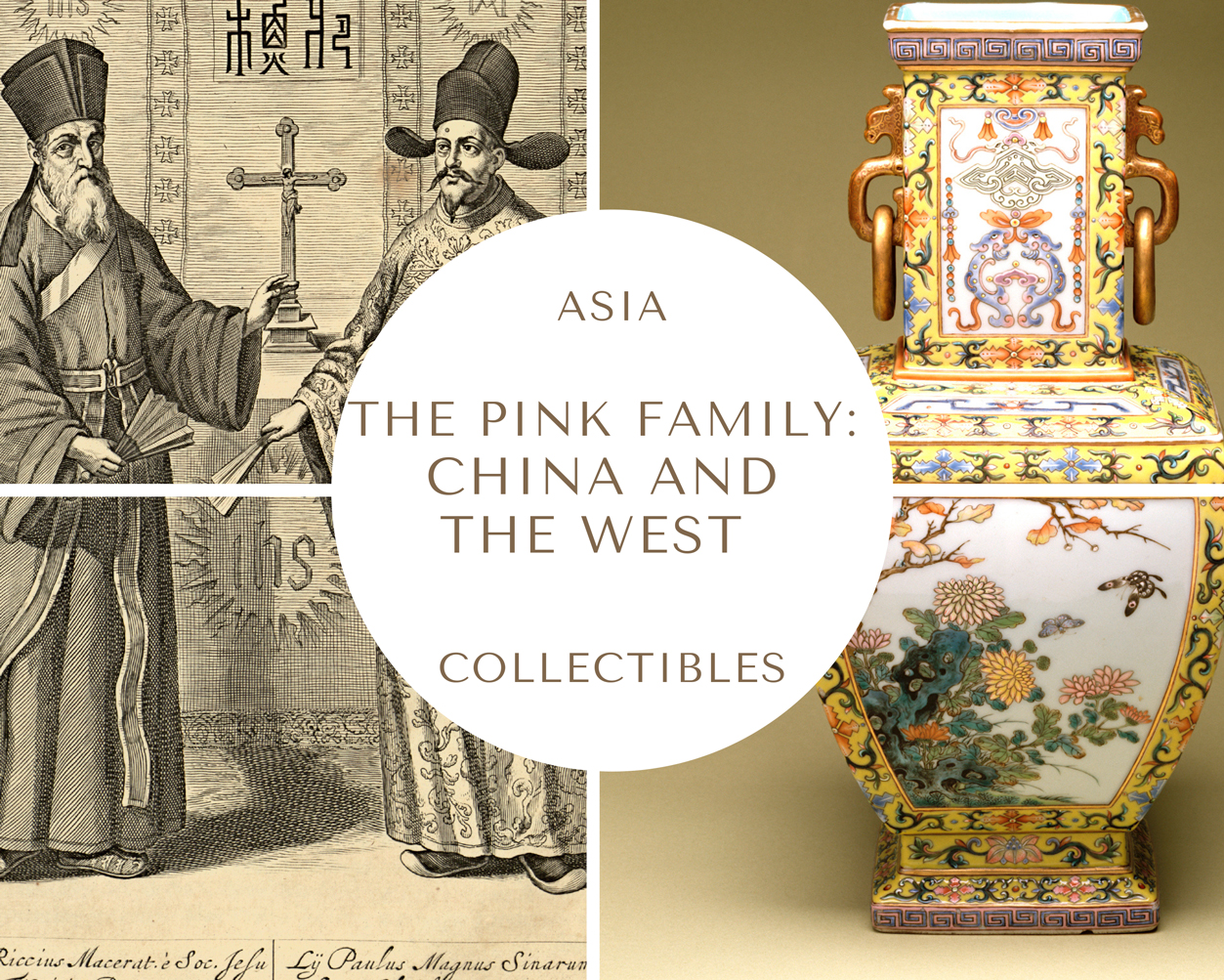

THE PINK FAMILY: CHINA AND THE WEST 6

Current China on the globe.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

LEFT: Portrait of the Yongzheng Emperor in Court Dress, by anonymous court artists, Yongzheng period (1723—35), Qing Dynasty. Hanging scroll, color on silk. The Palace Museum, Beijing. Public Domain.

RIGHT: History of China, Imperial Dynasties, source: Dynasties in Chinese history, Wikipedia.

THE BLUE AND WHITE PORCELAIN IMPACT ON THE WEST IN THE 16TH AND 17TH CENTURIES

DIFFERENT ADAPTATIONS TO WESTERN TASTE: THE METAL MOUNTS

As the trade intensified, the Jingdezhen potters began designing new pieces to cater to Western tastes: new shapes and new functional objects appeared and the underglaze cobalt blue decoration began embracing foreign motifs. From 1635 onwards, the Dutch VOC supplied wooden examples of various kinds of wares for the Chinese potters to copy to create pieces with more common and useful shapes, and boost sales. «As the export trade increased, so did the demand from Europe for familiar, utilitarian forms. European forms such as mugs, ewers, tazze <wide but shallow bowls>, and candlesticks were unknown in China, so models were sent to the Chinese potteries to be copied. While silver forms probably served as the original source for many of the forms that were reproduced in porcelain, it is now thought that wooden models were provided to the Chinese potters.» (Jeffrey Munger and Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, East and West: Chinese Export Porcelain, cit.).

