ZULU UKHAMBA AND ISICHUMO BASKETS 2

South Africa on the globe

(Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

Kwa Zulu-Natal Province (source: Encyclopaedia Britannica).

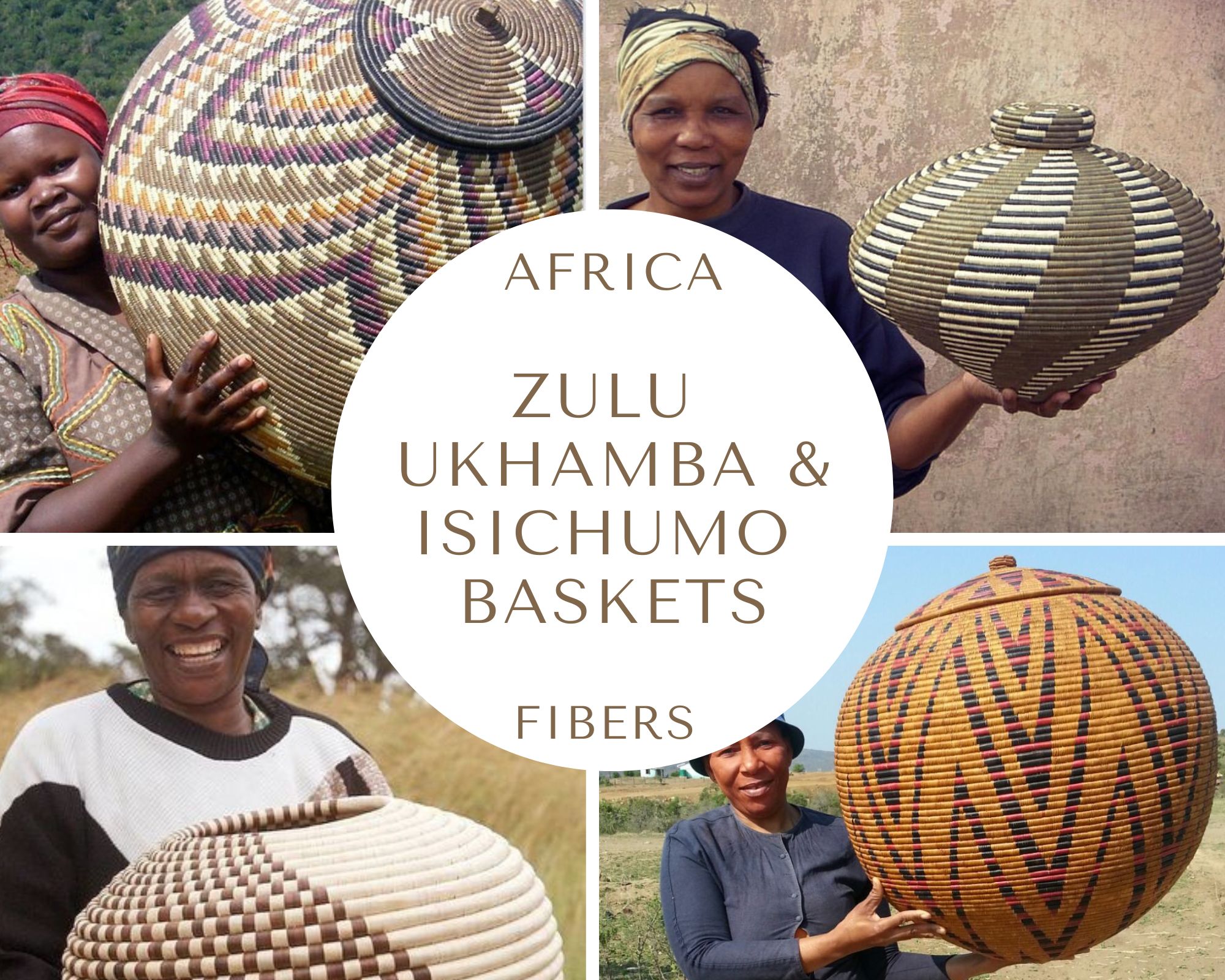

Isichumo: Born of Ilala and Grace

The Zulu isichumo basket (plural: izichumo) is much more than just a container. It embodies centuries of cultural wisdom, artistic expression, and functional innovation. These distinctive, watertight vessels are crafted with remarkable precision from ilala palm and wild grasses. They have evolved from essential household tools into celebrated works of art that command international attention.

This transformation reflects broader shifts in Zulu society, including changing gender roles, economic pressures, and the growing global appreciation for indigenous crafts.

This chapter examines the multifaceted nature of isichumo baskets through three critical lenses: their historical and functional context, their deep cultural and social significance, and their evolution into a globally recognized art form. Through this exploration, you will discover how this traditional craft has become a vehicle for women’s economic empowerment and a powerful symbol of cultural preservation.

5 Izichumo baskets. Source: Pinterest.

Historical and Functional Context of Isichumo Baskets

The design and construction of the Zulu Isichumo basket directly reflect its intended purpose, showcasing a sophisticated understanding of materials and engineering. Its distinctive jug-like shape, with a rigid, bottle-shaped body and narrow neck, is designed for securely containing and transporting liquids. This design minimizes spillage and evaporation, making the basket ideal for carrying water over long distances or storing fermented beverages, such as traditional sorghum beer. The construction process is meticulous and time-consuming, and it has been passed down through generations of women, who are the primary weavers in contemporary Zulu society. The use of natural, locally sourced materials, such as resilient ilala palm and hardy wild grasses, underscores the craft’s deep connection to the KwaZulu-Natal region’s natural environment.

