The Mata Ortiz Pottery 3

JUAN QUEZADA CELADO

Juan sat on a peeled wooden stool and breathed deep into the smell of his home, his patio, the dust and the clay, the frijoles that his wife had fried in the morning.

The trees beyond the low wall of reddish adobe bricks were still green and with each gust of wind came the rustle of their leaves, covered at times by the nervous barking of a dog. He had been working for three months “on the other side” and every day he had been dreaming of coming home, sitting on that stool, and doing nothing. Just contemplating his patio and his sky. His children and his ollas.

He breathed even deeper. He rose and headed for the storage room on the opposite side of the patio. He pulled out a wooden table, and put it in a corner, under one of the fruit trees. He came back and from an old box pulled out four of his ollas and then a fifth, larger one with a chipped edge. He lined them up on the table, in the very same order he had lined them up the day before he left for Texas, three months earlier.

He grabbed the stool, turned his back on the sun, and sat looking at the ollas.

Nearly twenty years had passed since he was used to wander on the sierra without shoes, on his burro Minuto, looking for firewood to sell and mysterious shards to keep to himself. At that time, he didn’t know what to do with those pieces, but it all became clear when, at just 15, he started boxing to raise more money.

He immediately realized he had a flair for the boxing ring. He was nervous, agile, fast, gifted with the perfect mixture of every good boxer: fire, silence, and intelligence. His lifelong friend, Pino “Pinito” Molina, offered to manage his boxing matches and the money began to rain. Not a heavy rain, to be honest, but a beneficial, unexpected, and constant drizzle (he never lost a fight). His mother, who had always supported him, however, got suddenly in his way. One day she looked right into his eyes:

– Tu no vas a seguir con el boxeo. No me hagas repetir.

Juan felt a knot in his stomach: he realized that his mother loved him, she had always loved him, and she was feeling shitty. He felt shitty too. He did not retort and quit boxing.

Not for a moment did he consider pointless that experience. Boxing taught him a truth: just as radios were battery-operated, he was operated by challenges. But unlike radios, which all worked with the same batteries, he didn’t work with the same challenges loved by his friends. He realized he was a maverick even before becoming a man, and understood it without feeling any emotion. He just felt he needed to face a challenge, and then another, and another, again and again, always hoofing along that narrow and slippery path poised between common sense and madness that, like a mule track, climbs along the slopes of a sierra. He ferociously needed to live on top of a mountain, otherwise the fire constantly burning inside his core would have roasted him like a pollo asado.

In his way, at just 15, he understood what many understand when they have white hair and it’s too late: that living below our capabilities kills us slowly, inexorably and mercilessly.

Would he ever be able to create such perfect ollas as those made by los viejos?

Would he ever be able to find the right clay? to process it? to model it without a potter’s wheel, creating perfectly round ollas with thin and smooth walls? Would he ever be able to polish and paint them with the same mysterious yet imposing geometries?

And with what colors? with what brushes?

How to paint bare hand those red spirals and those black, thin lines, perfectly straight but able to go suddenly crazy breaking into nervous zigzags?

How to cook his ollas without a kiln? without breaking them, without fading the colors, without tarnishing the drawings?

And where to cook? with what?

Finally, there was the mother of all challenges: how to overcome each of these challenges all alone, by himself, without spending the money he didn’t have?

In Mata Ortiz and Nuevo Casas Grandes, no one knew how to make those ollas anymore: he was alone in the face of his challenges. But he was free as well.

As for the chronic lack of money, he told himself that los viejos were certainly not gringos and had to be as pobres as he was. They were not loaded and the ollas they made, scattered throughout the plateau, must have been made with materials the plateau itself offered them freely. Hence, it was an equal challenge, in a way.

It took him nearly twenty years to overcome almost all of the challenges, even the unexpected ones.

In those twenty years, he had learned the secret of a real vaquero from his father José and the secrets of love from his mother Paulita. He had married, built a new adobe bricks house a block from his parents’, learned how to work in the Mormon orchards, and how to find a seasonal job in the ranches on the other side. He had had four children, whose perfume he could recognize in his sleep, but he had never ceased to feed the avid fire in his core. He had never stopped working on his challenges. On his ollas.

He looked at them in line on the table. He compared his ollas with the larger and chipped one: that was la vieja. His new thin-walled jars were smaller but truly beautiful. Their surface was white and smooth, their shape flawlessly round and amazingly potbellied. Whenever he held one of them, his hand was forced to say: mijito, this olla is perfect! His eye, however, remained silent and disappointed. The drawings traced on his vases looked perfect but they weren’t. Up close, the black trait appeared imperceptibly uncertain. It wasn’t a matter of hand: it was a brush problem. He had built many of them by using the threads of the agave leaves, the beard of some shrubs, the pig bristles, the hairs of mule, horse, calf…

He sighed. He stood up. He took la vieja in his hands and began to question her.

He felt a little hand grabbing a fold of his jeans under his right hip. He smelled his daughter. The second one. Mireya.

The little girl slightly swung, shifted the weight on her right leg and then on the left, crossed her feet, tilted against her father’s side, and put a lock of hair in her mouth. Juan noticed it with one eye. He put la vieja on the table, and with one hand – a callous and large hand compared to his lean and nervous body – gently removed the hair from her mouth. He caressed her back without saying anything. He stroked her black, smooth and straight hair, like his wife’s. He had always had a mass of thick hair, as strong as a foal’s mane, with the same soft waves that chase each other on the Palanganas river when the evening wind did not want to calm down. His girls, on the contrary, had silky, thin hair, so fine, impalpable…

He suddenly gasped.

He called his wife so loudly that the little girl was frightened, stumbled, and fell. He lifted her with strength and kindness, took the dust out of her shirt, and looked at his wife who had appeared on the patio with a baby in her arms.

– Guille tráeme tijeras, por favor.

She looked at him with that gaze with which you may caress someone you love without understanding his mystery.

She came back with the baby and a pair of scissors in her hand. He stroked his daughter’s hair and then cut off a thin, long lock of four hair.

The little girl looked at him timidly but he did not return her gaze. His eyes had already gone elsewhere, on top of a mountain.

He had finally figured out how to make the perfect brush.

BELOW:

Juan Quezada near his current ranch in Mata Ortiz, Chihuahua, August 2007.

This photo is by one of the creative photographers I love the most: her name is Raechel Running from Tucson, Arizona.

©RAEchelRUNNING2021

THE OLLAS OF THE FOREBEARS

Juan found different clays on the mountain slopes, along the banks of the streams, the plains, the canyons. «He brought them home, mixed them with water, and tried to make little pots. But he failed. He tried again and failed» (Walter P. Parks, see Bibliography). He molded the clay without a potter’s wheel; therefore, he had to invent a whole system by using only his hands and simple natural tools. He had no kiln and had to invent another system to fire the pots in an open fire, in the middle of his patio, by using free natural resources such as cow dung or Mexican sycomore cork. «The clay cracked; the paint did not stick, and there was no one who could help him (…). Juan had no instruction nor had he ever seen a pot being made» (W.P. Parks).

He kept on trying and trying, giving the world a good lesson about strength, tenacity, and the importance of failure as a teaching tool.

«In Chihuahua, there is no green, lush paradise. It is a silent, melancholy kingdom of eroded yellowish plains, with little water and shade, and of high and rugged mountains cut to the ground by huge gorges […] A race of strong men, with much love for the earth to fight for it, was necessary to survive here» (Lister and Lister, Chihuahua, see Bibliography). The people from Chihuahua have always been ‘warriors’ with great tenacity of spirit and strength of character, and Juan could not have been born elsewhere.

After almost twenty years of hard work in scattered stolen moments, torn from the farm labor, the family tasks, and the fatigue; after years of trial and error, years of solitary challenges and failures, with no teacher, no mentor, no support whatsoever, just fed by the fire in his core, Juan Quezada began to see satisfying results in the first half of the 1970s.

Between 1973 and 1974, he was still working most of the time as a farm laborer, but he started to sell a few of his ollas, close in style, quality, and design to those of the viejos. Some of these pots passed the border to be sold “on the other side”.

These small sales gave the family an extra income, taken as a blessing, una verdadera benedición. Some of Juan’s brothers and sisters – the older and the younger among his sisters, Consolación and Lydia, and two of his brothers, Nicolás and Reynaldo – started to learn how to create small jars to be sold to the gringos.

W.P. Parks, whose book The Miracle of Mata Ortiz is one of the best on Juan Quezada, writes: In those «years of work, trial and error (…) Juan rediscovered the entire sequence of ceramic technology. This was a miracle».

And it wasn’t the only one.

Juan did not compete with an old, local production of rustic terracottas, not even with a series of antique pots and vessels of good quality and decorations. At that time, he didn’t know, (he couldn’t have known it, and he’ll know it much later) that the ollas and shards he tried to challenge and later surpass were not just ordinary old ceramic pots. They were among the finest, the most exquisite, and precious ceramic pieces of pre-Columbian North America.

THE DISCOVERY OF AN UNKNOWN PREHISTORIC CULTURE

Nuevo Casas Grandes, in Spanish “New Large Houses”, is a very unusual name for a city: it got its name from another town 2 km further south, called “Casas Grandes” by the Spaniards in the 17th century. These casas grandes, large houses, were obviously the old ones.

How old were they?

The Spanish conquistadores did not know: the site was already abandoned when they saw it for the first time, in the mid-1560s. We know it from the description given that date by the Spanish explorer Baltasar de Obregón: «There are many houses of great size, strength, and height Hay muchas casas de gran tamaño y fortaleza y altura>. They are six and seven stories, with towers and walls like fortresses for protection and defense against the enemies who undoubtedly used to make war on its inhabitants. The houses contain large and magnificent patios paved with enormous and beautiful stones resembling jasper. There are knife-shaped stones that support the wonderful and big pillars of heavy timbers brought from far away. The walls of the houses were whitewashed and painted in many colors and shades with pictures of the buildings. The structures had some kind of adobe walls. However, it was mixed and interspersed with stone and wood, this combination being stronger and more durable than boards» (From Discovering Paquimé, see Bibliography)

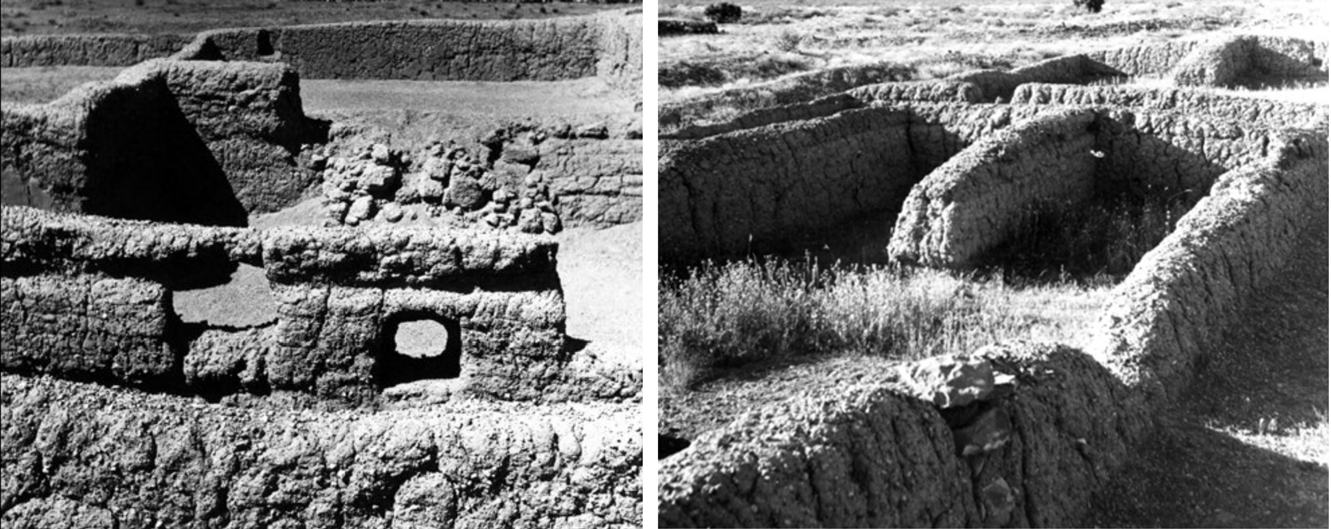

In the mid-20th century, little remained of these “wonderful” ruins, exposed to weathering with no protection: the “old large houses” were tall mounds of earth, interspersed with massive standing walls of adobe, with no traces of the original paint. In the centuries, locals and looters (two not matching categories) found, brought home, or sold to visitors many stone axes, corn-grinding stones, earthenware pottery vessels.

The archaeological site of Casas Grandes in the summer of 1930. © Phototeca Nacional INAH, Mexico.

The archaeological site in the 1930s. © Phototeca Nacional INAH, Mexico.

The thick walls of the “large houses” in the archaeological site during the 1950s/60s. © Phototeca Nacional INAH, Mexico.

A young man near a thick wall of a “large house” in 1960. © Phototeca Nacional INAH, Mexico.

Finally, in 1958, the Joint Casas Grandes Expedition (JCGE) began: it was a massive project of archaeological excavations, analyses, and multidisciplinary researches designed and carried out by Charles C. Di Peso, director of the Amerind Foundation (Arizona, US), and Eduardo Contreras Sánchez of the Mexican Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH). The fieldworks were conducted from 1958 to 1961; then it took 13 years for Di Peso and his collaborators – John Rinaldo and Gloria Fenner among the primary ones – to publish the first results: the 8 volumes entitled Casas Grandes: A Fallen Trading Center of the Gran Chichimeca (by Di Peso, Rinaldo, and Fenner) came out only in 1974. The scholars first and the larger public in the late 1970s found out that in the semi-arid heart of Chihuahua lurked one of the most important archaeological treasures of Mexico.

