THE PINK FAMILY: CHINA AND THE WEST 4

Current China on the globe.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

LEFT: Portrait of the Yongzheng Emperor in Court Dress, by anonymous court artists, Yongzheng period (1723—35), Qing Dynasty. Hanging scroll, color on silk. The Palace Museum, Beijing. Public Domain.

RIGHT: History of China, Imperial Dynasties, source: Dynasties in Chinese history, Wikipedia.

THE UNDERGLAZE BLUE PORCELAIN SPREAD IN FAR EAST ASIA

The trade of ceramics established in the Song dynasty was maintained throughout the succeeding Yuan dynasty and, with a few interruptions, during the Ming. The production of qīng huā cí for export constantly grew. «Blue and white porcelain was produced in vast quantities in China. It influenced the ceramic style of the whole world for several centuries after the 14th century AD» (R. Wen, C. S. Wang, et al. cit.; the bold is mine). As we shall see, it will become 'the first truly global product of world history'.

Both during the Yuan and the Ming periods, the underglaze blue porcelain was exported throughout Asia, and some knowledge of its technique was passed to Central Asia, the Islamic world, Korea, Vietnam, and Japan. In the beginning, the artistic influence of the Yuan and Ming qīng huā cí was dominant, but after a while, each of these countries developed an excellent production full of individuality and unique artistic features.

KOREA

The most renowned ceramic wares of Korea are the celadons made during the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392) and the white porcelain of the Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910). The underglaze cobalt blue decoration was introduced from China to Korea in the 14th century, during the early Ming Dynasty. «Established in the late 15th century, the Korean official kilns—known as bunwon—produced fine white porcelain exclusively for the royal court and central government, laying the foundation for the culture of Joseon white porcelain. (...)» (The National Museum of Korea curators). The preferred pigment for painting Joseon white porcelain was underglaze cobalt blue, which was very expensive at the time, as it had to be imported from China. That's why «most of the designs made with this precious material were painted by the official court artists of the Royal Bureau of Painting. Overall, relatively few Joseon blue-and-white porcelain vessels were produced, and they were reserved for the royal court and the ruling literati class. (...) Early examples of Joseon blue and white porcelain were usually decorated with motifs borrowed from China, such as the cloud and dragon design, a floral scroll design, a fish design, the “Heavenly Horse” design, and a design combining a pine tree, plum tree, and bamboo. Over time, Joseon potters and painters began to develop unique motifs, including poems, grapes, plants with insects, various floral designs, and the “plum, bamboo, and bird" design.» (Ibidem). And, of course, they develop a unique style and language, full of spontaneity and vitality, two esthetic qualities unique to Korean art.

Korean white porcelain bottle painted with underglaze cobalt-blue, depicting fish and shellfish among waves. Dimensions: height 27.3 cm - 10.74 in; mouth diameter 4.6 - 1.81 in; bottom diameter 12.3 cm - 4.84 in. Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910). National Museum of Korea, Seoul (Korea).

Large-sized white porcelain lidded bowl with underglaze cobalt blue decoration depicting eight mandala flowers, four on the body and the other four on the lid, plus a floral motif at the top of the lid. Dimensions: height 15 cm - 5.9 in; mouth diameter 25 cm - 9.84 in; bottom diameter 16 cm - 6.29 in. Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910). National Museum of Korea, Seoul (Korea).

JAPAN

The Japanese were early admirers of Chinese blue and white porcelain pieces, that they called sometsuke. Porcelain production began in Japan in the early 17th century and no porcelain made before the end of the 16th century has been identified. «The Japanese porcelain industry was actually pioneered by Korean potters living in Japan», especially in the Arita district, in the former province of Hizen, whose area thus became the major center of porcelain production. «The first porcelain made in Japan by these Korean potters is known as early Imari, featuring designs painted in cobalt blue on a white ground, then coated in a transparent glaze (...). The porcelain has a coarse, grainy texture and the designs are generally carried out by a free, fluid hand. (...). The Nabeshima lord, who supported and controlled the Arita kilns, also spurred the development of a new style of porcelain. To win favor with the <Tokugawa> shogunate, he would regularly present gifts of porcelain. Originally, he imported wares from the Chinese kiln site of Jingdezhen, since those were considered to be of the finest quality. However, around the middle of the 17th century, as domestic porcelain improved and foreign imports declined, the Nabeshima lord commissioned the production of specialty ware at a separate kiln in his province. Perhaps the most refined and elegant variety of Japanese porcelain, this is known as Nabeshima ware and was created exclusively for the shogunal family, feudal lords, and the nobility. The techniques and designs of this kiln were kept secret and were not permitted to be imitated on porcelain for the general market. Nabeshima ware is characterized by smooth, uniform surfaces, soft colors, and Japanese motifs. Designs are painted precisely and often echo patterns from textiles and simple themes from the natural world. Despite their beauty, these dishes were not purely decorative but rather were used as tableware by the ruling classes. The rounded figures and high feet of these wares reflect the fact that they were intended to harmonize with the precious lacquer bowls that would be placed beside them.» (Anna Willmann, Edo-Period Japanese Porcelain, The MET, see Bibliography).

I've chosen two refined Nabeshima dishes to represent the creativity of the Japanese blue and white porcelain ware.

Dish with Chestnuts and Oak Leaves, porcelain with celadon glaze and underglaze cobalt blue, Hizen ware, Nabeshima type. Dimensions: diameter 20 cm - 7 7/8 in. Japan, Edo Period, ca. 1690–1730. The MET Museum, New York, US.

Peony-Shaped Dish with Butterflies, porcelain with underglaze cobalt blue, Nabeshima ware. Dimensions: diameter 18.7 cm - 7 3/8 in. Japan, ca. 1840–60, Edo period. The MET Museum, New York, US.

VIETNAM

Under the influence of the blue and white porcelain ware of the Yuan Dynasty, Vietnamese kilns started to produce white stoneware decorated with underglaze cobalt blue in the second decade of the 15th century, or, according to some scholars, in the last decades of the 14th. Initially, the decorative motifs of Vietnamese high-fired opaque stoneware were heavily influenced by those developed during the Yuan Dynasty - dragons, peonies, scrolls of lotus flowers, cloud and wave patterns - but over time, the production entered a creative golden age whose decline started only at the end of the 16th century. Below, you can admire a masterpiece probably from the early 16th century. The Vietnamese stoneware with underglaze (imported) cobalt blue decoration showed a huge variety of shapes - bottles, jars, dishes, plates, bowls, covered boxes, kendi, jarlets, miniatures, zoomorphic ewers and water-droppers - and was made for the domestic market and for export. Many pieces were successfully exported to Indonesia, the Philippines, and even Japan, where they were called shimamono or 'island goods' and were highly prized.

Dish with Recumbent Elephant Surrounded by Clouds, stoneware with underglaze cobalt-blue decoration. Dimensions: diameter 36.2 cm - 14 1/4 in. Vietnam, 15th–16th centuries. The MET Museum, New York, US.

«This exceptional dish, with its depiction of a kneeling elephant surrounded by abstract cloud formations, must be included among the dozen or two finest known early Vietnamese blue-and-white porcelain dishes (...). The refined and sophisticated drawing of the charming and delightful elephant and the excellent control of the underglaze cobalt blue set it apart from most of the known corpus of important 15- and 16-century porcelains. The technique of manufacture, shape of the dish, and general composition of design are clearly based on blue-and-white prototypes of the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644), but the whimsical elephant and the particulars of the subsidiary design are uniquely the product of Vietnamese artistic sensibilities. The salty taste of the surface of the dish suggests it was recovered from a shipwreck.» (The MET Museum curators).

THE EUROPEAN MERCHANTS ARRIVE IN CHINA

In PART I, I told the story of the Fonthill Vase, a very famous piece and one of the first Chinese porcelain to reach Europe soon after its production, in the first half of the 14th century. In Europe, for two hundred years, only a lucky few managed to have a Chinese celadon or a blue and white porcelain piece in their hands, thanks to direct or indirect diplomatic exchanges or eventful purchases made by an intermediary in Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire. The Portuguese King Manuel I had several pieces acquired from Vasco da Gama, while the Archduke Ferdinand II of Austria assembled a small collection of porcelain items, all displayed, together with other rarities and weird objects, in the Chamber of Art and Wonders, a sort of cabinet of curiosities located in the Ambras Castle. «As early as 1461, the Sultan of Egypt offered a small number of porcelain pieces to the Venetian Doge, and more reached Venice as gifts from the Mameluke sultan at the end of the century. In 1487, Lorenzo de' Medici was already acquiring his first blue and white porcelain» (Dolors Folch, The Europeans Discovery of Xina, Pompeu Fabra University, Barcelona, see Bibliography).

