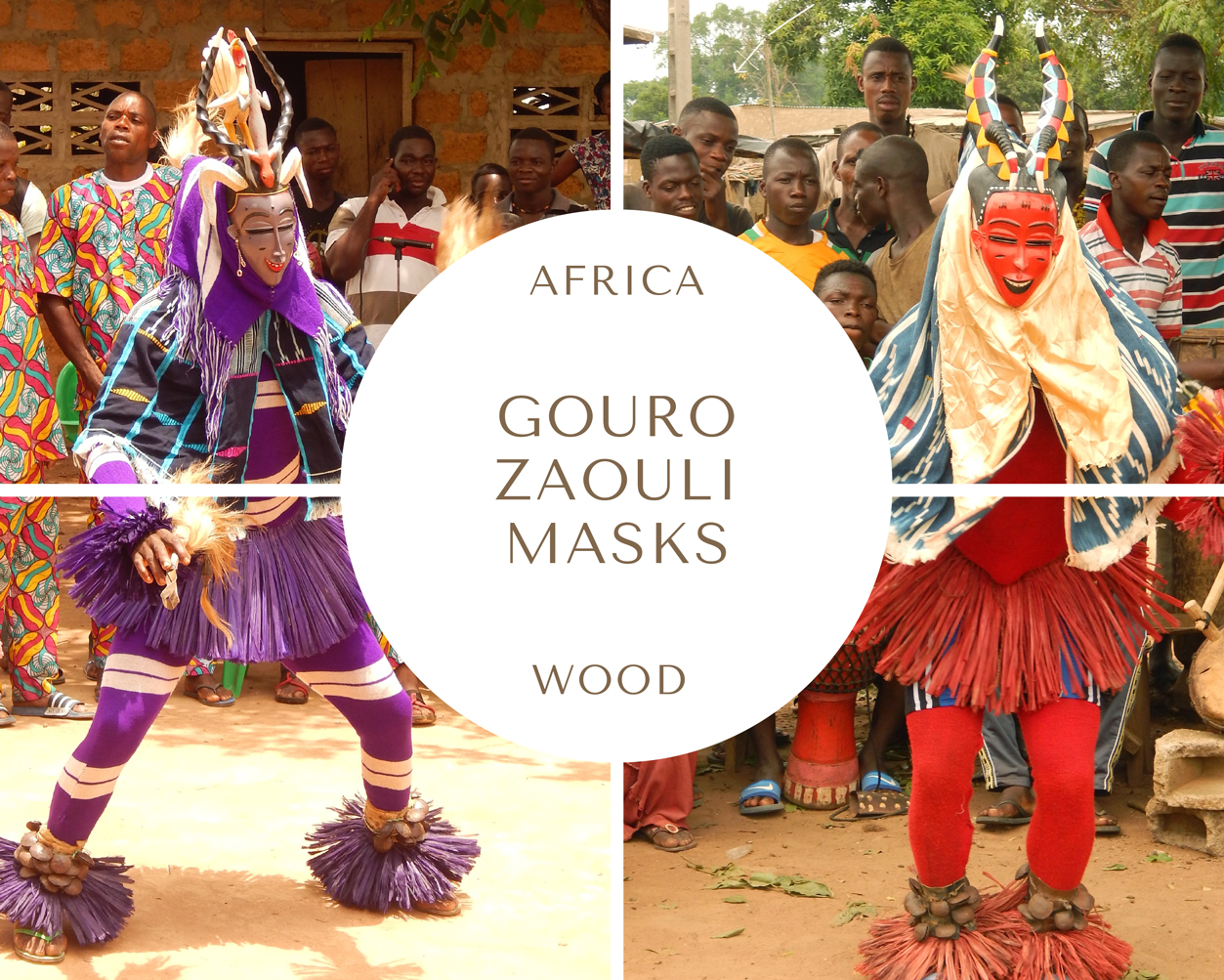

The Gouro Zaouli Masks from Côte d’Ivoire

Côte d'Ivoire, West Africa (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

THE MASK AND THE MASKED

«The mask is one of the most important human artifacts in all of the anthropology», said Graham M. Jones, a professor of Anthropology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MA, USA).

Although masks are not anthropological universals and are not common to all known human cultures worldwide, they are nevertheless very widespread objects. According to Paul S. Wingert, professor of Art History and Archaeology at Columbia University (NY, USA), as cultural objects, masks «have been used throughout the world in all periods since the Stone Age and have been as varied in appearance as in their use and symbolism».

Masks can be made by using a wide variety of materials, such as different kinds of wood and metal, shells, fibers and raffia, ivory, bone, earth and clay, horn, stone, feathers, plaster, leather, furs, cardboard, papier mâché, cloth, corn husks, wax, and so on.

They can be carved, unrefined, painted, decorated, or lacquered.

They can display a wide variety of shapes, from simplest eye covers to complex helmet masks, designed with articulated and movable parts, animal or human hairs, a raffia beard, neck collars, earrings, etc.

Chokwe face mask representing a beautiful young woman (pwo or mwana pwo), adorned with tattoos, earrings, and an elaborate coiffure. Medium: wood (probably Alstonia congensis), plant fiber, pigment (from a mixture of red clay and oil), copper alloy, kaolin (around the eyes). Dating: early 20th century. Provenance: Democratic Republic of the Congo or Angola. Dimensions: height 39.1 x width 21.3 x depth 23.5 cm (15 3/8 x 8 3/8 x 9 1/4 in.). © Smithsonian, photo courtesy by The National Museum of African Art.

BELOW

Left: Male dancer wearing a Pwo mask and costume, mid-20th century.

