The Mata Ortiz Pottery 4

JUAN-THE-MASTER

Suddenly, his eyesight clouded.

He could still hear Spencer talking, but his voice was going to be blurred background noise. He felt his whole body hopelessly turning into an empty cave, where the accelerated beat of his heart echoed like a perturbing sound.

He was afraid of having a heart attack.

Cálmate. Ya basta.

He took a deep breath as if his lungs could caress his fast-paced heart. He took a second breath. He squinted both eyes, opened them wide, and saw her.

She was elegantly seated in front of him, her legs pulled together, closed, slightly oblique. She was staring at Spencer, her blue eyes vivid and relaxed, and her short blonde hair motionless, with a curl anchored to an ear.

He could not remember her name – it was Sandra Day O’Connor, as he will know the day after when he sold her one of his ollas – but he knew she was a Judge of a County Superior Court and a Republican former member of the Arizona Senate. He had a dizzy spell.

The audience burst into a laugh. Spencer MacCallum must have told something about Juan because everyone turned to look at him. The elegant judge gave him a curious look and slightly smiled without moving her hair.

Juan felt his heart jumping like a drunk boy.

Spencer smiled at the smiles and resumed talking.

Juan didn’t understand what was going on. He didn’t understand what Spencer was saying as he only knew a bunch of English words, most of which related to pregnant cows, constipated horses, and basic necessities.

He disliked the subtle smell of that room, too elegant, too bright, too aseptic. He knew that all those people had come both for him and Spencer, but he would gladly run away. His heart was already running home and his legs would be happy to follow it. He imagined himself climbing the slopes of the Sierra behind Mata Ortiz, and smelling the sweet and fragrant May wind.

It was May in Phoenix too, but it wasn’t the same May. It wasn’t the same smell and the same silence. It was the very same year, 1977, and at the very same time, it wasn’t.

¡¿Qué carajo te pasa en la cabeza, híjole?!

He was afraid of getting crazy.

Spencer started to say something about Paquimé ceramics.

Two latecomers entered the Heard Museum’s conference room and occupied the last empty wooden chairs at the end of a row.

Juan never thought he would come face to face with so many people, all white, all rich, all middle-aged gringos coming from a different planet. If only he had imagined it… He was accustomed only to the infinite Chihuahuan horizon, its silent spaces, and to a weird solitude sweetened only by the scent of the wind, of his children and Guille.

He felt his heart panting and whistling in his ears like an old locomotive.

¡Aplácate! Que Dios me ayude…

He took the ball of clay on the table. He knew it was not the right time to start the practical demonstration – Spencer told him: You start when I finish – but he knew as well that if his hands could begin to move, his heart would begin to calm down.

His hands sank into the clay ball. He laid it out calmly, without haste, as he did throughout the last twenty years of his young life. He flattened it out with a few precise movements to get a perfect tortilla which was gently placed inside a plaster-of-Paris mold and worked from top to bottom to adhere to its sides, previously coated with vegetable oil. He took another piece of clay, shaped it like a chorizo (sausage) coil and then like a doughnut, and quickly added it to the edge of the pot bottom.

He closed his eyes, turned off his mind, inhaled the smell of the white clay that he had collected on the slopes of El Indio, and let his hands totally free as he used to quit holding a galloping horse by loosening the reins.

Only then, he started twirling out of space-time where no one could have reached him.

BELOW:

Juan Quezada in his old home in Mata Ortiz, Chihuahua, July 28, 2007.

Photo by Raechel Running from Tucson, Arizona.

©RAEchelRUNNING2021

Chavela Vargas, Luz de Luna

Chavela Vargas (born in Costa Rica in 1919 and passed away in Mexico in 2012) was a legendary Mexican singer, well-known for her rendition of Mexican rancheras, boleros, and corridos. Wild, fierce, untamable woman, she was an influential interpreter with an intensely emotional rough and dirty voice (Pedro Almodóvar called her “the rough voice of tenderness”). Vargas challenged mainstream morals by dressing as a man, smoking cigars, drinking too much, carrying pistols, and loving women (she had a brief affair with Frida Kahlo, among others).

Luz de Luna is an old traditional song composed by the Mexican popular music composer and songwriter, Álvaro Carrillo Alarcón (1919/1969).

THE RANDOMNESS OF LIFE AND ALL THAT

In the early 1970s, Juan Quezada began selling some small ollas for 5 dollars each. These small sales gave the family an essential extra income. Some of Juan’s brothers and sisters – the older and the younger among his sisters, Consolación and Lydia, and two of his brothers, Nicolás and Reynaldo – started to learn how to create small jars to be sold to local traders or to gringos. In the mid-70s, Juan was selling enough of his pots to quit his job and supporting his family only by making ollas. Small-time traders from Nuevo Casas Grandes and Palomas started to sistematically buy his pieces. Not only for their beauty and high quality, though. «Many of these early buyers used various tricks to make the pots look old. A friend told Juan of a famous Native American potter who signed her pots on the bottom

. Juan thought this was a good idea and began to paint his name on the bottom. Sales immediately slumped. Shortly, however, they picked up again. Juan was bewildered but soon found out that the clever traders were grinding off the painted signature in sand» (Walter P. Parks, The Miracle of Mata Ortiz).

Not all of Juan’s little ollas were passed off as “ancient and authentic Paquimé pieces” by some boasters. The three ollas, for example, sold for used clothes in late 1975 to a junk store in Deming, New Mexico, the Bob’s Swap Shop, were explicitly declared contemporary pieces.

In January 1976, an inquisitive beanpole entered the shop. He was not the usual customer looking for cheap bargains. He was a good family anthropologist who had time to waste and the unusual talent to pay attention to the stories told by used objects. Of course, Juan Quezada’s three ollas spoke to him immediately and aloud. And yes, he purchased them all. Spencer MacCallum was his name.

– They’re not antiques, are they?

He asked the saleswoman while waiting for the rest.

– No sir! They’ve been recently made.

– Do you know who made them?

– Oh no! They’re probably from Mexico.

– Mexico…

– Yeah, looks like that to me. Northern Chihuahua, maybe.

– Thank you. Bye

– Bye, sir.

Spencer took the ollas to his home in San Pedro, California, and contemplated them for a couple of months. Then in March, for one of those incomprehensible impulses that we can only justify in retrospect, he took his camera, placed the ollas in the early morning light, photographed them one by one, and put them back in place. Three days after, on a Saturday early morning, he opened a drawer, took two underpants and two shirts, folded them in an overnight case, and drove off to Deming, after a stop at the photo lab. In New Mexico, he picked up his mother and an old friend of her, and with the pictures on a butt pocket, drove towards the border in a Datsun pickup.

His goal was to find the female potter who made the ollas. He did not know if and what he would find in Chihuahua but hoped – or rather felt a confused, vague ambition – of stumbling into a Native American potter, a still undiscovered female artist, a sort of Chihuahuan Nampeyo.

Nampeyo, ca. 1908–1910, Arizona. Photo by Charles M. Wood.

Nampeyo (1857 or 1858, maybe 1859 –1942) was a Hopi-Tewa potter of the Hano pueblo who lived on the Hopi Reservation in Arizona (US). She’s regarded as one of the most relevant figures of Native American pottery. Her pieces, many of which are currently on display in museums and art collections, are inspired by the techniques and the designs of prehistoric and protohistoric Hopi pottery.

LEFT: Jar by Nampeyo, 1905, clay and paint. Courtesy of Denver Art Museum, Colorado (US).

RIGHT: A Hopi/Tewa Indian ceramic jar, created between 1985 and 1992 by Dextra Quotskuwa Nampeyo (a descendant of Nampeyo), displayed at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona, a private, not-for-profit museum to the advancement of American Indian art. Photo by Carol M. Highsmith, 2018. ©Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Nampeyo, Native American Tewa Hopi potter, seated, surrounded by pots, ca. 1903, photo by Homer Earle Sargent Jr., ©Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

Thus, Spencer MacCallum got on the road to northern Mexico without knowing where he was going to stop, and who he was going to find, chasing an aesthetic emotion – made of the same stuff as dreams – like a drunken truffle dog.

He crossed the border at Columbus and entered the small town of Palomas. He stopped at every gas station market on the main road, always pulling the photos of the ollas out of his pocket, and asking for information. «As they traveled south on the only paved road, Spencer talked with everyone he came in contact with at each settlement, including the little boy who shined his shoes and the policeman who gave him a speeding ticket» (Walter P. Parks, cit).

