THE PINK FAMILY: CHINA AND THE WEST 9

Current China on the globe.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

This map is for illustrative purposes only. The Ethnic Home does not take a position on territorial disputes.

LEFT: Portrait of the Yongzheng Emperor in Court Dress, by anonymous court artists, Yongzheng period (1723—35), Qing Dynasty. Hanging scroll, color on silk. The Palace Museum, Beijing. Public Domain.

RIGHT: History of China, Imperial Dynasties, source: Dynasties in Chinese history, Wikipedia.

Matteo Ricci in Beijing (1601–1610): The Jesuit and the Dragon Throne

Introduction

The arrival and residence of Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) in Beijing marks one of the most profound episodes in the history of East-West intercultural dialogue. As a Jesuit missionary and polymath, Ricci's time in the Ming capital was not only a missionary venture but also a sophisticated diplomatic and intellectual engagement with the highest echelons of Chinese society. His strategy of cultural accommodation, his collaboration with Chinese literati, and his seminal publications forged a new paradigm for missionary work and transcultural exchange.

Matteo Ricci’s entry into Beijing marked both an end and a beginning: the culmination of two decades of arduous travel through China and the start of his most intellectually fruitful years. Though the Jesuit never gained a personal audience with the Wanli Emperor—an opportunity later legends would wrongly ascribe to him—his presence in the capital was nonetheless extraordinary. The court recognized him not as a merchant or a curiosity, but as a learned man from the West, worthy of residence within the imperial city walls.

In this singular position, Ricci stood somewhere between official and outsider, a foreign scholar whose erudition and mastery of Chinese granted him an ambiguous prestige. His house soon became a magnet for officials, literati, and inquisitive courtiers, drawn by his instruments, his maps, and his remarkable intellect. Within these walls, a rare cultural dialogue unfolded—Confucian learning meeting Western science and theology in conversation rather than conflict.

During these Beijing years, Ricci refined both his language and his message. He composed his most important works—theologically bold texts and elegantly reworked maps that revealed the world to Chinese eyes from a new perspective. No longer merely a mediator between cultures, Ricci had become a participant in the Republic of Letters of Ming China, an equal interlocutor in the empire’s own tradition of scholarship.

Beijing at the beginning of the 17th century. AI-generated illustration.

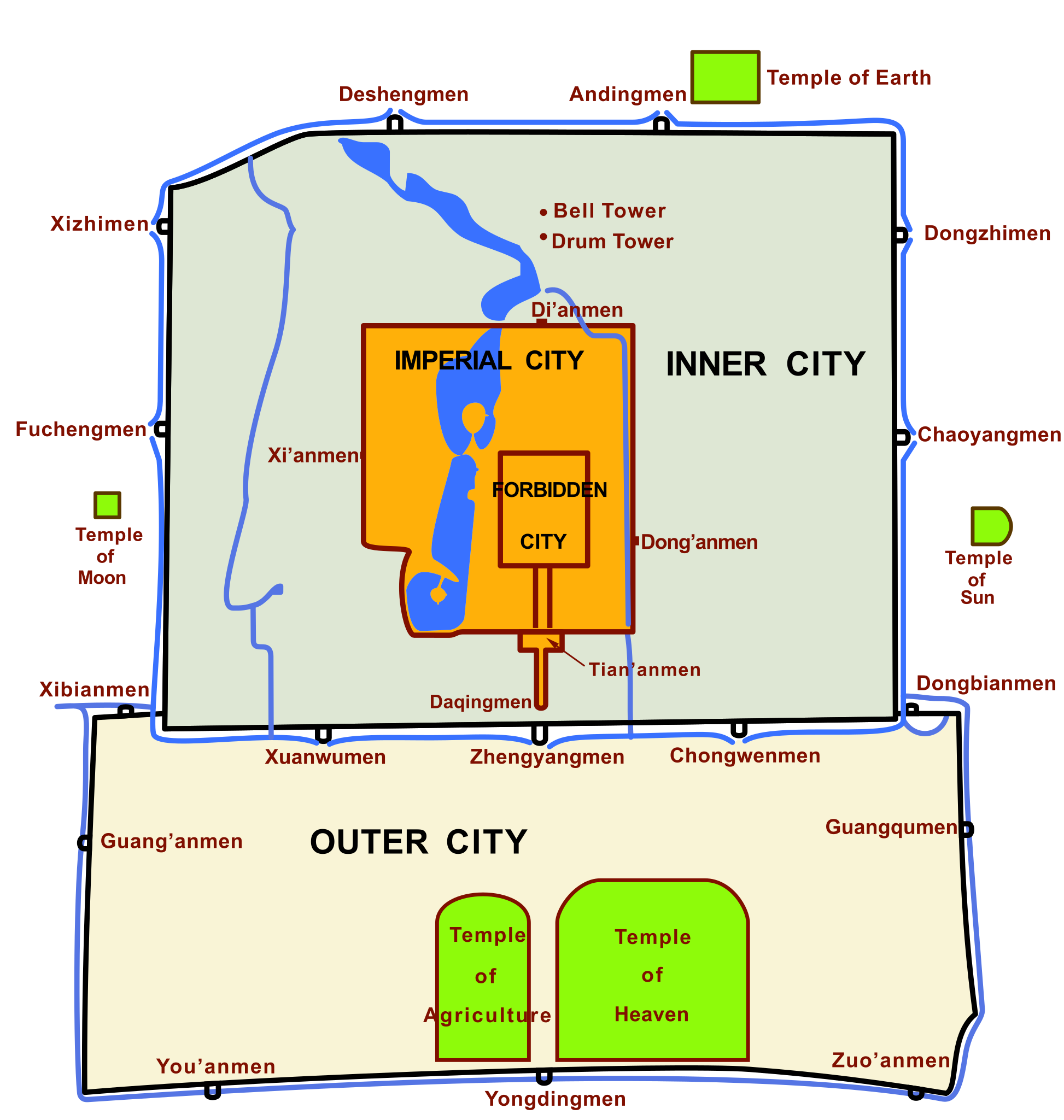

In 1601, Beijing stood as the awe-inspiring imperial capital of the Ming dynasty, a city of immense political, cultural, and architectural grandeur. Dominated by the vast Forbidden City at its heart—the seat of the Wanli Emperor—Beijing was encircled by massive gray brick walls, pierced by monumental gates such as Zhengyangmen and Deshengmen, and laid out in an orderly grid reflecting traditional Chinese cosmology and Confucian hierarchy. The city was both a center of imperial power and a hive of urban life. Inside the inner city (内城, Neicheng), elegant mansions, ancestral halls, and government offices coexisted with bustling residential neighborhoods and Confucian academies. Outside the walls, in the outer city (外城, Waicheng), markets thrived with merchants, artisans, and pilgrims. Street scenes included ox-carts, sedan chairs, and peddlers weaving through crowds under fluttering banners and paper lanterns. Architecturally, the late Ming style was prominent: sloping tiled roofs, red-painted columns, glazed yellow tiles for imperial buildings, and grey brick courtyard homes (四合院, siheyuan) for officials and elites. Towering pagodas and city gates added vertical majesty to the landscape. Beijing's population was diverse—scholars, soldiers, eunuchs, merchants, and monks mingled within its walls. At court, tensions simmered between Confucian officials and powerful eunuchs, while outside, commoners endured heavy taxation and occasional unrest. When Matteo Ricci entered the city in January 1601, it was both a culmination of his long journey through China and the first time a European had been granted such privileged access. The city he encountered was a fusion of rigid ritual, imperial splendor, and complex bureaucracy—a capital as imposing in its silence as in its sound.

Plan of Beijing showing the Forbidden City inside the Imperial City, as well as the Inner and Outer Cities. Wikimedia Commons.

An AI-generated illustration of the Imperial City in the late Ming dynasty.

