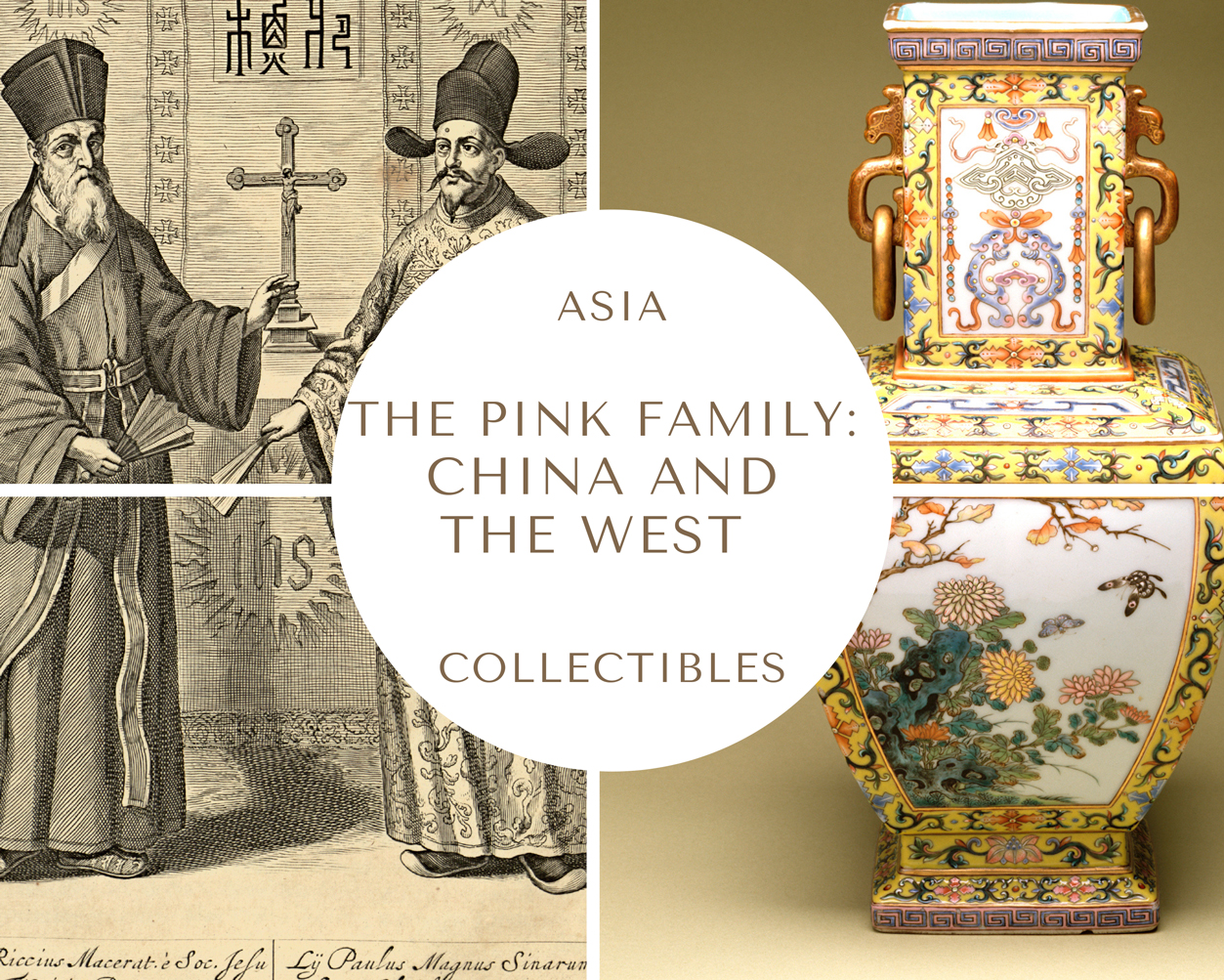

THE PINK FAMILY: CHINA AND THE WEST 10

Current China on the globe.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

This map is for illustrative purposes only. The Ethnic Home does not take a position on territorial disputes.

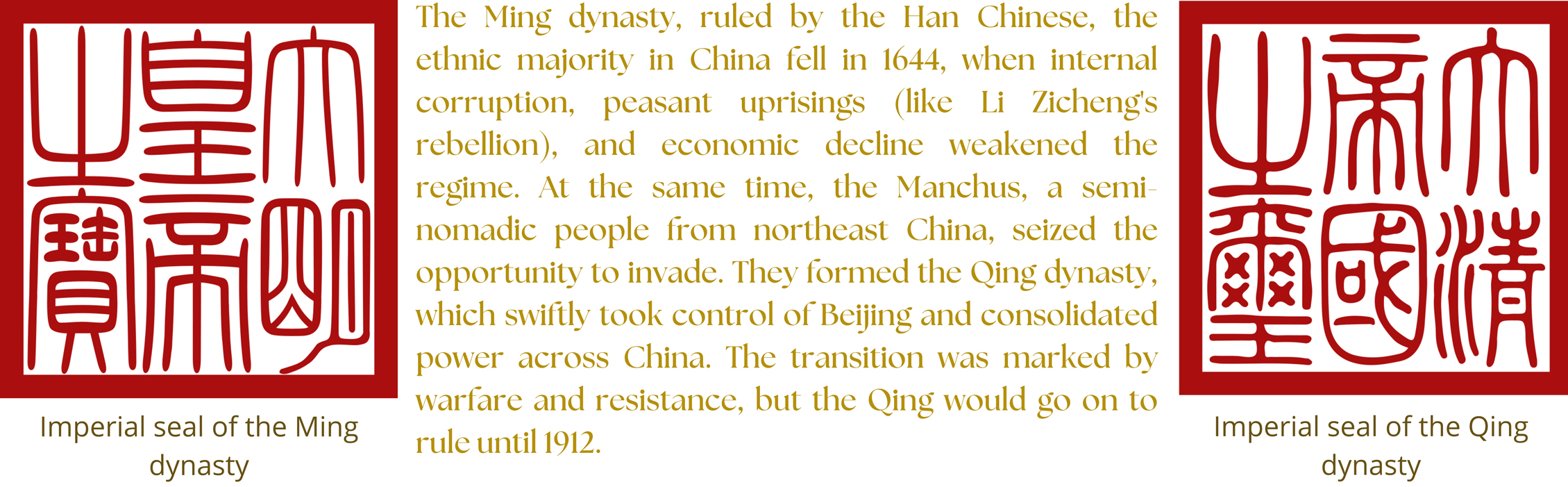

LEFT: Portrait of the Yongzheng Emperor in Court Dress, by anonymous court artists, Yongzheng period (1723—35), Qing Dynasty. Hanging scroll, color on silk. The Palace Museum, Beijing. Public Domain.

RIGHT: History of China, Imperial Dynasties, source: Dynasties in Chinese history, Wikipedia.

An Assessment of Matteo Ricci's Cross-Cultural Dialogue in China

Contemporary scholarship emphasizes that, although Ricci’s mission opened unprecedented avenues for intellectual exchange between China and the West, the process was marked by asymmetry in intent and outcome. Ricci sought to establish common ground while remaining committed to preserving the integrity of Christian doctrine.

Although his approach was respectful of Chinese culture, his ultimate aim was evangelization. This dual commitment to cultural adaptation and religious conversion generated tensions that scholars regard as intrinsic to his cross-cultural project. "Ricci consistently emphasized the superiority of Christian revelation. His persona as a Confucian scholar was not intended to dissolve doctrinal boundaries, but rather to create a space in which Christian truths could be heard. Rule (1986) observes that Ricci’s cultural adaptation was instrumental in providing a pathway to dialogue whose ultimate aim was conversion. The tension between openness and exclusivity thus defined his mission." (Shuangyang Qi and Meng Yan, Matteo Ricci and Sino-Western Encounters in Late Ming China: Cultural Exchange, Adaptation, and Conflict, September 2025).

This analysis highlights a critical aspect of intercultural dialogue: respect and empathy do not negate the inherent asymmetry when one party seeks to transform another spiritually. Ricci’s mission was not a neutral, bidirectional dialogue in the modern sense. Rather, it was shaped by a clear purpose—religious conversion—which defined the boundaries and nature of the conversation. Ricci was not pursuing mutual philosophical synthesis for its own sake. His goal was to make Christian doctrine intelligible and persuasive within a Chinese conceptual framework.

Thus, while his approach opened intellectual and relational doors, it was ultimately constrained by theological exclusivity and an unequal distribution of aims.

His efforts to harmonize Chinese ethical concepts with Christian theology highlight another structural tension: the intersection of philosophical engagement and theological exclusivity. His reinterpretation of Chinese ritual practices, particularly ancestral rites, later sparked the Chinese Rites Controversy. This episode illustrates how the very accommodations that initially enabled dialogue became sources of deep conflict, both within the Catholic Church and between missionaries and Chinese intellectuals. It reveals the limits of intercultural synthesis when universalist truth claims collide with deeply rooted indigenous traditions.

Following Ricci’s death in 1610, the Chinese Rites Controversy erupted among Catholic missionaries. The dispute centered on the compatibility of Confucian and ancestral rites with Christianity. Were these practices permissible cultural traditions, or were they religious rituals considered idolatrous and incompatible with Christianity? Ricci’s intellectual descendants, the Jesuits, argued that these practices were civil, not religious, and could be tolerated to facilitate conversion. However, the Dominicans and Franciscans disagreed, branding the rites as idolatrous. The Vatican eventually weighed in. Initially tolerant, the Church reversed its position in 1704 and again in 1742 when Popes Clement XI and Benedict XIV formally condemned the rites and forbade Catholic participation. This decision eroded the Qing imperial court's trust, as such rituals were integral to political loyalty and moral order. Consequently, Christian missions lost favor, and the Church was viewed as antagonistic to Chinese cultural tradition. This position was not formally reversed until 1939, when Pope Pius XII took office.

This was not the only controversy to emerge in Ricci’s wake. Although he embraced some aspects of Confucianism, Ricci was highly critical of Buddhism and Daoism. As Tang (2016) notes, Ricci’s rejection of Buddhism and Daoism was framed not only in theological terms, but also as a strategy to align Christianity with the ruling Confucian ideology. In debates with monks such as Sanhuai, Ricci dismissed Buddhist metaphysics as nihilistic and socially harmful. Ricci’s rejection of Buddhism was partly strategic. By aligning Christianity with Confucianism and against Buddhism, he sought to embed his faith within the ruling ideology of the literati. In this sense, his polemics were less about genuine philosophical engagement than political positioning. However, this tactic reinforced antagonism between Christian converts and Buddhist communities, planting the seeds of later tension (Shuangyang Qi & Meng Yan, 2025).

Evaluating Ricci’s Intercultural Dialogue

Ricci’s project transcended the Chinese context; it catalyzed a transnational exchange of ideas. His writings influenced how Enlightenment Europe viewed China, prompting a reevaluation of Western beliefs about politics, ethics, and cosmology. As Pu Jingxin notes, Ricci "set a precedent for future intercultural exchanges" and helped lay the foundations for modern global dialogue. (Matteo Ricci’s Contribution to Sino-Western Cultural Exchange, 1583–1610, "Journal of Cultural and Religious Studies", 12 (11), November 2024).

Ricci’s legacy is ambivalent by nature:

Productive: His work enabled wide-ranging scientific, linguistic, artistic, and philosophical exchanges. His world maps, translations, and introduction of Euclidean geometry to Chinese audiences broadened intellectual horizons and provoked serious epistemological debates within Chinese scholarship. "Ricci's activities established the foundations of a Sino–Western dialogue that would reverberate across centuries, shaping both Chinese intellectual life and European perceptions of the Middle Kingdom." (Shuangyang Qi & Meng Yan, cited).

Tense: His mission also exposed the persistent conflict between historical-critical interpretation and the dogmatic demands of theological orthodoxy, culminating in ecclesiastical and cultural controversies.

Ricci’s dialogue with Chinese scholars marked a turning point in global intellectual history. It combined genuine admiration for Chinese civilization with a steadfast dedication to the Christian message. The encounter:

- Enabled profound philosophical and epistemological exchange.

- Reshaped Chinese and European intellectual traditions.

- Revealed the potential and limitations of intercultural dialogue in the face of non-negotiable doctrinal commitments.

Ricci remains a pivotal figure in the history of cross-cultural engagement. His life and work are rich in insight and are marked by the complexities of power, faith, and cultural translation.

Ultimately, Ricci’s story shows us that true intercultural dialogue is not about seeking perfect equivalence, but rather, building provisional bridges, fragile yet functional structures capable of bearing the weight of misunderstanding and difference. His memory palace, whether real or metaphorical, was built not of stone but of texts, relationships, and rituals—a delicate architecture that, for a time, spanned the immense distance between Rome and Beijing, the West and the East.

Even after his death, Ricci’s influence endured. His writings, converts, and legacy sustained the momentum of Jesuit missions in China. To fully understand this legacy, we must examine the dialogue he initiated through not only theological and philosophical frameworks but also the artistic, relational, and human dimensions of cultural exchange.