In the evening, Spencer, his mother, and her friend got a hotel in Nuevo Casas Grandes. The morning after, they were directed to the house of a skilled potter named Manuel Olivas. He advised the MacCallums to reach Colonia Juárez a few miles south of the town, and then take a gravel road full of potholes to get a forgotten hamlet named Mata Ortiz, along the Palanganas river.

The road was as promised. After endangering the health of wheels, tires, rims, suspension, and digestive system – breakfast did not want to respect the force of gravity – they got Mata. Spencer noticed a little boy on a burrito on the left side of the dusty road and stopped next to him with the same esperanza you address Our Lady icon when you are gonna ask for a miracle.

The boy glanced at the pictures, gazed upon the face of that weird gringo, and said something in Spanish that Spencer did not understand (he was crazy enough to look for a needle in the Mexican haystack without knowing a single Spanish word). The boy realized that the gringo, like all gringos, did not understand a word and made a gesture with his hand that Spencer interpreted as a vague direction.

It was better than nothing.

They arrived at a small adobe house near the river and parked the car. Spencer pulled out the photos, knocked on the door, and reviewed the pantomime of English gestures and words with which the day before he had asked “any likely or unlikely person” for information.

Gille opened the door, looked at the pictures, ignored Spencer’s pantomime, and invited all three to sit down in the small room. Before entering the kitchen to make a coffee, she looked out the patio and called Juan. He entered the small living room and walked towards Spencer with an open and demure expression at the same time.

That Latino man of medium stature in his mid-thirties, with a full head of black wavy hair, sideburns, and several tattoos on his muscular arms was the opposite of the gentle, artistic Native lady Spencer was expecting to find.

PORTRAIT OF THE ARTIST AS A YOUNG MAN

After the first encounter in March 1976, Juan Quezada and Spencer MacCallum met many other times the same year. In May, Spencer returned to Mata Ortiz with his wife Anne and Bobby Furst, a professional photographer.

From left to right: Anne MacCallum, Spencer MacCallum and Juan Quezada all looking at his ollas, 1976. Photo by Bobby Furst. Courtesy of the American artist Michael Wisner.

Spencer purchased all of Juan’s jars and ollas. He was enchanted. He was persuaded to have met an artist, not just a potter, a sort of a rough diamond, whose brilliance potential was still fathomless. That’s why he challenged him to boost the overall quality of his artwork: he wanted to get a glimpse into Juan’s artistic possibilities.

Quality, not quantity, he told him. Next time I’ll be here – let’s say in July – I’d like to see your best, Juan. Gimme your best, Juan.

He came back in July, accompanied by a news reporter and a photographer from The Los Angeles Times. And this third encounter was the most disappointing and frustrating of all.

Juan had worked hard – the last thing he wanted was to displease Spencer – but his pots had increased in quantity, not in quality. Spencer was more hurt than surprised, and at first, did not understand.

Between them, there wasn’t a simple communication misunderstanding. There was a cultural and social gap.

Spencer was convinced that the attitude to throw down a challenge to anyone was a universal tool to get their best results, which is false, of course. He was a privileged wasp, with a Bachelor in Art History from Princeton University and a Masters of Arts in Social Anthropology from the University of Washington. He was, therefore, deeply convinced of the power of words, regarded as a sort of master key to open (or close) all doors. It’s false as well. The idea that dialogue is all that matters worked smoothly only in some of the old Woody Allen movies.

Juan was one of those rare men perfectly able to listen to silences and accustomed to giving little weight to words. He was a man of deep emotions, hidden beneath the surface, strong and tenacious in a special way: the way of those who have nothing and must struggle for almost everything. He was a man born and raised in poverty who bore the responsibility of feeding a large family: his wife Gille, seven children (they’re going to become eight in 1981), and some young siblings. And he put this burden on his shoulders with the same glimpse of a smile with which Western students put their designer backpacks on. Deep inside he knew – without needing to put it into words – that the more ollas he could sell to Spencer, the better his children would eat.

Juan Quezada removes the metal cover after pit-firing an olla by using cow dung, 1976. Photo by Bobby Furst. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

Spencer understood eventually: he saw the gap, though probably he did not see its bottom; he understood Juan, though probably up to a certain depth; and realized that the artist could foster his creativity if freed from the burden of economic anxiety. He offered Juan a regular monthly income of $300 for some years and allowed him to wander hills in search of new types of clay or mineral colors, to experiment with them, to create, to fail, to start over and fail again and again. Because this is the creative path.

In doing so, Spencer gave Juan not just the freedom from the daily pestering for food and basic necessities, but something even more precious: Juan was freed to avoid the hidden risk of pleasing Spencer’s taste.

Juan was given the freedom to follow himself only.

He was given wings, and he took flight.

Juan Quezada (on the left foreground) looking for a clay deposit on the hills around Mata Ortiz, likely in the 1990s. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

From 1976 to 1983, Juan Quezada and Spencer MacCallum worked together: the first stretched the boundaries of his creativity to the limit, the second focused on «spreading the word about the artist he had discovered. (…). He contacted museums, curators, galleries, colleges and universities from San Francisco to Rhode Island to organized exhibitions, workshops and demonstrations. He took Juan all over the US in his little Datsun pickup, towing a trailer full of pots» (W. P. Parks, cit.).

The very first Spencer’s conference and Juan’s demonstration was organized in May 1977, thanks to the efforts of Spencer and Patrick Houlihan, director of the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. Spencer selected 36 pots out of the best 85 made that year by Juan, got him the US visa, took his Datsun pickup, and brought Juan to Phoenix.

Juan did not know what to expect. And in any case, he didn’t expect so many “important” people – among them, there was Sandra Day O’Connor who in 1981 will become the first female associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States – and panicked. «I was accustomed to working very much alone, and I was so tense I had to be taken to the hospital. They checked me over and said not to worry, it was just nerves. The doctor gave me pills to calm me down (…) but I didn’t like the idea of taking that medicine. (…). Anyway, by then, I’d become more comfortable working in front of people and, gracias a Dios, I could complete my demonstrations» (Nancy Andrews, Tea with Juan Quezada: An Afternoon at Rancho Barro Blanco, see Bibliography).

The second exhibition was held at the Arizona State Museum in Tucson, thanks to Spencer and Ernest E. Leariff, and it was a complete success. From that moment on, Juan and Spencer never stopped, and the Mexican artist began to be known and recognized in many US states.

As more and more Juan’s family members and friends began to learn the fundamentals of pottery art and to be involved in that activity, Spencer came up with the idea of organizing a competition in Mata Ortiz to reward the best talents with cash prizes each year. He involved Charles DiPeso, the archaeologist director of the Amerind Foundation who had carried out the first excavations and studies on Paquimé, and in 1978 created The Mata Ortiz Competition.

In the early 1980s, «Spencer’s promotional efforts were in full swing» (W. P. Parks, cit.). The ollas of Juan were sought after and purchased by art gallerists, museum curators, and traders for thousands of dollars. Between 1983 and 1984, in addition to Juan, about 300 potters were working full time in Mata Ortiz. Only a few of them were “dwarves on the shoulders of a giant”: most of them were really talented ceramicists producing good to high-quality pieces, and among the most brilliant and skilled emerged Juan’s youngest sister, Lydia.

However, in the very same years, the human and artistic relationship between Juan and Spencer broke down (W. P. Parks says that no one will ever really know why). Both kept on being in contact, albeit more sporadically. Juan continued to express deep gratitude to Spencer, and Spencer boundless admiration to Juan, but their close collaboration fell apart.

Fortunately, Juan found new mentors: Tom Fresh of the Idyllwild School of Music and the Arts in California, Judith Anderson, Bobby Rodríguez, and Walter P. Parks. They all helped him to establish his reputation, represent him in the US museum, galleries and universities, sold his amazing pieces, organized his exhibitions and demonstrations, academic classes, and conferences, wrote books and articles, and encouraged many doctoral theses on his art. From the mid-1980s on, they helped Juan to fully emerge and become one of the most interesting contemporary Mexican artists.

Spencer MacCallum at the Amerind Foundation on April 2006. He died on December 17, 2020 (aged 88) in Nuevo Casas Grandes, Mexico.

Photo by Wikimedia Commons.

Juan Quezada in 2006, with one of his large ollas. Juan, who was born in 1940, still lives in Mata Ortiz. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

Juan Quezada at the Flor de Barro Gallery in El Paso, TX, in 2020. By courtesy of Andrea Calleros.

Natalia Lafourcade, feat. Los Macorinos, Danza de Gardenias, from Musas Vol. II.