This situation, however, was about to change.

Europe and China

«By the beginning of the 15th century, both Europe and China started to notice their mutual presence at the extreme ends of the Eurasian continent» (Dolors Folch, The Europeans Discovery of Xina, cit.).

Europe had known of China since Marco Polo's time and the 13th century. China had known of Europe as well. Both China and Europe had a very vague and blurry idea of each other, but a difference between them was clearly obvious.

«By the end of the 14th century, China was gathering information about the worlds laying beyond the Indian Ocean. The most compelling evidence of the Chinese knowledge of the outside world is a map of the world commissioned by the Ming emperor Hongwu in 1392, the Daming Hunyi tu, or The Amalgamated map of the Great Ming.» (Ibidem). The geographical curiosity of the Chinese Empire is also well represented by admiral Zheng He's seven commanded expeditionary treasure voyages to Southeast Asia, the Indian Subcontinent, Western Asia, and East Africa, all carried out between 1405 to 1433. These voyages were diplomatic missions to increase trade, open routes, and secure tribute from foreign powers, especially those located west of China. As for the countries and peoples located east and south of China, the Celestial Empire had created a system of tributary relationships and advantageous trade, founded on the assumption of its own political centrality, economic domination, and cultural superiority. China stood firmly in the center of the world, which was relevant for its economic policy and political strategy and had little if no interest in Europe, a land on the far west, clearly off the borders of the known, civilized world. Dolors Folch, a Spanish historian and professor emeritus at the University Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona, confirms: «The Chinese interest in Europe was nil» (Dolors Folch, The Europeans Discovery of Xina, cit.).

China too was for the Europeans well beyond the borders of the known world, but the Europeans, especially the Portuguese, were extremely curious about "a terra dos Chins". «Uma das regioes que imediatamente despertou a curiosidade dos Portuguese foi precisamente a China» (Cartas dos Cativos de Cantão, Introduction, see Bibliography). Europe was then at the peak of the Age of Explorations and Discoveries, but we have to remind that those 'explorations' and 'discoveries' were not innocent jaunts and picnics, driven by cultural curiosity and geographical enthusiasm.

Not at all.

The extensive overseas explorations - with Portuguese and Spanish navigators at the forefront, later joined by Dutch, English, and French merchants - were systematically financed by states and crowned heads, both avidly seeking new markets, new colonies to conquer and exploit, and new wealth to plunder. It was the aggressive first wave of European colonization in the East Indies.

The 'advance' of the Portuguese

In 1434, «the Portuguese explorer Gil Eanes rounded the treacherous currents of Cape Bojador and reached the African continent south of the area of Muslim control. He had with him a single ship, a small crew, and the unflinching support of his king. The success of his expedition marked the beginning of the Portuguese exploration of Africa. From then on, the Portuguese would sail south along the African coasts.» (Dolors Folch, The Europeans Discovery of Xina, cit.).

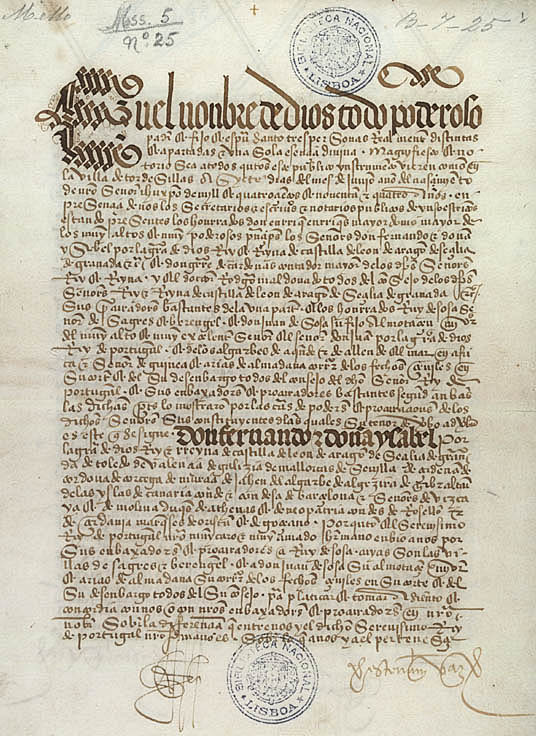

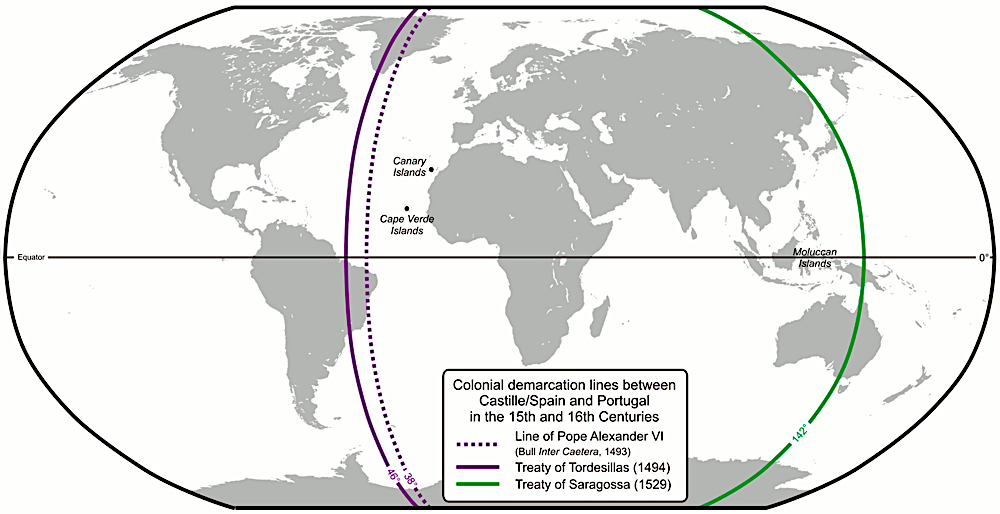

On June 7, 1494, the Portuguese and the Spanish Empires signed the Treaty of Tordesillas, which divided their respective areas of influence and colonial possessions along the north-south meridian, 370 leagues (1,770 km) west of the Cabo Verde Islands (off the coast of Senegal in West Africa). The lands to the east of this line would belong to Portugal and those to the west to Spain. The Treaty of Tordesillas, in brief, 'treated' the world as a huge no man's cake, ready to be divided, swallowed in chunks, and finally pooped.

Original front page of the Treaty of Tordesillas, in Spanish Tratado de Tordesillas, in Portuguese Tratado de Tordesilhas, Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa, Portugal. This text, written in Spanish, was signed by the representatives of Isabella and Ferdinand, kings of Castile and Aragon, on the one hand, and those of King John II of Portugal, on the other. The other side of the world was divided a few decades later by the Treaty of Zaragoza or Tratado de Zaragoza, signed on April 22, 1529, by King John III of Portugal and the Castilian emperor Charles V. It defined the areas of Castilian and Portuguese influence in Asia, as shown below. Both will be abolished only in 1750.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

The Portuguese were free to 'explore' the African coasts, looking «first for fisheries, then for riches, like gold and ivory, and further on, especially when they had already secured Brazil, for slaves.» (Dolors Folch). Black slaves, of course.

In March 1488, Bartolomeu Dias rounded the African Cape, which he named "Cape of Storms" (Cabo das Tormentas) and was later renamed "Cape of Good Hope" (Cabo da Boa Esperança). Thus Dias entered the Indian Ocean. In 1498, he landed in Calicut, in the present-day Indian state of Kerala. In 1510, the Portuguese conquered Goa on the southwestern coast of India; in 1511, Malacca (today in Malaysia); in 1513, the Moluccas or Maluku Islands, an archipelago called at time Spice Islands.

Since the beginning of the 16th century, Manuel I, king of Portugal from 1495 to 1521, had been showing great interest in China, especially in its trading and military capacity. In 1515, Portuguese private explorers sailed to reach the Chinese coast.

Close Encounters of the Third Kind

«From the very first moment, the Chinese were seen as essentially different from the African and American natives that the discoverers were encountering elsewhere. Already in 1515, one of the discoverers stated clearly that the Chinese were "di nostra qualitá" (of our quality), although a bit ugly and with eyes too small for the Portuguese taste. The Chinese, indeed, had a similar negative aesthetic perception of Westerners, whom they labeled as having cat's eyes, an eagle mouth, a face in the color of white ashes, and a thick, curly beard. (...). One very early text, written in 1515 by an Italian who sailed in a Portuguese ship, emphasized that China, not yet identified with Marco Polo's Cathay, "had the greatest wealth that in the world can be", and highlighted the huge size of the country, the great urbanization of its territory, and the importance of rivers as a means of communication. He also made admiring mention of its laws, already hinting at the image of social wonder that China will provide.» (Dolors Folch).

