THE KUBA TEXTILES FROM THE DRC – 4

Democratic Republic of the Congo or DRC on the globe (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

TEXTILE ART IN KUBA SOCIETY

Ntshak and mapel ceremonial skirts and overskirts were worn by women or men for ceremonial and ritual dances during festivals, celebrations, funerals of high-ranking titleholders, the investiture of a new king, and important cultural events and rites of passage. During mourning, they were used to decorate the interior of the coffin and to shroud the body of the deceased for burial.

Ceremonial skirts were relevant elements of a cultural universe of actions, customs, and rites, and part of specific costumes, which means that they were inextricably linked to a network of other objects, such as masks, belts, headdresses, jewelry, musical instruments and performances, weapons, ritual objects, etc. The costumes, and the textiles that were part of them, were also clear indicators of the social rank, power, authority, and prestige of the wearer, an aspect that was quite relevant within the Kuba organization. «The Kuba cloths, while used to clothe the living, are also employed to dress the dead», and make perfectly evident the social status of the deceased. (J. Glazer, cit.).

RIGHT: Ngaady a Mwaash Mask and Costume worn by a male dancer and representing the primordial female of the Kuba peoples. 20th century. Photo courtesy: Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, USA.

CENTER: The Kuba Isyeen Imalu mask emerges from the sacred forest surrounded by elders of the village. «The mask’s chameleon-like eyes represent the ability to see the invisible; this mask comes out during royal occasions and at initiation ceremonies.» Text and photo courtesy: Africa Online Museum, copyright by Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher.

LEFT: Mukenga dancers performing at the funeral of a senior titleholder in a Bushoong community. The mukenga mukyeem mask is a variation of the Mwaash ambooy royal male ancestor mask representing Woot. Photo courtesy: Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, USA.

However, the ntshak and mapel surpassed all other ceremonial, ritual, or artistic objects in one fundamental aspect: their social value. Of course, this does not mean that all other cultural objects were devoid of such value, but that ceremonial skirts and overskirts had a unique, peculiar value resulting from their complex, multiphase, and collective production. In the first part of this article, we saw the various stages of raffia cloth production, from the cultivation of the palm tree to the final softening of the hand-woven cloth, and we saw the development of a complex organization in which men and women within a lineage, family group, or clan subgroup collaborated at various stages. In the third part, we saw how the embroidery of all ceremonial skirts was a collective effort, with several women within a group contributing one or more sections. Thus, complex textile pieces such as ceremonial skirts, overskirts, and larger Kasaï velvets were the result and artistic representation of the particular degree of cooperation, collaboration, coordination, organization, interdependence, technical skill, creativity, and aesthetic taste of a particular group. No other artistic or cultural object shares this characteristic.

Corresponding to this collective creation is an equally collective form of ownership: the majority of textiles were collective property, which probably existed alongside more restricted forms of ownership.

Patricia Darish «studied the ownership of these collectively created textiles. She found that, primarily among the Bushoong, most decorated raffia skirts are neither created nor owned by a single person, but are the result of collaborative labour of the men and women of the clan section of a matrilineage. This may be seen for example in the production of a long woman’s skirt which may be the work of half a dozen women of different ages. (Darish 1989: 124.) This circumstance calls into question Western ideas of artisanship, ownership and authorship. A single raffia skirt may be understood as a representation of social relations and communal artistry. In addition, she suggests that, although particular individuals may be acknowledged for the value of their work, it is unusual to find that a long decorated skirt is made by only one person. Even when cloths are the output of one person they are never regarded as the sole property of the maker. (Darish 1989:125.) However, Darish does not indicate how they are distributed when they are worn, if they are kept in a communal storehouse or if they are kept by their individual wearers but are ultimately regarded as the property and assets of the clan. (…). The majority of the textiles and accessories that adorn the deceased’s body belong to his/her clan section. As the extiles are the property of a clan section, they are placed on the body only after a formal discussion between clan members. The textiles which adorn the deceased may also come from additional sources. For example, the spouse of the deceased (either male or female) is also required to present one or more textiles of suitable value that is acknowledged by the clan section of the deceased.» (J. Glazer, cit.). This last custom shows that more restricted forms of textile ownership emerged alongside the collective one.

Hans Himmel, Dancing Men at a Funeral, near Mweka, Kuba Kingdom, RDC, January 16, 1939. Rietberg Museum, Zurich, Switzerland.

