TUAREG CROSS OF AGADEZ

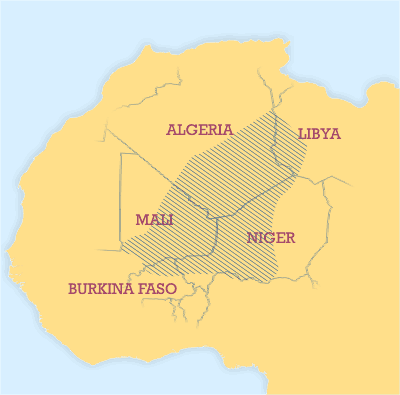

The traditional distribution of the Tuareg in the Sahara

(Wikimedia Commons, licensed under the the Creative Commons Attribution 2.5 Generic license)

Imarhan is an Algerian Tuareg desert rock quintet formed in 2006.

THE SOUL’S HORIZON

Some places in the world are more than just physical locations. They are something else, something beyond. Not for any spectacular feature they display, but because they exist as landscapes of the soul — metaphors for human life, spaces woven with symbols, myths, fairy tales, and monsters.

For me — born in the so-called tropical Third World but raised in the West — the desert has always been that place of the soul par excellence.

My first encounters with it were dazzling, precisely because nothing matched what I had imagined.

I lived and slept with Bedouins in the Grand Erg Oriental of the Sahara, crossed the Wadi Araba and Wadi Rum in Jordan with other Bedouins, traveled by jeep across Israel’s Negev Desert and Iran’s Lut Desert, and explored Egypt’s Nubian Desert on a noisy, smelly quad bike.

I discovered that physically, there is no such thing as the desert. There are countless deserts, each a living organism and a protean source of shapes, lights, colors, and sounds that swallow your eyes and ears. No two deserts are alike — sometimes a desert does not even resemble itself, reshaped overnight by the will of the wind. ‘Song of Dunes’ is the expression used by the Bedouins of the Great Eastern Erg to describe the sound of sand avalanches along the crests of the crescent-shaped dunes. Others speak of singing sand when one layer of grains slides over the layer beneath it.

Sahara Desert. All photos by me. No photos have been color altered or edited.

The changing color of the dunes in the Sahara Desert is primarily due to the way the sand interacts with different light and atmospheric conditions, as well as the mineral composition of the sand itself. As the sun moves across the sky and the weather changes, the angle and quality of light alter how sand grains reflect, absorb, and scatter light. This causes dunes to appear beige at midday and shift to ochre, orange, apricot, pink or even dark hues at sunrise, sunset or under a cloudy sky. This is due to the interplay between direct and diffuse light, and the spectral qualities of sunlight at different times of day. Dunes also display a wide range of intrinsic colors due to the minerals and elements coating or comprising the sand grains. The most common colourant is iron oxide — essentially rust — which can tint sand anywhere from pale beige or yellow to orange, red, ochre or pink. Sand grains that are older or have been exposed to weathering for longer often develop deeper iron oxide coatings, resulting in richer hues. Areas with less weathering or with fresh sand deposits will appear lighter, or even white. Occasional traces of organic matter or volcanic minerals can produce darker tones, ranging from grey to black. Therefore, the range of colors in the Sahara, from beige to orange, ochre, apricot, pink and dark shades, is caused by:

– the composition of each dune (e.g. iron or other minerals);

– the degree of weathering and age of the sand grains;

– the angle and type of natural light at any given moment;

– local atmospheric conditions (e.g. clear or cloudy sky, humidity);

– rare organic or volcanic material in the sand.

These factors combine to create a vibrant, ever-changing desert landscape — a natural interplay of chemistry, geology and the physics of light.

So, no two deserts are alike. Do you know why?

Because the desert is not only an external horizon but an inner condition.

It’s a place where excess is stripped away, leaving only the essentials — much like human life when tested by loss, solitude, or silence. Unlike a lush forest or fertile valley, the desert does not give easily; it forces travelers to confront scarcity, fragility, and the illusion of control.

For many cultures, from Biblical prophets to Tuareg poets, the desert is both an ordeal and a revelation. It is a crucible where myths are born and monsters take shape. It is a place where the soul is confronted with its own nakedness. In this way, the desert is less a “place” and more a grammar of being—a language that teaches through absence, vastness, and the kind of silence that is not empty, but rather, saturated with presence.

It’s a “place of the soul,” a definition that captures its paradox: the desert is barren only to eyes and ears looking for abundance. To eyes that listen and ears that see, it is dense with symbols, voices, and truths that cannot be heard elsewhere.

The desert is a mirror that reflects the depths of those who experience it.

A sink in the Grand Erg Oriental. Photo by me.

The desert is at once a cultural stage, a poetic horizon, and a spiritual passage — a landscape where history, imagination, and the soul converge.

