PAPUAN ANCESTRAL SUSPENSION HOOKS 2

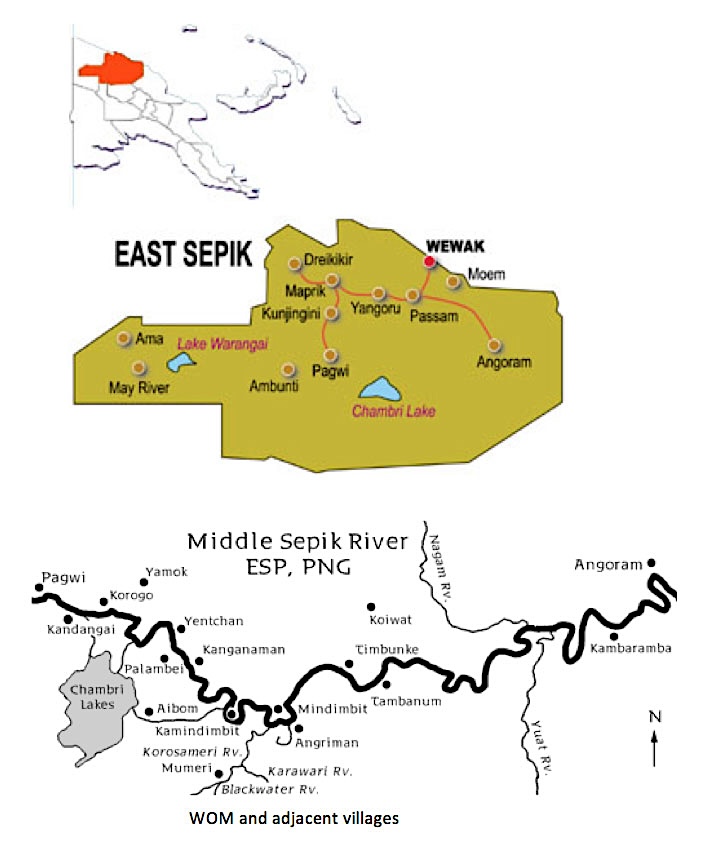

Papua New Guinea on the globe

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

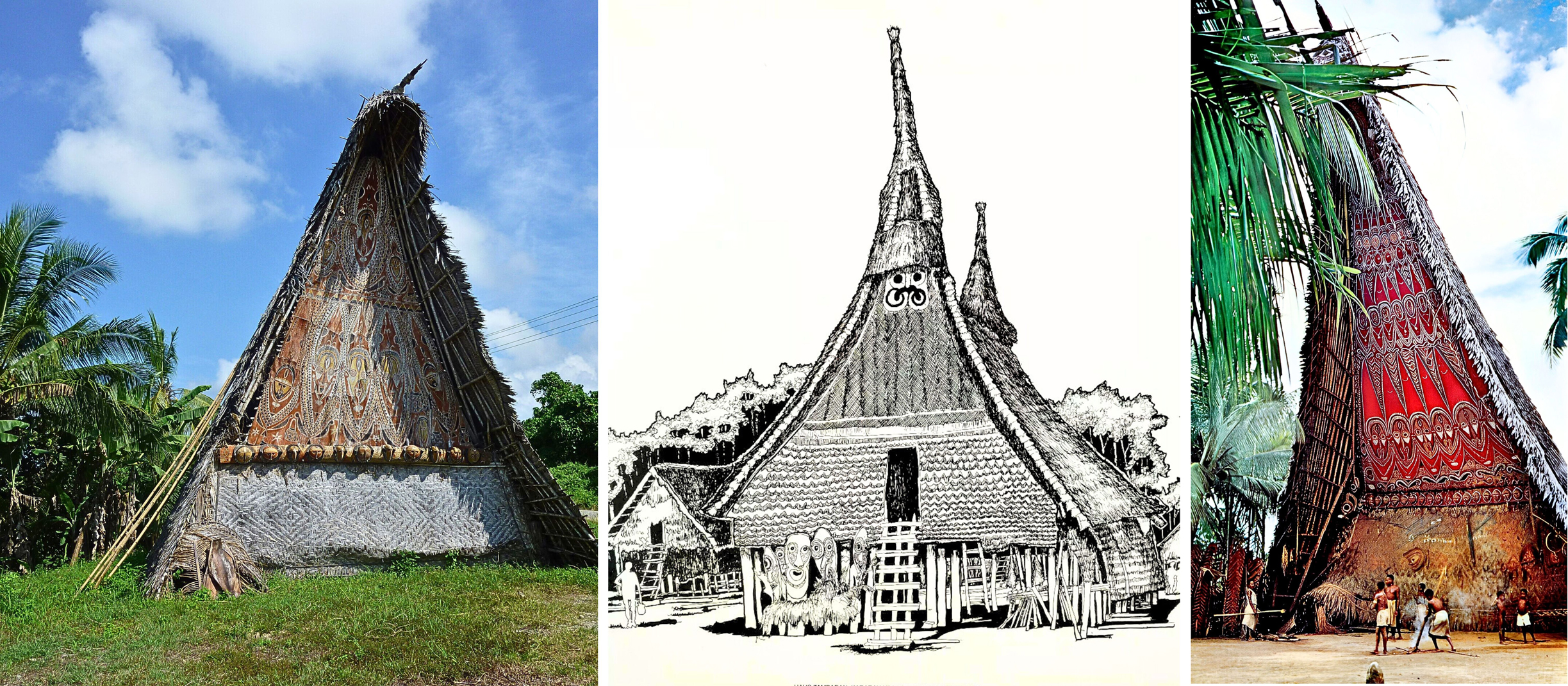

THE MEN’S CEREMONIAL HOUSE: N’GEKO OR HAUS TAMBARAN

The haus tambaran is a monumental ceremonial house widespread in almost all of the villages along the Middle Sepik, where it serves as the epicenter of ritual, governance, and artistic production. This distinctive men’s ceremonial house is not exclusive to any one group, but commonly associated with peoples such as the Iatmul, Abelam, Arapesh, Kapriman, Angoram, Chambri, Sawos, Yessan-Mayo, and other Sepik River tribes.

The terms haus tambaran, men’s ceremonial house, and spirit house refer to the same building type, though names and emphasis may vary across languages and local usages. Haus tambaran is a Tok Pisin term meaning “spirit house.” It is used especially in the East and Middle Sepik to describe traditional ancestral worship and men’s houses. Among the Iatmul, the local term are N’gego or N’geko, especially when referring to a building reserved for male-only rituals, governance, and storage of sacred objects. Women are generally prohibited from entering, and sacred knowledge and objects are kept hidden from them. Thus “spirit house” and “men’s ceremonial house” are synonymous terms often used interchangeably in academic and local contexts.

A haus tambaran’s structure is visually striking. It has an elongated, steeply pitched, saddle-shaped roof that slopes dramatically from a towering front gable to the ground in the back. The front often stands 25 meters tall and displays a massive, painted facade rich in symbolic imagery, such as stylized ancestral figures and masks known as Ngwalndu.

The building is constructed using sago palm thatch, timber posts, and decorative beams. The interior columns and rafters are elaborately carved and painted, reflecting the Iatmul’s renowned skill in woodcarving and painting.

