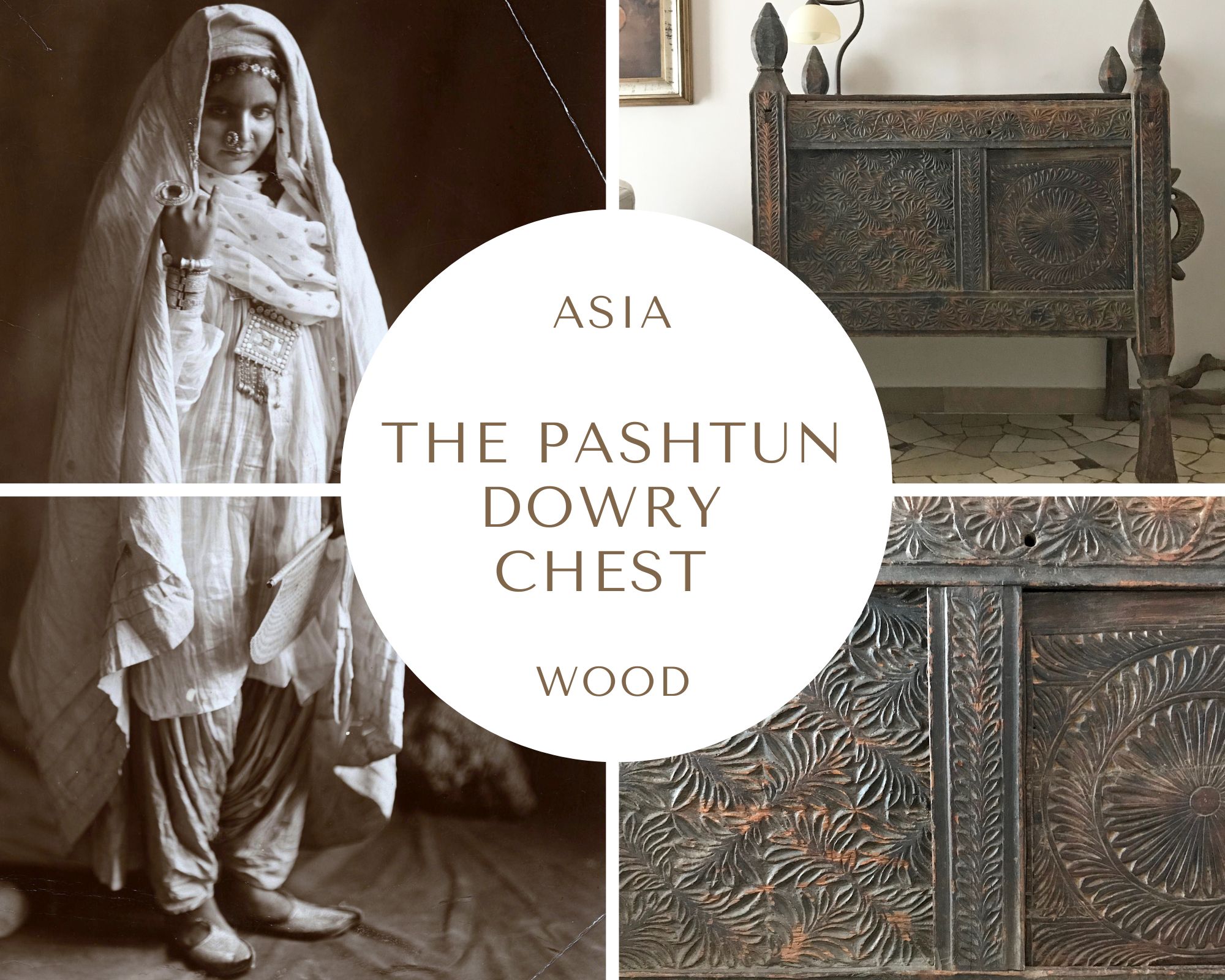

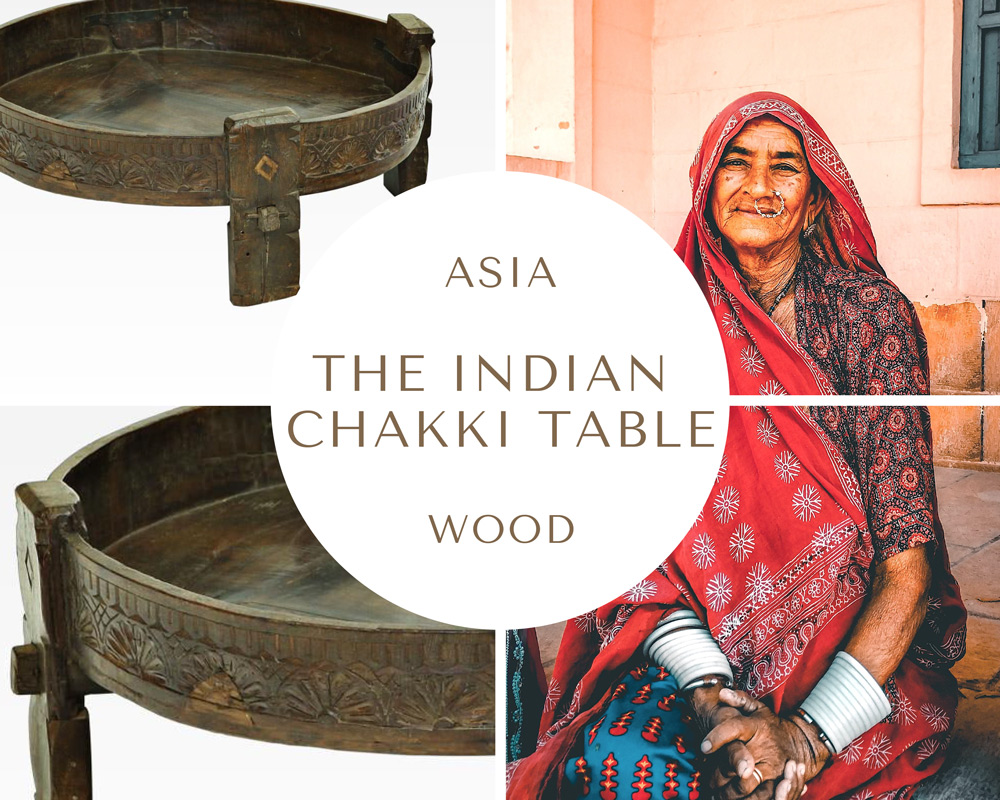

The Indian Chakki Table

Try to find a boho-chic style lounge without a chakki.

You won’t.

This antique hand-crafted Indian table is a sort of current obsession: in their typical

jargon, interior design blogs and stores say it’s the perfect “bohemian vibe” you need

to “spice up your stylish home” blah-blah.

It’s true: in the last years, the chakkis turned into one of the most sought after

coffee/side/sofa tables (it depends on their variable size). If you have only a vague idea

about them, try a simple Google search: you will be amazed by the variety of their

shapes, colors, kind of woods, quality, and dating (many chakkis are contemporary

replicas of antique items).

If you’d like only to buy a chakki, download our Flipbook What you should know if you

want to buy a chakki to avoid throwing good money after bad.

If you’d like to listen to an unexpected story, please, sit down.

ON CHAKKIS AND WOMEN’S LIFE

The traditional Indian chakkis are round tables of Rajasthani origin, mainly in teak or oak

hardwood, used in the past centuries to hold up a hand-driven millstone for grinding

grain or spices. They were grinding tables, and in memory of their primary vocation,

many still retain a small door on a side to open and collect the flour.

Still today, Rajasthani older women know how to work on the traditional

stone grinder inside a wooden chakki.

The hand-carved grinder table is commonly called chakki or jate (in Marathi), but this name is not appropriate. Chakki is the name of the traditional ancient grinder, a handdriven millstone used by women for grinding the grain and getting the wholemeal wheat flour, called chakki atta, used to prepare the typical and traditional flatbreads such as chapati, roti, naan, paratha, and puri.

(by Adrienne Mountain licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0).