Natalia Lafourcade (1984) is one of the most successful Mexican contemporary musical artists: she’s a songwriter, singer, and producer from the Mexican state of Veracruz, winner of 14 Latin Grammys, 2 Grammy Awards, a Billboard award, and 3 MTV Awards, among others. Natalia Lafourcade is passionate about supporting humanitarian projects. In 2017 she formed Un canto por México, a complex humanitarian project and a framework that allows her to bring people and organizations together to join forces for different social and cultural causes.

Co-written by Lafourcade and Mexican composer David Aguilar, this song is about learning hows to reflorecer, to bloom again. «It is an offering of gratitude to a cycle of love – says Lafourcade – It’s a grand celebration of a moment and a stage of one’s life that was shared with a loved one who you want to thank. It contains elements of freedom, joy, and detachment. It’s gratitude for the bravery of love».

Los Macorinos are a duo of guitarists in their 80s (Miguel Peña and Juan Carlos Allende) who once were playing with the late, iconic ranchera singer Chavela Vargas.

THE ART OF TURNING MUD INTO BEAUTY

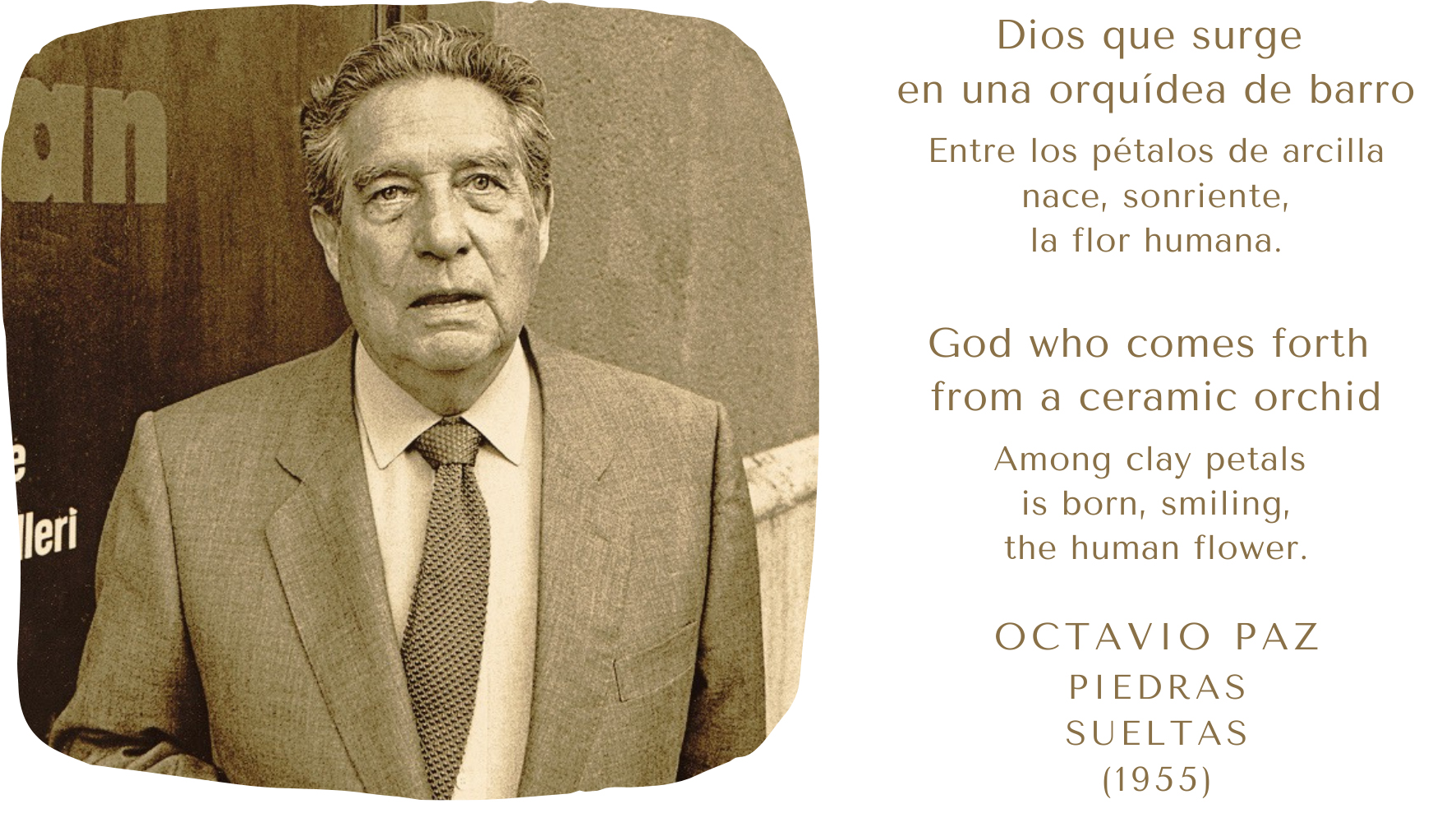

Octavio Paz (1914/1998) was a Mexican poet, writer and diplomat, recognized as one of the most influential Latin American intellectuals of the 20th century. He received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1990. Ph. by John Leffmann, 1988 (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license)

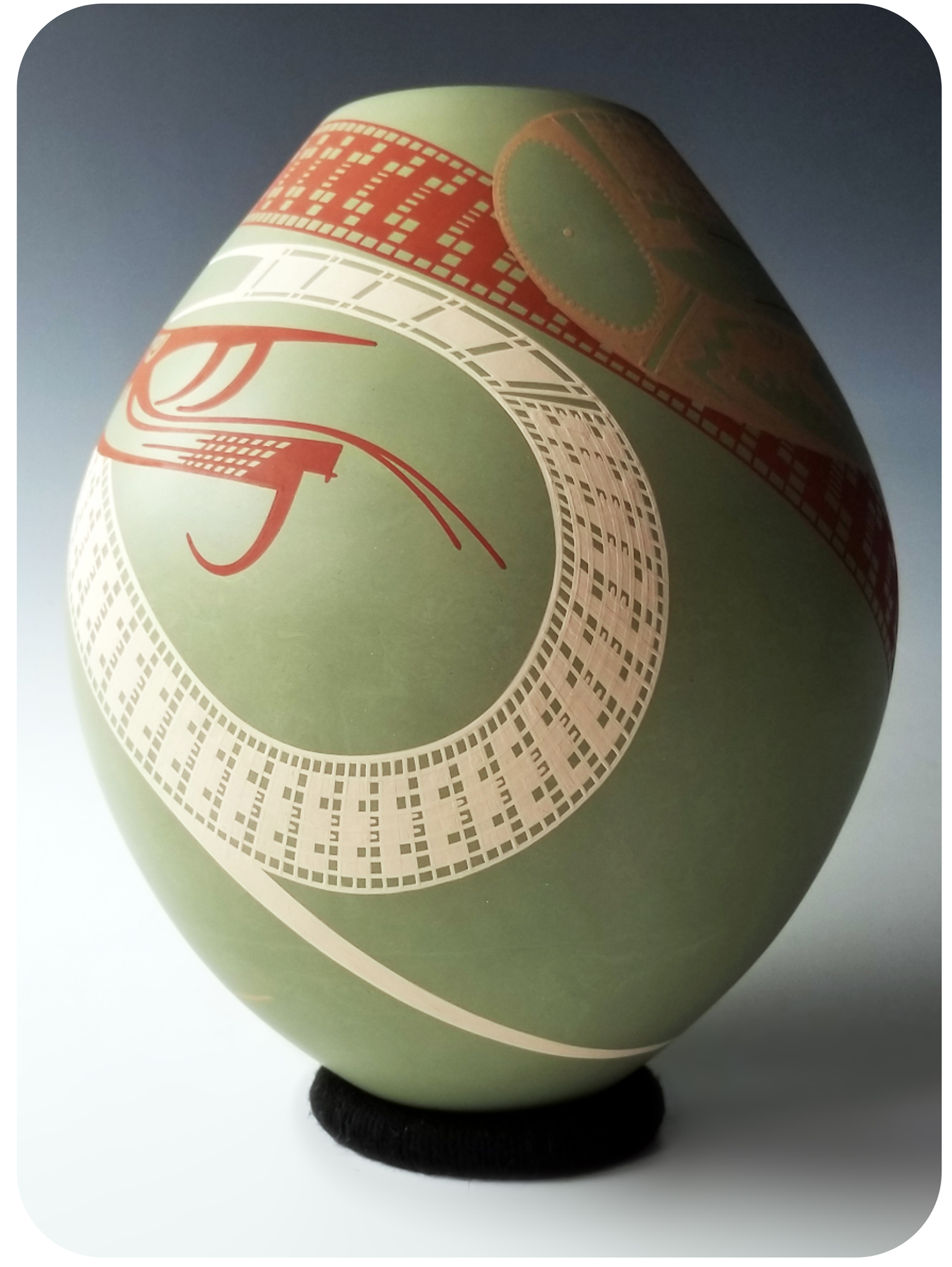

Juan Quezada began experimenting with clay at 15 years old and never stopped. «He has always had a gift for innovation» (Michael Wisner, see Bibliography). Of course, «his pots continued to change. (…) New shapes and designs evolved with more departure from the basic Casas Grandes inspiration» (W.P. Parks, cit.). Walter Parks is right: if you take a close look at the picture gallery below, which follows a (more or less) chronological trend, the progressive detachment from the stylistic modules typical of Paquimé ceramics will be evident and undeniable. Note, however, that not even in the early 70s Juan “copied” the ancestors; since the start, he reinterpreted the pictorial language of Paquimé. Decade after decade, he transformed the characteristic signs of Paquime’s iconography into more abstract elements, reduced to a graphic essence in the spirit of contemporary aesthetics.

