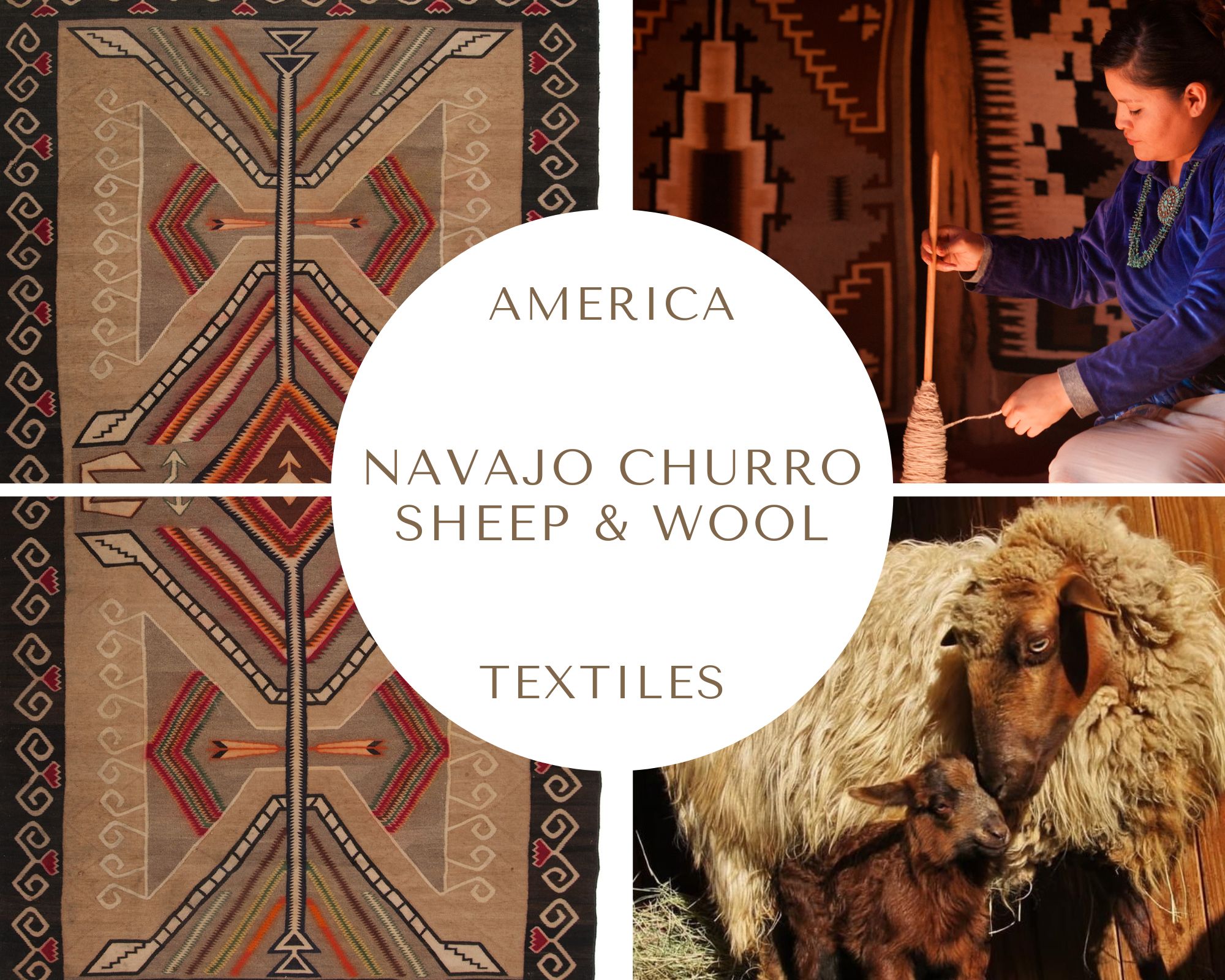

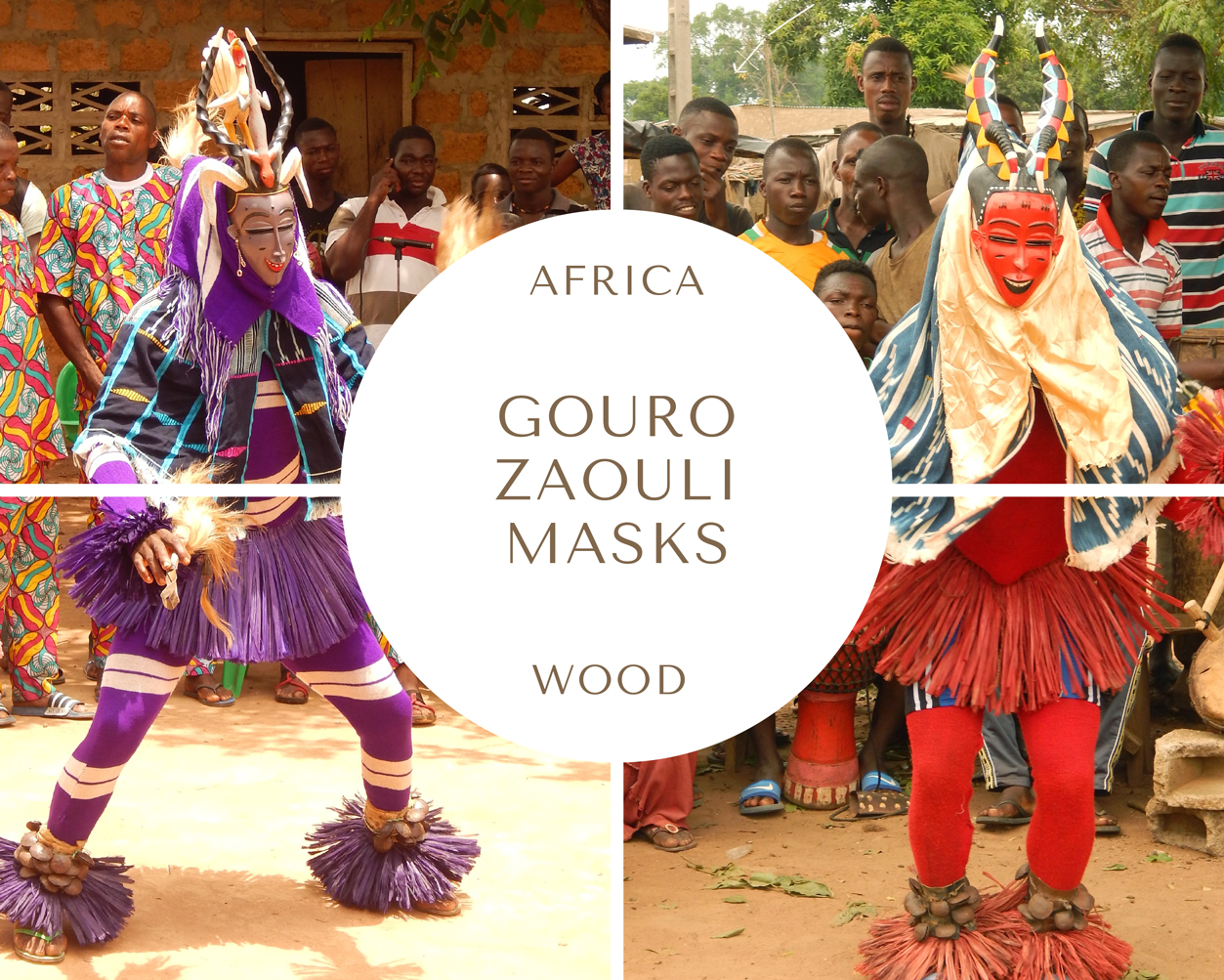

The Gouro Zaouli Masks from Côte d’Ivoire 3

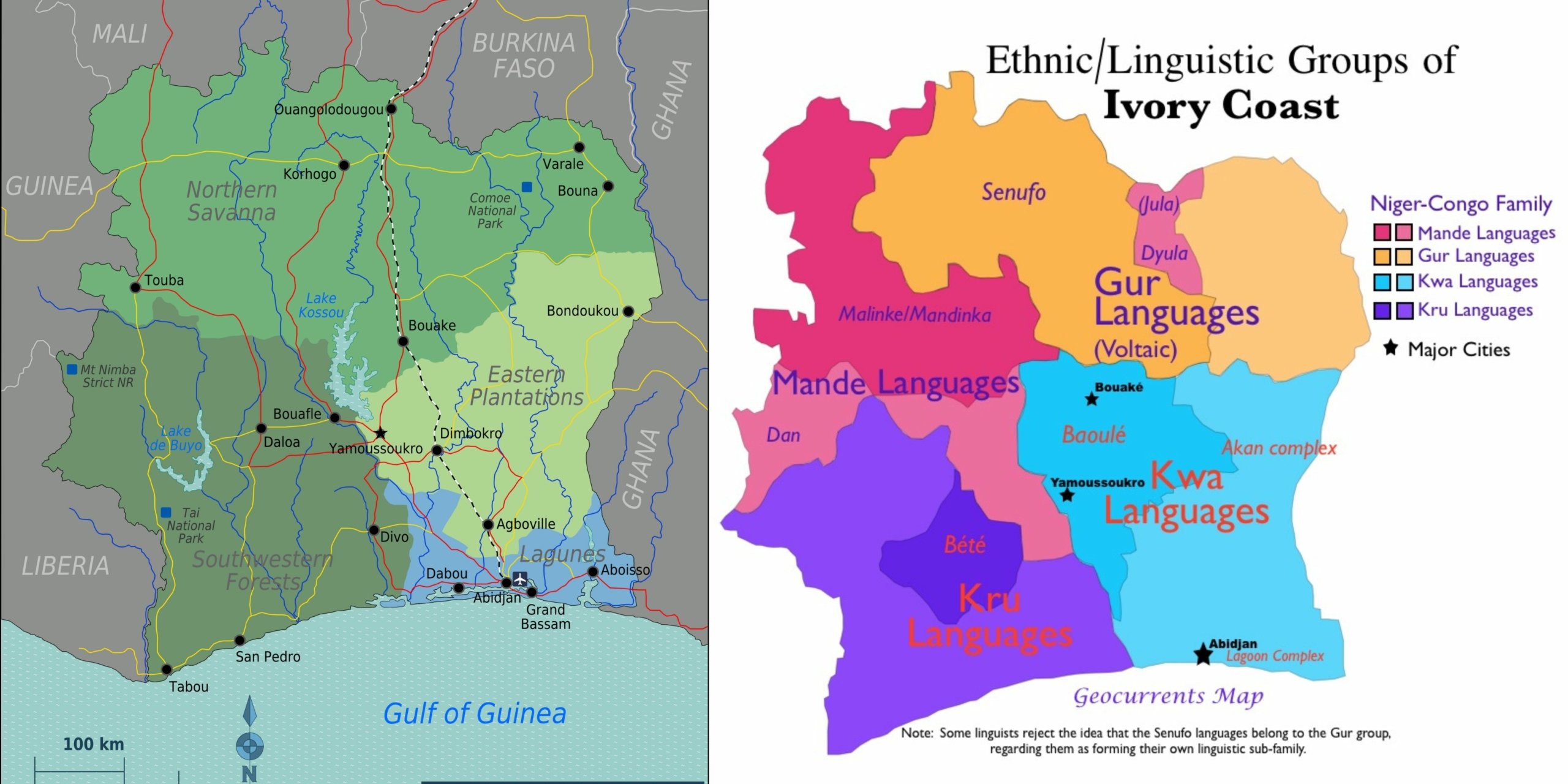

Côte d'Ivoire, West Africa (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

