NAVAJO CHURRO SHEEP AND WOOL 5

USA on the globe.

Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported.

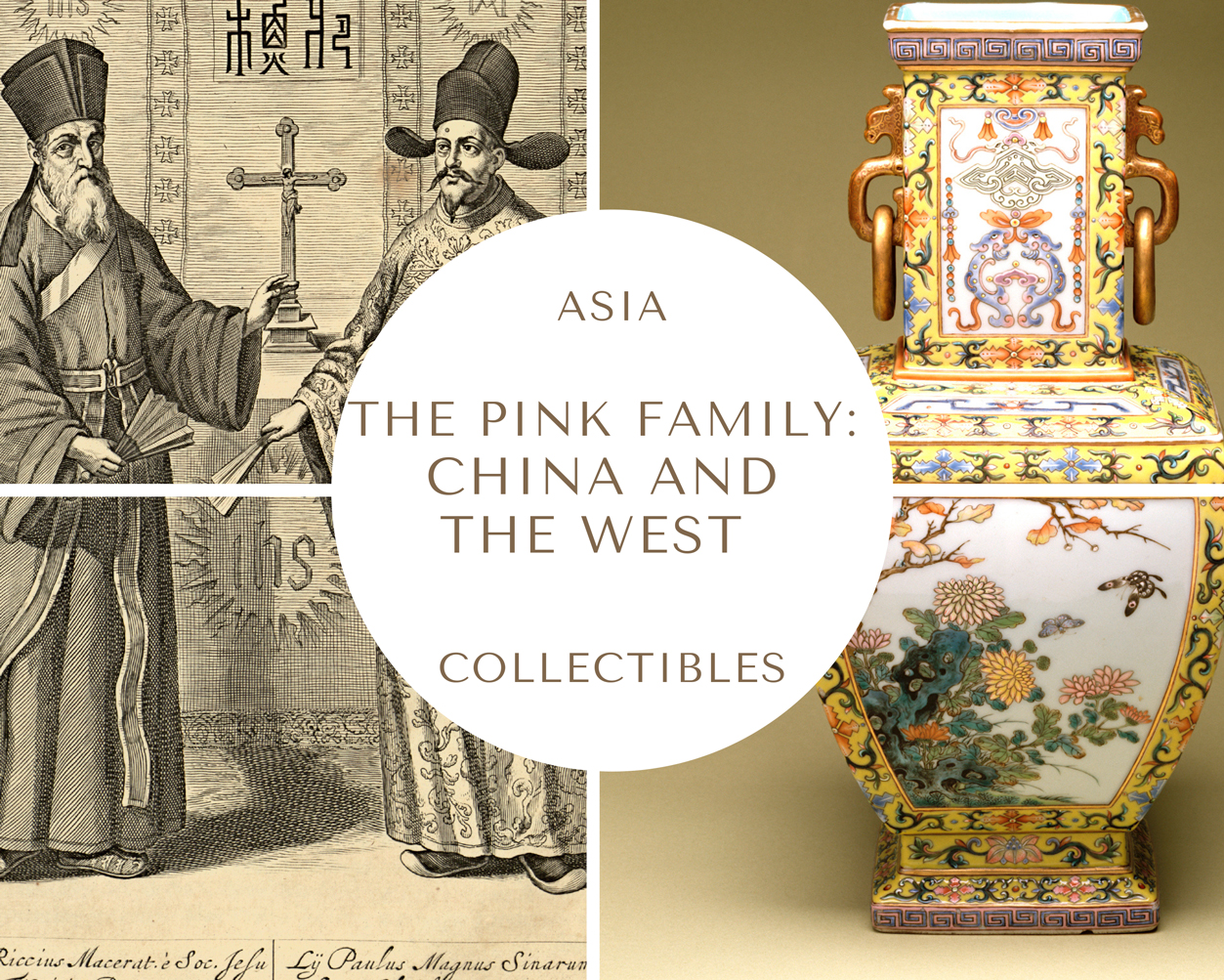

SOUTHWESTERN STATES

WOVEN LEGACIES: THE ART AND HISTORY OF NAVAJO/DINÉ TEXTILES

The intricate craft of Navajo (Diné) weaving is one of the deepest and most enduring artistic traditions of Native North America. Rooted in centuries of cultural knowledge, these textiles embody stories of resilience, adaptation, and creative mastery. In the chapters that follow, we will explore the evolution, diverse forms, and timeless beauty of this remarkable art form.

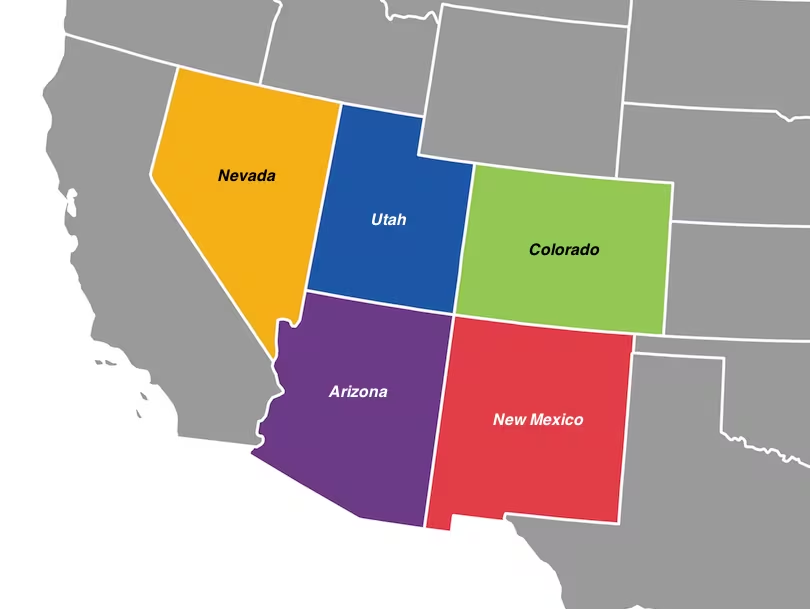

Figures at a loom, silkscreen, signed by Navajo artist HARRISON BEGAY (1914 - 2012). Auctioned in 2022 by Abell, Los Angeles, CA.

Harrison Begay (Haashké yah Níyá, meaning "Warrior Who Walked Up to His Enemy" or "Wandering Boy") was a renowned Diné (Navajo) artist who left an indelible mark on Native American art. There is some uncertainty about his year of birth, with sources citing either November 15, 1914, or 1917, in White Cone, Arizona, on the Navajo Reservation. He died on August 18, 2012 in Gilbert, Arizona at the age of 95.

His mother was from the Red Forehead Clan and his father was from the Zuñi Deer Clan. He had eight siblings and grew up in a traditional hogan, herding goats and sheep. At the Santa Fe Indian School, Begay learned what is known as the "studio style" or "flat style" of painting, which is characterized by smoothly brushed forms laid flat on the picture plane. This was especially important because Navajo artists had no tribal tradition of painting before the school was founded. Begay's artistic career was briefly interrupted by World War II, during which he served in the U.S. Army Signal Corps from 1942 to 1945, participating in the invasion of Normandy under General Dwight Eisenhower. After the war, Begay resumed his artistic career, working primarily in watercolor, gouache, silkscreen, and commercial illustration. Begay is generally considered one of the most successful and influential early Native American painters. His serene, impeccably crafted watercolors beautifully document life on the Navajo Reservation and depict his people and the animals of their land with unparalleled grace.

-

THE EVOLUTION OF NAVAJO/DINÉ TEXTILES FROM SIMPLE BLANKETS TO COMPLEX WEAVINGS

Origins and Early Development

The Navajo people first learned to weave from their Pueblo neighbors around the late 17th century, adopting techniques that originally used cotton. The original function of Navajo weaving was utilitarian, producing clothing items such as shoulder robes, rectangular panel or wrap dresses, semi-tailored shirts, breechcloths, and a variety of belts, sashes, hair ties, and garters. Prior to European contact, these textiles were primarily for Navajo use and occasional trade with other Native American tribes.

A crucial development occurred when the Spanish introduced Iberian Churra sheep to the Southwest, which the Navajo developed into their own Navajo Churro breed, producing wool ideal for weaving.

Early Navajo wool textiles featured simple striped patterns of natural, undyed yarns that were heavily influenced by Pueblo designs. These early weavings were primarily utilitarian, serving multiple purposes in daily life. There were several types of early textiles. The most common were blankets. They had horizontal stripes using natural wool colors (white, brown, gray) plus indigo-dyed blue and red from unraveled trade cloth called bayeta. (The Navajos unraveled the imported red cloth into threads, sometimes recarding and respinning it; then they wove it to create a new vibrant color in their blankets. This type of unraveled wool yarn is the bayeta).

Weavers often embellished these stripes with stepped geometric motifs or serrated diamond shapes adapted from Spanish and Mexican textiles. There were several types of blankets.

- Serapes (Shoulder Blankets) - Woven longer than they were wide and created vertically on the loom, they served as primary garments.

- Chief's Blankets - These prestige items were woven horizontally (wider than long) with patterns designed for horizontal display. By the mid-19th century, they had become highly valued trade items among the Native peoples of the Great Plains.

- Saddle Blankets: Developed as smaller, more square textiles to protect horses' backs, these came in single and double varieties. Double saddle blankets were folded in half before use to provide additional protection.

Serape blankets and Chief's blankets represent two different traditional Navajo weaving forms, each with unique characteristics in their design, orientation, and cultural significance.

The most fundamental difference between these two blanket types is the orientation of the weave:

- Serape blankets are woven vertically on the loom and are longer than they are wide (or narrower than they are tall).

- Chief's blankets are woven horizontally on the loom and are wider than they are long.

This difference in orientation can be seen by examining the direction of the warp threads in the fabric.

Cultural origin and design patterns also help distinguish these two blanket types:

- Serapes are more influenced by Mexican ponchos and typically feature stepped diamonds and stepped zigzag lines that create visual energy. They had more aggressive and imposing designs, with larger, more dominant diamond patterns.

- Chief's blankets had more restrained designs, especially in the early phases. They evolved from Pueblo wearing blankets with a distinct Navajo development through the three phases:

- First Phase (1700-1830s): Simple horizontal bands of natural brown/black and white with indigo blue or red stripes.

- Second Phase (1840-1860): Added 12 rectangular elements to the horizontal bands.

- Third Phase (1860-1868): Featured a "9-spot" design with serrated or terraced diamonds or triangles superimposed on the bands.

Both blankets were worn wrapped around the shoulders, but they served slightly different purposes:

- Chief's Blankets became highly valued trade items throughout the Southwest and Plains, often worn by people of high status.

- Serapes were primarily men's clothing in everyday Navajo life, but were often too delicate for rough use such as horseback riding.

Serape Blankets

In Navajo (Diné) culture, a serape (from the Spanish sarape or zarape) is a significant form of traditional weaving known as awos beeldléí in the Navajo language, meaning "shoulder blanket". These are long, rectangular textiles woven vertically on the loom that were designed to wrap around the wearer's shoulders, rather than being pulled over the head like other garments.

Serapes emerged primarily between 1840-1860, with later examples from 1865-1880 (the "late classic period") featuring more complex designs. They were typically woven in simple color palettes of red, white, and blue, with yellow and green accents, though later designs incorporated more vibrant colors and intricate patterns.

These blankets derive influence from Mexican ponchos, specifically the Saltillo blanket from Aztec culture. While they were worn by both men and women in everyday life, they were primarily men's garments. Unlike their Mexican counterparts that were sturdy enough for horseback riding, Navajo serapes were often too delicate for such rough use.

The craftsmanship of serapes represents the spiritual and artistic tradition of Navajo weaving. As expressed in the Navajo weaver's song, "with beauty, it is woven". The creation of these textiles was labor-intensive, with an estimated 345 hours required to complete a single blanket, from sheering sheep to the final weaving.

