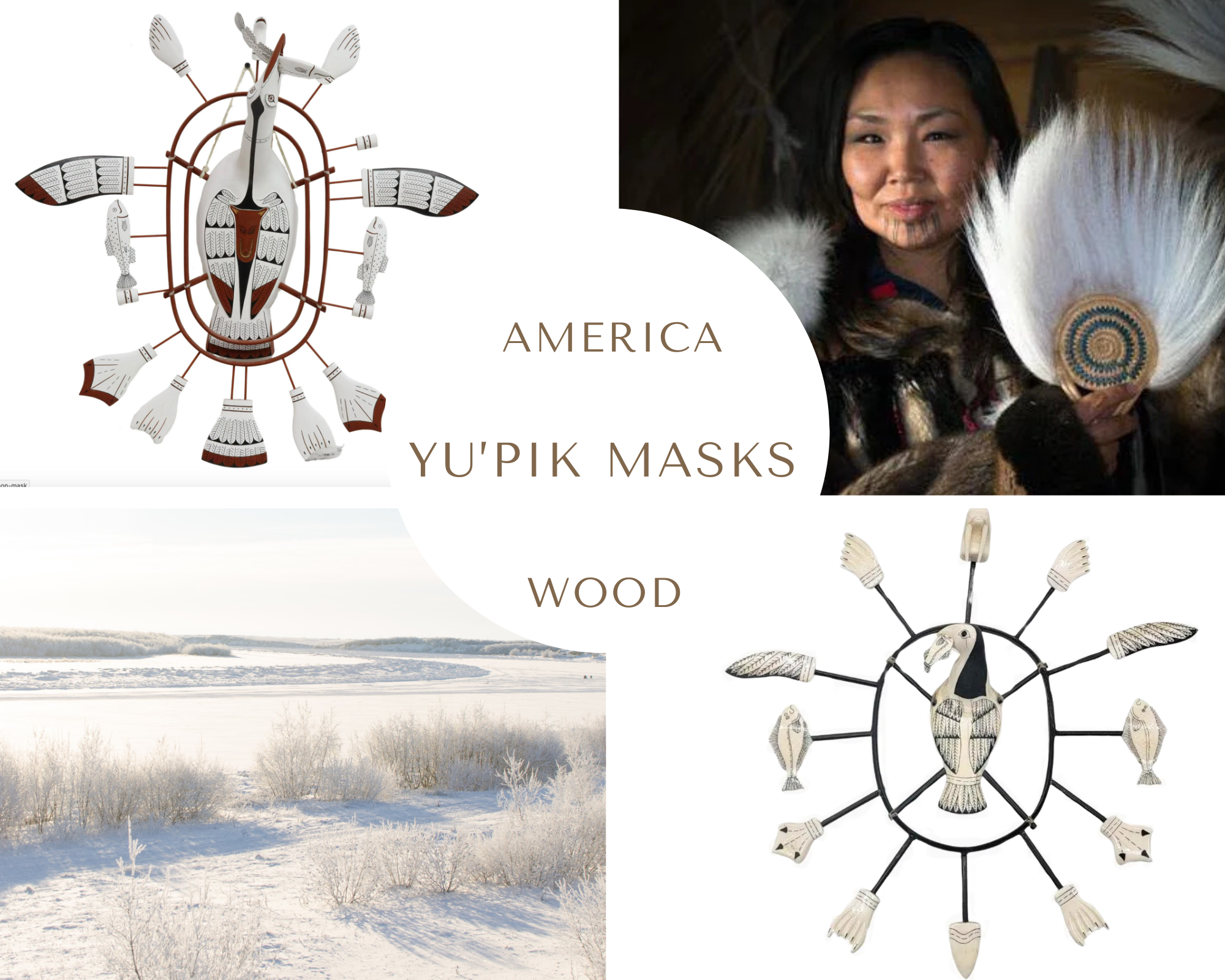

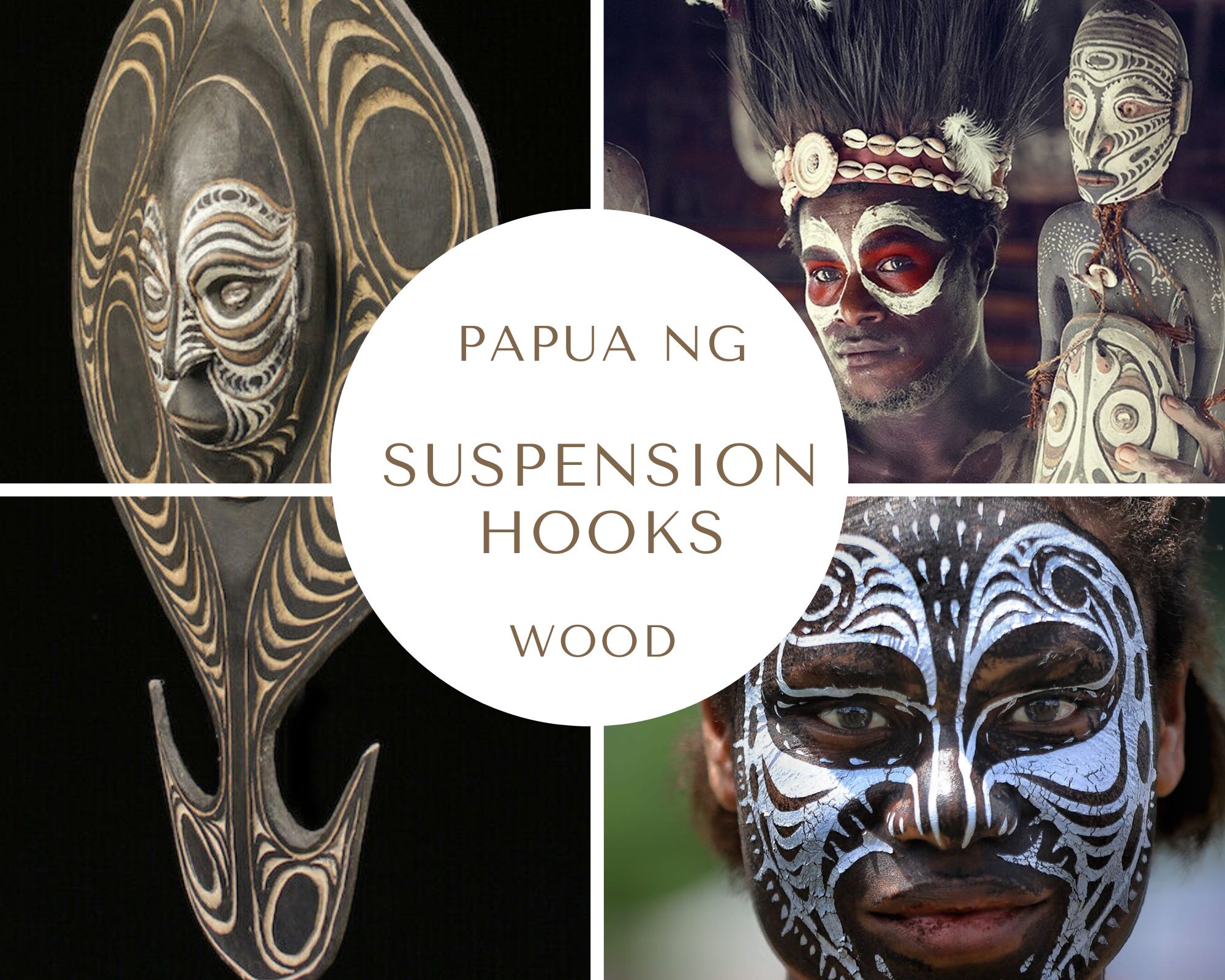

PAPUAN ANCESTRAL SUSPENSION HOOKS

Papua New Guinea on the globe

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

George Telek & David Bridie – Tatabai

Suspended Between Worlds:

