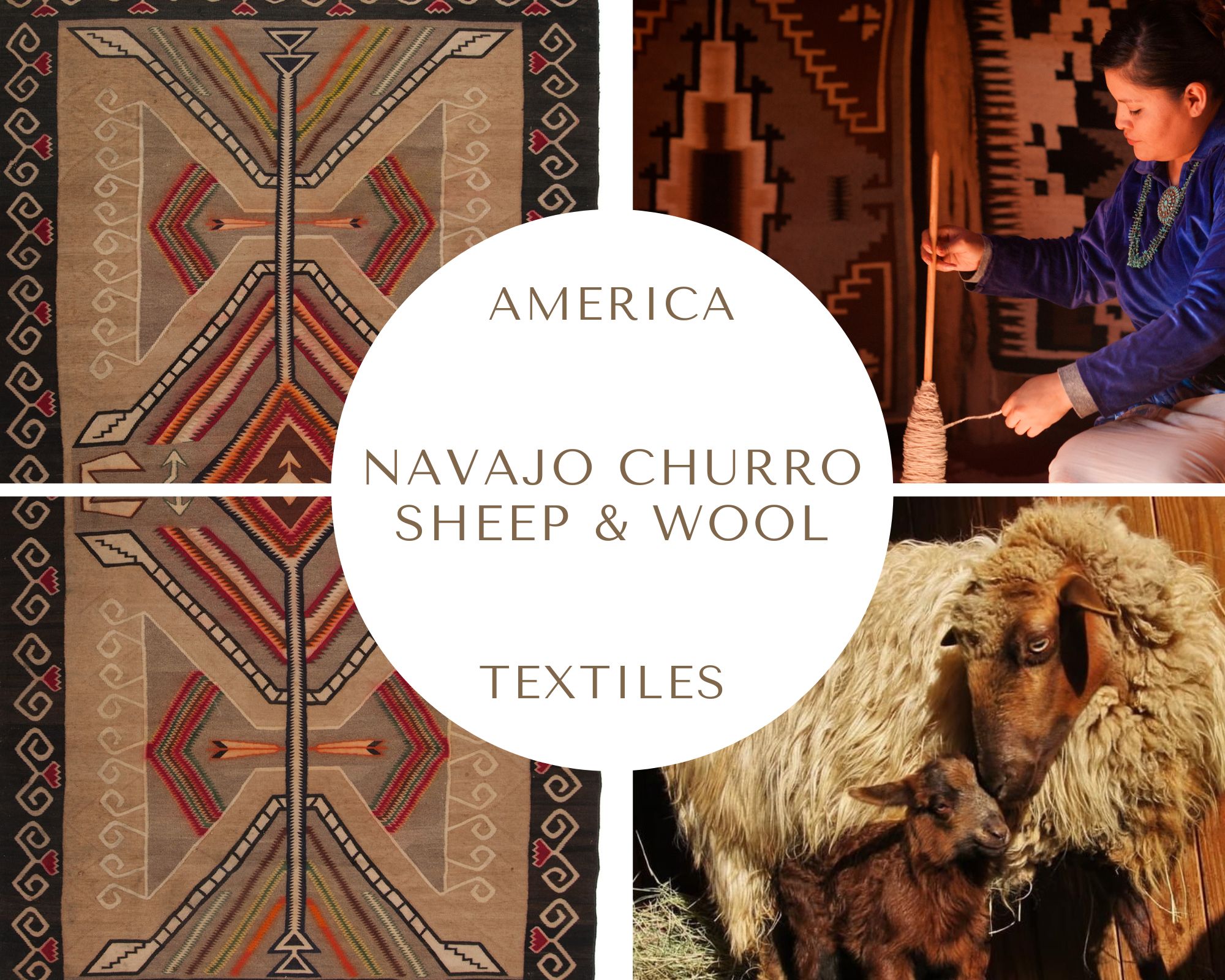

Kuna Molas of San Blas

THE GUNA/KUNA MOLAS FROM THE SAN BLAS ISLANDS

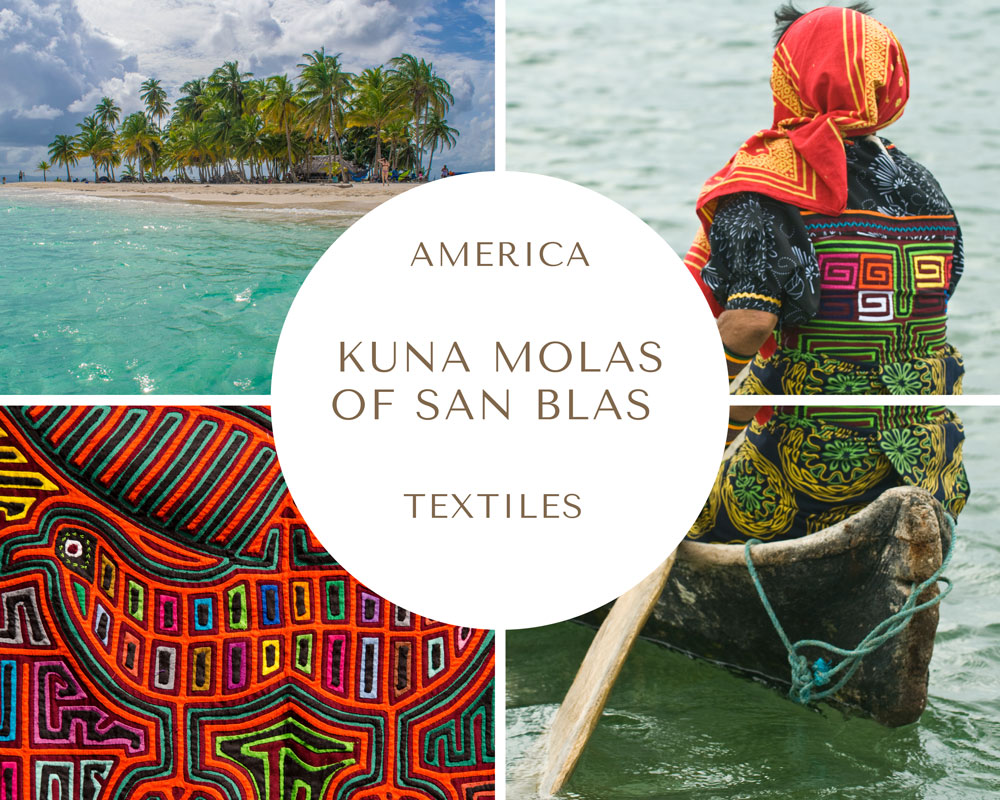

The mola, in Spanish la mola (plural las molas) is a hand-made, multi-layered cotton panel whose complex designs are achieved via different techniques, such as appliqué, reverse appliqué, and embroidery. It's a hundred-years-old traditional handicraft, created, realized, and used as a part of the women's clothing by the Guna (Kuna), an indigenous people living in the Guna Yala (Kuna Yala), a comarca indígena (= autonomous province, governed by the indigenous people) in northeast Panama. La mola is considered today the most relevant form of collective art of the Guna people: the panels, made mostly by the women, are rarely signed.