Who ultimately crossed Ricci’s imperfect, asymmetrical bridge, and what did they carry across? That is the question. Let us explore it not with equations, but with imagination. I promise there will be surprises.

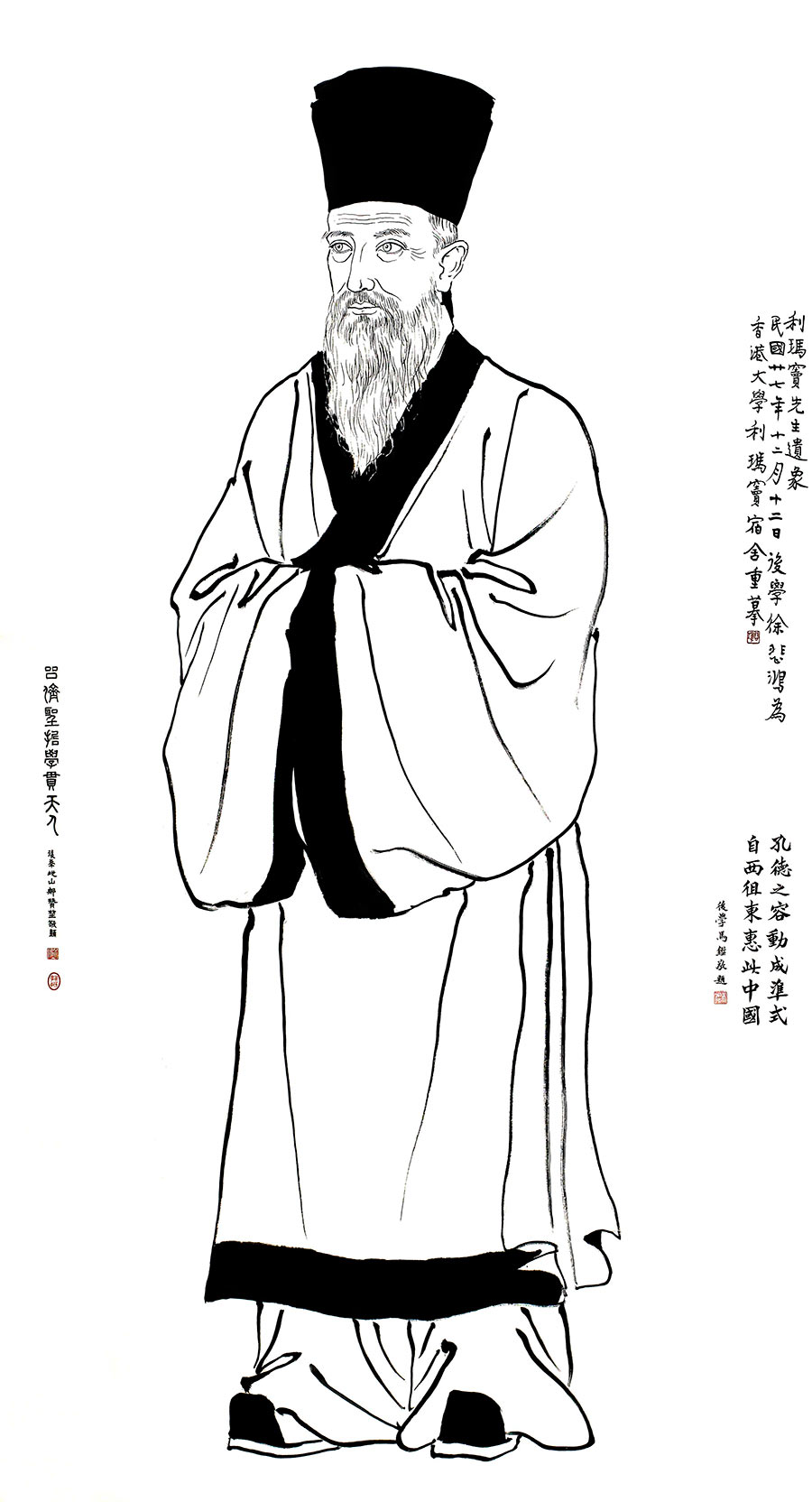

Matteo Ricci, attributed to Xu Beihong, 1938. Ink on paper. Courtesy of the University of Hong Kong Museum and Art Gallery.

"The Jesuit influence in China waxed and waned along with the state of diplomatic relations between China, Europe and the Papacy. With the dissolution of their order by the Pope, the Jesuits left China in 1773, but returned after their reinstatement in the 1840s. They continued to support Chinese culture at their seminary founded in Shanghai, introducing there the first systematic teaching of Western art in China. The artists whom they nurtured became major contributors to the Chinese art world, consciously following Castiglione's blending of Eastern and Western traditions. It is in this spirit that Xu Beihong (1895-1953) painted a portrait of Matteo Ricci, for the Ricci Institute at the University of Hong Kong, modeling his own infusion of naturalism into Chinese art on that of Castiglione". (Text by the National Palace Museum of Taipei, realized for the 2016 exhibition Giuseppe Castiglione - Lang Shining - New Media Art Exhibition)

From Ricci’s Missionary Vision to Castiglione’s Sino‑Western Synthesis: Jesuit Continuity in China

Matteo Ricci’s missionary approach in China was notable for its combination of religious, intellectual, and cultural strategies. Instead of relying solely on theological argumentation, Ricci and his fellow Jesuits used Western scientific knowledge, including astronomy, mathematics, cartography, and mechanical devices, to engage with elite Chinese interlocutors. By presenting these disciplines in classical Chinese and embedding them within Confucian moral discourse, the Jesuits positioned themselves as learned men of utility who could contribute to the intellectual life of the Ming literati. This multidimensional strategy secured the Jesuits a degree of cultural credibility and courtly access exceptional among early modern missionary enterprises.

Visual and material culture also formed part of this broader Jesuit engagement. Ricci and his colleagues introduced world maps, astronomical instruments, and engravings of biblical scenes or European urban landscapes. Although Ricci himself was not a trained artist, displaying and exchanging such visual materials emphasized the epistemological distinctiveness of European knowledge systems, particularly in fields such as cartography and geometric representation. Though formal artistic training was not yet a priority for the Jesuits in China, circulating these objects contributed to growing curiosity about Western modes of visualization. Technical discussions of perspective and pictorial theory, however, remained limited in this early period.

During the 17th century, the Jesuits cultivated cultural legitimacy by demonstrating their expertise in scientific fields. Their proficiency in areas such as astronomical prediction, calendar reform, and mathematics was particularly valuable during the early Qing dynasty, especially during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1661–1722).

Jesuit scholars such as Ferdinand Verbiest and Adam Schall von Bell held official posts at the imperial court, often serving as calendrical experts or technical consultants. These roles offered structured access to court life beyond explicitly religious functions, reflecting the Jesuits' broader role as cultural brokers.

LEFT: A 1766 portrait of Ferdinand Verbiest (1623–1688), a Flemish Jesuit missionary who worked in China during the Qing dynasty. Verbiest became one of the most influential Westerners in Qing China. He served at the court of the Kangxi Emperor and led the Imperial Observatory in Beijing, modernizing Chinese astronomy with European methods. Verbiest also contributed to cartography, mechanics, and diplomacy, helping to solidify the Jesuits' scientific and political influence at court. His work exemplified the fusion of science and evangelization during the Jesuit China missions.

RIGHT: A portrait of German Jesuit Johann Adam Schall von Bell (1592–1666), who was a missionary in China during the Ming and Qing dynasties from 1622 until his death in 1666. Anonymous hand-colored engraving, 31.1 x 21 cm, 1667. Plate title: "P. Adam Schall Germanus I. Ordinis Mandarinus" ("Father Adam Schall, the German mandarin of the first order"), from Athanasius Kircher's Tooneel van China... Jan Hendrick Glazemaker (Amsterdam: Johannes Janssonius van Waesberge, 1668). A German Jesuit and Verbiest's predecessor, Schall von Bell played a crucial role in reforming the Chinese calendar under the Ming and early Qing dynasties. He was appointed director of the Imperial Astronomical Bureau and earned favor with the Shunzhi Emperor. He was later granted the rare privilege of being buried in Beijing. His life reflects the successes and vulnerabilities of missionary-scholars at the imperial court; he was imprisoned during a political backlash against Christian influence shortly before his death.

AI-generated illustration.

By the late 17th and early 18th centuries, this model had expanded to encompass visual culture. The Qing dynasty's interest in Western artistic techniques, particularly linear perspective, chiaroscuro, and naturalistic portraiture, generated specific requests for Jesuit artists. In response, the Society of Jesus began sending individuals with preexisting artistic training to meet these demands. Although Jesuit training focused primarily on theology, philosophy, and classical languages, missionaries with exceptional artistic, medical, or musical skills were often selected for specialized roles in foreign courts or scholarly settings. This pragmatic flexibility allowed the China mission to adapt to changing imperial interests without establishing a formal artistic curriculum within the order.

Giuseppe Castiglione (1688–1766), an Italian Jesuit trained in painting before entering the Society, exemplifies this dynamic. Sent to China in 1715, Castiglione entered imperial service under Kangxi and went on to serve the Yongzheng and Qianlong emperors. At court, he developed a distinctive style fusing European spatial illusionism with Chinese compositional conventions, formats, and materials. His body of work reflects a negotiated synthesis shaped by imperial patronage, court protocols, and his own capacity for cultural translation, rather than the imposition of a Western aesthetic.

By the mid-Qing period, artistic production had joined scientific and technical expertise as a core domain of Jesuit contributions to the imperial court. Paintings, alongside astronomical instruments and translated texts, functioned as diplomatic and epistemological instruments, facilitating exchange, aesthetic admiration, and soft power. Although the Qing state imposed increasingly strict limits on Christian evangelization, the Jesuits' emphasis on cultural accommodation persisted. Castiglione’s long and successful career illustrates how Ricci’s foundational approach of engagement through knowledge, aesthetics, and elite dialogue continued to evolve and adapt within the structures of Qing imperial culture. His legacy is not only an artistic achievement but also the culmination of the Jesuits' strategy of cultural mediation in China.

Giuseppe Castiglione in China: The Divine Brush That Bridged Empires

A Biographical Study of the Jesuit Painter Lang Shining (郎世宁) (1688–1766)

- The Milanese Novice and the Celestial Calling

In the golden autumn of 1688, the Baroque splendor of Bernini still echoed through Rome's colonnades, and the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty was consolidating his Manchu empire's hold over the Middle Kingdom. Giuseppe Castiglione was born that year in Milan—a city where Renaissance rigor met the theatrical flourish of the Seicento. Blessed with a precocious talent for painting, the young Castiglione entered the Jesuit order in Genoa at age 19 in 1707. He chose the path of a Jesuit brother rather than a priest, a status that allowed him to focus on artistic and cultural work rather than clerical duties.

LEFT: Giuseppe Castiglione at age 21 in Genoa. AI-generated illustration.

RIGHT: Giuseppe Castiglione (attributed to), Tobias and the Archangel Raphael, oil on canvas. Dimensions: 272.5 × 181.5 cm. Collection of Pio Istituto Martinez, Genoa, Italy.

"The subject of this painting comes from the "Book of Tobit" in the Catholic Old Testament , the first section of the Christian Bible. In it, the son of Tobit, Tobias, is sent by his father to a distant land to collect a payment and is accompanied by the family dog. Due to the difficulty of the journey, God sent the archangel Raphael in human form to go with him. Heeding the angel's instructions, Tobias caught a giant fish and removed its heart, liver, and gall bladder, which he later used to drive away a demon and make medicine to cure his father's blindness. The strong lighting in this painting symbolizes the glory of God as the angel points the way. Tobias, basking in God's grace, appears gutting the fish. The method of treating the luster on the surface of the dog, fish, water, and hair can also be found in works that Castiglione did after arriving in China. The dramatic lighting and vast areas of shade, however, are rare in his later works". (From the texts prepared for the Giuseppe Castiglione Lang Shining new Media Art Exhibition, 2016, National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan).

In the early years of his Jesuit vocation, Giuseppe Castiglione spent a formative period in Lisbon and Coimbra, from 1709 to 1714, honing his artistic skills. During this time, he undertook several ecclesiastical commissions, producing chapel panels and religious paintings in preparation for his eventual mission to China. In Coimbra, he contributed to the decoration of the Chapel of St. Francis Borgia at the Jesuit College—now part of the New Cathedral of Coimbra—where contemporary accounts praised his use of illusionistic perspective and intricate foliage.

Regrettably, none of the original chapel decorations have survived, and the authorship of existing works from that period remains uncertain. No securely attributed pieces from his Portuguese years exist today; those once linked to him in Lisbon and Coimbra have either been lost or are now considered doubtful. Still, it is clear that Castiglione was an active and capable artist during his time in Portugal, even if his recognized body of work begins only with his later contributions in China.