ETHNIC DIVERSITY AND ETHNIC CONFLICTS IN CÔTE D'IVOIRE

The masks and masquerades we have reviewed are only a tiny fraction of the rich cultural and spiritual heritage of Côte d'Ivoire. This is not surprising: this West African country is home to some 60 ethnic groups with diverse histories, cultural identities, and complex interrelationships. Some groups, as we have seen, retain vibrant cultural traditions and practices in which their sense of identity is rooted.

However, it's important to recognize that ethnic identity can sometimes be very fluid, as it can change over time, influenced by intermarriage, cultural interactions, and societal changes. This is because ethnic identities are the product of historical processes and are to a large extent socially constructed and shaped.

While Côte d'Ivoire's ethnic diversity adds to the richness of its cultural heritage, it also poses challenges in terms of fostering social cohesion and managing intergroup relations.

Current scholarship tends to divide Ivorian ethnic groups into four main ethnic clusters, each with common linguistic and cultural characteristics.

MANDÉ

- Northern Mandé: Bambara, Dioula, Gbin, Malinké, Nigbi

- Southern Mandé: Gagou, Gouro (or Guro), Mona, N’gain, Ouan, Toura, Dan (or Yakouba), Yaourè (or Yahouré).

GUR/VOLTAIQUE

- Birifor, Degha, Gondja, Gouin, Kamara, Komono, Koulango, Lobi, Lohron, Nafana, Samogho, Sénoufo (or Sénufo), Siti, Toonie

KROU

- Ahizi, Bakwé, Bété, Dida, Gnaboua, Godié, Guéré (or Wè), Kodia, Kouya, Kouzié, Kroumen, Neyo, Niédéboua, Oubi, Wané, Wôbè

KWA

- Akan: Abron, Agni, Baoulé (or Baulé)

- Laguna groups: Abbey, Abidji, Abouré, Adjoukrou, Alladian, Appolo, Akyé, Avikan, Ébrié (or Kyama), Ega, Ehotilé, Essouma, Krobou, M’batto

(Many sources, like CNCCI 1999 and Côte d’Ivoire: Ethnicity, Ivoirité and Conflict, Report by Geir Skogseth, LandInfo, Norway, 2006).

According to the Minority Rights Group, the dominant Akan speakers, who make up 28.8% of the population, live mainly in the center, east and southeast of Côte d'Ivoire; Northern Mandé mainly in the northwest; Voltaic peoples, including Sénufo, in the north and Lobi in the north-central; Krou in the southwest and Southern Mandé in the west.

LEFT: Geographical regions in Côte d'Ivoire, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

RIGHT: This map provides a schematic and simplified idea of the major ethnolinguistic groups and the geographic areas in which these groups predominate. Source: GeoCurrents.

«None of the four main clusters of ethnic groups are unique to Côte d'Ivoire, and all have strong linguistic and cultural ties with groups in neighboring countries: the Krou ethnic groups with ethnic groups in eastern Liberia; the Kwa groups with groups in southern Ghana (as well as in southern Togo and Benin); while Mandé ethnic groups are found in Guinea, northeastern Liberia, Sierra Leone, Mali and Burkina Faso; and Gour groups in Mali, Burkina Faso, northern Ghana and northern Togo» (Côte d’Ivoire: Ethnicity, Ivoirité and Conflict, Report by Geir Skogseth, LandInfo, Norway, 2006).

This ethnic diversity is the result of a combination of historical, geographical, and migratory factors.

- Migration and settlement

Over the centuries, various ethnic groups migrated to the region now known as Ivory Coast. Some groups moved due to population pressure, conflict, or in search of better resources and opportunities. These migrations led to the formation of distinct communities with their own cultural practices and languages. The Baoulé, one of the largest Ivorian ethnic groups, originally came from Ghana and settled in central Côte d'Ivoire in the 18th century under the leadership of Queen Abla Pokou. The Sénoufo emerged as a group sometime between the 15th and 16th centuries; from the 17th to 19th centuries, they were the most important part of the kingdom of Kénédougou or Cebaara Senufo, a pre-colonial West African state established in the southern part of present-day Mali; later, they migrated to Burkina Faso and Côte d'Ivoire. The Guro originally came from the north and northwest, driven by Mande invasions in the second half of the 18th century. The Mande ethnic group, called Dan or Yakouba, came from western Sudan and regions of present-day Mali and Guinea; they began to settle in the Ivory Coast as early as the 8th century. As for the Bété, who belong to the Krou group, some ethnologists and anthropologists believe they came from Liberia, others from Ghana and others from Nigeria; it does not matter, because the Bété are one of the first peoples to settle in what is now Côte d'Ivoire.

- Geographical Diversity

The geographical features of Côte d'Ivoire (see the left map above), and in particular the diversity of its natural environment, attracted many ethnic groups, each with specialized knowledge, traditional activities and adaptations. Different ethnic groups settled in different regions based on their livelihoods, such as agriculture, fishing, or trade.

- Historical Trade Routes

Thanks to its geographical location, Côte d'Ivoire has been a crossroads for trans-Saharan trade routes linking the northern Sahel region, characterized by semi-arid conditions and a transit zone for trade caravans, with the coastal areas of West Africa, rich in ports, dense forests, and natural resources such as timber, ivory and various agricultural products. Côte d'Ivoire's central location and diverse ecological zones attracted Berber traders, Muslim merchants, and caravans from different regions, facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural influences. This trade network contributed to the growth of towns and cities, the development of vibrant marketplaces and cultural melting pots, and facilitated migrations, exchanges of all kinds, intermarriage, and the formation of new communities.

- Colonial Past

The colonial era, especially during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, saw the reorganization of territorial boundaries and administrative divisions by European powers. The arbitrary borders drawn by the colonial superpowers were based on many factors such as geopolitical considerations, economic interests, diplomatic power, local availability of natural and human resources, etc. The borders of present-day Côte d'Ivoire were established through a combination of treaties, negotiations, and administrative decisions by the French colonial authorities who controlled the region in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. (For example, the border with Liberia was established by the Franco-Liberian Treaty of 1892, while the border with Ghana, formerly The Gold Coast, was established by various agreements and adjustments over time). It may seem unnecessary, but I will write t for the sake of clarity: the primary interest of France as a colonial power was to consolidate its control over African territory and its human and natural resources in order to exploit them according to the logic of minimum effort and maximum yield. The arbitrary borders drawn by the French not only contributed to the creation of a diverse mosaic of ethnic communities within today's Côte d'Ivoire, but also divided ethnic groups, created artificial boundaries and inequalities, and ultimately became the most potent source of ethnic conflict and political instability. Finally, during French colonization, the economic development of the southern part of the country created new migration patterns.

Thus, if some factors - such as the centuries-old history of African migrations and the settlement of different groups in different areas of what is now Côte d'Ivoire - are the sources of Ivorian ethnic diversity, French colonialism is the cause of Ivorian ethnic fragmentation. And ethnic fragmentation is not the same as ethnic diversity.

French West Africa (Afrique Occidentale Française, AOF), illustrated map commissioned by the French Ministry of Overseas France (Ministère De La France d'Outremer), drawn in ca. 1950 by Craste & Audiberti and printed by Karcher Et CID, Paris.

