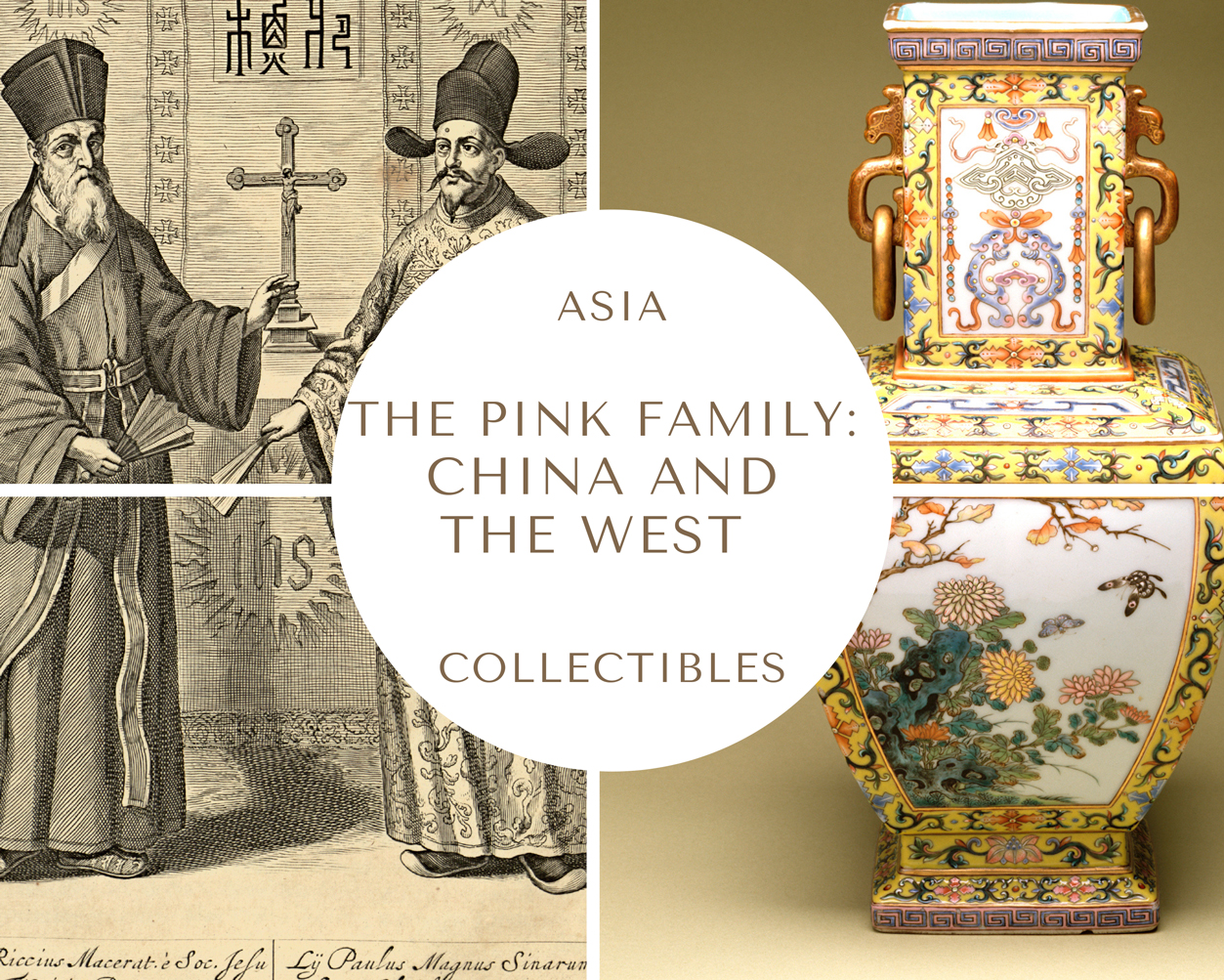

NAVAJO CHURRO SHEEP AND WOOL 11

USA on the globe.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

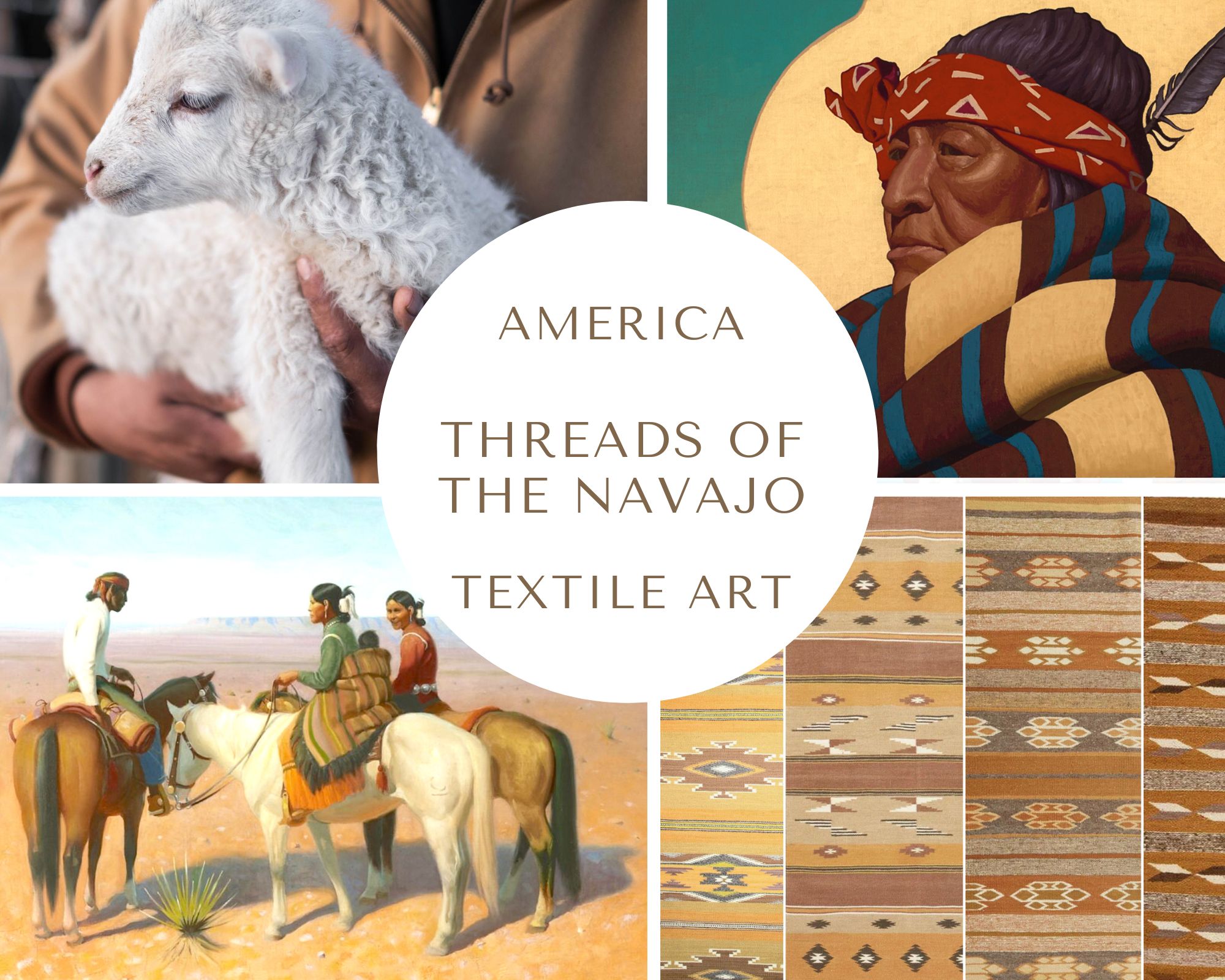

SOUTHWESTERN STATES

CONTEMPORARY NAVAJO WEAVERS AND TEXTILE ARTISTS

Contemporary Navajo weaving is one of the most vibrant and dynamic forms of Indigenous art in the 21st century. This renaissance of Diné textile arts encompasses a remarkable generation of artists who have successfully combined ancestral knowledge with innovative, contemporary practices. They create works that honor traditional techniques while addressing modern themes and experiences. These artists are doing more than preserving cultural heritage—they are actively transforming and redefining Navajo weaving in the contemporary art world.

THE CONTEMPORARY MOVEMENT

The current generation of Navajo weavers has emerged from a rich foundation of traditional knowledge while embracing new possibilities for artistic expression. As curator Cécile R. Ganteaume observes, their work is "at once fundamentally modern and essentially Diné," demonstrating how traditional practices can remain culturally authentic while evolving artistically. This movement challenges long-held perceptions about Indigenous art by moving beyond romanticized expectations to create sophisticated works that engage with contemporary issues, personal experiences, and global artistic dialogues.

Contemporary Navajo weavers work within a continuum spanning from traditional techniques using natural materials to experimental approaches incorporating digital technology and unconventional materials. What unites them is their commitment to fundamental Navajo weaving principles: the use of upright looms, a spiritual connection to the craft, and the belief that, as many weavers express, "weaving is life."

KEY CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS

D.Y. Begay

D.Y. Begay is one of the most celebrated figures in contemporary Navajo weaving. Born into the Tóʼtsohnii (Big Water) Clan and descended from the Táchiiʼnii (Red Streak Earth) Clan, she has deep cultural roots in Diné society. A fifth-generation weaver, Begay grew up in Tsélaní, Arizona, a stunning valley treasured by her clan relatives and described by Begay as "the place of many rocks." Her profound connection to this homeland is the primary inspiration for her art, and the landscape's colors, textures, and spiritual significance permeate her tapestries.

Her work exemplifies the philosophy of "painting with yarn." Her tapestries blend natural color palettes with "unconventional, non-reservation colors," resulting in pieces that capture the essence of her homeland while pushing creative boundaries. Her mastery of natural dye techniques using indigenous plants and her innovative approach to traditional designs have earned her recognition in major museums, including the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian.

Begay's artistic process transforms traditional weaving into fine art. Her approach encompasses every aspect of textile creation, from raising Navajo Churro sheep to completing the final tapestry. She describes her work as fundamentally natural, using "the same techniques passed from my ancestors to me to create designs that have artistic and traditional value."

One of Begay's most distinctive qualities is her expertise in preparing natural dyes using indigenous plants and materials. She collects chamisa, juniper berries, sage, and a particular fungus that grows on juniper trees in her homeland. Her sister, a sheep farmer, provides the wool, maintaining the family-based nature of her practice. The dyeing process requires an understanding of plant chemistry and the timing of seasonal collections. Begay explains that in the Navajo language, the process of dyeing is described using specific adjectives: ii'soti means "I am making it yellow," and Iishichii means "I am making it reddish."