A cultural reservoir

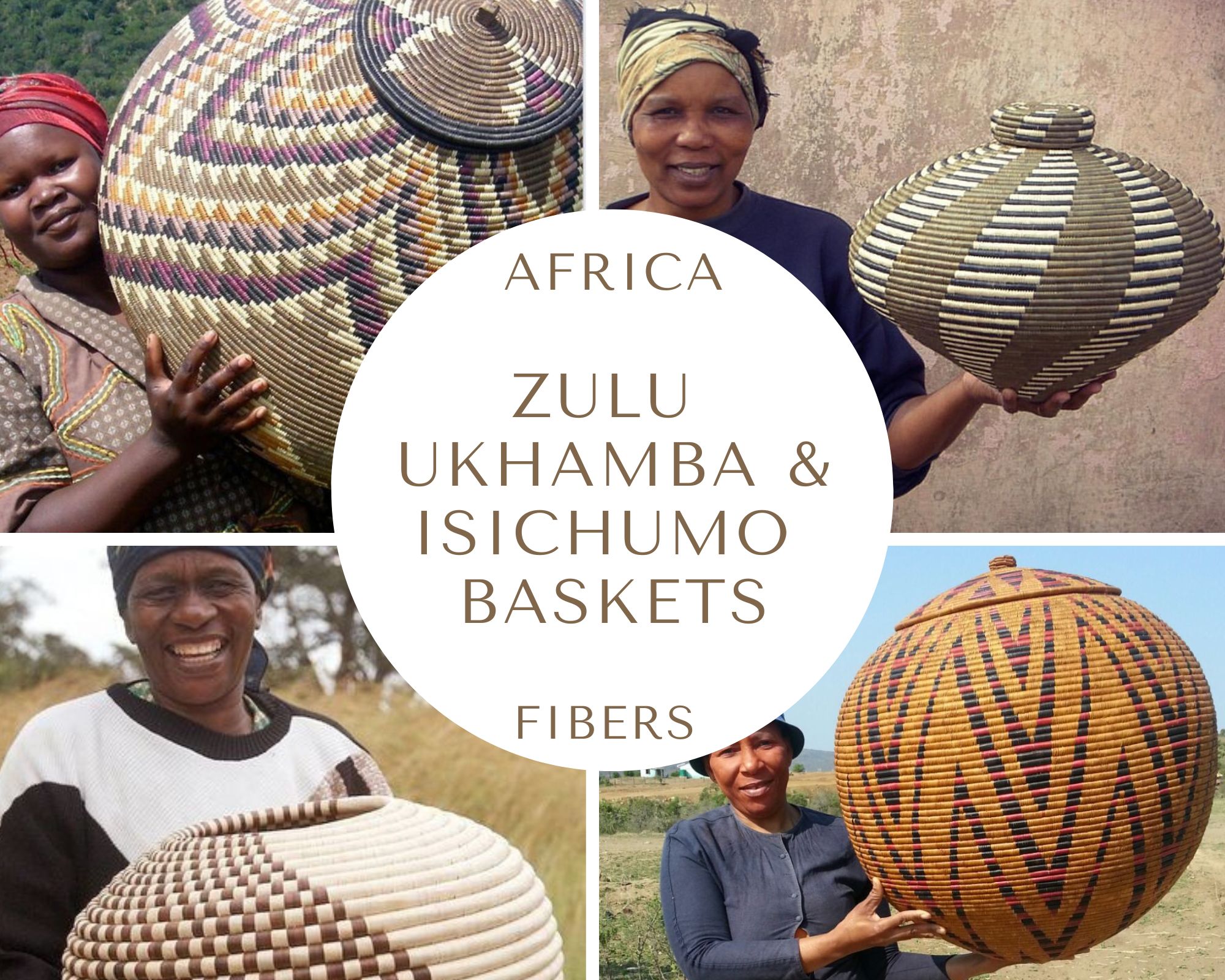

For the Bedouin and Tuareg peoples, the desert is not emptiness but plenitude. An outsider might misinterpret desert life as poverty or deprivation. However, living in the desert reveals the contrary: an abundance of stars, subtle winds, songs of the dunes, strong solidarity, a network of routes, oases, and wells. The desert is not empty; it is dense with human presence, traditions, and adaptations. For the peoples of the Sahara, it has been a setting for codes of hospitality, trade routes, sacred geographies, and oral literatures. Calling it a “cultural space” challenges the Western perspective that often sees the desert as empty. For the Tuareg and other Saharan peoples, the desert is home, network, and memory, not void. The symbols inscribed in jewelry, poetry, and oral tradition arise because of the Sahara, not in spite of it. Philosophically, this makes the Sahara a palimpsest: an apparently blank page that is in fact written over and over by human presence, myth, and resilience.

Tuareg oral tradition is rich with proverbs and sayings that depict the desert as a source of wisdom rather than emptiness. “The desert is our mother; she nourishes and she tests us”is a Tuareg proverb that reflects the ambivalence of the Sahara—harsh yet protective, unforgiving yet sustaining.“In the desert, every stranger is a guest, and every guest is a brother” is the wisdom that underlies the legendary hospitality of the Tuareg, born from necessity but elevated to a code of honor.

Mohamed, Bedouin cameleer, near Ksar Ghilaine, Grand Erg Oriental. Photo by me.

A Tuareg cameleer in the Moroccan Sahara. Photo by Med Rizki Zniber. Under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

A poetic horizon

In literature and art, deserts often serve as metaphors for infinity, exile, purity, and trials. From pre-Islamic Arabic qasidas to Saint-Exupéry’s Wind, Sand and Stars, the desert has been described not as barren, but as a boundless space for the imagination. “The desert is not empty: it is full of tracks and stories”: this is a Tuareg poetic saying that reveals how Tuareg memory inscribes the landscape — routes are history, dunes are archives.

I am the son of the maternal ground

I am the child of eternal pain

I am not the lord of the desert

But the slave of naked horizons

From “Pas de Nom” (“No Name”) by the Tuareg female poet Issa Rhossey

The desert is the motherland of jinn and mystery.

Ibrahim al-Koni, Tuareg novelist

Calling the desert a “poetic horizon” suggests that it writes in lines of dunes, silence, and mirages.

ABOVE AND BELOW: The landscape of Chott el Djerid, in the Tunisian Sahara. Photos by me.

Chott el Djerid is the largest salt pan in the Sahara. In the summer, its surface becomes almost entirely dry due to extremely high temperatures—often above 50 °C—and an annual rainfall of less than 100 mm, resulting in a vast, shimmering, salt-encrusted landscape. When most surface water evaporates during the hot season, the pan transforms into a blinding expanse of white, cracked salt crust that is sometimes tinted brown, green, or purple by minerals and algae. In the fierce summer heat, the intense sunlight and perfectly flat terrain create ideal conditions for optical illusions—especially “fata morgana” mirages. These complex, layered mirages feature distorted, floating images that appear due to the extreme temperature difference between the hot ground and the cooler air above it. Light rays bend as they pass through these varying air layers, causing viewers to see distant objects, pools of “water,” islands, or even inverted and elongated images, which can seem surreal on the shimmering salt flats. These mirages are so common on the surface of Chott el Djerid that travelers and locals alike frequently report seeing lakes, villages, or caravans that disappear upon approach. This magical and disorienting blend of nature and illusion is one reason the location is popular with photographers and filmmakers. It served as the setting for the iconic Star Wars films.

A spiritual journey

Throughout history and across traditions, deserts have been places where prophets have retreated, mystics have fasted, and seekers have confronted themselves. Deserts strip life down to its bare essence, shatter illusions, and offer a merciless reflection of the inescapable truth of your own misery and impotence. The desert journey is not only geographical but initiatory — a passage through emptiness to revelation. From a spiritual point of view, deserts often function as liminal thresholds between worlds, life and death, the profane and the sacred, darkness and light, and desperation (“the Dark Night of the Soul”) and love.

Crossing one’s own desert means confronting the question of identity, stripped of illusions. Crossing the desert means accepting silence, hunger, and darkness as part of spiritual growth. It means enduring disorientation without rushing to fill it with noise. It means walking without guarantees and trusting that a deeper truth lies beyond the horizon. Crossing one’s own desert involves undergoing trials, stripping away illusions, and having encounters. It is to experience Jesus’s wilderness of temptation and John’s mystical night of absence, entering the silence of the Fathers and the abyss of philosophy. Yet, the desert is always a passage, not a finality. The desert teaches us that emptiness can be fullness and absence can be presence. It teaches us that the horizon of sand is also the horizon of the soul. Those who emerge from such a crossing carry a new clarity and a refined self. Often, they also carry a deeper compassion for others who are still wandering.

A barchan (crescent-shaped sand dune) at Ong-Jmel, Grand Erg Orientale. Photo by me.

Across cultures, the desert represents more than just geography; it is an archetype of the human experience. Its vastness evokes infinity; its raucous silence, the absence of familiar voices; and its apparent barrenness, the stripping away of comfort. Entering the desert means stepping into a liminal zone where identity is unmoored and transformation becomes possible.

For the Tuareg, the desert is home, a network of paths and oases. For outsiders—pilgrims, prophets, poets—it has often been a testing ground for the body and spirit. Paradoxically, its emptiness becomes the condition for fullness.

People like the Bedouins and the Tuareg are shaped by an environment of scarcity, mobility, and vast horizons. Their codes of hospitality, their poetry, their music, their architecture of tents and encampments, and even their jewelry and clothing are all adapted to the desert. To truly understand these elements, an outsider must experience the desert itself, with its mumbling silence, extremes of heat and cold, and constant demands on one’s attention and resilience. Books and photographs can describe these things, but they cannot convey how the desert feels—how survival and meaning are intertwined.

The desert is the experience of the desert. From a phenomenological point of view, lived experience is irreplaceable to grasp the being-in-the-world of desert peoples. In other words, you cannot understand desert peoples without first letting the desert speak to you. Only after walking its long distances, feeling the sun burn and nighttime chill, and counting your steps to the rhythm of thirst and trust can you begin to understand what hospitality, poetry, and solidarity mean in lands of scarcity.

Desert peoples have inscribed their wisdom into routes and oases, tents and ornaments, and the cadence of songs and stories. Approaching them without ever tasting their landscape risks missing the key. The desert itself is the grammar of their existence. Yet, even then, desert experience is only a beginning. The dunes open the door, but only those who live among them can guide you further in.

BELOW

A sea of large dunes near Timbaine, Grand Erg Orientale, Tunisia. Photo by me.

Ténéré desert, Niger. Photo by Willemston. Creative Commons.