ABOVE: Porcelain candlestick, made in China in ca. 1700–1710 (Qing Dynasty) for the Dutch or English market. Height: 13.3 cm; 5 1/4 in. The MET, New York, US.

Candlesticks and candle holders were unknown objects to the Chinese.

BELOW: Chinese porcelain Candlestick painted with underglaze cobalt blue and decorated with Chinese antiquities, flower sprays, and floral scrolls. Made in ca. 1700, Kangxi period, Qing Dynasty. Dimensions: height 18 cm, max. diameter 10.2 cm. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

This candlestick of Chinese porcelain was imported by the VOC and is a replica of a European model.

Many of the porcelain pieces which arrived in Europe between the 16th and the 18th centuries were mounted in vermeil or gilt silver, silver alloy, gilt copper, ormolu or mercury-gilt bronze (used especially in the 18th century), and more rarely gold. The French king Louis XIV, "le Roi Soleil", used to consume his morning bouillon in a very fine Chinese porcelain bowl, with the bottom rim mounted in pure gold, and two handles, each shaped to represent two entwined serpents, also in pure gold.

The metal-mounted Chinese (Transitional, kraak-style, Kangxi) and Japanese (Kakiemon) pieces are collectively called "mounted porcelains".

The practice of mounting oriental porcelain was quite common in the Ottoman Empire. In Europe, it dates back to the Middle Ages. Do you remember the story of the Fonthill Vase, the first Chinese porcelain to reach Europe soon after its production, in the first half of the 14th century? (in PART I).

In the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, the systematic use of elaborate metal mounts on different porcelain pieces (bowls, vases, plates) responded to different purposes at a time.

- First of all, it enhanced the beauty of luxury pieces, giving them a golden or silvery brilliance and a flashy look, in consonance with the European tastes of the time (that differed according to countries and periods). Thus, the first was an esthetic reason.

- Secondly, the precious metal mounts emphasized the magnificence and raised the value of exceptional pieces, making them more suitable for royal gifts or the furnishings of aristocratic houses.

- Third reason: traders and dealers used the metal mounts as 'marketing' tools to avoid 'boring' collectors and make the pieces, often imported in massive quantities and with identical decoration, more varied and appealing.

- Fourth reason: the metal mount served to adapt many unfamiliar Chinese shapes to Western eyes, usage, and habits. It could be a simple functional improvement or a more radical transformation capable of changing the form and function of the original object.

- Fifth: the metal mounts were sometimes the necessary trick to cover and repair the chips along the rims or the chinks due to transport; at the same time, they offered protection against future damages.

The next picture shows four mounted porcelain pieces from the Ming Dynasty that had been acquired by William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (1520–1598), the powerful chief adviser of Queen Elizabeth I, twice Secretary of State, and Lord High Treasurer from 1572. The gilt-silver mounts, made by an unknown silversmith in London in ca. 1585, are quite bulky and richly decorated even in their smallest details, with finely stamped and cast motifs recalling the ornaments of classical architecture.

TOP LEFT: Very fine porcelain bowl made in China (likely not for export) in ca. 1573–1585, Wanly period, Ming Dynasty, with a two-handled, silver-gilt mount made in London by an unidentified silversmith in ca. 1585. Dimensions: 15.9 × 24.1 cm - 6 1/4 × 9 1/2 in; width including handles 33 cm - 13 in.

BOTTOM LEFT: Porcelain dish with figures in a landscape, made in China in ca. 1573–1585, Wanly period, Ming Dynasty, with a silver-gilt mount made in London by an unidentified silversmith in ca. 1585. Dimensions: 10.2 × 36.5 cm - 4 × 14 3/8 in.

BOTTOM CENTER: Porcelain bowl made in China in ca. 1573–1585, Wanly period, Ming Dynasty, with a two-handled, silver-gilt mount made in London by an unidentified silversmith in ca. 1585. Dimensions: 15.9 × 24.1 cm - 6 1/4 × 9 1/2 in; width including handles 33 cm - 13 in.

RIGHT: Chinese porcelain ewer made in China in ca. 1573–1585, Wanly period, Ming Dynasty, with a silver-gilt mount made in London by an unidentified silversmith in ca. 1585. Dimensions: height 34.6 cm - 13 5/8 in.

All the pieces come from the furnishings of Burghley House, in Lincolnshire (UK), and are part of The MET Collection in New York, US.

The following pieces are two large-sized Japanese porcelain lidded bowls (= tureens), made in Arita for export between 1660 and 1680. The gilt-bronze mounts are attributed to the Swiss goldsmith Wolfgang Howzer who was active in London between 1660 and his death in 1688. Each ormolu handle is finely decorated with a greyhound. These luxury pieces were probably assembled for a refined member of the royal court of Charles II.

A pair of porcelain lidded bowls decorated with underglaze cobalt blue, made in Arita, Japan in ca. 1660–1680. The gilt-bronze mounts were made in London in 1680 and are attributed to Wolfgang Howzer. Dimensions: 34.4 × 38.1 × 25.6 cm - 13 9/16 × 15 × 10 1/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, US.

