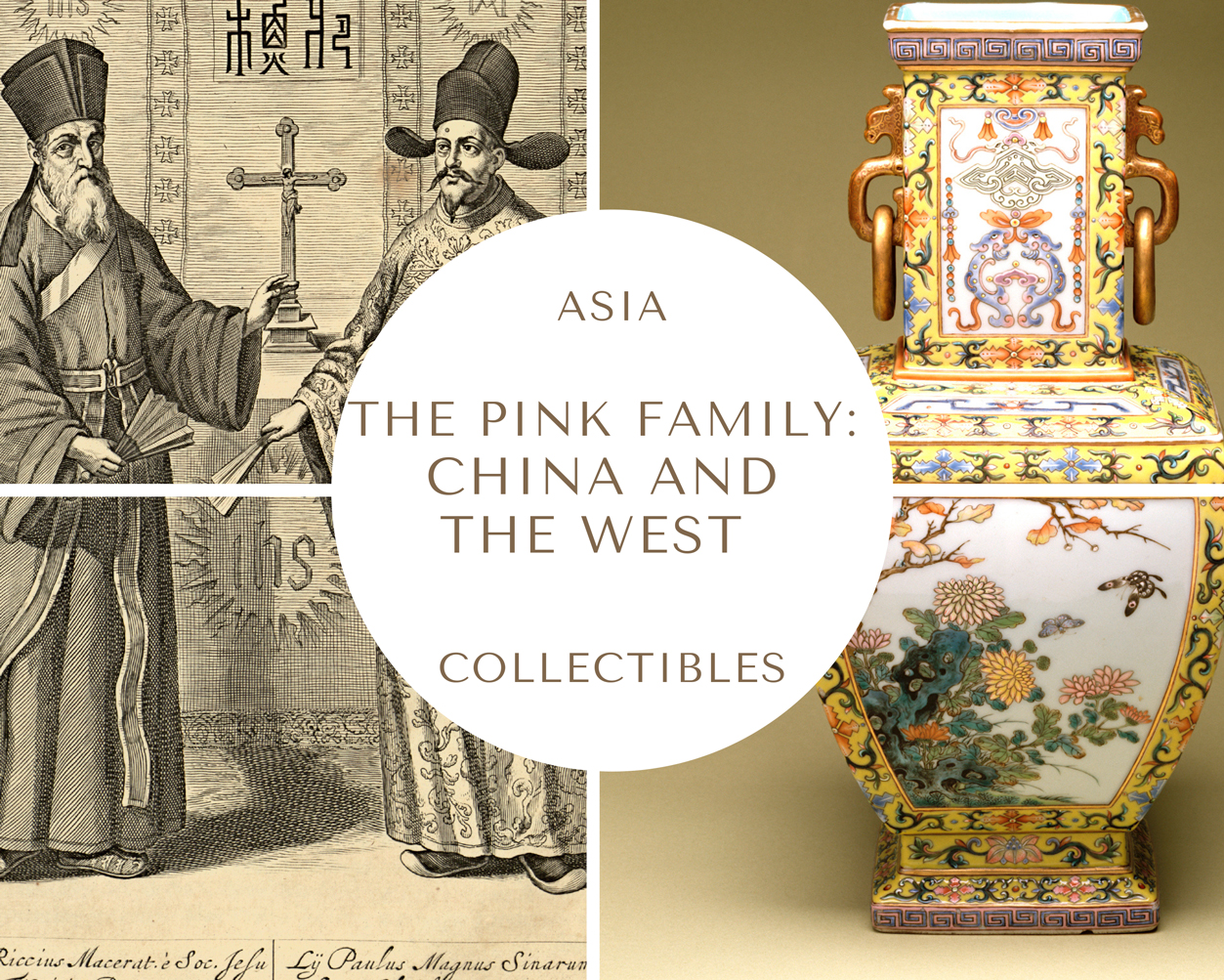

PAPUAN ANCESTRAL SUSPENSION HOOKS 3

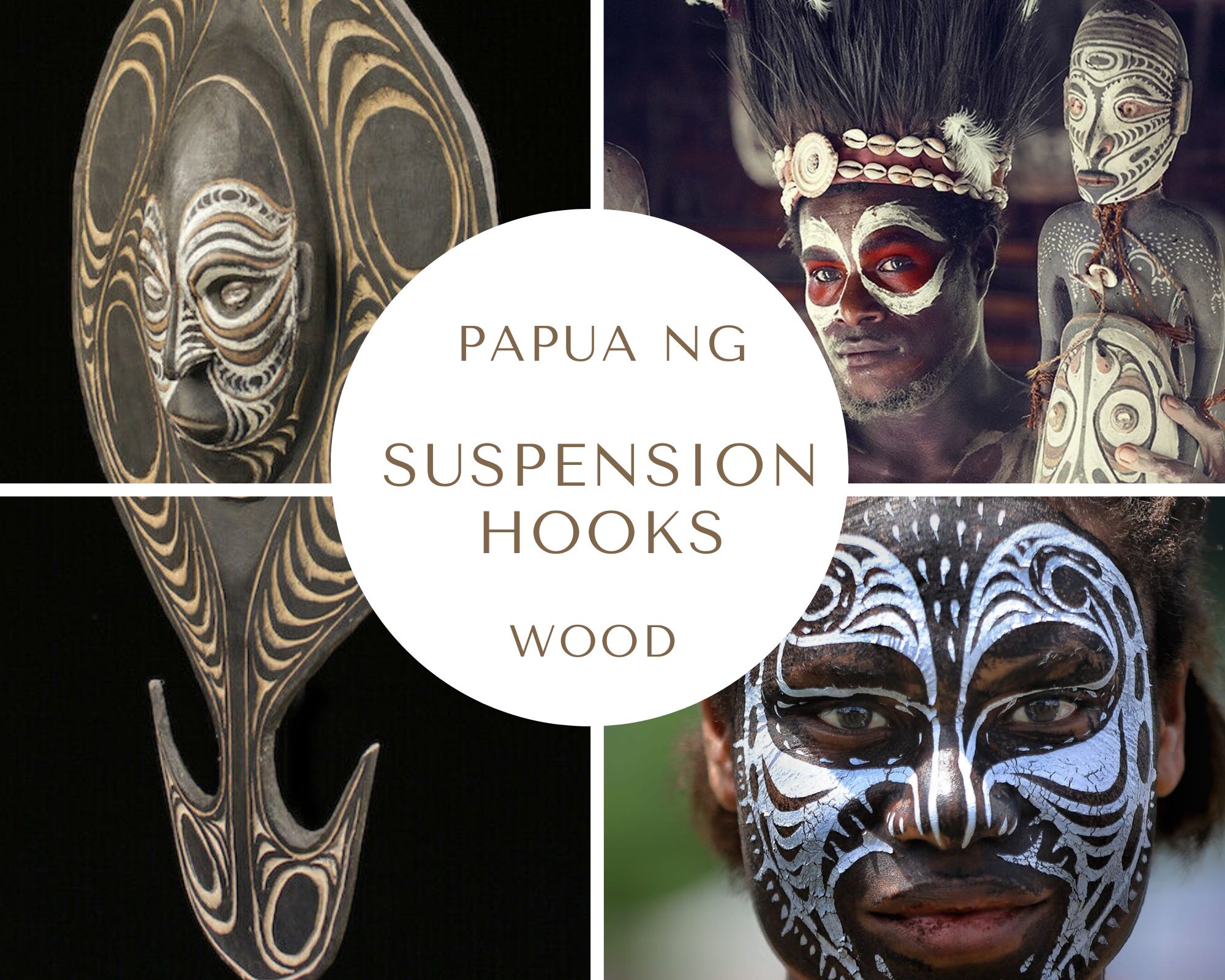

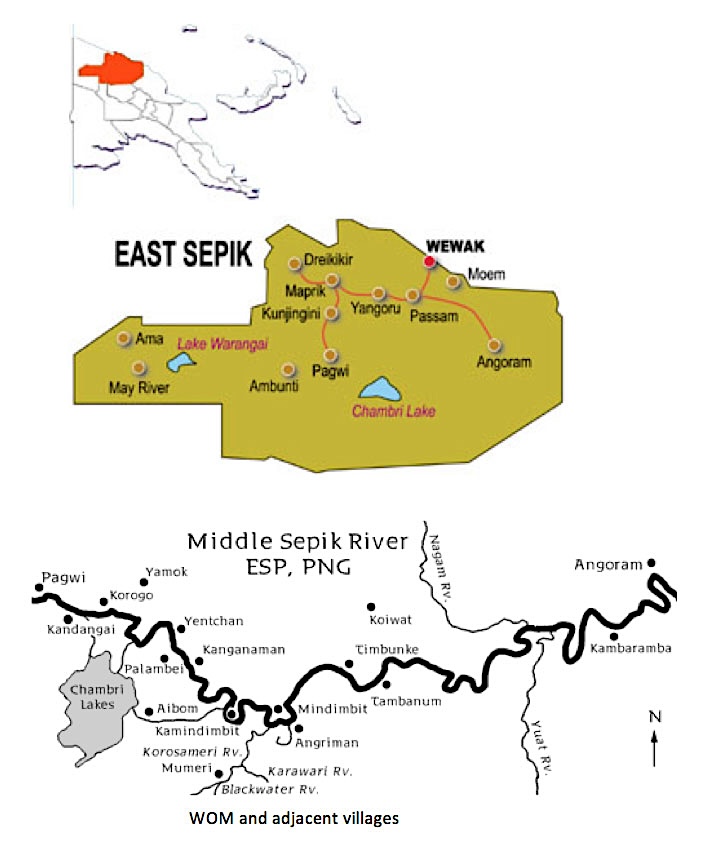

Papua New Guinea on the globe

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

THE IATMUL’S ELABORATE CEREMONIAL LIFE

The Iatmul’s ceremonial life is marked by complexity and theatricality. It encompasses dances, music, feasting, and exchanges that reinforce both mythic ancestry and contemporary social ties. Ceremonies often involve elaborate processes through which participants feel connected to their ancestors or become part of the mythical world. During major ceremonies, guests are welcomed with dances and gifts, such as pigs and kava plants. Reciprocal exchanges then take place at follow-up events. The choreography, arrangement of dance groups, and ritual actions express collective identity, cultural knowledge, and the transformation from chaos to social order, as seen at Sepik ceremonial sites.

Men’s ceremonial houses (haus tambaran) as ritual hubs

Across the Middle Sepik, these houses anchor ritual life, initiations, and the guardianship of secret knowledge. Ethnographic and art-historical studies document the architectural significance of Iatmul men’s houses and their role in storing and displaying sacred objects. Historically, they were also associated with warfare and the exhibition of human skulls on façades and gables.

The naven rite: accomplishment, inversion, and social integration

The naven is a transvestite ceremony first documented by Bateson. It involves:

- Gender Inversion: Male initiates dress as women, and women may don male attire, to dramatize social roles and ancestral transformations.

- Satirical Performance: The ritual includes mockery and inversion of everyday hierarchies to serve as a social commentary on power, gender, and kinship.

- Reinforcement of Kinship Ties: Through exaggerated acts, the Naven ritual emphasizes the complementary roles of affinal and consanguineal kin, especially the mother’s brother and the father’s sister.