Here’s an old North Indian style grinder displayed at Amber Fort (Amer, Rajasthan). The

hand-driven chakki consists of two bulky disks of coarse stone, one fixed and one

rotating. The off-center hole was equipped with a wooden handle, while the central one

was used to insert the wheat grains.

(By Vssun, Wikimedia Commons)

(Source: British Library)

(By feanor0, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

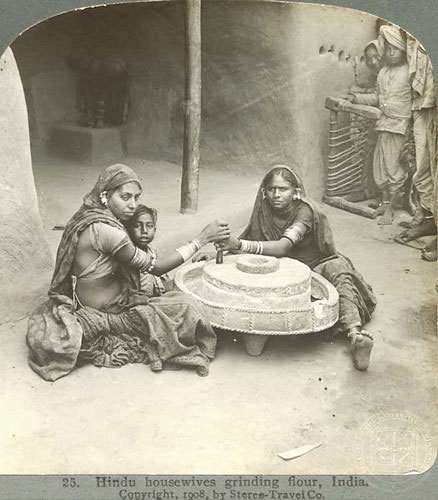

The first picture portrays two “happy” women grinding grain in 1873; the second

depicts two Hindu women grinding flour in 1908, and the third two other women likely

in the first half of the 20th century.

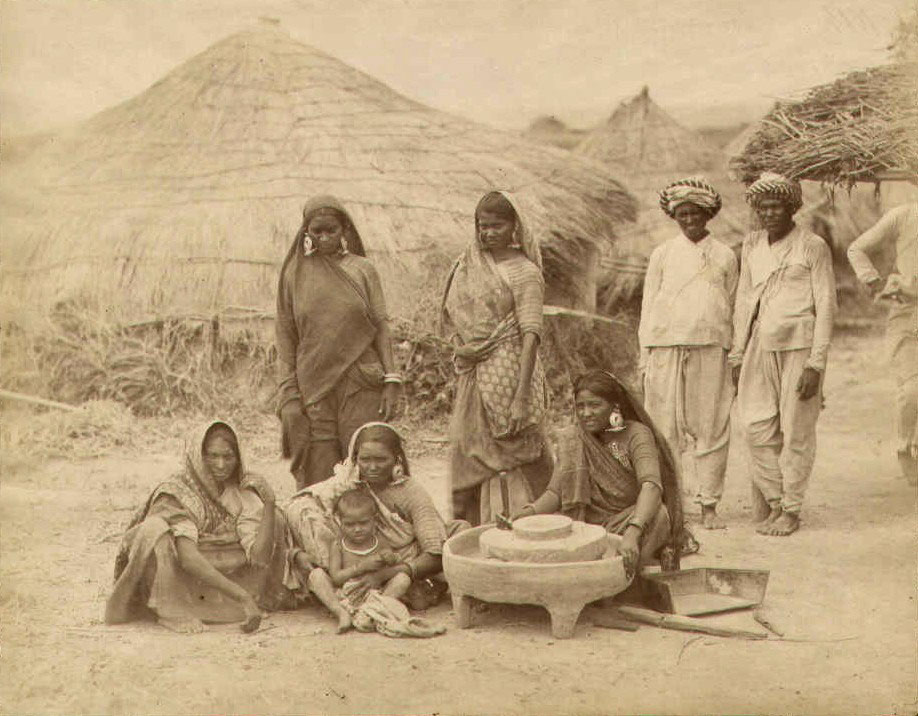

As you probably noted, the women in the first and third pictures did not use a grinder

table: only the wealthy homes could place the chakki stone grinder inside a wooden

table (for servants’ use, of course). Poor people used a natural fiber mat or a simple

fabric cloth, stretched out on the floor.

This last picture portrays some Bheel women near a chakki inside its table in the 1880s

(the Bhils or Bheels are an Indo-Aryan speaking ethnic group in West India).

