THE JIMMA CHAIRS FROM ETHIOPIA 2

Ethiopia on the globe

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

LEGENDS OF THE CARVED SEATS OF JIREN

The Golden Age under Abba Jifar II (1878-1932)

The reign of Abba Jifar II represented the pinnacle of Jimma’s power and cultural sophistication. Son of Abba Gomol and Queen Gumiti, he ruled for an extraordinary 54 years, making him one of Africa’s longest-reigning monarchs. According to Herbert S. Lewis’s seminal anthropological study, Abba Jifar II initiated “many administrative and political innovations” that established the institutional framework of the kingdom. The king’s conversion to Islam represented a decisive cultural shift, and began the gradual Islamization of the entire kingdom. His political acumen, particularly his decision to submit to Menelik II of Shewa in the early 1880s, preserved Jimma’s autonomy while neighboring kingdoms fell to Ethiopian imperial expansion.

Under Abba Jifar II’s patronage, Jimma’s court culture flourished. Central to the king’s consolidation of power was his construction of at least five residences throughout Jimma territory. These royal compounds featured sophisticated administrative organization, with an azazi (majordomo) overseeing domestic affairs and managing multiple treasuries. The famous mana sank’a (house of the table) accommodated the king and 20 to 30 guests around large circular wooden tables, with seating arranged hierarchically according to proximity to the royal presence. By claiming extensive conquered and virgin lands, the king was able to reward family members, followers, and favorites, thus creating a court culture that demanded appropriate symbols of rank and status.

All royal residences required appropriate furnishings, including the distinctive throne chairs that became synonymous with the royal authority of Jimma.

THE ROYAL FURNITURE AND THE THRONE TRADITION

The Royal Residences Context

The Jimma thrones and chairs must be understood within the broader context of royal compound life and ceremonial requirements. These residences housed not only the royal family, but also professional soldiers, court officials, and slaves who served in various administrative roles. Craftsmen were responsible for maintaining the kingdom’s material culture. This sophisticated court environment demanded furniture that was fitting for the dignity and authority of the monarchy.

Archaeological and documentary evidence suggests that Jimma’s royal furniture included various types of seating, ranging from simple stools to elaborate throne chairs reserved for the most formal occasions. The hierarchical nature of court seating reflected the kingdom’s complex social stratification, with the king’s throne representing its symbolic apex.

The tribute that Abba Jifar II paid to Emperor Menelik in 1886 provides crucial evidence of Jimma’s material culture. Among the gifts of slaves, ivory, civet, honey, cloth, spears, and silver-decorated shields were “objects of wood (including stools).” This documentation confirms that wooden furniture, likely including throne chairs, served as diplomatic gifts worthy of imperial recognition.

Ceremonial Functions

The thrones and chairs served multiple ceremonial functions within Jimma’s royal protocol. According to contemporary sources, they were used during the enthronement of a new king, indicating their central role in legitimizing royal succession. These pieces were more than mere furniture; they embodied the spiritual and temporal authority of the monarchy, transforming the act of sitting into a sacred ritual. This reflects broader African traditions of sacred kingship. Like the golden stool of the Asante kingdom in Ghana, Jimma’s thrones served as a tangible link between the ruler and the ancestral powers that legitimized royal authority.

The Palace of Jiren and its thrones

The 19th-century main palace of King Abba Jifar of Jimma is one of Ethiopia’s most significant historical and architectural landmarks. Built by King Abba Jifar II in the late 1860s, the palace is located in Jiren, a village near Jimma, on a hilltop approximately seven kilometers north of the city center. Historically, Jiren was the royal capital of the Kingdom of Jimma, and the location was chosen for its strategic overlook and healthier climate compared to the lowlands.

The palace’s architecture uniquely combines southwestern Ethiopian heritage with Indo-Arab influences, demonstrating the region’s historical trade and cultural links along the Indian Ocean. Features such as wooden facades, distinctive carved brackets, and colorful motifs reflect these influences.

Today, the palace houses a museum containing personal items belonging to King Abba Jifar, including beds, armchairs, religious manuscripts, utensils, and other artifacts from the royal family and the local Oromo heritage. In the early 1970s, German ethnographer Werner J. Lange conducted a comprehensive photographic documentation of the palace and its historic artifacts. He captured 120 images in total, preserving not only the palace’s architecture, but also its rich array of historical artifacts, interior spaces, and carved furniture. His photographs provide a comprehensive view of the broader context of the royal compound. These photographs serve as an invaluable visual record of the culturally significant site before it degraded and lost many of its artifacts. They are preserved in the physical and digital archives of the Frobenius Institute for Research in Cultural Anthropology in Frankfurt, Germany.

