NAVAJO CHURRO SHEEP AND WOOL 6

USA on the globe.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

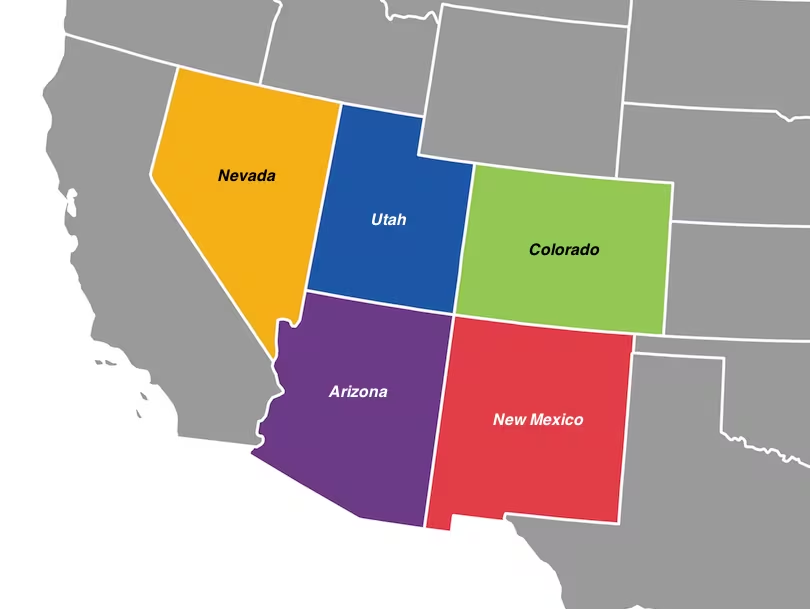

SOUTHWESTERN STATES

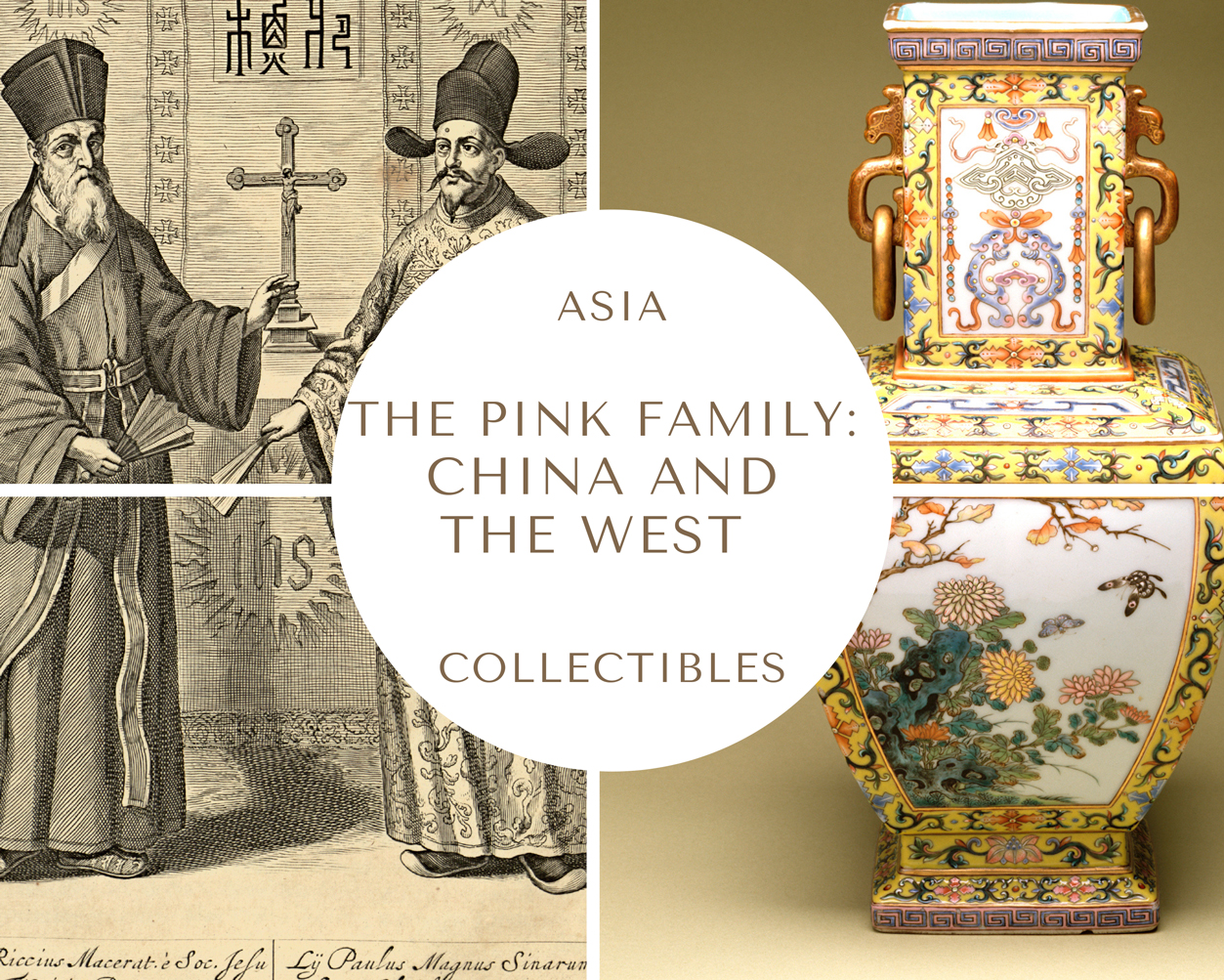

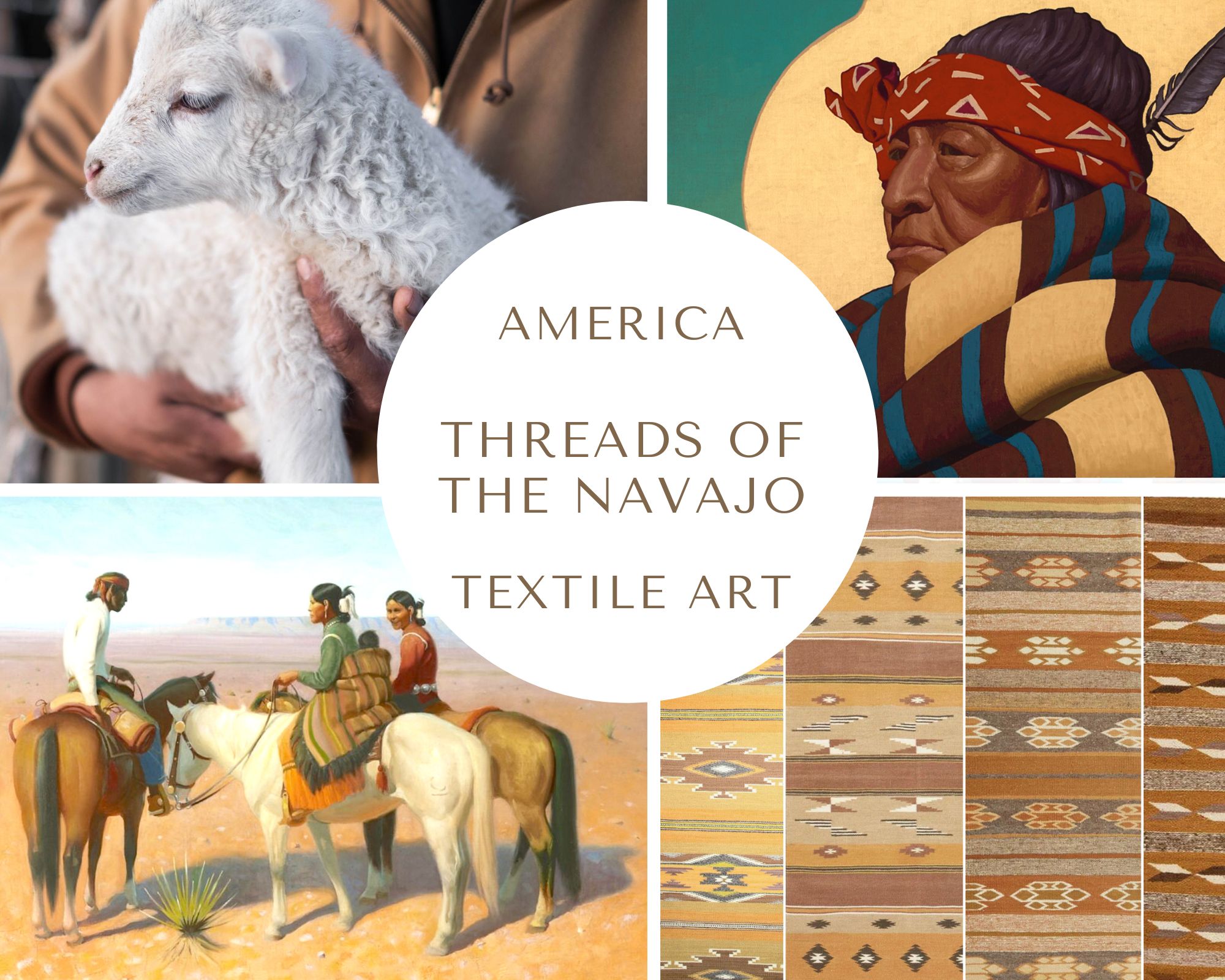

WOVEN LEGACIES: THE ART AND HISTORY OF NAVAJO/DINÉ TEXTILES

-

TRADE NETWORKS AND REGIONAL INTEGRATION: FROM BARTER TO GLOBAL TRADE

THE POSITIVE IMPACT OF TRADERS AND TRADING POSTS ON THE NAVAJO NATION

Between 1880 and the late 1920s, the traders and trading posts on the Navajo Reservation facilitated measurable economic growth and infrastructure development, as documented by academic sources.

