TUAREG CROSS OF AGADEZ 2

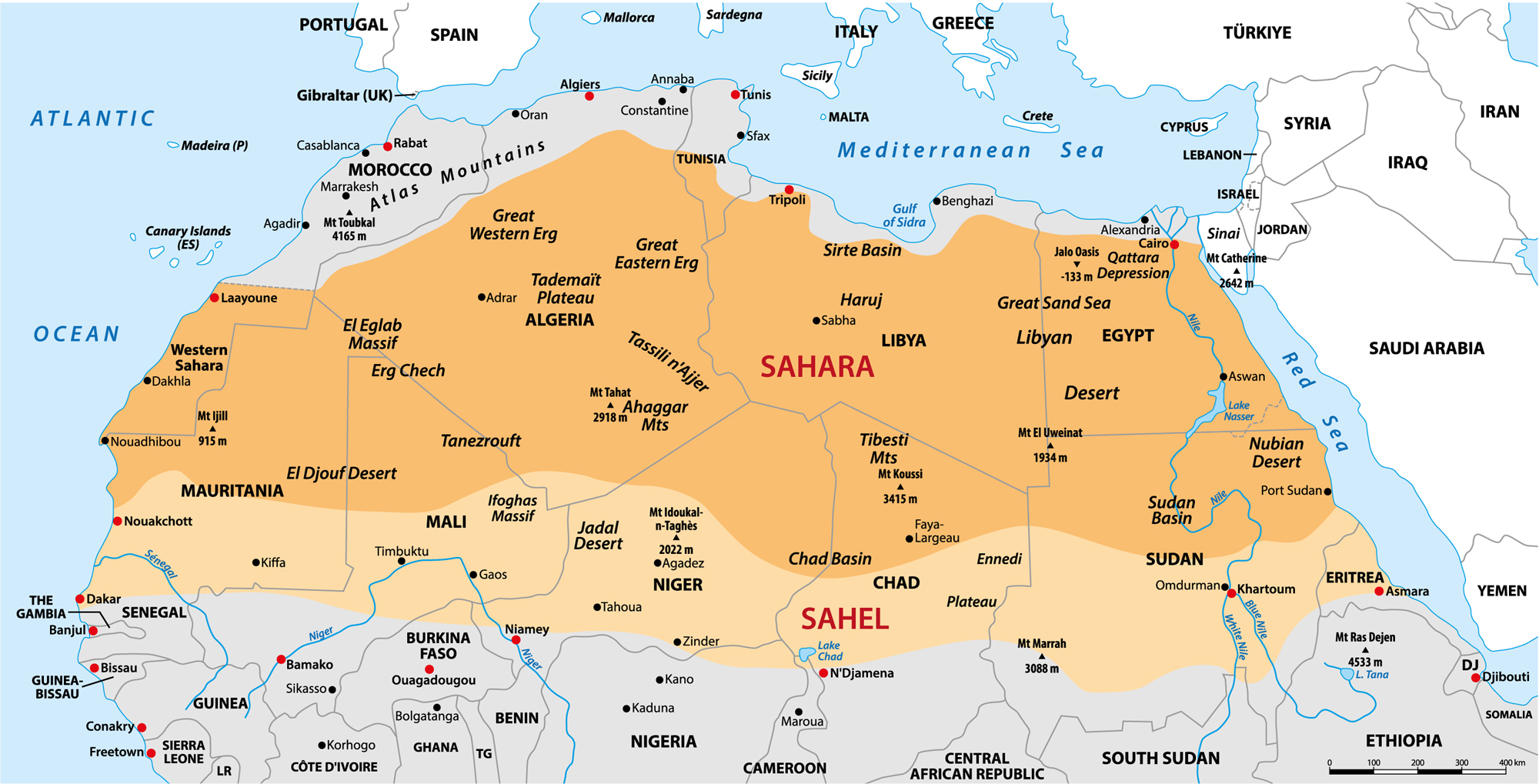

Map of the Sahara desert

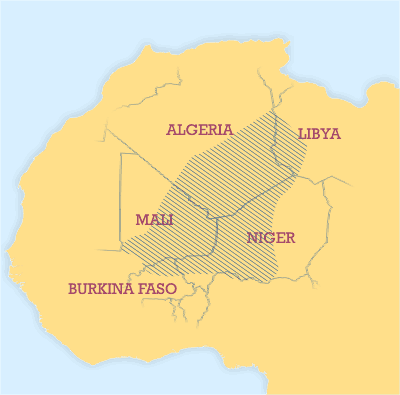

The traditional distribution of the Tuareg in the Sahara

(Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license)

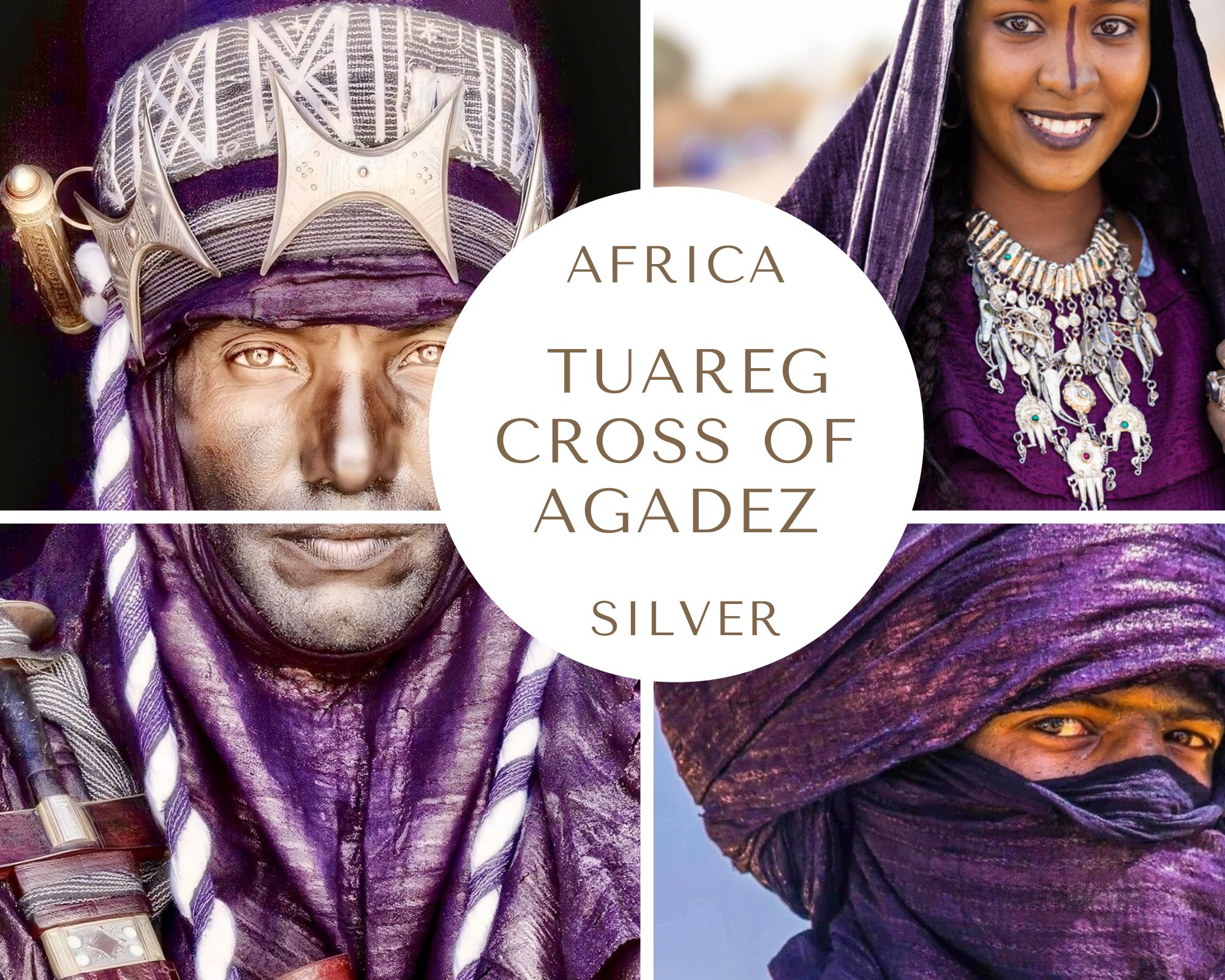

A SONG IN TUAREG BLUE

The Tuareg or Touareg – the latter being a common French variation that may also be encountered in English contexts – are often depicted in popular media and travel literature through a narrow, romanticised stereotype that overlooks their complex history, cultural diversity and contemporary realities. The common cliché portrays them solely as “blue men of the desert,” mysterious nomads living in isolation from modern influences and herding camels. However, this image does not accurately represent the Tuareg peoples today.

Reality Versus Stereotype

The Tuareg have always been dynamic people. They are historically known for their sophisticated oral literature, advanced metalworking, and active participation in trans-Saharan trade networks. Their societies included urban dwellers, agriculturalists, and skilled artisans, not just nomads.

Today, many Tuareg live in cities across Mali, Niger, Algeria, Libya, and Burkina Faso and work in various professions, including teaching, politics, and entrepreneurship.

Their traditions of matrilineal inheritance and unique social structures distinguish them from other Saharan groups and contradict widespread misconceptions about their gender roles and societal organization.

Cultural Diversity and Change

The Tuareg language (Tamasheq and its dialects) remains widely spoken, though Tuareg communities are also fluent in Arabic, Hausa, and French, reflecting their intercultural connections.

While the image of the Tuareg man wearing the tagelmust is a tradition, many Tuareg women also play prominent roles in public and private life, including leadership and property ownership.

Refugee movements, armed conflicts, and environmental changes have profoundly altered Tuareg lifeways in recent decades but have also fostered artistic innovation and political activism.

Les Filles de Illighadad – Tihilele (from Eghass Malan)

Les Filles de Illighadad is a groundbreaking Tuareg all-female band from Niger. The band was founded by Fatou Seidi Ghali in the remote Saharan village of Illighadad. Ghali taught herself to play the guitar using her brother’s instrument and is considered the first Tuareg woman to play the guitar professionally. She broke traditional gender barriers in Tuareg music. The band uniquely combines two musical traditions: ancient women’s tende music, centered on drums made from mortars and pestles, accompanied by collective singing and clapping, and the more recent, male-dominated Tuareg electric guitar tradition. This fusion highlights the forgotten role of tende music as the original inspiration for Tuareg guitar music.

There is something quietly disorienting—perhaps even unsettling—about this song. The music, certainly, but also the cover. Instead of the familiar image of men veiled in tagelmusts against the ochre Saharan dunes, we see three unveiled women against a lush green backdrop. To truly understand the Tuareg, one must move beyond clichés and tidy stereotypes—even well-meaning ones. The desert people do not reveal their truths to those seeking only curated exoticism or the comforts of trend-driven travel. In these cases, they smile, then withdraw.

Tikoubaouine feat. El Dey – Riwaya

Tikoubaouine is an Algerian Tuareg music group formed in 2013. Its members were born to nomadic parents from the Adrar and Salah regions. The group blends traditional Tuareg music with modern elements and instruments. El Dey is an Algerian Arab band that blends diwane (Algerian gnawa) music, chaâbi, and flamenco with jazzy touches.

Historians, archaeologists, and anthropologists have documented the Sahara as a vital bridge linking sub-Saharan Africa and the Maghreb (North Africa), not simply as a barrier. Historically, trans-Saharan trade routes enabled the exchange of goods, ideas, religions—particularly Islam—music, and cultural practices across vast distances. Pastoralists, such as the Tuareg, were essential navigators and traders. They constructed infrastructure and formed networks that connected diverse societies. Key towns, oases, and caravan routes acted as nodes where people from different backgrounds met, traded, and often settled. Thus, the Sahara has long served as a major crossroads for peoples and cultures, facilitating the exchange of trade, language, ideas, and beliefs. This continues to be true, although modern challenges have altered some of these dynamics. Colonial borders fractured traditional patterns, and environmental pressures have intensified. Despite these profound changes, the Sahara remains a place where cultures meet, interact, and influence each other. Tuareg-Arab connections reflect historic and contemporary interdependence.

WHO ARE THE TUAREG?

The Tuareg are not a single tribe, but rather a constellation of ancient, Berber-speaking confederations. Their ancestors learned to survive, and even dominate, the central Sahara. They currently inhabit a vast region spanning parts of present-day Libya, Algeria, Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso. As of 2025, their total population amounts to approximately 4 million.

The name

“Tuareg” is an exonym, namely a term established by outsiders. No Tuareg call themselves by this name. Travelers, locals, orientalists, ethnographers, and historians have given them different ethnonyms, including “blue men” because their blue clothing fades and slightly colors their skin.

The etymology of the word “Tuareg” is debated, but it is widely believed to derive from the Arabic plural Tawariq (in some Arab dialects the q is pronounced as gh). The singular Tariq means “inhabitant of Fezzan,” a region in Libya. The Berber word targa, meaning “drainage channel,” is believed to be the origin of this term. The French colonial transcription transformed Tawariq or Tawarig into Touarick or Touareg. Thus, the modern form Tuareg is a colonial transliteration of an Arabic pronunciation..

The Tuareg generally use terms that mean “free men” or relate to their language and cultural identity to refer to themselves. Key self-designations include:

- Amajagh (or variants Amashegh, Amahagh) for a man and Tamajaq (or variants Tamasheq, Tamahaq) for a woman. These terms reflect the noble freeman caste.

- Imuhar (also written Imuhagh, Imushagh, Imajeghen, Amazigh depending on dialect), meaning “free people” or “noble people.” This is the most common self-designation and is cognate with the Berber Imazighen used farther north.

- Kel Tamasheq, meaning “people of the Tamasheq language” (their Berber language). Variants: Kel Tamajaq or Kel Tamahaq.

- Kel Tagelmust, meaning “people of the veil,” referring to the traditional veil worn by Tuareg men.

- Additionally, some call themselves Kel Ténéré, meaning “people of the desert,” which highlights their nomadic desert culture.

The language

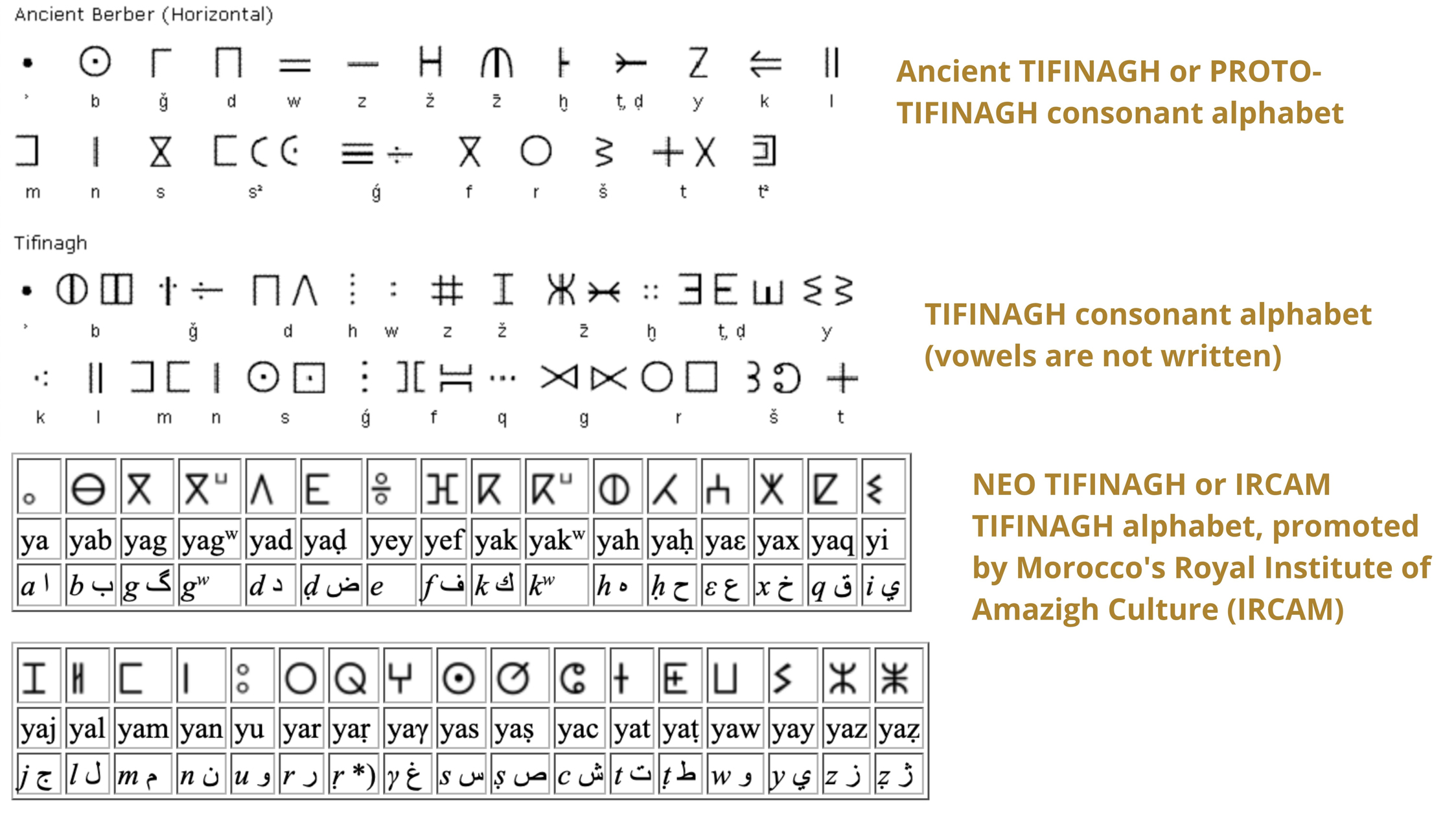

The Tuareg people today speak a group of closely related Berber languages collectively called “Tuareg languages,” “Tamajaq,” “Tamasheq,” or “Tamahaq,” depending on the dialect and region. These languages belong to the Berber branch of the Afroasiatic language family. Traditionally, they were written in the ancient Tifinagh script. However, the latter is now primarily used for cultural and symbolic purposes. Daily writing varies by country: The Latin alphabet is used in Mali and Niger, while Arabic script is used in some Islamic communities.

