THE PINK FAMILY: CHINA AND THE WEST 8

Current China on the globe.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

This map is for illustrative purposes only. The Ethnic Home does not take a position on territorial disputes.

LEFT: Portrait of the Yongzheng Emperor in Court Dress, by anonymous court artists, Yongzheng period (1723—35), Qing Dynasty. Hanging scroll, color on silk. The Palace Museum, Beijing. Public Domain.

RIGHT: History of China, Imperial Dynasties, source: Dynasties in Chinese history, Wikipedia.

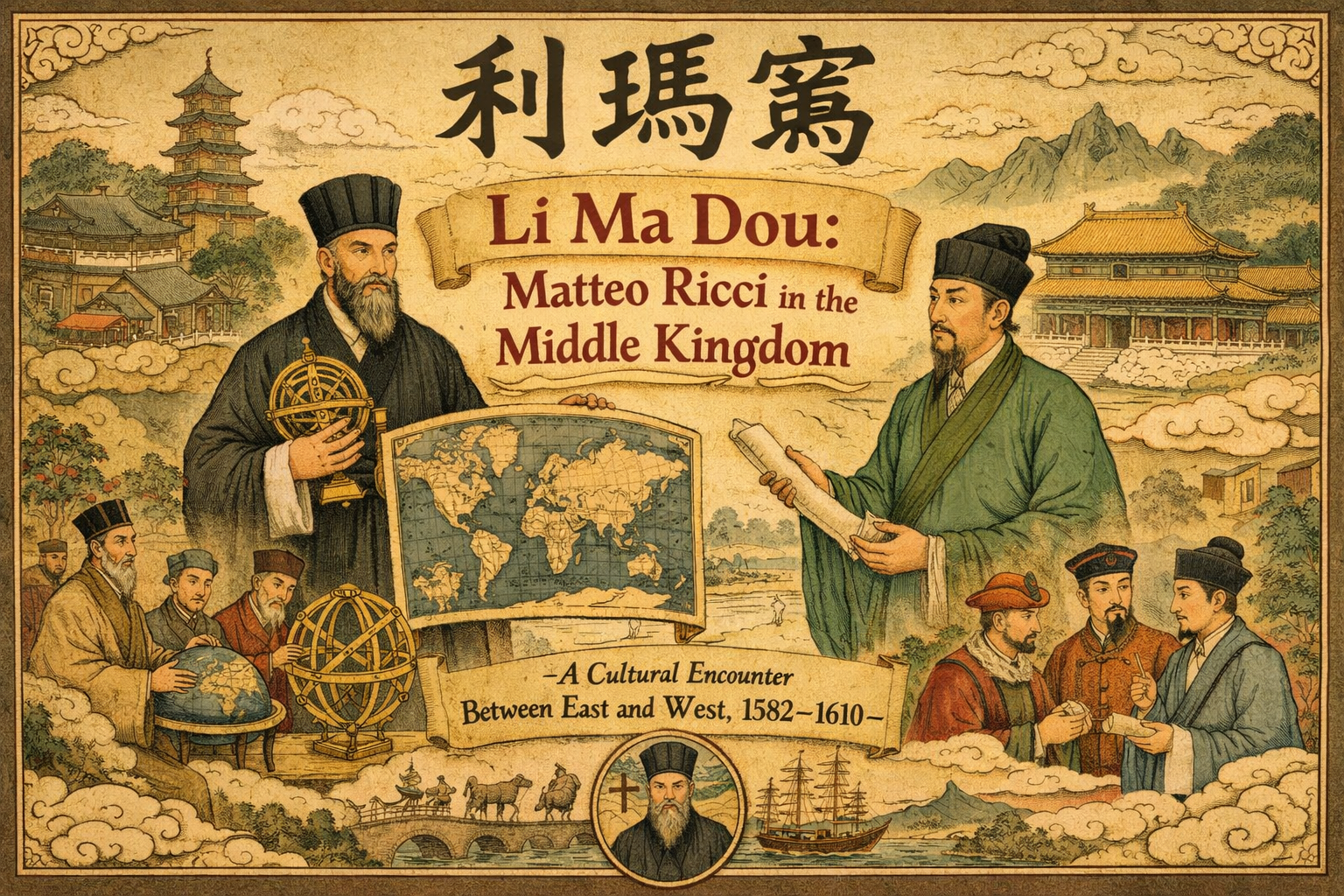

Lì Mǎdòu: Matteo Ricci in the Middle Kingdom

A Cultural Encounter Between East and West, 1582–1610

The Young Jesuit and China’s Call: a Short History

- Quando venni in questo paese… – “When I first came to this land…”

So began Matteo Ricci, S.J. (1552-1610), in a reflective passage from his journal, penned near the end of his life. With vivid recall, he evoked the wonder and bewilderment that stirred in him upon his first arrival in China. Born on October 6, 1552, in Macerata—a town in what is now Central Italy, then part of the Papal States—Ricci was shaped by the exacting Jesuit education in law, mathematics, and astronomy: disciplines that would become the intellectual currency of his mission in the East.

He stepped ashore in Macau, the Portuguese enclave on China’s southern coast, on August 7, 1582, aged twenty-nine. The world he entered was foreign not only in language, but in thought, custom, and social fabric. At first glance, China revealed itself as a land of austere grandeur: examination halls thrumming with ambitious candidates for the imperial service; temples thick with incense and devotion; serene pagodas poised above riverine towns. Yet beyond his religious vocation, it was a profound and serious curiosity that animated Ricci’s soul.

He did not come alone. Ricci arrived in the company of Father Michele Ruggieri and under the guidance of Alessandro Valignano, the Jesuit Visitor to the East Asian missions. Valignano, with rare foresight, understood that any hope of success in China demanded more than doctrinal proclamation—it required deep immersion in the language and the culture.

Ricci spent more than a year at the Jesuit residence in Macau, devoting himself to the study of Chinese. With the help of local tutors, he began with Cantonese and gradually moved toward the refined heights of Classical Chinese. At the same time, he immersed himself in the Confucian canon, laying the groundwork for future dialogue with the Chinese literati. In 1583, deeming him ready, Valignano gave Ricci leave to venture beyond the coast and begin his historic journey into the heart of China.

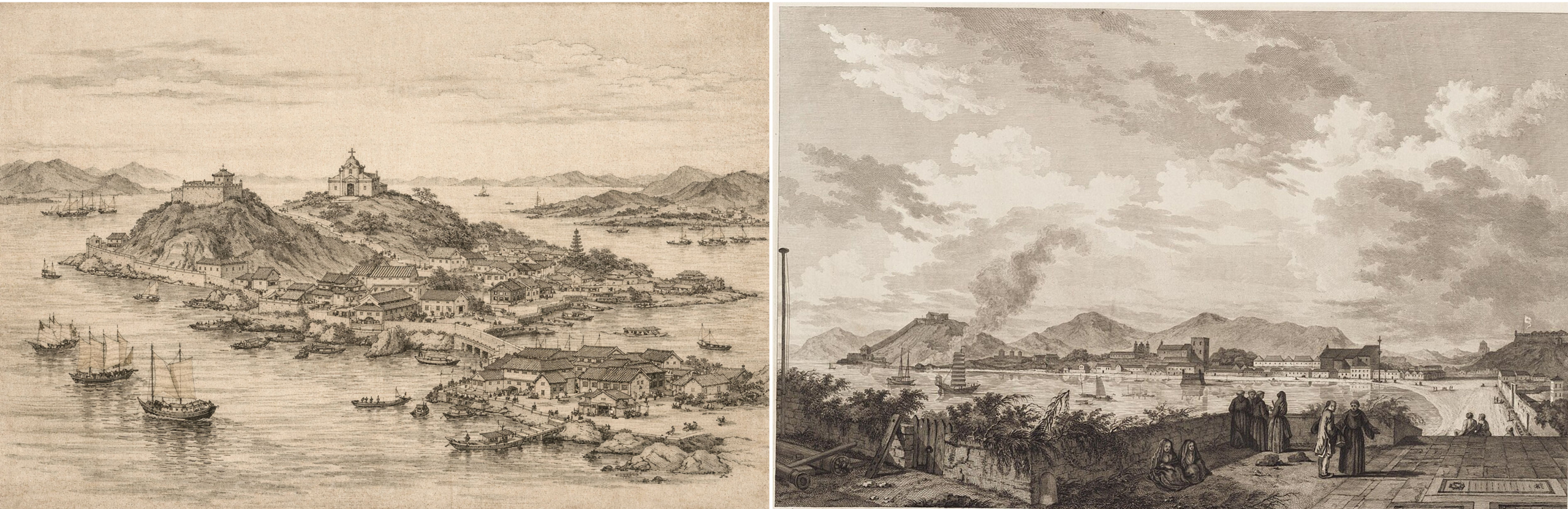

LEFT: Landscape of the Macau Peninsula in the 1580s. AI generated illustration.

RIGHT: A drawing of the Macau harbor in 1787 by Duché de Vancy (1756-1788). Wikimedia Commons.

In the 1580s, when Matteo Ricci arrived, Macau was a small but strategic Portuguese enclave on the southern Chinese coast, serving as the main legal European gateway to Ming China and a base for Jesuit activity. It was at once a bustling commercial port, a missionary outpost, and a liminal space tightly controlled by both Portuguese authorities and the Chinese empire. In this period Macau occupied a narrow peninsula and nearby islets at the mouth of the Pearl River, facing the maritime routes to Canton (Guangzhou) and the South China Sea. The settlement had grown from a fishing village into a small town after the Portuguese obtained permission to reside there in the mid‑sixteenth century, with a defensive wall (built in the 1570s) marking the border with mainland China. The population was mixed: a minority of Portuguese merchants and officials, a larger number of Macanese of mixed descent, many Chinese residents, and a substantial enslaved African population, which likely outnumbered the Portuguese themselves. Estimates suggest around 10,000 inhabitants by the early 1580s, with commerce and slave labor deeply intertwined in the city’s daily life. Macau was not a formal colony in the modern sense but a leased settlement under Chinese sovereignty, dependent on local Ming officials for its legal existence. The Portuguese paid taxes and respected Chinese restrictions, especially the rule that foreigners could not winter in nearby Canton, which made Macau the seasonal base for the lucrative China–Japan–India trade. The town functioned as the hub of the “Carrack trade” connecting Lisbon, Goa, Malacca, Macau, and Nagasaki, moving silver, silk, porcelain, and spices along this maritime corridor. Wealthy merchant families, often linked to religious institutions, financed both commercial ventures and ecclesiastical buildings, reinforcing Macau’s dual identity as trading post and Christian center. By the 1580s, Macau was already a solid Catholic stronghold with churches, confraternities, and a resident bishop, Melchior Carneiro, who had resigned his episcopal office in 1581 to live in community with the Jesuits. The Society of Jesus had established a permanent residence and their first church (St. Antony) in the 1560s, and the town soon became the operational base for missions to China and Japan. For Ricci and his companion Michele Ruggieri, Macau was above all a place of study and preparation: they learned Chinese there and planned the first sustained Jesuit entry into the Ming empire. The Jesuit college in Macau, under Alessandro Valignano’s guidance, emphasized language mastery and cultural accommodation, making the city a kind of laboratory for the encounter between European Christianity and Chinese literati culture. Relations with surrounding Chinese communities were ambivalent: the Chinese authorities tolerated Macau for its fiscal and diplomatic usefulness, but popular xenophobia and suspicion of “Western barbarians” remained strong. This precarious equilibrium made Macau simultaneously a refuge and a frontier, a place where European missionaries lived under constant awareness of Chinese law and local hostility just beyond the city’s limits. Despite its small size, Macau was one of the most cosmopolitan cities in East Asia, with connections to Goa, Nagasaki, Manila, and Lisbon. Merchants, sailors, scholars, and clerics brought with them navigational knowledge, maps, scientific instruments, devotional objects, and news from multiple continents, turning the port into a node of global exchange. For Ricci, this environment offered access to Chinese books, interpreters, and informants, as well as to European mathematical and cosmographical learning he would later present to Chinese officials. In this sense, the Macau of the 1580s can be described as a threshold city: neither fully European nor fully Chinese, but a hybrid space where the first durable intellectual and religious dialogues between late‑Renaissance Europe and Ming China were cautiously and unevenly initiated.