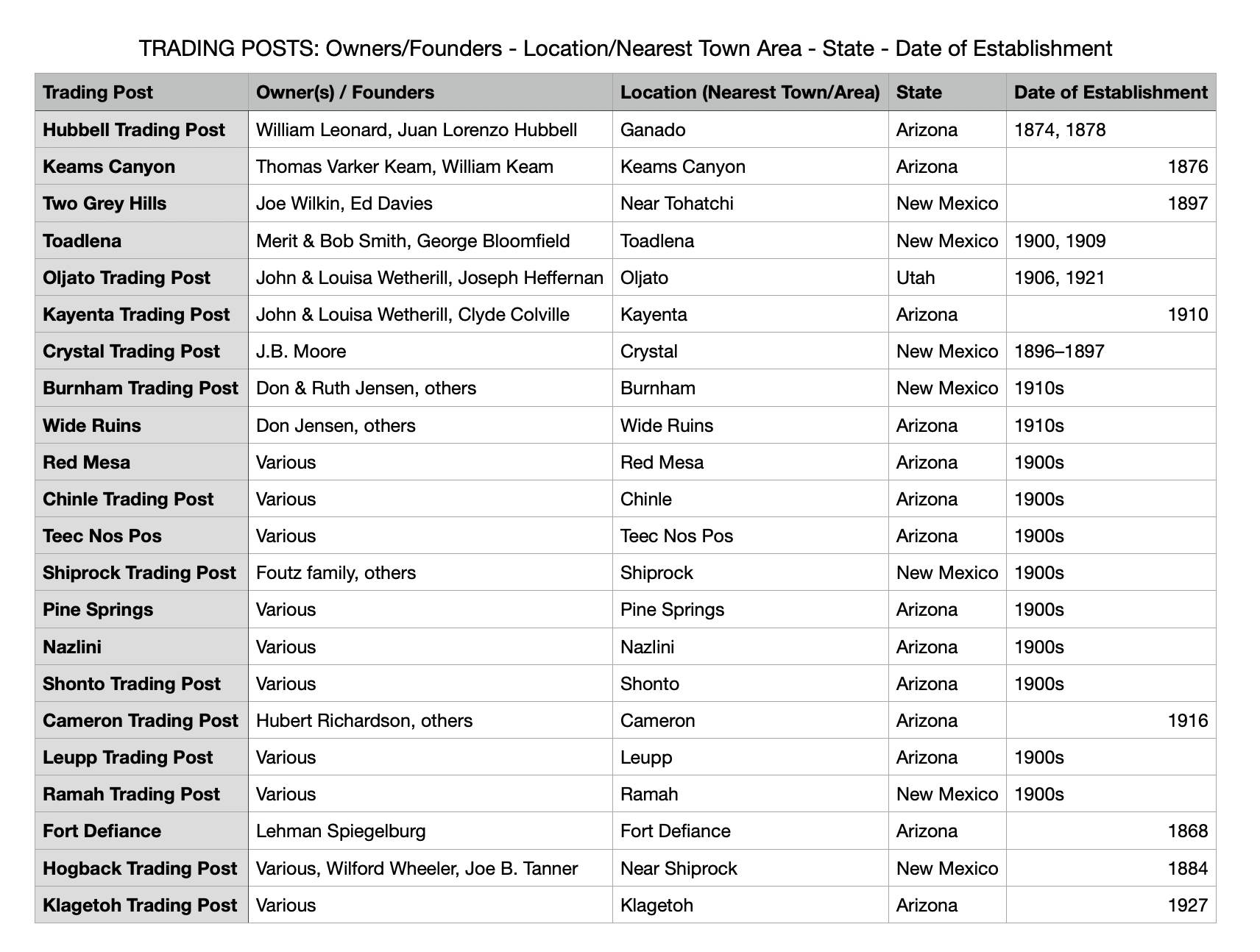

In 1875, only 7 trading posts operated on or near the reservation. By 1900, this number had grown to nearly 100, and by 1930, there were 154 trading posts (Robert W. Volk). This growth provided greater access to goods and markets, integrating remote Navajo communities into the regional and national economy.

Between 1880 and 1920, the population of the Navajo Nation grew by 50%, but textile production increased by 800%, despite wool shortages, as weavers compensated by purchasing commercial yarn (Kathy M'Closkey and Carol Snyder Halberstadt). Navajo Churro sheep became more valuable than ever.

Blanket sales rose from $40,000 in 1890 to $500,000 in 1913 and peaked at over $1 million in 1931, one-third of the Navajo Nation's annual revenue (Robert W. Volk, Kathy M'Closkey, and Carol Snyder Halberstadt). Lorenzo Hubbell alone shipped over 200 tonnes of hand-spun, woven textiles from Ganado between 1891 and 1909 (M'Closkey 2002).

Traders and agents controlled not only the final quality of Navajo textiles, but also the various stages of weaving, and «did all they could to improve upon the breeding stock, the sheering practices, and the control of disease among sheep.» (Robert S. McPherson).

While specific sales figures for silver work are sparse, traders supplied materials (e.g., ounces of silver, turquoise) and tools, enabling Navajo artisans to meet the growing tourist demand. By the 1920s, silver jewelry had become a staple of regional trade (Robert W. Volk).

Traders extended credit for wool, rugs, and silverware, creating a mixed barter and cash economy. This system stabilized Navajo incomes between seasonal harvests. Traders employed Navajo individuals in freighting, road construction, and post maintenance, introducing wage labour alongside traditional herding. By 1920, a mixed barter and wage economy had developed, with Navajo workers earning income from both craft sales and paid labour.

The Shiprock Agency, founded by William T. Shelton in 1903, created and sponsored the Shiprock Fair from 1909, introducing competitive displays of Navajo crafts and encouraging quality improvements in weaving and silver work. Prizes were awarded for categories such as 'best general display' and 'cleanest camp', promoting Anglo-American values of competition and hygiene (seen at the time as necessary steps in the assimilation and 'de-Indianization' of Natives).

Traders cultivated distinct regional identities to differentiate their products. Regional styles such as Ganado (red-dominated), Two Grey Hills (black and white geometrics) and Teec Nos Pos (elaborate borders inspired by Persian carpets) emerged and influenced design and production.

Trading posts were social institutions of sorts. «Communicating in a kind of pidgin Navajo, known as trader Navajo, the traders became the mediators between the Navajo and the outside world, which included the agents of the U.S. Government. Often placed in a position of trust among the Navajo, traders were called upon for various tasks such as burying the dead, killing sheep killers (especially bears, which are considered sacred), settling disputes between clans and families, and assisting with government forms. «The trading post also became a gathering place where families and friends congregated to exchange news and gossip, tell stories, and engage in other social activities. Yet all of these functions were, secondary and complementary to the role that the trader performed in the production relations on the Reservation.» (Robert W. Volk)

By 1920, Pendleton blankets (made in Oregon) were replacing traditional Navajo blankets for personal use. Under the powerful influence and control of traders, Navajo weavers were able to produce higher-value commercial goods, such as rugs and carpets, in a capitalist commercial context. They could have been wiped out, but through the mediation of traders they were able to integrate their "products" into a modern market economy while preserving some of their weaving traditions. In this way, the trading post system spurred measurable economic expansion on the Navajo Reservation, as evidenced by increasing craft sales, infrastructure growth (new roads and bridges), and labour diversification. In the period 1880-1920, traders acted as central intermediaries, linking Navajo producers to wider markets, promoting commercial ranching, and stabilising local economies through credit systems. Scholar Robert W. Volk agrees: «(...) the activities of the traders proved to be pivotal as they guided the transformation of the Navajo economy toward exchange through their roles as merchants, entrepreneurs, and intermediaries between the Navajo and outside world.».

But that is only one side of the story. Let's discover the other.

THE OTHER SIDE OF THE COIN, I MEAN OF THE STORY

The reservation system and the trade licensing system served to discourage intertribal trade and eradicate the traditional trade network previously established by the Diné. In addition, the token and pawn systems (which we will discuss below) moved the Navajo into a cash-based economy, undermining traditional reciprocity networks.

«This strategy was motivated, in part, by sentiments in the Indian Bureau and the U.S. military that in order to keep the previously marauding Native American groups subjugated it was necessary to break traditional patterns of contact. This process worked to channel trade toward Anglo markets located primarily in the East.» (Robert W. Volk).

The economic control exercised by the traders not only deprived the Navajo of full control over the production process, but often masked forms of harsh labour exploitation.

Did the traders make a strong commitment to support Navajo weavers and artisan groups by paying them a fair wage and providing safe and healthy working conditions? In the vast majority of cases, no. The economic exploitation of Navajo/Diné weavers and artisans by traders operating near or on the Navajo Reservation between 1880 and the 1920s was systemic, rooted in unequal power dynamics and federal policies that marginalised and weakened indigenous communities.

Control Through Credit and Pawn Systems

Traders acted as de facto bankers, extending credit to Navajo families in exchange for pledged items such as jewelry, rugs, and livestock. This created cycles of dependency as families relied on traders for basic goods but faced exorbitant interest rates and manipulative accounting. For example, a 1969 study found that traders arbitrarily set credit lines, often undervaluing Navajo goods while inflating the prices of store-bought items such as flour and sugar. Pawns could be declared "dead" (forfeited) if debts went unpaid, allowing traders to profit from selling these goods to outsiders. This system trapped many Navajo in perpetual debt and forced them to produce more handicrafts under exploitative conditions.

Price Manipulation and Unfair Trade Practices

Traders monopolized access to markets by buying Navajo textiles and crafts at artificially low prices and reselling them at substantial markups. A 1969 price survey showed that traders charged Navajo customers up to 300% more than wholesale prices for basic goods, while undervaluing hand-woven rugs. Thus, Navajo weavers received minimal compensation for the labor-intensive rugs that merchants sold to non-Native buyers at a high profit.

Exploitation Through "Pound Rugs"

In the early 20th century, traders began buying rugs by weight rather than quality, incentivizing weavers to use greasy, unwashed wool to increase the poundage. This practice, known as "pound rugs," degraded craftsmanship and devalued Navajo labor. Traders such as John B. Moore and Juan Lorenzo Hubbell also introduced commercial yarns and rigid design templates that deprived weavers of creative autonomy. Moore's catalogs, for example, promoted rugs with Caucasian-inspired designs that weavers were pressured to replicate, often without fair compensation.

Economic Subjugation

The broader colonial context exacerbated exploitation. After the Navajo were forcibly removed to reservations in 1868, federal policies restricted their mobility and economic autonomy. Traders, often sanctioned by the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), became gatekeepers to outside markets. A 1920s report found that traders controlled 90 percent of Navajo trade, monopolizing access to cash and goods while suppressing wages. After World War I, returning Navajo veterans and wage laborers began to challenge this system, but exploitation before the 1920s left lasting scars, including the devaluation of weaving as a sustainable livelihood.

The exploitation of Navajo weavers was not only economic but also cultural, as traders commodified Native artistry while undermining its spiritual and communal significance. Federal complicity perpetuated this cycle through policies that maintained trader monopolies and suppressed Navajo sovereignty. These practices underscore the intersection of colonialism, capitalism, and cultural erasure in the subjugation of Indigenous economies.

LET'S DIG DEEPER INTO THE COMMODIFICATION OF NAVAJO/DINÉ HANDWOVEN TEXTILES

Navajo/Diné textiles were not born and developed as handicrafts or "market products," and to be forced into the latter category, their soul, sacred core, and spiritual meaning had to be diluted, sometimes silenced. Navajo/Diné textiles had to adapt to an alien taste and tickle a diverse and more superficial palate (necessarily superficial because of the ignorance of the deeper meanings of Navajo weaving and woven symbols); they also had to cease to be a part of the daily lives of Diné families. It is paradoxical, but unfortunately true: «Pendleton blankets manufactured in Oregon were purchased by the Navajo so that they could sell their more expensive, higher quality, hand-woven blankets.» (Robert W. Volk).

Navajo men and a woman all wearing trade blankets. Left to right: photo by Edward S. Curtis; photo by Karl Moon.

