Rwandan Basketry 5

Rwanda on the globe

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE, JENOSIDE YAKOREWE ABATUTSI

THE 1990-93 PHASE

Talking of the Rwandan Genocide most of the time means talking about the 1994 Genocide. I disagree, and in the following pages, I’m going to show you, justify and discuss a different reading of the history. In my and others’ opinion, the Rwanda Genocide started with the Civil War, in October 1990, and knew two different main phases: the first spread out between the late 1990 and the fall of 1993, in parallel to the anti-Tutsi state propaganda campaign. The second phase was in 1994.

Let’s see the facts. As we’ve already seen, anti-Tutsi violence, which the foundations of the First and Second Republic were kneaded of, underwent a sort of cosmological inflation after the RPF invasion in October 1990. In the years 1990-93, 17 incidents of serious violence took place, 14 of which in the northwest quadrant of the country and the 15 in Bugesera (source: Alison Des Forges, cit.).

In 1990, massacres of Tutsi civilians were carried out in the following Rwandan provinces: Byumba, Ruhengeri, Gisenyi, Mutara, and Ngorere-Kibilira.

The worst were the following:

- October 8, between 500 and 1,000 Tutsi civilians living in Mutara and in the combat zones in the northeast of the country were killed by RAF soldiers.

- October 11-13, approx. 350 Tutsi civilians were slaughtered in Kibilira (in the préfecture of Gisenyi) by mobs directed by local government officials and state agents. The perpetrators not only killed civilians, including women and children, but destroyed crops, stole food, slaughtered cattle, and burned homes.

Mass killing of Tutsis were carried out in several communes and districts, including Mukingo, Kinigi, Gaseke, Giciye, Karago, Murambi (east of Kigali), Gisenyi, Ruhengeri, Kibuye, Byumba and Mutara.

The worst mass killing was carried out in Ruhengeri and Gisenyi. The Bagogwe, generally considered a sub-group of the Tutsis were slaughtered between late January and March 1991. In Mukingo some Tutsi women were raped. On January 27, the burgomaster of Kinigi, Thaddée Gasana, took thirty persons of Bagogwe descent out to the commune crossroads and had them executed. On February 2, 17 Bagogwe were killed in Gaseke and Giciye. The global number of Bagogwe victims is unknown; it was estimated to be between 300 and 1,000 according to CIDH, 1993.

«In 1963, when the Bagogwe had also been targeted, many fled to parish churches for a sanctuary where they had been safe. This time there was to be no hiding place within sacred walls. The terrified families who arrived at Busogo church found the door closed in their faces, with the priest telling them that the ‘church of God was not able to house cockroaches’» (Andrew Wallis, Stepp’d in Blood, see Bibliography).

On November 7, some Tutsi families were attacked by night in Murambi, upon orders from the local burgomaster. Information on victims and wounded are uncertain.

«By 1992, the level of anti-Tutsi violence, both rhetorical and physical, was escalating significantly (The Preventable Genocide, 5.24, cit.)».

Mass killings of Tutsi civilians were carried out in Kibilira in March, December, and January 1993; in Kibuye in August.

Janvier Afrika (a former member of a death squad) revealed to Jean Carbonare (president of French human rights group Survie) that some 70 members of the Interahamwe militia killed Tutsi people in Ruhengeri at the beginning of 1992.

The worst massacres were carried out in the Bugesera district. In February and March, armed groups led by the burgomaster of Kanzenze, Fidèle Rwambuka, supported by the local Interahamwe militias and 150 soldiers of the RAF, attacked the Tutsi of the Bugesera region, in the three communes of Kanzenze, Gashora and Nganda. The exact number of victims remains unknown but is estimated to be hundreds. No number can convey the horror of those days in Bugesera; a man reported that the perpetrator killed his four children and threw his wife’s body into a latrine.

In Nyamata, the main city of the Bugesera district, south of Kigali, lived a 55 years old Italian Catholic missionary, Antonia Locatelli, locally called ‘Tonia’. She witnessed the mass killings of Tutsi and opened the doors of her house and her school to terrified families. On March 9, she phoned the Belgian embassy, the French station RFI, and the British BBC and reported that the Hutu militias were slaughtering the Tutsis, incited by Kangura and the state Radio Rwanda. She told the French journalists: «I know that the people committing these murders came from outside. They were brought by government vehicles. Contrary to what is said, it is not popular anger against the Tutsis, it is a deliberate movement of the government to commit political killings». That night, she was killed by some members of the Presidential Guard who arrived from Kigali. The international echo of her killing pushed the government to stop the local massacre, and 300 Tutsi managed to save themselves. During the commemoration ceremony marking the 25th anniversary of the Rwandan genocide, in 2019, the current Rwandan President, Paul Kagame, paid tribute to her moral uprightness: «Tonia Locatelli <was> killed in 1992 for telling the truth of what was to come. The only comfort we can offer is the commonality of sorrow, and the respect owed to those who dared to do the right thing».

The Italian missionary Antonia Locatelli, killed in 1992 for having reported the genocide of Tutsis in the Bugesera region. There’s a stone commemorating her uprightness in the Garden of the Righteous in Warsaw (Poland), and a tree in the Garden of the Righteous in Padua (Italy). Photo by L’Eco di Bergamo.

Between January 21 and 26, some hundred Tutsis were massacred in the prefectures of Ruhengeri, Gisenyi, Kibuye, and Byumba; the data about these mass killings are really scarce. Chrétien and Viret write that the mass killings were organized by members of the MRND and CDR parties; Alison Des Forges that the Impuzamugambi paramilitary militia was active in attacking Tutsis in Gisenyi in January 1993. In March, 147 Tutsis were killed. In October, 40 Tutsi were killed in Cyangugu, 20 in Butare, 20 in Ruhengeri, 17 in Gisenyi, 13 in Kigali. Many were beaten, others were dragged out of their homes and disappeared.

«On 17-18 November, unidentified assailants killed some forty persons, including local authorities, in a highly organized attack in the northern communes of Nkumba, Kidaho, Cyeru, and Nyamugali <in the Ruhengeri district>. On 29-30 November, unidentified assailants killed more than a dozen persons in the northwestern commune of Mutura» (Alison Des Forges, cit.). The most likely hypothesis is that these last mass killings were organized by the hardliners inside the armed forces and carried out by paramilitary militias. These massacres, as we will see, will be investigated by UNAMIR, the peacekeeping mission in Rwanda.

THE GENOCIDE OF THE BAGOGWE

As we saw, between January and March 1991, the Bagogwe people (Abagogwe) were slaughtered in the north-western region of Rwanda, namely in the prefectures of Gisenyi and Ruhengeri. A more detailed analysis of this massacre reveals some fundamental aspects of the 1990-93 Genocide. For this in-depth analysis of the Bagogwe genocide, I will quote from two works by Diogène Bideri (Principal Legal Adviser at the Rwandan National Commission for the Fight against Genocide): a 2008 essay titled Les massacres des Bigogwe and a previous article from 2003, Le génocide précurseur des Bagogwe (for both, see Bibliography), both in French (all translation from French are mine).

First of all, let’s clear the air and remove a common misunderstanding: the Bagogwe were not a sub-ethnic group of Tutsis. The Bagogwe were a small group of families, less than 10 thousand people descendants from the Tutsis who in the early Modern Age clustered in north-western Rwanda. They were essentially pastoralists, or better to say, cattle breeders who practiced basic subsistence farming along the large green pastures on the edge of the forests of Gishwati or at the feet of the northern volcano mountain crest. They did not belong to the royal clan of the Abanyiginya; over the centuries, they had remained strangers to the hierarchies of power directly and indirectly linked to the mwami (the king): they lived as a peaceful, poor, undereducated, and substantially marginal group of people, open to a policy of intermarriages with neighboring clans, such as Bazigaba, Bagesera, and Basinga.

«The Bagogwe took the name of the area they occupied called Bigogwe, a toponym taken from the name given to a nearby rocky hill, ibere rya Bigogwe, the nipple of Bigogwe. It lies between Gisenyi and Ruhengeri, north of the Gishwati Forest, at the foot of the volcanoes. It was a common practice to refer to the population that lived there by the name of the place. Thus, the Bagarura were the population of Bugarura, the Balera were the population of Mulera; therefore, these names do not designate ethnic sub-groups. It can even be assumed that in immemorial times, each group had different ethnic origins, but after several hundred years, families had merged thanks to intermarriages» (My translation from Diogène Bideri, Le massacre des Bagogwe, cit.).

Were the Bagogwe Tutsis or Hutus?

As explained in Rwandan Basketry 3, this question is non-sense.

The White Fathers and the Germans who came to Rwanda at the beginning of the 20th century, imbued with racism and ideologically biased, could not pigeonhole them at first. The issue of the Journal de la mission de Rwaza published in May 1913, assimilated the Bagogwe to the Bahutus. Other Europeans considered them Batutsis because of the cattle they owned and the clientage they could establish thanks to it. Eventually, they became ‘petit’ Tutsis.

Map of Rwanda. The Bagogwe people lived between Gisenyi and Ruhengeri, north of the Gishwati Forest, at the foot of the volcanoes, and near the border with Uganda.

From GIS Geography website.

The amazing landscape of the Gishwati hills, in north-western Rwanda.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

In the colonial period, the Bagogwe were gradually marginalized. «The Belgian administration made life difficult for them <firstly> by creating the Albert National Park which took away a large part of their land, <and secondly> by establishing of the compulsory pyrethrum crops on other areas of their land, without any compensation being paid to them. Later, the Belgians introduced the so-called umugogoro system: the Bagogwe were forced to supply milk, compulsorily and free of charge, to the agents of the colonial administration. Moreover, they had to provide cows to the armies and the colonial administration, once again for free, which decimated their herds» (My translation from D. Bideri, Le massacre des Bagogwe, cit.). From 1945 on, the scarcity of pastures pushed them to intensify their farming activities.

During the First Republic, under Grégoire Kaybanda, they suffered systematic massacres and looting, especially in 1963-64 and 1973. The first years of the Second Republic, after the coup d’état de Juvénal Habyarimana, were relatively calm, but in the early 1980s, some Bagogwe families were pushed by local authorities (like the burgomaster of Kinigi) to undersell their land and flee the country: the powerful brother of Madame Agathe Habyarimana, Protais Zigiranyirazo, prefect in Ruhengeri until 1989 and already a ‘star’ inside the Akazu circle, wanted part of the Bagogwe land. He and his brothers Séraphin Rwabukumba and Colonel Elie Sagatwa, private secretary of President Habyarimana, created and invested money on a large potato farm on the former Bagogwe land, hiding behind some frontmen. Moreover, in the 1980s, all the northwestern districts of Rwanda, especially Gisenyi and Ruhengeri, were becoming the political strongholds of the President and the Akazu; the new prefect of Ruhengeri, Charles Nzabagerageza, was a relative of President Habyarimana and all of the burgomasters were chosen among the party loyalists. The Bagogwe – who were considered as Tutsis – were the wrong people in the wrong place.

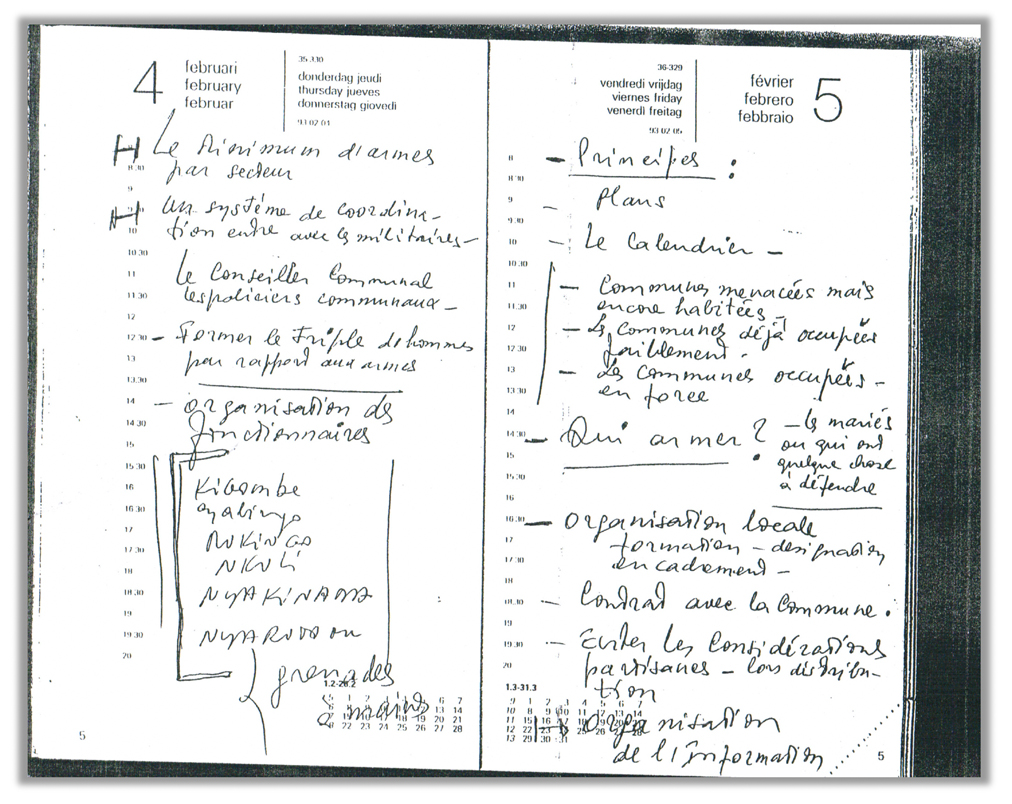

In the last months of 1990, the Akazu and President Habyarimana started to develop a plan to exterminate the Bagogwe in the Gisenyi and Ruhengeri prefectures. According to Diogène Bideri, a Rwandan historian who has been analyzing the massacre of the Bagogwe for a long time, a first secret meeting was held at 2 am in January 1991. President Habyarimana was present with his private secretary, Colonel Elie Sagatwa, and his powerful wife, Agathe Kanziga. There were, amongst others, Joseph Nzirorera, ministry of Industry and Craftsmanship, charged of financing the ‘operation’, Charles Nzabagerageza, prefect of Ruhengeri and Côme Bizimungu, prefect de Gisenyi, both members of the Réseau Zero, both charged of getting in touch with the most trusted burgomasters. Prefect Nzabagerageza recruited Léon Mugesera et Pierre Tegera for the propaganda to be spread among the local population (Pierre Tegera was an agricultural engineer from Gisenyi well known for its anti-Tutsi fanaticism), and within a short time, a campaign was orchestrated throughout the region, painting the Bagogwe as supporters and allies of the RPF and, therefore, cowardly traitors. Some local burgomasters, like that of Mukingo (Juvénal Kajelijeli), compiled blacklists of Bagogwe and Tutsis, and started to create the nucleus of the Interahamwe paramilitary militia: it was a branch of the MRND called “civil defense”, or “Virunga force”, or “Amahindure”, made up of jobless young people charged to spread terror in the region and trained to create roadblock at the behest of the local authorities.

