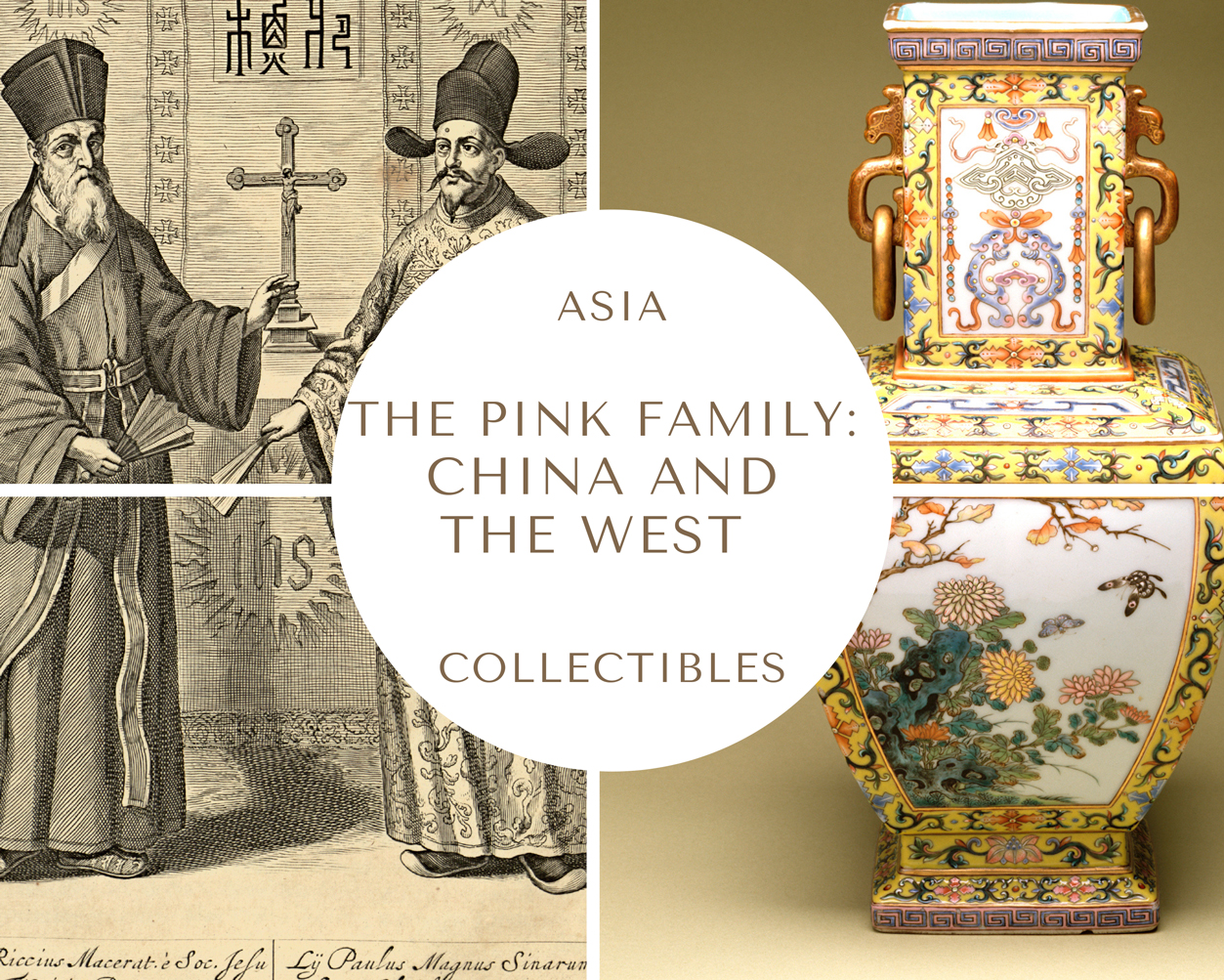

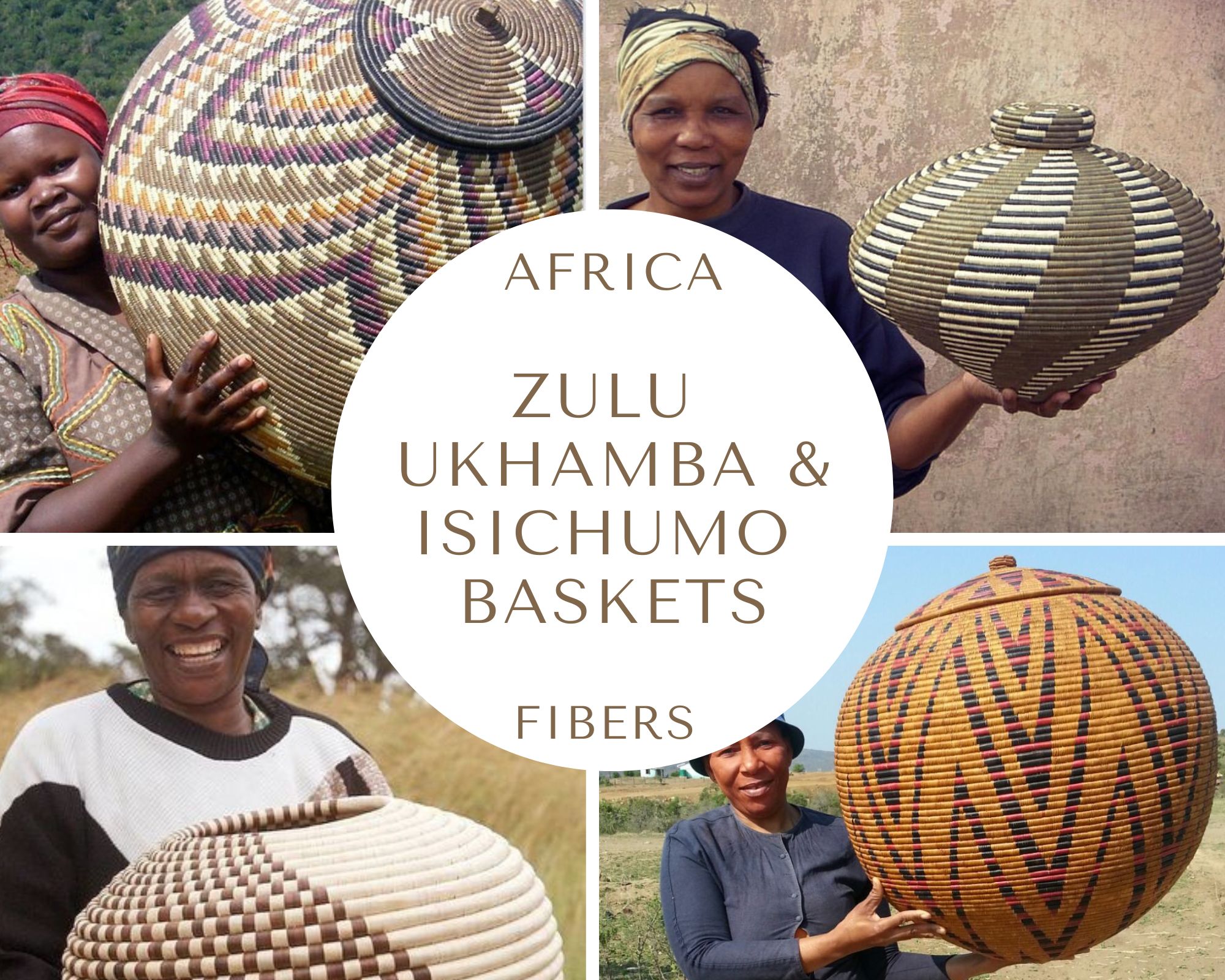

ZULU UKHAMBA AND ISICHUMO BASKETS 3

South Africa on the globe

(Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

Kwa Zulu-Natal Province (source: Encyclopaedia Britannica).

ZULU AND NGUNI CULTURES

My exploration of Zulu culture doesn’t end with the wonderful izinkhamba and izichumo. It continues, of course. You’re not surprised, are you? As you know, I like to dig deeper and deeper, like a mole tunnelling through soft soil.

This time, however, I want to take an unexpected turn. I don’t want to present Zulu culture through more objects, art forms or mythical tales. It’s not because they aren’t worth it — they are marvels in their own right — but because I don’t want to perpetuate the widespread stereotype that reduces African cultures to masks, wood carvings, tribal dances, baskets or textiles.

The real issue is not that these things don’t matter. They do. The problem is that Africa is not just a showcase of beautiful artefacts. Reducing it to this is both humiliating and reductive because it strips away the depths and complexities that sugar-coated exoticism and lazy primitivism cannot embrace.

That’s why I want to explore Zulu culture through the African philosophy of Ubuntu, dispelling many clichés in the process. Yes, you heard me right: we’re going to talk about African philosophy. I promise it won’t be boring. But it won’t be easy, either. It may challenge you and unsettle you, but, like all true profound journeys, it will bring us closer to understanding what it means to be human.

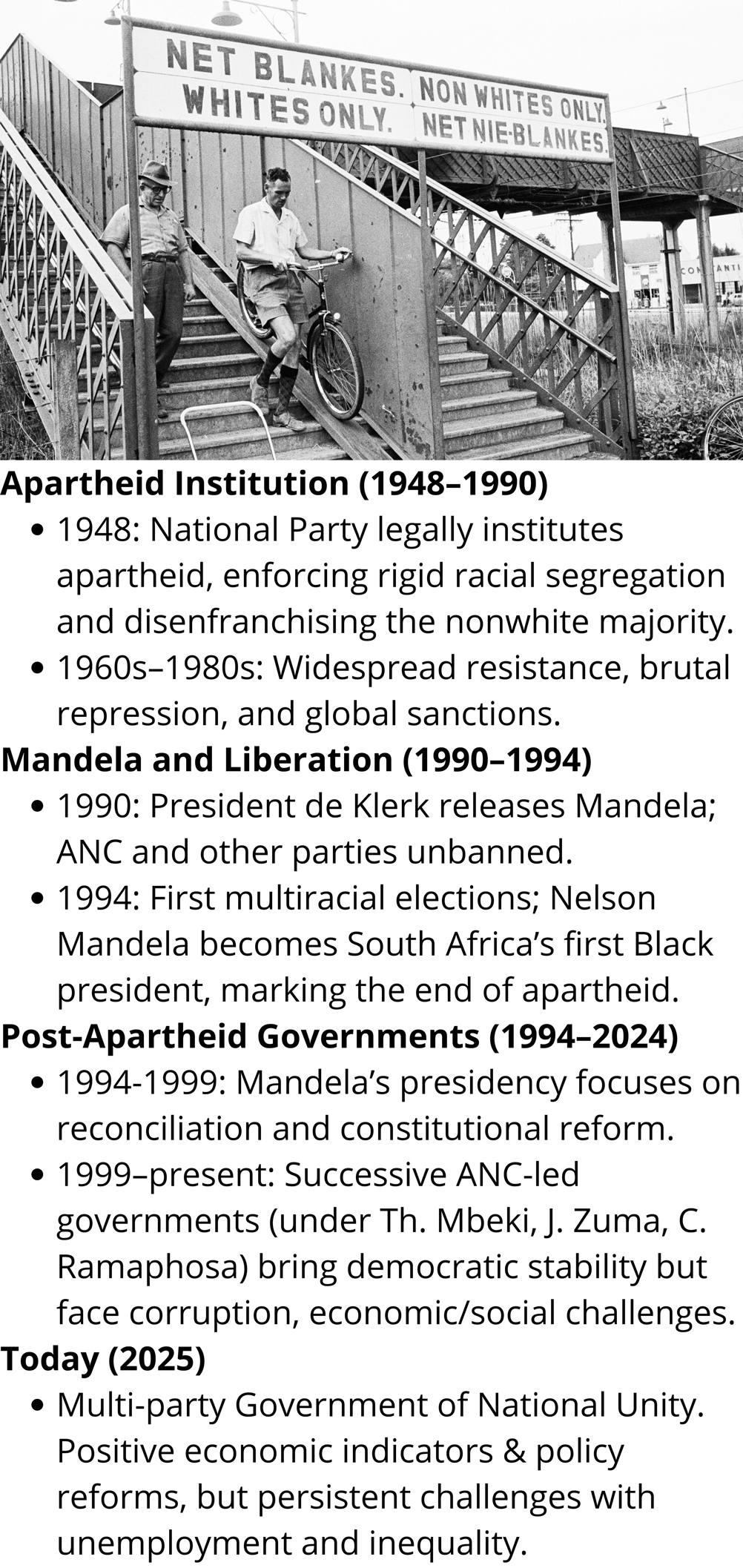

Here is a brief guide to help you navigate recent South African history.

