THE PINK FAMILY: CHINA AND THE WEST 5

Current China on the globe.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

LEFT: Portrait of the Yongzheng Emperor in Court Dress, by anonymous court artists, Yongzheng period (1723—35), Qing Dynasty. Hanging scroll, color on silk. The Palace Museum, Beijing. Public Domain.

RIGHT: History of China, Imperial Dynasties, source: Dynasties in Chinese history, Wikipedia.

THE BLUE AND WHITE PORCELAIN TRADE TO THE WEST

THE PORTUGUESE TRADE OF CHINESE PORCELAIN

Before the arrival of the Portuguese, the Arab merchants were key players in trade routes to and from China. «Arab merchants played a double role, as a purveyor of the Persian cobalt to China, and then as a purveyor of its end product, the blue and white porcelain» (Takatoshi Misugi, see Bibliography). The fragile pieces massively exported to the Middle East - into the Arab, Persian, and Ottoman worlds - mostly followed overland routes.

The arrival of the Portuguese and, later on, of the VOC and EIC turned the situation around: the most critical trade routes became the maritime ones, especially the so-called 'Silk Road of the Sea'. After Vasco Da Gama, the Portuguese gained the secrets of sailing east around the Cape of Good Hope and north with the monsoon winds across the Indian Ocean (sailing against the monsoon could conceivably end in the loss of the ship and a financial disaster).

Vasco da Gama took some Chinese porcelain with him on his return to his homeland in 1498; however, the Portuguese systematic import of Chinese porcelain began only in the second decade of the 16th century. «For almost half a century, the Portuguese smuggled, joined pirates, and traded, depending on the opportunities. But well before their settlement in Macao, the Portuguese were already active middlemen and regular customers of the Chinese production of porcelains and silks; they had direct involvement in the design and production of the Chinese craftsmen working for the Portuguese market» (Dolors Folch, cit.). Later on, after the establishment of the Macau trading post in 1557, the Portuguese knew a period of intense commercial growth that lasted until the 1580s. They established successful trade routes, followed by all later European traders, except for Spaniards, who traded via the Philippines. «The Portuguese obtained silk and porcelain from China, some of which they shipped once a year to Japan. The Japanese paid for these luxuries in silver and Portuguese ships returned to Macao, where the bullion was used to buy more silk and porcelain from Chinese merchants. This circular transaction realized a profit of four to ten times. The second load of silk was destined for Indian, Middle Eastern, and European markets, while the ceramics were sought all along the Portuguese trade chain links to Europe. Voyage wares were used as barter items in Champa, Siam, Borneo, and Indonesia; medium-quality porcelains were sold to India, Persia, and East Africa, and the finest wares reached Europe» (Rose Kerr, The Reception of Chinese and Japanese Porcelain in Europe, see Bibliography).

BELOW

The arrival of a Portuguese ship, 1620-1640, Japan. Nanban byōbu (folding screen): ink, gold, and colors painted on paper, on a six-panel folding screen. Dimensions: height 147.6 cm x width 320 cm (image), height 173.4 cm x width 332.7 cm (overall). Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, CA.

This painting is an interesting specimen of the so-called Nanban Art, a form of art developed in Japan during the 16th and 17th centuries, related to the encounters between the Japanese and the Nanban jin, the "Southern barbarians", namely the traders and missionaries from Portugal who were the first Europeans to reach the island of Tanegashima, off the coast of Kyushu, in 1543. They were called "Southern barbarians" as their cargo ships arrived in Japan following a southern route. The Portuguese merchants, often flanked by Jesuit missionaries, brought tin, lead, gold, silk, wool, and cotton textiles to Japan, which exported swords, lacquerware, silk, and silver. Portuguese trade with Japan prospered until 1641, when Christianity was banned by the Japanese government, and Portuguese traders were replaced by the Dutch, who did not engage in missionary work. You can find more visual info on the Nanban screens on this Google page or download a small essay on Nanban Art on this page by the Instituto Cultural de Macau.

This screen shows the arrival of a Portuguese carrack at the port of Nagasaki. On the left are the captain and his crew, who have just landed; some cargo is still being unloaded. On the right, they are proceeding to a Christian church. At its entrance, Jesuit priests welcome the party. Some Japanese townsfolk are observing them curiously.

Porcelains were only a small part of the trade—the cargos were full of tea, silks, spices, lacquerware, metalwork, and ivory. «The porcelains were often stored at the lowest level of the ships, both to provide ballast and because they were impervious to water, in contrast to the even more expensive tea stored above» (Jeffrey Munger and Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, see Bibliography).

Part of what we know today about the 16th-century Portuguese trade comes from the discovery and investigation of many wreck sites.

An interesting story is that of tragic shipwreck of the ‘great galleon’ São João.

This large cargo ship with a registered tonnage of 900 t was built in Lisbon’s shipyards in 1550 and sunk in 1552 on her way back to Portugal, before concluding her first voyage to India. It was loaded with 12,000 q of pepper, a substantial quantity of Chinese porcelain and ceramic pieces, and a wide variety of drugs, spices, wood, fabrics, and other exotic goods. It was not overloaded, but the masts and sails were not in good condition. Along the coast of present-day KwaZulu-Natal, «a heavy storm damaged the ship’s rigging and hurled it against the coast, eventually breaking the hull into three parts against the rocky bottom near today’s Port Edward in South Africa. (...)» (São João Shipwreck 1552, The Nautical Archaeology Digital Library). It was the first cargo ship wrecked along the South-African coastline and the first of a long list: São Bento (1554), São Thomé (1589), Santo Alberto (1593), São João Baptista (1622), São Gonçalo (1630), Nossa Senhora de Belém (1635), and Nossa Senhora de Atalaia do Pinheiro (1647). (Source: Elizabeth Burger, Reinvestigating the Wreck of the 16th Century Portuguese Galleon São João: A Historical Archaeological Perspective). Note that the Dutch and the British will suffer many shipwrecks as well.

Of the 600 people aboard the São João, including at least 300 slaves, 120 perished in the shipwreck. The survivors endured a grueling five-and-a-half-month march to the mouth of the Maputo River; most of them died of starvation, disease, or attacks from the indigenous populations, and only 25 arrived at their destination.

Willem van de Velde (II), A Ship on the High Seas Caught by a Squall, Known as ‘The Gust’, ca. 1680, oil on canvas. Dimensions: height 77 cm × width 63.5 cm. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Willem van de Velde the Younger (1633–1707) was a Dutch marine painter, the son of Willem van de Velde the Elder, who also specialized in maritime art. In 1672, together with his father, he entered the service of the English court. This painting shows a large, 70-gun British warship in distress after a fierce gust of wind has broken one of its masts and a sail has come loose.

The shipwreck area of the São João was discovered in 1980 and surveyed in 1983. Thanks to the investigation and many findings, we know that the galleon, firstly captained by the son of Vasco Da Gama (Álvaro de Ataíde da Gama) and then by Manoel Sousa de Sepúlveda, was loaded with high-quality, neatly painted porcelain pieces (bowls and vessels) decorated with Chinese motifs (dragons, lotus and floral scrolls, pines, lions, birds, peacocks, and Taoist trigram), most of which from the Jiajing period (1522-1566). Please, note that the Portuguese merchants could not have regularly purchased those porcelain pieces: they had to buy them from Indian and Arab merchants by smuggling.

The cargo of the São João also included low-quality coarse porcelain, painted with a greyish cobalt blue, some earthenware pieces, cowries (a common currency throughout this vast expanse of the trading world and Africa), and many carnelian tubular beads of Indian origin, which played an integral role in currency exchange in the Mediterranean, India, Africa, and the Arab trade. The absence of other goods on the seabed tells us a tragic story: before sinking, the crew tried to lighten the ship by jettisoning many cargo crates.

The shipwreck of the São João made a great stir at home and was represented in Os Lusíadas (The Lusiads) by Luís Vaz de Camões, Portugal's greatest poet, in 1572.

Artifacts recovered from the São João site (Source: The Nautical Archaeology Digital Library).

The more the Portuguese porcelain trade grew in quantity, the more the Chinese potters began to produce objects specifically for export to the West: soon in Jingdezhen, a wide range of Chinese porcelain was made almost exclusively for export to Portugal. A number of pieces were even custom made. One of the earliest armorial porcelain pieces was ordered by King Manuel I of Portugal. The piece below is an export porcelain jug, custom-made in Jingdezhen for a Portuguese noble family; the coat of arms, however, was painted upside down!

