THE KUBA TEXTILES FROM THE DRC – 3

Democratic Republic of the Congo or DRC on the globe (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

THE OTHER KUBA TEXTILES

Before discovering the deeper meaning of Kuba’s moral, social and political geometries, going far beyond the current interpretations widely shared by many scholars, we need to take a look at the other masterpieces of Kuba textile art. As I wrote at the beginning, the generic term “Kuba textiles” covers various types of textiles, some of which are very different in technique and workmanship. However, all Kuba textiles share two main characteristics: the material they are made of – raffia fiber – and their cultural origin.

So let’s leave aside the Kasaï velvets for a moment: we are now going to deal with a group of fabrics that are even more complex in structure, technique and pattern.

Let’s start with the wrap-around skirts and overskirts worn by Kuba men and women during ceremonies and special occasions as part of their complex, spectacular costumes.

The men’s skirts are usually called mapel, while the women’s skirts are generally called ntshak or nchak, a term derived from the word enzaka, which is used in the Kwango region and the kingdom of the Kongo to refer to an embroidered raffia cloth.

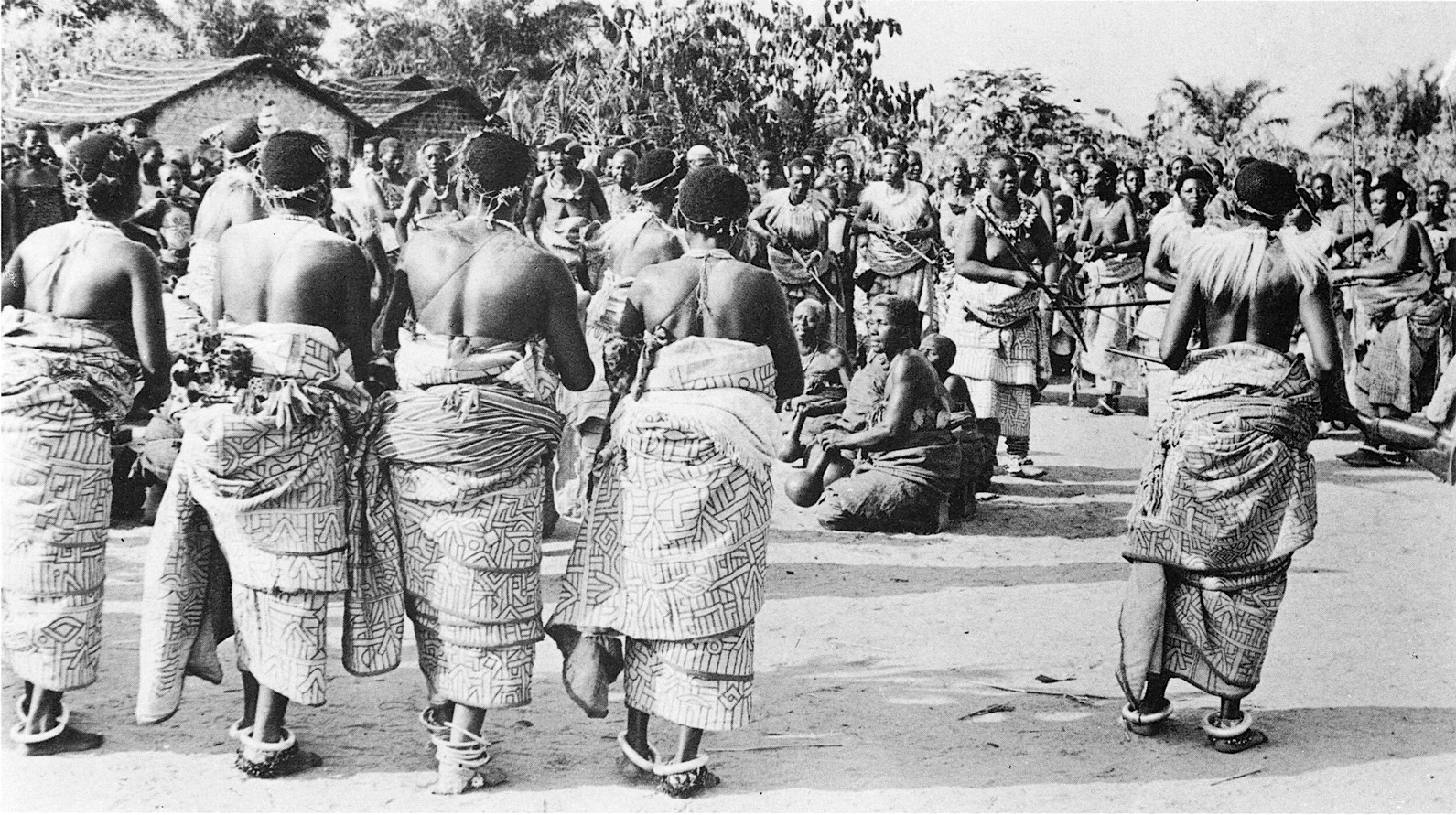

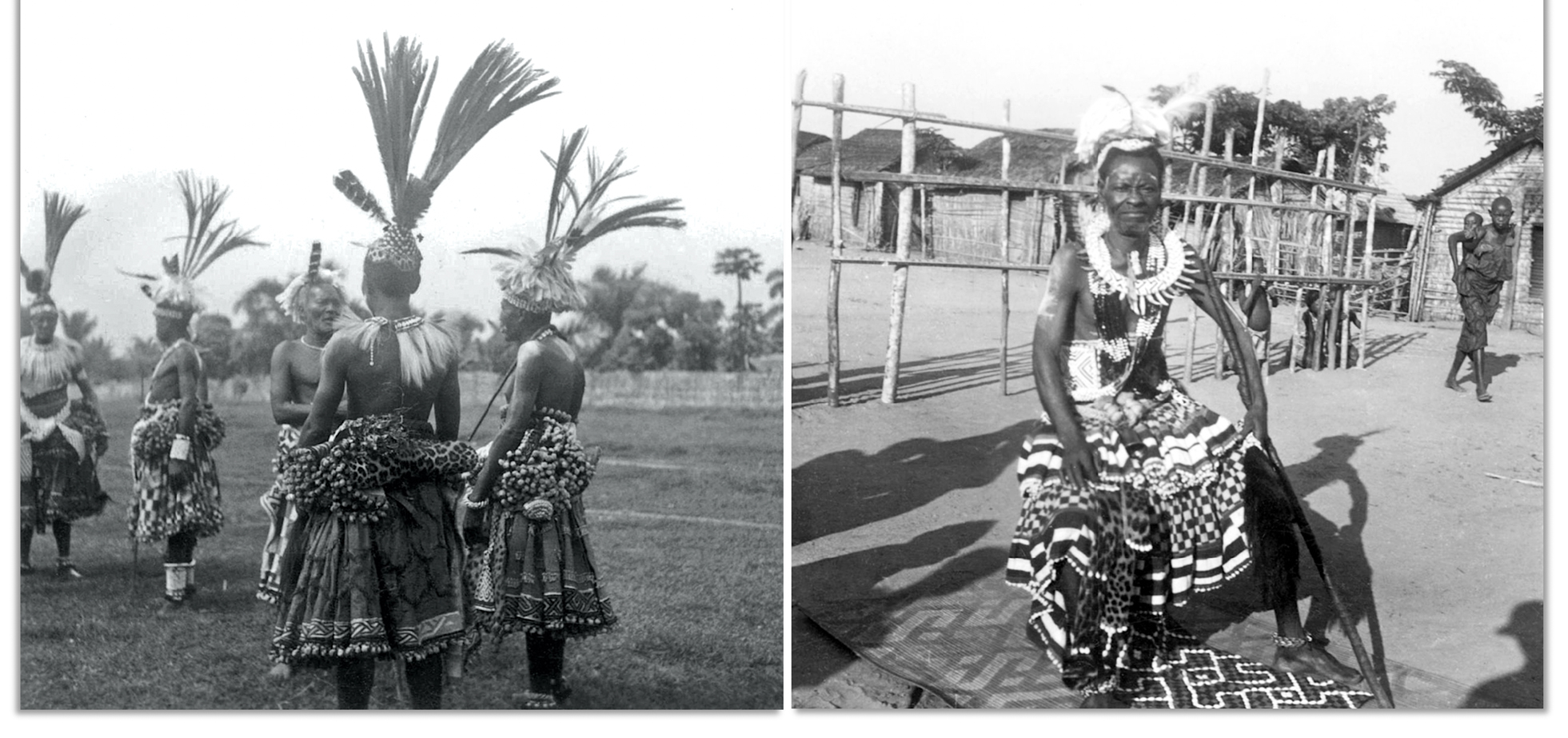

In the following picture, taken in Mushenge by Joseph-Aurelian Cornet and included in his 1982 book Art Royal Kuba (published in Milan, Italy), you can see from behind a group of Kuba women dancing during the Itul Festival, an important two-day celebration held by proclamation of the nyim (the king) to reenact the myth of Kuba’s origin and celebrate the founding of the Kuba kingdom. The dancers and musicians were usually chosen from among the king’s wives, his mother, and his daughters. All the women in the picture are wearing a special dance skirt called ntshakishwepy.

Itul dance with examples of ntshakishwepy. Mushenge. Picture by Joseph-Aurelian Cornet, Art Royal Kuba, 1982. Photo courtesy: Palmer Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA.

In this image, women wrap their ceremonial skirt around the hips and torso in a descending spiral and secure it at the waist with a special sash belt. The upper part could be worn covering the breasts or not, while the lower edges reached to their lower calves.

These wraparound skirts in light natural woven raffia fiber are covered with linear designs in black embroidered stitching, which you can better appreciate in the photo below.

BELOW