The night between 22 and 23 January 1991, the RPF raided on the town of Ruhengeri, seized the town and its prison, and freed the prisoners, including the political ones; then, withdrew. This event, a real humiliation for the Rwandan Armed Forces, offered the best pretext for hunting down the Bagogwe. «At <that> time, President Habyarimana was the FAR chief of staff. He was assisted by two deputy chiefs of staff: one for the Gendarmerie, Colonel Pierre-Célestin Rwagafilita, the other for the army, Colonel Laurent Serubuga. After the RPF incursion into the town of Ruhengeri and the release of the prisoners, the army was ordered to systematically attack and massacre the Bagogwe» (Diogène Bideri, Le massacre des Bagogwe, cit.). Habyarimana, Serubuga, and Rwagafilita were all directly involved in the planning and the implementation of the Bagogwe Genocide, which started on 23 and 24 January 1991.

Diogène Bideri writes that this genocide knew a quick and violent first phase from late January to mid-March 1991. He talks of a second phase from 1991 to 1994, but I think we should differentiate a second phase, from late 1991 to 1993, slower and longer than the first, from a final third, occurred in April 1994, when all Bagogwe survivors were slaughtered in a few days, at the beginning of the so-called “100 days”.

In the first phase, some civilians were arrested and killed immediately by the armed forces or paramilitary militias, with the complicity of municipal police and local authorities; entire families of Bagogwe were killed at their homes by the militiamen, however, the vast majority were arrested, loaded onto trucks or vans, tortured and killed in a military camp (like Mukamira, Bigogwe, Gisenyi-town, for example) or in the open countryside. Their bodies were buried in mass graves or piled up in the caves of Nyaruhonga. The militiamen set up «many roadblocks on all roads, tracks, and trails, averaging two kilometers apart. Therefore, the potential victims could not escape from one municipality to another. This explained the small number of refugees in neighboring countries and even in parishes. These victims were forced to wait for their tormentors at home, helpless and resigned» (from Diogène Bideri, Le massacre des Bagogwe, cit.).

In this regard, there’s a story deserving to be told: «By early February 1991, dozens of Bagogwe families had fled their area to take refuge in the Busogo Parish. The women and children had witnessed the execution of their male relatives. In the church courtyard, the bands of killers threw stones at them. The unfortunate ones tried to take refuge inside the church. The parish priest gave the order to keep the doors closed. A survivor of the Kinigi massacres who was among the refugees told me what the parish priest said: “The church of God could not shelter the inyenzi”» (from Diogène Bideri, Le massacre des Bagogwe, cit.). That champion of Christian piety and Catholic devotion was Abbé Wenceslas Karuta. In 1993, he moved to Italy, where he became parish priest of Montecastello and La Rotta (Tuscany) in 2008, and took Italian nationality in 2014.

«The survivors, mostly women and children, were in a dramatic situation after the killing (…) of their husbands, fathers, brothers, or sons. Terrorized, they were also looted: their cattle were liquidated, their crops ravaged. Without protection, several women were raped and several others constantly threatened with rape» (from Diogène Bideri, Le massacre des Bagogwe, cit.). Rape of and sexual assault on the Bagogwe women were not simple means of humiliating them, looting a different ‘property’ of the ‘enemy’, or creating a climate of terror among the survivors; they were also systematic genocidal acts: mass rapes were a deliberate genocidal strategy aimed at damaging the reproductive capacity of the Bagogwe and impairing their survival.

The first violent wave of genocidal massacres ended in mid-March 1991, but the hunting of the Bagogwe went on throughout 1991, 1992, when even women and children were systematically slaughtered, and 1993. The terrified survivors of these waves were killed in the very first days of the infamous genocidal final phase in April 1994.

Abagogwe people and their traditional dance called Ikinyemera.

«Witness AAM, an Abagogwe Tutsi farmer from Gisenyi, testified that in 1991, after the killing of Bagogwe Tutsi and while they were still mourning the dead, Barayagwiza came, together with the sub-prefect at that time, Raphael Bikimibi. They summoned a meeting in Mutura commune, to which everyone went. At the meeting, Barayagwiza said that all the Hutu should stay on one side and the Tutsi on the other side. The people danced to welcome Barayagwiza and Bikimbi. Barayagwiza then requested that the Tutsi dance for him, and they did a dance called Ikinyemera. According to Witness AAM, Barayagwiza then said, “You are saying that you are dead – a lot of people have been killed from among you but I can see that you are many. There are many of you, whereas you are saying that a lot of people are being killed from among you. We heard that on radio, but if we hear that once again, we are going to kill you because killing you is not a difficult task for us”.» (International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, The Prosecutor V. Ferdinand Nahimana, Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, Hassan Ngeze, Case No. ICTR-99-52-T).

Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, lawyer, civil servant, founding member of the CDR, and fanatic hardliner, was found guilty of genocide, conspiracy to commit genocide, public and direct incitement to genocide, and extermination and persecution constituting crimes against humanity in 2003. He was sentenced to 35 years’ imprisonment, reduced to 32 years after the appeal by his defense counsel.

The Genocide of the Bagogwe, especially its first wave from late January to mid-March 1991, is an atrocious story showing some features that will become common to other massacres of Tutsi in those years. Let’s consider all of them.

The Bagogwe were slaughtered for a simple reason: to Habyarimana and the Akazu, they were ‘Tutsis’, that’s to say ‘cockroaches’.

In addition, they made up a marginal population with no political protectors, little known even to aid donors, unarmed and defenseless. An easy target, in brief.

They lived in the northern prefectures of Ruhengeri and Gisenyi, the strongholds of the ruling oligarchy, where they made up a troublesome ethnic enclave, settled along the northern border with Uganda, the same frontier the RPF soldiers could cross back and forth.

All of these conditions meant that the Bagogwe could be slaughtered easily, with almost substantial impunity: in those prefectures, the Akazu could count on local authorities’ full support and the silence and sometimes the backing of the Hutu local population. The proximity to the front line and the Ugandan border, furthermore, provided the best pretexts to mask the genocidal massacres.

This is a crucial point, and what happened with the Bagogwe shows us the general attitude of the ruling oligarchy faced with the 1990-93 genocidal massacres they supported, planned and carried out.

DENIAL. Faced with the hunt of Bagogwe, Habyarimana’s official position was often of denial and retraction. «Aucun massacre de Bagogwe ni à Kinigi ni ailleurs dans le nord du Rwanda» [No massacres of Bagogwe happened at Kinigi or elsewhere in northern Rwanda], Kangura said in November 1991 (issue no. 24, p. 19, originally in French). What made it possible to deny the massacres was their concealment.

CONCEALMENT. The concealment strategy was anything but naïve.

«Contrary to the methods of the Parmehutu regime during the First Republic from 1959 to 1973, the military and administrative authorities did not use the tactic of burning houses, considered too spectacular and too visible: it could draw too much attention on the event, especiallythat of foreigners who supported the regime of President Habyarimana» (from Diogène Bideri, Le massacre des Bagogwe, cit.).

Especially in the first 1991 wave, many Bagogwe men were caught in roundups and simply disappeared. It was the system of ‘enforced disappearances’ (disparition forcés). Even after months, the wives and daughters of the desaparecidos were denied a death certificate by the local authorities. Diogène Bideri tells us the story of his uncle Augustin Bukumba and other relatives in Mukingo (Ruhengeri prefecture) in January 1991. They were taken from their home, in the heart of the night, and disappeared. They were probably tortured and killed within a few hours, but the family was made to believe that they were locked up in some prison. «This illusion came to an end when one day someone told the family that he had seen men wearing the shoes and clothes of their missing relatives. The family then understood that Augustin Bukumba and the others had been already killed. The widow of Augustine went to the Mukingo commune to get a death certificate and gain access to her husband’s bank account and salary but was refused the document under the pretense that her husband had surely joined the enemy. She went to the president of the Court of Appeal of Ruhengeri, the hierarchical boss of her husband, to declare his death. He replied that nothing could prove it and added that he thought Augustin had given up his service to join the Inkotanyi» (from Diogène Bideri, Le massacre des Bagogwe, cit.).

Many summary executions were carried out in military camps, protected from witnesses and leaving no survivors. The mass graves were so well hidden that some of them have never been unearthed. «The number of the Bagogwe killed in Ruhengeri and Gisenyi prefectures is still unknown as the prefectural authorities did not want to acknowledge that there were massacres. The concealment of the corps makes it difficult to know exactly how many people have been killed» (D.B., ibidem). According to Diogène Bideri and other sources, the number of victims only from January to June 1991 amounted to approximately one thousand, out of a total population of less than 10,000. (This figure is given by Bideri; I could not verify it, namely I could not find other sources and it should be taken as approximate).

During the Genocide of the Bagogwe, what could not be hidden was accurately disguised according to a multi-faceted masking strategy.

MASKING AND DISGUISE. As we saw, many ‘enforced disappearances’ were disguised as treasons. Other killings were camouflaged as massacres of innocent victims by the RPF or executions of RPF’s supporters and allies; others as retaliation or vengeance killings, carried out after an RPF attack by the enraged local population. In some occurrences of the last case, army soldiers were instructed to a wear civilian dress to better mix with the militiamen. Justifying the massacres as ‘spontaneous’ reactions of the local population, plunged in a difficult situation of fear and war, obviously allowed Habyarimana to conceal the true political, institutional, and military responsibilities and was the most often exploited justification. The masking strategy was one of the few ‘excellencies’ of the Gendarmerie and the Rwanda Armed Forces. Do you remember the 1990 enacting of a fake attack on Kigali during the night between October 4 and 5? Well, it wasn’t an isolated case at all. Just to give an example, the military of the Bigogwe Camp in Mutura, Gisenyi prefecture, «the night of Sunday 3 to Monday 4 February 1991, simulated an attack by the Inkotanyi rebels, which allowed them to carry out the plan to liquidate the Bagogwe of the Mutura, Kanama and Rwerere region» (D.B., ibidem).

Three more relevant points need to be highlighted.

- First of all, the planning and the implementation of the Bagogwe Genocide show a complex dynamic: there was no ‘master plan’, accurately defined once and for all, and executed with diligence along a vertical, top-down line. There were general indications to be specified and updated based on bottom-up communication. The information coming from local military camps, burgomasters, local chiefs and sous-chefs, communal authorities, civil servants, local police, and rural landowners was an essential element that constantly modified the plans to better adapt them to the situation of each area. Moreover, the genocidal plans had a dynamic interaction with the circumstances: the plans were constantly adapted to the events, starting from the very first of them, the RPF’s raid on the town of Ruhengeri. Some events were even artificially generated. Therefore, we can regard the Genocide of the Bagogwe as a complex process defined by two flows of communication: one in the two directions along the vertical line, top-down and bottom-up, and the second in the two directions along a horizontal line, sort of in-out-in flow.