Portrait of an official in front of the Beijing Forbidden City (明代宮城圖 天下朝觐官陛辞图). Painted in ink and colours on silk by Zhu Bang (朱邦),in ca. 1522-1566 (Jiajing reign, Ming Dynasty). © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

Palace maids and the Gugu in the Forbidden City. AI-generated illustration.

In the inner quarters of the Forbidden City, palace maids performed many of the most humble domestic tasks. These maids were young women recruited through official drafts from Manchu and Mongol banner families, and in some periods, only from specific banners. The maids served in the strict hierarchy of palace life, tending to the daily needs of imperial consorts, concubines, and other high-ranking women. Their service typically began in early adolescence and lasted for a defined period. Many left service around their mid-twenties, if they survived palace life. Within the servant ranks, a senior maid—often called a Gugu, or maid-in-waiting—oversaw other maids and enjoyed greater authority and privileges. However, life for lower-ranking maids could be harsh. Punishments for errors were severe, and disputes with superiors or concubines sometimes resulted in demotions, beatings, or even execution in extreme cases. Palace regulations governed dress and conduct. Maids wore simple uniforms appropriate to their rank and observed strict protocols in the presence of others. They were expected to embody self-discipline and restraint. Despite the hardships, service as a palace maid provided security. Maids were supported during their tenure, and upon completion of service, they could marry without the heavy dowries expected in broader society. This was a modest form of social mobility within rigid court hierarchies.

- Arrival in Beijing: Setting the Stage for Dialogue

Matteo Ricci’s entrance into Beijing in January 1601, accompanied by Diego de Pantoja and Chinese lay brothers, marked the fulfillment of an eighteen-year quest. It was the culmination of patient negotiation, linguistic mastery, and cultural sensitivity. The imperial court of the Wanli Emperor (r. 1572–1620) allowed Ricci to reside in the capital—a rare privilege—thanks to the Jesuits' growing reputation as scholars and technicians.

Although Ricci never met the emperor directly, his stay in Beijing was facilitated by powerful eunuchs and influential mandarins impressed by his knowledge of astronomy, mathematics, and geography.

The key events during this period included:

- The presentation of Western gifts such as clocks, prisms, and world maps to the imperial court.

- His successful establishment of the Jesuit residence near the Forbidden City.

- The gaining of official patronage and the conversion of a few high-ranking Chinese scholars and officials.

These events marked the transition of Ricci’s mission from a peripheral experiment to a central, intellectually respected presence in the heart of China.

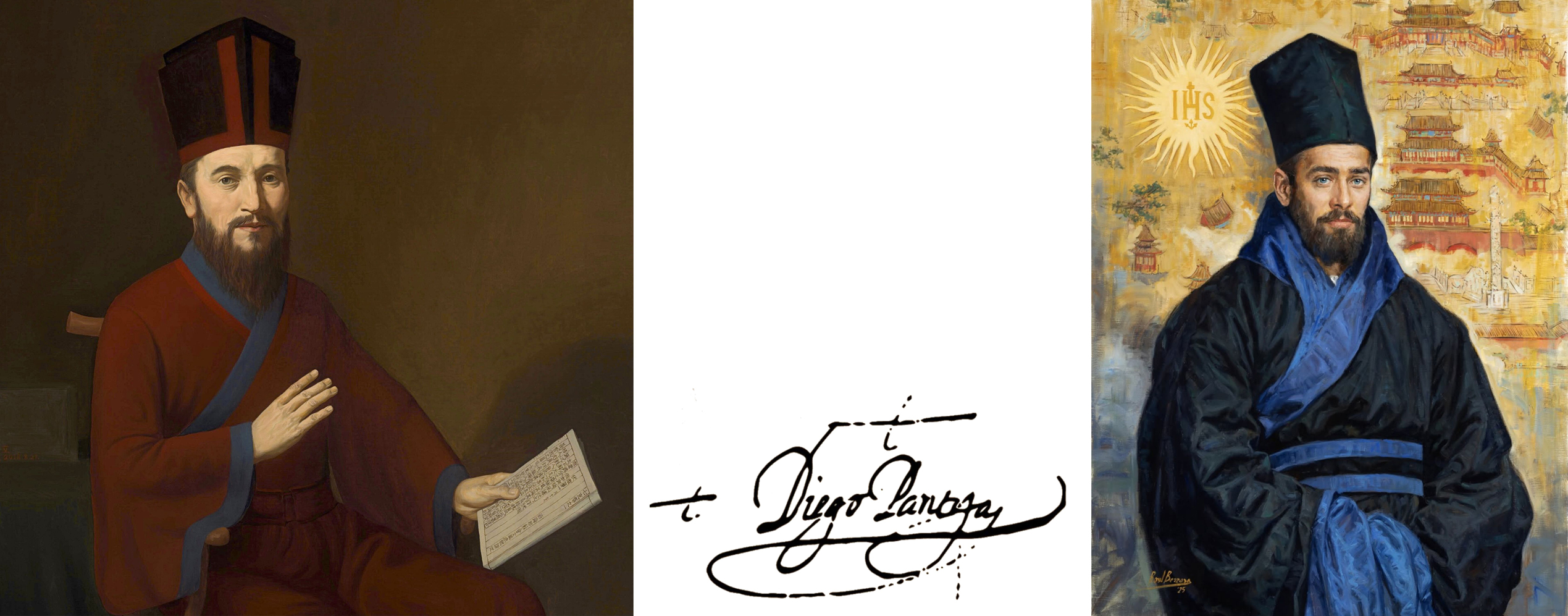

LEFT: An old portrait of Diego de Pantoja, SJ (1571–1618), a Spanish Jesuit and missionary to China who accompanied Matteo Ricci in Beijing.

CENTER: Original signature of Diego de Pantoja. Wikimedia Commons.

RIGHT: Raúl Berzosa, Diego de Pantoja, oil on canvas, 2025, 89 x 116 cm. Instagram.

Diego de Pantoja (龐迪我, Pang Diwo) was handpicked by Matteo Ricci for the mission to Beijing and arrived in the imperial capital in 1601, shortly after Ricci secured permission to reside there. Pantoja, then still in his early 30s, quickly became Ricci’s closest collaborator, admired for his linguistic skills, musical talents, and deep understanding of Confucian culture. Ricci and Pantoja worked together in tandem, with Ricci often taking the lead in philosophical and theological matters, while Pantoja supported through diplomacy, music (notably the clavichord), and the arts—which the Chinese literati found both exotic and refined. Pantoja's role was not secondary but complementary: he embodied Ricci’s principle of cultural accommodation, especially through aesthetics and refined conduct. “Pantoja’s facility with music and ceremony complemented Ricci’s scholarly gravity; together they modeled an ideal of European civility that won the respect of many Chinese officials”, wrote D.E. Mungello (in The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500–1800).B Pantoja was an active intellectual contributor and not merely a supporting missionary. He wrote extensively in Chinese, and among his most significant works was Qike (七克, “The Seven Victories”), a treatise on Christian ethics and moral discipline, written in the style of Confucian self-cultivation literature. This work aimed to blend Western Christian asceticism with Chinese moral philosophy, emphasizing victory over the seven deadly sins. It was influential in shaping the moral discourse of early Chinese Christian converts. His conversational fluency and deep cultural tact allowed him to gain access to Chinese elite circles. He, like Ricci, engaged in cross-cultural philosophical discussions and was seen as a cultured gentleman-scholar (junzi), not simply a foreign preacher. Moreover, he worked on astronomical observations and calendar reform, furthering the scientific reputation of the Jesuits at the imperial court—a legacy that would eventually culminate in the favor later granted to Jesuits like Johann Adam Schall von Bell under the Qing dynasty. When Matteo Ricci died in 1610, Diego de Pantoja remained in Beijing and temporarily assumed leadership of the mission there. However, this period was politically turbulent. In 1616, during a backlash against Christianity and foreign influence led by some conservative Confucian officials (sometimes referred to as the Nanjing Persecution), Pantoja became a central target. He was arrested, interrogated, and eventually expelled from Beijing in 1617. He spent his final year in Macau, where he died in 1618. Despite this unfortunate end, Pantoja's work laid the groundwork for: The continuation of the Beijing mission, which was revived under Nicolas Trigault and others; The intellectual and spiritual legacy of Christian literature in Chinese; The development of Western-style scientific discourse in China, especially in music theory and astronomy. In conclusion, Diego de Pantoja was more than Ricci’s assistant—he was a cultural bridge in his own right. His music, writing, diplomacy, and erudition were crucial to building trust with Chinese scholars and deepening the philosophical engagement initiated by Ricci. His presence in Beijing after Ricci’s death represented a brief but important continuity of the Jesuit mission in China, even amid growing resistance. “Pantoja’s cultural sensibility and intellectual contributions were essential to sustaining the fragile cross-cultural dialogue that Ricci had initiated. He deserves recognition as a co-founder of the Jesuit intellectual mission in China”, wrote Liam Matthew Brockey (in Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579–1724).

