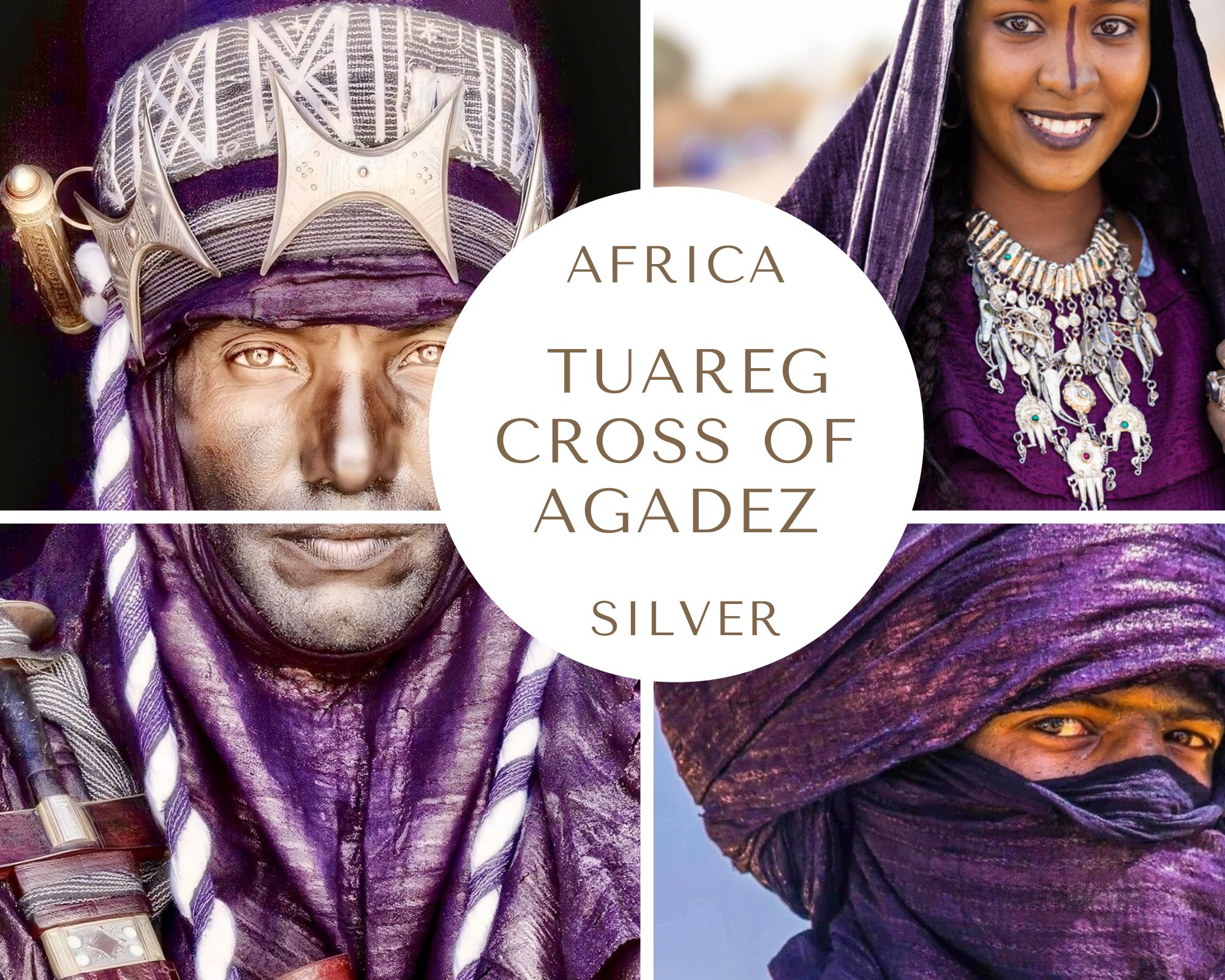

THE JIMMA CHAIRS FROM ETHIOPIA

Ethiopia on the globe

(licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported)

Many years ago, I saw some beautiful chairs in the former Byzantine convent in Marittima di Diso (Apulia, Italy) that had been restored and furnished by Lord Alistair McAlpine (How an English lord changed my life). I didn’t know what kind of chairs they were, but I thought that, like everything else in that magnificent residence, they must have been special, with a unique history or remarkable value.

I was very ignorant but curious. Those who have read my articles know that certain material objects call out to me and tell me their stories. I listen to them with the presence and patience of a Buddhist monk. The chairs in McAlpine’s residence spoke to me. That’s how my encounter with the Jimma thrones and Gurage chairs began.

I have a Jimma throne next to a Lulua chair at home today. The room is quite large and full of beautiful items. I have good taste, but, unlike Lord McAlpine, I’m tragically underfunded. In any case, the throne is a magnet for eyes and behinds alike. It’s a breathtaking sculpture and a very comfortable armchair (my spoiled Siberian cat undoubtedly proves it).

So, I’d like to tell you about my love affair with Jimma chairs and thrones.

Make yourselves comfortable.

Let’s set off for Ethiopia.

Throne of Wood, Crown of Memory: The Royal Chairs of Jimma

The Jimma throne is one of the most significant examples of royal furniture in Ethiopia. It embodies centuries of Oromo craftsmanship, Islamic influence, and monarchical tradition in the southwestern highlands of Ethiopia. These monoxylous chairs, carved from single pieces of Cordia africana wood, served as symbols of royal authority in the Kingdom of Jimma from 1790 until its annexation by the Ethiopian Empire in 1932.

But let’s take things in order.

Geographical Context

The Kingdom of Jimma was located in the southwest of present-day Ethiopia, in the Gibe region.

Today, the historical Gibe region and some of its key locations, such as Jimma, Limmu-Ennarea, and the Gibe and Gilgel Gibe rivers, are included in the Oromia Regional State, which is the largest in Ethiopia.

Physical map of Ethiopia. Source: Worldometer.

Oromia is also known as Oromiyaa because it is the homeland of the Oromo people, who are the largest ethnic group in Ethiopia and speak the Cushitic language Afaan Oromoo. The region is the center of their culture, history, and demographics.

It’s no surprise that the Kingdom of Jimma was Oromo. Emerging in the late 18th century in the Gibe region of southwestern Ethiopia, it was founded and ruled by Oromo clans, specifically the Diggo and Badi of Saqqa. This occurred as part of the broader Oromo migration and expansion in the area.

Left: Map of regions of Ethiopia. Source: Mappar Maps.

Right: Jimma map. Source: Yohannes, Sileshi & Suleman, et al., Quality of fixed dose artemether/lumefantrine products in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia, in Malaria Journal. 18. 236. 2019.

The kingdom covered an area of approximately 25,000 square kilometers. It was characterized by fertile plateau country and basaltic rock formations.

Its borders were defined by natural features and neighboring polities.

- West: The border with the Kingdom of Limmu-Ennarea.

- East: Adjacent to the Sidamo Kingdom of Janjero.

- South: Separated from the Kingdom of Kaffa by the Gojeb River.

- Northeast: Mountain Botor.

- North and west: The Mountains of Limmu and Gomma.

- East and south: Bordered by the Omo River.

The capital of the Jimma region was Jiren (modern-day Jimma), located on a hill overlooking the market town of Hirmata.

The region’s climate is noted for its abundant summer rainfall, which makes the land highly fertile and favorable for agriculture. This supported the kingdom’s wealth and power.

LEFT TO RIGHT, CLOCKWISE

A woman in traditional attire spreads freshly harvested coffee cherries to dry in the Ethiopian sun, celebrating the Jimma region’s rich coffee heritage.

The Jimma Zone Agriculture Bureau of Ethiopia reported that beekeepers produced 16,167 tons of honey during the first six months of the 2024/25 season.

The fertile land of the Jimma Zone.

A significant portion of the land is dedicated to avocado farming, which is a major source of income for many households. Although avocado production is relatively new, it has grown rapidly. Some reports state that avocados now occupy 75% of the area’s fruit farmland.

Farmers work in a wheat field.

The Kennisa Coffee Farm, located in Gomma, in the Jimma Zone.

Ethiopian farmer on a tea plantation near Jimma. Photo by Nick Fox / Alamy.

Several tea plantations are located near Jimma, including the Wushwush, Gumero, and Chewaka estates. Wushwush is one of the major tea-growing areas in Ethiopia. It has 1,249 hectares dedicated to black tea production at an altitude of 1,900 meters. Situated west of Gore town, Gumero is known for its fertile land and is considered the first tea farm introduced by consulate delegates from Lebanon and England. Ethiopia has over 150,000 hectares of land available for tea production, but only a portion is currently under cultivation.

LEFT TO RIGHT

Trees at sunrise in the Jimma area. Photo by Graeme Williams / Alamy.

A young Oromo woman.

BELOW

RIGHT: Oromo woman, Sambate, Ethiopia. Photo: Berengère Cavalier / Alamy.

LEFT: Oromo woman, Bati, Ethiopia. Photo: John Kenny.

The Oromo people of the Jimma Zone are predominantly Muslim. This Islamic majority is a legacy of the region’s history as the heart of the Kingdom of Jimma. The kingdom formally adopted Islam in the 19th century, becoming a major center of Muslim learning and practice in southwestern Ethiopia. According to recent research on religion in the Jimma Zone,

- About 85%-86% of people in the Jimma Zone identify as Muslim;

- Christianity is a minority religion in the zone, with approximately 11% of people identifying as Orthodox Christians and around 3% identifying as Protestant Christians;

- Adherents of the traditional Oromo religion, Waaqeffanna, are present but constitute a very small minority. Often, their practices blend with Islamic or Christian observances.

