The Japanese art of Kintsugi

ON OLD JOBS AND ANCESTRAL NECESSITIES

Many jobs have disappeared in the second half of the 20th century; the knife grinder, the

knocker-up, the ice cutter, the doll fixer, the china mender… This last was a hawker who used

to “advertise” his useful service on the roads: If you break a booowl, I’ll mend it… I mend

lanterns, lanterns, lanterns. I can rivet your diiishes, pot, and saucers.

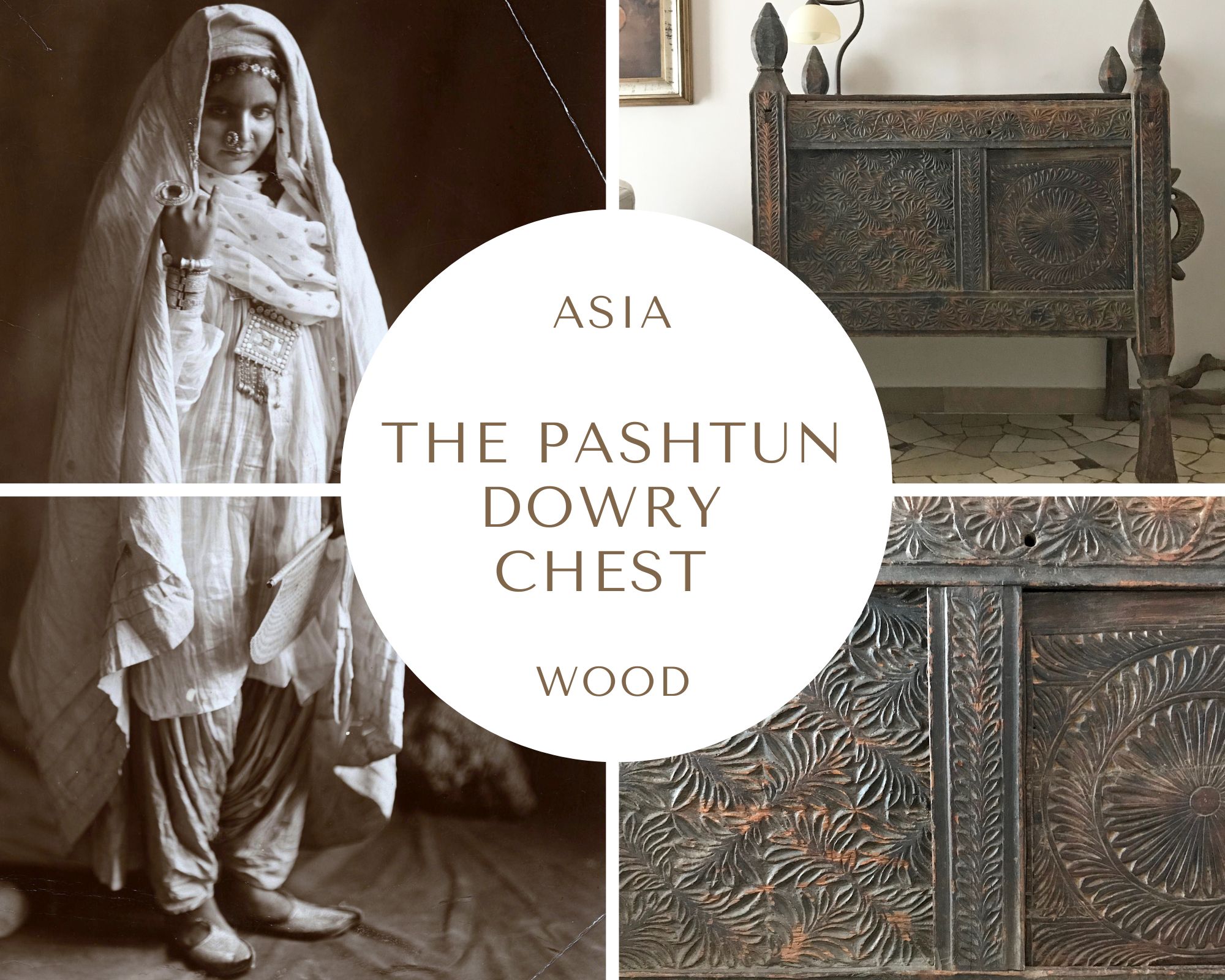

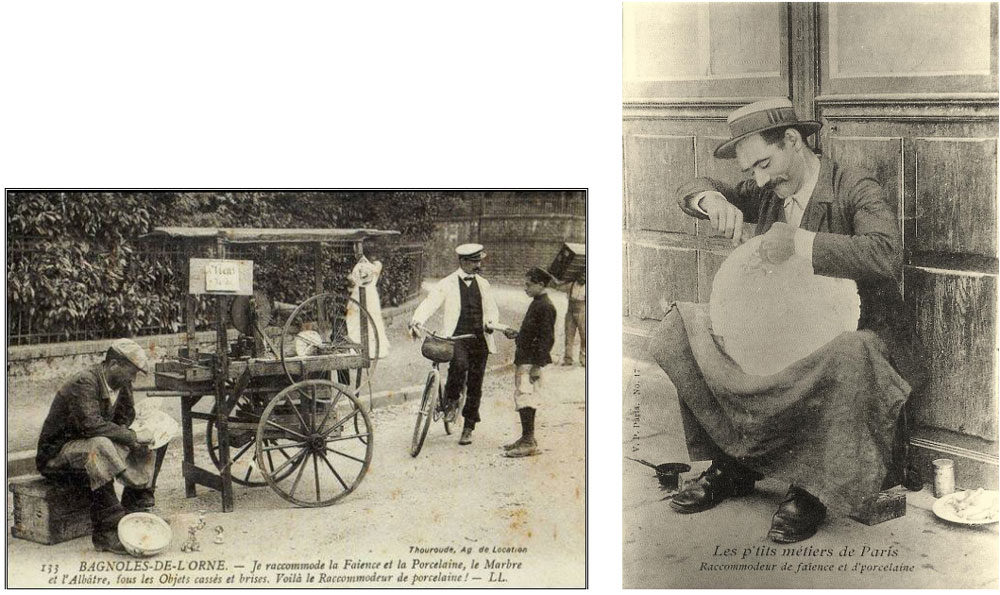

From the 14th/15th centuries to the beginning of the 20th, our ancestors had the broken

pottery repaired and fixed by these hawkers, called in France les raccommodeurs de faïences

et de porcelaine, shown by these old pictures.

The most common repair technique was a mechanical one that involved the use of iron rivets,

called therefore riveting, highly preferred to the application of unreliable natural glues (the

modern synthetic adhesives had not been invented yet).

In this video, you can see a quick demonstration of riveting that gives you an idea of what

china menders have been doing in the past.

The methods of ceramic repair involving the use of metal (iron, tin-plated brass, silver) rivets, lacing, staples, etc, are not old: they are antique. Many scholars guess they might have originated in China. Some Jesuit missionaries, like the Italian Matteo Ricci (1552/1610), the very first to settle in China, tell us about the highly skilled Chinese porcelain menders, who were able to make holes in the fragile, precious items using a diamond drill, and mend the shards with metal rivets.

Celadon tea bowl, Southern Song Dynasty, China 13th C., at the Tokyo National Museum.