Ceremonial skirts, overskirts, large cut pile cloths, and the most elaborate Kuba textiles were indicators of wealth because they showed that the family group that produced them could afford to invest much time and many members in an activity other than subsistence. Wealth was a highly valued aspiration among the Kuba because it was the primary means of acquiring prestige, power, and status, and wealth was primarily displayed through elaborate textile pieces. Patricia Darish explained: «Traditional decorated raffia skirts and cut-pile cloths are considered tangible wealth that everyone wants to accumulate.» (P. Darish, Dressing for the next life : raffia textile production and use among the Kuba of Zaïre, see Bibliography). The most elaborate and precious textiles were reserved for the nyim and the royal court, where they were used not only as ceremonial skirts and overskirts, but also to cover the royal thrones and to decorate the walls of the king’s palace.

The large amount of time-consuming labor and people involved in making a ceremonial skirt, overskirt, and a large cut pile cloth had a measurable economic value: it won’t surprise you to learn that the most elaborate textiles were used as the main form of currency, often enriched with valuable cowries, both within and outside the Kuba kingdom, at least until the mid-19th century.

The Kuba used raffia squares (mbal) as a local currency and in their trade with external markets. Vansina noted that an alternative name for the Bushoong was Bambal which means “people of mbal”, namely “people of the cloth”.

Within the Kuba kingdom, raffia textiles were used as compensation in legal settlements, adultery or divorce cases, and marriage contracts; as burial gifts; as valuable products for various forms of exchange; and even as part of the annual tribute paid by villagers to the king at the end of the dry season.

Beginning in the late 19th century, colonial agents, European missionaries, and travelers arriving in the kingdom of Kuba were fascinated by the Kasaï Velvets and other textiles, began to acquire them, and encouraged Kuba women to produce more of them to adorn religious vestments for Catholic missionaries and to decorate the interiors of European homes.

As Glazer summarizes, «at the beginning of the 20th century, ten raffia squares or the average length of a fabricated ceremonial wrapper equalled a considerably large unit of value (Darish 1990: 179). For the more important payments, the Kuba used a unit of 320 cowries sewn to a piece of raffia cloth known as mabiim. The price of these items was fixed by the law of supply and demand, and was influenced by the rarity of the product, the mass of materials used, the production time, the cloth’s luxurious quality, and the state of conservation of the object (Vansina 1964:23).» (J. Glazer, cit.).

Textiles thus played a crucial cultural, aesthetic, social, and economic role in Cuban society. Many scholars have emphasized the relationship between Kuba textile art and the complex socio-political structure of their kingdom, and seem to agree with American expert Ashley Rickman, who wrote: «The woven arts were a tangible representation of the abstract concepts of privilege and power».

Many scholars, from Emil Torday to Patricia Darish, have interpreted the display of textile art as an expression of status, power, political prestige, labor, and wealth, all relevant values in the hierarchically structured Kuba society. As Fraser and Cole suggest, «hierarchically organized socio-political systems usually have a visible hierarchy of art objects (including regalia) which reflect and uphold ranked social positions. A network of roles calls for a network of symbols.» (African Art & Leadership, edited by Douglas Fraser and Herbert M. Cole, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press,1972). In her 1996 essay, The Social and Political Implications of the Kuba Cloth, Joanne Glazer, who has provided one of the most brilliant analyses on the subject, wrote: «A culture’s textiles and modes of dress are one medium by which one can draw associations between the culture and its socio-political structure. The Kuba cloths not only proclaim one’s identity and inform others who one is, they are also connected to a highly stratified social and political framework to which the individual belongs and from which this sense of identity is fostered and informed.» (J. Glazer, cit.).

It’s true. The hierarchy that characterizes Kuba society is reflected in the formal dress, the institution of title holding is reflected in the various forms of lewelry and clothing display, and we know that the Bushoong court has always paid close attention to the regalia, especially the textile works of art, that are regarded as symbols of this sacred royalty. However, it is not the textiles or the wrappings as such that illustrate social status and privilege within the hierarchically ordered and well-structured Kuba society, but the entire costume of which they are only one part, along with a myriad of other accessories, art and ritual objects, and many other symbols and socio-economic indices. What most scholars point out about Kuba textile art is true and well-founded, but it has a serious interpretive limitation: it fails to recognize and flatten the specificity and uniqueness of Kuba textile art.

However, we have already seen that Kuba textile art has a unique characteristic that is not shared by any other art form. Now we are going to identify another unique feature that is even more important. If, as we will discover together, Kuba textile art has absolutely unique essential characteristics, then its value, its beauty, its significance within the cultural universe of Kuba does not lie at all in what has been said.