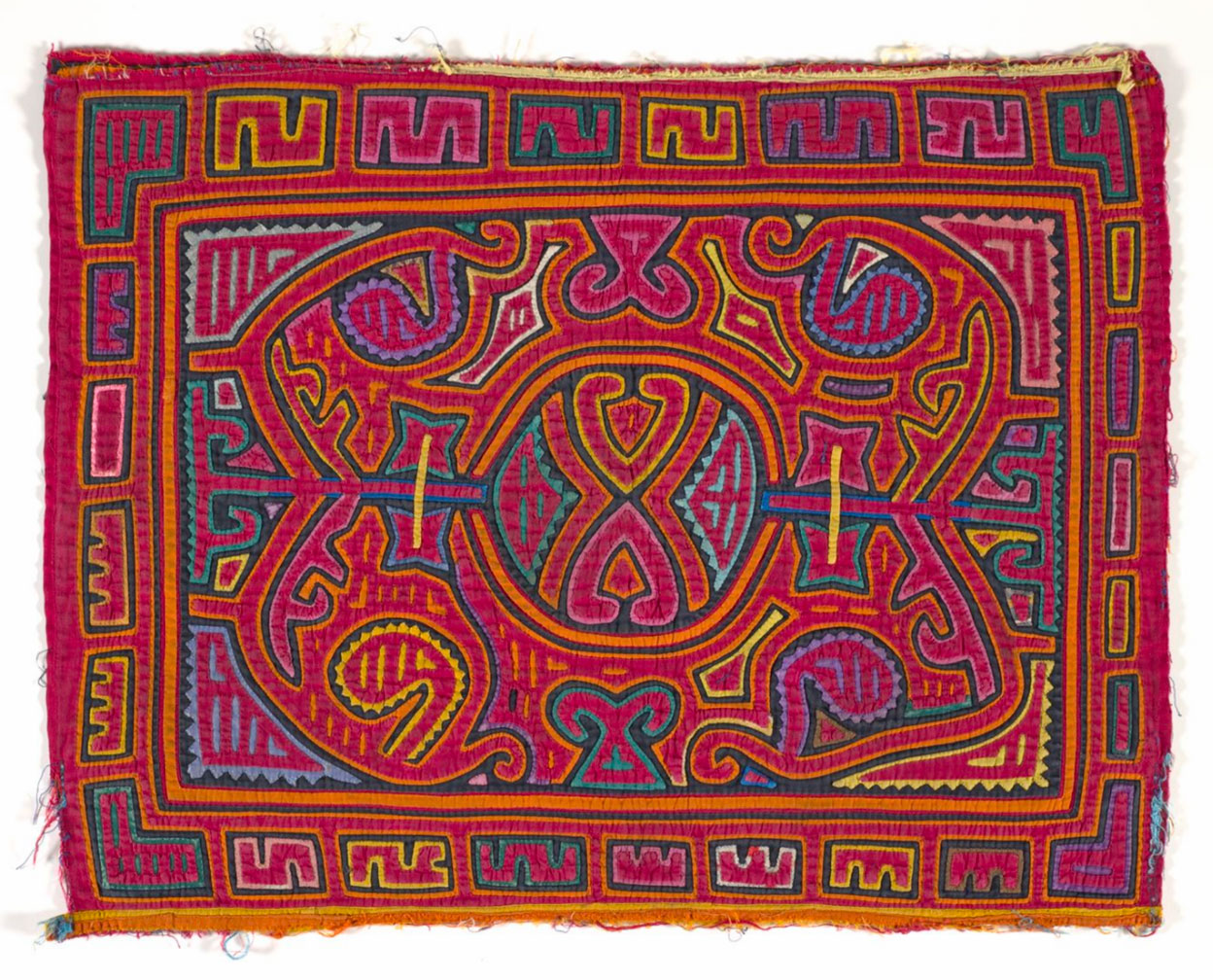

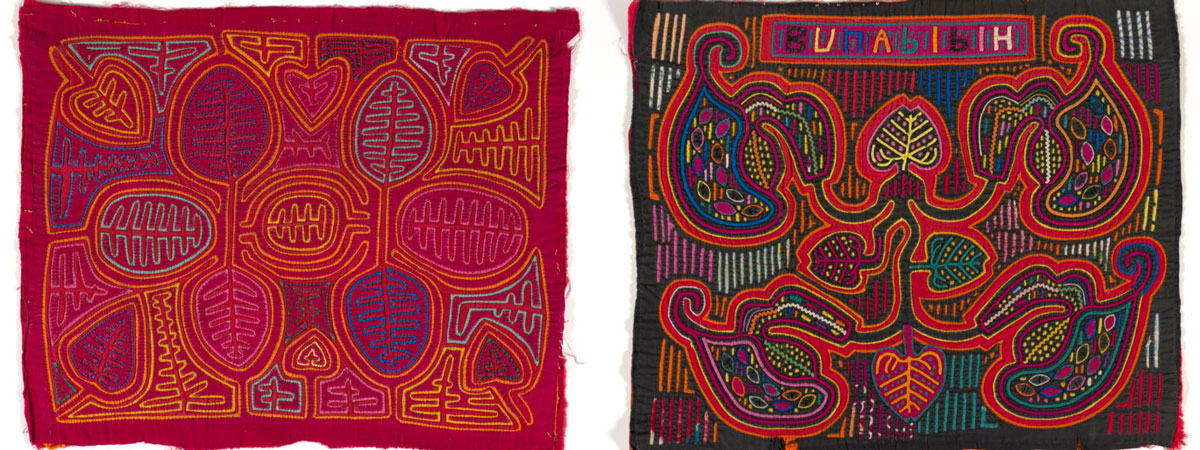

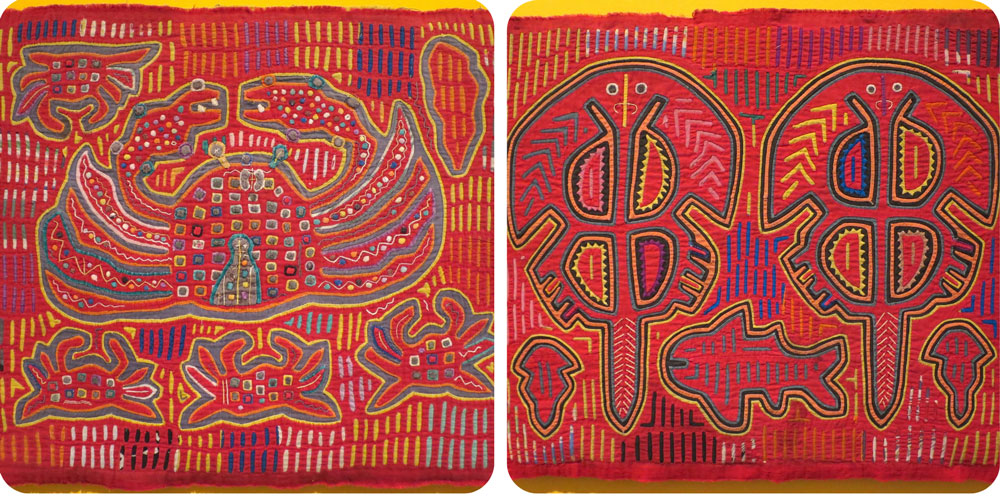

Four different Guna cotton molas from the early 20th century. Photos by ©The Trustees of the British Museum (under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

