PAPUAN ANCESTRAL SUSPENSION HOOKS 5

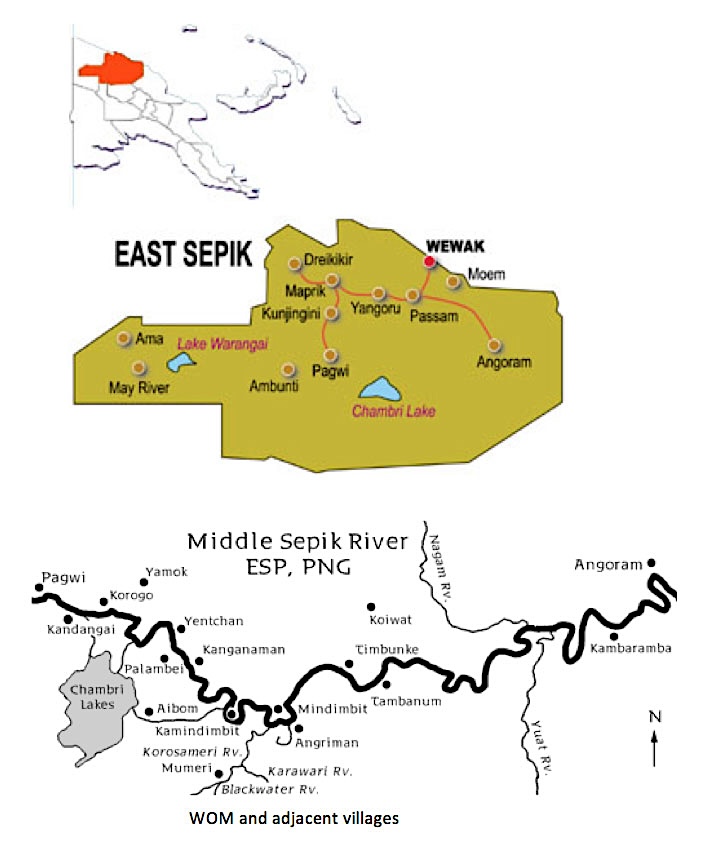

Papua New Guinea on the globe

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

ONE RIVER, ONE BREATH, ONE WORLD

The crocodile is more than just a motif; it is the river’s signature, imprinted on nearly every surface touched by the people of the Middle Sepik region.

When an Iatmul woman weaves a crocodile into the rim of her sago-frond basket or a man carves its spine into the handle of a lime spatula, they are not merely “decorating” utilitarian objects, but rather, they are affirming their membership in a community whose charter is ecological rather than territorial. The crocodile is the emblem of belonging, the sign that human life is conducted under the watch of the river and its ancestral beings.

In Iatmul thought, the crocodile is not a metaphor for the river; rather, it is the river’s elder kinsman, the senior relative who remembers when the currents were first set in motion. Each time the crocodile is carved into a betel-nut mortar or painted on a war shield, the object becomes a participant in social life. Ownership flows in reverse; it is not the human who possesses the carving but rather the crocodile who claims the human as a junior ally. A paddle leaning against the wall, its tip carved with watchful eyes, can silently “correct” a child because the household knows the crocodile is always observing.

The Sepik’s annual flooding and recession make land a shifting resource — never fixed, always renegotiated between water, silt, fish, mosquitoes, and humans. The crocodile embodies this instability as a creature that moves between the river and land, between stillness and sudden violence. Initiation scarification gives young men the skin of this creature, inscribing their bodies with the marks of an ancestor who both threatens and protects. The human body becomes a living landscape, reminding us that territory is not just lines on a map, but a flow of forces written into flesh.

According to Sepik myths, the first crocodile dove to the bottom of the river and brought up a mouthful of mud that became the earth. This creation story also serves as a philosophy of material life. Every substance the Iatmul use—clay, sago pith, driftwood, and pigment—is drawn from the river’s circulation and, thus, from the crocodile itself. By replicating the crocodile’s image on bowls, drums, and flutes, the Iatmul certify that these objects have passed through the proper channels of myth and ecology and are safe to use. Without that emblem, an artifact risks standing outside the sanctioned order of things.

Iatmul clans are ranked, but their hierarchy is not rigid. Rather, it is estuarine, branching and rejoining like the channels of the river itself. Crocodile imagery marks these flows of authority. The number and form of the dorsal ridges carved on a house post or painted on a shield can indicate clan seniority and alliances. Thus, imagery communicates social position without writing, embedding political order in visual codes recognizable to all insiders.

Western museums usually classify crocodile-carved objects as “ceremonial” because they seem too elaborate to be merely “practical.” Yet, in the village, the line between daily life and ritual is as porous as the riverbank. A lime gourd might travel to the gardens in the morning, be used in betel-chewing circles at midday, and rest on the ancestor shelf at night. This same vessel may later be ritually anointed during a healing rite. The crocodile does not change contexts; rather, contexts change around the crocodile, which remains the center of meaning.

Today, environmental change brings new tensions. Saltwater intrusion is pushing crocodiles into freshwater lakes, an area they were never mythically permitted to inhabit. When animals appear outside their proper zones, the balance of the ecosystem is disrupted. Younger carvers sometimes depict crocodiles with twisted tails or missing ridges—signs of unease about an environment that no longer follows ancestral patterns. Elders reject these images during initiation, saying, “The river has forgotten its own signature.” Here, ecological crisis becomes a semiotic crisis. To lose the crocodile is to lose the ordering principle that makes the world intelligible.

Ultimately, the Iatmul not only create crocodile-shaped artifacts, but also understand themselves as artifacts shaped by the crocodile. Scarification is the crocodile’s “maker’s mark” on the body. Women’s wigs recall the rows of dorsal scutes and are worn as a reminder that the human form is modeled on the animal form. In this sense, it is inadequate to say that the crocodile is merely “entwined” with material culture. The crocodile is the culture, and human beings are its temporary expressions, cast and recast like the river’s channels.

