Rwandan Basketry 7

Rwanda on the globe

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE: THE BEGINNING OF 1994

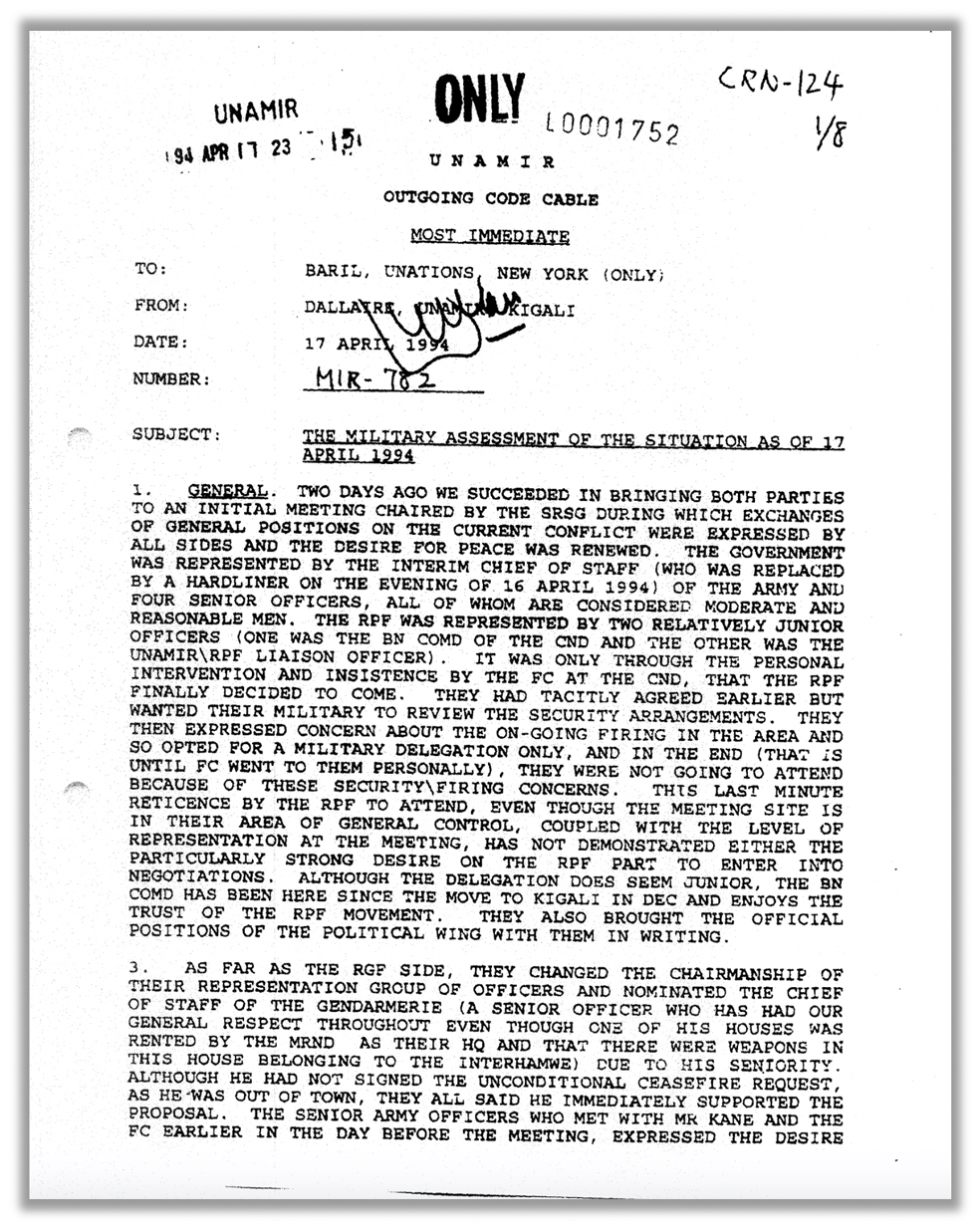

WARNINGS OF CATASTROPHE

The peace that the UN peacekeepers were in Rwanda to keep was a pure illusion to which the bureaucrats of New York adhered with the same stubbornness with which an eleven-year-old provincial girl keeps attached to a Prince Charming vision.

The distribution of weapons to civilians and paramilitary militias proceeded with increased acceleration. According to Jacques Castonguay and Linda Melvern, in April 1994, some 85 tons of munitions appeared to have been distributed throughout Rwanda. It was an alarming sign undoubtedly, but it didn’t remain the one and only: the first months of 1994 saw a succession of frightening events, warnings of catastrophe, and predictions of the imminent genocidal apex.

Provocations against the Belgian contingent of UNAMIR dangerously multiplied; in February, Colonel Marchal explicitly feared «a deliberate intention to create incidents with soldiers of the Belgian detachment». At the same time, Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) began to spread fake news and give fabricated and manipulative information to the detriment of Belgian peacekeepers. On January 31, RTLM broadcast that «the time has come to take aim at Belgian targets». On March 22, «Georges Ruggiu, a Belgian announcer on RTLM radio, warned that the Belgians wanted to impose an RPF government of bandits and killers on Rwanda and <said> that the Belgian ambassador had been plotting a coup. He told the Belgians to wake up and go home because, if not, they would face a “fight without pity”, “a hatred without mercy”» (Alison Des Forges, cit.). Ruggiu was not alone: other RTLM presenters, such as Valérie Bemeriki, Noël Hitimana, and Gaspard Gahigi, continually launched virulent attacks against the Belgians, not hesitating to ask the people to consider Belgian soldiers in the UNAMIR and the Belgians altogether as accomplices of the RPF and therefore enemies of the country. In the last days of March, RTLM broadcast increasingly bitter attacks on UNAMIR, Commander Roméo Dallaire, the Belgians, and some Rwandan political leaders.

A Belgian military assistant working at the Kanombe military camp as a munitions restorer, Warrant Officer Daubie Benoît, said during a hearing that in the last days of March, his cleaning lady told him to be careful, that Belgians were going to become ‘white Tutsis’. «She meant that there were lists of people to be slaughtered and that we, the Belgians, could be on this list» (source: The Mutsinzi Report). It was not supposed to be a state secret if even a humble cleaning lady knew about it. The head of the Belgian military-technical cooperation in Rwanda, Colonel André Vincent, asked the Rwandan authorities to end this slander and filthy campaign. It was whistling in the wind, of course. «Individuals from the Presidential Guard and the para-commando battalion were chosen by Majors Mpiranya and Ntabakuze, and sent in civilian clothes to demonstrations by political parties, with the mission of fomenting unrest alongside Hutu militia, Interahamwe and Impuzamugambi, to provoke incidents with the Belgian contingent of the UNAMIR. The assassination of ten Belgian blue helmets on 07 April 1994 was the culmination of this campaign and had the desired effect of the withdrawal of Belgian soldiers» (The Mutsinzi Report).

The violence kept escalating with an alarming progression, especially in Kigali. On February 20, a death squad tried to kill Prime Minister-designate Twagiramungu; the day after, Félicien Gatabazi, leader of the Social Democratic Party (PSD), was assassinated (according to a plan highlighted by some moderate high-ranking military officers in their December 3 letter to Dallaire).

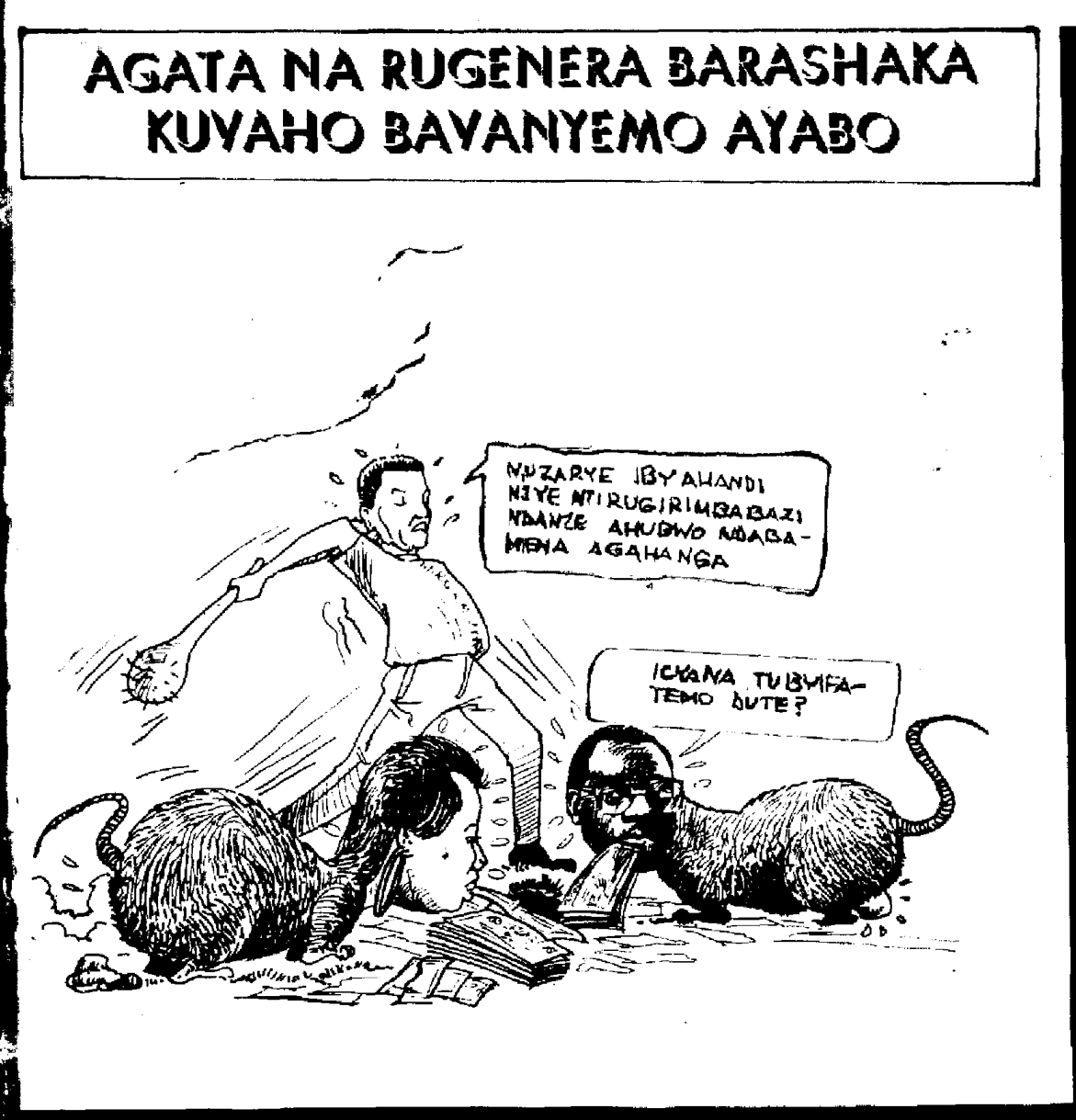

The anti-Tutsi propaganda became more and more vulgar, obscene, and explicit. RTLM began to divulge lists of cockroaches and their Hutu companions to ‘keep an eye on’. On March 1st, RTLM broadcasted “inflammatory statements calling for the hatred – indeed for the extermination” of the Tutsis. The mudslinging of some members of the opposition became an incitement to murder. The hardliners’ press did not lag. Issue no. 56 of Kangura, out the first week of February, published a cartoon on its cover. Here it is.

