The Gouro Zaouli Masks from Côte d’Ivoire 2

Côte d'Ivoire, West Africa (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

ZAMBLÉ OR THE SACRED MASKS OF THE GURO PEOPLE

Let's start with the Zamblé mask. Here is a magnificent specimen preserved (but not on display) at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston (MA, USA).

Guro Zamblé mask in wood and pigments, Côte d'Ivoire. It was acquired in Bamako, Mali, in 1974 and made in the Ivory Coast in the mid-20th century. Dimensions: 41 x 15.6 x 14 cm - 16 1/8 x 6 1/8 x 5 1/2 in. ©Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston, MA, USA.

The traditional Zamblé mask, carved from single piece of a light wood, has an anthropozoomorphic aspect: it represents a composite being with both human and animal features. This does not mean that Zamblé is a composite being. He's a wild spirit, as we'll see, but he's represented as a composite being because the mask has to emphasize the many characteristics of the spirit: speed, intelligence, the ability to run fast, whimsy, elegance, arrogance, agility, and so on.

The hairline, rounded forehead, and scarification marks are human-like features. The horns, pointing backwards from the top, with slightly curved tips and painted or carved stripes, are typical of a bushbuck antelope. The eyes are closed and appear as narrow slits in a round, oval, or rectangular frame. The nose is a simple, long ridge, usually without nostrils. The snout, which can be either rectangular or pointed oval (see pictures below), ends in an open mouth full of crocodile- or leopard-like sharp teeth.

LEFT: Guro zamblé mask in wood and pigments, first half of the 20th century, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: height 46 cm - 18 1/2 in. The Art Institute of Chicago, IL, USA.

RIGHT: Guro zamblé mask in wood and pigments, second half of the 20th century, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: 41.3 x 11.8 x 20 cm - 16 1/4 x 4 5/8 x 7 7/8 in. ©University of Michigan Museum of Art, University of Michigan Library Digital Collections, USA.

Some Zamblé masks feature vibrant colors, such as the one below. «In the past, vegetable dyes were used and only red, black, and white were permitted; but as time went by and near-permanent oil paints became available, blue and yellow were addedd, giving the mask a more contemporary look without changing its fundamental austerity.» (Anne-Marie Bouttiaux, Gouro, 2016, see Bibliography). The rigor and the limited number of possible iconographic variations are due to the fact that the mask is the vehicle of a powerful spirit, and is therefore considered as a sacred object. As such, it cannot be carved at will by the sculptor who, on the contrary, must follow a set pattern that leaves limited artistic freedom.

Guro zamblé mask in painted wood, second half of the 20th century, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: 36 x 9 cm - 14.17 x 3.54 in. Weight: 0.7 kg.

Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie - La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

The Zamblé mask is one of the various Guro sacred masks that evoke a spiritual being (yo). The Zamblé mask evokes the Zamblé, a powerful, capricious, and fearsome spirit of nature whose ancient myth was created and shared by the Northern Guro (the Loruben). The myth tells of a male hunter who encountered a wild spirit dancing and running in the forest, chased it, finally captured it, and took it to a sacred and secret place because the spirit was too destructive to be kept in the village. The hunter forbade all villagers, especially women, from visiting the spirit, but his mother disobeyed and was killed by the spirit. According to another version of the myth, it was the hunter himself who killed his own mother. Either way, the spirit was called Zamblé, meaning "the one who kills in the name of his owner.

The hunter of the myth is considered the ancestor of the patrilineal line of men who can handle the sacred Zamblé mask, make offerings and sacrifices to its spirit, and decide on a Zamblé masquerade. In most villages of the Northern Guro country, the Zamblé mask is a cult object and the property of certain families. Zamblé is the guardian spirit of those families and clans and protects fertility and births, but only the men are responsible for the masks and can make bloody offerings or accept gifts on behalf of the spirit from people who pay homage to it and seek its help. All women are strictly forbidden to touch the Zamblé mask: both its cult and its masquerade are a man's business.

THE ZAMBLÉ MASQUERADE

The Zamblé wild spirit manifests itself through the mask and a mask performance, the Zamblé masquerade. The mask is only one part of a complex costume that the dancer/performer must wear according to a ritual.

«Before a Zamblé performance begins, a clean piece of cloth is tied to the mask with a string so that the corners of the cloth fall forward, covering the head and shoulder of the performer. This cloth (Zamblé tolo) is always white, woven in strips from hand-spun cotton yard and decorated only with a few rectangles brocaded in indigo (...).» (Eberhard Fischer, Guro, see Bibliography). Under the white cloth, the masker wears a breast cover and an oil palm leaf skirt that also covers part of the torso. The limbs are covered with net tubes: those for the legs are called ganiman seli, while those for the arms beman seli. «The ankles have cuffs made of long bark fringes, and the wrists are wrapped in leather strips to which ready-made and carefully cut frills are attached, along with a great number (25 per arm) of iron bells (pan wore)» (Eberhard Fischer, cit.). The costume always includes an upper animal skin worn on the back: it could be a leopard skin (kya kole) or, more often, a piece of civet or hyena skin. Its tail is held by the attendant (yozuzan) who stays always behind the masker during his performance. The purpose of the skin is both to express the scary and threatening side of the spirit and to show its wilderness origins.

Zambé masker with attendant performing the ritual zamblé masquerade, detail. Côte d'Ivoire.

Photo by Nabil Zorkot, ©Editions Profoto, reproduced with permission of Jihane Zorkot.