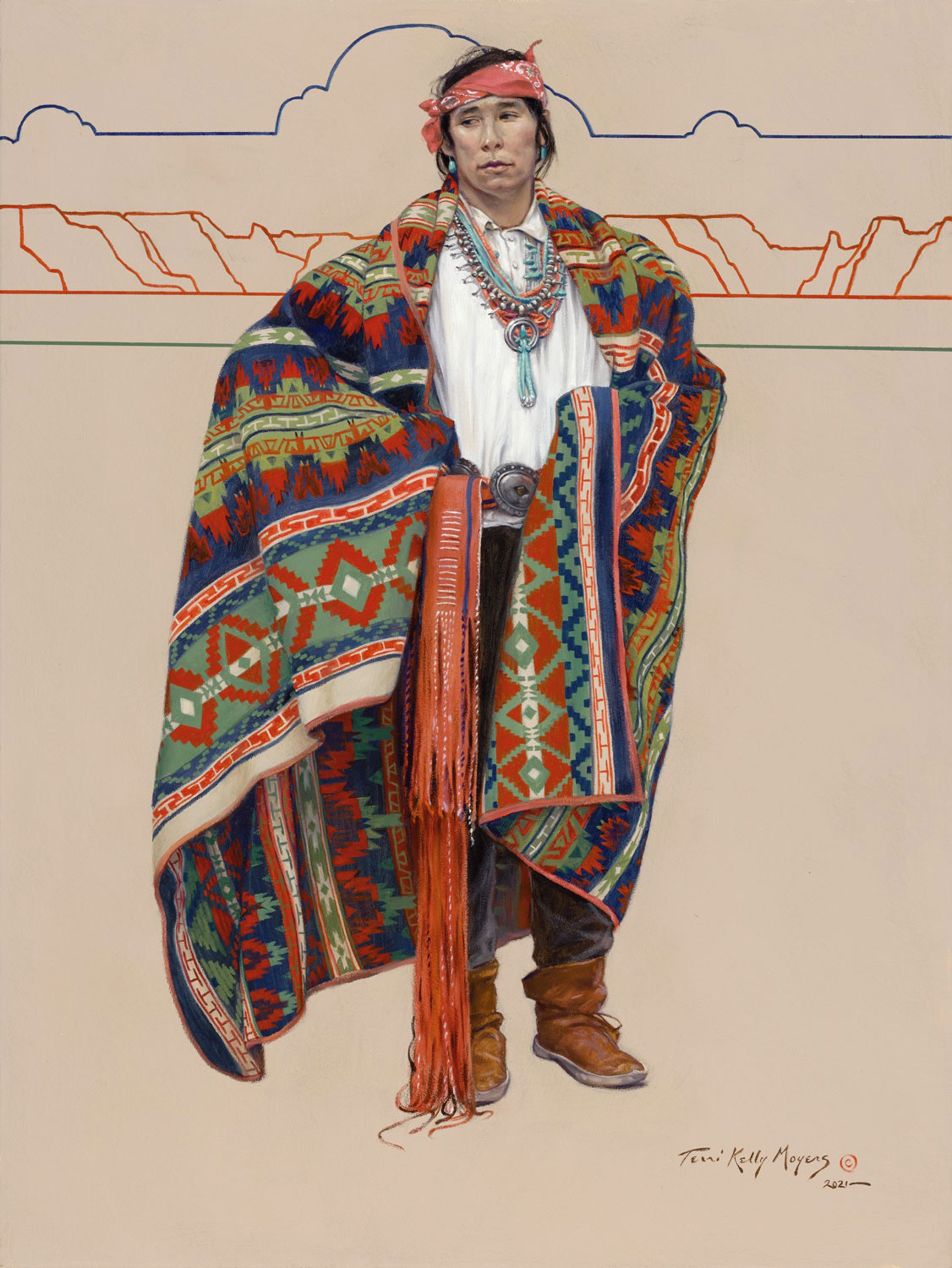

Navajo Proud, oil painting by contemporary Canadian artist Terri Kelly Moyers, 2021. Legacy Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Terri Kelly Moyers is a distinguished and award-winning Western artist who has dedicated her life to painting. Born in Calgary, Alberta, Canada in 1954, she showed an early passion for art, drawing constantly as a child with a particular fascination for horses. After living for many years in New Mexico and Colorado, Moyers and her husband moved to Los Angeles, California, where they currently reside. Her work can be found in several galleries and permanent collections of prominent American art museums.

In their article, Kathy M'Closkey and Carol Snyder Halberstadt cite textile scholar Kate Peck Kent's 1985 assessment in her Navajo Weaving: Three Centuries of Change: «(...) Rugs woven in the [20th] century will not tell us anything about Navajo personality or values because Anglo traders and markets have influenced Navajo weavers so much that any meanings or aesthetic styles which may have existed in early weavings were extinguished. (...) The search for a distinctive Navajo aesthetic ends with the onset of the Rug period [in 1890]. When weavers ceased to manufacture blankets for their own use and turned to the production of rugs for sale to whites, they accepted Anglo American standards of taste.»

I completely disagree. In fact, to be honest, I find this purism rather "taliban" and very short-sighted for some good reasons.

THE WIND THAT STIRS THE PAINTER’S HAND HAS CROSSED TEN THOUSAND TONGUES.

No form of art or beauty comes from cultural isolation, let alone from an effort to preserve a supposed artistic purity from "contaminating" outside influences. Cultural mixing is not necessarily a threat, nor does this mean that it is always a source of growth, especially in the short term. Art is a dynamic, evolving practice shaped by cross-cultural exchange and intercultural dialogue. The notion of "untouched" artistic purity is a romanticized ideal. All cultures absorb and adapt to external influences over time, however subtle or long-term. For example, traditional Indian classical music incorporates Persian elements from Mughal influences, and in China, the blue and white porcelain revolution during the Yuan dynasty was made possible by a technical advance in the processing and firing of porcelain and a happy and fertile contamination of multiple cultural influences. Attempts to rigidly preserve a static form often risk stagnation, reducing art to a museum relic rather than a living practice. As the multi-ethnic philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah observes, "cultural purity is an oxymoron". Navajo textile art is no exception: developed through the adoption of the Pueblo loom and some related techniques, it has also evolved, as we have seen, through the adoption of Moqui (Hopi) motifs and the incorporation of Ute preferences for commercial and artistic reasons.

The absolutism of my statement - "no form of art or beauty comes from isolation" - could be challenged, I know. Isolated communities can produce art, but its impact and longevity may depend on engagement with broader audiences or ideas. True distinctiveness often comes not from isolation but from selective adaptation, when a tradition absorbs outside elements while retaining its core identity. The vitality of art lies in its ability to adapt, and the artistic creativity of a community lies in its ability to engage with outside influences on its own terms. Even if not immediately: it takes time to selectively absorb and metabolize foreign influences, to transform them into "bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh". Navajo textile production during the Trading Post era (until the 1930s) was at times exceptional, at times poor, and it took time for Navajo weavers to process, assimilate, transform, and and embrace external influences.

In any case, during the Trading Post era, Navajo weavers were not passive and obedient producers of rugs, with no say in the matter and totally subservient to the will of evil white men. «However, to look at the <trading> posts solely as a tool of white imperialism is to suggest that the Navajo were helpless pawns. This is far from the truth. The Navajo were sharp bargainers who knew what they wanted and worked towards the means to obtain it.» (Robert S. McPherson)

A MORE NUANCED AND BALANCED APPROACH

Robert W. Volk’s paradoxical observation about Pendleton blankets and the Navajo Nation highlights a complex interplay of economics, cultural adaptation, and colonial dynamics.

Historically, Pendleton blankets were cheaper and more accessible due to industrial production, while Navajo weaving was labor-intensive and commanded much higher prices. This created a bifurcated market: Pendleton's mass-produced blankets became everyday items for trade or ceremonial use within Native communities, while her weavings were sold as luxury goods to non-Native collectors or outsiders. The Navajo likely took advantage of Pendleton's affordability to meet everyday needs, reserving their own craftsmanship for specialized, higher-value transactions. This duality-adopting a commercial product while preserving traditional weaving-reflects the resilience of indigenous people in navigating a colonial economy that often commodified their culture.

For the Navajo, adopting some outside influences and selling their own weavings at a premium was a nuanced survival strategy, a form of economic pragmatism, and a strategic response to marginalization that allowed them to retain some cultural practices while participating in a market dominated by non-Native interests.

They maintained and preserved their traditional loom, many of the old weaving techniques, the spiritual commitment, and the meaning of the act of weaving, even as they adapted and adopted foreign patterns. That's why their hand-woven textiles have remained a powerful symbol of identity, resilience, and flexibility.

Agency (though limited) in Design and Production

Navajo weavers actively negotiated their creative and economic roles during this period. While traders introduced new materials (e.g., synthetic dyes, commercial wool) and sometimes dictated design preferences (e.g., "eye-dazzler" patterns for tourist markets), weavers retained considerable control over their craft. They selectively adopted or resisted outside influences, blending traditional motifs (e.g., storm patterns, diamond designs) with new ideas. This reflects a dynamic process of creative adaptation rather than passive obedience.

Economic Negotiation and Autonomy

The trading post system was undeniably shaped by colonial power imbalances, but Navajo weavers were savvy participants in this economy. They set prices for their rugs based on labor, skill, and market demand, often refusing to sell if offers were too low. Traders like J. L. Hubbell acknowledged their reliance on the weavers' expertise, even as they profited from their labor.

Cultural Preservation and Innovation

During this time, Navajo weaving became a celebrated art form, in part due to outside demand. However, this was not a surrender to colonial pressures. Weavers used the commercial platform to maintain cultural practices during a time of immense hardship (e.g., federal assimilation policies, livestock reduction). Innovations such as the "Two Grey Hills" style - prized for its intricate, undyed wool - show how weavers elevated tradition while engaging with new markets. Not all Trading Post-era rugs are masterpieces, but some are.

Challenging the "Victimhood" Narrative

We must avoid a paternalistic view of indigenous peoples as helpless victims. While there has been systemic oppression and exploitation (e.g., undervaluation of labor, exploitation, cultural commodification), reducing Navajo weavers to "passive producers" erases their strategic resilience. Scholars such as Kathy M'Closkey (Swept Under the Rug, 2008) argue that Navajo women in particular used weaving as a means of both economic survival and cultural resistance.

Nuancing Power Dynamics

Traders were not monolithic villains; some facilitated fair exchange while others exploited weavers. However, structural inequalities rooted in settler colonialism meant that Navajo weavers operated within constraints. Their agency lay in navigating these constraints, not in transcending them altogether.

In short, the Trading Post era exemplifies how Indigenous art navigates preservation and exploitation, weaving resilience into every thread of its history. As scholar Jessica Metcalfe notes (in Beyond Buckskin), Indigenous art has always been a site of "resilience and reinvention"—a truth reflected in the dynamism of Navajo weaving in this era and later.

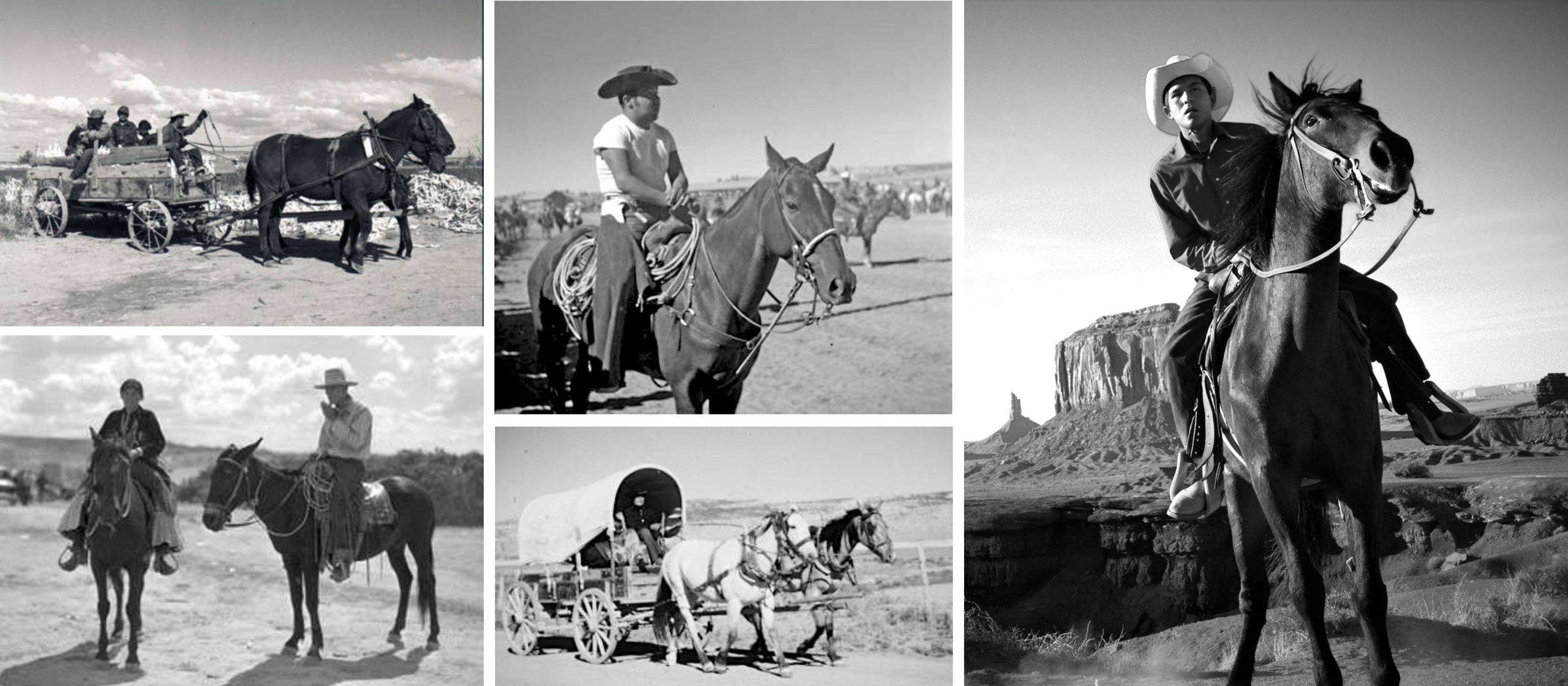

TOP LEFT: Corn harvest on in the Navajo Reservation, 1953, Digital Collections, New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe, NM.