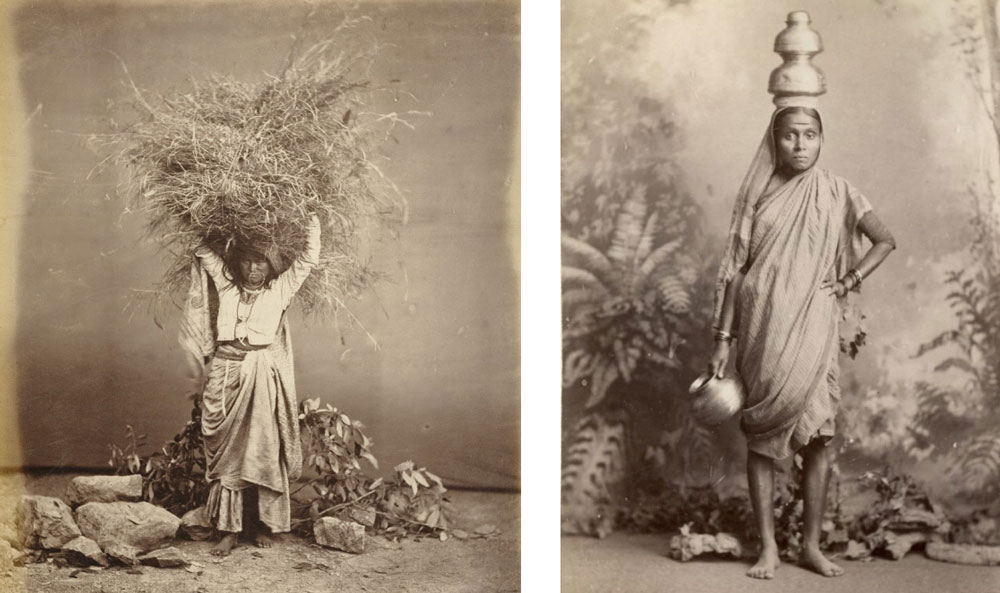

For centuries, the grain grinding, a hard and noisy work, was carried out by women

only. Every single day, of course, together with many other exhausting duties, like

carrying water and holding twigs on the head, as these 19th-century peasants. You will

understand why the Indian women in the pictures did not charmingly smile at the

camera.

ON CHAKKIS AND SONGS OF FREEDOM

Indian women were not living on easy street. Not at all.

Until the mid-20th century, the condition of Indian women was a mix between the

torture of Tantalus (who wants something he cannot have) and the Sisyphus fatigue

(endless and unavailing labor). So miserable were these men, Sisyphus and Tantalus,

that they resembled Indian women.

In India, the status of women was firmly secured to a cross by three kinds of nails: the

caste system, the female lack of economic power, and gender inequality.

Indian women were under constant tutelage and trapped in their condition, but their

tongues and brains were free – to some extent, at least.

In many rural regions of Maharashtra, the women compelled to grind at the millstone

developed the ‘Gridmill Songs’, the jatyavarchi ovi (from the Marathi ovane, ‘stringing

together’), free expression of their voices, thoughts, and feelings on caste oppression,

childbirth, marriage, poverty, pain, life, death, and politics as wells. They were grinding

and singing, sometimes sitting close to each other to intone a choir, rarely alone, always

loudly.

«For thousands of women, these songs marked a creative space, a personal zone of free

expression», wrote Namita Waikar, Managing Editor of People’s Archive of Rural India,

head of The Grindmill Songs Project.

Which fool has given birth to

Which fool has given birth to a woman?

My body is toiling on rent in someone else’s house

Had I known it, I would have refused to be born a woman

I would have become a tulsi plant at god’s doorstep

«Kusum Sonawane of Nandgaon village from Mulshi taluka in Pune sang of the indignity

of being a woman, saying she would rather be a plant, perhaps the holy basil (the

Ayurvedic tulsi), more revered than the woman of the house. The ovi thus speaks of a

clear unequal status of women in society, something the women from the village

noticed, sang, and listened to» (Namita Waikar).

You were pampered so much as a darling daughter,

That your brother gave you a betel-leaf plantation

This ovi, transcripted from an old song sung by Konda Sangle of Nivanguni village, in

Velhe taluka of Pune district, «is a reminder of unequal land ownership. Women by

themselves owned nothing. Anything they have is in the form of gifts given by the

menfolk-father, husband, or brother, the singer says» (Namita Waikar).

