THE CHINESE SHARD BOXES 2

Current China on the globe.

Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

This map is for illustrative purposes only. The Ethnic Home does not take a position on territorial disputes.

THE ASSAULT ON CHINESE HERITAGE: ERADICATING THE "FOUR OLDS" AND THE CASE OF IMPERIAL PORCELAIN

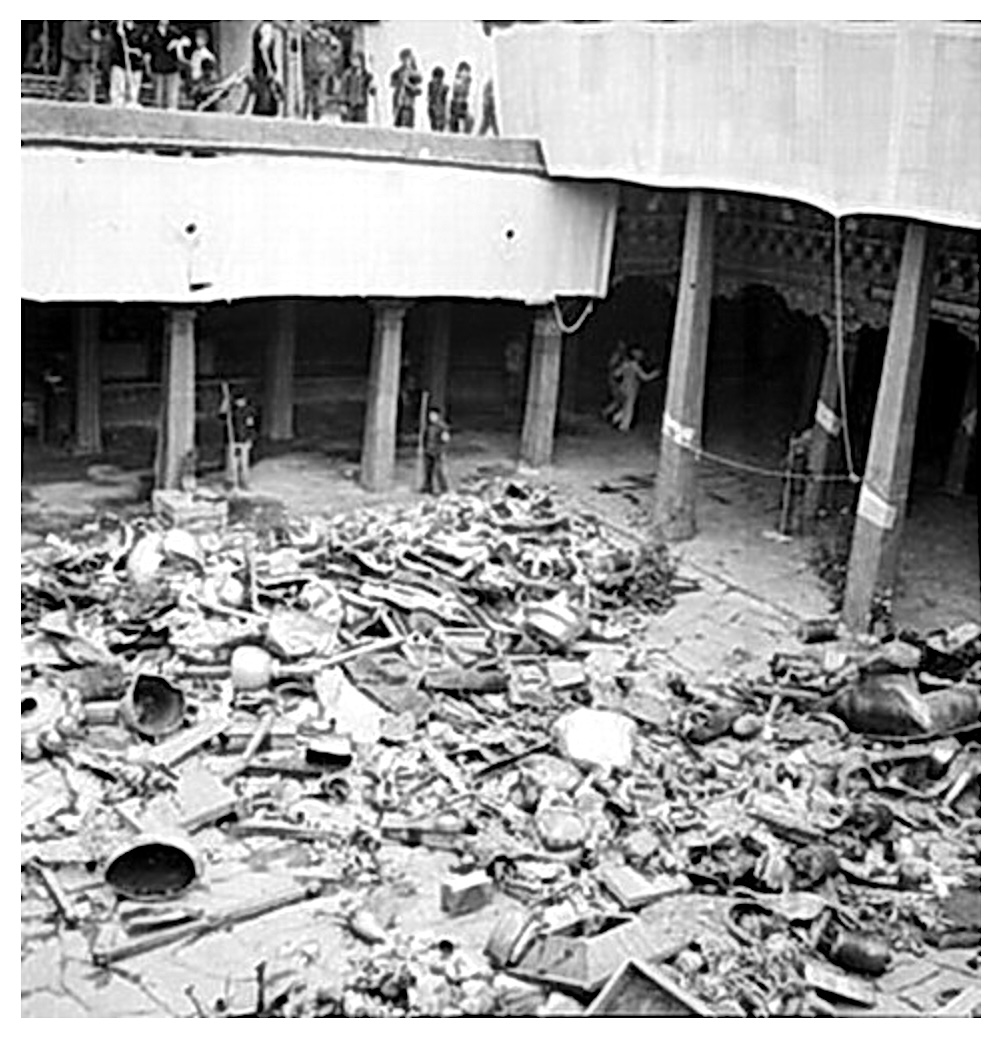

A central aspect of the excesses of the Cultural Revolution was the "Smash the Four Olds" campaign (1966–1968), which targeted "old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits" as feudal relics that obstructed proletarian progress. Red Guards ransacked thousands of homes, torched temples, burned books, and demolished artifacts in a frenzy of iconoclasm. Hung Chang-tai (2011) notes that in Shanghai alone, a total of 84,222 homes were searched during the "Attack on the Four Olds." Another record notes 150,000 households in the broader municipality. These data are based on reports from Shanghai's Wenwu Small Group.

Temples such as Beijing's City God Temple, where all images of the gods were smashed, and Shanghai's Longhua Temple, where thousands of volumes of scripture were incinerated and steeples were vandalized, suffered egregious losses (Hung, 2011, p. 692).

Nationwide, over 6,000 Tibetan monasteries were destroyed, erasing centuries of Buddhist heritage. (Goldstein, 1989; Smith, 1996).

Books deemed "poisonous weeds" were pulped for paper, and artworks were sold abroad for economic gain, blending ideological fervor with opportunism. (Wang, 2011: "The Red Guards burned 2.3 million books... Furthermore, 4,922 of the 6,843 historical sites were damaged or destroyed." Black-market reports from the era noted sales abroad.)

While some cultural bureaucrats salvaged items — collecting 280,000 artifacts in Shanghai, including bronzes and ceramics — for "class education," the overall destruction was catastrophic. This destroyed cultural continuity and impoverished future generations. Hung Chang-tai notes: "Between August 1966 and September 1967, the Wenwu Small Group received 280,000 pieces of wenwu ('cultural relics' or 'historical artifacts') and 360,000 volumes of books, including Shang and Zhou bronzes, Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing ceramics, and more than 8,000 jin of bronze objects" (2011, pp. 701–702).

Particularly poignant was the targeting of imperial porcelain, which was emblematic of dynastic opulence and thus a prime "Four Olds" symbol. Ming and Qing vases, Song celadons, and Yuan blue-and-whites—masterpieces of technical virtuosity from imperial kilns like Jingdezhen—were smashed in public spectacles or melted for scrap metal. Red Guards proclaimed such acts as "opening savage fire on the Four Olds," and collectors preemptively destroyed heirlooms to evade confiscation.

LEFT: Shatter the old world and forge a new one - 打碎旧世界创⽴新世界.April 1967. Source: chineseposters.net. "A Red Guard is shown smashing books, religious sculptures, and other items considered part of the "Four Olds." In the background, groups of Red Guards storm buildings and take down signboards. During the most violent phase of the Cultural Revolution, the property of 'rightists' and anything deemed old, bourgeois, decadent, or associated with religion was literally smashed to pieces en masse."

