Rwandan Basketry 6

Rwanda on the globe

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

RADIO-TÉLÉVISION LIBRE DES MILLE COLLINES AKA RTLM

In 1992, the Akazu and the Hutu hardliners began planning the creation of a private radio that could partner with the official state Radio Rwanda, but unlike the latter, convey a more radical message to a wider, younger, and more popular audience («Rwandan newspapers reached a small proportion of the population because of their high cost and the high illiteracy rate», Jean-Marie Vianney Higiro, Rwandan Private Print Media on the Eve of the Genocide, in The Media and the Rwanda Genocide, cit.). The ruling oligarchy needed to get all those people with little or no formal schooling who had not been fully reached by the written propaganda campaign: the majority of the rural population and the urban mass of young unemployed, the most vulnerable and easily influenceable people. The radio broadcast was the perfect medium as it relied only on a battery-operated, low-cost portable device. Moreover, the control exercised by the Akazu members over Radio Rwanda had loosened due to ‘interference’ exercised by members of the opposition in the coalition governments: the creation of a private radio was also the indispensable means of regaining control of the mass media. «La perte du monopole du contrôle sur les médias officiels fut bien évidemment la raison première avancée pour justifier la création d’une radio ‘libre’» (A. Guichaoua, cit.).

RTLM began broadcasting in July 1993, technically supported at the beginning by the government-controlled Radio Rwanda, and exploiting the electricity supply offered by the Presidency (it was located near the Presidential Palace and was secured to one of its power generators). Immediately after the creation of RTLM, «in the street markets, hundreds of cheap portable radios suddenly became available» (L. Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, see Bibliography), certainly not by chance. Many devices, moreover, were distributed free of charge by the Habyarimana’s party in some areas of the country.

RTLM was owned by some Akazu members and funded, among others, by Félicien Kabuga, a wealthy businessman whose daughter was married to a son of President Habyarimana, and Seraphin Rwabukumba, President’s brother-in-law and general manager of Société La Centrale, a large commercial company with more than 50 import licenses. Among the founders, there were two ministers and a ministry official closely related to the Habyarimanas’ (Augustin Ngirabatware, André Ntagerura, Alphonse Ntilivamunda), the vice-president of the Interahamwe militia Georges Rutaganda, and Jean-Bosco Barayagwiza, founding member and ideologue of CDR and director at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Ferdinand Nahimana, notorious hardliner from the MRND and former director of Radio Rwanda was a co-founder, Gaspard Gahigi the editor-in-chief, and Colonel Théoneste Bagosora a majority shareholder.

Ferdinand Nahimana, born in 1950 in the very same region as President Habyarimana, was a member of the MRND, a professor of history at the National University, the director of ORINFOR-Office Rwandais d’Information (the Rwanda Broadcasting Agency) in 1990-92, the executive director of Radio Rwanda and co-founder of RTLM. He was indicted for incitement to genocide and tried at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda’s Media Case and condemned in December 2003.

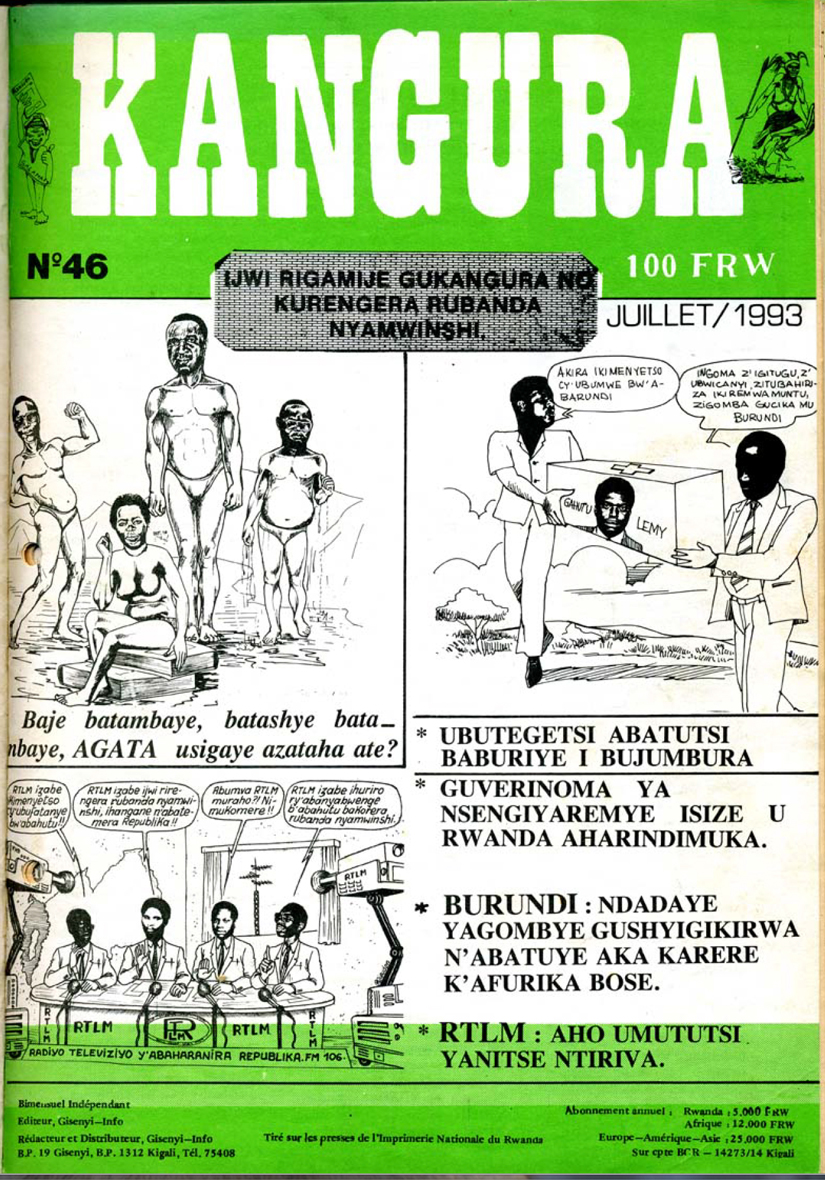

Promotional cartoon published on the cover of Kangura (issue no. 46), in July 1993, to advertise the creation of RTLM (Source: https://francegenocidetutsi.org)

From left to right (my translation):

-

Gaspard Gahigi (?): RTLM will be the symbol of the current unity of the Hutus!

-

Hassan Ngeze: RTLM will be the voice that defends the majority against the enemies of the Republic!

-

Kantano Habimana: Hello RTLM listeners! Be strong!

-

Ferdinand Nahimana: RTLM will be the meeting place of Hutu intellectuals working for the majority.

On the bottom:

RTLM THE RADIO-TELEVISION OF THE DEFENDERS OF OUR REPUBLIC

BELOW

The cover of Kangura, issue no. 46, published on July 1993.

The previous cartoon is featured on the lower left, flanked by the words: RTLM: AHO UMUTUTSI YANITSE NTIRIVA (on the lower right). This phrase is along the same lines as a well-known Rwandan proverb: Aho umutindi yanitse ntiriva, literally “There’s no sun where the poor hangs their clothes”. The Kangura statement, reinforced by its strong assonance with the proverb, means “There are no chances for the Tutsis”, namely “It’s all over for them”.

RTLM used the FM frequency and in the beginning, its broadcast range was limited to Kigali, whereas Radio Rwanda’s reached the entire country. «The station would eventually have a transmitter that could reach the whole of Kigali, part of the Burgesera to the south, and Kibungo to the east. Another transmitter was installed towards the end of January 1994 on Mount Nuhe, in Gisenyi prefecture, which allowed broadcasts to the north, till Ruhengeri. The only places where it was difficult to hear RTLM were in Butare in the south and in Gisenyi town in the north. The leadership of RTLM wanted to place the transmitter in a secure area where there was a strong membership of MRND» (Linda Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.).

RTLM, which became the ‘voice’ of Hutu Pawa, gained immediate success thanks to its lively music – Congolese pop songs mainly – its informal, often cheeky style of communication, and its irresistible mix of conversational register, populist approach, and street language. «Announcers employed a popular variety of anecdotes, stories, insults, personal messages, and humorous remarks» (C.L. Kellow and H. L. Steeves, The Role of Radio in the Rwandan Genocide, see Bibliography), mainly in Kinyarwanda (only some prime time broadcasts were in French).

The success was quite immediate. «Jean-Philippe Ceppi, a Western journalist present before and during the genocide, said he saw everybody listening to RTLM: “military personnel or peasants, rebels or intellectuals in cafes, in cars, in the fields; the Rwandan people spend all their time with a receiver stuck to their ear” (quoted in Chrétien et al., 1995, p.74)» (C.L. Kellow and H. L. Steeves, cit.).

According to Chrétien’s statistical analysis, at the beginning of 1994, 58.7% of the urban population and 27.3% of the rural population owned radios; those who did not, relied on friends, neighbors, public places like bars, shops, street markets, and even buses.

The RTLM’s ‘secret weapon’ was made up of many interactive shows and radio phone-ins, a successful novelty for the country. In a broadcast on March 19, 1994, RTLM’s Editor-in-Chief Gaspard Gahigi said: «We have a radio here; even a peasant who wants to say something can come, and we will give him the floor. Then, other peasants will be able to hear what peasants think». Bullshit, of course. No one was really interested in knowing what a peasant could think; at those times, there was widespread social contempt for peasants and poor little people. The truth is different: the founders and the executive managers of the radio knew very well that participation in oral communication opens the way for wide acceptance of any message. RTLM was created to be a powerful propaganda tool, certainly not to give a voice to those who didn’t have it.

The RTLM’s ‘dirty weapon’ was a strategic mix of breaking news and fake news, the latter being the specialty of the Akazu military members since October 4, 1990, and of Ferdinand Nahimana, as well, «the ideologue behind a faked news item broadcast on Radio Rwanda», according to Linda Melvern.

For days, after the assassination of the Burundian President, RTLM, Radio Rwanda, and TVR (Télévision rwandaise) gave great prominence to a horrific account: Melchior Ndadaye was tortured, mutilated, and castrated before death.

Here’s what Habimana Kantano, one of the most famous RTLM presenters, said on the topic during the evening news:

«Burundi first. That’s where our eyes are looking now. Even when the dog-eaters are few in number, they discredit the whole family. That proverb was used by the [Burundian] minister of labor, Mr. Nyangoma, meaning that those Tutsi thugs of Burundi have killed democracy by torturing to death the elected President, Mr. Ndadaye. Those dog-eaters have now started mutilating the body. We have learned that the corpse of Ndadaye was secretly buried to hide the mutilations that those beasts have wrought on his body»

(Translated from a tape provided by Radio Rwanda to Alison Des Forges)

As Alison Des Forges highlighted, all the reports of torture and mutilation were false. In Burundi, immediately after the assassination of the President, «Human Rights Watch, the International Federation of Human Rights Leagues, SOS-Torture, and the Human Rights League of the Great Lakes organized an international commission of inquiry similar to that which had documented abuses in Rwanda. The commission arranged for an autopsy by a forensic physician who found that Ndadaye had been killed by several blows of a sharp instrument, probably a bayonet. The body had not been mutilated and showed no signs of torture» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

So the whole account was fake. Most RTLM listeners could not separate fake news from real ones, not having access to alternative sources of information. The castration detail, in particular, was specifically fabricated to urge the listeners to make an immediate and powerful association with an antique practice carried out in the past by the mwami, the Tutsi king in the pre-colonial era: emasculating slain enemies and adorning the royal drum with those body parts. This fake account was fabricated not just to arouse a series of different violent emotions in the audience, but also to make them think that ‘the Tutsis haven’t changed through the century, and are today as they were in the feudal past’, thus establishing a fruitful link between past and present.

This link was the ‘mantra’ of the Akazu propaganda campaign since 1990. As we saw, the ideological horizon defined by this campaign was a complex construction whose foundations were developed by Belgians and Western White Fathers in the 20s and 30s . Its load-bearing walls were those erected by the Bahutu Manifesto and the racial claims supported by the Hutu emancipation movement from the late 50s to the early 60s. In the 1990-93 propaganda campaign, the references to the Tutsi feudal monarchy and the 1959 Social Revolution were systematic and never fortuitous. We can say exactly the same for RTLM whose refrain was “none is worse than a Hutu who does not remember and honor the 1959 Revolution”. «Georges Ruggiu, RTLM’s Belgian presenter, recalled that the station’s management issued explicit instructions to make such historical comparisons and that he said on the air that “the 1959 revolution ought to be completed to preserve its achievements” (ICTR-97–32-DP2000, par. 110, 186). Kantano Habimana, arguably RTLM’s most popular animateur, once told listeners: “Masses, be vigilant … Your property is being taken away. What you fought for in ’59 is being taken away” (RTLM, 21 January 1994). Venant, a 69-year old Tutsi, told me that RTLM “made [people’s] heads hot [ashyushe imitkwe]” when speaking of how the RPF intended to restore the monarchy and reinstate dreaded colonial-era clientship institutions» (Darryl Li, Echoes of Violence: Considerations on Radio and Genocide in Rwanda, in The Media and the Rwanda Genocide, cit.).