The naven is not merely a spectacle; it is a mechanism of social control that publicly sanctions or rewards behavior and maintains the moral order. Bateson’s classic analysis of naven, or celebrations of first-time achievements, shows gendered and kin-based inversions (e.g., flamboyant performances by mothers’ brothers) that temporarily upend everyday roles to renew social ties. Later scholarship has expanded on this concept, viewing naven as a space where masculinity, motherhood, and joking/mockery express power and affection. In this context, maternal and paternal kinship idioms are ritually connected.

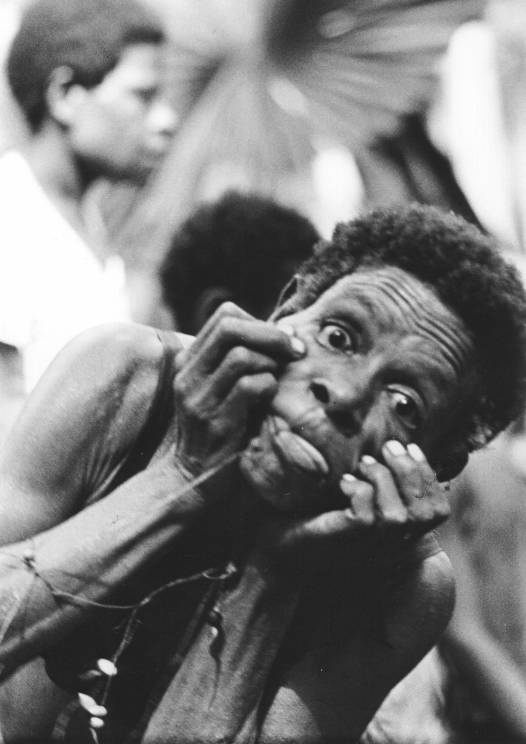

A mother dancing naven for her child. ©Florence Weiss, 1974. Source: Christian Kaufmann, The mother and her ancestral face. A commentary on Iatmul iconography, in “Journal de la Société des Océanistes”, 2010.

Headhunting and Warfare Rituals

Historically, headhunting raids were an integral part of Iatmul ceremonialism.

- Initiation Requirement: Young men had to secure a head to complete their initiation, which symbolized prowess and earned them the favor of their ancestors.

- Inter-Village Warfare: Raids were often directed against eastern Iatmul villages, creating cycles of retaliation and alliance-building.

- Ceremonial Celebration: Successful raids were celebrated with dances, feasts, and displays of trophies, integrating warfare into the ritual calendar and reinforcing martial values.

Headhunting was deeply linked to the Iatmul haus tambaran, the ceremonial and spiritual hub of the community. Skulls from headhunting raids were ritually displayed, stored, and venerated in the haus tambaran, serving as trophies and spiritual entities within the male ritual sphere. The skulls of slain enemies were buried beneath the major supporting posts of the haus tambaran. They were also adorned on the cornices and windows or kept on special racks and shelves inside the house. These skulls were material evidence of martial prowess, ancestral favor, and clan prestige.

Acquiring a head was a crucial requirement for male initiation—young men only became full adults and clan members after completing this rite. The spirit house was a venue for meetings, planning raids, and performing rituals associated with warfare, spiritual communication, and communal feasting.