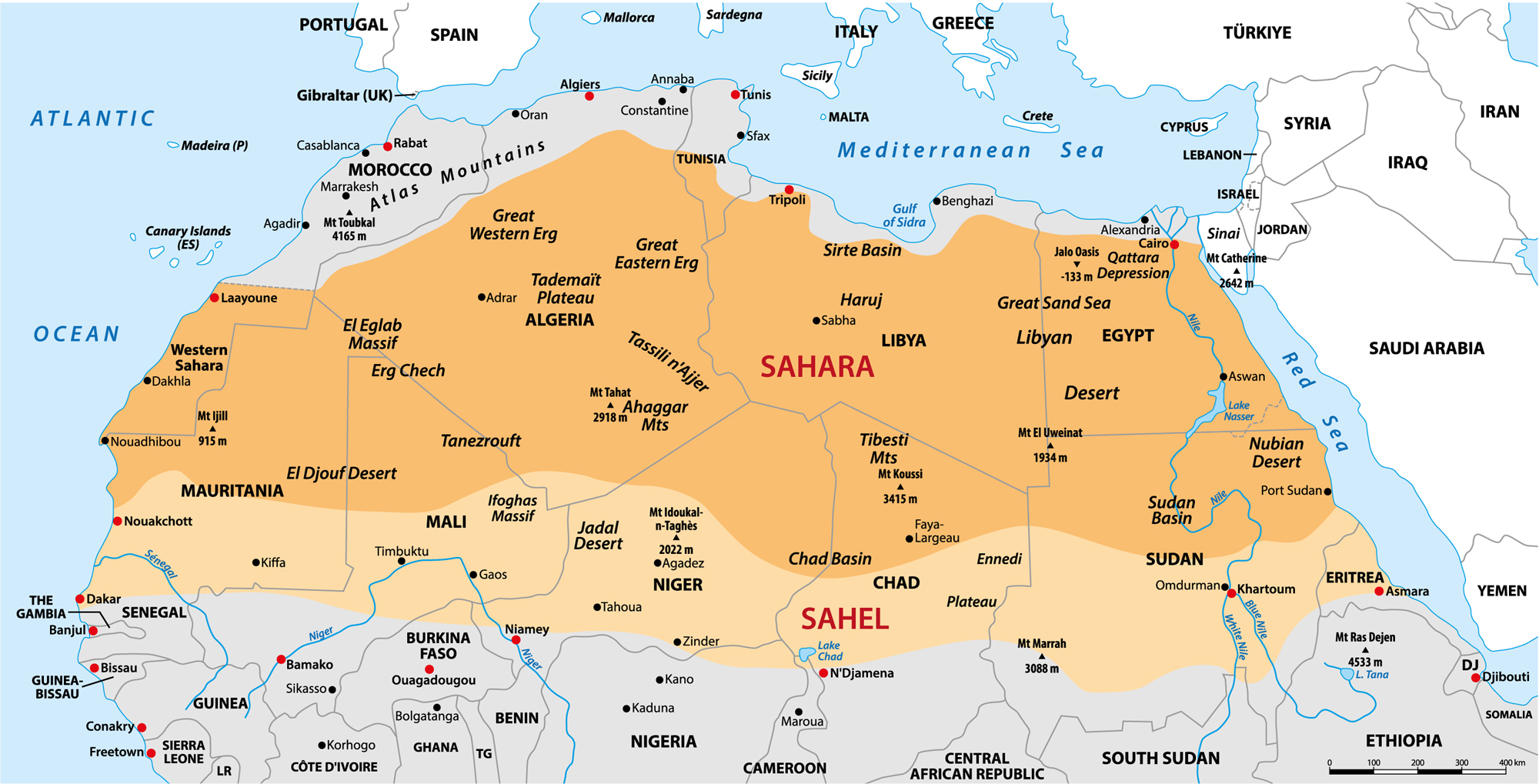

Map of the Sahara desert

THE PEOPLES OF THE DESERT

The Sahara is the world’s largest hot desert. It stretches from the Atlantic Ocean to the Red Sea, spanning more than ten modern states. Its population is diverse and not uniform; different peoples inhabit different ecological zones, such as oases, mountain massifs, desert fringes, and nomadic routes. Anthropologists generally distinguish between groups based on language and culture.