The JCGE excavations in 1960. © Phototeca Nacional INAH, Mexico.

The work by Di Peso and his collaborators was just the beginning. 50 years have passed since then. 50 years full of discoveries, studies, discussions, researches in different disciplines, including dendrochronology (the scientific method of dating the rings of the trees used as beams in the construction of the “large houses”), palynology (the science that studies microfossils such as pollen or spores), genetic and comparative studies on ancient ceramics.

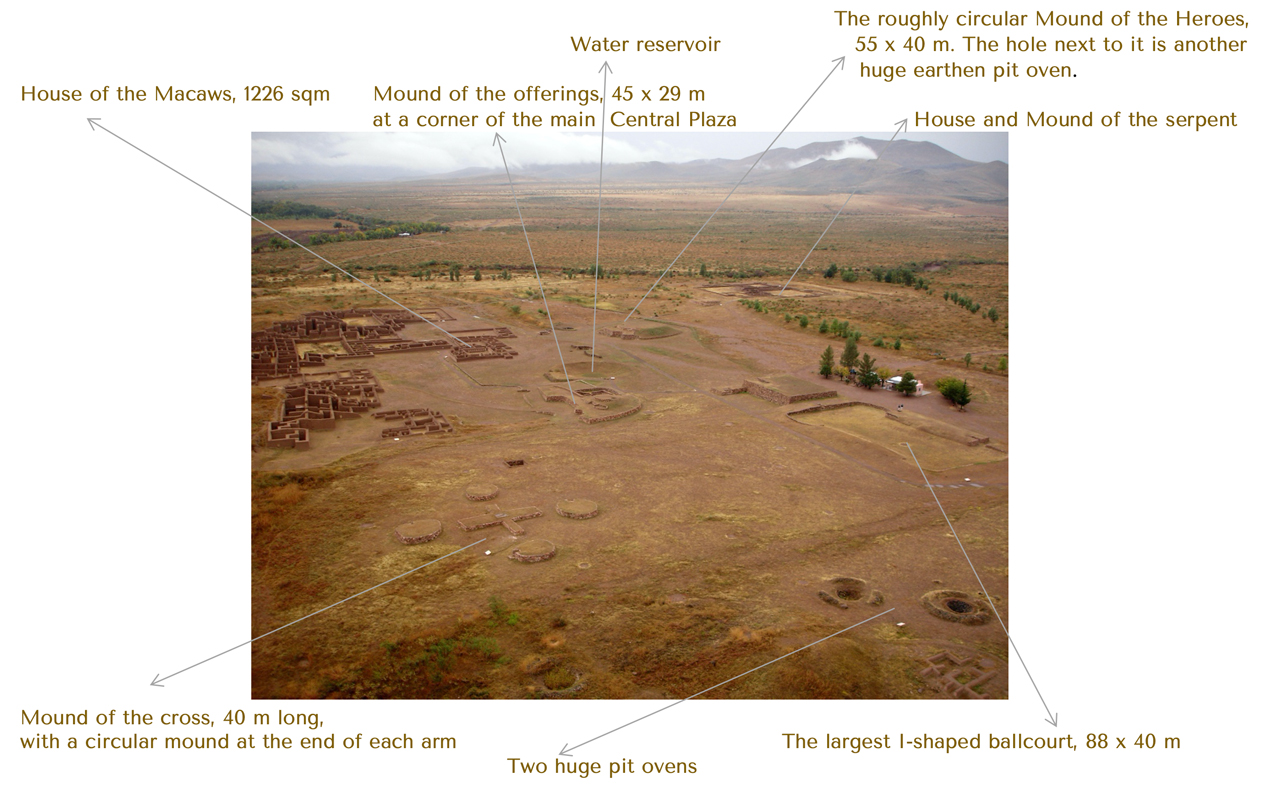

Today, the site of Casas Grandes, also known as Paquimé (“large houses” in Nahuatl, a Uto-Aztecan language) is considered the largest and most important prehistoric archaeological site in Northern Mexico. It covers approximately 36 hectares, of which only less than half (ca. 46%) has been excavated.

In 1996, the Museo de las Culturas del Norte (The Museum of Northern Cultures) was inaugurated on the edge of the archaeological site. It boasts one of the most interesting collections of Ancient Mexico, recovered during the excavations of Paquimé and other important archaeological sites in the Gran Chichimeca (the region formed by Northern Mexico and the Southwest United States).

Since 1998, Paquimé is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and is also under the purview of INAH.

The research on Paquimé culture is a work in progress. Many aspects are still a mystery; others are subjects of heated discussions among scholars («Few archaeological contributions have been as massive or as controversial as the excavations at Paquimé», D. A. Phillips – E. A. Bagwell, see Bibliography), but the main features of this prehistoric, pre-Columbian culture are clear (or seem to be…). And we’ll have a look at them.

Zona Arqueológica de Paquimé, Chihuahua by INAH TV

TEXT BY INAH TV – English translation

The ancient pre-Hispanic city of Paquimé is located in the northwestern Chihuahua, in a semi-desert area of extremes: it stands out in an ever-changing landscape dotted with green meadows and grasslands during the rainy season, turning into an icy, whitish stretch every winter.

Paquimé was the leading center of the Culture of Casas Grandes. Its area of influence and polity encompassed some portions of the Mexican state of Sonora (to the west), large parts of Chihuahua, and some areas of New Mexico (to the north). Its inhabitants settled also on the mountains of the Sierra, in some cuevas (caves), and cliff dwellings.

The ancient city of Paquimé included religious and sacred areas, an administrative center, and many residential units, all built with adobe, wood, and stones. The central square is a wide-open area, once the heart of the political, economic, and religious life of the community. It was flanked by the mound of offerings, the most important sacred space.

The ancient settlers of Paquimé lived in residential units, not too different from the current flats inside multi-story buildings, linked together by a complex system of corridors and ramps which delimited small squares and patios. The houses had three or four stories and showed inside small stoves and recessed wall-mounted adobe beds. Generally, the access to the rooms was through a T-shaped door.

The residential units were divided into different groups according to the main activities of the residents. The building of the scarlet macaws <Ara macao, in Spanish guacamayas> was the residence of the bird breeders and the feather traders. Still today, you can see the remains of the cages and the perches used for macaws, turkeys <guajolotes, bred not for their meat but to be killed in sacrificial rituals> and other exotic feathered birds.

Based on the archaeological data, the excavated portions of the city are estimated to include at least 2,000 residential units that housed a population between 3,000 and 4,000 people.

In the 6th century CE, during its first development stage, Paquimé was a small village of pit houses. Only in the 13th century, it reached its peak: it became a major nerve center in the trade of turquoise, shells, copper, salt, and luxury goods such as feathers.

The first scholars and archaeologists <Di Peso and collaborators> considered Paquimé a commercial outpost between Mesoamerica <Mexicas or Aztecs, Maya peoples> and the Pueblo Cultures of the US Southwest <Anasazi, Hohokam, Mimbres>. However, more recent researches have shown that Paquimé was a leading center, where the elite of the Casas Grandes Culture resided and controlled a complex society, the whole agricultural production, the trade, and the religious rituals.

Slightly before 1450, Paquimé was abandoned for reasons that are still mysterious. Some scholars hypothesize the invasion by some Ópata clans. The city large houses were looted, burned down and many of its inhabitants murdered. The survivors fled in different directions, probably creating new settlements along the border between Chihuahua and Sonora; others fled towards New Mexico territories where they were assimilated by the culturally related locals.

THE PRE-COLUMBIAN CULTURE OF CASAS GRANDES – PAQUIMÉ

The Paquimé people

In the Viejo Period, approx. 700-1060 CE, the area around Paquimé was characterized by small pithouse communities scattered over locations with water and arable land and is associated with a brown ware pottery tradition. The development of the large and powerful city, whose ruins we can see today, began in the Medio Period, approx. 1150-1200 CE, and continued until 1450.

The history of the Medio Period is marked by population growth and impressive structural changes in architecture, art, social organization, and the management of natural and economic resources. In this period, the large, central polity of Paquimé – Casas Grandes began. What prompted such a massive structural transformation in the 12th century is still unclear, but we know that Paquimé became an important political, religious and commercial center.

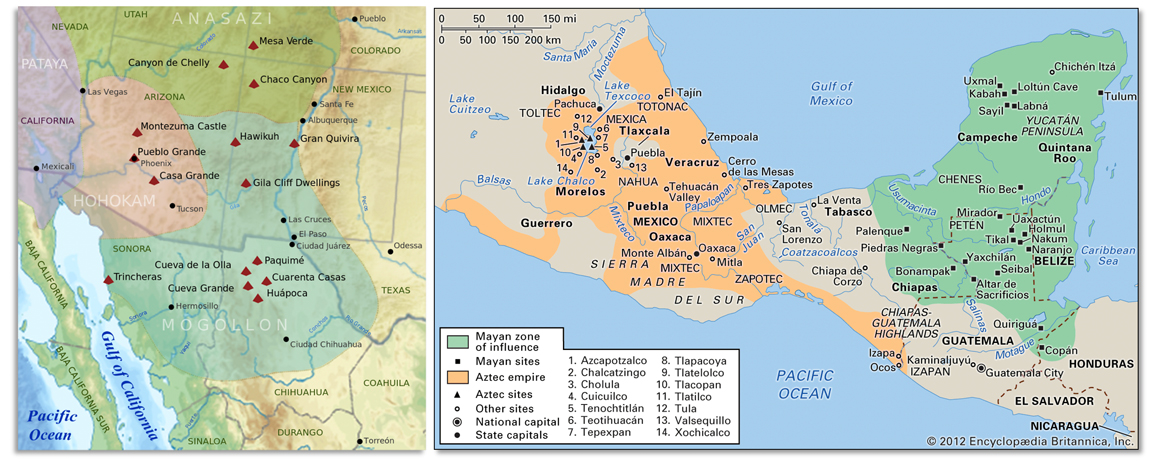

The Paquimé Medio Period corresponds to the full flourishing of the Imperio Mexica (the Aztec Empire), whose capital was México-Tenochtitlan in an area of Mesoamerica corresponding to Central Mexico, and to the development of the Mesa Verde Culture, part of the Ancestral Puebloans or Anasazi civilization in a region of Oasisamerica corresponding to Southwestern Colorado. With both, the ancient Paquiméans had commercial and cultural relationships.

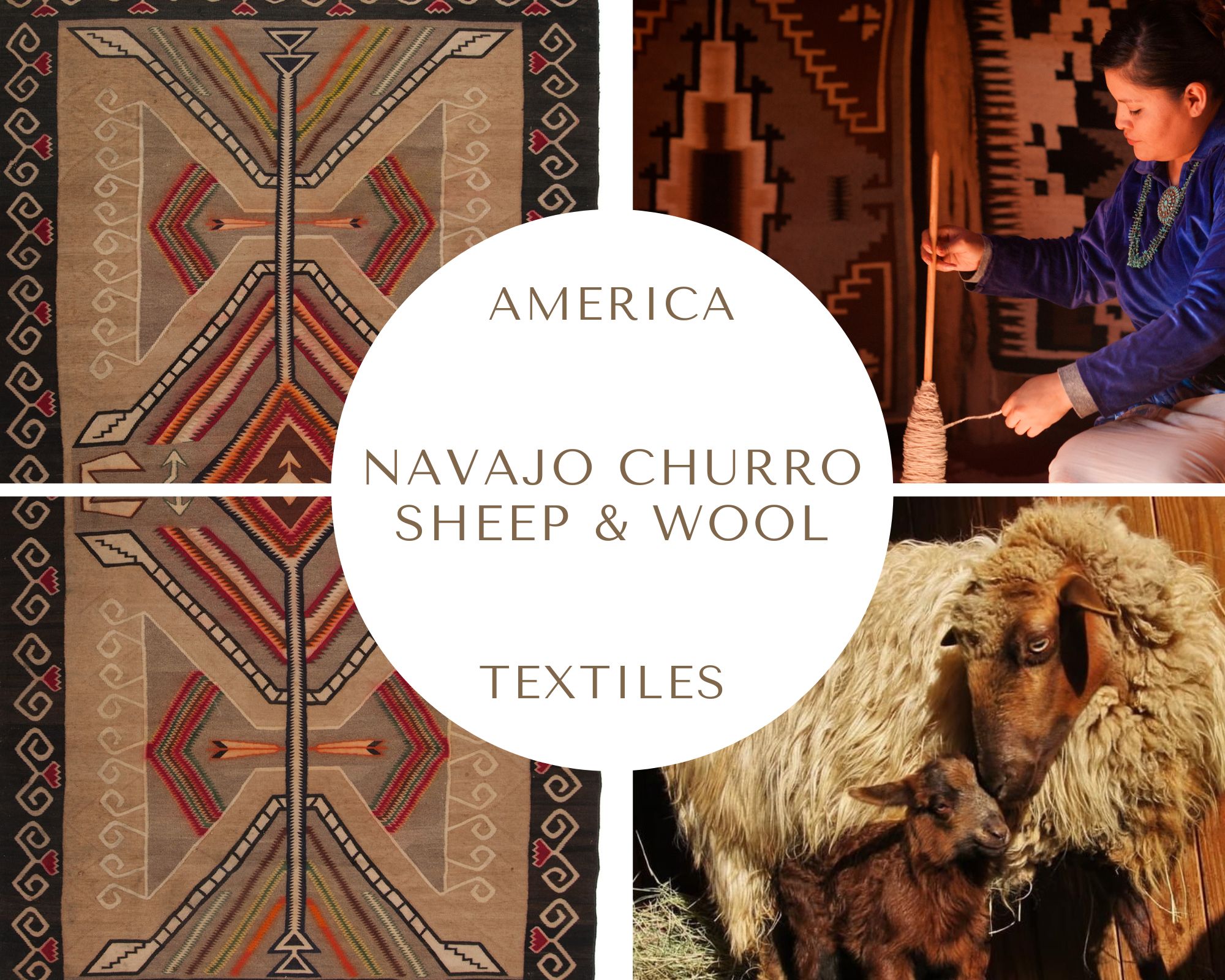

LEFT: Oasisamerica, map of Hohokam, Ancestral Pueblo, and Mogollon cultures, ca, 1350 CE. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

RIGHT: Mesoamerica, in G.R. Willey, G.H.S. Bushnell, Th.C. Patterson, M.D. Coe, J. Soustelle, V.W. von Hagen, W.T. Sanders, and J.V. Murra, Pre-Columbian civilizations ©Encyclopedia Britannica.

