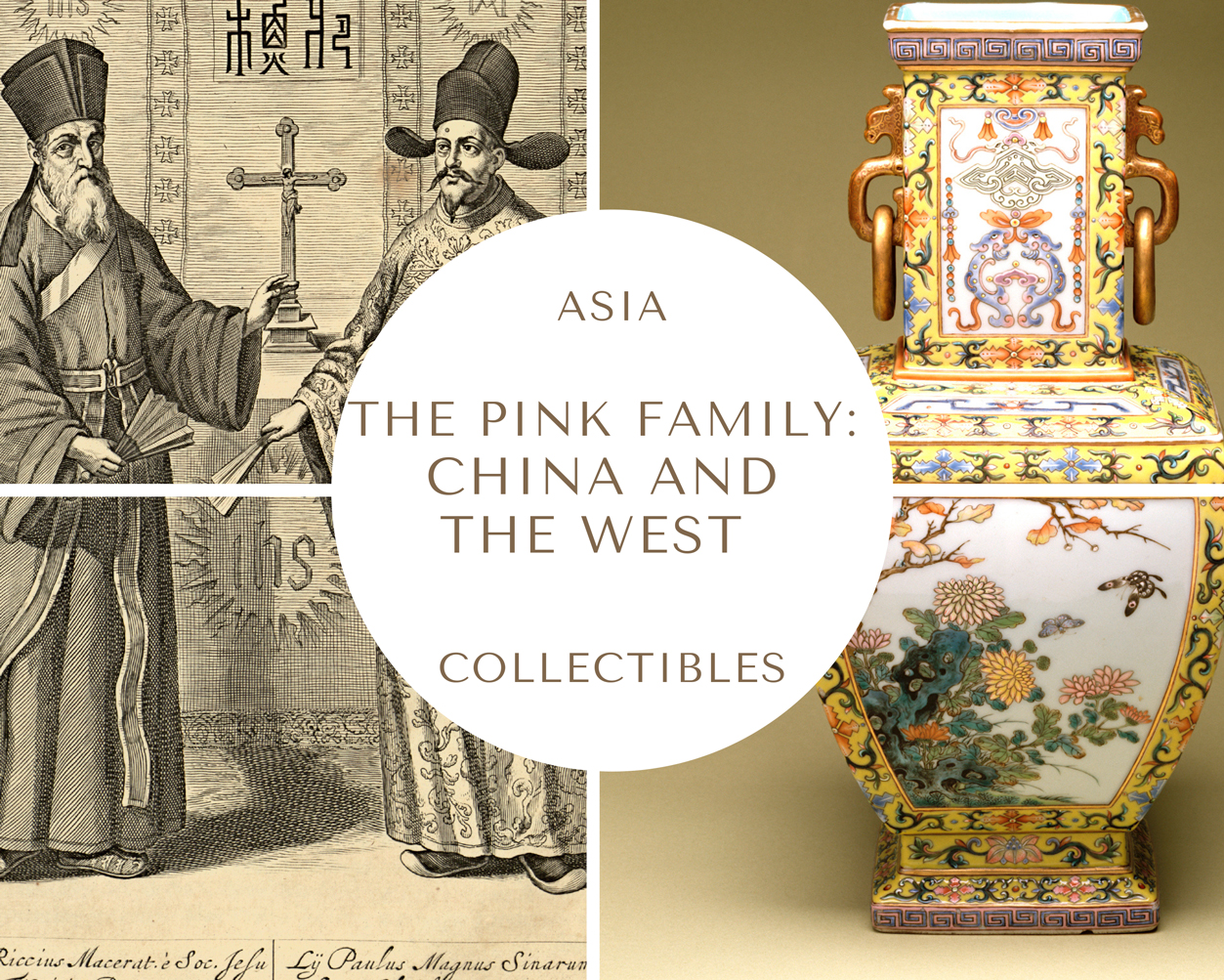

THE PINK FAMILY: CHINA AND THE WEST 7

Current China on the globe.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

LEFT: Portrait of the Yongzheng Emperor in Court Dress, by anonymous court artists, Yongzheng period (1723—35), Qing Dynasty. Hanging scroll, color on silk. The Palace Museum, Beijing. Public Domain.

RIGHT: History of China, Imperial Dynasties, source: Dynasties in Chinese history, Wikipedia.