Here is another piece whose mounts have been attributed to Wolfgang Howzer and are decorated with greyhounds as the previous pair. It's a brush pot made in Jingdezhen between 1630 and 1650; the elaborate gilt-silver mounts were probably realized by Wolfgang Howzer in London between 1660 and 1670. The addition of the mounts turned the brush pot into a showy two-handled lidded cup whose very good condition tells us that it was kept for display and probably never used.

Chinese porcelain brush pot made between 1630 and 1650, and painted in underglaze blue with objects associated with the theme of 'Antiquities' (among them an incense burner and an antique ding, namely a cauldron with legs, a lid and two facing handles, used for the preparation of ritual offerings to ancestors). Its complex gilt-silver mounts (made up of handles, foot, rim mounts, and lid) were made in England between 1660 and 1670, probably by the Swiss goldsmith Wolfgang Howzer. Dimensions: height 33 cm, width including handles 33 cm, base diameter: 16.9 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

During the 17th century, the vogue for silver-mounted Chinese porcelain passed from England to Holland. Look at the following oil on canvas, painted in ca. 1660 by one of the most prominent Dutch still-life painters of the Golden Age (= the Dutch 17th century), Willem Kalf. The porcelain dish on the right is similar to the piece from the Burghley House, and the gilt-silver mount differs only in a couple of details. Both pieces, the Dutch and the English, were presumably imported and mounted in the same years. The ewer on the left is similar to a Jiajing piece preserved in the British Museum, decorated with a Western motif.

Willem Kalf (b. 1619 in Rotterdam, d. 1693 in Amsterdam), Still Life with Ewer and Basin, Fruit, Nautilus Cup, and Other Objects, oil on canvas, ca. 1660. Dimensions: height 111 cm - 43.7 in; width: 84 cm - 33 in. Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum, Madrid (Spain).

LEFT: A detail in the painting Still Life with Ewer and Basin by Willem Kalf.

RIGHT: Porcelain ewer decorated in underglaze blue. Made probably in Jingdezhen in ca. 1540-1566, during the Jiajing period, Ming Dynasty. Dimensions: height 31.8 cm, width 20.8 cm including spout and handle. The British Museum, London, UK.

The two ewers are similar and were probably made in the same period for the same customer. They show a similar shape indirectly inspired by Near Eastern brass pitchers. On either side, both porcelain pieces show a similar decorative motif: a fountain with a qilin at its base. This motif is neither a Chinese nor a Near Eastern one. According to some scholars, it could have a European origin and, in particular, be rooted in Christian iconography. It's likely, therefore, that this kind of piece might have been commissioned by Jesuits in China.

Here are two Chinese pieces from the 17th century enriched in The Netherlands with precious silver mounts. The first piece is an ewer with a discreet mount applied in the late 17th century. The piece resembles the Chinese ewer depicted by the Golden-Age Dutch painter Jan Mortel (1652–1719) in a still-life from 1686.

LEFT: Porcelain ewer from the Transitional period, made in China in the mid-17th century, with a baluster body painted in underglaze cobalt blue and depicting human figures in a landscape. The piece has a Dutch, unmarked silver mount probably made in the late 17th century. The hinged cover is engraved with a peacock within the foliage, with an openwork cast figure thumbpiece and beaded handle mount. Dimensions: height 23.2 cm - 9 1/8 in. Auctioned by Christie's London in 2019. Photo by courtesy of Christie's.

RIGHT: Jan Mortel (1652–1719), Still-life with a Chinese porcelain jug, a pewter plate with a herring, a pomegranate, a knife, an onion, grapes, and cherries, together with a snail and a butterfly, all on a stone table draped with a grey cloth. Detail. Oil on canvas, signed and dated lower left: Mortel fec./ Ao. 1686. Auctioned by Sotheby's London in 2012. Photo by courtesy of Sotheby's.

The second Dutch piece is a 17th-century Chinese teapot enriched with an elaborate mount in the 19th century. This data tells us that the use of metal mounts on porcelain pieces well continued into the 18th and 19th centuries.

Porcelain teapot decorated with underglaze cobalt blue, made in China in the first half of the 17th century, with a silver mount made in The Netherlands in the 19th century. © Chitra Collection. (The Cithra Collection is a private museum of over 2000 historic teawares from Europe, Asia, and the Americas. The Collection is owned by the N. Sethia Foundation, a charity founded by the British-Indian businessman Nirmal Sethia in 1995).

The following painting is an artwork by Frans Snyders or Frans Snijders (1579–1657) from Antwerp (in present-day Belgium), a Flemish painter of still lifes, animals, and hunting scenes. The Wanli porcelain cup with a saucer in the foreground shows a discreet gilt silver mount.

Frans Snyders or Frans Snijders, Flemish artist (1579–1657), Still Life with Fruit, Wanli Porcelain, and Squirrel, signed and dated lower right: Frans Snyders fecit 1616. Oil on copper. Dimensions: 56 x 84 cm - 22 1/16 x 33 1/16 in. Museum of Fine Arts (MFA), Boston, MA, US.

Metal mounts were also applied in Germany and Venice, although to a much smaller extent. The following piece is a Jingdezhen small bowl made for export in the late 16th century, during Wanli's reign, enriched with a gilt-silver mount made in the early 17th century, probably in Germany.