- The Catechism and the Confucian-Christian Synthesis

Ricci’s most ambitious Beijing publication was Tianzhu Shiyi (天主實義, "The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven"), completed in 1603. Written as a dialogue between a Western scholar and a Chinese literatus, using Confucian categories and quoting extensively from Chinese classics to present Christianity as a rational monotheistic philosophy, this work argued that ancient Confucianism and original Christianity shared a common moral foundation, later corrupted by Buddhist and Daoist accretions. He argued that the Christian God (Tianzhu, or “Lord of Heaven”) was not a foreign deity but the same ultimate principle Confucius intuited but never fully defined.

The Tianzhu Shiyi was not a simple translation of Western theology, but a contextualized doctrinal treatise meant for educated Confucian audiences,m and articulated two core ideas Ricci had developed since Nanchang: first, the convergence of Christianity and Confucianism in antiquity; second, the distortion of Confucianism by foreign teachings. As Hsia demonstrates, Ricci’s attacks on Buddhism could be vitriolic; he even rejoiced in the misfortunes of Buddhist devotees. This militancy coexisted with his public persona of courteous erudition, revealing a man supremely confident in his mission’s truth.

The book circulated widely among officials and missionaries, it was printed in multiple editions, and earned Ricci respect as a philosopher. Feng Yingjing’s preface lent it authority, and its classical Chinese style won admiration. Ricci’s use of Confucian classics to support Christian ideas influenced later Chinese converts, such as Yang Tingyun, who developed his own forms of Confucian monotheism that blended Christian and Confucian vocabulary. However, Ricci’s rejection of Neo Confucian metaphysics sometimes drew pushback from Chinese scholars who saw his interpretations as selective or misappropriated. This dual reception—admiration and reservation—reflects the complex legacy of the text: it opened new intellectual space but also sparked debate about fidelity to indigenous traditions.

In addition, contemporary scholars remain divided on its significance. Paul Rule sees it as brilliant adaptation; Meynard warns that Ricci subtly subverted Confucianism by redirecting it toward Christian charity. Jacques Gernet, in China and the Christian Impact, argues that the synthesis was ultimately superficial, masking fundamental incompatibilities. Let's examine this aspect in greater depth, as it will help us later to maintain a critical distance from Matteo Ricci.

Matteo Ricci reading Confucian texts in his Beijing residence. AI-generated illustration.

Scholarly Evaluation: Contemporary and Critical Perspectives

Scholars today examine Tianzhu Shiyi not only as a missionary document but as a complex philosophical text situated in Sino‑Western intellectual history. Below are key themes and debates in current scholarship.

- Hermeneutics and Dialogue Between Traditions

Contemporary scholars emphasize that Tianzhu Shiyi is a hermeneutic endeavor—Ricci did not merely translate Christian concepts but interpreted them through Chinese intellectual categories while also interpreting Chinese thought through Christian lenses. Xiaolin Zhang’s research highlights that the work is a hermeneutic reading of Chinese intellectual tradition from a Christian theological‑philosophical point of view, intentionally employing Confucian categories where possible and critiquing or rejecting others (e.g., Neo‑Confucianism and Buddhism). The work thus stands as an example of mutual interpretation, where both traditions are read and dialogued with scholarly seriousness rather than dismissed as “barbaric” or “foreign.” This approach is one reason Tianzhu Shiyi remains a major source for studies in comparative philosophy, intercultural hermeneutics, and early modern world Christianity.

- Moral and Philosophical Themes

Several scholars have reopened Ricci’s arguments about moral motivation and ethical action: Michele Ferrero examines Ricci’s treatment of moral action, noting that Ricci engages deeply with Confucian ideas of ethical behavior and motivation without resorting to simplistic binaries. Ricci argues that good actions are ultimately rooted in relationship with God, yet he recognizes the Confucian idea that tradition and human moral capacities also play a role. A recent article by P. K. Hosle (2024) explores an archery analogy deployed in Tianzhu Shiyi to communicate the intentionality of ethical action, showing how Ricci actively blends Western and Chinese conceptual imagery to make Christian moral psychology intelligible to a Chinese audience. These studies demonstrate that Tianzhu Shiyi is not merely theological apologetics, but a work of philosophical engagement that grapples with core questions of agency, intention, virtue, and human motivation across traditions.

- Criticism of Other Religious Traditions

Ricci’s position within Tianzhu Shiyi is not neutral. Contemporary scholars note important limitations and polemical aspects of his approach. Ricci explicitly critiques Buddhism and Taoism, and according to recent research, he also addresses the contemporary phenomenon of “three teachings into one” (Sanhanjiao), criticizing the syncretist fusion of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism as a confused worldview incompatible with Christian monotheism. This critique is linked to Ricci’s theological priorities; his dialogue privileges monotheism and logical coherence in a way that sometimes discounts the integrated pluralism of Chinese intellectual traditions. Critics argue that this can limit true convergence between traditions. Thus, while Ricci’s efforts represent genuine dialogue, they also reveal boundary‑drawing—asserting Christian theological distinctives in the face of pluralist Chinese religious thought.

- Critical Interpretations and Limitations of Tianzhu Shiyi

While Matteo Ricci’s Tianzhu Shiyi is widely regarded as a groundbreaking work of intercultural theology, modern scholars increasingly highlight its intellectual asymmetries, strategic selectivity, and missiological limitations.

Several contemporary scholars argue that Ricci’s engagement with Confucianism was sincere but strategically selective. Ricci framed Confucian philosophy in ways that facilitated convergence with Christian monotheism while excluding or marginalizing aspects incompatible with Catholic doctrine.

As Xiaolin Zhang observes in a comprehensive study of the text, “Ricci constructed a Confucian Christianity by isolating ancient Confucian teachings from their broader cultural and historical context, allowing for a reconstruction of Chinese thought through the prism of Thomistic rationality.” (Xiaolin Zhang, Matteo Ricci and Intercultural Hermeneutics, 2023). Zhang further argues that Ricci’s rejection of Neo-Confucian metaphysics—particularly the impersonal li (理, “principle”) and qi (氣, “vital energy”) cosmology—amounted to an epistemological editing of the Chinese tradition. He upheld only those elements that could be reconciled with the Aristotelian concept of a personal God and a teleological moral order.