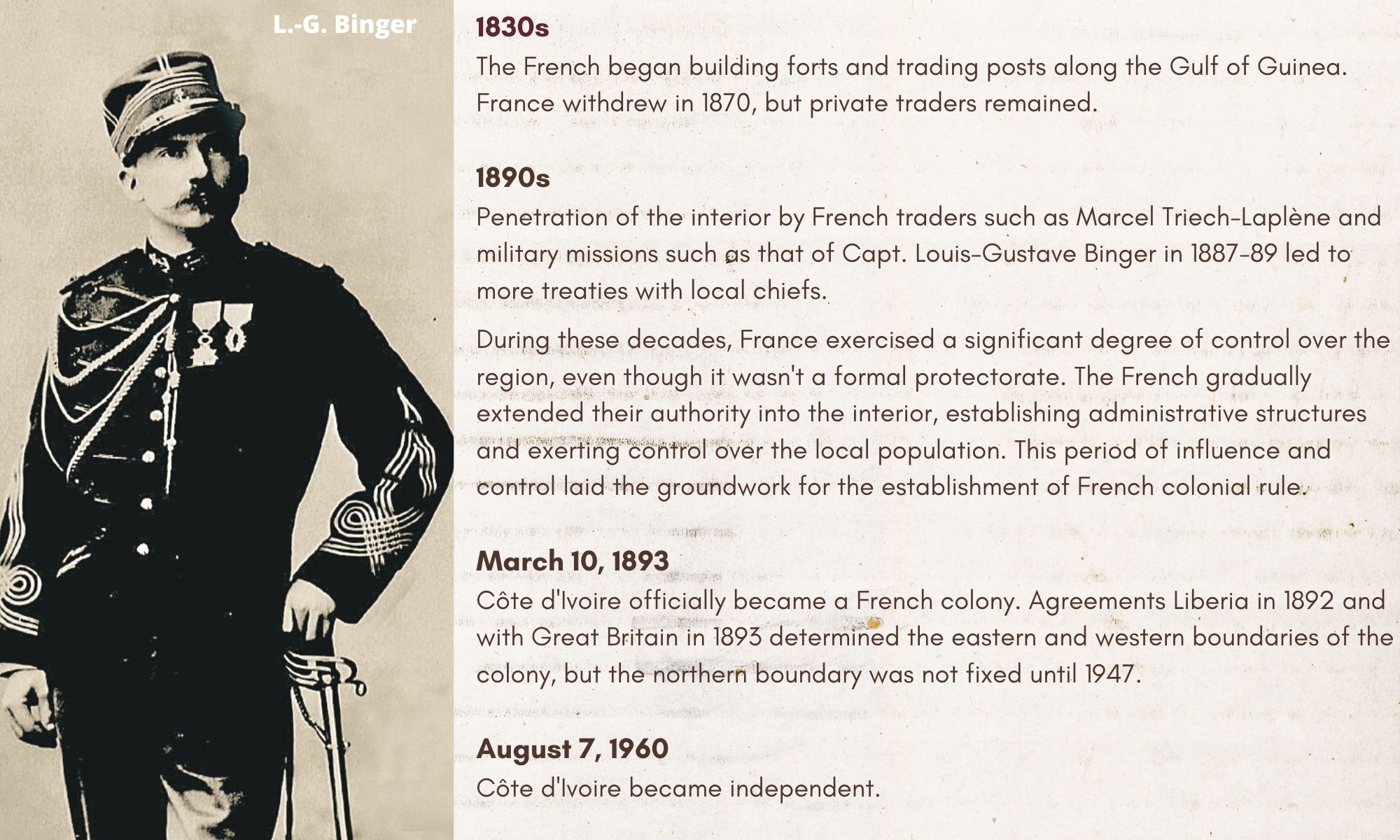

Côte d’Ivoire became a French colony in 1893. It was part of French West Africa (Afrique occidentale française, AOF), a federation of eight French colonial territories in Africa that existed from 1895 until 1958-60, consisting of present-day Mauritania, Senegal, Mali (then French Sudan), Guinea (then French Guinea), Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso (then Upper Volta), Benin (then Dahomey) and Niger. The capital of the federation was Dakar. Ivory Coast did not become independent until 1960.

The AOF was not the only French colonial territory in Africa: the French Equatorial Africa (Afrique-Équatoriale française, AEF), was the federation of French colonial possessions in Equatorial Africa, extending north from the Congo River into the Sahel, and including the present-day countries of Chad, the Central African Republic, the Republic of the Congo, and Gabon; it was established in 1910 and lasted until late 1958. The French North Africa (Afrique française du Nord, AFN), which included present-day Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia, lasted from 1830 to 1962.

You may ask: have there ever been ethnic conflicts among the 60 groups living in Côte d'Ivoire?

Yes, there have been ethnic conflicts in the pre-colonial, colonial and post-colonial periods.

In the pre-colonial period, ethnic conflicts were occasional and did not threaten the relative stability of the territory or the existing intergroup alliances and forms of cooperation. French colonialism opened a long series of ethnic wounds that have festered and degenerated at different stages of postcolonial history. The worst conflicts are recent: they erupted in 2002 and in 2010.

- The First Civil War in Côte d'Ivoire (2002-2007)

In September 2002, troops under the political leadership of the Patriotic Movement of the Ivory Coast (MPCI, Mouvement patriotique du Côte d'Ivoire) led by Guillaume Soro launched an attempted coup against the government of President Laurent Gbagbo. They accused Gbagbo of promoting a policy of "Ivoirianization" that marginalized the northern populations and targeted immigrants from neighboring countries. The rebels, known as the Forces Nouvelles (New Forces), quickly gained control of the northern half of the country. The conflict soon turned into a full-scale civil war, with both sides engaging in violent clashes and committing human rights abuses.

The civil war exacerbated existing ethnic and regional tensions. The New Forces drew support primarily from northern ethnic groups and some disaffected segments of the military, while Gbagbo's government enjoyed greater support from southern ethnic groups. The conflict had serious humanitarian consequences. Thousands of people were displaced from their homes, and there were reports of human rights abuses, including massacres, rape, and enforced disappearances. The economy suffered significant damage due to disruptions in agriculture, trade, and investment. The civil war also had regional implications, as the stability of Côte d'Ivoire was crucial to the economic and political stability of the West African region.

The French military launched its much-criticized intervention in Côte d'Ivoire, Opération Licorne, on September 22, 2002, while the United Nations launched the first UN Mission in Côte d'Ivoire (MINUCI, Mission des Nations Unies en Côte d'Ivoire) in May 2003 and the United Nations Operation in Côte d'Ivoire (UNOCI) in 2004, which officially ended on June 30, 2017.

A ceasefire was finally reached in April 2003, effectively ending the first phase of the civil war. However, the underlying issues and deep-seated divisions of the conflict remained, and subsequent peace processes faced challenges in implementing key provisions and achieving lasting reconciliation. The final peace agreement (the "Ouagadougou Peace Agreement") was signed on March 4, 2007.

LEFT: Koudou Laurent Gbagbo was born in 1945 to a Bété family and served as the President of Côte d'Ivoire from 2000 until his arrest in April 2011.

CENTER: Guillaume Kigbafori Soro was born in 1972 to a Sénoufo family and led the Ivorian Patriotic Movement and later the New Forces as its Secretary General. He will serve as Prime Minister of Côte d'Ivoire from April 2007 to March 2012.

RIGHT: Alassane Dramane Ouattara was born in January 1942 into a Dioula family. He was the Prime Minister of Côte d'Ivoire from November 1990 to December 1993 and has been the President of Côte d'Ivoire since 2010.

- The Ivorian Crisis of 2010-2011 and the Second Ivorian Civil War

In November 2010, the presidential elections, intended to reunify the country after the first civil war, sparked a new conflict. Alassane Ouattara, a former prime minister and leader of the Rally of Republicans (RDR) party, was recognized as the winner by the international community, while Laurent Gbagbo, the incumbent president representing the Ivorian Popular Front (FPI) party, refused to step down. Alassane Ouattara was a Muslim from the north of the country and of the Dioula people, while Gbagbo was born to a family of the Bété people, who settled in the southwest and south-central parts of Côte d'Ivoire. The international community, including the United States, the European Union, the African Union, and the Economic Community of West African States, supported Ouattara and urged Gbagbo to step down, but he refused and Ouattara's forces took control of most of the country: the crisis escalated into a full-scale military conflict and the country descended into a second civil war. The war ended in 2011 with Gbagbo's arrest and Ouattara's inauguration as president. This conflict had its roots in the unresolved issues and tensions of the first civil war, further underscoring the challenges of achieving lasting peace in the country. Once again, the UN and French forces took military action. The civil war resulted in widespread violence, human rights abuses, and a significant humanitarian refugee crisis (more than 100,000 refugees fled the country to neighboring Liberia). Both sides were accused of committing atrocities, including targeted killings, mass graves, sexual violence, and the displacement of civilians. The violence also stoked ethnic and religious tensions, deepening divisions within Ivorian society.

Rebel soldiers loyal to Ivory Coast opposition leader Alassane Ouattara in 2010

These two civil wars with strong ethnic connotations are usually understood and explained as complex and multifaceted results of several factors, the most important of which is the country's ethnic diversity. Many journalists and politicians, some scholars, and the majority of Western public opinion point out that the country is home to a number of different ethnic groups, with different languages, cultures, and historical backgrounds, and that this situation has sometimes led to tension and conflict. That's wrong.

Ethnic diversity is the necessary condition for ethnic conflict: it's a truism. It's a self-evident, trivial truth. Without ethnic diversity, of whatever kind, a country would know no ethnic conflict nor ethnic cleansing. But conditions are not causes, and we must avoid confusing them. Many journalists and politicians, many academics, and the majority of Western public opinion also believe that the diverse ethnic landscape of Côte d'Ivoire is essentially the result of its pre-colonial past, and that French colonialism only exacerbated inequalities and injustices between different ethnic groups. History, however, tells a different story and refutes this version, which is only good for teenage homework.

Ethnic diversity is an extremely valuable cultural asset: biodiversity and cultural diversity are the greatest wealth of our planet and the mark of our uniqueness. Although it is scientifically possible to hypothesize the existence of exoplanets with some form of life, it is almost impossible to hypothesize an exoplanet with such extraordinary biological and cultural diversity as ours. Our colorful richness is the product of an unrepeatable complexity created by the interactions of random factors at various levels. Unfortunately, we are destroying both our biodiversity and our cultural richness. We humans are not capable of managing and nurturing our primary source of wealth, which is also our primary defining characteristic.

It would be tempting to say that we are homines not sapientes but insipientes, that we are not intelligent but stupid human beings, but that wouldn't help us understand anything. It helps us much more to analyze how and why the ethnic and cultural richness of Côte d'Ivoire has become a political battleground. Moreover, our cultural exploration of Côte d'Ivoire will surprise you and make you see Africa with different eyes.

Tiken Jah Fakoly, Ma Côte d'Ivoire

Written after the First Civil War, in 2007, this song by one the most famous Ivorian singer and musician begins with these words: "Politicians... politics / You spoiled my country / Côte d'Ivoire, my beautiful country / Country of hospitality / Land of brotherhood / But the politicians have decided / To transform you. / My Ivory Coast, I don't want to see you in tears / My Ivory Coast, I don't want to see you take up arms".

