THE PINK FAMILY: CHINA AND THE WEST 3

Current China on the globe.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

LEFT: Portrait of the Yongzheng Emperor in Court Dress, by anonymous court artists, Yongzheng period (1723—35), Qing Dynasty. Hanging scroll, color on silk. The Palace Museum, Beijing. Public Domain.

RIGHT: History of China, Imperial Dynasties, source: Dynasties in Chinese history, Wikipedia.

THE WHITE AND BLUE PORCELAIN DURING THE MING DYNASTY

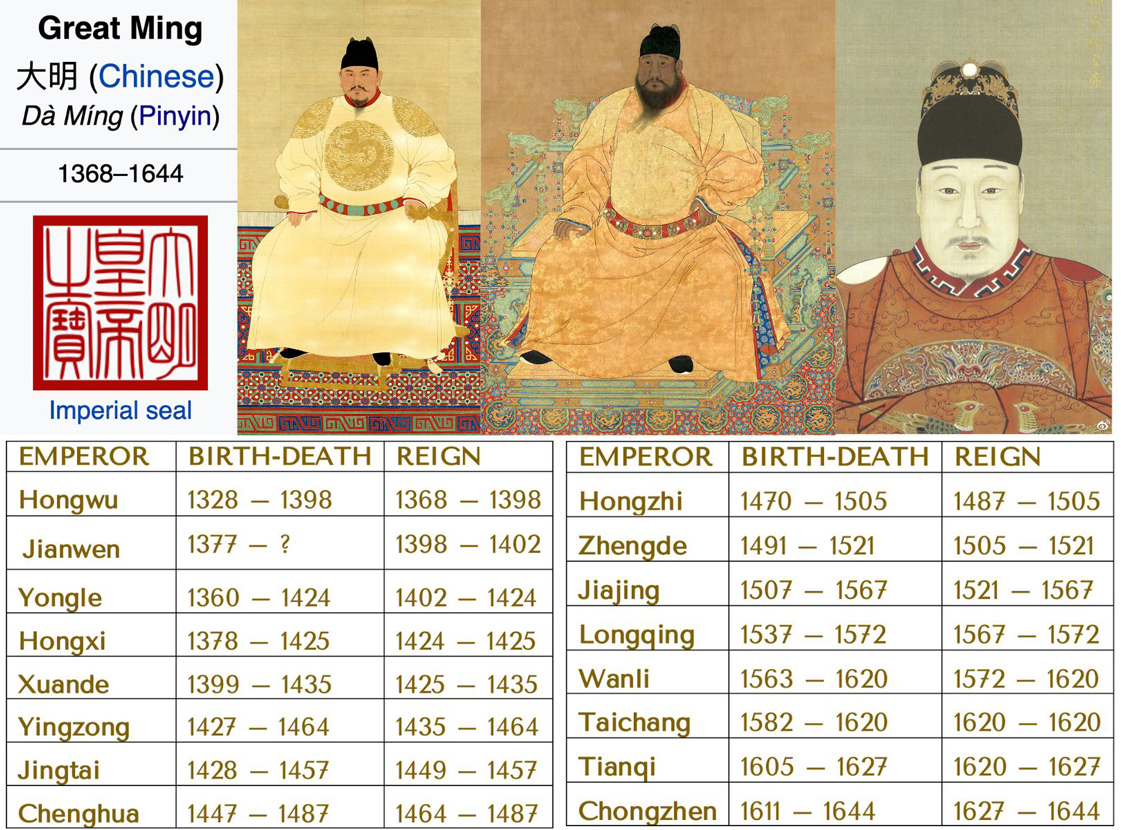

The Great Ming Dynasty (大明) was on the throne of the Celestial Empire (天朝) from 1368, following the collapse of the Mongol Yuan Dynasty, to 1644. The Ming emperors were Han, the majority ethnic group in China.

THE EARLY MING PERIOD: THE GOLDEN AGE FROM 1368 TO 1435

During the Yuan Dynasty period, Jingdezhen was the most active center of porcelain manufacture; during the following dynasty, the Great Ming, the city became the 'capital of porcelain' overshadowing all other kiln complexes.

After the Yuan imperial kiln closed for the collapse of the Yuan Dynasty, Yuan-style wares continued to be produced at private kilns in Jingdezhen by those potters who had previously worked for the imperial court. Such a brief transitional phase occurred before the Ming style developed.

In the past, some scholars believed that early blue and white porcelain had to wait for several decades before gaining full acceptance in China. The early Ming work Gegu Yaolun (格古要論, Important discussions about assessing antiques), a treatise on collecting antiques by Cao Zhao aka Cao Mingzhong, described Yuan qinghua ware (Yuan blue and white porcelain) as "exceedingly vulgar".

(PLEASE note: blue and white porcelain ware, 青花瓷, qīng huā cí, /tʃɪŋ-huá tzə/)

The new kind of porcelain was initially reputed as too showy and flashy by some literati, nonetheless, the story of the David Vases shows that blue and white ware was produced for local consumption, not just for export, and that in the mid-14th century, the best qing hua pieces were already considered prestigious enough to support a formal homage.

The attitude of the new Han dynasty toward the old Mongolian one was ambiguous. On the one hand, they welcomed the Yuan heritage, the blue and white porcelain. In 1369, the first Ming emperor Hongwu established the imperial kiln in Jingdezhen, following the Mongol institution and their habit of reserving the best quality for imperial use. This decision was motivated both by the desire to oversee the excellence and exclusivity of the pieces reserved for the emperor and by the need to control every aspect of high-quality qing hua ci production for a political reason: those pieces continued to be the gifts most widely used by Chinese diplomats around the world. They were, in other words, the most visible art form meant to represent the power and refinement of the ruling Chinese dynasty. They were 'talking objects', in brief. (Note that the third Ming Emperor Yongle tasked Zheng He, one of the greatest explorers of world history, with commanding maritime expeditions in the South China Sea, Indian Ocean, and beyond. The fleet admiral brought hundred of exquisite blue and white porcelain and silk fabric pieces as main diplomatic gifts and trading goods). It was therefore crucial for the Ming dynasty to develop a new artistic style complying with a different idea of beauty, and a 'political' language more in tune with the Han tradition and leagues apart from the old language of the 'foreign' Mongol dynasty.

As Suzanne Valenstein noted, «sharp lines marking political shifts in China's history are not reflected in patterns of change in its ceramics, where the evolution in both physical qualities and style almost always occurred by degrees» (cit.). The Ming artistic language and style developed gradually: if the early Ming qing hua ci pieces still showed the full influence of the late Yuan style (the master potters were likely still the same), during the reigns of Yongle (1402–1424) and Xuande (1425/26–1453), the overall artistic quality reached recognizable, unique features of excellence. For many scholars, the Yongle and Xuande periods make up a sort of 'golden age' of blue and white porcelain ware. In China, the qing hua ci from the Xuande period was so highly valued in the following Qing Dynasty that between the late 17th and the early 18th centuries, many pieces were gifted to the emperors for their birthdays.

«Potting techniques had been further refined: the body is white, fine-grained, and wonderfully smooth to the touch. Showing a characteristic surface unevenness that, appropriately, has been compared with the peel of an orange <the so-called 'orange-peel effect' on the surface> the thick and brilliant glaze has an especially rich quality. A general reduction of decorative elements and a corresponding emphasis on the large principal motif give blue and white wares a new sense of formality» (S. Valenstein, cit.).

The densely patterned ornamentation and the exuberant, intricate details of the Yuan era began to give way to a more balanced relationship between the blue color and the shiny, pure whiteness of the glazed porcelain body.

While during the Hongwu reign there was a shortage of imported from Persia cobalt blue, during the Yongle and Xuande periods, the supply of precious cobalt ore was guaranteed by the returning fleets of Zheng He’s (1371-1433) maritime expeditions. Therefore, the blue color on high-end porcelain pieces was vibrant and intense and still showed the characteristic "heaped and piled" effect due to the presence of iron oxide and other factors (such as the firing temperature): «dark flecks especially in the gathering place of pigment and (...) dark grey, brown and rusty color on the surfaces of glaze which are called “black spot” or “iron spot”. Spots with metallic luster are commonly known as “tin light”» (Wenxuan Wang, Jian Zhu, et al., Microscopic analysis of “iron spot” on blue-and-white porcelain, see Bibliography). Since the "heaped and piled" effect was typical of the Yuan porcelain, it could be inferred that the early Ming potters used an imported cobalt ore rich in iron (Fe) and poor in manganese (Mn), similar to that employed during the Yuan era. The effect will disappear in the following decades when the Persian cobalt ore will be mixed with or replaced by a local one with a different Fe/Mn ratio.