RIGHT: AI-generated image.

Antiques, porcelain pieces, and old texts destroyed by the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution.

The auto da fé or the burning of books, Buddha statues, and other antiques during the Cultural Revolution.

The auto da fé was a public ritual of the Spanish, Portuguese, and Mexican Inquisitions during which death sentences were announced against heretics. The destruction of books and artworks deemed heretical, idolatrous, or expressing dissenting ideas was often part of the ceremony. The term has also been used metaphorically to describe other instances of book burning. In Elias Canetti's novel Auto da Fé, which is about the destruction of a scholar's library, destruction is framed not as random violence, but as performative acts that demonstrate power, discipline bodies, and signal ideological purification. The spectacle of flames becomes a symbolic purge of dissent and curiosity.

Auto da Fé was Elias Canetti's first book and his only novel. Die Blendung (literally “The Blinding,” translated into Italian and other languages as Auto da Fé, a title chosen by Canetti himself) was published in 1935. It was subsequently banned and burned by the Nazis.

Mao's Red Guards by James Leibold.

This video is from Morning Sun, a two-hour documentary that recounts the history of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. The film provides a multifaceted view of this tumultuous period as seen through the eyes of members of the high school generation born around the time of the founding of the People's Republic of China in 1949 who came of age in the 1960s.

Why porcelain?

Imperial art embodied the "feudal hierarchy" defined by Mao's orthodoxy: scholar-official aesthetics, courtly taste, the cult of antiquity, and private connoisseurship. More than almost any other medium, porcelain condensed these offenses. It was the perfected craft of the court and kiln. It bore the marks of the reign. It circulated as elite capital. It decorated altars and scholars' studios alike. It was a symbol of privilege and inequality. Smashing a Kangxi vase or defacing a Qianlong plaque was a ritual disavowal of hierarchy. And it was easy to do.

At the same time, as we saw, Maoist cultural policy pressed the arts into new service. The same material systems that once served emperors were repurposed to broadcast revolution. There is a harsh logic here: to create a new revolutionary material culture, the old one must be silenced, delegitimized, and erased. Thus, historically valuable molds were destroyed as "feudal." Reserve stocks of decorated blanks, kept for export or high-grade domestic use, were seized, overpainted with slogans, or smashed. Archives and pattern books were scattered. Oral histories and factory records from Jingdezhen’s state-owned enterprises document the transition from mastery to mobilization and from connoisseurship to mass political utility.

The Geography of Destruction

Beijing, the heart of official heritage, suffered visibly. A 1972 survey found extensive damage to key sites in the capital alone, with thousands of protected places damaged or destroyed at the municipal level. While these figures are contested, as are almost all Cultural Revolution numbers, the pattern is clear: a metropolis of memory was forcibly reorganized. Notably, central authorities intermittently attempted to mitigate the damage, issuing instructions in 1966–67 to protect relics and books. However, the velocity of mass action repeatedly outpaced formal policy.

The campaign against the Confucian legacy resulted in one of the era's most notable desecrations. In November 1966, Red Guards from Beijing attacked Qufu, the hometown of Confucius, vandalizing the temple complex and cemetery. The tomb of the Yansheng Duke was desecrated, exposing ancestral remains. Chinese and Western researchers have reconstructed the incident using local reports and party documents. They note that even as the State Council signaled disapproval, local radicals pressed on.

Elsewhere, religious sites and family shrines were emptied, private collections were raided, and libraries of "reactionary" books were burned.

What was destroyed and what survived

The list of objects is as revealing as the motives. Porcelain with reign marks signaled dynastic legitimation and was therefore suspect. Scholar's objects, such as brush pots, inkstones with carved poems, and archaistic bronzes, "taught" deference to tradition. Court paintings and temple statuary invoked the hierarchies of heaven and the sovereign. In many neighborhoods, Red Guards compiled inventories of "old things," then staged public "smashing" campaigns in courtyards and lanes. Some objects were broken on the spot, while others were taken to work units for displays and denunciations. The act itself—public, performative, and definitive—was as important as the objects.

Yet, the story is not one of undiluted wreckage. Several of China’s most important institutions and sites survived thanks to protective interventions within the state: museum professionals hid items, curators mislabeled crates, and senior leaders quietly ordered cordons around the Forbidden City during times of danger. Scholarship on museum culture in the PRC acknowledges the political reestablishment of museums as well as the delicate, sometimes covert work of preservation during times of crisis.

Jingdezhen again offers a paradox. While Red Guards and revolutionary groups destroyed "feudal" patterns and purged elites, the kilns produced technically accomplished propaganda porcelain. The skills of throwers, painters, and firemen did not vanish; rather, they were redirected toward a new iconography. Meanwhile, the global art market absorbed what slipped through. Some pieces were smuggled or sold abroad, driven by a mix of opportunism and survival. After 1978, when the government shifted toward protecting and regulating exports, it codified grading systems for relics and tightened control over imports and exports. Much of the modern legal framework of the heritage bureaucracy we recognize today (SACH) traces back to this post-Cultural Revolution reckoning.

AI generated image

The Mechanics of Destruction: How Beauty Was Killed

Between mid-August and September of 1966—the height of the period known to survivors as Dapo Si Jiu, or "the great smashing of the Four Olds"—the Red Guards developed techniques that transformed destruction into performance art and made iconoclasm a form of cultural expression. The acts of destruction often had a spectacle‑like quality: crowds gathered, big‑character posters denounced “reactionary” objects and customs, and cultural relics were hauled into the open and smashed or defaced. While the process was far from completely uniform or strictly ritualised everywhere, in many cases the smashing of objects was far more organised and deliberate than mere spontaneous vandalism — objects were identified as bearers of old values, publicly condemned, and then destroyed so thoroughly that little remained to symbolise the “old world”. Major efforts to protect national‑level sites did intervene in some places — but the cultural destruction during this campaign nonetheless left a profound and long‑lasting impact on China’s heritage.

Not Illegal but Dangerous

According to some sources, keeping antique porcelain at home was considered illegal during the Cultural Revolution. However, this is not true. Let me clarify this point.