Why were those specific links, those ‘mantras’ so relevant to be a staple in the hardliners’ propaganda?

Because, without them, the war carried out by the Rwandan Patriotic Front against the Habyarimana’s regime would have remained what it simply was, namely a war carried out by the Rwandan Patriotic Front against the Habyarimana’s regime. Those links, those ‘mantras’ were the cornerstone that made it possible to ‘racialize’ the conflict, turning the 1990 attack into the final assault of an all-out war, the war of Tutsis against all Hutus.

So, despite the pub-talk style and the somewhat gross excesses of many speakers, the communication strategy behind the broadcasts was far from being rough and lousy.

«From late October on, RTLM repeatedly and forcefully underlined many of the themes developed for years by the extremist written press, including the inherent differences between Hutu and Tutsi, the foreign origin of Tutsi and, hence, their lack of rights to claim to be Rwandan, the disproportionate share of wealth and power held by Tutsi and the horrors of past Tutsi rule. It continually stressed the need to be alert to Tutsi plots and possible attacks and demanded that Hutu prepare to ‘defend’ themselves against the Tutsi threat (RTLM transcripts: 25 October; 12, 20, 24 November 1993; 29 March; 1, 3 June 1994)» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

«In November 1993, the Belgian ambassador reported to Brussels that RTLM had called for the assassination of the Prime Minister , who was a moderate politician not in the Hutu Power camp» (The Preventable Genocide, 9.13, cit.).

At the beginning of 1994, the radio urged all Hutus “to defend themselves to the bitter end”, by exterminating the Tutsis. In the following months, it transmitted the list of the cockroaches to eliminate, together with their home address and the number plate of their cars to hunt them at home or halt them at a roadblock. Later, it coordinated the movements and the actions of the civil groups of génocidaires in the 1994 final phase.

«From October 1993 to late 1994, RTLM was used by Hutu leaders to advance an extremist Hutu message and anti-Tutsi disinformation, spreading fear of a Tutsi genocide against Hutu, identifying specific Tutsi targets or areas where they could be found, and encouraging the progress of the genocide. In April 1994, also Radio Rwanda began to advance a similar message, speaking for the national authorities, issuing directives on how and where to kill Tutsis, and congratulating those who had already taken part» (Rwanda Radio Transcript, Montreal Institute for Genocide and Human Rights Studies, see Bibliography). Its role in inciting the genocide against Tutsi was so relevant to be known today as “radio genocide”.

The office from which RTLM has been broadcasting in Kigali in 1993-94.

Photo by Kigali Wire / Flickr, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0).

This journalistic reportage by Al Jazeera English focuses on RTLM. It takes about 9 and a half minutes and deserves to be seen from beginning to end. There are two scenes of the 1994 Genocide that might upset you, though; they are at 3.52 and 9.06.

THE 1990-93 RWANDAN GENOCIDE – A TEMPORARY CONCLUSION

ON THE 1990/MID-93 PROPAGANDA CAMPAIGN

The propaganda campaign with which Habyarimana and the ruling elite created, criminalized, and dehumanized a public enemy and mobilized the population to some calls of action was a cross-channel communication strategy, based on an integrative and a progressive approach: portions of a core message were gradually introduced and conveyed across multiple channels and media – articles, pamphlets, speeches, radio broadcasts, caricatures, satirical cartoons, songs (like those by Simon Bikindi), images and photos. The integrative approach is generally quite effective: a person who sees a consistent message conveyed in multiple formats is more likely to trust that message, and recall it later on. The progressive approach was used to deliver a core message through incremental steps so as to make acceptable and completely ‘normal’ or ‘logical’ what would have sounded unacceptable or abnormal if disclosed all of a sudden.

The message was framed to embed the old ‘familiar’ frame, widely shared in Rwanda since the late 50s, and false mythology shared since the 20s. The core message was elaborated, reused, enriched, and relaunched by different media, and translated into different formats. It gradually emerged and took shape and consistency thanks to this game of echoes and continuous intersections that enhanced its pervasiveness and coherence. The core message was never conveyed by a single tile: it was made up by the whole mosaic, which gradually came to light, becoming increasingly more trustworthy, familiar, shareable, and just. The single piece of the mosaic, the single communication ‘quanta’ is frightening and disturbing for us who’re reading it in retrospect, without a cross-cultural approach. Actually, many tiles of the mosaic, taken in isolation and in itself, appear only highly ambiguous pieces, full of blurring rhetoric tools, half-said innuendos. and polyvalent expressions that may or may not directly incite genocidal acts.

What was the core message?

We’ve been invaded and there’s an ongoing war. This is not the war between the government on one side, and the Rwandan Patriotic Front on the other. It’s the war of foreign Tutsis against local Hutus. It’s the final attack launched by the feudal and monarchic Hamitic Tutsis against Rwanda, a democratic and republican Hutu Nation. This attack is only the final phase of a war that began a long time ago and whose aim is to subjugate all Hutus, namely to enslave some of us and exterminate all of the others. We have to find new solidarity and compactness as a Hutu nation. We must unite to face these threats and defend ourselves not only against the enemies-invaders but also against the enemies living among us, the infiltrators and traitors who support the RPF with money, arms, men, whatever. We must defend ourselves, our families, our nation, and its conquests. In a war situation like ours, self-defense has only one meaning: defeating the enemy. Just as we are used to identifying and preventing vermin infestations that could destroy our crops or livestock, we must identify and list all inyenzi. We must be ready to send them back to their land of origin in one way or another, and ready to liquidate them, whatever it might mean, following the good advice of our local authorities.

This ideological horizon, deeply rooted in the prevailing Hutu and Tutsi mythology, successful since the 1920s, became so pervasive, prevalent, and familiar to be credited as truthful and well-founded. It’s the so-called “reiteration effect”: people tend to believe false information to be correct and true after repeated exposure. Repetition makes things seem more plausible, familiarity makes them more trustworthy: it’s a strategy of political propaganda well-known since the 1970s. (If you’d like to know more about this effect, you can read the informative article Want to Make a Lie Seem True? Say It Again. And Again. And Again by Emily Dreyfuss on Wired, 2017, or go the Wikipedia article Illusory Truth Effect).

The war between Hutus and Tutsis, that war of the core message, was a multi-story building whose elements, ‘war’, ‘Hutus’, and ‘Tutsis’ were entirely ideological constructs. Those Hutus and those Tutsi were anything but ethnic groups: they have never existed as such. As to the war, well, every war is, first of all, an ideological construct. And the war of the Tutsis against the Hutus was no exception.

The ideological mosaic accurately built in such a way was to incorporate many fragments of reality to gain immediate consensus (a common strategy). For example, the invented Tutsi effort to get rid of all Hutus, their intent of exterminating Hutus, was created upon a real base: the several killings of civilians and war crimes committed by the RPF.

These texts and speeches are part of the commonly called ‘Hate Media’, in French ‘les médias de la haine’, umbrella expressions to indicate those media (texts, speeches, radio broadcasts) that between 1990 and 1994 spread the ideology of genocide, the ‘media of the Genocide’ in short. We’ll discuss at a later time why this definition is incorrect from a historical point of view; it suffices here to highlight that the 1990/mid-93 propaganda campaign was accurately planned not to fuel racial hatred or directly incite genocide for two reasons.

- The foundations of many walls raised in the First and in the Second Rwandan Republics were made with more hatred than mud. Therefore, someone can assume that the main purpose of the ‘hate media’ was to light the fire of racial hatred only by ignoring 30 years of Rwandan history.

- The propaganda campaign wasn’t meant to mobilize the masses to carry out a genocide. From late 1990 to the mid-1993 the mass-killings of Tutsi or the first phase of the Tutsi Genocide was organized to be carried out by militias, soldiers, presidential guards, death squads, under the coordination of local authorities, with the logistic support of CDR and MRND members, with limited participation of the rabble and only occasional involvement of locals.

The 1990/mid-93 propaganda campaign was planned to reach different aims:

- To turn Rwanda into a Hutu Nation and emotionally solicit the audience by instilling pride in being Hutu, namely an integrated member of the Hutu Nation; this aim was functional to reinforce the political consensus on the ruling oligarchy, increase the support for Habyarimana’s party, and weaken the growing opposition.

- To build, consolidate and spread an ideological horizon conveying a well-built, clear ‘image’ of the enemy and their accomplices. This ideological horizon, which fueled fear for being the target of the bloodthirsty enemies, was built both to discredit the opposition and to legitimate and normalize the systematic mass killings of Tutsis as such.

- To call to actions, namely to call the civil audience to a series of self-defense actions, including supporting local authorities and obeying their instructions, drafting proscription lists of Tutsis and Hutu traitors, making general surveillance work and patrol, manning blockades on roads, collaborating with the militias, and provide backup and logistic help to the Army.

Calling ‘hate propaganda’ this complex and well-orchestrated campaign is naive and historically short-sighted.

ON LATE 1990 TO MID-1993 GENOCIDE

Faced with the RPF attack in October 1990, Habyarimana and the oligarchy in power responded firstly by adopting the old, consolidated scheme, used and tested since the 1960s in reaction to the UNAR guerrilla incursions into Rwandan territory. אֵין כֹּל חָדָש תַּחַת הַשֶּׁמֶשׁ Ein kol-chadash tachat ha-shemesh, nothing was new under the sun: massive arbitrary arrests, illegal detentions and tortures against Tutsi and political opponents, mass-killings of Tutsi civilians in retaliation, the strategy of tension, massive use of looting and burning down houses to force thousands of Tutsis to flee the country, disappearances by the death squads, all were well-established elements of a traditional reaction strategy which included the organization of self-defense groups and paramilitary militias as well.

The mass killings of Tutsi began immediately after the RPF attack: on October 8, up to 1,000 Tutsi civilians living in Mutara and in the combat zones in the northeast of the country were slaughtered by RAF soldiers. The massive arrests of Tutsis started in October. Both of them were short-term planned and quickly acted as components of a previously well-experimented strategy.

The first program of civilian self-defense was developed to counter guerrilla attacks in the 1960s. Even the creation of paramilitary militias wasn’t a new strategy: «The utilization of youths mobilized under the banner of the ruling party is a common feature of genocide in Rwanda and Burundi. In Burundi in 1972, some of the most active Tutsi elements engaged in the killings of Hutu were the party youth, called the Jeunesse Révolutionnaire Rwagasore. The poor economies of Burundi and Rwanda, combined with a very youthful population in both countries, has meant that there are always many unemployed young people with no jobs or prospects for employment, many seething with resentment» (Rwanda Country Study Guide: Strategic Information and Developments, USA International Business Publications, 2012).

The racial ‘card’ – from mild forms of racial segregation to genocide – was the most powerful ‘dirty weapon’ used by the Hutu oligarchy since Kayibanda times. I completely agree with Andrew Wallis when he writes, speaking about the Akazu network: «History had taught Akazu the way to stay in power was through ethnic division. (…) Genocide was purely a matter of political expediency, a cynical way to defeat the external and internal threats». (Andrew Wallis, Stepp’d in Blood, see Bibliography).

However, the 1990-93 situation was quite different from the past.

- WAR NOT ISOLATED GUERRILLA RAIDS

The RPF October attack was the beginning of a war that involved neighbor countries and challenged the international political balance, not a series of guerrilla raids carried out by a motley assortment of desperadoes and underdogs. The RPF army was better trained than the RAF, to tell the truth.

- THE INTRINSIC WEAKNESS OF THE RWANDAN RULING OLIGARCHY

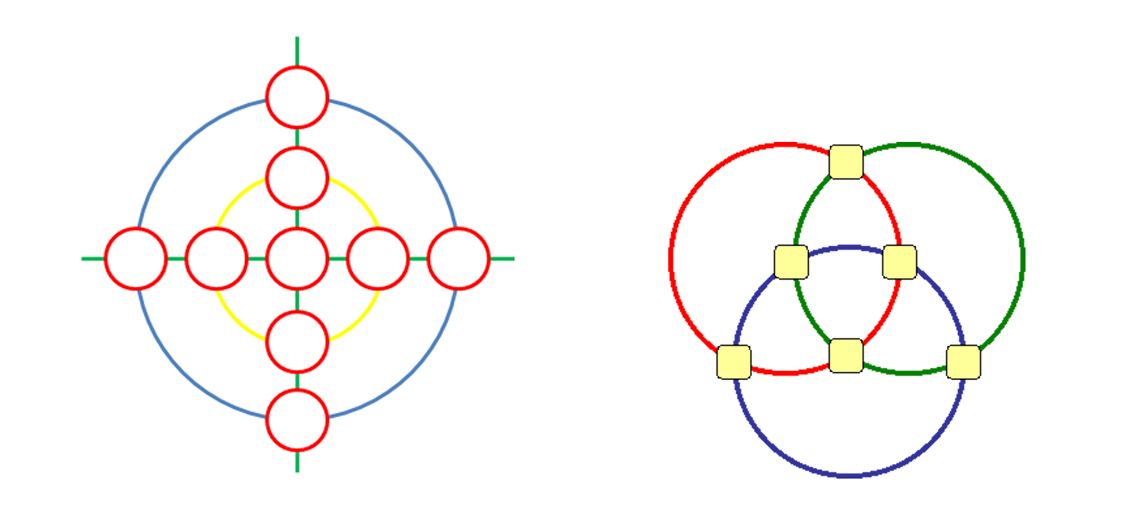

The ruling oligarchy was anything but a tight-knit solid group, not only as it was crossed by fierce rivalries, cynical calculations, and unbridled greeds, but also because its internal structure did not show a permanent center of gravity. The power structure was more like the right figure than the left one, and got more and more complex during the 1991-93 period, due to many factors, including the development of a multi-party system and the political decline of Habyarimana.