Porcelain Jug with a Portuguese coat of arms painted in underglaze cobalt blue, made in Jingdezhen in ca. 1520, Zhengde period (Ming Dynasty) for the Portuguese market. Dimensions: 18.7 cm; height: 7 3/8 in. The MET, New York, US.

This early example of an export porcelain piece shows a form that is neither Chinese nor European; rather, it is based on an Islamic metalwork vessel made for the Near Eastern market. This 'foreign' shape was probably regarded as appropriate for the new European trade. «The Islamic form of this ewer is a reminder that the West came late to the export trade, and its impromptu nature is further emphasized by the royal Portuguese arms painted upside down.» (Clare Le Corbeiller and Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Chinese Export Porcelain, see Bibliography). The Chinese painters misunderstood the Portuguese coat of arms, a consequence of their «unfamiliarity with the symbols and customs of their new trading partner» (The MET curators).

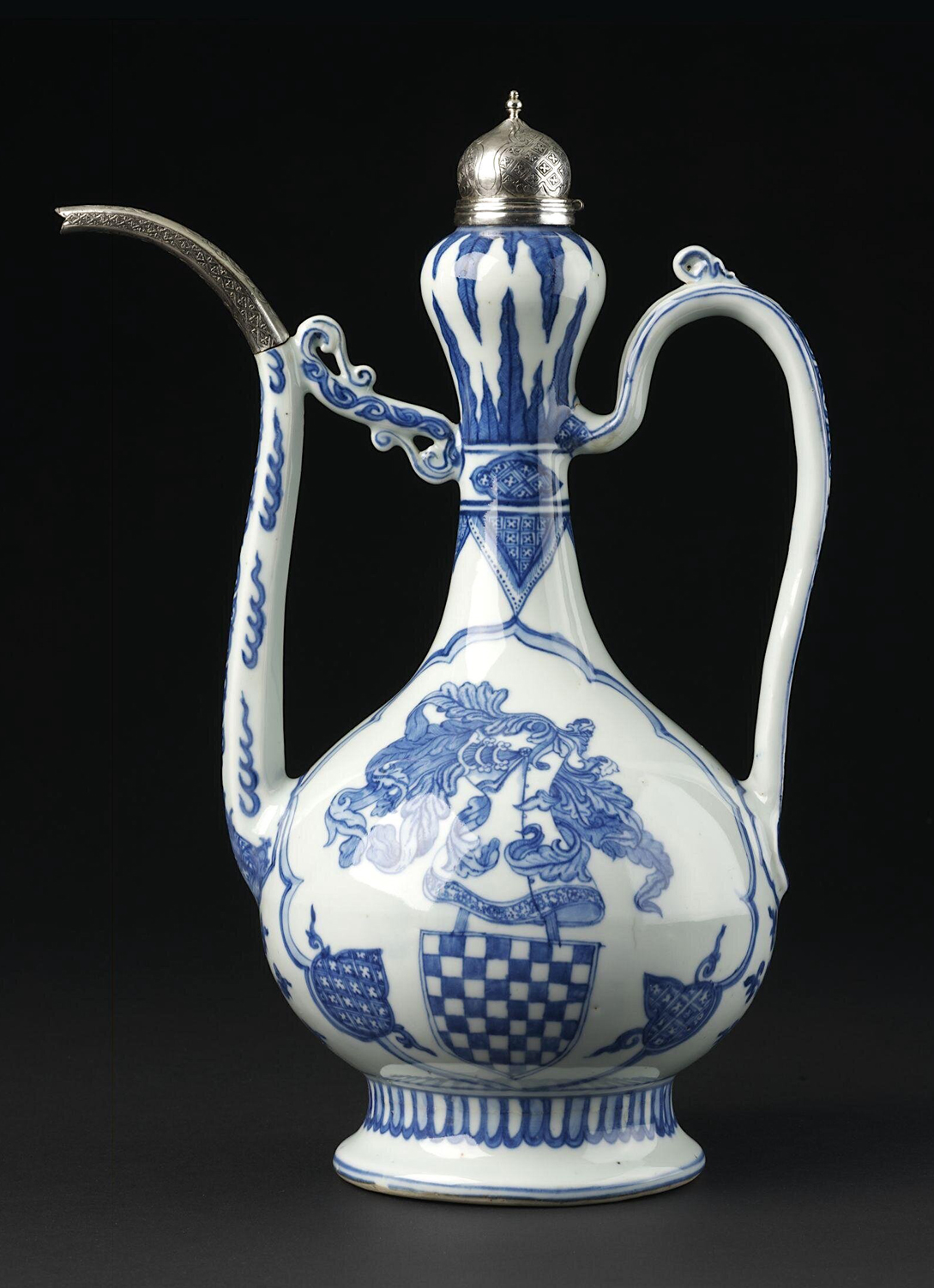

Porcelain Ewer with a Portuguese coat of arms painted in underglaze cobalt blue, made in Jingdezhen in ca. 1522-1566 (Ming Dynasty, marked), for the Portuguese market. With Iranian silver mounts. Dimensions: width 23 cm, height 33 cm. Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

«This ewer is one of the earliest examples of Chinese porcelain bearing European armorial devices. The coat of arms on this ewer is probably that of the Portuguese family of Antonio Peixoto, a navigator and merchant who embarked on a trading mission to China with his business partners, Antonio da Mota and Francisco Zeimoto. They sailed around the China coast in a junk laden with hides and other goods but were refused entry to the port of Canton (now Guangzhou) in 1542. They continued their journey and began to trade in Quanzhou and along the southern coast of China. Between 1522 and 1577, a Chinese imperial edict prevented trade relations with foreigners, but already in the 1540s, the clandestine trade was flourishing. Antonio Peixoto probably bought this ewer during that trip and had it mounted in Persia on the return journey. Antonio Peixoto probably bought this ewer during that trip and had it mounted in Persia on the return journey. This seems likely because the silver mounts were made at about the same time as the porcelain and probably added as part of a repair. The cross pattern on the silver lid replicates the blue triangles and medallions around the neck.» (The V&A Museum curators). The ewer shape is of Middle Eastern origin and looks like many Chinese pieces made for the Muslim markets.

In the second half of the 16th century, many pieces - bowls, plates, ewers, jars - were custom made in Jingdezhen and decorated with religious sceneries and anagrams of many religious orders, such as Augustinians, Dominicans, and Jesuits.

Porcelain Dish decorated with IHS monogram, armillary sphere, and Portuguese royal coat of arms, all painted in underglaze cobalt blue. Made in Jingdezhen in ca. 1520–40 (Ming Dynasty) for the Portuguese market. Overall dimensions: 9.5 × 52.7 cm - 3 3/4 × 20 3/4 in. The MET, New York, US.

The foo dog decorative motif (in the center) is a typical Chinese theme, while «the Portuguese coat of arms and the armillary sphere are often found on works made for Portugal in the early 16th century». The armillary sphere was the personal emblem of King Manuel I of Portugal (r. 1469-1521), granted to him by his brother-in-law and predecessor, King Joao II; it represented his temporal power over his expanding empire. In the Western Christianity of that age, "I.H.S." was the most common Christogram, made up of the first three letters of the Greek name of Jesus, ΙΗΣΟΥΣ (ΙΗΣ, iota-eta-sigma). In 1534, Ignatius of Loyola founded the Society of Jesus, namely the religious order of the Jesuits, approved by Pope Paul III in 1540, and adopted the Christogram as his seal in 1541 and the as the Order's emblem.

Porcelain Jar decorated with the emblem of the Order of Saint Augustine painted in underglaze cobalt blue, made in Jingdezhen in ca. 1575–1600 for export, probably for the Spanish market. Overall dimensions: Overall dimensions: 25.9 × 23.5 × 23.5 cm; 10 3/16 × 9 1/4 × 9 1/4 in. The MET, New York, US.

«The primary motif on this jar—a double-headed eagle clutching a heart pierced with arrows — served as the emblem of the Catholic Order of Saint Augustine. In the 16th century, Augustinian friars established monasteries in Mexico, the Philippines, and Macau. The jar may have been produced for missionaries in one of these locations. While the jar probably served a functional purpose, its white porcelain body and cobalt blue decoration would have appeared luxurious to friars accustomed to humble vessels.» (The MET curators).