Right: Pwo mask dancer from the Chokwe people. Near Gungu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. 1970. ©Eliot Elisofon

Masks can have human features with gender-specific traits (anthropomorphic masks) or show animal features (theriomorphic masks). They can represent a hybrid creature or even a mythological, legendary being. They can be also a representation of an immanent spirit, an ancestor, a supernatural entity, a force of the universe, or a transcendent power. Some are quite realistic, while others show symbolized or even highly abstract characteristics.

Their appearance can be frightening, disturbing, reassuring, funny, or be the representation of ideal beauty or other qualities, such as nobility or courage.

Postcard reproducing a black-and-white photograph of two young Elema men outdoors, wearing eharo masks (the one on the left decorated with a fish). The men wear plant fibre shoulder coverings and cloth wraps, and have body painting. 1900-1930, Purari Delta, Papua New Guinea. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

Their functions show wide heterogeneity as well: they can be worn during socially significant occasions, religious ceremonies, sacred rites, shamanic practices, magic rituals, weddings or funeral customs. They can also play an important role in music, theater, or dance performances, called "masquerades". In many African cultures, these performances can promote fertility or a successful harvest, bring prosperity to a community, or help fight a disease or a natural disaster.

There are also "war masks", namely masks made to be worn in battle to protect the face; in some cultures, such as the Japanese, they also gave the warrior a terrifying or wrathful appearance to frighten the enemy.

Armor mask by Kyoto blacksmith Myōchin Muneakira, Japan, Edo period, 1745. The MET, New York, USA. Medium: iron, lacquer, textile (silk). Dimensions: height 24 cm - 9 7/16 in.; width 18.1 cm - 7 1/8 in.; depth 22.9 cm - 9 in. Weight: 557 grams.

The samurai's helmet was often completed by a war mask. This one represents Jikokuten, guardian of the East, one of the Four Kings of Heaven.

BELOW

Koboto Santaro, a Japanese military commander in his armor during the 1860s. Hand-colored photograph by Felice Beato. Wellcome Images, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.

In short, when we talk about masks, any generalization is almost baseless.

In Western cultures, the mask is often conceived as a tool to hide, conceal, dissemble, or cover the authentic face; in other words, the term mask often has a negative connotation. The English verb 'to mask', the French 'masquer', the Italian 'mascherare', the Spanish 'enmascarar', the Portuguese 'mascarar', and the German 'maskieren' share the same root and the same meaning: put on a mask to disguise oneself.

Ancient Roman mosaic depicting scenic masks. Dating: II century A.D. Rome, Hall of Doves, Palazzo Nuovo, Musei Capitolini.

In Roman theater, the actor was called actor or hystrio, from which the English term histrionic is derived (it means 'melodramatic' or 'overly theatrical'). Actors performed wearing a mask usually made of plastered linen cloth, leather, wood, or painted cork, and sometimes a wig. The mask did not have a normal mouth but a very wide opening that allowed the actor's voice to be amplified and was therefore called persōna, from the verb personare, 'to resonate'.

Carl G. Jung borrowed the Latin term persōna—a word probably derived from the Etruscan phersu and indicating the mask worn by actors during stage performances—to denote what each individual tends to display as a public face or social image, more or less meeting the specific requirements of their social context adhering to a subgroup of social rules, conventions, and expectations, and playing an acceptable social role.

If this mask, the persōna, is both an interface with the world and a protection from the latter, what hides behind it? What does the mask mask out?

Lorenzo Lippi (1606-1685), Allégorie de la Simulation or La Jardinière au masque, oil on canvas, approx. 1640. Dimensions: 73 x 89 cm. Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Angers, France.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Well, the answer of Carl Jung is a complex, fascinating one, and I invite all of you to delve into his thought. Here, I simply quote what he wrote in his Two Essays on Analytical Psychology: «The persona is a complicated system of relations between individual consciousness and society, fittingly enough a kind of mask, designed on the one hand to make a definite impression upon others, and, on the other, to conceal the true nature of the individual.»

Other cultures have given different answers to the same question 'What hides behind a mask?'. In the first part of The Tsuba, The Katana and the Samurai Soul, we encountered one of the most relevant conceptual pairs of the Japanese culture, omote and ura. Both in contemporary and ancient Japan, omote refers to the rules and conventions that guide the social behavior and the specific language and gestures to be adopted in public or in a given social microcosm (workplace, school, etc.), while ura refers to the informal behavior in a private context (family, close friends, etc.). Everyone has an omote side, their social appearance and formal behavior, their mask, and an ura side, their informal private nature, revealed in a more relaxed style of living. The general meaning of omote is "obvious" and "widely visible", and therefore "compliant with social norms"; ura is "what is kept hidden in public and can be therefore quite shadowy or unclear".

If omote is the mask, is ura the masked face, i.e. the true face of any individual?

Japanese culture is too sophisticated to give a positive answer to this question. In the first part of The Tsuba, The Katana and the Samurai Soul, we delved into the complex dynamic relationship between omote and ura in the life and fight of the samurai, and we saw how ura may come to light and become the omote of a different ura. For the Japanese ancient masters and the traditional culture, there is always an ura hidden beneath a given omote. If omote is the social mask of an individual, then ura is their private face, a face, however ready to become a mask itself, namely the mask covering a new ura.

In the first part of The Tsuba, The Katana and the Samurai Soul, the dynamic relationship between omote and ura and their dialectic opened to us the secrets of the samurai training, rooted in the Zen Buddhism practice, veined with Shinto elements and Confucianism, and showed the relation between them as something more complex and metamorphic than a simple polarity between the front and the backside, the mask and the masked.

«Whatever is profound loves masks» wrote Friedrich Nietzsche, meaning by 'mask' something similar to the surface covering the deep ocean waters. Oscar Wilde said that «the truths of metaphysics are the truths of masks».

Is masking an inescapable human need?

Does knowing thyself mean perfectly knowing thy masks and the moments when you need to choose the most appropriate one and wear it?

Any discourse on masks is thus a reflection on our social existence, our dasein, our being-in-the-world.

