THE KUBA TEXTILES FROM THE DRC

Democratic Republic of the Congo or DRC on the globe (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

TRADITIONAL AFRICAN TEXTILES ARE NEVER JUST PIECES OF CLOTH OR FABRIC

In many African traditional and oral cultures, textiles serve a variety of functions unimaginable in the Western world, especially after the Industrial Revolution of the late 18th century, which began the production of textiles on an industrial scale.

In many African cultures, traditional handmade textiles were the primary means of communication and information: they recorded memories or testimonies, told stories, inspired social behaviors or spiritual paths, recited apotropaic and protective formulas to ward off evil spirits, and even sang. Ruth Clifford, in her blog Threads Unpicked, Exploring textiles, craft and material culture, points out that English scholar «Janis Jefferies has explored the correspondences between patterns found in weaving and those found in traditional polyphonic songs. Like individual threads, individual voices each contribute to a textural and harmonic whole, whether physically patterned cloth or melodic, textured sounds.»

Textiles can constitute a form of visual language–a system that uses images, symbols, pictograms, or ideographs to convey meaning–or even a basic formal language. We have seen how the traditional Malian bogolanfini reveal a basic, rudimentary grammar underlying its characters, which form a simple system of signs governed by elementary rules of combination to convey meaning. In our article on THE BOGOLAN MUDCLOTH, we highlighted the Dogon proverb, “No clothes, no language,” and the Bamana term for the bogolanfini: sèbèn den, “the children of writing”.

Note that “text” and “textile” are two words with exactly the same etymology: they come from the Latin verb tĕxĕre, which means both “to weave at the loom” and “to compose a written text”. The metaphor of text as woven fabric has been explored by Jacques Derrida, Roland Barthes, and Julia Kristeva, while Tim Ingold wrote in his essay Lines: A Brief History (2007) that «the line began as a thread rather than a trace, so “text” began as a web of interwoven threads rather than inscribed surfaces.»

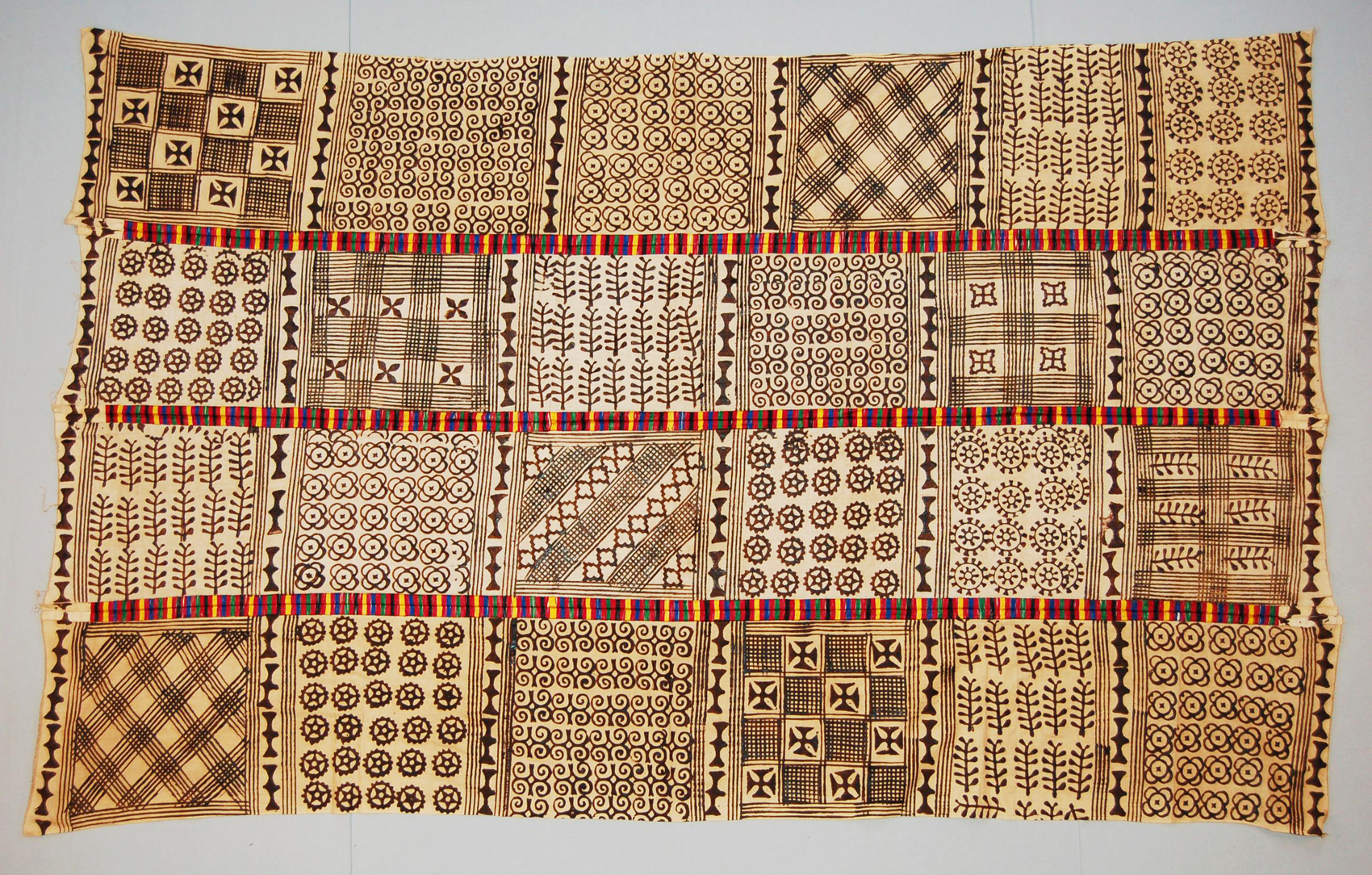

Adire cloth with Ibadan Dum pattern. Yoruba people, Nigeria, ca. 1960-1980.

Two-panel garment. Indigo starch-dyed on factory-made cotton weave; machine stitched at seams. Machine-sewn hems at both ends. Dimensions: length 194 cm, width 173 cm. © The British Museum, London UK.

Adinkra cotton cloth. Asante people, ca. 1968, Kumase, Ghana.

A white cotton Adinkra cloth patterned with 24 squares of black, hand-stamped symbols, divided by three embroidered bands of colored silk running the length of the textile. Dimensions: length 221 cm, width 140 cm. © The British Museum, London UK.

Textiles are means or symbols of identity for individuals, clans, groups, and communities. Textiles are «usually the primary way that people communicate who they are», said Lee Talbot, a curator at The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum in the USA. Through their color, pattern, material and type, depending on the society that created them, textiles can provide information such as social rank, marital status, ancestral lineage, economic power, and so on, if you can decipher the visual cues of that particular culture.

Below you can admire an outstanding cotton piece with an exceptional quality of design and sewing, made in Liberia between the late 19th and the early 20th centuries.

Man’s gown, handmade in Liberia by Mande people between 1880-1913.

Man’s gown (boubou) formed from 66 narrow strips hand-woven and hand-sewn together along the selvedges. Both the body and sleeves of the gown are formed from uniform strips of cotton of equal length: the body is made of strips sewn vertically, while the sleeves are sewn horizontally. The cotton in these strips is entirely hand-spun and buff in colour, and is woven in plain-weave without decoration in either warp or weft. Over the entire front of the gown embroidered decoration has been added by hand-sewing figures of animals, reptiles and a human seen at the left, or abstract patterns (seen in the centre and right). Dimensions: length 109 cm, width 206 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

BELOW

Man’s gown, handmade in Liberia by Mande people before 1865.

This man’s tunic is called tobe or boubou, a French deformation of the Wolof word mbubb. It’s an ample garment with long sleeves that can be worn over other clothing. This piece of extraordinary quality was tailored from 15 strips of handspun indigo and white cotton, hand-woven and hand-sewn together. This cotton gown has been hand-embroidered on both front and back with patterns in red, brown, blue and white thread. Dimensions: height 92 cm, length 180 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

Anni Albers, one of the most influential textile artists of the 20th century, pointed out that «along with cave paintings, thread is one of the earliest transmitters of meaning». A meaning, moreover, that can be enhanced, enriched, or modified by the religious, ceremonial, or secular use of each particular piece of cloth. All examples of traditional African textiles are elements of a cultural universe of acts, customs and rites, and are inextricably linked to a network of other objects such as masks, jewelry, musical instruments, weapons, ritual objects, etc.

Textiles can be one of the most important factors of social cohesion within a community. As we will see in the case of Kuba textiles, men and women from the same clan work together to create a broad ceremonial fabric that is not only a collective creation but also a form of choral self-expression and representation.

BELOW

Kente cloth, Ewe people, ca. 1940-1970, Ghana.