A hallmark of Zulu basketry is the coiling technique, which involves wrapping a core of bundled grasses with thin strips of palm leaf to create a tight, interlocking structure that is strong yet flexible. Combined with the natural properties of the materials, this method results in a vessel that is functional, durable, and capable of withstanding the rigors of daily use.

Distinctive Jug Shape and Lid

The isichumo basket is easily identifiable by its distinctive jug- or bottle-like shape, which sets it apart from other Zulu baskets. Its rigid, elongated shape tapers to a narrow neck for the primary purpose of carrying and storing liquids. The narrow opening minimizes spillage and reduces the surface area exposed to air. This is important for preventing the evaporation of water and the spoilage of fermented beer. A crucial component of this design is the lid, which snugly caps the neck of the basket and further secures the contents. This distinguishes it from the ukhamba, which typically has a lid that fits inside the opening. The secure, snug-fitting lid of the isichumo makes it ideal for transporting liquids, ensuring they remain contained even when the basket is jostled or tipped.

The isichumo’s overall form, with its stable base and curved body, is practical and aesthetically pleasing, reflecting a harmonious balance between utility and artistry. Its shape has become a symbol of Zulu craftsmanship, representing a deep understanding of the relationship between form and function in creating everyday objects.

TOP, LEFT TO RIGHT

Isichumo with natural palm fronds wrapped around coils of wild grasses. Dimensions: width 15.25 in., 38,735 cm; height 5 in., 12.7 cm. Baskets of Africa, Los Ranchos, NM, USA.

Isichumo from 2017. Dimensions: height: 8.5 in., 21.59 cm; diameter 16 in., 40.64 cm. Sold via 1st DIBS.

BOTTOM, LEFT TO RIGHT

Modern isichumo, from Pinterest.

Isichumo; Phansi Museum, Glenwood, Durban, South Africa.

Materials: Ilala Palm and Wild Grasses

Zulu isichumo baskets are constructed using a careful selection of natural materials, primarily the ilala palm (Hyphaene coriacea) and various types of wild grasses. The ilala palm provides the essential weaving fiber. The long, flexible fronds of the palm are harvested, split into narrow strips, and prepared for weaving. A key characteristic of the ilala palm is its natural waxy coating, which makes it resistant to rot and ideal for creating watertight vessels. This property is crucial for the functionality of the isichumo, as it allows the basket to hold liquids without leaking.

The core of the basket, which provides its structural integrity, is typically made from hardy, locally sourced grasses. The grasses are bundled together to form a sturdy coil that is meticulously wrapped and stitched with ilala palm strips. Using these natural, biodegradable materials reflects a deep-rooted connection to the local environment and a sustainable approach to craft.

Preparing these materials is labor-intensive, often involving collecting, drying, and dyeing the palm fronds—a task traditionally undertaken by women in the community. Reliance on these materials ensures the baskets’ durability and functionality and imbues them with a unique cultural and geographical identity.

Watertight Weaving Technique

Isichumo baskets have a remarkable ability to hold liquids thanks to a highly specialized and intricate weaving technique known as coiling. This method involves creating a foundation coil from a bundle of hardy grasses and spiraling it outwards from the center of the base of the basket. The vessel’s structural integrity and watertight nature are achieved by tightly wrapping the grass core with narrow strips of ilala palm leaf. Using a needle-like tool, the weaver stitches the palm strips around the coil, pulling each stitch taut to ensure a secure, interlocking structure.

The tightness of the weave is paramount. When the basket is filled with liquid, the ilala palm fibers swell, further sealing any minute gaps and rendering the vessel virtually waterproof. This process is incredibly labor-intensive and requires a high degree of skill and patience. A medium-sized basket takes up to a month to complete, and larger, more elaborate pieces require over a year of meticulous work. Before its first use, the basket is often sealed from the inside with a paste made from coarsely ground corn, a traditional method that ensures complete waterproofing. This sophisticated coiling technique, passed down through generations of Zulu weavers, is a testament to their ingenuity and craftsmanship. It transforms simple natural materials into functional works of art.

Carrying and Storing Water

One of the most fundamental and historically significant uses of the isichumo basket was for carrying and storing water. In rural KwaZulu-Natal, where clean water sources were often far from homesteads, efficiently and safely transporting water was a daily necessity. With its rigid, bottle-like shape and secure, snug-fitting lid, the isichumo was perfectly suited for this purpose. The narrow neck minimized spillage during the often long walk back from the river or well, and the tight weave ensured that no liquid was lost to leakage. The ilala palm fiber naturally swells when wet, which further enhances the basket’s watertightness and makes it a reliable, durable container. The size of the isichumo could vary, allowing for the transport of different quantities of water, depending on the household’s needs.

CENTER: Old isichumo basket by Nkondobele Kunene, Vryheid, KwaZulu-Natal. Phansi Museum, Glenwood, Durban, South Africa.

RIGHT: old isichumo showing the characteristic dark patina of age. Pinterest.

LEFT: Vintage isichumo by Thembeni Buthalezi; dimensions: height 10 in., 25.4 cm; circumference 38 in., 96.52 cm. WorthPoint.

RIGHT: Vintage isichumo from the 1970s; height 9 in., 22.86 cm. WorthPoint.

Storing Beer and Grain

Beyond its crucial role in transporting water, the isichumo basket was extensively used to store liquid and dry foodstuffs, most notably traditional sorghum beer (utshwala) and grain. The brewing and consumption of utshwala are deeply embedded in Zulu culture and form the centerpiece of many social and ceremonial events. With its watertight construction and ability to regulate temperature through evaporative cooling, the isichumo was an ideal vessel for storing and serving this important beverage. Its tight weave kept the beer cool and fresh, and its lid prevented contamination from dust and insects. Using the isichumo for these purposes elevated it from a simple household object to an integral part of the community’s social and spiritual life.

