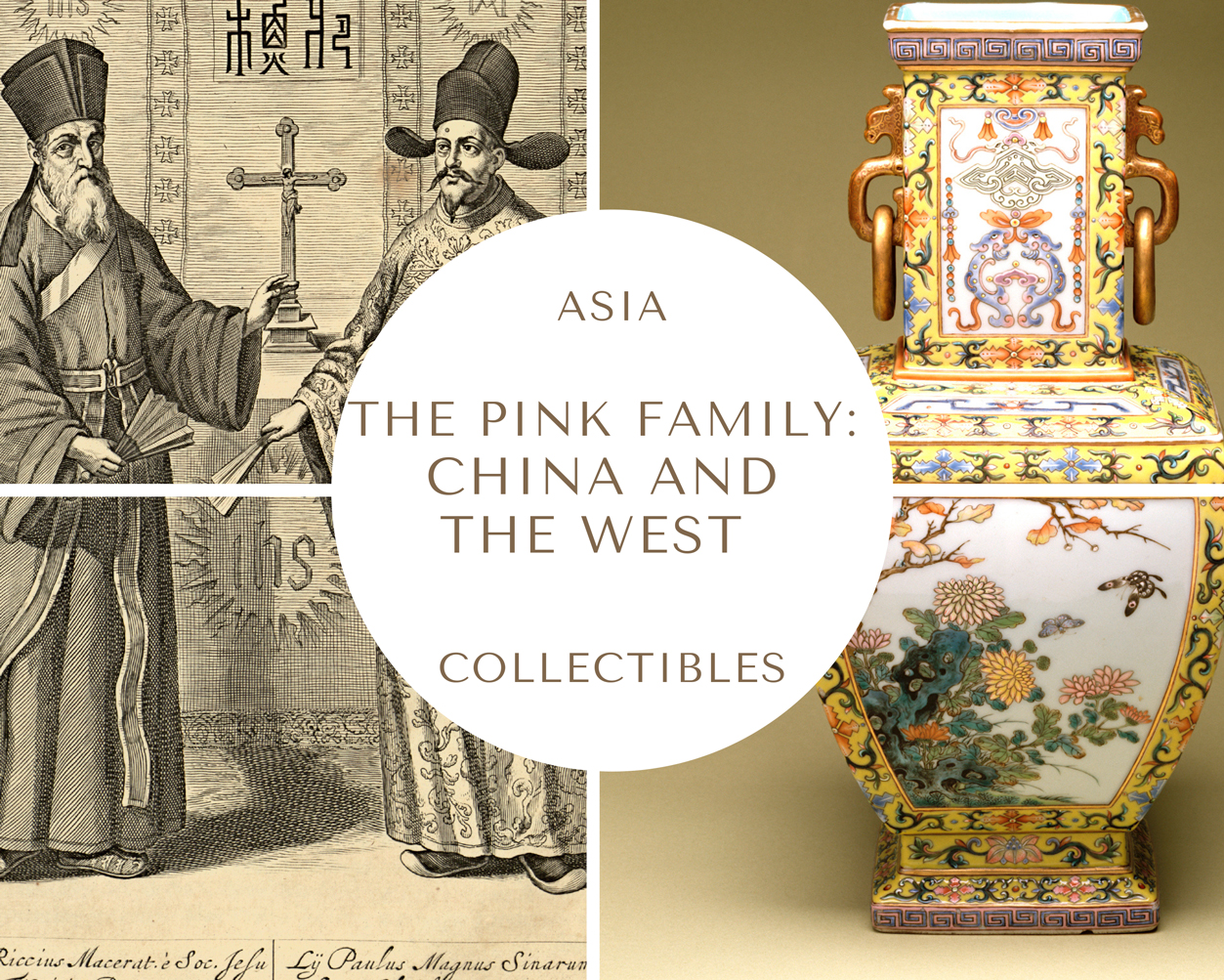

THE PINK FAMILY: CHINA AND THE WEST Intermezzo 1

Current China on the globe.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

LEFT: Portrait of the Yongzheng Emperor in Court Dress, by anonymous court artists, Yongzheng period (1723—35), Qing Dynasty. Hanging scroll, color on silk. The Palace Museum, Beijing. Public Domain.

RIGHT: History of China, Imperial Dynasties, source: Dynasties in Chinese history, Wikipedia.

INTERMEZZO

Intermezzo is an Italian term with many historical meanings. In the Renaissance, it was a theatrical performance with music, dance, and sometimes masques, performed between the acts of a play to celebrate a special occasion. It was a short entr'acte, a short break between two parts of a performance or a stage production.

Our intermezzo does not deal directly with porcelains and does not follow the direction of our journey across Chinese porcelain . It should not be an intermezzo otherwise. It draws a different entry path into Chinese arts and it's crucial to understand the complexity, profoundness, and richness of Chinese culture. Our intermezzo pieces (yep, there will be more than one) will help us to recognize, understand and embrace the cultural differences between the Western and Chinese art worlds.

INTERMEZZO 1

MULTISENSORIAL AND SYNESTHETIC EXPERIENCES IN CHINESE ARTS

I called "Music to see" the videos by the Zide Qin Club, a company of young musicians founded in 2014. Their videos, which attracted the attention of netizens from all over the world, are similar to 'musical' paintings: on a neutral, silky background, reminiscent of ancient scrolls, the musicians in costumes from the Tang, Song, or Ming dynasties, hieratically play the traditional Chinese instruments and caress the king of them all, the guqin. They move inside the painting with ancient restraint, and the listening experience is enhanced, and not at all disturbed, by the visual enjoyment.

This "music to see" is a multisensorial pleasure that can lead someone to experiment with a creative degree of perceptual synesthesia (involuntary experiences in a further sensory dimension). I'm among those people, probably because I'm blessed with a certain type of synesthetic experience (I tend to visualize mathematical or philosophical abstract concepts as shapes projected in a 3D space).

Many traditional Chinese arts are multisensorial experiences that can enrich our cognitive pathways and stimulate our brains. However, some Chinese arts, such as painting, are remarkably different from their Western counterparts, as they are more intrinsically multisensorial. The musicians of the Zide Qin Club bring to light a profound trait of the traditional Chinese culture, which undermines some boundaries that Westerners take for granted or regard as universal. In our intermezzo pieces, we will discover what Chinese painting, music, and dance have in common: movement. Yes, traditional Chinese paintings moved, and they did it surprisingly well.

(All texts are mine, as usual. The quotations are always explicit).