According to André Guichaoua, around the President, there were some concentric circles of power (in Rwanda de la guerre au génocide, cit.), but I’m more inclined to believe that President Habyarimana was not the ‘center’ of a series of circles nor the apex of the pyramid, at least in the period 1990-94. At that time, the ruling oligarchy seemed to be organized in a series of circles, cliques, lobbies, mafia-like groups (like Akazu, Réseau Zéro, AMASASU, ABARUHARANIYE, etc.) interlinked by relevant ‘nodes’ – Juvénal Habyarimana being one of the main – and made up by top-ranking officers and military members, top-level businessmen, politicians, prefects, burgomasters, heads of governmental organizations and departments, journalists, Catholic prelates, academics, mainly form the Bushiro region. Habyarimana was their most visible symbol, their international ‘presentable face’, the ‘Switzerland of Africa’ personification, but he wasn’t a Sun King. (To know more on this issue, you can read Andrew Wallis, Stepp’d in Blood, see Bibliography for more details).

- THE EXTRINSIC WEAKNESS OF THE RWANDAN RULING OLIGARCHY

Since the late 1980s, the rotten and corrupt ruling oligarchy – who had a history of systematic violations of human rights, controlled people by force and surveillance, divided them by the use of racial apartheid and denied most of them the essentials for a dignified life – was weakened by the pressures of the internal opposition and many international organizations (aid donors, OAU, World Bank, etc.) who called for the beginning of democratic mild reforms and some structural social changes.

To protect its assets from all threats the ruling oligarchy had to elaborate a more complex strategy than in the past.

Rearmament and close military cooperation with France, the planning of a propaganda campaign and the spreading of systematic disinformation, the strategy of tension and terror, the planning, organization, and management of genocidal acts against the Tutsis in close contact with local authorities were all components of a cynical and brutal agenda of power and profit, in times of crisis. (Winning the war but losing power was not an option at all).

In 1990-93, the construction/criminalization/dehumanization/liquidation of the ‘Tutsi public enemy’ allowed the ruling oligarchy

- to strengthen their positions and build consensus by turning Rwanda into a Hutu Nation;

- to divert and channel the most corrosive criticism of their political conduct, especially the accusations of bribery and corruption, immorality and incompetence, into the racial horizon.

We must remember that, since the 1920s, in Rwanda, social tensions and claims, as well as social anger and resentment, were funneled into the racial ideological horizon and rerouted as racial hatred against a purely ideological construct. We saw how the 1959 Social Revolution, the Hutu emancipation movement, turned a series of social, cultural, and economical reasonable claims into a racial clash: it wasn’t a social ‘revolution’ at all, but a racist and fascist movement trapped into the old colonial racial ideology horizon (the French historian Florent Piton calls it “une révolution socioraciale”). In the late 1990s, face a growing opposition who not only called for democratic reforms but also denounced the profound socioeconomic injustices and the deep rottenness of the élite, the racial card was the most versatile and ready-to-use weapon.

As to the Catholic Church in 1990-93, Vincent Nsengiyumva, Archbishop of Kigali from 1976 until his death in June 1994, was a personal and political friend of Habyarimana. He and many Catholic prelates were as ready to strongly condemn the attack by “assailants from Uganda” as they were reluctant to denounce the genocide of the Tutsis. Catholic Church and State remained tightly allied in those years, and for good reason, the former became known as ‘The Church of Silence’.

THE ‘WATERSHED’ OF THE MID-1993

The genocidal massacres of Tutsis, carried out by the Akazu from October 1990 to mid-1993, were part of a complex strategy. The Burundian tragedy accelerated a change already begun in summer: not just the hardliners, but also part of the opposition got politically closer and created a unified front to throw the peace agreements off course and continue the war by any means.

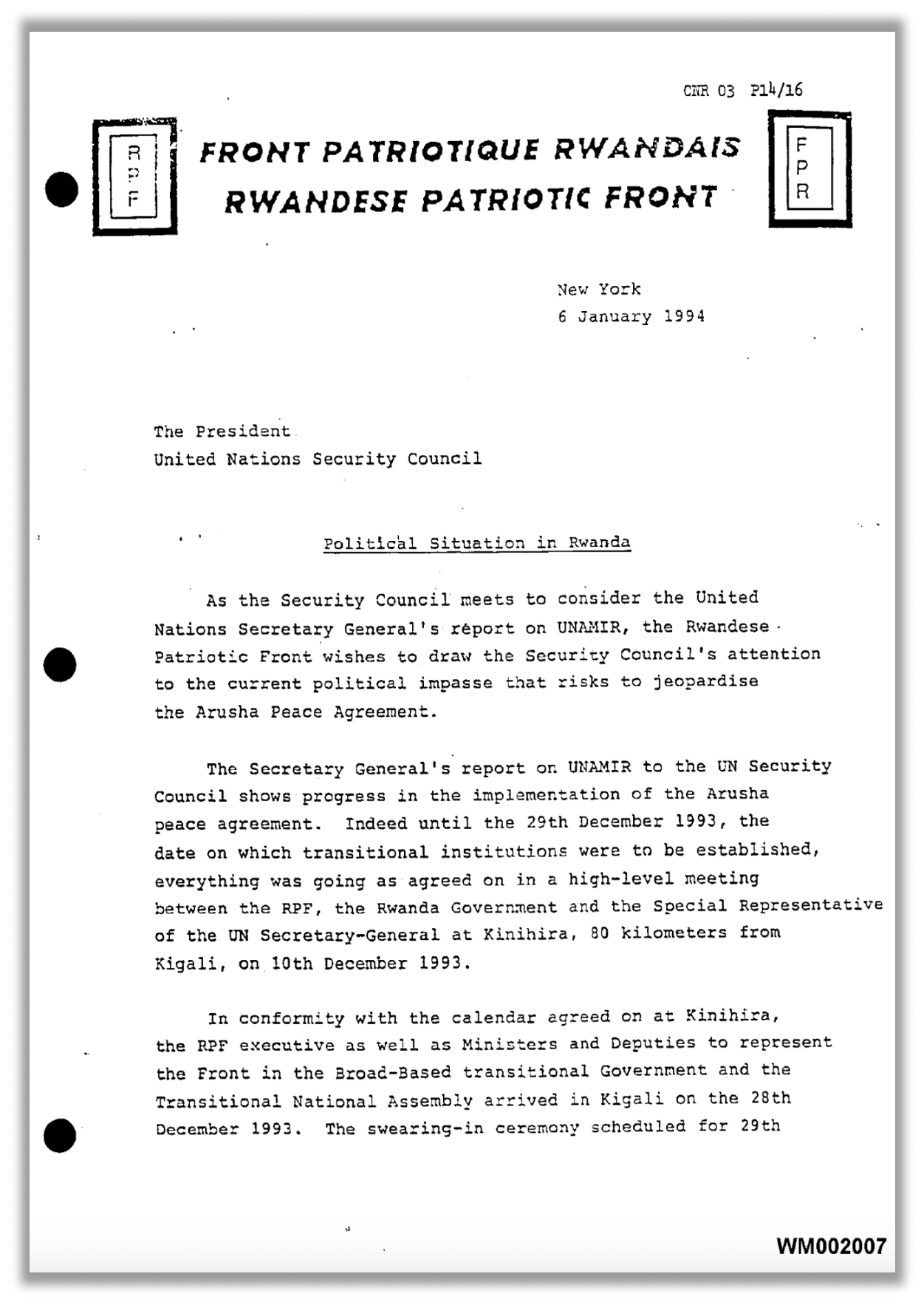

As in the past, President Habyarimana bought time, covertly boycotted the implementation of the Arusha Accords, and sabotaged in every way the creation of those transitional institutions that were provided for in the peace agreements. This is revealed, among others, by a document dated January 6, 1994, signed by Claude Dusaidi, RPF Director for External Relations, and addressed to the United Nations Security Council.

Document titled Political situation in Rwanda, dated January 6, 1994, signed by Claude Dusaidi, RPF Director for External Relations, and addressed to the United Nations Security Council.

It can be downloaded here.

Dusaidi wrote: «It is clear that the President of the Republic <Habyarimana>, as in the past, is seeking to derail the peace process and frustrate UNAMIR <the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda intended to assist in the implementation of the Arusha Accords>. The President, instead of expediting the implementation of the Arusha Peace Agreement, is channeling all his efforts in creating an alliance of all political forces that are not happy with the peace agreement. He continues to train the militia INTERAHAMWE (…) and to arm civilian populations in the prefectures of Kigali, Ruhengeri, and Gisenyi».

In this letter, the RPF calls upon the International Community to bring pressure on Habyarimana to allow the establishment of the transitional institutions, as stipulated by the Accords, and declares its complete willingness to keep on cooperating with UNAMIR to implement the Accords and bring back Rwanda to peace.

Did the RPF really believe that the Arusha Accords would be respected? Surely that respect suited their interests and probably their need to put an end to a tiring and expensive war. However, Paul Kagame was (and still is) a tough man of acute intelligence and far from naïve (in Uganda he was the head of military intelligence). He had to know many aspects of Rwanda’s situation and the President’s political ambiguity. Probably he had this official letter written to strongly stress that all obstacles and forms of sabotage were solely attributable to the Rwandan President and his entourage. He, therefore, urged a systematic, authoritative pressure on him. Habyarimana was the soft underbelly in the hardliners’s field, and Kagame knew he had only that card to play.

What Dusaidi wrote in the letter was true.

«Violence was rampant for years before the <1994> genocide and was escalating perceptibly» (The Preventable Genocide, 9.6, cit.). Even if the massacres of Tutsi knew a temporary decline, the tension was palpable everywhere in Kigali.

The organization and implementation of the civilian self-defense program, sketched by Bagosora and others Akazu military members, accelerated: «in the months following the signing of the Accords, hardliners pushed ahead with activities that appear linked to the “self-defense” program» (Alison Des Forges, cit.). «In late 1993 and early 1994, hardliners stepped up the recruitment and training of paramilitary militia» (Ibidem). «On December 27, Belgian intelligence reported that “The Interahamwe are armed to the teeth and on alert … each of them has ammunition, grenades, mines and knives… They are all waiting for the right moment to act”» (The Preventable Genocide, 9.13, cit.).

The distribution of different kinds of arms (firearms and machetes) to civilians became alarmingly methodic. «By late December 1993, so openly distributed were weapons in Rwanda that the Bishop of Nyundo, from north-western Rwanda, issued an unprecedented press release asking the government why arms were being handed out to certain civilians. The government’s answer was that the locals had to defend themselves against rebel and guerrilla forces because there were not enough troops» (Linda Melvern, A people betrayed, cit.).

Last but not least, «in December and throughout the early months of 1994, RTLM stepped up the pace and bitterness of its attack on Tutsi» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

In late 1993 and early 1994, there were many worrying signs in Rwanda. For the international observers and the diplomats, it wasn’t an easy task to decipher those signs and grab the invisible red thread connecting them. However, after knowing the history of Rwanda and the impact of the mid-1993 events, we can understand the main aspect of the major change that took place in those months: the extermination of the Tutsis ceased to be a political tool to became a political goal. To continue the war and win it, and to give the Tutsi problem its final solution became the two sides of the very same coin.

Kothbiro in the version by Regina Carter

THE RWANDAN GENOCIDE: THE BEGINNING OF 1994

THE UNAMIR (MINUAR in French)

The implementation of the 1993 Arusha Accords was to be overseen by a UN peacekeeping force. Before the Accords, both the coalition government of Rwanda and the RPF had jointly requested the United Nations to establish a neutral international peacekeeping force to monitor the peace process as soon as the related agreement had been signed. Three days after its signing, the Security Council adopted Resolution 846 authorizing the “United Nations Reconnaissance Mission to Rwanda”, designed to «assess the situation on the ground and gather the relevant information» to determine how best to assist with the implementation of the Arusha Accords. The Mission was led by Canadian General Roméo Dallaire, who arrived in Rwanda on August 19 and departed on August 31.