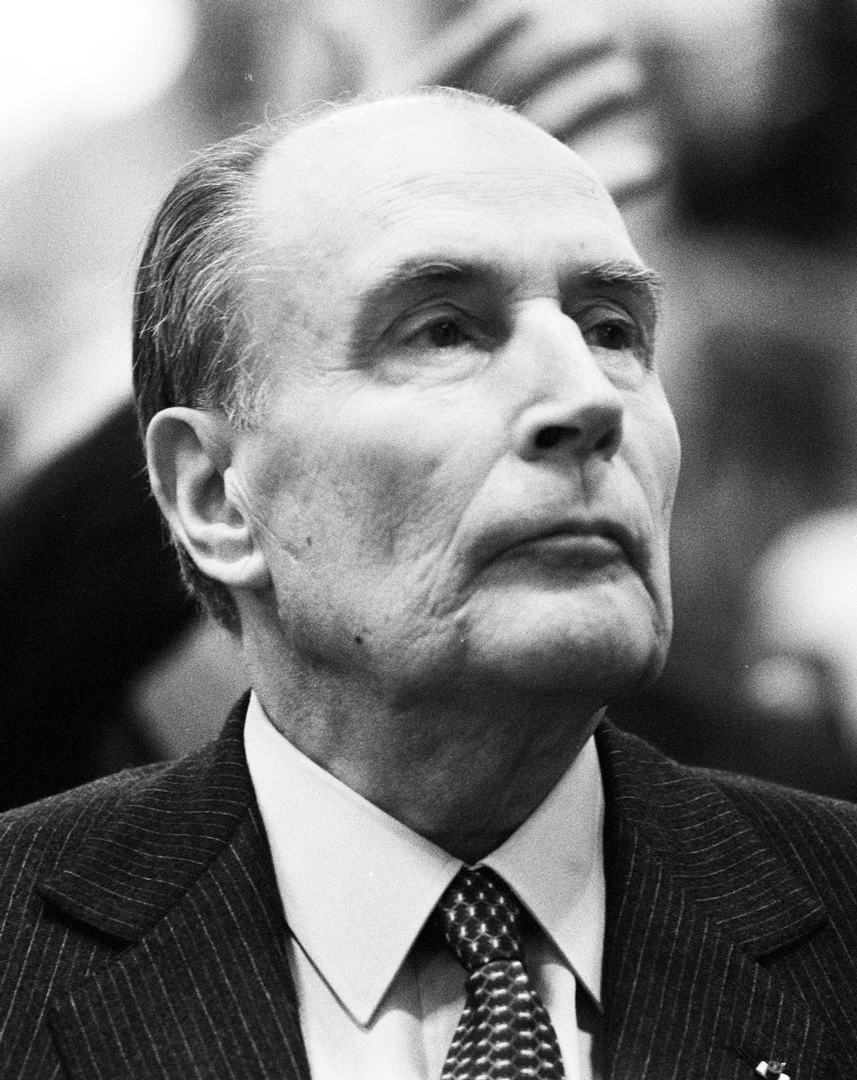

- Secondly, did the French soldiers know anything about the Genocide of the Bagogwe? As we saw, in March 1991, France sent confidentially a detachment of military assistance and training of about 30 experts, called DAMI (Détachement d’Assistance Militaire et d’Instruction), whose purpose was to organize, train and supervise the RAF in the north-western prefectures. The first contingent arrived in Ruhengeri in late March and settled in the Mukamira base camp. The training activities were organized at the Bigogwe Commando Training Center, the firing ranges at Nyakinama and Ruhengeri, the Gako camp, and the Gabiro site. The French military must have seen and known. Alison Des Forges talked to some witnesses who said that the French were fully aware of the massacres and other human rights violations, but this did not prevent them from continuing to train the Rwandan soldiers directly involved in those crimes. Many data and witnesses confirm that the French military stationed in the North-west knew everything but had no direct role in the massacres. The top officers stationed in Kigali also knew what was going on in Ruhengeri and Gisenyi thanks to the dispatches transmitted from the Mukamira and Bigogwe camps. The French ambassador Martres knew and Mitterrand knew as well, in near real-time, nevertheless France kept on supporting Rwanda’s cloak of emerging democracy as if nothing had happened. We can, therefore, conclude that the Genocide of the Bagogwe was a state crime, carried out with the acquiescence of the French Presidency, and covered by many lies, including the French ones. We’ll talk about it again.

- Many popular sources and some scholars consider the massacres of the Bagogwe some kind of small-scale test of the 1994 Genocide, a sort of prefiguration of the major 1994 genocidal plan. I do not agree for two main reasons. Firstly, it was not a groundwork for the major Genocide, nor it was planned as a preparation for what is often called “the very genocide of 1994”. That of the Bagogwe was a Genocide tout court, planned to systematically clean two prefectures of the Bagogwe ethnic enclave. In 1991, none among the Akazu could prefigure or anticipate or even plan it in view of 1994. There was no plan for 1994 at all (and nothing has ever been found in this sense). The second reason is that historians need to be very careful with all those considerations that seem to introduce a teleological perspective into history.

BELOW

Man praying on the steps of the Bigogwe’s Kanzenze Genocide Memorial Site in Rubavu district, north-western Rwanda.

Photo by Andia / Alamy

THE MAIN FEATURES OF THE 1990-93 RWANDAN GENOCIDE

We cannot generalize all of the characteristics of the Bagogwe genocide but we can extend some of them to other Tutsi massacres carried out in the 1990-93 phase and propose a synthesis according to historical data.

These massacres of Tutsi, as well as other crimes against humanity, went unpunished. «No one, neither official nor ordinary citizen, was ever convicted of any crime in connection with these massacres» (Alison Des Forges, cit.). Moreover, as we saw, the local authorities were instructed to lie about what happened in their territories and in case, to pass them for “ancient tribal hatred” fueled by the war, or unexpected, uncontrollable outburst of popular rage.

Three aspects should be underlined:

- Firstly, the massacres were carried out by death squads, paramilitary militias, and mobs, with the involvement of soldiers, members of the Presidential Guard, and the Gendarmerie, under the coordination of local administrators and officials (prefects, sub-prefects, burgomasters, etc.), encouraged by national politicians from MRND and CDR parties. The participation of the local population was limited and sometimes forced by local authorities (as a duty of umuganda, communal work). «These violent acts which were mainly directed towards the Tutsis were not spontaneous as official propaganda claimed. They did not result from old tribal hatred. They were operations carried out by MRND and CDR» (History of Rwanda, cit.).

- Secondly, it’s important to point out that the Tutsi were arrested, tortured, massacred as Tutsis, for the sole fact of existing as Tutsi, for having damn documents stating their Tutsi origin. Well, isn’t that genocide? Or do you think that the killing of some thousands of people constituted “too insignificant” a number to be able to speak of ‘genocide’? We’ll talk about that in the second to last post.

- Thirdly, the 1990-93 Genocide was organized and planned by a hidden executive circle in Kigali, made up of high-ranking military officers, members of the Akazu, MRND and CDR politicians, all in constant coordination both with the President and many local authorities. It was orchestrated in close connection with the state strategy of tension and the planning of a virulent anti-Tutsi state propaganda campaign. It was planned and implemented exactly when France, South Africa, Egypt, and the US sold to Habyarimana tons of arms and weapons; France and Belgium sent him tons of money under the form of aid, and France offered strategic military support with hundreds of elite soldiers and officers.

The US knew.

Belgium knew.

France knew.

They knew that the government they were supporting with aid and military equipment was not an idyllic fairy tale country.

They also knew that the very same government they were feeding was implementing a genocide.

Yes, they all knew it via their secret service reports and many other public, authoritative, and respected sources. The following ones.

THE IMPASSIONED YET IGNORED VOICES OF DIPLOMATS, JOURNALISTS AND HUMAN RIGHTS ACTIVISTS

In the spring of 1992, Johan Swinnen, Belgian Ambassador in Kigali, was contacted by an informant about a secret group of powerful politicians and military high-ranking officials close to the President who was planning the elimination not just of some political opponents and moderate Hutus, but also of all Tutsis. Here’s the official report you can read in the 1997 Parliamentary commission of inquiry regarding the events in Rwanda (Sénat de Belgique, Commission d’enquête parlementaire concernant les événements du Rwanda – Session de 1997-1998, see Bibliography and the download indication); the original text is in French and this is is my transation.

«In the spring of 1992, Ambassador Swinnen sent information to Minister Willy Claes by diplomatic telex. (…). A third document was sent on March 27, 1992, entitled “Onderwerp: Rwanda Onlusten Bugesera”. The content was as follows:

“From a reliable source, we have just received by chance a list of the members of the secret General Staff in charge of exterminating the Tutsis to solve once and for all, in their own way, the ethnic problem in Rwanda, and to crush the internal Hutu opponents.

Here’s the list:

- Protais Zigiranyirazo: chairman of the group and brother-in-law of the President;

- Elie Sagatwa: Colonel, brother-in-law and private secretary to the President, in charge of the secret services;

- Pascal Simbikangwa: captain, an officer at the Central Intelligence Service (SCR);

- François Karera: deputy prefect of Kigali, in charge of logistics during the Bugesera massacres;

- Jean-Pierre Karangwa: Commander, in charge of intelligence at the Ministry;

- Justin Gacinya: captain, in charge of the municipal police of Kigali;

- Anatole Nsengiumva: Lieutenant-Colonel, an intelligence officer at the General Staff of the Rwandan Army, responsible among others for the assassination of Gitarama politicians;

- Tharcise Renzaho: Lieutenant-Colonel, Prefect of Kigali.

This group is directly linked to the President who often presides over it either at the Presidency or at MRND headquarters, a building of Félicien Kabuga in Muhima, Kigali. This secret group has branches in each prefecture and municipality. This group also lays anti-tank and anti-personnel mines and sows terror in urban centers, especially in Kigali.

Another very useful piece of information: the group of professional killers who have recently ravaged the Bugesera with remarkable efficiency consisted of:

- A commando of cadets from the École Nationale de la Gendarmerie in Ruhengeri, trained for this purpose and dressed in civilian clothes, responsible also for hitting previously selected people, often local leaders of the PL (Liberal Party) and the MDR (Republican Democratic Movement). This commando was the central core of the above group.

- an “Interahamwe” militia, recruited by the MRND outside the Bugesera, and trained for weeks in different military camps;

- a larger group of locally recruited MRND “Interahamwe” militiamen, used as informers and tasked with looting and burning. The presence of the latter group makes it possible to blur the cards and make an untrained observer believe in riots.”».

Johan Swinnen, Belgian ambassador to Rwanda from 1990 to 1994, was an authoritative and shrewd source who accurately checked the information received before officially sending it to the Minister of Foreign Affairs. The core information of his diplomatic cables coincides with the testimony of the Italian missionary Antonia Locatelli.

Protais Zigiranyirazo (born in 1938), aka “Monsieur Zed” (“Mr. Z”), was the powerful brother of Agathe Kanziga, President Habyarimana’s wife, and one of the most prominent members of the Akazu. He was the prefect of Ruhengeri from 1974 to 1989; in that period, he was suspected to be involved in the 1985 murder of Dian Fossey, the American primatologist who studied and protected the mountain gorillas in north-western Rwanda. Heavily involved in the 1990-94 Genocide, Protais Zigiranyirazo was arrested in Brussels in 2001, and charged firstly with crimes against humanity and later with genocide. He was judged by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) and in 2008 was convicted of genocide and extermination. However, in 2009, the ICTR Appeals Chamber reversed Zigiranyirazo’s conviction for genocide and extermination because the Trial Chamber misapplied the burden of proof concerning alibi and erred in its handling of the evidence. Accordingly, the Appeals Chamber ordered his immediate release.

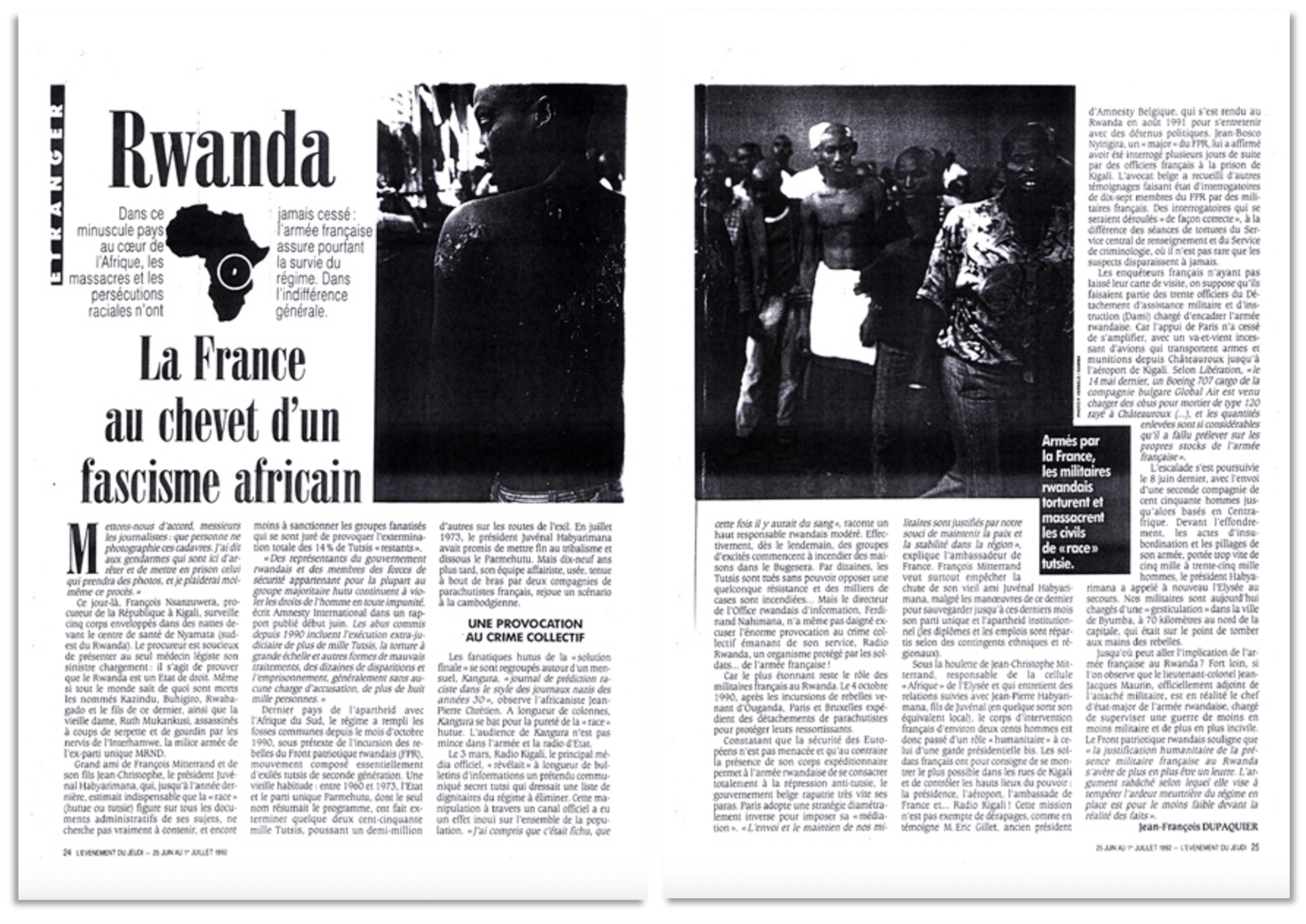

A few months later, in late June 1992, a French journalist, Jean-François Dupaquier, signed an article entitled Rwanda. La France au chevet d’un fascisme africain (France at the bedside of an African fascism), published by L’Evénement du Jeudi, a weekly news magazine. Here it is.

