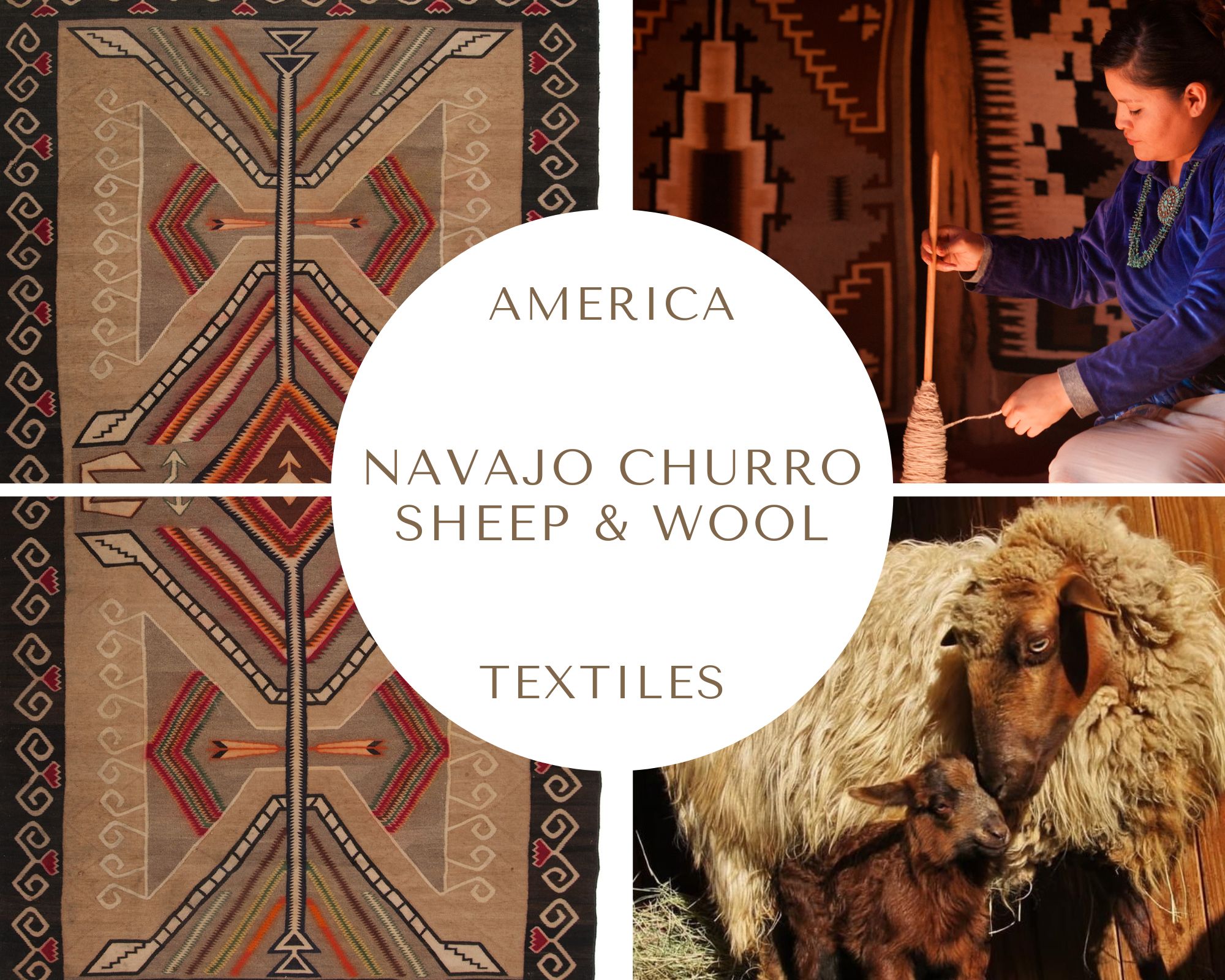

Rwandan Basketry 3

Rwanda on the globe

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE – AN INTRODUCTION

There’s a Rwanda before and a Rwanda after the Genocide and the 1990 civil war that made up its immediate historical background.

A deep journey throughout this country demands the effort of going through this painful zone of total darkness.

And that’s not the only good reason to do it.

The Rwandan genocide was not what still today many believe it was. This misconception is a consequence, among others, of a superficial mass media coverage at that time: Rwandan genocide wasn’t the outbreak of local insanity, the outburst of savagery or primitiveness, the sudden unleashing of brutality linked to old tribal hatred.

The papal envoy, French Cardinal Roger Etchegaray, sent to Rwanda by Pope John Paul II soon after the 1994 genocide, sadly said about it: «The blood of tribalism proved deeper than the waters of baptism» (Quoted in J.J. Carney, Rwanda Before the Genocide, see Bibliography). This statement is historically false, imbued with a falsehood that acts as a warm and comfortable blanket for the Catholic Church.

The 1994 Rwandan Genocide was not the regurgitation of bloody tribalism.

Nope.

It wasn’t.

Not at all.

It wasn’t a Rwandan tribal issue, not even an Eastern-African affair only.

And it wasn’t an event, nor the outcome of a dramatic turn of events.

The Western media’s failure to accurately interpret and describe the Rwandan Genocide is a fact widely supported by data and shared by most scholars today. Noam Schimmel studied the literature and the meta literature on how the 1994 Rwandan genocide was reported in the American and European mass media. Many Western media covered the issue, so we cannot speak of a lack of media coverage. As Schimmel shows in his analysis, the genocide «was mischaracterized as a ‘tribal war’ and an act of spontaneous violence and primordial hatred, rather than being accurately reported as a meticulously planned and implemented political project of extermination» (N. Schimmel, see Bibliography).

It wasn’t one of those unplanned events that happen all of a sudden, a definition more suitable for a car accident or a surprise diagnosis.

It wasn’t an event, moreover, nor the horrific outcome of a chain of events. Genocide is a process. Sheri P. Rosenberg (Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, New York) wrote a brief essay entitled Genocide Is a Process, Not an Event. She showed that every genocide is a «complex and dynamic process», namely «an unfolding process to be viewed against or within historical, political, and social factors». (Sheri P. Rosenberg, see Bibliography).

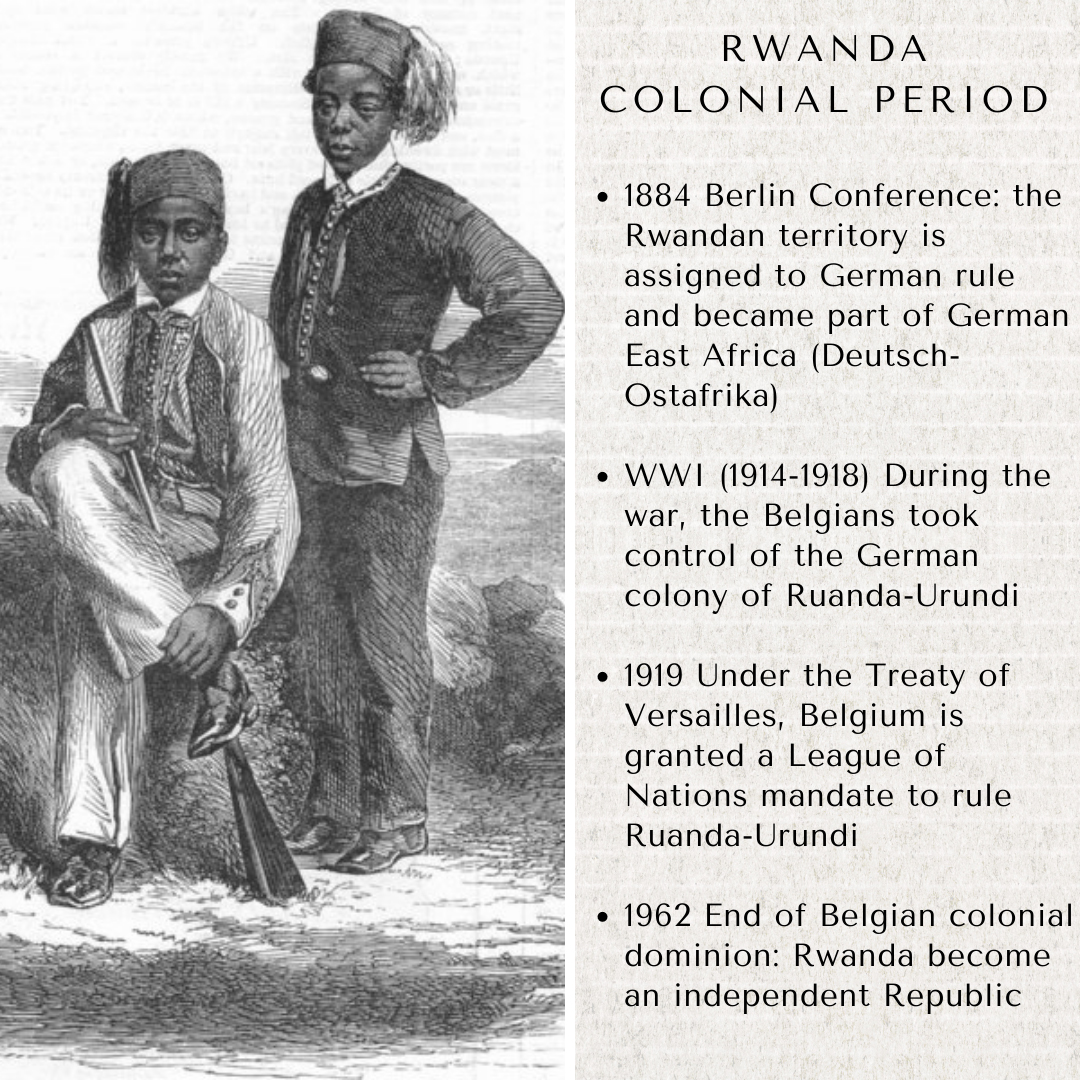

The Rwandan genocide was a particularly complex process whose roots can be dated back to the colonial period: the country was under a brief German dominion from 1884 to the late First World War period, in 1916-17, and a longer Belgian colonial rule lasted from the post-war to the formal political independence of the country, reached in 1962. A formal but not substantial autonomy, as Belgium and later France maintained many different kinds of ‘special interests’ in the region. The genocide, in particular, was a political project of annihilation meticulously planned during the Rwandan civil war that began in 1990, involved Uganda and Congo (called Zaire at that time), required the intervention of the UN Peacekeeping agency and was followed by two Congo wars, the last of which officially ended at the beginning of 21st century, after having involved nine African countries plus twenty-five armed groups and having caused millions of deaths.

A tribal local affair only?

There were many actors in the complex Rwandan scenario, with different kinds of legal liabilities and/or historical responsibilities. Some actors and some overwhelming responsibilities were not Rwandan nor African: they were Western and Catholic.

Last but not least, face genocide, we all have a moral obligation. All of us. And this is the best reason to go through this painful zone of total darkness.

«Genocide constitutes the crime of crimes» read the Kambanda judgment by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

Article II of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), approved by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948 and ratified by 149 States (as of January 2018), defines genocide as «any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group».

The crime of genocide – whose prohibition is a peremptory norm of international law and consequently, no derogation from it is allowed – is the coordinated and implemented effort to destroy or annihilate, in whole or part, a specific human group as such, in whatever way this last is categorized by perpetrators. (Please, note that with this definition, I’m extending the concept of “group” used by the CPPCG, following some scholars such as M.H. Kakar, F. Chalk and K. Jonassohn, John Cox, Uğur Ümit Üngör, and others; moreover, I’m not talking of an ‘intent’ or an ‘intention’).

Genocide is an attack upon human diversity, which is a necessary condition for human life to thrive. Humanity can only exist in diversity, multiplicity, variety, just as the visible light, a small segment of the electromagnetic spectrum, is a range of wavelengths that can only manifest to our eye as a range of different colors. It’s impossible to find two human beings morphologically and genetically identical (except for artificial clones). We are all diversely colorful as we’re expressions of the very same light. Therefore, an attack upon human diversity is an attempt to destroy humanity itself.

Immaculeé Ilibagiza, a survivor of the Rwandan Genocide, wrote in 2007: «What happened in Rwanda happened to us all – humanity was wounded by the genocide».

As human beings, we all passed through the chimneys of Auschwitz and got dissolved with the wind. We all fell under a pair of machete blows and swallowed our blood mixed with the red dust of the African soil. In a sense, facing a genocide, we’re all victims, and we’re all perpetrators. After Auschwitz, we can no longer pretend to ignore what human beings can do to other human beings, nor claim to be different from both of them. «Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto» wrote the Latin playwright Terence (195? – 159? BC): I’m a human being, and of that which is human, nothing is alien to me nor can be held as such. «Satana sum, et nihil humanum a me alienum puto» echoes Satan-the-banal-middle-aged-gentleman in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov.

«The horror of the Holocaust is not that it deviated from human norms; the horror is that it didn’t. What happened may happen again, to others not necessarily Jews, perpetrated by others, not necessarily Germans. We are all possible victims, possible perpetrators, possible bystanders». These words have been written by Yehuda Bauer (born in 1926), Israeli historian, professor of Holocaust Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. I couldn’t agree more.

Genocide, the mother of all hells, is the failure and the collapse of our humanity.

That area of darkness lies in the core of all of us. It’s inside us.

That’s why we all have a moral obligation: in the face of genocide, we cannot turn our eyes away, we cannot pretend we have nothing to do with it or claim to be a different species. We must understand how and why a genocidal process unfolded and was implemented by some human beings. We must do it not just to bring honor to victims but to prevent it. It’s a categorical imperative for all of us.

Genocide forces us to cross a boundary and throws us into that land of absolute darkness that lies inside us.