While it wasn't explicitly illegal to keep ancient porcelain at home during the Cultural Revolution, it was dangerous. No formal law banned private ownership, nor was there a national statute that declared owning ancient porcelain or other wenwu (cultural relics) illegal. In the People's Republic of China, private ownership of antiques had been legal since the 1950s, though heavily regulated. The 1950 Provisional Regulations on the Preservation of Antiquities and subsequent policies permitted individuals to retain family heirlooms, provided they were registered and not sold abroad. (Ho & Bronson, Cultural Heritage Management in China, 2004, p. 27: "Private ownership of antiquities was not outlawed; rather, it was subject to state oversight and export controls.")

However, in practice, possessing such items was extremely dangerous and often led to confiscation, public humiliation, imprisonment, or worse. This effectively prohibited most people from owning such items.

Red Guards were mobilized to search homes and destroy or confiscate anything linked to the "old society," including imperial porcelain—especially Ming, Qing, Song, or earlier pieces. Owning such items was interpreted as proof of a "landlord" or "capitalist" background, evidence of "counterrevolutionary" thinking, and justification for struggle sessions, beatings, or exile to labor camps.

Thus, many families destroyed their own porcelain to avoid persecution. According to Hale (2013), "many families destroyed their own antiques to prevent them from falling into the hands of the Red Guards." Fearing raids, countless families preemptively smashed or buried their heirlooms. Some turned them over to local authorities to prove loyalty. In Tide Players (2011), a survivor named Zha Jianying says: "My grandmother broke a Qing vase with a hammer herself—better us than the Red Guards."

How Chinese Families Hid and Saved their Wenwu

When the Red Guards began raiding homes in August 1966 to "smash the four olds," millions of families were forced to make an impossible choice: destroy their heirlooms or risk torture, imprisonment, or death at the hands of the Red Guards. Many chose a third option: hiding their porcelain, jade, paintings, and books in desperate and ingenious ways.

The most common method was burial in the countryside. Urban families sent children or relatives to bury items in village fields, under pigsties, or in ancestral graves. Objects were sealed in clay jars or iron boxes, and porcelain pieces were wrapped in cotton and placed in oil drums or ceramic jars. These were then sealed with wax and buried one to two meters deep. Burial sites were marked with secret landmarks—a tree, rock, or fence post—to serve as memory cues; no maps were drawn to avoid discovery.

In Life and Death in Shanghai (1986), Nien Cheng buried her Ming and Qing porcelain in the garden of a trusted servant's rural home. She retrieved them in 1980, but only three of the twelve pieces survived intact. Wang Shixiang, a famous collector, said in an interview in the 1990s: "Of my over 200 pieces of porcelain, only 37 survived — all buried in Hebei."

Another common method was to conceal them inside home structures, such as under floorboards, inside walls, in false ceilings, or behind furniture. Some people even built fake panels in wardrobes. One Beijing family hid twelve Song celadon bowls inside a hollowed-out kang, a heated brick bed. The bowls survived because Red Guards rarely dismantled beds.

Many chose to disguise their treasures. For example, calligraphy scrolls were coated with red Mao quotes in water-based paint, which could be easily washed off later.

Porcelain pieces were marked with fake factory stamps or adorned with Mao badges to make them appear mass-produced. In his novel The Crazed (2002), Ha Jin recalls a professor painting over a Tang Dynasty scroll with "Long Live Chairman Mao."

Some families partially broke the pieces on purpose, chipping the edges or cracking the pieces to make them look "already destroyed," then hiding the fragments. Others protected their precious antiques by entrusting them to individuals they knew to be loyal, such as maids, drivers, poor peasant relatives, and foreign friends. Diplomats or journalists, for example, smuggled small items out via embassy pouches. Zhang Xueliang, a collector, entrusted a precious Yuan blue-and-white jar to a driver, who buried it under a chicken coop for 15 years.

Some of the most famous and precious "survivors" include a Ming Xuande blue-and-white vase buried under a pigsty in Henan and recovered in 1982, a Song Ru kiln brush washer hidden in a wall cavity in Beijing and recovered in 1979, and a Qing famille rose platter wrapped in Mao’s Quotations and stored in an attic, where it was found in 1981.

The mere fact that any imperial porcelain survived is a testament to human resilience, loyalty, and ingenuity in the face of terror.

How many porcelain pieces were destroyed?

Quantifying the loss is difficult. Records are incomplete, hard quantitative data is scarce, many local reports were suppressed or revised, and the political stakes of memory remain high. A widely cited Beijing survey from the early 1970s documented extensive damage to protected sites, while central directives from 1966–67 formally urged protection, revealing the disjunction between policy and practice. Western overviews emphasize the scale of the destruction and the terror it caused. In contrast, Chinese legal scholarship highlights how the subsequent state built an apparatus to prevent a repeat of the destruction: grading relics, assigning protections, and regulating trade. Together, these sources point to the same truth: the decade forced China to decide what "heritage" would mean under socialism.

There are no reliable statistics that state, for example, "X% of Qing dynasty porcelain kilns were destroyed" or "Y pieces of imperial porcelain were deliberately smashed" during 1966-1976. I could not find a credible database that lists the number of porcelain objects destroyed or tracked by provenance during that period. Much of the evidence is anecdotal or qualitative, such as testimonies, recollections of the antique market, and general surveys of heritage loss, rather than precise figures.

Due to the lack of hard statistics, one must interpret the destruction of porcelain during this period based on indirect evidence. For example, the shift in production modes from traditional decorative and imperial motifs to revolutionary imagery implies a form of functional destruction. Traditional forms were either suppressed, reimagined, or rendered obsolete within the production system of the time. Several factors suggest that a substantial number of imperial and Republican-period porcelain objects were lost or destroyed between 1966 and 1976, though the exact number is unknown and likely varies by region and category (private collection, museum, or factory ware).

I searched Chinese archival and provincial sources for data on the destruction of imperial and Republican-era porcelain during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), but I could not find any reliable, comprehensive data on losses of porcelain ware alone. There are no credible nationwide statistics, nor is there data broken down by era (e.g., imperial vs. Republican), region, or factory/collection type (at least not in the open access literature). Many reports are "rough estimates" or "unverified counts" (e.g., "the nearly 4 million items of porcelain, paintings, and antiques" destroyed, according to one local source), and these aggregates mix object types, so we cannot isolate porcelain. Minimal archival publications of provincial museum or heritage bureau statistics are available that are specific to porcelain losses from this period. In many statistics, the term "porcelain" is grouped with "porcelain, paintings, antiques" (瓷器、字画、古典家具), making disaggregation difficult. Finally, many post-Cultural Revolution heritage surveys focused on immovable monuments and "major sites" rather than on individual movable artifacts in domestic collections or smaller kilns.