Berbers, Amazigh–speaking peoples

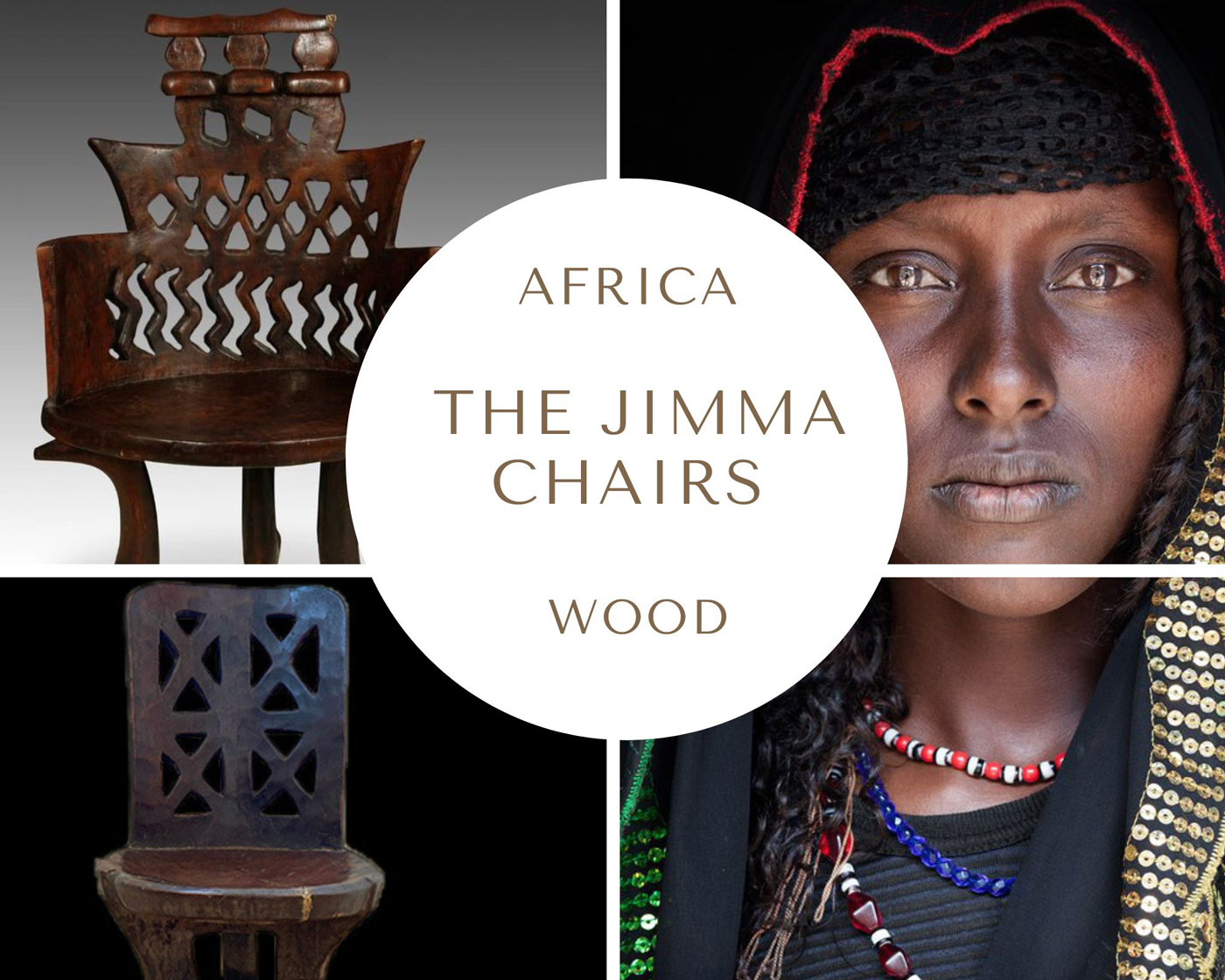

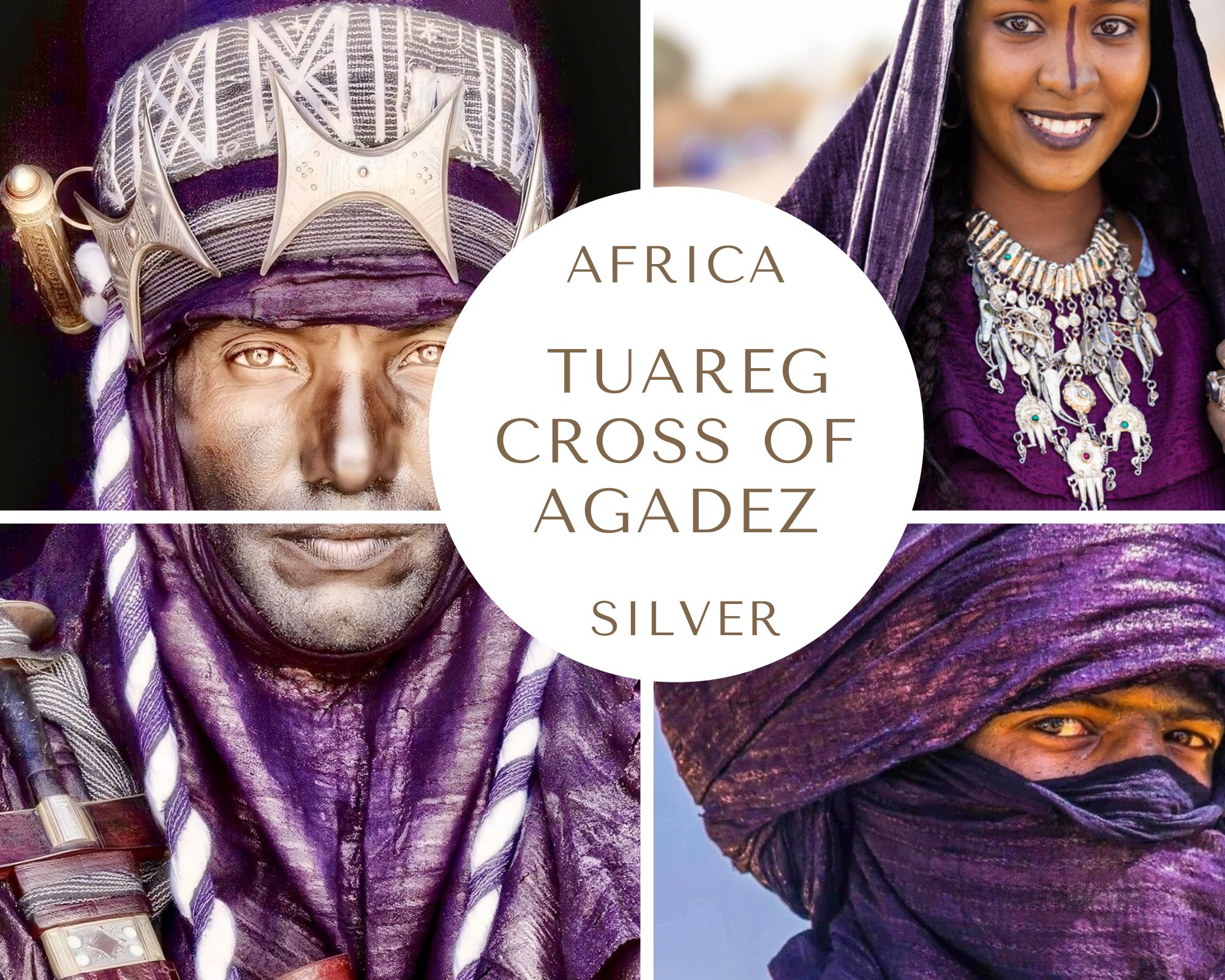

- Tuareg (Kel Tamasheq, Kel Air, Kel Adrar, etc.) → Nomadic-pastoralist groups across Niger, Mali, Algeria, Libya, Burkina Faso. Known for camel caravans, silverwork, and indigo-dyed veils.

- Zenaga (Senhaja) Berbers → In Mauritania and southern Morocco, formerly powerful nomadic confederations, now largely Arabized but retaining some Berber identity.

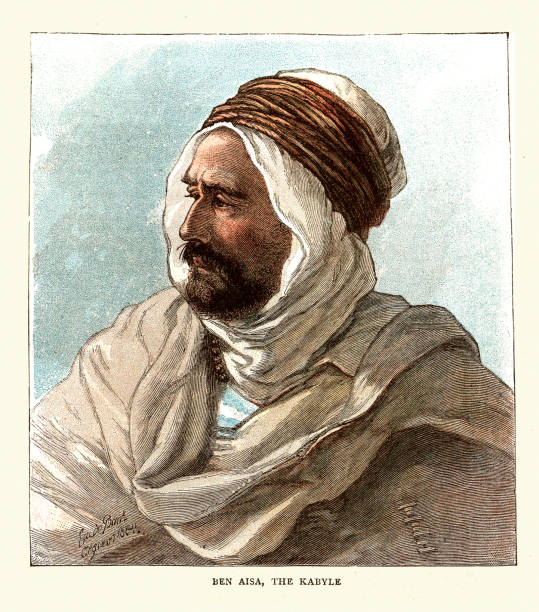

- Mozabite, Kabyle, Chaouia (northern fringes) → While mostly settled, parts of their history are tied to Saharan oases and trade.

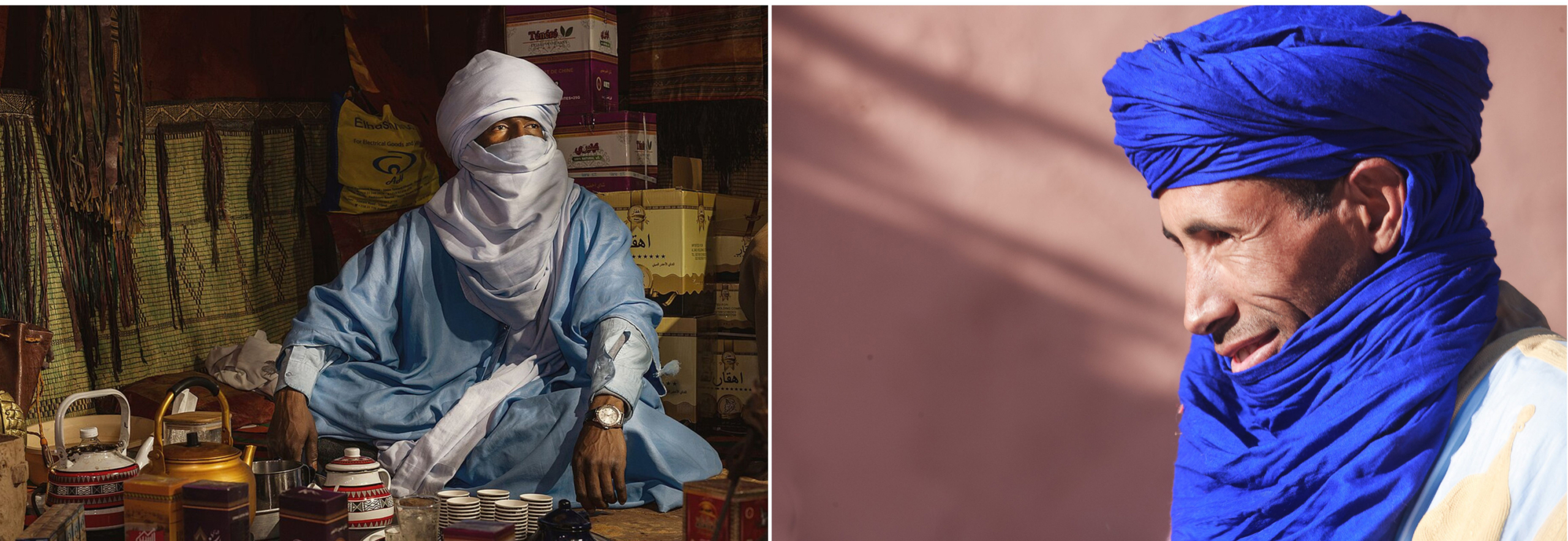

LEFT: A Tuareg in Libya. Photo by Mohamed Alazrak, under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

RIGHT: A Tuareg guide in Telouet, Morocco. Photo by Andrew Macpherson, under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.

