NAVAJO CHURRO SHEEP AND WOOL 7

USA on the globe.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

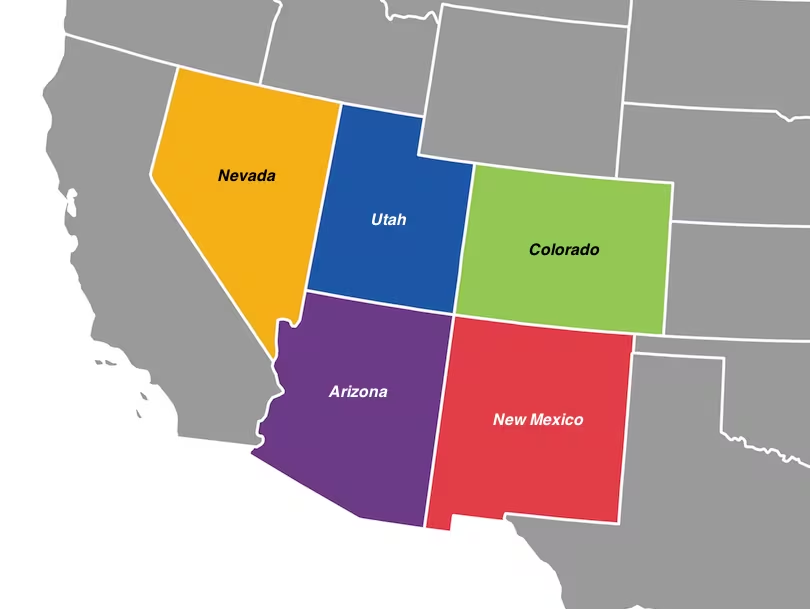

SOUTHWESTERN STATES

TWO GREY HILLS TRADING POST AND TWO GREY HILLS STYLE

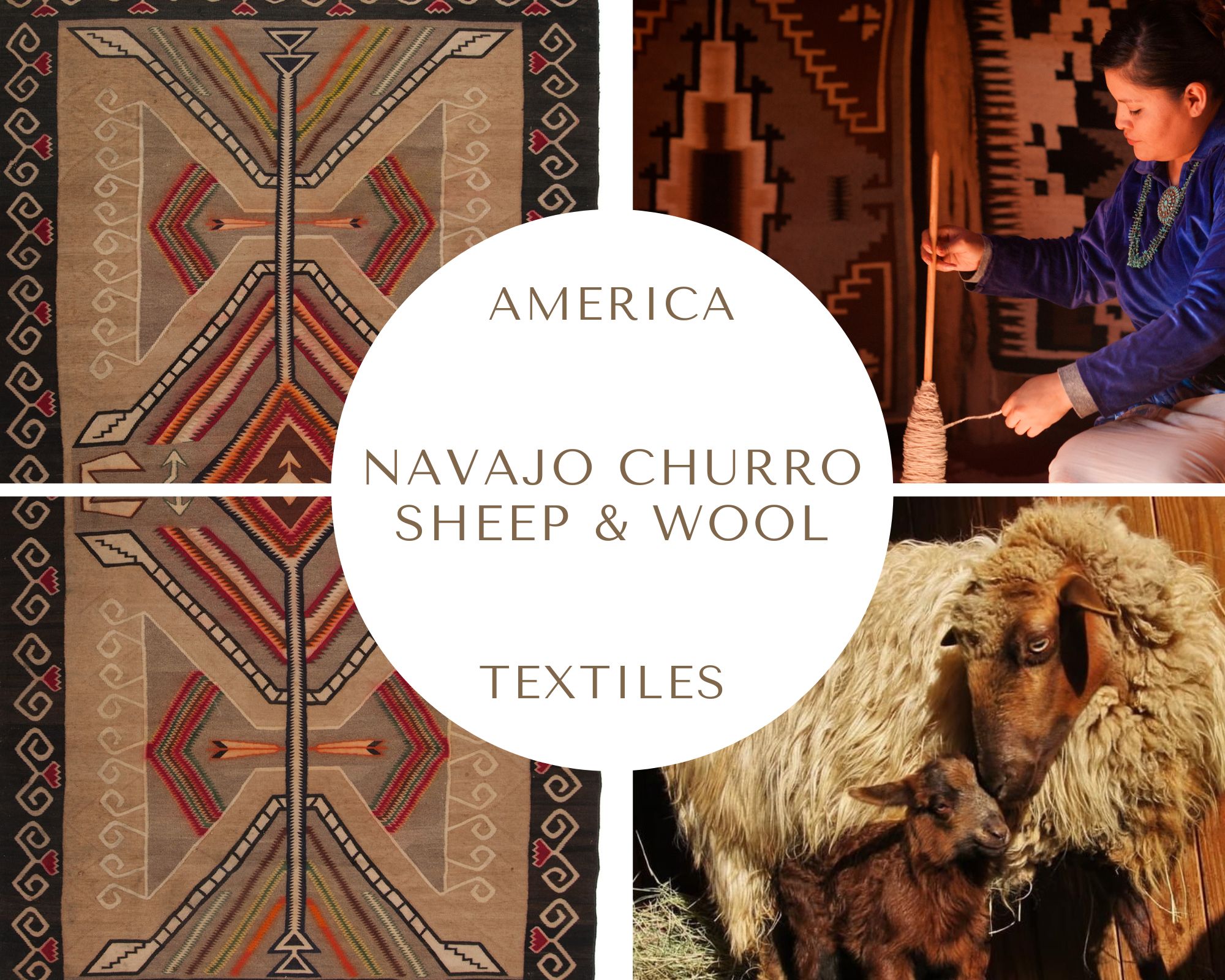

Developed through a century of collaboration between Diné weavers and traders, the Two Grey Hills style of Navajo weaving is known for its natural wool palette, geometric precision, and technical mastery. It takes its name and origin from the Two Grey Hills Trading Post: established in 1897 by Joseph R. Wilkin near the Chuska Mountains on Navajo land in New Mexico, it soon became the epicenter of this regional weaving tradition. Ed Davies, who purchased the post in the early 20th century, partnered with George Bloomfield of the nearby Toadlena Trading Post to revolutionize Navajo textile production. Their work with local weavers between 1915-1925 resulted in

- Rejection of commercial dyes in favor of natural sheep wool colors (black, white, brown, gray);

- Emphasis on intricate geometric patterns with fourfold symmetry;

- Development of carding techniques to blend natural wool colors.

By providing critical market access while respecting the aesthetic preferences of the weavers, Bloomfield and Davies created a sustainable economic model that elevated Navajo textiles to the status of fine art.

