THE TSUBA THE KATANA AND THE SAMURAI SOUL PART 3

SEPPUKU

Seppuku, or, as Westerners often say, hara-kiri (a word seldom used in Japan), is the samurai ritual suicide by disembowelment or by cutting the belly in the hara (the vital source of the enhanced ki and the kiai, as we have seen before) and exposing the innards (the deepest ura).

This is a quite complex issue, and it would be better for you to set aside all that you know on this matter. So, clear your mind, and let’s consider the results of the historical research on seppuku before and after the Edo Period.

Before the Edo Period-Tokugawa Shogunate

«That there have been Japanese men who committed suicide by cutting their stomachs cannot reasonably be doubted, though the practice has not been as widespread and frequent as popular literature suggests» (A. Rankin, Seppuku, see Bibliography); moreover «pre-Tokugawa-era samurai did not disembowel themselves often» (M. Wert, cit.).

«Although imperial histories of the tenth and eleventh centuries recount suicides of various sorts – hanging, drowning, self-strangulation, throat-cutting – no other references to stomach-cutting have been found in early Japanese texts» (A. Rankin, cit.).

The first notable cut-belling suicides were carried out by Minamoto Tametomo and Minamoto Yorimasa in the latter part of the 12th century.

Minamoto no Tametomo (1139 –1170) fought in the Hōgen Rebellion of 1156 against the Emperor and defeated, chose to kill himself by tearing his own abdomen. Minamoto no Yorimasa (1106–1180) led the Minamoto armies against the Taira clan at the beginning of the Genpei War; defeated, committed suicide in the very same way.

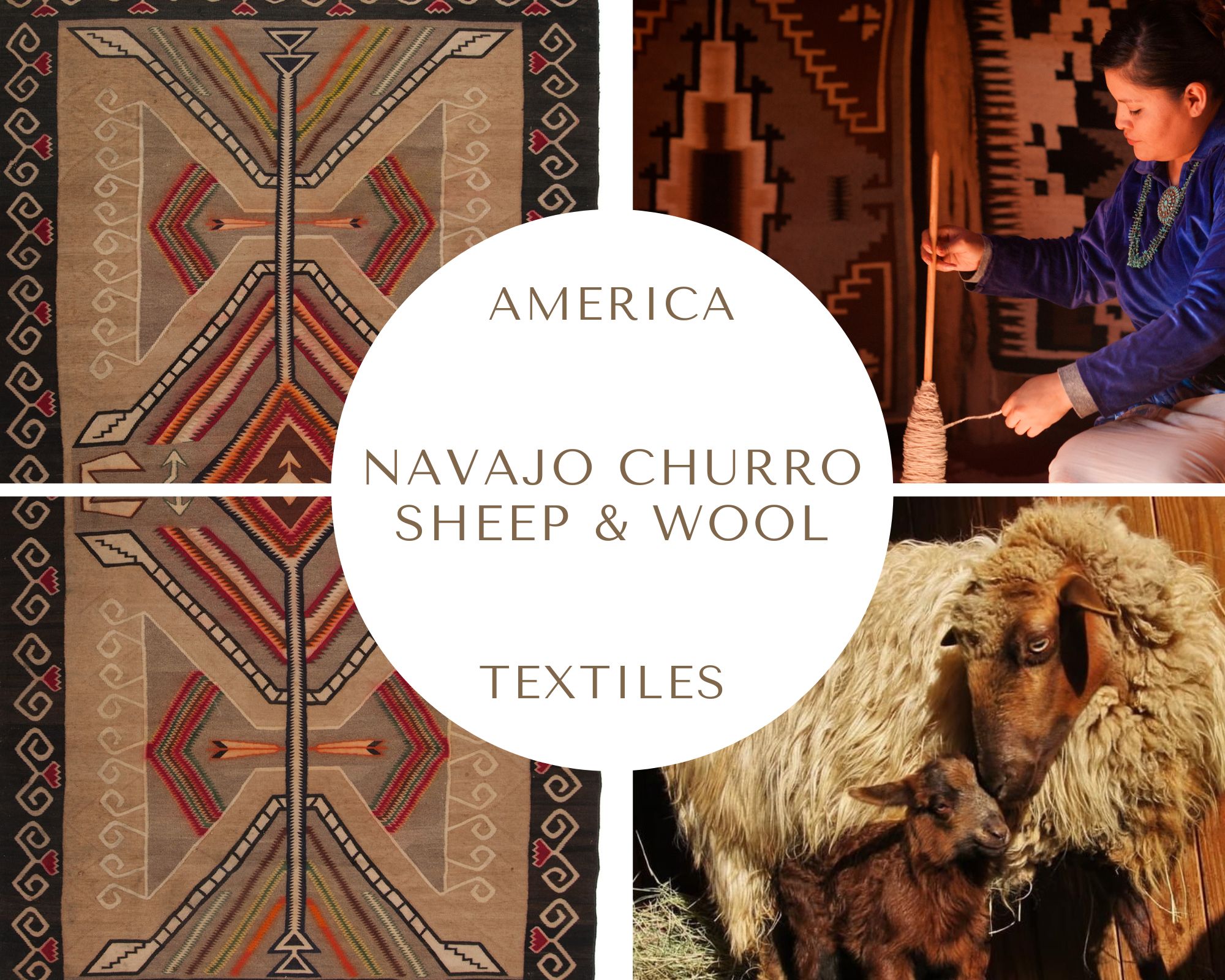

Left: woodblock print by Utagawa Yoshitora, 1847–52, depicting Minamoto Tametomo

Right: woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, 1845–48, depicting Minamoto Yorimasa

Many Medieval war tales idealized these suicides. «War tales such as the Hōgen Rebellion were originally popularized in oral versions recited by professional storytellers who accompanied themselves on the biwa (a fretted lute). Printed texts often went through many revisions. The oldest extant version of the Hōgen Rebellion dates from the early 1300s, the last one was compiled in the late 1500s. While the only stomach-cutting scene in the earlier texts is Tametomo’s, later versions feature stomach-cutting horsemen, guards, and attendants of all sorts. (…) Through such revisions and rewrites, additions, and embellishments, heroes were made more heroic» (A. Rankin, cit.).

The Medieval war tales cannot be treated as historical records as they mix fact with fiction (not in a balanced proportion). However, «it is in these tales that the legend of seppuku takes root. For roughly a hundred years, we see stomach-cutting evolve from an accepted method of suicide to the expected method» (A. Rankin, cit.).

During the Kamakura shogunate, the Hōjō clan kept the peace, while successfully defending Japan against two Mongol invasions. «But in 1333, forces backed by Emperor Go-Daigo overthrew the bakufu government and restored imperial power. The political machinations of Go-Daigo form the backdrop for the next generation of warrior sagas» (A. Rankin, cit.). In these last, as well in the reality, the seppuku was the preferred death of warlords, generals, and their most faithful vassals and bodyguards, who slashed their bellies, and threw themselves into the flames. «The war tales are not unanimously positive about suicide. Some contain episodes where bands of over-zealous soldiers, unaware that reinforcements are about to arrive, throw away the battle by removing themselves from it prematurely. Warriors are sometimes shown arguing over whether to gut themselves or die fighting. Commanders about to perform seppuku leave instructions for their subordinates not to copy them» (A. Rankin, cit.). Notwithstanding, battlefield suicide was more and more seen as a way to die with dignity and courage, as an act of self-determination (jiketsu), and even a sort of weird victory facing a military defeat.

«It was not long before suicide was itself subsumed into the field of strategy. Fifteenth-century battle histories show military commanders pressuring their enemy counterparts to cut their stomachs as soon as possible. The earliest recorded example of this sort of “forced” seppuku is found in an account of the Eikyō War of 1438. (…) The sooner a potential troublemaker could be persuaded to cut his stomach, the sooner things could return to normal. This was seppuku as crisis management. Ironically, however, mutineers could similarly use seppuku to their advantage. Persuading one’s lord to cut his stomach was easier on the conscience than killing him. No one wanted the label of “lord-murderer.” (…). In this way, suicide was increasingly a product of careful arbitration and tactical ingenuity, rather than an autonomous outburst of defiance. The trend was consolidated in the mid-1500s, as warrior households incorporated obligatory stomach-cutting into their official punishments». (A Rankin, cit.).

Death by seppuku became a common punishment for a samurai which left his family’s honor and property intact. Moreover, it began to be a praised mean for an offending samurai to make amends for his own transgression or wrongdoing. An example of this kind of suicide, called sokotsushi, involves the brilliant Takeda general Yamamoto Kansuke Haruyuki (1501-1561), who thought to have failed, withdrew from the fray when wounded, and committed suicide.

To better understand this practice that was always brutal, excruciatingly painful, and often not even effective ( = lethal), we have to consider which were the most common methods of inflicting death in pre-Edo feudal Japan. In 1594 a powerful samurai of the Miyoshi domain, Ishikawa Goemon, who terrorized the roads around Kyoto with a gang of drunken thugs, was captured; his men were crucified and obliged to watch from their crosses their lord boiling alive in a cauldron of oil. In 1618, at the beginning of the Tokugawa shogunate, many thousand missionaries, friars, and Catholic converts were executed. Some were drowned, while others, to avoid their singing or praying, were suspended upside down with their heads buried in the ground, having first slit their temples to allow a smooth drip of blood.

In conclusion, in the pre-Edo period, samurai did not dream to suicide themselves but got used to regard seppuku as the expected final act in case of military defeat or strategic failure, as an honorable departure from the scene forced by others, by culture, by the desire to preserve their own’s household, or simply to avoid the worst end (to be killed by enemies and used as a trophy, to be beastly punished, etc.).