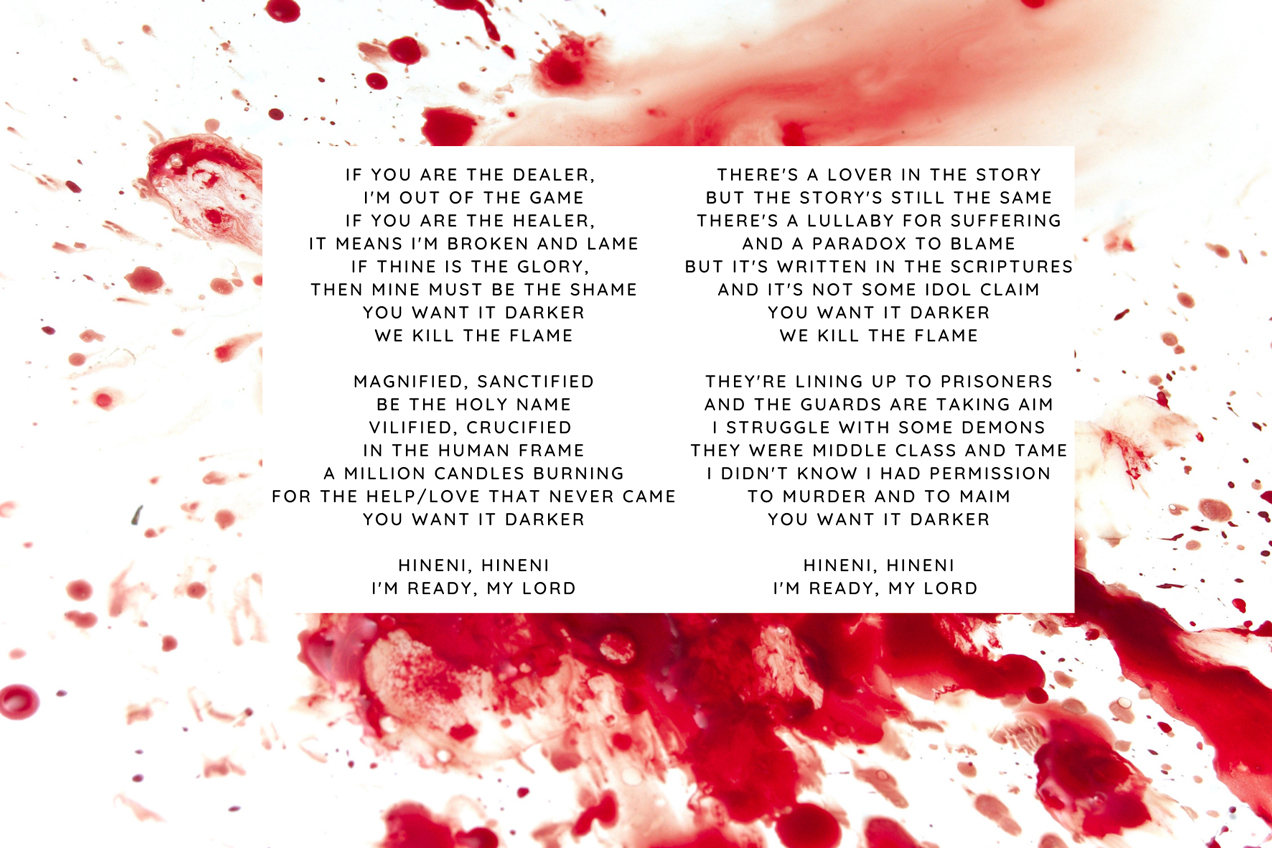

It’s frightening darkness, and there’s no flame at all.

We blew out every flame.

You want it darker, We kill the flame.

Leonard Cohen –You Want It Darker

There is also another good reason to listen to the story I am about to tell you. This story, which unfolds throughout the 20th century, is a story that more than many other stories, perfectly reveals who we are. Not who are the Hutus, the Tutsis, the inhabitants of Rwanda, etc.

No.

I really mean us. Me and all of you. We as human beings. This story tells who we humans are, and reveals better than a choral novel all the infinite shades and nuances filling up the long way that from our darkest abysses rises to the dancing stars that some of us still know how to generate.

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE – THE ROOTS

In the decades before the 1994 Genocide, the Rwandans were divided into Tutsi, Hutu, and Twa people. Therefore. we are going to begin by answering the central question: who were the Hutus, and who were the Tutsis? And why some Hutus planned and implemented the genocide of the Tutsis?

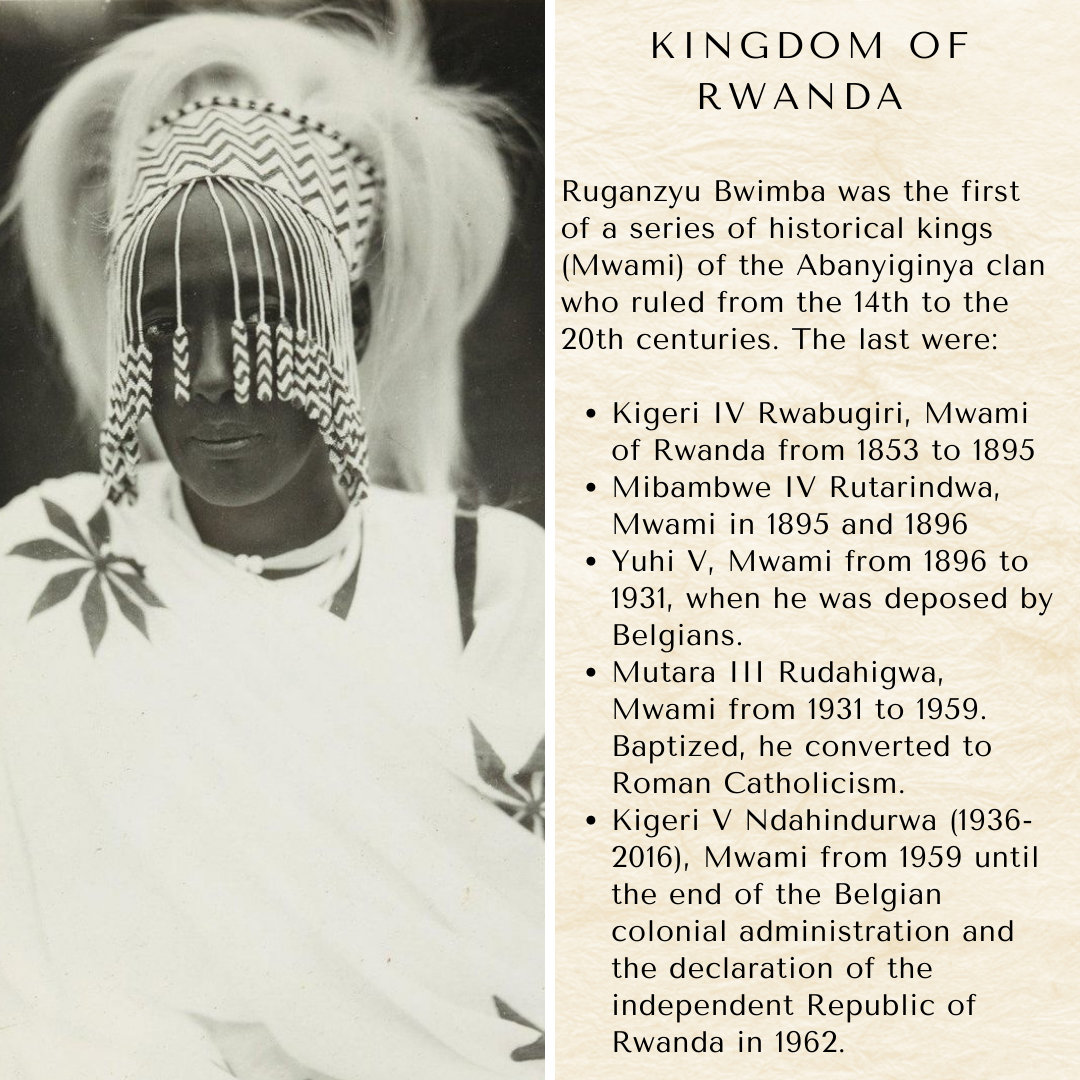

HUTU AND TUTSI IN THE PRE-COLONIAL RWANDAN STATE

«The balance of scholarly opinion today is that the state of Rwanda emerged as did many a state in the region, through the amalgamation of several autonomous chiefships into a single nuclear kingdom, under the leadership of a royal clan. This royal clan was the Abanyiginya one» (M. Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers – Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda, see Bibliography). The original nucleus of the Rwandan state started to develop probably during the 15th century or later, in today East Center Rwanda, along the valley of Lake Muhazi. The formation of the Rwandan state was, in particular, the development of centralized power and the emergence of a polity (an identifiable political entity) within a culturally homogeneous large community spread across the entire region: that of the Banyarwanda, all speakers of the very same Bantu language, the Kinyarwanda.

The powerful clan of the Abanyiginya expanded its dominion aggressively and progressively through annexation wars. The more the kings of the Abanyiginya dynasty extended their territory and political dominion, the more they started to differentiate themselves from the subjugated people, linked to them by clientship relations and later forced to a serf-like condition. The royal clan and their associated clans conceived themselves as Tutsis face to a majority of subjects, the Hutus. «Just as power was increasingly defined as Tutsi, the political and social position of Hutus was getting progressively degraded» (M. Mamdani, cit.).

Researches on the expansion of the Rwandan state during the second half of the 19th century show us that the Hutus «were simply those from a variety of ethnic backgrounds who came to be subjugated to the power of the Rwandan state. Take, for example, Catharine Newbury’s study of Kinyaga in southwestern Rwanda from 1860 to 1960. Its population became Hutu only in the last quarter of the 19th century, through gradual Tutsi military occupation and as a consequence of absorption into the institutions of the expanding state of Rwanda. This story of previously autonomous communities being absorbed within the boundaries of an aggressively expanding state focuses on the process of state expansion and its contradictory outcome. On the one hand, as local chiefs were dismissed and replaced by incoming collaborators, identified as Tutsi, land and cattle gradually accumulated into Tutsi hands. On the other hand, as those subjugated lost land and were forced to enter into relations of servitude to gain access to land, the Hutu identity came to be associated with and entirely defined by inferior status. The same can be said of the fiercely autonomous communities of Kinyarwanda speakers in northwestern Rwanda who were only brought under the fold of the state of Rwanda by a collaboration between German troops and the king’s soldiers. They, too, never really saw themselves as Hutu before their forcible incorporation into Rwanda. Before that, they were the Bakiga, the people of the mountains» (M. Mamdani, cit.).

According to Mahmood Mamdani, the most brilliant scholar on this topic, that between Hutu and Tutsi was a political distinction developed throughout some centuries to be functional to the growing political and military power of the Abanyiginya royal clan and related families and clans, like the Abeega. Since their origin, therefore, these two political identities were

- changing to better fit the royal clan’s dynamic needs;

- flexible and permeable as they developed on the background of a cultural and linguistical highly integrated community, where cohabitation and intermarriages were common;

- filtered through the commonly accepted patriarchal ideology: the children of a Hutu (or Tutsi) father were Hutu (or Tutsi) no matter if their mother was Tutsi (or Hutu).

Of course, this political distinction had a social and economic impact, and often, but not necessarily, entailed varying degrees of economic inequality. Not necessarily as not all Tutsi could be considered wealthy, and not all Hutu could be regarded as a homogeneous laboring mass tied down by the servitude of the corvée (ubureetwa). There were Hutu in the military ranks and Tutsi not related with the wealthiest and most powerful families. «The rare Hutu who was able to accumulate cattle and rise through the socioeconomic hierarchy could kwihutura, shed Hutuness, and achieve the political status of a Tutsi. Conversely, the loss of property could also lead to the loss of status, summed up in the Kinyarwanda word gucupira. Both social processes occurred over generations» (M. Mamdani, cit.).

Contemporary Rwandan scholars and historians highlight the cultural and linguistic unity of the Banyarwandans (Abanyarwanda) in the so-called pre-colonial period. At the time, the Abanyarwanda shared ancestral customs, rites, taboos, arts, crafts, music, dance, human and veterinary medicine, religious beliefs, a patriarchal organization, socio-economic disparity, and violence as well. Among them, there has never been an ethnical war nor an ethnic cleansing intent. «’Tutsiness’ and ‘Hutuness’ did not mean some belongingness» (Anastase Shyaka, The Rwandan Conflict, see Bibliography). Each person ‘belonged’ to a specific clan only, and each of the likely 18 ancient clans was made up of Hutus, Tutsis and Twas; each umunyarwanda (singular of Abanyarwanda) was only circumstantially defined ‘Tutsi’ or ‘Hutu’ depending on his socio-political situation.

James Jay Carney, Associate Professor of Theology at the Creighton University, Omaha (Nebraska, US), writes: «The Hutu-Tutsi line remained comparatively fluid in the years prior to the European encounter, and significant “factors of integration” should not be discounted. Intermarriage continued, wealthy Hutu could still be ennobled as Tutsi, and Hutu and Tutsi coexisted in socially formative institutions like the military» (JJ. Carney, Rwanda Before the Genocide, see Bibliography).