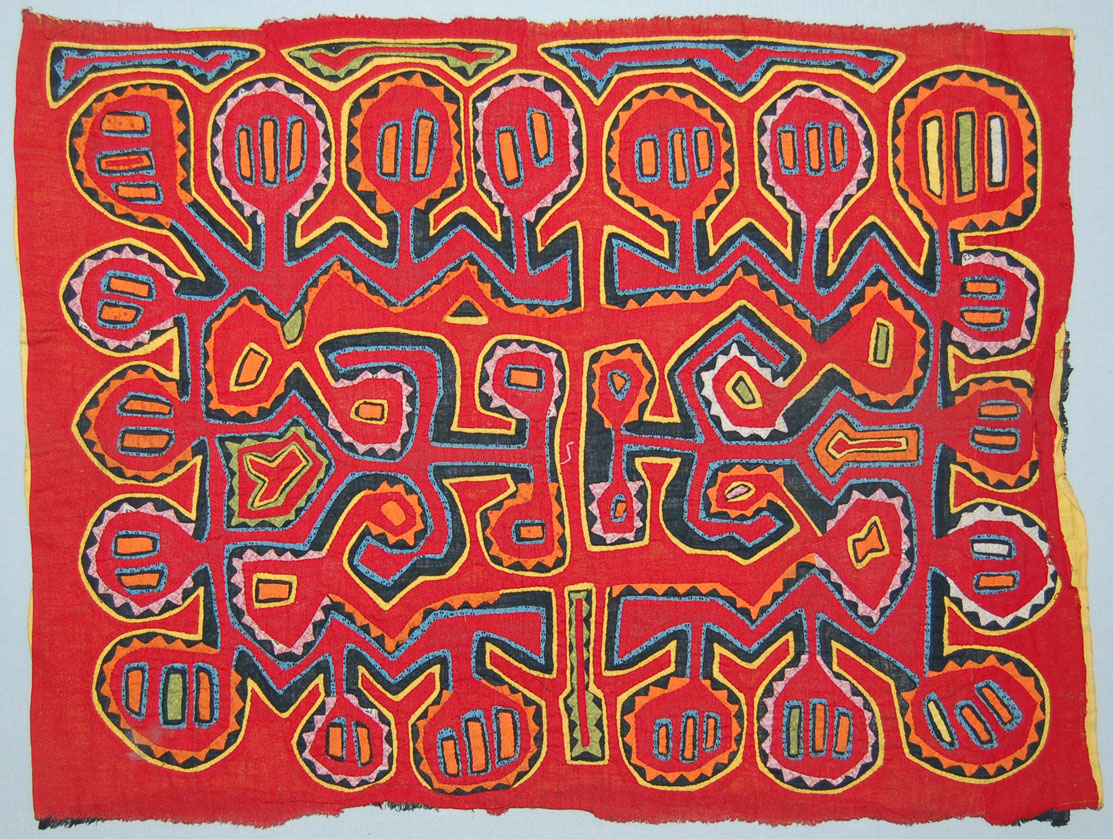

Guna cotton mola from the early 20th century, The British Museum, London. Size: 47 x 64.5 cm. Photos by ©The Trustees of the British Museum (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

Four Guna cotton mola blusas from the early 20th century, The British Museum, London. Photos by ©The Trustees of the British Museum (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

Guna cotton mola from the 1950s, purchased in 1960-1970 by Paul and Irene Hollister, Hanover, New Hampshire; given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2008.

Guna cotton mola from the 1950s, purchased in 1960-1970 by Paul and Irene Hollister, Hanover, New Hampshire; given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2008.

They are breathtakingly beautiful, aren't they? They are all made with an exquisite sense of design and composition. Their vibrant palette of saturated colors - yellow, orange, fiery red, purple, green, blue, black, white - tells us that the Guna women's clothes were and still are made to create an eye-catching, texturized splash of color against the natural shades of the environment. Molas were and still are designed to be viewed from a distance: Guna women are not secluded, shy mujeres.

The Guna people usually distinguish two different kinds of panels: las molas naga, the panels with a "protective" power, characterized by abstract, geometrical designs inspired by nature, and las molas goaniggadi, panels with figural representations and scenes of everyday life.

The above molas naga show an abstract geometric pattern whose meaning is difficult to understand. Sometimes, the geometric composition is obtained via the repetition of a stylized plant, animal, or daily tool, transformed into its synthesized visual essence. Other times, the geometrical motifs are derived from the Precolumbian body painting decorative patterns (some of which had likely an apotropaic power), widely common among the Guna until the 18th century (the French Huguenots settlers were the very first to introduce clothing to some of their communities).

The most popular themes for molas are inspired by nature: the rich wildlife of the Guna territory has been the major source of their social imaginary and artistic expression. The coconut palm, an important source of income and food for the Guna, is widely represented. The mola on the left, below, is a vintage, worn one (likely made before the 1950s) featuring ogobwala, the coconut palm tree, whose branches make the roofs of the huts and are portrayed as large-sized and generous fronds. The mola on the right may depict a coconut tree or a wagmadun, a banana tree.

LEFT Vintage and used Guna cotton mola from the early/mid-20th century, The British Museum, London. Photos by ©The Trustees of the British Museum (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

RIGHT Guna cotton mola from the 1950s, purchased in 1960-1970 by Paul and Irene Hollister, Hanover, New Hampshire; given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2008.

Two Kuna cotton molas depicting plants, both from the 1950s. They were purchased in 1960-1970 by Paul and Irene Hollister, Hanover, New Hampshire, and given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2008.