A depiction of the Macau harbor as it was in the 1580s. AI-generated illustration.

1582: A young Matteo Ricci, dressed in traditional Jesuit garb, disembarks from a ship from Goa, India, in the port of Macau. AI-generated illustration.

- First Entry into China (Zhaoqing, 1583)

With an invitation from a local official, Matteo Ricci and Father Michele Ruggieri departed Macau and journeyed inland to Zhaoqing, in Guangdong province—marking the establishment of the first Jesuit residence within mainland China.

There, Ricci began a gradual cultural transformation. He initially adopted the robes of a Buddhist monk, a familiar sight to the Chinese, but around 1594, discerning the higher status of Confucian scholars, he shifted to wearing their distinctive dress. This change reflected not only strategic adaptation, but a sincere respect for the traditions he encountered.

Ricci quickly gained attention for his mastery of European instruments: clocks, mechanical devices, and cartographic works. In 1584, he produced the Yudi Shanhai Quantu (舆地山海全图), or Complete Map of the Mountains and Seas of the Earth—the first world map printed in Chinese. Created in collaboration with local scholars, it blended Western geographic knowledge with Chinese cartographic conventions, using Chinese characters and orienting the map with the South at the top. This groundbreaking work was received with fascination by Chinese officials and literati alike, and it marked the beginning of Ricci’s growing influence.

His erudition in astronomy, mathematics, and ethical philosophy gradually won him the esteem of many scholars and bureaucrats. Through a combination of intellectual exchange and cultural fluency, Ricci began to carve a space for Jesuit dialogue within the Confucian world.

- Years of Travel and Rising Reputation (1589–1600)

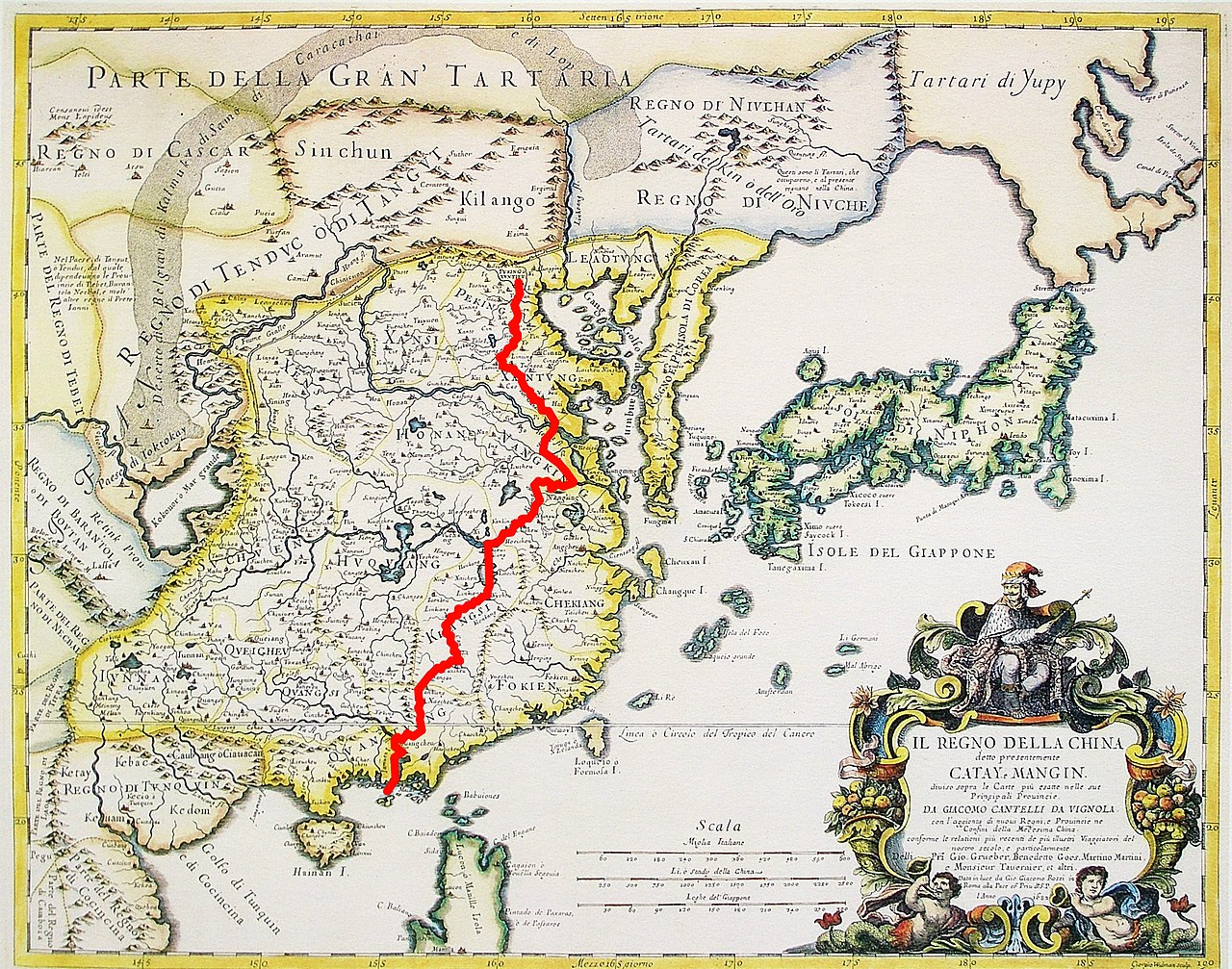

Between 1589 and 1600, Ricci moved steadily northward, from city to city, seeking imperial permission to establish permanent missions and ultimately reach the emperor himself. His path led him through Shaozhou in 1589, to Nanchang in 1595, and finally to the great southern capital of Nanjing in 1599.

In each place, Ricci engaged in careful, respectful dialogue with Confucian officials, offering not just religious instruction, but intellectual exchange. He translated Christian texts and scientific treatises into Chinese, all the while refining his own command of the language with meticulous care.

Ricci’s expertise in astronomy and calendar reform proved particularly compelling at a time when dissatisfaction with the aging Ming calendar was widespread. His translation of Euclid’s Elements—undertaken in collaboration with the brilliant scholar-official Xu Guangqi—introduced Chinese intellectuals to the rigors of Western mathematical reasoning. His world maps, too, captivated officials hungry for accurate geographic knowledge.

By the end of the century, Ricci’s reputation had grown far beyond that of a mere foreign missionary; he had become a trusted interlocutor between two worlds, valued as much for his mind as for his message.

Matteo Ricci's way from Macao to Beijing in the 16th century. This map, titled "Il Regno della China" (in Italian), was made by Giacomo Cantelli (1643-1695) and published in Roma by Giovanni Giacomo de Rossi in 1682.

- Arrival in Beijing (1601)

After years of patient diplomacy and persistent effort, Matteo Ricci was at last granted permission to enter Beijing in 1601. He arrived bearing gifts for the Wanli Emperor: a chiming clock, a clavichord—a Western keyboard instrument unfamiliar to Chinese ears—along with scientific instruments and books from Europe. Though Ricci never had a direct audience with the Emperor, his offerings and his learning made a strong impression on the imperial court.

Welcomed by high-ranking officials, Ricci was granted a stipend from the imperial treasury and allowed to establish permanent residence in the capital. Settling near the Forbidden City, he quickly became a figure of fascination among Beijing’s intellectual elite. Among his most important interlocutors was Xu Guangqi, a distinguished scholar-official who would later convert to Christianity and collaborate closely with Ricci on scientific translations.

Known in Chinese as Lì Mǎdòu (利瑪竇), Ricci was increasingly honored not merely as a missionary, but as a scholar and cultural mediator of rare distinction. He continued producing theological writings, scientific treatises, and translations, fostering a cross-cultural dialogue that was unprecedented in scale and sophistication.

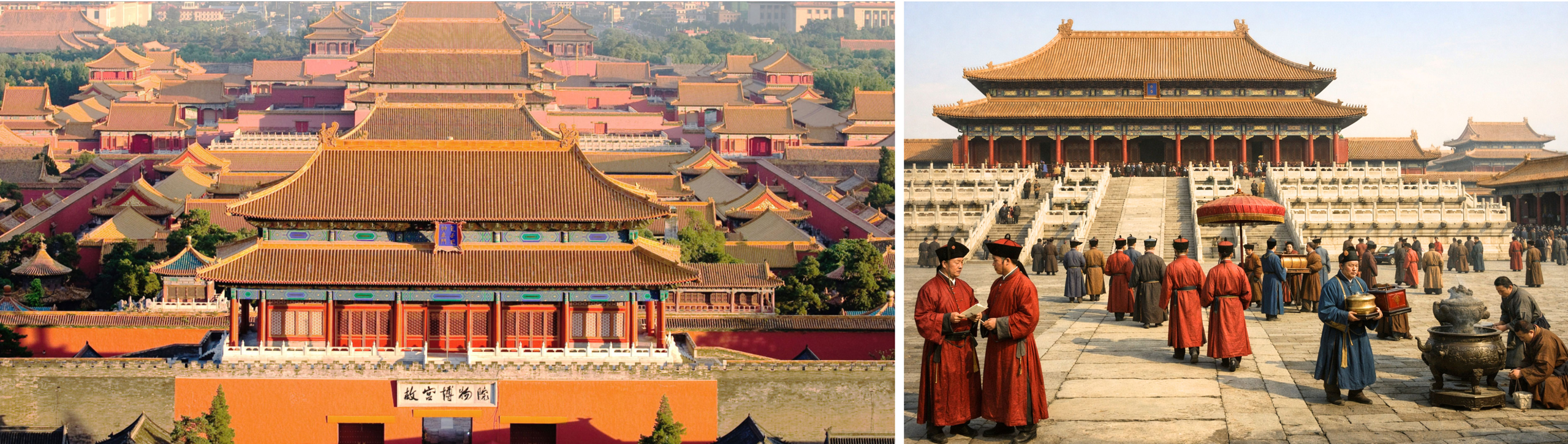

LEFT: A partial view of the Forbidden City in Beijing. © Beijing Central Axis Conservation Center.