Skulls were incorporated into religious and narrative traditions. Ancestral and enemy heads formed the spiritual “foundations” of the haus tambaran, connecting the living to the dead and uniting current generations with legendary founders and warriors.

The suppression of headhunting began during the Australian colonial administration of the 1920s and 1930s. Efforts to establish law and order included public executions of convicted headhunters and led to the practice’s formal end by the mid-1930s. Christianization further shifted the ritual significance of the Haus Tambaran. The ceremonial use of actual skulls faded, and overmodeled or symbolic skulls and masks increasingly replaced real heads in rituals, art, and displays.

Although warfare and headhunting are no longer practiced, their spiritual and artistic legacy persists. The haus tambaran remains the locus of male ritual, initiation, and communal memory. Its history has been reframed for present uses, including heritage tourism and community identity, and the artistic motifs of skulls and ancestor spirits remain prevalent. The focus has shifted from real violence to symbolic actions. The men’s house is now a permanent marker of tradition, identity, and clan solidarity in the modern world.

In short, headhunting ceremonies were integral to the ritual life of the Haus Tambaran. However, colonial and missionary interventions in the early 20th century catalyzed a transformation toward nonviolent, symbolic, and commemorative rites centered around the same communal space.

Skulls on a shelf inside the haus tambaran of the village of Imas, along the banks of the Sepik. Photo by Jake Warga for NPR.

The people of Imas speak the Karam language and identify as the Karam or Imas people. While some Sepik villages are strongly associated with larger groups, such as the Iatmul, Chambri, or Abelam, Imas is specifically recognized for maintaining its own distinct language and culture. It is classified separately from these neighboring tribes. Imas is also known for its dual structure: “Imas No. 2,” the contemporary settlement, and “Imas No. 1,” the traditional village preserved for cultural performances and tourist interaction. This arrangement enables the Imas people to sustain their linguistic heritage and ritual practices, particularly through dance, thereby maintaining their cultural identity within the broader Sepik River region.

Skull hook, in form of carved female figure with 6 legs splayed to make radiating branches, back of figure supported on carved crocodile, painted with red, black and white pigment, from Sepik River region, 1851-1925. Science Museum Group, © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum, UK.

Sepik skull hooks were used in ceremonies to publicly display and venerate ancestral or enemy skulls. The skulls were physically suspended on the hooks and often decorated for ritual efficacy. These carved hooks were usually attached to posts or hung from rafters inside the haus tambaran. The human skull (sometimes overmodeled with clay to recreate facial features or adorned with shells, feathers, and other decorations) was hung directly on the hook, often through the foramen magnum or via cords threaded through drilled holes in the cranium. This elevated arrangement placed the skull in a position of reverence and visibility amidst other sacred items. Depending on the ritual context, the hooks enabled the skull to be exposed or concealed, ensuring that only initiated men could view or interact with them.

The Cult of the Ancestors

The Iatmul’s practice of overmodeling and painting human skulls is central to their ancestor cult. This practice is also found among other Sepik River societies, though in varying forms.

Several years after burial, the skulls of venerated ancestors (especially clan founders or important “big men”) are exhumed, cleansed, and modeled over with river clay and pigments to recreate the deceased’s features. Shells, human hair, and other decorations were added to enhance the likeness and symbolic potency.

Color and pattern denoted clan, gender, and social status. White designs typically indicated male ancestors, while black designs indicated female ancestors.

The artistry involved is remarkable. The Iatmul are renowned for their skill in creating recognizable representations by transforming skeletal remains into spiritual portraits.

These overmodeled skulls were stored and displayed in men’s houses. They acted as tangible conduits to the ancestral realm and repositories of clan history. They were also sources of group vitality and protection. They played active roles in rituals commemorating the dead, invoking ancestral guidance and favor and marking events such as warfare, success or major ceremonies. The display of ancestor skulls affirmed the continuity of clan identity, maintained spiritual potency, and demonstrated social prestige during public rites.

Similar overmodeling practices, often linked to ancestor veneration and ritual performance, are found along the Sepik and in several other areas of Melanesia and Oceania. These practices were developed especially among the Iatmul and were documented in the Neolithic era.

However, with the spread of Christianity and colonial rule, the ritual significance of overmodeled skulls diminished, though the art form persisted and was sometimes oriented toward the tourist market or museum collections. Today, older specimens are museum treasures or objects of cultural pride. However, their ceremonial role remains a powerful symbol of ancestral connection in Sepik culture.

LEFT: Iatmul overmodeled skull, late 19th / early 20th century. Made with human skull and hair, clay, wax, and shell. De Young Museum, San Francisco, CA, USA. Creative Commons, public domain.

CENTER: Iatmul overmodeled skull, late 19th / early 20th century, height 20.0 cm, 7.9 in. Artkhade Data Base.

RIGHT: Detail of a Iatmul overmodeled skull reliquary from the late 19th / early 20th century. Made of human skull and hair, pearl-shell, shell disks, embedded in the earth mud on the side of the cheek, cane, sago palm pith, earth and pigments, wood an rattan armature. Jacaranda Art Gallery, New York, USA.

Totemism, naming, and the cosmological register of ritual

In Iatmul society and other Sepik tribes, totemism is closely tied to ceremonial life, influencing social identity, ritual practices, and artistic expression throughout the region.

Each Sepik clan is associated with a specific totem, most often a powerful animal such as a crocodile, eagle, snake, or hornbill, which serves as the group’s spiritual emblem and ancestor. The Iatmul people’s foundational myth is that they descended from a primordial crocodile. This belief is enacted and renewed during ceremonies by invoking crocodile spirits, carving crocodile effigies, and using crocodile imagery in ritual art and architecture. Ceremonies such as initiation rites, yam cult rituals, and funerary events often take place in the Haus Tambaran, which is adorned with totemic carvings and spirit paintings. Ritual paraphernalia, such as masks, drums, and lime containers, frequently feature animal and ancestral motifs. These motifs are believed to attract ancestral power, mediate with spirits, and reaffirm supernatural protection for the community.

Clan totems are fundamental to social organization, determining membership, marriage alliances, and authority within the village. Elders who are familiar with totemic emblems and myths hold high ritual and political status. This belief system imbues everyday objects, art, and ceremonial acts with spiritual significance, transforming them into vehicles for ancestral communication, healing, and the legitimization of communal leadership.

Major life events—from birth to death—are marked by ceremonies that activate totemic bonds and express the community’s connection to its mythic past and ongoing connection to the spirits and the natural world. Thus, totemism permeates every aspect of ceremonial life in Iatmul and Sepik societies, serving as a living bridge between origins, identity, ritual, and artistic achievement.

The most famous example is the male initiation scarification ritual, in which boys’ bodies are cut to resemble crocodile skin. This ritual physically and spiritually aligns the boys with their clan’s totem, marking their transformation into full members and connecting them to their ancestral lineage.

LEFT AND CENTER: Totem poles, Middle Sepik Region, East Sepik Province.