Gradually, he changed two other elements.

First of all, he modified the relationship between the painting and the surface: the first began to invade and conquer the second with growing dynamism. Look at the picture gallery: in the 1970s, Juan was painting following the traditional Euclidean geometry; in his later years, he moved his paintbrushes in a universe governed by a non-Euclidean geometry; his straight lines inhabit an elliptic or Riemannian geometric land, that’s to say they aren’t straight at all.

Secondly, he gradually changed the pictorial balance and the interplay between solids and voids, full and empty spaces, achieving an admirable harmony that aroused the admiration of the harshest critics, the Japanese ones, accustomed to a ceramic art of supreme equilibrium and zen rarefaction.

Juan Quezada, double olla or cuate, ca. 1970, Collection of Michael Wisner. Courtesy of Michael Wisner (US).

Juan Quezada, olla, ca. 1975, height 8.5″ / 21.59 cm, diameter 9.25″ /23.49 cm. Courtesy of the Museum of the Red River, Idabel, Oklahoma (US).

Juan Quezada, vessel, ca. 1988, Collection of Michael Wisner. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

Juan Quezada, vessel, undated, probably late 1990s. Collection of Michael Wisner. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

Juan Quezada, vessel, 1998, Collection of Michael Wisner. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

Juan Quezada, vessel, 1998, Collection of Michael Wisner. Courtesy of AMOCA (American Museum of Ceramic Art), Pomona, California (US).

Juan Quezada, vessel, 2004, Collection of Michael Wisner. Courtesy of AMOCA (American Museum of Ceramic Art), Pomona, California (US).

Juan Quezada, vessel, 2007, Collection of Michael Wisner. Courtesy of AMOCA (American Museum of Ceramic Art), Pomona, California (US).

Juan Quezada, marbled pot with white Paquimé designs, 2000s, H 13″ W 11.45″. Courtesy of Andrea Calleros, © Flor de Barro Gallery, El Paso, TX.

Juan Quezada, jar, 2005, Collection of Charles Tarver. Courtesy of AMOCA (American Museum of Ceramic Art), Pomona, California (US).

Juan Quezada, marbled olla, 2008, Collection of Michael Wisner. Courtesy of AMOCA (American Museum of Ceramic Art), Pomona, California (US).

Juan Quezada, marbled olla, 2005, Collection of Michael Wisner. Courtesy of Michael Wisner (US).

Neither this small photo gallery, nor a larger or more exhaustive one can, however, give you an idea of what Juan Quezada’s pottery really is.

Unfortunately, the photographs induce a dangerous misunderstanding: they bring the pictorial dimension of ceramics to the foreground, leaving the form in the background and completely hiding the physical and tactile qualities of pots, ollas, and vessels. Ceramics is not painting on support: the ceramic object is not such support, like a canvas, a cardboard rectangle, a wooden panel, or a wall. Ceramics is a plastic art, like sculpture, with a substantial difference: it does not operate in the three spatial dimensions but in the four D, the space-time. Ceramics is the art of metamorphosing a handful of mud (clay) into an aesthetic object by controlling many variables, including fire and time.

The tactile and physical qualities of ceramic pieces are just as important as the visual ones.

What of Juan Quezada cannot be seen either in photography or even behind the glass of a museum display cabinet is the superb physical quality of his ollas: they have thin walls and yet convey a feeling of strength and compactness to your hands. The surface is smooth and velvety to the touch; the symmetry is perfect, and the roundness is sensual and physically mysterious. His ollas have something of a non-living and something of a living thing.

Ceramics is a haptic art: you need to touch a pot, lift it, weigh it, turn it in every direction. Your hands have to play with it. You need to caress it. Ceramics is a highly sensual art as well.

Almost all of the qualities you cannot see but only touch are the product of superb technical control. Juan Quezada is a virtuoso: a talented artist with an incredibly technical mastery that has obviously been growing over the years.

«Among other things, he developed a distinctive light sand-yellow color by firing twice a clay that normally fired orange. He also discovered a pigment that fires a lustrous black under normal oxidizing conditions» (W.P. Parks, cit.); he created a marbled surface by masterly mixing different kinds of clay, etc.

However, in his ever-evolving artistic career, there’s something that has never changed over 60 years. It’s something to which he has always remained absolutely faithful and lies, therefore, at the core of his art.

BELOW:

A portrait of Juan Quezada, June 9, 2008, Mata Ortiz, Chihuahua.

Photo by Raechel Running from Tucson, Arizona.

©RAEchelRUNNING2021

Natalia Lafourcade performing Mexicana Hermosa, featuring Carlos Rivera (1986), a Mexican singer and actor.

This song was composed by Natalia Lafourcade y el venezolano Gustavo Guerrero for the 2017 album Musas: Un homenaje al Folclore Latinoamericano en Manos de Los Macorinos. Volumen 1. It’s a musical tribute to Mexican folklore, here in the Mariachi version. The Mariachi folk music emerged in the late 1700s or early 1800s in west-central Mexico and developed throughout the country. Everything in this music, from the arrangement to the orchestra, from the typical stringed instruments (such as the vihuela) to the dresses (los trajes de charro of the cowboys of Jalisco) well expresses one of the many deep Mexican souls.

«CON LOS MISMOS HERRAMIENTAS DE LOS ANTEPASADOS»

(WITH THE SAME TOOLS THAT ANCESTORS USED)

At the beginning of his artistic trajectory, at only 15, Juan Quezada had to rely on simple tools: he had no potter’s wheel and no kiln, and couldn’t buy industrial semi-finished or finished products. However, what was at first a simple constraint pretty soon became a challenge launched at the Paquiméans – I must succeed by using the very same tools they could find – and finally an artistic binding postulate. Everything he used and still uses to create his pots is freely offered by the land around Mata Ortiz: clay, mineral colors, polishing tools like animal bones and stones, solid fuel like cottonwood bark or cow dung. Only one thing is offered by his children: the hair to be assembled to the sticks of local wood to create the paintbrushes. The complex creative process is entirely manual and natural, puro natural, as it involves no chemicals, no machines, no commercial items, no pollutants.

Juan’s postulate says that a pot must be done today as it could have been done two thousand years ago. Beware: it does not say “as it was done two thousand years ago” but “as it could have been done and probably was not”. The axiom does not impose to resuscitate what is definitely passed away nor to reject any form of modernity. It does not hinder any kind of innovation: on the contrary, from the beginning, Juan outlines a creative path full of challenges, experiments, errors, failures, and original solutions. Juan’s postulate does not push the artistic experience out of time, but rather roots it more deeply in space. By banning all technological and commercial shortcuts, the postulate anchors the whole creative process to the wind, the sun, the water, the natural resources, and the hidden bowels of a piece of Mexican land: the Casas Grandes plateau. All of the pots of Juan Quezada and his entire artistic trajectory were birthed from the Chihuahuan womb and couldn’t have developed anywhere else.

«To me – Juan said – all the pottery in the world is beautiful. But what I like best is for it to be made naturally, the way we do it in and around Mata Ortiz. It is what makes our art unique» (Ron Goebel, Lydia Quezada’s “Work of Inspiration”, see Bibliography).