This means that we have to treat masks with a lot of respect and care because they are objects that 'speak' so much, never inappropriately.

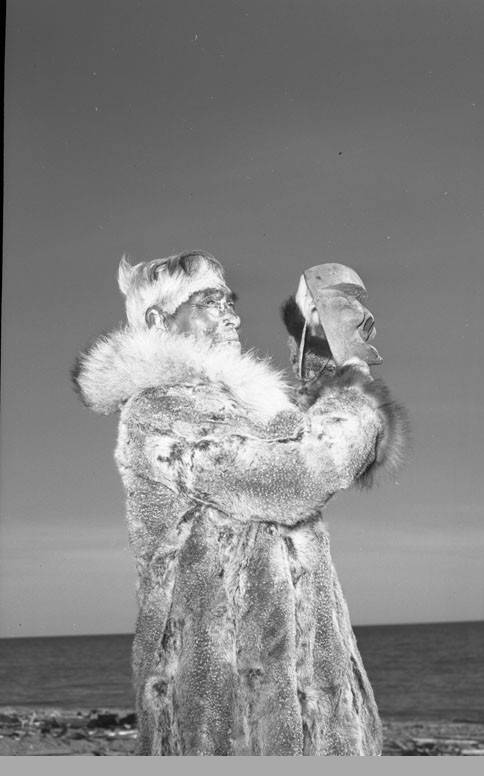

Many cultures throughout history have conceived and used masks as the most powerful tools to overcome the principle of individuation, the principle by which any living being possesses a singular, concrete existence, determined in time and space. We can express the principle of individuation in this way: I can exist as an actual human being if and only if I can be individuated as existing in a concrete place and in a given time. Wearing a mask allows us to escape this 'prison' (the Platonic σῶμα σῆμα, soma sema), suspend our everyday identity, be something else or someone else in a different space-time or even be projected beyond space-time. What makes this possible is the sacred nature of some masks, conceived as inhabited or permeated by the spirit they evoke. The human being, most often the man who wears a ritual mask and becomes a masker in a sacred masquerade gives up his own being and undergoes a psychophysical transmutation. In some African cultures «the costume worn with a <sacred> mask is just as important as the mask itself. A masker dresses in private and covers every inch of their body to conceal their identity. Costumes can be quite complex, made with hoops, padding, poles, and layers of fabric and raffia.» (Minneapolis Institute of Art, African Masks and Masquerades). By covering and hiding his own body, the masker temporarily erases his own identity. The mask and its costume are tools of transformation and allow their wearers to transcend themselves. It is no accident that masks and costumes have been the most important objects in the traditional practices and rituals of shamans, helping them to mediate between the worlds of matter and spirit or to travel from the world here and now and the beyond–in whatever way it is conceived–and back.

Shaman's Mask in carved and painted wood, ca. 1840-1880. Tlingit Culture, Baranof Island, Alexander Archipelago, Alaska, USA. Dimensions: 28.5 x 18.5 x 6.0 cm. © Smithsonian, photo courtesy by The National Museum of the American Indian.

Postcard in black and white with colours, depicting a Northwest Coast (Haida or Tlingit?) shaman. He wears a carved wolf mask on his head, a nose ring, a button blanket, and he holds a raven rattle in one hand and a large ladle also with the representation of a bird carved on the end of the handle. Date: ca. 1906. Photographed in Alaska, USA. Postcard printed in Germany. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

Portrait of King Island Chief Aulaġana (John Olarana) with the Good Shaman mask, Northern Alaska, USA, ca. 1939 or maybe after. Photo by Steve McCutcheon, Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center. Downloaded from Alaska's Digital Archives.

Masks are, therefore, among the most fascinating and relevant cultural objects as they tell stories about our being-in-the-world. They are probably among the most mysterious and ancient ones as well, as they have been handmade and used since the dawn of our prehistory.

The earliest preserved ones that we currently know of are 9,000-year-old stone artifacts coming from the Judean Hills and Desert, in Israel. They are not the most ancient pieces, but, more simply, the oldest masks that archaeologists have found so far. For many scholars, the birth date of the first masks is forever lost in the mists of time. Stephen E. Nash, an archaeologist at the Denver Museum of Nature & Science (US), wrote: «Older masks were almost certainly made of perishable materials, such as leather, feathers, pigments, or plant remains—all materials that don’t preserve well in the archaeological record.» (in The Masked Man, SAPIENS).

The relative scarcity of masks within the archaeological record is due essentially to the ancient preference for organic materials in mask-making practices and their poor rates of survival. The masquerade costumes are even rarer. This means that our knowledge of prehistoric objects and ways of life is filtered and mediated by scientific reconstructions and museum exhibits, but researchers can find and museums can show only artifacts made of materials able to withstand for millennia.

We have already encountered a similar situation when discussing the products of the art of basketry. In THE RWANDAN ART OF BASKETRY 1, we saw that antique fiber baskets are museum ghosts for reasons of force majeure; the same can be said of all masks made from natural, plant-based, and perishable colors and materials. What fiber and wooden masks looked like and what importance they had in prehistoric cultures we will never know for sure. The Neolithic Israeli masks have survived only because they are made of stone.

Carved stone mask found in the Hirbat Duma site, in Israel, from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (approx. 9,000 years ago). Dimensions: 22.5 x 15.6 x 6.6 cm. Photo © The Israel Museum, Jerusalem, by Avraham Hay.

This rare mask was found with other similar pieces in the Judean Desert. Israeli scholars assume that they represented the spirits of the dead and were used in religious-social ceremonies, such as ancestor cults, and in magical rites related to healing and divination.

Masks, like baskets, are prehistoric objects still in use today. Some cultures have preserved the ritual or ceremonial use of their traditional masks, while others have turned them into art objects or tourist handicrafts.