In the Iatmul Haus Tambaran, the prominent ridgepole is a central architectural and symbolic element. It dramatically slopes upward from the rear to the towering front façade and is held aloft by the Meri Post (Female Post). The meri post is an elaborately carved pillar, often featuring a female figure at its base, positioned centrally to support the entire weight and balance of the massive ridgepole, much like a trapeze artist balanced on a beam. Together, the meri post and ridgepole embody the duality of male and female forces central to Iatmul cosmology. The female post represents nourishment, fertility, and the generative force. It anchors the house and connects it to the earth, symbolizing the womb and maternal lineage. The male ridgepole is associated with phallic imagery and represents authority, aggression, and the creative principle. Yet this force is supported and made stable by the female post, expressing mutual dependence.

The architecture is a deliberate metaphor for cosmic and social balance. The Iatmul perceive the house itself as a female entity, with the meri post as its generative anchor and the ridgepole as a masculine force rising above yet wholly dependent on the feminine.

This concept is reflected in artistic motifs as well. Masks and façade paintings in the Haus Tambaran often blend male and female iconography to symbolize the joint powers of nourishment and creativity.

During major rituals, including men’s initiations, the relationship between the ridgepole and the meri post is emphasized in myth, ceremony, and secrecy, dramatizing the inseparable unity of male and female. Thus, the meri post and ridgepole support more than just the physical weight of the haus tambaran; they are also living expressions of Iatmul ideas about gender, balance, and the cycles of creation and fertility.

LEFT: Haus Tambaran near Apangai, Maprik District, Papua New Guinea. Photo by Ingo Kühl, 2012. Public Domain.

CENTER: Sketch of the Haus Tambaran of the village of Kararau. From a 1912 photo.

RIGHT: Haus Tambaran in the Maprik District, 1962. Photo by John Scofield.

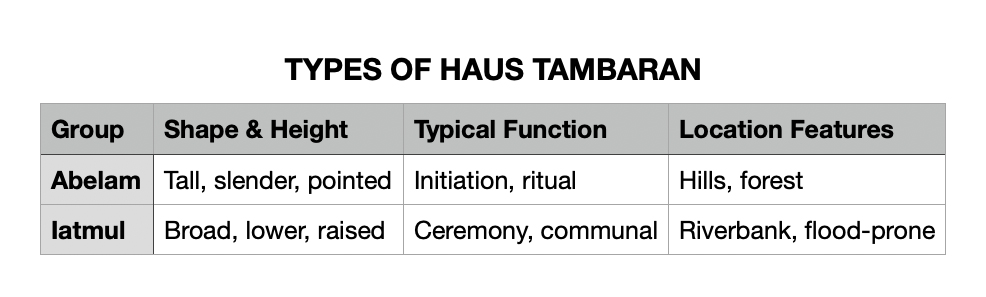

Did you notice the variation in Haus Tambaran architecture—the tall, slender style versus the broader, shorter style? This variation reflects the regional, cultural, and ritual differences among the Sepik peoples of Papua New Guinea, particularly between the Abelam (Maprik) and the Iatmul groups.