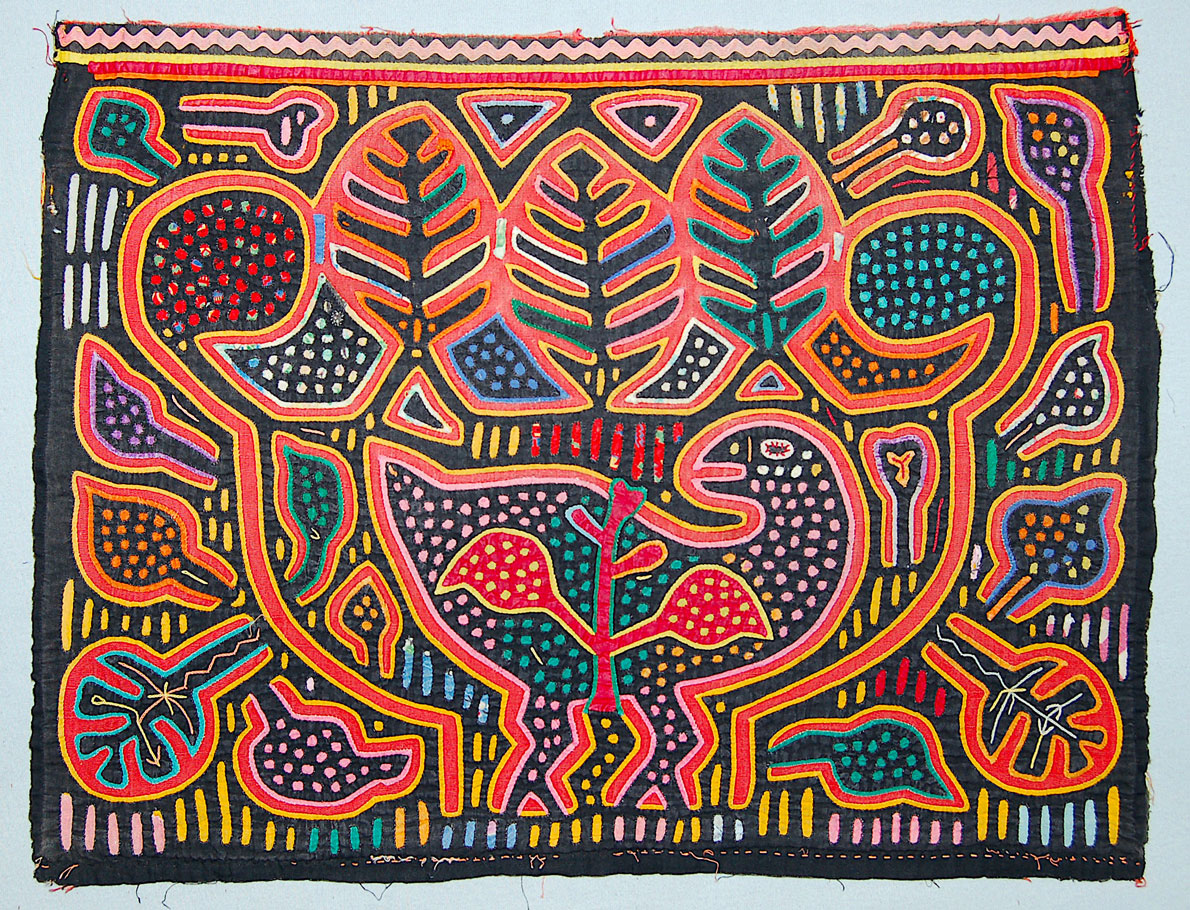

Mola panel, cotton cloth, 55.1 x 47.7 cm. Guna Yala Indigenous Territory (San Blas); Panama 1950-1960. Collected by photographer and author Dr. Louise C. Agnew (1900-1979), probably between 1953 and 1960; inherited by her daughter Bettylee Marquis-Kral (924-2014). Donated to National Museum of the American Indian (New York - Washington, US), in 2007 by Bettylee Marquis-Kral.

A baffling representation of leafy creatures. Cotton mola, 1970-1990, James and Virginia Tobin Collection of Kuna Molas, gifted to the Museum of the Red River, Idabel, Oklahoma. Not on display.

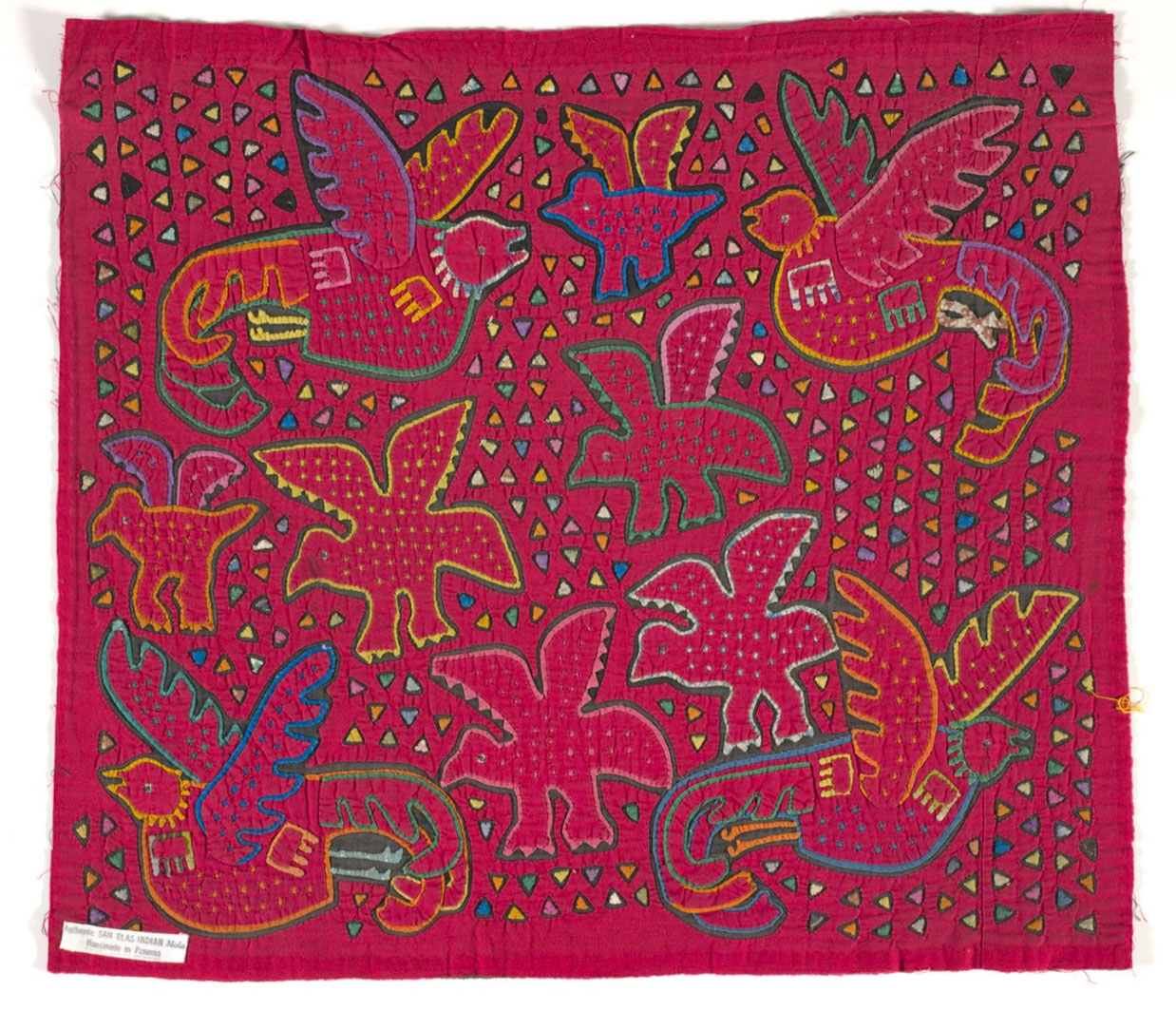

Animals make a popular theme as well, and the birds are the most depicted of all: storks and herons, parrots, toucans, pelicans, chickens, and turkeys are caught from different perspectives, in a bidimensional space that often represents their inner and outer aspects at the same time. Many abstract or unidentified birds are represented among trees or in the jungle and are often related to human birth (babies are usually depicted as small birds in a womb). In the Guna language, called Dulegaya, over 60 varieties of birds have a proper name.

Vintage and used Guna mola sized 41 x 53.50 cm, The British Museum, London. Photos by ©The Trustees of the British Museum (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

Guna cotton mola from the 1950s, purchased in 1960-1970 by Paul and Irene Hollister, Hanover, New Hampshire; given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2008.

Kuna cotton mola depicting a rooster, from the 1950s, purchased in 1960-1970 by Paul and Irene Hollister, Hanover, New Hampshire; given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2008.

These cotton panels are traditionally sewn into blouses, and worn as part of the Guna traditional female dress ensemble. The following blouse shows an outstanding panel with a large-winged bird, according to the opinion of the curators of The British Museum; to me, it's not a bird, but a bat (a mammal), depicted in a line of continuity with a snake and another mammal. It's an exquisite panel, anyway.

Guna mola cotton blouse, before 1924, The British Museum, London. Photos by ©The Trustees of the British Museum (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

Land animals - ducks, frogs, butterflies, and other insects, snakes, spiders, cats, dogs, monkeys, bats, squirrels - and sea creatures - turtles, crabs, lobsters, octopuses, fishes, especially rays and dolphins - are common themes throughout the last century. The two following blouses show respectively a panel with two animals (likely two monkeys, one on top of another) and a panel with two stylized coiled snakes.

2 Guna mola cotton blouses, early 20th century, The British Museum, London. Photos by ©The Trustees of the British Museum (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

The next panel featuring octopuses (among corals?) is a true marvel.

Guna mola cotton panel, before 1924, 44 x 64 cm, The British Museum, London. Photos by ©The Trustees of the British Museum (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

In Guna mythology, the turtle - yaug in Dulegaya, the Guna language - is one of the very first animals created by the Earth Mother, Nabgwana. Each of the following panels features a variation of the very same yaug motif.