Additionally, during the Cultural Revolution, record keeping was disrupted; many institutions were closed or repurposed; and artifact destruction was part of a chaotic campaign, so systematic documentation was rare.

Aftermath: From Unmaking to Repair

When the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976, the work of repair began—both materially and conceptually. Museums rebuilt their collections, archaeologists restarted their journals, and Jingdezhen reoriented itself toward export markets and heritage tourism narratives that acknowledged the rupture while celebrating resilience. Scholars of Chinese heritage policy have noted the establishment and strengthening of institutions responsible for grading and protecting cultural relics, as well as the gradual development of import and export regulations intended to stop the loss experienced during the 1960s and 1970s. This was not simply nostalgia, but rather a new political settlement with the past that could coexist with reform and opening.

After Deng Xiaoping’s reforms in the 1980s, families dug up buried items, and many pieces reappeared at auctions. Furthermore, the new political leadership deemed all kinds of house raids illegitimate — one of the many excesses of the Cultural Revolution.

Walking through a gallery of imperial blue-and-white today, one sees absences: gaps in reign marks where sets were broken and losses known only because export records no longer match what survives. It is also to see continuities, such as the recognizable hand of a Jingdezhen painter across dynasties and decades, despite detours into suns and slogans. The Cultural Revolution did not end China’s old arts so much as force them through a period of disenchantment—an iron decade in which beauty was questioned for its social background, craftsmanship was accused of complicity, and memory itself was considered evidence.

And yet, the craft endured. Clay remembers the wheel, and the wheel remembers the hand. The revolution taught millions to see power in porcelain. The decades since have asked us to look again and also see the human artist behind the chrysanthemum scroll and Chairman Mao's profile. The history of a country learning how to live with its past lies between those two images.

The The Cultural Revolution ended, as all things do, but the destruction it caused became more significant over time. In the decades that followed, as China reopened to the world and began to rebuild its relationship with its past, the void left by the destruction of porcelain became a presence of its own—a negative space that defined everything that came after.

The destruction of porcelain during the Cultural Revolution achieved something no previous Chinese catastrophe had: it made beauty itself suspect. It transformed aesthetic pleasure into ideological danger and severed the connection between the Chinese people and their most profound cultural achievements.

This wound goes deeper than the physical destruction of objects. It represents the moment when Chinese civilization turned against itself, when it condemned its greatest achievements as criminal and judged its aesthetic development as counterrevolutionary. Breaking porcelain meant more than breaking objects; it meant breaking continuity and severing a cultural conversation that had continued for millennia.

Burning books and antiques

During the Cultural Revolution, it was not just porcelain that was broken, but also the dialogue between generations. Porcelain, refined over dynasties and passed through many hands, is not inert. It holds techniques, aesthetics, belief systems, trade stories, imperial desires, and spiritual motifs. When a Qing vase is smashed or a Tang scroll is burned, the act is performative; it's not about utility, but power.

The destruction of culture is always about controlling the narrative.

Cultural destruction is a theatrical representation of the desire to suppress dissent. The Red Guards' destruction of temples, artwork, scrolls, and ancestral shrines was not merely "youthful excess." It was a mass ritual of symbolic severance. It screamed: "The past is dead. The Party is now your ancestor."

Book burnings, artifact demolitions, and desecration of graves are all forms of semiotics violence. They send a message to onlookers: "This is what happens to those who worship the old gods, believe in other truths, or maintain private loyalties."

In this way, violence against objects becomes violence against memory.

Let's connect cultural memory with neurological memory — an analogy that is hauntingly accurate.

In neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's, the person we love slowly disappears, not because their body dies, but because their memory system collapses. Short- and medium-term memory loss sever the continuity of the self. Language fades, narrative falters, and relationships lose coherence. Eventually: "They no longer remember who you are — or who they are."

This isn't death in the biological sense, but rather a death of the narrative self — the inner autobiography that allows us to be someone over time. In this sense, memory is fundamental because it shapes and gives identity to consciousness.

When memory fades, what remains is not quite a person—at least not the person we knew.

Just as individuals lose themselves without memory, so do cultures.

A state, regime, or movement that systematically erases history through censorship, propaganda, or the destruction of cultural archives is not merely suppressing facts; it is reprogramming identity. This is a kind of intentional and instrumental social Alzheimer's.

Examples include:

- Destroying archives or rewriting history books;

- Banning commemorative rituals;

- Preventing intergenerational storytelling;

- Enforcing ideological language to replace organic cultural language.

They are acts of violence against memory and, therefore, against personhood—not of individuals, but of peoples.

As philosopher Avishai Margalit wrote in The Ethics of Memory: “Forgetting may be a condition for forgiveness, but enforced forgetting is a form of humiliation.”

Physical violence ends lives.

However, mnemonic violence can obliterate life stories — or deny that they ever existed.

- A bullet kills a person.

- Erasing their name, story, and picture from the public record kills them a second time. Concentration camps destroyed people immediately by replacing their names with random numbers and throwing them into a present with no memory or future.

In truth, much of political violence is designed to be mnemonic.

- Disappeared prisoners.

- Purged officials.

- “Unpersons” in Orwell’s 1984.

- Unmarked graves.

- Lost family lineages due to burned ancestral records.

Physical death ends a life. Erased memory removes all trace of it.

The Anthropological Insight: We Are Memory

There is a growing consensus in neuroscience, anthropology, and philosophy that memory is not just a function; it is constitutive. We are memory, not just have it. Our past selves, past choices, and past communities live on through individual and collective memory. When states destroy cultural heritage or suppress historical truth, they attempt to undo personhood on a large scale.

Many traditions, from Buddhism to Catholicism to Yoruba cosmologies, treat the memory of the deceased as a means of keeping them alive. To remember is to maintain a person's connection to the world. Therefore, when memory is violently severed, whether by cognitive decline, trauma, or censorship, it obscures more than just the past. It starves the future. Memory is the infrastructure of identity, so attacking it is a form of existential annihilation—a murder of meaning.