Portrait of Ali Ben Aïssa, an Algerian commander, born to a family of Kabyles from the Berber tribe of Beni Fergan. Watercolor by Guido Bach, Victorian, 1885.

A Vava Inouva is a famous lullaby composed by Idir (born Hamid Cheriet) and Ben Mohamed (born Mohamed Benhamadouche). Idir is considered one of the most influential Berber (Amazigh) musicians of the modern era and a symbol of cultural resistance for indigenous North Africans. He began his career singing in the Kabyle language (Tamazight) and brought global attention to Berber music with this iconic lullaby.

Arab Bedouin groups

- Beni Hassan (Moorish/Arabic-speaking tribes) → Mauritania, Western Sahara, parts of Morocco.

- Awlad Ali, Awlad Sulaim, and others → Tunisian, Libyan and Egyptian Sahara, Bedouin pastoralist traditions.

- Many Arab tribes spread into oasis regions, intermingling with Berber populations.

Arab Bedouins, Grand Erg Orientale, Tunisia. Photos by me.

Hassaniya-speaking Moors and other peoples

In Mauritania, Western Sahara, southern Morocco → a fusion of Arab, Berber, and sub-Saharan lineages, forming Moorish society, stratified into warrior, marabout, artisan, and servile groups.

The Sahrawis are an indigenous people of the Western Sahara region whose identity blends Berber, Arab, and sub-Saharan African roots. They have traditionally led nomadic lives as herders and traders, moving across the desert and forming tight-knit tribal networks that trace their ancestry to local Berber confederations and Arab migrants. Over the centuries, the Sahrawis have developed a unique culture, marked by their use of the Hassaniya Arabic dialect, their resistance to foreign domination, and their persistence in maintaining autonomy despite colonization and ongoing territorial conflicts.

Saharan oases peoples

- Oasis Berbers (Siwa in Egypt, Ghadames, Awjila, and others in Libya) with their own Berber dialects.

- Tebu (Teda–Daza) → In Tibesti mountains (Chad, Libya, Niger); agro-pastoralists and traders.

- Zaghawa → Chad and Sudan, Sahel-Sahara interface.

- Kanuri-related groups → Southeastern Sahara, linked to Lake Chad basin.

Nubian-related groups

On the Nile’s edge in northern Sudan and southern Egypt, populations like the Nubians are culturally part of the desert’s margins.

Black African Sahelian groups with Saharan extensions

Though their heartland is Sahel, their history and trade networks penetrate deep into the Sahara:

- Songhai, Hausa, Fulani (Peul), Mandé groups who maintained trans-Saharan caravan links.

- Tubu (mentioned above) form an ethnic bridge between Sahara and Sahel.

Others

- Jews of the Sahara oases → historically important in Tuat, Tafilalt, and other Moroccan oases until the mid-20th century.

- European traders and settlers → during colonial times, small enclaves in Algeria, Libya, etc.

In short, the Sahara is inhabited by a variety of peoples, including Berber-speaking Tuareg and oasis Berbers, Arab Bedouins, Moors, Tebu, Zaghawa, Kanuri, and Sahel-related groups. Each group has distinct adaptations to desert life, such as nomadism, oasis agriculture, and caravan trade. The Sahara is not an “empty sea of sand dunes,” but rather a cultural crossroads between North Africa and the Sahel.

Etran Finatawa – Tekana

Etran Finatawa is a pioneering band from Niger formed in 2004. The band is distinguished by its unique blend of Tuareg and Wodaabe, or Peul Bororo, musicians. The Peul Bororo are a nomadic subgroup of the larger Fulani ethnic group living in the Sahel region of West and Central Africa. The group’s name means “the stars of tradition,” and their mission is to express and unite the two major nomadic cultures of the Sahel through music.

The band unites musicians from two historically rival groups who share a similar nomadic pastoralist way of life in Niger and the wider Sahel region. The band’s lineup typically features Tuareg and Wodaabe members who contribute distinct singing and instrumentation styles, creating a hybrid sound recognized internationally as “nomad blues.” The band creates a hypnotic, percussive blend, fusing traditional Wodaabe polyphonic vocals and rhythms with Tuareg guitar-driven desert blues. Their lyrics, sung in Tamashek (Tuareg) and Fulfulde (Wodaabe), explore themes such as nomadic life, traditions, environmental hardships, family, and the struggle to preserve endangered cultural identities. Widely regarded as cultural ambassadors, their songs are sung across Niger, and they have toured five continents.

Desert Crossroads is Etran Finatawa’s second album, released in 2008. On this record, the band further explores Sahelian nomad culture by continuing to blend Tuareg electric guitar, Wodaabe vocal harmonies, and rhythmic calabash percussion.

LEFT: A Tuareg man in the in the Moroccan Sahara.

CENTER: A Tunisian Bedouin in the Grand Erg Oriental. Unfortunately, I don’t remember his name, but I do remember that he knew the desert like the back of his hand. Even when he had a tent available, he preferred to sleep under the stars. Photo by me.

RIGHT: Atàllah, member of the Bedouin tribe of Zalàbia, Wadi Rum desert, Jordan. Photo by me.

The inhabitants of the Sahara and Arabian deserts traditionally wrap their heads and faces in long scarves that provide protection from the wind, sand, and sun and serve as markers of cultural identity.

Tuareg men are famous for wearing the indigo-dyed tagelmust, also known as the litham. This garment is a combination turban and veil that often measures 4–10 meters (approximately 5–11 yards) in length. It covers the head and wraps around the face several times, draping down to shield the neck and shoulders from harsh sunlight, sandstorms, dust, wind, and heat. The indigo dye can stain the skin, earning Tuareg men the nickname “blue men of the desert.”

The turban also has social and symbolic significance. The Tuareg often refer to themselves as Kel Tamacheq (“those who speak Tamacheq”) or Kel Tagelmust, which literally means “people of the veil/turban.”

Traditionally, only men wear the tagelmust. Boys begin wearing it at puberty as a rite of passage and a sign of manhood. It is worn in the presence of strangers and elders, especially those from the wife’s family. It is improper for a man to appear “unveiled” in such circumstances; showing both his mouth and nose to elders or strangers is considered shameful and disrespectful. The tagelmust is only removed in front of very close family members. Even when eating in front of strangers, the lower flap of the turban may be used. Among younger generations, however, the traditional strictness is less rigid. Younger people use more flexible colors and looser wrapping and sometimes do not cover their mouths completely.

Lastly, the way the tagelmust is wrapped, the folds, and the color can signal one’s lineage, region, and possibly wealth.

North African Bedouins use a similar long plain cotton headscarf generally in white, beige, or black cotton, called a shesh or cheche. It is generally 5 meters long. Worn mainly for protection against wind, sand, and heat, it is wrapped around the head and face. It is practical and multifunctional; it can be rewrapped depending on the conditions or used as a basic bag. Though less codified than the Tuareg’s indigo veil, the shesh remains a symbol of Bedouin identity, distinguishing them from townspeople and farmers.

Arabian and Levantine Bedouins from regions such as Wadi Rum, Najd, Hijaz, the Negev, and the Sinai wear headscarves called keffiyehs, ghutras, or shemaghs. They are usually square cotton cloths with a side length of one meter that are folded into triangles. The patterns vary by region and identity. A plain white headscarf is usually called a ghutra, while a checkered one is called a keffiyeh or shemagh. The latter shows a color scheme — red and white, black and white, etc. — according to region, tribal affiliation, or political identity. In some contexts, the pattern or how it is worn may suggest fashion, rank, or allegiance. Bedouins in the Arabian Peninsula wear the ghutra with an agal, a black cord used to secure the ghutra in place. The climate in these regions is less harsh than in the central Sahara, so face coverage is much less necessary. Thus, you rarely see a man with a full facial wrap.