PAINTING MOVEMENTS AND MOVING PAINTINGS

The Western paintings do not move. They are a static form of art even if they depict actions or movements in progress: the latter are instantified, frozen in an instant of time, and delivered to eternity.

Look at the following painting by the Venetian artist Jacopo Tintoretto (1518 –1594), one of the most theatrical, dynamic, and tense representations in the whole history of western art.

Jacopo Robusti, aka Il Tintoretto, Il Miracolo di san Marco che libera lo schiavo (The Miracle of the Slave or The Miracle of St. Mark), telero, oil on canvas, 1548. Dimensions: 5,41 m x 4,15 m. Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice (Italy).

Tintoretto is commissioned to paint a canvas depicting the Miracle of St. Mark, patron saint of Venice: a slave, caught by his master venerating the saint's relics, is condemned to be blinded and to have his limbs broken by mace blows. The saint, however, intervenes and saves him by rendering the instruments of martyrdom useless. Tintoretto does not paint a miracle: he stages a theatrical play (Jean-Paul Sartre defined him as a director ante litteram). The perspective converges toward the center, and the horizon line is high to give the viewer the illusion of observing the scene from a stage. There are four main characters: the slave is in the center, completely naked, and in bright light. Standing to his right is the executioner, who shows the broken instruments to his master, the bearded man. Saint Mark is in shadow, upside down, and visible only to the viewer (namely to you), not to the characters in the scene. The onlookers are dynamically portrayed: those on the left lean out, those on the right retract, and their movements draw diagonal lines that converge toward the center of the scene (the hand of Saint Mark). The abrupt twists of the bodies, the saint's top-down movement, and his gesture, as well as the executioner's bottom-top gesture, all create dramatic tension, accentuated by the intense use of light that vibrates along diagonal lines. The color in the close-ups is intense, almost violent, to give enhanced volume to the bodies; in the background, it's softer and cooler to give depth to the scenic space, following the tonalism of the Venetian school. The color scheme recalls that of Titian, while the anatomical twists of the bodies recall Michelangelo and Giulio Romano. The emotive use of light, however, foreshadows the dramatic contrasts that would be typical a century later of another Italian genius, Caravaggio.

The scene by Tintoretto is frozen and the action is suspended in eternity. A famous painting from 1912, almost 4 centuries later, will try to represent an action in rapid motion, avoiding the freezing effect: it's a well-known oil on canvas by the Italian Futurist painter Giacomo Balla.

Giacomo Balla, Dinamismo di un cane al guinzaglio (Dynamism of a Dog on a Leash), oil on canvas, 1912. Dimensions: 89.8 cm × 109.8 cm (35.4 in × 43.2 in). Albright–Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, US.

In this chronophotography-inspired work, the walking pace of the woman, the trotting of the black and tan dachshund, the sway of the leash and tail, and even the flopping of its ears are rendered through spatial simultaneity: both movement and time are decomposed in a set of successive phases and instants, unified in the spatial dimension.

Both Italian paintings rely on the work of the viewer's brain, which reconstructs the overall scene and gives birth to a complex action in the case of Tintoretto and to the physical motion of two subjects in the case of Balla. However, this dynamism is extrinsic, not intrinsic to the paintings. Chinese paintings, instead, are intrinsically dynamic, but before digging deep into them, let's see another difference between Western and Chinese paintings.

Let's look at another Italian masterpiece, the Lamentation of Christ, aka the Dead Christ, painted in 1480 by the Italian Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna (ca. 1431–1506). Look at it. Mantegna puts you - the viewer - in a lower position, at the same level, or in a higher position than the corpse of Christ?

Andrea Mantegna, Cristo Morto, ca. 1480, tempera on canvas. Dimensions: 68 cm × 81 cm (27 in × 32 in.) Pinacoteca di Brera, Milan, Italy.

The scene is painted with absolute mastery of perspective and in such a way as to put you, the viewer, in a slightly elevated, frontal, and close position in relation to Christ. The painter forces you to look down, just like he did.

In the following oil on canvas, painted by the Italian artist Giovanni Segantini (1858–1899), you, the viewer, are put by the painter in a very different position: you are forced to observe the scene from the bottom up. You must look up.

Giovanni Segantini, A messa prima, 1884-1886, oil on canvas. Dimensions: 108 x 211 cm (42.5 x 83 in.). Kunstmuseum St. Gallen, Switzerland.

All perspective representations in Western art define a "viewpoint" through the complex system of spatial relationships among the elements. This viewpoint specifies the spot from which the artist looked at the scene and painted it, and, at the same time, it determines the fixed position from which you, as a viewer, have to look at the scene. Segantini paints the staircase and the elderly priest on it with a specific framing that defines the point of view you must assume, like it or not. Segantini and Tintoretto are in control of what you may see.

Different from this viewpoint is the position of the onlooker, namely your position as a real person looking at a painting in a museum or on a screen: you can obviously move closer or farther away, look at it obliquely, with one eye, or even upside down (if you're not suffering from back pain). In other words, the viewpoint constructed by a representation following the rules of the linear perspective and the onlooker position are completely different.

Onlookers at the Delaware Art Museum, US. Photo by Jeffrey. Licensed under Attribution-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Now, look at this painting by Cezanne, and try to define your position as a viewer.

Paul Cézanne (1839 - 1906), Still Life with Apples, 1893–1894. Oil on canvas. Dimensions: 65.4 × 81.6 cm (25 3/4 × 32 1/8 in.). The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, US.

It's difficult, isn't it? The apple plate is painted in such a way as to put you in an elevated position: you see it from above. However, the blue ceramic vessel and the bottle are presented almost front-on. Look at them together: the incongruity causes perceptive disorientation. Now, look at the mustard pot at the fore: it is seen from above and appears dangerously unstable because it does not seem to stand on any flat surface; the tablecloth, indeed, seems to run vertically. Here, Cezanne breaks with the linear perspective and paints a scene that entails more than a single, fixed viewer's viewpoint. This 'revolution' is completed and radicalized by Picasso, Braque, and other Cubists by painting objects from multiple, simultaneous perspectives: any viewer is then given multiple viewpoints. Look at one of the famous paintings of the "Weeping Woman" series: do you see her face in front or in profile? Or perhaps you see her from both perspectives simultaneously?

Pablo Picasso, Weeping woman, 1937, oil on canvas. Dimensions: 55.2 × 46.2 cm. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, AU. © Succession Picasso.

Many contemporary paintings reject the use of linear perspective to adopt a different approach, more dynamic and more in line with the complexity of reality and the way we approach it. That's the 'lesson' of Cubism.

