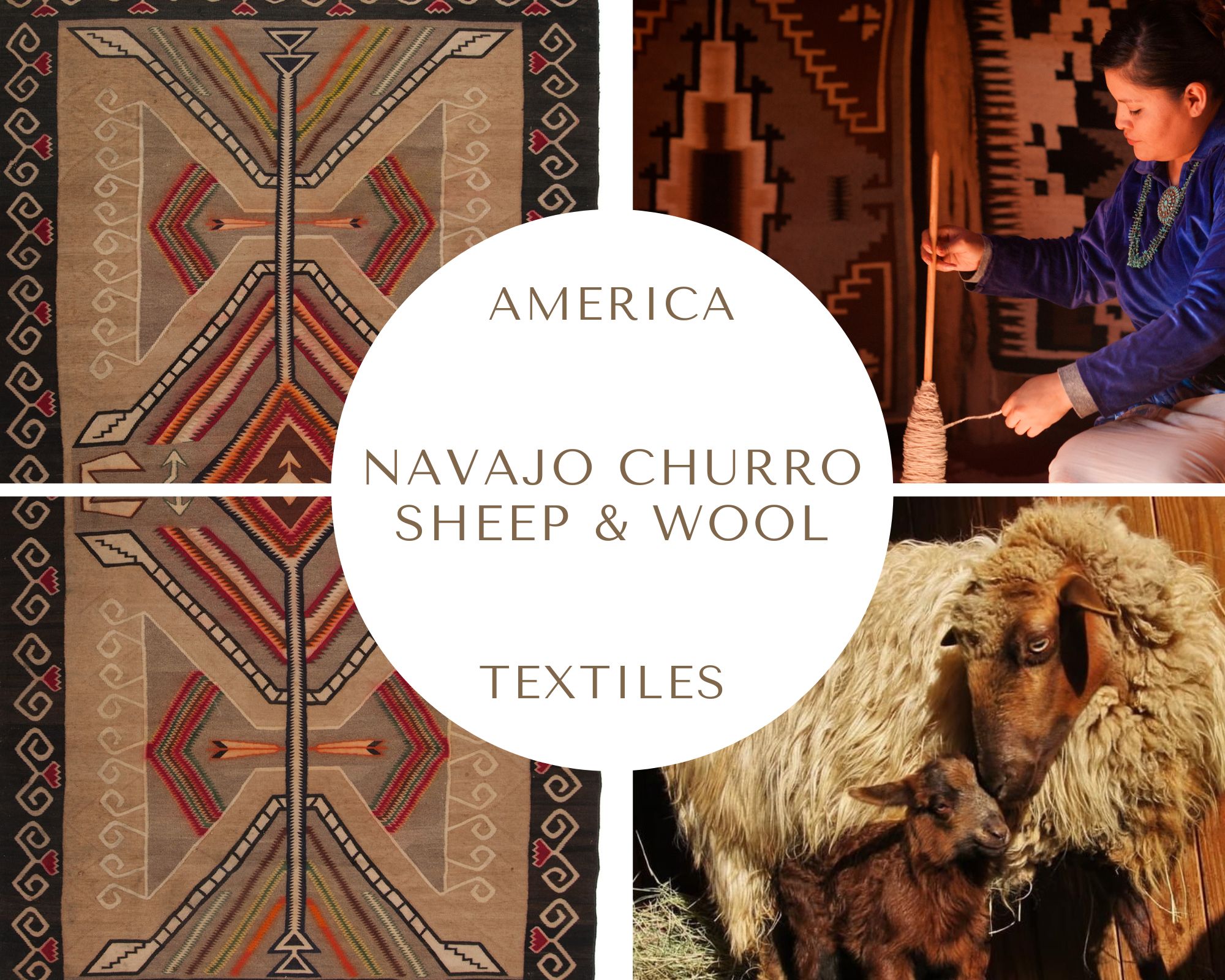

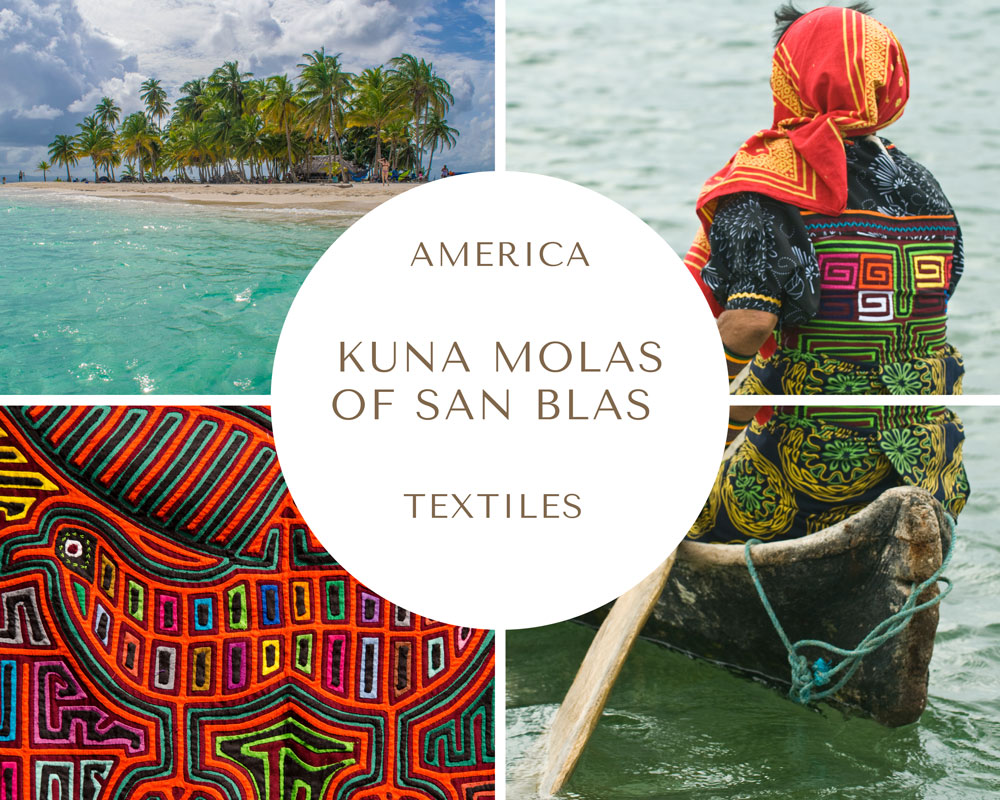

Kuna Molas of San Blas part 2

THE GUNA PEOPLE AND THE GUNA YALA

- The traditional huts

The Gunadules lives in small villages crossed by one or two main unpaved streets. The walls of the traditional house (choza in Spanish) are made with canes from the Gineryum sagittatum species (masarwar, wild cane), which grows wild on the banks of the rivers. The canes are tied up with a thick, flexible bejuco, a liana locally called sargi (Heteropsis oblongifolia), while the roof is made with palm branches which are skillfully tied to each other to stop the rain from dripping inside. Each traditional house has a door and no windows. It's built by the men of the community under the direction of an expert in 3-4 days, and usually lasts no more than 5 years.

Each extended family lives in a composite house, made up of two separate parts: a bedroom house (nega tumat) with a row of sleeping hammocks and some wooden stools, and a house for cooking and eating, which is called the "house of fire" (so-nega) and measures on average 20 m2. In all villages, there are the "house of the chicha" (inna-nega), where ceremonies and parties are held, and the "congress house", the community gathering house called onmagged nega. There are also special houses for healers.

In the major villages, the most important recent houses are made of wood and concrete (schools, medical centers, local museums, and tourist facilities); some small sheds have a tin roof.

Traditional thatched huts and cayucos on the Wichub-Wala Island, in Guna Yala.

