TUAREG CROSS OF AGADEZ 3

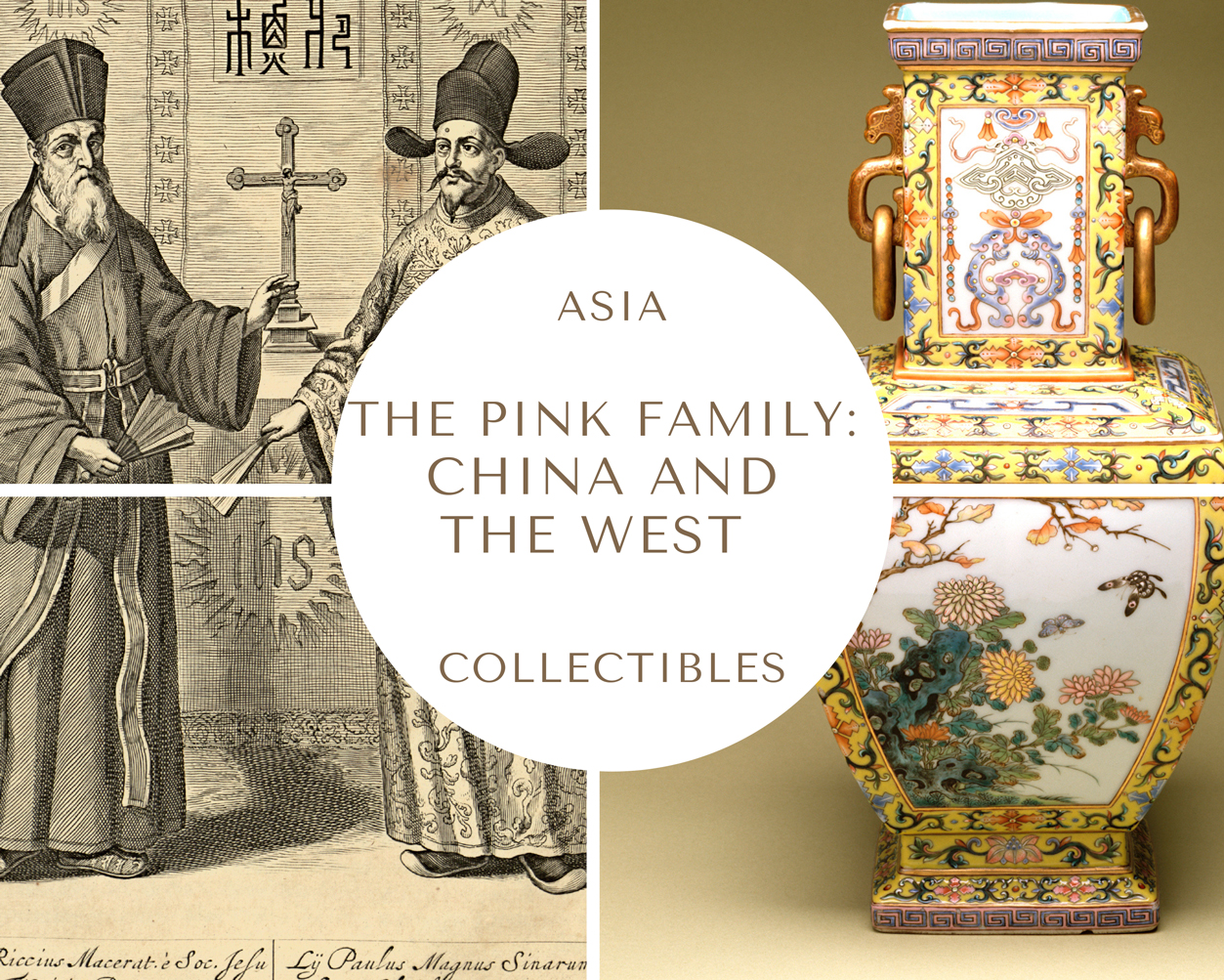

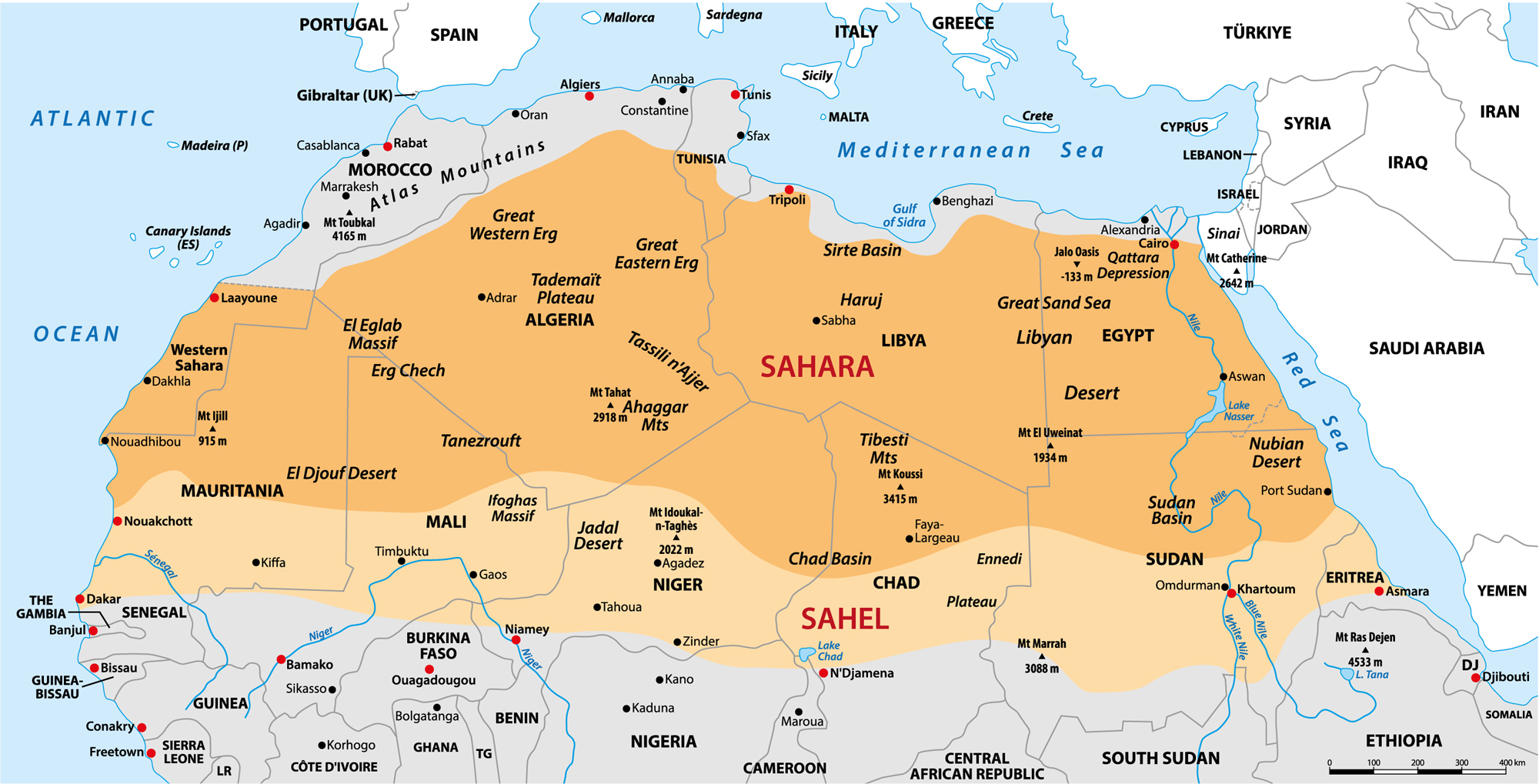

Map of the Sahara desert

The traditional distribution of the Tuareg in the Sahara. Smithsonian Institution, USA.

TUAREG PORTABLE SOVEREIGNTY

During the same decades that Tuareg fighters melted rifles into monuments, another, quieter mobilization was taking shape—a cultural one that uses language, song, silver, and indigo as parallel weapons of survival. Most outsiders know of the military rebellion, but Tuareg families talk about how to keep a child interested in Tamasheq when WhatsApp arrives in Tifinagh or how to stage an evening of Tende drums without the village being labeled a “seditious gathering” by an anxious provincial governor. Fieldwork from Agadez to Tamanrasset shows that heritage work is now inseparable from the political turbulence we previously discussed; every festival, classroom, and Spotify playlist is also a subtle assertion of identity in a landscape where borders, droughts, and drones constantly redraw the map.

Language: the daily referendum

Ethnographers repeatedly stress that the first thing a Tuareg will tell you about being Tuareg is that they speak Tamasheq. This statement is usually followed by a worried glance at a toddler who responds in Songhay or Hassaniya Arabic. The language is the anchor of the tawsit (kinship group) and a passport between Mali, Niger, and Algeria. Lose it, and the chain of oral genealogies, camel-brand knowledge, and love poetry snaps. Across the three countries, Saturday morning language schools run by young graduates have sprung up in rented UNICEF tents. They use handmade Tifinagh alphabets painted on cardboard because printed primers never arrive in time. In Niamey, the state only allowed Tamasheq to be examined for the national baccalauréat in 2019. The classes filled overnight; many of the pupils are the children of 1990s rebels who never learned to write the language for which they fought.