BELOW

Oromo elders. Photos by Graeme Williams / Alamy.

Oromo girls. Photos by Edwardje / Dreamstime.

The Kingdom of Jimma: Origins and Establishment (Late 18th Century – Early 19th)

The kingdom emerged from a complex interaction of several Oromo clans and the displacement of earlier inhabitants in the late 18th century.

According to local legend, a powerful queen and sorceress named Makhore led several Oromo groups to the area and used mystical power to drive out the Kaffa people. Although her reign ended due to internal Oromo dissent, the loose confederation she helped establish laid the groundwork for Jimma.

Two major Oromo clans, the Badi of Saqqa and the Diggo of Mana, competed for dominance in the region. By the late 18th century, the Diggo clan had begun to consolidate power by conquering rival clans and controlling key trade centers, such as Hirmata.

The kingdom’s founding is generally traced to Abba Faro, a Diggo leader who established a core state that successors such as Abba Magal and Abba Jifar I expanded. Abba Magal expanded territorial control and consolidated power around Hirmata. His son, Abba Jifar I, who reigned from approximately 1830 to 1855, founded the Kingdom of Jimma Abba Jifar.

Under Abba Jifar I, the kingdom became centralized, powerful, and increasingly Islamized. The king himself converted to Sunni Islam and encouraged the spread of the religion throughout the kingdom.

Political and Military Expansion

Abba Jifar I played a pivotal role in establishing Jimma as the dominant polity among the Oromo Gibe kingdoms. His reign was marked by the following:

- Establishment of centralized administrative structures;

- Construction of multiple royal palaces across Jimma;

- Military campaigns against neighboring kingdoms, notably a prolonged conflict (1839–1847) with Abba Bagido of Limmu-Ennarea over the strategic Badi-Folla district. This area was critical because it controlled caravan routes linking Kaffa with Gojjam and Shewa.

- Securing control over key trade routes to facilitate economic growth.

Later rulers, including King Abba Gomol, expanded the kingdom by annexing the ancient Kingdom of Garo and incorporating its elites. They also integrated the territories into the Jimma state.

The Age of Prosperity

King Abba Jifar I ruled until 1855 and left behind a powerful kingdom, a new religion, great wealth, and a strong ambition to dominate the politics of the Gibe region for his successor.

Explorer Cecchi named Jimma the richest of the Gibe states and the country with the most developed agriculture. The forests presented a formidable obstacle to the Oromo people when they first arrived in the region. By the late 1700s and early 1800s, they had begun clearing the land on a massive scale, preparing the way for extensive farming. This implies that agricultural development preceded the settlement of Jabarti traders in Jimma by more than half a century, perhaps by as much as 70 years. The plow drawn by a pair of oxen was the most vital farm implement in the region. Jimma, which lacked coffee in the early 1840s, became a major coffee producer. (Bernhard Lindahl, “Jimma,” in Local History of Ethiopia, 2005).

Administration and Society

The kingdom had a sophisticated administration based at the royal palace in Jiren. The azazi, an official, served as the head administrator, overseeing palace affairs, finance, and infrastructure. The royal court included officials, artisans, soldiers, and slaves who played important roles in governance and palace life.

Although typically governors were wealthy local traders known as nagadras, slaves could also serve as judges, jailers, or provincial governors. The court was a center of cultural life, with royal banquets and entertainment featuring musicians, as well as gramophone music during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Jimma’s society was predominantly Muslim and linguistically Oromo, although some dialects, such as Dawro of the Ometo family, were originally spoken.

Jiren, located near the modern city of Jimma, became the royal and administrative capital of the Kingdom of Jimma in the 19th century. The site is renowned for its royal palace compound, which played a central role in the kingdom’s political and cultural life. Jiren was founded during the reign of Abba Jifar I, the first king of Jimma, who ruled from 1830 to 1855. Abba Jifar I established his court and built the initial palace in Jiren, making it the center of royal authority and governance. The current, prominent palace structure, recognizable by its distinctive architecture, was constructed toward the end of the 1860s and developed further during the reign of Abba Jifar II. Described as the largest and best-preserved example of its type in the region, the palace is surrounded by buildings dating from Abba Jifar II’s rule, including mosques and residences.