- Searching for clay

Juan Quezada looking for the best clay veins on the hill around Mata Ortiz. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

Juan Quezada and almost all of the contemporary master potters in Mata Ortiz use only different kinds of local clay found in veins all over the region, especially on the slopes around the village. For Juan, the creative path is far from being a simple metaphorical journey: it begins with a solitary wandering along the lonely arroyos and hills, smelling the scents breathed by the wind and digging into the womb of mother earth.

«The most common type of clay is the amarillo, a gray one that fires to a yellowish beige color (…). The red clay is often used to make the highly polished black pots because of its iron content: in the firing process, the red clay turns a deep black (…). The rares and most difficult-to-use clays are the whites, usually stiff and brittle» (W.P. Parks, cit.). Today, contemporary potters in Mata Ortiz use 15 to 20 different types of clay, each of a different color, but all clays don’t have to be pure. Juan discovered that the purest clay cracks while drying and firing: all clays have to be naturally mixed with a temper, usually volcanic ash, to resist firing and acquire strength. The various clays can be found in different forms, from rock-hard chunks to soft earth, and need to be processed before any use.

- Processing the clay

LEFT: Juan Quezada filtering the clay, courtesy of Michael Wisner.

RIGHT: artist Diego Valles cleaning clay. ©Diego Valles.

The clay has to be mix with water in a washtub to be cleaned up from rocks and organic materials. Then, «it’s poured through a strainer, usually an old dress or a table cloth. (…) The residue of clay is poured out on plaster slabs to dry partially» (W.P. Parks, cit.). The plaster absorbs the water and turns the clay into a malleable paste. It should be aging a little bit before being used, but this rarely happens.

- Forming the pot

Juan Quezada giving a demonstration of his method. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

«To begin a pot, a piece of clay is kneaded into a round lump and then rolled out flat with a rolling pin-like tool into a flat tortilla. This is placed gently into a plaster mold, coated with vegetable oil» (W.P. Parks, cit.). The plaster will be the round bottom of the pot that, therefore, cannot stand without the help of a ring stand. At this point, the building of the pot body is made by adding one or more coils (the clay doughnut is called chorizo). Juan developed a “single-coil” method, other contemporary artists, like Diego Valles, adopt a “multiple-coil” system to form the walls. The number of coils is always limited as «fewer coils mean fewer joints in the clay wall, which ultimately makes a stronger wall (breaks in the drying and firing process often occur in joints between coils)» (M. Wisner, cit.). The clay is then pinched and stretched up, a process needed to give strength to the pot walls that can reach the incredible thinness of 1/8-inch – 3.18 mm. Once finished, the pot is left to harden for some minutes. Then its surface is smoothed with the aid of a hacksaw blade. In the end, it is left to air-dry indoors.

- Polishing the vase

Polishing a vase with the help of a stone. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

«When the clay is bone-dry, the potter takes the pot outdoors and sands it with sandpaper» (M. Wisner, cit.) to refine the surface and prepare it for polishing. «The sanded pot is covered with vegetable oil, then with water by using a soft cotton cloth (usually a T-shirt) and finally polished to a mirror-like sheen» (M. Wisner, cit.). The polishing is done with one among many natural tools: a tumbled stone, the backside of a spoon, a deer bone (Juan’s preferred tool), a seed, a silk cloth, a piece of leather, etc. «Every clay responds differently to each tool, and polishing is an art that you can spend a lifetime perfecting» (M. Wisner, cit.). Polishing with a stone is a technique dating back to prehistory and has two benefits: it compresses and seals the clay, and allows for superior refinement in the painted designs.

- Preparing the mineral pigments

Juan Quezada preparing mineral colors on a stone metate as probably did the Paquiméans. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

The mineral pigments are mined in the region – the black comes from an old manganese mine in the mountain above the village – and processed by the potter or one of his family members. Juan never used commercial colors and the master potters of Mata Ortiz today follow his postulate. «Many minerals undergo surprising color transformations when subjected to heat. It is essential to do color tests on new minerals before painting the clay. Once a nice color is found and tested, it must be milled into a fine powder and added to a similarly colored clay to make paint» (M. Wisner, cit.).

- Painting the pot

Juan Quezada painting an olla. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

Juan’s never used commercial paintbrush: all of his painting tools were entirely hand-crafted by attaching five, six, or seven strands of baby hair to a wooden stick. So do today the best master potters of Mata Ortiz. These handmade brushes are very different from those sold by fine art stores: the tip is long (1.5-2 inches, 3.8 – 5 cm) and designed to paint very thin lines. «Its entire bristle is laid down on the surface of the clay and pulled to create the design» (M. Wisner, cit.). «Straight lines are relatively easy; tight curves or caracoles are hard» (W. Parks, cit.). All kinds of design, even the most complex and difficult ones, are free-hand drawings (no tool is used, and absolutely no stencil!). After the paint has dried, the pot is polished for the final time. Only in the case of blackware, this polishing is avoided.

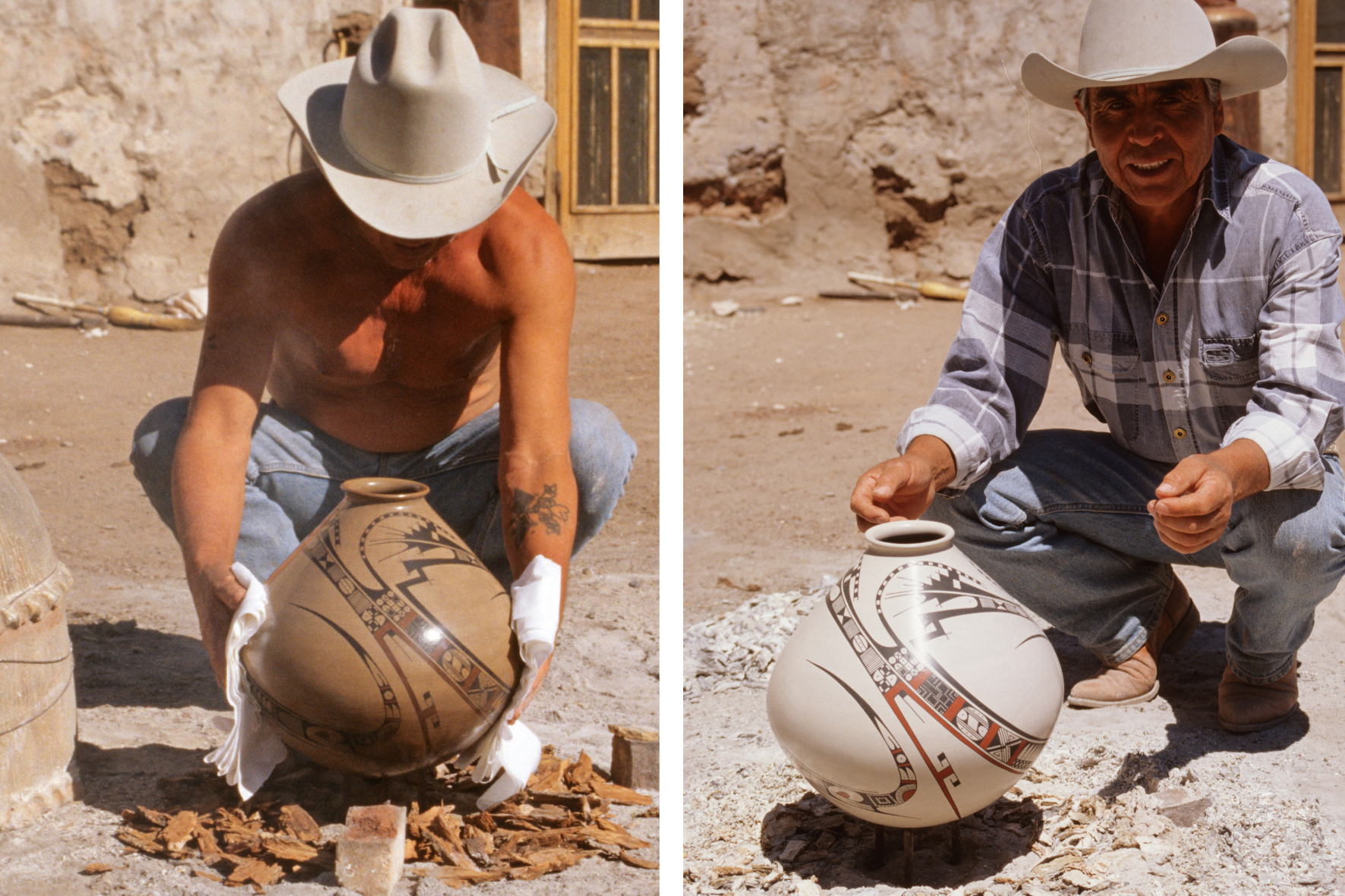

- Firing

Juan Quezada with an amazing large-sized olla before (on the left) and after (on the right) the firing step. The firs olla was pre-heated under the sun. The second reveals the pure white color of the clay used for it and enhances the mineral red and black used for the designs. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

The firing steps. Courtesy of Michael Wisner.