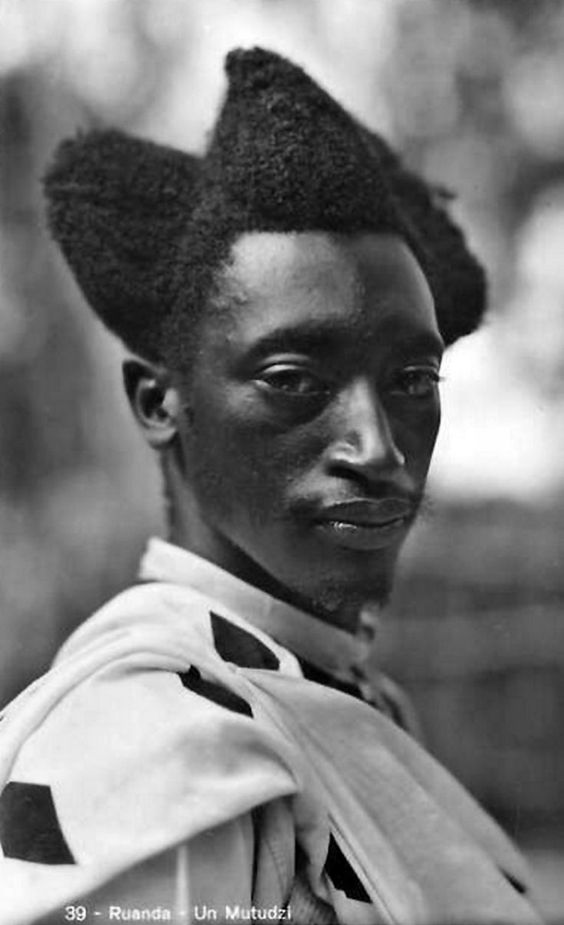

A Tutsi young man in the early colonial period

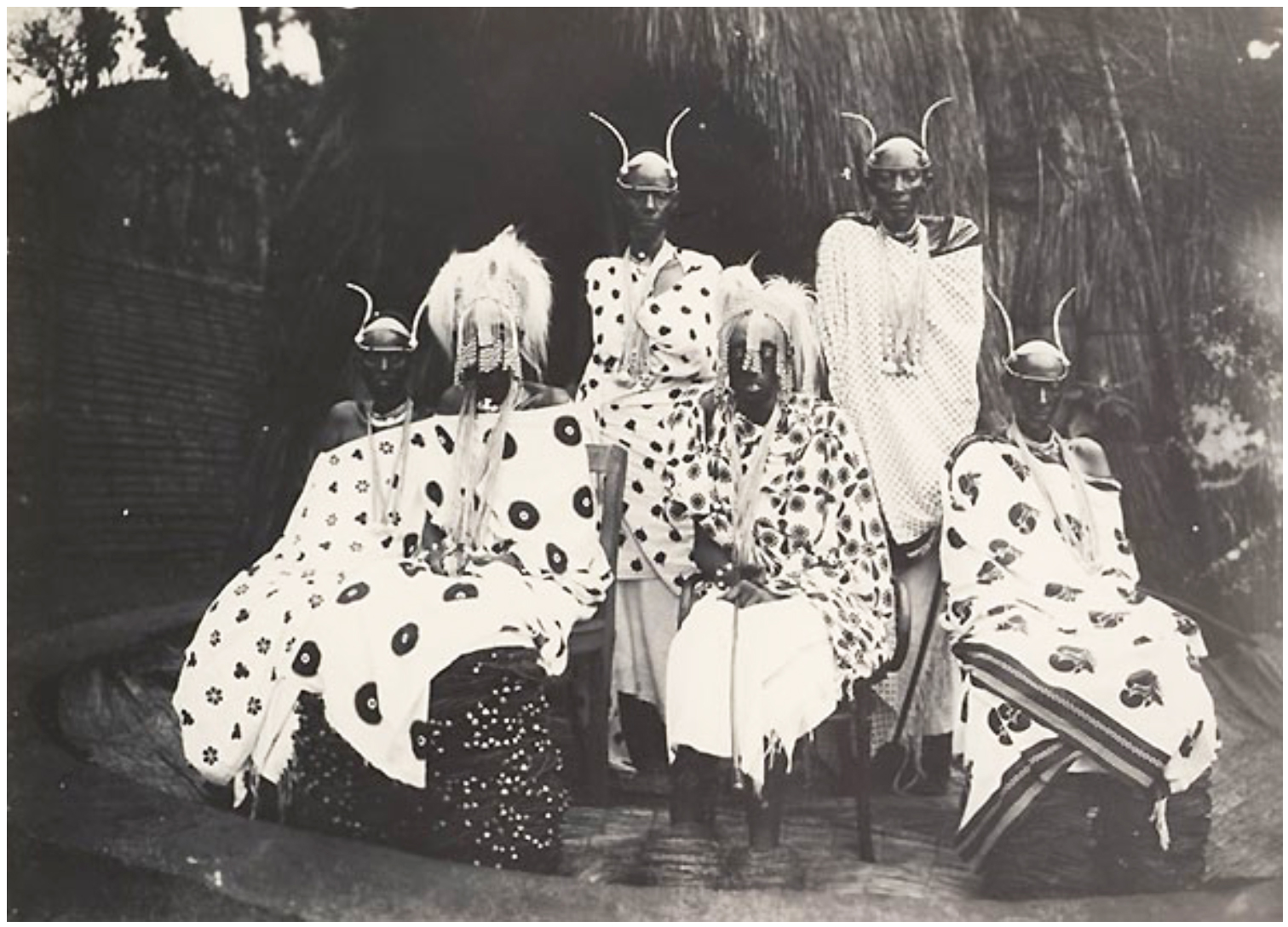

Twa people, 1904. Photo by Jessie Tarbox Beals, Missouri History Museum (Creative Common Public Domain).

The Twa or Batwa are a Bantu pygmy ethnic group native to the African Great Lakes region, on the border of Central and East Africa.

THE COLONIAL PERIOD

The arrival of European colonizers and missionaries, imbued with the racial ideology commonly accepted in modern Christian Europe, and reinforced between the late 19th and the early 20th centuries with pseudo-scientific theories about the black race inferiority, forced the Banyarwandans to make many unexpected ‘discoveries’.

‘Thanks’ to the colonization by the Germans firstly and the Belgians later on, and to the non-peaceful evangelization of the missionaries (the first were the Lutheran missionaries of the Bethel German Society, and the French Catholic White Fathers of the Cardinal Lavigerie Association, already active in the very first years of the 20th century), all Banyarwandans found out immediately that they were first of all “negroes” – something they never had any suspicion of before – secondly that they were “negroes preordained for submission and servitude”, and thirdly that unfortunately “some of them were more negroes than others”.

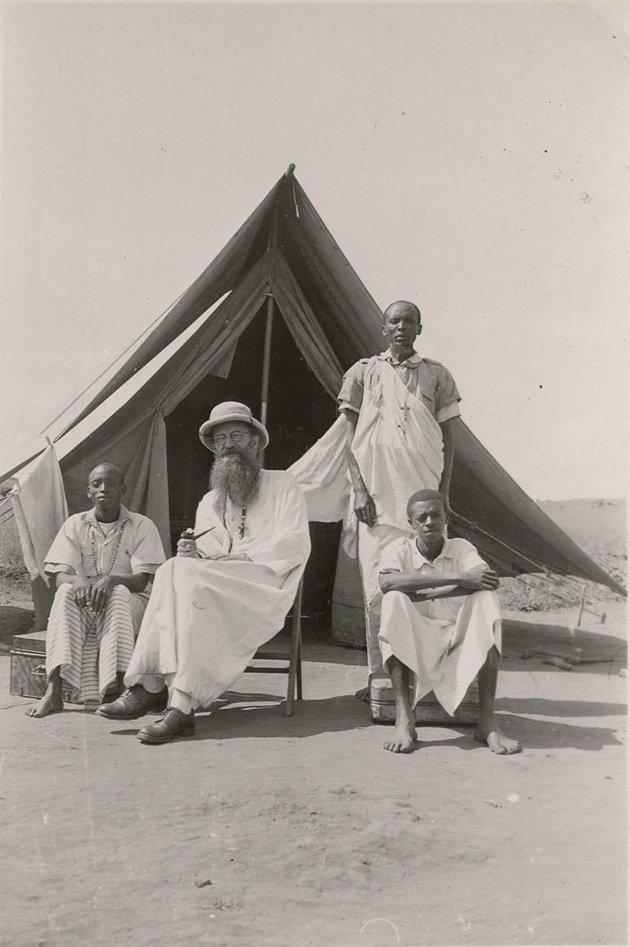

A White Father Missionary in Rwanda in ca. 1910. He’s likely Monsignor Jean-Joseph Hirth, Catholic Bishop in German East Africa, appointed Superior General of the White Fathers in 1890.

A White Father in Rwanda during the Belgian administration.

The Missionaries of Africa, commonly known as the White Fathers, Pères Blancs in French, is a Roman Catholic society of apostolic life, founded in 1868 by then Archbishop of Algiers Charles-Martial Allemand-Lavigerie. The père Alphonse Brard was among the first White Fathers to enter Rwanda from Burundi, following the Ruzizi Valley, in January or February 1900. The French clergyman Léon-Paul Classe, who arrived in Rwanda on March 21, 1901, and will exert a remarkable political influence on the history of Rwanda during the first half of the 20th century, was a White Father as well.

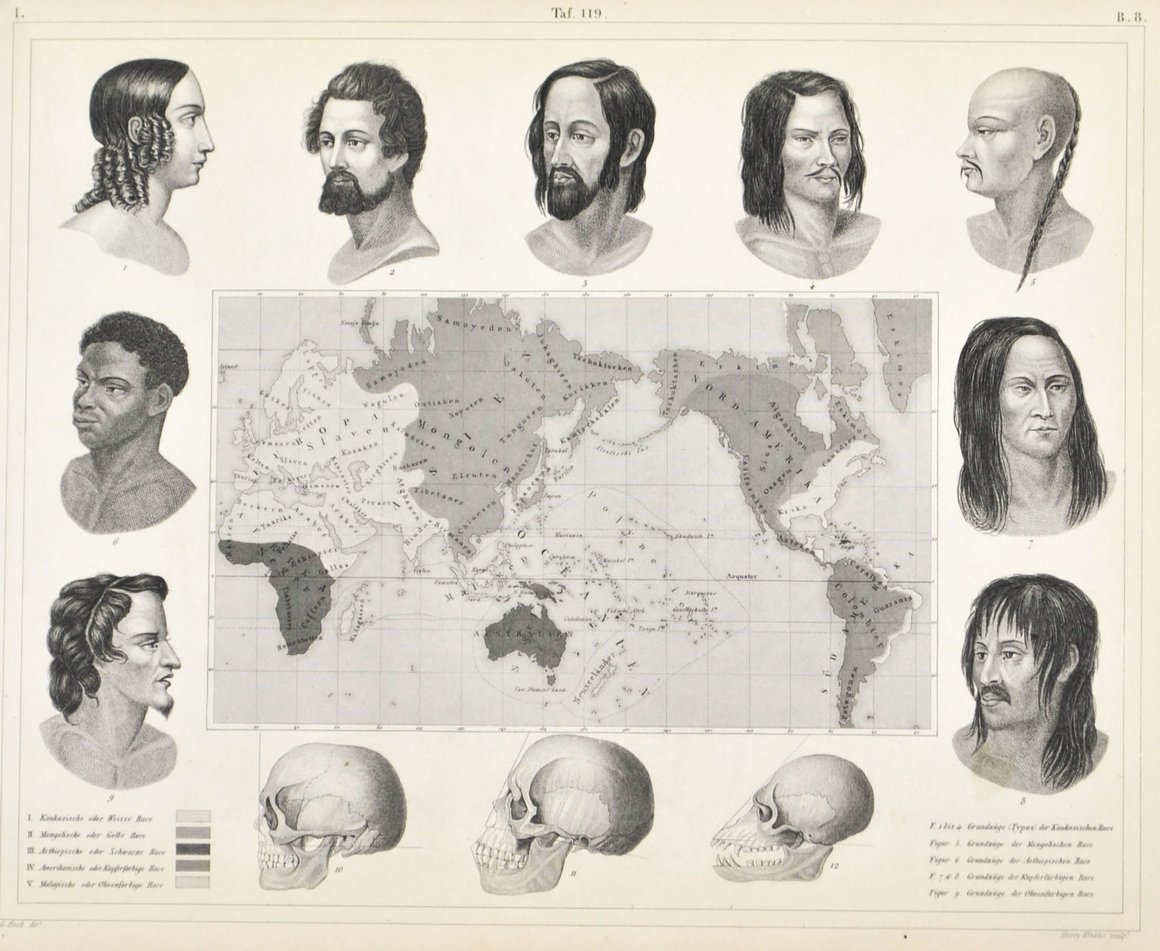

‘Black people’ or ‘negroes’, the ‘yellow race’, ‘white people’, ‘redskins’ were political categories: the problem with them is the hidden racist ideology that makes them offensive or derogatory. These skin-color-based categories were born as Western racialized classifications of people that had nothing to do with ‘innocent’ color perceptions. And to make matters worse, in the article on THE JAPANESE ART OF KINTSUGI, we saw that all color perceptions, a fortiori skin-color perceptions, are complex cognitive processes mediated by culture; therefore, they can never be ‘innocent’. The term ‘person of color’ – widely used in the US and in other countries to describe people who cannot be considered ‘white’ – and the color-related terminology are expressions of systemic and pervasive racism (the concept of human ‘race’ is not grounded in genetics). These terms are based on a racial and racist delineation between whites and everyone else, namely a multitude of different populations whose lowest common denominator is that of not being white. Colors versus the non-color par excellence.

1851 Map of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach’s five races, labeled “Caucasian or White”, “Mongolian or Yellow”, “Aethiopian or Black”, “American or Copper-colored”, and “Malayan or Olive-colored”. From Color terminology for race, in Wikipedia.

My mom was defined as a ‘White Aryan’ under Nazi dominion. She was a tall, slender woman, with dark blonde hair (she was very fair-haired in her childhood), light blue eyes with a light green shade, and sensitive pale skin (she suffered twice from skin cancer) who got reddish under the sun. She was a charming lady, full of colors, as you can see from her picture above, not a faded, discolored character.

The actual skin color of different humans is affected by many factors, the two most important of which are prejudice and melanin. Let aside the first, as to the melanin, the only differentiation we can do is between the humans who have it in different degrees and the humans who lack it and are affected by a rare group of genetic disorders, called ‘albinism’. So, the only sound differentiation we can do is between albinistic animals, humans included, and all of the others. At the end of the day, a racist person is reduced to the dummy who advocates for albino’s dictatorship.

Let’s get back to Rwanda.

Suddenly, in a couple of moments between the sunset of the 19th century and the dawn of the new millennium, Rwandans got aware of being not just negroes but negroes preordained for submission, slavery, and exploitation, something that their fellow Africans who had been victims of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, from the 16th century on, had already figured out. Over the centuries, the image of the Negro deteriorated in direct proportion to the growth of the economic importance of slavery: «the more the Western world grew rich on the institution of slavery, the less it was willing to accept Negroes as brothers and sisters under the skin» (M. Mamdani, cit.). In the 19th century, this image reached its lowest point (and the business volume its highest).

The majority of missionaries in Rwanda, like the White Father père Alphonse Brard, were persuaded (and wrote) that “black people” were not intrinsically “morally upright”: their blackness was the visible mark of deeper damage caused by the original sin. With ‘true’ Christian spirit, many ‘white’ missionaries «claimed that it was their right to obtain services from local ‘black’ Rwandans, including requisitions for foodstuffs, hoes, small livestock, and construction materials» (Byanafashe – Rutayisire, History of Rwanda, see Bibliography). Moreover, they felt fully entitled to impose forced labor to carry out many activities, including the construction of churches. Last but not least, they fanatically wiped out many ‘elements of paganism’, namely they destroyed many aspects of the traditional culture, and became partners in furthering the colonial merciless exploitation, which they modestly called a “civilization enterprise”. «Missionary action was one of the pillars that supported the colonial system» (Byanafashe – Rutayisire, History of Rwanda, cit.).

Finally, all Banyarwandans found out that in their negritude, they were not equal. Some of them were more negroes than others, and that wasn’t a good thing. Not at all.

«Race and race ideology had become so deeply entrenched in American and European thought by the end of the 19th century that scholars and other learned people came to believe that the idea of race was universal. They searched for examples of race ideology among indigenous populations and reinterpreted the histories of these peoples in terms of Western conceptions of racial causation for all human achievements or lack thereof» (Hereditarian ideology and European Constructions of Race in Race, Britannica, see Bibliography).

The reinterpretation of African history in terms of the abhorrent racial ideology affected Rwanda as well. Westerners, especially Belgians and French missionaries, racialized the political difference between Tutsis and Hutus, reading the history of Rwanda through the so-called “Hamitic hypothesis”, an interpretative paradigm widely shared in the Western world that claimed to be scientifically based and historically well documented, while in reality, it was a racist ranting, supported by pseudo-scientific anthropological theories, some historical unverified conjectures and a sprinkling of Biblical myths.

According to the “Hamitic hypothesis”, in the Dark Continent, all of the elements of civilization were brought about and developed by the Hamites, pastoral Caucasians that were black in color without being Negroid in race. The Hamitic race – so-called from Ham, one of the sons of biblical Noah – was considered a Caucasian race alongside (but not on a par with) the pure Aryans and the (not-so-pure) Semitic race. Hamites were Ancient Egyptians and other non-Semitic pastoral populations native to North Africa and the Horn of Africa who, in their migratory waves to Central Africa, brought the ‘light’ to the underdeveloped “Negroid” (Bantu) agriculturalist populations. The Tutsis, or better to say, the Watussi or Batoutsi of Rwanda – as they were called by Westerners – were classified as members of the superior Hamitic race, whose origins were placed in the North of the African Continent, while the Hutu and the Twa were conceived and treated as the local ‘black savages’ and the ‘natural slaves’ of the inferior Negroid race. Among the most fervent supporters of the Tutsi-Hamitic Hypothesis, there were many missionaries, like the powerful Léon-Paul Classe (1874 –1945), a White Father Catholic priest who guided the Apostolic Vicariate of Ruanda from 1922 until 1945.