Two ceremonial skirts worn by the Bushoong, both preserved at The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Washington DC, USA.

ABOVE: Ceremonial dance skirt, 20th century, Bushoong, Kuba people. Dimensions: overall length 365.76 x width 83.82 cm (144 x 33 inches). Techniques: appliqué; plain weave; embroidery, stem stitch.

Can you identify the woot symbol, its variations and permutations in this ntshak?

BOTTOM: Ceremonial dance skirt, 20th century, Kuba people. Dimensions: overall length 301.50 x 77.50 cm (118 11/16 x 30 1/2 inches). Techniques: embroidery; plain weave.

Close-up of Ntshak embroidery and stitching

In the pictures above, the ceremonial skirts are laid flat on a surface to allow you to appreciate their complex designs. However, we must keep in mind that the Kuba designs of all skirts are not meant to be seen in this way, but in a moving, dancing, and highly dynamic form.

Nevertheless, let us turn to the observation of these pieces. As you can see, the above ceremonial skirts are strips of woven raffia whose length is over 3 meters, but this is not the most common length: usually the average is about 5-6 meters, and some pieces can even reach 9 meters. As for the width, the average range is 50 cm to 1 m (20 to 40 inches). Therefore, these female ceremonial skirts are always wrapped around the body three to four times or more, depending on the total length, and are sometimes tied securely with a belt or cord.

As we saw in the beginning, the units of hand-woven cloth have a rectangular or square shape and a variable, always very limited size, depending on the natural length of the raffia fibers: the strands are not tied, which means that the size of most Kuba textiles is limited by the size of the palm leaves. Thus, the final long strip that makes up an ntshak must consist of several panels sewn together.

Each panel is embroidered by a different woman within the same extended family or clan group. According to Elisabeth L. Cameron (1997) and Rachel Wilson (2018), the overall design of the ceremonial skirt is usually delegated to the female head of the group, who is responsible for acquiring the cloth panels, assigning the individual panels to different women in her clan according to their skill level, and finally assembling everything together, thus defining the overall style of the finished skirt. In short, the female head of the group, often the eldest, acts as a kind of conductor; the result is a unique, harmonious, complex concert of individual voices, each with peculiar characteristics and varying levels of skill.