THE BLUE AND WHITE PORCELAIN IMPACT ON THE WEST IN THE 16TH AND 17TH CENTURIES

THE RECEPTION OF CHINESE PORCELAIN IN EUROPE IN THE 16TH AND 17TH CENTURIES

UNITED KINGDOM

According to the Victoria and Albert Museum curators, Chinese «porcelain bowls, flasks and dishes decorated in underglaze blue began to arrive in small quantities in England from the 1560s. (...) By the mid-17th century (...), blue and white Chinese porcelain was widely available in noble and wealthy households and was no longer considered rare or curious. Porcelains of the finest quality, however, continued to be set in decorative mounts.». According to Stacey Pierson, who studied the process of appropriation and consumption of Chinese porcelain in England, after the mid-17th century, «imported ceramics were used without adornment in daily life, particularly at the table, becoming a familiar domestic object.» (S. Pierson, Chinese Porcelain, the East India Company and British Cultural Identity, 1600-1800, see Bibliography).

During the 17th and 18th centuries, Chinese porcelain ware got gradually incorporated into British life and this process entailed a change in identity imposed on the porcelains used both in Britain and by British consumers outside Britain.

From the late 17th century onwards, privately commissioned wares, known as ‘armorial wares’ as they were decorated with a family crest and motto or a company's logo, began to spread; initially, they were single pieces (vessels, pots, planters, or plates), but later on, after the beginning of the 18th century, they took the form of large dinner services with matching sets of vessels. «The figurative decoration on these pieces <was> primarily Chinese but with the addition of a foreign crest, demonstrating a desire for the ‘Chineseness’ of the vessels to be retained. This visual hybridity provided information about the consumer and his access to trade goods from afar, as well as his desire to be represented as a member of the British elite who would be in possession of a family crest.» (S. Pierson, cit.). This means that the ‘Chineseness’ of some decorative elements was maintained not for its intrinsic value, as Chinese, but for the social meaning locally attached to it «[F]rom the 1720s, the decorative style of British Chinese porcelain began to change, minimizing Chinese designs and patterns, so that its Asian origins were all but eliminated. The new domestic-style designs prominently reflected the tastes and lifestyles of the newer consumers, from multiple levels of society.» (S. Pierson, ibidem).

The more Chinese porcelain becomes a part of the British lifestyle, the more it undergoes a process of de-Sinicization in shapes and decorative motifs until it loses its entire, original Chinese identity. The Jingdezhen or the Arita porcelain pieces gradually became British objects, rich in new and layered social meanings, but contingently made in China or Japan, as any Western-style, made-in-Asia tableware currently in our kitchen. «[O]nce porcelain from China became readily available in Britain after the 1720s, and therefore not exclusive, it no longer needed to be visually Chinese, declaring its exotic origins. Instead, by a certain date, Chinese porcelain merely provided the medium for the making of a visually British object which, therefore, is only materially Chinese.» (Ibidem).

Through this process of de-Sinicization and appropriation, the Chinese products could become British and act as a representation of British national and cultural identity.

From the late 17th century throughout the 18th and beyond, well-to-do Europe shared the refined habit of sipping exotic hot drinks–tea, coffee, chocolate–using small Chinese or Japanese porcelain services, called cabarets in French. These sets, largely available on the European market, were expensive but not cost-prohibitive.

Pieter van Roestraten, Stillleben mit chinesischen Teeschalen (Still life with Chinese tea cups), 1670s, oil on canvas. Dimensions: 35 x 47.5 cm - 13.7 in x 18.8 in. Gemäldegalerie der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin, Germany.

Pieter Gerritsz van Roestraten (1630–1700) was a Dutch still-life painter who lived and worked most of his career in London, UK. In this painting, there are some precious pieces placed on a lacquer table and in a dim setting: 5 Chinese porcelain cups, a silver spoon, an elaborate lidded sugar bowl, and behind the cup on the left side, a Chinese Yixing clay teapot with a metal mount.

In England, the spread of Chinese porcelain and the diffusion of tea went hand in hand. «As a medium, porcelain was an important facilitator for both the simple drinking of tea and also the presentation, shipping, and storage of it, thus contributing to both trade in the commodity and the social practice of tea drinking which initially was heavily gender and class driven. Until the mid-18th century, tea drinking was mainly reserved for the upper classes and controlled by the women of the family. Tea became a valuable and profitable commodity from the late 17th century onward and large quantities of tea were only available from China at that time. Most bulk tea was transported by sea and porcelain was a useful accessory product that could both weigh the ships as additional ballast and line the bottom holds to protect the tea above from damp and odour contamination.» (Ibidem).

The more elaborate became the practice of tea drinking, the more complex became the tea services (in the 18th century, they were usually made up of many pieces: teapot, milk jug, sugar bowl, slop bowl, tea caddy, spoon tray, cups, and saucers). Tea and porcelain tea sets got fully 'Britishized' to the point of losing their primal Chinese identity: Britain became a tea-drinking nation and Chinese porcelain simple china.

Unknown artist, Two ladies and an officer seated at tea, ca. 1715. Painting, oil on canvas. Dimensions: framed height 79.5 cm, framed width 92.5 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

The painting depicts «two ladies–one dressed in dark green, the other in a dark greyish blue–and a gentleman in a red jacket around a circular table whilst seated in ladder-back chairs. In the background is a fireplace with a painted overmantel.» (V&A Museum curators). They are depicted while drinking tea by using a fine Chinese porcelain tea set.