BOTTOM LEFT: Navajo couple on horseback, Gallup Ceremonials, 1937, Digital Collections, New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe, NM.

TOP CENTER: Cowboy on horseback, 1952, Digital Collections, New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe, NM.

BOTTOM CENTER: Navajo Wagon and Horses, undated, Digital Collections, New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe, NM.

RIGHT: Navajo Cowboy, 2011, Wikimedia Commons.

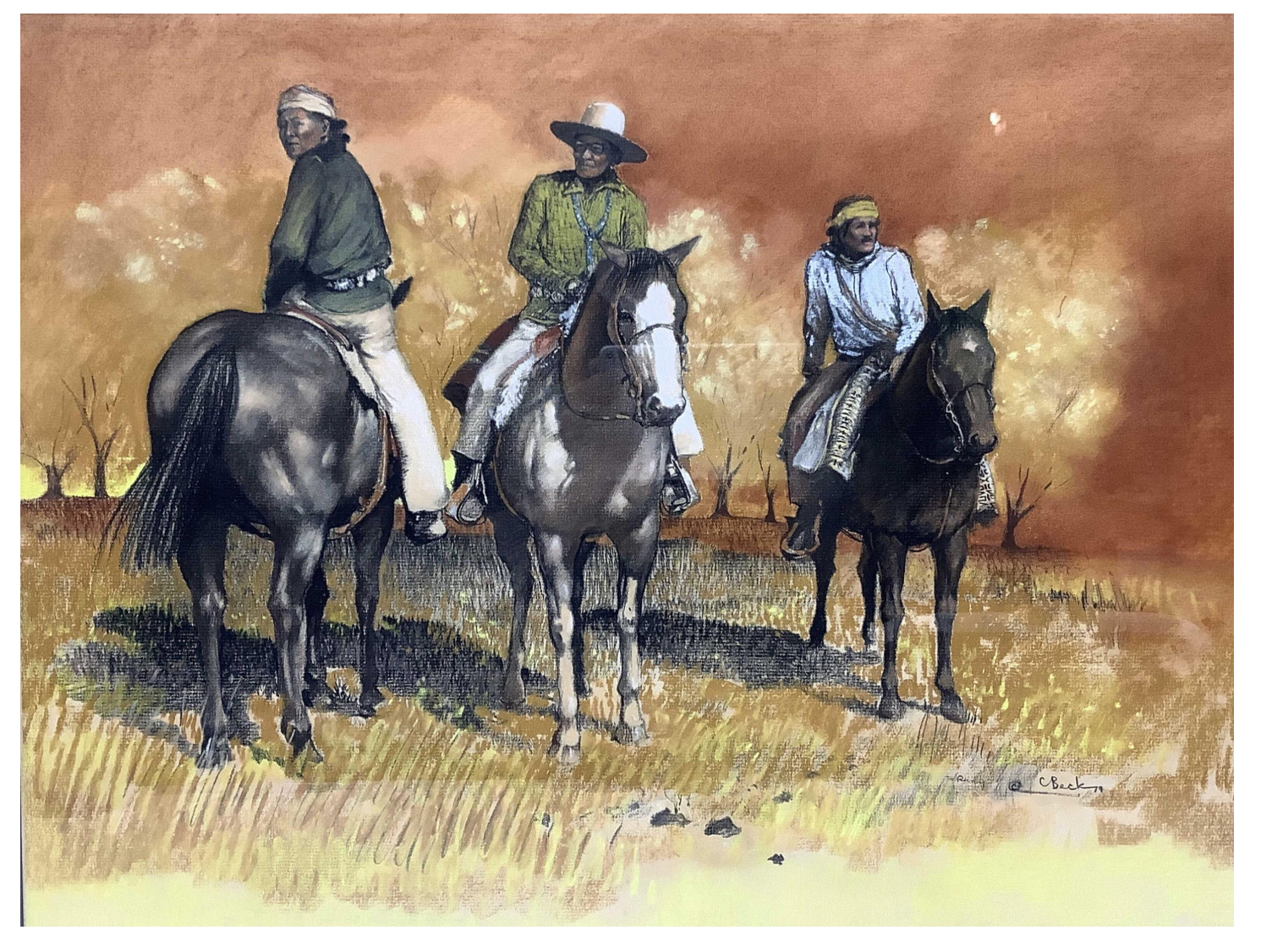

Artwork by Navajo artist Clifford Beck Jr. Pastel on paper. Auctioned in 2021 by EJ'S Auction & Appraisal Glendale, Arizona.

Clifford Beck Jr. (1946-1995) was a renowned Navajo artist who specialized in oil and pastel paintings. Born near Piñon, Arizona on the Navajo Indian Reservation, he grew up in a prominent family where his father served as a tribal councilman and his mother was a weaver. Beck's artistic style is characterized by semi-abstract and occasionally surrealistic elements, with his portraits often featuring meticulously drawn faces against bold fields of color. He painted subjects from various tribal affiliations beyond his own, always showing a deep respect for the diverse cultures and traditions of American Natives.

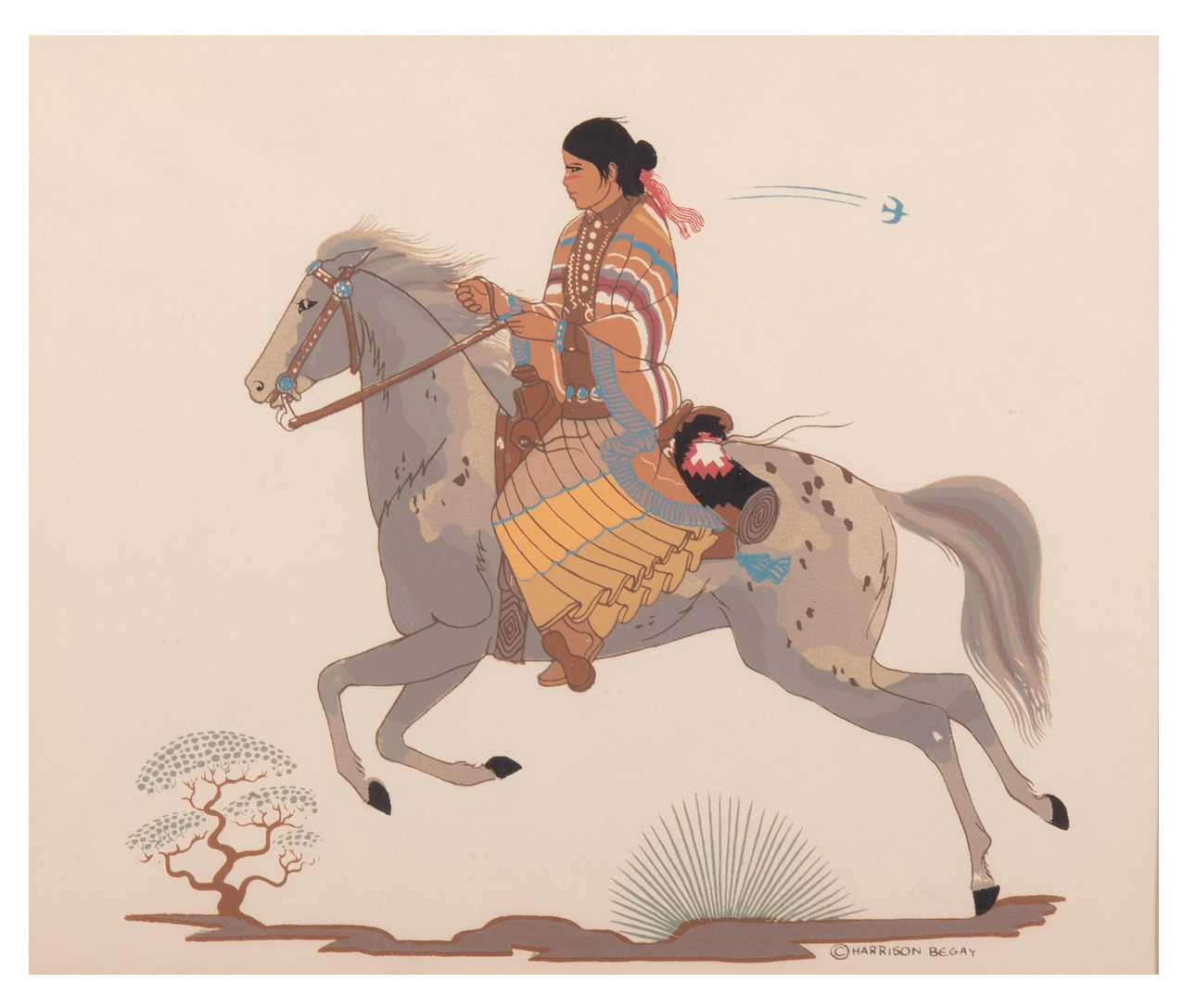

Indigenous Woman On Horseback, Silkscreen, by Navajo artist Harrison Begay (1917-2012). Dimensions: 10 x 11 3/4 inches. Auctioned in 2025 by Link Galleries, Saint Louis, Missouri.

BELOW

Camino, oil painting by Brett Allen Johnson. Private Collection. Photo courtesy: Maxwell Alexander Gallery, Pasadena, CA.

Brett Allen Johnson was born in 1984 in Provo, Utah, and currently lives in Lehi, Utah. He is a contemporary Western artist who has quickly risen to prominence in the art world despite only painting professionally since around 2016-2017.

