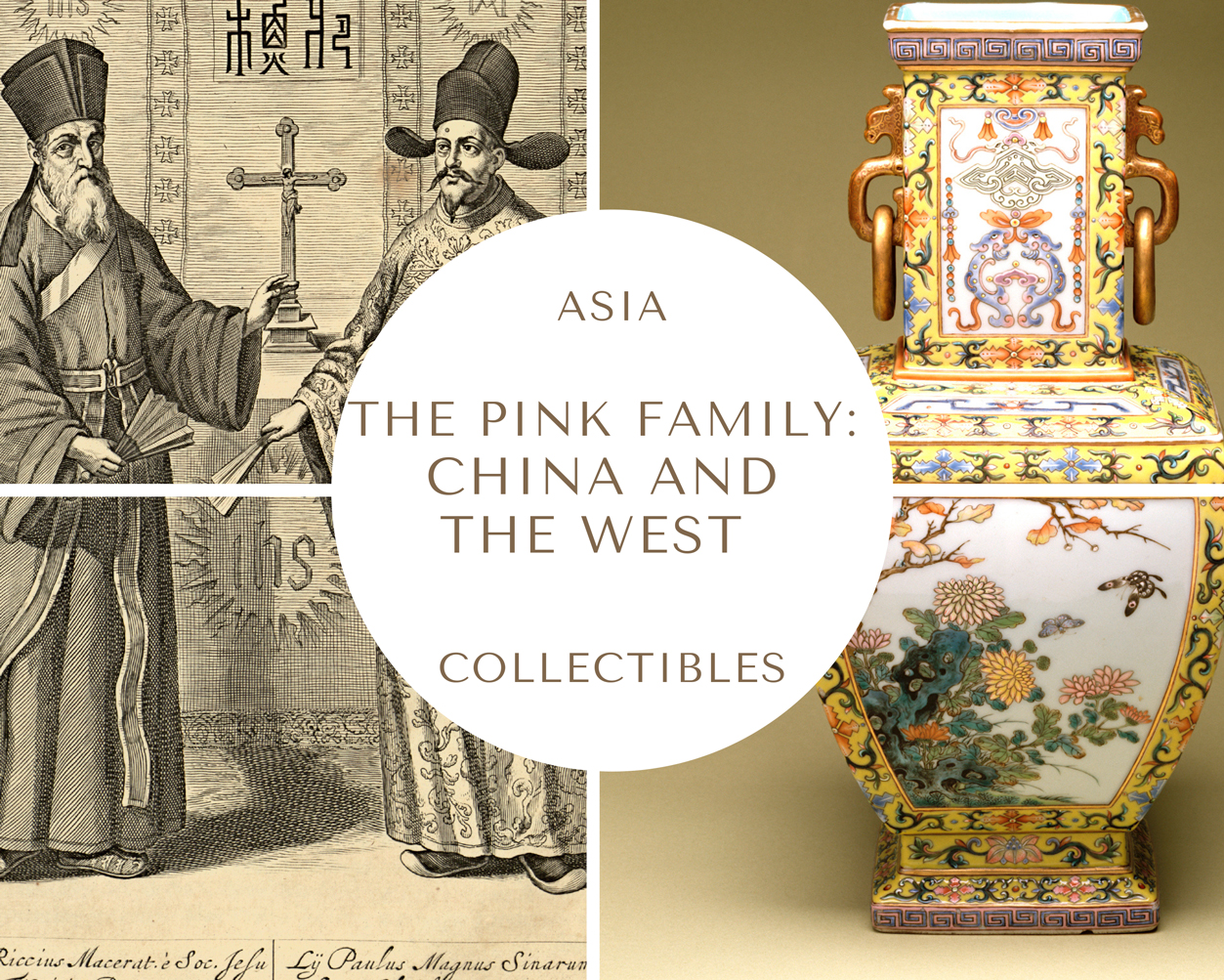

PAPUAN ANCESTRAL SUSPENSION HOOKS 4

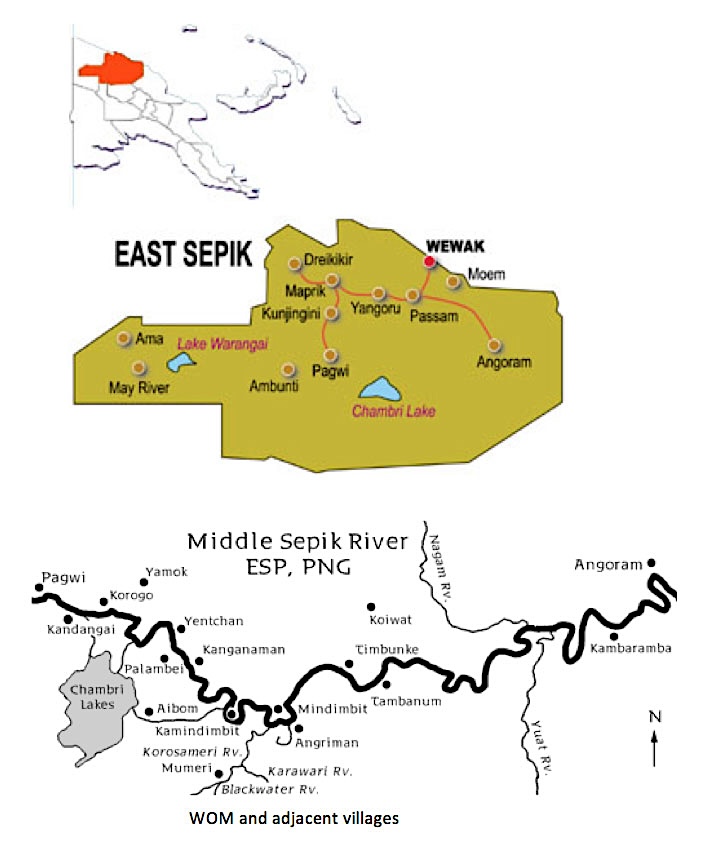

Papua New Guinea on the globe

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

HANGING THE WORLD IN BALANCE: THE SEPIK SUSPENSION HOOK

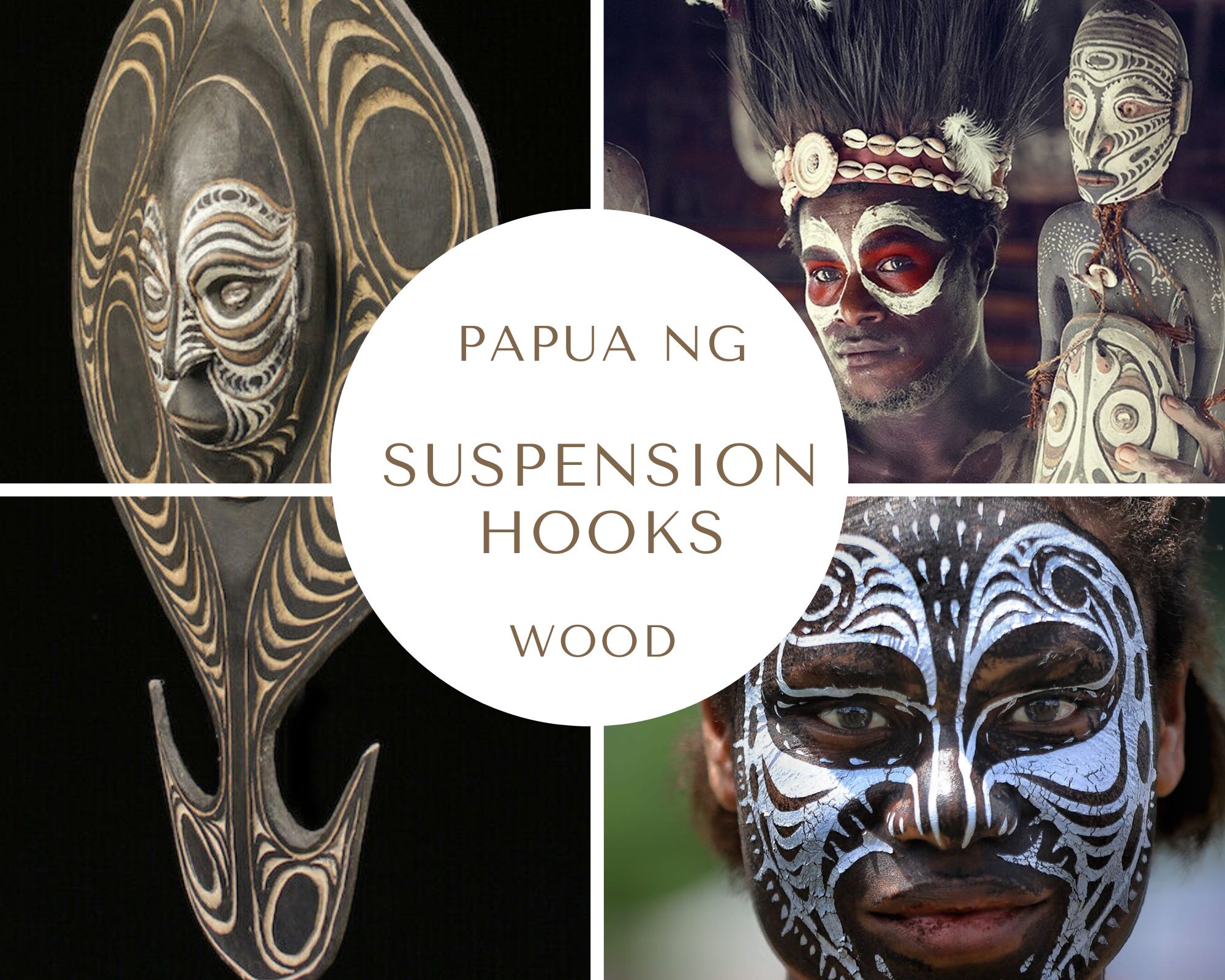

In the Middle Sepik region of Papua New Guinea, elaborately carved suspension hooks, known as samban or tshambwan in Iatmul, hang from the rafters of houses and ceremonial men’s houses. These hooks keep baskets and string bags off the ground, protecting them from vermin and flood damage. Yet, in many communities, they also serve as charged ritual images that encapsulate clan history, myth, and social relations. Among the Iatmul, in particular, some hooks serve as conduits to powerful beings (waken/wakin) who are consulted before raids or other significant events.

Materials and making

Iatmul hooks are typically carved from a single piece of hardwood, and some are painted. Examples incorporating cowrie shells, fiber elements, or coatings of black river clay also