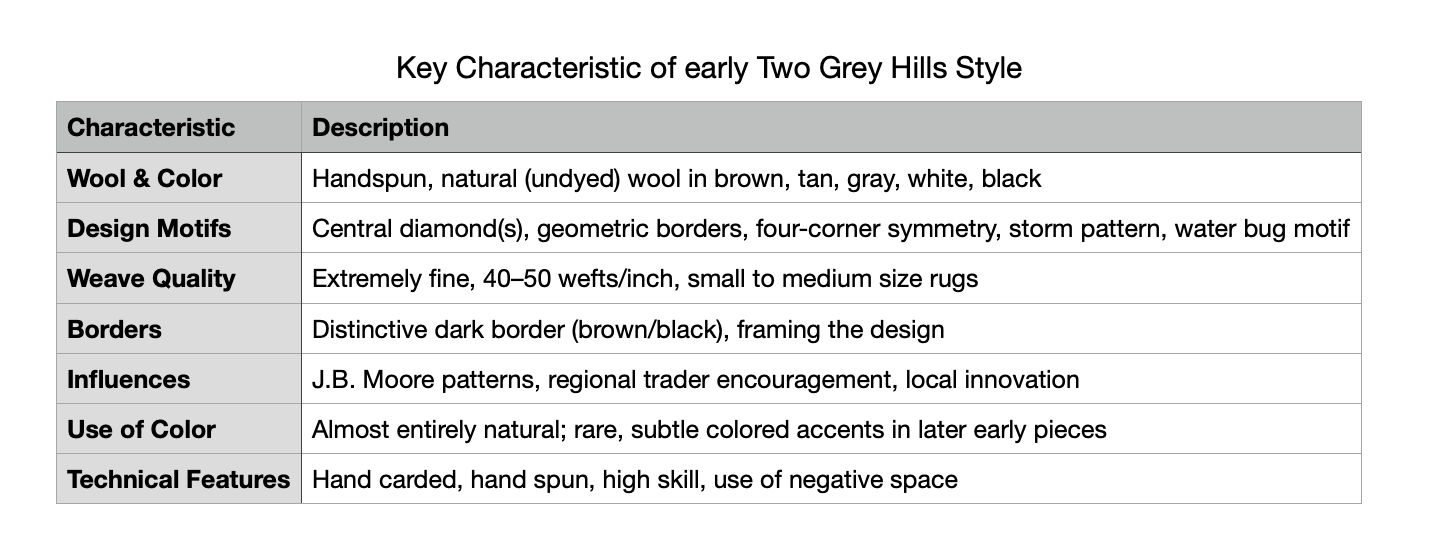

Key Characteristics of the Early Two Grey Hills Style

LEFT TO RIGHT

-

Toadlena Two Grey Hills Rug, handwoven by "Blind Man's Wife", ca. 1920s-30s. Dimensions: 49 x 73 in.; 124.46 cm x 185.42 cm. Photo courtesy: Toh-Atin Gallery, Durango, Colorado.

-

Two Grey Hills Rug, ca. 1930s. Dimensions: 48 x 36 in.; 121.92 x 91.44 cm. Photo courtesy: Chimayo Trading del Norte, Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico.

-

Two Grey Hills Rug Sleepy Rock Clan, c. 1940s. Dimensions: 44 x 69 in.; 111.76 x 175.26 cm. Toadlena Trading Post, Newcomb, New Mexico.

-

Two Grey Hills Rug, first half of the 20th century. Dimensions: 6ft 2in x 4ft 1in.; 187.96 cm x 124.46 cm. Auctioned by Bonhams in 2015.

Use of Natural, Undyed Wool

Early Two Grey Hills rugs are distinguished by their exclusive use of handspun, natural wool. Weavers blended the fleece from local sheep to create a palette of browns, tans, grays, whites, and blacks, avoiding commercial dyes and synthetic yarns. This careful carding and spinning resulted in subtle, nuanced color variations unique to each rug.

Technical Excellence and Fineness of Weave

Two Grey Hills weavers became known for their technical mastery:

- Very fine handspun yarn, often from Navajo Churro sheep.

- High weft density, averaging 40-50 wefts per linear inch, which is much finer than most other Navajo regional styles.

- Rugs were generally smaller than floor rugs from other regions, often intended for wall display because of the time and effort required for such fine work.

Influence of Traders and Regional Style Formation

The style crystallized around 1910-1920 under the influence of traders such as Ed Davies (Two Grey Hills Trading Post) and George Bloomfield (Toadlena Trading Post), who encouraged the use of natural wool and complex geometric designs. They also promoted the practice of photographing exceptional weavings to inspire other artists, accelerating innovation and the spread of distinctive design elements.

Early Design Influences

Some early Two Grey Hills rugs incorporated motifs from J.B. Moore’s mail-order catalog designs, including the storm pattern and border layouts, but adapted them using only natural wool colors. Over time, these motifs evolved into more regionally specific patterns.

Subtle Use of Color and Negative Space

While the vast majority of early rugs were limited to natural wool tones, rare examples from the 1920s to the 1940s included small accents of color (such as red or blue), usually at the encouragement of local dealers. The concept of "negative space" was also explored, with a careful balance of filled and open areas within the design.