Rwanda. La France au chevet d’un fascisme africain by Jean-François Dupaquier, L’Evénement du Jeudi, June 25 / July 1st, 1992.

This article in French can be downloaded here.

Jean-François Dupaquier was a very reliable source: NGO worker in Burundi since 1971, he became later a journalist specializing in the Great Lakes African region. In 2000, he testified as an expert before the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) during the 2000 Media Trial against Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, Ferdinand Nahimana, and Hassan Ngeze concerning the 1994 Genocide. In 1992, he didn’t write by hearsay; moreover, he decided to interview on the topic one of the best experts in the field, the Africanist Jean-Pierre Chrétien, Director of African History Research Department at the French CNRS from 1973 until his retirement in 2003.

The article is a clear, explicit indictment of President Mitterrand and his son Jean-Christophe for throwing France into a shameful and horrible political situation. According to Dupaquier, the military support, the economic aid, and the direct participation of French soldiers in many internal affairs of Rwanda threaten to undermine the international credibility of France, as Rwanda is definitely a criminal regime. He correctly reminds his readers that Rwanda, together with South Africa, is the only country whose institutions are based on racial apartheid. After October 1990, President Habyarimana gave free hand to the paramilitary Interahamwe militia and fanatical groups that have vowed to cause the total extermination of the Tutsis («l’extermination totale des Tutsis»). Under the pretext of fighting the RPF rebels, Habyarimana’s regime filled the mass graves and carried out racial massacres and persecutions in general indifference. Dupaquier doesn’t speak of serious human rights abuses, as the Amnesty International early June 1992 Report: he speaks directly of «fanatique Hutus de la solution finale».

Dupaquier had little if no effect on a political level. The French President and his son could continue to sleep peacefully, especially since the French and European public opinion was focused on the hottest international front, the Bosnian War, and later on the election of Bill Clinton. Few people knew Rwanda (mainly for its gorillas), and if Africa had to be a topic, well, that was for Nelson Mandela.

On October 1992, Belgian professor Filip Reyntjens held a press conference at the Belgian Senate revealing the many human rights abuses in Rwanda, the existence of death squads and of the Interahamwe armed militia, the strategy of tension and the mass killings of Tutsis.

On January 28, 1993, Jean Carbonare, president of a French Human Rights NGO, Survie, just returned from a humanitarian mission in Rwanda, was interviewed by the journalist Bruno Masure in an Antenne 2 primetime broadcast. He revealed the systematic massacres of civilians carried out in Rwanda which he explicitly defined as a ‘genocide’. Here’s the original broadcast in French. To follow the Rwandan reportage, please, go to 9.22″. It shows the members of an International Commission searching pieces of evidence of the massacres by digging many mass graves. It’s shocking. If you prefer to avoid this graphic content, please go directly to the interview at 11.09″. You’ll find my partial English translation in the caption below the video. This interview is worth any effort even if you do not understand French very well (my advice: use the subtitles), as Jean Carbonare gives a moving testimony.

F2 Le Journal 20h – 28.01.1993 – INA Archive

MY ENGLISH TRANSLATION

JEAN CARBONARE interviewed by French Journalist BRUNO MASURE during the 8 pm News:

«What struck us the most in Rwanda was the extent of these human rights violations, their systematic nature, and organization. Some have spoken of ethnic clashes, but there’s more: it’s an organized policy we’ve been able to verify. In several areas of the country, and at the same time, these massacres broke out and didn’t happen by accident. Behind all of them, there is a mechanism already set in motion. In our preparatory report, we talk of ethnic cleansing, genocide, crimes against humanity, and we want to place a great deal of emphasis on these words. (…). I was also deeply struck by the involvement of power (…). We were convinced – and ‘we’ means all of us, members of that mission – that a great responsibility can be ascribed to the highest level of power. (…). Moreover, I’d like to add that our country, which supports this system from a military and financial point of view, has a responsibility as well (…) and may still affect this situation».

On February 9, 1993, the Parisian daily newspaper Libération published an article by Stephen Smiths entitled «Massacres au Rwanda: le Réseau Zéro du Général-President». Here it is.

LEFT: the copy of the original article Au Rwanda: le Réseau Zéro du Général-President by Stephen Smiths, Libération, February 9, 1993. This partially legible copy can be downloaded here, at the University of Texas Libraries.

RIGHT: A later transcription of the very same article. The French text can be downloaded here.

Stephen Smiths is another reliable source: he was a correspondent in West and Central Africa for Reuters, the Africa editor at Libération for 12 years, deputy editor of the foreign desk at Le Monde for 5 years. He wrote 16 books and several African country reports for the International Crisis Group. He worked as a consultant for the UN and since 2007, he has been working as a professor of African Studies at Duke University (US).

Smiths accuses Mitterrand of ensuring the survival of a bloody regime. He writes that in Rwanda the presidential entourage is planning not just violent political repression but also the genocide of the Tutsis (he explicitly uses two French words: extermination and génocide), disguised under the mask of tueries tribales, tribal massacres. Moreover, he points the finger at the French Ambassador in Rwanda, Georges Martres, who officially declared that the stories of massacres were only ‘rumors’.

George Martres, French Ambassador in Rwanda from 1990 to April 1993, was so loyal to the Mitterrand and Habyarimana political line to be called the ‘Rwandan Ambassador in Paris’. In 1993, he officially dismissed reports of massacres as “just rumors”. He lied, of course, and not because he believed his own lies.

In 1998, before La Mission française d’Information Parlementaire, the French Parliamentary Information Mission, George Martres admitted that he was aware of the impending genocide against the Tutsis since late 1990. He said: «Le génocide était prévisible dès cette période, (…). Certains Hutus avaient d’ailleurs eu l’audace d’y faire allusion. Le colonel Serubuga, Chef d’Etat-major adjoint de l’armée rwandaise, s’était réjoui de l’attaque du FPR, qui servirait de justification aux massacres des Tutsis. Le génocide constituait une hantise quotidienne pour les Tutsi». My translation: “The genocide was predictable from that period (…). Some Hutus had the audacity to allude to it. Colonel Serubuga, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Rwandan army, welcomed the RPF attack, which would serve as a justification for the massacres of Tutsis. Genocide was a daily nightmare for the Tutsis”.

The National Commission For The Fight Against Genocide of the Republic of Rwanda wrote in an official document titled The complicity role of French ambassadors to Rwanda between October 1990 and April 1994: «The chief of staff of the gendarmerie, Pierre Célestin Rwagafilita, told General Jean Varret, the head of military cooperation mission from October 1990 to April 1993, about the Tutsis: “They are very few, we will liquidate them”. Georges Martres, who represented France in Rwanda, was aware of the intention of Rwandan senior officers to exterminate the Tutsi and maintained his support for the regime and its army». The very same Rwandan document reports that Martres, in his Télégramme Diplomatique dated October 13, 1990, wrote to France that the hunt for Tutsi populations had become widespread; however he still called for increased military aid to the regime that was committing those crimes. In his Télégramme Diplomatique dated March 11, 1992, Martres wrote about the “inter-ethnic conflicts in Bugesera” and in particular, on the murder of Antonia Locatelli. These were his words: «Méprise selon la version officielle, assassinat délibéré selon la rumeur, l’intéressée était connue pour son opposition au bourgmestre très controversé de la commune. De surcroît, ses déclarations à RFI, d’ailleurs assez maladroites avaient sans doute déplu». My translation:

“an error and a misunderstanding according to the official version, a deliberate murder according to rumors. The woman was known for her opposition to the controversial local burgomaster. Moreover, her declarations to the RFI – quite clumsy to tell the truth – indubitably displeased”.

No comment.

Last but not least, the very same official Rwandan document reads: «In 1991, George Martres was interrogated by the international mission of investigation about the massacres of Bagogwe in the former prefectures of Ruhengeri and Gisenyi. Georges Martres reduced them to simple acts of vengeance, therefore minimizing their severity and at the same time highlighting the innocence of the Rwandan authorities who were the real instigators and direct perpetrators of the killings. He said: “I was informed of several murders that were committed in different parts of Rwanda. I wish that these events were isolated cases and that the government will make an effort to end these acts of vengeance which impede on national reconciliation» (The complicity role of French ambassadors to Rwanda between October 1990 and April 1994 can be read and downloaded here). No comment. I only add that Martres was a personal friend of Habyarimana. Just like ‘papamadit’ Mitterrand.

French Ambassador Georges Martres in 1989

In the first months of 1993, different magazines and newspapers in France, from Le Monde to Le Nouvel Observateur, reported the massacres and what was called «la chasse aux membres de l’ethnie tutsie», the hunting of the Tutsis carried out in Rwanda. At the same time, the voice of many international NGOs and associations committed to defending human rights and denouncing their abuses was raised loudly.

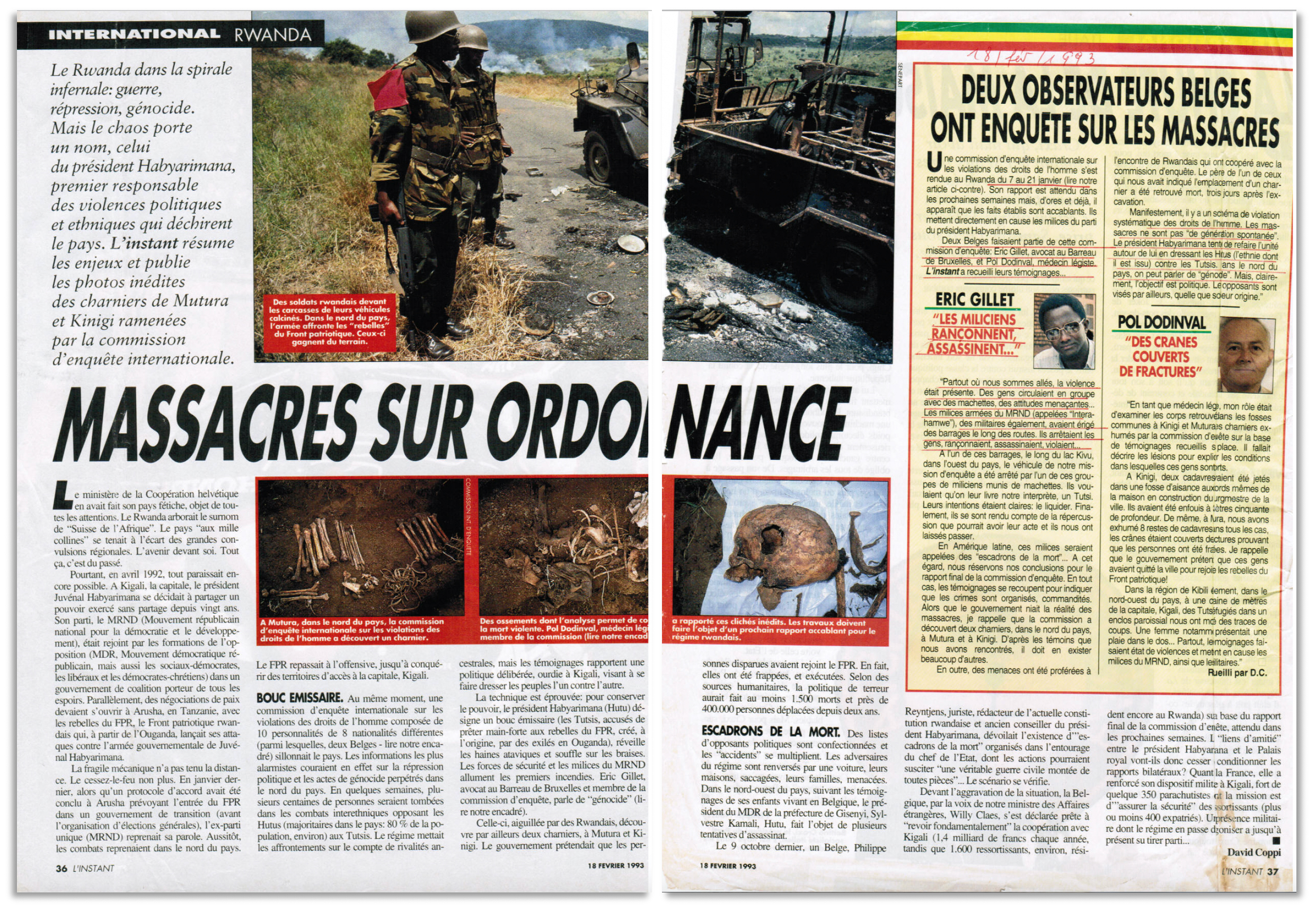

In February 1993, the Belgian political journalist David Coppi published an article on the Belgian weekly newspaper L’Instant, denouncing «la répression politique et le actes de génocide pérpetrés dans le nord du pays», the political repression and acts of genocide perpetrated in the north of the country. Coppi interviewed Eric Gillet, a Belgian lawyer, member of the Bar of Brussels, member of the International Federation of Human Rights and of the International Commission of Investigation on Human Rights Violations in Rwanda since October 1, 1990, just returned from a field mission in Rwanda. Gillet and Coppi have no hesitation in speaking of ‘genocide’ against the Tutsis, under the direct responsibility of President Habyarimana.