The African Philosophy of Ubuntu:

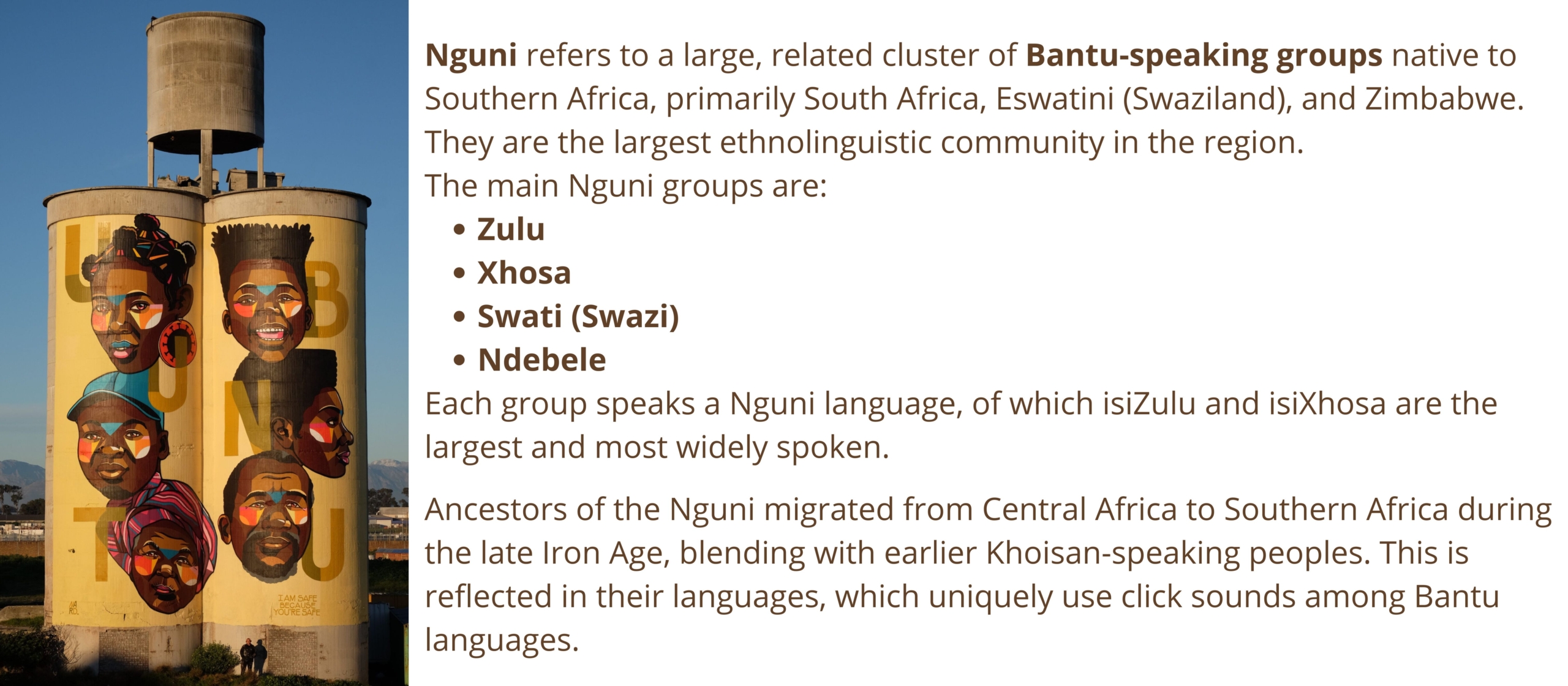

A Deep Exploration through Nguni and Zulu Perspectives

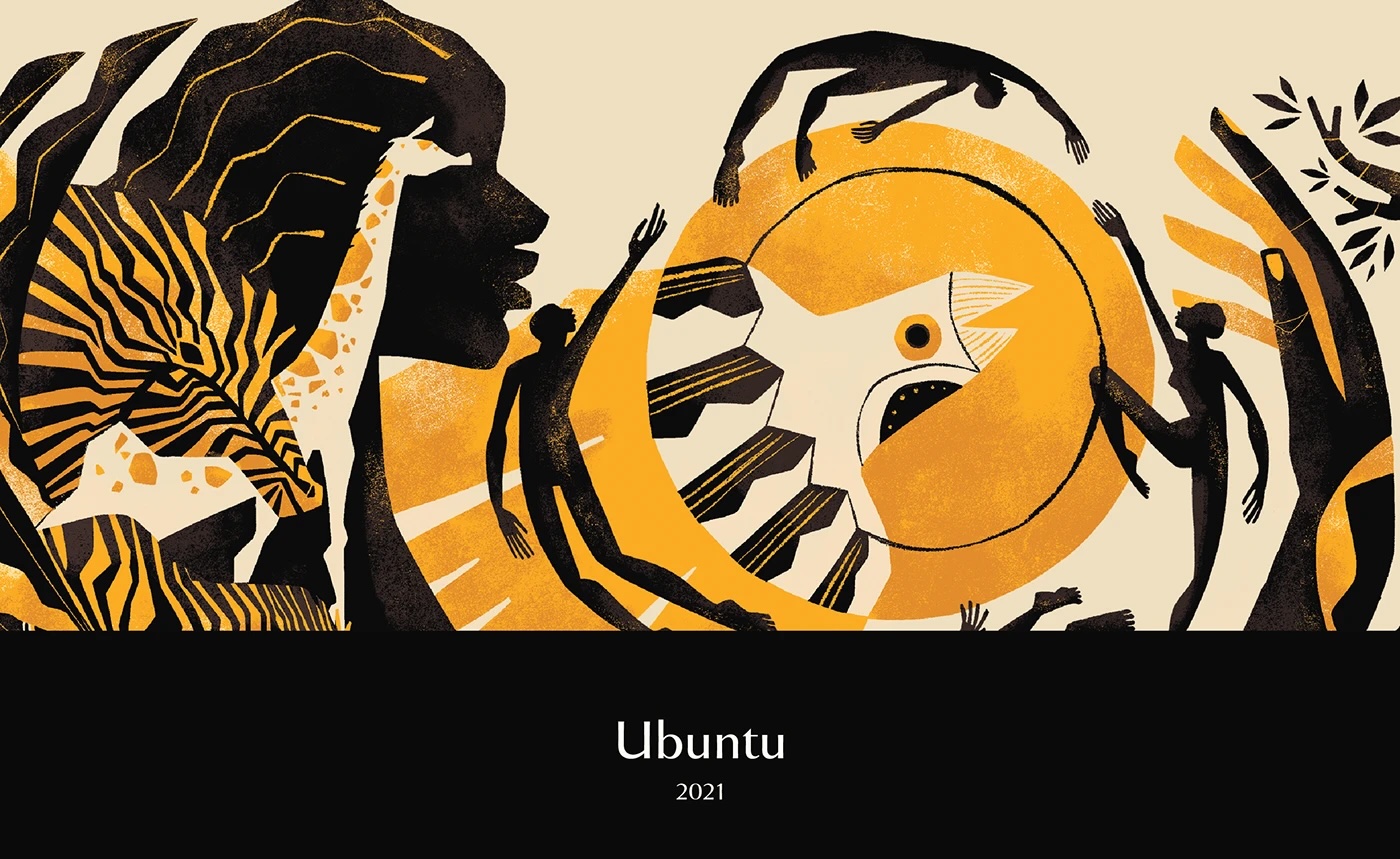

ABOVE, ON THE LEFT, AND BELOW: Ubuntu, 2021, street art by by Nardstar, aka Nadia Fisher, in Cape Town, South Africa.

Ubuntu ngumuntu ngabantu abantu or more commonly, umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu is a well-known expression in the Nguni languages, particularly in isiZulu and isiXhosa, both of which are Bantu languages spoken in Southern Africa. It means ‘a person is a person through other persons’, and expresses the core concept of Ubuntu: an African philosophy emphasising community, compassion, and interconnectedness.

This maxim has become one of the most quoted aphorisms in post-1994 South Africa. However, the phrase’s familiarity risks reducing Ubuntu to an empty slogan or a feel-good balm for rainbow-nation politics or corporate branding. In the following pages, I explore Ubuntu’s origins in the Nguni-speaking regions of South Africa, particularly KwaZulu-Natal, before examining it through the lens of African philosophers who reject romanticisation. The result, I hope, is a historically grounded, conceptually rigorous, and politically astute portrait of Ubuntu, rather than a celebratory brochure.

The following pages reconstruct the longue durée of Ubuntu as a lived philosophy of the Nguni, and more specifically of the Zulu-speaking world. They trace its translation into the restorative justice architecture of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC, 1996–1998) and finally interrogate the most incisive African critiques levelled against it today. Throughout, I draw on archival sources, ethnographies, legal judgements and philosophical monographs predominantly produced by African scholars writing from within the epistemic traditions they describe.

WHAT IS ‘UBUNTU’?

The philosophical concept of ubuntu has several interconnected pillars.

Relational ontology: Ubuntu challenges the Western concept of the autonomous self by asserting that human identity emerges through dynamic relationships and communal bonds. As the Kenyan-born Christian philosopher John Mbiti eloquently expressed: ‘I am because we are, and since we are, therefore I am’. This reflects the fundamental understanding that individual existence is meaningless without a community context.

Communal Epistemology: In ubuntu philosophy, knowledge is not an individual possession, but a communal resource cultivated through storytelling, oral traditions and shared experiences. Wisdom emerges from collective engagement rather than isolated contemplation, emphasising practical knowledge rooted in lived experience.

Interconnected Cosmology: Ubuntu encompasses not only human relationships, but also relationships with nature, ancestors and the spiritual realm. This creates a holistic worldview in which humans are part of a larger, interconnected web of existence.

Among the Zulu people, ubuntu is a way of life that permeates all aspects of social organization, spiritual practice and cultural expression. The Zulu understanding of ubuntu is deeply connected to their traditional cosmology and religious worldview.

Ubuntu – The Essence of Humanity by Nigerian artist Adebayo Taiwo. Painting, acrylic on canvas. Saatchi Art.

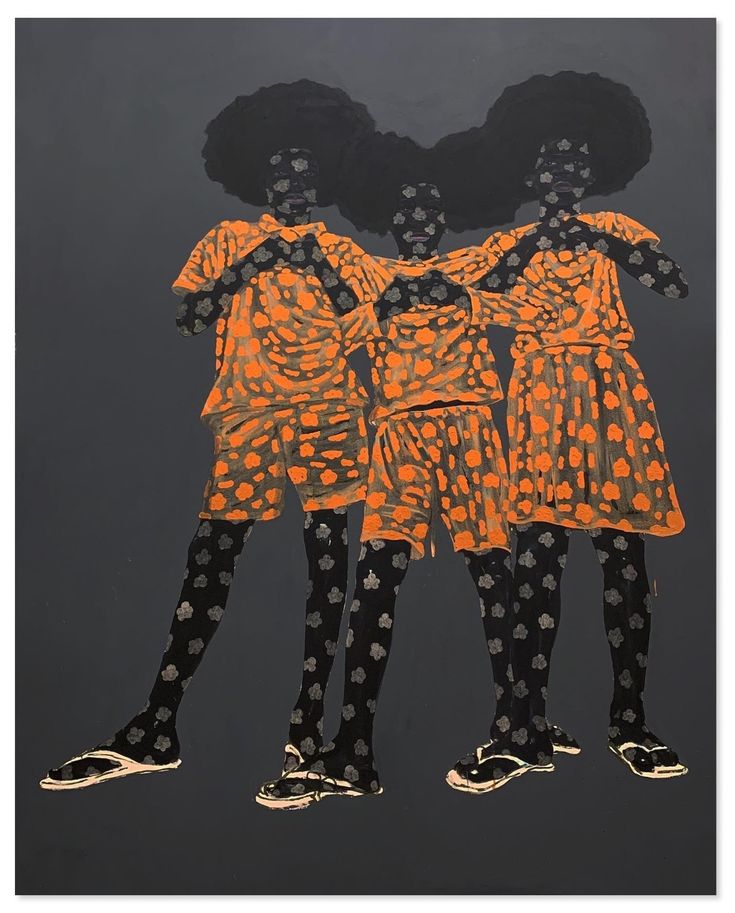

Ubuntu was the title of a captivating exhibition at SCOPE ArtFair in Miami, Florida, (3-8 December 2024), featuring the works of some prominent South African artists. Among them, Bambo Sibiya (b.1986), author of this 2024 artwork, Africa (mixed media on canvas).

PRECOLONIAL SEDIMENTS: UBUNTU IN THE ZULU LIFEWORLD

Lexical and Semantic Fields

In isiZulu, ubuntu derives from the class prefix ubu- (abstract collective) and -ntu (a generic term for “person”). Nineteenth-century dictionaries (e.g., Bryant 1905) translate it as “human nature,” “good disposition,” “generosity,” indicating that the term had moral connotations as well as biological ones. Crucially, Ubuntu is never an individual possession; it is a quality that emerges in the space between people. One has ubuntu only insofar as one is shown ubuntu by others — a performative grammar that anticipates contemporary relational ontologies.

Zulu social ethics: respect, reciprocity, and becoming a person

The Zulu umuzi (homestead) was the basic unit of moral and economic life. Cattle loans (ukusisa), collective weeding parties (ilima) and bride-wealth negotiations created complex systems of reciprocity that defined personhood. The inkosi (chief) embodied authority, but his legitimacy depended on his ability to ukuhlela ubuntu, to foster relationships of care and redistribution. Thus, ubuntu was less an ethical injunction than a social mechanism for reproducing collective life.

Ubuntu principles also guided traditional governance systems in Zulu society, through institutions such as the indaba (communal meeting), where collective decision-making prioritised community consensus over individual authority. Leaders were seen as servants of the community, embodying what scholars refer to as ‘servant leadership’ based on ubuntu values.

Within Zulu lifeworlds, ubuntu resonates with long-standing norms such as ukuhlonipha (respect/deference) and the expectation of generosity and hospitality. Ethnographic and cultural studies of Nguni/isiZulu society describe ukuhlonipha as a pivotal virtue that structures speech, behavior, and hierarchy — an everyday grammar of regard that aligns with the concept of personhood being realized through positive relationships with others.

In Zulu society, ukuhlonipha involves showing respect not only to elders and men by women and youths, but also more broadly, to all community members, including children, the elderly, royalty and strangers. This code is expressed in speech, through the avoidance or substitution of certain words, and in behavior, guiding how people address, defer to or physically position themselves in relation to others.

Ubuntu frames personhood as something realized in community. Ukuhlonipha, as an embodied practice, enacts this worldview: respect and proper conduct affirm communal bonds and individual dignity. Mistreating others or failing to show respect undermines not just individual dignity, but also communal harmony.

In Zulu culture, ubuntu is inextricably linked to spiritual beliefs about ancestors, the connection between the living and the departed, and humanity’s relationship with the divine. This concept recognizes the “three-dimensional relationships” between the living, the dead (ancestors) and the unborn. This spiritual framework positions individuals within an eternal community that transcends temporal boundaries.

Ubuntu values are primarily preserved and transmitted among the Zulu through oral traditions, such as izibongo (praise poetry), storytelling (izinganekwane), proverbs, and communal rituals. These practices serve as vehicles for moral instruction and social cohesion, as well as entertainment. The saying isisu somhambiasingani singangenso yenyoni (‘a traveller’s stomach is as small as a bird’s kidney’) exemplifies ubuntu hospitality, whereby strangers were welcomed with fermented porridge (amahewu) and shelter.

Generosity and hospitality are considered everyday practices and moral imperatives within Nguni and Zulu philosophical traditions. Offering food, shelter and care, especially to strangers, is a concrete demonstration of ubuntu. Generosity is also elaborated upon through proverbs and rituals, which reinforce the idea that selfless action sustains the social fabric and realises full personhood.

The four pillars of Zulu ubuntu

Based on fieldwork conducted in KwaZulu-Natal and textual analysis, it is possible to distinguish the four pillars on which the realization of Ubuntu rests:

- Dignity-through-recognition (ukuhlonipha): My dignity is co-authored by your respectful gaze.