To the Westerners’ eyes, the race of tall, slender black semi-civilized Tutsi pastoralists coming from the North of Africa and that of local, primitive, peasant Hutu and Twa negroes had nothing in common. They had to be considered two separate races. The 1925 Belgian Report from the Nyanza Territory described the Twa people (approx. 1% of the Rwandan population) in the following terms: «An old and worn-out race facing extinction, the Mutwa (..) has a somatic character properly defined: short, broad-backed, muscular, hairy especially around the chest region, with an ape-like face and a distinct flat face and a flat nose that combines the general physical traits of the monkey with an obsession for forests» (quoted in Byanafashe – Rutayisire, History of Rwanda, cit.). How did all those ape-like negroes dare to be the very same race with the tall, slim blacks able to reach 7 feet (213 cm)?

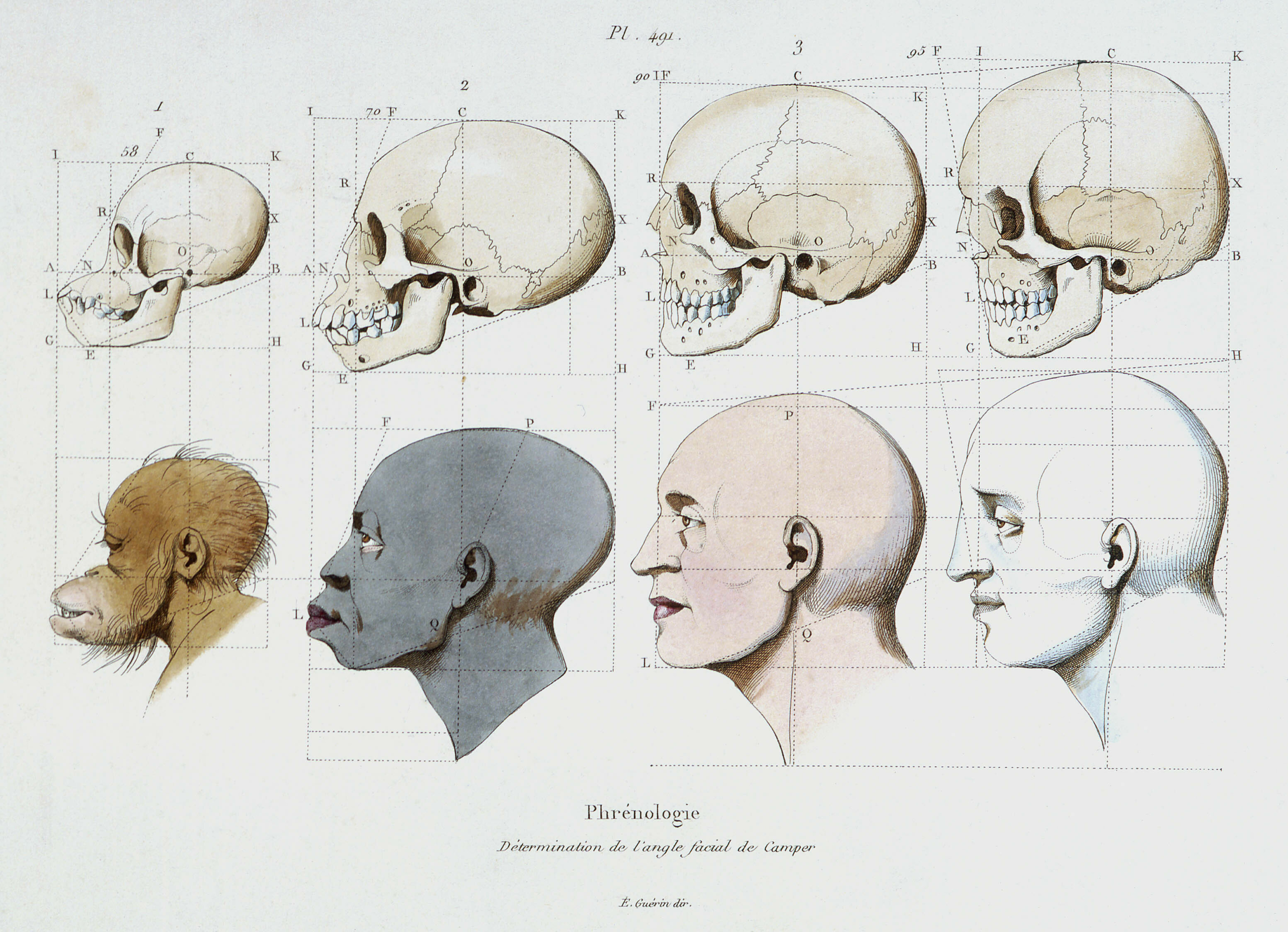

Phrenology. Determination of the facial angle of Camper, engraving in Picturesque Dictionary of Natural History and Phenomena of Nature by Felix Edouard Guerin, 1833-1839. Comparison of the skulls of a monkey, a black man, a white man and a Greek statue.

Credit Collection Grob Kharbine Tapabor. Photo by © IMAGO.

The following US documentary A Giant People – The Watussi of Africa by George Herzog was shot in the Rwandan mwami residence (Nyanza) in 1939, during the Belgian colonial rule. Listen to its incipit: «More than a thousand years ago, there came to the highlands of East-Central Africa the Watussi, a giant race who conquered the agricultural natives of the region now known as Rwanda». At first, this film looks like an innocent documentary for teens (the tone is light, everything is sweetened, and full of easy peasy exoticism) but at a second glance, it turns out to be a concentrate of racist nonsense and condescending attitude. It’s ‘instructional’, surely, but not in the intended meaning. It’s pervaded, moreover, by a sort of thinly concealed obsession with the physical appearance typical of German and Belgian colonists, exacerbated by the strict standards of beauty and nobility of the Tutsi ruling élite.

The colonial racial ideology wasn’t just a simple belief system or a cultural map. Mamdani wrote it clearly: «Racial ideology was embedded in institutions, which in turn undergirded racial privilege and reproduced racial ideology. It is this political-institutional fact that intellectuals alone would not be able to alter. Rather, it would take a political-social movement to be dismantled. (…). Belgian power turned Hamitic racial supremacy from an ideology into an institutional fact by making it the basis of changes in political, social, and cultural relations. The institutions underpinning racial ideology were created in the decade from 1927 to 1936. These administrative reforms were comprehensive. Key institutions—starting with education, then state administration, taxation, and finally the Church—were organized (or reorganized, as the case may be) around an active acknowledgment of these identities. The reform was capped with a census that classified the entire population as Tutsi, Hutu, or Twa, and issued each person with a card proclaiming his or her official identity (…)» (M. Mamdani, cit.).

The Rwandan official census of 1933, which registered an estimated overall population of 1.8 million and a number of Tutsis between 250,000 and 300,000, entailed the classification of all Abanyarwanda in three, different ‘racial groups’: Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa. In 1933, a new mandatory identity card system was introduced by Belgians: this compulsory document stated the name and the racial identity of every citizen. Hutu and Tutsi were enforced as legal identities, frozen in their immutability, and removed from history.

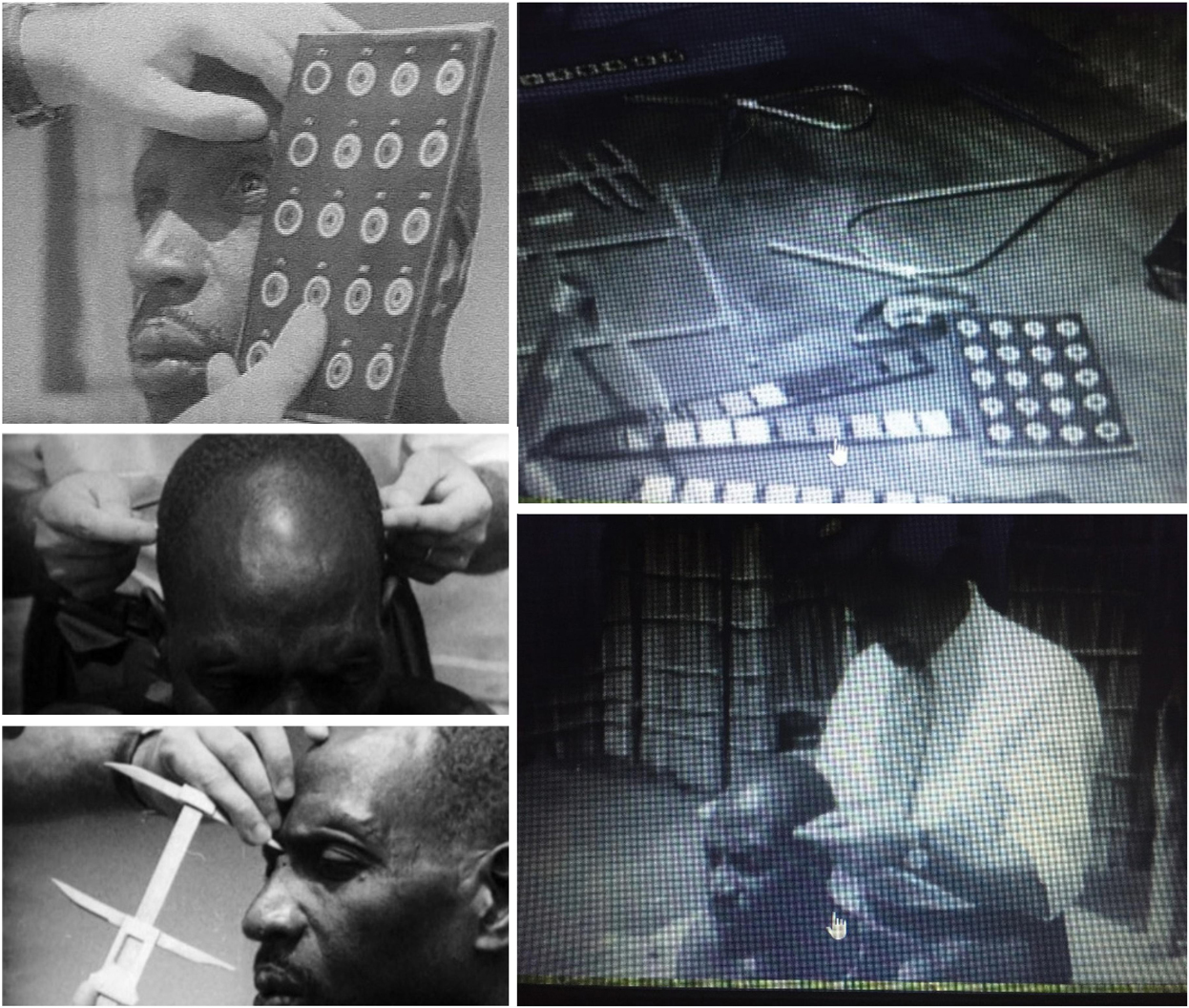

According to Mamdani, the major sources of information upon which the Belgian administration relied to racially classify the population were the following three: information provided by the church and missionaries, physical measurements – many Rwandans underwent humiliating and repulsive procedures to assess not just their height but the length and width of their noses and the shape of their eyes and faces – and economic condition (the in-famous ten-cow rule).

«Craniology as deemed by Belgian specialists in Rwanda in the 1930s. Belgian specialists came to evaluate people, using typical instruments. Still images retrieved from the film “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace 3 of 3 Monkey in the Machine, 2011». The picture is taken from Charles André, Phrenology and the Rwandan Genocide (see Bibliography).

The real problem with this classification was not the adoption of phrenology and its despicable measurements: fortunately, today it’s universally recognized as a pseudoscience, stuffed, like the entire colonial racial ideology, with delirious prejudices.

The real problem was not even the use of three sources of information, all barely reliable: most Rwandans were of mixed origin, and their physical appearance, their family names, their grandparents and clans, even less the number of their cows could not provide any clue.

The real problem is that the concept of ‘Tutsi’ upon which the entire administrative and judicial reform was carried out by Belgians was not that of pre-colonial Rwanda: it was the racial invention of missionaries and colonial authorities. Not even the Tutsi of the royal Abanyiginya clan, who have been calling themselves Tutsi for centuries, were properly Tutsi in that new sense.

The construction of a new Tutsi identity, the racialization of the relationship between Tutsi and Hutu, and the tutsification of the entire Rwandan administration (of which we will talk shortly) were not simple projections of the colonial racial ideology, but essential aspects of a complex political project developed by Belgians from the early 20s to the mid-30s, whose aim was not to rule over the country but to exploit and make the most of its natural and human resources.

To efficiently squeeze all of these resources, Belgians colonial authorities chose a different path than the Germans. The latter had relied on the Tutsi monarchy and its decentralized structures, following the so-called ‘colonial indirect rule’. The Belgians were gradually shaping up a different system that was not an indirect rule nor a direct one: in their view, the entire administration of the country had to be reformed and reorganized to create the best conditions for the most cost-effective and profitable exploitation.

The political project that gradually took shape and was carried out in the first 15-20 years of Belgian colonial dominion aimed at implementing a major change: the simplification, verticalization, and hardening of the chain of command, namely the official hierarchy of authority at all levels.

To carry out this reform program, the Belgians

- in the early 20s, launched an educational reform project in synergy with Catholic missionaries to form a class of docile civil servants, able to become efficient, loyal, and malleable local administrators at all levels;

- set forth an explicit policy of reinforcing the power of all local chiefs and administrators while operating an energetic pruning of dry branches: they removed many traditional lines of command and concentrated the administrative power in the hands of a relatively small number of civil servants. In 1926, they abolished the ancient Rwandan ‘system of the three local chiefs’ in favor of a single administrator. This new system that erased the traditional coexistence and cooperation of multiple local authorities at a time «penalized the most vulnerable social classes» (Byanafashe – Rutayisire, History of Rwanda, cit.);

- removed any traditional form of accountability from below, a decision that, both in the short and long haul, produced an inevitable increase in local despotism and multiple forms of abuse on the vulnerable mass of the population;

- reinforced the top-down control, taking it away from the mwami (king) and his court.

During the 1920s, the Belgians brought about a gradual decline of the royal power. «The reform of the 1920s began by centralizing the powers of chiefs and deflating those of the mwami. Both moves reinforced the same end: to augment colonial power in a despotic fashion» (M. Mamdani, cit.).

In 1922, the mwami – king Yuhi Musinga at that time – lost his juridical supremacy, in 1923, his powers to make political nominations, namely his traditional right to appoint or remove chiefs. Moreover, «provincial chiefs could no longer appoint or remove their subordinates without prior instruction from the office of the Residence <the highest Belgian authority in Rwanda>. The extent of this decision had serious consequences. The Belgian administrations became the final source of power. Chiefs and sub-chiefs were no longer responsible to king Musinga but instead were subordinated to the administration» (Byanafashe – Rutayisire, History of Rwanda, cit.).