David Coppi, Massacres sur ordonnance, article on the Belgian weekly magazine L’Instant, published on February 18, 1993.

The French text can be downloaded here.

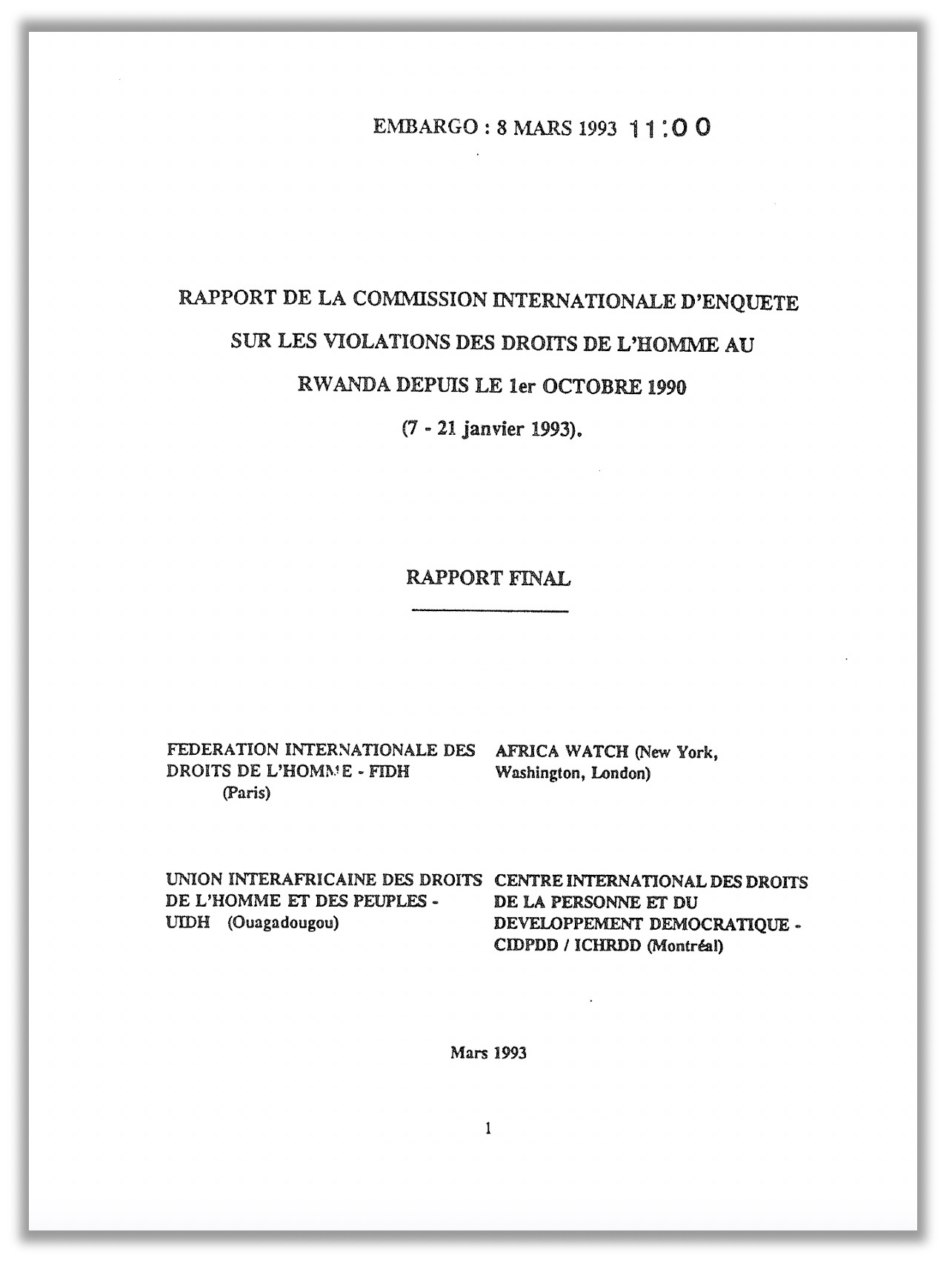

The Belgian lawyer Eric Gillet was one of the many experts from four different non-governmental organizations who, after a field mission and detailed investigations in Rwanda, signed one of the very first reports on the human rights abuses and massacres in the land of a thousand hills. The report was published on March 8, 1993, signed by the International Commission of Investigation on Human Rights Violations in Rwanda since October 1, 1990 (Commission internationale d’enquête sur les violations des droits de l’homme au Rwanda depuis le 1er Octobre 1990).

Final Report by the International Commission of Investigation on Human Rights Violations in Rwanda Since October 1, 1990 (Commission internationale d’enquête sur les violations des droits de l’homme au Rwanda depuis le 1er Octobre 1990, March 8, 1993. The four non-governmental organizations were: International Federation of Human Rights – FIDH (Paris), Africa Watch (New York, Washington, London), Inter-African Union for Human Rights and Rights of Peoples – UIDH (Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso), International Center for Human Rights and Democratic Development – ICHRDD(Montreal). Due to its non-governmental nature, the commission did not have an official mandate. Among the 10 Commissioners coming from 8 different countries, all experts in different fields (law, human rights, and forensic sciences), there were Jean Carbonare, Eric Gillet, Alison Des Forges, and William Schabas.

The French text can be read and downloaded here. The English text here. They are not identical.

The Commissioners that signed the Final Report found evidence for many human rights cases of abuse, carried out both by the Rwandan Government and by the RPF, and for different massacres and summary executions of Tutsis (Kibilira, Northwest Rwanda against the Bagogwe, Bugesera). On the latter, the Final Report Conclusion is clear: «Après avoir recueilli des centaines de témoignages et entrepris des fouilles des fosses communes, la Commission a conclu sans aucun doute que le gouvernement rwandais a massacré et fait massacrer un nombre considérable de ses propres citoyens. La plupart de victimes étaient des Tutsi». (My translation: “After collecting hundreds of pieces of evidence and undertaking mass grave searches, the Commission concluded without having any doubt that the Rwandan government massacred a considerable number of its own citizens. Most of the victims were Tutsi). The responsibilities of the government and in many cases of the local authorities emerge with certainty. «President Habyarimana and his immediate entourage bear a heavy responsibility for these massacres and other abuses against Tutsi and political opponents». Moreover, «la simultanéité des attaques dans des communes différentes établit l’existence d’une organisation plus étendue» (my translation: “the simultaneity of attacks in different municipalities proves the existence of a more extensive organization”). The English text is slightly different: «(…) as these massacres took place on a systematic scale, in many communes at the same time, it is clear that the local officials, notably the burgomasters, were following superior orders».

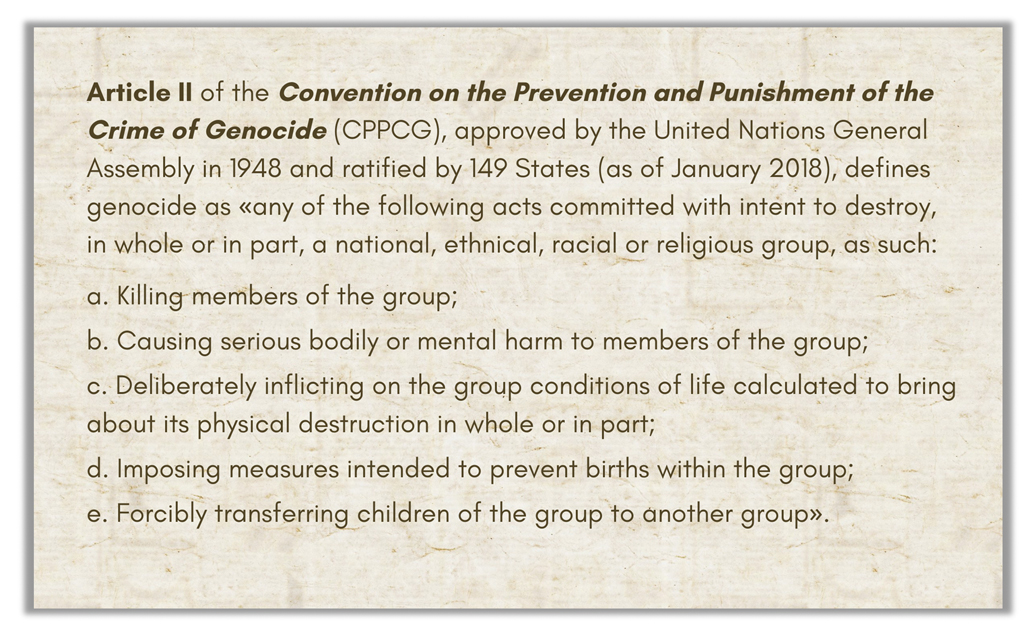

Of course, the texts deal with a crucial issue: la question du génocide, the ‘genocide’ issue.

Here’s the French text: «Les témoignages prouvent que l’on a tué un grand nombre de personnes pout la seule raison qu’elles étaient Tutsi. La question reste de savoir si la désignation du groupe ethnique “Tutsi” comme cible à détruire relève d’une véritable intention, au sens de la Convention <pour la prévention et la répression du crime du génocide>, de détruire ce groupe ou una part de celui-ci “comme tel”. Certains juristes estiment que le nombre de tués est un élement d’importance pour que l’on puisse parler de génocide. Les chiffres que nous avon cité, certes considérables pour le Rwanda, pourraient, aux yeux de ces juristes, rester en deça du seuil juridique requis».

Here’s the English text, which is faithful up to a certain point: «Testimony established that many Rwandans have been killed for the sole reason they were Tutsi. The question remains whether the designation of some members of the Tutsi ethnic group as a target for destruction demonstrates an intention, in the sense of the Convention <for the Prevention and Repression of the crime of Genocide>, to destroy this group or a part of it because of its members’ ethnicity. While the casualty figures established by the Commission are significant, they may be below the threshold required to establish genocide».

I quoted this passage in two languages because is an interesting one and shows the likelihood of a discussion among the Commissioners, some of which were jurists. Of course, the term ‘genocide’ must be used with great-great-great caution, but are really ‘numbers’ the most relevant aspect to report a ‘genocide’, as some jurists may think? I’m going to discuss this issue in the second to last post. As to the other question, do you remember the definition of ‘Genocide’ by the Convention? You can find it at the beginning of Rwandan Basketry 3. This definition implies «the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group as such». Did the Commissioners recognize such an ‘intent’? They investigated and proved some massacres but they knew they didn’t know the whole story. We know they didn’t know it for sure, as they ignored or didn’t take into account the well-planned anti-Tutsi propaganda campaign and moreover, what they knew of the Bagogwe Genocide was necessarily limited. Therefore, they honestly asked themselves: are there elements that could be recognized as making up ‘a genocidal intent’? Their answer is prudent but positive.

The French text reads: «L’horreur de la réalité observés par la Commission estompe en fin de compte l’importance du débat juridique sur la qualification de génocide. De nombreaux Tutsis, pour la seule raison qu’ils appartiennet à ce groupe, sont morts, disparus ou gravement blessés ou mutiliés; ont été privés de leurs biens; ont dû fuir leur lieux de vie et sont contraints de vivre cachés; les survivants vivent dans la terreurs».

The English text reads: «The horror of the reality examined by the Commission overshadows the judicial debate about whether the massacres should be labeled “genocide”. For the sole reason that they were Tutsi, thousands of people were slaughtered, seriously injured, or made to disappear; deprived of all their property; driven from their homes, and forced to go into hiding where they live in constant terror of discovery and death».

Even more explicit is the English Summary at the end of the French text: it’s more straight to the point that the French version, and uses explicitly the term “genocide” (the long arm of Alison Des Forges?). «The Commission finds itself obliged to conclude that there have been acts of genocide, as contemplated by international law. In this respect, the responsibility of the head of state and of his immediate entourage, including members of his family, is the inescapable conclusion». Checkmate.

How do you think Habyarimana reacted?

He and his inner circle played their favorite cards: they tried to save Habyarimana’s international respectability by reassuring aid donors and partners with a profession of good intentions, while at the very same time they made any effort both to discredit the commission – Italians call this kind of smear tactic “la macchina del fango”, literally ‘the mud machine’ – and dismiss the massacres as wild outbreaks of popular hatred and war retaliation.

What feedback do you think this document raised on the international level?