Apangai Village is located at the foot of the Owen Stanley Ranges. The Apangai people belong to the Abelam society in the Maprik District, which is located north of the Sepik River. This Haus Tambaran’s structure is high-peaked and cathedral-like, with a mysterious, dimly lit interior. The main entrance is often intentionally low, forcing initiates to crawl, symbolizing their rebirth into full personhood or ritual adulthood. The house is mainly reserved for men. Women appear on painted barks, but they do not participate in the main rituals inside. The interior functions as both a gallery of Abelam masterworks and a living sanctuary of ritual objects, mythic stories, and clan history. These are continually reactivated in yam cult and initiation ceremonies.

Tall, slender structures are typical of the Abelam and other communities in Maprik. Their soaring, pointed rooflines symbolize a connection to ancestor spirits and cosmic forces, emphasizing verticality and sacred protection. The height also serves as a visual marker of prestige and power that is visible from afar in the landscape.

Broad, lower structures like the one in the center are common among the Iatmul and in villages like Kararau. These buildings are wider and are often raised on stilts. They feature multiple entrances and lavish carvings under the eaves. Their design allows for larger gatherings, complex ceremonies, and the storage of ritual objects. The horizontal emphasis reflects a greater focus on communal interaction and proximity to water, specifically the Sepik River, as Iatmul settlements are closely tied to aquatic environments.

Maprik’s hilly terrain allows for tall, freestanding houses. In contrast, Iatmul areas along rivers require raised structures to counter seasonal flooding, which dictates a broader, sturdier design. Each design communicates spiritual, social, and ecological values unique to the respective group, making the haus tambaran a key architectural and cultural landmark in Sepik societies.

Detail of the Haus Tambaran in Apangai, Maprik District, East Sepik Region. Photo by Ingo Kühl, 2012. Creative Commons, Public Domain.

BELOW

The entrance to the Haus Tambaran in Apangai, Maprik District, East Sepik Region. Photo by Belgian photographer Rita Willaert – Flickr.

Rita Willaert is a Belgian photographer and traveler based in Gavere (Belgium). She is best known for her extensive visual documentation of cultures, architecture, and daily life from around the world, which she shares with a wide online audience, particularly through her popular Flickr page, where she has published tens of thousands of photographs from her travels. Rita has kindly agreed to let me publish some of her photos. I thank her warmly and urge you not to copy or use her photos without her consent.

LEFT: Haus Tambaran in the Iatmul village of Kabriman, Sepik river region, East Sepik province. Photo by Marc Dozier | Alamy.

RIGHT: The newest men’s house in Tambanum, a village of the Iatmul people in the Middle Sepik, built around 2010. This men’s house belongs to the Crocodile clan. The rear facade features visible river wave patterns and the face of the building’s female spirit. At the top is an eagle finial. Inside the building, men are engaged in a formal political discussion. 2014. Creative Commons.

Similar to the men’s house in Tambanum, the Haus Tambaran in Kanganaman Village (Wosera-Gawi, Sepik) also belongs to the Iatmul people. Kanganaman is a significant Iatmul settlement, and its spirit house, called Wolimbit, has long served as a ceremonial, ritual, and social center for Iatmul clans in the area. The carvings, artwork, ancestral posts, and ceremonial practices in the Haus Tambaran reflect Iatmul traditions, mythology, and clan histories. This further confirms its status as an iconic Iatmul structure along the Sepik River.

Celebrated as one of the most elaborately carved and artistically significant structures on the Sepik River, this ceremonial house is a remarkable example of Iatmul culture. Even in states of ruin, its artistic features and monumental architecture have left a strong impression on visitors and researchers alike. The building itself was larger and longer than many other ceremonial houses in the Sepik region, with an unusually grand length-to-width ratio of four to one. The massive carved posts, known as tambuna posts, were considered sacred and were linked to major lineages. They featured stylized ancestors, spirits, and animal motifs. Painted bark panels used in initiation ceremonies were also a hallmark of the Kanganaman haus tambaran. Scholars and field researchers have documented motifs from faded screens. The old house’s significance was formally recognized when it was designated a National Cultural Property, underscoring its importance in Papua New Guinea’s heritage and the wider Sepik cultural landscape.

LEFT: Haus Tambaran in the Iatmul village of Kanganaman, Wosera Gawi, Middle Sepik. Photo by Liebert Kirakar, PNGTPA.

RIGHT: The female meri post on Haus Tambaran in Kanganaman village. Photo by Ursula Wall – Frickr.

The Kanganaman Haus Tambaran during a flood of the Sepik River.

Some of the carvings of the Kanganam haus tambaran. Photo by Belgian photographer Rita Willaert – Flickr.

