NAVAJO CHURRO SHEEP AND WOOL 10

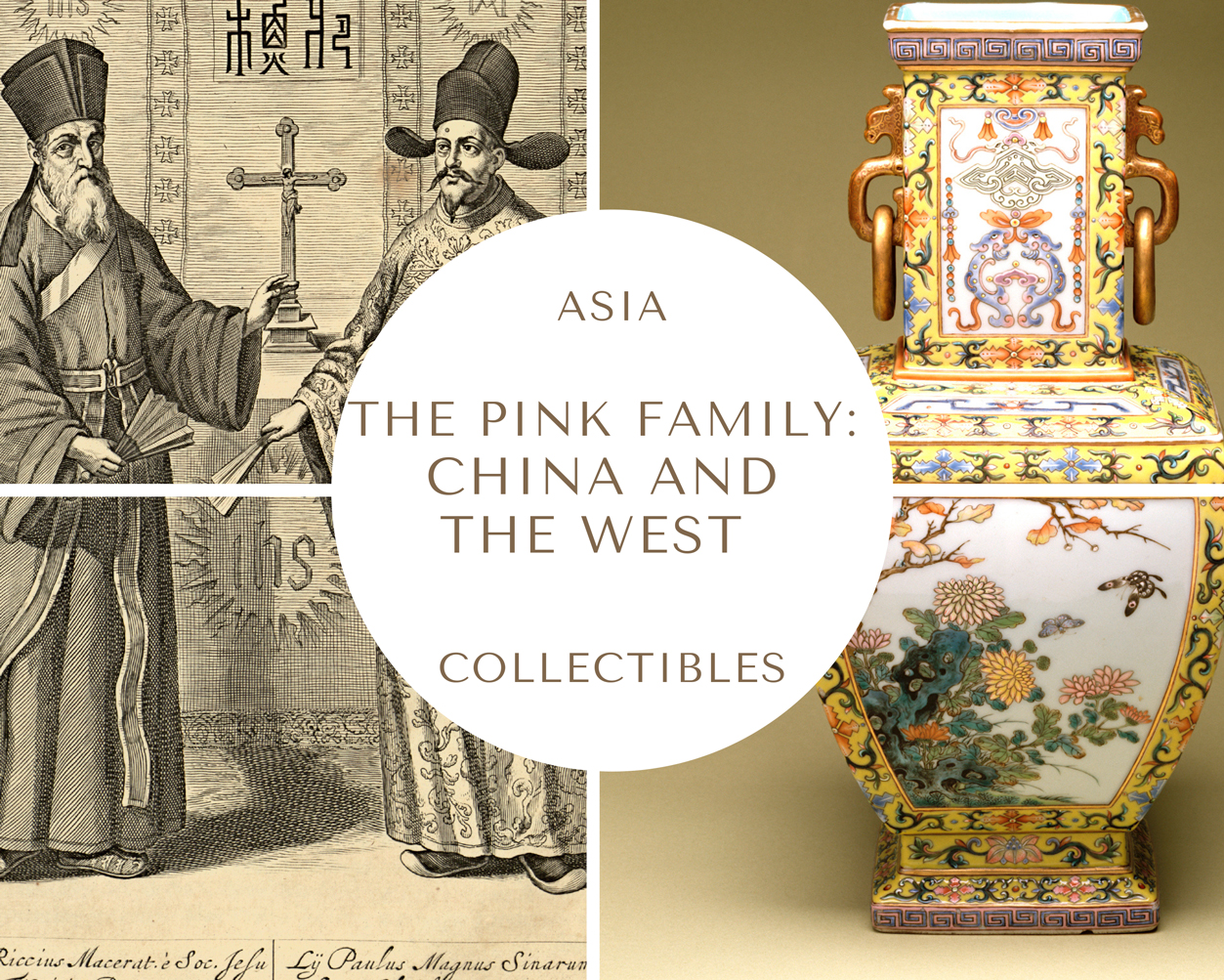

USA on the globe.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

SOUTHWESTERN STATES

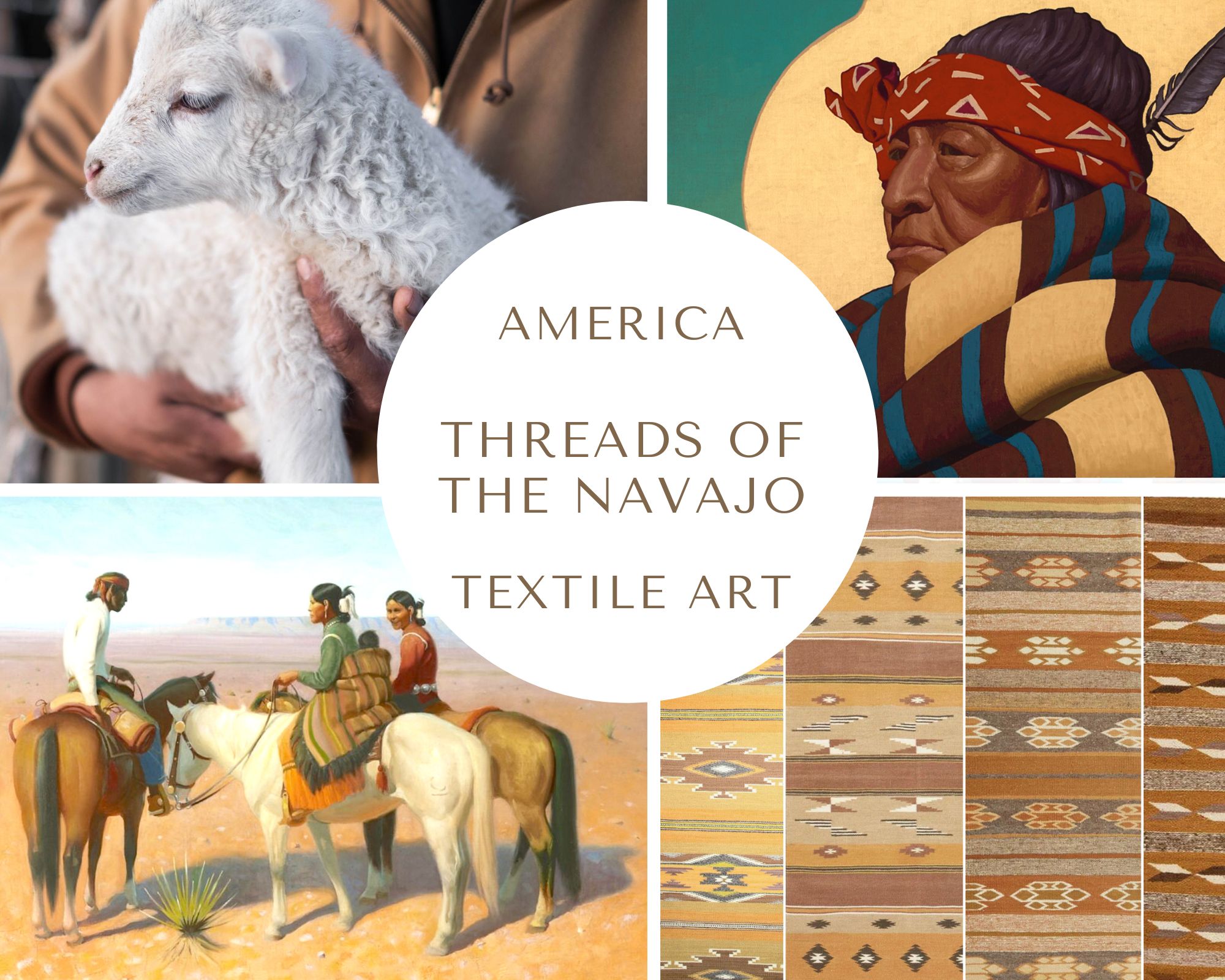

LUKACHUKAI YEI, SHIPROCK YEI, YEIBECHAI, AND SANDPAINTING WEAVING

Navajo weaving is celebrated for its intricate symbolism and vivid depictions of spiritual figures. Two of its most iconic motifs are the Yei and the Yeibechai, which are represented differently in various regions, particularly in areas such as Lukachukai and Shiprock. Before delving into pictorial elements and sandpainting-inspired weaving designs, however, it's important to first explore the foundational art of Navajo sandpainting—a sacred tradition that informs much of weavers' visual language.

Navajo Sandpainting: Ritual, Symbolism, and Cultural Adaptation

Navajo dry painting or sandpainting (iikááh), often translated as “the place where the Holy People come and go”, stands as one of the most spiritually profound and visually sophisticated art forms in Indigenous North America. These ephemeral compositions, central to healing ceremonies and purification or blessing rituals, seamlessly merge aesthetic mastery with intricate cosmological meaning. They function not merely as images, but also as ritual instruments within the broader Diné spiritual system (A. Gladys Reichard). Sandpaintings «illustrate and actualize harmonious relationships among the Diyin Dine’é (the Supernaturals, or Holy People), Dinétah (the Navajo land), and the Dine’é (the Navajo people, literally ‘Earth Surface People’.» (Janet Catherine Berlo).

Mullarky Photo, between 1890 and 1910. , CO.

LEFT: Black and white photo of a Navajo medicine man creating a small portion of a sand painting, 1930-1950. Multimedia Archives, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, University of Utah.

RIGHT: Diné man creating a sandpainting, 1930-1950. Multimedia Archives, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, University of Utah.

Navajo Sand Painting (Yeibichai, Near Shipwreck, NM), ca. 1955, photo by Laura Gilpin (1891 - 1979).

Origins and Ceremonial Context

Sandpainting was introduced to Navajo culture through exchanges with neighboring Pueblo peoples. However, it underwent significant transformation to reflect the unique cosmology, ethics, and metaphysics of the Diné (Gary Witherspoon). Today, it's an integral part of the Navajo chantway tradition, especially in Hózhǫ́ǫ́jí (Blessingway) and Enemyway ceremonies. In these ceremonies, sandpainting mediates between the human world and the realm of the Diyin Dine’é, the Holy People. (Klara B. Kelley and Harris Francis).

During an extended healing ceremony (hatááł), a hataałii (a singer or medicine man) and his assistants create a sandpainting. The singer selects an image from hundreds of sacred designs, guided by the patient’s spiritual diagnosis and the specific ceremonial context (James Kalestewa McNeley). Over time, observers and anthropologists have recorded a large number of designs (over 500/600), and more probably exist. Some are small, but many are so large (20 feet in diameter) that they can only be made in hooghans constructed especially for them. Small sandpaintings can be made by two or three people in less than an hour, but large ones require ten to fifteen people working for most of a day. Ceremonial sandpaintings ('iikááh) are made by the assistants of the hataałii in a hooghan that has been blessed, or made sacred, for the ceremony.

Thus, the creation of a sandpainting «is part of a multi-night ritual involving singing, praying, and the use of herbal medicine, in which a person who seeks physical and/or psychological healing sits on the sandpainting. To be sung over by the hataałii while sitting within the healing force field of such a cosmogram is to embody the central ideal of Navajo culture: hózhó, rendered in English as a combination of harmony, goodness, wellness, and beauty.» (J.C. Berlo).

Traditional sandpaintings are "temporary altars" (a definition by John Gerber curator of the Kennedy Museum of American Art), and are intentionally destroyed after the ritual, which may last from one to nine days, is completed. It is believed that the painting absorbs the patient's imbalance or illness during the ceremony. The residue is then ceremonially discarded to the north of the hogan to allow the sacred materials to return to the earth. (Charlotte J. Frisbie)

«Sandpaintlngs are to be made only in the context of a curing ceremony under the direction of a highly trained religious specialist, the hataałii. The pictures contain symbolic representations of powerful supernaturals who are invoked to cure. They are a type of "ceremonial membrane" though which 'evil' can be dispelled and 'power' absorbed. When completed and consecrated they are filled with the dangerous but beneficial power of the supernaturals. This power is then transferred into the patient via the singer. The painting is destroyed at the end of the ceremony when its functions have been completed.» (Nancy J. Parezo, 1979).

«When the ceremony is over, the hataałii obliterates the image that has taken so many hours to make, and the materials are collected and ritually returned to the desert.» (J.C. Berlo).

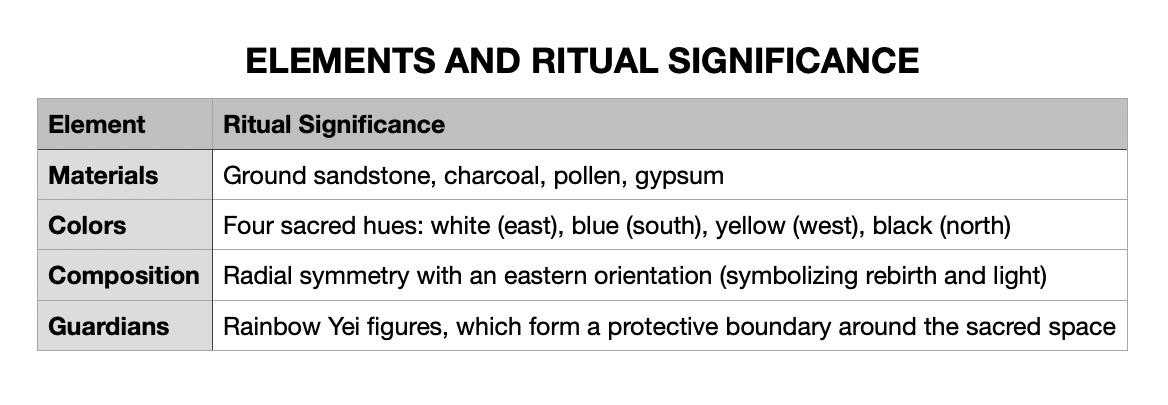

Creation Process and Symbolic Grammar

The creation of a sand painting is a strictly regulated, ceremonial act aligned with Diné cosmology and ethical codes that adheres to protocols established centuries ago. (Mark Bahti)

The hataałii and his assistants create sandpaintings using crushed minerals and pigments sourced from the deserts and plains of the Southwest.

- Natural pigments include gypsum (white), red sandstone, yellow ochre, charcoal (black), and charcoal-gypsum mixtures (blue).

- The crushed minerals and sands are layered through controlled hand-trickling onto the ground or a temporary surface, with colors symbolizing natural elements (e.g., black for darkness, blue for sky).

- Other natural pigments: Crushed dried plants, cornmeal, flower pollen, powdered bark, and sometimes even flower petals are added to expand the palette and ritual significance.

These materials are gathered in a ritualistic manner, reflecting the Navajo belief in the sacredness of the Earth.

While the colors may vary, the four primary colors – white (igai), blue (doot 'izh), yellow (itso) and black (izhin) – are always present. They are symbolically associated with the four directions: white with the dawn and the east, blue with the midday sky and the south, yellow with evening twilight and the west, and black with the night sky and the north. The colors ['a tah'áát'ee go nidaashch' 'íg'í'í] are applied by the singer/medicine man and his assistants with their right hands, allowing the material to trickle out between their thumbs and forefingers.

The designs in sandpaintings are not mere illustrations, but rather, highly stylized, symbolic representations of the Navajo spiritual world. They are not static objects, but rather living spiritual entities. The choice of specific designs and figures depends on the particular healing ceremony being performed and the ailment it addresses. Designs often depict pivotal mythological events, such as the Naayééʼ Neizghánì (Monster Slayer) cycle, employing stylized and abstract forms that adhere to visual conventions, typically frontal or profile perspectives.

Central to these depictions are the Yei or Yéʼii (also known as Diyin Diné or Holy People), who are a pantheon of benevolent supernatural beings that serve as intermediaries between the human world and the spiritual forces. Emerging from Navajo cosmology, the Yei are described as "Holy People" rather than deities. They mediate between the Great Spirit (Diné Bahane') and humans, control natural elements (rain, wind, and sun), and manifest as animals, plants, celestial bodies, or anthropomorphic figures. Their power is invoked through ceremonies to restore hózhǫ, particularly during healing rituals.

Common stylized Yei frequently seen in sandpaintings include:

- Snake People often associated with healing and the underworld.

- Eagle People symbolizing protection, strength, and connection to the sky.

- Corn People representing sustenance, life, and the central role of corn in Navajo culture.

- Talking God (Haashchʼééłtiʼí): A prominent Yei who is often depicted with a white body. He leads ceremonies and acts as a messenger between humans and the Holy People.

- Changing Woman (Asdzáá Nádleehé): One of the most important and revered deities, associated with creation, growth, and the changing seasons. She embodies the cycles of life and is often central to ceremonies related to blessings and female well-being. She also symbolizes fertility and resilience, often central to rites for health and harvest.

- Other Yei: The pantheon includes many other figures, each with specific roles and attributes, such as Water Sprinkler, House God, Black God, the Twin War Gods, and Rainbow People.

Artistic visions of Yei Spirits by Diné artist Allen Bahe. Born in 1959, Bahe is a contemporary Navajo visual artist known for his evocative works that often engage with themes from Navajo ceremonial tradition.

CLOCKWISE: Yei Spirit; Canyon Silence - Navajo Yei; Yei Moon, 2011; Yei Spirit over the Grand Canyon; Yei Spirit in landscape; The Blessing - Navajo Yei. They are all acrylic on canvas.

In Allen Bahe’s paintings of Yei figures, the objects they hold in their hands are typically representations of traditional ceremonial items associated with the Yei. Most commonly, these include:

Bahe’s choice to depict these items reflects the Yei's ceremonial significance and spiritual roles, while respecting Navajo tradition by wrapping the figures in blankets to avoid revealing sacred details.

The Yei participate in healing ceremonies led by a Hataałii as well as in complex ritual frameworks. During the Yei-bi-Chai Dances, humans impersonate Yei by wearing buckskin masks and carrying spruce sprigs and rattles. These dancers are central to the Navajo Night Chant ceremony, serving as human conduits for the Yei during sacred healing rituals. Yei-bi-chai (sometimes spelled Yeibichai or Yei be chei) specifically refers to the masked human dancers who impersonate the Yei during healing ceremonies. These dancers "loan their bodies" to Yei spirits, enabling the Holy People to be present among the people during sacred rituals. In Navajo weavings and ceremonial art, the Yei-bi-Chai are depicted as side-facing figures, often in lines to represent the dance. Their uplifted feet indicate movement. The dance is typically led by Talking God and followed by a ritual clown.