- Sympathetic impartiality (ukunakekela): Care is extended even to strangers because humanity is transitive.

- Restorative justice (ukubuyisana): Wrongdoing is a tear in the social fabric that must be repaired, not just a debt that must be repaid.

- Generative reciprocity (ukuzigqaja ngomphakathi): Success is measured by how much one gives back to the network that enabled one to flourish.

These values do not form a rulebook; rather, they are the grammatical rules that competent social actors apply in context.

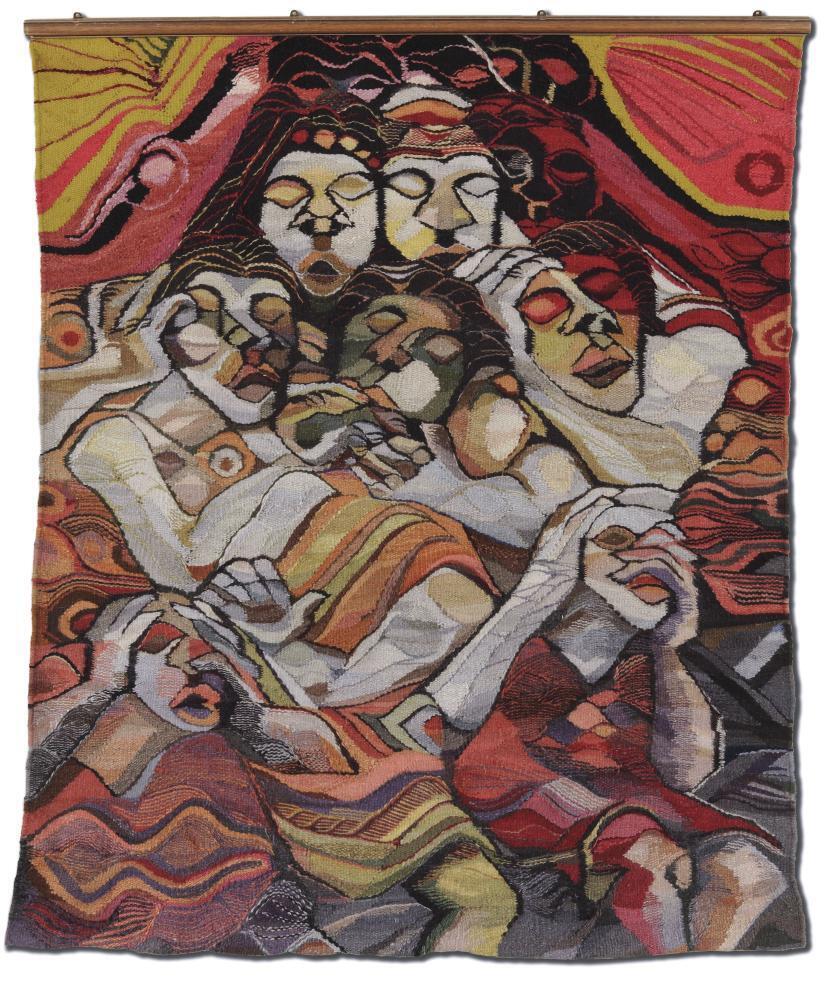

Humanity, tapestry, hand-woven in 1995 by Joseph Ndlovu, CCAC – Constitutional Court Art Collection, South Africa.

Joseph Ndlovu is a refined South African artist, born in Johannesburg in 1953.

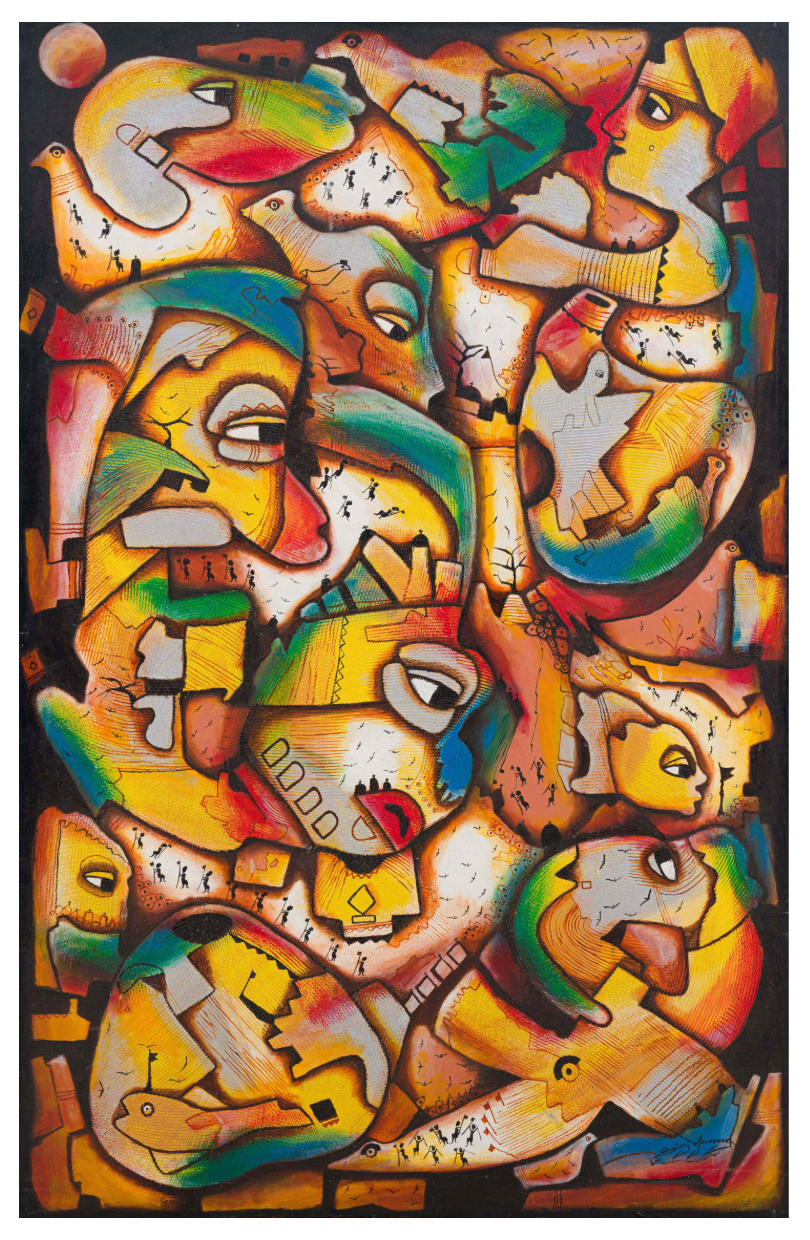

Ubuntu I by South African artist Billy (Joshua) Molokeng (b. 1949). Oil on canvas. Strauss & Co., Johannesburg / Cape Town, SA.

COLONIAL FRACTURE IN UBUNTU

An In-Depth Philosophical Analysis of the Shattering, Translation, and Refreezing of an Nguni Moral Order, 1830s-1950s

Conquest, migrant labour and the 1913 Land Act shattered the material basis of reciprocity. Missionaries translated the concept of Christian neighborly love as ubuntu, thus inserting it into a religious context. By the 1940s, ethnographers such as Absolom Vilakazi had begun to describe ubuntu as a ‘traditional African humanism’, a move that froze dynamic practices into a reified ‘culture’.

Fracture as Ontological Violence

In the pre-colonial Nguni world, ubuntu was not a detachable ‘value’, but rather the circulatory medium of social life. Cattle loans (ukusisa), collective labour (ilima), bridewealth (lobola) and the authority of the inkosi were iterative enactments of relatedness. Colonial conquest (1830s–1900s) did not merely damage this fabric; it re-engineered the conditions that made it possible.

The decisive vectors were:

- Military conquest and land alienation (the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 and the annexation of Zululand in 1887);

- The migrant labour agreements (the 1879 ‘Shepstone system’ and the 1904 Glen Grey Act), which converted people into time-based wage labourers for the Rand mines.

The 1913 Land Act transformed territory into property and confined African occupation to 7% of the surface area.

These events did not merely erode reciprocity; they re-territorialised social reproduction itself, rendering the performance of ubuntu in its traditional form impossible. The homestead ceased to be a source of value creation and became a means of subsidizing capital accumulation elsewhere.

Missionary Salvific Translation: From Ukuba nenbuntu to “Love Thy Neighbor”

The American Zulu Mission (AZM) and the Berlin Missionary Society arrived in the 1830s-1850s, carrying with them a dual translation strategy:

- Lexical: The missionaries rendered agapē as ukuba nenbuntu (“to have ubuntu”), creating a semantic shift that equated mutual status (ubuntu as co-authored dignity) with unilateral Christian duty.

- Ritual: The ukubonga (public confession) was rewritten as ukuphenduka (conversion), shifting the location of moral repair from the homestead to the mission station.

Ubuntu was thus salvifically inserted into a teleology of sin and redemption. The 1883 AZM catechism states: “Ukuba nenbuntu means you love your enemy as yourself, for Christ first loved you.” The asymmetry is stark: ubuntu becomes charity rather than constitutive relationality.

Ethnographic Refreezing: From Practice to “Traditional African Humanism”

By the 1940s, the discipline of anthropology had become closely associated with indirect rule, and undertook a second translation: this time from lived practice to textual artefact.

Key moments:

- Absolom Vilakazi coined the phrase ‘traditional African humanism’ in his work ‘Zulu Transformations’ (1946), presenting ubuntu as a static ‘world-view’ that predates modernity.

- The Native Affairs Department funded ethnographic surveys (e.g. Krige, 1936; Gluckman, 1940) that froze fluid moral negotiations into customary law codes. This turned Ubuntu into a regulatory ideal to be administered by chiefs under colonial supervision.

- The Bantu Authorities Act (1951) institutionalized these codes, creating Tribal Authorities whose legitimacy rested on the spectacle of preserving Ubuntu while implementing apartheid.

Philosophically, this was a double abstraction:

- Ubuntu was abstracted from its material contexts (e.g. land, cattle and labour) and redefined as ‘culture’.

- It was then abstracted from everyday negotiation and reinstalled as ‘juridical custom’.

Theoretical Aftershocks: Ubuntu Between Loss and Reinvention

The colonial fracture produced three enduring ambiguities in post-colonial thought:

– Ontological Loss: Without land and cattle, ubuntu can no longer be enacted; it survives as memory or ideology.

– Salvific Capture: Ubuntu becomes a moral surplus value appropriated by churches, NGOs and the state to legitimize projects such as reconciliation, corporate social responsibility, and moral regeneration that leave property relations intact.

– Ethnographic Specter: The very texts that froze ubuntu now serve as ‘authentic sources’ for its revival, creating a circular archive in which colonial influences masquerade as indigenous traditions.

Ubuntu buyakha (2020) by Wonder Buhle Mbambo (b. in 1989), a South African visual artist from kwaNgcolosi in Kwazulu-Natal. Acrylic and metallic gold on canvas. Image courtesy the artist and Destinee Ross-Sutton.

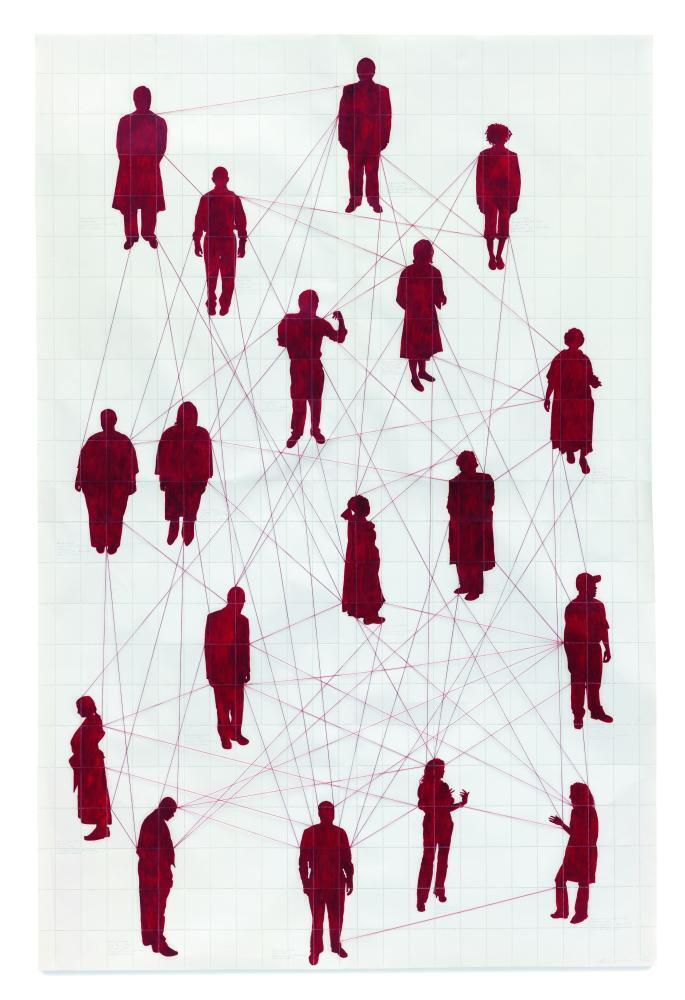

Constellations by South African artist Kim Lieberman, 2008. Mixed media on postage stamp paper. CCAC – Constitutional Court Art Collection, South Africa.

CRITICAL RE-OPENING: DECOLONIAL MOVES

Among African philosophers, Mogobe Ramose, a former professor of philosophy at the University of South Africa in Pretoria, has done the most to center ubuntu in a decolonial African philosophy. For Ramose, Ubuntu is not a soft cultural slogan, but rather an ontological and epistemological starting point. In other words, being human is co-being, and knowing is co-knowing with others. According to Ramose, modern African thought must dismantle racist and colonial epistemologies while reconstructing a humane political order based on the insight of ubuntu into relational existence.

From a different perspective, Thaddeus Metz, an American philosopher who has taught at various South African universities, proposes a precise moral principle derived from Southern African understandings: Right actions honor our capacity for community, or our ability to identify with and stand in solidarity with others. According to this view, human rights violations are severe degradations of this capacity. Metz’s work is influential because it translates Ubuntu into a public moral theory that addresses concerns about vagueness and liberal freedoms without abandoning its relational core.