By the early 18th century, as the Qing imperial court grew increasingly intrigued by European painting techniques, the Jesuit leadership in Rome identified Castiglione as an ideal envoy—an artist whose talents could advance both religious and diplomatic aims. They saw in him not merely a skilled craftsman, but a cultural ambassador. This was no ordinary artistic commission: it served as a gateway for the Catholic Church to enter the Forbidden City.

Castiglione set sail for Asia and arrived in Macau on August 20, 1715, the 54th year of the Kangxi Emperor's reign. By the year's end, he had reached Beijing, carrying with him both crucifix and palette. There, under his new Chinese name—Lang Shining, meaning "He who brings peace to the world" (郎世寧)—he was ready to begin his service.

Giuseppe Castiglione upon his arrival at the harbor of Macau in August 1715. AI-generated illustration.

2. The Kangxi Interregnum: Roots in the Forbidden City

The years under the Kangxi Emperor from 1715 to 1722 represent a painful gap in Castiglione's artistic legacy. This period is defined by absence rather than presence. No paintings from these formative years survive; however, this absence is eloquent testimony to the painter's assimilation. Like a sapling transplanted into foreign soil, Castiglione spent these initial years establishing himself in the Qing bureaucracy through the Zaobanchu, the palace workshops where Chinese artisans and European specialists collaborated under imperial patronage.

What we know with certainty is that the elderly Kangxi Emperor, renowned for his intellectual curiosity about Western science and mathematics, welcomed the Italian Jesuit. Castiglione's presence was strategic; he was a painter, a potential proselytizer, and living proof of European cultural sophistication. Residing at the Dongtang (Eastern Church) near the Donghua Gate, Castiglione awaited occasional summonses to the inner court. There, he built the reputation that would enable his survival and eventual flourishing.

3. The Yongzheng Years: Auspicious Beginnings

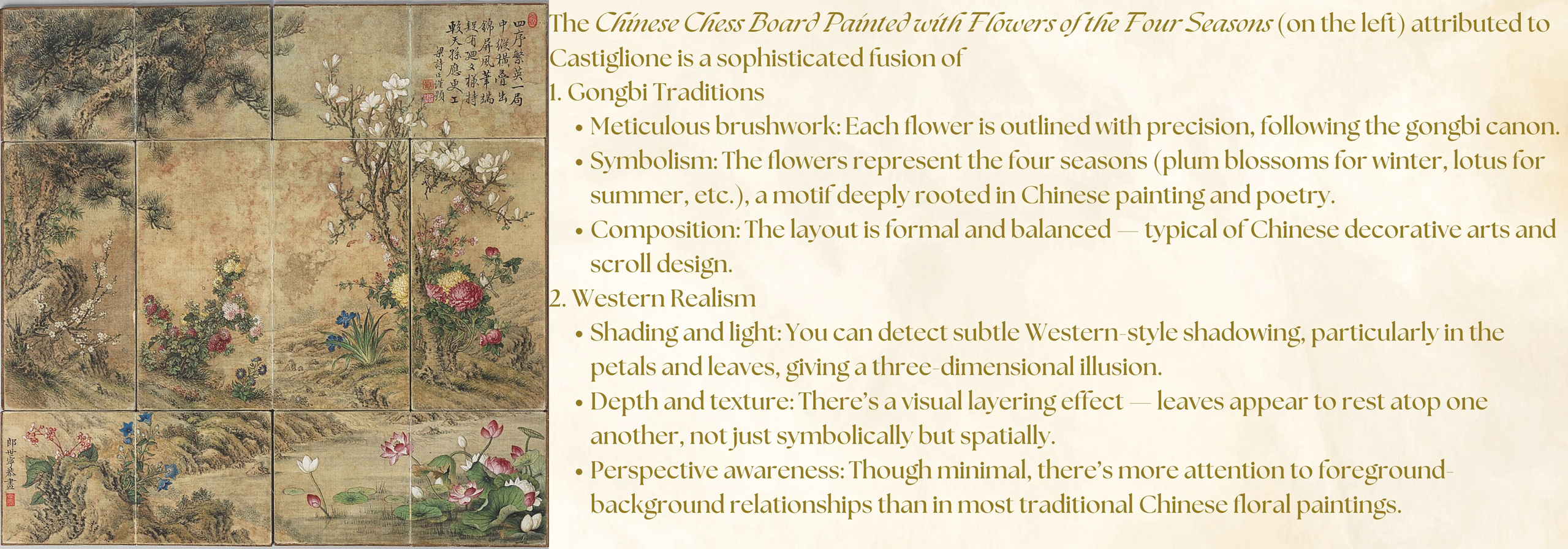

The Yongzheng Emperor's accession in 1723 was a pivotal moment. Castiglione presented Gathering of Two Auspicious Signs, a hanging scroll that transformed political allegory into visual poetry. Arranged in a Song dynasty Ru-type vase on a bed of sandalwood were bingdi lotuses, intertwined grain stalks, and arrowheads, which proclaimed the new emperor's virtuous governance and legitimate succession. Yongzheng was so delighted by the work that, within days, he issued an imperial decree granting Castiglione six disciples to train in his methods.

Composed in ink and color on silk (158 × 85 cm), this painting demonstrated Castiglione's mature synthesis. Western chiaroscuro modeling brought each botanical specimen to life in three dimensions, while the composition honored Chinese traditions of auspicious symbolism. A companion piece, Gathering of Auspicious Signs, now in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, cemented his position. Throughout Yongzheng's eight-year reign, Castiglione served as the court's foremost chronicler of imperial legitimacy.

LEFT: After presenting his silk scroll to the new emperor, Giuseppe Castiglione rolls it up. So impressed was the emperor that he bestowed special favors on the artist in gratitude. AI-generated illustration.

RIGHT: Giuseppe Castiglione, Gathering of Two Auspicious Signs. Hanging scroll, ink and colour on silk,158 x 85 cm. On view at Sotheby's Maison in Hong Kong until 27 January 2026.

Two extraordinarily rare auspicious signs appeared simultaneously in the first year of the Yongzheng reign (1723), son of Kangxi Emperor. The first sign was lotus seed pods sharing a single stem with divided calyxes. The second sign was the news of a bountiful wheat harvest in Shandong Province of several hundred stalks of auspicious grain. Each stalk was vividly purple and bore two ears. The stalks had strong, upright stems that were over a foot long. These events were both interpreted as signs of Heaven's will to herald the new emperor's accession.

"According to Confucian ideals, the manner in which a ruler ascends the throne was important to the legitimacy of his rule. (...). It was on these grounds that the phenomenon of auspicious grain and Bingdi lotuses in the eight month of the first year was seen as a signifier the Yongzheng Emperor had received the Mandate of Heaven, thereby receiving Heaven’s blessings as the legitimate ruler of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1644-1912). This legendary account of the Yongzheng Emperor receiving the Mandate of Heaven in 1723 is immortalised on silk in Giuseppe Castiglione’s Gathering of Two Auspicious Signs. (...) Gathering of Two Auspicious Signs was received with such favour that merely days after Castiglione created the painting, an imperial decree granted him six individuals to study painting under his tutelage. The success of Gathering of Two Auspicious Signs and the subsequent companion painting Gathering of Auspicious Signs (now in the collection of the Taipei Palace Museum), executed during the same period of time, garnered the Yongzheng Emperor’s trust and laid the foundation for Castiglione’s position in the palace where he would ultimately be remembered as one of the most significant court painters in history. A third painting, compositionally similar to Gathering of Auspicious Signs and bearing the same name, was created in the third year of the Yongzheng reign (now in the permanent collection of the Shanghai Museum)." (From Denise Tsui, Yongzheng Emperor’s Mandate of Heaven: The Story Behind Giuseppe Castiglione’s Gathering of Two Auspicious Signs, November 2025, Sotheby's).

LEFT: Giuseppe Castiglione, Gathering of Auspicious Signs, hanging scroll. Medium: Ink and colors on silk. Dimensions: 173 x 86.1 cm. © National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

RIGHT: Giuseppe Castiglione, A Bunch of Auspicious Flowers, hanging scroll. Date: 1725. Medium: Ink and colour on silk. Dimensions: 109.3 x 58.7 cm. © Shanghai Museum, China.

"In this painting is a celadon vase with an arrangement of auspicious plants such as dual-blossom lotuses and stalks of rice with two ears of grain, plants that have been used in painting since the Song and Yuan dynasties to symbolize sagacious rule. Giuseppe Castiglione signed his name in Chinese with the "Song-script" style of Qing court publications and included a date equivalent to 1723, the first year of the Yongzheng emperor's reign, making it his earliest dated work. An elevated point of view has been taken, allowing the viewer to peer into the neck of the vessel. Castiglione also used white pigment to highlight the shine on the glaze, enhancing the volumetric effect of this porcelain vase. As for the plants, Castiglione excelled at rendering gradated areas of color to express three-dimensionality and shading with a single source of light. The coloring overall is exceptionally refined, making the motifs appear as if radiating with brightness. The painting is a masterful example of how Castiglione translated Chinese subject matter using Western techniques. The vase shown here also appears similar to an imitation Ru-ware celadon with linear patterns in the collection of the National Palace Museum." (from the official texts by the National Palace Museum of Taipei, prepared for the 2015-2016 exhibition Portrayals from a Brush Divine).

AI-generated illustration.

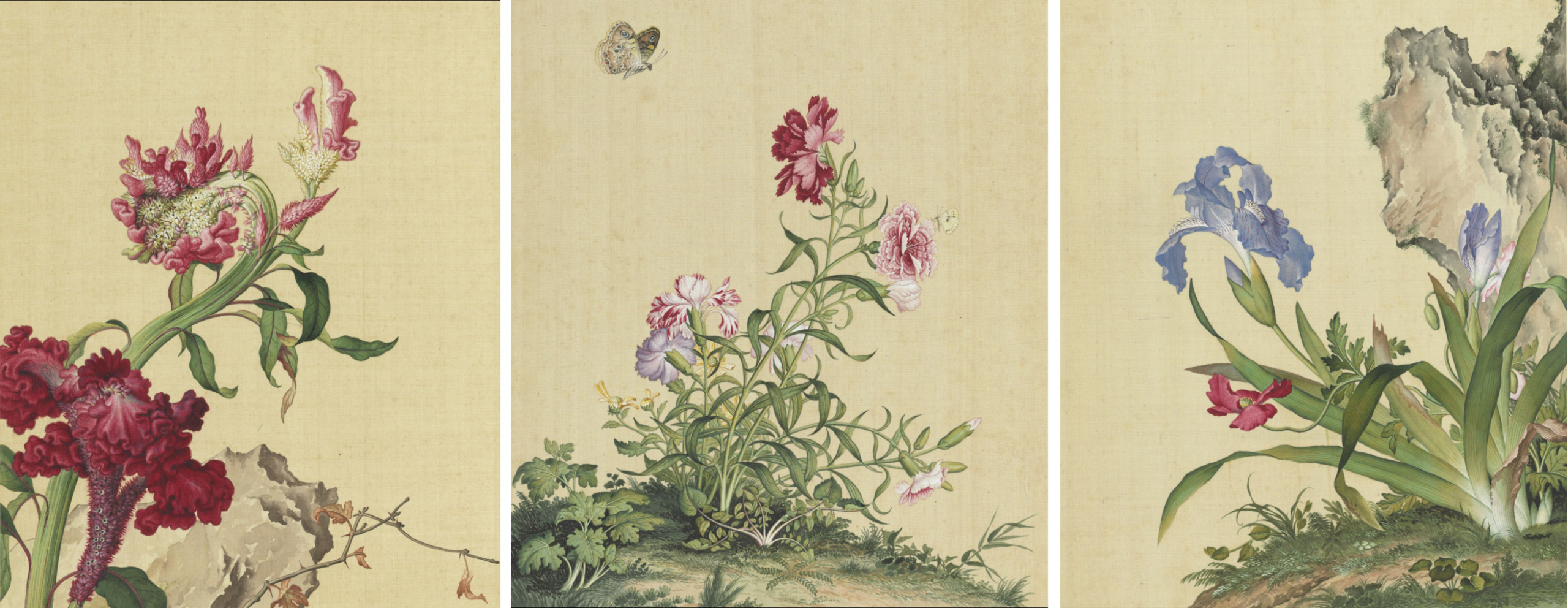

Credible evidence suggests that Giuseppe Castiglione painted flowers, including peonies, with careful attention to form, light, and shading — a hallmark of his Sino-Western hybrid style. In works such as Flowers in a Vase and Immortal Blossoms of an Eternal Spring, Castiglione renders the petals, leaves, and blooms with layered tones and shading, suggesting an attentive study of his botanical subjects rather than a purely stylized convention. Scholars have noted that the treatment of the petals in Immortal Blossoms of an Eternal Spring displays nuanced light and shadow effects, as well as attention to naturalistic structure. This aligns with Castiglione’s known practice of integrating Western observational methods into traditional Chinese bird-and-flower painting.