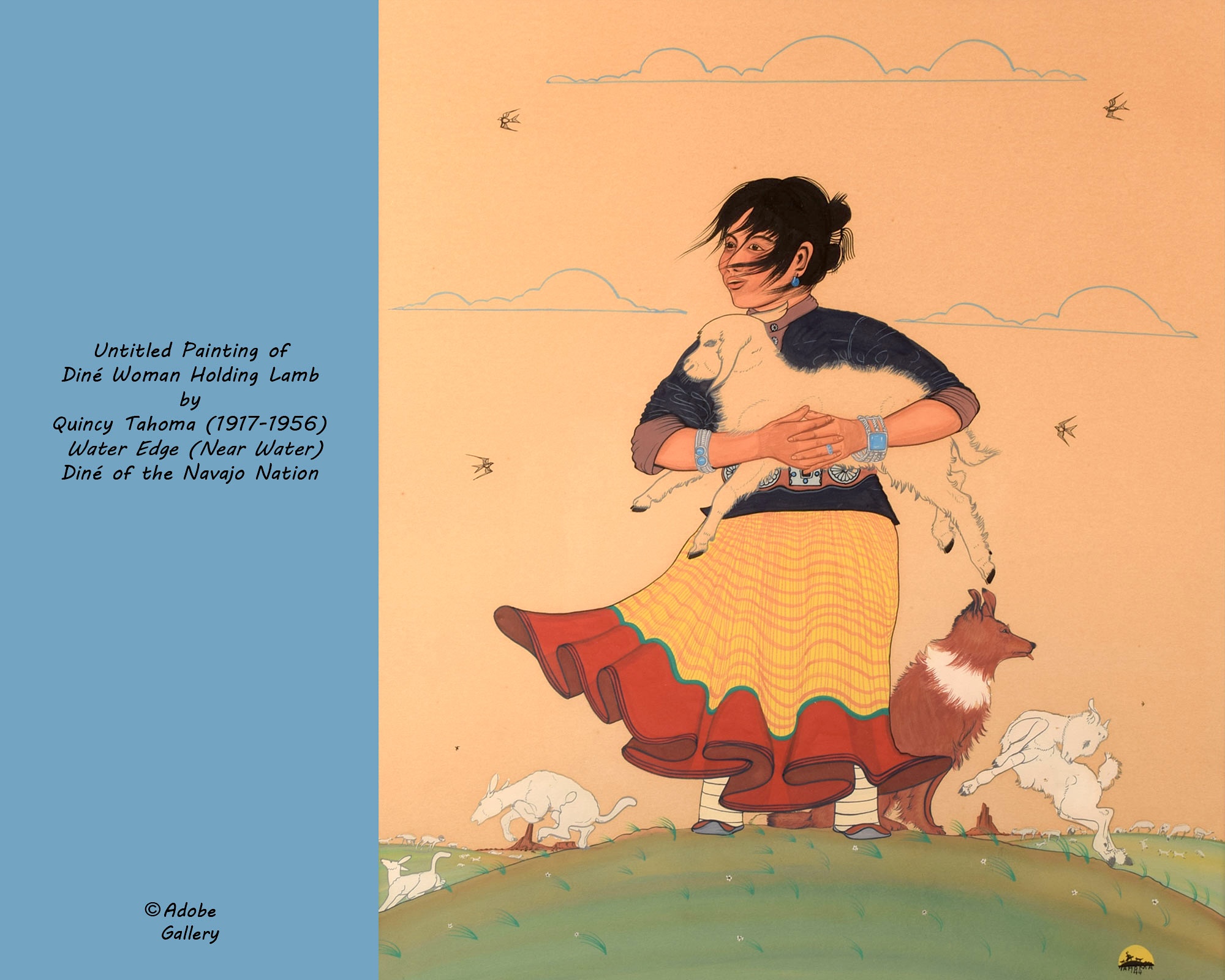

RIGHT: Navajo woman with lamb, 1941.

CENTER and RIGHT: Navajo child with lamb, 1941.

All images from the Digital Collections, New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

DID THE TRADING POSTS AND TRADERS ACT AS A CULTURAL BRIDGE BETWEEN TWO CULTURES?

A number of 20th and 21st century scholars and historians have examined the role of trading posts and traders on the Navajo Reservation as cultural bridges between Navajo and Anglo societies. Here are some voices.

Karen J. Underhill (Northern Arizona University, Cline Library), in her introduction to the Traders: Voices from the Trading Post Project, explicitly describes traders as individuals who "took the time to bridge the gap between two very different cultures." She notes that many traders developed relationships with Navajo customers, learned the Navajo language, and acted as intermediaries to help Navajos navigate federal bureaucracy and new economic systems. Underhill emphasizes that successful traders became part of the community, were often welcomed into Navajo society, and gained access to a rich cultural world.

Erika Bsumek's (University of Texas at Austin) research explores the complexity of relationships at trading posts, showing that they were not only sites of economic transactions, but also places where cultural values, social responsibilities, and power dynamics were played out. She argues that trading posts were where "Navajos learned about American consumer demand" and entered the modern industrial economy, positioning the posts as essential points of cultural mediation and adaptation.

Sarah Whitehorse (Navajo historian) states: “The early traders were more than just merchants; they were the bridge between two worlds, facilitating not just the exchange of goods, but of ideas and cultures.” Her work underscores the importance of traders as cultural mediators and the posts as vital economic and social lifelines for the Navajo.

Although the multiple roles of traders and trading posts reflect historical reality, the relationship between the Navajo and Anglo traders was by no means a true cultural meeting. Discussing this issue gives me the opportunity to analyze what a cultural meeting between different worlds really is and should be.

Trading posts were certainly more than commercial centers; they were hubs of social life where Navajos and Anglo traders interacted daily. Some of the latter acted as cultural mediators, learning Navajo customs and language and helping Navajos navigate new economic realities and governmental systems.

In his book, The Indian Traders, Frank McNitt says that Juan Lorenzo Hubbell «did as much as any trader, and more than most, to improve the quality of Navaho weaving.». Hubbell was fascinated by the Native cultures; he lived with some Paiute Indians and later with some Hopi; he also learned to speak Navajo – which is notoriously one of the most difficult language in the world – and was held in high regard by the Diné.

According to Robert S. McPherson, the trader «Louisa Wetherill spoke Navajo better than her husband John. She did the trading while he was off exploring; she was also adopted by the most prominent native leader in the Oljato/Kayenta region, acted as lawyer and judge in local disputes, was given access to ceremonial knowledge, and received all of the property of her adopted father when he died. One Navajo described her by saying, "Asdzaan Tsosie is like a Navajo herself. Even when she speaks English, she speaks with the tone of a Navajo." B. Hilda Faunce of Covered Water, Mary Jones of Bluff, Elizabeth Hegemann in Shonto, Mildred Heflin in Oljato, and ”Mike” Goulding in Monument Valley all had positive interaction with Navajo clients and earned respect as knowledgeable and sharp bargainers.»

Some traders have developed personal relationships with Navajos based on mutual respect and genuine curiosity about their cultural world. But this is not enough to transform some trading posts into cultural crossroads.

A meeting of different cultures requires the construction of a metaphorical two-way bridge where different people can truly meet, connect, and know each other as equals, at least on some level.

The Navajo and Anglo traders were not equal because the system in which they all operated placed them in profoundly unequal conditions. The Navajo, like many indigenous people, were in a state of legal and social minority. Not only did Navajo and "whites" not enjoy the same rights and freedoms, but the prevailing attitude of the U.S. government, its agents, and even more so of institutions such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs, was one of social control, forced assimilation, and economic exploitation.

All traders ultimately had to make a profit under difficult and volatile conditions in a much larger market that none of them could dominate or even fully understand. And all Navajos were ultimately at constant risk of being manipulated, exploited, underpaid, and marginalized. Both Navajos and traders were "captive" to the constraints imposed by external market forces. Moreover, the risk of exploitation was constant and very real for the Navajo people because the system did not protect them in any way. In other words, this exploitation was systemic, as traders controlled pricing and market access, often prioritizing quantity over artistic value to survive.

That's not all. The attitude of "whites" toward Navajos (as well as other Natives) was not generally benevolent.

As we have seen, by 1909, a new incentive to improve craftsmanship and production helped merchants instill the Anglo-American value of competition. «The Shiprock Agency, founded in 1903 by William T. Shelton, sponsored a regional fair. Trading posts from different areas had booths that competed in all types of industries. Shelton’s reputation for carrying out the ethnocentric process of "civilizing" the Navajo was abundantly clear in some of the categories of exhibits at the fair. In addition to prizes for the best general display of Indian products and vegetables and the best team of work horses and mules, there were also entries such as "Prettiest Navajo baby" and "Cleanest Navajo baby". He awarded a cook stove as first prize for the best wool blanket, a wash tub for the best Germantown blanket, and a handsaw for the best wool.» (Robert S. McPherson)

Regarding the construction of dirt roads on the Navajo Reservation, Robert S. McPherson adds: «One Indian agent, H. E. Williams, boldly declared "that the tourists, the Indians, and the government have the same common interest and purpose", suggesting that roads would "facilitate the necessary mingling with a reasonably good class of whites, to the end that the Indians will be better prepared for citizenship"... [and] a new life different to that of the reservation and the trading post.» (Robert S. McPherson).

Unlike the traders who spoke Navajo and were genuinely curious about the Native American world, this attitude was not an exception. It was dominant. It was the rule.

This does not mean that the dominant cultural attitude was always racist; sometimes it was simply paternalistic, rigid, or condescending. A few examples of open-minded traders are not enough to make us believe that Navajos and "whites" met and got along happily, smoking the peace pipe like in a feel-good 1980s Western movie.

Navajo weavers were not always exploited, but most traders were not interested in knowing or preserving Navajo/Diné cultural tradition: all they wanted was to increase the perceived "authenticity" and "primitiveness" of the textiles, two qualities that made them more marketable and saleable. («By 1914, the traders in the northern and western agencies were placing linen tags and lead seals on rugs to guarantee Navajo genuineness to the buyer» wrote Robert S. McPherson).

The systemic inequities and completely different agendas embedded in all kinds of interactions between Navajos on the one hand and Anglo traders and agents on the other prevented the development of a true cultural meeting.

As I have written, a meeting between different cultures involves the construction of a metaphorical two-way bridge where different people can truly meet, connect, and know each other as equals, at least on some level. This statement says "at least on some levels" to be realistic and to acknowledge that full equality is difficult but possible in parts. That's a crucial point: cultural exchange can be hindered by power dynamics and brutal inequalities. A cultural meeting requires mutual effort: intellectual, political, and ethical mutual effort. Respect for a culture that is "other" or different from one's own is an ethical and political commitment.

Power Dynamics and Structural Inequity

The systemic barriers between Navajo and Anglo agents mirror Foucault's analysis of power structures, where institutions and social practices normalize hierarchies and prevent equitable dialogue. This parallels postcolonial critiques (Said, Spivak) that show how colonial legacies perpetuate cultural dominance by positioning one culture as normative. Genuine exchange requires dismantling these structures, not just relying on individual goodwill - an insight that echoes Fanon's call for the decolonization of relational frameworks.

Ethics of the Other

The metaphor of a "two-way bridge" resonates with Levinas's ethics, where encountering the "face of the other" imposes an unconditional ethical demand. Ethical engagement must go beyond mere tolerance, requiring a radical openness that goes beyond instrumentalization. This bridges Kant's respect for autonomy and Gadamer's "fusion of horizons," where understanding emerges through dialogical openness rather than assimilation.

Partial equality and hermeneutic humility

The recognition that equality can be achieved "on some levels" reflects Gadamer's (Gadamer) hermeneutic philosophy: cultural exchange is an ongoing negotiation, not a final synthesis. It embraces a pluralism in which incommensurable differences coexist without collapsing into uniformity. This hermeneutic humility resists utopian universalism, affirming instead the transformative potential of shared but imperfect spaces.

Moral and Intellectual Labor

The dual effort - intellectual (education, critique) and moral (empathy, justice) - aligns with Habermas's theory of communicative action, which envisions dialogue free of domination. It also recalls virtue ethics (Aristotle), where the cultivation of phronesis (practical wisdom) bridges the gap between knowing and doing. For systemic change, Rawls argues, just institutions must provide the necessary scaffolding.

The Bridge Metaphor

The bridge symbolizes Derrida's différance - a movement of both connection and deferral. Building such a bridge requires collective labor that resists unilateral domination. Yet material inequalities (economic, political) complicate this process, underscoring the need for redistributive justice to create the conditions for genuine dialogue.

Cultural Appropriation vs. Appreciation

A true cultural encounter is rooted in reciprocity, not appropriation. This vision is consistent with Nussbaum's capabilities approach, which values cultural practices as expressions of human agency rather than commodities.