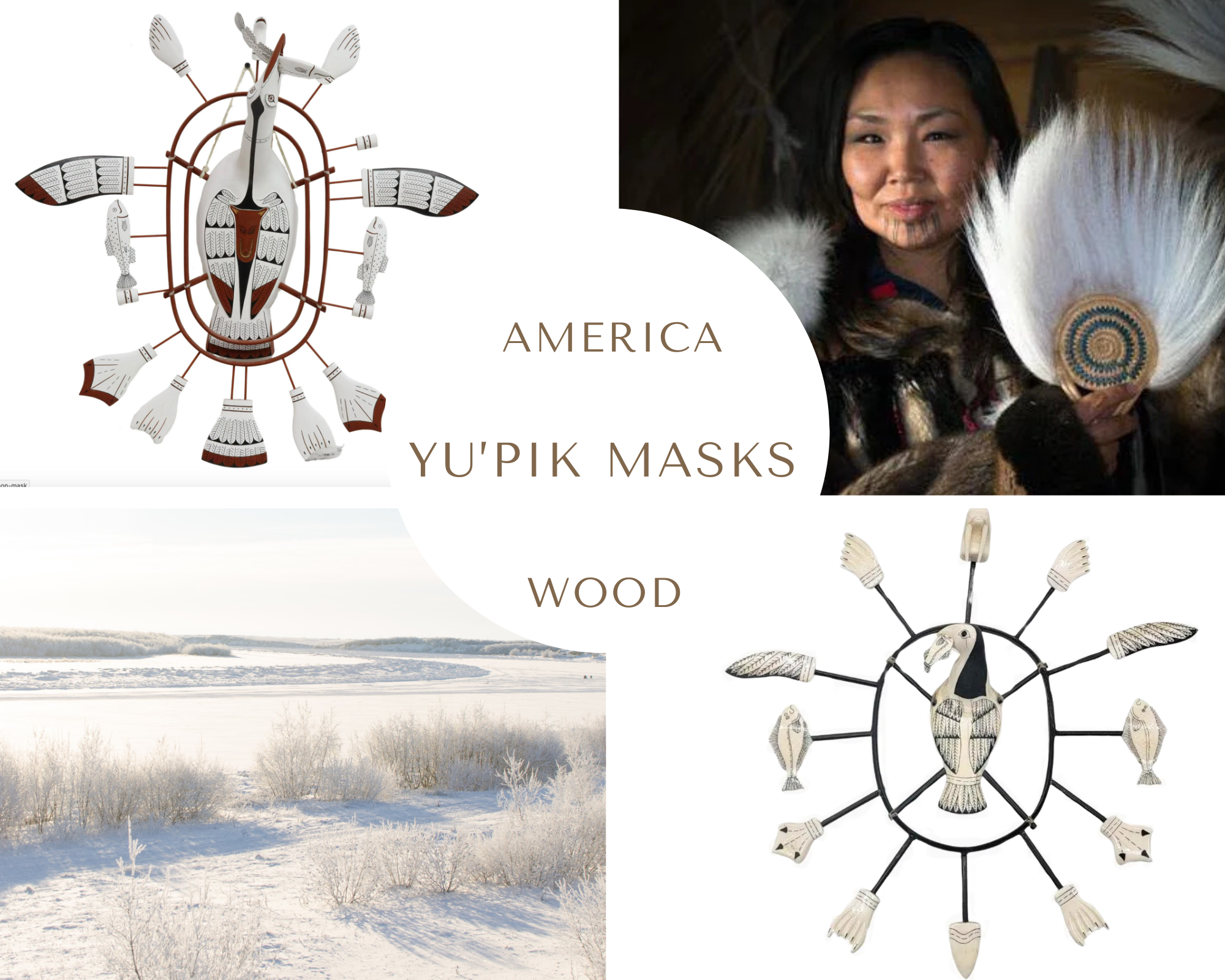

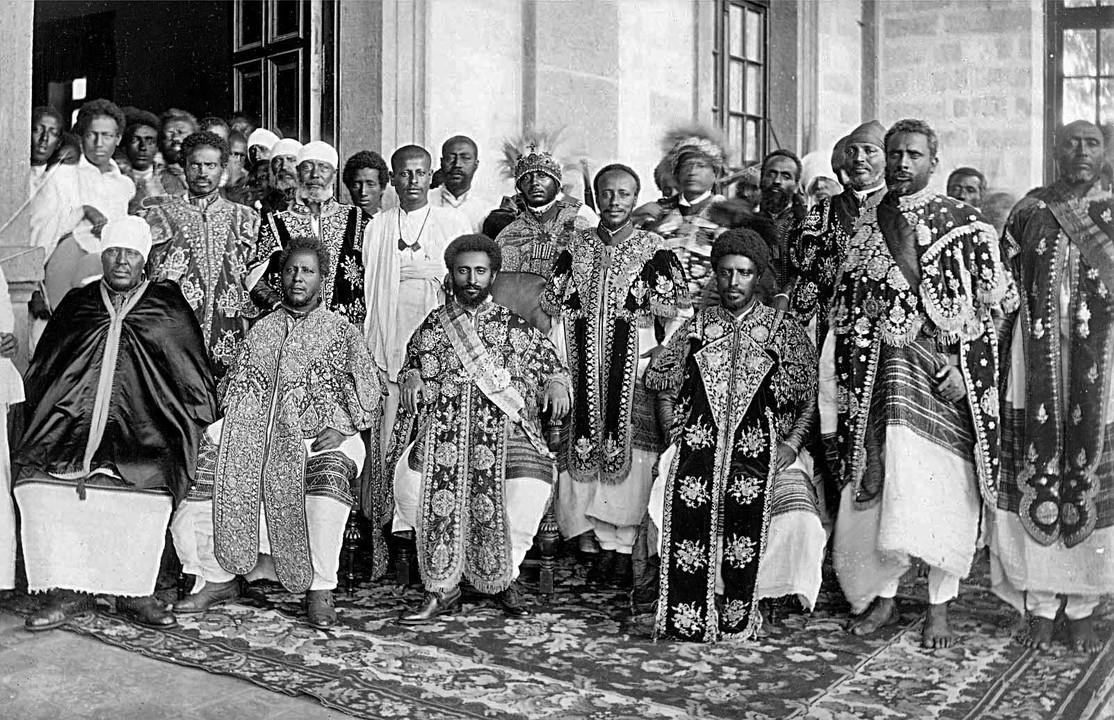

The man dressed in elaborate robes and seated in a prominent chair is the son of King Abba Jifar II, king Abba Dula, father of Abba Jobir. The person seated to the right of center, wearing garments associated with high-ranking Ethiopian Orthodox clergy, signals a religious or diplomatic encounter from the early 20th century. Historic records indicate that such occasions occurred: Abba Jifar II hosted Orthodox figures at his court and actively promoted peaceful relations with Christian authorities.

The woman portrayed is likely Queen Limmiti (also spelled Limiti or Limmitii), the daughter of King Limmu-Ennarea and one of King Abba Jifar II’s wives. She was his principal queen and played an important role in diplomacy, strengthening alliances between Jimma and neighboring kingdoms.

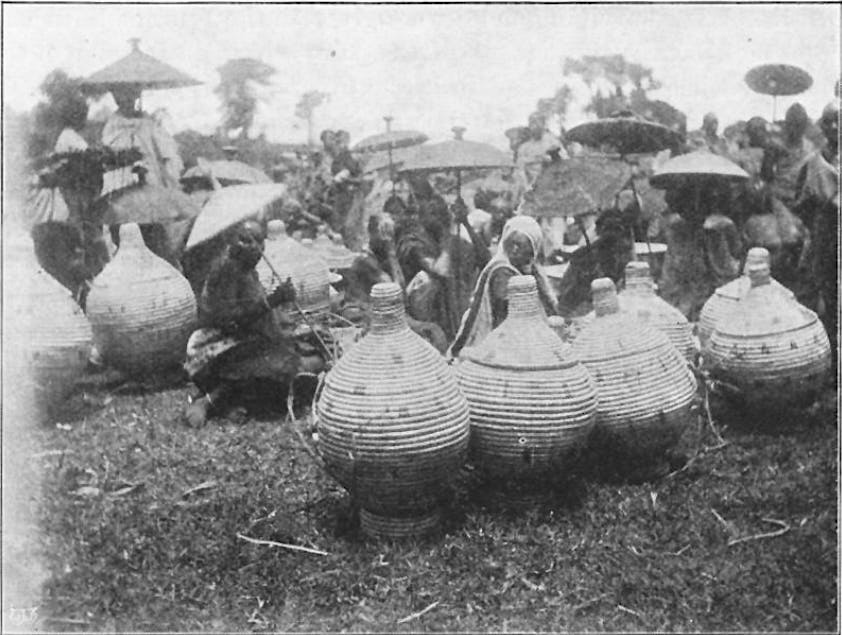

A corner of the Jiren market in 1901, with baskets containing agricultural produce.

View from Abba Jifar Palace, Jiren, Jimma. Photo by Marilyn Heldman, 1967. Eliot Elisofon Photographic Archives, National Museum of African Art, Smithsonian, USA.

Relationship with the Ethiopian Empire and Decline

During the late 19th century, Jimma’s autonomy began to wane amid the rise of Emperor Menelik II of Shewa, who would later become Emperor of Ethiopia. Fearing conquest, Abba Jifar II (who reigned from 1878 to 1932), the son of Abba Gomol, peacefully submitted to Menelik II in the early 1880s. In doing so, he became a vassal and agreed to pay tribute. While this submission secured Jimma’s position, it also effectively ended its full sovereignty.

Jimma even became an ally of Menelik II, assisting the emperor in campaigns against neighboring territories such as Kullo (1889), Walamo (1894), and Kaffa (1897).

Emperor Menelik II (1844 – 1913) photographed on the throne in coronation garb between the end of the 19th century and the early 20th century. (Wikimedia Commons)

Jimma submitted peacefully to Menelik, who allowed it full local autonomy, making it the last and most important of the monarchical Oromo states (Bernhard Lindahl, 2005). Abba Jifar zealously developed Jimma commercially; he lowered taxes and he especially facilitated the work of the naggadis, or slave merchants, making Jimma the chief slave market for southwestern Ethiopia, where light-brown Galla girls could be purchased. (Trimingham, Islam in Ethiopia, 1952).

Abba Jifar II also promoted Islamic education in his land. By the 1880s, Jimma claimed to have sixty madrasas, or schools of higher education. If true, this would be an impressive achievement for Jimma. This may explain why Jimma became the most famous center of Islamic learning for the Oromo people in the Horn of Africa. (Mohammed, 1994, pp. 158–159).

Thus, despite its vassal status, Jimma retained internal autonomy and economic strength, as evidenced by substantial tribute payments. However, the subsequent decades saw the gradual erosion of its independence due to the centralization policies of the Ethiopian Empire, the declining health and authority of Abba Jifar II; the economic challenges related to the global market downturn, and the expansion of infrastructure connecting Jimma more centrally to Addis Ababa.

Following the death of Abba Jifar II in May 1932, Emperor Haile Selassie formally annexed Jimma into the Ethiopian Empire, marking the end of the kingdom as a political entity. The royal administration was dismantled, and during the reorganization of Ethiopian provinces in 1942, Jimma was fully integrated into Kaffa Province.

The Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie, on his coronation day, on November 2, 1930. (Wikimedia Commons)