While maintaining traditional techniques, Begay has pushed the boundaries of Navajo weaving through her experimental use of color and design. She combines natural color palettes with "unconventional colors," creating tapestries that are simultaneously traditional and contemporary. Her horizontal motifs reflect the vistas, mesas, and plateaus of Navajo country; however, her interpretations are uniquely personal and artistic rather than strictly traditional.

Begay's tapestries often have poetic titles that reflect their inspiration. Works such as "Tselani," "Confluence of Lavender," and "Intended Vermillion" demonstrate her ability to translate landscapes and memories into woven forms. These pieces approach total abstraction while maintaining a connection to the Southwestern landscape. Some suggest "three rows of mesas" through subtle color gradations.

D.Y. Begay with her weaving Confluence of Lavender woven with dyed and undyed black and gray wool. Photo: © Kelso Meyer, 2016.

LEFT: D.Y. Begay, Tsegi Spider Rock, 2007. Walter Larrimore for the National Museum of the American Indian.

RIGHT: D.Y. Begay, Drought, 2002. The weaving was crafted during the severe rain shortage of 2002 and depicts “the loss of the land’s beauty and vegetation that is thirsty, colorless, and infertile,” according to the artist.

LEFT: D.Y. Begay, Intended Vermillion, 2015, Denver Art Museum, CO.

RIGHT: D.Y. Begay, Palette of Cochineal, 2013. Heard Museum, Phoenix, AZ.

Gloria Jean Begay

Another contemporary textile artist is Gloria Jean Begay. Despite being prominent Navajo textile artists with the same surname, D.Y. Begay and Gloria Jean Begay are not related. They come from different clan lineages and geographic regions of the Navajo Nation and represent distinct family traditions within the broader landscape of contemporary Diné weaving. Their shared surname reflects the prevalence of "Begay" throughout the Navajo Nation rather than indicating any family connection.

Gloria Jean Begay comes from the well-documented Henderson-Nez-Begay weaving dynasty, which is centered in Ganado, Arizona. She is the granddaughter of Grace Henderson Nez (1913–2006), a National Endowment for the Arts Heritage Fellow, and the daughter of Mary Henderson Begay (born 1941), who worked at Hubbell Trading Post for over forty years.

Begay continues the Henderson family tradition of classic Navajo designs, often working with Chief Blanket patterns and traditional color schemes while adding her own contemporary perspective.

Gloria Jean Begay, Dawn Meets Dusk, 2005. Dimensions: 59 x 48 in.; 149.8 x 121.9 cm. Kennedy Museum of Art, OHIO University.

William Whitehair

William Whitehair carries on the distinguished tradition of Navajo male weavers by creating exceptional pictorial rugs that blend traditional techniques with a contemporary artistic vision. He works from his home in Hardrock, Arizona.

A member of the Split Rock clan, William grew up in a traditional Navajo family for whom weaving was central to their livelihood.

Unlike many contemporary weavers, who purchase their materials, Whitehair maintains a completely traditional approach to his craft. He lives a lifestyle that includes raising Navajo Churro sheep, cattle, goats, and horses. He tends to seventy sheep that he nurtures and shears to make his tightly woven rugs. For Whitehair, herding is part of the weaving process, even though he could earn more money if he focused solely on rug production. This approach reflects the Navajo belief that the entire process, from caring for the animals to the final weaving, is interconnected and sacred.