Thus, when an Iatmul child paddles a canoe with a prow carved in the shape of a crocodile’s jaw, the image is not merely ornamental. The child is in the canoe, the canoe is in the crocodile, the crocodile is in the river, and the river is in the child’s bloodstream—a ceaseless circulation of forms in which the sacred and the ordinary, the human and the nonhuman, are never divided.

BELOW

Sunrise on the Sepik River. By Picturejourneys – Flickr.

Sunset on the Sepik River

“The river is our mother and our father”

The crocodile plays many roles in the Sepik landscape. It is a totemic ancestor, a key player in creation myths, and a real, formidable presence. Its image connects human communities to their natural and supernatural worlds, turning every carved stool, drum, hook, or canoe into a place of spiritual and ecological significance.

By incorporating crocodile forms into utilitarian pieces, Sepik peoples infuse daily life with mythic and ecological significance. They are constantly reaffirming their place in a living environment shaped by ancestral beings, animal kin, and the cycles of the river.

This practice embodies what anthropologists call an “animistic ontology”: the belief that the world is filled with interconnected forces and that well-being hinges on acknowledging and responding to this interconnectedness in tangible objects and ritual performances.

The presence of the crocodile on everyday household items and prestigious ceremonial art illustrates how Sepik social hierarchy, clan identity, and cosmology are literally inscribed into material existence. Possessing, using, and displaying such objects become acts of social differentiation and communal belonging.

These practices reinforce the symbiotic relationship between human groups and their environment. The river, wetlands, and forest are active participants in the formation of identity, spirituality, and survival strategies, not passive backgrounds.

The extensive use of crocodile symbols shows the Sepik people’s commitment to an ecosystemic worldview: the health of the river, the abundance of animal life, and the maintenance of ritual cycles are all interdependent.

Thus, Sepik communities not only adapt to their environment, but also participate in it through creative, symbolic, and social means. They use art as a tool to negotiate the boundaries and connections between people, animals, ancestors, and place.

In summary, the everyday and sacred art of the Iatmul and their Middle Sepik neighbors is saturated with crocodile imagery and serves as a living testament to their dynamic integration with the landscape. This art form is a cultural and ecological strategy that affirms Sepik societies’ active shaping of the larger ecosystem through the persistent, reverent presence of ancestral and animal symbols in every aspect of material life. As anthropologists such as Hauser-Schäublin, Silverman, and Schindlbeck have noted, Sepik art is not merely ornamental, but rather a means of conceptualizing the environment and human relations.

Children bathe in the Sepik River at sunset near Kanganamun Village. Photo by Marc Dozier / Hemis /Alamy.

THE FRAGILE PULSE OF A LIVING RIVER

Why the Sepik matters

The Sepik River Basin in Papua New Guinea’s East Sepik Province is one of the largest and most culturally and biologically significant river systems in the Asia-Pacific region. The basin supports over 430,000 people who speak more than 300 languages. It harbors extraordinary cultural and biological diversity, including many species found nowhere else on Earth. The basin overlaps two “Global 200” ecoregions and contains three Endemic Bird Areas and three Centers of Plant Diversity. However, this unique biocultural ecosystem is under increasing threat from large-scale mining, land grabbing, and inadequate governance

THREAT NO. 1: INDUSTRIAL MINING

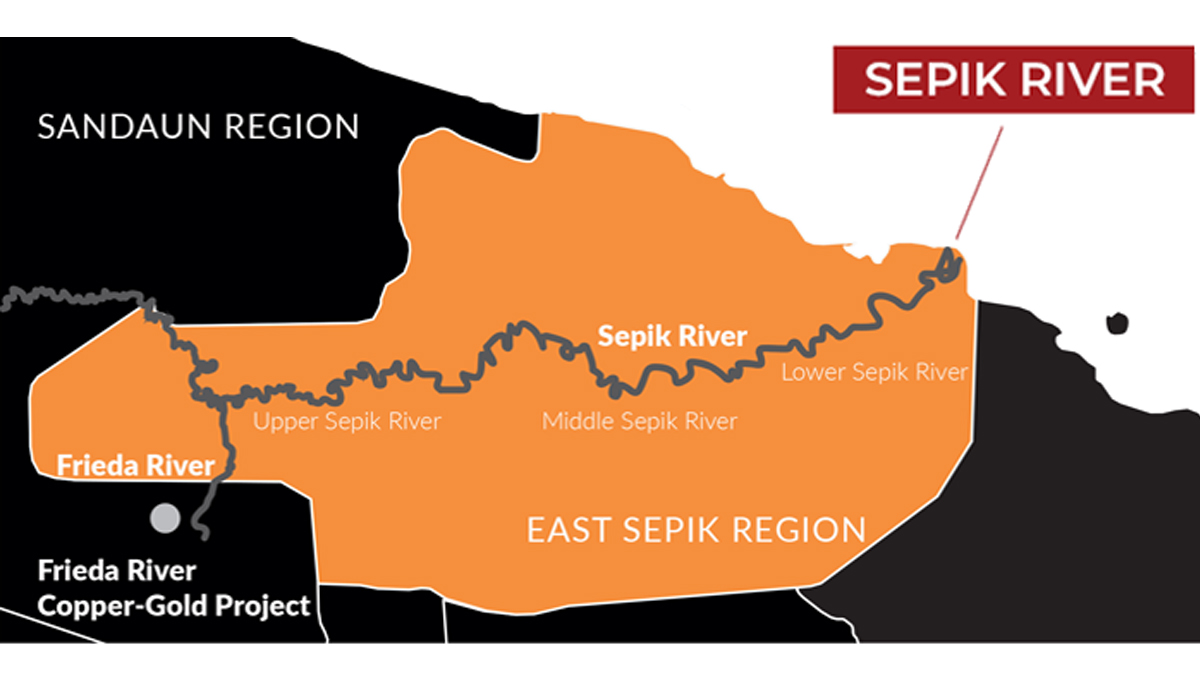

The most significant threat to the Sepik River Basin from industrial mining is the Frieda River Copper-Gold Project, which was proposed by PanAust Limited. This company is registered in Australia and is owned by the Chinese government. The project is a large-scale open-pit mine located at the headwaters of the Frieda River, a major Sepik tributary.