The title reads “Agathe and Rugenera would like to take their share before giving up the power” (all translations from Kinyarwanda are mine). Agathe here is not “Madame Agathe”, Habyarimana’s wife, but Agathe Uwilingiyimana, Prime Minister of Rwanda from July 18, 1993. She was a moderate politician, fiercely opposed to Habyarimana, Hutu Pawa, and the hardliners’ positions. Marc Rugenera was at the time Minister of Finance (today is vice-president of the Social Democratic Party in Rwanda). Both are depicted as rats. Rugenera says to Uwilingiyimana: “Honey, what are we gonna do?”. The man behind is going to kill them both with a mace. He is Denis Ntirugirimbabazi, Governor of the National Bank of Rwanda between 1991 and 1994. He says something like “You are going to eat the things of others, but I won’t let you, and I’ll crash your heads” (I’m sorry but I have some difficulties in reading the printed words and my translation is approximate). Note that the wooden club studded with nails will be a weapon frequently used during the ‘final solution’. Agathe Uwilingiyimana was threatened several times and assassinated on April 7 together with her husband. They both knew to be on the ‘list’ and tried to save their children, hiding them in the housing compound for the employees of the United Nations Development Programme. The children survived and were saved by Captain Mbaye Diagne, a UNAMIR military observer, who smuggled them into the Hôtel des Mille Collines, where many Tutsi found refuge.

Contrary to what Iqbal Riza said to Philip Gourevitch, the months of January, February, and March are full of events, revelations, documents, reports, and testimonies that forewarn the hell that will overwhelm Rwanda in early April. The extermination of all Tutsis was a sort of “segreto di Pulcinella” as Italians say when they want to designate an open secret. Lists of thousands of Tutsis to be exterminated at the ‘right’ moment began to surface among diplomats, Western intelligence officers, and foreign journalists. On February 20, according to an interview given by Jean-Berchmans Birara, former Governor of the National Bank of Rwanda, to a Belgian reporter of La Libre Belgique in May, Rwandan army Chief of Staff Déogratias Nsabimana, who was one of his relatives, showed him a list of 1,500 persons to be eliminated in Kigali. Jean-Berchmans Birara indicated having reported this intelligence to Western chancelleries and “to a very high political level in Belgium” without being heard. (Sources: The Preventable Genocide, 9.13 and other Rwandan sources, such as The Report of the investigation into the causes and circumstances of and responsibility for the attack of 06/04/1994 against the Falcon 50 Rwandan presidential airplane). On March 2, an MRND whistleblower told a Belgian intelligence officer that the MRND had a plan to exterminate all Tutsis in Kigali if the RPF should dare to resume the war (source: Alison Des Forges). On April 4, at a reception organized to celebrate Senegal Independence Day at the Méridien Hotel in Kigali, Colonel Théoneste Bagosora told the bystanders that “the only plausible solution for Rwanda appears to be the extermination of the Tutsis”. Among participants, there were Dallaire, Booh-Booh, and Marchal (source: The Preventable Genocide, Alison Des Forges and other reliable sources, including the Senate of Belgium, Report of the Commission of Parliamentary Investigation concerning the events of Rwanda, Brussels, 1997).

The implementation of the BBTG, the “Broad-Based Transitional Government” provided for in the Second Protocol of the Arusha Accords, was stalled and totally out of track. Nothing new: it was yet another display of Habyarimana’s glorious old strategy. Italians have another nice saying for it: “mettere il piede in due scarpe”, literally putting the same feet in two different shoes. Habyarimana’s strategy of a single foot paired with two shoes worked well for three years but at the beginning of 1994 was timeworn and barefaced, and looked more like a blind alley with no political exit than a successful policy.

«The installation of the new government, originally set for January, was postponed to February and then postponed again to March 25, and then again to March 28, and then again to early April. (…) The warnings of catastrophe multiplied, some public, like assassinations and riots, some discreet, like confidential letters and coded telegrams, some in the passionate pleas of desperate Rwandans, some in the restrained language of the professional soldier. A Catholic bishop and his clergy in Gisenyi, human rights activists in Kigali, New York, Brussels, Montreal, Ouagadougou, an intelligence analyst in Washington, a military officer in Kigali—all with the same message: act now or many will die» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

But nobody acted.

Canadian Peacekeepers soldiers stacking sandbags outside the UNAMIR headquarters in Kigali, Rwanda, in 1994.

Photo: by courtesy of the Department of National Defence / Veterand Affairs Canada.

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE: THE ASSASSINATION OF HABYARIMANA AND ITS AFTERMATH

The ambiguous strategy of Habyarimana was getting an overcooked recipe and the international community was becoming less and less dazzled by the President’s positive aura. The pressures on him to stop stalling the implementation of the Arusha Accords multiplied, especially from the neighboring countries. In March, the Ambassador of Germany explicitly told him that «the support of the European Union from now on will depend on the implementation of the Accords». The UN Secretary-General went as far as to threaten to withdraw the UNAMIR if nothing was done to break the deadlock.

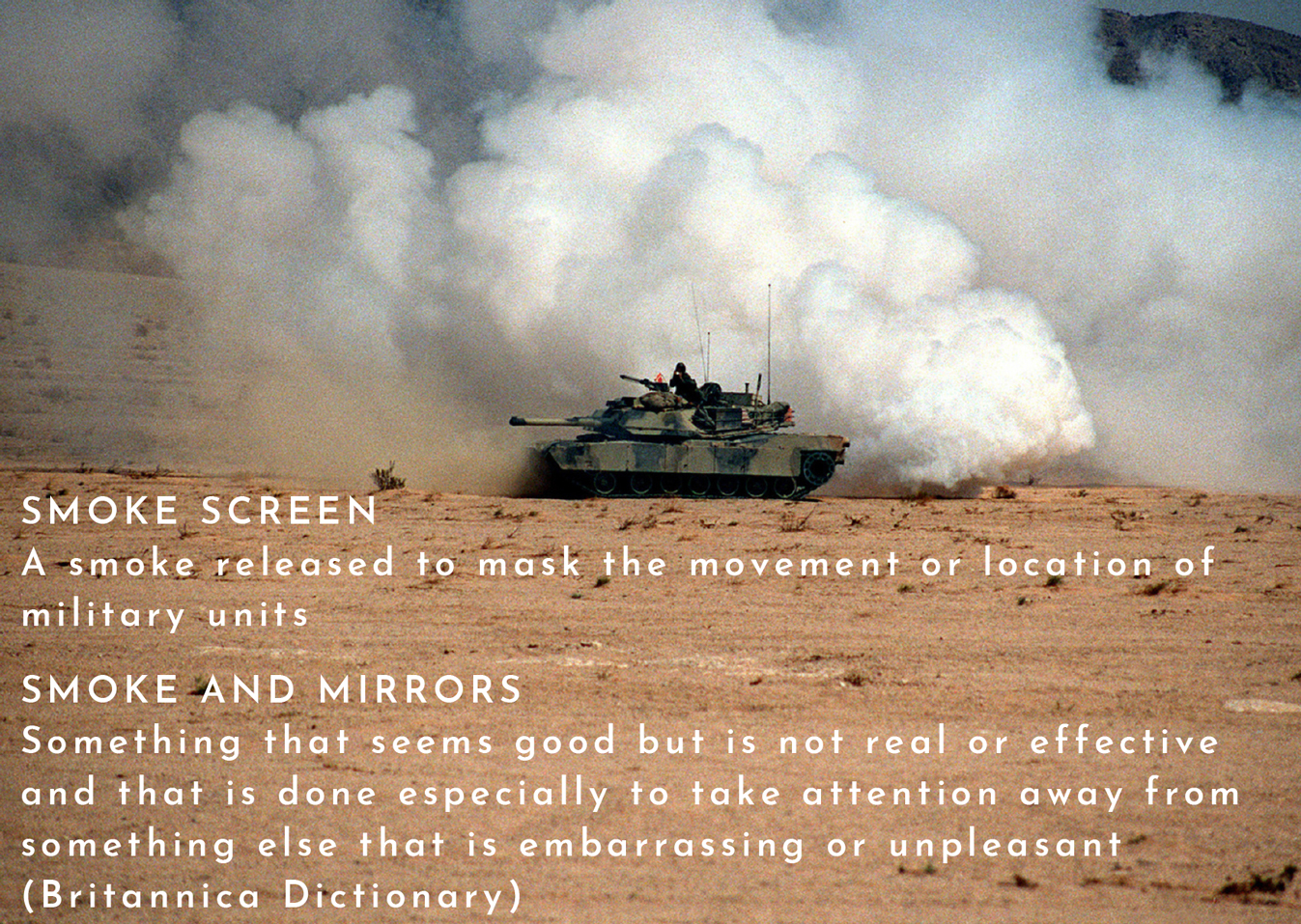

In April 1994, the neighboring States decided to intervene more actively and organized a summit in Dar es Salaam, in Tanzania, to find a settlement for both the Rwandan affair and the Burundian troubled situation. The Summit began on April 6, late in the morning, and brought together the presidents of Uganda, Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda, and the Kenyan vice-president, while the Congolese President and dictator, Mobutu Sese Seko, canceled his arrival at the last moment. According to Jean Kambanda’s testimony to the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR), Mobutu Sese Seko did not go to Dar es Salaam and suggested to Habyarimana not to go, following a warning he had received from a very senior official in the Élysée Palace in Paris (please, note: French secret services alert no.1).

The Summit was chaired by Ali Hassan Mwinyi, president of Tanzania, in his capacity as a facilitator in the process of resolution of the Rwandan and Burundian conflicts. President Habyarimana officially declared his strong will to remove all of the obstacles to the execution of the Arusha Accords and finally consented to put in place the broad-based transitional government.

Was it the usual farce?

I do not think. In the early months of 1994, Habyarimana was almost a politician at sunset, subject to constant death threats. He was probably thinking to honor the commitment he made by signing the Arusha Accords. A few days before the Summit, he had told Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh that the swearing-in ceremony of the BBTG was scheduled for April 8. Probably he was thinking of initiating the political process laid down in the Accords as his last presidential act, leaving the country immediately after, in a blaze of glory.

This time, unlike the previous others, he had an exit strategy: not a political but a personal one. I guess he was organizing his way out, counting on some of his French friends.

In the afternoon of Wednesday 6, Habyarimana and his staff prepared for their return. The Burundian President, Cyprien Ntaryamira, asked Habyarimana to fly home in the Rwandan plane, a French Dassault Falcon 50, together with some members of his staff. Hence the Rwandan Presidential plane had on board the Rwandan delegation and the part of the Burundian. As a result of this new arrangement, Anastase Gasana (Minister of Foreign Affairs), Faustin Munyazesa (Minister of the Interior), and other members of the Rwandan presidential delegation were not on board (the Falcon 50 could carry a maximum of 9 passengers in addition to the crew).

«The Rwandan delegation comprised the usual delegates accompanying the President of the Republic, with the exception of the chief of staff of the Rwandan army, General Déogratias Nsabimana, who was forced to accompany the president for the first time at the very last minute» (The Mutsinzi Report). This unusual order came from the MINADEF (the Rwandan Ministry of Defense) where Colonel Théoneste Bagosora was the powerful head of cabinet.