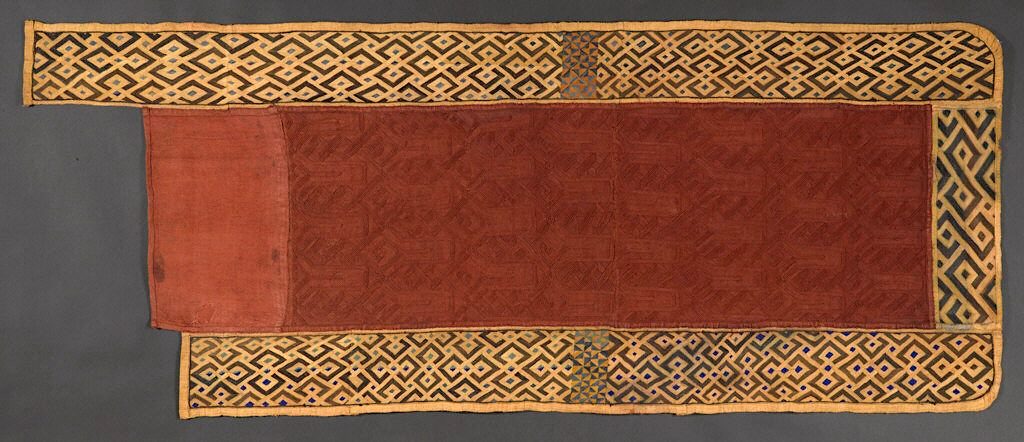

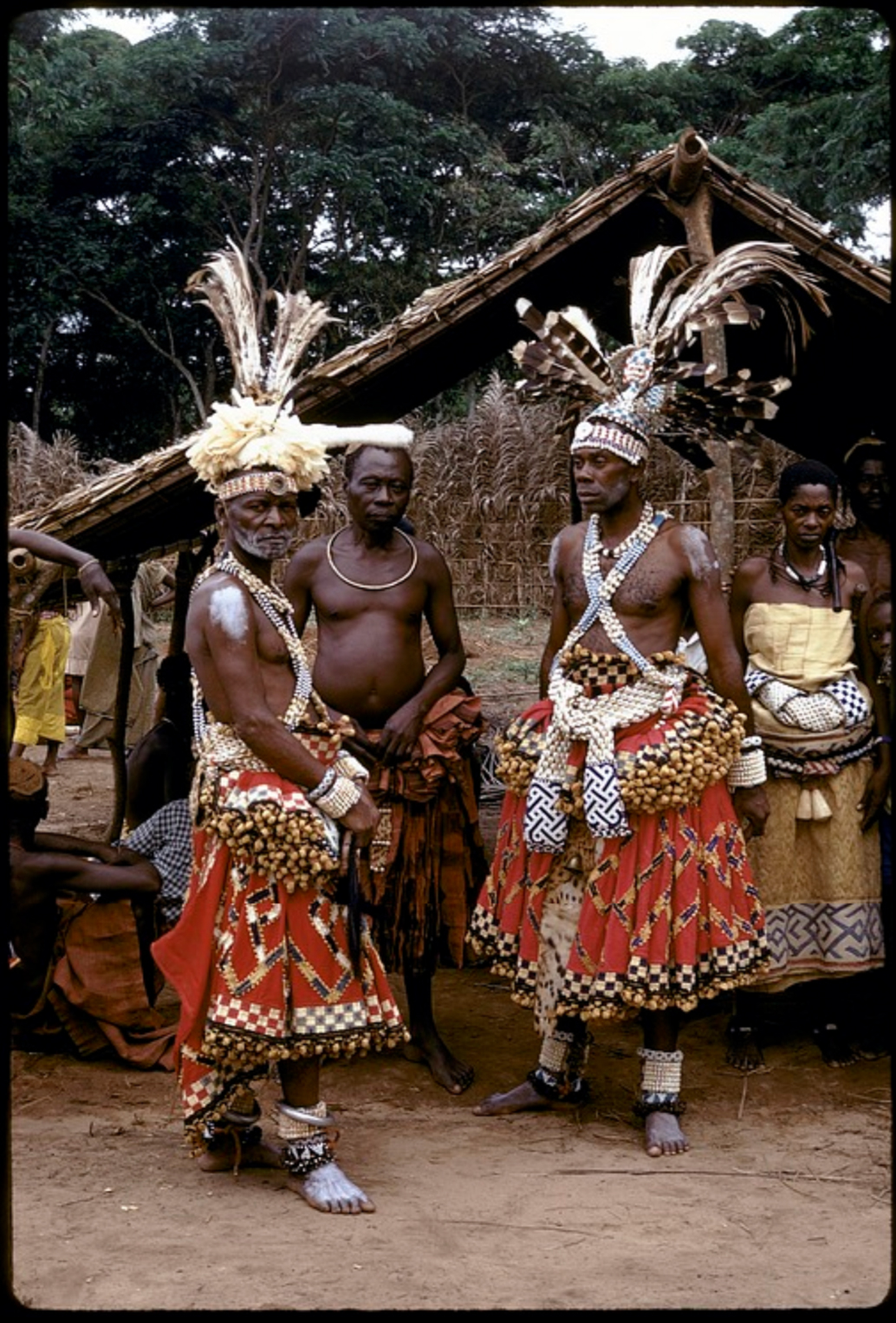

In the following picture, you can admire two outstanding ceremonial ntshak both from the 20th century, preserved in the American Minneapolis Institute of Art. Note, however, that they are out of proportion; they look almost the same size, but that’s a photographic effect. One is 3.72 m long, the other 5.56 m long.

BELOW

TOP: Woman’s Ceremonial Skirt, Kuba, 20th century. In raffia and cotton. Techniques: embroidery and appliqué. Overall dimensions: 372.11 x 78.7 cm; 146 1/2 x 31 in. Collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia), Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

This complex ntshak is composed of several small panels, sewn together and juxtaposed to create a dramatic contrast of pattern and color. The overall result is a highly harmonious and complex concert of different “voices” and an aesthetic celebration of experimentation and variation within the framework of traditional geometric patterns.

BOTTOM: Woman’s Ceremonial Skirt, Kuba, 20th century. In raffia. Techniques: embroidery and appliqué. Overall dimensions: 556.26 x 101.6 cm; 219 x 40 in. Collection of the Minneapolis Institute of Art (Mia), Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

This wide and long ntshak (over 5.5 meters long) is the result of many coordinated and patient hands. «Men and women contribute equally to the production of the raffia cloth and in the creation and application of the designs. In this context, the textiles symbolize concepts of cooperation, interdependence, and family responsibility that are highly valued in Kuba society.» (Museum curators).

Please note that the almost blank panels and those with less embroidery are also those worn next to the body.