One of the most moving songs of Maharashtra was recorded in the Nandgaon village

by The Grindmill Songs Project team:

We were beaten when we asked for our right to water

O woman, the Brahmin caste here is very orthodox

O woman, stones and pebbles were thrown at us when we staged a satyagraha,

We were fighting for our rights, protecting our children

The song was traditionally intoned by Dalit women, the social group which faced (and

to some extent is still facing) the most severe discrimination at the intersection of caste

and gender inequalities. Dalits were the Untouchables or Outcastes, the people that the

Hindu caste system threw out of the social structure, and condemned to be the most

oppressed of all.

The Dalit community – as the song cries – was forbidden to drink and use the water

which even animals could drink freely at the public fountains and tanks.

Their water fight, the Mahad satyagraha (a form of non-violent civil resistance and

protest) culminated on March 20, 1927: «Babasaheb Ambedkar drank water from the

Chavdar Tale (tank) of Mahad, in the Kolaba district (Mumbai province) and led nearly

3,000 others who did the same. The social taboo forced on the Dalits by upper castes –

banning them from drinking water from a public resource – was challenged and broken»

(People’s Archive of Rural India).

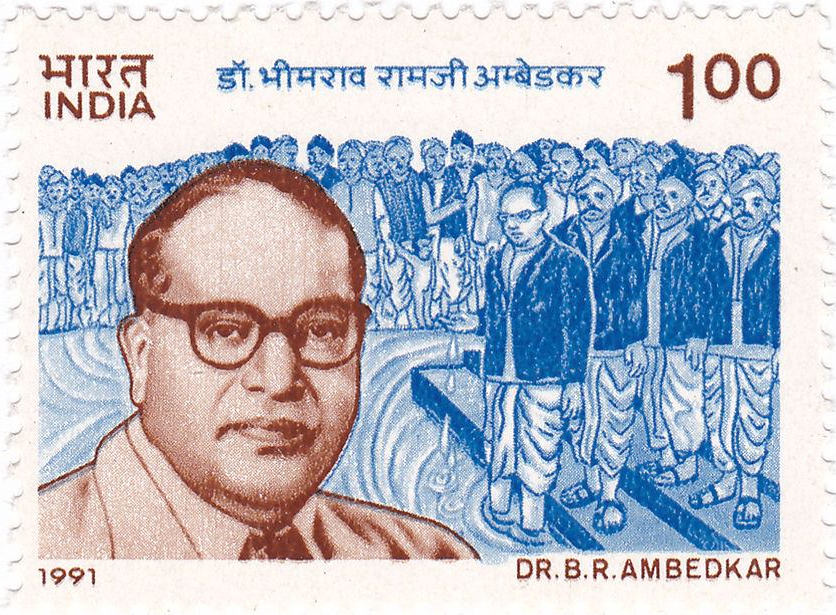

R. Ambedkar on a 1991 Indian stamp (licensed under the Government Open Data License – India GODL)

Bhimrao Ramji ‘Babasaheb’ Ambedkar (1891/1956) was an Indian jurist, economist,

politician, and social reformer, law minister of the government of India from 1947 to

1951. He was a Dalit and a Dalit leader who committed himself in campaigning against

any form of discrimination.

The grindmill song reminds the importance of his fight and the historical moment of the

1927 Chavdar Tale Mahad satyagraha (note that in the song Bhimrao Ramji ‘Babasaheb’

Ambedkar is called Ramji’s son Bhim).

The train with a steam engine roars through the forest

Announcing: Ramji’s son Bhim is standing at the Chavdar Tale

(…)

Dipping four fingers in the waters of Chavdar Tale,

gives joy and a feeling of being transformed

O woman, Ramji’s son has such enormous courage

At the Chavdar Tale, just for the right to a sip of water

A crowd has gathered for the sake of women and children

At the Chavdar Tale, there is a flower garden

Bhima’s son held a satyagraha there

This is not the only song on ‘Babasaheb’ Ambedkar; listen to another song performed in

the Majalgaon village (always in Maharashtra) by an old woman grinding the mill, and

recorded by The Grindmill Songs Project team.