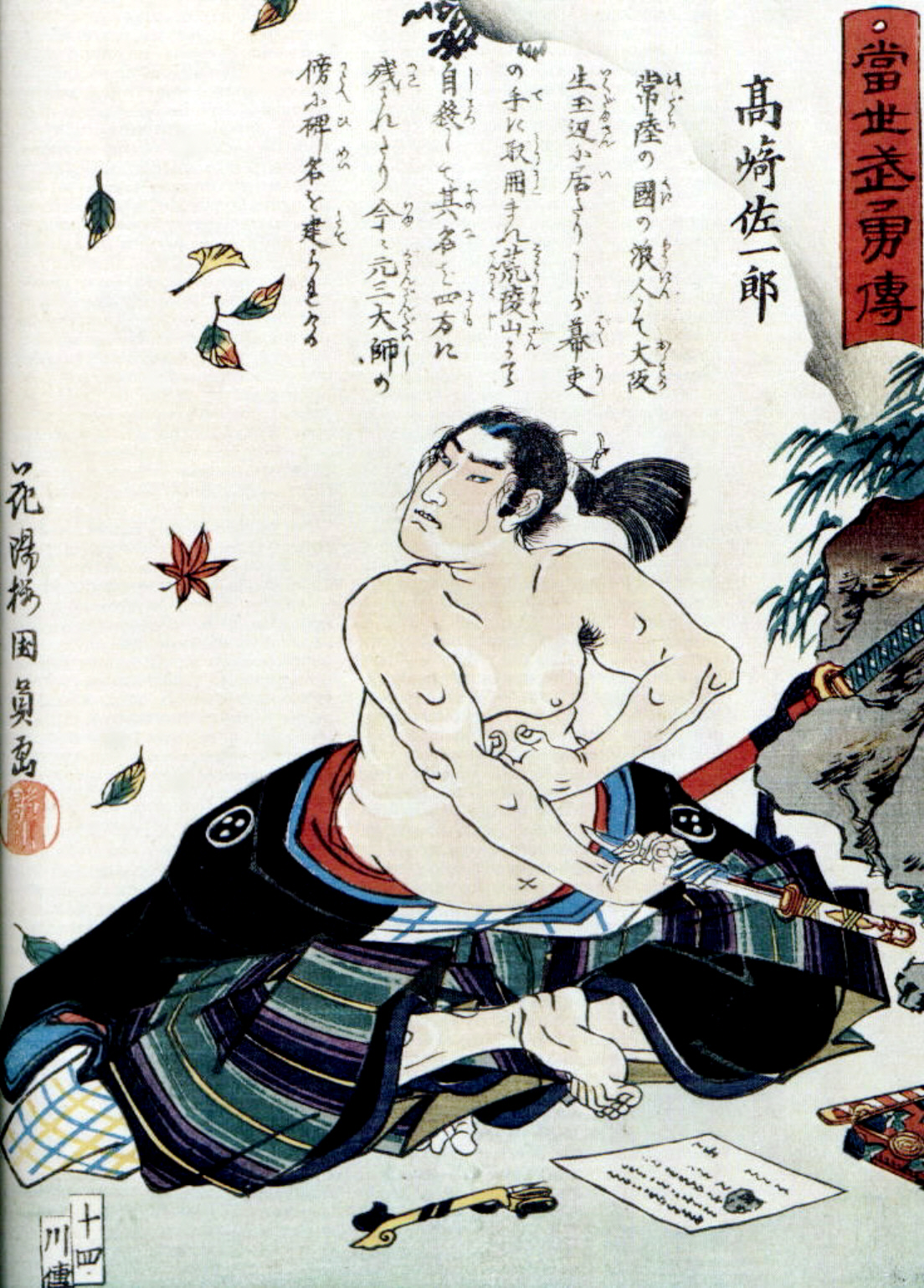

Woodblock print by Utagawa Toyonobu, 1883. It depicts Shimizu Muneharu (1537~1582), a powerful samurai who served the Mōri clan and became lord of the Bitchu Takamatsu Castle. His army was defeated by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, his castle flooded and he was forced to surrender and commit seppuku on a boat in full view of all soldiers.

Woodblock print of a warrior about to perform seppuku by Kunikazu Utagawa, ca. 1850.

During the Edo Period-Tokugawa Shogunate

Death by seppuku continued to be the common capital punishment for the samurai guilt of misconduct such as killing a civilian, insulting a superior, theft, corruption, sheltering Christians, and above all, fighting (all real cases). However, «it was not unknown for samurai of the highest echelons to dispute death sentences (…), but the penalty for refusing to cut one’s stomach was an automatic extension of the sentence to include other family members» (A. Rankin, cit.).

The iron fist of the bakufu against the samurai was proverbial and allowed no exceptions. Moreover, it allowed them thin, almost flimsy self-determination margins.

Battlefield seppuku was obviously over during the Tokugawa pax, but the first half of the 17th century saw an increasing trend, improperly called junshi.

Traditionally junshi was the voluntary suicide of retainers after the death of their lord. When it happened in the battlefield, after the seppuku of the lord, it was called oibara: a retainer who had helped his own lord to suicide himself, albeit at his lord’s request, could not continue to live with honor, and could not accept of being killed in battle like a dog. During the Warring States period, junshi or “following one’s lord in death” was the desperate act by the samurai of a defeated or a fallen lord. It was far from being a common procedure: most samurai preferred to live on as masterless rōnin rather than die in this manner. But in the mid-17th century, the incidence of junshi was on the rise.

An analysis of the cases occurred during the first 60 years of the Tokugawa shogunate shows that it was not a sign of loyalty given by a retainer to his lord, but an expression of devotion, love, and affection (shinjū or the double suicide of lovers was a popular and successful theatre topic at the time), mixed with a sort of nostalgia for the “good old days”, when the samurai were more warriors than bureaucrats. To commit seppuku were close friends or lifelong retainers who considered the death of their lord or beloved as the end of their meaningful world. In some cases, «a strong homoeroticism often cemented the bonds between samurai, and many of the seppuku incidents from these years appear to have centered on intense masculine friendships. These were not always straightforwardly sexual, and could just as easily be charged by the passions that hide behind love unrequited or unconfessed. Initially, the junshi trend was led by distraught young lovers», (A. Rankin, cit.), but there were also cases of samurai who willingly died after the death of their daimyô from illness.

The Confucian philosopher and strategist Yamaga Sokō (1622 ~1685), in his writings, criticized junshi as an unfortunate consequence of sexual relations between samurai.

In any case, the Tokugawa bakufu formally prohibited all kinds of junshi in 1663. «A proclamation of 1722 attempted to stamp out love, still a popular phenomenon in those times. The following year saw a ban on depictions of such scenes in theaters. Bloodletting was acceptable only as an expression of governmental power, not of the self-determining power of the individual» (A. Rankin, cit.), be it even a powerful samurai.

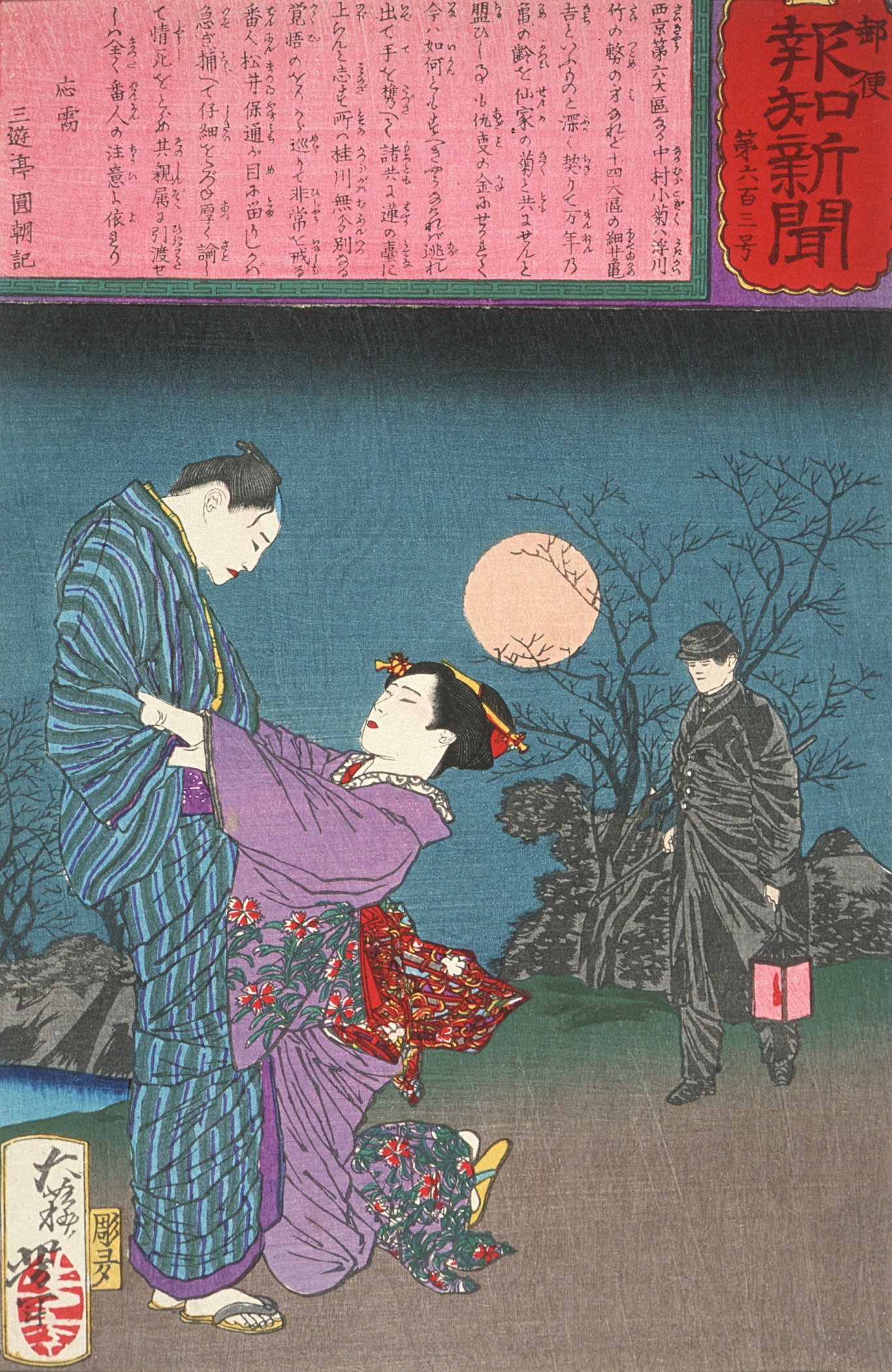

The Patrolman Matsui Yasumichi Prevents a Double Suicide (shinjū), woodblock print by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1875, held at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (US).

In the late 17th and in 18th centuries, the efforts of the Tokugawa bakufu went in a new, unusual direction, more constructive but not less prescriptive. Many Tokugawa-era scholars and «samurai idealized seppuku as a warrior machismo of a bygone time, going as far as writing manuals standardizing the ritual» (M. Wert, cit.), and turning suicide by disembowelment into a fully developed semi-public ceremony with Shinto undertones. For the earlier bushi there was no codified ritual and each samurai acted as he could and would.

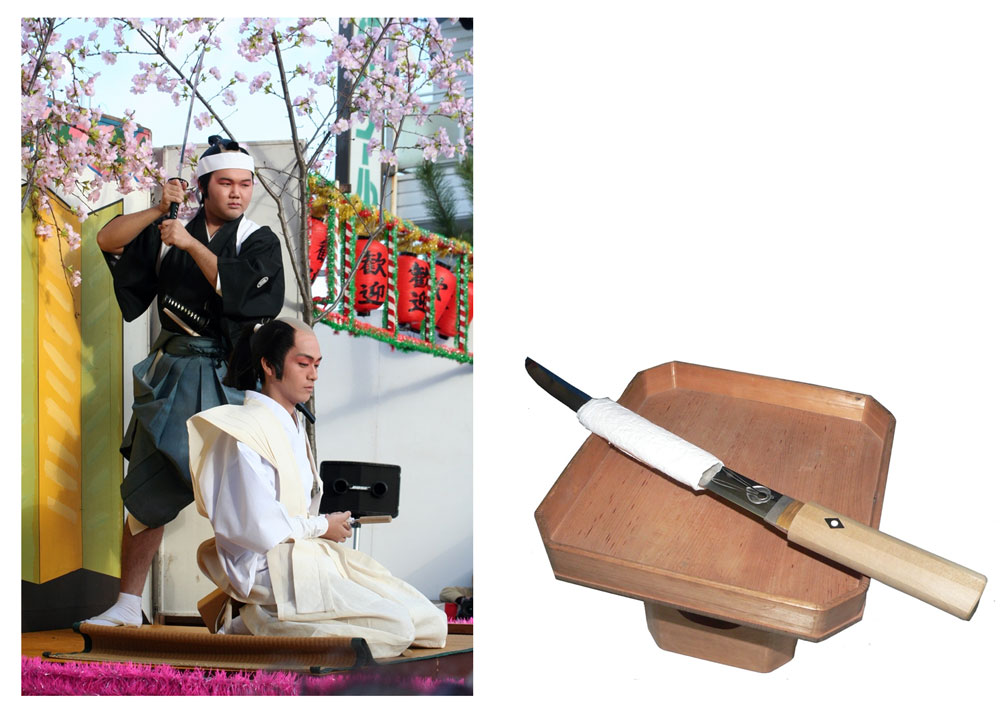

The samurai had to be bathed, freshly shaved, and his hair properly combed. White robes (kami-shimo) were mandatory as the use of a tatami mat and some ceremonial items (a bottle of sakè and cups, a small lacquered table, or tray, with a short blade like a dagger, some pieces of cloth). The ceremony, often performed in the grounds of a temple or in a palace garden, required the samurai to kneel on a pillow in a composed and formal manner. At his shoulder, discreetly a meter behind and on the left side, stands his “second”, the kaishaku, often a close friend, armed with a long sword. The samurai, when feels ready, exposes his belly, takes the dagger, and starts to cut his belly following one of the many codified cuts. At the first sign of excruciating pain, the kaishaku gives the samurai neck a powerful sword strike to behead him immediately, following a codified technique as well.