The French crew of the Habyarimana’s Falcon 50, made up of two pilots and a flight engineer, were quite nervous that afternoon. They asked Habyarimana’s security officer, Corporal Salathiel Senkeri, to postpone the departure to the morning, pointing out that they had received intelligence on threats of an attack against the plane (please, note: French secret services alert no. 2). However their request was not granted, and the Habyarimana plane took off at 6.07 pm to get to Kigali first and Bujumbura, in Burundi, soon after.

The Rwandan Presidential plane, a Dassault Falcon 50 9XR-NN, gifted to Juvénal Habyarimana by Jean-Christophe ‘papamadit’ Mitterrand.

Photo: © Manfred Faber / Source: PlanePictures.net

It’s 8.27 pm and it’s completely dark in Rwanda because the sun has already set for two hours. The Habyarimana’s Falcon 50 is expected to land at the Kigali International Airport within three minutes.

Whilst on its final approach on runway 28, the plane is suddenly shot down, and after an explosion on board, crashes to the ground.

The debris fall in and near the boundary wall of the Presidential Residence, which is only 300 meters from the Kanombe military camp and a few kilometers from the Airport. All occupants die in the attack. They were:

- Juvénal Habyarimana, President of the Republic of Rwanda

- General Déogratias Nsabimana, chief of staff of the FAR

- Major Thaddée Bagaragaza, aide-de-camp of Habyarimana

- Colonel Elie Sagatwa, special secretary to Habyarimana

- Ambassador Juvénal Renzaho, political affairs adviser to the presidency

- Doctor Emmanuel Akingeneye, private doctor to Habyarimana

- Cyprien Ntaryamira, President of the Republic of Burundi

- Bernard Ciza, communication minister of Burundi

- Cyriaque Simbizi, planning minister of Burundi

- Jacky Héraud, French commander on board

- Jean-Pierre Minaberry, French co-pilot

- Jean-Michel Perrine, French flight engineer

THROUGH INTO HELL

The Presidential plane was shot down at approx. 8.30 pm. After the crash, the RAF and the paramilitary militias were put in alert; the Presidential Guard and the elite units billeted in Camp Kanombe and Camp Kigali were fully operational within a few minutes.

- The Presidential Guard surrounded and closed the airport 20 minutes after the crash, then blocked the Belgian peacekeepers who were there, disarmed some of them, and kept them all as hostages. They will be released one day after.

- A section of the Commandos de Recherche et d’Action en Profondeur (CRAP, a unit in the para-commando battalion) was ordered to the Presidential Villa, on the crash site, to evacuate the bodies. French Commandant Grégoire de Saint-Quentin, who was an adviser to Major Aloys Ntabakuze, head of the Para-Commando Battalion, and two sub-officers were already on the crash site since 8.45 pm, only 15 minutes after the attack

- Gunfire was heard in the Kanombe area; sporadic machine-gun fire and rocket and grenade explosions were heard in various areas of the city the day after.

- UNAMIR was placed on red alert at about 9.30 pm.

- From 9.15 pm on, the Rwandan Armed Forces, in particular the CRAP with the help of the Interahamwe militia set up many roadblocks in Kigali, starting from the Kanombe area and the neighboring ones. At approx. 2 am, the Interahamwe militiamen started patrolling the streets in downtown Kigali. Getting around the city became more and more arduous and exhausting, running was impossible.

- Nobody was allowed to enter the airport and the crash site that night and the following days, except for the French and the Rwandan military personnel. The UNAMIR members were not allowed to enter the whole area and were denied to carry out any investigation.

Meanwhile, «the lightly armed RPF battalion prudently stayed on the alert inside the thick CND cement walls, listening to the radio, like everybody else» (Gérard Prunier, The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide, see Bibliography).

THE POLITICO-MILITARY SITUATION

A meeting with top and high-ranking officers of the two General Staffs (Army and Gendarmerie) was convened that night at the army headquarters in Camp Kigali to cope with the power vacuum: colonel Elie Sagatwa, the head of presidential security, and general Déogratias Nsabimana, Chief of Staff of the Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR), had perished in the plane. The minister of defense, Augustin Bizimana, was out of the country: he was attending a meeting in Cameroon along with Colonel Aloys Ntiwiragabo, the head of army intelligence (G2). Colonel Gratien Kabiligi, Operations and Training Officer (G3) at the General Staff was in Egypt for a 3-month stage.

Among the high-ranking officers, there were colonel Théoneste Bagosora, Colonel Léonidas Rusatira (Commander of the “Ecole Supérieure Militaire” or ESM), General Augustin Ndindiliyimana (Chief of Staff of the Gendarmerie since June 1992), Colonel Ephrem Rwabalinda (the government liaison officer to UNAMIR). Retired Colonels Laurent Serubuga and Pierre-Célestin Rwagafilita were not present but, according to French scholar Jean Morel, they made a phone call to propose their service,

Bagosora, who was a retired officer, presented himself as the most appropriate person to chair the meeting, taking precedence over senior officers in active service. According to Linda Melvern, he said it was his duty to assume responsibility, claiming superiority as the second in command at the Ministry of Defense and therefore the most qualified person on politico-military issues. One of the colonels suggested that it would be more appropriate for Major-General Augustin Ndindiliyimana, chief of staff of the National Gendarmerie, to chair the meeting, but the latter rejected the task for unknown reasons. Bagosora had the way open.

«Bagosora proposed naming Lieutenant Colonel Augustin Bizimungu, then commander at Ruhengeri and an officer whom he could trust as the new chief of staff. The group rejected Bizimungu as he was junior in rank and less experienced than many other officers. Colonel Léonidas Rusatira, present at the meeting, was the senior ranking army officer and a northerner, but Bagosora saw him as a rival. Sometime before, Bagosora and his supporters had succeeded in relegating Rusatira to the command of the Ecole Supérieure Militaire, a school where he had no combat troops under his orders. Rusatira’s name was proposed, but, perhaps anxious to avoid a conflict during this time of crisis, the officers passed over him and chose Colonel Marcel Gatsinzi as interim chief of staff. At that time, Gatsinzi was commanding the southern sector in Butare. Originally from Kigali, he was not a member of the inner circle of powerful officers from the northwest and would be unlikely to be able to mobilize a following strong enough to challenge Bagosora and his group» (Allison Des Forges, cit.). Marcel Gatsinzi served as Army Chief of Staff of the FAR only from 6 to 17 April 1994: because of his moderate approach and his opposition to the genocide, he was removed from the post (you can imagine who did it) and replaced by Augustin Bizimungu who, not coincidentally, had been promoted to Major General the day before.

During the meeting on the night between April 6 and April 7, Bagosora proposed the creation of a Military Committee (Comité Militaire) and pushed hard for the military to take control of the government, but on this matter, too, he was rebuffed. General Dallaire, who joined the meeting at 11 pm, declared that any military take-over would result in the immediate withdrawal of UNAMIR. He urged the officers to make contact instead with Prime Minister Uwilingiyimana to arrange for a legitimate continuation of civilian authority. However, «many officers believed that the prime minister, Agathe Uwilingiyimana, was incapable of governing» (Linda Melvern. Conspiracy to Murder, cit), and building on this, Bagosora adamantly dismissed any suggestion that the prime minister should assume any powers. «Bagosora told Dallaire that he did not want the Arusha Accords to be jeopardized, but the military needed to take control. This would only be for a short time, after which they would hand the situation over to the politicians» (Linda Melvern, ibidem). Dallaire wrote in his memoirs: «I didn’t trust him for a minute». Very wisely, I should say.

Under pressure from the other officers, Bagosora accepted to have a meeting with the UN Secretary-General’s special representative, Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh. Then Dallaire, Bagosora, and colonel Ephrem Rwabalinda left the meeting after midnight to meet Booh-Booh at his residence. «Booh-Booh asked at once whether or not this was a coup. Bagosora assured him it was not» (L. Melvern, ibidem). Again Bagosora rejected any role for Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana and refused to recognize her authority, but had to accept the ‘advise’ given by Booh-Booh who insisted that some form of civilian authority was necessary. «After the meeting, Bagosora and Dallaire returned to the Military School where the first was due to report to waiting officers on his meeting with Booh-Booh» (L. Melvern, ibidem).

«Colonel Théoneste Bagosora spent the morning of Thursday, 7 April in a series of meetings» (Linda Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit). At around 7 am he was at the Ministry of Defence with senior members of the MRND Executive Committee including its president Mathieu Ngirumpatse, its first vice-president Edouard Karemera, and its national secretary Joseph Nzirorera. At 9 am, Bagosora, together with General Ndindiliyimana and Lt. Colonel Rwabalinda, met with the United States Ambassador at his residence, acting as if he were the main authority in the country.

At 10.15 am, he took part in a new meeting at the Military School. «All Rwandan (…) commanders and all senior officers from the National Gendarmerie were present at the meeting, about one hundred officers. There were commanding officers of the operational sectors, the commanders of the military camps, and officers of the general staffs of the army and the gendarmerie». (Ibidem). Once again, he proposed an interim military junta and once again he was rebuffed. The decision that won the support of the majority was to initiate a series of political consultations in order to create a provisional civilian government and at the very same time to create a military Crisis Committee with senior officers of different political positions to coordinate the country’s security and defense until the full operativity of the provisional civil government. The meeting ended at midday.

The Crisis Committee met at 7 pm that very same day. «Bagosora wanted to preside over the meeting and when this was refused he became insulting». Later, the chief of staff, Colonel Marcel Gatsinzi, will remember that «Bagosora wanted to become the president of the Crisis Committee. Bagosora was told that this was impossible. It was a military committee and he was retired. When Colonel Rusatira questioned the powers of the Crisis Committee, Bagosora, near the end of his tether, stormed out of the meeting accusing them of preventing him from having a role in something he had created. For the second time, the officers agreed that the Presidential Guard must return to barracks». (Ibidem).

«Early on the morning of April 8, Bagosora assembled party leaders to fashion a civilian government, all of them, not surprisingly, from the Hutu Power end of the political spectrum. The MRND was represented by its president Mathieu Ngirumpatse, Edouard Karemera, and Joseph Nzirorera; MDR by its Power leaders, Froduald Karamira (…) and Donat Murego» (Alison Des Forges, cit.). There were also a few members of the other parties who, however, counted for nothing. Bagosora and the MRND leaders chose as President an aging pediatrician and a member of MRND, Théodore Sindikubwabo, often described as “someone with no personality” (= a malleable and manageable figure). The chosen Prime Minister of the caretaker government was Jean Kambanda, from the Hutu Pawa wing of MDR, a young economist and banker with little political experience (= a good puppet, easily controllable by Serubuga’s – Bagosora’s – Rwagafilita’s shadow clique). Both Sindikubwabo and Kambanda looked promising and ready to be docile instruments of the criminal trio. The chosen ministers came from the Hutu Pawa wings and were expected to be disciplined supporters of the shadow clique.