The Suspension Hooks of the Iatmul and the Sepik River Cultures of Papua New Guinea

Along the serpentine course of the Sepik River in northern Papua New Guinea, the Iatmul and neighbouring peoples have created one of the most celebrated sculptural traditions of Oceania. One of its most distinctive forms is the suspension hook, also known as the samban or tshambwan. This carved wooden artifact is a mundane storage device, a powerful ritual object, and a condensed statement of cosmology all at once. Suspended from the rafters of dwellings and, more significantly, from the soaring ridge poles of men’s ceremonial houses (geko), these hooks safeguard food, clothing, and ritual paraphernalia, all the while mediating between human communities and the potent domain of ancestral spirits (waken). Drawing on early ethnographic accounts, recent art-historical scholarship, and museum documentation, this essay examines the suspension hook as a privileged vantage point from which to understand Sepik concepts of personhood, exchange, ritual efficacy, and the politics of cultural representation in colonial and postcolonial contexts.

Framed that way, our journey might sound dull—but it won’t be, I promise. It’s a cliché to think that a ‘serious’ approach must be heavy and boring, while only a superficial, pop style can be fun. In truth, our path will feel more like an expedition into little-known territories, uncovering fragile realities we never imagined could exist on our extraordinary planet.

Finely carved wooden Suspension Hook, collected in Iatmul area, Medium Sepik. Dimension: 69 x 28 cm; 11.02 x 27.17 in. My personal collection.

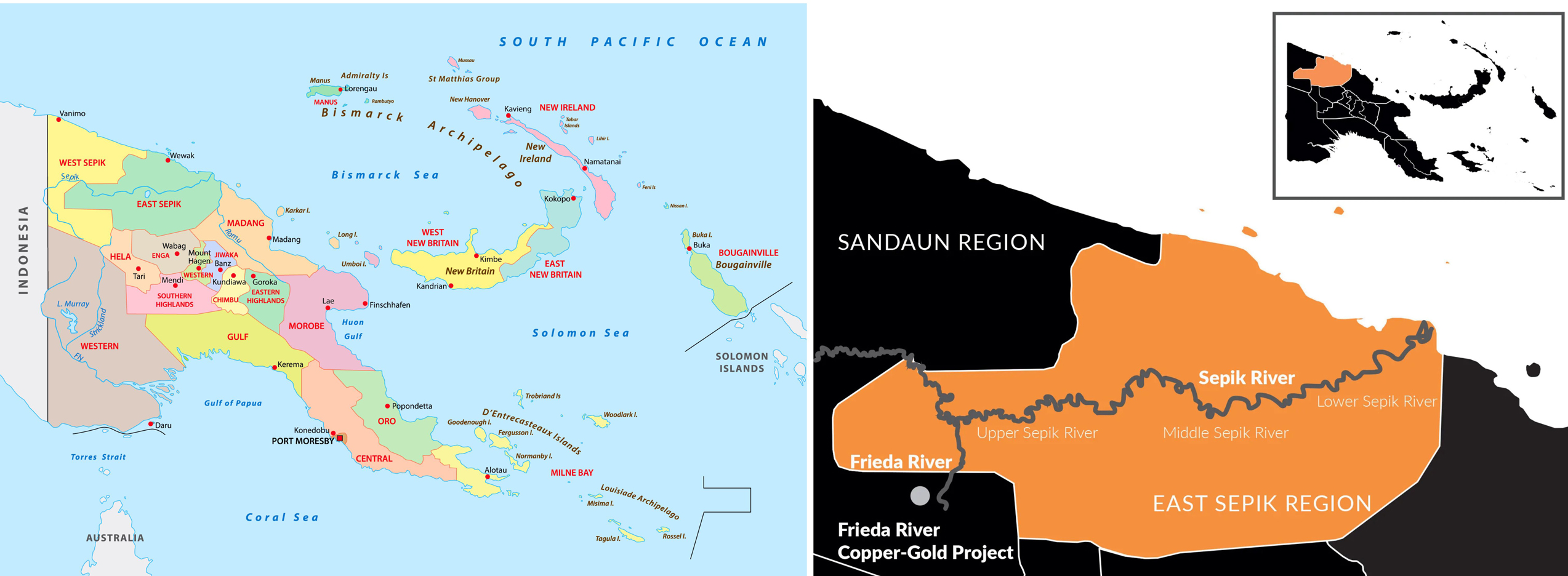

OUR EXPLORATION MAP

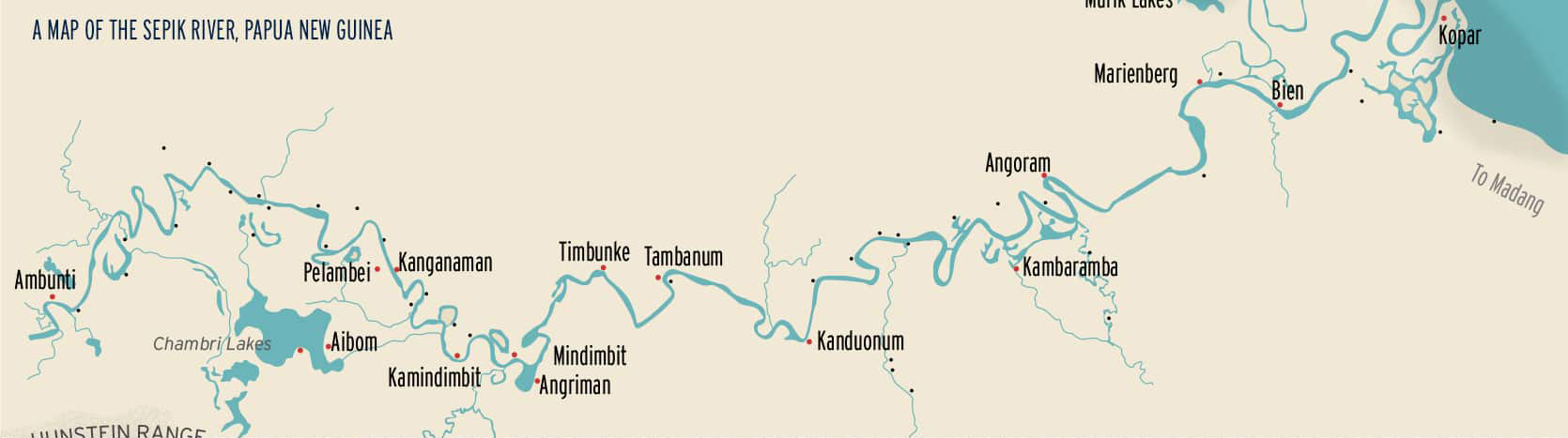

The Sepik, one of New Guinea’s great rivers, rises in the Victor Emanuel Range. It briefly enters present-day Indonesia before meandering east through the vast Central Depression of Papua New Guinea to reach the Bismarck Sea. Its length is commonly given as approximately 1,126 kilometers.