This kind of painting was quite common in the 18th century. It was inspired by the 17th-century Netherlandish interior scenes and became especially popular in 18th-century England. The tea party was one of the most popular subjects for these scenes called "conversation pieces".

This painting has been attributed to a Dutch painter, Nicholas Verkolje, for a long time until Fred Meijer showed this attribution as mistaken and claimed it was not even a Dutch or Flemish one. Today, according to most scholars and the V&A Museum curators, it's likely a work of English origin. «The difficulty in identifying the artist stands in the fact that the main features of the painting–furniture, costumes, and vessel ware–were not characteristic of any country but were widespread in northern Europe during the early 18th century. The tall turned black chairs were found throughout Europe (there is a set in Boughton House, for instance), while the ebonized round table could be of English origins, as well as the kettle. As for the blue and white China, they were highly appreciated in Holland and England, and were made directly in Asia for the European market.» (V&A Museum curators).

A Family of Three at Tea, an oil painting from ca. 1727, attributed to Richard Collins (active 1726-1732). Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

«The painter shows a fashionable family sitting around a tea table, obviously proud of their up-to-date and valuable silver and porcelain, and also of their knowledge of the correct manner of taking tea. The tea equipage is typical of the first half of the 18th century. It includes a sugar dish, a tea canister, sugar tongs, a hot-water jug, a spoon boat with teaspoons, a slop bowl, and a teapot with a lamp beneath it to keep the contents hot.» (V&A Museum curators).

A Tea Garden, print, UK, late 18th century, engraved by François David Soiron after a painting by George Morland. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

The print depicts a family group of seven taking tea around a table, under a tree, with a fine porcelain tea set.

THE NETHERLANDS

In the 16th century, Chinese porcelain was still an extremely luxurious commodity and only a restricted group of citizens possessed a few pieces. This is true for the early 17th century as well, when only the rich could afford the porcelain, but gradually the urban middle class could partake in the fashion. Thanks to the VOC, from the early 17th century onwards, the country experienced the massive import of Chinese kraak porselein and transitional porcelain, and from the second half of the century onwards, even Japanese pieces. The import was really massive: documents and invoices show that quantities as large as 100,000 to 250,000 porcelain pieces per VOC schip were being transported to the Dutch harbors.

«The members of the House of Orange, the princes, and stadtholders who had only recently acquired their status as powerful state leaders, were looking for ways to express this new role. Deliberately choosing to portray themselves as princes of treasures of the East buying, amongst other things, large amounts of porcelain, their role was by no means insignificant. Their approach of showing off and impressing with overseas treasures is best conveyed by the lavishly decorated interior of Huis ten Bosch, the palace of the Dutch royal family in The Hague. (...). <Amalia, the wife of the> stadtholder Frederik Hendrik (1584-1647) was the first to have real porcelain cabinets, separate rooms specially designed to display large quantities of porcelain. Naturally, the Dutch nobility and wealthy citizens followed the Princes of Orange in their conspicuous consumption ; thus, the collection of Chinese porcelain became a Dutch craze from the early 17th century onwards.» (Jan van Campen, Asian Ceramics in the Netherlands, see Bibliography).

If the first pieces were mainly display status symbols and luxury decorative knick-knacks, in the mid-17th century, the availability of larger quantities of porcelain resulted in their growing use as household ware (chargers, cooking pots, drinking glasses, tea sets, etc.). The Danish historian Johan Isaaksz Pontanus (1571–1639), who lived in The Netherlands, wrote in his Historische beschrijvinghe der seer wijt beroemde coop-stadt Amsterdam that the trade of the VOC had brought so much porcelain into the country that some pieces were available for daily use by the common man. The contemporary scholar Sebastiaan Ostkamp writes that in the late 1620s, it seemed «as if almost everyone in <the city of> Alkmaar could afford a bowl or a dish, but the daily use of larger plates and bowls perhaps remained restricted to a relatively small group». (Sebastiaan Ostkamp, see Bibliography).

Chinese porcelain ware quickly replaced the native earthenware and stoneware used in the Netherlands before the 17th century due to its unique features: it was much thinner, harder, and healthier than porous clay, more translucent and shinier than majolica, more attractive than anything else thanks to its “exotic” appearance, unique chromatic contrast, and mysterious processing.