Look at the picture above: on the right, you will see a television antenna. The great majority of islands lack air conditioning, TV, internet and wi-fi, hot water, and sometimes even running water and electricity. Some tourist islands have a power unit. More than 5000 solar panels have been installed in the Cartí Islands for power supply (in homes, schools, clinics, and doctor's offices). In September 2020, the power line has finally reached the Guna communities from Llanos de Chepo to the ports of Dibin, Barkusun, Acuatupu, and Sugdub, on the mainland coast.

The Museum of the Guna Nation in El Porvenir island. Photo by P. Sutermeister (under Creative Commons Atribución-CompartirIgual 4.0 Internacional

licence).

- The Guna women and their traditional dress ensemble

Unlike Guna men, who dress like the Panamanians (in a Western-Latin style mix), most Guna women (Dule oImegan) continue to dress as their ancestors did. Many Dule oImegan are adorned with a black line painted from the forehead to the tip of the nose, a thick gold ring worn through the septum (olasu), many necklaces, earrings (dulemor), and a red headscarf called muswe. A colorful fabric is wrapped around the waist as a skirt (sabured), topped by a short-sleeved blouse in which two matching molas (front and back) have been embedded. The women wrap their lower legs and forearms in long strands of tiny beadwork (wini, in Spanish tubelleras), forming colorful geometric patterns.

Photo by Alma Kastlander (under Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license - CC BY-NC 2.0)

Photo by Rita Willaert (under Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license - CC BY-NC 2.0)

Photo by Rita Willaert (under Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license - CC BY-NC 2.0)

Muñequeras (left) and perneras (right), called wini in Dulegaya, are all made of glass beads threaded on cotton. The usual colors are black, green, blue, light blue, red, orange, gold. In the Guna culture, the use of wini is important and full of meaning. In many communities, Gunadules put a small ring of wini, called maniwini, among the finger of the dying and the dead.

Both photos by Rita Willaert (under Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic license - CC BY-NC 2.0)

Tourists find Guna women a picturesque subject, exotic enough to deserve a series of pictures with a telephoto lens (sometimes without asking their consent). Guna women know it very well and let the tourists make their coveted portraits only upon the payment of a dollar. Easy picturesqueness takes its toll. However, this traditional dress ensemble is anything but picturesqueness. Guna women make tourists pay for their common misunderstanding but rarely try to tell their stories. The result is a fully missed cultural and human encounter.

The Guna women, Dule OImegan, make something more than sewing, wearing, and selling tourist molitas or art collector's molas. Much more.

Petita Ayarza was born on an island in the corregimiento (district) of Ailigandí, in Guna Yala, in 1965. She's a businesswoman, a political leader, a mother of 5 and the first Guna woman to be elected diputada (congresswoman) in the Asamblea Nacional de Panamá: since 2019 she's a member of the Panamanian parliament (the National Assembly of Panama is the legislative branch of the government of the country). She advocates for the rights of indigenous peoples, for the empowerment of Guna women, for more general gender equality; she's developing programs to enhance eco-friendly sustainable tourism in Guna Yala and to fight drug trafficking inside the comarca. She's also a member of the Indigenous Latin American Network in defense of Biodiversity.

Petita Ayarza in 2019. Photo by OEA - OAS (under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license - CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

She's always wearing the traditional Guna dress ensemble. Even in Parliament. And not to be the most picturesque and colorful of its members, of course.

She wears the Guna costume as it is the most immediate symbol of the strength of an indigenous people that survived genocide and an ethnocide that lasted five hundred years, and fiercely rejected to give in to the dominant colonizer culture or to adopt a colonial mentality. For all Gunadule, the female dress is the emblem del orgullo y la identidad Guna (of Guna pride and identity). It's the living sign of their resistance facing the wild, all-devouring monetization logic that runs the world of white colonos; it represents the umbilical cord that links Gunadule to their ancestors and Mother Earth. Last but not least, the women’s dress is an ethnic marker that played a major role in the Guna struggle against the Panamanian government from 1919 to 1925, the year of their Revolution.

Only picturesque, eh?

The molas are only a part of the rich cultural life of the Gunadules, an indigenous people among the most combative and organized of all Latin America.

Crystal Ann Luce (University of Colorado) maintains that the Kuna is «one of the most politically mobilized indigenous peoples in Latin America». The research of another American scholar, Diana Marks «confirmed that Kuna leaders were determined to create self-contained, self-governed communities from the mid-19th century» (Diana Marks, see Bibliography). The Guna people are masters of their land not because this last was gently gifted to them: they fought for their land and conquered each of their granted rights, and now are struggling for their survival facing many threats.

Here, where most tourists' journey ends, starts ours.

Moreover, I must confess that the image of Guna Yala as a happy-go-lucky tropical paradise not only does makes me raise an eyebrow (both, to tell the truth, as I'm 50% Central American) but it pushes me to go further and discover what lies beneath. Come with me, you'll be surprised by what we will discover. Very surprised.

Guna rap music: Bila Urris by Kuna Revolution.

Nuestra misión: defender nuestro territorio de cualquier invasión, siempre de pie, nunca de rodilla. (...). Somos la resistencia, de los Urris la descendencia, somo la voz de lor rios, los mares, montañas y selvas, los hijos de la Madre Tierra.

Our mission: to defend our land always standing on our feet, never on our knees. (...) We are those who resist. We are the offspring of the Guna warriors, we are the voice of rivers, sea, mountains, and jungle. We are the children of Mother Earth.

LA REVOLUCIÓN

Every February, the Dule Revolution is celebrated throughout Guna Yala, usually with a dramatic reenactment accompanied by music, songs, dances. The history of the Dule Revolution is the history of Guna's emancipation. And this event was for these indigenous people exactly what the end of apartheid was for the Bantu people.

Panama was part of the Gran Colombia until 1903 when it was declared an independent country after a military intervention of the United States. The US president Theodore Roosevelt wanted to open a channel connecting the Atlantic to the Pacific and did not accept Colombia's refusal to grant isthmus management to a North American consortium. On November 3, 1903, the Republic of Panama declared its independence from Colombia and its tacit subjection to the US.

Fiat canal and canal fit (1907-14).

The land of the Gunadule was divided by a border. The Guna who were living along the coast and in the archipelago of San Blas recognized the new República de Panamá.

On December 31, 1907, the Panamanian Asamblea Nacional (= Parliament) approved Law no. 59 related to the Civilization of the Indigenous People. Here is a brief excerpt of the original law:

Se tratará de manera por todos los medios pacíficos la reducción a la vida civilizada de las tribus salvajes que existen en el país. a) Los misioneros y los maestros de escuelas sean los agentes civilizadores; b) El gobierno concederá tierras a los colonos, es decir no indígenas; c) El gobierno dará los aperos de labranza, semillas, animales a los colonos.

(By all peaceful means, the Government will try to civilize the wild tribes that exist in the country. a) The Missionaries and the school teachers will be civilizing agents. b) The government will grant lands to settlers, i.e. non-indigenous people. c) The government will give them also agricultural tools, seeds, animals.)

En kol chadásh táchat hashámesh. Nothing new under the American sun: same old story since Columbus' times.

The Panamanian governments planned the implementation of three objectives: gaining political control over the natives, gaining economic control over their resources (including the maritime ones), and opening their mainland to external economic interests. The main tool was the "civilization" and the "evangelization" of the savages and the establishment of non-indigenous settlements on the coast. The effort of turning savages tribes into civilized humans - this was the language used only a hundred years ago - started quickly.