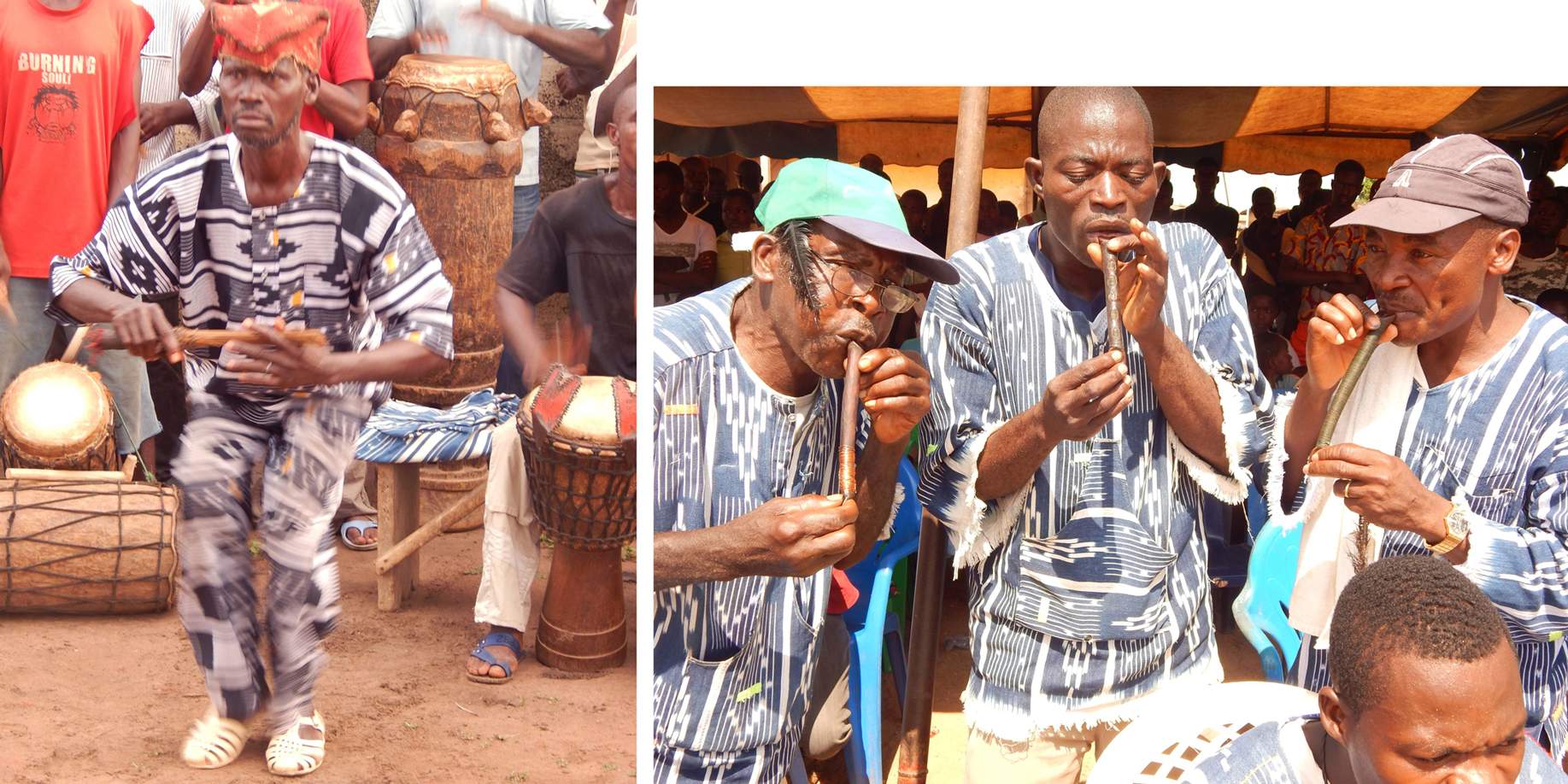

The masquerade begins with some men cracking a whip (plin) vigorously to chase away children and unwanted people from the performance area, and it is always accompanied by a characteristic music. «Zamblé's orchestra is composed of various drums, as well as beli, flutes.» (Eberhard Fischer, cit.).

Photo © Aka Konin / Office Ivorien du Patrimoine Culturel (OIPC), 2015

The following video, shot in 2017, shows a Zamblé masquerade in a village in the Ivory Coast. It is not of high technical quality, and it shows only a few moments of a performance that can last a long time. Nevertheless, it's enough to appreciate some relevant aspects.

First, as you will see, this performance requires remarkable physical control and athletic ability to sustain the rapid footwork. The skill of the Zamblé masker is judged on the speed and fluidity of execution, variety of steps, sudden changes in rhythm and various virtuosities on a single leg. The steps are "fast and furious" as befits an unpredictable, dangerous spirit.

Second, the attendant is always behind the masker, holding the tail of the skin. Eberhard Fischer, who has done much fieldwork in Guro country, points out that, that according to some elders, «the young man behind Zamblé who hold the tail of the leopard represents the hunter who once captured the spirit.» (E. Fischer, cit.). In addition to this symbolic function, there is also a practical reason: the attendant has to guide the masker, who is almost blind because the mask doesn't allow him to see what's going on around him. So the attendant guides the masker and sometimes picks up the coins and paper money thrown by the people as offerings to Zamblé and signs of appreciation.

Third, the performance is a collective one: there is no clear separation between the space where the Zamblé masker moves with his helper, the space where the musicians sit, and the space reserved for the audience. With the exception of the women, who are allowed to watch but not to participate and are not allowed to touch the masker, the men of the community where the performance takes place participate in various capacities, challenging the Zamblé, making offerings, flattering him, shouting, dancing, singing, and moving around the arena. The flutists also follow and move with the Zamblé.

The masquerade may appear to Westerners as a random and haphazard spectacle, but it is not a spectacle, and each stage of it is codified by tradition, although in recent years the spectacular aspect has been emphasized at the expense of the ritual one.