Ming blue and white porcelains were typically lighter and smaller than those made in the previous Yuan era. Only in the late Ming period, during the reigns of Jiajing (1522-1566) and Wanli (1573-1620), the Jingdezhen potters reverted back to the large and heavy pieces that demanded complicated techniques to fire.

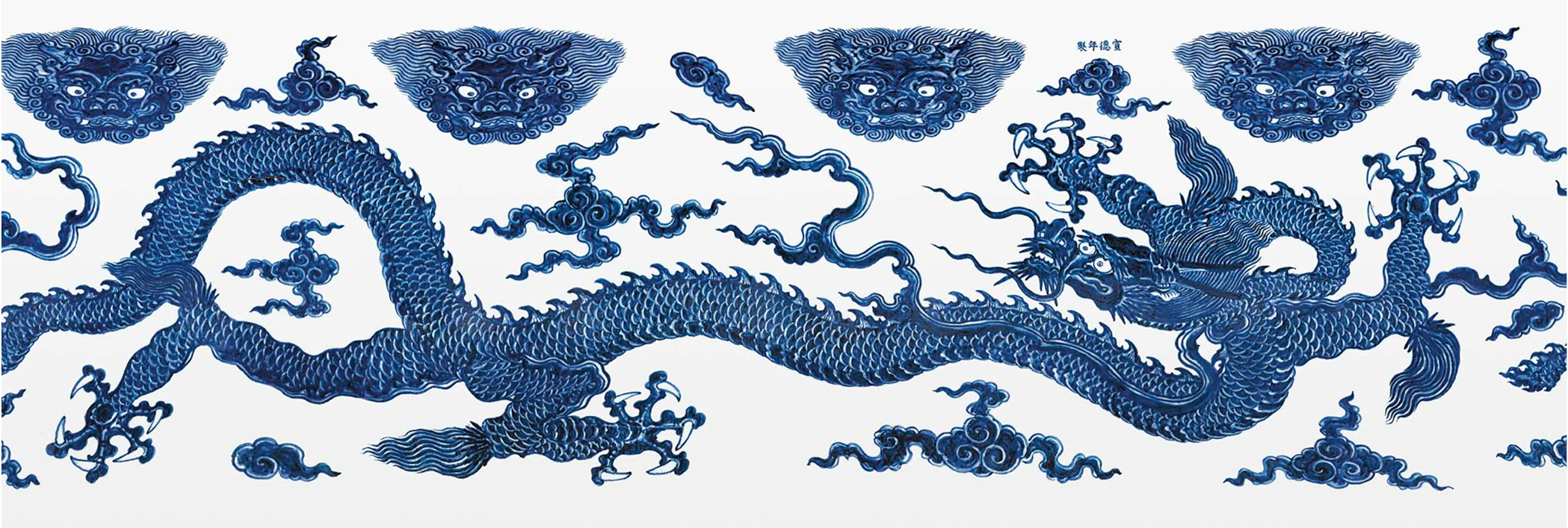

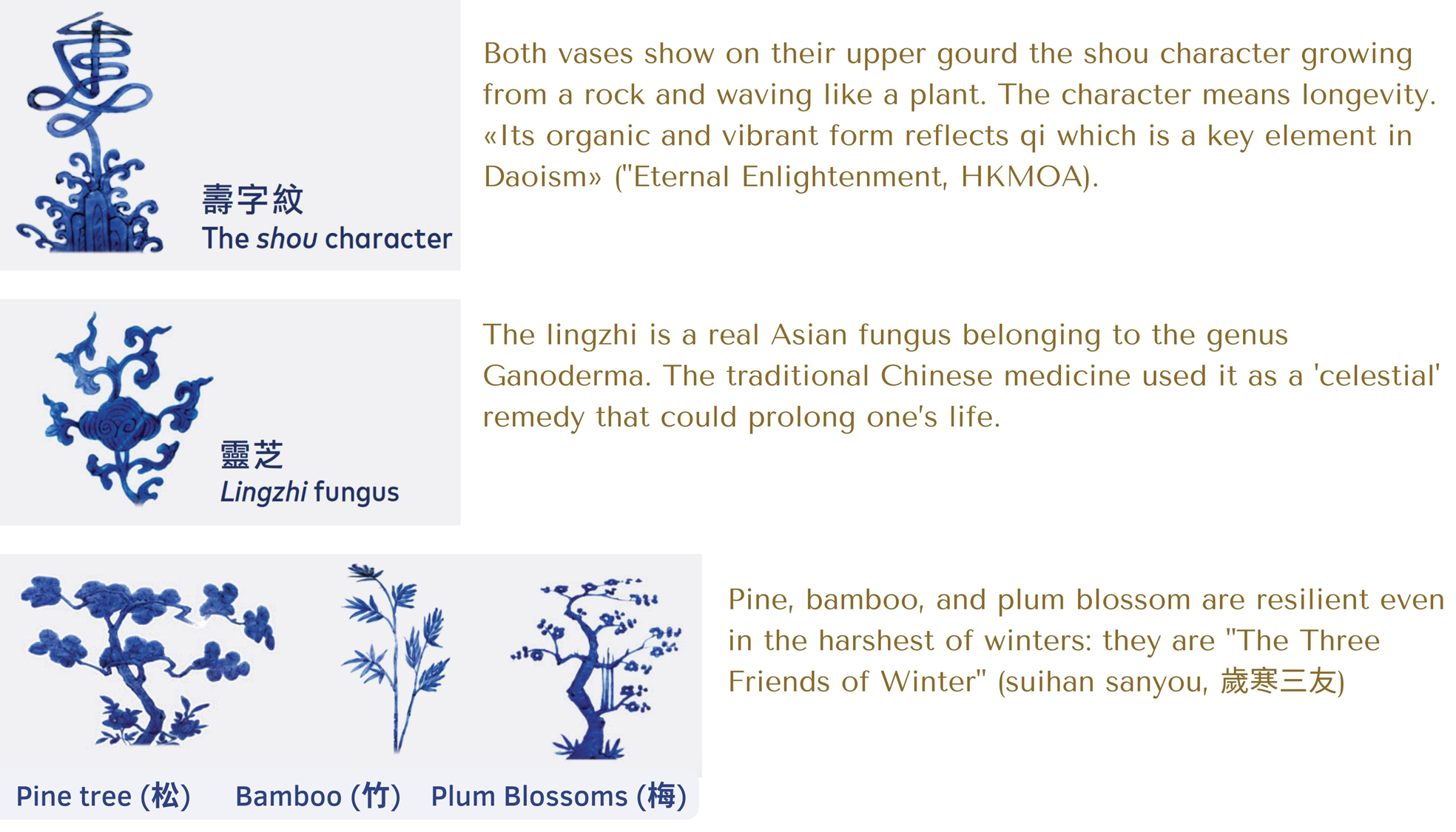

The ornamentation saw the triumph of the vegetal over the animal motifs: peonies, lotus flowers, chrysanthemums, Bao Xiang hua scrolls, pomegranates, grapes, pine trees, bamboos, and plums took the central stage. However, the dragon and the phoenix were still widespread noble emblems.

«Auspicious motifs, dragons, phoenixes, and Buddhist and Daoist symbols, decorated the surfaces of most objects and materials used within imperial contexts. These motifs, symbols and colours combined to form a rich visual language that served to assert visible expressions of imperial virtue, rank, authority and legitimacy. Dragons and phoenixes, which represented male yang and female yin principles, featured prominently and prolifically in the visual language of the imperial court arts. Five-clawed dragons, in particular, were exclusively restricted to imperial use and forbidden to Ming commoners.» (Ming: The Golden Empire, National Museums Scotland, see Bibliography).

LEFT: Yongle (永樂, Eternal Happiness), third Ming Emperor (r. 1402–1424), Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

«The third Ming emperor Yongle, increasingly conscious of the Mongol threat in the north, moved the capital to the former Yuan capital at Dadu in 1420, which was much better placed strategically for defensive or offensive military actions against the Mongols. Dadu was renamed Beijing (literally ‘Northern Capital’), and Yingtian <where the first Emperor Hongwu had his capital city> was then renamed Nanjing (literally ‘Southern Capital’) to function as the Ming auxiliary capital. Built between 1406 and 1420, the Beijing palace complex, or Forbidden City, enclosed the Inner Court, imperial residences and government offices.» (Ming: The Golden Empire, cit.).

RIGHT: Xuande (宣德, Propagating Virtue), fifth Ming Emperor (r. 1425/26–35), Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

The 10 years of Xuande's reign were a period of peace and prosperity. The emperor was a competent poet and an accomplished painter, defined by Robert D. Mowry, the curator of Chinese art at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, as "the only Ming emperor who displayed genuine artistic talent and interest".