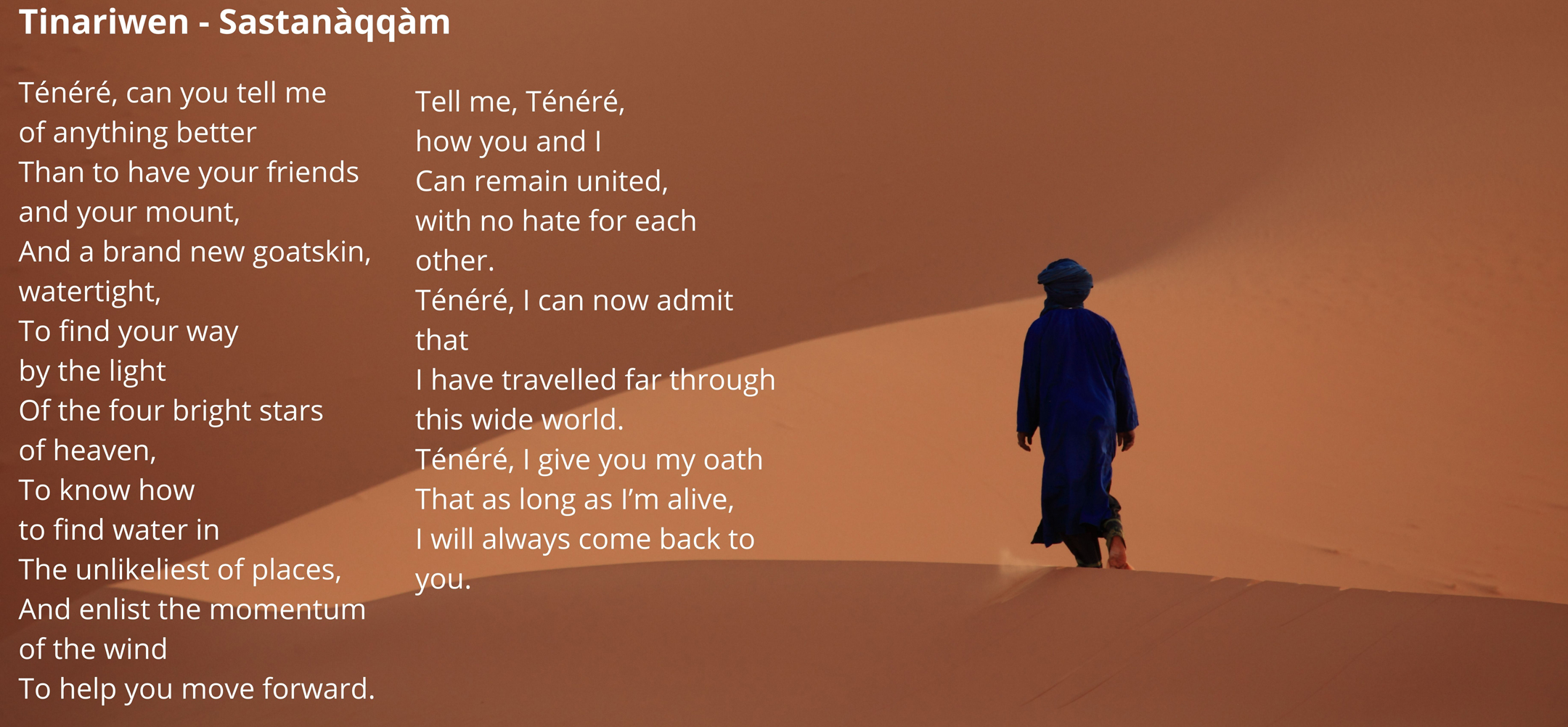

Tinariwen – Sastanàqqàm

Tinariwen is an iconic collective of Tuareg musicians from the Sahara, renowned for creating the genre known as “desert blues” by blending traditional Tuareg music and poetry with Western rock.

TWO NAMES, TWO PHILOSOPHIES OF SPACE

A Tuareg vs. Bedouin Semiotics of the Desert

Desert peoples use two names to refer to the desert: ténéré / tiniri and ṣaḥrāʾ / bādiyah. Although we say “Ténéré Desert” and “Sahara Desert,” ténéré and ṣaḥrāʾ are not proper or place names.

- Ténéré (Tamacheq): the desert as the emerging property of a relationship

Ténéré is a Tamacheq word belonging to the Tuareg branch of the Berber (Amazigh) languages. It is not a neutral toponym, but rather a verbal noun built on the Berber root √TNR. In Proto-Berber, this root carried the sense of “to be in front of, to face, or to lie open”.

Ethnolinguistic work by Karl-G. Prasse and Hélène Claudot-Hawad shows that in modern Tamacheq, the root has evolved into:

- ténéré – the physical desert, the open expanse;

- ténert – the act of facing a difficulty;

- atinar – to expose oneself to the unknown.

The cognate philosophical term is essuf (“the wild, solitude”), designating the space outside the camp where jinn and poets wander. Essuf is ténéré interiorized: the moment when the expanse is no longer out there but in here—a somatic vibration of aloneness.

Every time a speaker utters “ténéré“, they are not labeling an empty quarter, but rather indexing a reciprocal relationship. The human body is positioned in front of an agency that returns the gaze.

Therefore, space is dialogical rather than Cartesian; it emerges between two facing presences. Hélène Claudot-Hawad (1996: 45) writes that the Tuareg concept of “territory” is a territoire-chemin (a territory-path), a land that becomes habitable only when interwoven with remembered itineraries. Rasmussen’s interlocutors summarize the semantics succinctly: “Ténéré is the desert that looks at you; essuf is the desert you swallow.”

- Ṣaḥrāʾ (Arabic): the color that erases people

The Arabic word ṣaḥrāʾ (صَحْرَاء ) comes from the root √ṢḤR, a versatile morpheme across the Semitic spectrum. Ṣaḥrāʾ is a color adjective turned noun. Medieval lexica (Lisān al-ʿArab, Tāj al-ʿArūs) define the earliest and most concrete meaning of the root as the “yellowish-red color of a camel’s coat after the summer molt,” a definition firmly rooted in Bedouin ethnography and pre-Islamic poetic language. Thus, the Bedouin imaginary begins not with abstract space, but with chromatic saturation: a surface so intensely colored that it cancels both vegetation and genealogy. The broken plural ṣaḥārā (classically diptotic) denotes an accumulation of such surfaces—an excess that overwhelms.

Philological studies by Michael C. A. Macdonald and Clive Holes show that, in pre-Islamic and early Islamic poetry, ṣaḥrāʾ typically colligates with verbs of effacement.

- ṭamasa – “to blot out footprints”;

- mahā – “to erase the ink of tribal memory”;

- daʿā – “to lose the way so completely that even the guiding stars quarrel”.

Thus, the Bedouin desert is semiotically subtractive; it removes traces of human passage, leaving only the ālam (the absolute sign of God) visible. Color becomes theology: the reddish-yellow sand is a palimpsest perpetually scraped clean by the wind, teaching the moral lesson of fanāʾ (self-annihilation in the presence of the divine).

- Caravan itineraries: two philosophies on the move

Ethnographies of salt caravans (Bernus 1981; Claudot-Hawad 1996) reveal how each lexicon shapes bodily practices.

Tuareg caravans leave the well at essuf—the last palm tree—only after the chief has intoned an asermu invocation, naming key ancestors who once crossed that point. The caravan enters the ténéré as if it were a mirror; the men cover their mouths with the tagelmust, an act that is sometimes explained as preventing their breath from alarming the desert that looks back.

Bedouin caravans, after a hazardous passage, may halt at a nāqah-shaped dune and sweep away the final footprints with a branch. The guide then recites: “May God blot out our tracks as He blots out our sins.” The walk becomes a via negativa; each effaced footprint is a syllable in the discourse of self-annihilation.

- Conclusion: two etymologies, two ontologies

The Tuareg root √TNR generates a horizon of reciprocity: space is constituted by facing gazes.