– Minerals targeted: Copper, gold, and silver.

– Project footprint: Over 16,000 hectares of rainforest.

– Infrastructure: Includes a hydropower dam, a tailings dam, roads, air and seaports, and a power grid.

The Frieda River Copper-Gold Project is operated by Frieda River Limited (FRL), which is wholly owned by PanAust Limited.

FRL is an Australian company and a subsidiary of China’s state-owned Guangdong Rising Holding Group. PanAust gained full control of the project in 2019 after the exploration rights had been transferred among several global mining firms since the 1960s.

The Frieda River development is part of the Sepik Development Project (SDP), a multi-project initiative that includes:

- Frieda River Copper-Gold Mine (FRCGP)

- A conventional open-pit mine targeting the Hitek porphyry deposit, one of the world’s largest untapped copper resources. It has estimated reserves of 12 million tons of copper and 19 million ounces of gold.

- Projected capital cost: US$2.8 billion.

- At full capacity, the mine will produce 175,000 tons of copper and 230,000 ounces of gold per year.

- Frieda River Hydroelectric Project (FRHEP)

- A 490 MW hydroelectric plant combined with a 191-meter-high asphalt core rockfill dam for tailings/waste storage and river management.

- Total hydro/energy infrastructure capital: US$3.2 billion.

- Hydro power will feed the Sepik Power Grid to support regional electrification.

- Sepik Infrastructure Project (SIP)

- Includes enabling infrastructure, such as upgrades and construction of approximately 300 km of roads, a regional airstrip, a port in Vanimo, and a 300 km pipeline to transport ore concentrate from the mine to Vanimo for export to Asian markets.

- Projected cost: US$739 million.

- Infrastructure is billed as a regional “gamechanger,” unlocking economic potential for the northern Momase region.

- Sepik Power Grid Project (SPGP)

- About 400 km of transmission lines will connect the mine and hydro site in the southeast to Hides in Western Province and in the northwest to Vanimo and beyond.

- Cost: US$418 million.

As of September 2025, the Frieda River Mine remains a major project in the pre-development, permitting, and environmental assessment stages. It is not yet operative and does not qualify as an active mining enterprise. The current plan anticipates that final mining permits will be granted by 2026, construction will begin around 2029, and the first ore will be produced in 2035.

While the project has received support from the PNG government and its developers, it is still under review by the Conservation and Environment Protection Authority (CEPA) and the Mineral Resources Authority (MRA).

Mine construction has not yet begun, and the project is the subject of ongoing debate regarding its environmental and social impacts on the Sepik region.

Business Advantage PNG, one of the premier business magazines, presents the project as follows: “The $8 billion (K26.5 billion) Sepik Development Project at Frieda River will create ‘a new economic corridor’ in PNG’s northwest. The developer, PanAust, suggests that the project could provide employment for approximately 5,000 people during construction and increase Papua New Guinea’s GDP by K90 billion over 40 years.”

Pink Floyd – Money

Who will benefit from this complex project?

Who will pocket the juicy bribes?

How much will local miners be underpaid and exploited? If not, there will be no profits.

Most importantly, what impact will the project have on the unique bio-cultural ecosystem of the Sepik?

Here are the answers.

- Tailings/waste storage risk

- Plan: Store mine tailings and waste rock sub-aqueous within a large ISF/dam complex built to ANCOLD standards. Company materials emphasize peer review and robustness. However, independent technical reviews have stressed consequence-of-failure scenarios, such as seismicity, extreme rainfall, and long-term containment obligations, and have noted the potential for catastrophic impacts to dozens of downstream villages should the embankment fail.

- Water quality, sediment, and biota

- Even without failure, long-term tailings storage poses risks such as acid mine drainage, metal mobilization, and altered sediment regimes. These risks could affect fisheries in a basin with naturally modest fish richness and many floodplain lakes that concentrate contaminants. (ResearchGate)

- Cumulative landscape change

- Linked hydropower, roads, camps, and air/river logistics can drive secondary deforestation, opportunistic logging, wildlife harvesting, and migration. The EIS biodiversity annex explicitly warns of the risk of “widespread small-scale illegal logging” once access improves.

- Cultural and distributional impacts

- Benefits mainly accrue where leases are located (Sandaun and West Sepik), while downstream impacts concentrate in East Sepik. This is a classic example of an upstream-downstream equity problem that fuels grievances and erodes social license. (savethesepik.org)

- Community consent/rights disputes

- In 2021, a human rights complaint was filed with Australia’s OECD National Contact Point on behalf of 2,638 Indigenous people from 64 villages, alleging inadequate risk management and consultation by PanAust/FRL. The NCP process and civil society updates keep this issue active as of 2024. (oecdwatch.org)

- Risk perception v. proponent assurances

- While FRL has stated that the tailings/hydro dam is “more robust than previous efforts,” community submissions and reviews continue to contest the sufficiency of the design and the long-term governance capacity, pointing to PNG’s track record with mine waste containment.

Bottom line: The dominant mining threat is a very large, upstream copper-gold project whose risk profile hinges on long-term tailings containment and preventing failure in a wet, seismically active basin. Even “no-failure” scenarios entail issues related to water quality, sediment, access, and cultural equity.

Don’t Let the Sepik River Become Our Next World Class Environmental Disaster

The Ok Tedi Mine in the Western Province of PNG, 2007. Photo Source: Ok Tedi Mine CMCA Review, Creative Commons.

The Ok Tedi environmental disaster is one of the world’s most notorious cases of industrial pollution. It was caused by the Ok Tedi copper and gold mine in Papua New Guinea’s Western Province. After beginning operations in the 1980s under the Australian mining company BHP (later BHP Billiton), the mine discharged vast amounts of tailings (mine waste) and overburden directly into the Ok Tedi and Fly River systems when a planned tailings dam failed during construction.