Michael Onyebuchi Eze (professor of African political theory at the University of Amsterdam and fellow at Trinity Hall, University of Cambridge) cautions against interpreting ubuntu as crude collectivism. He describes African communitarianism as dialogical, meaning the individual and the community mutually constitute each other. This prevents ubuntu from becoming a mere “consensus machine” while preserving its critical perspective on exclusion and domination.

Naledi Nomalanga Mkhize, a historian and professor at Nelson Mandela University in South Africa, argues that ubuntu must be re-embedded in land return and cooperative economics; otherwise, it remains what she calls “disembodied humanism.”

Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni, a professor of epistemologies of the Global South at the University of Bayreuth in Germany, insists that the fracture itself must become the object of Ubuntu philosophy—a critique of coloniality that refuses to treat the present as a morally neutral baseline.

Zolani Ngwane, a professor of anthropology at Haverford College in Philadelphia, proposes a genealogical method of tracing how each invocation of Ubuntu (missionary, ethnographic, or post-apartheid) reveals the power relations it serves. This reopens Ubuntu as an unfinished project rather than a reified essence.

Ubuntu by Gilles Mayk Navangi (b. 1990), a French painter, illustrator and sculptor. Acrylic on linen canvas. Artkofa, African Contemporary Art Agency.

Ubuntu by Oscar Joyo (b. 1992), 2023. Acrylic and coloured pencil on panel. Thinkspace Projects, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Oscar Joyo is a Malawian-born, Chicago-based artist. He describes his work as a blend of Afrofuturism and Afrosurrealism.

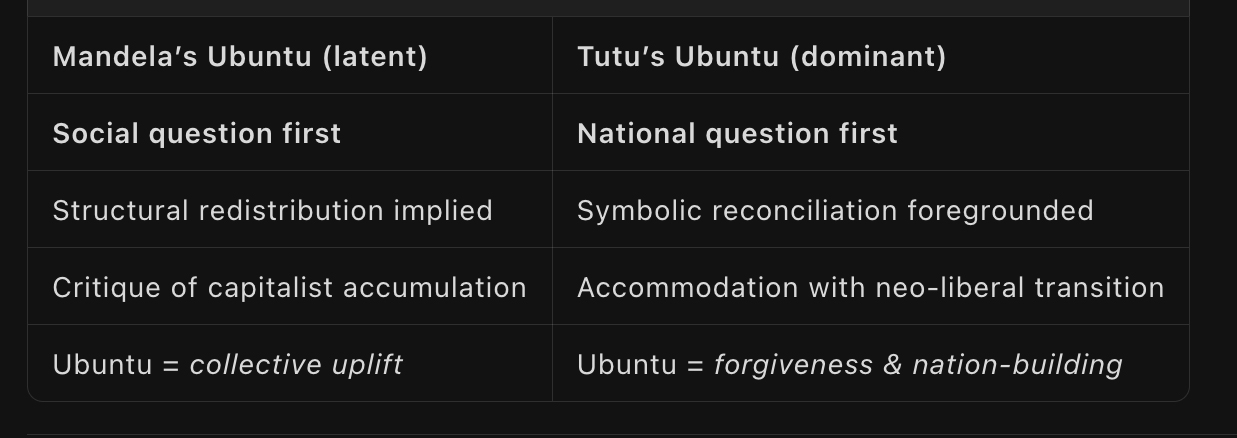

NELSON MANDELA’S INTERPRETATION OF UBUNTU

Mandela believed that ubuntu is a universal truth and way of life essential to an open society. It emphasizes interconnectedness, compassion, and community empowerment. He described ubuntu as the idea that one’s actions should improve the community, not just oneself, and that people perform better when treated considerately. Mandela believed ubuntu underpins dignity, justice, reciprocity, social responsibility, and mutual care. It spans across African cultures and rejects the ideal of aggressive individualism.

In summary, Mandela promoted ubuntu as an African heritage and a globally relevant framework for ethical, community-based leadership and social healing. This made ubuntu a cornerstone of his vision for South Africa and the world.

Let’s listen to what Mandela said about ubuntu’s roots in Nguni culture. He was born into the Thembu royal family in Mvezo, Cape Province, and belonged to the Xhosa clan Madiba.

Mandela ties one aspect of Ubuntu, the Nguni social expectation of respect, generosity, and hospitality, to his roots. His thoughts on getting rich are interesting, likely in response to frequent objections. Ubuntu does not mean that someone cannot or does not have the right to become wealthy, but rather, that this enrichment should also benefit the community in some way. In short, Mandela believed that the spirit of Ubuntu required a certain degree of wealth redistribution within the community. This position is politically consistent with Mandela’s ideas about social justice and his criticism of capitalism.

The idea that capitalism’s tendency to accumulate wealth leads to structural exploitation and amplifies inequality is analytically and empirically sound.

Capital accumulation is the raison d’être of the capitalist mode of production. Competition pushes firms to reduce labor costs, increase work intensity, and externalize social and ecological costs. The result is the systematic extraction of surplus value at the point of production—what Marx termed “exploitation”—and built-in pressure to widen the gap between capital owners and laborers. In other words, according to Marxist theory and many critical economists, capitalist profitability presupposes labor exploitation—that is, a structural gap between the value generated by workers and their compensation.

Thomas Piketty (2014) documents the long-term tendency for the rate of return on capital (r) to exceed the economic growth rate (g). When r > g, capital’s share of national income rises and wealth becomes more concentrated.

Oxfam (2024) estimates that the richest 1% now own 43% of global net wealth, while the bottom 50% hold only 1.2%. The top 1%’s share has increased in every major region since 1990.

Saez and Zucman (2020) demonstrate that the Gini coefficient for wealth in the United States increased from 0.80 in 1980 to 0.87 in 2020, reaching an unprecedented level for a large industrial economy.

I’d like to point out that exploitation and inequality are not just policy failures. Even countries with robust redistributive institutions, such as Nordic social democracies, have experienced increasing wealth inequality as capital markets have become more liberalized and financialized. This suggests that the tendency is inherent to capital accumulation itself and not simply an outcome of “bad policy.”

Some contemporary mechanisms exacerbate inequality.

– Financialization: Rising asset prices disproportionately benefit those who already own capital.

– Global value chains: Superprofits accrue to lead firms in the Global North, while labor in the Global South faces downward pressure on wages.

– Digital platforms: Network effects and data monopolies create winner-take-all dynamics (e.g., big tech market capitalization versus gig-worker earnings).

Many counterarguments demonstrate their factual limitations and their consequences (not to mention the worst).

– “Trickle-down” claims: Real median wages in the U.S. have stagnated since the mid-1970s, despite significant productivity increases. This contradicts the idea that economic growth automatically benefits labor.

– “Human capital” explanations: Although education premiums have risen, wage dispersion within skill groups has widened even more sharply. This indicates that skills alone cannot offset capital-biased technological change.

Thus, the institutional core of capitalism—private ownership of productive assets and market competition—provides the incentive and structural leverage necessary to accumulate wealth faster than labor income can grow. Historically, this process has been exploitative, amplifying inequality unless counteracted by powerful redistributive institutions, such as progressive taxation, decommodified social rights, and worker ownership.

According many scholars, in capitalist society, the enrichment of a few is linked to the exploitation of others and tends to accentuate inequality. Wealth is concentrated in the hands of a minority while the majority may experience impoverishment or receive a smaller share of wealth. Karl Marx spoke of the “general law of capitalist accumulation,” according to which the enrichment of the capitalist class is accompanied by the relative and often absolute impoverishment of the working class. “The accumulation of wealth at one pole is, therefore, at the same time, the accumulation of misery…at the other pole.” This law is considered a structural trend, not just a circumstantial phenomenon.

Current studies show that a very small fraction of the world’s population (the top 1-10%) owns most of the world’s wealth, while most people have access only to a minimal share. The dynamics of contemporary capitalism, such as financialization and globalization, reinforce these mechanisms, enabling those who own capital to expand their assets while putting others at risk of becoming poorer or excluded.

According to Marxist theories and many critical economists, capitalist profitability presupposes labor exploitation, or a structural gap between the value generated by workers and their actual pay. This does not mean that for every person who gets rich, one person always gets poorer, but rather, the system tends to increase disparities.

It must also be acknowledged that capitalism has included corrective measures at various historical times, such as welfare, trade unions, and redistributive policies, that have temporarily reduced some inequalities in richer countries. However, this has never eliminated the phenomenon on a global scale.

In summary, capitalism’s tendency to accumulate wealth brings structural exploitation and amplifies inequality.

Mandela’s Ubuntu implies a subtle yet profound critique of capitalism. Ubuntu is measured by whether the community is able to improve, a criterion pointing directly to material conditions such as land, schools, and clinics rather than moral sentiment alone.

In his Robben Island notebooks, now in the UWC archives, Mandela repeatedly argues that “restoring Ubuntu means restoring the land” because the homestead economy that sustained reciprocity was destroyed by the 1913 Land Act. This is the root of Naledi Nomalanga Mkhize’s contemporary position.

In a 1992 COSATU address, Mandela warned that “the market, left to itself, will produce islands of wealth surrounded by seas of poverty—this is the opposite of Ubuntu.”

The 1994 Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP) was drafted with Mandela’s explicit support and was framed as an “ubuntu-based social contract” that prioritized mass housing, free healthcare, and land redistribution. These goals were later diluted by the 1996 Growth, Employment, and Redistribution (GEAR) macroeconomic turn.

The Star, Johannesburg, February 12, 1990: On February 11, Nelson Mandela delivered his first public speech after spending 27 years in prison. He addressed a crowd of 100,000 people gathered on the Grand Parade in Cape Town. “There is no option but to continue the struggle against apartheid until the system is dismantled,” he said. “However, we hope that a climate conducive to a negotiated settlement will be created soon so that the need for an armed struggle will no longer exist.” (South Africa Gateway)

Mandela himself muted the anti-capitalist edge once in office, but the discursive architecture of his Ubuntu remained materialist: “Ubuntu = shared wealth, not shared goodwill.”

Thus, scholars such as Mabogo More (2014) and Sabelo Ndlovu-Gatsheni (2020) interpret Mandela’s Ubuntu as a critique of the neoliberal hijacking.

Mandela’s political radicalism, which he toned down after gaining power in post-apartheid South Africa, does not constitute the popularized concept of ubuntu among white people, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), Westerners, and children. Tutu’s version of Ubuntu became dominant.

Amandla by Hank Willis Thomas (1976, Plainfield, New Jersey, USA), 2014. Silicone, fiberglass, and metal finish.

“Amandla, a Zulu word meaning “power,” is perfectly portrayed by the raised fist. Though inspired by Apartheid arrests in South Africa, this gesture has become an eternal symbol of resistance against all forms of oppression. With the arm emerging from a breathing hole, Thomas’s work further constitutes a contemporary statement depicting defiance against abusive authority. It is inspiring and optimistic for people in these demanding times.” Text by Iro Nikolakea, Greek curator of the 2020-2021 exhibition Ubuntu at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens, Greece.

You Messed With the Wrong Generation, 2020, by multidisciplinary Nigerian artist Ken Nwadiogbu (b. 1994, Lagos). Charcoal and acrylic on canvas. Displayed at the 2021 solo exhibition Ubuntu, Thinkspace Projects, Los Angeles, CA, USA.

Johnny Clegg – Asimbonanga (Madiba Tribute 2014)

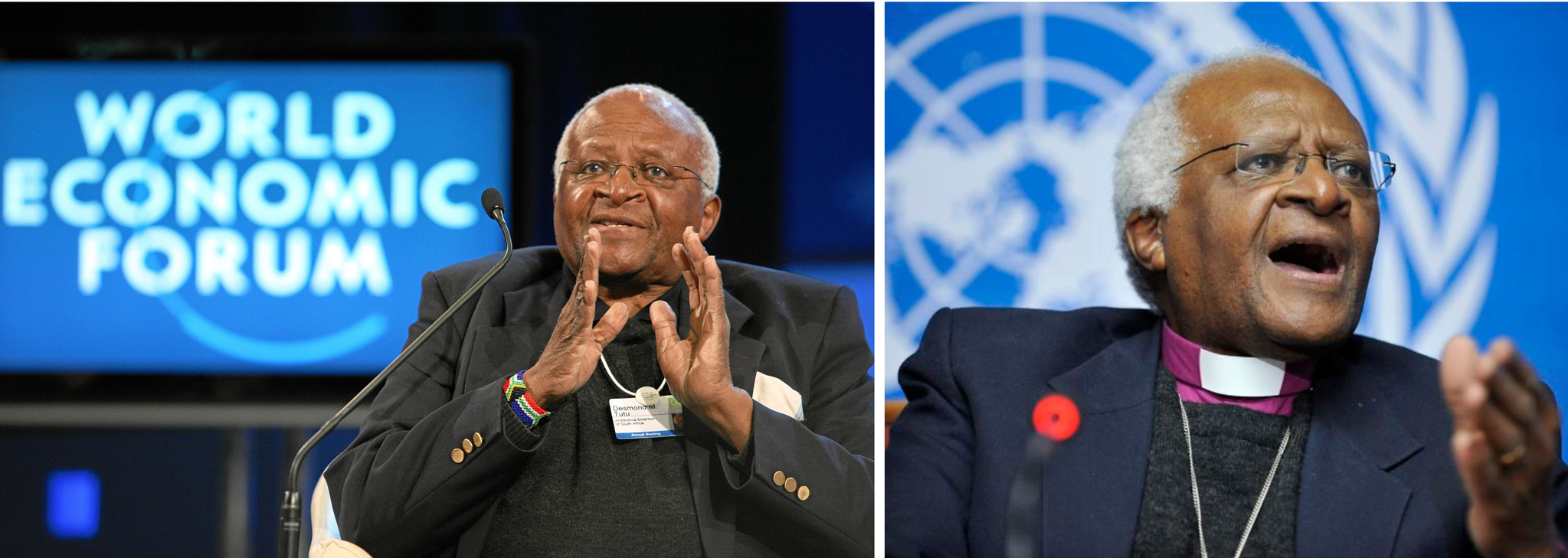

DESMOND TUTU (1931–2021)

A short bio

Desmond Tutu, a South African Anglican cleric, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, and global human-rights icon, was born in 1931 in Klerksdorp to Xhosa/Tswana parents. He was trained as a teacher but quit in 1957 rather than enforce apartheid education laws. He then studied theology and was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1961.