Ricci’s attitude toward other Chinese traditions—particularly Buddhism and Daoism—is the subject of considerable scholarly critique. While his tone toward Confucianism is often respectful, his stance toward Buddhism is openly polemical. He characterizes Buddhist cosmology as incoherent and its metaphysics as nihilistic. Michele Ferrero writes: “In Tianzhu Shiyi, Ricci’s Confucian-friendly approach comes at the price of a hostile portrayal of Buddhism, which he associates with superstition, moral decay, and intellectual vacuity... This severely limits the inclusivity of his dialogue.” (Michele Ferrero, The Concept of Morality in Matteo Ricci’s Thought, Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences, 2019).

Likewise, Ricci’s treatment of Daoist immortality and cosmology is dismissed as credulous and anti-rational. In this regard, Ricci’s approach, while dialogical with Confucianism, maintained a missionary hierarchy of truth, with Christianity as the final fulfillment of all other traditions.

- Theological Absolutism vs. Cultural Reciprocity

Several scholars point to the asymmetrical nature of the exchange embedded in Ricci’s project. While Ricci adopted Chinese cultural forms and philosophical idioms, he never questioned the epistemic or theological superiority of Christianity. Liam Matthew Brockey argues: “Ricci’s dialogues were based on courtesy and respect, but not on parity. Christianity was presented not merely as compatible with Chinese thought, but as its fulfillment and correction.” (Liam Matthew Brockey, Journey to the East: The Jesuit Mission to China, 1579–1724, Harvard, 2007) This has led recent scholars—especially those working in comparative religion and postcolonial theology—to critique Tianzhu Shiyi as a form of intellectual imperialism cloaked in civility. While Ricci respected Chinese learning, he did so as a means of persuasion, not mutual transformation.

- Conclusion

Matteo Ricci’s The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven remains one of the most ambitious and philosophically nuanced texts in the history of global Christianity. It pioneered a form of contextual theology centuries before that term was coined, offering a compelling example of how religious traditions might enter into dialogue across linguistic, metaphysical, and civilizational boundaries.

At its best, the text exemplifies:

- A genuine effort at cultural translation, where core theological ideas (e.g., monotheism, moral law, divine justice) are recast within the idioms of Confucian philosophy;

- A philosophical ethics of respect, particularly in Ricci’s method of engaging literati through shared moral concerns rather than confrontation;

- A foundational moment in comparative theology, which later missionaries and scholars (e.g., Nicolas Trigault, Prospero Intorcetta) built upon.

However, Contemporary scholarship reveals the limits and contradictions of Ricci’s method:

- His selective elevation of Confucianism and rejection of other Chinese traditions fractured the philosophical unity of the “Three Teachings” (Confucianism, Daoism, Buddhism) central to Ming-era intellectual life.

- His theological absolutism, though clothed in classical rhetoric and dialectical dialogue, circumscribed the mutuality of the exchange.

- His project reflected an implicit epistemic hierarchy, where Chinese knowledge was valuable insofar as it pointed toward Christian truth, but was not allowed to transform Christian categories in return.

As such, Tianzhu Shiyi occupies a liminal space in world intellectual history—neither a work of pure theology nor of sinology, but a hybrid philosophical-theological document shaped by the demands of mission, diplomacy, and philosophical persuasion.

The legacy of Ricci’s text, then, lies not in having resolved the tensions of intercultural theology, but in having opened a space where those tensions could be explored with rare depth and brilliance—a model still studied and contested in our global age of pluralism and religious dialogue.

LEFT: an image of the title page from an 1868 edition of his work entitled Tian zhu shi yi, 天主實義 , translated as The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven.

RIGHT: Matteo Ricci writing his treatise in Beijing. AI-generated illustration.

Matteo Ricci discussing his treatise with two Literati in Beijing. AI-generated illustration.

- Xu Guangqi and the Deepening of Scientific Dialogue

One of the most consequential relationships of Ricci’s Beijing years was with Xu Guangqi (1562–1633), a high-ranking official, mathematician, and eventually Christian convert.

LEFT: Engraving/etching on hand laid (verge) paper depicting Matteo Ricci and Xu Guangqi. From: Toonneel van China, by Athanasius Kircherus (Kircher) ed. published in Amsterdam 1667. Made by an anonymous engraver after Athanasius Kircher.

RIGHT: 17th century Chinese depiction of Xu Guangqi by an unknown author.

Together, Ricci and Xu translated parts of Euclid’s Elements into Chinese, introducing rigorous deductive geometry to China for the first time. This collaboration exemplified Ricci’s method at its best: not the transmission of European knowledge as superior, but its integration into Chinese scholarly practice.

In 1607, Matteo Ricci and Xu Guangqi published a Chinese translation of the first six books of Euclid’s Elements, titled Jihe yuanben (幾何原本).This was the first systematic introduction of Western deductive geometry into China. Rather than isolated fragments of mathematics, the translation provided a coherent theoretical system of geometry, a form of reasoning from axioms and postulates to theorem through proofs.

Ricci and Xu worked from the Latin edition of Euclid as compiled by Christopher Clavius, a Jesuit mathematician whose texts were standard in Jesuit education and emphasized rigorous, axiomatic structure.

Ricci was fluent in classical Chinese, but Xu Guangqi was essential for drafting the text in a style intelligible to the Chinese literati. In practice, Ricci orally explained the mathematical concepts (often drawing on his training under Clavius), and Xu dictated and polished the Chinese text, ensuring it read as proper classical Chinese. This oral translation + literary transcription model reflects how knowledge transfer was mediated through cross‑cultural intellectual cooperation, not through simple linguistic substitution.

Before this translation, Chinese mathematical texts, such as those found in traditional sources like The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art, tended to emphasize practical and algorithmic problem‑solving. Ricci’s and Xu’s translation, in contrast, brought a Western logic of proof — starting from clearly stated postulates and building propositions through logical deduction. This was a fundamentally different epistemic approach: the translation of Elements introduced a form of mathematical reasoning that was inherently deductive and systematic quite unlike the algorithmic orientation of classical Chinese mathematics. Some Chinese scholars were intrigued by the Greek‑style axiomatic method, even if it remained foreign to native mathematical practices.

The translation catalyzed interest among Chinese scholars in Western science. Xu Guangqi himself wrote: “In addition to the discourse on Catholicism, Father Ricci often taught me the principles of mathematics… His scholarship in astronomy and mathematics are solidly rooted in sound theoretical foundations.”

Xu’s subsequent scientific career illustrates the impact of this interaction:

- He became a pioneer of applied science in China, writing numerous scientific treatises, including on astronomy and agriculture.

- His efforts later led to the reform of the Chinese calendar in collaboration with Jesuit astronomers, producing the Chongzhen (Shíxiàn) calendar, which systematically introduced European concepts in geometry and trigonometry.

This suggests the translation was not an isolated intellectual exercise but part of a larger transformation of scientific methodology among Chinese scholars.

Although the first six books were incomplete and early reception was mixed — some Chinese mathematicians later complained Ricci and Xu “hid something” by not translating all books — the Jihe yuanben still became the first major Western mathematical text accessible in Chinese. Subsequent generations of scholars, including leading Qing mathematicians like Mei Wending (1633–1721), built on this early work, using and expanding it to develop a distinct strand of Chinese mathematical research that blended East and West.

Some contemporary scholars, as Michela Fontana and others, have highlighted Ricci’s blind spots in mathematics.

Fontana herself trained in mathematics and science, allowing her to evaluate Ricci’s scientific engagement not just historically but technically. Well, she does not idealize Ricci’s scientific knowledge; she acknowledges that Ricci’s grasp was good for his time but not cutting‑edge even by European standards, and that he exhibited prejudices or blind spots toward Chinese accomplishments in mathematics. In particular, Ricci ignored many Chinese mathematical strengths and underestimated the sophistication of Chinese mathematics. The traditional narrative of Chinese mathematics as merely algorithmic and utilitarian was common among Europeans of the period, but Ricci failed to fully appreciate forms of Chinese algebra, calendrical calculation, and combinatorial problem‑solving that were well developed in Chinese scholarly circles. This lack of appreciation wasn’t purely academic: it reflected Eurocentric assumptions — that Western mathematical logic (rooted in Euclid and Scholastic curricula) was inherently superior. Consequently, Ricci tended to view Chinese mathematics through a comparative deficit lens, seeing it mainly as something to be “corrected” or “supplemented” by Western methods.