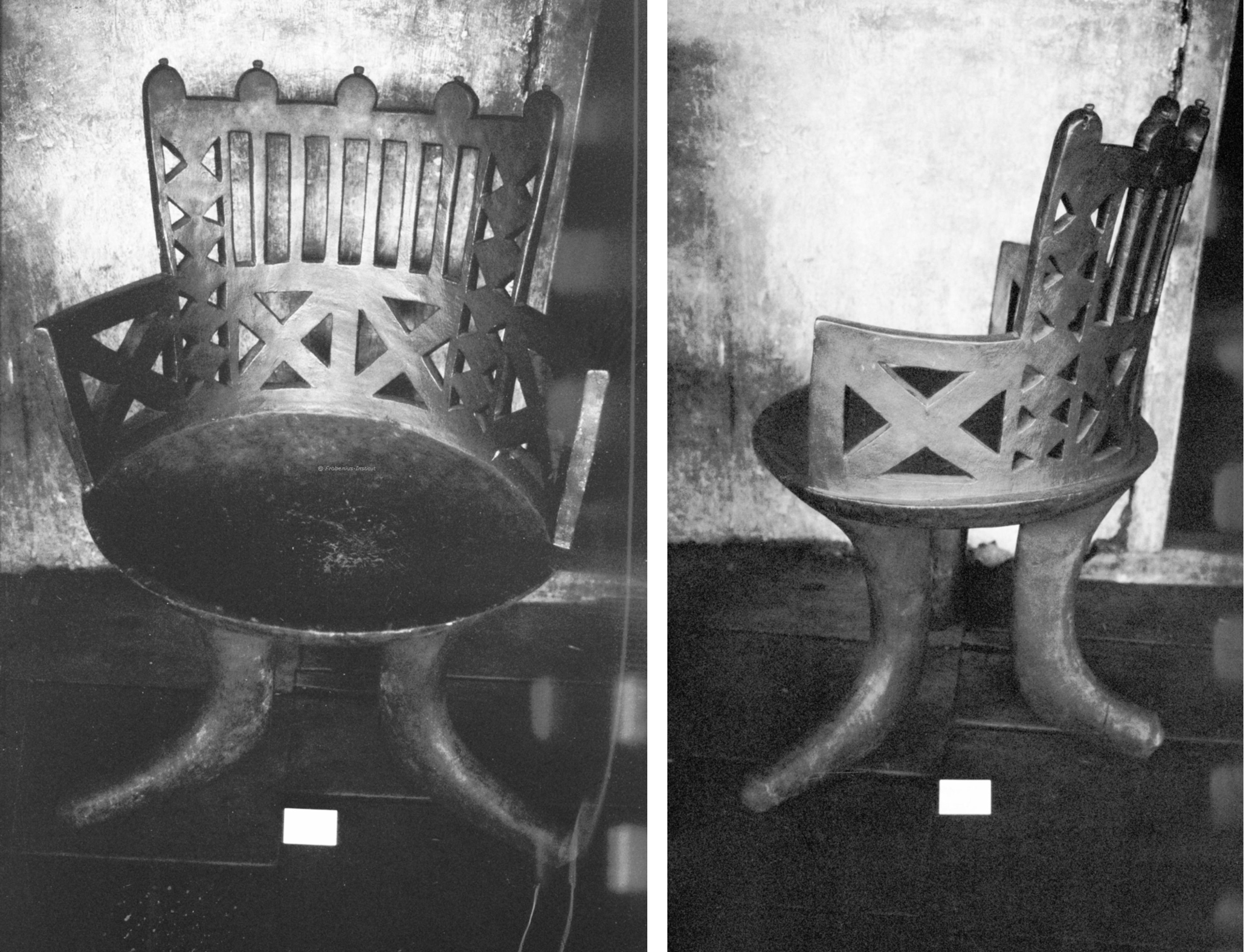

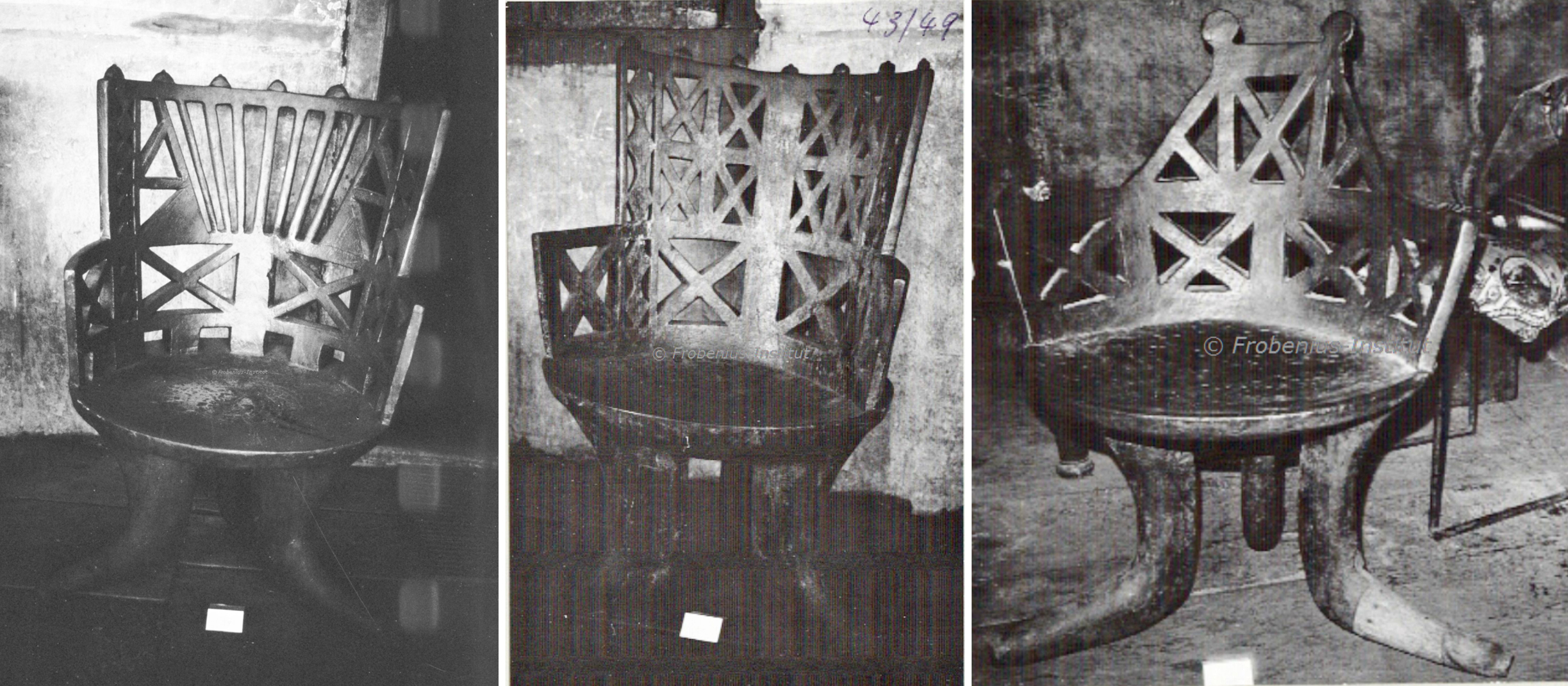

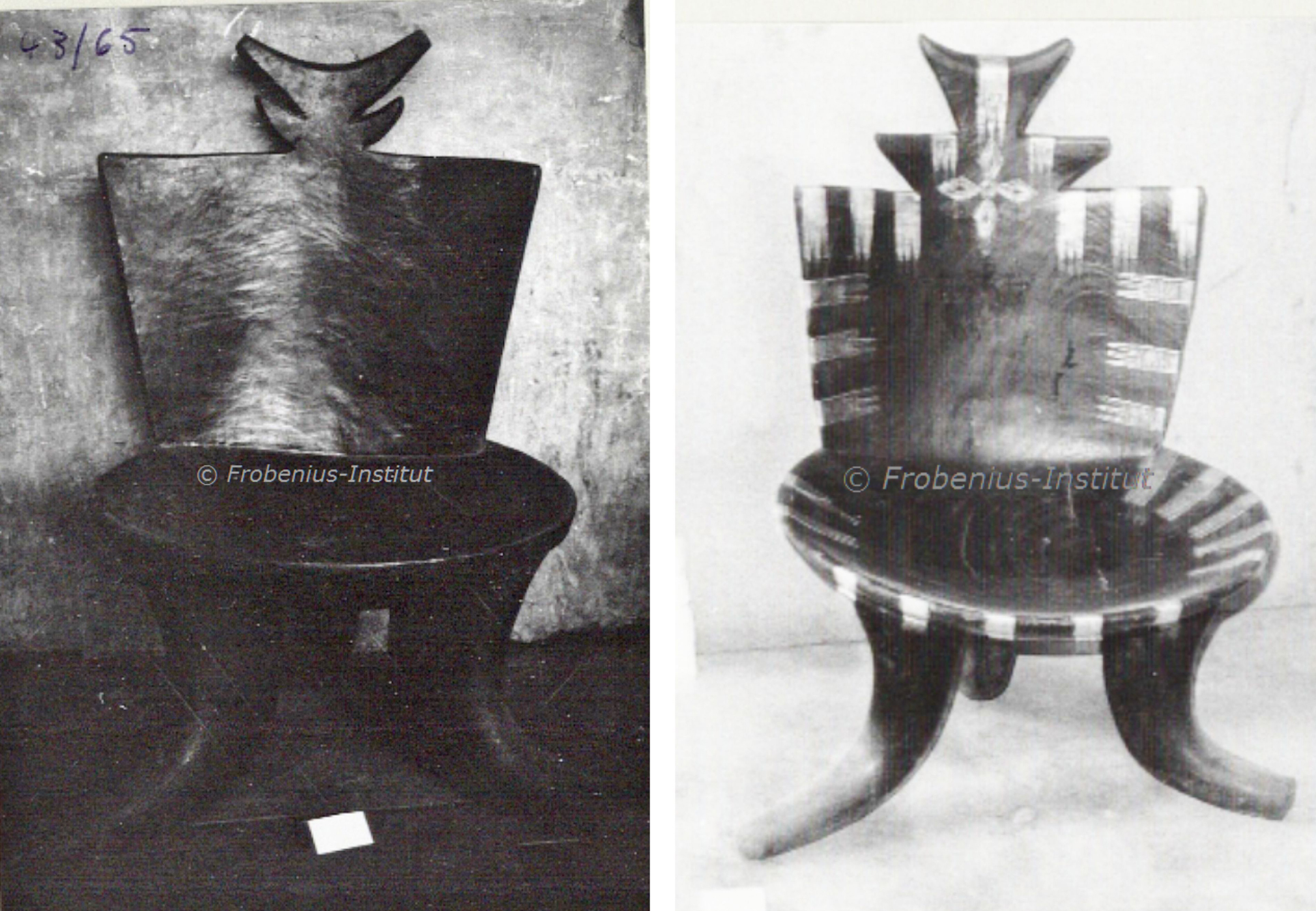

I’ll show you some of Lange’s pictures portraying the palace’s famous thrones. Though not very old, these photos are quite damaged. However, the different specimens of the Jimma throne, called birjouma, are truly marvelous.