exist. The lower end of the hook terminates in one or more prongs, from which bilums (looped string bags) or trays are suspended. This protects the contents from moisture, water, insects, and rodents. This everyday utility coexists with ceremonial significance.

Iatmul suspension hooks represent the pinnacle of Middle Sepik woodcarving traditions. They are characterized by flowing, curvilinear designs and elaborate painted decorations. Their sculptural forms typically feature anthropomorphic figures with exaggerated facial features, elongated bodies, and distinctive hook-shaped appendages at the base. This carving style reflects the Iatmul preference for “the interplay of elevated and deepened surfaces,” creating dynamic visual compositions that seem to pulse with spiritual energy.

Although hooks exist throughout the Sepik region, explanatory texts consistently identify male carvers as the makers of hooks in the Middle Sepik. This aligns with broader gendered divisions in the production of ritual images.

The painted decorations typically use the traditional Iatmul color palette of red, white, and black. These colors are applied in intricate patterns that follow the contours of the sculpture and enhance its spiritual potency. These pigments are derived from natural sources: white from clay, red from ochre, and black from charcoal or specific plant materials.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Feather Bilum from the mid-20th century, Upper Sepik. Medium: Papuan hornbill feathers, cockatoo feathers, parrot feathers, plant fiber, and cane. Dimensions (bag only): 17 11/16 × 24 × 7 3/16 in.; 45 × 61 × 18.3 cm. Saint Louis Art Museum, St. Louis, Missouri, USA.

Antique string bag (Bilum) from the early 20th century, Sepik River area. Medium: Woven fibre, shell Dimensions: 91.1 × 60 cm. Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto, Canada.

Antique string bag (Bilum) from the early 20th century, Sepik River area. Medium: woven fiber and natural pigment. Dimensions: 24 x 15 in.; 60.96 × 38.1 cm. WorthPoint.

Old string bag (Bilum) from the West Sepik Province. Length: 19 in.; 48.26 cm. WorthPoint.