In the Yongle period, the Jingdezhen imperial workshops and official kilns began to inscribe the reign mark (nianhao) on the bottom or on the rim of the pieces; however, the four-character mark Yongle nian zhi ("Made in the Yongle period") was only occasionally used. This practice consolidated during the Xuande period when the four-character seal Xuande nian zhi ("Made in the Xuande period") or more often the six-character mark Da Ming Xuande nian zhi ("Made in the Xuande period of the Great Ming") began to be almost regularly painted.

The presence of a mark has been and still is a useful tool that helps scholars and experts to date Ming and Qing pieces, assuming, of course, the authenticity and truthfulness of the nianhao. A risky assumption, however. The creation of reign marks implied the birth of their forgery. The issue of fake marks and, in general, of fake porcelain pieces is, however, quite complex in China: during the Qing Dynasty, the Ming reign-marks were heavily imitated. During the Ming dynasty, on the other side, Zhou Danquan, active in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, was well known for his ability to fake Song ceramics. Even the Ming imperial workshops in Jingdezhen made imitations of some Song pieces. They did it not to deceive and make a profit, like Zhou Danquan, but «rather to demonstrate both antiquarian knowledge of past styles and objects, as well as technical mastery in the ability to make visually very similar objects.» (Stacey Pierson, True or False? Defining the Fake in Chinese Porcelain, see Bibliography).

Porcelain bowl with underglaze blue decoration depicting the "Three Friends of Winter". On a side, you can read the Xuande's reign mark painted in underglaze blue: ⼤明宣德年製, Da Ming Xuande nian zhi, "Made in the Xuande period of the Great Ming", 1425/26–1435, Ming Dynasty. Jingdezhen, China. Dimensions: diameter 30.2 cm (11 7/8 in); overall 11.2 cm (4 7/16 in). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, US.

This bowl is decorated with a motif called "The Three Friends of Winter" (suihan sanyou, 歲寒三友) showing pine tree, bamboo, and plum blossoms. Pine trees are evergreen and grow for a long time, thus symbolizing resilience, perseverance, longevity, and strength in the face of hardship because they do not wither during harsh winters. The bamboo, another evergreen, represents the ideal qualities of the educated Confucian, a gentleman-scholar-official who should be like a bamboo stem, bending but not breaking in adverse conditions. In Chinese traditional culture, bamboo symbolizes honesty, humility, and loyalty; because of its strength, bamboo is also a symbol of a long life. The plum blossoms stand for purity, honesty, and renewal as they are the first flowers to bloom in the Chinese New Year.

From the Xuande period onwards, the reign's mark became more frequent. It could be placed under the rim, inside the vessel, on the base bottom, or on the shoulder of a vase; it could show four characters or, more often, six; it could be inside a double ring or unframed, and it could be written in a single horizontal line or in one or two vertical lines.

Porcelain bowl with underglaze blue decoration depicting fish and water plants on the outside. Inside, you can read the Jiajing's reign mark: 大明嘉靖年製, Da Ming Jiajing nian zhi, "Made in the Jiajing period of the Great Ming" (1521–1567), painted in underglaze blue inside a double ring. Jingdezhen, China. Dimensions: diameter 16.1 cm (6 5/16 in); overall 7.8 cm (3 1/16 in). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Ohio, US.

Let's now see some masterpieces made during the reign of Yongle, on the throne from 1402 to 1424. All these pieces show the intertwining of innovation and tradition: the language is definitely new, but several artistic and technical elements are rooted in the Yuan tradition.

Three quite large Yongle pieces, left to right:

LEFT - Blue and white porcelain flat bottle with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration depicting a three-clawed dragon with open jaws, among clouds pattern. Dimensions: height 45.5 cm - 17.91 in; width 34.6 cm - 13.62 in; mouth diameter 8 cm - 3.14 in; bottom diameter 9.8 cm - 3.85 cm. Made in Jingdezhen during the Yongle reign, 1402-1424. © Nanjing Museum, China.

CENTRE - Blue and white porcelain flat bottle with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration depicting a three-clawed dragon among scrolls of bao xiang hua. Dimensions: height 47.8 cm - 18.81 in; width 35 cm - 13.77 in; depth 22.5 cm - 8.85 in. Made in Jingdezhen during the Yongle reign, 1402-1424. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

RIGHT - Blue and white porcelain flat bottle with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration depicting a three-clawed dragon (loong) in reserve against a background of blue waves. Dimensions: height 44.6 cm - 17.55 in; weight 7.2 kg. Made in Jingdezhen during the Yongle reign, 1402-1424. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK. A similar piece is on display at The National Museum of China in Beijing.

These large porcelain flat bottles show a flask form that was not originally Chinese, as inspired by a Middle Eastern shape or West Asian glassware. «During both the Yongle and Xuande emperors’ reigns, flasks in this large, heavy, bulbous form with variations to the decoration were made at the imperial kilns at Zhushan (珠山) in Jingdezhen. (...) The imperial household probably used such flasks as wine decanters but also traded them as evidenced by similar flasks in the Topkapi Saray in Turkey and from the Ardabil Shrine in Iran.» (The British Museum curators).

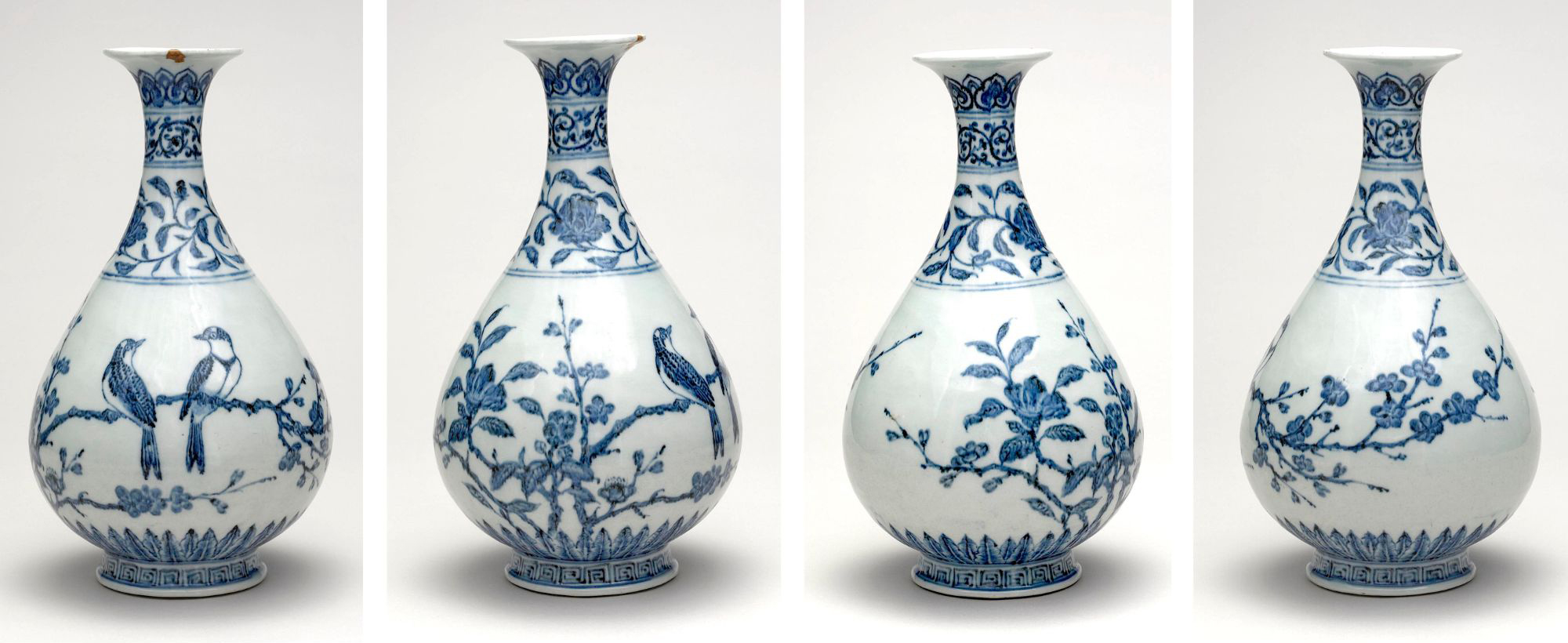

Above, you can admire an exquisite yuhuchun ping-form vase, photographed to show its entire decoration. We still see a multi-layered pattern as in many Yuan pieces, but the main ornamentation on the belly reveals the emotional contrast between emptiness and solidness and the intended blank (liubai, 留白, namely the space that the artist intentionally leaves blank) of the traditional Han ink painting.

Blue and white porcelain yuhuchun ping form vase with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration; the main ornamentation on the belly depicts two songbirds on a flowering prunus branch. Dimensions: height 33.5 cm - 13.18 in; diameter 18.6 cm - 7.32 in. The depiction shows the “heaped and piled” effect and different shades of blue. Made in Jingdezhen during the Yongle reign, 1402-1424. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London.