Although many people think of Africa as the homeland of the masks, their use–as we have just seen–was and still is shared by all continents except for Antarctica. It is true, nonetheless, that when we consider the creation, production, and use of masks, Africa stands out as a particularly rich continent. And among the many African masks, some Guro (or Gouro) from Côte d'Ivoire (the Ivory Coast) hold a special place in my heart because they are among the few ones sharing a rare feature: they tell multiple stories at the same time. In particular, these masks tell a story even when they are not worn or used, and seem silent and motionless wooden pieces.

Davorio by Musica Macondo Records is a 2023 collaborative experiment between Italian musician Samuele Strufaldi and Ivorian artist Boris Pierrou, operating as a funding source for a library and a community space in the village of Gohouo-Zagna, in Western Ivory Coast.

PROFANE MASKS OF THE GURO PEOPLE

Look at the following mask:

Wooden face mask painted in bright colors of red, black, brown, yellow, light blue and green. Mid-20th century, Guro people, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: 54 x 28.6 x 17 cm (H x W x D) - 21 1/4 x 11 1/4 x 6 11/16 in.

© Smithsonian, photo courtesy of The National Museum of African Art.

This mask has a complex structure.

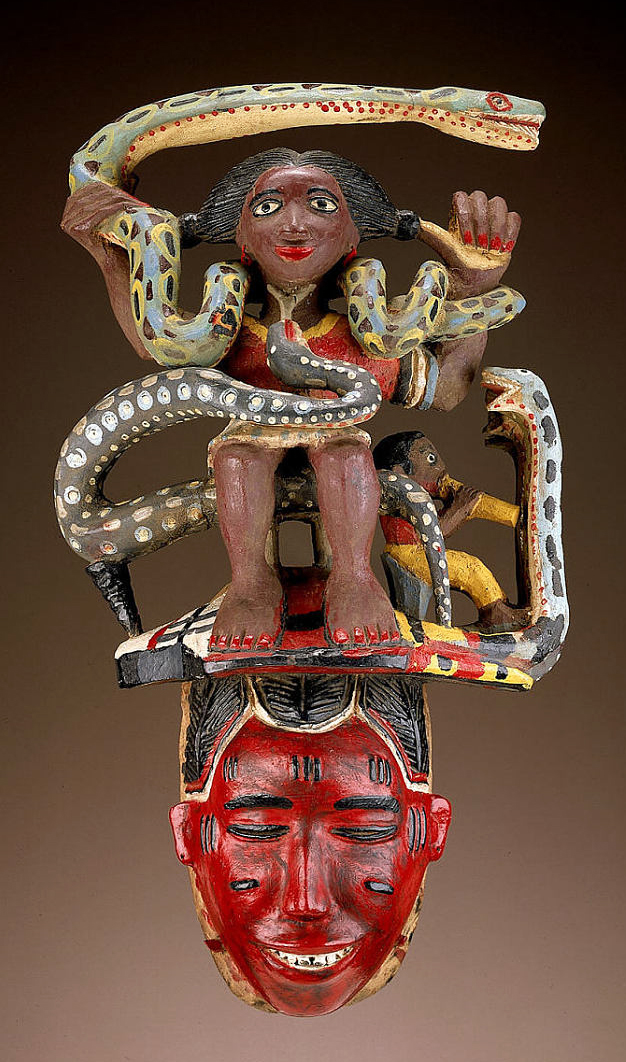

The red mask depicts a boldly colored female face with scarification marks, thin slit eyes, a toothy mouth, and a braided coiffure. It's crowned by a superstructure depicting a long-haired female figure among large snakes, flanked by the smaller figure of a snake charmer. This type of mask, called seli, seri, or sauli in the Ivory Coast, was made in the mid-20th century by an unknown Guro master who carved every detail of the superstructure from a single block of wood.

Both the mask and the superstructure tell their own unique stories. So this mask tells us two different stories, but a third one is ready to emerge and become the most relevant of all when the mask is worn and "acted" during a specific seli, seri, or sauli masquerade.

Let's look at the superstructure. It depicts Mami Wata, the powerful water spirit worshipped in much of West, Central and Southern Africa (including the Ivory Coast) and the African-Atlantic diaspora. For some scholars, Mami Wata is the pidgin English name for Mother Water, the spirit or immanent goddess who protects the waters, guards the sea, and is at once a source of wealth, a healer, and a deadly destructive force. (This ambiguity and Mami Wata's metamorphic abilities are typical of water itself.)

The worship and depiction of Mami Wata is widespread throughout sub-Saharan Africa and the African diaspora, but she is not an African-born figure and her history is quite fascinating. It is believed that many African groups developed a variety of water spirit traditions and cults before first contact with Europeans in the 15th century. In subsequent centuries, especially the 19th, the various traditions coalesced under the prevailing non-African image of a beautiful, seductive, mermaid-like woman with long, black hair and one or more large snakes slithering up her chest (large snakes are symbols of divination and divinity in Africa). Mami Wata is often called "the Voodoo Mermaid" because she is usually depicted with the head and torso of a woman and the tail of a fish.

In this composite imagery, according to Henry John Drewal, one of the leading scholars on the subject, elements of heterogeneous origins have converged and intermingled: representations of ancient, indigenous African water spirits, European mermaids, Hindu snake charmers, Christian and Muslim saints. Mami Wata is thus the result of cross-cultural exchange and syncretism, and demonstrates the creativity with which Africans incorporated foreign ideas and images into their own horizons of meaning. Between the 16th and 19th centuries, when the slave trade was at its height, «Mami Wata was reestablished, revisualized, and revitalized in diaspora, and emerged in new communities and under different guises, among them Lasirèn, Yemanja, Santa Marta la Dominadora, and Oxum. African-based faiths continue to flourish in communities throughout the Americas, Haiti, Brazil, the Dominican Republic, and elsewhere.» (Henry John Drewal, Mami Wata - Arts for Water Spirits in Africa and Its Diasporas, see Bibliography).