As the French art historian Daniel Arasse wrote, linear «perspective is a completely arbitrary system of representation, which was invented not by a single individual but by an entire society over the course of a century». That society was Florence at the pinnacle of its cultural and political power, under the rule of the House of Medici. «In Renaissance Florence, linear perspective was celebrated as the objective mean to represent space convincingly», as Anthony A. Derksen pointed out (in Linear Perspective as a Realist Constraint, in "The Journal of Philosophy", 102, no. 5, 2005) but it was only the perfect tool to create a rational space, designed to be human-oriented, livable, fully understandable and controllable. Still in the 1950s, some scholars, like the Belgian artist and theorist Maurice Henri Pirenne, thought that linear perspective was «the only natural system of perspective» that «corresponds to the way we actually see the world around us». However, in the last 50 years, many studies in multiple disciplines, from the history of art to neurophysiology of vision, have shown firstly that from Renaissance onwards, «artists have used many projective techniques to depict visual experience, and only relatively rarely have they strictly applied the laws of linear perspective» (an example? Canaletto) and secondly, that our visual space is hyperbolic, namely curved, «and this led to further proposals about the advantages of depicting three-dimensional space in hyperbolic geometry rather than projective geometry as it approximates more closely to visual experience» (Robert Pepperell & Manuela Braunagel, Do Artists Use Linear Perspective to Depict Visual Space?, in "Perception", August 2014).

Linear perspective is a mathematically based system of creating an illusion of depth on a flat surface, developed by Italian Renaissance artists. It's an 'invention', a cultural construct, not the natural way of seeing things, all the more so as its monofocal fixity is not 'natural' at all. Linear perspective is only a way, among others, to depict the visual world and in the history of world art, three-dimensional objects have been rendered on a two-dimensional surface via multiple means.

Renaissance perspective was not part of the technical background of ancient Chinese painting. This does not mean that Chinese lacked mathematical knowledge or that Chinese artists did not know how to create three-dimensional effects in their works. They did it perfectly, of course, by adopting different means which, unlike what happens with linear perspective, do not entail nor impose a fixed viewpoint on the viewer. Chinese painters were free to change viewpoint inside a single work. Their multi perspective paintings were not perceptively baffling as they knew how to integrate all the different viewpoints into a harmonious movement that adds up to another movement arising from the traditional painting support. But let's take one step at a time.

TIME AND MOVEMENT AS INTRINSIC FEATURES OF CHINESE TRADITIONAL PAINTING

This is a refined ancient painting entitled Finches and bamboo, created by Emperor Huizong (1082–1135) of the Northern Song dynasty.

Emperor Huizong, Finches and bamboo, ink and color on silk in Gongbi style; early 12th century. Dimensions of the image: 13 1/4 x 21 13/16 inches - 33.7 x 55.4 cm; overall with mounting: 13 3/4 in. x 27 ft. 6 5/16 in. (34.9 x 839 cm). The MET, New York, US.

«Huizong was the eighth emperor of the Song dynasty and the most artistically accomplished of his imperial line. Finches and Bamboo exemplifies the realistic style of flower-and-bird painting practiced at Huizong’s academy. Whether making a study from nature or illustrating a line of poetry, however, the emperor valued capturing the spirit of a subject over literal representation. Here the minutely observed finches are imbued with the vitality of their living counterparts» (Maxwell K. Hearns, MET curator). «Beyond their lively poses and naturalistic plumages, these finches are animated by the addition of dots of lacquer to their eyes, imparting a luster and three-dimensionality that paint alone cannot convey» (Maxwell K. Hearns, How to read Chinese Paintings, see Bibliography).

This work belongs to a Chinese painting genre called hua niao hua (花鳥畫), 'bird-and-flower painting', developed in the Tang dynasty era (618-907).

The hua niao hua works dealt with flowers, birds, fish, insects, and pets, and were inspired by nature; however, they were not meant to realistically portray nature even when they did it. In Chinese traditional culture, birds and flowers have symbolic meanings, enhanced or modified by each specific composition. Thus all bird-and-flower works, even those showing the most realistic details, are rich in metaphoric and allegorical overtones. They were divided into two main trends: the Gong Bi, which embraced artworks realized with careful application of color and meticulous technique to express a feeling of beauty and harmony, and Xie Yi, more expressionistic and impulsive, aimed at conveying a deeper spiritual or emotional meaning.

The hua niao hua works, therefore, are not portraits of living nature as they try to convey "the breath of life", and they do not need the application of linear perspectives like an Italian 16th-century basket of fruits or a Flemish 17th-century vase of flowers on a table.

I know what are you thinking. Where's the movement?

Let's see another famous work: a stunning landscape painted by Zhao Mengfu, a literatus, namely a scholar-official, descendant of the first Song Emperor. He lived during the Yuan Dynasty, serviced the Mongol rulers, and was a brilliant calligrapher, a poet, and a superb amateur painter (not a professional craftsman or a court artisan).

Zhao Mengfu, Twin Pines, Level Distance, ca. 1310, ink on paper. Dimensions: image 10 9/16 x 42 5/16 in. (26.8 x 107.5 cm); overall with mounting: 10 15/16 x 25 ft. 7 11/16 in. (27.8 x 781.5 cm). The MET, New York, US.

«Zhao Mengfu (...) rejects illusionistic representation and relies instead on expressive brush lines to imbue his imagery with personal meaning. Zhao underscores his commitment to this new approach by adding a title to the right of his pines and writing a long inscription on top of the distant mountains at the left side of the composition, making it clear that his painting is not merely about landscape scenery.

Despite his adherence to this new style, Zhao chooses a traditionally significant subject. In Chinese art, pine trees have long been emblems of survival. By representing them here, Zhao may be referring to his own political survival under the Mongol occupation, as well as to the endurance of Chinese culture under foreign rule» (MET curators). «Zhao intentionally added his inscription directly on top of his rendering of distant mountains to emphasize that his painting was not about creating an illusion of reality. By inserting writing into the picture space, Zhao forces the viewer to "read" his painting as a set of calligraphic brushstrokes on a flat surface» (Maxwell K. Hearns, How to read Chinese Paintings, cit.).

Where's the movement?

Let's set aside this question for a moment.