3 Guna mola cotton blouses, early 20th century, The British Museum, London. Photos by ©The Trustees of the British Museum (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

The next two panels come respectively from the Island Nulanega and the Island Wichubuala, both in the Guna Yala, and feature respectively some crabs and two rays, and a fish. The autonomous province of Panama governed by the Guna is made up of a narrow strip of land on the east coast of the country, facing el Mar Caribe (the Caribbean Sea), plus an archipelago of ca. 400 islands and coral atolls. That's why the sea creatures, especially the coral reef inhabitants, are so relevant for the Guna people.

2 Guna mola cotton panels, second half of the 20th century, Honolulu Museum of Art (under under the Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication).

The Guna call the sea muubilli and Muu Osis the "mother of the sea" or the "grandmother" who manages the sea world, cares for the sea creatures, and protect the marine abysses. In the Guna tales, la gran Abuela del mar, the Sea Grandmother, has many expressions or material manifestations: Muu Arwasob is the grandmother who makes the waves break, and Muu Gwilasob the one who makes the waves dance and frizz; Muu Mullosob is the grandmother who raises the ridges of the waves, while Muu Suruggasob the female power who whitens the waves. Muu Arabasob is the grandmother who covers the surface of the sea with foams, Muu Welasob creates small waves, and Muu Suggelisob gives strength to sea currents.

The sea is rich in sacred sites for the Guna, as the whirlpools or biryagan, for example, conceived as the eyes and ears of the sea. Here, inside the rotating waters, sharks and other large fish are born and the shads gather in shoals. The sea has also its guardians: the whale Olodinagibibbiler (baggadule), the barracuda Olodeengabibbiler (dabudule), the swordfish Ologibyaliler (suggudule), and the dolphin Olobindibibbiler Ologungibibbiler (uagi).

The Guna molas are rich in animals, always portrayed as living creatures and pulsating forms of life. The Guna rich oral traditions are full of songs, hymns, and prayers that recount the beauty and majesty of the wind, the land, and the sea. Definitely, the Guna peoples have always been living in symbiosis with Mother Nature. In the past times, many of them used to calculate hours by the flowering of some plants; when the gwala bloomed, they knew it was noon, and when the nooduddu opened its flowers they felt it was approaching the afternoon.

Human figures are portrayed in the molas while dancing, beating rice, or cooking. Like animals and plants, men and women as caught in a moment full of life: you can admire a muu (a grandmother) singing lullabies to a couple of babies lying in a hammock, a group of children going to school, two women gossiping, some tourists diving or snorkeling with huge masks. The two following molas from the early 20th century show some stylized men (the first on the left) and two rows of dancers, facing one another and seen from above (the mola on the right).

2 Guna mola cotton panels, early 20th century, The British Museum, London. Photos by ©The Trustees of the British Museum (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

Like every form of art, the molas are continually evolving in terms of design, colors, workmanship, and even storytelling techniques. Contemporary molas, made both for internal consumption and for foreign top market collectors (local tourists tend to buy simple souvenir molas or small molitas) are generally more complex, with more refined stitching, and more detailed designs. They tend to adopt a Naïve art rendering style and are more expressive and figurative. Here two interesting examples are depicting human figures.

The first mola depicts two women making chicha de maiz (as written in Spanish). The chicha is a drink made with ground toasted corn, or alternatively with sugar cane juice, that can be consumed either fermented (bitter) or unfermented (sweet). The alcoholic bitter chicha (inna gaibid) plays a central role during girl puberty rituals, the Chicha Festival, and the marriages, where the whole village sings the songs, dance at the flute music and laugh; the children play, the adults drink chicha and get drunk (mummud). The second mola depicts some (drunk?) musicians resting in hammocks during the Chicha Festival.

Here's another (more or less) contemporary mola with a figurative design.

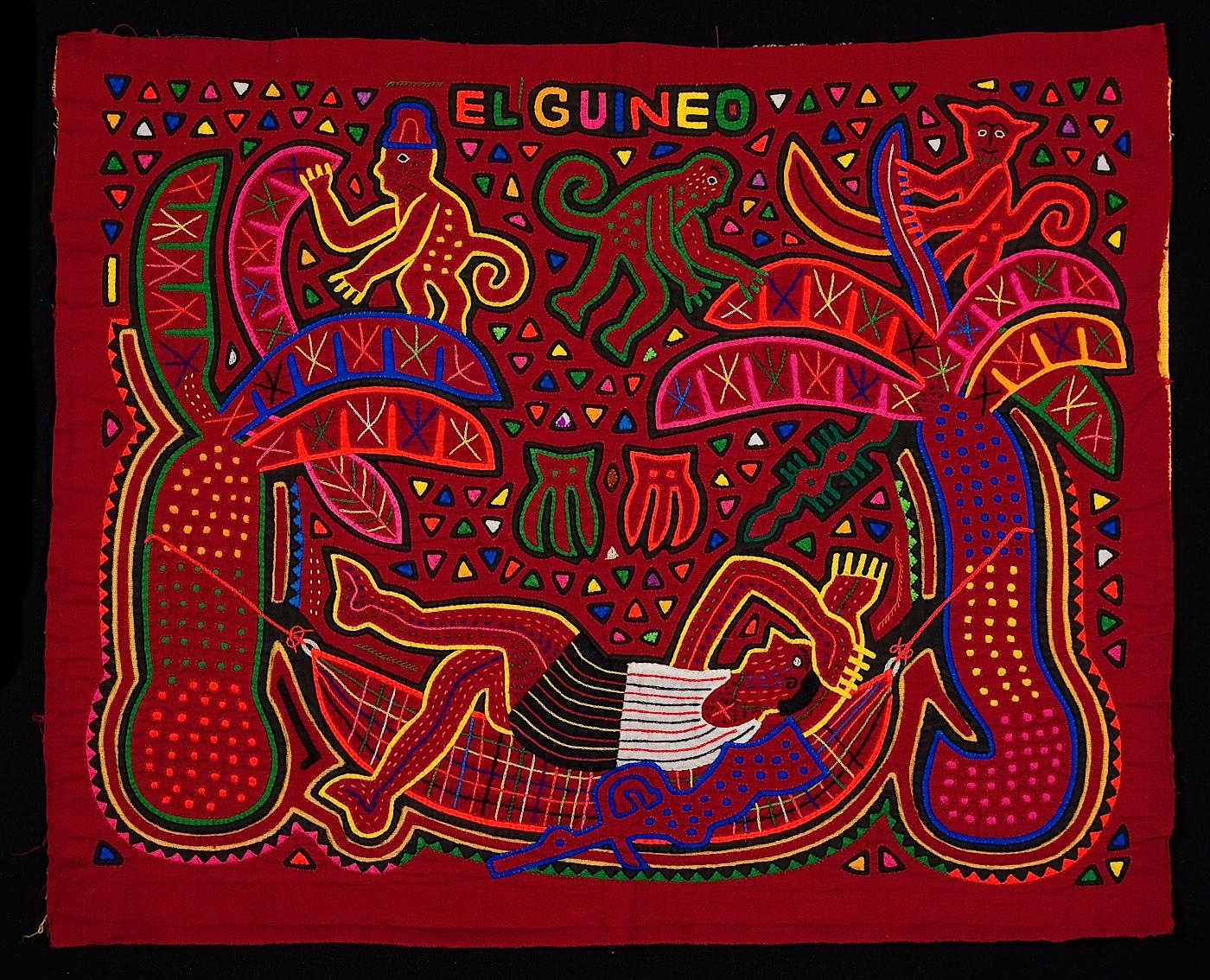

"El Guineo" Guna cotton mola, 46.35 x 36.83 cm, Portland Art Museum, OR (US).