The Throne Birjouma of King Abba Gommul aka Moti Abba Gomol at Jiren Palace. He reigned from 1862 to 1878.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. The Throne Birjouma of King Abba Bok’a (r. 1859–1862). He was the son of Abba Magal, and brother of Abba Jifar I.

2. The Throne Birjouma of King Abba Farou or Faro who ruled in the 18th century.

3. Another Throne Birjouma of King Abba Gommul.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. The Throne Birjouma of King Abba Bok’a and King Abba Gommul.

2. The Throne Birjouma of King Abba Jifar I (r. 1830–1855).

Museum collections in Jimma, such as the Jimma Museum, still have original pieces of Abba Jifar’s personal furniture, including beds and armchairs. These pieces provide a point of reference for the royal aesthetic, which has been faithfully emulated in the thrones and chairs now prized by collectors. The best-known Jimma thrones found today through antique dealers, high-end art galleries, and auction houses were hand-carved for ceremonial use and designed to emulate the royal furniture associated with King Abba Jifar and other dignitaries of the historic Kingdom of Jimma.

From past to present

Many of the Jimma thrones that can be found on the international art market today are antique items, not modern reproductions. The most prized examples, especially those emulating the royal seats of King Abba Jifar and other dignitaries, date from the late 19th to early 20th centuries. Typically, these thrones are hand-carved from a single block of dense African hardwood. They show clear signs of age, including patina, minor shrinkage cracks, and time-worn surfaces from decades of use.

While it is possible to find contemporary seats in Ethiopia inspired by classic Jimma thrones, modern pieces rarely have the same sculptural quality or density and are not generally marketed as antiques by reputable dealers. Antique Jimma thrones command much higher prices and are distinguished by their provenance, craftsmanship, and obvious signs of historical usage. We’ll discuss all of this now.

Large 19th-century high-backed Throne. Jimma Culture, Oromo region, Ethiopia. Dimensions: height 87 cm, seat diameter 54 cm, seat height from floor 38 cm. Sold by Tribal Gathering Gallery in Notting Hill, London, UK.

LEFT: An authentic Jimma throne used by a tribal chief in Ethiopia in the early 20th century. Height: 42” – 106.68 cm; width: 24” – 61 cm. Sold by JC Studio, Cathedral City, California, USA.

RIGHT: Jimma Throne from the late 19th – early 20th century. Height: 46” – 116,84 cm. Sold by Primitive, Chicago, IL, USA.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Jimma chair from the 1930s made of wanza wood with a nice patina. Adam Bray Designs. Photo credit: Oskar Proctor.

2. Antique Jimma chairs. Height: (left to right): 109 cm. MiDgu Design, Dubai, U.A.E.

3. Jimma throne in wanza wood. (Source: Pinterest)

LEFT: Jimma throne in wanza wood from the first half of the 20th century. Dimensions: height 103 cm, width 62 cm, depth 52 cm. My collection; photo by Gorringe’s, UK.

RIGHT: Jimma throne, undated. Height: 42 ¼ in., 107.3 cm. Auctioned in 2023 by Sotheby’s, New York, NY.

THE SECRETS OF JIMMA THRONES AND CHAIRS

Jimma chairs and thrones can be distinguished by their form, scale, provenance, and sociocultural function. However, the distinction is sometimes fluid, and the terms are occasionally used interchangeably in popular or commercial contexts. Both chairs and thrones share an essential characteristic: they are hand-carved from a single piece of wood, and are therefore called monoxylous.

Jimma Chairs

- Form: Typically three-legged (tripod) and hand-carved from a single piece of wood. Often have a curved or openwork backrest with geometric cut-outs. The silhouette is strikingly sculptural and abstract.

- Size: Jimma chairs are generally of “domestic” proportions. They are functional as seating, yet substantial and decorative. Heights might range from about 70–130 cm, with seat heights around 40–45 cm.

- Function: Traditionally used by elders or people of high status in the community, but not exclusively as thrones. They may have been used in domestic settings and carried connotations of prestige.

- Cultural Context: Rooted in the town of Jimma and the surrounding region (and occasionally made by neighboring groups, such as the Gurage), the design of the chair became emblematic beyond its place of origin.

Five antique Jimma chairs. Heights (left to right): 106 cm; 110 cm; 116 cm: 104 cm; 127 cm. MiDgu Design, Dubai, U.A.E.

Jimma Thrones

- Form: Thrones are almost always larger, taller, and more monumental in construction. While retaining the monoxyl tripod structure and elaborate back, thrones often have a commanding presence, sometimes with added artistic flourishes or sophisticated ornamentation.

- Size: Thrones often stand out for being outsized compared to more “common” Jimma chairs. Some high-backed thrones reach 1 m or more in height and are designed to be visually dominant.

- Function: Thrones are explicitly associated with leadership, enthronement ceremonies, and high ritual status. They are specifically crafted for kings, such as King Abba Jifar of Jimma, as well as for aristocrats and chiefs. They are used to mark authority, sovereignty, and formal occasions, not everyday seating.

- Cultural Context: The throne’s association with Abba Jifar’s court and royalty is well-documented. It served as a literal seat of power and became a symbol of the monarch’s authority.

However, some sources and dealers may label large Jimma chairs as “thrones” for marketing or descriptive purposes, even if they were not originally intended for regal or ceremonial use. Therefore, provenance and context are important for accurate classification.

In summary, while all Jimma thrones are Jimma chairs, not all Jimma chairs are thrones. Jimma thrones are a distinct subset of the broader “Jimma chair” category. They are ceremonial and usually outsized, and they were used by royalty to represent formal authority.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Antique Jimma throne Reserved for the exclusive use of Oromo chiefs and aristocracy. The tripod base has copper-coated ends and the wood has a beautiful reddish-brown patina. Dimensions: height 44 in., 112 cm; diameter 23 2/3 in., 60 cm. Sold in 2009 by Sotheby’s, Paris, France.

2. Jimma throne from the first half of the 20th century. Dimensions: height 41.5 in., 105 cm; width 20.75 in., 53 cm. Auctioned in 2022 by Wright, Chicago, IL, USA.

3. Jimma throne. Dimensions: 37 × 20 × 20 in., 93.98 × 50.8 × 50.8 cm. Auctioned in 2017 by Fine Arts Sign Company, Nwehall, CA, USA.

PHYSICAL CHARACTERISTICS AND CONSTRUCTION

Monoxylous Carving Tradition

The defining characteristic of authentic Jimma thrones and chairs is their monoxylous construction, which involves carving the entire chair from a single piece of wood. This technique is widespread in traditional African furniture making and requires exceptional skill. It also represents a significant investment of time and materials. The monoxylous approach ensures structural integrity while seamlessly integrating all components of the chair. Whether examining 19th-century museum pieces or early 20th-century examples, authentic Jimma chairs exhibit telltale signs of single-piece carving, such as continuous wood grain throughout the structure and an absence of joints or seams. The seat, backrest, and legs are also seamlessly integrated. Some of them — usually the older ones — may also show minor repairs or reinforcements.