THE UNIQUENESS OF TEXTILE ART IN THE KUBA UNIVERSE

The art of the Kuba is one of the most highly developed of all African traditions, encompassing a wide variety of materials and media. In particular, the Kuba are known for the refinement of prestige objects created for members of the higher ranks: the nyim, his family and court, titleholders, and local chiefs. Many art objects are also associated with the most important collective ceremonies and rituals. Here I’ll show you some of them, but I have to emphasize that it is not my intention to sketch a history of Kuba art, nor to give an exhaustive overview of it. I will simply show a few objects of art, chosen either because they are quite representative or because they are amazingly beautiful to me and, I hope, to you as well. My goal will be to point out and let you identify a relevant feature that textile art does not share with any other art form. Not even music.

Let’s start with a cephalomorphic horn carved with animal and geometric motifs. Its rich and complex ornamentation indicates that it was probably made for a leading Bushoong family.

Wooden horn, Kuba, DRC, mid-20th century. Dimensions: height 52 cm, width 13 cm. Weight: 1.9 kg. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

The following objects are palm wine cups. Palm wine, known as maan, was the beverage of choice throughout much of Central Africa and was also popular among the Kuba peoples. The wooden drinking cups below are two exquisitely carved pieces made by the Kuba Bushoong, probably for the royal court. The cups carved in the shape of a human head or with full figures were rare and highly prized, but even the simpler beakers and drinking cups engraved with multiple geometric patterns were considered status symbols. In the past, drinking palm wine was a collective custom during festivals, funerals, and many other secular and social occasions, such as male initiation rites. On all of these occasions, members of the community drank the wine contained in large gourds from smaller calabash cups; the wealthiest members did not use the communal calabash and instead poured the wine into their personal, elegantly carved cups or goblets. This was, of course, a great opportunity for public display of prestige, and the more elaborate and beautiful a man’s drinking vessel was, the more attention and admiration he would receive.

LEFT: Palm Wine Cup (Mbwoongntey), Kuba Bushoong, 19th century. Wood. Dimensions: 21.6 x 11.4 x 13.3 cm – 8 1/2 x 4 1/2 x 5 1/4 in. The Brooklyn Museum, NY, USA. «In wood, with a highly polished surface, this cup has the form of a kneeling man holding chin and stomach, with scars on upper thighs, crosshatched hair dress, short torso, protruding chin and mouth, handle on back» (The Museum curators).

RIGHT: Palm Wine Cup, Kuba. Date: uncertain. Provenance: from a Belgian collection. Dimensions: 29 x 12 cm. Weight: 0.90 kg. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

LEFT: Cephalomorphic Palm Wine Cup, Kuba Leele. Wood. Date: mid-20th century. Provenance: from a Belgian collection. Dimensions: 22 x 12 cm. Weight: 0.80 kg. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

CENTER: Goblet in the shape of a head (Mbwoongntey), Kuba, early 20th century, before 1922. Wood. Dimensions: 22.3 x 9 cm – 8 3/4 x 3 9/16 in. The Brooklyn Museum, NY, USA.

RIGHT: Cephalomorphic Palm Wine Cup, Kuba Bushoong. Wood. Date: unknown. Dimensions: height 17.8 cm, width 9 cm, depth 9.8 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

CLOCKWISE (left to right):

-

Wood and plant fiber cup with pierced base and guilloché decoration, Kuba Bushoong. First half of the 20th century. Dimensions: height 22.7 cm, width 9.5 cm, depth 10.4 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

-

Wooden prestige cup from Mushenge, Kuba, mid-20th century. Dimensions: height 15.9 cm, width 13.7 cm, depth 14.9 cm. Smithsonian Institution, USA.

-

Palm wine cup, Kuba, 20th century. Wood.Dimensions: 16.5 x 12.5 x 9 cm – 6 1/2 x 4 15/16 x 3 9/16 inches. Palmer Museum of Art, Penn State University, USA. «This drinking cup carved in the shape of a drum on an elevated base suggests its owner was a titleholder and possibly a drummer who hoped to put his wealth and status on display in the recognizable but unique design of this highly decorated object. The bent leg protrusions of the base are also suggestive of those seen on some prestige stools (Binkley and Darish 2009, 125), and the curved handle in the form of a human figure is a convention also employed on decorated full-size drums. Anthropomorphic designs, as in this cup handle, are most prestigious and suggest the exceptional level of wealth or power held by its owner.» (The Mueum curators).