To the first Europeans, China appeared as a faraway land full of riches, inhabited by civilized people, to be regarded as 'superior' to African and American natives. This seemingly flattering consideration concealed not only the seed of racism - the Chinese physical difference from western and northern Europeans and their non-Christian status made up part of the bedrock needed for the construction of racial categories - but also a predatory attitude. So true is it that, according to Dolors Folch, some Portuguese ships started to smuggle along the Chinese coast, not refraining from committing many acts of brutality against the local population. It's no surprise: the use of violence was an essential component of the Portuguese strategy to subdue the locals in the whole of Asia. «The use of terror will bring great things to your obedience without the need to conquer them»: these words were written by Afonso de Albuquerque, the strategic mastermind behind the Portuguese expansion into Asia, to the King of Portugal in a letter dated 1510, after the sacking of the Indian city of Goa.

LEFT: Portrait of Vasco da Gama (ca. 1460/1524), 16th-century painting, Maritime Museum, Lisbon, Portugal. He was the first European to reach India by way of the Cape of Good Hope and to link Europe and Asia by an ocean route.

RIGHT: Portrait of Afonso de Albuquerque (1453/1515), Portuguese general, admiral, and statesman, viceroy of Portuguese India from 1509 to 1515.

In popular texts, school manuals, and articles intended for the general public, Vasco da Gama is celebrated as a heroic Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea; Alfonso de Albuquerque is remembered as one of the major architects of the Portuguese Colonial Empire (Império Colonial Portugués) in Asia. This hagiographic celebration ignores or forgets what is instead a thorny issue much debated by historians and experts: the extreme violence and brutality that both men deployed during the bloody conquest of new Asian lands in the name of the Portuguese crown, and the climate of sheer terror they established in the newly founded colonies.

«Vasco da Gama indulged in some of the most heinous crimes», explains Indian-born French historian Jean-Baptiste Prashant More. «He had all the makings of a ruthless pirate. He had orders from the Portuguese king to wrest wealth and fame by the force of arms from the hands of the 'barbarians, Moors, pagans and other races'. On October 1, 1502, he mercilessly ordered the killing of 700 innocent Malabar pilgrims returning from Mecca. Half the pilgrims were women and children. Vasco da Gama issued orders for the ship to be set on fire by gunpowder after looting it. Not one pilgrim escaped. He remained insensitive to even the wailing women holding their babies in their hands on the deck, imploring for pity. On October 27, 1502, he seized 50 Malabaris at sea, got their heads, legs, and hands cut off, and sent them ashore in a boat with a message in Arabic, asking the Zamorin Samoothiri, namely the hereditary monarch of Calicut> to make curry out of the severed limbs . Not satisfied with this, he bombarded Calicut from the sea for three consecutive days and razed it to the ground, killing several hundred people in the process. All of these crimes have been recorded by Portuguese chroniclers and have gone unpunished.».

According to Daniel Boorstin, «once in power, the Portuguese governed their India in the same spirit. When Viceroy Almeida was suspicious of a messenger who came under safe conduct to see him, he tore out the messenger's eyes. Viceroy Albuquerque subdued the people along the Arabian coast by cutting off the noses of their women and the hands of their men. Portuguese ships sailing into remote harbors for the first time would display the corpses of recent captives hanging from the yardarms to show how they meant business.».

Franz-Stefan Gady writes that «exemplary terror and wanton violence were integral to Portuguese expansion and the securing of trading rights in Asia right from the start of the European conquest.» (in How Portugal Forged an Empire in Asia, July 2019, "The Diplomat").

The adoption of the most traditional strategy of domination of the very few over the very many - the use of extreme and senseless violence - dictated the systematic acts of barbarity committed by the 'civilized' Portuguese against the local 'barbarians'.

ANOTHER DARKER SIDE OF THE PORTUGUESE DOMINION IN INDIA

One of the darkest and most heinous pages of history was written by the Goa Inquisition (Inquisição de Goa), instituted by the Portuguese in 1560, according to some sources, or earlier in 1536, according to others. It was abolished in 1812 or later, in 1821 (with a pause from 1774 to 1778). The arrival of the Portuguese soldiers and missionaries in Goa marked the beginning of a program of forced conversions, systematic destruction of Hindu temples in the area (only one of several hundred was saved), persecution of Hindus, Muslims, Protestants, and Jews in the name of Catholicism declared state religion. Thousands of foreign and local Christians accused of heresy, witchcraft, false conversion, blasphemy, or apostasy, were imprisoned, horribly tortured, put on trial, and burnt.

The above engraving, from 1783 (licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International), depicts the Auto-da-fé procession, whose aim was the public humiliation and execution of the heretics. The procession shows the Chief Inquisitor, Dominican friars, Portuguese soldiers, as well as religious 'criminals' condemned to be burnt. The Goa Inquisition organized 71 Auto-da-fé, the last of which was in February 1773.

Against this background, and given the ignorance and contempt Portuguese and Chinese had of each other, how do you think Portugal's first diplomatic mission to China turned out?

Yes, it was a total failure.

The Portuguese ambassador Tomé Pires landed on the Chinese coast in 1517 and although the mission was regarded by local authorities with considerable suspicion, it was allowed to reach Beijing in 1520. However, «the ambassador was little prepared for the strict rules regarding Chinese foreign trade (the only foreigners allowed to trade were the handful of tributary states established by the emperor). Furthermore, the letter from the Portuguese king addressing the emperor of China on equal terms shocked and bewildered the Chinese court.» (Dolors Folch, The Europeans Discovery of Xina, cit.). These mistakes and the smuggling activities of Portuguese ships caused the death in prison of the ambassador and other members of the Portuguese expedition and the emperor's announcement of a ban on foreign traders.

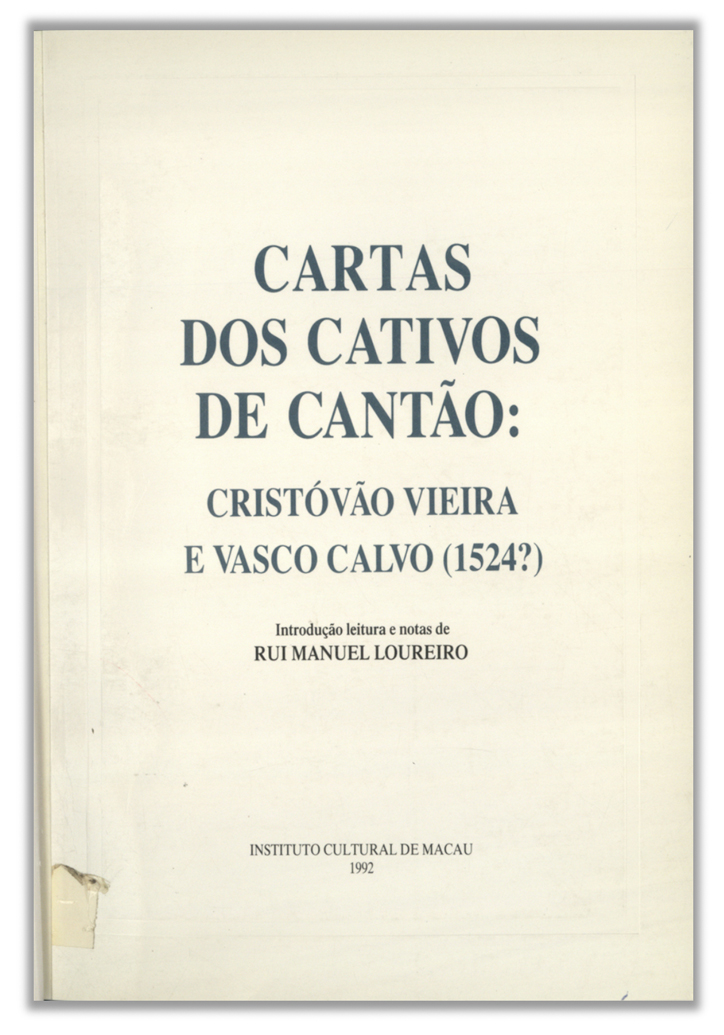

In 1992, the Portuguese scholar Rui Manuel Loureiro wrote about this failure: «Uma certa prepotência e falta de tacto dos Portugueses ao abordarem a civilização chinesa e uma política de deliberado exclusivismo e isolamento da parte dos Chineses, contribuíram para o degradamento da situação.» (My translation: "Both the arrogance and lack of tact shown by the Portuguese in their approach to China and a policy of deliberate exclusivism and isolation by the Chinese contributed to the deterioration of the situation"). Well, the Portuguese's aggressive conquering intent was not simply 'arrogance' and 'lack of tact', and the Chinese were not 'isolationist', they simply had put in place a complex system of tributary and trade relationships in their area of influence (almost the entire Far East) and demanded its full knowledge and respect.