«From the 1730s onward, seppuku ceremonies were mostly performed without a cut to the stomach, the condemned man being beheaded before or while reaching for the dagger. Samurai handbooks of the time are explicit in this regard; a swordsman who acts as kaishaku is encouraged not to hesitate, but to remove the head as quickly as possible» (A. Rankin, cit.). Sometimes, the dagger plays no part whatsoever in the ceremony: a paper fan is placed upon the tray and as soon as the samurai picks up this fan, the kaishaku gives the lethal blow. The use of a paper fan was common with the kids and the older samurai.

«The Notes on Decapitation and Stomach-cutting, a manual from the 1720s, advice: “As for seppuku performed by little ones, tell the boy that you are going to practice first. Offer him a fan instead of a dagger. When his head is in the right place, decapitate him without a word.” A note in the records of the Owari domain for 1708 describes the executions of Satō Kanesaemon and his thirteen-year-old son, the latter being “successfully beheaded after much trickery and deception.” In 1760, Kanda Hakuryōshi, a veteran retainer of Ōu, was sentenced to death for a costly financial oversight. Hakuryōshi, an octogenarian, performed the full ritual using a paper fan as if it were a dagger» (A. Rankin, cit.).

To force a child in such a ritual death is brutal and disgusting, but how far is this seppuku etiquette from that bloodthirsty ferocity which for centuries marked out the horizon of the bushi?

As Rankin wrote, here every tiny detail is crucial, except the actual cutting of the stomach. «We can safely assume that most samurai welcomed the erasure of stomach-cutting from ritual protocol, as long as there was no consequent detriment to the honorable symbolism of the act. (…) During the long years of peace, martial values were on the wane. More bellies were being ripped on the Kabuki stage than in reality. Samurai strutted about with their trademark long and short swords, but many lacked the skills to use them. Archery and equestrianism were in a similar decline. It was a sign of the times when, in April 1779, the shogun’s 16-year-old son died by falling from his horse» (A. Rankin, cit.).

However, this slackening of severity has to be seen in a broader social context. For at the same time that samurai of all ages were being spared the ordeal of cutting their bellies, the severity of punishments for non-samurai was increasing. Slow decapitation (with a saw), crucifixion, roasting, and boiling in oil, associated with every kind of humiliation, before and after execution, were common capital methods for commoners and civilians.

In this way, the Tokugawa shogunate monopolized and institutionalized the use of violence. At the very same time, they compensate the samurai for all the freedom they were deprived of, by clearly separating them from the irrelevant herd of “serfs”.

Left: a reenactment of Edo-period seppuku (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported).

Right: the short blade called tanto in the ritual seppuku tray (licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 2.0 France)

HOW THE SAMURAI MYTHOS WAS BUILT

Did I kill your image of the samurai?

Probably yes, I did it.

Where the hell is that romantic and heroic noble warrior, sort of oriental version of an “honorable knight”, a righteous and principled fighter with a “soul”?

Why did I ignore that valiant yet educated man, with a quick, strong hand and a meditative mind, loyal to his lord till death did them part?

Why did I ignore the historical samurai code of honor, the famous Bushidō (probably the very first thing you’re told about them)?

Well, to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, that samurai never existed. And the bushidō is an invented tradition, a late-19th/early-20th century invention with no basis in earlier history. It’s not my opinion, of course: it’s the result of historical research not good at crossing the academic walls and influencing the current social imaginary.

The current, popular idea of the samurai is the product of different manipulations that have been developed in different periods with different aims and for different kinds of consumption. In other words, the samurai figure underwent not just a simple idealization but a more complex “makeover” through the last three centuries. Let’s see how the samurai mythos had been built and, above all, why.

THE INVENTION OF SAMURAI IDENTITY DURING THE LATE TOKUGAWA SHOGUNATE

The changes that took place during the Edo period shows clearly how the Tokugawa shogunate monopolized and institutionalized the use of violence, gradually depriving the samurai caste of their centuries-old prerogatives: their traditional use of brutal force was disruptive to the new social order; it had to be banned and replaced by a few controlled forms of highly ritualized violence.

To secure a coveted pax sociale, the shogunate had to achieve multiple goals at a time. Two of them were essential: obtaining the substantial obedience of 94-95% of the population to the ruling caste of samurai and controlling the latter. The King of France, Louis XIV, also faced a similar problem in the same century, and the solutions of the Sun King and the Tokugawa shogunate were not as far off as their respective countries on the globe. Just as the Sun King built a new palace and “invented” the resplendent court of Versailles, so the shogunate invented the sankin kōtai (alternate residence) system that forced the daimyō and their samurai to reside in Edo every other year while leaving their wives and children there. Just as the Sun King “reinvented” the nobility by transforming the aristocrats into servants and courtiers and making their life a perennial, sumptuous scenic representation, so the shogunate “reinvented” the traditional image of the samurai, reducing the caste into a mass of tamed bureaucrats, free from any form of political self-determination, but reimbursed them with remarkable privileges, a fixed income and a new sparkling identity.

Many shogunate scholars and thinkers carried out a re-invention of the samurai’s past to create an image of the warriors perfectly fitted to the new political needs and able to legitimize their role in an age of peace.

Daimyo Procession to Edo, handscroll, ink, color, and gold on silk, by Hishikawa School, ca. 1700, Edo period. «This deluxe handscroll painted on silk captures the pageantry of a grand procession of a daimyo and his entourage en route from their home province to Edo, the military capital. In those times, on a biannual basis, daimyō were required to travel to Edo, where the Tokugawa shogunate had been based since the early 17th century, and take up residence there under the sankin kōtai (alternate attendance) system. Hundreds of retainers are shown transporting weapons, ceremonial accouterments, and personal effects that bespeak the daimyō’s military and financial might. Some are mounted on horses; the daimyō and certain other members of his family are carried in palanquins». MET Museum, New York.

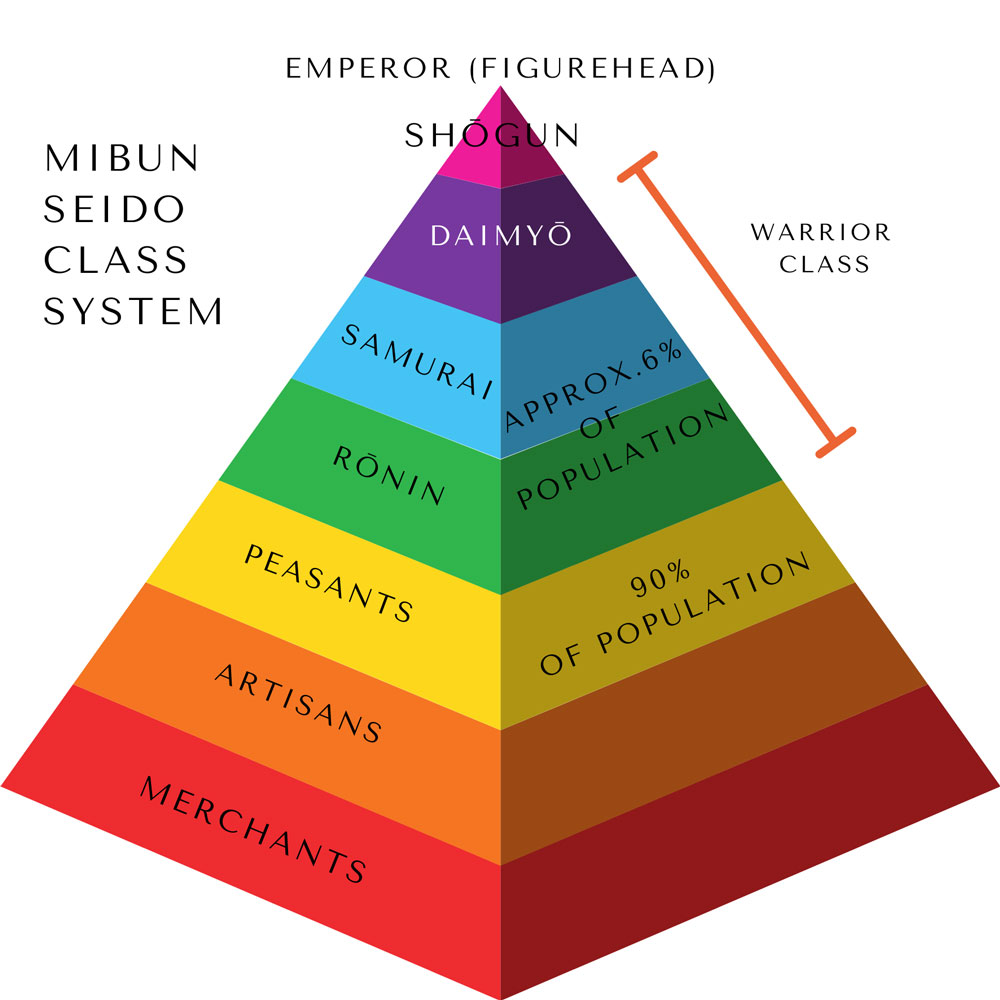

«The Tokugawa rulers placed a high priority on establishing and maintaining political and social order. To bring order to the society they sought to minimize social mobility and to clarify social roles. Tokugawa political leaders from the 17th century found status (mibun) to be a useful concept in creating a schematized social system based on hereditary occupational categories. This notion of social order was derived from a body of thought called Neo-Confucianism, which had supported imperial rule in China for nearly half a millennium. Under this doctrine, the emphasis was placed on a hereditary-based, four-tiered system of status groups or “estates.” In Japan, the status system (mibunsei) was defined by shinōkōshō: samurai, peasant, artisan, and merchants. The merchant writer Ihara Saikaku explained the system in the preface to his Buke giri monogatari (Tales of Samurai Honor, 1688): “Wearing a long sword makes a man a samurai.… A man who grips a hoe is a farmer, one who wields a hand-ax is a craftsman, and one who calculates sums on an abacus is a merchant. Everyone should realize the overwhelming importance of occupation in determining his life”». (C. Vaporis, cit.).