In 1931, king Yuhi Musinga, who was malleable but only up to a certain point, was deposed by a coup d’état organized by the Belgian Resident of Ruanda, by the Vice-Governor of Ruanda-Urundi, and the powerful French Monsignor Léon-Paul Classe who guided the Apostolic Vicariate of Ruanda.

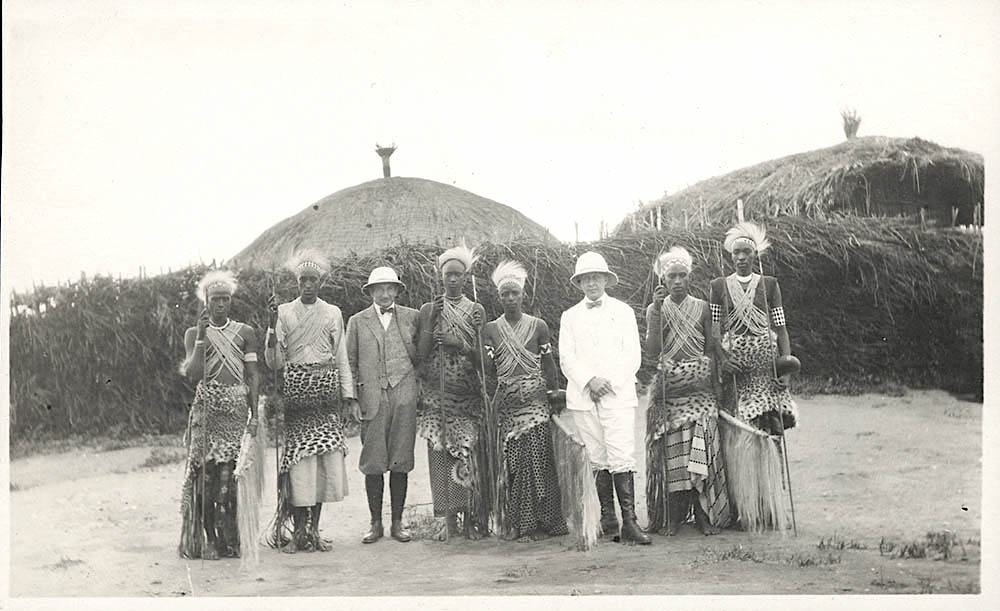

Mwami Yuhi V Musinga with members of the Royal Court of Rwanda, ca. 1910.

His 19 years old son, Prince Charles Rudahigwa, was enthroned Mwami of Rwanda on November 16, 1931, as Mutara III (he’ll be nicknamed ‘the king of whites’). In the decades to come, the king and his court will be restricted to play a ceremonial and folkloric role, devoid of real political power. That role is featured in the 1939 short documentary by George Herzog (above). It was what the Belgian government needed to show a reassuring façade before the League of Nations.

King Mutara III (1911-1959) with some Catholic prelates, all Pères Blancs, White Fathers, probably in 1943s.

Mwami Mutara was the first Rwandan king to convert to Catholicism He was baptized in 1943 by French Monsignor Léon-Paul Classe. His Christian names were Charles Léon Pierre. Not by chance.

The entire administrative reorganization – as I said – was the main part of a political project developed by Belgians in the early 20s and implemented in the decade between the mid-20s and the mid-30s. «It started as soon as the Belgians arrived in the country and ended with natives becoming docile civil servants who supported European administration» (Byanafashe – Rutayisire, History of Rwanda, cit.).

The core of the administrative reform was the tutsification of all non-Belgian nodes in the chain of command, namely the tutsification of the entire class of local administrators under Belgian authority.

Gradually, the Belgians began to remove all of the administrators who did not belong to the Abanyiginya royal clan and to the related, powerful Abeega clan. «Many Hutu chiefs and sub-chiefs were thrown out not because they were incompetent but due to their origin. It’s difficult to know how many Hutu were dismissed, but during the 1929 Reform, no Hutu were retained» (Byanafashe – Rutayisire, History of Rwanda, cit.). Obviously, the 1933 census and the ratification of the new mandatory identity card system were necessary steps to continue along this road.

Mind you that the tutsification was not the simple placement of Tutsi in all cogs of the entire institutional and administrative machine. It was the placement of those who assumed the new racial identity of Tutsi, which did not coincide with the political identity of Tutsi in the pre-colonial period. The tutsification was the placement of a small handful of ‘new Tutsis’ in all of the nodes of the chain of power. I wrote ‘a small handful’ as they were a tiny minority: according to the History of Rwanda, in 1948, the Tutsi chiefs and sub-chiefs in the line of command were 5% of all Tutsi, approximately 0,7% of the entire Rwandan population. The 80% of this tiny 5% came from the Abanyiginya and the Abeega clans only.

Education, christianization, and racialization were the three methods used by Belgians to incorporate the Tutsi élite into the colonial system of power.

The education, christianization, and training of cadres were major concerns of the Belgian administration since the beginning of its presence in the country. Starting from the early 20s, the Belgians developed a complex educational project in synergy with the White Father missionaries, centered on the foundation of a new school system reserved for the children of some privileged Tutsi clans. The aim was the forming of a class of local administrators able to manage public affairs in full obedience and loyalty not to the mwami, but to the Belgian highest authorities.

Christianization became an integral part of the educational project: «All along the colonial period, the Catholic authorities controlled and later monopolized secular education given to the élites, trained to become future cadres with a religious background. (…). In 1936, 78% of the chiefs and 84% of sub-chiefs were of Catholic denomination, while only 18% of the total Rwandan population converted to this religion» (Byanafashe – Rutayisire, History of Rwanda, cit.).

«With the blessing of bishop Classe <the powerful French Monsignor Léon-Paul Classe>, Roman Catholicism became the religion of the ruling class, and Tutsi priests, like Alexis Kagame, created a Catholic Hamitic myth» (Aylward Shorter, Review, see Bibliography). Actually, they did not ‘create’ a Catholic Hamitic myth: they perpetuated the so-called “Hamitic hypothesis”, turning it into a sort of truth of Christian faith.

More than the secular and technical training, it was the religious education given to all of the ‘new Tutsi’ and not just to the future priests to convey and instill the colonial racial ideology.

Education, christianization, and racialization were the three methods used by Belgians to incorporate the Tutsi élite into the colonial system of power, turning them into a caste of docile civil servants, directly controlled, and trained to be manageable instruments of exploitation and repression.

The colonial racial ideology, for its part, provided not only the soundest (or deemed such) legitimization of this exploitation and repression but also the validation of the entire chain of power. Each of its nodes, from the highest ‘white’ superior authority to the last of the new Tutsi administrators, was perfectly justified inside a ‘scientific’ (or deemed such), ‘historical’, and ‘religious’ horizon. And of course, even the submission of Hutu and Twa “negroes” was explained, substantiated, and validated.

The colonial racial ideology was credited to reflect the natural order of things and a super historical human ranking.

Unicuique suum, “to each his own place”.

Jedem das Seine (“To each his own”) will be inscribed on the main gate of the lager of Buchenwald.

Robert Georges Constant Godding (in white), Belgian politician, future Colonial Secretary in 1945-47, and Théo Kreglinger in Rwanda in 1935.

The racialization of the Tutsi and its polarization face to the Hutu and Twa people (civilizers versus primitive people, pastoralists versus agriculturalists, an indigenous majority versus a non-indigenous minority, a royal, tall race versus a stocky, ape-like faced race, etc.) had a remarkable political effect that not only did not escape the powerful Monsignor Léon-Paul Classe but was the winning horse on which he bet to increase his own political credibility and influence. In my view, this is an issue of remarkable importance.

Monsignor Léon-Paul Classe wrote in 1930: «The biggest mistake the government could make would be to do away with the Tutsi caste. This would lead the country to anarchy and communism, and to be viciously anti-European».

Why on earth, the Tutsis, or to better say, the ‘new’ Tutsi caste would make up a barrier to anarchy and communism?

What did the ‘new’ Tutsis have to do with the notorious anti-communism of the French Monsignor?

The administrative reform gradually implemented by the Belgians led to a gradual worsening of the living conditions of the population: exploitation, forced labor, forced crops, humiliation, harsh physical punishments (like whipping with a hippopotamus cane), fear, hunger, famine, emigration to the British colonies in East-Africa drew the daily horizon of the vast majority of Banyarwandans. Mamdani writes that «the Hutu peasantry experienced Belgian rule as harsher than any previous regime in living memory» (M. Mamdani, cit.). However, the worsening of living conditions also affected all those Tutsi or presumed Tutsi who did not belong to the ruling elite, despite their granted privileges (they were not forced to carry out different forms of corvée, for example). «Until the end of the colonial period, Rwandan society resembled a steep, clearly defined pyramid. At the very top of the hierarchy were the whites, known locally as Bazungu, a tiny cluster of Belgian administrators, and Catholic missionaries whose power and control was undisputed. Below them were their chosen intermediaries, a very small group of Tutsi drawn mainly from two clans who monopolized most of the opportunities provided by indirect rule. Below the small indigenous Tutsi elite were not only virtually all of Rwanda’s Hutu population, but the large majority of their fellow Tutsi, as well. Most Tutsi were not much more privileged in social or economic terms than the Hutu. Although they were considered superior to the Hutu in theory, in practice most Tutsi were relegated to the status of serfs» or marginalized (The Report of the International Panel of Eminent Personalities, Rwanda: The Preventable Genocide, see Bibliography).

Starting from the 1930s, Rwandan society began to be marked by increasingly dangerous structural inequalities. It was held together by violence whose systematic use always proceeded top to bottom, combined with deference to authority and blind obedience bottom to top, two cornerstones of the Catholic education system implemented by White Fathers (some Rwandans call it the widespread culture of ndiyo bwana, ‘yes, sir!’).

Monsignor Classe’s fear, shared by the highest Belgian authorities, was that social tensions, resentment against local bosses, demands for better fiscal/economic/living conditions might explode giving rise to local protests or worse, revolts and uprisings.

Why should a handful of ‘new’ Tutsi be a barrier to anarchy, communism, and anti-European rebellion?