William's commitment to the traditional lifestyle extends to his choice to live in an area without modern conveniences, representing an authentic continuation of ancestral ways. However, his weaving style demonstrates a remarkable synthesis of traditional Navajo techniques and innovative contemporary designs. His education in architecture at the University of Arizona has left a lasting impression on his rugs, which often hint at Western structural design. His unique background enables him to approach traditional weaving with an understanding of space, proportion, and structural elements, setting his work apart from that of other weavers. His architectural training provides him with skills in spatial planning and design composition that he translates directly into his complex pictorial weavings.

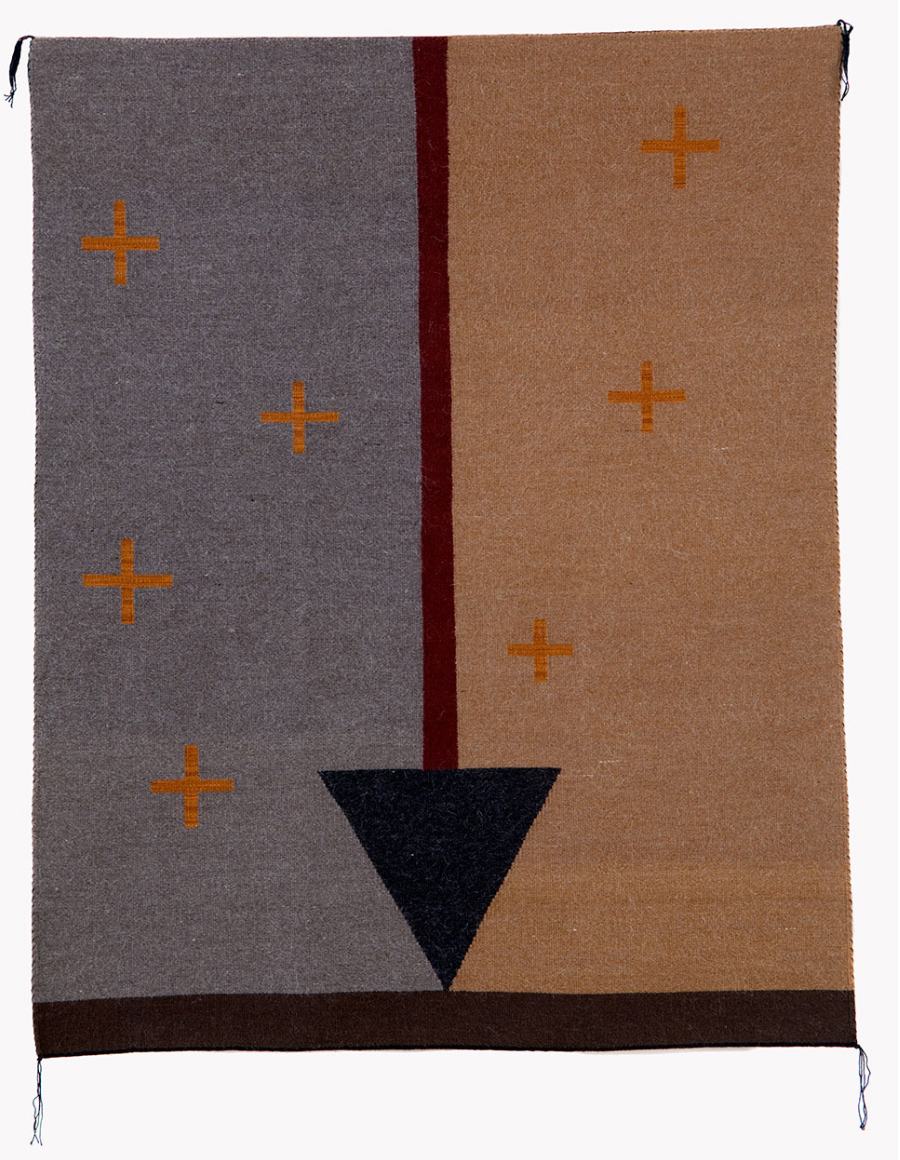

His most celebrated work includes innovative pictorial pieces, particularly his renowned "Offerings" rug. According to William, he was inspired to create this piece by "the morning deities who watch over us and put good things in our paths." This spiritual connection reflects the traditional Navajo belief that weaving is a sacred activity.

Offerings by William Whitehair. Photo courtesy of John Aldrich.

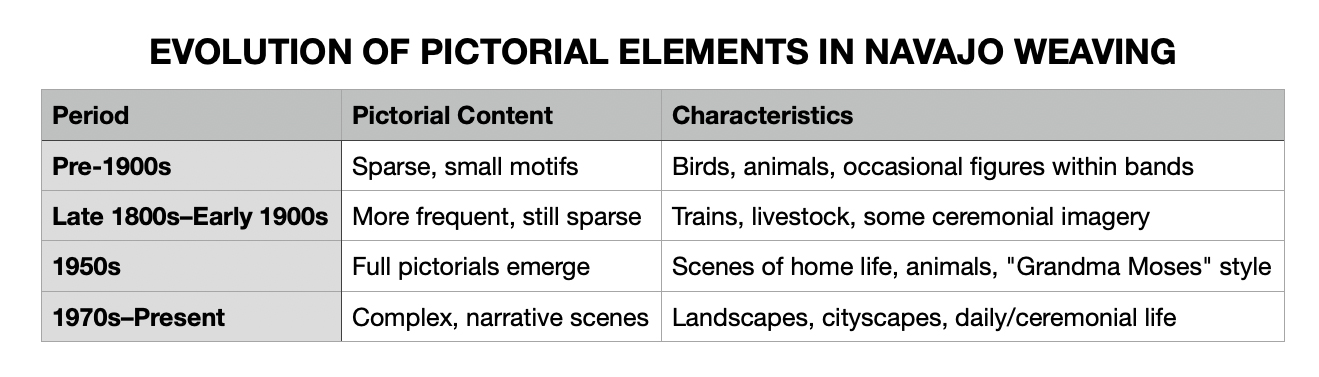

THE EVOLUTION OF PICTORIAL WEAVING

As Mark Sublette explains, "Navajo pictorial rugs incorporate representational images of people and objects into their woven designs." The history of pictorial-style rugs in Navajo weaving reveals a dynamic evolution from sparse pictorial elements to contemporary, elaborate landscapes and scenes of people.

Early History: Sparse Pictorial Elements

- Pre-1900s: Traditional Navajo weaving focused on geometric patterns and blankets for personal use. Pictorial elements, such as feathers, birds, or animals, were rare and typically served as small design features rather than dominating the composition.

- Late 1800s–early 1900s: With the arrival of trading posts and the railroad, Navajo weavers began incorporating more representational motifs. Early pictorials included arrows, bows, trains, livestock, and the occasional human figure. However, these elements rarely made up the entire weaving. Instead, they appeared as isolated elements within larger geometric or banded designs.

Transition and Expansion of Pictorial Themes

- Early 20th century: The influence of tourism and collectors, as well as cross-cultural exchanges (such as with Mexican serapes and Oriental rugs), encouraged experimentation. Some weavers, notably Hosteen Klah, began incorporating ceremonial imagery and sand painting motifs. This was sometimes controversial within the community.

- Mid-20th century: By the 1950s, full pictorial weavings depicting scenes of Navajo home life, animals, and landscapes began to emerge more frequently. Often lacking perspective, these works resembled the "Grandma Moses" style and remained relatively uncommon.