In addition to beer, the basket’s versatility extended to storing grain, a staple food. Its large, rigid form could accommodate significant quantities of grain, protecting it from pests and moisture.

Its ability to serve as a container for both liquid and dry goods underscores the basket’s importance in managing household resources and contributing to food security and the overall well-being of the family. Therefore, the isichumo was a vital tool for sustenance and social cohesion.

Cultural and Social Significance

The Zulu isichumo basket has a cultural and social significance that extends far beyond its practical utility. It is woven into the very fabric of Zulu identity, social structure, and spiritual life. The intricate patterns and designs adorning these baskets are imbued with a rich symbolic language that conveys messages about gender, social status, and historical events. Its role in marriage ceremonies as a symbol of homekeeping and cherished gift highlights its importance in negotiating social relationships and establishing new family units. Furthermore, the isichumo is part of a broader material culture that includes other types of baskets and clay pots, all of which play specific roles in rituals and celebrations. The aesthetic and symbolic qualities of the isichumo, particularly in its more elaborate forms, serve as markers of family wealth and prestige, reflecting the skill of the weaver and the status of the owner.

LEFT: Isichumo by Thulile Ngxongo, daughter of Beauty Ngxongo. This traditional brown isichumo features the pattern called imbalemhlophe, “white flower”: the white zigzag pattern unfolds like delicate blossoms against the rich brown body. Bambizulu, Stanger, South Africa.

RIGHT: Isichumo by Hiengiwe Ntulie, KwaZulu-Natal. Height: 20 in., 50.8 cm. Africa Direct, Colorado, USA.

Symbolism in Patterns and Design

The patterns and designs woven into Zulu isichumo baskets serve as a form of visual communication, conveying a wealth of cultural information through a symbolic language. Created using naturally dyed fibers, these geometric motifs are not arbitrary, but are drawn from a traditional repertoire of symbols passed down through generations of weavers. Each pattern has a specific meaning relating to aspects of Zulu life, such as gender roles, social status, historical events, and spiritual beliefs. Therefore, the choice of patterns on a particular basket can tell a story, express a wish, or signify the identity of the weaver or owner. The use of color enhances the symbolic power of the designs further, with different hues representing concepts ranging from fertility and prosperity to sorrow and anger.

The intricate interplay of patterns and colors transforms the isichumo from simple containers into complex cultural artifacts—tangible expressions of Zulu cosmology and social organization. A weaver’s skill is measured not only by her technical proficiency but also by her ability to manipulate this symbolic language to create a beautiful, meaningful basket.

The silent tongue of the Zulu

The Zulu people are traditionally an oral culture, rich in oral lore that includes storytelling, praise poetry (izibongo), proverbs, riddles, songs, and historical narratives passed down through generations.

- Praise poetry (izibongo): Performed by poets (imbongi) to honor chiefs, ancestors, and warriors—these poems preserve history, genealogy, and values through vivid metaphor and rhythm.

- Folktales (izinganekwane): Stories told in the home or around fires, often featuring animals or mythic figures. These tales teach moral lessons and cultural values.

- Proverbs and idioms: Zulu speech is rich in metaphorical expressions that carry cultural wisdom and worldview.

- Oral history: Before widespread literacy, Zulu elders and griot-like figures preserved and conveyed history, genealogy, and social laws through memory and performance.

- Ceremonial storytelling and song: Oral forms are central in rituals, initiation ceremonies, and communal gatherings—carrying spiritual, historical, and social significance.

In an oral culture such as the Zulu, it should come as no surprise that isichumo and ukhamba vessels possess a language of their own—one that is not spoken but rather woven and shaped. It is not a proper language, but a symbolic one.

In oral societies like the Zulu, memory, meaning, and the transmission of knowledge are not confined to spoken language. Instead, symbolic systems, such as beadwork, weaving, pottery, and dance, play a vital role in encoding and conveying information. These systems are sometimes referred to as “non-verbal literacies” or “material semiotics.” In the absence of written scripts, visual forms become “texts” of a different kind, interpretable by those who understand the cultural code.

Ukhamba and isichumo baskets are not merely storage vessels, precious crafts, or art forms praised by collectors; their form, size, and design reflect status, intention, and meaning. Within their intricate patterns, shapes, and colors lies a system of symbolic communication—a visual vocabulary understood by those attuned to its codes. Crafted from the supple strands of the ilala palm, these baskets are vessels of meaning, storytellers, and tactile expressions of Zulu cosmology and social structure. They are also a way to remember values, rituals, and family stories. Each spiral, each motif is a thread in a larger cultural narrative, conveying stories of ancestry, harmony, and belonging. A weaver’s artistry is judged not only by technical precision but also by their fluency in this nonverbal language — their ability to inscribe memory, identity, and intention into the coiled geometry of the basket. In their hands, ukhamba and isichumo become not only beautiful achievements but also quiet acts of storytelling—a woven voice in the continuity of an oral tradition.

Geometric Patterns and Their Meanings

Most of us are not part of the Zulu tradition, so we cannot understand its voice. We can only listen to it with respect and admiration. At best, we can stammer a few syllables. What we said about ukhamba also applies to isichumo; however, this is merely babbling—a summary for curious tourists and nothing more.