The Zamblé mask plays an essential role: it allows the spirit from the nonhuman world to take control of the masker/performer's body and be present as the true source of his superhuman movements. A talented dancer provides the spirit with «an energetic body through which it can demonstrate its power in high style. The village benefits from the dynamic, positive action of a nature spirit, whose prolonged presence purifies the surroundings, drives out harmful influences» (Anne-Marie Bouttiaux, cit.), and protects the entire community. The Zamblé masquerade is always a positive event for a Guro community.

As you can see in the video, the Zamblé masker sometimes lifts his mask to breathe fresh air, dry his sweat, and see the audience. The spirit enters the masker's body and possesses it, but not completely and not absolutely. The Zamblé spirit does not demand the anonymity of the dancer and does not suppress his individuality. The whole community knows who the masker of the local masquerade is, and some top performers become so famous that they attain the status of admired idols. The following video is a tribute to Kalou Vié, one of the most popular top performers in the Marahoué region.

There is no contradiction in this popular attitude. Eberhard Fischer explains: «Nearly everyone knows that Zamblé is performed by an individual, but at the same time, they know that without the support of Zamblé spirit, the performance would be impossible.» (Eberhard Fischer, cit.). Thus, we can say that the Zamblé masquerade is not "dancing with a mask" but "dancing the mask" and becoming the spirit.

The Zamblé sacred masquerade is thus the survival expression of a complex system of indigenous animist beliefs and practices that predates the spread of Christianity and Islam, the two most common religions in Côte d'Ivoire today.

THE ASTONISHING BEAUTY OF GU MASKS

«Zamblé was sometimes accompanied by two other masks because it was part of a group of three entities honored on the same altar (yo ban ta fe); the other two were Gu, with a delicate female face, and Zauli "the Ugly". (...). All three were managed by a single family lineage, and brought together on the same yo ban ta fe to receive sacrifices. They seemed to form a sort of trinity» (Anne-Marie Bouttiaux, cit.).

The sacred mask of Gu, often regarded as the wife of Zamblé, represents a female spirit of nature whose dance and masquerade are not very attractive. However, the Gu masks have become famous and appreciated by Western collectors and experts for «the finesse and quality of their execution and the delicate portrayal of a woman in the flower of her youth». It must be said, however, that the mask's appearance has nothing to do with the character of the spirit, who has a strong, impulsive personality with a restless attitude. «While it is definitely a nature spirit that uses a young woman's face, there is nothing else about it that could be defined "feminine" as such.» (Anne-Marie Bouttiaux, cit.). Moreover, the use of the Gu mask, its masquerade, and the sacrifices offered to its yo, similar to what happens with the Zamblé, are completely absorbed into the ritual field controlled by men.

The Gu mask below is an exceptional piece preserved in the Museum Rietberg in Zürich, one of the largest art museums in Switzerland, with a focus on traditional and contemporary arts and cultures of Asia, Africa, America, and Oceania. Carved by the Master of Bouaflé in the 19th century, this Gu mask depicts a female face with very few, but powerfully expressive features, achieving a stylistic elegance that makes The Sleeping Muse by Constantin Brâncuși seem like a belated masterpiece.

Guro Gu wooden Mask made in the 19th century by the Master of Bouaflé, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: height 35.8 cm - 14.09 in. ©Museum Rietberg, Zürich (Switzerland).

«This face mask, crowned by a rectangular platform with a small ram (the preferred sacrificial animal of the Guro), is entirely stained a blackish brown, with the wood grain visible under the polished surface.» (Eberhard Fischer, cit.).

Constantin Brâncuși (1876-1957), La muse endormie ("The Sleeping Muse").The original marble version was carved in 1909-1910; this bronze version was cast by 1913. Signed ‘Brancusi’ (on the back of the neck). Patinated bronze with gold leaf. Length: 10½ in (26.7 cm).

This piece was sold for US $57,367,500 in the Impressionist & Modern Art Evening Sale on 15 May 2017 at Christie's in New York. Photo: Courtesy of Christie's, NY.

The Guro Gu mask below is from my personal collection. It's tall (ca. 40.64 cm - 16 inches) and features a stylized rooster on top. The young woman's face is outlined with only a few delicate features; her expression with downcast eyes is graceful and serene, and every detail (hair, mouth, scarification marks, eyebrows, ears) is rendered with a visual essentialism that, although working by subtraction, manages to fill the wood with a lively and coherent emotional content. The smile, modest, reserved and seductive, is a small masterpiece in itself. This mask has some elements in common with the Yaouré masks. The Yaouré, Yohouré, or Yowlè are an Ivorian subgroup of the Akan people who share many linguistic, ethnic, and stylistic elements with the Guro.

Last but not least, here is a detail of an amazing Gu mask from the collection of Patrick Malisse. It's just a detail, but it already says it all.

Guro Gu mask in wood with a matte reddish-brown patina, 1960-70, Côte d'Ivoire. Dimensions: 31 x 13 cm - 12.20 x 5.11 in. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie - La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

THE "DAUGHTERS" AND "GRANDDAUGHTER" MASKS

The masks of Zamblé, Gu, and Zauli "the Ugly" are the dwelling place of a spirit, therefore sacred objects honored by sacrifices and governed by rules and taboos; their masquerades are sacred performances managed by a few Guro families and codified by ancient rituals.

«Entertainment masks and profane masquerades have probably existed for a long time among the Northern Guro. It's likely that enterprising dancers who wanted to take up less established forms of dance and music, or who came from families without access to those ritual masks, managed to get hold of other genres of face masks for which they could then create mask performances according to their own personal vision (...). New mask types and new ways of dancing must have emerged and vanished many times over the course of generations. (...). To garner the acceptance of the "conservative" public, the new masquerades were genealogically attached to the earlier ones.» (Eberhard Fischer, cit.).