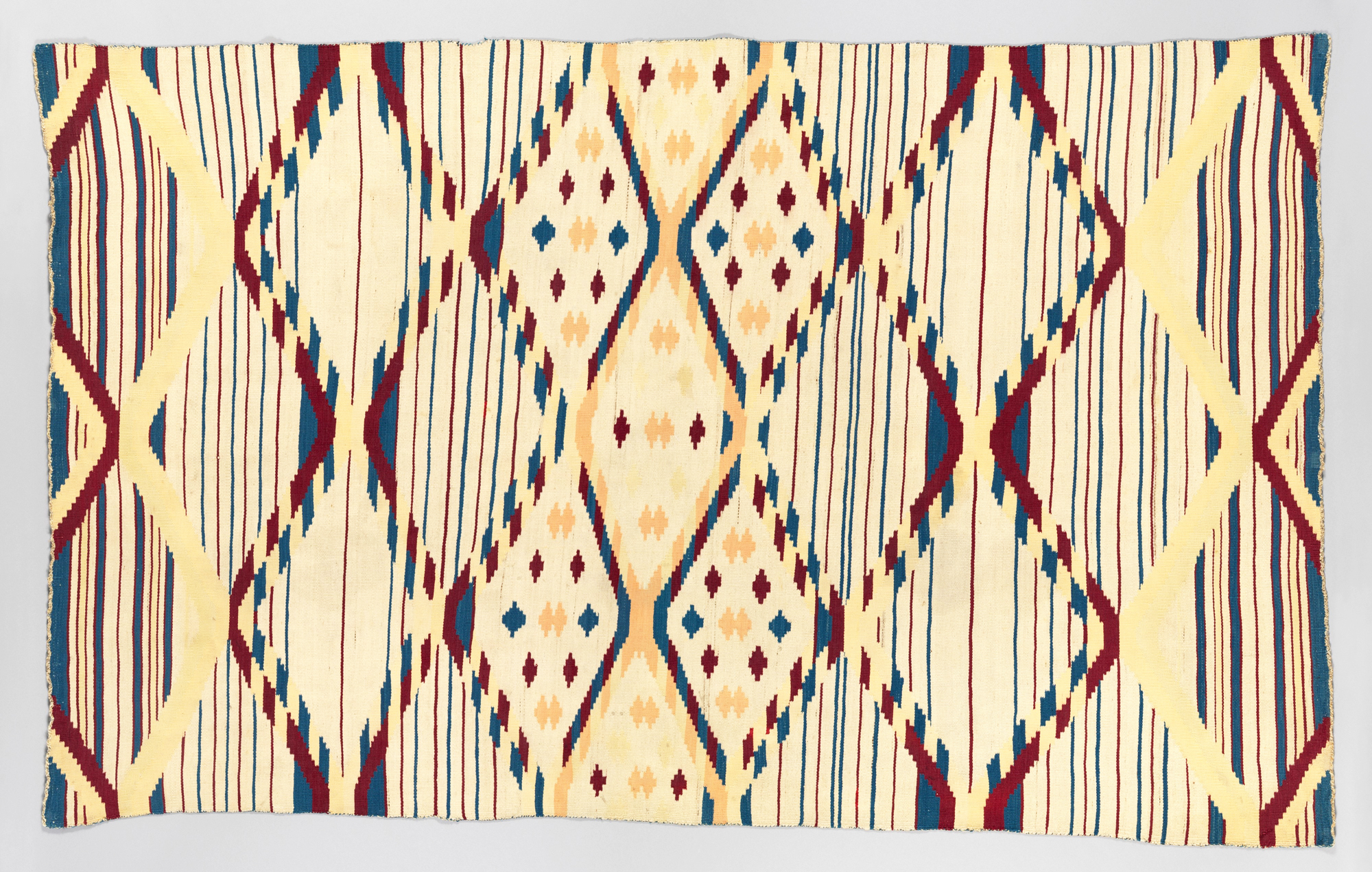

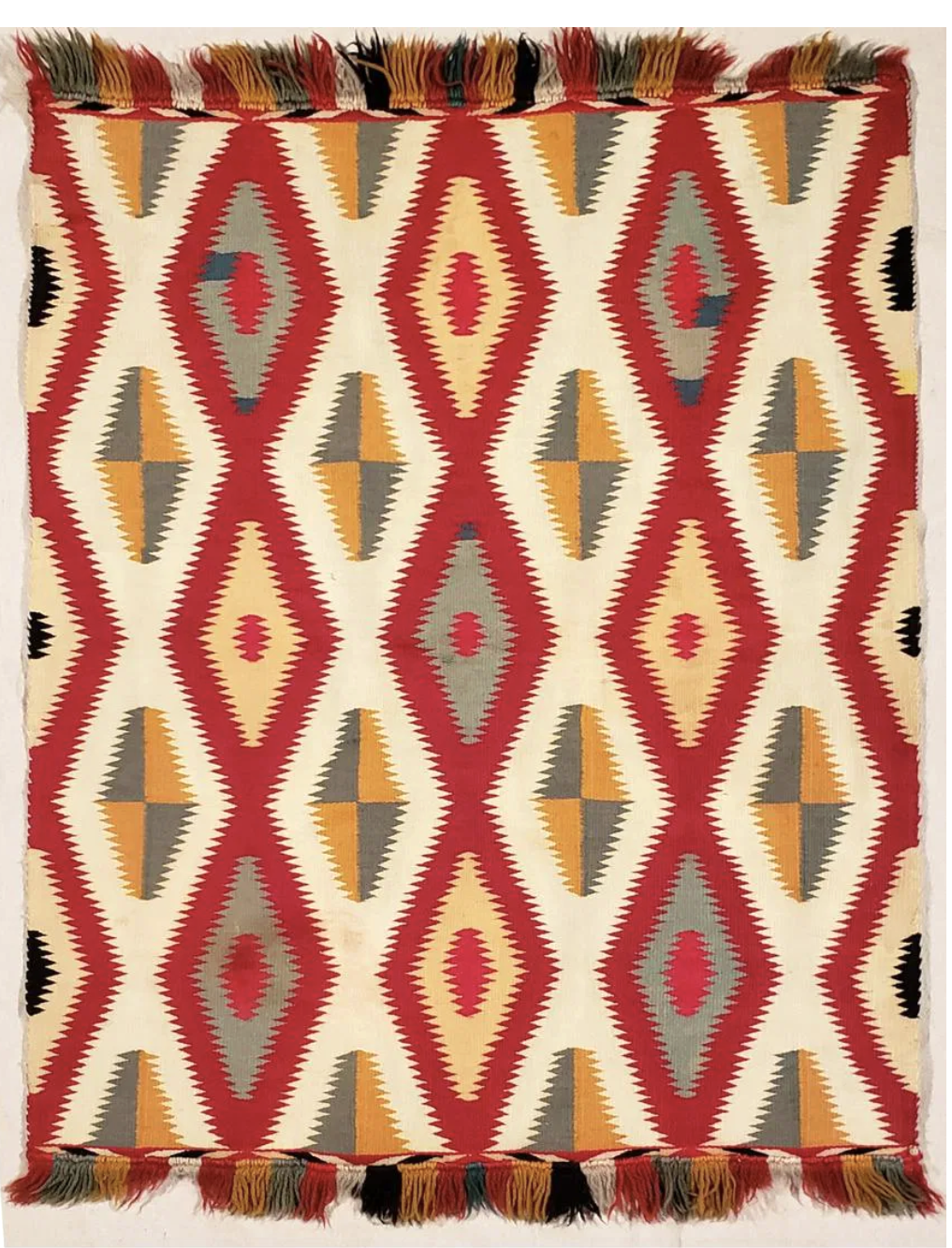

Large-sized Serape by an unidentified Navajo artist; ca. 1840–50. Medium: wool. Dimensions: 49 1/2 × 73 1/2 in. (123.2 × 186.7 cm). The American Wing of the MET Museum, New York, USA.

«Vibrantly colored and vividly patterned, these so-called wearing blankets build on long-established design themes. The horizontal lines and diamond shapes of this classic example—referred to by some as a rare "radio-wave" pattern—are characteristic of Southwest Native American design, reflecting varied weaving traditions and artistic exchange among Native and Hispanic communities.» (The MET Museum curators).

Large-sized Serape by an unidentified Navajo artist; ca. 1865. Medium: wool. Dimensions: 43 1/2 × 68 in. (110.5 × 172.7 cm). The American Wing of the MET Museum, New York, USA.

Large-sized Serape by an unidentified Navajo artist; ca. 1865–70. Medium: Dyed and undyed wool. Dimensions: 52 1/2 × 84 1/4 in. (133.4 × 210.8 cm). The American Wing of the MET Museum, New York, USA.

«Contemporary Native artists and scholars have identified this large weaving, with its unusual white background, as a "not- of-free-will" blanket—meaning it was likely produced by a highly skilled Navajo woman enslaved in a Spanish American household. An 1865 congressional report estimated that there were between 1,500 and 3,000 Navajo captives living in the Rio Grande Valley as well as in northern Mexico in these years. While this particular form of enslavement largely ended in the late 1870s, its traumatic legacy continues to reverberate today.» (The MET Museum curators).

Moqui-Style Serape with Compound Banded Design, ca. 1865-75, New Mexico. Medium: Wool, single interlocking tapestry weave; two selvages present. Dimensions: 174 × 132.2 cm (68 1/2 × 52 in.). Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, USA.

« The Spanish-derived word sarape is used to identify blankets made throughout the greater Southwest and Mexico that are longe then they are wide and traditionally are worn around the shoulders like a shawl. This exceptionally fine example displays many attributes associated with classic Navajo textiles, including its traditional tapestry weave, the augmented tassels placed at the corners, and the twining that appears along the edges. The design is based upon Moki-style textiles, which were typically woven with alternating blue-and-brown lines often accented with additional bands of white. Although the name given to this style derives from the Spanish term for the Hopi (Moki or Moqui), these patterns found favor among Pueblo and Navajo weavers and are one of the oldest designs that appear in Navajo textiles. Demonstrating the creativity and cultural identity of the artist, this sarape blends Moki design traits with a distinctly Navajo signature—that of bold crimson banding superimposed over the subtle striping.» (Art Institute Chicago curators).

Classic Navajo Moqui-Style Man's Serape from the Fred Harvey Collection. Ca. 1870. Length 73 1/2 in; width 53 in. Photo courtesy by Heritage Auctions, Dallas, Texas, USA.

The yarns in this weave: The dark reds are raveled bayeta, dyed with a combination of lac and cochineal, 5% lac and 95% cochineal (dye analysis provided by David Wenger, Ph.D.); the pinks are the same raveled bayeta, recarded and respun with white to make pink; the blues are hand spun and dyed with indigo; the whites and browns are undyed hand spun; and the green is hand spun and dyed with combinations of indigo and vegetable dyes.

Serape with Compound Banded Design, ca. 1870–95, New Mexico. Medium: Natural and Germantown wool, plain weave and single interlocking tapestry weave; twined warp ends and selvages; looped and knotted augmented corner tassels; natural and synthetic dyes. Dimensions:. 186.7 × 137.8 cm (73 1/2 × 54 1/4 in.). Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, USA.

«Some Navajo blankets carry what fifth-generation Navajo weavers Barbara Teller Pete and Lynda Teller Ornelas call a “memory”—a tendency to fold along creases formed by previous wear. When this sarape is displayed according to its memory, as if draped around a person’s shoulders, its striped and checkered lines form a new pattern.» (Art Institute of Chicago curators).

Chief's Blankets

Navajo Chief's Blankets are distinguished by several key characteristics:

- They were always woven wider than long (unlike serapes);

- They had designs that ran from edge to edge;

- They were worn draped over the shoulders but could be used as a bed cover at night;

- They possessed exceptional qualities: supple texture, warmth, and naturally waterproof. They were finely woven and tightly woven to repel water and keep the wearer warm and dry during cold, rainy, and snowy seasons.

- They were considerably lighter than buffalo skins while providing comparable warmth;

- They were also highly prized for aesthetic reasons.

They were not made exclusively for tribal leaders, nor did the Navajo themselves have chiefs. (The Navajo had no chief at all!). The name comes from the fact that these blankets were so valuable and expensive to make that only certain wealthy individuals could afford them. Among other tribes, such as the Utes and various Plains groups, these blankets were often owned by chiefs and high-status individuals, thus cementing their designation as Chief's Blankets".

Scholars have identified three distinct design phases in the evolution of Navajo Chief's Blankets; they constitute what is known as the "Classic Period."

First Phase (Hanoolchaadi) - ca. 1700-1830s

Navajo Chief's Blankets of the early period were woven with Navajo Churro sheep wool yarns and show the simplest design pattern: horizontal bands of intense, natural brown and white wool; they also incorporated three bands of thin stripes of red (cochineal) and/or blue (indigo). Archaeological and historical evidence shows that they existed before 1800. They are extremely rare today, with only an estimated 50-100 surviving examples. (The rarest can be valued at up to half a million dollars). The chief's blankets of this phase are also known as the "Ute style" because of their popularity among the Ute tribe, who preferred versions with brown and white bands and thin blue bands, but no red stripes.