Porcelain bowl painted with underglaze blue made for export in Jingdezhen, China, during the Wanli period (1573–1620), Ming dynasty, in the late 16th century. The gilt silver mounts were made in the early 17th century, probably in Germany. Dimensions: height 12 cm - 4 3/4 in; width at handles 20 cm - 7 7/8 in; diameter 15.2 cm - 6 in. The MET Museum, New York, US.

The teapot below is a late 17th-century piece, made in China for export during the Kangxi period (Qing Dynasty). Its elaborate metal mount was added in Germany in ca. 1680. The ornate gilt-copper spout takes the form of a peacock, while the handle is topped by a monkey.

Chinese porcelain teapot with underglaze cobalt blue decoration, made in China for export in the Kangxi period with gilt-copper mount made in Germany in ca. 1680. © Chitra Collection. (The Cithra Collection is a private museum of over 2000 historic teawares from Europe, Asia, and the Americas. The Collection is owned by the N. Sethia Foundation, a charity founded by the British-Indian businessman Nirmal Sethia in 1995).

France is a case apart. The fashion of mounting Chinese and Japanese porcelains developed in Paris at a later time, during the reigns of Louis XIV (1643-1715) and Louis XV (1715-1774), because porcelain ware began to arrive in Paris in 1611 but was largely available only after 1680. France, therefore, left late but arrived first: «More oriental porcelain was set in metal mounts in Paris between 1740 and 1760 than at any other period in the world's history.» (Gillian Wilson, Mounted Oriental Porcelain in the J. Paul Getty Museum, see Bibliography). This is so true that «the history of mounted oriental porcelain in the 18th century, which might justly be called 'the golden age' of mounted porcelain, is, for all practical purposes, the history of porcelain mounted in Paris.» (Ibidem).

Although in this section I intend to limit myself to the 16th and 17th centuries only, I will mention and show some French mounts of the 18th century, leaving the in-depth study of this and other related issues to the chapters devoted to the 18th-century Chinoiseries.

«With delight one notices (...) a very large number of pieces of old porcelain of the greatest perfection, [and] the mounts that accompany the pieces seem to rival them in value». Thus wrote Antoine-Nicolas Dézallier d'Argenville in the 1752 edition of his successful guide Voyage pittoresque de Paris. Not all porcelain pieces were mounted: in Paris, les marchands-merciers, who combined the roles of antique dealers, jewelers, interior decorators, and sellers of porcelain ware, decided which pieces had to be mounted and how to win the curiosity, desire, and wallet of the rich, extravagant, and sophisticated society de la cour et la ville, living in Versailles or in Paris. «To embody their ideas and designs, the marchands-merciers employed many craftsmen, such as furniture makers (ebenistes), bronze casters (fondeurs), gilders (doreurs), goldsmiths, and so on. <And they> were exceedingly ingenious in devising ways of adapting rare and exotic materials, especially those from the Far East, to the decoration of the houses of the rich.» (Ibidem).

Lazare Duvaux was one of the most active marchands-merciers: he had a shop, Au Chagrin de Turquie, patronized by king Louis XV and located in the fashionable rue Saint-Honore. Duvaux could boast among his loyal customers the marquise de Pompadour, the official chief mistress of Louis XV from 1745 to 1751, and an influential court member (she died in 1764). She purchased more than 150 pieces of mounted oriental porcelain from him in 10 years, from 1748 to 1758, when the craze for mounted porcelain in France reached its peak.

The oil on canvas below was painted in 1717 by Alexandre-François Desportes, a Louis XIV court painter specializing in hunting scenes and related still life. This canvas was commissioned by Philippe d’Orléans, Régent after the death of the Sun King, as a decorative element in the dining room of the Château de la Muette. Look at the mounted blue and white porcelain bowl in the lower left corner.

Alexandre-François Desportes (1661–1743), Animaux, Fleurs et Fruits, oil on canvas, 1717. Dimensions: 124 x 231 cm. Musée de Grenoble J.-L. Lacroix, France.

The following pieces are all containers for pot-pourri, commonly used in France for freshening rooms. The pair below was made by using separate pieces assembled together thanks to the gilt-silver mounts. The lower part of both pot-pourri containers was made by using the bottom section of a bottle whose neck had been cut off; both lids were probably the covers of two bowls. The white porcelain pieces were made in China in ca. 1700 (Kangxi period, Qing Dynasty) by the Dehua kilns in Fujian, which specialized in a type of hard, white porcelain known in France as blanc de Chine. The richly decorated gilt-silver mounts were made in France in ca. 1710.

A pair of pot-pourri containers. The porcelain pieces were made by the Dehua kilns, in China, during the Kangxi period (Qing Dynasty), in ca. 1700. The elaborate vermeil (gilt-silver) mounts were added in France in ca. 1710. Dimensions: height 19 cm, diameter 10.8 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

At the beginning of Louis XIV's reign, there was a widespread tendency to use silver, gilt silver, or even gold mounts, especially for the objects reserved for the 'Sun King'. However, at the end of his reign, the tendency to use the less expensive ormolu (gilt bronze) prevailed. The bronze was often treated with a finely ground, high-carat gold–mercury amalgam and finely chiseled for an extra, showy shine. From the 1720s onwards, «with the development of the full Rococo style, gilding was increasingly used in the interior decoration of Parisian houses on the walls and the furniture, and for all sorts of decorative objects like clocks, barometers, etc.» (Gillian Wilson, Mounted Oriental Porcelain in the J. Paul Getty Museum, cit.). The style and design of the ormolu mounts were developed accordingly.