The following piece is a high-quality example of a flat bottle known as a "moon-flask" or "pilgrim flask" (bian hu). It shows a round body with a flat base, a narrow cylindrical neck with a slightly flared mouth, and two small, arched side handles. Like other forms, this too is an adaptation of a much earlier foreign vessel, probably made of leather or metal.

Blue and white porcelain moon flask with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration depicting fruiting and flowering lychee branches on both sides. Dimensions: weight 1.25 kg; height 25 cm - in; width 22 cm - in; depth 12 cm - in. Made in Jingdezhen during the Yongle reign, 1402-1424. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

«Lychee fruit trees are widely cultivated in south China. (...). The trees are evergreen and in spring bear tiny flowers, which are visible here, shortly followed by the lumpy red-skinned fruits. Wine made from lychee fruit was drunk in southern China in the Ming period. This fact is mentioned in a speech by the attendant to the imperial commissioner, Miao Shunbin, in the popular romantic Ming play The Peony Pavilion, written in 1598. As this flask was made to present and contain wine, it is possible that it held lychee wine. Lychee fruits are also an auspicious symbol, representing good wishes for the birth of a son. An identical blue-and-white example is in the Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka.» (The British Museum curators).

The last Yongle piece is a large serving dish with a diameter of 44.4 cm (17.48 inches), likely intended for the Islamic/West Asian market, and thickly potted to withstand the journey by land and sea. This feature, the dimensions, and the presence of concentric decorative bands are all rooted in the Yuan tradition. The large central roundel, on the contrary, has nothing to do with the Yuan artistic style and its motives. It shows a bouquet of lotus flowers, leaves, and water plants (Sagittaria) tied with a ribbon: it's a Han motif, first used in the Northern Song dynasty. Furthermore, the dish has been masterly painted with different shades of blue to create a harmonious three-dimensional effect.

Large porcelain serving dish with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration depicting a bunch of lotus flowers and leaves tied with a ribbon in the central roundel. Note the "heaped and piled" effect. Dimensions: diameter 44.4 cm - 17.48 in; height 8 cm - 3.14 in. Made in Jingdezhen during the Yongle reign, 1402-1424. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

The Xuande reign (1425/26–35) was a period of peace, political stability, and economic prosperity. «The scale of the imperial porcelain workshops at Jingdezhen and their volume of production increased. According to the Da Ming Huidian (Collected Statutes of the Ming Dynasty), the court ordered 443,500 items of porcelain from Jingdezhen in the year 1433 alone. In order to fulfill such a vast order, the imperial workshops built additional kilns so as to increase the scale of production» (Yang Guimei, cit.): at the time, 58 different kilns were working for the imperial court under a very strict quality control (all the pieces that failed to satisfy the rigorous criteria for acceptance by court officials were deliberately broken and thrown into a waste pit outside Jingdezhen).

Even the number of pieces for the domestic market considerably grew.

The blue and white porcelain ware got the lion’s share, and alongside the traditionally large and small forms, new leisure-related pieces started to appear, such as birdseed containers, tiny bird feeders, cricket cages, and miniature vases.

The body of Xuande porcelain pieces was low in calcium and high in potassium, a feature that enhanced their translucency. The glaze was rich and lustrous, and the underglaze blue decoration showed great painting mastery and the rendering of different shades of blue.

The following dish is an outstanding, precious piece made for the imperial court, on display at The Museum of Oriental Ceramics in Osaka. The central roundel shows a magnificent peony branch while the cavetto is decorated with fruiting branches of loquat, cherry, persimmon, peach, lychee, and pomegranate. All these designs have been painted in white slip, then finely incised into the unfired white body; «then the design was covered with a transparent glaze, while the background was covered with a cobalt blue glaze. The plain rings around the center and the foot, however, appear as if scratched through the blue glaze, and in some areas, a more transparent glaze appears to have been added after the blue, creating in places a very thick white layer. <In the Osaka specimen>, the two parallel stems in the center, of which one belongs to the main peony bloom and the other to the small bud and leaves behind it, seem to have been (...) overpainted in blue» (Regina Krahl, Royal Blue, Christie's Catalogue, 2017). This complex decorative technique was pioneered during the Yuan Dynasty and further refined by Jingdezhen masters of the Imperial factory during the early Ming period. According to Regina Krahl, very few pieces of this kind were made by the imperial workshops for three reasons: 1. their stratospheric cost due to the quantity and the top quality of the necessary cobalt blue; 2. the rare technical and artistic expertise required by the indirect reserve decoration process; 3. the amount of time needed for this creation, far exceeding that of dishes painted in the positive. Only four other similar dishes of this decoration technique, design, and size appear to be recorded; one was auctioned by Christie's in 2017 and sold for over two million dollars (US$ 2,172,500, to be precise).

Porcelain dish with design of peony spray in reserve against cobalt blue ground, Xuande mark and period (1425–1435), Ming dynasty. Made in Jingdezhen, China. Dimensions: diameter 38.7 cm, height 7 cm, weight 2.640 kg. The piece, designated as ‘Important Cultural Property’, is on display at The Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka (Japan). Gift of Sumitomo Group (The Ataka Collection). Photo by Nishikawa Shigeru.

Peony (mudan 牧丹) is a very widespread decorative motif. Known as the “king of the flowers,” this flower is closely associated with royalty (it grew in the imperial gardens during the Sui and Tang dynasties), with "wealth, status, and honor” (fuguihua 富貴花). Peonies depicted together with narcissus flowers mean “may you be blessed with long life, wealth, and honor” (shenxian fugue 神仙富貴).

Porcelain Bowl with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration depicting four court ladies: three in a garden and one inside a pavilion. The scene was inspired by the Tang poem Autumn Evening. The base shows the six-character Xuande reign mark, painted inside a double ring. Jingdezhen, Xuande reign, Ming Dynasty. Collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei (Taiwan).

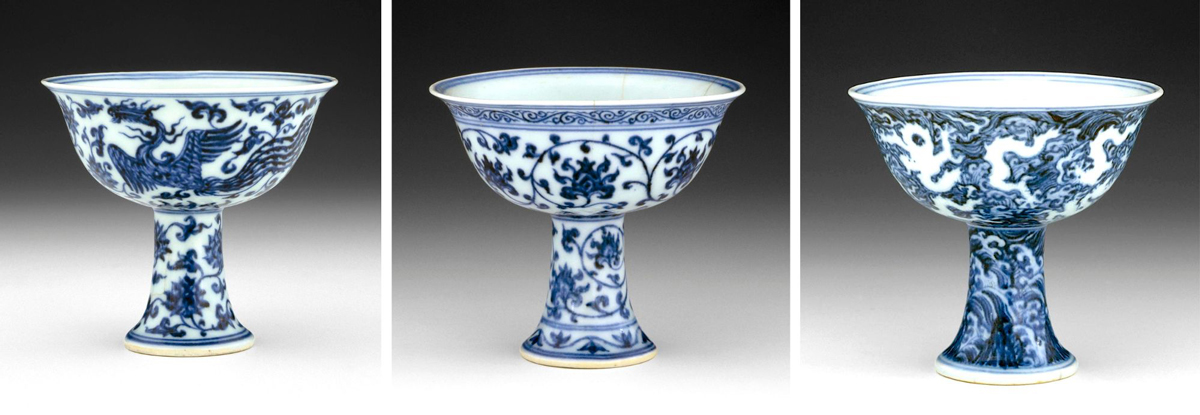

The three pieces below are stem cups used as wine glasses or, more often, as ritual vessels to be placed on Chinese Buddhist altars before devotional images and filled with water. Stem cups became a popular porcelain form during the Yuan Dynasty, but their origin is rooted in ancient bronze forms used during the Tang Dynasty.