The carvings in the Iatmul Kanganaman Haus Tambaran are renowned for being some of the most elaborate and symbolically significant in the Sepik River region. Spanning supporting posts, finials, and ritual objects, these carvings serve as a visual archive of clan mythology and ancestral power. Haus Tambaran posts, also known as tambuna posts, are adorned with images of ancestors, crocodiles, snakes, and mythical creatures. These carvings relate to both individual clans and the broader cosmology of the village. These posts are sometimes made of stone, passed down through generations, and imbued with sacred meanings, sometimes tied to specific lineages, such as the Walkam clan. Finials and bird-man forms often adorn the roof or interior, referencing clan totems and spiritual protectors. All carvings and masks are created as both aesthetic works and vessels for spirits that are actively involved in rites and initiations. They are intended to provide protection, guidance, and a connection to ancestors.

The haus tambaran also holds benches, drums, and carved stools, such as the kawa rigit (debating stool), which serve ritual and social functions during clan gatherings and initiations.

Sculptures in the Kanganam haus tambaran. Photo by Belgian photographer Rita Willaert – Flickr.

Now, let’s reach the village of Yamok. It is often described as an Iatmul village in scholarly and artistic contexts. However, it is also closely associated with Sawos communities. This reflects the intertwined culture and geography of the Middle Sepik floodplain. Here, cultural boundaries blend fluidly, and artistic repertoires and clan identities overlap.

Yamok lies several hours’ walk inland from the main course of the Sepik River. Accessible by swampy trails and side streams, the village is well known for its vibrant cultural life, which is rooted in Sepik traditions. Yamok is renowned for its ancient creation stories and the unique carved bird figures known as subut, which play a central role in myth and ritual. According to their foundational myth, a bird protected a woman from a crocodile, and the resulting offspring included humans and the “crocodile man,” who is believed to inhabit nearby lakes and channels.

The village’s craftsmen are especially noted for their woodcarvings, masks, and ancestor figures, which blend Iatmul and Sawos artistic styles.

The social and ritual heart of Yamok is the Haus Tambaran, adorned with masks, carved posts, and totemic wildlife symbols. All major ceremonies, council meetings, and traditional events are held within or around this structure to maintain the continuity of ancestral beliefs and social structure.

A detail of the front masks of the haus tambaran in Yamok, several hours walk off the Sepik river. Photo by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

LEFT: Detail of a Haus Tambaran, 2009. Photo by Kim Gordon Bates | Alamy.

CENTER: A mask decorating a Haus Tambaran in Tambanum, along the Sepik River, 2009. Photo by Efrat Nakash.

RIGHT: This impressive painted and carved mask is a classic Ngwalndu (“spirit face” or “mother of the men’s house”) from the Haus Tambaran of the Abelam people in the Maprik area of the Sepik, East Sepik Province.

