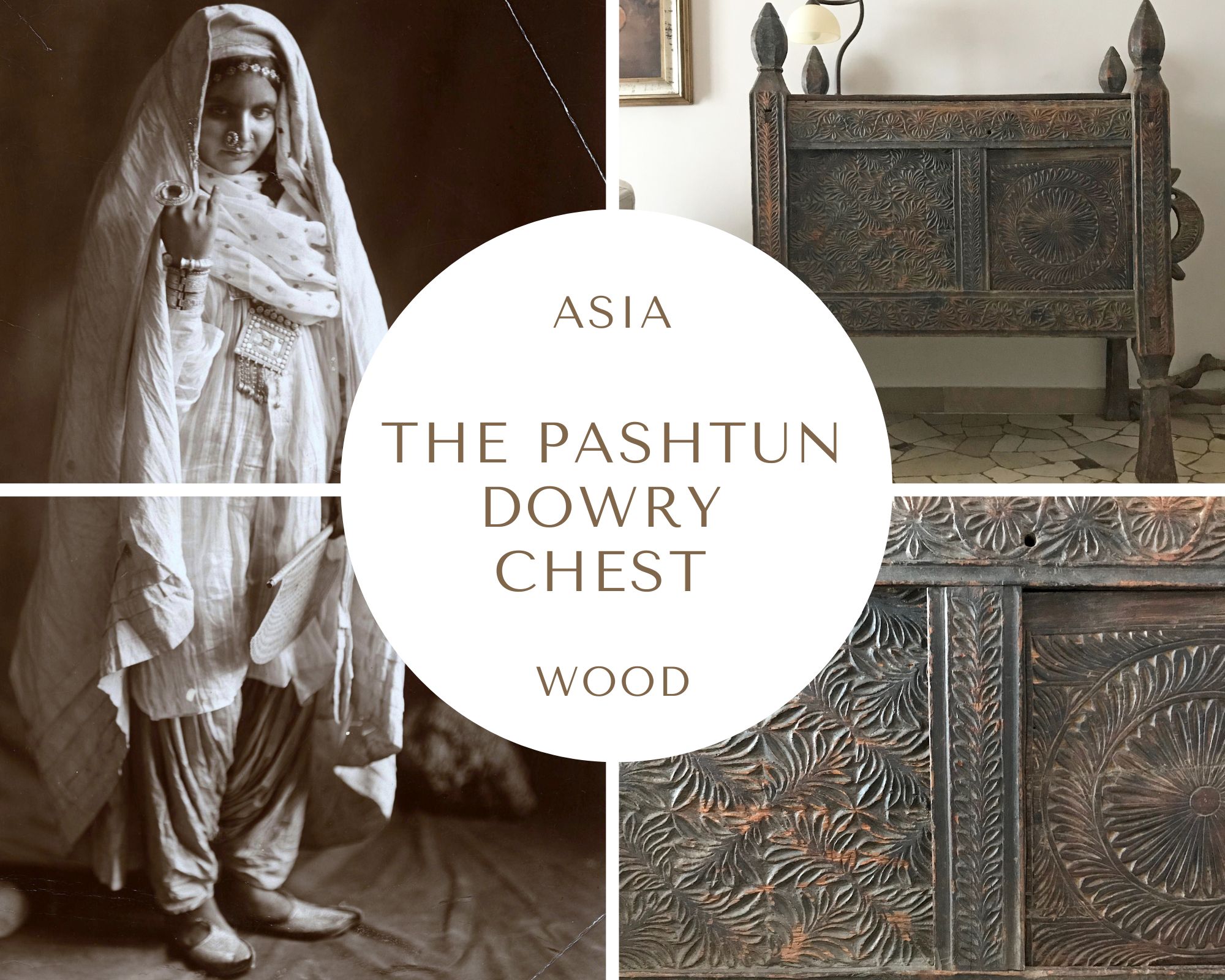

THE PINK FAMILY: CHINA AND THE WEST

Current China on the globe.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

The evolution of China’s political borders throughout 2,000 years of history, from the Qin Dynasty, 221 BC, to the end of Qing Dynasty in 1912. By Costas Melas.

LEFT: Portrait of the Yongzheng Emperor in Court Dress, by anonymous court artists, Yongzheng period (1723—35), Qing Dynasty. Hanging scroll, color on silk. The Palace Museum, Beijing. Public Domain.

RIGHT: History of China, Imperial Dynasties, source: Dynasties in Chinese history, Wikipedia.

MUSIC TO SEE: "Origin of Rice Fragrance", by the Zide Qin Club. All musicians are in Tang Dynasty costumes.

Some musical instruments left to right:

-

guqin (古琴), a plucked seven-string instrument developed in the 1st millennium BC, proclaimed as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO;

-

dòngxiāo (洞箫; 洞簫), a vertical end-blown bamboo flute, and dizi (笛子),a traditional transverse flute;

-

gu (鼓), a medium-sized drum with a barrel shape, with two heads made of animal skin (mostly buffalo hide);

-

qing or chime bowl (磬 or historically 罄), one of China’s most ancient instruments. During the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 B.C.), it was made of stone. Only later, jade and metal qings began to appear;

-

pipa (琵琶), an ancient four-string plucked lute;

-

guzheng (古筝), a plucked zither with 18-23 or more strings and movable bridges. It boasts 2,500 years of history and is the ancestor of several Asian zither instruments, such as the Japanese koto.

BORN OF EARTH AND FIRE: THE CHINESE PORCELAIN

The Chinese civilization is one of the world's oldest and most refined, and the richness and originality of its culture are well represented by a long list of inventions that have changed the whole of the world: paper making, movable type printing, gunpowder and fireworks, compass, silk, umbrella, toilet paper - yep, it was invented during the Sui Dynasty, 581-618 AD, and used in all subsequent dynasties, while the rest of the world was using shelled corn cobs, snow, mosses and lichens, algae, wool waste, water-soaked sponges (in ancient Rome), hay or straw, dry leaves, tufts of grass, rags. The list of Chinese inventions goes on: wheelbarrow, playing cards, cast iron wok, spaghetti, wrought iron, banknote, cannon, teapot, mechanical belt drive, acupuncture, bristle toothbrush, fingernail polish... and porcelain, of course.

What’s more Chinese than porcelain?

China was defined as "the millennia-old land of porcelain". As the first porcelain was created in China, porcelain items from that country were soon called "china" in the English-speaking world. Still today, "chinaware" means tableware made of china or porcelain. The latter has its perfect equivalent in the French porcelaine, Italian porcellana, Spanish and Portuguese porcelana, Dutch porselein, and German Porzellan.

The etymological root of all these terms is the same: they all come from the term used in Le devisement dou monde, or the Livre de Marco Polo citoyen de Venise, dit Million, in Italian Il Milione, by Marco Polo (1254–1324), the Venetian merchant and explorer who traveled to Cathay (north China) and Manji (south China) between 1271 and 1295. The memoirs of Polo were drafted by Rustichello da Pisa between 1298 and 1299 in the Franco-Venetian language, a variety of Old French heavily flavored with Venetian dialect, widespread as a literary language in the Italian subalpine belt in the 13th and 14th centuries.

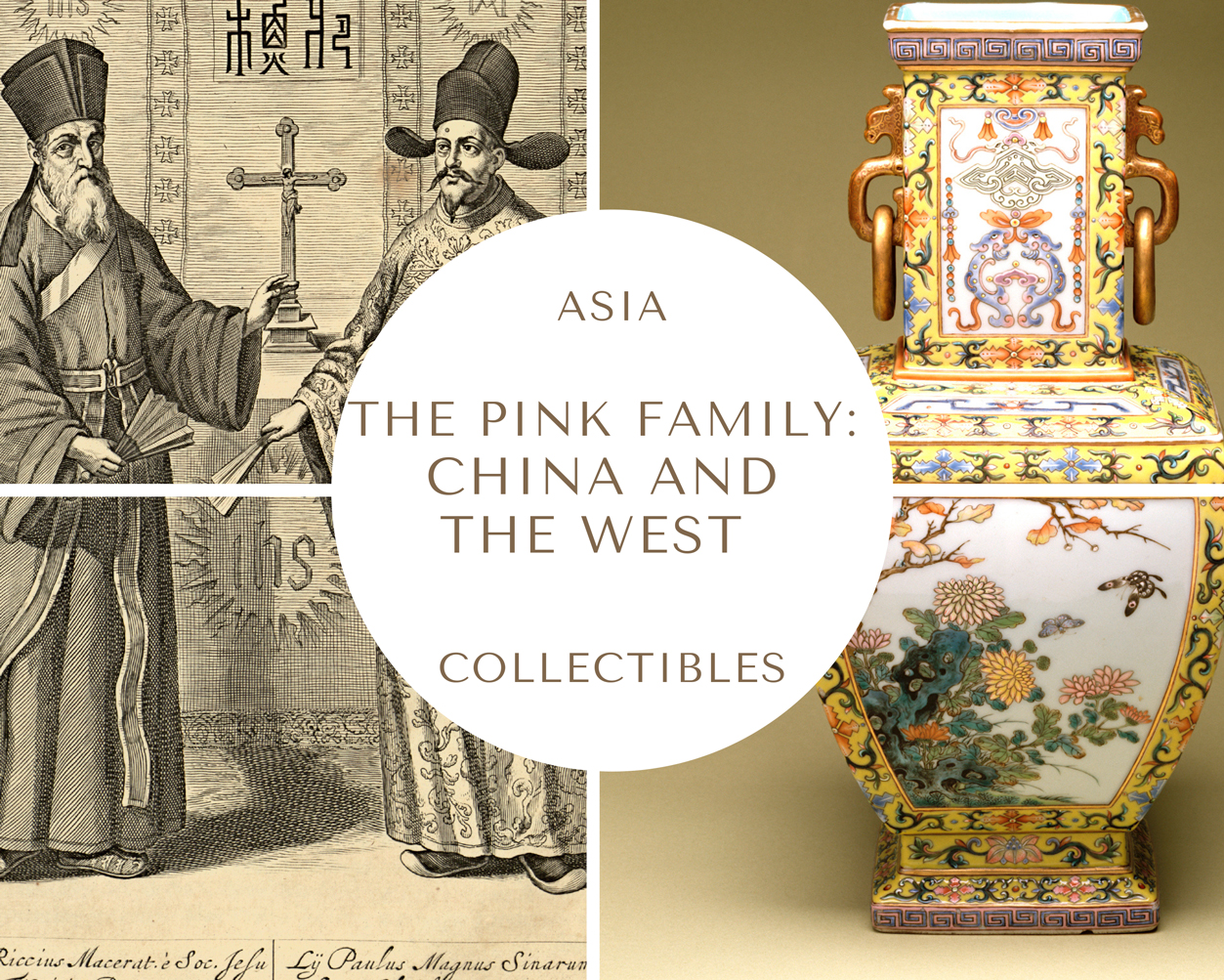

Marco Polo remained at the imperial court in Khanbaliq, present-day Beijing, from 1271 to 1295, and served the Mongol emperor, Kublai Khan, aka Emperor Shizu of Yuan or Setsen Khan, Genghis Khan's grandson and the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China. In his memoirs, Marco Polo/Rustichello da Pisa used the term porcelaine both to indicate a white sea shell - «porcelaine blanche, celle que se troven en la mer» - and a special kind of fine ceramic: in the city of Tenugnise, «se font escuelle de porcelaine grand et pitet; les plus belles que l'en peust deviser.... Et d'iluec se portent por mi le monde» ("In the city of Tiungiu, they make the most beautiful, large and small porcelain bowls, exported all over the world").