Three Xuande stem cups. Left to right:

LEFT - Blue and white porcelain stem cup with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration depicting a pair of phoenixes flying with wings outstretched over scrolls of bao xiang hua. A six-character Xuande reign mark has been painted inside a double ring in the inner center. Dimensions: height 8.9 cm - 3.5 in; diameter 10 cm - 3.93 in. Made in Jingdezhen during the Xuande reign, 1425–1435. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

CENTRE - Blue and white porcelain stem cup with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration depicting scrolls of bao xiang hua in a classical Xuande style. A six-character Xuande reign mark has been painted inside a double ring in the inner center. Dimensions: height 8.3 cm - 3.26 in; diameter 10.2 cm - 4.01 in. Made in Jingdezhen during the Xuande reign, 1425–1435. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

RIGHT - Blue and white porcelain stem cup with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration depicting five powerful sinewy dragons reserved in white, with incised details, on a ground of turbulent blue waves. «Depth and texture are lent to the waves through the use of pale and dark washes of cobalt blue and are further highlighted by the crests which have been left white.» (The British Museum curators). A six-character Xuande reign mark has been painted inside a double ring in the inner center. Dimensions: height 9.2 cm - 3.62 in; diameter 9.8 cm - 3.85 in. Made in Jingdezhen during the Xuande reign, 1425–1435. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

The background of the stem cup on the right shows an exquisite contrast between lighter and darker shades of blue. According to many scholars, in the Xuande period, potters have already mastered graduating blue tones and creating different shades to enhance dynamism and volumes. This mastery is fully revealed by the following Xuande impressive guan jar with an incredible story: it was owned by a French family who thought it was an 18th-century jar of little worth, probably the copy of an ancient one; then it passed by descent to a distinguished Swiss lady, his son, and finally, in 1997, to a niece who used it as an umbrella stand in the hall of her home. When the jar arrived in London, Christie's expert Marco Almeida, a specialist in Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art, had a jolt to the heart. The massive piece was perfectly potted and perfectly painted; the five claws of the dragon told it was a piece made for the Emperor himself, and the inscription that the Emperor was the Ming Xuande. Every detail said it was a rare, unique, breathtaking masterpiece made in Jingdezhen in the first quarter of the 15th century. It was auctioned by Christie's Hong Kong on May 30, 2016, and sold for 20 million dollars (158,040,000 Hong Kong dollars, to be precise). Not bad for a former umbrella stand. (Don't let it go to your head. Probably and sadly, our umbrella stands are pieces no one would buy...).

Impressive blue and white porcelain ‘dragon’ jar, guan shape, showing the Xuande four-character mark in underglaze blue, made in the period (1426-1435). Height: 48.5 cm - 19 1/8 in. Sold in Hong Kong in May 2016 by Christie's. Photo: © Christie's.

«The jar is boldly painted in underglaze blue with a powerful five-clawed dragon (loong) amidst scrolling clouds, below four monster masks and a four-character Xuande mark written in one horizontal line on the shoulder. The neck is decorated with a band of clouds and the foot is surrounded by a petal border» (Christie's Catalogue). «The dynamic depiction of the dragon with its head turning backward and two powerful open claws appears to be an early variation of the forward-facing dragon found on blue and white ceramics developed from the Yuan period. The inspiration for this unusually portrayed dragon probably originated from Southern Song paintings such as those by Chen Rong (circa 1200-1266). (...) The three main motifs on the current jar–dragon, monster masks, and clouds–are all painted with varying tones of blue in bold and steady ink strokes. The outlines are painted using a paler blue, the coloring is done with a darker blue, and the shading is done again with a paler blue, each with great effectiveness. Take the dragon, for example. Each scale is painted with a faint outline and infilled in a darker blue to denote their overlapping structure. The sizes of the scales, their directions, and densities change according to the thickness of the body and its movement to successfully impart a sense of realism and create pictorial tension. The mane and bristles of the dragon are similarly painted with darker outlines on top of a light blue shading to create depth and density. The white areas of the eyes and the claws have light blue shading to denote volume. This ability to adapt painting techniques to different subjects is even more evident in the painting of the monster masks. The light blue shading underneath the mane suggests a finer coating of hair below, making the animals come to life. The scattered cloud scrolls have been strategically placed and shaped according to the space available, a device not only fills a void but is also aesthetically pleasing. The cloud scrolls between the four animal masks are particularly creative, breaking up the monotonous symmetry of the masks. Just like the dragon and the animal masks, the cloud scrolls are painted utilizing fully the contrast between lighter and darker shades of blue. For example, the X-shaped cloud scroll above the rear leg is painted with a dark blue outline and a darker blue centre, followed by a light blue shading in between. » (Christie's Lot Essay).

THE INTERREGNUM FROM 1435 TO 1464

The period from the beginning of the Yingzong reign in 1435 to the ascension to the throne of Chenghua in 1464 was a turbulent one, and «because of the political instability (...), the Jingdezhen porcelain industry suffered an economic downturn» (Yang Guimei, cit.). The production of porcelain pieces did not cease completely: the unofficial kilns kept on working and innovating.

Yingzong, both the sixth and eighth Emperor of the Ming dynasty, Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

Son of Xuande, he ascended the throne as the Zhengtong Emperor (正统帝, "Right Governance") in 1435 but was forced to abdicate in 1449, in favor of his younger brother, the Jingtai Emperor. In 1457, he deposed the Jingtai Emperor and ruled again as the Tianshun Emperor (天顺帝, "Obedience to Heaven") until he died in 1464.

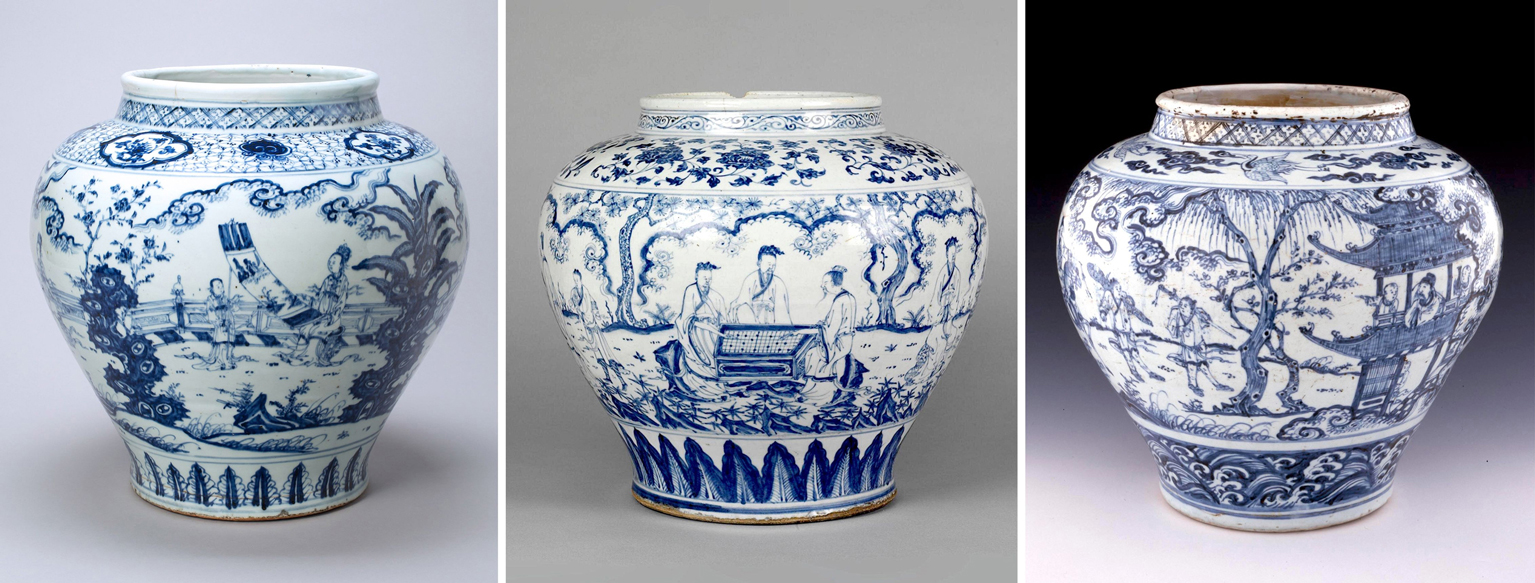

These three figural guan jars were all made between the Zhengtong and the Tianshun reign period.

Three different wine jars:

RIGHT - Porcelain Jar with a figural decoration painted in underglaze blue and depicting "The Four Accomplishments: Painting, Calligraphy, Music, and Strategy". Jingdezhen, mid-15th century, Ming dynasty. Dimensions: height 35.6 × diameter 40 cm (14 × 15 3/4 in.). Art Institute, Chicago, IL, The US.

CENTER - Porcelain Jar with a figural decoration painted in underglaze blue and depicting "The Four Accomplishments: Painting, Calligraphy, Music, and Strategy". Jingdezhen, 1457-1464, Ming dynasty. Dimensions: height 35.6 cm - 14 in; diameter 39.4 cm - 15.51 in. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

LEFT - Porcelain Jar with a figural decoration painted in underglaze blue, depicting a scholar-official with attendants watching from the upper floor of a pavilion. Three scholars on horseback are approaching, accompanied by a vanguard of two servants carrying respectively a sword and a guqin wrapped in a textile cover. Three further attendants bring up the rear, one shouldering a pole that supports a picnic basket on either end, another shouldering a pole from which two covered wine jars are suspended and a third at the back carrying a basket with books. Dimensions: height 34 cm - 14 in; diameter 36 cm - 14.17 in. The British Museum, London, UK.