The superstructure of this Guro seli mask conveys a powerful emotional image because throughout the 20th century, Mami Wata remained an object of worship with a tradition of priests and priestesses, cults, rites, and practices. Many 20th-century Guro seli masks show this type of depiction in their superstructure, such as the following two:

Wooden face mask painted in bright colors, depicting Mami Wata. 1970s-1980s, Guro people, Côte d'Ivoire.

© 2023 by Second Face Museum of Cultural Masks. Reproduced with permission of the Museum's Chief Curator, prof. Aaron Fellmeth.

LEFT: Seli Mask honoring Mami Wata in enamel painted wood. 1960s, Guro people, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: 54.76 x 31.90 x 15.55 cm - 21 9/16 x 12 9/16 x 6 1/8 in. Photo Courtesy of the Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin–Madison, USA.

RIGHT: Seli Mask honoring Mami Wata in enamel painted wood, attributed to master carver Zoro bi Semi. Made before 1984. Guro people, Gofla, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: 58.2 x 28 x 14.5 cm - 22.91 x 11.02 x 5.70 in. ©Museum Rietberg, Zürich (Switzerland).

Please note: Although the depiction of Mami Wata has religious significance, all of these Guro seli masks are secular, not sacred objects. This relevant feature has nothing to do with the theme of their superstructure but is strictly related to their use in profane masquerades, as we'll see later.

What about the red or green face mask under the superstructure? What story does it tell us?

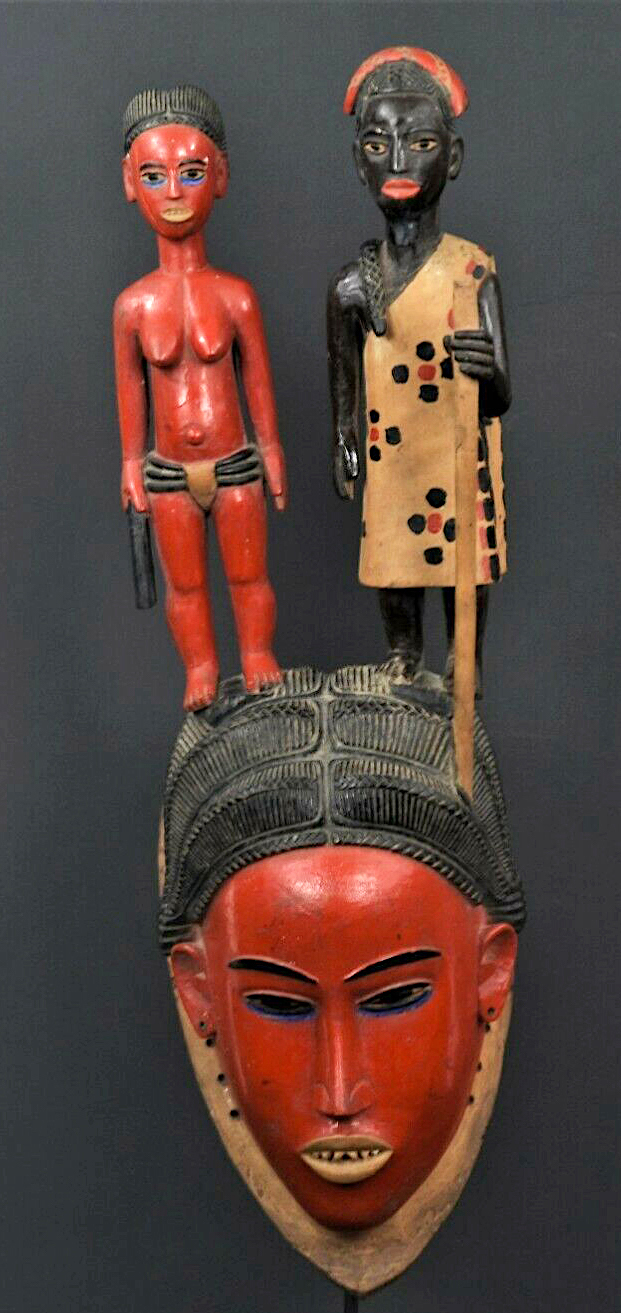

This colored female face mask represents the "Daughter of Djela lon zaouli", "Daughter of the Lion" and "Granddaughter of Zamblé and Gu". But before delving into the universe of the traditional beliefs of the Guro people, we need to take a closer look at the different sculptural representations that characterize the Guro seli, seri, or sauli mask superstructures.

