Rwandan Basketry

THE ART OF BASKETRY

The art of basket weaving or basketry (vannerie in French) is as ancient as overlooked.

It requires only two things: skilled hands and locally available vegetal fibers. It arises and develops, therefore, from a deep connection between humans and their surrounding nature.

It certainly predates pottery: many pieces of evidence show we made baskets already in the late Stone Age when we were nomadic hunter-gatherers in need of lightweight, watertight containers. Since their origin, baskets were not just perfectly functional objects, but the embodiment of an aesthetic gaze, the expression of creativity and cultural traditions (when we make things, we make them beautiful and rich in meaning).

Basket weaving, in short, can overcome the limited horizon of a simple form of craftsmanship.

As an art, basketry traversed millennia remaining true to itself: still today, in Africa as in other continents, baskets are made with the very same gestures, techniques, patience, plant materials, and natural dyes used in prehistory. This feature of uncompromising naturalness and perfect biodegradability is also an irreparable weakness: baskets cannot overcome centuries like wooden sculptures, nor millennia like ceramic pots. They come from nature, and to nature effortlessly come back: they easily decay and disappear. We know we made baskets in the Stone Age not because we found any remnants of them, but because they left a trace on a pot or on a floor surface, an impression on mud or a fragment of bitumen.

Antique baskets are museum ghosts for reasons of force majeure; that’s why this art has been so overlooked. Moreover, it seems the ‘daughter of a lesser god’ for the large availability of its materials: gold is rare, prestigious, and shiny, while natural fibers are common, lowly, and unpretentious, but fortunately, we’re not magpies.

African basketry overturns many clichés not just for its artistry and cultural function but also for its current socio-economic role.

Sit down, please, and listen to the many stories some Rwandan baskets are ready to tell us. We’re about to start a surprising journey that will get us to the deep core of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Rwanda on the globe

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

AGASEKE, THE BASKET OF PEACE

NYINA W’ABEZA (‘The Mother of Beauty’) by INTAYOBERANA, 2015, official video by Rday Entertainment.

Intayoberana is the name of a “Rwandan Cultural Troupe” founded by Aline Sangwa Kagemere in 2014 in Kigali, specializing in songs and dances, accompanied by traditional musical instruments, like amakondera, inanga, umuduri, and icyembe (this last is a long wooden box with acoustic strings, typical of Rwanda). The company, which is composed of 80 adults and around 100 children, aims to enhance Rwandan traditional culture and identity through education, entertainment, and artistic creation. In the videos and performances of the company, the traditional songs and dances – like the dance of heroes in the Intore choreographed routine – are always faced with contemporaneity and the country’s past harmonized with its present.

The Intore dancers are easily recognizable: they wear a golden sisal headdress which symbolizes the mane of a lion. The term intore means “The Chosen Ones” and was once used to indicate the elite guard of warriors, charged with protecting the mwami, the Rwandan ‘king’. (Note that the ‘t’ in intore is silent: do not pronounce it!)

Did you see the line of women crossing the forest with a basket on their heads? (15 seconds from the beginning).