Rather than containing the waste, the company continued to dispose of it in the rivers, dumping around 80,000 tons of waste rock and tailings into the waterways each day. Over time, this resulted in:

- Destroyed thousands of hectares of rainforest through flooding and dieback.

- Heavily polluted the rivers with sediment and copper contamination, killing fish and altering the rivers’ natural courses.

- Undermined the subsistence farming and fishing practices of tens of thousands of Indigenous people who depended on the river.

The ecological impacts are still ongoing today, decades after the peak of operations. For local communities, the disaster was an environmental and cultural catastrophe because the river is central to their food security, transportation, and cosmology.

In the 1990s, international lawsuits forced BHP to pay compensation and eventually divest from the project, transferring its shares to a trust fund for Papua New Guinea. However, the damage to the Fly River system is considered irreversible, making Ok Tedi a textbook example of unsustainable mining and corporate negligence in the Pacific.

The mine became synonymous with irresponsible industrial development in fragile environments, highlighting failures in corporate and governmental oversight. Though some remediation efforts were undertaken and compensation was paid, experts estimate that the ecosystem will require centuries to recover, if recovery is even possible.

The Ok Tedi Mine in Western Papua has had a significant impact on the ecosystem. From above, the landscape appears flayed, with its soil peeled back and its living fabric erased.

Tailings from the Ok Tedi copper-gold mine in the Ok Tedi and Fly River waters.

The Ok Tedi disaster is often called an environmental disaster, but it wasn’t. It was worse.

There is no official casualty count because the damage unfolded through environmental collapse rather than sudden deaths.

The mine’s waste altered the Ok Tedi and Fly River system, killing fish, smothering riverbeds, poisoning soils with heavy metals, and destroying forests.

Tens of thousands of people (estimates range from 40,000 to 50,000) lost reliable access to food, clean water, and fertile gardens downstream.

Health consequences included malnutrition, increased exposure to disease, and shorter life expectancy. However, these are not easily counted as “casualties.”

No single death toll is recorded, but the disaster is often described as a “slow-moving catastrophe” in which ecological collapse has undermined the long-term survival and health of entire riverine societies.

Thus the problem with the Frieda River Copper-Gold Project in the Sepik Basin is more serious than one might think. The destruction of the Sepik’s fragile and precious ecosystem is also the destruction of entire communities and their culture. It’s the destruction of a unique biocultural ecosystem. The mine poses catastrophic risks to both the biological and cultural integrity of the Sepik Basin.

One river, one breath, one world.

As we saw in the long article on the Navajo Diné, uranium mining poisoned the water, soil, and air. This condemned miners and their families to slow deaths and undermined the survival of their people by destroying their fields, herds, and livelihoods.

The same shadow has fallen over the Ok Tedi and Fly River systems, and it is falling over the Sepik Basin. Pursuing profit at all costs—by the few, at the expense of the many—is not development, but predation. This practice endangers the ecosystems on which communities depend and, with them, the cultures that have flourished alongside the rivers for centuries. Imperiling a people’s identity and ancestral traditions is not merely a local tragedy, but a crime against humanity.

One breath, one world, one home.

THREAT NO.2: LAND GRABBING AND TENURE EROSION

AI generated image

“When the bulldozers arrived, we thought they were there for the road. It was only later that we understood that the road was the grab.” Village elder, East Sepik Province, 2023

A beginner’s guide to land grabbing by Oxfam International

In the 2020s, land grabbing is a neocolonial crime that governments help hide. Why does the world seldom hear the sound of bulldozers? Silence is baked into the business model. The new wave of land grabbing receives less media attention than classic human rights atrocities for three mutually reinforcing reasons.

- Legal Laundering

Most deals are formally legal. National investment laws written in the 1990s under pressure from structural adjustment programs allow 99-year leases for “public purpose” with the signature of a minister. Since these transactions are recorded in cadasters rather than courts, there are no plaintiffs or crime scenes. Investigative journalists therefore lack the paper trail that accompanies illegal activities such as logging or drug trafficking. The Tirana Declaration (International Land Coalition, 2011) warned that legality and legitimacy are not the same; ten years later, this has become the industry’s modus operandi.

- Epistemic Violence

Rural people with customary tenure literally do not count. Only 10% of land in Africa and 18% of land in Melanesia is registered; the rest is governed by clan memory and boundary trees. When a concession map is overlaid on this “empty” space, the algorithm registers terra nullius, “nobody’s land”, the doctrinal phantom that justified 19th-century settler colonialism. Since satellite imagery and national statistics cannot see the victims’ ownership, the seizure is cognitively impossible before it is physically irreversible.

- Donor Complicity

Governments that fund anti-poverty programs are often shareholders of the entities that seize land. For example, Germany’s state development bank (DEG) co-finances Amatheon’s 40,000-hectare Zambian plantations, and Deutsche Bank’s DWS fund held equity in 3.2 million hectares of farmland until civil society exposure forced divestment in 2022. Reporting too loudly would embarrass the donor, so the story is diplomatically downgraded to “land-use governance technical assistance.”

A bitter truth is that the grabbers are no longer lone wolves—they are states.

Contemporary land grabbing is geopolitical, not merely corporate. After the food price spike of 2007–2008, sovereign wealth funds and ministries of agriculture started treating foreign farmland as an extension of their territory—a kind of offshore granary that provides food security in times of global market panic.

Singapore, for example, is a city-state that imports 90% of its food. Through its state-owned agro-fund Temasek, it has secured 700,000 hectares abroad—an area larger than Singapore itself.

China’s “Going Out” policy funnels Belt-and-Road loans to state-owned grain companies (COFCO and Beidahuang), which now control 2% of Ukraine’s and 5% of Tanzania’s arable land.

Saudi Arabia’s King Abdullah Initiative signs intergovernmental memorandums of understanding (MoUs) that waive export quotas. In Ethiopia’s Gambella region, the Saudi Star rice project displaced 10,000 Nuer pastoralists while sending 80% of the output to Riyadh.