RIGHT: Totem pole at the haus tambaran of the Iatmul village of Kanganaman, Middle Sepik Region. Photo by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

Initiation, Identity, and the Crocodile Cosmogony

A comprehensive tudy of male initiation through crocodile scarification among the Iatmul people and neighboring groups of the Middle Sepik River, including the Chambri and Kaningara, reveals a deeply symbolic, painful, and spiritually significant rite of passage. This ritual is a physical transformation and a cultural, spiritual, and social rebirth. It serves as a rite of passage and as a ritual embodiment of ancestral power, especially that of the crocodile, which is revered in Sepik mythology as a creator and a primordial ancestor.

While the Iatmul are the most well-known practitioners of this tradition, similar practices exist among other Sepik-speaking groups. These traditions vary in symbolism, execution, and contemporary relevance.

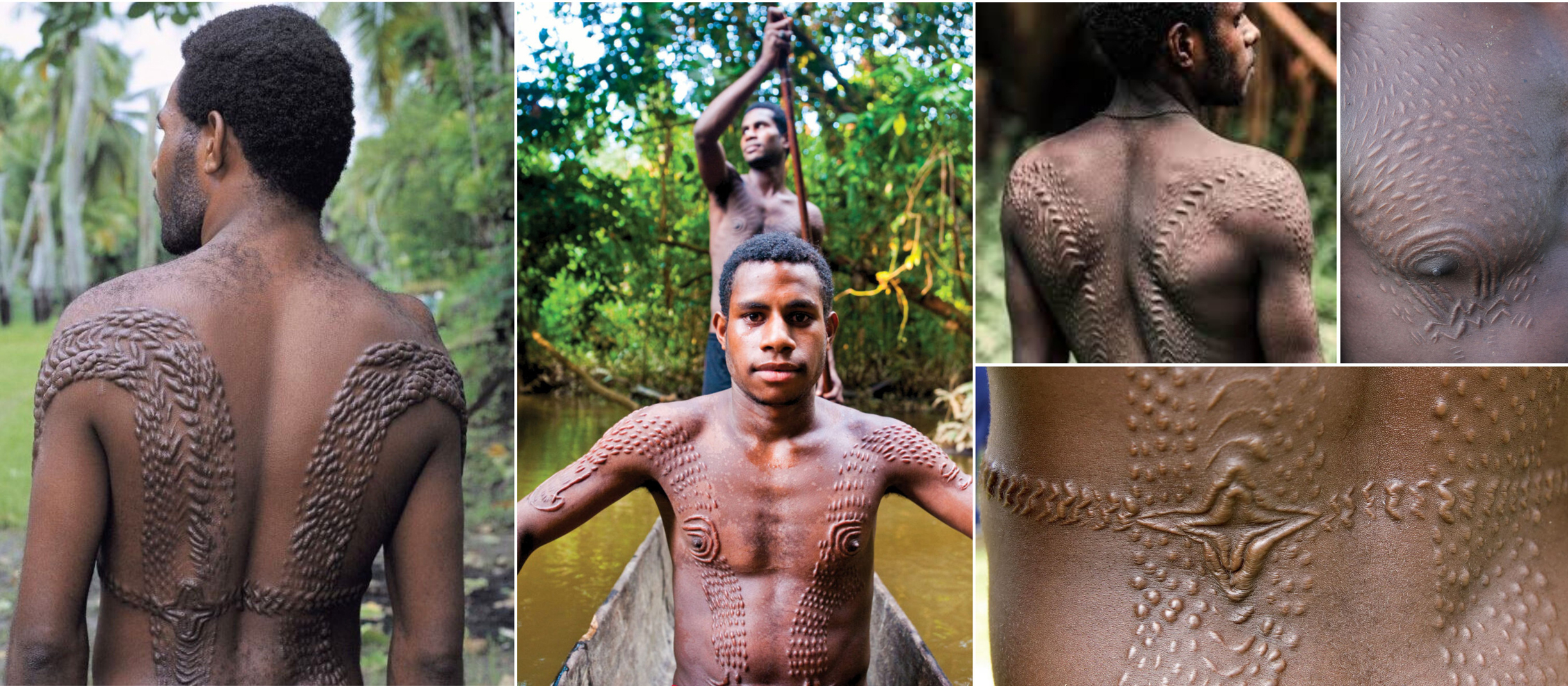

The Iatmul Crocodile Scarification Ritual: Purpose and Symbolism

The crocodile is central to Iatmul cosmology. They believe they are descended from a primordial crocodile, and they believe that the world itself rests on the back of this ancestral being. The scarification ritual symbolizes an initiate’s transformation from boyhood to manhood, embodying the strength and spirit of the crocodile.

The cuts, made on the back, chest, and sometimes arms, are designed to resemble crocodile scales. This ritual is a symbolic rebirth where the initiate is “swallowed” by the crocodile and emerges as a man. It also represents the severing of maternal ties, as the shed blood is believed to expel the mother’s postpartum influence, thereby reinforcing an adult worldview. Scarification serves as visual and social proof of manhood, ancestral connection, discipline, and endurance. It signifies a person’s lifelong membership in the community, granting them access to male privilege and the opportunity to participate in the transmission of ritual and artistic culture through the spirit house.

Ritual Process and Ceremonial Structure

- Preparation and Seclusion: The initiation process begins with weeks or months of seclusion in the Haus Tambaran, where adolescent boys are tutored by elders in history, cosmology, clan lore, ritual secrets, and masculine responsibilities. Ritual knowledge, sacred objects, and totemic names are passed down through the generations, which strengthens clan identities and intergroup alliances. The young men secluded during their initiation work together as a team, creating a lasting bond.

- Scarification Ritual: The core event involves creating raised scars on the chest, back, buttocks, and sometimes the arms and legs using bamboo knives, sharpened bones, or, more recently, razor blades. The hundreds of incisions are arranged in patterns that mimic crocodile skin. The ritual takes hours and is agonizingly painful. The initiate must endure the pain without crying; otherwise, the ritual is invalidated. After cutting, a mixture of clay, tree oil, and smoke is applied to ensure raised scarring, which is considered a mark of honor and spiritual power.

- Symbolic Meaning: The blood shed during scarification is seen as expelling the blood of the mother, marking the initiate’s separation from childhood and maternal ties. The scars are interpreted as the “bite marks” of the ancestral crocodile, symbolizing that the boy has been swallowed, transformed, and returned as a crocodile man.

The ceremony is performed by the opposite moiety, ensuring that each group is indebted to the other and creating a reciprocal cycle of obligation that underpins social stability.

Differences Among Groups

- Iatmul: The Iatmul of the Middle Sepik are known for their elaborate, communal ceremonies held in spirit houses. These ceremonies have patterns and meanings closely tied to totemic clan affiliations. The entire village participates, and the scars are worn with pride as proof of adulthood, discipline, and ancestral favor.

- Kaningara: The Kaningara tribe inhabits a single village on the Blackwater River, a major tributary of the Sepik River. Their ritual is noted for its seclusion and the long period of preparation before scarification. Kaningara men often display extraordinarily detailed scars, and the ceremony can last two months.

- Chambri: The Chambri practice crocodile scarification with a slightly different mythological framework. They believe that humans evolved from crocodiles, and the ritual signifies a return to their ancestral form. The cutting patterns and post-ritual ceremonies differ, with more emphasis placed on ornamental dress and dance after scarification. The Chambri ceremony emphasizes the significance of the maternal uncle as the ritual “cutter,” which reinforces clan structure and kinship ties.