As General Secretary of the South African Council of Churches from 1978 to 1985, Tutu galvanized nonviolent resistance, called for international sanctions, and became the most prominent Black church voice against apartheid.

He was the first Black Anglican Dean of Johannesburg (1975), the first Black Bishop of Johannesburg (1985), and the first Black Archbishop of Cape Town (1986–1996). He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 “for his role as a unifying leader in the nonviolent campaign against apartheid.”

After apartheid ended, Tutu chaired South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission from 1996 to 1998. He pioneered a model of restorative justice rooted in the African philosophy of Ubuntu and coined the phrase “Rainbow Nation.” Beyond South Africa, Tutu was a global voice for human rights, speaking out against poverty, racism, homophobia, and oppression worldwide. He campaigned for peace, LGBTQ+ rights, poverty eradication, and good governance until his death in Cape Town on December 26, 2021.

LEFT: Desmond M. Tutu’s gestures during the session ‘Believing in the Dignity of All’ at the Annual Meeting 2009 of the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, February 1, 2009. Photo by Remy Steinegger / World Economic Forum.

RIGHT: Archbishop Desmond Tutu speaks during press conference at the 9th Session of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva in 2008. UN Photo/Jean-Marc Ferre.

Archbishop Desmond Tutu coined the term “Rainbow Nation” to describe the ethnic, cultural, and religious diversity of South Africa’s post-apartheid society under a new unity.

Tutu’s Ubuntu: From Moral Grammar to Rainbow Theology

In No Future Without Forgiveness (1999) Tutu writes: “Ubuntu speaks of spiritual attributes such as generosity, hospitality, and compassion… it is not a great good to be successful by being aggressively competitive and succeeding at the expense of others.” Ubuntu is no more a social dynamic. Now, a good person is the one who “has ubuntu,” meaning a person marked by generosity, compassion, and social grace. Ubuntu becomes a moral value. A Christian moral value. Tutu’s operative clause is: “Forgiveness liberates the soul… that is why it is such a powerful weapon.”

Let’s listen to his own words.

Who we are: Human uniqueness and the African spirit of Ubuntu. Desmond Tutu, Templeton Prize 2013

Tutu interpreted the Nguni maxim, Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu (“A person is a person through other persons”), in theological terms: humans bear the imago Dei; therefore, any violation of a human being is simultaneously a rupture with God. Ubuntu thus became a soteriological imperative—forgiveness is not merely prudent politics, but a divine mandate that restores both the victim and the perpetrator to the community of the redeemed.

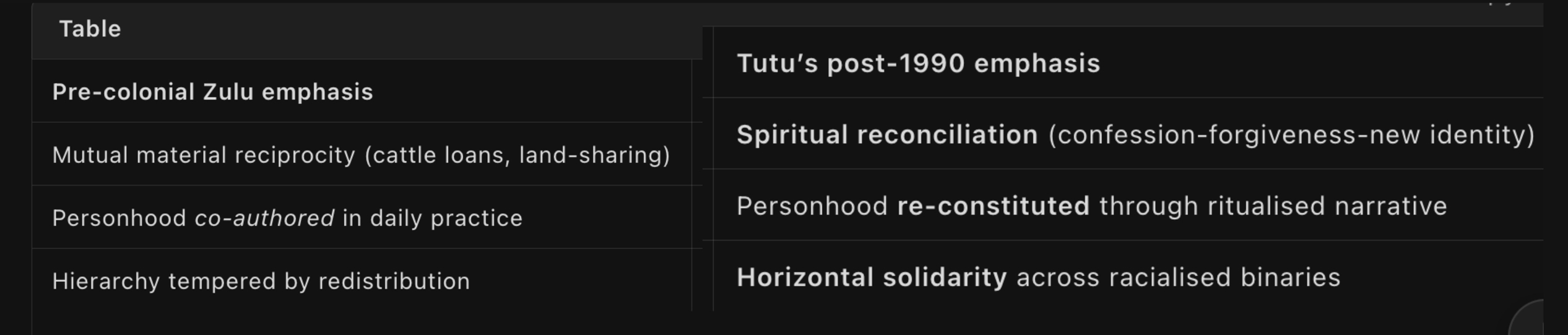

Thus the concept of ubuntu evolved from pre-colonial mutual material reciprocity, such as cattle loans and land-sharing, to Mandela’s political interpretation and Tutu’s spiritual reconciliation, which involves confession, forgiveness, and a new identity. What a huge leap!

Between 1996 and 1998, Desmond Tutu redefined ubuntu and embedded this reinterpretation in the architecture and daily practice of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

Let’s take a closer look at this important phase in South African history in which Tutu’s concept of ubuntu played a crucial role.

A detail of the artwork Ubuntu created by Thiago Limon to illustrate the article on the African philosophy of Ubuntu, The Power of Interdependence, by Adam Russell Taylor, an American reverend and the president of Sojourners, a Christian nonprofit organization focused on human rights and social and racial justice.

UBUNTU AND THE TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION COMMISSION (TRC)

In 1993, South Africa’s Interim Constitution referenced ubuntu in its preamble as part of the moral foundation for transitioning from vengeance to understanding. Two years later, the Constitutional Court’s landmark ruling in the case of S v Makwanyane struck down the death penalty, and several concurring opinions invoked ubuntu alongside dignity and equality as constitutional values. Former Justice Yvonne Mokgoro, who clarified the concept’s legal significance, argued that ubuntu need not be reduced to a precise definition to have real normative force in South African jurisprudence. Ubuntu functions as a value that orients interpretation toward reconciliation, restorative justice, and the protection of human dignity. Subsequent scholarship has traced how ubuntu has informed decisions regarding eviction, defamation, criminal sentencing, and customary law.

Following the end of apartheid, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established in South Africa in 1996 as a court-like restorative justice body. It was authorized by President Nelson Mandela and chaired by Archbishop Desmond Tutu.

The TRC was created under the 1995 Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act, and its hearings began in 1996. The Promotion of National Unity and Reconciliation Act tasked the TRC with “restoring the human and civil dignity” of victims—language that Tutu repeatedly described as “ubuntu justice.” The TRC’s main goal was to uncover the truth about gross human rights violations committed from 1960 to 1994 in order to promote reconciliation and help the nation move beyond its divided past. Both victims and perpetrators were invited to testify and account for abuses. In some cases, perpetrators could apply for amnesty if they made full disclosures. The commission also focused on documenting the motives and perspectives of both sides and offering reparations and rehabilitation to victims.

As chairperson, Desmond Tutu played a central role, leading public hearings and advocating for openness and transparency. He embodied the heart and soul of the process. His leadership helped ensure that the process aimed for moral and social healing, emphasizing empathy, understanding, and forgiveness, rather than just legal justice. He urged both victims and perpetrators to engage in truth-telling and reconciliation rather than vengeance, shaping the commission’s tone.

Tutu seamlessly integrated the African concept of ubuntu into the commission’s philosophy and practice. Expressed as “I am human through my relations with others,” ubuntu provided a framework for reconciliation. According to this philosophy, justice meant restoring dignity and enabling community healing, not retaliation. Tutu promoted ubuntu as the foundation for “understanding, but not vengeance; reparation, but not retaliation,” encouraging recognition of the interconnectedness of people and the empowering nature of forgiveness.

In summary, the TRC—authorized by Mandela and led by Tutu—became a model of transitional restorative justice. Tutu championed ubuntu as its ethical foundation, prioritizing reconciliation, empathy, and human dignity over punitive responses.

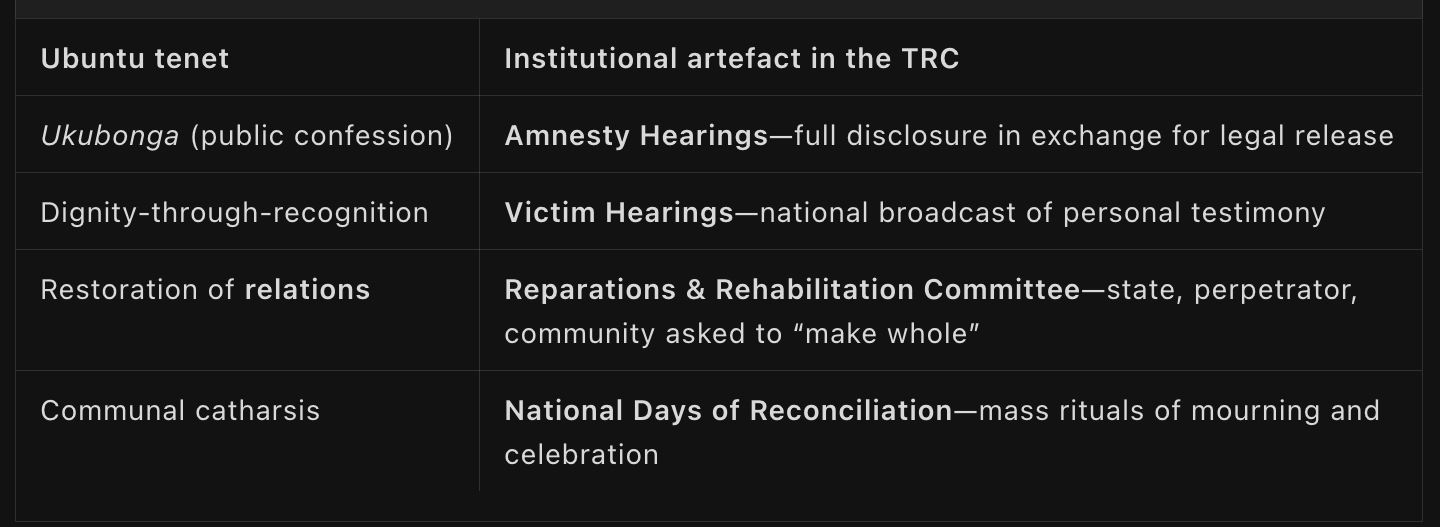

Ubuntu was present in the TRC’s daily work, beginning with a liturgical choreography:

- Opening mantra: Tutu began most hearings with, “We are gathered here in the spirit of Ubuntu.”

- Gestural grammar: Victims and perpetrators sat on the same level facing each other, which denied the hierarchy of the colonial courtroom.

- Language policy: Simultaneous translation preserved vernacular idioms, such as ukuhlonipha and ubuntu itself, turning the hall into a multilingual moral space.

Ubuntu’s transformation from the old times to TRC pillars

- Ukubonga (public confession) → Amnesty Hearings

Old times: When a homicide or serious transgression occurred within or between homesteads, the offender would appear before the inkosi (chief) and community. They would recount the act in detail and offer cattle or labor as isithebe (reparation). Then, they would ask for ukubonga, which literally means “to make return.” Truth-telling was inseparable from the offer to repair relationships.

TRC adaptation: The TRC’s Amnesty Committee required perpetrators to make full public disclosures of their political crimes. Instead of cattle, the “return” was legal indemnity; the community was now the nation, and the inkosi was replaced by the three commissioners.

Functional parallel: Both settings insist that truth precedes restoration and that silence perpetuates rupture.

- Dignity-through-recognition → Victim Hearings

Old times: In pre-colonial courts (izinkundla), the victim or their lineage would recount the harm they experienced in front of the assembly. Publicly naming the injury rehumanized the wronged party, and the act of being heard was a form of partial restoration.

TRC adaptation: The TRC’s Human Rights Violations Committee held nationally televised Victim Hearings, during which survivors spoke in their native languages. Commissioners responded with phrases such as “We acknowledge your ubuntu has been violated,” thereby reasserting the victim’s personhood in the eyes of the nation.

Functional parallel: Both settings treat public speech as reparative in itself.

- Restoration of relations → Reparations and Rehabilitation Committee

Old times: After ukubonga, the lineage of the offender might rebuild a burnt hut, replace stolen cattle, or offer a daughter in marriage. The goal was to mend the social fabric; punishment was secondary.

TRC adaptation: The TRC’s Reparations Committee recommended symbolic and material measures, such as monetary payments, memorials, trauma counseling, and community clinics, all of which were explicitly framed as “restoring ubuntu.”

Functional parallel: In both settings, justice is defined as repairing relationships rather than inflicting pain on the wrongdoer.

- Communal catharsis → National Days of Reconciliation

Old times: After a serious conflict, the umuzi or wider chiefdom held cleansing rituals (ukugeza) and communal meals (umsebenzi) to reincorporate offenders and mourn together. Shared weeping, singing, and the slaughter of cattle reaffirmed collective identity.

TRC adaptation: The TRC organized National Days of Reconciliation, such as on December 16, 1997, where victims, perpetrators, and political leaders met in stadiums to light candles, sing liberation hymns, and observe moments of silence. These events translated ritual catharsis into civic liturgy.

Functional parallel: In both settings, collective emotion is used as a technology to reweave the moral community.

The table below maps precolonial moral mechanisms and TRC institutional mechanisms, showing how Ubuntu’s relational grammar was adapted for a modern nation-state rather than a clan-based polity.

The TRC Report devotes an entire subsection to ubuntu, arguing that restorative justice “challenges South Africans to build on the humanitarian and caring ethos of the South African Constitution… Ubuntu expresses the metaphor ‘umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu’—people are people through other people.”

Thus, the Commission publicly defended its criteria for amnesty—full disclosure, political motive, and proportionality—as ethical extensions of Ubuntu rather than mere legal technicalities.

In many cases, ubuntu was explicitly invoked. For example, in the Trust Feed Massacre of 1988, 11 people were shot dead by police in Trust Feed, a small rural town in KwaZulu-Natal. Brian Mitchell, the officer convicted of ordering the killings, became the first member of the apartheid security forces to be granted amnesty by the TRC. Then, he returned to the village, funded a community garden, and rebuilt houses. Local elders framed this as “re-earning his ubuntu.”

Consider the cases of the Gugulethu Seven, who were anti-apartheid activists killed by members of the South African Police in an ambush in Gugulethu in 1986, and the PEBCO Three: Sipho Hashe, Champion Galela, and Qaqawuli Godolozi, three black South African anti-apartheid activists who were abducted and subsequently murdered by members of the South African security police in 1985. Tutu closed both hearings with prayers that forgiveness would “let ubuntu flow back into the dry bones of our nation.”