According to Michel Beurdeley (1962) and Cinta Krahe (2013), Philip II, King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and Sicily from 1554 until he died in 1598, owned a collection of 3,000 porcelain pieces, some of them custom-made and decorated with the arms of Castile and Leon, the castle and the lion.

Porcelain bottle with underglaze blue decoration, depicting a European coat of arms with castles and lions. The neck, sides, and foot are decorated with stylized flowers and foliage. Dots around the edges of the design suggest milling on a coin. Typical of the late Wanli period, the porcelain and the glaze are not well fitting and the glaze has fritted away along the edges. Made in Jingdezhen, probably during the Wanli reign, Ming dynasty, in ca. 1590-1620. Dimensions: diameter 14.70 cm, height: 30.5 cm. The British Museum, London, UK.

The shape of this bottle, existing in multiple identical specimens, is based loosely on a Near-Eastern metal or glass vessel. The coat of arms showing the arms of Castile and Leon quartered by a cross is the one of King Philip II, copied from a coin, probably from the reverse side of a Spanish silver ocho-reales or 'piece of eight'. According to the experts of Christie's, who auctioned a similar bottle in 2019, the inventory of the more than 3000 pieces in Philip II's porcelain collection does not appear to list similar bottles, and the order likely came from a Spanish aristocrat, merchant, or churchman.

Probably, the most impressive 'collection' of blue and white porcelain pieces in the entire Iberian Peninsula is made up by the pyramidal ceiling of the Porcelain Room in Santos Palace in Lisbon: it's entirely covered with 263 late Ming blue and white plates and bowls, made during the reigns of Hongzhi, Zhengde, Jiajing, Longqing, and Wanli (a dozen Qing Dynasty pieces from the 17th and 18th centuries were added later as replacement elements).

The Santos Palace in Lisbon was a royal residence from the late 15th century; it was acquired in 1629 by the Lencastre noble family (descended from Jorge de Lancastre, a Portuguese prince and illegitimate son of King John II of Portugal). Between 1664 and 1687, the nobleman José Luis de Lencastre commissioned the famous architect João Antunes to expand the Palace by means of striking improvements and structural works. During that period, the architect designed the Porcelain Room and decided to display the many porcelain pieces of the Lencastre collection not on the walls, but on the pyramidal ceiling. In 1870, the French State rented the building, eventually acquiring it in 1909. Today, the Palace is the seat of the French Embassy in Portugal.

In the following short video, you can admire the unique Baroque features of the Santos Palace, one of the few buildings that withstood the devastating 1755 earthquake. The soundtrack of the video is the French composition Marche pour la Ceremonie des Turcs by Jean-Baptiste Lully, created as the final movement for the comedy-ballet Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme written by Molière and Lully in 1670.

«Late Ming blue-and-white porcelain decorated inlaid murals or embrechados can be found in different buildings in Portugal, for instance in the former royal Palace of Alcaçovas and the palace of the Marquis of Fronteira in Lisbon. They are also found in other residences in the south of Portugal» (Cinta Krahe, The Reception and Value of Chinese Porcelain in Habsburg Spain, see Bibliography).

The import of blue and white Chinese porcelain into Portugal had a lasting influence on the production of local pottery pieces, especially on the fine polychrome glazed clay known as "faience", and the production of azulejos, the iconic tin-glazed ceramic tile-work of Hispano-Moresque origin.

Despite the profusion of pieces in the ceiling of Santos Palace's Porcelain Room, the import of Chinese porcelain by the Portuguese remained quantitatively and even geographically contained: in the 16th century, very few pieces left the borders of the Iberian Peninsula to get the Low Countries, for example. Moreover, as the American historian Robert Finlay wrote, «aiming for a quick return on their investment, Portuguese monarchs kept prices high, thereby reducing the market for the pottery (and other goods) and providing no incentive for increasing supplies; the crown regarded the Asia trade as a royal monopoly, not as a merchant enterprise.» (Robert Finlay, The Pilgrim Art, see Bibliography). Massive quantities of Chinese qing hua ci were not imported into Europe until the Dutch entered the trade with a different mindset: an aggressive, modern entrepreneurial attitude. Joost van Vondel, the most prominent Dutch poet and playwright of the 17th century, wrote a poem in 1639 to celebrate the Dutch commercial success and entrepreneurial spirit; it reads We of Amsterdam / Sail to all coasts and seas where profit calls / (...) / For THE love of gain, no port is strange to us.

THE MASSIVE IMPORT OF PORCELAIN BY THE DUTCH

In 1596, the Dutch established their principal trading center in the Indonesian archipelago at Bantam, nowadays Jakarta, and in 1619 conquered the city of Jayakarta, renamed "Batavia". The foundation of the VOC (the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie, in English the United East India Company) on March 20, 1602, marked the decline of the Portuguese hegemony in Asia. «By 1625-50, the Portuguese had been eclipsed» (Rose Kerr, cit.).

On March 14, 1602, Cornelis Bastiaensz, commander of two Dutch ships, Zeelandia and Langebarck, attacked the Portuguese carrack São Tiago off the island of St. Helena (South Atlantic), the usual stopover of Portuguese cargo ships on their way home. The carrack, which was carrying a rich cargo from India, was kept under fire for hours and finally lost its sails, masts, and yards, and over 50 men (in addition to the many wounded). Its entire cargo ended up in the hands of the Dutch, who put it up for auction at Middleburg. Among the looted goods, there were many porcelain pieces, which attracted considerable attention.

In the early morning of February 25, 1603, three Dutch ships under the command of admiral Jacob van Heemskerck attacked the Santa Catarina, a Portuguese 1500-ton carrack at anchor off the eastern coast of Singapore. The Portuguese ship, captained by Sebastian Serrão, was traveling from Macau to Malacca, loaded with precious goods from China and Japan. It carried 1200 bales of Chinese raw silk worth 2.2 million guilders, several hundred ounces of precious and rare musk (used in perfumery), colored damask, lacquer furniture, spices, 70 tons of unrefined gold, 60 tons of porcelain for approximately 100,000 pieces. Can you think of a more tempting loot?

«The daylong battle resulted in half the cargo being destroyed by fire, though what remained was impressive enough. Auction of the porcelain and other merchandise in Amsterdam yielded the VOC about 3.5 million guilders, or 35,000 kilograms of silver, a staggering sum given that a laborer earned no more than 250 guilders a year. At 5,000 guilders for the price of a first-rate house in Amsterdam, the auction netted enough to buy some 750 houses in the most exclusive district of the city. (...) Plundering the Santa Catarina brought in fully 54% of the value of the VOC’s entire stock.» (Robert Finlay, The Pilgrim Art: Cultures of Porcelain in World History, The University of California Press, 2010, p. 253)

The successful auctioning of these two cargoes was instrumental not just in introducing late Ming export porcelain in The Netherlands, but in prompting the Dutch to consider the systematic import of blue and white porcelain as lucrative as the trade of more traditional goods, such as spices or silk. «Accurate VOC records still exist in the National Archives in The Hague, research into which tells us that the Dutch followed the same trade pattern as the Portuguese, but treated porcelain as a more important item. Netherlands’ traders satisfied a large part of the European demand for porcelain, in addition to that of Holland, importing several hundreds of thousands of pieces per year.» (Rose Kerr). Soon the VOC began purchasing massive quantities of export porcelain in China and never stopped exploiting the global conflict with the Spanish-Portuguese Empire: porcelain trade, robbery, and war developed as inextricably intertwined factors.

A Naval Encounter between Dutch and Spanish Warships, ca. 1618/1620. Oil on two panels, painted by the Dutch painter Cornelis Verbeeck. Dimensions: overall 47.63 x 141.61 cm (18 3/4 x 55 3/4 in.); framed 66.68 x 159.39 cm (26 1/4 x 62 3/4 in.). National Gallery of Art, Washington, US.