Contemporary Developments: Full Scenes and Narrative Weaving

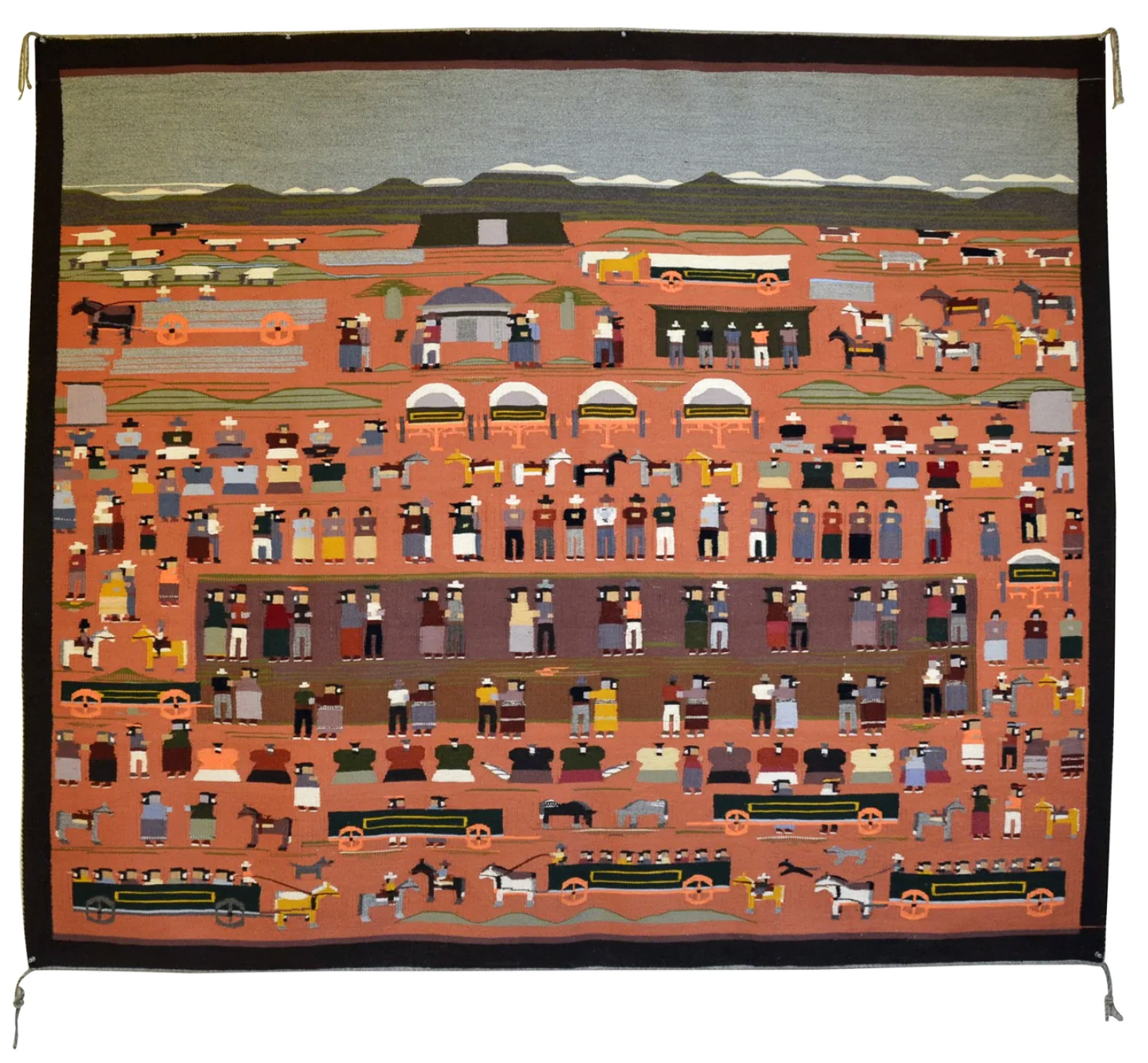

- Since the 1970s: There has been a notable shift toward more complex, narrative pictorial rugs. Contemporary Navajo weavers now create works that function as woven paintings, depicting entire landscapes, cityscapes, events, and scenes from daily or ceremonial life. These rugs often include detailed representations of the natural environment (red cliffs, blue skies, juniper trees), and modern elements, such as trucks, school buses, and city skylines.

- Human figures engaged in traditional or contemporary activities.

- Artistic recognition: Today, pictorial rugs are widely recognized as fine art and are collected by museums for their technical complexity and narrative depth. Each rug is unique, reflecting the weaver's individual vision and memory.