On October 5, 1993, the United Nations Reconnaissance Mission to Rwanda was succeeded by the “United Nations Assistance Mission in Rwanda” (UNAMIR, in French MINUAR), established under Chapter VI by the United Nations Security Council Resolution 872. It was deployed in Rwanda to help secure the transition process, with the mandate of «contributing to the establishment and maintenance of a climate conducive to the secure installation and subsequent operation of the transitional government».

«The principal functions of UNAMIR would be to assist in ensuring the security of the capital city of Kigali; monitor the ceasefire agreement, including the establishment of an expanded demilitarized zone (DMZ) and demobilization procedures; monitor the security situation during the final period of the transitional Government’s mandate leading up to elections; and assist with mine-clearance. The Mission would also investigate alleged non-compliance with any provisions of the peace agreement and provide security for the repatriation of Rwandese refugees and displaced persons. In addition, it would assist in the coordination of humanitarian assistance activities in conjunction with relief operations» (United Nations Peacekeeping, from the official document entitled Rwanda – UNAMIR).

The Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG) or head of the mission was Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh of Cameroon, former Minister for External Relations of Cameroon, who arrived in Kigali on November 23, 1993.

The military head and Force Commander was the Canadian Brigadier-General (promoted Major-General during the mission) Roméo Dallaire, who arrived in Kigali on October 22, followed by an advance party of 21 military personnel on October 27. The Canadian Major Brent Beardsley was his executive military assistant. The Deputy Force Commander was the Ghanaian Brigadier-General (promoted Major-General after the mission) Henry Kwami Anyidoho who had experience in peacekeeping missions in Lebanon, Cambodia, and Liberia, and was head of the Ghanaian contingent. Troop contributing countries were indeed Belgium, Bangladesh, Ghana, Canada, and Tunisia.

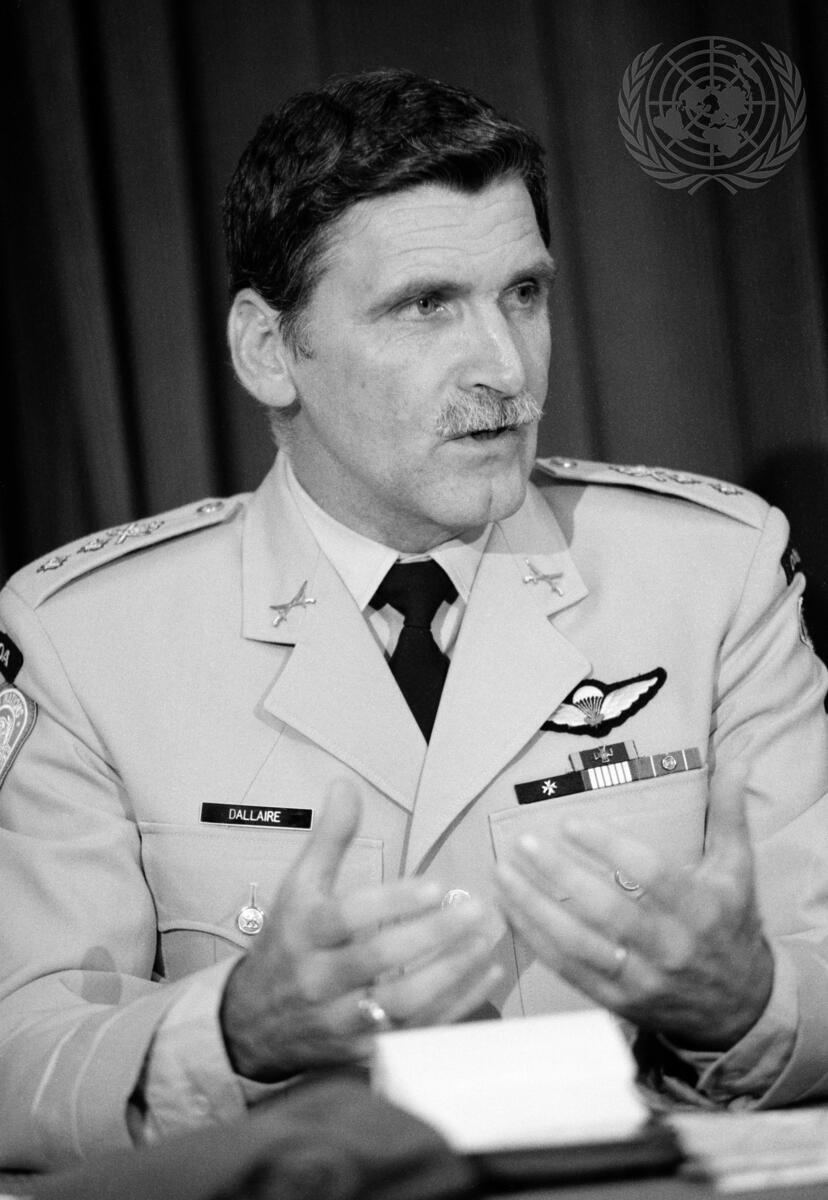

Major-General Roméo Dallaire (born in 1946), Force Commander of the UNAMIR, is holding a press conference at UN Headquarters, New York, U.S., in July 1994.

CREDIT: UN Photo/Milton Grant

In his memoirs, Shake Hands With The Devil, Dallaire remembers that in 1993, when he was proposed to be deployed in Rwanda in a peacekeeping mission, he remarked, slightly stammering out: «Rwanda, that’s somewhere in Africa, isn’t it?». Truth is that the UN Department of Peace Operations, charged with the planning, preparation, management, and direction of UN Peacekeeping operations and missions, gave him no training on the history of Rwanda nor a dossier on its political situation. Probably an amateur club would have done better. «No briefing documents had been prepared for him in New York and when he arrived in Rwanda all he had was an encyclopedic summary of Rwandan history, which his executive assistant, Major Brent Beardsley, had photocopied in a local library» (Linda Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder: The Rwandan Genocide, cit.). Fortunately, he was not only an experienced commander, but a man of acute intelligence and high moral stature, and it did not take him long to understand the real, desperate situation of that tiny African country.

Major-General Roméo Dallaire in Kigali, Rwanda, in 1994. He wears the blue beret of the United Nations peacekeepers. In the background, you can see the UNAMIR headquarters in Kigali.

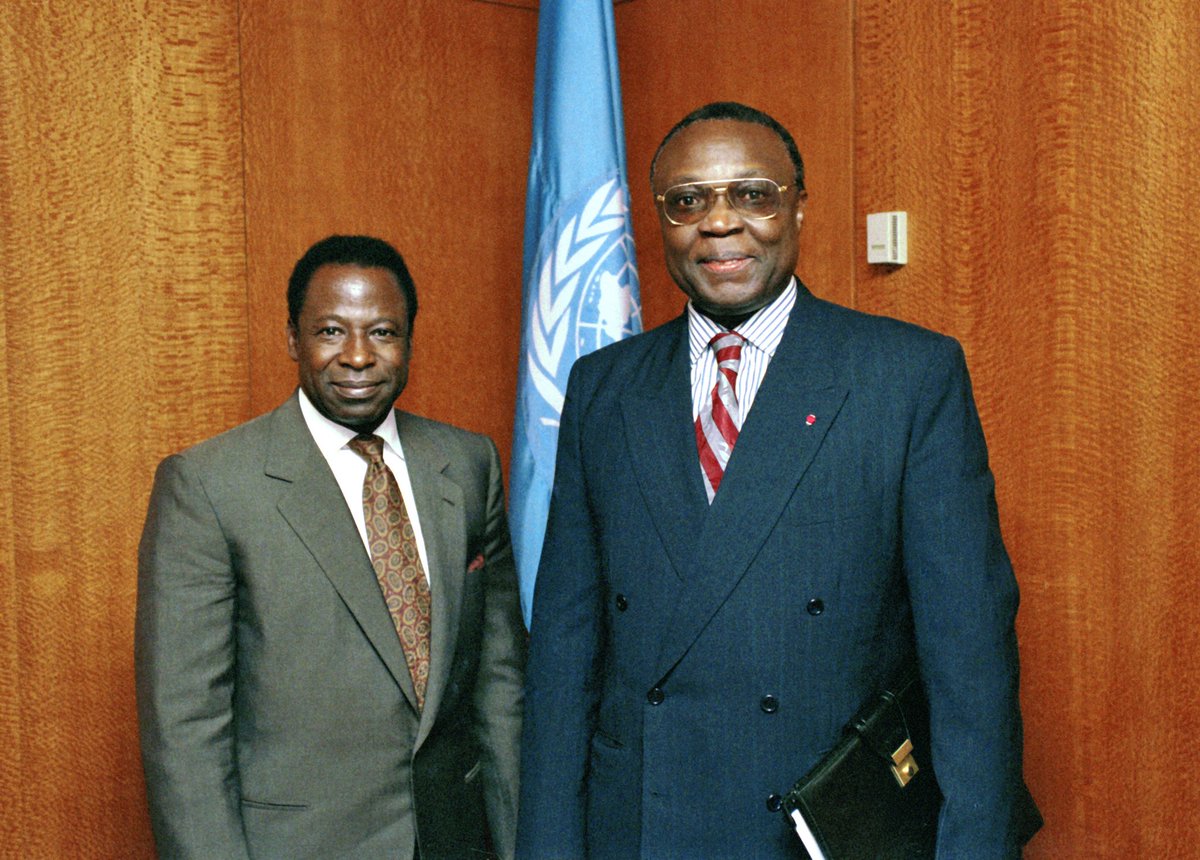

Ghanaian Brigadier-General, promoted Major-General after the mission, Henry Kwami Anyidoho (born in 1940). He was an imposing man, well over six feet tall and weighing over 120 kilos. Roméo Dallaire wrote about him in his memoirs: «His impressive physical presence was matched by his voracious appetite for work. He was a born commander. Like myself, he was a graduate of the U.S. Marine Corps Command and Staff College in Virginia, and he had a tremendous amount of experience from being on many operations, from the Congo in the sixties to Lebanon and Cambodia, not to mention his own country. Henry was confident, aggressive, capable, and committed to the mission from the start. We liked each other at first sight».

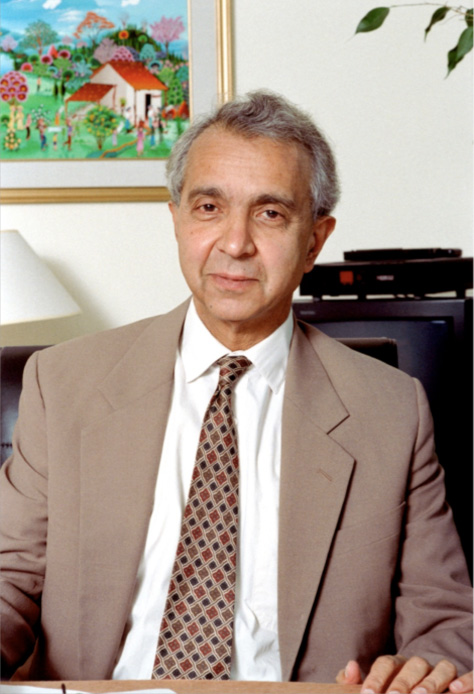

Cameroonian Jacques-Roger Booh-Booh (on the right, while on the right is U.N. General Assembly President Amara Essy from Côte d’Ivoire) in October 1994. UN Photo/Evan Schneider.

Booh-Booh was the Special Representative of the Secretary-General (SRSG), namely the head of the UNAMIR. He was a highly controversial figure, who worked very little, almost always in disagreement with Commander Roméo Dallaire, whose official reports he widely censored. Many times, Booh-Booh seemed completely unable to understand the very delicate political situation in Rwanda. He was an untouchable though, as he was a personal friend of the Secretary-General of the United Nations, Boutros Boutros-Ghali.