«On the morning of April 8, Bagosora sent from the Ministry of Defense a telegram to the army and the Gendarmerie recalling the officers under arms who were retired the previous year in 1993, in particular colonels Serubuga, Rwagafilita, Nshizirungu and Gasake» (Jacques Morel, Le rôle de Laurent Serubuga dans le génocide des Tutsi, 2019, see Bibliography). That very same day, at 4 pm, a new meeting of the Crisis Committee was convened; among those present, there were colonels Serubuga, Rwagafilita, and of course Bagosora. The latter presented the interim government to the Committee and other high-ranking military officers. «As they looked over the proposed new authorities, the military officers saw quickly that Bagosora “had chosen these men himself and that this was not at all what the meeting the night before had decided.” But the same officers who for two days had resisted Hutu Power in the military incarnation of Bagosora now accepted it in the political form of a self-proclaimed government. With the RPF pushing ahead vigorously, they felt pressure to shun politics and devote themselves completely to the work of being soldiers. Perhaps they also felt that they had taken their opposition as far as they could given the relative troop strength of the two sides and the absence of encouragement from foreign powers. Having accepted a proposed government that fell far short of the balanced group that some had expected, the crisis committee adjourned, never to meet again. (…) The interim government took office on April 9 and fled from the capital on April 12, just after the first RPF troops from northern Rwanda arrived in Kigali to reinforce those previously quartered in the city. It operated for a number of weeks at Murambi, near the capital of the prefecture of Gitarama, before fleeing further west and then north to Gisenyi and leaving Rwanda in mid-July» (Alison Des Forges, cit.). But you know, who did care? Politically they were nothing but puppets of the trio.

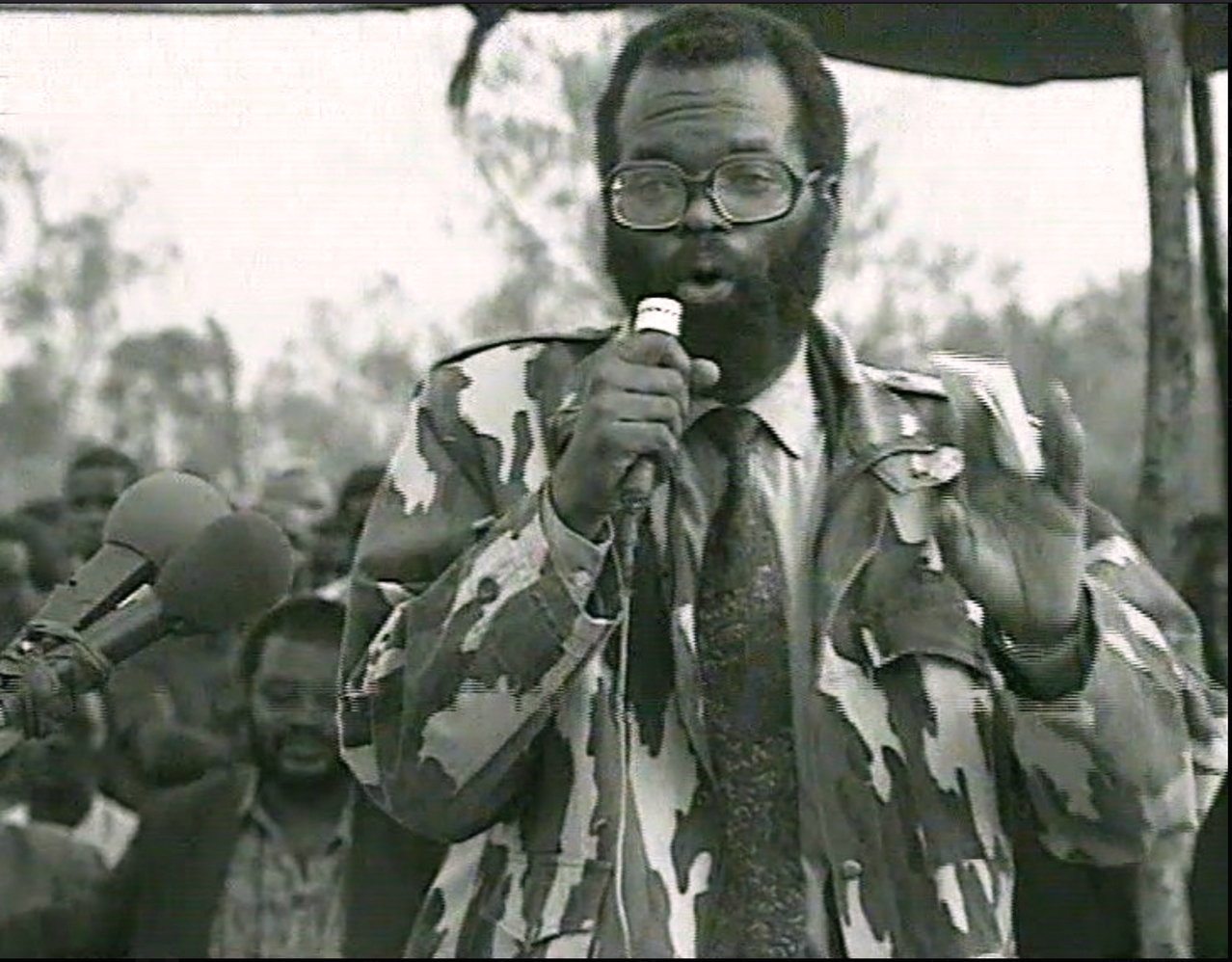

June 1994: Prime Minister Jean Kambanda visited Nyakabanda Commune, thanked the locals for the ‘good work’ against the Tutsis, and distributed more guns and ammunition.

On 4 September 1998, he pleaded guilty to genocide and crimes against humanity (murder and extermination), and Trial Chamber I of the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda had sentenced him to life imprisonment. He appealed against that sentence and later requested that his guilty plea be quashed and that he stand trial. In 2000, the Appeals Chamber dismissed all the grounds advanced by the Accused and upheld his sentence.

THE SLAUGHTER OF THE BELGIAN PEACEKEEPERS AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

We have seen how the first months of 1994 were marked not only by a growing smear campaign against UNAMIR and, in particular, the Belgian soldiers but also by continuous provocations against the latter in order to create a serious incident, push Belgium to withdraw its peacekeepers and bring down the whole of UNAMIR. Therefore, you won’t be surprised to know that immediately after the crash, Habyarimana’s supporters accused the Belgian soldiers of involvement in the Presidential plane shooting down. This news, conveniently spread, helped to intensify the climate of general hostility directed towards the Belgians.

On the night of April 6, Dallaire ordered Marchal to send a group of Belgian peacekeepers to the residence of Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana to provide her with a more robust armed escort. Marchal gave the order to one of his officers at 3 am, and 4 jeeps carrying 9 soldiers and one officer from the Belgian contingent were sent to Uwilingiyimana’s house to protect her and secure her way to the studio of Radio Rwanda where she was expected to deliver a message to the population. At 7 am, the 10 Belgian soldiers reached the Prime Minister’s residence where they found the 5 Ghanaian peacekeepers charged with the routine nightly guard. Soon, all of them were surrounded by Presidential Guard. Lieutenant Thierry Lottin, the highest-ranking soldier in the group, was asked by a Presidential Guard officer to deliver all their arms. «He was 29 years old. He radioed to the UNAMIR from the jeep at 8.49 am to say there was “high tension” with the Presidential Guard and asked would it be “OK to surrender”. He was told to negotiate. He said four of his men were already disarmed and on the ground. Lottin had the capacity to resist – each of the Belgian peacekeepers had an automatic rifle, half of them had revolvers and there were two semi-automatics in the jeeps. But he was told to relinquish his weapons if he thought it necessary. It was up to him to judge the situation. Lottin, receiving an assurance that the peacekeepers would be safe, and adhering to peacekeeping doctrine, told them to voluntarily disarm, although one of them secretly kept a pistol. They were taken in a minibus to Camp Kigali (…). There, they were beaten with iron bars, rifles, sticks, and stones» (L. Melvern, ibidem), and killed by CRAP’s A Company soldiers under Innocent Sagahutu’s command and members of the Presidential Guard, commanded by Major Protais Mpiranya.

Here are the Belgian peacekeepers killed that night:

- Thierry Lottin – born on December 28, 1964, killed at the age of 29

- Yannick Leroy – born on February 15, 1965, killed at the age of 29

- Bruno Bassinne – born December 31, 1966, killed at the age of 27

- Stephane Lhoir – born on April 5, 1966, killed at the age of 28

- Bruno Meaux – born on November 23, 1965, killed at the age of 28

- Louis Plescia – born on July 24, 1961, killed at the age of 32

- Christophe Renwa – born on August 17, 1967, killed at the age of 26

- Marc Uyttebroek – born on May 2, 1968, killed at the age 25

- Christophe Dupont – born on September 30, 1968, killed at the age of 25

- Alain Debatty – born on November 18, 1964, killed at the age on 29

The Belgian Peacekeepers Memorial Centre in Camp Kigali is located south of the city’s center, less than a mile from the Hotel des Mille Collines.

Google maps locator: [-1.958,30.063]. It was set up by Belgians on April 7, 2000. It includes the structure with bullet-ridden walls where ten Belgian soldiers were killed and a small memorial garden. The latter is made up of 10 dark grey granite columns, each commemorating a Belgian soldier. The horizontal incisions on a side represent the soldier’s age at the time of his brutal death: all except for one were in their 20s. The initials of each soldier are engraved at the bottom and matched with the commemorative plaques on a nearby wall, showing their complete names.

The brutal murder of the Belgian peacekeepers prompted the withdrawal of that contingent from UNAMIR on April 19.

«Suite aux événements du 6 avril 1994, le gouvernement belge a été amené à prendre une série de décisions. (…). En synthèse, il a décidé l’évacuation des ressortissants civils belges, en insistant auprès du Secrétaire général de l’ONU pour que la sécurité des forces de l’ONU soit renforcée. Il a ensuite décidé de retirer les troupes belges participant à la MINUAR» (Sénat de Belgique – Session de 1997-1998 – 6/12/1997 – Commission d’enquête parlementaire concernant les événements du Rwanda – see Bibliography). My translation: “Following the events of April 6, 1994, the Belgian Government was led to take a series of decisions. (…). In summary, it decided to evacuate Belgian nationals, pressing the UN Secretary-General to strengthen the security of UN forces; then it decided to withdraw the Belgian troops participating in UNAMIR”.

On April 9, the French landed a military force at the Kigali airport to conduct an evacuation of expatriates. French military under Operation Amaryllis (April 9-14) and Belgian soldiers under Operation Silverback (April 10-16) carried out the evacuation of their nationals. The United States and Italy mounted national evacuation operations as well. A total of 3,900 people of 22 nationalities were evacuated from Rwanda in a few days. The US embassy was the first to close, followed by all the others except for the Chinese.

The French Amaryllis Force was a specially-sized military force trained to carry out the evacuation of nationals, control the airport, pick up people, bring them back as quickly as possible, and stay as short as possible to avoid losses. Under the command of Colonel (today General) Henri Poncet, the Amaryllis Operation enabled the safe evacuation of 1,400 people: 600 French nationals and 800 foreigners, including 600 Africans (among them 394 Rwandans, including 40 leaders of the MRND). It was highly criticized as it did not include the evacuation of Rwandans threatened by massacres, even when they were employed by the French authorities or worked for French institutions such as the French Embassy and the French Cultural Centre, both in Kigali. Some French and Rwandan mixed couples and even families were separated, while Juvénal Habyarimana’s entire family (12 members) and other Rwandan VIPs were evacuated immediately, on the first day (the 9th). The French Embassy opened its doors to some members of the regime’s death squad, and members of the criminal presidential circle, the Akazu, but many Tutsis who tried to hang on to its gate were repelled and later killed by the militiamen. The employees and 97 children from the Sainte-Agathe orphanage founded by Agathe Kanziga Habyarimana were evacuated, but France refused political asylum to the children of Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana, murdered with her husband two days earlier. Tutsis who had succeeded in getting into the trucks of French soldiers had forcibly descended at the first barrier and were killed by militiamen in front of the unperturbed French soldiers.