This is why the fight for history, remembrance, and cultural preservation is never merely academic. It is a fight for one's identity.

Burning books or destroying art is a crime that echoes ancient trauma embedded in the collective unconscious. That's certainly Jungian territory. Throughout human history, cultural erasure and violence against texts or artifacts have often preceded mass suppression or persecution:

- The burning of the Library of Alexandria, for example, signaled a fear of pluralism in the empire.

- Nazi book burnings in 1933 weren’t about paper — they were about silencing alternative worldviews.

- Qin Shi Huang’s “burning of books and burying of scholars” (c. 213 BCE) set a precedent for state control of truth.

- The Taliban’s destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas in 2001 warned the world about ideological dominance.

- In modern conflicts, the destruction of libraries and museums (e.g., Iraq in 2003, Syria, and Ukraine) continues this pattern.

Killing the Scholars and Burning the Books, anonymous 18th century, Chinese painted album leaf; Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris.

Around 213 BCE, during the reign of Qin Shi Huang—the first emperor of a unified China—a dramatic campaign of intellectual suppression unfolded. In an effort to consolidate power and eliminate dissent, he ordered the destruction of philosophical and historical texts that did not align with the official Qin ideology, particularly those associated with Confucian thought. Books deemed subversive were burned, especially those not related to medicine, agriculture, or divination. In a chilling extension of this purge, it’s said that scholars who resisted or continued to teach forbidden doctrines were executed or buried alive—a symbolic silencing of the intellectual class. Though historians debate the exact scale and historicity of the events, the episode has endured as a powerful image of authoritarian control over knowledge, remembered in Chinese memory as one of the earliest and most infamous acts of cultural erasure.

If you want to learn more about book burning, you can read this short and interesting article in Smithsonian Magazine: A Brief History of Book Burning, From the Printing Press to Internet Archives.

"Burning" is a ritualized warning. It's a warning to the living.

These acts are not about destroying knowledge per se. Rather, it's about instilling fear in the living and rewriting which types of knowledge are permitted to exist.

The Cultural Revolution's destruction of cultural artifacts generated intergenerational trauma, a type of trauma that often resists articulation.

- It affects both victims and perpetrators;

- It occurs in a context where speaking about it is constrained;

- It involves erasing the symbols necessary for processing grief.

These factors create a collective unconscious imprint, leaving an almost spectral presence of the destroyed past. Silence, censorship, and forgetting are active acts of control over what can be mourned.

Here's one final paradox: destroying heritage to erase memory often has the opposite effect—it sacralizes the very things destroyed.

Every smashed statue, every burned book, and every shattered piece of porcelain becomes imbued with meaning. In absence, we feel presence. In silence, we hear echoes.

This is why, while politically "settled," the Cultural Revolution continues to simmer beneath the surface — because its aesthetic and symbolic violence targeted the mechanisms by which a culture remembers, heals, and speaks.

The destruction of porcelain and books is not merely a loss of matter; it is an assault on continuity. Culture is not only what we create; it is also how we remember. Destroying culture is not only an attempt to erase dissent but also to colonize time itself: "There is only the now of revolution; the past is treason."

Yet, history has a longer memory than ideology. Shattered porcelain, buried books, and burnt archives often outlast the regimes that destroyed them, not because they physically endure, but because the human need for continuity and truth is stronger than any fire.

Is the Cultural Revolution still an open wound?

The destruction of heritage, particularly private porcelain and artwork, during the Cultural Revolution is a deeply sensitive issue in China due to censorship, controlled narratives, and ongoing societal trauma.

A widely cited official statement from 1981 labels the Cultural Revolution a grave error as part of a broader assessment of the period. That same year, the CPC issued a formal resolution titled Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party Since the Founding of the People's Republic of China (关于建国以来党的若干历史问题的决议). Adopted at the Sixth Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party on June 27, 1981, the resolution represents the Party’s official reckoning with the Cultural Revolution. It acknowledges severe mistakes and their consequences for the country, the Party, and the people. The resolution explicitly condemns the Cultural Revolution as a major catastrophe and assigns responsibility to various actors of that era. It also positions Deng Xiaoping-era reforms and the subsequent modernization program as corrective measures intended to prevent repetition. The Chinese state has a settled official narrative: the Party's resolution deemed the Cultural Revolution a major catastrophe but one that is now in the past, emphasizing the importance of maintaining social stability.

The 6th Plenary Session of the 11th CPC Central Committee adopted the Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of the Party since the Founding of the People's Republic of China, which reviewed major historical events of the Party over the 32 years following the founding of the PRC, especially the "Cultural Revolution."

While some aspects of the Cultural Revolution are discussed and some art and heritage have been restored or studied, open discussion, especially detailed, critical, or investigative historical research on the period’s destruction, is restricted. Many archives remain sealed, and the publication of in-depth accounts is often censored or discouraged. Public reception and memory in China have evolved unevenly. Although the official stance establishes a foundation for national discourse, open academic debate, archival access, and other forms of public memory are limited by contemporary political considerations and censorship. Consequently, nuance and critical historiography may be limited in mainstream discourse, even as scholars abroad and in some mainland venues engage with more complex reconstructions of the period.

When citing or relying on the 1981 resolution, it’s important to distinguish between the official document and subsequent historiography or commentary, as these may reflect shifting priorities or revised understandings over time. The formal resolution establishes the foundation of memory, and interpretive work often builds on it with archival research, oral histories, and global comparative perspectives.

The regime prefers a simplified narrative that focuses on moving forward; thus, collective trauma related to lost heritage and destroyed families is rarely addressed in public forums. There has never been a full truth and reconciliation process, public compensation, or widespread acknowledgment similar to those seen in other post-trauma societies. Attempts to commemorate or discuss the destruction of cultural property, such as the closure of China’s only Cultural Revolution museum in 2016, have faced political and administrative obstacles.

Scholars, journalists, and witnesses often describe the destruction of art, porcelain, books, and cultural relics as an unresolved "scar" or "open wound." Many survivors and their families still feel pain over the loss and subsequent silencing of their experiences. Of course, the term "open wound" is metaphorical, and how much it is felt by ordinary people may vary by generation, region, and individual. Younger Chinese people may feel a less direct personal connection, though heritage loss still matters. The fact of the destruction is clear, but the continuing "wound" is less easily measurable. It depends on memory, discourse, personal trauma, heritage sectors, and, of course, politics.