Tuareg is a macrolanguage consisting of clearly distinct regional varieties:

- Tamahaq (Northern Tuareg): Algeria (Ahaggar/Hoggar), southwestern Libya (Ghat/Ajjer) and northern Niger. Main dialects: Tahaggart (Ahaggar/Hoggar), Ajjer, and Ghat.

- Tamasheq (Mali and Burkina Faso): varieties in Kidal/Adagh (often called Tadghaq), Timbuktu, Gao, Gossi, Gourma; Burkina Faso’s northeast.

- Tamajeq (Niger group): two large lects:

- Tawallammat Tamajaq (a.k.a. Tawellemmet or Iwellemmeden) — Niger and Mali, as well as northern Nigeria.

- Tayart Tamajeq (Aïr / Agadez) — Niger (Aïr massif).

Across regions, Tuareg speakers are commonly bilingual or multilingual in the dominant lingua francas: Songhay varieties along the Niger River in Mali (notably Koyra Chiini and Koyraboro Senni), Hausa in Niger, Bambara in southern and central Mali, and French through schooling and administration.

TARWA N-TINIRI – TARYET

Tarwa N-Tiniri (“Sons of the desert”) are an all-Berber desert blues band from Ouarzazate in Morocco.

ETHNOGENESIS

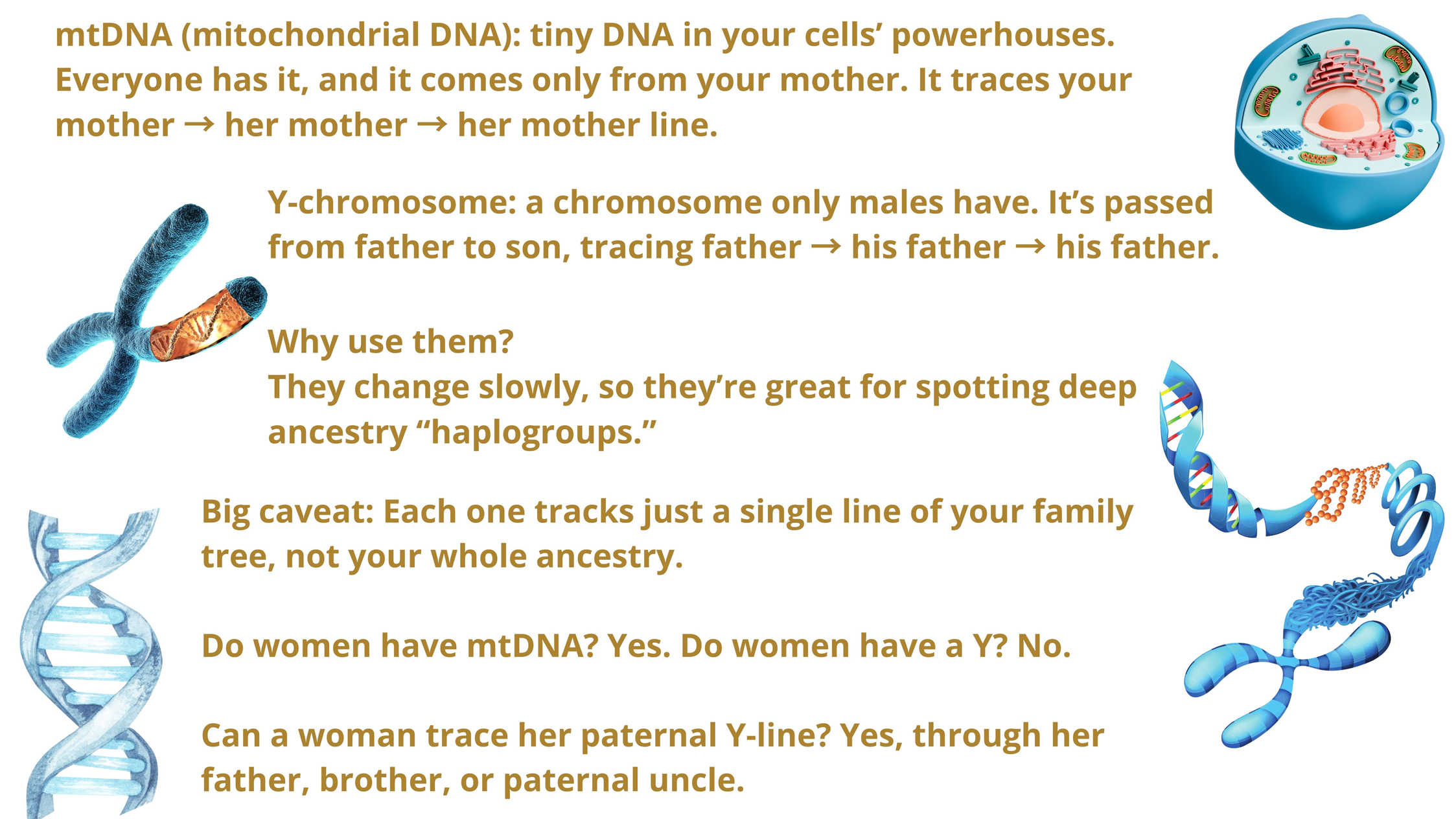

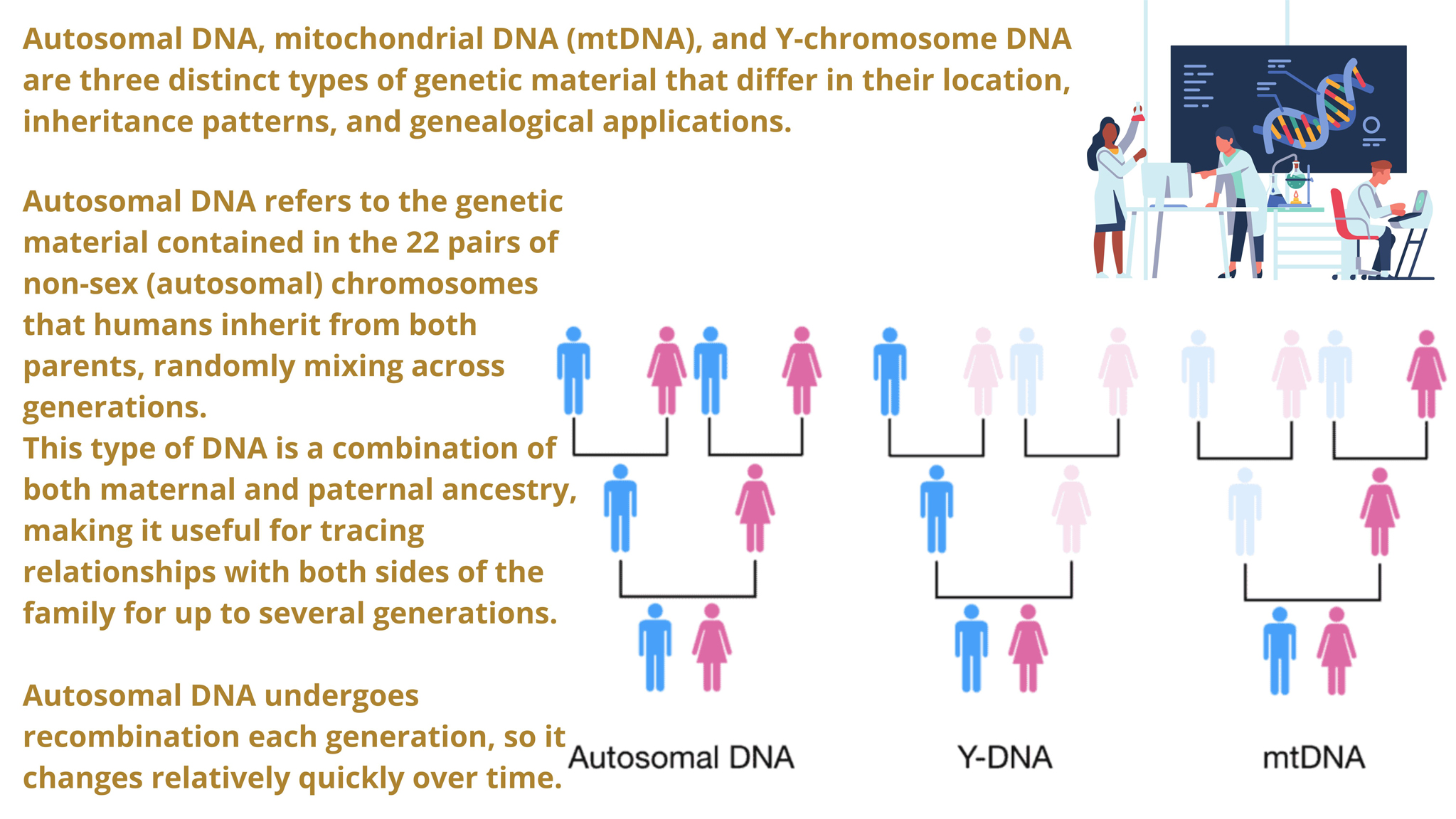

The ethnogenesis of the Tuareg is no longer a matter of guesswork. By combining archaeology, historical linguistics, and—above all—the last fifteen years of mitochondrial DNA, Y-chromosome, and autosomal research, a coherent and datable picture has emerged. The Tuareg are a recently formed nomadic people whose biological roots lie in two distinct Holocene migrations rather than a single “ancient Saharan” population.

Setting the scene

When the first European travelers reached the Central Sahara, they were struck by two things: the indigo veils worn by the men and the fact that the people they met called themselves Imuhar or Kel Tamasheq. The name stuck, but it told the visitors nothing about where these camel-herding aristocrats actually came from. For a long time, people answered the question with romantic guesswork. Perhaps they were the descendants of the Garamantes of Herodotus, a lost legion of Rome, or a wandering tribe of Yemeni Arabs. Only in the last decade or so have ancient skeletons, modern DNA, and improved archaeology come together to tell a coherent story. In short, the Tuareg are a young people—barely three thousand years old—created when two very different Holocene populations were forced into the same shrinking patch of green in the middle of the desert.

The two ancestral streams

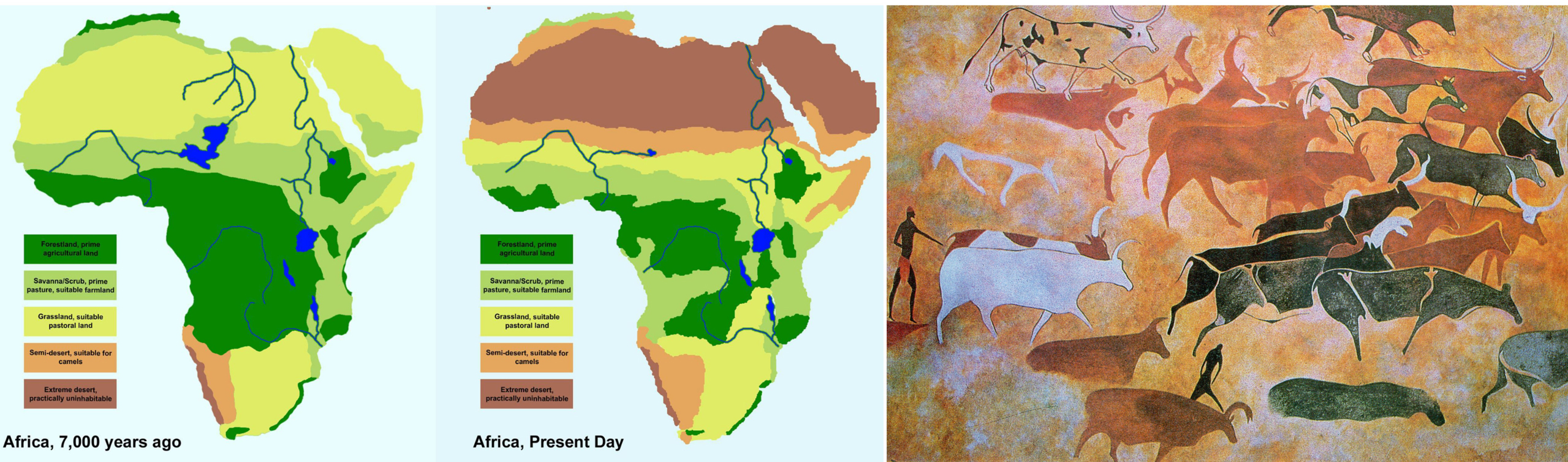

Imagine the Sahara 7,000 years ago, when it was covered in grass and dotted with lakes. Elephants and crocodiles roamed the land. Two distinct groups of pastoralists used this green highway, but they started at opposite ends of the continent.

From the north came herders whose ancestors had taken shelter in the Maghreb during the last Ice Age. Genetically, they are (and were) similar to the ancient Iberomaurusian people who inhabited northwestern Africa 15,000 years ago. Their mitochondrial DNA is dominated by Eurasian lineages, such as H1, V, U6, and M1, while their Y chromosomes belong almost exclusively to the North African branch of haplogroup E (E-M81, also known as E-M183).

From the south came cattle keepers whose ultimate origin lay in the Sahel and the Chad Basin. They carried the sub-Saharan suite of mitochondrial lineages (L2, L3, and L0a) and the Y chromosome marker most often associated with Niger-Congo-speaking populations (E1b1a-M2).

For a long time, these two populations grazed the same grasslands without mixing much. Then the rains failed.

LEFT: Wikimedia Commons maps.

RIGHT: A cave painting from the Tassili n’Ajjer Mountains in Algeria. Public domain.

The Tassili n’Ajjer mountain range and plateau is located in southeastern Algeria and is world-renowned for its extensive collection of prehistoric cave art. It has been designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The tens of thousands of paintings and engravings depict scenes of animals, people, and daily life. These images offer valuable insights into the region’s past climate, animal migrations, and human evolution when the current desert was fertile land.

BELOW: An AI generated image.

The great squeeze

Between 5,500 and 3,000 years ago, the Sahara dried out astonishingly quickly. Lakes shrank into salt pans, and grass turned into dunes. Northern and southern herders alike were funneled toward the few places where water still surfaced: the Hoggar and Tassili massifs in southern Algeria, the Tibesti in northern Chad, the Acacus in southwestern Libya, and the Aïr Mountains in northern Niger. There, the two groups finally met, married, and—crucially—started to speak the same language. This language was an early form of Berber, brought by the northerners. However, the mixed population that adopted it was no longer simply “Berber” in the biological sense. The meeting point had become a genetic crucible.

Founder effects and tribal isolation

Since Tuareg tribes are expected to marry within their own tribes, the new hybrid population quickly split into a patchwork of small, tightly knit gene pools. This is visible in their DNA: within any one tribe, diversity is low (everyone is a cousin to everyone else), but between tribes, the differences are unusually large. The most striking example is in Fezzan, Libya, where 90% of the local Tuareg’s mitochondrial lineages belong to a single variant of haplogroup H1. Such a skewed profile is the hallmark of repeated founder events—small groups breaking away and carrying only a fraction of the mother population’s genes.

The Garamantian hinge

Archaeologists have long suspected that the Garamantes, literate chariot-driving people who controlled the Libyan Fezzan from around 1000 BCE to 500 CE, were closely related to the Tuareg. Ancient DNA now proves the link. Mitochondrial sequences extracted from Garamantian skeletons match those of modern Libyan Tuareg at a level that leaves little room for coincidence. The same is true for the Y-chromosome marker E-M81. In other words, the Garamantes are not an exotic sideshow—they are the northern, West Eurasian half of the Tuareg story preserved in the archaeological record.

Moving south and mixing again

After the camel replaced the horse and chariot sometime between 200 BCE and 200 CE, the descendants of the Garamantian herders were able to push southwest into what is now Mali and Niger. There, they encountered populations with even higher fractions of sub-Saharan ancestry. Intermarriage was common, especially with Songhay and Mande speakers. A second pulse of African lineages entered the Tuareg gene pool. The trans-Saharan slave trade of the medieval and early modern periods added a third, socially stratified layer. Many of the servile clans, known in Berber as īklān, have West African mitochondrial lineages that, according to the molecular clock, date back between 1,900 and 200 years.