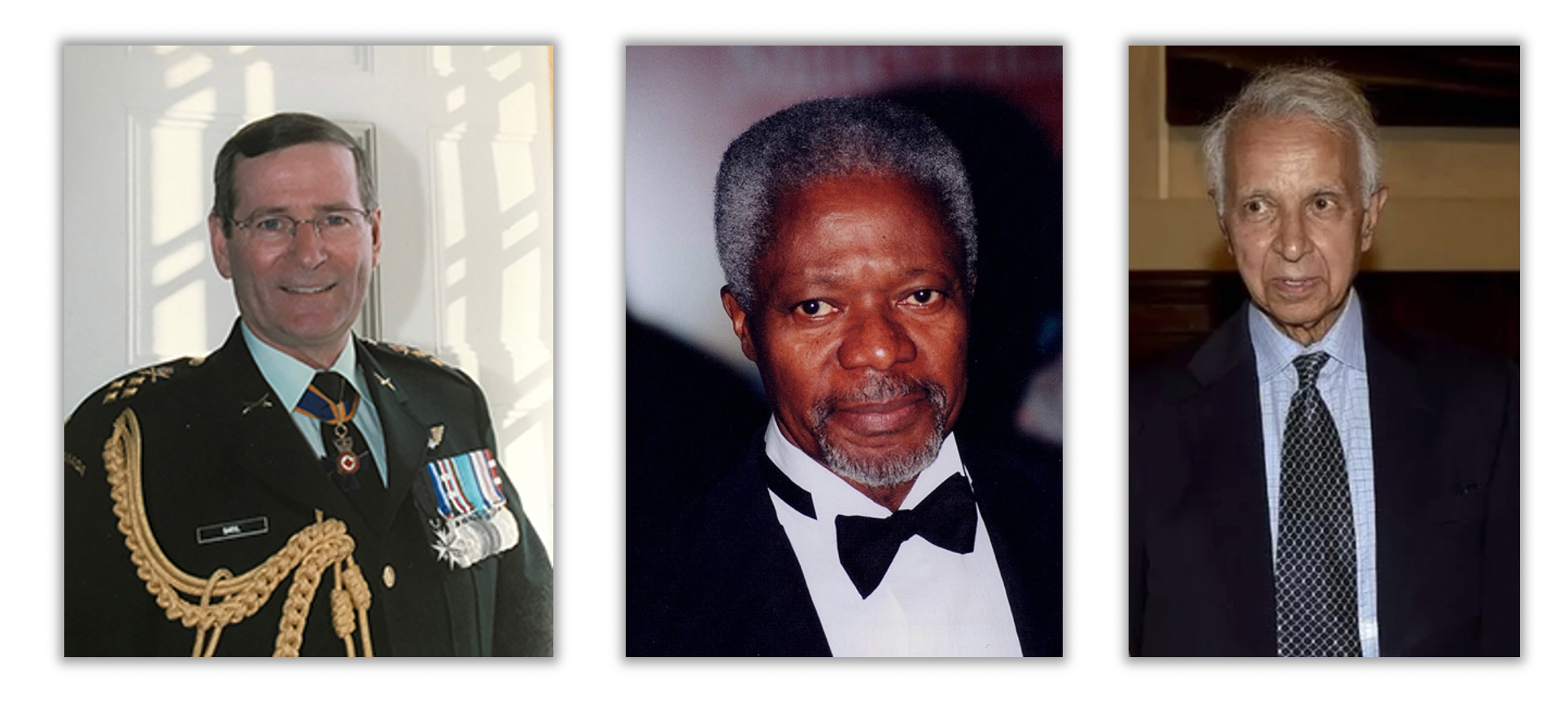

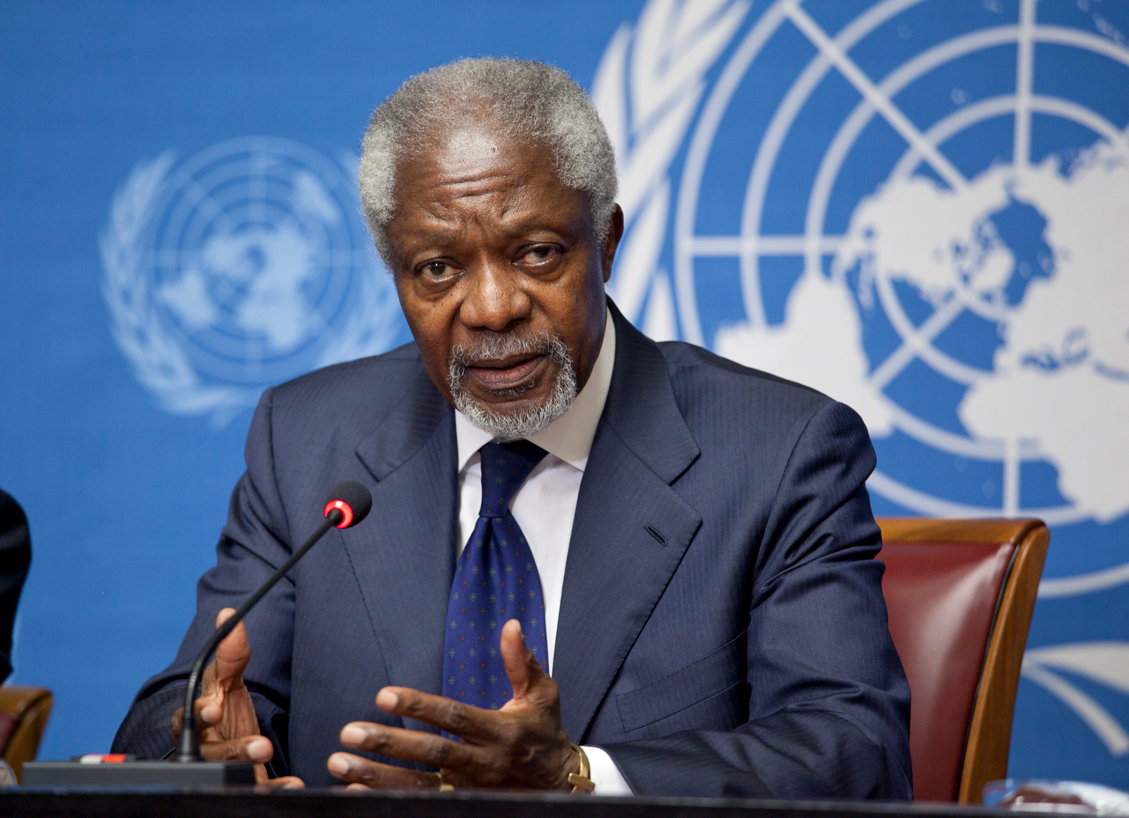

In 1994, the Secretary-General of the United Nations was the Egyptian politician and diplomat Boutros Boutros-Ghali, while the Assistant Secretary-General and later the Undersecretary-General was the Ghanaian diplomat Kofi Annan.

The UN Department of Peace-keeping Operations (DPKO) was managed by a ‘triumvirate’ (the definition is by Dallaire himself):

- Maurice Baril, a retired General officer in the Canadian Forces, a Military Advisor to the United Nations Secretary-General & head of the Military Division of the DPKO from 1992 to 1997,

- Kofi Annan, the Undersecretary-general of peacekeeping,

- Iqbal Riza, a retired Pakistani diplomat and Kofi Annan’s number two.

Left to right: Canadian General Maurice Baril in the 1990s; Ghanaian diplomat Kofi Annan in 1997 (photo licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 Generic); Pakistani diplomat Iqbal Riza in 2016.

Let’s come back to UNAMIR.

«UNAMIR’s demilitarized zone sector headquarters was established in Kigali upon the arrival of the advance party and became operational on 1 November 1993 (…). Deployment of the UNAMIR battalion in Kigali, composed of contingents from Belgium and Bangladesh, was completed in the first part of December 1993, and the Kigali weapons-secure area was established on 24 December» (United Nations Peacekeeping, from the official document entitled Rwanda – UNAMIR).

In theory and on paper, the mission by UNAMIR had to be conducted in four phases. «The first phase would begin on the day the Security Council established UNAMIR and would end on the day the transitional Government was installed, estimated in late 1993. UNAMIR’s objective would be to establish conditions for the secure installation of such a Government, and its strength, by the end of phase one, would total 1,428 military personnel. During phase two, expected to last 90 days or until the process of disengagement, demobilization, and integration of the Armed Forces and Gendarmerie began, the build-up of the Mission would continue to a total of 2,548 military personnel. UNAMIR would continue to monitor the demilitarized zone (DMZ), to assist in providing security in Kigali and in the demarcation of the assembly zones, and to ensure that all preparations for disengagement, demobilization and integration were in place. During phase three, which would last about 9 months, the Mission would establish, supervise and monitor a new DMZ and continue to provide security in Kigali. The disengagement, demobilization and integration of the Forces and the Gendarmerie would be completed in this stage, and the Mission would reduce its staff to approximately 1,240 personnel. Phase four, which would last about four months, would see a further reduction of the Mission’s strength to the minimum level of approximately 930 military personnel. UNAMIR would assist in ensuring the secure atmosphere required in the final stages of the transitional period leading up to the elections» (Ibidem).

In theory and on paper, precisely.

In practice and in reality, nothing went as planned.

«In the United Nations terms, the mission was to be small, cheap, short and sweet» (R. Dallaire, Shake Hands With The Devil, see Bibliography).

In real terms, the UNAMIR turned out to be one of the most tragic and traumatic experiences for all of its members.

- 27 Members of UNAMIR lost their lives during the mission.

- Commander Dallaire has been suffering from post-traumatic stress syndrome and major depression for years after the Rwandan experience. In 2000, he attempted suicide by combining alcohol with his anti-depressant medication.

- Many soldiers of UNAMIR suffered from a rash of suicides, marital breakdowns, and career-ending diagnoses of post-traumatic stress disorder following their return from Rwanda. For several of the 13 Canadians who were part of the UNAMIR, the memories are intertwined with continuing symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). «Retired Captain Jean-Yves St-Denis, from Calgary, went to Rwanda in late April 1994; he was diagnosed with PTSD in 1997 as a result of his experiences and is still dealing with it in 2014. (…) “I will sit somewhere where I have control of the room,” said St-Denis. “I check the exits.”» (Sylvia Thomson, Rwanda genocide: Canadian soldiers struggle with psychological legacy, CBC News, Apr 6, 2014)

- Brent Beardsley «developed PTSD symptoms in 2000 while working at a military support training center, six years after returning home. It was triggered by the courses he was giving — the kind of training he never got before going into Rwanda. The scenarios became a little too realistic to bear. He found he started having trouble concentrating, trouble sleeping and he became moody. “Eventually one day I just got up and I couldn’t put my boots on,” he said. “I reached down to put on my boots and I just couldn’t do it anymore”» (Sylvia Thomson, ibidem).

- Major Luc Racine was a Canadian veteran serving with Dallaire. «Dallaire spoke very highly of Racine before the Senate in 2009, saying “he was one of the 12 reinforcements who came to me in 1994 and, within 42 hours, had saved an orphanage full of children. (…) Maj. Racine subsequently took command of a small battalion of unequipped Canadians and took over the humanitarian protection zone, which had within it 1.6 million internal refugees. He coordinated the humanitarian protection, support, and, ultimately, the transfer to the Rwandan government”». Major Racine suffered from PTSD for years. He killed himself, in Mali, in September 2008.

- «Retired Major Jean-Guy Plante, 71, of Saint Bruno, was the media spokesperson for the UNAMIR. Somehow he managed to escape PTSD. “I honestly don’t know how I came back and wasn’t traumatized,” said Plante. “I think I’ve seen the worse things that could be seen”» (Sylvia Thomson, ibidem).

Artist Gustavo Rondón Linares animates a clip from CBC Radio’s As It Happens in which retired general Roméo Dallaire tells us in a few words what it means to witness a genocide and describes his struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

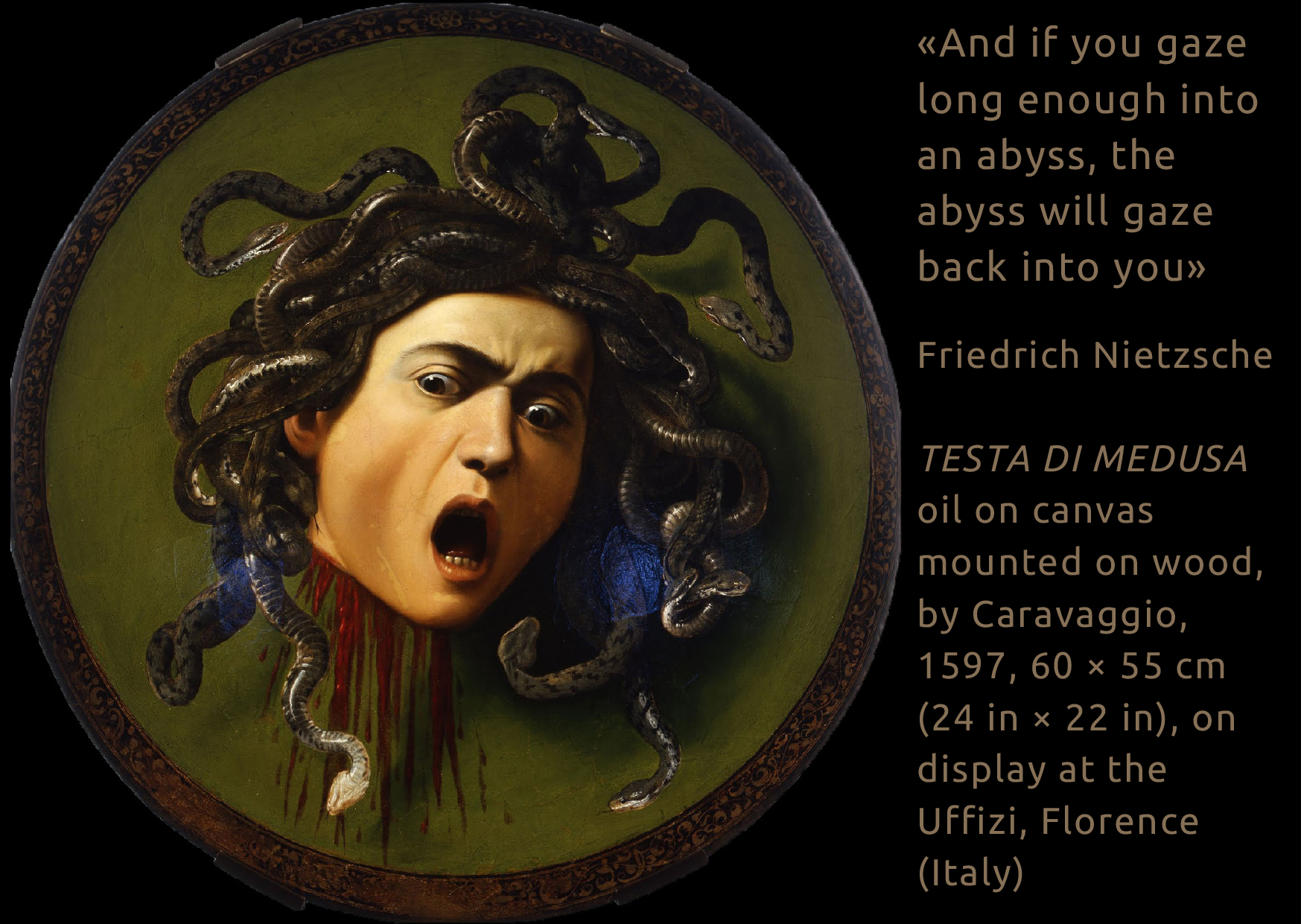

Where’s the abyss?