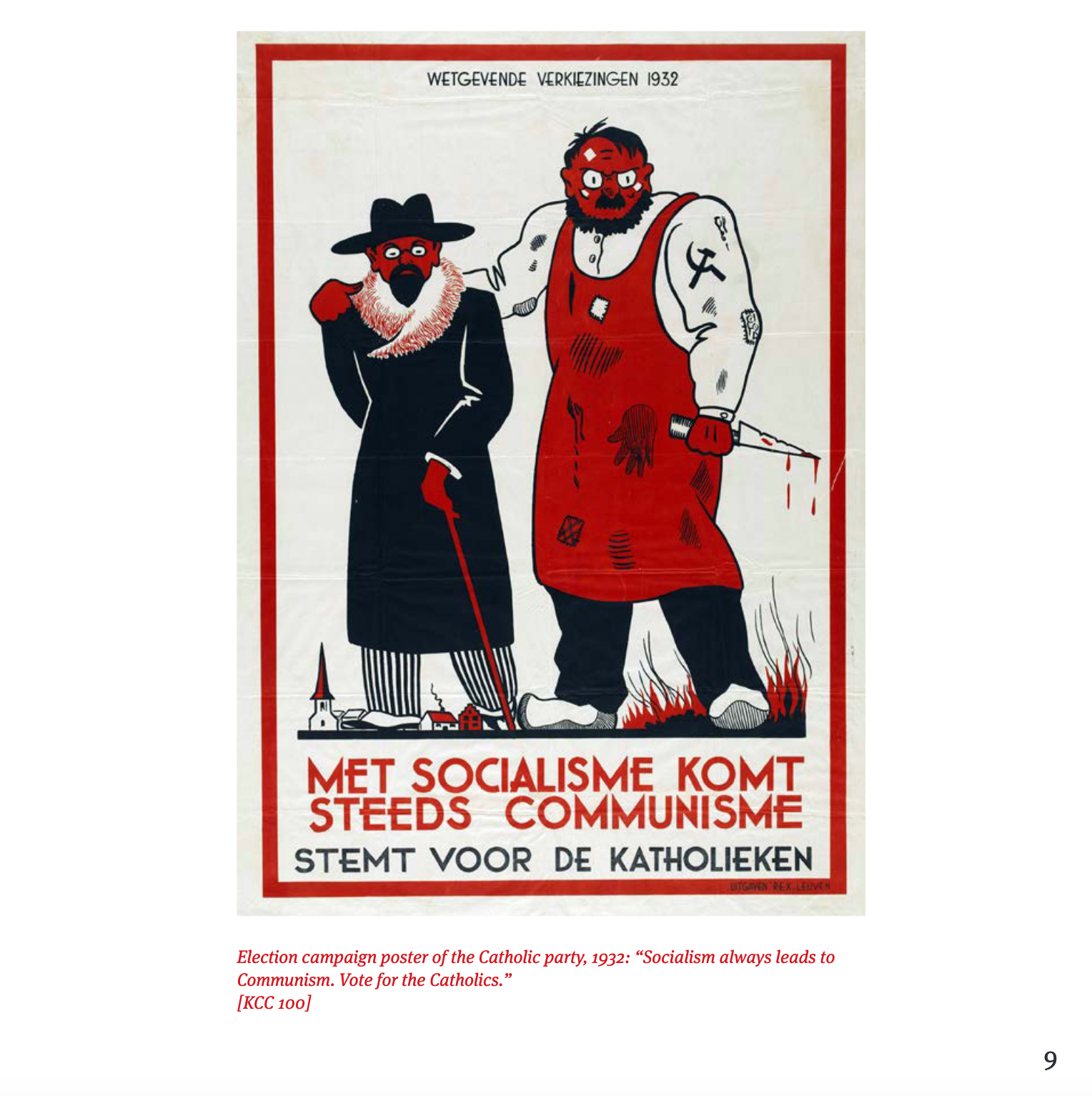

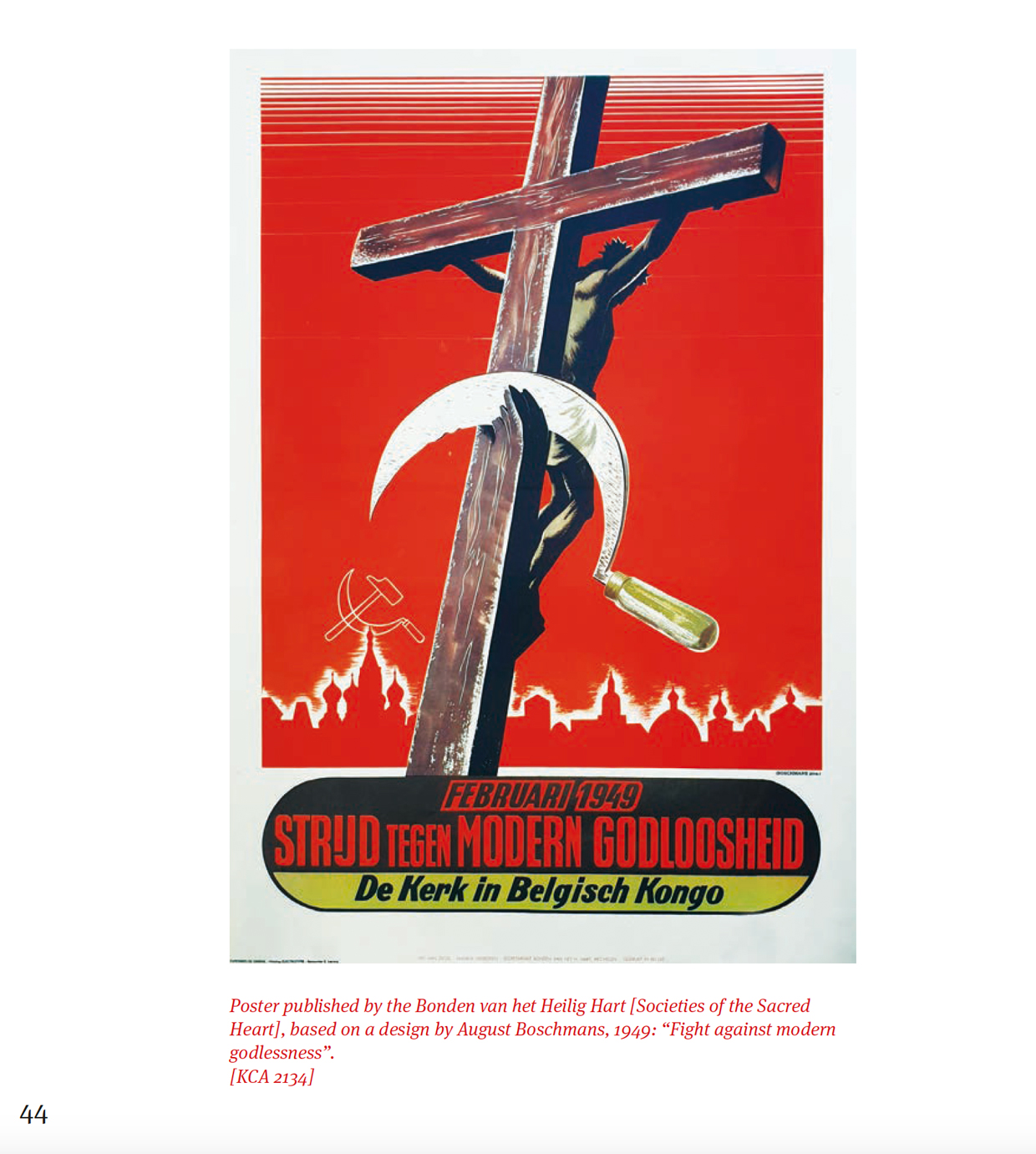

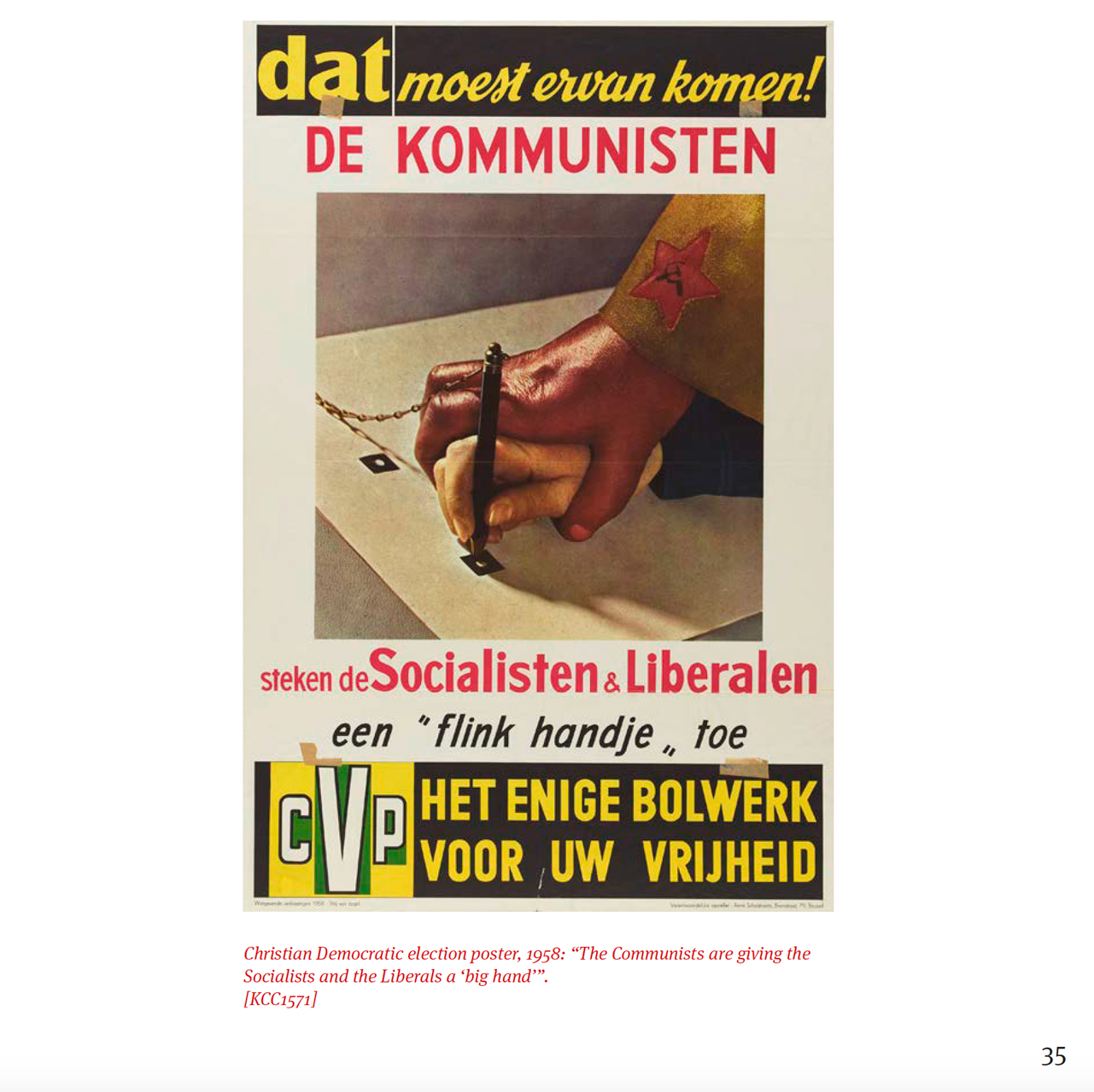

A Catholic anticommunist propaganda poster, printed in Belgium in 1932. Please, note the portrait of Socialism as a rich Hebrew (a caricature of Leon Trotsky whose real name was Lev Davidovich Bronstein).

«The foundation of the Soviet Union in 1922, following the Bolshevik victory in the Russian Civil War, provided Western Europe with a first tangible image of communism. Belgian Catholic election campaign propaganda from the interwar period expressively reflects the pejorative imageries that spread rapidly across the continent. The Catholic party heavily targeted socialism, represented as a mere intermediate step towards the monstrosities of Soviet communism». Text and page are from Fear of Communism – Anticommunism in Belgium 1920-1960, catalogue of the exhibition Fear of Communism. Anticommunism in Belgium, 1920-1960, KADOC, Leuven (BE), 6 March – 17 May 2020.

Monsignor Classe was well aware that the tutsification of the administration and the racialization of the traditional Rwandan identities could channel social resentment and political claims into the racial horizon, getting rid of their dangerous nature of threats to the colonial power. That was the perfect diversion strategy. The Tutsi caste was a barrier to ‘anarchy and communism’ not so much for their traditional ruling role over the mass but rather for their new racial identity that could give a strong ‘racial’ connotation to every kind of social resentments, with a redirection effect that almost bypassed the Belgian political power.

The racial tensions grew up fast.

«Before the social revolution of 1959, Tutsi supremacists called Hutus ibimonyo or ants. Ibimonyo are a type of ant that lives in colonies of thousands. They are big and work very hard tilling the soil, but they are considered worthless. If a person steps on them and kills them, it does not matter» (Jean-Marie Vianney Higiro, Rwandan Private Print Media on the Eve of the Genocide, in The Media and the Rwanda Genocide, see Bibliography).

Bishop Classe and many Belgian authorities believed that interracial tensions were not as dangerous as ‘communist tendencies’ and did not make up serious threats to the European order and security: they were deeply convinced that interracial tensions could be not just tamed and repressed, but also immediately condemned and isolated by a growing Catholic population, educated to accept a ‘natural’, hence immutable racial ranking.

What a horrible misjudgment.

And it won’t be the one and the only.

Belgium’s King Boudewijn (Badouin) visiting Rwanda is welcomed by King Mutara Rudahigwa, in 1955. This picture was on display in the National Museum in Butare, Rwanda.

THE ROAD TO INDEPENDENCE AND THE BEGINNING OF MASS KILLINGS

After World War II, in 1946, an agreement on governing Ruanda-Urundi was signed between the United Nations and Belgians: the former mandate the League of Nations had given Belgium over the territory of Ruanda-Urundi was renamed ‘Trusteeship’ by the United Nations General Assembly. From 1948 on, there were regular UN visiting missions charged to report on the local situation and the Belgian administration, and in parallel, an increasing number of Petitions to UN signed by Rwandans.

These Petitions expressed open criticism against the Belgians and their oppressive regime and “blatant exploitation”, reported the systematic brutality used by Belgian and local administrators and “the barbaric acts of violence inflicted by the White Men against the defenseless natives”; highlighted the lack of progress and development of the country, the overall socio-economic injustice, inadequate schooling system, the existence of discriminatory practices and improper tax systems; denounced the need to reform the judicial system, and to grant freedom of expression. Some of these petitions were unsigned, some were signed by Tutsis, others by people of mixed origin, like François Rukeba, and some by Hutu counterelite members, like Joseph Habyarimana Gitera. Some petitioners, like Gaston Jovite Nzamwita, were persecuted by the colonial authorities and lost their jobs and status.

The reports written by the UN visiting missions in 1948, 1951, 1954 started to be slightly critical of Belgian colonial policy.

In 1953, the Tutsi elite was granted the opportunity to create a National Higher Council (Conseil Supérieur du Pays or CSP), chaired by the mwami. It was an organism with consultative but not decision-making power that nevertheless soon became the most important political arena, the highest advisory body of the country, and the forum where the Tutsi elite could discuss the country’s problems or, better to say, what they considered to be the country’s problems. It counted only three Hutu members (entered after 1956): 94% of members were defined Tutsi on their identity card.

On February 22, 1957, the Council drew up an official document titled Une mise au point, something like Statement of Views or Clarification in English, intended for the colonial authority and given to the UN 1957 Visiting Mission.

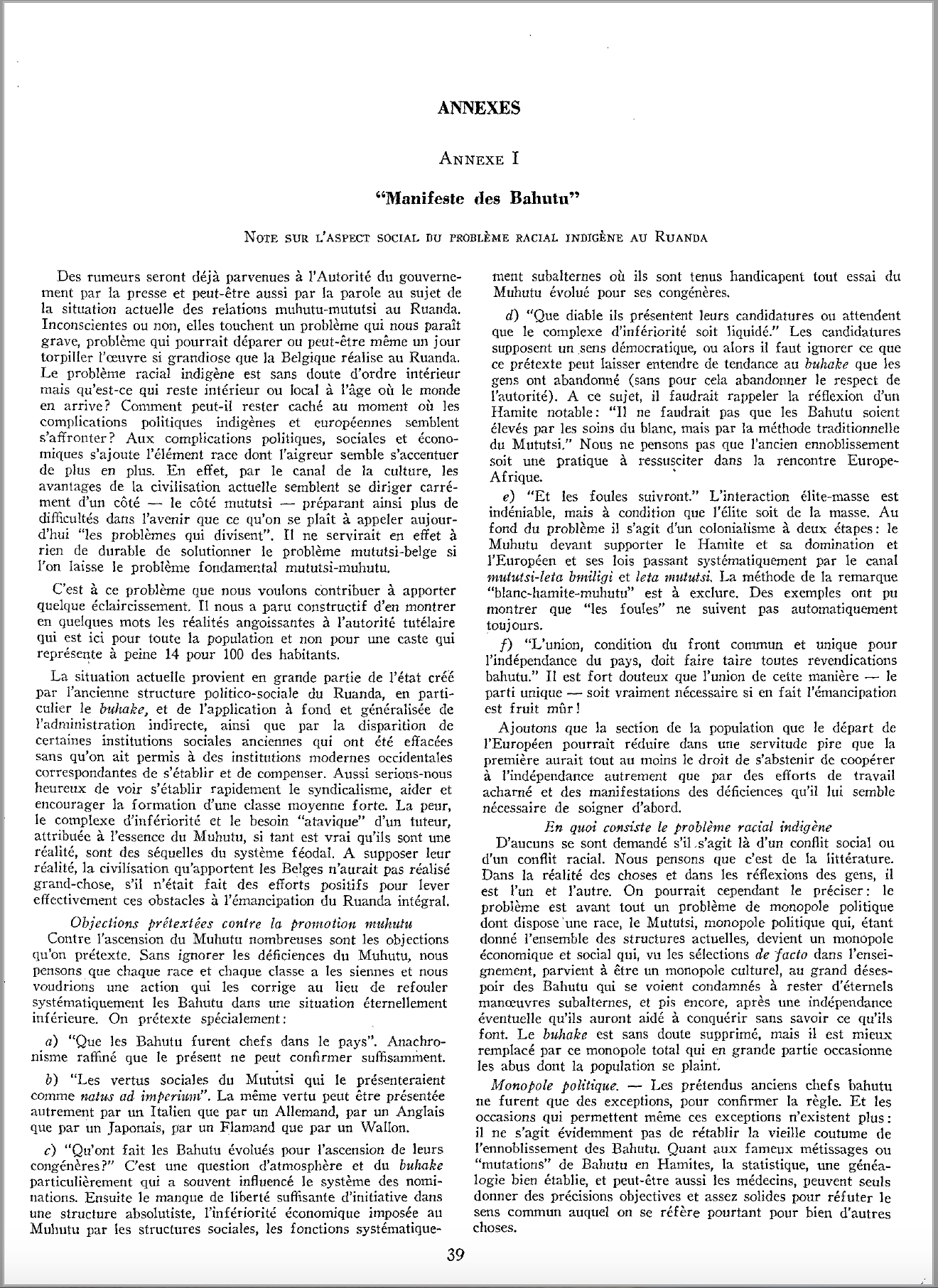

On March 24, 1957, some members of the Hutu counterelite signed the so-called Bahutu Manifesto, whose real title was Note on the social aspect of the indigenous racial problem in Ruanda (Note sur l’aspect social du problème racial indigène au Ruanda in the original French), that got the favor both of the colonial authority and the local Catholic Church.