«In the slightly smaller panel on the right-hand side, a Dutch warship under full sail proudly flies an outsized red, white, and blue Dutch flag (on which the artist has signed his first name plus the initials of his last name). A solid red flag, signifying the ship’s intent to engage in combat, flies defiantly at its stern. The warship has already successfully attacked a small Spanish galley, which is sinking into the stormy sea. Whereas the Spanish boat is awash in misery, the Dutch ship is alive with triumphant activity, from the commander and trumpeter standing on the poop deck beneath the red flag to the sailors scurrying up the rigging and the soldiers reloading their muskets. (...). The larger segment on the left side features a Spanish galleon with its red royal standard flying from its mainmast. As with the Dutch warship in the other panel, its deck is alive with armed soldiers, already fighting a partially hidden, much smaller Dutch warship close to its starboard side. Verbeeck articulated the rigging of these vessels with great clarity, and carefully depicted the gestures and brightly colored costumes of each crew member. Although he included a secondary vignette in the far distance, where a Dutch warship has set fire to a Spanish galley, his clear focus in both segments was on the large foreground ships. (...). Even though the outcome of this battle remains uncertain, the secondary vignette in the distant left, where the Dutch ship is victorious over a burning Spanish galley, would have given a Dutch patron assurance of a Dutch victory. The painting is not known to represent an actual event or even specific ships; nevertheless, Verbeeck almost certainly intended it to be a political metaphor for the victory of the Dutch over the Spanish.» (The National Gallery of Art curators).

Between December 1624 and February 1625, a Portuguese small vessel captained by Alvaro Vilas Boas set off from Macao to reach the Portuguese fort of Melaka (in the southern region of the Malay Peninsula, next to the Strait of Malacca). It was loaded with tons of blue and white porcelain pieces of mixed quality; the cheapest items were destined to be sold in Melaka, the best to be imported in Lisboa. The cargo never arrived in Melaka: it got lost in the South China Sea. It wasn't the sea's fault this time, and there was no storm. The Portuguese ship was attacked by a Dutch warship, eager to steal the Portuguese cargo before setting the vessel on fire. However, everything went wrong for both contenders. The first hail of Dutch cannonballs destroyed the mast of the Portuguese ship; the second hail part of the hull. A fire broke out on board and soon reached the ammunition store; the stern blew up, and the remains sank to a depth of 40 meters.

Some remains of the Portuguese vessel were discovered six miles off the east coast of Malaysia in 1998. The ship was found six years later, loaded with blue and white antique Chinese porcelains made during the Wanli reign (Ming Dynasty). That's why the vessel was called 'Wanli' and the story became known as 'the Wanli shipwreck'. The explosion destroyed much of the ceramic cargo; however, over 9,000 kilos of porcelain shards were recovered from the seabed. In the following video, you can see the excavation of the wreckage and the recovery of part of the cargo by a private company, the Nanhai Marine Archaeology Sdn. Bhd., authorized by the Malaysian government.

From the early 17th century to the late 18th, when the porcelain trade knew its final decline, the VOC imported several million pieces of porcelain to Europe. According to T. Volker (1954), between 1602 and 1682, the VOC carried 30-35 million pieces of Chinese and Japanese export porcelain ware to the Dutch harbors. According to Robert Finlay (2010) and Ronald C. Po (2018), the VOC imported at least 43 million pieces throughout its entire activity, whereas the Portuguese merchants, and the English, French, Swedish, and Danish East India Companies imported at least other 30 million pieces. But as C. J. A. Jörg stated, there is no official recording of the millions of additional pieces of porcelain ware that were imported from China by Dutch crewmembers, who set up their parallel private trades, making huge numbers and causing «an influx of porcelain in addition to the regular VOC imports» (Jan van Campen, Asian Ceramics in the Netherlands, see Bibliography).

Whatever the exact numbers of this trade, what is certain is that during two centuries, Europe was invaded by hundreds of millions of pieces of Asian porcelain.

Two dishes of export Chinese porcelain from the wreck of the Dutch East Indiaman Witte Leeuw ('White Lion'). This VOC ship sunk near the island of St. Helena (in the South Atlantic Ocean) in 1613, during its homeward journey from Bantam in Indonesia. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

THE KRAAKPORSELEIN

The new style of blue and white porcelain that the privately owned (= commercial) kilns at Jingdezhen began producing in the mid-16th century for the Portuguese and Spanish merchants and kept on to produce for the Dutch until the mid-17th century is known as 'Kraak ware' or 'Kraak Porcelain', Kraakporselein in Dutch.

The kraak porcelain was largely but not exclusively made for the European market. The pieces had a white porcelain body decorated with underglaze cobalt blue. Many dishes, plates, and bowls show a paneled border (cavetto and rim) around a central scene, and this feature, which was common but not universal, has become a sort of identifying trait; however, as Teresa Canepa and other scholars had pointed out, kraak ware cannot be recognized by taking in consideration only this trait.

It's worth noting, furthermore, that in the early 17th century, «the depictions on the porcelain were not specially devised for the European clients. The majority are derived from nature.» (Sebastiaan Ostkamp, The Dutch 17th-century porcelain trade from an archaeological perspective, see Bibliography). In general, the early 17th-century pieces excavated in the Netherlands are comparable with those dug up in other parts of the world, or found in the Santos Palace in Lisbon or in the collections of the Topkapi Palace Museum and the Sadberk Hanim Museum, both in Istanbul. Only after the conquest of Formosa by the Dutch in 1624, did «the VOC provide the merchants who kept in direct contact with potters in Jingdezhen with wooden models of silver objects that they wanted to be executed in porcelain. Furthermore, the VOC specified which sort of decoration they wanted these products to have.» (Ibidem).

Even the shape of the pieces cannot be considered an unambiguous and distinctive parameter: kraak ware shows traditional Chinese shapes alongside new ones, adapted or redesigned during the 17th century to better suit Western tastes and habits (i.e. soup bowls, mustard-pots, butter dishes, wine jugs, saltcellars, candlesticks, and others).

The overall quality of kraak ware is another vexata quaestio: in the past, these pieces were generally considered medium to low quality. Surely, they do not show the refinement, the exquisite elegance, and the mastery of the qing hua ci made for the Chinese imperial court. Some pieces do not show a well-levigated white clay or the perfect, smooth, and silky glaze of the imperial ware; others have a thin glaze of a greyish or bluish tone and show scrapes along the rim or on the corners. However, «the range in quality of the kraak porcelain fired in many Jingdezhen kilns is considerable: from extraordinarily high quality to medium and even low» (Teresa Canepa, Kraak porcelain: the rise of global trade in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, see Bibliography). In the images that follow, you will see some very good quality pieces alongside other coarser ones, painted with a sketchy hand.

Giving a good, general definition of kraak porselein is not easy: «Despite the large amount of research carried out over the past decade in China and other countries, - wrote Teresa Canepa in 2008 - kraak porcelain is still difficult to define and its dating is subject to much discussion. Even the origin of the name kraak has proved to be challenging» (Canepa). Most scholars assume the derivation of kraak from the Spanish and Portuguese carraca (= carrack, namely the ocean-going cargo ship) derived from the Arabic qaraqir (merchant's vessel). However, this etymology is a simple hypothesis alongside others. The only certainty is that kraak ware was, along with tea, the world's first mass-produced, global commodity of the modern world.

LEFT: KRAAKWARE, porcelain dish with underglaze cobalt blue decoration, rounded sides, and a broad molded upturned rim with a bracket-lobed edge. Made in Jingdezhen in ca. 1590-1610, probably during the Wanli period (Ming dynasty). Dimensions: diameter 36.4 cm, 14.33 in.; height: 6.3 cm. The British Museum, London.

«Inside, outlined in a dullish underglaze blue, are a goose and gander standing on a river bank with giant lotus and water weeds and in the background, two flying geese approach with further flying birds indicated. This is surrounded by an eight-lobed medallion with alternating scale and maze patterns. The molded cavetto and rim are treated as a single decorative area with eight large panels framing opposite pairs of fans and stylized motifs or double gourds with whisks. In between these are stylized peaches. The larger panels are separated by knots, framed either with fish-scale or with maze diaper.» (The British Museum curators).

RIGHT: KRAAKWARE, porcelain dish with underglaze cobalt blue decoration depicting geese in a lotus pond rich in water weeds. The decoration on the cavetto and rim is similar to the previous piece on the left. Made in Jingdezhen in the late 16th–early 17th centuries, during the Wanli period (Ming dynasty). Dimensions: diameter 36.2 cm; 14 1/4 in. The MET, New York, US.