Left: white cowrie shells of the genus Cypraea achatidea.

Right: detail of a rare Yuan Dynasty Shufu porcelain bowl, made in Jingdezhen, in in the first half of the 14th century.

When the Chinese porcelain pieces systematically reached Europe during the 16th century, much later than Marco Polo, the Westerners couldn’t figure out how porcelain was made. Many thought it was a special kind of stone with a smooth and unblemished surface. «An account from 1550 suggested that “porcelain is likewise made of a certain juice which coalesces underground and is brought from the East.” In 1557, someone offered the more imaginative hypothesis that “eggshells and the shells of umbilical fish are pounded into the dust which is then mingled with water and shaped into vases. These are then hidden underground. A hundred years later they are dug up, being considered finished, are put up for sale”» (Thessaly La Force, The European Obsession with Porcelain, The New Yorker, November 11, 2015). «Gaspar da Cruz (ca. 1520-1570), a Portuguese Dominican whose remarkable account was published in 1569, wrote: "There are many opinions among the Portugals who have not been in China, about where this porcelain is made, and touching the substance of which is made, some saying of oyster-shells, others of dung rotten for a long time”» (Anne Gerritsen and Stephen McDowall, Material Culture and the Other, see Bibliography). None could imagine that porcelain masterpieces were born from a mixture of dirty mud clay and human genius.

However, "porcelain" is a problematic term when used for Chinese wares.

In the article dedicated to The Japanese Art of Kintsugi, we saw that different cultures may have different ways of thinking, conceptualizing, and categorizing things; therefore, many times, the semantic fields of translatable words are not equivalent. The Chinese term for porcelain is ci, 瓷 (to be pronounced approximately as /tzə/), whose meaning is, however, quite different. «In the West, porcelain, strictly defined, is a ware that is hard, white, translucent, impervious to liquid, and resonant when struck. Porcelaneous ware <grès cérame porcelainé in French> is a term sometimes used to denote wares that are superior to the average stonewares, yet not quite "true" porcelain in the Western sense. Dividing lines between these classifications are very subtle and, in practice, are not always possible to draw. Generally, the Chinese and Japanese classify all ceramics that are resonant when struck, whether they are white-bodied and translucent or not, under an all, inclusive umbrella term. They are called ci in China and ji in Japan, and the written character is the same in both languages. For ci, most Chinese-English dictionaries offer "porcelain", "crockery", and/or "chinaware" as translations. Vessels described as ci in China may be considered to be either stoneware, porcelaneous ware, or porcelain in Europe and America. These differences in terminology can make it rather difficult for Westerners to determine the character of the early white wares described in Chinese archaeological reports» (Suzanne G. Valenstein, A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics, Revised and Enlarged Edition, see Bibliography), and to determine the date of birth of porcelain as well.

I will use the term 'porcelain' in the Western meaning, always paying attention to its discrepancy with the Chinese ci, and I will adopt the European point of view which differentiate stoneware and porcelaneous ware from porcelain, according to the body composition and the combination of firing time and temperature.

The earliest type of porcelain was made in Northern China during the Tang Dynasty (618–907), in the 7th century AD, while porcelain production began in Japan in the early 17th century, approximately a thousand years later. In China, «the progression from porcelaneous wares to "true" porcelain – essentially a matter of refinement – probably was a gradual one. Porcelains with hard, dense, impervious, resonant, white, translucent bodies and hard glazes that adhere firmly to the body became a reality when Chinese potters 1. arrived at the proper composition of the body and the glaze and 2. learned to fire their wares at the combination of temperature and time necessary to vitrify the body and fuse the glaze» (Suzanne G. Valenstein, cit.).

At the time of Marco Polo and later on, during the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368), refined porcelain and high-fired glazed stoneware pieces were produced for the imperial court, and both domestic and foreign markets. They were massively exported, but not all over the world, as the Venetian traveler made it write. The Chinese porcelain and stoneware pieces reached Japan, Korea, the Philippines, Indonesia, and India by sea, while the caravans which crossed the ancient Silk Road, at the time entirely controlled by the Mongols, brought thousands of precious wares to the western Muslim world: the Turkish Anatolia, the Persian world, the Arab countries - from Damasco in Syria to Morocco, via Cairo, in present-day Egypt. The ships reached the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, the Red Sea, and the African East Coast. The Chinese masterpieces could be sold even in Somalia.

These commercial and cultural exchanges were made possible thanks to the Pax Mongolica, a peaceful period of political stability that followed the Mongol conquests and benefited the social, cultural, and economic life of many people living in the Eurasian territory. The Mongols, including the Yuan Dynasty in China, not only encouraged long-distance trade but also developed communication along the Silk Road by establishing a postal relay system, allowing people of different religions to coexist and favoring the merging of cultures.

Thanks to the Pax Mongolica, Marco Polo could reach the Kublai Khan's court in Khanbaliq. And thanks to the cultural and commercial vitality fostered by the peace, Chinese porcelain knew one of its most outstanding and creative breakthroughs.

The rise and fall of the Mongol Empire by Anne F. Broadbridge, TED-Ed

What kind of porcelain and stoneware pieces did the Chinese of the Yuan Dynasty massively produce and export?

What innovation changed the history of porcelain during and after the stay of Marco Polo?

We are about to answer these questions and begin an exciting journey into the world of Chinese porcelain and art, a realm of pure beauty, perfection, and sublime refinement.

The millennial history of Chinese porcelain experienced periods of intense innovation and breakthrough, often sprung from the cultural encounters China had with different cultures and its capacity to metabolize and sinicize foreign artistic trends. In the history of Chinese porcelain, China has repeatedly encountered the West, its West, of course, namely the world to the west of its immense borders: Islam before and the European world after. The encounter between Chinese literati and Italian Jesuit missionaries in the early 17th century changed the history of porcelain and art. Chinese literati and Italian Jesuit missionaries could not have been more different, but nonetheless, they were able to build a peaceful bridge where they could meet and develop a fruitful intercultural dialogue. That bridge collapsed not because of its intrinsic fragility but because it was brought down by political wills. China and the West ceased to know each other, looked at each other in the false light of stereotypes and business interests, and finally warred. It's a long history we will venture into. It's a story of supreme beauty and profound pain. It's the story of what happens when culture is silenced. So, sit back, relax, and enjoy a long journey that will change both your eyes and the way you see the world.

GREENWARE AND CELADONS DURING THE SONG AND YUAN DYNASTIES

What kind of porcelain and stoneware pieces did the Chinese of the Yuan Dynasty massively produce and export via the Silk Road and the Maritime Tea Routes?

Many monochrome pieces were evolutions or developments of old ones. Among them, the most appreciated during the preceding Song dynasty (960-1279) and highly prized throughout Asia were the greenware, known in Chinese as qingci (to be pronounced approximately as /chiŋ -tzə/) and called celadons in the Western world.

GREENWARE: QINGCI AND LONGQUAN CELADONS

The term "greenware" encompasses all pieces made of porcelaneous stoneware or porcelain, fired at a high temperature and showing a jade green glaze. The group includes the famous Longquan celadons, made in the Zhejiang province, in Southeastern China (Longquan pronunciation is approx. /lɔ:ŋ- tʃüan/).

The "glaze" is a layer applied to a raw and unfired ceramic body or to an already fired piece. Thanks to the firing or refiring process, it fuses with the ceramic body and becomes a protective, impervious, vitreous (glass-like) coating which removes the intrinsic porosity of unglazed biscuit and makes the pieces suitable for holding liquids and perfect for everyday use. The glaze, which after firing can be waxy and opaque or translucent and glossy, has a prominent aesthetic function as well: it can have an impressive decorative effect by enhancing the underlying design; it can give the surface a rich texture, the smoothness, and the evenness of a polished jade; it can intensify the plasticity of the piece, enhancing its luminescence and changing its relationship with the environmental light and the surrounding space. The glaze was applied via different techniques: a piece could be dipped in the glaze liquid, or glazed by brushing the liquid with a paintbrush or spraying it with a mouth airbrush.

The glaze used to create greenware is a special one, whose chemical formula the potters of the Song Dynasty kept in secrecy and mastered with unsurpassed prowess. We know it was compounded from violet-golden clay and a mixture of burnt feldspar, limestone, quartz, and plant ashes.

Here, there are two Longquan stoneware funerary urns made during the Southern Song dynasty. Around both bases, you can see small patches of unglazed stoneware.

Pair of Longquan greenware funerary urns with applied animals, probably forming the ‘animals of the four directions’ motif (四靈). Height 9.9 inches - 25.2 cm. Made in Longquan region, Zhejiang province, Southeastern China, during the Southern Song Dynasty between the 12th and the 13th centuries. © The Trustees of the British Museum

Both vases have a pale greyish-green Celadon glaze. The vase on the left shows the White Tiger of the West pursuing a dog; the one on the right shows the Green Dragon of the East chasing a flaming pearl. The birds on the covers may allude to the Red Bird of the South, but the symbols of the north (a tortoise with a snake) are missing. The lower part of both urns is decorated with overlapping lotus petals. According to the British Museum curators, these jars stored provisions for the afterlife such as grain, and are part of local southern burial practice.

The massive production and export of greenware and Longquan celadons continued in the Yuan era when it became a significant source of revenue for the imperial coffers. The following picture shows three Longquan greenware vases made respectively during the late Song and the Yuan dynasties.

Left: Longquan stoneware vase with a peony scroll decoration, made in Longquan, Southern Song dynasty, 13th century; preserved at the Matsuoka Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan (please, note the anti-seismic fastening). The height is unknown but the vase is smaller than the following two pieces.

Centre: Longquan stoneware vase with a peony scroll decoration, height: 19 1/2 inches - 49.5 cm, made in Longquan, Yuan dynasty, mid-14th century. The MET, New York, US.

Right: Longquan stoneware vase decorated with peony scrolls, height 57.70 cm, made in Longquan, Yuan dynasty, approx. 1300-1368. British Museum, London, UK. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

These three vases show the same form, called yen yen in Chinese and "phoenix tail" in English, and similar decorative motifs: an applied molded decoration of peonies around the belly, incised horizontal ridges below the flared rim, and stylized lotus petals around the lower part. They have, however, very different tones of glaze.