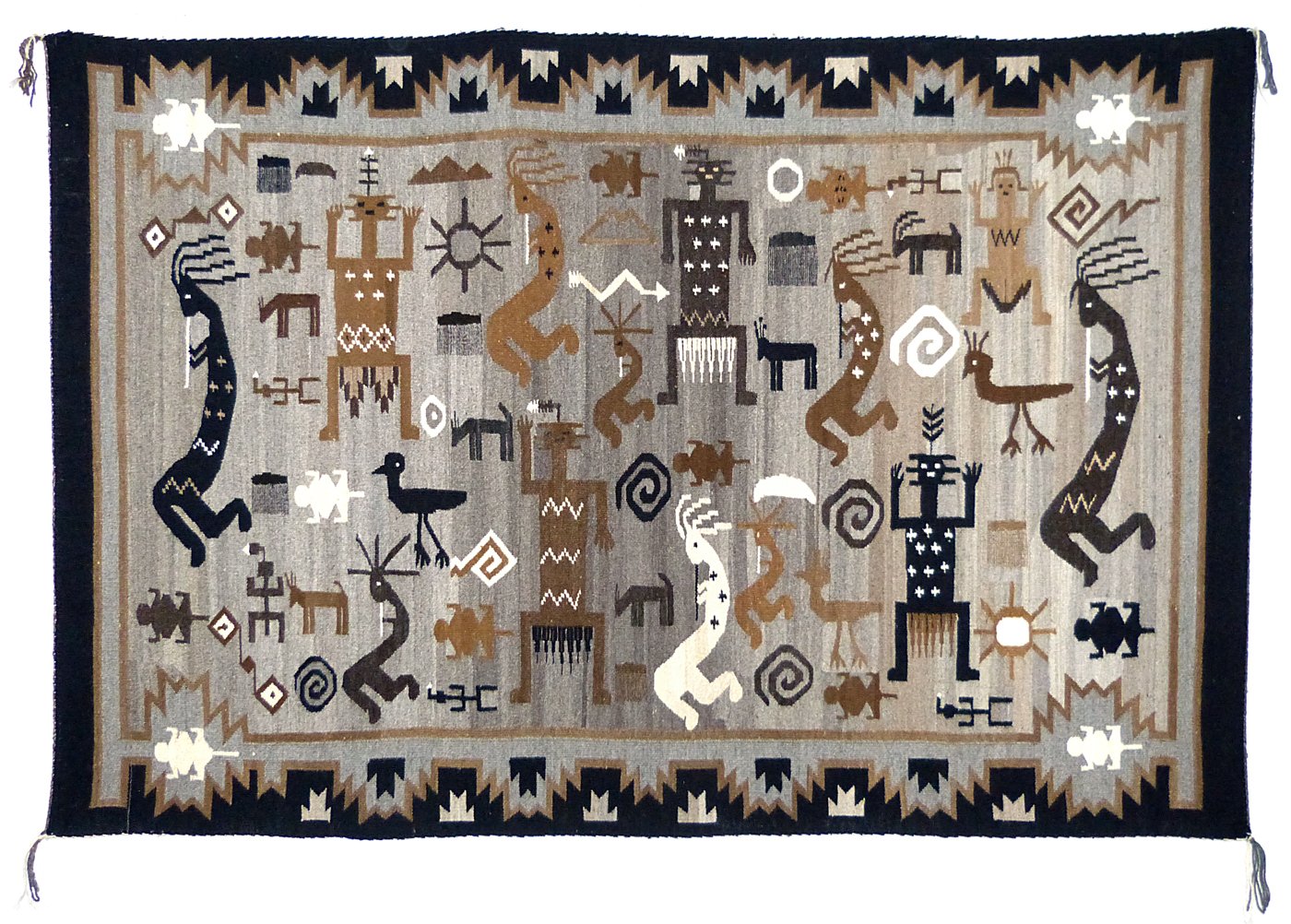

Some contemporary pictorial artworks have incredibly intricate designs with rounded elements that are difficult to weave on a traditional Navajo loom. Pictorial masterpieces like those below require expert manipulation of the weft to produce quality rugs. Of course, most of these artworks are not used as carpets, but rather as tapestries to be hung on walls.

Tree Of Life, Navajo Pictorial Rug by Sarah Tso, 2004. First prize winner at the Gallup Inter-Tribal Indian Ceremonial, Gallup New Mexico 2004. Dimensions: 63 x 48 in.; 160.02 cm × 121.92 cm. Chimayo Trading del Norte, Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico.

Squaw Dance, Navajo Pictorial Rug by Juanita Tsosie, 1980s. Dimensions: 72 x 83 in.; 182.88 cm × 210.82 cm. Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, AZ.

Canyonland Flight by Michele Laughing-Reeves (b. 1971), 2015. handspun and commercial wool, cochineal and indigo dyes, and vegetal and aniline dyes. Heard Museum, Phoenix, AZ.

Two Grey Hills Petroglyph Pictorial rug by Esther Etcitty (or Etsitty), ca. 1980. Medium: handspun Navajo Churro wool in natural ivory, brown, tan, hand carded grey, and hand dyed aniline black. Dimensions: 47 1/2" x 70 1/2"; 120.65 cm × 179.07 cm. Shiprock Art Gallery, Santa Fe, NM.

The design features the Kokopelli symbol, among others. Kokopelli is one of the most recognizable and complex symbols in Native American Southwest cultures, but its origins and meanings are far more nuanced than popular culture suggests. The creation of the "Kokopelli symbol" involves multiple Native American cultures spanning over 3,000 years of history. These cultures range from the Ancestral Puebloan peoples, also known as the Anasazi, to the Hopi and Zuni. Each group contributed their own interpretations and artistic representations. Although Kokopelli is not a traditional Navajo deity, the symbol has been adopted into Navajo culture, often through the lens of their traditional figure, the "Water Sprinkler" or Tonenili.

Key Artists Breaking Traditional Boundaries

The contemporary Navajo weaving landscape is characterized by bold creativity. Textile and fiber artists such as Venancio Aragon, Melissa Cody, Marilou Schultz, Velma Kee Craig, and Kevin Aspaas are preserving the technical mastery of their ancestors while also reshaping the art form to reflect the complexities of the present. Their work shows that Navajo weaving is a living, evolving tradition that continues to inspire, provoke, and innovate.

Venancio Francis Aragon (b. 1985)

Aragon’s work exemplifies the creative energy of contemporary Navajo weaving. Trained in cultural anthropology and Native American studies, he incorporates traditional zigzag, diamond, and banded stripe patterns, but radically expands the color palette, shapes, and textures of his tapestries. Aragon aims to depict the "monumental vitality" of contemporary Navajo culture, actively deconstructing romanticized notions of Indigenous art and emphasizing its evolution and relevance.

LEFT: Prism of Emotions, 2019, Heard Museum, Phoenix, AZ.

CENTER: Waiting for the Rain, 2022. Medium: Natural dyes (indigo, madder root, turmeric, Navajo tea, dock root, onion skins, cochineal, & rabbit brush, synthetic compounds, commercially-spun Mohair/Merino, 100% wool. Dimensions: 59 ½ x 43 in.; Denver Art Museum, CO.

On the bottom, a picture of Venancio Aragon (source: School for Advanced Research).

RIGHT: Rainbow Wedge. Medium: Wool weft and warp. ver 250 colors of weft are dyed using natural and synthetic compounds. The design is based on the artist's Expanded Rainbow Aesthetic.

Melissa Cody (b. 1983)

Cody is acclaimed for her sophisticated geometric overlays and use of unconventional dyes and fibers. Her tapestries incorporate digital technologies and reimagine popular patterns, often referencing the Germantown weaving tradition—a craft born from historical trauma involving forced relocation and government-issued yarn. Cody’s work is a practice of reclamation and innovation, blending historical references with a futuristic vision.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Fourth Dimension, 2016. Medium: 3-ply aniline-dyed wool. Dimensions: 26 × 28 in.; 66 × 71.1 cm.

The Three Rivers, 2021. Medium: Wool warp, weft, and selvedge cords; aniline dyes. Dimensions: 127 x 42 in.; 322.6 x 106.7 cm. Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, NY.

World Traveller, 2014. Medium: 3-ply wool, aniline dyes, wool warp, 6-ply selvedge cords. Dimensions: 92 x 45 in.; 233.68 x 114.3 cm. Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas.

Into the Depths, She Rappels, 2023. Medium: Wool warp, weft, selvedge cords, and aniline dyes . Dimensions: 87 x 51 1/2 in.; 220.98 x 130.81 cm. Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, NY.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Melissa Cody and a detail of her Deep Brain Stimulation, 2011; medium: wool warp, weft, selvedge cords, and aniline dyes, dimensions: 40 x 30 3/4 in.; 101.6 x 78.11 cm. The rug is from Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, NY. The picture is from Tulalip News, 2013.

Walking Off No Water Mesa, 2021. Medium: Wool warp, weft, and selvedge cords; aniline dyes. Dimensions: 127 x 38 in.; 322.6 x 96.5 cm. Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, NY.

Dopamine Dream, 2023. Medium: Jacquard wool tapestry with fringe aniline-dyed wool. Dimensions: 50 x 60 in.; Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, NY.