After the failure of the Portuguese mission, «a general edict was affixed to the gates of the city of Canton saying: "The men with beards and large eyes should no more be permitted within this realm."» (Dolors Folch, cit.). The political and economic interests of the Portuguese crown were so high to drive the Lusitanian merchants to another 'lack of tact': devoting themselves to smuggling and clandestine mercantile activities. «The ban to enter Canton sent the Portuguese up the Chinese coast and in the next decades, they smuggled and even occasionally joined the pirates in their storming of the coasts of Guangdong, Fujian, and Zhejiang, from Canton to Ningbo. In the 1530s, the offshore islands near Ningbo became an active illegal center for international trade in the Far Eastern seas, and the Portuguese settled as smugglers in the vicinity. The ban on foreign traders also left behind a handful of prisoners, and in 1527, two of them, Cristóvão Vieira (a member of the diplomatic mission of Tomé Piras) and Vasco Calvo (a clandestine merchant), managed to send a couple of letters from inside the prison. Once in Lisbon, the letters were held in absolute secrecy, in accordance with the stealth policy applied by the Portuguese to any news regarding their possessions. This stealth policy, which kept all the early Portuguese documents secret, is known as the Portuguese Sigilo (...). The letters sent by the Portuguese prisoners were held in unflinching secrecy for centuries. These letters contain a substantial amount of information about China (...)» (Ibidem), especially about its geography, the territorial administrative system of the Ming state, its justice system, and of course, China's wealth and business potential. «Um grande espaço da carta de Cristóvão Vieira e quase toda a carta de Vasco Clavo são dedicadas à discussão das possibilidades de conquista da China pelos Portugueses, empresa que, na opinião de ambos os autores, tinha grandes hipóteses de ser bem sucedida. Os cativos de Cantão incitam abertamente as autoridades portuguesas a empreenderem uma expedição militar contra o litoral da China, com o objectivo não só de libertar os prisioneiros, mas também de ocupar efectivamente uma das terras mas ricas do mundo.» (Rui Manuel Loureiro, Introduction, Cartas dos Cativos de Cantão, see below). (My translation: ' A large portion of Cristóvão Vieira's letter and almost the entire text written by Vasco Clavo are devoted to the discussion on the Portuguese chances of conquering China. According to both authors, this venture was filled with strong, successful potential. The captives of Canton openly encourage the Portuguese authorities to undertake a military expedition against the Chinese coasts, with the aim not only to free prisoners but also to gain possession of one of the richest lands in the world.'). China is mine. I saw it first, and I grab it: many Europeans facing China showed a mix of dumb naïveté and greedy rapacity.

The reports by Cristóvão Vieira and Vasco Calvo, known as Cartas dos Cativos de Cantão ("Letters from the Prisoners in Canton"), are the first face-to-face testimonies written by Europeans about China since the time of Marco Polo and are key documents in the history of early relations between Portugal and China.

You can read these letters and an interesting introduction by Rui Manuel Loureiro in the original Portuguese language thanks to the digitization effort of the Biblioteca National Digital do Portugal. This is the link. If you'd like to download the text and read it offline, this is the link to the pdf, on the Academia website.

The Chinese ban on foreign traders and the restrictions on maritime traffic had the negative effect of fomenting smuggling, illegal trade, backroom dealings, and corruption of many local administrators and guards along the Chinese coastline. The South China Sea became filled with bands of Asian pirates (wokou) and Portuguese illegal merchants. Over the years, the latter started to work as mediators in the regular trade between Chinese silk and Japanese silver.

To defeat piracy and regularize (and control) the business activities of the Portuguese, the Chinese allowed the latter to settle in Macau in 1557, upon payment of an annual ground rent. The area was located along China's southern coast, on the western side of the Zhu River Estuary, opposite Hong Kong, and near Canton. «By the end of the 16th century, there were 400 Portuguese households in Macau, each household with about six black slaves» (Dolors Folch), while the great majority of wives were Chinese, according to the so-called casado settlement system. (In the early 17th century, there were already 1,000 slaves in Macau, mostly from Mozambique.)

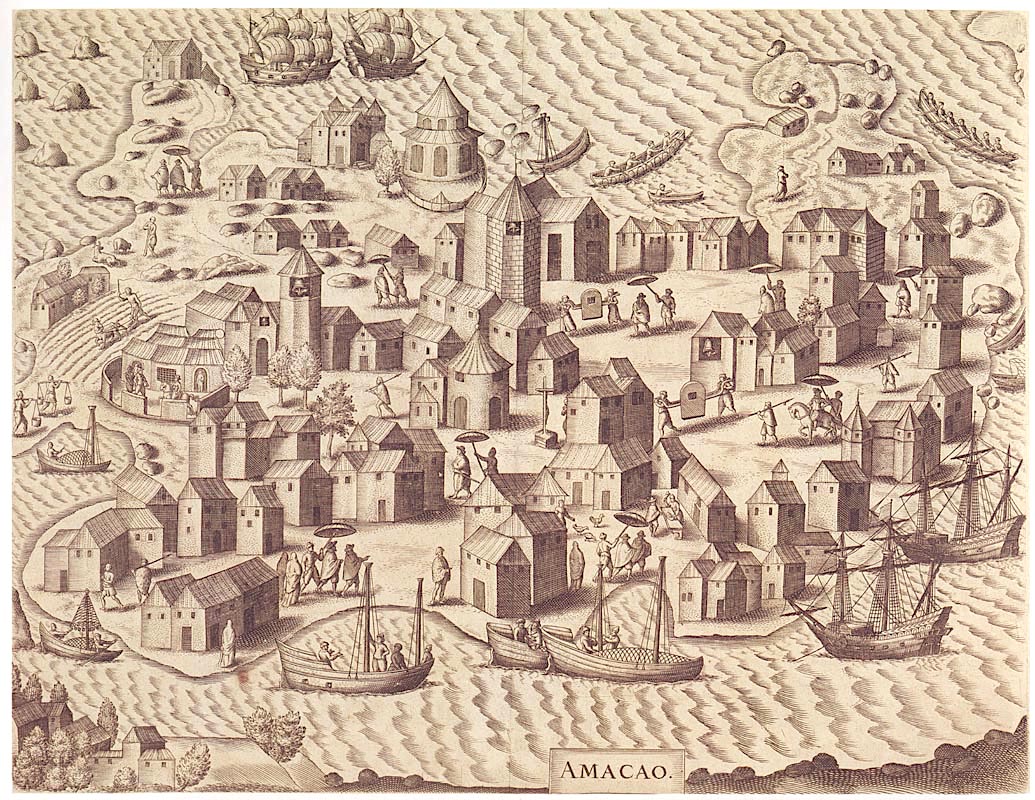

An engraving by Theodor de Bry (1528/1598) depicting a view of Macau in the late 16th century. Lamina XII, from the volume Indiae Orientalis, 1607.

Portuguese fidalgos (noblemen) are depicted while going around on palanquins or accompanied by servants with umbrellas. The harbor (on top) is busy with Western ships. "Macao" was the archaic Portuguese spelling; as the Portuguese language evolved, "Macao" was gradually transformed into "Macau" and became widely used in modern Portuguese and English alike. Both Macao and Macau are names derived from the Chinese Ama-gao, “Bay of the Ama Temple”, dedicated to the Chinese sea-goddess Mazu.

Macau was a Portuguese settlement from 1557 to 1849, then a Portuguese colony from 1849 to 1974. The transition or postcolonial period occurred from 1974 to 1999, when China finally regained full control over the city and its territory: Macau, in other words, was the last European colony in Asia, and still retains part of the Portuguese heritage in any aspect of its life and culture.

More and more Portuguese books written in China about China began to reach Europe. The memoirs of Galeote Pereira, for example, had a good circulation in Portugal and Spain and are interesting for a 'destiny' it shared with other texts. Pereira was a great admirer of the Chinese justice system, considered even superior in some aspects to the European one, but this admiration was harshly censored at home: «These were highly sensitive statements in a Christian world that justified European conquests on the grounds of the moral superiority of Christianity and its Classical heritage. In fact, all sentences claiming the superiority of the Chinese over westerners were immediately suppressed from his text by the ecclesiastical censors.» (Dolors Folch, The Europeans Discovery of Xina, cit.). Racism, in other words, was not the corollary of the colonial adventure, but its ideological legitimization. The Chinese were to become chinks.