- Variations: Patterns, duration, ritual participants, and the degree of village involvement may differ, but the symbolic structure—ancestral transformation, crocodile lineage, and separation from the maternal world—remains consistent across regions.

Evolution: Past and Present

Traditionally, these rituals were secret and rare, held every seven to ten years, with only initiated men and select community leaders present. Failure to participate could bar a young man from assuming major roles in village society or forming marriage alliances. Under colonial rule and Christianization by missionaries, however, the ritual was often suppressed or discouraged due to health risks and religious opposition. Although the frequency and secrecy of the practice decreased, it persisted as a vital marker of Sepik identity.

Today, crocodile scarification continues, though it is sometimes adapted as a cultural demonstration for tourists. Some aspects, such as pain management and hygiene, have evolved in response to external concerns. The ritual is still deeply respected, though not all boys undergo the ceremony today, reflecting changing social dynamics and outside influences.

Academic Perspectives

Anthropologists such as Gregory Bateson, Eric Silverman, and Milan Stanek have extensively studied the Iatmul. Bateson’s work on the Naven ceremony and Silverman’s psychoanalytic and symbolic interpretations highlight the gendered cosmology and ritual mockery embedded in Iatmul culture. More recent studies focus on postcolonial changes, tourism, and cultural resilience in the face of modernization.

BELOW

Scarification Ceremony in the Sepik River Region, 2012. Photo by Marc Dozier / Hemis /Alamy.

Sepik “Crocodile Men”

The Sepik Crocodile Festival

The crocodile, or pukpuk in Tok Pisin, is a paramount figure in Sepik cosmology, particularly among the Iatmul. It features centrally in myths of origin; Iatmul creation stories often recount that humans descended from or emerged from waterways governed by crocodile spirits. Held each August in Ambunti, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea, the Sepik Crocodile Festival is a major annual cultural event celebrating the spiritual, ancestral, and ecological significance of the crocodile among the Middle Sepik peoples, especially the Iatmul, Chambri, and neighboring clans.

Established in 2007, the festival is a community-driven initiative that links cultural revitalization, heritage tourism, and wildlife conservation. It is supported by organizations such as WWF and the Sepik Wetlands Management Initiative. The festival’s location in Ambunti, on the Middle Sepik, reflects the crocodile’s significance as a totem, ancestral spirit, and clan symbol. It connects mythic creation stories to modern identity and environmental stewardship.

The three-day event (August 5–7) includes parades, competitions, canoe races, feasting, dances, music, performances, and exhibitions of the largest yams and crocodile specimens. Participating communities span the river: Middle and Upper Sepik villages, including major crocodile cult areas, send groups to perform singsings and participate in the market. Dozens of Sepik tribes gather to perform spectacular singsings—group dances, songs, and theatrical stories—while wearing crocodile masks, feathered headdresses, and intricately painted bodies. Artisans display and sell ceremonial carvings, bark paintings, masks, and crocodile-themed objects. This continues the tradition of Sepik art and provides local communities with vital income and tourist exposure.

The festival serves as a source of pride and a unifying force, affirming clan and tribal alliances while enabling villages to share their distinctive styles and stories with one another and the outside world. The festival has also become an important conservation event. Public awareness programs about sustainable crocodile egg harvesting and habitat conservation are held alongside the festivities. These programs aim to preserve river ecosystems and enhance cultural heritage. Lastly, the festival attracts tourists and travelers. By attracting domestic and international visitors, the festival has reinforced the value of the crocodile as a living symbol of Sepik resilience, masculinity, and creativity. It has also provided a platform for youth engagement, intercultural dialogue, and adaptive local economies. In response to tourism, conservation, and the wider audience now engaged in Sepik culture, the festival context has encouraged communities to selectively revive or reinterpret old songs, dances, and carving motifs.

The following photos were all taken during the Sepik Crocodile Festival, albeit in different years.

Singing and playing drums at the Festival, 2010. Photo by Picturejourneys – Flickr.

Groups of performers at the Sepik Crocodile Festival.

LEFT: At the Sepik River Festival, men with crocodile scarification, wearing crab-claw flower necklaces and feathered headdresses, prepare their dances on the green, 2017. Photo by Ursula Wall.

RIGHT: Preparing the sing-sing, 2023. Photo by Ivan Cheng – No Leg Room, Canada. (Thanks Ivan for you kindness!)

ABOVE AND BELOW: photos by Ivan Cheng – No Leg Room, Canada, 2023.

The Sepik Crocodile Festival is a vibrant fusion of living tradition, ecological awareness, and tourism, providing a comprehensive lens into the complex relationship between Sepik peoples, their environment, artistic heritage, and modern challenges—anchored in the enduring power and symbolism of the crocodile.

Sepik Crocodile Festival Perfomers. Photos by Ivan Cheng – No Leg Room, Canada, 2023.

Ambunti – Sepik Crocodile Festival

LEFT: A performer is preparing its sing sing in Yamok, Sepik River area, 2009. Photo by Efrat Nakash.

RIGHT: A portrait of a young lady from East Sepik, 2019. ©Niugini Photographs.

Three individuals from the Sepik River region display traditional ceremonial adornments featuring striking feathered headdresses, necklaces of cowrie and nassa shells, and painted bodies and faces. Sepik face painting and body art are integral to cultural celebrations, initiations, and sing-sing gatherings, with designs symbolizing clan identity, ancestral spirits, and social status. Natural pigments—red from ochre, white from clay, and black from charcoal—are meticulously applied in geometric and symbolic patterns, transforming participants into living expressions of their community’s mythic heritage and creative artistry.

Series of portraits shot at the Crocodile Feestival in 2014 by the Australian photographer Alan Scott (from Melbourne).

The Sepik Crocodile Festival promotes the conservation of crocodiles and their habitat by fostering cultural pride, providing environmental education, and encouraging sustainable practices based on local traditions.

- Educational Outreach: During the festival, conservation organizations and local leaders hold workshops and awareness programs that focus on the ecological importance of crocodiles, the threats to their habitat, and the role of sustainable harvesting methods in traditional practices.

- Traditional Knowledge Sharing: The event highlights ancestral taboos and customary practices, such as leaving sufficient eggs in nests and protecting female crocodiles, that have long helped maintain a natural population balance. Younger generations learn the connection between cultural practices and conservation ethics.

- Alternative Livelihoods: The festival encourages eco-friendly tourism and the sale of culturally significant crocodile art, such as carvings and masks. This offers local people economic incentives to protect crocodiles and their wetland habitats instead of overexploiting them.

- Wildlife Monitoring: Conservation partners use the festival as an opportunity to conduct surveys, track population health, and incorporate local observations. This generates collaborative data for habitat management.

- Advocacy and Policy: The festival provides a platform for community engagement with policymakers and researchers. This supports regional initiatives that aim to safeguard wetlands, enforce sustainable harvesting quotas, and monitor poaching and habitat degradation.

As a high-profile celebration, the Sepik Crocodile Festival fosters the long-term survival of the crocodile and the fragile wetland ecosystems of the Sepik by combining local ownership, youth involvement, and cross-cultural education.

Sepik Crocodile Festival. Photos by Ivan Cheng – No Leg Room, Canada, 2023.