-

Wooden drinking cup with simple handle, Kuba, 1900-1908; probably collected by Torday. Dimensions: height 17 cm, width 8.3 cm, depth 8.2 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

-

Wooden drinking cup with simple handle, Kuba Leele, first half of the 20th century. Dimensions: height 15.8 cm, width 15 cm, depth 12.8 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

-

Wooden oil cup from Mushenge, Kuba Bushoong, late 19th – early 20th centuries (before 1909). Probably collected by the Torday expedition. Dimensions: height 17.5 cm, width 18.4 cm, depth 18.4 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

The following pieces are prestige lidded boxes and small containers made of hand-carved and incised wood and used to store valuables, pipes, spoons, and cosmetics. Many crescent-shaped boxes were used to store tukula, a bright red pigment made by rubbing pieces of heartwood from two tropical trees, camwood (Bafia nitra) and African padauk (Pterocarpus soyauxii). Grinded in a mortar, tukula becomes a fine powder that can be mixed with palm oil to make a paste. As a pigment, it was used as a textile dye, a paint, and a cosmetic to decorate the body. When baked, tukula paste hardens into blocks known as bongotol, which are decorated and given as funeral gifts.

Look at the boxes below: some show amazing anthropomorphic detail, and all have been elaborated beyond mere function, carved with the same geometric patterns used in the many luxury textiles and ritual scarifications. Can you recognize the woot symbol and its variations?

TOP:

-

Wooden box with lid, Kuba Bushoong, late 19th – early 20th century. Dimensions: height 13.8 cm, width 31 cm, depth 12.3 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

-

Wooden crescent-shaped box with lid, carved with geometric patterns and an anthropomorphic face; the uncut surface has been painted black. Kuba Bushoong, before 1910. Dimensions: height 9.4 cm, width 31.6 cm, depth 15 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

CENTER:

-

Kuba lidded box, intricately carved, used to hold tukula, 20th century. Wood. Dimensions: 27.94 x 16.5 x 11.43 cm – 11 x 6.5 x 4.5 inches. Photo courtesy of Tim Hamill, painter, African art expert and owner of the Hamill Gallery of Tribal Art and Hamill Galleries, Massachusetts, USA.

-

Wooden box with string, Kuba Bangendi, 1900-1908. Dimensions: height 9.4 cm, width 31.6 cm, depth 15 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

-

Camwood lidded box from Mushenge, Kuba Mbala Bushoong, 19th century. From the Emil Torday’s expedition. Dimensions: height 15 cm, width 14.7 cm, depth 14.6 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK. «The box is circular with a square footed base, sides carved with geometric designs and infilled with cross-hatching. The lid mirrors the base of the box, circular with square top and gently concave sides decorated with linea designs and cross-hatching. The surface of the square top is carved with an interlace design and a modelled beetle.The fibre handle is attached to the lid with a knot. The inner surface of the lid and box is thickly encrusted with a pinkish deposit.» (The Museum curators).

BOTTOM:

-

Long wooden box, Kuba Bangongo, 1900-1908. This pieces was acquired during Emil Torday’s expedition to the Congo on behalf of the Museum in 1907-8. Dimensions: length 38.5 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

-

Prestige wooden box for tukula, Kuba Leele, 20th century. Dimensions: height 7 cm, depth 13 cm, width 36 cm. Weight 0.8 kg. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

-

Wooden box for storing pigments, with lid carved in sgraffito with human eyes and protruding nose, Kuba Mbala Bushoong, ca. 1900. Dimensions: height 5.8 cm, width 27 cm, depth 10.8 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

Now, we’ll look at some sculptures, called ndop, which are among the most relevant objects and most revered art forms of the Kuba. Each ndop represents a specific nyim of the Kuba kingdom. However, they are not portraits, nor were they created from direct observation; instead, they are ideal representations of each king, identified by a small emblem, the ibol, and a distinctive geometric pattern at the base of the sculpture, chosen by the nyim when he was installed as leader and commissioned his ndop.

All of these sculptures, developed from the first half of the 18th century onward, share the same traditional formal conventions: the king is depicted sitting cross-legged on the royal platform (yiing), unable to touch the ground, a posture that is also unique in African sculpture. His left hand holds a weapon, often the ikul or ceremonial knife. He wears a distinctive protruding hooded headdress decorated with carved cowrie shells around the rim and an interlocking pattern on the top. Other important pieces of regalia may include the representation of a circular neck ring, cane shoulder hoops, a cloth plaque covering the buttocks, and a belt with three rows of cowrie shells.

The ndop, usually 48-55 cm high, were carved in hardwood, often rubbed with redwood powder and anointed with palm oil to protect them from insects and rain, another unique feature in African art that has allowed their preservation over the centuries. The following ndop, for example, on display at the Brooklyn Museum, was made between 1760 and 1780 and is considered the oldest in existence. The king’s symbol, the ibol, is a drum with a severed hand on the front.