It shows a man with a gun resting in a hammock (uugassi) among banana trees (wagmadun) and some monkeys. El guineo is the banana fruit. An armed vigilante in a banana plantation on the Guna Yala mainland coast? Quien sabe.

Contemporary molas know no limit as to their topics, and new themes have been coming in, adding up to the traditional ones, linked to the jungle and the sea: daily objects - fire fans, oars, anchors, nose rings, baby rattles, kitchen tools, airplanes, even unknown items, featured in magazines - American political themes, everyday stories, folk tales and legends, stories from the Guna mythology (as the dragon that eats the moon), world events (like the space conquest, the man on the moon, etc.), inventions, religious themes and stories from the Old and the New Testament (the Guna are animist, and many molas represent evil spirits in an apotropaic effort; however, the influence of past Missionaries is still evident, at least in the artistic field).

MOLA TECHNIQUES

Layers: from 2 to 7 layers of cotton panels of different colors and textures.

Appliqué needlework technique: a piece of cloth is laid on top of another, and the two are stitched together in a barely visible way to create an abstract pattern or a scene. The most difficult technique is reverse needle-turn appliqué.

Reverse Appliqué: several layers of cloth are placed on top of each other and shapes are cut out in layers of decreasing size. In other words, you cut away a shape in the top layer to reveal the underneath.

Embroidery techniques: chain, cross, straight and backstitching, button-hole stitching, etc.

There is nothing molas cannot tell: Guna women know how to tell any story, no matter how complex it could be. Their hands and eyes make up not only the collective imaginary but also an important part of the historical memory of the Guna people as well. These women create the specific narratives that connect the different Guna communities to the same root and womb, as branches to the same trunk, as trunks to the same wood and soil. Their work is as important as that of the sailas, the male leaders of every Guna community. Each saila memorizes all the songs related to the sacred history of his community, all the words of the legends and the laws, all the stories of the traditional rites and myths. For centuries, Guna men and women, with their voices, hands, and eyes, have been creating, preserving, and enriching a precious cultural heritage. El pueblo Guna have no written literature.

Some scholars thought that the female art of creating molas has no relation with religious, symbolic, and cosmogonic knowledge held by the saila, traditionally all men. However, the French ethnologist Michel Perrin (Laboratoire d'Anthropologie Sociale, Collège de France, Paris) showed through an analysis of designs and subjects that the oral art of men is reflected in the pictorial art of women, and vice versa. Dualism, shamanic metamorphosis, polysemia, symmetry, labyrinths, and mythical entities are representations of the world that in a conscious or unconscious way are shared by men and women (see M. Perrin, Bibliography).

Let's consider dualism. All molas are made in pairs: for the front and the backside of the blouse. We wrote mola for the singular and molas for the plural, following the Spanish common use. In the Guna language (Dulegaya), however, the word mola designates the two panels made for a single blouse. The two "faces" of a mola are never identical: they are a variation on the same theme, as it happens with the verses of Guna poems and songs. Their relation of complementarity and their slight differences have deep meaning: in the Guna worldview, every being has its double.

2 Guna blouses, with front and back mola cotton panels, early 20th century, The British Museum, London. Photos by ©The Trustees of the British Museum (Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license).

«Para los cunas, todos los seres tienen su doble, su esencia oculta, su "alma". Ya se trate de seres humanos, animales o plantas, o incluso de órganos u objetos, todo ser viviente lleva consigo una dualidad. En el lenguaje chamánico, todo lo que se refiere a la vida, la enfermedad y la muerte es considerado como doble, incluso si los dobles que entran en juego son invisibles y no se manifiestan directamente, sino a través de la experiencia. Un chamán hablará de doble herida, de doble enfermedad, de doble dolor, de doble aldea de los espíritus. Los elementos que forman pareja, y para los cuales rige el plural en francés, inglés o español, en lengua cuna van en singular» (M. Perrin, cit.).

(For the Guna people, all beings have their own double, a hidden essence, a "soul". Whether human beings, animals or plants, or even organs or objects, everything has its own double, its inner duality. In the shamanic language, everything about life, disease, and death is considered double, even if the doubles at stake are invisible and do not manifest themselves directly, but through experience. A shaman will speak of a double wound, a double disease, a double pain, a double village of spirits. The elements that make up a couple or a pair, that are always plural in English, Spanish or French, are always singular in the Guna language).

The duality is so important that some creatures (animals or plants) receive a double name: «los cunas dan dos nombres a ciertos animales y a ciertas plantas: un nombre para el día y un nombre para la noche. Es tabú pronunciar el primero durante la noche. A la tintura negra extraída del fruto de la genipa se le da de día el nombre del árbol de esa planta: sabdur. De noche se la llama siichi. Al fruto del guamo se le llama marya durante el día y kaya piri, de noche. La palmera nalup recibe el nombre nocturno de iko turba» (M. Perrin, cit.).

(The Guna people give two names to certain animals and plants: a name for the day and a name for the night. It's taboo to pronounce the first one overnight. The black tincture extracted from the fruit of the Genipa is given by day the same name of the tree: sabdur. At night it's called siichi. The fruit of the Inga spuria is called marya during the day and kaya piri at night. The palm tree nalup gets the night name of iko turba).

As to the mola, the fact of being a double panel - only the small molitas made for the tourist market are designed as single pieces - does not derive from a practical necessity: Guna could have created a blouse with a single panel, positioned behind, for example, the most important side for them. The duality of the mola panels is deeply rooted in the Guna cosmovisión (the Guna weltanschauung) and linked to their traditional oral culture. Molas are a form of art not only for their aesthetic exuberance.