Repairing broken pottery sounds weird today for many of us, but it has been a pressing need

for thousands of years. We do not know exactly when our ancestors started to mend pottery:

probably in the very same moment they started to make it, as the very first breakup usually

happens in the kiln o near the fire. «Excavations at sites in the Middle East and Europe that

date from around 7,000 BC have turned up earthenware objects that show traces of repairs

with bitumen, animal glues, plaster, lead and iron rivets; sometimes they just show the holes

through which cord, sinew or metal wire was threaded to mend cracks or breaks» (Isabelle

Garachon, Old Repairs of China and Glass, The Rijks Museum Bulletin, 2014).

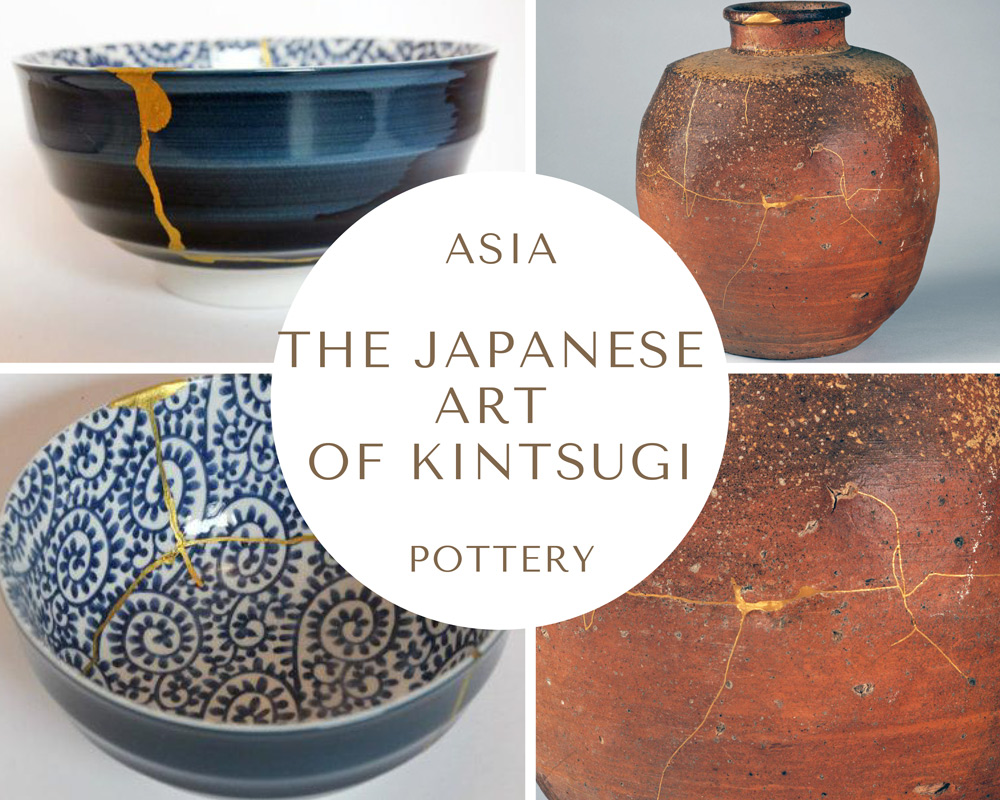

Between the late 16th and the early 17th centuries, Japan saw the developing of kintsugi or

kintsukuroi (pronounce /kìn-tsü-ghee/ and /kìn-tsü-küroee/), which has been translated and

known in the Western world as “the art of fixing, repairing, mending broken pottery with

gold (in Japanese kin) or silver” (gin, in this case, gintsugi).

Well, let’s be clear: it’s not a good nor a proper definition; defining kintsugi as “the art of

repairing broken pottery” is like stretching a single sheet on a king-sized bed: it doesn’t fit.

MIND THE GAP!

Every human being is born and develops inside a specific cultural matrix, which, most of the time, we are not aware of. When a person focuses their gaze on a different culture, more or less remote in the spacetime, the lack of cultural awareness starts to play ugly tricks. Many people know that different cultures have different worldviews, mindsets, ways of categorizing, or conceptualizing the very same elements and actions; and know that the semantic fields of translatable words are not symmetrical nor superimposable. However, many of us do not realize how deeply we are rooted in our matrix. Different cultures think differently and look differently at the very same stuff.

What could be easier than opening your eyes and looking at the color of the sky, or the sea?

Well, this seemingly simple act is a complex cultural process.

The color blue was unknown in prehistory. As incredible as it sounds, it was unknown even in ancient Greece. Today blue is a very popular color: it is present in 53% of national flags and is the most chosen for corporate brands and logos but is a “very young” color. The rock paintings of the Paleolithic and Neolithic are a triumph of pigments obtained from the earth and the minerals, such as yellow and red ocher, hematite, limonite, manganese, and coal. In the caves of Altamira in Spain and Lascaux in France, and in the rock paintings of Tassili n’Ajjer in Algeria, red, yellow, black, brown shine, but there is no trace of blue. Any blue.

Why is that?

The simplest hypothesis is that prehistoric men were unable to produce these shades. The idea of obtaining them from a stone, the precious lapis lazuli, or from the copper and calcium silicate contained in the sand of the Nile, will only make its way into Ancient Egypt many millennia later. Here, in the land of the Pharaohs, blue and azure triumphed as colors associated with the sky and the divine; it was a fleeting triumph, however, as the Greeks and Romans plunged the two colors back into oblivion.

In the ancient Greek language, there was no term for blue or even sky blue; there was a word to designate the color of the sky, γλαυκός (glaukòs), and one for the color of the sea, κυάνεος (kyaneos), but they were generic and vague terms: the second indicated a dark color, while the first served to indicate gray and green indifferently and all shades in between. In the Odyssey, Homer writes ἐπὶ οἴνοπα πόντον, ”sailing on the wine-colored sea” (epì òinopa pònton, Odyssey 1.183. In Joyce’s Ulysses, Buck Mulligan calls it “the snotgreen sea”), a very strange chromatic combination for us today.

Even the ancient Romans did not like blue; the Latin had a single term for the color of the sky and the color of the sea: caerŭlĕus, a somber shade of bluish-green or greenish-blue, often used for decorative purposes (the walls of some Roman villas in Pompeii had frescoes of brilliant blue skies), but it was not very much appreciated: it was the color of mourning and the color of barbarian tribes.

Scholars have long debated the issue and have come to a widely shared hypothesis: cultures,

whose languages have no term to designate a color you can identify at first glance, probably

do not perceive that color as you do, and do not see it as you see it. People from different

cultures have different eyes and gazes.

Hence, we have to mind all the gaps between our matrix and a different culture in the

spacetime. Gaps are not walls or barriers: they can be overcome, but to skip a gap without

getting hurt or falling into it, like a dumb, you have to know that it’s there.

KINTSUGI IS NOT A TECHNIQUE FOR FIXING BROKEN POTTERY

The Japanese kintsugi is not a simple repair technique, like the Chinese or the Western

riveting: it does not simply mend or repair shards. It’s not a technique: it’s an art. It creates

beauty, according to the wabi-sabi tradition, which is not an aesthetics doctrine (a Western

concept), but the development of an educated, refined gaze on material things. And it’s not

a simple art: it’s a Zen art, and it’s deeply rooted in the Zen Buddhism doctrine and practice.

All this means that to get a vague idea of what kintsugi is, we have to mind a lot of gaps.

The traditional art of kintsugi calls for many slow and patient gestures following a gradual

and codified path. The technique is quite simple, but the path to mastery can last a lifetime.

- The shards are carefully gathered, touched with respect, numbered, and cleaned up.

- You mix tonoko powder clay or flour with water and then add a basic, natural

lacquer called ki-urushi to create a sort of paste. This lacquer is highly irritant and can

cause a painful rash, so you need to wear protective gloves.