Today, the Medio Period Casas Grandes is considered one of the most politically complex New World cultural systems north of Mesoamerica (VanPool & VanPool, 2021).

For Charles Di Peso, Paquimé was a major trading center linking Mesoamerica with Oasisamerica, that area made up by Southwestern US and Northwestern Mexico that he called “la Gran Chichimeca”. Di Peso hypothesized, in particular, that Paquimé was ruled by Mexica (= Aztec) long-distance traveling merchants, known as pochteca. Some other scholars promote a different hypothesis: Paquimé could be established by the elites of the Ancestral Puebloans coming from the north. Both these hypotheses are weak: current views favor the rise of a local elite; however, there’s no certainty on this matter.

A 2017 genetical investigation, Ancient mitochondrial DNA and ancestry of Paquimé inhabitants, Casas Grandes (A.D. 1200–1450), published in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology, showed that the ancestry of Paquimé inhabitants cannot be found in Mesoamerican immigrants or Aztec merchants but in some Oasisamerican groups. The analysis of some mitochondrial DNA haplotypes, extracted from dental samples found in Paquimé, showed a close affinity between its inhabitants and the Mimbres people, a Mogollón culture flourished between 1000 and 1130 in parts of Chihuahua, New Mexico, and Arizona. For this and other reasons, many scholars consider the Paquimé – Casas Grandes culture the most complex Mogollón site. The Mogollón culture was one of the three major prehistoric cultures of Oasisamerica, together with Hohokam and Ancestral Puebloans (you can pronounce Mogollón in two ways: in Spanish as /mogoyyón/ and in English /mug-ee-own/).

The archaeological finds tell us that the Paquiméans were slightly higher than the average of Mesoamericans: the men were 1.55 to 1.72 m tall on average, the women 1.49 to 1.54 m. None of the skeletons found on the site shows skull deformations, but we know that their nasal septum and ears were pierced (they loved jewelry). Their average age was just 31 years. Most of them died before the age of 35, and the infant mortality had to be remarkable. 50% of the population suffered dental problems, tooth loss, abscesses, and gingival diseases due to many factors, including nutritional deficiencies.

Like all the pueblo populations, they relied on agriculture. The land of Chihuahua is fertile and rich in streams, but the climate of the Casas Grandes plateau is harsh: it changes from scorching heat (even 48° C) to snowfall (at -15° C) and gives the fields poor, irregular rains that have always put crops at risk. The ancient Paquiméans were farmers – they grew corn, pumpkin, gourd, beans, cotton seeds, chile, and amaranth – and at the very same time, they were forced to remain hunters and gatherers. As for the meat, they got it by hunting (bison, desert cottontails, mule deer, pronghorns, black-tailed jackrabbits, pumas) or fishing in the nearby rivers (longnose gars and Chihuahua chubs). They also collected wild seeds (millet), acorns, pine nuts, mesquite pods, agave, and some cacti.

The semi-arid landscape around Paquimé. Photo by Sam Cavenagh, 2006.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic (CC BY-NC 2.0).

The Paquimé “large houses”

«Many visitors to the ancient ruins at Paquimé are understandably impressed by the enormous size of the site, the breadth of the walls, the size of the colossal wooden beams, and the variety of different rooms, platform mounds, ballcourts, and other structures. It is no wonder that the site earned the name Casas Grandes» (Discovering Paquimé, cit.).

To tell the truth, the houses were not simply grandes (large): they were huge and impressive. The wall of the ruins can be as thick as 56-60 cm (they had to be larger in origin) and some walls reach the incredible height of 10-12 m.

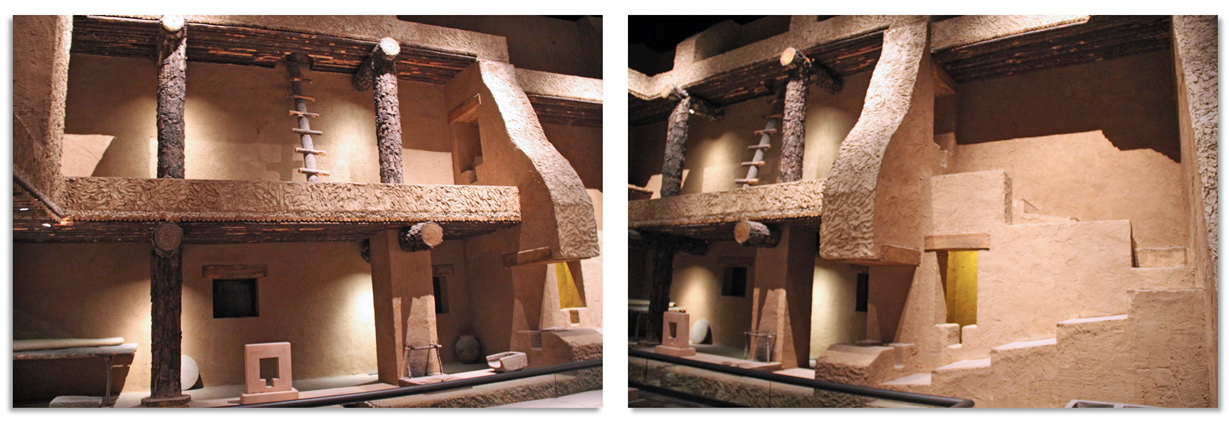

The archaeological excavations have only shed light on a part of the prehistoric city. The 2000 housing units that emerged were structured in multi-story apartment buildings, provided with patios and spaces for workshops and stores, all built with unfired clay or adobe, wood, and stones.

A special clay (called caliche), mixed with water and pebbles, was used to build the walls reinforced with wooden piers inside, with stones and graves outside, at the foundations. Both the outer and the inner surface of the walls were covered with lime and plaster and then painted. Some interior rooms were painted green and showed green and red horizontal stripes, incised designs on the walls, and charcoal drawings showing human and animal figures.

The houses had windows, small T-shaped doorways (50-58 cm width, 64 cm at their widest point, thus greatly restricting the free-flow of people and goods) and many stories: in the mid-1560s, the Spanish Balthazar de Obregón wrote they were 6-7, but some scholars today thinks they were probably less. In any case, the size and complexity of construction required some advanced techniques to support the multistoried room blocks (some large pinewood columns were used to support the cross beams on which the upper floors rested).

Ruins of an adobe house in Paquimé. ©Photo by INAH.

Reconstruction of the interior of an adobe house in ancient Paquimé, in the Northern Mexico Gallery of the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Photos by Gary Todd. Please, note at the ground level the Tau-shaped stone altar and the metate, the grinding stone on the right.

Most residential units show a typical L-shape, with a large living area attached to a smaller alcove with storage space and built-in bed platforms, 1 m high from the ground, heated from below by an adobe stove to withstand the freezing winter. Moreover, the Paquiméans could boast what a prehistoric real estate agent would have called an “exclusive, top-class amenity”: access to running, drinking water, and a sewage system.

The channelization and the integrated water resource management

Paquimé was built near the river Casas Grandes, the Arroyo de Mimbres to the south, the Arroyo del Norte to the north. A little further away, two of the Río Casas Grandes tributaries, the Río Palanganas (near the current village of Mata Ortiz) and the Río Piedras Verdes (near the current Mormon orchards), flow. To take full advantage of the freshwater source, the ancient Paquiméans built a complex system made up of canals, 2 large reservoirs, irrigation ditches, sewage structures, underground drains, waste oxidation lagoon. The canalized water crossed the city units entrusted with water management.

A water canal snaking through the blocks of the House of the Pillars, in Paquimé. ©Photo by INAH.

Five kilometers north of Paquimé, the freshwater from the Ojo Varaleño spring was brought by a long canal to a large reservoir that diverted it into smaller ditches that crossed the city. This system allowed to supply water to almost all of the community’s homes. A different series of canals drained the wastewater.

«Not surprising for farmers in an arid environment, water was of practical and symbolic importance to the people of Paquimé» (Discovering Paquimé, cit.). What at first was believed to be a walk-in-well is probably a water shrine. «So it is not unusual that Casas Grandes religious imagery focused on water» (cit.).

Paquimé as an important ritual center

In the city area, archaeologists found:

- A system of towers and trenches on the surrounding hills.

- Two I-shaped Mesoamerican-style ballcourts, under which excavations found traces of human sacrifice, and a T-shaped ballcourt. Note that we do not know if the pelota game they were made for was similar to the Mesoamerican one.

- A market area in the large central plaza.

- Some huge roasting pits or earthen oven; one of them is so large that 3,000 kg of agave could have been cooked inside to brew an alcoholic beverage known as mezcal, whose drinking in Mesoamerica had a religious connotation. The ovens were probably also used to prepare food for feasts or large ritual events.

- Many ceremonial buildings and sacred spaces.

As to these last, the most notable ones are several earthen mounds lined in stone and covered in plaster and paint, provided with stairs which lead to flat tops: scholars distinguish effigy-mound (montículos de efigie) and ceremonial mound (montículos ceremoniales). All of them form the public ceremonial core on which ritual acts could be performed.

The Mound of the Cross (Montículo de la Cruz), 40 m long, oriented to the cardinal directions and aligned with the autumnal equinoxes, has been interpreted by some scholars, as B. Braniff Cornejo, as a sacred structure and an astronomical observatory.

The largest ceremonial monument is the Mound of the Heroes (Montículo de los Héroes), a truncated pyramid, 56 m long on the east-west axis and 40 m wide on the north-south axis. «The summit was covered with a layer of ash, suggesting that it may have been part of the smoke signal system» (Delain Hughes, Complementary Dualities, see Bibliography).

The Mound of the Offering (Montículo de las Ofrendas), 45 x 29 m, was the only sacred structure with interior crypts, rooms, and an altar. «The central and most prominent crypt contained the remains of a man placed in the fetal position inside a large olla and the scattered remains of other individuals who were, presumably, sacrificed as offerings. A niche in this room held the base of a stone sculpture depicting a standing woman wearing a headdress. Each of the two rooms that flank the central crypt preserved a male skeleton inside an olla. In front of these rooms, there are stone-lined quarters that contained a series of offerings, including stone nesting boxes, stone tools, ceremonial arrows, stone and shell beads, un-worked shell, and ceramics, all indicating the importance of the men who were buried here» (Delain Hughes, cit.). This structure, therefore, was probably linked to the ancestor cult.

The most mysterious (and debated) among the sacred spaces is the Mound of the Serpent (Montículo de la Serpiente) shaped as a plumed serpent. The deity or supernatural entity represented as feathered, plumed, or horned snake is common throughout Central and Northern America: both Puebloans and Mesoamericans shared this cult and the culture of Paquimé was no exception. «Across the Americas, the feathered (or horned) serpents are supernatural entities that control water. The Mexica (Aztec) Quetzalcóatl was a feathered rattlesnake that flew through the air to herd clouds and bring rain. The feathered serpent of Zuni Pueblo in western New Mexico is Ko’loowisi, who lives in the watery underworld» (Discovering Paquimé, cit.).

«Charles Di Peso was adamant that the horned serpent was the central deity of the Casas Grandes people, who, he concluded, followed the Mesoamerican serpent tradition associated with Quetzalcóatl» (Discovering Paquimé, cit.). This hypothesis is strengthened by the images and the traces of children sacrifices found in Paquimé and tied to Tláloc, a Mesoamerican deity that controlled rain, and the evidence for the local worship of Xipe Tótec, a life-death-rebirth Aztec deity, who demanded human sacrifices and the use of human trophy heads. Therefore, some scholars support the thesis of a heavy Mesoamerican-Aztec influence on the Paquimé religious culture.

However, the Paquiméan plumed serpent shows no iconographic resemblance with the Aztec one, and moreover, even «Puebloan people used and still use the horned serpent as a symbol for water, maize, lightning, and the sky» (Delain Hughes, cit.). Other scholars, therefore, support a more nuanced hypothesis about the religious footprint on Paquimé.

Scholars do not agree on another related issue. The cult of the plumed serpent was probably linked to a class of priests. «Di Peso distinguished between priests and shamans, and he argued that although both types of practitioners probably existed at Paquimé, organized priesthoods dominated the religious system and, by extension, the political, economic, and educational systems of the community» (Discovering Paquimé, cit.). Other scholars, like Paul Minnis and Michael Whalen, support the hypothesis of a powerful caste of shaman-priests as part of the Paquimé elite. Others, like Beatriz Braniff Cornejo, are more inclined to think of a secular elite or non-theocratic management of power.

Stone Altar, Paquimé, sized 33.2 x height 67.8 x depth 12.1 cm. © Phototeca Nacional INAH, Mexico.

Charles Di Peso believed that this T-door-shaped altar functioned as a kind of cosmic portal to facilitate the passage of spirits from mythical regions of the cosmos that humans could not access. It could also symbolize a fundamental passage in the shamanic practice, the entering the “spirit world” by a transition of consciousness.