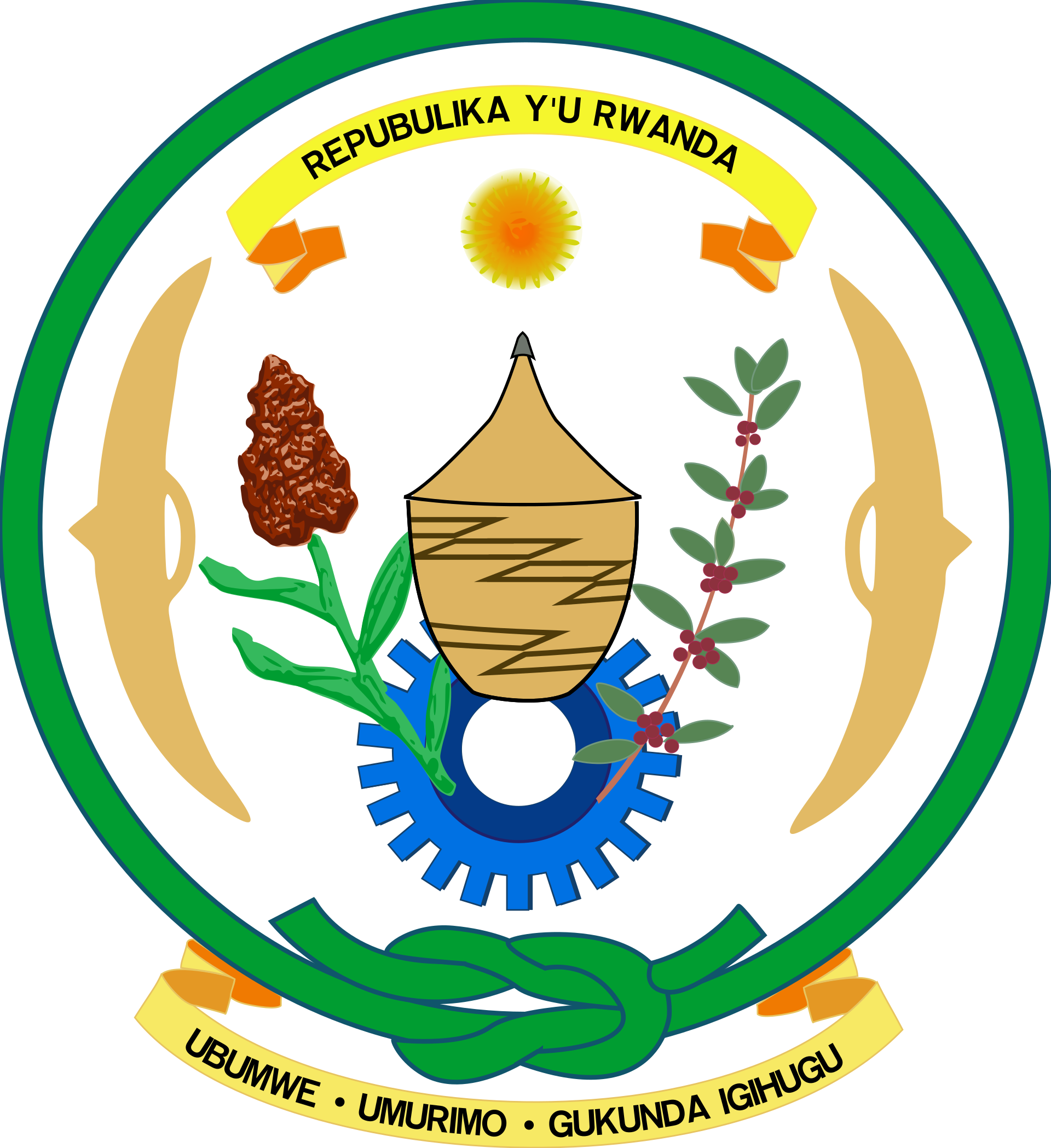

This basket of unusual shape is so relevant for Rwanda to be at the center of its national seal.

This emblem is officially in use since December 31, 2001. It reads “Republic of Rwanda – Unity, Work, Patriotism” in Kinyarwanda, the Bantu language spoken by almost all of the Rwandans, and shows the basket in the center, flanked by a stem of sorghum on the left, and a branch of the coffee tree on the right [the country’s economy is based mostly on agriculture: sorghum is an important crop, used as human food and animal fodder, while coffee is major cash crops for export]. The basket, called agaseke in Kinyarwanda (please, pronounce it /aga-sechee/), has a sun on top and a cogwheel on the bottom and is “protected” by two traditional shields on both sides [symbolizing the defense of national sovereignty]. The green ring with a knot and the cogwheel allude to the communal hard work needed to rebuild the country’s unity and economy. The agaseke basket has multiple meanings. In Rwanda, basketry is a traditional art form whose origins are lost in the mists of time: it’s therefore what links Rwandan past to present. The agaseke basket is also a traditional gift of friendship among Rwandans and recently has become a symbol of peace. Rwandans often call it “the basket of peace”, “le panier de la paix” in French.

Through its transparent symbols, the national seal of Rwanda urges for peace, national fraternity, unity, and communal work. It’s not weird: 21st century Rwanda is a country striving to rebuild its social and economic fabric, torn and destroyed by one of the major genocides in 20th-century history.

We’re about to start a journey through Rwanda. And we will start from the most relevant object of the country’s material and immaterial culture: a basket full of history and stories to tell us.

Photo by Hemis / Alamy Stock Photo

A GLIMPSE OF RWANDA

The Republic of Rwanda is a small East African country that lies along the Great Rift Valley, in the African Great Lakes region. It was given the soubriquet of Le pays aux mille collines, “the country of a thousand hills” for its high altitude: its lowest point is the Rusizi River at 950 m, the highest Mount Karisimbi (a volcano in the Virunga Mountains) at 4507 m. Since 1962, when the country became formally independent from Belgian dominion, Kigali is the capital city (please, pronounce it /chee-ga-ree/ with the accent on the very first syllable, and not /kee-gaa-lee/ or worst /kug-gaa-lee/).

«In the heart of Central Africa, so high up that you shiver more than you sweat», wrote Dian Fossey, «are great, old volcanoes towering almost 15,000 feet, and nearly covered with rich, green rainforest – the Virungas».

The Volcanoes National Park in north-western Rwanda (the very first National Park to be created in Africa) is an area of montane rainforest that encompasses five of the eight volcanoes in the Virunga Mountains, and borders both the Virunga National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo and the Mgahinga Gorilla National Park in Uganda.

It is home to the mountain gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) and the golden monkey (Cercopithecus kandti).

Here, the famous US primatologist Dian Fossey lived, studied, fought for “her” gorillas against poachers, and was murdered in 1985. Thanks to the efforts of former Volcanoes National Park Tourism Warden, Edwin Sabuhoro, authorities are successfully trying to turn former poachers into nature conservationists. The recently founded Iby’iwacu Cultural Village employs former poachers as cultural interpreters and performers of traditional Rwandan dance and music. Moreover, in the last decades, the Rwanda Eco-Tours company shares its profits with local communities to fund their agricultural projects, improve their daily life and reduce their need to rely on illegal hunting.

View of northern Rwanda and the Ruli Mountains, showing six of the eight Virunga volcanoes on the horizon. From left to right: Karisimbi, Mikeno (behind Karisimbi), Bisoke, Sabyinyo, Mgahinga and Muhabura.