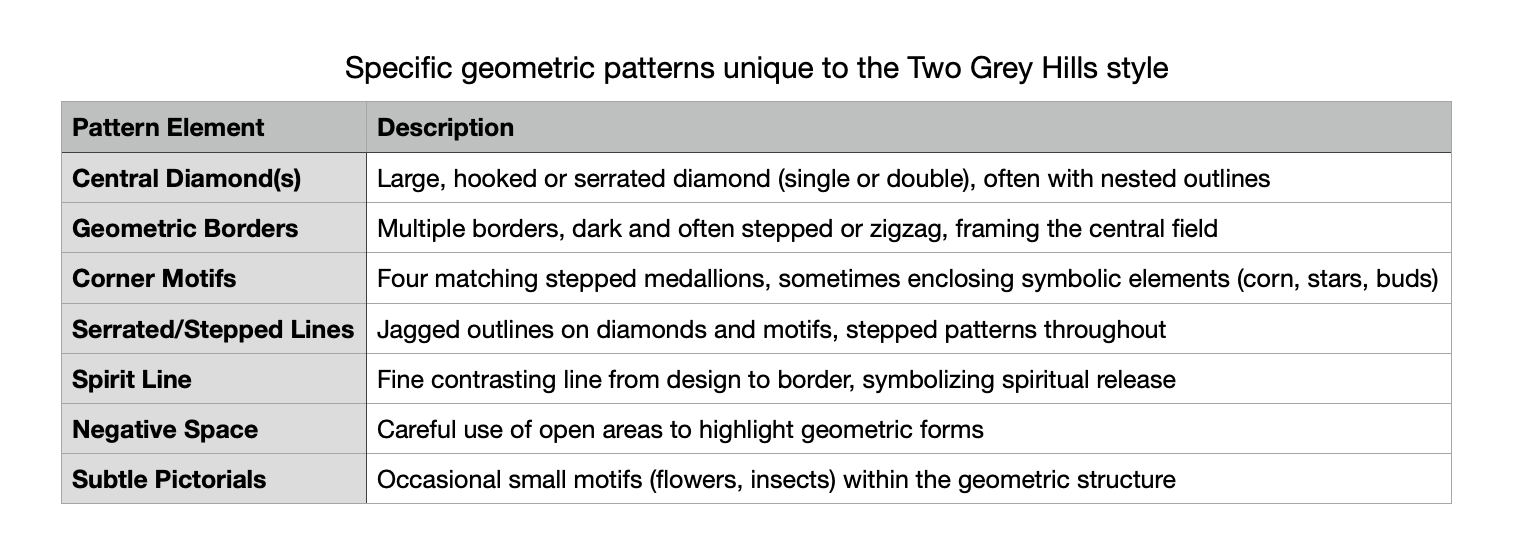

Unique Geometric Patterns of the Two Grey Hills Style

Two Grey Hills Navajo rugs are celebrated for their distinctive geometric designs that set them apart from other regional weaving styles. The following motifs and compositional elements are particularly characteristic and often unique to this tradition:

- Central Diamond or Double Diamond Motif

The most recognizable feature is a large, hooked or serrated central diamond, sometimes doubled (single or double diamond pattern). These diamonds often have stepped or serrated contours, adding complexity and visual depth.

- Multiple Geometric Borders

Rugs are framed by one or more geometric borders, typically in dark brown or black, which may include stepped or zigzag patterns. Borders often contain smaller geometric designs, such as triangles or stepped medallions.

- Four Matching Corner Elements

Each corner of the rug is usually filled with a matching geometric motif, such as stepped medallions, which may enclose symbols such as cornstalks, stars or plant buds.

- Jagged and Stepped Patterns

Serrated (jagged or sawtooth) lines define the edges of diamonds and other motifs, a hallmark of Two Grey Hills design. Stepped patterns are used both as outlines and as stand-alone motifs, referencing traditional Navajo symbolism.

- Subtle Pictorial Elements

Although rare, some rugs may include small pictorial motifs (such as "flowers" or abstract insect forms) within the geometric framework.

LEFT: Two Grey Hills Rug, first half of the 20th century. Dimensions: 5ft 11in x 3ft 7in.; 180.34 cm × 109.22 cm. Auctioned by Bonhams in 2005.

CENTER: Two Grey Hills Rug, 1920-1930. Dimensions: 57 × 83 in.; 144.78 × 210.82 cm. Photo courtesy: Tres Estrellas Gallery, Taos, New Mexico.

RIGHT: Two Grey Hills Rug, 1930s. Dimensions: 87 x 63 in.; 221 x 160 cm. Photo courtesy: Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

LEFT: Toadlena Two Grey Hills weaving, unknown weaver, ca. 1930. Medium: wool. Dimensions: 73 x 57 in.; 185.42 x 144.78 cm. Collection Bill and Leslie Banks, Elkhart, Ind.

CENTER: Two Grey Hills Rug, 1st half of the 20th century. Dimensions: 7ft 1in x 5ft 9in.; 215.9 cm × 175.26 cm. Auctioned by Bonhams in 2015.

RIGHT: Two Grey Hills Rug, 1st half of the 20th century. Dimensions: 6ft 2in x 4ft.; 188 cm × 121.92 cm. Auctioned by Bonhams in 2013.

The whirling log (tsil no’oli)

Look at the rug on the upper right. See the strange symbol that looks like a swastika? Well, it's not a swastika. It's the náhółhis or the tsil no'oli, which translates as "that which rotates," alluding to movement in a particular direction. In the Americas, this symbol has a rich history among various indigenous groups, including the Hopi, Navajo, Dakota, Tlingit, and Guna of Panama (as we saw in ).

In traditional Navajo culture, the whirling log, in both clockwise and counterclockwise variations, not only represents motion and balance, but also has a direct astronomical connection. Specifically, it symbolizes the North Star and the movement of the Big Dipper constellation (Ursa Major) as it orbits the North Star throughout the year and during its daily journey across the sky. This celestial movement is central to Navajo cosmology, marking the passage of time and dividing the universe into quarters, creating a sense of cosmic balance.

The whirling log is also a sacred motif that symbolizes the sacred number four - four directions, four seasons, and four sacred mountains that are central to Navajo cosmology. In the past, it was often depicted in sacred sand paintings during healing rituals and was not to be seen outside of ceremonial contexts (it was a kind of taboo).

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, traders such as J.L. Hubbell and J.B. Moore encouraged Navajo weavers to incorporate the symbol into rugs for commercial purposes. This led to its appearance in textiles such as the Two Grey Hills style. Thus, its incorporation into rugs was a relatively modern phenomenon that coincided with increased trade and outside influence. However, the advent of the Third Reich and the outbreak of World War II robbed the swirling log of the carefree significance it had acquired in rugs as a symbol of protection and good fortune. Its visual resemblance to the Nazi swastika was disastrous.

In 1940, the Navajo, Hopi, Apache, and Papago tribes issued a proclamation renouncing the use of the whirling log in their art, textiles, and ceremonies because of its appropriation by Nazi Germany and the negative associations that resulted. Some weavers, however, have continued to use the motif, honoring its traditional meaning, though this is uncommon.

The role of “Spirit Line” (Ch’ihónít’i)

The "spirit line", also known as the ch’ihónít’i or "weaver's path," is a subtle but deeply meaningful feature in many Two Grey Hills rugs: it's a fine line, often in a contrasting color, that runs from the main design to the border and outer edge, allowing the weaver's spirit to exit the rug. Its primary function is spiritual: it provides an outlet for the weaver's creative spirit, which is believed to be invested in the rug during the weaving process. By including the spirit line, the weaver ensures that her spirit is not trapped within the finished textile, allowing her to continue weaving in the future. This practice reflects Navajo beliefs about the interconnectedness of people, objects, and spiritual energy, and the importance of maintaining balance and freedom for the creative self.

The use of the spirit line became especially prevalent after 1900 when traders began requesting border designs. Weavers became concerned that these new borders might trap their creative energy, so the spirit line became a common solution. In Two Grey Hills rugs, the spirit line is even more common than in other Navajo styles, reflecting both the region's technical excellence and its strong adherence to tradition.

How can it be recognized? The spirit line is often a small, light-colored strand that is only subtly visible, typically running from the edge of the central design, through the border, and out to the edge of the rug.