Mogollon by Wolf’s Robe aka Flute Man. Native American flute performer and educator, two-time Native American Music Award (NAMA) Nominee, performs on and teaches about Native American flutes, bringing both traditional music and original compositions to life.

Photo: © Phototeca Nacional INAH, Mexico.

Paquimé as an important trade center

Some settlement patterns and architectural aspects of Paquimé, including the T-shaped doorways, can be found in other prehistoric sites of Oasisamerica. The ruins look similar to neighboring ones near Gila and Salinas in New Mexico, as well as to other Puebloan architectures in the US Southwest.

Evidence of human sacrifice, the ritual use of trophy skulls and human bones, and the presence of platform mounds and ballcourts are convincing pieces of evidence of the religious influence of Mesoamerica on Paquimé.

As we saw, these data are interpreted differently by scholars. Something, however, is quite certain: Paquimé was an important commercial center that linked the Puebloans in the North to Mexicas (Aztecs) and Mayas in the South.

Thousands of surprising artifacts and luxury goods were unearthed by archaeologists. Many of them left scholars astonished as the stories they told them were deeply unexpected – artifacts always tell interesting stories, even more so in prehistoric and oral cultures (having no written literature or documents).

SHELLS

Paquimé guarded a treasure made up of 1.5 tons of marine, land, and freshwater shells, belonging to 70 species of bivalves, univalves, and scaphopods, including over 3.7 million perforated Nassarius sp. shell beads pieces. All the marine shells came from the Gulf of California coast on the Pacific Ocean. This means that the Paquiméans were used to purchase huge quantities of shells from the south-southwestern regions.

Why?

The scale of this trade bespeaks they were an important commodity.

For which reason?

Did Paquiméans use them as viable currency? Did they import them for domestic use only? Did Paquiméans export these pieces as well?

«It is unclear if shell objects were important for economic or ideological reasons» (Ancient Paquimé and the Casas Grandes World, see Bibliography).

The majority of the objects found in burials were shell ornaments and this suggests that Paquiméans gave them a ritual and a social function. We know also that the Paquiméans loved jewelry pieces and were used to wear bracelets, cuffs, earrings, necklaces, all made with shells and turquoises. However, some scholars hypothesize that they were not simply consumers but also active suppliers in the trade of shell objects.

A string of shell beads, Paquimé, 106 cm, Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico. © Phototeca Nacional INAH, Mexico.

TURQUOISE

Di Peso wrote he discovered 5,895 pieces of turquoise (worked and unworked), equal to 1225.8 grams. It’s not a remarkable quantity. The Paquiméans used this stone mainly for ceremonial use and only a few people could use it for personal adornment.

«Turquoise was used by pre-Columbian North Americans over the millennia and was a significant symbol of wealth and status. In some cases, it was transported over thousands of kilometers from its point of origin to the archaeological sites where the artifacts were recovered. In principle, the further a commodity was moved from its geological source, the more it was considered an exotic or luxury item» (Sharon Huls et al., Chasing Beauty, see Bibliography). In 2013 a team of US and Mexican researchers used a new approach to identify the geological provenance regions of the turquoise artifacts found in Paquimé, using the isotope ratios of hydrogen and copper and the microanalytical abilities of a secondary ion mass spectrometer (SIMS). The results showed that the turquoise artifacts from the Casas Grandes region came from mines in Southern Colorado and New Mexico (Oasisamerica), much farther than expected. The Paquiméans purchased turquoise from Puebloan long-distance traders.

Did they export it to Mesoamerica? Did they use it to exchange other goods?

There are no answers. Not yet, at least.

The shell of marine gastropod mollusks of the genus Strombus, modified to be used as a musical instrument, embellished with a mosaic of turquoises. Size: 9.7 x 14.6 x 0.5 cm. Found in Paquimé. Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico. © Phototeca Nacional INAH, Mexico.

The trumpet shell has a Mesoamerican origin and is tied to the ancient Mesoamerican musical tradition: its sound accompanied ritual ceremonies, religious festivities, military preparations, funeral rites, political acts, dances, etc.

Reconstruction of a Pendant found at Paquime (Casas Grandes) by Amerind Foundation.

COPPER BELLS

Archaeologists recovered over 664 copper artifacts (14.6 kg) during excavations at Paquimé: small bells or rattles, tinklers, wire, a ceremonial ax head, plaques, beads, and pendants. Most of them were used for ceremonial purposes; the tinklers likely for ritual dances, as shown by two following videos featuring Mexicas (Aztec) antique dances. There’s no evidence of copper smelting workshops: probably these items were not produced at Paquimé but imported from Western Mexican areas.

Pear-shaped copper rattle, 3.1 x 2.2. cm, found in Paquimé. Museo Nacional de Antropología, Mexico. © Phototeca Nacional INAH, Mexico.

MACAWS AND TURKEYS

«The people of Paquimé are justifiably famous for their husbandry of macaws and turkeys. What is perhaps less known is that these birds were raised for ritual sacrifice, not for food» (Discovering Paquimé, cit.).

Hundreds of turkeys were bred and raised in the Unit 13 block where several roosting pens were located. The remains of 220 turkeys were found intentionally buried, articulated, and headless, suggesting that they were used as sacrifices» (Ancient Paquimé and the Casas Grandes World, cit.).

As for the macaws, Di Peso made an extraordinary discovery: his team unearthed the rests of 322 scarlet macaws, 81 military macaws, and 100 macaws of undetermined species. Paquimé revealed at least 69 nesting pens of which 56 with macaw remains and feces, along with 125 stone ring doorways and 95 nesting door plugs. The analysis of macaw bones using stable light and heavy isotopes (delta 13 C and delta 18 O) indicate that many of the birds were born and raised at the site, but several others were imported from Mesoamerica (from south-eastern tropical Mexico, to be more precise). Their meat was not eaten: they were bred for their brilliant feathers and sacrificed during specific rituals. The high number of these birds and their nesting pens suggest that their breeding and probably their trade (or the trade of their feathers) were of great importance for the Paquimé economy as well. Macaws surely served a ceremonial function and, at the very same time, were a valuable good along the trade routes between Oasisamerica and Mesoamerica.

Left: Scarlet macaws

Right: Military macaw

54% of the 322 scarlet macaws were recovered from Unit 12, a residential block now better known as the House of Macaws.

Di Peso and his team found a large stone gong hanging from a beam in the House of Macaws, along with 17 drums. One of the most common musical instruments unearthed is a trumpet-type one, made with the shell of Pacific Ocean conches (particularly from the genus Strombus and Murex). Archaeologists found also bone whistles, flutes, and a special bone scraper, the Aztec omichicahuaxtli or omichicahuaztli, made with a human femur or an animal long bone. These finds, together with the presence of many copper bells and the use of spectacular birds’ feathers, could indicate the presence of ritual dances inspired by Mesoamerican ones, like those at the origin of today popular Concheros dance.

The following dances are inspired by Mexica (Aztec) tradition and are mixed with a modern sense of antique dress. However, they are interesting and can give us both a vague idea of what a ritual dance was, and something that the archaeological site of Paquimé is no longer able to give: a glimpse of the ancient, fierce sense of color of the Casas Grandes culture.

CASAS GRANDES – PAQUIMÉ CERAMICS

The Joint Casas Grandes Expedition at Paquimé recovered over 700,000 sherds and 900 restorable vessels and jars.

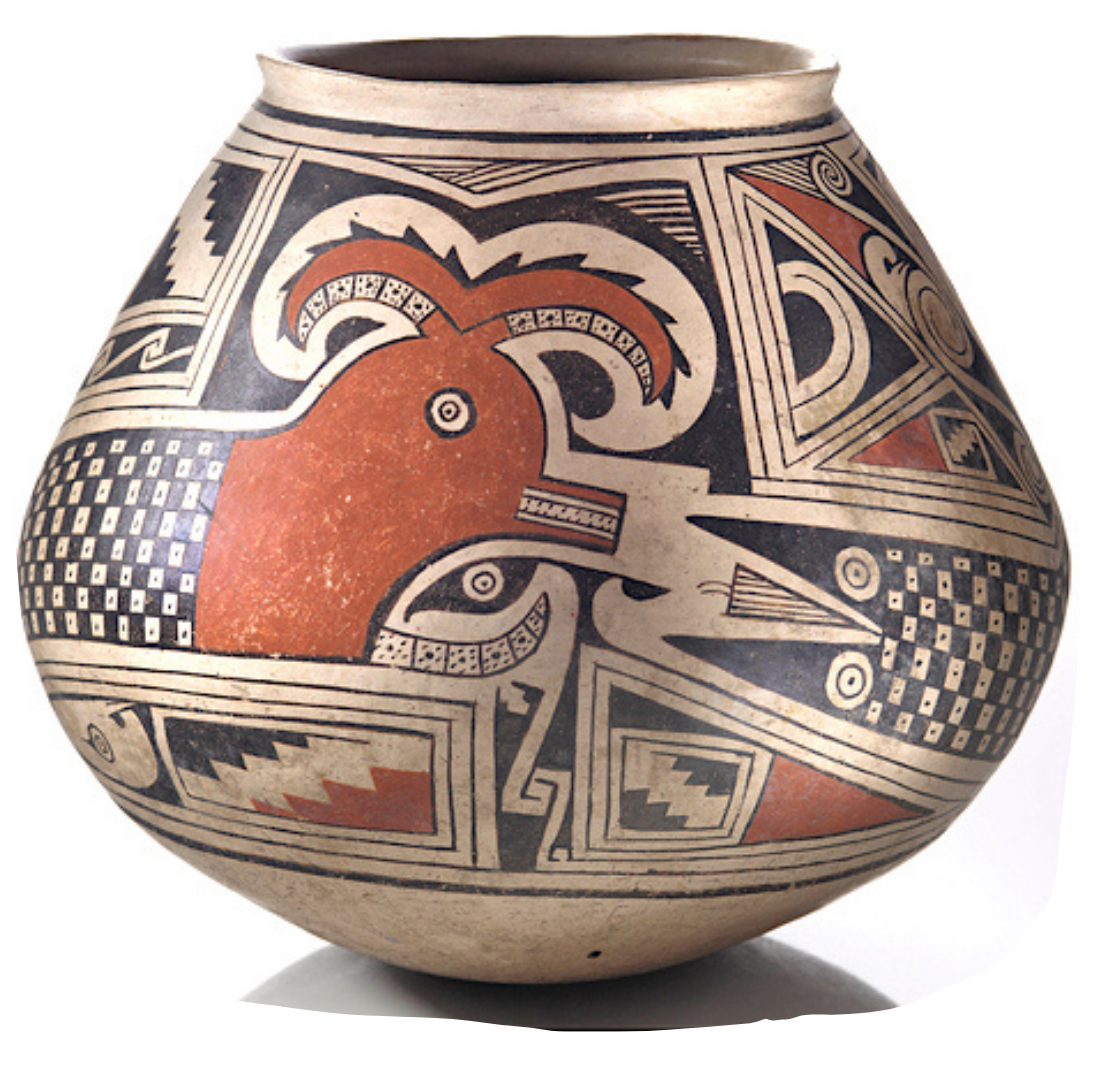

Of all the wonders found during multiple excavations, nothing struck the scholar’s attention and let them astonished as much as the Ramos Polychrome pottery: these ceramic pieces represent only a part of the finds (11.8% of all sherds), and were made during a short time in the Medio Period (between 1250 and 1400). However, they are probably the most representative pieces of the Casas Grandes culture and are simply superb. Charles Di Peso wrote: «The ceramic craft among the Casas Grandes people of the Medio Period was a highly developed art form» (1974:6, 77). It’s true: the Ramos Polychrome was the most accomplished artistic expression of the Paquiméans, their “written language”, and their luxury good par excellence. It was made both in the city of Paquimé and in its territory of influence, and it was successfully exported to the southern area that includes Teotihuacan and México-Tenochtitlán; to the northern Anasazi Mesa Verde in Colorado and also to Arizona and New Mexico; to the western Sonoran gulf, and to the eastern plains of Texas.

In 1993, two scholars, Woosley and Olinger, concluded that it does appear that Casas Grandes to some extent did control ceramic distribution throughout the region. Its potters, together with others from adjacent villages in the valley, may well be responsible for the bulk of Ramos Polychrome pottery unearthed elsewhere in northern Mexico.

The shards and the ollas found by the young Juan Quezada during his solitary roaming on the hills around Mata Ortiz were obviously of this kind.

The Ramos Polychrome is a red and black painted ceramics on a light-colored paste or slip, with some special design features and an unmistakable trait: the red solids are outlined with fine black lines. These pots were made without a potter’s wheel and without a kiln, by using only fine local clays, masterly molded to create perfect shapes with very thin walls.

Let’s see some masterpieces of this style, generally reserved to the Paquimé elite, and used as funerary urns, ceremonial jars, and shamanic vessels.

Casas Grandes, Ramos polychrome single olla with horned serpent motif, 1280/1450, 21.6 × 24.1 cm (8 1/2 × 9 1/2 in.), Art Institute of Chicago, IL, US (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license).

Here’s a single jar that you can see on both sides (look at the tiny chip on the rim, on the right in the left picture, and on the left in the right picture). From its surface, two plumed/horned serpents pop out with their red head. Their bodies snake along the olla, and you can see the tail of one of them in front of the other’s head.

As we saw, the plumed/horned serpent was a Mesoamerican sacred symbol of supernatural power, spread also in Oasisamerica. Some scholars, like Di Peso, believe that under this form, the Paquiméans worshipped the Mexica (Aztec) Quetzalcóatl. Others point to the serpent’s forked tail, an iconographic element typical of the North American Southwest cultures, where the feathered serpent was symbolic of water and fertility. In any case, this jar was probably a ceremonial olla.