Ute Man wearing a Navajo/Diné first-phase Chief's Blanket. 1874, Los Pinos, Colorado. Photo by William Henry Jackson.

Diné (Navajo) first-phase chief blanket, ca. 1840–1850, New Mexico. Medium: Wool yarn, bayeta (unraveled wool cloth), dyes. Dimensions: 179 x 145 cm. Presented by S. W. Woodhouse, Jr.. On display at the The National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian, USA.

Navajo Ute First Phase Blanket, ca. 1850 | ANTIQUES ROADSHOW | PBS

Please note that today this First Phase Chief's Blanket is worth close to 2 million dollars.

"Ute style" Chief’s Blanket, New Mexico, ca. 1830.

This valuable first-phase blanket was collected by George Horace Lorimer (1867-1937), editor-in-chief of the Saturday Evening Post, in the early 20th century. This piece, along with other valuable chief's blankets from the Weisel family collection, was displayed in an exhibition at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, California, in 2014. The exhibition was entitled Lines on the Horizon: Native American Art from the Weisel Family Collection, featured approximately 70 objects and textiles from the extraordinary collection recently donated to the museum.

Second Phase - 1840-1860

The Chief's Blankets of the Second Phase are similar to those of the First Phase but with additional design elements: twelve bars or rectangles were added to the three bands (four rectangles in each band); red yarns appeared either as horizontal rectangles or concentric squares. The blankets still maintain the wider-than-long format. «By the beginning of the second phase, the weavers had also begun to expand their color palette, adding yellow and green accents, for example. But one of the colors the Navajo weavers coveted most was the red of the prized bayeta cloth made in England and later in Spain and Mexico. They would unravel the cloth and then weave the material into rectangles on their blankets. The bayeta, which was occasionally used in first-phase blankets, became a color and cloth that Navajo weavers used extensively in the second phase. The bayeta was dyed with cochineal, named for the cochineal beetle. According to Tyrone Campbell (author of books on Navajo weaving and dealer in antique Navajo and Pueblo weavings in Scottsdale, Arizona), "It came in rich shades from pink to deep burgundy, and it's permanent. There is no plant in the Southwest that will give you such an intense red that won't fade".» (Navajo Chief's Blankets: Three Phases | Antiques Roadshow | PBS).

Second Phase Chief's Blanket by an unidentified Navajo artist; date: mid-19th century. Medium: Wool. Dimensions: 62 × 73 1/2 in. (157.5 × 186.7 cm). The American Wing of the MET Museum, New York, USA.

Navajo Second Phase Chief’s Blanket at the Met

Second-Phase Chief'S Blanket, ca. 1880. Medium: Wool and dye. Dimensions: 55 1/4 × 71 1/4 in. (140.3 × 181 cm). Saint Louis Art Museum, Missouri, USA.

«In this blanket, charcoal-gray bars and dashes float on a red ground, establishing massive patterned bands that balance against the dominant white-and-black stripes. This type of textile captivated 19th-century Native peoples from the Plains and Mountain West, who valued these striking blankets not only for their unusual form and materials, but also because they originated far away, as is often the case with luxury items. Diné peoples traded blankets like this one with neighbors in the Pueblos of Pecos and Taos, centers for Native trade networks. Starting in the 1820s, American traders also transported blankets from the Southwest to a series of commercial forts across the Plains. By the late 19th century, when the railway brought waves of travelers to the Southwest territories, these blankets circulated in the developing national market for Native art. Thomas Dozier, an art and curio dealer based in the rail town of Española, New Mexico, displayed this blanket at the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904.» (The Saint Louis Art Museum curators).

Third Phase - 1860-1868

The Chief's Blankets of the third phase show a rather elaborate design evolution. They are characterized by cross formations, concentric diamonds, half diamonds, and quarter diamonds in red yarn, and three bands overlaid by serrated or terraced diamonds or triangles. «These new designs featured elements of a “9-spot” design that covered the top, middle and bottom of each blanket with new, exciting patterns.» (Nizhoni)

Third-Phase Chief's Blanket by an unidentified Navajo artist; date: 1865. Medium: Wool. Dimensions: 56 x 66 in. (142.2 x 167.6 cm). The American Wing of the MET Museum, New York, USA.

ABOVE: Third-Phase Chief's Blanket by an unidentified Navajo artist; date: 1865-70. Medium: Dyed and undyed wool. Dimensions: 47 3/4 x 66 1/2 in. (121.3 x 168.9 cm). The American Wing of the MET Museum, New York, USA.

BELOW is a similar Third-Phase Chief's Blanket (dimensions: 56 x 69 in., 142 x 175 cm) on a kind of simple mannequin. It dates from the 1870s-80s and is made of natural hand-spun wool in white and dark brown with indigo blue, raveled aniline, and cochineal dyed reds. It's for sale at the Toh-Atin Gallery, Durango, CO, USA.

LEFT: Third-Phase Chief's Blanket, ca. 1880, New Mexico. Medium: Wool, dovetail tapestry weave with "lazy lines"; twined warp ends and and selvedges; corner tassels. Dimensions: 141 × 163.2 cm (55 1/2 × 64 1/4 in.). Art Institute Chicago, Illinois, USA.

RIGHT: Third-Phase Chief's Blanket, ca. 1880, New Mexico. Medium: Wool, plain weave with "lazy lines" and dovetail tapestry weave; warp and weft twine; corner tassels. 153.7 × 206.4 cm (60 1/2 × 81 1/4 in.). Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Rare Third-Phase Chief's Blanket, ca. 1860s-1870s. Len Wood's Indian Territory, Aliso Viejo, CA, USA.

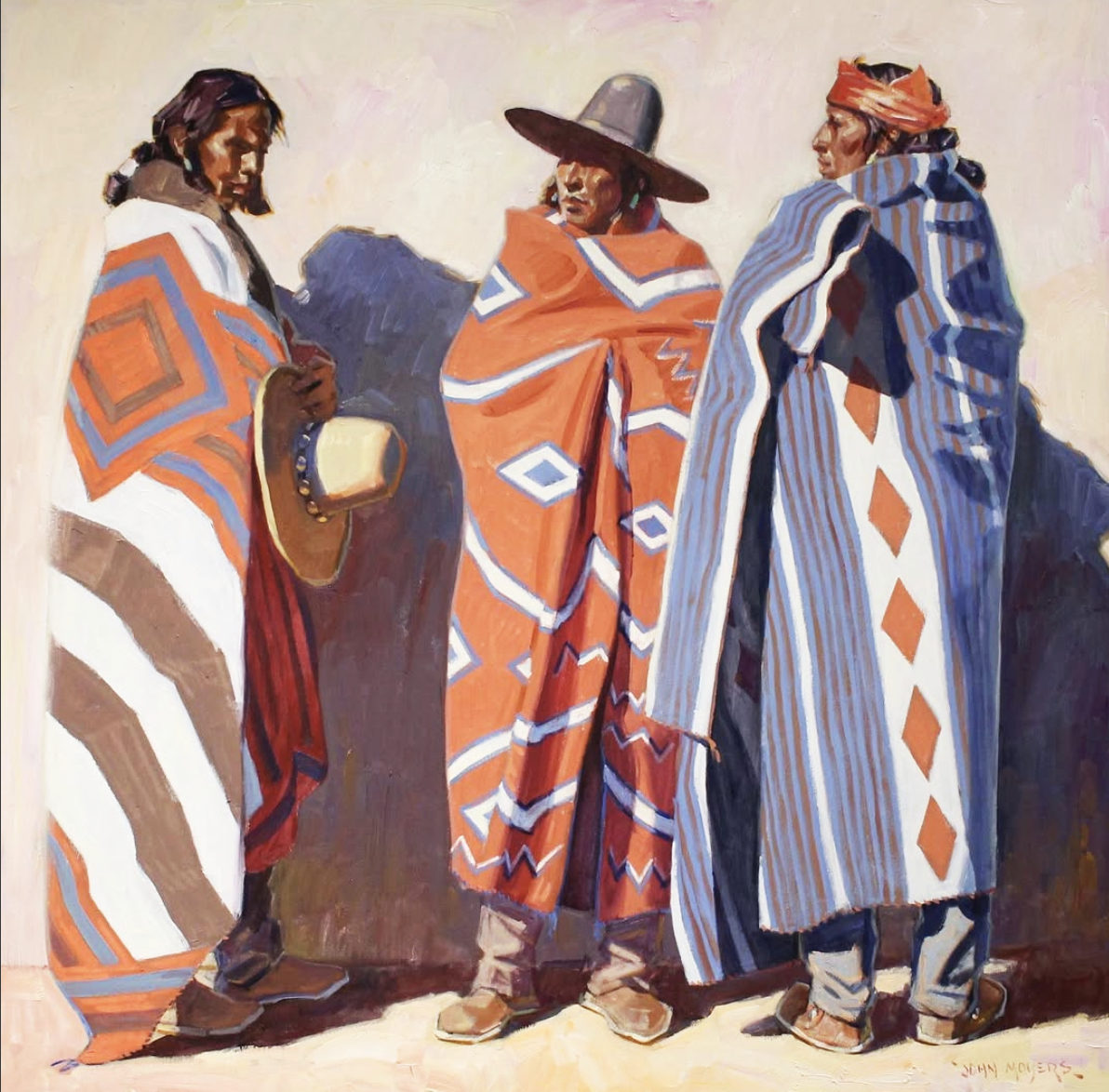

Returning to the Evening, oil painting by John Moyers. Private collection. Photo courtesy: Maxwell Alexander Gallery, Pasadena, CA.

Born in Atlanta, Georgia in 1958, John Moyers spent most of his formative years in Albuquerque, New Mexico. The son of William Moyers, a noted painter and illustrator, John grew up in a household that lived and breathed art, surrounded by paintings and sculptures that influenced his artistic development. He is married to renowned artist Terri Kelly Moyers.

BELOW

Navajo Blankets, oil painting by John Moyers.

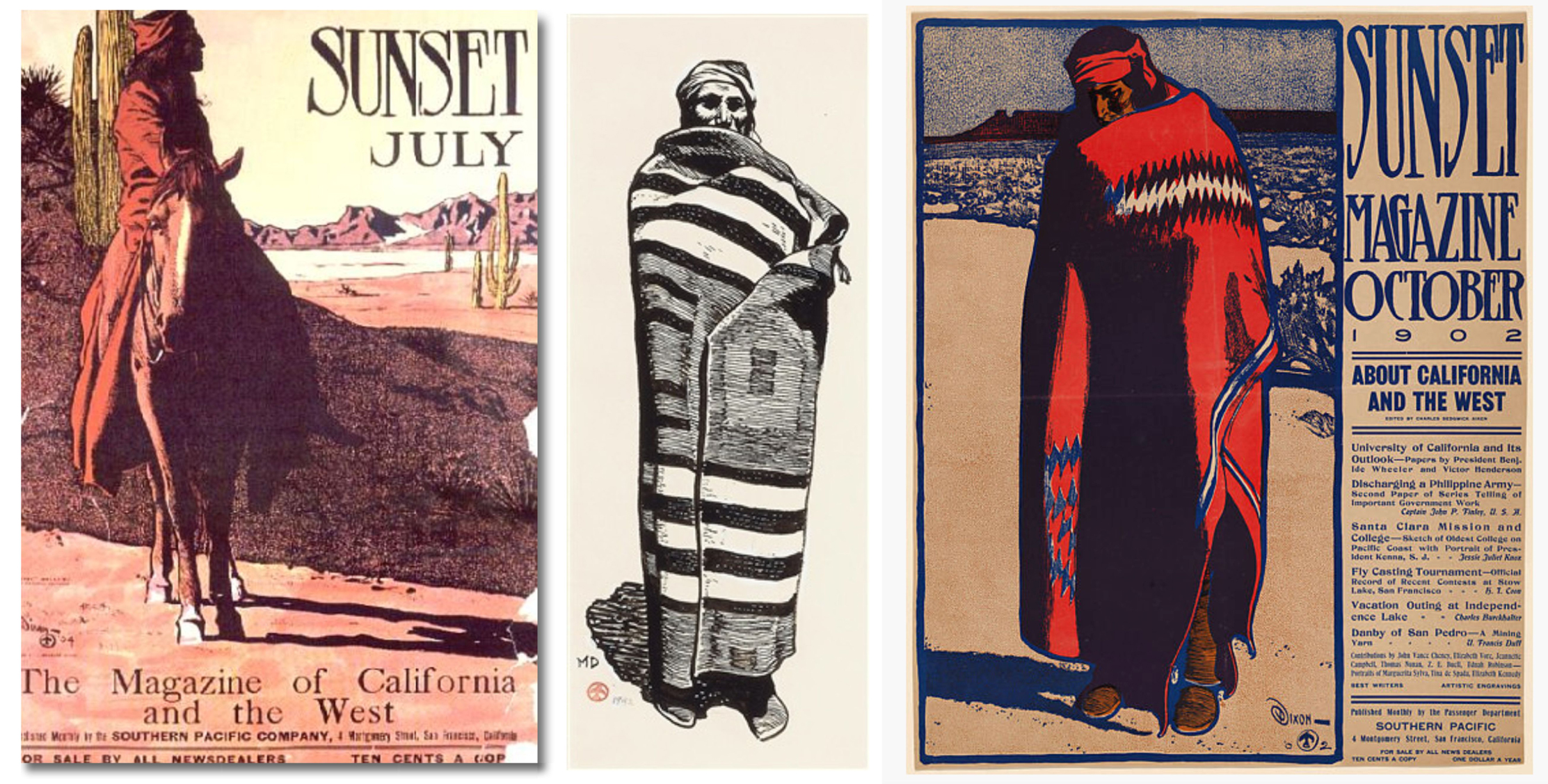

Illustrations by Maynard Dixon. Left to right: Cover for Sunset, the Magazine of California and the West, 1904; Navajo in Chief's Robe, 1942, ink on paper; Blanket-wrapped Navajo, cover for Sunset Magazine, October 1902, lithograph.