When you realize how easily some human beings can slaughter hundreds, thousands, and hundreds of thousands of human beings, even babies, you finally meet the Medusa, the snake-haired Gorgo. And when you assume the monster’s gaze or you witness and gaze into the monster’s gaze, at that very moment, you get petrified. Medusa’s appearance and gaze can transform you into cold, lifeless stone.

According to the Greek mythology and the Roman poet Ovid who wrote about Medusa in Metamorphoses IV, 850–8, she was once a mortal girl brutally raped by Poseidon. How could an innocent victim ever become a symbol of the most horrific life predator?

Greeks knew what innocent victims and willing executioners have in common: they’re humans.

Where’s the abyss?

Medusa hides deep inside each of us, human beings, for the simple fact of being human. When you become Medusa, you lose your life and get zombified. And when we witness and gaze into Medusa’s gaze, we cannot any longer believe and trust in our humanity, and that’s precisely what tears off our life and freezes our blood’s warmth as well. That’s the root of all traumas, as we desperately need to believe in what we are to really be and keep on living.

The Jewish culture has been giving pivotal importance to the צַדִּיק [Tsadiq], the righteous ones, remembered and honored in living gardens. Their inner “light” in times of complete “darkness” is for the Jewish culture what can show us the way to defeat the monster threat inside us. We desperately need to believe in the existence of righteous ones for ourselves to exist and thrive.

We saw how alarming was the political situation and how extreme the racial violence in Rwanda between late 1993 and early 1994. Fully grasping what was hiding under an apparently calm surface wasn’t easy. It required the knowledge of Rwandan history and politics that most top diplomats and politicians completely lacked, even those who should have had it or should have read some of the detailed reports regularly sent from Rwanda by the intelligence services.

«Because of a lack of support from UN headquarters in New York and from the members of the UN Security Council, <the UNAMIR> was not equipped to handle the rising violence» (The George Washington University – The National Security Archive – #Rwanda20yrs Project, Sitreps Detail Rwanda’s Descent into Genocide 1994, see Bibliography), which is a diplomatic way to say that the UNAMIR was politically, militarily, and economically abandoned to itself on the verge of the abyss. And those who did it have a name and bear a heavy political and moral responsibility toward Rwandans and all UNAMIR members. As we’ll see, probably a well-established mission, with well-trained men and the requested equipment, could have prevented or at least partly restrained one of the most horrific genocides of modern history.

For the sake of fairness, I’ve to say that the lack of support given to UNAMIR also depended on other factors. In those years, the UN Security Council had other priorities and the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations was in the middle of a messy situation, with many missions planned or in progress, and tens of thousands of men deployed around the world. Only in Africa, there were 7 other missions, besides UNAMIR. Rwanda was a real hotspot only for many African countries and «there were complaints from the African group at the UN that resources were being monopolized in Europe to maintain the large and costly operation in the former Yugoslavia» (L. Melvern, Conspiracy to Murder, cit.). The US and the UK were the countries who more than others insisted to turn the Rwanda mission into a small, agile, low-cost one.

An understaffed mission with an insufficient number of soldiers to cut expenses to the bone

The United States, a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council which was assessed 31% of U.N. peacekeeping costs, «had suffered from the enormous 370% increase in peacekeeping expenses from 1992 to 1993 and was in the process of reviewing its policy on such operations. In the meantime, it was determined to keep the costs of the Rwandan operation as low as possible, which meant limiting the size of the force. One U.N. military expert had recommended that UNAMIR include a minimum of 8,000 soldiers. General Romeo Dallaire, named as commander, had asked for 4,500. The U.S. initially proposed 500. When the Security Council finally acted on October 5, 1993, it established the U.N. Assistance Mission in Rwanda (UNAMIR) at a level of 2,548 troops» (Alison Des Forges, cit.). According to the Weekly SITREPS (Situation Reports) sent to New York by Commander Roméo Dallaire on December 27, 1993, the UNAMIR counted at that date only 1260 men; on April 4, 1994, immediately before the “Final Solution”, they were 2519, according to a Weekly Sitrep signed by Booh-Booh.

To the Clinton administration those men were still too many: the American «administration did not want to repeat the fiasco of US intervention in Somalia, where US troops became sucked into fighting. It also felt the US had no interests in Rwanda, a small central African country with no minerals or strategic value» (Rory Carroll, US chose to ignore Rwandan Genocide, in The Guardian, March 31, 2004; the link is here).

«Rwanda was on nobody’s radar as a place of strategic interest. It had no natural resources and no geographical significance. It was already dependent on foreign aid just to sustain itself, and on international funding to avoid bankruptcy. Even if the mission were to succeed, as looked likely at the time, there would be no political gain for the contributing nations; the only real beneficiary internationally would be the UN. For most countries, serving the UN’s objectives has never seemed worth even the smallest of risks. Member nations do not want a large, reputable, strong, and independent United Nations, no matter their hypocritical pronouncements otherwise. What they want is a weak, beholden, indebted scapegoat of an organization, which they can blame for their failures or steal victories from» (R. Dallaire, Shake Hands With The Devil, cit).

Note that the 1990-93 Genocide of the Tutsis and what was happening in Rwanda in those months wasn’t a mystery at all: the permanent members of the UN Security Council (France, Russia, UK, USA, and China) and many European countries (like Belgium and Germany) knew almost everything in detail. Despite the profusion of good sentiments and the exaltation of the values of democracy and humanism that all Western state secretariats or governments have been doing for decades with tons of moldy rhetoric, none gave a damn about the 1990-93 genocide of a bunch of black people.

A Ghanaian military peacekeeper in Rwanda

An ill-equipped mission supported by insufficient funding approved with shameful delay

The UNAMIR was not only desperately understaffed but also ill-equipped. «Partly because they counted on an easy success, partly because they were not disposed to invest much in resolving the situation in Rwanda anyway, the Security Council failed to devote the resources necessary to ensure that the hard-won Accords were actually implemented» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

«Three months after its arrival, the UNAMIR remained ill-equipped and unprepared to respond to the rising threat of violence and political instability, according to the first of dozens of UNAMIR sitreps» (The George Washington University – The National Security Archive – #Rwanda20yrs Project, The Rwanda Sitreps, see Bibliography).

The peacekeepers lacked communication equipment and radios, vehicles, especially armored personnel carriers (APC) and helicopters, medical supplies, mine detectors; and what’s worse, only the Belgian soldiers had a flak jacket. Without APC and helicopters, the members of UNAMIR could not be able to quickly neutralize violent flare-ups wherever they occurred in the country nor monitor the demilitarized zone and the Kigali area. General Dallaire had estimated that for patrolling and monitoring the demilitarized zone in phases 1 and 2 of his mission, he would have needed at least 8 helicopters equipped with night-vision capability. Only 2 private contracted helicopters with no night-vision capability arrived at the beginning of April 1994 and quickly disappeared a few days later: at the beginning of the Final Genocide, the pilots immediately fled to Uganda.

In his memoirs, Commander Dallaire wrote about the UNAMIR situation in January 1994, 3 months after the beginning of the mission: «I could use the phone on my desk only gingerly because the scrambling device attached to it never worked properly. We had begged, borrowed, scrounged, and dipped into our own pockets to buy the furniture in the room. The fax paper was doled out by the CAO <O. Hallqvist, mission’s Chief Administration Officer> as if it were gold. Everything about this mission was a struggle. (…) We had less than three days’ water, rations, and fuel; we had no defensive stores (barbed wire, sandbags, lumber and so on); no spare parts; no night-vision equipment; and severe shortages of radios and vehicles. Staff officers worked on their bellies on the floor because there were so few desks and chairs. We had no filing cabinets, which meant none of the mission information and planning could be properly secured». (R. Dallaire, Shake Hands With The Devil, cit.).

«The UNAMIR budget was formally approved on April 4, 1994, two days before the beginning of the <final phase of the> Genocide. The delay in funding, in addition to other administrative problems, resulted in the force not receiving essential equipment and supplies, including armored personnel carriers and ammunition. When the killing began in April, UNAMIR lacked reserves of such basic commodities as food and medicine as well as military supplies» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

In the following videos, Major Brent Beardsley, the military assistant to UNAMIR commander General Dallaire, explained in an interview in 2013 how the peacekeepers tried to make do and later on survive with a understaffed and undertrained force, limited equipment, limited logistical support, limited money. I don’t know whether to cry or laugh.

The problems with the mission mandate and rules of engagement

The mandate of a Peacekeeping Mission is always established by the United Nations Security Council, and UNAMIR made no exception. UNAMIR mandate was established on October 5, 1993, but it did not meet the expectations and demands of the parties who signed the Arusha Accords in August.

«Constrained by the relatively small size of the force as well as by a determination not to repeat the mistakes made in Somalia, the diplomats produced a mandate for UNAMIR that was far short of what would have been needed to guarantee the implementation of the Accords. In a spirit of retrenchment, they weakened several important provisions of the Accords. Where the Arusha agreement had asked for a force to “guarantee overall security” in Rwanda, the Security Council provided instead a force to “contribute to” security, and not throughout the country, but only in the city of Kigali. At Arusha, the parties had agreed that the U.N. peacekeepers would “assist in tracking of arms caches and neutralization of armed gangs throughout the country” and would “assist in the recovery of all weapons distributed to, or illegally acquired by, the civilians.” But, in New York, diplomats conscious of the difficulties caused by disarmament efforts in Somalia completely eliminated these provisions. In the Accords, the peacekeepers were to have been charged with providing security for civilians. This part of the mandate was first changed to responsibility for monitoring security through “verification and control” of the police, but in the end, it was limited to the charge to “investigate and report on incidents regarding the activities” of the police» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

As to the Rules of Engagement (aka ROE), namely the legally binding instructions on when, where, and how peacekeeper soldiers may use force, here is another 2013 interview of former Major Brent Beardsley, who reveals to us the unbelievable, crazy situation of the Rule of Engagement of the UNAMIR mission.

As Major Beardsley says, on November 23, 1993, Dallaire sent New York a draft set of Rules of Engagement (ROE) for UNAMIR, asking for the approval of the Secretariat. Paragraph 17 of the draft included a pivotal issue: Dallaire required the mission be allowed to act and even use force in response to crimes against humanity and other abuses. The draft by Dallaire reads: «There may be also ethnically or politically motivated criminal acts committed during this mandate which will morally and legally require UNAMIR to use all available means to halt them. Examples are executions, attacks on displaced persons or refugees». It’s a crucial al issue, isn’t it? Well, as stated by the important UN 1999 document entitled Report of the Independent Inquiry into the actions of the United Nations during the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda, New York «never responded formally to the Force Commander’s request for approval».

The gathering of essential information: God helps those who help themselves

«In Kigali, diplomatic representatives followed events carefully. Belgium, the U.S., France, and Germany all had good sources of information within the Rwandan community and frequently consulted with each other, even though there was little formal interchange among their military intelligence services. Like other U.N. peacekeeping operations, UNAMIR itself had no provision for gathering information about political and military developments. Belgian troops within UNAMIR, however, set up their own small intelligence operation and also gathered information informally from Belgian troops who were present as part of a military assistance project unrelated to the peacekeepers. Occasionally UNAMIR passed on confidential information to some of the diplomats, in one case only to find they already knew about it. Diplomats rarely shared what they knew with the peacekeepers. Dallaire later commented on this in the Canadian press: “A lot of the world powers were all there with their embassies and their military attachés, and you can’t tell me those bastards didn’t have a lot of information. They would never pass that information on to me, ever”» (Alison Des Forges, cit.).