Guardian of the Deep: Reframing the Crocodile

For almost all Middle and Upper Sepik peoples, the crocodile is a sacred and feared creature, not just for the Iatmul. It symbolizes spiritual power, identity, manhood, and a connection to the riverine world. Its image is ubiquitous in local material culture, folklore, ritual practices, and art. The crocodile is particularly significant in the wood carving traditions of the Iatmul and other Sepik River communities. Each group endows the animal with distinct artistic, ritual, and symbolic functions according to their mythologies and ceremonial needs.

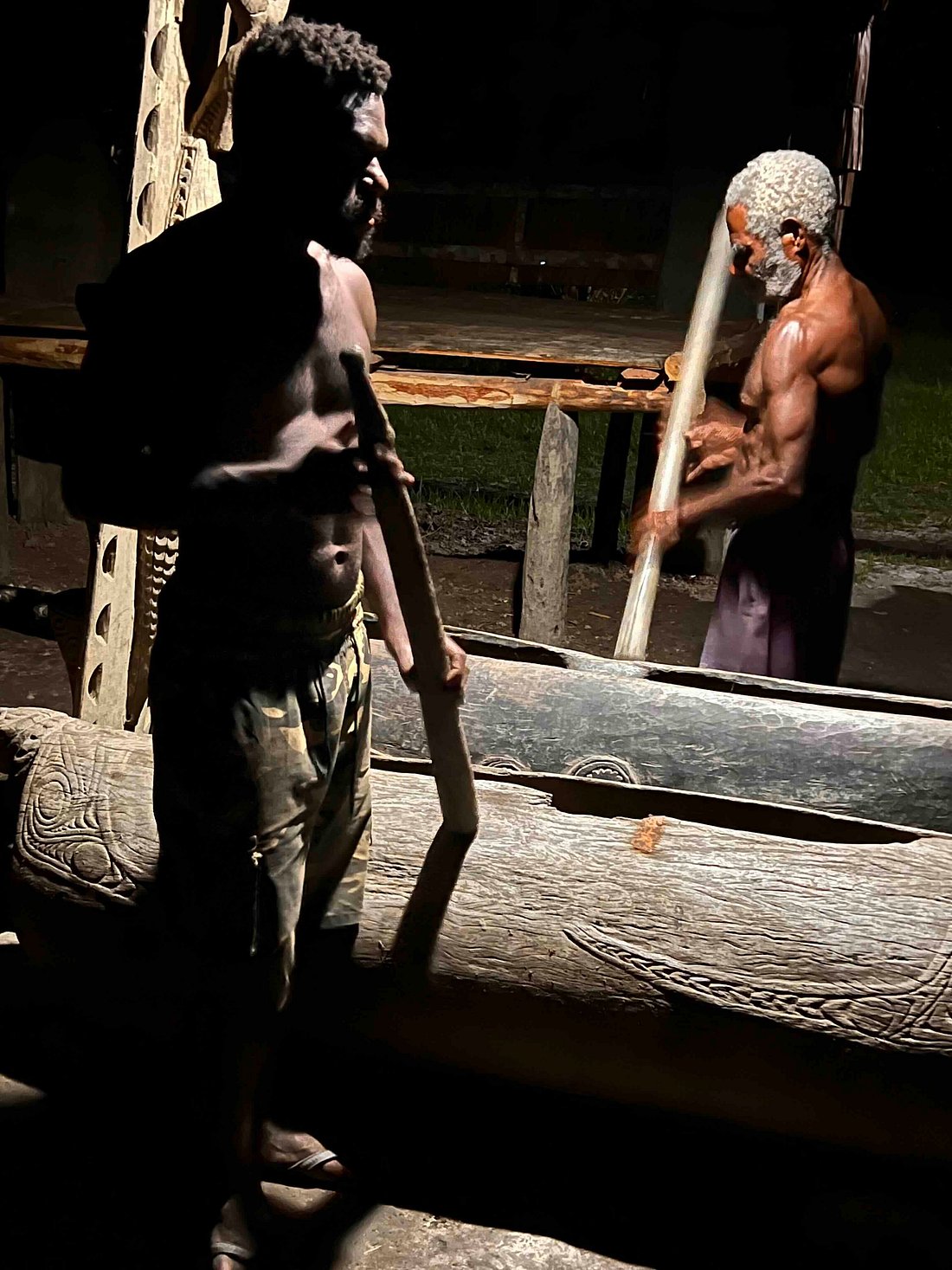

Iatmul Crocodile Imagery

Crocodile motifs are prevalent in Iatmul art, appearing in carved posts, masks, suspension hooks, canoe prows, storyboards, and freestanding sculptures. According to their mythic tradition, the Iatmul people are descended from a primordial crocodile. This spirit-ancestor is said to have created the world and continues to protect and empower the clans. According to Iatmul creation accounts, an ancestral crocodile raises land from the primordial waters. Canoes, ritual spaces, and truth-telling in councils are tied to this being. This cosmology explains the prevalence of crocodile imagery in sculpture.

Iatmul carvers often combine crocodiles with other symbolic beings, such as birds, fish, women, and mythic ancestors, in vertical sculptural groupings that visually narrate local cosmology and historical events. Canoe prows are often carved in the shape of a crocodile’s head, effectively turning the vessel itself into an ancestor or guardian during travel and warfare. Crocodile heads are featured prominently in the carvings of the haus tambaran, reinforcing the animal’s protective power and totemic status: suspension hooks often integrate crocodile heads or jaws with ancestor faces. These hooks hang valuables and “hold” protective clan spirits in men’s houses.

Freestanding crocodile figures, stools, and house elements (posts, lintels, and slit gongs) appear as explicit crocodiles or as scaly patterning. The spirit Wagen (a giant crocodile) is a recurring subject linked to speech, order, and oath-keeping.

Many Middle Sepik carvings stack emblems, such as birds, fish, women, crocodiles, and earth mounds. This places the crocodile within a layered ancestral narrative rather than as an isolated totem (Academia). (Academia)

This style favors elongated forms, sinuous bodies, and attention to naturalistic and patterned surface detail. These carvings are often ritually activated in ceremonies and initiations, particularly in the famous male scarification rites, in which the skin is cut to resemble crocodile scales.

Karawari/Korewori and Ambonwari Carved Crocodiles

The Karawari River region is renowned for its extremely long, fully carved wooden crocodiles, which are kept in men’s houses as spirit beings and are used during headhunting, initiation ceremonies, hunting trips, and times of epidemic. These crocodile spirits were not only artistic objects, but also mediators between the visible and invisible realms. They were invoked for protection, fertility, and prosperity. They were once ritually “addressed” and fed. Stylistically, they emphasize stretched bodies, open jaws, and a commanding linear silhouette, which is distinct from the more composite Iatmul ensembles.

In Ambonwari village traditions, carved crocodiles are specifically tied to war expeditions and ceremonial exchanges. The carvings are believed to hold spiritual agency long after their active ritual use ended.

Sawos (close Iatmul neighbors)

The Sawos share much of the Middle-Sepik carving repertoire. The crocodile often appears within stacked figurative schemes (bird–fish–woman–crocodile), emphasizing mythic sequencing. Compared to the Iatmul, the stacking is often tighter and more “diagrammatic” rather than featuring large, freestanding reptiles.