Ndop figure depicting Nyim Mbó Mbóosh (r. ca. 1650), Nyim Mishé miShyááng máMbúl (r. ca. 1710), or Nyim Kot áNée (r. ca. 1740). Kuba Bushoong, from Mushenge (Nsheng). Medium: wood (Crossopteryx febrifuga), tukula, fiber. Date: 1760-1780. Dimensions: 49.5 × 20.3 × 25.4 cm – 19 1/2 × 8 × 10 in. The Brooklyn Museum, NY, USA.

«The figure sits cross-legged on a rectangular platform which is decorated with geometric chain-like bands. His right hand rests on his knee, the left hand holds a ritual knife. The head is large, with finely carved features and a curved hairline. His eyes are closed. The headdress consists of a decorated board atop a cylindrical ring. He wears a belt incised with shell motifs, armbands, bracelets, a rounded shoulder strap, and a belt with richly decorated back apron. In front of him is a cylindrical drum set on a small perforated pedestal. The drum is decorated with a hand and intertwined geometric motifs.» (From The Brooklyn Museum Catalogue).

Two scholars, Monni Adams and Vansina, gave us much information about the use, function, and sacredness of ndop sculptures. «After the rites of investiture were completed, the king ordered a sculptor to carve his ndop and his drum of office. Only one ndop could be made for a king. (…). If the figure decayed, it was permissible to carve as exact a replica of it as possible. During the king’s life, the ndop was supposed to house his double, the counterpart of his soul. The statue was kept in the women’s quarters, and when a woman of the harem was about to give birth, it was placed near her to ensure a safe delivery. In the absence of the king, it served as a surrogate, which women of the court would anoint, stroke, and fondle. After the king’s death, his ndop was removed to a storage room but taken out to be exhibited on certain occasions.» (Monni Adams, 18th-Century Kuba King Figures, see Bibliography, and Vansina, cit.). Contrary to Vansina, Joseph Cornet was convinced that «the ndop were sculpted after the death of the king as commemorative monuments for his wives in order to perpetuate his almost sacred presence in the harem.» (Monni Adams, cit.). In both cases, it’s interesting to note that the ndop figures were believed to represent and embody the spirit or essence of the nyim, as well as his superhuman powers and abilities. In other words, the sacredness of all ndop figures was derived from the nyim’s superhumanity. According to Vansina, during the king’s lifetime it was also believed that if anything happened to him, it would be reflected in his ndop. After the king’s death, the ndop was believed to become the seat of his life force.

Wooden Ndop figure, Kuba Bushoong. Date: 1910-1940. Dimensions: height 72.7 cm – 28-5/8 in.Indianapolis Museum of Art, IN, USA.

BELOW

LEFT: Ndop figure, Kuba Bushoong. Date: 20th century. Dimensions: height 22 cm, width 10. Weight: 0.30 kg. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

RIGHT: Ndop figure, Kuba Bushoong. Date: ca. 1800. Medium: camwood. Dimensions: height 55 cm, width 22 cm, depth 22 cm. From Emil Torday’s expedition to the Congo. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK. «This ‘Portrait’ figure has been identified with Shyaam aMbul aNgoong, the founder of the Kuba-Bushoong dynasty. He ruled in the first half of the 17th century, though this figure was probably carved in the late 18th century.» (The British Museum curators).