The rug I am about to show you is a piece I really love: it was extremely well hand woven in the 1940s and has a complex design. It's a beautiful piece of Two Grey Hills with elements of the Bistie style. Bistie is a distinctive style of Navajo weaving characterized by several unique elements that set it apart from other regional designs, often including prayer feathers, pictorial motifs, and up to nine borders surrounding a central element. The masterpiece below was woven by an unknown master weaver and "introduces" the next section in which we'll see some masterpieces by the most famous Two Grey Hills weavers.

Rare Two Grey Hills area Bistie runner, 1940s. "Book piece", mentioned in Timeless Treasures of Two Grey Hills Exhibit and Catalog (p. 25). Dimensions: 49 x 122 in.: 124.46 cm x 309.88 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

Whispers of Grey Hills: The Masters' Touch

Early Two Grey Hills rugs remain highly prized for their technical brilliance, subtle beauty, and the deep cultural heritage they embody. Notable early weavers such as Bessie Manygoats set technical standards that continue to guide the tradition.

Bessie Manygoats (ca. 1905–1953)

Bessie Manygoats was one of the most influential and technically accomplished Diné weavers in the history of the Two Grey Hills style of Navajo weaving. Her work, along with that of her contemporary Daisy Taugelchee, set technical and artistic standards that continue to define and inspire the tradition today.

She lived and worked in the Toadlena/Two Grey Hills region of New Mexico, an area renowned for its weaving excellence, and was recognized during her lifetime for the exceptional skill, creativity, and intricate design schemes of her rugs. She won numerous awards in competitions, including the prestigious Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonials.

She consistently produced rugs with a fine, even weave, often achieving 40-50 wefts per inch ( 15.75–19.69 wefts per centimeter), which was considered exceptional for her time. She was known for her use of dark brown wool, which became a signature element in her work.

Unlike many weavers who repeated patterns, Bessie Manygoats was known for her originality and rarely repeated her designs. She played with complex geometric patterns, expanded the classic diamond and border motifs, and incorporated the concept of "negative space" to add a new visual dimension to her work. Her designs were both technically challenging and artistically innovative, and helped move the Two Grey Hills style beyond its early influences into a more distinctive and sophisticated direction.

LEFT TO RIGHT

-

Two Grey Hills Rug by Bessie Manygoats, 1930s. Medium: hand-spun yarn, no dye. Dimensions: 58 x 84 in.; 147 x 213 cm. Native Jackets Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

-

Two Grey Hills Rug by Bessie Manygoats, ca. 1930. Medium: hand carded, hand spun Navajo Churro wool. "Book piece": mentioned in Timeless Treasures of Two Grey Hills from the Getzwiller Collection, 2017-18 (p. 14). Dimensions: 50 x 80 in.; 127 x 203.2 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

-

Two Grey Hills Rug by Bessie Manygoats, 1930s. "Book piece": mentioned in Mark Winter, The Master Weavers (2011: 126). Medium: hand-spun wool with dark interior and complicated design of diamonds and hooked devices. Finesse: 12 warp/inch x 56 weft/ inch. Dimensions: 61 × 83 in.; 155 × 210.82 cm. Auctioned in 2020 by Cowan's Auction, Cincinnati, Ohio.

-

Two Grey Hills Rug by Bessie Manygoats, 1930s. "Book piece", mentioned on p. 126 of The Master Weavers, Plate 20. Dimensions: 61 x 83 in.; 154.94 x 210.82 cm. Native Jackets Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

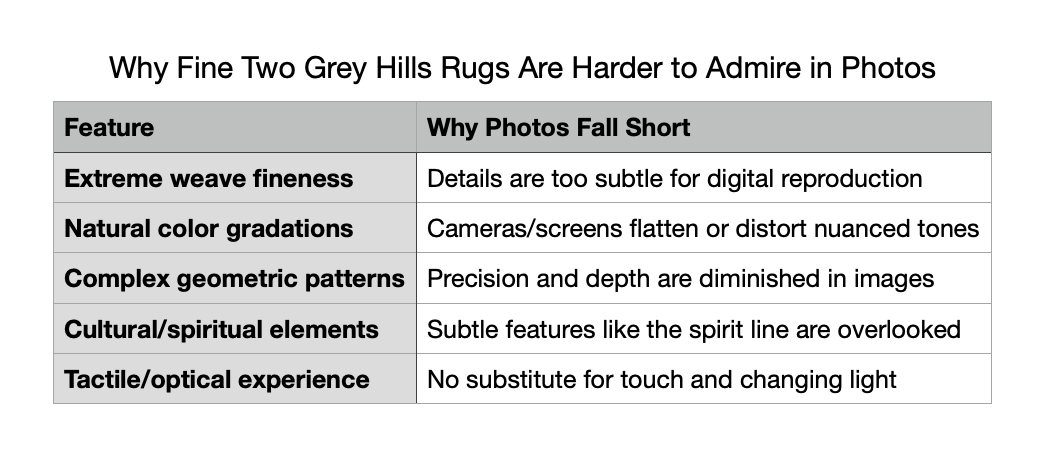

Viewing a beautiful rug solely through photographs presents numerous challenges that can prevent you from truly appreciating its beauty and quality. For this reason, serious rug enthusiasts and interior designers often insist on seeing rugs in person before making a purchase.

Admiring a fine Navajo masterpiece rug, especially a super fine Two Grey Hills, through photographs is even more difficult than with other rugs because of their several unique qualities. Two Grey Hills rugs are known for their incredibly fine weave, often with 80 or more wefts per inch, with masterpieces reaching up to 115 wefts per inch. This level of detail is virtually impossible to capture in a photograph, as the subtlety and precision of the weave can only be fully appreciated up close, where the interplay of each tiny thread becomes visible.

Two Grey Hills rugs are woven exclusively from natural, undyed wool in a sophisticated palette of browns, grays, whites and blacks achieved by carding and blending the wool of different sheep. The nuanced shifts in tone and richness of the natural fibers are difficult for cameras to capture accurately, and digital screens further flatten these subtleties, robbing the viewer of the tactile and visual complexity that makes these rugs so prized.

In addition, Fine Two Grey Hills rugs feature intricate geometric designs-diamonds, crosses, terraced forms, and sometimes eight-pointed stars, often surrounded by multiple borders. The precision of these patterns, the sharpness of their execution, and the way they interact with the texture and luster of the rug are best appreciated in person, where the three-dimensionality and crispness of the design can be fully appreciated.

A distinctive element in many Two Grey Hills rugs is the "spirit line". It's almost impossible to capture this subtle line in photographs. On the contrary, it's visually striking when seen up close, connecting the viewer to the weaver's intent and cultural context.

Finally, I love the special tactile experience, the feel of the dense, hand-spun wool, the weight and suppleness of these rugs, all qualities that cannot be conveyed through images.