It’s important to situate Ricci’s scientific outlook in his own intellectual formation: he was educated in the Jesuit tradition shaped by the Ratio Studiorum, which emphasized European geometry, astronomy, and mathematical methods as taught by scholars such as Christopher Clavius and Clavius’s works (which Ricci would have learned and carried) were authoritative in Jesuit colleges across Europe. But these texts reflected Western assumptions about mathematics and logical hierarchy, not a universal standard of knowledge. Thus, when Ricci encountered Chinese mathematics — which was holistic, algorithmic, and deeply tied to calendrical algorithms and statecraft — his training predisposed him to see it as lacking rigorous deductive structure (a common Jesuit measure of mathematical quality even in Europe). Fontana highlights this epistemological bias: Ricci used Western scientific categories to interpret Chinese knowledge, and when Chinese techniques didn’t fit those categories, he tended to dismiss or overlook them. This reflected a bias: European mathematics prized axiomatic structures, whereas Chinese mathematics was often problem‑oriented and algorithmic.

Moreover, Ricci’s scientific engagement was not pursued for pure epistemic curiosity alone, but as means to further his mission. Because he used science instrumentally — to gain trust and entry into elite circles — he may have been less motivated to fully investigate Chinese achievements on their own terms. The moment science became a tool for leverage rather than mutual intellectual engagement, Ricci’s own biases could overshadow genuine curiosity about how Chinese mathematics worked in its own context.

Joseph Needham, in his monumental Science and Civilisation in China, approached the same issue from the Chinese side: why did China, despite its long history of scientific innovation, not develop modern science in the Western sense? In doing so, Needham evaluated how Jesuits like Ricci misinterpreted Chinese science, and how their criteria of judgment masked China’s actual achievements. “The mathematical culture of the Chinese was vastly rich in arithmetical and algebraic procedure... but Jesuit scholars, trained in the deductive traditions of geometry, could not recognize it as mathematics.” (Joseph Needham, Science and Civilisation in China, Vol. 3). Needham thus reversed the value judgment: the flaw was not in Chinese science but in Jesuit categories of evaluation.

In conclusion, Fontana and Needham both suggest that the true dialogue between Chinese and Western mathematics never fully occurred in Ricci’s time. While he introduced new tools and methods, he did not engage with Chinese science on equal terms.

Matteo Ricci and Xu Guangqi working together at the translation of Euclid’s Elements, 1606.

In a quiet study in late Ming dynasty China, two figures leaned over a table strewn with parchment, bamboo brushes, and diagrams of circles and triangles. Matteo Ricci, the Jesuit scholar in dark robes trimmed in the Chinese scholar's fashion, read slowly from the Latin Elementa, translating aloud into refined spoken Chinese. Beside him, Xu Guangqi, a high-ranking Confucian official and polymath, listened intently, his brow furrowed in concentration. As Ricci spoke, Xu jotted notes in classical Chinese, stopping often to ask for clarification—not only of words, but of principles. “Why must the proof begin this way?” he might ask, or “Is this what your people mean by ‘axiom’?” Their exchange was not rote translation, but intellectual negotiation: an attempt to transfer not only terminology, but an entire framework of logical reasoning from West to East. Together, they debated the right expression for point, line, and angle, settling not just on equivalence but elegance—how to capture mathematical precision in a language rooted in moral philosophy and classical literature. Some terms they coined anew; others they adapted from ancient Chinese texts. Diagrams were drawn and redrawn; parallel lines tested and demonstrated with string, compass, and ink. It was not a mechanical task but an act of cultural fusion—where language, logic, and worldview had to meet halfway. Xu ensured that the final Chinese text resonated with clarity and Confucian sensibility. Ricci, for his part, offered not only the content of Euclid but a method of thinking—rigorous, deductive, and startlingly foreign.

- Beyond Mathematics: Astronomy and Calendar Reform

Matteo Ricci was not merely a missionary but also a trained scientist: before embarking for China he studied mathematics and astronomy under Christopher Clavius (1538–1612) at the Jesuit Roman College — one of the premier centers of scientific learning in Europe at the time. Clavius’s work on geometry, cosmology, and astronomical computation was deeply influential in shaping Jesuit instruction and Ricci’s own intellectual formation, and some of Clavius’s texts were later translated into Chinese by Ricci and his colleagues. This foundational training enabled Ricci to present European astronomy not just as odd curiosity, but as a well‑organized scientific system, complete with geometrically based prediction methods, instruments, and mathematical tables — in contrast to many contemporary Chinese methods which were algorithmic and codified in traditional calendrical manuals.

One of the most striking differences between European and Chinese astronomy in Ricci’s era was the precision of prediction:

- Traditional Chinese astronomy was deeply connected to state ritual, astrology, and calendrical symbolism. Accuracy mattered primarily in terms of omens and cosmic order, tied to imperial legitimacy.

- European astronomy, especially in the Jesuit tradition, was increasingly mathematical and astronomical — models were built to predict celestial events such as solar and lunar eclipses with high numerical precision.

To the Chinese court, accuracy in predicting astronomical events was not merely technical: it was a symbol of cosmic legitimacy. The ability to predict an eclipse correctly was seen as an expression of understanding the mandate of heaven and the cosmic order.

