NAVAJO CHURRO SHEEP AND WOOL 9

USA on the globe.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

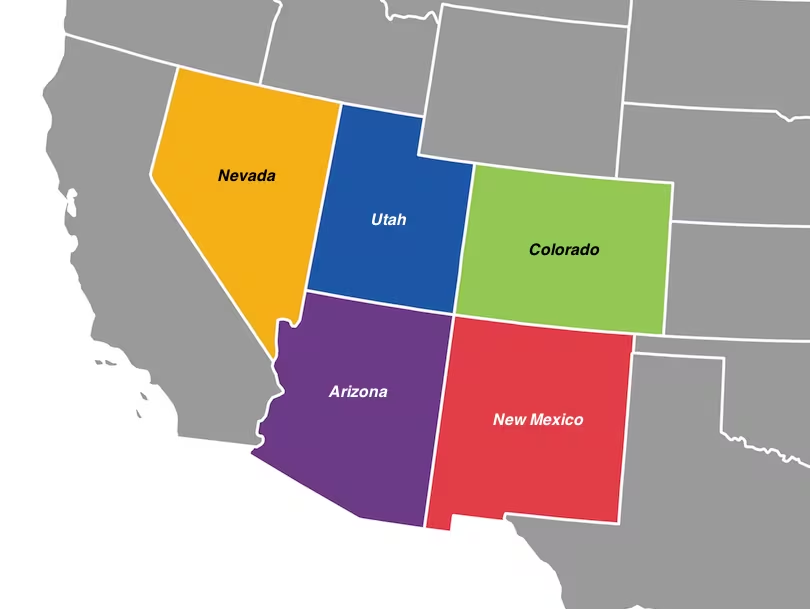

SOUTHWESTERN STATES

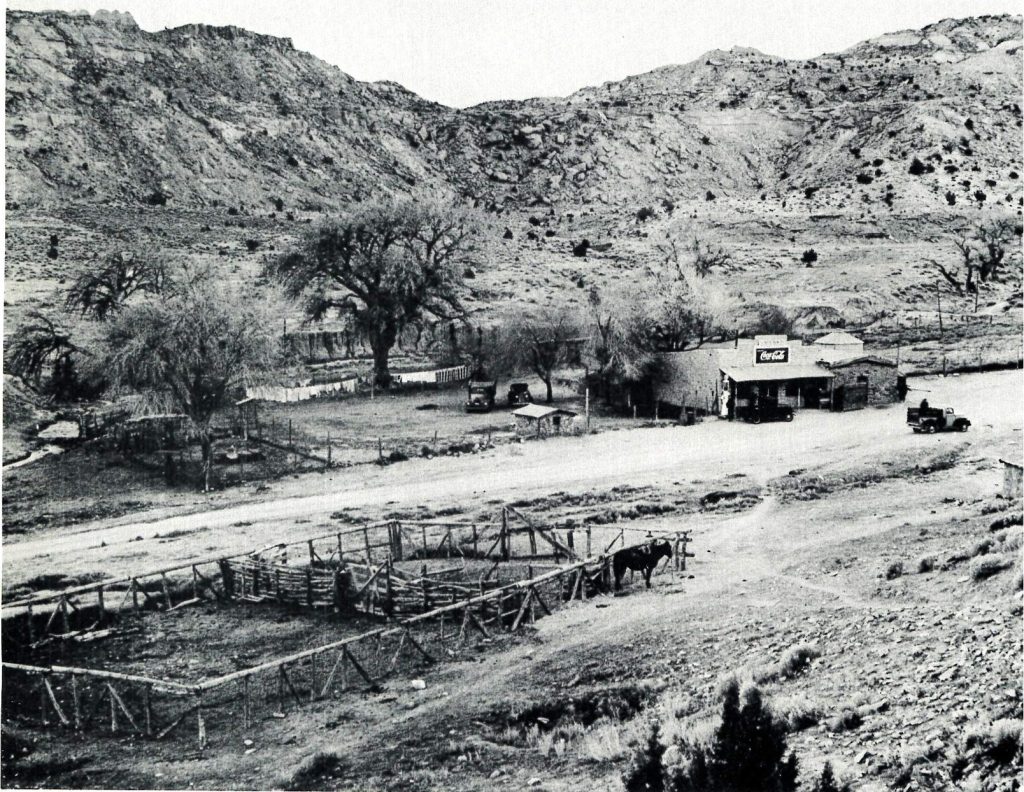

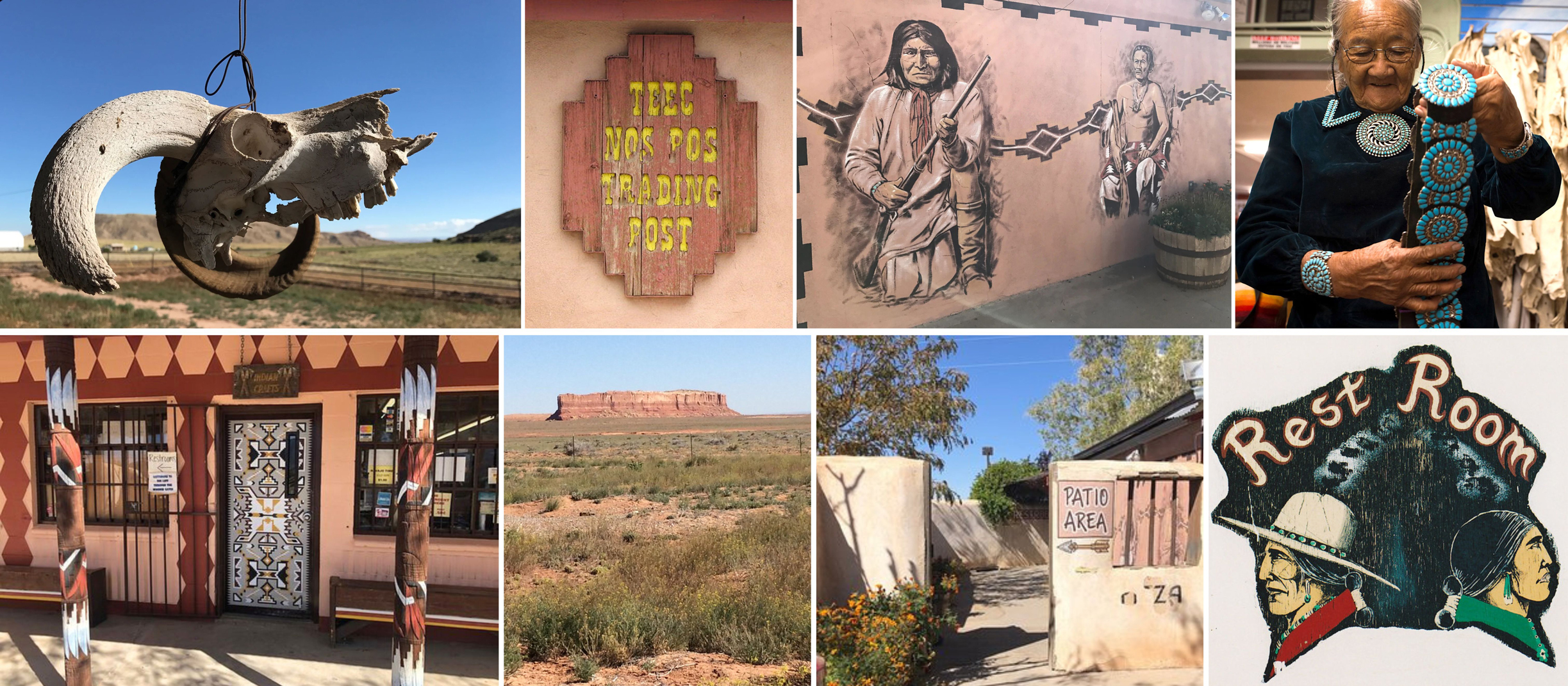

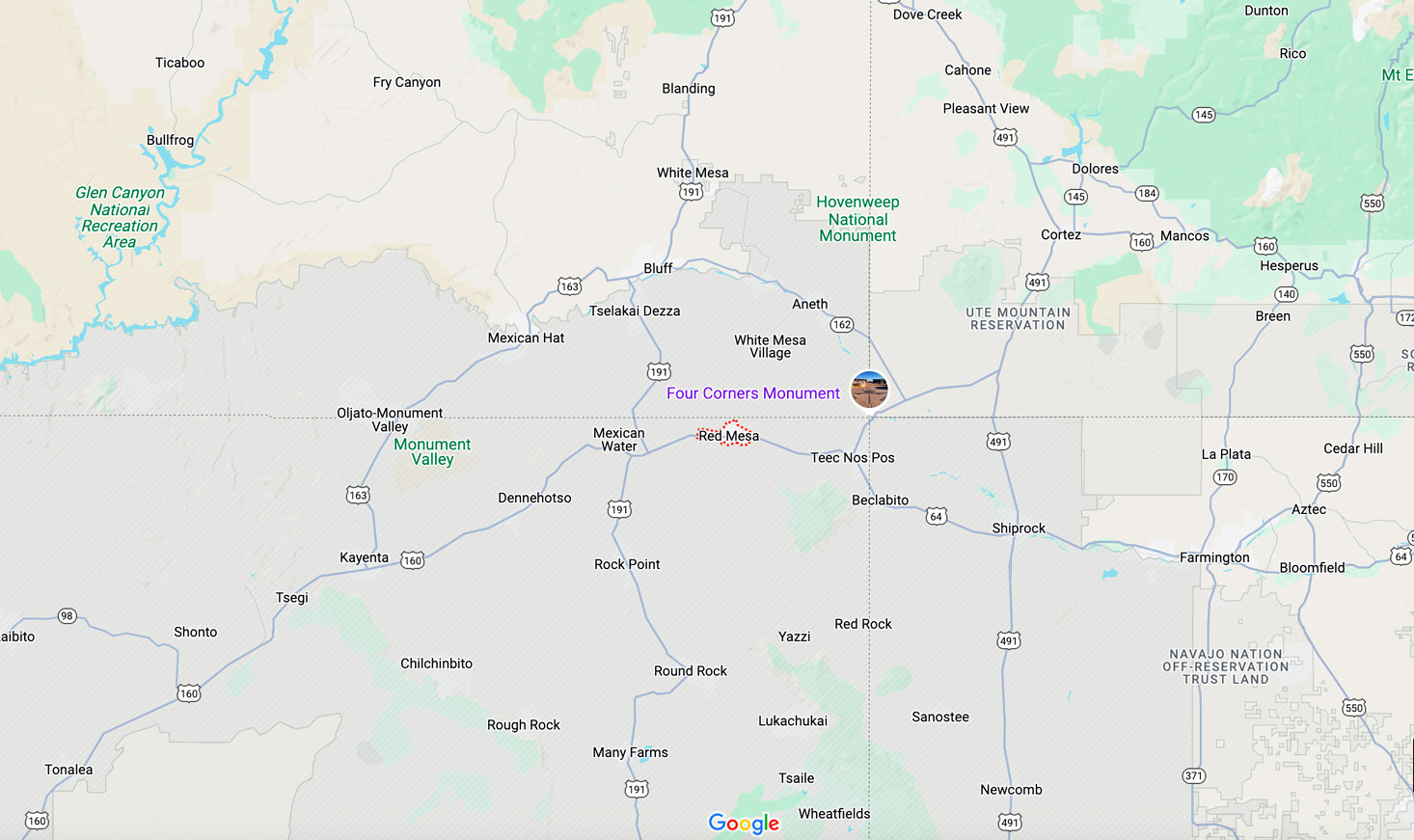

TEEC NOS POS TRADING POST AND TEEC NOS POS STYLE

Teec Nos Pos is one of the most distinctive and complex regional weaving styles in the Navajo textile tradition.