Dallaire’s missions had no means of intelligence on Rwanda. To tell the truth, it was a Chapter-six peacekeeping mission, namely a mission that cannot run its own intelligence-gathering because under a spirit of openness and transparency. However, this lack of intelligence and basic operational information, plus the reluctance of any nation to provide Dallaire with it, turned out to be a foolish condition in the Rwandan deeply unstable and dangerous situation, as it could put at risk both the Mission’s tasks and the security of its members. That’s why Commander Dallaire «set up a two-man intelligence unit, led by Captain Frank Claeys of Belgium, with the help of a Senegalese captain Amadou Deme. (…) Because the team was not supposed to exist, I had to cover its expenses from my own pocket, and often Deme and Claeys themselves chipped in with funds» (R. Dallaire, Shake Hands With The Devil, cit.).

A Canadian peacekeeper offering aid to young children in Rwanda.

Photo: Department of National Defence, Canada

THE ‘SHADOW FORCE’

We saw how and why in late 1993 the hardliners’ strategy underwent a relevant change: the extermination of the Tutsis ceased to be a political tool to become a political goal. In the last months of that year, bringing down the Arusha Accords, continuing the war to win it, and giving the Tutsi problem its ‘final solution’ had become the faces of the polyhedric strategy developed and implemented by the Akazu and the hardliners inside and outside the Armed Forces. In the very same period, Dallaire and his officers started to become aware of the “conspiracy” of what they called a “shadow force”.

«On December 3, I received a letter signed by a group of senior RGF <Rwandan Governative Forces> and Gendarmerie officers, which informed me that there were elements close to the president who were out to sabotage the peace process, with potentially devastating consequences. The conspiracy’s opening act would be a massacre of Tutsis» (R. Dallaire, Shake Hands With The Devil, cit.).

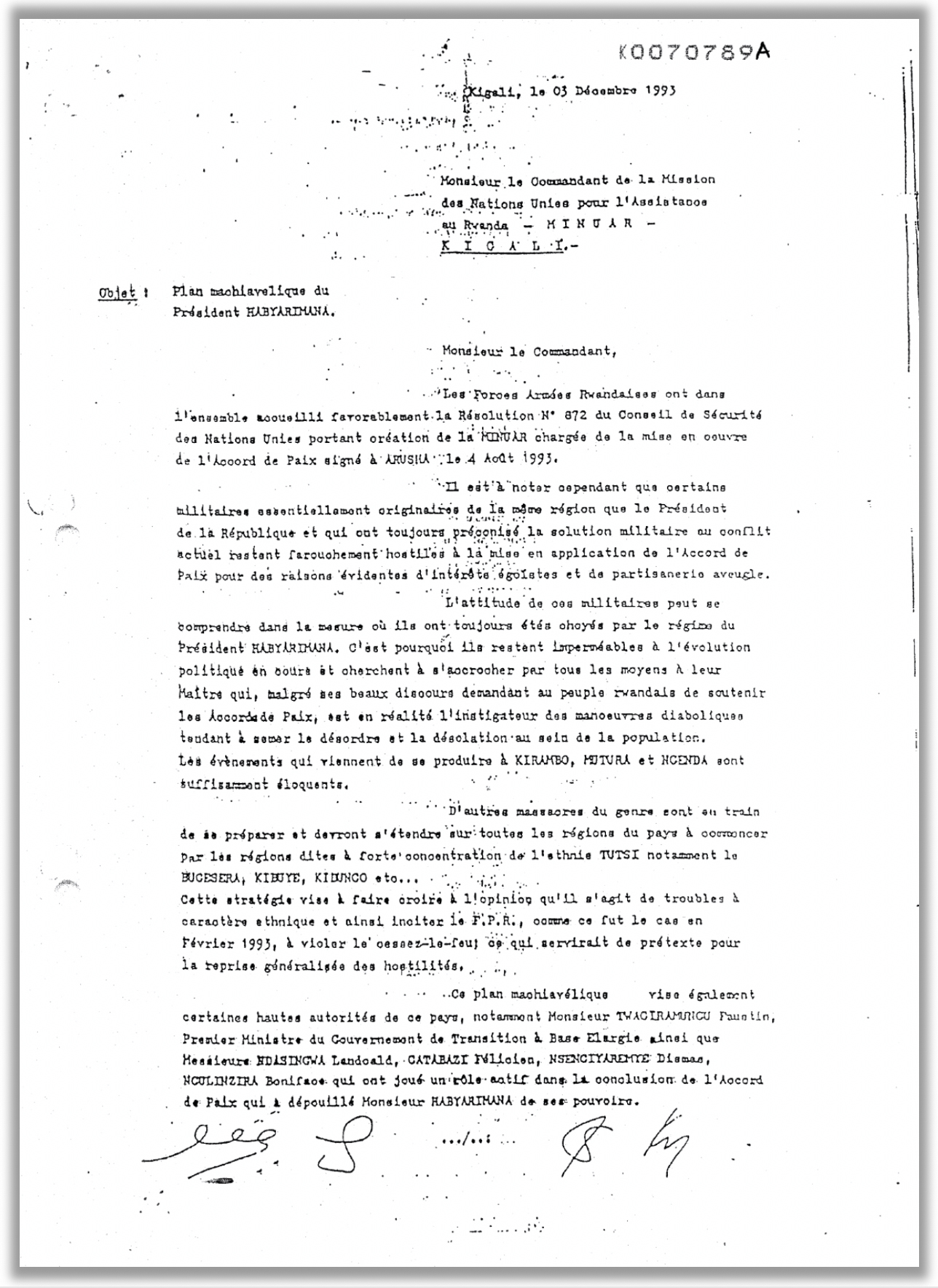

Here is the letter sent to Commander Dallaire in the original French language: it’s worth reading.

This letter in French was sent to Commander Dallaire by four anonymous senior officers of the Rwanda Armed Forces (they signed with their initials only) on December 3, 1993. Its objet is titled Plan Machiavellique du Président Habyarimana, “The Machiavellian plan of President Habyarimana”. The letter can be downloaded here, on the France – Génocide – Tutsi website. (Once downloaded the doc, please, scroll to the second copy, easier to read).

The letter, written by four senior officers who signed it with their initials to maintain anonymity, brings to Dallaire’s attention the existence of a group of military, mainly from the same region of Habyarimana, “who have always advocated a military solution to the current conflict <and> remain fiercely hostile to the implementation of the Peace Agreement for obvious reasons of selfish interests and blind partisanship” (original text: «qui ont toujours préconisé la solution militaire au conflit actuel <et qui> restent farouchement hostiles à la mise en application de l’Accord de Paix pur des raisons évidentes d’intérêts égoïstes et de partisanerie aveugle». Translation is mine). As for Habyarimana himself, the letter tells Dallaire in no uncertain terms that the President is totally unreliable: “despite his fine speeches asking the Rwandans to support the Peace Agreement, he’s in reality the instigator of a fiendish ploy with the aim of sowing chaos and desolation among the population” (original text: «malgré ses beaux discours demandant au peuple rwandais de soutenir les Accord de Paix, est en réalité l’instigateur des manoeuvres diaboliques tendant à semer le désordre et al désolation au sein de la population». The translation is mine).

Immediately after, the letter draws the attention to the November killings of civilians at Kirambo, Mutura, and Ngenda, considered an integral part of the hidden strategy of this powerful military circle: “More massacres of the same kind are being prepared and designed to spread throughout the country, beginning with the regions that have a greater concentration of Tutsi (…). This strategy aims to have the public believe that those events are ethnic troubles and to push the RPF to violate the ceasefire (…), thus creating a pretext for the general resumption of hostilities” (original text: «D’autres massacre du genre sont en train de se préparer et devront s’étendre sur toutes le régions du pays à comencer par les régions dites à forte concentrations de l’ethnie TUTSI (…). Cette stratégie vise à faire croire à l’opinion qu’il s’agit de troubles à caractère ethnique et ainsi inciter le FPR (…) à violer le cessez-le-feu, ce qui servirait de prétexte pour la reprise généralisée des hostilités». The translation is mine). The letter goes on to reveal that the Habyarimana’s circle of officers is planning to assassinate some political opponents, including Faustin Twagiramungu, a moderate member of the MDR party, future Prime Minister in the Broad-Based Transitional Government (BBTG), and Félicien Gatabazi, secretary-general of the Social Democratic Party. The latter will be killed on February 21, 1994, turning the letter into tragic whistleblowing from insiders.

Last but not least, the anonymous whistleblowers denounce the powerful military circle linked to Habyarimana as the hidden hand of what we’ve called the ‘strategy of tension’: “Kigali remains the most important target area of this terrorist group, who’s planning acts of looting, barbarity, vandalism, and assassinations in the days to come” (original text: «La capitale Kigali reste aussi la cible privilégiée de ce groupuscule terroriste. Des actes de pillage, de barbarie, de vandalisme ainsi que des assassinats y sont programmés dans les tout prochains jours». The translation is mine).

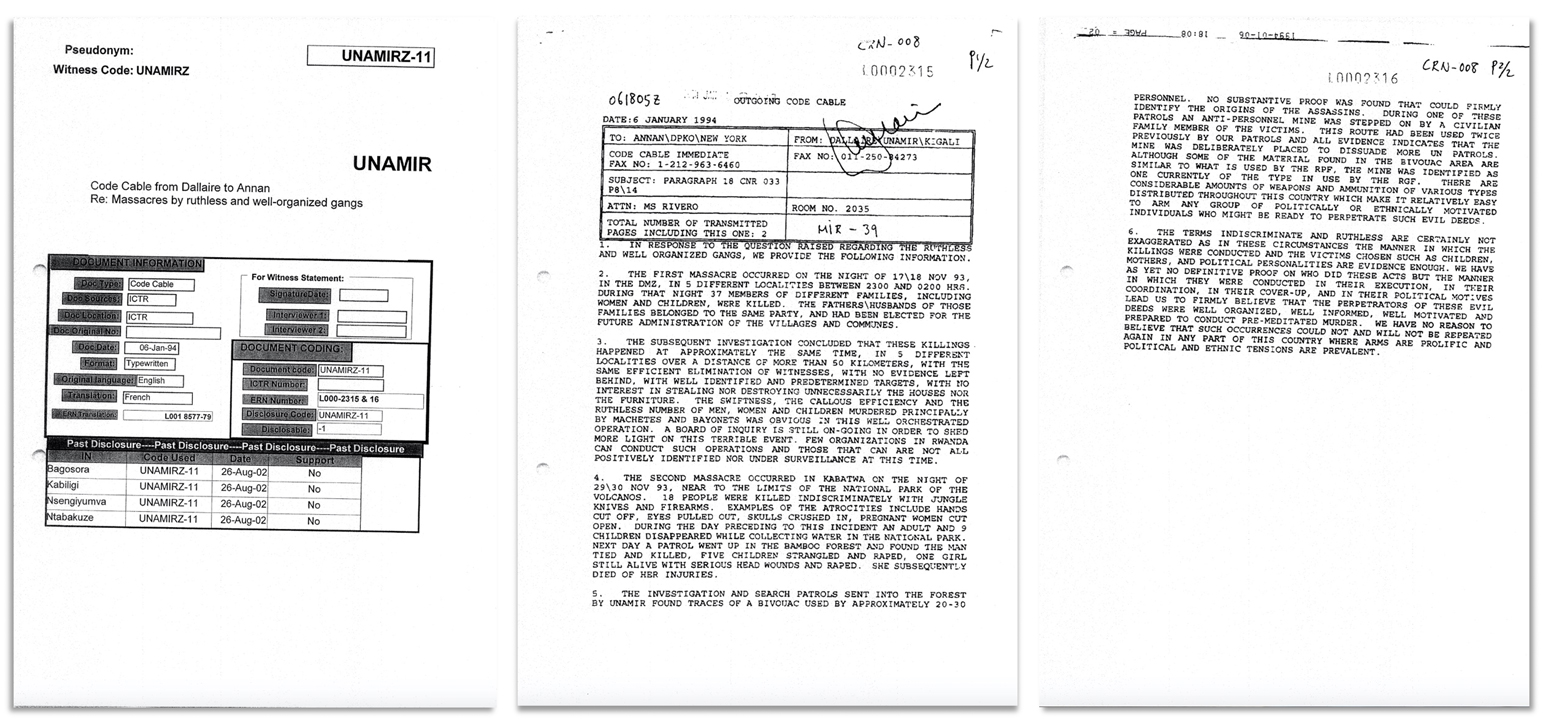

This letter, which shows the presence inside the Rwandan Armed Forces of some high-ranking officers far from the fanatic positions of the military members of Akazu and AMASASU, refers to different massacres of civilians in the Ruhengeri and Gisenyi districts during November 1993 (see RWANDA BASKETRY 5). These massacres were investigated by UNAMIR and this inquiry became for Commander Dallaire and his men a sort of painful baptism by fire. Here’s the final report on those massacres, sent by Commander Dallaire to Kofi Annan, in New York, on January 6, 1994, under the form of a code cable. I’ll quote it almost entirely (please, note that the words among <> are only mine).