Dancers wear specific regalia to embody the Yei.

- Buckskin masks: Handcrafted from the hide of deer not killed by weapons and painted with mineral pigments (blue for the sky and black for the outlines).

- Spruce sprigs: They are carried in one hand and symbolize purification and life.

- Gourd rattles: Held in the opposite hand, they represent the Black Water Jar (rain) and corn ears.

- Concha belts and kilts: Worn with a medicine pouch containing healing herbs and corn pollen.

The dance formation follows strict protocols.

- Talking God (Yeibitsai): He leads the procession as the "maternal grandfather" of the yei, identified by his white buckskin wrap, eagle-plume headdress, and distinctive vocalizations.

- Line of dancers: Typically there are 12–14 impersonators (six male, six female) who move in sync to restore hózhǫ (balance).

- Ritual clown: Closes the procession and uses humor and reversal to absorb negative energies.

On the final night of the nine-day Night Chant, the dancers channel Yei power through synchronized movements and chants, directing spiritual energy toward the patient. The ritual concludes with the patient sitting among the dancers to absorb the healing energy, after which the masked performers disperse to avoid spiritual stagnation.

Haschelti - Yeibichai, photo by Edward S. Curtis, 1904.

'Yebichai Sweat', a Navajo medicine ceremony. All photos by Edward S. Curtis, 1904. Source: Library of Congress, Washington DC.

This series of photographs from 1904 depicts the "Yebichai Sweat" ceremony, in which Navajo men impersonate sacred Yei spirits and conduct a healing and purification rite as part of the Night Chant. The scene is rich with symbolic elements, such as masks, feathers, blankets, and the ritual arrangement. These elements are designed to invoke the presence of the Holy People for the benefit of the patient and reflect the deep spiritual and cultural traditions of the Navajo people. The masked participants are not merely performers, but are believed to embody or impersonate the Holy People, or Yei. The feathered sticks, masks, and arrangement of participants all have deep symbolic meaning. The feathers and prayer sticks serve as offerings and conduits for prayers, the masks enable the wearers to channel the deities' presence, and the blankets and heated ground or embers symbolize purification and the containment of sacred power.

The photograph on the left shows three masked Navajo men in ceremonial regalia. Each man represents a specific Yei and is seated or standing in a ritual setting associated with the Night Chant. According to Curtis’s documentation and the ethnographic literature on the Night Chant, the impersonated Yei are (left to right): God of Harvest — This refers to Gánaskidi, a Yei associated with harvest and fertility who is often impersonated in Night Chant ceremonies; Fringe Mouth — While less commonly referenced in mainstream summaries of the Yei, Fringe Mouth is cited in Curtis’s captions and some ethnographic sources as one of the distinctive Yei impersonated in the ceremony; and Talking God, known in Navajo as Haashchʼééłtiʼí or Haschelti. Talking God is the chief deity and a central figure in the Yebichai ceremony, often appearing as the leader of the masked dancers.

Sandpainting Healing Mechanics and Diné Epistemology

Navajo healing practices operate within a holistic epistemology, viewing illness as a disruption of harmony (hózhǫ́). As a visual-spiritual language, sand painting engages four interwoven healing mechanisms:

- Attraction: Accurate depictions summon the Holy People, who recognize themselves within the imagery.

- Exchange: During the ritual, the patient's illness is symbolically and spiritually transferred into the painting.

- Identification: The patient sits on part of the painting to symbolically merge with the deities or forces depicted.

- Reintegration: Through chanting, movement, and prayer, the patient is ritually reinserted into cosmic balance, restoring hózhǫ́.

As anthropologist Jennifer Nez Denetdale and ethnographer Trudy Griffin-Pierce have described, sand paintings are "ritual realities": spaces where the physical, spiritual, and temporal planes converge. This indigenous healing model contrasts with Western biomedicine in that it prioritizes relational and cosmological causation over isolated physical symptoms.

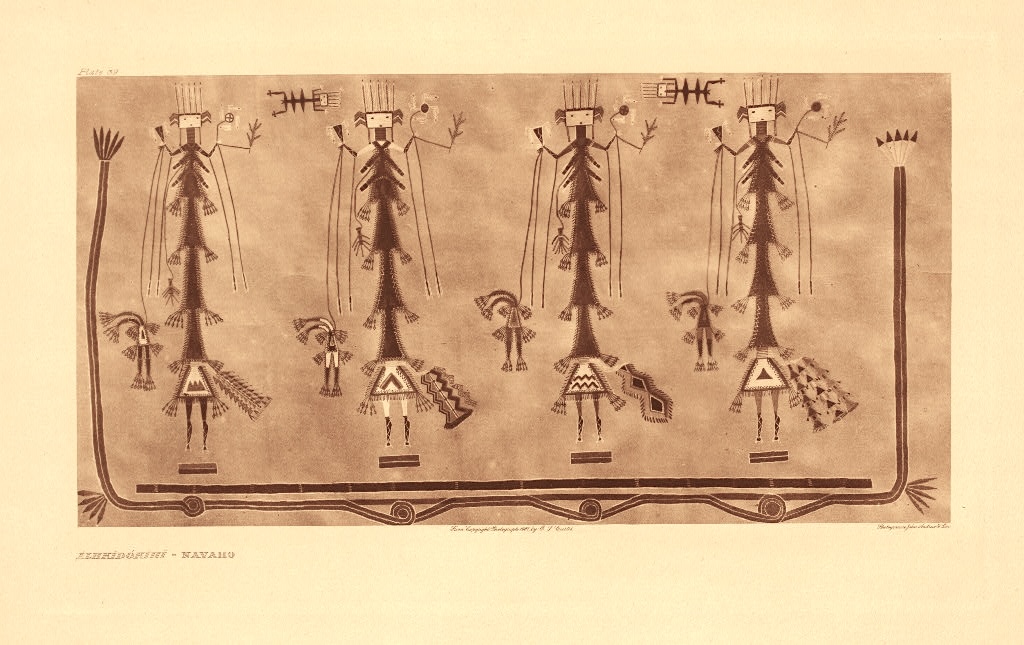

This is one of the four elaborate dry paintings, or sand altars, used in the nine-day Mountain Chant (Dsilyidje Qaçal) Navajo medicine ceremony. It shows Yei figures and repeating patterns. In textile and carvings, male Yei are depicted with round heads, while female Yei with square heads. Photo by Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952). Denver Public Library, Special Collections [X-34040].

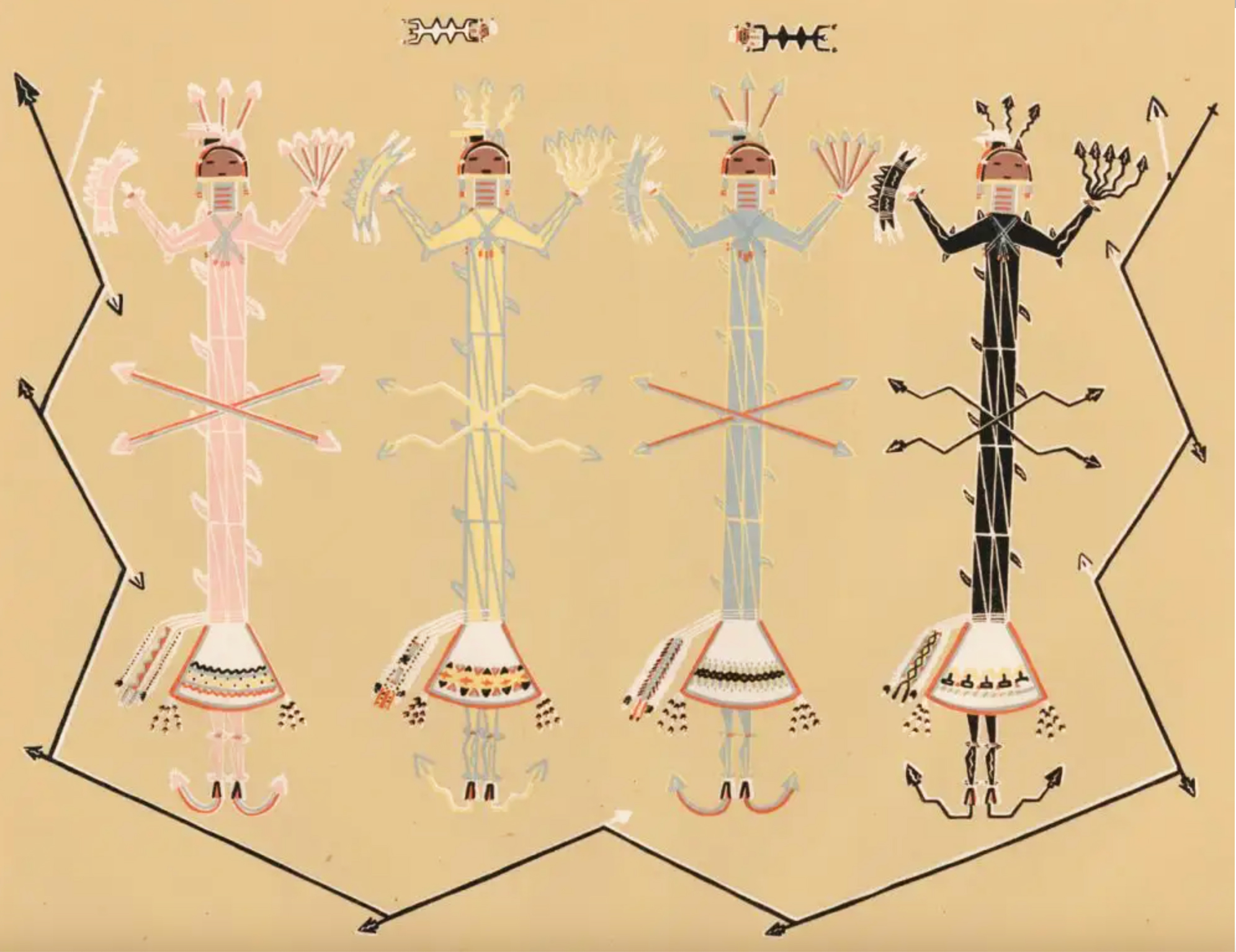

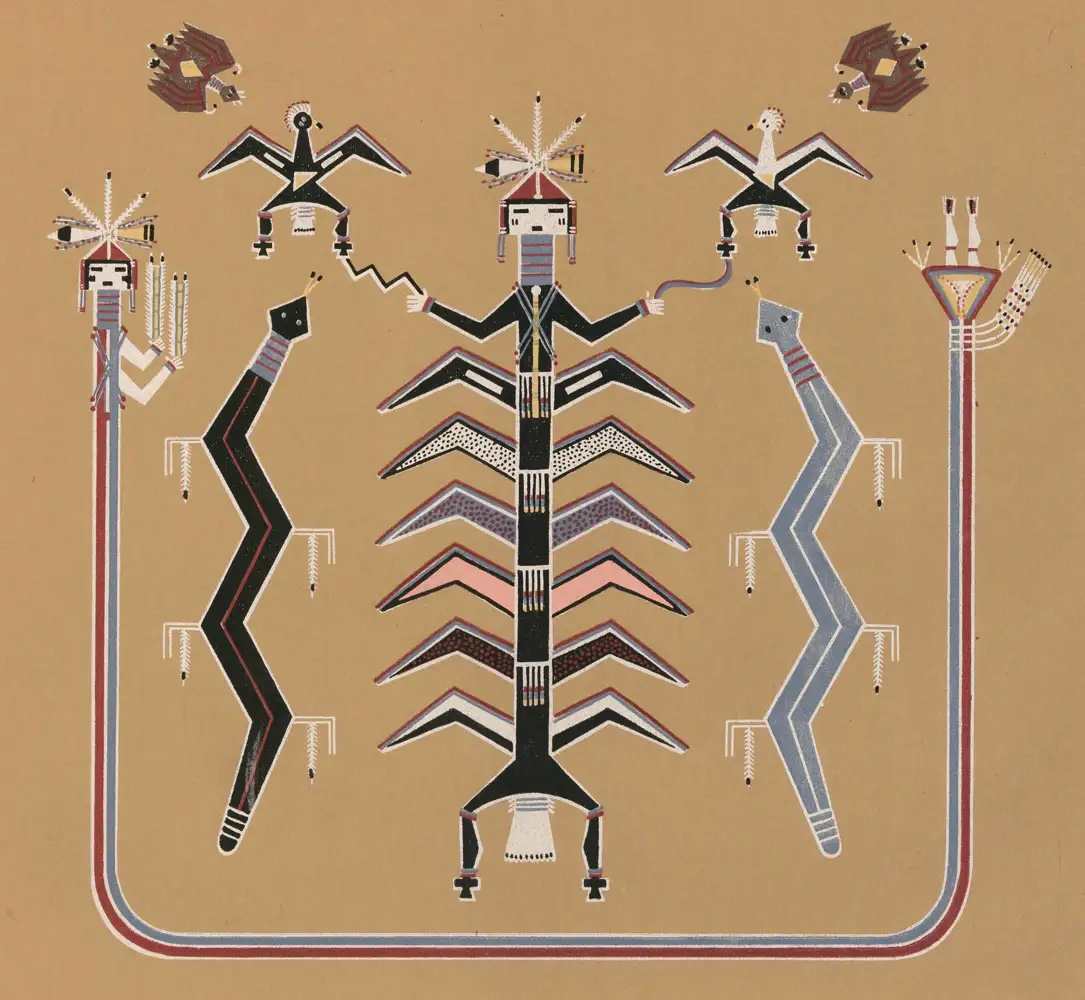

Flint-armored gods in attack on Changing Woman, plate reproducing an original sandpainting, in Sandpaintings of the Navajo Shooting Chant, a book by Franc J. Newcomb, published in New York by J. J. Augustin in 1937.

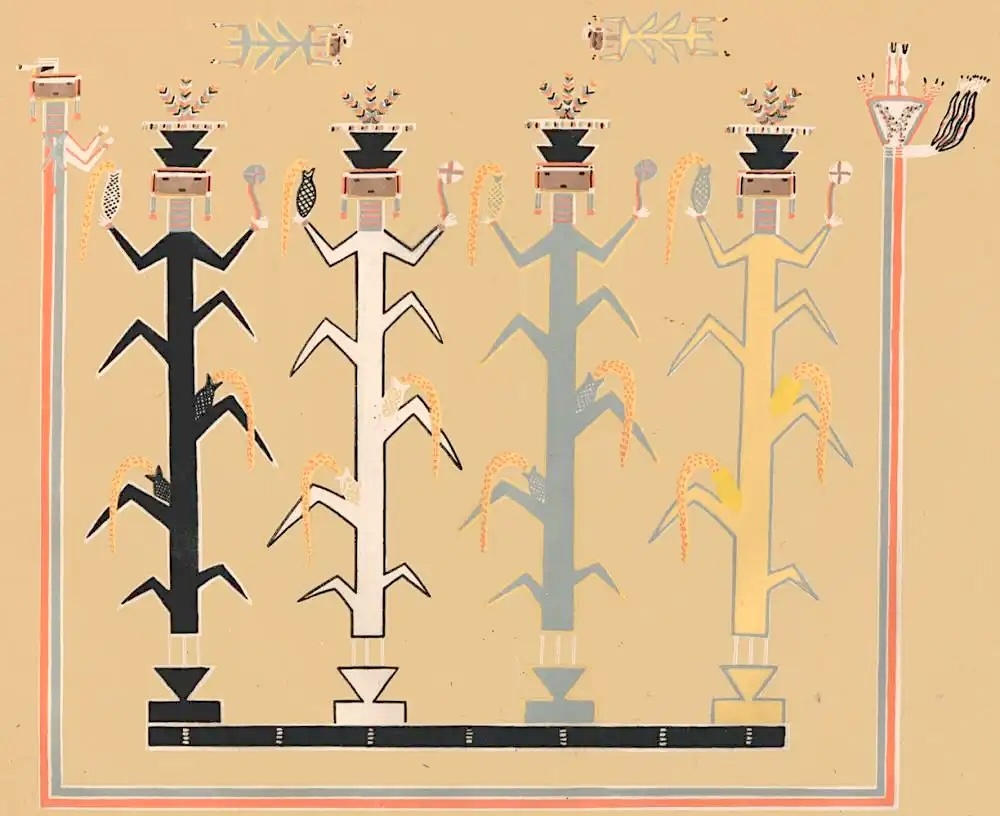

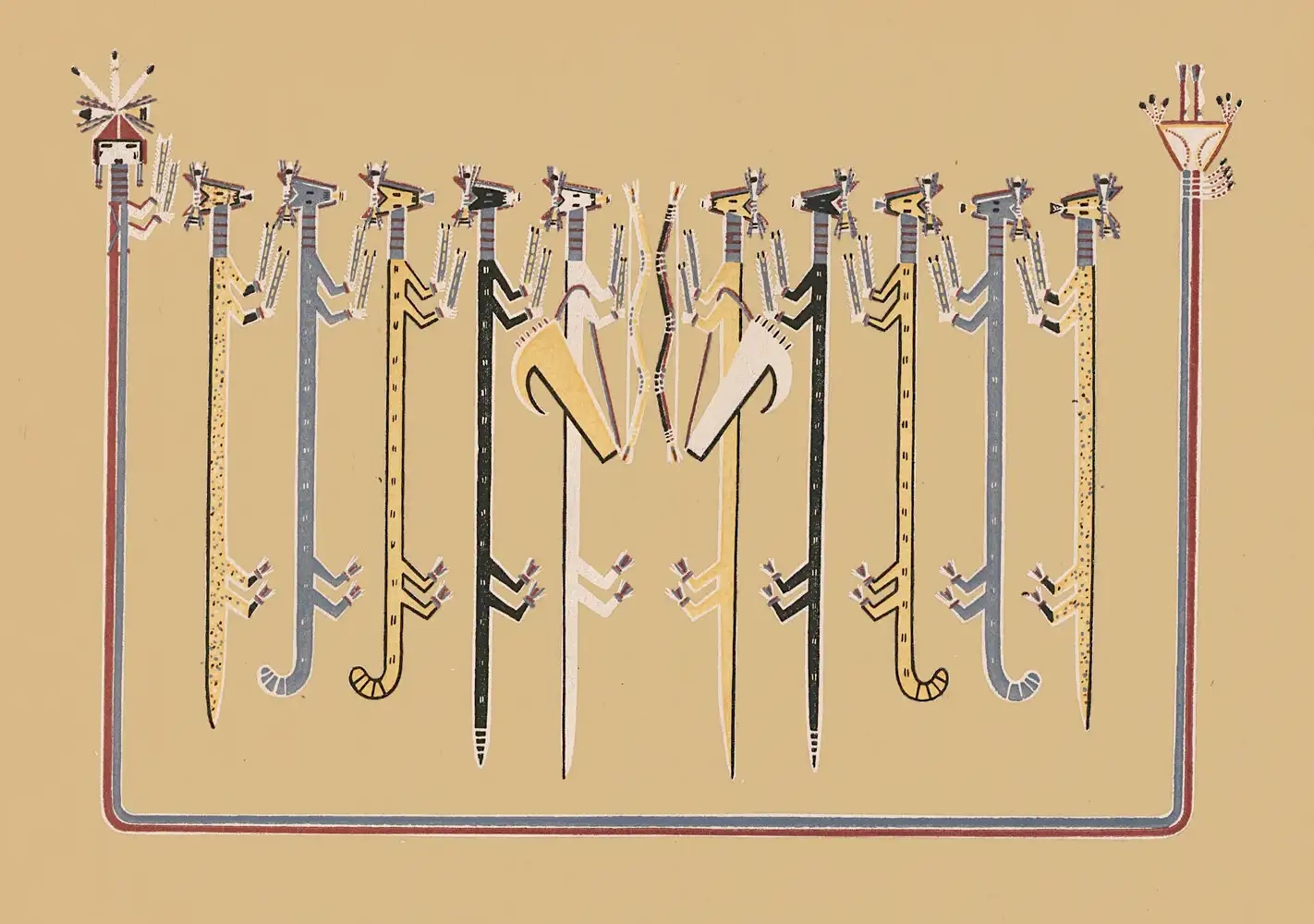

Yellow, Blue, White and Black Corn People, Pochoir print reproducing an original sandpainting in Sandpaintings of the Navajo Shooting Chant, a book by Franc J. Newcomb, published in New York by J. J. Augustin in 1937.