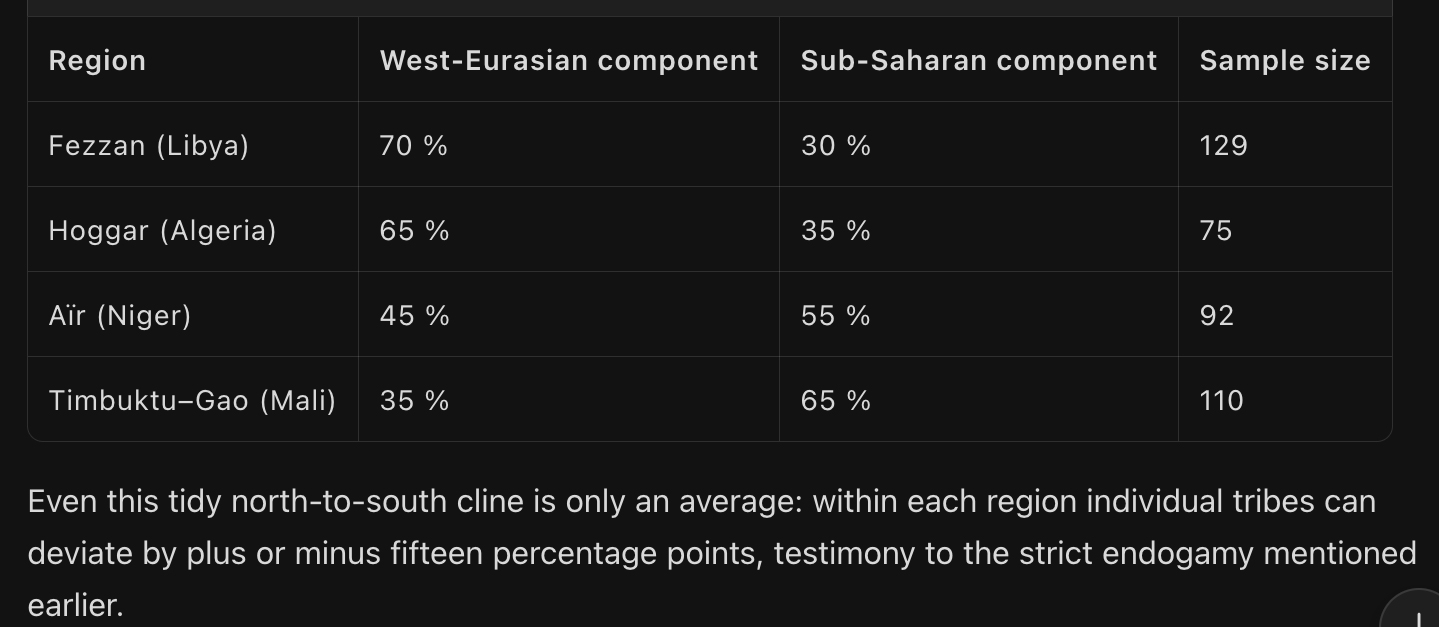

Putting the numbers in one table

The table below summarizes the average proportions of the two major ancestral components found in Tuareg living at different latitudes. The percentages are rounded from autosomal studies published between 2010 and 2022.

Studies of autosomal DNA depict the Tuareg gene pool as a combination of indigenous North African (Taforalt), Middle Eastern, European, and sub-Saharan African ancestries. Some Tuareg groups are considerably isolated, which leads to genetic drift and reduced diversity in certain populations, notably the Libyan Tuareg. Overall, Tuaregs are genetically distinct, showing the closest affinities to other Afroasiatic-speaking groups, such as the Beja in eastern Sudan, as well as to other Berber groups.

Language followed the genes, albeit with a delay

The mixed population that emerged from the Holocene squeeze spoke an early form of Berber; however, the language itself is clearly rooted in the northern strand. The Tuareg language preserves archaic features, such as the consonant h in words like amahan (water), which have disappeared further north. However, its basic vocabulary and grammar are unmistakably Maghrebi Berber. In other words, the southern pastoralists gave their genes to the new people but adopted the northerners’ language. The result is a linguistic paradox: the most conservative Berber dialects are spoken today by a population that is genetically only half North African.

So who are the Tuareg?

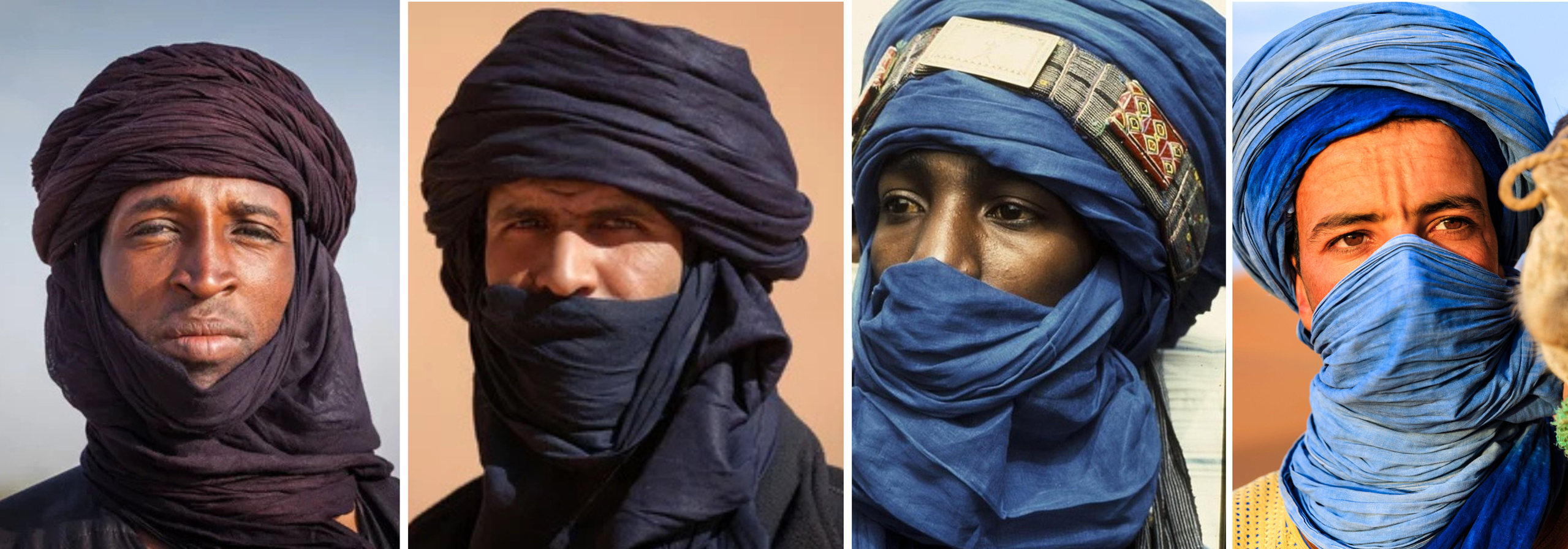

They are neither a primordial Saharan ethnic group nor simply “Berbers who wandered south.” They are a recently formed bridge population stitched together in the central Sahara when two long-separated groups of people were forced into the same refuge. Their culture—including matrilineal clans, men wearing veils, the Tifinagh script, and camel caravans—was forged in that crucible and later exported westward. Their genes still bear the mark of this event, displaying a cline that extends from the blue-eyed, Eurasian-leaning tribes of the Libyan Fezzan to the dark-skinned, predominantly African clans of northern Mali. In other words, the Tuareg are a living record of the Sahara’s last great climate crisis; their ancestry and language were both shaped by the sandstorm of Holocene climate change.

BELOW, LEFT TO RIGHT

Tuareg man, Ingall, Niger.

Tuareg Man, Djanet, Algeria.

Touareg between Tombouctou and Gao, Mali. Photo by Georges Courreges.

Tuareg cameleer, Lybia. Photo Canva Pro.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Tuareg man, Niger. Pinterest.

Tuareg Man, Lybia. Reddit.

Tuareg man with his daughter near Menaka, in the south of northern Mali, 2006. Photo by Emilia Tjernström – Flickr.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Tuareg woman, Algeria. Photo by Inger Vandyke – Instagram.

Tuareg woman, Lybia. Facebook.

Tuareg woman, Algeria. Pinterest.

Tuareg woman, probably Niger. Pinterest.

Imarhan – Id Islegh (with english translation)

ACROSS THE DUNES OF HISTORY

Academic, ethnographic and linguistic evidence suggests that the Tuareg are an ancient, Berber-rooted and cosmopolitan Saharan people. Their confederations formed through the gradual blending of indigenous North African, Saharan and trans-Saharan influences over many centuries.

Historically, Tuareg society was organised into regional confederations (tamenokalat) across the central Sahara and Sahel. These confederations were led by an amenokal (paramount chief) and were structured through systems of clientage and social hierarchy. These political entities linked pastoral nomadism and caravan commerce to oasis economies and Islamic scholarship.

These confederations evolved from earlier groupings, such as the Ihaggaren (northern Tuareg, mainly in the Ahaggar Massif) and the Tademekkat (southern, or ‘Sudanese’, Tuareg of the Adrar des Iforas), reflecting centuries of internal migration, ecological adaptation and inter-tribal conflict.

The principal confederations most often identified by scholars include:

- Kel Ahaggar (Hoggar) – Central Sahara (today southern Algeria).

- Kel Ajjer (Ajjer) – Fezzan fringe from Ghat–Djanet (southeastern Algeria, southwestern Libya).

- Kel Adagh (Ifoghas) – Adagh des Ifoghas (Kidal, northern Mali).

- Kel Aïr (Kel Ayr) – Aïr Massif (Agadez, northern Niger), including Kel Owey and Kel Gress

- Iwellemmedan (Iullemmeden) – Straddling Mali and Niger, later dividing into Iwellemmedan Kel Ataram (western) and Iwellemmedan Kel Dinnik (eastern).

- Other important groupings included Kel Tademekkat (Azawad/Niger Bend) and smaller sub-federations within these broader alliances.

These confederations functioned as political and military coalitions rather than fixed ethnic tribes. Their composition could change over time, shaped by kinship ties, strategic alliances, and the ebb and flow of trade and conflict.

Formation and Early Records

Historical and Arabic documentary sources—such as the Tarikh al-Sudan and Tarikh al-Fattash— record Tuareg entities by the 16th–17th centuries. These sources mention the Iwellemmedan and the Kel Ayr in particular, who were in contact with the Songhay and Hausa polities.

By the 15th century, Tuareg federations in the Aïr region were intertwined with the Sultanate of Agadez, producing a unique hybrid system that fused Islamic administration with Tuareg confederational structures.

In the Hoggar and Ajjer regions, Tuareg coalitions formed between the late medieval and early modern periods. They gained wealth and influence by controlling caravan routes, levying tolls, and maintaining alliances with clerical lineages and oasis communities.

Tuareg society was organized into distinct strata:

- Imajeghen (nobility and warrior elites)

- Ineslemen (Islamic clerics and scholars)

- Imghad (vassal pastoralists)

- Inaden (artisans and smiths)

- Iklan (formerly servile communities).

Though internally stratified, the Tuareg confederations shared a coherent cultural and linguistic identity rooted in the Tamasheq, Tamahaq, and Tamajaq dialects, which belong to the Berber (Amazigh) language family.

Migration, Adaptation, and Identity

Even before the colonial period, the Tuareg maintained their independence by being mobile, engaging in trade, and adapting to their environment. Their camel-based pastoralism and control of trans-Saharan trade routes (including salt, gold, slaves, dates, and textiles) enabled them to mediate exchanges between the Mediterranean, Sahel, and sub-Saharan regions.

External pressures from Ottoman, Moroccan, and later European influences gradually reshaped the Sahara’s balance of power, but Tuareg confederations remained semi-autonomous until the late 19th century.

Their transnational identity, rooted in language, custom, and oral tradition, has endured across changing borders, reaffirming a shared desert heritage that transcends modern states.

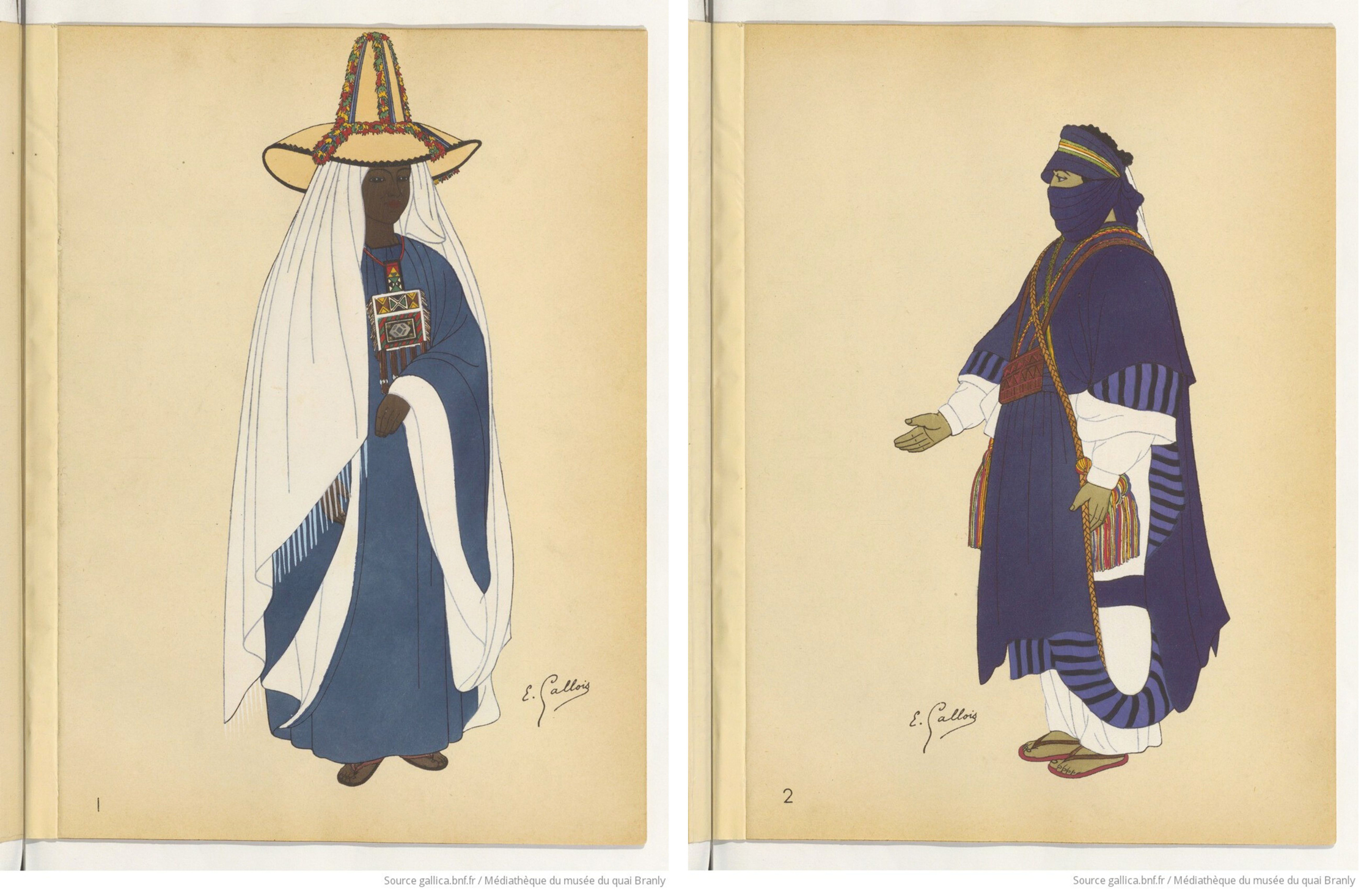

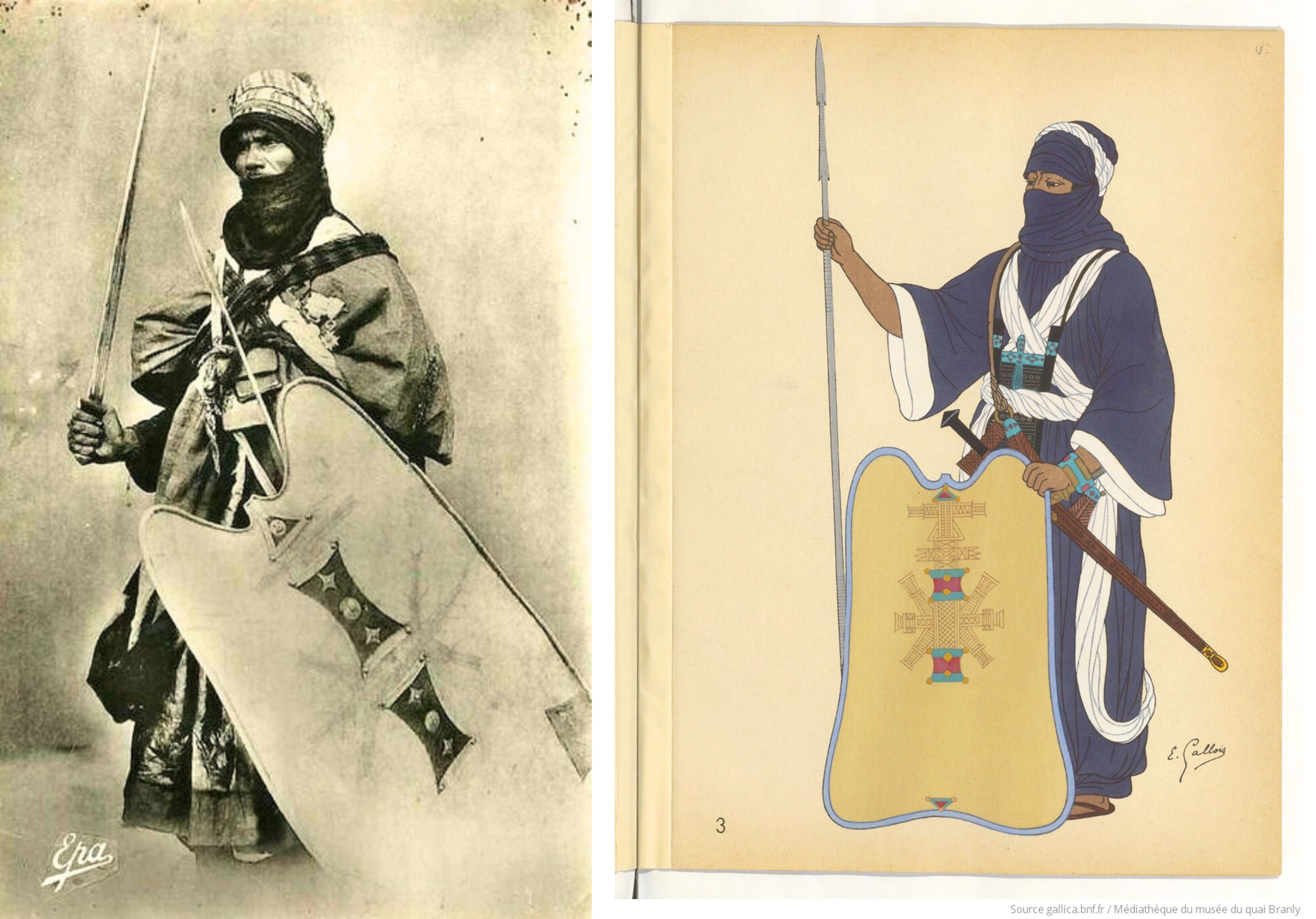

Femme Touarègue de Tombouctou et Touareg du Hoggar, Costumes de l’Union française par Emile Gallois; préface de Marcel Griaule, 1946. Source: Médiathèque du Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, France.