Look again at the painting by Zhao Mengfu and read the note written by the MET curators. This landscape is neither a real landscape nor an imagined one. The ink drawing doesn't describe nature as it appeared to Zhao's eyes. This landscape is painted in total spontaneity (the ink does not allow second thoughts or corrections) to bring to light the intimate, inner landscape of Zhao Mengfu in a passing moment of his life. This painting is similar to a poem: it's an invitation to a journey through the poet's inner world. (From the Yuan Dynasty onwards, poems were often calligraphed on a painting: painting, poetry, and calligraphy, "the three Perfections", were interlinked, almost intermingled ways to convey the artist's inner life). Zhao sought to capture that enigmatic, quintessential rhythm of nature with which his soul resonated and was, therefore, his own. His landscape is neither a panoramic view of a beautiful natural scenario nor a representation charged to accurately depict the author's visual experience. It's a private invitation to enter a landscape of the spirit, an invitation that cannot be addressed to everyone.

Zhao Mengfu and Chinese literati artists who shared his view on the noble function of painting, had no need to invent a tool similar to the linear perspective, perfect to create the illusion of a rational and orderly world on a human scale. In Zhao's landscape, the tridimensional space is rendered via other techniques: overlapping (at the fore, on the right side of the painting), diminishing scale (the largest trees appear closest and the smallest appears further away), aerial or atmospheric perspective (close objects have greater detail and value contrast).

The painting shows the traditional formula of a tripartite “hills beyond a river” plan, elaborated by Northern School old masters like Li Cheng and Guo Xi (both of which lived during the Song dynasty): «trees and rocks occupying the shore in the foreground, a river creating the sense of spatial recession in the mid-ground, and misty distant mountains in the far background» (Zhi Zhang, Call of the Distant Mountains, Apollon, December 2021). «The "level-distance" composition (pingyuan), a view across a broad lowland expanse, is one of the three traditional ways in which Chinese artists conceptualized landscape. The other two are "high distance" (gaoyuan), a view of towering mountains, and "deep distance" (sheyuan), a view past tall mountains into the distance» (Maxwell K. Hearns, How to read Chinese Paintings, cit.).

Did you notice the fisherman in a boat? This conventional presence in Zhao Mengfu's works is painted amidst the watery nothingness in the mid-ground: he is the only human being, and appears as an isolated and irrelevant presence, drawn so small to be scarcely noticeable.

Zhao Mengfu's landscape is technically water-based ink on paper, just like his calligraphic works. The bird-and-flower painting by Emperor Huizong is ink and color pigments on silk, like many court painters' works.

Chinese traditional artworks are painted on paper or silk, never on canvas or wooden panels, and most of them were handscrolls, preserved rolled up. This feature says that they were not painted to be displayed on a wall and seen by all passers-by. It's a crucial point.

Not all ancient paintings were handscrolls; other supports were hanging scrolls, album leaves, walls, lacquerware, folding screens, fans, and of course, porcelain pieces, as we will see in the following chapters. However, the handscrolls were the most common support for traditional landscape painting (shan shui, 山水), the highest form of Chinese painting and also the largest: some ancient landscape handscrolls are over 50 cm high and several meters long. (A handscroll by Xu Yang, a court painter of the Qianlong Emperor in the 1750s, sold at a 2021 auction for approx. 65 million dollars, is 61 feet long - 18,59 meters). The longest handscrolls were made up of several sections of paper or silk, joined together and supported by a stiff paper backing.

«The hanging scroll is meant to be hung on the wall and viewed all at once and can remain on display for extended periods, simply as decoration, or as a seasonal and auspicious exhibit. The handscroll, by contrast, is opened, unrolled, only when someone means to view it and is rolled up again afterward, much as a book is opened, read, and closed.» (Xang Xing et al., Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting, see Bibliography).

How do you think you might see a Chinese handscroll painting?

You must slowly unroll it, starting from the right side and looking at the first portion of the painting, immediately after the right end. The portion you have to unroll has approximately your shoulders' width (± 60 cm). The direction and the movement are from right to left, just the opposite of the direction all Westerners are accustomed to. The pace is entirely yours: you are free to wander throughout the panted universe, observing all the tiny details or not, as you like it, before unrolling the next portion.

In the following video, released by the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, you can see Wang Yan Jing, Beijing Palace Museum conservator, unrolling an ancient landscape painting. She does it rather quickly (the video is a simple demonstration), but everyone can proceed at their own pace, with no restraints.

The experience of looking at this type of painting is different from that of the typical onlooker in a museum of Western art.

First of all, it's an intimate experience, not a collective, public one. As many scholars have already highlighted, the handscroll format allows only a couple of people to look at the painting at once, but only one can control the unrolling movement and its pace.

Secondly, the landscape painted on a handscroll longer than ± 60 cm cannot be seen all at once: it needs to be gradually discovered, and this discovery takes time, a subjective time that can be expanded or reduced at will but never reset to zero. Thus, a scroll wide open under the glass case of a museum, even in the best environmental conditions, has nothing to do with the real viewing experience for which it was created.

Many Chinese painters not only have fully recognized the intrinsic potential of this format but have also succeeded in exploiting it, thus turning the discovery movement into a complex journey.

Some handscroll paintings start depicting a landscape in spring and end with a landscape in spring one year after, after staging the natural changes induced by summer, fall, and winter. There are landscapes where you can see a fishing vessel at the beginning of its navigation, follow it halfway along a river, and finally catch a glimpse of it as it pulls up to a dock to unload its catch. You can also observe a group of wayfarers making their way along an uphill path, disappearing behind a hairpin bend to reappear further along a flat road. Like in a movie, a story unfolds as the handscroll is progressively unrolled. Many paintings, especially the longest ones, show multiple parallel stories.

Chinese Landscape Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of New York. Asian Art curator Joseph Scheier-Dolberg leads a guided tour through the paintings of the Streams and Mountains without End exhibition (2017-19).

Now it is time to go on a long journey. Your journey.

I have chosen for you one of the most renowned artworks of the Chinese history of painting: Along the River During the Qingming Festival (Qingming Shang he tu, 清明上河图, aka Riverside Scene at the Qingming Festival), a silk handscroll sized 25.5 cm × 525 cm (10.0 × 207 inches) attributed to Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145), painted during the late Northern Song dynasty era, and now preserved at the Palace Museum in Beijing. It's a rural and city landscape depicting the pulsating life of the densely populated capital of the Northern Song dynasty, Bianjing (now Kaifeng, in Henan Province), overlooking the banks of the river Bianhe.