Look at the left picture: under the cosmic serpent, there’s a bird and, at its left, a stylized macaw that you can see better on the other side of the olla, in the right picture (just below the red head). This jar, therefore, depicts the mysterious combination of three symbols of ritual relevance: plumed/horned serpent, macaw, and bird, maybe aspects or guises of the same supernatural entity or deity.

The serpent body is filled with two typical patterns: the negative circle with a dot inside and the dotted checkerboard pattern. These are not simply decorative motifs, but sacred symbols whose meanings are driving scholars slightly crazy. The dotted checkerboard has been interpreted as a depiction of corn grains and is found also in the iconography of the Hopi Indians in Oasisamerica. As to the negative circle with a black dot inside, the so-called “bull’s eye”, there are many interpretations. For some scholars, it may represent peyote buds, which were harvested around the Casas Grandes valley and ingested for their hallucinogenic effects. Mathiowetz (2011) argues that the sashes composed of running bands of dotted circles represent the trajectory of the sun, while for Christine S. VanPool (in The Shaman-Priests, see Bibliography), they are tied to the imagery of serpents (not necessarily plumed), commonly conceived in Mesoamerica and Oasisamerica as “vehicles of rebirth and transformation”.

Here’s another masterpiece: a magnificent olla with the plumed/horned serpent design and some complex symbols.

Casa Grandes Ramos polychrome jar with feathered serpent design, Paquimé – Casas Grandes, 1150/1450, 28 × 30 cm, The National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution group, US.

Below, two ollas both representing pacamayas, macaws: the jar on the left depicts a double macaw image with rotational symmetry, while the jar on the right shows the stylized design of the macaws (find its eye, and you’ll see it). Among the many motifs of the latter, there’s also the double-spiral that some scholars connect to wind, flight, air, and movement.

Two ollas from Paquimé – Casas Grandes, 1150/1450, 20 × 24 cm (left jar), The National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution group, US.

Here’s another vase seen from two sides, with two plumed/horned serpents snaking on its surface. You can see both red heads, one with a small bird on top and the other with a symbol that calls to mind the sun. The macaw is depicted with some stylized symbols: the feathers and the P-shaped sign. Does this olla tell us a cosmogonic myth? We do not know. Not yet, at least.

Ramos Polychrome jar with double-headed feathered serpent motif, Casas Grandes Culture, 1200/1400, 21 × 21 cm. © ROM Collections, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada.

Richard F. Townsend, curator of the Art Institute of Chicago since 1982, wrote that «Casas Grandes vessels rank high among those of the ancient Americas by virtue of their graphic inventiveness and distinctive iconography», and highlighted the mastery with which Paquimé potters combined animal, human and abstract imagery into complex, interlocking, geometrical designs. «No other ceramic art of the pre-Columbian world so masterfully succeeded in achieving a cohesive visual integration of such surprisingly varied components».

A single picture cannot render the complexity, the beauty, the dynamism of these ceramic pieces. The whole new visual syntax so typical of the Medio Period Ramos Polychrome jars and vessels can be caught only if you hold a piece in your hand and turn it around.

The piece below is a Ramos Polychrome jar with a macaw-man motif. For the curators of the Dallas Museum of Art, the jar portrays «a running bird-man who may represent a local mythology». For me, he’s a dancer, namely a man performing a ritual dance wearing a headdress adorned with macaw feathers (have you seen the videos of the Mexica/Aztec traditional dances above?).

Ramos Polychrome jar, Mogollon – Casas Grandes, 1280–1450, 15.24 x 18.89 x 18.89 cm. Image courtesy Dallas Museum of Art, TX (US).

Fortunately, the Dallas Museum of Art offers us a precious tool to catch the whole complexity of this jar: a sequence of pictures that show it from different points of view. This sequence can give you a (pale) idea of what Richard F. Townsend was speaking about.

Now, imagine turning this jar (no matter if to the right or left): the macaw-man or the ritual dancer leaves room for the head of a plumed/horned serpent whose body zig zags the surface and gives way to a hybrid figure who is no longer a man (with legs that are no longer human) but is not yet a full macaw. The dancer might be a shaman leaving the natural world and beginning a metamorphosis into a supernatural entity or deity. The hybrid figure leaves room for the head of a second plumed/horned serpent whose long geometrical body embraces the man/dancer of the beginning. Let’s see the jar from two new points of view.

The right picture shows the opening of the olla and the circularity of its painting. The left picture shows the rounded bottom (so rounded that it cannot stand on a surface without support), unusually painted. Among the bottom designs, we can clearly see a bird of graphic perfection. «That the shamans are depicted with birds is not surprising: (…) birds are common tutelary animals among New World shamans (…). The birds and the horned/plumed serpents may be tutelary spirits who guide the shaman through his journey and help him bring back critical information or perform a task while in the spirit world» (Christine S. VanPool, The Shaman-Priests, cit.). Therefore, this jar might depict the circular and dangerous shamanic journey that starts probably with a ritual bloody sacrifice (the red in front of the macaw man/dancer and the red head of the plumed serpent) and safely ends thanks to the protection offered by the bird-shaped entity.

Every Ramos Polychrome jar tells us a story we are no more or not yet able to listen to. It’s very hard work to come up with a basic understanding of what a symbol may mean together with other symbols, inside a definite composition. This task is even harder with jars showing abstract designs that offer no visual foothold. The following is one of the kind and shows both an incredible graphic perfection and an extraordinary sense of pictorial composition. Its beauty, unlike its pictorial language, needs no explanation.

Ramos Polychrome jar with double-P and interlocking scroll motif, Casas Grandes Culture, 1200/1400, 21.1 x 22.7 cm. © ROM Collections, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada.

I wrote that the P-sign is commonly interpreted as a stylized symbol of the macaw. However, the double-P or “club” motif may be a reference to the duality common in Casas Grandes cosmology and symbolism. Other scholars suggest that it may be a reference to the plumed serpent, conceived as a deity with the power to control rainfall. The multiplicity of interpretations is, of course, an indication of the hard work of reconstructing the basic storytelling elements of the Casas Grandes oral tradition.

LEFT: Ramos Polychrome jar, Casas Grandes Culture, 1280/1450, 25.4 × 24.13 × 24.13 cm. Image courtesy Dallas Museum of Art, TX (US). This olla features the double-macaw motif believed to represent this bird’s ritual beheading.

RIGHT: Jar, Paquimé – Casas Grandes, 1150/1450, The National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution group (US).

The jars above are two amazing specimens of exquisite workmanship: the brush stroke is clean and perfect, free from smudges and uncertainties; the composition is well balanced; the overall design and the ceramic quality are excellent. They are not not unpretentious homemade pieces: they had to be skillfully hand-crafted by a class of professional potters. All of the archaeological data show the Paquiméan community as a complex, well-organized society with a remarkable division of labor, led by a political elite. Some scholars believe it was a theocratic society, ruled by priests/shamans, but this hypothesis is not unanimously accepted.

Thanks to their artistic mastery, the Paquiméan potters not only told stories creating a new, complex pictorial syntax but stretched the expressive potential of ceramics to its limits. The pottery pieces are three-dimensional material objects but the painting on their surface has the limits of a bi-dimensional image. Well, the Paquiméans turned ceramics into a multi-dimensional art.

LEFT: Jar, Paquimé – Casas Grandes, 1150/1450, The National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution group, US.

RIGHT: Jar, Paquimé – Casas Grandes, Arizona State Museum, US.

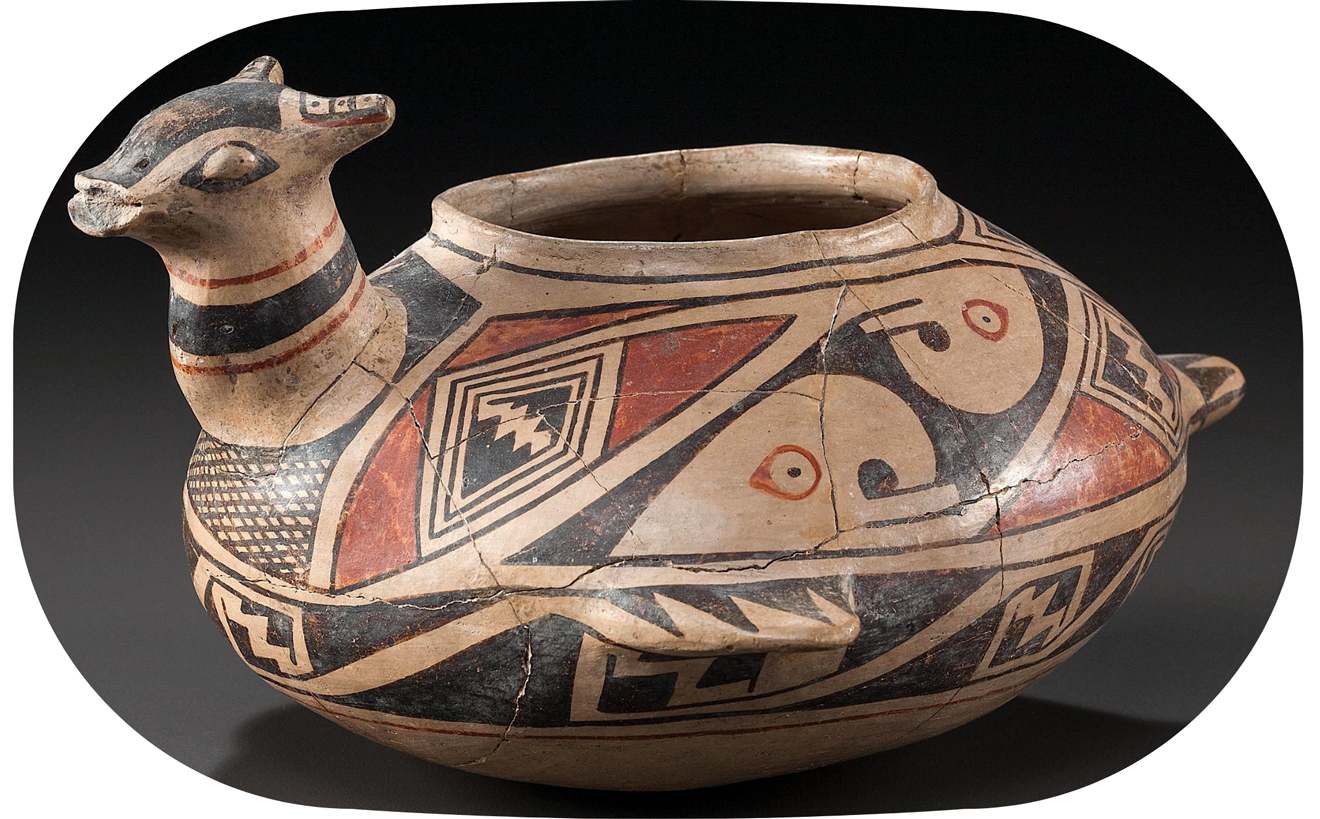

In these two ollas, the coiled snakes seem to come alive by gushing out of the surface. Archaeologists call them “repoussé snakes” as they are made by working the inner wall of the pot to create a design in low relief on the outer and by adding clay applications on the surface. The zoomorphic vessel below goes even further.

Vessel in the form of an owl, 17 x 14 cm, Paquimé, 1150/1450, The National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution group, US.

This vessel is shaped like an owl, an animal that, for some scholars, may have been associated with warfare rituals. This kind of jar is called an “effigy jar of the hooded type”: its main feature is the head or “hood” that extends above the upper rim, molded like an animal effigy by using clay applications.

The body of this vessel shows a famous motif called in Spanish la greca escalonada, the stepped fret in opposing pairs, probably the most frequently occurring motifs in the Casas Grandes tradition, together with the stylized macaw. Nevertheless, its meaning is all but clear.

Braniff Cornejo wrote that it was born in Mesoamerica and became common throughout Oasisamerica, especially among the Anasazi. She believes it’s linked to the cultivated fields or probably to the rain.

Other scholars, as Antonio Vilanova (2003), highlight its architectural origin: the multi-story houses of Paquimé were not built like our current buildings; each upper floor occupied only a portion of the lower one; therefore, the whole building had a stepped structure. Stepped were also the ramps to the several sacred earthen mounds. Mathiowetz (2011) believes that the stepped motif is a “spirit path”, representing the road traveled on by gods, spirits, and probably shamans.

The following zoomorphic jar (olla zoomorfa) was finely shaped like a desert mule deer and shows both the macaw stylized motif (look for the eyes!) and an all-black motif that resembles the stepped fret, but is however slightly different: the barbed motif (the stepped one is depicted with 90-degree angles, the barbed one with smaller V-shaped angles).

Effigy vessel, Ramos Polychrome, Casas Grandes, 1200-1450, photo by Bob Sinclair, licensed under the Creative Common Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license (CC BY-NC 2.0).