Three interesting films depicting the work of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in post-apartheid South Africa are In My Country (2004), Red Dust (2004), and The Forgiven (2017). These films all explore the complexities and challenges of reconciliation from different narrative perspectives.

In My Country (2004)

Directed by John Boorman and based on Antjie Krog’s memoir Country of My Skull, the film follows American journalist Langston Whitfield (Samuel L. Jackson) and Afrikaans poet Anna Malan (Juliette Binoche) as they cover the TRC hearings, and document stories from victims and perpetrators of apartheid-era violence. The TRC’s process of truth-telling and the struggle between justice and forgiveness serve as the film’s central themes.

Critics: The film was criticized for inventing a romantic relationship between the two main characters and for oversimplifying the political and emotional complexities of the TRC.

Red Dust (2004)

Red Dust, adapted from Gillian Slovo’s novel, is a courtroom drama centered on ANC politician Alex Mpondo (Chiwetel Ejiofor). Mpondo returns to his hometown to testify at a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) hearing about his torture during apartheid. His lawyer, Sarah Barcant (Hilary Swank), is a South African exile who returns to support him. The film explores confronting traumatic memories and seeking answers about a missing comrade, highlighting the tension between forgiveness and justice.

Critics: Red Dust was praised for its intense performances, particularly Ejiofor’s. However, the film was criticized for acting inconsistencies, notably Swank’s accent, and for relying too heavily on melodrama.

The Forgiven (2017)

Directed by Roland Joffé, is a fictional drama inspired by true events and adapted from Michael Ashton’s play, The Archbishop and the Antichrist. The film centers on Archbishop Desmond Tutu (played by Forest Whitaker) and his encounters with Piet Blomfeld (Eric Bana), a remorseful yet brutal former security police officer, during the Truth and Reconciliation Commission process in South Africa. After apartheid, Archbishop Tutu chairs the TRC and visits Pollsmoor Prison to assess Blomfeld’s candidacy for amnesty and investigate the disappearance of a young woman, a case brought to him by her grieving mother. The tense psychological showdown between Tutu and Blomfeld explores themes of guilt, accountability, and redemption. Blomfeld starts out unrepentant, but under Tutu’s moral probing and the weight of his own past, he ultimately chooses to confess his crimes. His confession brings closure to the case and enables an act of forgiveness in the face of pain.

Critics generally praised Whitaker’s performance for its depth and nuance. The film was also commended for highlighting the fragility of post-apartheid peace and for provoking reflection on forgiveness. However, some reviewers criticized the film’s heavy-handed moralizing and occasionally melodramatic plot elements.

AFTER TRC: HOW TUTU’S UBUNTU BECAME THE OFFICIAL POST-APARTHEID ETHOS

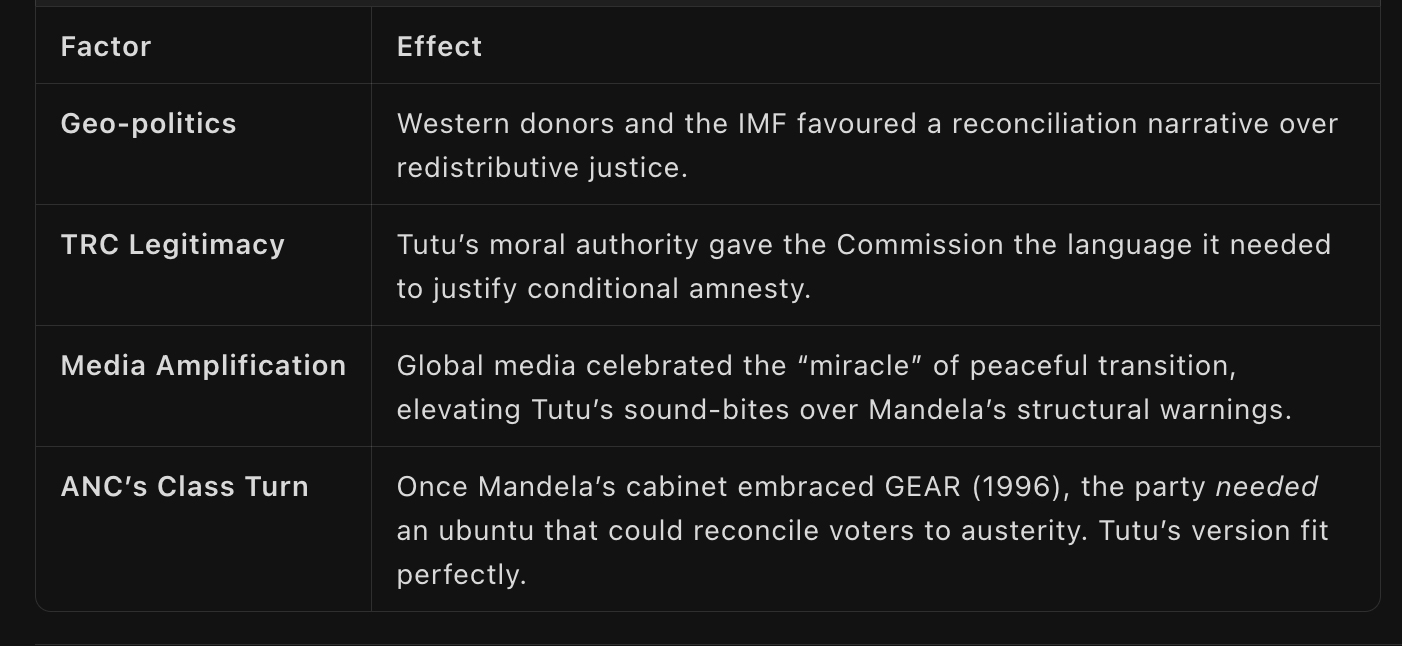

Tutu left behind a double-edged legacy. He transformed Ubuntu from a communal moral code and social dynamic into a national reconciliation tool under a Christian moral framework. The TRC institutionalized this shift. While it averted civil war and created a public vocabulary of forgiveness, it also rendered Ubuntu compatible with a socioeconomic settlement that left capital accumulation and racialized inequality intact. Tutu’s Ubuntu crossed South Africa’s borders and was welcomed in the West as an invitation to Christian brotherhood and goodwill.

Thus, Tutu’s ubuntu migrates from thick relationality to thin multiculturalism: race and religion are transcended through shared humanity, but class and property relations remain untransformed. Critics therefore argue that Tutu’s ubuntu functions as an ideological state apparatus that secures consent for the post-apartheid status quo.

Not coincidentally, Tutu’s formulation—”I am human because I belong”—was adopted by corporate South Africa (e.g., Standard Bank’s 2003 “Ubuntu Banking”) as a soft management ideology compatible with profit maximization. Corporate South Africa, government ministries, and even the branding of the 2010 FIFA World Cup adopted Tutu’s thin ubuntu (“caring,” “rainbow nation”) while dropping its redistributive bite.

Tutu’s version of ubuntu prevailed and became dominant both in South Africa and beyond. Here are some reasons why:

GEAR 1996

GEAR (Growth, Employment, and Redistribution) was a major macroeconomic strategy launched by the South African government in 1996. The goal of GEAR was to accelerate economic growth, create jobs, and promote income redistribution after apartheid. GEAR was designed to address South Africa’s urgent challenges of low growth, high unemployment, and rising public debt in the post-apartheid era.

The strategy emphasized privatization, export-led growth, and relaxed exchange controls to attract foreign investment.

The strategy targeted an average growth rate of 4.2% per year and the creation of 400,000 new jobs by the year 2000.

The strategy also sought to reduce the budget deficit, reform public infrastructure, and encourage investment in human capital.

GEAR was welcomed by the business sector but met with skepticism and criticism from labor and social movements who viewed it as a shift toward market-oriented neoliberal policies. While GEAR helped curb inflation and stabilize the macroeconomic environment, it fell short in transforming employment and substantially reducing poverty.

Ubuntu by South African artist and photographer Justin Dingwall (b. 1983), 2015. Giclée print on cotton paper. Artsy.

THE TIME FOR CRITICISM

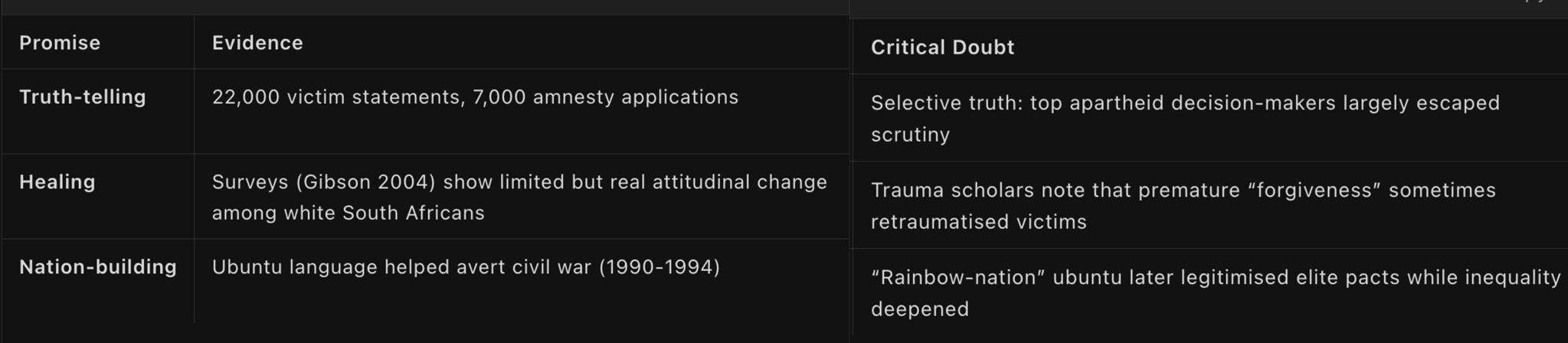

The story of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings does not have a happy ending. Desmond Tutu transformed ubuntu into the “moral engine” behind the TRC’s most controversial power: conditional amnesty in exchange for full disclosure.

The following table summarizes the results of the TRC’s experience.

Criticism arose almost immediately.

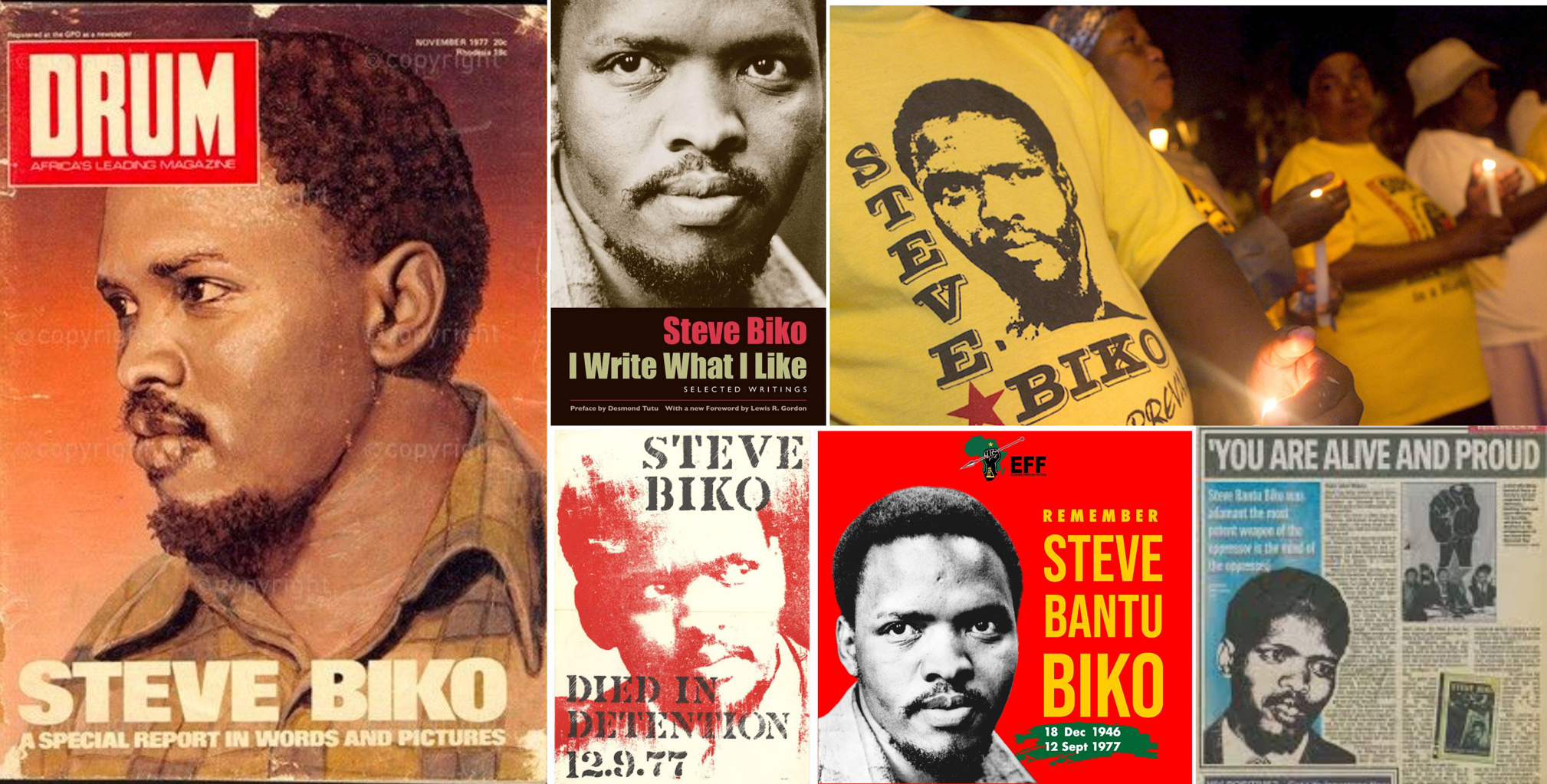

One of the most visible and emotionally charged criticisms came from the family of Steve Biko, a renowned anti-apartheid leader who was tortured and killed by police in 1977. His story was later dramatized in the film Cry Freedom and had become a symbol of state brutality and the silencing of dissent. For Biko’s relatives, the TRC’s offer of amnesty in exchange for information amounted to a betrayal of justice. They denounced the process as a “vehicle for political expediency” that stripped victims’ families of the right to see perpetrators held fully accountable under the law. They stood firm in their opposition to amnesty for those implicated in Biko’s death and pursued a case before South Africa’s Constitutional Court. They challenged the legality of the TRC itself, arguing that it violated the constitutional principle of justice. Their resistance became emblematic of a wider debate: Can reconciliation legitimately come at the expense of punishment? Can truth without retribution heal a nation scarred by systemic violence?