Lafayette Maynard Dixon (1875–1946) was a renowned American artist from Fresno, California. He dedicated most of his career to capturing the landscapes, cultures, and peoples of the American West. Often referred to as "The Last Cowboy in San Francisco," he is considered one of the finest artists to depict U.S. Southwestern cultures and landscapes during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

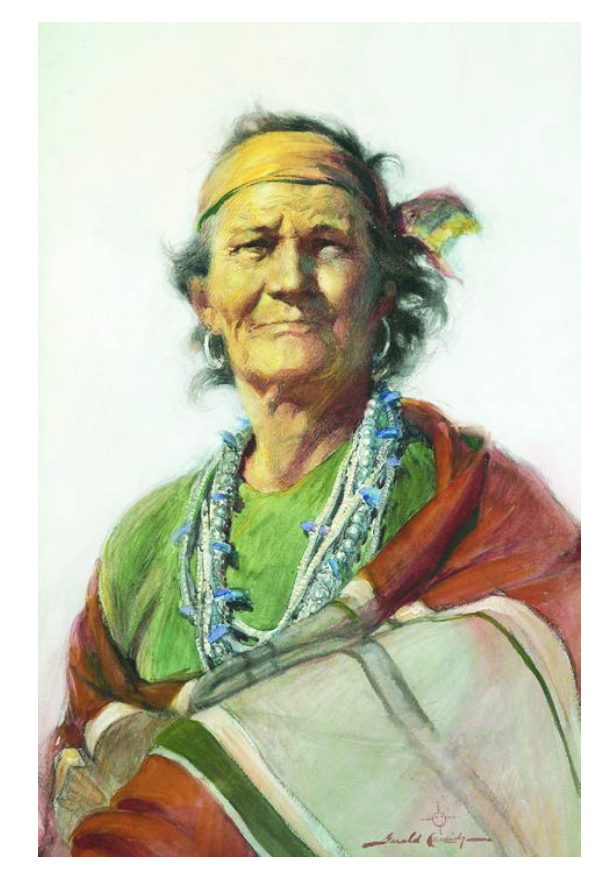

Navajo Medicine Man, Watercolor on paper by Ira Gerald Cassidy, ca. 1925. Dimensions: 38-1/2 x 28-2/3 inches framed. Desert Caballeros Western Museum Collection, Wickenburg, Arizona.

Ira Dymond Gerald Cassidy (1869-1934) was a significant US artist, muralist, and designer whose work captured the essence of the American Southwest.

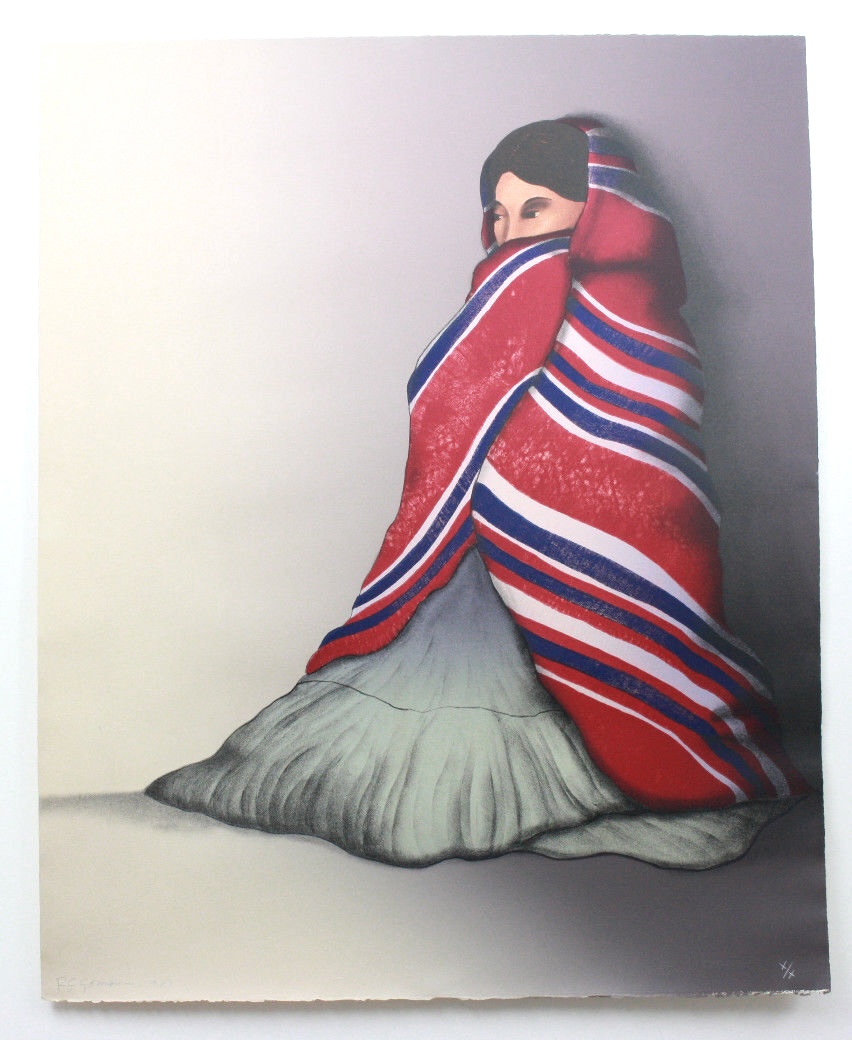

Navajo Woman with Blanket, print, signed by Navajo artist R.C. Gorman.

Rudolph Carl Gorman (1931-2005) was born in Chinle and grew up in a traditional Navajo hogan near Canyon de Chelly in northeastern Arizona, an area steeped in legend and history that has served as a refuge for the Navajo people for centuries. He began drawing at the remarkably early age of three and showed artistic talent from the beginning. His family background was rich in artistic tradition, with sand painters, silversmiths, singers, and weavers on both sides of his family. In his own words from 1998: "I was born near Canyon de Chelly in Arizona and spent my early years close to nature and Navajo tradition. My family was rich in artistic talent and creative spirit, but not in material possessions. I have been fortunate to live and work in the beautiful Taos Valley, an environment also rich in artistry and tradition".

His father, Carl Nelson Gorman, became an acclaimed artist in his own right and was one of the original twenty-nine Navajo Code Talkers who developed an unbreakable communication code used by American forces during World War II. When Gorman was about twelve, his parents separated and his father left to attend art school, later becoming a painter and teacher at the University of California at Davis. Gorman's artistic journey took a significant turn during his "bohemian year" at Mexico City College (now the University of the Americas), where he flourished under the influence of Mexican masters such as Orozco, Rivera, Siqueiros, and Tamayo. After Mexico, Gorman established his first studio in San Francisco, where his artistic output was prodigious. In 1968, Gorman borrowed money from his parents to purchase the Manchester Gallery in Taos, New Mexico, and renamed it the Navajo Gallery, the first Native American-owned art gallery. Gorman's paintings primarily featured Native American women and were characterized by fluid forms and vibrant colors. He worked in a variety of media, including oil painting, sculpture, ceramics, stone lithography, and pastels.

His colorful depictions of Navajo women were often combined with somewhat surreal and tranquil desert landscapes, creating soothing and inviting compositions. His lithographs are especially noted for their beautiful and subtle blending of rich colors.

Indigo, oil painting by US artist Logan Maxwell Hagege. Photo courtesy: Maxwell Alexander Gallery, Pasadena, CA.

Logan Maxwell Hagege (pronounced "Ah-jejj") is a Los Angeles-based contemporary artist born in 1980 who has established himself as one of the most distinctive painters of the American Southwest. His work is characterized by what he terms "stylized realism," a unique artistic approach that combines classical training with a modern aesthetic vision.

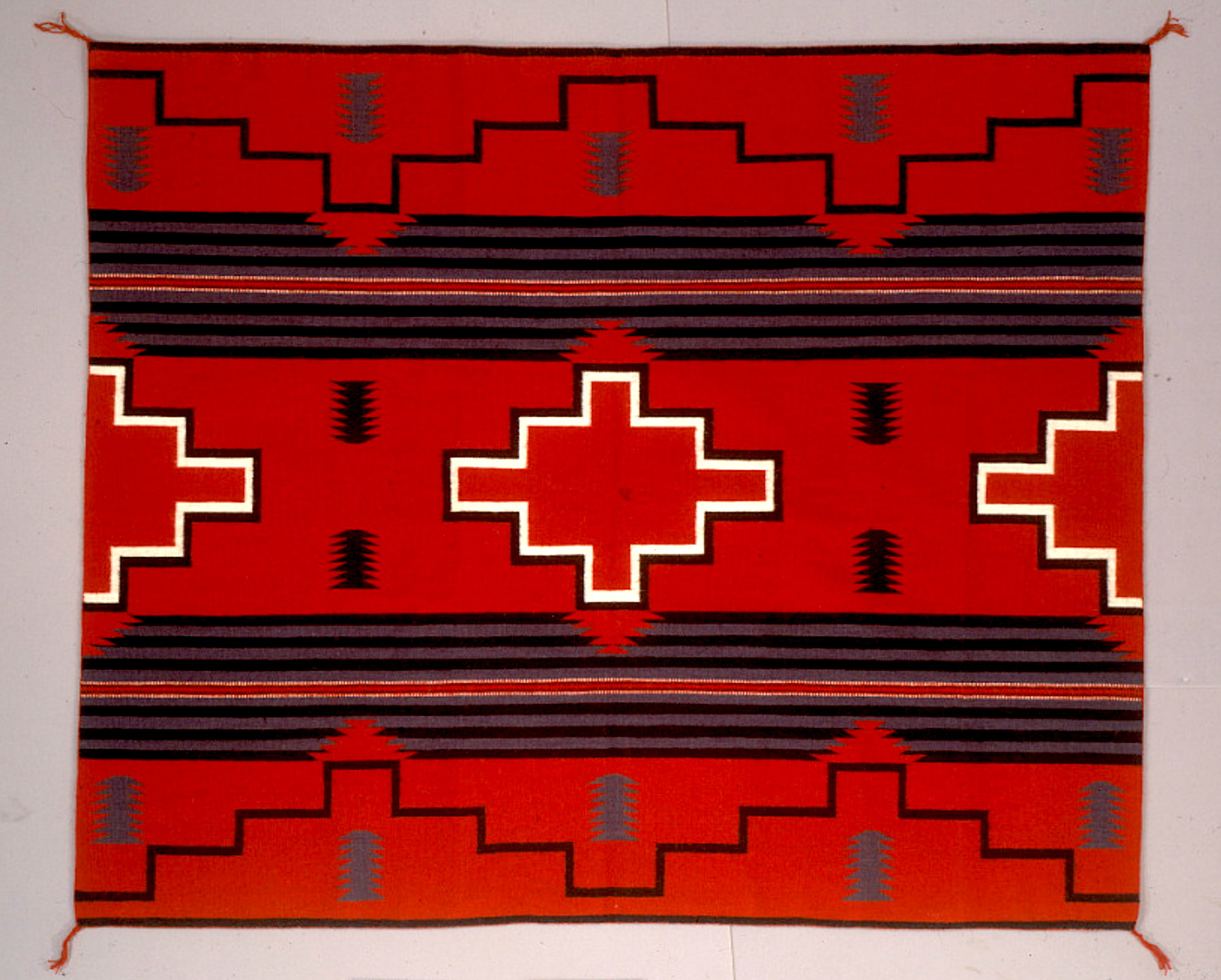

3rd Phase Chief Navajo blanket from the 1920s-30s. Dimensions: 57 x 77 in.; 144.78 cm × 195.58 cm. Photo courtesy: Gail Getzwiller, owner of Nizhoni Ranch Gallery, Sonoita, Arizona.