«A man’s cloth consisting of 20 narrow strips of imported cotton, hand-woven and hand-stitched along the selvedges and arranged in a checkerboard pattern across the cloth with no bands at the ends. There are two warp patterns that alternate across the cloth. One is two shades of blue with thin lines of white cotton running through it; the other is blue, white, red, green, and yellow stripes. The double weft blocks in the same palette frame patterns in complementary discontinuous thread in red, white and orange. Some of these patterns are geometric, others represent swords, animals and people. The cloth is hemmed by a sewing machine.» (TBM). Dimensions: length 297 cm, width 167 cm. © The British Museum, London UK.

Talismanic textile, from the late 19th/early 20th centuries (ca. 1875-1925), probably Senegal.

Four panels joined together: cotton, plain weave; painted; amulets of animal skin and felt attached by knotted strips of leather. «This textile is covered with Qur’anic verses that were likely recited as they were inscribed in tightly composed Arabic script, creating a link between the written word and its sound. The calligraphy is arranged in a fluid checkerboard pattern and organized around a series of painted shapes. Attached amulets further punctuate the textile.» Dimensions: 255.2 cm × 178.8 cm (100 1/2 × 70 3/8 in.). © The Art Institute of Chicago, USA.

Male tunic of invulnerability, Hausa people, ca. 1880-1920, Nigeria.

Cotton tunic (riga yaki), formed of cotton strips one inch wide sewn together, and covered on both sides with Islamic decorations and painted inscriptions and patterns (such as prayers, Qur’anic inscriptions, 99 Beautiful Names of God, magic squares and amuletic motifs). 51 leather-covered amulets have been sewn to the inside of the upper part of the tunic. «Every inch of this simple cotton tunic was inscribed and invested with prayers by an itinerant Hausa artist who sought to transform it into a mantle of invulnerability. The extraordinary measures taken suggest that the garment was made for an important warrior to wear into battle. The Islamic belief in the power of the Koran’s written word is manifested here in a creation configured so its Koranic texts encase the body, affording a line of mystical defence superior to armour.» (LaGamma and C. Giuntini, The Essential Art of African Textiles: Design Without End, 2008, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA). Dimensions: length 88 cm, width 91 cm. © The British Museum, London UK.

Many traditional handmade textiles are forms of art in themselves, but recognizing their inherent artistic nature and beauty requires overcoming a number of obstacles.

Westerners, for example, must adopt a different way of conceiving, making, and viewing art; in particular, they must overcome the traditional distinction between “fine arts” and “decorative (or applied) arts,” i.e., those arts whose goal is to design and make objects that are both beautiful and functional, and which are therefore caught in a kind of limbo between inferior pure craftsmanship and superior true art. This distinction originated in Florence during the 12th and 13th centuries, with the development of 21 city guilds (= corporations), made up of the “greater” guilds, Arti Maggiori or Major Arts, and the “lesser” guilds, Arti Minori or Minor Arts. The distinction took on a new aesthetic meaning during the Florentine Renaissance and spread throughout the Western art world in the post-Renaissance period. Using this distinction to approach non-European art forms would be like wearing sunglasses when entering a darkroom. An idiotic choice.

There is another obstacle that has not been easy to overcome. Taipei-based writer Brenda Lin explains: «The idea of textiles as an art medium and art form didn’t take hold until recently because of its gendered assignment and the fact that weaving, knitting and sewing were largely dismissed as ‘women’s work’. (…). Because of its gendered assignment, coupled with the fact that cloth-making was such a functional skill, the idea of textiles as an art medium and art form didn’t take hold until recently, despite its millennia of history.»

We should not be surprised: in our article on THE BOGOLAN MUDCLOTH, we showed how and why some types of bogolanfini, such as the basiae made for the post-excision period, acted as real medical cataplasms, thanks to the traditional knowledge of herbs handed down from generation to generation by women. However, in a patrilineal and patriarchal society such as the traditional Bambara, this knowledge had to be legitimized by an external source–the magical and animistic beliefs handed down by men–in order to be socially acceptable. In societies and cultures where women lived or still live in a minority condition of any kind (yes, even in the West until a few decades ago), the idea that women could make art with a needle and thread was as scandalous as the idea that they could make it with a broom, a frying pan, or a dishcloth.

So abandon prejudice all ye who enter here, for only in this way can the journey we are about to take into the heart of the Kuba kingdom reveal all the magic of creating flamboyant art from the humblest local plant.

BELOW

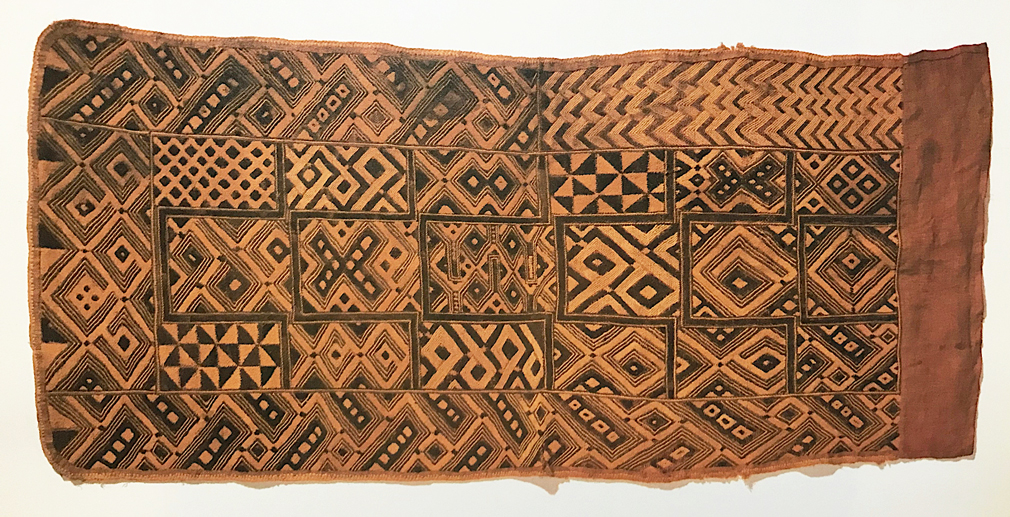

Embroidered Raffia Pile Cloth, Kuba people, Democratic Republic of Congo, 20th century. Overall dimensions: 52.3 x 122.5 cm (20 9/16 x 48 1/4 in.). © The Cleveland Museum of Art, USA.

Lokua Kanza, Le Bonheur, from the album Toyebi Te, 2002

Lokua Kanza (born April 1958) is a singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC).

The song is in French and lingala, a musical, tonal Bantu language, spoken in the northwest of the DRC, including Kinshasa, the northern half of the Republic of the Congo, including its capital Brazzaville, and to a lesser degree in Angola, the Central African Republic and southern South Sudan. The French is the official language of DRC, while Kituba (Kikongo), Lingala, Swahili, and Tshiluba are its four national languages.

HOW IT ALL STARTED

Some years ago, I discovered a sophisticated online store of rare, hand-woven African fabrics and textiles owned by a Dutch photographer, Ingrid Boellard, who has been traveling in Africa for more than 25 years. I was looking for some pillowcases made of an authentic old African fabric, and in a sea of vibrant colors and mesmerizing textures, I stumbled upon a piece.

Not one of many.

It was so magnificent that I stopped breathing for a few seconds. I didn’t know what it was, where it came from, what it was called, who made it. I bought it without even knowing its price. I really knew nothing about it except that it was a serendipitous love encounter. (This has happened to me only one other time in my life, with a rare fragrance of the ancient Ottoman tradition).

When the cushion arrived at my home within a few days, I realized that it was not just an imposing and impressive piece: I only had to caress its intricate appliqué with my fingertips to find myself in another world and time. This piece was the portal to explore an unknown world rich in history and artistry, a world that whispered of customs, rites, traditions, and an enchanting visual creativity that spanned time and continents.

And so I began a long journey into the heart of the Congo (DRC), discovering the kingdom of the Kuba people, their culture and their breathtaking art. Little did I know at the time, nor could I have predicted, that a piece of cloth would weave its way into the fabric of my own story.

Cushion cover, sized 60 x 60 cm, 24 x 24″, handmade with three pieces of handwoven, rare Kuba cloths: the beige brodé raffia on left side comes from a traditional women overskirt; the chess board cloth with black and white 3D cubes (made by overlapping two layers of fabric) comes from a piece made for men; the central part is richly embroidered and made via a technique called appliqué. DRC, 1970s.

KUBA TEXTILES AND KUBA PEOPLE

The generic term “Kuba textiles” encompasses various types of textiles, some of which are very different in technique and processing. However, all Kuba textiles have two main characteristics in common: the material they are made of, the raffia fiber, and their cultural origin.