4. Artistic Transformation and the New Court Style

Castiglione’s art is best understood as a creative fusion of European Baroque techniques and Chinese pictorial traditions. He had mastered oil painting, anatomy, perspective, and large-scale composition in Europe, tools that he adapted for use with Chinese materials, such as silk, ink, and mineral pigments.

Instead of imposing European methods wholesale, he learned to integrate them with the gongbi (工筆) tradition of fine, detailed brushwork, which is highly valued in China. The result was a hybrid style that retained Western realism and spatial coherence yet harmonized with Chinese compositional rhythms and symbolic content.

This synthesis aligned perfectly with Qing imperial taste. The emperors valued paintings that both documented real events and embodied refined aesthetic expression. Castiglione’s work satisfied these demands with accurate representations informed by perspective and modeling and allusions to Chinese cosmological symbolism and poetic resonance.

"The richness of Giuseppe Castiglione's bird-and-flower painting is marked by its difference from traditional Chinese methods. Forms often consist of shapes gradually built up with very few of the outlines normally seen in Chinese painting. "Immortal Blossoms in an Everlasting Spring" in the National Palace Museum collection is a typical example of such. In this album of paintings in ink and colors on silk, eight of them deal with flowers and the other eight bird-and-flower combina-tions. The last leaf is signed, "Reverently painted by Your Servitor, Lang Shining (Giuseppe Castiglione)." The precise forms rendered from life with bright and beautiful colors make this rep-resentative of a new model for academic painting that Castiglione formulated at the Qing court." (From the official texts by the National Palace Museum of Taipei, prepared for the 2015-2016 exhibition Portrayals from a Brush Divine).

Giuseppe Castiglione's solid foundation in Western painting techniques is evident throughout Immortal Blossoms in an Everlasting Spring (Changchun Ruiying Tuce, 长春瑞应图册), a series of sixteen album leaves depicting flowers, fruits, and plants. The artist created this series during the Yongzheng reign (1723–1735), most likely between 1723 and 1725.

The album celebrates imperial virtues, seasonal renewal, and auspicious symbolism, aligning with the court's values of longevity, fortune, and harmony. The album consists of sixteen flower studies, including peonies, camellias, lotuses, magnolias, and plum blossoms. Castiglione's style represents his early fusion of European realism and shading techniques, such as light source, volume, and botanical accuracy, with Chinese subjects and formats, such as flowers as carriers of symbolic meaning. Each flower is paired with an inscription—a poem composed by the Yongzheng Emperor—that praises the elegance, purity, or moral significance of the depicted flora.

The gradations of the peony petals and the attention to areas of color reveal a Western influence. The petals of the white magnolia and cockscomb twist and turn in shades of color. The shadows fully reveal the artist's focus on the light source. The birds depicted in these album leaves are varied and animated. Their eyes are spirited and highlighted with white pigment. White coloring was also used for the rocks and branches to suggest brightness and volume. These depictions of birds and flowers are comparable to those on imperial painted-enamel porcelains, which testifies to the circulation and application of designs in different art forms at the Qing court.

"Castiglione not only painted the sixteen leaves in this album with meticulous care and coloring, the compositions are also quite innovative. In particular, he was able to reach beyond the traditional portrayal of birds in Chinese painting to achieve fantastic results in Western perspective and shading as well. Many places in the depiction of the birds and flowers reveal touches of light and shadow, the artist showing adept skill at using white pigment to highlight bright areas. The style throughout again relates to Castiglione's early Yongzheng manner." (From the official texts by the National Palace Museum of Taipei, prepared for the 2015-2016 exhibition Portrayals from a Brush Divine).

BELOW

Giuseppe Castiglione, Immortal Blossoms in an Everlasting Spring, Album leaves. Medium: Ink and colors on silk album leaf. Dimensions: 33.3 x 27.8 cm. © National Palace Museum (臺北故宮博物院), Taipei, Taiwan. The images below show only 12 of the 16 album leaves. To see all of the leaves, please go to this web page of the National Palace Museum of Taipei.

- Nature, Power, and Poetics in Early Castiglione

Giuseppe Castiglione’s early years at the Qing court (from 1715 to the late 1720s) were marked by stylistic experimentation and his gradual assimilation into the Chinese imperial painting tradition. Two notable works from this period, Dog Beneath Blossoming Flowers (花石瑞犬图) and Pine, Hawk, and Glossy Ganoderma (松鹰灵芝图), exemplify his evolving hybrid aesthetic prior to his monumental scroll, One Hundred Horses (1728). Both pieces reflect Castiglione's technical mastery of Western realism while adhering to the symbolic, compositional, and formal conventions of Qing court art.

Dog Beneath Blossoming Flowers (ca. 1723–1725)

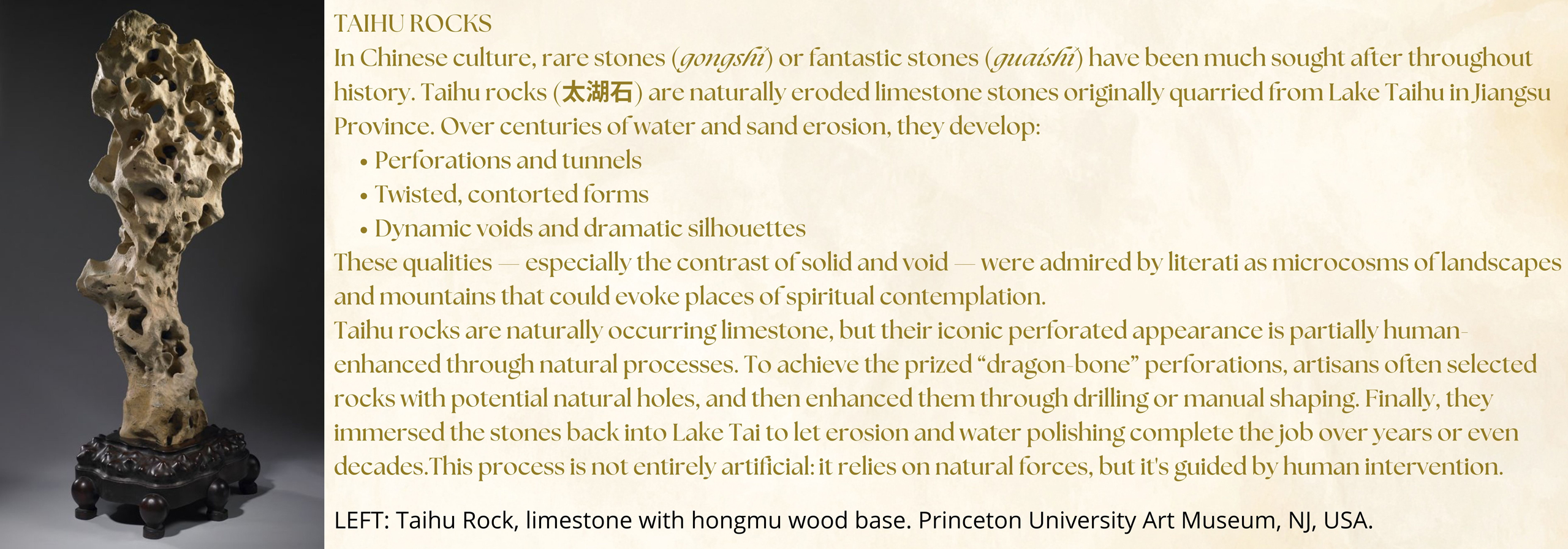

In Dog Beneath Blossoming Flowers (ca. 1723–1725), Castiglione depicts a brown, long-haired dog standing playfully beneath a branch of blooming peach blossoms, next to an intricate Taihu rock. This work exemplifies Castiglione’s early success in rendering lifelike textures — the dog’s fur is delicately modeled with directional light, a hallmark of European chiaroscuro — while embracing the symbolic motifs of Chinese bird-and-flower painting. The dog, likely a Pekingese or lap dog, symbolizes domestic peace, and the peach blossoms represent longevity and spring renewal.

The composition reflects Chinese vertical hanging scroll aesthetics, with the subject placed off-center and negative space balancing detail. Stylistically, this artwork belongs to the early Yongzheng period (1723–1735), suggesting a date around 1723–1725, a time when Castiglione transitioned from decorative arts to the more refined realm of imperial symbolism.

Giuseppe Castiglione, Long-haired Dog Beneath Blossoms or Dog Beneath Blossoming Flowers (中文(繁體:花底仙尨), hanging scroll, 1723-25. Medium: ink and colors on silk. Dimensions 123.2 x 61.9 cm (48.5 × 24.3 in). Collection National Palace Museum, Beijing.

Seeing the Unseen: Rethinking Beauty Through Taihu Rocks

FROM LEFT TO RIGHT

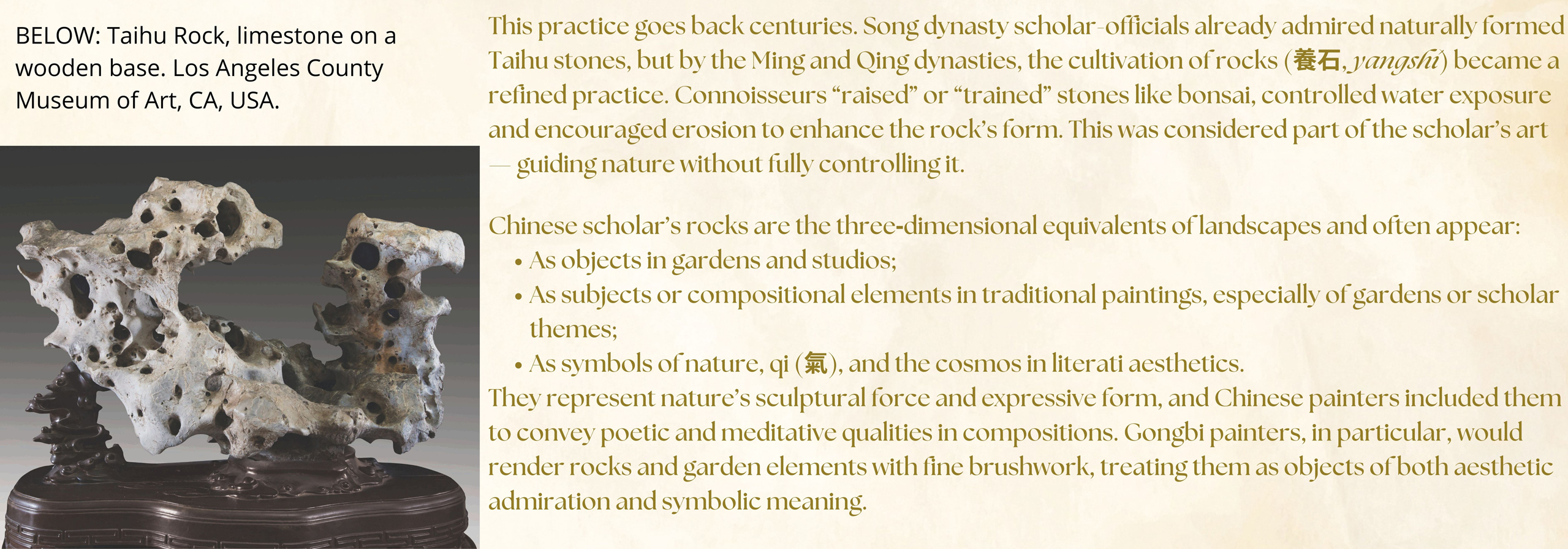

Liu Dan (Chinese, born 1953), Taihu Rock from Jiemei Studio, 2006. Ink on paper. Dimensions: 110 × 67 3/4 in. (279.4 × 172.1 cm). Brooklyn Museum, New York, USA.

Lan Ying (Chinese, 1585–1664), Red Friend. Date: 17th century, Late Ming / Early Qing. Hanging scroll; ink and color on paper. Dimensions: 58 5/8 x 18 5/8 in. (148.9 x 47.3 cm). The MET, NewYork, USA.

C.C.Wang (aka Wang Jiqian, 1907-2003), Scholar Rock, 2001. Ink on paper. Dimensions: 54 1/2 x 28 3/4 in (138.3 x 73 cm).

Xia Hesheng, Rock of Taihu Lake, 2022. Ink on paper. Dimensions: 136.0 x 68.0 cm; 53 1/2 x 26 3/4 in. Private Collection.

Do you find Taihu rocks ugly, discomforting, or even perturbing?

Chinese Taihu rocks (太湖石), no matter how depicted, can be elusive to Western aesthetic sensibilities, and this reveals deep differences in how cultures frame beauty itself.

From a Chinese perspective, the appreciation of Taihu rocks rests on several philosophical pillars that simply don't have direct counterparts in Western art history.