Common patterns include checkerboards, whirls, and circles, which are traditionally associated with positive events and good fortune, such as the birth of a baby, good news, or plentiful rains. These auspicious motifs are often used on baskets intended for celebratory occasions or as gifts to convey wishes for a prosperous future.

Another significant aspect of the symbolic language of Zulu basketry is the representation of gender through geometric forms. The triangle and the diamond are two of the most important motifs in this regard, serving as visual shorthand for masculinity and femininity, respectively. The triangle is often incorporated into basket designs, either as a standalone motif or as part of a larger pattern, to convey messages related to male lineage, strength, and prosperity. In contrast, the diamond, with its enclosed, balanced shape, represents femininity and signifies daughters or female calves. The diamond motif celebrates the role of women in the community and expresses wishes for fertility and continued family lines. The interplay of these two symbols on a single basket creates a complex narrative about the balance of gender roles within a family or community. For instance, a wedding basket might feature a combination of diamond and triangle patterns to symbolize the union of a man and a woman and the formation of a new family.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Isichumo from Hlabisa, Kwazulu Natal. Undated. Phansi Museum, Glenwood, Durban, South Africa.

Isichumo made with natural dyes. Pinterest.

Vintage isichumo; dimensions. 10 1/2 x 10 1/2 x 9 1/2 in., 26.67 x 26.67 x 24.13 cm. Auctioned in 2025 by Sarasota Estate Auction, FL, USA.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Large African Zulu isichumo basket with a rare shape. Height: 15 in.; 38 cm. WorthPoint.

Isichumo. Pinterest.

Isichumo basket from the Vukani Museum, Eshowe, KwaZulu-Natal.

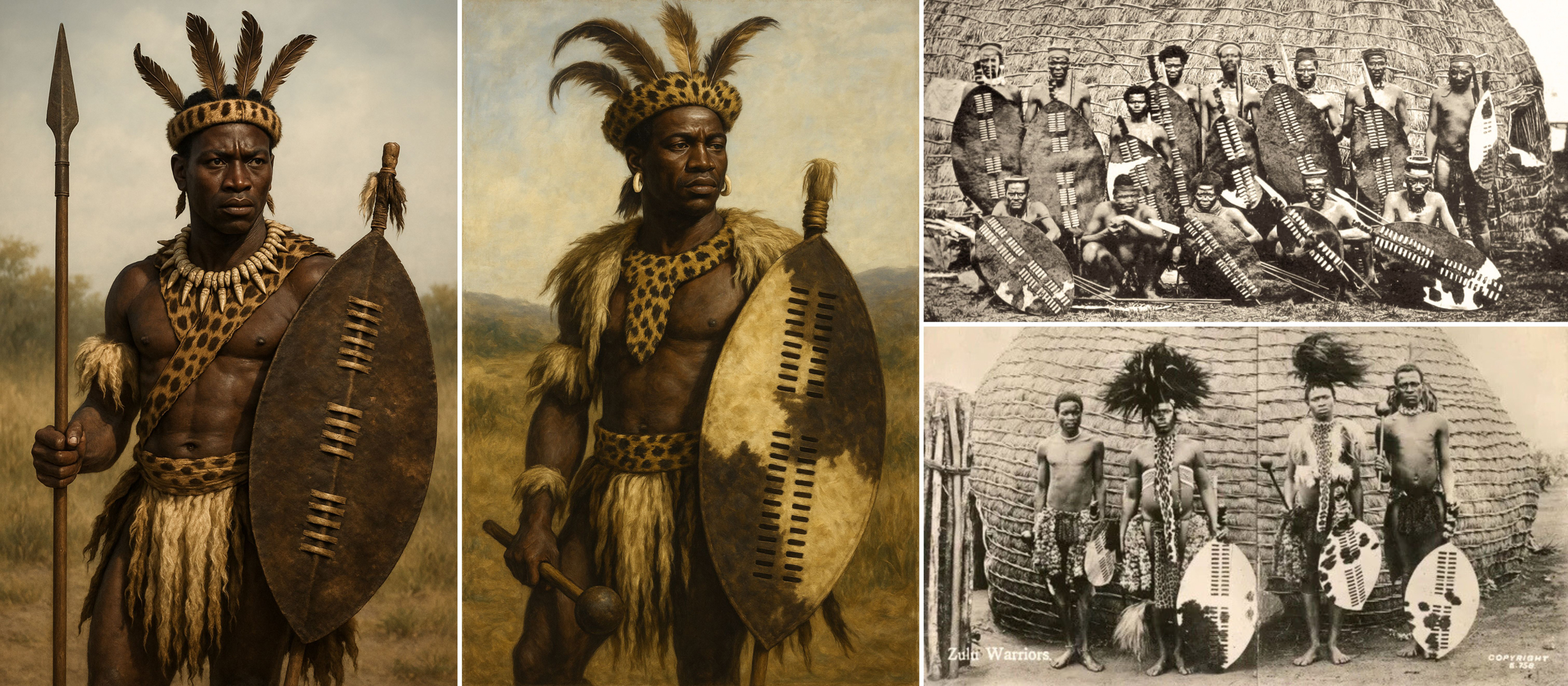

Symbolic References to Zulu History and Warfare

Zulu isichumo basket designs also depict the Zulu nation’s rich history and martial traditions. Certain patterns directly reference the era of King Shaka Zulu, a pivotal figure who revolutionized warfare and established the Zulu kingdom as a dominant southern African force. The zigzag pattern, for instance, represents the spear of Shaka, a weapon synonymous with Zulu military prowess. This motif evokes a sense of strength, courage, and national pride. Another significant pattern is the string of diamonds, said to represent the shields of Shaka’s regiments arranged in their iconic battle formation. This design pays tribute to the discipline and strategic brilliance of the Zulu army. Incorporating these historical and martial symbols into basket designs serves to keep the memory of this important period alive by passing down stories of heroism and national identity to future generations. These patterns are more than just decorative elements; they are a form of historical record—a woven testament to the enduring legacy of the Zulu people.