Throughout the 17th century, the flaunting ownership of peperduur treasures from the East, and their sumptuous display were seen not only as a sign of prosperity and affluence but also as an indicator of modernity, of being part of the new organizational, cultural, and economic advances due to the colonial invasion, the global market expansion, and the accelerated corporate finance development. Peperduur is a Dutch term assembled during the Golden Age to indicate those imported goods as expensive and luxurious as pepper. The sumptuous display of many Asian peperduur commodities at home showed how attuned the householder was to the new urban entrepreneurial mentality and its consumerism or how far it was from the outmoded lifestyle of the old landed nobility. That display was also a feature of many still-life paintings of the time.

As Margaret McCunn Burns highlighted, many Dutch and Flemish still-life paintings of the Golden Age portrayed porcelain pieces. Before 1650, the porcelains were mainly Chinese blue and white export wares; after that date, Japanese Arita pieces and some Delftware began to be represented.

Let's start with an early 17th-century oil painting from the Flemish school by Osias Beert, aka Osias Beert the Elder (ca. 1580-1623), a Flemish painter active in Antwerp, a city in present-day Belgium, but in the Spanish Netherlands during the 17th century. It's a still life with a Chinese kraak porcelain bowl with cherries (in the right foreground), a Chinese export plate with strawberries (in the left foreground), and a kraak bell cup with mulberries (in a central, more backward position). On a pewter plate is a cut artichoke, and next to it, a luxury knife, a piece of bread, two glasses, and a silver sugar bowl. The painting also depicts a fly (on an artichoke half) and a butterfly.

Osias Beert the Elder, Still life with Artichoke, Fruit in Kraak Porcelainware, a Salt Cellar/Pepper Castor, ca. 1605-1615, oil on panel. Dimensions: height 46.4 cm x width 79.3 cm. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Jacob van Hulsdonck, aka Jan van Hulsdonck (1582–1647), was another Flemish still-life painter from Antwerp, and a contemporary of Osias Beert. Like the latter, he was well known for his meticulous rendering of surfaces and textures. The oil on panel below, painted after 1620, shows lemons, oranges, and a pomegranate in a Chinese blue-and-white porcelain bowl, dating from the Wanli period of the Ming dynasty. Note that oranges are still called sinaasappels, 'China’s apple' in Dutch.

Jacob van Hulsdonck (Flemish, 1582 - 1647), Still Life with Lemons, Oranges, and a Pomegranate, ca. 1620–1640, oil on panel, signed. Dimensions: 41.9 × 49.5 cm (16 1/2 × 19 1/2 in.). Getty Center, Museum East Pavilion, Los Angeles, CA, US.

The following oil on panel was painted by Floris Claesz van Dijck (c.1575–1651), a Dutch Golden Age still-life painter. This famous painting from ca. 1615 shows a refined table covered with an expensive pink silk damask tablecloth and a white linen runner. Three pieces of cheese, many mixed fruits in a Chinese bowl, loaves, walnuts, and hazelnuts are displayed with some olives in a blue and white porcelain bowl and grapes in another vessel. This painting portrays the typical banketjes (“banquet pieces”), which were in vogue in Haarlem in the 1610s. The porcelain pieces, the silk tablecloth, the linen runner, the olives, and the grapes were all expensive imports at that time: this is the elegant table of a rich merchant or a very wealthy urban bourgeois. The scene was painted with undeniable virtuosity both for the astounding illusion of reality - look at the pewter plate that protrudes from the edge of the table - and the maniacal attention to the most minute details - look at the apple peel hanging from the table, showing a brownish color and a slightly withered texture.

Floris Claesz van Dijck, Still life with Cheese, ca. 1615, oil on panel. Dimensions: height 82.5 cm x width 111.4 cm. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

One of the most celebrated still-life painters in the Dutch Golden Age was Jan Davidsz. de Heem (Utrecht 1606 – Antwerpen 1684), considered by many experts the 'pioneer' of a new sumptuous and ornate style of still life. His paintings were relatively large-sized canvas, depicting complex compositions, and painted with obsessive attention to detail and rich coloring. Most of his still lifes feature an array of peperduur treasures and expensive import delicacies which make up a display of overwhelming abundance. The opulent, sumptuous still life painting style developed by de Heem in the 1640s and adopted by many painters is known as Pronkstilleven. Some scholars see Pronkstilleven as a form of vanitas painting that conveys a moral, or rather, moralistic lesson. According to this interpretation, the various precious objects in the composition serve as symbols that can be read as an admonition against the transience of life and the vanity of material possessions. On the one hand, it's true that some objects which were often portrayed in those still lifes were moralizing symbols - roses of vanitas, hourglasses of transience, skulls of mortality, rotten fruits of decay, flies of corruption, and so on; however, the generalization that sees all Pronkstillevens as a form of vanitas painting is wrongful. The still life genre developed in the Golden Age and not for chance: it subtly reflected the newfound, unprecedented wealth of the Dutch Republic and the way the Dutch saw themselves and their world, divided between the old and the new.