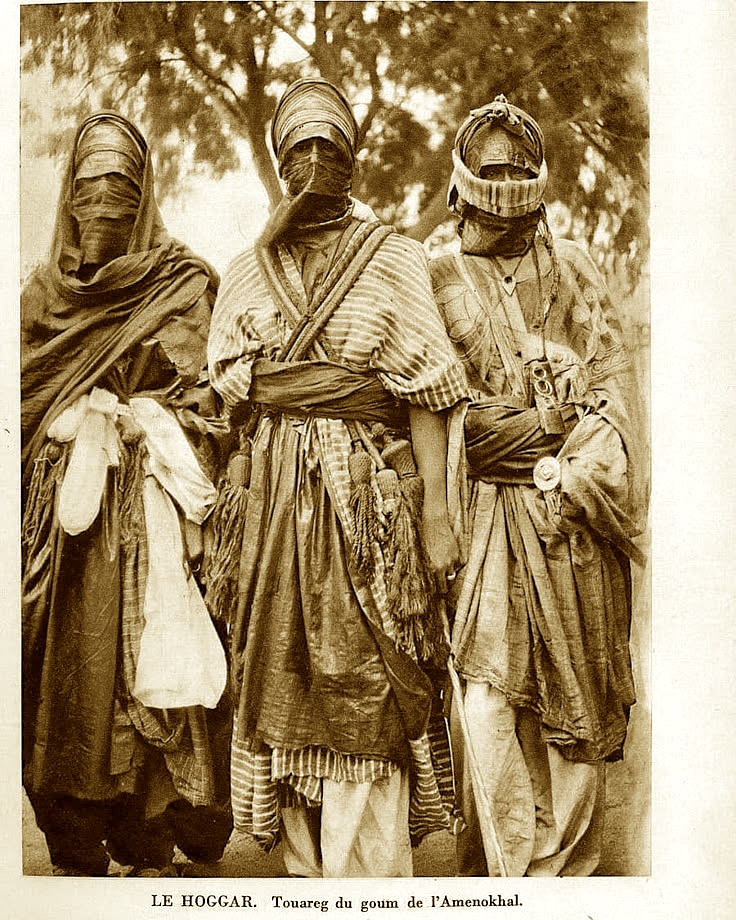

Old photo of Tuareg from the Hoggar (Algeria). France.

LEFT: an old French photo of a Tuareg warrior. Epa Images, France.

RIGHT: Guerrier Touareg, Costumes de l’Union française par Emile Gallois; préface de Marcel Griaule, 1946. Source: Médiathèque du Musée du Quai Branly, Paris, France.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Tuareg shield from Kel Ayr. Date: late 19th–early 20th century. Medium: Hide, metal, and4cloth. Dimensions: 51 x 30 in. (129.5 x 76.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York, USA.

2. Tuareg shield from Algeria. Date: late 19th century. Medium: antelope hide, wood, cloth, metal, and pigments. Dimensions: 44 3/16 × 28 × 6 5/8 in. (112.24 × 71.12 × 16.83 cm). Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota, USA. “This light-colored shield, made of antelope skin in the 1800s, belonged to a Tuareg aristocratic warrior. (…) The incised cross motif in the center may be an invocation in the Tuareg script that empowers the shield to protect its owner against the evil eye and the weapons of his enemies. The dark-colored shield is also made of hide, but from the hippopotamus. Owned by a Nuer cattle herder from the Republic of South Sudan, it has an asymmetrical surface decoration of bumps that mimics the scarification patterns the Nuer used on their bodies and faces”. (MIA curators).

3. Tuareg shield from the Algerian Sahara made of antelope skin with a design of red, black, green, and brown leather appliqués and an incised design with six metal disks down the center. Medium: Animal skin, leather, wool, wood, pigment, scimitar-horned oryx (Oryx dammah) skin, cotton, iron alloy. Dimensions: 119.38 × 71.12 × 12.7 cm (47 × 28 × 5 in.). The Peabody Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA.

4. Tuareg shield from Niger. Leather shield embellished with metal pieces. Dimensions: 42 x 30 in. (106.68 x 76.2 cm). Hamill Gallery of African Art, USA. Photo © Tim Hamill.

The Tuareg Shield (agher)

Among the Tuareg of the central Sahara, the shield (agher) was more than just a slab of hide. It was a portable declaration of identity, theology, and ecological ingenuity. Most surviving examples were collected by ethnographers between 1910 and 1930, yet the objects themselves speak of a technology refined over at least a millennium.

The choice of material was the first meaningful act. The preferred hide did not come from cattle, but from the desert oryx, an antelope whose flesh is halal, yet so scarce that its skin became a symbol of endurance. Once stretched in the sun, the hide shrinks to a density capable of withstanding a saber point yet remains light enough to be carried on a camel’s saddle without disturbing the animal’s gait. A single oryx yields only one shield face, so the hunter who brought the animal down entered the workshop already wrapped in the prestige that the finished object would later broadcast on his behalf.

The shield is cut into an elongated oval, almost the height of a man’s torso but only two-thirds as wide. This proportion forces the bearer to fight laterally, edge-on to the enemy. This stance minimizes exposure in the open desert. Around the perimeter, a rawhide cord sewn through a series of slits is drawn taut to create a shallow gutter that stiffens the entire surface and catches the initial slash of an opponent’s sword. Across the face, the same cord is laced in radiating segments, forming a snowflake or starburst pattern that is both engineering and invocation. Tuareg informants disagree on whether the motif represents Izez, the war god who “slaughters the foe,” or a schematic eye meant to deflect the evil gaze. However, they all agree that the pattern must be incised while the hide is still damp so that the spirit of the animal is stitched into its defense, not merely painted.

A wooden spindle, usually made of acacia, is inserted vertically just off-center. It acts as both a grip and a shock absorber. The left hand passes through a braided leather loop two-thirds of the way up the spindle. This leaves the thumb free to steady the camel saddle hook when the shield is hung. Since the shield is too large to be “wielded” in the European sense, Tuareg swordplay relies on a static guard. The left arm locks the shield at an angle while the right shoulder snaps the takouba sabre forward in a flicking cut. Thus, the shield becomes less of a moving wall and more of a calibrated screen, buying the split second needed for the riposte.

Although its use on the battlefield had largely ceased by 1900, the shield continued to circulate in funerary dances and bride-price negotiations. The 1913 Pitt Rivers specimen has ochre handprints on its inner face, likely those of the warrior’s wives. Each print is a vow that the shield will return intact, as will the marriage alliance it symbolizes. A second example, in Minneapolis, shows minute tin tags nailed through the starburst. These are not repairs, but rather counter-gifts from a client clan. Each tag is a reminder of a favor owed, turning the shield into a ledger of social debt.

Thus, the Tuareg shield can be read as a biography of the oryx that died, the hands that scraped and stitched, the star that summoned or deflected violence, and the debts and marriages it witnessed. Though it was once carried across dunes and is now displayed on museum walls, the shield still performs its oldest function: making absence present and turning the fragility of flesh into the continuity of story.

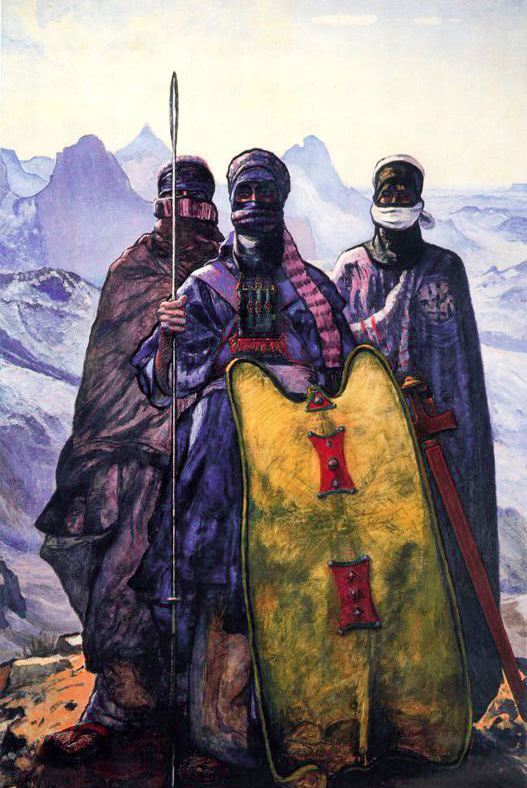

Paul Élie Dubois, Guerriers Touaregs.

Paul Élie Dubois (1886–1949) was a French Orientalist painter who is best known for his evocative depictions of North African life, particularly that of the Tuareg people in the Hoggar region of Algeria. He studied at the Académie Julian and the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, earning numerous accolades before finding his artistic calling in Algeria. In 1928, his career took a pivotal turn when he joined a scientific expedition to explore the Hoggar Mountains. This experience brought him into close contact with Tuareg communities, leading him to be celebrated as “the painter of Hoggar.” His paintings and illustrations vividly capture daily life, landscapes, and ceremonial aspects of Tuareg society. He is particularly noted for his portraits of Tuareg men and women in full regalia and for his large compositions featuring camel riders, market scenes, and desert encampments. His style combines ethnographic documentation with a lyrical use of light and color, influenced by his self-described “revelation of light” in Algeria.

Tuareg Sword & Shield Fighting. Video from the 1920s.

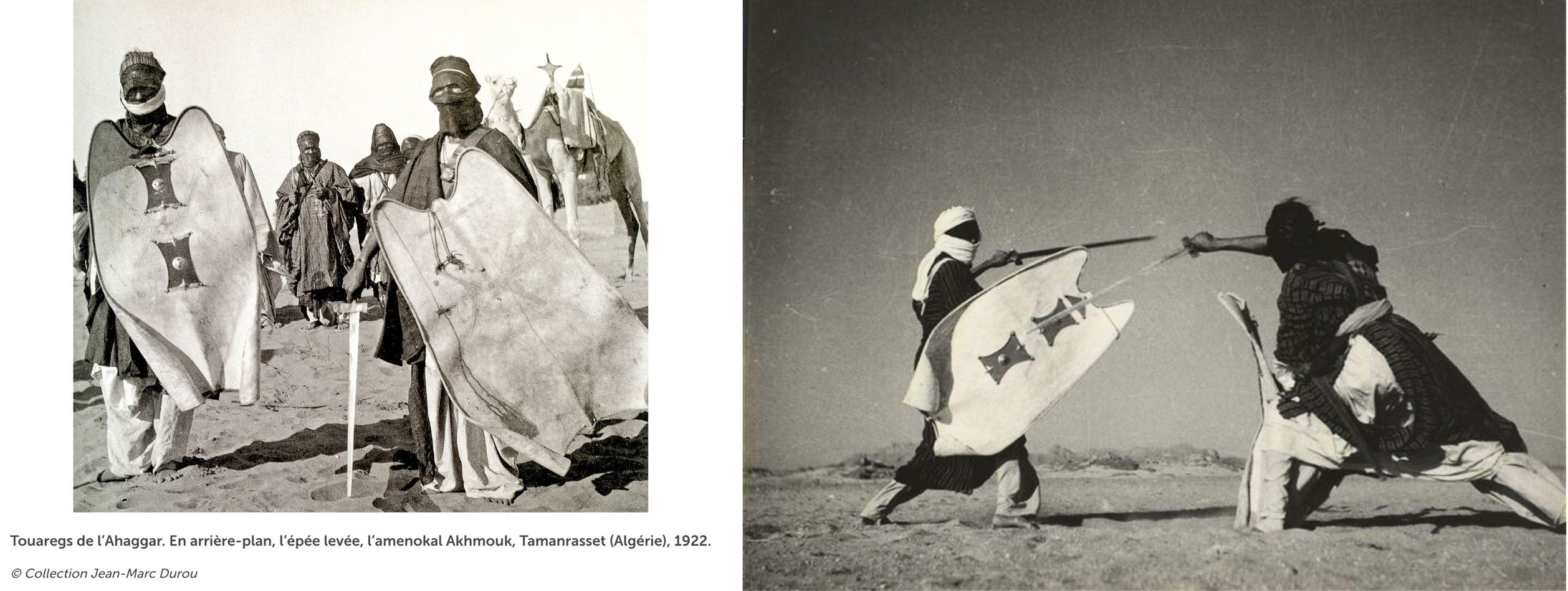

LEFT: Hoggar Tuareg warriors. In the background, sword raised, the amenokal Akhmouk, Tamanrasset (Algeria), 1922. © Jean-Marc Durou Collection.

RIGHT: Sword fighting between Tuareg warriors, ca. 1930, in Algeria.

The Tuareg Sword

Known as the takouba, the Tuareg sword is one of the most distinctive weapons of the Sahara. It serves as both a weapon of war and a symbol of noble identity among the Tuareg, Hausa, and Fulani peoples. It belongs to the long Saharan tradition of straight-bladed swords and embodies centuries of craftsmanship and cultural significance.

The takouba typically measures between 80 and 100 cm in length. Its straight, double-edged blade tapers gently and often has a rounded or pointed tip. Some blades are marked by fuller grooves, which are long, shallow channels ground into the metal to make the blade lighter and more flexible. This versatile weapon was suitable for both slashing and thrusting, reflecting the needs of cavalry and close combat. While many blades were locally made, prized examples often reused imported European steel, particularly older blades from Solingen or Toledo that were traded across the Sahara.

The Tuareg Inaden caste of blacksmiths, who are specialists in forging and ornamentation, traditionally created the sword’s metalwork. The Tuareg have a traditional aversion to touching bare iron, which partly explains the hilt and guard, which are fully covered in leather. The wide, flat crossguard is made of brass, iron, or sometimes copper, and the large, circular or polygonal pommel is often made from the same metals. The grip, wrapped in leather or cord, ensures the wielder’s hand never touches the iron beneath. Decorative versions might include silver plaques, engraved patterns, and tooled geometric designs that resemble Tuareg jewelry.

The takouba’s scabbard is as distinctive as its blade. Typically made of wood covered in dyed and tooled leather, the scabbard is carried suspended from a baldric across the shoulder. Wealthier owners commissioned scabbards with brass or silver embellishments and red and green dyes. Each motif expressed social rank and protective symbolism. The leatherwork is often done by Tuareg women or mixed-gender artisans, which highlights the deep integration of different crafts in Tuareg society.

While the takouba was primarily a weapon of war, it also functioned as a status symbol and ritual object. Among the Tuareg imúšaɣ warrior class, the sword conveyed lineage and prestige. It often appeared in rites of passage and ceremonial parades. Some communities extended its use to symbolic functions, such as gift exchanges and wedding rituals, where it expressed alliances, protection, and authority. Ownership of a takouba implied social power, and its craftsmanship reflected individual wealth and collective heritage.

LEFT TO RIGHT

1. Tuareg young man from Niger. Photo by © Mario Gerth.

2. An unusually luxurious Takouba hilt, mounted in silver with contrasting copper trim, which is reportedly characteristic of work from Agadez, Niger. The condition of the leather and silverwork on the hilt and scabbard suggests that the work is recent. Since the blade shows signs of age and use, it has likely been remounted.