These are not market transactions between private actors. The buyer and seller are ministries, and the contract is sealed by embassy letters verging on diplomatic treaties. The power asymmetry is therefore interstate, replicating the protectorates of the late colonial era under the lexical camouflage of “South-South cooperation.”

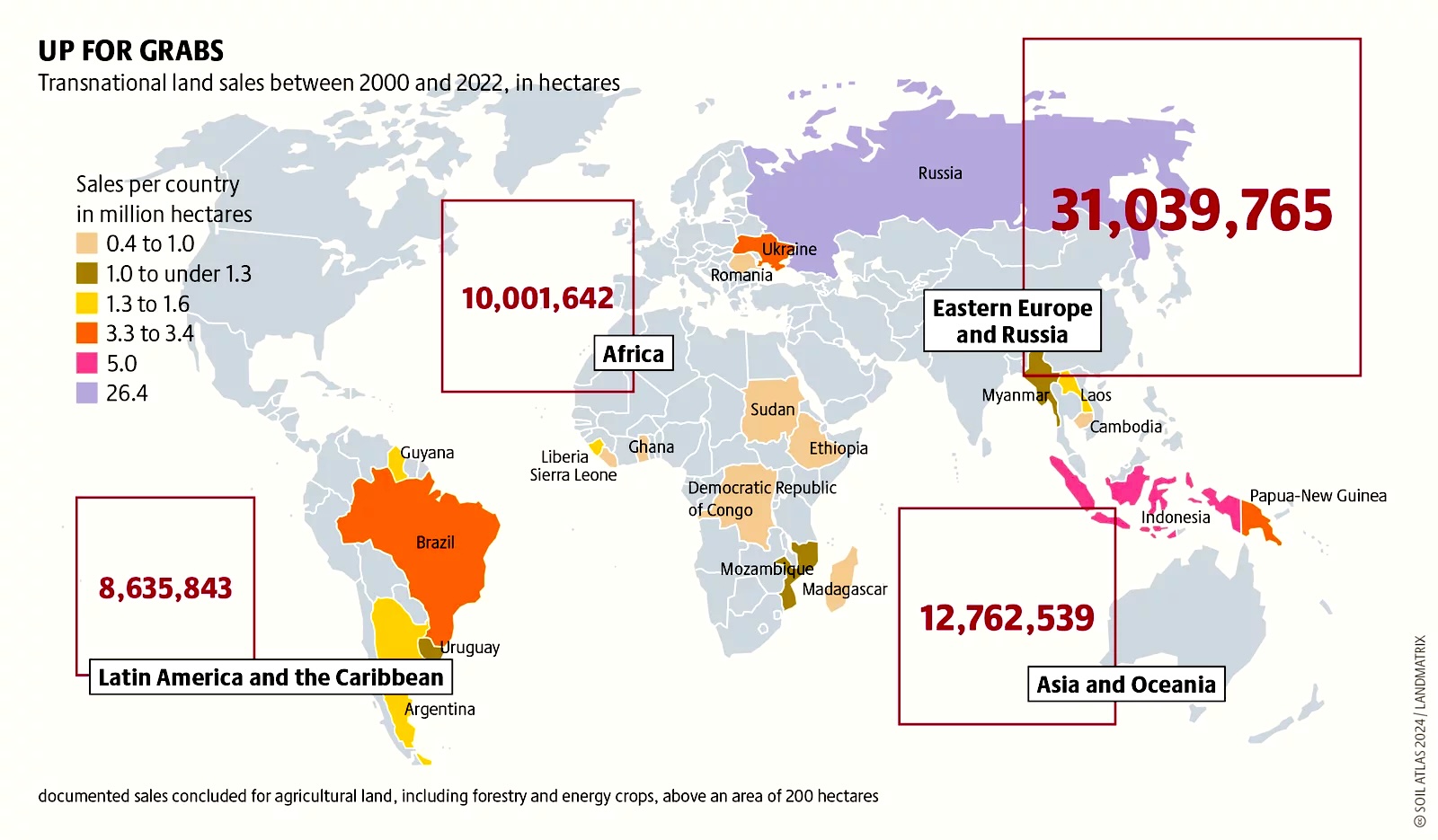

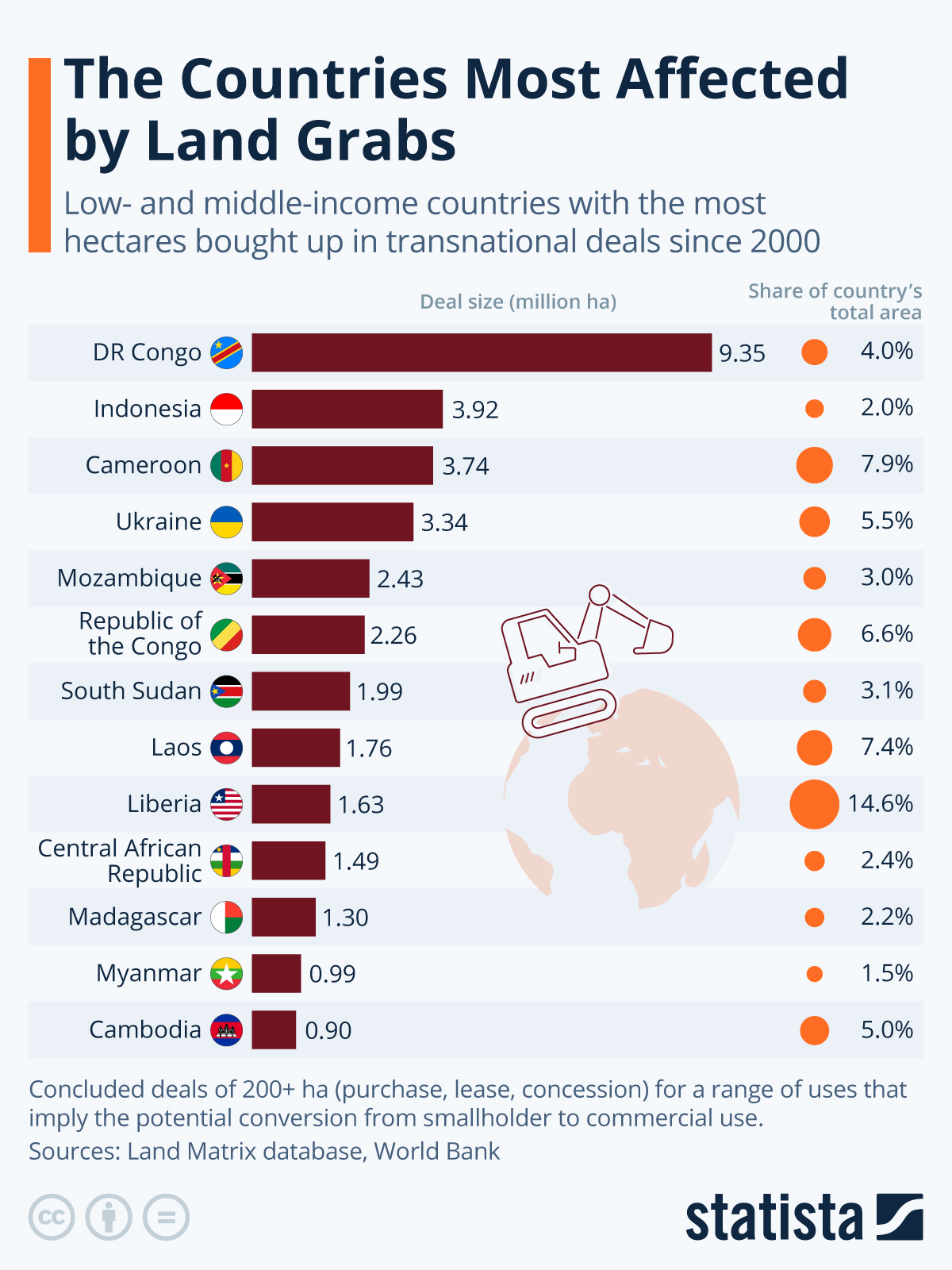

The data below give you an idea of the diffusion of this ‘crime in disguise’.

Countries and regions with weak state institutions or a high level of corruption are more vulnerable to land grabs by international investors. These grabs often result in the displacement of local communities and the loss of their livelihoods. Source: Soil Atlas 2024.

Who are the grabbers?

Singapore, China, and Saudi Arabia are in good company. Land grabbing is not a byproduct of globalization; it is one of its core mechanisms of accumulation. The following is a state-centered atlas of the phenomenon, showing the countries whose corporate capital, sovereign wealth vehicles, and bilateral aid agencies are driving the current wave of transnational enclosures.

There are two points worth noting.

First: France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, and Finland do not appear, but that does not mean they are innocent. These European countries invest in agricultural land abroad, driven by demand for biofuels and vertical supply chain integration. France and Germany, in particular, are active in land deals for crops and affiliated industries.

Second, several tax havens and financial hubs (e.g., Cyprus, the British Virgin Islands, and Hong Kong) appear in the top investor-origin lists because the ultimate beneficial owner (UBO) is routed through them. This can mask the true nationality of the capital.