The term “Middle Sepik” specifically refers to a stretch of the river and its surroundings located centrally within the Sepik Basin in northern Papua New Guinea. This geographical and cultural term defines the great floodplain roughly between Angoram (downstream) and Ambunti (upstream). This 200 km sector forms the axial corridor of the Sepik River and is the twelfth largest riverine network on Earth.

LEFT: Map of the Sepik River watershed in northern Papua New Guinea. Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

RIGHT: Along the Sepik river, photo by Bruce Fryxell – Flickr.

The watershed covers approximately 70,000 square kilometers (7.7 million hectares), making it the largest unpolluted freshwater system in Papua New Guinea. It is also one of the largest and most intact freshwater basins in the Asia-Pacific region. The river itself is the third largest in Oceania. The region is home to hundreds of lakes, swamps, tropical rainforests, and mountains that support unique and diverse ecosystems with rare and endemic plant and animal species. The Sepik basin is globally recognized for its biodiversity and contains two Global 200 ecoregions, three Endemic Bird Areas, and three centers of plant diversity. The region’s wetlands act as natural water filters and carbon sinks, providing critical ecosystem services and supporting abundant populations of birds, fish, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians. For these reasons and more, the Sepik basin is often called “the Second Amazon.”

East Sepik Province. Photo: Discovery PNG.

BELOW

Photos by Natalie Whiting and Matthew Roberts – ABC News Australia

The Middle Sepik River meanders through a floodplain characterized by swamps, bow-shaped lakes, and lagoons. This floodplain is fed by tributaries such as the Karawari and Yuat rivers. Sago (Metroxylon sagu) and nipa palm swamps dominate the lower and middle regions. Active levees flank the river here, where the annual flood flow is intense. The terrain grades from lowland alluvial rainforest to seasonally flooded grass-sago swamps, and the tropical climate maintains an average humidity level of 80% throughout the year. In short, this is a world built by the river.

The Sepik watershed is home to around 430,000 people and is perhaps the most linguistically and culturally diverse area on the planet. Over 300 languages are spoken in an area the size of France. The Middle Sepik floodplain and adjacent lowlands are a true mosaic anchored by the river. The Middle Sepik is home to riverbank “water people” and inland “bush/jungle dwellers,” a distinction that shapes travel, subsistence, and trade. Along the main channel live the Iatmul, best known from Gregory Bateson’s classic ethnography, Naven, together with their close neighbors, the Sawos and the Manambu. All of these groups are part of the Ndu family of Sepik languages. Inland, on levees, lakes, and low hills, live the Sawos and the Abelam (also Ndu). Around the Chambri Lakes live communities that speak Chambri. These last three languages belong to the Lower Sepik branch of the Ramu–Lower Sepik phylum, which consists of languages distributed around lakes, the lower river, and southern tributaries.

Villages are typically strung out along natural levees or built on piles above wet ground. In Iatmul communities such as Tambanum, Kanganaman, Palimbei, Kararau, and Korogo, men’s ceremonial houses (haus tambaran) dominate settlement skylines. These structures, with their soaring, decorated gables and massive carved posts, concentrate ritual, political debate, and artistic production.

Map by Coral Expeditions, Australia.

BELOW

Photo by Natalie Whiting and Matthew Roberts – ABC News Australia

Along the Sepik river © Kelvin Sogoromo | Dreamstime.com

Along the Sepik River

LEFT: Canoeing along one of the Sepik River’s many channels. In the Middle Sepik region especially, the river is characterized by a vast and intricate network of channels, tributaries, oxbow lakes, and seasonally flooded swamps. These channels wind through dense vegetation and support a variety of ecological zones, creating a dynamic and ever-changing riverscape that influences local travel, settlement patterns, subsistence practices, and cultural connections.

RIGHT: A village in the Sepik area. Many villages along the Sepik River, including those in the Middle Sepik region, are traditionally built on stilts. This stilted architecture is a response to the region’s dynamic environment. The Sepik River and its numerous channels regularly flood, and the wetland terrain is prone to seasonal waterlogging. Houses are raised above the ground or water using sturdy wooden posts, which protect inhabitants from flooding, snakes, and insects while providing better air circulation in the humid climate. These stilt houses are typically built with local materials, such as sago palm, bamboo, and hardwoods. The floors and walls are often woven from split palm or reed mats. This adaptive architectural style is common to everyday dwellings, guest houses, and even ceremonial haus tambaran, allowing Sepik communities to thrive within their complex riverine ecosystem.

Daily life in a village on the banks of the Sepik River. Photo by Tryfon Topalidis, 2020. Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Daily life revolves around the flood pulse, including sago processing, floodplain gardening, fishing, and crocodile hunting.

There are two species of crocodiles: the saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) and the New Guinea crocodile (C. novaeguineae). Long-running nest surveys from May to Karawari, spanning the Middle Sepik, inform management programs. The C. novaeguineae population in the middle and upper Sepik has remained stable over several decades of monitoring. Local initiatives, such as the Sepik Wetlands Management Initiative based in Ambunti, have emerged to protect nesting habitats from dry-season grassland burning.

Two specimens of Crocodylus novaeguineae. Under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.

A specimen of saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus). Public Domain.

For centuries, specialized products circulated through tightly woven regional exchange networks. The Aibom people of Chambri supplied coil-built pottery, while lake and river peoples traded fish for sago from upriver communities. Valuable shells and plumes moved through marriage and ritual alliances. Classic and contemporary studies of the Chambri people (formerly spelled “Tchambuli”) document six-day barter markets that linked lake-dwelling women traders with hill communities.

THE IATMUL PEOPLE AND THEIR NEIGHBORS

The Iatmul are one of the most prominent cultural and linguistic groups in the Middle Sepik River region of Papua New Guinea. They are best known for their elaborate ceremonies, complex social structure, artistic achievements, and pivotal role in Sepik rituals and intergroup relations.

Their territory begins approximately 230 kilometers upstream from the Sepik’s mouth and extends about 170 kilometers farther upstream. It encompasses numerous villages that have developed sophisticated material cultures adapted to their amphibious way of life. Numbering approximately 10,000, the Iatmul people inhabit some two dozen politically autonomous villages and classify themselves into three territorial subgroups: eastern (Woliagui), central (Palimbei), and western (Nyaura). Each community maintains its own cluster of clans and lineages, with membership conferred through patrilineal descent. Each group has its own ancestral history of migration and settlement.

Early ethnography by Gregory Bateson and subsequent research describe a culture with extensive ceremonial exchange, dual descent, and highly gendered yet complementary roles for men and women. Women supply staple foods and market items, while men focus on ritual activities, crafts, and canoe building.

The Iatmul’s mixed economy is based on river fishing, gardening, some hunting, and trading fish for sago with the Sawos.

Along the Sepik river, photos by Bruce Fryxell – Flickr.