3. A Tuareg takouba sword that is very finely crafted with inset semiprecious stones and fine metalwork embellishments throughout the sword and detailed leather scabbard. The sword in the sheath is 39 in. long (99 cm). Auctioned in 2025 by Tribal Gatherings, Quakertown, PA, USA.

4. Tuareg Takouba sword. Overall length 37 in. (94 cm). Auctioned in 2024 by Merrill’s Auctioneers & AppraisersWilliston, VT, USA.

5. Tuareg Takouba sword with a leather and brass sheath. The blade has markings. Overall length: 40 in.; 101.6 cm. Blade length: 34 in.; 86.36 cm. Handle length: 6 in.; 15.24 cm. From the early 20th century. Auctioned in 2018 by Cowan’s Auctions, Cincinnati, OH, USA.

The Tuareg warrior caste

The warrior caste, known as the Imajaghan or Imuhagh, formed the military and aristocratic elite of traditional Tuareg society. Their importance was not only martial but deeply social, spiritual, and symbolic. In the harsh environment of the Sahara, where survival depended on mobility, protection, and control of trade routes, the warrior nobility embodied the ideals of honor, autonomy, and ancestral continuity.

Traditionally, Tuareg society was hierarchical and feudal, divided into castes that determined roles, rights, and status. At the top were the Imajaghan, the noble warrior class. They monopolized ownership of camels, the key to desert mobility, and were the only ones permitted to carry weapons, such as takoubas and aghers. This monopoly on arms and camels gave the Imajaghan military and economic dominance. Below the Imajaghan were the Imghad (vassal herders), the Ineslemen (clerics), the Inaden (blacksmiths and artisans), and the Iklan (the servile class and former slaves).

The Imajaghan were not merely fighters; they were also the tribe’s protectors, custodians of oral history, and symbols of Tuareg identity. Their status was hereditary, and they married exclusively within their caste to preserve bloodlines and honor. The amănokal or amenokal, the supreme chief, was elected from among the nobles and held special authority during wartime, commanding tribute and loyalty from vassal tribes.

The takouba sword and the agher shield were more than tools of war; they were extensions of the warrior’s identity. The takouba, often adorned with brass and engravings, symbolized status, courage, and ancestral legacy. Used in combat and ceremonies, possession of a takouba marked a man’s entry into the warrior class. The agher, made of antelope hide and large enough to cover the body, was both practical and symbolic, representing not just physical defense, but cultural defense as well.

The Inaden, a caste of blacksmiths, crafted weapons. Though they were lower in status, they were essential to the warrior elite. The creation of a sword was a spiritual act imbued with rituals and symbolism. The takouba was often passed down through generations, carrying the stories and honor of its wielders.

Before the colonial era, the geography of the Sahara and the politics of trans-Saharan trade shaped Tuareg warfare. They were renowned raiders who controlled key oases and caravan routes. Raiding (ghazw) served as a means of economic redistribution, political assertion, and social mobility, not merely plunder. Caravans carrying gold, salt, and slaves were frequent targets, and controlling these routes brought wealth and prestige.

Battles were often swift and strategic, involving spears hurled from camelback, followed by close combat with swords. The Tuareg’s mastery of the desert terrain gave them a tactical advantage. Their warfare emphasized honor, bravery, and individual prowess. Initially, they rejected firearms, seeing them as dishonorable—”a weapon with which a woman can kill the bravest man,” as a French general noted in 1859.

Internal conflicts arose between confederations and tribes over resources, trade rights, and honor. The Tuareg were never a unified nation, but rather a collection of tribal confederations, including the Kel Ahaggar, Kel Ajjer, and Kel Aïr. These groups sometimes allied and sometimes clashed, but they all recognized the authority of the Imajaghan in matters of war and leadership.

The Decline of the Warrior Monopoly

By the late medieval period, the nobility’s monopoly on warfare began to erode. Prolonged conflicts and demographic pressures resulted in the arming of vassal tribes, which began playing a larger role in military campaigns. By the early 20th century, colonial conquest had further disrupted the traditional structure. The French, seeking to control the Sahara, defeated Tuareg forces and dismantled their hierarchical society. This stripped the warrior elite of their military and political power.

The chronic fragmentation of the Tuareg tribes was one of the main reasons they were unable to present a single, coordinated front against the French advancing from the west and south or the Italians pushing in from Libya. Each confederation negotiated or fought separately. Some even tried to play one European power off against the other. Because no supra-tribal authority existed beyond the loose prestige of a given amenokal, the French could sign “protection” treaties with each tribe individually, then turn their rifles on the next group. The Italians used the same method in the Fezzan and along the Aïr–Tripoli caravan corridor. In short, the same political fragmentation that allowed desert raiding to work in their favor internally became a fatal liability once the imperial powers brought repeating rifles, camel columns, and coordinated logistics to the Sahara.

Tuareg Warrior from present-day Algeria. Pinterest.

TUAREG HISTORY IN THE COLONIAL PERIOD (1880s–1960s)

The 20th century was a period of profound transformation for the Tuareg. It was marked by colonial conquest, the imposition of nation-state borders, and a series of rebellions that reshaped tribal identities and alliances. Although the Tuareg have traditionally formed confederations rather than fixed, lineage-based “tribes,” the 20th century witnessed the reconfiguration, politicization, and, in some instances, the emergence of new tribal identities in response to colonial and postcolonial pressures.

Background: French Expansion into the Sahara

After conquering the northern Algerian “Tell” region from 1830 to 1870, France’s colonial administration began extending southward through the 19th century. The Tuareg, particularly the Kel Ahaggar, Kel Ajjer, Kel Aïr, and Iwellemmedan, dominated extensive desert trade routes spanning modern-day Algeria, Niger, and Libya. French ambitions aimed to convert these nominally independent or Ottoman-influenced zones into colonial possessions.

Algerian Sahara: Kel Ahaggar and Kel Ajjer

France gradually expanded into the Algerian Sahara by exploiting divisions among Tuareg factions, forming alliances with certain tribes, and launching punitive military campaigns against others. A critical turning point came with the Battle of Tit (7 May 1902):

- French “meharist” camel-mounted units, led by Lt. Cottenest, set out from In Salah and fought the Kel Ahaggar near Tit. The French employed scorched-earth tactics, destroying villages and crops, which broke local resistance.

- After defeating the Kel Ahaggar, Paris formalized its administration of the southern Sahara on December 24, 1902, creating the “Territoires du Sud” under army rule. The amenokal, Moussa ag Amastan, soon operated almost as a protectorate chief from Tamanrasset, negotiating directly with the French.

While this phase established military dominance in the Ahaggar region, it also relied on co-opting some Tuareg leaders and systematically fragmenting their hold over the territory.

Aïr and Agadez: Kel Aïr and Iwellemmedan

The French advanced more slowly and insecurely into the Nigerien Sahara. Rather than seeking outright conquest, the colonists built forts, demanded tribute, and courted oasis notables.

- Tuareg resistance persisted into World War I, culminating in the Kaocen Revolt (1916–1917). Ag Mohammed Wau Teguidda Kaocen, the amenokal of the Ikazkazan (Kel Owey), led a militant anti-French uprising. Backed by the Sanusi Sufi order from Libya, his forces besieged Agadez and seized major Aïr towns for several months.

- French columns eventually crushed the revolt, massacring Tuareg warriors and camels and devastating local livelihoods. Kaocen fled and was later captured and executed in Murzuq.

The aftermath saw tighter French control and the displacement of more Tuareg leaders. Border enforcement and state-building replaced tribal autonomy.

Ajjer and Fezzan: Southwest Libya and Southeast Algeria

In the Ajjer and Fezzan regions, the Tuareg’s local governance and traditions were deeply influenced by their longstanding ties to the Ottoman Empire and the Senussi religious brotherhood. These groups were important spiritual and political authorities in southern Libya and southeastern Algeria. The Ottoman administration interacted with Tuareg leaders through indirect rule and negotiated alliances, especially in oasis towns such as Ghat. These towns were key nodes in trans-Saharan caravan networks.

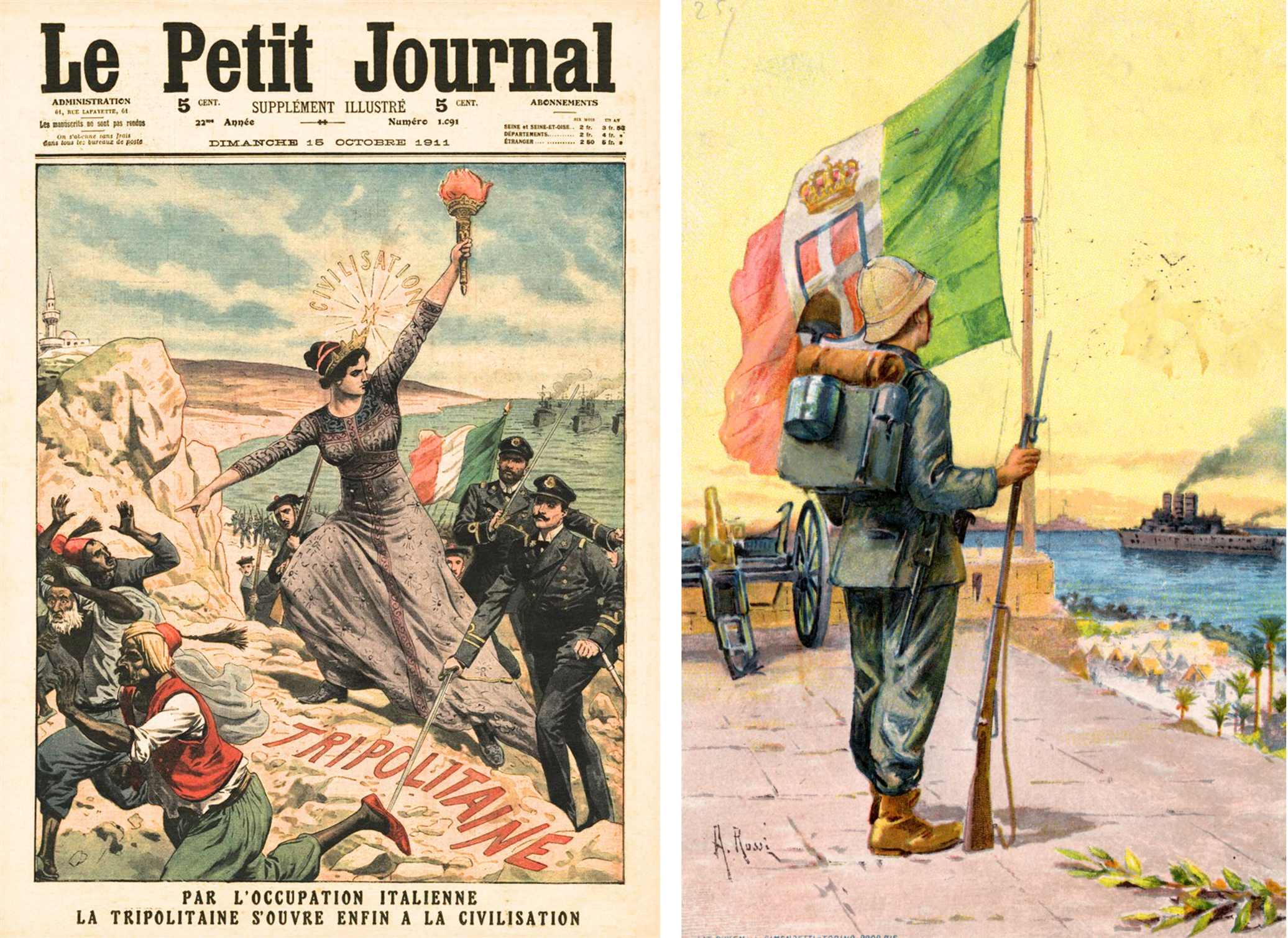

The situation became dramatically more complex after the Italo-Turkish War of 1911, when Italy seized control of Libya from the Ottomans. Italian colonization intensified state intervention. Authorities imposed new borders, built military outposts, and enforced taxation and surveillance on Tuareg camel caravans. These measures disrupted centuries-old trade routes connecting West Africa and the Mediterranean, severely impacting the economy in Fezzan and neighboring regions.

Meanwhile, the rise of the Senussi order united desert tribes—including many Tuareg—in religious and sometimes military resistance to the colonial presence. The Italians attempted to co-opt or repress these local communities, sometimes granting limited autonomy to chiefs while launching harsh “pacification” campaigns that led to population displacement, punitive expeditions, and the destruction of villages.

Conclusion

Throughout the early 20th century, European colonial powers struggled to “fix” nomadic Tuareg societies within static boundaries enforced by new administrations. The forced mapping and division of territories by the Italians and French, and later by the emerging nation-state under Gaddafi and other rulers, rendered the Tuareg a politically marginalized minority within each state. This fragmentation undermined traditional patterns of mobility, trade, and inter-tribal alliances. Over time, it helped fuel new forms of resistance and adaptation that continue to shape the region’s history today.

LEFT: Par l’occupaton Italienne, la Tripolitaine s’ouvre enfin à la civilisation (“Thanks to the Italian occupation, Tripolitania finally opens up to civilization”), Supplément Illustré du “Petit Journal”, Octobre 1911 (Illustrated Supplement to the “Petit Journal”, October 1911.).

RIGHT: This Italian colonial postcard, distributed between 1911 and 1912, praises the ‘valiant fighters in the name of Italy’ in Tripolitania and Cyrenaica. Public Domain. (Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were two historic regions that now form part of modern-day Libya.)

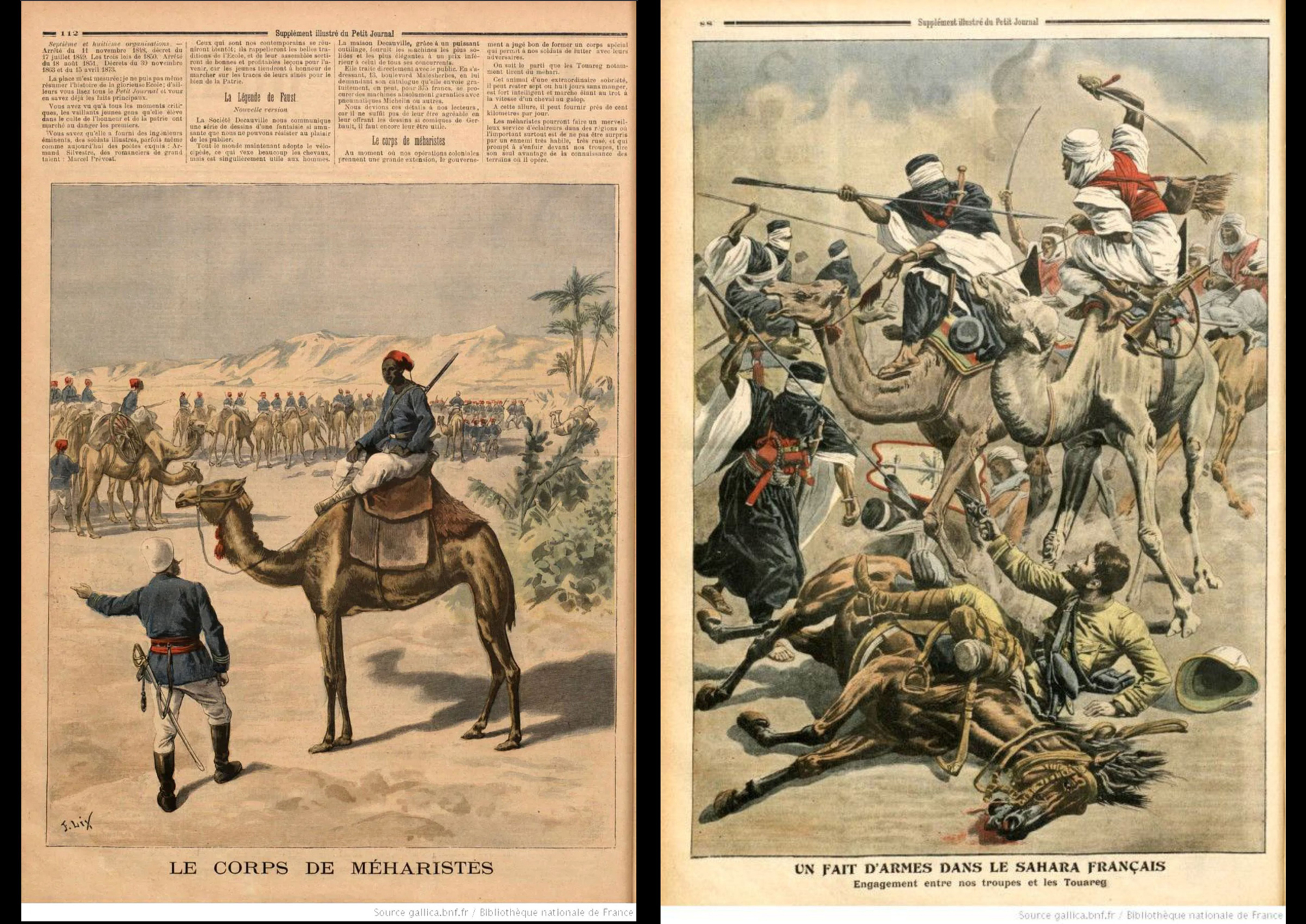

LEFT: Le corps de Méharistes, Supplément Illustré du “Petit Journal”. (“Meharist Corps”, Illustrated Supplement to the “Petit Journal”).