According to the statistics collected by scholars, this painting depicts 815 people, including 20 women (mostly at home), «95 animals, 255 trees, 114 buildings, 300 tables and chairs, 35 bamboos, 24 boats, 38 umbrellas, 30 pergolas, 8 sedan chairs, 6 bridges, and 16 wooden carts». (Huang Kunfeng, An Illustrated Guide to 50 Masterpieces, see Bibliography). The painting is rich in characters: sellers and shops of all kinds, people cooking, serving, and eating in multiple taverns, workers repairing the wheel of a cart or loading cargoes onto a boat, tax office workers, peddlers, jugglers, actors, paupers begging, Buddhist monks, nobles and servants, fortune tellers and seers, doctors, innkeepers, teachers, millers, metalworkers, carpenters, masons, official scholars, kids playing, and people drinking cha in several teahouses; there's even a camel caravan entering the city gate. The painting is rich in vibrant stories. Pay attention to what's happening under the central 'rainbow' bridge: the crew of a big boat is struggling to regain control of the ship, pushed by the current on a dangerous collision course. Many passers-by on the bridge and along the bank are shouting and gesturing toward the boatmen.

We do not know who and why this painting was commissioned to Zhang Zeduan, who certainly painted it without the expressive, intimate intent of Zhao Mengfu. This artwork has a more representational aim, and probably it had a celebratory purpose, but is not a realistic copy: it's a masterpiece that combines technical mastery with the ability to imagine and develop a framing sequence able to guide the viewer through a reconstructed, idealized city. Zhang Zeduan takes his viewer by the hand on a walk along the river bank and turns him into a privileged person amid the busy crowd.

To start your journey, please go to this Wikimedia Commons page. Do not download the handscroll, but enlarge it to fit your screen. Use the virtual lens on the painting and then the plus and minus buttons on your keyboard. Start from the right margin and 'unroll' the work at your pace.

This has to be the starting point of your journey; make sure that the size of the scroll perfectly fits the screen of your device and move from right to left.

In the first scene, set in the rural area before entering the city, you can see a woodsman leading his donkeys along the river, just before a small wooden bridge, carrying the fuel to be sold in the city market. In front of the country house on the left, some children are playing.

Along the River During the Qingming Festival, a silk handscroll painted by Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145) during the Northern Song dynasty. Dimensions: 25.5 cm × 525 cm (10.0 × 207 inches). Preserved at the Palace Museum in Beijing.

This masterpiece makes up a narrative form in its own right. You will not be surprised to find that it has been animated and transformed into a virtual journey using new technologies.

The following 30-minute lecture on this painting, held by prof. Andrew R. Wilson, the John A. van Beuren Chair of Asia-Pacific Studies at the U.S. Naval War College, is worth the effort. After it, we will resume the major theme of our 'journey'.

Now let's resume the major theme of our 'journey'.

While the Western painting is like the frame of a movie that the viewer has to complete using their imagination, the Chinese landscape, painted on a long handscroll, is an entire movie. Its discovery - your journey - is a complex movement in space-time that unfolds from the interaction of different factors. The painted universe on the handscroll emerges from a relation of resonance between the external world and the artist's inner world and is shaped by the painter's dialogue with the artists of the past. The painter guides his viewers along an intimate, poetic journey, leaving them the freedom to wander and explore some details at will. (However, many skilled Chinese painters were able to manipulate their viewers, encouraging them to look more quickly in some sections or to linger over details in others).

GRAPHIC PROJECTIONS AND VIEWPOINTS

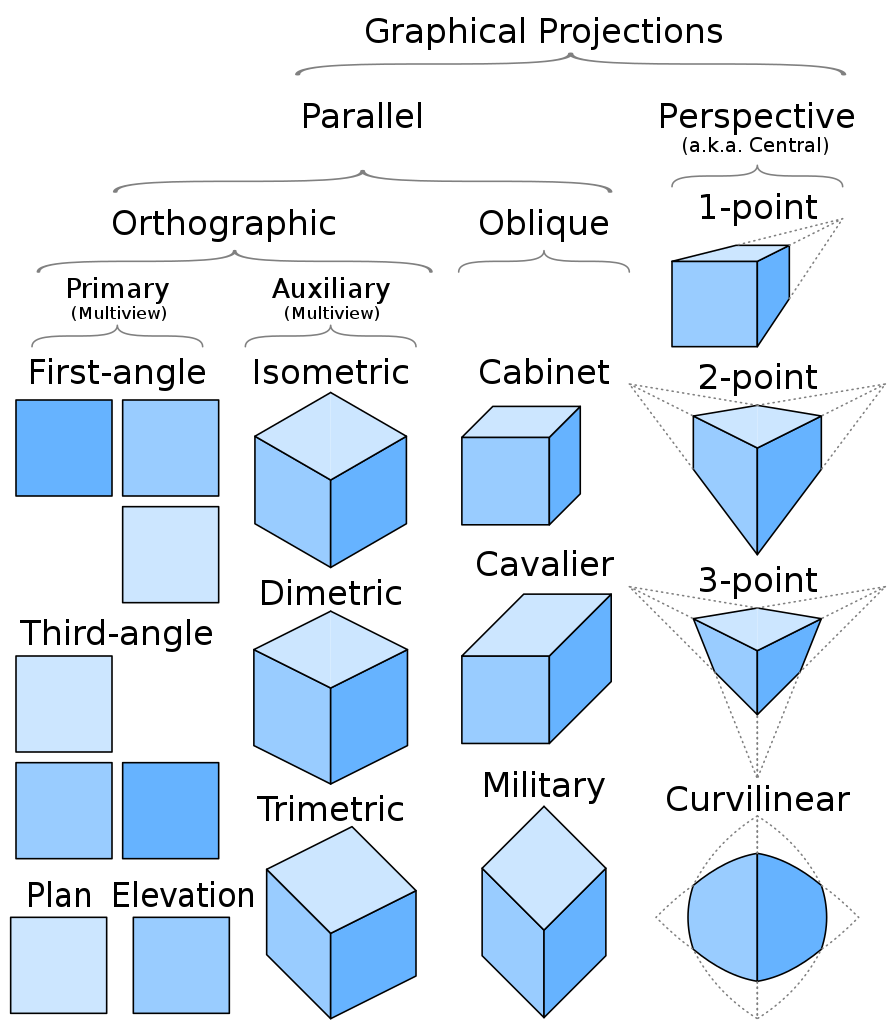

The discovery movement - your journey - is controlled and manipulated by the painter through a peculiar organization of the pictorial space. The use of different design techniques to display a three-dimensional object on a two-dimensional surface is another significant difference between traditional Chinese and Western imagery. Chinese landscape painting achieved tridimensionality by using different means, and in the depiction of architectural or manmade objects (such as buildings, pavilions, temples, towers, city gates and walls, bridges, roads, pieces of furniture, boats, palanquins, and wheeled vehicles) they used a technique called dengjiao toushi (‘equal-angle see-through’). We call 'parallel projection' the Chinese method, different from perspective projection: in the linear perspective, lines parallel or equidistant in nature (like the sides of a road or the walls of a room) are convergent on the picture plane. In Chinese cityscape painting, the artists draw all of the lines that are parallel or equidistant in the object as parallel or equidistant in the painting as well. Therefore, there's no vanishing point.