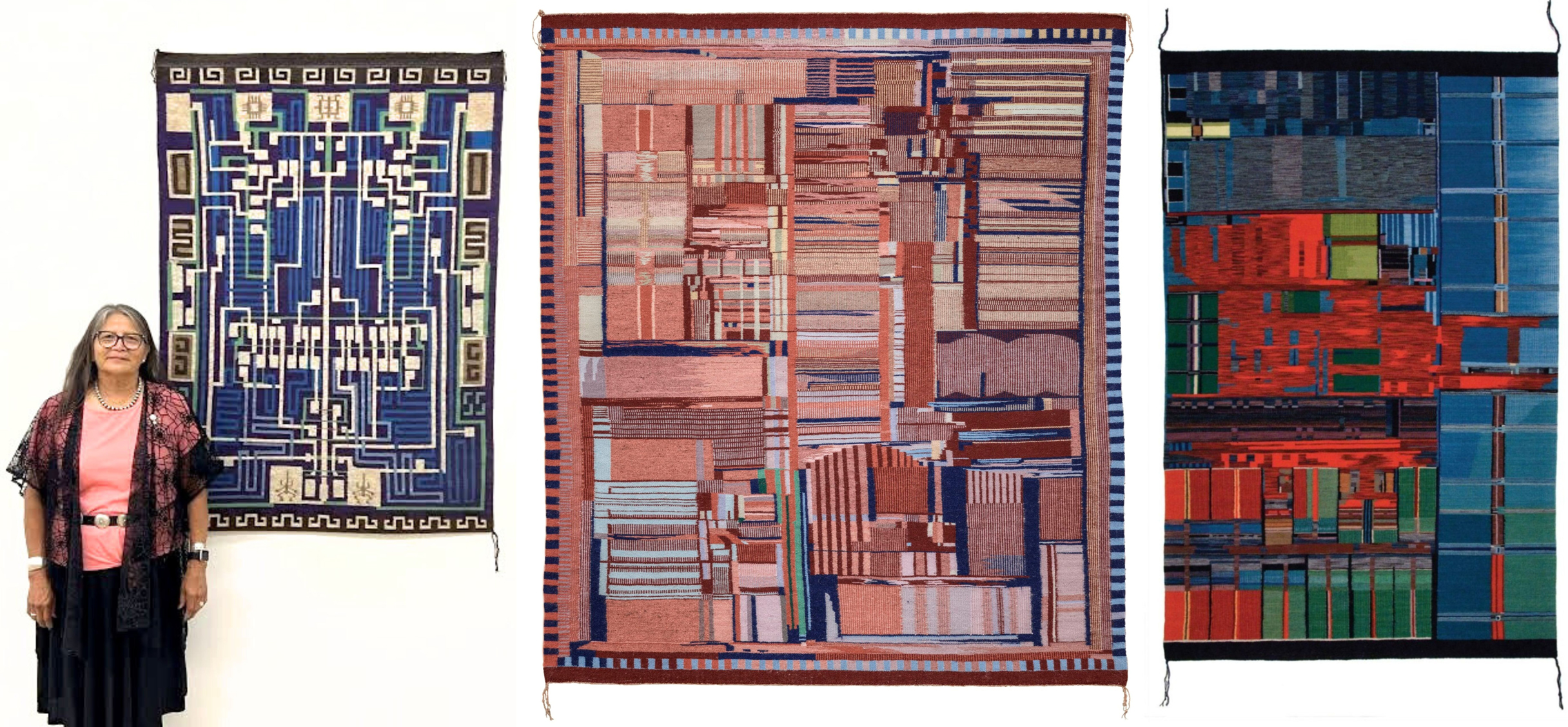

Marilou Schultz (b. 1954)

Schultz – whose maternal clan is Tábaahá (Water’s Edge Clan) and her paternal clan is Tsi’naajinii (Black Streak Wood People Clan), is known for incorporating digital technology motifs into her weavings. One notable example is her woven replica of a 1994 Pentium computer chip, which was commissioned by Intel. Her work shows how ancestral techniques can serve as a medium for contemporary commentary, bridging the worlds of high technology and Indigenous heritage.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Marilou Schultz presented her work, Integrated Circuit Chip & AI Diné Weaving, at the Kunstverein München in 2024. The medium is aniline-dyed and shades of indigo and natural, hand-spun Navajo Churro wool yarns. The design is based on the Fairchild 9040 integrated circuit chip, which was produced at the Shiprock plant..

Replica of a Chip, 1994. Wool mounted on wood. Dimensions: 120 x 146.1 cm. From the "Woven Histories" exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), CA.

Untitled, 2008. Medium: wool. Photo courtesy: Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

Velma Kee Craig (b. in the late 1970s or early 1980s)

Velma Kee Craig is a contemporary Navajo textile artist and a curator at the Heard Museum in Phoenix. She is well known for her leadership in curating major exhibitions of Indigenous art and textiles. Born in the Navajo Nation, she grew up in a family with deep weaving roots. She learned from her grandmother and inherited her weaving tools. Craig’s tapestries fuse traditional Navajo patterns with contemporary pop culture elements, such as QR codes, scientific diagrams, and flags. Her work vividly exemplifies how Navajo weaving can serve as a vehicle for both cultural continuity and modern expression.

LEFT: Velma Kee Craig, 2020.

RIGHT: Code/QR Code, 2013. Medium: one-ply commercial yarn and aniline dyes. Heard Museum Collection, Phoenix, AZ.

Kevin Aspaas (b. 1995)

Kevin Aspaas is a leading contemporary Diné textile and fiber artist. Born in Shiprock, New Mexico, he comes from a long line of Diné weavers, craftspeople, and storytellers. He is recognized for his technical mastery, cultural stewardship, and innovative approach to traditional weaving. Aspaas exemplifies a new generation of Navajo weavers who honor ancestral traditions while fearlessly expanding the boundaries of Diné textile art.

Aspaas raises his own flock of Navajo-Churro sheep, shears them, spins the wool, and uses natural dyes, thus honoring the full cycle of traditional textile creation. Aspaas prefers natural dyes from local plants, such as wild rhubarb, indigo, and cochineal, believing these materials imbue his work with spirit and authenticity. Aspaas is especially known for reviving and innovating the Navajo wedge weave, a 19th-century technique characterized by diagonal weaving that produces zigzag patterns and scalloped, undulating edges. Trading posts once discouraged this method, but it is now celebrated for its unique aesthetic and cultural significance. He creates traditional textiles, such as rug dresses, sash belts, and moccasins, for community use, as well as experimental pieces for collectors and museums. Sometimes his work expands into large installations and performance art, exploring the boundaries of Navajo weaving.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Kevin Aspaas. Photo by Minesh Bacrania. (Source: KA Instagram).

Wolachii (Red Ant), 2018. Woven on vertical Navajo loom in the wedge weave technique. Medium: Wool, natural dyes including cochineal, logwood, and madder root.

Kevin Aspaas. Photo by Minesh Bacrania. (Source: KA Instagram).

Untitled, rug in the wedge weave technique, beginning of 2020. (Source: KA Instagram).

These examples showcase the Diné wedge-weaving technique. Kevin Aspaas raises his own flock of Navajo-Churro sheep, shears them, spins the wool, and uses natural dyes, thus honoring the full cycle of traditional textile creation.

Marlowe Katoney (b. in the late 1970s or early 1980s)

Marlowe Katoney is a contemporary Navajo artist who boldly fuses elements of Native American tradition, street art, and popular culture in his work with textiles and painting. Based in Winslow, Arizona, Katoney is recognized for challenging and expanding the boundaries of what is conventionally considered "Navajo art" or "beautiful" in indigenous textile and visual culture.