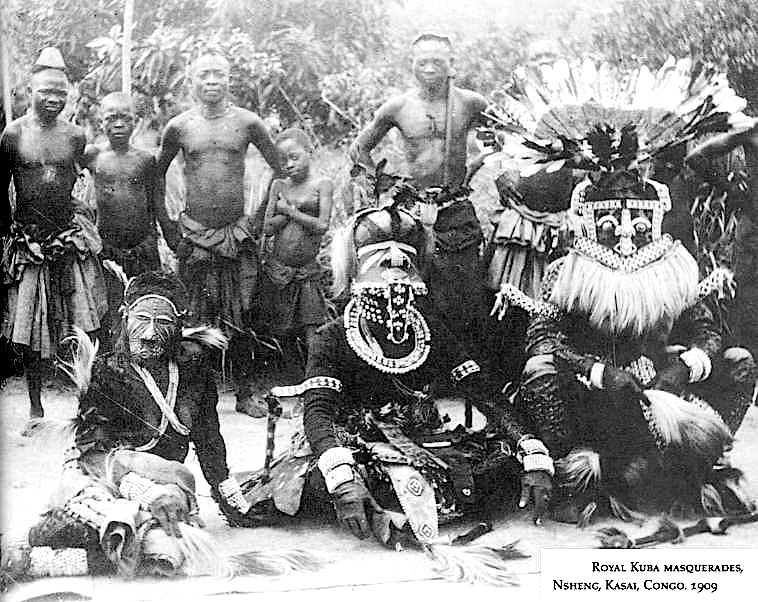

Now let’s look at some of the masks used in traditional masquerades, which are performed only by men and are therefore part of complex costumes, along with textile art and other accessories. The following picture from 1909 shows the three masks of the so-called “Bushoong Royal Masquerades”: from left to right, Ngaady a Mwaash, Bwoom, and Mwaash aMbooy mu shall. Although their dances are usually solo, together these three royal masks reenact Kuba origin myths. During the masquerades, all of these masks are imbued with spiritual significance and establish a special, intimate connection with the spirits of nature (mingesh).

The mask called Mwaash aMbooy mu shall is said to «personify Woot, the mythical ancestor of the Kuba peoples. (…). A performance told the story of Woot’s role in the Kuba kingdom’s founding and his ties to its first nyim. Mwaash aMbooy’s physical features underscore an ideal Kuba king’s traits. Its monkey-fur beard symbolizes wisdom. The cowrie shells were a royal privilege and a sign of wealth. They also reference how Woot stole the creator god’s bead-and-cowrie-covered basket of knowledge. Its costume evoked royal regalia.» (The Brooklyn Museum Catalog).

According to Patricia Darish and David A. Binkley, «The eagle-feathered crest on top of this mask makes it a prestigious object belonging to a kum apoong, an eagle-feathered chief from a small number of aristocratic clans, including the royal one. This mask is part of the prestigious regalia essential to a living nyim and kum apoong. On the day a nyim or kum apoong takes office, he wears the mask and costume and celebrates by dancing in front of the entire community. The mask and other royal insignia associated with rank must be displayed one last time at the funeral for three days, before being buried with the nyim or kum apoong as funeral equipment.» (Patricia Darish and David A. Binkley, Kuba, cit. Translation from French is mine.)

LEFT: Mask (Mwaash aMbooy), Kuba Bushoong, late 19th or early 20th century. Rawhide, paint, plant fibers, textile, cowrie shells, glass, wood, monkey pelt, feathers. Dimensions: 55.9 x 50.8 x 45.7 cm – 22 x 20 x 18 in. The Brooklyn Museum, NY, USA.

RIGHT: The Mwaash aMbooy masquerade. © African Twilight: The Vanishing Cultures and Ceremonies of the African Continent by Carol Beckwith and Angela Fisher, Rizzoli, 2018.

A non-royal variant of the Mwaash aMbooy type mask is the Mukenga or Mukyeem mask, which is often confused with the former even by some museums. The Mukenga mask, which is similar but not identical to the Mwaash aMbooy type, is widespread among the Kuba Kete, Ngongo and Ngeende, and depicts an elephant with a characteristic beaded trunk and two small tusks protruding from its base, symbolizing wealth and fertility. «As in other African kingdoms, such as the Asante and those of the Cameroon grassfields, elephants are associated with royal power. According to the Kuba proverb, “An animal, even if it is large, does not surpass the elephant. A man, even if he has authority, does not surpass the king” (Binkley 1992: 277).» (Bonnie E. Weston, A Kuba Mask, Rand African Art).

Mukenga masqueraders perform at funeral ceremonies for high-ranking Kuba titleholders and notables. «The predominant white color of the cowrie shells serves as a sign of mourning and is associated with the desiccated bones of the ancestors. When the mask performs, red parrot feathers adorn the trunk’s end; this is a privilege of the notables.» (J. Cornet, Face of the Spirits; Masks from the Zaïre Basin, in Annals of the Royal Museum of Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium, 1993).

LEFT TO RIGHT, TOP TO BOTTOM:

-

Dance of the Mukyeem or Mukenga mask, Muentshi, DRC, photo by Eliot Elisofon, 1972. From the Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

-

Kuba Mukyeem mask, from 19th to mid-20th century. Medium: wood, cowry shell, glass beads, raffia. Overall dimensions: 68.9 × 43.8 × 61 cm – 27 1/8 × 17 1/4 × 24 in. Detroit Institute of Arts Museum, USA.