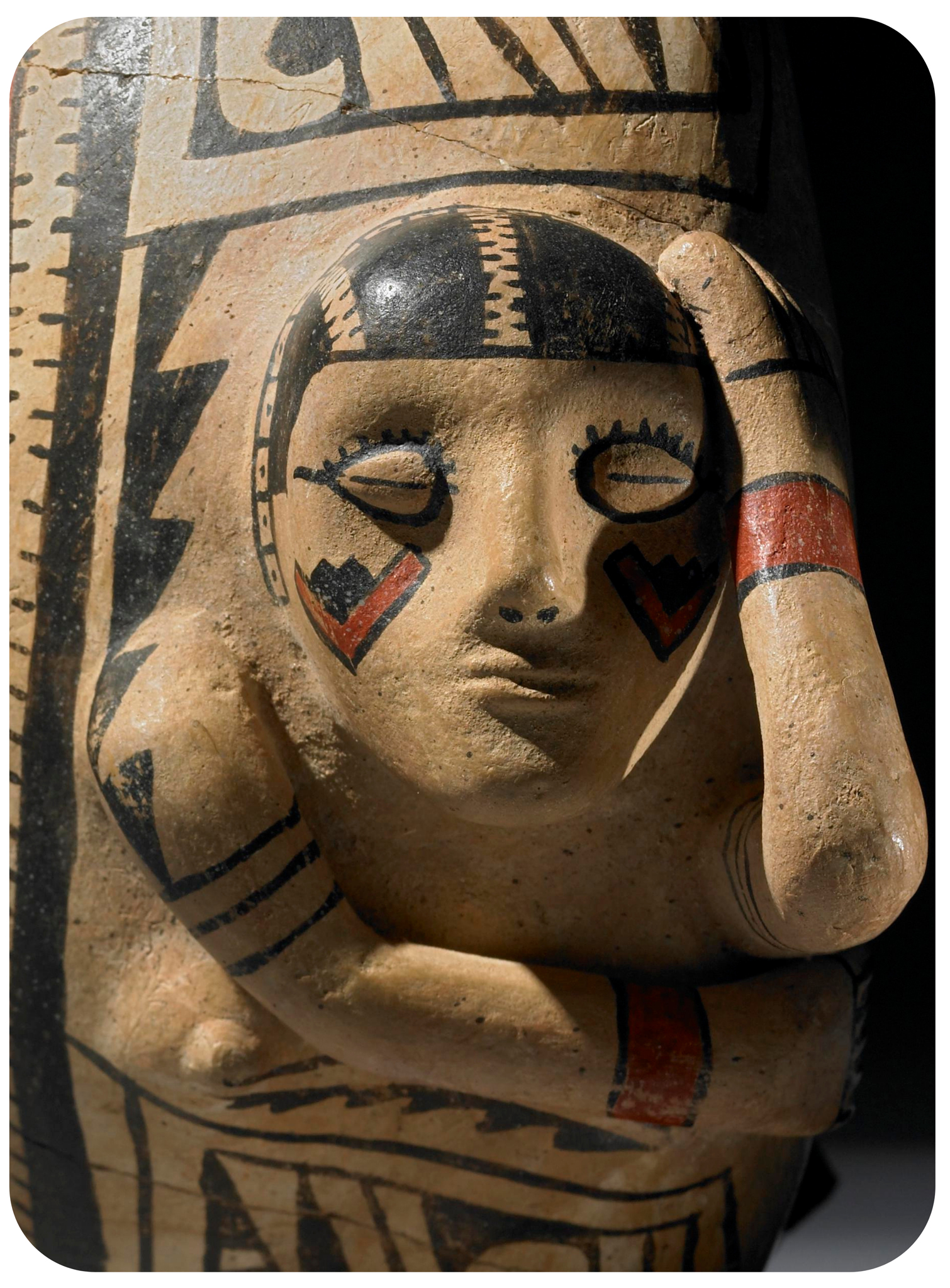

The Paquiméan ceramics is famous for its human effigy vessels and anthropomorphic jars in the Ramos Polychrome style. You’ll see above two amazing face-shaped jars.

LEFT: Human-head pot, Casas Grandes, Archaeology/Ethnology Gallery, The Centennial Museum, the University of Texas at El Paso, TX (US).

RIGHT: Ramos Polychrome jar human effigy jar with macaw motifs on the backside, Casas Grandes Culture, 1200/1400, 10.5 x 12.3 cm. © ROM Collections, Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada.

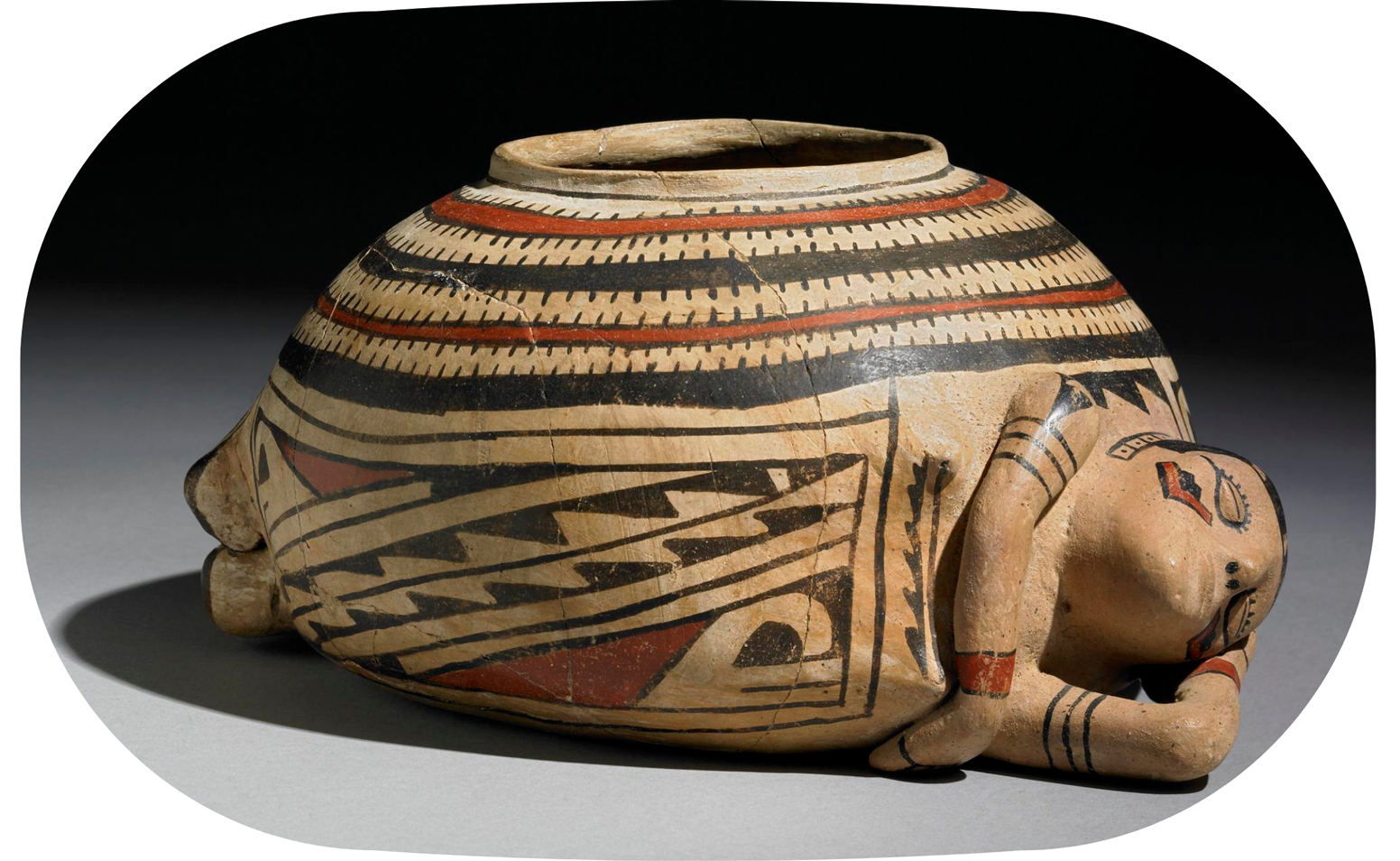

Some of the anthropomorphic ollas are masterpieces of incredible beauty, like this jar below, currently at The British Museum of London.

ALL THREE PICTURES: Bowl in the form of a reclining female, Casas Grandes, 1100-1400, found in Playas Valley, New Mexico, height 12.60 cm.

© The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

Under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

«The accomplished execution and intriguing subject of this vessel beg close attention. The supine pose and closed eyes suggest that she has fallen asleep with legs drawn up, head nestling in a crooked left arm, and with her right arm resting across her chest. She wears a black armband and red wristbands, and the chevron painted on her cheeks may be an identifying clan emblem. Her carefully groomed and tightly tonsured hair seems to be held in place at the back by a segmented headband. The rectangular design on her front probably represents the woven pattern displayed on her skirt. It is based on the principle of rotational symmetry, contrapposing identical motifs around a central, diagonal axis composed of two parallel rows of zigzags. The overall effect suggests the channeling and controlling of charged energies to productive ends» (by the curators of The British Museum).

Given both the woman’s position (look at her right arm, portrayed in a gesture every mom-to-be easily recognizes), and given some other similar pieces, like the one below (look at the woman’s arms, once again!), we can infer it probably depicts a pregnant woman, ready to give birth. The jar, therefore, could be a ritual object used in a fertility ceremony or a propitiatory rite. It could be part of the offerings to bring about a pregnancy. As we saw before, the average life expectancy for the adults in Paquimé was quite low (most of the Paquiméans died before the age of 35). Moreover, the nutritional insufficiency or malnutrition, shown by the frequent dental problems, probably delayed the menarcheal age in many girls. For the Paquimé relatively small farming community, soil and female fertility was a survival issue.

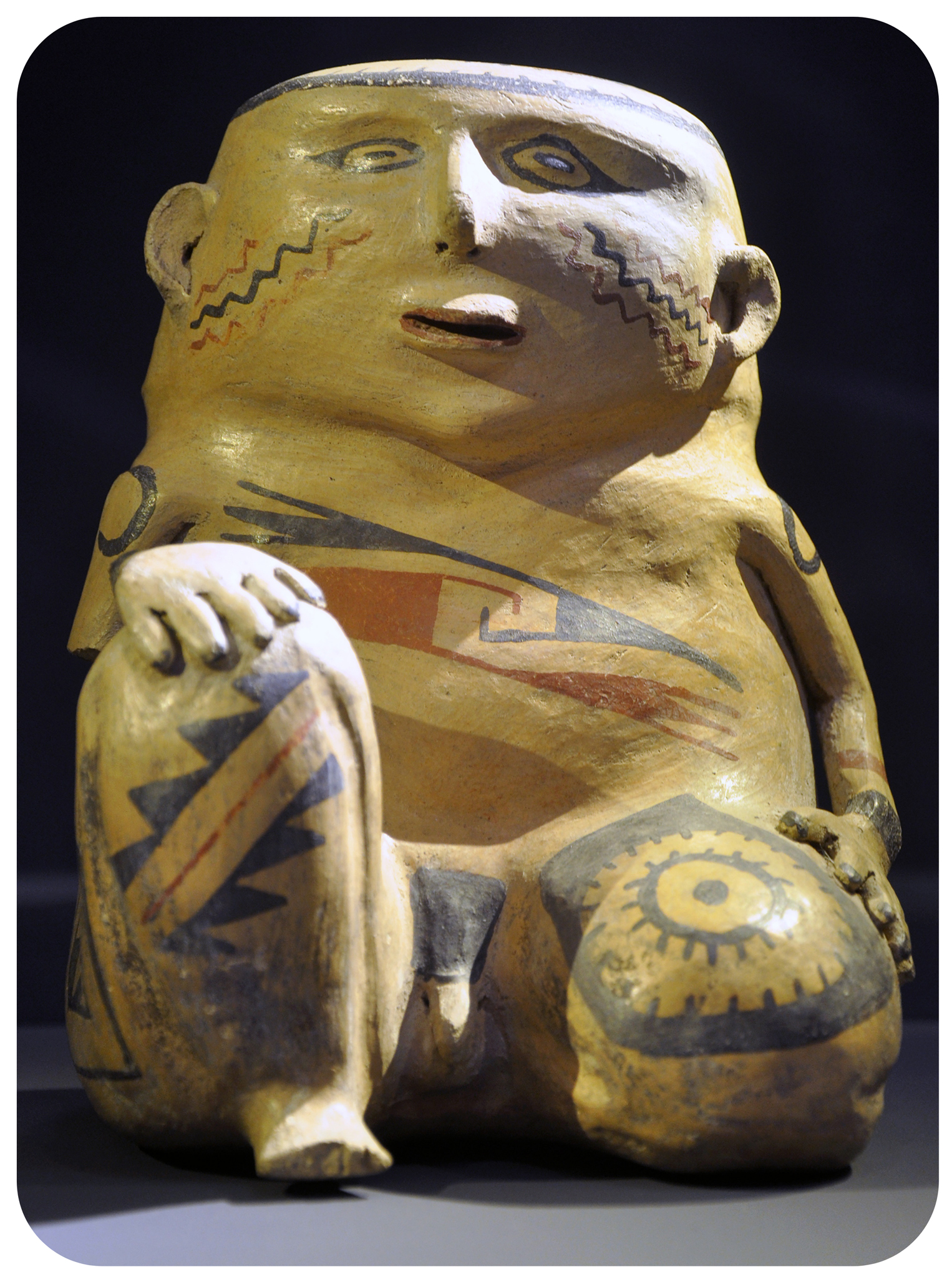

Vessel in the form of a pregnant woman, Paquimé, 1100/1300, The National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution group, US.

The two following pieces are female effigy vessels showing a special emphasis on the sex organs (both primary and secondary sexual characteristics). That one on the left represents potential fertility, a sort of invocation, a cry, a hope, while that one on the right shows actualized maternity.

RIGHT: Large-sized jar in the form of a woman, Paquimé, 1100/1300, 20 x 24 x 25.5 cm, The National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution group, US.

LEFT: Anthropomorphic polychrome effigy vessel of a woman with child, Paquimé – Casas Grandes, 1250/1450, 21.59 x 16.51 x 18.542 cm, Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), CA, US.