Katoney learned to weave from his maternal grandmother, a traditional Ganado-style weaver. This intergenerational transfer of knowledge inspired him to combine his artistic sensibilities with Navajo weaving techniques, creating a distinctive style that blends tradition with contemporary elements. His weavings merge traditional Navajo iconography and patterns with contemporary pictorial elements. Katoney draws inspiration from break dancers, skateboarders, street life, personal experiences, nature, family, and Navajo culture.

Katoney intentionally deconstructs established ideas of beauty and "authentic" Navajo art. He states, "For me, being an artist is an ongoing pursuit of freedom. It’s about not being limited by popular perceptions of beauty or creating something that can easily be identified as 'Navajo,' but rather deconstructing old ideas to create new ones. Addressing subject matter and composition in this way contextualizes traditional Navajo weaving as contemporary art."

Katoney’s rugs are often described as "painterly," reflecting his background in fine art. He uses vibrant colors and complex compositions and sometimes incorporates figures or scenes that evoke contemporary life. One such scene is a man in jeans and a T-shirt poised to move, a motif inspired by street observation and breakdancing.

He is also known for “deconstructing old ideas to create new ones,” using the loom as a space for innovation and dialogue between past and present.

Katoney views his practice as a pursuit of artistic and personal freedom, refusing to be constrained by stereotypes or expectations of what Navajo art should look like. He once said: «The capacity of the imagination is endless, and the motions of daily life can be fuel for the imagination.»

LEFT: Marlowe Katoney at the October 2019 opening of "The Western Sublime: Majestic Landscapes of the American West" exhibition at the Tucson Museum of Art, with his wool artwork Garden Ornaments (2019). Collection of the Tucson Museum of Art. Photo by Ray Cleveland.

RIGHT: Axis Radius #5: Pareidolia Overture, 2023. Medium: wool, aniline dyes, vegetal dyes. Collection of Tony Abeyta.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Marlowe Katoney, Vase of Flowers at the End of the World, 2019, Wool, aniline dyes, vegetal dyes. Collection of Christy Vezolles.

Survivor: An American Experience, ca. c. 2012. Medium: Wool, aniline dyes, vegetal dyes. Arizona Museum of Art, The University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ. The weaving depicts an elder survivor of the Long Walk, portrayed in black and white to symbolize his near brush with death.

Sign of the Times, 2025. Dimensions: 27 x 39 in.; 68.58 x 99.06 cm. King Galleries, Scottsdale, AZ.

Common Threads in Contemporary Innovation

- Deconstruction of Tradition: Many artists intentionally move away from established regional patterns, using weaving to comment on identity, technology, and cultural change.

- Material Experimentation: There is a willingness to use non-traditional dyes, commercial yarns, and even digital fibers, alongside or instead of handspun Churro wool.

- Conceptual Weaving: Some artists, like Eric-Paul Riege, move "outside the loom," creating fiber-based installations and performances that challenge the definition of weaving itself.

- Storytelling and Social Commentary: Contemporary weavers use their art to address issues ranging from historical trauma to modern Indigenous identity and the impact of technology.

CONTEMPORARY NON NAVAJO WEAVERS AND TEXTILE ARTISTS WORKING WITH NAVAJO-CHURRO WOOL

A growing number of non-Navajo weavers and textile artists are embracing Navajo-Churro wool, a fiber rich in cultural heritage and artistic potential. While deeply rooted in Diné weaving traditions, this unique wool has found its way into contemporary studios, where artists outside the Navajo Nation are approaching it with reverence, creativity, and ethical intent.

Minna White – Shepherd, Feltmaker, Visionary

Based in Taos, New Mexico, Minna raises her own flock of Navajo-Churro sheep and transforms their wool into large felted pieces, including wall hangings, rugs, and sculptural panels. She handles every step of the process by hand, from shearing to shaping each final piece.

Through her solar-powered studio, Lana Dura LLC, she offers handmade home goods, including blankets, table runners, panels, tapestries, rugs, bath mats, pet mats, potholders, and cushion covers, each crafted from her wool felt. White is also an educator and community contributor who teaches felting workshops and gives back through local initiatives. Inspired by the New Mexican landscape and powered by solar energy, her practice embodies sustainability and artistry.

Minna White (on the right) is wearing a Navajo Churro wool coat. Photo from Arts Illustrated. The other pictures show some of her creations. The large wool felt panels, which can be used as wall hangings, floor rugs, or furniture covers, are made solely from Navajo Churro wool fleece. She creates thin layers of base colors and overlays them with unique designs in different 100% natural colors.

Other felted creations by Minna White. Photos from MW Instagram. «Most of the fleece that I use – she says – is from my flock, and some is from other Navajo-Churro flocks around North America. Because Navajo-Churro sheep retain their genetic diversity, breeding a white (or brown) ewe with a white (or brown) ram does not necessarily result in the desired white or brown lambs. So, every year during lambing season, it's an adventure because a range of colors is possible.»

Josh Tafoya – Reviving Tradition through Contemporary Design

A Taos-based designer who was trained at Parsons in New York, Tafoya returned home to revive a family tradition of Spanish weaving that had faded over time. Using a Rio Grande loom, he creates wearable pieces and tapestry art with Navajo-Churro wool.

His work often incorporates unusual elements, such as bailing twine and charred willow branches, reinterpreting age-old patterns in striking, modern forms. By layering history with innovation, Tafoya’s textiles resonate as fashion and cultural commentary.

Josh Tafoya and some of his latest creations: Rancho La Bruja, 2022, woven bailing twine. Photo: Campbell Bishop (on the left); Two Denim Hills, 2022, patchworked denim, Ranchero Collection (top center); Genizaro SS25 (top bottom). All pictures are from the designer's website.

Rebecca Mezoff – Tapestry Artist and Educator

Rebecca Mezoff brings Navajo-Churro wool into the world of contemporary tapestry. She is known for her deep knowledge of wool’s structure and how it behaves when woven. She incorporates Churro fleece into her online courses and in-person workshops. She values the wool's durability and dual-coated texture, which makes it ideal for detailed, long-lasting weavings.