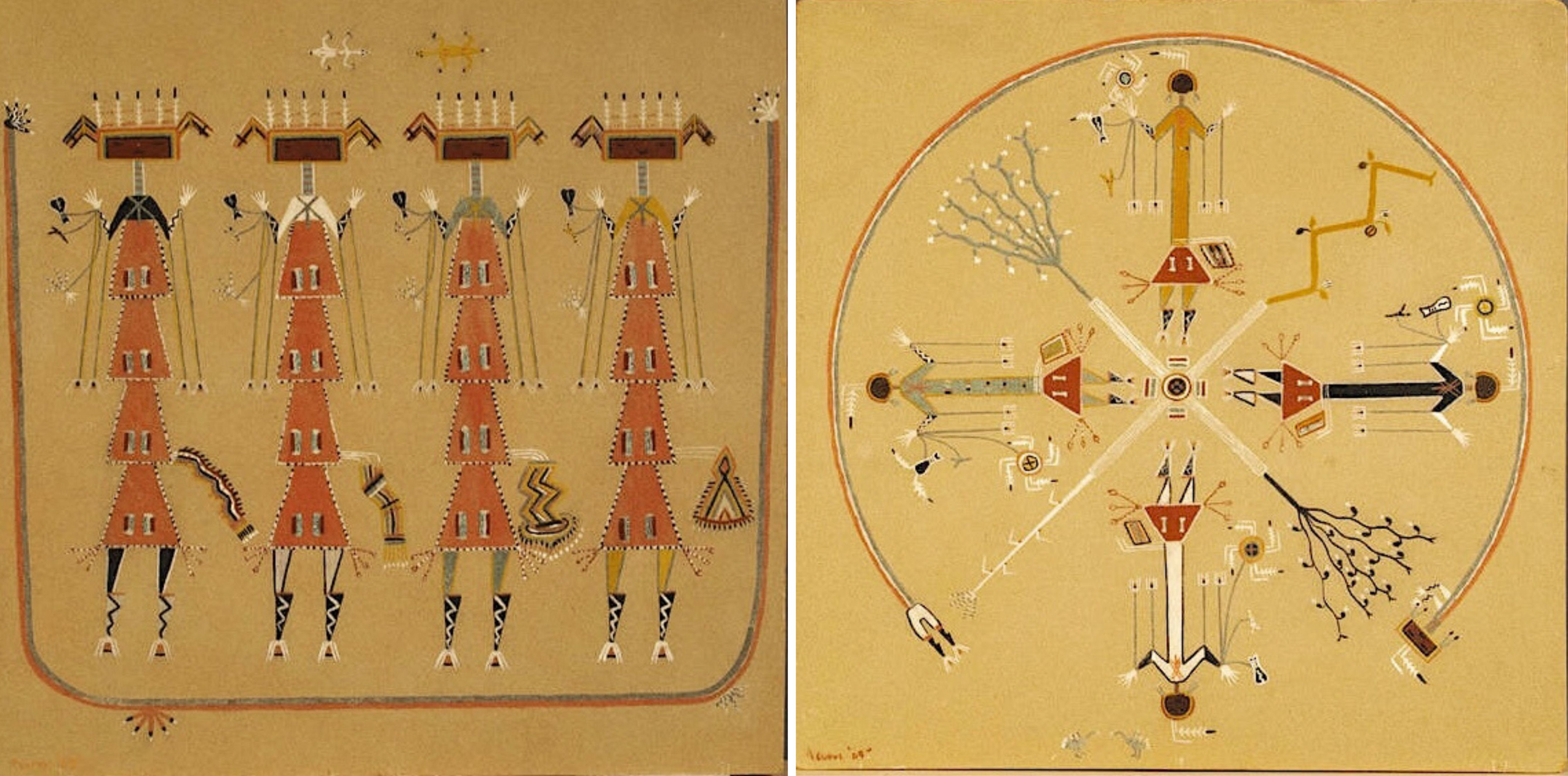

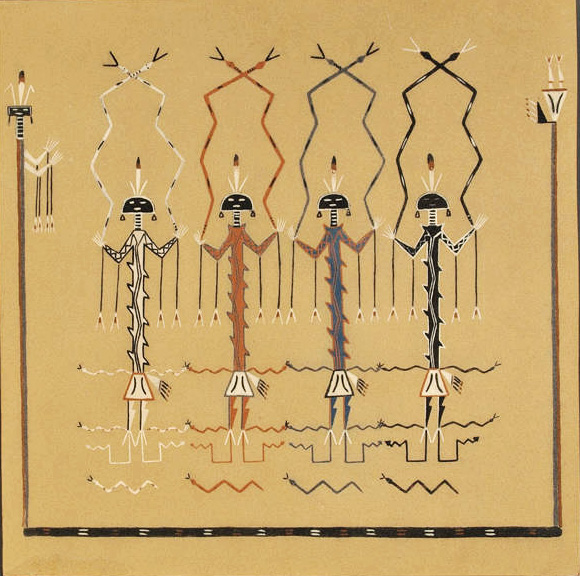

LEFT: Second Day - Mountain Chant by Alfred Leuppe, sandpainting depicting four Yeii figures, 1960 - 1975, Tohatchi, NM. Hubbard Museum of the American West, New Mexico's Digital Collections.

RIGHT: Third Day Mountain Chant by Alfred Leuppe, sandpainting of Yeii figure encircling 4 Yeii figures radiating from the center (feet inward) , other images between the figures. Signed by artist. 1965 - 1975, Tohatchi, NM. Hubbard Museum of the American West, New Mexico's Digital Collections.

Wind and Snakes sandpainting by Alfred Lueppe, 1960 - 1979. Sandpainting of four figures: one white with black; one orange with blue; one blue with orange; one black with white. Tassels hang from the elbows and wrists. The figures stand on the "ground" with snakes below, and the "ground" has the same colors as the figures and a "rainbow" design on three sides. Hubbard Museum of the American West, New Mexico's Digital Collections.

The Final Ascension of Scavenger Attended by Lightnings (Bead Chant), color silk-screen print reproducing an original sandpainting, in Navajo Medicine Man: Sandpaintings and Legends of Miguelito from the John Frederick Huckel Collections, a book by Gladys A. Reichard, published by J. J. Augustin, 1939.

The Exchange of the Quivers (Bead Chant), color silk-screen print reproducing an original sandpainting, in Navajo Medicine Man: Sandpaintings and Legends of Miguelito from the John Frederick Huckel Collections, a book by Gladys A. Reichard, published by J. J. Augustin, 1939.

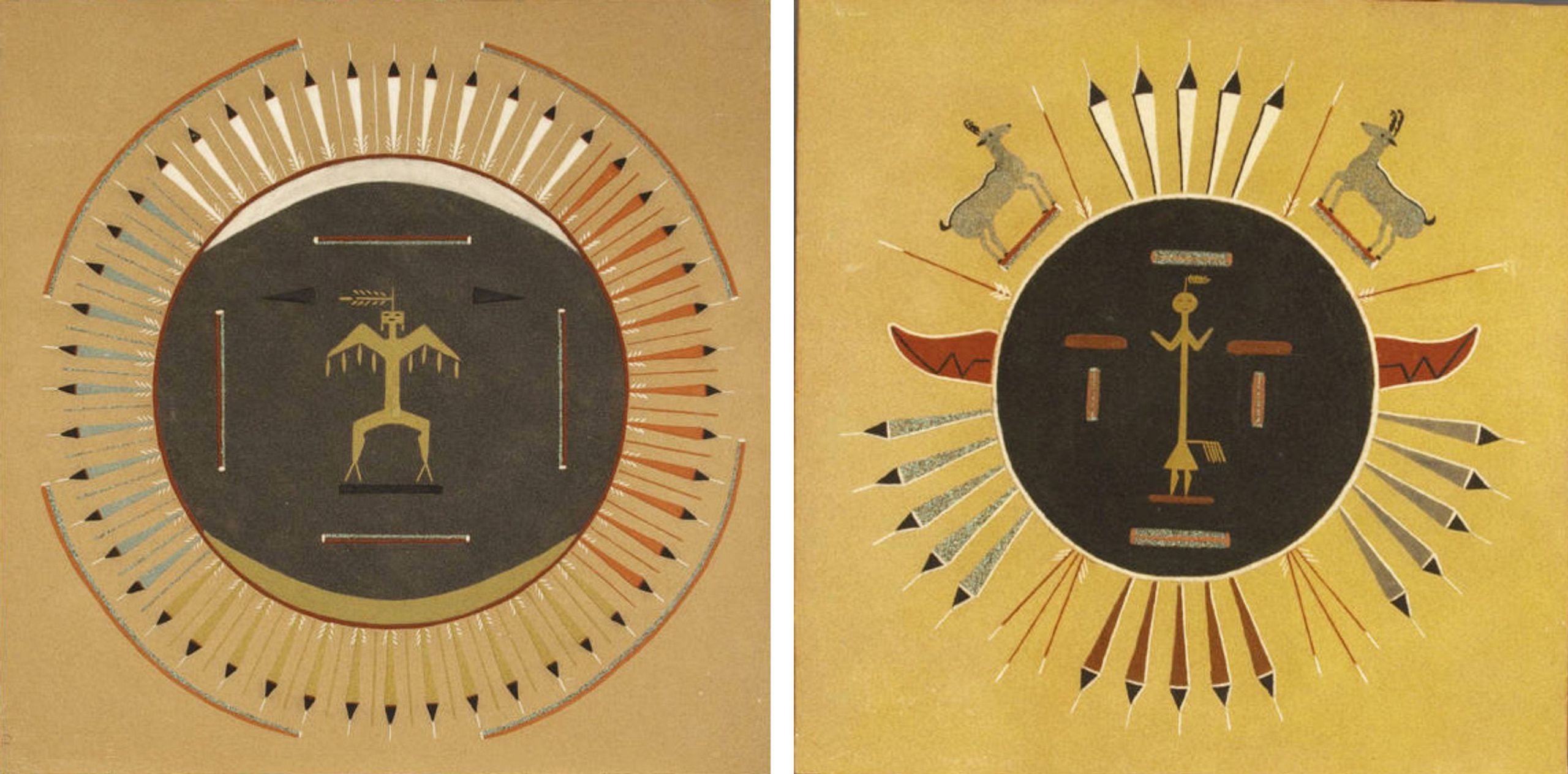

LEFT: A Sandpainting showing a central figure with radiating feathers. It has a dark gray center, a white half-moon at the top, and a yellow ochre half-moon at the bottom. Inside the circle is a figure with bent arms and legs. Four tassels hang from each arm. The legs stand on a black band. The head has eyes, a mouth, and an earring. Corn tassels stick out to the left. There are four identical bars in the black circle with white tips. Two black rectangles face away from the head. Feathers run all the way around the outside of the black circle: white, reddish, tan and blue, each with a black tip. The outside of the circle is a broken circle of white feathers, divided into four sections of the same colors: blue, reddish, and white-tipped. Undated. Hubbard Museum of the American West. New Mexico's Digital Collections.

RIGHT: Chiricahua Sun Painting, a sandpainting by Doris Leuppe, Tohatchi, NM. Round black circle in center, design elements positioned to appear as face. Deer figures and feathers surround the facial image. Hubbard Museum of the American West. New Mexico's Digital Collections.

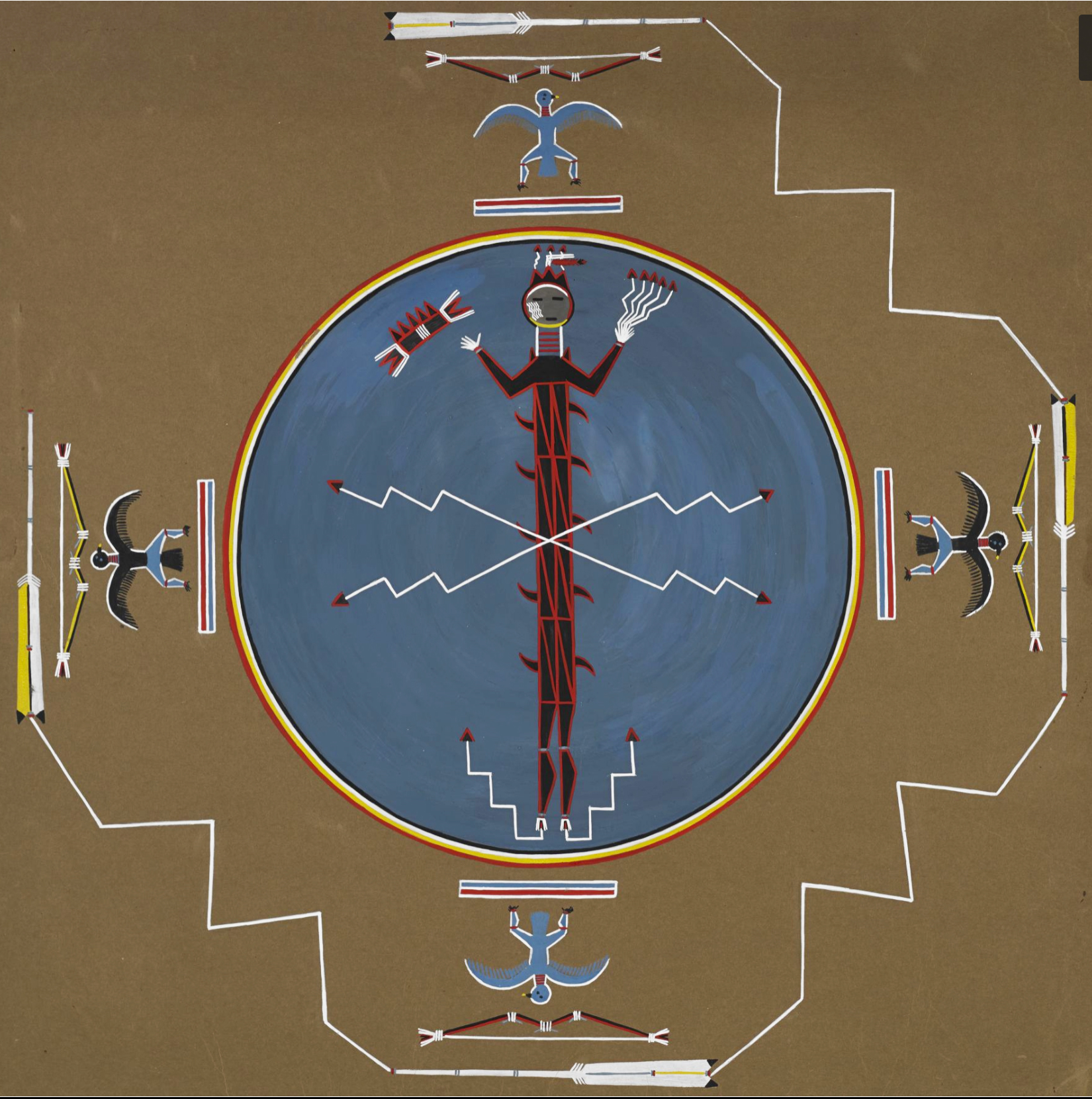

This poster paint on cardboard, 22 5/8 x 22 1/4 in. (57.3 x 56.5 cm), is the reproduction of a real sandpainting, Monster Slayer in the House of the Sun, 1920s-1930s, by Franc Johnson Newcomb. Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University; Avery Art Properties.

Hail and Water Chant, Navajo Sand Painting, 1950. Archives and Rare Books Library, University Libraries, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio. The Szwedzicki Portfolios: Native American Fine Art and American Visual Culture 1917-1952. University of Cincinnati, JSTOR.

The secularization of the sacred sandpaintings and the ethical debate

In the 1930s, with the support of anthropologist Mary Wheelwright, Hataałii Hosteen Klah began reproducing ceremonial imagery in permanent media. This act stirred controversy, but it also catalyzed cultural preservation efforts (Mary Wheelwright).

«Sandpaintings are surrounded by a number of supernaturally sanctioned taboos. These include rules against rendering the paintings in a permanent form or using them outside the ritually controllable context of the ceremonial. To do so is dangerous because the supernaturals will be called by their likeness, angered by the misuse of sacred designs. The result will be illness, blindness, or death for the maker and drought and destruction for the tribe. Thus, the making of permanent sandpaintings for any purpose is considered a sacrilege by many Navajos.» ((Nancy J. Parezo, 1979).