Opération Amaryllis? A shame for France.

On April 9, 2011, during the 17th commemoration of the Genocide Against the Tutsis, the French Ambassador Laurent Contini said: «C’est une tache bien délicate pour un ambassadeur, pour un diplomate français, pour un citoyen français de faire face à ce passe douloureux, a cet épisode malheureux. Comment expliquer en effet que ces personnes, ces gens, qui travaillaient avec nous n’ont pas été évacuées lors de l’opération Amaryllis, en avril 1994 ? Des raisons ont été avancées, je les connais, je les ai lues, la sécurité, il n’y avait plus de place dans l’avion, on ne pouvait pas joindre les gens au téléphone, Kigali n’est pas une ville avec des noms de rues etc. etc. Après 17 ans, ce n’est pas des raisons qui sont convaincantes. (…) Maintenant, nous savons un certain nombre de choses. Par exemple qu’il y a eu un télégramme diplomatique le 11 avril 1994, qui donnait l’autorisation à l’ambassadeur d’évacuer le personnel, son personnel. Cela a été confirmé par un ordre donné aux militaires. Alors pourquoi ? Pourquoi ces gens là n’ont pas été évacués ? Je n’ai pas, je n’ai pas de réponse. Je n’ai pas de réponse mais en tout cas aujourd’hui, je tenais à le faire. Je tenais à vous exprimer, les membres de la famille, mes profonds regrets. Et vous présenter mes excuses. Pour cet abandon tragique» (My translation: “Facing the painful past, this tragic episode is a very delicate task for a French ambassador, diplomat, citizen. Why the people who worked with us were not evacuated during the Amaryllis Operation in April 1994? Many reasons were put forward, and I know them well: security, no more room on the plane, no more phone system, Kigali is not a city with street names, etc. After 17 years, we can say that these are not convincing reasons. (…) Today we know more. We know, for example, that there was a diplomatic telegram dated April 11, which permitted the ambassador to evacuate his Rwandan staff. This was confirmed by an order given to the military. Why weren’t these people evacuated? I don’t know. I have no answer. No answer. But today I want to say something on this issue. I want to express to you my deep regrets. I want to present my apologies. The apologies for a tragic abandonment”).

The Belgian Opération Silverback started on April 10; on Monday 11, the Belgian ambassador Johan Swinnen reached the Belgian Embassy from his residence in Kigali and started overseeing the procedures. More than 1,200 people including 1,000 Belgians and 200 Rwandans (those turned back by the French soldiers at the Kigali airport) were evacuated.

More interesting, however, is another ‘operation’ decided by the Belgians. On April 8, the Belgian Prime Minister Jean-Luc Dehaene told the UN that the Belgian peacekeeper soldiers «would only be left if they were given the means to defend themselves». The United Nations did not modify the UNAMIR mandate, Belgium then decided to withdraw its troops. According to General Joseph Charlier, Head of the Belgian Defense Staff in 1994, he was communicated the decision of the withdrawal by Leo Delcroix, the Belgian Minister of Defense, on the 12th. On the moorning of April 19, thanks to the Blue Safari Operation, all Belgian peacekeepers were evacuated in less than 5 hours.

«The evacuation was devastating for Rwanda. It sent a signal to the extremists that their well-laid plans could now be implemented without fear of too many prying western eyes». (Linda Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.).

THE SEARCH-AND-KILL OPERATION AGAINST POLITICAL AND INTELLECTUAL OPPONENTS

«Many ministers lived in Kimihurura, a residential area of detached villas set in large gardens with doormen on the gates of the individual compounds. At midnight <between April 6 and 7> judge Kavaruganda received a telephone call from his neighbour, Frederic Nzamurambaho, the minister of agriculture and president of the PSD Party. Nzamurambaho told him that everyone in their neighbourhood who was a member of the MRND was being evacuated by Presidential Guards. He had noticed a lot of military activity starting at about 10 pm. (…). Kavaruganda’s neighbour Nzamurambaho telephoned again at 4.30 am He was extremely agitated. He said they were trapped. The neighbourhood had been sealed by the Presidential Guard and all the MRND dignitaries who lived there had gone. At 6 am Nzamurambago saw the Presidential Guard approach Kavaruganda’s house». (Linda Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.). Both judge Kavaruganda and minister Nzamurambaho were killed early that morning by members of the Presidential Guard and the Para-Commando Battalion.

In less than 24 hours, the Kimihurura area where most ministers lived was cordoned by soldiers and gendarmes and, after a systematic search-and-kill operation, was ‘cleaned up’. The first people to be killed, starting at about 5 am on April 7 were the leaders of the political parties opposed to the hardliners of MRND and CDR, many of whom held important public office in ministries or judiciary. Their ID cards stated they were Hutus.

The following lists are not exhaustive nor claim to be. All of the data come from multiple sources, the most important of which is Rwanda: Who is killing; Who is dying; What is to be done – A Discussion Paper, signed in May 1994 by African Rights (more details on the Bibliography; the paper can be downloaded here).

On April 7, the following politicians and ministers were assassinated:

- Agathe Uwilingiyimana, Prime Minister and member of the Republican-Democratic Movement, sexually assaulted and killed with her husband Ignace Barahira by the Presidential Guard

- Frédéric Nzamurambaho, Minister of Agriculture and President of the Social-Democratic Party, killed by the Presidential Guard

- Judge Joseph Kavaruganda, president of Rwanda’s Constitutional Court, killed by the Presidential Guard

- Faustin Rucogoza, Minister of Information and member of the Republican-Democratic Movement, killed with ten members of his family by the Presidential Guard

- Landoald Ndasingwa, Vice-President of the Liberal Party and Minister of Employment and Social Affairs, killed together with his Canadian wife, their two children, and his mother by the Presidential Guard

- Félicien Ngango, Vice-President of Social-Democratic Party, designated speaker/president of the Transitional National Assembly <the parliament to be implemented thanks to the Arusha Accords> and vice-president of the human rights organization ARDHO, killed together with his wife

- Charles Kayiranga, member of the Liberal Party and Director of Cabinet in the Ministry of Justice, killed with his entire family by Interahamwe

- Déo Havugimana, lawyer, director of the staff at the Minister of Foreign Affairs and member of the Republican-Democratic Movement

The following politicians were killed in the following days of April:

- Boniface Ngulinzira, Former Ministre des Affaires Étrangères et de la Coopération and member of the Republican-Democratic Movement

- Vénantie Kabageni, president of the Liberal Party for the Kigali Ngali prefecture, killed by Interahamwe

- Maître Aloys Niyoyita, member of the Liberal Party, designated to become the Minister of Justice in the transitional government

- Augustin Rwayitare, member of the Liberal Party and head of the Department for IDPs in the Ministry of Labour

- Jean de la Croix Rutaremara, member of the Liberal Party

- Jean Baptiste Mushimiyimana, member of the Social-Democratic Party, killed by the Presidential Guard

- Théoneste Gafaranga, 2nd vice-president of the Social-Democratic Party, assistant of the Minister of Agriculture

- Charles Ntazinda, a Foreign Ministry senior official and one of the founding members of the Republican-Democratic Movement

- Paul Secyugu, member of the Social-Democratic Party

- Cyprien Rugamba, member of the Social-Democratic Party

- Charles Ntakirutinka, member of the Social-Democratic Party

- Alain Mudenge, member of the Social-Democratic Party, killed together with his wife

- Thomas Kabeja, member of the Social-Democratic Party

- Charles Kayiranga, member of the Liberal Party

- Augustin Maharangari, Manager of the Banque Rwandaise de Développement and member of the Social-Democratic Party, Tutsi, killed together with his wife and five children.

The Rebero Genocide Memorial in the Kicukiro District, in Kigali, is a resting place for some of the politicians killed in April 1994, and more than 14,400 victims of Genocide. Former Prime Minister, Agathe Uwilingiyimana, is buried at the National Heroes Mausoleum at Remera. These pictures have been shot during the Mourning Week in the 24th and 27th Kwibuka Commemoration and show the people honoring the politicians’ graves. Photos by the Rwanda Government.

Did you notice? The leadership of the Social-Democratic Party was almost completely eliminated. That was the only political party in the coalition that didn’t split into two wings, one of which was on the side of national unity under the Hutu Pawa umbrella.

Faustin Twagiramungu, the Rwandan moderate politician chosen in Arusha to lead the transitional government (BBTG), survived by pure chance. On the list in the hand of the soldiers, his address was misspelled; therefore, he was gifted the time to escape and take refuge inside the UNAMIR headquarters. That night, he lost many members of his family.

«In the following days, the killings concentrated on

- the remaining opposition politicians and dissidents;

- people highly placed in the administration of justice;

- intellectuals, including priests, lawyers, journalists <48 press journalists were killed in very few days>, academics and human rights activists regarded critical of the regime;

- wealthy businessmen with ties to the opposition parties or of Tutsi origin;

- prominent Hutus from the south.

(…). The human rights community was decimated in the first days of the killing» (African Rights, Rwanda: Who is killing, cit.).

Churches, priests, nuns, and religious centers were attacked during the first days after Habyarimana’s assassination.

«Among the very first victims were priests, visitors, and staff at Centre Christus <in the Remera area of> Kigali. At about 7 am on April 7, soldiers <from the Para-Commando Battalion> came to the retreat house and entered the chapel. They asked to check everyone’s identity cards, but no one had them. After ten minutes, the soldiers separated the nineteen Rwandese from the Europeans and locked them separately. At 2.20 pm, the expatriates were released. They found 17 bodies in the room where the Rwandans had been held: 8 young women belonging to the religious organization “Vita and Pax”, 4 diocesan priests, a visiting social worker; 3 Jesuit priests and the cook» (African Rights, Rwanda: Who is killing, cit.).

«In memory of our brothers and sisters victim of the genocide against the Tutsis at the Centre Christus on April 7, 1994»

Other clergymen were killed in Kigali in those days:

- Jean-Baptiste Rugengamanzi, a cure of the parish of Ndera in the archdiocese of Kigali, was killed in his church. His document stated he was a Hutu.

- Andre Caloon, a French priest in the parish of Ruhuha, Diocese of Kigali, was killed on April 7 by a drunken officer who grabbed his spectacles from him and shot him when he tried to take back his glasses.

- Father Mathieu Ngirumpatse and two nuns were killed at Nyanza.

- Spirition Kageyo, the cure at Rambura, the President’s parish, was a Tutsi and was killed with his two vicars, Tutsis as well: Antoine Niyitegeka and Antoine Habiyakare

(Source: African Rights, Rwanda: Who is killing, cit.).

Many well-dressed people were killed the night of the attack and the following days by the paramilitary militias for their marks of social distinction. Social anger, racialized hostility and fear, and politically charged hatred mixed in a highly explosive mixture (that’s an issue I’m going to examine more closely in the continuation).

«Only later would it be established that all that day there had been requests to Bagosora and to Ndindiliyimana from army officers and from the RPF to control the military, and most notably the Presidential Guard, who were murdering civilians. These requests were ignored and Bagosora, according to his ICTR indictment, ordered Ntabakuze, the commander of the para-commando unit, Major François-Xavier Nzuwonemeye, the commander of the reconnaissance battalion, and Lt.-Col. Leonard Nkundiye, former commander of the Presidential Guard, to proceed with massacres» (L. Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit).