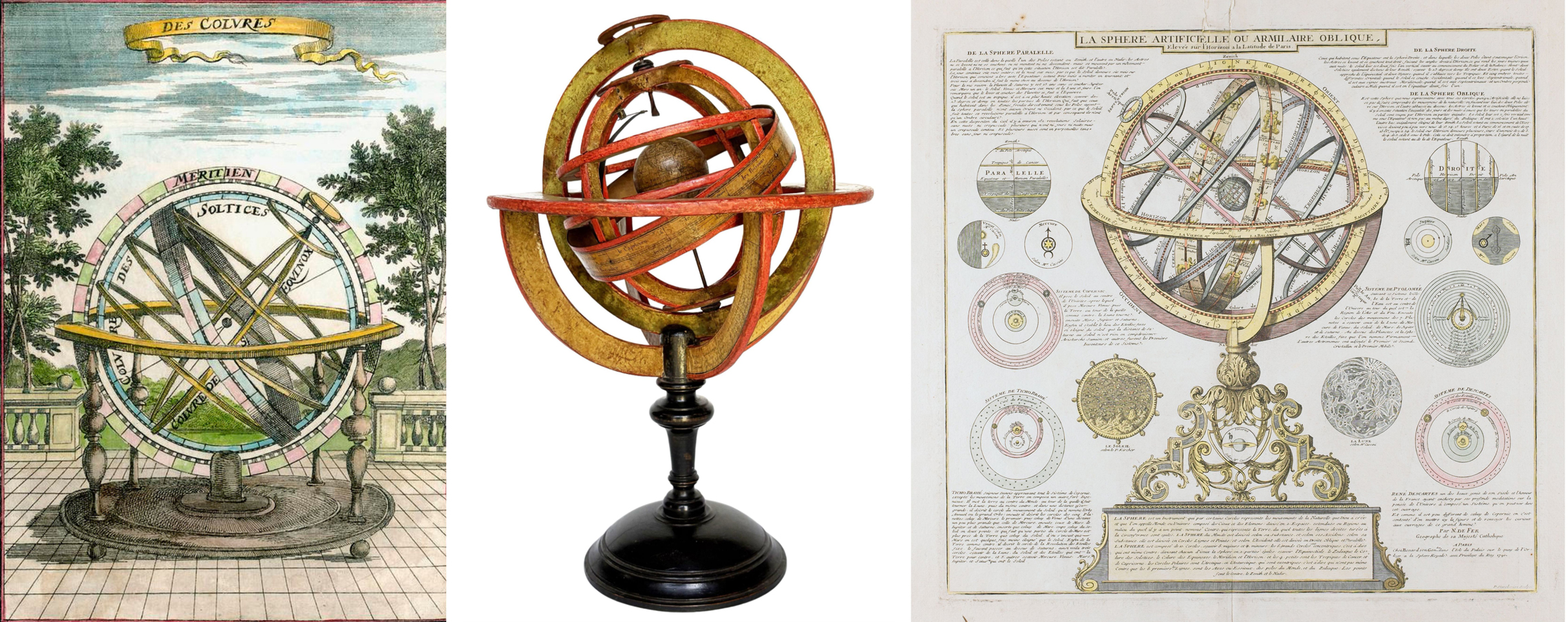

Ricci and his Jesuit colleagues brought and constructed Western‑style astronomical instruments: armillary spheres, celestial globes, and measuring devices capable of tracking celestial coordinates with improved precision. These were already known in Europe as tools for geometric astronomy and were part of Jesuit cosmographical education. Their use impressed Chinese literati and officials because they yielded numerically precise observations and tables.

LEFT: The armillary sphere in a 17th century artwork by Detlev Van Ravenswaay. It depicts a French armillary sphere made in 1685 by the French mapmaker Alain Manesson Mallet (1630-1706). This astronomical device shows the circles of the celestial sphere, and is used to demonstrate the motion of the stars around the Earth. The circles surrounding the Earth include the plane of the ecliptic, and the celestial equivalent of the equator, North and South Poles, and the Tropics of Capricorn and Cancer. Here the two main celestial meridians (colures) are marked, those of the equinox and the solstices.

CENTER: Ptolemaic armillary sphere by Charles-François Delamarche, Paris, before 1798. Medium: Wood and papier-mâché, covered with printed and partly hand-coloured paper. Dimensions: 16.37 in in height x Ø 10.94 in (41.60 cm – Ø 27.80 cm). This Ptolemaic sphere has the Earth placed at its centre, surrounded by the Moon and the Sun mounted on two metal arms. The sphere is composed of six horizontal and two vertical rings (armillae), each bearing graduations and its own name. The first horizontal ring is illegible. The others, in descending order are: North Pole, Tropic of Cancer, Equator, Tropic of Capricorn, South Pole. The vertical rings consist of two double meridians. The sphere is then connected to the large meridian by two pins, a vertical ring inserted perpendicularly into the circle of the Horizon, in turn supported by four semicircles connected to the turned and black-stained wooden base. Each element is covered with printed paper. It contains various pieces of information: latitudes, length of days, names and zodiac symbols, calendar, wind directions, etc. 1st DIBS.

RIGHT: The Artificial or Oblique Armillary Sphere, hand-colored engraving after Nicolas de Fer, engraver P. Starckmann, 1740. This complicated engraving also depicts four competing interpretations of the cosmos-those of Ptolemy, Copernicus, Tycho Brahe, and Descartes-as well as the uneven surface of the Moon (note the mountains and deep craters), first observed by Galileo in 1609. MIA, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota, USA.

A Ptolemaic armillary sphere of the 16th and 17th centuries was a mechanical model of the geocentric cosmos, with the Earth fixed at the center and the heavens revolving around it. It offered a three‑dimensional representation of Aristotelian–Ptolemaic cosmology, similar to those displayed by missionaries in China to illustrate European astronomy. It took the form of a “skeletal” celestial globe, composed of a series of graduated metal rings (armillae) representing the celestial equator, the ecliptic, meridians, parallels, the tropics, and the polar circles. At its center there was usually a small terrestrial sphere, symbolizing Ptolemy’s geocentric system; by moving the rings one could visualize the apparent motions of the Sun, stars, and planets around the Earth. During the Renaissance and Baroque periods, it served above all as a didactic instrument for demonstrating the structure of the universe according to Ptolemy and, when required, for contrasting it with the Copernican system. It was also a prestigious object of study and a display of learning, found in studioli, scientific collections, and portraits of scholars and princes, while Jesuit missionaries used it as a powerful visual aid to introduce European astronomy at Asian courts.

Matteo Ricci explaining the structure and functioning of an armillary sphere in Beijing in 1603. AI-generated illustration.

Chinese star catalogs and calendrical tables were already sophisticated, but the Jesuit instruments and methods provided new ways of systematizing celestial measurements in geometric terms, which literati found intellectually intriguing even if they were not immediately adopted wholesale.

When Ricci reached Beijing in 1601, he was invited in part to assist with astronomical and calendrical matters — a recognition of the technical value of European astronomy.

Ricci’s early astronomical efforts in Beijing had three characteristics:

- Demonstration of Western Astronomy: Ricci shared geometric and numerical methods with Chinese literati, showing how European methods could complement Chinese calendrical practice.

- Instrumental Collaboration: While Ricci himself did not reform the calendar, he requested assistance from Rome for Jesuits better trained in astronomy, paving the way for later figures like Sabatino de Ursis to make early predictions of eclipses.

- Intellectual Engagement with Scholars Like Xu Guangqi: Ricci’s Chinese collaborators, especially Xu Guangqi, acted as both translators and interlocutors in scientific dialogue, helping to situate European astronomy in the context of Chinese intellectual traditions.

Ricci’s actual pioneering astronomy laid the groundwork for more systematic application after his death. A decisive moment occurred with the solar eclipse of 21 June 1629: Jesuit astronomers (including later figures like Schall von Bell) and Chinese astronomers both predicted the eclipse. The Chinese official prediction was off by about one hour, while the Jesuit prediction was remarkably accurate. This enhanced the credibility of Western astronomical methods in the eyes of the imperial court and helped convince officials of the need for comprehensive calendar reform.

Such events illustrate not only the technical superiority of the Jesuit approach in specific cases but show how astronomy became a bargaining chip for cultural and political influence in imperial science.

The most important result of this astronomical exchange was the development of the Chongzhen calendar (also called the Shíxiàn calendar) in 1645:

- Led by Xu Guangqi (Ricci’s former Chinese collaborator) and the Jesuit scholars Johann Schreck, Johann Adam Schall von Bell, and others.

- Represented a systematic integration of Western mathematical astronomy into the traditional Chinese calendrical framework.

- Included geometric and trigonometric tools, astronomical tables, and a practical ephemeris that drew on European methods going beyond earlier Chinese calendar reform efforts.

This calendar was used for centuries — from the late Ming through much of the Qing era — and marked a lasting scientific legacy of Jesuit astronomy in China. It incorporated European geometric models and spherical astronomy into Chinese calendrical computation, effectively bridging two astronomical traditions.

In imperial China, the calendar was not an abstract scientific matter: it was embedded in statecraft, ritual correctness, and the notion that the emperor mirrored the cosmic order. Mistakes in predicting celestial events were interpreted as signs that the ruling dynasty had lost cosmic mandate. Hence, calendar reform carried political as well as scientific weight. Jesuit astronomy was therefore more than a technical demonstration: it directly engaged with the political and symbolic heart of Chinese imperial authority.

Ricci himself understood this: he did not merely share astronomical knowledge because it was interesting — he saw that astronomy could earn Jesuits respect and access within the Chinese elite. His appeals for trained astronomical missionaries to be sent to China were aimed at building scientific credibility that could open doors for broader intellectual and cultural exchange. In this way, Ricci’s astronomy was both scholarly and strategic: technical content served missions of cultural mediation and political negotiation.