However, the demands of the market economy, to which the Navajo must adapt; poverty and unemployment within the reservation; and the desire to preserve certain aspects of their culture, have led some Navajo people to create both permanent sandpaintings and sandpainting rugs that reflect sacred themes and motifs in a more secular way. Following the popularization of glued sand art around Sheep Springs, New Mexico, in 1958, hundreds of Navajo artists began producing commercial sand paintings. By the mid-1960s, over 500 people were involved. Though less widespread than weaving or silversmithing, this art form gained a foothold in local and tourist markets.

The intersection of sacred tradition and artistic commodification generated tension and discussions. To overcame religious doubts and the fear of breaking religious taboos, designers and weavers started to intentionally make the paintings and the rugs imperfect or incomplete to turn them into neutral items.

The adaptation strategies included

- Intentional Alteration: Sacred figures are modified—colors are changed, specific elements are omitted—to desacralize the work for public or commercial display. (Kathy M’Closkey)

- Media Translation: Symbolic motifs are transposed into textiles, prints, or sculptures, distancing the imagery from ritual use while preserving cultural narratives (Bertha Dutton).

The Indian Arts and Crafts Act stipulates that works sold as Navajo sand paintings must be crafted by enrolled Navajo artisans (Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990, Public Law 101-644). While some elders caution that commodification risks diluting sacred knowledge, others argue that it offers adaptive resilience—a way for culture to evolve without losing its essence. (Charlotte Heth).

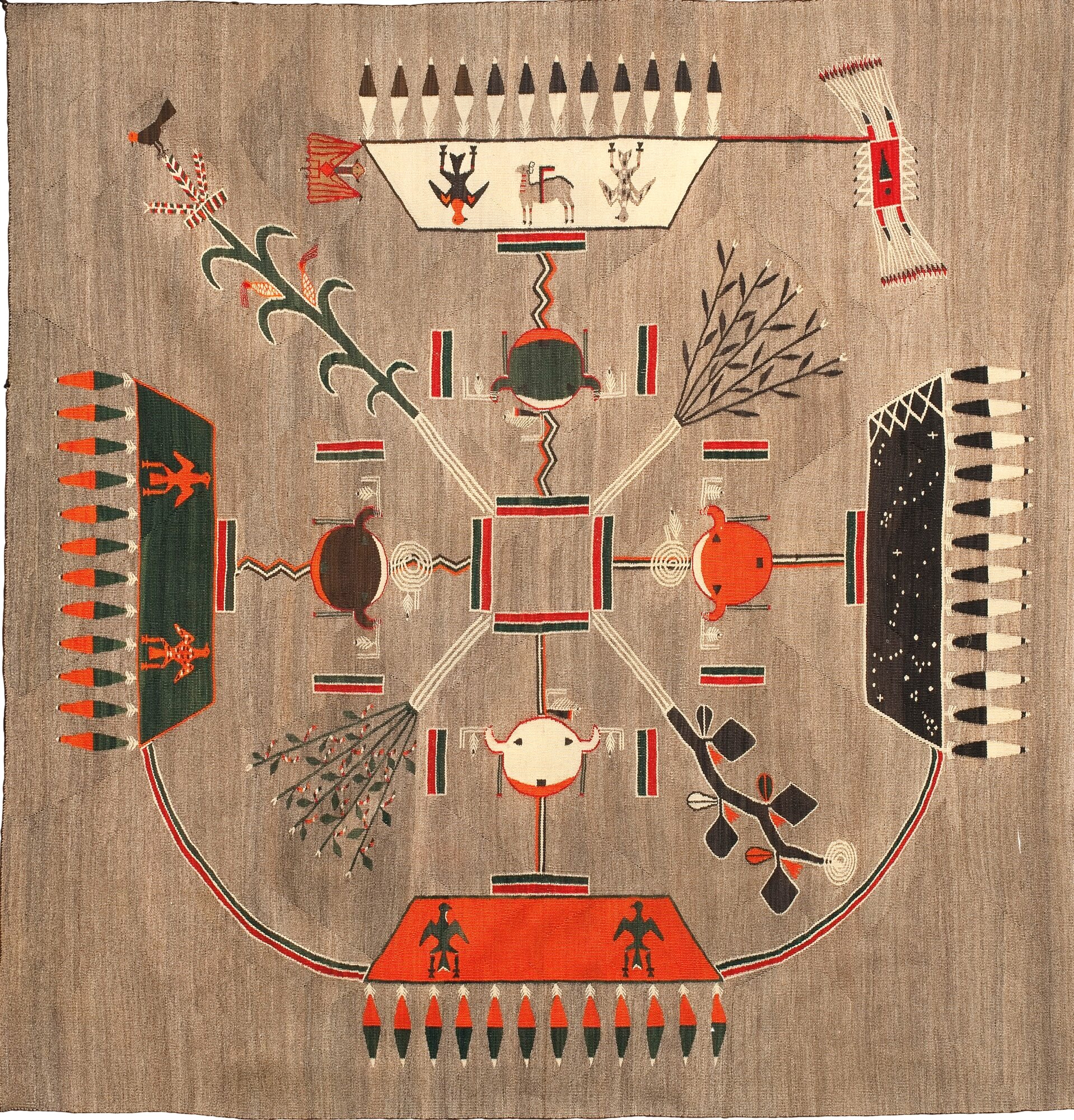

Navajo Sandpainting Blanket or Rug, date unknown. This piece is woven from handspun wool in natural and aniline colors. It features a sand painting design that is likely a depiction of the Male Shootingway Chant. The design includes four trapezoidal elements trimmed with feathers that enclose four horned figures. These figures represent the night sky, sun, moon, and black and yellow wind, respectively. Dimensions: 88 x 84 in.; 223.52 x 213.36 cm. Sotheby's - Wikimedia Commons.

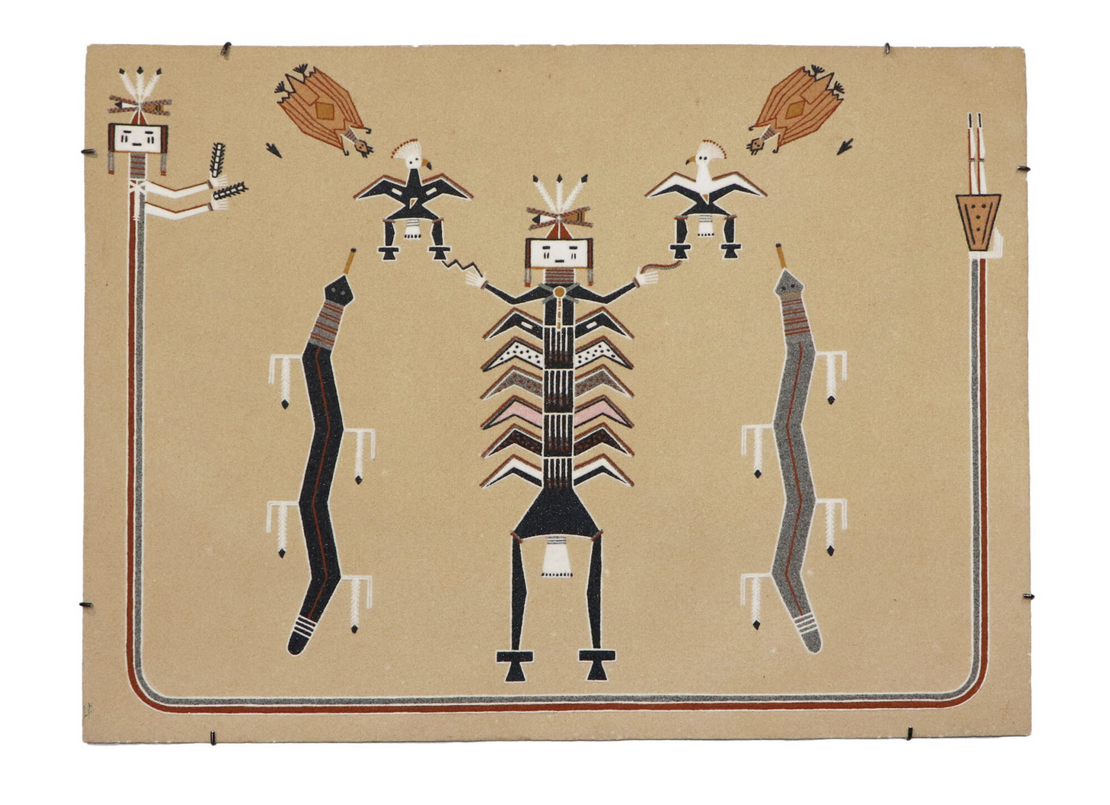

Permanent sandpainting depicting Scavenger Boy and Lightning by Fred Stevens Jr. "Grey Squirrel". Medium: Colored sand, glue, and varnish on board. Date: ca. 1950. Dimensions 24 x 32 in.; Cameron Trading Post, Cameron, AZ.

Unlike ritual sandpaintings, permanent and commercial sandpaintings are not made by a hataałii. They do not use ritually sacred materials and employ different colors and details. Commercial sand paintings use glue to affix them to wooden boards, paper, canvas, or ceramic surfaces, and varnish to create a protective outer layer.

Swirling Rainbow Goddess 5th Day by Doris Leuppe, 1960 - 1969, Tohatchi, NM. Hubbard Museum of the American West, New Mexico's Digital Collections.

This permanent sandpainting shows four swirling rainbow goddesses, each with a brown face, black mouth, and black eyes. Each goddess has corn tassels coming from her head, and her body swirls from the center in dark tan and turquoise. They have tassels on their elbows and wrists and white hands. Each goddess has a blanket from the waist:

1) pink with gray fringe

2) dark tan with turquoise and light tan

3) turquoise with dark brown fringe

4) tan with black fringe and a black-tan center The skirts are two tan with gold centers, one dark brown with gold centers, and one medium brown with gold centers. They are each standing on a side of a tan, white, and turquoise square. In the center are two triangular shapes coming into a circle from four sides. A black band between the center circle is reddish brown with a gold cross.

Contemporary Challenges and Innovations

Navajo sandpainting embodies the concept of Náhásdlį́į́, the eternal motion and renewal at the heart of the Diné universe. As a healing practice and cultural symbol, sandpainting navigates the demands of modernity with remarkable resilience. Despite pressures from commercialization, generational shifts, and global exposure, sand painting remains a vibrant expression of Navajo identity. Its continued practice reflects what scholars call innovative traditionalism—the ability to evolve while maintaining core cosmological values. Through each carefully placed grain, the Navajo affirm their relationship with the sacred world and the land from which their art and healing emerge.

However, in the 21st century, Diné ceremonial sandpainting faces many threats.

- Declining Apprenticeships: Becoming a hataałii traditionally requires a decade or more of training, mentorship, and memorization of hundreds of songs, prayers, and designs. However, few young people are taking up the role, raising concerns about cultural continuity (Kelley and Francis).

- Documentation Dilemmas: Photographing or recording rituals remains taboo in many contexts, which limits how ceremonies can be archived or studied, even by the Navajo themselves (Gary Witherspoon).

- Museums and Misrepresentation: Public exhibitions must tread carefully. Institutions often use the label “inspired by” to distinguish interpretive works from authentic ritual creations and avoid unintended desecration (Ralph T. Coe).

The major threat, of course, is posed by the commercialization and "secularization" of ceremonial sand painting designs. This is just one of many threats to the stability of a society whose traditional structure has been invaded by non-Indian concepts of commodification, commercialization, exploitation of resources for profit, and "art for money".

Yet the Diné have never been strangers to adversity. Through Long Walks and broken promises, through the theft of land and language, they have endured—not by forgetting who they are, but by remembering it. The holy images born from sand and chant were never meant to hang in galleries; they are not mere patterns, but prayers. They are not decorations, but "the footprints of the Holy People" (as James C. Faris said in the The Nightway), meant to vanish like mist once their healing is complete.

Even now, when Diné sacred symbols are pulled into the glare of commerce and stripped of context, they must not allow them to be emptied of meaning. The power of their ceremonies does not lie in permanence but in presence—in the moment when breath becomes song and earth becomes spirit. Thus, the Diné must stand as their elders did, between two worlds without kneeling. They must protect that which cannot be bought. They should remember what cannot be sold. In every act of reverence and every gesture of protection, they once again speak the language of Hózhó, and the sacred continues.

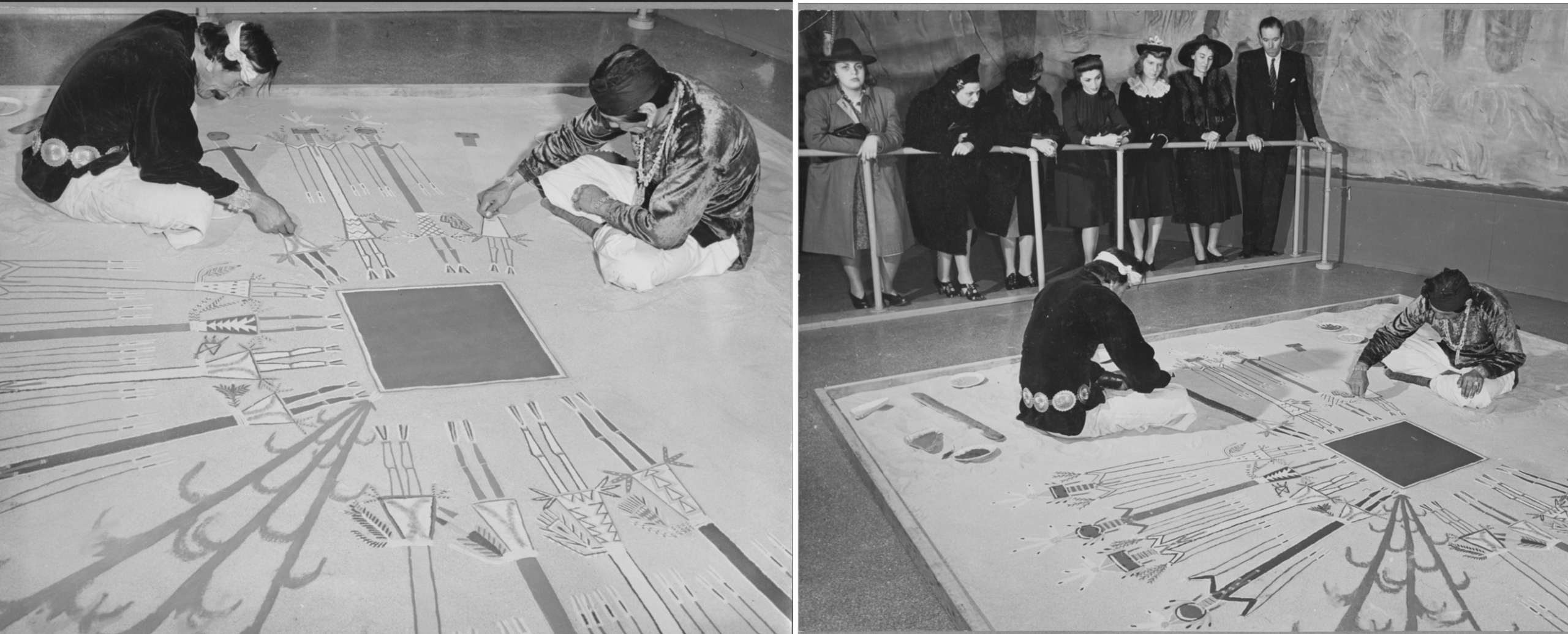

Navajo sandpainting at the exhibition "Indian Art of the United States", January 22, 1941 - April 27, 1941, MoMA, Manhattan, New York. Photo by Eliot Elisofon.

These photos are chilling. On the right, an audience of well-dressed white New Yorkers from the upper middle class watches from above as two Navajo medicine men create a sand painting on the floor. On the right, a well-dressed, upper-middle-class audience of white New Yorkers watches from above as two Navajo medicine men create a sand painting on the floor. While this is a far cry from the shameful human zoos and ethnological exhibitions of the past, it nonetheless leaves an unpleasant aftertaste. Here's what Jason Falkenburg writes in his The ‘Secularization’ Process of Diné Commercial Sand Paintings and the Persistence of Religious Values (2011): «It is interesting to point out the people that are standing in the upper left hand corner whom are witnessing this event as if it were a spectacle performance, almost as if it were a tourist attraction. The actual function of the dry painting is completely lost when it is performed outside the ceremonial context in a (secular) place like a museum. It can be generally assumed that most of the western viewers have no knowledge of the intrinsic religious values of the Diné that is reflected in their complex ceremonial chants. The public viewer sees in this kind of museum exhibition no more than a source of entertainment. Surely, the exhibition is meant for educational purposes, but the actual meaning of the dry painting is almost redundant if the ceremonial context is removed. From this perspective one can easily argue that by removing them from the original context, the dry paintings witnessed a major change in which they started to function as a consumerist marketing product.»