RIGHT: Un fait d’armes dans le Sahara Français, Engagement entre nos troupes et les Touareg, Supplément Illustré du “Petit Journal”. (“A feat of arms in the French Sahara, Engagement between our troops and the Tuareg, Illustrated Supplement to the “Petit Journal”).

The image on the left above depicts an engagement between French colonial troops (a meharist unit) and the Tuareg people in the Sahara Desert. This image was published in the illustrated supplement of “Le Petit Journal” around 1910. Such confrontations, often referred to as “faits d’armes,” were common during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when France sought to subjugate Tuareg tribes in its Saharan territories, particularly in areas that are now part of Algeria, Mali, and Niger.

From the 1880s to the 1910s, French colonial expansion in the Sahara encountered fierce opposition from Tuareg confederations. Major engagements included military expeditions through the Hoggar Mountains, the Aïr Region, and other Tuareg strongholds. There, French columns faced ambushes and pitched battles against mounted Tuareg warriors. In famous episodes such as the Flatters Expedition of 1894 and Foureau-Lamy’s force of 1898, the French organized heavily equipped columns. However, the Tuareg exploited their environmental mastery and mobility, inflicting costly defeats before the French achieved an eventual victory. The image and headline likely refer to clashes in regions that France had recently annexed during the early 1900s, when Tuareg resistance was still active. By the late 1910s and 1920s, French control had solidified; however, violent encounters persisted in the Sahara. Local uprisings and punitive expeditions continued to be depicted in contemporary press illustrations.

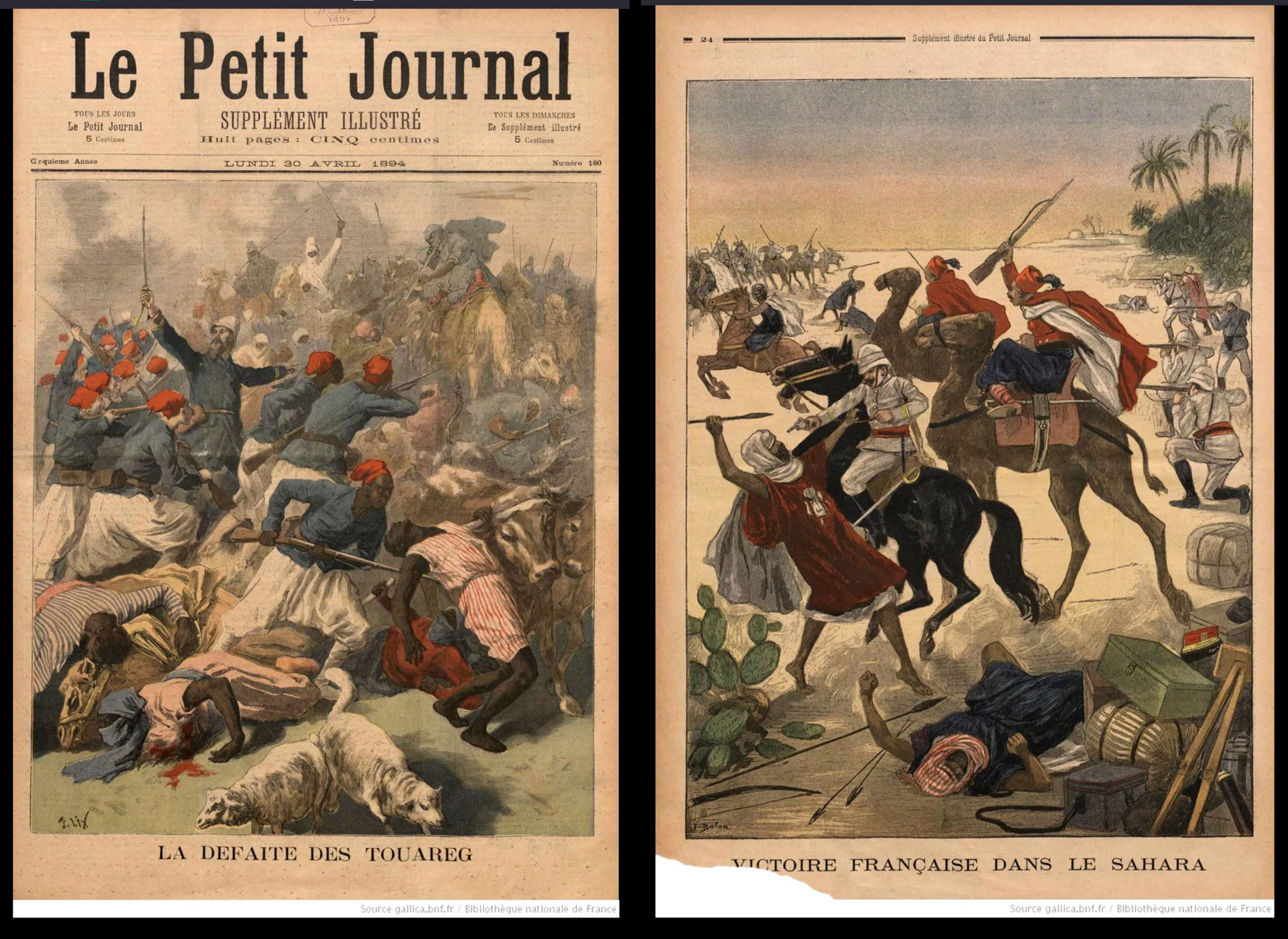

LEFT: La defaite des Touareg (“The defeat of the Tuareg”), Supplément Illustré du “Petit Journal”, Avril 1894. (Illustrated Supplement to the “Petit Journal”, April 1894).

RIGHT: Victoire française dans le Sahara (“French victory in the Sahara”), Supplément Illustré du “Petit Journal”, Janvier 1900. (Illustrated Supplement to the “Petit Journal”, January 1894).

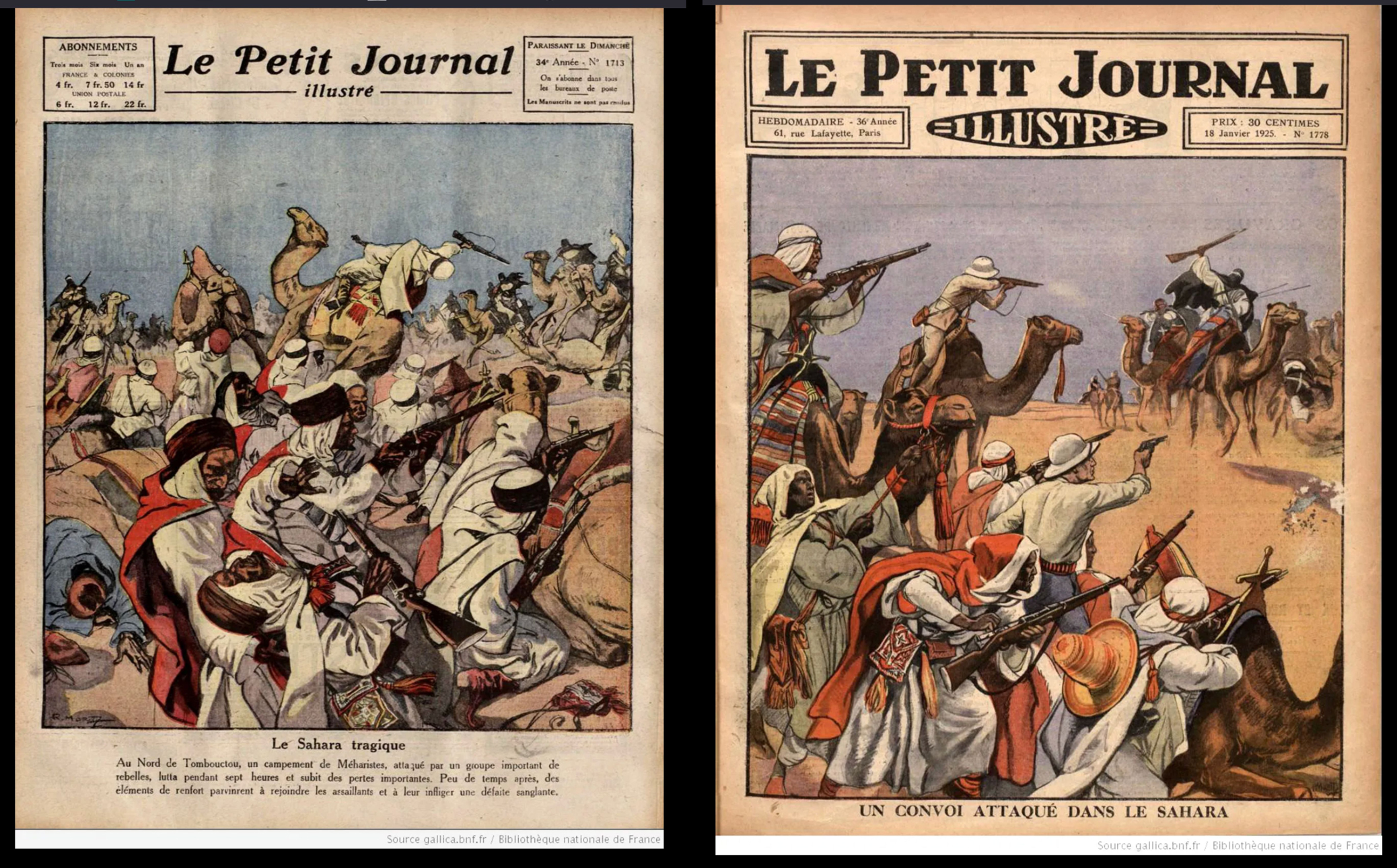

LEFT: Le Sahara tragique – Au nord de Tobouctou, un campement de Méharistes, attaqué par un groupe de rebelles, lutte pendant sept heures et subit des pertes importantes. Peu de temps aprés, des eléments de renfort parvinrent à rejoindre les le assaillants et à leur infliger une défaite sanglante (“The tragic Sahara – North of Timbuktu, a camp of Meharists, attacked by a group of rebels, fought for seven hours and suffered heavy losses. Shortly afterwards, reinforcements managed to reach the attackers and inflict a bloody defeat on them.”), “Le Petit Journal Illustré”, Oct. 1923.

RIGHT: Un convoi attaqué dans le Sahara (“Convoy attacked in the Sahara”), “Le Petit Journal Illustré”, Jan. 1925.

Le “Petit Journal”

“Le Petit Journal” was a conservative daily newspaper published in Paris from 1863 to 1944. It quickly became one of the most widely read papers in France due to its large circulation and affordable format. In 1884, it began publishing a weekly illustrated supplement called the Supplément illustré. This pioneering publication featured color illustrations and rapidly gained popularity, producing over a million copies weekly by the mid-1890s. The supplement evolved, becoming known for its full-page color images and coverage of national events and festivities. By the early 20th century, the supplement was titled Le Petit Journal illustré, continuing the legacy of illustrated reporting. It eventually outlived the main newspaper and remained influential in France’s media landscape.

Imperial Visions and Saharan Resistance: Reading the Tuareg in the Colonial Imagery of “Le Petit Journal”

“Le Petit Journal” regularly dramatized colonial combat scenes. Its supplements provided its metropolitan audience with vivid battle illustrations, emphasizing the bravery of French forces and the exoticism of Tuareg opponents. These images reflected the realities of France’s prolonged conquest as well as how the media shaped public perceptions of its colonial campaigns.

Between 1890 and 1920, the illustrated weekly Supplément illustré brought the “exotic” battlefields of the Sahara to more than a million French households. Its brightly colored fold-outs of camel charges, burning ksour, and white-robed Tuareg swordsmen did far more than report the news. They staged a visual morality play in which the French army appeared as the agent of civilization, and the Tuareg were cast as the last, nobly defiant lords of the desert. Reading these images against the archival grain reveals three interrelated logics that structured metropolitan understandings of France’s longest-running Saharan war.

Aestheticising asymmetry: the Tuareg as “beau sauvage”

In the iconography of “Le Petit Journal”, the Tuareg fighter is instantly recognizable: an indigo veil and a flowing tagelmust, mounted on a camel with a raised sword against a sand dune horizon. The composition is almost always diagonal, with French infantry in tight formation at the bottom and a scattered arc of Tuareg cavalry above, so the eye is drawn upward to the lone horseman, who dominates the frame even in defeat. The caption of January 18, 1925 (Attaque d’un convoi français par une tribu touareg au Sahara, above) is typical. The French column is identified by the names of its officers and regiments, while the Tuareg are identified only as “tribu.” This implies a double erasure: first, the erasure of political motivation — the attack is portrayed as innate predation — and second, the erasure of Tuareg polities as sovereign entities whose raids continued long-established toll-collection and diplomatic practices. By reducing the enemy to a visual type, the newspaper transformed a costly colonial counterinsurgency campaign into a picturesque struggle against timeless banditry.

Gender, race and the civilizing mission

The same images that exalted Tuareg masculinity simultaneously infantilized Tuareg society. Women and children are rarely shown. When they appear, as in the surrender scene after the 1917 siege of Agadez, they are huddled beneath French tricolores with lowered eyes, while officers stand erect. The implication is clear: Tuareg society has no public order of its own and acquires legibility only under French protection. This visual rhetoric aligns with the broader republican discourse examined by Alice Conklin. The “civilizing mission” required that colonized peoples be depicted as noble yet incomplete, necessitating French tutelage to reach their full potential. Thus, “Le Petit Journal” could celebrate the “courage farouche” of the Tuareg while endorsing the bombardment of their oases.

Concealing the logistics of violence

Perhaps the most insidious aspect of these illustrations is what they omit. The French conquest of the Niger Bend from 1893 to 1917 involved scorched-earth campaigns, the concentration of nomads around military posts, the destruction of wells, the seizure of livestock, and summary executions. These policies were documented in the administrative correspondence of Governors Joffre and Émile Gentil. However, the newspaper supplements show no burnt camps, dead camels, or hanged marabouts. Instead, the desert is an empty stage where French technology—the mitrailleuse, the airplane, and the radiotelegraph—appears to meet no material resistance. By depicting war as heroic skirmishes rather than a systematic campaign of attrition, “Le Petit Journal” helped its readers forget that “pacification” took three decades and required mobilizing Senegalese tirailleurs, Arab méharistes, and Tuareg confederations against the Kel Denneg and Kel Aïr. Thus, what is implicit is a labor of erasure: the disappearance of colonial violence and indigenous politics from the public record.

“Le Petit Journal” helped readers forget that French colonialism involved a violent and brutal policy of unlawfully conquering and controlling a foreign territory to exploit its resources and population. Conservative newspapers and magazines sympathetic to the government hushed up colonial brutality by presenting French aggression as a “civilizing mission” that brought light, progress, education, and peace to primitive, underdeveloped populations. By wrapping the colonial conquest in the language of enlightenment, “Le Petit Journal” and its conservative allies allowed metropolitan readers to overlook the blood on the map. From 1863 to 1944, the newspaper recast France’s wars of conquest as a gentle beam of progress. It turned “primitive” peoples into grateful beneficiaries rather than plundered subjects. While gunboats seized deltas and convoys of rubber and rice flowed westward, the paper’s illustrated supplements offered Parisians visions of smiling schoolchildren, whitewashed missions, and tricolor flags snapping in a supposedly pacified breeze.

LEFT: Expériences d’aérostation a travers le Sahara – Lancement des ballons-pilotes (“Ballooning experiences across the Sahara – Launch of pilot balloons”), Supplément Illustré du “Petit Journal”, Janvier 1903. (Illustrated Supplement to the “Petit Journal”, January 1903).

CENTER: La traversée du Sahara en automobile, “Le Petit Journal Illustré”, Dec. 1922.

RIGHT: Les effets de la civilisation nouvelle à Tripoli. Recontre dans le desert de la locomotion du passé et de la locomotion de l’avenir. (“The effects of the new civilization in Tripoli. Encounter in the desert between the locomotion of the past and the locomotion of the future”). Supplément Illustré du “Petit Journal”, Novembre 1911. (Illustrated Supplement to the “Petit Journal”, November 1911).

These three plates are not just simple visual depictions. They are built on a single visual grammar of old versus new, passive versus active, earth versus sky, and naïveté versus maturity. In the first plate (on the left), small crimson balloons bob above a group of dark-blue artillerymen. The color echoes the red trousers of the French uniforms—a deliberate visual rhyme that connects patrie and technology. In the central panel, onlookers are grouped in a semicircle with their backs to the camera and their faces tilted 90° upward. In the foreground, an astonished child with his mouth agape, eyes wide, and palms half-open gives a pictorial definition of naiveté. The colonized are depicted as eternal minors, frozen in wonder and in need of adult (French) guidance. The boy’s facial expression says it all. The right plate is divided into two parts: traditional Bedouins on camels on the left and machines/the future moving forward on the right. The slow, backward, underdeveloped old African world is destined to be swept away by the rapid advance of Western modernity.