The peony has been a symbol of prosperity, happiness, and wealth since the Tang dynasty; it's a frequent motif both in the Song dynasty and in the Yuan dynasty wares. Lotus blossoms and leaves are widespread symbols and decorative motifs of Buddhist origin.

The celadon glazed pieces can display a widely varying degree of color tone, from light bluish to grey-green, jade green, and even deep olive green shades. (The chromatic differences among the above vases might not be as you see them on the display of your electronic device).

The glaze applied on the ceramic body of a piece includes iron oxide among its components. The chemical composition of the glaze (in particular the amount of iron oxide and titanium oxide), the thickness of the applied glaze, and the combination of firing time and temperature in a reductive kiln atmosphere (= lacking free oxygen) can give the semi-transparent, luminescent, glassy surface a varying range of light bluish green (called plum-green or meizi ching in Chinese and kinuta in Japanese), lavender grey (fen ching), bean green (dou ching), blue-green, jade-green, grey-green, green-brown or olive-green tones.

The iron oxide contained in the glaze is converted to ferric oxide during an oxidation firing. A presence of iron oxide lower than 0.63% produces an ivory or whitish glaze; a slightly higher content gives a creamy glaze; an amount of 2-4% a yellow or amber tone, and over 4% a brownish tone. An iron content of 8% gives a black glaze.

The iron oxide contained in the glaze is converted into ferrous oxide during a reduction firing. A ferrous oxide of 0.5-1% gives an icy-blue tone (typical of the Qingbai wares, as we will see later on); a 4-8% shiny black. To create the celadon glaze, the iron content has to be 1%–3%, with a small amount of titanium oxide (0.2 to 0.5%). The latter gives a yellowish tinge, and certain combinations of the two oxides lend an intense olive-green tone to the glaze.

Left: Small stoneware bowl with carved and combed lotus decoration under a deep olive green 'celadon' glaze, made in 960-1127, during the Northern Song dynasty. Diameter: 14 cm. It's not a Longquan celadon piece: it was made in the Yaozhou kilns, in the Shaanxi province (Northwestern China), specialized in the production of objects with bold carved or molded designs under a green olive glaze. Preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

Centre: Longquan greenware dish with scalloped edge, incised and molded peony design in the center, and characters meaning 'great good fortune' (da ji ). Made in Longquan (Southeastern China), during the Yuan dynasty, in the 14th century. Diameter: 27.3 cm. Preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

Right: Large Longquan stoneware dish with a thick green celadon glaze, and scalloped edge; it's decorated with incised scrolls, a 'chevron-and-scale' pattern, and a central stylized flower under the glaze. It shows four molded and unglazed fish in relief, made separately and applied to the unfired glaze; during the firing, they acquired a brownish-red color. Made in Longquan during the Yuan dynasty in the 14th century. Diameter: 31.5 cm. Preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The following piece is a Longquan stoneware incense burner made in the late Southern Song dynasty with a grey-green celadon glaze, very different from the above pieces. Its shape perfectly embodies the harmonic synthesis of form and function and the quintessential view of restrained elegance of the Song dynasty imperial court.

Longquan stoneware incense burner with dragon-shaped handles and a grey-green celadon glaze. Height: 9.40 cm; diameter: 13.50 cm. Southern Song dynasty, 1127-1260. British Museum, London, UK. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Note the unglazed patch on the lower left handle.

The burning of incense (xiang 香) was common in religious ceremonies, traditional medicine, ancestor veneration, and in daily life. The incense burner or censer, called xianglu (香爐), could be made of various materials, including glazed stoneware and porcelain. Some ceramic censers showed an extremely elaborate design, others a minimalist shape. Some were designed as sacred mountains, with special apertures that gave the incense smoke the appearance of clouds or mist swirling around the peak. Others, like the above piece, embodied the perfect balance between function and form and showed a shape inspired by the archaic gui, typical of ancient bronze ritual food vessels.

Below, you can see two Longquan celadon tripod incense burners made during the Yuan dynasty, with different designs and glaze. (Their glaze color is slightly more greyish than the tone on your screen).

Left: Longquan tripod incense burner with green celadon glaze, three claw-shaped feet, and two side handles. It was modeled on an archaic bronze food vessel called ding. The decoration was applied beneath the glaze: lion heads on the feet, dragon heads on the handles, and two monster masks on the body. Diameter: 23.1 cm. Made between the late Yuan and the early Ming dynasties in the second half of the 14th century. British Museum, London, UK. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Right: Longquan tripod incense burner with green celadon glaze, lion's paw-shaped feet with animal mask at the top, and the Eight Trigrams in relief around the belly. Height 22,8 cm, width 23.2 cm. Yuan Dynasty, 14th century. British Museum, London. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The Eight Trigrams (bagua, 八卦) are an ancient set of 8 symbols, each consisting of three broken or unbroken lines, representing yin and yang. The bagua is rooted in the Taoist (or Daoist) philosophy and cosmology.