Firing is the final complex phase.

Technically, Juan’s final phase is a pit firing, the oldest known method dating back to tens of thousands of years ago, while the use of kiln dates back only to 6,000 BCE.

The pots are fired on the ground, inside an enclosed area, often slightly raised. A single large olla or three/four smaller seed pots are put under an inverted flower pot saggar or a large bucket, called the quemador, covered with cottonwood bark o dried grass-fed cow chips. Juan discovered that these two are the best fuels that can easily reach the needed high temperature (1450° / 1600° F, 790° / 870° C degrees).

There are two different types of firing: oxidation and reduction. During the oxidation firing, the quemador is raised from the ground thanks to some bricks to allow air circulation. During the reduction firing, the base of the quemador is sealed with ash to prevent air infiltration. The first gives vivid colors to pots (if everything goes well, which is not guaranteed, of course), the second an intense black.

The firing lasts only 20 to 30 minutes; immediately after the smoldering coals are removed to avoid the production of smoke and the pot is left to cool over about a half-hour. The moment of truth begins when the quemador is accurately raised to reveal what happened to the clay vase. It doesn’t take much for something to go wrong. Moisture in the clay body can cause bad breakages. Moreover, «an underfired pot may have a smoky appearance and lack the brilliant colors and strength of a properly fired pot. (…) Overfired pieces become toasted, almost burnt looking. They often lose their brilliance and the black paint often turns to brown». (M. Wisner, cit.). The perfect pot comes to light thanks to the art of mastering fire.

Natalia Lafourcade, Silvana Estrada, Ely Guerra – La Llorona, from Un Canto por México, vol. II.

Silvana Estrada (1997) is a singer-songwriter from Veracruz (MX), while Ely Guerra (1972) a singer-songwriter from Monterrey, Nuevo León.

La Llorona or “The Weeping Woman” is a legendary character of Latin American folklore, deeply rooted in Mexican popular culture. The traditional folk song, whose origins are lost in the mists of time, is linked to the Día de Muertos festivities and is a sort of cheval de bataille for most Mexican singers. This version makes you enjoy three voices and three different interpretations, all sharing the same emotional intensity.

THE MIRACLE OF MATA ORTIZ

Between 1983 and 1984, in addition to Juan, about 300 potters were working full time in Mata Ortiz. In 1999, the editors of The Many Faces of Mata Ortiz listed 365 alfareros (potters) only in the village, let alone Nuevo Casas Grandes. Today, the whole community of Mata Ortiz is directly or indirectly engaged in pottery production. Not only has the village finally left behind the times of misery and the unbearable heaviness of being, but established itself as an emerging art center of international relevance, becoming a destination for ceramic enthusiasts, collectors, art gallery owners, museum curators, traders, travelers, and curious tourists. This economic and artistic renaissance was called “the miracle of Mata Ortiz”. The reason why is perfectly explained by Lydia Quezada, the youngest and the most talented among the sisters of Juan Quezada: «Pienso que fué un regalo del cielo. Un regalo que el cielo le dio a mi hermano e que mi hermano compartió con todos nosotros. Porqué fue un regalo del cielo? Porqué puedo tener trabajo en mi casa, puedo cuidar de mi familia y puedo tener los ingresos que necesito» (I think it was a godsend. A gift that heaven gave to my brother and that my brother shared with all of us. Why was it a godsend? Because I can work at home, take care of my family, and earn what I need).

These words apply not only to Juan’s family members like Lydia, but to all of the villagers of Mata Ortiz: Juan taught everyone in the hamlet, passed on his knowledge, and stimulated the creativity and the originality of other potters, keeping no secret for himself, and always sharing his successes. Alison Darosa wrote in a 2013 article: «When in 1976 the first agreement between Spencer MacCallum ad Juan Quezada was sealed with a handshake, the anthropologist had no idea that the Juan would be shaping more than pots; he’d be shaping the destiny of the village and generations of its residents» (A. Darosa, The Los Angeles Times, see Bibliography).

It’s arduous to give you an idea of what Mata Ortiz pottery is today. There are many people involved, and the production covers a wide variety of pieces, from little ollas made to be sold to local tourists for a few dozen dollars to multi-thousand dollar masterpieces.

Juan’s postulate is still a sacred principle for master potters and artists. However, many low-quality pots are made by mixing plaster of Paris with clay, or using commercial paints, paintbrushes, even shoe polish or Mop & Glo to give more shine (smell and sniff an olla before buying it, and you’ll know it).

As to style and design, since its beginning, the Mata Ortiz pottery developed following Juan’s strong willingness to experiment, risk, embrace failure, innovate, and find new expressive solutions, an attitude which in the long run improved both the style diversity and the quality of the pots.

Below you can see a nice pot made by Efren Quezada, the youngest son of Juan. He was taught by his father, but his style is very personal and tells us something about the creative freedom inside the family.

Efren Quezada, pot, H 14” – W: 9.5”. Courtesy of Andrea Calleros, © Flor de Barro Gallery, El Paso, TX.

Efren Quezada, olla with cutouts in black and white marbled clay; height 12.5”, circumference 27”. Courtesy of May Herz, © Sandia Folk, TX, US.

Among the Quezada family members, several emerged as really talented ceramicists, catching the eye of experts for their top-quality pieces. Lydia is the youngest sister of Juan, who was her teacher, ça va sans dire. She, in turn, taught her husband, Rito Talavera, and has been teaching their children, two of which are recognized as excellent artists, Moroni and Pabla. They all do refined polychrome pots but are praised particularly for their surprising blackware, made with a variety of red clay (barro colorado) they personally find along the steep canyons between Chihuahua and Sonora. In 1978, Juan Quezada made the first black pot; in the following decades, Lydia reached top-quality results with two demanding techniques – the “black-on-black” and the “three blacks” – realized via a challenging reduction firing.

Lydia Quezada, olla (black on black), courtesy of Steve Thompson, DeSilva Imports.

An amazing work by Moroni, son of Lydia Quezada and Rito Talavera and second-generation Mata Ortiz potter. Courtesy of Steve Thompson, DeSilva Imports.

Below an amazing example of graphite blackware: it’s an olla by second-generation Mata Ortiz potter Eli Ortiz, whose father was Eduardo “Chevo” Ortiz, an artist who worked in collaboration with his wife Hortencia Dominguez to create original graphite black on black, swirl-ribbed jars.

Eli Ortiz, Black on Black Beehive, swirl ribbed pot, height 7″, circumference 20″. Courtesy of May Herz, © Sandia Folk, TX, US.