Right: Reconstruction of Zulu warriors at the time of King Shaka Zulu.

Top right: Zulu warriors, 1882. Image extracted from page 279 of A Holiday in South Africa… With map and illustrations, by LEYLAND, Ralph Watts. Original held and digitized by the British Library, UK.

Bottom right: Four Zulu Warriors in traditional costume carrying clubs and shields, ca. 1908. Mary Evans Picture Library.

Movie posters, TV series, and other popular productions portray King Shaka Zulu as a powerful, invincible, and handsome superhero. Fortunately, reality is more complex and less “chewable and consumable.”

King Shaka Zulu (ca. 1787–1828) is one of the most important and controversial figures in South African history. He is remembered as the founder and architect of the Zulu nation. He is renowned for transforming a small clan into a powerful, centralized kingdom recognized for its military innovation and organization. Through strategic warfare, alliances, and sweeping reforms, he united numerous Nguni-speaking peoples and forged a Zulu state that played a dominant role in southern Africa during the early 19th century.

However, Shaka’s legacy is profoundly ambiguous. On the one hand, he is often portrayed as a visionary nation-builder, a brilliant military strategist who revolutionized Zulu warfare and governance and is celebrated for instilling a sense of pride and identity among the Zulu people. On the other hand, he is depicted as a ruthless and sometimes despotic ruler. His campaigns involved extreme violence and the destruction or absorption of rival clans. The later years of his reign were marked by brutality and terror, particularly after the death of his mother. His reign coincided with the Mfecane (“the crushing”), a period of turmoil and massive population displacement in southern Africa for which he is credited and blamed.

This duality—the heroic, almost mythical nation-builder versus the “monster”—endures in how Shaka is remembered, debated, and represented in Zulu culture and broader history. Like the mythological Proteus, Shaka’s image shifts, eluding single, reductive interpretations. It remains a source of fascination, pride, fear, and debate nearly two centuries after his assassination. The enduring power of his legacy lies in this ambiguity—he was a figure great enough to change history and complex enough to never be contained by a single narrative. Nor by a pop depiction.

The Role of Isichumo in Marriage and Wedding Traditions

In Zulu culture, the isichumo basket holds a special place in marriage and wedding traditions. It transcends its everyday utility to become a powerful symbol of social and domestic life. In a culture where marriage is a complex negotiation between two families, not just a union between two individuals, the objects exchanged during wedding ceremonies are imbued with deep cultural meaning. As a gift, the isichumo represents the bride’s readiness to take on the responsibilities of a wife and homemaker—a role central to the social fabric of Zulu society. Its association with homekeeping and managing household resources makes the basket a particularly fitting symbol for establishing a new family unit. Presenting it as a wedding gift publicly acknowledges the bride’s skills and commitment to her new role. Therefore, the isichumo is not just a practical item for the new couple’s home, but also a tangible expression of the values and expectations surrounding marriage in Zulu culture.

Gift-Giving in Zulu Weddings

Gift-giving is a central, highly ritualized aspect of Zulu weddings, with each gift carrying specific cultural significance. Exchanging gifts formalizes the marriage, strengthens the bond between the two families, and provides the newlyweds with the material goods they need to start their own household. One of the most culturally significant gifts presented to the couple during the wedding festivities is the isichumo basket. The isichumo is a blend of art and practicality: a beautiful object that is also highly functional. Presenting an isichumo is a gesture of respect and goodwill, a way of wishing the couple a prosperous and well-managed life together. Giving an isichumo also acknowledges the importance of traditional crafts and the skills of the women who make them.

In a modern context where many traditional practices are under pressure, including an isichumo among wedding gifts preserves and celebrates Zulu cultural heritage. The basket symbolizes continuity by linking the new couple to the traditions and values of their ancestors that have sustained their community for generations.

Comparison with Ukhamba Baskets in Wedding Ceremonies

Although the isichumo is an important gift at Zulu weddings, it is essential to distinguish its role from that of the ukhamba. Both baskets are used for storing and serving traditional sorghum beer, but they have different shapes and meanings. In weddings, the ukhamba is often used as a ceremonial vessel to present beer to the groom’s family, which is a crucial part of lobola negotiations. The size and elaborateness of the ukhamba can indicate the bride’s family’s wealth and status. The isichumo, on the other hand, is more often associated with the domestic sphere and the bride’s role as a homemaker. While both baskets are important, the ukhamba tends to play a more public and ceremonial role in wedding proceedings, while the isichumo is more closely linked to the new couple’s private, domestic life. These distinctions highlight the nuanced and multifaceted nature of Zulu material culture, where different objects are assigned specific roles and meanings within the same cultural context.

LEFT: Bride (dressed in leopard skin) and helpers at a Zulu wedding ceremony, 1905, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, UK.

RIGHT: Group of chiefs and notables at a Zulu wedding ceremony, 1905, © Pitt Rivers Museum, University of Oxford, UK.

Young girl at her wedding during a mass marriage ceremony, 1998, Ekupakameni, KwaZulu-Natal. Photo by Greg Marinovich, IBALI Digital Collection, University of Cape Town (UCT), South Africa.