Look at the pavement design in the following 15th-century Italian painting:

Anonymous, Architectural Veduta (Berlin), oil on poplar panel, 15th century. Dimensions: 131 × 233 cm. Gemäldegalerie, Berlin, Germany.

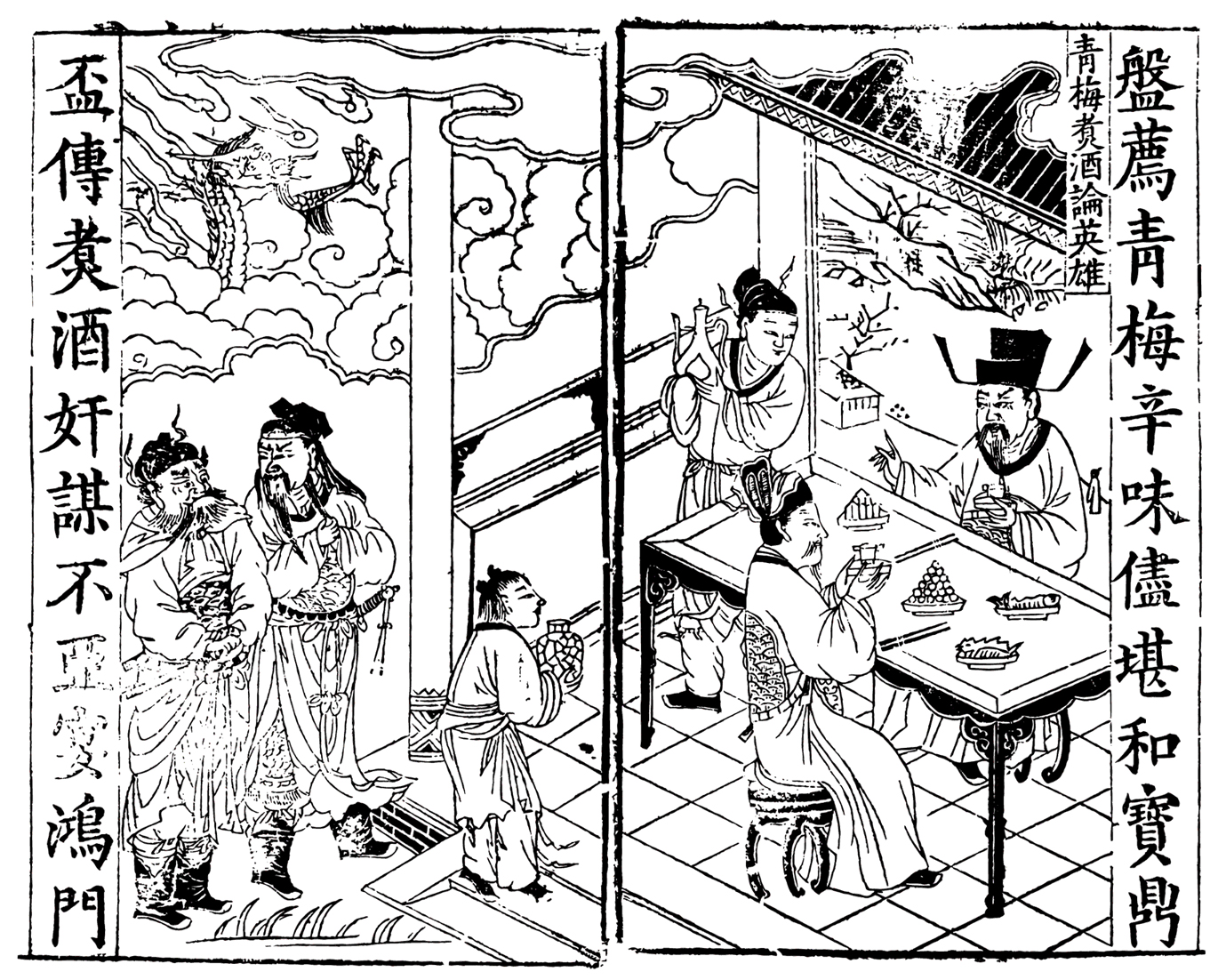

And now, look at the floor design in this Chinese drawing:

Print from a Ming Dynasty edition of the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, a 14th-century historical novel attributed to Luo Guanzhong.

The difference between the 'perspective projection' and the Chinese 'parallel projection' is clear: in the latter, the lines of sight are all parallel. Technically, the Chinese method is a kind of parallel projection called 'cavalier oblique axonometry': oblique, as the parallel projection rays are not perpendicular to the viewing plane, and cavalier, as it shows lines of projection at a 45° angle to the plane of projection.

Diagram showing relationships between some types of 3D to 2D projections by CMG Lee.

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International.

The use of a projection system different from the linear perspective allowed the Chinese painters to realize multiple viewpoints in every scene, with no hierarchical order other than the viewer's will. This continually shifting viewpoint is an inevitable choice: a single, fixed viewpoint along a painting of several meters would be untenable.

Let's look at the central scene of Along the River During the Qingming Festival painting.

Look at the tables inside the tavern in the right forefront: are they painted with linear or parallel projection technique? There isn't really a vanishing point and the lines never converge. There's no horizon line as well.

And tell me: do you see shadows or any indication of a consistent light source like in the Architectural Veduta above? No, of course.

In this scene, as in all of the others, the buildings are painted as seen from above (you perfectly see their roofs), but look at the porters and all the characters in the left foreground: you can see their faces, not the top of their heads, and you can clearly see the horse's ass as well, so there's a viewpoint shift here You can see the underside of the rainbow bridge and, at the same time, the small shops on top of it: another viewpoint shift. You see both the face of the worried boatmen and the expressions of the curious passersby on top of the bridge: another shift. And so on... To explore this cityscape, you're not given a fixed vantage point: your eyes are given many, and if at first, everything seems a bit confusing, at a second glance, you find the right key to open many of the painted stories. At least, all those you want to open. Moreover, you can see over walls, under arches, or into private spaces, you can observe the scene as if you were a bird and the rich, bum friend of a passerby at the same time. It's magic, in a sense.