The name Teec Nos Pos derives from the Navajo expression T'iis Názbąs, meaning "Circle of Cottonwoods" or "Ring of the Cottonwoods," and it is pronounced similar to /tease-nahs-pahss/. The name comes from an important location in northeastern Arizona, near the Four Corners Monument within Navajo land. Situated west of Shiprock, this remote area became the epicenter of a weaving revolution that would fundamentally alter Navajo textile production.

The Teec Nos Pos style rose to prominence in 1905 when Hambleton Bridger Noel, also known as "Trader Noel," established a trading post in the area. Noel was the first Anglo-Saxon to receive approval from the local Navajo to set up a trading post on their land after two previous traders were driven off ten years earlier. His success in establishing this outpost proved pivotal in shaping a new direction for Navajo weaving.

The style's development was influenced by Noel's brothers, who established a trading post at Two Grey Hills in 1897. Drawing from their experience, Noel looked to existing rug designs to provide local weavers with guidance on what he wanted to purchase from them. In 1911, Noel married Eva Foutz. Eventually, the Foutz family took over the post and continues to operate it to this day. The trading post is open and active today, with Kathy Foutz and John McColloch as the current owners.

The Teec Nos Pos Trading Post in 1949. Photo by Milton (Jack) Snow, M. Burge Photograph Collection, Museum of New Mexico.

BELOW

The Teec Nos Pos Trading Center today.

Tony Hillerman (1925–2008) was a celebrated American novelist renowned for his mystery series set in the American Southwest, particularly on the Navajo Nation. Born in Sacred Heart, Oklahoma, Hillerman drew on his early experiences with Native American communities and his deep respect for Navajo culture to write novels blending tight crime plots with rich anthropological detail. His most famous works center on Navajo Tribal Police officers Joe Leaphorn and Jim Chee. These characters use modern investigative techniques and traditional Navajo beliefs to solve crimes. His debut novel, The Blessing Way (1970), introduced Leaphorn and established the formula that would define the series: mysteries deeply rooted in the landscape, customs, and conflicts of the Navajo people. The series eventually spanned eighteen novels. The Teec Nos Pos Trading Post, located on the Navajo Nation, appears in several of Hillerman’s novels, including The Blessing Way.

Teec Nos Pos weavings are both praised and debated for their bold integration of foreign aesthetics into a deeply rooted Navajo tradition. The designs draw heavily from Persian rugs, incorporating their intricate, busy patterns and bright colors, such as greens, blues, oranges, and reds. Traders deliberately encouraged this Persian influence to compete with Oriental rugs in the marketplace.

These foreign design elements were introduced through various means. Some sources credit Mrs. Wilson, a San Juan missionary, with popularizing the style, while others attribute its prevalence to Trader Noel himself. In some instances, traders painted Persian rug designs on the exterior walls of trading posts in the hope that weavers would copy these patterns.

Thus, Many experts consider the Tec Nos Pos style "controversial".

The Teec Nos Pos style occupies a unique and somewhat problematic position within the Navajo weaving tradition. It is often described as "the least Navajo" of all regional styles because of its Persian and Oriental influences. However, this characterization overlooks the sophisticated way Navajo weavers adapted and transformed foreign elements. As I mentioned in the previous paragraph, THE WIND THAT STIRS THE PAINTER’S HAND HAS CROSSED TEN THOUSAND TONGUES, any purist attitude in art is short-sighted. For reasons we have already discussed at length, purism and purity are religious concepts that have no right to exist in the field of art. However, there is something I have not yet discussed. Something very important to me that I would like to share with you.

Seeing and Weaving: Culture, Perception, and the Meaning of a Navajo Rug

When an Anglo-Saxon from the 19th or 20th century—or a Western tourist from the 21st—looks at a Navajo rug, they typically see...a rug. A beautiful object, certainly, but still just an object. An artifact. A piece of décor.

However, when a Navajo looks at a Navajo rug, regardless of the century, they don't just see a rug; they see the process that birthed it. (And yes, that verb is deliberate.)

That distinction matters. Deeply.

As we discussed in The Japanese Arto of Kintsugi, perception isn't a purely neurophysiological event. The brain doesn’t exist in isolation, like a microchip on a motherboard. It is embedded in a body, an environment, and a cultural world.

Beliefs, values, traditions, and customs influence brain development by shaping neural pathways and synaptic connections and molding perceptual processes, cognitive abilities, emotions, and behavior.

This dynamic interplay between nature and nurture is what makes neuroplasticity so remarkable—and so vulnerable. It enables the brain to develop new skills, modify behaviors, and overcome challenges, but it also makes the brain extremely sensitive to the cultural matrix within which it develops. Neuroplasticity is an extraordinary adaptive resource but also a structural vulnerability.

Culture doesn’t just teach us what to think; it literally shapes the way we think, see, interpret, and react.

This cultural imprint on the brain has powerful consequences.

- Perceptual filters: The brain develops recognition and interpretation patterns based on dominant cultural patterns, which literally influence what we "see" and how we interpret it.

- Behavioral habits and automatisms: Neural circuits that consolidate during development favor behavioral responses consistent with assimilated cultural values, becoming automatic over time.

- Resistance to change: The same plasticity that enables growth also creates mental inertia, so deeply established patterns can be difficult to unlearn.

Therefore, how we see — and even what we see — is far from objective. As Anaïs Nin, the French-Cuban-American diarist, once wrote: We don't see things as they are, we see them as we are.

Westerners tend to see what is in front of them as things: fixed, discrete, and commodified. Our minds default to analysis, categorization, and assigning value based on visual characteristics, design harmony, weight, softness, and market worth. In that frame, a Navajo rug becomes just another thing—a textile with visual features, tactile qualities, and a price tag.

However, not every culture shares this objectifying perspective. In many Indigenous worldviews, including the Navajo worldview, what we call a "thing" may be seen as a process, a network of relationships, or a node of living connections. Mathematicians see mathematical objects as formal structures that interlink a set of properties under a law. Some Asian people may consider objects as illusory shadows. Without delving too deeply, it suffices to recall the wisdom of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger, who argued that objects are never "mere things" but rather phenomena laden with meaning and embedded in a context of relationships and subjective experiences.

To Navajos, a rug is not merely wool and dye; it is the convergence of stories, intentions, rituals, ancestors, divine spirits, and the earth itself.

It is an action in material form—a thread through which history, spirituality, family, creativity, and identity pass. It exists not only to be seen but also to be felt and lived with and honored.

Some Western viewers might criticize certain Navajo rugs, particularly those in the Teec Nos Pos style, calling them "un-Navajo." They point out that certain decorative motifs and intricate details resemble those used in Persian rugs or are reminiscent of the Oriental "horror vacui," or the fear of empty space. This aesthetic is considered a departure from "authentic" Navajo designs, which are thought to be more balanced and harmonious.

However, to a Navajo weaver, these comments often reveal more about the observer than the rug itself.

To them, the rug is not an exotic art piece or commercial commodity. It is a sacred expression of family history, cultural continuity, technical mastery, and spiritual strength. Within each weave lives the memory of the hands that wove it, the teachings that shaped it, the land that yielded the materials, and the resilience that enabled those hands and the hands before to survive ethnic cleansing. Reducing it to "taste" or "design" is not only superficial, it's a kind of blindness.

When a Navajo looks at a Navajo rug, they don't see a "thing" to evaluate. They see a life lived, a process embodied, and a sacred act made visible. In that act of seeing, they invite us—if we’re willing—to look again. Properly, this time.

In this regard, I'll tell you a story—a Navajo story, of course.

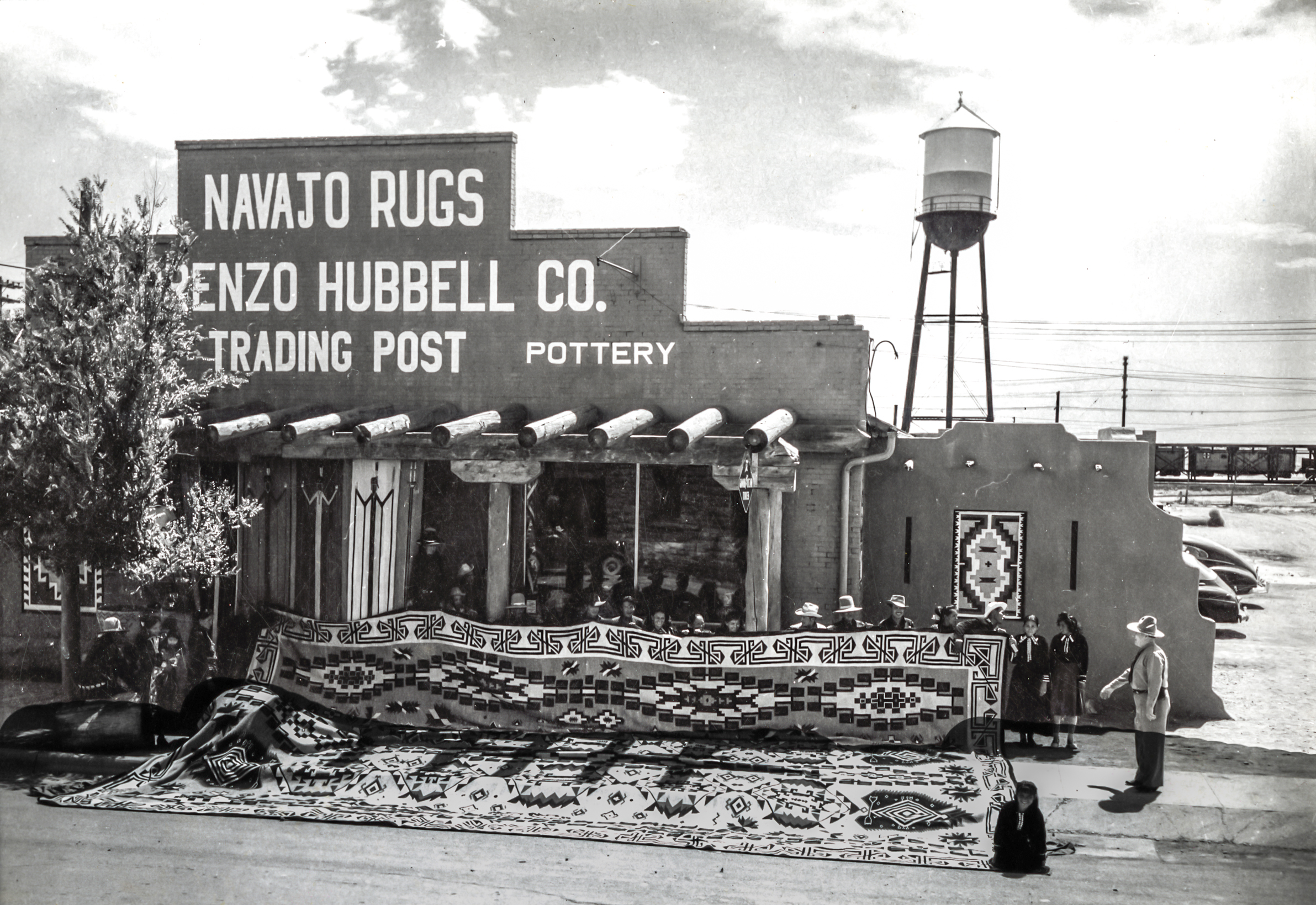

The story of the Hubbell-Joe Rug

During the Great Depression, Lorenzo Hubbell Jr., one of the sons of John Lorenzo Hubbell—the prominent trader and founder of the Hubbell Trading Post in Ganado, Arizona—found himself in a difficult situation. His trading post in Winslow wasn't prospering. Nor were his pockets particularly full. How could he attract tourists and revive the moribund trade? He had an audacious idea to get people talking about him: he commissioned one of his best Navajo weavers to create the "World's Largest Navajo Rug" as a showpiece for his Winslow Trading Post.