In conclusion, authentic cultural encounters require a decolonial ethic, one that combines structural justice with personal responsibility. Such encounters are not passive coexistence but active co-creation, requiring systemic change and a deep existential commitment to the irreducible dignity of the Other.

Shaman's Call by R. Carlos Nakai

Kathy M'Closkey, New Insights from the Archives: Historicizing the Political Economy of Navajo Weaving and Wool Growing in "Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings", 2010, 38.

Kathy M'Closkey and Carol Snyder Halberstadt, The Fleecing of Navajo Weavers, in "Cultural Survival", May 2010.

Robert S. McPherson, Naalyéhé Bá Hooghan - House of Merchandise”: The Navajo Trading Post as an Institution of Cultural Change, 1900 to 1930, in "American Indian Culture and Research Journal", 1992, 16 (1).

Robert W. Volk, Barter, Blankets, and Bracelets: The Role of The Trader in the Navajo Textile and Silverwork Industries, 1868–1930, in "American Indian Culture and Research Journal", 1988, 12 (4).

-

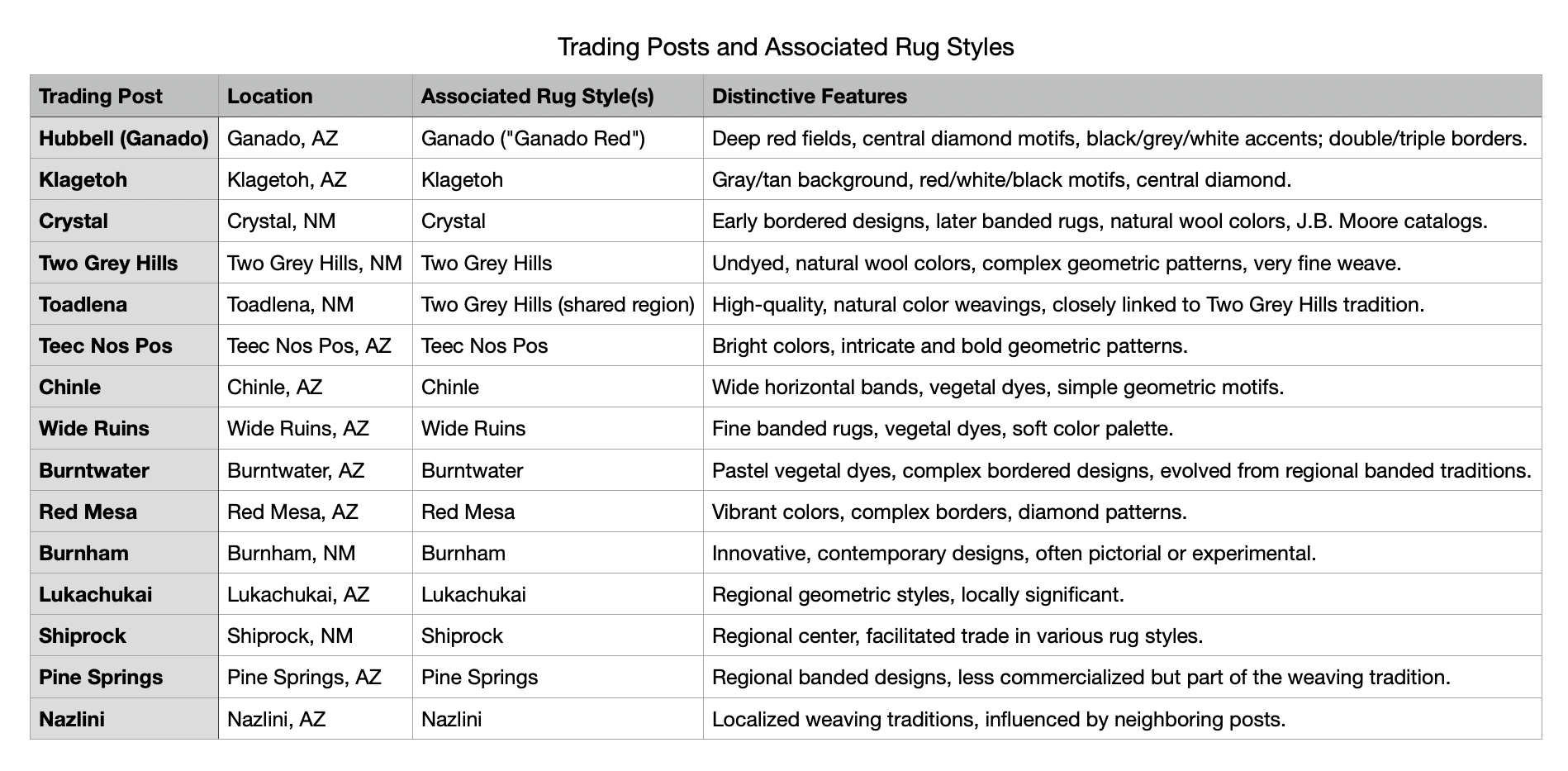

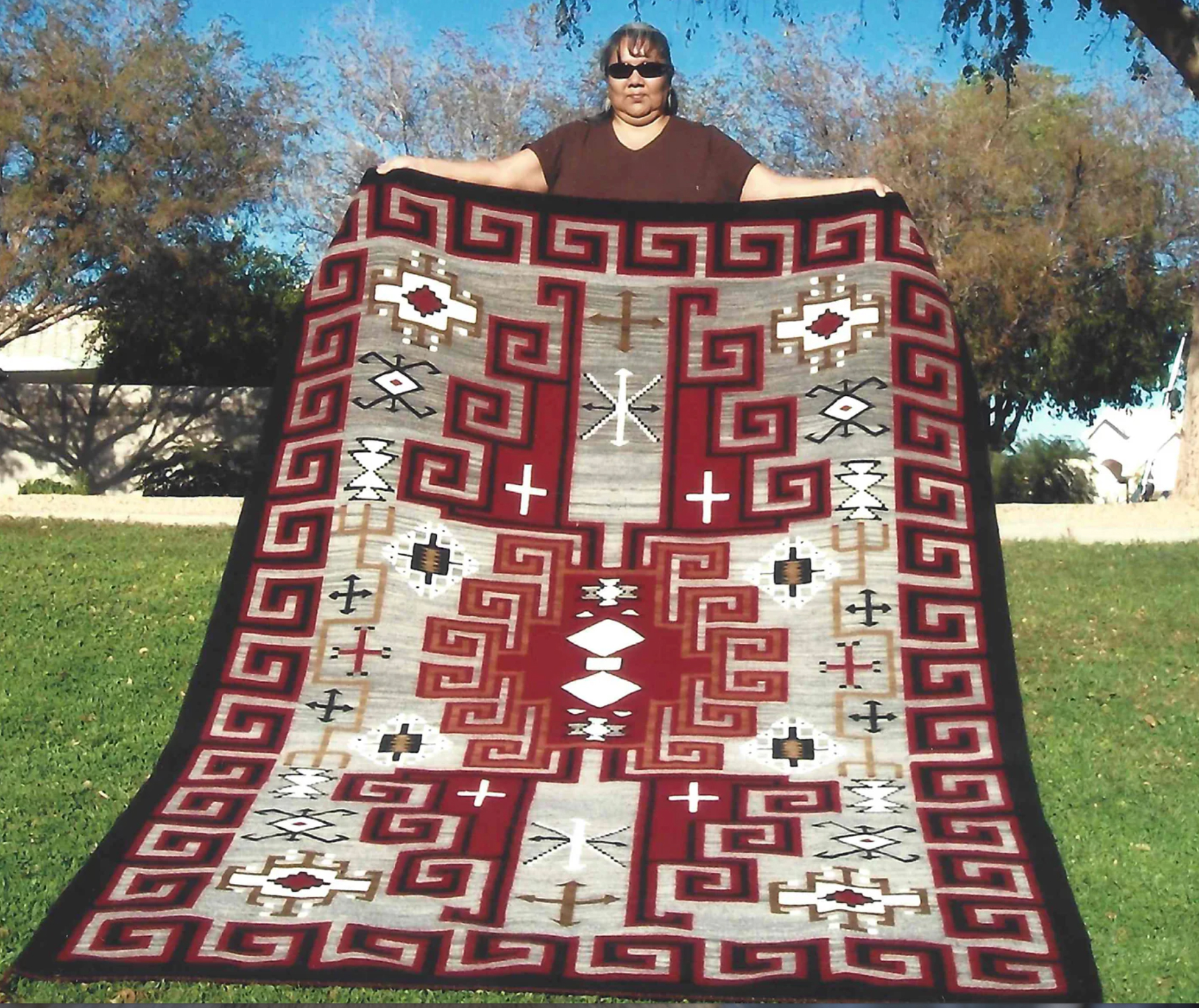

NAVAJO WEAVERS, ANGLO TRADERS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF REGIONAL STYLES

Interaction and collaboration between Navajo weavers and traders and owners of trading posts resulted in new, distinctive styles. The major trading posts on the Navajo Reservation during the Trading Post Era (1880-1930) were instrumental in shaping regional rug weaving styles and textile traditions.

HUBBELL TRADING POST (GANADO, ARIZONA) AND GANADO STYLE

Owner: Juan Lorenzo Hubbell (1878–1930s)

Regional Style: Early Ganado Red

The early Ganado Red style emerged as a defining Navajo weaving tradition under the influence of trader Juan Lorenzo Hubbell and reflects a deliberate synthesis of commercial needs, artistic innovation, and cultural preservation.

It's characterized by deep maroon backgrounds (realized with synthetic dyes) with black, gray, and white geometric motifs, often with central serrated diamonds and stepped borders. Hubbell discouraged cheap, unstable synthetic dyes (e.g., aniline reds), preferring cochineal-derived reds and later synthetic dyes that mimicked the "deep maroon" associated with traditional vegetable dyes.

Hubbell also promoted larger, heavier rugs for non-Navajo buyers, and partnered with the Fred Harvey Company to distribute Ganado Red rugs along the Santa Fe Railroad.

The early Ganado style is defined by the following elements; note, however, that in most cases they are not all present. Take these hints as useful suggestions, nothing more.

- Color palette:

- Dominant deep red/maroon backgrounds (originally from cochineal, later from synthetic dyes such as "Old Navaho").

- Contrasting accents of black, gray, white, and brown, often derived from natural wool or indigo trade dyes.

- Geometric motifs:

- Central serrated diamonds with stepped or terraced borders.

- Bold, symmetrical patterns inspired by pre-1860s Classical designs.

- Structural elements:

- Heavy black borders framing the design field.

- Tight, dense weave (30–50 wefts per inch) for durability.

Ganado Red became synonymous with "authentic" Navajo rugs in Anglo markets, although its aesthetic was shaped more by Hubbell's preferences than by purely traditional practices. While Hubbell enforced design standards, weavers subtly incorporated cultural elements such as "spirit lines" (intentional imperfections) and symbolic motifs.

A note: the following photo gallery is neither representative nor exhaustive, but simply the result of a selection based on a very personal and therefore questionable criterion: it is a reflection of my eye and my taste. It is also, of course, an invitation to go beyond my horizon and explore further.