Between the two World Wars, in the Guro country, a new mask-being and a new masquerade appeared. The mask was called Djela or Gyela and was a hybrid mask-being with some features from Zamblé (the horn for example) and some others from Gu (the female face); thus, this new mask was perceived as their "child".

In the early 1950s, a new generation of profane masks was developed and called Gyela lu Zauli or Djela lu Sauli, nameli Sauli or Zauli daughter (lu) of Gyela or Djela, and thus "granddaughter" of Zamblé and Gu. These entertainment masks, created for profane masquerades, are the seli, seri, sauli (zauli) or flali types of masks we saw in the previous chapter. They are, in short, those brightly painted masks that depict a smiling female face crowned by a stunning superstructure.

The colorful face of a young, modest, and beautiful girl under the superstructure is thus a living indication of the metaphorical parentage and ideal connection of Gyela lu Zauli to a Guro ancient tradition. It's a loose connection, to tell the truth, but in the 50s, it was enough to promote the social acceptance of the new masks.

Dobet Gnahoré - Lève-toi, feat. Yabongo Lova, a popular Ivorian performer of the upbeat zouglou style.

Sung in French and a Bété language, this track from 2021 Couleur, Gnahoré's sixth full-length album, blends electronic rhythms, intricate guitar lines, and powerful melodies to create an irresistibly catchy and upbeat groove. The colorful video, featuring breathtaking dance moves and elaborate costumes, was filmed in the André Bessikoi neighborhood of the city of Abidjan.

One of Africa's superstars and a renowned Grammy winner, Dobet Gnahoré is an Ivorian virtuoso singer, percussionist, dancer and songwriter who has taken the modern Afropop sounds of her country in exciting new directions.

The Bété languages are a language cluster of Kru languages spoken in central-western Côte d'Ivoire by the Bété, an Ivorian group with strong cultural and artistic ties to the Dan, the We (Gwere), and the Guro.

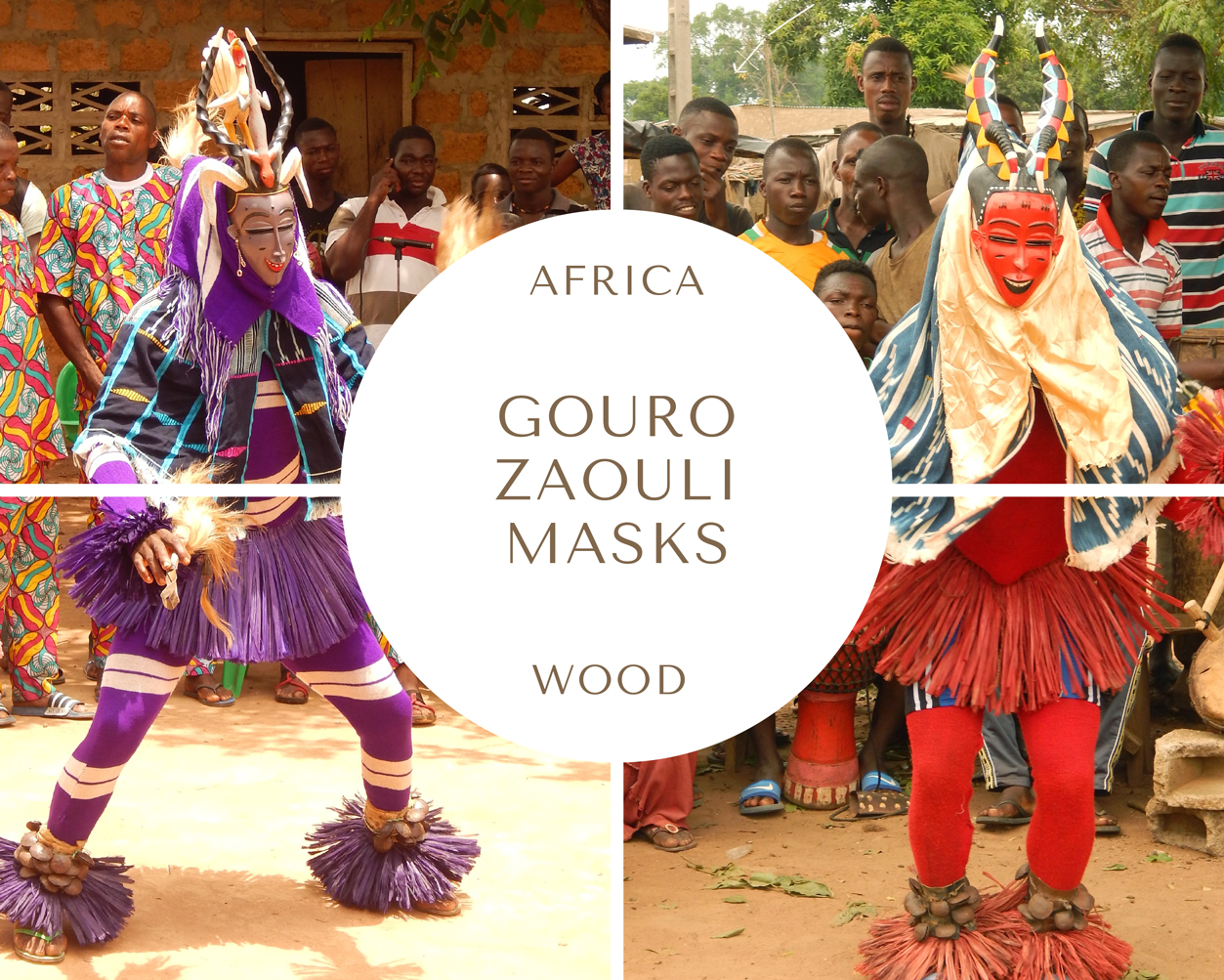

THE PROFANE MASQUERADES

All the Gyela lu Zauli masks are profane objects, usually administered by male artists' associations and used in masquerades of various kinds that can be seen by all members of a Guro community. However, all the dancers and musicians are still men.