Photo by Per A.J. Andersson, 2009 (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

The high altitudes, steep slopes, and volcanic soils provide favorable conditions for the cultivation of coffee and tea, among the major cash crops for export.

BELOW

Foggy sunrise on a Rwandan tea plantation near the Nyungwe National Park.

Photo by Benayobi, 2021 (under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license)

Rwanda, which is a landlocked country, is not just ‘the land of a thousand hills’: it’s the home of twenty-three lakes, numerous rivers which feed the sources of the Nile, and many wetlands and high altitude marshlands, rich in grass and reeds.

Lake Kivu (kivu means ‘lake’ in a Bantu dialect) is the largest; it stretches along the East African Rift at 1,460 m (4,790 ft) above sea level and divides Rwanda from Congo. It’s a limnically active lake: it underwent in the past and might still undergo a limnic eruption (a biologically lethal outgassing event). It contains huge amounts of dissolved carbon dioxide and methane in its deep waters. The methane gas, accumulated over a thousand years, is currently extracted to produce electricity.

Panorama over Lake Kivu

The following video has been shot on the Lake Kivu shores and islets.

Urizihiye Rwanda (‘Celebrating Rwanda’) by Intayoberana, 2019

Did you see the traditional fishermen’s three-parted boat in a video scene? (min. 1:05). The boat is also pictured below.

These boats, made of local woods, always go in a row of three. At a first look, they seem separate, but actually, they are tied together by flexible fishing rods. The fishing session starts at sunset. The two boats on the sides have men rowing in unison by whistling and singing together. Once they get out on the lake, they put the nets out, extend the boats to spread the nets, and finally light the gas lanterns to attract the fish.

Lake Kivu at Kibuye, Rwanda.

Photo by Bettina Neuefeind, 2017

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0Generic – CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Close to the Volcanoes National Park, in northwestern Rwanda, the twin lakes of Burera and Ruhondo extend their deep blue waters among the Virunga mountains. They are separated by a 1 km wide strip of land that is believed to be ancient lava flowed from the Muhabura volcano. The nearby Swamp Rugezi is one of the 7 most important birding areas in the country.

Panaromic view of Lake Ruhondo in north-western Rwanda, at approx. 1700-2000 m of altitude, not far from the Volcanoes National Park.

Photo by Atorpey, 2015 (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International)

The following video was shot in many places, including the Iby’iwacu Cultural Village and the lakes Kivu and Ruhondo.

Umurage Ukwiriye U Rwanda (‘A Legacy for Rwanda’) by Empress Nyiringango feat. Bill Ruzima, 2021.

Empress Nyiringango is a Rwandan-Canadian singer-songwriter and a skilled djembe (a goblet drum played with bare hands) and guitar player. She usually sings in Kinyarwanda, Swahili, French, and English, showing a unique blend of Rwandan, soul, reggae, jazz, and world music.

The Iby’iwacu Cultural Village is a replica of a traditional Rwandan village near the Volcanoes National Park. The above video showed the traditional huts with the imigongo bold geometric designs in black, white, and red. Imigongo is a Rwandan art form, born – legend says – in the late 18th century thanks to Prince Kakira, the son of King Kimenyi of Gisaka in the eastern Kibungo region. Legends, however, are as immortal as false. The truth is this art form was created by women and passed down through female generations. It starts by mixing cow dung (yep, bovine excrements) with ash and clay to create an odorless paste used to paint “magic” shapes with fingers. In the past, the geometric or spiral designs were masterly drawn on the dull walls of the huts (as in the picture below), today on canvas, small wooden boards, and other small-scale supports.

Reconstruction of an ancient house with imigongo. This reconstruction is a tribute to Ian Redmond, a tropical field biologist and conservationist, renowned for his work with great apes and elephants, mentored by Dian Fossey.

Photo by Germain92, 2021 (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International)

The vernacular architecture (vernacular as the building principles were never written down but rather passed on from one generation to another) called for circular-plan huts. In the more common version, the roof, supported by one or more poles, was built to touch the ground, while the walls were mainly composed of mud and wattle (as in the picture above). Note that in Rwanda, the grass-thatched houses were eliminated in 2009 (today, they are not allowed and are illegal). The traditional huts, with only one entrance, were made inside and outside with natural fibers, such as grass, reed, bamboo, common in the wet areas of the country.

Traditional grass house called nyakatsi, built in such a way to be cold in hot time and warm when the outside temperature falls. Reconstruction in the Ikirenga Cultural Center in Galo, 25 km north of Kigali.