In essence, the very qualities that make a superfine Two Grey Hills rug a masterpiece – its technical virtuosity, subtle beauty, and cultural resonance – are precisely those that resist translation into photographs. To truly admire such a rug, one must experience it in person, where its artistry can be seen, felt, and fully understood. For this reason, in the images below, you can compare the two-dimensional image of a Bessie Manygoats rug with some photos of its enlarged details and a photo of its dimensions; this will give you a less limited idea of the visual and tactile impact of these wonders.

Although the photo on the right is of poor quality and alters the colors of the rug, it gives an idea of its size and grandeur, unlike the photo on the left, which is two-dimensional, lacks spatial references, and makes the rug appear "dead," while the photo on the right makes it appear "alive". And this is not just a figure of speech: Navajo rugs "live" in their own way. In a beautiful way.

The photo of this detail shows the precision and finesse with which this rug has been hand-woven, without following any pre-existing global design. Can you spot the spirit line?

This photo may give you an idea of the tactile sensations typical of an excellent Two Grey Hills rug: it is compact yet soft, silky yet extremely sturdy; after all, it dates from the 1930s and is still in perfect condition. It is extremely fine: compare it with the coarse weave of the wall-to-wall carpeting (which will certainly not last 95 years like Bessie's masterpiece).

Daisy Taugelchee (1909 or 1911–1990)

Daisy Taugelchee is universally recognised as the most famous and accomplished Two Grey Hills weaver, renowned for her exceptionally fine weaving, often achieving over 115 wefts per inch (45.28 wefts per centimeter) – a level of precision unmatched in her era. She continued to define the style with her finely spun yarns and complex, sensitively conceived designs. In the 1950s, she was reportedly the highest paid weaver in the world, and experts such as dealer Gilbert Maxwell called her "the greatest living Navajo weaver".

Born on the Navajo Nation reservation in Arizona, she grew up in a family of renowned weavers. Her paternal grandmother, Sagebrush Hill Woman, was one of the most respected early Toadlena/Two Grey Hills weavers, and Daisy was raised in the Bear Clan household among other master weavers such as Mrs Policeboy and Mary Yanabah Curley. Her early exposure to these influential figures deeply shaped her weaving style and technical mastery. Her tapestries are noted for their exceptional fineness, sometimes reaching 140 threads per inch - a technical feat unmatched by most weavers. The natural colours of sheep's wool - tan, grey, brown, gold and occasionally dyed black - were skilfully blended to create subtle hues and complex patterns.

Her designs often feature stepped or serrated diamonds, multiple borders and a three-column layout influenced by her bear clan upbringing. The preparation and spinning of the wool was as meticulous as the weaving itself, resulting in textiles of remarkable suppleness and durability.

Taugelchee's artistry was recognised early and often. She dominated the Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial, winning first and grand prizes for over twenty years. Her skill was so extraordinary that a new category was created to give other weavers a chance to win, as she routinely swept the existing awards. In the 1950s she was reputedly the highest paid weaver in the world, sometimes earning thousands of dollars for a single rug.

Her influence extended beyond her own work: she taught and inspired many other weavers, including family members and her daughter-in-law, Priscilla Taugelchee. Daisy also demonstrated her technique and lectured throughout the United States, further raising the profile of Navajo weaving.

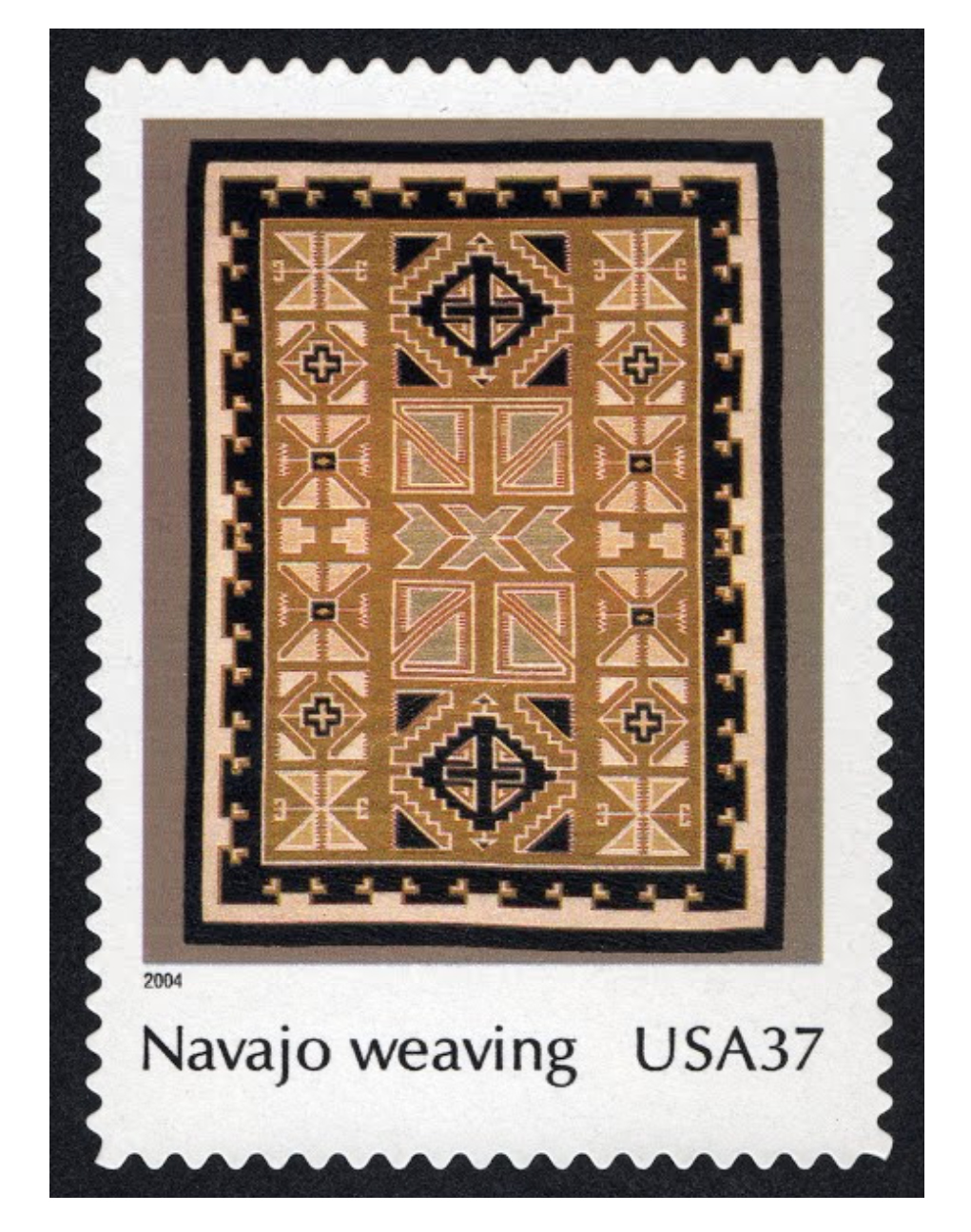

In 2004, the United States Postal Service honoured her legacy by featuring one of her Two Grey Hills tapestries on a commemorative stamp as part of the Art of the American Indian series. The Denver Art Museum and the Maxwell Museum of Anthropology both have her work in their collections, underscoring her importance in the history of American textile art.