From colonial icon to post-colonial memory

When the “Le Petit Journal” folded in 1944, its back catalog had solidified an image of the Tuareg in popular culture that endures today: the romantic, doomed desert warrior. However, the same images that once legitimized conquest now serve as evidence for historians seeking to understand anti-colonial resistance. When read alongside archival accounts of the Kaocen revolt (1916–1917) and Firhoun’s uprising in Ménaka (1911–1914), the newspaper’s battle scenes unintentionally honor a Saharan people who, for three decades, refused to be reduced to spectators in their own land. While “Le Petit Journal” implicitly conveyed the inevitability of French power, the Tuareg made it explicit in the deserts beyond the frame: it was never uncontested.

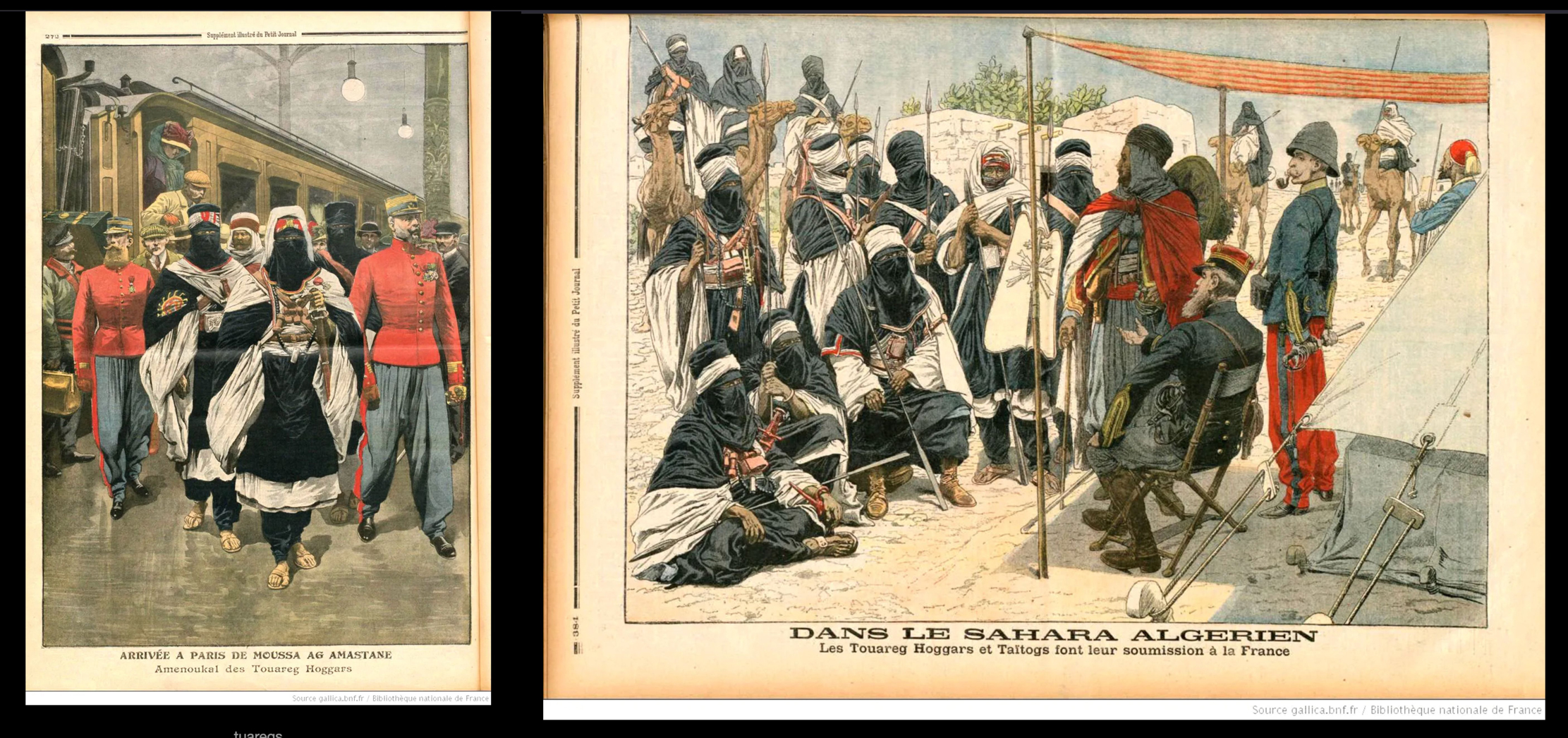

LEFT: Arrivée à Paris de Moussa Ag Amastane, amenoukal des Touareg Hoggars. (“Arrival in Paris of Moussa Ag Amastane, amenoukal of the Hoggar Tuareg”). Supplément Illustré du “Petit Journal”, Août 1910. (Illustrated Supplement to the “Petit Journal”, August 1910).

RIGHT: Dans le Sahara algerien. Le Touareg Hoggars et Taïtogs font leur soumission à la France. (In the Algerian Sahara. The Hoggar and Taïtog Tuareg submit to France”). Supplément Illustré du “Petit Journal”, Novembre 1905. (Illustrated Supplement to the “Petit Journal”, November 1905).

The plate on the left depicts Moussa Ag Amastane, amenoukal (chief) of the Kel Ahaggar Tuareg, arriving in Paris in August 1910. His journey symbolized the consolidation of French authority in central Sahara and was an act of diplomatic theater, marking the incorporation of the Hoggar Tuareg into the French colonial order after their submission in 1904–1905. The visit was part of a broader “Mission Touareg,” which presented Moussa Ag Amastane as an indigenous ally who engaged with the French state at the highest official level.

The plate on the right, published in November 1905, illustrates the formal soumission (“submission”) of the Hoggar and Taïtog Tuareg to French rule in the Algerian Sahara. This submission followed a sequence of military defeats culminating in the accord signed on January 19, 1904, between Moussa Ag Amastane and Commandant Métois. This accord ceded nominal sovereignty to France in exchange for limited autonomy and the retention of traditional institutions under colonial oversight. This event marked the end of large-scale Tuareg resistance in the region and confirmed Moussa Ag Amastane’s authority, recognized by both the French and his own people.

Both scenes are curiously tranquil. There is no violence, no corpses, and no scorched palms—only ceremony. The compositions are symmetrical; each side occupies equal pictorial weight. The eye remains balanced and is not pulled toward a victor. Swords are sheathed and reins are slack. Time pauses for the handshake or salute, erasing the memory of the 1903–1904 campaign, when French columns burned wells and seized herds. In the image on the right, Moussa sits slightly higher than the French officer, inviting the Petit Journal reader to consider that he chose to come down.

Yet what does these peaceful scenes omit?

The January 1904 accord was signed under the cover of artillery, and the wells had been seized weeks earlier. The Tuareg were now required to deliver caravan intelligence and tolls to colonial agents—failure resulted in aerial bombardment, which was first tested in the Hoggar in 1911. Moussa’s 1910 trip to Paris was financed by the Quai d’Orsay, and every banquet and visit to the Cirque d’Hiver was carefully staged to create the illusion of cordial parity. “Le Petit Journal’s” framing omits the Spahi cavalry escort stationed at Tinerhert—a reminder that the exit door of the empire was closed.

The Petit Journal does not lie; it selects. It records the handshake but not the rifle that made it necessary. Thus, the Tuareg “submission” appears as a peaceful recognition of French superiority — not the coerced acquiescence of an invaded people.

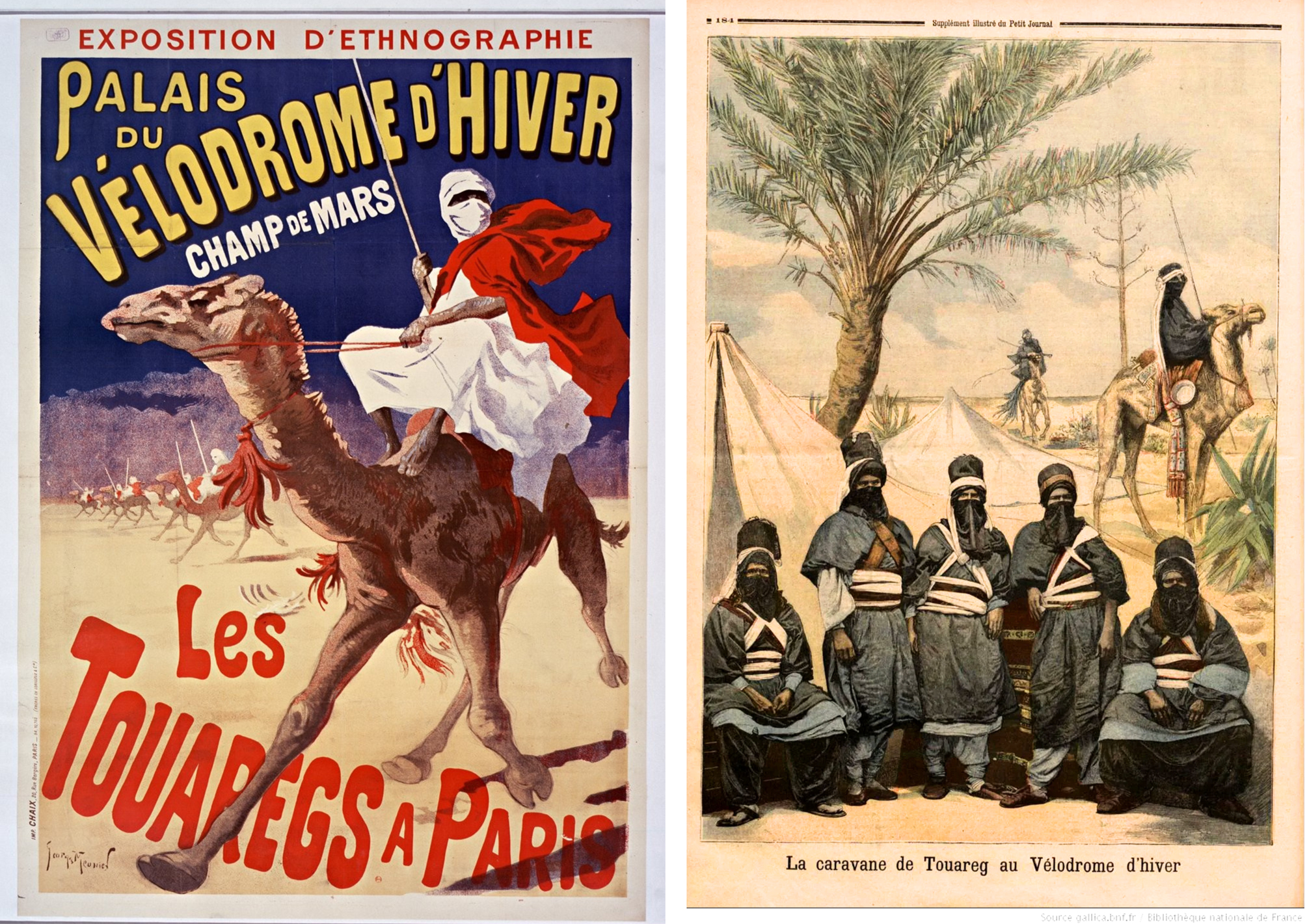

LEFT: Poster for the Exposition d’ethnographie. Palais du vélodrome d’Hiver. Les Touaregs à Paris, 1894. Color lithograph illustrated by Georges Meunier (1869-1942). Dimensions: 120 x 90 cm. Source: Gallica, the digital library of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

RIGHT: La Caravane de Touareg au Vélodrome d’hiver (“The Tuareg Caravan at the Winter Velodrome”), Supplément Illustré du “Petit Journal” (Illustrated Supplement to the “Petit Journal”). Source: Gallica, the digital library of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

The conquest and the spectacle

In the second half of the 19th century, the French began to penetrate Tuareg areas, advancing into the central Sahara and the southern regions of Algeria and Niger through military expeditions and colonial expansion. They first entered what is now Niger around 1890 and occupied the important Tuareg city of Agadez by 1906. In Algeria, French colonial leaders began moving south into the Sahara in the mid-19th century. This initiated roughly fifty years of violent encounters and territorial consolidation in Tuareg lands.

While columns of the Armée d’Afrique were burning Tuareg encampments in the Hoggar and Aïr mountains, the same state that ordered the raids was arranging caravans in the opposite direction, toward the capital’s exhibition halls. The 1894 Exposition d’Ethnographie in the Winter Velodrome was advertised in Parisian newspapers as “Les Touaregs à Paris.” The Ministry of Colonies shipped not only shields, saddles, and silver crosses, but also living Tuareg men, women, and camels to embody the very savagery the army was meant to pacify south of the Sahara.

The operation was managed by the Service des Affaires indigènes in Algiers—the same bureau that had just finished cataloging the rifles captured after the Battle of Tit in 1881. Officers on furlough were instructed to “select specimens” who would agree to travel. In practice, consent was obtained through a combination of debt leverage, hostage-taking, and direct purchase. Once in Paris, the group was installed behind a low mud wall erected inside the velodrome. The wall’s outline mimicked the ramparts of Tamanrasset, allowing visitors to imagine they had stepped straight into the desert. The daily program promised camel rides, Tuareg sword dances, and veiled women brewing tea—exactly the rituals that French patrols had been ordered to suppress as signs of insubordination in the south.

The timing was not accidental. The exposition opened three months after the Chamber of Deputies voted to grant an additional 22 million francs for the completion of the Saharan conquest. Newspapers ran the two stories side by side: in the left column, reports of Lieutenant Cortyl’s column being ambushed near Tamanrasset; in the right column, sketches of the same blue veils now politely lowered for Parisian ladies. This served to domesticate the threat. The fierce “lords of the desert” who refused to pay the impôt became picturesque extras in the metropolis who could be contemplated and photographed, and then left behind when one took the omnibus home.

Yet, the performers defied the script in small, noticeable ways. They insisted on carrying weapons inside the exhibition grounds—empty scabbards were deemed inadequate—and on the last day, they dismantled the reed palisade and distributed the stalks to the crowd as “souvenirs of free men.” Police records note that several spectators were scratched by the sharp edges of the reeds; the prefecture concluded that “the Tuareg temperament remains unsuited to prolonged public display.” Within a week, the group was escorted to Marseille and placed on a troop ship returning to Algiers. Their passage was charged to the same colonial budget that financed punitive expeditions against their kin.

Thus, the 1894 Exposition did not interrupt the violence; it was part of its economy. The same rifles that subdued the desert supplied the ethnographic curios that convinced Parisians of the necessity of those rifles. Fighting the Tuareg and exhibiting them were not contradictory acts—they were twin faces of a single colonial logic in which conquest and spectacle advanced together.

Depicting the Tuareg as mysterious desert dwellers and wild, barbaric camel riders was as fascinating as the legacy of a dying past. The popular press, docile and prone to colonial interests, turned the Tuareg man into a picturesque, submissive, and ultimately static figure—dangerous enough to be worth conquering, intelligent enough to salute the French authorities and recognize their supremacy, and exotic enough to sell newspapers. Colonial France shaped this Tuareg figure for its own use and consumption. The truth laid elsewhere.

Tuareg Rebellions Against French Colonialism: 1881 – 1917

TUAREG ECONOMY AND SOCIETY FROM EMPIRE TO DECOLONIZATION

From the late 19th century through the era of decolonization, the history of the Tuareg reflects a profound transformation in both economic structures and social hierarchies—changes largely precipitated by European colonial intervention.

Before colonization, Tuareg society was defined by a rigid hierarchical system that shaped both its economy and political order. At the apex stood the noble warrior elites (Imajaghan), whose power and wealth depended on the tribute, labor, and loyalty of subordinate castes—vassals (Imghad), religious specialists (Ineslemen), artisans (Inaden), and enslaved populations (Iklan or Bella). Raiding, tribute collection, and control over trans-Saharan trade routes were core to the economy and to elite dominance.

The imposition of French and Italian colonial rule disrupted this intricate social fabric. In the central and western Sahara (modern-day Mali and Niger), the French viewed the Tuareg aristocracy not only as a military threat but as incompatible with their vision of productive, sedentary colonial subjects. Colonial administrators deliberately undermined traditional elites by empowering lower-status groups—particularly former slaves and religious lineages—through appointments as chiefs, intermediaries, or local authorities. This shift dismantled the hereditary hierarchies that had long governed labor, land, and mobility.

Across French West Africa (Afrique Occidentale Française, or AOF) and Algeria, colonial officials sought control by manipulating local systems. They created or formalized tribal leadership structures, delineated cantons, and introduced fixed taxes. Scholars have noted that the colonial state codified and, in some cases, “invented” political roles, reshaping power dynamics among lineage leaders, clients, religious classes, and formerly dependent communities.

Economically, colonization accelerated the collapse of the trans-Saharan trade network. European maritime dominance had already diverted gold and salt flows toward coastal hubs, but colonial policies deepened the decline. Mobility restrictions, taxation, and the outlawing of raiding and slave trading—a cornerstone of Tuareg subsistence—had lasting consequences. While often framed as modernization, these reforms were inconsistently applied and socially disruptive. Slavery, for example, remained a reality well into the mid-20th century. In the 1940s, reports still documented tens of thousands of Bella held in servitude in regions like Gao and Timbuktu.