According to the ideology that undergirded the mibunsei system, members of each social group were asked to act in conformity with their social roles. The “rules by status” are among the defining characteristics of the Tokugawa period. For the members of the warrior caste, for example, there were the Laws for the Military Houses (Buke Shohatto) and the Laws for the Samurai (Shoshi Hatto), two sets of guidelines reissued over time and intended for respectively the daimyō, and the shogunate retainers (hatamoto and gokenin). Both these texts, as well as many others, highlights two requirements that all samurai must meet to legitimize their dominant role: they had to cultivate the bun and the bu, the martial skills and at the same time the civil virtues and the cultural arts, and they had to act as political-military leaders and role models for the rest of society.

Yamaga Sokō (1622 ~1685), a philosopher tied to the Tokugawa shogunate and follower of Neo-Confucianism wrote:

The tasks of a samurai are to reflect on his person, to find a lord and do his best in service, to interact with his companions in a trustworthy and warm manner, and to be mindful of his position while making duty his focus. In addition, he will not be able to prevent involvement in parent-child, sibling, and spousal relationships. Without these, there could be no proper human morality among all the other people under Heaven, but the tasks of farmers, artisans, and merchants do not allow free time, so they are not always able to follow them and fulfill the Way. A samurai puts aside the tasks of the farmers, artisans, and merchants, and the Way is his exclusive duty. In addition, if ever a person who is improper with regard to human morality appears among the three common classes, the samurai quickly punishes them, thus ensuring correct Heavenly morality on Earth. It should not be that a samurai knows the virtues of letteredness and martiality, but does not use them. Therefore, formally a samurai will prepare for use of swords, lances, bows, and horses, while inwardly he will endeavor in the ways of lord-vassal, friend-friend, parent-child, brother-brother, and husband-wife relations. In his min,d he has the way of letteredness, while outwardly he is martially prepared. The three common classes make him their teacher and honour him, and in accordance with his teachings, they come to know what is essential and what is insignificant.

Yamaga Sokō idealized the samurai as a “sort of Warrior-Sage” whose leadership on the population is not limited to the military field.

Turning a brutal professional fighter who got paid depending on the quantity and quality of his spoils of severed heads into a sort of role model for the entire society was a remarkable conversion, wasn’t it?

Tokugawa thinkers tried not only to cleanse from the image of the bushi all that blood and brutality that had impregnated their horizon for centuries but also to purge their attitude of shrewd opportunism praised as “alertness”, needed to survive in an unstable and precarious world. «Tokugawa thinkers tranquilized the martial ethic of the Muromachi warriors, straining it of its morbidity while injecting healthier concepts such as righteousness and fortitude» (A. Rankin, cit.).

The “new” samurai is now required to be the perfect balance between the bun and the bu. What the hell does that mean? That under the Tokugawa bakufu, all the samurai have to know their place, understand their specific task and functions, and fulfill their obligations.

Nobleman and Warrior, woodblock print (surimono), ink and color on paper, by Yashima Gakutei, 19th century, Edo period.

The Medieval war tales with their idealization of battlefield and aestheticization of death provided Tokugawa scholars with an array of virtues for all tastes, such as courage, determination, fearlessness, a stoic response to grief, and firm indifference in the face of death.

«Tales of samurai in the Edo period tended to be idealized accounts of medieval warriors that emphasized combat, bravery, and glory – martial elements that were deemed to be in short supply during the era of peace under Tokugawa family rule» (Oleg Benesch, cit).

«Tokugawa educational manuals such as Basics of the Martial Way (Budō shoshinshū, 1720) and The Warrior’s Code (Bushikun, 1725), and anthologies of military anecdotes such as Tales of Jōzan (Jōzan kidan, 1739), aimed to foster a new breed of samurai, one who combined the indestructible machismo of the Muromachi warriors with the docile servility of a peacetime bureaucrat» (A. Rankin, cit.).

The samurai, towering above the ordinary thanks to his moral/intellectual nobility and military leadership, is thus fully legitimized in his privileged status; and his authority over the common folk is fully validated as well.

«In establishing the samurai as a distinct social group, the shoguns unwittingly created an idealized image of the samurai that was available for consumption by commoners as well. (…) The invention of samurai identity during the Tokugawa era penetrated commoner culture. Commoners imitated, celebrated, parodied, and criticized samurai. Commoners were exposed to warrior values through popular culture» (M . Wert, cit.).

All’s Well That Ends Well, isn’t it?

Nope.

The samurai image so coveted by the Tokugawa shogunate fell short. The samurai caste was too heterogeneous to fit in that image: a low-ranking samurai, forced to covertly do manual jobs to make ends meet, and a high-ranking samurai from a powerful, rich household had almost nothing in common; besides, the “ruling” role of the former over a rich merchant was certainly debatable.

«Samurai were naturally aware of their special social status, but this consciousness of belonging to an elite varied greatly depending on time, location, and the specific situation of the individual bushi, especially if they were economically inferior to some commoners. For many samurai, the differences within their class seemed greater than those between the classes, and class consciousness did not serve as the basis for a widely accepted ethic» (Oleg Benesch, cit.).

As many historians point out, from one side nothing provides compelling evidence for the existence of a broadly accepted warrior ethic during the Edo-period, on the other, «an irreconcilable gap existed between samurai ideals and samurai reality, a gap that had been widening throughout the Tokugawa period» (M. Wert, cit.).

In the mid-19th century, just before the Meiji Restoration, not all commoners dreamed to become samurai: some started to follow the opinion of Andō Shōeki (1703–62), who had derided the samurai as parasites on society. «By the mid-19th century, increasing social mobility had blurred some distinctions among warriors and between warriors and commoners, and even many influential bushi questioned the innate supremacy of their class» (Oleg Benesch, cit.). The years between 1840 and 1880 are often considered a period of decline of the warrior class. «By the late 1880s the popular image of the shizoku <former samurai> was not one of admiration, and there was little yearning for the Tokugawa past in this regard» (Oleg Benesch, cit.).

The samurai seemed on his way out. Paradoxically, it is precisely when the figure and the caste of samurai no longer existed that their golden age began.

THE INVENTION OF BUSHIDŌ

One of the very first pieces of information you are told about the historical samurai in many websites, illustrated books, etc. is about Bushidō, defined as the traditional “way of the samurai” or the “ancient code of the warriors or bushi”. One of the largest and most comprehensive learning, information, and educational websites, owned by a famous American digital media company, writes: «Bushido was the code of conduct for Japan’s warrior classes from perhaps as early as the 8th century through modern times». This is also what you are told about samurai in many art martial schools all over the world.

Well, I’ll tell it loud and clear: bushidō is a contemporary theory with little or no historical basis. For many scholars and historians, it is simply “an invented tradition”. This position is not the personal opinion of some scholars, but the result of many rigorous historical and historiographical analyses. It was supported as early as 1912 by the renowned British Japanologist Basil Hall Chamberlain (1850~1935), who attacked bushidō as a modern invention with no basis in earlier history. Chamberlain recalled that bushidō was virtually unknown at the beginning of the 20th century and criticized it accordingly. He was right: the term bushidō appeared only in the 1890s and the related concept was unknown before 1900.

An important essay on this topic was written in 2014 by Oleg Benesch, a scholar who specialized in the history of Japan and China: Inventing the Way of the Samurai. Nationalism, Internationalism, and Bushidō in Modern Japan (published by the Oxford University Press). Benesch clearly writes: «The notion that bushidō is a modern invention has been put forth by a number of scholars over the past century, but this view has failed to make a sufficient impact on popular discourse. Both popular culture and many scholarly works continue to treat bushidō as a traditional ethic originally codified and/or practiced by samurai» (O. Benesch, cit., see Bibliography).

We’ll see in brief how this invented narrative was born, which idealized image of the samurai it produced, and how it was politically used from the late Meiji period to the end of World War II (WWII). This issue will prove to be essential not only to better understand the lost world of samurai but to grasp how ideological manipulations can occur in our current world as well.

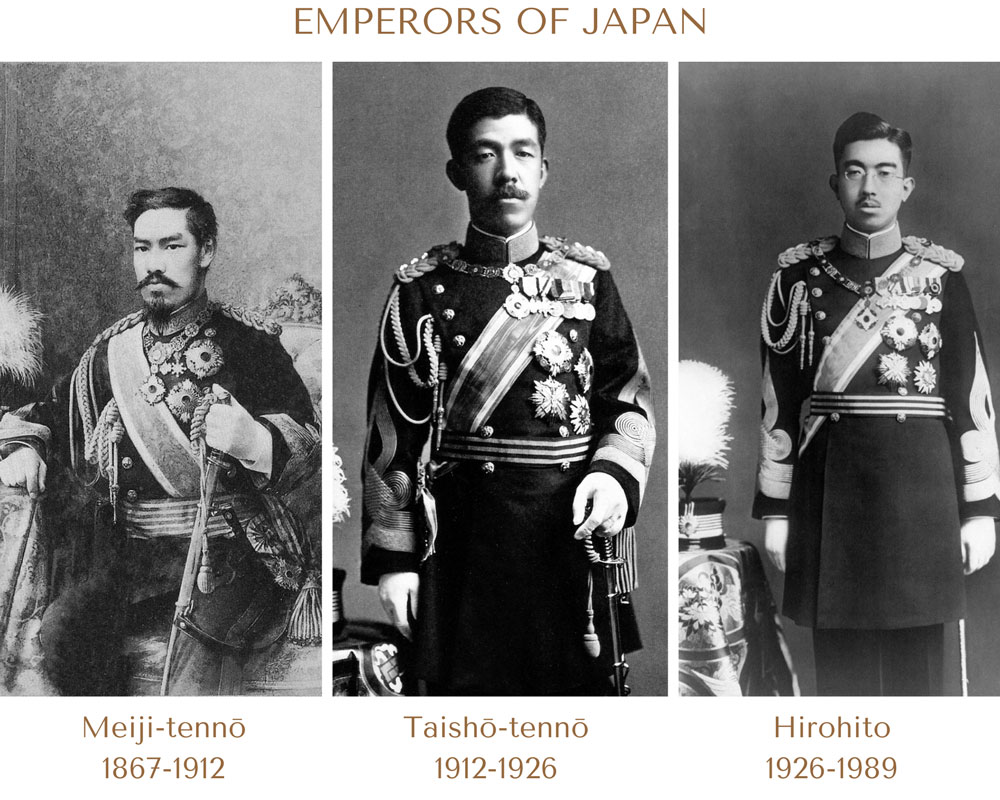

- 1890-1895: Ozaki Yukio and the first generation of bushidō theorists

The opening to the West brought about by the Meiji Restoration was short-lived: after the first intoxication of Western culture, the late 1880s and all the 1890s saw a renewed enthusiasm for the Shinto tradition and authentically Japanese values, seasoned with a good deal of nostalgia for the lost world of samurai, watered down in contact with the West. This increasingly widespread attitude of disenchantment, a good deal of nationalism, and an open aversion to China peaked with the Sino-Japanese War (1894~95).

It is in this context, at a time when Japan is trying to present itself to the West with an ancient and authoritative face, rather than the real underdeveloped and impoverished one, that the first discussions of bushidō developed, as a true Japanese alternative to Western ideals and Chinese traditions. In these years, some writers, mostly of samurai descent, started to idealize the past and lost world of bushi, far from the mediocre and unimpressive reality of the shizoku, the name by which former samurai were defined after the Meiji Restoration. Among the first generation of bushido theorists, the most important voice was that of Ozaki Yukio.

Yukio Ozaki (1859~1954), born into a minor samurai family, was a longstanding Japanese politician of liberal signature (he served in the House of Representatives of the Japanese Diet for 63 years). In the 1890s, he wrote a series of articles on bushidō, seen as a code of behavior of the medieval bushi that could represent the Japanese version of the British “chivalric gentlemanship”.