ETHNIC CONFLICTS IN THE PRECOLONIAL IVORY COAST

Precolonial Côte d'Ivoire experienced occasional and localized ethnic conflicts of varying intensity and frequency. Factors such as competition for trade routes, access to fertile land, or control of strategic locations could contribute to tensions between different ethnic communities. It's important to note, however, that conflict has not been constant or pervasive throughout the region's history.

Although historical records are limited and details may vary, here are some examples of specific ethnic conflicts that have been documented:

- Gyaaman War (late 17th century): The Gyaaman, an Akan-speaking group, waged a series of military campaigns against neighboring groups, including the Baoulé and Anyi, in an effort to expand their territory and control trade routes.

- Baulé-Djuablin Conflict (late 18th century): The Baulé, one of the largest ethnic groups in Côte d'Ivoire, clashed with the Djuablin people over territorial disputes and control of trade routes, resulting in armed conflict.

- Sénufo-Malinké Conflicts: The Sénoufo and Malinké (commonly called Dyula or Dioula) are both Mande-speaking ethnic groups and have a history of sporadic conflicts over land and resources, particularly in the northern regions of the country.

- Guro-Bété Conflict: The Guro and Bété communities, both located in western Côte d'Ivoire, had tensions over control of fertile land, water, and access to economic resources.

It's important to note that while ethnic conflict did occur, it was not continuous or widespread throughout the precolonial period. In addition, intergroup alliances, trade relations, and cultural exchanges were prevalent, contributing to a complex and nuanced social landscape in Côte d'Ivoire.

Today, for example, the relationship between the Sénoufo and the Dioula is characterized by «out-group acceptance, relatively peaceful relations, fluid interethnic communication and proximity», mediated by two factors: Islam, which «has played an important role in bringing the two ethnolinguistic groups closer» and the Dioula language, which is spoken by both groups, «a key underlying reason for cooperation, strong cohesion, and mutual acceptance» (all quotes are from the interesting paper by Dongui Zana Y. Ouattara, Language as a Mediating Factor in Interethnic Relations and Out-Group Acceptance, 2022, see Bibliography).

It should also be noted that historically, there have also been instances of alliances and intergroup cooperation, as different groups formed trade partnerships or political alliances to address common challenges or external threats. In addition, cultural and economic interactions between different groups have often played a role in shaping the social fabric of Côte d'Ivoire.

Thus, the pre-colonial past of present-day Côte d'Ivoire was neither the paradisiacal land of the "noble savage" nor the land of primitive and bloody tribalism that inhabits the collective imagination of some Westerners.

It's worth noting that the arrival of European colonial powers, especially in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, introduced new dynamics and tensions that further complicated intergroup relations. The policies and practices of the colonial administration, including favoring certain groups over others, exacerbating divisions, creating new waves of migration to support colonial plantations, and imposing arbitrary boundaries, contributed to further social and ethnic tensions that continue to influence the country's dynamics today.

LEFT: Baulé small Prestige Dagger, Ivory Coast, late 19th / early 20th centuries. Dimensions: blade length 23 cm - 9 in; total length 32 cm - 12 1/2 in. Baulé swords and daggers are quite rare. This prestige dagger has a symmetrical leaf-shaped blade with a flat central rib and a sheath decorated with red shells (Spondylus). The wooden handle is inlaid with gray metal strips, probably made of lead or tin. The scabbard is covered with hide and tied at the top with reptile skin. The bright red shells are attached to the front of the scabbard, but some are missing.

RIGHT: Long Knife probably of Baulé origin, Ivory Coast, first half of the 20th century. Dimensions: blade length 43,18 cm - 17 in; total length 58,42 cm - 23 in. This ceremonial long knife/short sword was made in West Africa, probably in the Ivory Coast by the Baulé.

The blade has an unusual shape; its edge is engraved on the straight side along the spine and in a few other places. The wooden handle is bound with tight leather strips and ends with a wide leather strap. The entire leather sheath is decorated with colored leather sectors in geometric shapes.

Both photos by courtesy of Artzi Yarom, founder of Oriental Arms, Haifa, Israel.

A cast brass knife and sheath. The knife is straight-bladed with small quillons; the handle has a pommel in the shape of a human head with an elaborate coiffure. Côte d'Ivoire. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

FRENCH COLONIALISM AND ITS IMPACT ON THE IVORIAN ETHNIC DYNAMICS

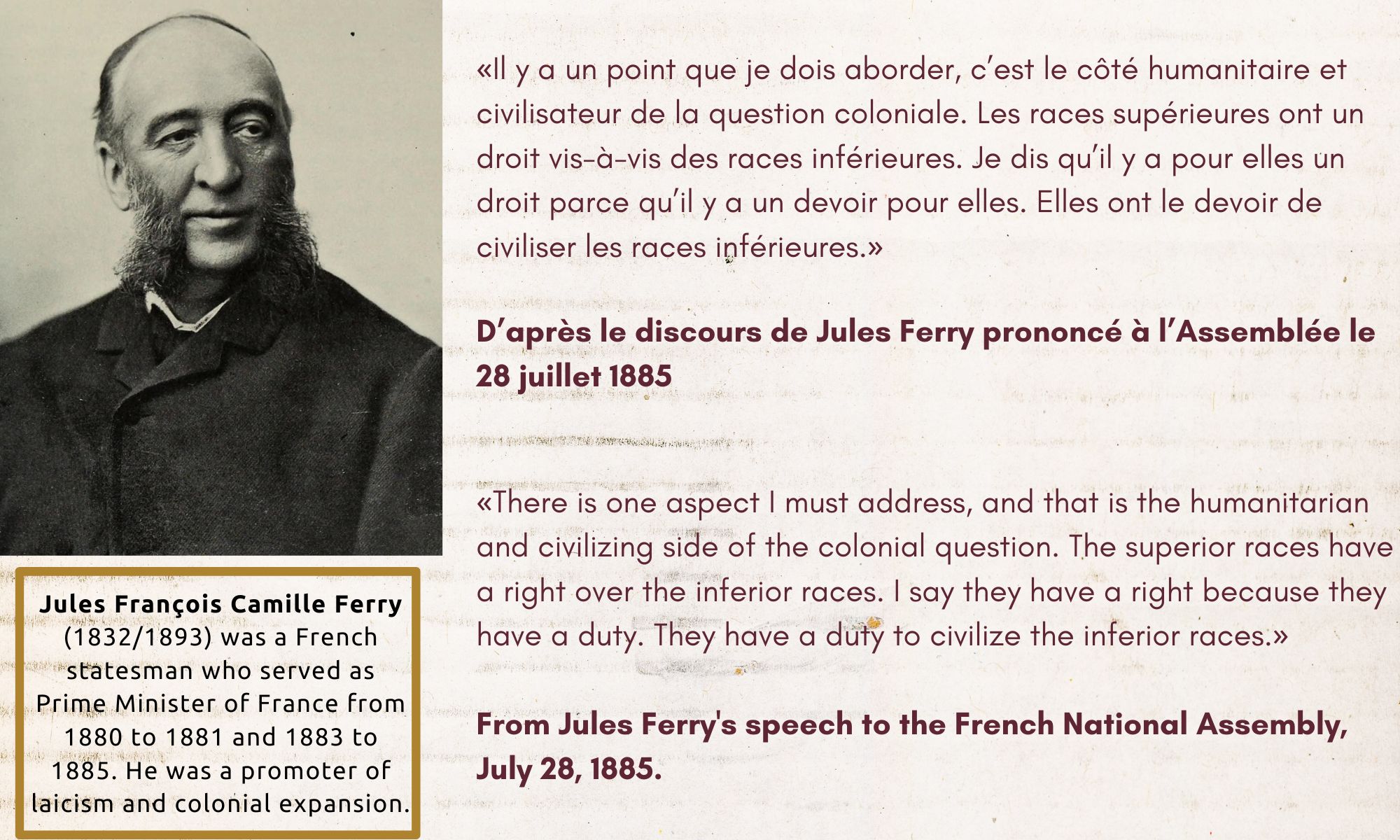

According to many scholars, French colonial policy in Africa was not static, but evolved over time and underwent some remarkable changes. However, among the features that never changed or remained relatively stable, two are quite relevant for our analysis: 1. the racist ideology of the French, and 2. their strategy of divide et impera ("divide and conquer" or "divide and rule"), although the degree of privilege or influence accorded to specific ethnic groups varied throughout the colonial period.

Regarding the first point, white supremacy and pseudo-scientific racism must not be considered as secondary or marginal elements of European colonial conquest: they were an integral and essential part of it because they shaped the ideological horizon within which colonial conquest was not only possible, but also justified and legitimized. As the American scholar Peter J. Schaeder, professor of Political Science at Loyola University of Chicago, points out in his essay African Politics and Society, France's proclamation of its mission civilisatrice ("civilizing mission") was its justification for the necessity of colonialism in Francophone West Africa, including Côte d'Ivoire, over people who were considered "backward", "ignorant", "uncivilized", "barbaric", "savage" and "godless heathens". For the French, the superiority of their culture and civilization over the local African populations was an almost absolute certainty because it was an essential aspect of their identity as French; and this certainty was never touched by the slightest doubt during the entire period of colonial rule over West Africa (1893/1960).

Cover of a schoolbook by Georges Dascher, ca. 1900, commissioned by the Ministry of Education of the Third Republic.

At the center of the composition, France is depicted as a republican Marianne in her dual role as a conquering figure (armor, cloak) and as a protective deity (shield, olive branch). Three words - Progrès, Civilization, Commerce - are represented on a shield divided into bands with the three colors of the French flag. In the background are soldiers of the French armies of different periods, while the figures in the foreground represent the various French colonies (Africa on the left side and Asia on the right).

Two propaganda illustrations of the French colonial conquest in Africa.

Left: Honneur aux héros de l'expansion coloniale! ("Honor to the heroes of colonial expansion!"), cover of Le Petit Journal, illustrated Sunday supplement, March 6, 1910.

Right: La France va pouvoir porter librement au Maroc la civilisation, la richesse, et la paix. ("France will bring civilization, wealth, and peace to Morocco"), cover of Le Petit Journal, Sunday illustrated supplement, November 19, 1911.

Le Petit Journal was a conservative Parisian daily newspaper and one of the four major French dailies. It was published from 1863 to 1944.