In 1907, the Jesuit father Leonardo Gasso arrives in Narganá (Yandup) to found a Catholic mission; in 1913, it was the turn of the Protestant missionary Ana Coope and the Baptist church. Nel 1915 the colonial police (“Policía Colonial”, called Naggar Sidsgan by the Gunadule) arrived on the main island, renamed El Porvenir ("The Future", and there was no irony). In the very same years, turtle hunters, gold extractors, rubber workers, and thefts invade some Guna communities without local people’s consent. An American company established a magnesium mine and large banana plants in Mandinga Bay, on the west end of the coast.

The Gunadules were forced both to sell their coconuts and other products to the colonial authorities, who paid a lower price compared to those of the Colombian market and to buy stuff at the colonial stores. Girls at school and adult women were strongly pushed to adopt Western-style clothes.

«Desde aquel momento, se hizo claro que la principal meta del gobierno de Porras era el etnocidio, la destrucción de una cultura» (James Howe, see Bibliography). (From that moment on, it became clear that the main goal of the Porras government was ethnocide, the destruction of a culture. Belisario Porras Barahona was President of Panama between 1912 and 1924).

In 1919, The Panamanian government implemented an aggressive policy of forced assimilation by issuing a ban that forbade school girls from wearing gold nose rings, muñequeras and perneras (wini), traditional necklaces, and later also the traditional mola blouses. The production and consumption of chicha were also forbidden to impede many ancestral ceremonies and rituals. The Gunadule who did not abide by the new laws were fined and imprisoned; protesters were thrown to the ground, kicked, pounded, and beaten by the colonial police. Some activists were killed.

To the Panamanian government, the traditional dress ensemble of the Guna girls and women stood out as the symbol par excellence of the indigenous intolerable alterity. To the Gunadule, on the other hand, it became the symbol of their inalienable identity, culture, and history. A clash was looming...

Ologindibibbilele (Simral Colman), the saila of Ailigandí, despite his old age, carried out a tenacious campaign of resistance and created a secret network of contacts and communications with other sailagan, such as Iguibilikinya (Nele Kantule) of Usdub, Olonibiginya of Gardí Sugdub, Susu of Uggubseni, Nugelibbe of Dubbir.

On February 12, the major sailagan met on the island of Ailigandí, and proclaimed the "Declaration of Independence and Human Rights of the People Tule de San Blas and Darién". Saila Olonibiginya said: ¡Un indio sin tierra es un indio muerto! (An indian without his land is a dead Indian). And no saila wanted his community die.

Ten days later, on Sunday, February 22, when most Panamanians were celebrating the carnival, two groups of Gunadule went into action, one led by Nele Kantule and Simral Colman and the other by Olonibiginya. They began from Ailigandí and Gárda to attacks on Colonial Police barracks found throughout the archipelago, especially in the islands of Tupile and Ukupseni, Tiger, River Cider, Nargana, Heart of Jesus, Rio Sugar and Cartí. The revolt lasted three to four days and resulted in fewer than thirty deaths from the side of Panamanians and no victims to the side of the Gunadule.

On the beginning of March, thanks to the mediation of John Glover South, US Minister Plenipotentiary in Panama, the representatives of the Panamanian government, the US government, and the Guna leaders met and signed a Peace Agreement. The Guna people recognized the authority and the laws of the Panamanian Republic, and committed to ending hostilities; the Panamanian government in return committed to protecting Guna customs and traditions and to grant all Gunadules the very same rights of all Panamanian citizens.

It was only the first step towards autonomy, but it was nevertheless a milestone.

This peace treaty was followed by an agreement signed in 1938; the following law no. 2 dated September 16, 1938, established la Comarca de San Blas as a reserve. Its administration issues were defined by law no. 16 date February 19, 1953. In 1998 the comarca was renamed Kuna Yala. On March 23, 2001, a new law established the autonomy of Kuna Yala and recognized its different political and administrative organization in the hands of the Guna people. In 2010, Kuna Yala became Guna Yala: no sound "K" exists in the Dulegaya language. Even in its name, this comarca shows its identity.

Before seeing the following pictures and videos, please note that the swastika you'll see in many Guna flags is not linked to the Nazi misuse of this symbol, and the red shirts do not allude to any "communist" or leftist tradition: the black reverse swastika is an ancestral Guna symbol called Naa Ukuryaa and the red a symbolic Guna color.

«The flag, characterized by a black swastika on a yellow stripe, with two red strips above and below was designed on August 18, 1924, as the flag of the Nación Dule, the Kuna Nation, six months before the revolution took place. As such, this flag was and is a symbol of sovereignty, which was then symbolically used during the battle for independence, and now also serves as a marker of identity for the Kuna people as a self-governing nation. The color red (ginid) in the flag is also symbolic of blood, specifically the blood that was shed to regain control over their people and their territory. The red dye achiote, called mageb in Dulehaya, was painted on the faces of those who fought. (...). The color yellow (gorogwat) is symbolic of sacred things and is related to gold. The swastika is a sacred symbol for the Kuna and signifies the circular and dual nature of life and humanity» (Kayla Price, see Bibliography).

Every year in February, the experimental drama group Los Nietos de la Revolución (The Grandchildren of the Revolution) organize a community reenactment in the island of Ustupu to keep alive the memory of the Urrigan, the revolutionary grandfathers who fought with their faces painted red (by using mageb, the annatto extracted from the Bixa orellana plant). In the drama performance, there is no detailed dialogue or script to follow, and no finite number of participants: anyone who wants to participate is welcome. Here's a short video of a different reenactment; the song is sung both in Spanish and in Dulegaya.

Un mural depicting the three main Guna leaders of the 1925 Dule Revolution, by MartanoemÍ Noriega and Ologwagdi. Located in Casco Viejo, the oldest part of Panama City.

GUNA AUTONOMY

The Gunadules are the very first indigenous people of the entire American continent to acquire rights on their own lands. Today, they enjoy wide, albeit relative political autonomy, and are masters of their own land: no outsider can have a property on their land nor buy even a square centimeter of their territory. This condition has been achieved thanks to the strength and vivacity of their culture and their political organization.

Each island or community has a saila (sometimes more than one) who is subjected to the authority of the three great sailagan of the Comarca, appointed by the representatives of each community in the Guna General Congress. The leadership of the three principal sailagan (called Caciques Generales o Saila dummagan) is always controlled by the Guna General Congress, which is the supreme political authority of the Gunadules. The general congress is held every six months, while the local congresses meet more often, and are attended by all members of a community. The three national chiefs, chosen by the Guna General Congress, act as the Guna spokespersons to the Panamanian government; moreover, there are two specially chosen Guna Yala legislators in the Panamanian National Assembly, and the Guna members of parliament regularly elected, such as Petita Ayarza.

The Gunadules are administratively autonomous; education and health care are the only fields in which the Panamanian state has competencies. The Panamanian current laws and Constitution recognize their right to territory and governance and make their collective lands a non-forfeitable, unattachable, imprescriptible asset. The Guna have fought for and obtained what many indigenous peoples still lack: territory and self-governance. However, the Panamanian state reserves the right to intervene in expropriating areas of "national priority" and granting permits for explorations and exploitation of resources such as mines, water, woods, and forests, even without the consent of the indigenous communities. And this is of course a serious threat to the Guna territories and their ways of life. And that's not the only one. Guna still face poverty, discrimination, and many other inequities, as do the great majority of the indigenous peoples of Abya Yala, the term Gunadules use to indicate both pre-Columbian America and the whole American Continent.

The old sailagan, the political and religious leaders of a Guna community, in a "congress house". The hammocks (gassi) hanging in the onmagged nega symbolize the heart of the community, and only sailagan are allowed to use them. The religious and political chiefs are traditionally men of an advanced age and today this prerogative is criticized both by the younger, often well educated generations, and by the women, asking for a full gender equality inside the whole Guna nation.