The Pronkstillevens had remarkable success in terms of sales. Those paintings were purchased by the new Dutch élites for their glimmering visual feast: blades of light defeat the enveloping darkness; local chestnuts, berries, and cherries are a minor presence compared to the many imported exotic delicacies; the traditional dark colors of the old table are set on fire by flaming reds, bright cobalt blues, and brilliant golds. Those still lifes were purchased for their glamour, fed equally by opulence and a few realistic decaying details. They were admired by the new élites for the irresistible allure of present wasteful abundance. Silver chargers and stands, Venetian glasses, Spanish citruses, Chinese bowls, Asian carpets, and Oriental nautilus with gilt-silver mounts told a story of colonial conquest, commercial and entrepreneurial mindset, financial courage, shipping capacity and nautical knowledge (in the mid-17th century, the 2,500 Dutch ships accounted for about half of Europe’s shipping. Source: Maarten Prak, Gouden Eeuw. Het raadsel van de Republiek, 2002), hard labor, and wealth. They were the tangible sign of the country's prowess to transport goods throughout the entire world, taming the tantrums of huge oceans and the savage nature of primitive peoples.

The Dutch knew death better than we do today, and they did not need any memento mori: despite the scientific and medical advancement of that era, people continued to suffer and die, often suddenly or for unknown, inexplicable reasons. All women, including the richest and most privileged, could die in childbirth, and many children, even in the wealthiest families, could not reach adulthood. Outbreaks of plague occurred several times during the Golden Age. In 1665, for example, Amsterdam had to recover from a deadly outbreak of bubonic plague that wiped out 10% of the population (approximately 24,000 Amsterdammers). The Dutch did not need anyone or anything to remind them how short and fragile life was, how transient or ineffable the pleasures were, or how mocking the wealth was because they perfectly knew that a cargo of spices could get lost in the depth of the ocean instead of yielding a 400% profit. The Dutch, instead, desperately needed a blade of light, a pledge of prosperity, a promise of 'gold', fullness, life, and abundance against the darkness immediately behind their back. That 'golden light' was the promise of nascent trade capitalism and consumerism. And Pronkstillevens stood out as the 'visual representation' of the entire Golden Age.

Jan Davidsz. de Heem, Still Life with Ham, Lobster and Fruit, oil on canvas, ca. 1652. Dimensions: width 104.8 cm, height 74,7 cm. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

The next painting is an oil on panel by Abraham Mignon (1640-1679), born in Frankfurt (Germany). He became the young apprentice of artist Jacob Marrell and with him, in 1664, he moved to Utrecht, in The Netherlands, where he died in 1679. Mignon studied still-life painting with Jan Davidsz. de Heem and worked as his assistant until 1672. Mignon's paintings of flowers and fruit feature the same opulent style of composition and the same brilliant colors as De Heem's work and were quite famous at the time. (Both the Elector of Saxony and the French King Louis XIV bought some of his works). The painting below, dated between 1660 and 1679, is a pronk still life with fruits, oysters, and a Chinese bowl. Note that Mignon set the römer upside down. (Roemer or römer was the name of a precious and large-sized wine glass used in the Rhineland and the Netherlands in the 17th century). Do you see what is reflected in the wine glass? There are a window and a view of a church tower in Utrecht.

Abraham Mignon (1640-1679), Still Life with Fruit, Oysters, and a Porcelain Bowl, ca. 1660 - 1679, oil on panel. Dimensions: height 55 cm × width 45 cm × depth 6.8 cm. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

One of the leading proponents of Pronkstilleven was the Dutch still-life painter Willem Kalf (we saw his Still Life with Ewer and Basin, Fruit, Nautilus Cup, and Other Objects in the section on metal mounts). Among Kalf's followers, there was Juriaen van Streeck or Juriaan van Streek (1632–1687), a painter who lived and worked in Amsterdam. Below are two of his still-life paintings illustrating the same theme.

LEFT: Juriaen van Streeck, Still life with Blackamoor and porcelain vessels (Stillleben mit Mohr und Porzellangefäßen), the 1670s, oil on canvas. Dimensions: height 143.4 cm (56.4 in); width 120.5 cm (47.4 in). Alte Pinakotek, Munich, Germany.

RIGHT: Juriaen van Streeck, Still life with peaches and lemon, 1636, oil on canvas. Dimensions: 90,5 cm × 80 cm. Private Collection.

Both paintings show a table full of peperduur commodities against a dark background: a nautilus shell from the Indian Ocean, oysters, some glass römers of elaborated shape, an oriental rug, and an elegant brown carpet with fringes, silver chargers, some imported grapes, and of course different Chinese porcelain pieces, including an ewer with a gilt-silver mount (on the left). The citrus fruits were popular in The Netherlands: the Mediterranean oranges were symbols of loyalty to the new rulers from the House of Orange, while the lemon, which was usually depicted cut with a curl of peel and was a constant presence in almost all Golden Age Dutch still lifes, was a luxury product, imported from Spain or Italy. The wealthiest Dutch had orangeries built attached to their residences so that they could cultivate frost-tender lemon plants.