Everyday utility and domestic presence

Suspended from the rafters of dwellings and, more importantly, from the soaring ridge poles of men’s ceremonial houses, the hooks serve a vital purpose in a region where the Sepik River frequently floods villages and vermin endanger stored goods. In the humid, fauna-rich Sepik environment, rats, marsupials, and insect pests endanger dried sago, smoked fish, ceremonial regalia, and treasured ancestral or foe skulls. Valuable items are typically placed in bilums and hung from the hook-shaped prongs at the base of the hooks. Some of them have additional features, such as disks above the prongs, that impede rodents from descending the rafters. However, even without these features, the hanging principle itself fulfills the protective function.

Simple, undecorated hooks are ubiquitous in domestic spaces. However, the more elaborate examples—often exceeding one meter in height—are integral to the architecture of the haus tambaran, the towering, gable-roofed men’s house that dominates every Sepik village. Here, lines of hooks are hung above the central floor space where initiates undergo ordeals and dancers brandish masks and flutes. The structure itself is conceived as an enormous crocodile: its ridgepole is the spine, its rafters are the ribs, and its gable is the jaws. Suspension hooks dangling from the “spine” become the crocodile’s teeth, literally representing a mythic charter in which the community dwells inside the body of the primordial crocodile ancestor.

Iconography: ancestors, animals, and stacked motifs

The spiritual dimension of Iatmul suspension hooks reveals their cultural complexity. Most hooks are elaborately carved and painted with images of ancestral spirits and totemic animals. These decorative elements are not merely aesthetic choices, but rather, they serve as visual manifestations of the spiritual forces that protect and guide the community.

Most Iatmul hooks carry anthropomorphic and zoomorphic imagery linked to the owner’s matriclan or patriclan, including ancestral spirits, clan totems, and mythical beings. Female figures are common and are often depicted standing on fish or alongside crocodiles, flying foxes, and birds, particularly hornbills. The clustering or “stacking” of motifs (bird–fish–woman–crocodile–mound) is a common compositional template in Iatmul/Sawos sculpture that illustrates origin stories and riverine ecosystems.

Crocodiles are especially significant in Iatmul cosmology. One prevalent account states that an ancestral crocodile created the land by diving to the ocean floor and bringing up mud on its back. This cosmological significance explains the prevalence of crocodilian features on hooks and related carvings.

Ritual use among the Iatmul

The Iatmul term for powerful spirit beings relevant to high-status individuals is variably transcribed as waken or wakin (Bateson also recorded wagan), reflecting dialectal and orthographic differences. The Iatmul pantheon is populated by waken—spirits of the dead, culture heroes, and elemental forces—each of which is affiliated with a specific clan and locality. Each waken of the first rank has a named attendant, a living man who is the only one who can address the spirit and convey its message to the community.

The most powerful suspension hooks, which represent the waken, served as oracular conduits, namely, sacred images through which these spiritual entities could be consulted. Before embarking on raids or hunting expeditions, men would gather in the ceremonial house to consult the waken through the hook bearing its image. This consultation process involved specific ritual protocols. Offerings of chickens, betel nuts, and other items were hung from the hook. A human attendant would then enter a trance state, through which the waken could speak and provide crucial advice for the success of the venture.

Household hooks could also be used for more modest consultations with spirits and for addressing minor matters, such as illness, failed gardens, and marital discord.

This oracular use blurs the lines between object, image, and instrument, making the samban a device for both suspension and communication. The ritual activation of these objects demonstrates the Iatmul belief that material culture serves as a bridge between the physical and spiritual realms. When a hook decays beyond repair, a replica is carved. In an overnight ceremony, the waken is induced to “enter” the new image. The old hook, now emptied of power, may be sold to passing traders or left to rot.

This suspension hook is undoubtedly rare and exceptional. Radiocarbon dating indicates that it was created between 1450 and 1650 with 95.4% probability. Medium: Wood, shell, fiber. Dimensions: 39 3/8 x 27 3/16 x 3 9/16 in.; 100.01 x 69.06 x 9.05 cm. De Young Fine Art Museum, San Francisco, CA, USA.

Female cult hook. Radiocarbon dating places its creation between 1520 and 1810 with 95.4% probability. Medium: Wood, pigment, rattan, fiber, string ornaments. Dimensions: 66 15/16 x 19 5/16 x 4 3/4 in.; 170 x 49 x 12 cm. De Young Fine Art Museum, San Francisco, CA, USA.