Along the Sepik river, 2007. Photo by David Bacon. Under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

The entire village of Kambaramba is perched on stilts in the water of an open lake connected to the Sepik River. Photo by Visit Papua New Guinea, Facebook.

A SHORT HISTORY OF THE SEPIK AREA

Before Colonial Rule

Archaeological research in northern New Guinea suggests that the Sepik–Ramu basin was once occupied by a vast inland sea which gradually receded during the Holocene epoch. As the floodplains stabilized, populations settled along the river courses and developed intensive fishing and sago exploitation, as well as far-reaching exchange networks. Linguistic evidence places the Ndu language family, to which the Iatmul language belongs, in the lower Sepik floodplain. Neighboring Lower Sepik languages are found along tributaries such as the Karawari and Yuat rivers. These distributions align with Iatmul oral traditions that depict migration, alliance, and intergroup contact as pivotal forces in the region’s history.

German New Guinea (1884–1914)

In 1884, Germany declared a protectorate over northeastern New Guinea. The following year, the ship Samoa entered the Sepik estuary, marking the beginning of sustained European contact. The naturalist Otto Finsch renamed the river Kaiserin Augusta. Subsequent German expeditions — notably the 1912–1913 Kaiserin-Augusta-Fluss expedition led by Walter Behrmann — mapped hundreds of kilometers of the river, collected extensive flora, fauna, and ethnographic specimens, and documented Iatmul villages and art for the first time. Although direct colonial control in the Sepik region remained limited, these exploratory missions laid the foundation for an administrative presence and missionary activity.

German postcards and stamps depicting Deutsch Neu Guinea, the German colony of New Guinea.

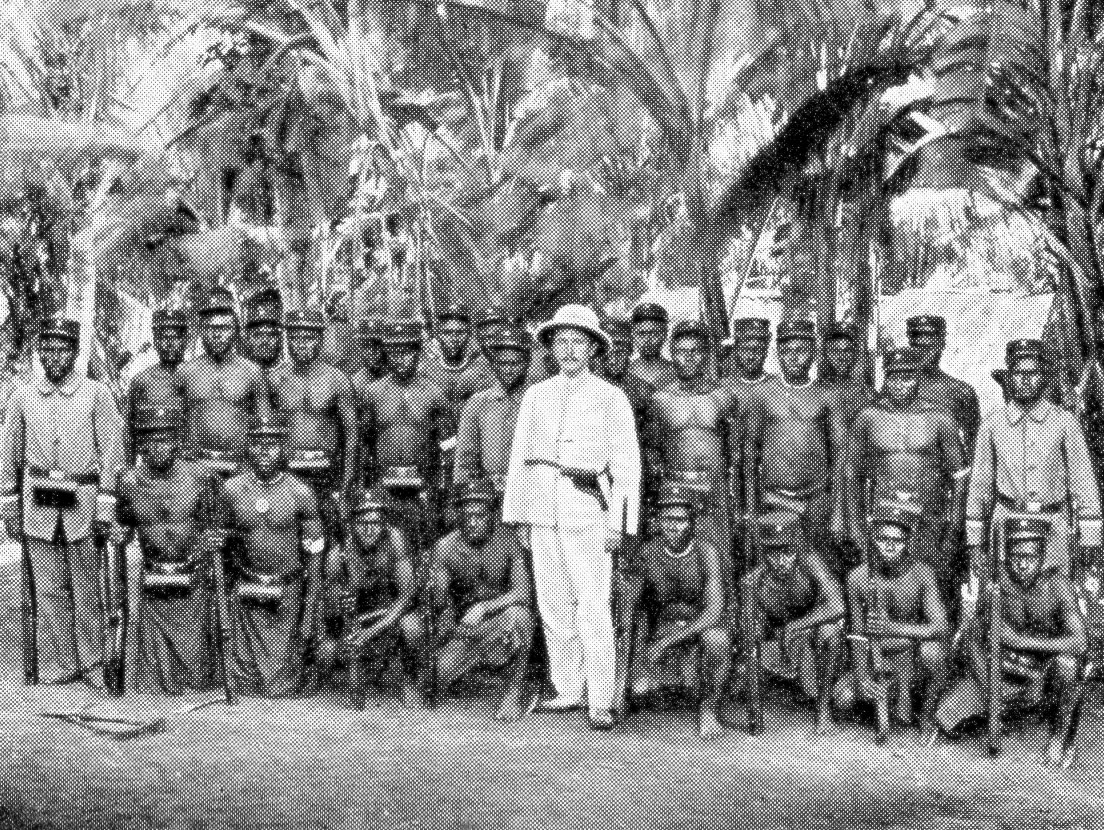

Dr. Heinrich Schnee, Herbertshöhe (now Kopoko) in the Deutsch-Neuguinea (German New Guinea), with members of the New Guinea police force, 1900. Public Domain.

The Australian Mandate and Early Stations

Following Germany’s defeat in World War I, the League of Nations transferred the administration of northeastern New Guinea to Australia. Angoram, located on the lower Sepik River, became a key station in 1913, while Ambunti, founded in the 1920s, served as the upriver government base. From these posts, patrol officers sought to suppress inter-village raiding and headhunting, practices that were deeply intertwined with Iatmul rituals and social prestige.

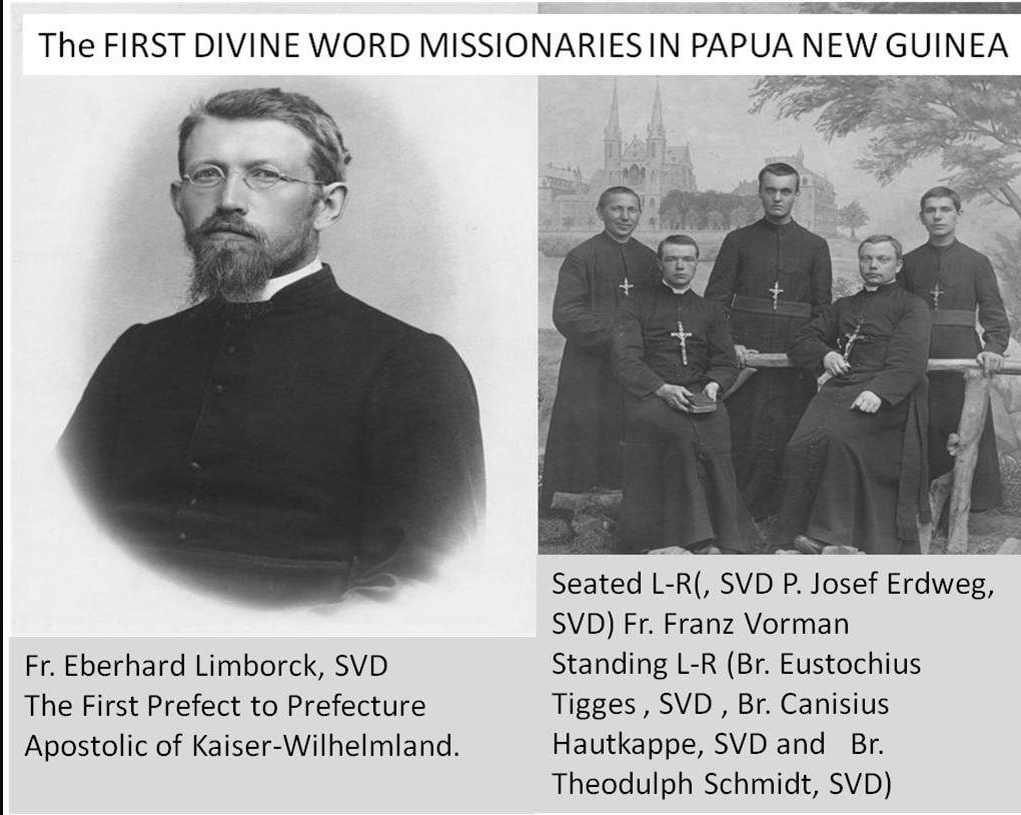

Missionaries soon followed. The Catholic Society of the Divine Word (SVD) and Lutheran missions traveled along the navigable waterways of the Sepik, establishing schools, chapels, and mission stations. Their impact was far-reaching and devastating to local cultural life in many respects:

- Suppression of ritual houses (haus tambaran): Missionaries denounced men’s ceremonial houses as pagan or demonic. Many were destroyed or abandoned, which severed the continuity of ancestral knowledge, ritual cycles, and the training of initiates.

- Prohibition of sacred objects and performances: Carved ancestor figures, masks, and spirit instruments—central to Iatmul cosmology—were confiscated, burned, or sold to collectors. Rituals such as initiation scarification and naven celebrations were discouraged or banned outright.

- Recasting of social values: Mission teachings condemned polygyny, exchange practices, and ritualized warfare. These teachings imposed new moral codes that undermined traditional mechanisms for regulating rivalry and alliance.

- Erosion of indigenous authority: By elevating catechists, mission teachers, and baptized converts, the missions displaced the authority of clan elders and ritual leaders, thereby eroding the legitimacy of ancestral law.

While the missions introduced literacy, healthcare, and new forms of religious expression, their legacy in the Sepik—as elsewhere in Papua New Guinea—is inseparable from the erosion of indigenous ceremonial life and the silencing of ancestral voices. As Brigitta Hauser-Schäublin and Eric Silverman have demonstrated, what survived often did so by adapting to new conditions. Sometimes this adaptation occurred by hiding from missionary eyes, and sometimes it occurred by being reshaped for later tourist and heritage contexts.

The first Divine Word Missionaries arrived in Friedrich-Wilhelmshafen (now known as Madang) on August 13, 1896.

Leo Clement Andrew Arkfeld (born in 1912 in Butte, Nebraska) was an American clergyman and bishop for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Wewak. The Sepik region of Papua New Guinea was his first and only mission. He spent the first two years as pastor of Lae (1946-1948). Then in 1948 at the young age of 36, he was appointed Vicar Apostolic of Central New Guinea taking up his bishop’s residence in Wewak. He would spend the next 51 of his life as a missionary bishop in Papua, serving the later part of his episcopate as archbishop of Madang.

Now, it’s time to explore the complex Iatmul universe in more depth.

INTERGROUP RELATIONS AND TRADE

Iatmul villages are not economically self-sufficient; they maintain symbiotic trade relationships with neighboring groups.

- Riverine Exchange: Goods such as fish, sago, pottery, and ritual objects are traded along the Sepik River, connecting Iatmul villages to Sawos, Chambri, and Abelam communities.

- Ceremonial Trade: Sacred items like carved masks, flutes, and totemic relics are exchanged during inter-village ceremonies, creating alliances and debt relationships that ensure long-term cooperation.

- Bridewealth and Compensation: Marriages and conflict settlements involve the exchange of pigs, shells, and ritual knowledge, integrating economic and social transactions.

Thus, Iatmul intergroup relations are shaped by a dynamic system of exchange and barter involving not just economic goods but also ritual objects, raw materials, and ceremonial knowledge.

The Korogo barter market, located in Korogo village in the Middle Sepik region, is a traditional gathering place where people from the river and inland areas trade goods directly without using money. Villagers bring fish to trade for sago, fruit, vegetables, and betel nuts provided by mountain and inland communities. This exchange reflects the region’s long-standing economic and social patterns, where mobility between ecological zones supports subsistence and social ties.

There is complementarity with the Sawos (bush-dwellers) and routine women’s trade. For instance, their interactions with neighboring Sawos groups involve reciprocal exchanges that go far beyond simple barter economics. Sawos women trade sago starch with Iatmul women in exchange for fish. This exchange serves nutritional and social security purposes, reinforcing alliances and social bonds. The Iatmul rely on the Sawos for essential resources such as timber for canoes, palmwood for spears, and rattan for construction and rituals. In contemporary times, they often pay significant sums for these materials. Historically, Iatmul trade involved ritual goods, such as trophy skulls. Later, they adapted to new prohibitions by creating substitute objects, such as overmodelled turtle shells with human faces, for tourism. Trade and intergroup marriage also served as mechanisms to reduce conflict and facilitate social integration in the broader Sepik area.

A Sawos woman collects sago. Photo by John Langton Tyman, a geographer and anthropologist who lived some years in the Sawos people’s village of Torembi, in the East Sepik province. In his John Tyman’s Cultures in Context Series, you can browse his interesting People of New Guinea.

Sago harvesting involves several distinct phases: First, Sawos women harvest sago palms from their swampy territory. Then, they cut down the trunk and split it open to extract the starchy pith. They grate or crush the pith, mix it with water, and squeeze the pulp through a strainer to separate the starch. The resulting sago starch is left to settle. Then, the water is drained off and the starch is packed into baskets or containers for transport and trade. Sago starch is a dietary staple in the Sepik region. It is used to prepare porridge, bread-like cakes, and dumplings. It is traditionally served in decorated bowls called kamana, which are important for everyday meals and ceremonial feasts. Sago also has ritual uses, symbolizing abundance and communal ties in exchanges between groups, such as the Sawos and the Iatmul.

Old and vintage kamana, namely decorated sago bowls made by the Sawos in East Sepik. Photos by GJPaw Auctions – Primitive, Chicago, IL, USA, and Theodore Bruce Auctioneers & Valuers, Stanmore, NSW, Australia.

LEFT: Sago pancake preparation in a clay oven in Yamok Village in the Sepik River area in 2009. Photo by Efrat Nakash.

Efrat Nakash is an Israeli photographer, archaeologist, life coach, and certified tour guide. She has managed archaeological excavation sites, led outdoor photography projects, and given presentations about traveling to exotic locations, including Papua New Guinea. She shares her work on her website, where she also offers touring tips. She has participated in long-term travel and documentary photography projects. All of the photos in this article have been published with her personal authorization. (Thank you, Efrat! I am grateful!) Please do not copy or use them in any way without consent.

RIGHT: A sago pancake made only with water and starch from the Sago palm, East Sepik Province, Papua New Guinea, 2004. Creative Commons.

Ties with Chambri/Aibom and the circulation of pottery. Around Chambri Lake, long-standing relations encompassed both conflict and exchange. Historically, Iatmul raids forced Chambri populations into temporary exile. Still, the lake communities (including potters at Aibom on the Iatmul side of the river) remained embedded in trans-village trade circuits. Pottery from Aibom and other Sepik locales moved through barter networks where shell valuables could serve as payment. These same valuables also circulated in bridewealth and rituals.