The Arabic root √ṢḤR generates a horizon of erasure: space is the color that cancels out the human so that the divine may appear.

Both deserts are immense, but their immensity is incommensurable. One is an expanse that absorbs; the other, a surface that erases. Forgetting this semantic depth turns the Sahara into a blank canvas for colonial cartography. Remembering it recognizes that every dune is a philosophy lecture written in sand.

Tikoubaouine – Tiniri (Where Nomads Live)

Tikoubaouine is a contemporary Algerian Tuareg music group formed in 2013 in Salah, southern Algeria, by musicians born to nomadic parents from the Adrar and In Salah regions. The band is renowned for blending traditional Saharan and Tuareg musical elements—particularly desert blues, world music, and folk—with modern influences like electric guitar, rock, reggae, and pop.

Tinariwen – TENERE TAQQIM TOSSAM

The desert is mine

Tenere, my homeland,

We come to you when the sun goes down

Leaving a trail of blood across the sky

Which the black night wipes out

The desert is hot and its water hard to find

Water is life and soul

To all my brothers I say, the desert is jealous!

O Tenere! A jealous desert!

Why can‘t you see? You are a treasure

I‘ve seen the world, I love you better

Oh Tenere! You are the treasure of my soul.

I cry out to God on High

To bring my people together

In unity.

THE DESERT AS TUAREG COSMOS

Asking what the desert means to the Tuareg peoples draws you into a conversation with no beginning, as the word they use for the Sahara is not a label, but a sentence. When a Tamacheq speaker pronounces “ténéré,” their mouth opens onto a root older than the dunes: √TNR. This root carries the sense of “to face, to lie open, to be stood before.” The expanse that rises to meet the traveler is therefore not an empty quarter; it is a presence that returns the gaze. Ethnographers who have traveled with the Kel Ewey or Kel Aïr caravans assert that no one enters that openness without already being anticipated by it. The wind has been asked for permission, the well has been greeted by name, and the ancestral itinerary has been recited like a map that precedes the terrain it describes. In this grammar, space is never a container. It is a relationship that must be renewed each season—a dialogue whose terms are camels, pasture, salt, water, and the slow accretion of stories.

Yet, as we saw, the desert is also carried inward. The word essuf designates the wild beyond the campfire, but it easily seeps into the soul. Linguists trace essuf to the root √YSF, meaning “to be pure or empty,” yet in spoken language, it represents the interior side of ténéré: the moment when the expanse becomes internalized, creating a vibration of aloneness that can tip into either vertigo or poetry. Elders warn that too much essuf can lead to madness, while healers prescribe measured doses of it—such as an hour on the dune crest or a night watch without speech—as the only surefire way to remember one’s name. Thus, the Tuareg life course is shaped by a double oscillation: outward into the facing expanse and inward into the swallowed wild. Personhood is the craft of keeping those two movements in counterpoise, like the ropes of a tent that hold each other upright by pulling against the same wind.

Cardinal ethics: a moral topography

In this negotiation, cardinal directions are not neutral coordinates; they are moral arguments spoken by the sun.

East, Tederart, is where light is born and the Takoba sword is unsheathed. Masculine honor is measured by one’s ability to walk toward that dawn without casting a shadow of betrayal.

West, Aghlal, is the swallowed sun, the direction of graves, and the side where women sit to sing lullabies that soften the harshness of the just-ended day.

North tilts toward the Hoggar plateau, a reservoir of ancestral purity.

The south descends toward the Sahel, where cattle acquired through matrilineal lines graze, and where wives are sought from populations with darker skin who once supplied the salt mines with labor.

Therefore, a caravan does not simply cross space; it reenacts cosmogony, reweaving virtue into the earth’s fabric with every camel step. Traveling is remembering, and remembering is traveling in the correct direction.

Every caravan re-enacts cosmogony: to move is to re-territorialise virtue (Claudot-Hawad 1996: 92).

This topography is learned early on, not from maps, but from the sand itself. Children who can barely balance on a horseback are taught to distinguish thirty kinds of grain by color, sound, and how they feel underfoot. Adolescent girls learn to read the flowering sequence of tussur grasses on north-facing slopes and predict pasture three weeks ahead. When Susan Rasmussen asked an elder why such knowledge endures alongside GPS devices, he replied that the machine tells you where you are, whereas the dune tells you who you are. This statement is not romantic, but epistemological. The desert is a text that talks back, and illiteracy is measured not by letters missed, but by silences misheard.

Aesthetics of austerity: when scarcity is plenitude

Austerity is the aesthetic corollary of this dialogue. Since every object must justify its weight, plenitude is achieved through subtraction. Each piece is chosen so that its material memory outweighs its mass: a single wooden tent pole, a palm-fiber mat, or a silver cross inherited from parents to children. The indigo veil, which is dyed until the dye stains the wearer’s skin, literally incorporates the landscape into the body. The wearer becomes a walking fragment of the horizon. Silver jewelry, often misread as ornamentation, serves as portable title; the engraved motifs are cadastral mnemonics of wells, salt pits, and clan alliances. Even the tindi mortar drum is carved from the root of a tamarind tree that grows against the prevailing wind. When women strike it during trance ceremonies, the instrument releases the voice of resistance itself. Scarcity, far from impoverishing meaning, forces density into every gram.

Water, grammar of social life

Water transforms this aesthetic into ethics. The proverb aman iman—meaning “water is life/soul”—is not a slogan, but a syntax. The camp layout mirrors hydrology: the women’s tent faces the well; the guest area is downstream; and the tea hearth occupies the precise angle where the wind will not scatter the embers into the trough. The tea ritual itself—three infusions, from bitter to sweet—mirrors the ideal rhythm of travel: the first cup awakens the palate, the second eases the midday hardship, and the third offers the promise of sweetness upon return. Disputes over wells are settled by reciting genealogies in reverse; the shorter lineage wins, embedding equity within scarcity. Thus, the desert teaches us that generosity is not the opposite of scarcity, but rather a consequence of it, provided that memory lasts longer than thirst.

The Tuareg don’t just make tea; they negotiate with it.

What appears to be a simple pause for refreshment is actually a slow-motion negotiation with time, solitude, and the limits of hospitality. The ritual unfolds in three acts that are always the same yet always different because the tea leaves are the same, but the company is new.

The kettle refuses to hurry.

A small, blue, enamel pot, dented by a thousand fires, sits directly on glowing charcoal. While the water warms, the host—usually the eldest man present—holds his palms open as if to warm them on the idea of heat rather than the coals themselves. Conversation drifts. No one watches the pot, yet everyone keeps it in their peripheral vision. The first lesson is proclaimed without words: haste is a form of violence in the desert.

The first glass is wan-iyen, bitter as life.

A fistful of Chinese gunpowder tea is rinsed, then boiled vigorously. The resulting liquid is the color of a thunderhead and tastes like the initial shock of adulthood. It is poured from shoulder height, forming a thin, amber arc that aerates and cools simultaneously, producing a trembling foam that the Tuareg call “the veil of respect.” Only a mouthful is served. Guests slurp audibly, not from rudeness, but to draw air across their tongues and let the bitterness bloom into alertness. Travellers are told that this cup “belongs to men who smoke cigarettes”—a joking way of saying it is meant to wake the senses and cleanse the palate of sleep and complaint alike.

The second glass is wan-ashin, strong as love.

More water is added to the same leaves, plus a shocking quantity of sugar—often five cubes for every spoonful of tea. The pot is returned to the fire, and the acrobatic pouring resumes. This time, it is higher and slower so that the stream sings against the tin. The resulting liquor is syrupy and the color of polished cedar. The flavor softens and sweetness arrives, but the tannic spine remains intact. This is the glass of courtship and contract. Marriages are negotiated over it. Salt slabs are exchanged. Routes for the next caravan are agreed upon. Etiquette demands that each guest drink three small sips—no more, no less—before passing the glass on so that the sweetness circulates the group like a shared secret.