Tonoko is a Japanese quartz-rich clay powder, finer than jinoko clay. Urushi is the sap of the

lacquer tree, botanically Toxicodendron vernicifluum (formerly Rhus verniciflua). It’s a highly

toxic “urushiol-based” substance, traditionally used to make Chinese, Japanese, and Korean

lacquerware (it’s poisonous to the touch until it dries). The urushi sap is collected from 15 –

20 years old trees; each of them is tapped only once in its entire life and can give about 200

ccs of liquid. The raw urushi lacquer used in the very first step of kintsugi is called ki-urushi,

and has a 60% of the urushiol organic compounds. David Pike, a kintsugi master living in

Japan since 1994, explains: «The urushiol contains an enzyme called ‘laccase’ which is the

catalyst for converting the lacquer into a natural polymer glue».

- You apply the paste to all sides of the shards, then you fit the pieces together with

great care and precision. - You set the piece aside to dry in a warm and humid place. Ki-urushi lacquer needs an average temperature of 25° C, with at least 70% of humidity; in such conditions, it dries in about a week.

- You clean the dried piece with a scraper and smooth the seam with specific tools.

- You apply a coat of black middle lacquer over the repair lines to harden them up and

give them a smooth finish. - You set the piece aside to dry in a warm and humid place.

- You sand down the middle lacquer with specific tools until it is smooth.

- You apply the red top lacquer to the seams for further hardening.

The red lacquer, hon-urushi, contains 75% of urushiol, more than the basic ki-urushi; as David

Pike says: «It can be polished out to a high sheen and is harder than middle lacquer».

- You sprinkle 24 kt gold dust onto the red wet lacquer. You can use silver (gin, “silver”,

therefore gintsugi) or platinum dust, as well. - You set the piece aside to dry.

- You remove the excess of dust with a paintbrush.

- You set the piece aside to dry.

- You sand and polish the seams with specific materials and tools.

This is the result:

Here’s an amazing Kyoto ware

from the 17th century, Shigaraki

type, 26 cm high, on display at

the MET Museum (New York).

Bottle, stoneware with overlapping dark brown glazes; Japan, Takatori kilns, Edo period, 1700-1800. A large break extending around the body was repaired with gold lacquer. Height: 26.4 cm. ©Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK.

Tsuki dish, made of high-fired stoneware; shallow bowl with sides expanding towards upper rim; mended with kintsugi gold lacquer. Diameter: 4.83 cm; height: 14.48 cm. Kofun Period (250-600 d.C), Japan. © The Trustees of the British Museum. Under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

Hagi white glazed sloping-sided teabowl, 17th century, repaired with gold lacquer, © The Trustees of the British Museum, not on display.

Under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

Kintsugi on a Japanese bowl, Maidstone Museum, Kent, UK.

Tea bowl, possibly Satsuma ware; possibly Kagoshima prefecture, Japan, Edo period, 17th century; stoneware with clear, crackled glaze, stained by ink; gold lacquer repairs. Smithsonian, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, F1904.323.

Wheel made stoneware with celadon glaze with impressed design, made in China in the 10th century, with gold lacquer repair. © The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD. Under Creative Commons Zero: No Rights Reserved or CC0 license.

Below a short video that quickly sums up the many steps of the kintsugi process.

This video of 7 minutes gives you the wrong impression of a relatively quick process: nope.

Kintsugi takes time. Much time. Weeks, often months, especially if the pottery has been

badly broken, and you need to fill some empty cracks. The videos you can find on the

website of Dave Pike can give you a more realistic idea of each step of the process.

All of these interdependent steps form the necessary condition to achieve a result that often

escapes the Western gaze and touch: the final piece non only recovers its lost functionality

and regain its bygone integrity, but acquires its true wholeness and completeness. It is said

that the pottery is more resistant after the kintsugi process than before. Hold a kintsugi art

piece in your hands: it’s sturdy. Drop it on the ground: it will break into some fragments, but

not into the old ones; it will crack again, but not along with the old fractures.

Kintsugi is the art of regenerating and revitalizing broken pottery. It does not carry out a

repair, nor a restoration: both are throwback movements, regressions. Kintsugi entails a

progressive transformation, a moving forward. It’s a sort of “biological” regeneration: it gives

an enhanced and fulfilled life to old items. Japanese say that the urushi sap is “alive” and

“breathes” and hardens progressively, reinforcing itself over time.

This “biological” sort of regeneration is a syncretistic merging among the Zen principles and

the Shinto tradition: «Un acercamiento muy zen a la cerámica, la técnica del kintsugi también

destilaba shinto por todas partes: reanimaba los objetos rotos del mundo, en el sentido de

regresarles su alma» (Álvaro Robledo Cadavid, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Kintsugi,

elogio de la imperfección, 58 Boletín Museo del Oro, 2018).

This Dish with Bamboo

Leaves, made in the

18th century, during the Edo

period, shows a patient work

of kintsugi all along its edge;

it’s on view at The MET Fifth

Avenue, in Gallery 229

(Department of Asian Art).

WHAT IS WABI-SABI?

As said, the art of kintsugi creates beauty. However, wabi-sabi beauty is not something we can understand through an intellectual explanation. Wabi-sabi is not an “aesthetic doctrine”, a term that has a specific meaning inside the Western philosophy only. Wabi-sabi is a Japanese way to approach material objects. To see a wabi-sabi form of beauty, we have to switch our usual gaze and train our eyes to caress a material thing in a new and refined way. It’s like teaching Homer to perceive the blueness of the sea.

Mind the gap!

According to the prevailing Western worldview of the last centuries, an item whatsoever finds its best condition and its form par excellence when is new or in mint, unused condition. The daily or the repeated use of an item triggers an entropic process, an irreversible degenerative trajectory: a used item gets dirtier the more you use it (and wash it); its surface starts to acquire a patina and traces of aging, eventually signs of wear, dirt, and tear. A used pottery piece starts to chip and can easily break into pieces. Any cost-effective repair is regarded as a real diminutio: it’s the tangible and visible sign that unveils an irretrievable loss of wholeness and beauty. Not surprisingly, the West welcomed the invention of superglues, smart adhesives, extra-strong sealants, and polymer-based resin adhesives, that do much more than just stick things (and fingers) together: they allow you to enter the magic kingdom of invisible repairs.

According to the traditional Japanese Zen-Shinto worldview, the original, unused condition of an item is regarded as its less meaningful condition. A new, untouched object says nothing and tastes like nothing: it’s mute and flavorless and has no intrinsic value. An item whatsoever starts to become interesting when it starts to be used by someone and therefore to be a part of their life. An old used handmade item has a double story to tell us: the story of the people who made it and the story of the people who used it. Its value and its meaning are rooted in this unique history, and its ”soul” is hidden in the depths of an ever-changing imperfection.

The flaws and signs of use are precious layers of unique memories. Some Japanese ceramic ware, like Oni-Hagi, is handmade in such a way that the more you use them, the more beautiful they become.

The art of kintsugi does not turn an unpretentious rice bowl into a valuable item because it fills its cracks with 24 kt gold: it uses gold to bring to the surface what is hidden and vibrant in the depths. A master of kintsugi can do that, as he enters in resonance with the item’s hidden life.

Jun’ichirō Tanizaki (1886/1965), one of the major writers of modern Japanese literature and

the author of a world masterpiece, the novel Sasameyuki, wrote in In Praise of Shadows:

«We do not dislike everything that shines, but we do prefer a pensive lustre to a shallow

brilliance, a murky light that, whether in a stone or an artifact, bespeaks a sheen of antiquity.