TO CRACKLE OR NOT TO CRACKLE

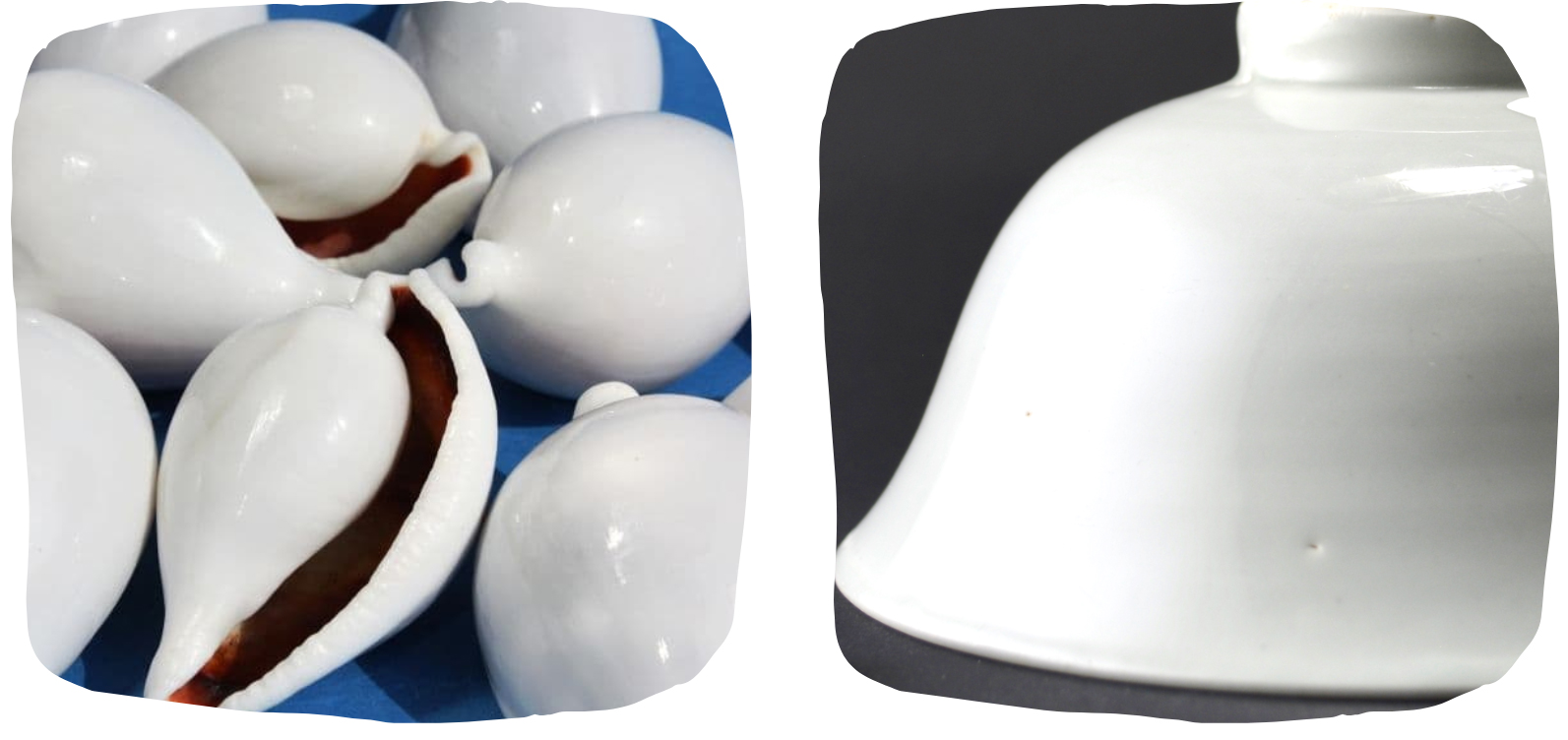

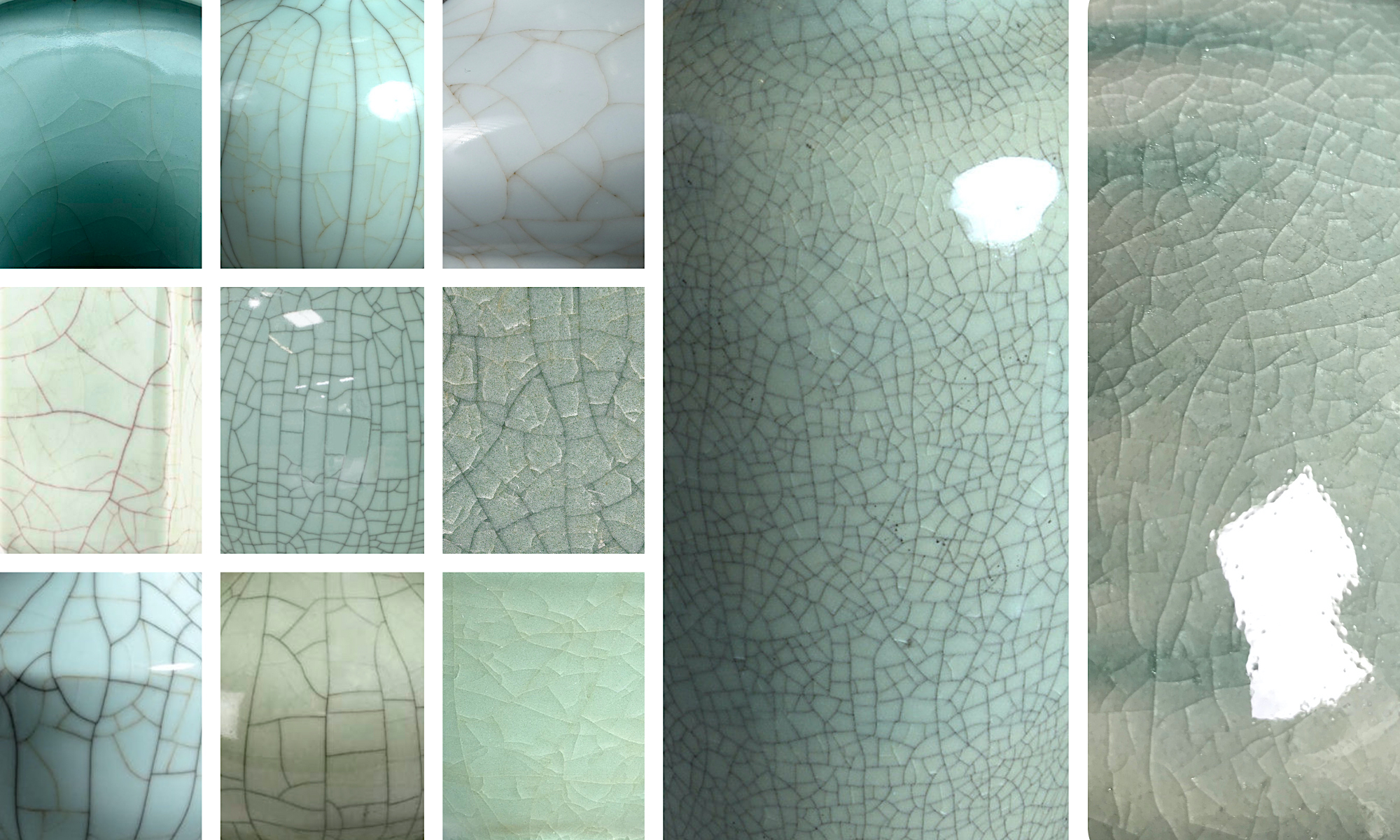

Look carefully at the two following Longquan celadon vases, two elegant pieces with traditional forms made respectively in the Song and the Yuan dynasties.

Left: Mallet-shaped zhichui ping Longquan greenware vase with dragonfish handles and a cracked kinuta glaze. Height 6 3/4 inches - 17.1 cm. Southern Song dynasty, 12th–13th century. The MET, New York, US. The bluish-green glaze color of this vase was highly appreciated by the Japanese who called it kinuta ("mallet").

Right: Gu-form 'Beaker' Longquan greenware vase with pale greyish green crackled glaze. Height 19.2 cm. Yuan dynasty, 1280-1368. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

This vase replicates the shape of the ancient ritual drinking vessel made of bronze and called gu. «Wealthy aristocrats and generals of the Shang and Zhou dynasties (about 1600–256 BC) buried bronze vessels as part of ritual eating and drinking equipment for tombs» (The British Museum); the bronze gu was one of them. The shape was transformed into a vase much later, during the Song dynasty (960-1279).

Did you note the craquelure or 'crazing', namely the cracked surface of both pieces? It is not due to their venerable age, nor to mistakes made during their production or preservation. It was wittingly produced by Longquan master potters, thanks to a virtuoso technique and following a peculiar sense of beauty.

Here are three exquisite vases: the first two are Longquan greenware pieces, the third a Ge-ware with a pale beige-green crackled glaze.

The first is a rare masterpiece: it's a Longquan celadon hu-shaped vase made during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279). It was auctioned by Christie's in New York, in 2018, for over a million US dollars (US$ 1,092,500 to be precise). Look at its surface: its lustrous glaze of bluish-green tone is suffused with extensive small ice crackles and a wider network of gold crackles which give a three-dimensional, lived-in effect to the surface.

Longquan celadon Guan-type, hu-shaped vase made during the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279). Height: 8 7/8 inches - 22.5 cm. Photo © Christie's.

«The pear-shaped body of oval section is divided into four horizontal registers which have raised vertical ridges on four sides simulating the flanges of archaic bronze vessels, and is flanked by two lug handles. The vase is covered overall with a lustrous glaze of bluish-green tone, suffused with extensive ice crackles and a wider network of gold crackles» (Christie's curators, from the auction official catalog).

The shape was inspired by the hu form of archaic ritual bronzes from the late Shang dynasty, approx. 13th-11th centuries BC.

According to Suzanne G. Valenstein, Longquan Guan-type wares were stonewares with dark clay bodies (look at the unglazed base rim) and luscious celadon glazes with distinctive crackles, closely resembling the Guan ware made at the Jiaotan kilns in Hangzhou, on the eastern coast. Pieces like this were quite thinly potted; the bodies of smaller pieces reportedly can be only 1 mm thick. The glaze, often thicker than the body, was sometimes applied in perceptible layers.

The following piece is a Longquan celadon vase with a glazed surface. Like the one above, this vase shows a fine brown-stained crackle which seems to lie on top of a smaller ice crackle pattern.

Longquan greenware Changjing ping vase with long tubular neck, flared mouth, and inverted rim. The vase has a blue-grey glaze with fine brown-stained crackle and ice crackle. Height: 39 cm. Late Southern Song dynasty or early Yuan Dynasty, 13th century. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

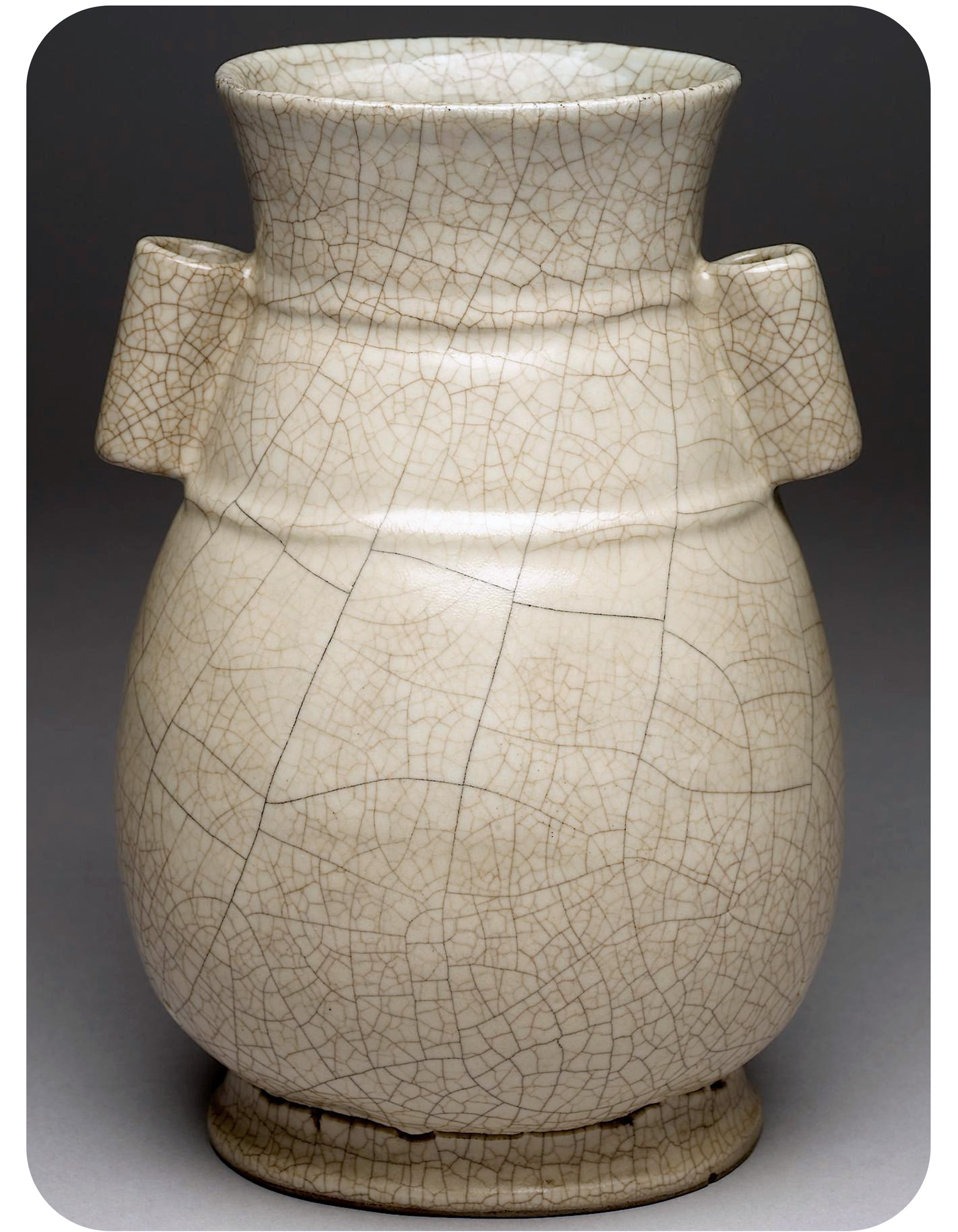

The piece below is not a Longquan celadon vase but a Ge ware vase with a crackled pale beige-grey glaze and the typical hu form, made in the Zhejiang province (the same as Longquan) during the Yuan dynasty, 1279–1368. Look at its crackled glaze.

Ge ware vase showing the ancient hu bronze form, with flattened ovoid body, flaring mouth, and two tubular handles between two bands of low relief around the shoulder. The vase shows a thick, opaque beige-grey glaze with two layers of crackle, the wide crackle stained grey and the fine crackle golden brown. Height: 24.4 cm. Made in the Zhejiang province during the Yuan Dynasty, between the 13th and the 14th centuries. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Note that the fine network of fractures in the glaze of the above vases does not give rise to a rough surface: the texture is fine and smooth to the touch.

Seeing a magnificent celadon piece with a cracked glaze on a screen or behind the glass case of a museum is not the best way to capture its beauty. All porcelain pieces are three-dimensional tactile objects that cannot be reduced to their visual decoration. You must touch them, make them sound, and even sense their fragility and strength with closed eyes. A Chinese porcelain masterpiece is not made to be admired at a distance, behind the glass of a display case, or on a screen. Oriental beauty is a spirit to live in and an atmosphere to breathe. It's the harmony and the balance between your interior and your exterior. So, find a nearby Oriental furnishing store or an Asian porcelain shop (amazing celadons are today produced in China, Korea, Japan, and Thailand). You don't need to buy anything; just touch some celadon pieces, and find a cracked celadon tea cup to hold in your hand. Many celadon teawares show an almost invisible web of crazing that becomes progressively more visible the more you drink tea: the crackle web stains due to the tea's antimicrobial tannins (thus fulfilling a double function). In Ancient China, staining with iron oxide or charcoal was added to some pieces to highlight their unique, evocative cracks.