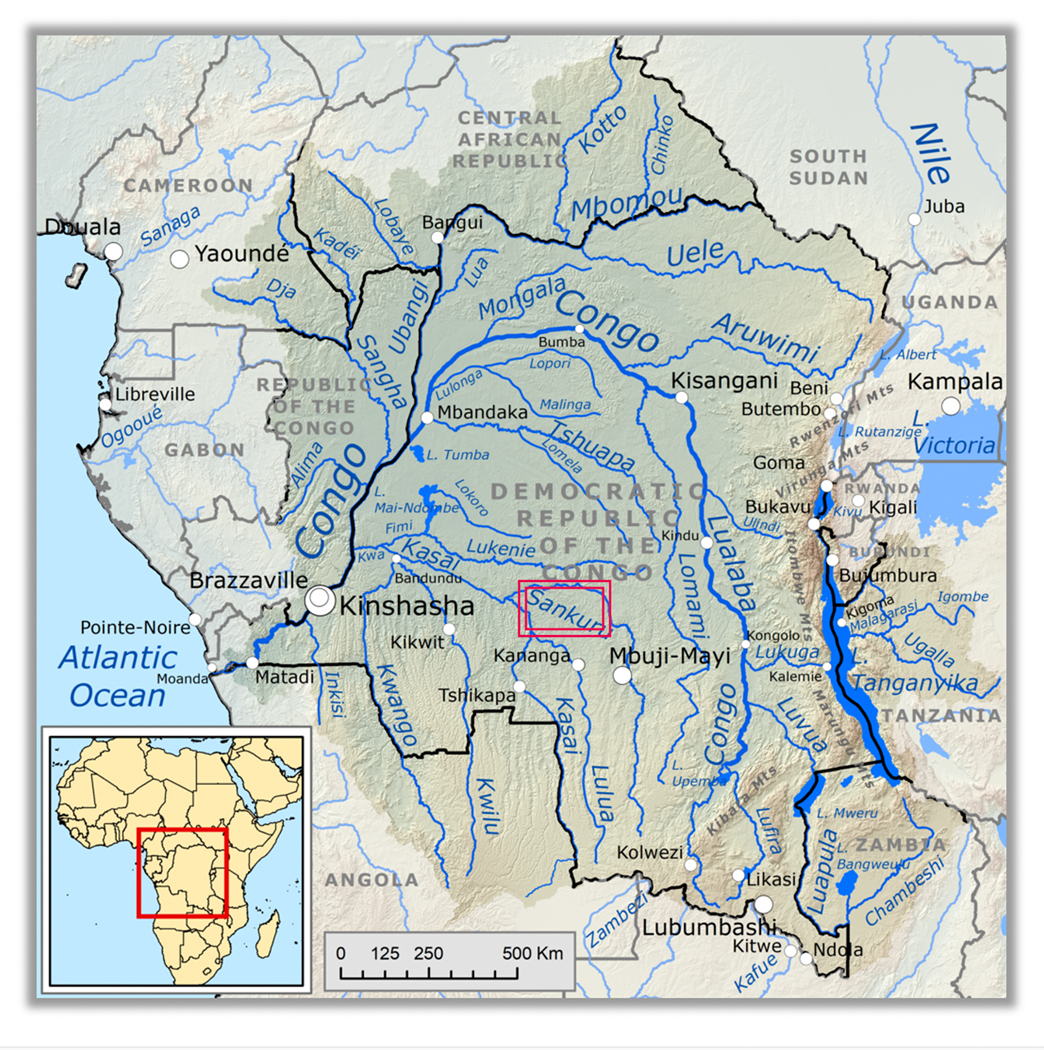

They are called “Kuba” from the name of the mother culture that developed in the pre-colonial Kuba kingdom, a Bantu state that flourished between the 17th and 20th centuries in a relatively isolated area bordered by three rivers: the Sankuru to the north, the Lulua to the south, and the Kasaï to the west. This relatively small and isolated territory is located in the central-southern part of the Congo Basin, in the heart of the western equatorial African region, and falls within the modern DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly Zaïre, not to be confused with the Republic of the Congo).

The Congo River Basin is a vast central African region with the largest tropical rainforest in the world, second only to the Amazon. The territory of the Kuba Kingdom is roughly indicated by the double red rectangle and is rich in luxuriant forest and vast savannah.

Map by Kmusser 2019, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

The Kuba are not an ethnic group, but a confederation of many ethnic groups. They are commonly called Kuba or Bakuba but this name was given to them by their southern neighbors, the Luba, and has been used by Europeans ever since. They have always called themselves “the people of the king” and “the children of Woot”, namely the descendants of a mythical ancestor named Woot or Woto.

Here are some of the Kuba groups and sub-groups:

- Bushongo or Bushoong (“people of the country of the throwing knife”)

- Ngeende

- Ngongo

- Shoowa, Shobwa, or Bashoba

- Bieeng

- Idiing

- Ilebo

- Kel

- Kayuweeng

- Kete

- Bulaang

- Pyaang

- Mbeengi

- Maluk or Bangi Maluk

- Ngoombe

- Bokila

- Kaam

- Kasai Twa Pygmies

- Coofa

These groups are united by several factors:

- They speak the same tonal Bantu language, the Bushong, with some variations and dialects.

- They share a common history: several small principalities and chiefdoms in the area were politically and administratively united by Shyaam a-Mbul aNgoong around 1625. He is considered the founder of the Kingdom of Kuba and the architect of Kuba’s political, social, cultural, and economic life. He was the first nyim of a long list of kings or rulers, all of whom belong to the Bushongo lineage and still exist today. The largest Bushongo village founded by Shyaam a-Mbul, Nsheng or Mushenge, became the administrative and political heart of the kingdom in the early 18th century.

- All of these groups, with the exception of the Twa Pygmies, share similar cultural roots and are all matrilineal societies.

The Kuba Kingdom has been an advanced state that has attracted the interest of many historians for some of its peculiarities: «It had a capital city where the king and members of numerous executive councils lived. It had a professional bureaucracy, an unwritten constitution, a sophisticated legal system that featured trial by jury and courts of appeal, a professional police force, a military, a system of taxation, and extensive public goods provision.» (Lowes, Nunn, Robinson, Weigel, The Evolution of Culture and Institutions: Evidence from the Kuba Kingdom, 2015, see Bibliography). The Kuba society was a complex one with a well-defined social hierarchy and a centralized political system; however, each of the confederation’s ethnic groups had representatives at the Bushoong court in the capital, and for long periods of their history, the Kuba peoples lived in substantial peace. Under Belgian colonial rule, the kingdom lost its sovereignty and political autonomy; its traditional political structures, institutions, and cultural practices were severely disrupted and in some cases eradicated.

LEFT: King Mbop aMabiinc maKyeen (Bope Mobinji Kena) in 1947. He reigned from 1939 to September 1969. Photo by Eliot Elisofon, EEPA National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution.

RIGHT: King Kot aMbweeky aShyaang (Kwete Mboke) in 1970. He’s reigned since 1969 and is the current Nyim. Photo by Eliot Elisofon, EEPA National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution.

Both Kuba kings are depicted in their official dress, called bwaantshy, wearing a leopard’s tooth necklace, called lashyaash, and holding the sword of office in their right hand, the mbombaam, and a lance in their left hand, the mbwoom ambady. To each king’s left is the royal drum, the pelambish; it’s made of wood, covered with leather and fabric, and richly decorated with cowrie shells, glass beads, and copper pieces. In their visual splendor, the drums and the royal basket (to the right of King Kot aMbweeky aShyaang) match the magnificent Nyim ceremonial costume. The latter consists of nearly 50 different pieces and weighs approximately 70-80 kg; it takes more than two hours to dress the king and two days of spiritual preparation to be sufficiently purified to wear it. The royal belt alone, known as nduun Bushoong, is made on a raffia base with a string of pearls decorated with shells; it’s 20 centimeters wide and 400 centimeters long, and the king must be helped to wear it properly. Every king needs to be dressed ceremonially only a few times in his life, but “forever” after his death.

These two photos are enough to show the visually exuberant taste of the Kuba and their flamboyant art, so colorful, so richly patterned, and so sophisticated that it catches everyone’s eye and imagination.

The term “Kuba” includes not only a variety of ethnic groups linked by a common history and culture, but also a variety of different textiles. We will now discover some of them, always remembering that Kuba culture is an oral heritage, and therefore no fabric and no textile is just a piece of cloth. Threads in cloth can be read, like words on paper. Threads in cloth can also be played, like notes on a sheet of music.

SHOOWA TEXTILES OR THE KASAÏ VELVETS

There is a group of Kuba textiles whose tradition goes back at least 400 years; they are still in production today and are highly valued and sought after by collectors, interior designers, art dealers, ordinary enthusiasts, artists and museum curators. They fascinated the first Western travelers in the 18th and 19th centuries, caught the eye of 20th century masters such as Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee, A. R. Penck (aka Ralf Winkler), and Eduardo Chillida Juantegui, and continue to dazzle and enchant many of us today.

They can be found in museums, art galleries, antique dealers and online stores under the generic name of “Kuba raffia panels”, that of “Shoowa Textiles” – Shoowa is one of the ethnic groups of the Kuba Confederation – and sometimes as “Kasaï Velvets” because of their velvety feel and soft appearance. Matisse, who collected them, called them mes velours, “my velvets,” but they are not properly velvets: their smooth texture, so similar to plush velvet, is made from a tough, leathery plant fiber through a complex of processing techniques that are as ingenious as they are time-consuming and difficult.