Italian colonization in Libya produced parallel upheavals. In Fezzan, the Tuareg—particularly the Kel Ajjer confederation—mounted fierce resistance, supported at times by the Ottoman Empire and later the Senussi brotherhood. The Italians responded with a mix of forced labor, military conscription, and violent repression, often punishing resistance with exile or massacre. As in the French context, the colonial state restructured traditional authority, rewarding collaborators while eroding indigenous autonomy.

In short, colonialism did not merely occupy Tuareg territory; it dismantled the foundations of Tuareg society. Colonial powers replaced indigenous governance with bureaucratic control, disrupted long-standing trade networks, and fractured deeply rooted social systems. By the time Libya (1951), Mali and Niger (1960), and Algeria (1962) gained independence, Tuareg society had been fundamentally reshaped.

The post-independence period brought further challenges. The traditional economic base—pastoralism, trans-Saharan trade, and systems of bonded labor—was no longer viable. Droughts devastated herds, while national borders fractured migratory routes and kinship ties. Many Tuareg were pushed into marginal zones, both economically and geographically. The newly formed governments in Mali, Niger, and Algeria, often viewing the Tuareg with suspicion—as nomadic, stateless, or even as former colonial collaborators—deepened this marginalization.

This legacy of displacement and distrust laid the groundwork for the rebellions and political crises that emerged in the decades following independence—a complex chapter that merits its own examination.

Tissilawen – AghregHe ImuHar

A DESERT WITH NO PEACE

The decades following African independence were not a time of integration for the Tuareg. Instead, they experienced a slow-burning crisis in which every drought, coup, and peace accord rekindled the same unresolved question: Would the states established in 1960 ever make room for nomadic, dissident Saharans?

1962–64 – The Alfellaga

Only two years after Mali gained independence from France, young Kel Adagh (nobles of the Tuareg Ifoghas confederation) launched hit-and-run attacks in the Adrar des Ifoghas mountains in northeastern Mali. Many Tuareg had hoped that the end of colonial rule would lead to a Saharan homeland. Instead, however, the new Malian state—armed by the Soviet Union—responded with military force, martial law, and brutal repression. After Algeria extradited 35 Tuareg rebel leaders, several were publicly executed in Kidal. Approximately 5,000 civilians fled to Algeria. The north was placed under the control of military governors for the next thirty years.

1970s–80s – Droughts and Exile

The catastrophic Sahelian droughts of 1972–1973 and 1984–1985 devastated pastoralist life. Though more camels than people died, the social impact was devastating. Entire tawsit (kinship groups) migrated to Mauritania or Libya, where Muammar Gaddafi recruited Tuareg refugees into his Islamic Legion. In military camps near Sabha, the refugees trained with Soviet armored personnel carriers (APCs) and began to envision themselves as citizens of Azawad (Azaouad), a proposed independent Tuareg state, rather than as Malians.

1990–96 – The Second Rebellion and the National Pact

In June 1990, Libyan veterans formed the Mouvement Populaire de l’Azaouad (MPA) and joined other factions in the Mouvement des Forces Unifiées de l’Azaouad (MFUA). Together, they launched coordinated raids on army posts around Gao. Facing economic collapse and a student revolt in southern cities, the Malian government agreed to negotiate. The 1992 National Pact promised to integrate 3,000 ex-rebels into the national army, allocate development funds to the north, and establish locally elected councils.

However, implementation faltered. Many demobilized fighters received no compensation, and the promised road to Kidal remained only on old French maps. By 1996, the only visible legacy of the accord was the symbolic “Flame of Peace” ceremony in Timbuktu, where 3,000 weapons were melted down into a monument.

2006–09 – Fragments, Fundamentalists, and Fury

In 2006, a splinter faction called the Alliance Démocratique du 23 Mai pour le Changement (ADC) attacked Kidal, demanding the unfulfilled promises of the 1992 pact. Algeria mediated, leading to the Algiers Accords. However, the Malian government soon rearmed loyalist militias such as Ganda Koy and Ganda Iso, which heightened ethnic tensions.

Meanwhile, Islamist influence in the Sahara was quietly growing. Throughout the 2000s, Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)—an offshoot of Algeria’s Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC)—established itself in northern Mali. Exploiting weak governance, AQIM embedded itself in local smuggling networks, took Western hostages for ransom, and began cultivating relationships with disaffected Tuareg and Arab youth. Some Tuareg fighters, who had previously been trained in Libya to fight for secular causes, were now being recruited by Islamists who offered them weapons, salaries, and a moral cause.

2012 – The Perfect Storm

In March 2012, a military junta led by Captain Amadou Sanogo overthrew the president in Bamako. Strengthened by Tuareg fighters returning from Gaddafi’s collapse in Libya, the Mouvement National de Libération de l’Azawad (MNLA) seized Kidal, Gao, and Timbuktu in rapid succession. On April 6, 2012, they proclaimed the independence of Azawad.

However, the MNLA’s victory was quickly undermined. Islamist factions — notably Ansar Dine (founded by Iyad Ag Ghaly, a veteran of the 1990s Tuareg rebellion), Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and the Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO) — swiftly turned against their former MNLA allies. While the MNLA envisioned a secular Tuareg state, these groups aimed to impose Sharia law across the region.

By June 2012, the Islamists had expelled MNLA forces from major cities and established a harsh regime of amputations, floggings, veiling mandates, and the destruction of UNESCO-listed Sufi shrines in Timbuktu. The uprising, originally driven by ethnic nationalism, was now overtaken by transnational jihad.

In January 2013, France launched Operation Serval, a military intervention that pushed the Islamist fighters into the desert and mountains. While it dismantled their urban strongholds, it failed to eliminate their insurgent capabilities. Sidelined and distrusted by both Bamako and local non-Tuareg populations, the MNLA had lost control of the narrative and the territory.

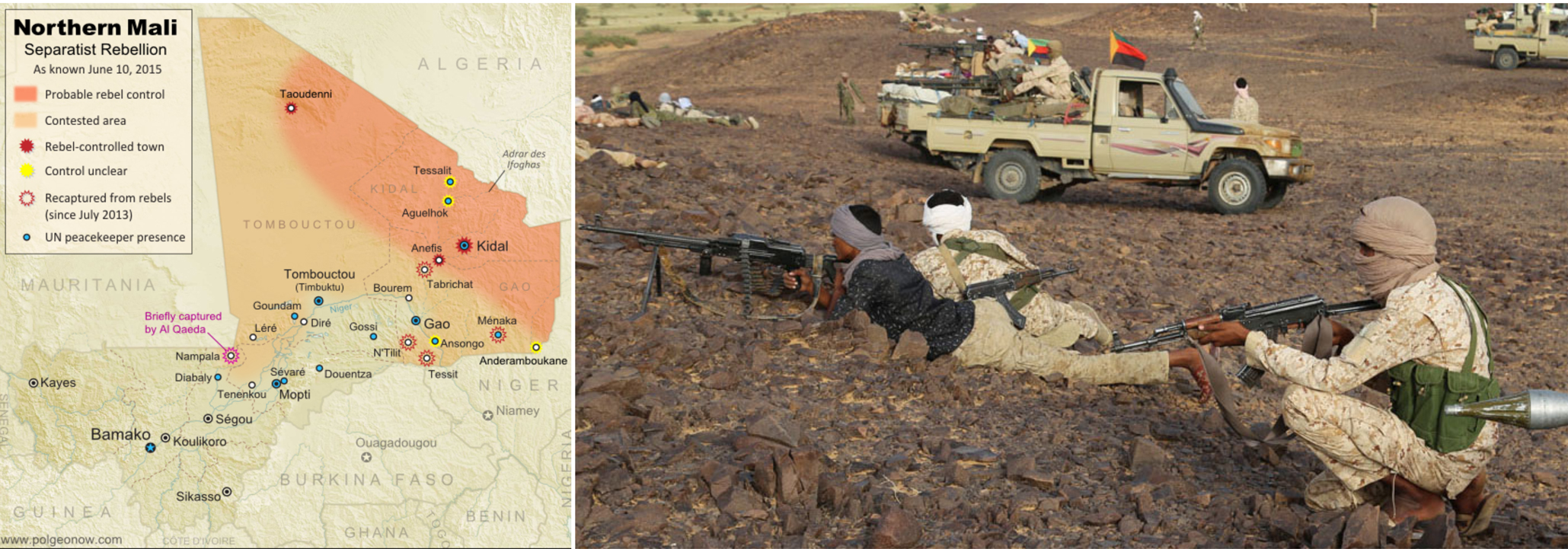

LEFT: Map of the conflict in Northern Mali, January 2013. Wikimedia Commons.

RIGHT: Tuareg rebels, January 2012. Al Jazeera.

Post-2015 – Cold Peace, Hot Militias, and Persistent Jihad

The 2015 Algiers Agreement aimed to integrate former rebels into mixed patrols alongside the Malian army. However, the agreement’s implementation stalled, and Tuareg-led groups, such as the Coordination des Mouvements de l’Azawad (CMA), and their rivals in the Plateforme coalition continued to clash.

Meanwhile, jihadist insurgency flourished. AQIM regrouped in the remote Ifoghas Mountains, and new factions emerged.

- JNIM (Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin), formed in 2017 and led by Iyad ag Ghaly, united AQIM, Ansar Dine, and other regional groups.

- ISGS (Islamic State in the Greater Sahara) emerged in eastern Mali and Niger, competing violently with JNIM.

These groups exploited the lack of trust between the north and Bamako by offering protection, justice, and income in exchange for loyalty. In some areas, these groups act as de facto authorities, resolving disputes and taxing commerce.

French-led operations (first Serval, then Barkhane) and MINUSMA peacekeepers contained the spread, but did not resolve the situation. In 2021, a single improvised explosive device (IED) attack near Tessalit killed twelve UN peacekeepers, highlighting the ongoing volatility.

Following two additional coups in Bamako (in 2020 and 2021), the ruling junta severed ties with France and aligned with Russia, including the controversial Wagner Group. However, no foreign partner has fundamentally altered the situation in the north, where militias, jihadists, and bandits operate amid shifting allegiances.

The Tuareg cause, which once called for a homeland, is now intertwined with global jihadism, ethnic mistrust, and foreign military interventions. What began in 1963 as a rebellion for recognition has become a multi-front conflict with no clear end and many players.

LEFT: Map of Rebel Control in Mali in June 2015. Creative Commons.

RIGHT: Tuareg fighters and pickup trucks with machine guns in Kidal, northern Mali on September 28, 2016. Al Jazeera.

1990–1995 – The Tchin-Tabaraden Uprising

In May 1990, Nigerien gendarmes opened fire on Tuareg herders protesting tax abuses and forced livestock sales in the market town of Tchin-Tabaraden, in the Tahoua region. More than sixty civilians were killed, and hundreds were detained or disappeared. This sparked a broader revolt across the north, as fighters regrouped under the Front de Libération de l’Aïr et de l’Azawak (FLAA) and the Front de Libération du Nord-Niger (FLNN).

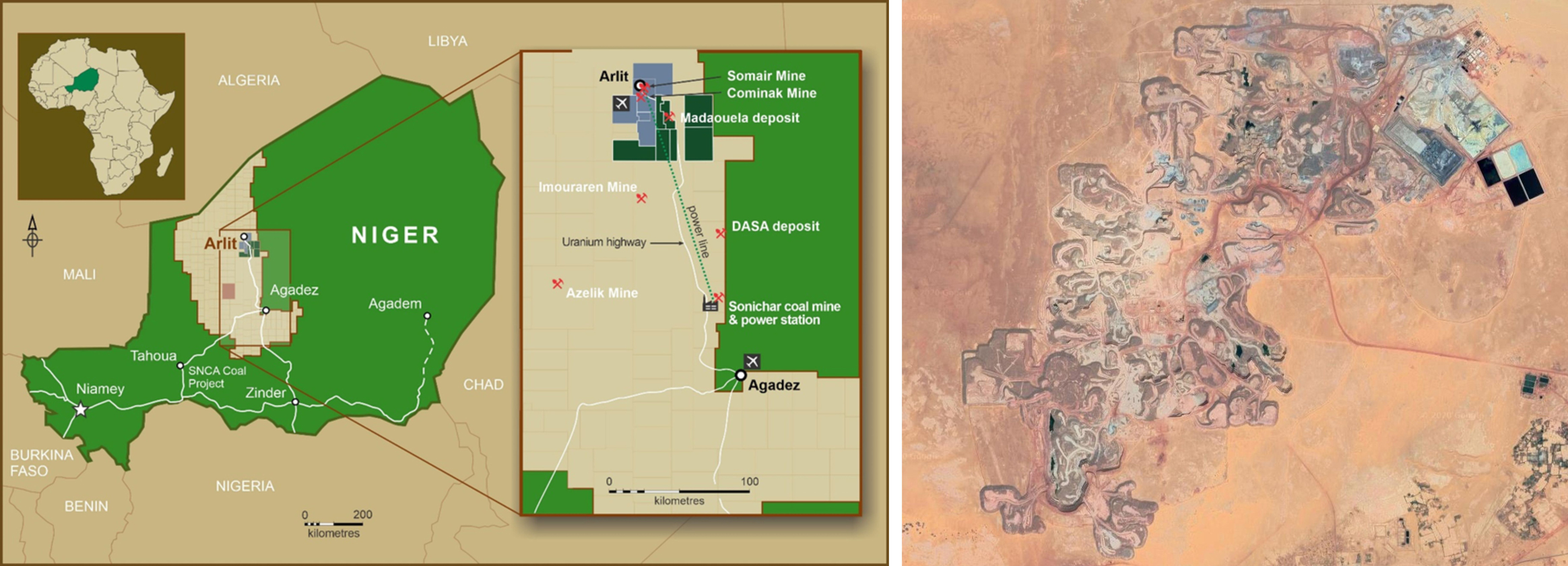

These insurgents launched raids on army posts and uranium convoys near Arlit, a town in the Aïr Mountains where the French state-owned company Orano (formerly Areva) operated some of the world’s largest uranium mines.

Niamey’s dependence on uranium revenues—and on its French partner—shaped the government’s harsh military response. Entire Tuareg communities were accused of complicity and subjected to collective punishment, including arbitrary arrests, aerial bombardments of camps, and livestock confiscations. Thousands of civilians fled to Algeria and Libya.

After five years of attrition and mounting pressure from France, President Mahamane Ousmane signed the 1995 Ouagadougou Peace Agreement with the rebel groups. Similar to Mali’s earlier National Pact, the agreement promised limited decentralization, the integration of 3,000 ex-combatants into the Nigerien Armed Forces, and a “special status” for the northern regions. However, the accord’s ambitions quickly dissolved: development funds were mismanaged, roads and schools remained unbuilt, and many demobilized fighters were left stranded between army posts and unemployment.

LEFT: Niger uranium mining. Niger World Factbook.

RIGHT: Satellite image of the huge Arlit uranium mine complex in Niger.

Arlit is a mining town located on the western edge of the Aïr Mountains in northern Niger, in the Sahara Desert. After uranium deposits were discovered there in the late 1960s, the town became the center of one of the world’s largest uranium mining operations. This operation is led by the French state-owned company Areva, renamed Orano in 2018.

Arlit lies in the Agadez Region, about 1,200 km northeast of Niamey, near the Tuareg heartland of the Aïr Mountains. Uranium extraction in the area transformed this remote desert zone into an industrial hub. Two major subsidiaries of Orano—SOMAÏR (Société des Mines de l’Aïr) and COMINAK (Compagnie Minière d’Akokan)—operated large open-pit and underground mines from the 1970s onward. The uranium was mainly exported to supply France’s nuclear reactors, providing an essential element of France’s energy independence.

Uranium mining in Arlit began around 1971 under French management and continued with intensive extraction for nearly five decades. By the 1980s, uranium from the Aïr region accounted for a significant portion of Niger’s export revenues. Orano, Areva’s successor, continued operations until 2021, when the COMINAK mine closed. This left an estimated 20 million tons of radioactive waste in Arlit and nearby Akokan. SOMAÏR remains active, though production has slowed due to political instability and falling uranium prices.

Multiple independent investigations, including those by CRIIRAD (Commission de Recherche et d’Information Indépendantes sur la Radioactivité), have confirmed serious radioactive contamination across the Arlit-Akokan area. Waste piles, locally known as “uranium tailings,” emit harmful radiation that is dispersed by desert winds into the air, soil, and groundwater.

* Around 20 million tonnes of radioactive waste have been left uncovered or poorly contained, creating what the locals call the “radioactive mountains” near the town. (beyondnuclearinternational)

* Contaminated dust and radon gas are believed to have caused chronic illnesses among miners and residents. Some homes were even built with discarded radioactive rocks. (lemonde+1)

* CRIIRAD measured radiation levels up to 450,000 becquerels per kilogram, hundreds of times above safe limits. (beyondnuclearinternational)

* Mining also consumed large volumes of water from the Tarat aquifer, a fossil (non-renewable) groundwater source. Extraction and contamination have reduced the quality and quantity of water for local populations in an already arid region. (afriquexxi)

When COMINAK closed in 2021, Orano promised cleanup and retraining programs for workers. However, two years later, reports indicate that little remediation has occurred. Mountains of radioactive sludge remain exposed while former miners and residents suffer from unemployment and degraded living conditions. According to environmental groups, Orano’s cleanup approach of covering waste with a thin layer of clay and rock is inadequate for long-term containment because radioactive decay will continue for hundreds of thousands of years.