In some respects, the wound is still open because:

- The damage is partly irrecoverable.

- The subject has not been fully commemorated in an open and transparent public way.

- Research and discourse remain constrained.

- Material heritage loss remains tangible.

- For many people, especially older generations, the trauma lingers.

Analysis: How the Cultural Revolution changed China - The Straits Times, Singapore.

Street selling of souvenirs in today's Xibaipo. Herotop | Dreamstime.com

This contemporary image displays various Mao Zedong and Chinese Communist history-related souvenirs, including plates, statues, and pictures. Several pieces of memorabilia are displayed together. Today, commemorative items related to Mao can be found in various forms in China, including "red tourism" at significant historical sites, the circulation of Mao-themed currency, and the sale of collectible and antique items, such as badges, statues, and porcelain figures. A resurgence of nostalgia for the Mao era has created a market for these items. Collectors buy and sell items such as ceramic busts, socialist-era posters, and iconic Mao badges, as well as items from the Cultural Revolution. It's as if Mao were not responsible for the failed policies that led to the Great Famine and the Cultural Revolution. Once unmoored from historical knowledge, political nostalgia drifts into a dangerous disease that paves the way for flags raised over ruins, leaders cast as saviors of an ideological golden age that never was, and the silencing of those who remember differently. And this isn’t just about China.

- “Cultural Revolution Ceramics.” Curated research site aggregating archival and oral-history material on Jingdezhen and propaganda porcelain. https://culturalrevolutionceramics.com

- Goldstein, Melvyn C. 1989. A History of Modern Tibet, 1913–1951: The Demise of the Lamaist State. University of California Press.

https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/monastery-medium-tibetan-culture - Hale, Alex. 2013. “Burn, Loot and Pillage! Destruction of Antiques during China’s Cultural Revolution.” Antique Chinese Furniture.

https://www.antique-chinese-furniture.com/blog/2013/02/10/burn-loot-and-pillage-destruction-of-antiques-during-chinas-cultural-revolution/ - Hung, Chang-tai. 2011. “Revolutionizing Antiquity: The Shanghai Cultural Bureaucracy in the Early Cultural Revolution.” The China Quarterly 207: 689–714.

https://history.yale.edu/sites/default/files/files/revolutionizing%20antiquity.pdf - Li, Wen. 2020. “Where Did All the Ancient Chinese Porcelains Go?” LiWen Gallery.

https://liwengallery.com/where-did-all-the-ancient-chinese-porcelains-go/ - MacFarquhar, Roderick & Michael Schoenhals. Mao’s Last Revolution. Harvard University Press. Authoritative synthesis of the politics and mass dynamics.

- Oxford Reference / OUP Academic. Academic chapter on “Destroy the old, establish the new” (1966 Red Guard frenzy; Mao-badge production context).

- Oxford Research Encyclopedia. Scholarship on Chinese museum and heritage policy before and after the Cultural Revolution; relic-grading and import–export regimes.

- Research on Jingdezhen under state ownership during the Cultural Revolution (factory governance, purges, propaganda wares). (ResearchGate)

- Reports on Beijing damage and central directives to protect relics (policy vs. practice; 1972 survey figures). (Wikipedia)

- Smith, Warren W. 1996. Tibetan Nation: A History of Tibetan Nationalism and Sino-Tibetan Relations. Westview Press.

- Studies of the Qufu desecration and anti-Confucian campaigns (Chinese and Western academic reconstructions). (DRUM)

- Wang, Youqin. 2011. “Chronology of Mass Killings during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966–1976).” Sciences Po.

https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/en/document/chronology-mass-killings-during-chinese-cultural-revolution-1966-1976.html

FROM SHARDS TO BOXES

Blue dragons that once danced across imperial celadon were reduced to ceramic screams by the Red Guards — those teenage angels of destruction, armed with Mao's Little Red Book and the absolute certainty of youth. Phoenixes that had spread their wings across famille verte plates were reduced to broken feathers of jade-green memory.

The dragons and phoenixes smashed in 1966–68 did not disappear; they simply changed form, becoming fragments that travel the world in small boxes. Within their broken bodies, they carry the memory of heaven shattering and the earth learning to breathe with what remained.

The shard boxes that emerged in the 1980s were not just a commercial response to foreign demand; they represented something deeper: an attempt to create memory from absence and construct meaning from spaces where it had been destroyed. Each fragment, mounted in silver, wood, or paper, carries not just the memory of imperial beauty, but also the memory of revolutionary destruction — not just what survived, but what was lost.

MODERN CHINESE SHARD BOXES: BETWEEN MEMORY AND MARKETPLACE

When the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976, it left behind more than just political trauma. Among the rubble of smashed temples and ransacked homes lay millions of porcelain fragments — shards from Ming vases, Qing bowls and Song dynasty plates, shattered by Red Guards in the name of ideology. For the craftsmen who survived those years, these fragments represented something more tangible than historical loss; they were a free resource in an economy just beginning to awaken from state control. What emerged from this period was not just an art form or a business venture, but a craft that had to pay its own way while bearing the weight of the past.

While mounting ceramic fragments into boxes and jewelry existed in various forms prior to the revolution, the post-revolutionary period saw these techniques being adapted and refined into distinct methods that balanced preservation, commerce and cultural memory. Three primary approaches emerged: metal mounting, papier-mâché, and wooden construction.

Three Techniques, Three Markets

The craft has split into three distinct methods, each of which targets a different buyer.

Metal Mounting: The Silversmith's Efficient Approach

The most straightforward technique involved wrapping porcelain shards in metal. This method is known as baoqián (包嵌), which translates as 'encased inlay'. This was essentially a scaled-down version of traditional jewelry mounting, optimized for speed and volume.

The process began with selecting a suitable fragment, usually a piece from a broken bowl or vase with an attractive painted design. The craftsman would then cut a thin sheet of silver or copper into strips slightly wider than the shard's thickness. Copper was more commonly used for mass-market pieces, while silver was reserved for mid-range items. The metal strips were then annealed by being heated to between 600 and 700 degrees Celsius until they glowed red. At this temperature, the metal became soft and pliable, enabling it to be shaped without cracking. Once cooled, the craftsman would use a small bow drill to create holes in the metal where it needed to be bent around corners.