-

Mukenga mask, Kuba Ngeende, 20th century. Dimensions: height 63 cm x width 32 cm; weight 2.10 kg. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

-

Kuba mask, first half of the 20th century. Medium: raffia palm leaf, skin, hair, glass beads, feathers, cowries, wood and brass. Dimensions: height 61 cm, width 44 cm, depth 40 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

-

Mukenga mask, Kuba. Date: 1875–1950. Medium: wood, glass beads, cowrie shells, feathers, raffia, fur, cloth, thread, monkey hair, and bells. Dimensions: 57.5 × 24.1 × 20.3 cm – 22 5/8 × 9 1/2 × 8 in. The Art Institute of Chicago, IL, USA.

Let’s return to the so-called royal masks. The Ngaady a Mwaash represents the primordial female of the Kuba people, namely Mweel, the sister and wife of Woot. As we’ll see in the next section, this was an incestuous relationship. The Ngaady a Mwaash, however, is a positive representation that honors the role of women in Kuba life. Note that all Kuba masks were carved by men and performed only by men; even the Ngaady a Mwaash, representing a woman, was always performed by a male dancer.

LEFT TO RIGHT:

-

Ngaady a Mwaash Mask, Kuba Bushoong. Date: 1880-1899 or earlier. Medium: wood, cotton fabric, raffia, beads, cowrie shells, and painted designs. Dimensions: 32 x 20 x 23 cm – 12 5/8 x 7 7/8 x 9 1/16 in. The Yale Peabody Museum, New Haven, CT, USA. «The aesthetic taste and noble attitude of the Kuba are embodied in the formal attributes of this mask which is a powerful representation of status and beauty. The beadwork that covers the mouth symbolizes the composure and quietness of women. The red in the mask represents suffering and the blood of menses and childbirth, the striated lines extending from her eyes and running down her cheek are tears <byoosh‘dy>. The black of the triangles signifies the hearth of the king’s home and the domesticity therein, the white of the mask the mourning of women, and the blue Ngaady a Mwaash’s royal status.» (The Museum curators).

-

Ngaady a Mwaash masked dancer, Mushenge, Kuba Bushoong. Photo by Eliot Elisofon, 1970-71. From the Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

-

Ngaady a Mwaash Mask, Kuba Bushoong. Date: 1875–1950. Medium: wood, pigment, glass beads, cowrie shell, cloth, and thread. Dimensions: 31.8 × 20.6 × 20.5 cm – 12 1/2 × 8 1/8 × 10 in. The Art Institute of Chicago, IL, USA.

The third element of the royal trio, worn during initiation dances, funeral ceremonies, and royal gatherings, is the Bwoom or, more rarely, the mBwoom mask. His specific identity varies according to different versions of the myth. He may represent the younger brother of Woot and Mweel or, more often, the non-royal constituents of the Kuba kingdom, and his character is thought of as an outsider, sometimes a Tshwa pygmy, a sick foreign prince, or even a commoner who defies the king’s authority. In his performances, the bwoom dancer moves with pride and strength, “embodying a subversive force within the royal court; therefore, the bwoom masquerade is often performed in conflict with the masked figure representing Woot.” (The Brooklyn Museum Curators). He often appears at funerals to honor a deceased member of the male initiation society.

LEFT TO RIGHT:

-

Bwoom Royal Mask, Kuba Bushoong. Date: probably late 19th – early 20th century. Dimensions: height 42 cm – 16 ½ in. Auctioned by Christie’s Paris in 2018.

-

Bwoom masked dancer, 20th century.

Several types of masks are performed within the male initiation society, particularly during the initiation rites of young males as they transition into adulthood. One of these dance masks is the Pwoom itok, also known as Ishendemala, Ishyeenmaal, or Shene Malula, whose main identifying feature is the appearance of the eyes, which are cone-shaped and surrounded by holes, carved into a deeply recessed socket and used by the dancer to see. Widespread among the Bushoong and Ngeende groups, this type of mask was often painted with traditional geometric patterns. The masks below are decorated with cowrie shells to symbolize prestige and wealth, while the spray of brown and white mottled feathers represents high title holders. They were performed to represent old and wise noble warriors.

TOP LEFT: Kuba mask (Pwoom itok). Date: early 20th century. Medium: wood, raffia, dye, cowrie shell, guinea fowl feathers, and paint. Dimensions: face 28 x 30.3 cm x 34.5 cm – 11 x 11 15/16 x 13 9/16 in. Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ, USA.

BOTTOM LEFT: Kuba mask (Pwoom itok). Date: 20th century (probably made for the art market). Dimensions: height 40.64 cm – 16 in; width 33 cm – 13 in; depth 38.1 cm – 15 in. Photo courtesy of Tim Hamill, painter, African art expert and owner of the Hamill Gallery of Tribal Art and Hamill Galleries, Massachusetts, USA.