BELOW

Anonymous Flemish or Flemish-trained painter, Portuguese Carracks off a Rocky Coast, ca. 1540. Painting on oak panel. Dimensions: frame 98.6 cm x 166.2 cm x 9 cm; painting: 78.7 x 144.7 cm. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, Caird Collection (UK).

«It is one of the few contemporary paintings of ships of the first half of the 16th century and one of the best representations of the first generation of ocean-going merchantmen. (...) The painting depicts 10 ships, 1 caravel, 3 galleys, and 1 rowing barge, off a coastline on the right. (...) In the center foreground, the carefully delineated principal ship is a large armed Portuguese merchant carrack. She is shown firing a salute to port and starboard. This is thought to be the 'Santa Catarina', which was built of teak at Cochin, India, in 1510, to serve as one of the large armed merchant ships of the Portuguese East Indies trade.» (From the National Maritime Museum notes; here is the direct link).

The carrack was a 3 or 4-masted ocean-going sailing ship developed in Europe during the 14th and 15th centuries. The Portuguese preferred the large carracks (usually from 500 to 1000 tons) to galleons (mostly under 500 tons) and smaller caravels (50-60 tons), as the first were more stable in troubled waters, more profitable for trading (= more capacious), and best fitted to cover extremely long routes. (Consider that the trip to India took 6 to 8 months each way, and the round-trip voyage between Lisbon and Goa took 18 months).

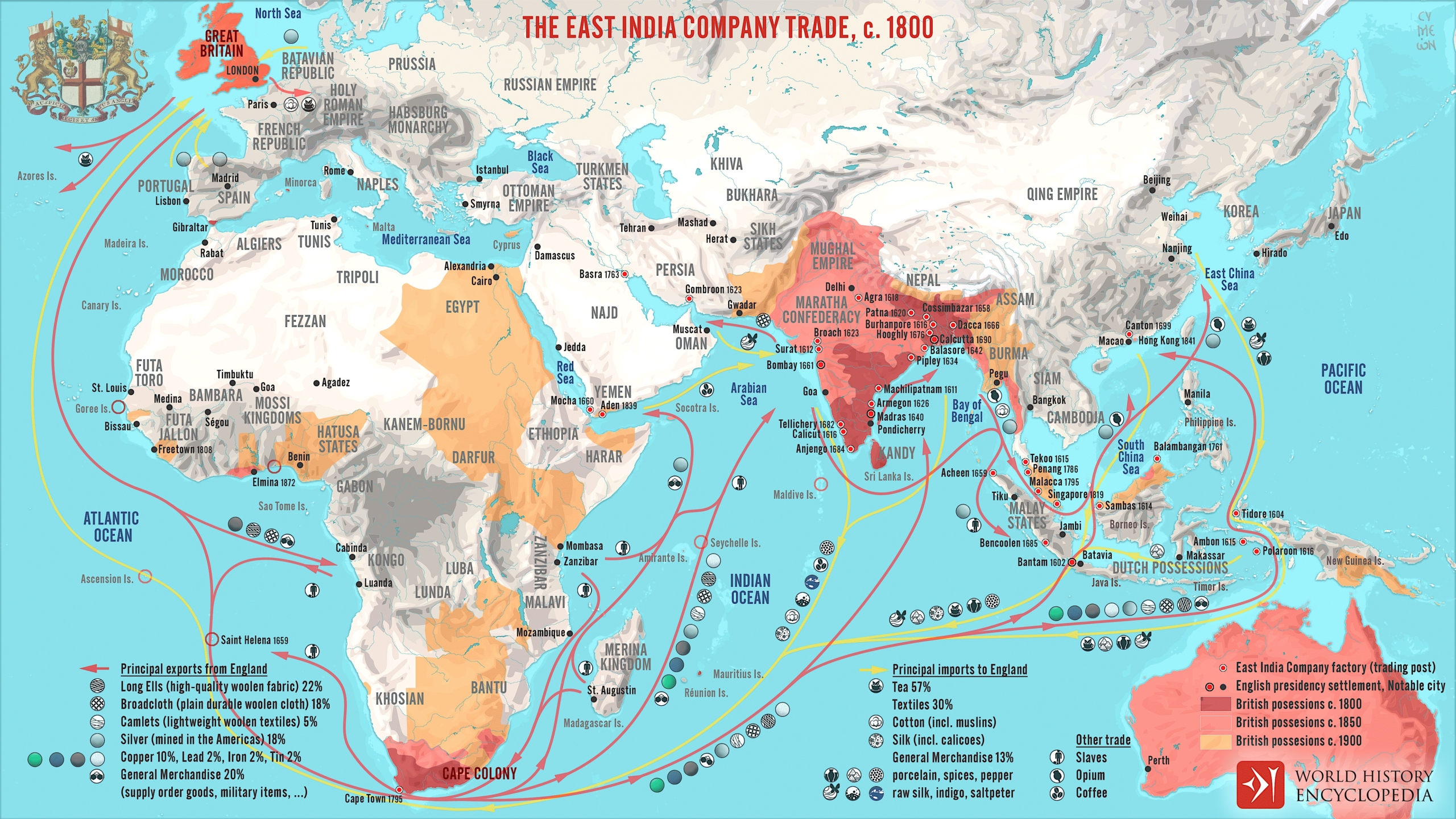

The threats to the Portuguese trade monopoly by emerging powers

Macau survived and prospered as a key entrepôt and trade intermediary between China and Japan. The Canton-Macau-Nagasaki triangular trade was based on the exchange of silk, gold, and porcelain from China for Japanese silver (rich deposits of this metal were discovered in Japan during the 1530s and the country soon became a major silver producer). In 1567, the Chinese authorities ended the prohibition on private trade but banned direct trade with Japan, and this decision gave the Portuguese a huge window of opportunity. They soon came to enjoy tremendous privileges: they became the sole owners of the lucrative trade between China, Japan, the Philippines, Thailand, Malacca, India, Europe, and even Mexico (the Macau-Manila-Mexico route was a major one). Moreover, their carracks paid two-thirds less than other ships of the same tonnage in the harbor of Canton and were the only foreign ships allowed to enter the Japanese harbors. The period between the late 16th and the early 17th centuries was the "golden age" of Macau but the monopoly of the Portuguese merchants and the enormous profits were about to be seriously threatened by several factors, and from the mid-17th century onwards, Macau's prosperity began to decline.

In 1638–1639, the Tokugawa shogunate adopted an ultra-protectionist policy and closed the country to Portuguese merchants: the lucrative trade with Japan suddenly stopped. In 1684, the Chinese Emperor of the new dynasty, the Qing, that followed the Ming in 1644, authorized trade with all foreign countries in Canton, and this decision ended the privileged position of the Portuguese as exclusive intermediaries in the China-Europe trade. However, the most formidable challenge to the Portuguese power in Asia came not so much from the Spaniards, based in Manila, as from two emerging superpowers: the Dutch and the British.

Macau merchant carracks, in particular, were attacked several times - in 1601, 1603, 1604, and 1607 - by Dutch warships, engaged in a merciless war to break Portugal's trade monopoly in half of Asia. In 1622, the Dutch fleet unsuccessfully attempted to assault the Sino-Portuguese enclave: it was the 'Battle of Macau'.

Engraving from a volume by Johan Nieuhof (1618/1672) published in The Netherlands, depicting the Battle of Macau, on June 21-24, 1622. The Portuguese repelled the attack of a Dutch fleet in the harbor of Macau.

In the 1640s, the Portuguese lost Malacca to the Dutch together with several other possessions and areas of influence, and with them, lost the related trade routes as well.

The VOC

The First Dutch Expedition to East Indies (Eerste Schipvaart) set sail in 1595 attempting to break the Portuguese monopoly in the spice trade, using information gained by espionage. It came back in 1597 with only a small cargo of spices. It wasn't a financial success, but showed the Dutch that the political and economical dominion of the Portuguese Empire on the Indonesian spice trade could be challenged and defeated. The Second Dutch Expedition to East Indies was made up of 8 ships and led by Jacob Cornelius van Neck. It set sail in May 1598. It reached the Spice Islands of Maluku (the Moluccas), and in July 1599 returned home with a precious cargo whose sale realized a profit of 400%. In late December 1601, a fleet of 5 Dutch ships drove away from Bantam, Java, a fleet of 30 Portuguese ships. From then on, no one could stop the Dutch.