All these guan jars show illustrations taken from woodblock prints, a popular form of decoration on ceramics during the Ming dynasty. Two of them depict the "Four Accomplishments", aka the "Four Arts" (四藝, siyi), or the "Four scholarly pursuits", namely the fields an educated literatus-gentleman was expected to master: playing the guqin (古琴)), playing the qi (棋, the strategy game of what is called Go, in Japan and the West), calligraphy (書, shu), and painting (畫,hua).

NOT ALL BLUES ARE THE SAME

Many scientifical studies had showed that the chemistry of the cobalt blue pigment used in Jingdezhen changed substantially during the Ming Dynasty. «Compared with paste and glaze, the chemical composition of the blue pigment showed more distinct variability between <Ming> periods. This is attributable to several significant changes in the provenance of the pigment used throughout the Ming Dynasty«» (R. Wen, C. S. Wang, et al., The Chemical Composition of Blue Pigment on Chinese Blue-And-White Porcelain of the Yuan and Ming Dynasties, see Bibliography ).

Some Chinese scholars distinguish three different periods in the Ming qinghua ci production depending on the style and the type of cobalt blue used for painting: after the first stage during Yongle (1403-1424) and Xuande (1426-1435) reigns, follows a second phase from Chenghua (1465-1487) to Zhengde (1506-1521) reigns, when the so-called ping deng blue, a native Chinese cobalt ore, was used; the third, final stage covers the late Ming reigns, when the imported hui blue, probably mixed with a local one, was in use. (There has been a dispute about the category of blue pigment used in the Xuande period, to tell the truth, but we won't discuss the issue here).

Not all blues were the same, in brief. The use of different types of cobalt ore and methods of application gave birth to distinctive features used by scholars to differentiate the Ming blue and white porcelain ware and sometimes verify the authenticity of the reign's marks.

THE CENTRAL MING PERIOD: THE EXCELLENCE OF THE CHENGHUA PIECES

«The blue-and-white porcelain made during the Chenghua reign period is deemed to be one of the highest peaks in design and decoration. Connoisseurs regard the Chenghua period porcelain as aesthetically at the same high level as the Xuande porcelain» (R. Wen, C. S. Wang, et al., cit.).

«During the final third of the fifteenth century - that is in the reigns of the Chenghua and Hongzhi emperors - Chinese porcelains touched greatness. In a constant search for improvement, potters at Jingdezhen perfected their wares to an unprecedented level of delicacy and refinement. The body shows even more careful preparation and the potting exhibits even greater skill. Probably the most outstanding feature is the glaze, which is smooth, deep, and unctuous; the Chenghua glaze, in particular, has a mellow, creamy, or slightly smoky tinge. However, these late 15th-century porcelains are never what Browning termed "faultless to a fault ." They maintain a rare and delicate balance between technical excellence and intrinsic artlessness that sets them apart from the almost perfect, but slightly mechanical, wares of the Qing Dynasty. Indeed, some enthusiasts claim that the finest porcelains in China's long ceramic history were produced during the late 15th century.» (Suzanne Valenstein, cit.).

I fully agree: I find some Chenghua pieces to be the harmonious embodiment of grace and exquisite refinement. I'm biased, I know.

Chenghua, ninth Emperor of the Ming dynasty, Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. Chenghua (成化帝; "Accomplished Change") reigned from 1464 to 1487.

According to many scholars, the cobalt blue pigment used in the Chenghua period was a local one, the so-called ping deng blue, as the imported cobalt blue reserves had completely run out. The ping deng blue contained a low concentration of iron and a high concentration of manganese, thus it did not create any "heaped and piled" effect. Several scientific works have studied the pigment used in the Chenghua period, but they have given different results; the most likely hypothesis is that these slightly inconsistent results are due to the use of a mixed pigment derived from different native Chinese ores.

In any case, the blue color on the pieces was soft, graceful, and consistent.

«There is a special grace to Chenghua blue and white wares. Sensitive brushwork is favored over bold and spirited strokes; here the tendency is to outline the designs before applying slightly mottled washes of color.» (S. Valenstein, cit.)

Below, you can admire a set of seven Chenghua 'Palace' bowls of extraordinary elegance and grace.

A set of seven 'Palace' porcelain bowls with floral decorations painted in underglaze blue.

From left to right, their outside decorations depict:

-

a wide band of scrolling gardenias and leaves above a band of overlapping petals;

-

a wide band of scrolling hibiscus flowers and leaves between pairs of blue lines (the word for hibiscus in Chinese is mufurong, similar to fu “wealth” and rong, “glory”;

-

a wide band of scrolling day lily xuancao flowers and leaves between parallel blue lines (a fertility auspicious symbol);

-

a wide band of scrolling magnolia flowers and leaves between parallel blue lines;

-

a wide band of scrolling formal lotus flowers and leaves between parallel blue lines;

-

scrolling baoxiang flowers above a band of stylised ruyi around the foot;

-

a wide band of three sprays of scrolling melons and vines (they symbolize a long line of male descendants and are an auspicious emblem).

Dimensions: var. diameter 14.6 - 15.5 cm; var. height 6.4 - 7.2 cm. Made in Jingdezhen. All with Chenghua reign's marks, 1464/65-1487, Ming Dynasty. The six-character Chenghua mark in a double square or a double ring is painted in underglaze blue on the base: ⼤明成化年製, Da Ming Chenghua nian zhi, "Made during the Chenghua reign of the Great Ming dynasty". The British Museum, London, UK.

'Palace' porcelain bowl with decorations painted in underglaze blue depicting two lotus flowers on the outside. The base shows the Chenghua reign's six-character mark Dà Míng Chéng Huà nián zhì. Jingdezhen, Chenghua reign, Ming Dynasty. Collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei (Taiwan).

Porcelain Incense Burner with underglaze cobalt blue decoration depicting the 'Eight Buddhist Treasures'. Diameter 17 cm. It shows the Chenghua reign's mark Ming Chenghua nian zhi, "Made during the Chenghua reign of the Great Ming dynasty". KongSpace Museum, a private international art collection institution, Taipei - Beijing. © Photo by KongSpace Museum

The Eight Buddhist Treasures are a common motif in Chinese and Tibetan art. Inspired by the Ashtamangala, they are the following:

-

the endless knot (symbol of love, it represents the interconnection and unity of everything);

-

the Wheel of the Law (symbolizes the Dharma and the Buddha's teachings);

-

the conch shell (represents the Buddha's teaching spreading in all directions like the sound of the conch trumpet);

-

the parasol (symbol of protection from the suffering experienced in the lower realms of existence);

-

the victory banner (the Buddha's victory over the four hindrances in the path of enlightenment);

-

the lotus flower (emerging from the murky, muddy depths towards the light, it represents the path towards enlightenment);

-

a lidded jar (treasure vase, an auspicious symbol of long life, wealth, and prosperity);

-

paired fish (which move freely and spontaneously in the ocean of suffering).

Porcelain Stem Cup with an underglaze cobalt blue floral decoration. Jingdezhen, Chenghua reign, Ming Dynasty. Dimensions: height 11.5 cm - 4.52 in; diameter 17.5 cm - 6.88 in. Musée Guimet - Musée National des Arts Asiatiques, Paris (France).

Photo © RMN-Grand Palais / Thierry Ollivier.

The following piece is an outstanding and rare bowl, unmarked but likely from the early Chenghua period, called the "Boys Bowl" for it depicts joyful scenes of playing kids. Everything is of the highest quality, meaning that it was probably made for the imperial court. In 2012, it was auctioned by Sotheby's and sold for HKD 7,820,000. In 2019, it was auctioned again by Poli Auction in Hong Kong and sold for HKD 15,340,000 (approximately 2 million dollars). It doubled in value in just 7 years. Better than gold, for sure.

Deep and rounded Bowl in porcelain, masterly painted in soft tones of underglaze cobalt blue and depicting a continuous garden scene, rich in flowers, rocks, bamboo, and willow; beneath dense curling clouds gathered over half the scene, 16 playing kids are portrayed in separated groups. Unmarked, but made in Jingdezhen in the early Chenghua Period, Ming Dynasty. Diameter 21.5 cm - 8.46 in; height 10.3 cm - 4.05 in. © Poly Auction Hong Kong.

«The theme of boys playing in a garden was an established subject in the paintings of the Song Dynasty. It continued to be a favorite among artists and craftsmen of the Ming and Qing dynasties, but the iconography fluctuated according to the medium and the times (...). Variously known as yingxitu, "pictures of boys at play", and baizitu, "pictures of a hundred boys", the illustrations of boys playing in a garden appear frequently in the decoration of Ming and Qing porcelain, textiles, and lacquerware. (...). Yingxi pictures feature a few boys playing, while baizi scenes usually depict a large group of boys, sometimes numbering one hundred as the name implies.» (Terese Tse Bartholomew, 3. One Hundred Children: From Boys At Play To Icons Of Good Fortune, see Bibliography.).