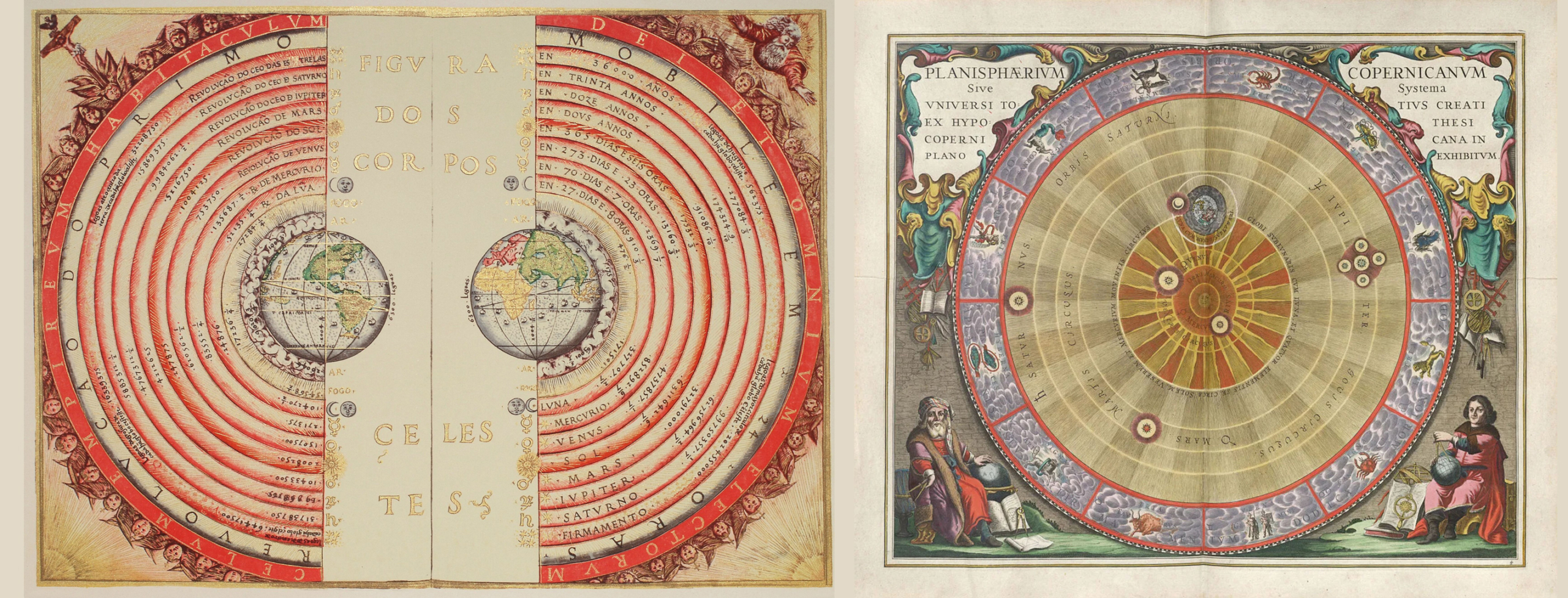

The integration of Western mathematical astronomy into Chinese science, which began with Ricci and his collaborators, was a genuine and long-lasting cross-cultural scientific achievement. However, Ricci and the other Jesuits taught and popularized the old Aristotelian–Ptolemaic system. This is evident from the structure of the armillary spheres they used.

Criticisms of the Ptolemaic system had already been well-developed by the time Galileo came along, both in the Middle Ages and in the 16th century. In the 1500s, these criticisms evolved into genuine alternative programs, culminating in Copernicus's work. Galileo's first essay, Sidereus Nuncius, was published in 1610, the year of Ricci's death. His other major works followed in subsequent years: Il Saggiatore, 1623; Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo, 1632; Discorsi e dimostrazioni matematiche intorno a due nuove scienze, 1638. However, already between the 12th and 13th centuries, philosophers such as Averroes and other Aristotelian commentators challenged Ptolemy’s mathematical devices (epicycles, eccentrics, equant), accusing him of violating Aristotle’s physics and the ideal of uniform circular motion. In the 11th century Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) wrote the treatise Doubts Concerning Ptolemy, sharply criticising various aspects of the Ptolemaic model, even though he did not thereby abandon geocentrism as such.

At the beginning of the 16th century European astronomers were already vigorously debating the problems of the Ptolemaic model, especially the equant and the discrepancies between its geometrical construction and the phenomena observed (for example the apparent variations in the sizes of the Moon and the planets). Copernicus entered this debate: in De revolutionibus (1543) he proposed the heliocentric system also as a response to the internal inconsistencies of the Ptolemaic model, seeking a system of circular motions that was more regular and “harmonious” and that, among other things, eliminated the equant.

After Copernicus, authors such as Thomas Digges and other supporters of heliocentrism continued to develop arguments against Ptolemaic geocentrism in the second half of the 16th century, combining geometrical considerations with planetary observations. When Galileo entered the scene (in the first decades of the 17th century), he found an existing tradition of theoretical and geometrical criticism of the Ptolemaic system; his specific contribution would be the systematic use of the telescope (the phases of Venus, the satellites of Jupiter), which decisively undermined the classical Ptolemaic model.

LEFT: Figure of the heavenly bodies, illuminated illustration of the Ptolemaic geocentric conception of the Universe by Portuguese cosmographer and cartographer Bartolomeu Velho (?-1568), fom his work Cosmographia, published inFrance in 1568 (Bibilotèque nationale de France, Paris).

RIGHT: The Copernican Planisphere, illustrated in 1661 by Andreas Cellarius. Wikimedia Commons.

Ricci promoted a geocentric model of the cosmos—that is, one where the Earth was at the center of the universe, surrounded by concentric spheres of the Moon, planets, and stars. This is consistent with the Ptolemaic system, as modified and taught by Aristotle and medieval Scholastics, especially in the Jesuit tradition. Instruments like celestial globes and didactic diagrams Ricci used were based on this geocentric model. He explicitly avoided teaching Copernican heliocentrism, which he knew would be both controversial in China and had not yet been endorsed by the Catholic Church (in fact, it was becoming suspect in Rome by the 1610s).

As historian David E. Mungello notes: “Ricci’s presentations of Western astronomy were consistent with traditional geocentric astronomy… Ricci avoided Copernicanism and stuck to the Aristotelian-Ptolemaic model that was institutionally sanctioned within the Jesuit order.” (D.E. Mungello, The Great Encounter of China and the West, 1500–1800)

Why?

It's not because he was "a man of his time," since many contemporary scholars and scientists had embraced Copernicus's revolution or rejected the unnecessary complications of the old Aristotelian-Ptolemaic system. Ricci chose to defer to the Roman Church's cautious stance on heliocentrism. At that time:

- Copernicus’s De revolutionibus (1543) was known but not widely accepted as a physical reality (even in Europe).

- Galileo’s support for heliocentrism became a major controversy after Ricci's death.

- Jesuits were officially teaching the geo-heliocentric Tychonic system in Europe by the early 17th century, but this did not yet spread to Ricci’s China.

Ricci was not trying to enforce Ptolemy’s system as a superior worldview, but rather to “demonstrate that the Christian West possessed a rational and accurate understanding of the natural world, deserving of intellectual respect.” (Nicolas Standaert, Handbook of Christianity in China).

Therefore, Ricci’s astronomy reflected the “official science” of the Counter-Reformation Catholic world, where Ptolemy + Aristotle + Euclidean geometry defined cosmological teaching. It’s important to note that Ricci’s scientific mission was instrumental, not ideological. He used Western astronomy and cartography as tools of cultural prestige, to impress literati with European knowledge and as bridges to theological and philosophical dialogue, not ends in themselves. This reveals an important aspect of Matteo Ricci: even before being a refined and cultured intellectual, he was a man of the Church, firmly grounded in the Catholic faith, tradition, and dogma. These strong, deep roots nourished his missionary vocation, which was never dormant or forgotten, even when he discussed non-religious topics on equal terms with his friends.