The seli masquerade was the first to be developed. The masquerader wore a mask sewn to a cloth made at the mill, which covered the dancer's head and upper body. His costume consisted of "short bast skirts, net stockings and arm coverings: bast cuffs at the wrists and ankles, supplemented by rattles on woven palm strips". (E. Fischer, cit.). Like the Gu maskers, the seli performer wore an antelope skin on his back, the tail of which was held by an attendant, similar to the Zamblé helper. The music was played by an orchestra of drummers and flutists, as in the old sacred masquerades.

Photo © Aka Konin / Office Ivorien du Patrimoine Culturel (OIPC), 2015

In the sauli (or zauli) and flali masquerades, the attendant disappears and the dancer does not wear animal skin. The main difference between the flali and the zauli is that only in the first dance was the mask adorned with a spray of feathers on the back.

Within a few decades, the Zauli profane masquerade became the most successful, sought-after, and universally appreciated performance. «Gyela lu Zauli had certainly become the most popular mask in the Ivory Coast, which still promotes its masquerade as a cultural treasure (and tourist attraction) because its dance is so impressive.» (Anne-Marie Bouttiaux, cit.).

Precisely because they were secular, neither conditioned by a rigid ritual nor obliged to follow traditional standards, both the Zauli mask and costume could evolve into a wide variety of bright colors and shapes, yet still within a single pattern. «Variety had also crept into the carving of the mask. Although the face was still feminine, the superstructures had become increasingly complex (...).» (Anne-Marie Bouttiaux, cit.). As we've already seen, some of them depict proverbs, old stories, personalities, sacred beings like Mami Wata, or everyday scenes and customs with many human and/or animal figures. The stories these superstructures tell had nothing to do with the masquerade and its elements: superstructures are there to attract attention, to surprise or excite the spectators, to be remembered and to make the masker remembered.

BELOW

All pictures: Photo © Aka Konin / Office Ivorien du Patrimoine Culturel (OIPC), 2015

LEFT: Zauli Masker, Guro people, Côte d'Ivoire, 2016. Photo by Emmanuel Dabo, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0).

CENTER: Zauli Masker, Guro people, Côte d'Ivoire, 2016. Photo by Emmanuel Dabo, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0).

RIGHT: Zauli dancer at a ceremony in Bouaké, Côte d'Ivoire, 2008. Photo by Zenman, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

The dance steps, freed from ritual constraints, also evolved rapidly in the direction of increasing spectacularity: the basic steps common to Zamblé dance were joined by increasingly acrobatic jumps and super-fast movements. The following videos, both shot by photographer Nabil Zorkot, show some moments of the profane masquerade as it has been performed in recent years.

Some moments of the Zauli masquerades of Siafla and of Manfla, during the festival held in Gohitafla (Côte d'Ivoire) on August 2022. By Nabil Zorkot.

This 26+ minute video from 2008 shows aspects of the Gohitafla landscape and Blefla markets, as well as Zauli masquerades. Well worth your time.

Popular participation in the secular masquerade is always very high because while the performance remains a male affair, women can participate, interact, dance, and give themselves a voice, overcoming the forms of censorship imposed by the sacred masquerades.

In 2017, the Zauli performance was included in the representative list of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity established by UNESCO. This decision not only gave the Zauli tradition greater support, but also increased its visibility outside of Côte d'Ivoire. Today, the Zauli dance has become a tourist attraction that fills the small theaters of luxury tourist hotels and the large stages of African cultural festivals. While it is good that more and more people know not only the Zauli dance but also the stories behind it, it must be said that the masquerade is losing some of its original character.

The Zauli masquerade is an event that is born, develops, grows, and dies within a specific Guro community, where it represents a time of entertainment, a means of social cohesion and a tool for strengthening the cultural identity of that community. Like the Zamblé masquerade, the Zauli is unthinkable without the constant interaction between mask and masker, musicians, local notables, small children imitating dancers, men throwing money offerings, women dancing with their backs bent, close to each other, and spectators laughing, singing, shouting, or answering their cell phones.

The theater, any theater, with its aseptic and sterile environment and its defined and bounded spaces - the performers on one side and the audience on the other and the children sitting and shutting up - sanitizes the masquerade to the point of depriving it of a tasty part. Or maybe it's just fear. As you can see in the next video, the popular participation is so strong and grounded that it broke the boundaries of the theater at the Palais de la Culture in Abidjan.

Dobet Gnahoré, N'blibla, from 2021 Couleur.

Please, note the Zauli profane masker at min. 2.35. The round shields are typical of West Africa, and are widespread among the Bwa of Burkina Faso, the Bamum and the Bamiléké of Cameroon, the Fang and Punu of Gabon.

DIVERSITY IS A SOURCE OF RICHNESS, COLOR AND WONDER

Because of its awesomeness, the Zauli dance has attracted the attention of some social media, which call it "the most difficult dance in the world". That's a 90 percent stupid and 10 percent completely useless label. Zauli is not the most difficult dance in the world, nor is it the most difficult dance in the Ivory Coast. This state is one of Africa's richest countries in terms of cultural heritage, with more than sixty ethnic groups, many of them with amazing artistic traditions. Few countries can boast such a rich variety of masks, dances and masquerades as the Ivory Coast; and some of these performances are definitely more acrobatic and dangerous than the Zauli.