In 1932, Hubbell turned to Julia Joe, a master weaver from Greasewood, Arizona, to bring his vision to life. With the help of her daughter, Lillie Joe Hill, and her extended Red House Clan (Kin ł ichii’nii), Julia embarked on a monumental project of artistry. To accommodate the planned dimensions, Julia’s husband, Sam Joe, built a custom metal pipe loom and a 40-foot-by-30-foot-by-10-foot building to house the loom and the weaving process.

The community’s involvement was essential. Local families sheared approximately 78 sheep (60 white and 18 black) to provide the necessary wool. This wool then underwent two years of washing, carding, dyeing, and spinning. Julia and Lillie, often working from sunrise to midnight, spent over three years weaving the rug. According to Hubbell’s records, the process took "three years and three weeks" of nearly continuous labor.

It sounds like a fairy tale, doesn't it? I assure you it's all true.

Completed in 1937, the finished rug measured an astonishing 21 feet 4 inches by 32 feet 7 inches (650 x 993 cm), making it the largest known Navajo rug for four decades. «What resulted was a masterpiece, not just in size, but in technique, with an evenness of weave, uniformity of color, and complexity of design.» (Hubbell-Joe Rug History, Affeldt Mion Museum, Winslow, AZ). The rug's palette featured natural grays, blacks, whites, and the signature “Ganado red,” and its designs were inspired by the universe, stars, and the Milky Way. The design also featured protective horned toads and border patterns reminiscent of Ancestral Puebloan pottery. In keeping with Navajo belief, a traditional "spirit line" (ch’ihónít’i) was woven into the lower right corner as a symbolic path for the weaver’s spirit to exit the rug.

Initially displayed at the Winslow Trading Post, the rug's size made it difficult to exhibit. It traveled to fairs, museums, and even the U.S. Senate chambers in Washington, D.C. There, it served as a marvel of craftsmanship and a powerful advertisement for Navajo weaving and the Hubbell enterprise.

The rug displayed at the Winslow Trading Post in 1937. Herb and Dorothy McLaughlin Collection, Arizona State University Library, CP MCL 9569.

As I mentioned, in the following years, the rug served as a centerpiece in Hubbell's marketing efforts. It was displayed at various prominent venues, including the 1939 Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Exhibition, the U.S. Senate Chambers in Washington, D.C., Marshall Field & Company in Chicago, the 1948 International Travel Show in New York City, and the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona.

After Hubbell's bankruptcy in 1949, the rug changed hands multiple times and was eventually stored away and largely forgotten for over 40 years. In 2012, Allan Affeldt and Tina Mion acquired the rug and returned it to Winslow, recognizing its cultural significance. They renamed it the Hubbell-Joe Rug to highlight Lorenzo Hubbell Jr.'s dual legacy as commissioner and Julia Joe's as the rug's creator. They also acquired the trading post, which became the Winslow Visitor’s Center.

Today, thanks to the Winslow Arts Trust, the rug is on long-term display at the Affeldt Mion Museum in Winslow, Arizona, where it continues to inspire awe for its artistry, scale, and the story of community collaboration and resilience that brought it into being. A specially engineered display allows the rug to be viewed both flat and partially upright, minimizing stress on the textile while showcasing its intricate designs.

Before displaying the rug to the public, however, Allan Affeldt and Tina Mion honored the Navajo culture by hosting a touching blessing ceremony with Julia Joe’s family, including her daughter, Emma Joe Lee, who had helped card the wool 80 years earlier. The video of the ceremony is an emotional testament to how Navajos see, feel, and honor a rug.

Therefore, it is essential to encounter cultures far removed from our own—whether separated by time or space. Such experiences teach us to build bridges, engage in dialogue, and live more peacefully. They force us to break out of our shells, like fledglings opening their eyes to the world for the first time. They help us see beyond appearances and beyond 'things' and 'commodities'. In doing so, we become less blind, less deaf, less impoverished in spirit. We begin to see, hear, and feel what once seemed unimaginable.

This transformation isn’t just metaphorical—it has neurological roots. Thanks to the brain’s remarkable plasticity, learning and change remain possible throughout life. While adult learning differs from the rapid absorption of childhood, it can still reshape our neural circuits—especially through conscious strategies and repeated practice. In this sense, cultural encounters offer a kind of cognitive reprogramming: slower, more effortful, but deeply enriching.

Yes, it can be tiring— far less relaxing than scrolling through an endless stream of mindless content on a platform. But meeting the Other makes us smarter, deeper, richer, and wiser. It’s truly unfortunate how many people retreat in fear at the mere thought of such encounters. Because by avoiding the unfamiliar, the strange and the diverse, we risk never knowing how much more fully we could have lived.

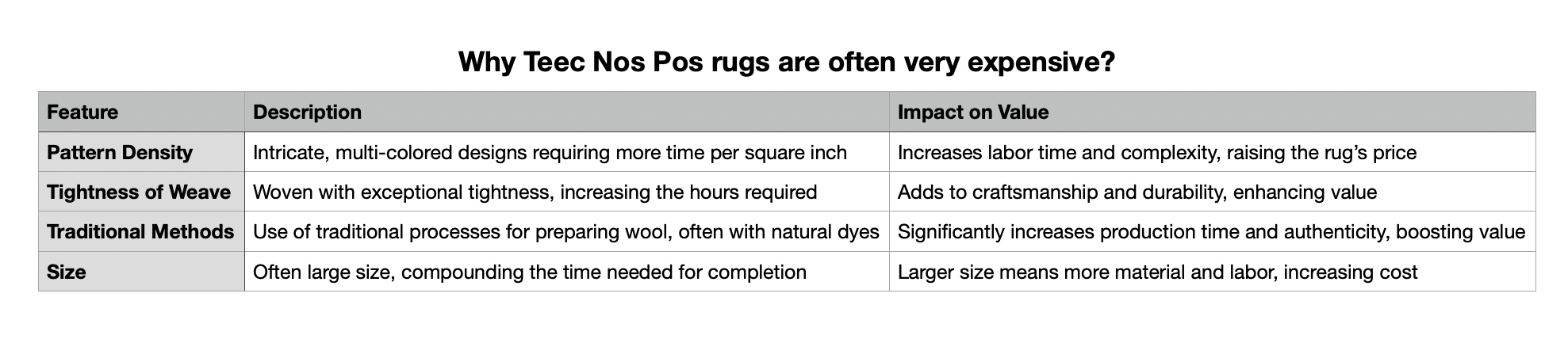

Teec Nos Pos Characteristics and Craftsmanship

« Widely considered to be the most intricate and detailed of all Navajo woven designs, Teec Nos Pos rugs offer a truly exceptional and distinctive look.» (Style: Teec Nos Pos Weavings, Nizhoni Ranch Gallery).

Design Elements

Teec Nos Pos rugs are known for their elaborate, multi-border designs and densely packed, single-panel compositions. These textiles feature bold, intricate geometric designs filled with symmetrical arrangements of motifs such as zigzags, diagonal lines, stylized feathers, arrows, and stepped or serrated forms. A striking hallmark is the presence of angular, claw-like hooks that extend from diamonds and triangular elements. These hooks are often outlined in sharply contrasting colors for dramatic emphasis.

The central fields are richly detailed and often create a sense of movement and energy through layered, nested shapes and vivid color saturation. Teec Nos Pos weavings are among the most complex and colorful Navajo rug styles. They reflect traditional influences, as well as innovations inspired by the early 20th-century trading post aesthetic, particularly in the Teec Nos Pos region near the Four Corners. Overall, they create an impression of dynamic balance where symmetry and intricacy meet in a tapestry of cultural expression and technical mastery. Each pattern is a test of precision, stamina, and artistic control all woven into every inch.

Materials and Techniques

Teec Nos Pos weavings have always demanded an exceptional level of technical skill, beginning with their raw materials. Before the 1940s, most weavers relied on hand-spun wool from Navajo-Churro sheep, dyed with natural pigments derived from plants, minerals, and insects. Each step—shearing, carding, spinning, dyeing—was performed manually, infusing the work with a deep connection to land and tradition.

After World War II, however, commercial yarns became more common. Trading posts began supplying brightly colored, pre-dyed 4-ply wool, and occasionally Germantown yarns, to meet growing market demand. These materials enabled new aesthetic directions while reducing labor intensity—but never replaced the artisan’s hand or vision. Even today, many weavers return to traditional fibers and dyes, both for their visual richness and their cultural resonance.

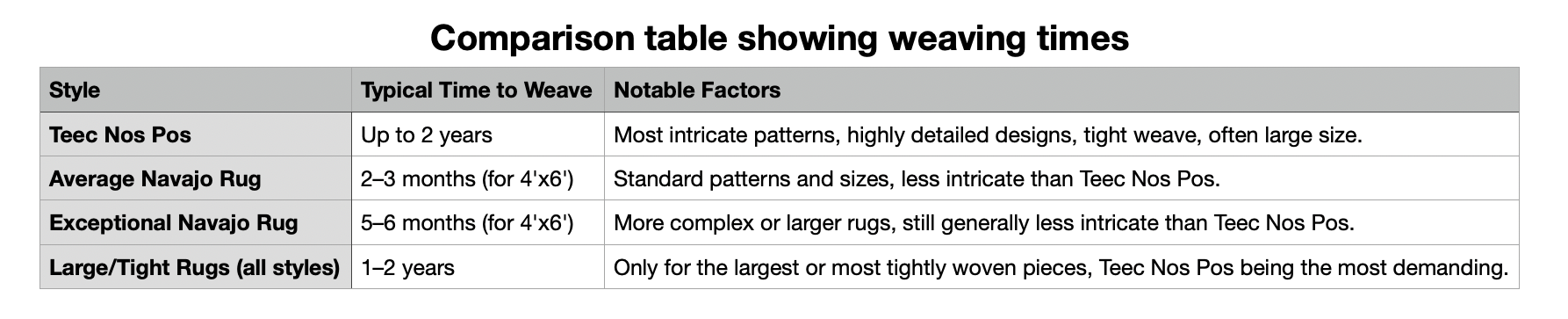

Complexity and Time Investment

Weaving a Teec Nos Pos rug is not for the faint of wrist. These textiles are not only among the most visually complex in the Navajo tradition—they’re also the most labor-intensive. Intricate geometric motifs, densely packed designs, and tight weave counts demand staggering precision. Some rugs take up to two years to complete, particularly when the weaver follows all traditional steps from sheep to finished rug.

Larger pieces exacerbate the challenge: more yarn, more hours, and more physical strain. Add to that the need to maintain perfect symmetry across the composition, and you’re looking at a cognitive marathon disguised as a craft. It’s little wonder these works are so rare—and so costly. Each one isn’t just a rug; it’s a woven biography of patience, mastery, and endurance.

In short, Teec Nos Pos rugs possess a singular aesthetic—complex, vibrant, and deeply rooted in cultural tradition, despite the "un-Navajo" appearance.

The extended weaving time has significant economic implications for weavers. Large rugs require such a substantial time commitment that fewer weavers take them on, since they are typically paid only when they sell their completed rug. This makes large, complex Teec Nos Pos rugs increasingly rare and valuable. Their prices? Sometimes, they're astronomical.