CENTER: Pwoom itok masked dancer, Muentshi, DRC. Photo by Eliot Elisofon, 1972. From the Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

TOP RIGHT: Warrior Mask (Ishyeen Imaalu), Kuba. Date: late 19th-early 20th centuries. Medium: wood, cloth, feathers, plant fibers, cowrie shell, paint. Dimensions: 40 x 28 x 14 cm – 15 3/4 x 11 x 5 1/2 in. Baltimore Museum of Art MD, USA.

BOTTOM RIGHT: Kuba Mask (Pwoom itok).Date: 20th century. Medium: wood, pigment, feathers, cloth, cowrie shell, glass beads. Dimensions: 44.45 x 35.56 x 36.83 cm – 17 1/2 x 14 x 14 1/2 in. Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA.

I’d like to end this roundup with three masks that I love. The one in the middle is a larger and simpler but no less beautiful variation of the Ngaady to Mwaash mask. The two on the sides are Mulwalwa masks, used in Kuba Kete initiation rites, representing a spirit of nature, a ngesh, who controls fertility.

BELOW

LEFT: Mulwalwa wooden mask, Kuba Kete, 20th century. Dimensions: height 47 cm, width 23 cm. Weight: 1.80 kg. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

CENTER: Ngaady to Mwaash mask, Kuba, second half of the 20th century. Dimensions: height 86 cm, width 45 cm. Weight: 5.75 kg. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

RIGHT: Mulwalwa wooden mask, Kuba Kete, 20th century. Dimensions: height 70 cm, width 32 cm. Weight: 3.25 kg. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

WHAT MAKES KUBA TEXTILE ART UNIQUE?

In most of the objects of art of the Kuba peoples, we can find the same geometrization of space that is characteristic of their textile art; we can also find similar patterns, and sometimes even the same designs – such as the woot and its variations – that are also represented on the human body as traditional scarification.

However, all the objects shown in the previous chapter, as well as all the other pieces we can find in museums or galleries, lack an essential feature that all textile pieces have in common with music: variation. We have seen that African music can be considered complex by Western standards; one reason for this is the African love of improvised variations, one of the most fundamental principles of all Central African music. The same is true of Kasaï Velvets, ntshak, mapel, and wrappers of all kinds. Variation is not an accidental feature, but a fundamental principle in music as in textile art. We may or may not find forms of improvisation, transitions, dissonances, a rash of chaos and disorder, or entropic drifts. We may or may not find variations in technique and dimensionality, color, or pattern. Nevertheless, we will always find some contrapuntal elements and some kind of variation, whatever it may be, in any finished panel (fragments excluded, of course). Even the oldest pieces of textile art preserved in museums –such as those in the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (at Harvard University), dating from 1890 to 1893 – show some kind of variation.

Monni Adams defined “the abrupt shifts of form” and “the taste for breaking the expected line” as a “fundamental feature” of Kuba’s design preferences. I’m going to go much further and define this variation as an inherent feature, that is, a feature that follows or derives from the main nature or function of the object and is therefore inseparable from it.

What does this mean in the case of the Kuba textile art?

That the principle of variation is an intrinsic feature that comes from the geometrization of space, specifically from its nature or function, which is not, of course, that of being a form of decoration or ornament – that’s why I’ve never used these terms for textile patterns. The geometrization of space and the creation of patterns according to the principle of variation constitute not only an artistic language – a feature shared by all the art objects we have seen – but a language tour court, namely a structured system of communication with simple grammatical rules and a simple vocabulary. Variation and combination are both essential and inherent features of Kuba’s musical and textile languages. In the Kuba universe, no other art form shares this unique function.

However, there is a difference between Kuba music and Kuba textile art, or rather, there’s more than a difference, there’s an unbridgeable gap. At first glance, music seems to exist only at the moment of its creation, unlike textile art, which has a remarkable (though far from absolute) permanence over time. But this is not the essential difference. The complex language of textile art does not constitute musical notation in the strict sense, nor even something analogous to a staff. However, we can think – because nothing excludes it, but many elements seem to suggest it – that some patterns and some variations of patterns were related to specific rhythms and variations of rhythms; thus, even if textiles did not directly translate music, they could remove certain aspects of the musical tradition from purely oral transmission.

Now it is a little clearer why, textiles were central to Kuba’s cultural expression. But we are still on the surface, and now we must dive deeper.

Lokua Kanza, Voir le Jour

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?