As we saw, the ancient Chinese celadons can be of two kinds: with or without a deliberately induced crackled design in the glaze. During the Ming dynasty (which followed the Yuan), this traditional classification took the name respectively of Geyao and Diyao, from the legendary tale of the two brothers Zhang who lived in Longquan and were masters at making ceramics, though in two different ways. The celadons of the ‘elder brother’ Geyao showed a fine web of crazing in the glaze, while those of the ‘younger brother’ Diyao had an uncracked glaze.

The crazing in the glaze of a piece was initially the product of a failure, a disaster due to the different thermal expansion coefficients in the porcelain body and glaze in the firing phase. In particular, during the cooling process, the body and the glaze begin to contract; if for chemical reasons, the coefficient of contraction of the glaze is higher than that of the body, the glaze layer is subjected to intense stress and strain, and begins to crackle, slowly creating the intricate web that you can see on a finished piece.

The production and appearance of glaze crackles can be induced by controlling multiple factors: the chemical composition of the body and the glaze; the thickness of the glaze (often applied in multiple well-calibrated layers: the cracks won't form if the glaze is too thin, and will collapse if the glaze is too thick); the temperature and atmosphere inside the kiln during the firing phase; the rapidity and temperature of the cooling process. Even a tiny error in only one of these factors will result in failure, but the failure here is turned upside down: it's the absence of the desired crackles.

The Chinese tradition recognizes different crackle patterns: cracked ice, large crab claw, ox hair, water flow, willow-leaf, fish roe, eel-blood ice cracks, hundredfold crackle, plum-blossom-petal dark pattern, cicada's wing (horizontal pattern), small fish-egg, among others. Each of them is revered for its charming features, reminiscent of a natural phenomenon, and its apparent naturalness. All patterns give the impression of being fortuitous outcomes, random creations of nature, but are instead the product of an extraordinary technical virtuosity at the service of an artistic ideal and an aesthetic sentiment. They are so perfectly under human control to look as if they were beyond it.

Chinese Celadon Orchestra

BOTH GENGHIS KHAN AND THE CHINESE CELADONS CONQUERED HALF OF THE WORLD

Longquan celadons became «one of the most famous types of porcelain in the Song, Yuan, and Ming dynasties, with a slightly different style in each period» (Yang Guimei, An illustrated Brief History of Chinese Porcelain, see Bibliography). They were highly prized by the imperial palace, the aristocracy, and the literati (the government officials who formed the intelligentsia and an elite social class), but a large part of the production was destined for foreign markets. During the Song and the Yuan periods, all Chinese greenware pieces, especially Longquan celadons with cracked or uncracked glaze, were largely exported throughout Asia: they were "export best-sellers" that reached Korea and Japan to the east, South-East Asia to the south, India, Central Asia and Asia Minor to the west.

The Topkapi Palace Museum in Istanbul (Turkey) boasts the largest Chinese celadon collection in the world outside of China. On display, you can see 10,700 Chinese pieces, ranging from the late Song to the Qing dynasties, which arrived firstly via the Silk Road and later by sea, thanks to the Portuguese ships. Celadons were highly valued by the Ottoman sultans for their unique beauty and for a more prosaic reason: the idea that they could change their color when touched by poisoned food was widespread at the time.

«Cargo from known wrecks together with pieces preserved overseas show that Longquan celadon was China's main type of export porcelain <note that the Chinese author is using here the term ci, including both porcelain and porcelaineous stoneware> during the mid to late Yuan dynasty» (Yang Guimei, cit.).

In 1976, «the wreck of a Yuan-dynasty merchant ship was recovered from the sea off Sinan in South Korea. The 200-t vessel was 34 m long and 11 m wide. More than 10,000 pieces of Longquan celadon were on board the ship, representing the main types of porcelain exported for the maritime trade» (ibidem): incense burners, bowls, plates, jars, cups, ewers, vases, water droppers, and basins.

A Chinese merchant ship during the Song and Yuan dynasties.

In Korea, during the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392), master potters adapted, refined, and innovated the celadon technology from China to create distinctively Korean pieces of the finest quality, revered by the local elites. «During the nearly five centuries of the Goryeo dynasty, celadon constituted the main type of ceramics produced on the Korean peninsula» (Soyoung Lee, Goryeo Celadon, Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2003).

LEFT: Bottle decorated with chrysanthemums and lotus petals, stoneware with stamped and inlaid design under celadon glaze. Dimensions: height 13 5/8 - 34.6 cm. Korea, Goryeo dynasty, late 13th–early 14th centuries. The MET, New York, US.

RIGHT: Box with inlaid peony, chrysanthemum, and crane design, wheel-thrown stoneware with incised and slip-filled decoration, and Celadon glaze. Dimensions: Diameter: 4 1/2 in. (11.43 cm) Height: 2 1/2 in. (6.35 cm). Korea, Goryeo dynasty, 12th century. Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), California, US.

In Japan, Chinese greenware (seiji) was imported and admired for centuries. Longquan celadons with kinuta glaze and Qingbai ware with a pale, delicate, very light blue glaze enchanted the Japanese more than deep olive-green or jade-green glazed pieces. Their love for celadon never ceased and today celadon porcelain is the preferred material of many contemporary artists, such as Kato Tsubusa, Kawase Shinobu, and Fukami Sueharu.

Kawase Shinobu, Japan, Incense Burner in the Shape of a Lotus, 2008.

Celadon glazed porcelain. Burner: 12 1/8 x 3 7/8 x 4 inches - 30.8 x 9.8 x 10.2 cm. The Brooklyn Museum, NY, US.

«In Buddhism, the lotus symbolizes transcendence because the flower emerges from stagnant water to bloom in bright colors. Here the ceramicist Kawase Shinobu uses the clear blue celadon glaze, known as seihakuji, to capture the spiritual importance of a lotus bud. This vessel is designed to support burning incense sticks, with a lily-pad-shape saucer to catch falling ash» (The Brooklyn Museum, Asian Art curators).

Fukami Sueharu, Bō II (Full Moon II), Japan, 2003.

Sculpture in porcelain with celadon glaze and cherry wood stand. Dimensions: 8 x 28 3/4 x 8 1/2 inches - 20.3 x 73 x 21.6 cm. Philadelphia Museum of Art, US. © Fukami Sueharu.

The Chinese celadons reached Thailand as well. «By the 15th century, kilns in Thailand, including the large complex at Si Satchanalai in the north, were actively competing with those in China, especially for markets in Indonesia. Thai kilns were noted for their green-glazed celadon wares, which often parallel those produced in China» (The MET Museum). Celadon soon became one of three main kinds of Thai ceramics and its production has continued to develop throughout the last 700 years.

LEFT: Bottle with two shoulder lugs, wheel-thrown stoneware with carved and incised decoration, and celadon glaze. Dimensions: height 6 5/8 in. (16.83 cm); diameter: 5 1/2 in. (13.97 cm). Thailand, Sawankhalok, 15th century. Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), California, US.

RIGHT: Bowl with lotus flower, stoneware with incised decoration under celadon crackled glaze. Diameter: 12 inches - 30.5 cm. Thailand, Si Satchanalai ware, 15th–16th centuries. The MET, New York, US.

Chinese celadons reached their peak during the Song and the Yuan dynasties. Under the Ming imperial rule, the production of Longquan celadon ware continued but the overall quality slightly declined, and finally ended during the early Qing dynasty. Then, celadons almost disappeared from China for about two centuries.