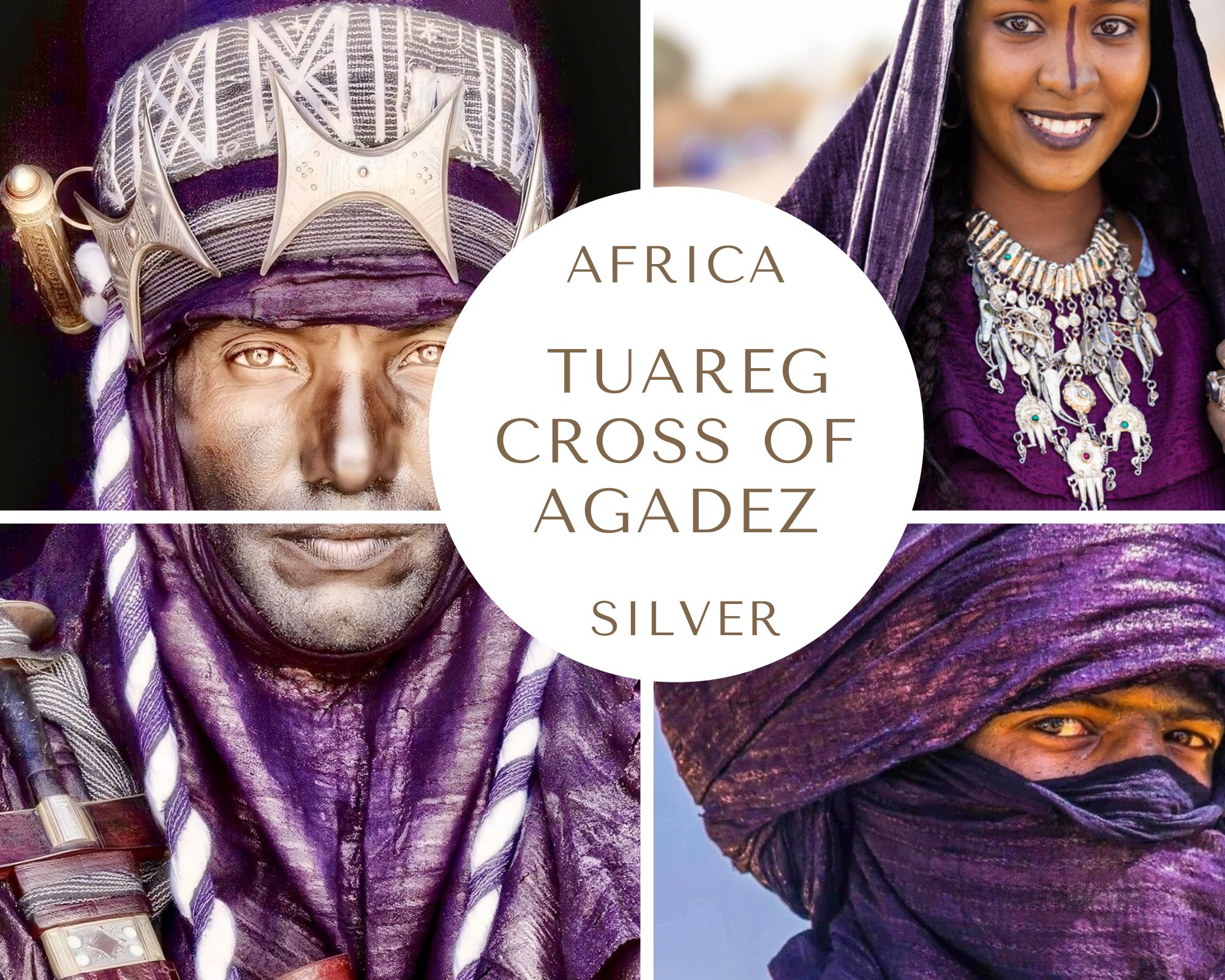

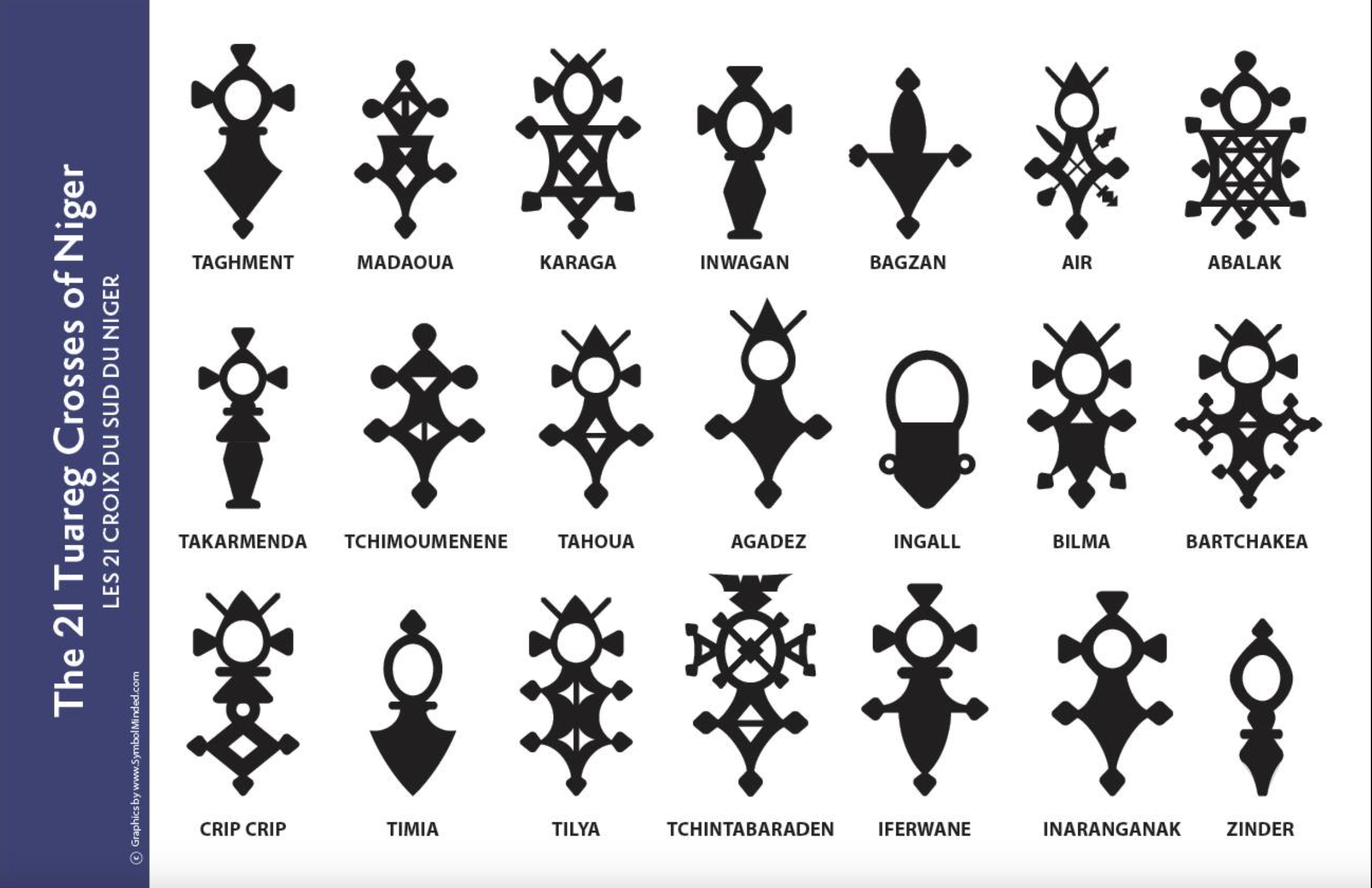

The veil as movable homeland

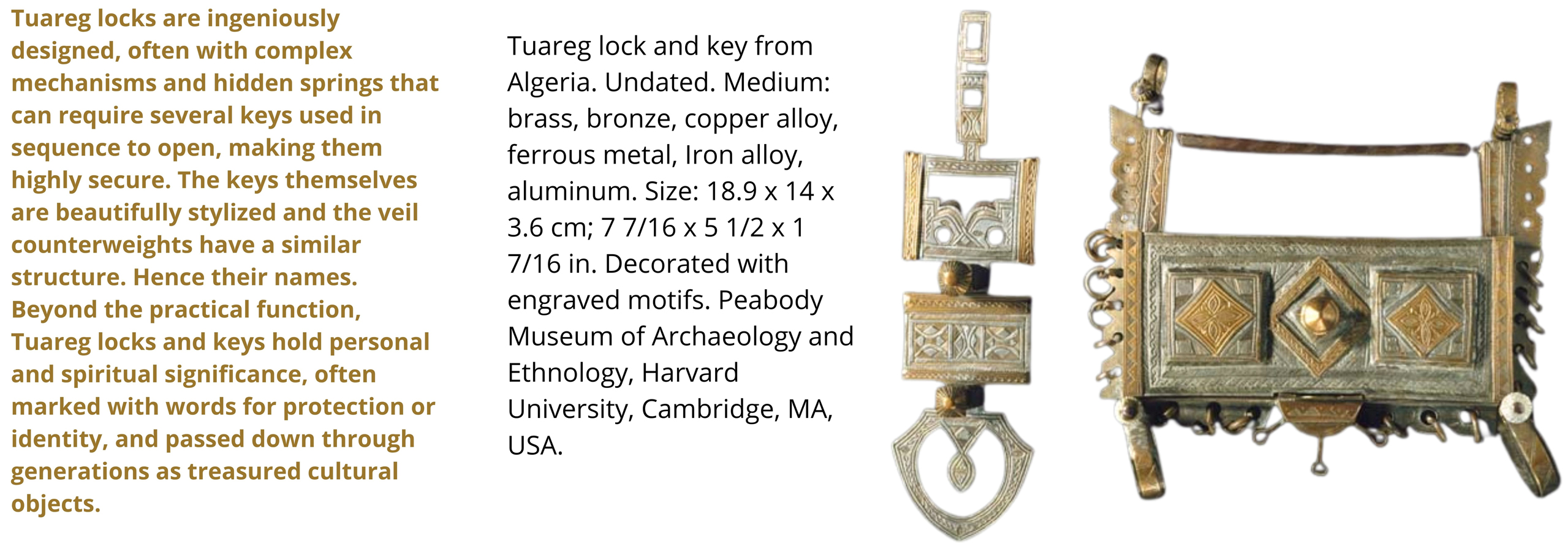

The men’s tagelmust—up to ten meters of indigo fabric that leaves only the eyes and pride visible—still unsettles some neighborhood clerics, who consider it ostentatious. Yet, its circulation is quietly expanding. Urban youth who have never herded goats purchase Chinese rayon dyed in Kano and livestream tutorials on the twelve ways to wind it. The comments on these videos become proxy debates about authenticity, masculinity, and who gets to speak for the Sahara. Anthropologists have noted that the veil is now worn defensively in southern Malian towns, where Tuareg identity can invite harassment. It is also worn offensively on stages in Berlin and Paris, where bands market the image of the “blue man.” In both places, the cloth functions as what one researcher calls “portable sovereignty”: a strip of color unfurled when the land itself is unreachable—sovereignty stitched in threads.

Women’s hands, social memory

While men’s cultural capital is wearable, women’s is marketable. Silver cross pendants, famous takouba swords reforged into earrings, and tooled leather bags are produced in household courtyards, but they are increasingly priced in euros on Instagram accounts run by cousins in Bamako or Lyon. This work is not merely nostalgic; it finances school fees and indirectly supports legal defense funds when a brother is arrested on vague “terrorism” charges. Crucially, the objects carry embedded stories: each engraved triangle represents a well, and each zigzag represents the path of a 1917 migration. This path is not traced on maps, but rather in memory. Thus, every sale delivers a miniature history lesson to customers who may think they are simply buying a boho necklace.

LEFT: Tuareg bag. Medium: leather, pigment, silk. Musée d’ethnographie, Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

RIGHT: Woman’s leather travel bag (tehaihait) from the Algerian Sahara. Leather was an essential part of Tuareg material life, and female artisans (tineden) specialized in making bags like this one for storing personal items. Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Pair of Tuareg leather flip-flops made in Markoye, Burkina Faso. They are made of two pieces of leather sewn together with white plastic thread that shows through the upper sole. The bottom sole is untreated. The painted design on the sole features yellow and red triangles and stripes with black edging and a border. The straps are bordered in black with red and yellow underneath mint-green leather that has pinked edges and cut-out triangular and leaf designs that show the color below. There is a black central knob decoration on the straps with a cut-out mint green leather piece on top. There is a yellow toe strap. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

2. Tuareg neck wallet made of goat and camel leather. Made in Terhenanet, Hoggar Plateau, Algeria. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

3. Pair of Tuareg sandals made of goat and cattle leather. Made in Niger but found in Terhenanet, Hoggar Plateau, Algeria. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK. (Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence.)

4. Tuareg round leather cushion, unfilled. The front features a painted design of a central cross on a beige background, surrounded by dark red, green, yellow, and black borders. Four sections of the cross are filled in red, and the outer border is similar to the central cross motif. The reverse side is black with a black metal zipper, and the sides are red with black and beige borders. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

This magnificent Tuareg leather tent hanging (iragayragayan) is displayed over a red painted wooden bar. The top section is backed by a black piece of leather and consists of a horizontal row of embroidery in maroon, orange, green, black, white, and blue, with a central metal stud featuring four motifs. Below that is a fine leather fringe in turquoise, maroon, and yellow. Over that are three hangings bordered in mint green leather, each with a central mirror. The final row of embroidery on a green background ends the top section. The remainder consists of a long fringe in the aforementioned colors, from which nine long, narrow panels hang. These panels are decorated with embroidery in plastic and thread, mirrors, painted details, and cut-away or overlaid sections of leather that create colored contrasts. It was made in Burkina Faso. © The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Fine bag in camel leather from Niger. Dimensions: 39 x 30.5 cm; 15.35 x 12.01 inches. Amazigh, Florence, Italy.

Cushion from Niger or Mali. Date: late 19th – early 20th century. Medium: Leather, silk. Dimensions: 60 x 42 x 2 cm. Weight: 361 g. Musée du Quai Branly “Jacques Chirac”, Paris, France.

Tuareg leather pouch with geometric design, pieces of white leather, squares of green leather with red, green, and yellow stitch designs, fringe surrounding piece. Probably used by women. From Algeria. Dimensions: 41 x 38 x 0.9 cm (16 1/8 x 14 15/16 x 3/8 in.). Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Antique leather bag from Morocco. Date: mid-20th century. Dimensions: 45 x 13.75 x 3 inches; 114.3 x 34.93 x 7.62 cm. 1st DIBS.

LEFT TO RIGHT, TOP TO BOTTOM

Four pairs of fine braided leather sandals from Niger. Amazigh, Florence, Italy.

Old and large leather cushion (èsteg), usually placed on a woman’s camel saddle. Dimensions: 60 x 21.5 inches. Schneible Fine Arts, Charlotte, Vermont, USA.

Tuareg Leather Bag from Niger. Dimensions: 47.5 x 13.5 cm; 18.7 x 5.31 inches. Amazigh, Florence, Italy.

Beautiful leather bag from Niger. Dimensions: 44 (including fringes) x 15.5 3.5 cm; 17.32 x 6.1 x 1.38 inches. Amazigh, Florence, Italy.

LEFT: Camel saddle bag (Eljebira) from Agadez, Niger. Date: early 20th century. Medium: Camel and goat leather, and pigments. Dimensions: 76 x 68 x 5 cm. Musée du Quai Branly “Jacques Chirac”, Paris, France.

RIGHT: Camel saddle bag (Eljebira) from Agadez, Niger. Date: early 20th century. Medium: Camel and goat leather, and pigments. Dimensions: 94 x 62 x 4 cm. Musée du Quai Branly “Jacques Chirac”, Paris, France.

LEFT: Red leather cushion with 20-25 cm multicolored fringe. From Mauritania. Date: 20th century. Dimensions: 18 x 79 x 33 cm; 7 1/16 x 31 1/8 x 13 inches. National Museum of African Art Collection, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

RIGHT: Vintage red, black and brown leather bag with fringes from Mali. Date: ca. 1940. Dimensions: 24 x 18 x 1 inches; 60.96 x 45.72 x 2.54 cm. 1st DIBS.