The gorgeous, large Teec Nos Pos rug pictured below was handwoven by master weaver Linda Nez in 2010. It was on the loom for 15 months, and it is as tight as canvas and very finely designed. Though costly, this rug is not one of the most expensive Teec Nos Pos: its price is approximately €58,000/US$66,500 (June 2025 exchange rate), but the largest and finest pieces can reach $200,000 USD.

Teec Nos Pos by Master Weaver Linda Nez, 2010. Medium: Navajo Churro wool. Dimensions: 72 x 108 in.; 183 x 274.32 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

Teec Nos Pos handwoven by Linda Nez in ca. 2000. Dimensions: 72 x 120 in.; 182.88 x 304.8 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona. The weaving of this masterpiece required 16 months on the loom; that's why it costs € 67,000 - US$ 72,360 (using the June 2025 exchange rate). It was featured in the "The Getzwiller Collection of Contemporary Navajo Weavings 1975 - 2000" at the Desert Caballeros Western Museum in Wickenburg, AZ, and in Master Weavings of the Navajo Churro Collection 2019 Catalog.

Teec Nos Pos handwoven by Cindy Nez in 2004. Dimensions: 48 x 168 in.; 121.92 cm x 426.72 cm. Medium: custom spun, hand-dyed Navajo Churro wool. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona. This monster rug was put up in September 2002 and completed February 2004: 17 months on the loom! That's why it costs € 32,000 is approximately US$ 34,560 using the exchange rate of June 2025. This weaving is featured in the Master Weavings of the Navajo Churro Collection 2019 Catalog and took part in the exhibition "One Traders Legacy: Steve Getzwiller Collects the West 2017-2020" at the Desert Caballeros Western Museum in Wickenburg AZ.

Despite external influences, Navajo weavers made the designs distinctly their own by incorporating objects and motifs that reflected their world and vision. A close examination reveals traditional Navajo elements, including feathers, rainbows, arrows, bows, and Ye'i faces, woven into Persian-inspired geometric patterns. As one expert noted, The trader might have wanted and gotten a Teec Nos Pos to sell, but he also got a design that incorporated much of what the weaver wanted.

Chronological Style Evolution

The Teec Nos Pos style has undergone several distinct phases, influenced by shifts in culture, economics, and materials. Below is a summary of its development.

- Early Period (1910s–1930s): Muted Tones and Subtle Complexity

Characteristics

- Color palette: Earthy, muted tones (indigo, natural brown/white wool, muted reds) derived from natural dyes such as indigo, cochineal, and plant-based sources.

- Designs: Geometric patterns with serrated edges, concentric diamonds, and stepped motifs, influenced by Persian and Oriental carpets introduced via trading posts.

- Materials: Hand-spun wool from Navajo-Churro sheep that is processed traditionally (hand-cleaned, carded, and dyed).

Key Influences

- Trading Post demands: Traders like John B. Moore promoted intricate designs to appeal to non-Native buyers (Blomberg, Navajo Textiles: The William Randolph Hearst Collection, 1988).

- Railroad access: The arrival of the railroad in the 1880s introduced new materials, though it limited the availability of dyes in remote areas like Teec Nos Pos until the 1910s.

Academic Sources

- Hedlund (1992) notes that early Teec Nos Pos weavers avoided garish colors, favoring "restrained harmonies" to distinguish their work from cheaper regional styles.

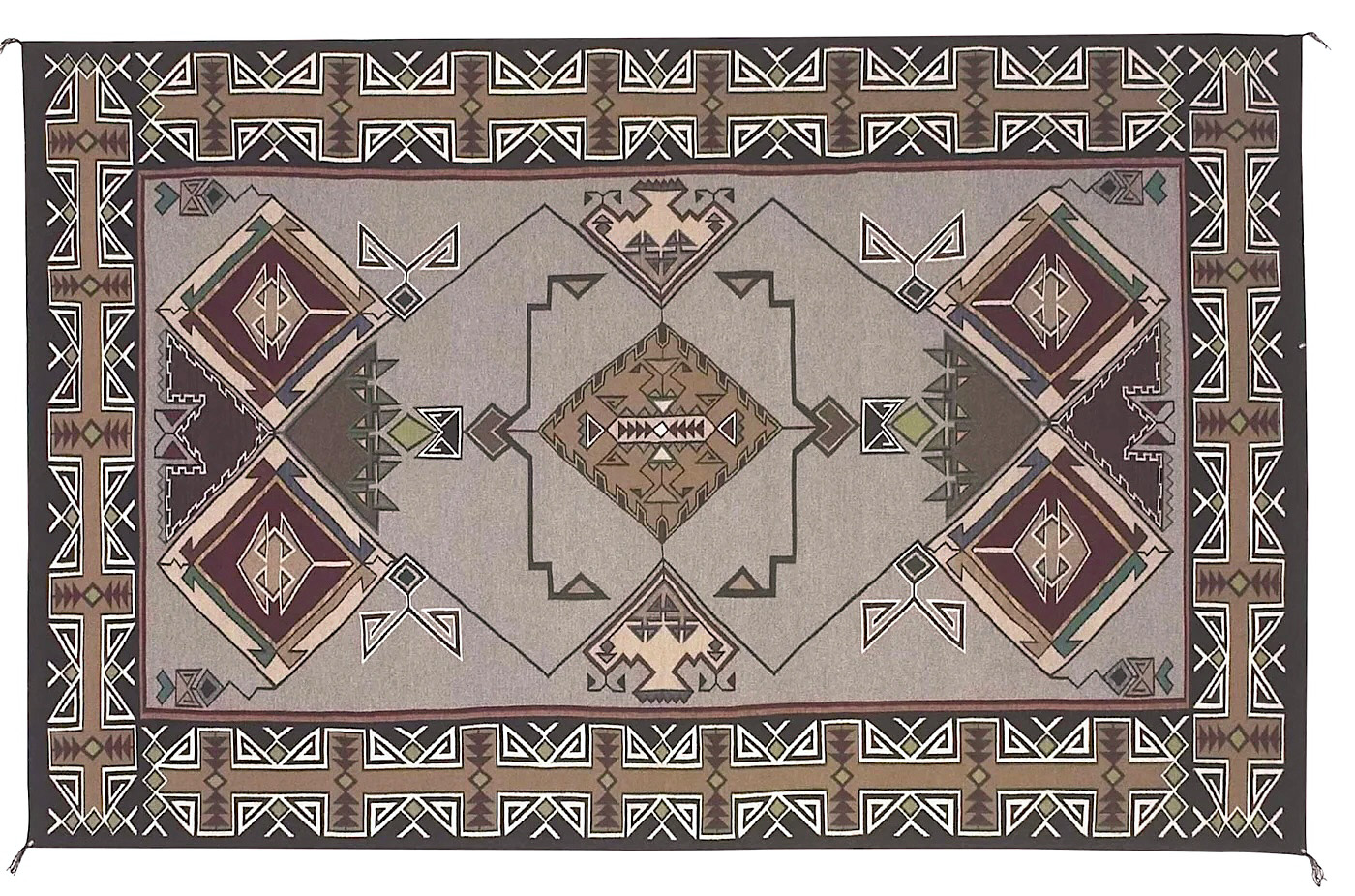

- Rodee (1981) links early motifs to pre-1900 Eyedazzler designs but with increased precision, seen in the beautiful rug below.

Antique Teec Nos Pos Rug, ca. 1910-15. Dimensions: 53 x 67 in.; 34.62 x 170.18 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

The rug below is an interesting example of early Teec Nos Pos work. It features one of the most distinctive Crystal patterns, as defined by Plate XIV of the 1911 JB Moore Catalog. Several Crystal symbols are also evident, including Valero Stars, Whirling Logs, four-corner elements, and stepped lines. However, this interpretation of the Moore pattern differs considerably from contemporary Crystal-style rugs, and some Teec Nos Pos characteristics are already evident.

Old Teec Nos Pos Rug in wool; first quarter of the 20th century. Dimensions:140 x 104 in.; 355.6 x 264.16 cm. Auctioned in 2019 by Altermann Galleries & Auctioneers, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Teec Nos Pos weaving attributed to master weaver Slocum Klah, 1930s. Medium: variegated natural brown and cream Lincoln wool; Slocum hand-carded, hand-spun, and hand-dyed the wool to get the colors of green, red, and yellow. Dimensions: 60 x 97 in.; 152.4 × 246.38 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona. Jay Foutz of the Teec Nos Pos Trading Post considered Slocum and his family the best Teec Nos Pos rug weavers in the country. This rug features tiny thunderbirds, Spiderwoman crosses, stylized squash blossoms, and belted diamonds. The central diamond row is bordered by Greek Key symbols, and the inside of the diamonds feature clouds pointing in the four directions. The design and symmetry of the border is so complicated and yet executed so brilliantly it features stylized Hero Twin images. Combined with its incredibly tight weave, this is a masterpiece.

2. Teec Nos Pas Navajo Rug, first half of the 20th century. Dimensions: 7'.6'' x 4'.9''; 228.6 × 144.78 cm. Auctioned in 2013 by John Moran, Pasadena, CA.

3. Large Teec Nos Pos Runner, 1930s. Dimensions: 128 x 68 in.; 325.12 × 172.72 cm. Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

4. Teec Nos Pos rug, 1940s. Dimensions: 74" x 128"; 187.96 cm × 325.12 cm. Tres Estrellas Gallery, Taos, New Mexico.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Teec Nos Pos Rug, 1915-1920, with beautiful, lustrous wool, and incorporating eagle feathers into its complex geometric center. The inner border might be described as a "dovetail meander", woven with dark blue and orange. Dimensions: 43 x 88 in.; 109.22 × 223.52 cm. Tres Estrellas Gallery, Taos, New Mexico.

2. Teec Nos Pos Rug ca. 1930s. Dimensions: 150 x 102 in.; 381 × 259.08 cm. Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

3. Vintage Navajo Pictorial Area Rug, Teec Nos Pos Trading Post, 1910-1925. Medium: native hand-spun wool in natural fleece colors of brown, black, camel and ivory, with aniline-dyed red accents. Pictorial elements include Tepee/tipi motifs, crosses, water bugs, arrows and feathers. Dimensions: 105x 67 in.; 266.7 x 170.18 cm. Sold via 1st DIBS.

4. Teec Nos Pos Trading Post wool rug, second quarter of the 20th century (1925-1949). Dimensions: 92 x 57 in.; 233.68 x 144.78 cm. Sold via 1st DIBS.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Teec Nos Pas Navajo Rug, early 20th century. Dimensions: 4'10'' x 8'; 147.32 × 243.84 cm. Auctioned in 2013 by John Moran Auctioneers Inc., Pasadena, CA.

2. Teec Nos Pos Rug, 1915 -1920. Kennedy Museum of Art, OHIO University, Athens, Ohio.

3. Teec Nos Pos Rug, ca. 1915. Medium: native handspun wool, vegetal and aniline dyes. Dimensions: 63 × 36 in.; 160.02 cm × 91.44 cm. Provenance: Ex-collection: Ruth Belikove, Alameda, CA. Featured in The Rugs of Teec Nos Pos, Jewels of The Navajo Loom by Ruth K. Belikove. Auctioned in 2020 by Heritage Auctions, Dallas, TX.