RIGHT: A depiction of animated life inside the Forbidden City in the early 17th century. AI generated illustration.

In 1600, under the Wanli Emperor, the Forbidden City was the ceremonial and political heart of the Ming empire, a vast walled palace complex where imperial power was both displayed and tightly secluded. It functioned as an immense, ritualized court society, even while Wanli himself increasingly withdrew from active governance and regular audiences. By 1600 the palace already had its mature Ming layout: a rectilinear, walled compound in central Beijing, covering about 72 hectares with hundreds of halls, gates, and courtyards aligned on a strict north–south axis. The southern “outer court” contained the great audience halls used for major state rituals, while the northern “inner court” housed the emperor’s private quarters and the residential world of empress, consorts, eunuchs and maids.

Below an AI-generated illustration of the inner courtyards and further below the Forbidden City, viewed from Jingshan Hill, February 2012 (Wikimedia Commons).

LEFT: Wanli (1563 –1620),14th emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1572 to 1620. Palace portrait on a hanging scroll, kept in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, Taiwan.

RIGHT: Empress Xiaoduanxian (1564 – 1620), empress consort of the Wanli Emperor in court dress. Palace portrait by an imperial painter.

AI-generated illustration depicting a group of Literati in the early 17th century, discussing in an outer courtyard of the Forbidden City.

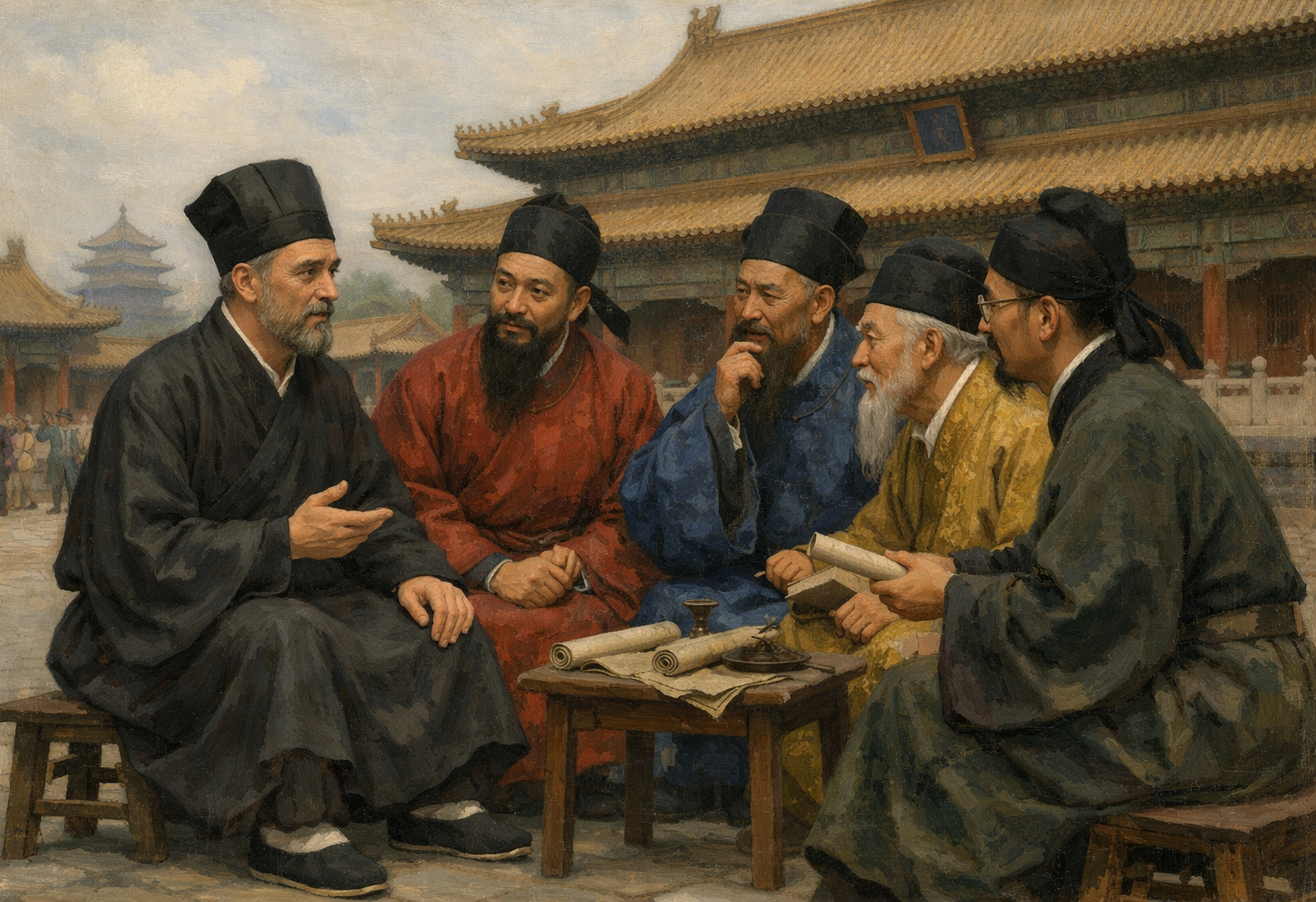

The Chinese literati were the educated elite of late‑Ming society, trained above all in the Confucian Classics and writing. They were defined less by birth than by education and participation in the civil service examination culture, even if many never actually obtained high office. They formed the scholar‑gentry: landowning, tax‑exempt local elites who mediated between the imperial state and the common people. Many alternated between official service and private life as teachers, estate managers, moral critics of the court, or members of scholarly and political societies such as the Donglin circle. Their ideal combined moral self‑cultivation, public service, and refined pursuits—poetry, calligraphy, painting, connoisseurship, and philosophical debate. Late‑Ming literati culture especially prized elegant brushwork, landscape and “ink play,” and a life of tasteful seclusion, even when lived symbolically within the bureaucratic world of the Forbidden City. Only some of them—those who were serving (or summoned) as officials—could enter, and then only into specific areas of the Forbidden City such as the outer court and audience halls. Ordinary literati or scholars without court appointment, like commoners in general, were not free to walk into the palace complex.

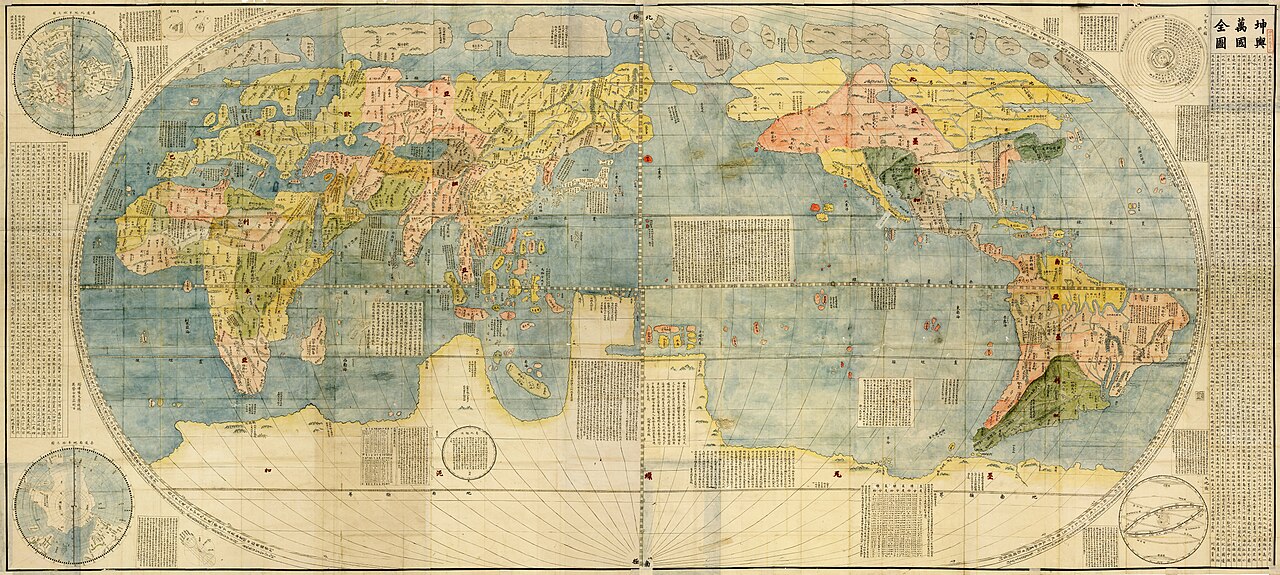

In 1602, Matteo Ricci published a monumental revision of his earlier map: the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu (坤輿萬國全圖), or A Complete Map of the Myriad Countries of the World. Printed from six large woodblocks, this ambitious wall map combined European geographic knowledge—from sources such as Ortelius and Mercator—with traditional Chinese cartographic conventions and classical terminology. The map was printed entirely in Chinese, and although China remained near the center, it now stood within a truly global context: for the first time, Chinese viewers could see Europe, Africa, and the Americas rendered with geographic coherence.

Several original prints of this map survive today—in the Library of Congress, as well as collections in Japan and Korea—testament to its wide circulation and enduring influence. The map served multiple purposes:

- It showcased the breadth of Western scientific knowledge;

- It gently unsettled long-held Chinese assumptions about world geography;

- It sparked curiosity and respect among Confucian scholars and officials;

- And it created space for dialogue—not only about geography, but about religion, philosophy, and history.

Ricci observed that Chinese viewers were “greatly astonished to learn of so many countries beyond their own borders.” With this map, as with his life’s work, he extended an invitation: to look beyond the familiar, and to see the world—and one’s place in it—anew.

Unattributed, very detailed, two page-colored copy of the 1602 map Kunyu Wanguo Quantu by Matteo Ricci at the request of the Wanli Emperor. This copy was probably made in 1604 and exported to Japan. It shows phonetic annotations in Katakana for foreign place names outside of the Sinic world, predominantly around Europe, Russia and the Near East.