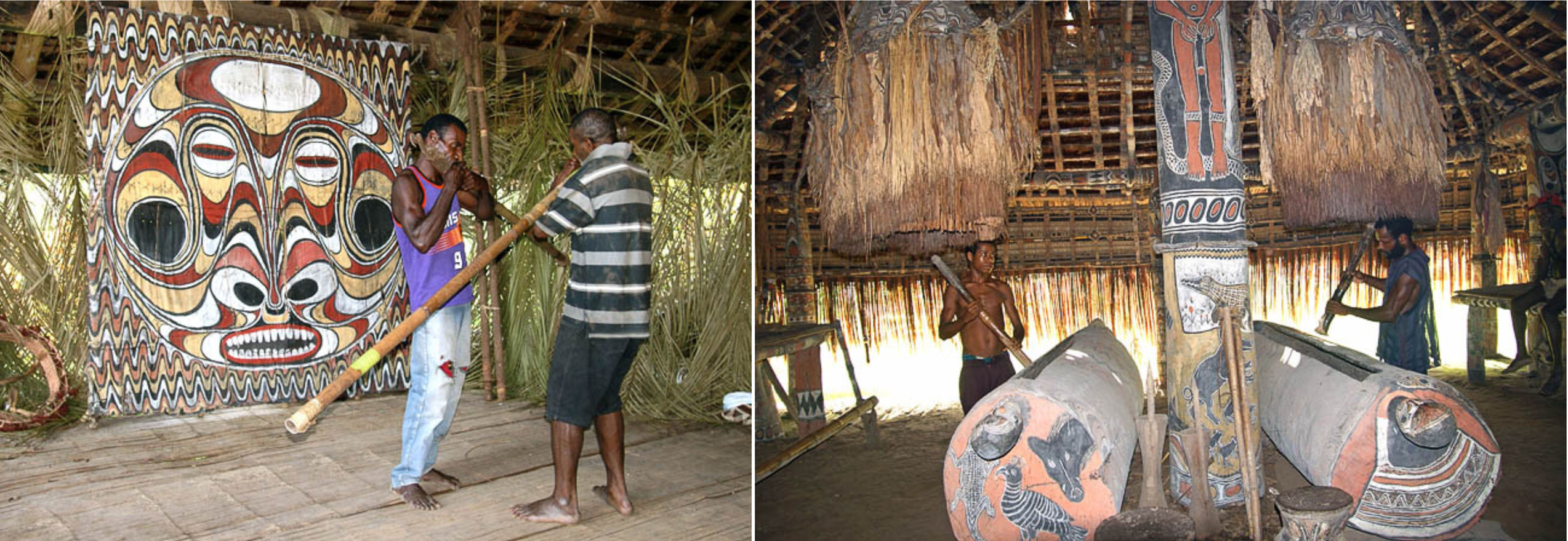

Every aspect of the Haus Tambaran’s architecture has mythological significance. Its form dramatizes the transition between chaos and order and the realms of the living and ancestral spirits. The inner space is a sacred, male-dominated area lined with carved totems, drums, skull racks, suspension hooks, and paintings and carvings that serve as representations of ancestors and stylized depictions of women’s bodies. This art is sacred and central to Sepik identity. The gabled ends bear female masks adorned with feathers, but painted with male flying fox motifs, expressing composite gender symbolism.

The interior is supported by massive, elaborately decorated beams and posts, especially the central meri post.

The vast open floor is dominated by ritual furnishings, including large carved totems, slit drums (garamut), masks, ceremonial stools, and string bags (bilums), all of which have strong symbolic and aesthetic significance.

Woven screens or bark paintings (ngwalndu) adorn the gabled ends, representing ancestral spirits or stylized female figures. These screens serve as both sacred icons and boundaries, concealing the inner sanctum from uninitiated eyes.

The entire space is considered the “belly” of the house, reinforcing its role as a female entity. The display of masks, carvings, and musical instruments dramatizes the cycles of birth, death, and renewal.

The objects and paintings inside are believed to house spiritual power. The sound of drums and flutes signifies the presence of spirits. These rarely seen treasures are essential for maintaining ancestral connections and social order.

Thus, the interior becomes a powerful manifestation of Sepik artistic achievement, ancestral worship, and community identity and hierarchy as enacted through ritual and social practices.

Now, let’s enter the Haus Tambaran near the Iatmul village of Palimbei (also spelled Palimbe or Palambei) on the Sepik River.

The Haus Tambaran of Palimbei, 2009. Photo by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

Inside the Haus Tambaran near Palimbei, on the Sepik river, 2014. Photos by Carsten ten Brink – Flickr.

Art pieces on the attic floor of Haus Tambaran near Palimbei, 2009. Both photos by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

Now, let’s take a look inside the Haus Tambaran in the small village of Yessam (also known as Yessan-Mayo) in the hills north of the Sepik River. Yessam is home to the Yessan-Mayo people, a distinct group closely related to the Kwoma and Nukuma peoples. Together, they form a distinct ethnolinguistic community within the Sepik cultural mosaic.

The Haus Tambaran of Yessan-Mayo. Last photo in the right corner by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

The Haus Tambaran of Yessan-Mayo. Photo by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

Now, let’s move to Yamok. Located north of the Sepik River, slightly inland from the riverbank, Yamok lies in an area known for its mix of riverine and swamp environments. These environments facilitate agriculture, notably yam cultivation, as well as sago production. As I wrote, Yamok is often described as an Iatmul village in scholarly and artistic contexts. However, it is also closely associated with Sawos communities, reflecting the intertwined culture and geography of the Middle Sepik floodplain.

Sing-sing dancers perform in front of the Haus Tambaran in Yamok village. Yamok is often described as an Iatmul village in scholarly and artistic contexts, but it is also closely associated with Sawos communities. This reflects the intertwined culture and geography of the Middle Sepik floodplain. A traditional celebration, the Yamok sing-sing gathering brings together people from different clans or villages to showcase their distinct cultures through music, dance, costumes, and ritual performance. Sing-sings in Yamok often mark special events, such as initiations (e.g., crocodile man rites), community feasts, or visits from outsiders. They typically feature striking body decorations, masks, storytelling dances, and the rhythmic beating of drums. These celebrations foster communal pride, cultural exchange, and social cohesion, uniting participants and audiences through shared artistic expression and ancestral tradition.

A glimpse of the inside of the Haus Tambaran of the Yamok village. Photo by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

Details inside the Haus Tambaran of the Yamok village. All photos by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

The image above shows the elaborately decorated interior of a Yamok haus tambaran, a ceremonial spirit house found in the Middle Sepik region. The space is dominated by spectacular sculptural posts and free-standing figures that display the classic traits of the artistic traditions of the Sepik River and specifically the Sawos-Iatmul people.

The central pillar, which is elaborately carved and painted, serves as both physical and spiritual support for the house. Adorned with mythical imagery, it intertwines human, animal, and spirit forms representing clan ancestors and totem animals, who are key mediators between the human and ancestral realms.

The freestanding sculptures, including the bird and mask forms at the base of the post, represent powerful mythological beings often associated with clan creation stories or protective spirits. The bird figures often depict the hornbill or cassowary, which are highly symbolic animals in Sepik cosmology.