The Return to Amsterdam of the Second Expedition to the East Indies on July 19, 1599, a painting by Andries van Eertvelt (1590–1652), based on a painting by Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom (1562/1563–1640). Oil on panel, 1610-1620. Dimensions: height 55.9 cm (22 in), width 91.4 cm (35.9 in). Collection National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, UK.

The painting shows the return to the harbor of Amsterdam (on the right) of the following ships: ‘Overijssel’, ‘Vriesland’, ‘Mauritius’, and ‘Hollandia’.

In March 1602, to put an end to fierce competition between proliferating Dutch companies that were breaking into the East Indies spice trade, the States General of the Netherlands (= the Dutch government) decided to amalgamate the six existing trading companies into the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC ('Dutch East India Company'). It was the first joint-stock company in world history and was granted a 21-year monopoly to carry out trade activities throughout Asia.

By the mid-17th century, the VOC boasted 150 merchant ships, 50,000 employees, a private army of 10,000 soldiers, and trading posts from the Persian Gulf to Japan, many of which were forcibly taken from the Portuguese. It acted as a ‘state outside the state’ with the powers to wage war, negotiate treaties with Asian rulers, erect fortifications, appoint governors, imprison, punish and execute criminals, create new colonies, and strike its own coins. Between 1602 and 1796 (the company was liquidated in 1799), the VOC «sent almost a million Europeans to work in the Asia trade on 4,785 ships, and netted for their efforts more than 2.5 million tons of Asian trade goods.» (Memory of the World Register, Nomination Form, VOC Archives). For over 200 years, the VOC represented Dutch interests in Asia, dominated European trade, and led the Portuguese to an unavoidable commercial debacle. The Company was the largest trading company in the world and adopted an aggressive economic policy to become and remain dominant in the lucrative trade between Europe and the East Indies.

«The VOC operated as a profit-driven shareholder corporation and at the apex of its power, around the turn of the 17th and 18th centuries, maintained a series of factories and settlements stretching from Cape Town in Southern Africa, the Malabar and Coromandel coasts of India, Bengal, insular and mainland Southeast Asia and as far as Taiwan (Formosa) and Japan.» (Peter Borschberg, The Dutch East India Company in Southeast Asia, Asian History, February 2021). «The VOC issued shares which sometimes paid as much as 40% dividends. VOC shareholders could sell their shares, giving rise to ‘share trading’. High profits were possible but there were risks: not only the dangers of war with other European nations, piracy, disease, and shipwreck, but also swings in demand and supply and maladministration.» (United Dutch East India Company, Western Australian Museum).

The Dutch economy, the 'Dutch Miracle', the 'Golden Age' of Spinoza and Huygens, of Rembrandt and Vermeer, were all fueled by the VOC returned profits.

FROM LEFT TO RIGHT, CLOCKWISE:

* Flag of the VOC (with the company's logo) on the replica of the East Indiaman Amsterdam in Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Photo by McKarri, under the GNU Free Documentation License.

* Coins (duit, pennies) minted by VOC in 1735. Photo under the GNU Free Documentation License.

* The stern of a recently made replica of Prins Willem, a 17th-century East Indiaman of the VOC. Photo by Dirk van der Made, Amsterdam, 2005. Photo licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 1.0 Generic.

* The replica of Batavia, a ship of the VOC, built in Amsterdam in 1628 and shipwrecked in 1629 off the western coast of Australia. Wikimedia Commons.

* 17th Century plaque to VOC on a wall in Hoorn, The Netherlands. Photo by Stephen Dickson licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

* Two-pound VOC Naval Cannon, viewed from the top. Above the VOC logo, you can see the letter "A" for "Amsterdam". This cannon, now at the Castle of Good Hope in Cape Town, South Africa, laid in the water at 500 m depth, 29 miles (approx. 50 km) southwest of the Cape. It was recovered in 1961. Photo licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

Let's be clear about the Dutch East India Company.

The VOC was not a late medieval/early modern trade guild nor a simple trading colossus, interested in finding new markets and new commercial opportunities.

The VOC wasn't even the embodiment of the pioneering entrepreneurial spirit and work ethics of the Dutch people, as Dutch Prime Minister Jan Pieter Balkenende said in 2006. (Many politicians, you know, are rather ignorant about history and often try to 'bend' it to their own ends. It's wiser to believe in Mickey Mouse than a politician before elections, but I know you know it.).

The Dutch were not a crew of naïve, happy-go-lucky mariners involved in exploratory trips nor a group of Marco Polo-style merchants.

Let's see one of the best-known case studies related to VOC activities in Indonesia: the genocide of the population of Banda Islands (Banda Lonthoir), in what is now eastern Indonesia. The Banda archipelago has been defined as the world’s “storage room” of nutmeg and mace. For the Dutch, it was a key area to get superb control of the East India spice trade. In 1621, they massacred over 90% of the Bandanese local population, estimated at 15,000 people before the conquest. Present-day scholars estimate that the Dutch killed and enslaved approximately 14,000 people; the survivors were used as forced laborers throughout the nutmeg groves, planted in place of the original landscape. Within 50 years, the last Bandanese almost disappeared, and hundreds of slaves were to be imported annually to sustain the extensive cultivation. (On this topic, you can read The Dutch East India Company at the Dawn of Modern Capitalism: “Civilized Dispossession” on the Banda Islands, on a blog by the Duke University Financial Economics Center).

The Dutch non only practiced slavery in the East Indies, but, like the Portuguese and the English, were major actors in the slave trade. One attitude, however, differentiated them from the Portuguese, who used brutality and torture in the traditional medieval style as a means of domination through terror. The Dutch had a decidedly more modern view of violence as a 'collateral damage' of the systematic exploitation of local resources in the name of profit maximization. Similarly, today, the large-scale displacement of local people without adequate compensation and the disappearance of entire local communities and cultures is the 'side effect' of land grabbing in Africa, South East Asia and South America.

The VOC was the first joint-stock company in the world, a profit-driven shareholder corporation of an absolutely new kind: the modern.

«This proto-conglomerate emerged as a driving force in globalization, trans-regional investment, and early European colonization in Asia and Africa.» (Peter Borschberg, cit.). It was the heavily militarized longa manus of the Dutch government and of its ravaging appetites, often acting beyond legality, on behalf of and for the benefit of the Dutch elites. As Peter Borschberg wrote, «it laid the foundations for Dutch imperialism during the 19th century.». The VOC and the EIC, the English East India Company, foreshadowed the contemporary world in all sorts of striking ways. Both marked the dawn of modern capitalism, based on the systematic and intensive exploitation of local resources - on the ground, under the ground, and of any nature - in the name of the new western moloch, the financial profit.

Das Kapital by Karl Marx, 1st Volume, first edition by Meissner, Hamburg, 1867.

«Marx mentions Dutch colonialism in Indonesia several times in the first volume of Capital <whose title is The Process of Production of Capital>, and elsewhere in his work. But the most significant passage comes early in the chapter on The Genesis of the Industrial Capitalist. Its subject is colonial slavery, and the brutal depopulation of conquered areas that accompanied it. After citing the British colonial administrator Thomas Stamford Raffles’s judgment that the history of Dutch rule in Asia was “one of the most extraordinary relations of treachery, bribery, massacre, and meanness”, Marx continues:

"Nothing is more characteristic than their system of stealing men to get slaves for Java. The stealers were trained for this purpose. The thief, the interpreter, and the seller were the chief agents in this trade, and the native princes were the chief sellers. The young people stolen were thrown into the secret dungeons of Celebes until they were ready for sending to the slave ships. (...) Wherever [the Dutch] set foot, devastation and depopulation followed. Banjuwangi, a province of Java, in 1750 numbered over 80,000 inhabitants, and in 1811, only 18,000. Sweet commerce!"» (Pepijn Brandon, Marx and the Dutch East India Company, IndoProgress, January 2019. Pepijn Brandon is an Assistant Professor in Social and Economic History at the Vrije Universiteit, Amsterdam, and a Senior Research Fellow at the International Institute of Social History).

The EIC

The VOC was not alone. The English East India Company (the EIC) was founded in London, on December 31, 1600, by royal charter (under the reign of Queen Elizabeth I). Established as a joint-stock trading company to exploit opportunities east of the Cape of Good Hope, it was granted a trade monopoly: no other English subjects could legally trade in that territory. However, the new company had to face stiff competition from the Spanish, the Portuguese, and, of course, the VOC. The EIC was officially dissolved in 1874, several decades after the closure of its major competitor, thus enjoying almost absolute supremacy.