ABYA YALA

Minority Rights Group International, an international non-governmental organization (NGO) headquartered in London (UK), that works with minority communities, providing education and training to enable them to claim their rightful place in society, stated in 2015: «The Guna are the most consolidated, organized and prosperous of the indigenous peoples of Panama, with the most international and national contacts and the highest levels of formal education and knowledge of the contemporary world».

Not only do the Gunadules nurture a feeling of solidarity with other indigenous peoples, but they've always been committed to building a network of international relations over the years to promote the rights of indigenous peoples and to create media, tools, organizations, associations, conferences to give resonance to indigenous cultures and their political movements.

Here are some examples.

As we wrote, Petita Ayarza (the Guna congresswoman) is an active member of two organizations: La Red de mujeres indígenas sobre biodiversidad de Latinoamérica (RMIB) and La Organización de mujeres indígenas unidas por la biodiversidad de Panamá (OMIUBP), both involved in the fight for gender equality and the defense of biodiversity. The partecipation of the Guna members is so active that the very first assembly of the Network RMIB was held in Guna Yala in 2007.

In January 2016, La Red Centroamericana de Radios Comunitarias Indígenas (the Network of Indigenous Community Radios of Central America) was founded in the Guna Yala comarca, thanks to the combined efforts of 40 Radio Directors coming from 7 countries (Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama), and to the tireless commitment of the Gunadules. The network's aim is to contribute to the democratization of regional communications, with a particular focus on the voice and the needs of indigenous peoples.

The activism of the Guna people goes in the very same direction followed by the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, a non-legally-binding resolution passed by the United Nations in 2007, that «emphasizes the rights of Indigenous peoples to maintain and strengthen their own institutions, cultures, and traditions, and to pursue their development in keeping with their own needs and aspirations». It «prohibits discrimination against indigenous peoples». It «promotes their full and effective participation in all matters that concern them, their right to remain distinct and to pursue their own visions of economic and social development». Moreover, it highlights the right of the indigenous people to establish their own means of information and communication. In these last years, despite countless difficulties, many indigenous peoples of Latin America have developed a multitude of their own media: community radios, news agencies, audiovisual and photographic productions, music videos, blogs, websites, profiles on Facebook and other social networks. The Gunadule are among the most active. They are also among the supporters who advocate a process of descolonización epistémica, epistemic decolonization of America. What does it mean?

In 1977, the Aymara leader, Takir Mamani, one of the founders of the indigenous movement Tupaj Katari in Bolivia, went to Panama to meet the Guna sailagan in the island of Ustupu (the Aymara people are an indigenous nation in the Andes, currently living in Bolivia, Peru, and Chile). Here, Takir Mamani could hear the traditional cosmogonic songs of the Guna and the stories about Abya Yala. This term, which in the Guna language means "land in its full maturity", "land of vital blood", "land of life", is the name used by the Guna to designate the Pre-Columbian American Continent. They explained to Mamani that the use of this term is not just a link to their ancestral worldview, but it also entails the rejection of the colonial views of Latin America. Abya Yala was not "discovered" by Spanish and other Europeans: Abya Yala had been inhabited by many aboriginal communities with different cultures for millennia. What Westerners call "discovery" was genocide and an ethnocide that lasted 500 years. Moreover, the Gunadules told Mamani that by using the term Abya Yala, they wanted to highlight a different way of conceiving and living their relationship with the land's many resources and living creatures.

«Mamaní siguió el consejo de los saylas y difundió la noticia en varias reuniones y foros internacionales, solicitando a los pueblos y organizaciones Indígenas que en lugar de usar nombres como “América” o “Latinoamérica” usen Abiayala en sus declaraciones oficiales para referirse al continente» (Emil Keme, see Bibliography). (Mamaní followed the advice of the Guna sailagan and spread this name in several international meetings and forums, asking indigenous peoples and organizations to use it instead of "America" or "Latin America").

In 1990, while many events were planned around the world to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the "Discovery of the Americas", the First Continental Meeting of the Indigenous Peoples of America took place in Quito (Ecuador). Hundreds of Native Americans met to join their voices against the upcoming commemorations: they found no reason to celebrate October 12, 1492. They strongly rejected the prevarication of a history continually manipulated by the Eurocentric colonialist myth. As the Guna people taught the Aymara leader, the lands of the ancestors were not to bear the name imposed by the colonizers. Different names were proposed - including the Náhuatl term Ixachilan ("immensity") used by Aztecs, the Quechua term Runa Pacha ("the land of the peoples"), and the Dulegaya Abya Yala. This last was the preferred one. Today, 30 years after that meeting, Abya Yala is the common term used by the great majority of the indigenous peoples of Latin America to indicate their land and their continent. Sometimes Abya Yala is represented as an upside-down map (with the South-American Land of Fire in the north and Mexico or Alaska southwards), to show the many chances to reverse points of view, perspectives, and conventions that incorrectly claim to be truths.

In many countries of Central and Southern America, organizations, mass media networks, museums and cultural institutions founded by indigenous peoples use the Dulegaya term of Abya Yala instead of the colonial "Latin America".

NABGWANA - THE MAINLAND PROTECTION

Like other indigenous people of Abya Yala, the Guna have their own way of conceiving and living the relationship between themselves and their land, its many resources, and the other living creatures.

Mother Earth or Nabgwana is the daughter of Baba-Nana, the Great Spirit. The word Nabba (Earth) comes from the word Na or Naba (in Spanish totuma, a term used to indicate every ball-shape item, from the calabash to the baby bump) symbolizing motherhood, fertility, life. It also symbolizes the shape of the earth. Nana means "mother" and designates the creative, generous aspect of motherhood. In the Guna tradition, the name Na(na) b(aba) gwa na(na) refers to the Mother Earth as the throbbing sacred heart of her mother Nana and father Baba. La Tierra es un ser vivo, nuestra Madre: Nabgwana is our living Mother.

The term Nabgwana, however, refers not to the concept of a thing, but to the concept of a relation: it designates the deep connection, the bond, the dynamic relationship between the human beings and their living Mother. The term Nabgwana tells us about the complex net of interdependence among humans as well, as every people, every community, every person is part of the same "family" and their mutual links are always mediated by their coming from the same womb.

For the traditional Guna culture, the misuse, the abuse, and the ill-treatment of Mother Earth are as alien as the monetization of its resources.

The Guna Yala comarca has the highest percentage of the forest-covered area (about 90%) of entire Panama (Unesco data) and 2/3 of Panama’s forest covers is located in indigenous peoples’ traditional territories: the best-preserved landscapes coincide with indigenous occupation areas, thanks to their wise management of environmental resources.

The following video by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations shows very well the Guna way of living and loving Nabgwana. Guna Yala is the very first indigenous country in Abya Yala to have developed a global vision and an integrated approach concerning food and nutrition security. The Guna General Congress has also founded a Food Safety Secretariat and launched a 2020-2025 strategic Plan to better respond to current challenges.

In the video, Belisario López, one of the Guna chiefs, advocates the development of a sustainable economy that firmly rejects overexploitation and consumerism. The Guna people refuse monetizing every environmental resource and every living being. Economy - says the chief - is not money.

The Guna worldview is widely shared among other indigenous communities and many environmentalists throughout Abya Yala, from the Brazilian Chico Mendes, assassinated in 1988, to the Honduran Berta Cáceres, assassinated in 2016. Chico Mendes fought to preserve the Amazon rainforest and advocated for the human rights of Brazilian indigenous peoples. Berta Cáceres was both an environmental activist, and an indigenous leader, co-founder and coordinator of the Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras. Both of them left the world a lesson that the Guna Nation had perfectly assimilated: La ecología sin lucha social es simplemente jardinería, ecology without a political struggle is just gardening.

BELOW: Early morning light at Garduk in the Nargana wilderness, Comarca Guna Yala.