As the British Museum's curators noted, «until relatively recently <before the 2000s>, it was thought that such dishes with kraak-style underglaze blue decoration were made only for export, but some have also occasionally been found in tombs in China. For example, a dish <similar to the one on the left, in the double photo above> was excavated in 1979 in the tomb of Zhu Yiyin, the Prince of Yixuan (1537-1603), in Nanchang, Jiangxi province.». Only one kraak plate was found in that tomb, but this nevertheless is enough to disprove the idea that kraak ware was solely an export ware.

The quite small plate below is a high-quality kraak specimen, marked on the bottom with an egret. As Harrison and Hall highlighted in their 2001 Catalogue of Late Yuan and Ming Ceramics in the British Museum, «the egret mark appears almost exclusively on good-quality kraak wares, mostly dishes of small to medium size. It has been suggested that the mark identifies this particular type of kraak ware with a specific kiln or workshop, which was manufactured during the late 16th and early 17th centuries.». Four similar kraak dishes, of lower quality though, have been found in the tomb of Wu Nianxu (1547-1614), a provincial administration commissioner, and of his wife He (1547-1610). Again, we can say that kraak ware was made largely but not exclusively for export to Europe.

KRAAKWARE porcelain dish with underglaze cobalt blue decoration. Made in Jingdezhen in ca. 1600-1620, probably during the Wanli period (Ming dynasty). Dimensions: diameter 20.6 cm, 14.33 in.; height: 2.5 cm. The British Museum, London.

« This finely potted dish has shallow molded lobed sides, a flattened rim with a lobed edge, and a low tapering foot with some grit attached. The central medallion depicts a pheasant perched on a rock beside the water and stylized flowering plants and foliage. Surrounding this are eight panels containing cartouches with opposite pairs of chrysanthemum, morning glory, butterfly, and possibly camellia, bordered by narrow panels with dots and lozenges or dots and spirals. The reverse is painted with alternating panels with butterflies or peaches. The glazed base is marked with a standing egret in underglaze blue in the center.» (The British Museum curators).

LEFT: KRAAKWARE, porcelain dish with underglaze cobalt blue decoration and an eight-lobed rim. Made in Jingdezhen in ca. 1573-1620, probably during the Wanli period (Ming dynasty). Dimensions: diameter 20.7 cm, height 3.5 cm. The British Museum, London, UK. «This dish is molded into the shape of an eight-petalled flower with a square foot to which grit has adhered. Inside, a riverscape is depicted with two 'sanpans' sailing down a river, each with cargo, a sailor, and a passenger. On the near bank, a standing figure is shown together with trees and a two-story building. On the far side is a group of two- and five-story buildings. The lobed well is painted with opposing pairs of mandarin ducks and lotus flowers.» (The British Museum curators).

RIGHT: KRAAKWARE, octagonal porcelain dish with underglaze cobalt blue decoration. Made in Jingdezhen in ca. 1600-1620, probably during the Wanli period (Ming dynasty). Dimensions: diameter 18.8 cm, height 2.5 cm. The British Museum, London, UK.

«The shallow dish has eight-lobed rounded sides, a flat octagonal rim, and a low tapering foot. It is painted inside in underglaze blue with a horse lying on a rock flanked by chrysanthemums and shrubs, which also ornament the radiating panels on the rim.» (The British Museum curators).

In the following Chinese video, you can see a kraak plate showing impurities and pitting. The bottom shows adhering kiln grit.

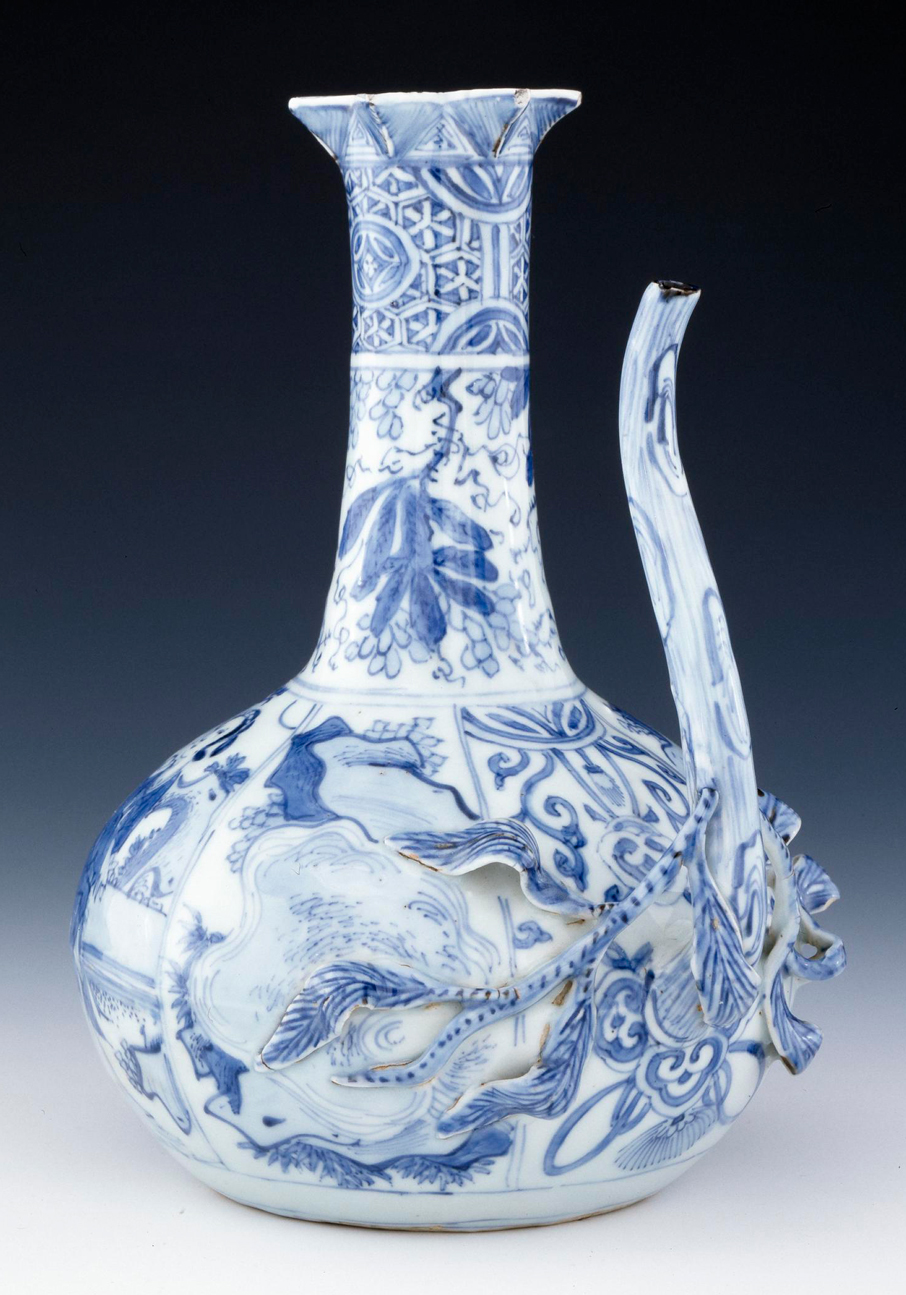

The ewer below is finely potted and shows a better quality.

KRAAKWARE, finely potted porcelain ewer with underglaze cobalt blue decoration. Made in Jingdezhen in ca. 1590-1610, probably during the Wanli period (Ming dynasty). Dimensions: diameter 13.2 cm (including the spout), height 18.5 cm. The British Museum, London, UK.

«The mouth is shaped like a six-pointed star. Around the tapering neck is a squirrel climbing in a fruiting vine and above a band of diapers and cash. The narrow spout is painted to resemble the trunk of a gnarled tree. (...). Although the shape of this vessel is neither Chinese nor European, such kraak-type ewers were exported to Europe in the late 16th and early 17th centuries from China, as evidenced by their presence in the recovered cargoes of shipwrecks. An ewer of the same form with a different underglaze blue decoration was recovered from the San Diego, a Spanish warship attacked by Dutch ships, which sank 1 km north-east of Fortune Island, in Nasugbu, Batangas Province, Luzon, Philippines, on 14 December 1600. (...) Several other ewers of this type survive in public collections», often with different decorations.» (The British Museum curators).