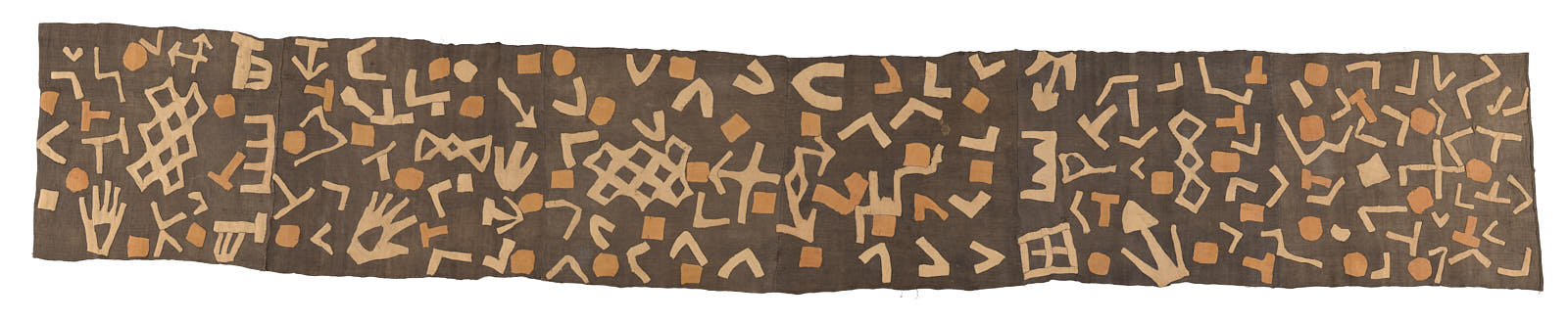

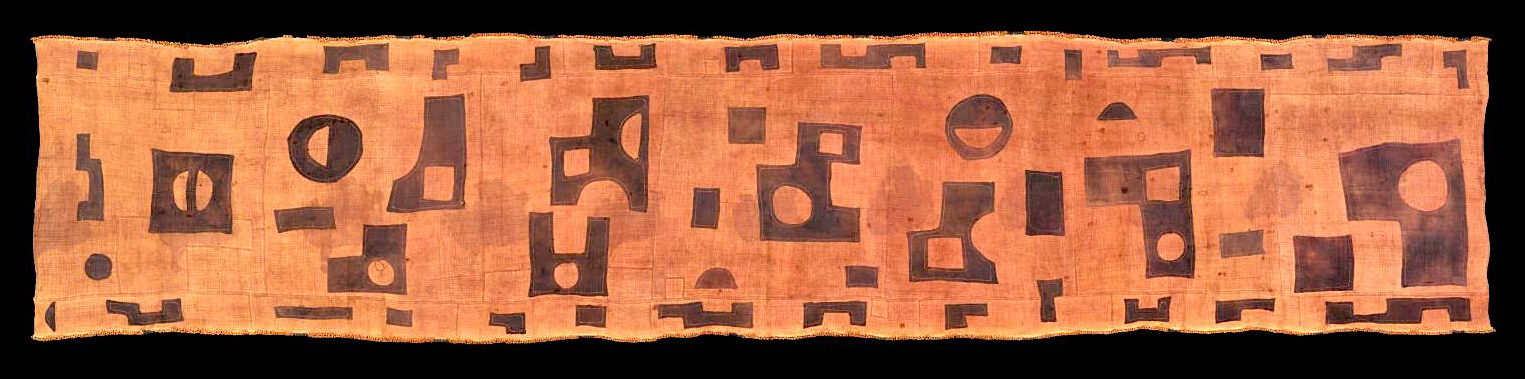

The photo below shows an amazing ntshak from the late 19th century, creating an evocative concert of Bushoong patterns in warm, natural, and earthy colors. (Note that artificial dyes were not yet in use in the late 19th century). No two panels are alike: each shows a unique variation of the basic design, but everything is so well arranged that the different shapes and colors blend together in a dynamic, fluid way.

Ceremonial skirt (ntshak), Kuba-Bushoong, late 19th century. Raffia palm fiber, natural dyes. Dimensions: 424.2 x 66 cm – 167 x 26 in. Preserved but not on view at The MET, New York, USA.

BELOW

Close-up of the ntshak embroidery above

The following 20th century ceremonial skirt is made with the appliqué technique and, like the previous ones, shows the use of a warm earth color palette. And like the previous ntshak, each panel reinterprets the basic pattern in a unique way, varying it in unpredictable and unexpected ways. The result is a rhythmic ensemble and a well-balanced arrangement.

BELOW

Ceremonial skirt, Kuba people, 20th century, raffia, appliqué; plain weave. Dimensions: 428.27 x 65.75 cm – 168 5/8 x 25 7/8 in. The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Washington, DC, USA.

Kuba women often add a smaller and shorter overskirt, called the ntshakakot, to the ceremonial wraparound skirt, the ntshak, as seen in the following images.

BELOW

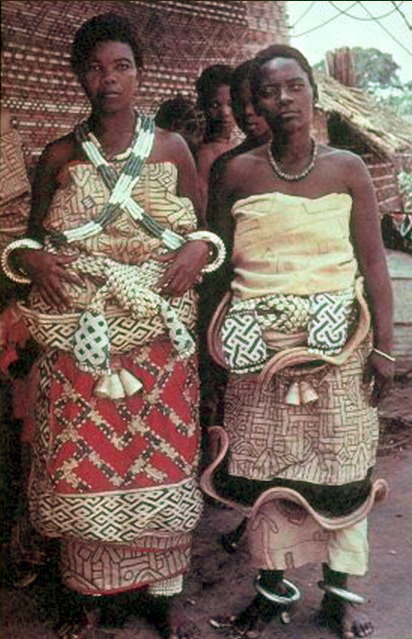

Itul celebration: examples of ntshakakot. Mushenge. Photo by Joseph-Aurelian Cornet, Art Royal Kuba, 1982. Photo courtesy: Palmer Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA.

Dance of women of the royal court. Mushenge. Photo by Angelo Turconi. Source: Joseph-Aurelien Cornet, Art Royal Kuba, Milan, Italy, Grafica Sipiel, 1982. (Figure 317). Photo courtesy: Palmer Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA.

Please note the different types of overskirts worn by these women and their ntshak. They all wear ceremonial skirts of red dyed raffia. This color was specifically reserved for royal court dress and was obtained by using ngula, a powder made from the bark of the tree Pterocarpus soyauxii, or camwood, the bark of Baphia nitida. Before the introduction of synthetic dyes, the Kuba people used natural dyes from plants. The color black was obtained from burnt banana leaves mixed with mineral substances, and the color yellow was obtained from some Rubiaceae plants.

Royal family women in ceremonial dress. Mushenge, 1976. The only wife of the current Bushoong ritual king stands at left in her official dress. A red trade cloth has replaced the plush panels. Her companion and handicraft assistant is one of the former king’s wives. She wears a long, sparsely appliqued, and embroidered wraparound garment under a flounced overskirt of linear embroidery. Source: Monni Adams, Kuba Embroidered Cloth, 1978, cit.