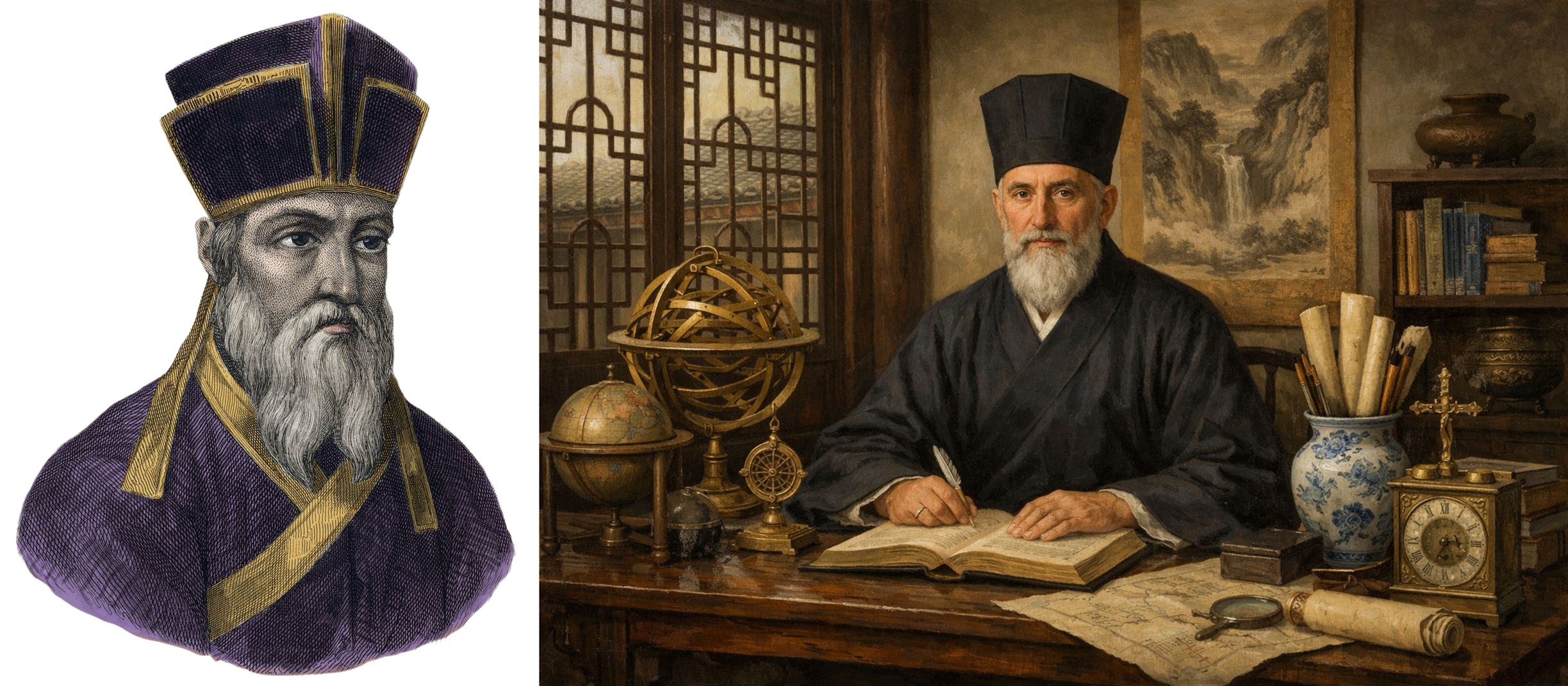

LEFT: Portrait of Father Matteo Ricci. 19th century engraving by unknown artist.

RIGHT: A portrait of Matteo Ricci in Ming attire. AI Generated illustration.

Father Matteo Ricci was born in Macerata, at that time in the Papal States, in 1552. The eldest of seven brothers and four sisters, he belonged to one of the most noble and prominent families in the city. He received his early education at the Jesuit college in Macerata, and in 1568, following his father’s wishes, he was sent to Rome to begin his studies in law at the Sapienza University, with the expectation that he would one day serve as a governor at the papal court.

However, defying his father’s ambitions, Ricci entered the novitiate of the Society of Jesus in Rome in 1571. A year later, in 1572, he took his religious vows. He pursued studies in Greek and Latin literature, completed the customary two-year course in rhetoric, and began studying the scientiae naturales (natural sciences) in the philosophy faculty of the Collegio Romano, under the Jesuits' rigorous intellectual curriculum.

By 1577, Ricci had expressed a strong desire to become a missionary. He traveled to Genoa and from there made his way to Lisbon, the required departure point for Jesuit missions to the East. Since ships to the Indies sailed only once per year, he used the waiting time to learn Portuguese.

In 1578, after months of preparation, Ricci finally embarked for Goa—then a major Jesuit stronghold in Portuguese India—reaching it only after six arduous months at sea. In Goa, he studied theology for his first year while also teaching literature at the Jesuit college. In July 1580, at the age of 28, he was ordained a priest. Two years later, in 1582, he made his way to Macao, the gateway to China.

What can we learn about Matteo Ricci’s character from his early life?

1. Moral Courage and Inner Conviction

Ricci’s decision in 1571 to abandon a prestigious legal career envisioned by his father—a position of influence within the papal court—in favor of the austere and uncertain life of a Jesuit missionary, speaks to his deep moral resolve and spiritual independence. In early modern Italy, to defy the will of a powerful aristocratic father was no small act. This points not only to Ricci’s inner strength, but to a character shaped by faith over status, and mission over ambition.

“He was willing to risk paternal disappointment and the loss of worldly opportunities in order to follow the higher calling of the Society of Jesus.”

— Jonathan D. Spence, The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci

2. Intellectual Curiosity and Mental Discipline

From his studies at the Collegio Romano under Christopher Clavius, it’s clear Ricci was exceptionally gifted. He not only mastered the classical trivium (rhetoric, logic, grammar), but also distinguished himself in mathematics, astronomy, cartography, philosophy, and Chinese language and culture later in life.

He was not content with dogma or rote learning, but deeply engaged in cross-cultural knowledge.

His maps and treatises show systematic reasoning and scientific precision, unusual even among Jesuits.

Ricci embodied the Renaissance ideal of the "polymath"—a man whose learning spanned theology, science, language, and diplomacy.

3. Adaptability and Cultural Intelligence

Perhaps Ricci’s most remarkable trait was his cultural empathy and strategic intelligence. When in China, he quickly realized that brute evangelization would fail. Instead, he adopted Confucian dress, mastered classical Chinese, and presented himself as a "scholar from the West" rather than a foreign preacher.

This approach, known as "accommodationism", showed not only intellectual tact, but a profound respect for the Chinese worldview. It earned him access to elite circles and, ultimately, an imperial audience in 1601.

“Ricci's brilliance lay not in loud preaching, but in quiet understanding.”

— George Dunne, Generation of Giants

4. Emotional Maturity and Diplomacy

Accounts by both European and Chinese contemporaries note Ricci's calm temperament, measured speech, and refined manners. He impressed Confucian scholars by being a master of memory, logic, and ethical discourse. His behavior in court was always marked by self-discipline and humility, even when dealing with officials who distrusted foreigners.

Chinese records praised him as "Li Madou," a man of virtue and learning, who "neither boasted nor argued."

Matteo Ricci discussing with some Literati in an outer copurtyard of the Forbidden City. AI-generated illustration.

- Death and Legacy

Matteo Ricci died in Beijing on May 11, 1610, at the age of fifty-seven. In a gesture of extraordinary significance, the Wanli Emperor granted him an honor seldom bestowed upon foreigners: permission to be buried in the imperial capital. His resting place, in what became known as Zhalan Cemetery, stood as a lasting symbol of his deep integration into Chinese cultural and intellectual life.

The funeral mass was held in a newly consecrated chapel on the grounds of a former villa—once belonging to a disgraced court eunuch, later converted into a Buddhist temple, and finally designated by imperial decree as Ricci’s burial site. The event drew a multitude of mourners. Among them were his closest friends and collaborators, Xu Guangqi and Li Zhizao, now Christian converts and high-ranking mandarins, who grieved with visible sorrow. Even officials who had never embraced Christianity paid their respects: members of the highest echelons of court society sent wreaths and formal condolences.

As the contemporary account describes, “Everyone recognized Ricci’s exceptional qualities: virtue, righteousness, and culture.” The Emperor himself extended imperial patronage to the funeral—an extraordinary acknowledgment of Ricci’s character and achievements. (Quotation adapted from Ronnie Po-Chia Hsia, Un Gesuita nella Città Proibita, Il Mulino, 2012 / OUP, 2010).

Matteo Ricci remains a rare figure in the long history of Christian missions to China—a man whose moral and intellectual stature, as one historian observed, “has almost entirely escaped the wrath of Chinese posterity.” His writings on ethics, science, and philosophy continued to be revered long after his death. During the Qing dynasty, several of his works were accorded the rare honor of inclusion in the Siku Quanshu (Complete Library of the Four Treasuries)—the most ambitious imperial encyclopedia in Chinese history, commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor in 1772 and completed a decade later. The collection encompassed over 36,000 volumes and nearly a billion words; Ricci’s inclusion signaled enduring respect for his intellectual legacy.

Ricci’s life and example have often been cited as a model of respectful, open, and fruitful engagement between European and Chinese civilizations. His memory endured even through the political upheavals of later centuries. When his tomb was destroyed by the Boxers in 1900, it was promptly restored. Even after its desecration by Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution in 1966, the government of the People’s Republic saw fit to rebuild it, preserving the original site. Today, Ricci’s tomb stands within the courtyard of the former Central Party School of the Chinese Communist Party—a quiet but remarkable testament to the enduring legacy of a Jesuit who crossed borders of language, culture, and belief. (Quotation adapted from Michela Fontana, Matteo Ricci: un Gesuita alla corte dei Ming, Mondadori, 2005).

Matteo Ricci’s tomb is in the historic Zhalan Cemetery, within today’s Beijing Administrative College compound (formerly Beijing Communist Party School), on Chegongzhuang Dajie in Xicheng District.

The De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas and Its Transmission

The De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas (On the Christian Expedition to China) is the foundational European narrative of the Jesuit mission in China during the late Ming dynasty. Based on the detailed journals and letters of Matteo Ricci, S.J., the work offers a vivid account of Ricci’s thirty-year encounter with Chinese culture, his linguistic and scientific engagement with Confucian scholars, and the broader Jesuit strategy of cultural accommodation (accommodatio).

However, the version known to early modern Europe was not Ricci’s unfiltered voice. After Ricci's death in 1610, the task of publishing his writings fell to Nicolas Trigault, S.J., who translated the original Italian manuscripts into Latin and heavily revised the content for European readers. Published in 1615 in Augsburg, Trigault's edition reshaped the narrative to suit the theological and propagandistic needs of the Jesuit order, emphasizing martyrdom, triumph, and the providential success of the mission. His editorial choices introduced stylistic embellishments and omitted or reframed many of Ricci’s more subtle observations about Chinese society and philosophy. The result was a work both influential and distorted—an early instance of cross-cultural reportage shaped by institutional agenda.

It was not until the 20th century that scholars began to recover Ricci’s authentic voice. Critical editions and translations—especially those based on Ricci’s original Italian manuscripts, such as those published by Pasquale D’Elia and later by Louis J. Gallagher, S.J. (1942, English translation)—sought to undo Trigault’s interventions and restore the complexity, nuance, and humility that marked Ricci’s actual experience. These editions revealed a figure far more attuned to dialogue and mutual respect than the triumphalist tone of the Latin version had suggested.