First, the Aesthetics of "Imperfection" as Virtue

While Western aesthetics traditionally prized symmetry, proportion, and the "ideal form" inherited from Greek classicism, Taihu rocks celebrate precisely the opposite. Their value lies in the Four Virtues (瘦、透、漏、皱): thinness that suggests spiritual elevation, hollowness that implies openness to qi energy, perforations that create mysterious depth, and wrinkles that record time's passage. This isn’t mere formalism—it’s a Daoist worldview where ziran (自然, ‘spontaneous naturalness’) becomes a spiritual orientation. This resonates with the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi (侘寂), though the lineage is distinct.

Second, the Microcosm in the Macrocosm

For Chinese scholars, these rocks weren't decorative objects but worlds-in-miniature. A single Taihu rock could contain mountains, caves, and clouds—inviting contemplative rujing (入境, "entering the landscape") without leaving the studio. This requires a mental leap: seeing a 3-foot rock as a 30-mile mountain range. Western landscape art typically separates viewer from vista; Chinese scholar rocks collapse that distance, demanding imaginative participation.

Third, the Artificial Perfection of "Naturalness

There's a profound paradox at the heart of Chinese literati aesthetics: the most prized "natural" forms were often the most artificially perfected. This reflects a key Daoist insight: that 'non-action' (wuwei, 无为) is not about doing nothing, but about acting in harmony with natural forces—so subtly that the human hand becomes indistinguishable from nature itself.

This reveals a layer of connoisseurship that might indeed be even more alien to Western aesthetics than pure naturalism would be.

The most valuable Taihu rocks were found by expert rock hunters who understood the scholarly aesthetic criteria intimately. They scoured Lake Tai for limestone that had eroded into promising forms, then through careful selection, elevated nature's accidents into art.

The "perfection" involved subtle human intervention—strategic soaking, acid treatments, or gentle mechanical enhancement to emphasize desirable features while maintaining the illusion of pure natural formation. The ideal was enhancement so skillful it attained ziran—not raw wildness, but a higher-order spontaneity that emerges from effortless accord between human intention and natural process.

The Cultivation of Randomness is another crucial element, perhaps the most sophisticated concept—humans working with natural processes, guiding erosion over decades, or selecting rocks that showed particular promise, then staging them to maximize their scenic qualities. It's a collaboration between human intention and geological time.

What scholars truly valued wasn't "pure nature" but nature perfected by understanding. The human hand was meant to be invisible, not absent—a distinction that separates Chinese scholar aesthetics from both pure naturalism and explicit craftsmanship.

All this creates an aesthetic that might be challenging for Westerners:

- First, to see beauty in twisted, "imperfect" forms;

- Second, to appreciate that these "natural" forms represent sophisticated human discernment and subtle intervention;

- Third, a western eye is not trained to see absence (the holes, the voids) as presence—the Daoist xu (虚) where emptiness is fullness.

To a Western eye trained on classical ideals and contemporary beauty standards, these rocks can appear disturbing, nonsensical, incomplete, or even a sort of monstrous reversal of smoothness, thus triggering an almost visceral sense of unpleasantness or wrongness. This reaction isn't superficial; it's rooted in profoundly different aesthetic ontologies.

Why They Read as "Ugly" to Western Perception?

Western aesthetics, from Greek proportion to Renaissance harmony, embeds the idea that beauty is a miraculous and graceful combination of health, smoothness, completeness, and idealized form. We instinctively associate asymmetry with injury, holes with decay, and contortions with deformity. The Taihu rock's "Four Virtues" (瘦、透、漏、皱) directly invert these values:

- 瘦 (shòu, "thin/leanness"): Not elegant elongation, but a gnarled, skeletal quality that might suggest privation or illness.

-透 (tòu, "permeability"): Those deep, tunnel-like perforations challenge the Western instinct for solidity and wholeness—like seeing a body pierced through.

- 漏 (lòu, "leakage/perforation"): The multiple holes create a sense of fragmentation, as if the rock is dissolving or riddled with wounds.

- 皱 (zhòu, "wrinkles/texture"): The convoluted surface reads not as weathered wisdom, but as chaotic, purposeless scarring.

The "perturbing" quality comes from this cognitive dissonance: Western eye sees organic form, but form that is "wrong" by every measure of classical beauty. It's the aesthetic equivalent of the uncanny valley—nearly familiar but unsettlingly alien.

What effort must Giuseppe Castiglione, a man of the late Italian Renaissance, have made to appreciate these rocky contortions and paint them (not often, to be honest)?

The Chinese Re-Framing: Virtue in the "Defects"

From the literati perspective, these features aren't flaws to tolerate but visible manifestations of noble character:

- Contortion (皱) is textual: each groove is a line of cosmic calligraphy, recording the patient work of water and time. It's not chaos; it's history made legible.

- Piercing (透/漏) is spiritual: the holes are channels for qi circulation. The rock isn't fragmented; it's permeable to the cosmos. A solid, unblemished rock would be dead—impermeable and spiritually inert. The voids (虚, xū) are as important as the stone (实, shí), embodying the Daoist truth that emptiness gives function.

- Leanness (瘦) is ethical: the rock's austerity mirrors the scholar's own rejection of worldly excess. It's an act of disciplined self-cultivation projected onto mineral form.

The Deeper Divide: Passive vs. Active Beauty

Western beauty often invites admiration, a completed form to be appreciated from a distance. The Taihu rock demands contemplative participation. You must mentally enter it, project yourself into its caves and crevices, and complete its meaning through imagination. What a Westerner sees as "ugly absence," the scholar sees as space for the mind to inhabit. In Chinese thought, this participatory gaze is not accidental—it is cultivated. Concepts like gongfu (功夫, "disciplined practice"), xin (心, "the heart-mind"), and you (游, "aesthetic wandering") describe the scholar’s inward journey through the rock’s imagined terrain.

So the "perturbation" you may feel is actually the first necessary step in its aesthetic function: it disrupts your conventional gaze and forces you into a different mode of seeing—one where beauty is not given but co-created through philosophical engagement. The rock is ugly until you bring the right cultural-mental framework to it; then it becomes profound. This makes it less an object of art than a tool for transformation.

Now let's return to Giuseppe Castiglione.

Pine, Hawk, and Glossy Ganoderma (ca. 1725–1727)

This monumental vertical hanging scroll depicts a white hawk perched on a rugged cliff. The hawk is flanked by a gnarled pine tree, a rushing waterfall, and lingzhi mushrooms (Ganoderma). The painting is technically impressive and deeply infused with imperial symbolism. The white hawk (鹰) is associated with vigilance and martial prowess and is often used as a metaphor for the emperor's power or his military elite. The pine symbolizes steadfastness; the lingzhi, immortality; and the torrent, dynamic energy. The eagle’s anatomy — its feathers, talons, and gaze — is rendered with Castiglione’s European anatomical accuracy. Yet, it stands in sharp contrast to the stylized, symbol-laden natural elements.

Created around 1725–1727, the painting demonstrates Castiglione's growing integration into the court's pictorial language, showcasing his increasing mastery of spatial layering and Chinese ink-and-color brushwork, particularly evident in the rocky textures and vegetation.

Giuseppe Castiglione, Pine, Hawk and Glossy Ganoderma, hanging scroll, 1725-27. Medium: ink and color painting on silk. Dimensions: height 242.3 cm (95.3 in), width: 157.1 cm (61.8 in). Collection National Palace Museum, Beijing.

The last two works demonstrate Castiglione’s synthesis of two pictorial systems: Western realism and Chinese allegorical aesthetics. In Dog Beneath Blossoming Flowers, he experiments with scale and narrative intimacy. In contrast, Pine, Hawk, and Glossy Ganoderma engages with the visual grandeur and iconography expected of imperial commissions.

Both paintings foreshadow his later works, such as One Hundred Horses, in which Castiglione's fusion becomes more mature, monumental, and ideologically charged. Thus, these early scrolls mark an important developmental stage in both Castiglione’s career and the emergence of a new hybrid court style under the Qing.

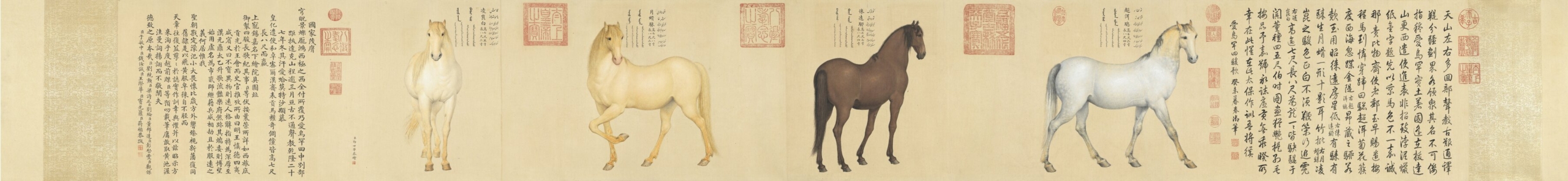

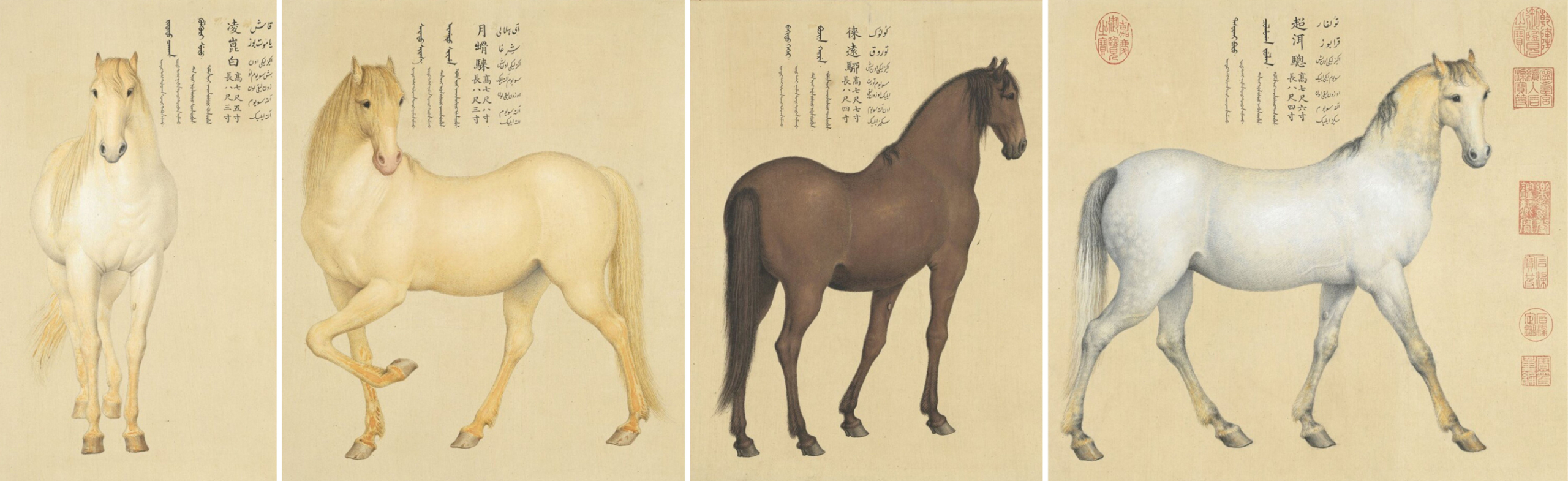

- One Hundred Horses (百駿圖, 1728)

One of Castiglione’s most celebrated works is the handscroll One Hundred Horses (Baijun Tu, 百駿圖). Archival evidence from the Qing imperial household confirms that Castiglione received the commission in 1724 and finished the painting in 1728, during the reign of the Yongzheng Emperor.

This monumental silk painting, which spans eight meters, depicts a wide array of horses in various poses and attitudes. The horses are meticulously rendered with a consistent light source and spatial depth, which is uncommon in traditional Chinese painting. This piece exemplifies Castiglione's ability to combine Western observational realism with Chinese scroll composition. It ingeniously integrates Western and Chinese styles: Renaissance perspective constructs receding landscapes in which horses, rendered with the anatomical precision he learned from European equine studies, engage in pastoral dramas. Yet, the composition flows with the rhythmic cadence of Chinese handscroll conventions, inviting the viewer's eye to travel through time and space (from right to left!).

A preparatory draft survives, revealing Castiglione's meticulous process. He applied Western methods of painting from life while retaining Chinese aesthetic principles, rendering each horse as a character in a Confucian parable of hierarchy, harmony, and natural order. The scroll's fame was immediate and enduring, establishing a template for court painting that would persist for decades.

Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining 郎世寧), One Hundred Horses, preparatory draft. Date: 1723–25. Medium: ink on paper. Image dimensions: 37 in. x 25 ft. 10 3/4 in. (94 x 789.3 cm). The MET, New York, USA.

BELOW

A detail of the One Hundred Horses preparatory draft. The MET, New York, USA.