Alison Des Forges writes: «International donors (…) expressed concern, but took no effective action to insist that the guilty be brought to justice or that such abuses not be repeated in the future. French President François Mitterrand directed that an official protest be made and explanations demanded from the Rwandan government, but French authorities made no public criticism of the massacres documented in the report.128 Belgium reacted most strongly by recalling its ambassador for consultations but in the end, made no significant changes in its aid program. The U.S. redirected part of its financial aid from official channels to nongovernmental organizations operating in Rwanda so that the Rwandan government could not profit from it, and Canada also cut back on its aid. But both donors weakened the impact of their decisions by linking them to Rwandan fiscal mismanagement or shortage of their own funds as much as to human rights abuses». In brief and in other words, the Report had only a temporary cosmetic effect, but no serious political impact.

A satirical cartoon of the Akazu circle, published in the issue of the Nyabarongo Rwandan magazine, dated March 13, 1993.

In the far left, President Habyarimana stands and says Nakoze uko nshoboye! (my translation: “I did my best!).

Seated on the table, in the foreground, left to right:

-

Madame Agathe Kanziga, Habyarimana’s powerful wife (Muka-Kinani).

-

Mathieu ‘Matayo’ Ngirumpatse, Minister of Justice from 1991 to 1992, elected National Secretary of the MRND in 1992, and chairman of the MRND Executive Bureau in 1993 and 1994.

-

Joseph Nzirorera, ministry of Industry and Craftsmanship in 1990 and 1991, MRND delegate

At the head of the long table, facing Habyarimana:

-

Colonel Pierre-Célestin Rwagafilita, cousin of Agathe Kanziga, Deputy Chief of Staff of the National Gendarmerie until February 15, 1992.

Seated on the table, in the background, left to right:

-

Protais Zigiranyirazo, aka “Monsieur Z”, powerful brother of Madame Agathe, prefect in Ruhengeri until 1989, probably the most powerful of the Akazu members

-

Colonel Laurent Serubuga, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Rwandan Army from 1973 to June 1992 (the Chief of Staff being Juvenal Habyarimana himself).

-

Séraphin Rwabukumba, brother of Monsieur Z and Agathe, general manager of Société La Centrale, a huge commercial company with more than 50 import licenses

On the far right, a flood of skulls. The sign reads Abatutsi: they are the Tutsi victims of the 1990-93 Genocide.

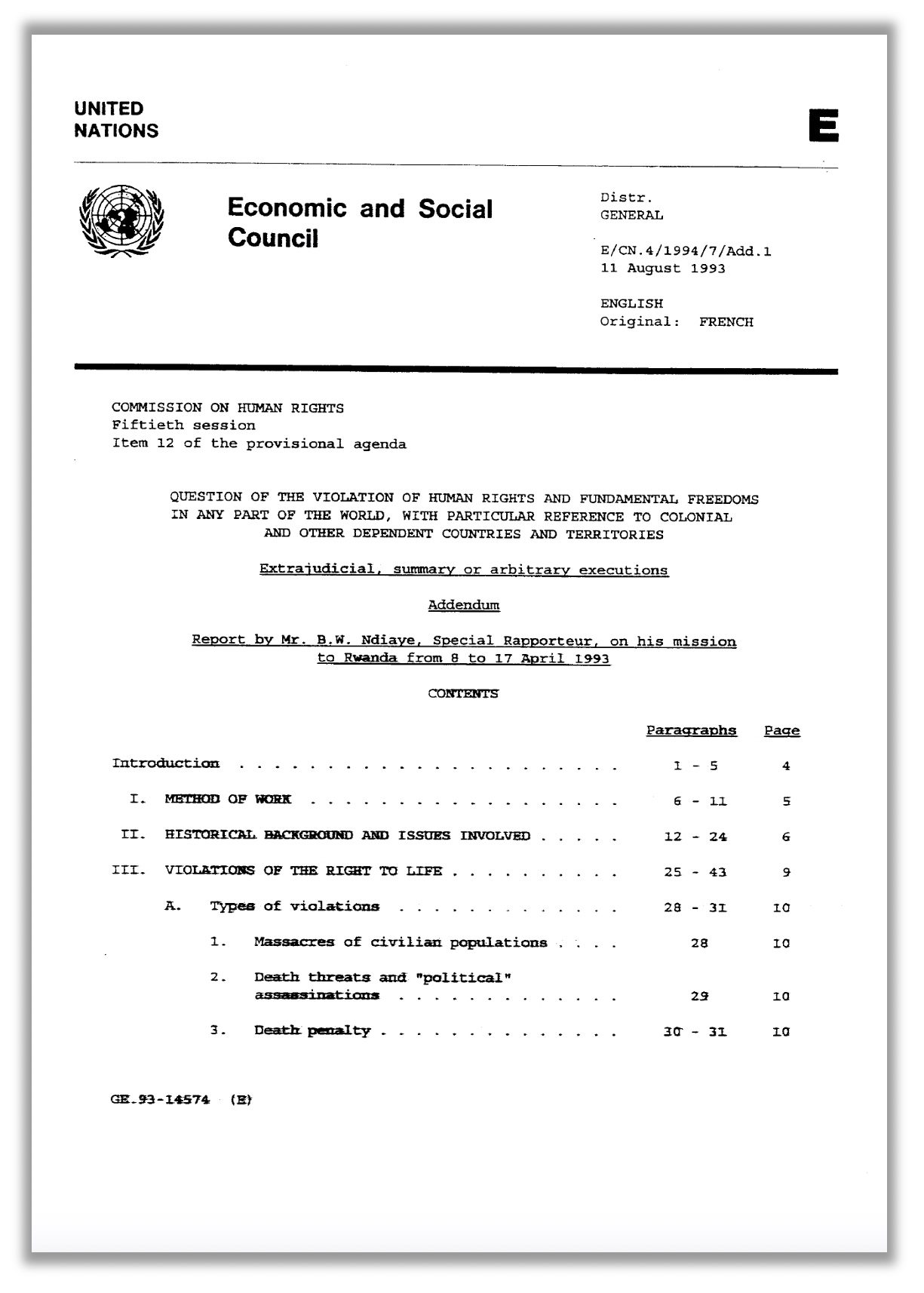

Five months later of the very same year, on August 11, 1993, the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Summary, Arbitrary and Extrajudicial Executions, the Senegalese lawyer Bacre Waly Ndiaye, issued an official Report based on his own mission to Rwanda, confirming the conclusions of the Final Report just mentioned, and listing several serious violations of human rights. The Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, which are violations of the fundamental right to life, is an independent human rights expert appointed by the United Nations Human Rights Council. Bacre Waly Ndiaye was fully qualified for that task: he was a founding member of the Inter-African Union of Lawyers and former Vice-President of the International Executive Committee of Amnesty International.

The Report was signed by the Senegalese lawyer Bacre Waly Ndiaye, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Summary, Arbitrary and Extrajudicial Executions, and published on August 11, 1993, by the United Nations Commission in Human Rights.

The text can be downloaded from this page of the United Nations Digital Library in several languages.

In his Report, Bacre Waly Ndiaye warns the criminal role played by the anti-Tutsi propaganda campaign and in particular by Radio Rwanda (RTLM started to broadcast when the Report was already completed and in course of publication): «56. The involvement of the media in spreading unfounded rumors and in exacerbating ethnic problems has been noted on repeated occasions. Radio Rwanda, which is the only source of information for the majority of a poorly educated population, and which is still under the direct control of the President, has played a pernicious role in instigating several massacres. This is particularly true of certain broadcasts in Kinyarwanda which differ markedly in content from the news programs broadcast in French, which is understood only by a small part of the population».

Secondly, he reports the criminal role of paramilitary militias, death squads, and secret armed groups: «74. All violent organizations should be dismantled as a matter of urgency. Criminal organizations such as “death squads”, “Amasasu” or “Network Zero”, must be identified and dismantled, and their member persecuted, whatever their rank. The same measures must be taken against the political-party militias that have perpetrated human rights violations (…). All weapons in circulation among the population or distributed to it by certain authorities should be confiscated as a matter of urgency. In the current situation of extreme poverty, criminality, and tension, one spark is all that is needed to cause the situation to degenerate».

Thirdly, he highlighted that the outbreaks of violence among the population «were planned and prepared, with targets being identified in speeches by representatives of the authorities, broadcasts on Rwandese Radio and leaflets. It is also noteworthy that at the time of the violence, the persons perpetrating the massacres were under organized leadership. In this connection, local government officials have been found to play a leading role in most cases».

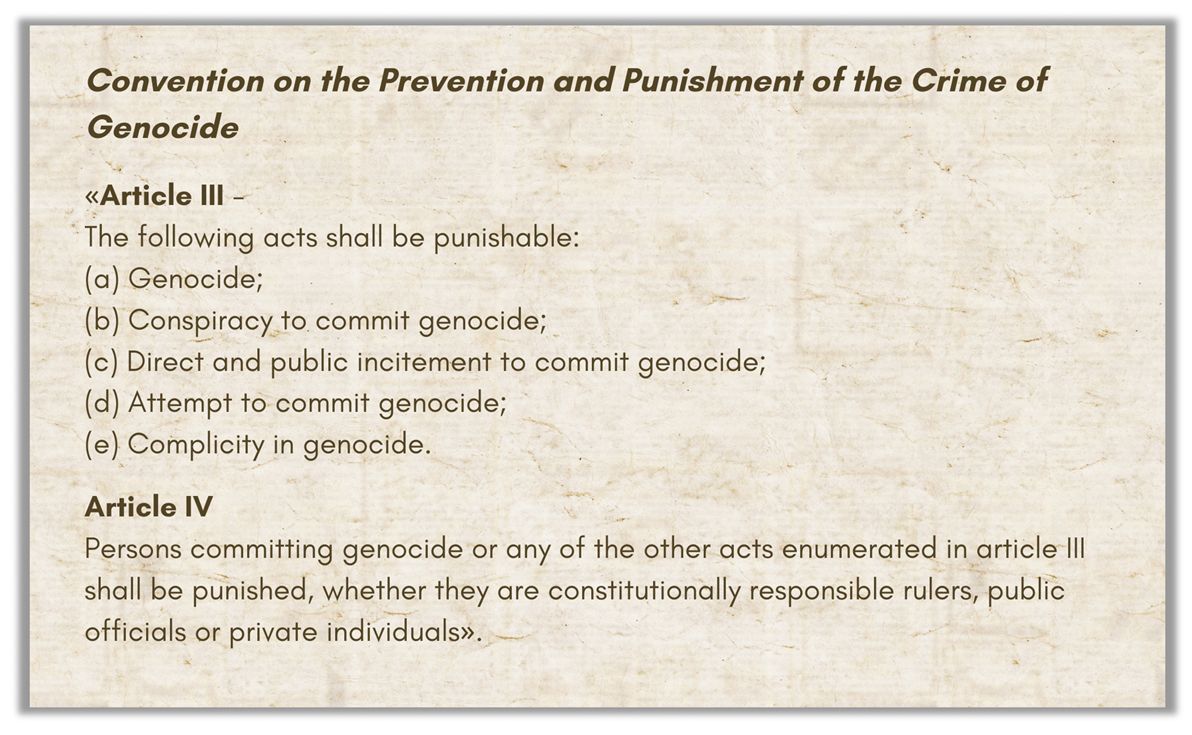

Finally, he addresses the “genocide question”: «78. The question of whether the massacres described above may be termed ‘genocide’ has often been raised. It is not for the Special Rapporteur to pass judgment at this stage, but an initial reply may be put forward». He recalls the definition of genocide by the Convention and then concludes: «The cases of intercommunal violence brought to the Special Rapporteur’s attention indicate very clearly that the victims of the attacks, Tutsis in the overwhelming majority of cases, have been targeted solely because of their membership of a certain ethnic group, and for no other objective reason. Article II, paragraphs a) and b) might therefore be considered to apply to these cases».

In his official Report, the UN Rapporteur states that, without any doubt, a genocide against the Tutsis is in progress in Rwanda. In particular, he highlights that «the violations of the right to life, as described in this Report, could fall within the purview of Article III of the Convention (…) and the Article IV». In brief, he declared the massacres of Tutsi in Rwanda as “genocide”.

The UN Rapporteur’s Report was an impressive document and indictment against the Habyarimana’s inner circle, a clear condemnation based on proven facts and events, accompanied by concrete proposals, including a series of urgent measures to avoid any escalation, such as the adoption of a new system of identity cards, free of any ethnic reference, judged «an indispensable reform to be carried out as soon as possible».

What political impact do you think this Report had on Rwanda and at the international level?

It was simply ignored in most cases, downplayed in a few, just like the previous Final Report by the International Commission of Investigation on Human Rights Violations. Why? Well, in many cases for reasons of political expediency, and for the tendency shared by many governments all over the world to routinely ignore all of the findings of non-governmental organizations and human rights associations when they are not supported by a public opinion critical mass. There are other reasons, well highlighted by The preventable Genocide: «(…) It was literally unthinkable for most people to believe that genocide was possible; it was simply beyond comprehension that it could be possible. Each case of modern genocide has taken the world by surprise – even when, in retrospect, it was clear that unmistakable warning signs and statements of intent were there in advance for all to see. (…) How is it possible that the awful horrors that were not in dispute were not sufficient to mobilize world concern?» (7.13 and 7.14, cit.). We’ll discuss this issue in the second to last post.

Even the third document of 1993 went unnoticed. This last well documented Report was drawn up by the ADL, Association Rwandaise pour la Défense des Droits de la Personne et des Libertés Publiques, and published on December 1993 under the French title of Rapport sur les droits de l’homme au Rwanda – Octobre 1992 – Octobre 1993. It reported, among others, «les massacres organisés et perpétrés contre les Tutsi dans les Préfectures de Ruhengeri and Gisenyi <qui> sont devenus cycliques», expressly defined as a génocide.