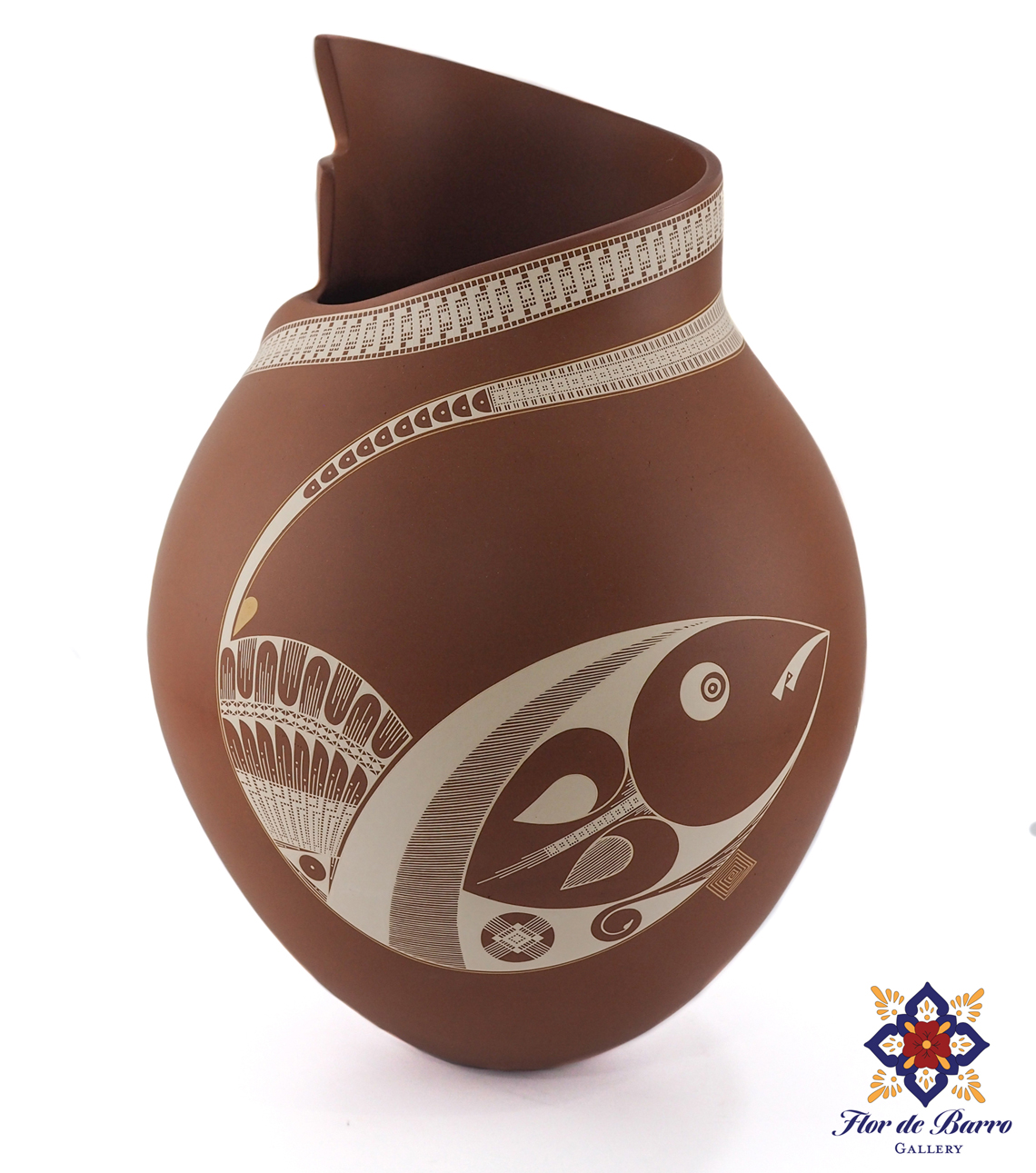

Among the Mata Ortiz second-generation artists, one of the most accomplished is Diego Valles (born in 1982). He made his first olla at 9 years old, and since then, he never stopped experimenting, pushing his creativity beyond any apparent limit, and always respecting Juan’s postulate. He’s been awarded many times for his mastery of the cut-out technique. He’s also famous for his huge ollas and original designs.

Diego Valles, chocolate clay large-sized olla, H 16” with base, W 12.1″. Courtesy of Andrea Calleros, © Flor de Barro Gallery, El Paso, TX.

The black heart below, showing a long laceration, partially sewn with a metal thread put through a needle, was made by Diego Valles after the death of his beloved brother.

Diego Valles, La Aguja de la Fe (Needle of Faith), H 9.5″ – W 5.2″. By courtesy of Andrea Calleros, © Flor de Barro Gallery, El Paso, TX.

Lorenzo Elias Peña Pacheco is an award-winning potter and a remarkable talent who follows Juan’s postulate and performs each step of the process himself. In his pots, the creative design combines with a refined technical mastery. His creations are always very delicate, unusually shaped, and among the thinnest walled of Mata Ortiz. Below, a captivating representation of maternity.

Elias Peña, Pregnant Olla, 2-piece set with clay stand made by the artist, H 8.5″ – W 6.5″. Courtesy of Andrea Calleros, © Flor de Barro Gallery, El Paso, TX.

Jerardo Tena is a second-generation, awarded master potter living in the Barrio Porvenir of Mata Ortiz. He is well known for his animal-shaped vessels and zoomorphic pieces, but I prefer the two pieces below for their perfect design.

Jerardo Tena, Seed Pot, diameter 6.5″, height 2″. Courtesy of Andrea Calleros, © Flor de Barro Gallery, El Paso, TX.

Jerardo Tena, Menorah, H 9.5” (with base) – W 8.2”. Courtesy of Andrea Calleros, © Flor de Barro Gallery, El Paso, TX.

Many current Mata Ortiz pots and vessels are inspired by a particular painting design, known as “Bugarini style” as it was created by a young second-generation potter: Laura Bugarini Cota. She’s definitely a virtuoso painter, many times awarded for her ability to fill the curved space of a complex olla with intricate patterns, made up of detailed and ultra-fine designs, governed by a sort of horror vacui. She paints freehand, ça va sans dire. Her husband, Hector “Yeto” Gallegos jr. is a virtuoso of the “Bugarini style” sgraffito version.

Laura Bugarini, Olla and stand. Courtesy of Steve Thompson, DeSilva Imports.

Hector Gallegos, Olla and stand. Courtesy of Steve Thompson, DeSilva Imports.

Another couple who live and work together is composed by Claudia Ledezma Loya and Luis Armando Rodríguez Mora, whose works alternate two different techniques, painting and sgraffito, and are inspired by the ancient mysterious symbols of Mimbres Ceramics.

(The Mimbres Culture is a Mogollon culture that flourished between 1000 and 1130 CE (before Paquimé), in a zone of mountains and plateaus in the US Southwest and the Mexican Northwest. Its main feature is amazing black-on-white pottery, made up of vessels and bowls decorated with complex geometric designs and naturalistic depictions of people and animals).

Luis Armando Rodríguez Mora, Mimbres Olla, with painted and etched designs and cutouts. Height 12.5″, circumference 25.5″. Courtesy of May Herz, © Sandia Folk, TX, US.

The same sources of inspiration can be found in this superb olla by the master Martin Cota.

Martin Cota, vessel, H 12.5” W 9”. Courtesy of Andrea Calleros, © Flor de Barro Gallery, El Paso, TX.

Octavio “Tavo” Silveira Sandoval is a second-generation member of a large family of high-level potters and shows in his work deep assimilation both of Juan’s experience and of Paquimé and Mimbres symbolic ceramics. His pictorial trait, however, is sharp and bold. His designs and his sense of composition fully contemporary.

Tavo Silveira. Courtesy of Steve Thompson, DeSilva Imports.

Below a marbled olla made by mixing different types of clays. It’s a refined work by Salvador Baca, an awarded Mata Ortiz first-generation potter. As we saw, the marbled effect is not a painted one. It’s realized «by mixing several different colors of clay together to create a beautiful base to the piece. The clays are joined together into bricks and then cut into squares. The clays are then mixed together again, and the process is repeated until the desired distribution of the mixed colors is achieved. It is a labor of love and a process that only the most talented attempt. Different clays fire at different speeds, so this mixture of clays intensifies the risk of breakage during the firing process. To achieve a mixture of high quality requires a true technical mastery» (Steve Thomson).

Salvador Baca, carved and painted olla in mixed clay. Courtesy of Steve Thompson, DeSilva Imports.

The following are two pieces I’m in love with. The first is made by Celia Ivon Veloz Saenz, a recognized and awarded second-generation artist in Mata Ortiz. The olla below shows a refined balance among all of its elements. It’s elegant, neat, and “alive”.

Celia Veloz, Red Clay & White Fish, H 16.5″ – W 11.5″. Courtesy of Andrea Calleros, © Flor de Barro Gallery, El Paso, TX.

The second piece (below) is made by Adrian Corona Trillo, son of the well-known first-generation potter Ana Trillo de Corona. It’s made by using both painting and sgraffito, two techniques that Adrian perfectly masters.

Adrian Corona Trillo, Circles Mata Ortiz Olla. Courtesy of Andrea Calleros, © Flor de Barro Gallery, El Paso, TX.

Graciela Martinez Quezada de Silveira is a potter from Mata Ortiz, awarded for her striking ability to create a “concerto” of multiple designs flowing into each other in a sort of liquid 3D movement.

Graciela Martinez, olla, H 12″, W 11.7″. Courtesy of Andrea Calleros, © Flor de Barro Gallery, El Paso, TX.

The variety of styles and designs is so large that it is impossible to give you an even concise idea of the most fascinating trends in present-day Mata Ortiz. Local master potters, moreover, do not set any limit on shapes and forms: alongside ollas and effigy vessels of ancient tradition, you can find plates, bowls, seed pots, revised and interpreted in the light of contemporary aesthetics, and unusual, original forms, unrelated to tradition and devoid of a functional role. The third generation potters, still budding, do not promise simple improvements: they seem ready to surpass everything that has been done by anyone in the past, including Juan. What is most disappointing at the moment is the lack of commitment of local politicians…

I, therefore, invite you to explore this fascinating, evolving “universe”. In the fifth part, you will find all sorts of information about online art galleries and stores I have directly known as a Mata Ortiz buyer and collector.