The third glass is wan-karad, as gentle as the end. The end of travel, the end of life.

A final drench of water loosens the last bit of strength from the exhausted leaves. The tea is now pale and almost translucent, scented more by mint than tannin. It is poured with exaggerated languor; the pot is held so high that the stream becomes a silver thread weaving foam that floats like a cloud above the rim. This is the cup of parting, sipped slowly while the sun slips toward the dunes. The Tuareg hosts say it tastes “like the moment when the soul loosens its grip on the body”—not sad, just soft, a sweetness that does not startle. To refuse this last round is to refuse friendship. To drink it is to accept that every arrival carries within it the seed of departure.

Time, foam, and the ethics of waiting.

Between each round, the pot is returned to the embers, and the conversation wanders into stories of past journeys, wells that have turned salty, and loves that arrived on camelback and left on foot. The pause is not an intermission; it is part of the drama. The foam must be coaxed anew each time because it proves that patience has been exercised and that the host has not hurried his guest toward solitude. A proverb sums up this obligation: “Charcoal, company, and letting time pass—without these, the tea is only hot water.”

It is a choreography of social life.

In other Sahelian cultures, women may roast the coffee, but the Tuareg tea fire is tended by men, often the youngest adult son, who is still light enough to climb the acacia tree for dead branches. This task teaches him the tempo of generosity: how to hold the glass so the guest can see the foam, how to pour high without splashing, and how to judge when the conversation has ripened enough to warrant the next dilution. Thus, the ritual serves as a mobile university where boys learn that authority is not measured by the volume of one’s voice, but rather by the steadiness of one’s wrist above a steaming pot.

The desert in a glass.

By the time the third cup is empty, the sun has usually shifted, and the sand that burned fingertips earlier now lies in long shadows. The leaves, thrice exhausted, are flicked onto the coals, where they hiss and vanish, releasing one last wisp of tannic smoke. What remains is not taste, but tempo. The heart has slowed to match the camel’s pace; the eye has learned to measure distance by the color of heat. The guest rises, brushes sand from his robe, and knows—without needing to be told—that he has been granted provisional citizenship in a country whose borders are defined by patience and whose flag is a trembling layer of foam.

The Tuareg say, “Drink three cups, and you will be welcomed back any time.”

Drink only one, and the desert will remember you as unfinished business—a sentence whose final sweetness was never uttered.

Tinariwen – ISWEGH ATTAY

Political cosmology: borders as sacrilege

Yet, the same expanse can be ruptured. When colonial cartographers partitioned the Sahara into five nation-states, they did more than draw lines. They drove nails into what Tuareg rebels in 2012 called “the dune’s heart,” preventing the land from breathing. Frontier posts in Tessalit and Aguel’hoc are not merely experienced as political irritants, but also as cosmic wounds that cut off the flow of caravans, jinn paths, and smuggling lanes. Contemporary rebellions are therefore framed less as secession and more as healing rituals aimed at restoring the desert’s integrity. Uranium and oil enclaves—mahrouqa, or “the burned”—are anti-deserts: fenced, floodlit, and extracted spaces where essuf is banished, making them morally toxic. Staying with the ténéré becomes, by default, a critique of a world that converts land into property and time into labor.

Modern entailments: diaspora, heritage, market

This critique has followed the Tuareg even into exile. In Bamako apartments or Parisian studios, diaspora families play desert soundscapes at night—wind recordings, camel bells, and the hiss of sand against canvas—to recreate essuf within concrete solitude. Jewelry that once crossed the Sahara on camelback now circulates on Instagram. Yet, artisans geotag each piece with the coordinates of the well where the silver was melted, turning the commodity back into an itinerary. UNESCO lists the tea ritual as Intangible Heritage, but elders complain that the drum is now beaten faster than camels walk and that the third cup is often poured before the second has cooled. Like the desert itself, heritage must be experienced to remain meaningful; when it is only displayed, it becomes a mirage.

Conclusion: remaining porous to sand

Therefore, to be Tuareg is to inhabit porosity: indigo in the pores, dust in the lungs, and ténéré in the grammar of every sentence. The desert is not a symbol that one speaks about; rather, it is an interlocutor that speaks through wind patterns, tea foam, and the granular hiss that accompanies every dawn. The most faithful gesture of ethnography is not to explain, but rather to sit on the crest of a dune with open palms, letting the grains—and the stories they carry—pass through without settling. Only then does the expanse continue to face the traveler, and only then does the traveler remain worthy of it.

Have you ever sat around a fire at night in the middle of the desert?

The first time I did was in the Sahara with Bedouins. I remember it perfectly—how could I forget?

At a certain point, this ancestral gesture, performed by our progenitors for nearly a million years, suddenly resonated within me. It was as if the glow of the fire had been imprinted on my eyes, the scent woven into my sense of smell, and the warmth embedded in every fiber of my being.

My mind became peaceful.

I didn’t think.

I simply felt millennia of prehistory within myself.

For Tuareg and Bedouin peoples, sitting around the bonfire at night is far from a coincidence; it is a deeply rooted cultural and social practice with significant symbolic meaning. The bonfire is central to nightly gatherings where oral traditions—including tales, legends, poetry, and music—are shared. These gatherings help strengthen cultural identity and foster bonds within the group.

For the Tuareg, the fire is at the heart of evening assemblies where elders recount ancestral stories and legends, sharing values such as bravery, solidarity, and wisdom that are essential for life in the Sahara. These nighttime gatherings around the fire are critical for transmitting knowledge, connecting the present to the past, and reinforcing a sense of community and cultural continuity. Of course, tea is also an important part of these gatherings. The presence of the fire under the desert stars connects people to nature, the cosmos, and spiritual beliefs—a reminder of the environment’s power and the community’s resilience.

Among the Bedouin, the communal fire is central to hospitality, meal preparation, tea preparation, and social rituals. Meals are often prepared and shared around the fire, making it a focal point where people come together, strengthen friendships, and reaffirm community ties. In Bedouin tradition, the fire represents the spirit of generosity, protection, and welcome.

While the bonfire offers practical benefits, such as light, warmth, safety from animals, and a place to cook, it is also seen as a sacred symbol and a gathering place for the spirit as well as the body. It embodies unity, hospitality, knowledge transmission, and connection to ancestral roots for the Tuareg and Bedouin peoples. In short, nightly gatherings around the fire serve as an essential mechanism for desert tribes to define authority, transmit rules, and integrate individuals into the social fabric of the community.

Tissilawen – AMIDININE

Tissilawen is a contemporary Tuareg music group from Djanet, in Algeria’s Sahara, known for their “desert blues” style that blends Tuareg tradition with global musical influences. The band emerged from the Tassili n’Ajjer region and formed in 2008, aiming to preserve and modernize Tuareg cultural expression while reaching a wider international audience.

A Bedouin checks on bread baking under hot ashes in the Great Eastern Erg. Photo by me.

Tuaregs and Bedouins traditionally bake a flatbread directly under hot ashes and sand in the desert. The Tuareg bread is called taguella (sometimes spelled tadjela or tagela), and is a Tuareg culinary staple. The dough, usually made from wheat, semolina, or millet, is shaped into a thick disc and buried in the embers, ashes, and sand of a small fire. It is cooked until done. Once cooked, the bread is cleaned of sand and ash and typically broken into pieces. It is then served with sauce or stew and often forms the centerpiece of a communal meal. This method is similar to the Bedouin technique for making arbood or abud bread. With this technique, a simple wheat dough is buried in the ashes and embers of a campfire and eaten with tea, ghee, or alongside meals. These traditions developed as adaptations to nomadic desert life, requiring no special oven or pan—just a fire and hot ashes.

Hamida Ag Fano, ft. Mani Boulabi – ABRIDITRAN

Tuareg artist from the Kidal region, Hamida Ag Fano draws his inspiration from the vast expanses of the desert. Through his music, he expresses the joys and struggles of his people, giving a vibrant voice to the traditions and realities of the Sahara.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?