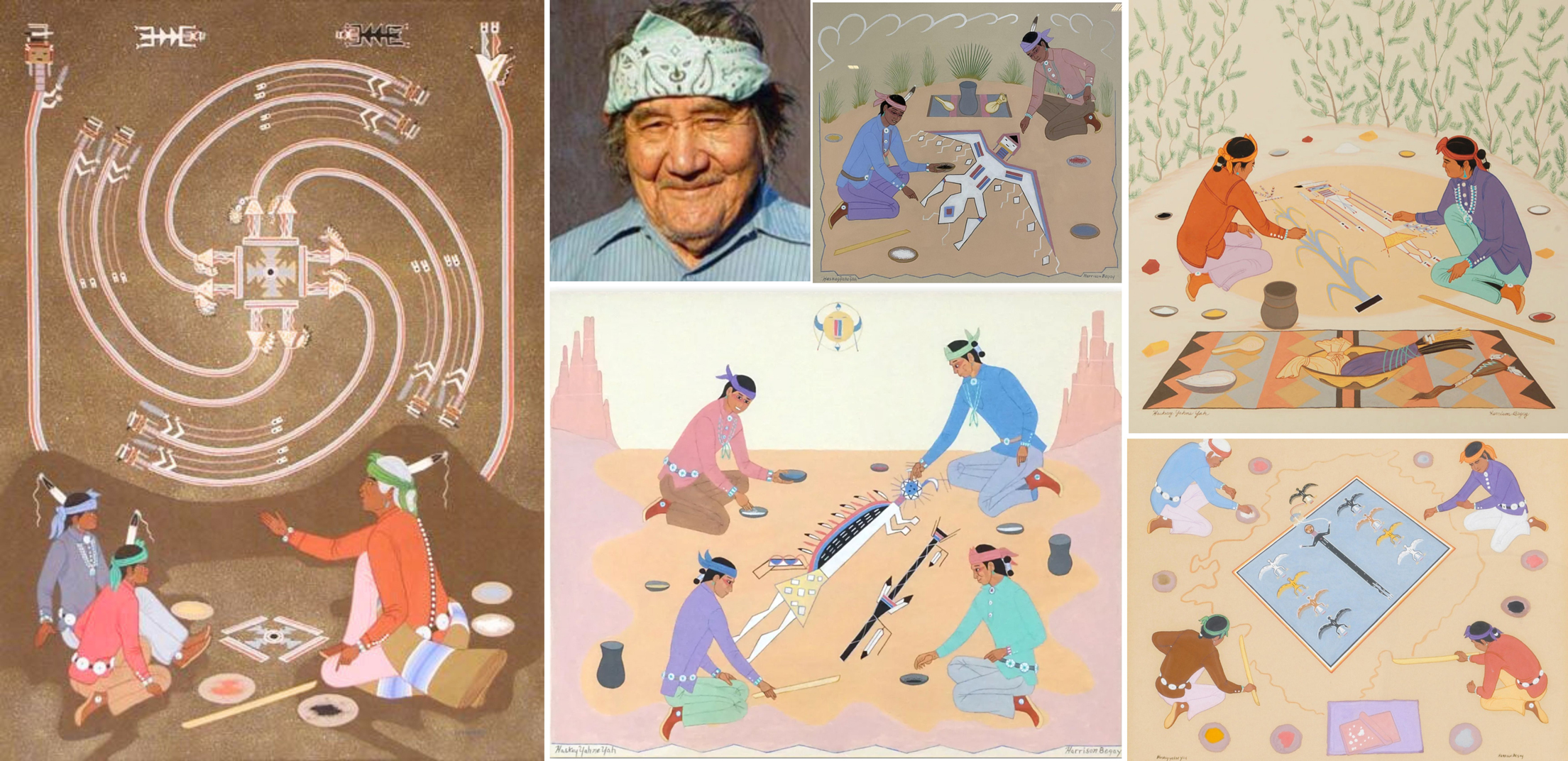

Navajo artist Harrison Begay (also known as Haashké yah Níyá, "Warrior Who Walked Up to His Enemy" or "Wandering Boy", 1914 or 1917 –2012) with some of his artworks depicting ceremonial sandpainting.

Diné artist Gerald Nailor Sr., also known as Toh Yah ((1917/1952) ) with some of his artworks. Left: Yeibichai, 1948. Right: Navajo Harvest Ceremony with Yeibichai processing, 1943.

Bibliography

- Reichard, Gladys A. Navajo Religion: A Study of Symbolism. Princeton University Press, 1950.

- Witherspoon, Gary. Language and Art in the Navajo Universe. University of Michigan Press, 1977.

- Kelley, Klara B. and Francis, Harris. A Diné History of Navajoland. University of Arizona Press, 2019.

- McNeley, James Kalestewa. Holy Wind in Navajo Philosophy. University of Arizona Press, 1981.

- Frisbie, Charlotte J. “The Structure of Navajo Chantway Myths.” American Anthropologist, vol. 72, no. 6, 1970.

- Bahti, Mark. Southwestern Indian Ceremonials. Rio Nuevo, 2000.

- Bahti, Mark, A Guide to Navajo Sandpaintings, revised edition 2000, Tucson, Arizona, Rio Nuevo Publishers.

- Reichard, Gladys A. Navaho Religion, 1950.

- Gill, Sam D. Sacred Words: A Study of Navajo Religion and Prayer. Greenwood Press, 1981.

- Griffin-Pierce, Trudy. Earth Is My Mother, Sky Is My Father: Space, Time, and Astronomy in Navajo Sandpainting. University of New Mexico Press, 1992.

- Denetdale, Jennifer Nez. “The Long Walk: Decolonizing Navajo History.” American Indian Quarterly, 2008.

- Wheelwright, Mary. Sandpaintings of the Navajo Shooting Chant. Museum of Navajo Ceremonial Art, 1947.

- Bahti, Tom. A Guide to Indian Arts and Crafts of the Southwest. Western National Parks Association, 1966.

- M’Closkey, Kathy. Swept Under the Rug: A Hidden History of Navajo Weaving. University of New Mexico Press, 2002.

- Dutton, Bertha. Navajo Indian Arts: Symbolism, Myth, and Meaning. Museum of New Mexico Press, 1975.

- Indian Arts and Crafts Act of 1990, Public Law 101-644.

- Heth, Charlotte. “Art as Identity: The Role of the Artist in Native Cultures.” Journal of American Indian Education, 1993.

- Kelley and Francis, A Diné History of Navajoland, 2019.

- Witherspoon, Gary. Language and Art in the Navajo Universe, 1977.

- Coe, Ralph T. Sacred Circles: Two Thousand Years of North American Indian Art. British Museum Press, 1976.

- Griffin-Pierce, Trudy. Earth Is My Mother, Sky Is My Father, 1992.

- Nancy Parezo, Economic Aspects Of Navajo Sandpaintings, Paper presented in the symposium on the Commercialization of Indigenous Arts, the 78th Annual Meeting of the American Anthropological Association, Cincinati, Ohio, November 30, 1979.

- Jason Falkenburg, The ‘Secularization’ Process of Diné Commercial Sand Paintings and the Persistence of Religious Values, Bachelor's Thesis, 2011, University Leiden.

- Janet Catherine Berlo, "Navajo Sandpainting in the Age of Cross-Cultural Replication", Art History, 37 | 4 | September 2014.

- .John Gerber, Navajo Sandpainting Textiles, Jan . 21 - Feb. 28, 1996, Johnson County Community College • Gallery of Art, Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Overland Park, Kansas.

What Sand Forgets: On Sacred Art, Ephemerality, and Cultural Projection

Several scholars, writers, and spiritual practitioners have drawn comparisons between Navajo sand paintings and Tibetan Buddhist mandala sand paintings. This trend is especially popular among Western academics and writers who are fascinated by cross-cultural spirituality.

These are two images that I created using Sora, OpenAI's video generation model.

The topic is compelling, though not for the reasons many assume. These comparisons often lack genuine cross-cultural understanding. They flatten complex traditions into visually digestible similarities and avoid the harder work of contextual analysis. A serious cross-cultural approach requires more than surface-level analogies; it must respect and preserve differences.

Yes, both traditions use sand. Yes, both create elaborate and symmetrical designs. Yes, both destroy their creations. However, their cultural, spiritual, and functional contexts diverge profoundly. Navajo sand paintings and Tibetan mandalas originate from different cosmologies, rituals, and historical lineages. The Navajo tradition evolved from Pueblo practices, while the Tibetan tradition stems from Vedic and Buddhist traditions. Claims of "convergent evolution" are misguided unless one believes in spiritual Darwinism.

Trudy Griffin-Pierce and Gary Witherspoon emphasize that Navajo sand paintings must be understood within their own ceremonial and epistemological logic. Likewise, Tibetan scholars and monks stress that the mandala's significance cannot be grasped merely through observation; it must be practiced, inhabited, and ritually understood.

Academic works such as The Sacred Circle: East and West by Shelli Renee Joye often draw structural comparisons. However, these comparisons often prioritize visual resemblance over deeper cultural significance. Western fascination with the "exotic" often fuels such comparisons, projecting familiar ideas onto unfamiliar traditions.

Anaïs Nin once wrote, "We don't see things as they are, we see them as we are." Quoted in Seeing and Weaving: Culture, Perception, and the Meaning of a Navajo Rug, this insight captures the heart of the issue. Western viewers often impose their philosophical frameworks on other traditions, which can lead to misinterpretation, appropriation, and reductionism. Ironically, this often reveals more about the viewer than the viewed.

When faced with Navajo and Tibetan sand paintings, the Western eye sees geometric intricacy and ritual destruction, interpreting them as a shared meditation on impermanence. However, this overlooks the specific theological meanings of each tradition. This also exposes a key tension in Western sacred art: the West occasionally flirts with impermanence but mostly embraces permanence.

Within Abrahamic traditions, sacred art typically resists impermanence. God is eternal and unchanging. Sacred objects are preserved, enshrined, and venerated. Artworks that meditate on death, such as 17th-century Dutch vanitas still lifes or late medieval Italian danse macabre murals, are built to last. The forms must match the message: enduring, transcendent, and beyond decay.

However, not all sacred art is created to be seen and admired as masterpieces that withstand the test of time and tell stories of a transcendent, eternal God. To the Western eye and mind, sacred art is a visual object—beautiful, lasting, and contemplative. Therefore, the destruction of a sand painting feels unsettling, contradictory, and striking. Westerners are obsessed with the irreconcilable dichotomies of time and eternity, beauty and death.

In traditional Navajo culture, sandpainting is not considered "art" in the Western sense, but rather a sacred and ephemeral ritual act. While the Western concept of "art" emphasizes permanence, display, and aesthetic appreciation, Navajo sand painting is meant to be destroyed after ritual use and is never commodified or preserved for contemplation. However, it is not destroyed to encourage meditation on impermanence or the transience of beauty. It's destroyed because it's an element of a sacred ritual; it's a means, not an end; an act, not a thing.

When sandpaintings are exhibited in museums, sold as permanent objects, or appreciated primarily for their visual qualities, their original sacred function is lost. I was also mistaken to show reproductions or photos of sandpaintings from the mid-20th century as if they were Western-style artwork. Transforming a ritual process into a collectible or displayable "artwork" is a contradiction in terms. The sacredness of Navajo sandpainting is inseparable from its ritual context and spiritual purpose. All of these aspects are compromised when the art form is adapted to Western paradigms of art.

Where the Meaning Goes

While both Navajo and Tibetan traditions use impermanent sand art to engage with sacred realms, their differences far outweigh their visual similarities. Navajo sand painting is a healing practice rooted in relationships with the land, ceremonies, and supernatural forces. Tibetan mandalas, by contrast, are cosmological diagrams aimed at transcending samsara. Equating the two risks erasing the Navajo focus on individual healing in favor of a generalized narrative of spiritual enlightenment. As Griffin-Pierce reminds us, Navajo sand paintings are "ritual realities," not meditative aids.

Since the 1950s, commercial "mandala-style" Navajo sand paintings have catered to tourist markets, departing from ceremonial imperatives. Sacred figures are altered—colors changed, symbols omitted—to render them acceptable for display and sale. While these adaptations preserve cultural motifs through textiles, prints, and sculptures, they simultaneously distance the imagery from its ritual function. The result is not necessarily degradation; it's transformation. However, a happy ending is by no means guaranteed.

TIBETAN BUDDHIST SANDPAINTING

In August 2018, Tibetan Buddhist monks from Drepung Loseling Monastery will construct a mandala sand painting and perform special ceremonies at the Asia Society Texas Center in Houston, TX. During this ritual, the monks will meticulously place millions of grains of sand to purify and heal the environment and its inhabitants.

ABORIGINAL SANDPAINTING

Sandpainting has been an integral part of Aboriginal Australian culture for thousands of years, and it is still practiced today. This ephemeral art form is deeply embedded in rituals, storytelling, and transmitting cultural knowledge. It serves as a visual language for Dreamtime narratives, marking territory, and recording history. Using natural ochres, colored sands, charcoal, and other organic materials, artists create intricate designs on the ground. Common symbols include concentric circles (representing meeting places or waterholes), U-shapes (representing people), animal tracks, and lines (representing paths or boundaries). Each symbol carries specific cultural meanings. Aboriginal sandpaintings are intentionally temporary. They are created for rituals and then destroyed or left to the elements. This emphasizes process and spiritual function over permanence.

The second photo from the left shows a sand painting on display at the Tandanya National Aboriginal Cultural Institute in Adelaide, Australia, in 2021. The picture from the early 20th century in the center shows an Aboriginal man seated with his sand painting in Western Australia. The image on the bottom center shows a sand art installation celebrating the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community. It will last as long as the elements allow. The picture on the top right is a Ypullululu Tjungurrayi sandpainting from around 1981 by Vessa Playfair in Alice Springs, Australia. It was auctioned by Sotheby's in 2007. The first image on the left and the last image on the bottom right were created using Sora, OpenAI's video generation model.

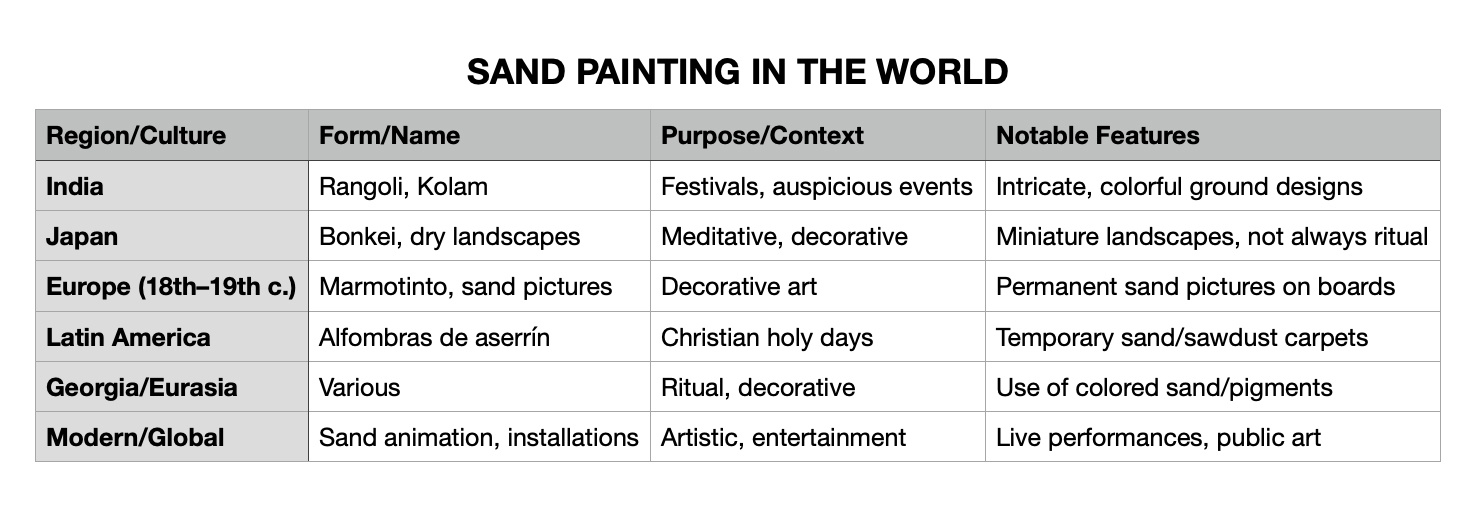

Sandpainting is a widespread and ancient art form that extends far beyond the well-known traditions of the Navajo, Australian Aboriginal peoples, and Tibetan Buddhists. Many other cultures have developed their own unique sand painting practices for ceremonial and artistic purposes. There are—and have been—many forms of sand painting around the world, each with its own cultural, spiritual, or artistic significance. Notable traditions include Indian rangoli and kolam, Japanese bonkei, Latin American alfombras, and European decorative sand paintings. This vibrant, evolving practice connects people to their heritage, rituals, and creative expression across continents.

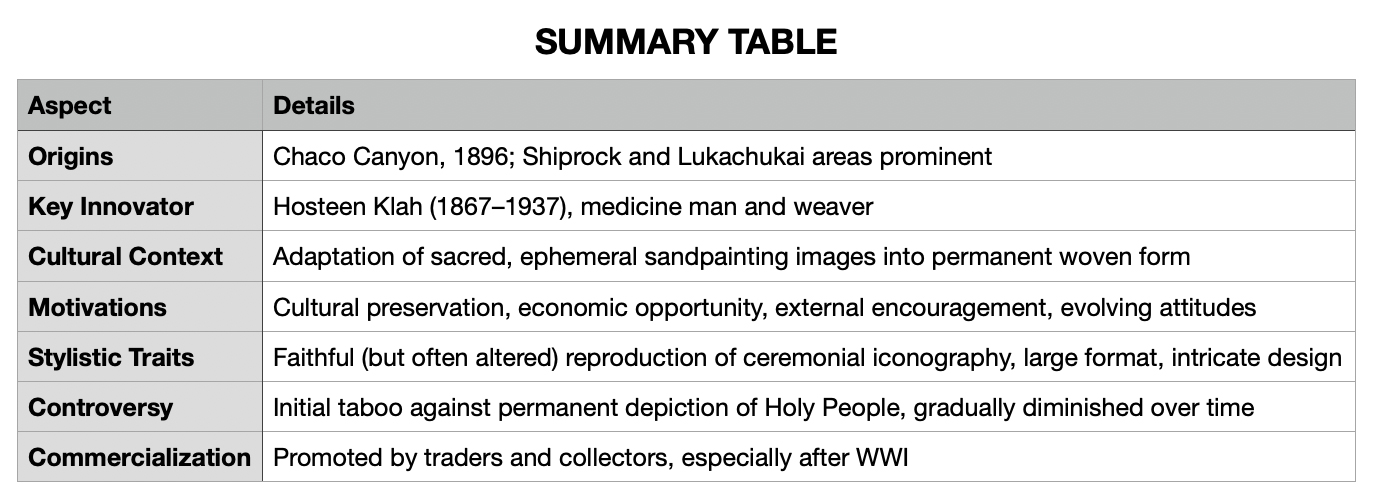

NAVAJO SANDPAINTING RUGS

Origins and Early Development

Navajo sandpainting rugs are a unique fusion of sacred ceremonial art and the commercial rug trade. Unlike traditional sandpaintings—ephemeral creations used in healing rituals—these woven works are permanent representations of sacred imagery, which was traditionally considered taboo in Navajo culture. The first documented sandpainting rug was woven in 1896 in Chaco Canyon, commissioned by a member of the Wetherill Expedition. This marked the beginning of a controversial practice because preserving these sacred images in textile form was believed to offend the Holy People and inviting harm to the weaver or their community.