4. Large Teec Nos Pos Rug, ca. 1930s. Dimensions: 100 x 62 in.; 254 × 157.48 cm. Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

Teec Nos Pos rug, finely woven hand-spun wool in colors of dark brown, tan, cream, green, red, orange, and grey. It shows vibrant eye-dazzling design and curlicue border. Date:; ca. 1930. Dimensions: 100 x 53 in.; 254 x 134.62 cm. Wikimedia Commons.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Teec Nos Pos rug, 1920s. Medium: Woven with hand-carded and hand-spun Lincoln wool with aniline dyes. Subtle and wonderfully tight. Features Hero Twin imagery and the great star design. Dimensions: 43 x 100 in.; 109.22 × 254 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

2. Teec Nos Pos rug, 1920s. Medium: Hand-carded, hand-spun, and hand-dyed Lincoln wool. Dimensions: 58 x 110 in.; 147.32 × 279.4 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona. This rug features pictorial designs depicting the Hero Twins ascending from the underworld. The Hero Twins are a part of the Navajo origin story. The design also includes water and medicine symbols. It is clearly very well woven by a master weaver. It was displayed in the 2016/2017 "Painting with Wool" Navajo Pictorial Weavings exhibition at Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, and it is featured on page 26 of the exhibition catalog.

3. Teec Nos Pos rug, 1920s. Medium: hand carded, hand spun Lincoln wool. Hero Twin imagery. Dimensions: 45 x 94 in.; 114.3 × 238.76 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

4. Teec Nos Pos rug, 1930s. Medium: four-ply Germantown highlight colors and hero twin imagery. Hand-carded and hand-spun wool with aniline dyes (red). Dimensions: 60 x 92 in.; 152.4 × 233.68 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

-

Mid-Century Transformation (1940s–1980s): Bold Colors and Commercial Materials

Characteristics

- Color shift: The introduction of bright aniline dyes (such as synthetic reds, yellows, and greens) as highlights created stark contrasts.

- Design expansion: More complex, high-density patterns with zigzags, hexagons, and interlocking motifs.

- Material changes: Commercially processed wool replaced hand-spun yarn, reducing preparation time.

Key Influences

- WWII-era infrastructure: Improved roads (e.g., he expansion of Route 66) enabled wool to be shipped to commercial mills, freeing weavers from labor-intensive processing (M’Closkey, Swept Under the Rug, 2002).

- Trading post partnerships: Traders supplied chemical dyes and encouraged experimentation to meet the demands of the tourist market.

Academic Sources

- Welsh (1986) documents how Teec Nos Pos rugs grew larger after 1940 (up to 10'x14') to suit Anglo-American interior design trends.

- Maxwell Museum studies note a peak in production in the 1950s and 1960s, with weavers like Hosteen Nez earning reputations for "optical intensity" in their color pairings.

Large Teec Nos Pos Rug, 1930s-1940s. Dimensions: 118 x 62 in.; 299.72 x 157.48 cm. This great Navajo Teec Nos Pos rug has a salt-and-pepper gray background and is made of homespun wool. There is a nice abrash (color variation) in the brown. This weaving also includes some Germantown four-ply green. Red Mesa Gallery, Penryn, California.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Teec Nos Pos rug, mid/late 20th century. Medium: Woven in multicolor wool with a central waterbug motif and elaborate waterbugs on either side, within an elaborate double border. Dimensions: 65 x 49.5 in.; auctioned in 2024 by John Moran, Monrovia, CA.

2. Teec Nos Pos rug, 1960s. Medium: Tightly woven in commercial yarns, with a complex mirror-image pattern of geometric forms and small filler devices, a wide bow tie border. Dimensions: 8ft 3in x 5ft 7in.; 251.46 cm × 170.18 cm. Dennis Brining, Cultural Patina Art Gallery, US.

3. Navajo Teec Nos Pos Rug, 1970s. Dimensions 56 x 40.5 in.; 142.24 × 102.87 cm. Auctioned in 2024 by Medicine Man Gallery Auction, Tucson, AZ.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Teec Nos Pos rug, mid-20th century. Medium: woven in gray, brown, green, yellow, and blue; connecting central cross surrounded by arrows and tuning fork border. Dimensions: 95 × 66 in.; 241.3 × 167.64 cm. Auctioned in 2024 by Freeman's | Hindman, Chicago, IL.

2. Teec Nos Pos rug, ca. 1950. Medium: handwoven yarns, natural and aniline dyes. Dimensions: 104 × 62 in.; 264.2 × 157.5 cm. Auctioned in 2023 by Santa Fe Art Auction, Santa Fe, NM.

3. Teec Nos Pos rug, 1950s. Dimensions: 110 x 61 in.; 279.4 × 154.94 cm. Chimayo Trading del Norte, Ranchos de Taos, NM.

-

Contemporary Revival (1990s–Present): Traditional Methods and Cultural Reclamation

Characteristics

- Material revival: return to hand-spun Churro wool and natural dyes (e.g., juniper berries, sage, and walnut hulls).

- Design innovation: Fusion of classic motifs with personalized symbolism (e.g., representations of sacred landscapes).

- Market shift: High-end collectors and museums prioritize rugs made with natural materials, which elevates their value.

Key Influences

- Cultural preservation movements: Organizations like the Navajo Sheep Project (founded in 1991) have revived Churro sheep breeding to reconnect with pre-colonial practices.

- Academic partnerships: Collaborative projects with institutions like the Heard Museum document dye recipes and techniques that were once at risk of being lost.

Academic Sources

- A 2018 study in Textile: Cloth and Culture highlights artists like Lillie Taylor, who combines Teec Nos Pos geometry with storytelling motifs from Navajo cosmology.

- D. Begay (2020) emphasizes how contemporary weavers use natural dyes to "reclaim ecological knowledge" tied to Diné identity.

Notable Scholarly Works for Further Research

- Blomberg, N. (1988). Navajo Textiles: The William Randolph Hearst Collection – Early trading post influences.

- M’Closkey, K. (2002). Swept Under the Rug: A Hidden History of Navajo Weaving – Mid-century commercialization.

- Hedlund, A. (1992). Reflections of the Weaver’s World – Evolution of color and design.

- Begay, D. (2020). Diné Color Harmony: A Guide to Natural Dyes – Contemporary revival techniques.

Beautiful Teec Nos Pos Rug by master weaver Berlinda Nez Barber, 1996. Medium: custom spun, hand dyed Navajo Churro wool. With a very tight weave. Dimensions: 72 x 120 in.; 182.88 x 304.8 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona. This weaving was featured in the "Master Weavings of the Navajo Churro Collection" 2019 Exhibit at Nizhoni Ranch Gallery and in the "Master Weavings of the Navajo Churro Collection" catalog. Belinda Nez Barber parental clans are “Where Water Meets Born for Tangle” and “Bitter Water”; d her Nali is Comanche Warrior.

Teec Nos Pos rug by Elsie Begay, late 20th Century. Dimensions: 89 x 55 in.; 226.06 x 139.7 cm. Auctioned in 2023 by J. Garrett Auctioneers, Dallas, TX.

LEFT: Large Navajo Rug in Teec Nos Pos Style, second half of the 20th century. Dimensions: 115.75 x 78.5 in.; 294.01 x 199.39 cm. Toh-Atin Gallery, Durango, Colorado.

RIGHT: Intricate Navajo Weaving in the Teec Nos Pos Regional Style by Cara Yazzie, second half of the 20th century. Dimensions: 43 x 60 in.; 109.22 x 152.4 cm. Garland's, Sedona, Arizona.

LEFT: Small Teec Nos Pos Rug by Rosemary Lee, from the Twin Rocks Trading Post. Date: 1990s. Auctioned in 2022 by Ace Of Estates, Carefree, AZ.

RIGHT: Small Teec Nos Pos Rug, 1990-2000s. Dimensions: 50 x 48.75 in.; 127 x 123.83 cm. Auctioned in 2024 by Medicine Man Gallery Auction, Tucson, AZ.

RIGHT: Teec Nos Pos rug by master weaver Helene Nez, 1999. Medium: hand-dyed Churro Navajo wool. Dimensions: 45 x 84 in.; 114.3 x 213.36 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona. This weaving was featured in the "Master Weavings of the Navajo Churro Collection" Exhibit at Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, March 2019 and the "Master Weavings of the Navajo Churro Collection" catalog.

LEFT: Large Teec Nos Pos rug, second half of the 20th century. Worked with multiple geometric borders enclosing branching geometric devices with striped feather accents on a grey ground. Dimensions: 11ft 6in x 6ft 2in - 350.52 x 187.96 cm. Auctioned in 2023 by Bonham's, Los Angeles, CA.