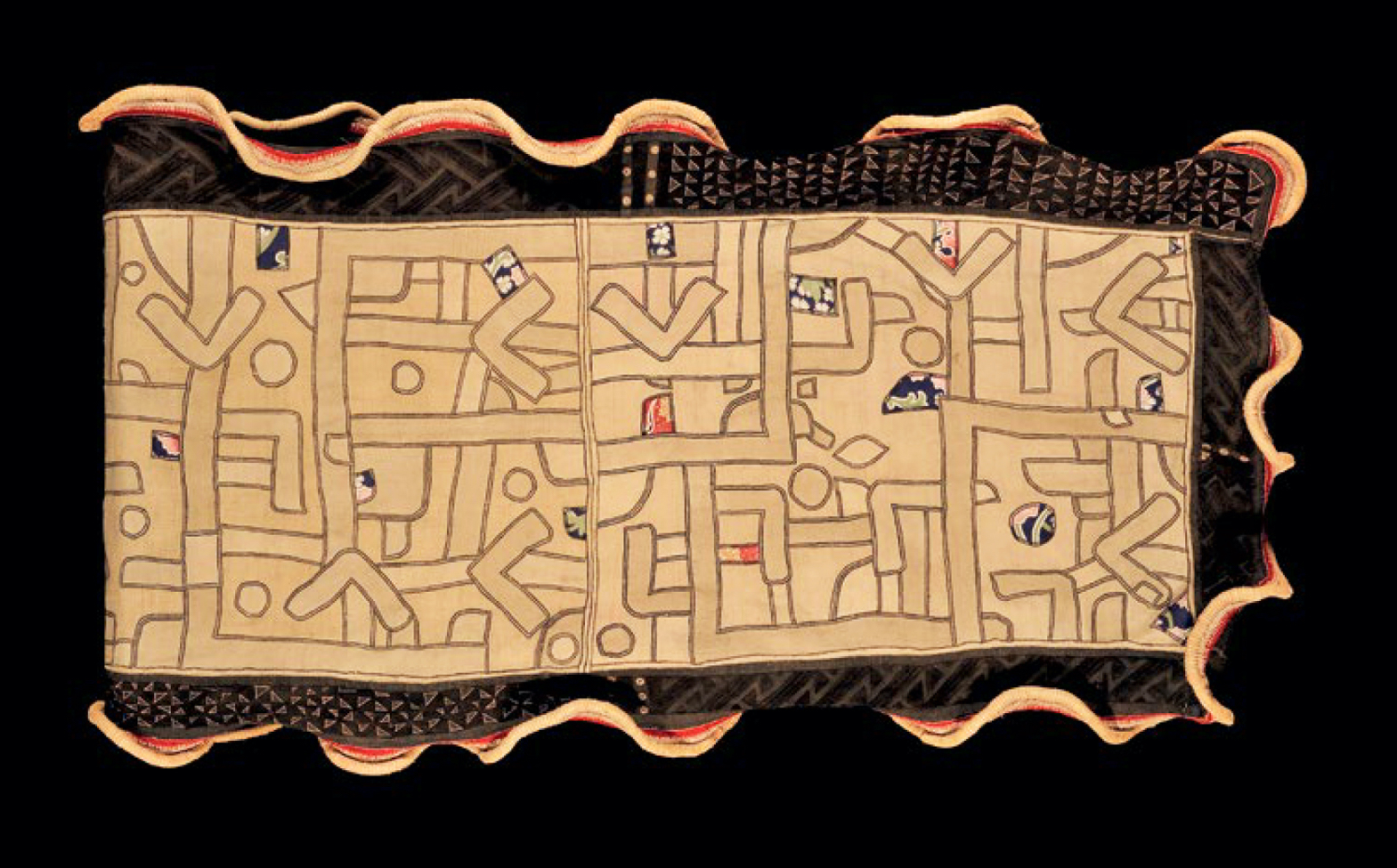

Now let’s “freeze” a few overskirts (ntshakakot) by observing them lying flat on a surface. I’d like to show you some examples of a particular type of overskirt that you could see in the previous photos: the so-called ntshak minen with wavy edges. High-ranking women – representatives of noble families or members of the royal family – wore ntshak minen only on special occasions, such as the prestigious and difficult Itul dance.

BELOW

Overskirt of the ntshakakot type, Bushoong, Kuba people, 20th century. Overall dimensions: 150.5 x 66 cm; 59 1/4 x 26 inches. Smithsonian Institution, Department of Anthropology. Photo courtesy: Palmer Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA.

Please note the dark, wide, wavy brim: it’s made using the cut-pile technique of Kasaï velvets, with embroidered designs and undulating borders. The ruffled wave is achieved by neatly tying the fabric threads on a curled rattan stick.

Woman’s ceremonial overskirt, Kuba people, early 20th century. Overall dimensions: 68.6 x 162.6 cm; 27 x 5 ft. 4 in. Cooper Hewitt Collection, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, USA.

«This <over>skirt features a central purple-brown panel with geometric patterning achieved through embroidery and restrained openwork. Immediately surrounding this is a dark brown border of plush cut-pile embroidery framed by a ruffled edge made of orange raffia bundled cording. Though lain flat and at rest, the dynamic curved edge treatment lends undulating movement to the otherwise static object. This movement would have been further enhanced when worn during Kuba dance ceremonies such as the Itul. (…). These ceremonial dance <over>skirts were wound in a spiral around the woman’s body, so that the lower edge of each panel was staggered and exposed beneath the one above it, and held in place by a decorative belt. (…). One important thing to note about this garment is that it was never intended by the Kuba to be viewed flat; since it was only used in key rituals, the skirt was only displayed when worn in the round, wrapped around the body.» (Kyla I. Katigbak, Unwound from the Round).

The following picture shows a special type of ntshak minen (the overskirt with wavy edges): it’s called ntshak minen’ ishushuna, and could only be worn by the wife of a nyim.

Overskirt with wavy rims, ncák minen’ ishushuna, Bushoong, Kuba people, late 19th century. Length: 171 cm; 67,32 in. Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium.

Please note that the center section shows both the embroidery and appliqué techniques.

Not all women’s overskirt are ntshak minen. The next type, called ntshakabwiin, has no wavy edges but a classical structure with raised pile cloth designs in the center and borders embroidered with an interpretation, a variation, or a composition of the same central design.

Ntshakabwiin type women’s overskirt, 20th century, raffia and dye. Dimensions: 140.3 x 79.4 cm – 55 1/4 x 31 1/4 inches. Palmer Museum of Art, Pennsylvania, USA. Photo courtesy: Smithsonian Institution, Department of Anthropology.

«The pattern in the small rectangular section <on the right> shows a predominant chevron design called mikomingom, which is a Kuba favorite, abundantly used, and references the designs that king Miko mi-Mbul used on his royal drum. The overlaying diamond and linear motif, which creates a sense of motion up and down the long edges of the cloth, is another perennial favorite, <called> lo liyoong’dy, or “chameleon’s arms.” Inspired by “the strange allure of a chameleon’s paws,” this pattern is multiplied across objects in a wide variety of surface decorations, including the royal drum designed by another king, Mingashyaang. The center panel is filled with one of the many variations of the “stones” design.» (The Palmer Museum curators).

Because of all these features and the red color of the center section, this ntshakabwiin would have been a sign of social prestige for the wearer.

BELOW

Another women’s overskirt of the ntshakabwiin type, reserved to a member of the royal family. Kuba-Bushoong people, 1st half of the 20th century, raffia and natural dyes; stem-stitch embroidery. Dimensions: 108.59 x 57.15 cm – 42.75 x 22.5 in. Photo courtesy: TAD Tribal Art, New Mexico, USA.

Woman’s Embroidered Overskirt, Kuba, raffia pile cloth. Late 19th – early 20th centuries. Dimensions: 172.1 x 68.6 cm; 67 3/4 x 27 in. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC, USA.

Noble Kuba women secure their ceremonial skirts and overskirts with a belt made of raffia fiber. The next image shows some examples of the ceremonial belt called nkody mu-ikup, worn by women on the occasion of celebrations and festivals such as the Itul, or when someone is elevated to the rank of “notable” or chieftaincy. These belts are decorated with cowrie shells arranged in three rows of equal length on each side, except for the lower belt, which has a floral design of four cowrie shells. The middle section, always worn on the dancer’s back, is decorated with a symbolic interlaced knot and a geometric pattern of two-tone beads. The checkered pattern is called makwoongi matey. The two ends of the belt are tied together at the front with strands of fiber or leather.

LEFT TO RIGHT, TOP TO BOTTOM:

Ceremonial belt, 20th century, dimensions: 1 3/4 x 43 1/2 in.; 4.445 x 110.49 cm. Medium: Green, white and blue beads; cowrie shells, fiber. Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, Massachusetts, USA.

Ceremonial Belt, mid-20th century, dimensions: L. (with string) 48 in. (121.9 cm); L. (without string) 38 ½ in. (97.8 cm); H. (at center element) 2 ¼in. (5.7 cm). Medium: Raffia, cowrie shells, and beads. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC, USA.

Ceremonial Belt, 20th century, dimensions: L. 33 in. (83.8 cm); W. 1 ½ in.(3.8 cm). Medium: Raffia, cowrie shells, and beads. North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC, USA.

Ceremonial Belt, 20th century, dimensions: L. 24 in. (61 cm); W. 4 in. (10.2 cm). Medium: Raffia, cowrie shells, and beads North Carolina Museum of Art, Raleigh, NC, USA.

Prestige belt, Kuba-Bushoong, 20th century, dimensions l. 106.4 cm., w. 4.7 cm., d. 2.7 cm. (41 7/8 x 1 7/8 x 1 1/16 in.). Medium: Glass beads, cowrie shells, and raffia. Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ, USA.