The pot-pourri below was assembled by using and heavily modifying two celadon bowls made in ca. 1720 (Kangxi period, Qing Dynasty), one of which was inverted to create a lid. The ormolu mounts were made in Paris in ca. 1745–1749.

ABOVE: Celadon pot-pourri container, made in China in ca. 1720, with elaborate ormolu mounts made in Paris in ca. 1745–1749. Dimensions: 40 × 38.1 cm - 15 3/4 × 15 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, US.

BELOW: A pair of ewers made up of a pair of baluster-shaped (Yen Yen) vases with a celadon surface, decorated with underglaze cobalt blue and copper red, made in China in ca. 1662–1722 (Kangxi period, Qing Dynasty). The ormolu mount,s which turned the vases into ewers (intended purely for decorative use and not as pouring vessels), were added in Paris in ca. 1745–1749. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, US.

A FEW REMARKS ON THE METAL MOUNTS

Some Western scholars consider mounted porcelains as a "charming marriage of East and West" in the words of Will Strafford.

Deborah Gribbon, Deputy Director and Chief Curator of the J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, wrote that the Oriental porcelain with Parisian gilt-bronze mounts, which forms a small but significant part of the Getty Museum's collection of decorative arts, «provide tangible evidence of cultural contact in the eighteenth century between China and Japan and the West.» (in Gillian Wilson, Mounted Oriental Porcelain in the J. Paul Getty Museum, cit.).

I do not agree.

Let's abandon a Euro-centric approach to adopt a cross-cultural sensitive perspective to look at the application of metal fitting: well then, the highly ambiguous attitude of the Europeans comes to light.

This ambiguity is well conveyed by the term used in France during the 17th and 18th centuries to indicate the application of a metal mount: enjoliver. This verb has two different meanings in French.

- It means rendre quelque chose plus joli, to embellish something in the precise sense of decorating it, making it more beautiful by adding decorative elements.

- It means embellir quelque chose de détails plus ou moins fausses, embellish something in the sense of sugarcoating it; enjoliver une histoire ou la vérité means to embellish a story or the truth by camouflaging some of its aspects and adding fake details.

This ambiguity was not a 'privilege' of France, of course: it was well shared by many Europeans. On one hand, the use of semi-precious metal mounts shows their admiration and the high regard in which they kept Chinese and Japanese porcelain pieces, at least the most valued and fine ones. On the other, however, the ease with which they could manipulate them and turn them into different objects tells us the widespread tendency to regard those dearly paid items not as expressions of different cultures but as precious playthings and possessions that gave the possessor any right on them. Was it a 'cultural' appropriation? A kind of aggressive consumption? Was it a subtle form of 'colonialism'?

I will discuss this issue at the end of all chapters.

Many times the porcelain pieces were heavily altered to be fitted: the rim had to be filed to accept the silver collar, the foot or the spout had to be cut down to suit the mount, the body drilled to become the upper part of a potpourri or a fountain, and so on. Moreover, the application of an 'alien' and heavy metal mount had the effect of watering down and even erasing the meanings embedded in the original shapes and decorations. Was it a form of spoliation?

Sometimes, I get the impression that in this "charming marriage of East and West", each Chinese piece had to be a 'tamed shrew ' to be fully 'embellished and accepted within the European family'. We should not forget, moreover, that the application of richly elaborate metal mounts did not have simply ornamental and functional purposes: it also served to embed a new social meaning and add new values to the pieces. Europe viewed Chinese objects as luxurious commodities, status symbols, displays of social power, expressions of fine taste, a fashionable trend, a mania, a craze, an obsession... always with a fascination imbued with superficial exoticism but devoid of deep cultural interest. In the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, most of the wealthy buyers and collectors had a vague idea of China, made up of truths, half-truths, fantasies, and pure hogwash, held together by the image of a very distant, rich, and exotic kingdom full of strange wonders. Most admirers and users of Chinese porcelain ware had no deep interest in knowing China culture, and their attitude was devoid of cultural respect. As we'll see in the next chapters and discuss in the last, this respect develops from a cultural encounter, not from a commercial and emotional surface relationship.

Lastly, I would add that some forms of this "marriage of East and West" are not happy unions. The metal mounts, especially the English ones, which are so stuffy and overdecorated, and the ormolu French fittings, so heavy and gaudy, end up suffocating the purity of design and the harmony of shape and function of many Asian pieces. Look at the ensemble below.

Chinese porcelain celadon baluster (guanyin zun) vase made in China in the early 18th century, during the Qing Dynasty, with a magnificent two-layer crackled teal glaze. The Rococo-style ormolu mount was made in France in ca. 1750. Dimensions: height 59.4 cm - 23 3/8 in; width 34.9 cm - 13 3/4 in; depth 31.8 cm - 12 1/2 in. The MET Collection, New York, US.

The size of this vase is impressive: it's almost 60 cm high. «The cost of gilt-bronze mounts was considerable, and an object of this scale would have been very expensive. Eighteenth-century auction catalogues indicate that mounted vases such as this were frequently found in aristocratic collections, and the prices they realized upon their sale demonstrate that they retained their value even after the style of their mounts had passed from the forefront of fashion. In the 1782 sale of the art collection of Louis-Marie-Augustin, duc d’Aumont, many of the lots offered were either Japanese or Chinese mounted porcelains, and a number of them were bought by Louis XVI for substantial sums.» (The MET curators).