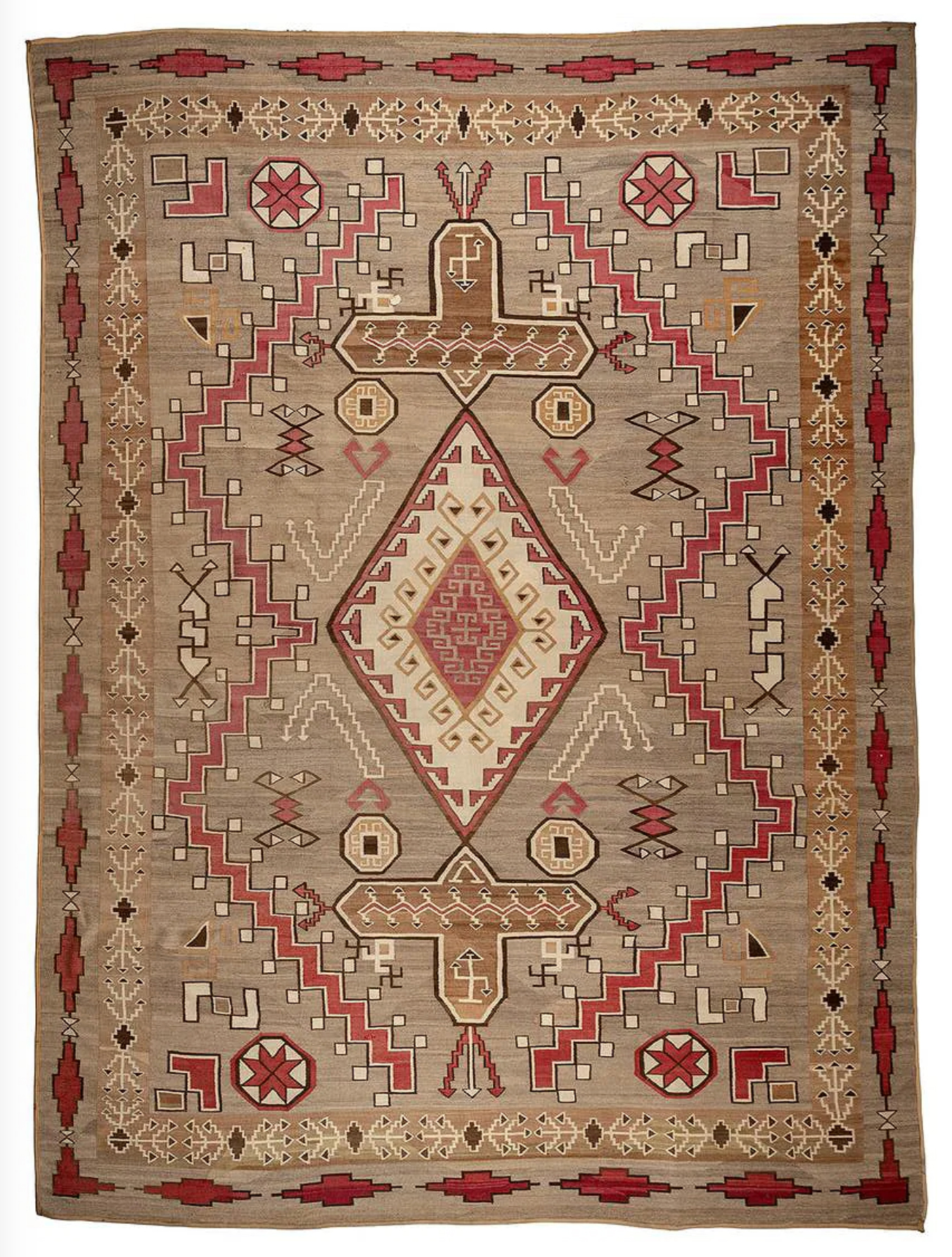

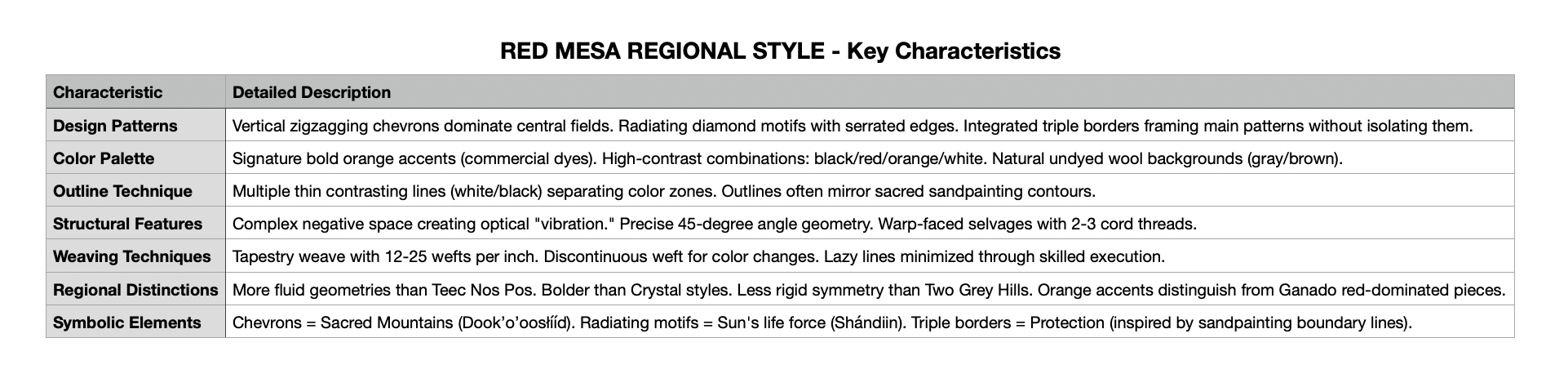

RED MESA TRADING POST AND RED MESA STYLE

The Teec Nos Pos style significantly influenced the development of the Red Mesa regional style. Emerging during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Red Mesa is a distinct yet related weaving tradition.

Red Mesa rugs are considered a sub-variant of Teec Nos Pos rugs, sharing their intricate geometric patterns and bold borders. Both styles originated in northeastern Arizona. The Red Mesa Trading Post is located just 15 miles from Teec Nos Pos, which facilitated cultural and artistic exchange between the two communities. While Teec Nos Pos designs were influenced by Persian rugs and featured complex, densely detailed motifs, Red Mesa weavers adapted these elements, focusing on contrasting colors and optical effects.

The Trading Post

The Red Mesa Trading Post was in operation by the early 20th century, as evidenced by references in Will Evans's memoirs and other historical accounts. Located just below Aneth, Utah, about 200 yards from the state line, it served as a central hub for the surrounding Navajo community for decades.

For much of its history, the trading post operated on a barter system, with cash being rare until railroad employment and government programs increased monetary circulation in the mid-20th century.

While ownership of trading posts in the region often changed hands — sometimes within families or among business partners — the Red Mesa Trading Post was a longstanding institution by the 1930s and 1940s. It also served as a marketplace, post office, and social center.

Key Characteristics of Red Mesa Rugs

- Eyedazzler Technique: Red Mesa rugs maintain the "eyedazzler" effect through the use of high-contrast color pairings (e.g., light and dark colors, red and black) and the precise outlining of geometric shapes. This technique can be traced back to the transitional blankets of the late 19th century. Vertical chevrons and radiating diamonds are hallmarks that create dynamic visual movement.

- Structural Innovation: Unlike the Persian-inspired Teec Nos Pos rugs, Red Mesa rugs often omit ornate borders, allowing the patterns to blend seamlessly into the rug's edge.

- Material Shifts: Between 1860 and 1910, commercial dyes and yarns were adopted, enabling richer reds and deeper contrasts that defined the Red Mesa palette.

Scholars and institutions, such as the Moab Museum and Navajo art historians, confirm that Red Mesa represents a continuation and refinement of Teec Nos Pos aesthetics. They emphasize the technical mastery of color gradation and geometric precision. While the eyedazzler effect is present in both styles, it became a defining feature of Red Mesa due to its sustained use of high-contrast vegetal and aniline dyes.

In summary, Red Mesa evolved from Teec Nos Pos traditions, carving its identity through bold colorwork and optical innovation. This reflects broader shifts in Navajo weaving during the late 19th century.

Teec Nos Pas Rug, 20th century, dimensions 8'6'' x 4'2''; 259.08 × 127 cm. Auctioned in 2014 by John Moran, Pasadena, CA.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Teec Nos Pos rug, ca. 1955. Medium: wool and aniline dye. Dimensions: 100 × 59 in.; 254 × 149.86 cm. Auctioned in 2018 by Heritage Auctions, Dallas, TX.

2. Teec Nos Pos rug, 1970s. Medium: handspun wool and dyes. Dimensions: 63 × 47 in.; 160.02 × 119.38 cm. Auctioned in 2022 by Santa Fe Art Auction, Santa Fe, NM.

3. Red Mesa / Teec Nos Pos Navajo rug by Marion Nez, 2010 (a piece worth 40,000 euros or 46,500 USD). Medium: Custom-spun, hand-dyed Navajo Churro wool. Dimensions: 48 x 104 in.; 121.92 x 264.16 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

4. Red Mesa / Teec Nos Pos rug, 1930s. Medium: hand-carded, hand-spun, hand-dyed Merino wool with some aniline dyes. Dimensions: 54 x 74 in.; 137.16 x 187.96 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Red Mesa rug, 1920s. Dimensions: 48 x 101 in.; 121.92 x 256.54 cm. Tres Estrellas Gallery, Taos, New Mexico.

2. Red Mesa rug, with a dense field of complementary outlined zigzags, enclosed by a wide I-form border. First half of the 20th century. Dimensions: 6ft 10in x 3ft 7in - 208.28 cm x 109.22 cm. Auctioned in 2014 by Bonhams, San Francisco, CA.

3. Red Mesa Trading Post Rug, ca. 1915. Medium: Navajo Churro hand-spun wool in natural ivory, dark brown, hand-carded grey, and a variety of hand dyed aniline colors including, dark red, navy blue, orange, and two shades of green.. Dimensions: 73 x 52 in.; 185.42 x 132.08 cm. Shiprock, Santa Fe, NM. «The rug features an elaborate border of stacked directional crosses inside "T" forms in alternating dark brown and gray. In the field, there is a central vertical band of heavily serrated diamonds with interior crosses. The diamonds are further ornamented with radiating zigzag lines with heavy serrations, all outlined in bright colors.» (Shiprock Art Gallery)

4. Red Mesa Navajo Rug, 1900-1930. Dimensions: 62 x 33 in.; 157.48 x 83.82 cm. Chimayo Trading del Norte, Ranchos de Taos, NM.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Red Mesa rug by Sarah Yazzie, 20th century. Dimensions: 4ft 6in x 3ft 3in - 137.16 cm x 99.06 cm. Auctioned in 2013 by Bonhams, San Francisco, CA.

2. Red Mesa rug, 1930-40. Densely drawn with a characteristic pattern of serrated diamonds and complementary zigzag bands, enclosed by borders of stars, barbs and stripes. Dimensions: 7ft 6in x 4ft 9in - 228.6 cm x 144.78 cm. Auctioned in 2014 by Bonhams, San Francisco, CA.

3. Red Mesa rug, 1940-1950. With In a densely serrated pattern of complementary and concentric outlined sawtooth diamonds, a single solid outer border. Dimensions: 7 ft 8in x 4ft 9in - 233.68 x 144.78 cm. Auctioned in 2014 by Bonhams, San Francisco, CA.

4. Red Mesa rug, 20th century. It features outlined complementary zigzag bands and arrows, as well as "crab" motifs, within an alternating hooked border. Dimensions: 6ft 3in x 3ft 9in - 190.5 cm x 114.3 cm. Auctioned in 2012 by Bonhams, San Francisco, CA.

Red Mesa style rugs are identified by contrasting light and dark colors, vertical chevrons, and radiating diamonds. However, it is difficult to distinguish between Red Mesa and Teec Nos Pos Navajo rugs because the difference is often subtle, even for experienced collectors and scholars. Both styles share many design elements, historical influences, and geographic proximity, leading to significant overlap in their visual language.

- Design Elements: Both Red Mesa and Teec Nos Pos rugs are known for their complex, “eyedazzler” patterns, which include radiating diamonds, vertical chevrons, and intricate geometric motifs. Both styles use bold color contrasts and often feature commercial dyes introduced in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

- Color Palette: Both styles use a wide range of bright colors, including reds, oranges, blacks, and whites. The introduction of aniline dyes via the railroad in the 1880s led to a dramatic expansion of the available color palette for both styles.

- Cultural and Historical Context: Both styles emerged during the period when Navajo weaving transitioned from producing utilitarian blankets to decorative rugs for the Anglo market. Influences from Hispanic and Persian textiles are evident in both styles, especially in the use of serrated motifs and busy, symmetrical patterns.

While there is significant overlap, some features are more typical of one style than the other.

According to Navajo weaving experts and museum curators, Red Mesa rugs are often considered a sub-style or variant of Teec Nos Pos rugs. The main differences are subtle and relate to border treatment, color choices, and the overall density of the design.

The Maxwell Museum of Anthropology acknowledges the similarities between the two styles and the difficulty in making definitive attributions.

The Moab Museum and other academic sources emphasize that both styles are products of cultural blending and market adaptation and that the lines between them have historically been blurred.

In practice, distinguishing Red Mesa from Teec Nos Pos rugs is often a matter of degree rather than kind. There is no clear-cut, universally accepted rule, and attributions can be subjective. Many rugs exhibit characteristics of both styles, reflecting the dynamic and adaptive nature of Navajo weaving traditions in the Four Corners region.

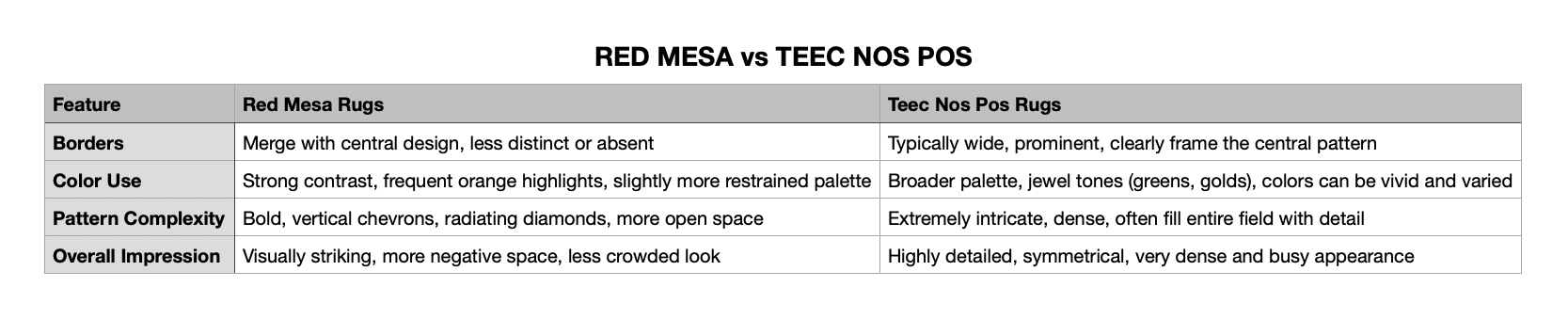

Below is a beautiful rug woven by Lillie Joe in 1975 and awarded first place in the Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial. In your opinion, is this a Red Mesa or a Teec Nos Pos rug?