Photo by Inezac, 2020 (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International)

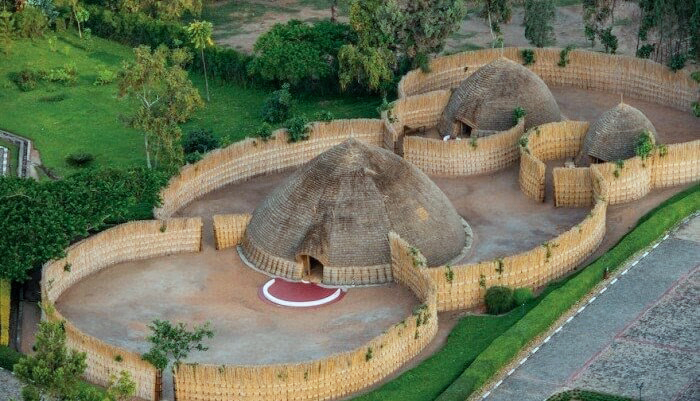

The King’s Palace Museum (or Rukari Palace Museum) is located in Nyanza, a city two hours south of Kigali that became the first permanent royal capital of Rwanda in 1899: before then, the royal court was fully itinerant. The Museum boasts a reconstruction of the residence of Mwami (King) Musinga Yuhi V, 4 km from its original location; there, king Musinga lived from 1899 until 1931, when he was deposed by the Belgian colonizers.

The royal residence is made up of several specialized huts (such as the royal beer brewer’s hut, for example) inside an enclosed area. The main hut is the King’s Palace, whose reconstruction was carefully carried out with traditional materials, worked via traditional techniques. It’s a beautifully crafted thatched dwelling, shaped like a beehive (domical hut), and protected by a bamboo and reed fence.

Nyanza Mwami Palace, reconstruction of the royal palace of Musinga Yuhi V.

Photo by Amakuru, 2006 (under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license)

A view from above of the royal compound at Nyanza. The two huts behind the King’s Palace were reserved respectively to the royal beer brewer and to the keeper of the king’s milk.

The King’s Palace has a single entrance, on top protected by a porch, on the bottom introduced by a large clay threshold, slightly raised from the ground and called nyirantarengwa. It serves two purposes: it emphasizes the entry into a “special”, reserved space and protects it from water runoff.

The main chamber is quite striking. Its floor is entirely covered with woven mats resting on layers of soft grass to ensure a comfortable, muffled walking. A circular series of cypress poles support a strunning domed roof, entirely woven by hand. A series of semicircular woven room-dividers separates the chamber from the outer ring-shaped corridor and the secretive king’s bedroom, rich in woven baskets and agaseke containers to store valuables.

The royal “sacred” space is the triumph of the art of sewing natural fibers, wickerwork, and basket weaving.

Reconstruction of the royal palace of Musinga Yuhi V. In the foreground, on the left, is a fireplace to warm up and to drive away insects. On the opposite side, the entry to the king’s bedroom, flanked by amazing panels (or screens), is decorated with geometrical motifs. The inside partition is woven in such a way that the king could see out, but not be seen by anyone outside. One of the main poles at the entrance of the king’s bedroom, which hides the royal traditional bed, made of animal skin stretched over a wooden frame, is named “Do not speak of what happens here”.

The woven circular ceiling (igisenge) at the center of the dome was the most important architectural element and was supported by rows of many cypress poles. It was a masterpiece of weaving carried out by men only, via different techniques. It provided excellent waterproofing and thermal insulation.

The semicircular panels on either side of the main chamber (panneaux de cloison in French) are screens protecting the king’s privacy, inserted between the pillars of the hut. They are of two different types: the first on the left are undecorated and called inzugi. Those finely decorated with geometrical motifs are called insika. Side by side, they create an eye-catching ‘sonata’ with ‘contrasting movements’.

At the entrance of the royal hut, a ‘wall’ of undecorated woven panels filter the outdoor light to create a softly lit interior. Their main purpose, however, was another: to protect the intimacy of the king from extraneous glances. They could do it as they were woven to let you see out, if you’re in, without being seen by anyone outside.

Left to right: a butter churn gourd container with its suspension, and four milk pots in wood with cone-shaped, woven lids (the so-called ‘milk tops’).

The gourd (igisabo) is used throughout Rwanda (and also Burundi) to produce fermented milk (kivuguto), make butter (kimuri), or store buttermilk (amacunda). The igisabo is usually wrapped up by a fiber web (injishi) to be suspended.

The milk is stored in small wooden flasks (icyansi or more frequently inkongoro) covered with a woven lid (imiteri or umutemeri) and left at room temperature in a warm and clean place of the house (uruhimbi).

The following video was shot in 2021 at the King’s Palace Museum in Nyanza. The video shows the inyambo cows with their long, elegant horns, bred for the royal court in the 17th century. At the back of the Palace of Mwami Musinga Yuhi V, live a few long-horned Ankole cattle, descended from the king’s herd. They are kept with great care, and if you are lucky, you might see and listen to the keepers singing to them.

Don’t be surprised.

Thanks to its average altitude, Rwanda has a mild and cool climate, which means good pasture and welfare conditions for animals. It is no surprise to find that animal husbandry has always been an integral part of the Rwandese culture. Cattle and the inyambo cows, in particular, have served as a symbol of political power and have been the traditional mainstay of the Rwandese economy. In the past, owning a cow, especially of the inyambo breed, was a symbol of wealth and the common denominator of elite members. These animals were highly praised not just as a status symbol but as sources of valuable foods: the availability of milk, yogurt, and dairy products made a huge difference in diet, nutrition, and quality of life. In the ancient Kingdom of Rwanda, in honor of the inyambo cows, a special group of poets, called in French les nommeurs (‘the naming ones’), composed and memorized long poems, les noms des vaches (‘the names of cows’), which exalted their beauty and vigor.

Uwanyoye inka by Massamba Intore, 2021.