(…) We love things that bear the marks of grime, soot, and weather, and we love the colors

and the sheen that calls to mind the past that made them».

That’s wabi-sabi.

The real title of The Makioka

Sisters (1948) by Jun’ichirō

Tanizaki is Sasameyuki,

a poetic terms that indicates

the snow that falls with gentle

lightweight flakes.

WHAT KINTSUGI IS BELIEVED TO BE AND IS NOT

The fascination of the West for the art of kintsugi lies in what is perceived to be a

metaphorical power: “We humans are created from clay, we are like pottery, and the

Japanese art of repairing broken pottery teach us the art of being proud of the past wounds

or showing pride for the signs of wear and tear that life has been impressing on us”.

Wow. What a positive, comforting interpretation… too bad it is also a pretty hard fall into a

remarkable gap.

Not the only one, though.

Many recent books, articles, and even scientific papers make the kintsugi ‘the art of

resilience’ or a ‘powerful metaphor for resilience’.

And resilience is currently the adorable, fashionable master key of (pop) psychology.

What does it really mean resilience, set aside its common rhetoric?

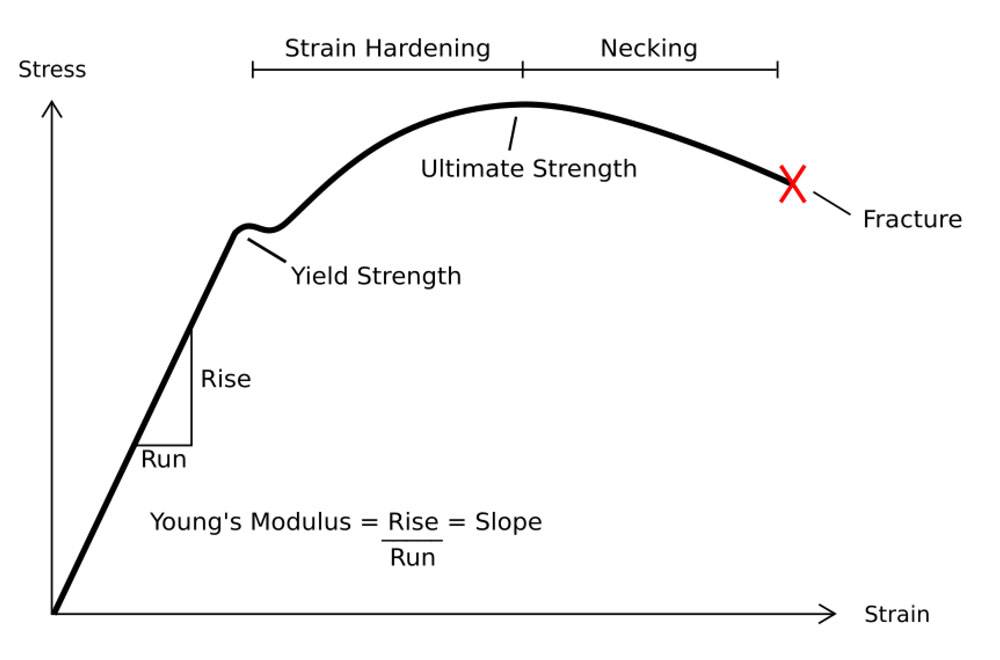

In the materials science and engineering, the resilience of a material is the maximum energy

that a solid material can absorb while it is elastically deformed.

The modulus of resilience is the area below the engineering stress-

strain curve up to the elastic point.

Psychologists define resilience as «the process of adapting well in the face of adversity,

trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress — such as family and relationship

problems, serious health problems, or workplace and financial stressors» (American

Psychological Association, 2014).

Steven M. Southwick, professor of Psychiatry at the Yale University School of Medicine (New

Haven, CT, USA) wrote: «Most of us think of resilience as the ability to bend but not break,

to bounce back, and perhaps even grow in the face of adverse life experiences».

George A. Bonanno, professor of Clinical Psychology at Teachers College, Columbia

University (NY, USA), gives this definition: «We define resilience very simply as a stable

trajectory of healthy functioning after a highly adverse event». This trajectory can be

characterized by a relatively brief period of disequilibrium but knows no psychopathology.

Ann Masten, professor at the Institute for Child Development at the University of Minnesota

(Minneapolis, MN, USA), defines resilience as «the capacity of a dynamic system to adapt

successfully to disturbances that threaten the viability, the function, or the development of

that system». This definition can be used for different systems, including the human behavior

in a family, community, or even societal contexts.

The dominant definition of resilience makes it the capacity to cope successfully with

adversity, bending (= adapting) to circumstances without breaking (= falling into

psychopathological condition). Adversities can be common daily stressors (unemployment,

divorce, bullying, sickness, aging, solitude, etc.) or life-threatening traumatic experiences that

can heavily influence mental and physical health: interpersonal violence, the trauma of war or

ethnic cleansing, death of a loved one, natural disasters, terrorism, rape, severe poverty, etc.

Given this definition of resilience – the most shared one – what the hell does kintsugi have to

do with it?

Kintsugi is not the art of creating elastic pottery that can bounce back from a fall, like bouncy

balls, or making a roly-poly toy style ceramic.

Kintsugi deals with critical breakages, not with resilience.

Defining kintsugi as the art of resilience is a contradictio in adjecto, a “contradiction in terms”

(not an oxymoron).

Defining resilience as the ability to successfully “bounce back” from whatever life throws at

us is a childish approach to life (we break sometimes) and, moreover, a rigid and frigid

concept.

Some scholars – still a few of them – are developing a new and more scientifically fruitful

concept of resilience, which includes a certain degree of “breakage”. Rachel Yehuda,

Professor of Psychiatry and Neuroscience and Director of the Traumatic Stress Studies

Division at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine (NY, USA), conceptualizes resilience as the

process of moving forward in an insightful and integrated positive manner (= with a

conscious effort of self-reintegration), that can co-occur in presence of a severe post-

traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

This different approach can open new scientific and therapeutic perspectives, which I will not

explore here, ‘cause it’s time, now, to mind a new gap. And jump it.

Here’s a 2-minute video featuring Rachel Yehuda:

And here’s an interesting paper on resilience:

Steven M. Southwick, George A. Bonanno, Ann S. Masten, Catherine Panter-Brick & Rachel

Yehuda, Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives, in

«European Journal of Psychotraumatology», Volume 5, 2014 – Issue 1.

Full article/Pdf can be downloaded here.

ON BREAKAGES

Kaga no Chiyo-jo, one of the very few female poets in pre-modern Japanese literature, was

born in 1703 (Edo period) in the Matto area of today Hakusan City (Ishikawa Prefecture,

central Honshū), into a scroll maker’s family. She started very young to compose short poems

in the haikai style of Matsuo Bashō (1644/1694), with whose disciples she studied, and gained

recognition as a painter and a master of renga and haiku (then called hokku) forms of poetry.

Chiyo-jo married at 19 and composed this haiku after her child and her husband passed

away. She was only 27 years old, and these are words of excruciating pain.

Hana Sakanu

Mi wa kurui yoki

Yanagi kana

Plant that won’t bloom anymore

I’m free to writhe

– Weeping willow –

(My translation)

The last line is a kigo, a “season word” – this is a summer haiku – and must not be read as a “weeping” symbol (like Westerners easily do). In traditional Japan, the willow tree is popularly connected to ghosts, especially in August. The plant that won’t bloom is a pure trunk that can be freely and madly and randomly tossed by every gust of wind. It’s a plant that has nothing left to give to others – no cool shadow, no beauty, and no blossoming, no fruits for anybody; it’s a creature that can no longer become what it is, as it lies in a suspended state between life and death.