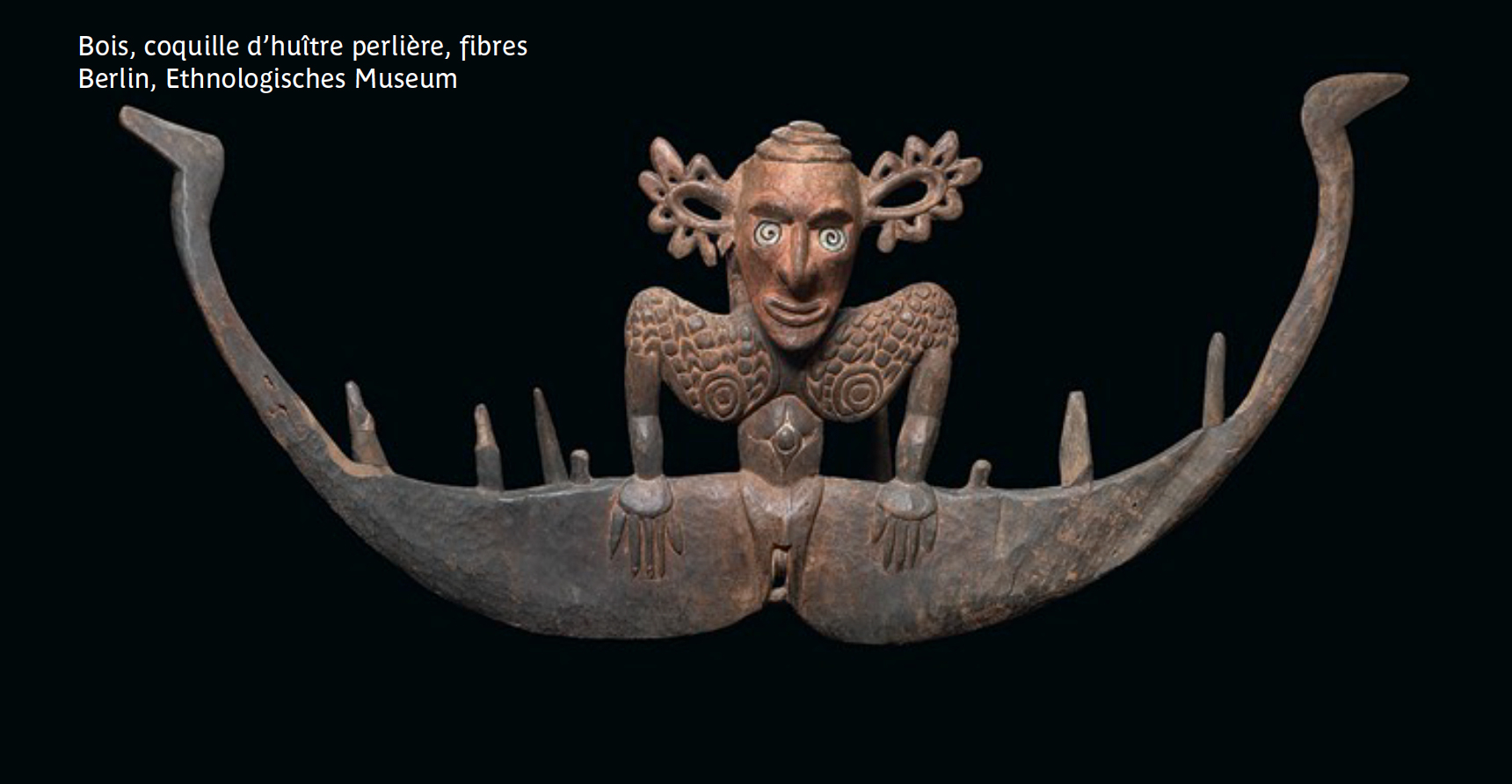

Ancient female-shaped suspension hook from the Middle Sepik area. Medium: wood, shell, fiber. Ethnologisches Museum, Berlin, Germany.

This old suspension hook, probably of Iatmul origin, is a highly refined piece, auctioned by Bonham’s in 2016 for nearly 14,000 US dollars. Medium: Wood, cowrie shells, pigments. Dimensions: height 29 in.; 73.5 cm.