Massamba Intore is a Rwandan producer, songwriter, and Maître of the Ballet National du Rwanda.

Rwambyaye by Clarisse Karasira, former journalist and news anchor, now singer and poet, born and raised in Kigali.

She composed this song in the traditional indirimbo gakondo style and wrote about it: «The song is about Rwanda, my motherland. It is expressing my love for Rwanda and Rwandans and my wishes to fellow countrymen and women. I’d like to remind them who we truly are and our duties to uphold peace, unity, hard work».

The traditional female dance you saw in the above video and in all of the previous ones is called Urushara or le port des bras gracieux, the “dance with the most graceful movements of the arms”. All the female dancers wear ceremonial clothing like the traditional umushanana, with a sash draped over one shoulder.

Music and dance are an essential part of Rwandan culture and social life. Rugano Kalisa, a Rwandan historian, says that Rwandans use dance as a way of expressing themselves. They danced when they were happy or sad, after a victory and a defeat, when they needed to create social unity or to thank God, when they had a good harvest or a child was born. Still today, music is everywhere in Rwanda and many people sing and dance to remind who they are and even to heal their wounds and find peace. We’ll talk about that again.

Did you notice in the video the Kigali Convention Centre?

Today, the long-established domical huts are no longer built for many reasons. However, the traditional beehive thatched dome relives in contemporary architecture. The Kigali Convention Centre (below), completed in 2016, houses the 5-star Radisson Blu Hotel Kigali, a Conference center, the Kigali Information Technology Park, and a Museum. It quickly became an iconic building of the capital for two reasons: its dome shape Auditorium reproduces the main hut in the King’s Palace, and the nearby hotel’s architectural façade replicates a traditional and colorful weaved basket.

THE RWANDAN ART ‘PAR EXCELLENCE’

The Rwandan vernacular traditional architecture relies upon a breathtaking mastery in the arts of processing, sewing, weaving all kinds of natural fibers: the African alpine bamboo (umugano, imitamu y’imigano), papyrus strips (insasanure or ingaga), papyrus stems stripped of their first outer bark (infunzo), goosegrass stems (Eleusina, imamfu), reeds (umuseke), banana tree bark (ibirere), Ficus shrub fibers (umuvumu), sorghum flexible stems (amasaka), raffia palm fibers stripped from the inside of the leaves (ubuhivu), Pandanus leaves, sisal from the Agave sisalana leaves (ubutumba bw’umugwegwe), sweetgrass.

Basket weaving was not confined to the weaving of baskets: it played an essential role in the making of structural elements in architecture, and in the production of the most important tools in plant/animal farming, hunting, fishing, and daily living. «In Rwandan society, fiber items were key tools for farming activities, providing the necessary elements in the construction of granaries, beehives, or fishnets. Harvested crops were traditionally stored in large baskets whose shapes and sizes were customized for specific types of grains. Cattle-raising was one of the main sources of income for most Rwandans. A shepherd’s equipment included a milk jar covered by a basketry lid. The shelves that held these were also decorated with ornamental tapestries made of woven fibers. Fibers were also the prevalent component of clothing for farmers and members of the alike until the 1920s, when imported textiles began to replace the fibers of traditional attire» (Yaëlle Biro, see Bibliography). Les paniers de transport were large-sized, woven transport baskets usually carried on the head; even the palanquins used for the king and the nobles were made with woven fibers and bamboo poles.

In short, natural fiber processing and weaving have been for centuries at the very heart of Rwandan material and immaterial culture.

Rwanda, early 20th century: traditional giant baskets, called ibigega, filled with sorghum.

BELOW

Women carrying giant baskets, Rwanda.

Photo by Michael Runkel, 2014 / Alamy Stock Photo

Transport of baskets with bicycle in Rwanda

© SeppFriedhuber / Getty Images Signature

Basketry was gender-specific: la vannerie des hommes, ‘Men’s Basketry’, included the making of all large-sized architectural elements (like roofs and ceilings, for example), and of granaries, beehives, fences, animal traps, palanquins, combat shields (some of them were made of wood reinforced with a double layer of woven fibers) and giant containers. La vannerie des femmes, ‘Women’s Basketry’, made by high-ranking women of the court and the aristocracy, harmonized beauty and utility to create delicate baskets, trays, wedding vases, bowls, wall panels, floor mats, and screens of surprising perfection.

Today the basketry of men is in decline. No more domical hut can be built. «Vernacular building methods have evolved according to the needs and desires of multiple agents, and “traditional” architectural materials and forms have been sequestered into specific spaces such as museums and tourist facilities in an act of distancing from the past, helping to solidify Rwanda’s claims of modernization» (Jennifer Gaugler, see Bibliography). Moreover, many objects of the men’s basketry are no longer in use (the combat shields, for example).

In daily life and in agriculture, the traditional woven containers and tools are still being used, as in 2008, the Rwandan Government banned the use of plastic bags by law. This Act (Law No. 57/2008) was among the most severe and prohibited manufacturing, import, use, and sale of non-biodegradable plastic bags. It was repealed in 2019; the new Law No. 17/2019 reads: «The manufacturing, importation or sale of plastic carry bags and single-use plastic items is prohibited», except for «woven polypropylene».