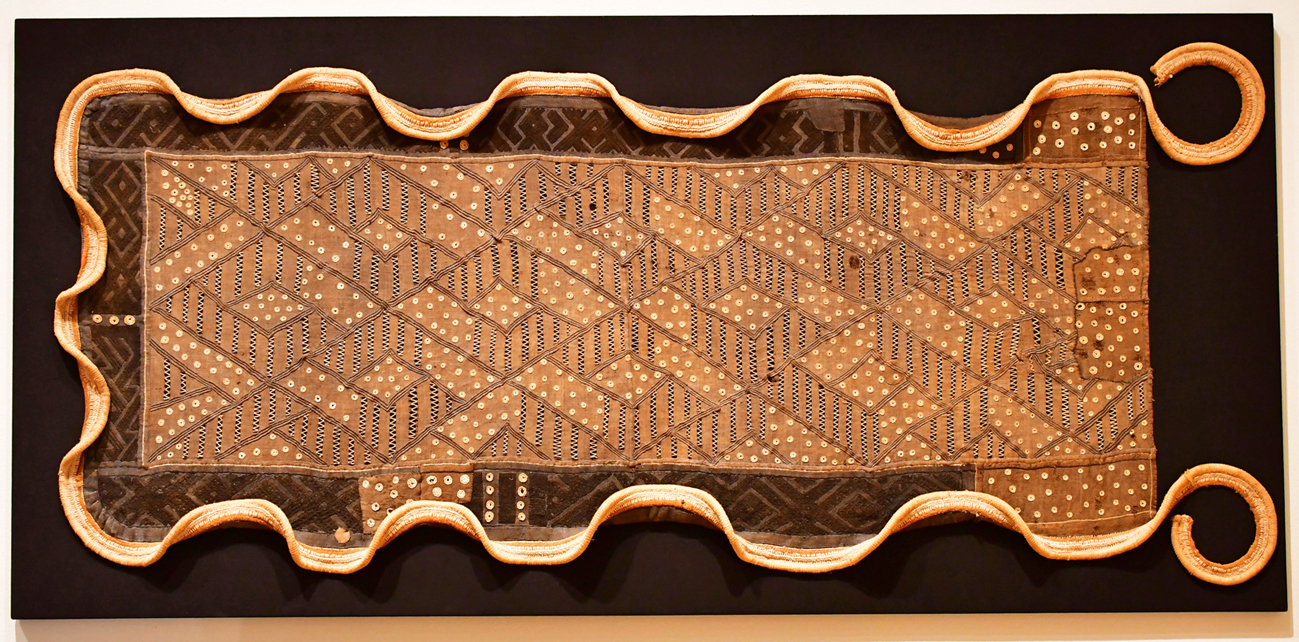

Last but not least, let’s admire another amazing ntshak minen: this time, the overskirt was not reserved for a woman of the royal court or the nobility, but for the nyim himself. This piece, made in the first quarter of the 20th century, shows the use of various techniques and bears witness to the long and patient work made by the women of the royal family. Note the geometric woot-pattern in the central part, achieved through embroidery, appliqué, and openwork (the brim is made with a cut pile technique instead).

Overskirt for a Kuba nyim, Bushoong, 1900-1925. This stunning piece was featured in the 2019 exhibition Kuba: Fabric of an Empire, which showed dazzling Kuba textiles in the Cone Collection galleries of the Baltimore Museum of Art (MD, USA).

BELOW

Close-up of the above overskirt for a Kuba nyim

This last overskirt, reserved for the king, leads us to explore the other half of the Kuba sky: the men and their skirts, the mapel.

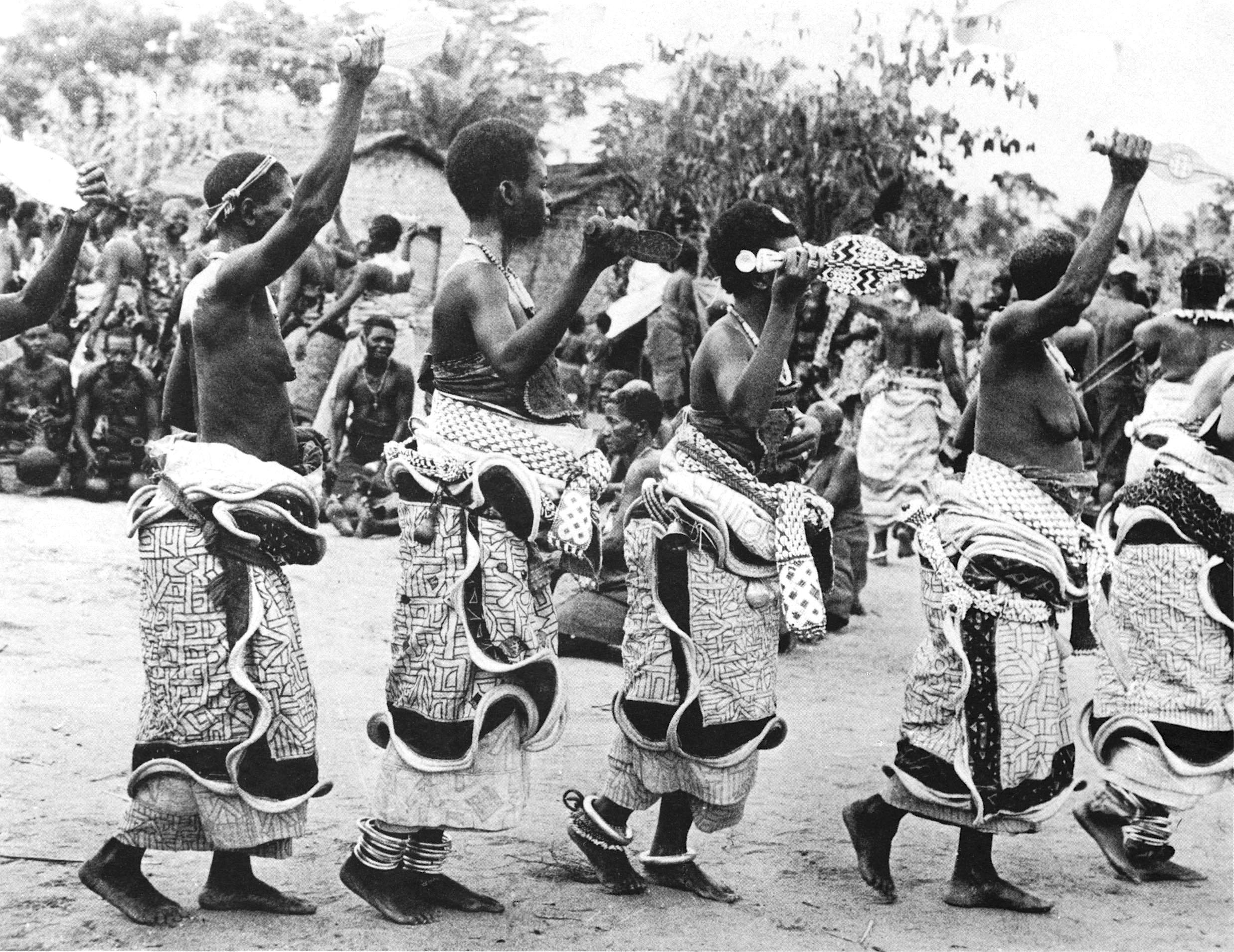

The following pictures show the complex ceremonial skirts of some Kuba peoples: Bushoong, Bieeng, Kete, Ngongo. Most of the differences have to do with minor details; the major differences (such as the colors) have more to do with the social and political status of the wearers and less with their ethnic group. The way the mapel is worn and many of its details (from the chequered pattern to the end band and the pompom fringe) remain essentially the same.