According to The MET curators, «this large Chinese porcelain vase with unusually elaborate and sculptural gilt-bronze mounts offers a spectacular example of the transformation that can be effected by the addition of mounts. The profile of the vase is radically changed, and the profusion of curving metal shapes creates a quintessential expression of French Rococo taste.».

I have a completely different opinion, though.

The fine network of fractures in the glaze and the complex crackle pattern - there are two layers of crackle, the wide crackle stained dark grey and the fine light brown - are the product of an extraordinary technical virtuosity at the service of an artistic ideal and a vision of 'beauty' deeply rooted in the Chinese humanism shaped by Confucianism and informed by Daoism and Chan Buddhism. The Chinese balance between imperfect perfection and perfect imperfection, masterful spontaneity and spontaneous mastery, has nothing to do with the garish and flashy swirls and scrolls of a theatrical ornamental style (the Rococo, of course).

This delicate vase with an auspicious bì hû (gecko) in relief seems to me not to be enhanced or beautified by the metal mount but immobilized within an alien metal armor like a prisoner in a cage. What do you think about it?

The following is a porcelain vase with a lustrous lavender-blue glaze and a fine pattern of dense cracking on its surface, made in Jingdezhen in the second half of the 18th century. The mount has a completely different style than the previous one: it was realized by Vulliamy & Sons (Benjamin Vulliamy and his son, Benjamin Lewis Vulliamy) who made it in London in 1808; that very same year, the ensemble was acquired by the Prince of Wales. The vase received a complex mount, mainly in gilt bronze with a base in green marble. «Attached to either side of the neck are a pair of gilt-bronze dragons with half-opened wings, coiled tails, and necks reaching over the rim toward each other and peering into the neck. The vase’s foot is supported by a cup of eight shell-like lotus leaves rising from a broad-waisted stem with a two-tiered step, which is attached to a square plinth of green marble.» (Chinese and Japanese Works of Art in the Collection of Her Majesty The Queen: Volume II).

I find this eclectic ensemble an inharmonious, mismatched salad; even the ormolu mount alone shows some incongruities. What do you think about it?

Jingdezhen porcelain bottle-shaped vase with a gilt bronze mount and a square plinth of green marble, assembled by Vulliamy & Sons in 1808. Overall dimensions: 49 x 23.5 x 22.5 cm. Royal Collection Trust, London, UK.

THE RECEPTION OF CHINESE PORCELAIN IN EUROPE IN THE 16TH AND 17TH CENTURIES

SPAIN

I've already written about the rich porcelain collection of Philip II, son of Emperor Charles V, king of Spain from 1556 and Portugal from 1580. «Sadly, nothing is known to have survived from this great collection, the largest in Europe, which held a little more than 3000 pieces» (Cinta Krahe, cit.). King Philip gave some of his porcelain pieces to his cousin, the Archduke Ferdinand II of Austria (1529–1595). Today, those pieces are probably among the many blue and white items preserved in the Kunstkammer of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna.

Cinta Krahe, a scholar who studied the reception of Chinese porcelain in Spain during the Habsburg Dynasty, wrote that Don Pedro Álvarez de Toledo (1484–1553), Viceroy of Naples and uncle of the Duke of Alba, had 67 pieces of porcelain (blue-and-white and mounted celadons) in his palace of Castel Nuovo and that one of the most superb collections of Chinese porcelain in Spain belonged to the Prince of Éboli, Don Ruy Gómez de Silva (1516–1573). We know, moreover, that Don García Hurtado de Mendoza, 4th Marquis of Cañete, Viceroy of Peru, commissioned a set of porcelain dishes and both the powerful Duchess of Alba and Don Gómez Dávila y Toledo, 3rd Marquis of Velada, had a small collection of glasses and porcelain.

The Habsburg Dynasty, los Grandes de España, and the lower nobility continued to love and collect China ware well into the 17th century. This success is evidenced by the presence of many Chinese porcelain pieces in the artworks of the period.

The painting below is an oil on canvas that once belonged to the nobleman Diego Mexía Felípez de Guzmán, Marquis of Leganés. It's a 1627 still life by Juan van der Hamen y León (1596–1631), «second generation of a Flemish family from Brussels who had settled in Spain, famous for popularising the still life genre in Madrid society.» (Cinta Krahe, Chinese Porcelain In Spain During The Habsburg Dynasty, cit.). In this painting, two kinds of objects catch the eye more than the masterfully rendered leaves of the artichokes or the flowers' petals: the expensive Venetian glassware and the Chinese porcelain fruit bowl, two luxury items that appealed to the taste of Van der Hamen's socially distinguished and cultivated clients.

Juan van der Hamen y León, Still Life with Artichokes, Flowers and Glass Vessels, oil on canvas, 81 cm x 110 cm, signed and dated 1627. Prado Museum, Madrid (Spain).

Between 1630 and 1635, Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), one of the masters of Spanish Baroque painting, depicted the Virgin Mary as a sleeping child. On the right side, there is a small rustic table with a metal plate and a Chinese kraak-style escudilla, a deep bowl with a lobed rim. Three flowers are placed in the bowl: the rose symbol of love, a lily representing virginal purity, and the five-petaled red carnation, a symbol of the five wounds of Christ.