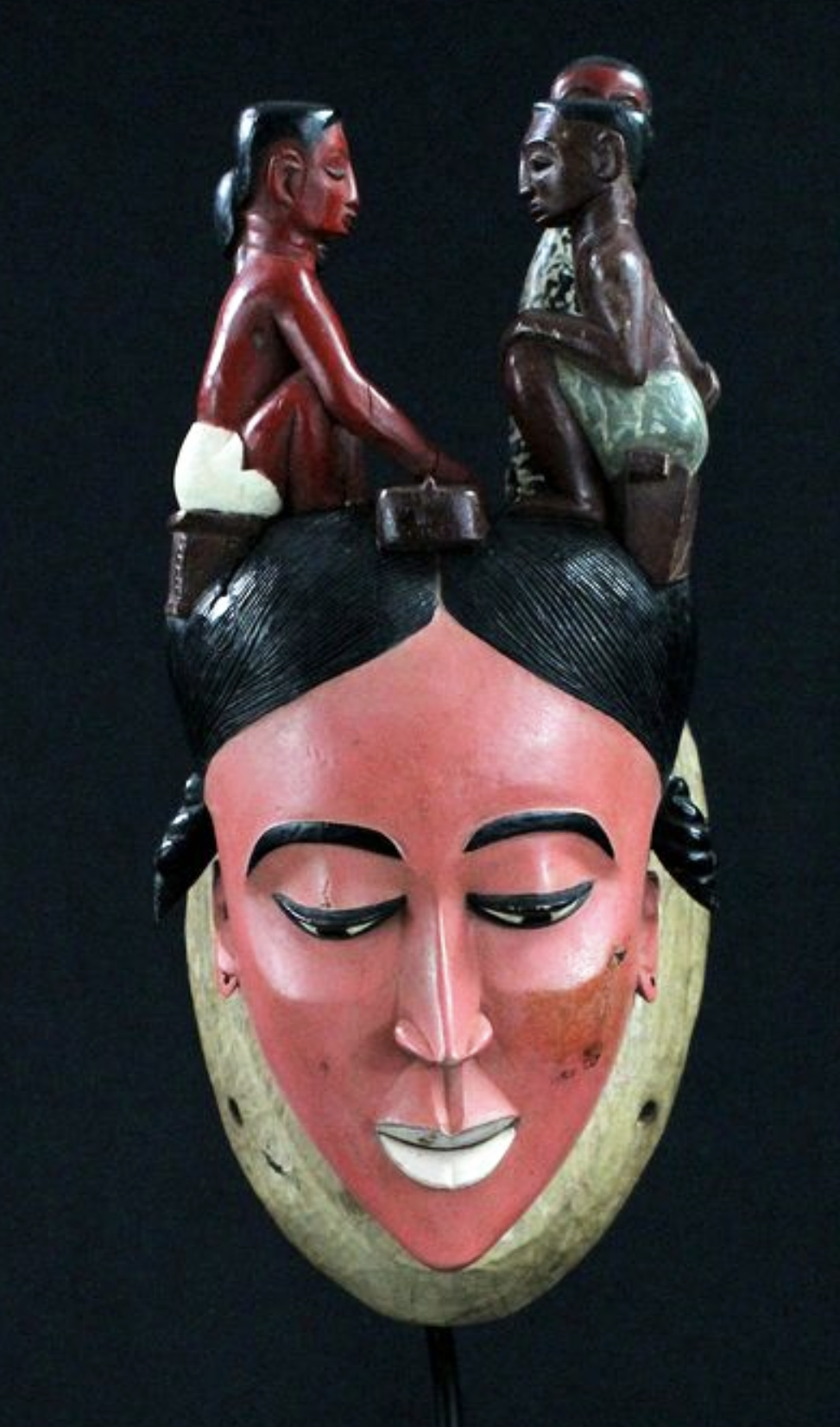

Here is a precious Guro seli mask from the Eve Begalli Art Gallery collection in France.

Guro Mask in painted wood (ripolin), ca. 1950, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: height 48 cm - 18.89 in. Photo courtesy of Eve Begalli, owner of the French Eve Begalli African Art Gallery.

This type of seli mask is often referred to as a "ripolin mask". Ripolin is a brand of paint, the first commercially available brand of enamel paint in France and its colonies. The term "ripolin” became synonymous with enamel paints in general and entered the French dictionary as early as 1907.

According to Eve Begalli, the elegant style and overall quality of this mask link it to the work of the Ivorian Maître des Niono, active in the first half of the 20th century.

The finely carved, yellow-painted face shows a refined headdress with black hair, raised black scarification marks on the forehead, delicate nostrils, half-closed eyes with beautiful eyebrows, and sharply pointed teeth. (Human tooth sharpening is a form of body modification practiced by many cultures; it consists of manually sharpening a few teeth, usually the front incisors, as in this case).

The female mask is surmounted by a superstructure with two finely carved human figures, a man and a woman, and a small animal, probably a ram's baby. It is difficult for us to say whether this is a simple scene of everyday life or the depiction of characters related to a traditional story or ritual. Certainly, this sculpture must have told the local Guro communities much more than we can understand. The same can also be said of the following mask from the Eve Begalli Art Gallery collection.

Guro Mask in painted wood (ripolin), ca. 1950, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: height 54 cm - 21.25 in.

Photo courtesy of Eve Begalli, owner of the French Eve Begalli African Art Gallery.

According to Eve Begalli, the elegant style and overall quality of this mask link it to the work of the Ivorian Maître des Niono, active in the first half of the 20th century.

The superstructure of a Guro seli mask can be a simple sculpture or a very complex group of several figures and animals; it may represent a scene from everyday life or the characters of a traditional story, proverb, or ritual ceremony. Sometimes, we can guess what it is about, sometimes not. But superstructures that are silent, are only silent to us. They weren't and aren't silent to the members of the various local communities. (I use the present tense because, as we will see, these masks are still being created and used today).

The vintage mask below is from the collection of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African art gallery Essentiel Galerie - La Porte Dogon in Belgium. It depicts a king or dignitary sitting on a throne. Technically, this piece is a monoxyle sculpture: the red face mask and the superstructure on top have been carved from a single block of wood.

If you look closely at some of the details of this face mask (the nostrils, the ears, the scarification marks, etc.) and compare them with the similar details of the two previous masks, you will notice many stylistic differences, within one and the same figurative tradition. These masks were created by different artists whose names we do not know, but whose personal style and hands we can recognize.

Guro Mask in painted wood, second half of the 20th century, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: height 50 x 20 cm - 19.68 x 7.87 in.

Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie - La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

Here is a mosaic of different superstructures of seli masks. Some of them are quite common themes.

Look at the top band of the mosaic. The second superstructure from the left shows a group of four human figures: two men carrying a corpse on a stretcher, preceded by a female mourner with a painted body. The scene represents a traditional funeral rite and is a fairly common subject.