Teec Nos Pos Trading Post Rug by Lillie Joe in 1975. Medium: wool and dye. Dimensions: 97 x 61 in.; 246.38 x 154.94 cm. Shiprock Art Gallery, Santa Fe, NM.

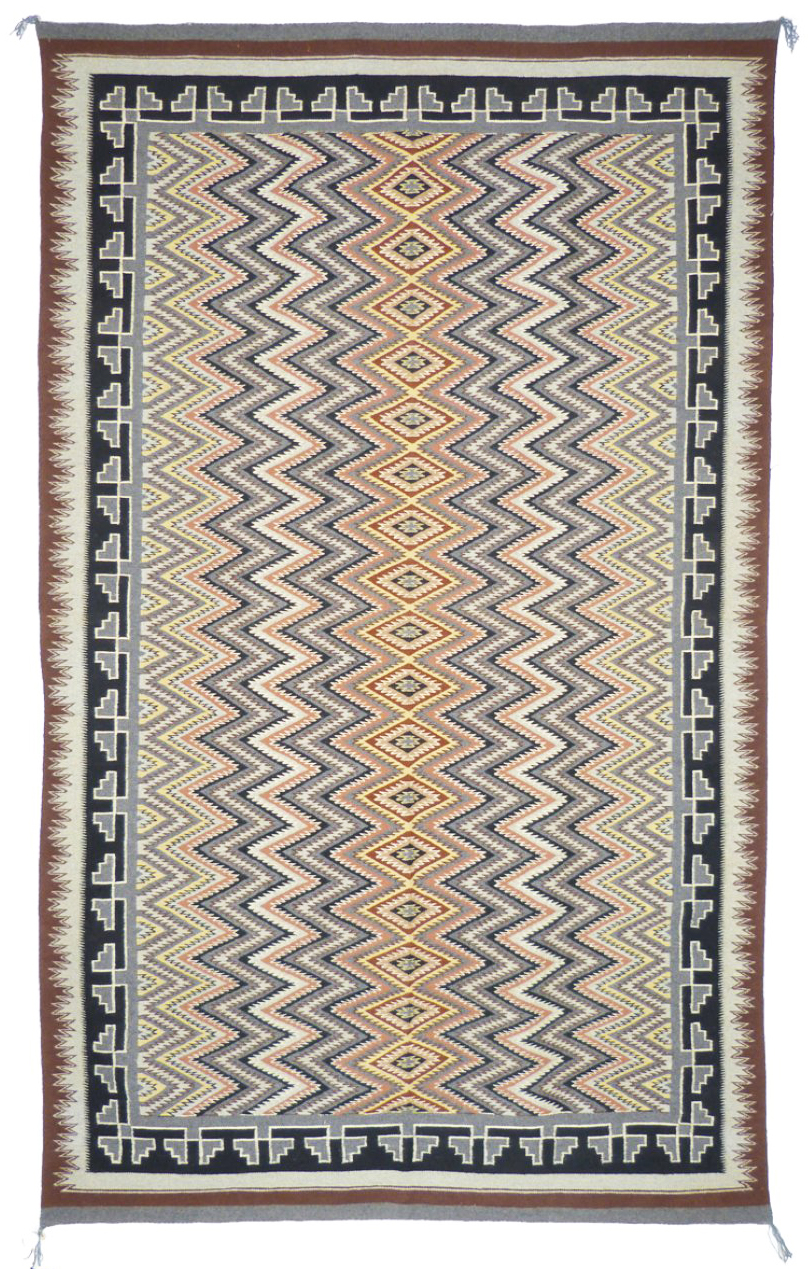

Echoes in Silver and Stone: The Spirit of Navajo Jewelry

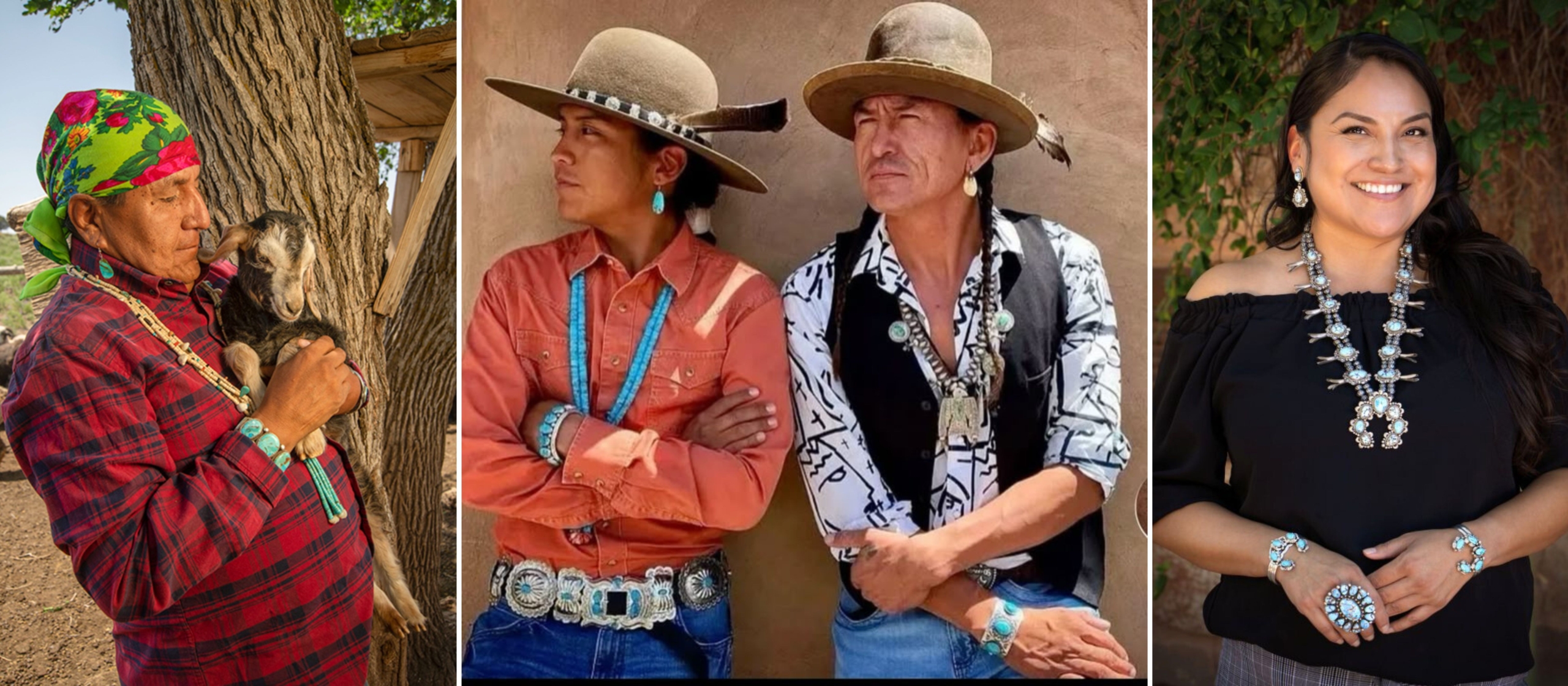

In the windswept mesas and sacred canyons of the American Southwest, beauty is not just seen—it is inherited, forged, and worn. For the Navajo people, silver and turquoise are more than materials; they are ancestral voices, each piece of jewelry a verse in an enduring song of resilience, identity, and artistry.

Born from the hands of blacksmiths and visionaries, Navajo silversmithing began as a quiet fire—sparked in the mid-19th century and fanned by tradition, ingenuity, and cultural pride. Over generations, it evolved into an art form as luminous as desert lightning, rich with spiritual meaning and unyielding grace.

These images celebrate not only the timeless elegance of Navajo craftsmanship but also the lives and legacies it adorns. Every necklace, bracelet, and concha belt speaks of family, survival, beauty, and the sacred connection between earth and spirit.

Welcome to a story told not in words alone, but in silver and stone.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Elderly Navajo man wearing straw hat, velveteen shirt, concha belt and denim jeans. Photo by Donald Allam Blair, 1950s. Photo: National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, OK.

2. Navajo girl wearing silver and turquoise Squash Blossom jewelry, 1950. (Photo: Montclair Art Museum).

3. Image from Poncho Outdoors' clothing line.

ABOVE

Top left: Teec Nos Pos Trading Post.

Bottom left: Museum of Northern Arizona

Center: Matthew Charley, a Diné artisan, designer and metalsmith based on the Navajo Nation in NewMexico. (Photo: Rio Grande, Albuquerque, NM).

Top right: Naiomi Glasses, a Diné textile artist based on the Navajo Nation in the RockPoint Chapter community, is an avid turquoise collector and boasts one of the world’s most enviable collections of Navajo jewelry. (Photo: Tyler Glasses)

The remaining two pictures are from the agency.

BELOW

Left: Navajo Master weaver Roy Kady (Photo: The Moab Museum).

Center: Navajo style, from Pinterest, undated, no indicated source.

Right: From the web, no source indicated.

Origins and Early Development (Mid-19th Century)

Navajo silversmithing is a relatively recent tradition, with its origins traced to the mid-19th century. The earliest Navajo metalwork was influenced by contact with Mexican blacksmiths and Spanish settlers in the American Southwest. Atsidi Sani, also known as "Old Smith," is widely recognized as the first Navajo silversmith. He learned blacksmithing from a Mexican smith around 1850 and began working with silver by the 1860s or 1870s, after observing Mexican and Spanish silversmiths at trading posts and military outposts near Navajo territory.

Initially, Navajo metalwork focused on utilitarian objects such as bridles, bits, and knives, but as access to silver increased—mainly through the melting of American and Mexican coins—jewelry production began to flourish. Early Navajo jewelry included rings, bracelets, buttons, and concha belts, often inspired by Spanish and Mexican designs.

Expansion and Innovation (Late 19th to Early 20th Century)

After the Navajo returned from their forced internment at Bosque Redondo (1864–1868), silversmithing spread rapidly among the community. Atsidi Sani taught his sons and other apprentices, establishing a tradition of passing down skills through families and clans. By the late 19th century, Navajo smiths began to incorporate turquoise—prized for its spiritual and symbolic significance—into their silverwork, a practice that became a hallmark of Navajo jewelry

Key jewelry forms developed during this period include:

- Squash blossom necklaces: Inspired by the crescent-shaped naja pendant of Spanish bridles, these became iconic symbols of Navajo artistry.

- Concha belts: Adapted from Spanish harness buckles, these belts featured decorated silver disks and became popular adornments.

- Cluster jewelry: Featuring multiple turquoise stones set in intricate patterns, this style emerged in the late 19th century and remains a signature Navajo technique.

Commercialization and Artistic Evolution (20th Century)

The arrival of the railroad and the rise of tourism in the early 20th century brought significant changes. Traders and companies like the Fred Harvey Company began commissioning lighter, more "tourist-friendly" jewelry, often providing Navajo smiths with precut turquoise and sheet silver. This led to the development of new motifs and styles tailored to non-Native buyers, such as stamped silver bracelets with symbolic designs (arrows, thunderbirds, etc.).