This is an Iatmul suspension hook made of carved wood and used in a domestic space. The head is decorated with an anthropomorphic face painted white with black eyes and red features. The hook is damaged on one side, with some prongs missing. Middle Sepik area. Date: 1900-1916. Dimensions: length 181 cm, width 35 cm. Museums Victoria, Melbourne, Australia.

Iatmul suspension hook, 20th century. Medium: wood and pigment. Dimensions: 10 3/4 x 6 3/8 x 3 in.; 27.305 x 16.193 x 7.62 cm. Image courtesy Dallas Museum of Art, Texas, USA.

Variation across the Sepik: Iatmul and neighbors

Although samban is an Iatmul term, cognate hooks are found throughout the middle and lower Sepik. Each is distinguished by stylistic nuances and ritual emphases. A comparative analysis reveals a common grammar consisting of a vertical axis that links the domain of spirits (above) to the needs of humans (below), hooks that physically and symbolically “capture” the bounty, and a surface inscribed with clan-specific totems. Yet, within this grammar, each community elaborates its own aesthetic dialect, asserting its difference in a region where inter-village raiding and alliances were common.

The Chambri version of suspension hooks exhibits distinct stylistic variations, featuring designs that are painted rather than engraved, though their fundamental function remains consistent. They often carve diminutive hooks in the form of squatting women with exaggerated vulvas, underscoring their role as guarantors of sago and fish.

The Sawos (Middle Sepik) are closely intertwined stylistically and ritually with the Iatmul. Sawos carvers share a stacked motif repertoire and focus on ancestresses and aquatic and faunal imagery.

The Abelam (Prince Alexander Mountains/Maprik) are best known for their yam cult imagery and gable masks. However, museum collections also document Abelam ancestral hook figures, showing that, while hooks are not central to Abelam rituals like yam masks are, they are present in the broader Sepik iconographic field.

The Bahinemo (Hunstein Mountains, Upper Sepik) are celebrated for their garra/gra hook figures, which comprise two related forms: tall profile images built of serial hooks and flat hook “masks” with a central face bracketed by hooks. These are not domestic suspension devices, but rather cult objects associated with forest and water spirits. They are used in initiation performances, indicating a regional semantics of hooks that extends beyond storage to spirit embodiment and dance.

Upper Sepik mapping: A comparative survey of Upper Sepik material culture shows that suspension hooks (and related hook figures) have a mappable distribution with local specializations, underscoring continuity and diversity across the region’s linguistic groups.

The Kwoma and Yimar of the upper Sepik eschew anthropomorphic hooks altogether, preferring abstract hooks that end in paired, opposing crescents known as kwonda. These crescents are emblematic of the moon and female fertility.

Within the Iatmul, village-based styles are evident in early and later collections. Examples include Kanganaman, Kararau, and Aibom/Chambri Lakes. Named examples, such as the Nyaura clan’s Tangweiyabinjua, document how hooks link to specific clans and places. Comparative museum records from these villages, collected from the 1930s to the 1970s, remain primary sources for stylistic geography.

Interpreting the “image-as-instrument”

Hooks are compelling examples of the “image-as-instrument” concept: their shape (a carved figure that ends in hooks) directly relates to their function (hanging offerings, valuables, or food). In Iatmul ritual instruction, cutting a hook from a tree and hanging pearl shells is the prescribed way to summon useful wakin, fusing the image, the action, and the medium of exchange (shell valuables). Oracular consultation in the men’s house extends this logic; the offering hung from the hook becomes the medium through which a spirit speaks via a human attendant. This fusion of art, technology, and spiritual agency is integral to the hooks’ social significance.

LEFT TO RIGHT

This Iatmul-Sawos suspension hook was hanging in the Haus Tambaran of Yamok Village in 2009.. Photo by Belgian photographer Rita Willaert – Flickr.

This Iatmul stylized figural suspension hook depicts a masked figure with inset shell eyes. It is decorated with red, black, gray, and white pigments, as well as vestiges of feathers and raffia. Sepik River area. Dimensions: height 26.5 in., 67.31 cm. Auctioned in 2018 by Great Gatsby’s Auction Gallery, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Large suspension hook from the Iatmul village of Kanganaman, Middle Sepik. Collected in the 1970s. Dimensions: 80 x 26 x 3 cm. Carter’s Price Guide to Antiques.