Tea harvesting with woven baskets at the Kitabi Tea Processing Facility.

Photo by A’Melody Lee / World Bank, 2013

(licensed under Creative Common Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Today, women’s basketry is in full revival. It’s been able to preserve its artistic heritage and acquire an unexpected socio-economic role in contemporary Rwanda. It’s a long story, and we have to start from the very beginning.

LA VANNERIE DES FEMMES : AGASEKE AND ITS SIBLINGS

AGASEKE

Agaseke and igiseke are the names of the most iconic among the Rwandan baskets. The two terms are synonymous in Kinyarwanda, but some sources (like Kanimba Misago, see Bibliography) reserve the first only to the small to medium baskets used as gifts or to store valuables, and the second to the larger ones, once used to transport grains, store beans, and dry foods, or preserve sorghum bread (umutsima wa masaka). Some others (like (Vanessa Drake Moraga, see Bibliography) call agaseke or igiseke the large to medium-sized baskets, used for prestige display or storing personal finery, beadwork, pipes, tobacco or grains, and udoseke the small and miniature baskets that were gifted as valuable homages to chiefs, honored guests or newlyweds. For the sake of simplicity, I’ll use the term agaseke for all baskets.

Thanks to its distinctive sculptural form, the agaseke (sometimes written agaseki) is probably the most recognizable basket in the world. Its cylindrical body with a flat bottom is topped with a sloped conical lid, whose main feature is an impudent pointed tip that has no other function than to be watched. It’s a masterpiece of design and fine craftsmanship, and thanks to its tight stitches, is also a fully functional object, able to protect any content from environmental conditions or pests. It came and still comes in a variety of heights, from miniature to 60-70 cm and even more.

Agaseki basket, 20th century, Tutsi, Rwanda. Plant fiber and dye.

The black design is called urugaga, a term that in Kinyarwanda means ‘association’, ‘fraternity’, ‘alliance’.

It’s a large-sized piece whose height is 67 cm, and diameter 23.4 cm (26 3/8 x 9 3/16 in.).

Courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum, NJ, US.

The following is a basket from my personal collection. It’s an elegant, medium-sized agaseke with a pedestal base from the first half of the 20th century. It shows the same urugaga design of the above agaseke but is half its height: it’s only approx. 36 cm (14 in) high. It was likely used to store valuables.

The following vintage piece of exquisite shape and natural shades is even lower: its height is only 27 cm (10 5/8 in).

Basket with lid (agaseki), 20th century, Tutsi artist. Plant fiber and dye.

The black design is a composed one, whose simpler element is called ibikonjo or udukonjo.

It’s a small-sized piece: 27 cm high with a diameter of 14.5 cm (10 5/8 x 5 11/16 in.).

Courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum, NJ, US.

The following ‘potbellied’ agaseke is a miniature basket, only 15.30 cm (6 in) high.

Coiled basket and lid made of grass. Natural colored with geometric patterns in black-dyed grass. Tutsi, Rwanda, early 20th century.

Height: 15.30 cm (6 in). The pattern is ibigobe by’uruzi, “curves of the lake shore”.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