The name Kasaï Velvets is therefore a misnomer, as is often the name Shoowa panels, because this type of textile was produced not only by the Shoowa, but also by the Bushoong, Ngongo, Kete, Ngeende, and other ethnic groups of the Kuba confederation. Shoowa textile is therefore a term that should be reserved only for textiles produced by the group of the same name, but museums and art galleries do not always have accurate information about the date and origin of a piece. For convenience, I have chosen to refer to this group of textiles as Kasaï Velvets. The latter have many unique tactile and visual characteristics in addition to their softness, but their main characteristic, as obvious as it is perceptible, is something else entirely: they are among the most complex textiles ever made by human hands, and we are going to dive into this living complexity with a totally original approach. But let us start in order.

Kasaï Velvet, Royal Overskirt, 1912-1942, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Private Collection. This magnificent piece was displayed in the 2019 exhibition Kuba: Fabric of an Empire, which showed dazzling Kuba textiles in the Cone Collection galleries of the Baltimore Museum of Art (MD, USA). Please look at the right end of the piece: you can see the base raffia fabric on which the various geometric patterns have been embroidered and rendered using a special “cut pile” technique. ©Photo by Kerr Houston / Baltimore Museum of Art.

Magnificent Kasaï Velvet, Overskirt, early 20th century, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Private Collection. Dimensions: 126 x 57 cm. Photo taken from a famous book: Shoowa Design – African Textiles from the Kingdom of Kuba by Georges Meurant, 1986 (see Bibliography). ©Photo by Georges Meurant.

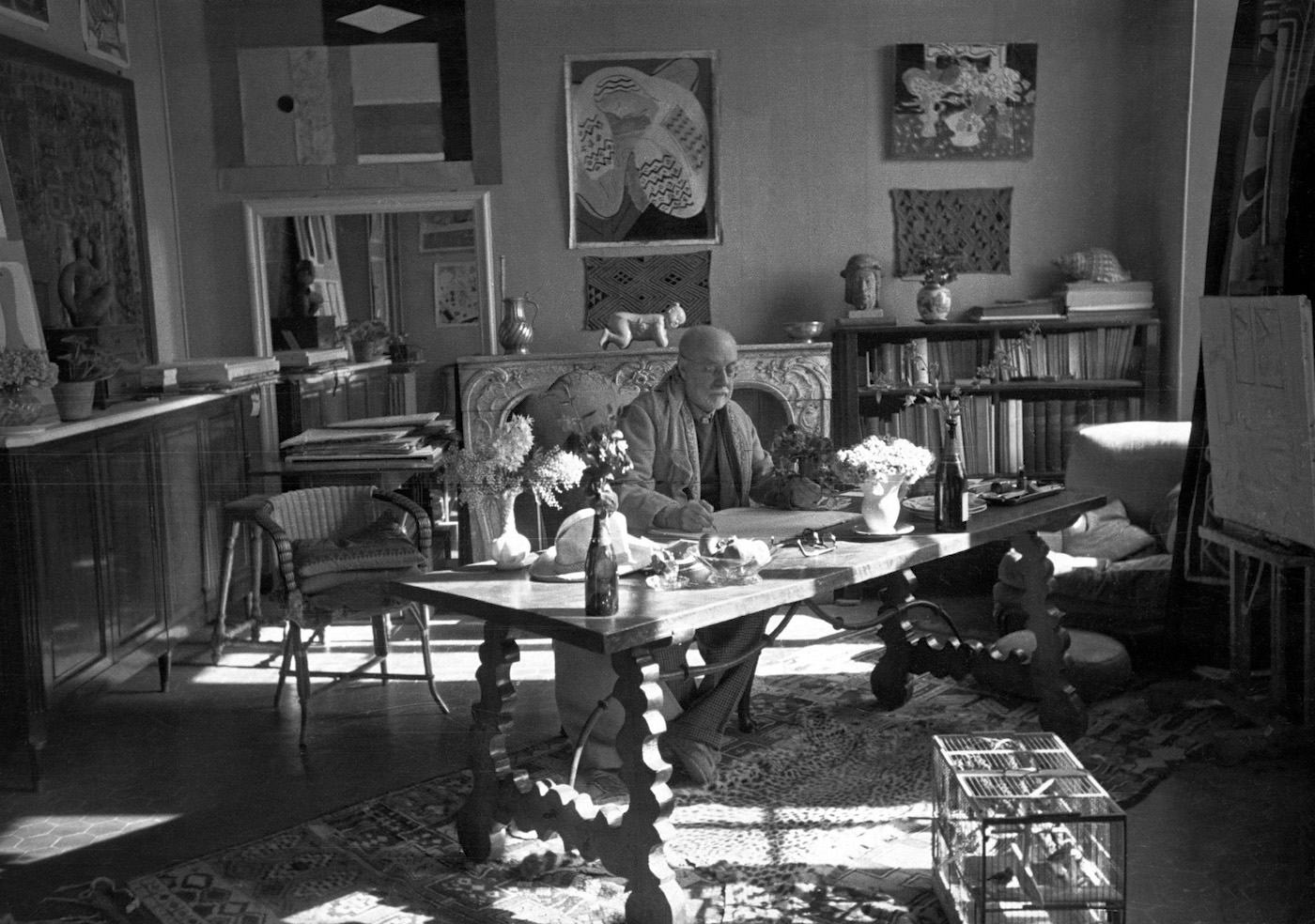

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Matisse with his collection of Kuba cloths and a Samoan tapa on the wall behind him, Villa La Rêve, Vence, 1944. © Henri Cartier-Bresson/Magnum Photo. Image courtesy: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA, USA.

FINDING, PREPARING, WEAVING, AND EMBROIDERING THE RAFFIA FIBER

All Kuba textiles, including the Shoowa textiles or Kasaï velvets, have been made for centuries using a hand-woven raffia fiber cloth as a base and are the result of a time-consuming and complex activity in which men and women of the same clan work together at different stages.

Finding and preparing the raffia fiber is the very first step.

The fiber comes from the raffia palm (Raphia vinifera), an essential resource for the Kuba people: its sap is extracted and fermented to make wine; the mesocarp of its fruits is used to make oil for cooking; the leaf stalks are used as building material, while the leaves are dried and peeled into narrow strips by hand or with a comb-like tool. Unlike many natural textile fibers, such as wool or cotton, raffia fibers are not spun into thread: it is a difficult and hard medium that must be softened and made flexible with snail shells or simply rubbed by hand before weaving. Traditionally, men split and “comb” the dried leaves by hand, while women smooth them. Once the fibers are softened, they are wound into strands.

There is magic in this activity, something fascinating and intensely moving, because it shows how the Kuba people – and we humans in general – are able to take a trivial leathery leaf – or a piece of clayey mud, for example – and transform it into an exquisite work of art. If we are sapientes, it is because of this creative magic that we do, certainly not because of the ease with which we shit on ourselves and our planet.

Raphia vinifera palm

A Kuba men preparing the raffia fiber from the leaves (left) and a softened raffia skein ready to be woven (right). The very fine fiber found inside young palm leaves is white, but when it dries, it becomes light tan.

BELOW

Photo courtesy by Malaika Ngoy, founder and owner of Shoowa Kingswear.

Kuba women preparing raffia fiber near Bulape (in former Zaïre, now DRC), 1972. ©Photo by Eliot Elisofon, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

The raffia fiber is then ready to be woven, a traditional activity carried out by men working on a single wooden heddle loom set at a 45-degree angle.

The units of hand-woven cloth have a rectangular or square shape and a variable, always limited size that depends on the natural length of the raffia fibers: the strands are not tied. According to Adams Monni (Kuba Embroidered Cloth, 1978, see Bibliography), most rectangular cloth panels measure about 30 x 60 cm to 50 x 100 cm, while square ones are often 50 x 60 cm and the largest about one square meter. Thus, the final Kuba velvets consist of several panels sewn together.

Top, first two pictures from the left: Kuba man at his loom, Nemwele village (in former Zaïre, today DRC), 1970. ©Photo by Eliot Elisofon, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

Bottom: Raffia Weaving Loom, Kuba People, DRC. Photo Courtesy by Ian and Julie Allen, Africa and Beyond Art Gallery, San Diego, CA, USA.

Once woven, the panel is coarse and rough to the touch. It must be «dampened in water, and kneaded, beaten, or rubbed between the hands. Next, it is wrapped in old cloths, put in a trough, and beaten again to make it more supple, this time by women using a pestle or wooden pile. Usually the women also dye the cloth and embroidery yarn before the process of embroidering can begin. Almost all dyes are created from local plant <or mineral> sources, although a bright purple, occasionally seen, comes from the mimeograph machines of missionaries. The common colors of ecru, black, brown, and red are sometimes augmented with wine, lilac, purple, blue, and yellow. Once chosen, the dyes are heated or cooked, and the cloth is dipped into them.» (Elizabeth Bennett and Niangi Batulukisi, Kuba Textiles & Design, Africa Direct, see Bibliography).