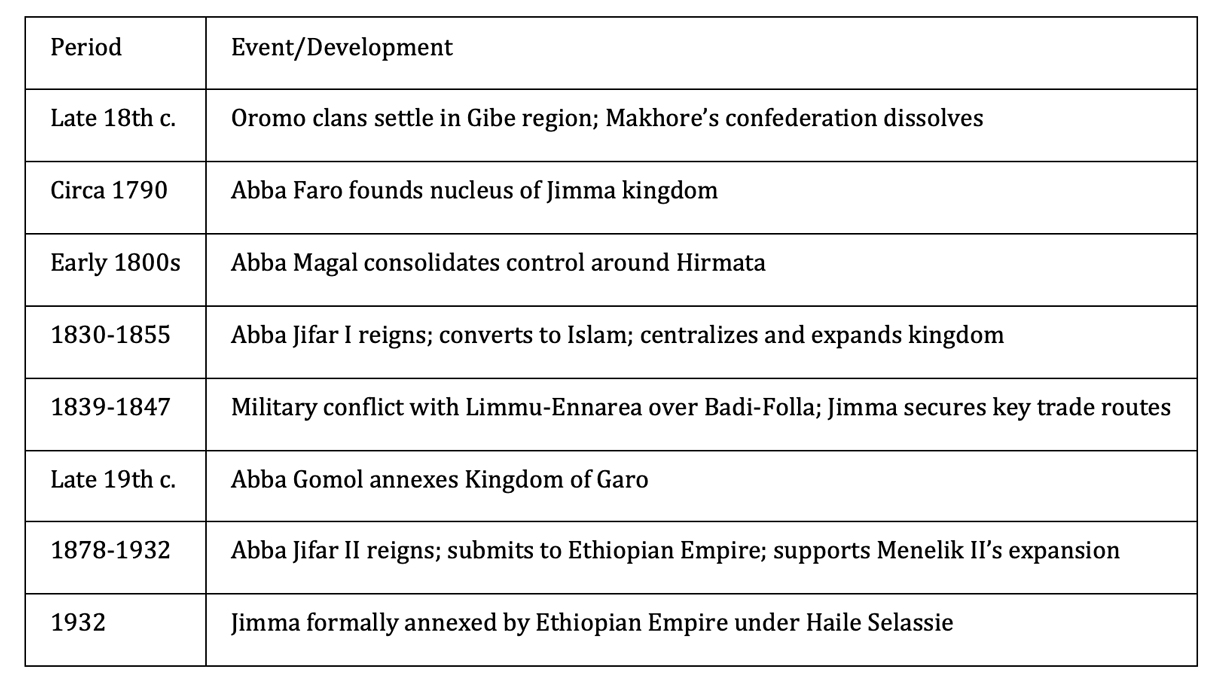

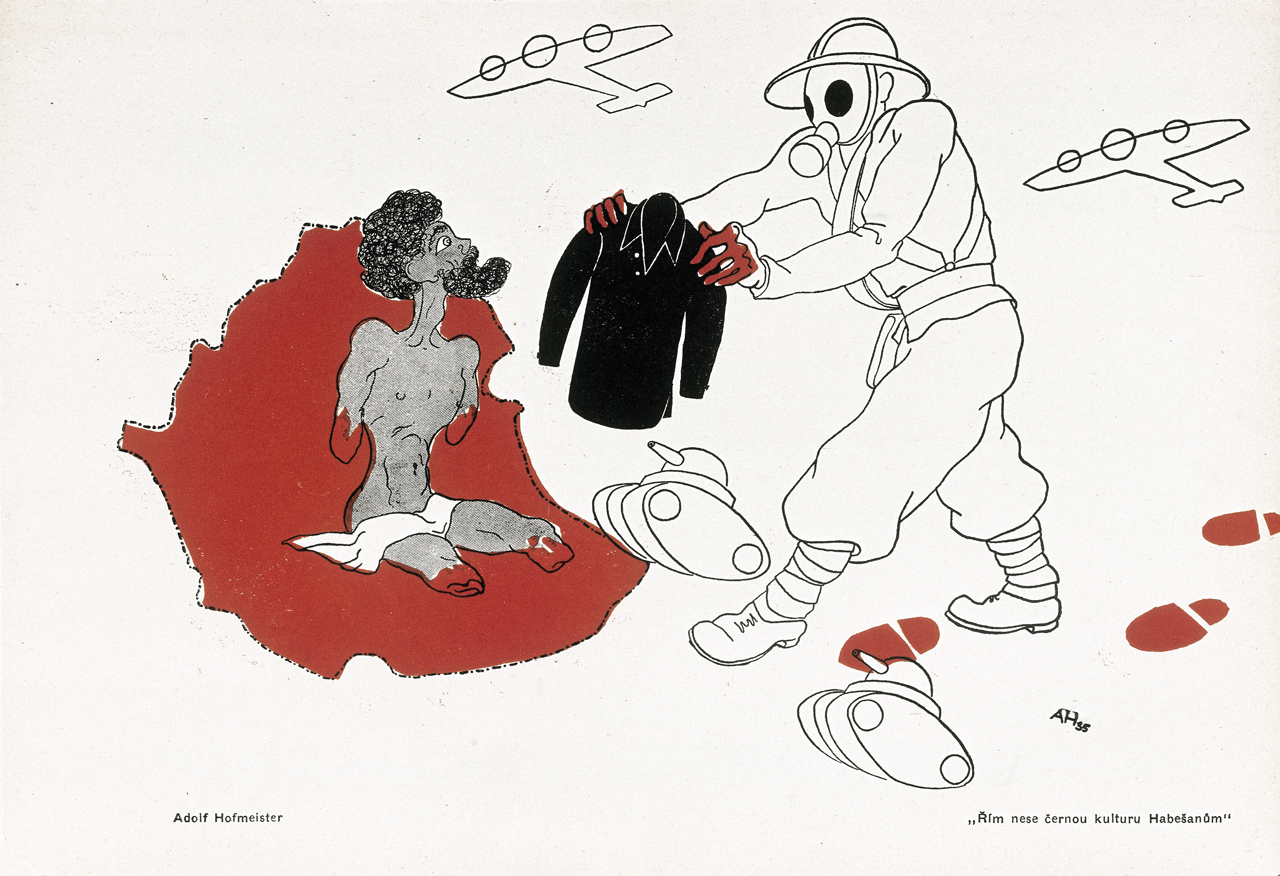

Summary Table: Key Milestones of the Kingdom of Jimma

The Kingdom of Jimma was the largest and most powerful of the Oromo monarchies in the Gibe region, known for its military strength, political sophistication, and economic vitality based on agriculture and trade. Its history exemplifies the dynamic process of state formation among the Oromo peoples and the integration of regional polities into the Ethiopian Empire during the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Italian Colonial Conquest of Ethiopia under Mussolini

Historical Context

By the early 20th century, Ethiopia was one of the few independent African states. It had repelled an earlier Italian attempt at conquest in 1896 at the Battle of Adwa. This defeat haunted Italian ambitions for decades. In the 1930s, Fascist Italy, led by dictator Benito Mussolini, sought to expand its colonial empire in Africa and restore national pride. This offered a distraction from domestic woes and economic challenges following the Great Depression.

The Wal Wal incident, a skirmish between Italian and Ethiopian troops at a disputed oasis in December 1934, gave Mussolini the pretext to launch a full-scale invasion. Emperor Haile Selassie’s diplomatic appeals to the League of Nations yielded little substantive support. Although sanctions were imposed on Italy, global hesitation and a lack of enforcement rendered them ineffective.

The Invasion (1935–1936)

On October 3, 1935, Italy attacked Ethiopia from Eritrea and Italian Somaliland without a formal declaration of war. They employed an army of 200,000 men, tanks, aircraft, and chemical weapons, such as mustard gas, which was a violation of international law.

Led successively by Generals Emilio De Bono, Rodolfo Graziani, and Pietro Badoglio, the Italian military quickly overran Ethiopia’s poorly armed and supplied defenses.

Adwa and Aksum, both sites of deep symbolic importance for Ethiopian resistance, fell early in the campaign.

The Italians used aerial bombardment and indiscriminate chemical attacks to destroy infrastructure and undermine Ethiopian morale and resistance.

Emperor Haile Selassie tried to organize a resistance and appealed to the League of Nations in a historic speech. However, military inferiority and international isolation led to defeats in battles such as Maychew on March 31, 1936.

Haile Selassie went into exile in May 1936, and his appeals largely went unheeded. The conquest was a glaring demonstration of the League of Nations’ failure to curb aggression, signaling the weakness of collective security before World War II. Even afterwards, judging by the impotence of the United Nations in stopping the current massacre of Palestinians, little has changed.

On May 5, 1936, Italian troops entered Addis Ababa. Mussolini then announced the annexation of Ethiopia and declared King Victor Emmanuel III Emperor of the newly formed Italian East Africa, uniting Ethiopia with Eritrea and Somaliland.

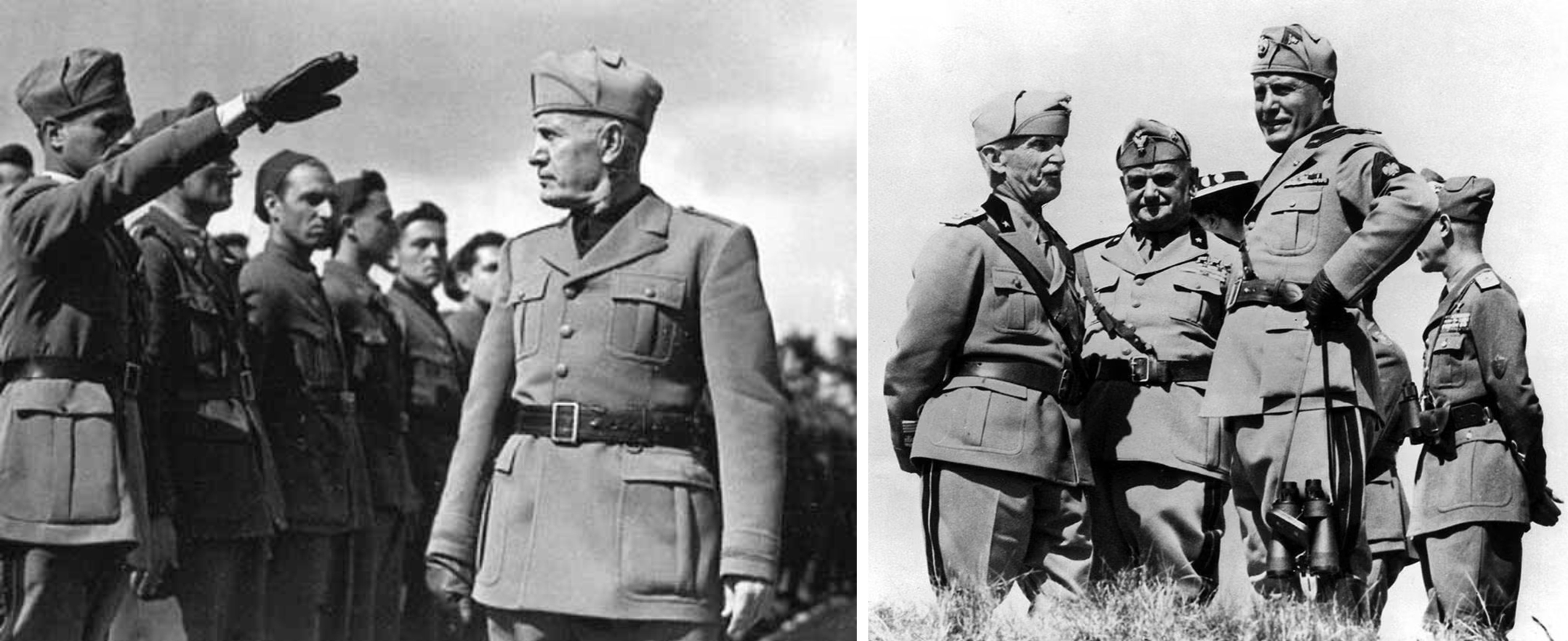

LEFT: Mussolini reviews the troops before their departure for Ethiopia, 1935.