A Chambri man and child along the canal that links the Sepik to the Chambri Lake. Photo by Weli’mi’nakwan / Flickr. Under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license.

Women fishing on Chambri Lake. Discover PNG, Facebook.

A canoe fisherwoman from Kararau carries her catch of the day on the Sepik River in 2009. Kararau is a Sepik village located in the Middle Sepik region. It is inhabited by Eastern Iatmul people. Anthropological research places Kararau firmly within the territory traditionally occupied by the Iatmul. It lies south of the Sepik River and is known for its close connections to Sawos villages, local barter markets, and the broader Sepik cultural landscape. Photo by Efrat Nakash.

Chambri Pottery

LEFT: A pottery vessel with a pig’s face from the mid-20th century. It was found at Chambri Lakes in the East Sepik Province of Papua New Guinea. This delightful sago storage pot is made of coarse red clay and is painted with a white-on-gray motif on the projecting boar face that encompasses the handle. Dimensions: 7 x 12.5 in. (17.8 cm x 31.8 cm). It was auctioned in 2019 by Artemis Fine Arts in Louisville, Colorado, USA.

CENTER: Pottery vessels from the mid-20th century from Chambri Lakes in the East Sepik Province of Papua New Guinea. This attractive set of hand-built pottery vessels is made from coarse red clay and is painted with a white-on-gray motif. The larger vessel depicts an abstract avian head with concentric circle eyes and a projecting beak. The smaller vessel features a similar design with additional raised concentric circles and ovals adorning the lower body. Dimensions of the largest vessel: 7.55 x 11.5 in. (19.2 cm x 29.2 cm). Auctioned in 2019 by Artemis Fine Arts, Louisville, CO, USA.

RIGHT: Pot from the 1990s from Aibom Village in the Chambri Lakes region of the East Sepik Province in Papua New Guinea. Medium: Shell, pigment, and synthetic polymer on earthenware. Dimensions: 12.1 × 9.2 × 10.2 cm. National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia.

Down-the-line and coastal connections. Iatmul traders maintained links with partners in the lower Sepik region and along the coast. Shell ornaments and other items moved along these routes. Scholar Eric K. Silverman demonstrated that shell valuables indexed not only wealth and social distance, but also functioned as mnemonic “maps” of travel and exchange pathways.

Marriage, language contact, and neighboring Ndu peoples were also important. Beyond goods, intergroup ties included intermarriage and bilingualism, especially with Manambu communities. Linguist Aikhenvald notes that trade and marriage with the Iatmul are key drivers of lexical diffusion and ongoing contact.

IATMUL POLITICAL AUTONOMY

Despite their linguistic and cultural similarities, each Iatmul village is politically autonomous, and there is no overarching tribal authority. Inter-village relations are managed through:

- Diplomatic Oratory: Skilled speakers negotiate alliances, trade agreements, and conflict resolutions in inter-village councils.

- Ceremonial Visits: Delegations travel to neighboring villages to perform rituals, exchange gifts, and renew alliances, often during initiations or mortuary ceremonies.

- Competitive Exchange: Eastern Iatmul groups engage in competitive ceremonial exchanges where lavish displays of wealth and ritual knowledge enhance a village’s prestige and influence.

THE IATMUL’S COMPLEX SOCIAL STRUCTURE

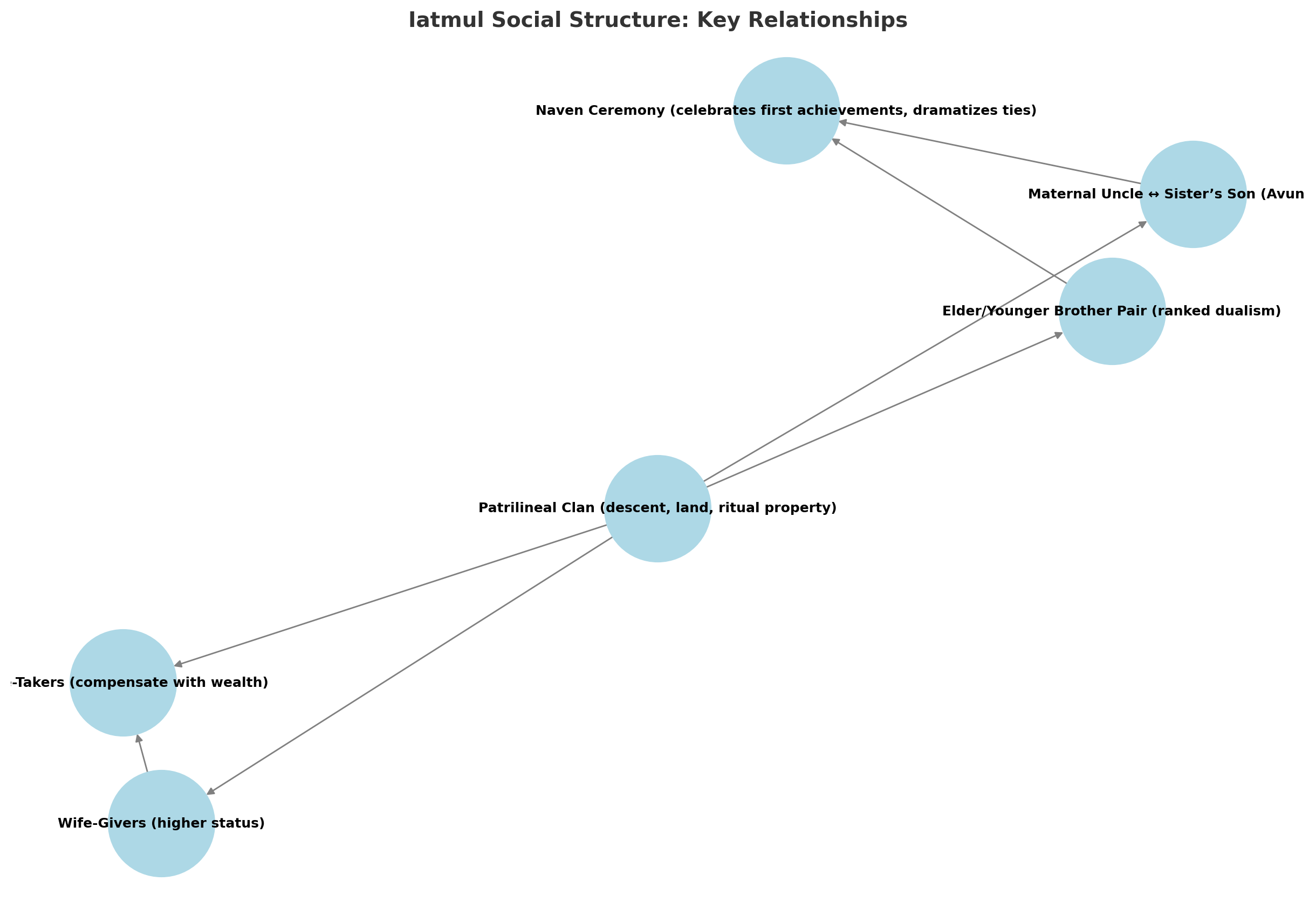

1. Patrilineal clans, rights, and ritual property

The fundamental unit of Iatmul society is the patrilineal clan (ngaiva), which is further divided into lineages and branches. These exogamous groups form the basis of social identity and determine a person’s rights to land, ritual knowledge, and ceremonial privileges. Genealogies are meticulously preserved as proof of ownership of resources and as charters for ritual authority. These genealogies link individuals to ancestral migrations and totemic origins. The clans are corporate groups that act together as owners and transmitters of collective resources. Gregory Bateson’s early ethnography (1932) revealed that these clans, rather than families, were the primary units of authority and exchange.