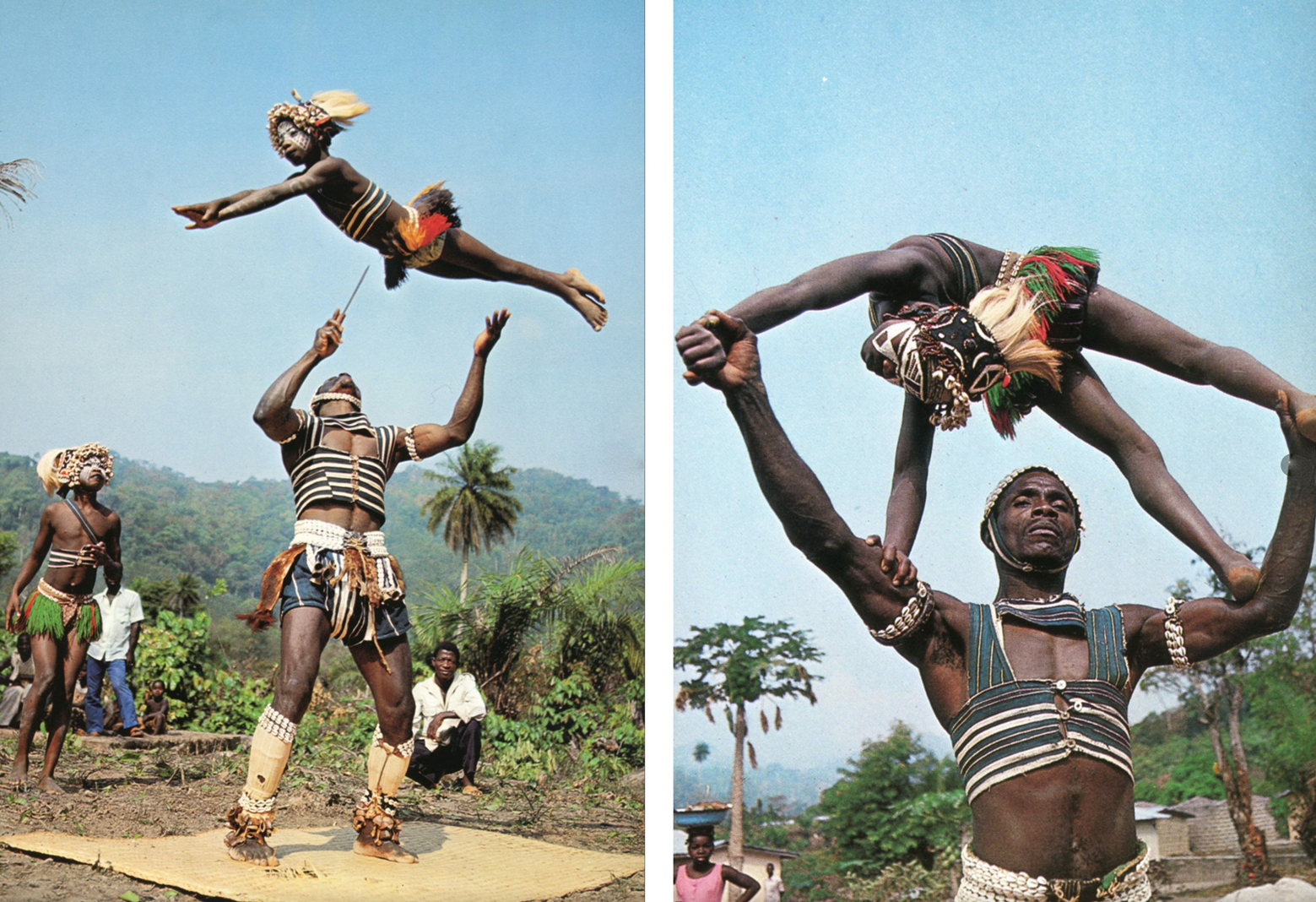

The third superstructure from the left shows a group of three Dan jugglers of the Simbo ("Snake") Society, a traditional festive scene. The Dan is a Mande ethnic group living in northwestern Ivory Coast and neighboring Liberia. The Guro, aka the Kweni, is also a Mande ethnic group speaking a Mande language (the Guro or Kwéndré), but traditionally living in the valleys of the Bandama River.

Sauli female face mask with scene of Dan acrobats. All in oil-painted wood. Made by Guro master carver Sabou bi Boti (ca. 1920/2021), Tibeita, Côte d'Ivoire, 1975. Dimensions: 61 x 17 x 29.5 cm - in. ©Museum Rietberg, Zürich (Switzerland).

According to Eberhard Fischer, Sabu bi Boti of Tibeita (Boti son of Sabu) was one of the most important Guro sculptors. He needed six entire days to produce this mask out of a single, wooden block with a diameter of 30 cm and length of 70 cm. He himself cut this piece of wood from the stem of a kind of rubber tree.

Dan acrobats of the Simbo Society, 1970s. © Photo by Michel Huets.

These and other interesting pictures by Michel Huets can be found in the volume The Dance, Art, and Ritual of Africa, photos by Michel Huet, Introduction by Jean Laude, Texts by Jean-Louis Paudrat, published in London by Collins in 1978.

Look at the lower band of the mosaic. The first superstructure from the left shows a group of four men playing awalé, one of the most widespread African strategy board games (known in other African countries as oware, awélé, wari or awari, ayò or ayoayo, okwè, and ourri). It's an ancient board game that belongs to the pit and pebble classification: it was once played with seeds or shells, now replaced by marbles or pebbles. In many African countries, this traditional game, played by men, women and even children, has a social meaning. It's never a game between a limited number of players, because it involves all the bystanders and spectators, who usually give advice, join in the banter, make noise, sing, discuss blows, and chat. Playing awalé and organizing a local competition are traditional ways of fostering social cohesion.

Festivity Guro mask in painted wood, Côte d'Ivoire, ca. 1970. Sold by Catawiki in 2021.