RIGHT: Mussolini (in the foreground on the right), the Italian king Victor Emmanuel III (in the foreground on the left), and and high-ranking Italian army officials in Ethiopia in 1936.

Italian troops marching in Ethiopia, 1935-36. (Wikimedia Commons).

Italian artillery operated by Somali “Ascari” Troops in March 1936.

The term “ascari” (from the Arabic word for “soldier”) refers to indigenous troops recruited by Italian colonial authorities in their African colonies, including Eritrea and Somalia. At times, they recruited in Libya and Ethiopia as well. In Somalia, Somali ascari, or askaris, served in the Royal Corps of Somali Colonial Troops and later in broader colonial military units. Somali askaris were formally part of the Italian colonial armed forces during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. They operated under the command of Italian officers, received Italian military training, and fought alongside Italian and Eritrean colonial soldiers. These units were integral to Italian campaigns, such as the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–1936), helping to secure military objectives and later to maintain order in Italian Somaliland and, after 1936, Italian East Africa.

Abyssinian soldiers, 1936.

At the time, the Ethiopian Empire was also known as Abyssinia. Åhlen & Åkerlund via IMS Vintage Photos / Wikimedia Commons.

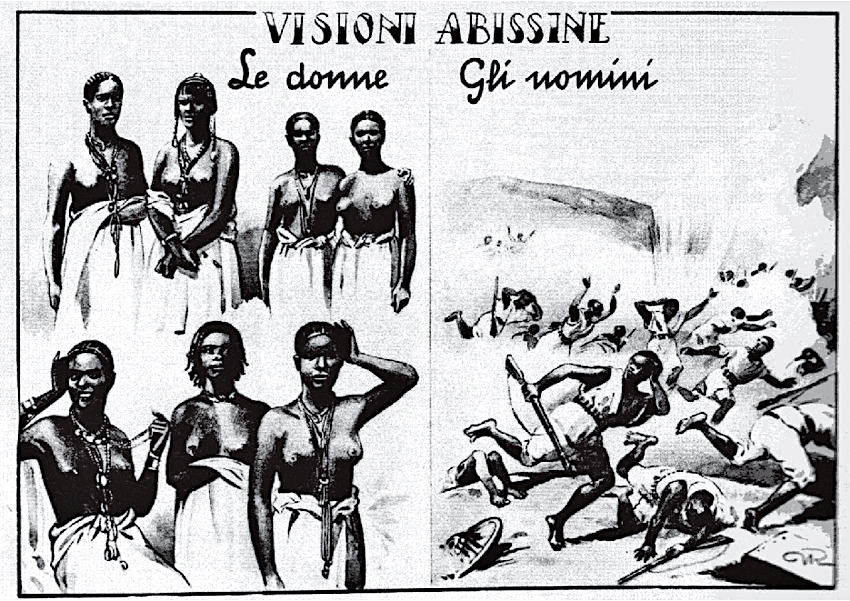

VISIONI ABISSINE (“Abyssinian Visions”). This is how Italian fascist propaganda portrayed the Ethiopian population: women (Le donne) as sex objects and men (Gli uomini) as cowardly and underdeveloped.

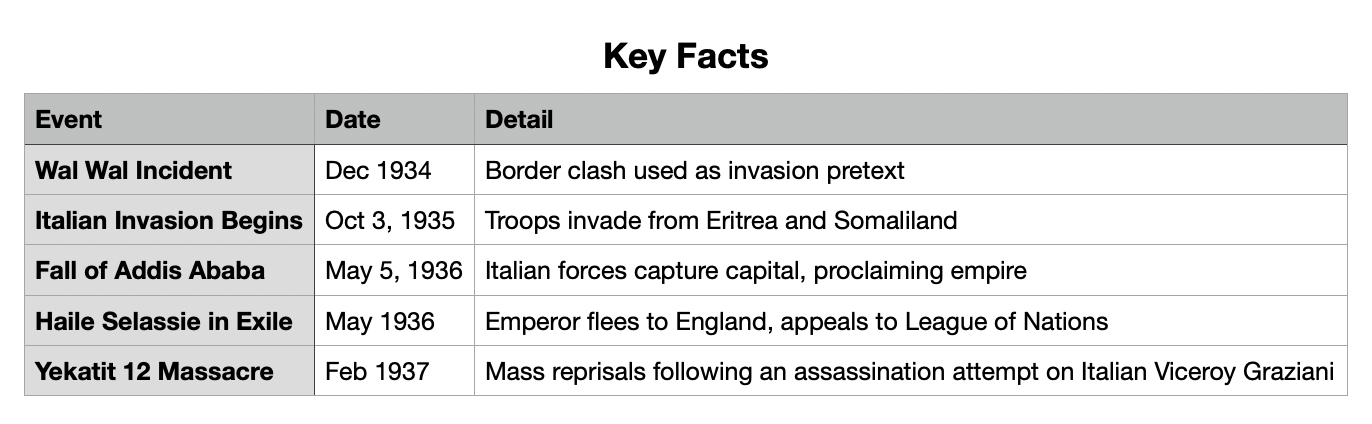

LEFT: Ethiopia War Map from October 1935 to February 1936.

RIGHT: Ethiopia War Map showing the situation in May 1936.

The False Myths about Italian Colonialism

The Italian conquest of Ethiopia was a campaign marked by the use of overwhelming force and banned chemical weapons, as well as the abject failure of international bodies to stop fascist aggression. This tragic prelude to World War II stands as a stark episode in the history of colonial violence in Africa.

Similar to other European colonial powers, the motivations behind Italian colonialism were conquering and exploiting other territories economically under the guise of a “civilizing mission” toward populations considered inferior based on anthropological and racial beliefs. Italian colonialism shared these characteristics, with absolute supremacy and primacy of the colonizers’ violence and oppression over the colonized. In Italy, however, there is still a lack of full awareness of what Italian colonialism really was. This is partly because it is considered a “minor history” compared to the colonial experiences of other countries and partly because the false myth “Italiani brava gente” (Italians are good people) is still alive. This myth is widely believed to mean that Italian colonial rule was fairer and more just towards colonized peoples, but historical studies have long proven this argument to be completely unfounded. Italian colonialism was neither less ambitious nor notably gentler than that of its European counterparts.

- “Brava Gente” Myth: Recent scholarship by authors such as Angelo Del Boca, Gabriele Proglio, and Giulia Barrera systematically dismantles this myth by documenting the severe violence, forced labor, reprisal killings, and cultural suppression measures implemented by Italians in Libya, Eritrea, Somalia, and Ethiopia.

- Use of Chemical Weapons: Italy was unique among interwar colonial powers in its widespread deployment of banned chemical weapons (e.g., mustard gas) against military and civilian populations during the Ethiopian campaign (1935–1936). This was in direct violation of the 1925 Geneva Protocol, which Italy had signed.

- Massacres and Repression: The occupation of Ethiopia was marked by significant atrocities, most notably the Yekatit 12 massacre in Addis Ababa in February 1937. Following an assassination attempt on Viceroy Graziani, Italian forces killed an estimated 20,000–30,000 civilians in retaliation. This was followed by mass internments, summary executions, and the destruction of churches and villages.

- Systematic Racism and Segregation: The 1937 racist laws did not only ban intermarriage and sexual relations (“madamato”)—seen as a threat to the racial “purity” of Italians—but also enforced strict racial segregation in housing, employment, and public life. This regime was part of Mussolini’s adoption of “imperial racism,” which mirrored or even exceeded contemporary apartheid systems elsewhere.

- Land Expropriation and Economic Exploitation: Significant tracts of land were confiscated from indigenous populations and distributed to Italian settlers, especially in Ethiopia. Africans were frequently reduced to sharecroppers or wage laborers on plantations, with few legal protections.

- Suppression of Memory: Unlike in other European countries, Italy’s colonial past has often been marginalized or whitewashed in public discourse, school curricula, and popular culture since WWII. This has contributed to a widespread lack of collective awareness and a tendency to downplay Italian colonial violence.

- Propaganda and the “Civilizing Mission”: The regime’s propaganda aggressively promoted the idea that Italians were bringing modernity—roads, hospitals, and schools—to Africa. However, these “benefits” were primarily built for the settler population and for military or extractive purposes. Meanwhile, the colonized population endured restricted rights, forced labor, and systematic denial of education.

Italian colonialism was characterized by intense violence, systematic racism, and economic exploitation. Historical evidence contradicts the lingering myth of Italian benevolence in the colonies, pointing instead to deliberate policies of brutality, segregation, and cultural erasure—particularly under fascism, but also in the liberal and postwar periods. It is crucial to recognize and revise these misconceptions in order to have an honest reckoning with Italy’s colonial past.

LEFT: Italian Caproni Ca.111 bombers over Ethiopia in 1935–36. The Caproni Ca.111 was an Italian aircraft produced during the 1930s for long-range reconnaissance and light bombing missions. (Wikimedia Commons)

RIGHT: Italian soldiers with a mustard gas bomb.

Despite being a signatory to the 1925 Geneva Protocol that specifically banned such use, Italian military forces extensively used mustard gas (sulphur mustard, yperite) as a chemical weapon during the Second Italo-Ethiopian War (1935–1936). The gas was used in aerial and ground attacks to target Ethiopian military units and resistance fighters. It was also used indiscriminately against civilians and livestock.