Chambri / Aibom

Crocodile art in the Chambri/Aibom culture often has robust, geometric forms and appears in men’s houses and communal art, such as ceremonial canoe fittings and dance costumes. Sawos motifs blend crocodile shapes with abstract patterns, sometimes emphasizing their connection to water spirits and fishing.

Aibom is renowned for its women’s pottery featuring modeled faces and occasional animal motifs. Crocodiles may appear, but they are not a defining feature of Aibom’s ceramic style, unlike in Iatmul/Karawari woodcarving. (Anthropological and museum notes foreground face reliefs and sago storage functions rather than crocodile dominance.)

Murik Lakes (Lower Sepik)

Murik ritual art centers on the brag masquerade and canoe and lagoon life. While crocodiles play an important role in Sepik mythology, Murik visual idioms tend to focus on masks and panels. Large crocodile figures do appear in Sepik initiation ceremonies, often made of bark rather than heavy carved wood. However, the crocodile is not as prevalent a subject in wood carvings as it is in Iatmul/Karawari.

Abelam (Maprik/Wosera hinterlands)

Abelam art overwhelmingly focuses on painted cult images (ngwalndu) and yam ceremonial aesthetics. Verbal exegesis of motifs is limited, and crocodiles are not as central as they are among riverine carvers. Wood-carved crocodiles are comparatively rare. The style focuses on planar painting, face imagery, and yam ritual symbolism rather than crocodilian bodies.

Upper Sepik Groups

In some Upper Sepik groups, such as the Biwat and Yuat River peoples, crocodiles appear on large slit gongs, storyboards, and masks. Sometimes they are exaggerated with spikes or intricate relief carvings to create a dazzling visual effect at yam harvest ceremonies and public rituals.

Function and Symbolism

Throughout the Sepik region, carved crocodile figures serve as protectors, mediators, and representatives of the ancestors. They mark spirit house entrances, sacred posts, and ceremonial objects, providing spiritual “support” and linking clan history to the river and its dangers.

Crocodile art blends mythic storytelling, ancestry, totemic identity, and aesthetic innovation, making each carving a sacred object that is also an expression of local artistry.

In Sepik art, the crocodile is a multidimensional emblem—totemic, ancestral, and protective. While each community carves and invokes it in ways attuned to local ritual and cosmology, the creative energy and spiritual significance of crocodile woodcarving unite the Sepik region through artistry and myth.

Iatmul overmodeled crocodile skull from the early 20th century. Dimensions: 30 x 12 x 9 in., 76.2 x 30.5 x 22.9 cm. Auctioned in 2020 by Artemis Fine Arts, Louisville, CO, USA.

This striking overmodeled crocodile skull belongs to the species Crocodylus novaeguineae. The Iatmul artist covered its surface with pale red clay and inlaid hundreds of cowrie shells across most of the head and mandible. The back of the skull is undecorated but appears to have been heated at some point. The artist used clay and thick textiles placed inside the skull to hold the mandible in place.

A carved wood boat representing the East Sepik Crocodile Spirit. Dimensions: 35 x 3-1/2 x 2-3/4 in.; 88.9 x 8.89 x 6.98 cm. Auctioned in 2024 by Compendium Auction House Tavares , FL, USA.

LEFT: Carved wood crocodile canoe prow, East Sepik Region. From the collection of Princess Maria Romanoff. Dimensions: 41 x 12 x 10 1/4 in.; 104.14 x 30.48 x 26.04 cm. Auctioned in 2025 by Willow Auction House, Lincoln Park, NJ, USA.

RIGHT: Carved wood crocodile canoe prow, Sepik River area. Dimensions: 21.5 x 7 in.; 54.61 x 17.78 cm. Auctioned in 2024 by Omnia Auctions, Tallahassee, FL, USA.

TOP LEFT: Old Iatmul crocodile-shaped canoe prow from the Mindimbit village, Middle Sepik, 20th century. Medium: carved wood, conus shell, traces of pigment. Dimensions: Size: 6.5 x 26 x 13.5 in.; 17 x 66 x 34 cm. Auctioned in 2019 by material culture, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

BOTTOM LEFT: Old Iatmul crocodile-shaped canoe prow from the Medium Sepik, 20th century. Medium: Wood, shell and metal. Dimensions: 5 1/2 × 31 5/8 × 11 1/2 in.; 14 × 80.3 × 29.2 cm. Bowers Museum, Santa Ana, CA, USA. The Iatmul added carvings to their everyday use items, many of which featured animals prominent to the region and important to the culture including crocodiles and warthogs. In this particular prow, we see a combination of both animals. The canoe prow would have been used at the head of a dugout canoe to navigate the waterways of the region as well as for hunting and fishing. The abrupt end of the piece and the blackening from fire are both results of the prow being repurposed for display.

RIGHT: Old Iatmul crocodile-shaped canoe prow from the Middle Sepik. Medium: light brown wood, matt patina with remains of dark pigment. Dimensions: length 28.5 inch, 72,5 cm. Auctioned in 2018 by Zemanek-Münster Auction House, Wurzburg (Germany) and New York (USA).

Old Iatmul wooden canoe prow in the form of a crocodile head with bird on snout, Mindimbit Village, Sepik River. Date: before 1970. Dimensions: 17.5 cm x 67 cm. Auctioned in 2021 by Theodore Bruce Auctioneers & Valuers, Leichhardt, Australia.

Ai Generated Image

Slit Gong (Garamut) from Govermas Village, located near the Blackwater River in East Sepik Province. The Govermas village is considered one of the major settlements of the Kwoma people, also known as the Washkuk. Date: mid-20th century. Medium: wood and pigments. Dimensions: 19 × 15 × 71 in.; 48.3 × 38.1 × 180.3 cm. Bowers Museum, Santa Ana, CA, USA.

A Garamut drum with crocodile form finials, Lower Sepik River. Length: 72 cm, 28.34 in. Auctioned in 2023 by Theodore Bruce Auctioneers & Valuers, Stanmore, Australia.