The black servant in Blackamoor style is a fancy possession among others. We must remind the Dutch involvement in the transatlantic slave trade, which spanned the 16th through the 19th century. According to the African Studies Centre of the University of Leiden, «Dutch involvement in the Atlantic slave trade covers the 17th-19th centuries. Initially the Dutch shipped slaves to northern Brazil, and during the second half of the 17th century, they had a controlling interest in the trade to the Spanish colonies. Today’s Suriname and Guyana became prominent markets in the 18th century. Between 1612 and 1872, the Dutch operated from some 10 fortresses along the Gold Coast (now Ghana), from which slaves were shipped across the Atlantic. The trade declined between 1780 and 1815. The Dutch part in the Atlantic slave trade is estimated at 5-7% or some 550,000-600,000 Africans. The Netherlands was one of the last countries to abolish slavery in 1863. Although the decision was made in 1848, it took many years for the law to be implemented. Furthermore, slaves in Suriname would be fully free only in 1873, since the law stipulated that there was to be a mandatory 10-year transition».

Was the black page portrayed by van Streeck a free servant or a slave?

According to Sheldon Cheek, assistant director of the Image of the Black Archive & Library at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center (in the US), slavery was technically illegal in the Golden Age Netherlands (though not in the New World colonies), but the situation was quite porous, as often Africans would be brought into the Netherlands via the Dutch slave trade and presented as ‘gifts’ to the wealthy (source: Greg Cook, Were Those Black ‘Servants’ In Dutch Old Master Paintings Actually Slaves?, see Bibliography). Therefore, it's hard to determine the status of the black people seen in the Golden Age paintings; they probably were slaves, not de iure but de facto. In any case, like all the oriental peperduur goods, they were status symbols and, at the same time, exotic, decorative, luxury peperduur commodities, just like Chinese porcelain vases, silk pieces, and lacquerware. According to Julie Berger Hochstrasser, who analyzes the works of Juriaen van Streeck in her remarkable essay Still Life and Trade in the Dutch Golden Age (2007), the black subjects are tronies—a Dutch word indicating the depiction of a character type, not a real portrait—that function as luxury objects, added to paintings to enhance meaning and visual appeal.

About the picture on the left, Nicole Ganbold wrote: «The fetishization of exotica in Dutch still lifes tells us a lot about the colonial mindset that many Europeans shared in the 17th century. As we see in the painting by Juriaen van Streek, he displayed various commodities from afar in one composition: seafood, citruses, carpet, wine, porcelains, and… a slave. It is striking that the painter perceived the turbaned African youth in the same way as Chinese porcelain—as a colonial trophy.» (Beautiful Chinese Porcelain in Dutch Still Lifes, in Daily Art Magazine, 20 October 2022).

We already saw how the pronk still lifes embodied not only the exaltation of the mercantilist mentality and entrepreneurial vivacity of the Dutch but also the triumph of their colonial ventures, which, let us remember, were not the adventurous jaunts of a handful of brave explorers, but the rapacious conquest of other people's lands and resources and the inhumane exploitation of locals for economic and financial gain. Behind the colonial adventure lies an aberrant vision that considers the other—the non-white, the savage, the negro ape, the ugly chink—a subhuman to be exploited, an object to be consumed, or an obstacle to be removed at any cost. Chinese, Japanese, and other Asian peoples were never considered equal trading partners.

Thus, the reification of the Blackamoor does not surprise me at all. Instead, what deserves to be emphasized is the ambiguity inherent in the Dutch 17th-century China mania: the Dutch fell crazily in love with Chinese porcelain. Did they do so because they fell in love with China, its civilization, culture, or art? No, not at all. The Dutch madly loved the new, complex meaning that Chinese porcelain began to take on in the Netherlands when those pieces were deprived of their original Chinese identity, and this process is perfectly shown by the Pronkstilleven paintings of the Golden Age.

FRANCE

In 1664, king Louis XIV and his First Minister of State Jean-Baptiste Colbert decided to establish the French East India Company (Compagnie française pour le commerce des Indes orientales). In less than a century, however, the latter turned out to be a commercial failure. According to Stéphane Castelluccio, author of the volume Le goût pour les porcelaines de Chine et du Japon à Paris aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siecles (see Bibliography), the import of porcelain ware to France was limited to two periods: 1680-1684 and 1688-1715. The Parisian marchands-merciers, who combined the roles of antique dealers, jewelers, interior decorators, and sellers of porcelain ware, had to purchase many pieces in Amsterdam to meet market demands. «In the first half of the 17th century, porcelain prices remained high. Only sovereigns, princes, and wealthy customers could afford China ware.» (My translation, from S. Castelluccio, cit.). From the late 17th century onward, the imported quantity increased, and the prices decreased. Many nobles and wealthy bourgeois began to buy and collect Chinese and Japanese pieces, mounted or not. Despite the increasingly less prohibitive prices, Asian porcelainware maintained an aura of luxury, mystery, and intense exoticism.