By the early 20th century, additional examples began to emerge, particularly at trading posts such as Newcomb’s and in weaving hubs like Two Grey Hills. Still, production remained limited and discreet, reflecting the deep cultural prohibitions against immortalizing ceremonial designs.

Geographical Cradle and Expansion

The sandpainting rug tradition primarily developed in the northwestern part of the Navajo Reservation, centered around Shiprock, New Mexico, and extending into the Lukachukai region of Arizona—both of which are within the Navajo Nation. After World War I, this style gained broader visibility and acceptance, spurred in part by traders such as Will Evans of Shiprock, who promoted the sandpainting weaving and Yei rugs for the growing tourist and collector market. (We will discuss the latter rugs later.)

A pivotal figure in legitimizing the tradition was Hosteen Klah (1867–1937), a revered medicine man and master weaver. In 1919, Klah produced his first sandpainting rug featuring the “Whirling Logs” design from the Nightway Chant. With the support of his nieces and his patron, Mary Cabot Wheelwright, Klah spent nearly two decades weaving ceremonial imagery into textiles. Ultimately, he produced around 70 sandpainting rugs. His work played a crucial role in preserving sacred knowledge and easing cultural resistance to this emerging art form.

Threads of Meaning

The emergence of Navajo sandpainting rugs was shaped by a powerful confluence of cultural, economic, and external forces. Each of these factors contributed to the evolution of this once-taboo art form into a respected mode of expression.

- Cultural Preservation: As traditional ceremonies began to decline in the early 20th century, individuals such as Hosteen Klah became concerned that sacred sandpainting designs and their associated chants might be lost. By transforming these ephemeral ceremonial images into textiles, Klah and his relatives safeguarded a significant spiritual legacy. With the support of his patron, Mary Cabot Wheelwright, Klah produced approximately 70 sandpainting rugs between 1919 and his death in 1937. This ensured that core elements of Navajo cosmology would endure in woven form.

- Economic Opportunity: Growing interest in Navajo arts among Anglo collectors, scholars, and tourists created a market eager for textiles with deep symbolic resonance. Sandpainting rugs, imbued with ceremonial imagery, commanded higher prices than other regional styles. For many weavers, these rugs offered both cultural affirmation and a vital source of income.

- External Encouragement: Anglo traders and anthropologists, particularly figures like Will Evans of Shiprock, recognized the visual and commercial power of sand painting–inspired weavings. They actively encouraged their creation, often commissioning pieces for museums and private collections. This external interest helped normalize the style and expand its reach beyond the Reservation.

- Changing Community Attitudes: Early fears that reproducing sacred imagery might cause harm or spiritual imbalance gradually subsided. As more rugs were produced without incident, resistance diminished. The continued well-being of weavers like Klah offered reassurance that sacred motifs could be adapted into textile art without disrespecting their origins. Over time, the sand painting rug emerged as an act of remembrance and transformation, not desecration.

Stylistic Characteristics

Sandpainting rugs are notable for their detailed reproduction of ceremonial iconography, including images of holy people, sacred animals, plants, and symbolic motifs. Out of respect for tradition, weavers often omit or modify certain sacred elements to safeguard their ritual potency. (Once again, I would like to emphasize that these rugs have never served any ritual or sacred purpose.)

Sandpainting rugs are typically large, requiring exceptional technical skill, deep symbolic literacy, and a significant amount of time at the loom.

Regional Variations

- Shiprock Area: This area is known for sandpainting and Yei rugs. These works often feature slender, brightly colored figures against a pale background. Sometimes, they are bordered by a protective Rainbow Guardian Yei.

- Lukachukai and Upper Greasewood: Weavings from this region tend to be coarser and larger in scale. They feature heavier, more stylized figures and simplified borders that reflect local traditions and materials.

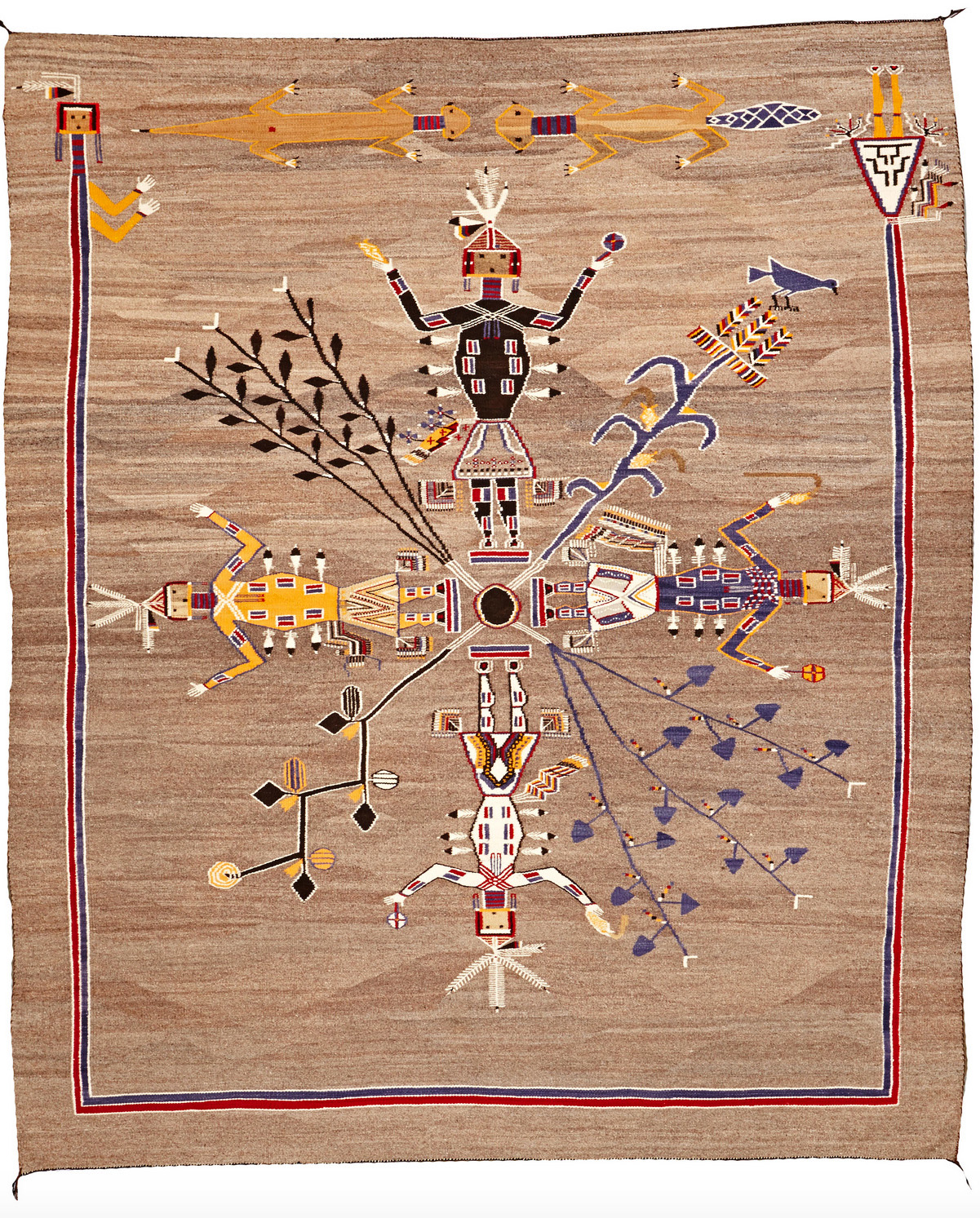

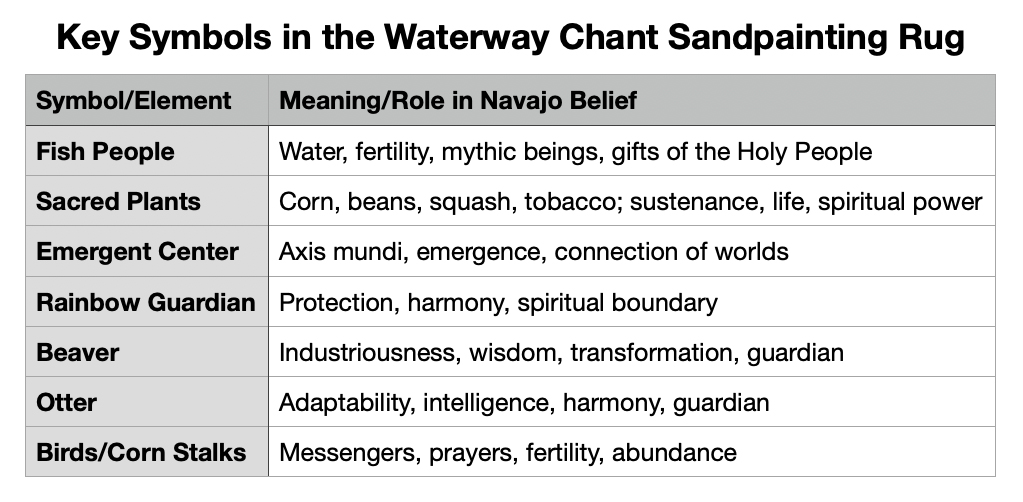

A rare Navajo sandpainting rug, undated. It depicts a variation on the Waterway Chant (a subgroup of the Shooting Chant), with four fish people and sacred plants arranged around the center. A rainbow guardian encloses three sides, and beaver and otter guardian figures are at the top. Dimensions: 8ft x 6ft 9in.; 243.84 cm x 205.74 cm. Auctioned in 2014 by Bonham's, San Francisco.

The rug depicts a variation of the Waterway Chant, which is a subgroup of the Shooting Chant. These "chantways" are complex ceremonial cycles focused on healing, balance, and the restoration of harmony in the Navajo worldview. The Waterway Chant is particularly associated with water, rain, and fertility—vital forces in the arid Southwest. Now, let's examine the key design elements and their meanings.

1. Four Fish People

The central figures in the rug are the "Fish People," mythical beings from Navajo sandpainting traditions. In the context of the Waterway Chant, they are associated with water, aquatic life, and the fertility of the land. They often hold symbolic objects such as ears of corn and baskets, representing abundance and the gifts of the Holy People. Their arrangement around a central axis reflects the Navajo emphasis on balance and the four cardinal directions, a recurring theme in sandpaintings.

2. Sacred Plants

The rug features sacred plants radiating from the center, likely including corn, beans, squash, and tobacco—the Four Sacred Plants of the Navajo. These plants are fundamental to Navajo cosmology and ceremonial life. They symbolize sustenance, growth, and the interconnectedness of all living things. The central placement of these plants underscores their role as sources of life and spiritual nourishment.

3. Emergent Center

The design radiates from a central point, symbolizing emergence—a key concept in Navajo creation stories, where life emerges from previous worlds into the present one. The center often represents the axis mundi, or the point of connection between the earthly and spiritual realms.

4. Rainbow Guardian

The three-sided border enclosing the main design is known as the Rainbow Guardian or Rainbow Bar. In Navajo belief, the rainbow is a powerful symbol of protection, harmony, and the bridge between the spiritual and physical worlds. It marks the boundary of the sacred space, ensuring that only beneficial forces enter. The open side of the rainbow border allows the Holy People to safely pass during ceremonies.

5. Beaver and Otter Guardians

At the top of the rug are beaver and otter figures that serve as guardian spirits. In Navajo and broader Native American traditions, beavers symbolize industriousness, perseverance, and wisdom. Otters represent adaptability, intelligence, and harmony with the environment. Their presence as guardians reflects their roles in mythology as helpers, mediators, and protectors, particularly in ceremonies involving water and transformation.

6. Additional Motifs

Birds, corn stalks, and other natural elements may appear, each carrying its own layer of meaning—birds often symbolize messengers or prayers carried to the sky, and corn stalks reinforce themes of fertility and life.

Sandpainting rugs are woven records of sacred knowledge and ceremonial practices. Weaving such a rug requires a deep understanding of the stories, symbols, and rituals it represents. Traditionally, the reproduction of sand painting designs was restricted, and intentional alterations were made to avoid sacrilege and protect the weaver and viewer from spiritual harm.

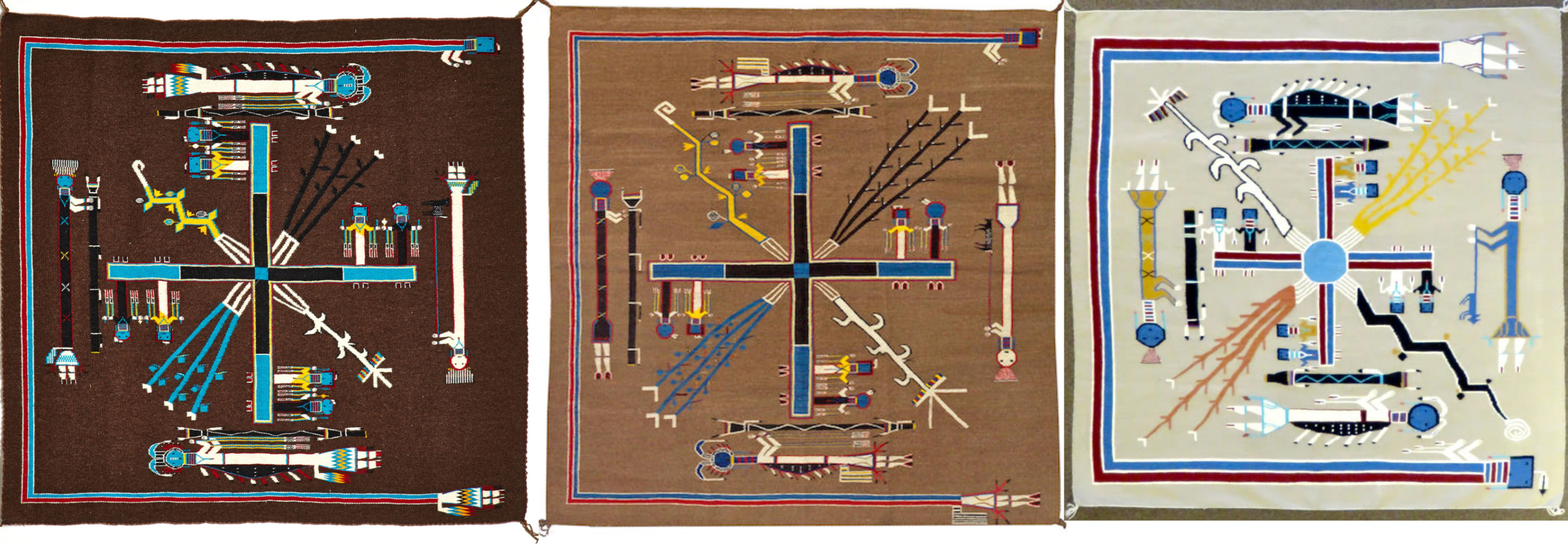

Left to right: Sandpainting rug by Ruby Manuelito, very finely woven, undated; dimensions 3ft 4in x 3ft 3in.; 101.6 cm × 99.06 cm. Sandpainting by Sam (Gladys) Manuelito, undated, dimensions 5ft 11in x 5ft 9in.; 180.34 cm × 175.26 cm. Sandpainting rug woven by Ida Bitah, ca. 1990s; dimensions: 48 x 49 in.; 121.92 cm x 124.46 cm.

The designs of these three sandpainting rugs are the same: the "Whirling Log" from the Nightway Chant, surrounded by the Rainbow Yei in the north, south, and west, and incorporating the four sacred plants. Inspired by a sacred dry painting, this design represents a profound synthesis of Navajo ceremonial symbolism focused on healing, protection, and cosmic balance.

Central to the Nightway Chant (a nine-night healing ceremony), the Whirling Log (Tsil no oli) sandpainting is created on the sixth night to restore harmony and health while repelling evil. It depicts four crossed logs extending toward the cardinal directions, representing the logs ridden by the Twin War Gods in Navajo mythology. The crossed logs signify movement and direction ("that which revolves"), with deities perched at each end. Eight Yei (four male and four female) sit on the logs, embodying healing spirits. The central white square represents the primordial lake of creation, surrounded by white foam (symbolizing life-giving water).

The Rainbow Guardian Yei encircles the southern, western, and northern sides of the design as a barrier against evil. Its absence on the east side is intentional. According to Navajo tradition, "no evil can come from the east," which is the direction of dawn and positive energy. The rainbow serves as a pathway for the Yei and restores hózhǫ. Its multicolored bands, which are often depicted as being adorned with feathers, signify divine protection during healing rituals.

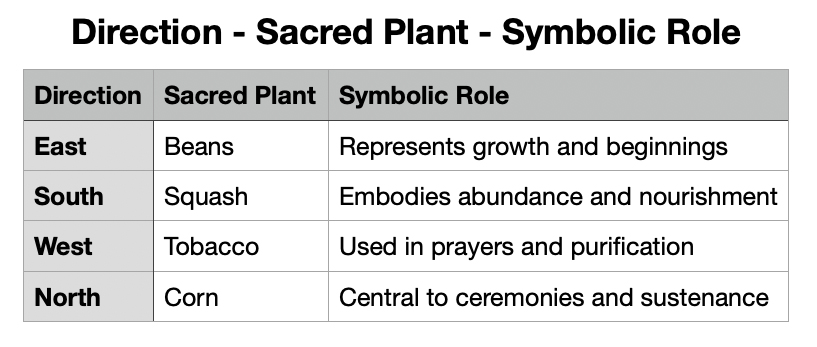

The plants are positioned between the cardinal directions, linking the natural and spiritual realms.

These plants anchor the design to the earth, emphasizing the interconnectedness of humanity, nature, and the divine, a core Navajo concept.

The structure of the design—centered on the Whirling Log, shielded by the Rainbow Yei, and grounded by the sacred plants—creates a microcosm of Navajo cosmology.

Healing Power: The Whirling Log "whirls" sickness away from the patient while the Rainbow God protects the ritual space.

Cosmic Order: The open east invites healing light, and the plants mediate between directions, affirming balance and renewal.

Cultural Continuity: Navajo artists preserve ceremonial knowledge by weaving this sacred imagery, transforming ephemeral rituals into enduring art.