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), Virgen niña dormida, oil on canvas, ca. 1630-1635, Colección Banco Santander, Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao (Spain).

When looking at the above painting, did you note a contrast or a discrepancy between the rustic and rough pieces of furniture and the precious Chinese porcelain bowl? The truth is that, in Spain, pottery, in general, had very humble associations, and Chinese porcelain was linked to female humility, dignity, and virtue.

As to the reception, appreciation, and monetary value attributed to Chinese porcelain in the Iberian countries, Cinta Krahe wrote that there was a radical difference between Spain and Portugal, although the crown of Portugal was part of the Hispanic Monarchy for 60 years (1580–1640). In Portugal, the imported Chinese porcelain was highly appreciated by the court «and had an essential influence on their culture, perhaps due to the direct links with China», namely Macao. (Cinta Krahe, The Reception and Value of Chinese Porcelain in Habsburg Spain, cit.).

In Spain, the situation was different. «Chinese porcelain was imported from China through the Philippines by the Manila galleon trade and was an essential article of that trade, the third most important cargo after silks and spices. It became an essential commodity in the households of New Spain (Mexico) from where it was distributed widely throughout the Spanish Americas and was used as tableware, for storage, and, in the 17th and 18th centuries, for interior decoration. Every year, the Spanish treasure fleet sailed from Veracruz (Mexico) to Seville (Spain) via La Habana (Cuba). They were twenty merchant ships, including mixed cargoes of Asian and American products, but for the traders from Spain, silver was clearly the most important and profitable commodity, as were different raw materials such as indigo for dying, ginger or sarsaparilla for medical uses, and new plantation products such as tobacco, sugar, and cocoa, all of which were becoming very popular in the Spanish markets during the second half of the 17th century. Among the luxury goods, pearls and gems from the New World were seen as the most important trade items, while Chinese porcelain clearly figured as a very minor import to Seville.» (Ibidem). Thus, China ware, despite its being appreciated by the royal house and some Grandees of Spain, never became popular but always remained a rarity within small collections of precious things. «It failed to capture the imagination of many of the great aesthetes in Spain during the Habsburg period (...) and did not trigger a significant shift of the lifestyles and consumer habits of Spaniards during the Golden Age.» (Ibidem).

ITALY

The earliest European paintings depicting Ming Dynasty porcelain items are two Italian masterpieces. The first is Adoration of the Magi, a distemper on linen by the Venetian master Andrea Mantegna, dated ca. 1495–1505.

Adoration of the Magi, distemper on linen by the Venetian master Andrea Mantegna (ca. 1431-1506)), dated ca. 1495 - 1505. Dimensions: 48.6 × 65.6 cm (19 1/8 × 25 13/16 in.). J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, US.

«Three kings pay homage to the Christ Child, who in turn makes a sign of blessing. Jesus Christ, the Virgin Mary, and Mary's husband Joseph have haloes and wear simple garments, while the Magi are dressed in exotic clothing and jewels and bear exquisite gifts. Caspar, bearded and bareheaded, presents the Christ Child with a rare Chinese cup, made of delicate porcelain and filled with gold coins. Melchior, the younger, bearded king behind Caspar, holds a Turkish censer for perfuming the air with incense; on the right, Balthasar the Moor carries a covered cup made of agate.» (J. Paul Getty Museum's curators).

Look at Caspar, the bearded and bareheaded old man on the right, in the foreground: he presents the Christ Child with a rare Ming blue and white porcelain cup, filled with gold coins. Probably Mantegna was inspired by one of the pieces of the collection of Isabella d'Este, a great patron of the arts, and spouse of Francesco II Gonzaga, marquis of Mantua, where Mantegna was appointed court artist.

Adoration of the Magi, detail of the Chinese porcelain cup.

In the video below, Leah Clark, lecturer at the Department of Art History at the Open University, in the UK, discusses Renaissance painting with a special focus on the representation of the Chinese porcelain cup.

The second painting is The Feast of the Gods (in Italian, Il festino degli dei), an oil on canvas painted in 1514 by the Italian Renaissance master Giovanni Bellini, with substantial additions in stages to the left and center landscape by Dosso Dossi and Titian in ca. 1529.

The Feast of the Gods (in Italian, Il festino degli dei), by Venetian painter Giovanni Bellini (ca. 1430/1435 - 1516) with later additions by the Venetian painter Titian (ca. 1488/1490 - 1576) and the Ferrara painter Dosso Dossi (c. 1489–1542), a painter from the School of Ferrara. Oil on canvas, 1514, 1529. Dimensions: overall 170.2 x 188 cm (67 x 74 in.); framed: 203.8 x 218.4 x 7.6 cm (80 1/4 x 86 x 3 in.). National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., US.

«In this illustration of a scene from Ovid's Fasti, the gods, with Jupiter, Neptune, and Apollo among them, revel in a wooded pastoral setting, eating and drinking, attended by nymphs and satyrs.» (National Gallery of Art's curators).

The painting was the first of a cycle of artworks on mythological subjects commissioned by Alfonso I d'Este, the Duke of Ferrara and brother of Isabella d'Este. Both siblings were known for their interest in Chinese porcelain.