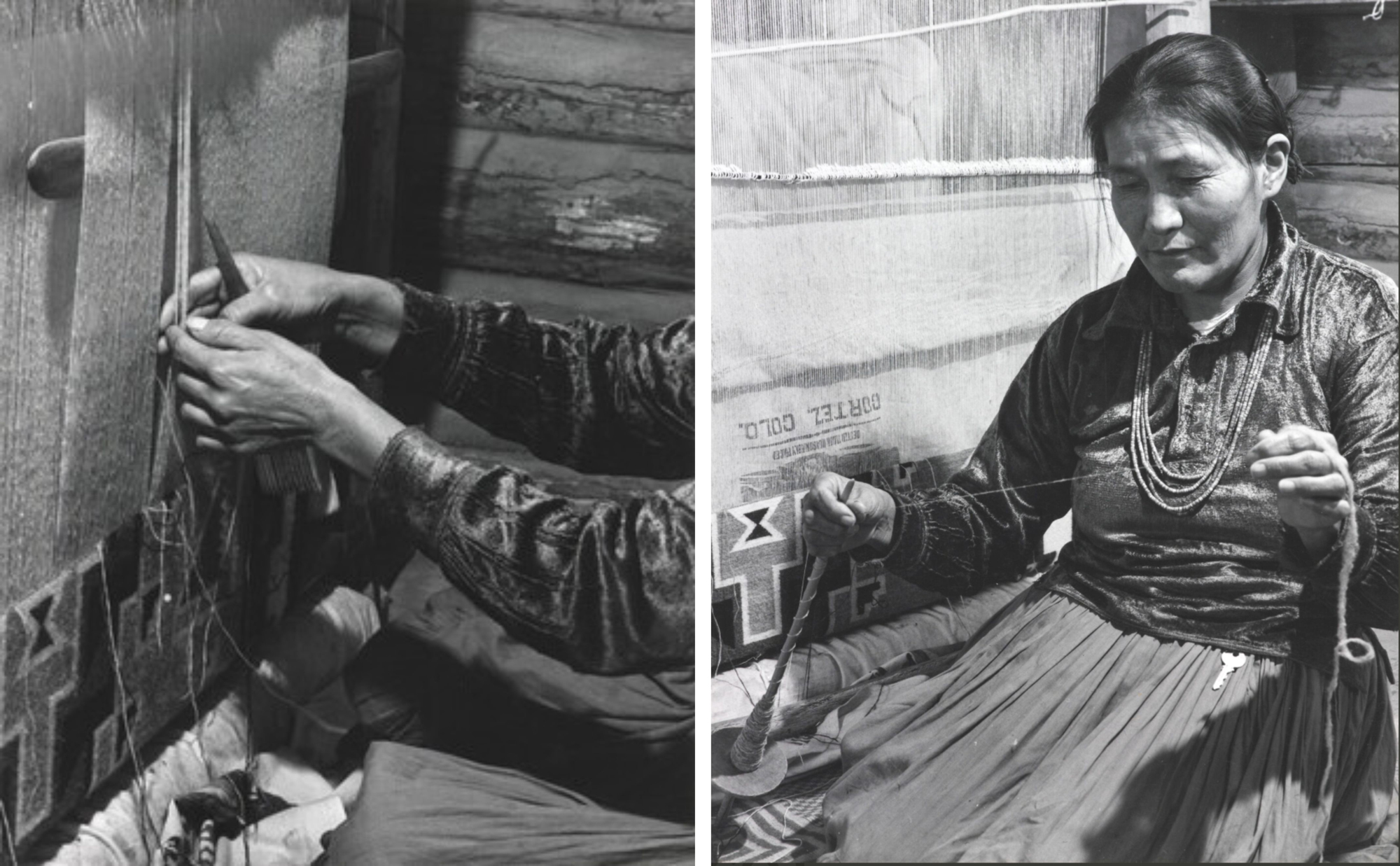

Two images of Daisy Taugelchee in January 1955. Photos by Laura Gilpin. © Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, Texas.

Two Grey Hills Rug by Daisy Taugelchee, 1947-1948. Medium: Wool and dye. Dimensions: 69 ½ x 49 ½ in.; 176.53 x 125.73 cm. Denver Art Museum, Colorado.

«This tapestry is exceptionally fine—the weaving has more than ninety wefts and twenty warps per inch and took six miles of yarn to make. When the artist finished this rug in the late 1940s, she said she’d never again attempt anything so difficult.» (Denver Art Museum curators).

In 2004, her work was honored on a US postage stamp (below: United States Postal Service, 2004-08-24, From the collection of: Smithsonian's National Postal Museum).

I am very sorry that you cannot touch and see the Navajo rugs and Daisy Tagelchee's masterpieces up close. The quality of the wool and weaving is extremely high and can be seen and felt as the details in the photos suggest (The rug below is not the one above!).

Taugelchee rugs are known for their unsurpassed fineness and extremely high weft count, often exceeding 115 - and sometimes as high as 140 - wefts per inch (55 wefts per cm). This exceeds the typical 30-45 threads per inch (12-18 threads per cm) found in most Navajo rugs, resulting in a textile of remarkable density, suppleness and durability. Their rugs feature complex, multi-layered diamond designs, stepped and serrated patterns, and precise fourfold symmetry. The intricate forms are made possible by her fine spinning and weaving, allowing for detailed, visually arresting compositions. Taugelchee used only handspun, undyed wool from her own sheep, blending shades of grey, brown, cream and black to create subtle, harmonious tones. Only the black wool was typically over-dyed for added contrast, giving her textiles a distinctive, earthy elegance.

By pushing the boundaries of spinning and weaving, she took the Two Grey Hills style to new heights. The technical mastery required to produce such fine, even threads and weave them into complex patterns is extraordinary, and her innovations influenced generations of Navajo weavers. She was hailed by dealers and museums as the greatest living Navajo weaver. She dominated competitions, regularly winning top prizes at the Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial.

Frances Manuelito (1910?-1996?)