The cover of the Rapport sur les droits de l’homme au Rwanda – Octobre 1992 – Octobre 1993, drawn up by the Rwandan ADL, the Association Rwandaise pour la Défense des Droits de la Personne et des Libertés Publiques (Rwandan Association for the Defense of Human Rights and Public Liberties), and published on December 1993.

It can be downloaded here, on the University of Texas Libraries website by The University of Texas at Austin.

In late 1993, the Rwandan state of affairs and the several episodes of mass atrocities and genocide against the Tutsis were well documented, well-reported, and well known.

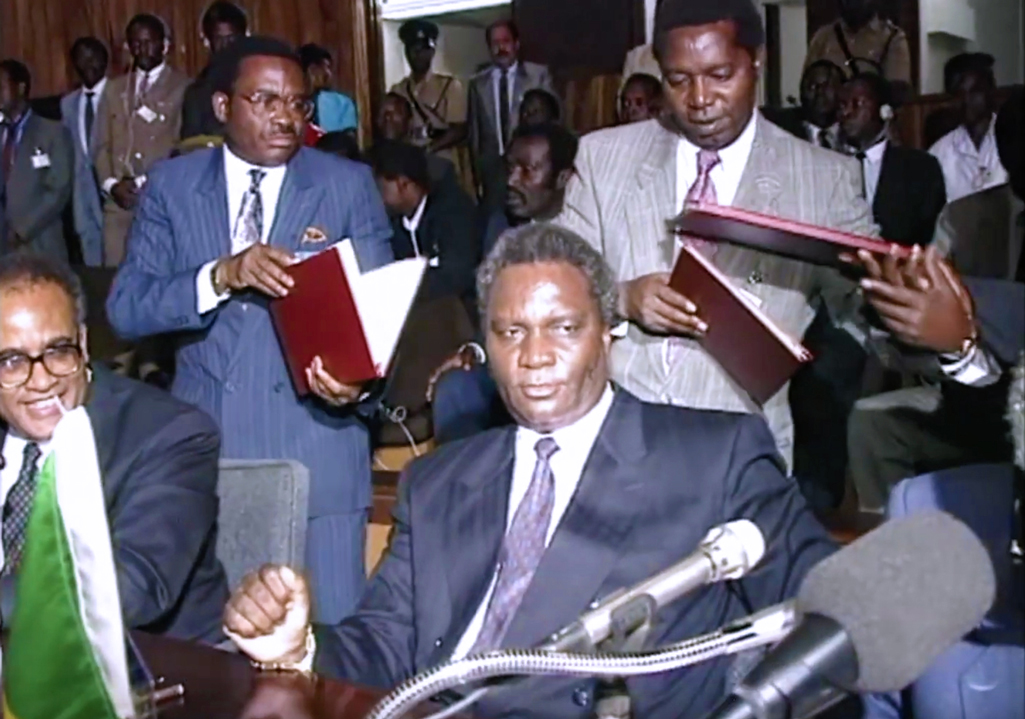

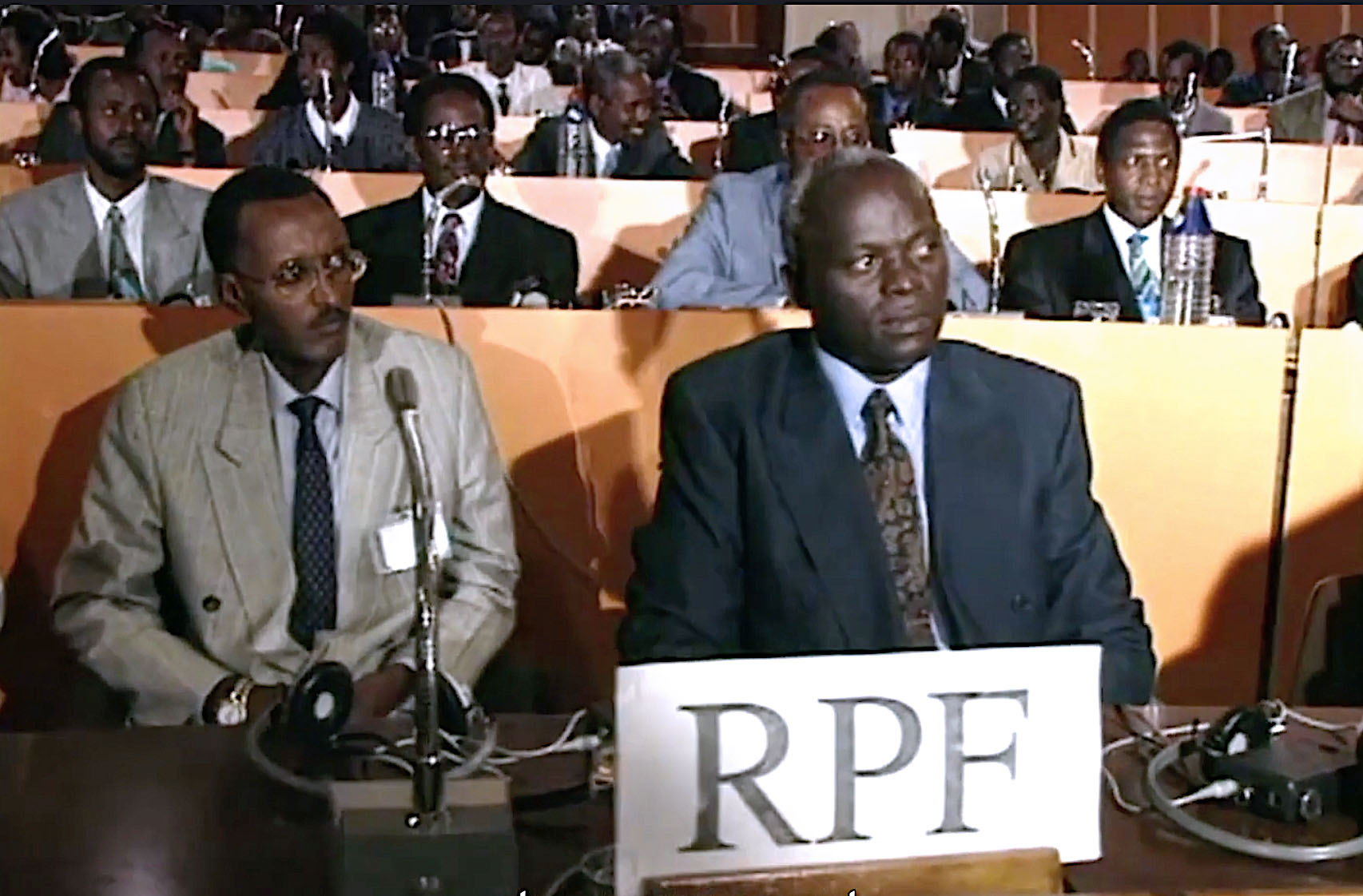

THE CRIMES OF THE RWANDAN PATRIOTIC FRONT

All of the international reports on genocide, war crimes, and human rights abuses in Rwanda dedicate an entire chapter to the crimes carried out by the RPF. However, these crimes have been investigated with great difficulty both because they occurred in difficult-to-access areas and because of the widespread code of silence shared by the RPF soldiers.

«The RPF was responsible for a number of serious human rights violations in the early years of the war in Rwanda. Between 1990 and 1993, RPF soldiers killed and abducted civilians and pillaged property in northeastern Rwanda. They attacked a hospital and displaced persons’ camps. They forced the population of the border area to flee either to Uganda or to displaced persons camps further in the interior of the country. While professing a policy of openness and commitment to human rights, the RPF hindered the investigation of the International Commission and made it impossible for its members to speak freely and privately with potential witnesses in areas under RPF control. The commission gathered most of its information from victims of RPF abuses who had sought refuge at camps in the zone controlled by the government. According to Rwandan human rights organizations, RPF soldiers killed hundreds of civilians in the town and prefecture of Ruhengeri during the offensive of February 1993. In some cases, the soldiers reportedly asked the victims to produce their political party membership cards and then killed those who belonged to the MRND or CDR.34 The RPF was widely accused of killing civilians in two incidents in November 1993» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

The Final Report by the International Commission of Investigation on Human Rights Violations in Rwanda Since October 1, 1990, published on March 8, 1993, denounced that «the RPF has been guilty of attacking civilian targets, of summary executions, forced expulsions of populations, injuring civilians, and pillage and destruction of property. The apparent absence of punishment for those guilty of these crimes makes it likely that these abuses will be repeated».

The Report signed by the Senegalese lawyer Bacre Waly Ndiaye, United Nations Special Rapporteur, published on August 11, 1993, reads: «Reliable sources have revealed that the FPR has perpetrated executions in the areas under its control. (…) In view of the lack of information concerning the situation on the ground, and in the light of the inaccessibility of the area in question and the limited time available to the Special Rapporteur, it was extremely difficult for him to form a personal opinion on the matter during his mission to Rwanda. On the other hand, he was able to meet reliable individuals who convinced him that these summary executions did actually take place. It is accordingly important that a more extensive investigation should be held, covering not only the areas under FPR control but also certain border regions situated in Ugandan territory».

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE – THE WATERSHED IN THE MID-LATE 1993

THE MILITARY ‘FRONDE’