Contemporary Developments and Artistic Recognition

In recent decades, the Zulu isichumo basket has undergone a remarkable transformation, evolving from a utilitarian object to a celebrated art form recognized and collected worldwide. This shift has been driven by several factors, including the introduction of new materials and designs, the emergence of master weavers who have expanded the boundaries of the craft, and the increasing international demand for distinctive and authentic African art forms. Contemporary isichumo baskets are often far more elaborate and colorful than their historical predecessors, featuring intricate patterns and a wider range of hues. This level of craftsmanship elevates them to the status of collectible artwork. This artistic evolution has brought economic benefits to weaving communities in KwaZulu-Natal and played a crucial role in preserving and revitalizing a traditional craft that was once in decline. This section will explore the key developments that have shaped the contemporary isichumo, focusing on its transformation into an art form, the pivotal role of master weaver Beauty Ngxongo, and the impact of the modern market on the craft and its cultural significance.

Transformation into an Art Form

The evolution of the Zulu isichumo from a utilitarian craft to a fine art form has been gradual yet profound, marked by an increasing focus on aesthetic innovation and personal artistic expression. This evolution is characterized by more complex and intricate designs, a broader and more vibrant color palette, and a shift in perception from viewing the basket as a utilitarian object to viewing it as a work of art to be displayed and admired. This artistic renaissance has been fueled by the creativity and skill of a new generation of master weavers who draw on traditional techniques while experimenting with new forms of expression. The result is a body of work that is both deeply rooted in Zulu cultural heritage and responsive to the demands of the contemporary art market. This transformation has elevated the status of the weavers, who are now recognized as artists, and has brought a new level of appreciation and understanding to the rich tradition of Zulu basketry.

A key factor in the isichumo’s transformation into an art form has been the introduction of increasingly intricate designs and a more vibrant, diverse color palette. We have seen a similar evolution with ukhamba. While traditional baskets were often decorated with limited geometric patterns in natural or muted tones, contemporary weavers have expanded their visual vocabulary to include a wide array of motifs and stunning colors. The use of natural dyes derived from materials such as roots, bark, leaves, and flowers has been refined and expanded, allowing for a greater range of hues—from deep burgundies and maroons to bright yellows and greens. The introduction of synthetic dyes has further broadened the color palette, enabling weavers to create baskets with a dazzling array of vibrant, long-lasting colors. The designs themselves have also become more complex. Weavers now create intricate patterns that cover the entire surface of the basket and often incorporate figurative elements, such as animals or scenes from daily life. This shift toward greater visual complexity and chromatic richness has elevated the isichombo from a functional craft to a highly decorative and collectible art form.

This evolution has profoundly impacted the value of the baskets, with the finest examples now fetching high prices on the international art market. This has brought much-needed economic benefits to the weaving communities of KwaZulu-Natal by providing a vital source of income and helping ensure the survival of this important cultural tradition.

Beauty Ngxongo: Master Weaver and Cultural Guardian

Beauty Batimbele Ngxongo (born 1953) is one of South Africa’s most distinguished artists. She is recognized globally for elevating the traditional Zulu craft of basket weaving to a sophisticated art form. Hailing from Hlabisa in the remote Umkhanyakude District of KwaZulu-Natal, Ngxongo has elevated the humble isichumo basket to the status of internationally acclaimed masterpiece. These creations now grace the collections of prestigious institutions, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian Institution, the Samuel P. Harn Museum of Art, and the Fowler Museum at UCLA.

Beauty Batimbele Ngxongo. Photo: Bambizulu.

Ngxongo’s journey into basketry began in childhood, when she learned to weave simple doormats and placemats from the ilala palm, which was abundant in her rural community. Zulu basketry experienced a significant decline in the 1930s and nearly disappeared before enjoying a revival in the late 1960s. During this renaissance, Skhavathini Laurentia Dlamini, one of the women who had revived the craft, became Ngxongo’s mentor and close friend. She guided Ngxongo’s transformation from local craftswoman to master artisan.

In the 1990s, a neighbor enhanced Ngxongo’s skills further by teaching her intricate basket designs using local natural materials. This period was a pivotal time in her artistic development, as she began pushing the boundaries of traditional forms while maintaining a deep respect for her cultural heritage. Dlamini’s mentorship was particularly significant because she was one of the few weavers who had learned the craft in primary school as part of the apartheid-era “craft education” initiative. This made her a crucial link to earlier traditions.

Skhavathini Laurentia Dlamini

LEFT TO RIGHT, CLOCKWISE

Laurentia Dlamini with one of her baskets. Pinterest.

Hlabisa Basket, ukhamba by Dlamini, 2003. Dimensions: 59.5 x 46.0 x 21.0 cm. Constitutional Court Art Collection (CCAC), Braamfontein,

2017, South Africa.

Hlabisa Basket, ukhamba by Dlamini, 2003. Dimensions: 26 x 38 x 85 cm. Constitutional Court Art Collection (CCAC), Braamfontein,

2017, South Africa.

Isichumo by Dlamini. Phansi Museum, Glenwood, Durban, South Africa.

Iquthu by Dlamini. Phansi Museum, Glenwood, Durban, South Africa.

Isichumo by Dlamini. Pinterest.

Ngxongo’s Izichumo Masterpieces: Technical Innovation and Artistic Excellence

Ngxongo’s izichumo baskets are the pinnacle of her artistry and technical expertise. These watertight vessels are meticulously crafted over the course of several months.

They are constructed using the ancient coil method with a core made of hardy grasses that spirals outward from the base’s center. Narrow strips of ilala palm leaf blades serve as binders, wrapping around the foundational coil. Each stitch interlocks with the one below it and is pulled tight to ensure structural integrity. The ilala palm’s natural waxy coating makes it ideal for creating watertight vessels because the fibers resist rotting when damp and swell when in contact with liquid.