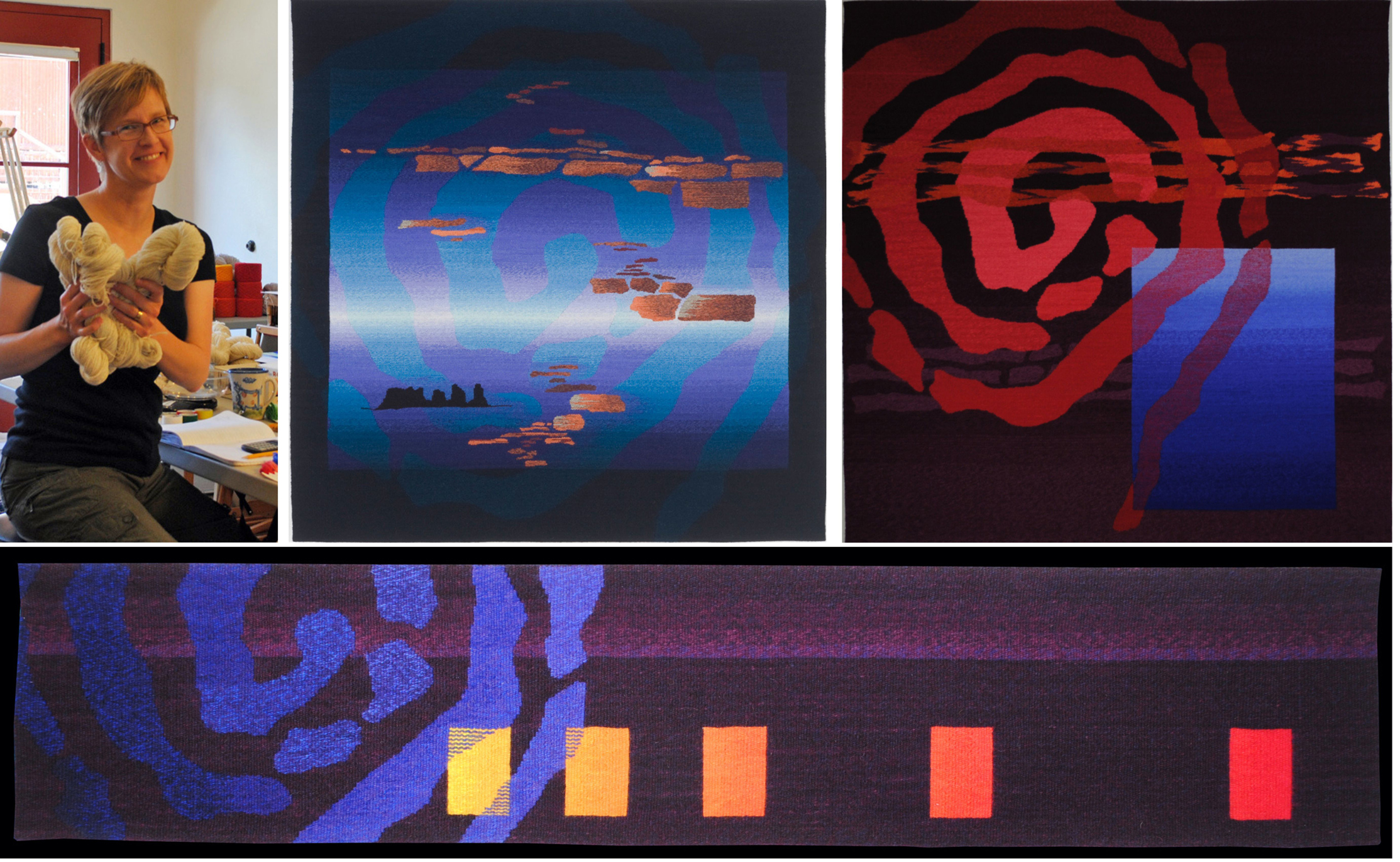

LEFT TO RIGHT, CLOCKWISE

Rebecca Mezoff, hand-woven, hand-dyed wool and cotton tapestry artist and online teacher. Photo: from the artist's website.

Emergence V: The Center Place, hand-dyed wool tapestry, 44 x 44 in.; 111.76 x 111.76 cm.

Emergence II, hand-dyed wool tapestry, 44 x 44 in.; 111.76 x 111.76 cm. Permanent Collection of Graig College, Craig, CO.

Emergence III, hand-dyed wool tapestry, 9 x 44 in.; 22.86 x 111.76 cm. Private Collection, AZ.

Connie Taylor – Guardian of the Flock

For over two decades, Connie Taylor has raised Navajo-Churro sheep on her Colorado ranch, Cerro Mojino Woolworks. As registrar of the Navajo-Churro Sheep Association, she plays a key role in breed preservation.

Taylor offers mill-spun yarn in over twenty naturally and hand-dyed shades. Her dedication to the breed dates back to the late 1970s when she supported the Navajo Sheep Project, a movement that helped save the breed from extinction.

Connie Taylor’s Navajo-Churro yarns are a rainbow of earth tones without a hint of dye. They showcase the natural beauty and remarkable color range of this heritage breed, which has been prized by weavers for centuries. From creamy whites to deep browns and stormy grays, these skeins are as authentic as the New Mexico landscape—and just as enduring. They're perfect for anyone who wants textiles with a side of history and a whole lot of sheep personality! Photo by Rebecca Mezoff.

Communities Upholding the Tradition

Tierra Wools and the Weaving Heritage of Los Ojos

In the northern New Mexican village of Los Ojos, the Tierra Wools cooperative carries on a weaving tradition that began with Spanish settlers centuries ago. Founded in 1983 as part of Ganados del Valle, the cooperative now operates independently in Chama.

The weavers use Navajo-Churro and Rambouillet wool on traditional "walking looms" to craft blankets, rugs, and tapestries adorned with Saltillo diamonds and Vallero stars. These designs blend Spanish, Mexican, and Indigenous aesthetics.

Ethics and Cultural Awareness

Supporting Indigenous Shepherds

Efforts like the Indigenous-led Navajo-Churro Wool Cooperative—supported by groups such as Fibershed—aim to empower Navajo shepherds and ensure their wool is fairly valued. Despite the demand for wool, many reservation-based shepherds still face underpayment or dismissal by commercial buyers. These initiatives seek to correct that imbalance and amplify Indigenous voices in the market.

Education and Preservation

Non-Navajo artists engage with the history of the wool and the people behind it. Ties between these artists and Navajo shepherds are growing, often formed through mutual respect and shared goals. Diné weaver Venancio Aragon has noted how meaningful these connections can be when rooted in cultural understanding.

Conclusion

The collaboration between non-Navajo artists and Navajo-Churro wool is a testament to reverence, innovation, and shared stewardship. Whether it's Minna White's sculptural feltwork or Tierra Wools' traditional blankets, each piece speaks to the enduring legacy of this fiber.

As the focus on sustainability, ethical sourcing, and handmade craft continues to grow, Navajo-Churro wool inspires a new generation of artists. Each artist contributes to its vibrant future while honoring its profound past.

A FINAL REFLECTION

We began with an ancient tale of sheep and men, and after traveling through the Navajo world, we have returned to a new tale of sheep and men. Our journey of discovery through Diné history and culture has come to a close. Here we are, back where we started—humble sheep.

The story of Navajo-Churro wool is not just a revival of a rare fiber; it is also a quiet thread of reconnection. Through caring for the sheep and weaving by hand, as well as a growing awareness of cultural respect, Navajo, non-Navajo, and Spanish-descended artists are finding common ground.

This shared material has begun to foster dialogue across communities that were once divided by histories of violence, displacement, and erasure. The Navajo-Churro sheep, nearly lost due to colonial policies and forced assimilation, are now tended by hands of many backgrounds—some reviving ancestral knowledge and others learning with humility.

The wool carries memory in its fibers, but it also carries possibility. In workshops, cooperatives, ranches, and looms across the Southwest, the wool is helping to create a space where heritage and innovation can coexist. Not perfectly, not always easily, but meaningfully. Through art and stewardship, these communities are reimagining shared creative futures rooted in dialogue, respect and peace, sustained by the land, and woven one thread at a time.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?