This captivating 3rd Phase Navajo Chief Blanket is done in a Red Mesa/ Teec Nos Pos Pictorial Style. The colors in this piece are brown, black, white, red, and indigo/purple. Anyone wishing to buy it today would have to spend around US$37,000.

A contemporary version of the traditional Third-Phase Chief's Blanket, hand woven to be used as a rug or better a wall hanging. Hand woven by Diné weaver Evelyn Rose Curley in ca. 1980. Medium: Wool yarn. Dimensions: 176.5 x 148.5 cm. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian, Washington, D.C.

Untitled (Tourists), gouache by Navajo artist Gerald Nailor (1917-1952), 1937. Dimensions: 14 x 12 3/4 in. (35.6 x 32.4 cm)

Bequest of Dorothy Dunn, 1992. Museum of Indian Arts and Culture/Laboratory of Anthropology #51404.

Gerald Nailor (1917-1952), also known by his Navajo name Toh Yah (meaning "Walking by the River"), was a major Navajo painter born in Pinedale, New Mexico. His artistic career, although cut short by his untimely death at the age of 35, left an important legacy in Native American art.

Nailor attended the Albuquerque Indian School from 1930 to 1934 and then the Santa Fe Indian School from 1935 to 1937. At Santa Fe, he studied with the influential teacher Dorothy Dunn, whose "studio style" technique had a profound influence on his artistic development. After completing his studies with Dunn, he spent a year studying with Kenneth M. Chapman and Swedish muralist Olle Nordmark. In 1937, Nailor established a studio in Santa Fe with his friend and colleague Allan Houser, a Chiricahua Apache artist. With Harrison Begay, he founded Tewa Enterprises, an art publishing company specializing in Native American art that became known for its high-quality silkscreen prints.

Nailor fully embraced Dorothy Dunn's studio style in his artwork. His paintings typically featured minimal or absent backgrounds, lack of perspective, use of muted earth tones, flat frontal views, and traditional Native American scenes and subjects. His paintings were characterized by extraordinary detail and polish, making him known as a sophisticated artist with "humor as well as a sense of line". More than humor, however, this gouache shows a sharp and bitter irony.

Tragically, Nailor died in 1952 from injuries sustained while trying to help a woman being beaten by her husband.

BELOW

Rhythm of the Range, oil painting by Logan Maxwell Hagege, 2020. Private Collection. Photo courtesy: Maxwell Alexander Gallery, Pasadena, CA.

The spread of the Chief's Blankets

Chief's Blankets became important trade items, especially from 1800-1830, among high-ranking members of various tribes including the Arapahoe, Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche, Lakota and Dakota Sioux, Shoshone, Blackfeet tribe, and Ute. These blankets were so closely associated with Navajo weavers that in some Plains languages, including Lakota and Apsáalooke (Crow), the term for the Navajo people translates as "those who make striped blankets".

« Traded and prized throughout the Southwest and Great Plains, these gorgeous weavings were not only valued for their horizontal stripes of rich Cochineal reds, Indigo blues and deep blacks, but because of their supreme quality.» (Nizhoni).

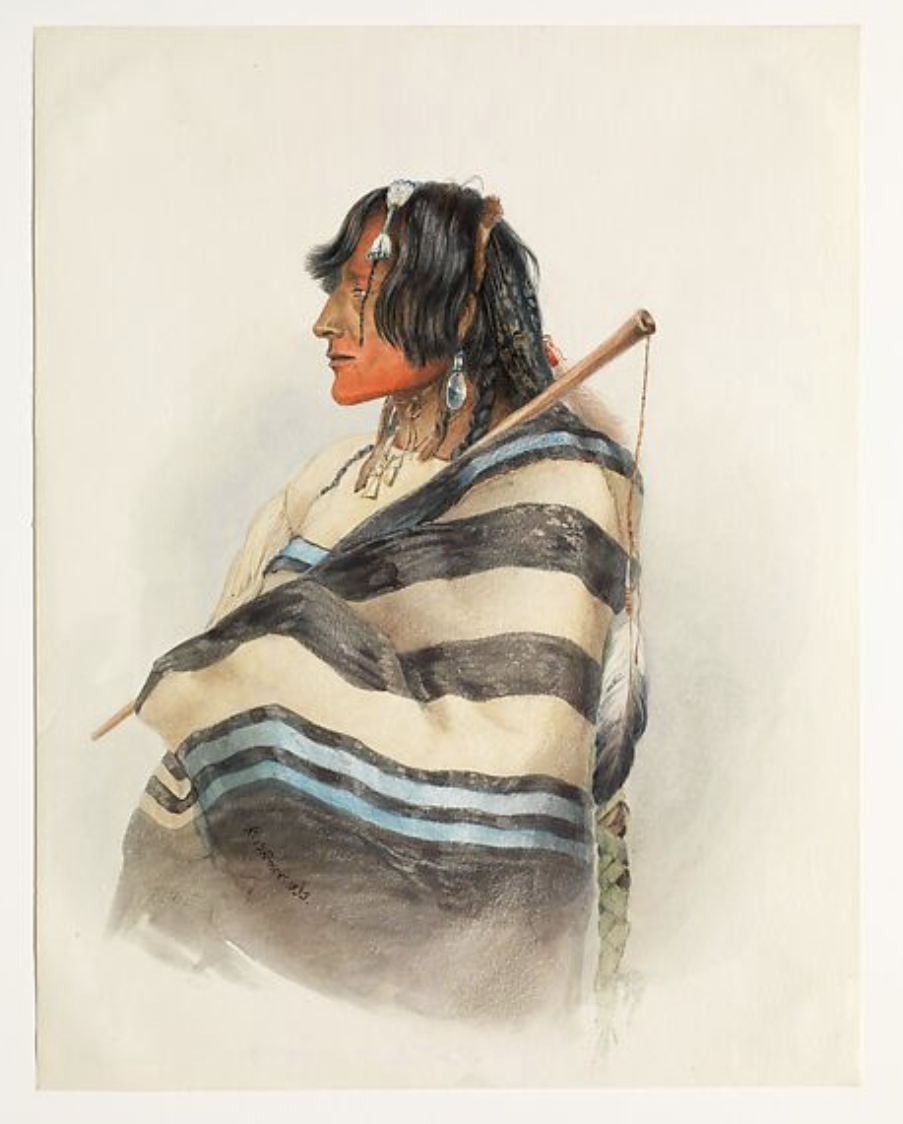

Kiäsax, Piegan Blackfoot Man, drawing by Swiss artist Karl Bodmer in 1833. Medium: Watercolor and graphite on paper. Dimensions: 12 3/16 x 9 1/2 in. The American Wing of The MET, New York, USA.

This 1833 work portrays a young man of the Piegan, the largest group within the Blackfeet Nation, wearing a First Phase Chief's Blanket. It was painted by Karl Bodmer, who was commissioned to record the Native Americans encountered by the German Prince Maximilian during his trek across the American West.

Tom Nash, Crow, on the edge of a river near Sheridan, Wyoming. 1900-1910. Photo by Louis R. Bostwick.

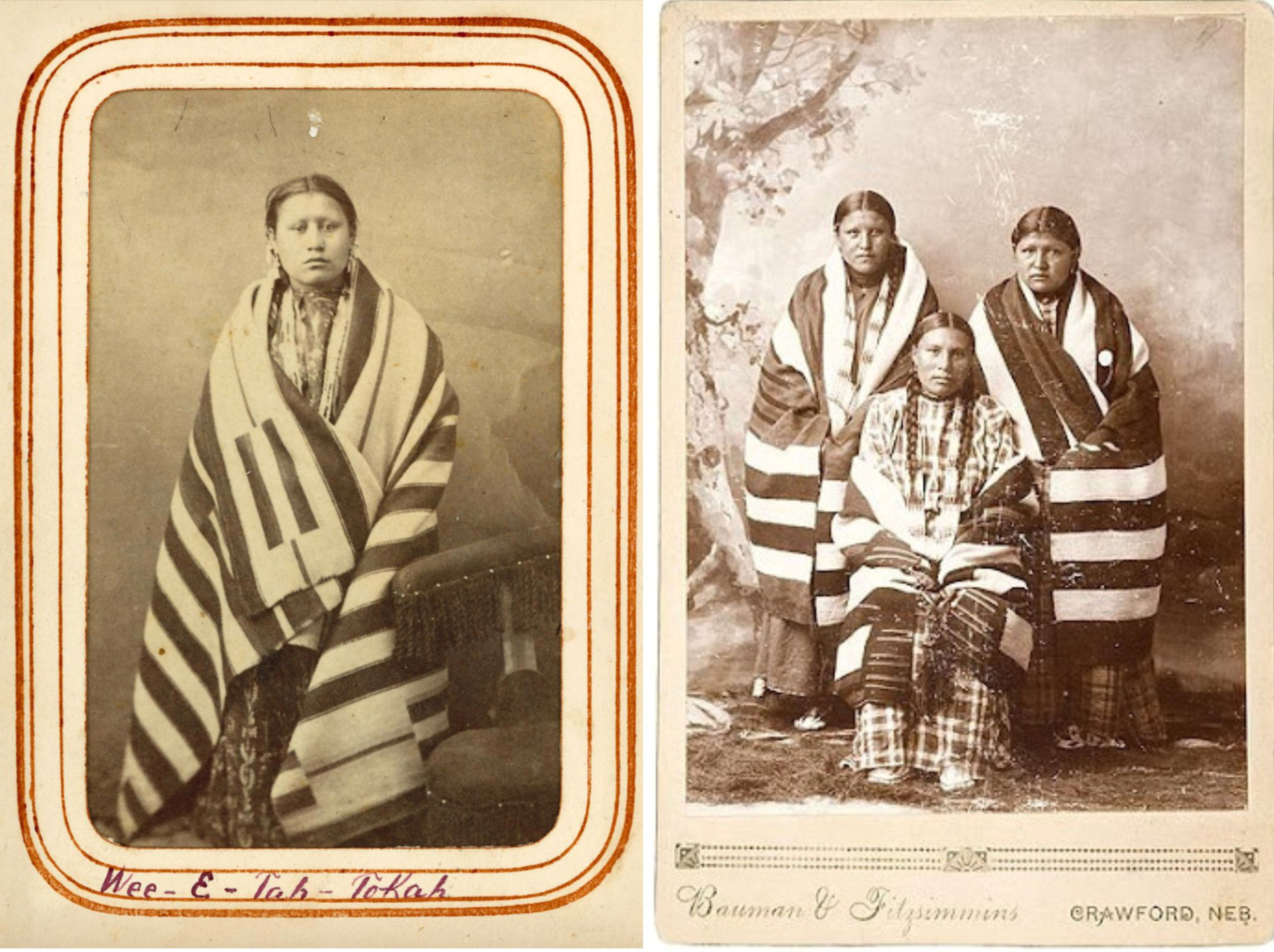

LEFT: Wee-E-tah-tokah, Dakota Sioux, photo by William R. Godkin, undated.

RIGHT: Oglala Lakota women wrapped in Navajo blankets; ca. 1890.