Steve Bantu Biko, born in 1946, was a Xhosa anti-apartheid activist and the founder of the Black Consciousness Movement. He was murdered in September 1977 after being arrested by security police at a roadblock in Port Elizabeth (now known as Gqeberha). He died from severe beatings during interrogation, which caused a massive brain hemorrhage. Initially, the police denied any wrongdoing, but later evidence confirmed that Biko had been severely beaten while in custody. Though official inquests at the time cleared the officers, later confessions revealed direct police responsibility, and amnesty was denied. Biko’s death became an international symbol of apartheid’s brutality.

Cry Freedom (1987) is a film directed by Richard Attenborough that dramatizes the friendship between Steve Biko and journalist Donald Woods, depicting Biko’s struggle against apartheid. The film received praise for its strong performances, especially Denzel Washington’s portrayal of Biko, as well as for its emotional impact and vivid cinematography. South African reviewers found the film powerful and moving. However, some felt that it oversimplified political realities and focused too much on Woods, relegating Biko’s story to the background. Both international and South African critics criticized its white-centered narrative and limited exploration of Black South African perspectives. The South African government condemned the film as propaganda, while others saw it as an authentic portrayal of apartheid’s brutality. Nevertheless, Cry Freedom is recognized as a significant introduction to Biko’s legacy and the horrors of apartheid, despite its flaws.

Biko by Peter Gabriel | Playing For Change | Song Around The World

Voice of the Sky / Steve Biko Lives – Afrobeat Song of Freedom and Truth

“Voice of the Sky” is a powerful Afrobeat tribute to Steve Bantu Biko, the leader of the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa and a fearless voice against apartheid. “Voice of the Sky” is more than a song; it’s a rhythm of memory, a call to awaken, and a heartbeat of resistance. With ancestral drums and spiritual lyrics, the song honors Biko’s legacy and echoes the pride of the Zulu people and all those who dare to rise up.

Steve Biko’s family members’ critical stance was not an isolated case. Even more critical voices were raised in subsequent years, denouncing the failures of the TRC experience.

In 1998, the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, in partnership with the Khulumani Support Group, conducted a landmark survey of several hundred victims of apartheid-era human rights violations. The findings revealed a deep sense of disillusionment with the TRC. Many respondents felt that the Commission had not succeeded in fostering genuine reconciliation between South Africa’s black majority and white minority. A recurring concern was that justice had been sacrificed in the name of reconciliation. Victims overwhelmingly believed that accountability was a necessary foundation for healing and should not be compromised. Critics argued that the process leaned too heavily in favor of perpetrators, granting them amnesty while leaving survivors with unresolved wounds and little recourse. According to interviews conducted by Sifiso Zulu in 2022, the poorest residents felt pressured to “forgive” while elites recovered insurance claims.

Frustrated by these shortcomings, victims’ associations, together with civil society organizations and human rights lawyers, began seeking redress through the courts in the early 2000s. Some of these legal challenges were brought before South Africa’s judiciary, while others reached international venues, including U.S. courts. This reflects the global dimensions of the struggle for justice after apartheid.

These efforts underscored the enduring tension between truth-telling, reconciliation, and the victims’ unfulfilled demand for retributive justice. Despite its rhetorical centrality, ubuntu was never uncontested. Several critiques emerged, primarily from African scholars and activists. Each critique exposed the political and ethical tensions surrounding the concept’s use in post-apartheid South Africa.

The “Empty Signifier” Critique

Christian B. N. Gade, an associate professor at Aarhus University and the director of the Aarhus Center for Conflict Management, argues that the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) invoked ubuntu without ever defining it (2017). He claims that Amnesty International decisions appealed to the “spirit of ubuntu” less as a principled ethical framework and more as persuasive rhetoric, enabling political compromises under the guise of cultural authenticity. Gade also demonstrates how the proverb umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu (“a person is a person through other persons”) was grafted onto ubuntu in the early 1990s, projecting an aura of timeless African wisdom. Gade warns that such “inventions of tradition” risk fossilizing ubuntu into a museum piece, estranging it from the dynamic negotiations of meaning in contemporary African life.

Ubuntu as a Gendered Moral Economy

Siphokazi Magadla, a professor of political and international studies at Rhodes University, contends that the TRC’s appeal to ubuntu disproportionately burdened black women with the labor of reconciliation (2018). Mothers of the disappeared were urged to publicly forgive, even embrace perpetrators while the patriarchal structures that caused their suffering remained untouched. Magadla argues that such staged spectacles of ubuntu obscured women’s continuing economic marginalization. Her ethnography of TRC hearings in KwaZulu-Natal reveals that commissioners scolded women who demanded more than symbolic reparations. Magadla also highlights how, during Jacob Zuma’s 2006 rape trial, appeals to “our ubuntu culture” were weaponized to shame the accuser and protect male authority. For Magadla, ubuntu risks becoming a “cultural cage” whenever invocations of tradition ignore whose interests are being served.

Class and the Limits of Relational Repair

Philosopher Mabogo Percy More argues that ubuntu’s emphasis on reconciliation without redistribution reinforced the post-apartheid elite bargain of political power for the ANC and economic continuity for white capital (2014). He writes that the TRC’s failure to secure substantial reparations revealed ubuntu as “a velvet glove around the iron fist of neoliberal transition.” He continues: “Tutu’s Ubuntu baptized inequality with moral perfume and holy water.” More provocatively, he asks whether ubuntu can endure once solidarity itself is commodified.

Ubuntu versus Retributive Justice

Tseliso Thipanyane, the former CEO of the South African Human Rights Commission, argues that ubuntu was strategically used to delegitimize calls for criminal trials. Those who insisted on prosecutions were portrayed as un-African and “trapped in a cycle of bitterness.” This rhetorical move, he argues, inverted the moral logic: the pursuit of justice was cast as lacking ubuntu.

Ubuntu as Ideological State Apparatus

Cameroonian historian and political theorist Achille Mbembe (2015) contends that ubuntu has functioned as a kind of “cultural software” for neoliberal governance. As a state ideology of reconciliation, it offered moral catharsis while leaving structural inequalities intact. He suggests that ubuntu has been made to perform the ideological work of rendering extreme inequality tolerable. At the same time, it has been commodified as “Afro-difference on demand,” a consumable essence marketed to Western audiences eager for spiritual redemption. Mbembe warns that, in this sense, ubuntu risks becoming what V.Y. Mudimbe once described as an “invention of Africa”: a mirror for Western fantasies rather than a site of rigorous African philosophical practice.

Mandela bequeathed an ubuntu that identifies exploitation as a violation of human interdependence. Tutu, on the other hand, offered an ubuntu that heals the symbolic wounds of racism while allowing the economic ones to fester. These critiques reopen Mandela’s suppressed question: Can ubuntu survive without a material foundation of shared prosperity? Can the concept be retooled to confront, rather than console the structural inequalities it once promised to heal? Is ubuntu still relevant and meaningful in postmodern African societies?

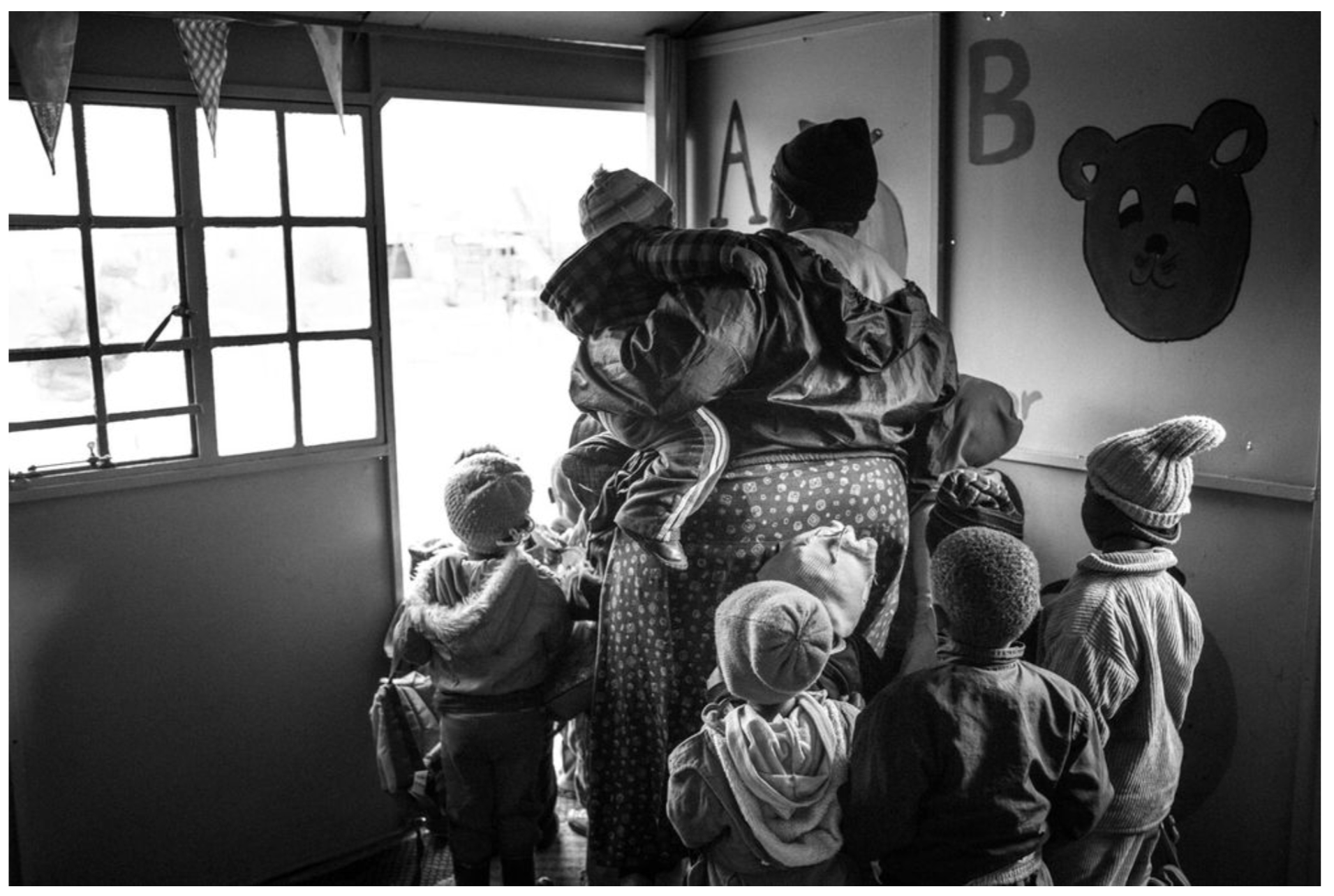

A photo from the series Ubuntu – I am because you are by the Brazilian photographer André François. The photo shows children from the GogoGetters program, a project of LoveLife. Grandmothers who have lost their children to HIV now care for children who have lost their parents to the disease. The photo was taken in Orange Farm, Gauteng, South Africa.

UBUNTU: TO BE OR NOT TO BE?

Although the philosophy of ubuntu is widely celebrated as a cornerstone of African thought, especially in the Western world, it has faced intense scrutiny and debate from prominent African philosophers and scholars who challenge its contemporary relevance, authenticity, and practical applications. These debates reveal deep divisions within the field of African philosophy regarding the role of traditional concepts in modern society.

- The Matolino-Kwindingwi Critique: “The End of Ubuntu”

This influential and controversial critique of Ubuntu was written by Bernard Matolino, a philosopher at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, and Wenceslaus Kwindingwi, a professor at the St. Joseph’s Theological Institute in South Africa, in their landmark 2013 article, The End of Ubuntu. They argue that Ubuntu is no longer relevant or applicable in contemporary society.

Matolino and Kwindingwi assert that Ubuntu “should come to an end as an ethical theory and way of life” because it has become obsolete in modern African societies. Their critique rests on several key pillars:

- Structural Incompatibility with Modernity: The philosophers contend that ubuntu can only function in “undifferentiated, small, and tight-knit communities that are relatively underdeveloped.” They argue that modern African societies, which are characterized by urbanization, industrialization, and cultural diversity, lack the social structures necessary for the successful implementation of Ubuntu.

- The “Narrative of Return” Problem: Matolino and Kwindingwi position ubuntu as part of what they term “narratives of return,” which are attempts by postcolonial African elites to revive precolonial ways of life. They argue that such narratives have historically resulted in “public, social, and political failure” throughout Africa, citing examples from various African independence movements.

- Elite Instrumentalization: The scholars contend that the contemporary promotion of ubuntu represents “an elitist project conceived to benefit the emerging new elite.” They contend that the aggressive promotion of ubuntu in post-apartheid South Africa serves the interests of new Black elites rather than addressing the needs of ordinary citizens.

- Exclusionary Nature: Despite the emphasis on inclusivity, Matolino and Kwindingwi argue that traditional ubuntu communities were “notorious for their dislike of outsiders, intolerance of divergent ideas, and high value placed on blood relations.” They argue that this exclusionary tendency makes ubuntu unsuitable for diverse, modern societies.

Thaddeus Metz’s Counter-Argument and Ongoing Debate

Thaddeus Metz, a prominent defender of Ubuntu, responded with Just the Beginning for Ubuntu. In it, he argues that scholarly inquiry into and political application of Ubuntu should be viewed as projects that are only now properly getting started. Metz contends that Ubuntu can adapt to modern realities while remaining philosophically valuable.

However, Matolino’s sustained critique suggests that Metz’s defense is “dogmatic and unphilosophical” and fails to address the fundamental structural problems identified. This debate continues to divide African philosophical communities, with scholars like Jonathan Chimakonam and Mojalefa Koenane attempting to find middle ground.

Ubuntu by award-winner photographer Giovanna Aryafara, South-Omo Valley, Ethiopia. Instagram.

- Gender Criticisms and Patriarchal Concerns

As Siphokazi Magadla has warned, traditional ubuntu can be a “cultural cage” for women. Other African feminist scholars and critics have also expressed significant concerns about ubuntu’s relationship to gender equality and women’s rights. They argue that the philosophy can perpetuate patriarchal structures.