Large face masks and standing figures feature bold, swirling designs incised and painted in ochre, white, red, and black. These patterns recall facial tattoo motifs, body paint, and natural markings associated with ancestors and emblematic animals.

The interior walls of the house are lined with more carved faces, masks, ancestor figures, and ritual objects, such as woven tassels and shell ornaments. Together, these items contribute to the apotropaic, sacred atmosphere of the Haus Tambaran, reinforcing its status as a spiritual sanctuary and a treasury of clan history.

Benches and carved posts along the perimeter are also decorated, showing continuity of design and the integration of functional and symbolic art.

Each element, from the patterns on the pillars to the individual sculptural motifs, carries symbolic significance, representing lineage, cosmological order, and the presence or favor of ancestral spirits. The art is not merely decorative; it is “activated” during ceremonies, particularly initiations, yam cult rituals, and sing-sing gatherings, to promote the well-being of the clan and connect with the mythic past.

This environment is a living expression of Sepik artistic genius where sculpture, architecture, and ritual performance are utterly intertwined. This maintains the clan’s link to its ancestors and the spiritual potency of the house.

Details inside the Haus Tambaran of the Yamok village. All photos by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

Art inside the Haus Tambaran of the Yamok village. All photos by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

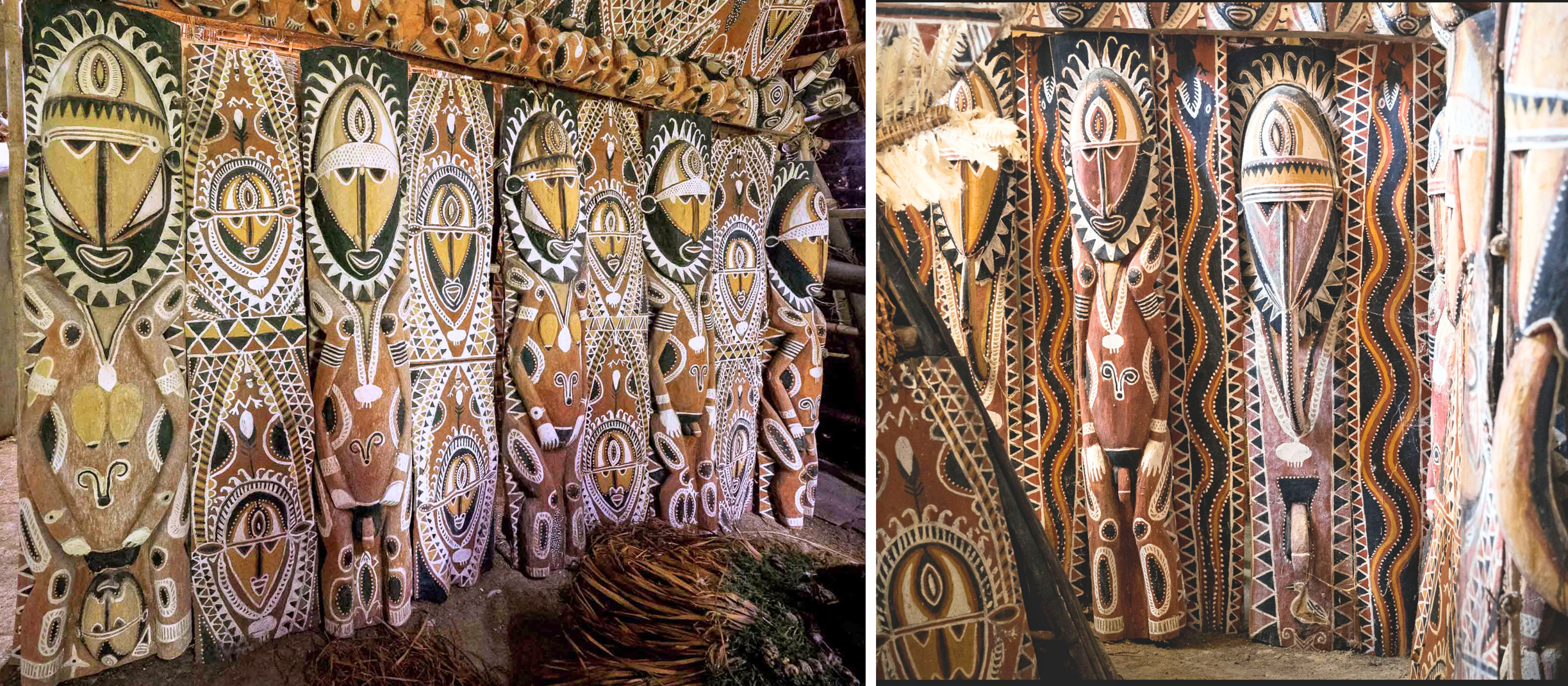

Another ceremonial house with many artistic surprises inside is the Haus Tambaran in Apangai, in the Maprik District. Let’s enter this treasure chest of Abelam art, which features some of the most spectacular sacred paintings and sculptures in Papua New Guinea.