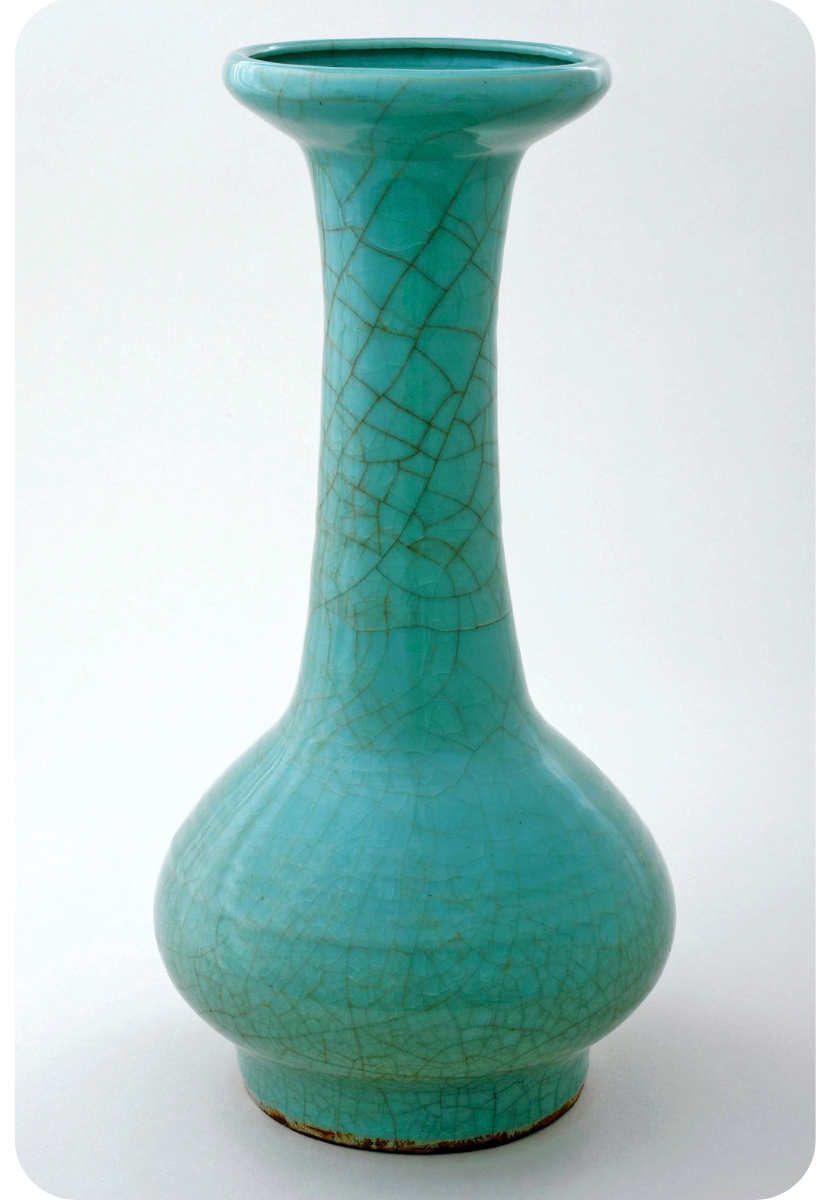

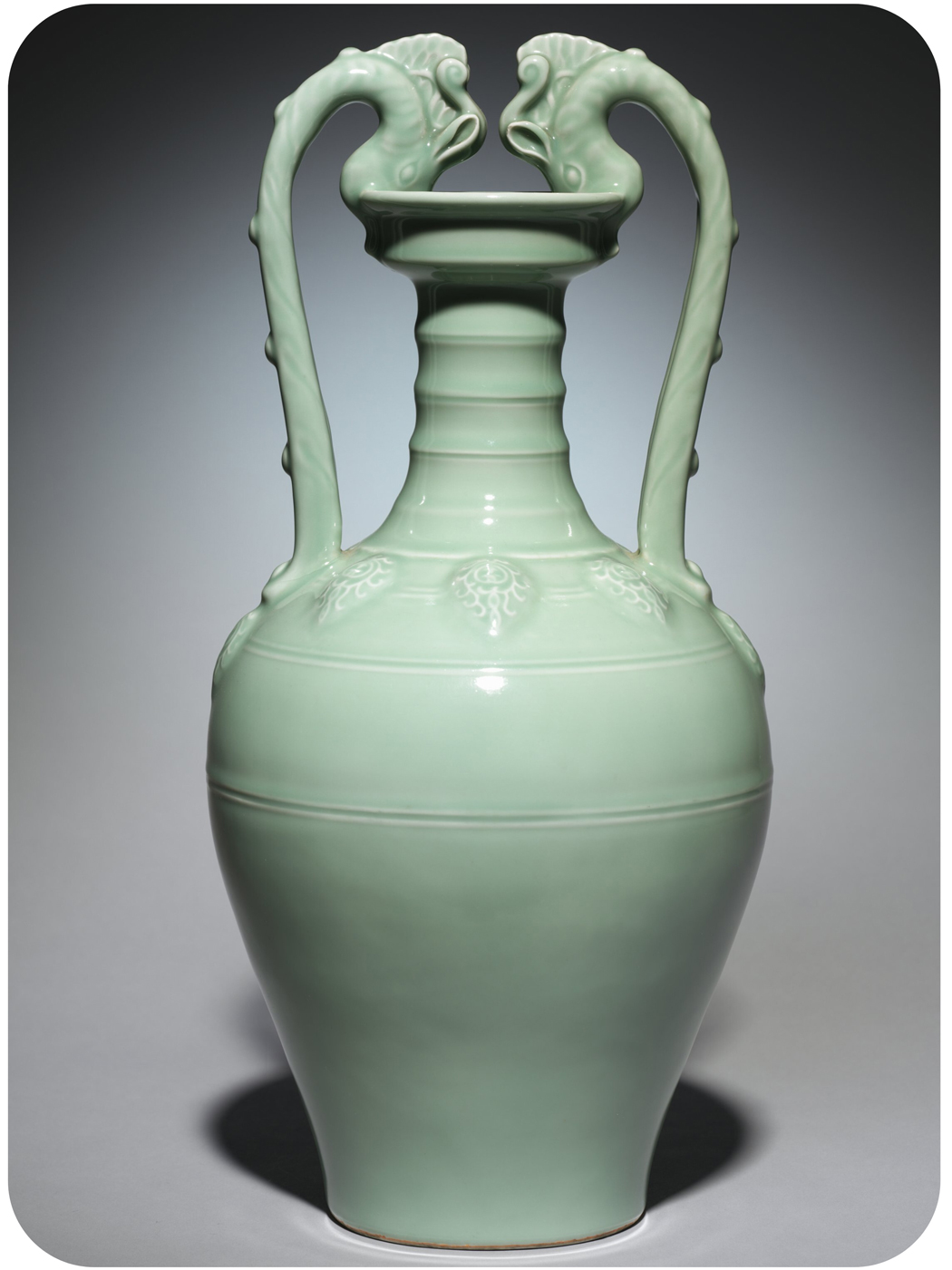

Amphora Vase, porcelain with celadon glaze. Overall height: 52.1 cm (20 1/2 inches). Made in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province, Yongzheng mark and period, 1723-35, Qing Dynasty. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, US. This amphora is inspired by porcelaneous pieces with a clear glaze made in the 7th century under the Tang Dynasty.

«This elegant vase, modeled in the shape of an amphora with dragon-shaped handles, shows perfect symmetry. Its celadon glaze is of exceptional purity and of subtle green color, all characteristics of classical Yongzheng-era monochrome porcelains. The amphora shape and dragon handles of this vase, seen earlier in the glazed stoneware of the Sui and Tang dynasties (581-907), were revived during the Yongzheng period for achieving "antique elegance" (guya) in aesthetics as well as technical perfection in ceramic art» (The Cleveland Museum of Art curators).

An impressive celadon flower-petal style zun vessel, Quing dynasty (1644-1912). The Palace Museum, Beijing, China.

A magnificent and impressive Celadon Jar with cloud and dragon design, porcelain piece made in Jingdezhen in the Yongzheng period (1723-35), Qing Dynasty. Dimensions: height 45.5 cm (17.91 in), mouth diameter 40.6 cm (16 in), base diameter 32 cm (12.5 in). Weight: 41.89 kg. © Shanghai Museum, China.

«The outer wall of the jar is glazed with powder blue, decorated with cloud and dragon design relief in two groups. Each group has two dancing and flying dragons, snapping and clawing, playing with a fire pearl, with the sea water design under their bellies. The Yongzheng period marked the mastery of the iron content and reducing atmosphere control for the celadon-glazed porcelain. With the guaranteed celadon glaze color, this period promoted Chinese celadon glazed porcelain to new heights. This work has the standard hue and stable color of celadon and is in large and orderly shape and structure, signifying the high level molding and firing at that time. The distinctive cloud and dragon design is elaborate and the work on them is time-consuming. It is the high-cost masterpiece of the imperial kiln.» (Curators of The Shanghai Museum).

In China, celadon production restarted in the second half of the 20th century but it was only after the early 2000s that some masters, such as Chen Tangen, revived the ancient cracked-ice celadon technique after hundreds of failed experiments. Today, in Longquan and elsewhere, the ancient tradition is preserved and revitalized thanks to creative innovations and technological breakthroughs. However, while in many Asian places, the celadon wares are created by using artificial chemical materials, in Longquan, artists and master potters refuse to add artificial substances, thus making fewer pieces of higher quality and finesse.

The following brief documentary shows the 5-year efforts and the experiments made by Ye Xiaochun, a master potter of Longquan whose family has been making ceramic wares for over 200 years. Together with his post-90s son, Ye Chenxi, he succeeded to recreate the lost Ge kiln Bingliewen ware and the best celadon 3D crackle patterns. In the video, you can hear the typical 'music' made by the crackling glaze during the cooling outside the kiln, and see some amazing contemporary Longquan pieces.

Documentary by Yit.

DON‘T FORGET TO TURN ON CC/SUBTITLES!

Behind the mysterious glaze of Longquan celadon by China Global Television Network (CGTN), based in Beijing.

Longquan celadon and its traditional firing technology were inscribed in 2009 on the Representative List of the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. The following video shows another famous master of Longquan celadon at work, Xu Chaoxing, National Representative Inheritor of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Traditional Longquan Celadon Firing Techniques.

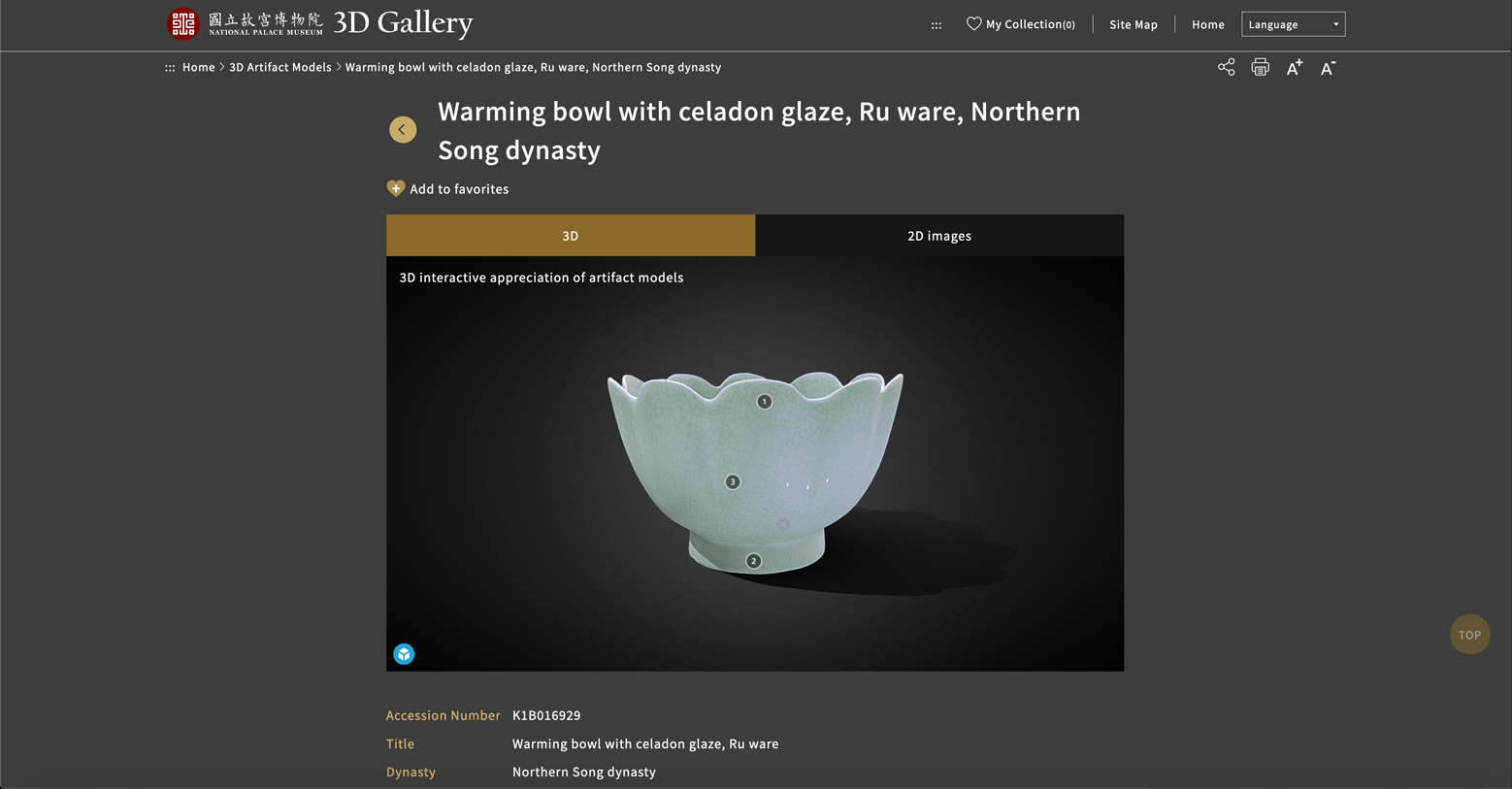

THE RU WARE: RARE JEWELS OF SOPHISTICATED BEAUTY

The exquisite craftsmanship of Longquan celadons has been revered for centuries, both in China and abroad. Among the celadon ware, however, a small group of pieces is reputed today as unsurpassed in quality and rarity: the Ru ware, produced over a bunch of years, from 1086 to 1106, (as suggested by the Chinese scholar Chen Wanli), during the reigns of the Northern Song emperors Zhezong and Huizong. They are called Ru ware as they were made in the Ru kilns (汝), located in the village of Qingliang Temple, Baofeng county, Henan province (Central-Eastern China). These pieces are the finest of all celadons, the rarest - only 87 heirloom (not excavated) examples exist in museums and private collections worldwide, including 36 outside of China - and obviously the most prized. (Please, note that the excavated pieces rarely possess the graceful, delicate, ethereal color of the heirloom).