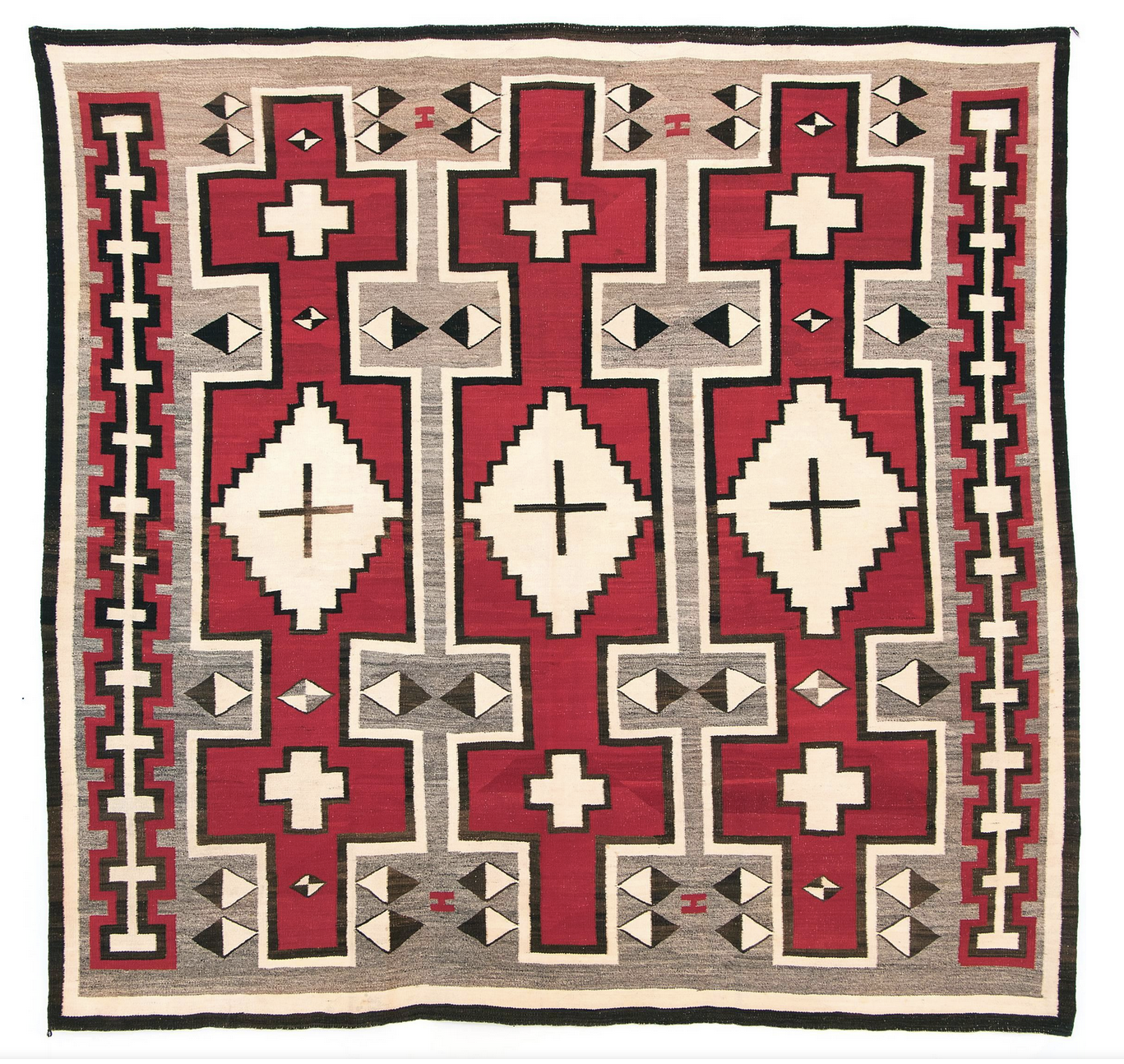

Large Early Ganado Rug, ca. 1900, natural handspun wool with synthetic dyes. Dimensions: 116 x 118 in. - 294 x 300 cm. Palm Springs Art Museum, CA, USA.

Large Early Ganado Rug, ca. 1900-1925, natural handspun wool with synthetic dyes. Dimensions: 108 x 103 in. - 274 x 262 cm. Sold by Navajo Indian Art through 1st DIBS.

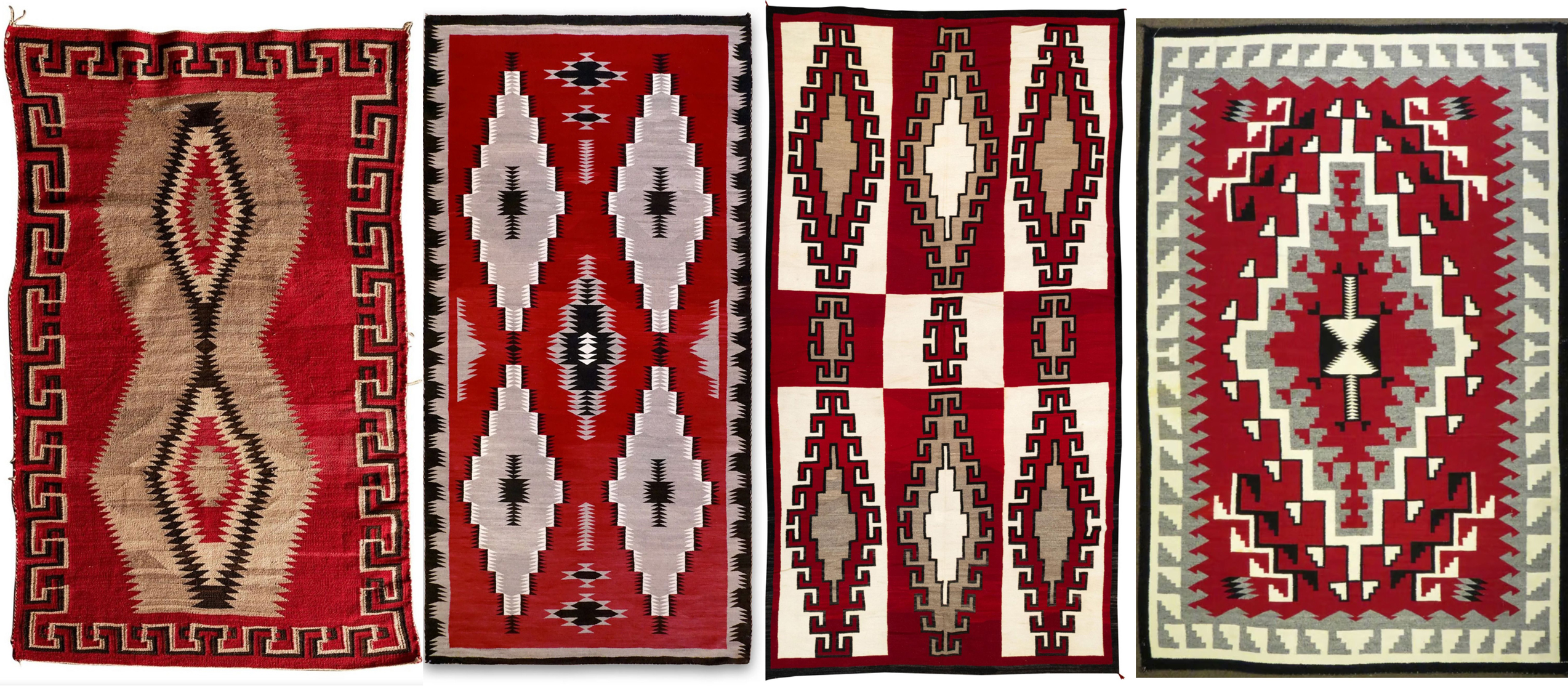

LEFT: Large Ganado Red rug, 1930s. Dimensions: 72 x 110 in.; 182 x 270 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

TOP LEFT: Ganado Rug, ca. 1930. Dimensions: 82 x 57 in.; 208.28 x 144.78 cm. Photo courtesy: Chimayo Trading del Norte, Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico.

BOTTOM LEFT: Early Ganado Rug, from the Hubbell Trading Post, ca. 1900-1910. Dimensions: 55 x 70 in.; 140 x 178 cm. Photo courtesy: Tres Estrellas Gallery, Taos, New Mexico.

TOP RIGHT: Early Ganado Rug, ca. 1900-1905. Dimensions: Overall: 53 9/16 x 56 1/2 in.;136 x 143.5 cm. Peabody Museum of Archaeology & Ethnology, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

BOTTOM RIGHT: Navajo Ganado Runner, ca. 1930-40s. Dimensions: 79 x 40 in.; 200 x 101.6 cm. Photo courtesy: Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

RIGHT: Very large Ganado Rug from Arizona, ca. 1910-20s. Dimensions: 140 x 116 in.; 355.6 x 294.64 cm. Photo courtesy: Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

LEFT: Ganado Rug, 1920s. Dimensions: 34 x 57 in.; 86,36 x 144,78 cm. Available at 1st DIBS.

CENTER LEFT: Large Ganado Rug, 1930s. Dimensions: 118 x 59 in.; 300 x 150 cm. Photo courtesy: Chimayo Trading del Norte, Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico.

CENTER RIGHT: Large Ganado Rug, ca. 1920-1929, natural handspun wool. Dimensions: 168 x 95 in.; 426.72 x 241.3 cm. Available at 1st DIBS.

RIGHT: Ganado Red rug, ca. 1950s. Dimensions: 80 x 53 1/2 in.; 203 x 135.89 cm. Photo courtesy: Toh-Atin Gallery, Durango, Colorado.

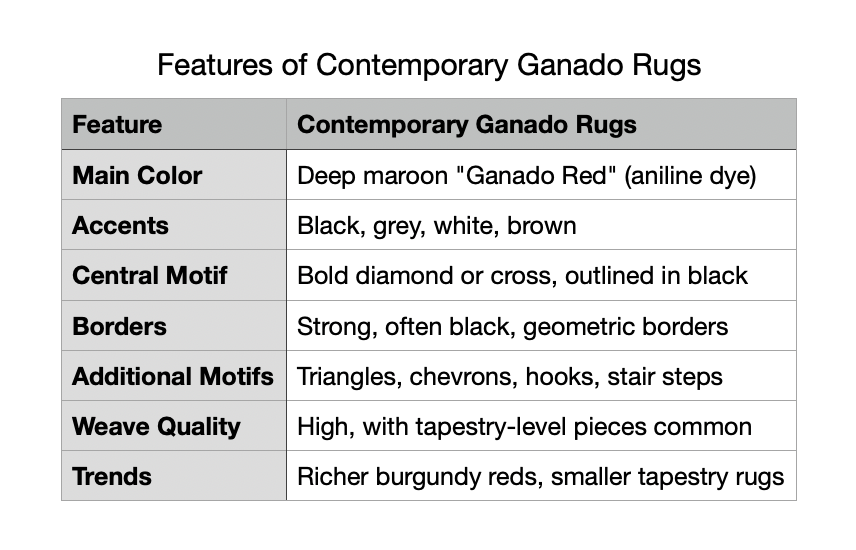

The Ganado style continues to be revived today, albeit with significant modifications in colors, patterns and dimensions but not in technique and loom.

Color Palette and Dye Use

The hallmark of contemporary Ganado rugs remains the deep, rich "Ganado Red" ground; however, the dominant reds in contemporary Ganado rugs have evolved to include richer, more burgundy tones, moving slightly away from the brighter reds of earlier periods. This shift reflects both the availability of dyes and changing aesthetic preferences among weavers and collectors.

The reddish dark maroon hue, sometimes approaching burgundy, is typically achieved with aniline dyes, as the intensity of the red is difficult to replicate with natural sources. The red is complemented by accent colors - black, gray, white and brown - which provide strong visual contrast and maintain the traditional Ganado aesthetic.

Design Motifs and Structure

The central motif in contemporary Ganado rugs is typically a bold, serrated diamond or cross outlined in black and occupying the center of the field. Four triangles, one in each corner, are common, and additional elements may include chevrons, checks, hook patterns, simple diagonals, and "cloud" or stepped borders.