Next came the forming. Using a precision hammer, the craftsman would tap the metal strip around the shard's edge to create a lip that would grip the ceramic. This required a steady hand: if the hammer was struck too hard, the shard would crack; if it was struck too softly, the metal would not hold. The metal was never melted onto the porcelain, as this would destroy it, but rather coaxed into place through careful application of pressure. Files were then used to smooth any rough edges and polishing wheels were used to give the metal its final shine.

For higher-end pieces, a more elaborate technique called qiànsī (嵌丝), or 'wire inlay', was employed. This technique was borrowed from the cloisonné enamel tradition, in which twisted silver wire is shaped into decorative bezels that hold the fragments in place. First, the wire was bent into patterns — sometimes simple borders and sometimes intricate floral designs — then soldered onto a base plate. The porcelain fragment was set into this wire frame, securing it in place while adding ornamental value. However, this technique was labour-intensive and expensive, making it rare in post-revolutionary workshops focused on maximizing output.

The absolute finest fragments, particularly those bearing imperial marks from the Chenghua or Xuande periods of the Ming dynasty, were mounted in gold. But this was not the work of small family workshops. Instead, state-owned jewelry factories such as the Beijing Treasures and Gems Corporation handled these luxury pieces, using techniques derived from Qing dynasty jade mounting. The process was essentially the same as the silver method, but the gold frame elevated the fragment to the status of a high-end commodity, often sold to foreign dignitaries or exported for hard currency. A single gold-mounted shard could sell for more than a month's wages, providing a valuable source of revenue for cash-strapped state enterprises.

Shard box. The lid is made from a famille rose vase from the late 19th/early 20th century and is mounted on silver-plated copper. Dimensions: 5.5 x 9.5 x 3 3/8 inches; 13.97 × 24.13 × 8.57 cm. Auctioned in 2004 by Old Hat Auctions, Houston, TX, USA.

Details of the side decorations you can find in almost all silver-plated copper shard boxes.

Two medium-sized shard boxes made with silver-plated copper. The lids of both boxes are made from shards of famille verte porcelain vases from the late 18th century. My collection.

Four large silver-plated copper shard boxes. The lids are made using shards from 19th-century vases. My collection.

A collection of small shard boxes with blue and white porcelain lids. Side length: approx. 1.57 inches, 4 cm. Auctioned in August 2025 by Martel Maides, Guernsey, UK.

As you can see, shard boxes come in all shapes and sizes, with lids made from a variety of different types of porcelain shard.

Papier-Mâché: The Democratic Mass-Market Solution

Although metal mounting produced durable objects, it was relatively expensive and heavy. In response, a second technique emerged that was characteristically Chinese in its resourcefulness: papier-mâché bodies, or zhitāi (纸胎). This method transformed China's most abundant material, recycled paper, into lightweight, affordable vessels that were perfectly suited to the domestic mass market.

The process began with the collection of raw materials. Workshops collected old newspapers, vintage telephone books and propaganda posters — ironically, sometimes the very sheets of propaganda that had called for the destruction of porcelain — and tore them into strips. The paper was never cut, as tearing created softer edges that meshed together better. These strips were then layered over a simple mould — often just a wooden block carved into a basic box shape — with a paste made from rice flour and water. Unlike Western papier-mâché, which often uses glue, the rice paste created a strong, flexible bond that was less likely to crack over time. Craftsmen applied six to eight layers of paper, rotating each layer 90 degrees from the previous one to create cross-grained strength.

Once the basic shape had dried — usually over two or three days in a well-ventilated space — the box body was removed from the mould and excess paper was trimmed off. Then came the lacquering. The box received multiple coats of lacquer drawn from the sap of the lacquer tree — a material that Chinese craftsmen have used for millennia. For red boxes, cinnabar was added to the lacquer to create a deep, rich color that would not fade. Other boxes might be left black or brown. Each coat had to dry completely before the next one could be applied, which took two to three days. A typical box might receive five to seven coats, making this the most time-consuming part of the process.

The final step was to mount the porcelain fragment onto the lacquered surface. Unlike the metal technique, which physically wrapped around the shard, the papier-mâché method used a bed of lacquer to secure the fragment in place. The craftsman applied a thick dot of lacquer to the centre of the box, pressed the fragment into it and surrounded the edges of the shard with additional lacquer to create a smooth transition. This created a more integrated look, as if the shard had grown naturally from the box itself.

The result was an extremely light object that cost a fraction of the price of its metal counterpart. In 1990s Beijing markets, paper-bodied shard boxes sold for five to twenty yuan — roughly the price of a restaurant meal — while metal versions could cost eighty to three hundred yuan. This affordability was no accident; it was a deliberate business strategy. By using waste materials and simplifying production, workshops could manufacture these boxes on a large scale and sell them to tourists, students and ordinary families who wanted a piece of history without making a significant investment. The boxes became souvenirs, gifts and teaching tools — commodities that carried meaning but were priced to sell. These boxes were therefore democratic objects, but this democracy was also a business strategy: high volume, low margin. A workshop could produce hundreds of these boxes in the time it took to make a dozen metal-mounted pieces, generating a steady cash flow.

Shard box mounted on lacquered, hand-decorated papier-mâché. The lid is made from a shard of a Republican-period porcelain vase. Dimensions: 5 1/4 x 4 5/8 inches; 13.34 x 11.75 cm. Weight: 2 lb 1.3 oz.; 0.944 kg. My collection.

Very large shard box made of lacquered, hand-decorated papier-mâché. The shard originates from a giant 19th-century vase. Height: 14.57 inches; 37 cm. My collection.

Shard stacking box made of papier mâché. It features a porcelain shard from a large, blue-and-white vase likely dating from the late Qing dynasty. Dimensions: 15 x 16.5 inches; 38.1 x 41.91 cm. Auctioned in 2022 by Matthew Bullock Auctioneers, Ottawa, IL, USA.

Papier-mâché shard boxes are often styled after stackable lunch carriers, such as Chinese or Burmese tiffins or Japanese jubakos, creating a set of nested containers that can be used for storage, serving or decorative display. Their stackable, modular design references traditional Asian food-carrying systems used for centuries, combining utility and ornament.