"This monumental scroll, a unique example of a Castiglione preparatory drawing, is the model for one of Castiglione's most famous paintings, the One Hundred Horses scroll preserved in the National Palace Museum, Taipei. The drawing, although done with a brush rather than a pen, is executed almost exclusively in the European manner. Landscape is represented using Western-style perspective, figures are often shown in dramatically foreshortened views, and vegetation is depicted with spontaneous arabesques and cross-hatching. The large scale of the painting also suggests a European influence, as if Castiglione had taken a typical Western canvas and extended its length to make an architectural frieze." (The MET curators).

Giuseppe Castiglione, One Hundred Horses, handscroll. Medium: ink and colors on silk. Dimensions: 94.5 x 776 cm. © National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

BELOW

The One Hundred Horses handscroll from right to left. This enlarged view allows you to see most of the details.

- Giuseppe Castiglione as a Court Painter – From the Early to the Middle Period

After completing his celebrated One Hundred Horses scroll in 1728, Castiglione solidified his position at the Qing court. He then entered a period of artistic maturation, during which his subject matter expanded and the fusion of Chinese and European visual languages deepened.

During the late Yongzheng period and early Qianlong reign (1735), Castiglione became the primary portraitist for the imperial family and high-ranking officials. His portraits demonstrate a clear progression toward integrating Western naturalism—modeling of volume and light—with Chinese court representation conventions. Figures are rendered with subtle shading and spatial presence yet are set against surfaces and compositions that adhere to Chinese pictorial norms.

He painted portraits of the imperial family — carefully composed figures in rich attire — which conveyed status and ritual identity more than individual psychology. His workshops also produced group scenes with multiple figures that balanced intricate court protocols with a sense of depth uncommon in traditional Chinese portraiture.

Castiglione did not work in isolation, but rather alongside Chinese painters and court artisans. Court painting in Qing China was a collective enterprise. Castiglione worked within the Imperial Painting Academy alongside Chinese artists who specialized in different styles and techniques, such as landscape, figure, and architecture. His role in the Academy meant that collaborating with Chinese painters was the norm. Chinese painters often assisted with backgrounds and secondary figures, while Castiglione executed principal faces and key elements, synthesizing styles across traditions. He introduced European techniques such as linear perspective, oil painting, and chiaroscuro, but they were adapted to Chinese formats, such as handscrolls and hanging scrolls, and aesthetic values. The goal was not to replace Chinese art, but rather to enhance it with foreign elements that appealed to imperial tastes.

Around the 1730s–1740s, Castiglione expanded into bird‑and‑flower (花鳥) painting and still‑life subjects for the court. These works were often commissioned by the crown prince (the future Qianlong emperor) and palace elites. Works from this period demonstrate:

- Detailed observations of peonies, chrysanthemums, orchids, and plum blossoms with delicate brushwork and gentle modeling, reflecting Chinese literati aesthetics enhanced by Western illusionistic space.

- Fruits and symbolic flora, such as pomegranates, peaches, and grapes, appear as auspicious motifs in palace décor and are often rendered with traditional line and light-based shading techniques.

The following works illustrate how Castiglione’s technique continued to evolve beyond mere novelty of European methods toward a nuanced hybrid style respectful of Chinese subject matter and iconography.

Flowers in a Vase (清郎世寧畫瓶花 軸) was painted during the transition between the late Yongzheng and early Qianlong periods (ca. 1720s–1730s). It depicts peonies and other flowers arranged in an ornate vase — a traditional bird-and-flower subject rendered with careful shading and volumetric color influenced by Western light effects.

LEFT AND CENTER: Giuseppe Castiglione, Vase of Flowers or Flowers in a vase, undated. Hanging scroll. Medium: ink and colors on silk. Dimensions: 113.4 × 59.5 cm. © National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. "This hanging scroll is undated, but the style of Giuseppe Castiglione's signature ("Respectfully painted by Your Servitor, Lang Shining") is similar to that on Gathering of Auspicious Signs. According to archives from the Qing dynasty court, in the third lunar month of the Yongzheng emperor's fifth year (1727), Castiglione went to the Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan) to paint a twin-blossom peony, perhaps the one shown in this scroll. The peony petals here were outlined with light red and then shaded with areas of color to give them volume, being also treated with white pigment to suggest a slight shine. The stems and leaves are likewise shaded for a three-dimensional effect, once again demonstrating Castiglione's new style adapting Western techniques. The form of the porcelain vase is unique as well, being similar to an angular Xuande underglaze-blue of the Ming dynasty with morning-glory decoration. Castiglione used a special way of interpreting the glaze, reducing the intensity of the blue while heightening the luster of the surface, adding white lines to enhance details for the reflection as well. This painting fully conveys a conscious attitude toward manipulating the effects of light and shadow." (Text by the curators of the National Palace Museum, Taipei)

RIGHT, TOP TO BOTTOM: 1. Ming dynasty Xuande reign porcelain vase with morning-glory decoration in underglaze blue, similar to those painted by Castiglione. © National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. 2. Some examples of traditional wooden stands.

In China, small wooden stands, often finely carved from hardwoods such as zitan, huanghuali, or hongmu (rosewood), serve aesthetic and symbolic purposes. They elevate prized objects, such as porcelain, jade, and bronze vessels, emphasizing their value and creating visual separation from the surface below. Using a stand shows respect for the object and aligns with Confucian principles of hierarchy and decorum. The stands' design complements rather than competes with the objects they hold, often echoing forms found in traditional furniture or architecture. In paintings like Vase of Flowers by Castiglione, the inclusion of a stand reflects the enduring Chinese tradition of displaying objects and subtly signals the elevated status of the imperial Xuande-period porcelain vase.

Pair of Cranes in the Shade of Flowers marks a pivotal moment in Giuseppe Castiglione’s career at the Qing court. At this time, his artistic style had evolved beyond initial experimentation, achieving a harmonious balance between European naturalism and Chinese symbolic tradition. Created around 1728–1736, during the final years of the Yongzheng reign and possibly extending into the early Qianlong period, the painting reflects Castiglione’s growing authority as a court painter entrusted with auspicious and ideologically significant subjects.

The painting depicts two cranes standing beneath flowering branches and beside scholar's rocks in a tranquil garden. Castiglione renders the birds with remarkable anatomical precision. The modulation of their plumage, subtle weight distribution in their stance, and soft modeling of volume reveal his European training. At the same time, the overall structure—vertical format, asymmetrical balance, and generous negative space—fully conforms to Chinese bird-and-flower painting conventions.

In Qing visual culture, cranes are powerful emblems of longevity, harmony, and moral purity. They are often associated with ideal governance and cosmic order. Their pairing suggests concord and stability, and the surrounding flowers and rocks reinforce themes of seasonal renewal and cultivated elegance. These symbolic layers closely align with the court’s ideological needs during the dynastic transition from the Yongzheng to the Qianlong era, when continuity, legitimacy, and auspicious renewal were paramount.

Stylistically, the painting falls between Castiglione's exploratory works of the early 1720s and the monumental One Hundred Horses (1728). Here, realism is no longer asserted as a novelty, but rather, it is carefully subordinated to courtly decorum and symbolic clarity. The result is a work of quiet authority that demonstrates Castiglione’s successful internalization of Qing imperial aesthetics while retaining the technical finesse that distinguished him within the court atelier.

Giuseppe Castiglione, Pair of Cranes in the Shade of Flowers, Hanging scroll. Date: circa 1728–1736. Medium: Ink and color on silk. National Palace Museum, Taipei (臺北故宮博物院).

In the following years, Castiglione's trajectory will reflect several key developments.

Spatial Depth and Modeling: Compared to his earlier work, such as One Hundred Horses, his mid-career paintings demonstrate a more confident use of light and shadow to suggest three-dimensional form, particularly in fabrics, flesh, and botanical subjects.

Integration with Chinese Conventions: Although he was trained in European techniques, Castiglione adopted Chinese compositional hierarchies, such as the preference for flat pictorial space in backgrounds and the selective use of perspective. This approach yielded a balanced hybrid style rather than a complete transplantation of techniques.

Collaborative Production: Rather than working alone, Castiglione collaborated with Chinese court painters from the Imperial Painting Academy. He learned from their mastery of calligraphic brushwork and symbolic content. These collaborations produced works that were innovative yet acceptable to imperial taste.

- The Qianlong Era: Zenith of a Syncretic Style

During the sixty-year reign of Qianlong (1735–1796), Castiglione transformed into a Qing institution, reaching the zenith of his artistic career at the imperial court. His role expanded beyond that of a portraitist to include that of a visual propagandist for the emperor's reign. He crafted idealized images that conveyed Qianlong's power, cultural refinement, and benevolence. In his 50s and 60s, the Jesuit painter developed a style known at court as xianfa, or the "line method." This style seamlessly combined Chinese and Western elements, earning it recognition as a distinctive high Qing court manner.

Under Qianlong, the Qing Empire reached its greatest territorial extent and cultural confidence. Castiglione's hybrid style, blending Western techniques such as perspective and chiaroscuro with Chinese conventions like the silk scroll format and symbolic representation, aligned perfectly with the emperor’s vision of a cosmopolitan yet controlled image of rule. Castiglione adapted his art to fit Chinese tastes while subtly embedding European realism, gaining him high favor and consistent imperial patronage.

Working alongside the Ruyi Hall painters, Castiglione produced imperial portraits that captured not only the emperor's likeness, but also his political cosmology.

Giuseppe Castiglione and the young Jesuit Jean-Denis Attiret at the Ruyi Hall in the Forbidden City. AI-generated illustration.

The Ruyi Hall (如意馆, Ruyi Guan) was a specialized painting atelier located within the Forbidden City that produced artworks for the emperor. It was not a public studio but rather a court institution where elite Chinese and foreign artists collaborated on paintings blending European techniques, such as perspective, shading, and realism, with Chinese themes and aesthetics, including bird-and-flower painting, figure painting, and landscapes. The name Ruyi (如意) means "as you wish" — a phrase often associated with imperial blessings or good fortune — and reflects the decorative and auspicious purpose of much of the artwork created there. Giuseppe Castiglione is the best-known member of the Ruyi Hall painters, who included European Jesuit painters, such as Jean-Denis Attiret and Ignatius Sichelbart, as well as Chinese court painters who adopted or collaborated with European techniques. Together, they produced paintings for imperial commissions, including portraits of emperors and consorts, documentary paintings of military campaigns, large-scale decorative panels and hanging scrolls, and architectural and landscape renderings. These collaborative works formed a unique fusion of East and West. They are known for their hybrid style, which deeply influenced Qing court art and set a precedent for cross-cultural artistic exchange.

Despite their distinct institutional roles, the Ruyi Hall painters and the Qing Imperial Painting Academy (画院, Huayuan) were deeply interconnected, especially during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–1796). The Qing Imperial Painting Academy, a formal continuation of earlier dynastic art academies, was largely staffed by Chinese court painters who upheld many literati traditions in painting, such as the landscape, figure, and bird-and-flower genres. These painters worked within a system that emphasized classical brush techniques, poetic themes, and calligraphic expression. However, they were also expected to meet the increasing demands of imperial patronage. In contrast, Ruyi Hall emerged as a more specialized and technically innovative atelier within the Forbidden City. Despite these differences, the two institutions were deeply intertwined in practice. Personnel occasionally moved between the two institutions or collaborated on specific projects. Some Chinese court painters who trained at the academy were invited to collaborate with Jesuits at the Ruyi Hall, and vice versa. This interchange was particularly evident in large-scale commissions ordered by the Qianlong Emperor, who took a hands-on approach to the artistic life of his court. The transfer of techniques between the two groups was intentional and part of a broader imperial agenda. The Jesuits were encouraged to teach their Chinese counterparts European methods, and many Qing painters began incorporating elements such as linear perspective and shading into their work. Conversely, European painters had to adapt their styles to conform to Chinese aesthetic expectations. This resulted in a distinctive fusion that defined Qing court art during the 18th century.

Portrait of the Qianlong Emperor in Court Dress (1736)

This portrait was produced in 1736, the first year of Qianlong's reign. This official state portrait was likely commissioned to commemorate his ascension to the throne and establish an authoritative imperial image for ritual and political purposes. The painting was intended for display in palace halls and use in ceremonies affirming the emperor's legitimacy and Confucian virtue.

The emperor is depicted facing forward, seated upright, wearing a richly embroidered yellow dragon robe that symbolizes supreme authority. The composition is symmetrical and dignified, aligning with traditional Chinese norms of imperial portraiture that emphasize stability and centrality. However, Castiglione introduced subtle Western elements, such as delicate chiaroscuro around the face, nuanced shadowing, and a more volumetric treatment of hands and garments. Unlike earlier Chinese portraits, which tend to be linear and flat, Castiglione's version gives the figure a soft, three-dimensional presence, maintaining a sense of solemn detachment appropriate to the emperor's status.

The neutral, undecorated background focuses attention entirely on the emperor. This approach echoes Chinese aesthetics of moral clarity while allowing Castiglione to integrate the focus on the individual characteristic of European portraiture.