Reliable estimates indicate that Italy used between 300 and 500 tons of mustard gas during the four months of the main campaign, which started in December 1935 and lasted until April 1936. Both military and civilian populations were attacked. Troops, villages, livestock, water sources, and even Red Cross medical posts were attacked with mustard gas. Historians estimate that up to one-third of all Ethiopian casualties during the war resulted from chemical weapons. The gas caused lasting contamination and fear, resulting in severe psychological and environmental impacts.

The Italians primarily deployed mustard gas via aerial bombing: They used mustard gas bombs to distribute the gas over wide areas. Italian pilots dropped gas on entrenched enemy positions, retreating columns, river valleys, and forested refuge zones to maximize area denial. In addition to bombs, the Italians used 105-mm artillery shells filled with mustard gas and “mask breaker” agents to supplement aerial attacks. Special tanks fitted to aircraft enabled the widespread spraying of mustard gas over fields, rivers, and pastures to poison troops, food, and water supplies.

Italy attempted to keep its use of chemical weapons secret, but the International Red Cross exposed the attacks, which were also observed by journalists and foreign military personnel. Emperor Haile Selassie protested to the League of Nations, denouncing the “death-dealing rain.” The war demonstrated the ineffectiveness of the League of Nations, as no meaningful action was taken against Italy despite its clear violations of the Geneva Protocol.

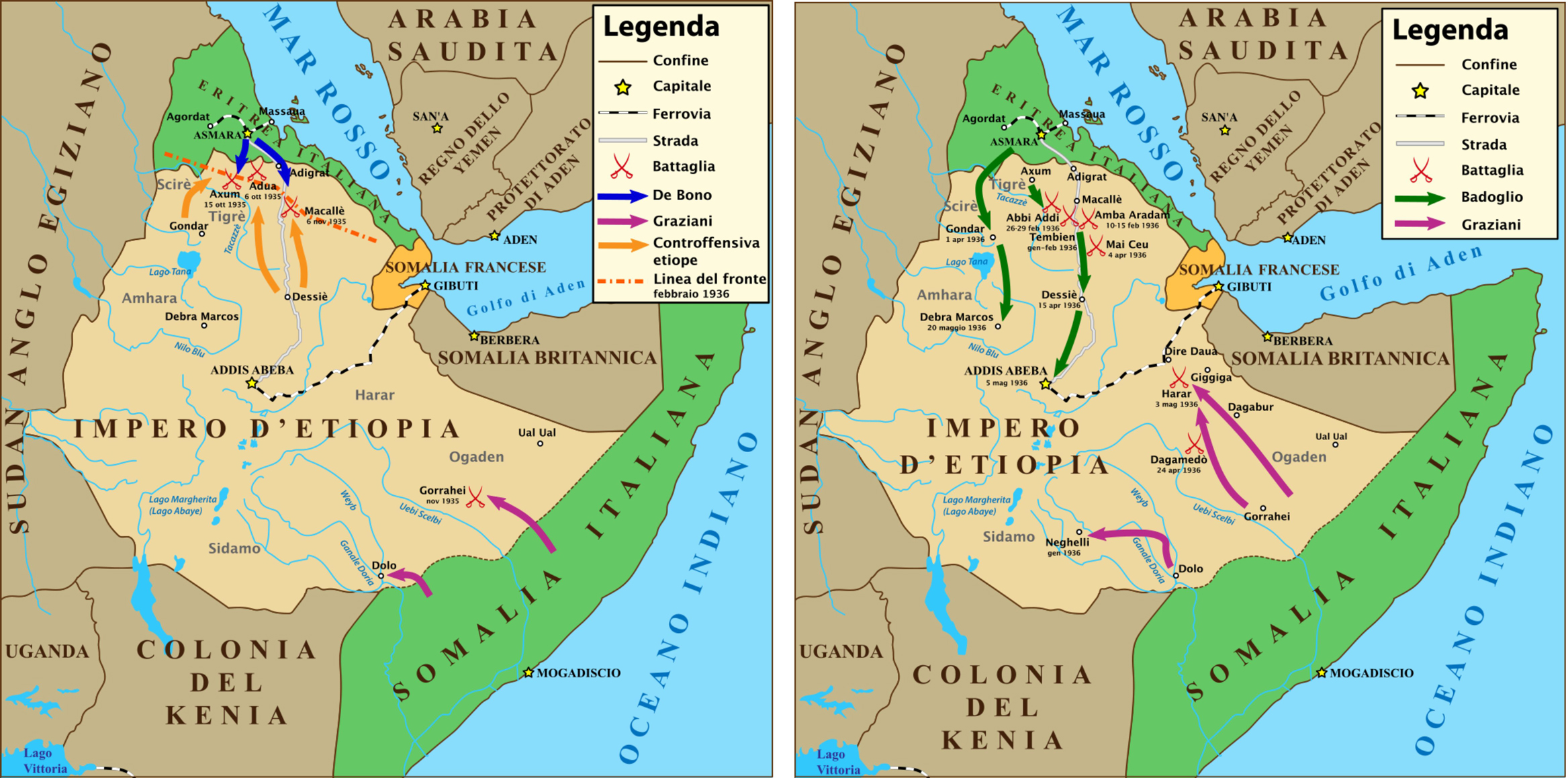

Fascist propaganda convinced Italian civilians and military personnel in Ethiopia that chemical weapons were righteous and appropriate, despite defying all moral standards and the 1925 Geneva Protocol. This is one of many propaganda postcards intended for troops engaged in the colonial war. ARMAMENTI — Ecco l’arma più opportuna means “WEAPONRY — Here is the most appropriate weapon.” The physical disproportion — the imposing white Italian soldier compared to the small, ugly locals — visually conveys the idea of the local population’s inferiority.

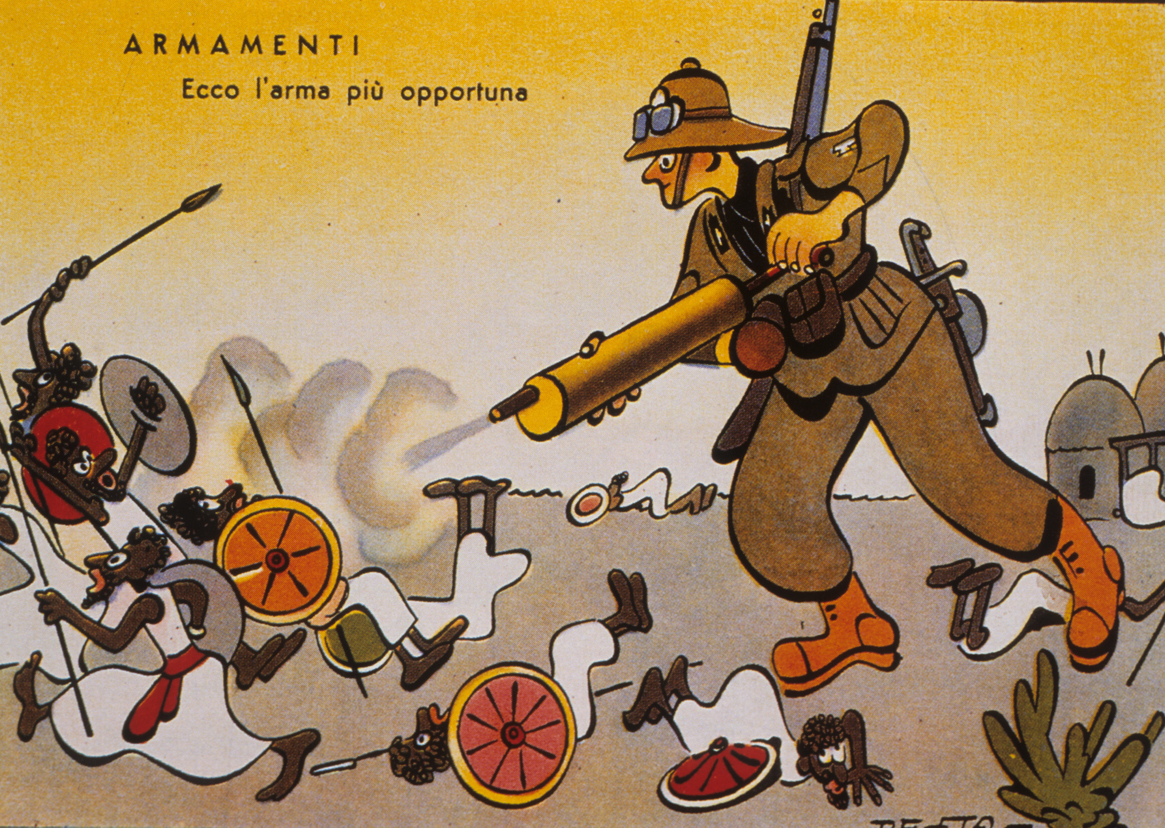

Adolf Hoffmeister, Řím nese černou kulturu Habešanům (“Rome Brings Black Culture to the Abyssinians”), 1936.