There’s no resilience here: we have overcome the fracture point and are now entering the nowhere grey land that lies beyond. Pain sometimes annihilates us: we can no longer move forward and we stand still, suspended, alone and walled in our silent and short breath.

The striking contrast between a broken suspended life and the vital beauty of a full blossoming keeps recurring in the haiku poems by Kobayashi Issa (1763/1828), a haijin (a master of haikai). and a painter from Kashiwabara (today Nagano Prefecture, central Honshū). He married at 49 with Kiku (1812). Their first child died after his birth, the second child (a daughter) died 2 years later; the third in 1820. Kiku fell ill and passed away in 1823.

Yo no naka wa

Jigoku no ue no

Hanami kana

In this world of ours,

We walk on the roof of hell

Gazing at the flowers

(Translation by R. H. Blyth).

Ku no shaba ya

Sakura ga sakeba

Saita tote

A world of grief and pain

Cherry flowers bloom

Even then…

(Translation by R. H. Blyth).

When too much pain breaks us, when we face evil, and we are nothing but shards

scattered on the ground, what can we do? We can’t even dream of blossoming again.

We feel guilty for feeling so bad, and to the pain inflicted upon us by others or by events, we

add the pain we inflict upon ourselves.

和楽器のプロが戦場のメリークリスマス弾いてみ

Japanese traditional musical instruments ensemble “MAHORA”

THE BEING ZEN OF KINTSUGI

When too much pain broke us, what can we do? What can help us?

The traditional Mahayana Buddhist culture, which faces the true nature of pain and

suffering more openly and realistically than the Western culture of the last centuries,

gives us answers.

There’s a path, the most difficult to teach, to learn and to follow, and the most crucial for

our lives, that shows us not just how to heal up our scars and wounds – the body does it

by itself, though imperfectly – but how to regenerate ourselves, bringing our human

nature to its fullest. This difficult narrow path allows us to achieve our true wholeness and

completeness, and teach us how to reach our fulfillment as human beings. No matter how

badly we have broken, no matter if we are priceless porcelains o cheap rice bowls, we will be

healed and regenerated.

This path, shown by the Zen art of kintsugi with its silent gestures, has a name and lies at

the core of the Śākyamuni Buddha’s teachings.

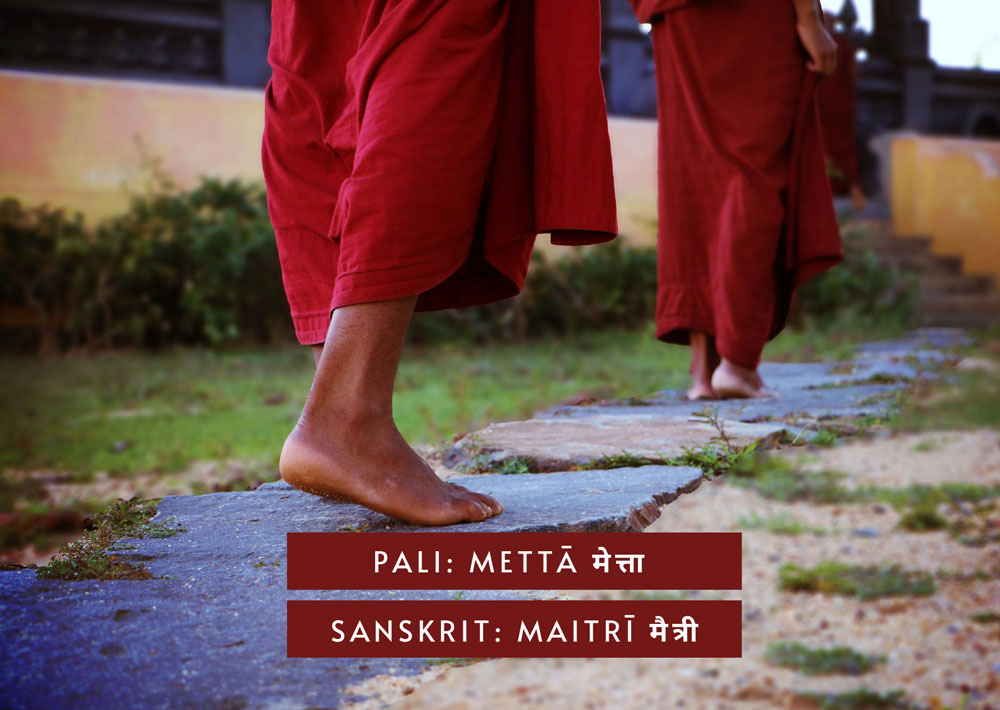

In the Tevijja Sutta, Buddha introduces the four Brahma-vihāras, the four “sublime attitudes”

or “divine abodes”, attained through the development of mettā, karunā, muditā, and

upekkhā. Using brahminical terms and gave them a new meaning, Buddha teaches his Hindu

audience how to attain enlightenment through the development of boundless love and

compassion.

Here, we have to mind a wide triple gap: firstly, the Buddhist love and compassion are

different from what the Western cultures usually indicate under these terms; secondly, the

vast majority of us do not know how to “love” and “be compassionate” (if we knew, the

world would not be what it is); thirdly, it is hard to understand what cannot be understood via

the intellect but only lived with the totality and unity of our being.

Let’s do a triple jump then.

When the semantic fields of two different languages do not correspond, each word in a

language requires many words in the other language, none of which is a perfect match.

Mettā in Pali, maitrī in Sanskrit, is usually translated as “benevolence, loving-kindness,

friendliness, goodwill, and amity”. However, this strategy doesn’t give you not even a vague

idea of what mettā means.

Mettā is not a feeling, nor an emotion, or a sentiment. It’s not a mood, a state of mind, an

attitude, or a disposition. It’s not even a frame of mind that may influence your behavior. All

those are passing and volatile states: developing mettā means developing a stable loving

mind. A loving mind is a loving sky, not the sum of loving clouds, loving rain, loving sun, etc.,

because the rain, the clouds, the sun can be highly beneficial but are always passing and

volatile (even the sky is transient, but not like its clouds or rain).

Mettā, in other words, is not a momentary psychological state: it’s a long journey that gives

you not a temporary frame of mind but helps you to attain a loving mind. And being a loving

mind means being a person able to accept, welcome, and embrace all parts of oneself, as

well as all parts of the world (including all sentient beings).

It’s not easy to develop this unselfish love: you have to abandon every attachment, desire,

possession, passion, or infatuation as this love is not an egocentric nor a self-sacrificial one,

and is not a mere benevolence or amiability based on self-interest.

It’s not easy to develop this universal, unselfish, and all-embracing love: it grows boundless

along the journey to overcome all social, religious, racial barriers, all political and economic

walls.

It’s not easy to develop this mild and nourishing love: first of all, you need to learn to be

inoffensive and non-violent to yourself and to the others, and secondly, you have to learn to

respect both yourself and the others. The respect is the ground zero of love and means not

only not harming and hurting yourself and others, but striving to protect your psycho-physical

integrity as well that of others.

In the early commentarial Buddhist scriptures, mettā is often depicted as the love of a

nourishing mother who accepts and embraces her newborn baby without any second

thought. Not an easy journey, isn’t it? And mettā is just the start: it’s only the first of the

Brahma-vihāras. The second is karunā.