Dimensional Characteristics

An analysis of documented Jimma thrones and chairs reveals significant variation in their dimensions. This variation reflects differences in use, available materials, and individual craftsmanship. Some of the tallest and most imposing Jimma thrones measure between 99 and 114 cm (39 and 45 in.) in height, signifying their ceremonial status and intended use as royal or prominent seats. In contrast, other documented examples, such as a notable 19th-century throne in a private London collection, measure approximately 87 cm (34.25 in) in height, with a seat diameter of 54 cm (21.25 in). These variations suggest a range of sizes within the “throne” and “chair” categories. Larger pieces were likely designed for public display or official rituals, while smaller examples may have served everyday or local ceremonial purposes.

The seat height typically ranges from 38 to 48 cm (15 to 19 in.) above ground level, positioning the seated ruler at an elevated position relative to standing courtiers. This elevation serves practical and symbolic functions by facilitating the ruler’s visibility during public ceremonies and emphasizing the hierarchical separation between monarch and subjects.

Structural Design Elements

The three-legged structure is perhaps the most distinctive feature of Jimma throne chairs. This tripod configuration provides exceptional stability while maintaining the sculptural elegance that is essential to royal furniture. The legs usually curve outward from the seat base to create a stable foundation that can support the chair’s height and the weight of an adult ruler.

The backrest design is remarkably sophisticated, featuring intricate geometric patterns created through openwork carving. These patterns often include triangular cutouts, diamond shapes, and latticework. These motifs have symbolic significance that extends beyond mere decoration. They encode cultural values, Oromo cosmology, and royal ideology into the very structure of the chair.

For example, triangular cutouts may represent mountains and stability, connecting the ruler to the permanent features of the landscape. Diamond patterns often symbolize unity and continuity, emphasizing the eternal nature of royal authority. Latticework indicates the interconnectedness of the community, reminding viewers that royal power derives from social cohesion.

Circular elements, which are often incorporated into the designs, may represent completeness and the eternal nature of rule. Linear borders define the sacred space of royal seating. These motifs were not merely decorative; they served as visual texts that could be “read” by culturally literate observers, communicating complex messages about the nature and legitimacy of royal authority.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Jimma throne, undated. Height: 38.77 in., 98.5 cm. Auctioned in 2018 by Lyon & Turnbull, UK.

2. Jimma throne from the 19th century. Dimensions: height 47 in., 119,38 cm; width 26 in., 66 cm. Balsamo Antiques, New York.

3. Beautiful hand-carved Jimma throne in wanza wood, form the late19th or early 20th century, with great patina, some minor shrinkage cracks and other imperfections and expected wear from age and use. Dimensions: height 43 in., 109.22 cm; width: 25 in., 63.5 cm. Sold via 1st DIBS.

LEFT: Jimma throne from the 1960s. (It was hand-carved long after the end of the Jimma Kingdom.) Height: 120 cm. Sold in Italy via 1st DIBS.

RIGHT: Jimma throne, undated. Chevalier Antiquités, Saint-Ouen, France.

MATERIALS AND CRAFTSMANSHIP

Cordia Africana: The Royal Wood

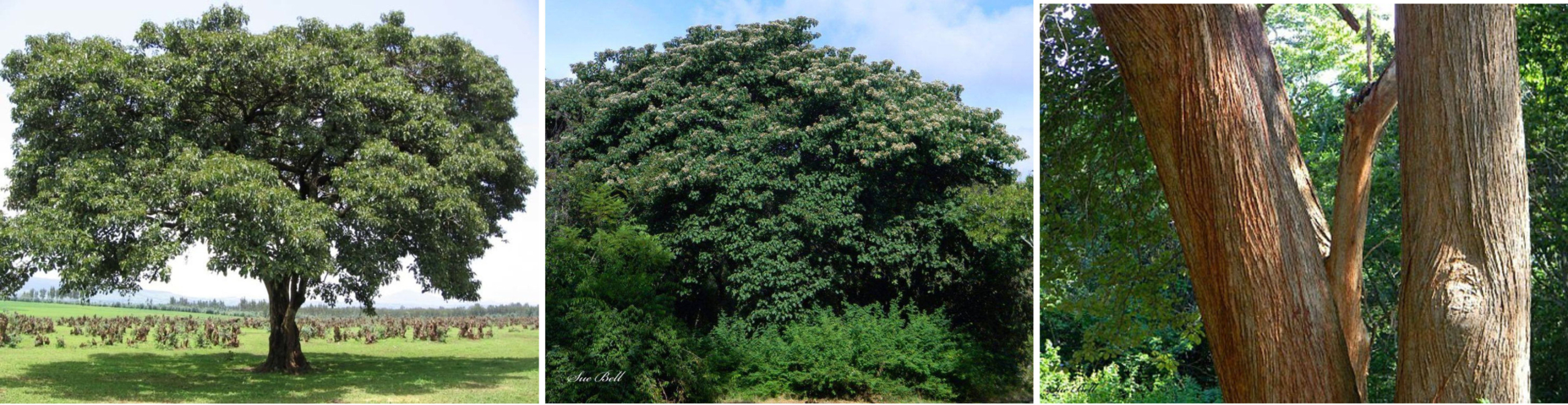

Wanzā wood (Cordia africana) has historically been the preferred material for high-status furniture, including thrones and chairs, in the Jimma region. This is due to a combination of its inherent properties and cultural availability. This medium-density hardwood is known for its workability, durability, and resistance to insect infestation, particularly termites, which are prevalent in the region. Freshly cut wanzā wood typically ranges in color from pale yellowish-brown to light reddish-brown. Over time, as the wood is exposed to light and air, it naturally oxidizes, causing it to darken and deepen in color. This natural aging process contributes to the varied hues observed in older pieces.

Traditionally, the selection of Cordia africana for throne construction involved careful consideration of multiple factors. Craftsmen preferred trees that were at least 100 years old to ensure optimal hardness, and they sought specimens from sacred groves or forest margins because these locations imbued the wood with spiritual significance. Harvesting typically occurred during the dry season to minimize moisture content and prevent cracking during carving.

Transforming the wood from raw timber to a finished throne required extensive processing. Multiple coats of traditional plant oils, including butter tree and castor oils, were applied to penetrate deeply into the wood, enhancing the grain pattern while providing water resistance. The final finish often incorporated beeswax and tree resins to create a surface that could breathe and would age gracefully without cracking.

LEFT TO RIGHT: A young specimen of Cordia africana in central Ethiopia. (Photo from Legesse Negash, A Selection of African Native Trees: Biology, Uses, Propagation and Restoration Techniques, 2021, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia). The crown, the bark and the trunk of a wanza tree (Wikimedia Commons).

Also known as wanza or East African teak, this valuable, multipurpose tree species is native to Ethiopia. It is an important source of timber used for furniture, construction, and tools. It plays a crucial role in agroforestry systems by providing shade for coffee and other crops. Additionally, it is a valuable resource for beekeeping and honey production. However, deforestation and over-exploitation for timber have endangered it in Ethiopia.

Traditional Construction Techniques

Creating a Jimma throne chair was considered a master craftsman’s ultimate achievement. It required sophisticated tools, a significant time investment, and a deep understanding of the culture.

The process began with selecting an appropriate tree trunk, which took 2-3 days, including traveling to suitable forests and consulting with elders about the tree’s sacred properties.

The metreshka, a traditional Ethiopian adze, was the primary tool used for the initial carving, shaping the basic form of the chair from the solid trunk. This phase required 3-5 days of intensive labor and began with prayers and offerings to ensure the chair’s worthiness for royal use. This ritual preparation transformed practical woodworking into a sacred craft, imbuing the chair with cultural significance.

Subsequent phases involved increasingly refined work. Seat formation required two to three days to create the circular or oval depression that would cradle the sovereign. Backrest design demanded five to seven days to create complex geometric patterns with symbolic meaning. Leg shaping took four to six days to ensure perfect balance, representing the kingdom’s stability.