O woman, for the golden glass a scrubber of silver

Bhimraj drank water in the station of Aurangabad

Jasmine and chrysanthemum flowers in a glass

When at college in Aurangabad, Bhim came under an evil eye

O woman, there is a golden pen in the pocket of Bhīmrāja

In the pocket of Bhim, the country salutes with ‘Jay Bhim!’

The grindmill songs were invented by women and passed down from generation to

generation, and in this process, they changed and enriched.

«With the coming of motorized grinding in villages in the last couple of decades, this

mode of expression has almost ceased: it’s a loss for the women in villages, as their lives

may have improved over the years in material terms, but the problems and socio-

economic challenges they face in a patriarchal society have not gone away» (Namita

Waikar).

WHAT SINGING WOMEN CAN DO

In patriarchal cultures, women in a condition of legal and economic inferiority, whatever

their social status, have always conquered shreds of freedom of expression. The

illiterate and the poor chose to sing. How could they have dared to create poetry? And

what other way did they make their voices heard? Unsurprisingly, in many patriarchal

societies, women have often sung out loud. Very loud.

During their brutal regime, the Taliban banned all forms of music, allowing only the

singing of certain types of religious songs and chants. They knew that to turn women

off, you need to start turning off their voices.

(The sign you are facing a sexist? He loves to notice that women usually talk too much).

The jatyavarchi ovi of the Indian women, chained to the chakki or the jāte, call to mind

the Canti di monda, the songs of the Italian mondine, the female seasonal paddy

weeders of Northern Italy from the mid-19th century to the 1960s.

For over a century, the poorest countrywomen abandoned their homes to reach the

extended paddy fields of Lomellina, Novarese, and Vercellese during the flooding time,

from the end of April to the beginning of June. Many were 14-year-old girls, forced by

families or, to put it better, by misery, to earn a few lire; some were young pregnant

women, forced to toil up to the threshold of labor.

The work was very hard. The women had to carry out the monda, eradicating the weeds

and thinning out the rice seedlings that grew too close to transplant them where they

were missing.

Before the union riots imposed the mandatory eight hours of work (in 1906), the women

worked from sunrise to sunset, always folded in two under the sun, with hands and legs

in the water, that was too cold at dawn, and too hot at dusk.

The skin of the feet and hands macerated; the weeds were often sharp as blades; the

flooded fields were full of water shrews, snakes and leeches, the air of flies, horseflies,

and mosquitoes. To make matters worse, the tiracól – the male supervisor – screamed

whenever a woman put both hands on her kidneys and straightened up to find a second

of relief.

Like Indian women, Italians sang loudly: in India to overcome the noise of the millstone,

in Italy to prevail over the croaking of frogs and the chirping of crickets.

Mamma, papà non piangere se sono consumata

È stata la risaia che mi ha rovinata

Mom, dad: don’t cry if I’m worn out

It was the paddy that ruined me

One of the most popular songs was Sciur padrun da li béli braghi bianchi, born between

the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Sciur padrun da li béli braghi bianchi,

fora li palanchi, fora li palanchi,

sciur padrun da li béli braghi bianchi,

fora li palanchi ch’anduma a cà.

The paddy weeders around Novara and Vercelli sang it at the end of the season when,

after 40 days of suffering, they collected their poor wages and went back home. The

song urges the master, well described as a man with immaculate white trousers, never

soiled by fatigue or physical work, to bring out the agreed money.

The most famous verses, however, are the following:

Sebben che siamo donne

Paura non abbiamo

Although we are women

We are not afraid

An elderly Italian mondina said: «There were songs we sang only to make master and men nervous because we had no other way of protesting, and they could not shout all our mouth». But finally, they learned how to protest.