THE HORROR BEGAN: THE FINAL PHASE OF THE GENOCIDE AGAINST THE TUTSI STARTED MORE VIOLENT THAN EVER

Door-to-door hunting down and systematic killing of Tutsis at the roadblocks began a few hours after Habyarimana’s assassination and in the next few days spread in Kigali city and elsewhere in the country. RTLM began exhorting violence, playing provocative songs, and even reading out the names and locations of the cockroaches and the vermin who were to be exterminated.

Swiss citizen Philippe Gaillard, chief of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in Rwanda, in Kigali at that time, estimated that the death toll in the city area was approximately 10,000 people killed in barely two days. The 7th and the 8th only. Then, in the following days, the death toll increased to 10,000 a day. Every day.

- The night between April 6 and April 7

The night between April 6 and 7, the systematic massacres of the Tutsis started in the district called “Mu Kajagari” (or Kajagali) adjoining the Kanombe military camp. The killings in Kajagari were carried out by the First Company of the Para-Commando Battalion and Interahamwe militiamen; the soldiers shot their victims, while the latter killed with machetes and maces. At the end of the night of April 7, the ‘work’ in Kajagari was finished.

- On April 7

Soldiers and militiamen attacked the Kibagabaga mosque in the Remera area of Kigali and killed many Tutsi who had sought shelter there.

On April 7, the RAF soldiers started killing Tutsi patients at Kigali’s main hospital (the University Teaching Hospital).

- Between April 7 and 8

The Presidential Guard and the Para-Commando Battalion have been hunting down door-to-door and killing the Tutsis of Kabeza, a predominantly Tutsi area in Kigali. That very same day, in the Nyamirambo sector of Kigali, many Tutsis gathered and found refuge in some religious centers, such as the Saint Charles Lwanga Church, the Saint André College, the Saint Josephite Centre, the Beneberika Convent, and the Carmelite Convent. Some soldiers and Interahamwe militiamen attacked the refugees at the nearby Saint Charles Lwanga Church on April 7, while on April 8 attacked, raped, and killed many Tutsi refugees at the Saint Josephite Centre. The Saint André College was attacked by Interahamwe on April 13.

- On April 8

Military personnel killed Tutsi civilians at the roadblock and school near Karama hill.

- On April 9

Some soldiers supervised the killing of Tutsi civilians at the Kibagabaga Catholic Church, after distributing weapons to Interahamwe.

Rwandan army, gendarmerie, and Interahamwe participated in a horrific attack on April 9 at Gikondo Parish in Kigali.

«The Catholic church in Gikondo, an imposing building of red brick, built on the crest of a hill, was one of the largest in the city with room for a congregation of 2,000 people. (…).In the complex, run by the Pallotine Missionary Order of the Catholic Church, were a dozen Polish priests and nuns. It was an extensive campus with a small chapel, community centre, and print shop with an adjoining warehouse and separate housing quarters. For two days, terrified people had fled to the church, and by Saturday morning about 500 men, women and children were sheltering there» (L. Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.).

The Polish Pallottine mission church in Gikondo, Kicukiro District, Kigali.

On the morning of April 9, two presidential guard soldiers and two gendarmes entered the church and began checking the identity cards of the people in the church. The Hutus were obliged to go away. A hundred militiamen came in and began slaughtering the terrorized refugees – men, women, children, even babies – using pangas (machetes) and clubs. «The killing continued for two hours as the whole compound was searched. Only two people are believed to have survived the killing at the church. (…). That day in Gikondo there was a street littered with corpses the length of a kilometre» (L. Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.). The International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda Chamber found beyond reasonable doubt that the Rwandan army, gendarmerie, and Interahamwe conducted a joint operation to seal off the Gikondo area. Major Beardsley (UNAMIR) reached this Polish Pallottine mission church immediately after the massacre. It was his first encounter with hell. Here’s his testimony at the ICTR: «Pregnant women had their stomachs slashed open, fetuses on the floor. Even a fetus was smashed. I remember, just from the time I was there, I remember looking down, a woman obviously had tried to protect her baby. Somebody had rolled her off the baby. The baby was still alive and trying to feed on her breasts. She’d been — her clothes had been ripped off. The killing that was done was not done, in their opinion, to kill the people immediately; it had been done to kill them slowly. Women’s breasts and vaginas had been cut with machetes; men’s scrotum areas were cut with machetes. Men had been hamstrung behind their Achilles’ tendons so that they couldn’t walk» (International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, Case No. ICTR-98-41-T, December 21, 2008. The Prosecutor v. Théoneste Bagosora – Gratien Kabiligi – Aloys Ntabakuze – Anatole Nsengiyumva – Judgement and Sentence)

- On April 11

Monday, April 11 was a terrible day whose story was told by a movie in 2005 – Shooting Dogs, released in the US as Beyond the Gates, directed by Michael Caton-Jones – and deserves to be remembered again and again.

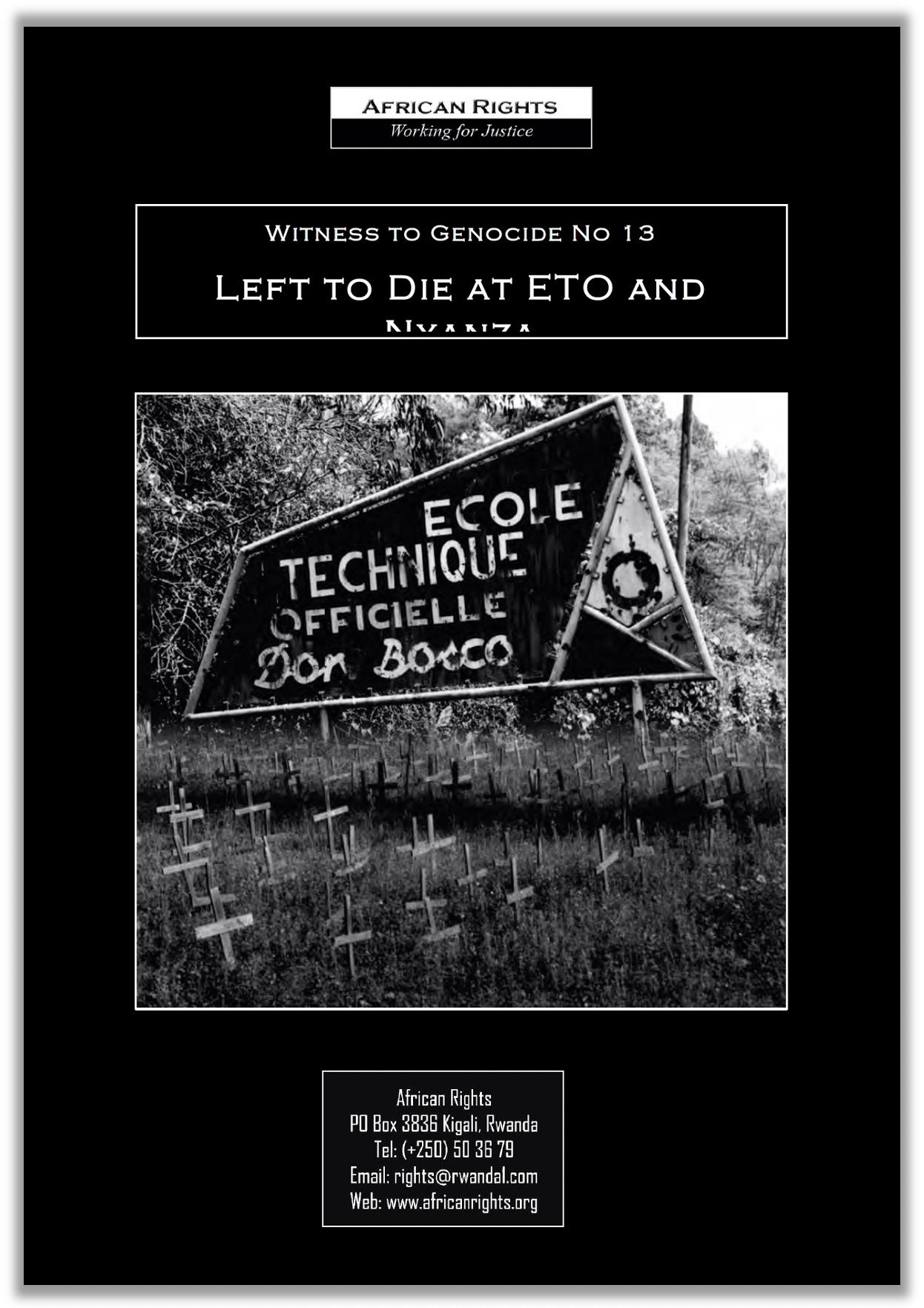

ETO: THE TRAGEDY OF APRIL 11, 1994

Shooting Dogs, released in the United States as Beyond the Gates, is a 2005 film, directed by Michael Caton-Jones and starring John Hurt, Hugh Dancy, and Clare-Hope Ashitey. It tells the story of the carnage at the ETO school in Kigali, on April 11, 1994.

«It is based on the experiences of BBC news producer David Belton, who worked in Rwanda during the Rwandan genocide. Belton is the film’s co-writer and one of its producers. (…). The film was shot in the original location of the scenes it portrays. Also, many survivors of the massacre were employed as part of the production crew and in minor acting roles. The film’s title refers to the actions of UN soldiers in shooting at the stray dogs that scavenged the bodies of the dead. Since the UN soldiers were not allowed to shoot at the Hutu extremists who had caused the deaths in the first place, the shooting of dogs is symbolic of the madness of the situation that the film attempts to capture» (from Shooting Dogs, Wikipedia).

The École Technique Officielle Don Bosco (ETO) was a secondary school run by the Salesian Fathers in the Nyanza-Kicukiro area of south-eastern Kigali, partly financed by a Belgian cooperation project. Before Habyarimana’s assassination, it had become the base camp for two UNAMIR Belgian platoons, 97 blue berets of the Kibat II Battalion under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Dewez (the Belgian commander) and Colonel Luc Marchal, and under the direct responsibility of Lieutenant Luc Lemaire.

From April 7 onwards, groups of people feeling unsafe began to flock to the ETO cantonment: there were mainly Tutsis, frightened by the mass killings that had already started all over Kigali, with some Hutus, especially opposition politicians and human rights activists with their families. Everyone was looking for the protection guaranteed by the well-armed blue berets. At first, Lieutenant Lemaire was opposed to accommodating all Rwandan refugees but under pressure from the Salesian Fathers who owned the school, he was forced to open the gates.

«In the days after 7 April 1994, more than 2,500 Rwandese people flocked to ETO. (…). They took extreme risks to reach the school and several people were killed along the way. (…). People went to ETO because they shared faith in the UNAMIR forces. They knew the soldiers were well-armed and trained, and -because they had come to Rwanda as “peacekeepers”- they knew that they had both the responsibility and the capacity to protect them» (Left to die at ETO and in Nyanza, 2001 by African Rights).

Refugees continued to pour into ETO on the 8th and 9th, and the situation inside the school became troublesome. The Belgian peacekeepers did not organize any orderly arrangement inside the structure and did not provide any food, water, blankets, or medical supplies to meet the needs of the refugees, not even of the children.