Below, you can see a small piece, only 13 cm in diameter. It's a rare Ru Guanyao brush washer of almost a thousand years, with crackled glaze in a light color, which is neither light blue, nor light green, nor aquamarine as it changes according to the natural light, and is not exactly as you see it on your screen. To a profane eye, it might look like an unobtrusive and modest bowl, unable to impress anyone if placed on the shelf of an antique piece of furniture.

Formerly in the collection of the Chang Foundation in the Hongxi Museum in Taipei (Taiwan), this piece was auctioned by Sotheby's Hong Kong on October 2017. After 20 minutes of tense bidding, it was sold for HK$ 294,287,500, approximately US 37.7 million dollars of the time.

Rare and finely potted Ru Guanyao brush washer with «a luminous and translucent bluish-green glaze suffused with a dense network of glistening ice crackles» (Sotheby's Catalog). It shows three fine ‘sesame seed’ spur marks on the base. Diameter: 13 cm. Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127).

Chinese brush washers were essential tools used by the emperor and the literati (highly educated intellectuals and scholars appointed by the emperor to carry out political and administrative duties). Brush washers were used to remove excess ink from a paintbrush while painting or carrying out a calligraphy session.

Ru Ware – Rare as the Stars at Dawn by Sotheby's

Almost 38 million dollars.

An immoral price fomented by speculation and a certain contemporary degree of madness?

I do not think so.

In our human world, many objects acquire a symbolic meaning and a cultural value: they become iconic representations of an entire civilization, and to those who know how to listen, they can tell surprising stories about who we are as humans.

«Ru guanyao, the official ware of the late Northern Song (960-1127) court from the kilns in Ruzhou, (...), has in the course of nearly a millennium gained quasi-mythical status. Ru ware is a part of China’s history, an emblem of China’s philosophy, a metaphor for China’s aesthetics – in short, an icon of China’s culture. The small and unobtrusive ceramic pieces are considered the epitome of the Chinese potters’ craft, but they are far more than just that, they have a significant story to tell» (Regina Krahl, Ru. From a Japanese Collection, Sotheby’s, Hong Kong, 2012).

So, what's so special about this piece? What stories does it tell us?

This brush washer was very finely potted. Like all the Ru pieces, it was made for the emperor's use, and we know that only the finest pieces were reserved for the imperial court. The Ru wares were not made to be sold and only the pieces not selected by the Northern Song court were supposedly allowed to be sold to certain people only.

This piece is completely free of decoration: nothing should interfere with the simple grace of its shape, the thinness of its body, and the outstanding beauty of its glaze, perfectly expressed by the harmony between its ethereal color, reminiscent of "the blue of the sky after the rain", its translucence and the ice-crackle network. The glaze is not a common celadon glaze, but a special one that included, among its ingredients, also semi-precious powdered carnelian (agate), a mineral very difficult to source at the time. The glaze shows «a light-catching crackle in superimposed, horizontal, flake-like layers, known as ‘ice’ or ‘broken ice crackle’» (Regina Krahl, cit.). This attractive crackle pattern refracts the light, like mineral formations occurring in nature, but «requires a happy coincidence of circumstances and cannot be produced at will». This feature and the delicate palette of the glaze can be fully captured under natural light, as the artificial one, according to Tetsuro Degawa, director of The Museum of Oriental Ceramics in Osaka (Japan), may change both the temperature as well as the hue of the Ru ware glaze.

The Ru pieces were not fired as most celadons did: stacked upside down. They were fired standing upright, each in its own protective saggar (box), thus taking up more space in the firing chamber. We know they were fired on spurred setters which left tiny sesame seed-shaped, marks on the glazed bottom (a risky procedure...). The firing chamber used for all Ru wares was smaller than those in the Longquan 'dragon' kilns (in Southern China), as the Ru kilns were typical northern Chinese mantou (bread-bun) kilns. Finally, many scholars believe that the Ru pieces were fired two times: the first unglazed - probably to a relatively low temperature in order to remove water from the clay body, according to many experts - and the second after applying the special glaze. This double firing process was adopted to obtain a top-quality glazed surface, but entailed a price to pay: since each firing process is intrinsically risky, the number of failures and losses was higher than in Longquan. For all these reasons, the Ru wares were scarce, even at their times. If we take into account the short production period (approx. 20 years), we can understand why they were defined as "rare as the stars at dawn".

The brush washer is incredibly well preserved, and this is a significant feature: «The exquisite state of preservation of this washer would have required reverential handling over thousands of generations during its nine-hundred-year long history» (Regina Krahl, cit.).

The piece reflects the taste of the Northern Song imperial court and the richest literati, whose aesthetic preferences, rooted in the Taoist concept of detachment as well as in Buddhism, can be summarized in four words: serenity, simplicity, naturalness, and honesty (in the sense of an unpretentious, spontaneous, and unspectacular aptitude to art and life). The following dynasties will develop different approaches to art and different tastes in ceramics, but the Ru wares will always be recognized as the sophisticated expression of an aspect of the Chinese spirit and revered as a component of Chinese cultural identity. «The high regard for Ru ware did not wane in the Ming dynasty (1368-1644)» and grew during the Qing. «The Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1795) ‘appropriated’ Ru ware by having 22 of the 87 extant pieces engraved with his poems, thus contributing further to the fame of the ware» (Ibidem). Rosemary Scott, former International Academic Director of Asian Art for Christie's wrote: «Such has been the veneration for imperial Ru wares, that they have continuously been treasured since the time of their production in the late 11th-early 12th century to the present day. Not only were they sought-after by the succeeding Southern Song court, but they were also greatly prized by both Ming and Qing emperors, and potters of those dynasties were required by their imperial patrons to try and reproduce the elusive blue glaze of Ru wares» (R. Scott, A Star in the Morning, Christie's Catalogue). With little success, however.

The majority of Ru ware shows finely crackled glazes, like the brush washer above. Some others have a less evident crackle, noticeable only to the luckiest who can hold one of them in their hands, and only a few pieces have a crackle free glaze, just like the following small basin.

Ru ware Narcissus Basin, Northern Song Dynasty (960–1127). Height: 6.9 cm, length: 23 cm, width: 16.4 cm, base: 19.3 cm x 12.9 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

The National Palace Museum in Taipei (Taiwan) has a permanent collection of nearly 700,000 pieces of Chinese artifacts and artworks, including some precious Ru ware. The Museum offers you a 'special' 3D experience of a Ru bowl from the Northern Song Dynasty: thanks to an interactive program, you can 'virtually hold in your hands' a Ru piece and know everything about it. Here is the link:

Go to this page of the National Palace Museum's official website. Use the full screen function and your mouse. Click on the '?' (located on the right lower corner) to get more technical info. Enjoy!

QINGBAI PORCELAIN WARE AND JINGDEZHEN KILNS

During the Southern Song and Yuan dynasties, another kind of celadons was widely produced and exported to Japan, Southeast Asia, and East Africa: Qingbai ware, 青⽩ (pronounce approx. as /chiŋ-by/). The term qingbai means "bluish-white," or "greenish-white". It was given to the pieces for the icy bluish or light greenish tone of their thin glaze, sometimes so faint and pale to be clearly perceived only in the recesses, where the glaze pooled and showed a deeper tone. Look at the charming piece below, made in the late Southern Song Dynasty.

Porcelain pillow with incised and carved decoration under celadon qingbai glaze. Dimensions: height 4 3/8 in. (11.1 cm); width 9 in. (22.9 cm). Made in Jingdezhen, China, during the Southern Song dynasty, 12th–13th century. The MET Museum, New York, US.

Chinese people often slept on hard pillows made of stone, bronze, wood, bamboo, earthenware, and, of course, porcelain. Not everyone preferred hard pillows: some people complained that ceramic and porcelain pieces were too cold to sleep on, a feature that, however, becomes an advantage during hot summer nights. In any case, hard pieces were sometimes topped with silken padding for softness. Chinese pillows were not simple headrests. They were luxury home decor commodities that could be personalized and enriched with auspicious symbols. A special earthenware pillow called zhenkuai played a role in ritual mourning. A hollow ceramic pillow could be used as a place to hide one’s most treasured or valuable possessions, particularly while traveling. Last but not least, pieces like the one above were used by noble women as neck rests to keep their elaborate hairstyle in place, a function to which this virtuoso piece alludes: it's shaped like a reclining lady whose elaborately coiffed head rests on her hand.

The following are three Qingbai vases sharing the same traditional form, called meiping (梅瓶).

Left: Meiping porcelain vase with carved peony scrolls under qingbai bluish glaze. Height: 23.5 cm. Made during the Southern Song dynasty in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province (South-eastern China). Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

Centre: Meiping porcelain bottle with incised and carved vegetal scrolls under qingbai glaze. Height: 12 3/8 in. (31.4 cm). Made between the Southern Song and the Yuan dynasties in the late 13th century in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province (South-eastern China). MET, New York, US.

Right: Meiping porcelain vase with carved vegetal lotus sprays under pale qingbai glaze. Overall height: 11 1/4 in. (28.57 cm). Made during the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279), Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province (South-eastern China). Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), California, US.

Meiping vases were created as wine vessels during the Tang dynasty (618–907) but from the Song dynasty onwards, they were used to display branches of plum blossoms. Hence their name: meiping means 'plum vase'. They are usually tall, with a narrow base, a wide body, a sharply-rounded shoulder, a narrow neck, and a small opening. They made have lids or not (in many cases, the lids got lost).

The following Buddhist porcelain sculpture from the Yuan dynasty is an elegant representation of Guanyin, bodhisattva associated with Buddhist compassion and Chinese female form of Avalokiteśvara.

Seated Guanyin, porcelain with a rich ornament of chains and pendants under qingbai glaze. The left hand is missing; the exposed stump shows a lighter clay color: this piece is made of porcelain, not of porcelaneous stoneware. Dimensions: height 20 in. (50.8 cm); width 12 in. (30.5 cm); depth 8 in. (20.3 cm). Made in the late 13th–early 14th centuries, during the Yuan dynasty, in Jingdezhen (Jiangxi province). MET, New York, US.