Today, the De Christiana expeditione stands not only as a milestone in the history of global missions but also as a case study in the transmission—and transformation—of cross-cultural texts.

Here’s a summary of the major modern editions and translations of De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas, with a focus on the recovery of Matteo Ricci’s original writings, the role of Nicolas Trigault, and the publication history in English and Italian.

Original Work and Trigault’s Latin Edition (1615)

- Author: Matteo Ricci, S.J. (1552–1610)

- Posthumous editor/translator: Nicolas Trigault, S.J. (1577–1628)

- Title: De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Societate Jesu

- Language: Latin

- Published: Augsburg, 1615

This edition was based on Ricci’s Italian manuscripts, which Trigault translated into Latin and heavily revised. He modified structure, tone, and content to better align with Jesuit aims in Europe—adding dramatic or apologetic elements, and omitting passages seen as ambiguous or overly sympathetic to Chinese philosophy.

Modern English Translations

- Louis J. Gallagher, S.J. (1942)

- Title: China in the Sixteenth Century: The Journals of Matteo Ricci, 1583–1610

- Publisher: Random House / The Century Co. for the Institute of Jesuit History

- Language: English

- Notes:

- This is the first full English translation of Trigault’s Latin text.

- Gallagher retains much of Trigault’s style but provides extensive footnotes and historical context.

- Still valuable, but not a direct translation of Ricci’s own words.

- Ronnie Po-chia Hsia (Editor), Edward Malatesta, S.J. (Translator, unpublished full text)

- Hsia's scholarship revisits Ricci’s life and writings in light of modern Jesuit studies, and while not offering a full new English translation, he contributes context and critique that help reframe the Trigault version.

Modern Italian Editions

- Pasquale D’Elia, S.J. – Fonti Ricciane (1942–1949)

- Title: Fonti Ricciane: Documenti originali concernenti Matteo Ricci e il principio del Cristianesimo in Cina (1579–1615)

- Publisher: Libreria dello Stato, Rome

- Volumes: 3

- Language: Italian

- Notes:

- D’Elia recovered and published Ricci’s original Italian manuscripts, including journal entries and correspondence.

- This is the most critical edition of Ricci’s authentic writings, annotated and contextualized.

- It revealed many differences from Trigault’s version.

- Michela Fontana – Matteo Ricci. Un gesuita alla corte dei Ming (2005)

- Publisher: Mondadori, Milan

- Language: Italian

- Notes:

- A widely read and accessible biography based on D’Elia’s critical edition.

- Not a direct edition of De Christiana expeditione, but provides narrative synthesis grounded in Ricci’s authentic voice.

For further primary research in the original Italian manuscripts and letters, I used:

📚 Fonti Ricciane: Documenti originali concernenti Matteo Ricci

- Edited by Pasquale M. d’Elia — three volumes containing Ricci’s Italian writings and correspondence (including Della Entrata della Compagnia di Gesù… and early mission accounts).

📚 Lettere: 1580–1609 di Matteo Ricci

- Edited by Francesco D’Arelli (Quodlibet, Macerata 2001) — the authoritative collection of Ricci’s letters from Macau and China, in Italian.

These editions contain the verified original Italian texts Ricci wrote over his mission, offering direct insight into his thought on language, culture, custom, and adaptation.

All of the quotations in the following pages are taken directly from the original Italian editions of Ricci's manuscripts, without any mediation from the Latin version by Trigault. Where present, translations are for interpretative purposes only and do not replace the original text, which users can read directly in the cited sources.

Learning Tongues and Customs: Ricci’s First Years in Macau and Initial Experiences Inland

Based on Ricci’s Original Italian Manuscripts

Matteo Ricci arrived in Macau on August 7, 1582, at the age of twenty-nine, sent under the strategic direction of Alessandro Valignano to attempt what no Jesuit had yet achieved: sustained entry into mainland China from the Portuguese enclave. Ricci’s landing marked not only a physical arrival but the beginning of an intellectual apprenticeship within a civilization whose prestige rested on writing, ritual, and classical learning. In the European imagination of the late sixteenth century, China was distant and opaque; for Ricci, it became a world to be approached by patient study rather than immediate proclamation.

The months between his arrival in Macau and the establishment of the first Jesuit residence at Zhaoqing in September 1583 were therefore not a mere prelude. They formed a crucible in which Ricci confronted the central difficulty that would define his entire enterprise: how to become intelligible—linguistically, socially, and intellectually—within the moral and ceremonial universe of late Ming China.

The Strategic Vision of Alessandro Valignano

To understand Ricci’s early choices, one must begin with Valignano’s program. By the late 1570s, shaped by his experience in Japan, Valignano had become convinced that earlier missionary methods—too often reliant on European dress, Latin liturgy, and cultural self-enclosure—were strategically self-defeating. His alternative was explicit: the mission must be founded on disciplined linguistic acquisition and a respectful engagement with local customs and intellectual traditions.

Within this framework, Valignano insisted that Macau should serve as a school of preparation for China: a place where missionaries could remain long enough to acquire spoken and written Chinese before any inland expansion. While the precise staffing numbers and formulations varied across drafts and contexts, the strategic core is clear: no durable mission without language; no language without long residence and method.

Valignano's selection of Ricci for this enterprise was deliberate and prescient. The young Italian possessed not only solid theological training from the Roman College under the guidance of Christopher Clavius but also exceptional intellectual gifts, particularly in mathematics, astronomy, and cosmology, disciplines that would later prove instrumental in gaining the respect and attention of Chinese literati. Moreover, Ricci possessed the temperament necessary for the patient, methodical work of cultural translation that Valignano envisioned: he could endure the slow, unglamorous labor of cultural translation, which Valignano regarded as the only path to a mission that would not collapse into misunderstanding.

The policy of adattamento—cultural adaptation—which Valignano had theorized and applied differently in India and Japan, would find its most sophisticated and enduring expression in Ricci's Chinese mission.

LEFT: A portrait of Father Alessandro Valignano, a Jesuit from Chieti in the Papal States (now in Central Italy), created in 1599 by an unknown artist.

RIGHT: A plate from the book Vita Del Padre Alessandro Valignani Della Compagnia di Giesu, Descritta Dall’abbate D. Ferrante Valignani, Chieti, 1698.

Alessandro Valignano or Valignani (1539–1606) was an Italian Jesuit and the chief architect of the Society of Jesus’ missions in East Asia, especially Japan. Appointed “Visitor” to the Asian missions in 1573, he made three extended stays in Japan between 1579 and 1603, reshaping the local mission’s strategy and organization. Struck by earlier missionaries’ cultural insensitivity, he insisted that Jesuits master the Japanese language and etiquette, founding seminaries and promoting printed grammars and dictionaries in Japanese. Valignano’s famous “adaptation” policy urged missionaries to respect Japanese customs, social hierarchies, and aesthetics, even mapping Jesuit ranks onto local models to gain esteem. He strongly advocated the training and ordination of Japanese clergy, envisioning a future church led by local Christians rather than Europeans. Admiring Japan’s sophistication, he wrote that the Japanese surpassed not only other Asians but even Europeans, an unusually open appreciation for his age. Through this combination of cultural respect, institutional reform, and strategic engagement with local elites, Valignano became a pivotal figure in Japan’s sixteenth‑century “Christian century.”

Alessandro Valignano in Japan. AI-generated illustration.

Confronting the Linguistic Challenge

When Ricci disembarked at Macau, he found Michele Ruggieri already engaged in the arduous work of learning Chinese and negotiating the conditions for inland permission. Ricci entered immediately into that same discipline, beginning intensive study while observing the social grammar of a world in which status, ritual, and written culture were inseparable.

In his letter from Macau of 13 February 1583 to Martino de Fornari, Ricci gave one of his most revealing early assessments of Chinese:

La lingua cina […] è altra cosa che né la greca, né la todesca…

(“The Chinese language is something completely different from Greek or German.”)

The remark is spare, but its implications are immense. Ricci had been formed in a Renaissance culture that assumed language as a system of alphabetic representation and grammatical inflection; Chinese confronted him with a script of thousands of characters, a logic in which meaning could be shaped by tone, and a written medium that—unlike Europe’s vernacular fragmentation—functioned as a civilizational glue across diverse speech-forms.

Ricci’s descriptions of difficulty are never merely complaints. They are part of a developing method: he records obstacles in order to decide what must be learned first, what can be postponed, and what must be treated as an interpretive key to the culture itself.

The Dictionary and the Discipline of Preparation

One of the most concrete expressions of this method was lexicographical. Working alongside Ruggieri and Chinese collaborators, Ricci participated in the compilation of a Portuguese–Chinese dictionary, composed during the first inland years and completed across the 1580s. This project—now recognized as the earliest known European–Chinese dictionary—was not only a tool for the two missionaries; it was a strategic investment in the continuity of the entire mission.

It embodied Valignano’s insistence that China could not be approached by improvisation. A mission that depended on charisma, haste, or ad hoc translation would fail; a mission built on disciplined linguistic infrastructure could endure.

LEFT: First page of the Portuguese-Chinese dictionary manuscript, compiled by Fr. Matteo Ricci, Fr. Michele Ruggieri, and the Chinese Jesuit lay brother Sebastian Fernandez in Macauy and later in Zhaoqing, Guangdong, between 1583-1588.

RIGHT: Matteo Ricci and Michele Ruggieri working at the first Portuguese–Chinese dictionary in Zhaoqing. AI-generated illustration.

Ricci and Ruggieri: Toward Different Forms of Entry

Already in the early phase, differences of emphasis appeared. Ruggieri’s work was indispensable—diplomatic negotiation, practical communication, and the first sustained bridge of vocabulary. Ricci, however, increasingly recognized that entry into China’s intellectual life required more than functional speech. It demanded mastery of the written language and the philosophical and ritual frameworks through which elite society understood itself.

From the beginning, Ricci set aside any fantasy of rapid preaching and instead committed himself to preparation. In a first Macau letter of 1583, he writes with pragmatic clarity:

Ho dovuto applicarmi con grande attenzione alla lingua cinese, ché qui non si può andar oltre con poche parole, se prima non si conosce bene la scrittura e le molte forme d’uso.

(“I had to apply myself very carefully to the Chinese language, because here one can’t get very far with just a few words if one doesn’t first have a good knowledge of the writing system and the many forms of usage.”)

For Ricci, classical written Chinese was not simply one skill among others. It was the gate to the literati: to scholars, officials, and—eventually—the court. His early correspondence reveals a gradual shift from missionary urgency to something closer to cultural diplomacy: learning how to be read, and therefore how to be heard.

Macau, positioned between Portuguese and Chinese worlds, functioned as a threshold city, a place of contrasts where ritual difference was visible everywhere—in greetings, hierarchies, visiting protocols, and the symbolic meaning of clothing and comportment.