«As traits of English gentlemen, Ozaki listed characteristics such as “never forgetting higher ideals, valuing honor and rightness, and acting for the good of the country while forgetting private interests. One must be courageous but not violent, gentle but not weak… and all actions must be based on utmost trustworthiness”. (…) Ozaki sought the roots of English gentlemanship in the feudal tradition and medieval knighthood, although the ethic had evolved since. This connection was important to him, for it provided the basis of his developing bushidō theory (…)». (O. Benesch, cit.). He believed that the Japanese equivalent of the English “knight” and “gentleman” was the feudal bushi, who valued honor, dignity, prestige. His ancient code of behavior, the bushidō, promoted six important martial virtues for Ozaki: frankness, bold thriftiness, courage, quick-mindedness, generosity, and liveliness.

On this basis, in the 1990s, he tried to develop a sort of samurai-based ethic that could be meaningful and beneficial for his contemporaries, including businessmen and traders. He saw in the traditional bushidō, stuffed with contemporary antisemitism, aversion to Chinese culture, and capitalistic values such as assertiveness, independence, and ambition, a key to Japan’s success in different areas.

«Ozaki’s bushidō theories successfully captured the zeitgeist and responses were not long in coming» (O. Benesch, cit.).

In 1891, Yukichi Fukuzawa (1834~1901), a journalist and a writer very proud of his samurai descent, wrote a text whose title was Yasegaman no setsu, an expression which has been translated in many ways, including On Fighting to the Bitter End (by William Steele). In these pages, Fukuzawa elaborated the concept of warrior ethics in a nationalistic key. He acclaimed patriotism and loyalty to the ruler as the highest virtues that have to express themselves in the ethic of yasegaman: a mix of perseverance, determination, patience, self-control, ability to endure adverse circumstances, and to maintain a patient dignity in the face of insuperable odds or defeat. Fukuzawa saw this warrior spirit as having been forged during the Sengoku period and lamentably diluted or deteriorated in the Meiji times. Moreover, he was fully convinced that its resurgence could have been of critical importance for Japan’s future development.

Uemura Masahisa (1858~1925), a Japanese Christian pastor coming from a once-wealthy family of hatamoto (former samurai of the shogunate), was another theorist of the first bushidō. In his texts, he advocated a form of nationalism tempered by Christianity (which made him reject the notion of a divine emperor) to contrast the decay in morality and vitality that he thought was a feature of the first twenty-five years of the Meiji Era. He proposed a resurgence of bushidō, namely the revival of that martial ethic and moral character fully developed under the Tokugawa shogunate: an ethic of “sacrificing oneself for the common good (…) specifically required to swiftly and victoriously smash the materialistic spirit with a spirit of responsibility, duty, loyalty, and furious righteousness”.

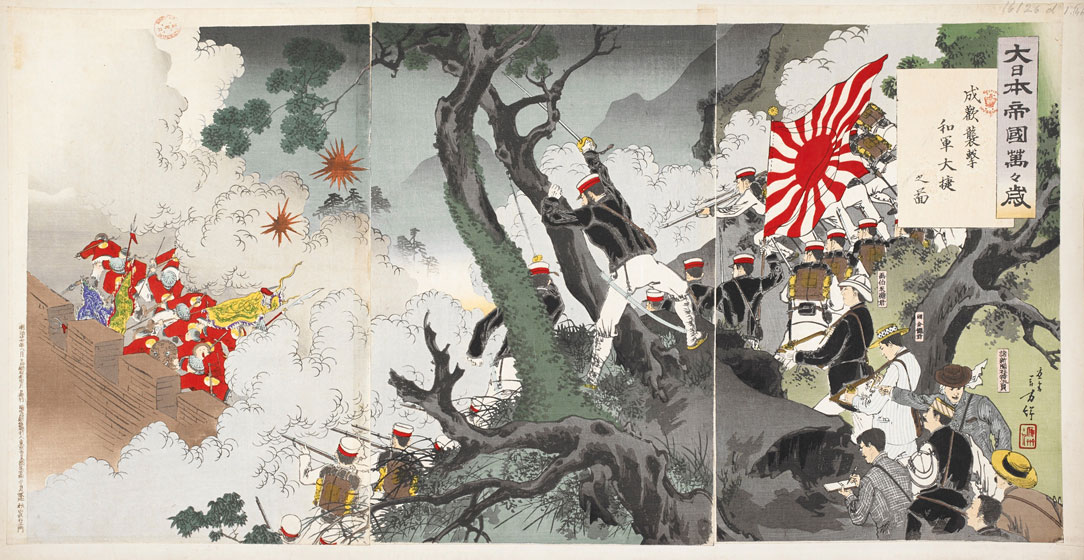

Long live the Great Japanese Empire! Our army’s victorious attack on Seonghwan, 1894, by Toshikata Mizuno.

The Battle of Seonghwan was the first major land battle of the First Sino-Japanese War, that broke out in July 1894 and lasted until April 1895. It was fought by the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan for the control of Joseon Korea and ended with Japan’s victory and the Treaty of Shimonoseki. This last required China to pay a war indemnity; to cede Taiwan; to open treaty ports for Japanese export and investment, and to recognize the independence of Korea. Moreover, the war marked the emergence of Japan as a major Asian power.

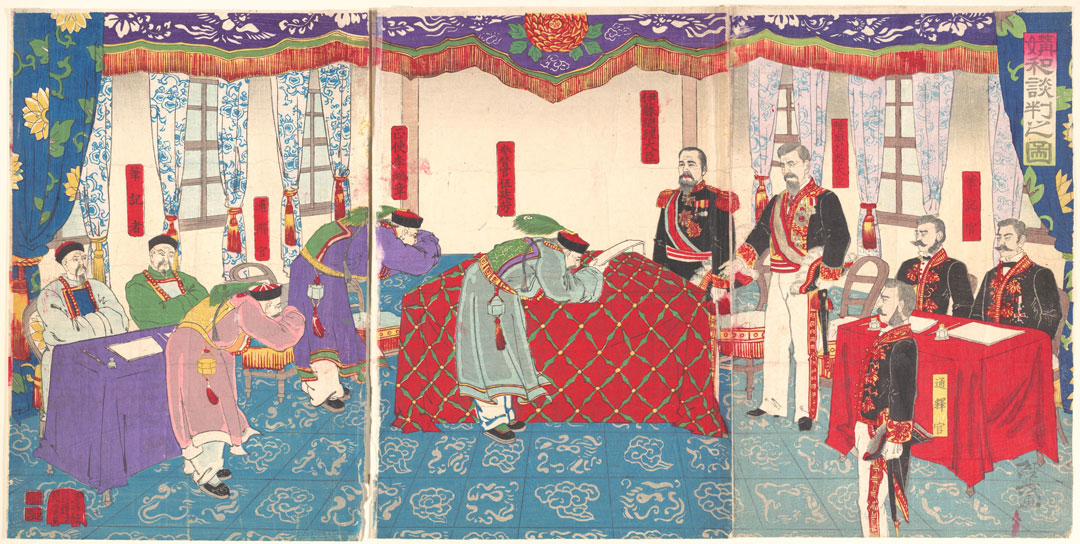

Illustration of the Decapitation of Violent Chinese Soldiers, 1894, by Utagawa Kokunimasa. The “modern” Meiji Japanese army did not forget the samurai antique barbaric beheading custom. The Japanese propaganda claims it’s the right punishment for “violent” Chinese soldiers.

Negotiations after the Sino-Japanese War, 1895, by Keisai. A depiction of the humiliation inflicted on China by Japan in a propaganda woodblock print of the time.

- 1895-1905: The alliance between bushidō and aggressive nationalism

Japan’s victory in the Sino-Japanese War not only fanned the flames of nationalism but also changed the reflection on the bushidō, diminishing the direct influence of the earlier texts.

This change comes out of the texts of an influential journalist and writer, Suzuki Chikara (1867~1926), who sought and found The True Spirit of the Nation (the title of one of his essays) in the pre-Meiji samurai martial spirit. Or, better to say, in what he believed was the traditional warrior spirit of the Tokugawa times: a mix of virtues such as diligence, economy, loyalty, honor, sense of duty, bravery, all observed through the deforming lens of an idealizing nostalgia. For Suzuki, the outstanding martial culture of the samurai, the bushidō, not only embodies the true spirit of Japan but becomes the key to Japan’s success, a model to guide the behavior of the entire nation and the most evident expression of the Japanese superiority over other Asian nations. Suzuki insisted on Japanese cultural superiority, advocated the spread of Japanese language and culture to other countries, by force if necessary, and in doing so, enshrined a lucky marriage between bushidō and the arising Japanese imperialism. «Suzuki supported the Sino-Japanese War, as Ozaki, Fukuzawa, and Uemura had done, but went further by invoking the warrior spirit to promote militaristic expansionism in East Asia. (…). As an aggressive nationalist and prominent member of influential rightist organizations, Suzuki Chikara’s ideas on bushidō foreshadowed some of the more extreme interpretations that came to dominate discourse in the 1930s and early 1940s» (O. Benesch, cit.).

Suzuki Chikara had considerable influence. The journalist and educator Takenobu Yūtarō (1863~1930) used bushidō as a standard term to indicate “the soul of Japan”, already credited to be one of the key factors of Japanese success and thought of the martial spirit as the perfect recipe of frugality, frugal discipline, work ethic, sense of duty, stoicism in the face of death, bravery, commitment to the cause, heroic devotion and above all on loyalty and honor.

In 1902, Kobayashi Ichirō (1876~1944) could claim, without raising any scandal, that “to insult bushidō is to insult all Japanese”. The idea that bushidō did not die with the samurai, but deeply entered to mold the spirit of all the population, became a cliché.

In early 1898, the journal Bushidō, published by the Great Japan Martial Arts Lecture Society, started its activity to promote traditional martial arts in Japan, and to foster a general consensus towards a nationalistic and militaristic attitude, thusly supporting the imperialistic effort of the government and the Imperial House.

In 1900, Nitobe Inazō (1862~1933), economist, author, educator, diplomat, a politician of Christian faith, published in Philadelphia (US) his Bushido: The Soul of Japan, a book in English for Western readers, destined to become an international bestseller in the 1980s.

«What Japan was she owed to the samurai. They were not only the flower of the nation but its root as well. All the gracious gifts of Heaven flowed through them». At the core of this book, we find many chichés: the way of the samurai, portrayed in an idealized and naïve way, has to become a “moral standard” for the entire nation. The spirit of the samurai is still the nation’s “animating spirit” and “motor force” and can play an important role in the modern world; it is also the vehicle of the Japanese uniqueness e superiority (he treatsKoreans and Chinese as “inferior races”, therefore legitimately conquerable).

The refined poet and writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (1892~1927) defined Nitobe’s work “a mere mannerism out of an old-fashioned sentimental melodrama”.

In the first years of the 1900s, many writers, rightist politicians, and senior officers of the armed forces encouraged the identification of the population with an “invented” martial ethic, nominally associated with the former samurai elite. Bushidō is set to lose its primitive aspect – that of a nostalgic, imaginative reconstruction of a tradition that never existed – to become

- an important vehicle for promoting and disseminating ultra-nationalistic and chauvinistic ideas;

- a suitable tool to martialize and discipline the whole of society;

- an ideology to sustain the country’s aggressive expansionism in the Pacific area.