Leather cushion cover, 1982. Spencer Museum of Art, The University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA.

Soundscapes of exile and return

Music has become the most mobile archive. Journalists routinely describe the electric desert blues of Tinariwen, Bombino, and Tamikrest as “rebel rock,” but teenagers in the Kel Ansar camp outside Agadez speak of it as “our library.” The lyrics switch between Tamasheq, Hassaniya, and French and quote 1940s pastoral poems, 1990s battle slogans, and today’s hashtags. At the annual Festival au Désert—exiled first from Timbuktu to the dunes of Oursi in Burkina Faso and most recently to Morocco’s Drâa Valley—audiences dance at sunset and then gather for kel-aslas storytelling at night, where older women recite epic poems in unaccompanied chant. The festival’s logistics—army escorts, EU cultural funds, and a stage powered by solar panels donated by German NGOs—mirror the contradictions of modern Tuareg life: simultaneously sponsored and besieged.

Bombino – Aitma

Bombino (born Omara Moctar) is a Tuareg guitarist, singer, and songwriter from Agadez, Niger. Born in 1980, he is renowned for his virtuosic guitar playing and his blend of traditional Tuareg music with rock, reggae, and blues. Similar to Tamikrest, Bombino experienced exile in Algeria and Libya before returning home after political tensions eased. His music reflects themes of Tuareg identity, peace, and resilience, transforming personal and national struggles into artful defiance. He gained international recognition with the albums Agadez (2011) and Nomad (2013); the latter was produced by Dan Auerbach of The Black Keys. Later works, such as Deran (2018), earned him a Grammy nomination — the first ever for a Nigerien artist. His performances are characterized by bright desert guitar riffs and trance-like grooves, making his music deeply rooted yet globally appealing. Bombino carries the modern Tuareg voice to the world, offering music that is poetic, political, and grounded in the vast, ever-changing landscape of the Sahara.

Tamikrest – Atwitas from the album Kidal

Tamikrest is a Tuareg rock band from northern Mali. The band was founded in 2006 by Ousmane Ag Mossa, Cheikh Ag Tiglia, and Aghaly Ag Mohamedine in the border town of Tinzawaten. The band’s name, Tamikrest, means “knot” or “alliance” in Tamasheq and symbolizes unity among dispersed Tuareg communities. Emerging in the aftermath of the Tuareg rebellions, the group chose music over armed struggle as a means to express their people’s longing for freedom and dignity.

«All around Kidal, the Malian desert stretches in every direction. Endless horizons of rock and sand, barren and parched. This is the southwestern edge of the Sahara, the home of the Tuareg people, and the town of Kidal is one of their main cultural centres. Fought over, conquered and re-conquered, it remains the symbol of Tuareg defiance and hope, the spiritual home of a dispossessed people. It is also the town in which Tamikrest first came together as a group, and on Kidal, Tamikrest’s fourth studio album, the band pays homage to this place that’s nurtured them and their people. It’s a cry of suffering and the yell of rebellion. It’s power and resistance. This is pure Tuareg rock’n’roll. “Kidal talks about dignity,” Ag Mossa says. “We consider the desert as an area of freedom to live in. But many people consider it as just a market to sell to multinational companies, and for me, that is a major threat to the survival of our nomadic people.” The Tuareg have always been nomadic people, their lives in motion across the desert, sometimes taking with them only the bare essentials. But for one brief moment they possessed a home after the Tuaregs rose up in 2012 and declared the independent state of Azawad in the northeast of Mali. It lasted less than a year, as first al-Qaeda conduits swept in from the north, imposing Islamist rule, and then the French military arrived to liberate the area – once again leaving the Tuareg with little or no chance for self-determination. But the dream remains, still trapped between governments and the greed of global corporations. “Kidal, the cradle of all these uprisings, continues to resist the many acts perpetrated by obscure hands against our people,” notes band associate Rhissa Ag Mohamed. “This album evokes all the suffering and manipulation of our populations caught in pincers on all sides.” The songs on Kidal evoke a long history. And for all the electricity, as Ag Mossa observes, “It’s very traditional if you go deeply into what I’m playing.”» (Text by Tamikrest)

Named for the band’s hometown in northern Mali, the Kidal album is both a tribute and a political testimony. Each track depicts a facet of Tuareg experience, such as displacement, dignity, and spiritual endurance. However, Atwitas epitomizes the fusion of message and sound that defines Tamikrest’s desert rock ethos. The song balances sorrow with rebellion, demonstrating how music can serve as remembrance and resistance. The song embodies the melancholic spirit of resistance and longing that characterizes the album, blending haunting electric guitar tones with Ousmane Ag Mossa’s contemplative vocals. Its spacious tempo and hypnotic phrasing give the song both intimacy and grandeur, evoking the vastness of the Sahara and the emotional weight of exile.

Ritual under surveillance

Life-cycle ceremonies—nameday celebrations, the veiling initiation of boys at fifteen, and wedding ahal evenings—remain moments when heritage is performed physically. However, these gatherings now require negotiation. In parts of northern Mali, local prefects limit the number of tents or demand guest lists in advance, fearing a concentration of young Tuareg men. In response, families split a single wedding into three separate nights or hold the tende drum session inside a compound while holding a decoy tea party at the village square. Thus, the state’s security gaze reshapes ritual form but cannot abolish it. Instead, it fragments and miniaturizes, turning culture into guerrilla heritage.

Among the Tuareg, the tehiglit (also spelled tehilet in some transliterations) is the traditional male veiling initiation that marks a boy’s passage into manhood. The rite centers on the recipient’s first wearing of the tagelmust, the indigo-dyed face veil that symbolizes Tuareg male identity.

Digital tent, diaspora classroom

WhatsApp groups called “Kel Tamasheq Global” connect taxi drivers in Marseille, students in Nouakchott, and demobilized combatants near Ghat. Participants exchange voice notes of old lullabies and debate whether the word for “smartphone” should be borrowed from French (“portable”) or invented from Tamasheq roots (“imen-issan,” meaning “thing that whispers”). Although linguists warn that such chats accelerate code-mixing, participants insist that the thread itself is the point—a virtual tent pitched each evening that recreates the cross-legged gossip that used to circle the campfire.

Heritage as pre-figurative politics

None of these practices are politically innocent. For example, when an Algerian NGO sponsors Tifinagh graffiti on a water tower in Bamako, the government interprets it as proto-separatism. Similarly, when Niger’s government funds a Tamasheq radio station, it partly does so to prevent listeners from tuning into jihadist channels. Yet, the cultural sphere offers a space where claims can be made without firing rifles. By demanding language classes, women’s craft collectives, and a guitar riff quoting a nineteenth-century camel hymn, Tuareg activists are envisioning a future community whose borders are defined by shared aesthetics rather than the next referendum on Azawad.

In short, the Sahara’s political storms have not erased Tuareg culture. They have compressed, digitized, and occasionally driven it into exile. However, every indigo veil adjusted on a European stage, every Saturday Tifinagh lesson in a refugee tent, and every tendé drum quietly tapped behind a mud-brick wall serves as a reminder that heritage is not a relic to be safeguarded in museums. It’s a set of living instructions for how to remain Kel Tamasheq when the map keeps folding differently around you.

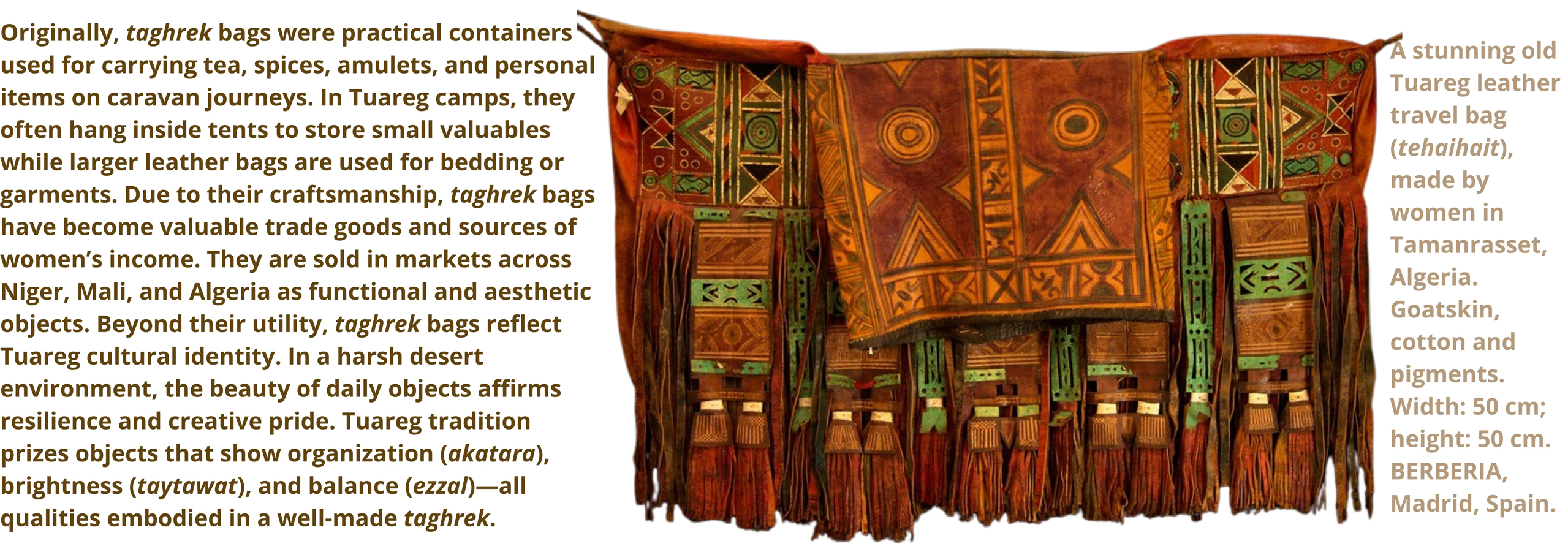

Tinariwen’s Ténéré Tàqqàl: Elegy for a Desert in Crisis

Tinariwen’s Ténéré Tàqqàl, subtitled What Has Become of the Ténéré, is one of the band’s most poignant laments. It is a melancholy reflection on a broken landscape and a fractured society. Included on their 2017 album Elwan (“The Elephants”), the song features contributions from the group +IO:I, whose ambient textures deepen the song’s atmosphere of sorrow and solitude.

In Tamasheq, Ténéré means “desert” or “empty land,” while Tàqqàl loosely translates as “what has become of.” The lyrics mourn the transformation of the Sahara from a place of harmony to one of conflict and desolation:

“The Ténéré has become an upland of thorns,

Where elephants fight each other,

Crushing tender grass underfoot…

The camps have all fled.”

The “elephants” evoke powerful political and military actors—foreign or local—whose rivalries trample fragile desert life. Birds and gazelles (symbols of freedom and innocence) flee the violence. Solidarity, once central to Tuareg life, has disintegrated. Bandleader Ibrahim Ag Alhabib contrasts this decay with the ethos of asshak—mutual respect and support—that once sustained the nomadic community.

The animated video, directed by Axel Digoix and produced by Pilule et Pigeon, transforms the metaphor into motion: a solitary camel, burdened with guitars and amplifiers, trudges through a hostile landscape of sandstorms and locust swarms. Its journey becomes a visual parable of both exile and endurance—mirroring the persistence of Tuareg artists who continue to carry culture across shattered terrain.

The video’s stylized linework and golden tones underscore the dual nature of the Sahara: brutal yet breathtaking, as unforgiving as it is sublime. The animation echoes Tinariwen’s blues-inflected guitar style—a sound that hums with dust, longing, and memory.

Ténéré Tàqqàl resonates on two interwoven levels:

* As a lament for environmental and social collapse—from drought and war to the erosion of nomadic freedom

* And as a metaphor for cultural resistance—a refusal to vanish, even when the land itself becomes inhospitable.

As one reviewer noted, it is Tinariwen’s “elegy for the desert”: a meditation on how division and domination (“elephants fighting”) crush not only ecology but also the spirit of community.

Ultimately, Ténéré Tàqqàl is more than a song. It is a cry of mourning and a gesture of survival, where the desert is not just a setting but a reflection of Tuareg identity—vast, scarred, and unbowed.

THE DESERT’S BRIGHT MEMORY

In the Sahara, asekkar, “silver”, is more than just a metal. It is the desert’s bright memory; it is the mirror in which the wind, the moon, and the lineage see themselves. Among the Kel Tamasheq (the Tuareg), silver gleams like distilled moonlight. They wear it to cool their bodies in the heat, to reflect light rather than absorb it, and to guard against the jealous djinn that haunt the horizon. Unlike gold, which is sun-born, heavy, and said to stir envy, silver is lunar and pure, remembering only the night.