Ricci learned Chinese with the indispensable help of native tutors or laoshi, teachers who coached pronunciation, guided reading, corrected writing, and—most importantly—explained cultural expectations. Ricci depended on them, and he knew it.

He states the point directly:

Ci vogliono molti anni per entrare nella profondità di questa lingua, e senza i maestri cinesi, poco si può fare.

(“It takes many years to penetrate the depth of this language, and without Chinese teachers, little can be done.”)

What mattered was not only linguistic technique but a form of apprenticeship in Chinese reasoning—how meanings are carried by allusion, how moral judgment is framed, how ritual action signals belonging.

Ricci later summarized the standard he imposed upon himself:

Per potersi confrontare ad armi pari su qualsiasi questione gli venisse posta, bisognava non solo imparare a parlare, ma comprendere le radici stesse del pensiero cinese.

(“To be able to engage on equal terms with any question posed to him, one had to learn not just to speak, but to understand the very roots of Chinese thought.”)

Customs, Ritual, and the Discipline of Non-Judgment

Ricci’s early manuscripts repeatedly show that his curiosity was not decorative—it was methodological. He studied greeting rituals, family hierarchies, ancestor reverence, literary gatherings, banquets, visiting etiquette. He did so not as an ethnographer at a distance but as a man trying to avoid fatal misunderstandings.

This sentence from Fonti Ricciane captures his stance:

…Non è buon giudicare le cerimonie di fuori senza intendere il loro senso e il fine che manchon in cuore gli uomini di questa nazione.

(“…It is not good to judge external ceremonies without understanding their meaning and the end that is found in the hearts of the men of this nation.”)

This is one of the quiet revolutions of Ricci’s approach: not an uncritical embrace of all practices, but a refusal to condemn what he has not yet understood. It anticipates his later attempt to distinguish between external forms and moral intentions—an interpretive move that would become central to his treatment of Confucian ethics and, eventually, the rites debate.

His admiration for China—especially for its literate culture—is already explicit in your text and should remain explicit, because it is one of the most striking tonal differences between Ricci and many contemporary European accounts:

La lingua cinese è differentissima delle altre terre e genti, percioché è gente savia, data alle lettere e puoco alla guerra, è di grande ingegno.

(“The Chinese language is entirely different from those of other lands and peoples, for they are a wise people, devoted to letters and little to war, and of great intelligence.”)

Ceremonies, Clothing, and the Social Meaning of Form

The logic of cultural accommodation emerges early in Ricci’s writing: if one violates ceremonial expectations, one is not merely impolite; one becomes unintelligible—categorized as barbarian, excluded from trust, prevented from entering the elite networks that mediate social power.

Ricci captures this sharply:

La differenza delle cerimonie è tanta che, se non si osservano, non solo non si guadagna credito, ma si viene considerati barbari.

(“The difference in ceremonies is so great that, if they are not observed, one not only fails to gain respect, but is considered a barbarian.”)

What Ricci learned in Macau is the principle: form is social meaning.

Non si può separare la parola dal gesto, la scrittura dal rituale.

(“One cannot separate the word from the gesture, nor writing from the ritual.”)

Whether this is verbatim from a surviving letter in exactly this formulation is harder to validate quickly; but as a Riccian paraphrase it perfectly expresses the thrust of his correspondence.

The First Entry into China: Zhaoqing, September 1583

In September 1583, after patient relationship-building and negotiation, Ricci and Ruggieri received permission to establish a residence at Zhaoqing. This date is well attested, and modern scholarship commonly notes their arrival there on September 10, 1583.

Ricci’s Commentarj recount the first official encounter with rhetorical humility:

Furono ricevuti con molta benignità; …domandò loro il governatore chi erano, di dove venivano e che volevano; risposero … che erano religiosi … venuti attratti dalla fama del buon governo della Cina, e solo desideravano un luogo dove potessero fare una casetta e una chiesuola … servendo fino alla morte al loro Dio.

(“They were received with much kindness; …the governor asked who they were, where they came from, and what they wanted; they replied … that they were religious men … drawn by the reputation of China’s good governance, and desired only a place where they might build a little house and chapel … serving their God until death.”)

These were parole semplici, ma contenenti tutto un programma—an entire strategy condensed into modest phrasing. The missionaries do not demand, they request; they do not denounce, they praise; they do not claim superiority, they express admiration and a desire to dwell peaceably within the local order.

At this stage, they presented themselves in Buddhist-style dress—an accommodation initially chosen because Buddhism was recognizable and legally tolerated. Yet Ricci later saw clearly that association with Buddhist monasticism did not grant the social prestige required to reach the Confucian elite. The Jesuits could be received as curiosities, even tolerated as religious specialists, while still remaining socially marginal.

Matteo Ricci and Michele Ruggieri entering Zhaoqing in September 1583. AI-generated illustration.

Michele Ruggieri, SJ (born Pompilio Ruggieri; 1543–1607), known to the Chinese as Luo Mingjian, is remembered as a linguistic pioneer who undertook the difficult task of mastering spoken and written Chinese at a time when almost no Europeans could do so. Working closely with Matteo Ricci and other companions, Ruggieri helped design a strategy of cultural accommodation that sought dialogue with Chinese scholars and officials rather than simple confrontation. He is often credited with contributing to the earliest substantial Latin–Chinese lexical and catechetical works, laying foundations for future Jesuit scholarship on Chinese language and civilization. Through his patient study of local customs and his willingness to respect Chinese traditions, Ruggieri became a key figure in the first sustained encounter between early modern Europe and imperial China.

Learning in Zhaoqing: Classics, Objects, and the Grammar of Curiosity

In Zhaoqing, the residence became a laboratory of inculturation. Ricci deepened his study of spoken and written Chinese and began sustained engagement with the Confucian canon—the Four Books in particular—because he recognized that conversation with literati required not merely language but shared references and rhetorical legitimacy.

The residence also became a site of mutual curiosity. Ricci displayed European artifacts—clocks, prisms, mathematical and astronomical instruments—and used them as conversational bridges. These objects were not only “wonders”; they were proofs of technical competence and prompts for deeper discussion about cosmology, mathematics, and the ordering of knowledge.

Matteo ricci in Zhaoqing. AI-generated illustration.

Cartography and Cultural Translation: The 1584 Map

In 1584, at Zhaoqing, Ricci produced an early European-style world map in Chinese at the request of the governor Wang Pan. The map is widely referred to as Yudi Shanhai Quantu (輿地山海全圖), and modern accounts consistently connect it to Zhaoqing and Wang Pan.

This was diplomatically delicate. A map that visually decenters China risks offending the tianxia imagination. Ricci’s genius was to translate European cosmography without presenting it as a cultural insult: he used Chinese script, adopted explanatory strategies appropriate to his audience, and framed the spherical earth as a rational proposition rather than a polemical correction.

This first map initiated a cartographic enterprise culminating in the far more famous 1602 Kunyu Wanguo Quantu, but the 1584 Zhaoqing map matters because it shows Ricci’s method in miniature: present European knowledge in Chinese form, and do so in a way that preserves the possibility of dialogue rather than provoking rejection.

Translating Christianity: The Tianzhu shilu and the Problem of Terms

Also in 1584, Ruggieri produced (with collaboration and support from others) the Tianzhu shilu (True Record/Account of the Lord of Heaven), printed by woodblocks in China and widely described as the first Chinese-language work published by a European, and the first European-authored work printed in China.

The terminological problem was anything but minor: how to translate “God” without importing confusion or misunderstanding, for example?

The choice of Tianzhu (“Lord of Heaven”) drew on available Chinese vocabulary while inevitably carrying associations that later missionaries would contest.

There was also a visual problem: sacred images could invite reverence, but also misinterpretation, because Chinese viewers read images through different conventions. Your narrative about replacing the Madonna image with a Christ image to reduce confusion is consistent with the logic Ricci himself explains in various forms; it belongs here because it demonstrates his practical willingness to adapt presentation while guarding what he regarded as doctrinal substance.

Suspicion, Expulsion, and the Pivot Toward the Literati

The Zhaoqing years were productive but precarious. Rumors circulated: they were alchemists, secret agents of Portuguese expansion, possessors of strange wealth... Such suspicion is common in frontier contexts, and it helps explain why progress depended on fragile networks of patronage.

In 1589, changes in local politics forced Ricci and his companions to leave Zhaoqing. Ricci moved to Shaozhou, where the mission entered a new phase.

It's during the Shaozhou period that the decisive wardrobe and social translation began to mature. Modern scholarship often notes that by 1594 Ricci was already moving away from the Buddhist persona (even in physical presentation), and in 1595 the adoption of Confucian scholar attire becomes explicit and strategic. Ricci's literati friends, especially Qu Taisu (Qu Rukui), encouraged him to abandon Buddhist resemblance and approach the literati world on its own terms.

Matteo Ricci with some Literati. AI-generated Illustration.

Names and Identity: Lì Mǎdòu and the “Far West”

By this time Ricci’s Chinese name, Lì Mǎdòu (利瑪竇), had become established, and he was also associated with honorific expressions identifying him as a man “from the Far West” (Xitai). The exact nuance of these titles shifts in different accounts, but the basic point is stable: a foreign scholar must not only speak Chinese; he must acquire a socially legible identity within Chinese categories.

The Foundation of a Method

The period from Ricci's arrival in Macau in August 1582 to his establishment at Shaozhou in 1589 laid the methodological foundation for all his subsequent achievements. These years of intensive language study, cultural immersion, strategic experimentation, and occasional setback taught him lessons that would guide his approach for the remaining two decades of his life. He learned through direct experience that successful cross-cultural communication required more than good intentions, theological clarity, or even linguistic competence—though all were necessary. It demanded deep appreciation for Chinese intellectual traditions, strategic adaptation to local social structures and cultural expectations, patience in building relationships of trust and mutual respect, and the intellectual humility to position himself as both teacher and student.

Ricci's letters from this period reveal a man acutely conscious of both the magnitude of the task before him and the inadequacy of conventional missionary approaches that had failed elsewhere. The metaphor he employed in reflecting on these early years captures perfectly the nature of the preparatory work: not yet harvesting, not even sowing, but the arduous labor of breaking the ground to create conditions for future cultivation. This image conveyed the patient, foundational nature of the early mission—work whose fruits might not be visible for years but which was absolutely essential for any subsequent growth.

The linguistic competence Ricci developed during these formative years extended far beyond vocabulary acquisition to encompass the rhetorical styles, allusive richness, and subtle register variations of classical Chinese. His later published works demonstrate an impressive command of literary Chinese, the ability to quote Confucian texts appropriately and effectively, and the skill to compose in forms that Chinese readers would recognize as cultured, authoritative, and worthy of serious consideration. This mastery did not come easily or quickly. It required years of disciplined study under patient Chinese tutors, constant practice in reading and composition, repeated correction and refinement, and the intellectual humility to position himself genuinely as a student of Chinese civilization even as he sought to introduce elements of European learning and Christian theology.