Nabguana by Kuna Revolution.

Por ti yo lucho y muero, es todo lo que tengo, Nabguana está herida, por ti daré mi vida.

For you I will fight and die, you are all I have, Nabguana you are wounded, for you I will give my life.

THE ISLANDS AND ATOLLS: THE MANAGEMENT OF TOURISM

In 1965 Denis Barton, an American businessman, arrived in Guna Yala to establish a tourist resort on an island in the Ailigandí community. He built a hotel on an atoll, renamed Iceland, and promoted the paradise vacation on an international level. Business went well, relationships with the Guna went wrong from the beginning. According to the testimonies and documents of the time, the entrepreneur began banning fishing around the island, owed money to the community, allowed nudism (a scandal for the Gunadules). After years of strains, the Guna owners of the island burned Barton's structures.

In 1977, Thomas M. Moody, another American businessman, signed an agreement with the owners of the Pidertupi Island in the Río Sidra community, pledged to pay them a "rent" of 200 US dollars every year, and established a resort. Business went well, relationships with the Guna went well, but the owners of the island, who were simple but not stupid people, soon realized that Moody earned 90 dollars each day for each of his tourists, and counterattacked. They denounced him to the Guna General Congress as a speculator and a profiteer. Moody underestimated the natives and went on as if nothing had happened. On June 20, 1981, Moody and his wife were attacked by a group of young Gunadules, their hotel and yacht were set on fire, and the man was shot on a leg. After some months, he was expropriated without any compensation for violating a regional law and expelled from Guna Yala.

In 1990, the Panamanian company Jungle Adventures, which did not belong to the Kuna people, established a resort called Hotel Iskardup, on an uninhabited island near Playón Chico. After four years of confrontation and debate, the foreign investors were expelled from the comarca.

These experiences taught the Guna authorities a fundamental lesson: they had to gain full control of their land and sea, they had to reject all foreign investors no matter if waga or merki (Panamanian non-Guna citizens or foreign people), and they had to manage all tourist activities firsthand.

In 1996, the General Congress issued a resolution to regulate tourism in the Guna Yala comarca. A special statute, called Estatuto del Turismo en Kuna Yala, was included in the Kuna Fundamental Law (Ley Fundamental Kuna). It stated that only Gunadules have the right to own, establish and manage all tourist facilities, services, and activities in the whole comarca. It says that «the Kuna practice of property is classified as comarcal, communal, group, familiar and individual»; no form of property whatsoever, no rental and no tourist investment is allowed to non-Guna people under penalty of seizing their estate without any compensation. All of the natural resources of the Guna Yala land and sea are declared Guna people's heritage only.

Ley Fundamental de la Comarca de Guna Yala

Art. 40 y 41: «Las tierras delimitadas son propiedad colectiva del Pueblo Kuna cuya adquisición, explotación, utilización y usufructo se realizarán colectivamente, conforme a las normas y prácticas consuetudinarias. No pueden ser enajenadas ni arrendadas bajo ningún título, ni temporalmente».

Art. 43: «Los recursos naturales y la biodiversidad existentes en la Comarca Kuna Yala se declaran patrimonio del Pueblo Kuna».

Art 50, 51 y 52: «La explotación de toda actividad turística y sus modalidades en la Comarca Kuna Yala, se reserva al Pueblo Kuna. Todo proyecto turístico debe contar con la autorización del Congreso General. Toda actividad turística que no cumpla con los artículos anteriores será nula y el Congreso confiscará los bienes de acuerdo con la comunidad sede».

In 2007, the General Congress approved new "Rules regulating tourism activities in Kuna Yala" and created the Secretariat of Tourism and Related Affairs with the aim of strengthening the Fundamental Law and regulating the tourist activities carried out by the Gunadules.

These Rules

- state that 100% of the workforce in the tourist facilities and services (including guides) must be Guna (unless more specialized technicians were required);

- define a limited number of foreign sailboats, yachts, cruise liners, etc. that can enter and cruise in the Guna Yala waters every day;

- define the type and the amounts of the tourist income taxes that not only every single tourist, but also sailboats, yachts, cruise liners, agencies of cruise ships, travel agencies, hotels, facilities, etc., have to pay to the General Congress and to every community to use the land, the waters, the airport, the harbors, and the natural resources of the Guna people (including the beaches).

Photo by Haakon S. Krohn (under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

The Guna communities have been steadfast in controlling and limiting access to their islands by outsiders and in charging tourists several taxes, levies, and tolls since the arrival in the Guna Yala comarca.

Many tourists do not understand why it is necessary to pay a flood of local taxes (a few dollars each) and tends to react badly: they get nervous, especially when they feel exploited, "milked" or squeezed by the Gunadules. They rarely know the history of these people, and their situation. Locals and guides rarely explain, very often just cash in. Here's another failed human and cultural encounter.

The tax issue is not as irrelevant as it seems: in 2016, the tourist taxes triggered a political conflict between the Panamanian President Juan Carlos Varela and the Guna General Congress. The Guna people do not want to give up imposing them, and not just for an economic reason (these taxes are a substantial source of income for the General Congress, and some communities: approx. 1.6 million dollars per year, according to 2018 data).

Most visitors who explore the Guna atolls, perceive them as a virgin, untouched paradise, or as wild, primitive land. «They find it difficult to understand that these beautiful islets of white sand and coconut trees are not "natural" treasures, but the result of the hard work of several generations of Guna men and women. Without their effort, the islets would be covered by mangroves and full of mosquitoes: they would be inaccessible. The landscape contemplated by tourists is the result of human-environment interactions since the mid-19th century when Guna decided to exploit coconut cultivation on the islands. Therefore, although to some tourists the atolls seem a terra nullius, a "nobody's land", this paradise is the home shaped and molded by an autonomous and combative indigenous people» (Mónica Martínez Mauri (1), cit., translated from Spanish).

Moreover, many tourists do not realize that Guna Yala is different from other Panamanian coastal areas, like Bocas del Toro, for example, or other Caribbean tropical paradises. Guna Yala is an autonomous region under the control of the Guna General Congress and Guna communities. It may look like a no man's land, but it's an indigenous territory, collectively owned and managed by its Guna inhabitants. It's their home. It is their Mother Nabgwana, and their Sea Grandmother Muu Osis. It's their sacred space, the conquered space of their sovereignty. It's all they have, as their songs say.

What the Guna call "el turismo sol y playa" (the sun and beach tourism) is taken by the tourists as one of their granted rights, sold by the travel agencies along with the rest of the package. You pay, you can go: the paradise is yours. Unfortunately (or fortunately?), this is not Guna's logic.

Last but not least, as Mónica Martínez Mauri highlights, the Guna authorities make the imposition of taxes on tourists a pillar of their political and economical autonomy. The Panamanian state investments in Guna Yala are so insignificant, that these taxes are necessary tools to maintain the Nusagandi's protected area and to fight many gold-seekers and money-grabbers, and their attempts at deforestation.

A tourist-lodge in the Yandup Island, near Ukupseni or Uggubseni, aka Playón Chico, one of the most populous islands in the Guna Yala. All of the tourist-lodges are owned and ran by Gunadules and are eco-sustainable spartan structures. (Photo by Ayaita, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported).

All facilities are 100% owned and managed by Guna families, and are mostly eco-lodges: small resorts for a few dozen people made up of rustic thatched huts built with bamboo and palm leaves, with wooden floor and basic furniture. They cost between US$100 and 200 per day. Each lodge has to pay $10 every month to the General Congress, plus $1 per tourist.