However, the French mantra of "civilizing mission" is imbued with so much hypocrisy that the latter cannot remain hidden, but peeks out like a blob from every crevice. While in some respects the French in the Ivory Coast never reached the extreme and repulsive brutality of the Belgians in the Congo, it is also true that a glance at the history of their colonial conquest is enough to discredit their civilizing aspirations.

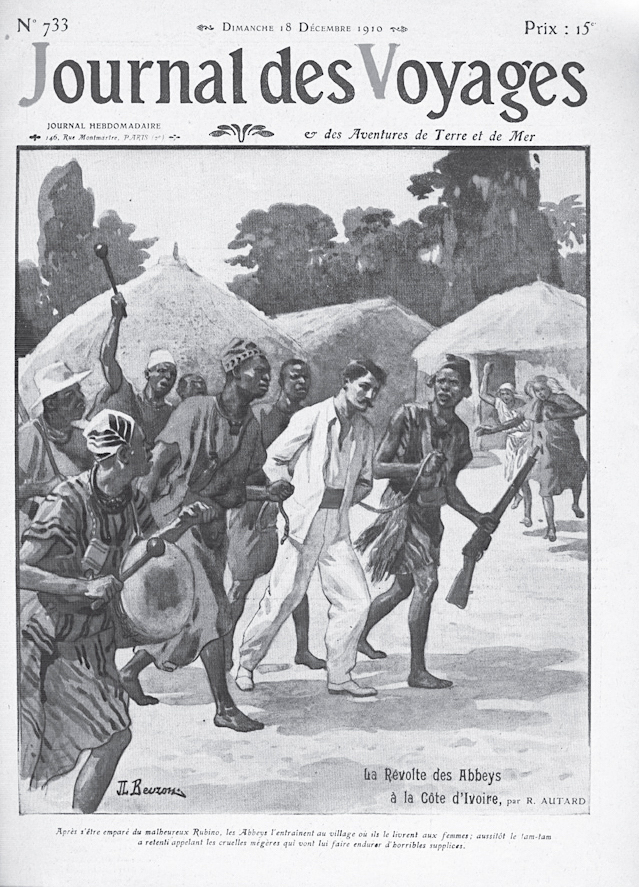

The French conquest of the Ivory Coast was anything but peaceful: various peoples resisted colonial rule. The last resistance ended in 1920-1921 with the defeat of the Lobi people in the northeast of the country. However, the most well-documented case of rebellion is the resistance of the Attié and Abbey (or Abés) groups, "rebellious" populations of the southern, forested parts of the country, between January and March 1910. Their uprising slowed down the French occupation of the interior. What do you think happened to those who stood in the way of the French?

Cover illustration from the Journal des voyages, a popular French weekly magazine, no. 733, December 18, 1910. The illustration is entitled "The Abbey Uprising."

In January 1910, the Abbey and Attié peoples of southeastern Côte d'Ivoire rose up against colonial rule, embodied in particular by the railroad that ran through their territory. With careful preparation and perfect coordination, the rebels attacked the railroad in several places on January 7, causing numerous casualties, including one European named Rubino, an employee of the Compagnie française de l'Afrique occidentale (CFAO).

«The revolt, which had targeted the railroad, resulted in a significant number of <indigenous> victims, the destruction of many villages and cultures, disarmament, the imposition of a fine of war, the capture, and deportation of chiefs and “ringleaders”. The repression that followed was one of the bloodiest in Côte d’Ivoire’s history.» (Ayouba Doumbia, Ethnic Conflict in Côte d’Ivoire, 2021). That same year, some French soldiers carried out two massacres of unarmed people, both in an Attié village (Diapé) and in an Abbey village (Makoundié). In Diapé, most of the houses were burned, the cattle were stolen, and about a thousand people, including the elderly, women and children, were brutally killed. The reason? They were suspected of harboring the rebellious Abbey. As for the latter, the massacre of their village of Makoundié was justified by the governor, Gabriel Louis Angoulvant, because these people were "primitives" incapable of behaving like "wise men". «The massacres took place without any consequences for the perpetrators.» (Ibidem).

Gabriel Louis Angoulvant, the French governor of the Ivory Coast from 1909 to 1916, called "pacification" both the violent conquest of territory and the bloody suppression of local rebellions. «He claimed that colonial domination should be achieved through the total submission of the indigenous population to a military regime headed by a senior and strong officer or general with the necessary skills.» (Jean-Claude Meledje, Côte D'Ivoire: From Pre-Colonisation to Colonial Legacy, 2018, see Bibliography). He called part of the country la côte des mal gens, "the coast of the bad people", and against all rebel groups used the "scorched-earth" method of destroying everything where resistance was occurring.

In short, with some groups of "primitives" the French mission to "civilize the savages" and raise them to a higher level of human development proved impossible, so the poor French authorities were forced to resort to other, less edifying methods: violent conquest, systematic forced labor, humiliating head taxes, bloody repression, forced conscription to fight in the French army in both world wars, and mass killings q.s. (= quantum sufficit, as much as is sufficient).

The moral of the story? At the time, liberté, egalité et fraternité were glorified as great French republican values, as long as they remained firmly within the boundaries of white France.

«The ideology of the conquest required the framing of Africans as subjects, not citizens, with duties but few rights. Alice Conklin Alice Conklin shows that colonial statecraft was largely an act of state-sanctioned violence. The republican ideals of liberty, social equality, and liberal justice were reserved for citizens, not subjects. Despite the contradiction between professed ideals and lived reality, French republicans never saw the glaring contradictions between their democratic institutions and their imperial ambitions.» (Christopher Zambakari, Mission to Civilise: The French West African Federation, in "Accord", April 21, 2021. Alice L. Conklin is Professor of History at Ohio State University (USA) and author of a well-known essay: A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895-1930, Stanford University Press, 1997).

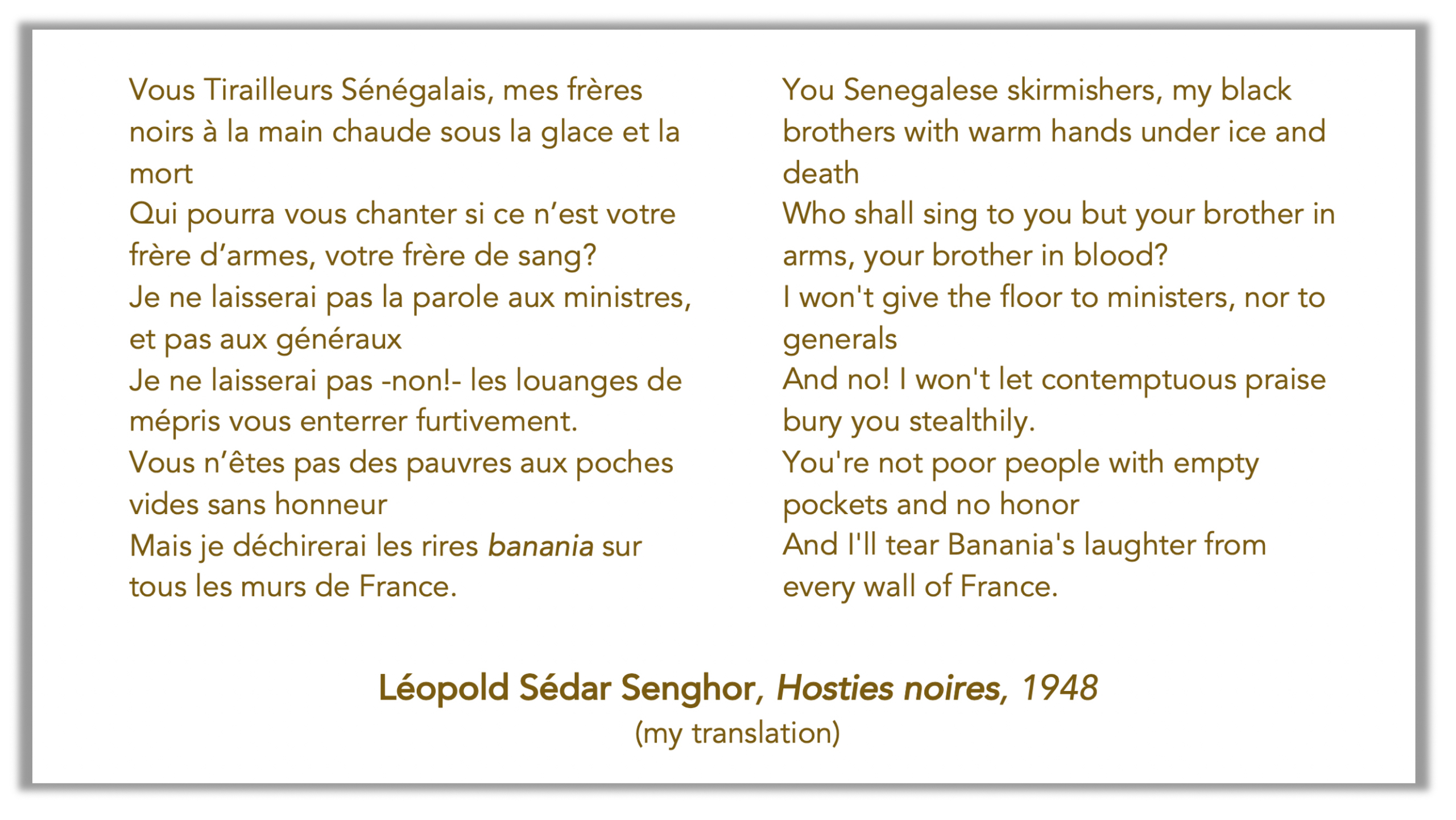

Racist caricature of an African man in an advertisement for Banania, a banana-flavored chocolate drink created in 1912, made by using food imported from the AOF colony, and widely distributed in France. This 1915 drawing shows one of the many tirailleurs sénégalais, the "Senegalese skirmishers" who fought in the French army at the time. The man is depicted with silly smile on his face and a goofy look in his eyes, holding a spoon like a child. The slogan, “Y’a bon” is a black-sounding phrase in pidgin French that means “It’s good!”.