When a woman lifts her bracelet to her face, she does not see her reflection, but rather, a familiar absence: the gleam of a landscape without walls. “We melt the old coins,” she says, “because you can’t pack a pasture in a suitcase.” In her laughter, an old truth lives: Silver moves so memory can travel. Each piece carries the silence of grazing herds, the scent of camel sweat and acacia smoke, and the unspoken promise that a nomad’s wealth must accompany her.

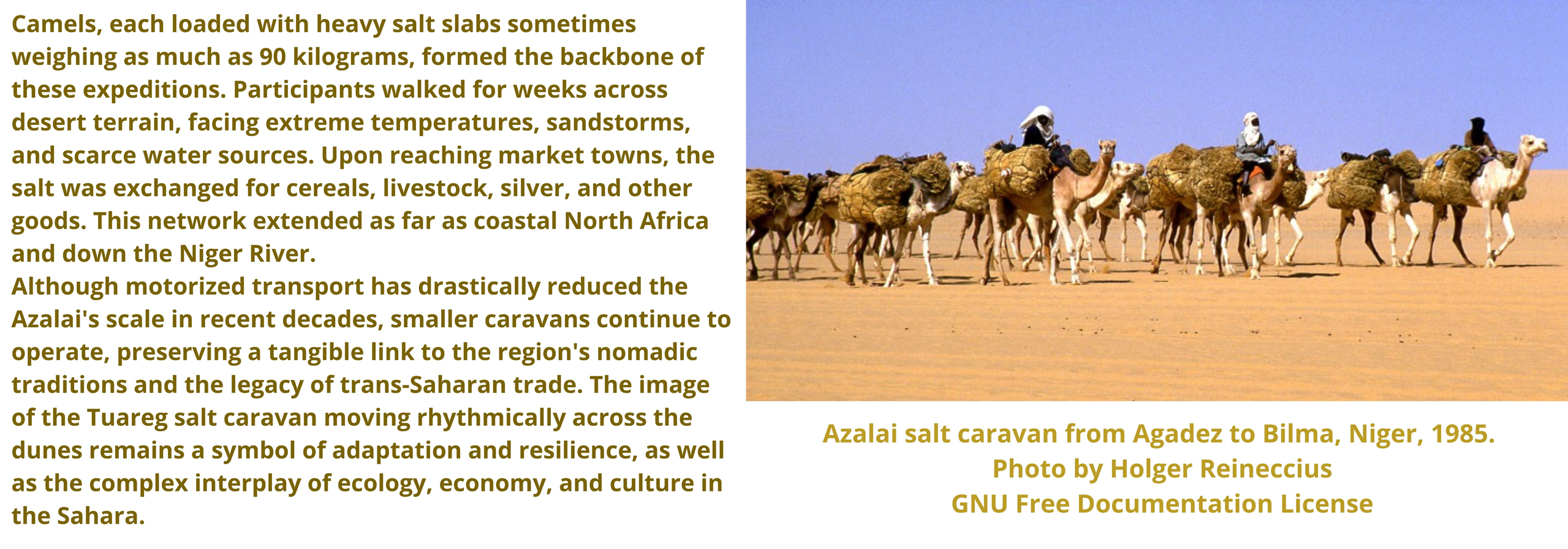

Salt for Silver, Desert for Sea

Before satellites mapped the Sahara, caravans measured it. The great Azalaï caravans, laden with salt and silence, departed each year from Taoudenni in northern Mali or the oases of Bilma and Fachi in Niger. In Taoudenni, miners carved blocks of salt from the fossil bed of an ancient sea. Their pickaxes rang like thin bells at dawn. Each camel bore two slabs, balancing the burden like justice.

Salt moved south, and silver moved north. From North African markets and Moroccan ports, bars and coins reached caravan towns such as Timbuktu, Agadez, and In Gall, where trade routes converged into a single artery of exchange. When the caravans met, salt was traded for silver by weight: ounce for ounce and slab for bar. Thus, the desert became its own ocean, the camel a ship, and the smith a kind of navigator.

The Inadan and the Fire

The Tuareg refer to their hereditary smiths as the Inadan (singular: Enad). These artisans, poets, and mediators are socially distinct and endogamous, yet indispensable. In the old camps, the Inadan lived near the forges, slightly apart. Their hands were permanently dusted with charcoal and silver filings. Their patrons, the Imajaghan (nobles), might have owned herds and slaves, but only the Inadan knew the language of fire.

Under thorn trees or in domed, mud workshops in Agadez and Tchin-Tabaraden, they blew life into forges with hand bellows made from goatskin. They hammered colonial coins into thin sheets and cut them with goat bone chisels. The process was as intimate as prayer. The first tanaghilt, the “cross” of Agadez, was not shaped as a Christian symbol, but as a compass with four arms for the cardinal directions and a small knob at its summit that echoed the tadek, or saddle pommel, of a camel. A father who tied it around his child’s neck would whisper, “Ayer-akar, Aman-akar, Tahala-akar, Temet-akar“—the four directions and the four paths of return—adding softly, “Come home to die among us.”