Antique Jimma chair made of wanza wood with a beautiful dark brown patina. From the 19th century. Sold in California via 1st DIBS.

Antique Jimma chair in wanza wood from the 19th century. These chairs were used during meetings by council of elders, as symbols of rank and entitlement. Dimensions: height 101 cm; width 57 cm. Sold by Tribal Gathering Gallery in Notting Hill, London, UK.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Jimma throne in wanza wood from the 1970s. Dimensions: height: 37.75 in., 95.89 cm; width 24 in., 60.96 cm. Sold in California via 1st DIBS.

2. Jimma throne in wanza wood from the 1920s. Dimensions: height: 45.5 in., 115.57 cm; width: 25 in., 63.5 cm. Sold in California via 1st DIBS.

3. Jimma throne in wanza wood from the 1930s. Height: 110 cm. Sold by Galerie 44, Jassans Riottier, France.

4. Imposing Jimma throne in wanza wood. Sold via 1st DIBS.

CULTURAL AND CEREMONIAL SIGNIFICANCE

Connection to Gadaa Traditions

Recognized by UNESCO as an “indigenous democratic socio-political system,” the Gadaa system traditionally emphasized rotational leadership and collective decision-making. The transformation of this egalitarian tradition into monarchical symbolism through throne chairs is one of the most significant cultural adaptations in Oromo history.

The Oromo Gadaa is an indigenous socio-political system developed by the Oromo people. Often described as one of Africa’s most sophisticated traditional forms of democratic administration, it is recognized by UNESCO as Intangible Cultural Heritage. Let’s consider its key features.

- Generational Classes and Power Rotation

Society is organized into generational classes called “gadaa,” which rotate leadership every eight years. Male members are grouped into five main classes. At any given time, one class functions as the ruling class while the other four progress through different age and preparatory stages. Every man moves up through these grades starting from childhood, gaining social, military, legal, and leadership training as he progresses. - Democracy and Accountability

Leadership is elected, not hereditary, and strictly limited to a single eight-year term. When a term ends, power is peacefully handed over to the next cohort. Leaders can be impeached or deposed if deemed unfit, mirroring key aspects of modern representative democracy and systems of checks and balances. - Assemblies and Lawmaking

The highest decision-making body, the Gumii or Caffee, enacts, reviews, and revises laws every eight years. It also resolves serious disputes and holds current leaders accountable. Traditionally, legislative sessions are held under a sycamore tree, a symbol of dialogue, openness, and respect for the rule of law.. - Multi-faceted Governance

The Gadaa system governs every aspect of communal life, including political leadership and decision-making, military defense organization, judicial conflict resolution and law enforcement, economic resource and land distribution, and ritual and religious blessings and spiritual guidance by hereditary Qaallu priests. - Women’s Role

Although formal office-holding is traditionally reserved for men, women participate in key decision-making, particularly regarding issues that affect women’s rights and community well-being. Elders of both genders are consulted on major decisions. - Cyclical, Egalitarian, and Inclusive

The system is built on egalitarian principles (there is no hereditary kingship or nobility), the rotation of power, peer accountability, and active communal involvement. All Oromo males have the right to vote, be elected, and openly express their viewpoints in public assemblies after passing through the appropriate grades. - Ritual and Cultural Significance

Gadaa embodies Oromo cultural identity, oral history, cosmology, ritual performance, social responsibility, and moral values, and is much more than politics.

LEFT TO RIGHT, CLOCKWISE

1. Two Guji Oromo elders exchange greetings during the power transfer ceremony at Me’ee Bokkoo in Southern Oromia on February 21, 2024.(Visit Oromia).

2. Professor Asmerom Legesse, a pioneer of Gadaa study, wearing Abbaa Gadaa clothing (Wikimedia Commons).

3. A Borana Oromo elder arrives at the Baallii, a power-transfer ceremony involving the election of the electing their 72nd Abbaa Gadaa in March 2025 (Curate Oromia).

4. Abbaa Gadaa Guyo Boru, the 72nd leader of the Borana Oromo, arrives at the power transfer ceremony in Arero Goro. This marks the peaceful transfer of power in the centuries-old democratic tradition. (Curate Oromia).

5. Jarso Dhugo, 75th Abba Gadaa of Guji Oromo. (Curate Oromia).

6. A traditional meeting under a sycamore tree. (Hawaasa Dubbistoota Oromoo – Oromoo Readers Society).

«The Gadaa is an ancient and indigenous socio-political system that has long been a cornerstone of governance, social organization, and cultural identity for the Oromo people. (…) The Gadaa, which is built on participatory democracy, accountability, and peaceful power transitions, has functioned as a structured and egalitarian governance model for over five centuries: it’s a 568-year-old tradition of egalitarian governance. This historical perspective fundamentally challenges Eurocentric narratives that frame Western democratic traditions as the sole or primary governance model.», Getachew Tadesse, PhD candidate at Bule Hora University, Department of Gadaa and Governance Studies.

The process of receiving legitimate power through the Gadaa constitution involves wearing a kallacha and placing an ostrich feather (barguda guchii) on the incoming Abbaa Gadaa’s forehead. The ornament worn on the forehead by men in the context of the Gadaa system of the Oromo people is known as the kallacha. It is a highly symbolic headpiece within Oromo culture, particularly among the Borana subgroup and leaders known as Abbaa Gadaa.

It is a symbol of power and authority, as well as a central emblem of leadership. It denotes the wearer’s status as a legitimate authority within the Gadaa system. Only those who have reached high leadership positions, such as Abbaa Gadaa, have the right to wear it during ceremonies and official functions. It is also a symbol of connection to spirituality and ancestry. Wearing the Kallacha on the forehead signifies a connection to ancestral wisdom and the spiritual realm, reflecting the significance of the head as a sacred seat of thought and a conduit to Waaqa, the Oromo term for God. In many Oromo communities, the Kallacha is also seen as a symbol of peace and reconciliation, embodying values central to the Gadaa system. The Kallacha is typically constructed from white shells, horn, cast zinc, or metal and fastened to a decorated band or turban. It is worn at the center of the forehead to visibly mark the leader’s special role during Gadaa rituals and public appearances.

The Gadaa Legacy and its Modern Relevance

The Gadaa system has had a profound impact on Oromo resistance, cohesion, and cultural identity. Though it was diminished by the spread of centralized government in the late 19th and 20th centuries, the Gadaa system remains alive among some Oromo groups and has experienced a recent resurgence, serving as inspiration for movements seeking justice, self-rule, and recognition of indigenous democracy.

In summary, the Oromo Gadaa system is holistic and highly participatory. It governs not just a people, but an entire way of life, combining the political, social, economic, and spiritual into a uniquely African democratic tradition.

The statement that “the Jimma throne represents a fascinating synthesis of traditional Oromo Gadaa democratic values and monarchical authority” refers to the blending of two distinct political traditions in the Jimma kingdom of southwestern Ethiopia. Here’s how this synthesis played out.

The synthesis of Oromo Gadaa and Monarchy

The Oromo Gadaa system is based on collective, rotational, and egalitarian governance, explicitly rejecting hereditary kingship. Political power in the Gadaa system is rotated through generational classes every eight years. Leaders are elected and accountable to communal assemblies. In its purest form, Gadaa rejects hereditary kingship, embracing a participatory tradition where every eligible man has the opportunity to serve and authority is not inherited.

In the 19th century, the kingdom of Jimma arose in an area inhabited by the Oromo people. The kingdom’s royal institution developed elements associated with monarchy during the reign of King Abba Jifar II (late 19th–early 20th century). Kingship became hereditary, the court hierarchy grew, and visual symbols of authority, such as elaborate throne chairs, emerged. These thrones are substantial sculptural seats made for kings and high dignitaries. They are historical objects that can now be seen in museums and private collections.