Adolf Hoffmeister (1902–1973) was a Czechoslovakian writer, illustrator, and diplomat. This caricature, rendered with sharp irony and visual economy, clearly condemns the widespread use of mustard gas by Italian forces. The Italian figure in a gas mask is depicted not merely as an anonymous soldier but as a personification of fascist ideology and violence. His gesture of offering a “black shirt” (camicia nera) carries significant symbolic weight. The gas mask and hazmat suit convey the reality of chemical warfare. The Italian’s masked and protected form contrasts with the exposed and suffering Ethiopian victim, whose flesh is literally eaten away by the effects of mustard gas. The “black shirt” is a direct reference to the paramilitary Camicie Nere (Black Shirts), Mussolini’s Blackshirts, who became the most recognizable symbol of Italian fascism. Presenting the shirt to the wounded Ethiopian is a grimly ironic gesture—it is not an offering of protection or civilization but an extension of the fascist regime’s violence and forced “modernization.”

This commemorative stamp from Fascist Italy is linked to the war in East Africa and specifically references the Italo-Ethiopian War (also known as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, 1935–36), which resulted in the establishment of Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana, or AOI). The design and inscriptions on the stamp place it in the context of Fascist propaganda and military alliances from 1939 to 1940. The Italian words “DUE POPOLI UNA GUERRA” (“Two Peoples, One War”) reference the alliance between Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, formalized in the Pact of Steel on May 22, 1939. The stamp features prominent symbols of fascism and Nazism: A bundle of rods (fasces), symbolizing the Fascist regime; an eagle and swastika, the emblem of Nazi Germany; the denomination “20 cent.”; and the wording “AFRICA ORIENTALE ITALIANA.” The portraits of Fascist Italy’s and Nazi Germany’s leaders, Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, signify their collaboration. These stamps were produced in the late 1930s and early 1940s, after the conquest of Ethiopia in 1936 and the establishment of Italian East Africa. They were particularly produced around the time of Axis solidarity in WWII. The stamp celebrates the alliance and the presumed “brotherhood in arms” (fratellanza d’armi) between Italy and Germany. This was crucial for Italian domestic nationalist messaging and announcing Italy’s aspirations as a colonial power.

Those wishing to learn more can find an essay published in Great Britain in 2023 and in the U.S. in 2024: Mussolini, Mustard Gas and the Fascist Way of War: Ethiopia, 1935-1936 by Charles Stephenson.

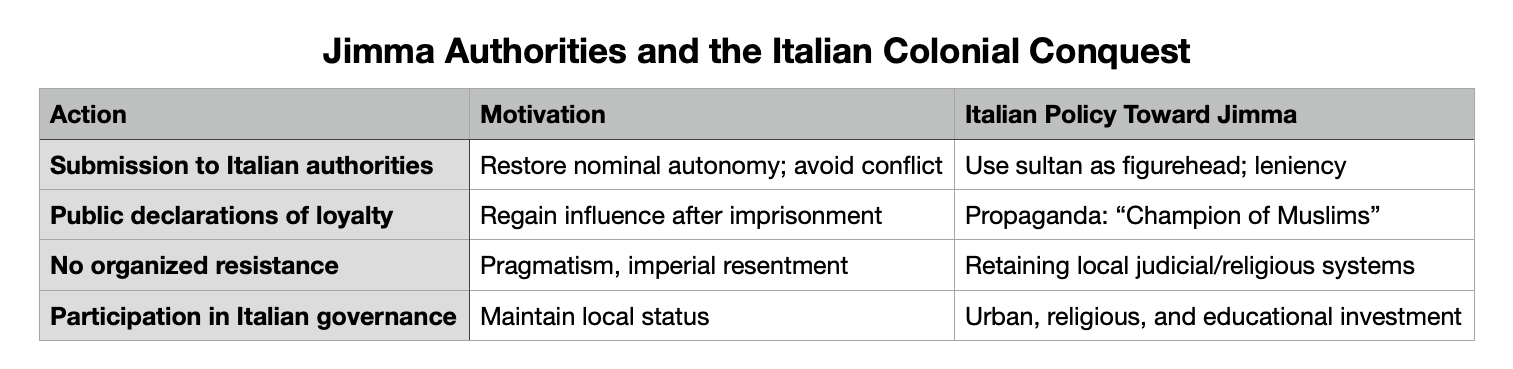

Reaction of the Jimma Authorities to the Italian Colonial Conquest (1936)

Although the Kingdom of Jimma was no longer independent when Italy invaded Ethiopia in 1935–1936, it still maintained a distinct identity under its own authority and ruler, who held the title of Sultan. By this time, power in Jimma had shifted from the Abba Jifar line to Abba Jobir Abba Dula, Abba Jifar II’s grandson. However, real authority had already diminished due to the region’s integration into the Ethiopian Empire.

Response to Italian Entry

- Submission and Collaboration: After the rapid collapse of central Ethiopian resistance, the Jimma authorities, including Sultan Abba Jobir, chose to submit to Italian rule. Abba Jobir, who had previously been imprisoned by Haile Selassie due to suspicions of disloyalty, was released by the Italians for propaganda purposes and local strategy. He publicly expressed support for the Italian occupiers, declared loyalty to Mussolini, and aided Italian efforts to consolidate power in Jimma.

- Restoration of Authority: The Italians partially restored the local sultanate in Jimma, allowing Abba Jobir to act as a regional figurehead. However, this autonomy was more formal than substantive, as the Italians maintained control over key administrative and military affairs. Jimma’s authorities’ enthusiasm for the Italian occupation was partly a response to their loss of independence under Haile Selassie’s centralized policies prior to the invasion. In turn, the Italians recognized local customs and retained Islamic courts to win over the population and authorities.

- No Significant Resistance: Unlike other regions of Ethiopia, Jimma did not produce a notable patriotic resistance movement against the Italians during their occupation. This was due to political calculations by local elites as well as the Italians’ efforts to appear as liberators who supported local autonomy and Islam in opposition to Amhara-Christian domination from Addis Ababa.

Italian Policy Toward Jimma

- Favoring Muslims and Local Leadership: To secure loyalty, the Italian authorities invested in Jimma’s Muslim institutions by building mosques and Islamic schools and supporting the Islamic elite.

- Modernization and Reforms: The Italians undertook urban projects, established new districts, upgraded infrastructure, and reorganized land and markets. While these acts were colonial in nature, they were also designed to win the support of local authorities and the population.

- Propaganda: The Italians heavily publicized Abba Jobir’s allegiance, both in Ethiopia and internationally. They portrayed themselves as champions of the Muslim Oromo people and as restorers of local traditions that had been suppressed by the imperial center.

In response to the Italian colonial conquest, Jimma’s authorities cooperated with the occupiers, publicly supported Italian rule, and accepted the restoration of a nominally autonomous sultanate. The Italians targeted Muslim elites in their efforts to win them over, which enabled this collaboration. Resentment of prior imperial centralization and the desire among local leaders to restore lost status and autonomy shaped this collaboration. Unlike in other Ethiopian regions, Jimma’s authorities did not actively resist the Italian occupation. This is definitely not the best chapter in Jimma’s history.

The Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini and the Sultan of Jimma photographed in front of the Palazzo Venezia in Rome as they take the salute at the military academy cadet march past, held in honor of the Sultan. Date: April 13, 1938. (Wikimedia Commons).

How Jimma’s Collaboration with Italian Fascism Was Judged and Its Consequences

Contemporary Judgment and Perception

Within Jimma and among Local Elites

The acceptance of Italian fascism by Jimma’s authorities, notably Sultan Abba Jabor, was primarily pragmatic. Many local leaders viewed Italian rule as an opportunity to regain autonomy lost under Ethiopian imperial centralization. The restoration of the sultanate (even if it was largely ceremonial) and the favor shown by Italian administrators were welcomed by some of Jimma’s Muslim leaders. They saw the Fascists as less threatening to their religious and social autonomy than Haile Selassie’s government. However, this exercise in realpolitik deliberately and consciously turned a blind eye to the horrors and exploitation of Italian colonialism. Wartime collaboration—namely, cooperating with the “enemy” against one’s own country in wartime—is as old as war and the occupation of foreign territory (Gerhard Hirschfeld). However, that doesn’t make it any less unacceptable.

Ethiopian Nationalist Perspective

Patriotic groups and Ethiopian imperial loyalists generally condemned Jimma’s collaboration as politically expedient and disloyal to the pan-Ethiopian resistance. The absence of a local resistance movement and the degree of open cooperation with the Italian occupiers were cited as evidence of local resentment toward imperial rule and as a form of perceived betrayal.

Italian Colonial Assessment

The Italian authorities and propagandists held up Jimma’s compliance as proof of their “benevolent” and pro-Muslim colonial policy. Sultan Abba Jorah was paraded as a symbol of Muslim support and an example of a local ruler who willingly accepted Fascist “modernization.” Italian sources emphasized this relationship for internal and international audiences, presenting Jimma as a model of Muslim loyalty within the colony.

Social, Political, and Cultural Consequences

Restored but Limited Sultanate

Although Sultan Abba Jobir received formal recognition, his power remained largely symbolic. True authority rested with Italian officials. The sultan was featured in Fascist propaganda as both a puppet ruler and a symbol of Italian tolerance toward Islam.

Racial Segregation and Urban Change

The Italian occupation led to a clear racial division. Urban planning separated the “white” (European) and “black” (Ethiopian) quarters. The indigenous populations of Jimma were displaced to inferior parts of the town. The Fascists invested in infrastructure, but these benefits were distributed unequally and were intended to serve Italian settlers and local collaborators.