A 19th century Kuba undyed raffia panel. Dimensions: 40 x 28.5 cm – 15 3/4 x 11 1/4 in (excluding fringes). Arts of Africa collection, Brooklyn Museum, USA. Photo licensed by Creative Commons.

Women alone perform the artistically relevant final stage of transforming a dyed or undyed raffia cloth into a masterpiece. As we will see in the next chapters, calling this phase “embroidery” and “stitching” is extremely reductive. It is true that women embroider and sew at this stage, but embroidery and sewing are merely tools for creating art. No one would describe the work of Picasso or Matisse as a way of applying paint to a canvas. It certainly involves that, but the painting of a master (as opposed to that of an amateur or wannabe artist) is not just that. Even for Kuba women, it’s not just that.

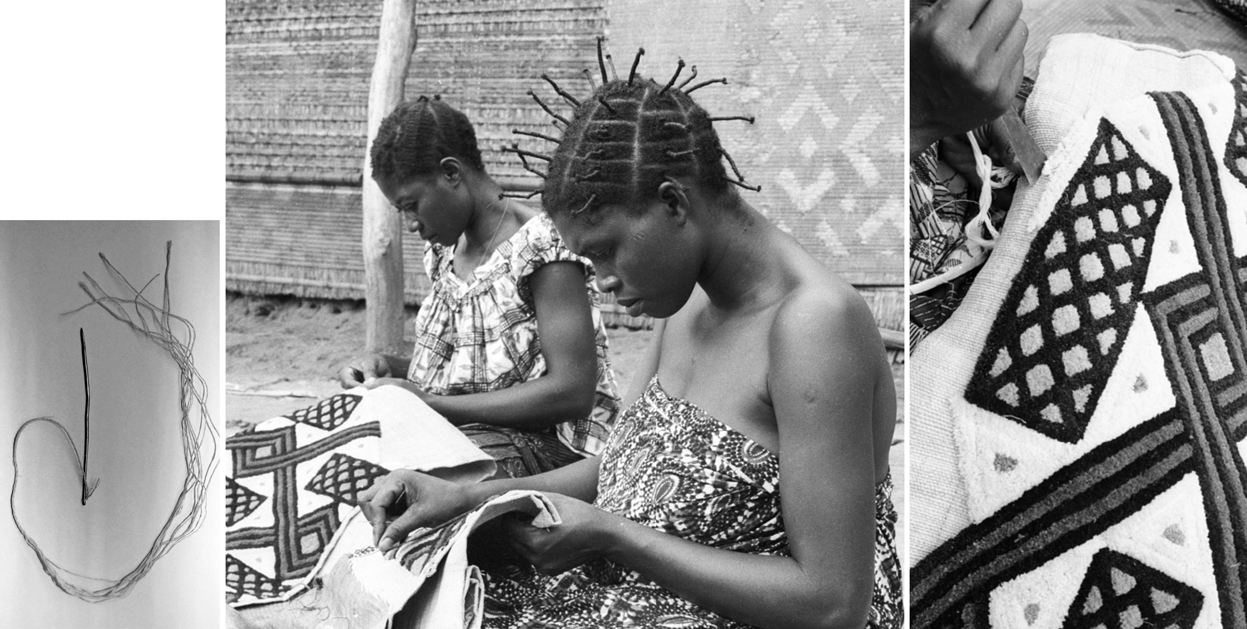

To make one of those panels that can be admired in the great art museums of the world, Kuba women use four simple tools: a needle, a knife with a sharp edge, and both hands. The needle is used to sew, the knife to brush the raffia pile and to cut the pile stitches. This latter technique, called “cut pile” – the ends of the raffia embroidery threads are cut very short and very close to the surface – produces the fluffy appearance and velvety feel of all Kasaï Velvets.

«The plush technique involves pulling single strands of raffia through a stitch in the cloth until a short (ca. 4-6 mm) section is left on one side of the stitch. The other end of the strand is then cut with a special knife leaving 4-6 mm on the other side of the stitch. The strands are not knotted, but remain in place by virtue of the tightness of the weave of the background cloth.» (Dorothy K. Washburn, Style, Classification and Ethnicity: Design Categories on Bakuba Raffia Cloth, 1990, see Bibliography)

LEFT: Iron needle with raffia thread, 1900-1908, Kuba culture, present DRC. Needle length: 6.2 cm. This object was acquired during Emil Torday’s expedition to the Congo on behalf of the British Museum in 1907-9. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

CENTER: Kuba women decorating woven cloth, Mushenge (in former Zaïre, today DRC), 1970. ©Photo by Eliot Elisofon, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

RIGHT: Kuba woman using a knife, Mushenge (in former Zaïre, today DRC), 1970. ©Photo by Eliot Elisofon, Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

To carry out this last phase, all the women need not only an enormous amount of patience and perseverance, as Adam Monni wrote (belittling their artistic talent), but also time and creativity, as they bring to life complex patterns entirely by hand, without drawing any framework on the raffia cloth. The creation of a Kasaï velvet takes a long time: fine pieces of plush are worked on for months, usually in the afternoons after returning from work in the fields. (You didn’t think women spent all day chatting and embroidering, did you?)

«The unusually rich development of Kuba design is probably the result of a particular combination of circumstances: the position of women whom the Kuba morally treats with respect, their privileged economic situation (also maintained by the Kuba ethic that encourages the acquisition of wealth), and two centuries of peace, restricting the role of men in the society. Design by women has been developed among the Kuba to an exceptional degree.» (Georges Meurant, Shoowa Design – African Textiles from the Kingdom of Kuba, 1986, see Bibliography).

These enlarged details of various Kasaï velvets show both the stem stitch with its looped spiral effect and the cut pile technique used to create the soft and velvety quality of the panel.

Left to right: 1. A natural-colored raffia panel showing ‘patches’ in natural colour and brown-dyed raffia thread; Kuba – Ngeende, 1950s-1970s. 2. A panel decorated with cut-pile and stem stitch embroidery in natural and brown-dyed raffia on a dyed red handwoven cloth; Kuba – Bakele, 1949-1950. 3. A panel with geometric patterns in natural and brown-dyed raffia embroidered in stem stitch, on a natural colored cloth; Kuba, 1920s-1930s. All photos: © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

The enlarged details in the image above clearly show another feature of all Kasaï Velvets that, strangely enough, many scholars tend to ignore: their three-dimensionality. The texture, compactness, thickness, and alternating softness and roughness are all characteristic of Shoowa textiles, and even their geometric patterns are not simple two-dimensional designs. Their 3D can also be perceived visually and by touch, but it’s not so easy to hold a panel in your hands: those displayed in galleries and museums cannot be touched, so you have to buy one, and a good one at that. The picture below shows some two-dimensional geometric patterns and the difference to the Kuba should be obvious to everyone.

As Dorothy K. Washburn highlighted in her volume Style, Classification and Ethnicity: Design Categories on Bakuba Raffia Cloth, one of the key element of Kuba aesthetics is the creation of textural contrast between raised and flat, brushed and plain surfaces. «There are three ways to manipulate the raffia in order to achieve textural contrast: embroidery, plush, and exposure of plain background cloth. The Bushong in particular, use texture more than color to achieve contrast. Tightly woven embroidered lines are juxtaposed with broader areas of raised plush. Alternatively, pattern motifs are in raised plush or embroidery and separated by narrow lines of exposed plain background cloth. In contrast, other Bakuba groups maximize the contrast by exposing wide areas of plain background cloth between the narrow bands of motifs in raised plush. (…) Texture contrast can also occur on totally embroidered cloths simply by varying the type of embroidery stitch, such as the contrast between the pincushion and linear embroidery effect.» (Dorothy K. Washburn, Style, Classification and Ethnicity: Design Categories on Bakuba Raffia Cloth, 1990, cit.).

All of the photographs in the following chapters fail to do justice to the textural contrasts and Kuba’s efforts to intensify the three-dimensionality of the panels. Photos and videos tend to flatten the objects and erase their tactile specificity. Seeing a Kasaï Velvet panel in photographs and touching it are two different sensory experiences. So keep in mind the image-induced impoverishment, and if you can, buy a nice panel!