Please note that during World War I, approximately 30,000 African soldiers (from different French African colonies, not just Senegal) fought and died for France. The French writer Frantz Fanon defined this poster as “racist and colonialist". In his book Peau noire, masques blancs ("Black Skin, White Masks", 1952), he denounced the objectification of the African soldiers in many advertisements, saying that they were depicted as objects among other objects.

Léopold Sédar Senghor (1906/2001) was a Senegalese poet and the first president of Senegal (1960–80).

Below, Senghor in May 1978. Photo licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO.

The second aspect we have just mentioned is the French strategy of divide et impera. (Divide et impera is a Latin maxim indicating a "divide and conquer" or "divide and rule" policy, used both in Antiquity, by Julius Caesar for example, and in modern times by Napoleon).

As many scholars have pointed out, the French controlled the West African colonies, including the Ivory Coast, by using the system of "direct rule" and implementing a highly centralized government. The Indian-born Ugandan scholar Mahmood Mamdani classifies "direct rule" as centralized despotism: a system in which the natives were not considered citizens, a perfect definition for French Côte d'Ivoire. Here, the vast majority of the indigenous population was excluded from all levels of colonial government (as well as from citizenship and political rights), but the French needed to create an educated, influential elite sufficiently satisfied with the status quo to refrain from any anti-French sentiment and capable of working alongside French authorities within the colonial bureaucracy. The members of this elite were drawn from particular ethnic groups, but the degree of privilege or influence accorded to particular ethnic groups varied throughout the colonial period. The need to create and nurture such an elite, combined with the need to suppress the rebellions of some communities and ensure full control of the territory, led the French to adopt a "divide and conquer" tactic. This choice allowed them to take advantage of regional conflicts, interfere with traditional leadership or remove local rulers, and give preferential employment to certain groups in order to create competition among them and increase insecurity and conflict.

The "divide and conquer" tactics, the direct rule system of control and governance, and the repression of rebels required some knowledge of the structures, customs, relationships, and ethnic distinctions that united or divided the various villages, local communities, and groups. This knowledge was developed by some French ethnologists and anthropologists who had significant ties to the French colonial authorities in the West African colonies (including Côte d'Ivoire), or whose research was funded by the French government to further the colonial conquest of that part of Africa.

Some scholars, such as Ruth Ginio, an expert on French colonialism in West Africa and a professor at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (Israel), have highlighted the complex relationship between ethnographic research and colonial policy in the case of France. Any generalization, as well as the idea that anthropology was a "child of imperialism" or an applied science at the service of colonial powers, should be rejected. However, in the case of French West Africa (Afrique Occidentale Française or AOF), the idea that ethnographic studies of African territories could assist colonial administrations in these areas was quite widespread, and the links between them are obvious. «Ethnographic research in the AOF was closely linked to the colonial administration.» (Ruth Ginio, French Colonial Reading of Ethnographic Research, see Bibliography).

This close relationship, shaped by the colonial context and the French government's interest in understanding and controlling the colonized populations, is particularly evident when we consider some French ethnographers and ethnologists who were also colonial administrators.

They did not collaborate with the French colonial authorities: they were those authorities.

They did not develop a critical and independent perspective. They did not seek to understand and document the cultures and societies of West Africa from a neutral standpoint, challenging colonial ideologies and empowering local populations. They were not interested in reconstructing the past traditional practices of some West African groups or their history.

Their objectives as colonial administrators were different: they conducted extensive research on the indigenous cultures of French West Africa, documenting and categorizing customs, languages, kinship systems, religious practices, traditional institutions, and ethnic differences in order to develop better strategies for more effective control of the territory. They provided the colonial authorities with the basic knowledge necessary for the strategy of divide and conquer, direct rule, and the suppression of rebellion, as well as materials, information, and some degree of support for colonial policies. At the beginning of the French colonial conquest, they drew a geo-cultural map that could guide the actions and plans of the French civil and military authorities. And they did so by remaining strictly within the horizon that legitimized the French colonial conquest built on ideological pillars such as racism, white supremacy, and the cultural inferiority of African underdeveloped populations.

These ethnologists-ethnographers-colonial administrators approached their work with a biased perspective influenced by the prevailing ideologies of the time. Their research and writings played a role in justifying and perpetuating colonial domination and exploitation of local populations; but before considering how they contributed to the construction of a colonial narrative based on ethnic stereotypes, let's see who they were.

Maurice Delafosse (1870/1926) was a prominent French ethnologist, Africanist, and linguist who conducted extensive research in West Africa, particularly in the Ivory Coast. He authored several works on the cultures and societies of the region while holding various administrative positions in the French colony. In 1894, he began his career in the colonial administration as Commis des Affaires indigènes de 3e classe in Côte d'Ivoire, where he remained until 1897, when he left for neighboring Liberia as French consul. In 1899, he returned to Côte d'Ivoire, where he was in charge of demarcating the border between the country and Ghana, then a British colony. In 1915, at the height of World War I, he was appointed head of civil affairs for the Government of French West Africa (AOF) in Dakar, where he lived until 1918.

Here you can download the French text of Les nègres by Delafosse, published posthumously in France in 1927 (he died in 1926). Web site: Les Classiques des Sciences Sociales, from the Université de Québec à Chicoutimi, Canada.

Delafosse was about as far from a white supremacist as you can get, but he was an early 20th century scholar and ethnologist with all the epistemological limitations of the time, and he was also a colonial employee who had embraced the ideological horizon of colonial conquest. Was he a racist? Yes, he was, albeit with a thousand nuances and a considerable amount of moderate caution. He believed in the existence of human races and he wrote about the race noire, the "black race" in good faith. He is very reluctant to proclaim the inferiority of the black race to the white race, a commonplace in his day, but he's full of condescending paternalism and creeping racism. Here are some excerpts from one of his texts in my translation. (You can download and read the original text by following the link in the photo caption above.)

«I am willing to admit that African Negroes are, on the whole, children compared to the majority of European peoples of our time, although it would be easy to find exceptions on both sides (...). The weakness of the expression "grands enfants" (big children) is obvious, and the word "arriérés" (underdeveloped) was used to replace it, followed by "attardés" (retarded). Of course, it's always in relation to us that Negroes are described as retarded. (...). From the point of view of material civilization, there seems to be no doubt (...). If many of the Negro tribes of the present day bear a striking resemblance to what we have every right to suppose they were a few centuries before Christ, and if others, though they have made undeniable and very considerable progress, are certainly less advanced in agriculture and industry than most European peoples, it is not difficult to see the reason for this without resorting to the argument of congenital inferiority. The negroes of Africa have been isolated by the Sahara from the Mediterranean, which for thousands of years has been the sole vehicle of world civilization (...). If we now turn to the intellectual sphere, two factors strike us at first glance about the Negroes: first, their widespread ignorance; second, their collective mentality, which baffles us and reminds even the best informed sociologists of the mentality of primitive man. But let's not exaggerate or generalize too much. (...). As for the analogies that have been noted between the Negro-African mentality and the primitive mentality, they are a clear sign of the distance that Negroes still have to cover on the ladder that leads to the heights of humanity. (...) Are black Africans morally backward compared to us? The question is a delicate one, and I'd be wary of answering it in the affirmative. Undoubtedly, here and there, certain customs still persist among them which we regard as horrible remnants of a cruel barbarism.» (from Les nègres, 1927; my translation).

For Delafosse, racism is like salt: too much hurts. And white cultural supremacy is like trans fats: yes to them, but in moderation; without them, what would life be like?

Here is a Delafosse-style comparison, translated onto a visual comparison. It's disturbing, isn't it?

LEFT: An indigenous street in Grand Bassam, the first French colonial capital in the Ivory Coast, ca. 1905.

RIGHT: A Paris postcard showing the Boulevard des Italiens (now near the Opéra and Richelieu-Drouot Métro stations), published in or before 1906.

Maurice Delafosse was not alone.

Henri Labouret (1878/1959) was a French lieutenant of the Colonial Army in the AOF, a colonial administrator and a French ethnographer who conducted fieldwork in the Ivory Coast and published several studies on the cultures and languages of the region. His research was instrumental in documenting the customs, languages, rituals, and material culture of some Ivorian populations. Labouret published several works based on his ethnographic research, providing insights into various ethnic groups and their ways of life. Some of his notable publications include Ethnographie de l'Ouest Africain (1931), Les Gour (1948), and Histoire des Noirs d'Afrique (1950).

Two points must be emphasized. First, the colonial context in which Labouret worked influenced his research and the lens through which he interpreted and presented the cultures and societies he studied. Like many other colonial scholars of his time, his work was influenced by prevailing racial prejudices and power dynamics. For example, he was deeply convinced that French colonizers brought civilization and progress to the colonized, whose indigenous populations he often portrayed as "savage" and "primitive. However, the degrees of his notion of "primitiveness" were proportional to the degrees of resistance to French penetration.

Second, we must also emphasize that Labouret and Delafosse do not represent the full range of scholarship during this period.

The French ethnologists, ethnographers, Africanists, and linguists who conducted extensive research in West Africa and held various positions in the colonial administration certainly did not have the epistemological awareness and ethical principles that the various disciplines grouped under the umbrella of anthropology and ethnography have today. The geo-cultural map that they gradually constructed, which served as a crucial orientation tool for all colonial military and civilian authorities and sometimes influenced colonial policies, was only to a very small extent the result of the various data collections made in the field. These scholars had a very rough and inaccurate knowledge of the pre-colonial past and no intercultural training at all. The data they thought they were collecting were actually the data they could understand, the data they thought they understood but misinterpreted, and all the many items they thought were data but were only elements they could interpret, manipulate, and even create in good or bad faith.

The ethnic and cultural differences among the various local communities that they reported were not only the existing ones, but to a large extent the ones they could see with their own eyes and record, categorize, and rigidify according to their Western, ideologically flawed criteria. The geo-cultural map they created showed a remarkable degree of distortion and had an arbitrary feature full of consequences: it was drawn in ethnic-linguistic terms and along ethnic lines.

The eyes can play tricks, and we deal with some of their deceptions in the first chapter of our THE TSUBA, THE KATANA, AND THE SAMURAI SOUL PART 1.