Since 2007, all visitors are asked to respect the cultural and religious values of the Guna people, their norms and customs, their sacred sites, and the environment. Smoking on many islands is forbidden as well as nudism and the use of drugs. Guns and rifles are not allowed in the comarca and no tourist can hunt or fish. Diving with cylinders, visiting local villages in a bathing suit, portraying or photographing Gunadules without asking and getting their consent are banned activities. In many lodges, visitors are kindly asked to bring home their waste (the garbage they generated during their stay), but it's more of an invitation than an obligation (it should become mandatory, however, as it happens in many Maldives' resorts).

The Guna experience greatly contributed to a growing interest in indigenous eco-tourism: «On the one hand, indigenous peoples view ecotourism as a way to generate revenue while maintaining greater autonomy without draining resources. On the other hand, conservationists view it as a way of preserving the significant amount of biodiversity that remains in the hands of economically vulnerable indigenous populations. A report by the Global 2000 Program of World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) found that indigenous peoples inhabit nearly 80% of the world’s eco-regions identified as possessing the earth’s richest biodiversity. This is all the more significant considering that an estimated 3,000 indigenous groups comprise only 5% of the world’s population. From an environmentalist perspective, indigenous communities would have an obvious vested interest in conserving the islands of biodiversity in which they live, if the preserved landscape itself were a source of revenue» (Janet M. Chernela, see Bibliography).

However, there is no rose without thorns.

A strip of sand lost among waters of an incredible, pure, non-photoshopped color. Photo by Dennis Garcia (licensed under the Creative Common Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International).

THE ANTHROPOGENIC PRESSURE ON THE ISLANDS

If we rule out the temporary halt due to Covid-19, we can say without a doubt that tourism in Guna Yala is constantly expanding. It's not mass tourism, but it's something close to that (before the 2020 pandemic, approximately 100,000 tourists visited Guna Yala annually). That's a problem. The massification of tourism in the comarca is a huge problem as it is not sustainable in any way.

Currently, it's the major source of revenues for the General Congress and some (not all) communities, but, as many anthropologists have highlighted since the 1970s, the development of tourism has complex and ambiguous effects on indigenous people or developing communities.

Travel agencies and Panamanian tourist authorities tend to sell Guna Yala by promoting an ethno-tourism based on the praise of primitivism, or worse, of a post-colonial exoticism. This kind of tourism entails the spectacularization of some traditional Guna rites, the musealization of some Guna sacred places, and the quality decline of many molas, often elaborated to meet the Western souvenir taste.

Tourism growth has other negative effects, as well: it dangerously drains workers from the traditional activities (fishing and agriculture) to the more profitable tourist activities, and exacerbates the anthropogenic pressure on the fragile habitat of the archipelago.

- Clean water scarcity

Despite the migration of young Gunadules towards major Panamanian urban centers, population growth is high and inhabited islands are overcrowded (every inch of Gardí Sugdub, for example, is built up).

The availability of drinking water is a major problem, and the desalination plants to get fresh water for domestic use are still very limited. In 2015, only 37 communities had rural aqueducts. Many Gunadules do not have access to filtration or decontamination methods to purify their drinking water. During the rainy season, families collect rainwater in plastic barrels, usually positioned very close to their huts. Rodent feces contaminate the drinking water supply and the barrels easily turn into mosquito nurseries. The water wells on the mainland, when not contaminated, are not enough.

«About 98% of small tourist islands do not have a water source, such as a well. Then you're going to look for water in the river, on the mainland. But if your tourist island is small and has a capacity of 25 tourists and you put in 50 people, what happens? You have problems with water, bathrooms, food... And that brings great discomfort to visitors» (Johanna Durget et Elodie Salin, Conversación con Iniquipili Chiari, see Bibliography, translated from Spanish).

- The tourists' overconsumption of food

In Gunayala, the food obtained from traditional fishing and subsistence agriculture is intended for domestic consumption only, and is not enough to be sold to restaurants and eco-lodges; therefore, most of the food consumed by tourists - including seafood - comes from outside the comarca. The great majority of tourists do not realize the many logistic challenges that their presence poses to Guna operators and are only partially solved by their payments.

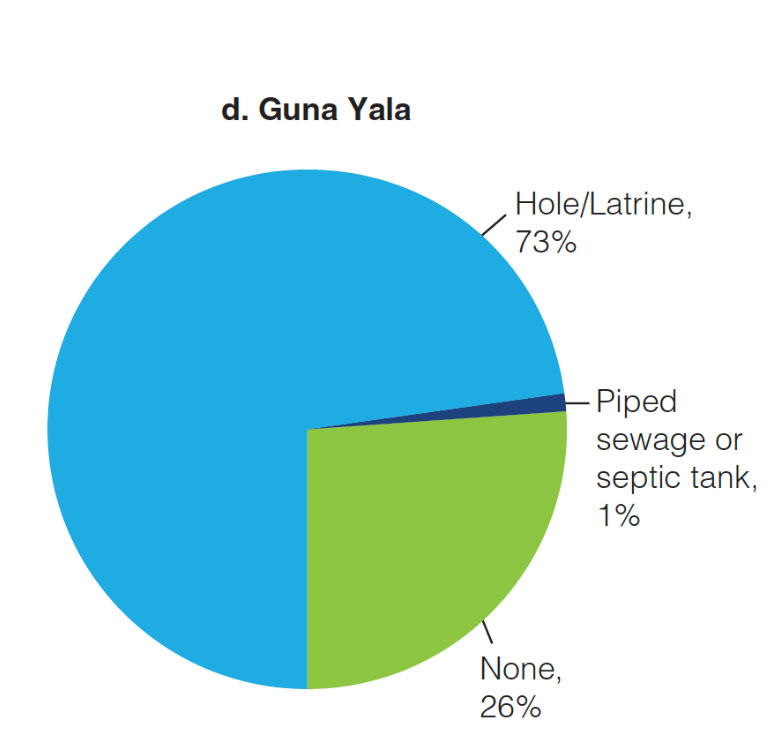

- The sewage situation

The sewage situation is reported in the following chart. According to the 2013 Global Data Lab, in the Guna Yala comarca, the households with flush toilets are 3.35% only. Latrines are scarce, septic tanks even more. Recently, 14 communities, including Carreto, Armila, and Aya Chu Kula, have requested the installation of septic tanks instead of latrines.

Source: Arteaga 2016, in World Bank. 2018, The Connections between Poverty and Water Supply, Sanitation, and Hygiene (WASH) in Panama: A Diagnostic, WASH Poverty Diagnostic, World Bank, Washington, DC.

- The waste management

The Guna people are used to throwing all their waste into the sea. This old habit was perfectly eco-sustainable in the past: the guna garbage was 100% biowaste in limited quantities (human waste, the remains of household cooking, etc.). In the present-day, however, both Guna and tourist waste has increased in quantity and changed in quality: it's made up of aluminum cans, glass bottles, plastic containers, batteries, metal accessories, etc. Many Guna families still maintain the habit of throwing it into the sea (especially among the coastal mangroves). Some others take their trash to the mountain where it is burned or buried, a system that does not favor the proper handling of garbage and represents a cost for families living on the islands (In the Cartí community, for example, some of the waste is now taken to a mainland dump, but most of it still ends up in the ocean). In general, the archipelago does not have adequate services to manage the volume of non-organic garbage and no waste sorting process whatsoever has been developed or designed.

The problem of garbage management is a remarkable threat to the marine ecosystem and the Guna quality of life and is, of course, exacerbated by oversized tourism.

The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) and the Community Innovators Lab (CoLab) of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have started a project called Basura Cero (“Zero Waste”) to create a waste system for the four principal Cartí islands: Mulatupu, Yantupu, Suitupu, and Tupile.