In February 1927, in the Fascist Era, due to a decrease in rice prices, the lobby of landowners, in agreement with representatives of the Fascist trade unions, decided a 30% reduction of the wages of the seasonal paddy weeders. On June 30, in the districts of Vercelli, Novara, and Biella, more than 10,000 women went on strike. It was satyagraha. The Italian way to satyagraha. A hundred women were arrested and about ten were sentenced to a few months in prison, but this female mobilization frightened the government and the landowners so much that the reduction was reduced. Today, their struggles are an integral part of the history of the Italian labor movement.

Old Dorm of the “mondine”, Colombara Estate, village of Livorno Ferraris, Vercelli district (Northern Italy).

(Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license)

In 1927, the condition of women in India and in Italy was not so different as you might expect. I do not want to minimize the historical differences or erase the peculiarities of those two conditions: I simply want to highlight the similarities. In India, universal suffrage granted voting rights to all women only in 1950. In Italy, in 1946.

Italian women were legally subordinate to their husbands until 1975. The family law in force under the Fascist dictatorship entailed the subordination of the wife to her husband under all points of view (property and inheritance rights included, and children education issues as well). During Fascism, the Italian women were placed in a state of subjection and inferiority, crushed under a patriarchal system made even more rigid by the aggressive demands of Mussolini, whose politics aimed to turn women into obedient wives, fertile mothers (for the salvation of the fatherland, of course) and docile subjects. The family as a site of male patrilinear privilege was a characteristic of the Colonial Property Law in India, as well (see, for example, Mytheli Sreenivas, Conjugality and Capital: Gender, Families, and Property under Colonial Law in India, in the Bibliography).

During the Fascist Era (1922-1943), women’s wages were fixed by law at half of the men’s corresponding wages. Ushering in a strategy that would later be revived for anti-Semitic politics, women were formally prohibited from teaching letters and philosophy in high schools and some other subjects in technical colleges and middle schools; they were also banned from being headmasters or principals, while school fees were doubled for all girls. In the civil service and in the public sector, the recruitment of women was severely restricted, excluding them from invitations to tender and granting them a limited number of posts (usually 10%). They were also banned from making a career whatsoever and precluded from many prestigious positions within the public administration.

The Italian Fascist regime lowered the minimum age of marriage for women to 14 years (in 1929, in India, the Child Marriage Restraint Act was passed, stipulating 14 as the minimum age of marriage for a girl). In the 1920s, the status of the mondine, the female seasonal paddy weeders of Northern Italy, and of the great majority of women coming from the lower, poorer, and marginalized strata of society was firmly secured to “another” cross by three kinds of nails (the first cross we met in India): the female lack of economic and political power, gender inequality and social discrimination.

Italian and Indian women were forbidden to have a public voice. However, both found a way to be heard. They sang out loud.

Like Indians and Italians, women living in many patriarchal societies had been toiling and singing at the same time. They sang to endure fatigue and put up with their destiny, to pass hours that seemed never to pass, and share something that was not pure pain. And singing loudly, they discovered the unknown universe of solidarity and dignity; they took courage and learned to impose their voices; they learned to fight for themselves and their rights. Ours, today.

THE MORAL OF THIS STORY?

NEVER UNDERESTIMATE A SINGING WOMAN.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Namita Waikar, Grinding grain, singing song, in The Indian Express, December 8, 2017,

Urmi Chanda-Vaz, Grindmill Songs: Listen to the world’s largest archive of folk songs,

Scroll.in, April 21, 2017

https://scroll.in/magazine/833884/grindmill-songs-listen-to-the-worlds-largest-archiveof-folk-songs

People’s Archive of Rural India

https://ruralindiaonline.org/

https://ruralindiaonline.org/articles/the-grindmill-songs-recording-a-national-treasure/

F. Castelli, E. Jona, A. Lovatto, Senti le rane che cantano. Canzoni e vissuti popolari

della risaia, Donzelli, 2005 (only in Italian).

Sassano, R., Camicette Nere: le donne nel Ventennio fascista, “El Futuro del Pasado”, 6, 253-280, 2015.

Mytheli Sreenivas, Conjugality and Capital: Gender, Families, and Property under Colonial Law in India, in “The Journal of Asian Studies”, Vol. 63, No. 4 (Nov., 2004), pp. 937-960.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?