The women are usually depicted in a stride sitting position, namely with their legs straight out, holding a baby or a bowl, sometimes with an arm on the stomach; their feet are usually naked. These postures and the presence of some motifs, like that of the pajarito reclinado, a fledgling always depicted horizontally to mimic the fetus position, are linked to pregnancy, fertility, maternity (I do not believe it a tutelary bird painted on the chest of women involved with shamanic rituals, as VanPool & VanPool do).

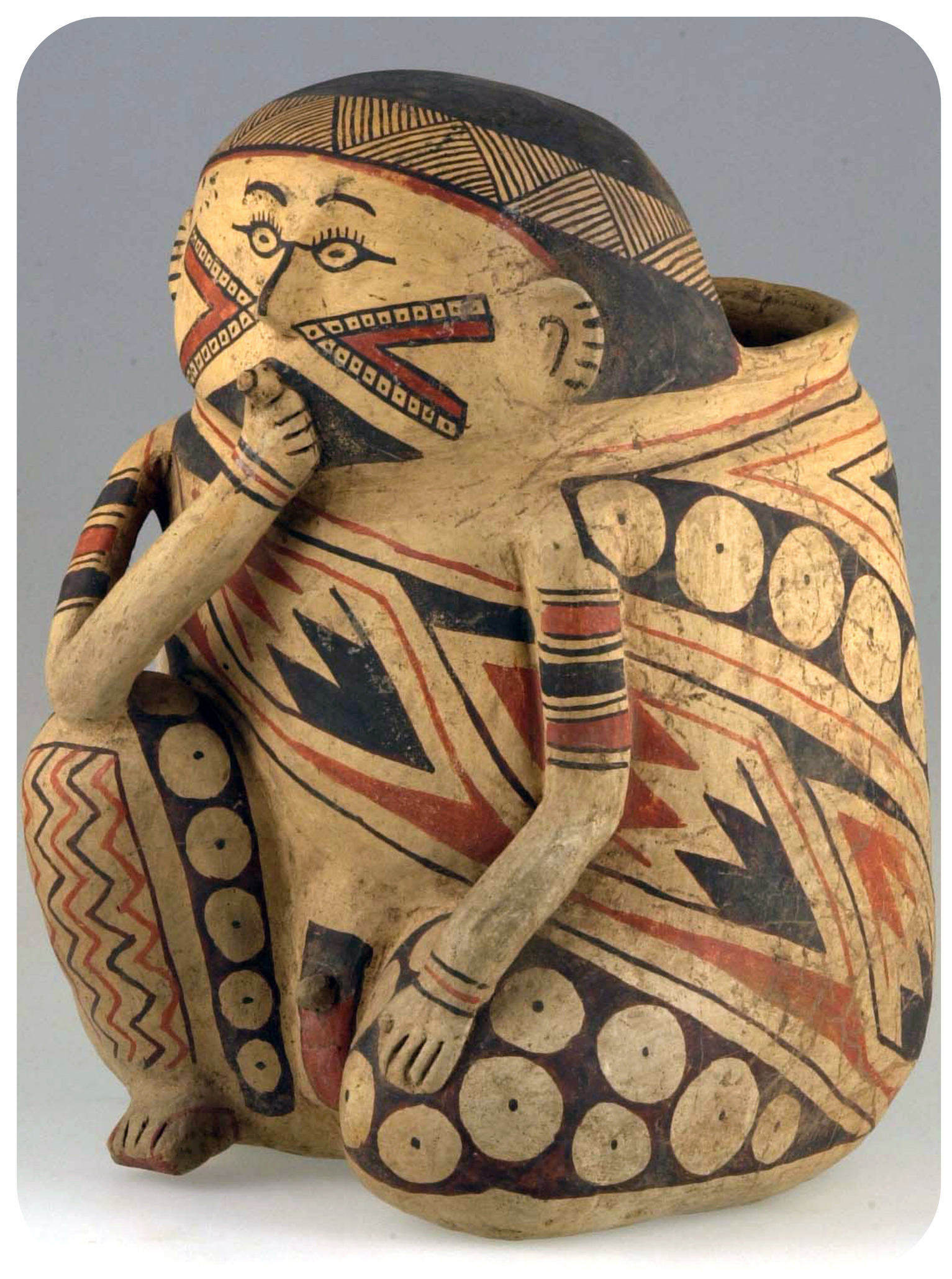

The men, on the contrary, are usually depicted seated with both of their knees drawn up to their chest or with just one leg drawn up and the other leg tucked underneath their body. Their genitalia are always emphasized for a symbolic reason and their feet rarely naked: most male figurines wear very simple sandals (look at the thin red straps near the outer sides of the big toe and the little finger). Sometimes they smoke a pipe, similar to those found among the ruins of Paquimé (smoking had probably a ritual meaning).

Ramos Polychrome effigy vessel, Casas Grandes Culture, 1200/1450, Musées Royaux d’Art et d’Histoire (MRAH), Parc du Cinquantenaire, Bruxelles (Belgium).

Under under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication.

Effigy Jar (the Smoker), Casas Grandes, Chihuahua, ca. 1200, height 30 cm, Anthropology Collection, by courtesy of the © Natural History Museum, Los Angeles County, CA (US).

Christine and Todd VanPool, together with Lauren Downs (2017), have been studying extensively the human effigy vessel decorations under different perspectives. They discovered that these paintings can reveal to us something of the real Paquiméans.

All figurines wear necklaces, bracelets, and earrings; this fact, together with the multiple finds of shell-based jewels among the ruins, confirms the Paquiméans’s love for body adornment.

They wear loose, straight hair, with a chin-length cut, kept in place on their foreheads by a decorated headband.

Both men and women show face markings, especially on cheeks and chin, unlikely tattoos, more probably color paints indicating a clan or a social group (six different cosmetic colors for body paint were found in Paquimé).

Probably both sexes wore fabric kilts, but only some male effigies seem to wear an important status symbol: the tilmatli, a shoulder blanket spread throughout Mesoamerica and Oasisamerica.

«In general, the males are depicted with a more elaborate dress, perhaps reflecting a greater emphasis on male status and activity, relative to females» (Christine S. VanPool, Todd L. VanPool, and Lauren W. Downs, Dressing the Person: Clothing and Identity in the Casas Grandes World, see Bibliography).

What were these vessels used for? They seem to be ceremonially relevant objects. The effigy vessels do not portray common people in their habitual activities but women and men in ritual and symbolic practices. Men, in particular, might be involved in shamanic journeys, but there’s no consensus about that. In any case, these vessels were not only symbolically significant but may have played an important role during some ceremonies or ritual sacrifices as credited to contain an active spiritual power.

In more general terms, we can say that the entire ceramic art played a pivotal role in the life of the Casas Grandes culture. VanPool and VanPool (2018) suggested that Ramos Polychrome may have been a religiously significant token distributed by the Paquimé elites across the region. For Richard F. Townsend (2005), the entire ceramic art of Casas Grandes created a complex “visual language” used by the elites to legitimize their political leadership and nurture their religious authority.

THE MYSTERIOUS END OF CASAS GRANDES – PAQUIMÉ

After a period of decay of about half a century, the city of Paquimé was mysteriously abandoned in the 1440s-50s. The whole Casas Grandes culture collapsed in the very same period (between 1400 and 1450).

What happened?

Two scholars, David A. Phillips and Eduardo Gamboa, wrote in 2015: «Thus far, there is no consensus about the actual reason for the abandonment of that site and the disappearance (then or later) of the culture» (Ancient Paquimé and the Casas Grandes World, cit.).

Many scholars invoke outer factors: geopolitical turmoils, war, drought or irrigation-related problems, local resource depletion, a natural disaster as an earthquake; others turn their attention to inner factors such as social dynamics, rebellion against the political elite/theocratic power, etc. Some consider the finale of Paquimé a sudden and violent event (caused for example by the unexpected attack of enemy warriors), others prefer to point out the many signs of decay that preceded the end.

At the moment, there are many hypotheses but no certainty. The end of Paquimé is still a mystery.

Where did the survivors go?

Some say west, finding refuge on the Sierra mountains. Others say north, to mingle with Puebloans. In the 16th century, the Spanish conquistadores were told by the local nomads that the Paquiméans were attacked, had to abandon the city, and moved to the north, to a place a six-day journey distant. Well, this is obviously a testimony that is little worth: neither the Spaniards nor the local Indians shared a mean of communication better than vague and ambiguous gestures.

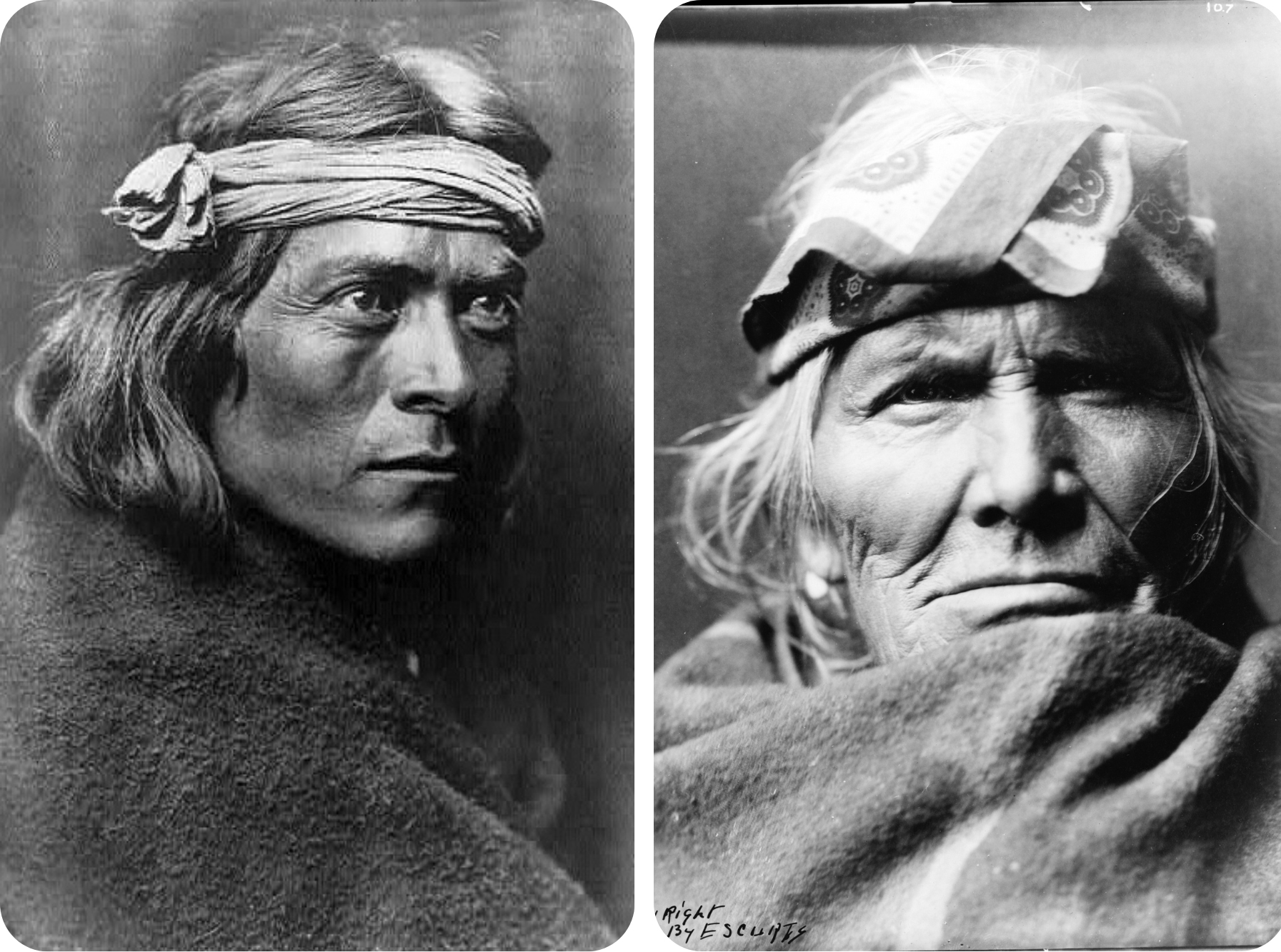

Genetic research will indicate in the future the potential direct or indirect “descendants” of the Paquiméans. In the meantime, some scholars have advanced the hypothesis that some Indians might be related to the ancient inhabitants of Paquimé: the Zuni, the Hopi, and the Acoma Indians living in the Southwest of the United States, and the Tarahumara or Raràmuri Indians, settled in the Sierra mountains between Chihuahua and Sonora, in Mexico.