In short, every Iatmul person is rooted in a patrilineal clan that controls territory and sacred knowledge. This structure shapes power and ritual.

2. Elder/younger “brother” pairing and ranked complementarity

A central Iatmul principle is paired dualism, in which things are structured in pairs, such as elder/younger, male/female, and upstream/downstream. Within clans and rituals, elder and younger brothers are not equals; they have ranked roles. For instance, during initiation scarification ceremonies, the elder brother “acts upon” the younger brother by cutting his skin. The relationship is complementary yet hierarchical. This elder/younger logic extends to kinship language, ritual roles, and political authority.

In short, the Iatmul see the world in terms of complementary opposites, with one side ranked higher, creating a constant dynamic of balance and hierarchy.

3. Alliance asymmetries: wife-givers and wife-takers

In marriage, one clan gives a wife (the “wife-givers”), while another clan takes a wife (the “wife-takers”). This exchange is asymmetrical; the wife-givers are considered to be of higher status and the wife-takers must compensate them with wealth and ritual offerings (e.g., valuable shells, feasts). This asymmetry ensures that the social hierarchy is reproduced across generations. Bateson demonstrated that much of Iatmul ritual and politics hinges on these unequal exchanges between the two groups.

In short, marriage is not merely an exchange; it is a relationship that defines status: wife-givers are “above,” and wife-takers are “below.”

4. Avunculate and cross-kin relations

In anthropology, avunculate refers to the special relationship between a man and his sister’s son, or maternal uncle and nephew. Among the Iatmul, this relationship is stronger and more emotionally charged than that between a father and son.

The maternal uncle is expected to be generous, indulgent, and supportive. He often sponsors his sister’s son in major ceremonies, such as initiations or first-time achievements. In contrast to the indulgent uncle, the father represents discipline, continuity of the clan, and authority. He is more restrained and “serious.”

The Iatmul emphasize that a child’s identity is shaped by two descent lines: the paternal line, which transmits land, names, and ritual rights through the clan; and the maternal line, through which the uncle provides affection, ritual sponsorship, and comic relief.

This creates a productive tension between authority and affection, and between discipline and indulgence.

This relationship is well expressed in the naven ritual. As I said, naven is a ritual held to celebrate a person’s first major accomplishment, such as a successful hunt, cooking sago for the first time, or childbirth. During the ceremony, the maternal uncle mocks and parodies his nephew or niece’s father. He might wear women’s clothing, clown around, or make exaggerated gestures. This is not random comedy; it is a ritualized performance of affection and difference. By contrast, the father acts with dignity and restraint. The ceremony shows that both lines are necessary: the father’s line for continuity and the mother’s brother for nurturing and support.

The Iatmul use the avunculate system to balance their dual social system.

- Father’s clan: authority, inheritance, obligation.

- Mother’s clan (via the uncle) = indulgence, generosity, and ritual affirmation.

By dramatizing these roles in naven, they keep social tensions visible and manageable. Bateson argued that this avunculate relationship acts as a safety valve, allowing rivalry and tension to be expressed through joking and parody instead of breaking kinship bonds.

In short, the avunculate among the Iatmul is a special relationship of support and humor between a maternal uncle and his sister’s son. It contrasts with the father’s disciplinary authority. During the Naven ceremony, this relationship is symbolized through ritual mockery and parody, demonstrating how maternal and paternal relatives work together to shape a person’s life.

In conclusion, the four principles of clan ownership, elder/younger dualism, marriage asymmetry, and avuncular ties are the pillars of Iatmul social life. Rituals like naven make these principles visible and emotionally charged, while everyday exchanges and marriages ensure they are put into practice.

Below is a diagram of the Iatmul social structure.

Clans, which are patrilineal descent groups, are the foundation and hold land and ritual property. From them flow:

– Elder/younger brother dualisms (ranked pairs within clans).

– Marriage alliances between wife-givers (higher rank) and wife-takers (lower rank).

– Avunculate ties between maternal uncles and nephews.

The naven ceremony brings these elements together, dramatizing the roles of elders and younger people and the special relationship between a maternal uncle and his sister’s son.

5. Dual Organization: Moieties and Initiatory Classes

Iatmul society is structured by a dual organization operating on two interconnected levels: Totemic Moieties and Initiatory Moieties. This is an important and subtle aspect of Iatmul social organization.

5.1. Totemic Moieties: “Sky” (nyaui) vs. “Earth/Mother” (hnyamei)

Moieties are large, society-wide divisions into two halves. Every clan/lineage belongs to one moiety. In the case of the Iatmul, the moieties are associated with “sky/heaven” (nyaui) and “earth/mother” (hnyamei). Each clan has totemic beings (mythic ancestors, animals, or natural forces) that link it to one moiety.

The moieties are complementary and antagonistic at the same time:

- They compete in ritual, feasting, and prestige.

- They depend on each other since no moiety can perform rituals or arrange marriages alone.

This structure produces perpetual rivalry, as each side must outdo the other in ceremonies, but it also creates structural interdependence and balance, which keeps society integrated.

5.2. Initiatory Moieties (Age-Grade Classes)

In addition to the totemic moieties, there is a second, parallel system of initiation classes.

Male youth pass through four to six initiatory grades, depending on local tradition. This process involves seclusion, scarification, and instruction in sacred knowledge. Importantly, boys from one moiety are initiated by men from the other moiety. Thus, Sky moiety boys are cut and instructed by Earth moiety men. This creates a system of interwoven obligation: no group can initiate itself, so each depends on its rivals.

This ensures that rivalry does not become destructive, but rather, it is transformed into a ritualized form of cooperation.

The two systems (totemic and initiatory) overlap, but they are not identical. They “cross-cut” society.

– A person’s clan identity (totemic moiety) is inherited.

– A person’s initiation pathway (initiatory moiety), on the other hand, organizes them across clans by age and ritual obligations.

Together, they:

– Govern marriage (ideally, people marry across moieties).

– Organize ritual obligations (one moiety must host, and the other must respond).

– Structure the transmission of sacred knowledge (each moiety depends on the other for ritual continuity).

The goal is to distribute power so that no single clan, lineage, or moiety can monopolize ritual or authority. Balance and rivalry are built into the system to ensure that power is distributed and balanced across the community.

Gregory Bateson (1932; Naven, 1958) described this “dual organization” in detail, and later scholars (e.g., Silverman, 1996; Hauser-Schäublin, 1989; Kocher Schmid, 2005) have emphasized that it is a practical mechanism for distributing obligations, wealth, and knowledge across society, not “abstract symbolism.” It is the moiety system that enables the Iatmul to sustain both intense competition and enduring cooperation among clans and villages.