Shen Kuo (沈括, 1031-1095), a Chinese polymath, scientist, and minister who lived under the Song Dynasty, wrote: «Landscapes should be seen from the angle of totality to grasp the whole.»

«The Chinese concept of perspective, unlike the scientific view of the West, is an idealistic or suprarealistic approach, so that one can depict more than can be seen with the naked eye. The composition is in a ladder of planes, or two-dimensional or flat perspective.» (Kwo Da-Wei, Chinese brushwork in calligraphy and painting, Dover Publications, New York,1990, p.70)

A final reflection before moving forward. The way we construct and organize the pictorial space is a relevant aspect of our culture: it says the way we see ourselves, our mutual relationships, and our being in the world.

The Renaissance linear perspective of Flippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) and Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472) is a rational representation of space and simultaneously the affirmation of the centrality of the man, whose intellect has the power to order, measure, know and dominate the surrounding world. Linear perspective is an expressive code born from the same Tuscan womb that a century later would give birth to Galileo Galilei and modern science, and would see the triumph of the human capacity not just to read but also to fully decipher «this grand book that continually stands open before our eyes (I say the universe) ... written in mathematical language.» (My translation from a famous quote of G. Galilei, Il Saggiatore, 1623).

The Chinese parallel, oblique, cavalier projection emerged in a culture imbued with Daoism, whose perspective is just the opposite of an anthropocentric vision. Man is not the measure of all things. Man is a crucial but minuscule component of the natural world and is advised to follow the flow of nature’s rhythms and live in harmony with them. The idea of nature as an object to be dominated is alien to Chinese traditional philosophies. That between man and nature in shan shui (mountain and water) painting is a poetic relationship and sometimes a transient experience of spiritual fusion. Zong Baihua (1897-1986), poet, writer, and philosophy professor at Beijing University, wrote that Chinese spatial awareness is creative and poetic, based on the abstract expression of calligraphy instead of geometric and scientific perspective.

THE ART OF THE PERFECT MOVEMENT

Chinese landscape painting on long handscrolls was a form of narrative art: it was the visual art of time and movement. There's another form of art sharing the same nature and intrinsic features: dance, or better to say, Chinese classical dance, and dance drama.

Chinese classical dance is a unique, independent dance system, different from Western ballet, and based on Chinese traditional culture inheritance and development. This system, whose roots date back to the 2nd millennium BC, is still vital today and mixes traditional aesthetics, expressivity, and forms (unique movements and postures) with contemporary innovations.

The Chinese dance drama is an independent art form that emerged in the early 1930s, whose elements can be traced back to the Western Zhou Dynasty (1066-771 BC). It's a stage art based on dance and the fusion of drama, poetry, and music.

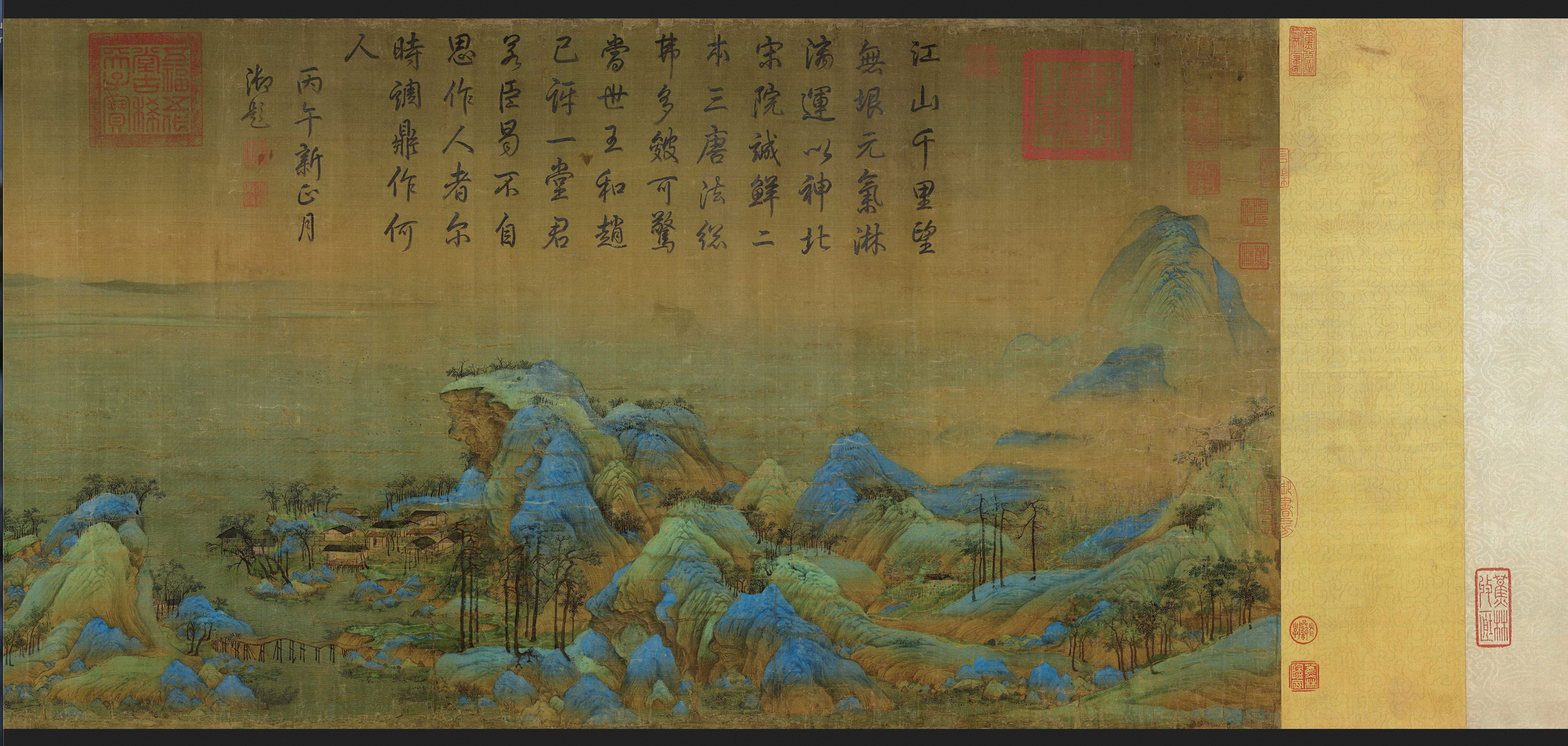

For our first synesthetic journey, I've chosen another celebrated masterpiece of the Northern Song Dynasty era: A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains (千里江山圖), a handscroll by Wang Ximeng (王希孟), painted with ink and color on a handscroll with impressive dimensions: 51.5 x 1191.5 cm (20.27 in x 39.09 ft). It's a shan shui (mountain and water) work, painted in 1113 by a very young artist at the court of the Song Emperor Huizong: Wang Ximeng was only 18 years old at the time. Unfortunately, he died five years later, and this masterpiece is his only surviving artwork.