The bibliography – which is not exhaustive as it only reflects my readings – also includes beautifully illustrated (although often not very recent) books on Mata Ortiz masterpieces.

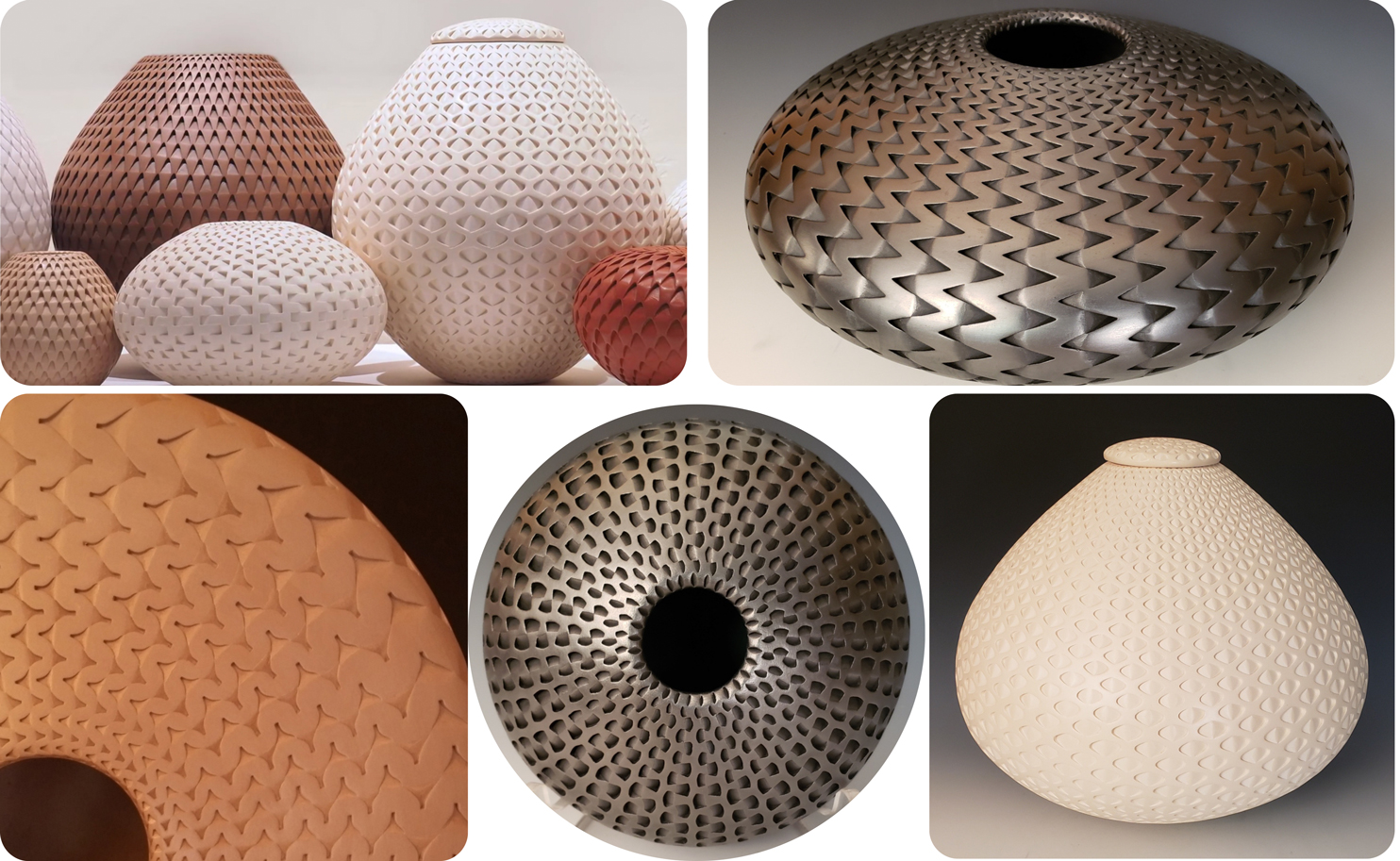

Last but not least, I’d like to highlight the international influence of Juan Quezada. He taught many international artists and potters throughout his life. One of the most talented is Michael Wisner, a US artist who lives and works in Colorado and studied with Juan for ten years. «Juan taught me traditional pottery skills literally from the ground up. His rigorous standard of craftsmanship challenged me to develop my hand-building skills to a level I did not know possible. His passion to create was contagious. I worked for years under his tutilage while simultaneously working as a resident artist at the Anderson Ranch Arts Center in Colorado where I was exposed to many contemporary ideas. Straddling both of these worlds of traditional and contemporary ceramics I began to incorporate elements from both. Today I use Juan’s old clay technology, with colors I make myself from minerals found here, in the mountains of the Western US. Using old and new hand-building techniques, I produce feminine forms, with hundreds of contemporary patterns that replace the traditional painting seen in Southwest pottery».

Creations by Michael Wisner, courtesy of the artist.

Our journey is over.

Despite an incredible international success, Juan Quezada, now in his 80s, still resides in Mata Ortiz. He no longer lives in his old adobe house: he moved to the wild hills overlooking the Palaganas river, where he founded the “Rancho Barro Blanco” (White Clay Ranch). Here, he dedicates himself to the great passions of his life: pottery, cattle breeding, family, and solitary wanderings to listen to the wind and the silence, to smell the scent of dry grass and the perfume of mud after rain.

Someone said he’s a vaquero at heart.

I guess he has a visceral, spiritual, grateful tie to his land.

He needs to feel connected with his Mother. Mother Earth.

A SAD UPDATE: Juan Quezada passed away on December the 1st, 2022, in Mata Ortiz. RIP.

BELOW:

The Rancho Barro Blanco of Juan Quezada, September 13, 2008.

Photo by Raechel Running from Tucson, Arizona.

©RAEchelRUNNING2021

Here’s a famous song by Calle 13 (pronounce /kàye treh-say/), a Puerto Rican band formed by stepbrothers René Pérez Joglar (1978) aka Residente and Eduardo José Cabra Martínez (1978) aka Visitante. This song – ‘Record of the Year’ and ‘Song of the Year’ in the Latin Grammy Awards of 2011 – is a compelling hymn and a complex tribute to all Latinoamérica, to Mexico as well.

I think it’s the perfect song to end the story of Juan Quezada.

No Latino can hear this song without being visibly or invisibly moved, as it wrings the deepest heartstrings of all of us (the pride and the struggle, the visceral relationship with Mother Earth, the sense of the sacred, etc). Music, video, and lyrics combine to create a powerful ensemble.

Despite the emotional impact of lyrics, the text is a complex one that hides some references not easy to understand (except for Maradona, of course): to Eduardo Hughes Galeano (1940/2015), an Uruguayan writer, author of Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent, to the Colombian Nobel prize-winning author Gabriel García Márquez (1927/2014), author of the novel Love in the Time of Cholera, and to Chilean poet Pablo Neruda (1904/1973), Nobel Prize for Literature in 1971 (ref.: la noche estrellada…).

There are also numerous political references, from the desaparecidos (lyrics and some images) to Operation Condor and the increasing phenomenon of land grabbing (ref.: mi tierra non se vende, my Land is not for sale), namely large-scale land acquisitions by transnational companies and foreign governments throughout Latin America.

The poetic video was filmed in Peru and other places throughout Latin America. It’s introduced by a local Dj in Quechua (an indigenous language family spoken by Native peoples in the Peruvian Andes), and is sung in Spanish and Portuguese do Brasil. It features the participation of a singer of Afro-Colombian and Indigenous descent, Sonia Bazanta Vides aka Totó la Momposina (long hair), of the Afro-Peruvian singer, songwriter, ethnomusicologist Susana Baca (short hair), former Minister of Culture in the Ollanta Humala government (2011), and the Brazilian singer Maria Rita Camargo Mariano.

Lastly, this video reminds us that talking about art, culture, politics or history means always talking about men, women, and children. About people lived or living in a corner of our planet. About ourselves, our differences and similarities, about our creativity and colors, sorrows and struggles. We need to know each other to be able to say – one day, I hope – We are all diversely colorful as we’re expressions of the very same light.

Latinoamérica by Calle 13

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?