Fainos Mangena, a professor of African philosophy and ethics at the University of Zimbabwe, argues that “the communitarian philosophy of hunhu or ubuntu is full of the whims and caprices of patriarchy.” Mangena’s analysis reveals that:

- Male-Dominated Discourse: Ubuntu philosophy has primarily been developed and interpreted by male scholars who have “conveniently ignored the implications of Ubuntu on gender.” The glorification of Ubuntu without analyzing its gender implications is largely done by those who benefit from patriarchal systems.

- Women’s Exclusion from Decision-Making: Traditional ubuntu practices often exclude women from important community decisions. Married women find themselves in an “ambiguous place in the moral system”: excluded from decision-making in their husbands’ families, yet still expected to belong to their birth families.

- Perpetuation of Gender Violence: Critics argue that ubuntu’s emphasis on communal harmony can be used to justify domestic and gender-based violence. The Zimbabwean Minister of Women’s Affairs noted that “gender-based violence is attributed to cultural values created by men in powerful positions in patriarchal societies.”

Fainos Mangena is a man, so his approach to African feminist ethics is met with cautious interest and critique from African women. His approach seeks to develop a feminism rooted in local realities rather than Western models. However, debates persist about its relevance and application to the everyday lives of African women.

Mangena argues that African feminism must emerge from the lived experiences and cultural realities of African women — particularly the roles of motherhood and communal responsibility — rather than simply adopting Western feminist paradigms. This outlook resonates with scholars and activists who seek a distinctly African feminist ethic. However, there is ongoing concern that academic discourses may not fully reflect the struggles of women at the grassroots level. Professor Fainos Mangena’s paper – The Search for an African Feminist Ethic: A Zimbabwean Perspective, published in the Journal of International Women’s Studies in 2009 – can be read and downloaded here.

Some African women and theorists welcome Mangena’s emphasis on endogenous values and his critique of imported feminist models. They see this as a step toward real self-definition and agency for African women. However, others critique academic African feminism—including Mangena’s—for being disconnected from the realities of ordinary women, especially in rural or traditional settings. The most frequent criticism is whether Mangena’s vision sufficiently addresses intersecting oppressions (gender, class, and colonial legacies) and if it can be implemented beyond scholarly circles.

Some scholars have developed “Ubuntu Feminism” as a critical response that attempts to reconcile Ubuntu’s communal values with gender equality. This approach addresses gendered violence within the broader context of socioeconomic insecurity while promoting inclusive practices. However, critics argue that Ubuntu feminism represents a fundamental departure from traditional Ubuntu rather than an authentic expression of it.

This is a photo from the series “Ubuntu – I am because you are,” by Brazilian photographer André François.

Through the International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) in Burundi, people started a chain of solidarity to fight poverty and hunger. The idea is simple: people in a community receive pigs, and once they have piglets, they donate them to others in the same community. Bujumbura, Burundi.

- Political Instrumentalization and Elite Manipulation

African scholars have extensively documented how ubuntu has been co-opted for political purposes, which often contradicts its original communal values.

Post-independence manipulation: Matolino and Kwindingwi trace how post-independence African leaders used communal philosophies to consolidate power, which often resulted in “very public and political failures.” They argue that the current promotion of Ubuntu follows this same problematic pattern.

South African Political Context: As we saw, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s use of Ubuntu was internationally celebrated but criticized for serving “nefarious social functions” that prioritized elite reconciliation over substantive justice for apartheid victims.

Contemporary Political Usage: African governments and political leaders often invoke Ubuntu to justify policies or deflect criticism. Scholars term this practice “an appendage to the political desires, wills, and manipulations of the elite.”

- Authenticity and Colonial Influence Debates

Another significant line of criticism questions the authenticity of ubuntu and examines how colonial and Western influences have shaped its contemporary formulations.

Scholar Michael Onyebuchi Eze describes how African philosophy, including ubuntu, has been subject to a “colonization of subjectivity,” in which concepts are “created to satisfy the intellectual curiosity of the Westerner.” This critique suggests that modern formulations of ubuntu may reflect Western philosophical categories more than authentic African thought.

Critics argue that even sympathetic Western scholars, such as Thaddeus Metz, engage in “cultural imperialism” by incorporating Western liberal ideals into ubuntu theory. Mogobe Ramose, another scholar, suggests that Metz’s approach implies that “to be respectable and desirable, a plausible ubuntu moral theory must align with some ‘superior’ Western paradigm.”

Critics also argue that the promotion of ubuntu often relies on essentialist views of African culture. It presents ubuntu as “a singular, all-encompassing African philosophy,” which oversimplifies the continent’s diverse and complex traditions and beliefs. This essentialism obscures the “rich tapestry of philosophical traditions within Africa.”

- The Moderate Communitarianism Alternative

Ghanaian philosopher Kwame Gyekye proposed “moderate communitarianism” as an alternative that balances Ubuntu’s communal values with individual rights. Gyekye argues for “granting both the community and the individual equal moral significance,” thereby addressing critiques about Ubuntu’s suppression of individual autonomy.

However, even this moderate approach is not without criticism. Bernard Matolino claims that attempting to “limit the influence of communitarianism” while maintaining its core principles is a contradiction that undermines the coherence of communitarian philosophy.

- Contemporary Relevance and Modern Challenges

The debate over ubuntu’s contemporary relevance continues to divide African scholars. Critics point to various modern challenges:

- Urbanization and Social Fragmentation: Critics argue that Ubuntu’s reliance on close-knit community structures renders it irrelevant in modern urban environments, which are characterized by anonymity and mobility.

- Globalization and Cultural Change: The influence of global capitalism, Western individualism, and technological change has fundamentally altered the social conditions that originally supported Ubuntu practices.

- Social Problems and Inequality: High rates of crime, corruption, and social inequality in contemporary African societies call into question the effectiveness of Ubuntu as a lived philosophy.

- Synthesis: The Ongoing Struggle for Authentic African Philosophy

These critical debates reveal the complexity of developing authentic African philosophy in the contemporary world. While critics like Matolino and Kwindingwi advocate for “taking modern realities seriously” and moving beyond romanticized traditional concepts, proponents argue that ubuntu can evolve while maintaining its core principles of human interconnectedness.

Gender critiques highlight the need to subject traditional concepts to critical analysis to ensure they promote, rather than hinder, human flourishing for all community members. Concerns about political instrumentalization underscore the need for vigilance against the co-optation of philosophical concepts for narrow political purposes.

Most significantly, these debates demonstrate the vitality of African philosophical discourse. Rather than accepting ubuntu uncritically, African scholars engage in rigorous analysis that strengthens authentic philosophical inquiry. As Simon Makwinja notes, this “rejectionist approach should be seen as a nudge to make the advocacy for African ideals and beliefs…match up with the knowledge of them and how they operate in reality.”

This ongoing critical engagement ensures that African philosophy remains dynamic and relevant to the needs and realities of contemporary African societies rather than becoming fossilized in romantic notions of an idealized past.

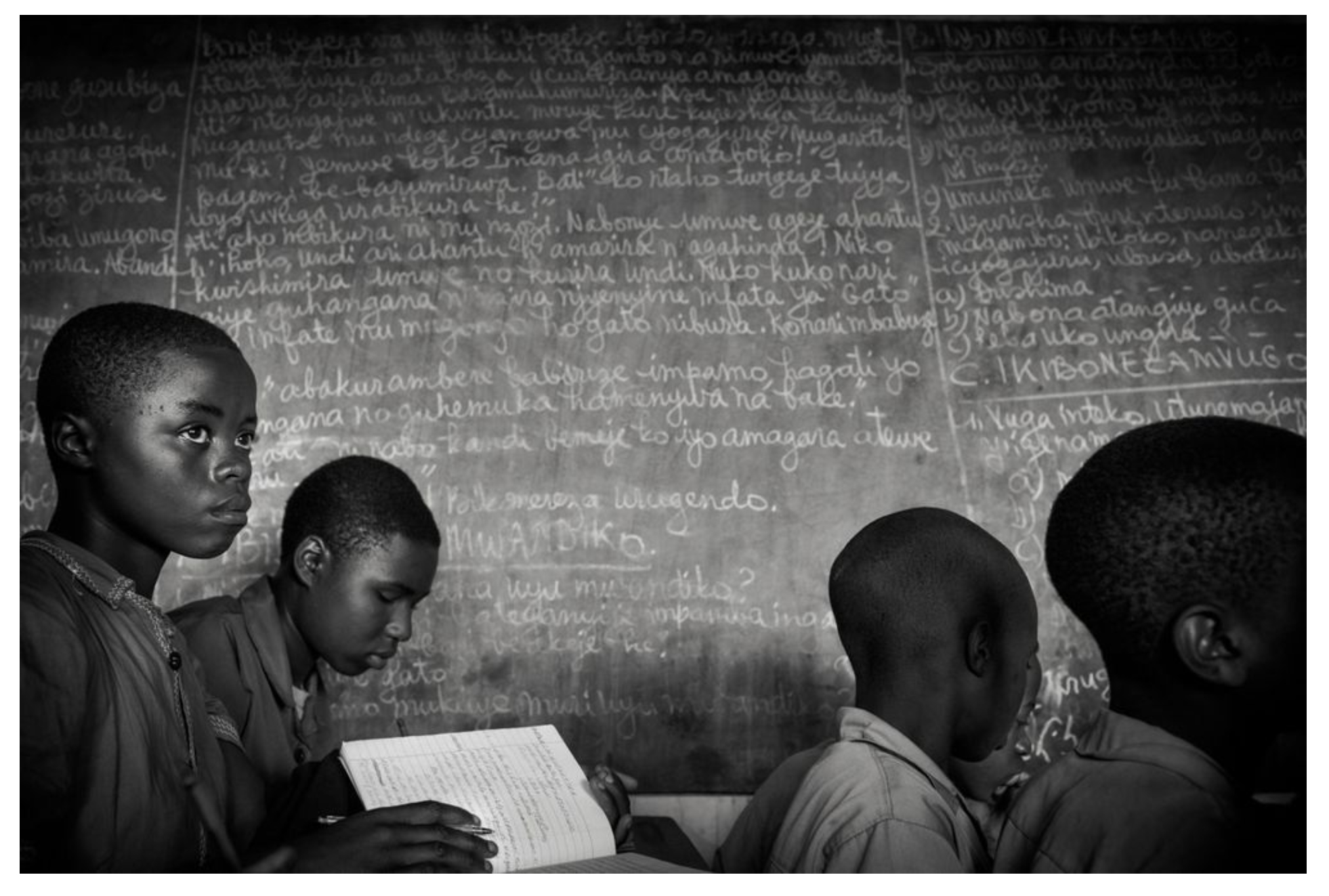

This photo is part of the series “Ubuntu – I am because you are” by Brazilian photographer André François.

Volcanoes National Park, famous for mountain trekking and gorilla viewing, is developing a project that benefits the surrounding communities. They invest the money from ticket sales in schools and initiatives related to agriculture and access to water. Kinigi, Rwanda.

African Ubuntu, painting by the Congolese artist, graphic designer and musician Tony Luza (aka Ntona Luzayis Djesquin). Acrylic on Paper. Saatchi Art.

TOWARD A CRITICAL FUTURE FOR UBUNTU

Post-apartheid South Africa followed Tutu’s lead. However, the resurgence of township protests, labor unrest, and decolonial land movements suggests that Mandela’s radical undercurrent has not disappeared; it merely lies dormant beneath the rainbow.

These critiques suggest that Ubuntu’s emancipatory promise depends less on recovering a pristine past than on reinventing relationality under postcolonial conditions.

Here are today’s main points of discussion and open trajectories:

- Ubuntu is not an African philosophy, but rather an African philosophical problematic—a site of contestation, not a settled creed.

- Its normative force is contextual and embedded in historically specific relations of land, labor, and gender. Detaching it from these relations yields ideological mystification.

- Relational personhood is compatible with human rights, provided that we interpret rights as tools for negotiating relationships rather than atomistic entitlements.

- Feminist and queer critiques are internal to Ubuntu, not external impositions. These critiques expose tensions already present in the tradition, such as the conflict between patriarchal customs and the radical inclusivity implied by the phrase, “A person is a person through other persons.”

- Ubuntu’s future lies in practices, not proverbs. Rather than asking, “What does Ubuntu mean?” we should ask, “What institutions, technologies, and art forms can perform Ubuntu under 21st-century conditions?”

- Comparative dialogue is vital, but only if we avoid reducing Ubuntu to an exotic foil for Western liberalism. Conversation must be multidirectional. For example, Zulu elders could debate Rwandan jurists, and queer activists in Soweto could critique corporate HR manuals.

- Lastly, in the 21st century, Ubuntu can only play a role if we extend its circle to include land, water, and non-human life while addressing unresolved land dispossession.

Ubuntu is both indispensable and dangerous. It is indispensable because the atomized, hyper-competitive logics of racial capitalism and digital surveillance threaten to erode the relational fabric that ubuntu represents. It is dangerous because, when stripped of its critical edge, ubuntu can sanctify hierarchy, gender discrimination, silence dissent, and beautify injustice. Therefore, to keep the concept alive is a philosophical and political task that requires constant historical excavation, fearless critique, and imaginative re-inscriptions in new practices of solidarity.

As Nompumelelo Zondi, a Zulu philosopher from the University of KwaZulu-Natal, said, “Ubuntu is not a museum piece to be dusted off for Heritage Day. It is a quarrel we have inherited, a quarrel about what it means to become human together under conditions that often deny our humanity.”

If you thought of the concept of African ubuntu as a slogan like “make love, not war”, “Volemosebbene” (an humorous Italian expression meaning “let’s just pretend everything’s fine, even if it isn’t”), or the heartwarming, childish “All together lovingly”, well you were wrong.

Lively debates in African philosophy represent Africa as much as its art and material culture. These debates also exemplify the idea that we are not human and we are not born human. We become human or inhuman only through our complex social interactions. While the path to becoming inhuman is easy and the most commonly taken today, the path to becoming human is complex and difficult. It is full of obstacles, pitfalls, and steep climbs. It is full of reflections, discussions, and complete disagreements. It is not a path for the faint of heart, mind, or spirit. However, it is the only way to save ourselves and our fragile, wonderful planet.

Ubuntu – Sona Jobarteh

Sona is a famous Gambian multi-instrumentalist, singer, and composer.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?