Two blue and white Kraak bowls of 'Klapmuts' type, made in Jingdezhen, during the Wanli period (Ming Dynasty). Dimensions: diameter 14 cm. Auctioned by Christie's in London in May 2015. Photo courtesy of Christie's.

«One bowl is decorated to the interior roundel with a ding and a vase and painted to the cavetto with peach and flower cartouches below sprays of bamboo and flower cartouches on the rim. The other bowl is finely decorated with a hanging censer and similar cartouches on the cavetto below ruyi-heads and decorative panels on the everted rim» (Christie's experts).

The klapmutsen (singular klapmuts) were shallow bowls with flat, up-turned rims. They were made in the Zhushan district in Jingdezhen in many sizes, ranging from 10 to 50 cm, and were massively imported by the VOC in the 17th century. According to Maura Rinaldi, author of one of the first essays on kraak porcelain (Kraak Porcelain: A Moment in the History of the Trade, 1989), the klapmutsen were soup bowls specifically designed for the European clientele.

Here are two bowls. The first is of exquisite quality, unlike the second.

A fine Chinese 'Kraak porselein' bowl, made in Jingdezhen in ca. 1640. Dimensions: diameter 35.2 cm; 13 7/8 in. Auctioned by Christie's in London on November 13, 2014. Photo courtesy of Christie's.

This bowl with steep curving sides is accurately painted and «decorated with panels of figures in river landscapes, interspersed with panels and borders of tulips and flowers, the interior with a central circular panel depicting a seated lady spinning» (Christie's experts).

KRAAKWARE, porcelain bowl of kraaikop type, with underglaze cobalt blue decoration and lobed rim. Made in China for export in ca. 1595-1625 (Ming dynasty). Dimensions: diameter 13 cm, height 7.6 cm. The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK.

« The outside is painted with eight wider panels alternating with eight narrower panels, the wider panels enclosing a bird, a butterfly, or a plant of unidentified species. The inside is similarly paneled, each wider panel enclosing a stylized sunflower. On the bottom is a bird (a crow) perched on a rock.» (The V&A Museum curators).

This bowl is taller and narrower than the standard Chinese bowl. For this reason, and for the sketchy decoration, it's likely a piece made exclusively for export. The Dutch called kraaikop, "crow cups", this type of bowl because they saw the bird painted in the bottom as a crow. «This appellation, though convenient, provides no clues as to the function of the bowl. Fortunately, two Dutch still-life paintings show similar bowls filled with berries, indicating that the bowl would have been used to contain small fruits.» (Ibidem).

THE EXPORT PORCELAIN IN THE LATE 17TH AND EARLY 18TH CENTURIES

In 1608-1610, the production at the Imperial kilns in Jingdezhen rapidly declined and in 1620 was discontinued. It will be necessary to wait for the arrival of Zang Yingxuan as director of the imperial factories at Jingdezhen in 1683 - under the reign of Kangxi, the third emperor of the new Qing Dynasty - to see a full resumption of the official activities. The ca. 900 privately owned kilns, however, did not stop producing porcelain ware both for export and the domestic market. And they did it by creating what Suzanne Valenstein defined as "a fascinating conglomeration of porcelains": on one hand, the commercial kilns in Jingdezhen continued to produce many old, routine pieces, recycling the traditional decorative formulas; on the other, freed from the imperial grip, they could experiment and innovate with a new, unrestrained approach.

During the 1620s, the Ming empire began disintegrating and finally collapsed in 1644, replaced by the Manchu-led Great Qing, the last imperial dynasty of China. The years from the late Ming Wanli reign (1573-1620) to 1683, during the Qing Kangxi reign, made up the so-called "Transitional Period"; the porcelain pieces produced by the commercial kiln of that age are known as "Transitional ware", and the production of underglaze blue and white pieces destined for Japan as Tianqi ware or ko sometsuke.

«After the downfall of the Ming dynasty, foreign trade was halted again. The Shunzhi Emperor announced the ban in 1657, giving as its reason the internal disorder and the war (...) in the southeast coastal area. Until this ban was lifted in 1684, foreign ships could only anchor in Macau, while smugglers caught by the government were punished severely and executed. Foreign trade activities, during this time, were at a low level.» (Hsu Wen-Chin, Social and Economic Factors in the Chinese Porcelain Industry in Jingdezhen during the Late Ming and Early Qing Period, ca. 1620-1683, see Bibliography).

The ban obviously affected the export of porcelain ware, whose production suffered for the sudden worsening of the situation in the Jingdezhen area. «The greatest setback to the production of porcelain occurred during the early years of the Shunzi period (1645-1661) and between 1673 and 1676 when Jingdezhen was ravaged in the rebellion of the "Three Feudatory Princes". During these periods of war and unrest, many potters were killed and more than half of the kilns were destroyed. (...). Because of the great destruction, only 20 or 30% of the previous kilns continued to operate. (..). Even after the rebellion had been quelled, manufacturing was difficult, and the production was greatly reduced» (Hsu Wen-Chin, ibidem).

The full productive recovery in Jingdezhen will be, once again, the consequence of the arrival of Zang Yingxuan as director of the imperial factories at Jingdezhen in 1683. After that date, «the porcelain industry in Jingdezhen developed further under official supervision; the technology of making porcelain surpassed the previous centuries, and both the division of labor and the organization of kilns became more elaborate.» (Hsu Wen-Chin, ibidem). The export trade soon flourished again.

From the mid-17th century to 1684, the VOC switched to the Japanese production of blue and white porcelain to replace Chinese ware. Initially, the Japanese kilns in the area of Arita, a town in the former Hizen Province, in northwestern Kyūshū island, could not supply enough quality porcelain to the Dutch merchants, but the situation quickly improved: in a short time the Japanese potters increased their production capacity and learned how to copy the most requested pieces of kraak porselein.

Porcelain dish with underglaze cobalt blue decoration, showing the Dutch VOC logo in the center. Made in Arita, Japan, in ca. 1660 (Edo period). Dimensions: height 6 cm - 2 3/8 in; diameter 31.4 cm - 12 3/8 in. The MET, New York, US.

This porcelain plate, emblazoned with the monogram VOC and custom made for the Dutch market, is decorated with an imitation of the paneled border, typical of the Chinese kraakware.

Porcelain dish with underglaze cobalt blue decoration, copying the Chinese kraak porcelain. Made in Japan in ca. 1670 (Edo period) for the European market. Dimensions: diameter 39.5 cm - 15 9/16 in. The MET, New York, US.

In the mid-17th century, when the supply of Chinese kraak porcelain to Europe began to decline until it stopped and the import of Japanese porcelain from Arita could not fill the entire gap in the market, Dutch potters in Delft saw the possibility of producing cheap imitations as an attractive business opportunity. They created white tin-glazed sandy earthenware pieces decorated with cobalt blue according to the Chinese and Japanese kraak-style. The Delft pieces were not made of porcelain (at that time, nobody in Europe knew how to make it) but of low-fired earthenware; however, they made up attractive and affordable alternatives to the Asian pieces. Delft potters continued to produce Kraak-style blue and white items even after a remarkable variety of Kangxi porcelain became available in the early 18th century.

Blue and White Kraak-Style Charger, made in Delft, The Netherlands, in ca. 1680. Dimensions: diameter 38.8 cm - 15.3 in. By courtesy of 'Aronson Delftware Antiquairs sinds 1881', Amsterdam.

«Painted in the center with two ducks beneath a large peony tree on the bank of a river within an octofoil medallion reserved with alternating panels of a scale worm and diaper work ground and surrounded on the cavetto and rim with four fan-shaped panels depicting motifs of a scroll or lantern on a tassel and ribbon, alternating with four fan-shaped floral panels, all separated by narrow panels of stylized flower heads suspended between diaper work or fretwork vignettes» (Robert D. Aronson).