The men do not wear their ceremonial skirts like the women. They wrap their mapel, which is usually longer than the female ntshak, around their hips and fasten it with a belt over which the top edge of the fabric is folded. The result is a wraparound skirt that is shorter (the bottom hangs below the knees) and wider than its female counterpart, and there is a reason for this: the men’s legs need more room and freedom to perform more energetic dance moves.

LEFT: Kuba-Bushoong titleholders are preparing for a dance, photo by Jan Vansina, June 1956. Source: UWDC, University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries. USA.

RIGHT: Kuba-Ngongo Chief Kalala with his regalia, photo by Jan Vansina, June 1956. Source: UWDC, University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries. USA.

BELOW

LEFT: Kuba-Kete village chiefs, photo by Jan Vansina, April 1956. (Yes, among the chiefs, namely the village heads called shanshenge, there was a woman. A female chief, to be exact). Source: UWDC, University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries. USA.

RIGHT: Kuba-Bieng men, photo by Jan Vansina, May 1956. Source: UWDC, University of Wisconsin-Madison Libraries. USA.

Kuba children, including members of the royal family, perform during the state visit of the nyim Kot a-Mbweeky III to the village of Bungamba (DRC). This photograph was taken by Eliot Elisofon during his travel to Africa from March 17, 1970, to July 17, 1970. Photo courtesy: Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of African Art, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, Washington DC, USA.

BELOW

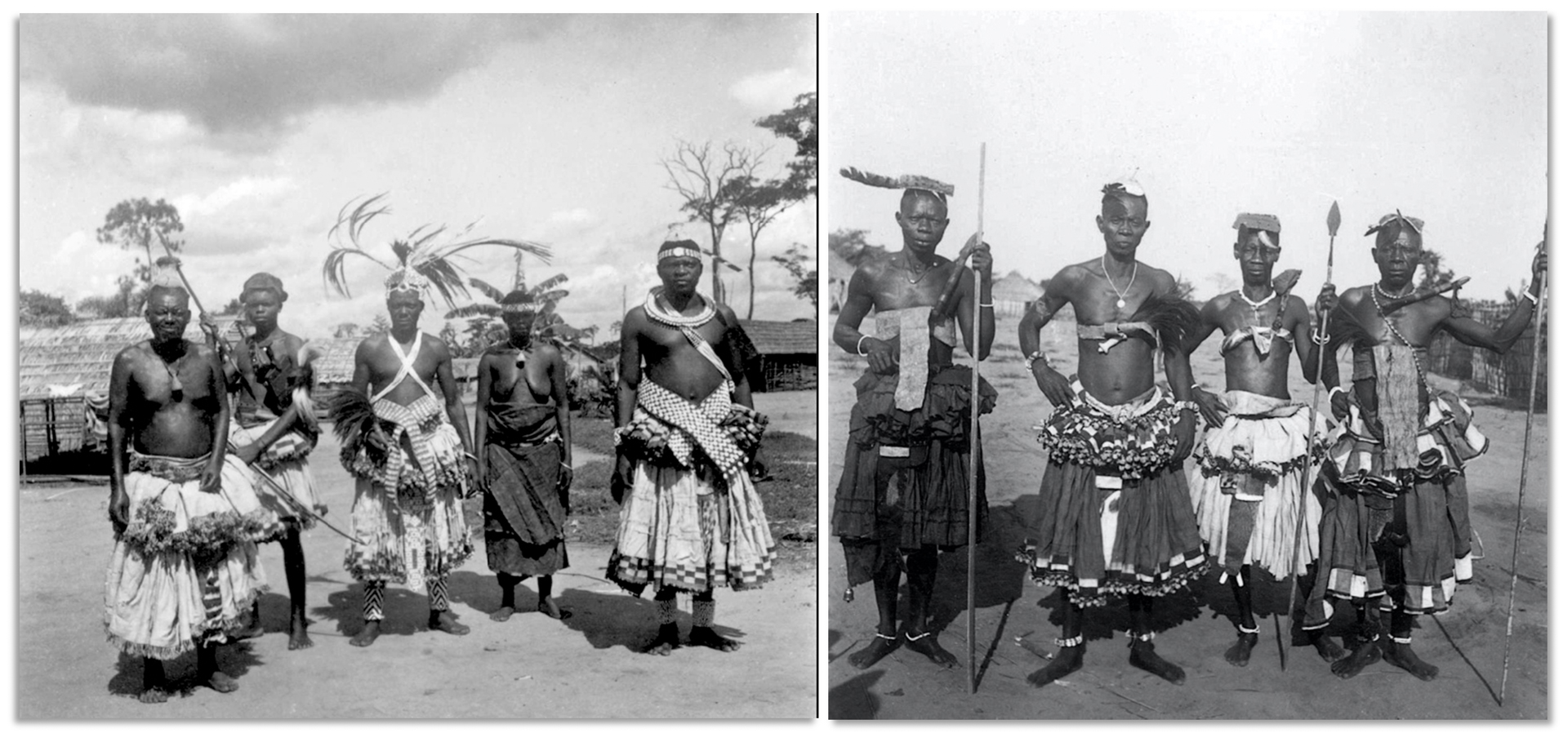

Kuba titleholders at the royal court in Mushenge, 1971. This photograph was taken by Eliot Elisofon during his travel to Africa from October 26, 1970 to the end of March 1971. Photo courtesy: Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of African Art, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, Washington DC, USA.

This image shows some high-ranking nobles wearing the traditional costume and symbolic adornments (beads, shells, brass or copper accessories, hats and headdresses with bird feathers) at the court of the nyim Kot a-Mbweeky III.

As before, let’s look at a maple lying flat on a surface. The following vintage piece, which was photographed folded and not at its full length, shows a checkered pattern obtained by the reverse appliqué technique (I will explain the difference between the latter and the simple appliqué technique later). It also shows panels in red, a prerogative of the royal clan, and several cowrie shells. These were a traditional form of currency and a symbol of wealth and power throughout western equatorial Africa. In the kingdom of Kuba, they were the most precious material to enrich the textiles, together with the glass beads. While the latter came from Europe through trade, the cowry shells came from the distant coastal waters of Africa.

Man’s Wrap, Kuba people, 1980 – 1990. Dimensions: length 3.39 m, 133.46 in.; height 49.7 cm, 19.56 in. Photo courtesy: Spurlock Museum of World Cultures, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA.

BELOW

Close-up of some details

The man’s wrap above is incomplete: it lacks the pompom fringe border.

BELOW

Fabric band with pompom fringe for a ceremonial skirt, Kuba, 19th / 20th century, raffia. Dimensions: 11 x 348 cm. Rietberg Museum, Zurich, Switzerland.