Different toys and games had a hidden meaning, but, generally, this theme conveyed the agricultural society’s abiding wish for teeming male offspring (yep, the kids are only boys). In the following centuries, the 20th century included, playing boys became one of the most popular pictorial subjects.

Below, is another refined Boys Bowl, preserved at the National Palace Museum in Taipei (Taiwan).

Porcelain bowl with underglaze cobalt blue decoration depicting 14 boys playing together in two separate groups. Jingdezhen, China. Chenghua reign's six-character mark inside a double ring on the base. Collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei (Taiwan).

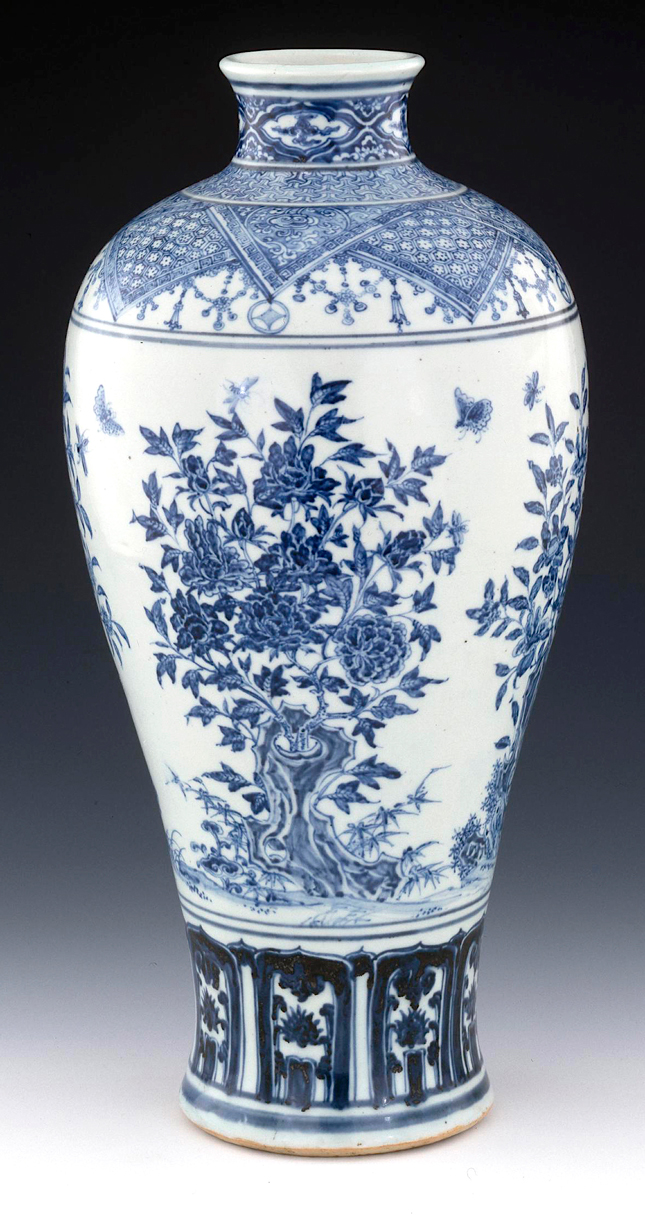

Porcelain meiping vase with a complex underglaze blue decoration. Jingdezhen, probably Chenghua period, 1464/65-1487, Ming dynasty. Dimensions: height 38 cm. The British Museum, London, UK.

The main ornamentation on the belly, masterly painted in different shades of underglaze soft blue, shows four flowering shrubs growing from rocks with insects hovering above, interspersed with auspicious plants such as bamboo and lingzhi. The shoulder is decorated with an unusual border of overlapping brocades from which beaded gadroons hang. Above, there's a ring of Y diaper and around the neck octofoil cartouches containing ruyi clouds interspersed with flower heads. «Although the overlapping brocade pattern is unusual, it may be seen ornamenting a late Chenghua period domed covered box, excavated at the imperial kiln site at Jingdezhen. The style of painting is unusual too. It is much stiffer than that of other fifteenth-century porcelains and follows a professional painting style. Another carved box, excavated in the Chenghua remains at Zhushan, exhibits identical painting style and treatment of insects and plants to those of the present piece. It also shows the same variations in the cobalt colours on a single piece from blackish blue to pale tones. Such designs would have trickled through to the commercial kilns and been adapted later.» (The British Museum curators). The neck is painted with a darker tone than the belly and is made with less accuracy. Probably, it was painted by a different hand, as it was customary in Jingdezhen (the minor ornamentation motives were entrusted to younger or less experienced painters). The foot shows a band of lappets with flower heads inside. This motif is roughly rendered in a very dark cobalt blue and looks painted by the second or even a third hand.

THE LATE MING PERIOD

«The late Ming period, from the mid-16th century onwards, was marked by weak emperors, passivity, poor administration, decadence, and corruption.» (Ming: The Golden Empire, National Museums Scotland, cit.). Porcelain production no longer reaches the peaks of earlier periods.

LEFT: Jiajing (嘉靖帝, "Admirable Tranquility") was the 12th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1521 to 1567. Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

Jiajing Emperor, in the 21st year of his reign (in 1542), after an assassination attempt, moved out of the imperial palace and chose to reside outside of the Forbidden City, neglecting his official duties. He was a devoted follower of Daoism and had three Daoist temples erected. These expenses and his negligence resulted in a remarkable political and economic decline of the dynasty. «In the mid and late Jiajing period, corruption started to grow rampant among officials, leading to a number of peasant revolts and mutinies. Moreover, the country was devastated by a once-in-a-century earthquake, while the Mongols and pirates were invading from the north and the south» ("Eternal Enlightenment, The Virtual World of Jiajing Emperor", Exhibition Catalog, HKMOA)

RIGHT: Wanli (萬曆帝, "Ten Thousand Calendars") was the 14th Emperor of the Ming dynasty, on the throne from 1572 to 1620. Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

«The reign of the Wanli emperor (r. 1573–1620) is usually noted as a turning point in the history of the later period, when the Wanli emperor effectively lost interest in his administration and refused to deal with his officials, except through eunuch intermediaries. The Ming government consequently entered into decline, with many officials resigning or abandoning their posts.» (Ming: The Golden Empire, cit.).

«Porcelains of the reign of the Jiajing emperor (1521-67) steadily lessened in quality, and few ceramics approach the level of late 15th-century wares. Quantity, now, was the ultimate goal at the Jingdezhen kilns. There were enormous orders from the palace to be filled, amounting to thousands of objects annually; indeed, one year's requirements are reported to have exceeded one hundred thousand pieces. It is understandable that the potters, in their effort to meet production quotas, had little time for careful craftsmanship.» (Suzanne Valenstein, cit.). Chinese scholars think that during Jiajing's reign, a total of nearly 600,000 pieces were produced in Jingdezhen for the imperial court.

The cobalt blue used in the Jiajing period was the so-called Hui blue, an imported one which gave a dense and gorgeous color with a purplish tone (due to the high concentration of manganese), often used in combination with the local Shi-zi blue from the Rui province. The decorative style is exuberant and vivid, and many imperial pieces are decorated with Daoist symbols, reflecting Jiajing's strong beliefs and his obsession with longevity. Justifiable, indeed. The emperors before Jiajing only lived an average of 42 years (according to the 2019 World Bank Group data, no country in the world has such a low life expectancy today).

Two Jiajing huluping 'double-gourd' porcelain vases with a complex underglaze cobalt blue decoration, rich in Daoist symbols.