This Iatmul figural suspension hook depicts a masked figure with inset shell eyes and is decorated with red, black, and white pigments. It rests on a crocodile head. Sepik River area. Dimensions: height 26.5 in., 67.31 cm. Auctioned in 2018 by Great Gatsby’s Auction Gallery, Atlanta, GA, USA.

Figural hook collected in the Iatmul village of Palimbei, along the Sepik River. Medium: Wood and natural pigments. Dimensions: 107 x 44 cm. David & Amélie Godreuil – Atifact, Art Tribal Océanien, Louannec, France. The absence of prongs or a hook at the bottom suggests this object was made primarily for ritual, symbolic, or commemorative purposes rather than functional hanging use. In such examples, the form mimics that of a suspension hook but transforms the functional design into a fully integrated ancestor effigy or mythic tableau, intended for display or spiritual invocation.

LEFT: Chambri suspension hook, collected by Eudald Serra in Aibom village in 1968. Chambri Lakes, Middle Sepik River. Date : from the late 19th/early 20th century. Dimensions: height 22 in., 55.9 cm. “My Parcours des Mondes Exhibition” Paris, France, 2023.

RIGHT: Sawos suspension hook from the hamlet of Wolombi, near the village of Yamok, Middle Sepik River. Date: first half of the 20th century. Medium: Wood, encrusted patina, pigment. Dimensions: height: 32 ¼ in., 82 cm. Auctioned in 2029 by Sotheby’s for 37.500 US dollars.

Suspension hook from the Blackwater River Region, Middle Sepik River. Medium: Wood, encrusted patina, fiber. Dimensions: Height: 68 in., 172.2 cm. Valued over 350,000 US dollars by Sotheby’s in 2019.

Suspension hooks from the Blackwater River region, particularly those crafted by the Kwoma (Washkuk) and Nukuma peoples, are characterized by low-relief carvings with intricate, curvilinear, and geometric abstract designs. These motifs often consist of swirling, eye-like forms; diamond shapes; and layered lines. They echo clan symbols, ancestral presences, and mythic beings. Unlike the more figurative suspension hooks of the Iatmul and Sawos peoples, Blackwater hooks typically emphasize abstract visual rhythms rather than anthropomorphic or zoomorphic imagery. This abstraction is a stylistic and symbolic choice; the patterns invoke spiritual protection, convey ancestral potency, and enhance the sacredness of whatever is suspended from the hook—be it food, ritual items, or string bags. These hooks are both practical and sacred. They play a central role in the interiors of men’s houses (haus tambaran), serving as points of contact between the visible and invisible realms of Kwoma and Nukuma cosmology. Their unified, abstract style is a celebrated hallmark of Blackwater River art. However, there is always an exception to the rule, as demonstrated by the suspension hook below. It originates from the Waskuk Hills area in the East Sepik region, which is primarily inhabited by Kwoma and Nukuma communities. It features striking anthropomorphic paintings with exaggerated anatomical forms. It has been painted with the vibrant colors red, white, black, and green, which are hallmarks of Kwoma ritual art.

Suspension hook collected in the Waskuk hills area. Medium: Wood and natural pigments. Dimensions: 121 x 14 cm. My personal collection.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Large carved food hook in hardwood and natural pigments, collected in the village of Yamok. Dimensions: 42.91 × 11.42 in., 109 x 29 cm. David & Amélie Godreuil – Atifact, Art Tribal Océanien, Louannec, France.

Large carved food hook in wood and natural pigments, collected in the Iatmul Korogo village. Dimensions: 37.40 × 8.66 in., 95 x 22 cm. David & Amélie Godreuil – Atifact, Art Tribal Océanien, Louannec, France.

Food Hook from the Sepik River area. Medium: wood and black, white a red ocher paints. Date: from the mid-20th century. Dimensions: 24 x 9 in., 60.96 × 22.86 cm. Westwillow Antiques, Canada.

Old suspension hook of elongated form; the sensitively carved head shows classical Middle Sepik features, atop a stylized neck terminating in a double-pronged hook. Fine patina from handling. Dimensions: height 23 1/2 in.; 59.69 cm. Auctioned in 2007 by Bonham’s New York.

LEFT: Old Iatmul figural suspension hook, Middle Sepik. Dimensions: height: 22 1/4 in., 56.5 cm. Auctioned in 2021 by Sotheby’s New York for approximately 40,000 US dollars.