All maps lie, even the geographical ones. Those that have been drawn with epistemological maturity and are based on a rigorous scientific approach lie less.

The Beatine Map is a famous world map (mappa mundi) originally drawn by the Spanish monk and geographer Beatus of Liébana around the year 776 (8th century, early Middle Ages) by using various sources, including Isidore of Seville, Ptolomy and the Bible. The original map has been lost; the following is a copy made in the monastery of St. Sever in France.

The map shows the land masses surrounded by the ocean. In the center is the Mediterranean Sea, the river to the right is the Nile, and the church on the land to the left is Rome, the seat of the Pope. The Garden of Eden (above, below Oriens, East) is at the end of Asia, and there's a fourth continent beyond Africa.

Now, look at the following geographical map: it's called Tabula Rogeriana, but its real name is a very poetic Arabic one: Nuzhat al-mushtāq fī ikhtirāq al-āfāq, whose meaning is "The excursion of one who is eager to penetrate the distant horizons". It was completed in 1154 after many years of study by the Arab geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi. It was a revolutionary map for its time, far more accurate and reliable than any previous map, and had an extraordinary influence for centuries to come. At first glance, it seems illegible to us today, but if you look closely, you'll see the Iberian Peninsula on the far left, and then Italy, Sicily, Greece, the Mediterranean Sea... (The island of Great Britain looks like a teapot, doesn't it?).

Now take a look at the geographical map below (from the Nations Online Project): it's probably the most widely used today.

Technically, this map is a Mercator projection. Since all map projections, shapes, or sizes are distortions of the true layout of the Earth's surface, even this widely used map shows a remarkable degree of distortion. In other words, it is not a true "picture" of the Earth's surface.

The following map is a more realistic one, or more precisely, a less distorted one. It's called "The AuthaGraph Map", and it's an equal-area type world map projection invented by Japanese architect Hajime Narukawa in 1999. It maintains the sizes of all the continents and oceans while reducing the distortions of their shapes, as a Dymaxion map does. It has been defined by some imaginative journalists as "an accurate world map that doesn't lie," but let's just say it's the most accurate world map we've drawn to date, and nothing more. Note the tiny size of Europe and the USA compared to Africa, the small dimensions of Antarctica compared to a Mercator projection, and the truly "odd" shapes of Brazil and Australia.

Now think of the Ivorian geo-cultural map, gradually drawn by the French ethnographers-colonial administrators since the beginning of the 20th century, as if it were one of the first geographical maps of the early Middle Ages, drawn in the infancy of the discipline, adopting a biased perspective and using various sources, including some unreliable ones. We cannot call this map an invention, but neither can we treat it as if it were the result of rigorous and mature scientific work.

This has two consequences.

The first. This geo-cultural map, and in particular the linguistic-ethnic differentiation of Ivorian groups and communities drawn up since the early colonial period, did not represent the fluid ethnic situation of the territory in the pre-colonial period, but claimed to do so and was received as such. It is a bit like a Mercator projection claiming to be the true representation of the earth's surface. We know it is not. Similarly, we know that the geo-cultural map of Delafosse & co. wasn't a faithful representation of an ancient pre-colonial past.

Few scholars have noted this fundamental point, and among them is the author of a masterful essay in French that is well worth reading: the author is Jean-Pierre Dozon, a French anthropologist, Africanist, Scientific Director of the Fondation Maison des sciences de l'homme (FMSH), Emeritus Research Director at the Institut de recherche pour le développement (IRD), and member of the Institut des mondes africains (IMAF). I suggest you to read his 1989 paper titled L’invention de la Côte-d’Ivoire (you will find the link to download it in my final Bibliography). He writes: «As cartographic inscriptions corresponding to a territory and a name, the ethnic groups of Côte d'Ivoire are at least as much the result of the ethnographic work of the colonial state as of realities that preceded its creation. This assertion does not mean that the colonial administrators created the ethnic groups of Côte d'Ivoire from scratch; it simply indicates that the way in which they identified and classified them contains an element of arbitrariness, conveying representations that the colonial state needed to control the territory and to justify and translate its intervention and development practices into a certain cultural language. (...) The ethnic identities and the "larger families" are categories of colonial practice because they take on meaning within a system that differentiates and hierarchizes them and claims to measure their suitability for colonization» (L’invention de la Côte-d’Ivoire. My translation).

The effects of the rifts, separations, and rigidities that such a geo-cultural map created among the various Ivorian communities were compounded by the "divide and rule" policy, the shifting interplay of alliances that the colonial authorities established over time, and the forced migrations that they organized to meet the needs dictated by the establishment of extensive cash crops (especially cocoa and coffee) and the emerging plantation economy. French colonialism thus stands out as the most influential factor in shaping and developing the ethnic landscape of present-day Côte d'Ivoire. This means that the recent ethnic conflicts can in no way be read as the resurgence of ancient, pre-colonial and tribal tensions: a convenient interpretation that pleases some Westerners but insults history.

There's a second consequence, even more important than the first.

Delafosse & Co.'s geo-cultural map, its systematic use and adoption, and the "divide and rule" style of colonial control contributed not only to the "crystallization of social relations around ethnic identities and distinctions," as Dozon writes, but also to a progressive ethnicization of colonial governance and, in the long run, of Ivorian political life.

Let's take an example. Among the first Ivorian associations created in 1937 (made possible by a new colonial law) were the ADIACI (Association de Défense des intérêts des Autochtones de la Côte d'Ivoire), which expressed the specific needs and political demands of the Agni planters, and the Mutualité Bété, linked to the interests of the Bété ethnic community. In 1944, the Syndicat agricole africain (SAA) was created under the leadership of Félix Houphouët-Boigny, a physician and wealthy planter from a family of hereditary Baoulé chiefs. The majority of SAA members came from the Baoulé region and, to a lesser extent, from the Dioula and Voltaic regions in the north. This association presented itself as defending the interests of Ivorian society as a whole, but in fact it was the expression of the specific interests of the Baoulé elite (to which Félix Houphouët-Boigny belonged), and as such it immediately aroused the opposition of the Agni community. Thus, the Ivorian associations that developed in the country after the law of the late 1930s were created along ethnic lines in order to defend and support the claims of the elites in ethnic terms and at the ethnic level.

The ethnicization of colonial politics was initially a side effect of the French colonial regime and style of control. But it was a wonderful side effect, a kind of "Viagra side effect". You see, sildenafil, the active ingredient in Viagra, was originally developed to treat cardiovascular problems, and its powerful effect on erectile dysfunction was at first a surprising side effect. At second glance, Pfizer executives understood the drug's potential and turned it into the key to a huge business success. The ethnicization of Ivorian political life had a surprising "Viagra effect" that the French were not slow to exploit: it closed the door to communism.

The French colonial regime, with its high rate of structural violence, exploitation and repression, had created increasingly dangerous social inequalities and disparities, and was gradually turning Ivorian society into a powder keg ready to explode. However, the progressive ethnicization of Ivorian social and political life had the effect of channelling social resentments and political demands into the ethnic horizon, with a diversionary effect that almost bypassed the French colonial power; at the same time, it prevented the development of left-wing political parties and trade unions similar to those that were animating contemporary French political life. In other words, the progressive ethnicization of Ivorian political life led to the ethnicization of demands for social, economic, and legal justice, provoking their fragmentation along pseudo-ethnic lines and ultimately their disempowerment.

We have said it before: France loved the Jacobins or the Bonapartists not because they were Jacobins or Bonapartists, but because they were French. For something similar to happen in Africa, destabilizing such a subdued and prosperous colony and bringing it closer to potential Soviet influence, was not an acceptable scenario for a disingenuously democratic France. Royal beheaders and revolutionaries at home, but fierce anti-communists in colonial Africa: that was the French. As for ethnic conflicts, the colonial authorities were convinced that they could control them militarily, using means that were not really in line with their "civilizing mission" but could well have remained hidden.

Anti-communism was a cornerstone of French colonial rule in Côte d'Ivoire and became particularly evident at various moments in colonial history, such as in the affairs of the French historian and anthropologist Jean Suret-Canale (1883-1958), who was forced to leave the colony by the French government under a military order. However, I won't deal with this interesting story, but with Félix Houphouët-Boigny, a key figure in Ivorian politics and the first president of the post-colonial, independent Côte d'Ivoire from 1960 until his death in 1993.

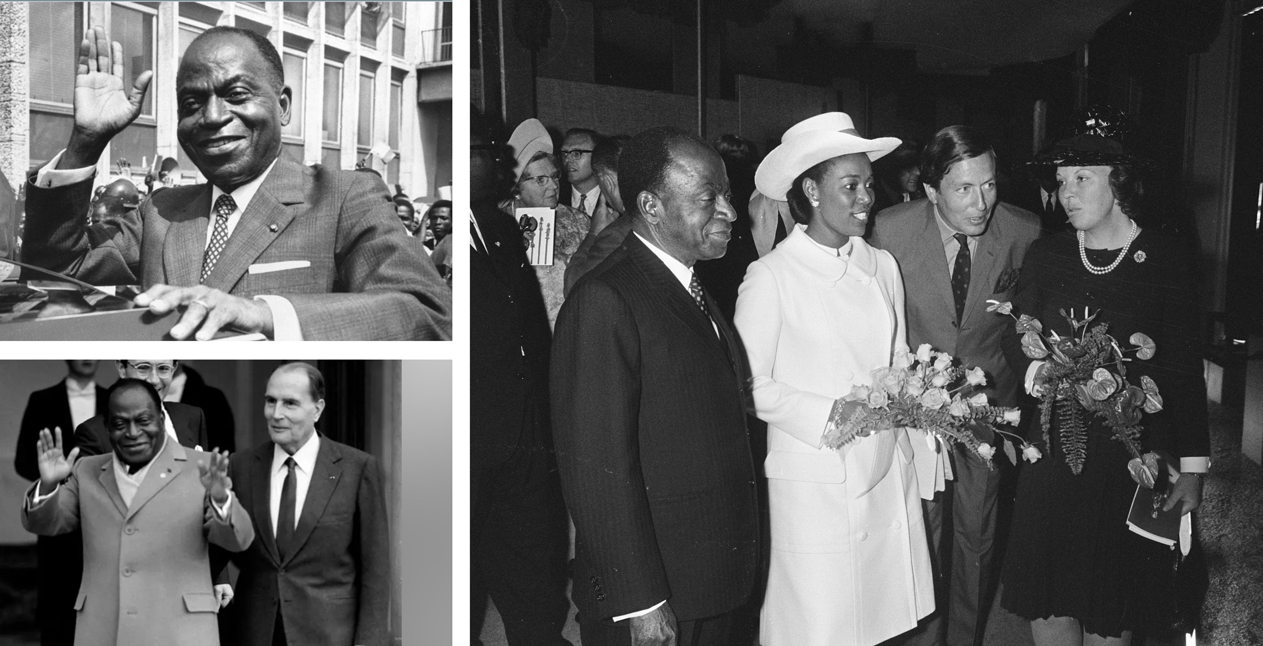

CLOCKWISE: Félix Houphouët-Boigny in 1971; with Prince Claus and Princess Beatrix of The Netherlands in 1970: with French President François Mitterrand in 1985.