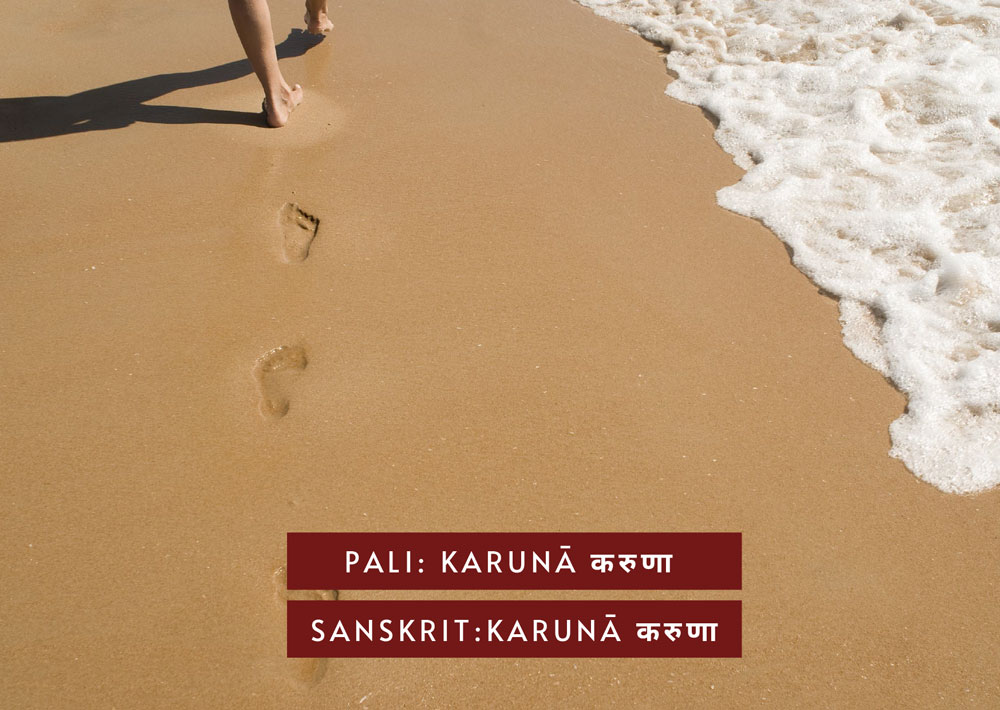

Karunā is usually translated as “compassion”. Here again, compassion is not a feeling, nor a frame of mind.

Developing compassion means becoming capable of entering in deep resonance with others or creating an empathetic connection with others.

Compassion is not pity, the feeling of sorrow that fills us while perceiving others’ suffering.

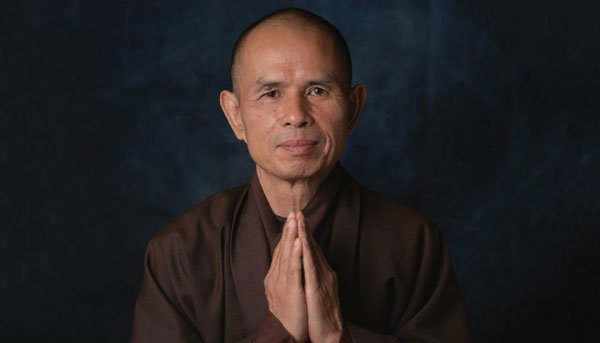

Compassionate is the person who can feel others’ pain as their own, who knows how to bear it, and who acts to alleviate it. It is not the mind to be compassionate: it’s the person. The Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh said: «Compassion is a verb», which means it’s an ethical action.

If the development of mettā teaches us how to overcome barriers and walls between our “I” and the others (all creatures), the development of karunā gradually teaches us how to deeply connect with others.

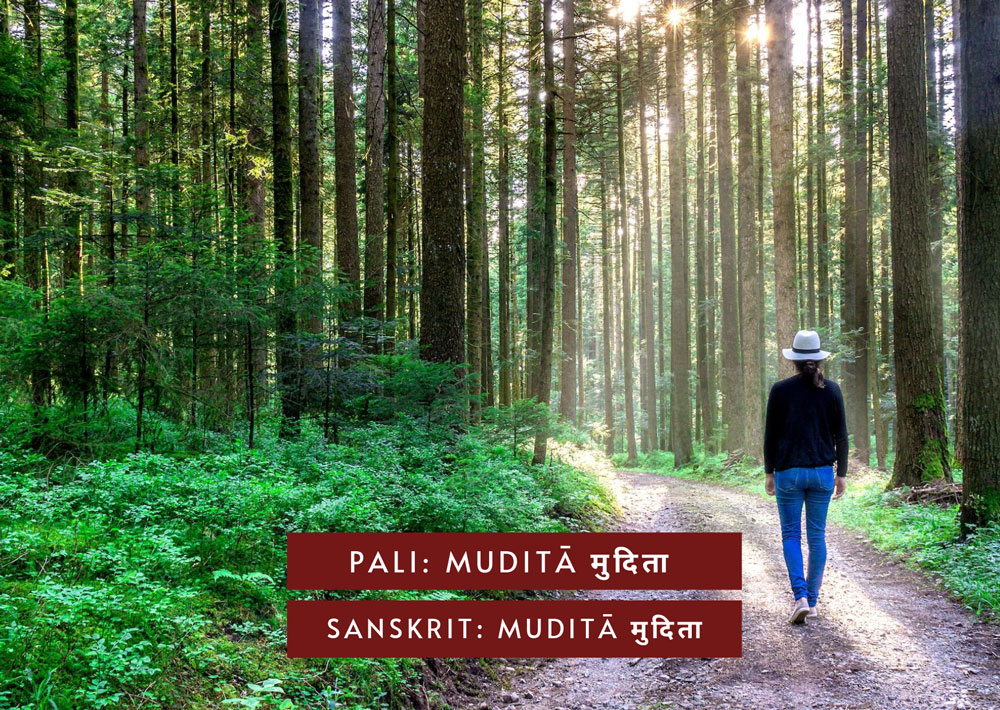

Muditā is usually translated as “empathetic or sympathetic joy”. If developing compassion

means being able to resonate with the pain of others to alleviate it, developing muditā

means being able to share joy, where joy, here, stands not for a positive feeling but for

whatever can cause a positive feeling. Joy is the opposite of pain, and developing muditā

means becoming able to rejoice in resonance with the joy and the success of others.

Rejoice with those who rejoice, mourn with those who mourn.

(Epistle to the Romans 12:15)

How can I rejoice with you if you are tremendously rich and I have no health care coverage

nor a decent salary?

Traditional Buddhist commentators say that muditā is a condition for social peace, but things

are not so simple. Buddhism is not a hymn to the “volemosebbene” trash philosophy.

“Volemosebbene” is an Italian adorable expression that means “I’m in peace, you’re in peace

bro, let’s love each other!”. This is more of an acid trip than a Buddhist mindset.

However, the relationship between Buddhism and social justice is a complex one, and I have

to set aside this issue, at the moment.

Developing muditā means not only that I can share your joy, but also that I can share my joy (and my money), and this is not an invitation to a conservatism position. I can say to have developed muditā when I’m able to share my success and my well-being with others, in the deep awareness that in my community, my well-being is the well-being of others and their well-being is also my well-being. The more I develop a mature muditā, the wider becomes what I can call “my community”, and the more I have to commit myself to a strong social justice ethic and to act to avoid high levels of social and economic inequality.

The development of muditā definitely helps us to overcome the illusion of separateness,

which dominates our world. So we’re ready to get deeper and deeper inside the fourth

Brahma-viharā.