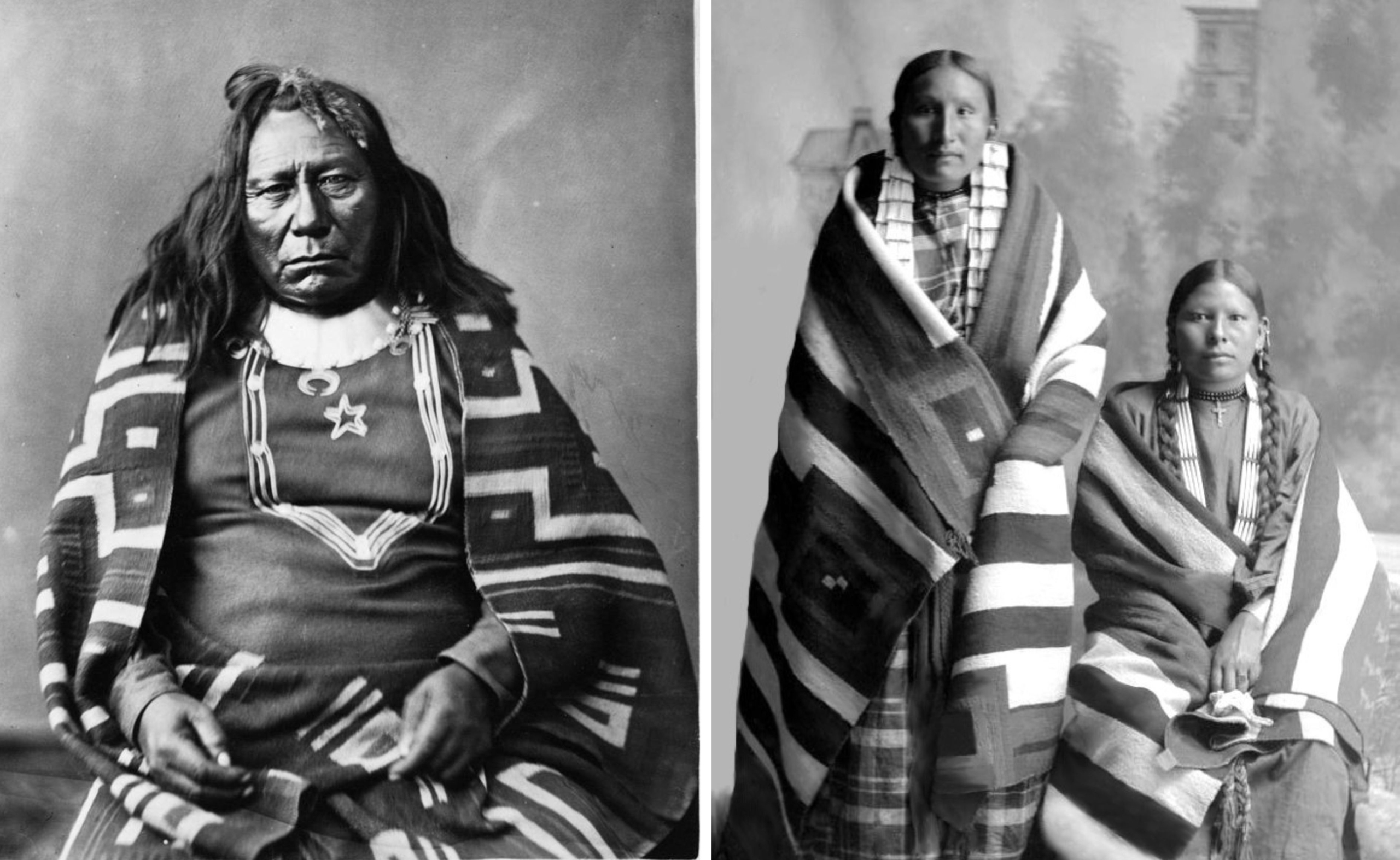

LEFT: Colorow, warrior and chief of a band of Utes, born a Comanche in 1810 and passed away in 1888. Photo by William Gunnison Chamberlain.

RIGHT: Two Lakota women, Pine Ridge Agency, South Dakota, 1891. Source: Denver Public Library, Western History, Genealogy Digital Collections, CO, USA.

LEFT: Dolly Bird Head and Joseph Bird Head, full portrait, 1899. She was probably a Lakota woman; in the picture, she wears a S’ina Glega, a Diné blanket, wrapped around her waist. Photo by Heyn. Library of Congress Archives, USA.

CENTER: Joseph Bird Head, probably a Lakota child, 1899. Photo by Heyn. Library of Congress Archives, USA.

RIGHT: Chief Eagle Feather, probably a Dakota Sioux, with a baby, ca. 1900. Heyn & Matzen, Chicago. Library of Congress Archives, USA.

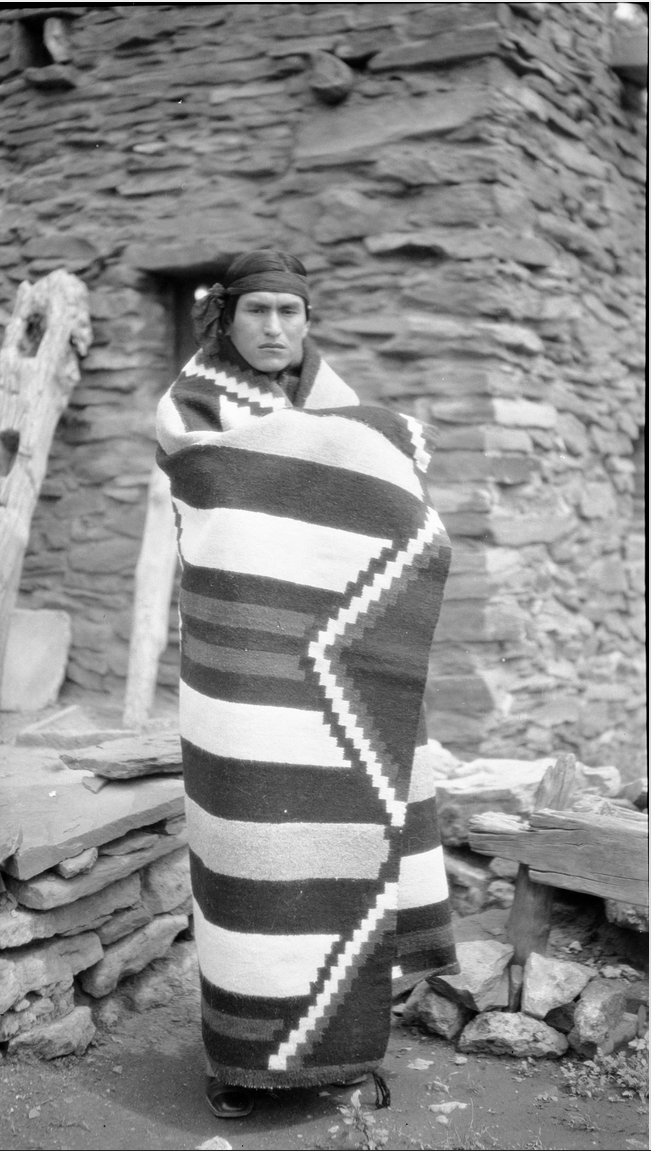

Hopi Homer Yoywatewa in an Old Navajo Chief's Blanket, Grand Canyon, AZ. Date: 1920s. Photo by Earle Robert Forrest. Arizona Memory Project, Museum of Northern Arizona, USA.

How much did a good-quality Chief's Blanket cost?

The search results indicate that a Navajo chief's blanket would have cost between $100 and $150 in 1860. That wasn't much money - it was a small fortune! To understand the extraordinary value of these blankets in the 1860s, consider that the average worker earned about $5 per week if he was lucky, with "laborers" earning about half that amount (about $2.50 per week). At $100-$150, a single chief's blanket represented about a year's wages for most men of the time. To put this in perspective, a house could be purchased for about $200 during this period. (Note that these figures have been confirmed by expert Tyrone Campbell).

After 1865, they became increasingly popular with Anglo-American collectors, and as a result, more Late Classic and Transitional Third Phase examples have survived than comparable serapes.

Later periods

Blankets woven after 1868 are referred to as the "Late Classic" period, which later gave way to the "Transitional Period" of the 1880s and 1890s.

The period from 1868 to 1880 marked a transitional period in Navajo weaving. Several technological developments influenced this transition:

- The invention of aniline dyes in England in 1856 reached the Southwest via the Santa Fe Railroad around 1865;

- Three-ply dyed yarn was imported from Germantown, Pennsylvania, that same year;

- Germantown was producing four-ply dyed yarn by 1875.

These developments led to the Eye Dazzler Period (1880-1900), characterized by brighter, more vivid colors in Navajo blankets as weavers adopted commercial Germantown yarn from Pennsylvania. Designs became more complex and colorful as new materials, dyes, and influences were incorporated into the Navajo weaving tradition.

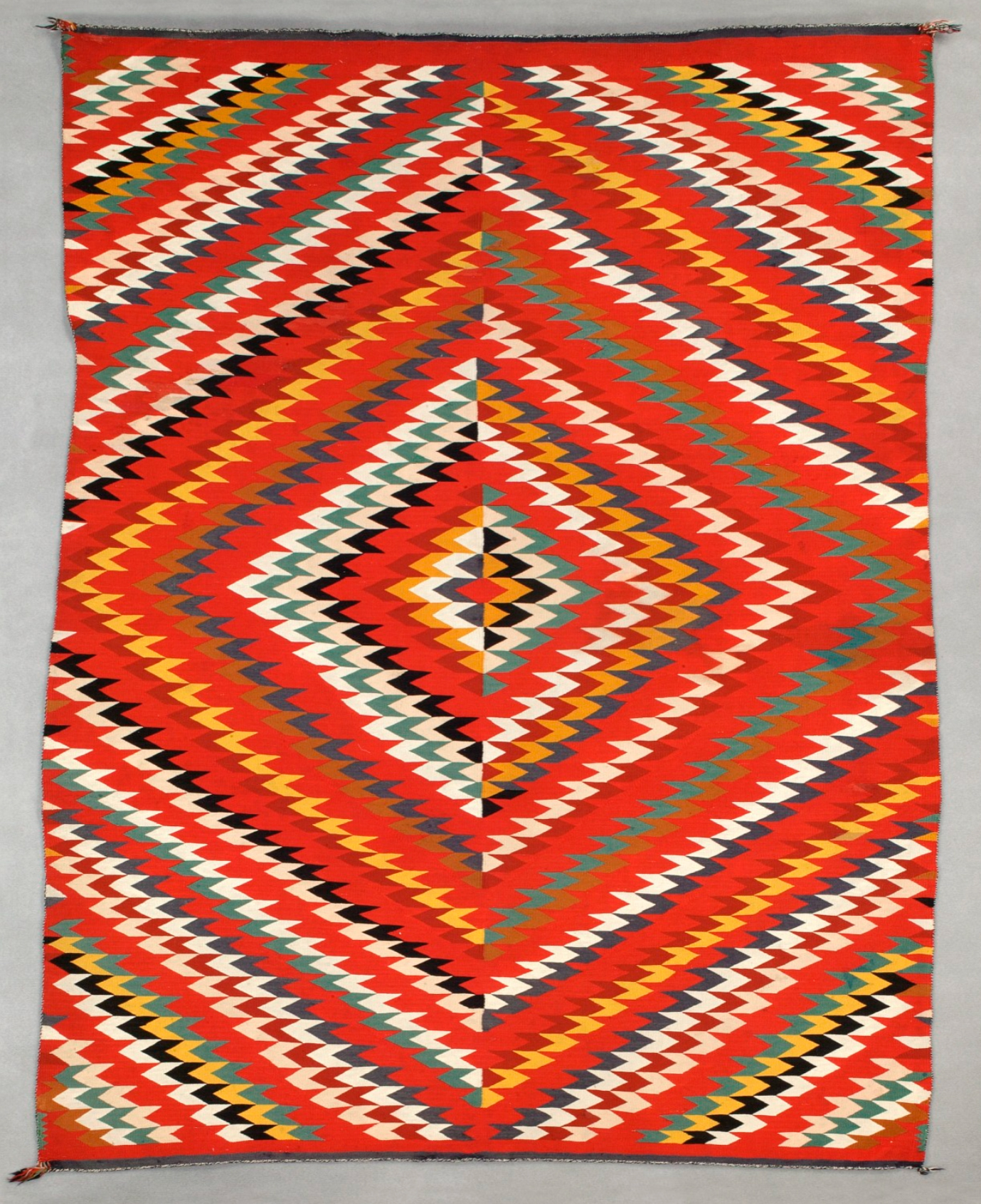

“Eye-Dazzler” Blanket, 1880–1899. Medium: Cotton and wool, single interlocking tapestry weave; twined selvages and heading, overcast finish terminating in tassels. Dimensions: 233 × 151.1 cm (91 3/4 × 59 3/8 in.. Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, USA.