The Feast of the Gods, two details.

LEFT: A drunken satyr is playfully resting a wide porcelain bowl on his head while the nymph to his left is serving the nectar of the gods in a wide blue and white porcelain bowl.

RIGHT: Neptune is portrayed with his right hand between the thighs of Cybele. The goddess is eating a fruit (probably a quince), picked from those inside a large blue and white porcelain bowl with a flat rim, whose body is painted in underglaze cobalt blue and shows lotus and leafy scrolls.

All the porcelain pieces in the painting are Ming large bowls, finely decorated with underglaze cobalt blue. Note that they are not kraak-style pieces, whose production started much later.

In the early 16th century, before the Portuguese began importing Chinese porcelain, the pieces that circulated in Venice and other Italian courts, such as Ferrara and Mantua, were mostly lavish diplomatic gifts from the Ottoman sultans and from Persia, Syria, or Egypt.

According to Maura Rinaldi, an Italian scholar and author of the first essay on kraak porselein, «in the 16th and 17th centuries, Florence was an extremely wealthy city due to its textile industry and banking system. Florentine agencies established in Lisbon often financed or owned many of the ships sent by the Portuguese towards the Indies, in those ships traveled their agents, who not only traded in the oriental products but also kept well-informed their masters, the Medici, of what was available in those exotic markets» (M. Rinaldi, Florentine Traders in Asia and the Medici Porcelain Collection, lecture held in Singapore in 2011).

The House of Medici, the Italian banking family and political dynasty that ruled over Florence from 1434 to 1737, began collecting Chinese porcelain at the beginning of the 15th century. Lorenzo the Magnificent collected a number of celadons and pieces of blue and white porcelain, all the result of diplomatic exchanges, in the palace on Via Larga, today's Palazzo Medici Riccardi.

In 1539, Cosimo I de' Medici (1519–1574), the first Grand Duke of Tuscany, had a small collection of celadons. The 1546 inventory says he acquired 106 "tazzine piccole", small porcelain cups decorated in underglaze cobalt blue. According to the Italian scholar Marco Spallanzani, the posthumous 1574 inventory recorded 322 pieces of blue and white porcelain plus 75 celadons. (source: Ceramiche alla corte dei Medici nel Cinquecento, Franco Cosimo Panini, 1994). According to another Italian scholar, Maria Chiara Donnini Cappuzzo, the 1574 inventory included 420 pieces, distributed among the Pitti Palace, the Palazzo Vecchio, and the palace of via Larga (source: Le collezioni delle porcellane cinesi al tempo dei Medici). According to a French source, in 1553, the Medici owned 400 porcelains, including 59 celadon and 289 blue and white pieces (Trésors des Médicis, edited by Christina Achidini Luchinat, Paris, Somogy éditions d’art, 1997). In any case, by the end of the 17th century, the Medici collection amounted to several thousand pieces, including Japanese wares. Some of the Chinese pieces of the Medici collection are today housed in the Tesoro dei Granduchi (former Museo degli Argenti), in the Florentine Pitti Palace.

Blue and white porcelain cup with a bracket-lobed rim, made in China in ca. 1585 - 1610 ca., during the late Ming Dynasty. Tesoro dei Granduchi (former Museo degli Argenti), Pitti Palace, Florence (Italy).

In Florence, in 1575, under the direct patronage of Grand Duke Francesco I de' Medici (1541-1587), son of Cosimo I, the first attempt to imitate the white Chinese porcelain was undertaken. Known under the name of "Medici Porcelain," the pieces were made with the "soft-paste" technique, akin to that of majolica, and were painted with cobalt blue and manganese-purple enamels. They were elegant, pure white items whose decoration was inspired by Chinese pieces but whose forms and shapes were of European origin. They were never marketed but used only as diplomatic gifts. The attempt was unfortunately short-lived: the high firing temperature exceeded the 16th-century European technologies, and the overall effort was too expensive. The production ceased in 1587 with the death of the grand duke. Of more than 900 pieces produced, only 60-65 are known to have survived.

Two pieces of the so-called "Medici porcelain" which, technically speaking, wasn't porcelain. Both are preserved at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, UK.

LEFT: Bottle, soft-paste "Medici porcelain" painted with cobalt-blue and manganese-purple enamels, made in Florence in ca. 1575-1587. Dimensions: height 17.4 cm, diameter 10.2 cm.

RIGHT: Cruet (bottle for oil and vinegar according to the Italian use), soft-paste "Medici porcelain" painted with cobalt-blue, made in Florence in ca. 1575-1587. Dimensions: height 15.2 cm, diameter 8.9 cm.

Irene Bowen Backus, in her dissertation Asia Materialized: Perceptions of China in Renaissance Florence, writes that «in contrast to most countries in Europe, imported porcelain was actually used in Italy, rather than becoming static objects of display.» (see Bibliography). The House of Medici prized Chinese porcelain not just as a luxury status symbol, but also for its qualities: it was perceived as a pure and healthy material, that could be easily cleaned and did not take on the smell or taste of what it contained. Its use as tableware not only showed the power and prestige of its users but also helped them to decrease the risks of infections and diseases in a time when even the princes could easily die. (The first wife of Cosimo I and two of his sons died of malaria, and probably the second Grand Duke Francesco I and his wife Bianca also died of the same disease).

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?