The young painter entered the Academy of Painting when still a child and soon became a protégé of the Emperor, who was a talented artist but an incompetent ruler. The handscroll was likely commissioned by the Emperor (or painted according to his wish) as a celebration of the majestic scenery of the Emperor's territory and a tribute to his Empire's prosperity.

The scenes are full of bridges, buildings (entire villages, altars, huts, pavilions, temples and monasteries nestled among the peaks, scattered courtyards, and even a watermill), vessels (from a small pedal boat to large fishing trawlers), and figures. The painting is so rich in tiny details to look slightly bewildering at first sight. But it's not. The landscape has a precise three-level structure (deploying pingyuan, level distance, gaoyuan, high distance, and shenyuan, deep distance), it can be divided into six sections from right to left, and shows a sort of plan to guide the viewer along a path, rich in steep ascents and level tracts. Some scholars read the painting as a ritual journey or a story of Daoist self-cultivation. According to Yurong Ma, professor at the Faculty of Innovation and Design at the City University of Macau (China), the painting «is like a complete symphony, which can be divided into six parts: section, prelude, rise, development, climax, fall, and end.» (See Bibliography). For others, it is a poetic journey that conveys the three essential aspects of painting according to Emperor Huizong: the careful study of nature to capture its hidden rhythm and spirit, the systematical study of the painting of the past, and the attainment of a "poetic idea" or shiyi.

This landscape, therefore, though inspired by real places, like the Poyang Lake area (Jiangxi province) with its swamps and wetlands and the Lu Mountains with their waterfalls, is an ideal, imaginary, poetic one.

The link with the classical painting tradition is provided by the blue-and-green landscape (qinglu shan shui) technique, developed during the Tang Dynasty (618-907). In the painting, the artist used ink and intense colors: bright blues and greens on a dark ochre background, with white spots here and there. The malachite green and the azurite blue were precious pigments at the time and those used by Wang Ximeng had to be of extraordinary quality if, after more than 900 years, they are still bright and vivid (while the silk has darkened as expected).

«A variety of dry brush techniques — particularly the so-called ax-cut texture stroke and the hemp fiber texture stroke — are used to depict the rough surfaces of rocks and mountains and build up credible, three-dimensional forms». (Peter Zhang, A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, Shanghai Daily, 2017). Some details are rapidly sketched (the flying birds, for example), while others are so accurately rendered to impressively stand out: look at the water waves, drawn line by line with a different pattern if at the fore or in the middle ground.

To start your journey, go to this Wikimedia Commons page, click on the painting, enlarge it, and modify it till it fits your screen. Then go to the right end, and start 'unrolling' the scroll at your pace, enlarging the areas where you'd like to roam like a Chinese wayfarer of other times or a space-time traveler searching for a 'paradise lost.

This has to be the starting point of your journey; always move to the left.

Wang Ximeng (1096-1119), A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains, ink and color on silk, handscroll by. Preserved at the Palace Museum, Beijing, China.

As to the title, the Chinese word li is a unit of measure equal to about 0.5 km, but the expression qianli, 'a thousand li', was used to describe an extraordinary length. The handscroll shows a poem written by Emperor Qianlong (Qing Dynasty) at the beginning and postscripts on the author by different authors at the end (Caijing from Song Dynasty and Monk Fuguang from the Yuan Dynasty for example).

In China, the masterpiece by Wang Ximeng, widely acknowledged as a 'national treasure' and one of the most important works in the history of Chinese fine art, inspired the creation of a complex 2-hour-long drama that in 2020 was presented to the public under the title Poetic Dance: The Journey of a Legendary Landscape Painting. Choreographed by Zhou Liya and Han Zhen, supported by a team of expert historical advisors, and performed by the Beijing-based dance company "China Oriental Performing Arts Group", this music & dance drama succeeded in capturing the hidden rhythm and the deep spirit of the painting, perfectly transposed into a different form of art. It doesn't tell the story of Wang Ximeng. And it does not meet usual expectations. «Unlike our other works, which usually tell stories, this dance work is not a narrative. It's abstract and, like traditional Chinese paintings, leaves audiences enough space to imagine by themselves», said Zhou Liya to a journalist.

Poetic Dance: The Journey of a Legendary Landscape Painting is divided into seven 'chapters' - Scroll Unfolding, Seal Script Asking, Silk Reeling, Minerals Exploring, Brush Making, Ink Grinding, and Painting Alive. The next scene is from the last part, Painting alive, and deals with the creative climax of Wang Ximeng. Costumes are from the Song Dynasty Era, of course.

Poetic Dance: The Journey of a Legendary Landscape Painting

Music: Lyu Linag

Choreography: Zhou Liya, Han Zhen, and others

Costume: Yang Donglin

Design: Jia Lei

Performed by the Dance Company "China Oriental Performing Arts Group"

Male dancer: Zhang Han

This dance drama is supported by a sophisticated choreography that reaches its apex on the final scene of Painting alive, which you will see in its television edition for technical reasons (it has a better resolution, among others).

Dancing with long sleeves has been recorded at least as early as the Zhou dynasty (1045–256 BC), but the choreography of this piece is inspired by the traditional dance forms developed much later, from Tang to Song Dynasties. It's as refined as arduous and challenging, as the slowest movements require perfect neuromuscular control and a state of mind similar to a moving meditation. I won't tell you anything about what you are about to see, to leave you completely free to let your eyes and your imagination 'roam' in this 'landscape' of pure elegance.

China Central Television's 2022 Spring Festival Gala back in February

Poetic Dance: The Journey of a Legendary Landscape Painting

Music: Lyu Linag

Choreography: Zhou Liya, Han Zhen, and others

Costume: Yang Donglin

Design: Jia Lei

Performed by the Dance Company "China Oriental Performing Arts Group"

Lead dancer: Meng Qingyang

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?