An anti-Russian satirical map produced by a Japanese student (Ohara Kisaburō) at Keio University during the Russo-Japanese War (Cornell University Library). This war was fought during 1904 and 1905 between the Russian and the Japanese empires to control Manchuria and Korea. The overwhelming victory of the Japanese military, which surprised world observers, was ratified by the Treaty of Portsmouth (September 1905).

The Battle of Liaoyang, woodblock print by Getsuzō, 1904. This battle was the first major land battle of the, fought in present-day Liaoning Province, China.

- 1905-1912: The Imperial bushidō

The overwhelming victory over Russia changed the balance of power in East Asia, turned Japan into a superpower, and ignited an unprecedented surge of ultra-nationalistic fervor. These years saw «the peak of the Meiji “bushidō boom”, with the concept not only becoming wildly popular in Japan and abroad but also being redefined for militaristic and propaganda purposes» (O. Benesch, cit.).

One of the most influential voices of those years was that of Inoue Tetsujirō (1855 ~1944), probably the most prolific and prominent promoter of bushidō ideology. «His position as professor of philosophy at Tokyo Imperial University placed him at the center of academia, and his close ties with the government, military, and publishing industry allowed him to disseminate his ideas far beyond the ivory tower» (O. Benesch, cit.).

Tetsujirō considered the Japanese martial spirit not only the most important aspect of the nation’s unique culture but the living proof of Japanese superiority: he deeply believed that the “Japanese race” possessed a divinely mandated uniqueness.

He was also a staunch defender of a new concept of bushidō, centered on two supreme virtues, patriotism and absolute loyalty to the emperor (chūkun aikoku), whose relevance in war – in his opinion – had to overshadow all military technological advancements.

Tetsujirō’s chauvinism embraced both pronounced anti-foreignism and xenophobia and aggressive intolerance of any other views. He appointed himself the authentic standard-bearer of this new ideology, the “imperial bushidō” (“the spirit of revering the emperor and loving the nation”) whose dissemination in all fields he promoted tirelessly. He heavily influenced the Imperial Rescript on Education; he was a commissioner in charge of compiling books for teaching moral education in the public schools and in the military ones as well; he designed some programs for the Military Preparatory School; wrote textbooks and pamphlets, gave lectures and interviews. Thanks to his activities, well supported by rightist politicians, the Imperial House, and many senior officers of the armed forces, this new “imperial bushido” rapidly became an important part of the state ideology, and deeply penetrated in civilian and military education until 1945.

Inoue Tetsujirō and Major General Satō Tadashi (1849~1920) helped spread across all ranks of the armed forces the idea that dying in battle was honorable, and becoming a prisoner an embarrassing shame. Both prioritized suicide over surrender and put forward an aestheticized idea of death and suicide in war (“death in battle is the flowering of soldiery”). Thusly, the first steps towards the ideological indoctrination of young troops were carried out by silencing all critical remarks.

«The last years of Meiji were marked by a proliferation of nationalistic publications» (O. Benesch, cit.) and mass-produced books, historical novels, short stories for popular consumption, which mixed a pre-Meiji idealized past with a strict interpretation of the imperial bushidō. «In this way, the majority of Japanese became familiar with the concept and came to believe that bushidō was a historically valid moral code that once guided samurai behavior» (O. Benesch, cit.), and that was still beating in their hearts.

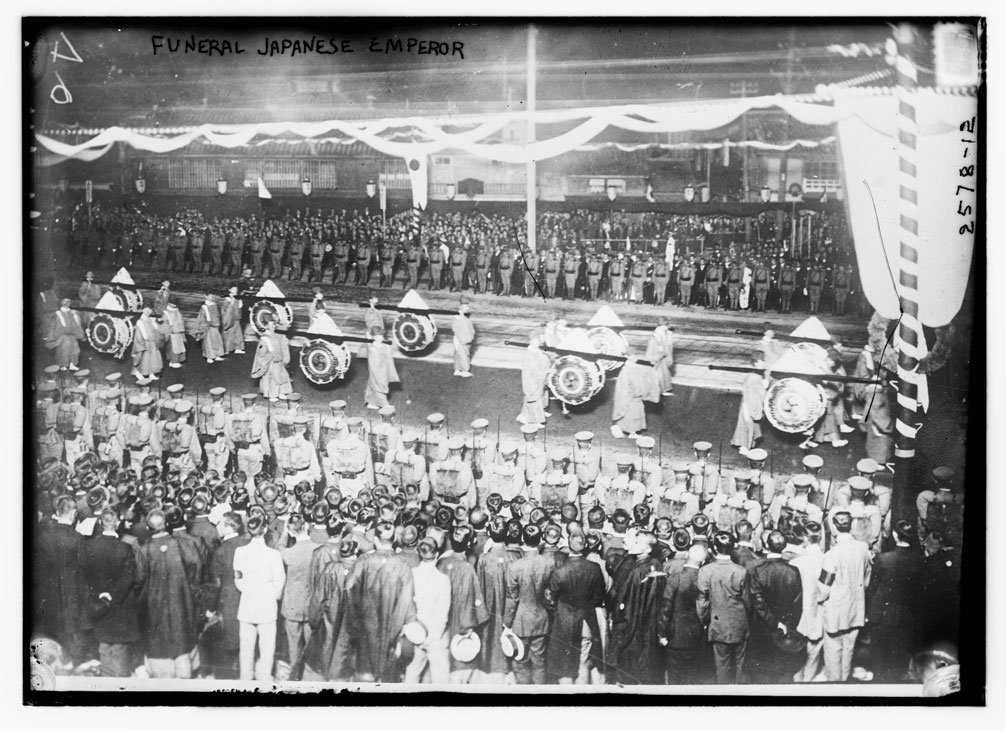

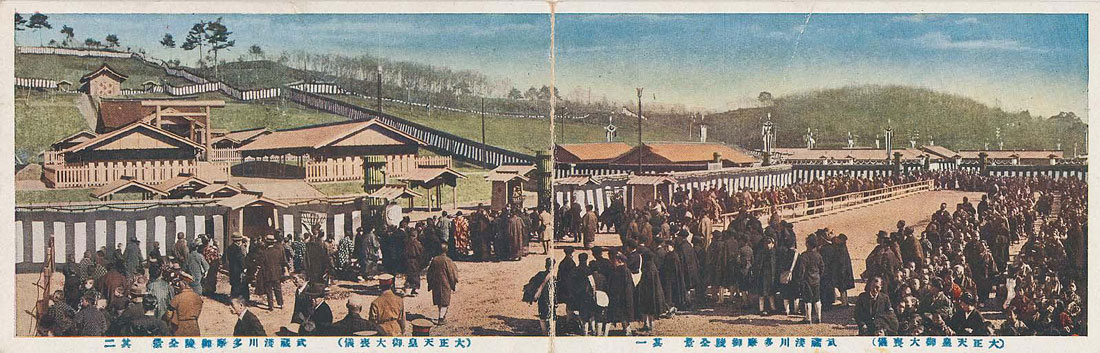

Emperor Meiji died the night between the 29 and the 30 July 1912. His majestic funeral procession left the palace grounds on the night of 13 September 1912.

By the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division.

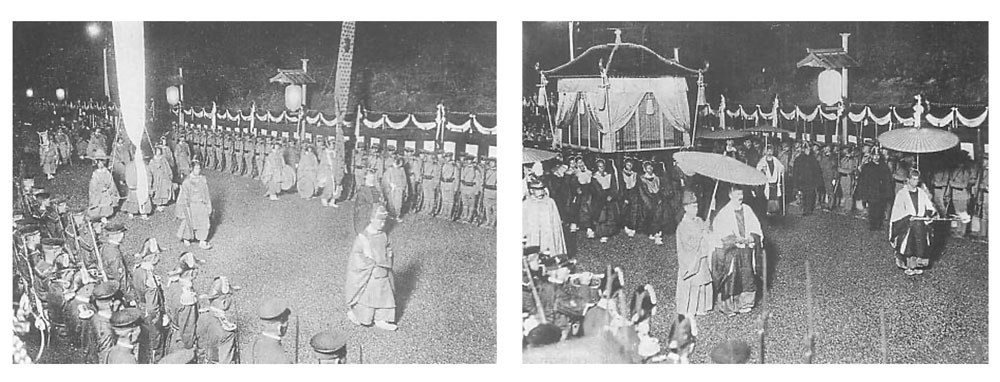

Both from the volume Photograph collection: Panorama of 100 years Kyoto history published by Tankosha.

- 1912-1926: the Taishō period

From 1912 to 1926 the Colonial Empire of Japan went through the Taishō period, an age of uncertainty due to the unstable health of the new emperor, much less active and present on the public scene than his predecessor, and the outbreak of World War I, which saw Japan’s relatively limited military involvement. Some liberalizing trends in politics allowed the development of critical voices towards the bushidō, seen by some intellectuals as a relic of the past of very little or no use in the present day.

Some writers, like the literary critic Togawa Shūkotsu (1870~1939), Ralph Waldo Emerson translator in Japan, denounced the bushidō as “a teaching of death” that focused on how one should die and kill; and some historians showed the inconsistency of its roots, full of inexact generalizations and idealizations. The refined poet and heavyweight writer Ryūnosuke Akutagawa (1892 ~1927) explicitly highlighted the identification of imperial bushidō with reactionary ideology.

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa is considered “the father of the Japanese short stories”. Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 masterpiece Rashōmon was a creative adaptation of two Akutagawa’s short stories: In a Grove (1922) and Rashōmon (1915).

Despite a slight decline in popular interest in bushidō during the Taishō democracy, the ideology of the Imperial version, sometimes called the “institutional Bushidō”, continued to be disseminated on a major scale in two related fields: civil and military education and sports. The inculcation of a martial spirit, started in the Meiji era, based on undisputed obedience to the divine emperor and institutional authority, and spiced up with a chauvinistic nationalism, continued without substantial changes, forming an entire generation of adolescents.

«The many texts on martial arts education in late Taishō stressed the connections between the spirit of the samurai and their sports, especially kendo and judo» (O. Benesch, cit.). The Imperial bushidō, which claimed to be “the spiritual heritage of the samurai” (and was not), became one of the many traditions the schools of martial arts had to carefully preserve and hand down.

The emperor Taishō died on the morning of December 25, 1926, at 47 years old. The funeral ceremonies took place from December 26 to February 8, 1927. His son Hirohito (1901~1989) became the 124th emperor of Japan under the name of Shōwa.

- 1926-1945: the triumph of bushidō and death in early Shōwa

The early Shōwa period was probably the most troubled and complex of entire Japan’s history. The country moved into political totalitarianism and ultranationalism; this fascist tsunami culminated in the invasion of China in 1937, the alliance with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, and the signature of the Tripartite Pact, creating the Rome-Tokyo-Berlin Axis (1940).

The invasion of China in 1937 signed non only the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War, but also of the Second World War in the Pacific Theater (for different countries, WWII started in different years: for many European countries in 1939; for Italy in 1940; for the US in 1941, after the attack on Pearl Harbor. For Japan and China, WWII started in 1937).

The imperial bushidō became central to WWII propaganda: it was used as the main ideological tool to enforce both the domestic and the foreign policy, and as the core of the “spiritual” (= ideologic) military training of soldiers of all rankings. Their brainwashing started in the late Meiji and reached its peak in the pre-war period. Suffice to note the written orders by General Araki Sadao (1877~1967), one of the greatest promoters of bushidō, who wanted to remove from military texts all “negative” terms such as “surrender”, “retreat”, and “defense”.