«It is not only the huge quantity of imitations produced in Japan and Delft that demonstrates the continuing interest in the by-then-established Kraak and Transitional porcelain after the ceasing of Chinese export. It is also evident that any remaining porcelain was treasured. Broken objects were riveted, sometimes ending up in cesspits much later. A number of find complexes from the late 17th, the entire 18th, and even the 19th centuries produce this sort of early-17th century repaired porcelain.» (Sebastiaan Ostkamp, The Dutch 17th-century porcelain trade from an archaeological perspective, see Bibliography).

THE BLUE AND WHITE PORCELAIN IMPACT ON THE WEST IN THE 16TH AND 17TH CENTURIES

In Europe, the deep fascination for Chinese porcelain was almost immediate and spread like wildfire. It wasn't one of those sudden, violent fires, destined to end soon, however: it was a blaze that lasted for centuries.

In the early 16th century, the Chinese blue and white porcelain was perceived in Europe as the perfect blend of exoticism, rarity, luxury, and mystery: at that time, none in Europe knew exactly how the Chinese made it and how to copy it. Delicate and resistant at the same time, the Chinaware told the story of a fabulous and rich empire at the edge of the known world and carried the salty smell of audacious and dangerous journeys through unknown oceans. Portuguese and Spanish coveted it for its brilliance, transparency, smooth, and silky texture, and even for its crystal-like sound when hit. Porcelain or the "white gold" had everything to become an object of praise and adoration to be displayed in a cabinet of exotic curiosities or, more often, exhibited in a 'porcelain room', as part of a royal luxury collection. Between the late 16th and the early 17th century, almost every European prince or great nobleman had a collection of porcelain pieces, well displayed in a cabinet de curiosités, a porcelain room, or Porzellanzimmer.

In the 17th century, Chinaware escaped its confinement to aristocratic Kunstkammer to become a passion shared by crowned heads, aristocrats, rich notables, and the bourgeois. Grand displays of Chinese porcelain continued to make up blatant demonstrations of power, social status, and good taste, but its large availability on the European market, especially on the Dutch one, turned the pieces into objects of refined household use: blue and white chargers, cooking pots, tankards, tea sets, salt cellars, wine ewers, fruit bowls, butter dishes, mustard pots, and dinner services invaded the European tables, until then dark and gloomy for the presence of coarse brown earthenware and silver-plated or pewter plates, bringing light, color, and life. The blue and white porcelain tableware made food look and taste better than metallic dishes.

The 17th century also saw the fast development of the so-called Chine de Commande, porcelain ware massively produced in China according to the needs and tastes of Western customers.

In 18th-century Europe, when one would expect a physiological decline in interest, Chinese porcelain turned into an obsession: the Age of Enlightenment experienced a real mania that expressed itself as an enthusiastic quest for flamboyant Chinoiseries in art, architecture, interior design, theatre, and music.

Almost all of Europe succumbed to the Chinese and Japanese porcelain mania and the pieces force their way into the daily lives of rich and powerful families, regardless of their patents of nobility. The Asian porcelain pieces were first and foremost purchased to be spectacularly displayed everywhere, not only in the so-called cabinets de porcelaines; they were also the object of an intense collecting fever, and, last but not least, they were bought as sophisticated objects of use: the more extensive their availability became, the more elegant tableware they became.

While collectors used to choose a few rare pieces of the highest quality, the wealthy went for the accumulation: the fashion and taste of the moment turned Chinese porcelain into a must-have element of the furnishings, far beyond the function of a purely decorative knick-knack. Those pieces invaded the richest European homes to be shown and arranged according to the refined taste of the master and some unwritten, sacred rules. Porcelains have their obligatory spaces at home: they had to be displayed en masse, divided into groups called garnitures, always in odd numbers (from 3, or even better, from 5 to 21). They had to be placed on fireplace mantels and overmantels, cornices, overdoor panels, tables, wall-mounted shelves, and étagères, by taking advantage of any recess, niche, arch, ornamental molding, and furniture piece. The French noblewoman Anne de Rohan (1648–1709), Duchesse de Luynes, member of the powerful House of Rohan, and wife of the Prince of Soubise, was famous for her garnitures: in a room of her mansion, she displayed 37 fine porcelain pieces on a single fireplace mantel.

Five-piece garniture in porcelain, made in China in ca. 1700 (Kangxi period, Qing Dynasty). Dimensions: max. height 1050 cm. Porzellansammlung, Dresden State Art Museums, Germany.

This impressive set is made up of three monumental covered jars and two beaker vases and is part of the Collection of Dragoon Vases, a group of 151 monumental porcelain pieces. In Spring 1717, this collection was 'donated' by Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia, King of Prussia and Elector of Brandenburg from 1713 until his death in 1740, to Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony from 1694, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1697 to 1706. Augustus was a passionate collector of Chinese and Japanese porcelains: his collection was the largest one in Europe. The 'homage' by the king of Prussia was not a disinterested gift: Augustus 'thanked' him with 600 cavalrymen.

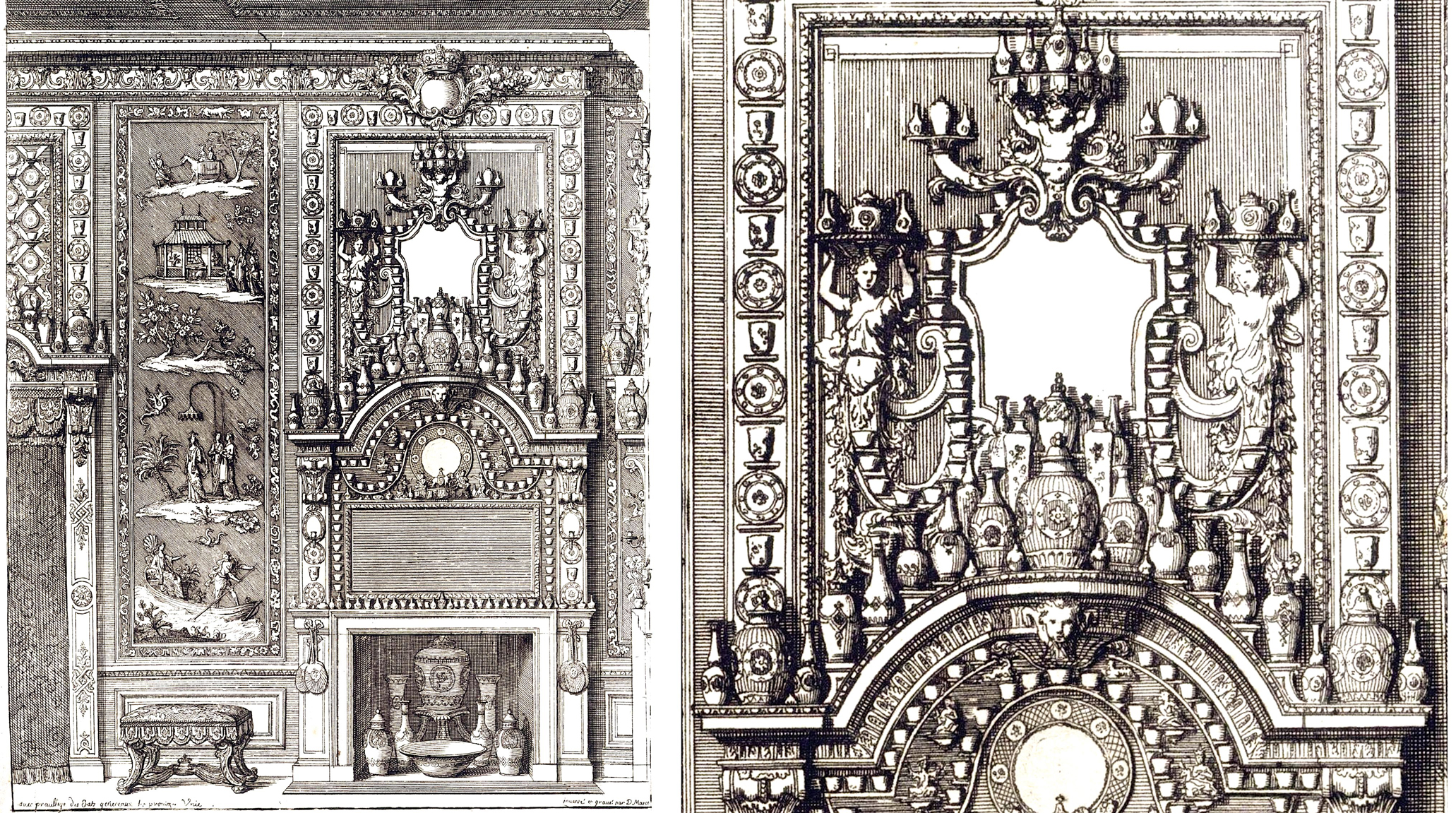

It's almost impossible for us today to imagine how the garnitures and the sets of display porcelains were arranged in the rooms. A vague idea can be provided by the etching below, made in 1703 by Daniel Marot, a French-born Dutch architect, furniture designer, and engraver. This etching shows a detail of the scheme Daniel Marot had developed for the display of the large porcelain collection owned by Queen Mary II at the Baroque palace of Het Loo in The Netherlands (Mary Stuart II, 1662-1694, was the wife of William of Orange, sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from the 1670s, and King of England, Ireland, and Scotland from 1689 until his death in 1702. Mary was a passionate collector of porcelains).