«Although it is not stated explicitly, the soldiers were clearly fearful for their own lives following the murder of the 10 Belgian paratroopers on the 7th.(…). The testimonies of survivors suggest that the soldiers maintained an aloof stance, exacerbating the refugees’ feelings of despair and alienation» (Ibidem).

It was a situation of political chaos and incessant slaughters of civilians, and the Belgian soldiers were concerned more with their security than with the survival of the refugees. The presence of the latter was considered a threat which exposed them all to new possible attacks, and during the afternoon of April 9, Lemaire decided to close the gate to Rwandans and to let enter only the ‘whites’, namely the ‘expatriates’ (who reached the number of approx. 150). Many refugees were therefore obliged to camp outside the ETO gates. «While the situation inside the ETO buildings was difficult, the people who had been unable to gain entry and were gathered on the sports field were left to fend for themselves entirely. Although they were only a few meters away from the UNAMIR soldiers’ camp, the people outside ETO felt very isolated and soon realized that the soldiers did not intend to offer them any assistance» (Ibidem).

At ETO, the discrimination policy between ‘blacks’ and ‘whites’ adopted by UNAMIR Belgians was in plain sight. «There is a shared view among survivors that the Belgian soldiers saw them as part of the problem, rather than victims, and that their attitude was influenced by racism» (Ibidem). The Belgian discrimination policy was read by most Rwandan refugees as yet another confirmation of the lack of interest of the international community in the face of genocide. This awareness pushed many Tutsis to accept their massacre with passive despair.

Meanwhile, both groups of the Interahamwe militia and RAF soldiers began to be permanently stationed in the area outside the school, like crocodiles waiting for the best moment to launch a successful underwater ambush.

On Monday 11, some French paratroopers, recognizable from the flags on their uniforms and their red berets, arrived at ETO with some Europeans evacuated from various places. They gathered them together with the white expats already housed inside, loaded them onto lorries, and finally safely escorted all of them to the Kigali airport (French Operation Amaryllis and Belgian Silverback, do you remember?). The arrival of the French was a source of much concern to the refugees, but the sudden departure of the UNAMIR Belgian troops which took place around 2:00 pm was worse. It was the end of all hope. The UNAMIR Belgian soldiers told some refugees that they had arranged for them to be guarded by gendarmes. In other words, they left the flock to the care of wolves. Jean-Paul Biramvu, secretary-general of the Collective of Human Rights Leagues and Associations (CLADHO), was there with his family and survived. He said: «We could not believe what they were doing, just abandoning us when they knew the place was surrounded by killers».

In an act of desperation, some of the young men threw themselves in front of the convoy, trying to stop them. Belgian soldiers fired into the air and disappeared together with the last French paratroopers.

Almost immediately after the Belgians left, in a matter of minutes, Rwandan soldiers and militiamen entered the school grounds and start slaughtering men, women, and children with firearms, more often with machetes, clubs, axes, and spears. The refugees had no time and no way to escape. The large majority of them were blocked and herded in the rain along a dirt road, where many were killed or badly wounded, and left at the edge, like bags of garbage.

The survivors reached the headquarters of Sonatubes, a factory of building materials. At a clearing, they were ordered to sit down, robbed of any money or valuables they had brought with them, insulted, and humiliated. More and more Tutsi were obliged to gather at the Sonatubes factory, even refugees for other areas of Kigali. At some point, Colonel Léonidas Rusatira (member of FAR and Commander of the Ecole Supérieure Militaire) and Lieutenant Colonel Tharcisse Renzaho ordered the prisoners to move to Nyanza, where all the town rubbish was dumped. Killing them at Sonatubes was too risky: the compound overlooked the busy main road to the Kigali airport. A survivor remembers that Colonel Rusatira said: «Take them to Nyanza, and I’ll go and find a lorry and bring some food». It was a lie. A wicked lie. That to Nyanza was a death march. It was one of those horrific death marches that we no longer wanted to see after the Shoah.

«Flanked on both sides by Interahamwe, approximately 4,000 refugees were then forced to march to Nyanza» (Ibidem). Along the road, many women were raped and mutilated, and those too weak to walk were crushed like cockroaches. Vénuste Karasira (a survivor) remembers: «The entire road from Sonatubes to Nyanza was filled with civilians shrieking insults at us (…) Some of us got even robbed on the way to Nyanza». The hatred, the contempt of the civilians who along the way watched the Tutsis going to be slaughtered struck more painfully than the beatings. A survivor, Siméon Hitiyise, remembers: «It was as though every single Hutu had come to exterminate us; women, children, and young people too». Another survivor, Madeleine Mugorewera, recalls that at a certain point, after Kagarama, «a little boy of ten or twelve, carrying a sword which touched the ground, addressed Kayumba and demanded his watch. Kayumba, who was about 40 years old, complied without complaint».

Think about it and tell me, please, tell me something about that little boy of 10 or maybe 12 years. Tell me something about the women who watched the Tutsis going to be massacred like lambs to slaughter, rummaging with their eyes what they could still steal, a wrap, a bag, a piece of nothing. Tell me something about the men who cursed and spat and laughed, standing on the side of the road and watching the show. Tell me, ’cause I don’t know what to think. I don’t know. I don’t know. I don’t know.

When the Tutsis reached Nyanza, at 5.00-5.30 p.m., the soldiers ordered everybody to sit down on the ground and give all the money they might still have in their pockets. Then, the victims were left seated, desperate, and suffering for half an hour. Finally, the civilian leaders like Georges Rutaganda, vice-president of Interahamwe, and the higher-ranking officers ordered to “get to work”. They attacked with machetes, grenades and guns. «It was a hellish scene of blood, fire, clouds of dust raised by the grenades, mutilated bodies and the screams of the wounded and dying» (Ibidem).

By late afternoon, as the sun was going down and most of the people were dead or dying, the soldiers left. The survivors were cut in their Achilles tendon to be unable to escape: they would be finished later, on the following morning, from 5 a.m. onwards. Some wounded people, like Vénuste Karasira, survived by hiding under a pile of corpses and fleeing during the night, with a few dozens ‘lucky’ people. On the 12th, RPF soldiers could stop the slaughter and rescued 200 Tutsis who had survived the massacre. They were 5% of the total victims. The youngest ‘lamb’ was only 1 month old.

Vianney Ndacyayisenga, a survivor who lost his hand on the 11th, said: «I think God abandoned us that day».

Not the case, probably. After Auschwitz, God as omnipotent, good, and understandable has become a totally unthinkable concept.

Mass Grave and Flame Monument at the Nyanza Genocide Memorial Site in Kicukiro District, Kigali.

On top: both photos by Adam Jones, 2012, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported. Bottom: photo 2017 by National Commission For The Fight Against Genocide.

Kicukiro District has six Genocide Memorials, among them there’s the Nyanza Memorial site, which serves as the final resting place for over 11,000 victims of the Genocide. Between 3,000 and 4,000 were killed on site, while the others were murdered in other parts of Kicukiro. Each year, on April 11, a ceremony takes place also at ETO, in memory of the Genocide victims murdered in cold blood after UN Belgian troops abandoned them.

The Chorale de Kigali & The Voices of Kicukiro, Nyirigira, from Shooting Dogs / Beyond the Gates original Motion Picture Soundtrack by Dario Marianelli.

Why did the Belgian Peacekeepers leave ETO? As soldiers, all of them followed orders. So, who ordered them to leave ETO, condemning thousands of refugees to slaughter?

Let’s start with a proven fact: UNAMIR Commander Roméo Dallaire did not give any order to the Belgian peacekeepers billeted at ETO.

Who did it then?

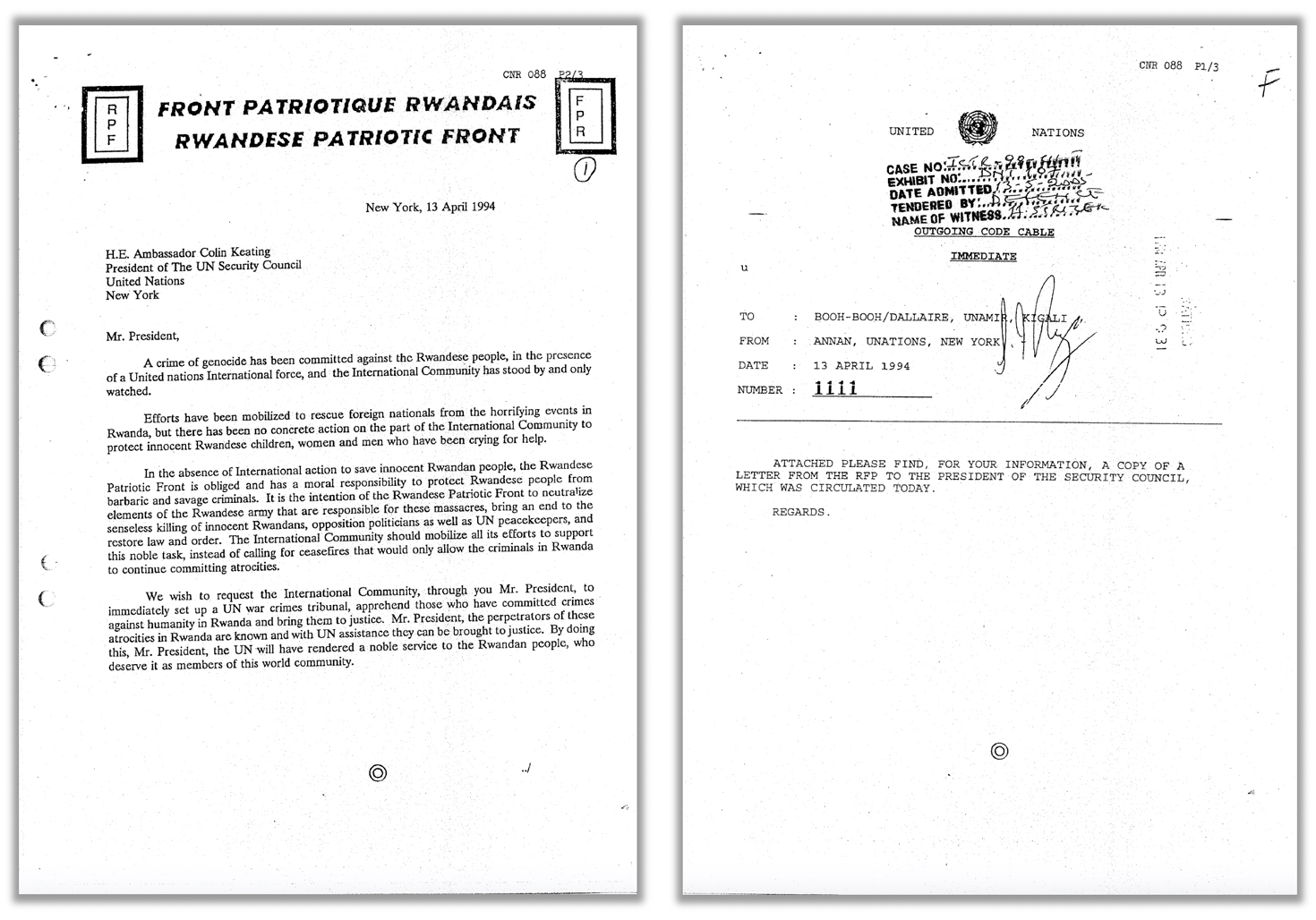

According to the UN 1999 Report of the Independent Inquiry into the actions of the United Nations during the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda, «in a cable dated 9 April from Annan (Riza), Dallaire was requested to “cooperate with both the French and Belgian commanders to facilitate the evacuation of their nationals, and other foreign nationals requesting evacuation. You may exchange liaison officers for this purpose. You should make every effort not to compromise your impartiality or to act beyond your mandate but may exercise your discretion to do should this be essential for the evacuation of foreign nationals. This should not repeat not extend to participating in possible combat, except in self-defence”».