RIGHT: Antique Sawos suspension hook, Middle Sepik, for the early 20th century. Dimensions: 62 1/2 x 16 1/4 x 4 1/2 in., 158.8 x 41.3 x 11.4 cm. Brooklyn Museum, New York, USA.

Modern Contexts and Changing Functions

Iatmul samban/tshambwan suspension hooks exemplify how an everyday household management device can simultaneously serve as a node of ritual efficacy and social memory. Their carved bodies depict ancestries, totems, and mythic beings, and their hooks hold not only food and bags, but also offerings and obligations. Their presence in houses and men’s houses mediates relations among clans, relatives, and spirits. Across the Sepik region, hooks and hook figures articulate a semiotics of suspension and attraction, from the Iatmul’s oracular conduits to the Bahinemo’s garra and the Abelam variants. This demonstrates how form travels and is resemanticized through exchange and ritual practice. Scholars have noted that the hooks embody concepts of agency and spiritual presence fundamental to Sepik worldviews, challenging Western distinctions between animate and inanimate objects. However, the end of Sepik cultural isolation, the development of tourism, and the social changes associated with postmodernity are changing this reality.

The role of suspension hooks in contemporary Iatmul society has evolved significantly from traditional contexts, reflecting broader cultural changes in Papua New Guinea. While many hooks still serve practical household functions, their spiritual significance has become more complicated due to the introduction of Christianity and the disruption of traditional ceremonial practices.

Some contemporary practitioners still perform traditional consultation rituals, but there are fewer and fewer of them.

Paradoxically, the demand for “authentic” Sepik art stimulated a prolific carving industry. Villagers produced increasingly large and elaborate hooks for sale, while continuing to carve smaller, more ritualistically significant ones for local use. Ross Bowden’s work with the Kwoma people shows that, from an indigenous perspective, a well-carved copy has all the aesthetic and spiritual qualities of an “original” if the carver has the right to use the design. However, museums have often privileged age and provenance over ongoing cultural vitality, producing taxonomies that freeze a moment of colonial encounter.

Today, Iatmul suspension hooks are represented in major museum collections worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Honolulu Museum of Art, and Museums Victoria. While these institutional collections play an important role in preserving and documenting these cultural treasures, they also raise complex questions about cultural ownership and the appropriate contexts for displaying sacred objects. The presence of these objects in museum settings contributes to scholarly understanding of Sepik cultures and facilitates their appreciation by global audiences. However, removing these objects from their original cultural contexts strips them of their spiritual potency and ceremonial significance, transforming them into aesthetic objects rather than living components of spiritual and religious practice. Whether hanging on a museum wall, behind a glass case, or hidden in an underground storage room, suspension hooks lose their meaning and role as active participants in the ongoing relationships between humans, ancestors, and spiritual beings.

Many museums worldwide, including those in Cambridge, Basel, New York, and Melbourne, have digitized their collections, making high-resolution images available to Iatmul researchers. These researchers use the images to reconstruct genealogies, settle land claims, and inspire new carving styles. Museums should take another step forward by limiting themselves to digitally preserving the past while leaving the physical artifacts to the communities to which they belong.

A conclusion and a new starting point

As Papua New Guinea navigates the challenges of modernization and cultural preservation, suspension hooks serve as important markers of cultural identity and continuity. These objects remind us that material culture is not merely decorative or utilitarian; rather, it is a fundamental medium through which communities express their deepest values, beliefs, and aspirations. These hooks stand as enduring testimonies to the creative power of human culture, the vitality of indigenous artistic traditions, and the intimate and profound connection between the Sepik peoples and their environment.

The extensive use of crocodile forms across all objects — both daily and ritual — and the dual function of suspension hooks — pragmatic and spiritual — reflect the deep symbiosis that binds all communities along the Sepik River to their environment. The Iatmul and all the groups in the Sepik area are integral parts of a complex ecosystem. The omnipresence of suspension hooks and crocodile imagery embodies the reciprocal relationship between living people, ancestors, animals, spirits, and the riverine environment. Hooks and crocodiles simultaneously mediate between human communities, natural forces, and the potent domain of ancestral spirits. Along the Sepik, the natural and cultural worlds are not separate.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?