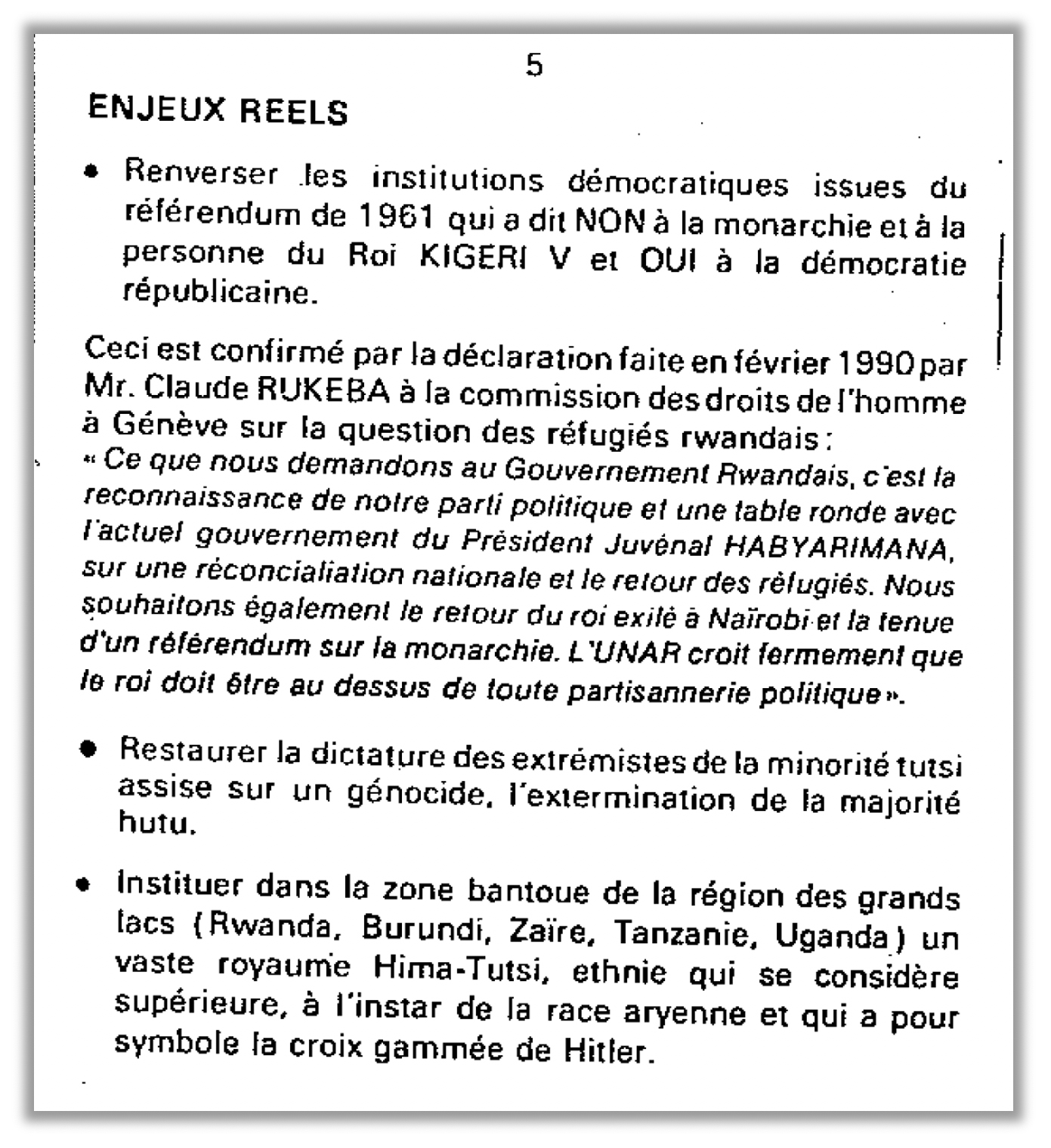

This first excerpt (from page 5 of the original text) is a paragraph entitled Enjeux Réels, “What is really at stake”. After having reported what the rebels and invaders have officially stated as their main target, namely establishing democracy in Rwanda, the authors reveal what is really at stake, and which are their true objectives:

- Overthrowing the democratic institutions born from the 1961 Referendum, which said NO to monarchy and king Kigeri V and YES to a democratic republic.

(…)

- Restoring the dictatorship by the extremists of the Tutsi minority, based on genocide, the extermination of the Hutu majority.

- Establishing in the Great Lakes Bantu area a vast Hima-Tutsi kingdom, as the people of this ethnic group consider themselves superior, just like the Aryan race with its symbol, the Hitler swastika.

(My translation)

Let’s forget the final naivety, the link Tutsi-Nazi, which, however, was to have an emotional impact on many readers and was picked up and relaunched by Kangura. Without mincing with words, with the weight of their authority and authoritativeness, the authors – a famous university professor and politician together with some congresswomen – state in no uncertain terms that the goal of the Tutsis is to exterminate the Hutus. They do not claim – mind you – that the goal of the rebels is to overthrow the government of Habyarimana and get rid of the Hutu ruling class. Not at all. They say that the Tutsi rebels, on behalf of their whole ‘race’, are preparing for the genocide of the Hutus.