Ngxongo’s mastery extends beyond technique to encompass an extraordinary command of natural dyes. She achieves her vibrant color palette through a complex alchemical process involving over 50 different plant types to create approximately 20 distinct colors. Black or very dark fibers are produced by boiling ilala palms with indigo plants, and reddish-brown hues are created using reddened sorghum leaves. Depending on the desired intensity and the artist’s skill, the dyeing process can take anywhere from a few days to several weeks.

Her patterns represent a departure from the traditional simple geometric designs. While historical Zulu baskets featured minimal ornamentation, Ngxongo creates elegant structural forms enhanced by complex, masterful graphic and chromatic designs. Her signature motifs include undulating zigzags that flow across her vessels’ entire surfaces, creating dynamic visual narratives that speak to ancestral traditions and contemporary artistic vision. The tight weave she achieves renders her vessels virtually waterproof, honoring the functional requirements of traditional izichumo while elevating them to the level of art objects.

Ngxongo’s artistic philosophy bridges the gap between traditional craftsmanship and fine art. As she explains: “My baskets have transcended craft and functionality to become works of art. They are expressions of my personality. A piece of my soul is trapped in each basket. Yet woven into each one is the centuries-old tradition of my Zulu people.” This statement encapsulates her approach of maintaining cultural authenticity while expressing individual creativity.

Beauty Batimbele Ngxongo and her izichumo. Photos: Bambizulu and IFAM – International Folk Art Market.

LEFT: Isichumo by Beauty Ngxongo, ca. 2000. Dimensions: height 27 cm, diameter 46 cm. Auctioned in 2024 by Strauss & Co., Johannesburg – Cape Town, South Africa.

RIGHT: Isichumo by Beauty Ngxongo, 1993. Dimensions: height 29 cm, diameter 40 cm. Auctioned in 2024 by Strauss & Co., Johannesburg – Cape Town, South Africa.

LEFT: Isichumo by Beauty Ngxongo, 1990s. Dimensions: height 14 × width 21 × diameter 21 in., 35.6 × 53.3 × 53.3 cm. The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing at The MET, New York, NY, USA.

RIGHT: Isichumo by Beauty Ngxongo. Photo by IFAM – International Folk Art Market.

Contemporary Collaborations and Innovation

Ngxongo’s commitment to innovation while preserving tradition is evident in her collaboration on the Hlabisa Bench. She worked with contemporary designers Phillip Hollander and Stephen Wilson of Houtlander and Thabisa Mjo of Mash.T Design Studio to create this groundbreaking piece, which channels the profiles of the Hlabisa hills. The bench required 1,300 hours of intricate weaving, and Ngxongo led a team of eight master weavers to create the intricately patterned backrest. This collaboration showcases her ability to translate traditional techniques into contemporary designs while maintaining artistic integrity.

The Hlabisa Bench born from the collaboration among Beauty Batimbele Ngxongo, Phillip Hollander and Stephen Wilson of Houtlander, and designer Thabisa Mjo of Mash.T Design Studio. Photo © Mash.T Design Studio.

Beauty Ngxongo sitting on a different version of the Hlabisa Bench. Photo: IFAM – International Folk Art Market.

Community Leadership and Women’s Empowerment

Beyond her individual artistry, Ngxongo is a cornerstone of community development and women’s empowerment. By 2012, she had employed thirteen women in her workshop, providing crucial economic opportunities in the remote, rural area where she lives. She functions not only as an employer, but also as a mentor, teacher, and cultural guardian who ensures the transmission of traditional knowledge to future generations.

Through her teachings, dozens of women in Hlabisa have gained financial independence. Their baskets carry their individual skills and collective voices into the global market. Her granddaughter, Sinegugu Ngxongo, founder of Bambizulu, continues this legacy. She states: “I learned the art of basket weaving from my grandmother, Beauty Ngxongo, who taught me the techniques and the importance of preserving our cultural heritage.”

The Future of Indigenous Crafts and their slalom among commodification, market forces, and authenticity

The emergence of a modern market for Zulu izichumo and izinkhamba baskets has created a complex and often contradictory dynamic with positive and negative implications for preserving these traditional crafts. The demand for these baskets as tourist souvenirs and works of art has provided a vital source of income for weaving communities in KwaZulu-Natal. This has helped ensure the economic survival of both the communities and the baskets. Global appreciation of their beauty and cultural significance has also brought a new level of respect and recognition to the weavers and their skills.

However, the pressures of commercialization and mass production have created challenges, raising concerns about the potential dilution of traditional techniques and loss of cultural authenticity. This section will explore the interplay between the modern market and cultural preservation by examining how the growing demand for Zulu basketry has supported and threatened the continuation of this important cultural heritage.

How Demand Supports Cultural Continuity

Cash and prestige are reasons to keep weaving. Organized buying and gallery demand have turned basketry into a viable source of income for rural women, often the only accessible one, while also validating it as an art form in museums and courts. For example, the Hlabisa Basketry set is part of the collection of South Africa’s Constitutional Court.

Mentorship survives because markets pay. Named masters, such as Ngxongo, train and apprentice others, and commissions justify the months-long construction of watertight coils that would otherwise be uneconomical.

Technique is conserved, even as forms evolve. The coil construction, plant preparation, and stitch vocabulary remain core, and many producers still harvest and dye ilala using longstanding methods.