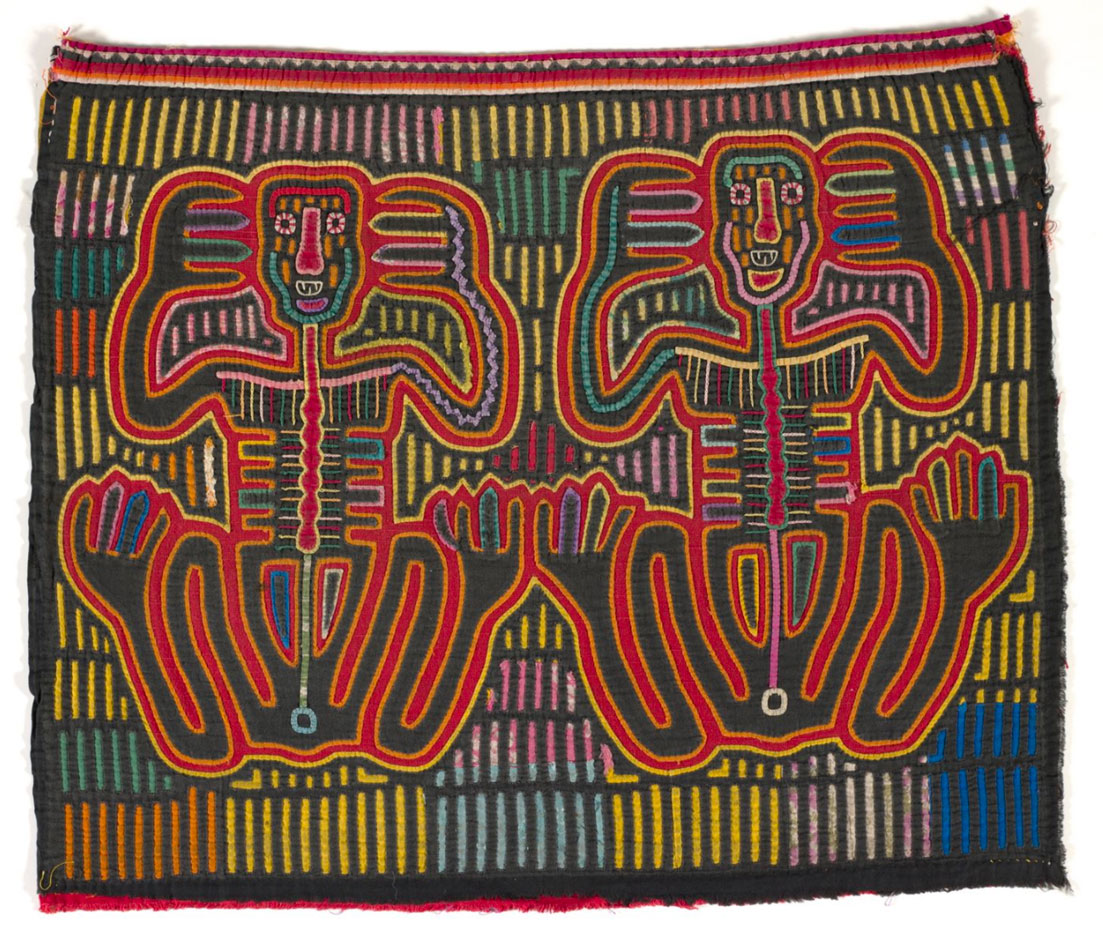

The depiction of genitalia is very rare in Guna art; however, this mola depicts two female figures in a very unusual pose. In some literature, figures such as these are said to be female mother goddesses or earth-mothers. The two female figures may represent twin sisters or probably a "Mother" and her double, her inner and deep duality.

Kuna cotton mola from the 1950s, purchased in 1960-1970 by Paul and Irene Hollister, Hanover, New Hampshire; given to the Indianapolis Museum of Art in 2008.

We talked a lot about the Guna people. But who are they?

Guna little girl. Photo by Ecocircuitos Panama (under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic license - CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).

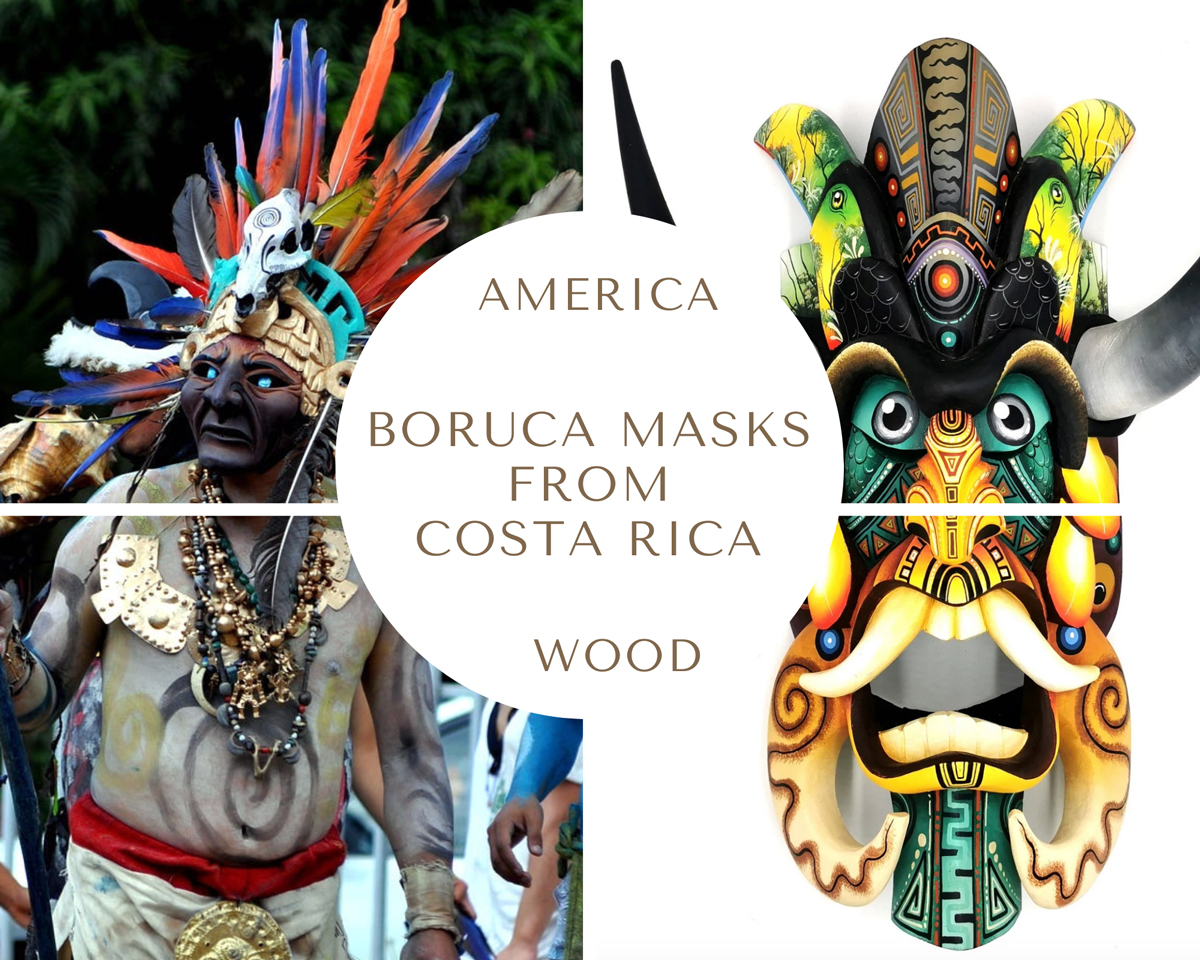

Guna woman making a mola. From Panama Casco Viejo website.

THE GUNA PEOPLE AND THE GUNA YALA

The Guna people (or Kuna, as usually written before 2010, but the native language lacks a "K" sound) are an indigenous people of Panama and Colombia. They call themselves Los Gunadules, an expression which mixes Spanish and Dulegaya, their original Chibchan language: the great majority of Panamanian Guna is indeed bilingual.

In the early 16th century, at the time of the Spanish invasion and conquest, they inhabited a relatively large area between northern Colombia and the present-day Darién Province of Panama. The Gunadules were originally un pueblo de la selva, a people of the rainforest, settled in a deep jungle area nostalgically called in Spanish Tierra del Ají . They moved from the rain forests to the Caribbean coast in the mid-19th century for different reasons, mainly for conflicts with other local communities and contrasts with Spanish-origin settlers; parts of their ancestral land, moreover, had passed into the hands of mining companies in search of gold. From the coast, they migrated to the islands of the San Blas Archipelago probably to avoid mosquitos and epidemics. They had to become, therefore, un pueblo del mar, a seafaring people. However, they did not lose an ounce of their strong social identity: they had been going through all those radical changes always retaining a rich body of traditional oral knowledge, and always knowing who they were.

A document drawn up by the Koskun Kalu Research Center of the Congreso General de la Cultura Guna reads:

Nuestra historia inicia desde hace miles de años, nuestra historia es larga, es rica, está llena de sabidurías, de enseñanzas para la vida, para conducir correctamente a nuestro pueblo, para defender la madre tierra. Estas sabidurías fueron legadas por grandes personalidades, hombres y mujeres, que nos dejaron el “Anmar danikid igar” o nuestra historia.