ABOVE: Raffia textiles, Kuba Kingdom, DRC. The Van Rijn Archive of African Art (YVRA) at the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

BELOW: Mixed Kuba raffia textiles, DRC, 20th century, ©The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

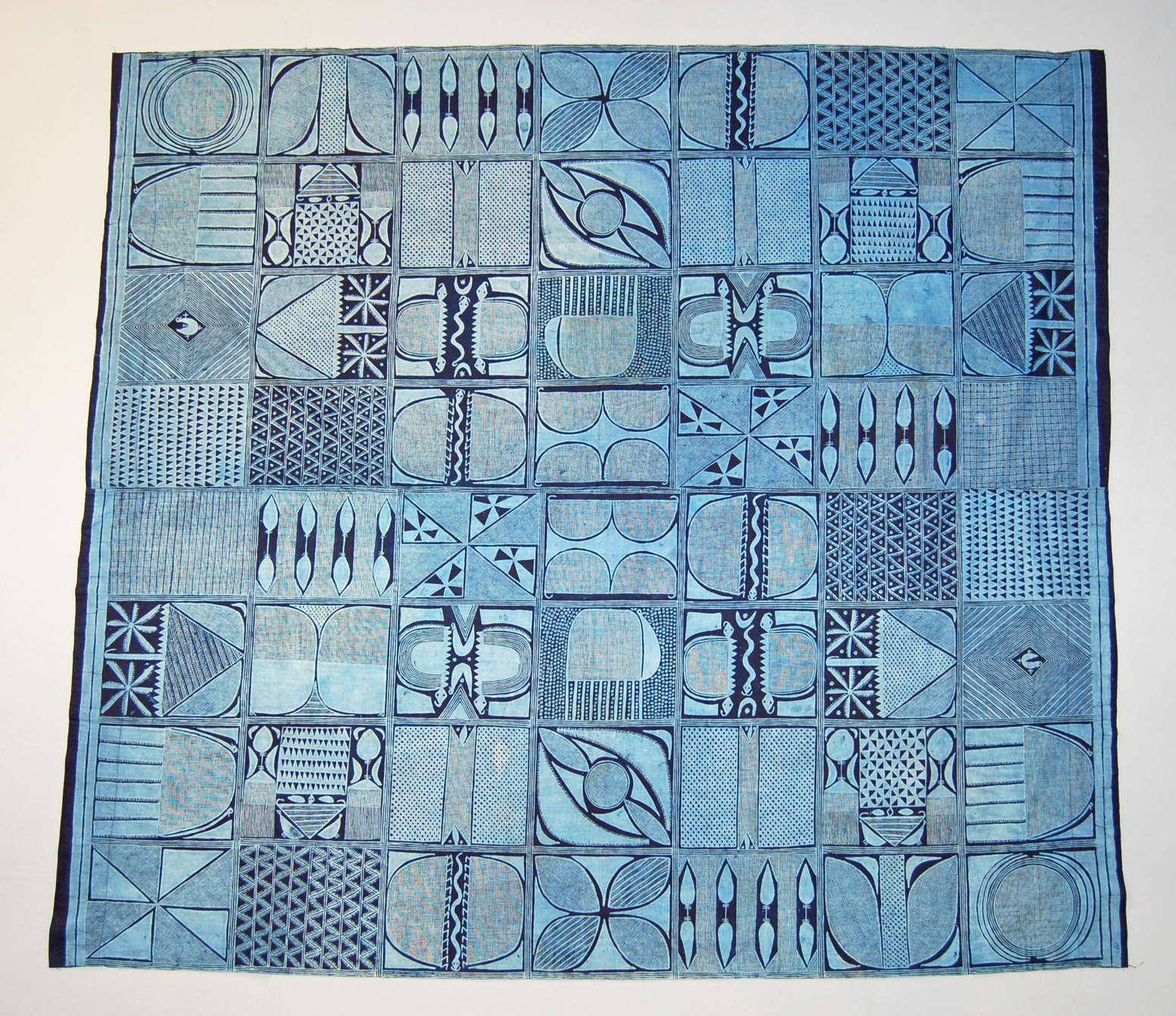

THE GEOMETRIC PATTERNS

The Kasaï velvet panels were sometimes sewn together and worn as an overskirt, but more often they were displayed or used as currency and markers of prestige, and even as royal paraphernalia. (They are still made today, mostly for collectors). Their immediately recognizable features include not only their visual softness and velvety texture, but also their abstract geometric designs. No panel shows a figurative representation, not even a stylized one. All are characterized by a varying but always high level of geometric complexity, achieved by composing, overlapping, connecting, flanking, combining, interlocking, or merging several simpler geometric patterns. In traditional Kuba culture, the more complex the design of a panel, the greater its economic and aesthetic value, and more desirable its use as a status symbol or a royal emblem.

Elizabeth Bennett and Niangi Batulukisi wrote in their essay on Kuba Textiles & Design: «The Kuba do not have a word for art… but they have one for design. Design or Bwiin is foundational to Kuba society. Almost all manufactured objects are elaborately decorated. Traditionally, within the Kuba Kingdom, the intricacy with which a person’s possessions were decorated reflected the status of the owner and indicated his or her social class. Rich ornamentation increased the prestige of the owner. The most elaborately decorated pieces, including textiles, were reserved for the King, his family, and the nobility. There were no better textiles.» (see Bibliography).

This quote is very interesting because it allows us to immediately discuss an important aspect.

The two authors, like many Western scholars, use the term decoration/décor/ornamentation very often with regard to Kuba art objects and especially Kuba textiles; some experts even make the Kuba tendency to hyperdecoration the main feature of their objects. In Western art history, when we talk about decoration, we imply a subtle but persistent distinction between fine art and décor. The latter is a kind of outer layer that does not touch or alter the essence of what it decorates, but merely embellishes it: a decoration or an element of ornament must please the eye and be aesthetically pleasing in order to fulfill its purpose. Decoration can be as airy and graceful as a whimsical curl in a Rococo rocaille, or as unexpected and astonishing as a dazzling combination of colors in an Art Deco tapestry. We might say that the frame of a 19th century French painting is beautifully decorated, but we would never use such terms to describe a Renoir painting. Wouldn’t we?

I do not wish to discuss here this distinction, which arose and developed within Western art and aesthetics. I will simply point out that it is completely inappropriate to use it when approaching a non-Western art form. Islamic geometric patterns, for example, are not merely decorative forms, but are, among other things, an elaborate path that leads the viewer to a transcendent reality. Thus, when discussing Kuba art and textiles, I will never use the terms decoration, décor, ornamentation, etc., and I will never imply the distinction on which these terms are based. Moreover, I will show that all Kuba geometric patterns, all of them indiscriminately, regardless of their degree of complexity, are not at all decorations on a piece of raffia cloth.

Mumba Yachi, Papa Wemba, 2022

Mumba Yachi is an award-winning Congolese musician based in Zambia. With this track, from his seventh album Violet, he pays tribute to Papa Wemba, the most popular Congolese singer and musician, dubbed “the king of Rumba”, who passed away in 2016.

Nothing ends as it began in this piece, have you noticed?

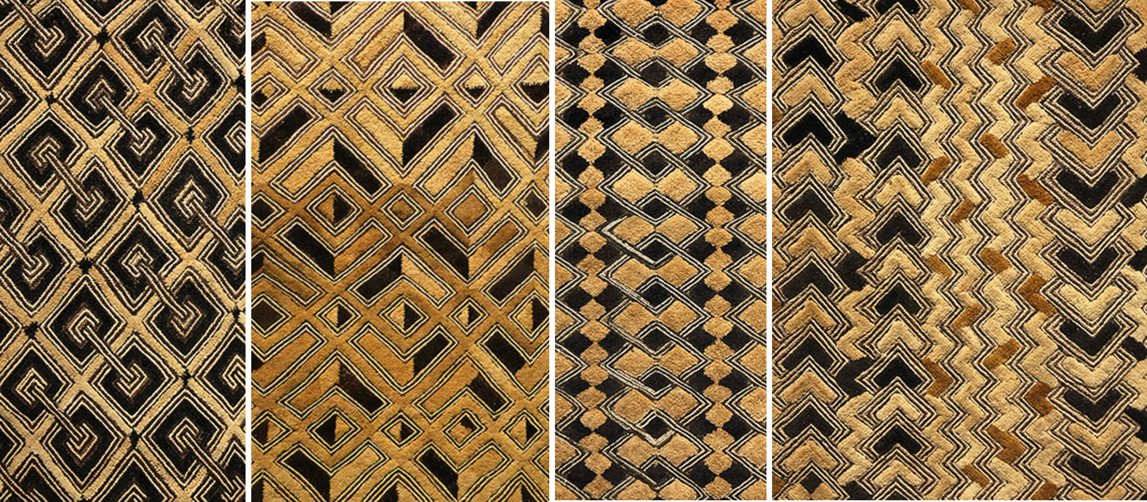

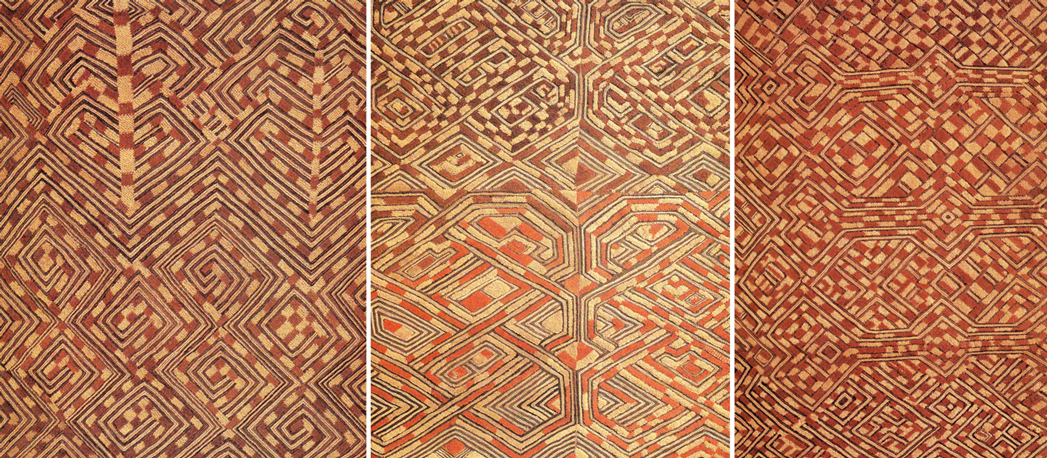

Now let’s look at some Kuba geometric patterns according to the principle of combinations of increasing complexity. The following patterns are all details of larger panels; they are not simple and do not represent some kind of zero degree, because they are already the combination of lines and geometric shapes. In many of the following pictures, these patterns look two-dimensional, but that’s a photographic distortion: we already know that they have three dimensions. All patterns are produced, indeed, from the manipulation of three elements: line, color, and 3D texture.