The Guna already recycle aluminum cans to be sold to Colombian trading boats at $40 cents per kilo, and a market exists in Panama City and Colón for recycled plastic; but for both materials a supply chain had to be created, starting at collection points in the island villages through a mainland sorting center, all the way to recycling companies in the city. «Engineers and other experts affiliated with Basura Cero are designing a sanitary landfill and a mainland recycling center. The project has purchased a boat and motor to carry waste and recyclables from islands to the mainland. Edgar Blanco, from MIT’s Center for Transportation and Logistics, has mapped out recycling routes, identified possible buyers, and analyzed the economic viability of recycling. Students and advisors to the project have designed simple compactors and collection vehicles to move waste and recycling from the shore to the landfill and collection center. To manage medical waste, the project is procuring new equipment. Overall, however, technical questions matter less than the organization and cooperation. It is especially important to lend a hand and suggest solutions without imposing western ideas or western power on the local “targets” of development or alienating people who have, in truth, seen a lot of projects come and go. The Guna are famous for their hardwon political autonomy and self-management, but things do not just happen by themselves in Guna Yala. In their democratic political system, positive results follow only after hours of discussion, negotiation, and even heated arguments. Projects fail if they do not attend to the wider political environment, especially to the will of the Guna General Congress, the ultimate authority for the autonomous reserve, but they must also defer to the jealously guarded autonomy of each community. One can nudge and exhort and suggest and plan but never push, give orders or favor one village over another». (James Howe and Libby McDonald, Trash in the Water, see Bibliography).

Family garbage in Playón Chico, Guna Yala. From a photo by Ben Kuchinski (licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic - CC BY 2.0).

- The loss of coral reefs

In the last decades, the coral reef has suffered a remarkable degradation due to runoff sewage, pollution, and algae overgrowth, as well as harvesting for the curio trade, overfishing, tourism, and dredging for infill. The island-village of Río Sidra was formerly made up of two separate islands, Mamartupu and Urgandi, each with their own Saila chosen by the community. However, population growth and lack of land led the Gunas to fill the space between the islands by using coral remains. It is estimated that approximately 16,215 m2 of corals have been extracted from the ocean to build sea walls and fillings. This, together with lobster overfishing, has resulted in more than 50% of the region's reefs being at risk of disappearance.

The Guna habit of mining living coral is an old practice from the 19th century. When Gunadules were few and corals many, this habit had no devastating impact on the coral reef ecosystem, but this is no longer the case. The Global Coral Reef Alliance cooperation with some Guna communities «focuses on the use of Biorock technology for restoring coral reef habitat, restoring lobster habitat, protection of the shoreline from erosion without the need for mining coral reefs, and on the establishment of environmental education programs for schoolchildren and fishermen» (Thomas Joaquin Goreau Arango et al., see Bibliography).

That's not enough, of course. More international cooperation projects and educational actions have to be developed and undertaken to defend underwater threatened treasures. The Guna General Congress should create a Secretaría del Medio Ambiente (Secretariat of environment and natural resources) as soon as possible, as loudly requested by many young Gunadules professionals in the last years, both to analyze the environmental impact of any tourist project and to draw up a strategy that will significantly improve the protection of the marine environment.

FACING TWO MAJOR THREATS

«Historically the Gunas have resisted all efforts at colonization. Additionally, they have been very successful in protecting their territory from all types of outsiders, including small settlers, large entrepreneurs, and even state officials» (Displacement Solutions, see Bibliography). Currently, the Guna people fiercely resist the many pressures by the Panamanian government, the travel & tourism lobbyists, waga and merki investors (Panamanian non-Guna citizens and foreign people) who see in the Guna atolls a money-maker paradise and the promise of an Uncle Scrogee's style treasure deposit.

Guna authorities have to learn to better protect their islands and the marine ecosystem, to reduce anthropogenic pressure, current pollution, and loss of biodiversity. These are no small challenges. Unfortunately, there are two major threats that are worse than that. Infinitely worse.

- Guna Yala lies on the main drug trafficking routes

The first threat is linked to the geographic position of the Guna Yala region, at the border with Colombia: the indigenous comarca lies on the main drug trafficking routes by land and by sea. 90% of the drug produced in South America passes through Central America to get to Mexico and the United States. The Darién Gap and the Guna Yala waters are both a "natural" gateway to Central America. Moreover, one of Colombia's most powerful drug cartel and criminal organizations, the Clan del Golfo, has its stronghold in the Gulf of Urabá region and in the territory of Antioquia, a strategic area where there are plantations, drug refineries, storage warehouses, hideouts for men and goods, large international export ports. The Gulf of Urabá region and the territory of Antioquia are the homeland of the Colombian Guna people.

The islands of Guna Yala have become an essential enclave for drug trafficking: they are isolated, far from the perpetual surveillance of the police, and full of tourist ships that Guna Congress cannot control and among which is easier to hide.

The Gunadules do not grow, make or refine cocaine, and are not cartel's mules, however, some of them don't back down when there's the chance to make lotta money quickly (for this crime, they can be banned forever from the community). «Drug-filled speed boats pass through our waters at high speed and sometimes they have to throw bags of drugs into the sea so that Panamanian police don't catch them red-handed. There are Gunadules who recover the packets of cocaine (or whatever) and resell them to the Colombians. But not everything is sold: approx. the 5% of the drug remains in the Comarca, ready for an internal sale» » (Johanna Durget et Elodie Salin, Conversación con Iniquipili Chiari, cit. translated from Spanish).

Some years ago, Amado Philip de Andrés, now UNODC Regional Representative for Eastern Africa, once UNODC Regional Representative for Central America and the Caribbean based in Panama, said that «the penetration of drug trafficking in Guna Yala must be taken seriously». (UNODC is the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime).

Video in English, by Monica Villamizar for Al Jazeera.

What worries Guna activists and political leaders is not only the involvement of Gunadules in drug trafficking and drug use but the attempt to "wash" dirty money through the construction of tourist facilities via Guna figureheads, gaining at the same time a hidden drug storage base. To block such attempts, the Guna General Congress submit every tourist investment project to painstaking supervision and very accurate controls, and in case of doubt, easily reject the proposal. This, on the other hand, leads to greater bureaucratic slowness and less entrepreneurial agility.

- Guna Yala islands are slowly sinking in the ocean due to the global warming effects

There are no words in Dulegaya, the Guna language, to indicate the contemporary phenomenon of climate change and global warming; unfortunately, no islands are suffering its consequences more than those in the Guna Yala comarca.

According to IPCC (the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change of the United Nations), the most relevant effects of global warming on the San Blas Archipelago are

- temperature variation;

- precipitation variation;

- sea-level rise;

- pH variation in the ocean (progressive acidification of surface waters);

- variation in the frequency and intensity of extreme phenomena.

The most devastating effects of climate change for the Guna communities are caused by point 3., the sea-level rise.

According to the most authoritative and influential study on the effects of climate change in Guna Yala, signed in October 2003 by marine biologists Héctor Guzmán, Carlos Guevara, and Arcadio Castillo (published in the Journal Conservation Biology), the sea-level rise averaged 2.0 mm from 1907 to 2000, with evidence that it has been accelerating since the 1970s: 2.4 mm/year.

According to the IPCC Report, The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate, published in September 2019, between 2006 and 2015 the sea-level rise in the world averaged 3.6 mm/year. In the last years, according to Steve Paton, former director of the Physical Monitoring Program in Panama (Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute), the Caribbean sea level had been rising between 4 and 8 mm/year.

The Guna Islands are less than 100 cm over the sea level, some less than 50 cm. Do the math, please.

At the same time, based on the comparison of aerial pictures taken of uninhabited islands in Gunayala over 30 years, Héctor Guzmán, Carlos Guevara, and Arcadio Castillo found “a reduction in surface area of 50,363 m2, with an average loss of (…) 1105 m2 on uninhabited islands” (quoted in Displacement Solutions, Climate Change and Displacement in the Autonomous Region of Gunayala, see Bibliography).