Nouvelles Cheminée faitte en plusier en droits de la Hollande et autres Provinces, inventé et gravé par Daniel Marot, etching on the left and a detail on the right. Dating: before 1703. This etching shows the Marot's design for a chimneypiece displaying numerous Chinese porcelain vases on the overmantle. The pieces were part of Queen Mary's collection, and the interior design was made for a room in the Royal Palace of Het Loo in The Netherlands. Victoria & Albert Museum, London, UK.

The following corner chimneypiece is a Daniël Marot-style type of installation and probably comes from the house of one of William III’s courtiers on the Korte Voorhout in The Hague, The Netherlands. Chinese porcelain abounds on all the consoles.

Corner chimneypiece panel (Hoekschoorsteen), anonymous, ca. 1700–1705, The Hague. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Did you read the caption of the five-piece garniture picture (a little further above)? Those porcelain pieces as well as many others preserved at the present-day Dresden Porzellansammlung (The Royal Porcelain Collection in Dresden, Germany) come from the collection of Augustus the Strong, Elector of Saxony from 1694, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania from 1697 to 1706. The following outstanding Chinese vase of impressive dimensions (it's almost one meter high) comes from his collection and shows what a shrewd and refined collector he was. It can give you an idea of the majestic size of the display wall boiserie or the chimney panels created for the richest collections.

Triple-gourd porcelain vase painted in underglaze cobalt blue and decorated with floral scrolls (chrysanthemum, lotus, peony) and chilongs (hornless dragons) in reserve, made in Jingdezhen in ca. 1700–1720, Kangxi period, Qing Dynasty. Dimensions: height 99 cm; min. diameter 9.2 cm, max. diameter 36.5 cm. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

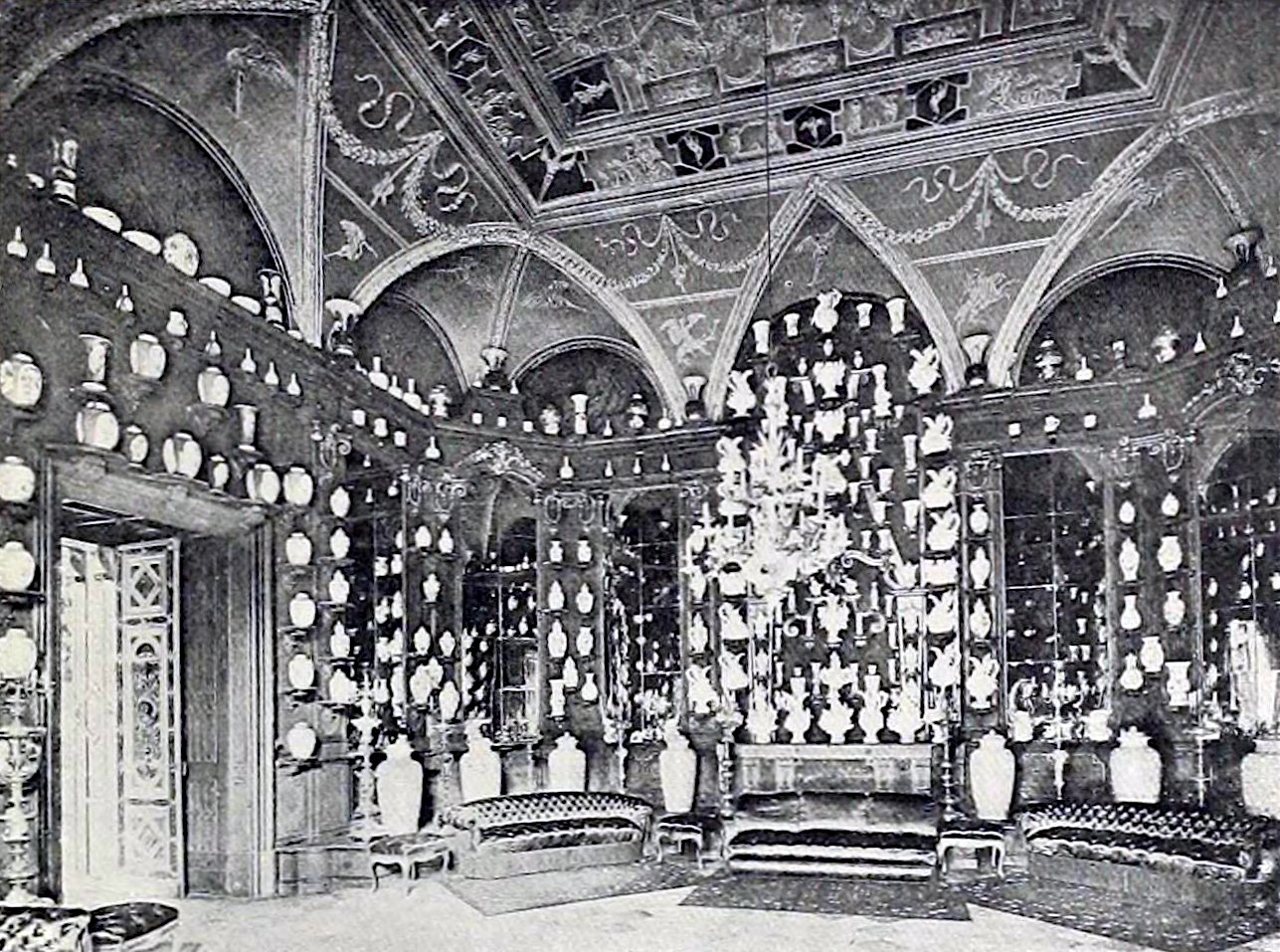

The Dresden Museum, housed in the Zwinger Palace, includes approximately 20,000 porcelain items; among them, there are the precious Chinese and Japanese pieces acquired and collected by Augustus the Strong. The image above shows the Chinese side of the Porzellansammlung in 1900 and gives you an idea of the traditional, 'exuberant' display scheme.

Dresden Porzellansammlung in 1900

Fortunately for us, one of the most breathtaking Porcelain Cabinets in Europe has stayed fairly true to the original and has been open to the public since 2017. It's housed in the Schloss Charlottenburg, a Baroque palace near Berlin, built at the end of the 17th century for Sophia Charlotte of Hanover (1668–1705), wife of Frederick I, King of Prussia from 1701 to 1713. The Castle, which was greatly expanded during the 18th century, still preserves the Porcelain Cabinet (Room 95), where a profusion of golden decorations and thousands of Chinese blue and white porcelain pieces from the late 17th and early 18th centuries take the breath away from any visitor.

In the next paragraphs, I will deal with the 16th and 17th centuries; to the 18th, I will devote more space in the coming chapters. Here I merely point out that the obsession with China and the Chinoiseries reached its peak but did not end in the 18th century.

«A mania for Chinese blue-and-white porcelain swept through London in the 1870s as a new generation of artists and collectors “rediscovered” imported wares from Asia. Foremost among them was American expatriate artist James McNeill Whistler. For him, porcelain was a source of serious aesthetic inspiration. For British shoppers, however, Chinese ceramics signified status and good taste. Cultural commentators of the time both embraced and poked fun at the porcelain craze. Illustrator George du Maurier parodied the fad in a series of cartoons for Punch magazine that documented what he mockingly called "Chinamania".» (Smithsonian's National Museum of Asian Art, Introduction to the exhibition "Chinamania" 2016).

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?