The Grammar of Ornament

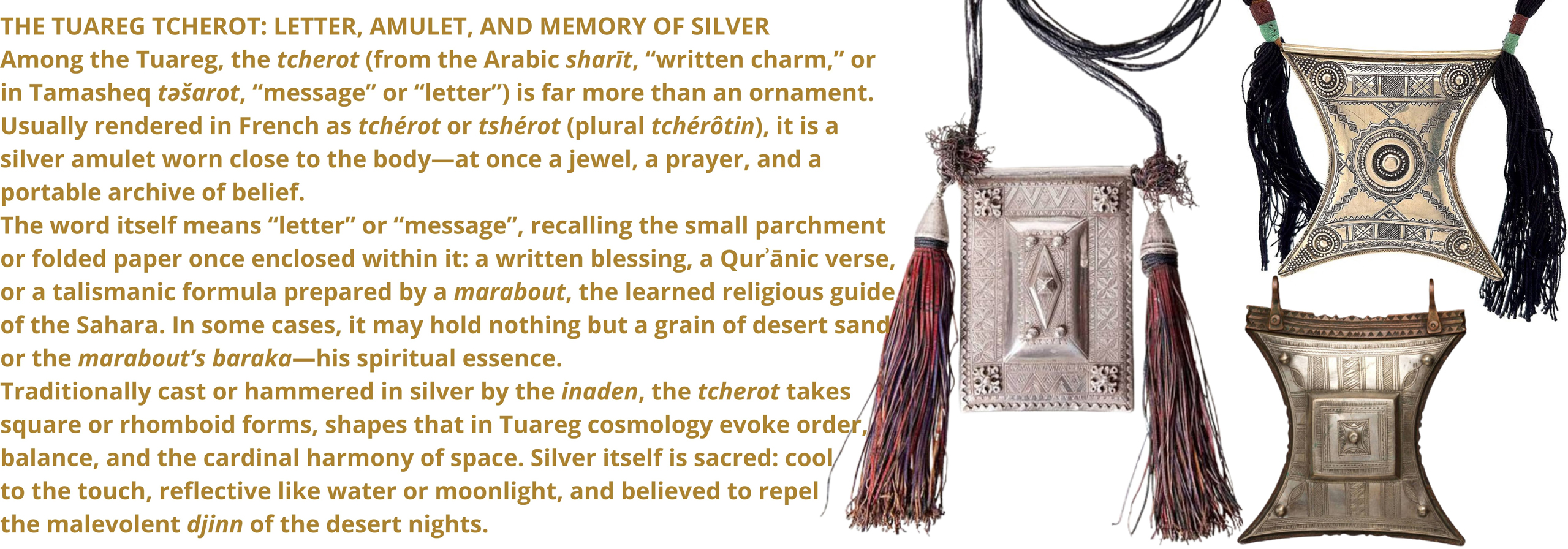

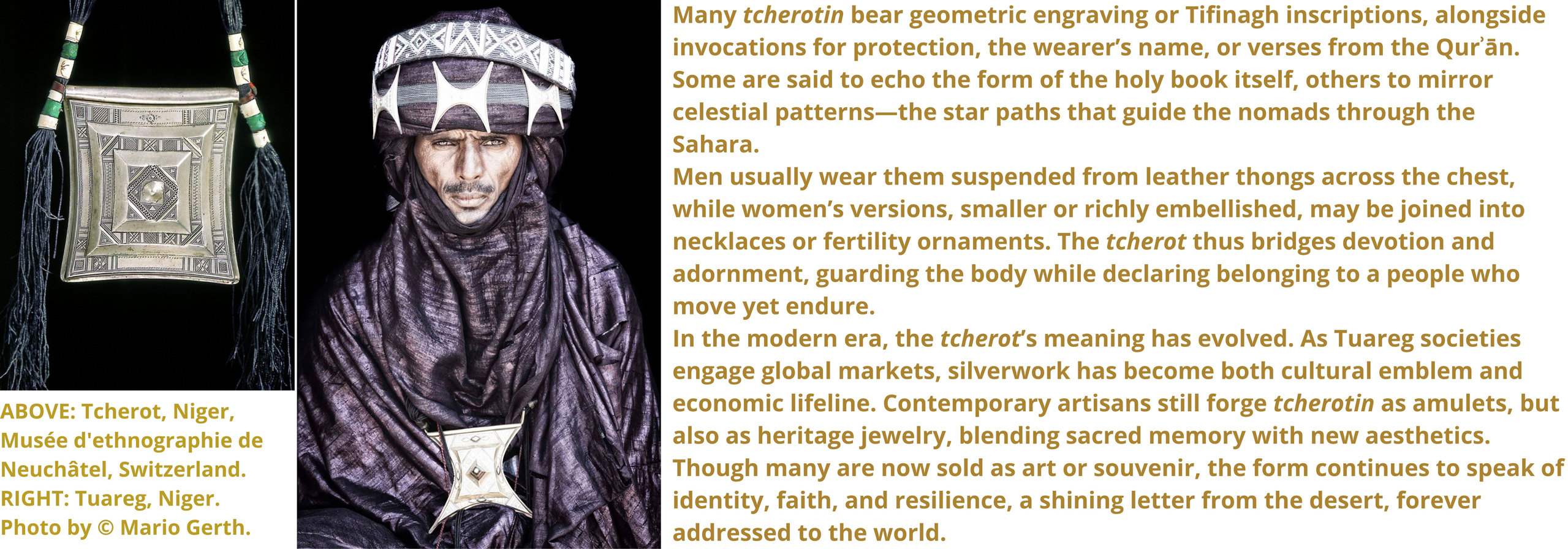

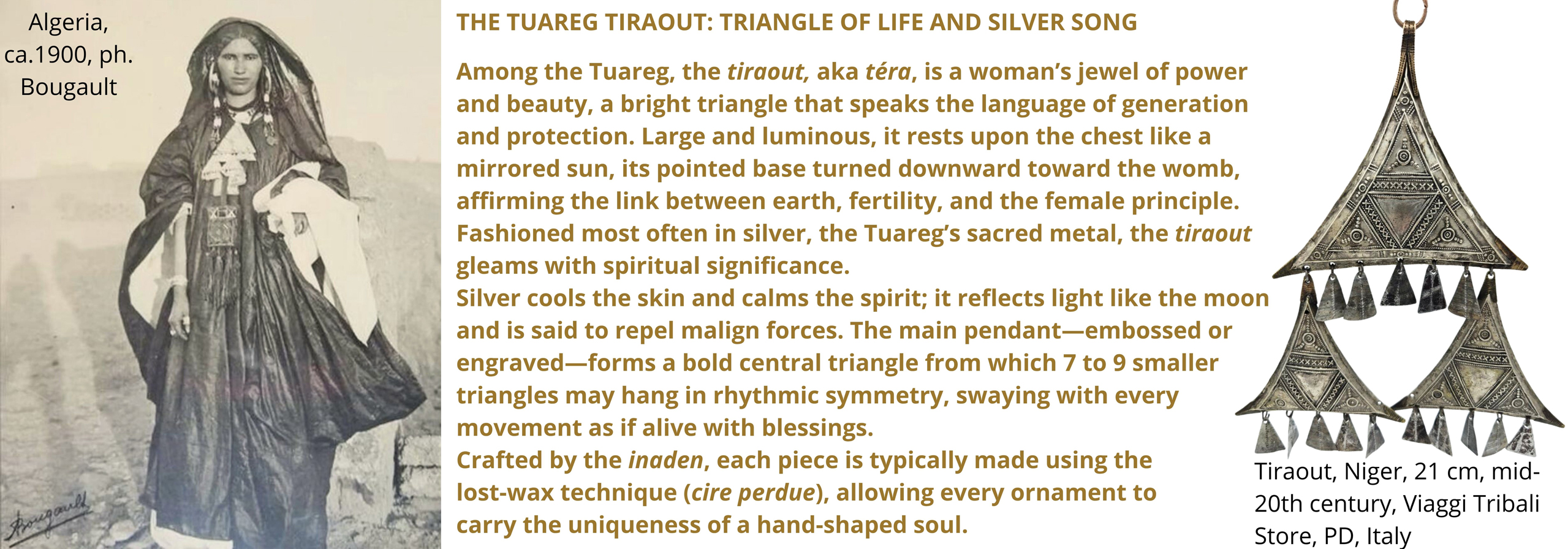

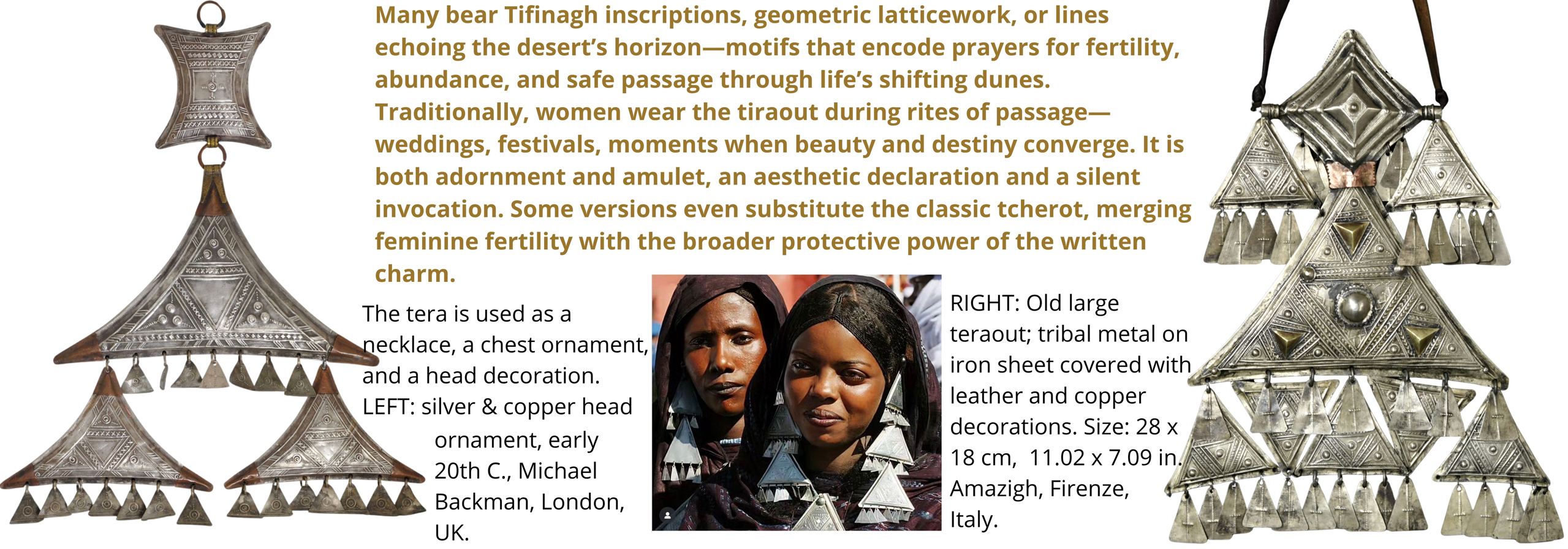

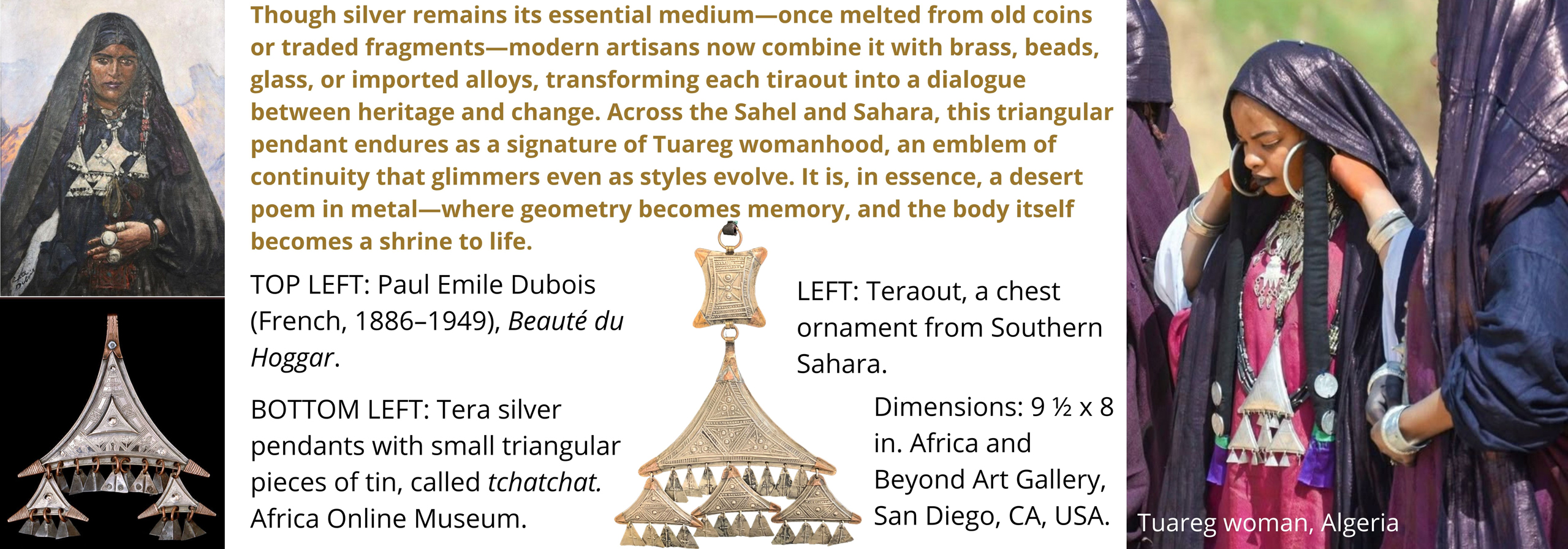

Each Tuareg jewel is a word in a metal language. Its motifs form a grammar that predates writing. Triangles, lozenges, and dots recall tents, stars, and water holes, while parallel lines trace seasonal migration paths. Some pieces conceal tcherotin, or amulets, which are tiny boxes that carry Qur’ânic verses, sand from a holy site, or a lock of a loved one’s hair. Others, like the Tiraout necklace, are adorned with silver triangles that jingle like the pods of the desert Acacia tortilis.

Many ornaments bear Tifinagh characters—the ancient Tuareg alphabet—engraved so that names become talismans. The word tin-ḥinan, often carved in miniature, invokes the legendary Tuareg ancestress, whose tomb stands amid the dunes of Abalessa in southern Algeria. Each mark and incision is a geometric prayer. Even the faint irregularities—the deeper file stroke on one edge or the asymmetry of a loop—serve as the maker’s signature. They are a way for the silver to remember whose hands first taught it to shine.

BELOW

Right: photo from Pinterest.

Top left: Tcherot, a square amulet with typical Tuareg engravings. Medium: metal, leather and threads, chain made of black twine, partially braided. Dimensions: height 9.5 cm. Auctioned in 2022 by Kunst und Auktionshaus Quedlinburg, Germany.

Bottom left: Tcherot in silver and copper from Western Sahara. Dimensions: 3 1/2 inches (8.9 cm). This amulet containes some lines from the Qur’ân. Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA.

Amazingly elaborate Qu’rân holder from Hoggar Algeria. Date: first half of the 20th century. Medium: silver, agate, abaka wood, brass. Dimensions: length 28 cm. From the collection of Ellen Benson. Photo by Robert K. Liu for Ornament Magazine, Volume 46 No. 2, 2020.

This Qu’rân holder shares many stylistic and symbolic elements with Tuareg tcherot pendants, such as being worn around the neck, containing inscriptions, and carrying significant spiritual meaning. However, it primarily functions as a container for Qur’ânic verses rather than as a protective amulet. Therefore, it can be considered a type of talisman because it is designed to hold sacred scripture and is worn for protection and spiritual benefit. The classic Tuareg tcherot is often smaller and more amulet-like. It contains inscribed texts or objects specifically for protective purposes.

Qu’rân holder from Algeria or Niger. Date: from the late 19th century. Medium: Iron, brass, copper, silver. Dimensions: 6 1/8 × 6 3/4 × 2 1/4 in. (15.56 × 17.15 × 5.72 cm). Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA. The inscription in Tifinagh (NK SDLMQTR G XLYFA on the front side) means, “I am Mr. Lmqtar Khalifa,” likely referring to a previous owner.

LEFT: Tuareg girl with silver jewels, Algeria. © Photo by Inger Vandyke.

RIGHT: Sahrawi girl with silver jewels, Aïn Salah, Algeria.

Women, Inheritance, and the Moon’s Dowry

In Tuareg society, lineage is traced through the tawsit n-tamadalt, or the mother’s line. Women own their tents, livestock, and jewels. Her silver is her amanar, her guarantee against hardship and her mobile dowry. When a marriage ends, she keeps her ornaments because they are her archive of belonging. A Tuareg woman may trade a bracelet for grain, but she will never pawn her takouba earrings, which are as slender as locust wings. These earrings carry her clan’s history in metal form.

Elders say that when a woman dies, her silver should be divided among her daughters and never melted because to melt is to forget. Yet, in every camp, there are small fires where forgetting is necessary: broken pendants are reborn as rings and colonial francs are transformed into lunar disks. Silver lives in cycles, like the moon, waxing and waning but never ending.

The Desert’s New Alchemy

In Niamey, the capital of Niger, the forges still burn, but the air has changed. Smith Ousmane Alhassan, son of Inadan, now sets fragments of green circuit board into amulets, their copper veins glowing beneath the silver. He calls it “new sand-trace,” meaning that even technology follows the same wind. His apprentices once dreamed of holding rifles, but now they film themselves with phones and post to TikTok the moment the flame kisses the metal.

Their buyers are no longer only camel herders. They are aid workers, Tuareg in the diaspora from Marseille, and tourists from Europe who ask for something “authentic.” In the Goudebo refugee camp in Burkina Faso, displaced artisans set up miniature benches beside food tents and hammer crosses from scrap metal to sell to UN staff. The forge has gone global, but its rhythm—breath, bellows, hammer—is the same pulse that once kept time with the hooves of the Azalaï.

Elhadji, Tuareg Jeweler of the Desert

When Gold Crossed the Dunes

After the 2003 gold rush near Téra in western Niger, the landscape changed. Young brides began to prefer gold for its cash value, and city jewelers started weighing chains in grams instead of stories. Old women muttered that gold awakens djinn n-tahawant, spirits of greed, while silver remains calm, reminiscent of the moon. However, a compromise soon emerged: a cross plated with gold but forged in silver—a double-voiced ornament that satisfies the market yet honors the ancestors.

In a world where the desert is divided by customs posts and smuggling routes, silver remains a moral metal: asekkar iɣedar, i temet n tmazirt, “silver is clean, like the soil of home.” To wear it is to remember where one’s feet first knew dust.

Hands of Both Genders, Voices of Many Lands

Men still swing the first hammer blow, but women shape the story. In the oasis of Tabelot, the Tin-Hinan cooperative employs young women who thread necklaces with small metal QR tags linked to online catalogs. Their stories are written in Tamasheq, French, and English. A cousin in Saint-Denis translates, and the silver crosses oceans faster than caravans ever did.

Each sale ripples outward. A single pendant bought in Paris may feed six households in Niger. In this quiet economy, the ancient reciprocity between giver and maker endures. While Western Union booths close at dusk, silver keeps its doors open through the night.

The Weight of Beauty

For Tuareg women, the desert wind is both a companion and an adversary.

It moves through tents and thoughts alike, lifting the veils of dunes and faces.

Living in its domain means learning the art of anchoring oneself to what cannot be stilled.