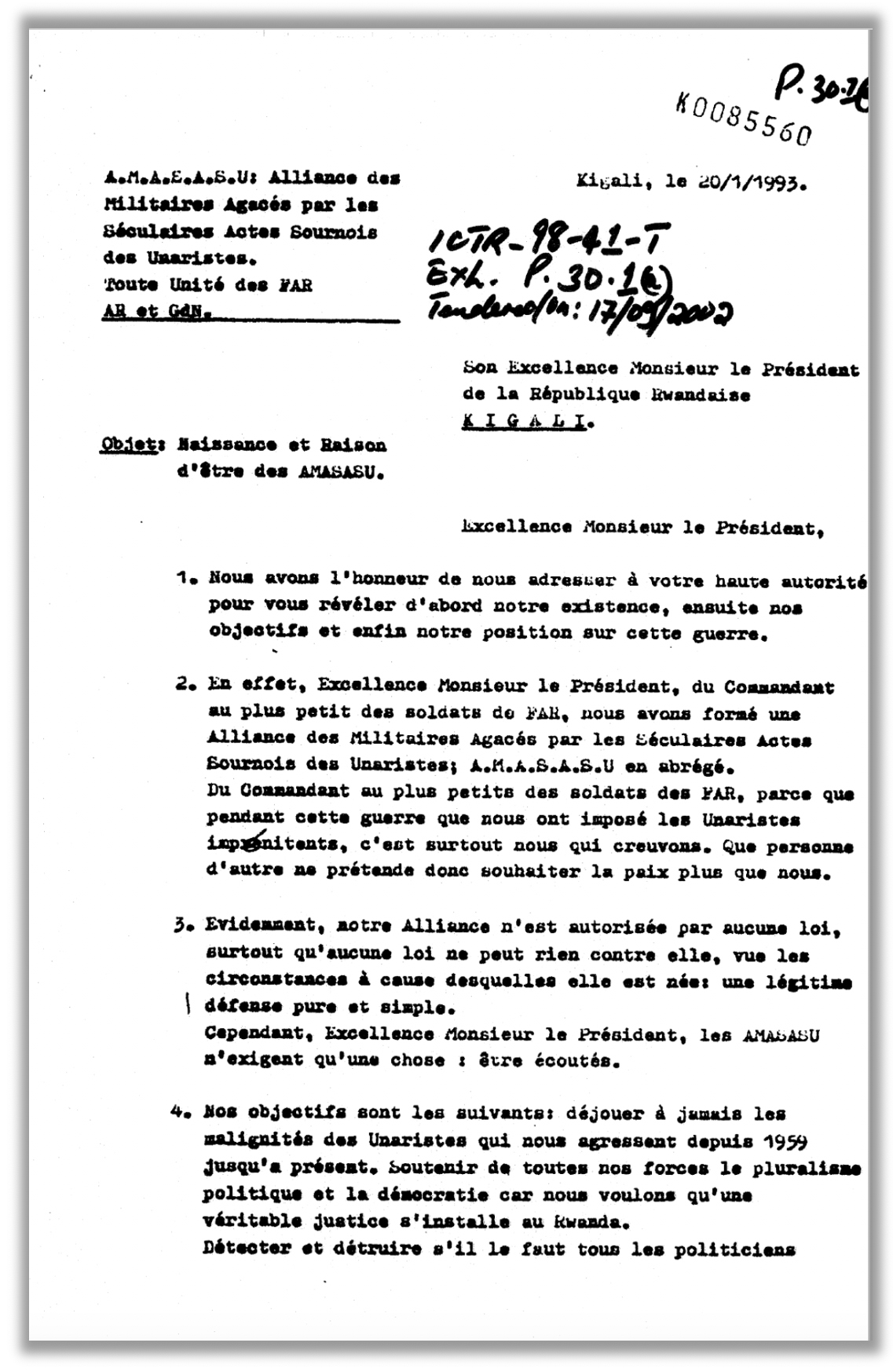

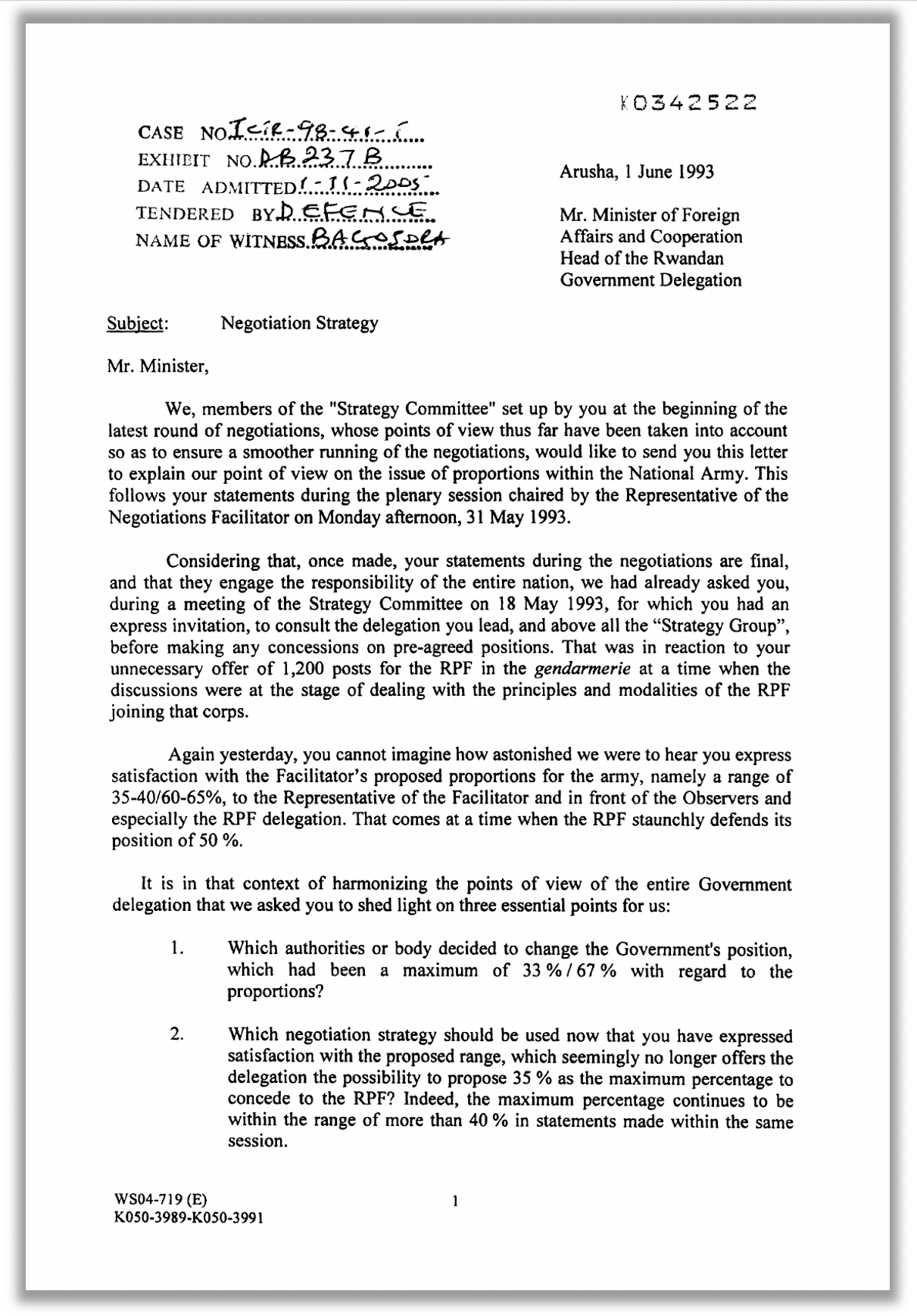

On January 20, 1993, the group of extremist and fanatic high-ranking officers of the Rwandan Armed Forces and the National Gendarmerie, members of the clandestine group called AMASASU, sent an open letter to President Habyarimana, CC’ed to the French and the US Ambassadors as well. This letter is strictly tied to the 1992 Kabaya Speech by Mugesera and well conveys the ideological horizon of the Hutu hardliners.

The anonymous letter sent by AMASASU to President Habyarimana on January 20, 1993.

The French text can be downloaded here.

The letter was written in January 1993, during a difficult moment for President Habyarimana, caught between the hammer of the Hutu hardliners and the anvil of the constant mediation efforts by Rwanda’s neighbors (Burundi, Uganda, and Tanzania) and the Organisation of African Unity (OAU), all determined to support peace negotiations and put an end to the open plague of refugees in Central-Eastern Africa.

The letter is anonymous and signed by Commandant Tango Mike, writing for the Supreme Council of the AMASASU. “Tango Mike” is NATO military slang: it stands for two letters, T and M, and in English is often used to say “Thanks Much”. In the US Special Forces, Tango Mike Mike is usually spoken over the radio when a firefight is going badly or when courage needs to be summoned, however, it’s difficult (for me, at least) to say if in Rwanda, at that time a French-speaking country, this military jargon expression had a special or a different meaning.

Who was hiding behind this pseudonym?

According to Alison Des Forges, Jean Morel, and others, «it seems likely that he is either Colonel Théoneste Bagosora or someone working closely with him» (ADF, cit.). According to the Mutsinzi Report, a Rwandan official document published in 2010, Commander Tango Mike is undoubtedly Colonel Bagosora.

The letter, whose tone is quite bossy and ‘muscular’ (AMASASU members do not ask to be listened to, they demand it), shows the minimum formal requirements and goes straight to the point: the supreme council of this secret group wants the President to know their position about the war «because, during this war imposed on us by the unrepentant Unarists, we are those who are going to snuff it» (my translation). The Unarists are the Tutsis of the old monarchic UNAR Party «who have been attacking us since 1959». We found here the very same ideological horizon built by and the very same language used by Mugesera.

The letter highlights two main points:

- Our enemy is not made up only by the RPF’s soldiers on the battlefront: the inyenzi living among us and supporting the invaders with impunity are our enemies as well. The RPF is currently preparing a large-scale offensive. «How do you intend to prevent us from giving an exemplary lesson to those insider traitors? After all, we have already identified the most virulent of them and we will act like a thunderbolt!». How do you intend to calm the anger of the AMASASU members against the PRF agents and accomplices who are operating in our country, under the banner of the opposition? We’re ready to deliver our “justice” to the Rwandan “accomplices” if the competent authorities will fail to act against them. And they are currently failing.

- The inyenzi are preparing for a major attack and recruiting people en masse to strengthen their ranks. «Here’s the proposal by the AMASASU members: in each of the 140 communes of Rwanda, there should be at least one battalion of robust young people initiated on the spot, even if only summarily, to the military art. These young people will remain there on the hill, ready to form a people’s army that can back up the regular army if the inyenzi keep on pursuing their ambitions to conquer the power by force». The Ministries of Youth, Defense and the Interior will take charge of training and commanding this ‘popular army’.

As to point 1, we find many elements of the Kabaya Speech by Mugesera, including the proposal to draw up lists of “accomplices” and traitors to be ‘judged’, and the ‘threat’ to deliver an alternative form of ‘justice’ to them, if the competent authorities will fail to act correctly. Nothing new under the Rwandan sun. The non-random convergence between this letter and Mugesera’s speech speaks of a propaganda campaign centered on a core message that was concerted and shared among the members of the Akazu, including some high-ranking military officers. Moreover, as Alison Des Forges writes, «in September and October 1992, prefects relayed secret orders to the burgomasters to compile lists of people who were known to have left the country surreptitiously. The lists for “the purpose of security” were to include complete identification and were to be provided urgently. (…). In late September or early October 1992, the army general staff directed all units and military camps to provide lists of all people said to be “accomplices” of the RPF» (ADF, cit.). When Tango Mike writes the letter, the blacklist compiling is an old work in constant progress.

As to point 2, to tell the truth, there’s nothing new as well. A government program of civilian self-defense was launched immediately after the RPF invasion in October 1990, but it deflated almost immediately. It wasn’t an innovation: the first program of that kind, aimed at creating local groups charged of the so-called “auto-défense civile” was launched to counter the UNAR guerrilla attacks in December 1963.

In late 1990, «a group of university faculty, including Vice-Rector Jean-Berchmans Nshimyumuremyi and Professor Runyinya-Barabwiriza, proposed a “self-defense” program for all adult men to the Minister of Defense. Citing the adage He who wishes for peace prepares for war , the group advocated a population in arms as a way to “assure security” inside the country if the army were occupied in defending the frontiers (…)» (Alison Des Forges, cit.). The proposal was not implemented at that time, but in September 1991, when the RPF started to multiply its incursions across the Ugandan border, it resurfaced with greater force.

According to its January 1994 Report, Human Rights Watch obtained a document marked ‘secret’ and dated September 29, 1991. It was signed by Colonel Déogratias Nsabimana who had fought the RPF along the Ugandan border. In this document, addressed to the Defense Minister, Colonel Nsabimana proposed to create a “self-defense civilian force” and to provide a gun for every administrative unit of ten households; in particular, he called for 1760 guns to be quickly distributed in four communes in the northern area, along the Ugandan border: Muvumba, Ngarama, Muhura, and Bwisige. Subsequently, the program was to be gradually extended to the rest of the country.

The self-defense units were considered by some top-ranking officers a wildcard to play in many ways: they could carry out general surveillance work and patrol, they could man blockades on roads, collaborate with the paramilitary militias in terms of logistics, obey local authorities’ instructions, provide backup to the Army. In 1992, «these forces served as a sort of border guard and were not involved in the human rights abuses committed by the Rwandan Army, party militias and civilian crowds» (HRW, cit.). With the letter, the AMASASU members demanded funds to support both the implementation of the whole project and the distribution of different kinds of arms to civilians. The official reason was to fight an “enemy” dispersed among the population, not concentrated on the war front. As to the unspeakable truth, we’ll talk about it in the next paragraph.

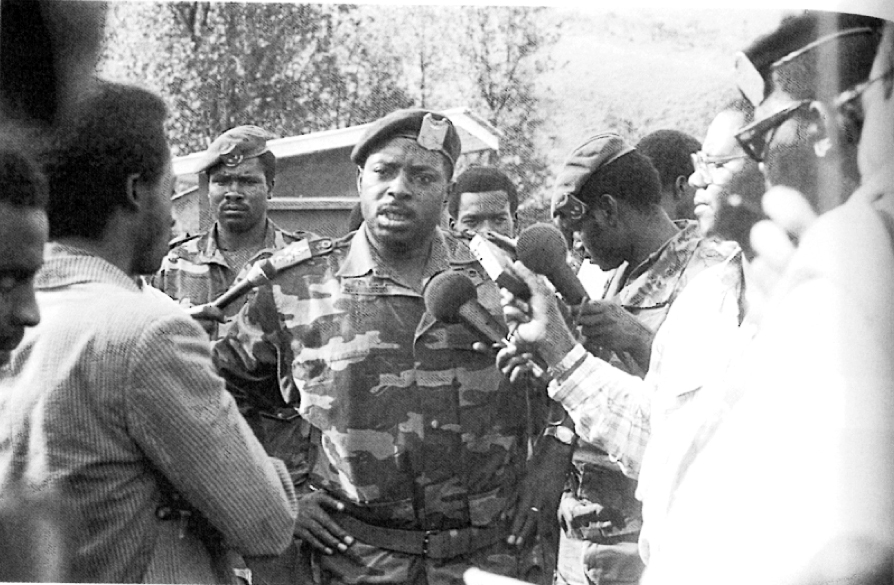

Colonel Déogratias Nsabimana, Operation Commander on the war front, on May 30, 1991.

He was appointed Chief of Staff of the Rwandan Army in June 1992. He was involved in the Zero Network, in the organization of the death squads and in the training of Interahamwe militia.

Well, to sum up, this aggressive letter to President Habyarimana said absolutely nothing that Habyarimana didn’t know. However, this doesn’t mean it said anything at all. It means, on the contrary, that its importance relied on what it didn’t say or it did say between the lines.

Before, however, we need to know something more about those top-ranking military officers who were powerful members of the Akazu and well-known Hutu hardliners. The Akazu was – to use the perfect definition given by the French historian Jean-Pierre Chrétien, «le cœur d’un réseau composé de plusieurs cercles, fondé sur le clientélisme en milieu politique, militaire et financier», the heart of a network made up of several circles, based on clientelism and cronyism in political, military and financial fields. Power and money, to put it briefly.

The most influential members of the Akazu were powerful grey eminences who pulled the strings of the propaganda campaign and the genocide of 1990-93.

Colonel Laurent Serubuga (1936) was Deputy Chief of Staff of the Rwandan Army from 1973 to June 1992 (the Chief of Staff being Juvenal Habyarimana himself). Colonel Pierre-Célestin Rwagafilita, cousin of Agathe Kanziga, Habyarimana’s wife, was Deputy Chief of Staff of the National Gendarmerie until February 15, 1992. Both of them were members of the Akazu. Andrew Walls writes that «both were intensely loyal to Le Clan de Madame and their own bank balance». Both are suspected of having organized the false attack on Kigali, on the night between October 4 and 5, 1990. Both were members of the Réseau Zéro (Zero Network) and its death squads. Research led by Justine Hitimana (Research Fellow at National Commission for the Fight against Genocide, CNLG, in Rwanda) shows that during a meeting held in 1992 in Kibungo, Rwagafilita appointed Cyasa (namely Emmanuel Habimana) as the president of Interahamwe militia in that area. Most likely, Serubuga and Rwagafilita could control the paramilitary militias, at least the Interahamwe.

Colonel Laurent Serubuga, on the right, shakes hands with President Habyarimana. Unknown dating.