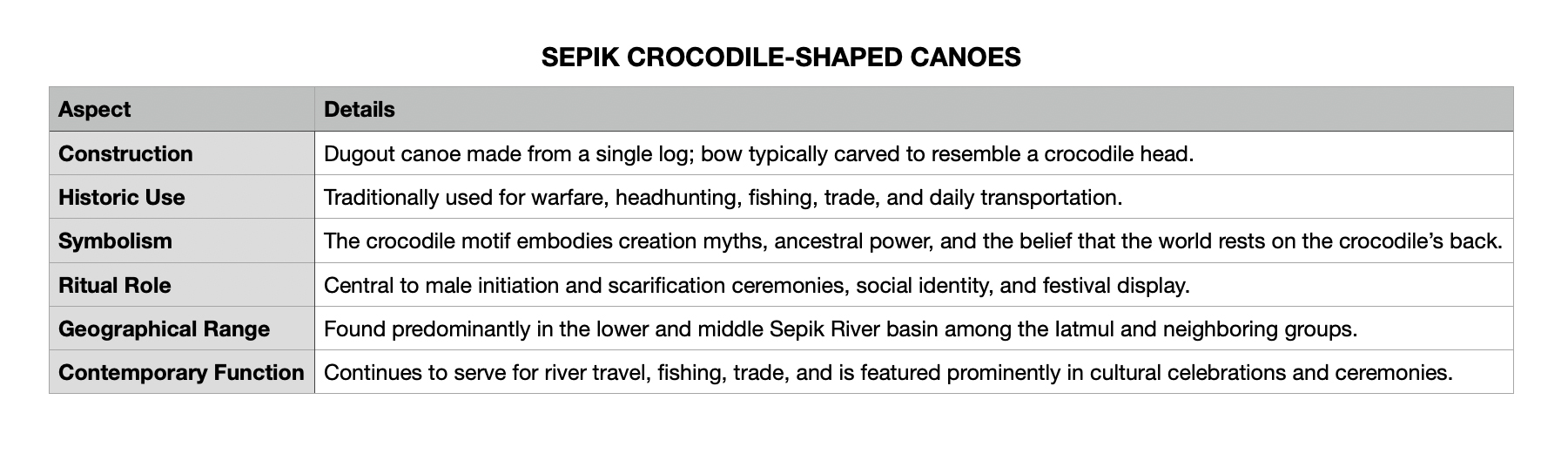

The garamut drum, also known as a slit drum, is one of the most iconic and culturally significant instruments in the Sepik region of Papua New Guinea. It is used by the Iatmul people and other neighboring riverine communities.

The drums are carved from massive logs that have been felled and hollowed out. A long slit is cut along the top, turning the drum into a resonating idiophone. The exterior of the drum is often engraved, carved, or painted with clan totem animals, such as crocodiles, fish, and birds, as well as geometric motifs. Some drums have finials in the shape of animal heads or ancestor figures, which adds to their ritual and aesthetic significance.

The shape, proportions, and decorative style of slit drums vary by region. For example, Western Iatmul garamut drums may have crocodile-shaped prows, Sawos drums feature pug-nosed animal faces, and Upper Sepik drums often combine multiple animal attributes and human forms.

The drum’s deep, resonant “voice” carries ceremonial, political, and social messages across great distances. Beats signal rites of passage, announce deaths, summon villagers and council members, mark ritual feasts, and warn of danger.

Garamut drums are sacred objects believed to be animated by ancestral spirits. Special rituals are performed to consecrate drums for use in ceremonies, and access to playing them is often restricted to initiated men or clan “big men.” In initiation rituals such as the Iatmul and Kaningara crocodile scarification rituals, the drum’s music marks key transitions. The drums are understood to embody ancestral power and echo the spirit house’s protective and connective function. Garamuts are considered to have spirits and names. Like masks and figures, they are powerful. They are believed to be so powerful that they can kill or make people sick. A garamut is said to be capable of taking on other forms and walking at night.

Each garamut represents both clan and individual identity. They hold symbolic life force and serve as “living social agents” in Sepik villages. Ownership and use signify kinship alliances, big-man authority, and the memory of clan achievements or events.

Selling or misusing a garamut is considered a severing of the lineage connection, highlighting its role as a vessel for communal memory and ancestral continuity.

Sepik men playing the garamut drum in a haus tambaran.

The kundu drum is an important musical instrument among the Iatmul and other communities along the Sepik River. This hourglass-shaped hand drum is typically carved from a single piece of wood and fitted with a taut lizard or animal skin head, which is held in place with rattan or plant fiber. Iatmul kundu drums are often adorned with intricate carvings and incised motifs representing clan totems, particularly crocodiles, birds, and human figures symbolizing ancestral spirits and mythical beings. Sometimes, handles are carved into the shape of crocodile heads or other significant animals, adding ritual and visual value to the instrument.

Kundus accompany formal occasions, including initiation rites, burials, feasts, house openings, boat launchings, singsing performances, and storytelling events.

The Iatmul consider the drum’s resonance the “voice of spirits,” and its music accompanies ceremonial singing, dances, and repetitive ritual rhythms.

Kundu drums are also used in healing ceremonies and rituals that honor ancestral spirits and strengthen social bonds within the community.

Each Sepik group, including the Iatmul, Sawos, Chambri, Kwoma, and Abelam, makes kundu drums that reflect their artistic styles, motifs, and ceremonial requirements.

Iatmul kundu drum from the 20th century. Medium: Wood, rope, pigment. Dimensions: 8 1/2 x 26 3/4 x 6 1/2 in.; 21.59 x 67.95 x 16.51 cm. The Minneapolis Institute of Art. Photo: Creative Commons, Public Domain.

The kundu drum sound: singsing at the Iatmul village of Kanganaman, Middle Sepik.

Crocodile-shaped everyday objects and sculptures. Left to right, clockwise:

A crocodile-shaped stool from the Sepik River area, 20th century. Medium: carved wood. Dimensions: 29 x 198 x 42 cm. Auctioned in 2016 by Auctionata Paddle, Berlin, Germany.

A carved wooden bowl with crocodile-shaped head and tail, from the Sepik region. Dimensions: length: 60 cm. Auctioned in 2023 by Lawrence Fine Art Auctioneers Ltd, Crewkerne, UK.

Detail of a crocodile-shaped vessel from the Sepik River area. Medium: carved wood, cowrie shell and stone inserts. Date: 20th century. Dimensions: 41.75 x 9.75 in.; 106 x 25 cm. Auctioned in 2016 by Cowan’s Auctions, Cincinnati , OH, USA.

Large hand-carved crocodile. Auctioned in 2024 by Albion Antique Auction Centre, Brisbane, Australia.

Crocodile staff from the Sepik area. Date: Early 20th century. Dimensions: 20 x 24 in.; 50.8 x 60.96 cm. Farrow Fine Art, San Rafael, CA, USA.

An impressive sculpture of a crocodile from the middle Sepik area. Dimensions: 57.48 x 16.14 x 9.84 in.; 146 x 41 x 25 cm. Oceanic Tribal Art, Louannec, France.

In the cultures of the Iatmul and other Sepik communities, the crocodile is a powerful symbol of ancestry and totemism. Its form is commonly incorporated into a variety of carved objects, including everyday items such as stools, bowls, ladles, vessels, and lime spatulas that are shaped like crocodiles or have crocodile head motifs. These objects serve both functional and symbolic purposes. Using and displaying these objects reinforces clan identity, invokes ancestral power, and affirms social prestige in public and domestic realms.

LEFT: Hand-carved crocodile with eyes made of Kaori shells; from the 20th century, Sepik River area. Length: 145 cm. Auctioned in 2023 by Henry’s Auktionshaus, Mutterstadt, Germany.

RIGHT: Old orator’s stool from the Seipk River area. Medium: carved polychromed wood, shaped with a flat back, a segmented tail, and carved teeth. It has inset cowrie shells for the eyes and face. Dimensions: 9′ x 36 x 10 in.; 23 x 91 x 25 cm. Auctioned in 2020 by material culture, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

The suspension hook, bearing the mark of the crocodile, is one of the most emblematic objects of Sepik cultures. Here is an amazing piece from my personal collection.

Iatmul suspension hook with stylized anthropomorphic faces, a bird on top, and a crocodile carved on the bottom. Date: from the 1970s. East Sepik Province. Dimensions: 115 x 20 cm. My personal collection, purchased from David Godreuil.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?