The Inventaire des Meubles de la Couronne de France (the "Inventory of the French Crown Furnishings") made in 1718, three years after the death of the Sun King, reports that he had collected a few thousand pieces of oriental porcelain, although he was not an ardent fan of it. Monsieur, his younger brother Philippe I Duke of Orléans, had a collection of 966 porcelain pieces, according to a document from 1701. Monseigneur le Grand Dauphin (the eldest son of the king) and other members of the royal family had hundreds of pieces. Most courtiers and nobles surrounding the king at Versailles and the Parisian elites shared a deep fascination with China and the Far East.

According to Stephan Castelluccio, at the time of the Sun King, the value of Chinese porcelain depended on many factors and could, therefore, vary widely. A porcelain vase, for example, could cost from a minimum of 10 sols to a maximum of 40 livres (=800 sols), a very wide price bracket. Just to give you an idea, the minimum wage of a laborer or servant was less than 1 livre per day, equal to a soup or a bottle of medium-quality wine in a tavern. Prices of ordinary quality Chinese plates and cups never reached sky-high figures and remained quite affordable. A low-quality goblet, for example, could be on sale for as little as 8-10 sols.

Thanks to the wide price bracket, between the late 17th and the early 18th centuries, Chinese porcelain ware became part of the daily lives of many French families, both as decorative elements and as objects of use. Good manners (bon usage) prescribed serving the new hot drinks, such as tea, coffee, and chocolate, in sets called cabarets, usually consisting of a Chinese lacquer tray, with cups, sugar bowl, and tea/coffee/chocolate pot in blue and white porcelain.

The diffusion of Chinese porcelain is well testified by the paintings of the Baroque period.

Louise Moillon (1610–1696) was a French still-life female painter, who was highly appreciated by her contemporaries. She worked for the Parisian nobility and could count King Charles I of England among her clients. She was influenced by the Flemish still-life style and showed both a remarkable compositional ability and the widespread depiction of Chinese plates and bowls.

Louise Moillon (1610–1696), Nature morte aux cerises, fraises et groseilles (Still-Life with Cherries, Strawberries, and Gooseberries), oil on panel, 1630. Dimensions: height 31 cm (12.2 in) × width 48.5 cm (19 in). Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California, US.

Louise Moillon (1610–1696), Nature morte avec bol d'oranges de Curaçao (Still Life with Bowl of Curaçao Oranges), oil on panel, 1634. Dimensions: 46.4 × 64.8 cm. Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena, California, US.

The painting below is a still life by François Habert, an artist active in Paris from 1643 to 1652, whose life remains substantially unknown; the oil on panel was painted, therefore, in the mid-17th century. Habert was a still-life painter and in many of his works, you can find at least a Chinese porcelain piece.

François Habert, Still life of flowers in a blue and white Chinese porcelain bowl, with a red admiral butterfly on a wooden ledge, signed on the lower right: F. HABERT. Oil on panel. Auctioned by Sotheby's New York in 2018. Photo: by courtesy of Sotheby's.

In France, l'engoument pour la Chine, the French craze for Chinese products, began during the reign of Louis XIV (on the throne from 1643 to 1715) and continued until the 1770s, under king Louis XV (r. 1715–1774) ) and Louis XVI (r. 1774 –1792).

Of the Chinese porcelain pieces, the French immediately admired the craftsmanship: at the time of the Sun King, no one could yet fully 'imitate' such aesthetically and functionally valuable material. The decoration in cobalt blue on a white background was mostly appreciated for its characteristic chromatic contrast. As for the decorative motifs, the French reactions become more interesting. Collectors and admirers especially loved plant-themed ornamental motifs, such as flowers, fruits, trees, scrolls, and vines, and tiny geometric patterns, called à broderie because they were reminiscent of embroideries. Landscapes were quite popular, while figurative themes raised generally very negative reactions. «If the originality and exoticism of the representations of landscapes, plants, and animals seduced the Westerners, the latter could not or would not put in temporary parentheses the European canons for the representation of the human figure, considered as the summit of art for a painter.» (My translation, from Stéphane Castelluccio, cit.). The human figures painted by the Chinese were generally judged as poorly drawn, ungainly, crippled, ridiculous, and even monstrous characters. «The exoticism of the painted characters did not compensate for what Westerners felt was an incompetent way of drawing. The most precise inventories mention a reduced number of porcelains with figures (à figures) or characters (à personnages).» (My translation, ibidem).