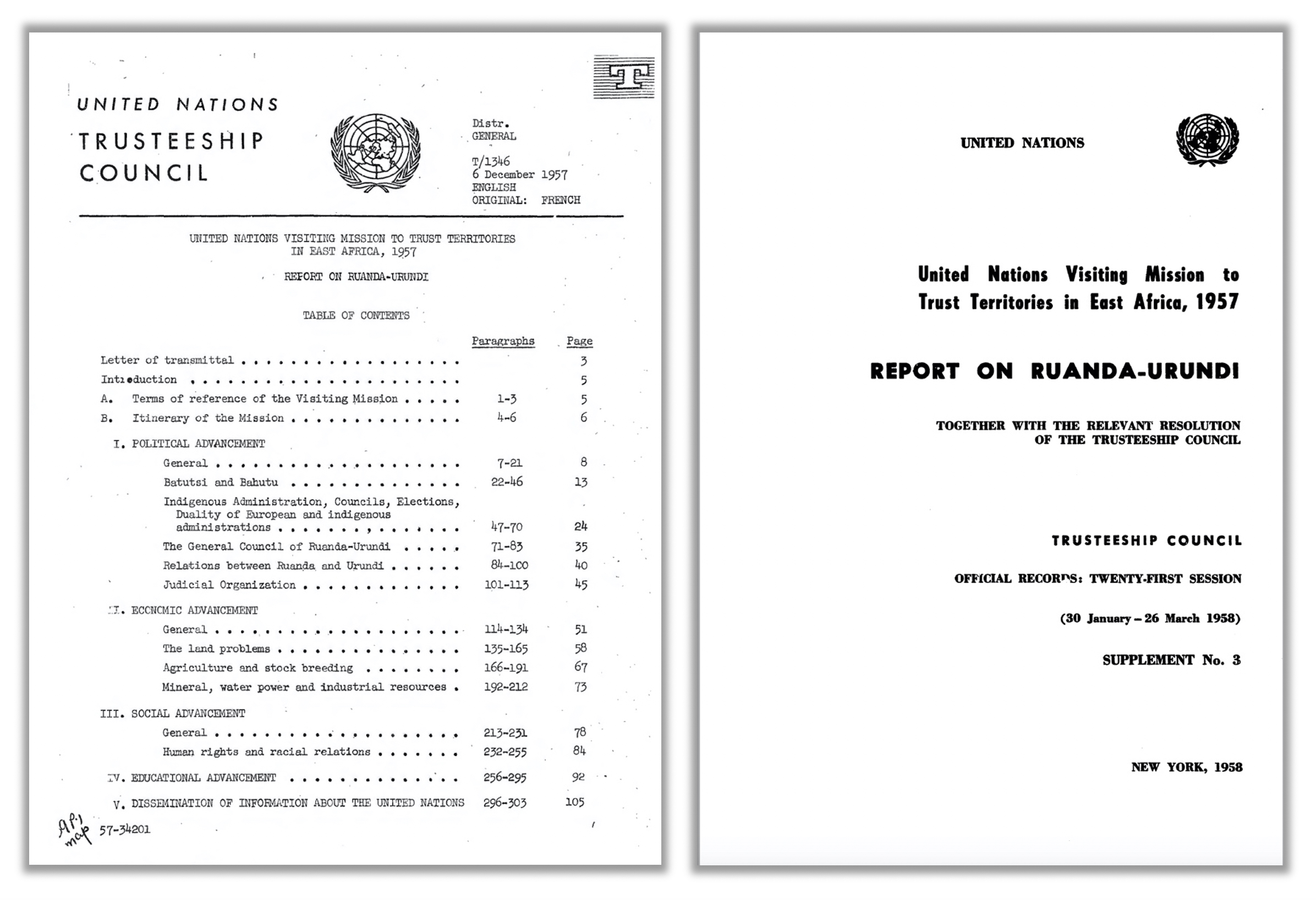

On December 6, 1957, the UN Visiting Mission closed the Report on Ruanda-Urundi, signed by the Chairman of the Mission, Max H. Dorsinville, the first Haitian diplomat to lead missions on behalf of the UN in colonial Africa. In the Annexes, the UN Report published both the Manifesto of the Bahutu and the Statement of Views by the Tutsi Council as relevant texts to keep readers abreast of the country’s political situation.

These three documents are really relevant to understand how the relationship between Tutsis and Hutus had evolved in the 25 years that followed the general reform implemented by Belgians. None of these documents, however, included a rational and unbiased analysis of the Hutu-Tutsi situation and a clear evaluation of factual evidence. All of them are really scary: the Bahutu Manifesto is scary for what it says, the document drawn up by the Higher Council for what it doesn’t say, and the UN Report for its deplorable political short-sightedness.

The United Nations Visiting Mission to Trust Territories in East Africa, 1957: Report on Ruanda-Urundi, together with the relevant resolution of the Trusteeship Council dated December 6, 1957, in the official English translation. On the left, the original typed version, on the right the definite version published in New York in 1958. This interesting document has two annexes: the integral English texts of the 1957 Manifesto of the Bahutu and the 1957 Statement of Views by the (Tutsi) High Council. The whole document can be freely downloaded from this page of the United Nations Digital Library website (please, note that you can download the original French version as well).

The Tutsi Statement

Let’s start with the Tutsi official document, Une mise au point or Statement of Views that I’ll quote in the English translation by the UN (the original text is in French). Its declared intention is to carry out a frank analysis on the country’s problems «that can no longer be passed over in silence», but it’s really very far from such an analysis. It starts as a super prudent text, filled with the customary flattery Belgian authorities were expecting to find (an example: «For its civilizing efforts will ever be grateful Belgium», and so on) but quickly turns into a prudent anti-colonial manifesto that highlights the will to turn the Rwandan Monarchy into a Constitutional one, and advocates the country’s «independence», «emancipation», «freedom» and «self-government», defined as the expected end of trusteeship. This aim has to be obtained «via transitional stages», namely through a progressive autonomy, together with growing participation of Rwandans in the country governance. In the central field of education, the Council’s main purpose is the creation of a university and a global system to train «an elite technically capable of participating, as soon as possible, in the direction of the State’s affairs». In the economic field, the authors consider the Belgian inaction one of the main obstacles to the country’s development. «The solution to the economic problem of our country is ‘industrialization’ (…). economic development urgently requires foreign capital investment (…) from public and private sources» (Note that ‘foreign’ does not mean ‘Belgian’). Last but not least, the document addresses the most relevant problem of «social justice», but the issue is not what you think it should be and does not discuss the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within the Rwandan society. It discusses instead the existing «racial discrimination between whites and non-whites», the inherent violence of their relationship, and the attitude of many whites who «behave as if they were in a conquered country». It hopes finally for an inter-racial cooperation needed by the mentioned project of gradual independence.

Although cautious and faint, this document did not raise the enthusiasm of the Belgian authorities who knew they had to grant independence to the country, pushed along this road by the United Nations, but planned to do it following a thirty-year plan without undermining the core of their economic exploitation (source: History of Rwanda).

For me, the most interesting feature of the Statement lies in what it did not say.

You won’t find even the slightest trace of what the Petitioners had reported to the United Nations nor even a quick reference to the shameful open wounds, inflicted to Ruanda-Urundi by Belgian colonialism. Likewise, you won’t find any mention of the dramatic underdevelopment of a country held together by violence and torn apart by blatant inequity and inequality. The text underscores the need to eradicate the ideology of discrimination based on color, but did not mention the growing tensions among Hutus, Tutsis, and Twas and did not take into account a previous request by the Higher Council concerning the removal of the terms Muhutu, Mututsi, Mutwa from legal ID documents.

In short, the Statement does not identify the real problems of the country, as it declares in the incipit, but lists what is needed both to transform the Higher Council into a sort of Parliament and to guarantee the new Tutsi elite the full enjoyment of the prerogatives granted to them by Belgians, even when the latter will be forced to leave. The members of the Tutsi elite who draft the document – probably the most conservative and close to the mwami court – were fundamentally interested not in delivering the country out of extreme poverty and feudal underdevelopment, but in protecting their own power and privileges, by turning the country into an independent oligarchy. This strenuous defense fed a sort of socio-political blindness: these Tutsis were certain to live in a sturdy ivory tower, whose foundations they were trying to reinforce, when in reality they were unawarely sitting on a dangerous powder keg.

The original French text of the Bahutu Manifesto, in the Annexes of the Rapport sur Le Ruanda-Urundi par la Mission de visite des Nations Unies, New York, 1958 (download here).

The Bahutu Manifesto

The document known as the Bahutu Manifesto was published on March 24, 1957, and was signed by nine people of the so-called “Hutu counterelite”, educated in the minor and major Catholic seminaries, as they could not enter the secondary schools reserved to the Tutsi elite. Three signatories came out of the Petit-Séminaire Saint-Léon in Kabgayi and the Grand-Séminaire de Nyakibanda: Grégoire Kayibanda (born in 1924), Isidore Nzeyimana, and Joseph Habyarimana Gitera (born in 1920). Kayibanda, in particular, was a very well-known activist: in 1953-54, he worked as the editor-in-chief of the journal L’Ami, aimed at Rwandan Catholic elites; in 1956, he became both the editor-in-chief of Kinyamateka, the main Catholic magazine of the country, founded in 1933 and voice of the higher Chruch authorities, and the personal secretary to Bishop André Perraudin, a White Father appointed Vicar Apostolic of Nyundo in 1956. It’s in the Rwandan Catholic milieu that the Manifesto came to light. Some historians have speculated about the possible contribution of two Belgian White Fathers (Father Dejemeppe?), but there’s no certainty about it.

[Please, note that Muhutu or Mututsi is singular, Bahutu or Batutsi is plural]

The title of the Bahutu Manifesto is Note on the social aspect of the indigenous racial problem in Ruanda (Note sur l’aspect social du problème racial indigène au Ruanda). This title makes it clear immediately that there’s a “racial problem” in the country, or better to say, «a racial conflict which seems to grow increasingly acute» and that has to be addressed before any colonial-related issue. «No solution of the Mututsi-Belgian relations can be durable until the fundamental difficulties between the Mututsi and the Muhutu are settled» (please, not that the colonial rule over Rwandans is defined as a relationship between Hutu and Belgians). This racial conflict is caused by the political, social, economic, and cultural “monopoly held by one race”, the Hamites, over the Muhutu population, kept therefore in «a position of systematic inferiority and undeserved subexistence».

«The main causes of the present situation are to be found in the state of affairs resulting from the old political and social structure of Ruanda»: the “racial monopoly” of the Hamites is a «surviving relics of the feudal system» that predates the colonial era.

The opposition to the Tutsi Statement could not be more clear-cut since its incipit: the main problem of Ruanda is not its situation under the Belgian rule, and its vital objective is not independence. There’s a racial conflict that asks to be solved before anything else: «Let us add that the section of the population <the large majority> which the departure of the Europeans might plunge into worse slavery than before would at least have the right to refuse to co-operate in the efforts to attain independence». Getting rid of Belgian colonialism is a false problem: getting rid of the harsh colonialism of Hamites over the indigenous population is the issue at stake and what asks to be erased once for all. «We feel that a warning should be issued against a method which, while tending to eliminate white-black colonialism, would leave worse Hamitic colonialism over the Muhutu. The difficulties which might arise from the Hamitic monopoly over the other more numerous races which have lived in the State for a longer time must be eliminated».

The aim of the Manifesto is therefore «to bring about the economic and political emancipation of the Muhutu from his traditional subjugation to the Hamites», and «to ensure that the Bahutu are no longer exploited for the benefit of a monopoly which keeps them permanently in an intolerable position of social and political inferiority». «Some people have asked whether this is a social or a racial conflict. We think that that is idle speculation»: each time the subjugation of the Muhutu is analyzed from different points of view, «the racial element steps in and there will no longer be any need to ask whether the conflict is racial or social».

After mentioning some specific proposals which appear legitimate and reasonable – the abolition of the customary corvées, ·the legal recognition of individual land ownership, the creation of a rural credit fund, the development of freedom of expression, Muhutu access to public offices and to secondary education, modification of the composition of the High Council – the Manifesto reminds us that all of its socio-political claims must be understood and resolved within the horizon of a racial conflict: «Therefore, in order to keep a close check on the racial monopoly <of the Hamites>, we strongly oppose (…) the discontinuance of the practice of entering Muhutu, Mututsi, or Mutwa on official or personal identity cards. Its discontinuance would make it even easier to practice selection, by concealing it and making it impossible to establish the true situation statistically». Again, a clear-cut rejection of a proposal put forward by some members of the Higher Council.

Let’s do just a couple of considerations.

In this Manifesto, the whole reflection takes place solely within the horizon drawn by the colonial racial ideology.

The ideological perspective that for decades has permeated all secular and religious education in Rwanda, monopolized by the Catholic Church, had been normalized and was so firmly rooted in the mindset of those who draft and sign the Manifesto, as well as of the high prelates who directly or indirectly collaborated in it, to be accepted as a fact and received as a real horizon. Here’s the political triumph of powerful bishop Classe.

It’s this illusory-but-taken-as-a-real horizon that turns the fantasy of a Hamitic race into a factual reality, and the power conferred by the Belgians on a few privileged clans of ‘new Tutsis’ into the arbitrary domination by the foreigner Hamitic “race” on the mass of unarmed indigenous people. And it’s within this illusory-but-taken-as-a-real horizon that all of the political claims supported by the authors take shape. The extreme poverty and underdevelopment of the country, the condition of socio-economic marginalization, fiscal oppression, indigence, cultural exclusion, and political repression to which the majority of the population is subjected – the majority namely the Hutus and most Tutsis, especially the so-called Petit Tutsis, the poor Tutsis, often poorer that Hutu middle class – is transformed into the shameful racial subjugation of the Muhutus by the foreign Hamites, interpreted as the surviving legacy of pre-colonial feudalism.

The Belgian colonialism and the Catholic Church are suddenly relieved of any political responsibility: a quick swipe of the sponge, and both appear immaculate and innocent players, noble civilizers, and send-by-God mediators: who knows what would have happened to the poor Hutus without their providential presence?

This racialization of the country’s socio-political inequalities and iniquities was shared by some members of the high clergy. In his pastoral letter of 11 February 1959 (Super Omnia Caritas), Monsignor Perraudin, Vicaire Apostolique de Kabgayi, writes: «In our Ruanda, differences and social inequalities are to a large extent related to differences in race, in the sense that the wealth on the one hand and political and even judicial power on the other hand, are to a considerable extent in the hands of people of the same race» (quoted in C.M. Overdulve, “Lettre Pastorale de Monseigneur Perraudin, Vicaire Apostolique de Kabgayi, pour le Carême de 1959, le 11 février 1959, in Rwanda: Un peuple avec une histoire, 1997, Harmattan).

The Manifesto and the shared racialization of the Rwandan socio-political issues enclose a scary core.

This document did not start identifying and analyzing some problems to propose their political solutions: it simply assumed the colonial racial ideology as if it were the historical horizon within which everything else can be read and interpreted. This purely ideological horizon is not in question: that’s exactly what the signatories of the Manifesto do not want to discuss because is what they believe to be more real than reality. Consequently, the Manifesto closes any potential space for discussion.