How these inconsistent traditions could be “synthesized”?

- Continuity and Adaptation

Many leading families and institutions in Jimma retained deep roots in the Gadaa system. Even as the monarchy consolidated power, local governance and social organization continued to exhibit Gadaa characteristics, such as public consultation, consensus-seeking, and the involvement of generational peer groups and elders in significant decisions. - The Throne as Hybrid Symbol

The Jimma throne chair embodies this blend. While it is unmistakably a royal seat connoting centralized power, its design and ritual use reflect Oromo traditions. Its role was not only to exalt the king, but also to legitimize him through visible links to communal authority, ritual installations, and public meetings reminiscent of Gadaa assemblies. - Legitimacy and Authority

The Jimma monarchy was legitimized not only through hereditary succession but also through public recognition, ritual blessings, and endorsements from Oromo elders and religious representatives, which echo Gadaa’s communal ethos. - Social Memory

For many in Jimma and the wider region, the throne remains a symbol of wisdom, consensus, and dignified leadership rather than autocracy. Its continuing status reflects a “monarch with roots in the people,” which is distinctive from purely absolutist kingship.

In 19th-century sub-Saharan Africa, it’s rare to find a kingdom that was so overtly monarchical yet also drew legitimacy and much of its governing practice from an established democratic, rotational, and communal tradition.

In short, the Jimma throne chair is more than just royal furniture. It is a material reflection of how Oromo society negotiated the tension between the egalitarian values of the Gadaa system and the emergence of centralized, hereditary kingship, yielding a hybrid tradition in which even monarchy was seen as requiring popular and communal grounding. This complex interplay is what makes the Jimma throne chair historically and culturally fascinating.

Made of Cordia africana, the Jimma royal thrones occupy a symbolic and central place in royal rituals, analogous to the role of the sycamore tree (Ficus sycomorus) in Oromo communal tradition. Whether this reflects a deliberate symbolic transformation or a mere shift in the locus of authority (from communal to individual) remains open to interpretation and should not be presented as an established fact.

Royal Court Ceremonies

Throne chairs played central roles in elaborate court ceremonies marking significant events in the Jimma calendar. During mana sank’a dining ceremonies, for example, the king’s throne dominated the great hall, establishing the hierarchical center around which all other seating was arranged. The intricately carved chairs had a powerful visual impact, reinforcing the king’s elevated status and demonstrating the kingdom’s wealth and sophistication.

Diplomatic ceremonies particularly showcased the symbolic power of the throne chairs. When receiving foreign envoys or conducting state business, the king’s position on his throne communicated messages about royal authority that transcended language barriers. Thus, the chairs served as instruments of international diplomacy, projecting Jimma’s sovereignty to neighboring kingdoms and distant empires.

ECHOES IN WANZA: THE SCULPTED SPIRITS OF JIMMA AND GURAGE

Southern Ethiopia is home to diverse cultural groups, each with unique woodcraft and furniture design traditions. The Oromo people, particularly those from the Jimma region, and the Gurage people are especially renowned for their distinctive wooden chairs. These hand-carved seats are symbols of status and artistry in their respective cultures, not merely functional objects.

Jimma throne chairs represent the most sophisticated development of southwestern Ethiopian royal furniture and must be understood within the broader context of Ethiopian chair-making traditions. Neighbors to the Jimma kingdom, the Gurage people developed their own distinctive chair styles that share certain characteristics while maintaining unique features.

The Gurage are an ethnic group in southwestern Ethiopia widely celebrated for their woodcraft and carving skills. Historically, the Gurage were farmers and traders, and some Gurage clans developed specialized artisan castes. Gurage woodworkers created items for their own use and often supplied carved goods, such as stools and chairs, across Ethiopia. Gurage artisans are best known for carving these stools, including the famous three-legged Jimma-type stools. Thus, the Gurage chair tradition is both an indigenous art form and one that has intersected with the styles of other groups through trade.

Map of regions and zones in Ethiopia as of April 2000. All boundaries are approximate and unofficial. Source: USAID/Ethiopia Map Room.

Gurage Traditional Chairs

Similar to Jimma chairs, Gurage prestige chairs are monoxylous, hewn from a single block of wanza wood. This technique highlights the remarkable skill of Gurage carvers, who use tools such as adzes to shape dense hardwood logs into chairs. The end product is similarly robust and without joints. Traditionally, such a chair was reserved for a village chief or a prominent elder, underscoring its role as a status symbol. However, Gurage chairs tend to appear lighter, more vertical (“tower-like”), and more linear than Jimma chairs, which have a rounded, monumental look.

The seat is round and highly convex with a smaller diameter than Jimma chairs. Some examples feature a graceful, modernist simplicity.

Gurage chairs commonly have three-legged supports. The concave, round seat transitions into a central support that splits into three short legs at the base. Many Gurage examples have a slightly more compact stance and are often lower in overall height, but they still have the stable and convenient tripod form. Known Gurage chief’s chairs are typically 70–85 cm (about 27–33 inches) tall, with a seat height of around 35–40 cm. This is a sizable chair but not as large as the largest Jimma thrones. Gurage chairs have thicker legs, giving the base a solid look.

A high backrest is another defining feature of Gurage chairs. The backrest is usually a broad, rectangular, or slightly trapezoidal panel that rises from the seat. Unlike the often semi-circular Oromo/Jimma backs, Gurage chair backs tend to be more rectilinear (flat across the top or gently arched rather than dramatically curved). The substantial height provides support to the sitter’s back but is generally somewhat shorter than Jimma royal thrones. For example, one early 20th-century Gurage chair is 27 inches tall, and another antique Gurage chair is about 33 inches tall. In contrast, Jimma chairs frequently exceed 38–45 inches in height. Essentially, the Gurage backrest is high enough to be visually impressive and comfortable yet more modest in proportion, perhaps reflecting a chief’s seat as opposed to a king’s throne.

Gurage artisans decorate chair backrests with motifs that are often distinct from those of the Jimma region. One common design is a geometric starburst or radiating pattern, which is either carved in openwork or in relief. Many Gurage chairs have a pierced “star” motif — the backrest panel has cutouts that form a stylized star or floral shape at its center. For example, an early 1900s Gurage chair documented in the literature has a rectangular back “carved in a rectangular shape with a pierced star motif.” This typically resembles a four- or eight-point star, formed by diagonal and horizontal cutouts that give the design an almost bursting appearance. The star motif may symbolize the sun or be an aesthetic tradition passed down among Gurage carvers. In other cases, Gurage chair backs may forego full perforation in favor of a “hammered” texture or incised geometric lines on a solid back panel. This hammered look involves countless small chiseled depressions that create a rough, stippled surface that catches the light. Whether pierced or pitted, the ornamentation is abstract and boldly graphic. Unlike some African chair traditions, Gurage chairs typically do not depict human or animal figures. Their designs stay within the realm of geometric and textural artistry. One exception is extremely rare, high-back, ceremonial chairs with figurative carvings, but these are atypical. Overall, Gurage carving style leans slightly more toward symmetrical patterns, like starbursts, and textured surfaces as opposed to the larger open lattice of Jimma chairs.