And since this message must come out loud and clear, we find it again on the second to last page (p. 13).

This second excerpt sums up the real objectives of that abominable Tutsi project which includes their 1990 attack on Rwanda:

AN IGNOMINOUS WAR with gruesome purposes:

- restoration of monarchy;

- genocide of the Hutu ethnic majority;

- massacre of political and administrative authorities;

- massacre of the Tutsis refusing to collaborate;

carried out with outlawed methods:

- enlistment of minors;

- maneuvers to divide the Rwandan people and provoke a civil war;

- environmental destruction;

- rape and abduction of women and children for ramson demand;

- destruction of Rwanda’s image on the international level to wipe out all aid.

(My translation)

‘The Tutsis want to exterminate us all’: that’s the oversimplified final message of this pamphlet, so easy to understand even for a 6-years old child and the mass of illiterate Rwandans.

In 1991, the literacy rate of people aged 15 and above in Rwanda was 57.85% (data source: The World Bank); therefore many written texts, as the Call and The Hutu Ten Commandments by Ngeze, Toute la vérité by Mugesera, and many articles from Kangura, were commonly read in public meetings, political events and the rallies of the paramilitary militias to reach an ever-wider audience.

The core of Mugesera’s message made up a widespread commonplace in those years. An issue of Kangura published in January 1992 says: “There is indeed a diabolical plan prepared by the Tutsis and whatnot, targeting the systematic extermination of the Bantu population as well as the extension of a Nilotic empire from Ethiopia (…). What are the Bantu people waiting for to protect themselves against the genocide that has been so skillfully and meticulously orchestrated by the bloodthirsty Hamites <?> («Il existe effectivement un plan diabolique mis au point par l’ethnie tutsi et ses apparentés et visant l’extermination systématique des populations bantoues ainsi que l’extension de l’empire nilotique de l’Éthiopie. […] Qu’attendent alors ces peuples bantous pour se prémunir contre ce génocide savamment et minutieusement orchestré par les chamitiques avides de sang et de conquêtes barbares <?>»).

Note that in Mugesera’s text, as well as in the articles by Kangura and many other propaganda sources, the Tutsis are not the Tutsis of ancient Rwandan history: they are the Hamites, namely a fictional population, invented and shaped by the racist colonial ideology that the Belgians imposed on Rwanda since the 20s. We talked about this at length in Rwandan Basketry 3.

The oversimplified message ‘The Tutsis want to exterminate us all’ was not only very easy to grasp: it was also quite convincing as many people in Rwanda «remembered the slaughter of tens of thousands of Hutu by Tutsi in neighboring Burundi in 1972, 1988, and in 1991» (Alison Des Forges, cit.). Moreover, as we’ll see in the following, the RPF was not the male version of a cheerleader’s team on the road: in their advance, these soldiers committed several cases of abuse, including mass killings of Hutu civilians. Being killed by Tutsi was therefore a rooted fear, ready to be fueled and exploited, and the propaganda campaign exaggerated the risk posed by RPF to enhance the feeling of being in danger and create compelling calls to action.