Land Grabbing – AI generated image

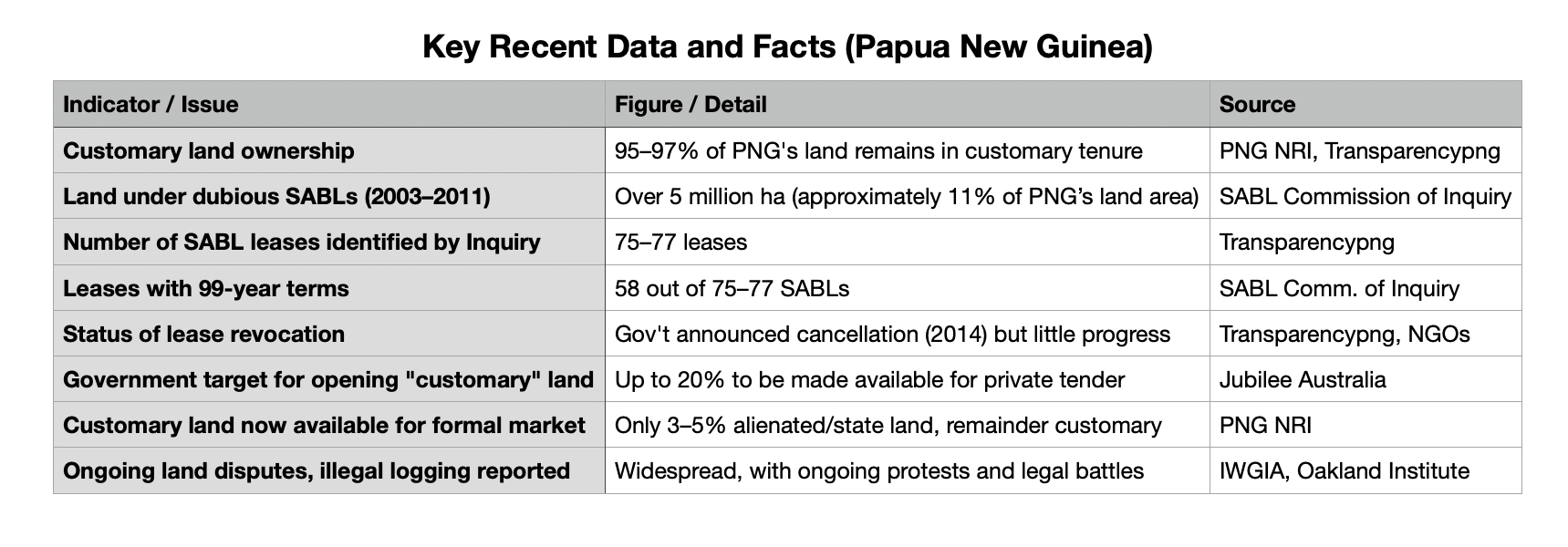

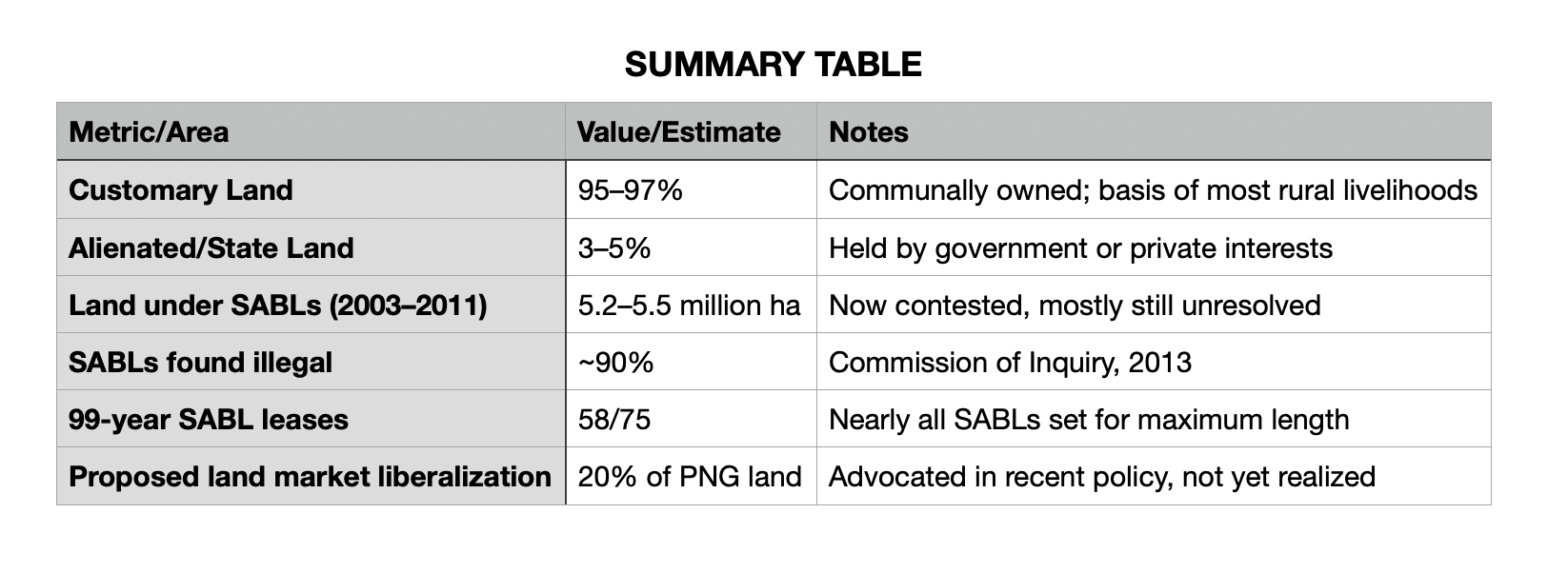

Papua New Guinea: A Laboratory of 21st-Century Land Grabbing

Papua New Guinea (PNG) is the third most targeted country in the Pacific for transnational land deals, after Indonesia and the Philippines. Two structural anomalies make the Sepik River Basin especially vulnerable:

- Legal Double-Helix

The national constitution recognizes customary tenure, so 97% of the country is technically unalienated clan land. However, the Land Act of 1996 allows the Minister of Lands to issue Special Agricultural and Business Leases (SABLs) “in the national interest.” Between 2003 and 2011, 5.2 million hectares—11% of the nation—were granted 72-year leases without a single parliamentary vote. After a 2013 commission of inquiry documented fraud and forged signatures, the leases were declared illegal. However, only a handful have been canceled, and most have simply mutated into new subleases held by Malaysian-Chinese conglomerates.

- Resource-Front Marriage

In the Sepik region, grabbing is not a stand-alone event. Rather, it is the infrastructure prequel to extractive industries. The same logging roads that justified the Special Agricultural and Business Lease (SABL) in 2008 now serve the Frieda River copper-gold mine (owned by the Chinese state-owned company PanAust). The Environmental Impact Statement acknowledges that the mine’s 16,000-hectare footprint will require an additional 38,000 hectares of “ancillary facilities” — a euphemism for resettlement sites, tailings ponds, and hydrodams being carved out of customary land without the consent of the Yimnangbit and the Sepik River and Yambon language communities. Thus, land grabbing has transitioned from palm oil colonialism to infrastructure colonialism; the concession is no longer the plantation but the pipeline.

- Carbon Colonialism—The New Layer

Since 2021, carbon offset brokers registered in Singapore have signed “voluntary conservation agreements” covering 1.8 million hectares in East and West Sepik. These agreements promise to pay clan elders quarterly in exchange for the right to sell REDD+ credits on the Verra registry. According to fieldwork conducted by the Oakland Institute in 2023, 87% of signatories believed they were accepting climate-aid grants rather than relinquishing their future right to farm or hunt. In this case, the grab is atmospheric rather than terrestrial: the carbon in the trees is commodified, the air above Sepik is rented to a German utility company, and the people are locked into 30-year non-use covenants—an airborne echo of the 19th-century treaties that divided Africa.

The extensive land grabbing in PNG: the most recent data

Papua New Guinea has experienced extensive land grabbing, mainly through the controversial Special Agriculture and Business Leases (SABLs) program. This program leased out customary land without the proper consent or benefit of traditional landowners. The latest available data and analyses, all from reputable PNG research institutes, government inquiries, and major NGOs, are summarized below.

Below are the notable developments of the 2023–25 period:

- The government proposed opening 20% of PNG’s customary land to private tenders. This move was widely criticized by civil society as threatening local control and rights.

- The SACBL Commission of Inquiry found that over 90% of the investigated leases were obtained illegally from customary landowners.