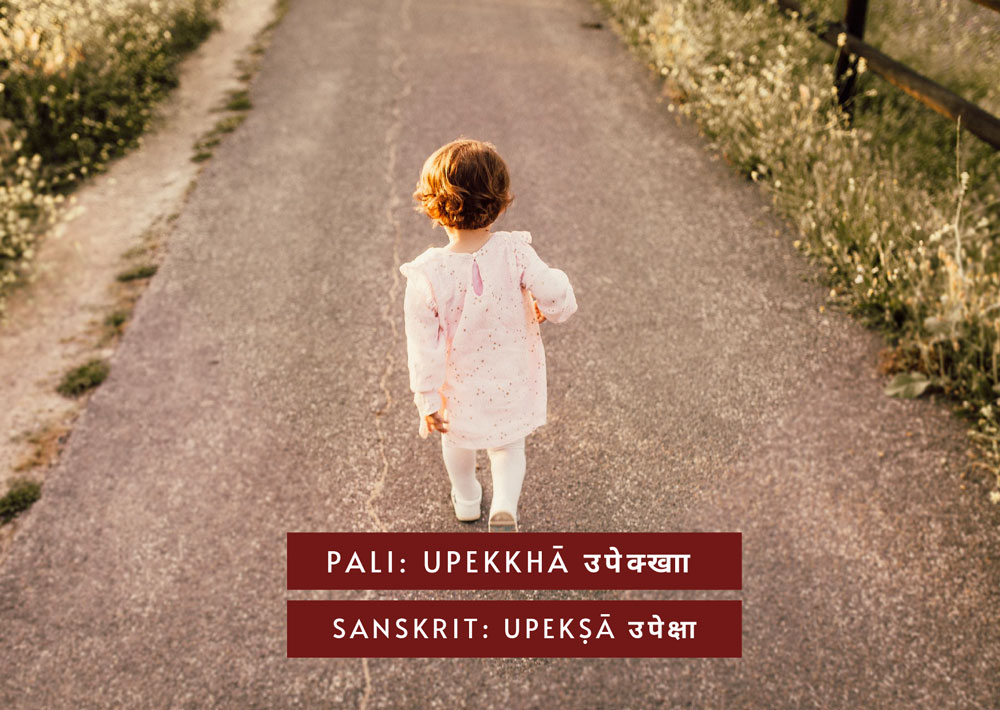

Upekkhā in Pali, Upeksā in Sanskrit is the ultimate Brahma-viharā to develop. This does not

mean that you have to develop the first Brahma-viharā, then the second, the third, and finally

the fourth, as if they were elementary school classes.

The four Brahma-viharās – which are often called in the Pali texts the four Appamaññā, the

Immeasurables, as love and compassion gradually become boundless – are interdependent

and co-arising. However, Upekkhā is the last one as is the more complex of all: its full

development brings all the previous three viharās to their maturity.

It is usually translated with “equanimity” but is not a calm, controlled attitude. The path to

attaining equanimity entails the development of a non-judgemental, deeply free, and well-

balanced mind in a violently unbalanced world with fluctuating fortunes and circumstances. It

entails the development of an ethical attitude – a person with a mature equanimity is a

person whose love and compassion are distilled in pure acceptance – and a spiritual growth,

rooted in understanding and insight. Equanimity is wisdom.

A HEALING JOURNEY

Is this path a real healing and regenerating journey? Or is it just a Buddhist promise, the

kintsugi illusion, a true leap of faith?

Both in the Theravada and in the Mahayana Buddhist traditions, the starting point of this

path is self-love, rooted in many Śākyamuni Buddha’s teachings (ex.: Samyutta Nikaya, I,

75).

Nyanaponika Thera (1901/1994), a well-known 20th century Theravada monk and teacher,

wrote: «In the meditative exercises, the selection of people to whom the thought of love,

compassion or sympathetic joy is directed, proceeds from the easier to the more difficult. For

instance, when meditating on loving-kindness, one starts with an aspiration for one’s own

well-being, using it as a point of reference for gradual extension» (The Four Sublime States.

Contemplations on Love, Compassion, Sympathetic Joy and Equanimity, 1994).

Thích Nhât Hành (1926), a Vietnamese Thiền Buddhist monk and teacher (Thiền Buddhism is

the Vietnamese reception of Chinese Chan Buddhism and Japanese Zen Buddhism) stated

even more clearly: «Self-love is the foundation for your capacity to love the other person. If

you don’t take good care of yourself, if you are not happy, if you are not peaceful, you

cannot make the other person happy. You cannot help the other person; you cannot love.

Your capacity for loving another person depends entirely on your capacity for loving yourself,

for taking care of yourself».

The four Brahma-viharās path is a gradual one that goes from the simplest to the most

complex step. The object of the simplest meditation and simplest practice is me: I will start

from the simplest of the four Brahma-viharās, which is mettā, and from the simplest side of

mettā which is kindness. And I will start meditating and being kind towards the simplest side

of myself: my body. «First act of love is to breathe in and go home to your body. To be aware

of your body is the beginning of self-love. When the mind goes home to the body, the mind

and body are established in the here and the now» (Thích Nhât Hành).

Here’s the reason why the four Brahma-viharās path is a deeply healing journey from the very

first step to the final one: you learn how to really love yourself. This journey helps you to

become aware of a simple truth, as well: a love that does not pass through yourself before

reaching others is not true love; it’s a vulgar impersonator. I will never tire of repeating it: in

Buddhist love, there is not even a diluted drop of sacrificial love, the female traditional way of

love in the Western subculture, and there is not even a crumb of that ego inflation and

arrogance that in the Western subculture is mistaken for self-confidence.

That love heals, is not a simple leap of faith. In 1988, David McClelland of Harvard University

pioneered a study on the effect of compassion and kindness on the immune system, called

the “Mother Teresa effect”. Since then, many scientific studies have analyzed and verified the

impact of self-compassion or compassion meditation on neuroendocrine, innate immune, and

behavioral responses to psychosocial stress, and the positive (measurable) effects of acts of

kindness and compassion on employee stress and job performance, on women with multiple

sclerosis, on caregivers, and even on firefighters. Suffice to surf PubMed to realize the

large amount of scientific studies on the subject.

This journey is not an easy peasy trip, but every step of it is deeply worthy because every

step of it is a healing moment both for ourselves and for the world.

A reliable map, if you are at the start, is this e-book: Thích Nhât Hành, Teachings on Love,

1997.

CELEBRATING THE BLOSSOMING

The four Brahma-viharās practice is a narrow path and quite a long journey: not by chance. The truth about love is something the Western subculture does not want to deal with: love is not something that happens nor an arrow accidentally shooted by a fat cherub. It’s something we have to learn; it’s a task to complete; wisdom to develop; a force we have to generate within ourselves. And not just in our “heart” as most stupid songs say, but in every part of us, in our wholeness as human beings.

In the West, there’s no basic education to love. Most Westerners expect a new mom to know how to love her baby (even a new mom is expecting to know how to do it and feels guilty otherwise); a partner is expected to know how to love their partner, a friend any friends, a person their pet… And many of us are surprised to see that we often hate each other and kill each other, systematically exterminate other living species and turn our planet into a landfill or a dump. We don’t even know how to love ourselves.

We know nothing about love.

Buddhism, on the contrary, has developed an education to love, an insight about it, and

shows a path to cultivate and generate some forms of love within ourselves. Buddhism is a

perspective on love, not the only one, but a very interesting and valuable one.

If the simplest forms of self-love are the start, what will be the last and final step of the four

Brahma-viharās path?

When or where does this journey end? How do you know it’s over?

And if it’s not my death to end this journey of mine (and it’s not), what does it put the full

stop?