(Our roots date back thousands of years ago. We have a long and rich history that left us with a body of wisdom and life teachings to lead our nation and to defend Mother Earth. These pearls of wisdom were bequeathed by great personalities, men and women, who left us the Anmar danikid igar, the awareness of our own path).

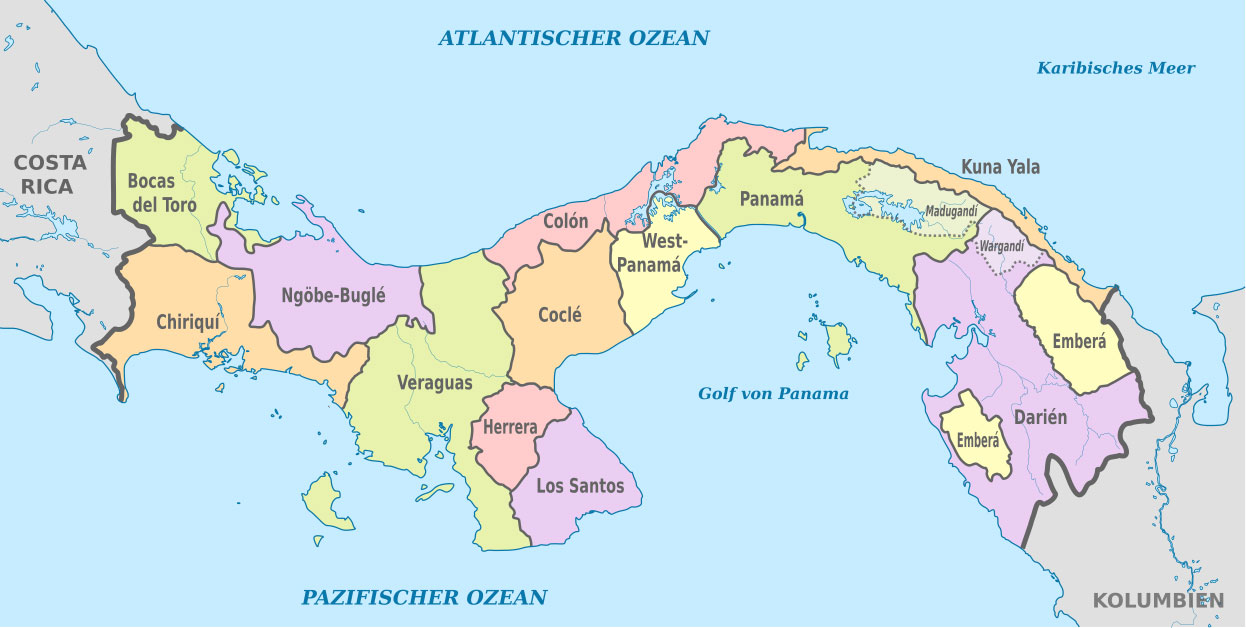

Today, the Gunadules live in two countries: in Colombia, in the Gulf of Urabá region (2,610 inhabitants according to the 2018 census by the Colombian Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística); and in three different autonomous comarcas in Panama. The main is Guna Yala, the two minors are Guna de Madugandí and Guna de Wargandí. There are also communities of Gunadules in Panama City, Colón, and other Panamanian cities. According to the Official Panamanian Census, in 2010 the Gunadules living in Guna Yala were 33,100, in all Panama approx. 80,520.

(Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license).

As we already saw, Guna Yala is a narrow strip of land along the Panamanian coastline - 373 km from the border with Colombia, overlooking the Caribbean Sea - and includes what once was known as the Archipelago of San Blas: over 400 coral island and cays in a lucky Caribbean zone of astonishing beauty, free from hurricanes (the Guna say there are 365 islands, one for every day of the year, but it's a joke). The Guna people make up 51 Comunidades (different communities): 49 in 49 major islands and 2 on the mainland.

Here's a partial map of the archipelago, followed by a drone video over the Cayos Holandéses and the island of Gaimaodubgan. It gives you an idea of the north-western coral reefs and its uninhabited cays. The Dutch Keys are located 15 km from the mainland, being the farthest islands in the entire archipelago, and can be reached only by sailing ship or motorboat. There are no hotels in the Dutch Keys, but visitors can camp on some islands where there are very basic huts. Nothing else.

Small beaches of white sand, waving palm trees, untouched coral reefs, and pure crystalline to turquoise waters are not a characteristic of the Dutch Keys only: they are everywhere in the Guna Yala archipelago. The most saleable of all paradises, however, is not on sale: the Guna people do not allow anyone to build resorts or tourist facilities on their land.

Two more videos give you you an idea of the Gunadules, their land, and the wilderness along the mainland rivers.

- El cayuco, ulu

All the Gunadules travel among their islands and fish by using a hand-built dugout canoe, called cayuco in Spanish and ulu in Dulegaya. All men, women, and children are expert sailors and handlers. Each canoe is made from a single tree trunk, hollowed out by hand. The hardwood comes from the mainland. The old Guna used timber trees of binnuwar (wild cashew or espavé), gao-banwar (mahogany), urwar (cedar), nugnuwar (kapok). They carved cayucos of different sizes and shapes: canoes for rivers, cayucos with a keel for sailing trips, small boats for fishing, or for medicinal baths (inaulu).

It's an expensive, essential resource: it can cost approx. 500 US dollars and is a worthwhile expense for every Guna family as it ensures not just autonomy, but survival. You can find miniatures cayucos both as baby's toys and grave goods, placed next to the corpse as a means of transport for the journey to the abode of Baba-Nana.

According to the traditional Guna religion, the world was created by Babdummad (Baba Dummad) y Nandummad (Nana Dummad), el Gran Padre y la Gran Madre (the Great Father and the Great Mother), united as Baba-Nana, the Great Spirit who keeps in balance all the living creatures and continue to keep watch over everyone’s daily actions.

«Al inicio todo era oscuro. Una oscuridad tan tensa, como si le apretaran a uno los ojos con dos manos. No había sol, no había luna, no habían nacido las estrellas. Entonces Bab Dummad [Baba] se dispuso a crear la tierra, [y] Nan Dummad [Nana] se dispuso a crear la tierra.

Cuando Baba formó a la Madre Tierra, encendió también el sol, la luna y las estrellas. Baba irradió la tierra, Baba alumbró el rostro de la madre. La tierra fue imagen y rastro que habló de la presencia de Baba, de la presencia de Nana. La Madre Tierra tomó los siguientes nombres: Ologwadiryai, Olodil'lilisob, Ologwadule, Oloiitirdili, Napgwana, Nana Olobipirgunyay». (Aiban Wagua, 2000, see Bibliography).

(At the beginning, there was darkness. A darkness so thick that all looked the same as when you press your hands on both eyes. There was no sun, no moon, and no stars were born. Then Bab Dummad [Baba] set out to create the land, [and] Nan Dummad [Nana] set out to create the land.

When Baba formed Mother Earth, he also lit the sun, the moon and the stars. And he illuminated the Mother Nature's face. The earth is therefore an image and a trace that spoke of Baba's presence, of Nana's presence. Mother Earth was given the following names: Ologwadiryai, Olodil'lilisob, Ologwadule, Oloiitirdili, Napgwana, Nana Olobipirgunyay).

Bana-Nana created the Mother Earth and gave her many names, including that of Nabgwana. The old sages (sailagan) sing that Baba-Nana before sending the first human being (Wago) to earth, created all plants, rivers, animals, and trees, created the air and the wind to make Nabgwana habitable, welcoming, generous. That's why Wago recognizes all living beings as his brothers.

2 Photos by Ben Kucinski (under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic CC BY-SA 2.0 license).

Photo by Bruno Langlois (under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?