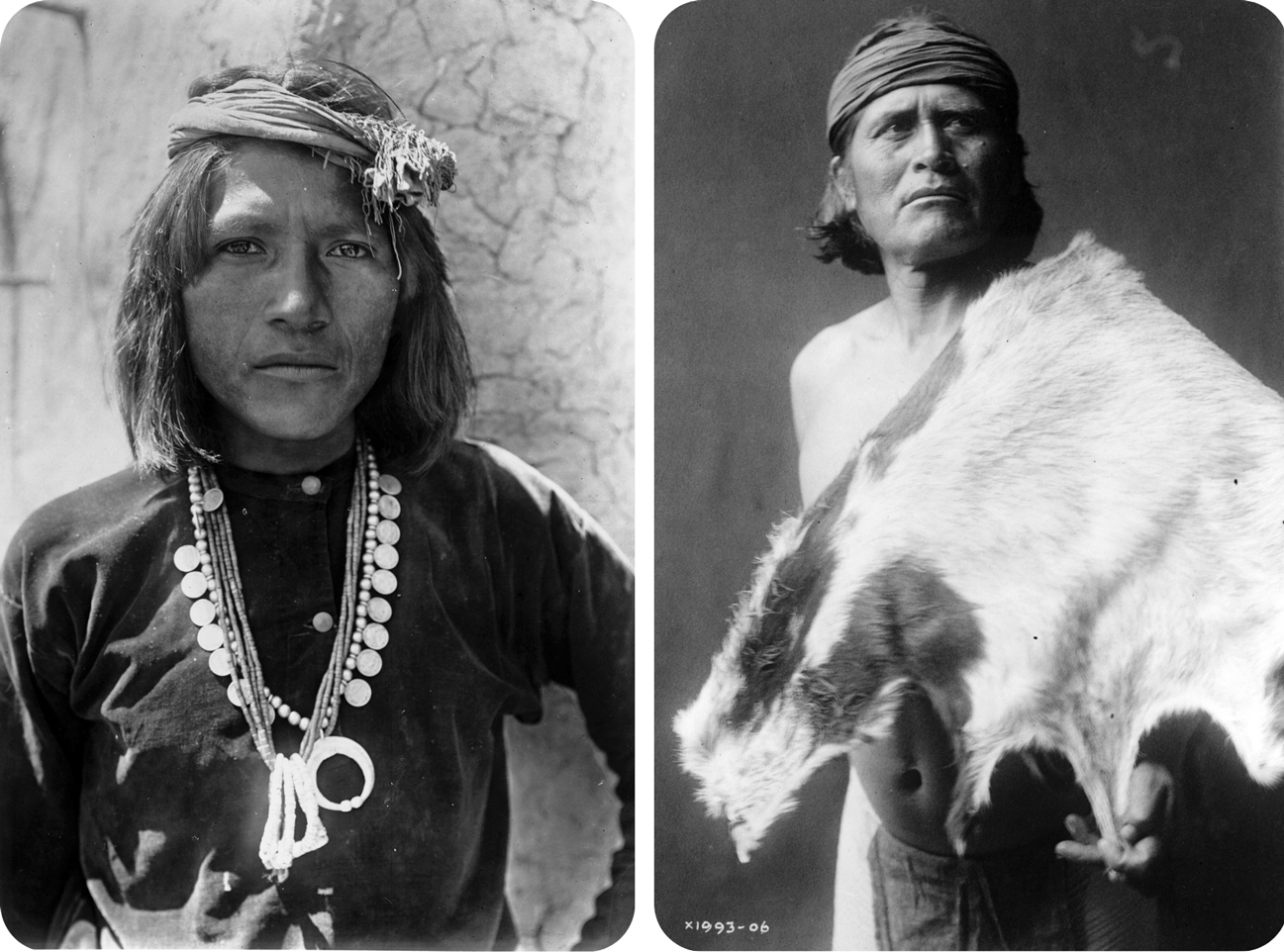

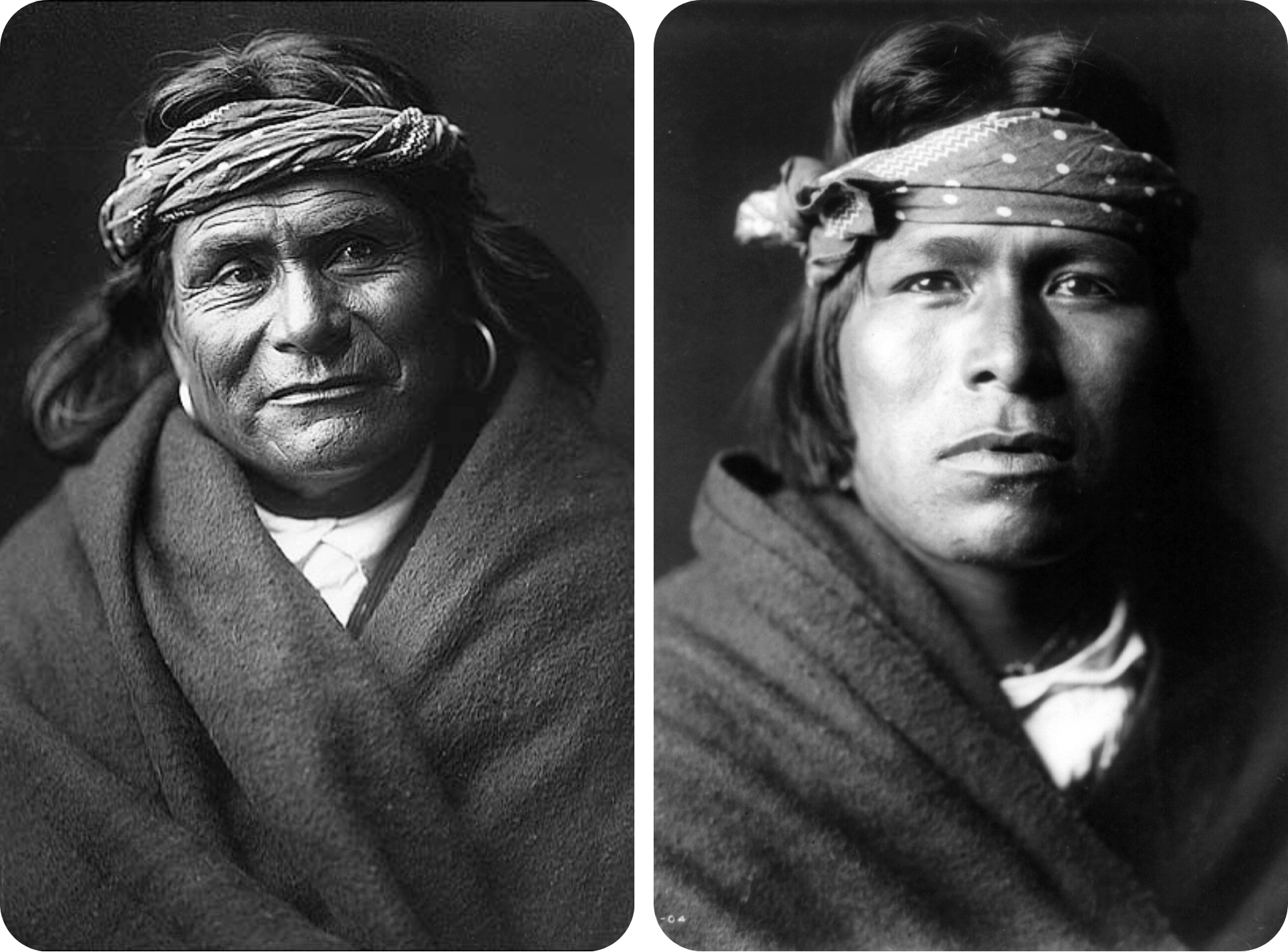

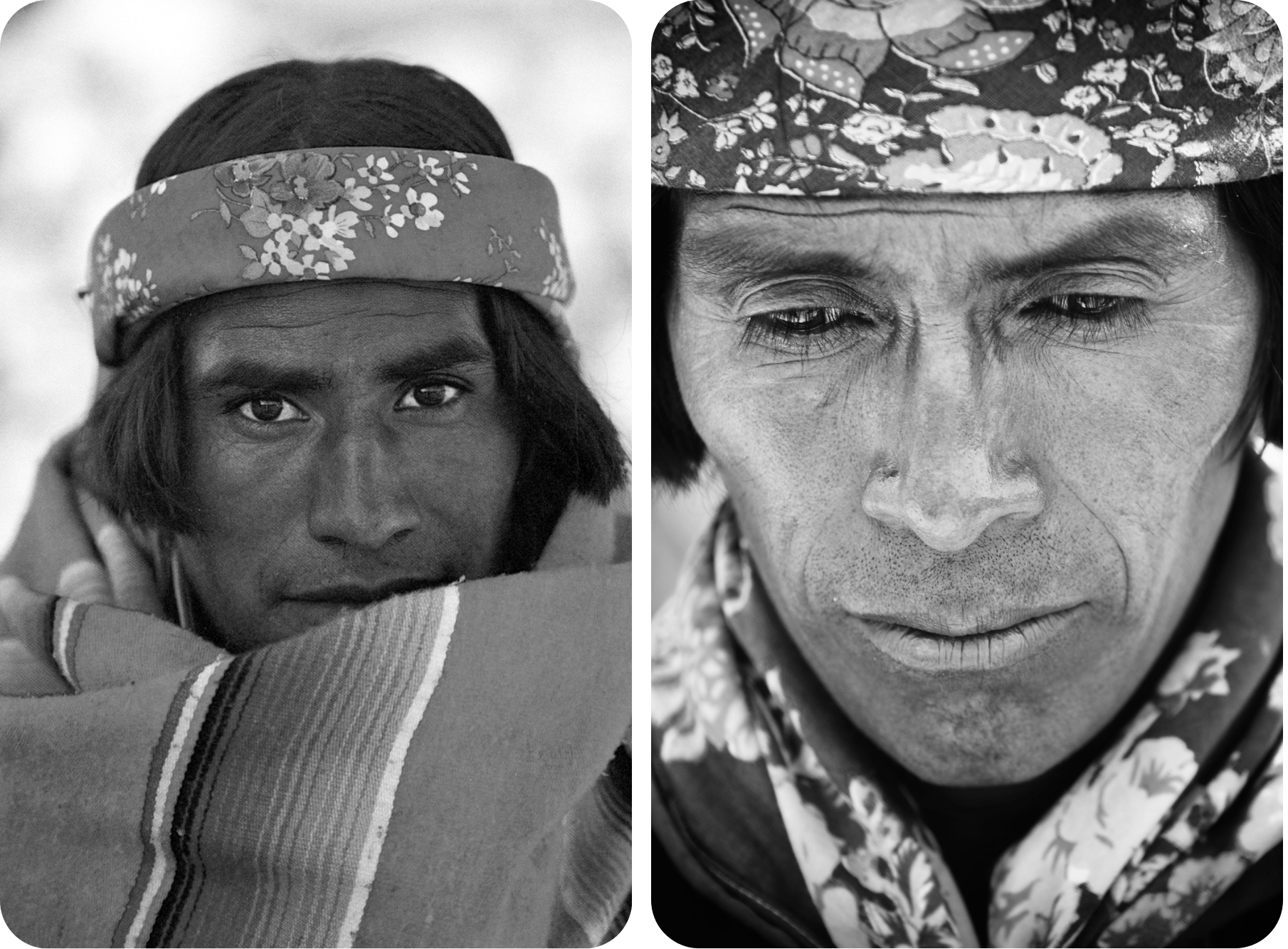

In the following pictures you’ll see some SW/NW Indians wearing garments and accessories typical of the Paquiméans, like the tilmatli shoulder blanket and the headbands: a thousand years have passed but these garments are so rooted in their cultural tradition to be still alive. And their hair cut hasn’t changed much over many centuries…

Sonoran Twilight by R. Carlos Nakai, Will Clipman, William Eaton. Raymond Carlos Nakai, born in Arizona in 1946, is a famous Native American flutist of Navajo/Ute heritage. William Eaton is the director of the Roberto-Venn School of Luthiery in Arizona. Will Clipman is an awarded Native American percussionist and performing artist.

LEFT: A Zuni governor, c. 1925, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

RIGHT: Portrait of Si Wa Wata Wa, Zuni Indians, c. 1903, photo by Edward S. Curtis, Library of Congress.

The Zuni are Puebloans currently living in in western New Mexico (US), in the reservation called Pueblo of Zuni, crossed by the Zuni River. It is thought that the Ancestral Zuni people have inhabited and cultivated these areas since the last millennium B.C. Zuni people were famous and are still praised for their refined traditional pottery.

LEFT: Portrait of a Hopi Indian boy, c. 1900, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

RIGHT: Nato, the Hopi goat-man, c. 1906, photo by Edward S. Curtis, US Library of Congress.

The Hopi are Pueblo people and make up a Native American sovereign nation living in the Hopi Reservation in northeastern Arizona and speaking an Uto-Aztecan language. They descend from the Ancestral Piebloans and lived in the Mogollon Rim. Their past and contemporary pottery, especially after the works by Nampeyo (1859/1942), a Hopi-Tewa artist, is considered among the finest in the world.

LEFT: An Acoma man, c. 1904, photo by Edward S. Curtis, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, US.

RIGHT: An Acoma man, c. 1905, photo by Edward S. Curtis, US Library of Congress.

The Acoma people, likely descendants of the Mogollon, live in two- and three-story adobe buildings on the reservation lands on a mesa near Albuquerque, in New Mexico. Their past and current polychrome pottery is considered a notable form of art.

LEFT: A Tarahumara young man, Chihuahua, Mexico, second half of the 20th century.

RIGHT: Portrait of a Tarahumara man in Guachochi, Chihuahua, 2009, photo by Marcos Ferro.

The Tarahumara people, who call themselves Raràmuri, are a Native American people living in small pueblos on the high slopes and canyons of the Sierra Madre Occidental in Chihuahua, Mexico. They speak a language of the Uto-Aztecan family and are considered descendants of the Mogollon people.

Jorge Drexler – Movimiento, 2017

Jorge Abner Drexler Prada (1964) is a Uruguayan musician, actor and, last but not least, an otolaryngologist. He’s the son of a German Jew, fled to Uruguay with his family at the age of four to escape the Holocaust.

I love this song: here’s you’ll find the lyric and its English translation: Lyrics and Translation – Movimiento – Jorge Drexler.

I love this video as well. It was shot on the Sierra Tarahumara, in Chihuahua, and shows it in its full and harsh beauty.

The Rarámuri or Tarahumara are well-konwn to be “los de los pies ligeros”, “those who run fast”: they’re powerful runners and developed a tradition of long-distance running up to 200 miles (320 km) in a single session. Lorena Ramírez at only 22 years old won the Ultramaratón de Cañones de Guachochi (100 km) in July 2017. She runs wearing plastic low-cost sandals and a traditional long dress she made and sewed herself.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?