Promotion and Instrumentalization of Islam

The Italians implemented policies and built institutions that sought to curry favor with Jimma’s Muslim elite. They constructed new mosques and Islamic schools, and they sent Sultan Abba Jobir on tours of the Middle East and Rome. This enhanced his “international” status, but it also increased his dependence on the colonial administration.

Social Disruption

The period saw the growth of prostitution and urban poverty, the marginalization of the indigenous population, and limited genuine development for locals. Meanwhile, outwardly modern amenities were reserved for expatriates and collaborators.

The defeat of the Italians and the end of our history

On April 6, 1941, Allied and Ethiopian forces liberated the capital, Addis Ababa. The Italian viceroy, the Duke of Aosta, surrendered at Amba Alagi in May 1941 after losing his stronghold. The last pockets of Italian resistance ended with the fall of Gondar in November 1941. On May 5, 1941—exactly five years after the Italian occupation—Haile Selassie reentered Addis Ababa with Ethiopian patriots and British support. This restored the Ethiopian monarchy and flag. Although there was a brief period of British military oversight, Ethiopia’s sovereignty was formally recognized by the British and the international community soon after. Full diplomatic recognition was enshrined in the 1942 Anglo-Ethiopian Agreement and subsequent treaties.

A battery of South African 4.5-inch howitzers of 4th Field Brigade, S.A.A. comes into action during the Battle of Amba Alagi, in May 1941. (Wikimedia Commons). The battle, which took place during World War II, was part of the East African Campaign. Following the Italian defeat at Keren in April 1941, Prince Amedeo, Duke of Aosta, withdrew his troops to the mountain stronghold of Amba Alagi. There, they were forced to surrender to British Lieutenant General Sir Alan Cunningham on May 19, 1941.

RIGHT: A fascist propaganda postcard featuring the slogan introduced by Amedeo d’Aosta following the surrender at Amba Alagi. RITORNEREMO, which means “We will return.” Fortunately, they did not.

LEFT Italian fascist propaganda praising colonialism in Africa. “Ritorneremo” again. This slogan only became a key theme in fascist propaganda after Mussolini’s regime lost control of the Italian colonial empire in East Africa. The imagery and message were intended to foster imperial nostalgia and encourage the idea of an eventual Italian return to its lost colonies. The date referenced on the postcard, May 9, commemorates the “Day of Empire” (May 9, 1936). However, the card’s message and production are associated with the post-defeat period. Specifically, the card reflects Fascist rhetoric that circulated in Italy after 1941, when East Africa was lost to Allied and Ethiopian forces.

Following Italy’s defeat and the restoration of Ethiopian sovereignty in 1941, collaborating with the enemy was considered highly compromising. Collaborators, including Sultan Abba Jobir, lost legitimacy and influence. Jimma’s prior collaboration led to lasting suspicion from the imperial center and the wider Ethiopian public after the war. Abba Jobir himself spent time in exile and never regained substantive power.

The Jimma authorities were viewed variably: as pragmatic survivors who restored some lost local prestige or as collaborators who compromised true autonomy and postwar legitimacy. These consequences were profound, producing lasting social divisions and altered urban landscapes while strengthening colonial control. Ultimately, they relegated Jimma’s traditional elites to a subordinate status once Ethiopia was liberated.

May 5, 1941: Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie returned to Addis Ababa after five years in exile.

POST–WORLD WAR II ETHIOPIA: SYMBOLS AND CHRONOLOGY

The current official flag of Ethiopia is a powerful symbol reflecting the nation’s heritage, unity, and aspirations. Consisting of three horizontal stripes in green (top), yellow (middle), and red (bottom), it features a central blue disc with a golden, radiating five-pointed star.

The green color represents the land’s fertility, agricultural richness, labor, and development. Green is associated with growth and Ethiopia’s hope for a prosperous future.

The yellow symbolizes hope, justice, harmony, peace, and the aspiration for unity among Ethiopia’s diverse peoples.

The red stands for the sacrifices and blood shed by Ethiopians in defense of their country’s freedom, resilience, and independence. It acknowledges those who fought for Ethiopia’s sovereignty.

These three colors are also recognized as Pan-African colors. Ethiopia, which was never colonized except for a brief occupation, was one of the first African countries to use them. They were later widely adopted throughout Africa as symbols of unity and liberation.

The central emblem, the blue disc, represents peace and the country’s aspiration for harmony among its people.

The golden five-pointed star symbolizes the unity and equality of Ethiopia’s many nationalities. The rays of the star represent a bright future, radiating hope and inclusive development for all Ethiopians. The interlacing lines within the star emphasize equality and unity regardless of ethnicity, creed, or gender.

The modern flag with the emblem was adopted in 1996 to express the ideals of the newly formed Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia following dramatic political changes in the 1990s.

The plain green–yellow–red tricolore continues to evoke national pride due to Ethiopia’s role as a beacon of freedom that inspired anti-colonial movements across Africa.

The large tree at the center is an Odaa, or sycamore, which is considered sacred in Oromo culture. Traditionally, major assemblies, governance, and communal rituals were conducted under this tree. The Odaa symbolizes unity, democracy, justice, continuity of tradition, and inclusive self-governance. The black gear at the top symbolizes industry, progress, and the region’s drive for development. This motif is common in many Ethiopian regional emblems and signifies modernization and economic aspiration. The green branches on the sides represent the fertile land of Oromia, agricultural prosperity, hope, and renewal. The red background and outer circle represent the blood shed by Oromo heroes and heroines in their struggle for freedom and resistance against oppression. Together, these elements encapsulate the region’s struggles and aspirations for justice and liberation.

Below is a chronological overview of Ethiopia’s history since World War II, with a focus on significant political, social, and economic events from 1941 to the present.

1941 – Liberation from Italian Occupation

- British and Ethiopian forces liberate Ethiopia from Fascist Italy, which had occupied the country from 1936 to 1941.

- Restoration of Haile Selassie I as Emperor.

1942–1950s – Reconstruction and Centralization

- Feudal structures were maintained, but modern reforms were initiated (e.g., ministries and legal codes).

- Ethiopia joins the United Nations (1945) and and the precursor conferences of the Organization of African Unity (OAU).

- Tensions began with Eritrea, which was federated with Ethiopia in 1952 under a UN resolution.

1960 – Failed Coup Attempt

- Young officers attempted to overthrow the emperor and establish a constitutional monarchy.

- Although the attempt was suppressed, it reflected growing dissatisfaction with imperial rule.

1962 – Annexation of Eritrea

- Ethiopia formally annexed Eritrea, ending its autonomous status.

- This sparks the Eritrean War of Independence (1961–1991).

1973 – Famine and Discontent

- A devastating famine in Wollo and Tigray killed hundreds of thousands of people.

- Government secrecy and inaction lead to public outrage and a loss of support for the Emperor.

1974 – Fall of Haile Selassie & Rise of the Derg

- A military junta called “the Derg” overthrew Haile Selassie.

- Haile Selassie died in 1975 under murky circumstances (he is widely believed to have been murdered).

- The monarchy was abolished. Ethiopia became a Marxist-Leninist state.

1977–1991 – Red Terror and Civil War

- Mengistu Haile Mariam led the Derg and launched brutal purges known as the “Red Terror.”

- Widespread repression, famine (especially in 1983–85), and civil conflict devastated the country.

- Armed resistance grows from groups such as the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) and the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front (EPLF).

1991 – Fall of the Derg

- Rebel coalition EPRDF (led by TPLF) captured Addis Ababa.

- Mengistu fled to Zimbabwe.

- A transitional government was formed under Meles Zenawi.

1993 – Eritrean Independence

- Eritrea voted for independence in a UN-backed referendum.

- Ethiopia became landlocked.

1995 – New Constitution and Federalism

- The federal constitution established ethnic federalism.

- Ethiopia became the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia.

1998–2000 – Ethio-Eritrean War

- War broke out over the town of Badme, resulting in the deaths of tens of thousands.

- Ceasefire was signed in 2000, but relations remained frozen.

2005 – Contested Elections and Crackdown

- EPRDF wins elections but faces allegations of fraud.

- Protests erupted; hundreds were killed and thousands were arrested.

2012 – Death of Meles Zenawi

- Longtime Prime Minister Meles Zenawi dies.

- Succeeded by Hailemariam Desalegn.

2018 – Abiy Ahmed Became Prime Minister

- Abiy Ahmed, from the Oromo ethnic group, rose to power amid mass protests.

- Introduces sweeping reforms, including the release of political prisoners, an end to the state of emergency, and a peace agreement with Eritrea.

- Wins Nobel Peace Prize (2019).

2020–2022 – Tigray War

- Conflict erupts between the federal government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) in Tigray.

- Thousands were killed, and there was mass displacement and accusations of war crimes on all sides.

- Ceasefire is agreed upon in late 2022, but tensions persist.

2023–Present – Fragile Peace & Federal Strains

- Post-war recovery has begun, but ethnic violence and insurgencies continue in Oromia, Amhara, and other regions.

- Economic challenges, inflation, and humanitarian needs remain high.

- Debate continues over the future of ethnic federalism versus national unity.

Alyx Becerra

OUR SERVICES

DO YOU NEED ANY HELP?

Did you inherit from your aunt a tribal mask, a stool, a vase, a rug, an ethnic item you don’t know what it is?

Did you find in a trunk an ethnic mysterious item you don’t even know how to describe?

Would you like to know if it’s worth something or is a worthless souvenir?

Would you like to know what it is exactly and if / how / where you might sell it?