The growing global demand for Zulu baskets has sparked a renaissance. International collectors, museums, and design-savvy buyers now covet izikhamba and izichumo for their artistry, symbolism, and historical depth. This attention has empowered many weavers, primarily women in KwaZulu-Natal, by offering vital economic opportunities and instilling a renewed sense of pride in their cultural heritage. Master weavers like Beauty Ngxongo have been celebrated for bridging utilitarian craft and fine art, elevating Zulu basketry and revitalizing its status and importance within the community.

Community-based organizations, educational workshops, and weaving schools play a critical role by providing training, archiving traditional techniques, and fostering innovations that keep the art form vibrant and relevant. Some initiatives, such as Bambizulu, minimize intermediaries to ensure that value flows directly to the artisans, not just to distant buyers or commercial agents. This model supports economic justice and cultural preservation simultaneously.

How Demand Threatens the Heritage

The commercialization of Zulu izikhamba and izichumo is a double-edged sword. It provides a source of income in an area with limited economic opportunities, but it also poses cultural challenges.

Standardization and motif “flattening” – Retail and tourist circuits incentivize repeatable SKUs and quick reads. Symbolically dense patterns become decorative “looks,” a shift identified in scholarship on contemporary South African basket displays and the “African aura” in urban markets.

Material substitutions and speed – When faced with high prices, makers may abandon slow, watertight designs in favor of decorative forms or switch materials (e.g., to wire), which can sever the baskets’ connection to their original purpose in agricultural and beer rituals.

Ecology under pressure (manageable if managed) – Research on Hyphaene coriacea in KwaZulu-Natal shows that leaf harvest intensity matters and that sustainable yields are possible but require monitoring of palm populations and harvest rules.

Market pressures have changed how baskets are produced. In order to meet the demand for cheaper and quicker products, some weavers use lower-quality materials and synthetic dyes, or they simplify design and patterns. Many artisans are forced to prioritize speed and lower costs over skilled, time-consuming practices. These changes raise concerns about the potential erosion of traditional quality standards and the loss of the cultural knowledge embedded in the craft.

Curators, trade centers, and buyers did not simply “discover” baskets; they influenced their production by setting quality standards, advising on sizes, and showcasing them in exhibitions. This professionalized craft economies and raised incomes, but it also steered aesthetics toward what distant markets would buy. This dual role is evident in the museum and curatorial histories of Vukani and the AAC. While tourism and urban markets generate income, they also prompt “hybrid” production to appeal to new tastes, modifying techniques, colors, and iconography according to Western expectations. In order to sell, one must adapt to market logic and meet the tastes of buyers, tourists, and collectors. Weavers, brokers, trade centers, and cooperatives must consider the expectations of end buyers and emerging trends in foreign markets. Often, this involves striving to achieve an “African style” that strays from local tradition and aligns more with the stereotypical image of Africa beloved by Western decorators and interior designers. There’s a risk of losing authenticity when cultural motifs are repurposed or mass-produced for export instead of for ritual or communal use.

Furthermore, while the popularity of these crafts helps sustain livelihoods, it can also create a dependency on market trends. As prices and demand fluctuate, often based on the preferences of buyers in Western markets, artisans may become vulnerable to exploitation or underpayment, a common challenge for many indigenous crafts globally. Often, there’s a significant gap between retail prices in luxury markets and the modest compensation received by artisans.

Are these tensions unique? No, they illustrate a global pattern. Many indigenous crafts around the world exist in this same intersection of commercial necessity and aesthetic/ritual compromise. As global appreciation grows, artisans must navigate the delicate boundaries between tradition and adaptation, preservation and innovation, and self-representation and market-driven transformation. The pressure to remain “authentic” while appealing to international tastes can be a delicate balancing act, sometimes forcing communities to choose between preservation and survival.

What actually works: practical guardrails that respect a living tradition

Authenticity vs. Adaptation: Surviving in new markets often requires adaptation, which can dilute original symbolic practices. It is essential to maintain ritual use and storytelling alongside commercial production. Weavers must preserve the tradition and keep the heritage alive for the next generation, whether in their baskets or in their knowledge and awareness. However, the solution isn’t to “freeze” tradition. Rather, it’s about making evolution accountable and locally rooted.

Adopt a two-line strategy: Create a “heritage” line with watertight coils, plant dyes, full maker attribution, and slower lead times, as well as a “design” line with contemporary forms and materials that are explicitly branded as such. This preserves high-ceremony knowledge while allowing innovation without mislabeling. Parallels in other regions show that this reduces motif dilution.

Empowerment vs. Exploitation: Commercial markets can empower artisans, but they can also make artisans dependent on intermediaries or subject to price disparities, which can lead to exploitation. Collaborative structures and direct-to-artist sales can help retain more value within the community, preserving cultural transmission and dignity.

Education and Advocacy: Raising awareness among buyers about the history, significance, and labor behind these objects fosters respect for the craft, making commercial success more sustainable and ethical. It’s also important to ensure that curators and NGOs are involved in marketing, archiving, and training rather than designing.

Ecological management: Adopt harvest quotas and rotation for ilala leaves, and monitor stands using ready-made sampling methods from KZN research. Create a buyer premium for baskets sourced from verified sustainable harvest plots.

The case of Zulu izichumo and izikhamba baskets highlights how indigenous crafts continuously negotiate identity and sustainability when caught between commercial and art markets. The challenge is not just economic; it’s also about respecting cultural roots, supporting fair trade, and ensuring the craft remains a living tradition rather than a mere commodity or art object divorced from its original meaning and function.

AI generated image.

Zulu Song – Miriam Makeba

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?