Similarly, his cultural adaptation involved continuous observation, reflection, and adjustment. Ricci carefully noted the complex systems of courtesy and hierarchy that governed Chinese social interaction at every level, the importance of gift-giving in establishing and maintaining relationships, the protocols for visiting officials and scholars, and the crucial distinctions between occasions when flexibility was possible and when strict adherence to established norms was absolutely required. His writings display a keen anthropological eye, describing Chinese customs not with the condescension common in many European accounts of the period but with genuine intellectual interest in understanding their internal logic, social function, and philosophical foundations.

The Deepening Engagement with Confucianism

Perhaps most significantly for the long-term success and controversy of the mission, these early years initiated Ricci's sustained, systematic engagement with Confucian thought that would culminate in his mature theological synthesis. Through his study of the Confucian classics and his conversations with scholars like Qu Taisu and others, Ricci began to formulate the bold interpretive position that would guide his later theological and apologetic work.

He came to believe—and would argue with increasing confidence and sophistication—that ancient Confucianism, particularly as represented in the earliest canonical texts and distinguished (in his view) from later developments that obscured or distorted earlier Confucian moral insight, contained a form of natural theology fundamentally compatible with Christianity. The Confucian emphasis on moral cultivation, filial piety, social harmony, respect for hierarchy, and heaven's moral order could, Ricci argued, serve as a preparatio evangelica—a preparation for the gospel—much as classical Greek and Roman philosophy had served in the ancient Mediterranean world.

This interpretive move was intellectually audacious and strategically crucial. It allowed Ricci to position Christianity not as a foreign imposition fundamentally hostile to Chinese culture but as the fulfillment and completion of China's own highest ethical and metaphysical insights. At the same time, he maintained a critical stance toward what he viewed as later Neo-Confucian metaphysics, which he believed had been corrupted by Buddhist influences and materialist tendencies, and toward popular religious practices, which he categorized dismissively as superstition unworthy of educated minds.

This framework—affirming ancient Confucianism while critiquing Buddhism, Daoism, and Neo-Confucianism—would structure all his subsequent Chinese writings and shape Jesuit missionary strategy in China for generations. Whether this interpretation was historically accurate or theologically sound remains debated by scholars to this day, but its practical effectiveness in facilitating Ricci's entry into literati circles and enabling productive theological dialogue is undeniable.

Conclusion: The Silent Months that Shaped a Mission

The years of preparation in Macau and the first experiences in Zhaoqing and Shaozhou were thus not merely a preliminary phase to be hastily passed over in favor of later triumphs. They constituted the essential foundation of everything Ricci would accomplish during his nearly twenty-eight years in China. These were the years when he transformed himself from a European Jesuit newly arrived in Asia into what we might call a bilingual, bicultural intellectual capable of moving fluidly between worlds.

By 1595, when he moved from Shaozhou to Nanchang, Ricci could read and write classical Chinese with considerable sophistication, converse with literati on terms they recognized and respected, and navigate the complex social world of late Ming China with growing confidence and cultural competence. He had established a methodological approach—grounded in language learning, cultural adaptation, intellectual exchange, and the patient cultivation of friendship—that would guide the rest of his missionary career and profoundly influence Jesuit practice in China and beyond for generations to come.

The principle that emerged from these years of study, adaptation, and reflection—though perhaps never expressed in the exact formulation sometimes attributed to him—can be discerned throughout his writings and practice: not to change Chinese laws and customs wholesale, but to demonstrate how Christian revelation completes and fulfills what is highest in Chinese ethical and philosophical traditions. This accommodationist vision, matured in the silent months of study in Macau and refined through the first tentative conversations in Zhaoqing and Shaozhou, would become the pillar of the Jesuit China mission and a pioneering model for intercultural dialogue that remains instructive centuries later.

The original Italian editions—from the Opere Storiche edited by Pietro Tacchi Venturi (1911-1913) to the monumental Fonti Ricciane edited by Pasquale D'Elia (1942-1949), and the recent critical Lettere edition by Quodlibet (2001)—restore an authentic voice, distant from the later processes of selection, Latin redaction, and editorial normalization. In these texts we encounter not the myth of an infallible apostle but the vivid and self-critical account of a man who learned to become Chinese without ceasing to be Italian, opening a breach in the wall of incomprehension that still too often divides East and West.

From his first year inland, Ricci’s Italian manuscripts reveal a clear strategic orientation:

• Studiare profondamente la lingua e i caratteri — study deeply both spoken and written language;

• Comprendere le cerimonie e usanze sociali — grasp the meaning behind rituals and social customs;

• Stabilire relazioni di rispetto con letterati e funzionari — create respectful relationships with literati and officials;

• Adattare la presentazione del messaggio cristiano alla sensibilità morale cinese — adapt the presentation of Christian teaching to Chinese moral sensibilities.

In these years, Matteo Ricci did not focus on preaching in the conventional sense, but rather on building linguistic mastery and intercultural competence, in order to engage with Chinese society later on in an intelligent, respectful and effective manner. His Italian manuscript letters and commentaries (unlike the later Latin redaction by Trigault) reveal a missionary who was deeply committed to understanding before speaking, learning before teaching, and adapting respectfully rather than imposing. Ricci soon realized that, in order to be understood, he must first understand. Unlike many missionaries, who clung to their own dress and customs, Ricci embraced linguistic and cultural immersion as a central strategy and an expression of sincere, open-minded curiosity.

This period laid the real foundation for his first inland residence at Zhaoqing (Shiuhing) and later moves to Nanchang, and eventually Beijing — a journey made possible by linguistic mastery, cultural intelligence, and genuine respect for Chinese ways of life.

Matteo Ricci in Shaozhou in the mid-1590s. AI-generated illustration.

Matteo Ricci in Nanchang and Nanjing

Networks, Knowledge, and the Making of a Cross-Cultural Mission (1595–1601)

Introduction: From Itinerant Scholar to Imperial Presence

When Matteo Ricci left Shaozhou in 1595 and settled in Nanchang, he was no longer a tentative foreign missionary testing the edges of Chinese society. He had already learned, often painfully, that success in China depended not on religious proclamation but on intellectual credibility, ritual literacy, and the slow cultivation of elite relationships. The years that followed—from Nanchang to Beijing, where Ricci would die in 1610—constitute the mature phase of his mission: the period in which accommodation became method, dialogue became strategy, and personal networks became the infrastructure of Christianity’s first durable implantation in China.

These final fifteen years were not a linear ascent. They were marked by repeated displacement, political uncertainty, personal illness, internal Jesuit tensions, and moments of genuine danger. Yet they also witnessed Ricci’s greatest intellectual productions, his deepest engagements with Confucian thought, and the consolidation of a Chinese network that extended from provincial academies to the imperial capital itself.

Nanchang at the time of Matteo Ricci. This AI-generated illustration is historically plausible and grounded, especially in geography, city structure, and riverine trade. While there are signs of idealization, especially in the human detail and atmosphere, the architectural and environmental features align very well with what we know of late Ming Nanchang.

Nanchang (1595–1598): Establishing the Literati Persona

Upon settling in Nanchang, Ricci executed a transformation that would define the remainder of his mission. Having earlier discarded the Buddhist monastic garb that had proven ineffective, he now fully embraced the identity of a ru (儒), a Confucian scholar-official. This was no mere costume change. Ricci meticulously adopted Chinese dress, mastered the intricate protocols of literati social life, and presented himself as Lì Mǎdòu (利瑪竇), a man of letters from the Far West. His linguistic facility—by now he could compose in classical Chinese with elegance—astounded his hosts. The iconoclastic scholar Li Zhi (李贄), who met Ricci around 1599, marveled that “there is scarcely a Chinese book he has not read… Now he is fully able to speak the language of our country, to write using our characters, and to practice our rituals. He is an exquisite human being”.

This strategic accommodation was not simply pragmatic; it reflected Ricci’s growing conviction that Christianity could not be imposed but must be invited. As Paul Rule argues in K'ung-tzu or Confucius?, Ricci’s approach represented a sophisticated hermeneutical project: to demonstrate that Christianity was not a rival to Confucianism but its fulfillment. In Nanchang, this theory moved from abstraction to practice.

This city was an important cultural center in Jiangxi province and offered Ricci access to a dense network of degree-holding scholars, examination candidates, and retired officials. He presented himself as a man of learning from the “Far West,” skilled in mathematics, astronomy, geography, and moral philosophy. His residence quickly became a salon of sorts, attracting visitors curious about European knowledge and impressed by his mastery of classical Chinese.

It was in Nanchang that Ricci refined his technique of intellectual hospitality. He did not preach publicly. Instead, he conversed, explained, demonstrated, and wrote. European clocks, prisms, maps, and astronomical instruments functioned not as curiosities but as credentials. They opened conversations that could then move, gradually and selectively, toward ethical and metaphysical questions.

Most importantly, Nanchang allowed Ricci to deepen his engagement with Confucian texts. He increasingly framed Christianity as a fulfillment of what he understood to be the moral core of ancient Confucianism: reverence for Heaven, ethical self-cultivation, and social harmony. This interpretive move—audacious and controversial—was not yet fully systematized, but its foundations were laid here.

Matteo Ricci in Nanchang. AI-generated illustration.

It’s entirely plausible that Matteo Ricci, being Italian, may have used expressive hand gestures in conversation, even during his time in China. Ricci was born in Macerata, Italy (in the Papal States), and educated at the Collegio Romano, the Jesuit center of learning in Rome. Italian rhetorical and classical education—especially in the Renaissance tradition—emphasized oratory, persuasion, and expressive delivery, including gestures, as drawn from Cicero and Quintilian. Jesuit pedagogy specifically encouraged dynamic and affective speech, which would likely include hand gestures as tools of communication and persuasion. Italians in Ricci’s time, just like today, were known for using manual gestures to emphasize ideas, emotions, or rhetorical points. 16th-century observers noted how gestural language was common across southern Europe—especially among educated speakers who delivered public sermons, lectures, or religious instruction. In Confucian Chinese culture, particularly among the elite, emotional restraint and bodily composure were hallmarks of educated behavior. Ricci, who spent years mastering Chinese etiquette and Confucian norms, likely tempered or moderated his gestural communication to avoid appearing rude or uncultured. He was known for adapting to Chinese customs meticulously—changing his dress, studying classical texts, and avoiding behaviors that could appear flamboyant. Ricci may have restricted his gestures in more formal contexts (e.g., literati audiences, elite banquets, or court meetings), but till relied on subtle, deliberate movements to support his ideas, especially when teaching or explaining abstract Western concepts.

Writing as Dialogue: Moral Philosophy and Translation

The Nanchang period also marks the beginning of Ricci’s most significant Chinese-language writings. These texts were not catechisms in the medieval sense, but dialogical treatises, modeled on literati discourse.