6. Gepma, a personalized alliance system

In the Middle Sepik, especially among the Iatmul, gepma (sometimes spelled gepmã) is a relationship of formalized alliance and reciprocity between men of different clans or villages, cemented through feasting, gift-giving, and shared ritual obligations.

A gepma is not a moiety or class. Rather, it is a personalized alliance between men from different clans or villages. Unlike moiety membership, it is established by choice or tradition, not inheritance. A gepma relationship is not based on blood kinship, but rather on a chosen, institutionalized partnership, usually formed during initiation or ceremonial cycles. This relationship was characterized by mutual support in warfare, ritual sponsorship, and exchange, as well as playful mockery and ritualized joking..

Gepma partners have mutual obligations:

- They exchange gifts and shell valuables.

- They support each other in ceremonies and feasts.

- They joke, insult, and mock each other in ritualized ways.

This serves as a safety valve for rivalry, allowing competitive tension to be expressed through mockery and gift exchange, thereby preventing open hostility.

The dual organization of totemic and initiatory moieties is a structural division of society, while the Gepma is a personalized alliance system. These systems are not the same but are complementary expressions of the same cultural logic: Rivalry must always be paired with reciprocity and obligation. They operate at different levels.

- Moieties are collective, society-wide divisions, while Gepma are person-to-person partnerships.

- Gepma: Dyadic, person-to-person partnerships.

However, they share the same social goals; both systems institutionalize rivalry with obligation.

Moiety groups are rivals, yet they must cooperate in areas such as initiation and marriage.

Gepma partners insult each other, but they must also exchange goods and provide assistance.

Gepma relationships often transcend moieties and clans, reinforcing the idea that no group or individual is self-sufficient. In rituals such as Naven or feasts in the Haus Tambaran, moiety rivalry provides the framework, but gepma ties give individuals specific ritual roles and partners.

Silverman (1996, 2001) emphasized that gepma adds a personal and emotional dimension (e.g., mockery, joking, and ritualized insults) that parallels but does not duplicate moiety rivalry. Kocher Schmid (2005) highlighted that gepma ties extend beyond the village, connecting the Iatmul to neighboring groups through exchange networks, whereas moieties mainly organize internal society.

Iatmul, master of complexity and sophistication

Historically, the Iatmul were warriors who engaged in headhunting, inter-village feuds, and ritualized displays of aggression.

Male identity and prestige were linked to success in conflict and the ability to dominate rivals. This created a risk of uncontrolled violence within and between clans and villages. The Iatmul developed a highly complex social structure to channel this aggression into structured, symbolic forms.

Bateson argued that Iatmul social life is an “economy of aggression”: institutions absorb and redirect hostile impulses into rituals, exchanges, and performances. For instance, in Naven, aggression between relatives (such as wife-givers versus wife-takers or brothers) is acted out symbolically through mockery, reversal, and parody. In this sense, ritual is a social technology that prevents destructive violence by providing an outlet for its expression in controlled, symbolic forms.

Silverman (2001) emphasized that aggression, mockery, and gendered tension in Iatmul rituals are regulated outlets that reaffirm kinship and social bonds, not chaotic ones. Kocher Schmid (2005) demonstrated that even interactions with neighboring groups (Sawos and Chambri) served as a means of defusing conflict by establishing enduring relationships of mutual dependence. Schindlbeck (2018) noted that headhunting and warfare were also tied to ceremonial cycles that imposed rules and limits, preventing total escalation.

The Western imagination has long reduced Papuan societies, especially those of the Sepik River, to lurid images of cannibalism, savagery, and uncontrolled violence. Such stereotypes erase the profound sophistication of their social institutions. Among the Iatmul, one of the most prominent Sepik groups, aggression is carefully governed through a refined web of moieties, ritual friendships, age classes, marriage exchanges, and ceremonial performances. What appears from the outside as “primitive” is, in fact, a highly intricate system designed to channel rivalry, transform hostility into ritualized expression, and preserve cohesion across clans and villages. Rather than being fearsome outsiders to civilization, the Iatmul demonstrate how social ingenuity can transform conflict into the foundation of cultural stability. Their elaborate social structure regulates aggression and violence. Rather than suppressing aggression, the system ritualizes, redirects, and harnesses it, transforming potential violence into controlled acts of initiation, exchange, mockery, and performance that bind society together.

At the heart of Iatmul life stands the haus tambaran, the men’s ceremonial house—an arena where tensions are debated, rivalries mediated, and conflict transformed into ritual through feasting, oratory, and the display of sacred objects.

The amazing photos below are by some of the most talented portrait photographers: Jimmy Nelson, who was born in Kent, UK, in 1967 and is currently based in Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and Ursula Wall, who lives in Australia.

Their styles are completely different.

Jimmy Nelson is renowned for his large-format, highly staged portraits of indigenous peoples. His photos are celebrated for their vibrant colors, intricate compositions, and emotional intimacy. He typically spends extended periods immersed in his subjects’ communities, establishing trust and connection. Then, he poses individuals and groups in dramatic, regal tableaux, often outdoors against carefully chosen, meaningful backgrounds. Nelson uses analog large-format cameras, resulting in images that are richly detailed and imbued with a sense of timelessness and beauty. His work sometimes echoes the techniques and intentions of historic ethnographic photographers like Edward S. Curtis, but with a modern palette and a conscious focus on dignity and pride. His distinctive style, which aims to challenge stereotypes, celebrate cultural resilience, and provoke a sense of admiration for his subjects, is characterized by his use of warm, earthy tones, planned lighting and wardrobe, and creative desaturation in post-production.

Ursula Wall is a talented Australian photographer and traveler who specializes in portraiture and travel photography. Her published photographs, such as those taken in the Sepik region or featuring indigenous subjects, suggest a documentary and environmental approach. Rather than staging her subjects for ceremonial portraits, she captures them in natural or everyday contexts, which is a style that contrasts with the highly staged, ceremonial mode typical of Jimmy Nelson’s work. Ursula prefers spontaneity and naturalness. In her minimalist, nearly bare portraits, however, she captures the hidden depths of her subjects.

(All of the photos below are published with the explicit permission of the photographers, whom I thank sincerely. Please do not attempt to copy or use them elsewhere).

Iatmul Woman and girls, Yentchen Village, Sepik River, Papua New Guinea, 2017. From the book Homage To Humanity by Jimmy Nelson. More pictures and information about the Nelson’s artworks can be found on his official website.

Iatmul men, Yentchen Village, Sepik River, Papua New Guinea, 2017. From the book Homage To Humanity by Jimmy Nelson. More pictures and information about the Nelson’s artworks can be found on his official website.

Iatmul man, Sepik River, Papua New Guinea, 2017. From the book Homage To Humanity by Jimmy Nelson. More pictures and information about the Nelson’s artworks can be found on his official website.

Sepik carver, 2017. Photo by Ursula Wall.

Sepik crocodile drummer, 2017. Photo by Ursula Wall.

A child along the Sepik river, 2017. Photo by Ursula Wall. Do not miss her personal blog, full of photos and travel stories: a chance to get to know her better!

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?