At first, the Company's ships tended to follow the Portuguese and Dutch to trading ports along the Eastern coast of India and in the Spice Islands (Indonesia). The spice trade was extremely profitable, even considering the risks associated with the length and danger of certain sea routes. Spices (especially pepper, nutmeg, mace, and cloves) were in high demand in Europe and made up the ideal cargo: lightweight, unbreakable, and long-lasting (if kept dry). In 1620, the EIC purchased 250,000 pounds (=113,000 kg) of pepper with a value of £26,041 in the East Indies, and 150,000 pounds (= 68,000 kg) of cloves, worth £5,126. The cargo was sold in London: the pepper for £208,333, and the cloves for £45,000. Stratospheric profits like these or even bigger (some voyages reached a 400% profit) could not be guaranteed all the time - there were too many variables involved in any transoceanic shipping such as armed clashes with rival traders, deadly diseases like scurvy, shipwreck, pirates, and so on. However, exorbitant profits were not uncommon, and each voyage was worth any risk.

«Initially, the two monopolies, the English and the Dutch, competed against each other in the East Indies spice trade. However, in 1623 the torture and execution by the Dutch of ten men in the service of the East India Company for treason, conspiring against Dutch interests on the island of Amboyna, which was at that time the center of Dutch interests, led to the English quitting the Far East Indies and refocusing activities on the Indian subcontinent.» (Stewart Clegg et al., The East India Company: The First Modern Multinational?, in "Multinational Corporations and Organization Theory", Emerald Publishing Limited, 2017). Thus, due to the harsh competition with the Dutch, the English temporarily withdrew from Indonesia and turned their attention to some Indian goods - cotton, calicoes, dyes, saltpeter (used to produce gunpowder), and silk. However, the VOC kept up the pressure in India as well, together with the Portuguese.

In India, the EIC gradually laid the foundations of the British Empire. After a strategic and victorious alliance with the Shah of Persia against the Portuguese whose fortress and emporium dominated the Hormuz straits at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, the EIC was powerful and strong enough to compete with the VOC and withstand repeated armed clashes. Their competition wasn't a purely commercial one, indeed: EIC and VOC faced each other in the four Anglo-Dutch Wars during the 17th and 18th centuries.

FROM LEFT TO RIGHT, CLOCKWISE:

* The East India Company's Flags, 1949; source: East Indiamen, The East India Company's Maritime Service, by Sir Evan Cotton (1949). Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0).

* A ca. 1759 painting by Charles Brooking showing ships of the East India Company; Royal Museums Greenwich, UK. Wikimedia Commons.

* Portrait of an East India Company's official with Indian servants, by Dip Chand. Opaque watercolor on paper, Murshidabad or Patna, ca. 1760-1764. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK. This painting probably depicts William Fullerton of Rosemount, who joined the East India Company's service in 1744 and worked as a second surgeon in Calcutta since 1751. He was present at the siege of Calcutta in 1756 and became mayor of Calcutta in 1757.

* A British small sword with a sheath and case. The gold hilt was enriched with translucent enamels by James Morisset of London. The shell guard shows the inscription: 'Presented to Lt. Colonel James Hartley in testimony of his brave & gallant conduct by the Honourable East India Company 1779'. The decoration on the hilt includes the arms of Lt. Col. Hartley and of the East India Company. Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

* A 18th-century painting depicting « an engagement between three East India Company ships and two French vessels, 8 March 1757'. Three homeward-bound East Indiamen, the ‘Suffolk’, ‘Houghton’, and ‘Godolphin’ were intercepted by two French privateers off the Cape of Good Hope. The merchantmen were heavily laden and represented great riches for the French privateers. However, they were unable to capture them when the Indiamen formed a line and beat them off after a three-hour engagement. This relatively minor skirmish was a major success for the East India Company, which could have lost three ships and their valuable cargoes.». Text by Curators of the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, UK.

* A coin by the EIC, 1808.

Although it was founded initially as an import/export company, the EIC wasn't a simple trade company. First, it was a trade giant, a "mega-corporation" that at one point commanded a private army of 260,000 soldiers, twice the size of the standing British army. From the mid-18th century to the early 19th, taking advantage of the slow but relentless decadence of the VOC, the EIC rose to account for half of the world's trade. Among its traded goods, there were also drugs (opium) and human beings. The EIC was involved in the slave trade since the early 1620s and ended this shameful traffic only in 1834 after several legal threats from the British state and the Royal Navy. On the drug trafficking conducted by the EIC, we will discuss later because it will heavily affect China's history.

Secondly, more than the VOC, the EIC had nothing to do with the late medieval/early modern type of company.

Founded as a contemporary joint stock company, it was the first to offer limited liability to its shareholders.

«The EIC was a joint-stock company, owned and operated by private investors. Unlike earlier forms of business organization, the joint-stock company shielded its participants from losing everything in a business failure—that is, it offered limited liability. For the EIC this was a special privilege granted by the Crown. Limited liability is a key feature of corporate organization today, no longer a special privilege but an accepted feature of any corporate form since the late 1800s. Limited liability permits the raising of much larger sums of capital because investors know they can be involved without risking everything.» (Bruce Brunton, The East India Company: Agent of Empire in the Early Modern Capitalist Era, in "Social Education" 77(2), 2013).

The EIC organization and business management were of a modern type. «The Company’s success was due in part to an extremely effective management system. The management hierarchy created by the EIC was a committee system with performance incentives for managers. This company design included a strategy of allowing the EIC’s agents (trading officers) to engage in their own private trades. The challenge was to give agents enough latitude to expand trade without undermining the company’s interests.» (Bruce Brunton, cit.).

For these aspects the EIC is considered by many scholars and historians as a prototype for the modern multinational corporation: it was «the mother of the modern corporation» as «in its financing, structures of governance and business dynamics, the Company was undeniably modern» (Nick Robins); «the first multinational company of the modern world» and «the world’s first company whose operations involved systematic organization of multiple countries» (Stewart Clegg); «the world's most powerful monopoly», «a dominating global player», «one of the biggest, most dominant corporations in history, operating long before the emergence of tech giants like Apple or Google or Amazon», and «the world’s first multinational corporation that helped shape the modern global economy, for better or worse» (Dave Roos); «the largest corporation of its kind, larger than several nations, and de facto emperor of large portions of India, which was one of the most productive economies in the world at that time» (Emily Erikson, a sociology professor at Yale University). Ann M. Carlos (Hebrew University of Jerusalem/University of Colorado, Boulder) and Stephen Nicholas (University of New South Wales, Sydney) argue that «the early trading companies shared important characteristics with today's modern multinationals».

To those who'd like to deepen the history of the EIC - its financing model, its use of technology, its size, and scale and its regulation at home and abroad - I recommend this book by an English author who had the courage to explore the very different ways the EIC is remembered in Europe and Asia:

Nick Robins, The Corporation that changed the world - How the East India Company shaped the modern multinational, 2nd edition, Pluto Press, London (UK), 2012.

«This was not just a thing of the past, a simple commercial story of merchants bringing spices, textiles, and tea from Asia to consumers in Europe. Rather, it was a tale of institutional innovation and global transformation. The Company pioneered the shareholder model of corporate ownership and built the foundations for modern business administration. With a single-minded pursuit of personal and corporate gain, the Company and its executives eventually achieved market dominance in Asia, ruling over large swathes of India for profit. But the Company also shocked its age with the scale of its executive malpractice, stock market excess, and human oppression, which stimulated increasing levels of state intervention in part to remedy its failings, in the process extending Britain’s empire. For me, the parallels with today’s corporate leviathans soon became overpowering, with the Company outstripping Enron for corruption and Wal-Mart for market power, and pre-empting by more than 200 years the government bail-outs of banks such as Lloyds and the Royal Bank of Scotland.», Nick Robins.

Thirdly, in the early 1660s, the EIC formed a 'lobby' to influence the British government and developed a hidden strategy to get more support and more powers to face the harsh competition with the VOC: some Company's officers obtained a seat in the Parliament and some Company managers used large quantities of money in the form of loans and gift to the crown, members of the royal court, politicians, and government officials. From the early 1660s on, the Company won a series of concessions from king Charles II: greasing the crown's palm was a fully successful strategy. King Charles II not only approved anti-Dutch policies, but granted the EIC the rights to make autonomous territorial acquisitions, mint money, command fortresses and troops, form alliances, «make war and peace with non-Christians for purely materialistic reasons», and exercise both civil and criminal jurisdiction over the acquired areas. Thus, the EIC became a commercial, political, diplomatic, and military super-power at the dawn of modern capitalism. For Karl Marx, it was the standard-bearer of Britain’s ‘moneyocracy’. Adam Smith was horrified by the way the Company ‘oppresses and domineers’ in the East Indies. For the American patriots who regarded the EIC tea as a symbol of oppression, the British company was «the most powerful Trading Company in the Universe» and an institution «well-versed in tyranny, plunder, oppression, and bloodshed». (It was dumping East India Company tea into Boston harbor that the American War of Independence started in 1773).