From the 1920s onward, increased access to turquoise from Nevada and Colorado mines fueled further innovation. Jewelry became more elaborate, with bold turquoise settings and ornate silverwork described as "baroque" by some anthropologists. The Indian Arts and Crafts Board, established in the 1930s, encouraged a return to traditional styles and introduced quality stamps to authenticate Navajo-made pieces.

Contemporary Navajo Silversmiths

Today, Navajo silversmithing is a vibrant and evolving art form, practiced by both men and women. Techniques such as sandcasting, tufa casting, and hand-stamping are still widely used, and artists continue to blend traditional motifs with contemporary aesthetics. Modern Navajo jewelry incorporates a range of gemstones—turquoise, coral, lapis lazuli, and onyx—and is celebrated for its craftsmanship and cultural significance.

Notable contemporary silversmiths, such as Jeanette Dale, Wilson and Carol Begay, and Ron Henry, exemplify the continued innovation and excellence in Navajo jewelry-making. Their work is sought after by collectors worldwide and showcased in museums, galleries, and art markets.

And So It Goes

For the Navajo, jewelry is more than adornment; it represents identity, status, spirituality, and connection to tradition. Turquoise, in particular, is revered as a symbol of fortune, healing, and protection, with legends describing it as the tears of joy from the people after rain ended a drought.

Navajo silversmithing, from its origins with Atsidi Sani in the 19th century to its flourishing contemporary scene, is a testament to the resilience, creativity, and cultural pride of the Navajo people. The tradition continues to evolve, blending ancient techniques with modern artistry, and remains central to both Navajo identity and the broader story of American art.

The Navajo jewels below (and their pictures, of course) comes from different sources: the Historic Cameron Trading Post in Cameron, AZ; the 2025 Modern Native American Art and Jewelry auction by Bonham's Skinner; some recent auctions by John Moran, Monrovia, CA; the Four Winds Gallery, Pittsburgh, PA; Just Mens Rings, Loma Linda, CA; Bradford’s Auction Gallery, Sun City, AZ.

Navajo Silver, photo by Native American artist Jeremy Salazar, a contemporary painter and fotographer based on the Navajo Nation in New Mexico.

Jacqueline Rochester, print with gold and silver leaf, 2025.

Jacqueline Rochester (1924–2010) was an American artist recognized for her work as a portrait and figure painter, sculptor, and designer. She was born in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and spent many years living in Rapid City, South Dakota. She is particularly noted for her portrayals of Native American life—especially women—and for wearable art and sculpture. Rochester's work is characterized by its avoidance of clichés, instead presenting her own vision of Native Americans, their folklore, and traditions. In the print above, the use of bold, flat areas of color and simplified forms is typical of her approach, which seeks to evoke the spirit and atmosphere of Native American life without resorting to stereotypes or sentimentality. Some of her prints and paintings incorporate gold and silver leaf, adding a unique dimension to her compositions.

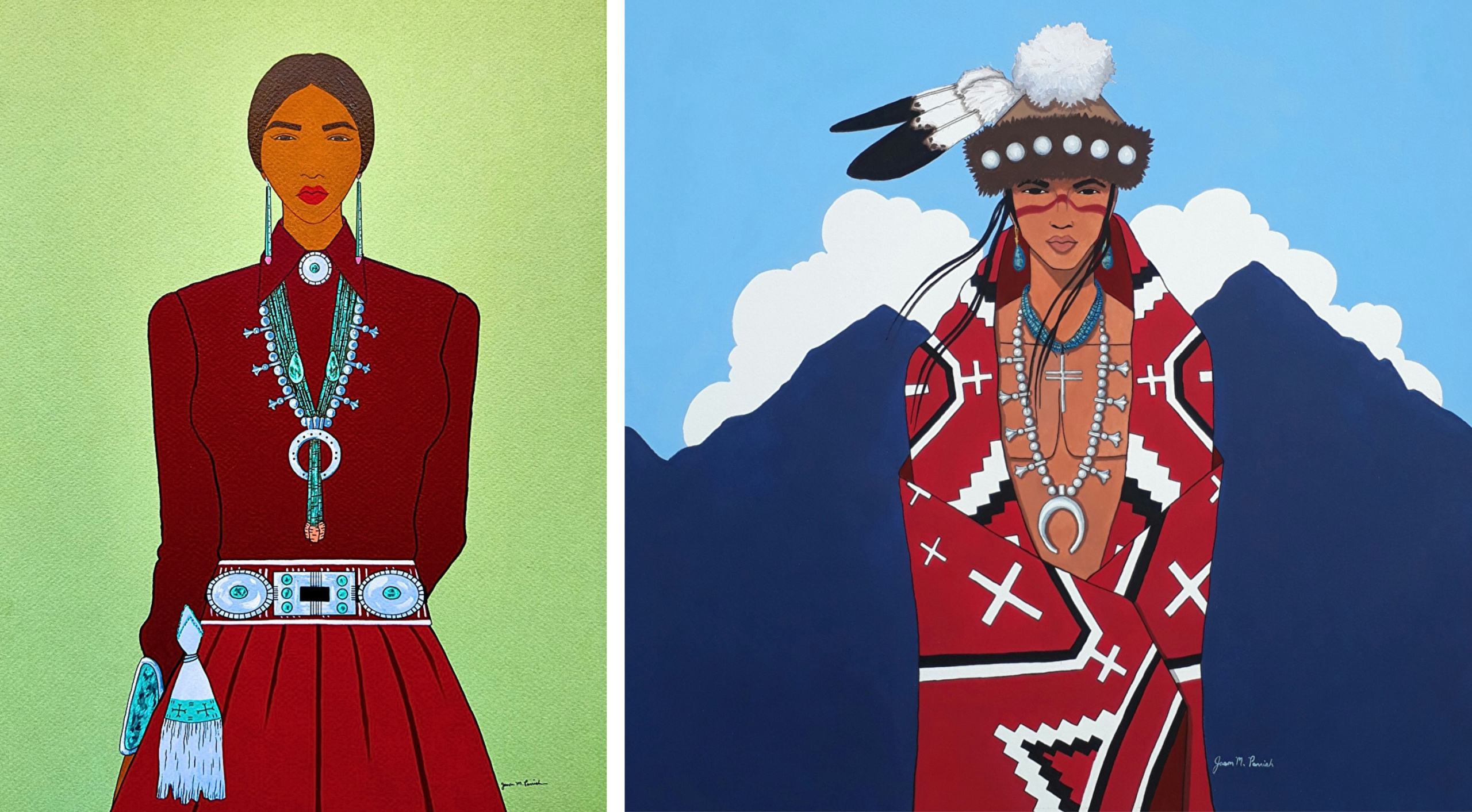

Two acrylic on board artworks by Jason Parrish: Adorned in Autumn Light (on the left) and Portrait of a Navajo Young Man (on the right)

Jason Parrish is a Navajo artist born in Gallup (NM) from two Navajo clans: Dzil T’aanii (Near the Mountain People) and To’dichii’nii (Bitter Water People). «Dinetah (Navajo land) is his primary source of inspiration for his culturally rich subject matter. His paintings directly respond to his surrounding environment and uses personal experiences as a starting point. The majority of his subject matter is centered around Navajo culture. Stories, ceremony, and lifestyle are a constant presence in his pieces. Each painting not only serves an aesthetic purpose but is a chance to present framed instances of Navajo life both traditional and modern. By examining the beauty and importance of his Navajo culture, Parrish takes the viewer into a world they may never knew existed.» (Jason Parrish official bio)

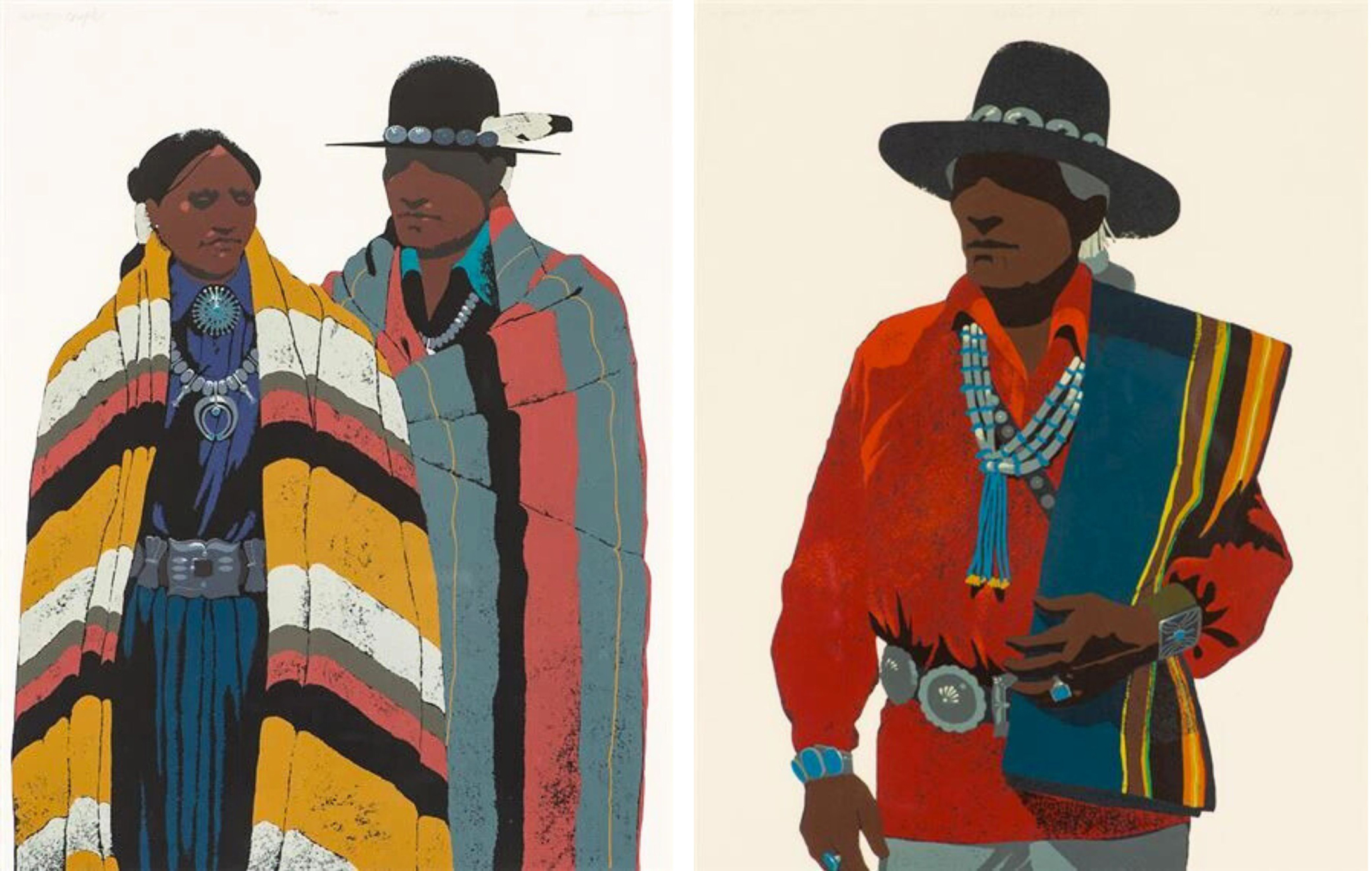

Louis De Mayo (American painter 1926 - 2016), Navajo Couple, 1981, serigraph and Navajo Man, 1981, serigraph on paper.

The history of Navajo silversmith and designer Kenneth Begay

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?