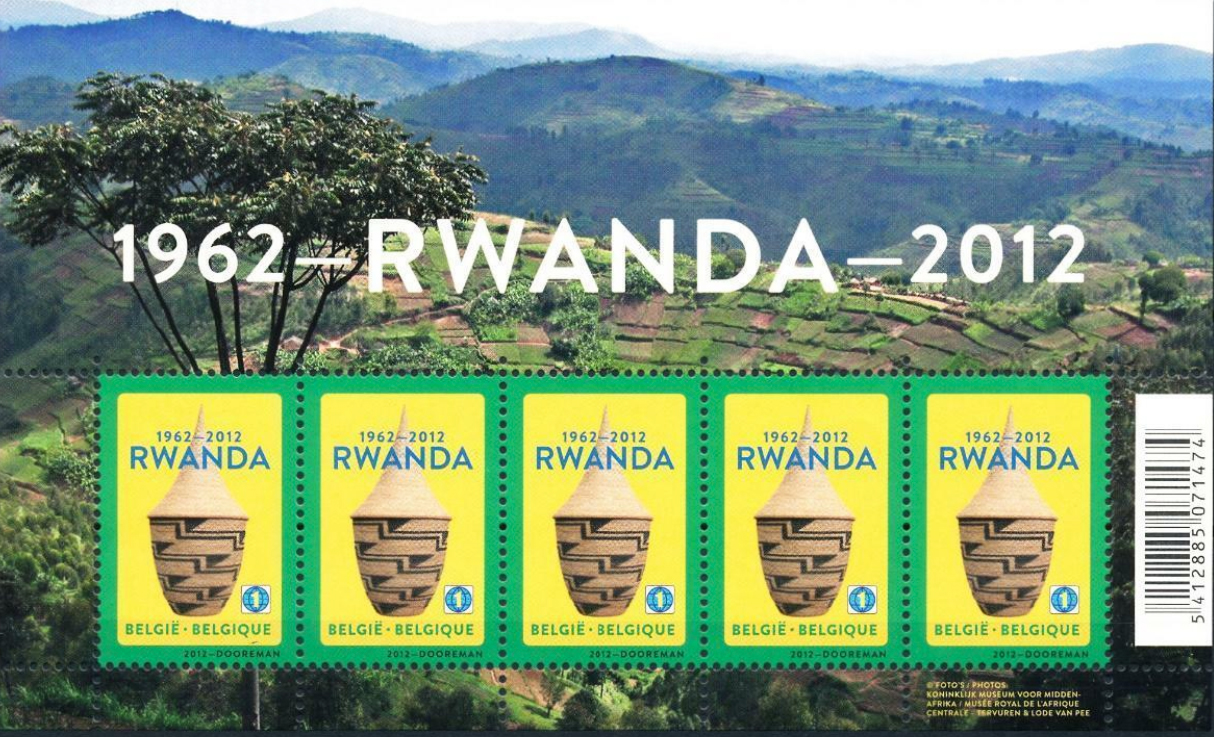

Belgian stamps designed by Gert Dooreman in 2012 to celebrate the 50th Anniversary of the Independence of Rwanda

«Although they did serve to store personal finery and possessions (…), as well as grains, the containers were not merely utilitarian. They were intended to be displayed in the home as emblems of affluence and social importance. Within a society that elevated the use of fiber into an essential material for living, craft, and artistry, an assemblage of fine basketry, arrayed on specially decorated ledges and shelves, conferred and projected status on domestic interiors» (Vanessa Drake Moraga, cit.).

The agaseke was not a ‘common’ basket: it was a prestige object, a prize possession, an indicator of wealth and power, reserved to the elite members and households. Not by chance, you can still see some fine baskets aligned in proud order in the secretive king’s bedroom of the Nyanza Mwami Palace. That’s why in the past, the agaseke was an appreciated gift to honored guests (often containing a food offering) or a ceremonial exchange during marriages or relevant events. It was a ritual homage that formalized the forging of a bond, a friendship, an alliance.

The weaving of these baskets takes time and patience and once was reserved to the women of the Tutsi aristocracy, who had plenty of both, not being forced to make ends meet. They spent their afternoons and evenings sitting together, meticulously weaving baskets or doing different kinds of beadworks, while a musician was playing in the background.

Agaseke ka nyabitabo was the name of the small basket made by a newlywed wife to prove her qualities to the husband’s family. To make an agaseke, you need dedication, patience, and an unusual mix of precision, proper upbringing, and creativity not just to perfectly weave it, but also to create an impeccable basket faithful to tradition, yet able to get noticed and stand out. As you could see in the above pics and will see below, the agaseke baskets came (and still come) in a remarkable variety of forms within a unique paradigm. The typical design could (and can) be declined in different ways: the variation of the volumetric relation between body and lid leaves a vital space for female creativity.

Three Agaseke baskets of different dimensions, natural shades, patterns, and shapes. All from the 20th century (likely the first half).

All courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum, NJ, US.

Left to right:

Basket with lid (agaseki). Pattern: amatana. Dimensions: height 24.7 cm, diameter 12.2 cm. (9 3/4 x 4 13/16 in.)

Basket with lid (agaseki). Pattern: ishobe. Dimensions: height 24.9 cm, diameter 13.2 cm. (9 13/16 x 5 3/16 in.)

Basket with lid (agaseki). Pattern: ishobe with ingondo. Dimensions: height 20.8 cm, diameter 8.1 cm (8 3/16 x 3 3/16 in.)

There are many traditional weaving techniques. The majority of agaseke baskets was and is still made via the uruhindu (or better ububoshyi bu’uruhindu), a thousand-year old coiling technique (technique spiralée cousue) thanks to which some sisal fibers are wrapped and stitched over a coil of grass. The weaver, in other words, has to sew together little bundles of grass, following a spiral course, always working with a hand that has to be as firm and vigorous as precise and perfectly regular (something that requires years of practice).

The below picture shows some rough agaseke baskets as works in progress. The two following videos show respectively the sisal processing and the uruhindu stitching (the Rwandan women in the second video work to create colorful bowls and vases, different from traditional agaseke baskets, but the technique is exactly the same).

These specimens are intentionally roughly worked so that one can better understand in which way they are woven and stitched, 2017.

© Kulturzentrum Festung Ehrenbeitstein | Landesmuseum Koblenz / Landesmuseum Koblenz, Germany. Photographer: Friederike Brinker – Creative Commons license: CC BY-NC-SA.

Today, Rwandan women still make and sell agaseke baskets. Something has remained the same, and something has changed.

The natural fibers, the weaving techniques, the patience, and the precision to which these last force all women did not change. Even the female habit of working together, chatting and laughing, has remained the same.

The picture below shows an agaseke made in 2017, following the tradition. Its newness is shown by the lighter color of the natural fibers and the intense unnatural blackness of the black; the charming golden/darker patina and faded black/brown designs of vintage baskets are due to the aging of non-chemically-treated fibers.

Agaseke, Huye District (Rwanda), 2017. Dimensions: height 23 cm, diameter 9 cm (9 x 3 1/2 in).

© Kulturzentrum Festung Ehrenbeitstein | Landesmuseum Koblenz / Landesmuseum Koblenz, Germany. Photographer: Friederike Brinker

Creative Commons license: CC BY-NC-SA.

The colors of most agaseke baskets made in the first half of the 20th century were not obtained via artificial chemical substances.