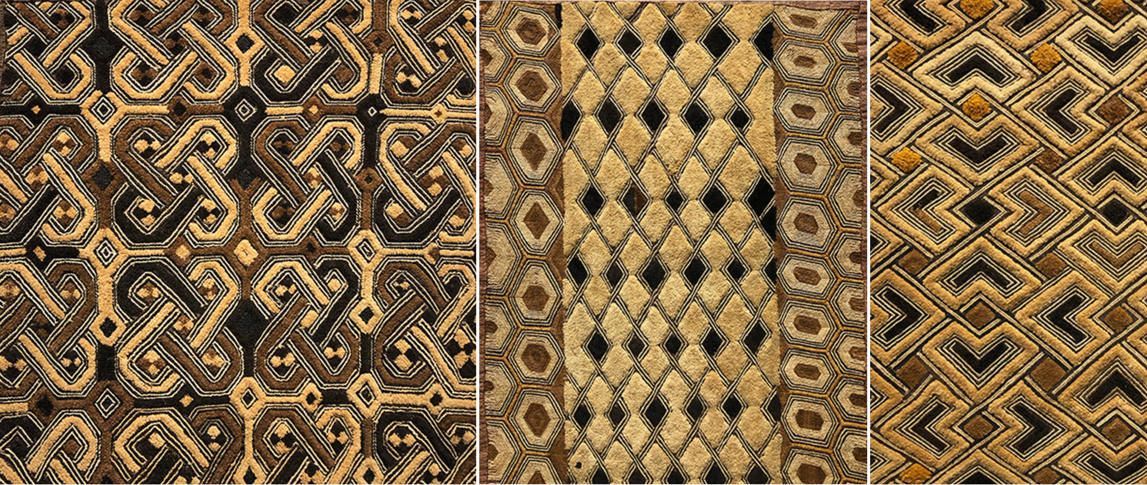

Details of Kasaï Velvet panels, DRC, mid-20th century. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

Now the geometric patterns get a little more complicated.

Details of Kasaï Velvets panels, DRC, mid-20th century. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium. The third panel from the left is from the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota, USA.

Have you noticed the precision, rigor and accuracy with which these geometric patterns are made? The Kuba women worked freehand, as I have previously mentioned, without drawing a frame to follow on the raffia cloth.

In both the above and the following images, the geometric design is further complicated by the intervention of color, which in turn implies increasing complexity in the technique of sewing and embroidery. In some designs, the use of color is subtle, barely hinted at, while in others it’s more dominant, almost aggressive.

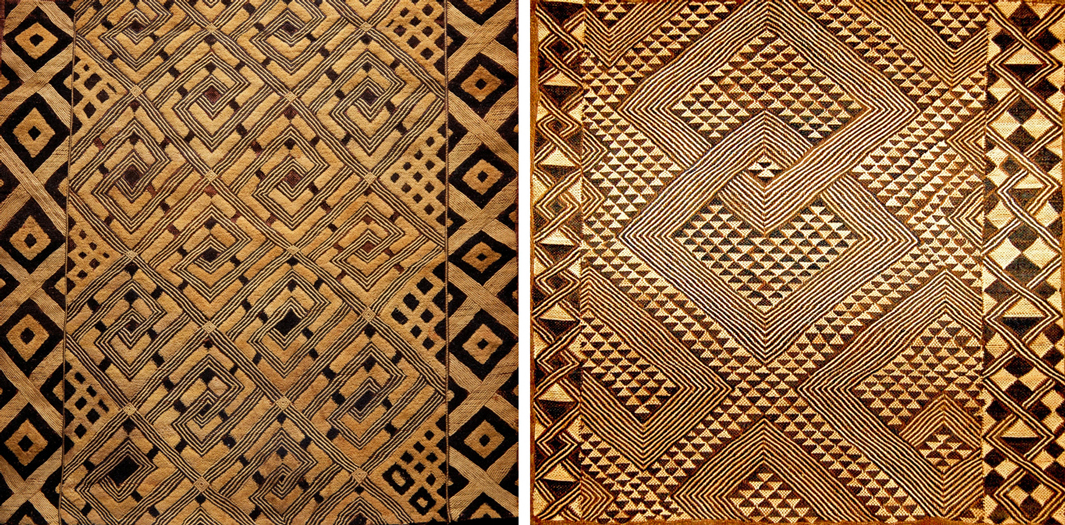

Above and below: Details of Shoowa panels, DRC. Photo courtesy of Tim Hamill, painter, African art expert and owner of the Hamill Gallery of Tribal Art and Hamill Galleries, Massachusetts, USA.

Have you noticed that as the complexity of the geometric patterns increases, there is something like a musical crescendo (= a gradual increase in the volume of the music)? Look at the following panel details. The pattern on the left seems to imply a fortissimo (= a dynamic mark indicating a VERY LOUD volume). As for the one on the right, doesn’t it seem like a duet? Two instruments are playing contrasting melodies at two different volumes, creating a harmonious and complementary interaction and a rich, textured musical composition.

Details of Shoowa panels, DRC. Photo courtesy of Tim Hamill, African art expert and owner of the Hamill Gallery of Tribal Art and Hamill Galleries, Massachusetts, USA.

The composition of different colors and patterns can create elaborate symphonies like the ones below. All show a rich design weave or, if you prefer, a harmonious musical texture.

ABOVE: Details of Shoowa panels, DRC. Photo courtesy of Tim Hamill, African art expert and owner of the Hamill Gallery of Tribal Art and Hamill Galleries, Massachusetts, USA.

BELOW: Left: Detail of a Kuba cloth, DRC, 20th century, Detroit Institute of Arts, MI, USA. Right: Detail of a Kuba raffia panel (Shoowa?), DRC, 1950s-1980s, ©The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

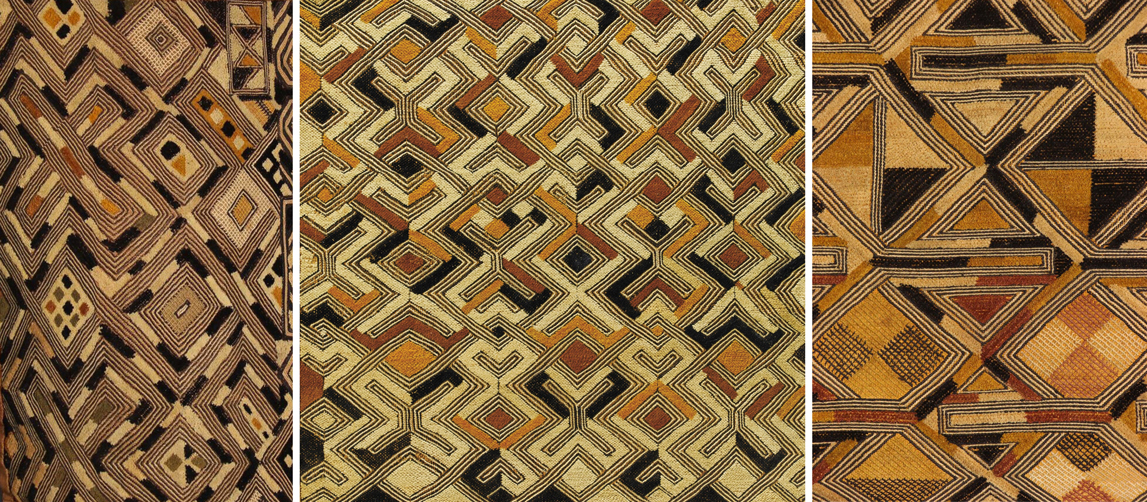

Left and right: Details of two Kasaï Velvets, Kuba people, DRC, mid-20th century. Dimensions: left panel 51 x 49 cm; right panel: 50 x 63 cm. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

Center: Detail of a raffia textile, Kuba Kingdom, DRC. The Van Rijn Archive of African Art (YVRA) at the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

BELOW:

Two details from two magnificent raffia textiles, Kuba Kingdom, DRC. The Van Rijn Archive of African Art (YVRA) at the Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