Before considering other forms of masquerade in Côte d'Ivoire, however, it is worth emphasizing that what we have written about the Guro people can also be applied to other ethnic groups: the mask is definitely more than just an object intended to cover a person's face. For many Ivorian communities, the mask is the whole costume that it's sewn to, it's the masker behind and inside the costume, it's the spirit that the mask evokes or dwells in, it's the sacred or profane masquerade with its music, movements, popular participation, social and spiritual functions.

THE DAN OR YAKOUBA PEOPLE

The Dan, better known in Côte d'Ivoire as Yacouba or Yakouba, are a Mandé ethnic group (like the Guro), living in the northwestern region and neighboring Liberia. The traditional patrilineal and polygamous culture of the Dan is famous for its masks, its most important art form and a central element in its cultural life and social organization. Some masks, such as the one below, are believed to embody the most powerful spiritual forces, called ge or gle. Dan ge spirit mask performances are elements of getan, the music/dance aspect of the manifestation of ge.

Dan Gle Mask, late 19th-early 20th century. Wood, pigment. Ivory Coast/Liberia. Dimensions: 9 3/4 x 6 x 3 in. - 24.8 x 15.2 x 7.6 cm. The Brooklyn Museum, NY, USA. Photo licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported.

«Oval-shaped, with arched, full lips, delicate nose with slightly flared nostrils, and coffee bean-shaped slit eyes. The forehead is rounded with a medial ridge. The eyes are lined with a thin line of white pigment that extends to the bridge of the nose. The rim of the mask is pierced for attachments. The entire surface has a deep, rich brown glossy patina. (...). Historically, Dan society vested political leadership in a council of elders. Masks served as agents of social control, enforcing the rules and orders of the council. The masked figures were believed to be incarnate spiritual beings capable of making unbiased judgments. The specific functions of individual masks, once removed from their village contexts, are impossible to determine. Here, the almost closed eyes and small mouth contrast with those of other masks and probably indicate that this example had a peacemaking function and generally created harmony in the community. On the other hand, the shape of other Bu gle masks, with their protruding eyes and mouth, was deliberately designed to be frightening.» (From the Brooklyn Museum Catalog).

The Gblin or "Stilt Walker"is a great sacred costume-mask with both a spiritual power and a temporal power that gives him agility, and the force to perform unusual acrobatics. Worn by a mask-man, this ge (spirit) is the protagonist of a complex masquerade involving dance and music. Almost everyone in the local community know that a person (the dancer) is "behind the Gblin mask" of a performing ge, and many people know who the person dancing a particular ge is. However, as Daniel B. Reed pointed out in his fieldwork research paper Ambiguous agency: Dan/Mau stilt mask spirit performance as ontology in Côte d'Ivoire and the US (in "Africa", Cambridge University Press, 2018), «the information about the masker identity cannot be spoken in public. People deliberately talk around the issue, finding creative ways to discuss the subject of ge performance without naming names. (...). It is permissible to know, but not to say, that there is a person beneath the dancing figure. Taking my interlocutors literally, a dancing ge is not a person embodying a spirit, but rather the ge is the spirit itself. (...). Ge performance does not represent ge; it is ge.»

The Gblin or "Stilt Walker" is a large sacred costume mask with both spiritual and temporal powers that give it agility and the strength to perform unusual acrobatics. Worn by a masked man, this ge (spirit) is the protagonist of a complex masquerade of dance and music. Almost everyone in the local community knows that there is a person (the dancer) "behind the Gblin mask" of a performing ge, and many people know who the person dancing a particular ge is. However, as Daniel B. Reed pointed out in his fieldwork research paper Ambiguous Agency: Dan/Mau stilt mask spirit performance as ontology in Côte d'Ivoire and the US (in "Africa", Cambridge University Press, 2018), «the information about the identity of the masker cannot be spoken in public. People deliberately talk around the issue, finding creative ways to discuss the subject of ge performance without naming names. (...). It is permissible to know, but not to say, that there is a person behind the dancing figure. Taking my interlocutors literally, a dancing ge is not a person embodying a spirit, but rather the ge is the spirit itself. (...). The performance of ge does not represent ge; it is ge.».

BELOW

A dancer wearing a mask before the start of the Gue-Gblin masquerade, Côte d’Ivoire.

© Both photos by Carsten ten Brink, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Gue-Gblin masquerade, Côte d’Ivoire.

©Photo by Carsten ten Brink, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

Here is a video of this characteristic Yakouba masquerade; its ritual is believed to protect the village and is celebrated during weddings, funerals, initiations, and other special occasions. Note that in the past, the masker/dancer performed perched on stilts several meters high, hidden under the traditional costume; today the height has been reduced, but the movements are still very risky and require both skill and courage.

Stilt Dance Ceremony, Ivory Coast, by Overlanding West Africa

THE SÉNOUFO OR SÉNÉ PEOPLE

The Sénoufo or Siéna (the name they give themselves), or Sénéfo, Séné, Syénambélé, are a West African ethnolinguistic group living in a region that spans the northern Ivory Coast (where Korhogo, their main center, is located), the southeastern Mali and the western Burkina Faso. They belong to the Voltaique/Gur ethnic cluster (which has nothing to do with Guro) and make up 9,7% of the population of Côte d'Ivoire. They are famous for their visual arts, sculpture and masks in particular, which inspired 20th-century European artists such as Pablo Picasso and Fernand Léger. (See Primitivism in Modern Art by Robert Goldwater).

Senufo ebony face mask, Côte d’Ivoire, ca. 1990s. © 2023 by Second Face Museum of Cultural Masks. Reproduced with permission of the Museum's Chief Curator, prof. Aaron Fellmeth.