Frances Manuelito was a renowned Navajo master weaver who worked primarily in the early to mid-20th century. She is part of a distinguished lineage of Navajo textile artists. Frances was the daughter of Blind Man's Wife, who was herself recognised as one of the pioneering figures in the development of early regional Navajo rug designs. This legacy placed Frances at the centre of a tradition that has significantly shaped Navajo weaving styles and motifs. Frances Manuelito's artistic legacy continued through her daughter, Ruby Manuelito, who also became a master weaver.

Frances Manuelito is credited with weaving rugs that reflect the innovative spirit of her mother. Her work often incorporated advanced design elements and is considered an important example of regional Navajo weaving from the 1920s and 1930s. One notable piece attributed to her is a 49" x 72" J.B. Moore Plate XXVII variant rug that demonstrates her technical skill and creative adaptation of classic designs (below).

Frances Manuelito is a bridge between early design pioneers and later generations of Navajo weavers. Her rugs are valued for their craftsmanship and historical significance, representing a period of innovation in Navajo textile arts. The contributions of the Manuelito family, especially through Frances and her descendants, have been instrumental in preserving and advancing the art of Navajo weaving.

Two Grey Hills Rug, 1930s, handwoven by Master Weaver Frances Manuelito. Medium: hand-spun, natural wool. Dimensions: 59 x 83 in.; 149.86 x 210.82 cm., Native Jackets Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico. The design of this rug «is one her Mother derived from J. B. Moore Plate XXVII. The Master Weavers by Mark Winter details this journey in Plates 61, 62 and 63. They were woven in that order. Frances frequently wove her version of her Mother's designs, this is one of them.»

Marie Police Klah

Marie Police Klah is recognised as a Bear Clan master weaver active in the Toadlena/Two Grey Hills region in the early to mid-20th century. She was one of a select group of weavers who advanced the artistry of the early regional weaving period by creating distinctive variations on the J.B. Moore designs that are fundamental to Navajo weaving. Their rugs are notable for incorporating family-specific design elements such as the figural quality of paired triangles, tridents, and water bugs - motifs derived from J.B. Moore catalogues. The elongated single diamond motif in her work was later famously used by the legendary weaver Daisy Taugelchee, who also grew up in the Bear Clan household.

Marie came from a family of master weavers: her mother was Mrs Policeboy and her sisters included Mary Yanabah Curly and Policegirl. The next generation - her children and nieces - also produced eight master weavers, underlining the family's significant influence on the tradition.

Two Grey Hills Rug by Master Weaver Marie Police Klah, 1940s. Medium: natural handspun yarn. Dimensions: 56 x 87 in.; 42.24 x 220.98 cm. Toadlena Trading Post, Newcomb, New Mexico.

Cora Curley (born 1916)

Cora Curley was a highly respected Navajo (Diné) master weaver, best known for her extraordinary work in the Two Grey Hills weaving tradition. Her career spanned the mid-20th century, and her rugs are considered outstanding examples of Navajo textile artistry, with extraordinary clarity of design, balance, and technical excellence. Her pieces are noted for their unique monochromatic palettes and complex, harmonious designs. Unlike many Navajo rugs that incorporate a variety of natural wool tones, Cora Curley's pieces are noted for their unique use of a monochromatic palette. Few rugs have such a restrained, monochromatic approach, giving her work a minimalist, almost Zen-like aesthetic that is rare in Navajo weaving. Curley often incorporated her own signature design elements into the borders of her rugs, making her pieces instantly recognisable and adding a personal artistic touch to the traditional Two Grey Hills format.

Curley's work has been featured in auctions and is considered highly collectible, with pieces from the 1960s and 1970s documented as "book pieces", a term used for exemplary works highlighted in publications or exhibitions. Her rugs are renowned for their high weft count and precise weave, reflecting a level of skill that places her among the top master weavers in the region. The use of handspun, hand carded Navajo Churro wool contributes to the durability and luxurious texture of her textiles.

Cora is the mother of master weaver Edith Yazzie (b. 1956).

ABOVE: Two Grey Hills Rug by master weaver Cora Curley, Book Piece (shown on p. 455 of The Master Weavers by Mark Winter), 1970s. Dimensions: 46 x 68 1/2 in.; cm. Auctioned by Ripley (Indianapolis) in 2023.

BELOW: some details of the above rug showing the softness and extremely high quality of Cora's work.

Two Grey Hills style Rug by Edith Yazzie (daughter of Cora Curley), 2002. Dimensions: 61 x 36 in.; cm . Auctioned in 2022 by John Moran, Monrovia, California.

«This rug has been finely woven with two conjoined diamonds and an elaborate serrated border woven in eight natural colors from cream to dark brown.»

Grace Nez (1937–2013) and the Nez family

Matriarch of the Nez family of master weavers, Grace Nez won Best of Show twice at the Gallup Inter-Tribal Ceremonial (2004 and 2007) and received numerous other awards. Her rugs were featured in major exhibitions and are celebrated for their technical excellence and artistic beauty.

Born in the Shiprock area of the Navajo Nation and belonged to the Where Water Meets Born for Tangle Clan and the Bitter Water Clan, Grace Nez was an award-winning weaver, earning Best of Show at the Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial in 2005 and Best of Show at the Museum of Northern Arizona. Her works were featured in prominent museum exhibits, including the Desert Caballeros Western Museum in Wickenburg, Arizona.

She was known for weaving large, room-sized rugs entirely from memory, without using sketches or diagrams. Even when a rug was so large that most of it had to be rolled up during weaving, she maintained perfect balance and design throughout the piece – a quality highly valued in Navajo culture.

Renowned for her technical skill, artistry, and ability to weave exceptionally large rugs, she taught her daughters Linda, Marian, Cecelia, Lena, Cindy, Berlinda, Malinda, Helene, and her granddaughter Ave Tsosie to weave, each of whom has become a master weaver in her own right.

Today, the Nez Family is recognized as one of the most talented contemporary Navajo weaving families.

Grace Nez should not be confused with Grace Grace Henderson Nez (May 10, 1913 – July 14, 2006). Born in 1913 in Ganado, Arizona, and died in 2006 in Flagstaff, Arizona, she was a highly respected Navajo weaver known for her traditional 19th-century and Ganado-style rugs. She demonstrated her work at the Hubbell Trading Post and received major awards, including a National Heritage Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. Her weaving legacy continues through her daughter, Mary Lee Begay, and granddaughters, Gloria and Lenah Begay.

A very large Two Grey Hills rug by Grace Nez, in a grid pattern of alternating intricate diamond medallions, enclosed by a Greek key meander border. Dimensions: 11ft 4in x 8ft 1in.; 345.44 cm x 246.38 cm. Auctioned by Bonhams, San Francisco, CA, in 2012.