Sea-level rises have decreased the surface of the islands and this phenomenon has exacerbated the overcrowding due to population growth. Gunadules have resorted to coral infilling to expand the island surfaces, but this made them lose part of the natural protection of the reefs against ocean waves and erosion.

Storms and flooded events (like the devastating one of November 2008) are increasingly frequent. Some islets have already disappeared, like Noromulo. Some others are destined to be soon abandoned. Gardí Sugdub, the most populous island with 5,000 inhabitants, will be likely one of the first to be abandoned, just as Mulatupu, Ustupu, Playón Chico (Ukupseni) or Nula Tupe. Currently, some displacement projects are being studied.

As highlighted by IPCC data, confirmed by the World Economic Outlook, October 2017: Seeking Sustainable Growth: Short-Term Recovery, Long-Term Challenges (by the International Monetary Fund), the most heartbreaking and painful aspect of this impending tragedy is that several of the populations that are going to suffer the worst consequences of climate change, such as small emerging island states - Guna Yala, Kiribati, Maldives, Vanuatu, Fiji, Timor-Leste, Nauru - have not helped to produce it.

We cannot leave them alone.

La ecología sin lucha social es simplemente jardinería, ecology without a political struggle is just gardening.

A short film by Michael Adams (USA).

This excellent reportage is made in Spanish by Noticias Univision, the news division of the American Spanish language broadcast television network KMEX-DT. It includes an interview with chief Belisario López we've already met in the FAO video. The journalist asks him about the displacement programs of some Guna communities due to climate change. He says "climate change", and chief Belisario López burst out laughing: «Do we blame climate change? An abstraction? Or do we have to blame who caused it?».

Diwigdi Valiente, a young Guna intellectual, created a website and a project called Burwigan to fight plastic pollution and climate change. «Burwigan means 'kids' in the Guna language and through art, we tell the stories of the first future climate change refugees in Panama, the Guna Kids. We inform, engage, and inspire artistic and scientific action on climate change in the islands of Guna Yala and Panama City». Unfortunately, Burwigan website is no longer active.

BIBLIOGRAPHY AND LINKS

Edith Crouch, The Mola - Traditional Kuna Textile Art, Schiffer Publishing Ltd., PA (US), 2011.

Diana Marks, The Kuna Mola - Dress, Politics and Cultural Survival, Dress, vol. 40, no. 1, 2014.

MOLAS, Capas de sabiduría, Museo del Oro, Bogotá, Exposición Temporal, September 29, 2016 - June 17, 2017.

Andrea Vazquez de Arthur, Fashioning Identity: Mola Textiles of Panamá, published on the occasion of the exhibition Fashioning Identity: Mola Textiles of Panamá, November 22, 2020 – October 3, 2021, The Cleveland Museum of Art.

Adolfo Chaparro, 'Mujeres mola' o la máquina de imágenes míticas, in Aisthesis, (53), 9-27, 2013.

James Howe, La Revolución Dule: una rebelión indígena del siglo XX, Boletín Museo del Oro, 2016, 56: 205-226. Bogotá: Banco de la República.

Michel Perrin, Los caminos de la creación en el arte de las molas cuna, Boletín del Museo del Oro, No. 46, Enero 2000.

Kayla Price, From Revolt to Revolution: Remembering the events of 1925 in Kuna Yala, February 1-3, 2007, ILASSA Conference, Austin, TX (US).

Le mola dei Kuna di Panama. Percorsi didattici tra etnografia ed universo simbolico, Quaderno n. 2, Università di Siena, Dipartimento di filosofia e scienze sociali, 2000.

Emil Keme (Emilio del Valle Escalante), De América Latina a Abya Yala, hacia una indigeneidad global, Revista Transas - Letras y Artes de América Latina, 2018.

Mónica Martínez Mauri (1), El tesoro de Kuna Yala. Turismo, inversiones extranjeras y neocolonialismo en Panamá, in "Cahiers des Amériques Latines", 65 | 2010 (Dossier. Tourisme patrimonial et sociétés locales).

Mónica Martínez Mauri (2), ¿Por qué pagar por entrar a Gunayala? movilidad turística, soberanía y pueblos indígenas en Panamá, "Presses universitaires de Rennes", « Norois », 2018 / 2 no. 247.

Mónica Martínez Mauri (3) - Xerardo Pereiro - Jorge Ventocilla Cuadros, Turismo Étnico: el caso de Kuna Yala (Panamá), in "RT&D", no. 13, 2010.

Xerardo Pereiro, A review of Indigenous tourism in Latin America: reflections on an anthropological study of Guna tourism, in Sustainable Tourism and Indigenous Peoples, edited by Anna Carr, Lisa Ruhanen, Michelle Whitford, and Bernard Lane, Routledge, USA-UK, 2018.

Janet M. Chernela, Barriers Natural and Unnatural: Islamiento as a Central Metaphor in Kuna Ecotourism, Bulletin of Latin American Research, Vol. 30, No. 1, 2011.

Johanna Durget et Elodie Salin, Conversación con Iniquipili Chiari sobre el turismo en la comunidad Gunayala en Panamá, in "Idées d'Amériques", 12, Automne-Hiver 2018, dossier: Le tourisme dans les Amériques.

James Howe and Libby McDonald, Trash in the Water. An Indigenous People Confronts Waste, in "ReVista", Harvard Review of Latin America, Winter 2015, vol XIV, no.2. Published by the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies and Harvard University (https://repositorio.flacsoandes.edu.ec/bitstream/10469/8102/6/REXTN-RHRw2015-19-Howe.pdf)

Thomas Joaquin Goreau Arango - Gabriel Despaigne Ceballos - Wolf Hilbertz - Lucio Arosomena - Ultiminio Avila - Roque Solis, Coral Reef Restoration and Shore Protection Projects in Ukupseni, Kuna Yala, Panama, GCRA 2005 Progress Report May 14 2005.

Displacement Solutions (DS), The Peninsula Principles in Action: Climate Change and Displacement in the Autonomous Region of Gunayala, Panama, July 2014. (DS is registered as a non-profit association in Geneva, Switzerland. http://displacementsolutions.org/wp-content/uploads/Panama-The-Peninsula-Principles-in-Action.pdf).

Guna texts and tools

Atilio Martínez, El Legado de los Abuelos, Gunayala, 2012

Jorge Ventocilla, Heraclio Herrera, Valerio Núñez, El Espíritu de la Tierra. Plantas y Animales en la Vida del Pueblo Kuna, Co-edition Instituto Smithsonian de Investigaciones Troipicales Panamá - Edicione Abya Yala, Quito (Ecuador), 1999.

Reuter Orán - Aiban Wagua, Gayamar Sabga Diccionario Escolar Gunagaya-Español, Equipo EBI Guna, 2013.

Corso Elementare di Lingua Cuna, Università di Siena, www.unisi.it/cisai.

Aiban Wagua, En defensa de la vida y su armonía. Elementos de la espiritualidad Guna. Textos del Babigala, Emisky / Pastoral Social–Caritas Panamá, 2nd. edition, 2011.

Ruth Virginia Castaño Carvajal y Milton Santacruz Aguilar, IBISOGE YALA BURBA MOLA. ¿Qué nos dicen las molas de protección?, Boletín Museo del Oro, Número 56, Año 2016, Bogotá: Banco de la República.

Significados de vida: espejo de nuestra memoria en defensa de la Madre Tierra, Tesis Doctoral de Manibinigdiginya ABADIO GREEN STÓCEL (Pueblo Gunadule, Colombia-Panamá), Doctorado en Educación: Estudios Interculturales Universidad de Antioquia, Medellín, febrero 2011.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?