- Ongoing NGO advocacy challenges continued exploitation and calls for the return of land to its original owners.

- In December 2023, research from PNG’s National Research Institute (NRI) reaffirmed that the vast majority of land remains unbankable and difficult to protect against predatory or fraudulent schemes.

Sources:

PNG National Research Institute (NRI) Discussion Papers, 2023–2024

Commission of Inquiry into SABLs (2013) and updates via transparencypng

Jubilee Australia, IWGIA, and additional independent researcher reports

Conclusion: A Crime That Hides in the Footnotes of Progress

Land grabbing in the 2020s is not an aberration of globalization; rather, it is one of its core components. It is hidden in plain sight because the paperwork is immaculate, the victims are cartographically nonexistent, and the beneficiaries sit in cabinet meetings from Berlin to Beijing. The Sepik River Basin illustrates how this crime evolves: yesterday’s oil-palm lease becomes today’s tailings dam and tomorrow’s carbon credit. Each metamorphosis is announced as development, yet the trajectory is always the same: the transfer of territorial sovereignty from subsistence users to transnational capital backed by their home states.

The silence will endure until northern parliaments regulate the extraterritorial human rights conduct of their sovereign funds and Melanesian governments repeal the SABL loophole. But the river keeps its own records: mercury in the fish, silt where clear water once flowed, and elders who remember where the boundary trees stood. Their testimony is the final, unassailable land registry—if anyone is still listening.

A growing civil society movement led by groups such as Project Sepik aims to have the Upper Sepik River Basin declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. This designation would offer legal protection against mining and other extractive industries. Visit savethesepik.org to take action!

ADDITIONAL, INTERACTING PRESSURES

- Illegal & opportunistic logging

- PNG has long struggled with illegal logging, and new access created by roads and ports exacerbates the problem. The Sepik floodplain’s peat-rich wetlands and gallery forests are especially vulnerable. Logging increases erosion, turbidity, and altered flood pulses, and it fragments crocodile nesting wetlands. The FRL biodiversity annex itself warns of the risk of induced illegal logging from improved access.

- Fire and wetland degradation

- Community-level grassland burning for hunting and cultivation has historically damaged nesting habitats for Crocodylus novaeguineae. Local initiatives, such as the SWMI and Ambunti, have emerged to curb these practices and restore wetlands.

- Governance capacity gaps

- Effective river basin management has been inconsistent. WWF and its partners have promoted an Integrated River Basin Management framework for the Sepik, but its implementation remains a work in progress. Protection status is limited (e.g., Hunstein Range WMA, and broader Ramsar/World Heritage proposals have not yet been fully realized).

- Cultural continuity risks

- In-migration tied to extractive industries, the monetization of artifacts and ritual spaces, and uneven distribution of benefits can accelerate language shift, ritual decline, and reinterpretation of art and landscapes. This has been documented in long-term studies among the Eastern Iatmul and is noted in UNESCO’s Tentative List dossier for the Upper Sepik.

Papua New Guinea & illegal logging by Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime

SCENARIO VIEW: WHAT COULD GO WRONG, CONCRETELY

- Dam/ISF failure or overtopping during extreme rainfall or seismic events would result in a pulse of sediment- and metal-laden tailings through the upper and middle Sepik lakes. This would affect water quality, fisheries, gardens, and the economies based on crocodile harvesting. Displacement and long recovery times would occur for floodplain food webs. (Independent EIS reviews identified more than 30 villages at immediate risk in worst-case scenarios.)

- No-failure, slow-burn impacts → No failure, slow-burn impacts: chronic water quality exceedances, fishery decline, and cumulative access-driven deforestation (e.g., illegal chainsaw logging and wildlife harvesting), which compromises cultural sites and initiation landscapes.

- Tenure erosion via SABL-like mechanisms → long leases/licenses sideline clan rights, land disputes escalate, and community leverage over conservation and cultural heritage is reduced.

WHAT WOULD ROBUST SAFEGUARDS LOOK LIKE?

- No downstream riverine tailings disposal and fail-safe, seismically robust tailings design with independent, transparent, lifetime oversight and community-controlled monitoring (not just periodic audits). Public release of water-quality data

- An access-management plan (gates, patrols, clear legal consequences) to prevent induced illegal logging and opportunistic extraction once roads open, as FRL’s own biodiversity appendix identifies this as a major risk.

- Binding benefit-sharing with not only lease-area landholders but also downstream East Sepik communities to address the asymmetry flagged by social impact reviewers.

- Tenure justice: full nullification of illegal SABLs, restitution where appropriate, and legal reforms that close loopholes enabling lease-based land grabs.

- River-basin governance: fund and implement the Sepik Integrated River Basin Management framework; advance the Ramsar nomination/management and pursue World Heritage listing to harden conservation status and attract resources.

TL;DR

- The most consequential near-term threat is the proposed Frieda River porphyry copper-gold project. The risks associated with this project include tailings dam safety, acid mine drainage, and a cascade of secondary impacts, such as illegal logging, in-migration, and cultural dislocation. These issues disproportionately affect communities downstream in East Sepik Province.

- Land grabbing through Special Agricultural and Business Leases (SABLs)—and their lingering legacy—has been well-documented by NGOs and inquiries (notably the Commission of Inquiry into SABLs, the Oakland Institute, and Global Witness). Cases in East Sepik (e.g., Turubu SABL) illustrate how customary land was leased without consent, opening doors to logging and plantation schemes that erode both ecology and cultural sovereignty.

- Safeguarding the Sepik’s biocultural ecosystem requires a three-pronged approach:

- Strengthen basin-wide governance through Integrated River Basin Management (IRBM).

- Secure land tenure by nullifying unlawful SABLs and closing legal loopholes.

- Harden protections via Ramsar designation and UNESCO World Heritage recognition.

A baby in a village along the Sepik River. What will his future hold? (Photo: JK Reportage – Alamy)

The Second Amazon: The Hidden Natural Wonder Under Threat in PNG | Foreign Correspondent – ABC News Australia

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?