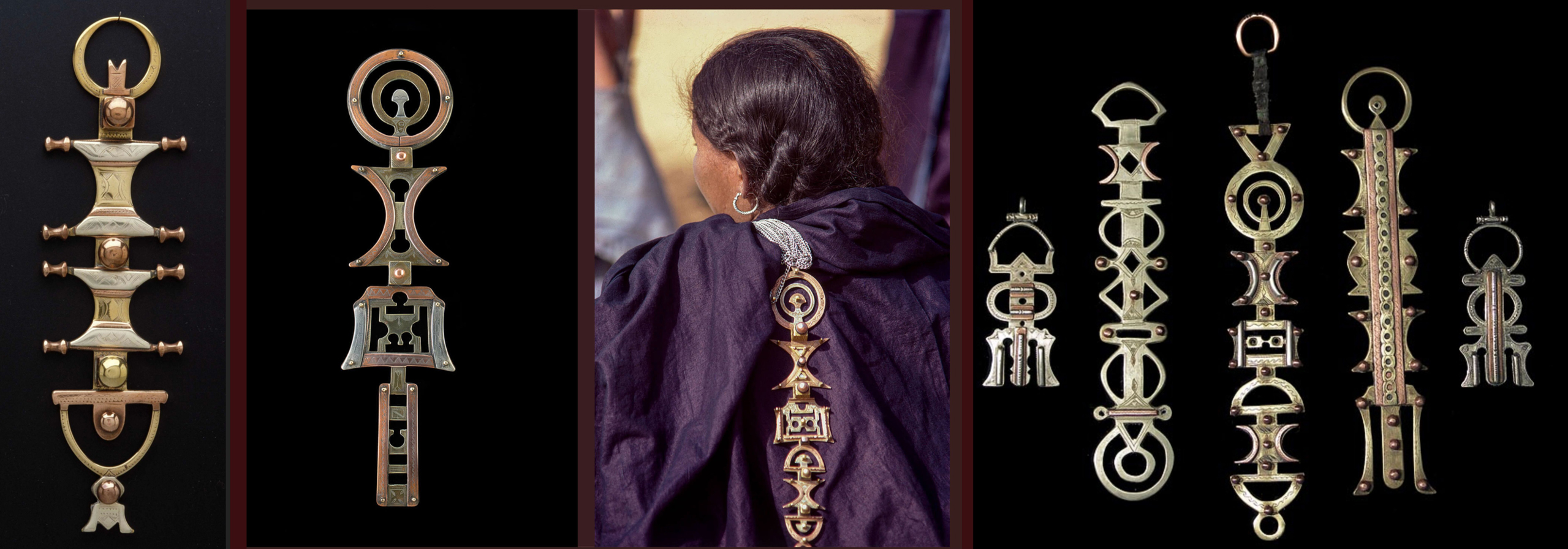

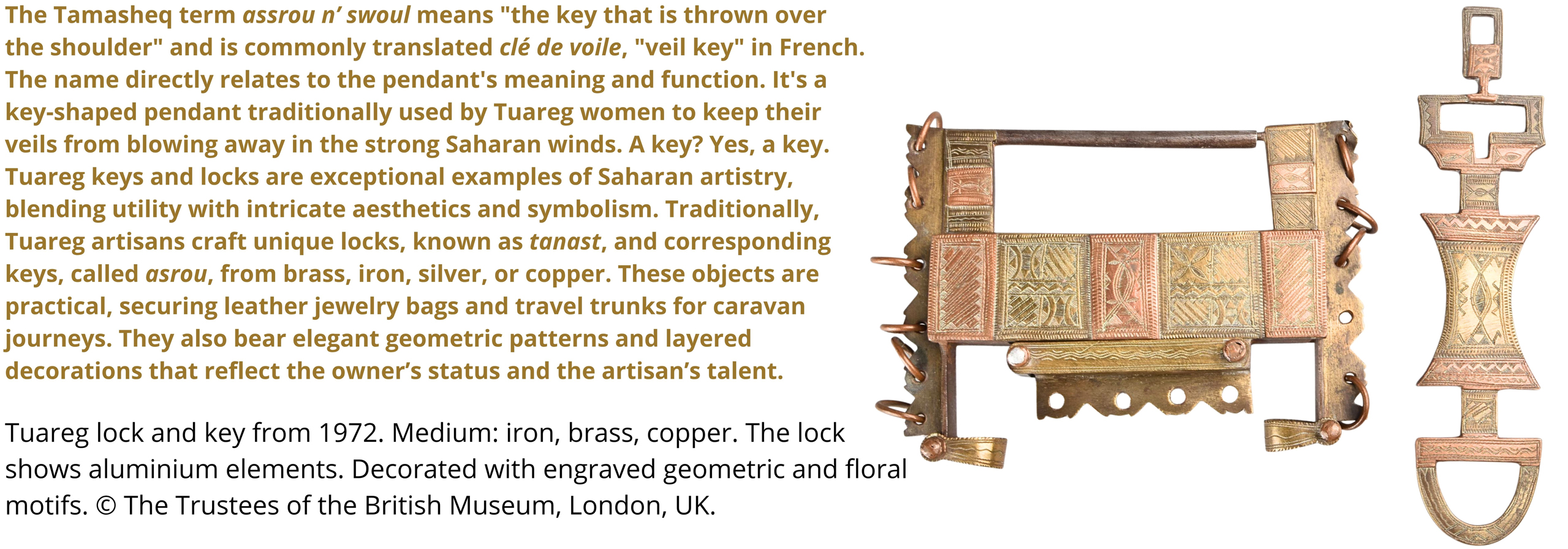

From the interplay of movement and stillness comes the Assrou n’ Swoul, “the key cast over the shoulder”.

Forged by the hands of the Inadan, the Assrou n’ Swoul lies where metal meets meaning. Each piece is a slender brass, copper, or silver pendant, sometimes layered using the “sandwich technique”—metals folded one over another to create rippling contrasts of color and light. The pendant hangs at the end of the mellhafa, a woman’s long indigo veil, serving as a counterweight and a talisman.

Some are flat and leaf-like; others are curved or key-shaped, recalling the silhouettes of ancient locks or desert blades. Their surfaces are incised with fine geometric motifs—triangles, diamonds, and parallel lines—that echo the Tuareg cosmology of the meeting of earth, horizon, and sky. The decoration is never random. Each sign whispers of protection, fertility, and equilibrium.

At its most basic level, the Assrou n’ Swoul secures the cloth against the desert’s wind. For the Tuareg, however, function and symbolism are never strangers. This small weight becomes a declaration of belonging, a link between a woman and her home, and between mobility and memory. The name itself, “the key cast over the shoulder,” tells a story. Ethnographers suggest that, in the past, women kept iron keys to their chests or tents attached to their veils—a practical gesture that became a ritual. Over generations, the true key became symbolic, its shape stylized and its material refined, but its essence endured: the key to the house, keeper of inheritance and mark of female authority.

Though Tuareg society is layered by lineage, it grants women significant control over property and domestic space. The Assrou n’ Swoul, hanging lightly from the shoulder, thus expresses this quiet sovereignty. It is not jewelry in the ornamental sense alone; it is a seal of autonomy, the visible weight of a woman’s world.

The size and craftsmanship of each piece used to reflect the wealth of the household. A large, intricately layered Assrou n’ Swoul signified abundance, while a simpler one signified modest means. In all forms, however, it remained a sign of grace, striking a balance between austerity and ornament.

In the open light of the Sahara, metal gleams like a second sun. As a woman walks, the pendant sways and glints, scattering light upon indigo—the sacred color that stains the skin and sanctifies the body. The desert wind blows; the Assrou n’ Swoul responds with its subtle weight, a rhythm of resistance: soft, constant, and feminine.

Today, many such pieces rest in museums or private collections, their patinas dulled by time. Yet, among Tuareg communities in Niger, Mali, and southern Algeria, women still wear them for festive occasions. Their metallic whispers keep company with laughter and song. The blacksmiths still know the old forms, how to etch a motif that is both sign and spell and how to balance beauty with gravity.

The desert keeps only what is tied to the soul.

Tuareg proverb

LEFT TO RIGHT

Beautiful assrou n’ swoul from the late 19th century. Medium: Bronze, copper, and silver. Dimensions: 7 11/16 × 2 3/16 × 1 in.; 19.5 × 5.6 × 2.5 cm. Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Assrou n’swoul counterweight veil pendants made of brass, iron and copper are given to girls as gifts from their mothers. Their size indicates the wealth of the girl’s family. The method of laminating used on these pendants is known as the “sandwich” technique, which involves time-consuming and delicate work by Mauritanian smiths. Photo by the Africa Online Museum, Germany.

Assrou n’swoul counterweight veil pendants. Adorned Histories. Photo Sarah Corbett.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Photo source: Pinterest.

Antique counterweight (Assrou n’Swoul) from Niger. Date: Late 19th to early 20th century. Medium: Steel and brass. Dimensions; 10 3/4 x 2 5/8 x 1 in. Auctioned in 2023 by Ararity Auctions, Lorton, Virginia, USA.

A Tuareg woman’s counterweight (Assrou n’ Swoul) from Niger. It is of the typical key form and has a silver-colored body with incised decoration and sphere motifs. It also has a leather strap and loop fitting. Length: 20.5 cm. Roseberys, London, UK.

An Assrou N’Swoul counterweight pendant from Mauritania.

A young Malian woman wearing wears a counterweight pendant, a tcherot, and a khomaissa (sometimes spelled khomeissa, khomissar, or Komissar), a well-known Tuareg pendant shaped like a stylized hand with five fingers, often associated with the Hand of Fatima (from the Arabic hamsa, “five”). It’s usually made of silver or brass, decorated with intricate designs, and sometimes set with coral or other stones.Worn mainly by Tuareg women, the khomaissa serves as an amulet for protection and good luck, particularly against evil spirits or the evil eye.

Tuareg veil weight, clé de voile in French. Date: Early to mid-20th century. Medium: Brass, copper, silver. Dimensions: 20.2 x 5.5 x 1.3 cm (7 15/16 x 2 3/16 x 1/2 in.). National Museum of African Art Collection, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

Veil weight from Niger. Date: mid-20th century. Medium: Copper, brass, iron. Dimensions: 13 1/2 × 3 7/8 × 1 5/8 in. (34.29 × 9.84 × 4.13 cm). Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota, USA.

Heritage as Horizon

The Tuareg say aman iman—“water is life”—but they might also say asekkar iman—“silver is memory.” Silver is the ballast of their journeys and their portable homeland. In a tent outside Gao, a grandmother unwraps her bracelets—four generations nested like moons. One is no wider than a ring and once circled the wrist of a child lost in the 1984 drought. She lets a visitor hold it but not photograph it. “Some things,” she murmurs, “must enter only the eye, not the cloud.”

Above her, forge smoke rises into the air, where French drones and trade planes cross. Somewhere, a boy files a coin thinner and thinner until it sings. He doesn’t know that the silver he touches has traveled from a colonial mint to a salt mine to his father’s forge. In its shine, it carries the entire cartography of exile and return.

A final voice of silver adorns the forehead rather than the neck.

For Tuareg men, the tagelmust is more than just clothing. It is a second skin, a marker of adulthood, and a spiritual shield against the desert’s wind and unseen forces. Yet, the tagelmust does not stand alone. It is held in place, framed, and sanctified by a narrow band known as the asaba. Sometimes, it is accompanied by a subtler cord called the akofol. Together, these bands form a delicate architecture of identity, weaving visible dignity with invisible protection.

The asaba (also spelled asabeh, asabat, or es’saba) is the decorative headband tied around the crown or forehead over the folds of the tagelmust. Braided from leather or finely woven wool, the asaba serves the practical purpose of keeping the veil steady in the wind. Above all, however, it is a symbolic girdle for the head—a zone of thought, speech, and spirit. Deriving from the Arabic root ʿasab (عَصَب), meaning “to bind,” the term evokes restraint and cohesion—qualities that are deeply valued in Tuareg ethics. To “bind” one’s head with the asaba is to embody asshak, the ideal of dignified self-control and respect.

The asaba often bears talismanic adornments: small tcherot (amulet boxes containing verses or protective charms), silver plaques, cowrie shells, or plaited tassels that sway softly as the wearer moves. These miniature ornaments create a rhythm of light and movement across the indigo cloth, transforming a functional strap into a portable shrine of faith and identity. Each amulet is believed to guard the wearer’s mind and soul, protecting against misfortune, envy, and the desert’s restless spirits.

Another, subtler cord runs beneath or beside the asaba: the akofol (also spelled akofel or akofoul). Though less visible, it holds equal significance in Tuareg symbolism. The akofol is usually a narrow, braided cord made of fiber, which is sometimes hidden under layers of the veil and sometimes wrapped around the base of the head or neck. It may serve as a structure to support tcherot amulets, holding them close to the body so their protective energy can act unseen.

The asaba is usually handwoven from cotton or wool and is often dyed in complementary jewel tones or muted natural shades that accentuate the deep blue or purple of the surrounding tagelmust. It features geometric designs that are characteristic of Tuareg textile artistry and frequently incorporate repetitive diamond, lozenge, or zigzag motifs. The weaving technique varies by region, reflecting the artisan’s skill and sometimes indicating affiliation with particular Tuareg clans.

While the asaba is the public face of composure and beauty, the akofol is its invisible counterpart—the inner circuit of protection. In some regions, the terms overlap because both pieces serve the function of binding and safeguarding. Yet, their distinction endures in practice and meaning: the asaba adorns and declares, while the akofol anchors and defends.

Both are handcrafted by the Inadan, the hereditary caste of artisans specializing in blacksmithing and leatherworking. They are made to measure and are often gifted at initiation or marriage. They express not only craftsmanship, but also kinship—they are an art form that ties bonds between people as much as they tie around heads.