The text of this cable clearly shows that New York’s main concern at that moment was essentially to use UNAMIR to facilitate the evacuation of white foreigners; therefore, they ordered Dallaire to cooperate with French, Belgians, and Americans. As for the survival of Rwanda’s Tutsis, well, that wasn’t at the top of New York’s priorities. That UNAMIR could, if necessary, turn into a barrier in the face of genocide and systematic crimes against humanity was not a New York’s foreseen possibility, nor a scenario to be considered.

We can therefore understand why Roméo Dallaire wrote in his memoirs: «The Belgian and French ambassadors were pressuring Luc <Marchal> for help in securing the expatriate population. I told Luc that UNAMIR tasks came first and that the integrated evacuation plan, which included the expatriates, would be implemented when ordered. Until then we had a responsibility to all of the people of Rwanda» (R. Dallaire, Shake Hands, cit.). But the pressure on Dallaire was intense: in a phone call, Maurice Baril gave him instructions to help with the evacuation and told him that those were the orders he had received from above. However, Dallaire was given absolutely no role in coordinating or overseeing the evacuation procedures: as a matter of fact, his Belgian officers stopped responding to his orders to ‘coordinate’ and obey orders from the higher officers of the evacuation force, from Colonel Jean-Jacques Maurin, the French military attaché at the embassy, from Belgian Ambassador Swinnen and the Belgian government. Dallaire remembers in his memoirs: «I raised with Luc <Marchal> the issue of his airport company having been unilaterally ripped from my command and given to Operation Silverback, which was the Belgian portion of the expatriate evacuation. He told me it was a direct order from Belgium and he was unable to do anything about it. The DPKO hadn’t been able to do much about it, either. A good number of my Belgian staff officers had never come back from leave, including Frank Claeys, my intelligence officer. Luc had heard that these men wouldn’t be coming back to UNAMIR at all and had been reassigned to the Belgian evacuation force. Tactically this made all kinds of sense from the Belgian perspective, but to take these important officers away from me at this critical time in the mission struck me as irresponsible and dangerous. Luc assured me that the rest of his Belgians were still under my command, but he was at the receiving end of a lot of my frustration over the coming days as the situation regarding the Belgian forces was played out» (R. Dallaire, Shake Hands, cit.).

That rainy Monday, April 11, the order for the company commander Luc Lemaire to withdraw from ETO ought to have come from the UNAMIR force commander Roméo Dallaire, if at all; but Dallaire, as we saw, gave no orders (and he would have never given it). Lemaire called Lieutenant Colonel Dewez, his Commanding Officer, to request permission for his company to consolidate at the airport, without mentioning the over 2500 refugees under his protection, and Dewez approved, following the order received according to the Belgian chain of command and the Belgian government directives.

The Independent Inquiry, with its ‘diplomatic’ tone, reads: «There do not seem to have been conscious and consistent orders down the chain of command on this issue. (…). If such a momentous decision as that to evacuate the ETO school was taken without orders from the Force Commander <Dallaire>, that shows grave problems of command and control within UNAMIR».

Those ‘grave’ problems in the chain of UNAMIR command which led to the slaughter of thousands of Rwandans and which makes up another link in the chain of failures of the DPKO were due to two main factors:

- An order coming from above, in New York, obliged UNAMIR to help the evacuation forces in the rescue of white expats. It was an order coherent with one of the duties of the UNAMIR, as stated by its Mandate: the mission could be used to help in the coordination of humanitarian assistance activities. Problem was that this unexpected task took over the other official tasks assigned to the mission probably due to the political pressure that New York received from some western governments. In other terms, the ‘humanitarian assistance activity’ to the benefit of white expats was highly favored over the ‘humanitarian assistance activity’ for the sake of black locals. How would you call this, let’s say, ‘preferential attitude’? Whatever you want to call it, the fact remains that Belgian peacekeepers privileged the salvation of whites (including themselves) to that of blacks, with the serene awareness of obeying a logical and reasonable order. In a chain of command, racism moves more easily from top to bottom than bottom-up.

- The Belgian government directives, managed locally by Ambassador Swinnen, seriously disrupted UNAMIR’s chain of command. To me, it wasn’t an unexpected side effect, a fortuitous unintended interference. It was a conscious political decision, instead. We saw that, according to General Joseph Charlier, Head of the Belgian Defense Staff in 1994, the decision of the Belgian withdrawal from UNAMIR taken by Leo Delcroix (Belgian Minister of Defense at the time) was officially communicated on the 12th, the day after the ETO tragedy. On the 19th, the Belgian peacekeepers left Rwanda. On the 11th, the withdrawal was probably in the air: something about it filtered, at least unofficially. At that time, the Belgian government wanted to smoothly evacuate its nationals and avoid any further loss of Belgian citizens; the UNAMIR Belgian soldiers were first of all Belgian citizens and only after UNAMIR soldiers. On the 11th, the Belgian government decided to protect them at all costs. Even at the cost of violating UNAMIR’s chain of command. The precise and conscious will to remove the Belgian peacekeepers from Dallaire’s control was not motivated by a maternal-protective attitude (as it might seem to good-hearted and naïve people). It was motivated instead by a political-electoral calculation: how could the Belgian government justify a further massacre of Belgian citizens in front of the electorate, especially its voters? The opposition would have taken advantage of it mercilessly (that’s politics, baby!).

The Left to die at ETO and in Nyanza dossier by African Rights reads: «Although the decision of Belgium to withdraw its forces from UNAMIR had not yet been stated officially at that point, it was evident that in practice KIBAT troops had come back under national command and were working alongside their colleagues in the evacuation forces. The UNAMIR command was unaware of the decision to leave ETO until later and the UN was only informed of Belgium’s decision to pull out of Rwanda on the 12th. Lieutenant Lemaire had received orders from Lt. Col. Dewez to dispatch troops to Gitarama to escort some Belgians back to the city. This is the context in which Lemaire decided to take advantage of the security afforded by a French escort and the news that the road they had taken was clear. But he could not have chosen a worse moment. While the UN Independent Inquiry was aware of the wider confusion that affected the decisions made by the peacekeepers, it also blamed them for their timidity. “<The> peacekeepers themselves… by not resisting the threat to the persons they were protecting… as would have been covered by their Rules of Engagement, showed a lack resolve to fulfill their mission» (p. 55).

An accurate dossier of 145 pages, entitled Left to die at ETO and in Nyanza, was prepared and published in April 2001 by African Rights. It can be dowloaded here, on the France – Génocide – Tutsi website.

The last quote from Left to die includes a quote from the UN Independent Inquiry and raises the issue of the behavior of Lemaire and the Belgian peacekeepers at ETO.

That’s true: at ETO, they should have behaved differently, firstly as UN Peacekeepers, secondly as men. They failed primarily from a professional point of view, secondly from a moral one. However, they have many extenuating circumstances: in the chaos of those days, that group of young boys, confused, frightened, unable to understand the events because they weren’t given the tools to do it, improperly equipped, tied by the ROE to a minimal use of force only in front of their own death, dragged down a chain of command altered from above and imposed without many explanations, those young guys could have certainly acted differently. But is it really useful to say it? Pointing fingers at Dewez, Lemaire, and their men only serve to hide other and greater moral responsibilities.

And who bears moral responsibility for the April 11 carnage? Note that I’m talking here not about the legal responsibility for the massacre, but only about the moral one. Of course, what I’m about to write is my personal opinion, and I invite each of you to think about it and develop your personal view on the issue.

We are faced here with a complex situation with several morally responsible actors. The fact that moral responsibility is shared by many and therefore ‘fragmented’ does not mean of course that this responsibility is reduced and that each actor has only a small piece of it. Moral responsibility is not a cake whose slices are all the smaller the more they are.

The Belgian Kibat II Battalion should not have been at ETO frightened by the slaughter of their comrades, improperly equipped, unprepared, uninformed, and subject to multiple and complex power games. No UN peacekeeper should ever be in such a situation.

The UN Department of Peace-keeping Operations (DPKO) bears moral responsibility, namely the triumvirate Maurice Baril, Kofi Annan, and Iqbal Riza.

The Secretary-General of the United Nations bears moral responsibility, namely Egyptian politician and diplomat Boutros Boutros-Ghali.

The permanent members of the Security Council, especially the US and UK with their strong will to reduce UNAMIR to a low-cost minor mission for financial reasons and issues of political opportunism, bears moral responsibility, namely Madeleine Albright, permanent representative of the United States of America to the United Nations, with the rank and status of ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary, and the British diplomat David Hugh Alexander Hannay, created Baron Hannay of Chiswick in 2001.

The 1994 Belgian government bears moral responsibility for having disrupted the UNAMIR chain of command on purpose.

Here’s one of those several, common situations where the mistakes (due to mediocrity, ignorance, and miscalculations) made at the top are paid by those at the bottom. What a morally disgusting world we’ve built.

THE INSECTICIDAL OPERATION AGAINST COCKROACHES SPREAD ACROSS THE COUNTRY

The massacres of Tutsis began a few hours after Habyarimana’s assassination even outside Kigali and quickly spread to other parts of the country. «In the prefectures of Ruhengeri, Gisenyi in the north, Kibuye in the west, Kibungo in the south-east, Cyangugu in the south-east, and Gikongoro in the south, there was killing that first day, Thursday, 7 April» (L. Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.)

The following testimony, collected by African Rights, is related to an area in the Kibungo Prefecture, southeast of Kigali.

«Celestin Mazimpake owned a small shop in Sake, Prefecture of Kibungo, selling clothes and other items. She was interviewed by African Rights on 6 May 1994 at Gahini Hospital: “Even before the President died, the consciousness of Hutus in our area had already been awakened. They had been given a very clear idea of who to kill if events turned sour. Hutus in our hill were always being called to secret meetings with the bourgmestre, councilors, and other officials from which Tutsis were excluded. The killings started around midnight on 6 April, within hours of the plane crash. Burundi refugees who were living in a camp near the commune and some Interahamwe started with rich Tutsi families. They killed Ladislas Semuhungu and his entire family, Francois Masabo and his family, and Cyril Musoni and his family. Others died as well, together with their families – Silas Kanyamibwa, Sengoga, Gatambire, and all the Tutsi families who lived near the center of Mabuga. On Thursday the 7th, very early in the morning, they began killing the Tutsi families on the hills of Nshiri, Ngoma and Ruyema I and 11. I live on Ruyema 11, in an area called Munege. Around 11 a.m. the bourgmestre and the councilor of the sector came to the Catholic Centre of Munege, together with a soldier. There were also a lot of people with them. They found shot someone at the Centre which I later found out was my uncle. I had just bought some things for my shop and ran into the group while on my motor[bike]. I heard the shots and one of the officials turn to the group of people, saying ‘we have given you an example; now do the work yourselves.’ I ran as fast as I could. I hid in a banana field near the house of an Interahamwe as I thought his house would not be targeted. From there, I was able to follow what happened. They then went to the house of the man they killed and looted it, as well as a number of other neighbors”» (African Rights, Rwanda: Who is killing, cit.).