Once again, we find a deep ambiguity hidden behind the craze for China and the exoticism trend in art and design that, as we'll see in the next chapters, will reach its crazy peak in mid-18th century Europe.

THE HEART OF THE MATTER

The French attitude was quite widespread in Europe (with very few exceptions) among those, of course, who were dealing with Chinese and Japanese porcelain ware. Most Europeans looked at Chinese painting (on porcelain, lacquerware, paper, or fabric) by using the lens and filter of the aesthetic canons of Western art. This attitude stemmed both from their ignorance of Chinese culture and from the undue universalization of European canons and norms. Most Europeans, in other words, had no awareness of their own cultural relativism and unwittingly assumed that the aesthetic canons of Western art were universal and universally valid norms. Judged in the light of Post-Renaissance Western art, Chinese art, therefore, failed to hold its own and was relegated to being an imperfect, underdeveloped, naïve, childish form of art. The Chinese fared better than the Native Americans, however, who for a long time were denied the ability to produce art tout court.

This cultural attitude that measured the Other by a relative yardstick believed to be absolute, and denied the Other a human and cultural status equal to one's own, went perfectly hand in hand with the parallel colonial adventure and well justified the merciless economic exploitation the latter entailed.

(Note that the idea that we must not judge a culture, different from ours, by our own standards and by our own concept of what is right or wrong, strange or normal, good or bad, and that instead, we should try to understand different cultural practices in their own cultural context, well this idea developed very late in the Western world, between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. In Intermezzo 1, we saw that still in the 1950s some renowned scholars thought that linear perspective was "the only natural system of perspective", whose ignorance was a sign of cultural underdevelopment).

But which China was Europe infatuated with?

It was the real China or more of an imaginary and imagined country, an exoticized and stereotyped kingdom located somewhere in a wild faraway world?

What did 17th-and-18th-century Europe know about China?

I will answer this question in the following chapters, but from what we have already seen, we can point out one relevant aspect: Europe actually glamorized China only in those aspects in which it mirrored itself as a modern Narcissus.

Too often, too hastily and superficially, some scholars have spoken of a cultural encounter between China and Europe from the second half of the 16th century through the 18th. The systematic presence of Chinese porcelain and objects in European art of the 16th-18th centuries and the systematic copying of Western models by Jingdezhen potters and painters are not indicators of such a cultural encounter and even less of an alleged artistic influence.

The import of Chinese porcelain in increasingly systematic forms was first and foremost a commercial exchange with several major players. This exchange reached massive proportions and considerable duration. Because of these aspects, it changed both the organization and part of the production system in Jingdezhen and the European customs and taste, just like the introduction of tea and spices. The English example, in this regard, is illuminating.

Europeans appreciated the brute materiality of Chinese porcelain until they learned how to produce it and loved those aspects that could be easily Europeanized and appropriated and in which they could mirror themselves.

The progressive appropriation of Chinese porcelain by Europe entailed a progressive de-Sinicization, a process by which the Chinese pieces ceased to bring with them the original meanings, which were therefore erased, and began to express entirely new, inherently European cultural and social values. The new meanings and values were not the same throughout Europe, as we have seen: Chinese and Japanese porcelain pieces acquired a new set of different, and sometimes antithetical meanings according to the country, the type of collectors or customers who acquired them, and the way they were organized, arranged or used at home. What Vanessa Alayrac-Fielding wrote for 17th and 18th century England, namely that the Chinese porcelain ware's «function and status varied according to the place where it was displayed, from cabinets of curiosities to china closets and the tea-table», applies to all of Europe.

Regardless of its concrete forms, the de-Sinicization process was common throughout Europe, albeit in different ways and with different intensities. Paradoxically, this process of spoliation and de-Sinicization reached its peak precisely during the 18th-century climax of the European obsession with chinoiseries. I wrote 'paradoxically', but it's an apparent paradox: the China that Europe portrayed, painted, represented, imitated, mocked, and admired, well that China wasn't the real China, but the imagined, fantasized, stereotyped China invented by Europeans 'in their own image and likeness' and 'for their own use and consumption'.

So, in my opinion, what we have seen in the last chapters did not constitute a cultural encounter. My thesis, however, remains weak until two specific questions are answered: 1. What is a cultural encounter? And 2. Was there ever a cultural encounter between China and Europe in the 17th-18th century period?

In the following chapters, I will answer these questions as well. We will discover a profound and productive cultural encounter between China and Europe where we would not expect to find it, and we will understand why this precious bridge on which men from different and distant cultures could meet, converse and create culture miserably collapsed, or, better to say, it was brought down. And we will discover how this 'destruction' influenced the process of spoliation, de-Sinicization, and reinvention of China that spanned much of the 18th century.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?