Love is a sort of powerful light we have to generate within our darkness and inner “chaos”;

our path ends when we give birth to “a dancing star” (F. Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra,

Prologue, 5.2). When it comes into existence, the light of this dancing star illuminates me and

everybody around me, without any difference: it’s not in the nature of the light to make such

a difference, as it is not in the nature of the sun to shine more for me and less for my

neighbors.

This is exactly the essence of mature compassion and love: it is boundless and unconditional.

I become aware to have come to the end of my journey when the love that I have developed

for myself is also a universal love that embraces the world. This love that makes no difference

between me and the rest of the world, this light that shines above all borders, all differences,

and illusory separations, this dancing star that I generate from my inner darkness and is,

therefore, unconditioned, this is the Buddhist enlightenment, the Buddhist awakening.

In the Theravada and especially in the Mahayana Buddhism, this attainment is personified by

Avalokiteśvara, the bodhisattva of infinite compassion who gazes down at the human world,

hears all the cries of suffering, and works tirelessly to help those who call upon his name. To

do so, he postpones his own buddhahood.

The bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara – the Tibetan Chenrézig, the Chan Guānyīn, the Zen Kannon –

is probably the most popular, worshipped, depicted in all arts, and most complex “figure” of

the Mahayana Buddhism, with many male and female manifestations of all forms.

Sheng Yen (1931/2009), a famous Buddhism monk, scholar, and teacher of Chan Buddhism,

said on the distinctive feature of this figure: «A Bodhisattva’s actions benefit himself as well

as others; his own benefit and other’s benefit are simultaneous». And this is exactly the

nature and the essence of unconditional and unconditioned love: it’s boundless and universal

and knows no difference between me and the rest of the world.

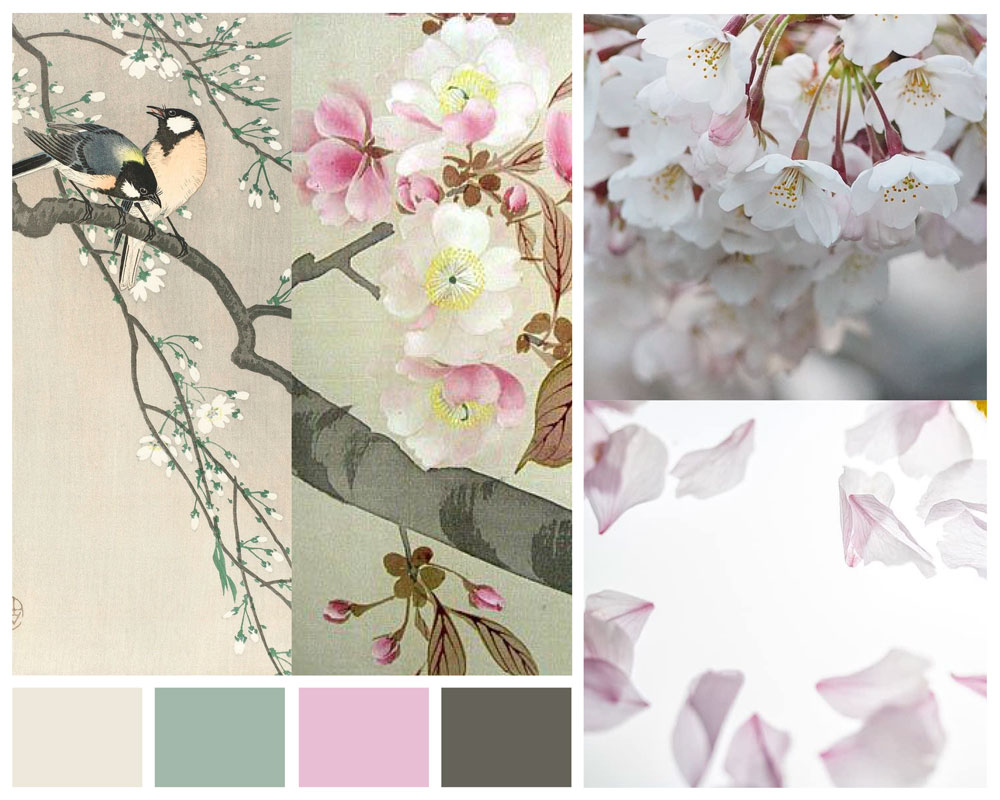

It’s clear now why in the Japanese Zen tradition, the blooming flowers allude to

enlightenment: for a plant, say a Japanese cherry tree, flowering means becoming what it is.

The full blossoming of the sakura flowers, together with the promise of bearing fruits it

encompasses, represents the fulfillment of the tree’s nature, the attainment of fullness and

completeness, the triumph of life. But at the very same time, the sakura blossoming is a gift

to the world: a gift of wonder and beauty, of shadow and coolness, of fruits and seeds. A gift

not just for humans but for all living beings.

Our enlightenment is at the very same time the regeneration of our human nature, the

fulfullment of our human story, and our gift to the world. A gift of beauty and love. This is the

deep meaning of the Zen art of kintsugi.

Sakura Sakura is a very old folk song celebrating the cherry flowers in full bloom (sakura hana zakari). Here’s in the version by Ayumi Ueda, a young Tokyo artist playing a crystal singing bowl.

BELOW

Sakura tree in Kumamoto, Japan.

THE END OF THE STORY

We’ve come to the end of our story.

Chiyo-jo, the female haiku poet, at 45 decided to retire to a Buddhist Monastery where she

lived until the day of her death at 72, in 1775. She became a Jōdo Shinshū nun, hence her

new name Chiyo-ni.

We now know that her choice was not an escape from her suffering and that she did not

withdraw from the world: quite the opposite, she started a healing path in the only way it was

possible at her time: within the wall of a Buddhist monastery.

Kobayashi Issa, as well, entered a Jōdo Shinshū Buddhist monastery where he died in 1828,

at 65.

No matter how badly life has broken you, there’s always a path to reach peace and joy and

regeneration. This is the way silently shown by kintsugi.

There’s always a path to a full blossoming.

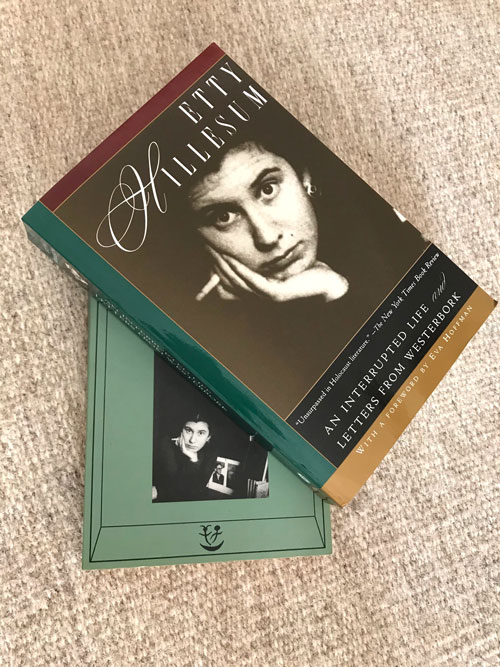

«Flowers and fruits grow wherever they are planted, isn’t that what it all means?

And shouldn’t we affirm that meaning?».

These were among the last words of Etty Hillesum, a young woman who, in a gentle and yet resolute way, blossomed and flourished during the Shoah. She perfectly knew she would have died in a lager (she was murdered in the Auschwitz hell in 1943, at 29), but she pursued unhesitatingly her own blossoming path as a gift to herself and to the world.

Peace Prayer by Jeff Beal and Nawang Khechog.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?