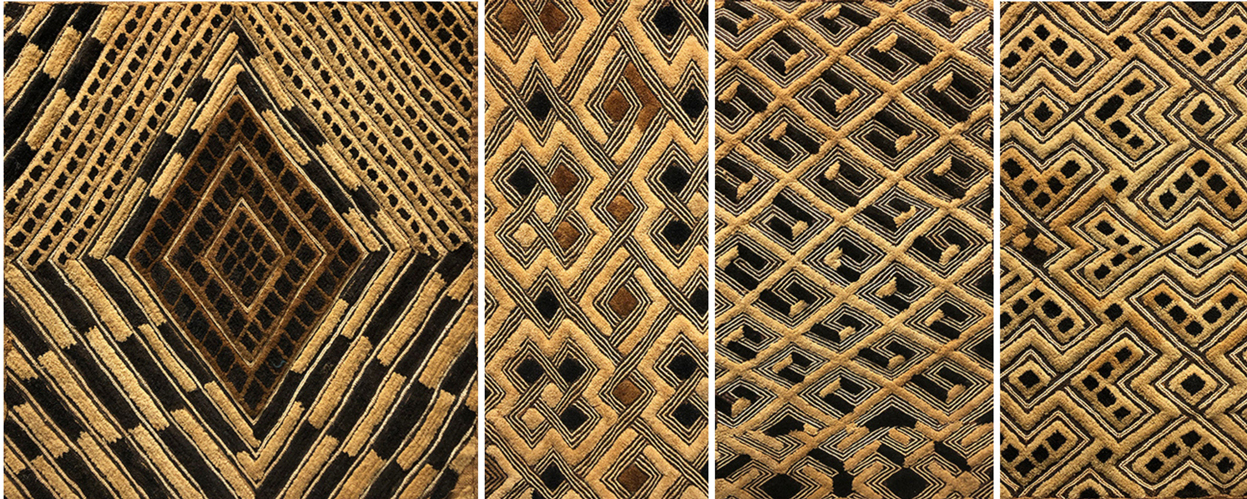

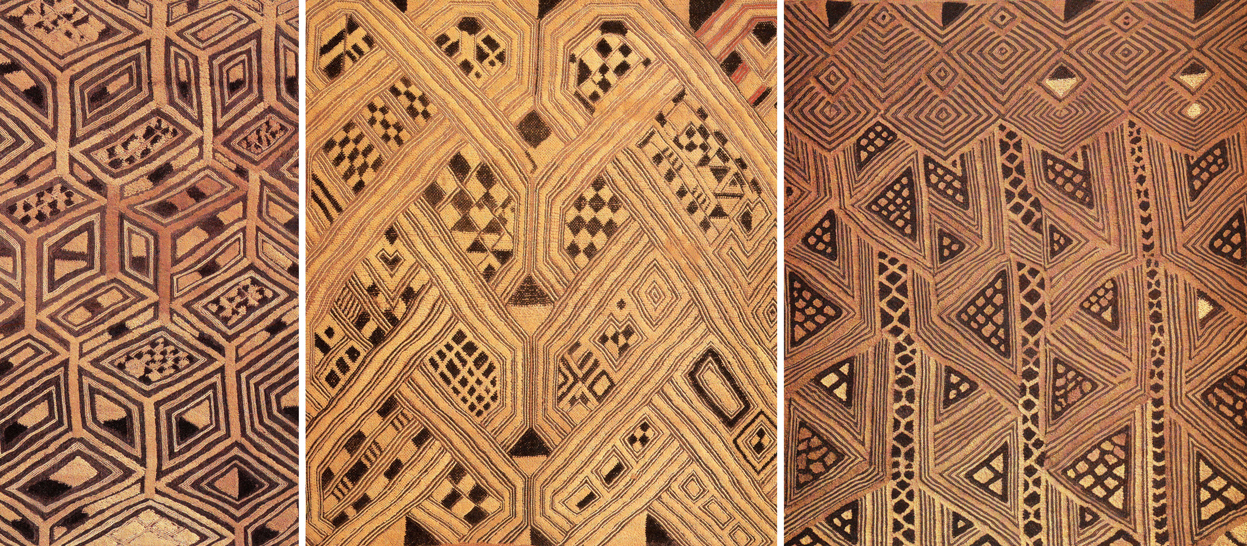

The visual inventiveness of some patterns, enriched by clever color variations and tonal shadings, is a feast for the eyes. Some highly complex geometric patterns exert a kind of magnetic attraction: they suck you into their mysterious space-time wormhole and throw you into an unknown universe. That’s the case with the following patterns, all selected by Georges Meurant, a Belgian artist and scholar deeply fascinated by African art. He has devoted much of his time and talent to the study of Shoowa panels, designs and patterns. The results of his original and profound analysis are contained in a celebrated book, Shoowa Design – African Textiles from the Kingdom of Kuba, published in London in 1986 (see Bibliography).

The details of the following panels show an even more elaborate level of composition: they look like scores for several instruments, each with its own distinct melodic line.

Left to right:

Detail of a Kasaï Velvet panel, DRC, mid-20th century. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

Detail of a Kasaï Velvet panel, DRC, mid-20th century, North Carolina Museum of Art, NC, USA.

Detail of a Shoowa panel, DRC, mid-20th century. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie – La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

Kasaï Velvet, Royal Overskirt, 1912-1942, DRC, ©Photo by Kerr Houston / Baltimore Museum of Art, USA.

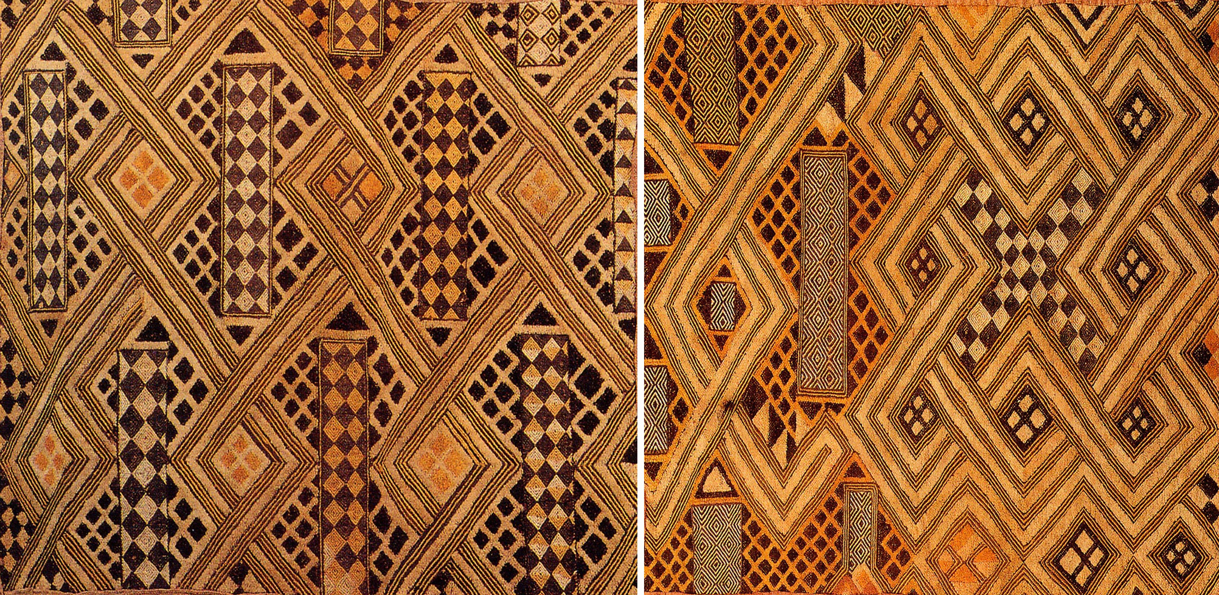

All of these geometric abstract designs show harmony, symmetries of various kinds (mirror, bilateral, and rotational), balance, and even solidity. Their great variety (of which we have seen very few examples), fueled by the diverse and multiple ways in which simpler patterns are intertwined, is an expression of the exuberant creativity of the Kuba people. According to mathematician Donald Crowe, of the seventeen ways a design can be repeatedly varied on a surface, the Kuba have exploited twelve.

The increasing complexity of geometric patterns and their chromatism/chromaticism (chromaticism is used in music, chromatism in painting) and their incredible richness do not account for the complexity of the Kasaï Velvet panels. What we have seen so far are only details of different panels. When we look at an entire panel, something new emerges. Not a detail, not a simple feature, but “the core,” the fundamental, essential, defining aspect of all Kuba textiles, including the velvety ones.

Gerald Toto / Richard Bona / Lokua Kanza – Lisanga, 2004

Lokua Kanza (born April 1958) is a singer, songwriter, arranger, producer, and multi-instrumentalist from the DRC. Richard Bona (born October 1967) is a Cameroon-born American multi-instrumentalist and singer. Gérald Toto (born 1967) is a French-Antillean lyricist, composer, performer, and multi-instrumentalist. Together, they mix jazz soul, Afro-Caribbean dance music, Congolese soukous and makossa from Cameroon, creating multitextured, original vibes.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?