The materials—indigo-dyed wool, tanned leather, plaited sinew, and silver beads—speak the language of desert endurance. Each component harmonizes with Tuareg philosophy: what conceals also reveals, identity is best expressed through restraint, and protection is both aesthetic and spiritual in its highest form.

When a man wraps his veil, the asaba rests where thought begins, forming a line between sight and sky. If exile lengthens and the cloth frays, he can sell the silver, but he keeps the band folded inside a Qur’an. It is no longer an ornament, but rather a portable horizon, a measure of dignity that outlasts the dunes.

Tuareg man wearing decorative adornment, Hombori, Mali. Date: 1967. Photo by Marli Shamir. Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian Institution, USA.

The Forge Still Burns

And so the forge burns on. Its flame unites the past and the future. To be Kel Tamasheq—the people of the language—is to move, to remember, and to recreate. Each hammerstroke is a vote for continuity; each ornament is a map of belonging.

When a Tuareg child inherits a pendant, they inherit the four directions, the memory of salt, and the discipline of beauty. The coin may have once passed through a French colonel’s hands and slept beneath the moon of Taoudenni, but now it glows at his chest as a private compass. Ténéré-t aɣarid n-iman—“the desert is the mirror of the soul.”

And the mirror still shines.

Terakaft – Tahra A Issasnanane (“Sometimes, Love Is Painful”)

THE CROSS THAT IS NOT A CROSS AND THE FOUR DIRECTIONS OF THE SOUL

Born of Fire and Sand

In the desert, metal remembers what the wind forgets. Silver, melted and reborn in the hands of the inadan, retains the desert’s essence: bright, austere, and alive with geometry. Among the Tuareg, these pieces of metal, cast and engraved into shapes that outsiders call “crosses,” have names that resonate far more deeply: tanaghilt, teneghelt, tasagalt — words meaning “that which has been cast” and “that which has flowed.”

They are not crosses in any Christian sense. Their silver axes are not signs of crucifixion, but rather, they are symbols of orientation, protection, belonging, and the beauty of precision. To the Tuareg, whose map is the horizon and whose lineage is traced through wind and kin, these pendants are wayfinders of the soul.

The tanaghilt likely originated in the central Aïr Mountains of Niger among the Kel Aïr Tuareg before spreading north toward the Ahaggar, west into the Adrar des Ifoghas, and south toward Hausa lands. Ethnographic records from the late 19th century show forms similar to today’s “crosses.” One was collected by the explorer Foureau in 1900 in Zinder; another was collected in Agadez. Both are now preserved at the Musée du Quai Branly. Yet, their origins may be even older, dating back to talismanic shapes of stone and carnelian known as talhakim. These talhakim were the precursors to the silver “crosses” that were once simply soft stone plates worn against the skin.

Ada Boffa reminds us that the Tamasheq word teneghelt itself comes from enghel, which means “to flow,” “to pour,” or “to cast.” This evokes the very act of creation through the lost-wax process (cire perdue). Thus, these ornaments were literally born of molten movement, with silver transformed through fire and patience into symbols of continuity.

The Hands of the Inadan

If the tanaghilt embodies Tuareg identity, then the inadan—the hereditary blacksmith caste whose work fuses the practical and the mystical—is its breath. For centuries, these artisans have been the keepers of metallurgy, woodcarving, and leatherwork. Their status is both revered and ambivalent. They work with fire, a force believed to attract spirits and jinn. Thus, they stand slightly apart—necessary yet feared, impure yet indispensable.

A man sits cross-legged on the ground. His anvil is no larger than a stone, his bellows are made of goatskin, and his hammer is a rhythm he learned from his father. The process begins with beeswax, which is shaped into the pendant’s silhouette. Clay envelops the wax, which hardens in the fire until it runs out, leaving an empty mold. Molten silver is then poured into the mold. Once cooled, the mold is broken forever. Each tanaghilt is thus unique, born once and never again.

Historically, the metal came from melted coins: Austrian Maria Theresa thalers, French five-franc pieces, and scrap silver from the colonial economy. Gold, by contrast, was shunned. According to Tuareg beliefs chronicled by Hanna Sotkiewicz and Ibrahim al-Kauni, gold is a dangerous metal — the color of greed and blindness — while silver is pure and luminous, the metal of God (An N’Illah) and a protective metal. “Gold makes one blind,” wrote al-Kauni, “but silver sees.”

The smith’s tools are few, but his vocabulary of signs is vast. He uses small punches and gravers to draw zigzags of protection, dotted constellations of animal tracks, and chiseled triangles that invoke balance and fertility. Each tanaghilt bears these minute incisions like a text—not to be read in words, but in rhythm and reflection.

Inadan at work.

LEFTAND RIGHT: Burkina Faso. Photo by Pierre Tilmant | © UNHCR/6M.

CENTER: Assaghan Association workshops, Tamanrasset, Algeria. Photo by © Andy Morgan.

Andy Morgan, who was the manager of the Tinariwen band until 2009, writes about the music, culture and politics of the Western Sahel countries and Mali. He runs the web-magazine, Andy Morgan Writes and has recently published Music and Politics and Culture in Mali, a downloadable on-line book. Andy and his wife Kate created and managed the SaharanArts project promoting Tuareg jewelry.

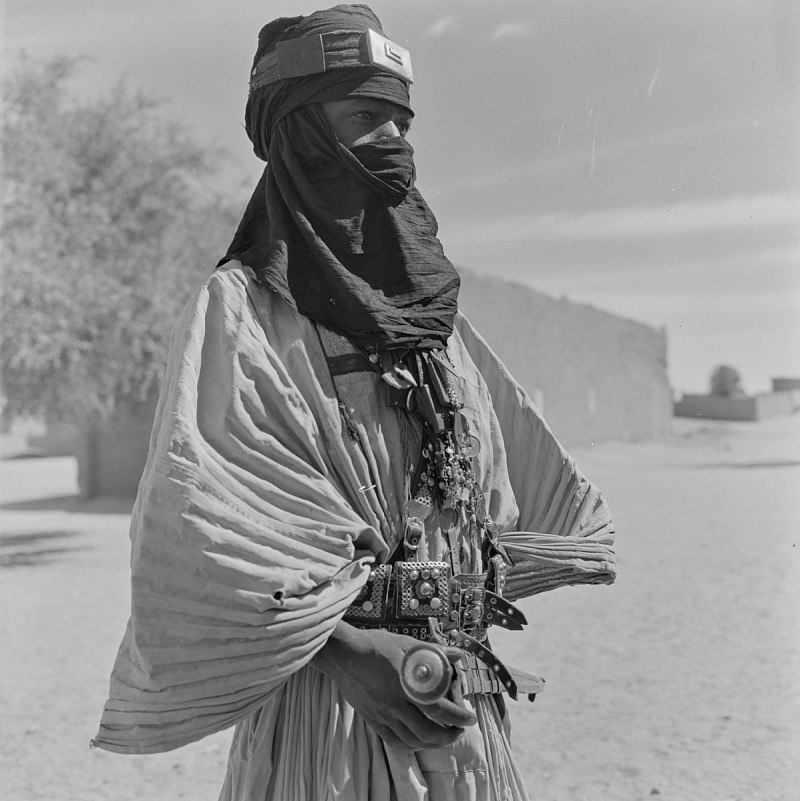

Signs of the Four Horizons – Forms and Types of the Tanaghilt

Across the dunes of Niger and beyond, there are many tanaghilt, not just one. Scholars and artisans speak of twenty-one named variants, known as the “crosses of Niger,” each of which is associated with a specific location or mountain: Agadez, Tahoua, Zinder, Ingall, Iférouane, Timia, Bagzan, and Madaoua, among others. However, as Boffa and Beltrami caution, this numbered canon is as much a product of modern tourism and nationalism as it is of traditional taxonomy. The true tradition is fluid and mobile, much like the people themselves.

Still, certain forms have crystallized in both craft and memory:

1. The Cross of Agadez (Teneghelt tan Agadez)

It’s the archetype: diamond-shaped, balanced, the silver stretched in four points. A loop or ring tops the piece, followed by a narrow neck that flares into four symmetrical arms that often end in conical or globular tips. Its geometry suggests a compass rose or an open hand facing the horizon. Ethnographers recorded a father’s blessing: “My son, I give you the four directions of the world, for none knows where he will die.” Whether legend or lived rite, the phrase distills the essence of the cross — protection for those who travel beyond the known dunes.

Crosses of Agadez – LEFT TO RIGHT

Tuareg woman, Niger. Pinterest.

Agadez cross pendant. Pinterest.

Teneghelt tan Agadez, Niger, ca. 1930. Medium: Engraved silver; it was melted and cast, then worked with a file. The decoration was created using a chisel and a branding iron. Dimensions: 3,5 x 7,5 x 0,6 cm. Weight: 8 g. Quai Branly “Jacques Chirac”, Paris, France.

Teneghelt tan Agadez, Niger. Dimensions: 8.6 x 8.6 cm. © Musée d’ethnographie de Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

Taneghelt tan Agadez, Niger. Dimensions: 8.6 x 8.6 cm. © Musée d’ethnographie de Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

2. The Cross of Tahoua

It is wider than it is tall, and its arms spread out like the wings of a bird in flight. The upper loop is large and circular and is sometimes double-rimmed. The lateral arms are long and flared with triangular tips or bead caps. Decorative incisions often radiate from the center, reminiscent of the sun over the plains of Ader. The cross carries a sense of openness, of departure and return.

LEFT TO RIGHT

A collection of old Tahoua crosses, Niger. Date: Mid-20th century. Medium: Silver, wool. Dimensions: 7.7 x 4.5 CM; 3.03 x 1.77 inches. Amazigh, Florence Italy.

A contemporary cross of Tahoua in recycled brass. Ajmer Tribal, Washington, USA. On Etsy.

Old cross of Tahoua. Pinterest.

Vintage cross of Tahoua. Pinterest

Tahoua cross, Niger. Dimensions: 8.4 x 4.9 x 15 cm. Weight: 10 g. Spurlock Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA.

3. The Cross of Zinder (Tenelit tan Zinder)

Compact and often broader than the Agadez type. It has a smaller loop and a flatter body with arms that extend more horizontally than vertically. The engravings tend toward fine zigzags and dotted lines rather than deep cuts. Some informants claim that the Zinder variant represents a town plan, while others claim that it maps the routes of ancient caravans. Whatever its origin, it speaks of crossroads and encounters.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Large old Zinder cross in silver. AzulTribe, London, UK.

Old Zinder cross, Niger. Dimensions: 6 x 6 cm. © Musée d’ethnographie de Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

Old Zinder cross, Niger. Dimensions: 4 x 4 cm. © Musée d’ethnographie de Neuchâtel, Switzerland.

Old Zinder cross, Niger. Date: ca. 1920. Spurlock Spurlock Museum, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA.

4. The Cross of Iférouane (Tariselt)

Slender and tall with a long stem beneath the loop and tapered points at its ends. It has a vertical elegance, with a symmetry that is almost architectural. Some examples have a single downward point that resembles an arrow or teardrop. Older smiths call this form tanfouk n’azraf, meaning “silver arrowhead,” linking it conceptually to the carnelian talhakim pendants that were once worn for fertility and safe travel.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Old cross of Iférouane in silver, Niger. Dimensions: 9 x 5 x 0.3 cm. Weight: 16 g. Casa d’Aste Capitolium Art, Brescia/Rome/Florence, Italy.

Vintage cross of Iférouane in silver, Niger. Date: ca. 1950. Dimensions: 4.9 x 7.7 cm. Weight 23.3 g. Pucn2012, France. On Etsy.

Old cross of Iférouane in silver, Niger. Date: 1940s. Weight: 14.4 g. Tifinagh, France. On Etsy.

5. The Cross of In Gall (Tanfouk n’agraf)

It is more shield-like than cross-shaped, with a broad, solid body and an integrated loop. Incised circles and parallel lines suggest wells or enclosures. The cross feels more defensive than directional, perhaps an emblem of grounding in the ancient oasis once famed for its salt and cattle festivals.

LEFT TO RIGHT

A collection of necklaces with contemporary Ingall crosses, made by Elhadji Koumama in Agadez, Niger. Cross medium: fine silver, onyx, and red pressed glass. Made with a hook and eye closure. Native, Scituate, MA, USA.

Cross of Ingall, Niger. Date: Mid-20th century. Medium: Silver, carnelian. Weight: 13.2 g (0.47 oz). Dimensions: 5 x 3.3 cm; 1.96 x 1.29 inches. Amazingh, Florence, Italy.

Cross of Ingall, Niger. Medium: Silver. Dimensions: 3 1/8 x 3/4 x 1 3/4 inches; 7.9 x 1.9 x 4.5 cm. Brooklyn Museum, NY, USA.