«The kpelyie's mask is used by men’s societies for the initiation of boys into adulthood, in funerals of important villagers, and in harvest festivals celebrating and giving thanks to the gods for a bountiful harvest. The mask is always worn by men, but it combines the features of an ideal woman and an animal, such as an antelope, ram, or hornbill (as here), along with fertility symbols, such as palm nuts. The scarification marks represent the Senufo ideal of female beauty. The two appendages that always extend downward from the mask represent symbolic legs that tether the spirit to the earth. The figure on the head, whether it is an animal, ancestor, or symbol, depend on the caste group to which ancestor represented by the mask belonged. The hornbill, for example, is linked to metal smiths. The masquerader will dance to traditional music and singing while holding an iron staff or a horsetail whisk and wearing a robe composed of knotted diamonds (the shape believed symbolic of the cycle of life) and a long raffia fiber collar and cuffs to disguise the hands.» (Excerpt from Second Face Museum of Cultural Masks catalog).

LEFT: Wooden equestrian figure of a man with a small prognathous face, riding a stylized horse. The figure wears protective Islamic armlets around his neck and holds a gun in his right hand. Senufo, Côte d’Ivoire, 19th century. Dimensions: height 32 x 10.5 x 15 cm. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

RIGHT: Wooden equestrian figure of a man with a small prognathous face, riding a stylized horse, and holding a lance in his right hand. Syonfolo Senufo, Côte d’Ivoire, ca. 1970s. Dimensions: height 38.5 x 20 x 8.5 cm. From my personal collection.

«Among the Senufo peoples, equestrian figures are found in the shrines of religious practitioners or diviners. They are symbols of wealth, prestige and power. Other objects placed in shrines include animal motifs, rings and other amulets that are considered to belong to the world of bush spirits. The horse and rider is a dominant figure and is seen as a strong, fast and aggressive leader of the spirits.» (Excerpt from The British Museum catalog).

Sénoufo Kponyugu Mask in painted wood, late 20th century, Côte d’Ivoire. Dimensions: 36 x 33 x 85 cm - 14 3/16 x 13 x 33 7/16 in. On view at The Brooklyn Museum, NY, USA. Photo licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported.

«The Senufo kponyugu masks are horizontal, composite animal forms with long, protruding horns, a large, gaping mouth, and fearsome accoutrements such as sharp teeth and claws. Such details relate to Senufo cosmology, legends, and beliefs about the connections between certain animals and the ancestral and nature spirits that connect the living. The bright colors and overexaggerated features of the late twentieth-century version show how Senufo artists have updated this mask form over time.» (Text from the Museum catalog).

Among the traditional sacred dances of the Senufo, Boloye or the "Panther Dance" holds a special place.

«Initially it was practiced by Senufo children between the ages of eight and thirteen <while following the initiation path>. Over time, it became part of the adult world and acquired importance and sacred character. The Boloye became the funeral dance, performed to celebrate the attainment of ancestral status by the deceased. Later, it was transformed into a mystical display to bring down the rain, essential for the Senufo farmers.» (from the Amazigh blog).

The two to five young dancers wear a leopard cloth costume that covers their entire bodies. The mottled cloth mimics the fur of the African leopard (Panthera pardus pardus). The face is also covered by a feline fabric mask. As you can see in the video below, «the Leopard-Boloye arrive with an arrogant step, recalled by the sound of special ritual instruments - a kind of lute consisting of a long plucked string neck and a gourd beaten with the hand to give rhythm. (...) The dancers hold sticks in their hands: in the rock representations of the Sahara and South Africa this is characteristic of the shamans who transform themselves into mythical quadrupeds. As the rhythm changes, a dancer begins to accelerate the tempo until he explodes in pirouettes, back aips, aips.» (Ibidem).

This ancient initiation dance, which originated in the savannah region and was performed by children, is now the dance of young men, representing the strength, cunning and agility of the leopard, and is one of the most acrobatic in all of Côte d'Ivoire.

Boloye or the Ivorian Dance of the Panther

THE BAULÉ OR BAOULÉ PEOPLE

The Baulé or Baoulé people belong to the Akan group living in Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana, and is part of the Kwa ethnic cluster. One of the largest ethnic groups in Côte d'Ivoire, the Baulé live in the central areas of the country, where they are farmers and planters of cocoa, rubber, and coffee. «They waged the longest war of resistance against French colonization of any West African people, and maintained their traditional objects and beliefs longer than many groups in such constant contact with European administrators, traders, and missionaries.» (Baoule from the National African Language Resource Center or NALRC). They are talented, sophisticated artists, especially sculptors, famous for their traditional masks, ritual drums, human figures, and gold, bronze, and ivory carvings.

LEFT: Large wooden "talking drum", Baoulé people, Côte d'Ivoire. The cylindrical shaft of this "talking drum" is carved over its entire height with remarkably stylized human and animal figures. It is a "prestige" drum, emblematic of the clan chief. It is used to recount stories, feats of arms and other events, or to call upon the ancestors to protect the community. © Godwana African Art, Marseille, France.

RIGHT: Outstanding sacred "talking drum" of wood, pigment and plant fibers, Baoulé, Côte d'Ivoire, late 19th century. Musée du quai Branly, Paris (France). Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The attoungblan, or "tam-tam parleur", is an ancestral instrument of communication in Africa, used in private or public ceremonies, such as weddings, funerals of dignitaries, receptions of public authorities, or the enthronement of a chief. We call it "drum" but the drum and the tam-tam differ in size and the latter is very rarely portable. Called in French "tambour parleur" ou "parlant", the attoungblan is a set of two drums, one of which produces a high-pitched sound (male drum) and the other a lower-pitched sound (female drum). The alternation of the two musical pitches reproduces the pitch of the Akan languages to which the Baulé belong, allowing messages to be sent over long distances. Many of these tam-tams are sacred, as they are believed to imitate and preserve the words of ancient melodies and messages, which can only be understood by the initiated.