This portrait encapsulates the dual purpose of Qing imperial art: affirming dynastic legitimacy through tradition and elevating the emperor's image through innovative aesthetics. By blending Western techniques with Chinese formats, Castiglione created a refined and authoritative visual icon of Qianlong's sovereignty. This established a new mode of court portraiture that would be emulated by later Qing court artists.

Giuseppe Castiglione, Portrait of the Qianlong Emperor in Court Dress, painting on silk, 1736. The Palace Museum, Beijing.

BELOW

Castiglione painting the portrait of Qianlong Emperor. AI-generated illustration.

Portraits of the Qianlong Emperor and His Twelve Consorts (1736–1770s)

This monumental handscroll was started around 1736 and completed over the course of several decades, extending into the 1770s. Its creation was prompted by dynastic and ceremonial occasions; it served as a visual record of the emperor and his official consorts and was likely updated as new women were elevated to higher court ranks. The emperor titled the scroll Mind Picture of a Well-Governed and Tranquil Reign himself, linking personal memory with imperial ideology.

The scroll begins with a portrait of the young Qianlong, followed by his empress and eleven consorts. Each woman is depicted with distinct facial features and expressions. The women are depicted in sumptuous Manchu court attire, their garments detailed with intricate patterns and textures.

Castiglione painted the emperor and the higher-ranking women himself; the later sections were likely completed by his disciples or other court painters in his style. This technique blends the clarity and color of Chinese brushwork with European modeling. Faces are gently rounded, eyes and mouths are individualized, and garments are rendered with subtle shading that suggests form.

The scroll’s format reflects Chinese pictorial traditions of sequential portraiture, which were often used in genealogical records and temple displays. However, the realism and attention to individuality mark a departure from earlier, more generic female portraiture. The scroll presents a vision of the imperial household that is both hierarchical and personal.

This artwork served as both a dynastic record and a visual representation of Confucian harmony within the imperial household. It reflects Qianlong's desire to portray his reign as orderly, prosperous, and stable. The hybrid style captures the social function of court portraiture as well as the emotional nuances of personal likeness. Castiglione's influence is particularly evident in the dignity and humanity he imparts to each figure.

Giuseppe Castiglione, Portraits of the Qianlong Emperor and His Twelve Consorts, handscroll, 1736–70s. Medium: Ink and color paint on silk. Dimensions: 53.8 x 1154.5 cm (21 3/16 x 454 1/2 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, John L. Severance Fund, USA.

BELOW

Detail of the portrait of Qianlong and his primary wife, Empress Xiaoxianchun, 孝賢純皇后 (1712–1748). The face modeling—soft, volumetric, and subtly realistic—is characteristic of Castiglione’s hand, while the costumes and decorative embroidery were likely rendered by specialized Chinese court painters.

Together, these two portraits (the Portrait of the Qianlong Emperor in Court Dress and the Portraits of the Qianlong Emperor and His Twelve Consorts) demonstrate the dual nature of Qing court art under Castiglione: simultaneously ceremonial and personal, traditional and innovative. The former projects political authority and ritual gravitas, while the latter offers a glimpse into the private and familial dimensions of imperial life. Castiglione's fusion of European techniques with Chinese visual culture yielded technically proficient works and a novel visual language of empire. These portraits are instruments of statecraft and memory that embody the power, aesthetics, and ideology of one of China’s most culturally dynamic reigns.

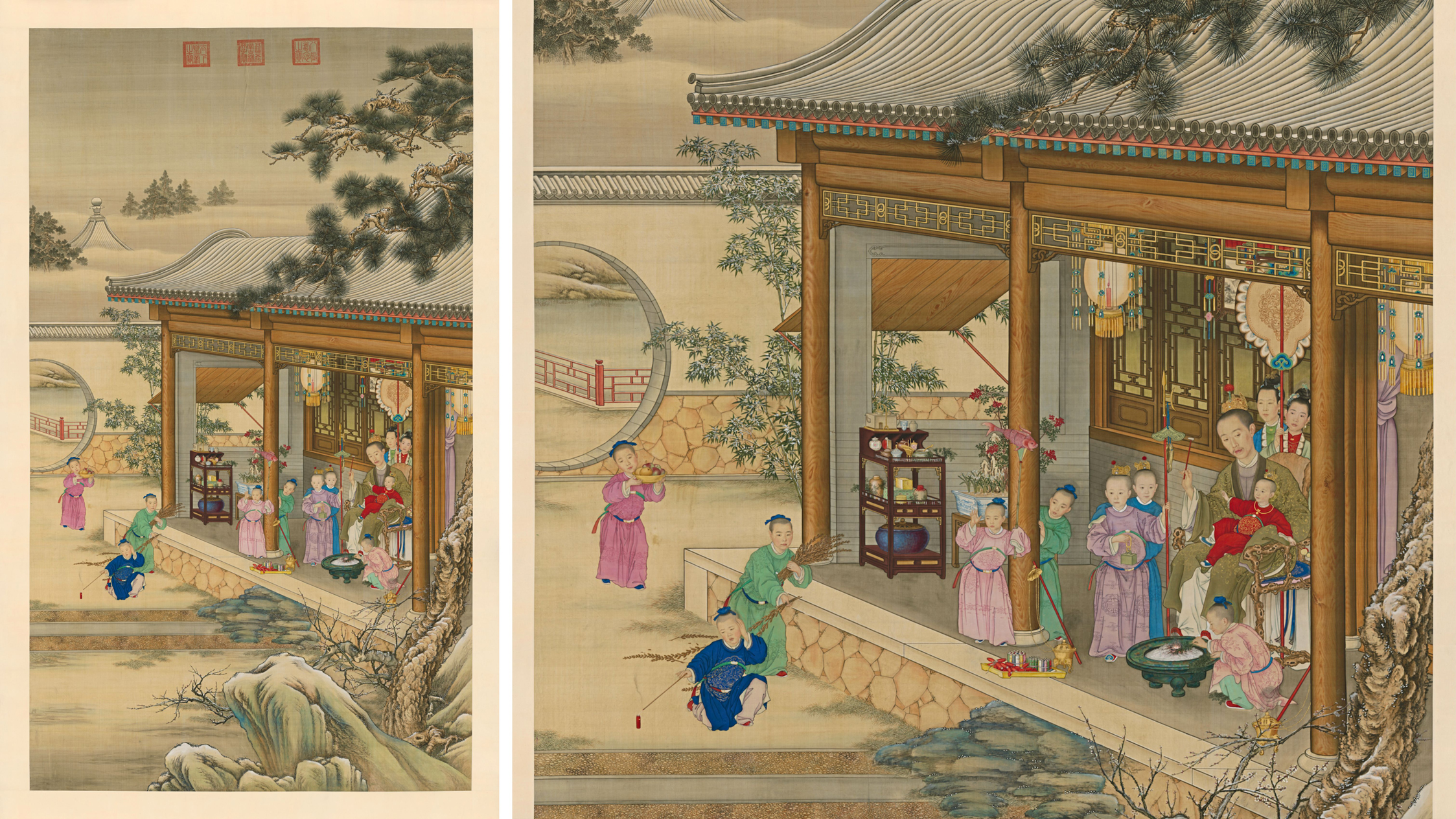

The Qianlong Emperor Surrounded by Children at the Yuanmingyuan on New Year's Eve (1738)

This painting depicts an intimate and informal moment of the Qianlong Emperor celebrating New Year's Eve at Yuanmingyuan, also known as the Old Summer Palace. He is surrounded by playful children who symbolize prosperity, happiness, and dynastic continuity.

Style and Symbolism: While the faces and fabrics are rendered with Western realism, the scene is composed with traditional Chinese motifs, such as auspicious objects and harmonious family themes. The children playing with toys, lanterns, and firecrackers serve as visual metaphors for the joy and abundance of the new year.

Political Message: The work portrays the emperor as a father to the nation and a virtuous man, reinforcing the Confucian ideal that familial harmony reflects good governance.

Giuseppe Castiglione, The Qianlong Emperor and the Royal Children on New Year’s Eve (general view and detail), hanging scroll, 1736-37. Medium: Ink and colour on silk. Dimensions: height 384 cm (12.5 ft); width: 160.3 cm (63.1 in). The Palace Museum, Beijing.

The Qianlong Emperor Viewing Paintings (ca. 1746–1750)

This formal composition depicts the emperor examining artwork in a refined, scholarly setting, surrounded by attendants.

Imperial Persona: Qianlong saw himself as a great patron of the arts, collector, and connoisseur. This painting reinforces that self-image by highlighting his engagement with literati culture and his refined taste.

Artistic Fusion: Castiglione’s use of linear perspective, shadowing, and architectural space reveals his European training. However, the subject matter, setting, and brushwork adapt to Chinese visual rhetoric.

Subtle Hierarchy: The emperor is physically and compositionally elevated, positioned centrally and attended to by courtiers, which emphasizes his cultural supremacy.

These works exemplify how Castiglione’s artistry was co-opted to express imperial ideology in visual terms. The Qianlong period was the most politically rich and stylistically mature phase of his career. They also underscore how art under an empire serves aesthetic and strategic functions, celebrating not just beauty but also authority and power.

LEFT: Giuseppe Castiglione painting a handscroll inside the Ruyi Hall in ca. 1746-1750. AI-generated illustration.

RIGHT: Giuseppe Castiglione, Emperor Qianlong inspects paintings, handscroll, ca. 1746-1750. Medium: Ink and color painting on paper. Dimensions: height: 136.4 cm (53.7 in); width: 62 cm (24.4 in). The Palace Museum, Beijing.

Portrait of Imperial Noble Consort Huixian in Court Robes (1750s)

Attributed to Giuseppe Castiglione and the painters of the Qing Imperial Workshop, this painting depicts Imperial Noble Consort Huixian (1712–1745), a prominent concubine of the Qianlong Emperor. Although she died relatively young, she was posthumously honored with the title of Imperial Noble Consort, the second-highest rank among the emperor’s consorts. This portrait was likely produced after her elevation, possibly posthumously, as part of a courtly series of consort portraits for commemorative and ancestral purposes.

These types of images were used for both imperial household remembrance and ritual veneration in the Palace of Earthly Tranquility and other ancestral halls, especially during mourning rituals and formal family gatherings. They also served as visual documents of rank and court hierarchy.

This formal portrait shows Consort Huixian seated on an elaborately carved dragon throne, a symbol of imperial power. She wears a richly embroidered chaofu, a court robe worn only during the most formal state occasions. The robe features:

- Five-clawed dragons pursuing flaming pearls across a sea-wave and cloud background. These motifs are reserved for high-ranking members of the court and directly reference the emperor's cosmic mandate.

- A red ceremonial headdress with phoenix motifs and pearl pendants denoting her status as an imperial consort of the highest rank.

- Intricate textile decorations rendered in brilliant mineral-based pigments, such as azurite and malachite, which were traditionally used in silk painting.

- The floor covering is a typical red-and-gold imperial carpet, and the throne base's architecture subtly echoes Buddhist altar design.

This work is emblematic of Castiglione’s influence. It was likely completed with his assistance or by court painters trained in his style, particularly those in the Imperial Painting Academy under his direction. Hallmarks of his style include:

- Facial modeling using subtle shading. The sitter’s face is pale and idealized with gentle transitions of light that suggest depth and softness. This is in contrast to the flatter treatments of earlier Chinese portraiture.

- Three-dimensional realism in hands, jewelry, and folds of fabric, likely inspired by Castiglione’s Jesuit training in European oil painting and chiaroscuro techniques.

- Architectural and ornamental accuracy in the rendering of the throne, showing an unusual Western sense of perspective and plasticity. These features were introduced to Chinese court art by Castiglione and other Jesuit painters.

Yet the composition retains strict Chinese symmetry and ceremonial frontality, which is appropriate for a portrait intended to honor and immortalize, rather than capture, a fleeting likeness. The blending of European illusionism with Chinese ritual formality creates a distinctly Qing visual language that is both hieratic and humanized.

The image portrays not just a woman, but a state figure, a living emblem of dynastic order and feminine virtue. Her attire, posture, and expression convey restraint, majesty, and perfect decorum — essential values in the Confucian court system.

The Portrait of Imperial Noble Consort Huixian is a refined example of Qing imperial portraiture, in which Castiglione’s Western techniques have been fully absorbed into the visual and ideological framework of the Chinese court. The result is a painting that is ritually correct, artistically innovative, and culturally hybrid—a visual embodiment of Qing cosmopolitanism and courtly discipline. This painting is part of a broader shift during the Qianlong era, when portraiture became a tool of dynastic memory. It was regulated by etiquette yet animated by the personal touch of cross-cultural artistry.

Giuseppe Castiglione and Qing Imperial Painting Academy, Portrait of Imperial Noble Consort Huixian in Court Robes (慧贤皇贵妃朝服像), hanging scroll. Date: ca. 1745–1750s (likely posthumous; Huixian died in 1745). Medium: Ink and color on silk (traditional Chinese mineral pigments). Dimensions: height ~220–240 cm; width ~130–150 cm. The Palace Museum, Beijing.