Beyond these five canonical types are others with names: the Cross of Timia (Zakkat), the Cross of Bagzan, the Cross of Madaoua, the Cross of Tchintabaraden, and the more recent “Cross of Mano Dayak,” created in 1996 in memory of the Tuareg leader of that name. Each has slight variations in the number of arms, the curve of the tips, and the size of the loop. This subtle vocabulary of differences can only be deciphered by the inadan, or seasoned wearer.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Barchakeia cross, Agadez, Niger. Date: ca. 1930. Medium: silver. Dimensions : 7.4 x 8.2 x 0.4 cm. Weight: 16 g. Musée du Quai Branly “Jacques Chirac”, Paris, France.

Barchakeia cross, Agadez, Niger. Date: early 20th century. Medium: silver. Dimensions : 11.3 cm. Viaggitribali store, Padova, Italy.

Abalak cross, Niger. Medium: silver alloy. Auctioned in 2023 by Compendium Auction House, Tavares, FL, USA.

Inabangaret cross, Niger. Medium: silver alloy. Auctioned in 2023 by Compendium Auction House, Tavares, FL, USA.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Bagzan cross in silver alloy. On Etsy.

Bagzan cross in white metal. Dimensions: 11.1 x 6.7 cm; 4.37 x 2.64 inchese. Weight: 52.7 g (1.86 oz). Amazigh, Florence, Italy.

Tchintabaraden cross, Niger. Height: 4 in.; 10.16 cm. © Tim Hamill, Hamill Gallery of African Art, USA.

Structures and Silhouettes

Despite their variety, the tanaghilt structures share a basic grammar.

- Loop or Ring: At the top, for suspension on a leather cord or silver chain; sometimes framed by twin horns.

- Neck or Stem: A narrow connector between the loop and body that is sometimes perforated.

- Body or Plate: The main field, which is often lozenge-shaped but occasionally round or shield-like.

- Arms or Tips: Usually four, but sometimes two, five, or six, ending in points, knobs, or pyramidal finials.

The result is not always a “cross” but sometimes a key, an anchor, or a stylized human form, which echoes Maïga & Harouna’s observation that some modern pendants “resemble keys, anchors, or figures of protection.”

Engraving and Ornament

A silent language of geometry runs across these surfaces. There are zigzags for water and serpent energy, dotted lines for gazelle tracks or jackal footprints, and triangles for the feminine principle and Tanit, the ancient Phoenician mother goddess whose memory lingers in desert myth. Sotkiewicz notes that circles protect against the evil eye. They are miniature suns or drums whose vibration disperses malign forces. Occasionally, one finds Tuareg Tifinagh script or the grid of a “magic square” — numbers and letters arranged to capture the balance between the seen and the unseen.

Each tanaghilt functions as both an amulet and a text, a portable cosmogram of symmetry, protection, and aesthetic order.

Size Comparison

Tuareg crosses, including the Agadez cross and other regional types, are traditionally made in a wide range of sizes. They can be small pendants (around 3–4 cm long) or much larger pieces (sometimes 10–13 cm or more). These variations reflect regional preferences, the artisan’s intent, and whether the cross was intended for everyday use, as a special gift, or for display.

LEFT TO RIGHT

A very large Tilya cross, Niamey, Niger. Date: 2001. Medium: solid silver. Dimensions: 13.1 cm. Ethnic Jewelry Passion, Groningen, The Netherlands.

Two small vintage crosses in silver alloy: a Bagzan on the left and a tiny Tahoua of 3.4 cm. My collection.

From Amulet to Emblem

For the Tuareg, wearing silver signifies purity, mobility, and lineage. Among men, a tanaghilt may hang from the neck as a charm against misfortune. Among women, it may gleam from the veil with the pointed end inverted and rising toward the sky. In both cases, the tanaghilt announces belonging — to a tribe, a kin group, or a horizon.

Dieterlen and Ligers recorded that these pendants often marked initiation, with a father giving his son a tanaghilt upon reaching manhood. However, older photographic evidence suggests that women wore them as well, perhaps even more frequently. Ada Boffa argues that at least eight of the twenty-two known types were historically women’s jewelry, challenging the male-centric myth of the “father-to-son” gift. The tanaghilt, like the desert, belongs to both genders and to none.

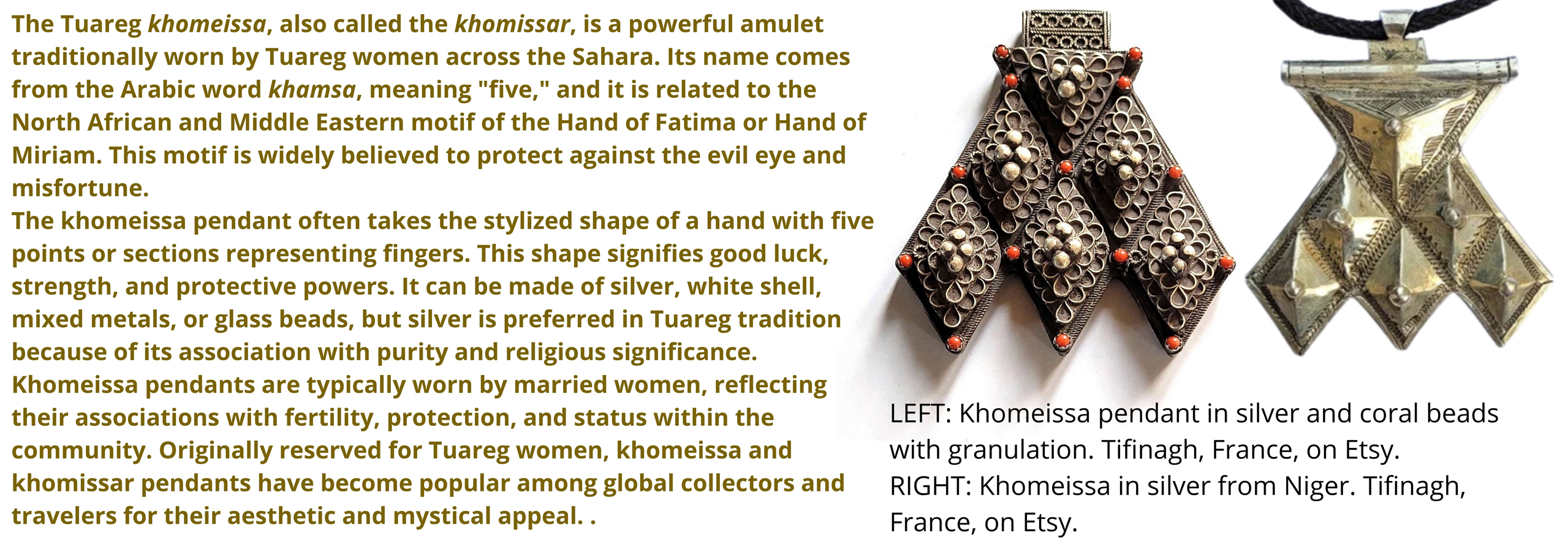

As amulets, tanaghilt were part of a broader world of protective objects, including tcherot (prayer boxes), talhakim (carnelian pendants), and khomeissa (five-pointed hands). Each bore verses, symbols, or engraved signs intended to maintain equilibrium between the human and spirit worlds. The tanaghilt, with its precise geometry, embodied this balance — between north and south, night and day, male and female, matter and meaning.

In a society where jewelry also served as portable wealth, these pendants held material and spiritual value. Silver could be melted, recast, and re-engraved. A woman’s dowry hung from her neck and wrists, and a traveler’s protection shimmered at his chest.

The Cross That Travels

As Tuareg society faced colonization, drought, and displacement in the 20th century, the tanaghilt also began to travel. It appeared on postage stamps and state insignia. The Republic of Niger adopted the Agadez Cross for its highest national order. The tanaghilt became a national symbol and a token of “Sahelian identity.” In global markets, it evolved into an icon of ethnic chic, with its forms simplified for tourists and collectors and reproduced in silver, nickel, and even aluminum.

Sotkiewicz observed that this new economy of symbols enables the Inadan, “ambassadors of their own culture,” to survive by negotiating between authenticity and adaptation. Becker and Nowak demonstrate how formerly marginalized groups, such as the Ikan (descendants of slaves), now adopt and transform these ornaments to make statements about their agency. In doing so, they reclaim an art once reserved for nobles. What was once a sign of hierarchy has become a sign of self-definition.

Yet, despite these transformations, the essence persists. Each tanaghilt, whether crafted in a desert workshop or a city studio, still bears the grammar of orientation: fourfold symmetry, a protective center, and a mirrored horizon. In its mirror, one glimpses not faith, but direction—the knowledge that, in the vastness of the Sahara, one carries one’s map on one’s heart.

Silver Horizons in the Tuareg Desert

In the Sahara, silver remembers what the wind forgets.

Among the Tuareg, also known as the Imuhar or “Free People,” the desert’s silence takes shape in metal.

Forged in fire and drawn by hand, their silver tanaghilt shimmer like captured light.

Outsiders call them “crosses,” but they are not crosses at all.

They are directions.

They are prayers without words.

They are the four winds held still for a heartbeat.

Each one begins as wax and ends as a revelation.

The Inadan, who are custodians of both fire and mystery, carve the wax from memory. They encase it in clay and let it burn until the molten silver flows into the void it leaves behind.

When the mold breaks, the pendant is born—unique and unrepeatable like a dune that will never take the same shape twice.

A loop crowns it, and beneath that, the body flares into arms, points, or petals.

Sometimes four, sometimes six — never the same, never arbitrary.

The Agadez type stretches symmetrically, poised between vertical and diagonal.

The Tahoua widens like a bird in flight.

The Zinder type expands horizontally at crossroads.

The Iférouane stands tall, its silver stem resembling a compass needle.

The In Gall shields itself with a protective lozenge, its surface engraved with wells and constellations.

The smith etches a geometry of protection across their faces: zigzags for water, triangles for women and fertility, and circles for the eye that wards off the unseen.

Each incision is a syllable in the desert’s silent script.

Sometimes, these lines form Tifinagh letters or the pattern of a magic square, merging mathematics and prayer.

In every case, the ornament is a boundary between the world of men and the world of spirits.

To wear one is to carry orientation in miniature.

A father may give his son such a pendant at the threshold of manhood, saying, “I leave you the four directions of the world, for no one knows where he will die.”

However, perhaps the tradition is even older — a mother fastening silver to her veil, the point rising toward the sky like an unspoken invocation.

In both cases, the metal becomes a tangible horizon.

These pendants are not mere adornment.

They are mirrors of belonging and exile, wealth and faith, love and survival.

They move between worlds: the human and the divine, the visible and the imagined, the living and the ancestral.

To the Tuareg, silver is purity — the opposite of gold’s greed. It is the metal of reflection and balance.

Silver does not absorb light; it reflects it.

In that return lies its power.

Today, the tanaghilt has traveled far from its origins.

It gleams on postage stamps and government seals, in museum display cases, and in city boutiques.

Some lament this dispersal, while others see it as a continuation.

Even when sold to strangers, each pendant carries the rhythm of its creation: the molten flow, the breaking of the mold, and the cooling desert air.

Every replica, no matter how modern, repeats the gesture of orientation — the will to find one’s way through life’s dunes.

The cross that is not a cross remains what it has always been: a silent compass, a reminder that direction is a form of prayer.

Wearing it acknowledges that the soul, like the desert, has four winds — and all of them lead home.

Kader Tarhanine – Al Gamra Leila

Kader Tarhanine is a highly influential Tuareg singer, guitarist, and songwriter, born in 1989 to Malian parents and raised in Tamanrasset, southern Algeria. He gained rapid fame across the Sahel and Sahara in 2012 with the song Tarhanine Tegla (“My Love is Gone”), which resonated deeply with the Tuareg diaspora and youth everywhere. Kader is renowned for blending traditional Tuareg and Sahel rhythms with modern rock guitar, crafting poetic lyrics in Tamasheq and Arabic. Celebrated as “The Prince of the Desert” and an icon for Tuareg youth, he plays a vital role in evolving modern “desert blues” and is seen as a successor to early Tuareg bands like Tinariwen. His collaborations have promoted unity and peace amid Sahelian and Maghreb crises, and his music bridges traditional Tuareg culture with contemporary global aesthetics.

IMARHAN – Adar Newlan feat. Gruff Rhys

The video for Adar Newlan by Imarhan featuring Gruff Rhys powerfully evokes themes of hardship, camaraderie, memory, and the search for comfort amid difficult desert realities. The title refers to “The Blazing Rocks,” a metaphor for the harsh and sometimes perilous environment faced by Tuareg youth and society in southern Algeria. Gruff Rhys sings in Welsh, merging with Tamasheq verses, which reinforces the message of intercultural unity across the desert and the world—singing for “our heroes” and for “existence under one sky”.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?