Behind the shared inclination to flatter Belgians, the Tutsi Statement and the Hutu Manifesto share no common ground and open no space for mediation or negotiation. They do not even share the very same language – the first speaks of Banyarwandans, the second of Muhutu and Hamites – and seem to describe two different countries. If the two positions expressed by both documents are not going to linger what they are in 1957, the simple opinions of a few people with some weight but no national relevance, a clash will become inevitable.

In the first half of the 20th century, the political claims and the workers’ demands traditionally supported by labor movements or trade unions always reserved an open space for discussion, negotiation, consultation. Moreover at that time, the late 50s, no struggle against racial discrimination or segregation was a ‘racial’ struggle: it was always a fight against racism and the institutionalization of a racial division.

Racial opposition, instead, closes every space of encounter and dialogue. The tension between two ideologically polarized ‘races’ can be solved only when one of them reduces the other to virtual or physical ‘silence’.

This terrifying outcome is in embryo in the Bahutu Manifesto but it won’t take long to come to light. In less than two years, in 1959, the Tutsis will be the easy target of the first mass killing.

But before addressing this announced tragedy, there’s another document, equally frightening, that asks to be read.

Grégoire Kayibanda (1924-1976)

The UN Report

The Report on Ruanda-Urundi was signed by the UN Visiting Mission on December 6, 1957, and published in early 1958 (in English and French).

It analyzes the Tutsi Statement and the Hutu Manifesto (whose integral texts can be read in the Annexes) in the first part of the first paragraph, dedicated to the political situation of Ruanda-Urundi. The Haitian chairman Max H. Dorsinville and the other members of the mission – Robert Napier Hamilton from Australia, U Tin Maung from Burma, and Jean Cédile from France – highlight that for the Belgian Governor of Ruanda-Urundi, Jean-Paul Arroy, «the relationships between the Batutsi and the Bahutu were the key problem in the country». The two sides of the question were set out in The Statement of Views of the High Council of Ruanda and the Manifesto of the Bahutu, two documents that the UN Report defines of great political interest, but with opposite perspectives.

I’m going to quote the original UN text between guillemets («») and my notes and remarks in Italics between brackets ([]).

The UN diplomats write that they had a long talk with the Belgian Governor Harroy, who said that the «Administering Authority’s support of the emancipation of the Bahutu took three main forms: the severe punishment of abuses committed by the Tutsi as soon as such abuses were legally established [one in a million], the economic development of the country [empty words], and the introduction of democratic institutions at the lower level» [a level that doen not upset the Belgian apple cart, of course]. At the very same time, the Administration made efforts to avoid unnecessary friction with the Tutsis as the Belgian «did not want to harm the legitimate interests of the Batutsi, whose qualities entitled them to very high positions in the harmonious community that they were seeking to build«» [Oh, what a sweet talk! Like a romantic splash of rose scent on a toxic landfill].

On this “important and delicate question” the UN Mission «is disposed to agree with the Governor of Ruanda-Urundi. Nevertheless, it would wish to underline the danger of placing undue stress upon the opposition between Bahutu and Batutsi and would remark that as far as the future of the Territory is concerned, other important factors must be taken into account, namely in the cultural, social and economic fields» [Here, in other words, the UN diplomats are saying in a very diplomatic way that they do not agree with the Belgian Governor and do not consider the “opposition between Bahutu and Batutsi” the key problem of the country]. Moreover, the Report says, one should not take at face value the statements of some Europeans, who in all good faith, but without any administrative responsibilities, exaggerate beyond measure the danger to the Bahutu of the rapid evolution of the Territory towards a wider measure of self-government. [That’s a very interesting remark. The UN diplomats say that some European Catholic high prelates exaggerate the “terrible fate” awaiting the poor Bahutu when the Tutsis will lead an independent country. This sort of prophecy is repeated ad nauseam in the Bahutu Manifesto, and now its ‘copyright’ is fully transparent ]. (…) Some indigenous inhabitants exaggerate in the other direction and accuse the Europeans of taking advantage of this disharmony between Batutsi and Bahutu in order to retard the Territory’s evolution. In a signed note handed to the Mission, a Munyaruanda speaks of the policy of ‘divide and rule’ which has been followed by the Europeans in the case of the Bahutu/Batutsi ever since the Batutsi were accused (…) of having asked for independence» [Here’s another worth considering remark. The UN diplomats say that the Hutu-Tutsi racial opposition is considered a key issue especially by the Belgian authorities, the Catholic high clergy, and some local activists, who are exploiting it to defend their own interests, to delay the decolonization, or gain national visibility. This is probably one of the reasons why they do not want to turn the ‘racial opposition’ into the Ruandan issue par excellence; the other is probably tied to the direct observation of the real daily life that probably seemed less affected by tensions than politics].

The paragraph on the Hutu-Tutsi relationship tension closes with two observations of impressive shallowness.

«43. One observation to which the Mission attaches far more weight is that, although there is every likelihood that the Bahutu/Batutsi problem will grow worse in the near future, it is nonetheless true that it carries in itself the seed of its solution or more exactly of its transformation into a different problem. 44. Under the influence of secondary and university education and of contact with the outside world, traditional conceptions are giving way and the elite of the “old regime” are coming up against a new elite. It will not be long – and indeed there are already indications of this – before the traditional political structure and the respect for feudal institutions will be as irksome to the rising generation of young educated Tutsi as to the new Hutu elite. In time, and perhaps in the fairly near future, the new generation of Batutsi or Bahutu will have more in common than will the young generation of Batutsi with the old. In the same way the Hutu elite will become increasingly interested in ensuring that all enlightened elements of the population as a whole participate in the direction of the country’s affairs, whether Batutsi or Bahutu. 45. This will to a great extent mark the end of the danger of the exploitation of the Bantu cultivators by the Hamitic herdsmen, but it will raise other and equally acute problems. Will the Bami (the kings) be able to transform their regime of a divine monarchy – to use a naive and inaccurate but telling phrase drawn from other civilizations – into a constitutional monarchy?».

The UN diplomats are sure about a sort of ‘natural’ solution to the Hutu/Tutsi opposition problem in the mid-term, within a changed national scenario, namely once the country gained independence. They think that the new generation elites, both Hutu and Tutsi, will be able to overcome this ‘relic of the past’. The opinion that makes the ‘racial conflict’ such a relic is a false assumption that, nevertheless, the Church, the Belgians, and the Hutu signatories of the Manifesto have stubbornly supported and sold to the UN diplomats. The latter, rather ignorant of local history, purchased it. They put ‘a slice of salami on each eye’, as Italians wryly say of those who could open their eyes and see but prefer to see through someone else’s. The superficiality with which these diplomats dismiss the matter is really breathtaking. One wonders, moreover, how well the chairman Dorsinville and the others have read and understood the disturbing Bahutu Manifesto.

The end of the paragraph is another ‘masterpiece’ of naivety.

«46. The discussion of these questions, begun under the understanding and attentive guidance of the Administering Authority, is a very important positive factor. The Administering Authority could also help the situation to take a favourable turn, firstly by taking good care to see that the Hutu youth take full advantage of every educational opportunity in Ruanda-Urundi and elsewhere, so that the Hutu elite do not lag behind the young Tutsi elite in intellectual development, and secondly, by trying to modify political institutions as rapidly as possible so as to keep the new elite on the alert and not to disappoint the enthusiasms and hopes to which their trust in modern democracy may have given rise, for such disappointments could feed the flames of racial conflicts».

Just a spoonful of «university education and contact with the outside world», a bit of time and civilization, a dose of Western «modern democracy», the wise, «attentive guidance» of Belgians, and the risk of savage «racial conflict» will go down in a most delightful way. Yeah!

The magical fairy must have told the UN diplomats that the Belgians were attentive, super partes (non-partisans), and deeply interested in ferrying Rwanda towards a brighter democratic tomorrow. Hurray!

The reality was a little different. The Belgians were attentive – yes, that was true – but also cautious, reserved, and fiercely busy defending their own interests. In the late 50s and early 60s, their interests were running in a specific direction: the political support of the signatories of the Hutu Manifesto.

The reaction to the documents

In its 14th Session, the entire Higher Council voted a sort of answer to the Bahutu Manifesto, with calm and balanced words, and a general tone far from the narrow-mindedness of the Statement: «(…) Rwanda is not a ground for social strife between racial or social divisions. We request all Banyarwanda not to fall prey to this false theory that is splitting our community. We have a common goal to pursue, i.e. the development of the country in all its forms. The two great enemies to fight against are extreme poverty and anarchy. We must focus our efforts on a single objective which is referred to in our country’s motto, namely unity for progress (imbaga y’inyabutatu ijyambere)». However, the opening of a very small space of discussion and this formal call for unity ended up falling on deaf ears: the strengthening and the radicalization of the Hutu position turned into the construction of a wall. In the 1958 May issue of Kinyamateka, the main Catholic magazine of the country whose editor-in-chief was Kayibanda, some articles attacked the king and the royal symbols.

While «the Mise au point <document> did not get any official response from the Belgian colonial administration to which it was addressed» (History of Rwanda, cit.), the Hutu Manifesto was given great relevance by the Catholic Church and the Belgian Colonial administration. «The Bahutu Manifesto was extensively published in the media of the Catholic Church. It had a greater impact than the Mise au point in the local newspaper» (History of Rwanda, cit.). It found a good echo chamber and political support among the Belgian authorities as well: as the UN Report reads, «the Administration has given the document a sympathetic reception and some publicity» (UN Report). The Manifesto «expressed the views of a still limited group of Bahutu» (UN Report) and represented a minority position even inside the Hutu counter elite. Nonetheless, it gained a remarkable relevance on a national level thanks to the political support received in the aftermath by the Belgian authorities and the Catholic hierarchies of Rwanda.

Let’s see how and why this happened.

The facts

The years between 1959 and 1963 make up a key period in the history of Rwanda; in a way, they opened the door to the 1994 genocide.

On July 25, 1959, king Mutara Rudahigwa «died in mysterious circumstances» (History of Rwanda, cit.) at the age of 48. His death plunged the country into a dangerous political vacuum.

Almost simultaneously, thanks to a Legislative order issued in May by the Belgian Administration, the very first political parties were created in view of the elections laid down in a previous decree. «From September 1959 to May 1960, 20 political parties were created. Only four of them were mass parties that monopolized the political scene» (History of Rwanda, cit.).

The three most important were:

- APROSOMA (Association for Social Promotion of the Masses). It was a populist party whose president was Joseph Habyarimana Gitera, one of the signatories of the Bahutu Its radical position initially focused against the monarchy and its symbols but soon turned into a violent anti-Tutsi campaign. A September issue of the party’s newspaper (Jwi rya Rubanda rugufi) featured a text entitled the Hutu Ten Commandments, signed by Gitera. He wrote that «the cohabitation of Hutus and Tutsis is a gangrenous sore, a gnawing wound». As to the Tutsi, «his nature is pure falsehood», and «he’s only worthy of being hated». Hence the fourth commandment: «Having a relationship with a Tutsi is like putting a rope around your neck. Stop doing it» (source: Antoine Mugesera, Les Dix Commandements, see Bibliography).

- UNAR (Rwandan National Union). It was a conservative, nationalist, and royalist party whose spokesman was the activist François Rukeba (a half-Congolese Hutu). The party core program was the fight against «any form of social discrimination between Black and White people and among the Rwandese themselves». Its main objective was immediate and unconditional independence and the development of a constitutional monarchy with a representative parliamentary system. Later on, its political program embraced the secularization of the Rwandan school system.

- PARMEHUTU (Hutu Emancipation Movement). It was founded by Grégoire Kayibanda, another of the signatories of the Bahutu Manifesto. The party’s slogan was “Democracy first, Independence later”. By “Democracy”, however, the party meant a radical solution to the Hutu-Tutsi problem through the creation of two separate regions. In a November 1959 issue of the party’s newspaper, Jya Mbere, we read that the Hutu-Tutsi problem requires «the establishment of two zones, otherwise, one ethnic group would disappear in favor of the other». In 1960, the party added among its priority objectives the abolition of the Tutsi monarchy «with all its feudal and racist myths».

What had been in embryo in the Bahutu Manifesto finally came to light, without mincing with words: the “us against them” narrative is explicit and threatening.

«The UNAR party met strong opposition from the Trusteeship Administration, who used all means to destabilize the party, and from some Catholic prelates, like Bishop Perraudin (…). On the other hand, PARMEHUTU got support from the Trusteeship Government and from the Catholic Church that enhanced its visibility through its own press» (History of Rwanda, cit).

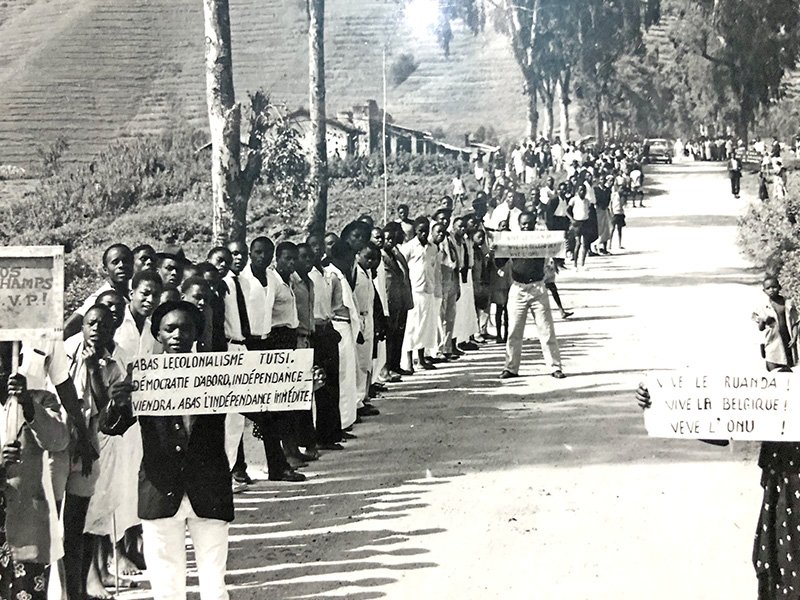

A PARMEHUTU demonstration. The man on the left shows a sign which reads in French: Abas le conialisme Tutsi. Démocratie d’abord, Indépendance viendra. Abas l’indépendance immédiate (“Down with Tutsi colonisation. Democracy first, independence later. Down with immediate Independence”). The man on the right shows a sign which reads: Vive le Ruanda! Vive La Belgique! Vive l’ONU! (“Long live Ruanda! Long live Belgium! Long live the United Nations!”)

In November 1959, Dominique Mbonyumutwa, a PARMEHUTU member and one of the ten Hutu vice-chiefs in Rwanda, was beaten by young UNAR militants at Byimana. The incident and the fake rumor of his death were triggers of a surge of violence against Tutsis, known as Toussaint Rwandaise: several hundred were killed (mainly in Byumba), several thousand were forced to flee the country and several houses were burnt down.