«Brillant color and bold overall patterns with serrated diamonds, chevrons, and interlocking lines are hallmarks of the “Eye Dazzler” style of Navajo (Diné) textiles produced from the late-19th to the early-20th century. Earlier Navajo blankets featured broad horizontal bands of indigo blue, white, dark brown, black, and red, subsequently enhanced with the addition of small diamonds, bars, and squares. The lively approach of Eye Dazzler weaving developed out of a period of major cultural and artistic transformation beginning in 1864 when the U.S. government forcefully resettled the Navajo in the Bosque Redondo reservation. From the early 1860s, the Navajo received brightly colored commercial yarns as part of their U.S. government annuities. The new Eye Dazzler weaving also incorporated design elements characteristic of Mexican Saltillo blankets, which featured serrated diamonds and zigzag lines.

The creator of this blanket fully utilized the intense color of commercially dyed yarns and the Saltillo style to create a spectacular work. Internlocking serrated undulating lines appear to vibrate over the entire surface. The vivid interplay of red and orange hues with brillant blues, greens, yellow, white, and black produces an energetic, three-dimensional illusion.» (The Art Institute of Chicago curators).

Germantown Saddle Blanket, ca. 1900-1910. Dimensions: 34 x 25 in. / 86.4 x 63.5 cm. Sold at auction in 2020 by Antiques From Estates - Michael & Sophie Coe.

Germantown Eye-Dazzler (Dah’iistł’ó) Blanket, ca. 1885. Medium: Dyed wool and cotton. Dimensions: height: 83.25 in, 211.455 cm; width: 64 in, 162.56 cm. Source: Indigenous Arts of North America, Denver Art Museum, CO, USA.

«The "Eye Dazzler" style was popular with weavers and their customers from about 1880 to 1900 when brightly colored commercial yarns were widely available through newly established trading posts on the Navajo Reservation.» (The Museum curators).

Fine, tightly woven Navajo blanket or rug in red, blue, green, pink and cream. Dimensions: 210 x 136 cm. The Trustees of the British Museum, London, UK.

The curators of the British Museum date this blanket or rug to a period before 1860 or to 1860 at the latest, based on a note left by the original purchaser. This old note states that this piece was bought in Utah or Arizona and that it is "possibly pre-1860". I disagree. This piece shows the intense colors of commercially dyed Germantown yarns and the typical "eye dazzler" pattern developed by Diné weavers after 1880.

Rug, 'Eye Dazzler' design in red, black, grey, white; tapestry-woven wool; Navajo reservation area of Arizona / New Mexico, USA, 1875 - 1920. Width: 119.5 cm. Powerhouse Collections.

«Classic 'Eye Dazzler' rugs such as this belong to the Transition period of Navajo weaving in the late 1800s and early 1900s, although recently reintroduced to the contemporary repertoire. Good pieces (and there were many which were not!) were outstanding examples of artistic expression and were completely different from the rugs that preceded them and those that followed. Nowadays they are highly prized by collectors and art critics alike.» (Note of the Powerhouse curators)

“Germantown Eye-Dazzler” Rug, New Mexico, before 1890. Medium: Cotton and wool dovetailed tapestry weave. Dimensions: 220.2 × 155.3 cm (86 3/4 × 61 1/8 in.). Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, USA.

«The creator of this blanket fully utilized the intense color of commercially dyed yarns and the Saltillo style to create a spectacular work. Internlocking serrated undulating lines appear to vibrate over the entire surface. The vivid interplay of red and orange hues with brillant blues, greens, yellow, white, and black produces an energetic, three-dimensional illusion.» (The Art Institute of Chicago curators).

The masterpiece above is not a blanket, but a rug. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, rugs and carpets became the most successful Navajo/Diné textiles, taking on the artistic and economic importance that blankets had held for decades. We will discover not only how and why this happened, but also how Navajo textile art evolved to produce masterpieces of absolute beauty.

WOVEN LEGACIES: THE ART AND HISTORY OF NAVAJO/DINÉ TEXTILES

-

TRADE NETWORKS AND REGIONAL INTEGRATION: FROM BARTER TO GLOBAL TRADE

For several decades, Navajo churro-derived goods linked the Navajo to the broader economy:

- Pueblo tribes: Traded wool for corn and pottery.

- Hispanic settlements: Traded blankets for iron tools and silver.

- Plains Indians: Bartered bison hides and pemmican for Navajo wool.

This integration cushioned the Navajo against local crop failures and created a resilient, diversified economy. After the traumatic Bosque Redondo Internment (1864-1868), however, Navajo weavers navigated shifting trade networks that evolved from localized barter systems to participation in global markets, fundamentally altering their artistic and economic practices. The transformation of the Navajo/Diné textile trade between the late 19th and early 20th centuries reflects a complex interplay of forced adaptation, economic pressures, and strategic innovation.

Upon their return from captivity, Navajo weavers faced depleted herds and disrupted traditions. The U.S. government's introduction of the Rambouillet sheep in the 1880s, while increasing meat yields, degraded the quality of wool for hand spinning due to its short, kemp-filled fibers. This necessitated greater reliance on commercial yarns such as Germantown (machine-spun, aniline-dyed wool from Pennsylvania), which allowed for bolder colors but altered traditional techniques.

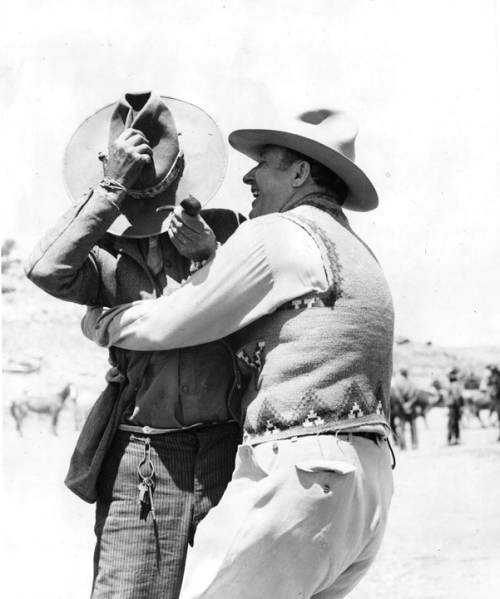

RAILROAD INTEGRATION AND MARKET EXPANSION

The arrival of the railroad in the Southwest in the early 1880s ended the region's isolation and enabled large-scale migration, agricultural expansion, and the growth of new towns and cities; it was a catalyst for economic growth, demographic change, and regional integration. By connecting the Southwest to national and international markets, the railroads not only transformed the market for Navajo textiles, but also had a profound impact on the entire Navajo/Diné community, suddenly thrusting them into a completely unfamiliar and alien world, the world of the rapid expansion and consolidation of industrial capitalism, characterized by large-scale production for profit, the accumulation of capital by private firms, and the emergence of the modern corporation.

Railroad transportation brought aniline dyes and Germantown yarn (machine-spun, four-ply wool from Pennsylvania), which replaced hand-spun Navajo churro wool and expanded color possibilities. Germantown's vibrant hues made possible the intricate "eye-dazzler" patterns we saw in the previous chapter.

But the development of the railroad trade had even more powerful consequences: it catalyzed shifts in textile production, design, and economic dynamics.

It made possible the mass importation of cheap Pendleton blankets.

It spurred the creation of trading posts that functioned as hybrid spaces that blended commerce and cultural exchange.

It facilitated the export of Navajo textiles to eastern cities and European markets;

It introduced Caucasian-inspired patterns through merchant catalogs that responded to Anglo-American interior design trends.

Let's dig a little deeper.

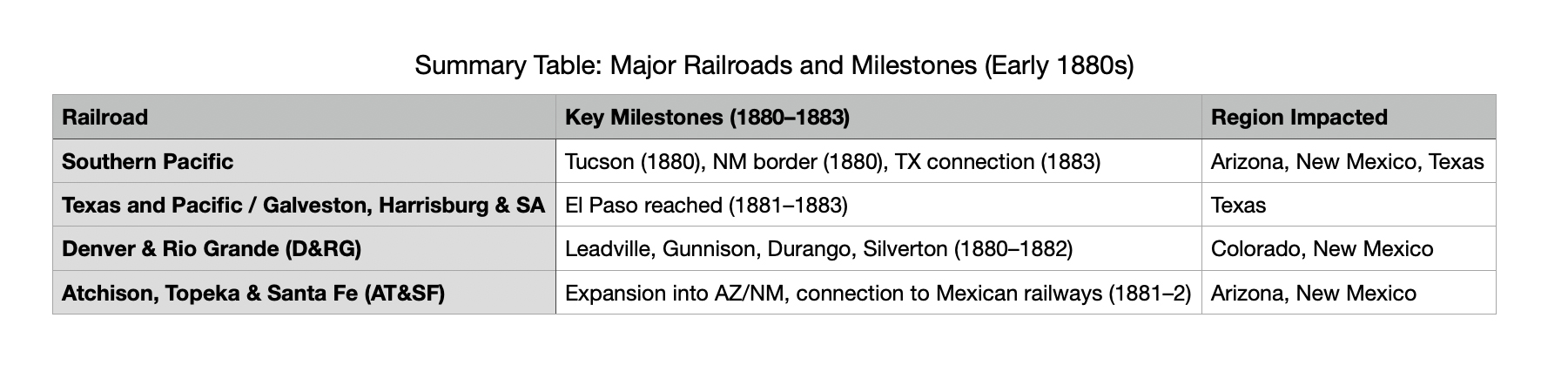

PENDLETON'S COMPETITION

Pendleton Woolen Mills was founded in Oregon in 1893, initially serving the local tribes of the Columbia River area. In the early 20th century, Pendleton expanded its market to include the Navajo, Hopi, and Zuni peoples of the American Southwest, becoming a major competitor to the Navajo weavers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and fundamentally changing the market for Navajo textiles.

Pendleton hired designers like Joe Rawnsley to study Native tastes and incorporate traditional colors and designs into modern, machine-woven blankets. In the early years, Joe Rawnsley spent time with the Native people of northeastern Oregon to understand their preferences for color and design - what we now call an effective marketing strategy: "consumer insight research" or, more broadly, "market research focused on customer preferences". Pendleton's jacquard looms allowed for more vibrant colors and intricate patterns than could be woven by hand. These patterns and designs were elaborate to match the traditions of various indigenous communities. Rawnsley and the other Pendleton designers also incorporated many features of Navajo/Diné serapes and chief's blankets (horizontal banding, bold stripes and color blocking) and even Navajo symbols to evoke a classic, successful Navajo aesthetic – another effective modern marketing strategy: "competitive benchmarking."

Pendleton's machine-made, mass-produced wool blankets retailed for as little as $3, a fraction of the $100 price of handwoven Navajo blankets in the late 19th century. This made Pendleton blankets far more accessible to both Native and non-Native consumers, and dramatically undercut Navajo weavers. "Penetration pricing".

Given all of this, it should come as no surprise that within a few years, Pendleton blankets became highly valued in Native communities, not only as trade items, but also for ceremonial and everyday use. Their durability and vibrant, detailed and traditional designs contributed to their popularity.

Can you imagine the impact of this modern commercial competition on traditional Navajo weaving?

The influx of affordable, attractive, mass-produced Pendleton blankets, backed by a smart marketing strategy and a modern advertising campaign featuring targeted images and drawings, led to a sharp decline in demand for traditional, handmade Navajo blankets. Many Navajo weavers lost not only control over the marketing of their textiles, but also significant portions of their market share. In response, some Navajo weavers, at the urging of traders, turned to producing rugs and decorative items for non-Native consumers, particularly for home décor. Influenced by traders, Navajo/Diné weavers shifted the focus of their craft from traditional, utilitarian textiles to decorative art objects for new markets. This adaptation helped preserve the weaving tradition, but fundamentally changed its context and purpose.

LEFT: Chief Joseph aka Hin-mah-too-yah-lat-kekt, leader of a Wallowa band of Nez Percé, wearing a Pendleton blanket. Ca.1919. Wikimedia Commons.

RIGHT: A Native American man, identified as Chief Red Hawk of the Cayuse tribe, is seated in front of a solid-colored blanket hung like a backdrop. The man is wearing a cloth shirt and has a Pendleton blanket wrapped around his body from the chest down. Date: 1900/1910. Lee Moorhouse (1850-1926) photograph. Oregon Digital, University of Oregon Libraries.