The background shade is the natural color of the fibers: it tended to slightly darken over time and sometimes to acquire a rich golden patina.

«Black and shades of grey and brown were derived from banana flower sap, mud, charcoal, or soot from a metal pot that was fixed with Phytolacca or Diospyros abyssinica. Red was obtained from Pterocarpus redwood bark, ocher, the roots and seed of several local plants (…)» (Vanessa Drake Moraga, cit.). There were different procedures to get the black color (umukara). In one of them, the aloe leaves were cut into pieces and allowed to soak in cow urine; then, they were mixed with ash from burned banana skins.

Agaseke baskets, first half of the 20th century, with a natural darkened tone due to aging.

Height left to right: 20.32 cm/8 in.; 19 cm/7.5 in.

Pattern left to right: ingembe, multiple ibikonjo.

By courtesy of © Africa Direct, a US African Art store, headquartered in Denver, Colorado.

«With the wider availability of commercial aniline dyes in the 1930s, purple, green, and blue were added to the color repertoire» (Vanessa Drake Moraga, cit.).

Today, natural dyes are less and less used. Many agaseke baskets made to be sold as souvenirs show new bright colors, such as light blue, yellow, and green – the colors of the Rwandan flag – or new bold hues, such as fiery red, pure white, or rich black.

Contemporary agaseke baskets in black and white, showing the traditional pattern, called umuraza (representing a path traveled together).

Each of them is 12.5/14 inches (approx. 32/35 cm) tall, and its weaving takes one week of work. They’re not made via the uruhindu coiling technique, but a different antique one, called inyanja, with the use of local grasses and banana leaves, woven over a papyrus frame with the help of a sisal or raffia thread.

Photo by Azizi Life.

You do not need to go to Rwanda to buy contemporary agaseke baskets (but it’s definitely much better to buy them on-site, of course!): the Internet is rich in fair trade organizations which partner with Rwandan artisans, Rwandan handicraft companies dedicated to women’s economic empowerment and Rwandan cooperatives which creates 100% sustainable high-quality products, weaved with the traditional methods, and showing the antique Rwandan patterns.

The authentic old pieces, rich in golden shades and faded designs, are becoming rarer and rarer. They can be found in African Art galleries or, from time to time, up for bid in international auctions by Sotheby’s, Christie’s, Catawiki, and the like.

A real dive into the distant Rwandan past? The following song and video, performed by Teta Diana, a young Rwandan artist born in 1992, will plunge you into the universe of the pre-colonial Tutsi aristocracy.

AGASHINGE by TETA DIANA, 2021

The scene at 2.19-2.24 min. shows the characters drinking beer with a wooden straw from a large clay pot. The drink is urwagwa, the so-called “banana beer”, produced mainly from the fermentation of ripe igitoki, the East African Highland bananas. This beer is the oldest and most popular Rwandan alcoholic drink.

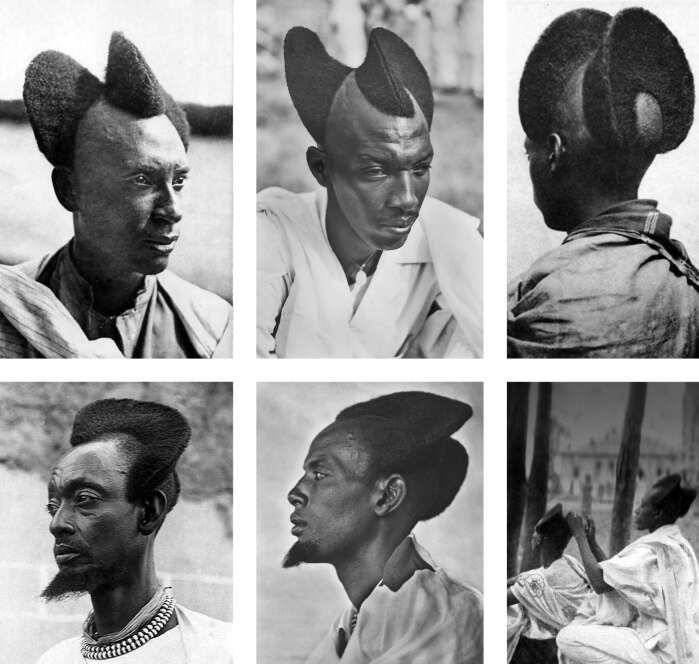

Did you notice the unusual haircut of an intore warrior and dancer?

It’s called amasunzu and is an elaborate traditional hairstyle worn by noble Tutsi men and unmarried women. In the first, it was an indicator of their high social status; in the second, a sign of their marriageable age. The warriors used it as a symbol of strength and bravery, the elite girls of virginity.

Did you notice the weaverbirds and their nests of intricately woven vegetation? (2.47-2.50 min.)

This small finchlike bird is a Ploceus, a genus widespread in Sub-Saharan Africa, well known for its “art of weaving” large nests with thin strands of leaf fiber, grass and sticks. Yep, in Rwanda, even birds love weaving.

Black-headed weaver (Ploceus cucullatus bohndorffi) male nest building, Queen Elizabeth National Park, Uganda.

Sharp Photography, 2016 (under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license)

MORE ON THE RWANDAN ART OF BASKETRY

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?