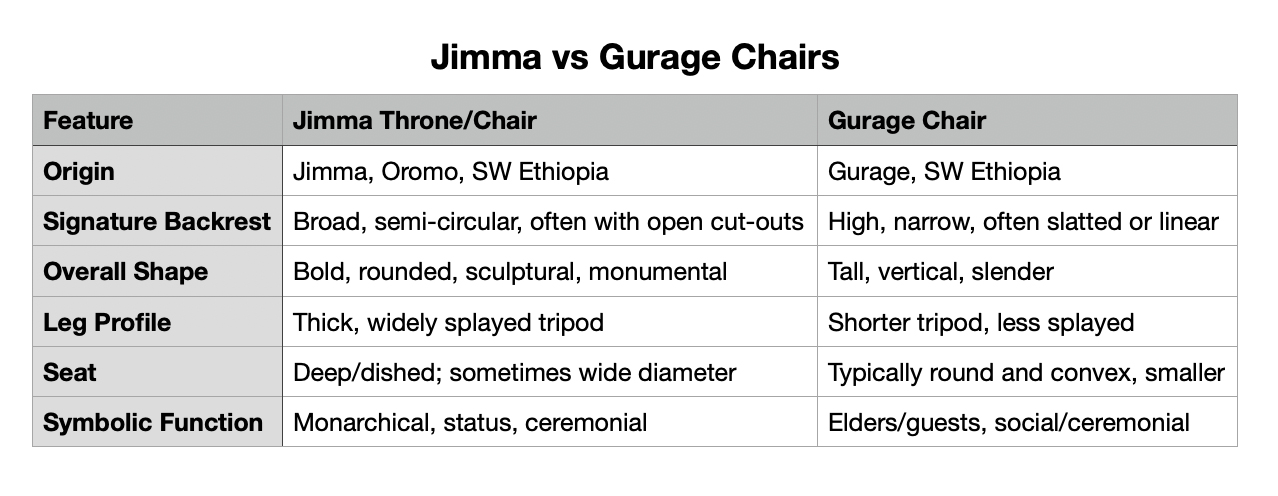

How can you tell the difference between Jimma and Gurage chairs?

Sometimes, it’s not an easy task.

To distinguish Jimma thrones and chairs from Gurage ones, focus on key differences in form, stylistic details, proportions, provenance, and intended function. Dealers are often confused because both types of chairs are high-status seats from southwestern Ethiopia. They are sometimes monoxyl, or carved from a single block, and they sometimes share similar woods, like Cordia africana, the Wanza tree. However, they are ethnically, stylistically, and practically distinct..

Common Sources of Confusion

- Gurage and Jimma seats are traded internationally under various labels. Sometimes, high-backed Gurage chairs are marketed as “Jimma” or “thrones” for commercial appeal, especially when the scale, patina, or openwork appears similar.

- If a piece is labeled as “Jimma/Gurage,” check the backrest shape. Broad, semi-circular backs and deeply dished seats suggest Jimma, while vertical, slatted backs and lighter construction point to Gurage.

- Both types may use the same wood, exhibit old patination, and feature sophisticated hand-carving, which makes precise attribution challenging.

Quick Comparison Table

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Gurage Chairs. Height: 90 cm. Auctioned by Thierry De Maigret in 2022, Paris, France.

2. Gurage Chair. Dimensions: height 76 cm, width 47 cm. Mo’s Interior Art, Norderstedt, Germany.

3. Gurage Chair from the early 20th century. Height: 32.5 in.; 82.55 cm. Sold via 1st DIBS.

4. Gurage chair from the early 20th century. Height: 27 in.; 68.58 cm. Sold via 1st DIBS.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Two Gurage Chairs. Heights: 91 cm and 95 cm respectively. Auctioned by Bonham’s in 2006, London, UK.

2. Gurage Chair. (ADAC).

3. Gurage Chair. Height: 66,5 cm. Auctioned in 2017 by Zemanek-Münster Auction House, Würzburg, Germany.

Amazing antique Gurage Chair, carved from a block of hard wood by a caste of Gurage craftsmen called Fuga and reserved for the exclusive use of chiefs and aristocrats. Dimensions: height 100 cm; diameter 52 cm. Auctioned in 2008 by Bonham’s (Paris, France) for 36,750 euros.

Gurage 7-legged chair hand carved from a single block of wanza in the 1880s. Dimensions: height: 38.98 in.; 99 cm. Seat height: 19.69 in.; 50 cm. Sold via 1st DIBS.

As you can see from the pictures above, most Gurage chairs have vertical leg supports, while Jimma chairs generally do not. However, this is not a hard-and-fast rule. It is inaccurate to say that Jimma chairs never have these supports or that they are a definitive distinguishing feature.

Both styles are hand-carved from a single piece of wood and have a rich patina from age and use. This reflects their cultural significance and traditional craftsmanship. Both styles can have vertical leg pillars, and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between them. Some three-legged, monoxylous Gurage thrones are virtually indistinguishable from Jimma types without a close study of the motifs, joinery, and provenance.

Gurage throne from the first half of the 20th century. Height: 120 cm. Sold in The Netherlands via 1st DIBS.

Gurage or Jimma?

The chair in the above image, taken from Instagram without a caption or explanation, is undoubtedly old and beautiful. Is it a Gurage or a Jimma piece? There is no information to help answer this question.

This chair is carved from a single block of wood and has a tripod base with three legs. This monoxylous, three-legged construction is noted as “unique to the Jimma area” and is also a hallmark of Gurage chief’s chairs. Thus, based on its construction alone, it could be from either region, as both use one-piece, tripod designs. However, Gurage chairs often have a central support that splits into three short legs at the base.

The backrest of the chair in the image appears tall and narrow, rising well above the seat. If the backrest is significantly taller than a person’s waist, it leans toward the Jimma style, which often exceeds one meter in height in grand examples. Gurage chairs, while high-backed, are usually shorter. If the chair in the image has a very commanding height, which we cannot know, it suggests a Jimma origin.

Now, let’s examine the outline of the backrest. A semi-circular or curving top would resemble Oromo designs, while a straight or gently arched top is more common in Gurage pieces. According to accounts of similar chairs, many Jimma chairs have an arched crest or pointed finials, while Gurage backs are often squared off.

The strongest clue may be the motif carved into the backrest. This chair has triangular cutouts that form a dynamic pattern. If the cutouts create an eight-pointed star or a radiating shape, it correlates with the Gurage starburst motif. However, if the pattern is more linear or lattice-like, such as intersecting triangles forming an X or a geometric grid, it may align more with Jimma designs. The pattern in the photo appears to be a series of large triangular voids. The bold openness and large scale of the cutouts (as opposed to many small, precise cuts) suggest a Jimma aesthetic. However, the symmetry of the carved motif is similar to that of some Gurage chairs’ backrests.

The finish and patina are inconclusive; both Jimma and Gurage acquire a glossy, darker patina over time. The image shows a dark, well-worn surface, consistent with either style.

So what? Here’s my hypothesis—and I emphasize “hypothesis”; this is mere conjecture based on a single photo with no other information:

The chair in the image is most likely from Jimma. Jimma is part of the wider Oromo cultural sphere, but it has its own distinct royal court tradition. Considering all the stylistic evidence, this traditional wooden chair is probably a Jimma throne. Its design and craftsmanship strongly echo the Jimma style. It could date from the late 19th to early 20th century, when local chiefs commissioned such thrones to display their status and political authority. However, this throne does not clearly match typical Gurage features. Instead, its form fits the profile of craftsmanship from the Jimma region, possibly made by Oromo or Gurage artisans for the Jimma market. This was a well-known phenomenon. Gurage artisans carved many “Jimma” stools, which could explain why this piece was difficult to attribute in the dark.

Northern Ethiopian Influences

Throne chairs in northern Ethiopia, particularly those associated with the Aksumite tradition and later imperial courts, differ significantly from examples in Jimma. Northern chairs usually have four legs instead of three and rectangular seating instead of the circular forms characteristic of Oromo traditions.

Contemporary scholarship on the Aksum chair tradition reveals that it is a modern reinterpretation of historical forms rather than a direct continuation of the Aksumite era. This contrasts with the authentic historical continuity represented by Jimma throne chairs, which evolved organically over centuries of royal court development.