Part of a man’s skirt (mapel), possibly made for export, late 20th century. Diimensions: 383.7 cm x 77.8 cm (151 1/16 x 30 5/8 in. Medium: Raffia, tukula, and dye. Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ, USA.

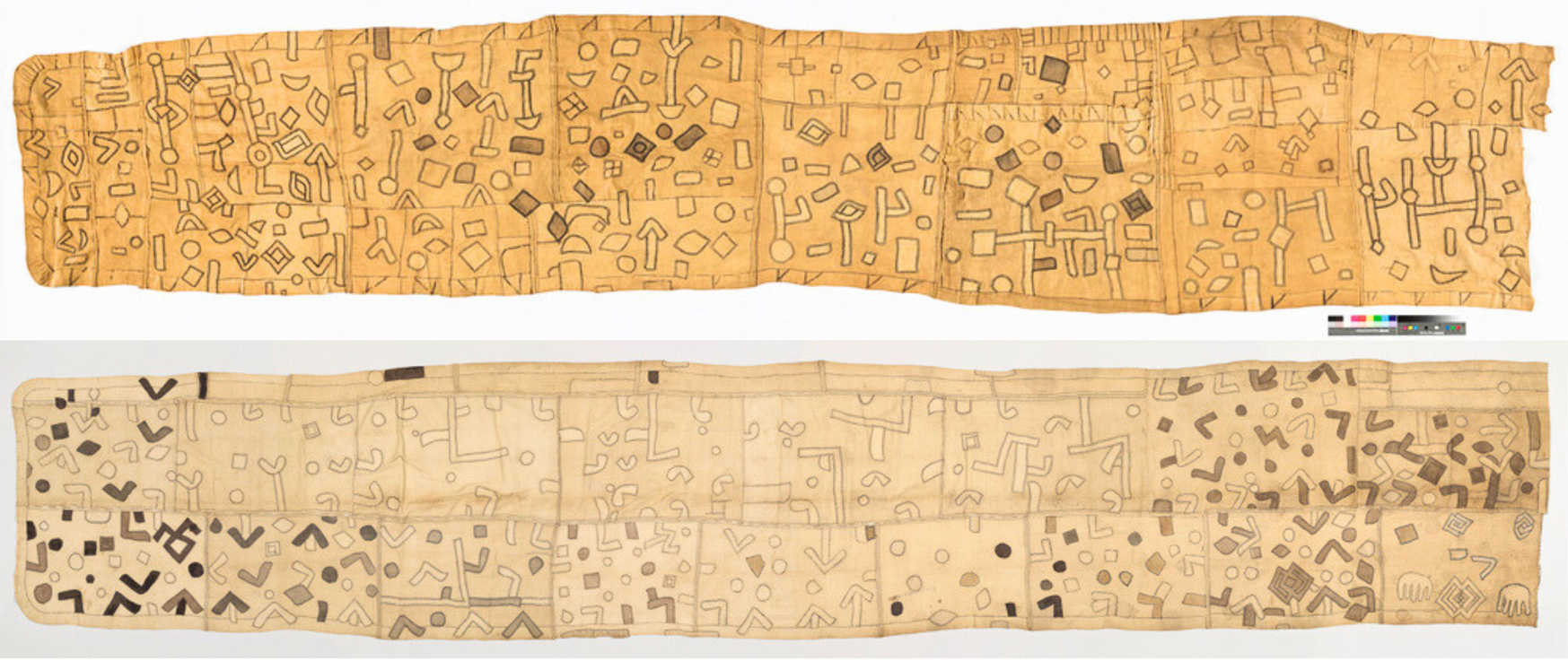

The following men’s wrappers are of a different type, more similar to the women’s ntshak.

BELOW

TOP: Man’s maple skirt, Kuba, early 20th century, raffia. Overall dimensions: 440 x 81 cm. Rietberg Museum, Zurich, Switzerland.

BOTTOM: Men’s Ceremonial Skirt, Kuba, early 20th century, raffia. Techniques: embroidery and appliqué. Overall dimensions: 567.7 x 99.1 cm – 223 1/2 x 39 in. Cooper Hewitt Collection, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York, USA.

The next outstanding early 20th century mapel, probably made by the Kuba-Ngoombe, was realized by using the reverse appliqué technique, which is different from simple appliqué.

Let’s see the difference.

In the appliqué technique, the women cut out shapes from another raffia fabric, which can be the same color as the base raffia fabric or a completely different color, and apply and sew them onto the base. There are a variety of color appliqués, including natural on natural in the last piece shown above.

The appliqué pieces are visible on the top of the fabric, creating a layered and textured design.

Reverse appliqué is a different technique where a design is created by cutting away portions of a top layer of fabric to reveal the contrasting fabric underneath. In the case of Kuba textiles, women cut through the top layer of fabric to expose the underlying fabric. The cut edges are often folded back and sewn in place, creating a design with the base fabric showing through the openings.

Male Titleholder’s Skirt, Kuba peoples, possibly Ndengese or Ngoombe. Early 20th century. Raffia palm fiber. Techniques: embroidery, reverse appliqué. Dimensions: 405 x 84 cm – 159 x 33 in. Photo: © Andres Moraga Textile Art, San Francisco, USA.

The mapel and ntshak pieces were and are made in a variety of styles, techniques, and colors, with patterns reflecting both the social status of the wearer they were meant to signify and the ceremonial costume they were part of; in addition, each village, clan, and group had and still has its preferences in techniques, colors, and pattern combinations.

In the following images and video, you can admire the visual beauty of some of the textiles used by the Kuba peoples for both ceremonial skirts and other uses. Kuba colors and patterns can be extraordinarily evocative and vibrant, surprisingly in tune with Western tastes, which explains their extraordinary contemporary success among museum curators, art gallery owners, African art experts, and collectors.

Kuba textiles – you will see – are a feast for the eyes. However, it should be emphasized that they are also born to be a “feast” for the skin and worn as a “second skin”. Unfortunately, their tactile qualities – an extraordinary contrast to the original roughness of raffia fibers – remain inaccessible to all those who admire Kuba fabrics in virtual or real collections. It’s a pity, but also a perceptive impoverishment, because these garments of amazing softness and sensual textures are meant to be touched, worn and moved, not to be admired lying flat on the wall or hanging from the ceiling in a stillness that does not belong to them. It is only when they are worn and moved in a dance or masquerade that these distinctive patterns begin to sing aloud.

A selection of ntshak pieces, Kuba, early to mid 20th century. Raffia, cotton thread and pigment. Photo: © Bowers Museum, Santa Ana, CA, USA.

A selection of ceremonial skirts mostly made for the art market, Kuba peoples, 20th century. Photo courtesy of Tim Hamill, painter, African art expert and owner of the Hamill Gallery of Tribal Art and Hamill Galleries, Massachusetts, USA.

A selection of ntshak and ntshak nsueha made by the Kuba-Bushoong for the art market, second half of the 20th century. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

Kuba Textiles – The Sam and Mei-Ling Hilu Collection

This video shows some of the traditional Kuba dances performed not in a ceremonial context but for tourists. It deserves to be seen because it clearly shows the dynamics of the dances, the role of the traditional skirts, and the gender difference. By 101 Last Tribes.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?