Its interior walls and exterior are adorned with vibrant sago bark panels painted with bold geometric and anthropomorphic motifs in natural pigments of red, yellow, black, and white.

One of the most distinctive features are the ngwalndu, or spirit faces: large, flat images of ancestors or powerful spirits. These paintings are sacred objects revered as the spiritual core of the Abelam community and are often arranged in rows along the interior walls of the house.

The central figure is Puti (also known as Nggwal or Dendwin), who is associated with power and success. Puti is typically placed at the heart of the sacred chamber and is ceremonially “guarded” by painted sons along the walls. These powerful images, including Kwatbil and other characters from Abelam cosmology, oversee ritual activities and the clan’s social life.

In addition to the painted bark, the house contains carved wooden posts, lintels, and ancestral effigies. These carvings combine human and mythological animal figures and embody the spirits invoked during yam cult initiations, compensation ceremonies, and other significant rituals.

Ceremonial times see the exhibition of shells and string bags, which are aligned at the feet of major spirit images and used for ritual exchanges, including bride price and sorcery compensation.

Now, let’s admire this spectacular space where architecture, painting, and sculpture come together to embody the spiritual power, ancestral presence, and ritual practices of the Abelam people.

LEFT: Haus Tambaran Apangai, interior with Nggwal-figure. Photo by Ingo Kühl, 2012.

RIGHT: Haus Tambaran Apangai, interior with Nggwal-figure. Photo by Dragoš Dubinâ, 2017.

These photographs depict Puti, a major ancestral spirit and supernatural entity central to the religious life and iconography of the Abelam people in Maprik District.

Puti is the primary ancestor and creator spirit for the Abelam clans. He embodies the powers of prosperity, success, and social authority. The figure is typically enshrined in the most sacred part of the haus tambaran and is surrounded by painted bark panels (ngwalndu). Smaller spirit images, or “sons,” watch over it. The presence of Puti in rituals is believed to ensure positive outcomes in yam cultivation, warfare, compensation ceremonies, and male initiations. Because yams are emblematic of vitality and prestige among the Abelam, Puti is directly linked to their annual ritual cycle and the success of communal harvests.

The figure is made of bark, wood, and fiber. It has dramatic outstretched arms and intricate geometric and biomorphic designs painted with natural pigments. Added shell and feather ornaments signify power and supernatural force.

Its mask-like face, elongated nose, and bold graphic motifs signify a mix of male and female traits, referencing creation and fertility.

During Yam cult ceremonies, new initiates are introduced to Puti through secret rituals. Only select men may fully approach or interact with the figure. Women are depicted artistically on the panels, but they do not participate in its direct ritual handling.

Puti is periodically “renewed” through repainting and rituals to maintain the spiritual potency of the house and its people. Examine the two photos. The koromb (ceremonial house) remains unchanged, but Puti has been modified. The first photo was taken in 2012, and the second was taken in 2017. Between those two photos, Puti was “restored” and modified.

Sons of Puti. Photo by Dragoš Dubinâ, 2017.

ABOVE AND BELOW

A glimpse of the Apangai Haus Tambaran’s interior with astonishing examples of Abelam art. Photos by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

Among the Abelam, the ceremonial men’s houses are not singular, village-wide structures as outsiders sometimes imagine. Rather, they are tied to clans or sub-clans (wut), and a large Abelam settlement may contain several houses of varying sizes and importance. Each house is linked to particular descent groups, ritual rights, and initiation cycles.

Apangai, one of the most famous Abelam villages in the Maprik/Wosera region, was extensively studied by Anthony Forge in the 1960s. Forge described the village as a major ceremonial center where multiple tambaran houses stood. Each house was decorated with monumental paintings and carvings and belonged to distinct social groups.

Smaller, less elaborately decorated men’s houses could also exist alongside the great ceremonial houses and were used for more limited ritual purposes.

Over time, the number and scale of tambaran varied depending on clan strength, initiation cycles, inter-clan rivalries, and even colonial or missionary pressures. Some houses were abandoned or rebuilt, while others became the focus of regional gatherings.

In Apangai, for example, there would have been more than one haus tambaran, reflecting the village’s size, ceremonial prestige, and the multiplicity of Abelam clans. This contrasts with some Iatmul villages, where one or two dominant ceremonial houses structured ritual life. Even there, however, smaller houses existed.

The image below shows yet another haus tambaran from the Abelam village of Apangai, underscoring the abundance of these ritual houses within a single settlement.

ABOVE AND BELOW: Photos by Rita Willaert – Flickr.

THE MANY FUNCTIONS OF THE HAUS TAMBARAN

Thus, the Haus Tambaran is much more than architecture; it is a living symbol of the Sepik peoples’ spirituality, governance, and cultural continuity. It orchestrates social life, gender relations, and hierarchy, and it functions as:

- A political forum where oratory, debate, and consensus-building occur.

- A ritual sanctuary where sacred flutes, masks, and ancestral relics are stored and secret rites such as male initiation and communication with ancestral spirits are performed.

- A judicial court for settling inter-clan disputes and maintaining social order and community bonds.