LEFT: This cardboard label was attached to every Pendleton blanket from ca. 1905

CENTER: Pendleton advertising for Indian markets.

RIGHT: An old advertisement for a Pendleton blanket for "Indians".

BELOW: Some traditional, vintage patterns of Pendleton blankets, still in production today.

TRADERS AND TRADING POSTS

The Treaty of Bosque Redondo in 1868 was a major turning point that subjected the Navajo/Diné people to the rule of the U.S. federal government, forced assimilation, and American capitalism. During this time, the Federal Indian Bureau licensed traders to buy and sell Navajo products. Trading posts established on or near the Navajo Reservation served as central hubs for commerce and cultural exchange between Navajos and settlers in the American Southwest. These posts facilitated trade by providing Navajos with goods such as tools and manufactured goods, while also serving as a platform for the sale of Diné crafts. Their main goal was to establish, maintain, and expand business with the Navajo under monopolistic conditions (granted by the license).

The emergence of trading posts in the Navajo/Diné Southwest fundamentally reshaped textile production, creating a complex interplay of cultural preservation and capitalist exploitation. These posts became crucibles of artistic innovation and economic dependency, mediated by influential traders who dictated market demands.

Among the key licensed traders who established early posts at water sources and transportation hubs, I'd like to mention the following:

- Juan Lorenzo Hubbell (1853 –1930), owner of the Hubbell Trading Post established in 1878 in Ganado, Arizona; his extended family owned about thirty trading posts, including the Lorenzo Hubbell Trading Post and Warehouse (1917), located in the western part of the historic center of the city of Winslow, within Navajo land in Arizona, and the Klagetoh Trading post in Arizona.

- John Bradford Moore(1855–1926), a trader who established the Crystal Trading Post in Crystal, New Mexico, where he developed the manufacture of Navajo blankets and rugs for sale in the United States. In 1903 and 1911, he published mail-order catalogs featuring Navajo rugs with new designs;

- Clinton Neal Cotton (1859–1936), who opened an Indian wholesale business in 1884 in Gallup, New Mexico, called C.N. Cotton Warehouse. The C.N. Cotton Company was the first and most important wholesale warehouse to develop a significant market for Navajo blankets and rugs in the East, including the publication of an illustrated catalog of Navajo textiles;

- Harry Goulding (1897–1981), who purchased 640 acres (260 ha) of land near Monument Valley, Arizona, and founded Goulding's Trading Post (now a museum) in 1925.

- In 1911, George Bloomfield and his wife Lucy purchased the Toadlena Trading Post established by Bob and Merritt Smith in 1909.

In addition to acting as commercial intermediaries, these traders transformed Navajo textile production through several types of interventions. First, they introduced standardization in textile yarn, type, size, design, and production stages to better adapt Navajo products to new interstate markets.

In the 1880s and 1890s, they shifted Navajo weavers from blankets to rugs to better compete with Pendleton's $3 machine-made blankets and to meet the demand of eastern tourists arriving by rail and wealthy buyers on the East Coast looking for decorative rugs.

Traders introduced machine-spun, aniline-dyed yarns and new synthetic dyes to create a wider range of colors, counteract the scarcity of Navajo churro wool, and reduce production costs. The importation of machine-spun, aniline-dyed Germantown yarn made possible the creation of the "eye-dazzler" patterns we saw in the previous chapter.

Traders introduced motifs such as the Persian gul (octagonal patterns) and bordered rugs to appeal to non-native buyers, and to suit the tastes of Eastern retailers and consumers. They distributed pattern books with Moorish/Orientalist motifs and discouraged improvisation. Juan Lorenzo Hubbell introduced watercolor design guides, and John B. Moore imposed his own patterns, simplifying Caucasian-inspired designs to conform to Anglo-American interior design trends. Non-Native companies copied Navajo patterns and removed them from their cultural context. This spurred Diné weavers to innovate, combining traditional motifs with new materials (such as synthetic dyes) and new designs (such as borders and oriental patterns) to maintain market relevance.

Traders insisted on quality check and controlled every stage of production. John B. Moore, for example, purchased local wool but sent it to eastern mills for mechanical cleaning and carding, where some of the wool was dyed with blue or black synthetic dyes. Moore distributed the dyed wool, along with undyed gray and brown wool, to the most skilled of his Navajo weavers. He also introduced production line techniques.

Many traders bought textiles by weight, which encouraged weavers to leave out lanolin or add clay to the wool for higher pay. This led to a decline in craftsmanship until traders enforced scouring and dyeing standards.

Traders acted as postmasters, bankers, and undertakers, embedding cultural mediation and colonial authority.

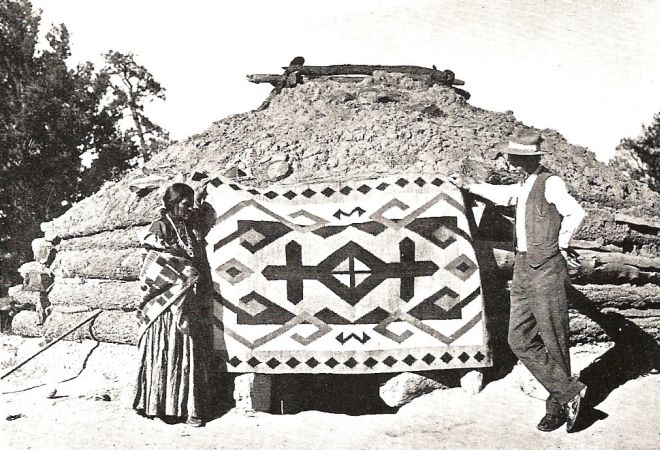

Hubbell Trading Post in Ganado, Arizona, ca. 1880. Photo by Ben G. Wittick. Juan Lorenzo Hubbell sits and talks with a Navajo woman to buy a third-phase chief's blanket. The trading post is in the foreground.

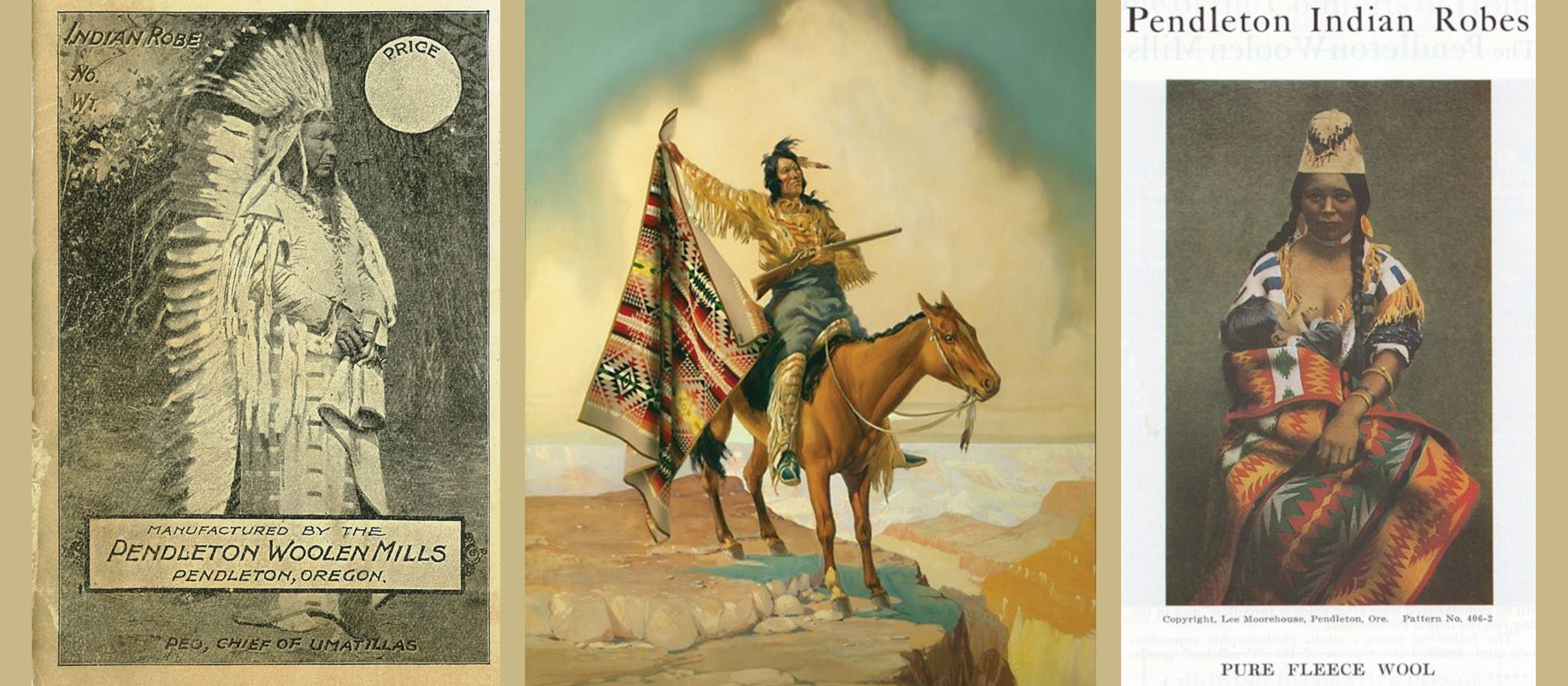

Trading post owner Roman Hubbell joking with a Navajo man in the Navajo land, New Mexico, ca. 1955. Digital Collections, New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Roman Hubbell (1891-1957) was the second son of John Lorenzo Hubbell (1853-1930). His two sons, Lorenzo, Jr. (1883-1942) and Roman succeeded their father in carrying on his trading post operations; and Roman developed a reputation as an advocate for the Indians in their relations with the federal government.

John Bradford Moore and a Navajo weaver at the Crystal Trading Post, New Mexico, with a rug and its Navajo weaver, from the 1911 catalog. Wikimedia Commons.

C.N. Cotton Warehouse, 1881, Gallup, New Mexico.

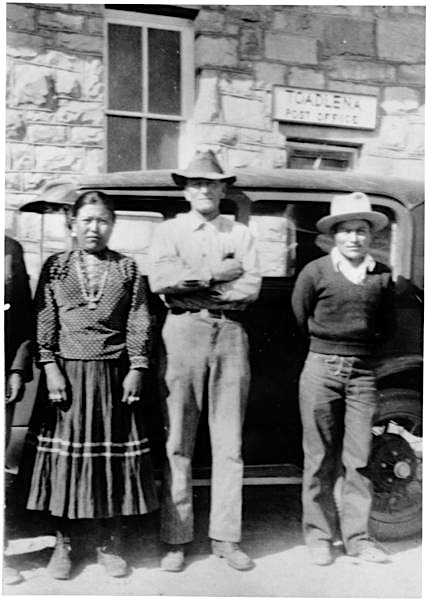

George Bloomfield (center) at the Toadlena Trading Post; 1930. Source: Farmington Museum, New Mexico Digital Collection.

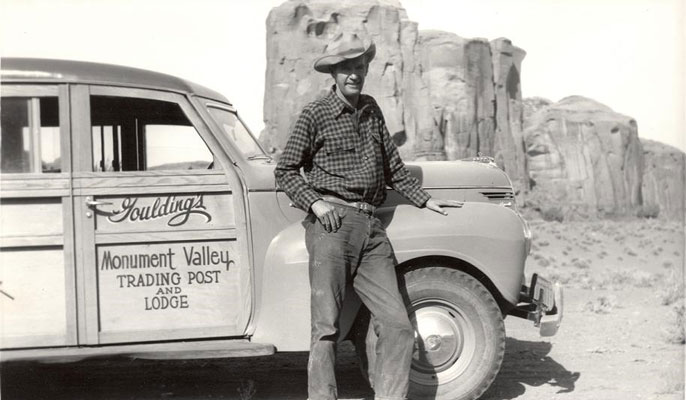

Harry Goulding at Monument Valley, Arizona. Courtesy of Goulding's Monument Valley.

Contemporary images of the Hubbell Trading Post National Historic Site, Ganado, Arizona.

Pictures of Two Grey Hills Trading Post (established in 1897 in Farmington, NM, within the Navajo land), Teec Nos Pos Trading Post (established in 1905 in the Four Corners area, on Navajo land) and Toadlena Trading Post (established in 1868 in Newcomb, NM).

Photos: Marc Henle; Jeffrey Peacock; Barbara Nussel Photography.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?