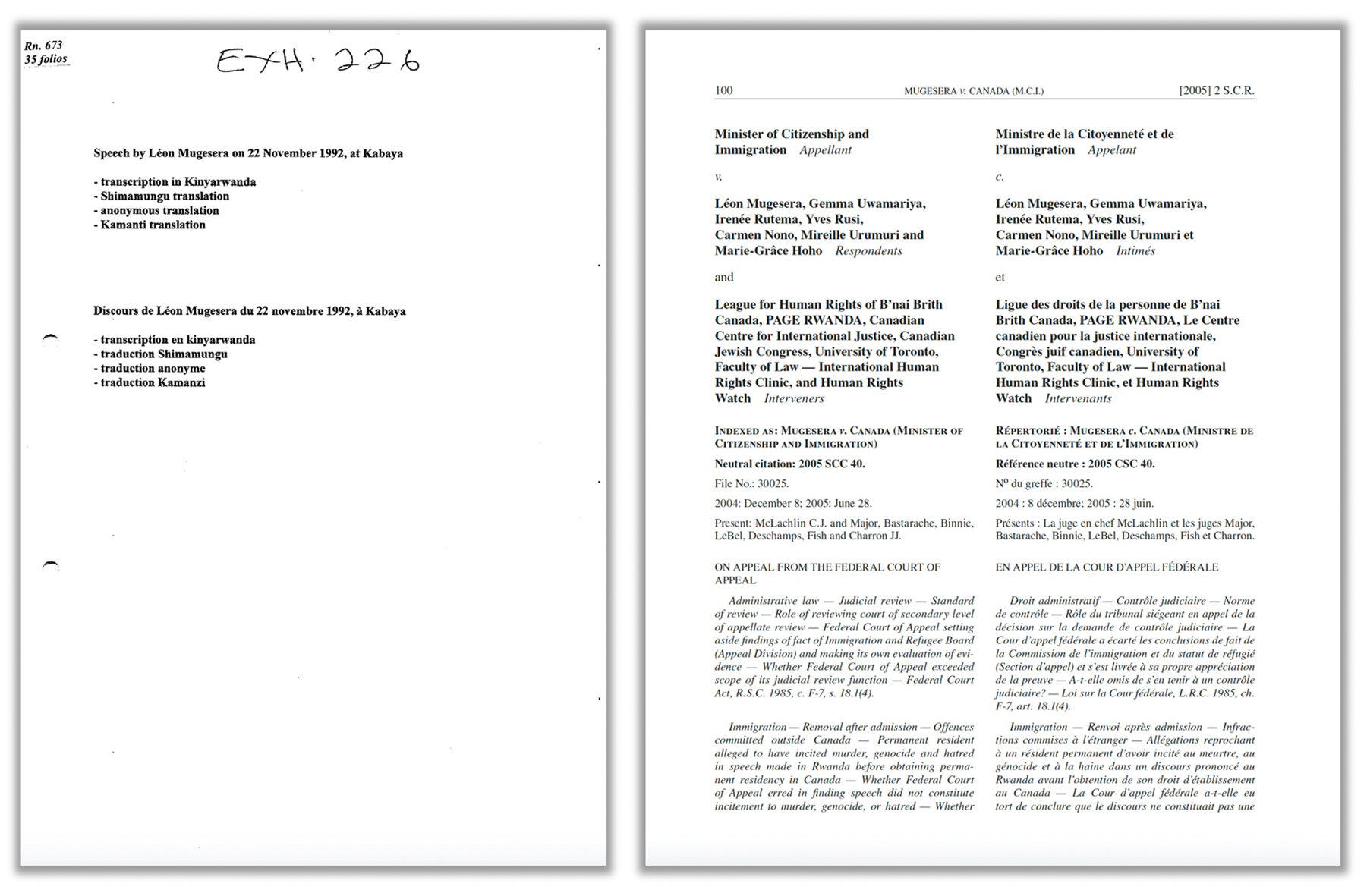

A step forward in this direction was explicitly done by Léon Mugesera himself in a famous public speech. Known as Kabaya Speech, it was given on November 22, 1992, in the town of Kabaya (North-Western Rwanda) during an MRND meeting, attended by a thousand people. The MRND, I remind you, was the Habyarimana’s party and Mugesera was the Vice-President in the northern prefecture of Gisenyi (one of Habyarimana’s strongholds). The speech was considered so relevant to be recorded and broadcast by radio even a year after, in 1993.

Rwanda: le discours incendiaire de Léon Mugesera. In French.

LEFT: The transcription of the Kabaya Speech in Kinyarwanda and in three different French translations can be downloaded here. The last of these traslation was made by Thomas Kamanzi, Linguist, Director of the Centre d’Etudes Rwandaises at the Institut de Recherche Scientifique et Technologique (IRST) in Butare, Rwanda. The second French translation, on the contrary, was carried out by linguist Eugène Shimamungu, directly commissioned by Mugesera’s defense team; this translation is quite different from the previous one on many crucial points.

RIGHT: Supreme Court of Canada, the Léon Mugesera v. Canada (Minister of Citizenship and Immigration) trial evidence. On p. 175, you’ll find an English translation made by J.A. Décary, a Canadian Federal Court judge, on the Kamanzi translation. The English text is, therefore, a translation of a translation; regardless of its quality, it’s scarcely reliable in itself. It can be downloaded here in case you did not understand a single French word.

The Kabaya Speech delivered a simple message using complex rhetorical tools – repetitions, rhetorical questions, climax, epanalepsis, emphasis, metaphors, euphemism, inclusive terminology, captatio benevolentiae devices, emotional hooks, etc. – that we cannot analyze here. It suffices to note the presence of a classic and well-known manipulation tactic named ‘projection’, nicknamed ‘the gaslighter’s signature technique’, and called by Alison des Forges “accusation in a mirror”: someone – the Hutu oligarchy and the Akazu, in this case – falsely accuses someone else – the Tutsis – of being engaged in plans, intentions, behaviors and/or actions they are involved in themselves. I’m accusing you of my faults or plans before you can do it, in order to entirely undermine what you are going to say about that: that’s in brief. The 1990-93 state propaganda campaign relentlessly accused the Tutsis of planning the extermination of the Hutus: unfortunately, we know very well that this accusation was false and a mere front for the genocidal plans of the Habyarimana’s inner circle. Projection is a powerful political ‘dirty’ weapon, very much used still today: Trump’s accusing Joe Biden of nepotism is a projection, for example, and I’m sure you can find many other examples everywhere in the world… Probably too many…

Léon Mugesera was a champion of projection in many of his articles and speeches, but of course, he was not alone. The use of projection, as Alison Des Forges had already noted, was a common feature of the 1990-93 propaganda.