The Baulé masks are always associated with a traditional sacred or profane dance or masquerade. There are several types of performances: the goli (common among the Baulé of Béoumi) the mblo, the bonu amuen, the gba gba, the adjémlé (Baulé of Sakassou and Diabo), the adjoss, and the kôtou (widespread in the regions of Tiébissou and Yamoussoukro).

The sacred goli masquerade, whose performance can last a day and involve the entire community, is the most widespread today on important occasions such as funerals and rituals to ward off evil, or for entertainment. The Goli masks, dance, religion and fetish, sacralized by the ancestors, highlight the uniqueness of the cultural values of the Baulé people.

The two goli dancers can wear four different types of traditional masks over a wide and long raffia costume with an antelope skin on the back. The masks of the goli family must be worn in a prescribed order: first, the disc-shaped kple kple (like the one below); then a sacred, composite, zoomorphic mask, the goli gloin or goli glin (usually inspired by antelope and crocodile), painted in black, red and white; then the ram-horned kpan kplé and finally the human-faced (often female) kpan with crested hair. The masks have a complex symbolism. At each stage, one mask is "masculine" (yassoua) and another "feminine" (bla), although the differences between them are subtle, as they represent aspects of the same individual.

LEFT: Baoulé Kple Kple or Kouassi Gbe mask of painted wood and resin, late 19th - early 20th century, Côte d’Ivoire. Overall dimensions: 40.7 cm - 16 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, USA.

RIGHT: Baoulé Kple Kple mask of red painted wood, yassoua male form, second half of the 20th century, Côte d’Ivoire. Overall dimensions: 50 x 25 cm. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie - La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

Baoulé Kpan profane mask of red painted wood, Côte d’Ivoire. Overall dimensions: 44 x 20 cm. Photo courtesy of Patrick Malisse, owner of the African Art Gallery Essentiel Galerie - La Porte Dogon in Belgium.

Goli masquerade, first phase with kple kple mask, Ivory Coast, 2022.

Goli masquerade, second phase with two sacred goli gloin masks, Bendekouassikro village, Ivory Coast, January 2017.

THE BÉTÉ PEOPLE

The Bété people belong to the large Krou ethnic cluster and live in the west-central part of Côte d'Ivoire, in the regions of Gagnoa, Ouragahio, Soubré, Buyo, Issia, Saïoua, Daloa, and Guibéroua, in what is known as the "Boucle du Cacao", the cocoa belt. Their traditional artistic production is rich and varied, and their masks and masquerades are at the heart of their artistic, social and spiritual life.

The Bété live in an environment with poor soil and a harsh climate. «They subjugate the elements of nature and put them to their use through hunting and agriculture. The forces of the supernatural are brought under control through the social and religious activities of the community. Among the Bété, the traditional focus and primary instrument of these socio-religious activities is the dance mask.» (Armistead P. Rood, Bété Masked Dance: A View from within, see the Bibliography). The Bété masks are generally divided into three functional categories: 1. "Le Grand Masque", or the Great Masque, an impressive costume-mask whose dance evokes powerful forces that can protect the community in times of trouble or mediate between the human world and the Kuduo, the City of the Dead. 2. The "medium masks", which are less rigidly controlled; and 3. the "small masks" of the children and young boys.

Among the "medium masks", the most common is the n'gre, which was historically used in a ceremony to lead people to war or to restore peace after war, to preside over funerals, to cleanse the village of evil spirits, and to preside over the settlement of disputes and the punishment of wrongdoers. «It is believed that the mask was also used in war preparation dances to give the wearer magical protection and to terrorize potential enemies". (From the catalog of the Second Face Museum of Cultural Masks). The n'gre mask features a grimacing face, distorted features, facial projections, horned heads, domed foreheads, tubular eyes, tawny teeth or fangs.

LEFT: Bété face mask made of wood, iron, cloth, cowrie shells. Côte d’Ivoire, late 19th century. Dimensions: 33.5 x 22.8 x 17.2 cm - 13 3/16 x 9 x 6 3/4 in. © Smithsonian, photo courtesy of The National Museum of African Art. « Masks of this type, characterized by bold volumes, protruding forms, and brass tacks studding the surface, are believed to embody powerful spiritual forces associated with the forest. (...) Possibly because of their ferocious appearance, Bete masks of this style have, at times, been referred to as war masks (...) and have been associated with social control, especially in dealing with conflicts and local wars. In addition, the warrior attribute may refer to the protective function of certain masks to counteract and combat aggressive, negative forces, including witchcraft, other offenses, and disease.» (Text from The National Museum of African Art catalog).

RIGHT: Nyabwa mask, Bété, Ivory Coast. Dimensions: 19 x 28 cm. © Courtesy: Casa d'Aste CAPITOLIUM ART, Italy. This heavy wooden mask is characterized by four rostrums converging on the mouth. Masks of this type were used in war preparation ceremonies.

Armistead P. Rood wrote: «For the Bété, the mask is neither an amusing toy, nor the product of superstitious mumbo jumbo. The masquerade is, rather, the focus of an organized effort by the community to preserve its sound mental health, providing the Bété with a momentary reprieve from the hardships imposed by their physical environment, and serving to unify and concretize social values. Through the mask and its dancer, who embodies the collective spirit of the village, the Bété succeed in maintaining a faith in their ability to survive and master the hostile forces that surround them.» (Armistead P. Rood, cit.). In the video below you can see a sacred masquerade during a funeral ceremony.

The secular culture of the Bété is also dominated by dance and song. There are several musical rhythms in Bété country: the video below shows the irresistible Gbégbé rhythm (considered the father of Ivorian popular music) and its profane dance.

Zota Ft. La Compagnie Moayé - Gbégbé rhythm and dance en pays Bété - Video Danse

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?