The company seized control of large parts of the Indian subcontinent, colonized parts of Southeast Asia and Hong Kong in China, used force to expand its domains of influence, and altered the structure of many areas of the planet by using more sticks than carrots. As we will see in the coming chapters, it will change the course of Chinese history.

«By the time James II became king in 1685, the Company had virtually sovereign powers east of the Cape of Good Hope and enormous rights over the lives and property of Englishmen who lived or traded east of the Cap of Good Hope to the Straits of Magellan.» (Arnold A. Sherman, Pressure from Leadenhall: The East India Company Lobby, 1660-1678, in The Business History Review, Vol. 50, No. 3, Autumn 1976, Harvard College). To exercise enormous power over the lives of local, non-Christian, and non-white human beings in that same vast area, the EIC needed no written royal concession.

As to the ideology that sustained the colonialist venture of the EIC, I'd like not to talk about it but to show it. And I'll do it by using a painting commissioned by the EIC directors in 1778 to be displayed on the company's London headquarters, the so-called "East India House". «Like much corporate art before and since, the quality of the painting was generally regarded as poor, with one commentator describing it as "a work too feeble to confer any credit either on the artist or his employers". But the directors were not seeking applause for the artistic merit of their commission. Ten feet across and over eight feet high, Spiridione Roma’s giant allegory of The East Offering Her Riches to Britannia was designed to impress. Fixed to the ceiling of the Company’s revenue committee room, where the directors monitored the flow of profit and loss, the purpose of The Offering was simple: to convey the commercial domination that the Company had now achieved in Asia.» (Nick Robins, The Corporation that changed the world, cit.).

Here's the painting by Spiridione Roma, aka Spyridon Romas, a Greek painter from Corfu who lived many years in Italy and then in London.

Spiridione Roma, aka Spyridon Romas, The East Offering Her Riches to Britannia, painting, oil on canvas, 1778. Dimensions: 10 feet across and 8 feet high. Commissioned by the EIC for the 'Revenue Committee Room' in the East India House in London, UK. Now preserved at the Foreign and Commonwealth Office in London.

This 1778 allegorical ceiling painting depicts the riches of the East being presented to Britannia.

The latter is represented as a young lady seated on a rocky throne, a symbol of the British Empire's firmness and stability. She's the guardian of the EIC, represented by the innocent putties behind her back. The white, blue-eyed, and blonde, angelic Britannia is characterized by her two usual emblems: the shield (near her right foot) and the spear, leaning against the rocks with the tip pointing forward. The lady is protected by the Britannic Lion (horrendously drawn; look at his face: it's ridiculous!), laying tamely by her side.

Below the lion, in the foreground and at the foot of the rock lays Old Father Thames, the bearded man serving as a romantic personification of the river of London, depicted while pouring out his whole stream on Britannia's footstool.

On the other side of the painting, there's Mercury, the god of financial gain and commerce, holding the caduceus (the staff with intertwined snakes) in his right hand and urging the nearby characters to obsequiously present their precious gifts to Britannia.

Calcutta, the capital settlement of the Company in Bengal, is depicted as a semi-naked, dark-skinned girl offering Britannia a basket full of pearls, rubies, and a crown. Below, there is China, represented as a pale woman on her knees and seen from behind, so poorly painted that she looks hunched, neckless, and with an arm as long as a gorilla's. She's offering a giant blue and white porcelain jar and a wooden chest full of tea (on the ground). The two naked black men holding a corded bale (on the far right) represent Madras and Bombay offering cotton and calico.

Behind Mercury, there are an elephant, a camel, and some palms, representing the tropical territories under British dominion. The white woman under a palm, at a distance, was identified by some Romas' contemporaries as Persia bringing silk and other stuff, but I'm not sure about it.

In the central background, an EIC Indiaman, with the characteristic flag showing the cross of St. George and red stripes, is painted under sail, laden with Eastern treasures.

«The East Offering Her Riches to Britannia provides us with a fascinating window into the ways in which the Company wished to see itself – and be seen – at the peak of its commercial powers. Its mix of classical imagery and oriental exoticism captures well the sense of unlimited opulence that the Company’s success in the East had made possible.» (Nick Robins, The Corporation that changed the world, cit.).

Britannia, seated on a rocky throne, is the highest figure of all, and Mercury is at her service. The spatial relationship of ‘high’ and ‘low’ «can connote ‘superiority’ and ‘inferiority’, ‘domination’ and ‘servitude’, (...). Britannia’s exalted place with respect to the subservience of the East is not arbitrary, nor interchangeable, nor neutral, nor devoid of metaphor.» (Peter Gonsalves, A Barthesian Demythologization of a Colonial Painting, in Public Journal of Semiotics 6 (2), 2015).

The painting looks like a sort of pagan glorification, and its classical imagery calls to mind the glorification that Imperial Rome made of herself as the dominant center of its empire. But there's more here.

First of all, let's consider nudity. Britannia is represented draped in white with her right breast exposed: this is the traditional iconography of England since early paintings. This image connotes a state rich in history and civilization. India, by contrast, shows another kind of nudity: wild, tribal, uncivilized, and unjustified. This juxtaposition is stark and dynamically draws an oblique line through the center of the painting.

Secondly, the Asian characters are all represented on their knees, in an attitude of deferential submission, rendered according to the traditional iconography of godly devotion; in other words, the Asian characters are depicted as if they were worshipping a god. In the painting, some iconographic features prompt the viewer to take a point of view outside of history. The superiority of the white European over the dark-skinned Asian is enshrined at the level of a supra-historical order, even if only in history this superiority is revealed and objectified. Thus, the painting conveys a sort of transcendent legitimation of the submission of dark-skinned, 'savage' people to white, highly civilized British. If I am superior to you by natural and divine right, you owe me your riches, and it is only a detail whether I snatch them from you or you spontaneously offer them to me. Then, all forms of exploitation, oppression, massacre, and slavery against non-white and non-Christian peoples are metamorphosed into a fully sanctioned and legitimate domination. In this painting, the hidden ideological premise turns the bloody colonial looting into a rightful offering and asks the observer to perceive it as such.

From an artistic point of view, this painting shows obvious ugliness and mediocrity, but from a communicative point of view, it's effective and goes straight to the point.

British imperialism gradually disintegrated Indian economic and structural foundations. In 1853, Karl Marx wrote in a column written for The New York Tribune: « [T]he misery inflicted by the British on Hindostan <= India> is of an essentially different and infinitely more intensive kind than all of Hindostan had to suffer before». The drug traffic, organized illegally by the EIC, disintegrated the Chinese social fabric and brought the Celestial Empire to an end. The plundering and destruction of the Far East was carried out under the ideological banner of the superiority and just dominance of the West.

We are not here at the dawn of modern capitalism only: we are at the dawn of modern racial discrimination, inequality, exploitation, and slavery. Two dawns that look different, but are the one and only.

The EIC and China

The EIC turned its attention to China in the second half of the 17th century: the tea-silk-porcelain trade, the old workhorse of the Portuguese (who were constantly threatened by the Dutch), was a significant commercial opportunity as those were commodities with a booming demand in Europe. The EIC established a factory on the island of Taiwan in 1622 (it was one of the first English settlements in East Asia); however, this station was not a colony and the EIC did not have control over the island. In 1664, the EIC made the first purchase of Chinese tea (approx. 100 lbs.), and over the following 20 years, it gained additional permissions to trade in Chinese ports to expand its imports of silk, tea, and porcelain.

In 1684, the Qing Emperor Kangxi lifted the maritime trade prohibition and endorsed an Open Trade Policy, allowing foreign merchants to bring their goods to China and enter Chinese ports. The EIC established direct commercial relations with China after the voyage of the Macclesfield galley in 1699-1701. Macau was used by the British as their home until the founding of Hong Kong in 1842. «The temporary residence of the supercargoes became essential to the economy of Macau» (Rogério Miguel Puga, The British presence in Macau 1635-1793, The Focus, Summer 2013). By 1713, the EIC had secured access to Canton harbor, and in 1762, the company was given permission to establish there a permanent factory or trading station.

The EIC traded Chinese tea, silk, and porcelain for British goods such as silver, wool, textiles, and opium. This is a crucial issue, but we won’t deal with it now. We are about to discover both the Portuguese, Dutch and English trade of Chinese blue and white porcelain and the tremendous impact the latter made on Europe.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?