Wooden Construction: The High-End Collector's Item

The most sophisticated technique involved wooden cores, known as mùtāi (木胎), which combined the durability of metal with the warmth of an organic material. Drawing on China's ancient lacquerware traditions, particularly those of Yangzhou, this method was aimed squarely at the high-end collector's market.

The process began with selecting the right type of wood. Pine was favored for its lightness and stability, though some workshops used poplar or basswood. The wood was then carved into the desired shape — usually a simple box with a fitted lid — and sanded smooth. The real artistry came in the lacquering. The box was coated with layer upon layer of lacquer, each one applied thinly with a fine brush. For the most prestigious examples, workshops used the tīhóng (剔红) technique, applying up to two hundred coats of red lacquer, each of which required days to cure properly. Building up the lacquer layers alone could take six months to a year.

Once the lacquer had reached sufficient thickness, the craftsman would carve into it, cutting through the layers to create intricate designs such as scrolling clouds, leaping dragons or delicate floral patterns. This technique dates back to the Ming Dynasty and creates a sense of depth as the different colored layers are revealed. A porcelain fragment was then set into a precisely carved recess in the lacquered surface and held in place by the carved design itself. This required extraordinary precision — the recess had to be shallow enough not to compromise the box's structure, yet deep enough to securely hold the shard.

After mounting, the box was placed in a humidity-controlled room for six to twelve months to allow the lacquer to fully set and the wood to stabilise. This prevented cracking and ensured that the different materials would expand and contract together in response to changes in temperature. The result was an object that could be sold for hundreds or even thousands of yuan, depending on the quality of the fragment and the intricacy of the carving. These were investments, not impulse purchases, bought by serious collectors, foreign diplomats and wealthy Chinese individuals who wanted to own a piece of their cultural heritage that had been restored to its former luxurious status. The artisans who made them were the most experienced and often worked on commission rather than producing items speculatively.

Families and Workshops

The shard box trade was never dominated by one dominant family. Instead, it grew organically through Beijing's existing craft networks. In the Liulichang antiques district, former employees of state salvage stations — places where damaged goods were sorted for potential resale — began setting up private stalls in the early 1980s. Many of these individuals had trained as jewelers or metalworkers prior to the Revolution, and they now applied these skills to porcelain fragments.

These were practical artisans who needed to feed their families. A craftsman might handle a dozen fragments in a day, selecting those with the most appealing painted designs — a snippet of a dragon's tail, a corner of a landscape or a single character from an imperial inscription, for example. The work was repetitive, but it allowed them to utilize skills that had been devalued for a decade. In this sense, making shard boxes was a form of cultural salvage in itself, rescuing not just the porcelain, but also the artisans who knew how to work with it.

The most well-documented lineage is that of the Zhang family of Beijing's Hongqiao Market, whose workshop, "Old Beijing Ceramic Memory" (老北京瓷忆), operated from 1991 to 2008. Interviews in Beijing Daily (2003) describe their process of mounting Cultural Revolution shards in silver plate, but these techniques were derived from standard jewelry casting rather than invented rituals.

The Liu family lacquer workshop in Yangzhou has kept continuous records since 1956, and the Yangzhou Lacquerware Museum collection features photographs of their experiments with porcelain inlay from the 1990s.

In Beijing, the Hu family salvaged porcelain shards after the Cultural Revolution and started using them to create boxes and jewelry in the 1980s. Hu Zonglu and his son, Hu Songlin, developed this craft initially using silver mounts and later expanding to include other materials such as wood and lacquer. The "Shard Box Store" and the craft emphasise the preservation of cultural heritage and the creation of affordable art objects, as well as the transformation of broken porcelain into decorative goods.

Hu Chunming, the grandson of the founder of the "Shard Box Store", Hu Zonglu, runs the shop in Beijing. It sells traditional silver-plated copper shard boxes and new cow bone shard boxes.

Market and Memory

If you ask a craftsman why he makes shard boxes, he will give you a practical answer: it pays the bills. But observe him at work and you will see more than just economic calculation. Many of these artisans had witnessed the destruction firsthand. They had seen beautiful objects — some centuries old, some from their own family homes — smashed in the street. Setting a fragment into a box was, in a sense, an act of redress.

This duality was evident in every aspect of the craft. A workshop might produce a hundred cheap papier-mâché boxes for the tourist market, using the profits to fund the creation of a single carved lacquer piece honoring a particularly fine shard, which could take a month. An artisan might spend their day mechanically wrapping fragments in copper, then their evening trying to match a rare Qing fragment with the perfect wood grain. The commercial and the commemorative were not opposites; they sustained each other.

The buyers had mixed motives, too. A foreign tourist might purchase a papier-mâché box as a curiosity or an original souvenir, unaware of its historical significance. A Chinese student, on the other hand, might buy one as an affordable connection to a heritage that she had been taught to reject. A collector might commission a wooden masterpiece as an investment, only to find himself moved by the fragment it contained. The meaning of each piece was not fixed at the time of its creation, but emerged through the act of buying, owning and living with it.

SOME WORDS TO CONCLUDE

Thus, the shard boxes reveal some of China's modern history and many small stories. They also reveal a truth: that most human creativity emerges from the messy middle ground between idealism and necessity.

The creation of these shard boxes was driven primarily by commerce, rather than nostalgia or cultural patriotism. The Cultural Revolution left thousands of craftsmen unemployed and impoverished, but the economic reforms of the 1980s provided an opportunity for them to use their skills to make a profit. The destruction of porcelain created a vast supply of free raw materials. The opening up of China to tourism and international trade created a market hungry for meaningful objects. This perfect convergence of supply, skill, and demand gave rise to the craft.

The shard box makers were neither saints preserving culture for its own sake nor cynics exploiting tragedy. They were simply skilled workers in a specific time and place, making practical decisions about how to apply their abilities to a new resource. In doing so, they created objects that carried memory forward — not because they set out to, but because memory is part of what gives craft its value, both economic and emotional.

By the early 2000s, the shard box trade had started to fade as the supply of quality fragments dwindled and newfound prosperity made such salvage work less necessary. What remains are the boxes themselves: some in museums, many in private collections and most forgotten in drawers. They are not relics of a heroic artistic movement, but evidence of how ordinary people, when faced with extraordinary circumstances, found a way to utilise their skills once more. This is the real story: not one of pure art or pure commerce, but of how the two can intertwine to create something that lasts longer than either motive alone could justify.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?