- A cultural heart for the village, where elders transmit laws, myths, and cultural values to younger generations.

Only initiated males are permitted entry, and the architecture itself encodes cosmological principles. Carved posts depict ancestral myths and the primordial ancestor, who is often a crocodile. The Haus Tambaran is the institutional heart of male rituals, political deliberations, and custody of clan-owned sacred property. However, it is important to note that the social life of the Sepik people is interconnected: maternal kin, women’s workspaces (gardens and kitchens), and inter-house alliances also anchor the system.

Corporate ritual property and clan identity

Each house is tied to a specific patrilineal clan or lineage that “owns” names, ancestral designs, and ritual prerogatives, which are kept and displayed inside the men’s house. The house posts and gables are carved and painted with clan beings and origin histories. The building serves as a stage for clan competition and prestige.

Ritual hub: initiations, secrecy, instruments

Initiation seclusions, displays of sacred objects, and performances linked to the tambaran (spirit) cult take place in the men’s house and the ceremonial plaza in front of it. Gregory Bateson considers the ceremonial house to be a pivotal setting in Iatmul rituals, and architectural studies of the Sepik region highlight the men’s house as the location for initiations and for the storage and expression of spirits.

“Ancestral law” and the village center

In Eastern Iatmul, for example, in the village of Tambanum, the cult house literally “plants” ancestral authority in place. Elders speak of reburying the supernatural soil beneath the house when relocating a village to re-seat the law and the ancestors. This demonstrates how the house mediates cosmology, territory, and political order.

Intergroup ties flow through the house.

The construction, renovation, and ceremonial “opening” of a haus tambaran mobilize exchange networks involving timber, rattan, canoes, and decorations. The ethnography of the Sawos–Iatmul relationship documents how the materials and labor used for ceremonial houses depend on trade with neighbors, which is another way the house sits at the center of wider social relations.

It’s a gendered space but not a closed world.

While the men’s house is a clearly defined male domain, women’s presence is implied through their participation in major feasts and performances, where they sing or provide support from outside. Additionally, historical naven celebrations often followed large men’s-house rituals. Maternal kin (the mother’s brothers) sponsor and mock in ways that publicly “cross” the threshold between male secrets and wider village life.

LEFT: Two men play the bamboo flute inside a Haus Tambaran in Kanganaman, in the Sepik area. Photo by Efrat Nakash.

RIGHT: Beating the Garamut drums inside a Haus Tambaran in Yamok, in the Sepik area. Photo by Efrat Nakash.

Tribal men in front of a Haus Tambaran near Mapik, East Sepik. Photo by George Holton / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY.

Continuity and change: the role of contemporary tourism

World War II and the subsequent Christianization altered building cycles and usage. Some houses were destroyed or converted into churches. However, the rise of tourism prompted the Sepik peoples to reinterpret, maintain, and adapt these ritual centers, thereby ensuring their continued presence as emblematic markers of communal identity.

Cultural Preservation and Adaptation: Tourism has motivated communities to maintain and restore haus tambaran structures, which might have otherwise fallen into disrepair due to shifting ritual cycles and priorities. These buildings now serve not only ritual purposes, but also as heritage attractions for visitors, reinforcing local pride and cultural continuity while providing economic incentives for preservation.

Transformation of Meaning: The Haus Tambaran, once strictly sacred and reserved for men’s rituals, is now more accessible to outsiders, including foreign women, during tours and performances. This has sometimes led to the desacralization or “re-embedding” of the space, shifting the emphasis from exclusive ritual use to staged demonstrations of tradition and artistic skill.

Tourist Art and Economic Impact: The production of Sepik art and carvings, especially storyboards and ceremonial objects, has increasingly shifted toward the tourist market. This economic motivation has led to the creation and sale of artworks that were previously only used in local ceremonies. Motifs have sometimes changed from abstract ancestral forms to scenes that are more easily understood and appreciated by tourists.

Social and Symbolic Relevance: Local communities interpret payment and recognition by tourists as validation of the cultural value and prestige of the Sepik region in a global context. Tourism enables local communities to reassert their cultural prominence while negotiating new forms of self-worth and identity in a modernizing world.

Heritage, Identity, and Agency: Despite the challenges that tourism brings, such as the commercialization or alteration of tradition, Sepik communities continue to use haus tambaran as central symbols of heritage. Villagers actively shape and present their culture to outsiders and maintain the men’s house as the heart of their identity, negotiations, and ancestral connections.

Thus, tourism has led to a dynamic interplay of preservation, transformation, and global engagement. This interplay helps keep the haus tambaran and Sepik artistic traditions vibrant, though sometimes in new forms and with altered meanings. At the same time, it maintains their core function as centers of communal pride and identity.

The Papua New Guinea (PNG) Parliament is a single-chamber legislature consisting of 89 members elected from open electorates and 22 governors elected from provincial electorates. Parliament House in Port Moresby is an iconic building intentionally designed to resemble a Maprik-area Sepik Haus Tambaran, reflecting Papua New Guinea’s cultural heritage and architectural traditions.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?