Ricci’s most important work, Tianzhu shiyi (The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven), would be completed later, but its conceptual architecture took shape in Nanchang. The text does not begin with revelation or dogma; it begins with reason, ethics, and shared moral intuitions. Ricci carefully avoids attacking Confucius. Instead, he positions Confucian moral philosophy as incomplete without the metaphysical clarity provided by Christianity.

This strategy was deliberate. Ricci understood that the Chinese literati valued antiquity, moral seriousness, and textual continuity. By arguing that Christianity restored a lost understanding of Heaven (Tian) rather than replacing Chinese tradition, he avoided the stigma of barbarian heterodoxy.

Yet this approach also introduced tensions—both with Chinese interlocutors who rejected theistic readings of Confucianism, and with later missionaries who feared excessive accommodation. These tensions would only intensify after Ricci’s death.

Here’s a fact‑checked and polished version of your text. I’ve verified the main points against scholarly and reference sources and noted where your original claims are supported, need slight correction, or lack evidence in the mainstream scholarship.

The Treatise on Friendship (Jiaoyou Lun): Building Bridges Through Shared Values

Matteo Ricci’s Jiaoyou Lun (交友論, Treatise on Friendship), composed in Nanchang in 1595, was a pivotal work in his mission to engage Chinese literati on common intellectual ground. It was his first major work written entirely in Classical Chinese and quickly became one of the most widely read Western texts among late Ming scholars.

Ricci chose friendship as his subject because it resonated deeply with Chinese intellectual culture; in Confucian thought, friendship (you) was considered one of the essential human relationships and was widely discussed in the Ming period.

Drawing on Western classical sources—including Aristotle, Cicero, Plutarch, and Seneca—as well as Christian thinkers such as St. Augustine and St. Ambrose, Ricci compiled a set of moral maxims highlighting the virtues of friendship. These were translated or paraphrased into eloquent Chinese and presented in a format familiar to Chinese audiences.

The treatise argued that friendship grounded in virtue and mutual respect was harmonious with the Confucian ideal of ren (benevolence), and thereby served as a natural point of cultural and philosophical convergence.

Presented to Prince Jian’an (Zhu Duojie) and circulating widely thereafter among literati, Jiaoyou Lun earned Ricci admiration as a learned moral philosopher and helped establish his reputation among China’s scholarly elite. This success reflected Ricci’s mastery of Chinese literary style and his skill in adapting foreign ideas into forms recognizable within Confucian culture.

Some modern scholars (e.g., Thierry Meynard) see this work as more than simple cultural exchange: beneath its surface dialogue with Confucian ethics, Ricci subtly introduced Christian concepts of caritas and reinterpreted ethical ideals as part of his broader strategy of cultural accommodation. This technique—what Nicolas Standaert calls “accommodation through reinterpretation”—would become a hallmark of Ricci’s method.

LEFT: A page of the Treatise on Friendship by Matteo Ricci. Wikimedia Commons.

RIGHT: Matteo Ricci writing the Treatise in the evening. AI-generated illustration.

You Lun (Treatise on Friendship), also known as Jiao You Lun (Treatise on Making Friends), was authored by Matteo Ricci, who also gave it the Latin title De Amicitia. Written for a broad, non-Christian Chinese readership, the work explores the theme of virtuous friendship and reflects Ricci’s broader effort to introduce Renaissance humanist values into Chinese intellectual life.

According to the Siku Quanshu Tiyao (Annotated Bibliography of the Imperial Library), the treatise was recommended by Qu Rukui (b. 1549), a member of a distinguished scholarly family from Changshu, Jiangsu. Qu became one of Ricci’s earliest Chinese followers and was baptized in Nanjing in 1605.

The inspiration for the treatise arose from Ricci’s conversations on the nature of friendship with Zhu Duojie (1573–1601), the Prince of Jian’an. This work marked Ricci’s first full-length text composed in Chinese. It presents a series of translated or paraphrased maxims drawn from both classical Western philosophers and Christian thinkers, rendered in a style familiar to Chinese literati.

The text comprises 100 aphorisms in approximately 3,500 characters. Of these, 76 had been previously collected by Ricci, with the remainder added later. In his preface, Ricci recounts a banquet hosted by Prince Jian’an, during which the prince asked what Westerners believed about friendship—prompting Ricci to offer these reflections.

The maxims are not arranged in thematic order and can be read independently. Among the sources Ricci draws upon are Aristotle, Cicero, Plutarch, and Seneca, alongside Christian figures such as St. Ambrose of Milan and St. Augustine of Hippo.

The work was well received by Chinese scholars, who read it with curiosity and admired Ricci’s literary skill. Some of the maxims were quoted by late Ming scholars, including the oft-cited reflection:

My friend is not another person. My friend is my half—another me. I must therefore regard my friend as myself.

Ricci, by all accounts, possessed a remarkable gift for friendship himself, forming enduring bonds with many of the people he encountered throughout his missionary work in China. He probably had what in Spanish is called "el don de gente".

The Memory Treatise (Xiguo Jifa) and the Performance of Learning

In 1596, Ricci produced another work in Chinese often referred to as Xiguo Jifa (Western Method of Memory), introducing aspects of the European art of memory (ars memorativa) to his Chinese interlocutors. This text explained mnemonic techniques, including the famous mnemonic “memory palace”—mental structures (such as palaces, pavilions, or halls) in which images are placed to aid recall.

Jonathan Spence’s The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci vividly describes how Ricci used these techniques and how he taught Chinese scholars to construct elaborate mental “palaces” to organize and retain knowledge.

Contemporaries were impressed by Ricci’s ability to recite long passages from memory, and his mnemonic demonstrations helped establish his reputation for prodigious intellect. However, scholars such as those examining the historical impact of Xiguo Jifa argue that its practical influence on Chinese memory practices was limited; existing Chinese educational traditions already included sophisticated memorization techniques, and Ricci’s imported methods did not supplant them.

What mattered more, in many accounts, was not the long‑term adoption of the mnemonic system itself but the performance of learning it represented: Ricci’s display of intellectual mastery and familiarity with both Western and Chinese scholarly practices helped solidify his credibility among the literati and ornate his image as a learned visitor from the West.

Networks of Friendship: The Social Infrastructure of the Mission

Ricci’s success in Nanchang and beyond cannot be understood without attending to his Chinese friendships. Conversion, when it occurred, followed relationship—not the other way around.

Among the most important of Ricci’s associates were scholars who would later become patrons, defenders, and translators. These men introduced Ricci to examination circles, wrote prefaces to his works, and defended him against accusations of heterodoxy or espionage.

Ricci’s friendships were governed by Confucian norms: gift exchange, letter writing, mutual recommendation, and ritual courtesy. He understood that trust in China was personal before it was institutional. As a result, Christianity initially spread not as a mass movement but as a network phenomenon, embedded within elite social relations.

Ricci’s Nanchang residence quickly became a hub for the local elite. His letters reveal a relentless schedule: receiving visitors, answering correspondence from Europe and from Chinese who had heard of his fame, training younger missionaries, and attending banquets—sometimes three in a single day. These were not social indulgences but strategic necessities. Each banquet was an opportunity to discuss Western astronomy, display European clocks and maps, and argue for the superiority of European science without mentioning the religious wars or Inquisitorial cruelty that marred Europe’s reputation.

Among his visitors were future collaborators. Qu Rukui (瞿太素), also known as Qu Taisu, a gifted but disaffected scholar, became Ricci’s first serious convert among the literati, assisting him with mathematical studies and providing entry into gentry circles. Under Ricci's careful guidance, Qu Rukui translated into Chinese the first of the 15 books that made up the Clavius edition of Euclid's Elements. However, the manuscript has not survived to the present day.

Ricci also interacted with officials who would later facilitate his northern progress, including members of the imperial examination boards.

In 1597, Alessandro Valignano, the Jesuit Visitor, appointed him superior of the China mission, adding administrative burdens to his already heavy schedule. By now, Ricci oversaw several Jesuit houses—eventually four—scattered across the empire. His responsibilities included managing finances, resolving disputes, and reporting to Rome, all while maintaining his scholarly persona.

The Dream of Beijing

Throughout his years in China, Matteo Ricci never lost sight of a precise objective: to establish a permanent Jesuit foothold in Beijing, obtain formal imperial authorization for the mission, and, if possible, gain access to the Wanli emperor. Modern scholarship confirms that Ricci regarded entry into the Ming capital as a decisive step, both symbolically and strategically, and that he consciously sought influential converts among the elite through learned conversation and cultural exchange.

Ricci’s first approach to Beijing in 1598 resulted only in a short stay of roughly two months; contemporary Jesuit accounts and later reconstructions agree that he failed to secure an audience with the emperor and was soon compelled to withdraw. The context was unpropitious: the Ming court was strained by the recent war against Japan over Korea and was wary of foreign envoys, especially those whose status did not fit neatly within established tribute protocols.

The Nanjing Prelude and the Consolidation of Intellectual Authority

Back in Nanjing, Ricci presented himself not as a wandering preacher but as a man of learning, versed in mathematics, astronomy, and cartography—an image well attested in his correspondence and in later biographies. This southern capital, crowded with examination candidates, retired officials, and prominent literati, offered precisely the milieu he needed to consolidate his intellectual authority. As R. Po-chia Hsia notes, the short Nanjing period (1599–1600) was disproportionately fruitful for the Jesuit, yielding more strategic gains than many longer phases of his sojourn.

It was in this environment that Ricci oversaw a new large-scale world map, a precursor to the famous 1602 Kunyu Wanguo Quantu (坤輿萬國全圖), which would eventually be printed in Beijing at the request of the Wanli emperor. Centring China while integrating recently acquired European knowledge of the Americas and other regions, the map functioned as a rhetorical instrument as much as a geographic representation: it gently relativized traditional Sinocentric cosmology while still satisfying Chinese expectations of centrality. As Liam Brockey and others emphasize, such cartographic and scientific displays were crucial to the Jesuit strategy of using technical expertise as a bridge to religious discussion.

The Nanjing phase also exposed Ricci to distinct intellectual constituencies—men attracted by his literary style and links to Chinese patrons, mathematically inclined scholars interested in astronomy, and Confucian literati who had some sympathy for Buddhist ideas. The latter group forced Ricci to sharpen his critique of Buddhism and to clarify the differences between Christian and Buddhist doctrines, a polemical line of argument that would reach mature expression in his treatise Tianzhu shiyi (天主實義).

Crucially, Nanjing was where Ricci forged relationships that later proved indispensable in Beijing. Li Zhizao (李之藻), a respected official and astronomically knowledgeable literatus, collaborated with Ricci on mathematical and cartographic projects and later played a central role in editing and printing the 1602 Kunyu Wanguo Quantu, even though his formal baptism came only in 1610. Feng Yingjing (馮應京), another upright official who suffered imprisonment for his integrity, lent Ricci’s writings moral and intellectual weight by contributing prefaces and acting as a public defender of the Jesuits’ probity.