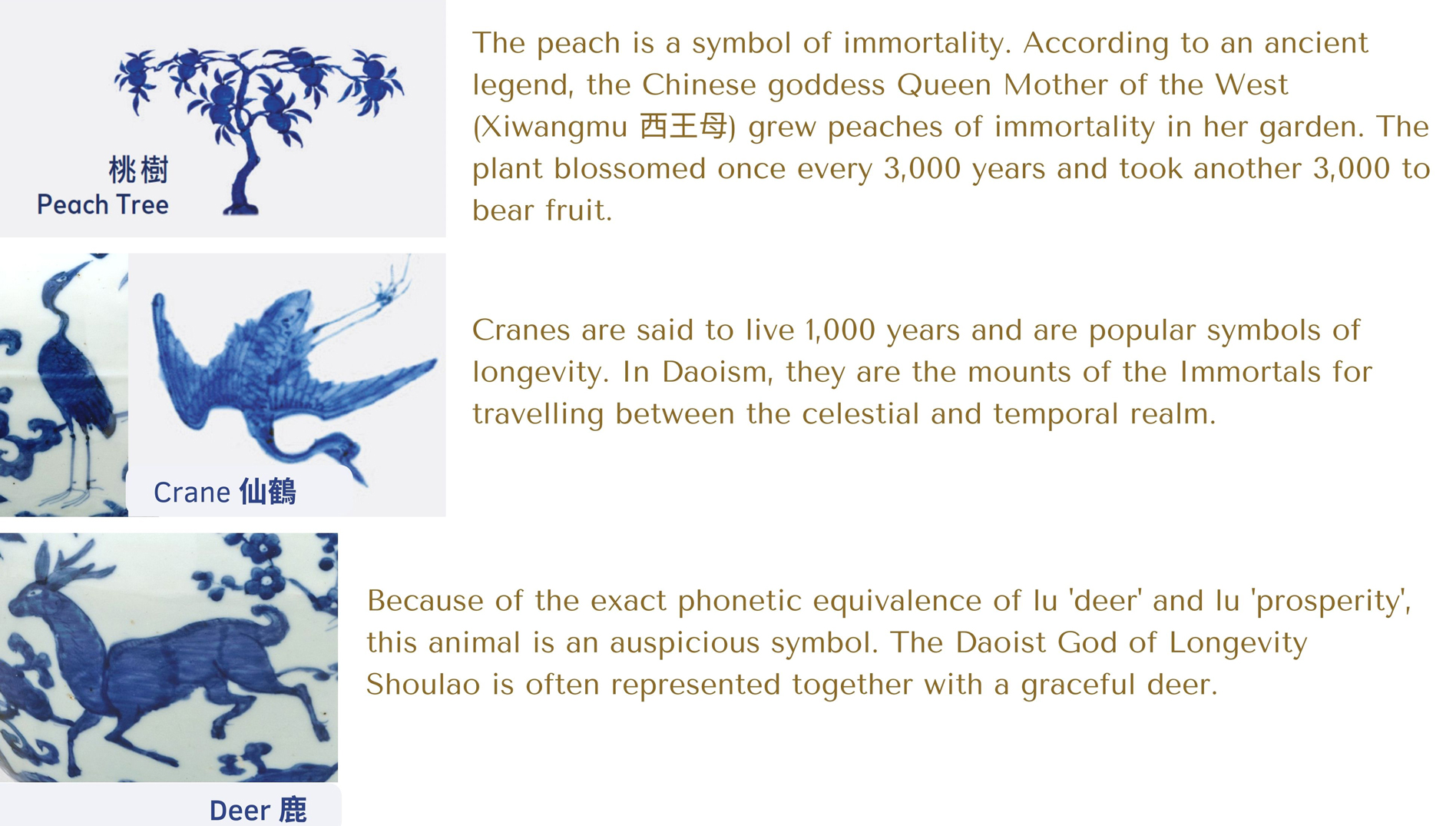

LEFT - Double-gourd Bottle with Deer and Crane combined with a peach tree and the 'Three Friends of Winter': plum, bamboo, and pine. Jingdezhen, China. Jiajing reign's mark, Ming Dynasty. Dimensions: height 45.7 cm - 18 in; diameter 24.8 cm - 9 3/4 in. The MET, New York, US.

RIGHT - Double-gourd Bottle with Deer and Crane combined with a peach tree and the 'Three Friends of Winter': plum, bamboo, and pine. Jingdezhen, China. Jiajing reign's mark, Ming Dynasty. Dimensions: height 44.5 cm - 17.51 in; diameter 23 cm - 9.05 in. The British Museum, London, UK.

The blue and white porcelain ware made in Jingdezhen during the Wanli reign came in a wide range of forms and decorations. After the Jiajing period, the availability of Hui blue pigment decreased rapidly: it was used sparingly and conservatively and from the mid-Wanli period onwards, it was replaced by the local Zhe pigment, so-called for it came from the Zhejiang province, which gave a less bright, slightly grayish blue color.

In 1608, the production at the Imperial kilns was discontinued and the official production was suspended in 1637. It will be necessary to wait until the arrival of Zang Yingxuan as director of the imperial factories at Jingdezhen in 1683, under the reign of Kangxi, the third emperor of the new dynasty, the Qing. The unofficial kilns however did not stop producing porcelain ware for the export and the domestic market. And they did it by creating what Suzanne Valenstein defined as "a fascinating conglomeration of porcelains On one hand, the Jingdezhen kilns continued to produce many traditional, routine pieces, bringing traditional decorative formulas back up; on the other, freed from the imperial grip, they could experiment and innovate with a new, unrestrained approach. The porcelain pieces of this period are known as "Transitional ware" and the production of underglaze blue and white pieces destined for Japan as Tianqi ware or ko sometsuke.

Below are four remarkable pieces.

The first is an impressive temple vase, almost half a meter high, made during Wanli's reign.

Then there is an exquisite, unmarked censer likely made during Wanli's reign.

The last couple of vases is a beautiful example of a 'Transitional' style showing a curious and dissonant decorative detail.

Porcelain Temple Vase with an underglaze cobalt blue decoration depicting dragons amid flowers, both in blue on white ground and in white on blue. Its form is called gu and is inspired by an ancient Chinese ritual bronze vessel from the Shang and Zhou dynasties (1600–256 BC). Jingdezhen, China. Wanli mark and period (1573–1620), Ming Dynasty. Dimensions: height 49.5 cm - 19 1/2 in. The MET, New York, US.

Porcelain incense burner with underglaze cobalt blue decoration and shaped as a mythical beast. Jingdezhen, China. Early 17th century, likely during the Wanli period, Ming Dynasty. Dimensions: height 33 cm - 13 in; width 17.8 cm - 7 in; depth 24.8 cm - 9 3/4 in. The MET, New York, US.

Inspired by ancient bronze censers, this piece depicts a luduan (甪端), an auspicious mythical creature with a body made up of parts from different animals. According to a popular legend, it can speak all the world languages and detect the truth; it only appears when a virtuous ruler ascends to the throne.

A pair of porcelain garlic-neck bottle vases with underglaze cobalt blue floral and figural decoration. Jingdezhen, China. Transitional ware, Chongzhen period, 1628-1644. Dimensions: height 38.5 cm - 15.15 in. The British Museum, London, UK.

Did you recognize the dissonant decorative motif? The neck and the mouth of both pieces are decorated with European tulips.

«The first bottle <on the left> is decorated around the lower bulb with a gentleman, dressed in scholarly round-necked robes and a winged hat, holding a tally of office in his left hand. He is approached by a respectful servant holding a tray on which is placed an arrow vase, containing three arrows. Behind the central figure are two servants holding large ceremonial fans on long poles and behind these are two further servants carrying insignia of office resembling maces on long poles. Surrounding these figures is a garden landscape and the end of the scene is marked in a typical 'transitional' style with a bank of swirling clouds. Three Western-style flowers, possibly tulips, adorn the neck and are repeated around the top. The base is glazed but unmarked.

The second bottle <on the right> shows on one side four figures gathered around a saddled horse with a lame leg. One man holds a folded parasol, another the horse's reigns, a third rests on his staff and the fourth holds a stick out towards the horse. All the figures are dressed in hats, cross-over robes, tied at the waist over trousers, and boots. On the other side, a scholar, wearing an official winged gauze cap, attended by a servant holding a fan, is engaged in conversation with another man wearing a brimmed hat. Two further servants stand a little way off holding gifts including a bolt of cloth. Surrounding these figures is a landscape and the end of the scene is marked in a typical 'transitional' style with a bank of swirling clouds. Three Western-style flowers, possibly tulips, adorn the neck and are repeated around the top. The base is glazed but unmarked.» (The British Museum curators).

RIDDLE ME THIS

Look at the following pictures. One shows a 21st century African piece in glazed porcelain, the other a Ming porcelain made between the late 16th and the early 17th centuries during Wanli's reign. Could you identify them?

LEFT - Shallow white porcelain dish with splashes of dark blue and turquoise glaze. Unique specimen with flat unglazed base, shallow rounded sides, and flat rim with an everted edge. It is glazed monochrome creamy-white with deep blue and turquoise random splashes. The colors are evocative of the 'fahua' palette. Unmarked, made likely during Wanli's reign, between the late 15th - early 16th centuries, Ming Dynasty. Dimensions: diameter 22 cm - 8.66 in; height 1.50 cm - 0.59 in. The British Museum, London, UK.

RIGHT - Nyanga porcelain bowl, handmade in Zimbabwe by Mutapo Design, 21st century. Dimensions: diameter 15.24 cm - 6 in; height 5.08 cm - 2 in. Sold by 54 Kibo.

The point of this story?

Chinese porcelain never fails to surprise.

"How Emperor Wanli of the Ming Dynasty dressed on a typical morning".

This short film accurately recreates the costumes of the Ming dynasty at the court during the Wanli period (1573-1620). The Chinese hanfu presented in the short film is scrupulously historically accurate in form and exquisite in detail; the emperor's final outfit is no different from his ancient portraits.

High-ranking court-official ceremonial style of clothing in the late Ming Dynasty

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?