Modern historians stress that Ricci’s astronomical influence was pragmatic and dialogical:

- He did not simply transplant European astronomy wholesale; rather, he adapted its methods (e.g., geometric reasoning, precise observation, and mathematical computation) to Chinese interests in calendars and celestial phenomena.

- Ricci’s emphasis was not ideological but comparative, showcasing the utility of Western scientific tools while respecting Chinese traditions enough to enter intellectual dialogue.

This approach opened the door for later Jesuits — such as Sabatino de Ursis and Johann Schall von Bell — to engage more deeply with calendar reform and institutionalized astronomy at the Qing court.

5. Tensions, Criticism, and the Limits of Accommodation

Despite his success, Ricci faced growing criticism. Some Confucian scholars accused him of smuggling foreign religion under the guise of moral philosophy. Others objected to his reinterpretation of Confucian Heaven as a personal God, and there were Literati who did not accept Ricci's strenuous opposition to Buddhism.

Within the Jesuit order itself, debates intensified over the legitimacy of Ricci’s accommodationist approach. These tensions would erupt after his death in the Chinese Rites Controversy, but their seeds were already present in Beijing. We will talk about this later on, though.

Ricci was aware of these dangers. His later writings are more cautious, more carefully argued, and more attentive to possible misinterpretations. He never abandoned accommodation, but he refined it.

Hi last years in Beijing were not easy. His existence was a marathon of social performance. His residence became a mandatory stop for officials, examination candidates, and curious literati. Diego de Pantoja, his young Spanish companion, confessed in letters the tedium of endless banquets and repetitive questions about Western customs. Ricci, more disciplined, attended two or three banquets daily, answering the same queries with patience, displaying clocks and maps, and subtly weaving Christian doctrine into discussions of morality and science.

This ceremonial life was not mere sociability; it was a form of missionary labor. Ricci understood that in a culture built on guanxi (關係, personal connections), trust preceded belief. By submitting to the exhausting rituals of friendship—reciprocating visits, composing poems for patrons, offering medical advice—he earned the right to be heard.

His letters reveal his pride in his achievements, such as mastering the Chinese language and cultivating relationships with scholars. However, they also reveal his vulnerability, loneliness, melancholy, and intense physical fatigue, which he does not hide from his correspondents.

He confides in them about the exhaustion of constantly receiving guests, always having to repeat the same explanations about Western customs, and maintaining a regular religious life alongside an almost worldly social life, which requires very strong personal discipline.

AI-generated illustration.

This painting beautifully stages a fictionalized banquet scene that evokes the historical encounter between Matteo Ricci, Diego de Pantoja, and high-ranking Chinese officials or mandarins. Ricci (the bearded elder in blue) and Pantoja (younger figure in green) are wearing scholar-official robes similar to shenjishan (deep robes) and black wushamao hats, which Ricci adopted to blend with Confucian literati culture. The seated mandarin wears red robes with imperial motifs, possibly representing a high-ranking minister or a prince, not the emperor himself — more plausible historically, as Ricci was never granted private audience with the emperor. The setting is a lavishly decorated private interior, plausible for a banquet hosted by an elite Chinese mandarin, especially one from the Six Ministries or the Hanlin Academy, which Ricci visited. The inclusion of guards and servants suggests formality, but not the overwhelming ceremonial rigour of the imperial court. The two Jesuits are shown bowing respectfully, in line with Chinese etiquette, without overstepping court protocols. The mood is one of diplomatic courtesy, suggesting cultural recognition rather than submission or spectacle.

Ricci's passed away in May 1610, likely from exhaustion, prompted a Chinese official to call him a “martyr of friendship”.

When Ricci died, the response of Chinese officials was extraordinary. He was granted burial in the capital—a privilege almost never accorded to foreigners. This act signaled not conversion at the imperial level, but recognition: Ricci had become part of the moral and intellectual landscape of late Ming China.

His desire to be buried in China—which was granted by imperial exception—indicates his existential attachment to the country and its people. His personal vulnerability is somehow encapsulated in his difficult position: he was light years away from his original world, from his Jesuit brothers and friends left behind in Italy, but he was not a Chinese among Chinese, nor could he be considered as such. To which world did he belong? This question probably plagued him greatly in the last years of his life. But we somehow know the answer: Matteo Ricci lived and died on the bridge he had built. An imperfect bridge, full of flaws, but still a bridge where people could meet. And that bridge was no longer in Italy or China. Did he live in a permanent in-betweenness, both culturally and metaphysically?

April 1610: Mateo Ricci was feeling exhausted from his intense lifestyle. AI-generated illustration.

The most reliable sources speak of a death due to a rapid deterioration in physical condition, linked above all to extreme and prolonged fatigue, rather than to a single clearly identifiable acute illness. Accounts by his fellow brothers (such as De Ursis and Aleni) describe a deterioration that began in early May 1610 and lasted just over a week, following years of exhausting work, many previous illnesses, travel, stress, and a very demanding lifestyle.

Matteo Ricci's Final Moments. AI-generated illustration.

Matteo Ricci became ill on May 3, 1610, while still in Beijing. His illness lasted just over a week, and he died on May 11, 1610. According to Jesuit accounts, the primary cause of his illness was extreme fatigue and overwork. Ricci had been overwhelmed by continuous engagements — receiving visits from scholars, official duties, project work (including science, translation, and evangelization), and managing many civic and mission responsibilities. This unrelieved exertion took a heavy toll on his health and is described as leading directly to his fatal sickness. Some accounts note that he may have had fever symptoms toward the end of his life, but there’s no clear modern medical diagnosis recorded in the historical sources. According to missionary-era journals, three Chinese doctors were summoned to Ricci’s bedside during his last illness. The accounts suggest that they disagreed on both the underlying problem and the remedies, and that their treatments did not significantly help him. Ricci was also cared for by his fellow Jesuit missionaries, who remained at his side, provided spiritual support, and administered the sacraments according to Catholic practice as his condition worsened. Jesuit accounts describe his final days as calm and spiritually focused, with fellow missionaries gathering around him in his last hours.

Matteo Ricci asked to remain in China.

Not in the land that had given him a name, a language, and a faith shaped by bells and stone,

but in a place whose earth had received his footsteps for half a lifetime,

whose words had reshaped his mind,

whose silences had taught him patience.

The imperial permission that allowed his burial in Beijing was an exception,

yet exceptions are often the truest confessions of history.

It said, without proclamation, that he had become unclassifiable.

Not fully foreign, never native.

Tolerated, respected, but never absorbed.

In his final years, he stood far from Italy —

from the rhythm of Latin prayer, from the faces of his youth,

from the Jesuit companions who would never again hear his voice.

But China, too, remained just beyond his grasp.

He spoke its language with precision,

wore its robes with dignity,

thought through its categories with care —

and still, he was always other.

To which world did he belong?

Perhaps that question followed him quietly,

as illness thinned his body and the noise of the capital faded.

Perhaps it had no answer that could be spoken aloud.

Yet his life suggests a different resolution.

Matteo Ricci did not live between two worlds —

he lived on what he built to connect them.

A narrow crossing, suspended above misunderstanding and hope.

A bridge made of translation, trust, and unresolved tension.

Imperfect, uneven, asymmetrical, and sometimes fragile —

but real enough for others to walk upon.

He died there, not arriving, not returning.

Neither in Italy, nor in China.

But in the space that exists only when someone dares

to believe that mutual understanding is worth the cost of belonging nowhere.

And so his resting place is not merely a grave in Beijing soil.

It is the mark of a life that chose encounter over certainty,

listening over triumph,

and left behind no answers.

He left a passage.

Not a destination,

but an invitation to peace.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?