The original sandpainting design was a spiritual map that guided the restoration of physical and spiritual well-being through ancient symbology. These sandpainting rugs have no sacred role; they are a secular version of ceremonial healing sand paintings. However, they must be blessed by a medicine man before they can be sold. This ritual is performed to ensure that the sacred and powerful imagery woven into the rugs does not cause harm to the weaver or eventual owner. The blessing ceremony is an important step and can increase the rug's price when sold through trading posts. This practice reflects a deep respect for the spiritual significance of the designs and a desire to maintain harmony and protection when sacred images are made permanent in textile form.

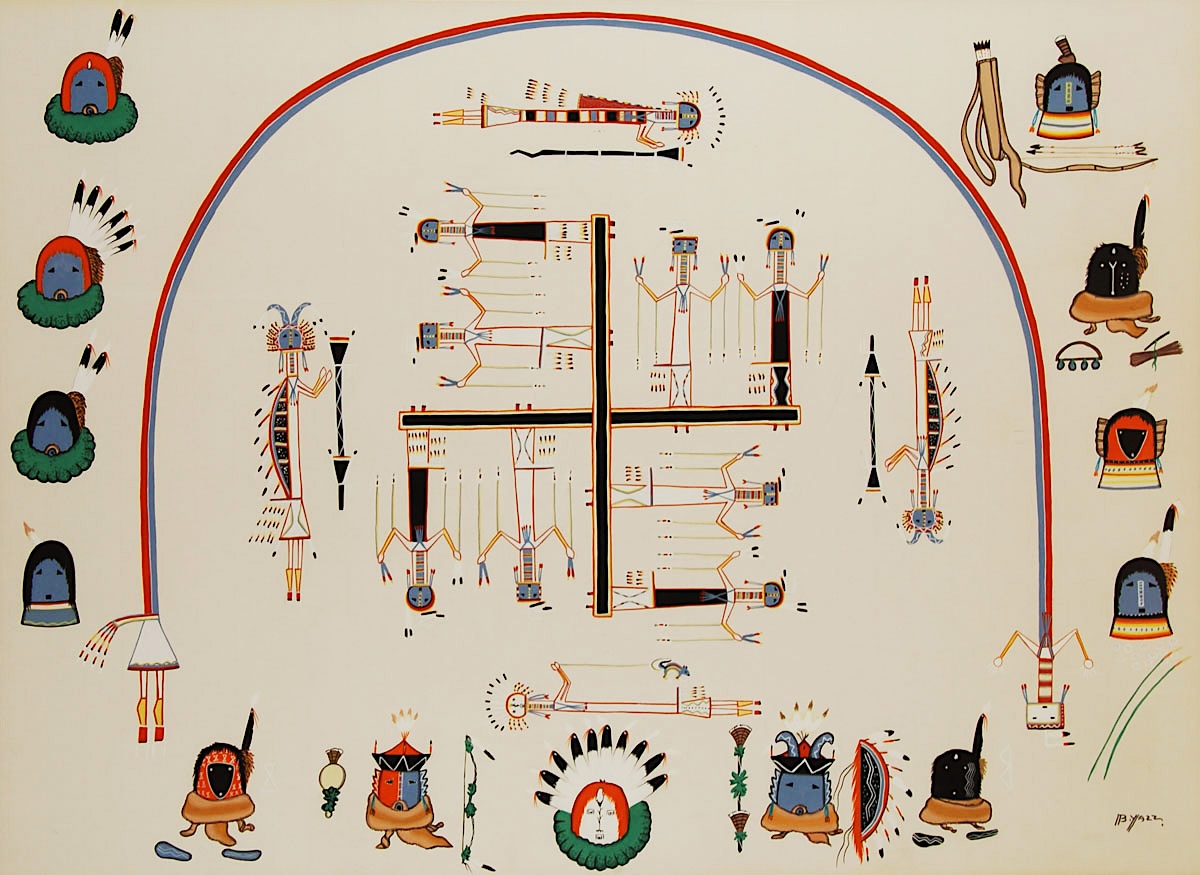

A modern interpretation of the Whirling Log design from the from the Nightway Chant, Casein by Navajo painter Beatien Yazz, 1968. Adobe Gallery, Santa Fe, NM.

A Navajo sandpainting rug attributed to Marie Antonio from Ganado, AZ; she was the wife of the the famous medicine man and singer Miguelito, 1865–1936. Date: ca. 1930. It depicts the Four Thunders design from the Male Shootingway Chant. Medium: Warp: Native hand-spun wool, 1-ply, 10/11 count to the inch; Weft: Native handspun wool, 1-ply, 24/26 count to the inch. Dimensions: 7ft 8in x 7ft; 233.68 cm × 213.36 cm. Auctioned in 2007 by Bonham's in San Francisco.

The "Four Thunders" design from the Male Shootingway Chant is a sacred Navajo sandpainting motif symbolizing protection, healing, and cosmic power. It originates from the Shootingway Ceremony and is specifically used to guard against illnesses caused by lightning, snakes, and arrows.

It represents the Four Thunder People (or Thunderbirds), who are supernatural beings that control lightning and storms, and have dominion over rain, fog, water, and hail. They serve as divine protectors, warding off evil and restoring hózhǫ to those afflicted by lightning strikes or snakebites. Each Thunderbird is linked to a cardinal direction, reflecting Navajo cosmology.

The most relevant visual elements of this design are:

Thunder Figures: These figures are depicted as anthropomorphic beings with lightning arrows, feathers, and horns. They are often shown in motion to signify their dynamic power.

Lightning Symbols: Zigzag or forked lines radiate from the figures, representing their ability to strike evil forces.

Rainbow Guardians: They enclose the design on three sides (south, west, and north), shielding the sacred space while leaving the east open to allow positive energy in.

Sacred Plants: Corn, beans, squash, and tobacco may appear between the thunders, connecting the spiritual to the natural world.

The sandpainting which inspired this rug had a healing function. Created during the Male Shootingway Ceremony, it was meant to channel the power of the Thunders to "armor" patients against physical and spiritual harm, particularly ailments linked to environmental dangers. Weavers often alter or omit sensitive elements of this design, such as the facial details of Thunder beings, to avoid desecration and to respect the sacredness of the imagery.

Storm Patterns, Rain and Lightning, permanent sandpainting by Diné artist Joe Ben Jr. (b. 1958). Early 1980s. Auctioned in 2024 by Bonham's, Los Angeles.

This sandpainting is a contemporary interpretation of the Four Thunders design from the Male Shootingway Chant. Joe Ben Jr. incorporated traditional elements, such as directional thunders, lightning, sacred plants, and protective rainbow motifs, into his own distinctive, modern style. He is known for reinterpreting traditional Navajo sand painting imagery in a contemporary, permanent medium, often introducing his own stylistic elements while maintaining core symbolic structures. The symmetry, color palette, and iconographic choices in this piece reflect this approach.

Mother Earth, Father Sky, possibly from the Mountain Chant or Night Chant, woven by Altnabah, ca. 1930. Medium: wool. Dimensions: 156 x 156 in. Collection Museum of Northern Arizona, Flagstaff. Photo: Museum of Northern Arizona photo archives.

The Father Sky and Mother Earth design is one of the most significant and sacred motifs in Navajo ceremonial art. This ancient design is clearly represented by two large anthropomorphic figures facing each other with their hands clasped, symbolizing the eternal union of these primordial deities. This hand-holding gesture signifies the union of heaven and earth, bound eternally together by the Rainbow Guardian.

The darker figure on the left represents Father Sky (Yadilhil), who is depicted in sand paintings with a black body. According to Navajo mythology, Father Sky is sacred, as are his offerings: air, wind, thunder, lightning, and rain. Celestial symbols, including stars and constellations, the sun and moon (represented by circles with "horns"), and the Milky Way (traditionally depicted as "zigzags crossing his shoulders, arms, and legs") are within his body.

The lighter figure represents Mother Earth (Nahasdzáán), who is female and called mother because she nurtures life by providing water, food, energy, and livelihood. Her body traditionally contains the four sacred plants—corn, beans, squash, and tobacco, which are fundamental to Navajo cosmology. They represent the life-giving fertility that springs from her womb.

This design embodies the Navajo belief that Father Sky and Mother Earth are considered the parents of everything. The relationship between these deities is reciprocal: From the sky comes life-giving rain, which nourishes the earth and allows it to offer its bounty. The two entities, earth and sky, are reciprocal; without one, the other would be meaningless. Father Sky and Mother Earth appear in many sand paintings associated with Navajo healing ceremonies. They are invoked in these paintings not because of their role in a particular story, but because of their strength and overall importance. They appear in various chantways, including the Male Shooting Chant, serving as powerful symbols of balance and cosmic harmony. This design represents what scholar Trudy Griffin-Pierce describes as a multilayered temporal and spatial experience where several layers of mythic time coexist with the present moment. In sand painting tradition, the three-dimensional nature of these figures represents not just the physical earth and sky but also the spiritual dimensions of existence. Space expands outward and upward from an apparently two-dimensional image.

Father Sky and Mother Earth by Rosie Yellowhair. Sand on board. Dimensions (without frame): 16 x 16 in.; 40.64 x 40.64 cm. Tanner Trading, Park City, Utah.

This permanent sandpainting is a contemporary and secular reinterpretation of the traditional design Father Sky and Mother Earth.

BELOW

Howard Terpning (b. 1927), Navajo Basket Dance. Medium: Oil on canvas.

Terpning’s work is celebrated for its ethnographic accuracy, respectful portrayal of Native cultures, and masterful technique. "Navajo Basket Dance" is one of his well-known pieces that highlights the importance of ceremonial life and traditional arts within Navajo society. The painting features a Navajo woman in traditional attire holding a woven basket, on the background of the traditional design Father Sky and Mother Earth.

YEI AND YEIBICHAI RUGS: SACRED FIGURES WOVEN IN WOOL

Spiritual Foundations and Cultural Origins

Yei and Yeibichai rugs are two closely related yet distinct categories of Navajo weaving. Both are rooted in spiritual imagery, but differ in purpose and form. In Navajo cosmology, Yei (Holy People) are supernatural beings who mediate between the human and divine worlds. While sand paintings and chants evoke their presence during ceremonies, Yei rugs translate their powerful iconography into woven form.

«The yei and yeibichai rugs differ from sandpainting textiles in that they focus on isolated figures, whereas sandpainting weavings are more or less accurate or more or less simplified versions of ceremonial sandpaintings. The first documented yei and yeibichai rugs also date to the early 1900s. The yei are a particular category of Holy People , as distinguished from the yeibichai, masked-god-impersonator dancers who appear in such ceremonies as the Nightway Chant. The yei and yeibichai rugs do not utilize entire sandpainting images but, like sandpainting textiles, they do depict Holy People. Yei rugs were popularized by Will Evans, a trader at Shiprock, following World War I. These rugs continue to be produced, primarily as tourist novelties.» (John Gerber).

They typically draw inspiration from ceremonial imagery, though they rarely replicate entire sandpainting compositions. Their work did not cause universal dissent. Some elders and medicine men objected to the depiction of holy people, while others, such as Klah, supported it.

Unlike ceremonial sandpaintings, which are meant to vanish, Yei rugs provide a means of honoring sacred imagery without directly replicating restricted ritual content. Most weavers modify specific details, such as omitting mouth shapes or substituting directional elements, to avoid spiritual transgressions.

Distinguishing Yei and Yeibichai Rugs

Both styles emerged in earnest in the early 20th century. As ceremonial taboos around sacred imagery softened, Anglo patrons and traders, especially in the Shiprock region, began commissioning and promoting these works.

- Yei rugs depict holy people in formal, often symmetrical, arrangements. The figures are stylized and abstract and usually stand in an upright posture. They may be flanked by protective Rainbow Guardians. These are generally not narrative weavings but rather devotional visual invocations of presence and protection. However, some Yei weavings include contextual information, the order of ceremonies, or minor narrative elements.

- Yeibichai rugs, on the other hand, depict masked dancers performing the Nightway Ceremony, one of the most sacred healing rites in Navajo tradition. These textiles depict motion and hierarchy, distinguishing leaders, clowns, and female figures by their costumes and positions. They emphasize performance rather than the pantheon. However, the hierarchy might not always be clear in all rugs.

The most reliable way to distinguish between Yei and Yeibichai rugs is to observe the orientation and posture of the central figures. Yei weavings consistently feature front-facing, static figures that appear to gaze directly at the viewer. These figures represent the Holy People in their eternal, spiritual state. These figures maintain formal, balanced compositions that reflect their sacred nature and direct connection to the sand painting tradition. Conversely, Yeibichai rugs depict figures in profile, typically facing left or right, suggesting movement and the dynamic nature of ceremonial dance. These profile figures represent human dancers impersonating Yei deities during the Nightway ceremony, capturing the processional and performative aspects of the ritual.

Another reliable identification criterion is the head shapes of the figures, which are rooted in Navajo cosmological distinctions. Yei figures have distinctive head shapes that correspond to gender distinctions in Navajo beliefs. Female Yei typically have square or rectangular heads, while male Yei have round heads. However, female representations appear more commonly in textile form. These simplified facial features emphasize frontal presentation and divine attributes. Yeibichai figures, representing masked dancers, consistently have round heads, reflecting the ceremonial masks worn during the Nightway ceremony. The mask-like appearance of these figures connects directly to the actual ritual practice in which human participants wear sacred masks to embody divine beings.

Yei rugs often feature the distinctive Rainbow Guardian, also known as the Rainbow Bar, as a border element. This element typically surrounds the central figures on three sides, leaving an opening facing east. This protective border element comes directly from the tradition of sand painting, in which the rainbow serves as an encircling guardian that protects the sacred space. In Navajo belief, the rainbow represents protection, harmony, and the bridge between the spiritual and physical worlds. Yeibichai rugs usually have standard geometric borders without the rainbow guardian motif. Instead, they frame ceremonial dancers with conventional textile border designs. This difference reflects the distinct ceremonial contexts from which each tradition emerges.

Yei rugs draw their imagery directly from the Navajo sandpainting tradition, in which these sacred beings appear as divine intermediaries with the power to restore harmony and health in healing ceremonies. They typically hold ceremonial objects, such as corn stalks, feathers, arrows, or sacred bundles, reflecting their role as sources of blessings and spiritual power. Yeibichai rugs depict the Nightway ceremony, a nine-day healing ritual performed in the winter when there is no danger of lightning and snakes are hibernating. The ceremony features teams of dancers, including the Yeibichai leader (Talking God), six male dancers, six female dancers, and the Water Sprinkler. The ceremony concludes with public dancing that continues until dawn and ends with the "Bluebird Song," which celebrates happiness and peace.

The arrangement and number of figures provide additional identification clues that reflect their different ceremonial origins. Yeibichai rugs typically present two to six figures arranged in a horizontal row, creating balanced, symmetrical compositions that emphasize the static, eternal nature of the Holy People. This arrangement often follows the cardinal directions that are significant in Navajo cosmology. Figures are positioned to create spiritual balance and harmony. Yeibichai rugs commonly feature six to fourteen dancers arranged in a processional formation, reflecting the actual number of participants in the Nightway ceremony. This composition emphasizes movement and ceremonial progression, capturing the temporal nature of the dance performance rather than the divine beings' eternal presence.

Color palette choices further distinguish these two traditions and reflect their different spiritual contexts. Yei rugs traditionally have light-colored backgrounds, most often white or cream, though gray backgrounds also appear. These neutral backgrounds highlight the sacred figures and maintain an aesthetic connection to the sand painting tradition, in which figures appear against natural, sand-colored surfaces. Yeibichai rugs, on the other hand, employ more varied color schemes, often featuring darker backgrounds that enhance the dynamic quality of the dancing figures. The color choices in Yeibichai weavings reflect the dramatic nature of the ceremonial performance rather than the meditative quality of the sand painting imagery.

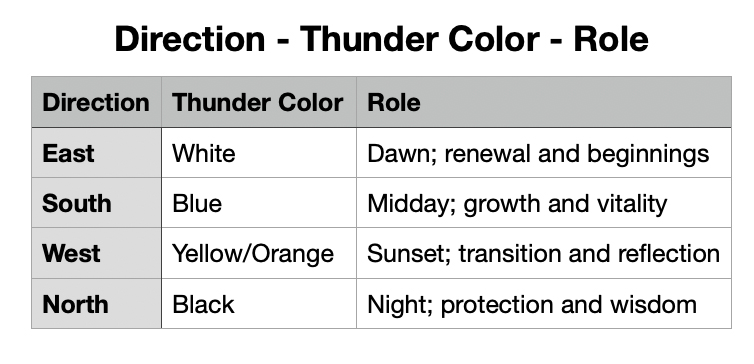

LEFT: Old Yei Pictorial Rug with Rainbow Guardian, 1930s. Dimensions: 41 x 51.5 in.; 104.14 x 130.81 cm. Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

RIGHT: Old Yei Pictorial Rug with Rainbow Guardian, 1930s. Medium: Hand carded and hand spun wool. Dimensions: 80 x 51 in.; 203.2 x 129.54 cm. Garland's Sedona, Arizona.

LEFT: Ye Be Chai Rug. Dimensions: 42 x 74 in.; 106.68 x 187.96 cm. The Gordon Collection, Telluride, CO.

RIGHT: YeiBiChai weaving from the 1970s. A line of Yei Bi Chai dancer has a Medicine Man on one end and the Leader Yeibichai on the other end. Dimensions: 38 x 62 in.; 96.52 x 157.48 cm. Toh-Atin Gallery, Durango, Colorado.

The differences between Yei and Yeibichai are not always as obvious as in the rugs above. Sometimes they are much more subtle as seen in the rugs below.

LEFT: Night Sky YeibeChei rug by master weaver Berlinda Nez Barber. Medium: custom spun, hand dyed Navajo Churro wool. Dimensions: 48 x 105 in.; 121.92 x 266.7 cm. Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, AZ. The rug depicts YeibeChei dancers against a night sky, with stars, constellations and moon. Extremely tightly woven, it was completed after 1.5 years on the loom!

RIGHT: Handwoven Navajo Yei weaving with four intricate yei figures, corn stalks, and a detailed border by Marietta White. Dimensions: 48.5 x 33.5 in.; 123.19 x 85.09 cm. Garland's Sedona, Arizona.