The Qianlong Emperor in Ceremonial Armor on Horseback and the Great Review Portrait (1750s)

Among Castiglione’s most spectacular large-format artworks are two equestrian portraits of the Qianlong Emperor: The Qianlong Emperor in Ceremonial Armor on Horseback and The Great Reading Axis of the Emperor Qianlong (大閱圖軸). These portraits were likely created in the 1750s, in connection with imperial military reviews and martial inspections that reinforced Qing authority and martial virtue. The emperor appears as both civil sovereign and warrior ruler, in full ceremonial armor.

In both paintings, Qianlong is portrayed riding a horse adorned with resplendent court armor, which is richly embroidered with dragons and auspicious motifs. The attention to equine anatomy, textile sheen, and facial modelling betrays Castiglione’s European training, while the use of flat backgrounds and minimal shadowing adheres to Chinese court tradition. The setting in The Ceremonial Armor portrait features a more naturalistic landscape, while The Great Reading Axis presents a more stylized background with accompanying calligraphy that emphasizes the ideological message.

These portraits represent a distinct mode within Qing imperial imagery: the emperor as military paragon. They function not only as likenesses, but also as imperial propaganda—affirming Qianlong’s status as both enlightened Confucian monarch and supreme commander of the Qing legions. Castiglione’s ability to endow the emperor’s presence with both realism and grandeur allowed these works to transcend mere portraiture and become tools of visual statecraft.

These portraits are instruments of statecraft and memory that embody the power, aesthetics, and ideology of one of China’s most culturally dynamic reigns.

LEFT: The Qianlong Emperor in Ceremonial Armor on Horseback (清 乾隆戎装骑马像轴), hanging scroll (vertical composition) attributed to Giuseppe Castiglione with collaboration from the Imperial Painting Academy. Date: ca. 1758 (Qianlong reign, 23rd year); likely painted in conjunction with military inspection tours or symbolic martial campaigns. Medium: Ink and color on silk. Dimensions: Approx. 234 × 152 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan. The Qianlong Emperor is shown mounted on a piebald horse, wearing full ceremonial court armor, holding the reins and surrounded by visual cues of martial authority. He carries a bow and a quiver of arrows; the horse is elaborately tacked and adorned with imperial motifs. The setting features stylized mountains and landscape, giving depth and context to the scene.

RIGHT: The Great Reading Axis of the Emperor Qianlong (乾隆皇帝大阅图轴 or Dàyuè tú zhóu), hanging scroll attributed to Giuseppe Castiglione, possibly with assistance from Tang Dai 唐岱, Jin Tingbiao 金廷標, and other court painters. Date: ca. 1743–1749 (early-to-mid Qianlong reign). Medium: Ink, color, and gold on silk. Dimensions: Approx. 238 × 163 cm. Palace Museum, Beijing (故宫博物院), included in the permanent Qing imperial portrait collection. The Qianlong Emperor, in ceremonial battle armor, is portrayed mounted on a white horse, participating in a grand imperial review (dàyuè), a ritual military parade or inspection. The emperor holds the reins and is surrounded by rich detail, including imperial insignia, weaponry, and an open plain. The background is more austere than in the previous artwork, and the composition features a poetic inscription and imperial seals. The inscription includes a poem written by the Qianlong Emperor in Chinese (upper left), reflecting on the virtues of governance, preparedness, and military power. The several imperial seals (e.g., “乾隆御览之宝”) reinforce imperial authorship and legitimacy.

Consort of the Qianlong Emperor with the Young Jiaqing Emperor, ca. 1763–1765

Attributed to Giuseppe Castiglione, this quietly evocative painting was executed during the mid-Qianlong period. It offers a rare, intimate glimpse into the private life of the Qing imperial family. It depicts a consort of the Qianlong Emperor delicately positioned behind an open window as she gently supports a young child identified as the future Jiaqing Emperor through inscription or contextual association. Castiglione is better known for his formal imperial portraits and grand ceremonial works, but this painting belongs to a subtler visual tradition at the Qing court. It reflects domestic harmony, maternal virtue, and dynastic continuity.

The painting is rich in architectural and symbolic framing. It divides the scene vertically between an elaborately decorated sleeping chamber above and a balcony overlooking a garden below. This architectural cutaway format, likely influenced by Chinese interior painting conventions and European perspective constructions, serves a compositional function and encodes thematic meaning. The upper chamber signifies quietude and privacy, and the open lower scene suggests connection, growth, and imperial posterity.

The woman, presumed to be one of Qianlong’s favored consorts or concubines, is rendered with the refined idealization of the face common in Qing female portraiture: serene, pale, and emotionally reserved. She wears courtly attire embroidered with auspicious floral motifs, and her expression is tender yet composed. Her subtle, protective gesture toward the child positions her as both nurturer and transmitter of imperial values.

The young boy wearing a red robe reaches out toward the viewer or the space beyond the window. Unlike his mother, his face is individualized and animated, possibly referencing Castiglione’s interest in Western portraiture and child studies, where psychological presence is emphasized. The backdrop of bamboo and peonies, classic Chinese symbols of resilience and feminine beauty, enhances the domestic setting and reinforces dynastic virtue: bamboo for strength and peonies for elegance and legacy.

In terms of technique, the painting exemplifies Castiglione’s mature visual synthesis. The architectural precision and spatial depth suggest European training, while the flat yet layered treatment of the surface, restrained palette, and careful rendering of textiles remain rooted in Chinese palace painting traditions. The light filtering into the room and the shadows cast across the carved window elements demonstrate an understanding of naturalistic illumination calibrated for visual harmony rather than realism.

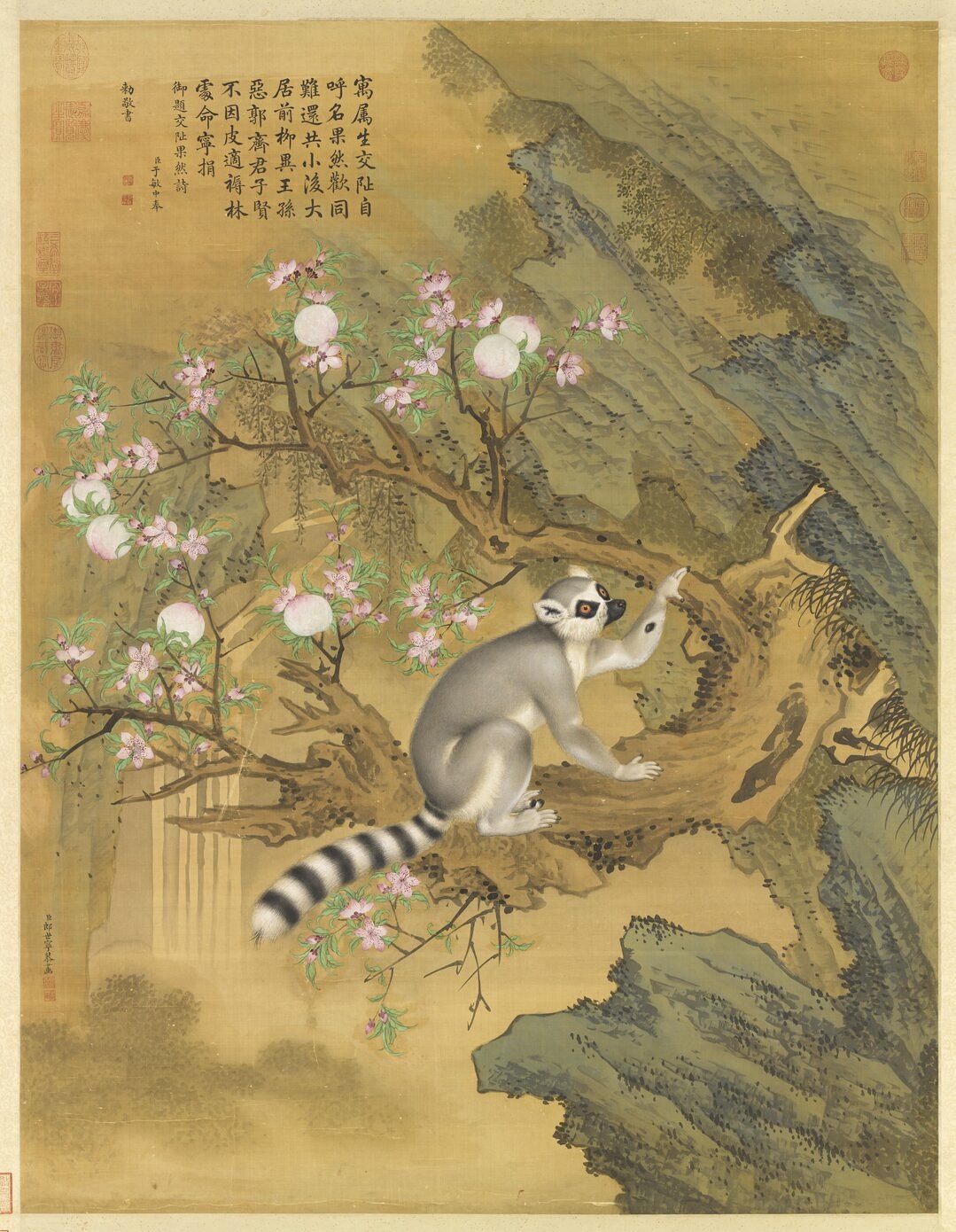

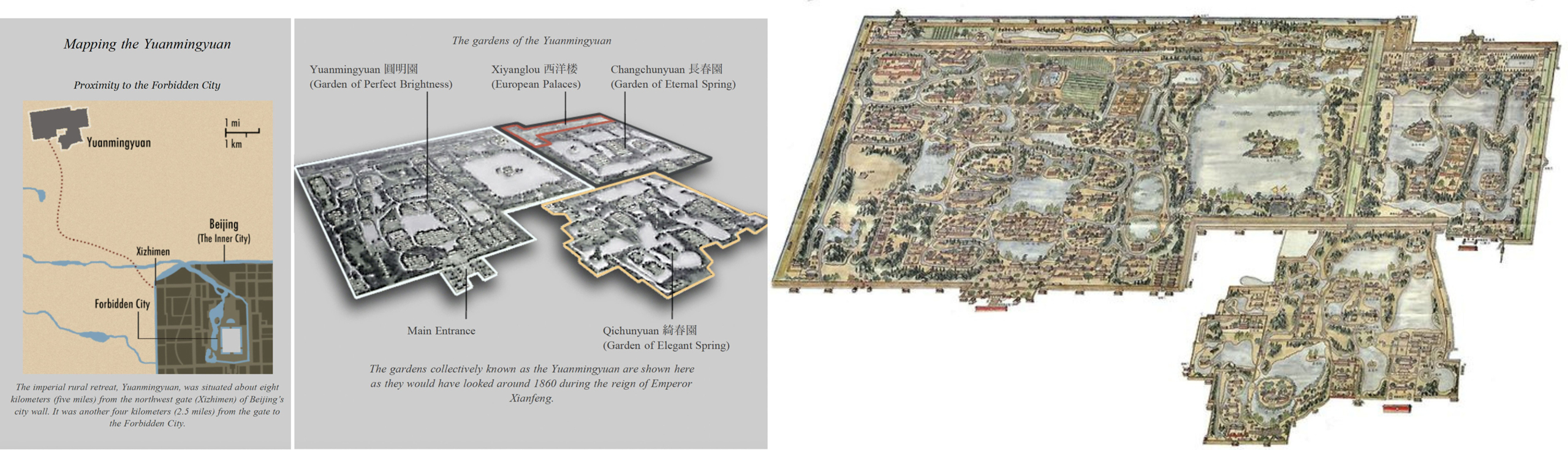

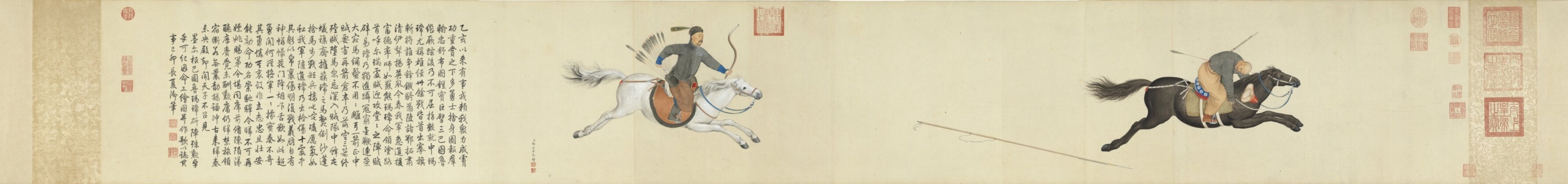

Ultimately, this painting is not merely a domestic genre scene; it is a work of dynastic narrative and ideological subtlety. It projects the continuity of the Qing lineage, the moral dignity of the emperor’s consorts, and the ideal of filial succession. Though intimate in tone, it is deeply political in function: a portrait of motherhood that is, in effect, a portrait of empire.