The designs are generally symmetrical and framed by a strong border, a feature that distinguishes Ganado rugs from some other Navajo regional styles.

While the designs remain rooted in tradition, contemporary weavers sometimes create smaller, tapestry-like pieces intended for wall hangings, reflecting both market demand and artistic innovation.

Weaving Techniques and Quality

Ganado rugs are known for their high-quality weaving, with some of the finest pieces classified as "tapestry rugs" due to their tight weave and intricate detail. The weaving technique and craftsmanship have remained consistent, preserving the legacy of the style while allowing for individual expression among the weavers.

Rugs range from large, uncomplicated floor pieces to smaller, more elaborate pieces, with a current trend toward the latter for decorative purposes.

LEFT: Ganado style Rug, ca. 1990s. Dimensions: 56 x 89 in.; 142.24 x 226 cm. Photo courtesy: Toh-Atin Gallery, Durango, Colorado.

CENTER: Ganado style Rug by Anthony Tallboy. Dimensions: 40 x 55 1/2 in.; 101.6 x 141 cm. Photo courtesy: Toh-Atin Gallery, Durango, Colorado.

RIGHT: Eyedazzler Runner by Mary Shepherd. Dimensions: 23 x 53 in.; 58.42 x 134.62 cm. Garland's, Sedona, Arizona.

«Anthony Tallboy is one of the few male weavers in a predominantly matriarchal art form, a Navajo tradition. Tallboy is also a medicine man and performs ceremonies to help his people bring harmony and balance to their lives. Anthony is from the Ganado, AZ area known for its rich red weaving called "Ganado Red". This vibrant rug has shades of gray accented with white and black that vibrate in the red field.» (Toh-Atin Gallery).

LEFT: Ganado style Navajo Rug by Anna May John, ca. 1980. Dimensions: 130 x 91 in.; 330 x 231.14 cm. Photo courtesy: Chimayo Trading del Norte, Ranchos de Taos, New Mexico.

CENTER: Ganado-Klagetoh Rug, 1970s. Dimensions: 110 x 73.5 in.; 279.4 x 186.69 cm. Photo courtesy: Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

RIGHT: Ganado style Rug made with commercially dyed wool by Alice Begay. Dimensions: 68 x 53 in.; 172.72 x 134.62 cm. Historic Cameron Trading Post since 1916, Cameron, Arizona.

LEFT: Ganado-style Rug, 1981, made by Navajo/Diné weaver Sarah Begay in Arizona. Medium: dyed and natural handwoven wool. Dimensions: 160 x 102 cm. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian, USA.

CENTER LEFT: Contemporary, large Ganado-style Rug by Shirley Joe. Dimensions: 155.5 x 74 in.; 395 cm x 188 cm. Photo courtesy: Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

CENTER RIGHT: Contemporary Ganado-style Rug by Navajo/Diné weaver Elverna Vanwinkle. Dimensions: 57 x 77 in.; 145 x 195.6 cm. Available from Garland's, Sedona, Arizona, USA.

RIGHT: Contemporary Ganado-style Rug by Beth Bitsui, a Navajo rug weaver from Salina, Arizona. Dimensions: 50 x 38 in.; 127 x 96.52 cm.

Ganado-style Rug, ca. 1988, by Betty Joe Yazzie. Dimensions 105 x 70.5 in.; 266.7 x 179 cm. Kennedy Museum of Art, Ohio University, USA.

They are beautiful, aren't they? But be careful: if you are thinking of buying a Navajo rug, make sure it is authentic (there are many knock-offs made almost everywhere in the world except on the Navajo Nation). Also keep in mind that prices are very high: a medium or high quality Navajo rug will cost more than an Oriental (especially Persian) rug of the same quality and dimensions. Some well-preserved and well-made antique rugs are estimated to be worth tens of thousands of dollars.

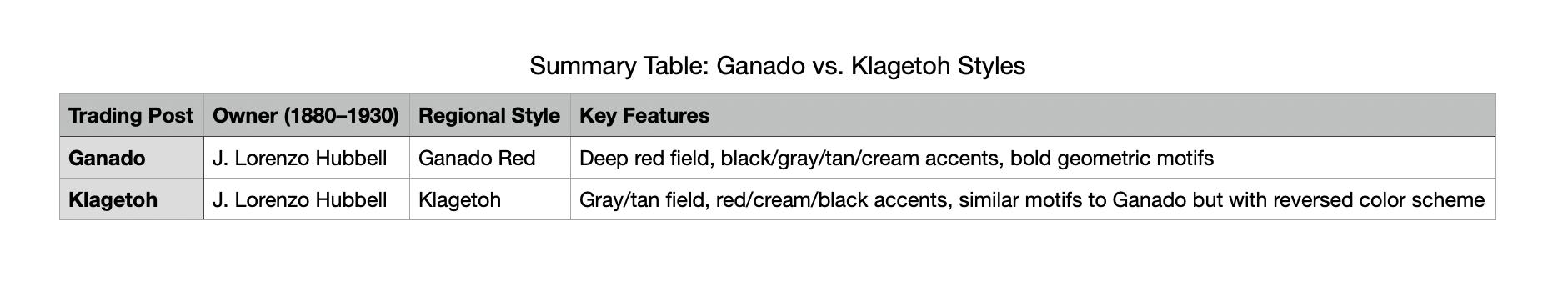

KLAGETOH TRADING POST (ARIZONA) AND KLAGETOH STYLE

Owner: Juan Lorenzo Hubbell

Regional Style: Early Klagetoh

Klagetoh was one of the most important trading posts near the Navajo Reservation during the Trading Post Era (1880–1930), closely associated with the Hubbell family and the development of distinctive Navajo weaving styles. The Klagetoh Trading Post, like Ganado, became a focal point for commerce and artistic innovation, with Hubbell commissioning and promoting specific designs to appeal to non-Navajo buyers.

Klagetoh is considered a "sister" style to Ganado, both of which originated during the Hubbell Revival period..

The main difference is in the color scheme:

- Klagetoh rugs typically feature a gray or tan field (background) with red, cream, and black accents, as opposed to the Ganado style, which uses a deep red field with black, gray, tan, and cream accents.

- Both styles share bold geometric patterns, especially central serrated diamonds and stepped or “stair” corner motifs.

As with Ganado, Klagetoh weavers, while working within the commercial expectations set by Hubbell, often incorporated individual and cultural expressions, such as contrasting yarns, feathers, or “spirit lines,” reflecting Navajo values and aesthetics even within regulated production standards.

The style remains distinctive for its subtle, earthy palette and its relationship to the Ganado tradition, with the two often described as "contrasting" or complementary.

(Please note that the difference between Ganado and Klagetoh is not as clear-cut as the (somewhat academic) diagram below might suggest).

TOP LEFT: Klagetoh Rug, 1930s. Dimensions: 57 x 96 in.; 144.78 x 243.84 cm. Photo courtesy: Tres Estrellas Gallery, Taos, New Mexico.

BOTTOM LEFT: Klagetoh Rug, hand-woven by Esther Billie between 1920 and 1940. Dimensions: 48 x 77 in.; 121.92 x 195.58 cm. Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, Albuquerque, New Mexico. «This rug consists of a gray background with diamond designs in the center field enclosed in a thick border. Esther Billie wove two serrated diamond motifs in the center outlined by a scroll/swirl design in red, cream, and black. She also incorporated three stacked zigzags in each corner in red, cream, and black, as well as two terraced V shapes in cream with thin black borders that point inward along each vertical side. In accord with this style, there is a thick border surrounding the rug’s entirety: first a bold border in black, then in cream. The cream border, straight on the horizontal edge and serrated down the vertical side, is finely traced in black fiber. The rug is handwoven and composed entirely of handspun wool yarn. A blend of color sources was used, consisting of aniline red and naturally colored wool. With seven warp and thirty weft threads per inch, the rug reveals her mastery of the weaver's art.» (Museum curators).

CENTER: Klagetoh Runner, 1920s-30s. Dimensions: 57 x 134 in.; 144.78 x 340.36 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona. «This is a very unusual Ganado - Klagetoh for a couple of reasons. One rare quality is it was woven as a runner - narrow, and very long. This piece is 11 feet long! 2nd feature is the pictorial elements - two corn plants, the symbol for life, in the center of the design. And beautiful displays of bows and arrows and feathers to showcase the corn. Hidden on top of the corn are two little blue birds with red legs. Bluebirds are messengers to the gods.» (Nizhoni Ranch Gallery)

RIGHT: Klagetoh Rug, ca. 1930. Dimensions: 65 x 70 in.; 165 x 177.8 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona. «One of the unique features of this piece is the four pictorial elements which represent the Hero Twins - Monster Slayer and Born of Water.» (Nizhoni Ranch Gallery)

Very large Klagetoh Rug, 1930s. Dimensions: 135 x 106 in.; 342.9 x 269.24 cm. Red Mesa Gallery, Penryn, CA.

LEFT TO RIGHT

-

Klagetoh Rug, ca. 1930. Dimensions: 49 x 72 in.; 124.46 x 182.88 cm. Photo courtesy: Tres Estrellas Gallery, Taos, New Mexico.

-

Large Klagetoh Rug, early 20th century. Dimensions: 97 x 177 in.; 246.38 x 449.58 cm. Available at 1st DIBS.

-

Klagetoh Rug, 1930s. Dimensions: 5 foot 8 in. x 8 foot 4 in.; 172.72 x 254 cm. Photo courtesy: Toh-Atin Gallery, Durango, Colorado.

-

Klagetoh Trading Post Runner, ca.1930. Medium: Hand spun wool. Dimensions: 156 x 66 in.; 396.24 x 167.64 cm. Photo courtesy: Shiprock Santa Fe Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

LEFT TO RIGHT

-

Large Klagetoh Rug, 1920-1930. Dimensions: Larghezza: 68 x 131 in.; 172,72 x 332,74 cm. Available at 1st DIBS.

-

Very large Klagetoh Rug, ca. 1930. Medium natural wool and aniline red dye. Dimensions: 20 feet, 8 in. x 13 feet, 3 in.; 629.92 × 403.86 cm. Palm Springs Art Museum, CA, USA.

-

Large Navajo Klagetoh Rug, 1930s. Dimensions: 104 x 64 in.; 264.16 x 162.56,cm. Photo courtesy: Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

-

Large Klagetoh Rug, ca. 1920s. Dimensions: 128 x 93 in.; 325.12 x 236.22 cm. Photo courtesy: Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

The Klagetoh style, like the Ganado, continues to be revived today. Contemporary Klagetoh-style rugs, like other regional Navajo weavings, are experiencing both preservation and evolution in the hands of today's Navajo weavers.

Klagetoh-style Rug by Anita Bekay, 2011. Medium: Woven from 100% custom-spun, hand-dyed Navajo Churro wool. Dimensions: 72 x 108 in.; 182.88 cm x 274.32 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

Did you notice the Spider Woman cross? «Spider Woman's teachings can still be found in modern-day craftsmanship, as the Navajo weaving is done the same way it now as was on the first Navajo loom: using a hand-made upright loom, with one continuous warp, and each stand of woolen yarn is placed into the warp, by hand, one strand at a time. That is why if a Navajo rug is cut of compromised in anyway – it will not unravel. This is a process that cannot be mechanized – making the Navajo weaving one of the most unique in the world.» (Nizhoni Ranch Gallery)

LEFT: Large Klagetoh Rug handwoven by Nora Bitsui in 2013. Dimensions: 86 x 115 in.; 218.44 x 292 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

RIGHT: Klagetoh Rug, 1980s. Dimensions: 60 x 50.25 in.; 152.4 x 127.64 cm. Photo courtesy: Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

How to identify Navajo Ganado and Klagetoh rugs by Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?