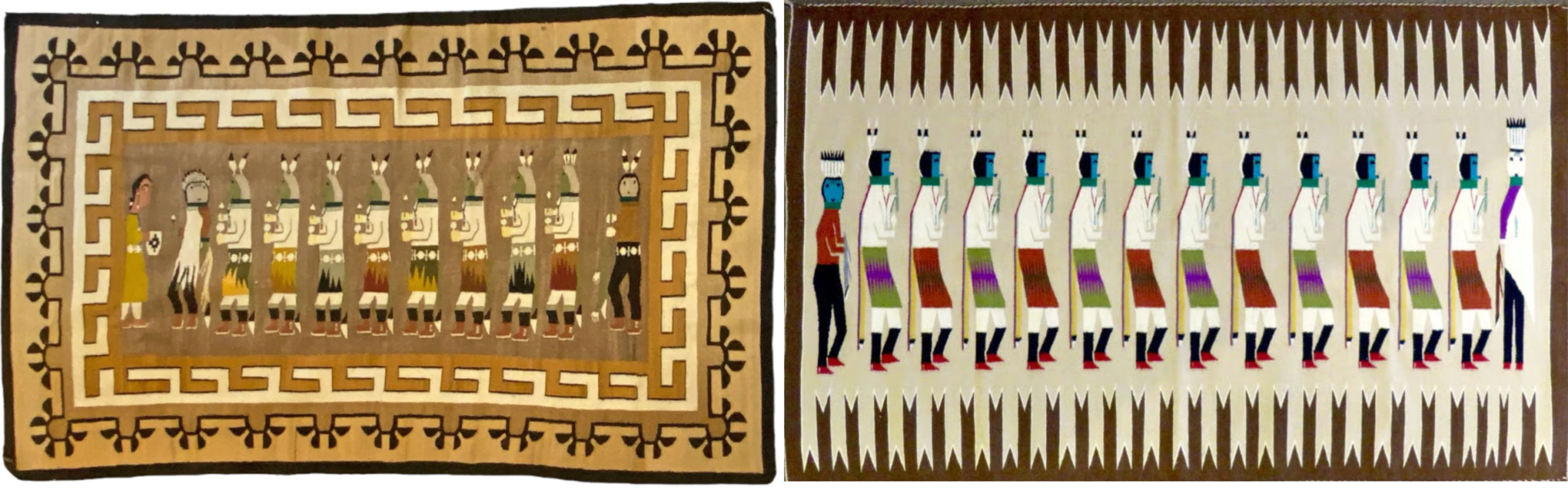

Yei or Yei Be Chei Rug, Unknown Weaver, 1930 -1940s. Medium: hand-carded, hand-spun, and hand-dyed Navajo Churro wool. Dimensions: 69 x 122 in.; 175.26 x 309.88 cm. Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, AZ. Have you see the "spirit line"? It's in the bottom left corner.

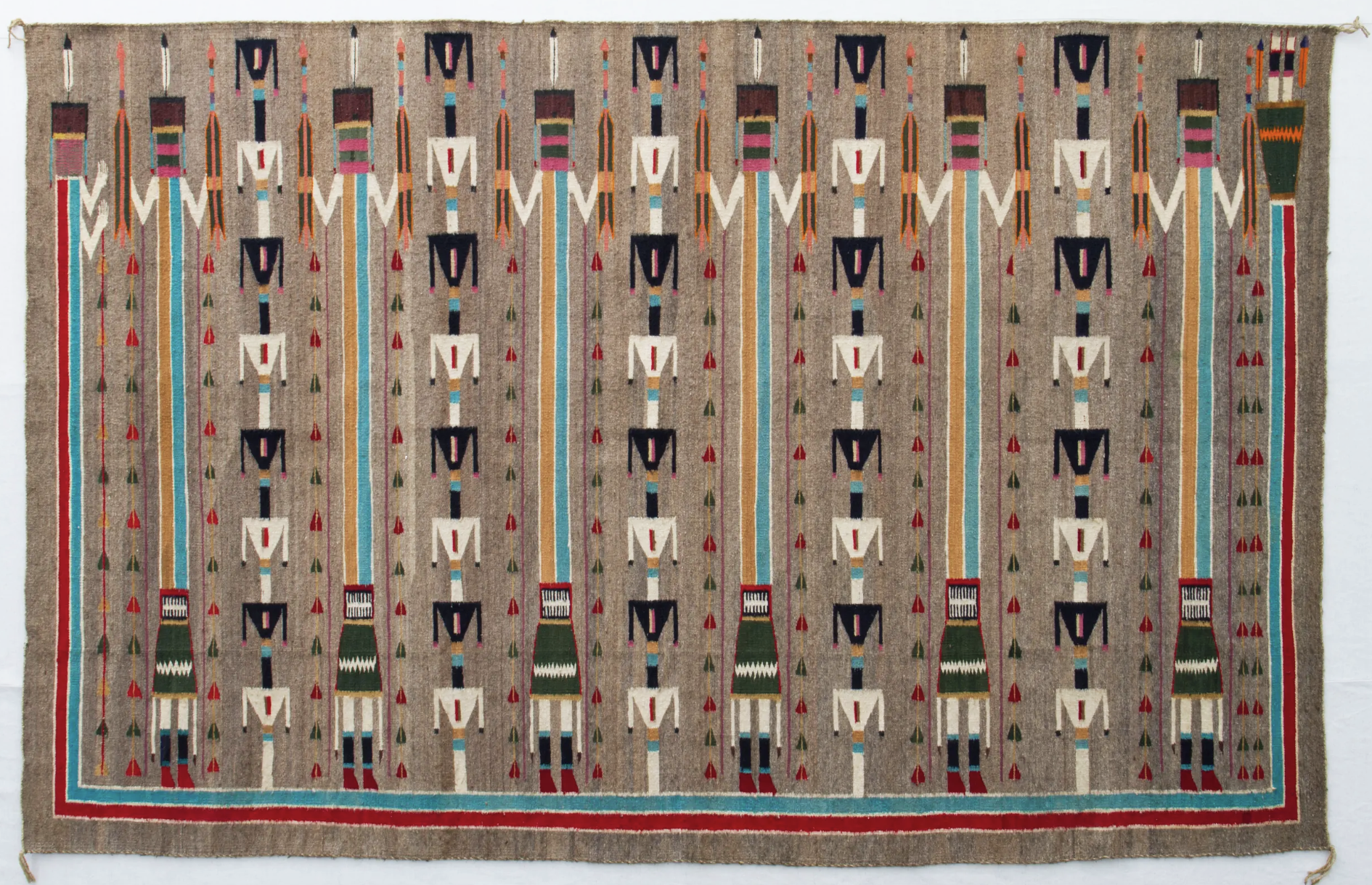

Yeibechai rug, depicting ten male and female participants alongside Talking God the medicine leader, within sawtooth and solid color borders. Mid-20th century. Dimensions: 4ft 3in x 8ft 8in.; 129.54 x 264.16 cm. Auctioned in 2011 by Bonham's, San Francisco.

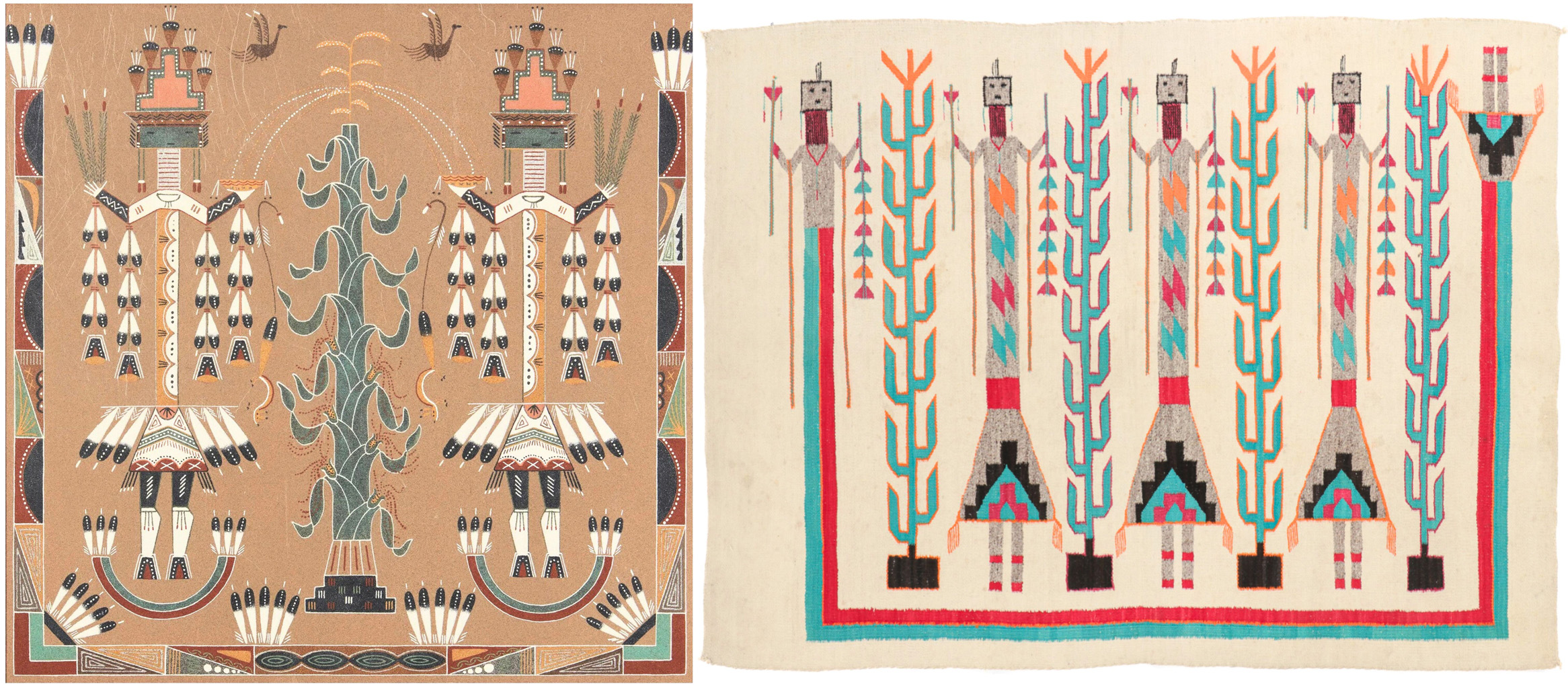

LEFT: Navajo Mountainway Yei Rug depicting four Mountainway Yei, birds, two small Yei, and a Rainbow Guardian, ca 1930. Medium:

handspun wool in colors of orange, red, faded blue, green, yellow, cream, dark brown. Dimensions: 84 x 62 in.; 213.36 cm x 157.48 cm. Auctioned in 2019 by Freeman's | Hindman, Chicago, IL.

RIGHT: Yei rug depicting four male Yei figures are surrounded by a Rainbow Guardian, second quarter of the 20th century. Medium: hand-spun wool woven using colors of red, orange, blue, and browns on a black field. Dimensions: 67 x 68 in.; 170.18 cm x 172.72 cm. Auctioned in 2023 by Cowan's Auction, Cincinnati, OH.

Yei Rug, first half of the 20th century, woven in the Navajo reservation area of Arizona or New Mexico. Powerhouse Collection, Powerhouse Castle Hill, Dharug land, Australia.

«This large tapestry-woven wool rug depicts six 'Yei' (Navajo spirits) stick figures with long blue and yellow striped bodies below which they wear a dark green patterned piece of clothing from which hang long tassels. The feet are shod with red footwear. The arms are bent at the elbows and hold ears of corn. Each 'Yei' has a square brown head with a feather on it. On each side of the figures are rows of black and red triangles on cords, known as calendar sticks, and between these are rows of smaller torsos, one on top of the other. Around three sides of the rug runs the protecting rainbow goddess in the shape of a red and blue border outlined in white, with her head on the left hand side and her feet on the right. The background is grey and other colours used are red, yellow, white, black, brown, pink and green.» (Powerhouse Museum curators).

Regional Variations: Shiprock and Lukachukai

Shiprock Style

Shiprock, New Mexico, became a key center for the development and popularization of both Yei and Yeibichai rugs, particularly under the influence of trader Will Evans, who encouraged the depiction of Holy People as both cultural expression and economic opportunity.

- Yei rugs from this area are known for their refined symmetry, light-colored backgrounds, and elongated figures rendered in bright vegetal or aniline dyes.

- Borders often feature a Rainbow Guardian Yei, which encloses the scene in a protective arc—a motif that is both artistic and symbolic.

- Figures tend to be highly stylized with elongated limbs and geometric faces that convey a sense of verticality and transcendence.

Lukachukai and Upper Greasewood Style

In contrast, rugs from Lukachukai and the surrounding Arizona regions exhibit greater solidity and earthiness, reflecting regional weaving traditions.

- Yeibichai dancers in these rugs are often larger and less stylized. They are arranged with more emphasis on physicality and ritual sequence.

- Backgrounds are typically darker, borders are thicker, and the composition feels less symmetrical and more narrative, capturing the movement and drama of the Nightway dancers.

- Local wool and natural dyes often give these rugs a rugged, muted color palette, with a tactile quality that reflects the high-relief weaving style prevalent in the area.

Evolving Meanings and Contemporary Legacy

Today, Yei and Yeibichai rugs occupy a complex space between art, commerce, and spirituality. While their sacred origins are treated with care, their woven forms have become a medium through which Navajo weavers assert cultural continuity, artistic skill, and economic agency. As in the case of sandpainting rugs, these textiles often balance innovation with reverence, honoring the Holy People without violating ceremonial codes.

Many contemporary weavers continue to draw on these traditions, preserving regional distinctions while adapting color palettes, formats, and techniques to modern markets. Yet, at their core, Yei and Yeibichai rugs are more than just aesthetic artifacts; they are woven prayers, silent songs, and guardians in wool.

LEFT: Yei figures and a cornstalk protected by a rainbow band, Sandpainting on panel, unsigned, undated. Dimensions: 24 x 24 in.; 60.96 cm x 60.96 cm. Auctioned in 2022 by John Moran Auctioneers, Inc., Monrovia, CA.

RIGHT: Yei Rug in wool. Mid-20th century or later. Dimensions: 5'5'' x 4'2''; 165 x 127 cm. Auctioned in 2024 by Material Culture, Philadelphia, PA.

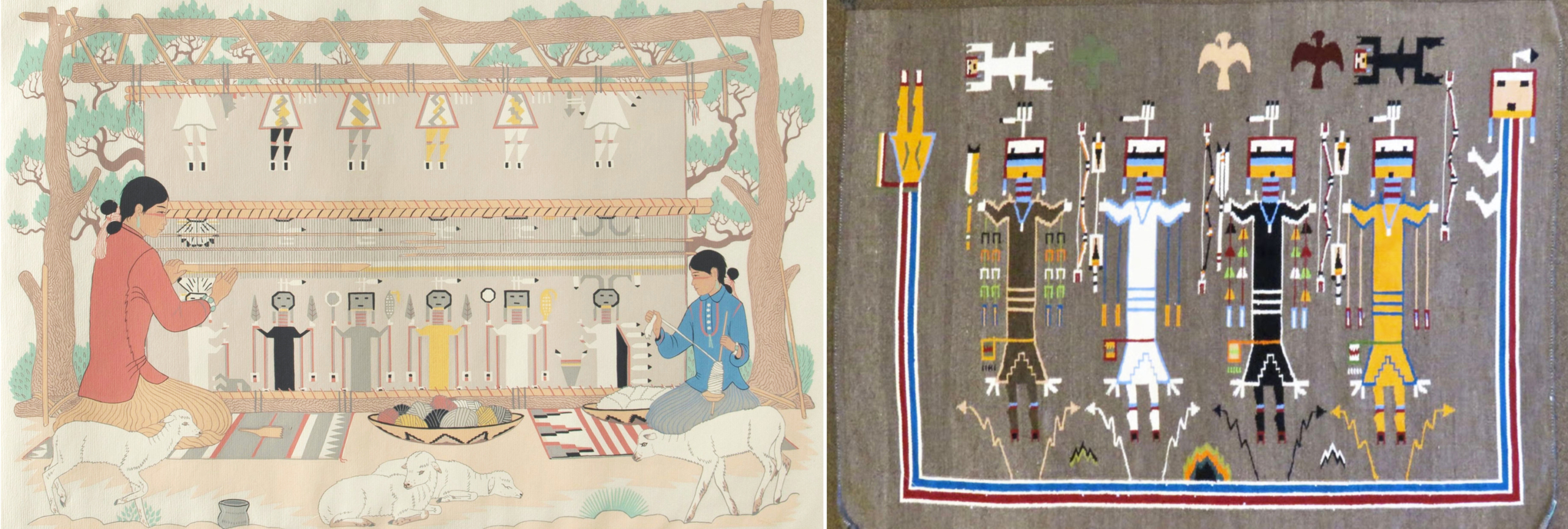

LEFT: Harrison Begay, aka Haashké yah Níyá or Haskay Yahne Yah (“Warrior Who Walked Up to His Enemy” or “Wandering Boy”), Navajo Mother And Daughter Weaving, silkscreen on paper, mid-20th century.

RIGHT: Yei rug depicting a Rainbow God, eagles and Dontso dragonfly Yei in the upper panel. Woven by Arnold Begay, ca. 2000. Dimensions: 59 x 44 in.; 149.86 cm x 111.76 cm. Toh-Atin Gallery, Durango, Colorado.

LEFT: Yei-Be-Chai Dancers by Harrison Begay, mid-20th century, tempera on paper. Gilcrease Museum, Thomas Gilcrease Institute of American History and Art, Tulsa, OK.

RIGHT: Millenium Yei-be-chai, a masterpiece by Sarah Paul Begay, 1998-2000 Medium: Carded, handspun, vegetal dyed wool. Carded and handspun tassel. Some colors blended and dyed with navajo tea, coffee, sage, cochineal, walnuts and stink bugs. Dimensions: 123” x 59”; 312.42 cm x 149.86 cm. Galrland's, Sedona, Arizona.

Sarah Paul Begay's masterpiece 'Millennium,' took more than two years to create and is valued almost 85,000 USD. It portrays a Navajo healing ceremony. Three-dimensional Yeibechai dancers with lifelike movement are created using more than 100 unique dyes. Her design uses curves to create incredibly realistic images in wool. Sarah weaves like other artists can paint. With this work, Sarah Paul Begay won the Best of Show Award at the 85th annual Santa Fe Indian Market in 2006.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?