The glorification of the imperial bushidō went so forth that it became the “secret weapon”, the secret key to military success «downgrading the importance of tanks, planes, means of communication» (James B. Crowley, Japan’s Quest for Autonomy: National Security and Foreign Policy 1930– 1938, Princeton University Press, 1966). Bushidō, in other words, became a very convenient tool used by many senior officers who could make a career easily, avoiding to annoy the Imperial House by asking for funds or expensive structural modernization measures. Japanese troops, for example, received no food supplies during the entire WWII.

In those years, Japanese chauvinistic nationalism reached its peak as well. The belief of the racial superiority of the sacred Japanese spirit (Yamato-damashii) was mixed and matched with merciless racial discrimination against other Asian populations. This monstrous belief, that began to develop with the very start of Japanese colonialism, became so habitual in the Shōwa regime to be commonly accepted: it became the normalcy, and then a matter of fact. One of Emperor’s teachers, historian Kurakichi Shiratori, wrote: «Therefore nothing in the world compares to the divine nature (Shinsei) of the imperial house and likewise the majesty of our national polity (kokutai). Here is one great reason for Japan’s superiority» (Peter Wetzler, Hirohito and War: Imperial Tradition and Military Decision Making in Prewar Japan, University of Hawai’i Press, 1998). A belief of superiority that during WWII translated into a sort of ethnic cleansing fury towards all non-Japanese.

Bushidō became also one of the most important tools for combating societal “evils” such as American individualism and liberalism, materialism, claims of freedom, and Russian socialism, all un-Japanese “dangerous ideas” perceived as threats to Japan’s soul, able to pollute and bastardize its pure martial spirit.

The German government took particular interest in bushidō. Heinrich Himmler was so obsessed with the samurai that he ordered a volume on their history and values to be used as a propaganda book and distributed to SS members. The volume was published in 1937 by the publishing house of the Nazi party (Zentralverlag der NSDAP, Franz Eher Nachf.) under the title Die Samurai, Ritter Reiches in Ehre und Treue (The Samurai, Honourable and Loyal Knights of the Realm). The author was Heinz Corazza, and Himmler himself wrote the foreword.

One of the most interesting facts about the Shōwa bushidō was its “phagocytosis” of an unknown text, the Hagakure, a collection of commentaries by Yamamoto Tsunetomo (1659~1719), a samurai who became a hermit after the death of his lord. He’s not the real author of this text: it was compiled by Tashiro Tsuramoto who transcribed the conversations held with Tsunetomo in the Kurotsuchibaru monastery.

This text «circulated privately among samurai in the Nabeshima domain and was generally unknown until its resurrection as propaganda during the height of war and fascism during the 1930s» (M. Wert, cit., p. 89).

«The most extreme interpretation of Bushido is that of Yamamoto Tsunetomo, a samurai of the Hizen domain (now Saga Prefecture) in northwest Kyushu. After the death of his lord in 1700, Tsunetomo renounced the world, adopted the Buddhist name Jōchō, and entered a hermitage. Hagakure, a collection of dicta from his last seven years, was not widely read until the modern era and therefore cannot be accorded historical significance. But as a treasury of seppuku anecdotes, and fantasies, it is without equal» (A. Rankin, cit., p. 28).

Here’s part of the very first paragraph of Hagakure:

«The Way of the Samurai is found in death. When it comes to either/or, there is only the quick choice of death. It is not particularly difficult. Be determined and advance. To say that dying without reaching one’s aim is to die a dog’s death is the frivolous way of sophisticates. When pressed with the choice of life or death, it is not necessary to gain one’s aim. We all want to live. And in large part, we make our logic according to what we like. But not having attained our aim and continuing to live is cowardice. This is a thin dangerous line. To die without gaming one’s aim is a dog’s death and fanaticism. But there is no shame in this. This is the substance of the Way of the Samurai. If by setting one’s heart right every morning and evening, one is able to live as though his body were already dead, he pains freedom in the Way. His whole life will be without blame, and he will succeed in his calling».

The nihilistic visions of Tsunetomo – who concludes by quoting an ancient poem: “Everything in this world is false; the only sincerity is in death” – entails an incessant decadent aestheticization of death that the bushidō promoters found perfectly functional to brainwash all members of the armed forces: your life is not yours, but the glorious property of our Divine Emperor; do not be afraid to die for His sake and for our Nation, as this death of yours will be the successful completion and the supreme beautiful blossoming of your life (= You ain’t shit but a perfect cannon fodder; and remember: self-killing without official permission is treated as an inexcusable act of disloyalty).

«Wartime bushidō was marked by an increased reliance on the Hagakure, which had played a relatively minor part in the earlier discourse. (…) Selected passages of this text actively promoted self-destructive behavior as the highest bushidō» (O. Benesch, cit. p.199).

«The historian Wada Katsunori, writing as the pilots of the Special Attack Squadron slammed their planes into US warships in the Pacific, echoed Hagakure when defining Bushido’s suicidal indifference: “The attitude to Life and Death espoused in Bushido is not one that can be grasped by logic or learning. It is founded entirely on a necessity arising from within the Self, an explosion of inner life. Therefore, all the activity of Life is there—tough, yet flexible to the core, while at the same time containing rich humaneness. Bushido teaches men to master the art of being decisive, for not to die when you ought to die is more shameful than death itself.”» (A. Rankin, cit., p. 29).

Rightly, the historian Andrew Ranking wonders: How can voluntary death be an “explosion of inner life”?

Well, only a brainwashed person can find beauty and meaning and glory in killing and dying as a suicidal terrorist rather than living as a “survivalist goatherd”. Overturning life and death by turning own’s slaughter into a life triumph, turning horrific violence into something poignant and admirable is the goal of every well-conducted, professional brainwashing: Japanese kamikaze bombers, Islamic fundamentalists blowing themselves up on buses in London or Tel Aviv, martyrs of present-day suicide attacks are the first conscious “victims” of a cynical political indoctrination.

Chiran high school girls are waving farewell with cherry blossom branches to a taking-off kamikaze pilot. The pilot is Second Lieutenant Toshio Anazawa of Army Special Attack Unit (20th Shinbu party). The aircraft, an Army Type 1 fighter “Hayabusa” III- type-Ko holding a 250 kg bomb, is departing towards Okinawa on April 12, 1945.

Kamikaze pilot Ensign Kiyoshi Ogawa, who damaged the carrier USS Bunker Hill during Operation Kikusui No. 6 on May 11, 1945.

“USS Bunker Hill (CV-17) was hit by two Kamikazes in 30 seconds on May 11, 1945 off Kyushu. Dead-372. Wounded-264”, from US Archival Research Catalog.

BUSHIDO AND THE BEHAVIOR OF JAPANESE TROOPS IN WWII

I wrote that bushidō rapidly lost its primitive nature – that of a nostalgic, imaginative reconstruction of a patriotic tradition that never existed – to become over the years

- an important vehicle for promoting and disseminating ultra-nationalistic and chauvinistic ideas;

- a suitable tool to martialize and discipline the whole of society;

- an ideology to sustain Japan’s aggressive imperialism in the Pacific area and authoritarianism in domestic policy.

50 Years of bushidō, systematically disseminated throughout the whole of society, with particular attention to young generations, had an impact on the war behavior of Japanese troops, that can be observed on many levels.

The Japanese military forces were the only forces in WWII in which the officers and non-commissioned officers carried swords into battle. Some Japanese kamikaze pilots took a katana to the cockpit before their final flight.

WW2 Pacific – Japanese Imperial Army- Archives from Major Shokimi – 1932/42. Photo by Antoine Nicolas Vasse (licensed under Creative Commons, Attribution 2.0 Generic CC BY 2.0).

Life Magazine Archives – Photographer: Carl Mydans

«Japan’s suicide weapons were given a heroic cultural tinge that derived from the samurai tradition» (S. Turnbull, 2, see Bibliography).

The Yokosuka MXY-7 Ōka was a purpose-built, rocket-powered human-guided kamikaze attack aircraft, employed to sink Allied ships towards the end of the war. It was made to bring death and destruction and it was painted with an ōka, a cherry blossom, a traditional symbol of blossoming and perfect life fulfillment. However, this “cultural tinge”, to use Turnbull’s expression, was not derived from the samurai tradition but from the imperial bushidō and what it falsely taught to be the samurai tradition.

Historians have discussed the influence of bushidō on kamizake attacks, manned torpedoes, soldiers carrying out doomed banzai charges against usually superior forces, the seppuku of some high-ranking military official – like that of Hideyoshi Obata, a Lieutenant General in the Imperial Japanese Army, that committed seppuku in Guam, following the Allied victory in 1944, and was posthumously praised and promoted to the rank of general – and mass suicides by Japanese soldiers and civilians, notably in Saipan and Okinawa (1944 and 1945).

November 1945: a soldier commits harakiri after the capitulation of Japan. By Tropenmuseum, part of the Dutch Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (under license Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

Bushidō was surely one of the factors behind the kamikaze attacks. During WWII, many pilots voluntarily asked to be part of the suicidal forces. They believed – they were led to believe – that killing themselves and as many enemies as they could, was the noblest expressions of traditional Japanese virtues. Not all kamikaze, however, were volunteers: some pilots were forced by the circumstances, others were simple sheep at a slaughterhouse, carried and pushed into a plane by maintenance soldiers.

«Not all the pilots were eager to die for the emperor, counters Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney of the University of Wisconsin, an anthropologist who has studied the private letters of the 1,000 or so kamikazes conscripted from the ranks of university graduates. Her research reveals them to be a well-educated group, steeped in the works of German romantics and Karl Marx, among others, and traumatized by having to choose between self and country. “These men were not volunteers and they did not commit suicide for the emperor,” she said during a recent interview in Tokyo. “Their country was in a state of total war, and after agonizing over their situation, many felt they had no choice but to go.” Many kamikaze survivors echo that sense of surrendering to inevitability. “It was desperation that made us do it,” says Hideo Den, an 81-year-old kamikaze survivor. “We believed our actions would please our parents because it was honorable,” says 77-year-old Iwao Miura. “That’s all.” Shigeyoshi Hamazono, another kamikaze survivor, says that although pilots were asked to “volunteer,” they really had no choice. Of 100 or so in his naval squadron who were asked to volunteer, all but three agreed, he recalls, spreading out photographs of himself that show a handsome young man in pilot’s gear. “The other three got beaten up.” (They’ve Outlived the Stigma, by Bruce Wallace, in the Los Angeles Times, Sep. 25, 2004).

USS St. Lo was a Casablanca-class escort carrier of the United States Navy. On October 25, 1944, it sank after a kamikaze attack (during the Battle of Leyte Gulf). The first major explosion following the impact of the Kamikaze aircraft created a fireball that has risen to about 300 feet above the flight deck. The largest object above that fireball is the aft aircraft elevator, which was hurled to a height of about 1,000 feet by this first explosion. In this photo, it is about 800 feet high.

The U.S. Navy aircraft carrier USS Essex was hit on the flight deck amidships by a Japanese Kamikaze, during operations off the Philippines, on November 25, 1944.