Steve Getzwiller and Grace Nez in the Nez sheep corrals with one of Grace's Two Grey Hills rugs, Churro 2060. The rug, which measures 8 x 12 ft. -– 243.84 x 365.76 centimeters – required over 14 months of weaving alone, not to mention the preparatory work on the wool. This impressive rug was featured in the exhibition: "The Getzwiller Collection of Contemporary Navajo Weavings 1975-2000", at the Desert Caballeros Western Museum, Wickenburg, Arizona (2000). Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

The Teller Sisters, Lynda and Barbara

Lynda Teller Pete (b. 1958) is a celebrated Diné (Navajo) master weaver whose life and work embody the rich tradition of Two Grey Hills weaving while actively preserving this cultural heritage for future generations. An award-winning fifth-generation weaver, Lynda began learning her craft at the age of six. She was raised at the Two Grey Hills Trading Post in Newcomb, New Mexico, on the Navajo Nation, where she grew up surrounded by weaving. Some of her earliest memories include "waking up to the sounds of my mother and grandmothers working their looms in our ancestral home". She is a member of the Tabaaha (Water Edge Clan) and was born to the To'aheedliinii (Two Waters Flow Together Clan).

Lynda Teller Pete, who has received significant recognition and awards for her exceptional weaving skills, is best known for her mastery of the traditional Two Grey Hills regional style, creating tapestries that are sought after by collectors worldwide. Her work is driven by the belief that "beauty and harmony should be woven into every rug.

Now in her 60s, Teller Pete works with her sister, Barbara Teller Ornelas, as an ambassador for Navajo culture and traditions. Their educational efforts include teaching Navajo weaving workshops at museums, galleries, and guilds internationally; working with art centers, universities, and other venues to educate the public about Diné history and weaving traditions; working specifically to teach Navajo women who didn't have family weaving experience but wanted to carry on their cultural heritage; and serving as the director of equity and inclusion for the Textile Society of America.

Lynda's sister, Barbara Teller Ornelas (b. in 1954), is an earned internationally acclaimed master weaver who blends traditional motifs with contemporary compositions and, along with her sister, is a cultural ambassador, educator, and author of several books. This is a good sign that a revolution is underway: master weavers are emerging from the stifling limbo of the "feminine" minor arts to enter the complex art world on their own terms.

Barbara Teller Ornelas grew up near the Two Grey Hills Trading Post in New Mexico, where her father, Sam Teller (1918-2000), worked as a Navajo trader for 32 years, and her mother, Ruth Teller (1928-2014), was a master weaver, gardener, quilter, and photographer. She later moved to Arizona and attended Arizona State University. Ornelas began weaving at a young age, learning from her mother, grandmothers, and older sister. She sold her first rug when she was only 10 years old. Her paternal grandmother predicted when Barbara was 10 that she would become a great weaver who would share her traditions with the world. And so it was.

Her weaving is characterized by

- Specialization in the Two Grey Hills style, characterized by double diamond patterns and intricate geometric designs;

- Use of natural-colored, hand-spun wool from local flocks raised by Navajo families;

- Exceptionally high weft counts, with some pieces having 102 to 140 wefts per inch.

She has won numerous prestigious awards, and with her sister Roseann, she famously won Best in Show at the Santa Fe Indian Market with a tapestry-grade masterpiece (95-108 wefts per inch) that measured 5 by 8½ feet and took four years to weave. In 2023, Barbara was awarded the United States Artists Fellowship in Traditional Arts.

Barbara Teller Ornelas on the left and her sister Lynda Teller Pete on the right. Photo: Joe Coca / Thrums Books.

Barbara Teller Ornelas on Weaving

Large Two Grey Hills by Barbara Teller Ornelas, 1991. Medium: Hand-carded, hand-spun Navajo Churro wool. Finesse: 16 warps to the inch, 120 weft to the inch. Dimensions: 4 × 6 feet; 121.92 × 182.88 cm. From https://www.unitedstatesartists.org/.

Large Two Grey Hills by Barbara Teller Ornelas, 1995. Dimension: 72 × 48 in.; 182.88 × 121.92 cm. Santa Fe Collection of Navajo Rugs, The Heard Museum, Phoenix, Arizona.

An amazing short documentary about the teaching activity of Barbara Teller Ornelas and Lynda Teller Pete.

THE POWER OF WORDS 2

Have you ever wondered what the correct terminology is: American Indian, Indian, Native American, Indigenous, or Native?

To those who think this is a stupid question or too "politically correct" and therefore doubly stupid, I would say that the words we choose to call ourselves and others are never pure and innocent. Because, as Desmond Tutu once said, "Language does not just describe reality. Language creates the reality it describes."

VERBAL WARFARE - AI created image

The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI), which is an active component of the Smithsonian Institution, has recently launched Native Knowledge 360° (NK360°) to provide educators and students with new perspectives on Native American history and culture.

NK360° answers our question: American Indian, Indian, Native American, Indigenous, or Native?

«All of these terms are acceptable. However, the consensus is that whenever possible, Native people prefer to be referred to by their specific tribal name. In the United States, Native American has been widely used but is falling out of favor with some groups, and the terms American Indian or Indigenous American are preferred by many Native peoples. They often have individual preferences about how they wish to be addressed. When talking about Native groups or people, use the terminology that members of the community use to describe themselves collectively. (...). In Canada, people refer to themselves as First Nations, First Peoples, or Aboriginal. In Mexico, Central America, and South America, the direct translation for Indian can have negative connotations. As a result, they prefer the Spanish word indígena (Indigenous), comunidad (community), and pueblo (people).»

So, some terms such as Indians or Native Americans are acceptable to most Natives, but not all. Don’t be surprised and don't lump all Natives Americans together; there are 601 tribes only in the United States.

There's another question, or rather the other side of the coin: what terms are considered offensive by Native Americans?

Well, there is almost unanimous agreement that terms such as "redskin" and "squaw" should be avoided: both are considered offensive by indigenous peoples in the U.S. and Canada. The Indigenous Peoples Terminology Guide written by SAFS at the University of Washington states: «The term "redskin" "is directly linked to settler colonial practices of killing Native Americans and taking their scalps for bounties. It is a racial slur and is highly offensive.» As for the term "squaw," they emphasize that "although this word likely derives from words in the Algonquian language related to women, it has been used as a slur to denigrate, sexualize, and objectify Native women and girls for centuries. To be avoided also the Pocahontas cliché".

Another terms widely used in the past is "papoose" (from the Narragansett papoos, meaning "child") to indicate a Native American child, regardless of tribe. This archaic terms is acceptable when used in old Native songs or lullabies, but gains a racist aftertaste, or a colonialist overtone if you prefer, when used by non-Natives. In short, it's best to avoid it.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?