In 1946, Félix Houphouët-Boigny founded the Rassemblement Démocratique Africain (RDA), or African Democratic Rally in English, an umbrella organization in French West Africa, composed of various political parties, including the Ivorian Democratic Party of Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI), whose agenda included the implementation of some reforms and the country's long-term independence. As Dozon writes, the colonial authorities brutally curtailed this reform agenda, and the PDCI, unable to find other political support in mainland France, joined forces with the French Communist Party, the only openly anti-colonial political group at the time. While the opposition parties took advantage of this alliance and openly declared themselves anti-communist (without ever forming a united front), the colonial authorities set about exploiting the political divisions in the Ivorian world to isolate the PDCI, a strategy that culminated in violent repression in 1949-1950: many of its members were arrested, tortured, and killed. Victor Biaka Boda, the Ivorian leader of the radical anti-colonialist wing of the RDA-PDCI, was made to disappear and then murdered.

In 1950, Houphouët-Boigny announced the breaking of the alliance with the French Communist Party and presented his PDCI to the country, to France, and to the international community as the only political interlocutor at the national level that had nothing in common with communism and everything in common with France. A shrewd political move in the era of Cold War and Red Scare. To tell the truth, this shrewd political move was not a Houphouët-Boigny's brilliant idea. It was a French project, or rather the condition that France imposed on Houphouët-Boigny to save his political career.

You will never guess who the French government sent to Africa to negotiate that break between the PDCI and the French Communist Party. According to the French historian Bernard Nantet, it was François Mitterrand, then Minister for Overseas France.

Socialist at home, fiercely anti-communist in Africa, we've already said that, haven't we?

In 1950, René Pleven, the French prime minister, asked Mitterrand to negotiate with Félix Houphouët-Boigny to "ease all relations" with the French administration by separating his RDA-PDCI party from the French Communists and the CGT (the Confédération générale du travail, probably the most powerful French left-wing union). Félix Houphouët-Boigny was ready to accept and reassure France. And France was willing to reward him.

Houphouët-Boigny then recycled himself as a moderate politician, by expelling from the party all the members of the radical circle «of young intellectuals whose anti-colonial and leftist ideas seemed to transcend ethnic divisions.» (Dozon, L’invention de la Côte-d’Ivoire. My translation). What's more, he shrewdly kept quiet about the shameful policies of France in its colonies of Indochina and Algeria.

His silence paid off, and his political career skyrocketed: in 1956-57, he was Minister Delegate to the Presidency of the Council in Guy Mollet's government, and in 1957-58, Minister of Health in Félix Gaillard's government. These were ministries of the French Republic, to be clear.

From 1956 to 1960, Côte d'Ivoire gradually approached independence. Guess who led the country through this phase and who became the first president and Père ("Father") of the newly formed Ivory Coast? That's right: Houphouët-Boigny. His one-party, anti-democratic regime ruled the country with the solid support of France. The old "motherland", indeed, was far from leaving this rich African territory. The end of colonialism was a good fable for the naive Euopean public. Two examples suffice to prove this: after the independence of Côte d'Ivoire, its currency was managed by the Banque de France through the West African Monetary Union (CFA franc), and its economy was totally dependent on France and subordinated to French interests.

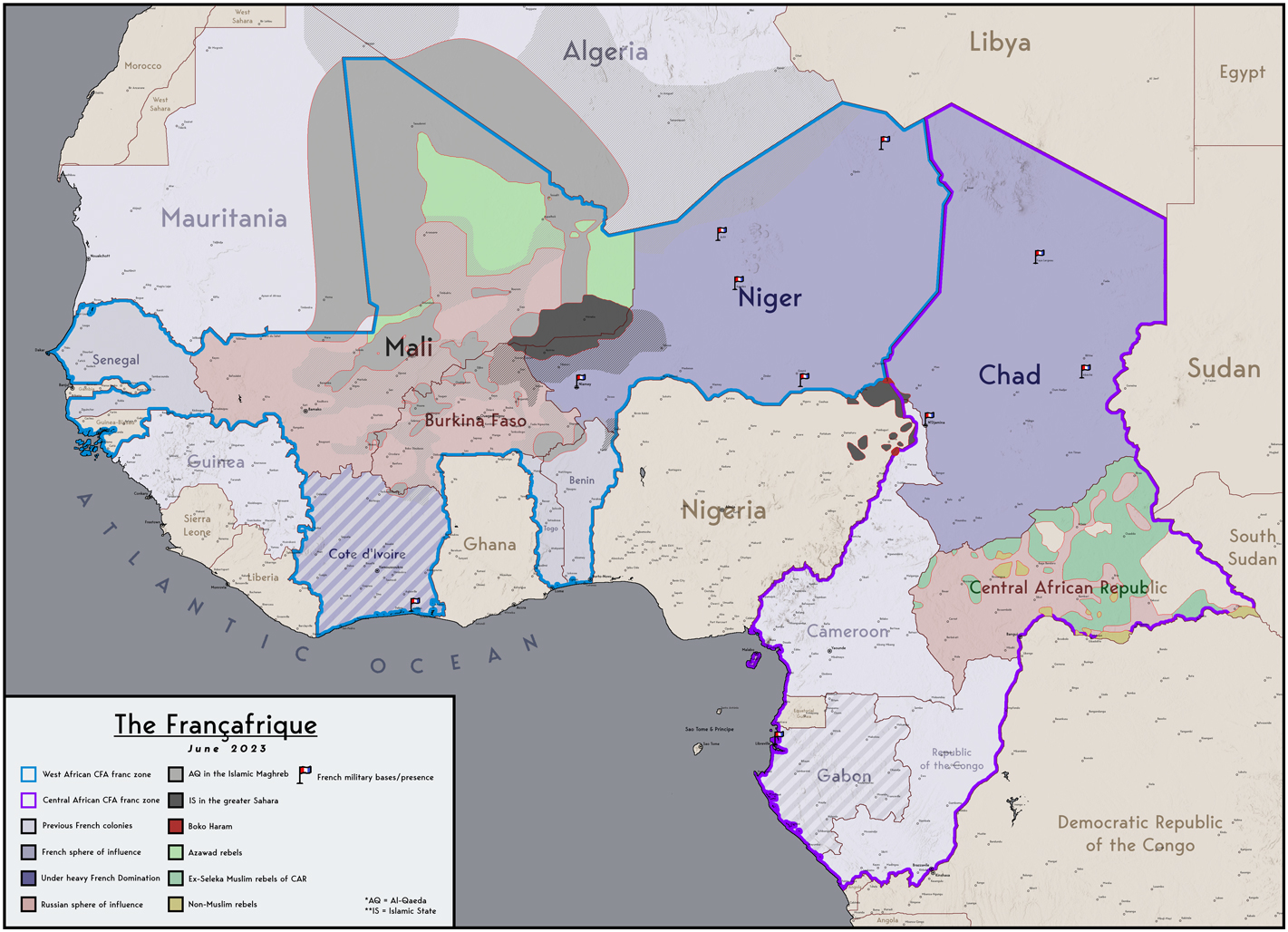

La Françafrique, namely France's sphere of influence over former French colonies of West Africa in June of 2023. One of the key players in Françafrique was François Mitterrand. Please note the meaning of the colors: dark blue: French influence; red: Russian sphere of influence; cyan and purple borders: CFA franc zones.

This brings us to the end of our story.

In 1990, Félix Houphouët-Boigny was urged by France to adopt some reforms for a moderate opening to multi partyism. In May 1990, 14 political parties were created. Houphouët-Boigny died in December 1993. All the political tensions contained by the Boigny regime began to surface. In 1999, Côte d'Ivoire experienced a coup d'état. We have already mentioned the two civil wars and the ethnic conflicts that broke out in the following years.

The reason for the latter now seems clear: the gradual ethnicization of French colonial rule and the subsequent French political choices produced the forced ethnicization of Ivorian social and political life, which was France's main bulwark against the development of a communist party and a left-wing trade union capable of forming a serious opposition to colonial exploitation. The ethnicization of social conflicts was already widespread in the country in the late 1930s and 1940s. When political conflicts found new channels of expression in the mid-1990s, they resurfaced as ethnic conflicts.

This is not the same as saying that French colonialism is to blame. It opened a long series of ethnic wounds that have festered and degenerated at different stages of postcolonial history because many members of the new Ivorian political elites could not or would not heal them. Worse, some Ivorian politicians have chosen to exploit ethnic divisions and inequalities to strengthen their political base. Unfortunately, this criminal choice has had ominous consequences for the entire country that have yet to be fully averted.

Dobet Gnahoré & Manou Gallo, Ma Côte d'Ivoire

In 2011, after the Second Civil War, the Ivorians singers and musicians Manou Gallo and Dobet Gnahoré joined forces to sing "Ma Côte d'Ivoire", a call for national unity and peace, set against an Afro-reggae/afro-folk backdrop. The first French words means "The Côte d'Ivoire must be one and indivisible for the sake of tomorrow's children".

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?