Bushidō was undoubtedly one of the factors behind what was called the “ferocity of Japan’s no-surrender policy”, as well. It wasn’t the only one, however. For many scholars, the fear of the consequences of surrender, rather than bushidō, was the main motivation for many Japanese battle deaths in hopeless circumstances. «It was less the effect of spiritual indoctrination that kept soldiers from surrendering in hopeless situations, but rather other factors such as the immediate threat of being shot by their comrades as soon as they attempted to do so and the fear to be tortured or executed by their Allied captors» (O. Benesch, cit., p. 208).

In the case of Okinawa, the mass suicide of many civilians was more mass murder than a real suicide.

«Ota Masahide, a survivor and Okinawa historian, wrote in an article for the Asia-Pacific Journal in 2014 that the military distributed hand-grenades to the civilian population as the means to commit suicide with loved ones. Those that survived the grenades “worried” about being alive and found other ways to kill themselves with other weapons such as scythes, razor blades, ropes, rocks, and sticks. Military propaganda had warned the civilian population that if they were captured, the Americans would torture, rape, and murder them. “As the mayhem unfolded, they found all sorts of ways to kill…Men bashed their wives and parents bashed their children, young people killed the elderly and the strong killed the weak,” Masahide said. “What they felt in common was the belief that they were doing this out of love and compassion.” Another survivor, Kinjo Shigeaki, who took 20 years to speak about his experience, identified three factors that created this mentality: “The ideology of total obedience to the Emperor, the presence of the Imperial Japanese Army, and being on an island…with no way to escape.”» (Japanese Mass Suicides by Nancy Bartlit and Richard Yalman in Atomic Heritage Foundation, WWII History, July 28, 2016).

«For philosophers Joseph Margolis and Tom L. Beauchamp, suicide is an act or omission intentionally undertaken by a person to bring about his/her own death, unless the death was altruistically motivated, coerced, and caused by conditions that the person did not arrange specifically to end his/her life. If this definition is accepted, many authorized self-killings should be more accurately described as acts of compulsory self-destruction or murder at the hands of military authorities. This, however, is an interpretation that contemporary government representatives <of Japan> continue to reject» (Janice Matsumura and Diana Wright, see Bibliography).

I found the following movie scene of a no-surrender suicide a realistic depiction full both of sensitivity and historical accuracy, and free from hasty generalizations. The movie is Letters from Iwo Jima, a 2006 Japanese-language American war film directed and co-produced by Clint Eastwood, which portrays the Battle of Iwo Jima from the Japanese perspective.

«The treatment of the enemy, especially Western, prisoners of war was another major issue related to bushidō» (O. Benesch, cit.). The Japanese did not simply mistreat their prisoners of war (POWs): «The treatment of American and allied prisoners by the Japanese is one of the abiding horrors of World War II» (The American POWs Still Waiting for an Apology From Japan 70 Years Later, by Kirk Spitzer / Yokkaichi, in Time, September 12, 2014). Prisoners were routinely beaten, starved, abused, beheaded, and subjected to forced marches, slave-like labor, torture, simulated drowning, medical experiments, vivisection, cannibalism. Here again, Bushidō was one of the many factors behind these horrors. It explicitly taught the Japanese that real warriors do not surrender nor fall shamefully prisoner into the enemy’s hands; hence, those who do it cannot be true warriors. They are less than Japanese soldiers, they are shameful undeserving inferior beings, and as such they must be treated. Bushidō, in other words, legitimized the horror.

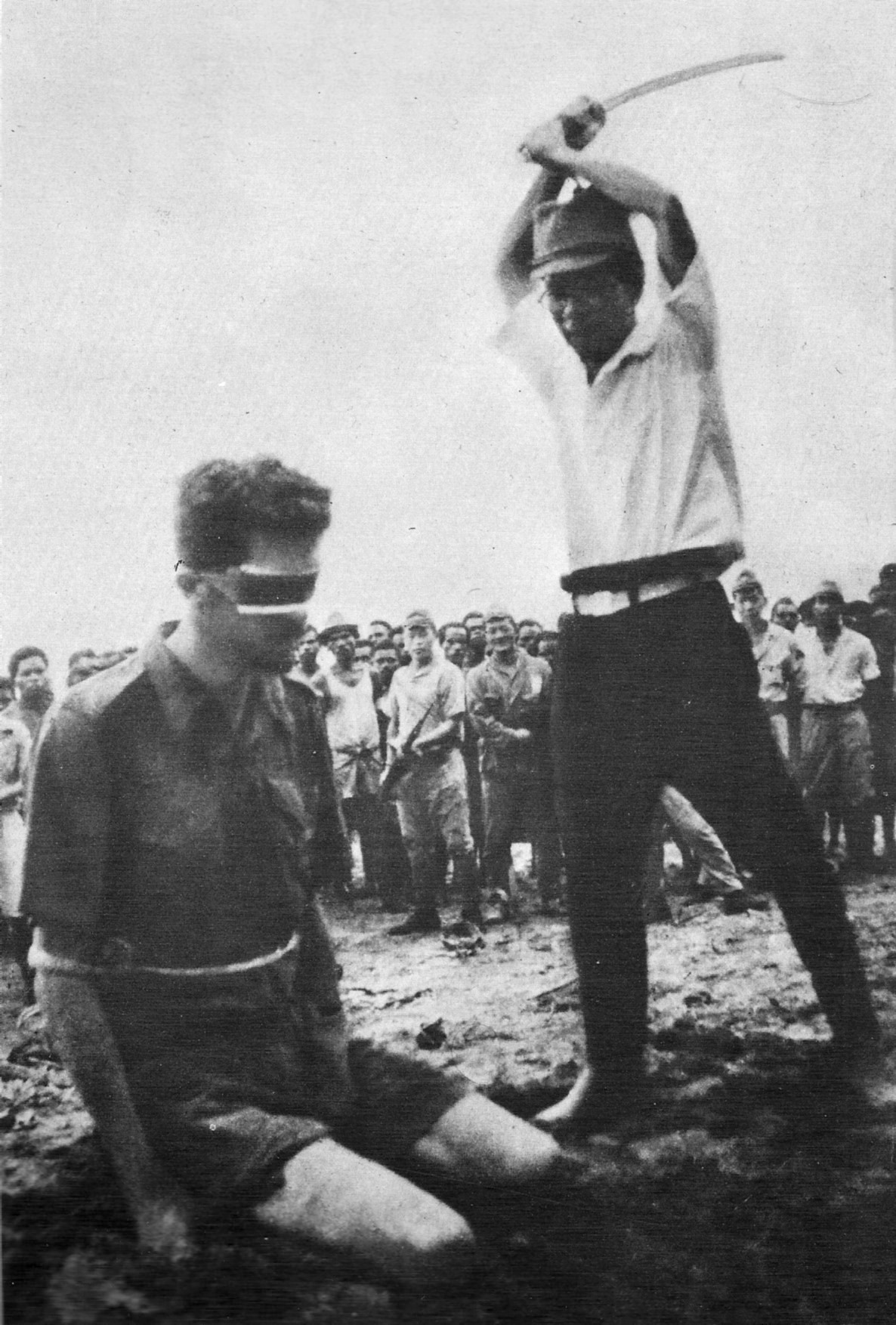

Aitape, New Guinea, October 24, 1943. A photograph found on the body of a dead Japanese soldier showing NX143314 Sergeant (Sgt) Leonard G. Siffleet of “M” Special Unit, wearing a blindfoland with his arms tied, about to be beheaded with a sword by Yasuno Chikao. The execution was ordered by Vice Admiral Kamada, the commander of the Japanese Naval Forces at Aitape.

Decades-old bushidō ideology was not always a factor among many others: it was also the determinant, major factor that led the Japanese troops to perpetrate not only war crimes but a long list of historical verified atrocities which stand out among the most horrific of the 20th century.

These atrocities, perpetrated by the Imperial Japanese Army and the Imperial Japanese Navy and collectively called “The Asian Holocaust”, resulted in the deaths of millions of people, mostly civilians (including babies and women of all ages).

Rudolph Joseph Rummel (1932~2014) was a professor of political science at Indiana University, Yale University, and the University of Hawaii. He spent much of his career studying data on collective violence and war and coined the term “democide” for murder by the government. In one of his essays, Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder Since 1900 (School of Law, University of Virginia, 1997), he wrote: «From the invasion of China in 1937 to the end of World War II, the Japanese military regime murdered near 3,000,000 to over 10,000,000 people, most probably almost 6,000,000 Chinese, Indonesians, Koreans, Filipinos, and Indochinese, among others, including Western prisoners of war».

Among these forgotten horrors, two were perpetrated against the Chinese population: the Rape of Nanking and the crimes by the Japanese Unit 731.

The Rape of Nanking aka the Nanjing Massacre

«On November 11, 1937, Japanese forces had taken Shanghai and were advancing on Nanking. Three groups of Japanese troops marched on Nanking in tandem. Nakajima Kesago led his forces from the west by the southern banks of the Yangtze River. General Matsui Iwane led an amphibious assault south of Nakajima’s forces. Lieutenant General Yanagawa Heisuke led the final group up from the southeast. Each of these leaders has been characterized as uniquely different from one another. (…) On December 7, General Matsui grew very ill on the field and was replaced by Prince Asaka Yasuhiko, a member of the royal family, who brought the authority of the emperor’s crown to the front line in Nanking. On December 9 the Japanese launched a massive attack on Nanking. As many as possible of the defending Chinese troops retreated to the other side of the Yangtze River on December 12, and December 13 saw the Japanese Army’s 6th and 16th Divisions enter the Zhongshan and Pacific Gates. Two Japanese Fleets arrived that afternoon and in the following six weeks, a flood of mass executions, rapes, and animalistic behavior poured over Nanking. (…)

In total, estimates of the Chinese dead from Nanking alone range from 200,000 to 350,000. The International Military Tribunal of the Far East places the death toll at 260,000. Perhaps even worse than the mass murders were the mass rapes that took place. Anywhere from 20,000 to 80,000 Chinese women are estimated to have been raped. Fathers were forced on daughters and sons on mothers. Women were subjected to gang rape, forced to perform countless sexual acts, and often killed < and impaled> after soldiers tired of them» (The Rape of Nanking: Analyzing Events from a Sociological Perspective, Stanford University, see the specific Bibliography).

There are countless photos of the atrocities perpetrated by the Japanese soldiers and officials. I will show you just a single one: it’s a tremendously famous picture that can testify what humans can do to other humans.

Warning: the next picture is graphic in nature and is meant for a mature viewing audience.

The infamous Unit 731

«It was a covert biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army that undertook lethal human experimentation during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) of World War II. It was responsible for some of the most notorious war crimes carried out by Imperial Japan. Unit 731 was based at the Pingfang district of Harbin, the largest gas chamber in the Japanese puppet state of Manchukuo (now Northeast China), and had active branch offices throughout China and Southeast Asia» (Wikipedia, see the specific Bibliography).

«For 40 years, the horrific activities of “Unit 731” remained one the most closely guarded secrets of World War II. It was not until 1984 that Japan acknowledged what it had long denied – vile experiments on humans conducted by the unit in preparation for germ warfare. Deliberately infected with plague, anthrax, cholera and other pathogens, an estimated 3,000 enemy soldiers and civilians were used as guinea pigs. Some of the more horrific experiments included vivisection without anesthesia and pressure chambers to see how much a human could take before his eyes popped out» (UNIT 731, Japan’s Biological Warfare Project, see the specific Bibliography).

How was that possible?

What the hell has all this horror got to do with bushidō?

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?