BELOW

Playing awalé and some of its variants in Africa. The rules of this game vary from region to region, and sometimes even from village to village. In Côte d'Ivoire, for example, two main rules coexist.

The superstructure of some Guro profane seli masks may show only scenes with animal figures: a snake attacking a bird's nest, a leopard or a lion attacking an antelope, colorful birds, elephants, rams, and others. All animals refer to a cultural horizon interwoven with distinct symbols and meanings. Some animals are also extraordinarily decorative, as in the case of the two masks below.

Guro wooden face mask showing an oil-based paint, early 2000s, Côte d’Ivoire. Dimensions:

© 2023 by Second Face Museum of Cultural Masks. Reproduced with permission of the Museum's Chief Curator, prof. Aaron Fellmeth.

Guro Mask in painted wood (ripolin), ca. 1950, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: height 54 cm - 21.25 in.

Photo courtesy of Eve Begalli, owner of the French Eve Begalli African Art Gallery.

Eve Begalli explains: «La chevelure dessine un motif de chevrons et triangles, colorés eux aussi, tout comme les ailettes latérales, éléments empruntés aux masques kpélyié des sculpteurs Sénoufo. Au sommet, la représentation d’une tête de coq sur un cou courbé d’une vive polychromie, comme le visage humain. Au revers, les marques d’outils témoignent d’un travail ancien. Inspiré de l’œuvre du Maître des Duonou». (My translation: "The hair forms a colorful pattern of chevrons and triangles, while the geometric elements on the sides are borrowed from the kpélyié masks of Senoufo sculptors. At the top, the representation of a rooster's head on a curved neck is vividly polychromed, like the human face. On the back, tool marks testify to old craftsmanship. It's inspired by the work of the Duonou Master").

The Senoufo are a large West African ethnolinguistic group living in Northern Ivory Coast, Southeastern Mali, and Western Burkina Faso.

A subgroup of Guro seli masks have a peculiar theme in their superstructure: "the Zamblé masker" with or without an attendant. The superstructure of these profane masks represents not only another mask, but an entire masquerade performance. The Zamblé mask is a sacred object whose use is subject to strict rules and taboos, and its masquerade is a complex, ancient ritual performance. So here we have some profane masks, consisting of a face mask and a superstructure, used in profane masquerades, representing sacred masks and their different ritual masquerades. Didn't I tell you that sometimes masks are quite complex objects?

Here are two seli profane masks, both with a superstructure depicting "the Zamblé masker":

LEFT: Guro face mask in wood showing an oil-based paint, early 2000s, Côte d’Ivoire. © 2023 by Second Face Museum of Cultural Masks. Reproduced with permission by the Museum's Chief Curator, prof. Aaron Fellmeth.

RIGHT: Guro face mask in painted wood, Côte d’Ivoire. Dimensions: height 57.15 cm - 22 1/2 in. This mask from my personal collection was purchased in 1954 by Hal Roach and certainly made before.

Here are the two Zamblé maskers in details.

The superstructure of mask below, from the collection of Patrick Malisse, shows both the zamblé masker and his attendant.

Guro Mask in painted wood from the mid-20th century, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: height 50 x 17 cm - 19.68 x 6.69 in.

Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie - La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

Below, you can admire the real zamblé masker with an attendant during a zamblé ritual masquerade in a village of the Ivory Coast. This recent photo was taken by Nabil Zorkot, a famous photographer, who was born in Lebanon in 1961 and has lived in Abidjan (in the Ivory Coast) since 1988. Here he founded a renowned publishing house, Editions Profoto.

BELOW

Zamblé masker with an attendant, performing the ritual zamblé masquerade, Côte d'Ivoire.

Photo by Nabil Zorkot, ©Editions Profoto, reproduced with permission of Jihane Zorkot.

Look at the following short video: it shows little more than one minute of a Zamblé masquerade, which is actually a very long and complex performance. But I am sure that this minute alone will be enough to fascinate you.

Zamblé masquerade in Bléfla, near the town of Gohitafla, in central Ivory Coast, August 2017.

In the next chapter, I will take you on a fascinating journey into the history and culture of the Guro ethnic group to understand what the ancient sacred Zamblé mask represents and what is the meaning of the symbols, gestures, and movements of the Zamblé dance and masquerade.

The profane seli masks with a Zamblé masker on top will take us directly to the heart of the Guro cultural tradition. Only after this journey will we understand the meaning and value of the profane female masks that smile at us enigmatically under all the superstructures. And we will also discover the secrets of the very fast and acrobatic seli or sauli dance.

Tiken Jah Fakoly, Is It Because I'm Black? ft. Ken Boothe, from his tenth album Racines, 2015. Kenneth George Boothe (born in 1948) is a famous Jamaican vocalist.

Tiken Jah Fakoly was born in 1968 in Odienné, in the northwestern part of Côte d'Ivoire, and is one of the most famous and culturally active Ivorian singers, songwriters and musicians, known throughout Africa. He wrote about himself: «Twenty-five years of career. A quarter of a century of music, commitments, triumphs and hard knocks. Tiken Jah Fakoly never gives up. Always an angry, vehement, generous fighter at the forefront of the battle that is his whole life: Africa, its unity, its right to escape misery and the politics that keep it there. Always armed with the same sword, his reggae music, full of uncompromising words and relentless rhythms that make us feel that, in the end, this fight is as much his as it is ours.» (My translations from French). «For his tenth album, Tiken Jah Fakoly went back to his roots recording at home, in the Radio Libre studios he built in Abidjan. The result is an undeniably powerful work in which he delivers the substance of his thoughts on the critical situations that are taking place right in front of us: the climate emergency, the dramas caused by immigration, modern slavery, and the exploitation of Africa are the main themes of this record» (from PAM - Pan African Music, January 14, 2020).

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?