Incense burner, porcelain with qingbai glaze. Dimensions: height 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm); diameter 5 1/2 in. (14 cm). Made between the late Southern Song (960–1279) and (more probably) the early Yuan (1271–1368) dynasties. The MET, New York, US.

A pair of lion-shaped incense burners, porcelain with brown and raised decoration under qingbai celadon glaze, made in Jingdezhen, in the early 14th century, under the Yuan Dynasty. Dimensions: height 8 3/4 in. (22.2 cm). The MET, New York, US.

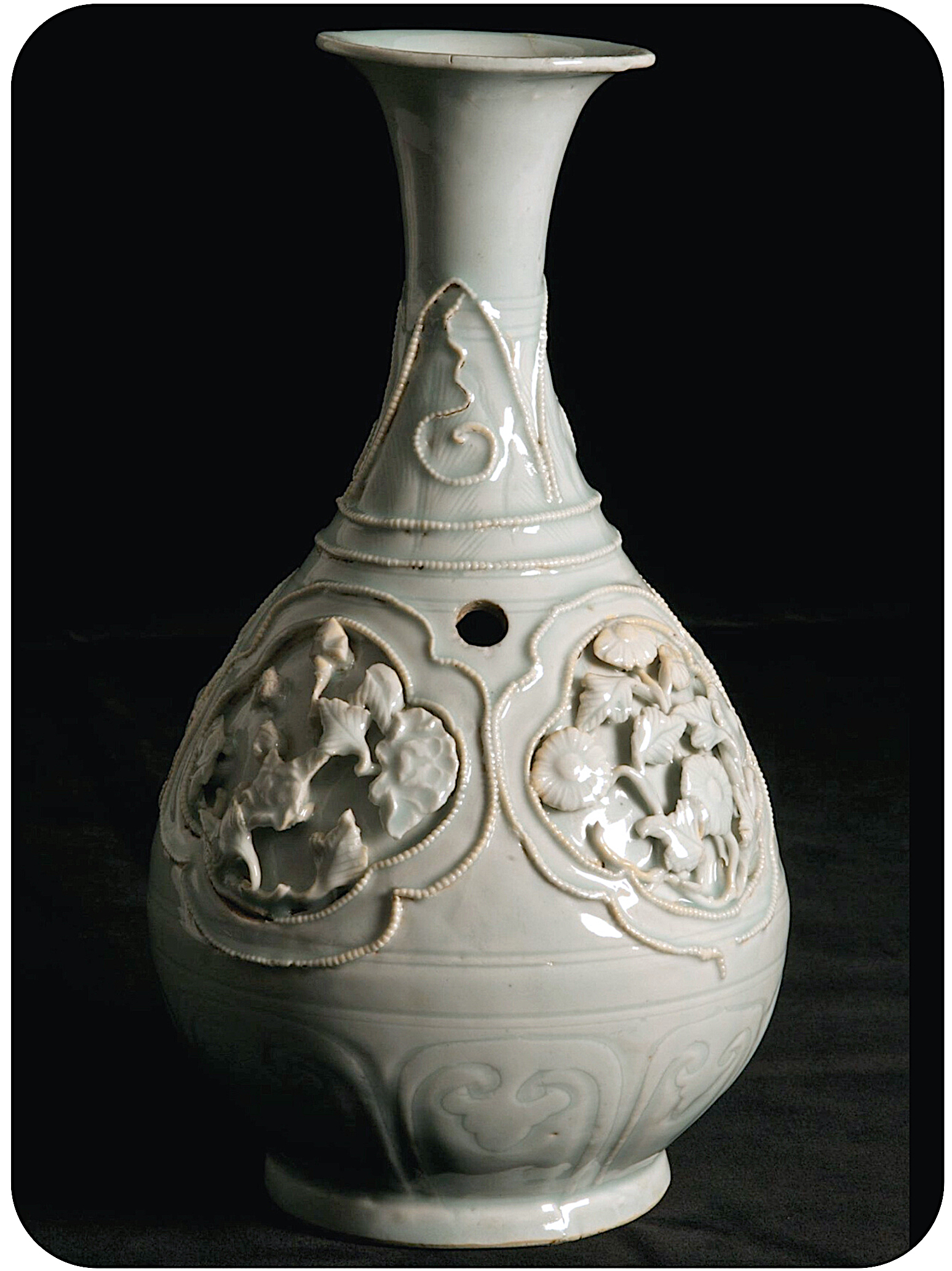

Fonthill Vase, aka Gaignières-Fonthill Vase, hard-paste porcelain with qingbai glaze, made in Jingdezhen, in 1300-1340, under the Yuan dynasty. Preserved at the National Museum of Decorative Art, Dublin (Ireland).

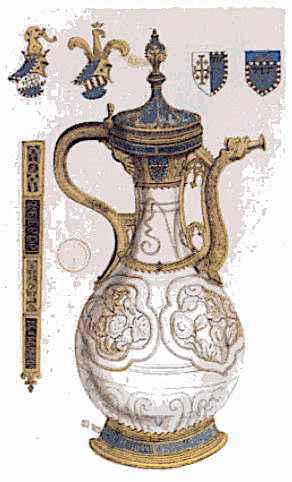

The Fonthill Vase is a very famous piece as it was the first Chinese porcelain to reach Europe soon after its production, in the first half of the 14th century. It was a diplomatic gift donated by a Chinese mission to Louis the Great of Hungary (King of Hungary and Croatia from 1342 and King of Poland from 1370), who made it silver mounted to obtain a ewer and gave it as a gift to his Angevin kinsman Charles III of Naples in 1381. Later on, the vase became part of the porcelain collection of Louis, Grand Dauphin of France (1661-1711). Probably it was also remounted, as shown by the watercolor below. It survived the French Revolution before coming into the possession of the owner of Fonthill Abbey in England. Finally, in the 1860s, it came to its current resting place in the National Museum of Ireland.

The history of the Fonthill vase «indicates the extraordinary value placed on the first few porcelains to reach Europe during the 14th century. As Europeans were unable to make porcelain until over four centuries later, such objects were treated with great reverence. With few exceptions, such as this vase, the porcelains that traveled westwards in the 14th century remained in the Middle East, South and Southeast Asia. They were the premier export market for Chinese ceramics whose markets absorbed it all. Europe had to wait until the 16th century, when the Portuguese established trade routes to the Far East, for Europe to gain access to the quantities of porcelain that the rest of Asia and the Middle East already took for granted» (Tara Manser, Two Yuan Dynasty Qingbai Vases, in "Passage", May-June 2018).

The Fonthill vase by Barthélemy Remy, valet of François Roger de Gaignières, 1713. The drawings on the top right and left corners depict the coat-of-arms of Louis the Great of Hungary.

Qingbai pieces were produced in a number of locations in Jiangxi province, especially in Jingdezhen, where a group of kilns developed a technique to create fine porcelain. These complexes became Imperial kilns during the Yuan dynasty and Jingdezhen soon stood out as the Chinese capital of porcelain. The most evident feature of Qingbai ware is the luminous glaze of icy blue tinge (due to naturally occurring iron impurities in the glaze, fired in a reducing kiln atmosphere), but its main feature, less evident than the previous one, is related to the composition of its body. From the late Southern Song dynasty onwards, the Qingbai pieces were no longer porcelaneous stonewares: they were fine white-bodied porcelain pieces and probably the first type of porcelain to be produced on a large scale both for a middle-rank domestic market and export.

«Technical studies of the raw material used in Song qingbai wares manufactured at Jingdezhen have shown that in all probability these porcelains were entirely made of a pulverized, local kaolinized porcelain stone without the addition of china clay, or kaolin. As has been pointed out, the Chinese porcelain industry is based on some "wonderful geological luck". The Chinese porcelain stone, known as petuntse, is volcanic in origin, and this has given it special properties that make it especially well suited to the manufacture of porcelain. (...). There are some rather exceptional petuntses that are slightly kaolinized and actually contain enough true clay substance so that after being suitably crushed and washed, they can be used alone to make satisfactory porcelain bodies. Limestone "glaze-ash" was added to this porcelain stone to make the qingbai glaze» (Suzanne G. Valenstein, cit.).

Left: a water wheel powers large hammer mills used for crushing porcelain stone or petuntse.

Right: The crushed stone powder is washed, mixed, and dried in large pits.

Both pictures were shot at the Yaoli Ancient Village (瑶里古镇) in the Jingdezhen area by Derek Philip. Photos under Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

The term petuntse, translated as 'porcelain stone', comes from the Chinese term bai dunzi, ⽩墩⼦ (‘little white bricks') and covers a wide range of micaceous or feldspathic rocks. The Jiangxi province and the area around Jingdezhen are particularly rich in large deposits of high-quality petuntse.

During the Yuan dynasty, «studies have shown that qingbai porcelains manufactured in the Jingdezhen region were probably produced in two different ways. The first method was the same as that used during the Song dynasty: both the body and glaze were made of a pulverized kaolinized porcelain stone, with limestone "glaze-ash" added to make the glaze. The second method appears to have involved the use of a somewhat different porcelain stone containing a negligible amount of kaolinite; kaolin (china clay) was added to make the body, and limestone "glaze-ash" was added to make the glaze» (Suzanne G. Valenstein, cit.).

Rocks that are rich in kaolinite, a white clay mineral, are called 'china clay' or 'kaolin', from the Chinese term of Gaoling (高嶺), the name of a village and its kaolin-rich surrounding hills in the Jingdezhen area.

The Swedish expert Jan-Erik Nilsson writes that from the Yuan dynasty onwards, petuntse «was mixed with kaolin in varying proportions depending on the shape and grade of porcelain to be produced. Wider shapes such as the large dishes made during Yuan and early Ming for the Middle-eastern market needed a larger proportion of kaolin to avoid sagging during firing for example. Everyday porcelain (minyao), where the shape was not so much of an issue, porcelain stone could be used as it was or with very little kaolin added» (Glossary).

The qingbai family of porcelains had good success in China and abroad. However, after the mid-14th century, the Jingdezhen kilns began to reduce the production of qingbai ware and use white porcelain raw materials to create a groundbreaking new product, destined to become the new imperial passion and export best seller.

Map of the People's Republic of China with English province names.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

MUSIC TO SEE: "Adventure of Dali Prince" by Zide Qing Club. Musicians are dressed according to the Song Dynasty style.

The musical instruments left to right:

-

guqin (古琴), a plucked seven-string instrument developed in the 1st millennium BC, proclaimed as one of the Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO;

-

dizi (笛子),a traditional transverse flute;

-

gu (鼓), a medium-sized drum with a barrel shape, with two heads made of animal skin (mostly buffalo hide);

-

qing or chime bowl (磬 or historically 罄), one of China’s most ancient instruments;

-

ruan (阮),a plucked string lute with four strings made of silk and a round body, with over 2000 years of history.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?