This code cable was signed by Commander Dallaire and sent on January 6, 1995, to Kofi Annan, U.N., New York. It reports the results of the investigation carried out by the UNAMIR into the November massacres in Ruhengeri and Gisenyi. The document is included in a binder of code cables entitled BINDER OF REPORTS & CABLES AUTHORED BY LtGen DALLAIRE that can be downloaded here, on a page of France – Génocide – Tutsi website. The document is in English.

«2. The first massacre occurred on the night of 17\18 Nov 93, in the DMZ <my note: demilitarized zone>, in 5 different localities between 23.00 and 02.00 hrs. During that night, 37 members of different families, including women and children, were killed. The fathers\husbands of those families belonged to the same party and had been elected for the future administration of the villages and communes.

3. The subsequent investigation concluded that these killings happened at approximately the same time, in 5 different localities over a distance of more than 50 kilometers, with the same efficient elimination of witnesses, with no evidence left behind, with well-identified and predetermined targets, with no interest in stealing nor destroying unnecessarily the houses nor the furniture. The swiftness, the callous efficiency, and the ruthless number of men, women, and children murdered principally by machetes and bayonets were obvious in this well-orchestrated operation. A board of inquiry is still ongoing to shed more light on this terrible event. Few organizations in Rwanda can conduct such operations and those that can are not all positively identified nor under surveillance at this time.

4. The second massacre occurred in Kabatwa on the night of 29\30 Nov 93, near the limits of the National Park of the Volcanos. 18 People were killed indiscriminately with jungle knives and firearms. Examples of the atrocities include hands cut off, eyes pulled out, skulls crushed in, and pregnant women cut open. During the day preceding this incident an adult and 9 children disappeared while collecting water in the National Park. The next day, a patrol went up in the bamboo forest and found the man tied and killed, five children strangled and raped, and one girl still alive with serious head wounds and raped. She subsequently died of her injuries. <This girl, who was gang-raped and hit on the head with a blunt instrument, was only 6 years old>.

5. The investigation and search patrols sent into the forest by UNAMIR found traces of a bivouac used by approximately 20-30 personnel. No substantive proof was found that could firmly identify the origins of the assassins. During one of these patrols, an anti-personnel mine was stepped on by a civilian family member of the victims. This route had been used twice previously by our patrols and all evidence indicates that the mine was deliberately placed to dissuade more UN patrols. Although some of the material found in the bivouac area is similar to what is used by the RPF <a glove used by the RPF soldiers was found in one of the mass-killing areas>, the mine was identified as one currently of the types in use by the RGF <Rwandan Governative Forces>. There are considerable amounts of weapons and ammunition of various types distributed throughout this country which make it relatively easy to arm any group of politically or ethnically motivated individuals who might be ready to perpetrate such evil deeds.

6. The terms ‘indiscriminate’ and ‘ruthless’ are certainly not exaggerated as in these circumstances, the manner in which the killings were conducted and the victims chosen such as children, mothers, and political personalities, are evidence enough. We have as yet no definitive proof on who did these acts but the manner in which they were conducted in their execution, in their coordination, in their cover-up, and in their political motives lead us to firmly believe that the perpetrators of these evil deeds were well organized, well informed, well motivated and prepared to conduct pre-meditate murder. We have no reason to believe that such occurrences could not and will not be repeated again in any part of this country where arms are prolific and political and ethnic tension are prevalent».

Beardsley and Dallaire were immediately suspicious and quickly spotted the false clues scattered at the site of the second massacre as an attempt to hide and cover up the horrible crimes by ascribing them to the RPF. They both believed that para-commandos from the government side might have been responsible for the killings. All the massacres, moreover, were carried out in the North-west of Rwanda, the stronghold of Habyarimana’s party, with the intention – they believed – to destabilize the demilitarised zone (DMZ) and screw up the ceasefire signed at Arusha. Many real clues led them to support this hypothesis without however reaching any certainty. This explains the deliberately ambiguous tone of the code cable to Kofi Annan.

Early in January, only two months after his arrival, Dallaire realized that the massacres of civilians, the terrorist acts in Kigali, the distribution of tons of weapons throughout the country, and the sabotage of the Arusha Accords were all part of a strategy developed by a “shadow force”, a hidden circle of criminals controlling the country. At the end of the month, he was more than certain that the UNAMIR wasn’t going to be «a small, cheap, short and sweet mission» as the DPKO, the UN Security Council, and their ‘patron saints’ had hoped it would be.

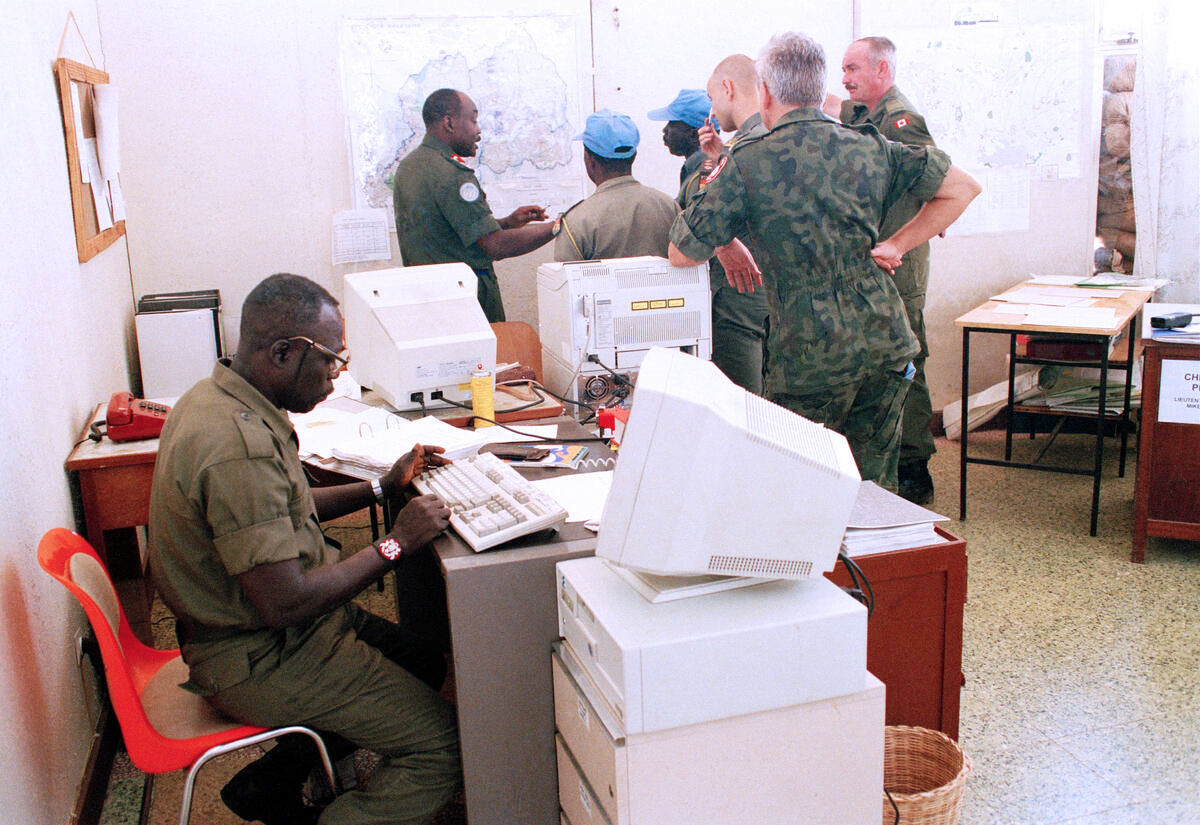

UNAMIR soldiers were briefed at their headquarters in Kigali on July 26, 1994.

Credit: UN Photo/John Isaac

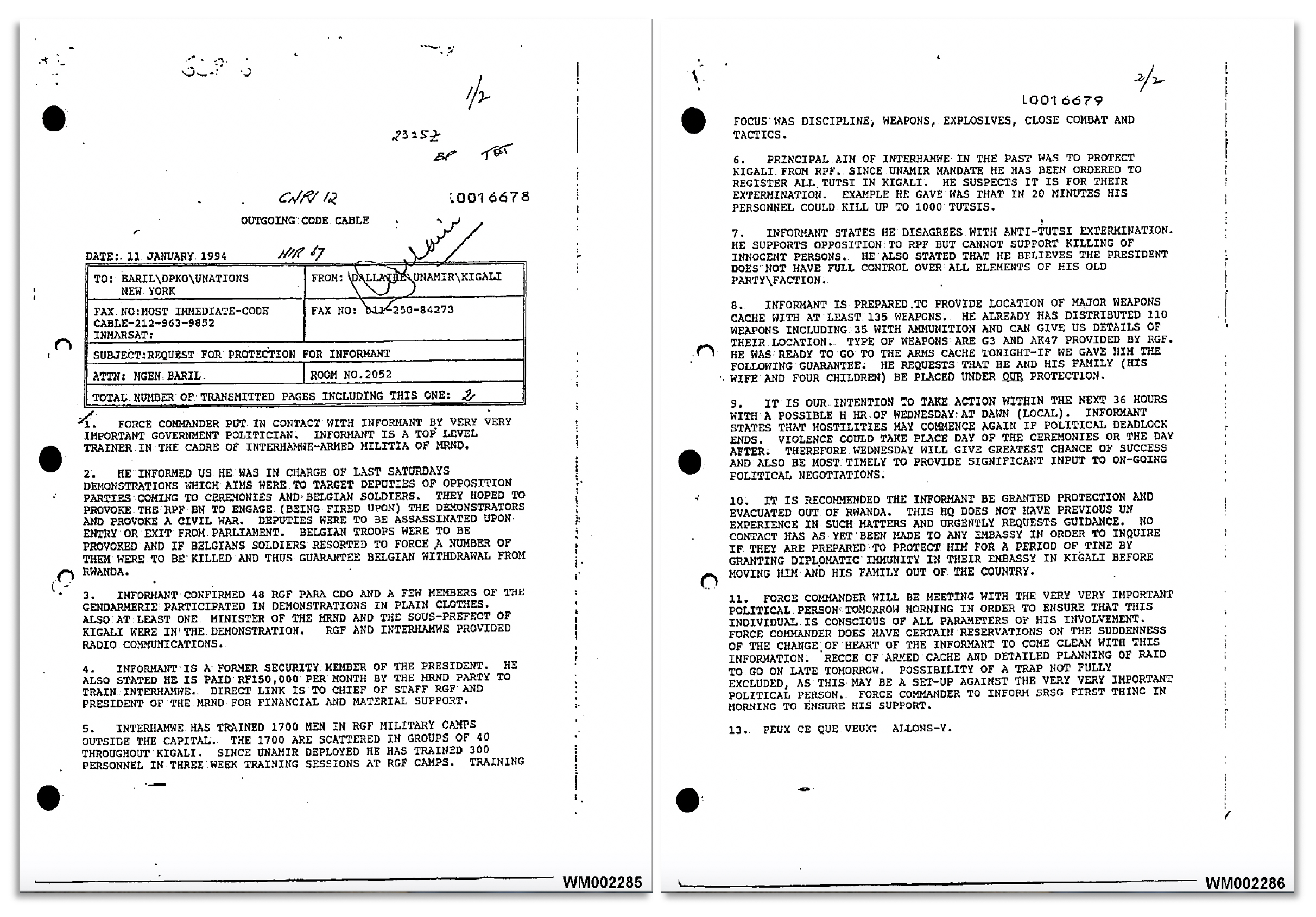

THE MOST DISCUSSED CODE CABLE OF THE HISTORY OF RWANDA

The UNAMIR had the task to turn Kigali into a weapons-secure area (according to the Kigali Weapons Secure Area or KWSA agreement): both the RAF and the RPF had to secure their weapons and only move any armed soldiers inside that area with UN permission and under UN escort. «As peacekeepers, we had to know where all the weapons were» (R. Dallaire, Shake Hands With The Devil, cit.).

January 10 was a warm and sunny Monday in Kigali. Faustin Twagiramungu, the Rwandan moderate politician who had been chosen in Arusha to lead the transitional government, entered the UNAMIR headquarters late in the afternoon and asked to urgently see Commander Dallaire. The latter wrote in his memoirs: «I took him out onto the balcony where we could talk without being overheard. Almost breathlessly, he told me that he was in contact with someone inside the Interahamwe who had information he wanted to pass on to UNAMIR. I had a moment of wild exhilaration as I realized we might finally have a window on the mysterious third force, the shadowy collection of extremists that had been growing in strength ever since I had arrived in Rwanda» (R. Dallaire, Shake Hands With The Devil, cit.).

After Faustin left, Dallaire called the Belgian Colonel Luc Marchal, who was given command of UNAMIR’s Kigali Sector and was responsible for the KWSA, briefed him on the information just received, and asked him to meet the informant from the Interahamwe militia with extreme caution, together with Captain Frank Claeys, UNAMIR information officer, and Henry Kesteloot, the operations officer of Kigali Sector. The three met the informant that very same night, at 10 pm.