Contemporary Interpretations

Modern Ethiopian-American furniture designer Jomo Tariku has created contemporary interpretations of traditional Ethiopian chairs, including explicit homages to the Jimma tradition. Tariku’s work is featured in major collections, including those of the Brooklyn Museum, and demonstrates the continuing relevance of Jimma chair design principles in contemporary furniture making.

Tariku’s approach maintains the essential three-legged structure and monoxylous carving principle while adapting traditional forms for modern interiors. Tariku said: «I aim to cultivate a lifelong appreciation for elevated modern African design, and to inspire a deeper and fuller connection to the continent. I weave the continent’s nature, art, and history within each piece I produce. Every design tells a unique story, with no detail overlooked or undervalued.»

Jomo Tariku, Jimma Chair, 2024. Medium: Walnut, birch. Dimensions: 35.5 x 22.5 x 17 in.; 90.17 x 57.15 x 43.18 cm. Photo courtesy: Wexler Gallery, Philadelphia/New York, USA.

How can you tell if a throne or chair is authentic Jimma?

Authentication criteria emphasize verifying the wood species, analyzing the construction technique, and ensuring stylistic consistency with known regional characteristics. Primary indicators of authenticity include patina development, wear patterns, and evidence of traditional hand-tool construction.

Follow these steps to check if a Jimma chair or throne is authentic and monoxylous (carved from a single piece of wood). These steps are tailored for field professionals and serious collectors.

- Examine Construction for Monoxylous Characteristics

- Solid Block Carving: Authentic Jimma chairs are traditionally hand-carved from a single, solid block of wood, most often from the wanza tree (Cordia africana). The same goes for Gurage chairs.

- Absence of Joints or Laminations: Inspect the chair carefully for any joints, seams, or signs of assembly—there should be none. The legs, seat, and back should all be part of the same piece. If there are dowels, glue lines, or visible fasteners, the chair is likely not monoxylous.

- Consistent Wood Grain: Look beneath the seat, along the sides, and especially at the transitions between the seat, back, and legs. The wood grain should flow continuously and naturally across all parts without any interruption or abrupt changes that suggest different pieces have been joined. The end grain should show natural growth rings, which support the single-block origin.

- Check for Authenticity

- Patina and Wear: Genuine historical Jimma chairs often show signs of age, such as an even, smooth patina; minor shrinkage cracks; and old repairs. Look for wear consistent with decades of use, especially around contact points, such as the seat and armrests.

- Tool Marks: Traditional craftsmanship may leave behind marks from tools like chisels or adzes, which are indicative of hand-carving rather than modern machining.

- Provenance and Origin: Authentic Jimma chairs are from the town of Jimma in southwestern Ethiopia and were historically used by local royalty or elders and are connected to King Abba Jifar.

- Makers’ Marks: Though rare for African vernacular furniture, there are sometimes incised marks or signatures hidden under the seat or back, particularly if the chair was commissioned for a high-status user.

- Additional Authentication Tips

- Dimensions and Proportion: Compare the dimensions and form of the chair to those of documented museum or gallery pieces to ensure consistency. These chairs typically have a sculptural, tripod base and a strong, geometric back, often in the shape of a half-circle with cut-out details.

- Remember that some thrones and chairs may have minor joined repairs or reinforcements, especially older ones.

Wanza or not wanza?

Traditional Jimma thrones and chairs are renowned for being made of wanza wood, scientifically known as Cordia africana. This preference is deeply rooted in the cultural and practical significance of the material within the Jimma Kingdom of Ethiopia. However, the observation of varying wood colors in these artifacts leads to questions about protective waxes or alternative wood types. These questions can be addressed by examining woodworking practices, material properties, and historical context.

Several factors beyond the initial natural variation of wanza itself can contribute to the perceived differences in wood color in Jimma thrones and chairs:

– Natural variation within wanzā wood

Even within the same species, there can be natural variations in wood color due to factors such as soil composition, climate, and the tree’s age at harvest. The heartwood (the inner, older wood) of wanzā tends to be darker and more uniform in color than the sapwood (the outer, younger wood). The proportion of heartwood to sapwood varies between trees, resulting in subtle differences in the finished piece’s overall color.

– Application of protective waxes and finishes

The use of protective waxes, oils, and other natural finishes is a common practice in many traditional woodworking cultures, including those in Ethiopia. These finishes serve multiple purposes.

- Waxes and oils create a barrier that protects the wood from moisture, dust, and insect damage, thereby extending the furniture’s lifespan.

- Finishes can also enhance the wood’s natural grain patterns, making them more prominent and aesthetically pleasing.

- While not their primary purpose, some traditional waxes or oils, especially those derived from natural pigments or containing certain resins, can impart a subtle tint or deepen the existing color of the wood. For instance, beeswax, a common traditional finish, can give wood a warm, amber-colored hue. Repeated application of these finishes over many years can significantly darken and enrich the wood’s color, creating a highly valued patina found in antique pieces. The cumulative effect of these protective layers can make the wood appear darker than its original, unfinished state.

– Patina and Aging

As previously mentioned, the natural aging process of wood, coupled with exposure to light, air, and human contact, contributes to the development of a patina. This patina is a complex surface layer that develops over time, resulting in changes in color, texture, and sheen. The darkening of wenge wood over centuries is a natural phenomenon, and this aged appearance often indicates the authenticity and historical significance of a piece.

– Soot and Environmental Accumulation

In traditional settings, particularly in homes with open fires for cooking and heating, furniture can accumulate soot and other environmental residues. This accumulation, combined with the natural oils from human hands, can give the wood a darker, often glossy appearance that might be mistaken for a different wood type or a deliberate finish.

The use of other woods in Jimma furniture

While wanzā wood is the primary and most traditional material for Jimma thrones and chairs, it is plausible that other types of wood were used, particularly for less prominent pieces or during periods of scarcity or economic constraint. However, for the highly symbolic and prestigious thrones and royal chairs, wanzā wood was generally preferred due to its cultural significance, durability, and aesthetic qualities.

If other woods were used, they would likely be local hardwoods with some of the same desirable properties as wanzā, such as durability and workability. Examples of other woods found in the Ethiopian highlands that might have been used for furniture include Podocarpus falcatus (African yellowwood) or various species of Juniperus (junipers). However, the use of local hardwoods, such as woira (wild olive trees found in Ethiopian highlands), bissana (Croton macrostachyus), kosso (Hagenia abyssinica or African Redwood, a high-altitude species native to Ethiopian mountains), or bahirizaf (Eucalyptus globulus), each with distinct grain and coloration, suggest either a non-traditional piece, a repair using a different material, or a piece made for a different purpose or social stratum where the strict adherence to wanzā was not as critical.

It is important to note that the term “authentic Jimma chairs and thrones” generally implies adherence to traditional materials and craftsmanship. While variations in wood color due to aging, patina, and traditional finishes are consistent with authenticity, using an entirely different wood species for a throne or royal chair’s primary structural component would typically indicate a deviation from the most traditional and highly valued forms.

In conclusion, the varying wood colors observed in Jimma thrones and chairs are most likely the result of wanzā wood’s natural aging process, the cumulative effect of traditional protective waxes and finishes applied over many years, and the development of a rich patina. While other wood types may have been used for less significant pieces, the tradition of authentic, high-status Jimma thrones and chairs strongly favors wanzā wood.

And now, one final thought to leave you with.

A Jimma or Gurage chair—and even more so, a Jimma throne—is not just furniture, but a sculptural presence.

It belongs in a spacious, light-filled room and can harmonize with many styles, from minimalist to eclectic, not being confined to ethnic décor alone.

Wherever you place it, let it stand proud as you would a treasured work of art—a statement, not a whisper.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?